Title: The Camp Fire Girls on the Open Road; Or, Glorify Work

Author: Hildegard G. Frey

Release date: June 21, 2011 [eBook #36485]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by Stephen Hutcheson, Dave Morgan,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

OR, GLORIFY WORK

By HILDEGARD G. FREY

Author of

The Camp Fire Girls Series

A. L. BURT COMPANY

Publishers New York

THE

Camp Fire Girls Series

By HILDEGARD G. FREY

Copyright, 1918

By A. L. BURT COMPANY

THE CAMP FIRE GIRLS ON THE OPEN ROAD

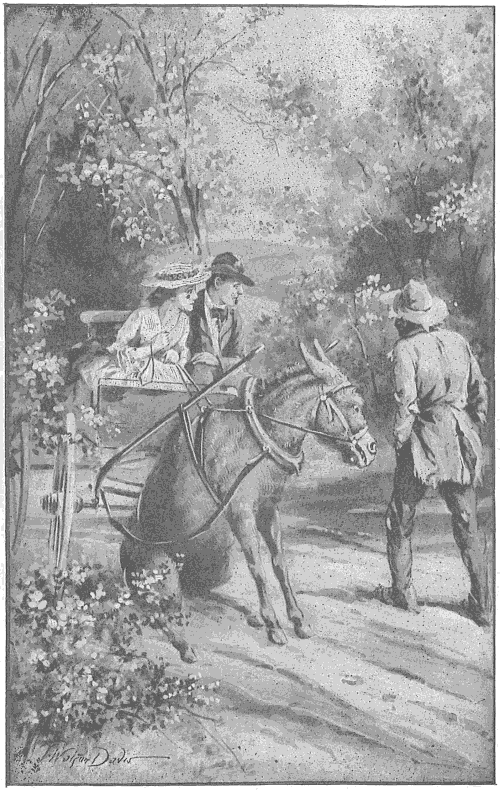

Just then a negro stepped suddenly from behind the bushes along the road and startled Sandhelo so that he promptly sat up on his haunches to get a better look at the apparition. Page 49.

“The Camp-Fire Girls on the Open Road.”

Oct. 1, 19—.

Dear First-And-Onlys:

When I got to the post-office to-day and found there was no letter from you, my heart sank right through the bottom of my number seven boots and buried itself in the mud under the doorsill. All day long I had had a feeling that there would be a letter, and that hope kept me up nobly through the trying ordeal of attempting to teach spelling and geography and arithmetic to a roomful of children of assorted ages who seem as determined not to learn as I am determined to teach them. It sustained and soothed me through the exciting process of “settling” Absalom Butts, the fourteen-year-old bully of the class, with whom I have a preliminary skirmish every day in the week before recitations can begin; and through the equally trying business of listening to his dull-witted sister, Clarissa, spell “example” forty ways but the right way, and then dissolve into inevitable tears. When school was out I was as limp as a rag, and so thankful it was Friday night that I could have kissed the calendar. I fairly “sic”ed Sandhelo along the road to the post-office, expecting to revel in the bale of news from my belovéds that was awaiting me, but when I got there and the post box was bare the last button burst off the mantle of my philosophy and left me naked to the cold winds of disappointment. A whole orphan asylum with the mumps on both sides would have been gay and chipper compared to me when I turned Sandhelo’s head homeward and started on the six-mile drive.

It had been raining for more than a week, a steady, warmish, sickening drizzle, that had taken all the curl out of my spirits and left them hanging in dejected, stringy wisps. I couldn’t help feeling how well the weather matched my state of mind as I drove homeward. The whole landscape was one gray blur, and the tall weeds that bordered the road on both sides wept unconsolably on each other’s shoulders, their tears mingling in a stream down their stems. I could almost hear them sob. The muddy yellow road wound endlessly past empty, barren fields, and seemed to hold out no promise of ever arriving anywhere in particular. All my life I have hated that aimlessly winding road, just as I have always hated those empty, barren fields. They have always seemed so shiftless, so utterly unambitious. I can’t help thinking that this corner of Arkansas was made out of the scraps that were left after everything else was finished. How father ever came to take up land here when he had the whole state to choose from is one of the seven things we will never know till the coming of the Cocqcigrues. It’s as flat as a pancake, and, for the most part, treeless. The few trees there are seem to be ashamed to be caught growing in such a place, and make themselves as small as possible. The land is stony and barren and sterile, neither very good for farming or grazing. The only certain thing about the rainfall is that it is certain to come at the wrong time, and upset all your plans. “Principal rivers, there are none; principal mountains—I’m the only one,” as Alice-in-Wonderland used to say. But father has always been the kind of man that gets the worst of every bargain.

Now, you unvaryingly cheerful Winnebagos, go ahead and sniff contemptuously when you breathe the damp vapors rising from this epistle, and hear the pitiful moans issuing therefrom. “For shame, Katherine!” I can hear you saying, in superior tones, “to get low in your mind so soon! Why, you haven’t come to the first turn in the Open Road, and you’ve gone lame already. Where is the Torch that you started out with so gaily flaring? Quenched completely by the first shower! Katherine Adams, you big baby, straighten up your face this minute and stop blubbering!”

But oh, you round pegs in your nice smooth, round holes, you have never been a stranger in a familiar land! You have never known what it was to be out of tune with everything around you. Oh, why wasn’t I built to admire vast stretches of nothing, content to dwell among untrodden ways and be a Maid whom there were none to praise and very few to love, and all that Wordsworth business? Why do crickets and grasshoppers and owls make me feel as though I’d lost my last friend, instead of impressing me with the sociability of Nature? Why don’t I rejoice that I’ve got the whole road to myself, instead of wishing that it were jammed with automobiles and trolley cars, and swarming with people? Why did Fate set me down on a backwoods farm when my only desire in life is to dwell in a house by the side of the road where the circus parade of life is continually passing? Why am I not like the other people in this section, with whom ignorance is bliss, grammar an unknown quantity, and culture a thing to be sneered at?

Although I can’t see them, I know that somewhere to the north, just beyond the horizon, the mountains lift their great frowning heads, and ever since I can remember I have looked upon them as a fence which shut me out from the big bustling world, and over which I would climb some day. Just as Napoleon said, “Beyond the Alps lies Italy,” so I thought, “Beyond the Ozarks lies my world.”

I don’t believe I had my nose out of a book for half an hour at a time in those early days. I went without new clothes to buy them, and got up early and worked late to get my chores done so that I might have more time to read. When I was twelve years old I had learned all that the teacher in a little school at the cross roads could teach me, and then I went to the high school in the little town of Spencer, six miles away, traveling the distance twice every day. When there was a horse available I rode, if not, I walked. But whether riding or walking, I always had a book in my hand, and read as I went along. It often happened that, being deep in the fortunes of my story book friends, I did not notice when old Major ambled off the road in quest of a nibble of clover, and would sometimes come to with a start to find myself lying in the ditch. The neighbors thought my actions scandalous and pitied my father and mother because they had such a good-for-nothing daughter.

All this time my father was getting poorer and poorer. He changed from farming to cotton raising and then made a failure of that, and finally, in despair, he turned to raising horses, not beautiful race horses like you read about in stories, but wiry little cow ponies that the cattlemen use. For some unaccountable reason he had good luck in this line for three years in succession, and a year or so after I had finished this little one-horse high school there was enough money for me to climb over my Ozark fence and go and play in the land of my dreams. One wonderful year, that surpassed in reality anything I had ever pictured in imagination, and then the sky fell, and here I am, inside the fence once more.

Not that I am sorry I came back, no sirree! Father was so pleased and touched to think I gave up my college course and came home that he chirked up right away and started in from the beginning once more to pay the mortgage off the land and the stock, and mother is feeling well enough to be up almost all day now; but to-day I just couldn’t help shedding a few perfectly good tears over what I might be doing instead of what I am.

A flock of wild geese, headed south, flew above my head in a dark triangle, and honked derisively at me as they passed. “Not even a goose would stop off in this dismal country!” I exclaimed aloud. Then, simply wild for sympathy from someone, I slid off Sandhelo’s back and stood there, ankle deep in the yellow mud, and put my arms around his neck.

