Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, vol. 3, no. 18, November, 1851

Author: Various Harper

Release date: June 25, 2011 [eBook #36516]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Graeme Mackreth and The Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

NAPOLEON BONAPARTE.

THE STORY OF REYNARD THE FOX.

A STORY OF AN ORGAN.

THE HOUSEHOLD OF SIR THOs. MORE.

THE FLYING ARTIST.

SEALS AND WHALES.

MAURICE TIERNAY, THE SOLDIER OF FORTUNE.

THE FLOATING ISLAND.

SIBERIA, AS A LAND OF POLITICAL EXILE.

APPLICATION OF ELECTRO-MAGNETIC POWER TO RAILWAY TRANSIT.

THE STOLEN ROSE.

THOMAS MOORE.

THE FAIRY'S CHOICE.

A GALLOP FOR LIFE.

SKETCHES OF ORIENTAL LIFE.

THE SHADOW OF BEN JONSON'S MOTHER.

LIGHT AND AIR.

THE WIDOW OF COLOGNE.

MY NOVEL; OR, VARIETIES IN ENGLISH LIFE.

A SCENE FROM IRISH LIFE.

SCOTTISH REVENGE.

POSTAL REFORM—CHEAP POSTAGE.

SYRIAN SUPERSTITIONS.

Monthly Record of Current Events.

Editor's Table.

Editor's Easy Chair.

Editor's Drawer.

Literary Notices.

A Leaf from Punch.

Fashions for November.

[Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1851, by Harper and Brothers, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the Southern District of New York.]

IV. THE SIEGE OF MANTUA.

Early in July, 1796, the eyes of all Europe were turned to Mantua. Around its walls these decisive battles were to be fought which were to establish the fate of Italy. This bulwark of Lombardy was considered almost impregnable. It was situated upon an island, formed by lakes and by the expansion of the river Mincio. It was approached only by five long and narrow causeways, which were guarded by frowning batteries. To take the place by assault was impossible. Its reduction could only be accomplished by the slow, tedious, and enormously expensive progress of a siege.

THE ENCAMPMENT.

Napoleon, in his rapid advances, had not allowed his troops to encumber themselves with tents of any kind. After marching all day, drenched with rain, they threw themselves down at night upon the wet ground, with no protection whatever from the pitiless storm which beat upon them. "Tents are always unhealthy," said Napoleon at St. Helena. "It is much better for the soldier to bivouac in the open air, for then he can build a fire and sleep with warm feet. Tents are necessary only for the general officers who are obliged to read and consult their maps." All the nations of Europe, following the example which Napoleon thus established, have now abandoned entirely the use of tents. The sick, the wounded, the exhausted, to the number of fifteen thousand, filled the hospitals. Death, from such exposures, and from the bullet and sword of the enemy, had made fearful ravages among his troops. Though Napoleon had received occasional reinforcements from France, his losses had kept pace with his supplies, and he had now an army of but thirty thousand men with which to retain the vast extent of country he had overrun, to keep down the aristocratic party, ever upon the eve of an outbreak, and to encounter the formidable legions which Austria was marshaling for his destruction. Immediately upon his return from the south of Italy, he was compelled to turn his eyes from the siege of Mantua, which he was pressing with all possible energy, to the black and threatening cloud gathering in the North. An army of sixty thousand veteran soldiers under General Wurmser, an officer of high renown, was accumulating its energies in the wild fastnesses of the northern Alps, to sweep down upon the[Pg 722] French through the gorges of the Tyrol, like a whirlwind.

About sixty miles north of Mantua, at the northern extremity of Lake Garda, embosomed among the Tyrolean hills, lies the walled town of Trent. Here Wurmser had assembled sixty thousand men, most abundantly provided with all the munitions of war, to march down to Mantua, and co-operate with the twenty thousand within its walls in the annihilation of the audacious foe. The fate of Napoleon was now considered as sealed. The republicans in Italy were in deep dismay. "How is it possible," said they, "that Napoleon, with thirty thousand men, can resist the combined onset of eighty thousand veteran soldiers?" The aristocratic party were in great exultation, and were making preparations to fall upon the French the moment they should see the troops of Napoleon experiencing the slightest reverse. Rome, Venice, Naples began to incite revolt, and secretly to assist the Austrians. The Pope, in direct violation of his plighted faith, refused any further fulfillment of the conditions of the armistice, and sent Cardinal Mattei to negotiate with the enemy. This sudden development of treachery, which Napoleon aptly designated as a "Revelation," impressed the young conqueror deeply with a sense of his hazardous situation.

Between Mantua and Trent there lies, extended among the mountains, the beautiful Lake of Garda. This sheet of water, almost fathomless, and clear as crystal, is about thirty miles in length, and from four to twelve in breadth. Wurmser was about fifteen miles north of the head of this lake at Trent; Napoleon was at Mantua, fifteen miles south of its foot. The Austrian general, eighty years of age, a brave and generous soldier, as he contemplated his mighty host, complacently rubbed his hands, exclaiming, "We shall soon have the boy now." He was very fearful, however, that Napoleon, conscious of the utter impossibility of resisting such numbers, might, by a precipitate flight, escape. To prevent this, he disposed his army at Trent in three divisions of twenty thousand each. One division, under General Quasdanovich, was directed to march down the western bank of the lake, to cut off the retreat of the French by the way of Milan. General Wurmser, with another division of twenty thousand, marched down the eastern shore of the lake, to relieve Mantua. General Melas, with another division, followed down the valley of the Adige, which ran parallel with the shores of the lake, and was separated from it by a mountain ridge, but about two miles in width. A march of a little more than a day would reunite those vast forces, thus for the moment separated. Having prevented the escape of their anticipated victims, they could fall upon the French in a resistless attack. The sleepless vigilance and the eagle eye of Napoleon, instantly detected the advantage thus presented to him. It was in the evening of the 31st of July, that he first received the intimation from his scouts of the movements of the enemy. Instantly he formed his plan of operations, and in an hour the whole camp was in commotion. He gave orders for the immediate abandonment of the siege of Mantua, and for the whole army to arrange itself in marching order. It was an enormous sacrifice. He had been prosecuting the works of the siege with great vigor for two months. He had collected there, at vast labor and expense, a magnificent battering train and immense stores of ammunition. The city was on the very point of surrender. By abandoning his works all would be lost, the city would be revictualed, and it would be necessary to commence the whole arduous enterprise of the siege anew. The promptness with which Napoleon decided to make the sacrifice, and the unflinching relentlessness with which the decision was executed, indicated the energetic action of a genius of no ordinary mould.

The sun had now gone down, and gloomy night brooded over the agitated camp. But not an eye was closed. Under cover of the darkness every one was on the alert. The platforms and gun carriages were thrown upon the campfires. Tons of powder were cast into the lake. The cannon were spiked and the shot and shells buried in the trenches. Before midnight the whole army was in motion. Rapidly they directed their steps to the western shore of Lake Garda, to fall like an avalanche upon the division of Quasdanovich, who dreamed not of their danger. When the morning sun arose over the marshes of Mantua, the whole embattled host, whose warlike array had reflected back the beams of the setting sun, had disappeared. The besieged, who were half famished, and who were upon the eve of surrender, as they gazed, from the steeples of the city, upon the scene of solitude, desolation, and abandonment, could hardly credit their eyes. At ten o'clock in the morning, Quasdanovich was marching quietly along, not dreaming that any foe was within thirty miles of him, when suddenly the whole French army burst like a whirlwind upon his astonished troops. Had the Austrians stood their ground they must have been entirely destroyed. But after a short and most sanguinary conflict they broke in wild confusion, and fled. Large numbers were slain, and many prisoners were left in the hands of the French. The discomfited Austrians retreated to find refuge among the fastnesses of the Tyrol, from whence they had emerged. Napoleon had not one moment to lose in pursuit. The two divisions which were marching down the eastern side of the lake, heard across the water the deep booming of the guns, like the roar of continuous thunder, but they were entirely unable to render any assistance to their friends. They could not even imagine from whence the foe had come, whom Quasdanovich had encountered. That Napoleon would abandon all his accumulated stores and costly works at Mantua, was to them inconceivable. They hastened along with the utmost speed to reunite their forces, still forty thousand strong, at the foot of the lake. Napoleon also turned upon[Pg 723] his track, and urged his troops almost to the full run. The salvation of his army depended upon the rapidity of his march, enabling him to attack the separated divisions of the enemy before they should reunite at the foot of the mountain range which separated them. "Soldiers?" he exclaimed, in hurried accents, "it is with your legs alone that victory can now be secured. Fear nothing. In three days the Austrian army shall be destroyed. Rely only on me. You know whether or not I am in the habit of keeping my word."

