Title: Anarchism

Author: Paul Eltzbacher

Translator: Steven T. Byington

Release date: July 10, 2011 [eBook #36690]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Fritz Ohrenschall, Martin Pettit and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

The corresponding scanned page can be seen by clicking on the page number at the right.

[-]

Anarchism

ELTZBACHER

[-]

[-]

[-]

[i]

Gerichtsassessor and Privatdozent in Halle an der Saale

Translated by

STEVEN T. BYINGTON

Je ne propose rien, je ne suppose rien, j'expose

NEW YORK: BENJ. R. TUCKER.

London: A. C. Fifield.

1908.

[ii]

Copyright, 1907, by

Benjamin R. Tucker

[iii]

Gratefully dedicated to the memory of my father

Dr. Salomon Eltzbacher

1832-1889

[iv]

[v]

CONTENTS

| Page | ||

| TRANSLATOR'S PREFACE | vii | |

| BOOKS REFERRED TO | xvii | |

| INTRODUCTION | 3 | |

| Chapter I. THE PROBLEM | ||

| 1. General | 6 | |

| 2. The Starting-point | 10 | |

| 3. The Goal | 13 | |

| 4. The Way to the Goal | 15 | |

| Chapter II. LAW, THE STATE, PROPERTY | ||

| 1. General | 18 | |

| 2. Law | 24 | |

| 3. The State | 31 | |

| 4. Property | 36 | |

| Chapter III. GODWIN'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 40 | |

| 2. Basis | 41 | |

| 3. Law | 42 | |

| 4. The State | 45 | |

| 5. Property | 53 | |

| 6. Realization | 58 | |

| Chapter IV. PROUDHON'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 65 | |

| 2. Basis | 67 | |

| 3. Law | 69 | |

| 4. The State | 72 | |

| 5. Property | 80 | |

| 6. Realization | 86 | |

| Chapter V. STIRNER'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 93 | |

| 2. Basis | 96 | |

| 3. Law | 97 | |

| 4. The State | 100 | |

| 5. Property | 106 | |

| 6. Realization | 109 | |

| [vi]Chapter VI. BAKUNIN'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 115 | |

| 2. Basis | 117 | |

| 3. Law | 119 | |

| 4. The State | 121 | |

| 5. Property | 127 | |

| 6. Realization | 132 | |

| Chapter VII. KROPOTKIN'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 139 | |

| 2. Basis | 141 | |

| 3. Law | 145 | |

| 4. The State | 149 | |

| 5. Property | 159 | |

| 6. Realization | 171 | |

| Chapter VIII. TUCKER'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 182 | |

| 2. Basis | 183 | |

| 3. Law | 187 | |

| 4. The State | 190 | |

| 5. Property | 201 | |

| 6. Realization | 209 | |

| Chapter IX. TOLSTOI'S TEACHING | ||

| 1. General | 219 | |

| 2. Basis | 220 | |

| 3. Law | 230 | |

| 4. The State | 234 | |

| 5. Property | 249 | |

| 6. Realization | 260 | |

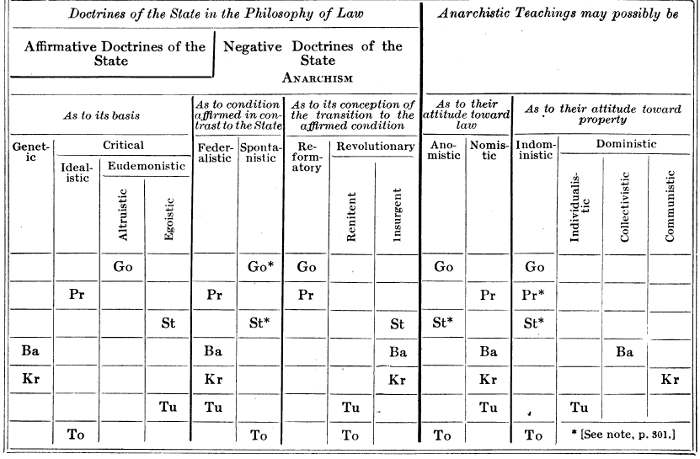

| Chapter X. THE ANARCHISTIC TEACHINGS | ||

| 1. General | 270 | |

| 2. Basis | 270 | |

| 3. Law | 272 | |

| 4. The State | 276 | |

| 5. Property | 280 | |

| 6. Realization | 284 | |

| Chapter XI. ANARCHISM AND ITS SPECIES | ||

| 1. Errors about Anarchism and its Species | 288 | |

| 2. The Concepts of Anarchism and its Species | 292 | |

| CONCLUSION | 303 | |

[vii]

Every person who examines this book at all will speedily divide its contents into Eltzbacher's own discussion and his seven chapters of classified quotations from Anarchist leaders; and, if he buys the book, he will buy it for the sake of the quotations. I do not mean that the book might not have a sale if it consisted exclusively of Eltzbacher's own words, but simply that among ten thousand people who may value Eltzbacher's discussion there will not be found ten who will not value still more highly the conveniently-arranged reprint of what the Anarchists themselves have said on the cardinal points of Anarchistic thought. Nor do I feel that I am saying anything uncomplimentary to Eltzbacher when I say that the part of his work to which he has devoted most of his space is the part that the public will value most.

