George Manville Fenn

"Adventures of Working Men"

"From the Notebook of a Working Surgeon"

Chapter One.

My Patients.

I have had patients enough in a busy life as a working surgeon, you may be sure, but of all that I have had, young or old, give me your genuine, simple-hearted working man; for whether he be down with an ordinary sickness or an extraordinary accident, he is always the same—enduring, forbearing, hopeful, and with that thorough faith in his medical man that does so much towards helping on a cure.

Wealthy patients as a rule do not possess that faith in their doctor. They always seem to expect that a disease which has been coming on, perhaps, for months, can be cured right off in a few hours by a touch of the doctor’s hand. If this result does not follow, and I may tell you at once it never does—unless it be in a case of toothache, and a tooth is drawn—the patient is peevish and fretful, the doctor is looked upon as unskilful, and, money being no object, the chances are that before the doctor or surgeon has had a chance, another practitioner is called in.

On the other hand, a quiet stalwart working man comes to you with a childlike faith and simplicity; he is at one with you; and he helps his cure by his simple profound belief in your skill.

A great deal of working-class doctoring and surgery has fallen to my lot, for fate threw me into a mixed practice. Sooner than wait at home idle for patients who might never come, I have made a point of taking any man’s practice pro tem, while the owner was ill, or away upon a holiday, and so improved my own knowledge better than I should have done by reading ever so hard. The consequence is that I have been a good deal about the country, and amongst a great variety of people, and the result of my experience is that your genuine working man, if he has been unspoiled by publicans, and those sinners, the demagogues, who are always putting false notions into his head, is a thoroughly sterling individual. That is the rule. I need not quote the exceptions, for there are black sheep enough among them, even as there are among other classes. Take him all in all, the British workman is a being of whom we may well be proud, and the better he is treated the brighter the colours in which he will come out.

Of course he has his weak points; we all have them, and very unpleasant creatures we should be without. A man all strong points is the kind of being to avoid. Have nothing to do with him. Depend upon it the finest—the most human of God’s creatures, are those who have their share of imperfections mingled with the good that is in every one more or less.

They are men, these workers, who need the surgeon more than ordinary people, for too often their lives are the lives of soldiers fighting in the battle of life; and many are the wounded and slain.

I used at one time—from no love of the morbid, please bear in mind, but from genuine desire to study my profession—to think that I should like to go out as an army surgeon, and be with a regiment through some terrible war. For it seemed to me that nothing could do more towards making a professional man prompt and full of resources than being called upon to help his suffering fellow-creatures—shot down, cut down, trampled beneath horses’ feet, blown up, bayoneted, hurt in one of the thousand ways incidental to warfare, besides suffering from the many diseases that follow in an army’s train. But I very soon learned that there was no need for any such adventure, for I could find ample demands on such poor skill as I possessed by devoting myself to the great army of toilers fighting in our midst. Talk of demands upon a man’s energy and skill; calls upon his nerve; needs for promptness and presence of mind! There are plenty such in our every-day life; for, shocking as it may sound, the tale of killed and wounded every week in busy England is terribly heavy. Go to some manufacturing town where steam hisses and pants, and there is the throb and whirr of machinery from morn till night—yes, and onward still from night to morn—where the furnaces are never allowed to slacken—go there and visit the infirmary, and you will find plenty of wounded in the course of the year. You have the same result, too, in the agricultural districts, where, peaceful as is the labourer’s pursuit, he cannot avoid mishaps with horses, waggons, threshing-machines, even with his simple working tools. In busy London itself the immense variety of calls upon the surgeon’s skill leaves him little to desire in the way of experience.

Many years of sheer toil have caused a kind of friendship to grow up between me and the working man. In fact I consider myself a working man, and a hard-worker. I have told you how I like him for a patient, but I have not told you of the many good qualities that I have found, too often lying latent in his breast. Those I will touch upon incidentally in the course of these pages, for years ago the fancy came upon me to make a kind of note-book of particular cases, principally for my own amusement. Not a surgical or medical note-book, but a few short jottings of the peculiarities of the cases, and these short jottings grew into long ones, so that now I present them to the reader as so many sketches of working men—adventures, that is to say, met with in their particular avocations.

Sometimes I have been called in to attend the workman for the special case of which his little narrative treats, for I have thought it better for the most part to let him tell his story in his own words; and now I come to look through my collection—the gatherings of many years—I find that I have a strange variety of incident, some of which in their peril and danger will show those who have never given a thought to such a subject, how many are the risks to which the busy ants of our great hill are exposed, and how often they go about their daily tasks with their lives in their hands.

Chapter Two.

My Patient the Stoker.

I would not wish for a better specimen of faith and confidence than was shown by one of my patients, Edward Brown, a stoker, with whose little narrative I will commence my sketches.

“Ah! doctor,” he said one day, “I wish you had had to do with me when I came back from the East.”

“Why?” I said, and went on dressing a very serious injury he had received to one hand, caused by his crushing it between a large piece of coal and the edge of the furnace door.

“Because I should have got better much quicker if I had known you.”

“Perhaps not,” I said, “your own medical man may have done his best.”

“Perhaps he did,” was the reply. “But, lor! hard down I was just then. It brings it all up again—those words.”

“What words?” I said. “There, don’t let that bandage be touched by anyone.”

“‘In the midst of life we are in death.’”

“Why, Brown!” I exclaimed.

“Yes sir, those were the words—‘In the midst of life we are in death.’ And they sounded so quiet and solemn, that Mary and I stopped short close to the old-fashioned gate at the little churchyard; and then, as if we moved and thought together, we went in softly to the funeral, and stood at a little distance, me with my hat off and Mary with her head bent down, till the service was over.

“There it all is again as I’m telling it to you, come back as fresh and clear as if I was looking at it now: a nice little old-fashioned church, with a stone wall round the yard, where the graves lay pretty thick and close, but all looking green and flowery and old, a great clump of the biggest and oldest yew-trees I ever saw, and a tall thick hedge separating the churchyard from the clergyman’s house. The sun was shining brightly, turning the moss-covered roofs of the church and vicarage into gold; from the trees close by came the faint twittering of birds, and away past the village houses bathed in the bright afternoon sunshine there were the fields of crimson clover, and the banks full of golden broom and gorse. Over all was a sense of such peace and silence that it seemed as if there was nothing terrible, only a quiet sadness in the funeral, with its few mourners round the open grave, and the grey-haired clergyman standing by; and last of all, when Mary and I went up and looked into the grave, and read on the coffin-plate, ‘Aged 77.’ one couldn’t help feeling that the poor soul had only gone to sleep tired with a long life.

“It was my fancy perhaps, but as we strolled round that churchyard, and read a tombstone here and a board there, it seemed as if no sooner had the parson gone in to take off his surplice, and the mourners left the churchyard, than the whole place woke up again into busy life. A chaffinch came and jerked out its bit of a song in one of the yews, the Guinea-fowls in a farm close by set up their loud crying, the geese shrieked on the green, and creaking, and rattling and bumping, there came along a high-filled waggon of the sweetest hay that ever was caught in loose handfuls by the boughs of the trees, and then fell softly back into the road.

“We were very quiet, Mary and I, as we strolled out of the churchyard, down one of the lanes; and then crossing a stile, we went through a couple of fields, and sat down on another stile, with the high hedge on one side of us and the meadow, that they were beginning to mow at the other end, one glorious bed of flowers and soft feathery grass.

“‘Polly,’ I says at last, breaking the silence, ‘ain’t this heavenly?’

“‘And you feel better?’ she says, laying her hand on mine.

“‘Better!’ I says, taking a long draught of the soft sweet-scented air, and filling my chest—‘better, old girl! I feel as if I was growing backwards into a boy.’

“‘And you fifty last week!’ she says.

“‘Yes,’ I says, smiling, ‘and you forty-seven next week.’ And then we sat thinking for a bit.

“‘Polly,’ I says at last, as I sat there drinking in that soft breeze, and feeling it give me strength, ‘it’s worth being ill only to feel as I do now.’