Regardless of hunger, sleeplessness, and fatigue, unincumbered by baggage or provisions, with a celerity, which to the astonished Austrians seemed miraculous, he pressed on, with his exhausted, bleeding troops, all the afternoon and deep into the darkness of the ensuing night. He allowed his men at midnight to throw themselves upon the ground an hour for sleep, but he did not indulge himself in one moment of repose. Early in the morning of the 3d of August, Melas, who but a few hours before had heard the thunder of Napoleon's guns, over the mountains and upon the opposite shore of the lake, was astonished to see the solid columns of the whole French army marching majestically upon him. Five thousand of Wurmser's division had succeeded in joining him, and he consequently had twenty-five thousand fresh troops drawn up in battle array. Wurmser himself was at but a few hours' distance, and was hastening with all possible speed to his aid, with fifteen thousand additional men. Napoleon had but twenty-two thousand with whom to meet the forty thousand whom his foes would thus combine. Exhausted as his troops were with the Herculean toil they had already endured, not one moment could be allowed for rest. It was at Lonato, in a few glowing words he announced to his men their peril, the necessity for their utmost efforts, and his perfect confidence in their success. They now regarded their young leader as invincible, and wherever he led they were prompt to follow. With delirious energy, they rushed upon the foe. The pride of the Austrians was roused and they fought with desperation. The battle was long and bloody. Napoleon, as cool and unperturbed as if making the movements in a game of chess, watched the ebb and the flow of the conflict. His eagle eye instantly detected the point of weakness and exposure. The Austrians were routed and in wild disorder took to flight over the plains, leaving the ground covered with the dead, and five thousand prisoners and twenty pieces of cannon in the hands of the victors. Junot, with a regiment of cavalry, dashed at full gallop into the midst of the fugitives rushing over the plain, and the wretched victims of war were sabred by thousands and trampled under iron hoofs.

The battle raged until the sun disappeared behind the mountains of the Tyrol, and another night, dark and gloomy, came on. The groans of the wounded and of the dying, and the fearful shrieks of dismembered and mangled horses, struggling in their agony, filled the night air for leagues around. The French soldiers, utterly exhausted, threw themselves upon the gory ground by the side of the mutilated dead, the victor and the bloody corpse of the foe reposing side by side, and forgot the horrid butchery in leaden sleep. But Napoleon slept not. He knew that before the dawn of another morning, a still more formidable host would be arrayed against him, and that the victory of to-day might be followed by a dreadful defeat upon the morrow. The vanquished army were falling back to be supported by the division of Wurmser, coming to their rescue. All night long Napoleon was on horseback, galloping from post to post, making arrangements for the desperate battle to which he knew that the morning sun must guide him.

Four or five miles from Lonato, lies the small walled town of Castiglione. Here Wurmser met the retreating troops of Melas, and rallied them for a decisive conflict. With thirty thousand Austrians, drawn up in line of battle, he awaited the approach of his indefatigable foe. Long before the morning dawned, the French army was again in motion. Napoleon, urging his horse to the very utmost of his speed, rode in every direction to accelerate the movements of his troops. The peril was too imminent to allow him to intrust any one else with the execution of his all-important orders. Five horses successively sank dead beneath him from utter exhaustion. Napoleon was every where, observing all things, directing all things, animating all things. The whole army was inspired with the indomitable energy and ardor of their young leader. Soon the two hostile hosts were facing each other, in the dim and misty haze of the early dawn, ere the sun had arisen to look down upon the awful scene of man's depravity about to ensue.

A sanguinary and decisive conflict, renowned in history as the battle of Castiglione, inflicted the final blow upon the Austrians. They were routed with terrible slaughter. The French pursued them, with merciless massacre, through the whole day, in their headlong flight, and rested not until the darkness of night shut out the panting, bleeding fugitives from their view. Less than one week had elapsed since that proud army, sixty thousand strong, had marched from the walls of Trent, with gleaming banners and triumphant music, flushed with anticipated victory. In six days it had lost in killed, wounded, and prisoners forty thousand men, ten thousand more than the whole army which Napoleon had at his command. But twenty thousand tattered, exhausted, war-worn fugitives effected their escape. In the extreme of mortification and dejection they returned to Trent, to bear themselves the tidings of their swift and utter discomfiture. Napoleon, in these conflicts, lost but seven thousand men. These amazing victories were to be attributed entirely to the genius of the conqueror. Such achievements history had never before recorded. The victorious soldiers called it, "The six days' campaign." Their admiration of their[Pg 724] invincible chief now passed all bounds. The veterans who had honored Napoleon with the title of corporal, after "the terrible passage of the bridge of Lodi," now enthusiastically promoted him to the rank of sergeant, as his reward for the signal victories of this campaign.

The aristocratic governments which, upon the marching of Wurmser from Trent, had perfidiously violated their faith, and turned against Napoleon, supposing that he was ruined, were now terror-stricken, anticipating the most appalling vengeance. But the conqueror treated them with the greatest clemency, simply informing them that he was fully acquainted with their conduct, and that he should hereafter regard them with a watchful eye. He, however, summoned Cardinal Mattei, the legate of the perjured Pope, to his head-quarters. The cardinal, conscious that not a word could be uttered in extenuation of his guilt, attempted no defense. The old man, high in authority and venerable in years, bowed with the humility of a child before the young victor, and exclaimed "peccavi! peccavi!"—I have sinned! I have sinned! This apparent contrition disarmed Napoleon, and in jocose and contemptuous indignation he sentenced him to do penance for three months, by fasting and prayer, in a convent.

During these turmoils, the inhabitants of Lombardy remained faithful in their adherence to the French interests. In a delicate and noble letter which he addressed to them, he said, "When the French army retreated, and the partisans of Austria considered that the cause of liberty was crushed, you, though you knew not that this retreat was merely a stratagem, still proved constant in your attachment to France and your love of freedom. You have thus deserved the esteem of the French nation. Your people daily become more worthy of liberty, and will shortly appear with glory on the theatre of the world. Accept the assurance of my satisfaction, and of the sincere wishes of the French people to see you free and happy."

In the midst of the tumultuous scenes of these days of incessant battle, when the broken divisions of the enemy were in bewilderment, wandering in every direction, attempting to escape from the terrible energy with which they were pursued, Napoleon, by mere accident, came very near being taken a prisoner. He escaped by that intuitive tact and promptness of decision which never deserted him. In conducting the operations of the pursuit, he had entered a small village, upon the full gallop, accompanied only by his staff and guards. A division of four thousand of the Austrian army, separated from the main body, had been wandering all night among the mountains. They came suddenly and unexpectedly upon this little band of a thousand men, and immediately sent an officer with a flag of truce, demanding their surrender. Napoleon, with wonderful presence of mind, commanded his numerous staff immediately to mount on horseback, and gathering his guard around him, ordered the flag of truce to be brought into his presence. The officer was introduced, as is customary, blindfolded. When the bandage was removed, to his utter amazement he found himself before the commander-in-chief of the French army, surrounded by his whole brilliant staff. "What means this insult?" exclaimed Napoleon in tones of affected indignation. "Have you the insolence to bring a summons of surrender to the French commander-in-chief, in the middle of his army! Say to those who sent you, that unless in five minutes they lay down their arms, every man shall be put to death." The bewildered officer stammered out an apology. "Go!" Napoleon sternly rejoined, "unless you immediately surrender at discretion, I will, for this insult, cause every man of you to be shot." The Austrians, deceived by this air of confidence, and disheartened by fatigue and disaster, threw down their arms. They soon had the mortification of learning that they had capitulated to one-fourth of their own number, and that they had missed making prisoner the conqueror, before whose blows the very throne of their empire was trembling.