“Oh, Sandhelo,” I croaked dismally, “you’re all I have left of my wonderful year up north. You love me, don’t you?”

But Sandhelo looked unfeelingly over my shoulder at the rain splashing down into the road and yawned elaborately right in my face. There are times when Sandhelo shows no more feeling than Eeny-Meeny. Seeing there was no sympathy to be had from him, I climbed on his back again and rode grimly home, trying to resign myself to a life of school teaching at the cross roads, ending in an early death from boredom.

Father was nowhere about when I rode into the stableyard, and the door into the stable was shut. I slid it back, with Sandhelo nosing at my arm all the while.

“Oh, you’re affectionate enough now that you want your dinner,” I couldn’t help saying a little spitefully. Then my heart melted toward him, and, with my arm around his neck, we walked in together. Inside of Sandhelo’s stall I ran into something and jumped as if I had been shot. In the dusk I could make out the figure of a man sitting on the floor and leaning against the wall.

“Is that you, Father?” I asked, while Sandhelo blinked in astonishment at this invasion of his premises. There was no answer from the man on the floor. Why I wasn’t more excited I don’t know, but I calmly took the lantern down from the hook and lit it and held it in front of me. The light showed the man in Sandhelo’s stall to be sound asleep, with his hand leaned back against the wooden partition. He had a black beard and his face was all streaked with mud and dirt, and there was mud even in his matted hair. He had no hat on. His clothes were all covered with mud and one sleeve of his coat was torn partly out.

Sandhelo put down his nose and sniffed inquiringly at the stranger’s feet. Without ceremony I thrust the lantern right into the man’s face.

“Who are you and what are you doing here?” I said, loudly and firmly. The man stirred and opened his eyes, and then sat up suddenly, blinking at the light.

“Who are you?” I repeated sternly. The man stared at me stupidly for an instant; then he passed his hand over his forehead and stumbled to his feet.

“Who am I?” he repeated wildly; then his face screwed up into a frightful grimace and with a groan he crumpled up on the floor. Leaving Sandhelo still standing there gazing at him in mild astonishment, I ran out calling for father.

Father came presently and took a long look at the man in the stall, and then, without asking any questions, he got a wet cloth and laid it on his head. That washed some of the mud off and showed a big bruise on his forehead over his left eye. Father called the man that helps with the horses.

“Help me carry this man into the house,” he said shortly.

“But Father,” I said, “you surely aren’t going to carry that man into the house? All dirty like that!”

Father gave me one look and I said no more. Together father and Jim Wiggin lifted the stranger from the floor and started toward the house with him, while I capered around in my excitement and finally ran on ahead to tell mother. They carried him into the kitchen and laid him down on the old lounge and tried to bring him around with smelling salts and things. But he just kept on talking and muttering to himself, and never opened his eyes.

And that’s what he’s still doing, while I’m off in my room writing this. It was five o’clock when we brought him in, and now it’s after ten and he hasn’t come to his senses yet. There isn’t a thing in his pockets to show who he is or where he came from.

I feel so strange since I found that man there. I’m not a bit low in my mind any more, like I was this afternoon. I have a curious feeling as if I had passed a turn in the road and come upon something new and wonderful.

Forget the lengthy moan I indulged in at the beginning of this letter, will you, and think of me as gay and chipper as ever.

Yours in Wohelo,

Oct. 15, 19—.

Darling Winnies:

And to think, after all that fuss I made about not getting a letter from you that day, I didn’t have time to open it for three whole days after it finally arrived! You remember where I left off the last time, with the strange man I had found in Sandhelo’s stable out of his head on the kitchen lounge? Well, he kept on like that, lying with his eyes shut and occasionally saying a word or two that didn’t make sense, all that night and all the next day. Then on Sunday he developed a high fever and began to rave. He shouted at the top of his voice until he was hoarse; always about somebody pursuing him and whom he was trying to run away from. Then he began to jump up and try to run outdoors, until we had to bar the door. It took all father and Jim Wiggin and I could do to keep him on the lounge. We had a pretty exciting time of it, I can tell you. Of course, all the uproar upset mother and she had another spell with her heart and took to her bed, and by Tuesday night things got so strenuous that I had to dismiss school for the rest of the week and keep all my ten fingers in the domestic pie.

I don’t know who rejoiced more over the unexpected lapse from lessons, the scholars or myself. I never saw a group of children who were so constitutionally opposed to learning as the twenty-two stony-faced specimens of “hoomanity” that I had to deal with in that little shanty of a school. They’d rather be ignorant than educated any day. I just can’t make them do the homework I give them. Every day it’s the same story. They haven’t done their examples and they haven’t learned their spelling; they haven’t studied their geography. The only way I can get them to study their lessons is to keep them in after school and stand over them while they do it. Their only motto seems to be, “Pa and ma didn’t have no education and they got along, so why should we bother?”

The families from which these children come are what is known in this section as “Hard-uppers,” people who are and have always been “hard up.” Nearly everybody around here is a Hard-upper. If they weren’t they wouldn’t be here. The land is so poor that nobody will pay any price for it, so it has drifted into the hands of shiftless people who couldn’t get along anywhere, and they work it in a backward, inefficient sort of way and make such a bare living that you couldn’t call it a living at all. They live in little houses that aren’t much more than cabins—some of them have only one or two rooms in them—and haven’t one of the comforts that you girls think you absolutely couldn’t live without. They have no books, no pictures, no magazines. It’s no wonder the children are stony-faced when I try to shower blessings upon them in the form of spelling and grammar; they know they won’t have a mite of use for them if they do learn them, so why take the trouble?

“What a dreadful set of people!” I can hear you say disdainfully. “How can you stand it among such poor trash?”

O my Belovéds, I have a sad admission to make. I am a Hard-upper myself! My father, while he is the dearest daddy in the world, never had a scrap of business ability; that’s how he came to live in this made-out-of-the-scraps-after-every-thing-else-was-made corner of Arkansas. He never had any education either, though it wasn’t because he didn’t want it. He doesn’t care a rap for reading; all he cares for is horses. We live in a shack, too, though it has four rooms and is much better than most around here. We never had any books or magazines, either, except the ones for which I sacrificed everything else I wanted to buy. But I wanted to learn,—oh, how I wanted to learn!—and that’s where I differed altogether from the rest of the Hard-uppers. They’re still wagging their heads about the way I used to walk along the road reading. The very first week I taught school this year I was taking Absalom Butts (mentioned in my former epistle) to task for speaking saucily to me, and thinking to impress him with the dignity of my position I said, “Do you know whom you’re talking to?”

And he answered back impudently, “Yer Bill Adamses good-for-nothing daughter, that’s who you are!”

You see what I’m up against? Those children hear their parents make such remarks about me and they haven’t the slightest respect for me. Did you know that I only got this job of teaching because nobody else would take it? Absalom Butts’ father, who is about the only man around here who isn’t a Hard-upper, and is the most influential man in the community because he can talk the loudest, held out against me to the very end, declaring I hadn’t enough sense to come in out of the rain. As he is president of the school board in this township—the whole thing is a farce, but the members are tremendously impressed with their own dignity—it pretty nearly ended up in your little Katherine not getting any school to teach this winter, but when one applicant after another came and saw and turned up her nose, it became a question of me or no schoolmarm, so they gave me the place, but with much misgiving. I had become very much discouraged over the whole business, for I really needed the money, and began to consider myself a regular idiot, but father said I needn’t worry very much about being considered a good-for-nothing by Elijah Butts; his whole grudge against me rose from the fact that he had wanted to marry my mother when she was young and had never forgiven father for beating him to it. That cheered me up considerably, and I determined to swallow no slights from the family of Butts.

Since then it’s been nip and tuck between us. Young Absalom is a big, overgrown gawk of fourteen with no brain for anything but mischief. His chief aim in life just now is to think up something to annoy me. I ignore him as much as possible so as not to give him the satisfaction of knowing he can annoy me, but about every three days we have a regular pitched battle, and it keeps me worn out. His sister Clarissa hasn’t enough brain for mischief, but her constant flow of tears is nearly as bad as his impudence.