“For you see I’d been very bad, else I dare say I’m not the man to go hanging about churchyards and watching funerals: I’m a stoker, and my work lies in steamers trading to the East. I’d come home from my last voyage bad with fever, caught out in one of those nasty hot bad-smelling ports—been carried home to die, as my mates thought; and it was being like this, and getting better, that had set me thinking so seriously, and made me so quiet; not that I was ever a noisy sort of man, as any one who knows me will say. And now, after getting better, the doctor had said I must go into the country to get strength; so as there was no more voyaging till I was strong, there was nothing for it but to leave the youngsters under the care of the eldest girl and a neighbour, and come and take lodgings out in this quiet Surrey village.

“Polly never thought I should get better, and one time no more did I; for about a month before this time, as I lay hollow-eyed and yellow on the bed, knowing, too, how bad I looked—for I used to make young Dick bring me the looking-glass every morning—the doctor came as usual, and like a blunt Englishman I put it to him flat.

“‘Doctor,’ I says, ‘you don’t think I shall get better?’ and I looked him straight in the face.

“‘Oh, come, come, my man!’ he says, smiling, ‘we never look at the black side like that.’

“‘None of that, doctor,’ I says; ‘out with it like a man. I can stand it: I’ve been expecting to be drowned or blown up half my life, so I shan’t be scared at what you say.’

“‘Well, my man,’ he says, ‘your symptoms are of a very grave nature. You see the fever had undermined you before you came home, and unless—’

“‘All right, doctor,’ I says; ‘I understand: you mean that unless you can get a new plate in the boiler, she won’t stand another voyage.’

“‘Oh, come! we won’t look upon it as a hopeless case,’ he says; ‘there’s always hope;’ and after a little more talk, he shook hands and went away.

“Next day, when he came, I had been thinking it all over, and was ready for him. I don’t believe I was a bit better; in fact, I know I was drifting fast, and I saw it in his eyes as well.

“I waited till he had asked me his different questions, and then just as he was getting up to go, I asked him to sit down again.

“‘Polly, my dear,’ I says, ‘I just want a few words with the doctor;’ and she put her apron up to her eyes and went out, closing the door after her very softly, while the doctor looked at me curious-like, and waited for me to speak.

“‘Doctor,’ I says, ‘you’ve about given me up. There, don’t shake your head, for I know. Now don’t you think I’m afraid to die, for I don’t believe I am; but look here: there’s seven children downstairs, and if I leave my wife a widow with the few pounds I’ve been able to save, what’s to become of them? Can’t you pull me through?’

“‘My dear fellow,’ he says, ‘honestly I’ve done everything I can for your case.’

“‘That’s what you think, doctor,’ I says, ‘but look here: I’ve been at sea thirty years, and in seven wrecks. It’s been like dodging death with me a score of times. Why, I pulled my wife there regularly out of the hands of death, and I’m not going to give up now. I’ve been—’

“‘Stop, stop,’ he says gently. ‘You’re exciting yourself.’

“‘Not a bit,’ I says, though my voice was quite a whisper. ‘I’ve had this over all night, and I’ve come to think I must be up and doing my duty.’

“‘But, my good man—’ he began.

“‘Listen to me, doctor,’ I says. ‘A score of times I might have given up and been drowned, but I made a fight for it and was saved. Now I mean to make a fight for it here, for the sake of the wife and bairns. I don’t mean to die, doctor, without a struggle. I believe this here, that life’s given to us all as a treasure to keep; we might throw it away by our own folly at any time, but there’s hundreds of times when we may preserve it, and we never know whether we can save it till we try. Give me a drink of that water.’

“He held the glass to my lips, and I took a big draught and went on, he seeming all the time to be stopping to humour me in my madness.

“‘That’s better, doctor,’ I says. ‘Now look here, sir, speaking as one who has sailed the seas, it’s a terrible stormy time with me; there’s a lee shore close at hand, the fires are drowned out, and unless we can get up a bit of sail, there’s no chance for me. Now then, doctor, can you get up a bit of sail?’

“‘I’ll go and send you something that will quiet you,’ he said, rising.

“‘Thank ye, doctor,’ I says, smiling to myself. ‘And now look here,’ I says, ‘I’m not going to give up till the last; and when that last comes, and the ship’s going down, why, I shall have a try if I can’t swim to safety. If that fails, and I can really feel that it is to be, why, I hope I shall go down into the great deep calmly, like a hopeful man, praying that Somebody above will forgive me all I’ve done amiss, and stretch out His fatherly hand to my little ones at home.’

“He went away, and I dropped asleep, worn out with my exertion.

“When I woke, Polly was standing by the bedside watching me, with a bottle and glass on the little table.

“As soon as she saw my eyes open, she shook up the stuff, and poured it into a wine-glass.

“‘Is that what the doctor sent?’ I says.

“‘Yes, dear; you were to take it directly.’

“‘Then I shan’t take it,’ I says. ‘He’s given me up, and that stuff’s only to keep me quiet. Polly, you go and make me some beef-tea, and make it strong.’

“She looked horrified, poor old girl, and was going to beg me to take hold of the rotten life-belt he’d sent me, when I held out my shaking hand for it, took the glass, and let it tilt over—there was only about a couple of teaspoonfuls in it—and the stuff fell on the carpet.

“I saw the tears come in her eyes, but she said nothing—only put down the glass, and ran out to make the beef-tea.

“The doctor didn’t come till late next day, and I was lying very still and drowsy, half asleep like, but I was awake enough to hear him whisper to Polly, ‘Sinking fast;’ and I heard her give such a heart-broken sob, that as the next great wave came on the sea where I was floating, I struck out with all my might, rose over it, and floated gently down the other side.

“For the next four days—putting it as a drowning man striving for his life like a true-hearted fellow—it was like great foaming waves coming to wash over me, but the shore still in sight, and me trying hard to reach it.

“And it was a grim, hard fight: a dozen times I could have given up, folded my arms, and said goodbye to the dear old watching face safe on shore; but a look at that always cheered me, and I fought on again and again, till at last the sea seemed to go down, and, in utter weariness, I turned on my back to float restfully with the tide bearing me shorewards, till I touched the sands, crept up them, and fell down worn out, to sleep in the warm sun—safe!

“That’s a curious way of putting it, you may say, but it seems natural to me to mix it up with the things of seagoing life, and the manner in which I’ve seen so many fight hard for their lives. It was just like striving in the midst of a storm to me, and when at last I did fall into a deep sleep, I felt surprised—like to find myself lying in my own bed, with Polly watching by me; and when I stretched out my hand, and took hers, she let loose what she had kept hidden from me before, and, falling on her knees by my bedside, she sobbed for very joy.

“‘As much beef-tea and brandy as you can get him to take,’ the doctor says, that afternoon; and it wasn’t long before I got from slops to solids, and then was sent, as I told you, into the country to get strong, while the doctor got no end of praise for the cure he had made.

“I never said a word though, even to Polly, for he did his best; but I don’t think any medicine would have cured me then.

“I was saying a little while back that I pulled my wife regularly out of the hands of death, and of course that was when we were both quite young; though, for the matter of that, I don’t feel much different, and can’t well see the change. That was in one of the Cape steamers, when I first took to stoking. They were little ramshackle sort of boats in those days, and how it was more weren’t lost puzzles me. It was more due to the weather than the make or finding of the ships, I can tell you, that they used to steer their way safe to port; and yet the passengers, poor things, knowing no better, used to take passage, ay, and make a voyage too, from which they never got back.

“Well, I was working on board a steamer as they used to call the Equator, heavy laden and with about twenty passengers on board. We started down Channel and away with all well, till we got right down off the west coast of Africa, when there came one of the heaviest storms I was ever in. Even for a well-found steamer, such as they can build to-day, it would have been a hard fight; but with our poor shaky wooden tub, it was a hopeless case from the first.

“Our skipper made a brave fight of it, though, and tried hard to make for one of the ports; but, bless you! what can a man do when, after ten days’ knocking about, the coals run out, and the fires, that have been kept going with wood and oil, and everything that can be thrust into the furnaces, are drowned; when the paddle-wheels are only in the way, every bit of sail set is blown clean out of the bolt-ropes, and at last the ship begins to drift fast for a lee shore?

“That was our case, and every hour the sea seemed to get higher, and the wind more fierce, while I heard from more than one man how fast the water was gaining below.

“My mate and I didn’t want any telling, though. We’d been driven up out of the stoke-hole like a pair of drowned rats, and came on deck to find the bulwarks ripped away, and the sea every now and then leaping aboard, and washing the lumber about in all directions.