It was during this campaign that one night Napoleon, in disguise, was going the rounds of the sentinels, to ascertain if, in their peculiar peril, proper vigilance was exercised. A soldier, stationed at the junction of two roads, had received orders not to let any one pass either of those routes. When Napoleon made his appearance, the soldier, unconscious of his rank, presented his bayonet and ordered him back. "I am a general officer," said Napoleon, "going the rounds to ascertain if all is safe." "I care not," the soldier replied, "my commands are to let no one go by; and if you were the Little Corporal himself you should not pass." The general was consequently under the necessity of retracing his steps. The next day he made inquiries respecting the character of the soldier, and hearing a good report of him, he summoned him to his presence, and extolling his fidelity, raised him to the rank of an officer.

THE LITTLE CORPORAL AND THE SENTINEL

Napoleon and his victorious army again returned to Mantua. The besieged, during his absence, had emerged from the walls and destroyed all his works. They had also drawn all his heavy battering train, consisting of one hundred and forty pieces, into the city, obtained large supplies of provisions, over sixty thousand shot and shells, and had received a reinforcement of fifteen thousand men. There was no suitable siege equipage which Napoleon could command, and he was liable at any moment to be again summoned to encounter the formidable legions which the Austrian empire could again raise to crowd down upon him. He therefore simply invested the place by blockade. After the terrible struggle through which they had just passed, the troops, on both sides, indulged themselves in repose for three weeks. The Austrian government, with inflexible resolution, still refused to make peace with France. It had virtually inserted upon its banners, "Gallia delenda est"—"The French Republic shall be destroyed." Napoleon[Pg 725] had now cut up two of their most formidable armies, each of them nearly three times as numerous as his own.

The pride and the energy of the whole empire were aroused in organizing a third army to crush republicanism. In the course of three weeks Wurmser found himself again in command of fifty-five thousand men at Trent. There were twenty thousand troops in Mantua, giving him a force of seventy-five thousand combatants. Napoleon had received reinforcements only sufficient to repair his losses, and was again in the field with but thirty thousand men. He was surrounded by more than double that number of foes.

Early in September the Austrian army was again in motion, passing down from the Tyrol for the relief of Mantua. Wurmser left Davidovich at Roveredo, a very strong position, about ten miles south of Trent, with twenty-five thousand men to prevent the incursions of the French into the Tyrol. With thirty thousand men he then passed over to the valley of the Brenta, to follow down its narrow defile, and convey relief to the besieged fortress. There were twenty thousand Austrians in Mantua. These, co-operating with the thirty thousand under Wurmser, would make an effective force of fifty thousand men to attack Napoleon in front and rear.

Napoleon contemplated with lively satisfaction this renewed division of the Austrian force. He quietly collected all his resources, and prepared for a deadly spring upon the doomed division left behind. As soon as Wurmser had arrived at Bassano, following down the valley of the Brenta, about sixty miles from Roveredo, where it was impossible for him to render any assistance to the victims upon whom Napoleon was about to pounce, the whole French army was put in motion. They rushed, at double quick step, up the parallel valley of the Adige, delaying hardly one moment either for food or repose. Early on the morning of the 4th of September, just as the first gray of dawn appeared in the east, he burst like a tempest upon the astounded foe. The battle was short, bloody, decisive. The Austrians were routed with dreadful slaughter. As they fled in consternation, a rabble-rout, the French cavalry rushed in among them, with dripping sabres, and for leagues the ground was covered with the bodies of the slain. Seven thousand prisoners and twenty pieces of cannon graced the triumph of the victor. The discomfited remains of this unfortunate corps retired far back into the gorges of the mountains. Such was the battle of Roveredo, which Napoleon ever regarded as one of his most brilliant victories. Next morning Napoleon, in triumph, entered Trent. He immediately issued one of his glowing proclamations to the inhabitants of the Tyrol, assuring them that he was fighting, not for conquest, but for peace; that he was not the enemy of the people of the Tyrol; that the Emperor of Austria, incited and aided by British gold, was waging relentless warfare against the French Republic; and that, if the inhabitants of the Tyrol would not take up arms against him, they should be protected in their persons, their property, and in all their political rights. He invited the people, in the emergence, to arrange for themselves the internal government of the country, and intrusted them with the administration of their own laws.

Before the darkness of the ensuing night had passed away Napoleon was again at the head of his troops, and the whole French army was rushing down the defiles of the Brenta, to surprise Wurmser in his straggling march. The Aus[Pg 726]trian general had thirty thousand men. Napoleon could take with him but twenty thousand. He, however, was intent upon gaining a corresponding advantage in falling upon the enemy by surprise. The march of sixty miles was accomplished with a rapidity such as no army had ever attempted before. On the evening of the 6th, Wurmser heard with consternation that the corps of Davidovich was annihilated. He was awoke from his slumbers before the dawn of the next morning by the thunders of Napoleon's cannon in his rear. The brave old veteran, bewildered by tactics so strange and unheard of, accumulated his army as rapidly as possible in battle array at Bassano. Napoleon allowed him but a few moments for preparation. The troops on both sides now began to feel that Napoleon was invincible. The French were elated by constant victory. The Austrians were disheartened by uniform and uninterrupted defeat. The battle at Bassano was but a renewal of the sanguinary scene at Roveredo. The sun went down as the horrid carnage continued, and darkness vailed the awful spectacle from human eyes. Horses and men, the mangled, the dying, the dead, in indiscriminate confusion were piled upon each other. The groans of the wounded swelled upon the night air; while in the distance the deep booming of the cannon of the pursuers and the pursued echoed along the mountains. There was no time to attend to the claims of humanity. The dead were left unburied, and not a combatant could be spared from the ranks to give a cup of water to the wounded and the dying. Destruction, not salvation was the business of the hour.

Wurmser, with but sixteen thousand men remaining to him of the proud array of fifty-five thousand with which, but a few days before, he had marched from Trent, retreated to find shelter within the walls of Mantua. Napoleon pursued him with the most terrible energy, from every eminence plunging cannon-balls into his retreating ranks. When Wurmser arrived at Mantua the garrison sallied out to aid him. Unitedly they fell upon Napoleon. The battle of St. George was fought, desperate and most bloody. The Austrians, routed at every point, were driven within the walls. Napoleon resumed the siege. Wurmser, with the bleeding fragment of his army, was held a close prisoner. Thus terminated this campaign of ten days. In this short time Napoleon had destroyed a third Austrian army, more than twice as numerous as his own. The field was swept clean of his enemies. Not a man was left to oppose him. Victories so amazing excited astonishment throughout all Europe. Such results had never before been recorded in the annals of ancient or modern warfare.

While engaged in the rapid march from Roveredo, a discontented soldier, emerging from the ranks, addressed Napoleon, pointing to his tattered garments, and said, "We soldiers, notwithstanding all our victories, are clothed in rags." Napoleon, anxious to arrest the progress of discontent among his troops, with that peculiar tact which he had ever at command, looked kindly upon him and said, "You forget, my brave friend, that with a new coat, your honorable scars would no longer be visible." This well timed compliment was received with shouts of applause from the ranks. The anecdote spread like lightning among the troops, and endeared Napoleon still more to every soldier in the army.

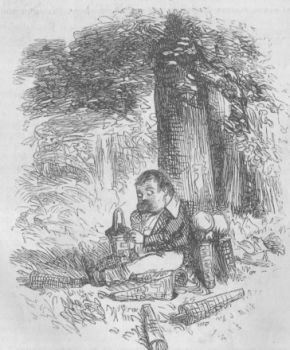

THE SOLITARY BIVOUAC

The night before the battle of Bassano, in the eagerness of the march, Napoleon had advanced far beyond the main column of the army. He had received no food during the day, and had enjoyed no sleep for several nights. A poor[Pg 727] soldier had a crust of bread in his knapsack. He broke it in two, and gave his exhausted and half famished general one half. After this frugal supper, the commander-in-chief of the French army wrapt himself in his cloak, and threw himself unprotected upon the ground, by the side of the soldier, for an hour's slumber. After ten years had passed away, and Napoleon, then Emperor of France, was making a triumphal tour through Belgium, this same soldier stepped out from the ranks of a regiment, which the emperor was reviewing, and said, "Sire! on the eve of the battle of Bassano, I shared with you my crust of bread, when you were hungry. I now ask from you bread for my father, who is worn down with age and poverty." Napoleon immediately settled a pension upon the old man, and promoted the soldier to a lieutenancy.