Taken all in all, you can guess that I didn’t shed any tears about having to close the school that Tuesday to help take care of the sick man. Anything, even sitting on a delirious stranger, was a relief from the constant warfare of teaching school. It was in the midst of this mess that your letter came, and lay three whole days before I had time to open it.

On Saturday the sick man stopped raving and struggling and lay perfectly motionless. Jim Wiggin looked at his white, sunken face, and remarked oracularly, “He’s a goner.”

Even father shook his head and asked me to ride Sandhelo over to Spencer and fetch the doctor again. I went, feeling queer and shaky. Nobody had ever died in our house and the thought gave me a chill. I wished he had never come, because the business had upset mother so. Besides that, the man himself bothered me. Who was he, wandering around like that among strangers and dying in the house of a man he had never seen? How could we notify his family—if he had a family? I couldn’t help thinking how dreadful it would be if my father were to be taken sick away from home like that, and we never knowing what had become of him. I was quite low in my mind again by the time I had come back with the doctor.

But while I had been away a change came over the sick man. He still lay like dead with his eyes closed, but he seemed to be breathing differently. The doctor said he was asleep; the fever had left him. He wasn’t going to die under a strange roof after all. When he wakened he was conscious, but the doctor wouldn’t let us ask him any questions. He slept nearly all day Sunday and on Monday I went back to school. When I came home Monday night I had the surprise of my young life. When I looked over at the lounge to see how the sick man was to-day I saw, not a man, but a boy lying there. A white-faced boy with a sensitive, beautiful mouth, wan cheeks and great black eyes that seemed to be the biggest part of his face. My books clattered to the floor in my astonishment. Father came in just then and laughed at my amazed face.

“Quite a different-looking bird, isn’t he?” he said. “The doctor was in again to-day and shaved him. It does make quite a difference, now, doesn’t it?” he finished.

Difference! I should say it did! I had thought all the while that he was a man, because he wore a beard; it had never occurred to me that the hair had grown out on his face from neglect, and not because he wanted it there.

“I suppose I must have looked frightful,” said the boy in a weak voice, but with a smile of amusement in his eyes. Those were the first words I had heard him speak to anyone, and that was the first time he had had his eyes wide open and looked directly at me. For the life of me I couldn’t stop staring at him. I couldn’t get over how beautiful he was. He had been so repulsive before, with his hair all matted and his face discolored by bruises; now his hair was clipped short and was very soft and black and shiny. One small transparent hand lay on top of the blanket. He didn’t look a day over eighteen.

He lay there half smiling at me and suddenly for no reason at all I felt large and awkward and sloppy. Involuntarily my hand flew to the back of my belt to see if I was coming to pieces, and I stole a stealthy glance at my feet to see if the shoes I had on were mates. I was glad when he closed his eyes and I could slip out of the room unnoticed. I suppose mother wondered why I was so long getting supper ready that night. But the truth of the matter is I spent fifteen minutes hunting through my bureau drawers for that list of rules of neatness that Gladys made out for me last summer, and which I had never thought of once since coming home. I unearthed them at last and applied them carefully to my toilet before reappearing in the kitchen. My hair was very trying; it would hang down in my eyes until at last in desperation I tucked it under a cap. As a rule I loathe caps. Just as soon as this letter reaches you, Gladys, will you send me that recipe for hand lotion you told me you used? My hands are a fright, all red and rough. Don’t wait until the letters from the other girls are ready, but send the recipe right on by return mail.

After supper that night we talked to the man on the couch. At first he seemed very unwilling to tell anything about himself. We finally got from him that his name was Justice Sherman; that he was from Texas, where he had been working on a sheep ranch; that he had left there and gone up into Oklahoma and had worked at various places; that he had gradually worked his way into Arkansas; that he had fallen in with bad men who had attacked and robbed him and left him lying senseless in the road with his head cut open; that he had wandered around several days in the rain half out of his head, trying to get someone to take him in, but he looked so frightful that everyone turned him out and set the dogs on him, until finally he had stumbled over a stone and broken his ankle and dragged himself into our stable and crept into Sandhelo’s stall. That’s what had made him crumple up on the floor the day I found him when he tried to get up. He had fainted from the pain.

We asked him if he wouldn’t like us to write to his family or his friends and he answered wearily that he had no family and no friends in particular that he would care to notify. Then he closed his eyes and one corner of his mouth drew up as if with pain. Poor fellow, I suppose that ankle did hurt horribly.

Now, you best and dearest of Winnebagos, let the dear Round Robin letter come chirping along just as soon as you can, and I’ll promise not to let it lie three days this time before I read it.

Lovingly your

Brownell College, Oct. 18, 19—.

Darling Katherine:

Well, we’re settled at last, though it did seem at first as though we were going to spend all our college life wandering around with our belongings in our arms. We came a day late and found the room we had arranged for occupied by someone else. Through a mistake it had been assigned to us after it had been once assigned to these other two, so we had to relinquish our claim. The freshman dormitory was full to the eaves and we realized that there wasn’t going to be any place for us. We made our roomless plight known and to make up for it we were told there was a vacant double in the sophomore dormitory that we might take provided no sophomores wanted it. We hadn’t expected such an honor and sped like the wind after our belongings. The sophomore dormitory is right across from the freshman one; they are called Paradise and Purgatory, respectively. It sounded awfully funny to us at first to hear the girls asking each other where they were and to hear them answer, “I’m in Paradise,” or, “I’m in Purgatory.” We were overcome with joy when we discovered that Migwan roomed in Paradise. Our room was way up on the third floor and hers was down on second, but to be under the same roof with her was such a comfort that all our troubles seemed over for good. We just had our things pretty well straightened out and Hinpoha was nailing her shoebag to the closet door when the sky fell and we were informed that a couple of sophomores wanted our room, and, as there was now a vacancy in the freshman dormitory, would we kindly move? So we were thrown out of Paradise and landed in Purgatory after all, and, for the second time that day, we trailed across the campus with our arms full of personal property, strewing table covers and laundry bags in our wake. We didn’t have time to straighten out before exams began and for two days we lived like shipwrecked sailors with the goods that had been saved from the wreck piled on the floor and when we wanted anything we had to rummage for half an hour before we found it. Even after we had survived exams we were half afraid to begin settling for fear we would be ordered to move once more. We couldn’t quite believe that we were anchored at last.

The first week went around very fast; we were so busy getting our classes straightened out and learning our way through the different buildings that we didn’t have time to feel homesick. But by Saturday the first strangeness had worn off; we had stopped wandering into senior class rooms and professors’ committee meetings, but still we hadn’t had time to get very well acquainted. Saturday afternoon was perfect weather and most everybody in the house had gone off for a walk, but we had stayed at home to finish putting our room to rights. When everything was finally in place we sat down on the bed and looked at each other. Hinpoha’s eyes suddenly filled with tears.

“I want the other Winnebagos!” she declared. “I can’t live without them. I want Sahwah and Nakwisi and Medmangi, and I want Katherine! Oh-h-h-h, I want Katherine! How will we ever get along without her here?”

And we both sat there and wanted you so hard that it seemed as if the heavens must open up and drop you down on the bed beside us. Katherine, do you know that you have ruined our whole lives? Why, O why did you come to us only to go away again? You got us so in the habit of looking to you to tell us what to do next that now we aren’t able to start a thing for ourselves. We knew that if you had been there with us that first week you would have had the whole house in an uproar and something wonderful would have been happening every minute. But for the life of us we couldn’t think of a single thing to do for ourselves.

We were still sitting there steeped in gloom when Migwan came in to see how we were getting on. She had some delicious milk chocolate with her and that cheered Hinpoha up quite a bit. It’s going to be a heavenly comfort to have Migwan just ahead of us in college. She knows all the ropes and the teachers and the gossip about the upper classmen and tells us things that keep us from making the ridiculous mistakes so many of the freshmen make all the time.