And yet there is much to be valued in the chapters that are of Eltzbacher's own writing,—even if one is reminded of Sir Arthur Helps's satirical description of English lawyers as a class of men, found in a certain island, who make it their business to write highly important documents in closely-crowded lines on such excessively wide pages that the eye is bound to skip a line now and then, but who make up for this by invariably repeating in another part of the document whatever they have said, so that whatever the reader may miss in one place he will certainly catch in another. The fact is that Eltzbacher's work is an admirable model of what should be the mental processes of an investigator trying to determine the definition of a term which he finds to be confusedly conceived. Not only is his method for determining the definition of Anarchism flawless, but his subsidiary investigation of the definitions of law, the State, and property is conducted as such things ought to be, and (a good[viii] test of clearness of thought) his illustrations are always so exactly pertinent that they go far to redeem his style from dullness, if one is reading for the sense and therefore cares for pertinence. The only weak point in this part of the book is that he thinks it necessary to repeat in print his previous statements wherever it is necessary to the investigation that the previous statement be mentally renewed. But, however tiresome this may be, one gets a steady progress of thought, and the introductory part of the book is not very long at worst.

The collection of quotations, which form three-fourths of the book both in bulk and in importance, is as much the best part as it is the biggest. Here the prime necessity is impartiality, and Eltzbacher has attained this as perfectly as can be expected of any man. Positively, one comes to the end of all this without feeling sure whether Eltzbacher is himself an Anarchist or not; it is not until we come to the last dozen pages of the book that he lets his opposition to Anarchism become evident. To be sure, one feels that he is more journalistic than scientific in selecting for special mention the more sensational points of the schemes proposed (the journalistic temper certainly shows itself in his habit of picking out for his German public the references to Germany in Anarchist writers). Yet it is hard to deny that there is legitimate scientific importance in ascertaining how much of the sensational is involved in Anarchism; and, on the other hand, Eltzbacher recognizes his duty to present the strongest points of the Anarchist side, and does this so faithfully that one often wonders if the man can repeat these words without feeling their cogency. So far as any bias is really felt in this part of the book it is the bias of over-methodicalness; now and then a quotation is made to go into the classification at a place where it will not go in without forcing, and perspective is distorted when some obiter dictum that had never seemed to its author to be worth repeating a second time is made to serve as illuminant now for this division of the "teaching," now for that, till it seems to the reader like a favorite topic of the Anarchist.[ix] However, the bias of methodicalness is as nearly non-partisan as any bias can be, and its effect is to put the matter into a most convenient form for consultation and comparison.

Next to impartiality, if not even before it, we need intelligence in our compiler; and we have it. Few men, even inside the movement, would have been more successful than Eltzbacher in picking out the important parts of the Anarchist doctrines, and the quotations that will show these important parts as they are. I do not mean that this accuracy has not exceptions—many exceptions, if you count such things as the failure to give due weight to some clause which might restrict or modify the application of the words used; a few serious exceptions, of which we reap the fruit in his final summary. But in admitting these errors I do not retract my statement that Eltzbacher has made his compilation as accurate as any man could be expected to. More than this, it may well be said that he has, except in three or four points, made it as accurate as is even useful for ordinary reading; he has overlooked nothing but what his readers would have been sure to overlook if he had presented it. As a gun is advertised to shoot "as straight as any man can hold," so Eltzbacher has, with three or four exceptions, told his story as straight as any man with ordinary attention can read. The net result is that we have here, without doubt, the most complete and accurate presentation of Anarchism that ever has been given or ever will be given in so short a space. If any one wants a fuller and more trustworthy account, he will positively have to go direct to the writings of the Anarchists themselves; nowhere else can he find anything so good as Eltzbacher. Withal, this main part of the book is decidedly readable. Eltzbacher's repetitiousness has no opportunity to become prominent here, and the man is not at all dull in choosing and translating his quotations. On the contrary, his fondness for apt illustrations is a great help toward making the compilation constantly readable, as well as toward making the reader's impressions of the Anarchistic teachings vivid and definite.