After the battle of Bassano, in the impetuosity of the pursuit, Napoleon, spurring his horse to his utmost speed, accompanied but by a few followers, entered a small village quite in advance of the main body of his army. Suddenly Wurmser, with a strong division of the Austrians, debouched upon the plain. A peasant woman informed him that but a moment before Napoleon had passed her cottage. Wurmser, overjoyed at the prospect of obtaining a prize which would remunerate him for all his losses, instantly dispatched parties of cavalry in every direction for his capture. So sure was he of success, that he strictly enjoined it upon them to bring him in alive. The fleetness of Napoleon's horse saved him.

In the midst of these terrible conflicts, when the army needed every possible stimulus to exertion, Napoleon exposed himself like a common soldier, at every point where danger appeared most imminent. On one of these occasions a pioneer, perceiving the imminent peril in which the commander-in-chief had placed himself, abruptly and authoritively exclaimed to him, "Stand aside." Napoleon fixed his keen glance upon him, when the veteran with a strong arm thrust him away, saying, "If thou art killed who is to rescue us from this jeopardy?" and placed his own body before him. Napoleon appreciated the sterling value of the action, and uttered no reproof. After the battle he ordered the pioneer to be sent to his presence. Placing his hand kindly upon his shoulder he said, "My friend! your noble boldness claims my esteem. Your bravery demands a recompense. From this hour an epaulet instead of a hatchet shall grace your shoulder." He was immediately raised to the rank of an officer.

The generals in the army were overawed by the genius and the magnanimity of their young commander. They fully appreciated his vast superiority, and approached him with restraint and reverence. The common soldiers, however, loved him as a father, and went to him freely, with the familiarity of children. In one of those terrific battles, when the result had been long in suspense, just as the searching glance of Napoleon had detected a fault in the movements of the enemy, of which he was upon the point of taking the most prompt advantage, a private soldier, covered with the dust and the smoke of the battle, sprung from the ranks and exclaimed, "General! send a squadron there, and the victory is ours." "You rogue!" rejoined Napoleon, "where did you get my secret?" In a few moments the Austrians were flying in dismay before the impetuous charges of the French cavalry. Immediately after the battle Napoleon sent for the soldier who had displayed such military genius. He was found dead upon the field. A bullet had pierced his brain. Had he lived he would but have added another star to that brilliant galaxy, with which the throne of Napoleon was embellished.

"Perhaps in that neglected spot is laid,

A heart once pregnant with celestial fire,

Hands which the rod of empire might have swayed.

Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre."

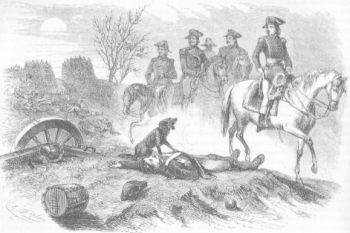

The night after the battle of Bassano, the moon rose cloudless and brilliant over the sanguinary scene. Napoleon, who seldom exhibited any hilarity or even exhilaration of spirits in the hour of victory, rode, as was his custom, over the plain, covered with the bodies of the dying and the dead, and, silent and thoughtful, seemed lost in painful reverie. It was midnight. The confusion and the uproar of the battle had passed away, and the deep silence of the calm starlight night was only disturbed by the moans of the wounded and the dying. Suddenly a dog sprung from beneath the cloak of his dead master, and rushed to Napoleon, as if frantically imploring his aid, and then rushed back again to the mangled corpse, licking the blood from the face and the hands, and howling most piteously. Napoleon was deeply moved by the affecting scene, and involuntarily stopped his horse to contemplate it. In relating the event, many years afterward, he remarked, "I know not how it was, but no incident upon any field of battle ever produced so deep an impression upon my feelings. This man, thought I, must have had among his comrades friends; and yet here he lies forsaken by all except his faithful dog. What a strange being is man! How mysterious are his impressions! I had, without emotion, ordered battles which had decided the fate of armies. I had, with tearless eyes, beheld the execution of those orders, in which thousands of my countrymen were slain. And yet here my sympathies were most deeply and resistlessly moved by the mournful howling of a dog. Certainly in that moment I should have been unable to refuse any request to a suppliant enemy."

THE DEAD SOLDIER AND HIS DOG.

Austria was still unsubdued. With a perseverance worthy of all admiration, had it been exercised in a better cause, the Austrian government still refused to make peace with republican France. The energies of the empire were aroused anew to raise a fourth army. England, contending against France wherever her navy or her troops could penetrate, was the soul of this warfare. She animated the cabinet of Vienna, and aided the Austrian armies with her strong[Pg 728] co-operation and her gold. The people of England, republican in their tendencies, and hating the utter despotism of the old monarchy of France, were clamorous for peace. But the royal family and the aristocracy in general, were extremely unwilling to come to any amicable terms with a nation which had been guilty of the crime of renouncing monarchy.

All the resources of the Austrian government were now devoted to recruiting and equipping a new army. With the wrecks of Wurmser's troops, with detachments from the Rhine, and fresh levies from the bold peasants of the Tyrol, in less than a month an army of nearly one hundred thousand men was assembled. The enthusiasm throughout Austria, in raising and animating these recruits, was so great that the city of Vienna alone contributed four battalions. The empress, with her own hand, embroidered their colors and presented them to the troops. All the noble ladies of the realm devoted their smiles and their aid to inspire the enterprise. About seventy-five thousand men were rendezvoused in the gorges of the northern Tyrol, ready to press down upon Napoleon from the north, while the determined garrison of twenty-five thousand men, under the brave Wurmser, cooped up in Mantua, were ready to emerge at a moment's warning. Thus in about three weeks another army of one hundred thousand men was ready to fall upon Napoleon. His situation now seemed absolutely desperate. The reinforcements he had received from France had been barely sufficient to repair the losses sustained by disease and the sword. He had but thirty thousand men. His funds were all exhausted. His troops, notwithstanding they were in the midst of the most brilliant blaze of victories, had been compelled to strain every nerve of exertion. They were also suffering the severest privations, and began loudly to murmur. "Why," they exclaimed, "do we not receive succor from France? We can not alone contend against all Europe. We have already destroyed three armies, and now a fourth, still more numerous, is rising against us. Is there to be no end to these interminable battles?" Napoleon was fully sensible of the peril of his position, and while he allowed his troops a few weeks of repose, his energies were strained to their very utmost tension in preparing for the all but desperate encounter now before him. The friends and the enemies of Napoleon alike regarded his case as nearly hopeless. The Austrians had by this time learned that it was not safe to divide their forces in the presence of so vigilant a foe. Marching down upon his exhausted band with seventy-five thousand men to attack him in front, and with twenty-five thousand veteran troops, under the brave Wurmser, to sally from the ramparts of Mantua and assail him in the rear, it seemed to all reasonable calculation that the doom of the French army was sealed. Napoleon in the presence of his army assumed an air of most perfect confidence, but he was fearfully apprehensive that, by the power of overwhelming numbers, his army would be destroyed. The appeal which, under the circumstances, he wrote to the Directory for reinforcements, is sublime in its dignity and its eloquence. "All of our superior officers, all of our best generals, are either dead or wounded. The army of Italy, reduced to a handful of men, is exhausted. The heroes of Millesimo, of Lodi, of Castiglione, of Bassano, have died for their country, or are in the hospitals. Nothing is left to the army but its glory and its courage. We are abandoned at the extremity of Italy. The brave men who are left me have no prospect but[Pg 729] inevitable death amidst changes so continual and with forces so inferior. Perhaps the hour of the brave Augereau, of the intrepid Massena is about to strike. This consideration renders me cautious. I dare not brave death when it would so certainly be the ruin of those who have so long been the object of my solicitude. The army has done its duty. I do mine. My conscience is at ease, but my soul is lacerated. I never have received a fourth part of the succors which the minister of war has announced in his dispatches. My health is so broken that I can with difficulty sit upon horseback. The enemy can now count our diminished ranks. Nothing is left me but courage. But that alone is not sufficient for the post which I occupy. Troops, or Italy is lost."