“The skipper was behaving very well, and he kept us all at the pumps, turn and turn in spells, but we might as well have tried to pump the sea dry; and when, with the water gaining fast, we told him what we thought, he owned as it was no use, and we gave up.

“We’d all been at it, crew and passengers, about forty of us altogether, including the women—five of them they were, and they were all on deck, lashed in a sheltered place, close to the poop. Very pitiful it was to see them fighting hard at first and clinging to the side, but only to grow weaker, half-drowned as they were; and I saw two sink down at last and hang drooping-like from their lashings, dead, for not a soul could do them a turn.

“I was holding on by the shrouds when the mate got to the skipper’s side, and I saw in his blank white face what he was telling him. Of course we couldn’t hear his words in such a storm, but we didn’t want to, for we knew well enough he was saying—

“‘She’s sinking!’

“Next moment there was a rush made for the boats, and two of the passengers cut loose a couple of the women; place was made for them before the first boat was too full, and she was lowered down, cast off, and a big wave carried her clear of the steamer. I saw her for a moment on the top of the ridge, and then she plunged down the other side out of our sight—and that of everybody else; for how long she lived, who can say? She was never picked up or heard of again.

“Giving a bit of a cheer, our chaps turned to the next, and were getting in when there came a wave like a mountain, ripped her from the davits, and when I shook the water from my eyes, there she was hanging by one end, stove in, and the men who had tried to launch her gone—skipper and mate as well.

“There were only seven of us now, and I could see besides the three women lashed to the side, and only one of them was alive; and for a bit no one moved, everybody being stunned-like with horror; but there came a lull, and feeling that the steamer was sinking under our feet, I shouted out to the boys to come on, and we ran to the last boat, climbed in, and were casting off, when I happened to catch sight of the women lashed under the bulwarks there.

“‘Hold hard!’ I roars, for I saw one of them wave her hand.

“‘Come on, you fool,’ shouts my mate, ‘she’s going down!’

“I pray I may never be put to it again like that, with all a man’s selfish desire for life fighting against him. For a moment I shut my eyes, and they began to lower; but I was obliged to open them again, and as I did so, I saw a wild scared face, with long wet hair clinging round it, and a pair of little white hands were stretched out to me as if for help.

“‘Hold hard!’ I shouts.

“‘No, no,’ roared out two or three, ‘there isn’t a moment;’ and as the boat was being lowered from the davits, I made a jump, caught the bulwarks with my hands, and climbed back on board, just as the boat kissed the water, was unhooked, and floated away.

“Then as I crept, hand-over-hand, to the girl’s side, whipped out my knife, and was cutting her loose, while her weak arms clung to me, I felt a horrible feeling of despair come over me, for the boat was leaving us; and I knew what a coward I was at heart, as I had to fight with myself so as not to leave the girl to her fate, and leap overboard to swim for my life. I got the better of it, though—went down on my knees, so as not to see the boat, and got the poor trembling, clinging creature loose.

“‘Now, my lass,’ I says, ‘quick’—and I raised her up—‘hold on by the side while I make fast a rope round you.’

“And then I stood up to hail the boat—the boat as warn’t there, for in those brief moments she must have capsized, and we were alone on the sinking steamer, which now lay in the trough of the sea.

“As soon as I got over the horror of the feeling, a sort of stony despair came over me; but when I saw that little pale appealing face at my side, looking to me for help, that brought the manhood back, and in saying encouraging things to her, I did myself good.

“My first idea was to make something that would float us, but I gave that up directly, for I could feel that I was helpless; and getting the poor girl more into shelter, I took a bit of tobacco in a sort of stolid way, and sat down with a cork life-buoy over my arm, one which I had cut loose from where it had hung forgotten behind the wheel.

“But I never used it, for the storm went down fast, and the steamer floated still, waterlogged, for three days, when we were picked up by a passing vessel, half-starved, but hoping. And during that time my companion had told me that she was the attendant of one of the lady passengers on board; and at last, when we parted at the Cape, she kissed my hand, and called me her hero, who had saved her life—poor grimey me, you know!

“We warn’t long, though, before we met again, for somehow we’d settled that we’d write; and a twelvemonth after, Mary was back in England, and my wife. That’s why I said I took her like out of the hands of death, though in a selfish sort of way, being far, you know, from perfect. But what I say, speaking as Edward Brown, stoker, is this: Make a good fight of it, no matter how black things may look, and leave the rest to Him.”

He nodded gravely at me, placed his bandaged hand in the sling I had contrived, and went away without another word.

Chapter Three.

My Patient the Well-Sinker.

“It’s no more than I expected, doctor,” said my patient, Goodsell, a stern, hard-featured, grey-haired man, with keen, yet good-natured eyes; and he shifted his head a little on the pillow to look at me. “Good job it’s no worse, ain’t it?”

“It is a mercy you were not killed,” I said.

“You’re right, doctor,” he replied, smiling. “Two inches to the left, and the iron rim of the bucket would have broken my skull instead of my shoulder, eh? and then my boy could have carried on the business.”

“You take it very philosophically,” I said.

“To be sure, doctor. Why not? A man must die some time; and he may just as well die at work, as a miserable creature in bed. I expects to die by my business, straightforward and honourable. The pitcher that goes oftenest to the well is sure to be broken at last,” he added, with a laugh. “I’m a pitcher always going to the well, and shall be broken at last.

“I’ve been a well-sinker ever since I was quite a lad; my father was a well-sinker afore me, and he got sent to sleep with the foul air at the bottom of a well, and never got waked again; and I, being the eldest of six, and only fourteen, had to set at it to keep the family, while father’s master, being a kind-hearted sort of man, took me on, and gave me as good wages as he could, for my father had been a sort of favourite of his, from being a first-class, steady workman. My grandfather was a well-sinker too, and he got buried alive, he did, poor old chap, through a fall of earth; while his father—my great-grandfather, you know—was knocked on the head by the sinker’s bucket; for the rope broke when they were drawing it up full of earth, and it fell on the old gentleman, and ended him. I ain’t got killed yet, I ain’t; but my turn’ll come some day, I suppose, for it’s in our profession, you know. But then you must have water; and ours is a very valuable trade—so what is to be will be, and what’s the good of fretting? It don’t do to be always fidgeting about danger in your way through life, but what we have to do is to go straight ahead, and do our duty, and trust to Providence for the rest.

“Now, after all these years—and I’m ’most fifty, you know—I never look down a well without having the creeps, and I never go down one without having the creeps; for they’re queer, dark, echoing, shadowy, grave-like sort of holes, and one thinks of the depth, and the darkness, and the water, and of how little chance there is of escape, and so on, if one fell; and perhaps this is a bit owing to one or two narrow escapes I’ve had, and them making me a bit nervous. Soon as I get right to work I forget all the fidgeting, but the first starting is certainly rather nervous work for me, though I don’t believe as I ever told any one of it before.

“That well down at Rowborough need to be like a nightmare to me, and laid heavier upon me than any, well ever did before; but I kept on to my work like the rest, and we gradually went on lower and lower, step after step, month after month, always expecting to strike a main-spring, but never succeeding. Now it was loamy earth, then yellow clay, then gravel, then blue clay, then more gravel, then sand for far enough, then flinty soil, and then chalk, and so on month after month; but never any water worth speaking about. Of course we struck water times enough, and it bothered us a good deal to stop it out, but it was only from little upper springs, while what we wanted was the deep spring from far below—one that, when we tapped it, should come up strongly and give a good supply of water for the deep well.

“We were years digging that well—years; for money being in plenty, and them wanting a good supply of water, our orders were to keep on, and we did dig—down, down a good six hundred feet; and, mind you, the farther you get from the surface the slower the work gets on, on account of the time taken in sending the stuff up. Now, when I talk of six hundred feet, you mustn’t suppose I mean a bored well, quite a little hole, perhaps six inches across, but one dug all the way, and a good nine foot in diameter.

“That was a fine well—is a fine well, I may say—with one of the best supplies of clear soft water in this country, and that too in a place where good water is terribly scarce. Our firm had the job; and I was one of the men put on at the beginning, and I was on it till it was finished.