“But just think how I felt here, all alone, last year,” said Migwan. “Perhaps I didn’t miss you girls, though! You were still altogether and had Nyoda, but here there wasn’t a soul who had ever heard of the Winnebagos. Now it seems like old times again. Think of it, three whole Winnebagos living together almost under the same roof! Didn’t we say that night when we had our last Council Fire with Nyoda that although we couldn’t be together any more, we were still Winnebagos and were loyal friends and true, and that wherever two Winnebagos should meet, whether it was in the street, or on mid-ocean, or in a far country, right then and there would take place a Winnebago meeting? Why, we’re having a Winnebago meeting this very minute!”

“Let’s keep on having meetings, as often as we can, just us three,” said Hinpoha, “and talk over old times and have ‘Counts.’ We can call ourselves The Last of the Winnebagos, like the Last of the Mohicans, and our password will be ‘Remember!’ That means, ‘Remember the old days!’”

Migwan smiled a little mysteriously, but she agreed that it was a fine idea.

We three sat down on the floor in a Wohelo triangle and repeated our Desire and promised to seek beauty in everything that came along, and to give service to all the other girls in college whenever we had the chance, and to pursue knowledge for all we were worth now that there was so much of it on every side of us, and to be trustworthy and obey all the rules to the smallest detail and never cheat at exams, and to glorify work until everybody noticed how well we did everything, and hold on to health by not sitting up late studying and eating horrible messes, and to be happy all the time and try to like every girl in college.

“Let’s clasp hands on it,” said Hinpoha, and we did, and then stood up and sang “Wohelo for Aye” until the window rattled. (It’s awfully loose and rattles at the slightest pretext.)

We had just gotten to the last “Wohelo for Love” when all of a sudden a face appeared at the window. We were all so surprised we stopped short and the last syllable of “Wohelo” was chopped off as if somebody had taken a knife. Our room is on the third floor, and for anyone to look in at the window they would have to be suspended in the air. So when that head appeared without any warning we all stood petrified and stared open-mouthed. It was a girl’s head with very black hair and very red lips. At first the face just looked at us; then when it saw our amazement it grinned from ear to ear in the widest grin I ever saw.

“Did I scare you?” said the face in a voice so rich and deep that we jumped again. “No, I’m not Hamlet, thy father’s ghost, I’m Agony, thy next door neighbor. I heard you singing ‘Wohelo for Aye’ and I just looked in to see if I could believe my ears.”

We all ran to the window and then we saw how easily the thing had been done. Our window is right up against the corner of our room and the window in the other room is right next to it, so that all the apparition had to do was lean out of her window and look into ours, which was open from the bottom.

“Come on over!” we urged hospitably.

The apparition withdrew from the window and appeared a moment later in the doorway, leading a second apparition.

“I brought my better half along,” said the deep, rich voice again, as the two girls came into the room.

They looked so much alike that we knew at a glance they were sisters. The one who had looked in at the window did the introducing.

“We’re the Wing twins,” she said, as if she took it for granted that we had heard about them already. “She’s Oh-Pshaw and I’m Agony.”

“Oh-Pshaw and Agony?” we repeated wonderingly, whereupon the twins burst out laughing.

“Oh, those are not our real names,” said Agony, “but we’ve been called that so long that it seems as if they were. Her name’s Alta and mine’s Agnes. I’ve been nicknamed Agony ever since I can remember, and Alta got the habit of saying ‘Oh-Pshaw!’ at everything until the girls at the boarding school where we went always called her that and the name stuck. You pronounce it this way, ‘Oh-Pshaw,’ with the accent on the ‘Oh.’”

We were friends all in a minute. How in the world could you be stiff and formal with two girls whose names were Agony and Oh-Pshaw?

“We heard you singing ‘Wohelo for Aye,’” Agony explained, “and it made us so homesick we almost went up in smoke. We belonged to the corkingest group back home. It nearly killed us off to go away and leave them.”

Here Oh-Pshaw broke in and took up the tale. “When we heard that song coming from next door Agony squealed, ‘Camp Fire Girls!’ and began to dance a jig. She wouldn’t wait until I got my hair done so we could come over and call; she just stretched her neck until it reached into your window. Oh, I’m so glad you’re next door to us I could just pass away!” And Oh-Pshaw caught Agony around the neck and they both lost their balance on the foot of the bed and rolled over on the pillows.

“I’m sorry you have such dandy nicknames,” said Migwan. “If you didn’t have them we could call you First Apparition and Second Apparition, like Macbeth, you know. But the ones you have are far superior to anything we could think up now.”

Then we told them about the Winnebagos and about you and Sahwah and the rest of them, and how we had formed THE LAST OF THE WINNEBAGOS and meant to have meetings right along. Of course, we asked them to come and “Remember” their lost group with us, and they were perfectly wild about it.

“Let’s have our first meeting right now,” proposed Agony, “and go on a long hike. It’s a scrumptious day.”

We flew to get our hats and Hinpoha was in such a hurry that she knocked over the Japanese screen that stands gracefully across one corner of our room and that brought to light the pile of things that we just naturally couldn’t fit into the room anywhere and had chucked behind the screen until we decided how to get rid of them. There was Hinpoha’s desk lamp, the one with the light green shade with bunches of purple grapes on it—a perfect beauty, only there was no room for it after we’d decided to use mine with the two lamps in it; and an extra rug and a book rack and a Rookwood bowl and quantities of pictures. You see, we’d both brought along enough stuff to furnish a room twice the size of ours.

“Whatever will we do with those things?” sighed Hinpoha in despair.

“Can’t you give them to somebody?” suggested Migwan. “That lamp and that vase are perfect beauties. I’d covet them myself if I didn’t have more now than I know what to do with.”

“The very thing!” said Hinpoha. “Here we promised not a half hour ago to ‘Give Service’ all the time, and yet we didn’t think of sharing our possessions. To whom shall we give them?”

“To Sally Prindle,” said Agony and Oh-Pshaw in one breath.

“Who’s Sally Prindle?” asked Hinpoha and I, also in chorus.

“She lives down at the other end of the hall in Purgatory,” said Agony, “in that tiny little box of a room at the head of the stairs. She’s working her way through college and waits on table for her board and does some of the upstairs work for her room, and she’s awfully poor. She hasn’t a thing in her room but the bare furniture—not a rug or a picture. She’d probably be crazy to get them.”

“Let’s give them to her right away,” said Hinpoha, beginning to gather things up in her arms. Hinpoha is just like a whirlwind when she gets enthusiastic about anything.

“But how shall we give them to her?” I asked. “We don’t know her, and she might feel offended if she thought we had noticed how bare her room was and pitied her. How shall we manage it, Migwan?”

“Don’t act as if you pitied her at all,” replied Migwan. “Simply knock at her door and tell her you’ve got your room all furnished and there are some things left over and you’re going up and down the corridor trying to find out if anybody has room to take care of them for you until the end of the year. Of course she has room to take them, so it will be very simple.”

“Oh, Migwan, what would we do without you?” cried Hinpoha, and nearly dropped the Rookwood bowl trying to hug her with her arms full. “You always know the right thing to do and say.”

Agony and Oh-Pshaw stopped into their room on the way up and came out with a leather pillow and an ivory clock to add to the collection. Their room wasn’t too full, but they wanted to do something for Sally, too. We had to knock on Sally’s door twice before she opened it and we were beginning to be afraid she wasn’t at home. When she did come to the door she didn’t ask us in; but just stood looking at us and our armful of things as if to ask what we wanted. She was a tall, stoop-shouldered girl with spectacles and a wrinkle running up and down on her forehead between her eyes. The room was just as bare as Agony had described; it looked like a cell.

“We’re making a tour of Purgatory trying to dispose of our surplus furniture,” I said, trying to be offhand, “Have you any room to spare?”

“No, I haven’t,” answered Sally with a snap. “You’re the third bunch to-day that’s tried to decorate my room for me. When I want any donations I’ll ask for them.” And she shut the door right in our faces.

We backed away in such a hurry that Agony dropped the clock and it went rolling and bumping down the stairway.

“Of all things!” said Agony. “I wish poor people wouldn’t be so disagreeable about it. I’m sure I’d be tickled to death to use anybody’s surplus to make up what I lacked. Well, we’ve tried to ‘Give Service’ anyway, and if it didn’t work it wasn’t our fault. I think there ought to be a law about ‘Taking Service’ as well as Giving. Now let’s hurry up and go for our hike before the sun goes down.”