Napoleon addressed his soldiers in a very different strain, endeavoring to animate their courage by concealing from them his anxieties. "We have but one more effort to make," said he, "and Italy is our own. True, the enemy is more numerous than we; but half his troops are recruits, who can never stand before the veterans of France. When Alvinzi is beaten Mantua must fall, and our labors are at an end. Not only Italy, but a general peace is to be gained by the capture of Mantua."

During the three weeks in which the Austrians were recruiting their army and the French were reposing around the walls of Mantua, Napoleon made the most Herculean exertions to strengthen his position in Italy, and to disarm those states which were manifesting hostility against him. During this period his labors as a statesman and a diplomatist were even more severe than his toils as a general. He allowed himself no stated time for food or repose, but day and night devoted himself incessantly to his work. Horse after horse sunk beneath him, in the impetuous speed with which he passed from place to place. He dictated innumerable communications to the Directory, respecting treaties of peace with Rome, Naples, Venice, Genoa. He despised the feeble Directory, with its shallow views, conscious that unless wiser counsels than they proposed should prevail, the republic would be ruined. "So long," said he, "as your general shall not be the centre of all influence in Italy, every thing will go wrong. It would be easy to accuse me of ambition, but I am satiated with honor and worn down with care. Peace with Naples is indispensable. You must conciliate Venice and Genoa. The influence of Rome is incalculable. You did wrong to break with that power. We must secure friends for the Italian army, both among kings and people. The general in Italy must be the fountain-head of negotiation as well as of military operations." These were bold assumptions for a young man of twenty-five. But Napoleon was conscious of his power. He now listened to the earnest entreaties of the people of the duchy of Modena and of the papal states of Bologna and Ferrara, and, in consequence of treachery on the part of the Duke of Modena and the Pope, emancipated those states and constituted them into a united and independent Republic. As the whole territory included under this new government extended south of the Po, Napoleon named it the Cispadane Republic, that is the This side of the Po Republic. It contained about a million and a half of inhabitants, compactly gathered in one of the most rich, and fertile, and beautiful regions of the globe. The joy and the enthusiasm of the people, thus blessed with a free government, surpassed all bounds. Wherever Napoleon appeared he was greeted with every demonstration of affection. He assembled at Modena a convention, composed of lawyers, landed proprietors, and merchants to organize the government. All leaned upon the mind of Napoleon, and he guided their counsels with the most consummate wisdom. Napoleon's abhorrence of the anarchy which had disgraced the Jacobin reign in France, and his reverence for law were made very prominent on this occasion. "Never forget," said he in an address to the Assembly, "that laws are mere nullities without the necessary force to sustain them. Attend to your military organization, which you have the means of placing upon a respectable footing. You will then be more fortunate than the people of France. You will attain liberty without passing through the ordeal of revolution."

The Italians were an effeminate people and quite unable to cope in arms with the French or the Austrians. Yet the new republic manifested its zeal and attachment for its youthful founder so strongly, that a detachment of Austrians having made a sally from Mantua, they immediately sprang to arms, took it prisoner, and conducted it in triumph to Napoleon. When the Austrians saw that Napoleon was endeavoring to make soldiers of the Italians, they ridiculed the idea, saying that they had tried the experiment in vain, and that it was not possible for an Italian to make a good soldier. "Notwithstanding this," said Napoleon, "I raised many thousands of Italians, who fought with a bravery equal to that of the French, and who did not desert me even in my adversity. What was the cause? I abolished flogging. Instead of the lash I introduced the stimulus of honor. Whatever debases a man can not be serviceable. What honor can a man possibly have who is flogged before his comrades. When a soldier has been debased by stripes he cares little for his own reputation or for the honor of his country. After an action I assembled the officers and soldiers and inquired who had proved themselves heroes. Such of them as were able to read and write I promoted. Those who were not I ordered to study five hours a day, until they had learned a sufficiency, and then promoted them. Thus I substituted honor and emulation for terror and the lash."

He bound the Duke of Parma and the Duke of Tuscany to him by ties of friendship. He cheered the inhabitants of Lombardy with the hope, that as soon as extricated from his present embarrassments, he would do something for the promotion of their independence. Thus with the skill of a veteran diplomatist he raised around[Pg 730] him friendly governments, and availed himself of all the resources of politics to make amends for the inefficiency of the Directory. Never was a man placed in a situation where more delicacy of tact was necessary. The Republican party in all the Italian states were clamorous for the support of Napoleon, and waited but his permission to raise the standard of revolt. Had the slightest encouragement been given the whole peninsula would have plunged into the horrors of civil war; and the awful scenes which had been enacted in Paris would have been re-enacted in every city in Italy. The aristocratic party would have been roused to perfect desperation, and the situation of Napoleon would have been still more precarious. It required consummate genius as a statesman, and moral courage of the highest order, to wield such opposing influences. But the greatness of Napoleon shone forth even more brilliantly in the cabinet than in the field. The course which he had pursued had made him extremely popular with the Italians. They regarded him as their countryman. They were proud of his fame. He was driving from their territory the haughty Austrians whom they hated. He was the enemy of despots, the friend of the people. Their own beautiful language was his mother tongue. He was familiar with their manners and customs, and they felt flattered by his high appreciation of their literature and arts.

Napoleon, in the midst of these stormy scenes, also dispatched an armament from Leghorn, to wrest his native island of Corsica from the dominion of the English. Scott, in allusion to the fact that Napoleon never manifested any special attachment for the obscure island of his birth, beautifully says, "He was like the young lion, who, while he is scattering the herds and destroying the hunters, thinks little of the forest cave in which he first saw the light." But at St. Helena Napoleon said, and few will read his remarks without emotion, "What recollections of childhood crowd upon my memory, when my thoughts are no longer occupied with political subjects, or with the insults of my jailer upon this rock. I am carried back to my first impressions of the life of man. It seems to me always in these moments of calm, that I should have been the happiest man in the world, with an income of twenty-five hundred dollars a year, living as the father of a family, with my wife and son, in our old house at Ajaccio. You, Montholon, remember its beautiful situation. You have often despoiled it of its finest bunches of grapes, when you ran off with Pauline to satisfy your childish appetite. Happy hours! The natal soil has infinite charms. Memory embellishes it with all its attractions, even to the very odor of the ground, which one can so realize to the senses, as to be able with the eyes shut, to tell the spot first trodden by the foot of childhood. I still remember with emotion the most minute details of a journey in which I accompanied Paoli. More than five hundred of us, young persons of the first families in the island, formed his guard of honor. I felt proud of walking by his side, and he appeared to take pleasure in pointing out to me, with paternal affection, the passes of our mountains which had been witnesses of the heroic struggle of our countrymen for independence. The impression made upon me still vibrates in my heart. Come, place your hand," said he to Montholon, "upon my bosom! See how it beats!" "And it was true," Montholon remarks, "his heart did beat with such rapidity as would have excited my astonishment, had I not been acquainted with his organization, and with the kind of electric commotion which his thoughts communicated to his whole being." "It is like the sound of a church bell," continued Napoleon. "There is none upon this rock. I am no longer accustomed to hear it. But the tones of a bell never fall upon my ear without awakening within me the emotions of childhood. The Angelus bell transported me back to pensive yet pleasant memories, when in the midst of earnest thoughts and burdened with the weight of an imperial crown, I heard its first sounds under the shady woods of St. Cloud. And often have I been supposed to have been revolving the plan of a campaign or digesting an imperial law, when my thoughts were wholly absorbed in dwelling upon the first impressions of my youth. Religion is in fact the dominion of the soul. It is the hope of life, the anchor of safety, the deliverance from evil. What a service has Christianity rendered to humanity! What a power would it still have, did its ministers comprehend their mission."