“We did not go straight down all the way, but when we got down to the chalk made a sort of chamber, and cut out sideways for a bit, and then began digging down again another shaft, this making it more convenient for the drawing up of the rubbish dug out; every scrap of which had, of course, to be taken to the surface.

“You perhaps hardly think of what it is being lowered down five hundred feet in a bucket, and then working by the light of a lantern in the bottom of the pit, whose walls you have to take care shall be carefully bricked up as you go on down, for fear they should fall in upon you. It is that hot you can hardly bear it, for very little fresh air comes down there; while, if it was not for smothering the thoughts, one might always be in dread of an accident. Now here, instead of feeling afraid of an incoming of the water, what we were most afraid of was that we should never get any water at all; and after all the labour bestowed on the place, it seemed quite disheartening to strike upon nothing but beggarly little rills worth nothing. But our governor was a George Stephenson sort of a man, and he had taken it into his head that we must get to water sooner or later, and he used to say that when we did strike it there would be plenty. So we dug on, slowly and surely, day after day, month after month, till some of the men got scared of the job on account of the depth, and left it. We had had no accidents, though, for everything had been worked out carefully and quietly, and though this was an underground place, every part was finished as carefully and truly as if it had been in full light of the sun.

“Last of all, we’d got down a good six hundred feet, while, according to appearances, it seemed that we might go on a good six hundred more before we got to water; while in my case it seemed to be now part of my regular life to go down there, day after day, to work my spell, and I used to dig and lay bricks, dig and lay bricks, without thinking about water, or when it was coming, though the governor used to warn us to be careful in case when it did come it should come very fast.

“We did most part of our work by buckets and windlass; but, all the same, we had stagings and ladders down to the bottom, ever so many feet; and one day when I was down with a mate—only us two right at the bottom, though, of course, there were others at the stages and top—I was digging away and filling the bucket, giving the signal and sending it up, when I got looking at the course of bricks my mate was laying, and, as you will see, bricklayers in wells lay their bricks one under the other, and not one on the top of another like they would in building a house.

“All at once he says to me, ‘Just shovel this gravel away again; there ain’t room to get a brick under.’

“‘There was plenty of room just now,’ I says, ‘for I took notice. The bricks give a little from up above.’

“Well, he thought so too, and went on with his work, while I went on with mine, picking and shovelling up the loose gravel and putting it in the bucket; but, though I worked pretty hard, I seemed to make no way; and, instead of him being able to go on and lay another course of bricks, he had to take a shovel and help me.

“‘It’s rum, ain’t it?’ he says, after we’d been digging hard for about an hour. ‘Something’s wrong; or else the place is bewitched. Here we haven’t sunk an inch this last hour, I’ll swear, though we’ve sent up no end of bucketfuls. There’s the last course of bricks just where it was, and I’m blest if I don’t think it’s sunk a bit in!’

“‘Well, it does look like it,’ I said, ‘certainly; and I ’spose the brickwork’s giving a bit from the tremendous weight up above. You’ve been working too hard, Tom,’ I says, laughing, ‘and your work hasn’t had time to set.’

“‘Well, I’ve only kept up with you,’ he says, quite serious; ‘but I ’spose it’s as you say, and we’ll take it a bit easier, for this is labour in vain.’

“It really looked so, for after another hour we seemed to be just where we were before, and I began almost to think it very likely something really was wrong, but what I couldn’t tell. This was something new to me, for I had never been in so deep a well before, and I felt puzzled. It seemed no use to dig, for we got no lower; and once I really thought that instead of our getting any deeper, we were making the well shallower; but the next moment I laughed at this stupid thought, and filled and started the bucket, when, dinner-time being come, we laid down our tools, and made our way up to daylight; but before I started, I could not help feeling more puzzled than ever, for now, on one side, there was the bottom course of bricks quite below the loose gravel and sand.

“I didn’t say anything to my mate, and, truth to tell, I forgot all about it the next moment, for I was thinking of dinner; and I didn’t recollect it again until after two, when we were nearly at the bottom, when it came back with a flash, and I then seemed to see the cause of it all.

“I was at the bottom, and Tom above me, and we were just below the last staging, when I heard a strange roaring, rumbling noise that turned my very blood cold; for it seemed to me then, as I stood on, the rounds of that bottom ladder, that a wild beast was breaking loose, and about to tear at me and drag me off the rungs, and for a few seconds I couldn’t speak or move, till Tom sings out:

“‘Hallo! what’s up?’ and that seemed to give me breath.

“‘Up, up!’ I shouted; ‘the water!’ and he started climbing again as hard as he could, and me panting and snorting after him, for, with a tremendous bubbling, roaring rush, the water, that had been forcing the earth slowly upwards for hours past, had now pushed its way through, and as we reached the second stage, we heard the one below us regularly burst up, and saw the ladder we had just left sink down.

“Heard in that hollow, echoing well, hundreds of feet from the surface, and under such circumstances, the roar of the water was something awful to listen to. We could not see it, but it was coming up seething and bubbling like a fountain, while the pressure beneath must have been something fearful.

“As we got higher our progress was slower, for the men on the upper stages were before us; and though they had taken the alarm from our shouts and the bellowing of the water, they did not travel so fast as we did. Stage after stage was forced up, and ladder after ladder sunk down as we got higher, and never did I feel such a relief as when we stood in the chamber cut out of the chalk, where we could look up and see the little ring of daylight far above us; and then, half a dozen men as we were, we clung to the bucket and rope, and gave the signal for them to wind up, the water leaping round our feet as we slowly rose.

“As it happened it was a new and a strong rope, or it must have given way with the tremendous strain put upon it, and I shivered again and again as we swung backwards and forwards, while my only wonder now is that some of us did not fall back from sheer fright.

“But we reached the surface safely, with the water bubbling and running after us nearly the whole way, for it rose to within fifty feet of the top, and has stayed at that height ever since; but though one man fainted, and we all looked white and scared, no one was hurt. Ah! it was the narrowest escape I ever had.

“Our tools we lost, of course, but a great deal of the woodwork and many of the short ladders floated up, and were brought out. It would take a good deal to make me forget the well that grew shallower the more we shovelled out the gravel. For a supply of water no town can be better off than Rowborough; and then, look at the depth—six hundred feet!”

Poor old Goodsell had a hard time of it, and suffered great pain before I got his shoulder well, and even then he never was able to carry on his occupation as of old. For it was a terrible accident, the rope breaking, and a bucket used in drawing up the earth from a well falling upon his shoulder; and, as he said, a couple of inches more to the left, and he would have been killed.

Chapter Four.

My Underground Patient.

I had a very singular case, one day, being called in to attend, in a busy part of London, upon a curious-looking man who lay in bed suffering from the effects of bad gas. He was a peculiar-looking fellow, with grizzled black hair, excessively sallow skin, piercing eyes, and his face was as strangely and terribly seamed with the smallpox.

I had some little trouble with his case, which was the result of his having been prisoned for some hours in one of the sewers that run like arteries under London. A sudden flood had come on, and he had been compelled with a companion to retreat to a higher level, where the foul air had accumulated, and he had had a narrow escape for his life.

As he amended! Used to chat with him about his avocation, and I was much struck by the coolness with which he used to talk about his work, and incidentally I learned whence came the seaming in his face.

“You see, sir,” he said, “the danger’s nothing if a man has what you call presence of mind—has his wits about him, you know. For instance, say he’s in danger, or what not, and he steps out with his right foot, and he steps out of danger; but say he steps out with his left foot, and he loses his life. Sounds but very little, that does; but it makes two steps difference between the right way and the wrong way, and that’s enough to settle it all; sound or cripple, home or hospital, fireside or a hole in the churchyard. Presence of mind’s everything to a working man, and it’s a pity they can’t teach a little more of it in schools to the boys. I don’t want to boast, for I’m very thankful; but a little bit of quiet thought has saved my life more than once, when poor fellows, mates of mine, have been in better places and lost theirs.

“I’m a queer sort of fellow, always having been fond of moling and working underground from a boy. Why, when I went to school, nothing pleased me better than setting up what we called a robbers’ cave in the old hill, where they dug the bright red sand; and there, of a Wednesday afternoon, we’d go and climb up the side to the steep pitch where it was all honeycombed by the sand-martins, and then, just like them, we’d go on burrowing and digging in at the side, scooping away in the beautiful clean sand, till I should think one summer we had dug in twenty feet. Grand place that was, so we thought, and fine and proud we used to be; and the only wonder is that the unsupported roof did not come down and bury some half-dozen of us. Small sets-out of that sort of course we did have, parts of the side falling down; but as long as it did not bury our heads we rather enjoyed it, and laughed at one another.