We went out and had the most glorious tramp over the hills and found a tiny little village that looks the same as it must have a hundred years ago, and then we came back and had hot chocolate in a darling little shop that was just jammed with students. Agony and Oh-Pshaw know just quantities of girls, and introduced us to dozens, and we went back to Purgatory too happy to think.

“I told you so,” said Migwan, as she came into the room with us for a minute to get a book.

“What did you tell us?” asked Hinpoha.

“I meant about us three trying to have meetings just by ourselves and trying to do exactly what we did when we were Winnebagos. It won’t work. You’ll keep on making new friends all the time that you’ll love just as much as the old ones. Don’t forget the old Winnebagos, but don’t mourn because the old days have come to an end. There’s more fun coming to you than you’ve ever had before in your lives, so be on the lookout for it every minute. ‘Remember!’”

Oh, Katherine, we just love college, and the only fly in the ointment is that you aren’t here!

Your loving

P. S. Medmangi writes that she has passed her exams and entered the Medical School. Sahwah is going to Business College and having the time of her life with shorthand. P.P.S. Hinpoha is dying of curiosity to hear more about the sick man. Please answer by return mail.

Nov. 1, 19—.

Dearest Winnies:

Well, Justice Sherman may be a sheep herder and a son of the pasture, but I hae me doots. I know a hawk from a handsaw if I was born and bred in the backwoods. I know it isn’t polite to doubt people’s word, and he seemed to be telling an absolutely straight story when he told how he beat his way across from Texas, but for all that there’s some mystery about him. His manners betrayed him the first time he ever sat down to the table with us. Even though he limped badly and was still awfully wobbly, he stood behind my mother’s chair and shoved it in for her and then hobbled over and did the same for me.

You can see it, can’t you? The table set in the kitchen—for our humble cot does not boast of a dining room—father and Jim Wiggin collarless and in their shirtsleeves, and the stranded sheep herder waiting upon mother and me as if we were queens. For no reason at all I suddenly became abashed. I felt my face flaming to the roots of my hair, and absentmindedly began to eat my soup with a fork, whereat Jim Wiggin set up a great thundering haw! haw! Jim had been a sheep herder before he came to take care of father’s horses, and it struck me forcibly just then that there was a wide difference between him and the stranger within our gates.

I said something to father about it that night when we were out in the stable together giving Sandhelo his nightly dole. Father rubbed his nose with the back of his hand, a sign that a thing is of no concern to him.

“Don’t you get to worryin’ about the stranger’s affairs,” he advised mildly. “If he’s got something he doesn’t want to tell, you ain’t got no business tryin’ to find it out. Tend to your own affairs, I say, and leave others’ alone. There ain’t nobody goin’ to be pestered with embarrassing questions while they’re under my roof.”

So I promised not to ask any questions. Just about the time the stranger’s foot was well enough to walk on, Jim Wiggin stepped on a rusty nail and laid himself up. Justice Sherman was a godsend just then because men were so hard to get, and father hired him to help with the horses until Jim was about again. Father begged me again at this time not to ask him anything about his past.

“Just as soon as he thinks we’re gettin’ curious he’ll up and leave,” he said, “and that would put us in a bad way. Help is so scarce now I don’t know where I would get an extra man. Seems almost as though the hand of Providence had sent him to us.”

It was perfectly true. Since so many men had gone into the army it was next thing to impossible to get any help on the farms except good-for-nothing negroes that weren’t worth their salt. It seemed, indeed, an act of Providence to cast an able man at our door just at this juncture. So I promised again not to bother the man with questions.

Indeed, it bade fair to be an easy matter not to ask him any questions. Beyond a few polite words at meals he never said anything at all, and as he had moved his sleeping quarters to a small cabin away from the house I saw very little of him, and I suppose we never would have gotten any better acquainted if your letter hadn’t come that Friday. Friday is the worst day of the week for me, because after five days of constant set-to-ing with Absalom Butts my philosophy is at its lowest ebb. This week was the worst because I had a visitation from the school board to see how I was getting on, and, of course, none of the pupils knew a thing and most of them acted as if the very devil of mischief had gotten into them. Elijah Butts gave me a solemn warning that I would have to keep better order if I wanted to stay in the school, and Absalom, who had been hanging around listening, made an impudent grimace at me and laughed in a taunting manner. If I hadn’t needed the money so badly I would have thrown up the job right there.

Then, on top of that, came your letter describing the supergorgeousness of your college rooms, and when I thought of the room I had planned to have at college this winter, adjoining yours, my heart turned to water within me and melancholy marked me for its own. I wept large and pearly tears which Niagara-ed over the end of my nose and sizzled on the hot stove, as I stood in the kitchen stirring a pudding for supper. Get the effect, do you? Me standing there with the spoon in one hand and your letter in the other, doing the Niobe act, quite oblivious to the fact that I was not the only person in the county. I was just in the act of swallowing a small rapid which had gotten side-tracked from the main channel and gone whirlpooling down my Sunday throat, when a voice behind me said, “Did you get bad news in your letter?”

I jumped so I dropped the letter right into the pudding. I made a savage dab at my eyes with the corner of my apron and wheeled around furiously. There stood the Justice Sherman person looking at me with his solemn black eyes. I was ready to die with shame at being caught.

“No, I didn’t,” I exploded, mopping my face vehemently with my apron, and thereby capping the climax. For while I had been reading your letter and absently stirring the pudding it had slopped over and run down the front of my apron, and, of course, I had to use just that part to wipe my face with. The pudding was huckleberry, and what it did to my features is beyond description. I caught one glimpse of myself in the mirror over the sink and then I sank down into a chair and just yelled. Justice Sherman doubled up against the door frame in a regular spasm of mirth, although he tried not to make much noise about it. Finally he bolted out of the door and came back with a basin of water from the pump, which he set down beside me.

“Here,” he said, “remove the marks of bloody carnage, before you scare the wolf from the door.”

So I scrubbed, wishing all the while that he would go away, and still furious for having made such a spectacle of myself. But he stayed around, and when I resembled a human being once more (if I ever could be said to resemble one), he came over and handed me the letter, which he had fished out of the pudding.

“Here’s the fatal missive,” he said, “or would you rather leave it in the pudding?”

“Throw it into the fire,” I commanded.

“That’s the right way,” he said approvingly. “I always burn bad news myself.”

“It wasn’t bad news,” I insisted.

“Then why the tears?” he inquired curiously. “Tears, idle tears, I know not what they mean——”

He was smiling, but somehow I had a feeling that he was trying to cheer me up and not making fun of me. I was so low in my mind that afternoon that anyone who acted in the least degree sympathetic was destined to fall a victim. Before I knew it I had told him of my shipwrecked hopes and how your letter had opened the flood gates of disappointment and nearly put out the kitchen fire.

“College—you!” I heard him exclaim under his breath. He stared at me solemnly for a moment and then he exclaimed, “O tempora, O mores! What’s to hinder?”

“What’s to hinder?” I repeated blankly.

“Yes,” he said, “having the room anyway.”

“What do you mean?” I asked.

“Why,” he explained, “you have a room of your own, haven’t you? Why don’t you fix it up just the way you had planned to have your room in college? Then you can go there and study and make believe you’re in college.”

I stared at him open-mouthed. “Make-believe has never been my long suit,” I said.

“Come on,” he urged. “I’ll help you fix it up. If you have any more tears prepare to shed them now into the paint pot and dissolve the paint.”

Before I knew what had happened we had laid forcible hands on the bare little cell I had indifferently been inhabiting all these years and transformed it into the study of my dreams. We cut a window in the side that faces in the direction of the mountains and made a corking window seat out of a packing case, on which I piled cushions stuffed with thistle down. We papered the whole place with light yellow paper, tacked up my last year’s school pennants and put up a book shelf. This last proved to be a delusion and a snare, because one end of it came down in the middle of the night not long afterward and all the books came tobogganing on top of me in bed. As a finishing touch, I brought out the snowshoes and painted paddle that were a relic of my Golden Age, and which I had never had the heart to unpack since I came home. When finished the effect was quite epic, though I suppose it would make Hinpoha’s artistic eye water.