Early in November the Austrians commenced their march. The cold winds of winter were sweeping through the defiles of the Tyrol, and the summits of the mountains were white with snow. But it was impossible to postpone operations; for unless Wurmser were immediately relieved Mantua must fall, and with it would fall all hopes of Austrian dominion in Italy. The hardy old soldier had killed all his horses, and salted them down for provisions; but even that coarse fare was nearly exhausted, and he had succeeded in sending word to Alvinzi that he could not possibly hold out more than six weeks longer. Napoleon, the moment he heard that the Austrians were on the move, hastened to the head-quarters of the army at Verona. He had stationed General Vaubois, with twelve thousand men, a few miles north of Trent, in a narrow defile among the mountains to watch the Austrians, and to arrest their first advances. Vaubois and his division, overwhelmed by numbers, retreated, and thus vastly magnified the peril of the army. The moment Napoleon received the disastrous intelligence, he hastened, with such troops as he could collect, like the sweep of the wind, to rally the retreating forces and check the progress of the enemy. And here he singularly displayed that thorough knowledge of human nature which enabled him so effectually to control and to inspire his army. Deeming it necessary, in his present peril, that every man should be a hero, and that every regiment[Pg 731] should be nerved by the determination to conquer or to die, he resolved to make a severe example of those whose panic had proved so nearly fatal to the army. Like a whirlwind, surrounded by his staff, he swept into the camp, and ordered immediately the troops to be collected in a circle around him. He sat upon his horse, and every eye was fixed upon the pale and wan, and wasted features of their young and adored general. With a stern and saddened voice he exclaimed, "Soldiers! I am displeased with you. You have evinced neither discipline nor valor. You have allowed yourselves to be driven from positions where a handful of resolute men might have arrested an army. You are no longer French soldiers! Chief of the staff, cause it to be written on their standards, They are no longer of the army of Italy."

The influence of these words upon those impassioned men, proud of their renown and proud of their leader, was almost inconceivable. The terrible rebuke fell upon them like a thunderbolt. Tears trickled down the cheeks of these battered veterans. Many of them actually groaned aloud in their anguish. The laws of discipline could not restrain the grief which burst from their ranks. They broke their array, crowded around the general, exclaiming, "we have been misrepresented; the enemy were three to our one; try us once more; place us in the post of danger, and see if we do not belong to the army of Italy!" Napoleon relented, and spoke kindly to them, promising to afford them an early opportunity to retrieve their reputation. In the next battle he placed them in the van. Contending against fearful odds they accomplished all that mortal valor could accomplish, rolling back upon the Austrians the tide of victory. Such was the discipline of Napoleon. He needed no blood-stained lash to scar the naked backs of his men. He ruled over mind. His empire was in the soul. "My soldiers," said he "are my children." The effect of this rebuke was incalculable. There was not an officer or a soldier in the army who was not moved by it. It came exactly at the right moment, when it was necessary that every man in the army should be inspired with absolute desperation of valor.

Alvinzi sent a peasant across the country to carry dispatches to Wurmser in the beleaguered city. The information of approaching relief was written upon very thin paper, in a minute hand, and inclosed in a ball of wax, not much larger than a pea. The spy was intercepted. He was seen to swallow the ball. The stomach was compelled to surrender its trust, and Napoleon became acquainted with Alvinzi's plan of operation. He left ten thousand men around the walls of Mantua, to continue the blockade, and assembled the rest of his army, consisting only of fifteen thousand, in the vicinity of Verona. The whole valley of the Adige was now swarming with the Austrian battalions. At night the wide horizon seemed illuminated with the blaze of their camp fires. The Austrians, conscious of their vast superiority in numbers, were hastening to envelop the French. Already forty thousand men were circling around the little band of fifteen thousand who were rallied under the eagles of France. The Austrians, wary in consequence of their past defeats, moved with the utmost caution, taking possession of the most commanding positions. Napoleon, with sleepless vigilance, watched for some exposed point, but in vain. The soldiers understood the true posture of affairs, and began to feel disheartened, for their situation was apparently desperate. The peril of the army was so great, that even the sick and the wounded in the hospitals at Milan, Pavia, and Lodi, voluntarily left their beds and hastened, emaciate with suffering, and many of them with their wounds still bleeding, to resume their station in the ranks. The soldiers were deeply moved by this affecting spectacle, so indicative of their fearful peril and of the devotion of their comrades to the interests of the army. Napoleon resolved to give battle immediately, before the Austrians should accumulate in still greater numbers.

A dark, cold winter's storm was deluging the ground with rain, as Napoleon roused his troops from the drenched sods upon which they were slumbering. The morning had not yet dawned through the surcharged clouds, and the freezing wind, like a tornado, swept the bleak hills. It was an awful hour in which to go forth to encounter mutilation and death. The enterprise was desperate. Fifteen thousand Frenchmen, with frenzied violence, were to hurl themselves upon the serried ranks of forty thousand foes. The horrid carnage soon began. The roar of the battle, the shout of onset, and the shriek of the dying, mingled in midnight gloom, with the appalling rush and wail of the tempest. The ground was so saturated with rain that it was almost impossible for the French to drag their cannon through the miry ruts. As the darkness of night passed and the dismal light of a stormy day was spread around them, the rain changed to snow, and the struggling French were smothered and blinded by the storm of sleet whirled furiously into their faces. Through the live-long day this terrific battle of man and of the elements raged unabated. When night came the exhausted soldiers, drenched with rain and benumbed with cold, threw themselves upon the blood-stained snow, in the midst of the dying and of the dead. Neither party claimed the victory, and neither acknowledged defeat. No pen can describe, nor can imagination conceive, the horrors of the dark and wailing night of storm and sleet which ensued. Through the long hours the groans of the wounded, scattered over many miles swept by the battle, blended in mournful unison with the wailings of the tempest. Two thousand of Napoleon's little band were left dead upon the field, and a still larger number of Austrian corpses were covered with the winding-sheet of snow. Many a blood-stained drift indicated the long and agonizing struggle of the wounded ere the motionlessness of death[Pg 732] consummated the dreadful tragedy. It is hard to die even in the curtained chambers of our ceiled houses, with sympathizing friends administering every possible alleviation. Cold must have been those pillows of snow, and unspeakably dreadful the solitude of those death scenes, on the bleak hill sides and in the muddy ravines, where thousands of the young, the hopeful, the sanguine, in horrid mutilation, struggled through the long hours of the tempestuous night in the agonies of dissolution. Many of these young men were from the first families in Austria and in France, and had been accustomed to every indulgence. Far from mother, sister, brother, drenched with rain, covered with the drifting snow, alone—all alone with the midnight darkness and the storm—they writhed and moaned through lingering hours of agony.

The Austrian forces still were accumulating, and the next day Napoleon retired within the walls of Verona. It was the first time he had seemed to retreat before his foes. His star began to wane. The soldiers were silent and dejected. An ignominious retreat after all their victories, or a still more ignominious surrender to the Austrians appeared their only alternative. Night again came. The storm had passed away. The moon rose clear and cold over the frozen hills. Suddenly the order was proclaimed, in the early darkness, for the whole army, in silence and celerity, to be upon the march. Grief sat upon every countenance. The western gates of the city, looking toward France were thrown open. The rumbling of the artillery wheels, and the sullen tramp of the dejected soldiers fell heavily upon the night air. Not a word was spoken. Rapidly the army emerged from the gates, crossed the river, and pressed along the road toward France, leaving their foes slumbering behind them, unconscious of their flight. The depression of the soldiers thus compelled at last, as they supposed, to retreat, was extreme. Suddenly, and to the perplexity of all, Napoleon wheeled his columns into another road, which followed down the valley of the Adige. No one could imagine whither he was leading them. He hastened along the banks of the river, in most rapid march, about fourteen miles, and, just at midnight, recrossed the stream, and came upon the rear of the Austrian army. Here the soldiers found a vast morass, many miles in extent, traversed by several narrow causeways, in these immense marshes superiority in number was of little avail, as the heads of the column only could meet. The plan of Napoleon instantly flashed upon the minds of the intelligent French soldiers. They appreciated at once the advantage he had thus skillfully secured for them. Shouts of joy ran through the ranks. Their previous dejection was succeeded by corresponding elation.