“Well, my old love for underground work seemed to cling to me when I grew up, and that’s how it is I’ve always been employed so much upon sewers. They’re nasty places, to say the best of them; but, then, as they’re made for the health of a town, and it’s somebody’s duty to work down in them, why, one does it in a regular sort of way, and forgets all the nastiness.

“Now, just shut your eyes for a few minutes and fancy you’re close at my elbow, and I’ll try if I can’t take you down with me into a sewer, and you shall have the nice little adventure over again that happened to me—nothing to signify, you know, only a trifling affair; but rather startling to a man all the same. The sewerage is altered now a good deal, and the great main stream goes far down the river, but I’m talking about the time when all the sewers emptied themselves straight into the Thames.

“Now, we’ve got an opening here in the street on account of a stoppage, and we’ve gone down ladder after ladder, and from stage to stage, until we are at the bottom, where the brick arch has been cut away, and now I’m calling it all up again, as you shall hear.

“I don’t think I ever knew what fear was in those days—I mean fear in my work, for, being the way in which I got my daily bread, danger seemed nothing, and I went anywhere, as I did on the night I am speaking of. It was a very large sewer, and through not having any clock at home, I’d come out a good hour before my time. I stopped talking to the men I was to relieve for some little time, waiting for my mates to come—the job being kept on with, night and day. Last of all, I lit a bit of candle in one of the lanterns, and, taking it, stepped down into the water, which came nearly to the tops of my boots, and began wading up stream.

“Now, when I say up to the tops of my boots, I mean high navigator’s boots that covered the thigh; and so I went wading along, holding my lantern above my head, and taking a good look at the brickwork, to see if I could find any sore places—it being of course of great consequence that all should be sound and strong.

“Strange wild places those are when you are not busy! Dark as pitch, and with every plash in the water echoing along quite loud when by you, and then whispering off in a curious creepy way, as if curious creatures in the far-off dark were talking about it, and wondering at you for going down there. Over your head the black, damp brickwork; both sides of you, wet, slimy brickwork; and under your feet slippery brickwork, covered inches deep with a soft yielding mud that gives way under your feet, and makes walking hard work. In some places the mud is swept nearly clean away, and then you go splashing along, while always in a curious, echoing, musical way, comes the sound of running water, dripping water, plashing water, seeming always to be playing one melancholy strange tune, sad and sweet, and peculiar. Busy at work, one don’t notice it, but when looking about, as I was, it all seemed to strike me in a way I can’t explain.

“Slowly on through the running water, holding my lantern up, and always looking at the same sight—a little spot of brickwork shining in the light of my bit of candle, and all beyond that black darkness. The light shone, too, a little off the top of the water in a queer glimmering way, as at every step I took there were little waves sent on before me to go beating and leaping up against the sides. But every now and then I could hear a little splash, and see the water on the move in a strange way in front, presenting just the same appearance as if some one was drawing a stick through it, and leaving a widening trail behind.

“I said ‘in a strange way,’ but it wasn’t a strange way to me, for I knew it well enough, and had seen it so often that I took hardly any notice of it. If I had had a strong light I should have seen a little dark shape leap from the opening of a drain into the water, and then disappear for a few moments, to come up again, and swim along quite fast; but with such a light as I had I could only see the disturbed water.

“Bats were old friends of mine, and did not trouble me in the least, as I went on, now turning to the right and now to the left, sometimes going back a little, and then pushing on again, till all at once, without a moment’s warning, out went my bit of candle, and I was in complete darkness.

“Well, I growled a good deal at that—not that I minded the dark, but it put a stop to the bit of overlooking I was upon; and though in most cases I had a bit or two of extra candle, it so happened that this time I hadn’t a scrap, and all I had to do was to get back.

“I suppose I hadn’t gone a dozen yards before I stopped short, with the cold sweat standing all over my face, and my breath coming thick and short, for, instead of the low musical, whispering tinkle of the water, there was a rushing noise I well knew coming along a large sewer to the left, and for want of the bit of presence of mind that I ought to have had then, instead of rushing up stream past the mouth of the opening, I must run down; and then came a curious wild, confused state of mind that I can always call back now when I like to go into the dark for a few minutes—when I was being borne along by a furious rush of water that seemed to fill the sewer, washing me before it now up and now down, like a cork in a stream.

“As a matter of course, I must try to do everything to make matters worse, and keep on fighting against a power that would have borne fifty men before it. But that was an awful minute—I call it a minute, though I dare say the struggle only lasted a few moments—when I seemed dashed against a corner, and there I was fighting my way with the stream carrying me swiftly along, but seeming weaker every moment; and at last I was standing, with my hands thrust into a side drain to keep me steady, while I coughed and panted, and tried to get my breath once more, feeling all the while dizzy and confused, and unable to make out where I was.

“The rush of water was now past, and the sewer two feet above its regular level; but, stunned as I had been, I could not get into my regular way of thinking, nor collect myself as to what I ought to do next; and it is no light thing to be fifty foot under ground in a dark tunnel with the water rushing furiously by, and you not able to think.

“When I say able to think, I mean not regularly, for I could think too much, and that too about things that I did not want to think about, for they troubled me. What I ought to have thought of then was the keeping of myself cool and trying to get out, but I couldn’t move, for I fancied that if I did I must be swept away again. Now, I had often been along the sewers when the water was deeper than it now was and running swifter, but for all that I was afraid to move.

“How I magnified the danger, and made out no end of fanciful images in the darkness, all of them seeming to point to my end, and telling me that I should never get out alive! Then I got calling up all the accidents and horrors of that great place where I was. First I recollected how two poor fellows came down not very far from where I stood—half a mile perhaps—and were working in one of the small drains that was half stopped with soil and rubbish; they were down on one knee, in a bent position, and shovelling the mud back from one to another underneath them, and working towards a man-hole, when a rush of water came, and they struggled on against it till a mate at the man-hole, who stood there with a lantern and shouted, just got hold of the first man’s hand, when there came a sharper rush than ever from above, and the poor fellow was gone. I was one of those who hunted for them the next day, now in one branch and then in another, going up culverts and drains of all sizes, where I thought it possible they could have been swept, for there had been a watch kept at the mouths, and hurdles put down to stop anything from being washed out. A whole week I was on that job before I found both, the last being in a narrow place, where the poor fellows must have crawled.

“Nice thing that was to think of at such a time! But it would come, and I seemed to have no power to stop it. Then I recollected about the mate of mine who lost his life in the foul air which collects sometimes in places where there isn’t a free current; and then, too, about the rat case, where the man who came up off the river-shore got amongst the rats, or else fell down in a fit, and the way he came out was in a basket, for there was nothing left but his bones.

“Ah! nice things these were for a man to get thinking of, shivering as I was there in the dark! But I didn’t shiver long, for I came all over hot and feverish, and I should have yelled for help but I was afraid, for the idea had come upon me that if I made the slightest noise I should have the rats about me; and although it was pitch dark, I seemed to see them waiting in droves, clustering like bees all over the sides of the sewer, clinging to the top and swimming across and across the surface of the water. There they all were plain enough, with their bright black eyes and sharp noses, while I kept on fancying how keen their teeth must be. We always supposed that they would attack a man in the dark, but as we never went unprovided with lights there was never any case known among us of a fight with them. But now, in the dark as I was, I quite made up my mind that they were waiting till I made a movement, and that then they would be swarming over me in all directions; and I shuddered, and my blood ran cold, as I thought of what would follow.

“Every drip—every little hollow splash, or ripple against the side seemed to me to be made by rats; the beating of my heart against my ribs with its heavy throb seemed to be the hurrying by of the little patting animals, and at times I fancied that I could hear their eager panting as they were scuffling by, hunting for me. Bats everywhere, as it seemed to me; and again and again I was feeling myself all over to see if any were clinging to me or climbing up, for the motion of the water as it swept on seemed for all the world like the little wretches brushing against my side.