Of course, it will never make up for not going to college, but it helped some, and in working at it I got very well acquainted with Justice Sherman all of a sudden. We had long talks about everything under the sun, and he continually bubbled over with funny sayings. He confided to me that he had never been so surprised in all his life as when I told him I wanted to go to college. You see, he had thought we were like the other poor whites in the neighborhood, and I was like the other girls he had seen. He didn’t take any interest in me until I bowled him over with the statement that I had already passed my college entrance exams.

All this time I never hinted that I suspected he was not the simple sheep herder he pretended to be. I had given father my word and, of course, had to keep it. But one afternoon the Fates had their fingers crossed, and Pandora like, I got my foot in it. I had driven Justice over to Spencer in the rattledy old cart with Sandhelo. On the way we talked of many things, and I came home surer than ever that he was no sheep herder. Once when the conversation lagged and in the silence Sandhelo’s heels seemed to be beating out a tune as they clicked along, I remarked ruminatingly, “There’s a line in Virgil that is supposed to imitate the sound of galloping horses.”

“Quadrupedante putrem sonitu quatit angula campam,”

quoted Justice promptly.

So he was on quoting terms with Virgil! But I remembered my promise and made no remarks.

A little later I was telling about the winter hike we had taken on snowshoes last year.

“You ought to see the sport they have on snowshoes in Switzerland,” he began with kindling eyes. Then he broke off suddenly and changed the subject.

So Texas sheep herders learn their trade in Switzerland! But again I yanked on the curb rein of my curiosity. I apparently took no notice of his remark, for just then a negro stepped suddenly from behind the bushes along the road and startled Sandhelo so that he promptly became temperamental and sat up on his haunches to get a better look at the apparition, and the mess he made of the harness furnished us plenty of theme for conversation for the next ten minutes.

“Lord, what an ape,” remarked Justice, gazing after the departing form of the negro shambling along the road, “he looks like the things you see in nightmares.”

Accustomed as I was to seeing low-down niggers, this one struck me as being the worst specimen nature had ever produced. He had the features of a baboon, and the flapping rags of the grotesque garments he wore made him look like a wild creature.

“Do you have many such intellectual-looking gentlemen around here?” asked Justice, twisting his neck around for a final look at the fellow. “I’d hate to meet that professor at the dark of the moon.”

“Oh, they’re really not as bad as they look,” I replied. “They look like apes, but they’re quite harmless. They’re shiftless to the last degree, but not violent. They’re too lazy to do any mischief.”

“Just the same, I’d rather not get into an argument with that particular brother, if it’s all the same to you,” answered Justice. “He looks like mischief to me.”

“He doesn’t look like a prize entry in a beauty contest,” I admitted.

With all that talk about the negro Justice’s remark about Switzerland went unheeded, but I didn’t forget it just the same. I thought about it all the rest of the afternoon and it was as plain as the nose on your face that there was some mystery about Justice Sherman. A sheep herder who spouted Virgil at a touch, quoted continually from the classics, had refined manners and had traveled abroad, couldn’t hide his light under a bushel very well. Another thing; he wasn’t a Texan as he had led us to believe. He talked with the crisp, clear accent of the North, and the fuss he made about the negro in the road that afternoon betrayed the fact that he was no southerner. Nobody around here pays any attention to niggers, no matter how tattered they are. We’re used to them, but northerners always make a fuss.

The question bubbled up and down in my mind, keeping time to the bubbling of the soup on the stove; why was this educated and refined young man working for thirty dollars a month as a handy man around horses on a third-rate stock farm in this God-forsaken part of the country? Then a suspicion flashed into my mind and at the dreadful thought I stopped stirring with the upraised spoon frozen in mid-air. Then I gathered my wits together and started resolutely for the table. I had promised father I would never ask Justice Sherman anything about his past, but here was something that swept aside all personal obligations and promises. I found him with father in the stable working over a sick colt. I marched straight up to him and began without any preamble.

“See here, Justice Sherman,” I said, “are you hiding yourself to avoid military service? Are you a slacker?”

Justice Sherman straightened up and looked at me with flashing eyes. “No, I’m not!” he shouted in a voice quite unlike his.

I never saw anyone in such a rage. His face was as red as a beet and his hair actually stood on end. “I registered for the service,” he went on hotly, “and wasn’t called in the draft. I tried to enlist and they wouldn’t take me. I was under weight and had a weak throat. If anyone thinks I’m a slacker, I’ll——” Here he choked and had a violent coughing spell.

I stared at him, dazed. I never thought he could get so angry. He looked at me with hostile, indignant eyes. Then he straightened up stiffly and walked out of the stable.

“I won’t stay here any longer,” he exploded, still at the boiling point. “I won’t be insulted.”

“I apologize,” I said humbly. “I spoke in haste. Won’t you please consider it unsaid?”

No, he wouldn’t consider it unsaid. He wouldn’t listen to father’s pathetic plea not to leave him without a helper. We suspected him of being a slacker and that finished it. He would leave immediately. Down the road he marched as fast as he could go without ever turning his head.

A worm in the dust was much too exalted to describe the way I felt. With the best of intentions I had precipitated a calamity, taking away father’s best helper at a critical time, to say nothing of my losing him as a companion. I was too disgusted with myself to live and chopped wood to relieve my feelings. After supper I hitched up Sandhelo and drove to Spencer to post a letter. I am not in the least sentimental—you know that—but all along the road I kept seeing things that reminded me of Justice Sherman and the fun we had had together. Now that he was gone the days ahead of me seemed suddenly very empty, and desolation laid a firm hand on my ankle.

Also, I had an uncomfortable recollection that it was right along here we had met the horrid negro, and I became filled with fear that I would meet him again. The fear grew, and turned into absolute panic when I approached that same clump of bushes and in the dusk saw a figure rise from behind them and lurch toward the road. I pulled Sandhelo up sharply, thinking to turn around and flee in the opposite direction, but Sandhelo refused to be turned. When I pulled him up he sat back and mixed up the harness so he got the bit into his teeth, and then he jumped up and went straight on forward, with a squeal of mischief. When we were opposite the figure in the road Sandhelo stopped short and poked his nose forward just the way he used to do when Justice Sherman came into his stall.

“Hello,” said a voice in the darkness, and then I saw that the figure in the road was Justice Sherman. His bad ankle had given out on him and he had been sitting there on the ground waiting for some vehicle to come along and give him a lift to Spencer.

“Get in,” I said briefly, helping him up, and he got in beside me without a word. We drove to Spencer in silence and he made no move to get out when we got there. I mailed my letter and then turned and drove homeward. About half way home he spoke up and apologized for being so hasty, and wondered if father would take him back again. I reassured him heartily and we were on the old footing of intimacy by the time we reached home.

We found father standing in front of the house talking to a negro whom we recognized as the one we had met in the road that afternoon. Father greeted Justice Sherman with joy and relief.

“You pretty nearly came back too late,” he said. “Here I was just hiring a man to take your place.” Then he turned to the negro and said, “It’s all off, Solomon. I don’t need you. My own man has come back. You go along and get a job somewhere else.”

The negro shuffled off and I fancied that he looked rather resentful at being sent away.

“Father,” I said, when the creature was out of earshot, “you surely weren’t going to hire that ape to work here?”

“Why not?” answered father. “I have to have a man to help with the horses, and this fellow came up to the door and asked for work, so I promised him a job.”

“But he’s such a terrible looking thing,” I said.

Father only laughed and dismissed the subject with a wave of his hands. “I wasn’t hiring him for his looks,” he answered. “He said he could handle horses and that was enough for me.”

So Justice Sherman came back to us and the subject of military service was never broached again.

About a week after his return, and when Jim Wiggin was able to be about again, Justice Sherman walked into the kitchen with a mincing air quite unlike his ordinary free stride. He had been to Spencer for the mail.

“Tread softly when you see me,” he advised. “I’m a perfessor, I am.”

I looked up inquiringly from the potato I was paring.