It was midnight. Far and wide along the horizon blazed the fires of the Austrian camps, while the French were in perfect darkness. Napoleon, emaciate with care and toil, and silent in intensity of thought, as calm and unperturbed as the clear, cold, serene winter's night, stood upon an eminence observing the position, and estimating the strength of his foes. He had but thirteen thousand troops. Forty thousand Austrians, crowding the hill sides with their vast array, were manœuvring to envelop and to crush him. But now indescribable enthusiasm animated the French army. They no longer doubted of success. Every man felt confident that the Little Corporal was leading them again to a glorious victory.

In the centre of these wide spreading morasses was the village of Arcola, approached only by narrow dykes and protected by a stream, crossed by a small wooden bridge. A strong division of the Austrian army was stationed here. It was of the first importance that this position should be taken from the enemy. Before the break of day the solid columns of Napoleon were moving along the narrow passages, and the fierce strife commenced. The soldiers, with loud shouts, rushed upon the bridge. In an instant the whole head of the column was swept away by a volcanic burst of fire. Napoleon sprung from his horse, seized a standard, and shouted, "Conquerors of Lodi, follow your general!" He rushed at the head of the column, leading his impetuous troops through a perfect hurricane of balls and bullets, till he arrived at the centre of the bridge. Here the tempest of fire was so dreadful that all were thrown into confusion. Clouds of smoke enveloped the bridge in almost midnight darkness. The soldiers recoiled, and trampling over the dead and dying, in wild disorder retreated. The tall grenadiers seized the fragile and wasted form of Napoleon in their arms as if he had been a child, and regardless of their own danger, dragged him from the mouth of this terrible battery. But in the tumult they were forced over the dyke, and Napoleon was plunged into the morass and was left almost smothered in the mire. The Austrians were already between Napoleon and his column, when the anxious soldiers perceived, in the midst of the darkness and the tumult, that their beloved chief was missing. The wild cry arose, "Forward to save your general." Every heart thrilled at this cry. The whole column instantly turned, and regardless of death, inspired by love for their general, rushed impetuously, irresistibly upon the bridge. Napoleon was extricated and Arcola was taken.

THE MARSHES OF ARCOLA.

As soon as the morning dawned, Alvinzi perceived that Verona was evacuated, and in astonishment he heard the thunder of Napoleon's guns reverberating over the marshes which surrounded Arcola. He feared the genius of his adversary, and his whole army was immediately in motion. All day long the battle raged on those narrow causeways, the heads of the columns rushing against each other with indescribable fury, and the dead and the dying filling the morass. The terrible rebuke which had been inflicted upon the division of Vaubois still rung in the ears of the French troops, and every officer and every man resolved to prove that he belonged to[Pg 733] the army of Italy. Said Augereau, as he rushed into the mouth of a perfect volcano of flame and fire, "Napoleon may break my sword over my dead body, but he shall never cashier me in the presence of my troops." Napoleon was every where, exposed to every danger, now struggling through the dead and the dying on foot, heading the impetuous charge; now galloping over the dykes, with the balls from the Austrian batteries plowing the ground around him. Wherever his voice was heard, and his eye fell, tenfold enthusiasm inspired his men. Lannes, though severely wounded, had hastened from the hospital at Milan, to aid the army in this terrible emergence. He received three wounds in endeavoring to protect Napoleon, and never left his side till the battle was closed. Muiron, another of those gallant spirits, bound to Napoleon by those mysterious ties of affection which this strange man inspired, seeing a bomb shell about to explode, threw himself between it and Napoleon, saving the life of his beloved general by the sacrifice of his own. The darkness of night separated the combatants for a few hours, but before the dawn of the morning the murderous assault was renewed, and continued with unabated violence through the whole ensuing day. The French veterans charged with the bayonet, and hurled the Austrians with prodigious slaughter into the marsh. Another night came and went. The gray light of another cold winter's morning appeared faintly in the east, when the soldiers sprang again from their freezing, marshy beds, and in the dense clouds of vapor and of smoke which had settled down over the morass, with the fury of blood-hounds rushed again to the assault. In the midst of this terrible conflict a cannon-ball fearfully mangled the horse upon which Napoleon was riding. The powerful animal, frantic with pain and terror, became perfectly unmanageable. Seizing the bit in his teeth, he rushed through the storm of bullets directly into the midst of the Austrian ranks. He then, in the agonies of death, plunged into the morass and expired. Napoleon was left struggling in the swamp up to his neck in the mire. Being perfectly helpless, he was expecting every moment either to sink and disappear in that inglorious grave, or that some Austrian dragoon would sabre his head from his body or with a bullet pierce his brain. Enveloped in clouds of smoke, in the midst of the dismay and the uproar of the terrific scene, he chanced to evade observation, until his own troops, regardless of every peril, forced their way to his rescue. Napoleon escaped with but a few slight wounds. Through the long day, the tide of war continued to ebb and to flow upon these narrow dykes. Napoleon now carefully counted the number of prisoners taken and estimated the amount of the slain. Computing thus that the enemy did not outnumber him by more than a third, he resolved to march out into the open plain for a decisive conflict. He relied upon the enthusiasm and the confidence of his own troops and the dejection with which he knew that the Austrians were oppressed. In these impassable morasses it was impossible to operate with the cavalry. Three days of this terrible conflict had now passed. In the horrible carnage of these days Napoleon had lost 8000 men, and he estimated that the Austrians could not have lost less, in killed, wounded, and prisoners, than 20,000. Both armies were utterly exhausted, and those hours of dejection and lassitude had ensued in which every one wished that the battle was at an end.[Pg 734]

It was midnight. Napoleon, sleepless and fasting, seemed insensible to exhaustion either of body or of mind. He galloped along the dykes from post to post, with his whole soul engrossed with preparations for the renewal of the conflict. Now he checked his horse to speak in tones of consolation to a wounded soldier, and again by a few words of kind encouragement animated an exhausted sentinel. At two o'clock in the morning the whole army, with the ranks sadly thinned, was again roused and ranged in battle array. It was a cold, damp morning, and the weary and half-famished soldiers shivered in their lines. A dense, oppressive fog covered the flooded marsh and added to the gloom of the night. Napoleon ordered fifty of the guards to struggle with their horses through the swamp, and conceal themselves in the rear of the enemy. With incredible difficulty most of them succeeded in accomplishing this object. Each dragoon had a trumpet. Napoleon commenced a furious attack along the whole Austrian front. When the fire was the hottest, at an appointed signal, the mounted guards sounded with their trumpets loudly the charge, and with perfect desperation plunged into the ranks of the enemy. The Austrians, in the darkness and confusion of the night, supposing that Murat,[1] with his whole body of cavalry, was thundering down upon their rear, in dismay broke and fled. With demoniacal energy the French troops pursued the victory, and before that day's sun went down, the proud army of Alvinzi, now utterly routed, and having lost nearly thirty thousand men, marking its path with a trail of blood, was retreating into the mountains of Austria. Napoleon, with streaming banners and exultant music, marched triumphantly back into Verona, by the eastern gates, directly opposite those from which, three days before, he had emerged. He was received by the inhabitants with the utmost enthusiasm and astonishment. Even the enemies of Napoleon so greatly admired the heroism and the genius of this wonderful achievement, that they added their applause to that of his friends. This was the fourth Austrian army which Napoleon had overthrown in less than eight months, and each of them more than twice as numerous as his own. In Napoleon's dispatches to the Directory, as usual, silent concerning himself, and magnanimously attributing the victory to the heroism of the troops, he says, "Never was a field of battle more valiantly disputed than the conflict at Arcola. I have scarcely any generals left. Their bravery and their patriotic enthusiasm are without example."