“I don’t believe now that there was a rat near me all the time, for it was all pure imagination. Still the imagination was so strong that it was worse than reality, and even in what came afterwards I don’t think I suffered more. It seems to be that one’s nerves at such a time get worked up to a dreadful pitch, and everything one thinks of seems to come strongly before one, so that if the horror was strung up much tighter, nature could not bear it.

“I could bear no more then as I stood there; and knowing all the while—or feeling all the while—that to move was to bring the rats upon me, I started off, bewildered so that I had no idea where I was, only feeling that I must go with the stream to get out of the sewer, whichever branch I was in. So I tore on with the water up to my middle, but getting deeper and deeper every minute as I ran my hand along the wall, now turning to the left, now to the right, and shuddering every moment as I fancied I felt a rat touch me. But I had been walking and wading along for a good half-hour before I felt one, and then just as I fancied I saw a gleam of light peer out of the darkness right in front, something ran hastily up my breast and shoulder, and then leaped off with a splash into the water.

“If I had not grasped at the slippery side of the sewer and supported myself, I must have gone down; and to have sunk down in four feet of water was certain death, in the state I then was in; but I kept up, and giving a shout, half-shriek, half-yell, I dashed on towards where I fancied I had seen the light.

“Fancied, indeed, for it seemed to grow darker as I went on, and I grew more and more confused every moment. If I could only have known where I was for a single instant, that would have been sufficient, even to knowing only what particular branch I was in; but I was too confused to try and make out any of the marks that might have told me.

“There it was again—a scratching of tiny claws and a hurried rush up my breast, over my shoulder, something wet and cold brushing my face, then the half-leap, half-start I gave, and the sharp splash in the water as the beast leaped off me. And then it came quicker and faster—two and three—six—a dozen upon me, and as I tore them off they bit me savagely, making their little teeth meet in my hands, and hanging there; while more than one vicious bite in the face made me yell out with pain.

“The horrible fear seemed now to have gone, strange as it may appear to say so. I was mad with rage now, and fought desperately for my life, as the rats swarmed round and attacked me furiously, without giving me a moment’s rest. I had a large knife, which I managed to get open and strike with, but it was more than useless, for my enemies were so small and active and constant in their attacks that I could not get a fair blow at them, and dashing away the blade I was glad enough to fight them with their own weapons, and bit and tore at them, seizing them one after another in my hands, and either crushing or dashing them up against the sides of the sewer.

“But it seemed toil in vain, for as I dashed one off half a dozen swarmed up me, over my arms and back, covering my chest, fastening on to the bare parts of my neck, and making my face run down with blood.

“‘Can’t last much longer!’ I remember thinking; but I felt that I must fight on to the last, and I kept on tearing the squeaking vermin off, and crushing them in my hands, often so that they had no chance of biting; but there must have been hundreds swarming round me, waiting until others were beaten off to make a lodgment. Now I was dashing up stream as hard as I could, in the hope that I could shake them off; and as I waded splashing along I tore those off that were upon me, but they hunted me as dogs would a hare; and though it was dense black darkness there, so that I groped my way along with outstretched hands, it seemed to me that the little beasts could see well enough, and kept dashing up me as fast as I could beat them off.

“Splashing along as I was, I had a better chance of keeping the vermin off; but then I could not keep it up. I must have been struggling about for hours now, and was worn out, for even at the best of times it is terribly hard work walking in water; and now that I was drenched with it, and had my great thigh boots full, the toil was fearful, and I felt that I must give in.

“‘I wouldn’t mind so much,’ I thought, ‘if I could find a dry spot where I could lie down;’ but the idea of this double death was dreadful, and spurred me on again to new efforts, so that I kept on rushing forward by spurts, my breath coming in groans and sobs, while I kept the vermin off my face as well as I could.

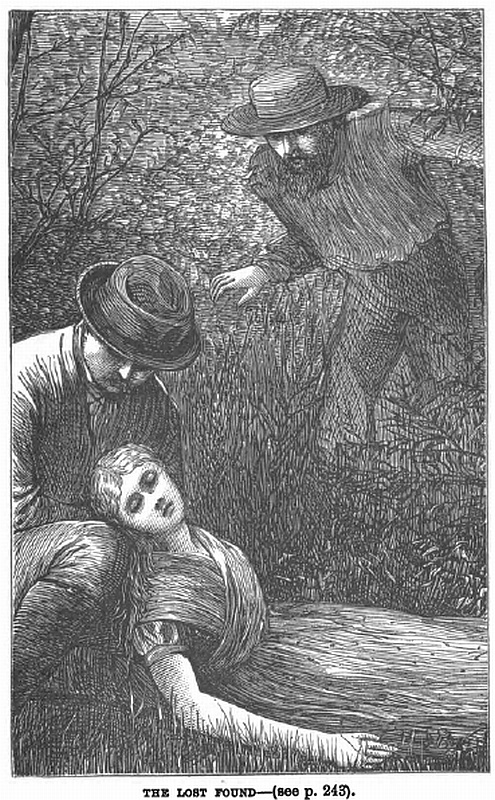

“‘It’s all over!’ I groaned at last, sinking on my knees close to the side of the sewer, and nearly going under, as my legs slipped in the ooze at the bottom. But I stopped that by trying to force my nails in one of the cracks between the slimy bricks, and as the rats came at me there was only my head and neck up above the filthy water; while I gave a long shriek that drove them back for a moment. And now it seemed to me that I could see the little wretches coming at me, and, yes—no—yes, I could see a faint gleam on the top of the water, and then it was brighter, and I heard a shout which I believe I answered, though I can recollect no more.

“Well, they ain’t such very deep marks, sir—only just through the skin, you know; but they spoil a man’s beauty, which they say is just skin-deep. Lots of people have thought as I’ve had the smallpox very bad, and I let them, for this here as you’ve heard the whole story about is one of the things as I don’t like to bring up very often. I always feel as if I’d been very close to the end and had been dragged back, which makes me feel solemn, and I always back out when any mate tries to draw the story out of me, for they’re uncommon fond of hearing it over and over again. Joe Stock—that’s one of them—he could tell you the part as I can’t about how they hunted for me and shouted till they were tired—going miles, you know, for it would surprise you to thoroughly know what there is under the streets of London.

“‘Harry,’ he’s said to me before now, ‘I never see such a sight in my life, and when I saw you get up off your knees, mate, and come a reeling towards me, I’m blest if I didn’t think it was somethin’ no canny, and I nearly dropped my lantern and ran for it. There was your face all streaming down with blood, and your hands the same, and as to the noise you was making—ugh!’ he’d say, ‘it was awful bad.’

“And now, just one word of advice, sir—don’t you never go down no sewers without two or three bits of candle in your pocket—high up in the breast of your jacket, you know—and plenty of lucifers in a watertight tin box, or perhaps you may get in such a mess as I did.”

Very good advice, no doubt; but after seeing the place where three men went down to work some short time since, listening to the hollow musical drip of the water, and the strange whisperings of the long tunnels; after listening to the history of the hard fight against a sudden rush of water told me by the sturdy toiler, who shuddered and turned pale as he recalled the desperate fight for life, and then, in lowered tones, narrated how he had found his poor mate’s body washed into a narrow culvert, I felt quite satisfied, and I don’t think I shall ever make any explorations in a sewer.

In fact, I never see a grating open, or meet one of the sturdy fellows in his blue Jersey shirt and high boots without thinking of my patient, and the risks such people run to earn their daily bread.

Chapter Five.

My Black Patient.

There’s a very terrible disease upon which a great deal has been written, but not a great deal done. In fact, it is difficult to deal with special diseases brought on by the toiler’s work. It is a vexed question what to do or how to treat the consumption that attacks the needle-grinders and other dry grinders; the horrible sufferings of those who inhale the dust of deadly minerals; the bone disease of the workers in phosphorus and many other ills brought on by working at particular trades.

The disease I allude to in particular is one that attacks that familiar personage, the chimney sweep, and I have often had to treat some poor fellow or another for it.

There was one man who stands in my note-book as J.J.—John Johnson, I had under my care several times, and we came to be very good friends, for under that sooty skin of his—I never saw it once really clean—there was a great deal of true humanity and tenderness of heart, as I soon found from the way in which he behaved to his wife.