“Behold in me,” he went on, “the entire faculty of the Spencer High School. I am instructor in Latin, Greek, mathematics, science, history, English and dramatics; also civics and economics.”

“You don’t mean really?” I asked.

“Really and truly, for sartain sure,” he repeated. “The last faculty got drafted and left the school in a bad way. I heard about it down at the post-office this afternoon and went over and applied for the job. The hardened warriors that compose the school board fell for me to a man. I recited one line of Latin and they applauded to the echo; I recited a line of gibberish and told them it was Greek, and they wept with delight at the purity of my accent. Then they cautiously inquired if I was qualified to teach any other branches and I told them that I also included in my repertoire cooking, dressmaking and millinery. This last remark was intended to be facetious, but those solemn old birds took it seriously and forthwith broke into loud hosannas. I was somewhat mystified at the outbreak until I gathered from bits of conversation that the extravagant township of Spencer had intended to hire two high school teachers this year, as the last incumbent’s accomplishments had been rather brief and fleeting, but what was the use, as one pious old hairpin by the name of Butts delicately put it, what was the use of paying two teachers when one feller could do the hull thing himself? Then he shook me feelingly by the hand and said he knowed I was a bargain the minute he laid eyes on me. O Tempora, O Mores! Papers were brought and shoved into my yielding hands, the writ duly executed, and I passed out of the door a fully fledged ‘perfessor’ with a six-months’ contract. Smile on me, please, I’m a bargain!” And he danced a hornpipe in the middle of the floor until the dishes rattled in the cupboard.

I stared at him speechless. He teach high school? And the things he mentioned as being able to teach! History, French, mathematics, physics, literature, philosophy, Latin, Greek! Quite a well-rounded sheep herder, this! The mystery about him deepened. It was clear now that he was a college graduate. Again I revised my estimate as to his age, and decided he must be about twenty-three or four. Why would he be willing to teach a farce of a high school like the one in Spencer?

Then in the midst of my puzzling it came over me that I did not want him to leave us, and that I would miss him terribly. Of course, he would go to live in Spencer.

“Are you going to board with any of the school board?” I asked jealously, that being what the last “faculty” had done.

“Board with the Board?” he repeated. “Neat expression, that. Not that I know of. I haven’t been requested to vacate my present quarters yet, or do I understand that you are even now serving notice?”

A thrill of joy shot through me. Maybe he would still live in the little cabin on our farm.

“I thought of course you would rather live near the school,” I said. “It’s six miles from here. Why don’t you?”

“‘I would dwell with thee, merry grasshopper,’” he quoted. “That is, if I am kindly permitted to do so.”

And so we settled it. He is to ride with Sandhelo in the cart every day as far as my school, then drive on to Spencer, and stop for me on the way home. What fun it is going to be!

Yours, summa cum felicitate,

P. S. Sandhelo sends three large and loving hee-haws.

Nov. 10, 19—.

Darling K:

This big old town is like the Deserted Village since you and the other Winnies went away. For the first few weeks it was simply ghastly; there wasn’t a tree or a telephone pole that didn’t remind me of the good times we used to have. Do you realize that I am the sole survivor of our once large and lusty crew? Migwan and Hinpoha and Gladys are at Brownell; Veronica is in New York; Nakwisi has gone to California with her aunt; Medmangi is in town, but she is locked up in a nasty old hospital learning to be a doctor in double quick time so she can go abroad with the Red Cross. Nothing is nice the way it used to be. I like to go to Business College, of course, and there are lots of pleasant girls there, but they aren’t my Winnies. I get invited to things, and I go and enjoy myself after a fashion, but the tang is gone. It’s like ice cream with the cream left out.

I went to the House of the Open Door one Saturday afternoon and poked around a bit, but I didn’t stay very long; the loneliness seemed to grab hold of me with a bony hand. Everything was just the way we had left it the night of our last Ceremonial Meeting—do you realize that we never went out after that? There was the candle grease on the floor where Hinpoha’s emotion had overcome her and made her hand wobble so she spilled the melted wax all out of her candlestick. There were the scattered bones of our Indian pottery dish that you knocked off the shelf making the gestures to your “Wotes for Wimmen” speech. There was the Indian bed all sagged down on one side where we had all sat on Nyoda at once.

It all brought back last year so plainly that it seemed as if you must everyone come bouncing out of the corners presently. But you didn’t come, and by and by I went down the ladder to the Sandwiches’ Lodge. That was just as bad as our nook upstairs. The gym apparatus was there, just as it used to be, with the mat on the floor where they used to roll Slim, and beside it the wreck of a chair that Slim had sat down on too suddenly.

Poor Slim! He tried to enlist in every branch of the service, but, of course, they wouldn’t take him; he was too fat. He starved himself and drank vinegar and water for a week and then went the rounds again, hoping he had lost enough to make him eligible, and was horribly cut up when he found he had gained instead. He was quite inconsolable for a while and went off to college with the firm determination to trim himself down somehow. Captain has gone to Yale, so he can be a Yale graduate like his father and go along with him to the class reunions. Munson McKee has enlisted in the navy and the Bottomless Pitt in the Ambulance Corps. The rest of the Sandwiches have gone away to school, too.

The boards creaked mournfully under my feet as I moved around, and it seemed to me that the old building was just as lonesome for you as I was.

“You ought to be proud,” I said aloud to the walls, “that you ever sheltered the Sandwich Club, because now you are going to be honored above all other barns,” and I hung in the window the Service Flag with the two stars that I had brought with me. It looked very splendid; but it suddenly made the place seem strange and unfamiliar. Here was something that did not belong to the old days. It is so hard to realize that the boys who used to wrestle around here have gone to war.

I went out and closed the door, but outside I lingered a minute to look sadly up at the little window in the end where the candle always used to burn on Ceremonial nights.

“Good-bye, House of the Open Door,” I said, “we’ve had lots of good times in you and nobody can ever take them away from us. We’ve got to stop playing now for awhile and Glorify Work. We’re going to do our bit, and you must do yours, too, by standing up proudly through all winds and weather and showing your service flag. Some day we’ll all come back to you, or else the Winnebago spirit will come back in somebody else, and you must be ready.”

I said good-bye to the House of the Open Door with the hand sign of fire and a military salute, and went away feeling a heavy sense of responsibility, because in all this big lonely city I was the only one left to uphold the honor of the Winnebagos.

And hoop-la! I did it, too, all by myself. The week after I had paid the visit to the House of the Open Door someone called me on the telephone and wanted to know if this was Miss Sarah Brewster who belonged to the Winnebago Camp Fire Girls, and when I said yes it was the voice informed me that she was Mrs. Lewis, the new Chief Guardian for the city, and President of the Guardians’ Association. She went on to say that she wanted to plan a patriotic parade for all the Camp Fire Girls in the city to take part in, and as part of the ceremony to present a large flag to the city. She knew what she wanted all right, but she wasn’t sure that she could carry it out, and as she had seen the Winnebagos the time they took part in the Fourth of July pageant, she wanted to know if we would take hold and help her manage the thing. I started to tell her that the Winnebagos weren’t here and couldn’t help her; then I reflected that I, at least, was left and it was up to me to do what you all would have done if you had been here. So I said yes, I’d be glad to take hold and help make the parade a success.

And, believe me, it was! Can you guess how many girls marched? Twenty-three hundred! Glory! I didn’t know there were so many girls in the whole world! The line stretched back until you couldn’t see the end, and still they kept on coming. And who do you suppose led the parade? Why, I did, of all people! And on a horse! Carrying the Stars and Stripes on a long staff that fitted into a contrivance on the saddle to hold it firm. Right in front of me marched the Second Regiment Band, and my horse pawed the ground in time to the music until I nearly burst with excitement. After me came the twenty girls, all Torch Bearers, who carried the big flag we were going to present to the city, and behind them came the floats and figures of the pageant.

I must tell you about some of these, and a few of them you’ll recognize, because they are our old stunts trimmed up to suit the occasion.