[x]

I do not mean to say that this book can take the place of a consultation of the original sources. For instance, the Bakunin chapter follows next after the Stirner chapter; but the exquisite contrariness of almost every word of Bakunin to Stirner's teaching can be appreciated only by those who have read Stirner's book—Eltzbacher's quotations are on a different aspect of Stirner's teaching from that which applies against Bakunin. (Stirner and Bakunin, it will be noted, are the only Anarchist leaders against whom Eltzbacher permits himself a disrespectful word before he has presented their doctrines.) It is to be hoped that many who read this book will go on to examine the sources themselves. Meanwhile, here is an excellent introduction, and the chronological arrangement makes it easy to watch the historical development and see whether the later schools of Anarchism assail the State more effectively than the earlier.

I have not reserved any expressions of praise for the small part of the book which comes after the compiled chapters, because it calls for none. All Eltzbacher's weak points come out in this concluding summary; the best that can be said for it is that it deserves careful attention, and that the author continues to be oftener right than wrong. But now that he has gathered all his knowledge he wants it to amount to omniscience, and most imprudently shuts his eyes to the places where there is nothing under his feet. He charges men with error for not using in his sense a term whose definition he has not undertaken to determine. He accepts all too unquestioningly such statements as fit most conveniently into his scheme of method. His most glaring offence in this direction is his classification of the Anarchist-Communist doctrines as mere prediction and not the expression of a will or demand or approval or disapproval of anything, simply because the fashionableness of evolutionism and of fatalism has led the leaders of that school to prefer to state their doctrine in terms of prediction. Eltzbacher has forgotten to compare his judgment with the actions of the men he judges; solvitur ambulando; if Kropotkin's proposition were[xi] merely predictive and not pragmatic, it would have less trouble with the police than it has. Again, he does one of the most indiscreet things that are possible to a votary of strict method when he asserts repeatedly that he has listed not merely all that is to be found but all that could possibly exist under a certain category. For instance, he declares that every possible affirmative doctrine of property must be either private property, or common property in the wherewithal for production and private property in the wherewithal for consumption, or common property. Why should not a scheme of common property in the things that are wanted by all men and private property in the things that are wanted only by some men have as high a rank in the classification as has Eltzbacher's second class? A look at the quotations from Kropotkin will show that I have not drawn much on my own ingenuity in conceiving such a scheme as supposable. He claims to have listed all the standpoints from which Anarchism has been or can be propounded or judged, yet he has omitted legitimism, the doctrine that a political authority which is to claim our respect and obedience must appear to have originated by a legitimate foundation and not by usurpation. The great part that legitimism has played in history is notorious; and it lends itself very readily to the Anarchist's purpose, since some governments are so well known to have originated in usurpation and others are so easily suspected of it. Nay, legitimism is in fact a potent factor in shaping the most up-to-date Anarchism of our time; for it is largely concerned in Lysander Spooner's doctrine of juries, of which some slight account is given in Eltzbacher's quotations from Tucker. And he claims to have recited all the important arguments that sustain Anarchism: where has he mentioned the argument from the evil that the State does in interfering with social and economic experimentation? or the argument from the fact that reforms in the State are necessarily in a democracy, and ordinarily in a monarchy, very slow in coming to pass, and when they do come to pass they necessarily come with all-disturbing [xii]suddenness? or the argument from the evil of separating people by the boundary lines which the State involves? or the fact that war would be almost inconceivable if the States were replaced by voluntary and non-monopolistic organizations, since such organizations could have no "jurisdiction" or control of territory to fight for, and war for any other cause has long been unknown among civilized nations? By these and other such unwarranted claims of absolute completeness, and by the conclusions based on these pasteboard premises, Eltzbacher makes it necessary to read his final chapters with all possible independence of judgment.

It remains for me to say something of my own work on this book. I have consulted the originals of some of the works cited—such as circumstances have permitted—and given the quotations not by translation from Eltzbacher's German but direct from the originals. The particulars are as follows:

Of Godwin's "Political Justice" I used an American reprint of the second British edition. This second edition is greatly revised and altered from the first, which Eltzbacher used. Godwin calls our attention to this, and especially informs us that the first edition did not in some important respects represent the views which he held at the time of its publication, since the earlier pages were printed before the later were written, and during the writing of the book he changed his mind about some of the principles he had asserted in the earlier chapters. In the second edition, he says, the views presented in the first part of the book have been made consistent with those in the last part, and all parts have been thoroughly revised. It will astonish nobody, therefore, that I found it now and then impossible to identify in my copy the passages translated by Eltzbacher from the first edition. In particular, I got the impression that what Eltzbacher quotes about promises, from the first part of the book, is one of those sections which Godwin says he retracts and no longer believed in even at the time he wrote the later chapters of the first edition. If so, a bit of the foundation for [xiii]Eltzbacher's ultimate classification disappears. Besides giving the pages of the first edition as in Eltzbacher, I have added in brackets the page numbers of the copy I used, wherever I could identify them. Throughout the book brackets distinguish footnotes added by me from Eltzbacher's own, and in a few places I have used them in the text to indicate Eltzbacher's deviations from the wording of his original, of which matter I will speak again in a moment.