“Why don’t you chimney sweeps—Ramoneurs as you call yourselves now—invent a better cry than svi-thee-up?”

“Ramoneur,” he said with a husky chuckle. “Yes, that’s it, doctor. Fine, aint it? I allus calls myself a plain sweep, though. That’s good enough for me.”

“But you might do without that yell of yours,” I said. “London cries are a terrible nuisance, though I don’t know that I’d care to have them done away with. Your svi-thee-up don’t sound much like sweep.”

“Svi-thee-up, svi-thee-up,” he cried, as he lay there in bed, to the utter astonishment of his wife. “Don’t sound much like sweep? No, it don’t; but then one has to have one’s own regular cry, as folks may know us by. Why, listen to any of them of a morning about the street, and who’d think it was creases as this one was a hollering, or Yarmouth bloaters that one; or that ‘Yow-hoo!’ meant new milk? It ain’t what we say—it’s the sound of our voices. Don’t the servant gals as hears us of a morning know what it means well enough when the bell rings, and them sleepy a-bed? Oh, no, not at all! But there’s no mussy for ’em, and we jangles away at the bell, and hollers a good ’un till they lets us in; for, you see, it comes nat’ral when you’re obliged to be up yourself, and out in the cold, to not like other folks to be snugging it in bed.

“But, then, it’s one’s work, you know, and I dunno whether it was that or the sutt as give me this here coarse voice, which nothing clears now—most likely it was the sutt. How times are altered, though, since I was a boy! That there climbing boy Act o’ Parliament made a reg’lar revolution in our business, and now here we goes with this here bundle o’ canes, with a round brush at the end, like a great, long screw fishing-rod, you know, all in jints, and made o’ the best Malacky cane, so as to go into all the ins and outs, and bend about anywhere, till it’s right above the pot, and bending and swinging down. But they’re poor things, bless you, and don’t sweep a chimbley half like a boy used. You never hears the rattle of a brush at the top of a chimbley-pot now, and the boy giving his ‘hillo—hallo—hullo—o—o—o!’ to show as he’d not been shamming and skulking half-way up the flue. Why, that was one of the cheery sounds as you used to hear early in the mornin’, when you was tucked up warm in bed; for there was always somebody’s chimbley a being swept.

“Puts me in mind again of when I was a little bit of a fellow, and at home with mother, as I can recollect with her nice pleasant face, and a widder’s cap round it. Hard pushed, poor thing, when she took me to Joe Barkby, the chimbley sweep, as said he’d teach me the trade if she liked. And there was I, shivering along aside her one morning, when she was obliged to take me to Joe, and we got there to find him sitting over his brexfass, and he arst mother to have some; but her heart was too full, poor thing, and she wouldn’t, and was going away, and Joe sent me to the door to let her out; and that’s one of the things as I shall never forget—no, not if I lives to a hundred—my mother’s poor, sad, weary face, and the longing look she give me when we’d said ‘Good bye,’ and I was going to shut the door after her. Such a sad, longing look, as if she could have caught me up and run off with me. I saw it as she stood on the step, and me with the door in my hand—that there green door, with a bright brass knocker, and brass plate with ‘Barkby, Chimbley Sweep,’ on it. There was tears in her eyes, too; and I felt so miserable myself I didn’t know what to do as I stood watching her, and she came and give me one more kiss, saying, ‘God bless you!’ and then I shut the door a little more, and a little more, till I could see the same sad look through quite a little crack; and then it was close shut, and I was wiping my eyes with my knuckles.

“Ah! I’ve often thought since as I shut that door a deal too soon; but I was too young to know all as that poor thing must have suffered.

“Barkby warn’t a bad sort; but then, what can you expect from a sweep? He didn’t behave so very bad to us little chummies; but there it was—up at four, and tramp through the cold, dark streets, hot or cold, wet or dry; and then stand shivering till you could wake up the servants—an hour, perhaps, sometimes. Then in you went to the cold, miserable house, with the carpets all up, or p’r’aps you had to wait no one knows how long while the gal was yawning, and knick-knick-knicking with a flint and steel over a tinder-box, and then blowing the spark till you could get a brimstone match alight. Then there was the forks to get for us to stick the black cloth in front of the fireplace, and then there was one’s brush, and the black cap to pull down over one’s face, pass under the cloth, and begin swarming up the chimbley all in the dark.

“It was very trying to a little bit of a chap of ten years old, you know—quite fresh to the job; and though Barkby give me lots of encouragement, without being too chuff, it seemed awful as soon as I got hold of the bars, which was quite warm then, and began feeling my way, hot, and smothery, and sneezy, in my cap, till I give my head such a pelt against some of the brickwork that I began to cry; for, though I’d done plenty of low ones this was the first high chimbley as I’d been put to. But I chokes it down, as I stood there with my little bare toes all amongst the cinders, and then began to climb.

“Every now and then Barkby shoves his head under the cloth, and ‘Go ahead, boy,’ he’d say; and I kep’ on going ahead as fast as I could, for I was afeared on him, though he never spoke very gruff to me; but I had heard him go on and cuss awful, and I didn’t want to put him out. So there was I, poor little chap—I’m sorry for myself even now, you know—swarming up a little bit at a time, crying away quietly, and rubbing the skin off my poor knees and elbows, while the place felt that hot and stuffy I could hardly breathe, cramped up as I was.

“Now, you wouldn’t think as any one could see in the dark, with his eyes close shut, and a thick cap over his face, pulled right down to keep the sutt from getting up his nose—you wouldn’t think anyone could see anything there; but I could, quite plain; and what do you think it was? Why, my mother’s face, looking at me so sad, and sweet, and smiling, through her tears, that it made me give quite a choking sob every now and then and climb away as hard as ever I could, though my toes and knees seemed to have the skin quite off, and smarted ever so; while I kep’ on slipping a bit every now and then, for I was new at climbing, and this was a long chimbley, from the housekeeper’s room of a great house, right from under ground, to the top.

“Sometimes I’d stop and have a cry, for I’d feel beat out, and the face as had cheered me on was gone; but then I’d hear Barkby’s choky voice come muttering up the floo, same as I’ve shouted to lots o’ boys in my time, ‘Go ahead, boy!’ and I’d go ahead again, though at last I was sobbing and choking as hard as I could, for I kep’ on thinking as I should never get to the top, and be stuck there always in the chimbley, never to come out no more.

“‘I won’t be a sweep, I won’t be a sweep,’ I says, sobbing and crying; and all the time making up my mind as I’d run away first chance, and go home again; and then, after a good long struggle, I was in the pot, with my head out, then my arms out, and the cap off for the cool wind to blow in my face.

“And, ah! how cool and pleasant that first puff of wind was, and how the fear and horror seemed to go away as I climbed out, and stood looking about me; till all at once I started, for there came up out of the pot, buzzing like, Barkby’s voice, as he calls out, ‘Go ahead, boy!’

“So then I set to rattling away with my brush-handle to show as I was out, and then climbs down on to the roof, and begins looking about me. It was just getting daylight, so that I could see my way about, and all seemed so fresh and strange that, with my brush in my hand, I begins to wander over the roofs, climbing up the slates and sliding down t’other side, which was good fun, and worth doing two or three times over. Then I got to a parapet, and leaned looking over into the street, and thinking of what a way it would be to tumble; but so far off being afraid, I got on to the stone coping, and walked along ever so far, till I came to an attic window, where I could peep in and see a man lying asleep, with his mouth half open; then I climbed up another slope, and had another slide down; and then another, and another, till I forgot all about my sore knees; and at last sat astride of the highest part, looking about me at the view I had of the tops of houses as far as I could see, for it was getting quite light now.

“All at once I turned all of a horrible fright, for I recklected about Barkby, and felt almost as if he’d got hold of me, and was thrashing me for being so long. I ran to the first chimbley stack, but that wasn’t right, for I knew as the one I came up was a-top of a slate-sloping roof. Then I ran to another, thinking I should know the one I came out of by the sutt upon it. But they’d all got sutt upon ’em—every chimbley-pot I looked at, and so I hunted about from one to another till I got all in a muddle, and didn’t know where I was nor which pot I’d got out of. Last of all, shaking and trembling, I makes sure as I’d got the right one, and climbing up I managed, after nearly tumbling off, to get my legs in, when pulling down my cap, I let myself through a bit at a time, and leaving go I slipped with a regular rush, nobody knows how far, till I came to a bend in the chimbley, where I stopped short—scraped, and bruised, and trembling, while I felt that confused I couldn’t move.