In the midst of all these cares he found time to write a letter of sympathy to the widow of the brave Muiron. "You," he writes, "have lost a husband who was dear to you; and I am bereft of a friend to whom I have been long and sincerely attached. But our country has suffered more than us both, in being deprived of an officer so pre-eminently distinguished for his talents and his dauntless bravery. If it lies within the scope of my ability to yield assistance to yourself, or your infant, I beseech you to reckon upon my utmost exertions." It is affecting to record that in a few weeks the woe-stricken widow gave birth to a lifeless babe, and she and her little one sank into an untimely grave together. The woes of war extend far and wide beyond the blood-stained field of battle. Twenty thousand men perished around the marshes of Arcola. And after the thunders of the strife had ceased, and the groans of the dying were hushed in death, in twenty thousand distant homes, far away on the plains of France, or in the peaceful glens of Austria, the agony of that field of blood was renewed, as the tidings reached them, and a wail burst forth from crushed and lacerated hearts, which might almost have drowned the roar of that deadly strife.

How Napoleon could have found time in the midst of such terrific scenes for the delicate attentions of friendship, it is difficult to conceive. Yet to a stranger he wrote, announcing the death of a nephew, in the following affecting terms: "He fell with glory and in the face of the enemy, without suffering a moment of pain. Where is the man who would not envy such a death? Who would not gladly accept the choice of thus escaping from the vicissitudes of an unsatisfying world. Who has not often regretted that he has not been thus withdrawn from the calumny, the envy, and all the odious passions which seem the almost exclusive directors of the conduct of mankind." It was in this pensive strain that Napoleon wrote, when a young man of twenty-six, and in the midst of a series of the most brilliant victories which mortal man had ever achieved.

The moment the Austrians broke and fled, while the thunders of the pursuing cannonade were reverberating over the plains, Napoleon seized a pen and wrote to his faithful Josephine, with that impetuous energy, in which "sentences were crowded into words, and words into letters." The courier was dispatched, at the top of his speed, with the following lines, which Josephine with no little difficulty deciphered. She deemed them worth the study. "My adored Josephine! at length I live again. Death is no longer before me, and glory and honor are still in my breast. The enemy is beaten. Soon Mantua will be ours. Then thy husband will fold thee in his arms, and give thee a thousand proofs of his ardent affection. I am a little fatigued. I have received letters from Eugene and Hortense. I am delighted with the children. Adieu, my adorable Josephine. Think of me often. Should your heart grow cold toward me, you will be indeed cruel and unjust. But I am sure that you will always continue my faithful friend as I shall ever continue your fond lover. Death alone can break[Pg 735] the union which love, sentiment, and sympathy have formed. Let me have news of your health. A thousand and a thousand kisses."

A vein of superstition pervaded the mind of this extraordinary man. He felt that he was the child of destiny—that he was led by an arm more powerful than his own, and that an unseen guide was conducting him along his perilous and bewildering pathway. He regarded life as of little value, and contemplated death without any dread. "I am," said he, "the creature of circumstances. I do but go where events point out the way. I do not give myself any uneasiness about death. When a man's time is come, he must go." "Are you a Predestinarian?" inquired O'Meara. "As much so," Napoleon replied, "as the Turks are. I have been always so. When destiny wills, it must be obeyed. I will relate an example. At the siege of Toulon I observed an officer very careful of himself, instead of exhibiting an example of courage to animate his men. 'Mr. Officer,' said I, 'come out and observe the effect of your shot. You know not whether your guns are well pointed or not.' Very reluctantly he came outside of the parapet, to the place where I was standing. Wishing to expose as little of his body as possible, he stooped down, and partially sheltered himself behind the parapet, and looked under my arm. Just then a shot came close to me, and low down, which knocked him to pieces. Now, if this man had stood upright, he would have been safe as the ball would have passed between us without hurting either." Maria Louisa, upon her marriage with Napoleon, was greatly surprised to find that no sentinels slept at the door of his chamber; that the doors even were not locked; and that there were no guns or pistols in the room where they slept. "Why," said she, "you do not take half so many precautions as my father does." "I am too much of a fatalist," he replied, "to take any precautions against assassination." O'Meara, at St. Helena, at one time urged him to take some medicine. He declined, and calmly raising his eyes to heaven, said, "That which is written is written. Our days are numbered." Strange and inconsistent as it may seem, there is a form which the doctrine of Predestination assumes in the human mind, which arouses one to an intensity of exertion which nothing else could inspire. Napoleon felt that he was destined to the most exalted achievements. Therefore he consecrated himself through days of toil and nights of sleeplessness to the most Herculean exertions that he might work out his destiny. This sentiment which inspired Napoleon as a philosopher, animated Calvin as a Christian. Instead of cutting the sinews of exertion, as many persons would suppose it must, it did but strain those sinews to their utmost tension.

Napoleon had obtained, at the time of his marriage, an exquisite miniature of Josephine. This, in his romantic attachment, he had suspended by a ribbon about his neck, and the cheek of Josephine ever rested upon the pulsations of his heart. Though living in the midst of the most exciting tumults earth has ever witnessed, his pensive and reflective mind was solitary and alone. The miniature of Josephine was his companion, and often during the march, and in the midnight bivouac, he gazed upon it most fondly. "By what art is it," he once passionately wrote, "that you, my sweet love, have been able to captivate all my faculties, and to concentrate in yourself my moral existence? It is a magic influence which will terminate only with my life. My adorable wife! I know not what fate awaits me, but if it keep me much longer from you, it will be insupportable. There was a time when I was proud of my courage. When contemplating the various evils to which we are exposed, I could fix my eyes steadfastly upon every conceivable calamity, without alarm or dread. But now the idea that Josephine may be ill, and, above all, the cruel thought that she may love me less, withers my soul, and leaves me not even the courage of despair. Formerly I said to myself, Man can not hurt him who can die without regret. But now to die without being loved by Josephine is torment. My incomparable companion! thou whom fate has destined to make, along with me, the painful journey of life, the day on which I shall cease to possess thy heart will be to me the day of utter desolation." On one occasion the glass covering the miniature was found to be broken. Napoleon considered the accident a fearful omen of calamity to the beloved original. He was so oppressed with this presentiment, that a courier was immediately dispatched to bring him tidings from Josephine.

It is not surprising that Napoleon should thus have won, in the heart of Josephine the most enthusiastic love. "He is," said she, "the most fascinating of men." Said the Duchess of Abrantes, "It is impossible to describe the charm of Napoleon's countenance when he smiled. His soul was upon his lips and in his eyes." "I never," said the Emperor Alexander, "loved any man as I did that man." Says the Duke of Vicenza, "I have known nearly all the crowned heads of the present day—all our illustrious contemporaries. I have lived with several of those great historical characters on a footing quite distinct from my diplomatic duties. I have had every opportunity of comparing and judging. But it is impossible to institute any comparison between Napoleon and any other man. They who say otherwise did not know him." Says Duroc, "Napoleon is endowed with a variety of faculties, any one of which would suffice to distinguish a man from the multitude. He is the greatest captain of the age. He is a statesman who directs the whole business of the country, and superintends every branch of the service. He is a sovereign whose ministers are merely his clerks. And yet this Colossus of gigantic proportions can descend to the most trivial details of private life. He can regulate the expenditure of his household as he regulates the finances of the empire."

Notwithstanding Napoleon had now destroyed four Austrian armies, the imperial court was still[Pg 736] unsubdued, and still pertinaciously refused to make peace with republican France. Herculean efforts were immediately made to organize a fifth army to march again upon Napoleon. These exciting scenes kept all Italy in a state of extreme fermentation. Every day the separation between the aristocratic and the republican party became more marked and rancorous. Austria and England exerted all their arts of diplomacy to rouse the aristocratic governments of Rome, Venice, and Naples to assail Napoleon in the rear, and thus to crush that spirit of republican liberty so rapidly spreading through Italy, and which threatened the speedy overthrow of all their thrones. Napoleon, in self-defense, was compelled to call to his aid the sympathies of the republican party, and to encourage their ardent aspirations for free government.