GIVE SERVICE was the most impressive, because it is the most important just now. It was in twelve parts, showing all the different ways in which Camp Fire Girls could serve the nation in the great crisis. There was the Red Cross Float, showing the girls making surgical dressings and knitting socks and sweaters. Another showed them making clothes for themselves and for other members of the family to cut down the hiring of extra help; and similar floats carried out the same idea in regard to cooking, washing and ironing. Yes ma’am! Washing and ironing! You don’t need to turn up your nose. One float was equipped with a complete modern household laundry and the girls on it had their sleeves rolled up to their elbows and were doing up fine waists and dresses in great shape, besides operating electric washing machines and mangles.

One float was just packed full of good things which the girls had cooked without sugar, eggs or white flour, and with fruits and vegetables which they had canned and preserved themselves, while the fertile garden in which said fruits and vegetables had grown came trundling on behind, the girls armed with spades, hoes and rakes. I consumed two sleepless nights and several strenuous afternoons accomplishing that garden on wheels and I want you to know it was a work of art. The plants were all artificial, but they looked most lifelike, indeed.

Besides those things we had groups of girls taking care of children so their mothers could go out and work; and teaching foreign girls how to take care of their own small brothers and sisters, so they’ll grow up strong and healthy.

There really seemed to be no end to our usefulness.

Behind the wheeled portion of the parade came hundreds of girls on foot, carrying pennants that stretched clear across the street, with clever slogans on them like this:

DON’T FORGET US, UNCLE SAMMY,

WE’RE ALWAYS ON THE JOB

* * * * * *

YOU’RE HERE BECAUSE WE’RE HERE

* * * * * *

AND THIS IS ONLY THE BEGINNING!

* * * * * *

WE ARE PROUD TO LABOR FOR OUR COUNTRY

And the people! Oh, my stars! They lined the streets for thirty blocks, packed in solid from the store fronts to the curb. And the way they cheered! It made shivers of ecstasy chase up and down my spine, while the tears came to my eyes and a big lump formed in my throat. If you’ve never heard thousands of people cheering at you, you can’t imagine how it feels.

One time when the procession halted at a cross street I saw a fat old man, who I’m sure was a dignified banker, balancing himself on a fireplug so he could see better, and waving his hat like crazy. He finally got so enthusiastic that he fell off the fireplug and landed on his hands and knees in the gutter, where some Boy Scouts picked him up and dusted him off, still feebly waving his hat.

Our line of march eventually brought us out at Lincoln Square, where the presentation of the flag was to take place. We stood in the shadow of the Lincoln Memorial monument, and who do you suppose presented the flag? Me again. In the name of all the Camp Fire Girls of the city, I ceremoniously presented it to the Mayor, who accepted it with a flowery speech that beat mine all hollow. Besides presenting the flag I was to help raise it. The pole was there already; it had seen many flag raisings in its long career and many flags had flapped themselves to shreds on its top. The thing I had to do was fasten our flag to the ropes and pull her up. In this I was to be assisted by a soldier brother of one of the girls who was home on furlough. He was to be standing there at the pole waiting for us, but when the time came he wasn’t there. Where he was I hadn’t the slightest idea; nor did I have any time to spend wondering. Mrs. Lewis had set her heart on having a man in soldier’s uniform help raise the flag; it added so much to the spirit of the occasion. Just at this moment I saw a man in army uniform standing in the crowd at the foot of the monument, very close to me. Without a moment’s hesitation I beckoned him imperatively to me. He came and I thrust the rope into his hands, whispering directions as to what he was to do. It all went without a hitch and the crowd never knew that he wasn’t the soldier we had planned to have right from the start. We pulled evenly together and the flag slowly unfolded over our heads and went fluttering to the top, while the band crashed out the “Star Spangled Banner.” It was glorious! If I had been thrilled through before, I was shaken to my very foundations now. I felt queer and dizzy, and felt myself making funny little gaspy noises in my throat. There was a great cheer from the crowd and the ceremonies were over. The parade marched on to the Armory, where we were to listen to an address by Major Blanchard of the —th Engineers.

The girls had all filed in and found seats when Mrs. Lewis, who was to introduce Major Blanchard, came over to me where I was standing near the stage and said in a tragic tone, “Major Blanchard couldn’t come; I’ve had a telegram. What on earth are we going to do? He was going to tell stories about camp life; the girls will be so disappointed not to hear him.”

I rubbed my forehead, unable to think of anything that would meet the emergency. An ordinary speaker wouldn’t fill the bill at all, I knew, when the girls all had their appetites whetted for a Major.

“We might ask the band to give a concert, and all of us sing patriotic songs,” I ventured finally.

“I don’t see anything else to do,” said Mrs. Lewis, “but I’m so disappointed not to have the Major here. The girls are all crazy to hear about the camp.”

Just then I caught sight of a uniform outside of the open entrance way.

“Wait a minute,” I said, “there’s the soldier who helped us raise the flag, standing outside the door. Maybe he’ll come in and talk to the girls in place of the Major.” I hurried out and buttonholed the soldier. He declined at first, but I wouldn’t take no for an answer. I literally pulled him in and chased him up the aisle to the stage.

“But I can’t make a speech,” he said in an agonized whisper, as we reached the steps of the stage, trying to pull back.

“Don’t try to,” I answered cheerfully. “Speeches are horrid bores, anyway. Just tell them exactly what you do in camp; that’s what they’re crazy to hear about.”

Mrs. Lewis didn’t tell the audience that the speaker was one I had kidnapped in a moment of desperation. She introduced him as a friend of the Major’s, who had come to speak in his place. The applause when she introduced him was just as hearty as if he had been the Major himself. The fact that he was a soldier was enough for the girls.

And he brought down the house! He wasn’t an educated man, but he was very witty, and had the gift of telling things so they seemed real. He told little intimate details of camp life from the standpoint of the private as the Major never could have told them. He had us alternately laughing and crying over the little comedies and tragedies of barracks life. He imitated the voices and gestures of his comrades and mimicked the officers until you could see them as plainly as if they stood on the stage. He talked for an hour instead of the half hour the Major was scheduled to speak and when he stopped the air was full of clamorings for more. Private Kittredge had made more of a hit than Major Blanchard could have done.

I never saw a person look so astonished or so pleased as he did at the ovation which followed his speech. He stood there a moment, looking down at the audience with a wistful smile, then he got fiery red and almost ran off the stage.

“I don’t know whether to be glad or sorry the Major’s not coming,” whispered Mrs. Lewis to me under cover of the applause. “The Major’s a very fine speaker, but he wouldn’t have made such a human speech. You certainly have a knack of picking out able people, Miss Brewster! You chose just the right girls for each part in the pageant.”

I didn’t acknowledge this compliment as I should have, because I was wondering why our soldier man had looked that way when we applauded him. He would have slipped out of the side door when he came off the stage, but I stopped him and made him wait for the rest of the program. A national fraternity was holding a convention in town that week and members from all the great colleges were in attendance. As it happened, our Major is a member of that fraternity, and, as a mark of esteem for the Camp Fire Girls, he asked the fraternity glee club to sing for us at the close of our patriotic demonstration.

The singers came frolicking in from some banquet they had been attending, in a very frisky mood, and sang one funny song after another until our sides ached from laughing. I stole a glance now and then at Private Kittredge, beside me, but he never noticed. He was drinking in the antics of those carefree college boys with envious, wistful eyes. At the end of their concert the singers turned and faced the great flag that hung down at the back of the stage and sang an old college song that we had heard sung before, but which had suddenly taken on a new, deep meaning. With their very souls in their voices they sang it:

“Red is for Harvard in that grand old flag,

Columbia can have her white and blue;

And dear old Yale will never fail

To stand by her color true;

Penn and Cornell amid the shot and shell

Were fighting for that torn and tattered rag,

And our college cheer will be

‘My Country, ‘tis of Thee,’

And Old Glory will be our college flag!”

The effect was electrical. Everybody cheered until they were hoarse. I looked at Private Kittredge. His head was buried in his hands and the tears were trickling out between his fingers. I was too much embarrassed to say anything, and I just sat looking at him until, all of a sudden, he sat up, and reaching out his hand he caught hold of mine and squeezed it until it hurt.

“I’m going back,” he said brokenly.

“Going back?” I repeated, bewildered. “Where?”