“After a bit I came round a little, and, whimpering and crying to myself, I began to feel my way about a bit with my toes, and then got along a little away straight like, when the chimbley took another bend down, and stiffly and slowly I let myself down a little and a little till my feet touched cold iron, and I could get no farther. But after thinking a bit, I made out where I was, and that I was standing on the register of a fireplace, so I begins to lift it up with my toes as well as I could, when crash it went down again, and there came such a squealing and screeching as made me begin climbing up again as fast as I could till I reached the bend, where I stopped and had another cry, I felt so miserable; and then I shrunk up and shivered, for there came a roar and a rattle that echoed up the chimbley, while the sutt came falling down in a way that nearly smothered me.

“Now, I knew enough to tell myself that the people being frightened had fired a gun up the chimbley, while the turn round as it took had saved me from being hurt. So I sat squatted up quite still, and then heard some one shout out ‘Hallo!’ two or three times, and then ‘Puss, puss, puss!’ Then I could hear voices whispering a bit, and then the register was banged down, as I supposed by the noise.

“Only fancy! sitting in a bend of the chimbley shivering with fear, and half smothered with heat and sutt, while your breath comes heavy and thick from the cap over your face! Not nice, it ain’t; and more than once I’ve felt a bit sorry for the poor boys as I’ve sent up chimbleys in my time. But there I was, and I soon began scrambling up again, and worked hard, for the chimbley was wider than the other one. Last of all I got up to the pot, and out on to the stack, and then again I had a good cry.

“Now, when I’d rubbed my eyes again, I had another look round, and felt as if I was at the wrong pot, so I scrambled down, slipped over the slates, and got to a stack in front, when I felt sure I was right, for there were black finger-marks on the red pot; so I got up, slipped my legs in, and taking care this time that I didn’t fall, began to lower myself down slowly, though I was all of a twitter to know what Barkby would do to me for being so long. Now I’d slip a little bit, being so sore and rubbed I could hardly stop myself; and then I’d manage to let myself down gently; but all at once the chimbley seemed to open so wide, being an old one I suppose, that I couldn’t reach very well with my back and elbows pressed out; so, feeling myself slipping again, I tried to stick my nails in the bricks, at the same time drawing my knees ’most up to my chin, when down I went perhaps a dozen feet, and then, where there was a bit of a curve, I stuck reg’lar wedged in all of a heap, nose and chin altogether, knees up against the bricks on one side, and my back against the other, and me not able to move.

“For a bit I was so frightened that I never tried to stir, but last of all the horrid fix I was in came upon me like a clap, and there I was, half choked, dripping with perspiration, and shuddering in every limb, wedged in where all was dark as Egypt.

“After a bit I managed to drag off my cap, thinking that I could then see the daylight through the pot. But no; the chimbley curved about too much, and all was dark as ever; while what puzzled me was, that I couldn’t breathe any easier now the cap was off, for it seemed hot, and close, and stuffy, though I thought that was through me being so frightened, for I never fancied now but I was in the right chimbley, and wondered that Barkby didn’t shout.

“All at once there came a terrible fear all over me—a feeling that I’ve never forgotten, nor never shall as long as I’m a sweep. It was as if all the blood in my body had run out and left me weak, and helpless, and faint, for down below I could hear a heavy beat-beat-beat noise, that I knew well enough, and up under me came a rush of hot smoke that nearly suffocated me right off; when I gave such a horrid shriek of fear as I’ve never forgot neither, for the sound of it frightened me worse.

“It didn’t sound like my voice at all, as I kept on shrieking, and groaning, and crying for help, too frightened to move, though I’ve often thought since as a little twisting on my part would have set me loose, to try and climb up again. But, bless you, no; I could do nothing but shout and cry, with the noise I made sounding hollow and stifly, and the heat and smoke coming up so as to nearly choke me over and over again.

“I knew fast enough now that I had come down a chimbley where there had been a clear fire, and now some one had put lumps of coal on, and been breaking them up; and in the fright I was in I could do nothing else but shout away till my voice got weak and wiry, and I coughed and wheezed for breath.

“But I hadn’t been crying for nothing, though; for soon I heard some one shout up the chimbley, and then came a deal of poking and noise, and the smoke and heat came curling up by me worse than ever, so that I thought it was all over with me, but at the same time came a whole lot of hot, bad-smelling steam; and then some one knocked at the bricks close by my head, and I heard a buzzing sound, when I gave a hoarse sort of cry, and then felt stupid and half asleep.

“By-and-by there was a terrible knocking and hammering close beside me, getting louder and louder every moment; and yet it didn’t seem to matter to me, for I hardly knew what was going on, though the voices came nearer and the noise plainer, and at last I’ve a bit of recollection of hearing some one say ‘Fetch brandy,’ and I wondered whether they meant Barkby, while I could feel the fresh air coming upon me. Then I seemed to waken up a bit, and see the daylight through a big hole, where there was ever so much rough broken bricks and mortar between me and the light; and next thing I recollect is lying upon a mattress, with a fine gentleman leaning over me, and holding my hand in his.

“‘Don’t,’ I says in a whisper; ‘It’s all sutty.’ Then I see him smile, and he asked me how I was.

“‘Oh, there ain’t no bones broke,’ I says; ‘only Barkby’ll half kill me.’

“‘What for?’ says another gentleman.

“‘Why, coming down the wrong chimbley,’ I says; and then, warming up a bit with my wrongs, ‘But ’twarn’t my fault,’ I says. ‘Who could tell t’other from which, when there warn’t no numbers nor nothink on ’em, and they was all alike, so as you didn’t know which to come down, and him a swearing acause you was so long? Where is he?’ I says in a whisper.

“One looked at t’other, and there was six or seven people about me; for I was lying on the mattress put on the floor close aside a great hole in the wall, and a heap o’ bricks and mortar.

“‘Who?’ says the first gent, who was a doctor.

“‘Why, Barkby,’ I says; ‘my guv’nor, who sent me up number seven’s chimbley.’

“‘Oh, he’s not here,’ says someone. ‘This ain’t number seven; this is number ten. Send to seven,’ he says.

“Then they began talking a bit; and I heard something said about ‘poor boy,’ and ‘fearful groans,’ and ‘horrid position;’ and they thought I didn’t hear ’em, for I’d got my eyes shut, meaning to sham Abram when Barkby came, for fear he should hurt me; but I needn’t have shammed, for I couldn’t neither stand nor sit up for a week arter; and I believe arter all, it’s that has had something to do with me being so husky-voiced.

“Old Barkby never hit me a stroke, and I believe arter all he was sorry for me; but a sweep’s is a queer life even now, though afore the act was passed some poor boys was used cruel, and more than one got stuck in a floo, to be pulled out dead.”

Chapter Six.

My Sheffield Patient.

Plenty of you know Sheffield by name; but I think those who know it by nature are few and far between. If you tried to give me your impressions of the place, you would most likely begin to talk of a black, smoky town, full of forges, factories, and furnaces, with steam blasts hissing, and Nasmyth hammers thudding and thundering all day long. But there you would stop, although you were right as far as you went. Let me say a little more, speaking as one who knows the place, and tell you that it lies snugly embosomed in glorious hills, curving and sweeping between which are some of the loveliest vales in England. The town is in parts dingy enough, and there is more smoke than is pleasant; but don’t imagine that all Sheffield’s sons are toiling continually in a choking atmosphere. There is a class of men—a large class, and one that has attained to a not very enviable notoriety in Sheffield—I mean the grinders—whose task is performed under far different circumstances; and when I describe one wheel, I am only painting one of hundreds clustering round the busy town, ready to sharpen and polish the blades for which Sheffield has long been famed.

Through every vale there flows a stream, fed by lesser rivulets, making their way down little valleys rich in wood and dell. Wherever such a streamlet runs trickling over the rocks, or bubbling amongst the stones, water rights have been established, hundreds of years old; busy hands have formed dams, and the pent-up water is used for turning some huge water-wheel, which in its turn sets in motion ten, twenty, or thirty stones in the long shed beside it, the whole being known in the district as “a wheel.”