The passages from Proudhon's works I translated from the original French as given in the collected edition of his "Œuvres complètes." In this edition some of the works differ only in pagination from the editions which Eltzbacher used, while others have been extensively revised. I know of no changes of essential doctrine.

Since in Stirner's case German is the original language, I have accepted as my original the quotations given by Eltzbacher. It is probable that they are occasionally condensed; but a fairly faithful memory, and the fact that it is less than a year since I was reading the proofs of my translation of Stirner's book, enable me to be confident that there is no change amounting to distortion. I have here made no use of that translation of mine[1] except from memory, because I well knew that in dealing with Stirner there is no assurance that the best possible translation of the continuous whole will be made up of the best possible translations of the individual parts. Neither have I used the extant English translations of Bakunin's "God and the State," Kropotkin's "Conquest of Bread," Tolstoi's works, or any of the other books cited. I have not had at hand any originals of Bakunin or Tolstoi, nor any of Kropotkin except "Anarchist Communism." Of this I had the first edition, and Eltzbacher, contrary to his habit, the second; but I judge that the two are from the same plates, for all the page-numbers cited agree.

Toward the Tucker chapter I have taken a special attitude. I[xiv] am myself one of Tucker's followers and collaborators; I may claim to be an "authority" on the exposition of his doctrine—

and I have tried to have an eye to the precise correctness of everything in that chapter. That I used the original of "Instead of a Book" is a matter of course; and I have not only taken Tucker's words where Eltzbacher had translated the whole, but have had an eye to all points where Eltzbacher had condensed anything in a way that could affect the sense, and have restored the words that made the passage mean something a little bit different from what Eltzbacher made it mean. (I did about the same in this respect with Kropotkin's "Anarchist Communism"; and indeed something of the kind is inevitable if one is to consult originals at all.) On the other hand, I have not, in general, drawn attention to passages where Eltzbacher makes merely formal changes for the purpose of inserting in a sentence of a certain grammatical structure what Tucker had said in a sentence of different structure.

The renderings of Tolstoi's biblical quotations are taken from the "Corrected English New Testament," a conservative version which is now spoken of as the best English New Testament extant. It fits well into Tolstoi, at least so far as the present quotations go.

I have spoken above of Eltzbacher's qualities as compiler; it here becomes necessary to say something of his work as translator. His translation is that of a very intelligent man, trusting to his intelligence to justify him in translating quite freely. He is confident that he knows what the idea to be presented is, and his main concern is to express that in the language best suited to the purpose. He even avows, as will be seen, that he has "cautiously revised" other people's translations from the Russian, without himself claiming to be familiar with the Russian language. I would as soon entrust this extremely delicate task[xv] to Eltzbacher as to anybody I know, for he is in general remarkably correct in his re-wordings. The justification of his confidence in his knowledge of the author's thought may be seen in the fact that in passages which happen not to affect the main thought he makes a few such slips as zahlen mit ihrer Vergiftung for "pay to be poisoned," Willkuer for "arbitrament," and even eine blutige Revolution ruecksichtslos niederwuerfe for "would do anything in his power to precipitate a bloody revolution" (can he have been misled by the chemist's use of "precipitate"?), but in passages where these blunders would do real harm he keeps clear of them, being safeguarded by his knowledge of the sense. But it makes a difference whom you translate in this way. Tucker is a man who uses language with especial precision: every phrase in a sentence of his may be presumed to contribute something definite to the thought; and Eltzbacher treats him as if the less conspicuous phrases were merely ornamental work which might safely be omitted or amended when they seemed not to be advantageous for ornamental purposes. I must confess that I have little faith in the Eltzbacher method of translation for the rendering of any author; but it works especially ill with an author like Tucker.

Of course all defects of translation are cured, silently, by substituting the original English. Therefore, at the expense of slightly increasing the bulk of the Tucker chapter, this edition gives American readers a much more accurate presentation of the utterances of the American champion of Anarchism than can be had in Eltzbacher's German; and, since I have the same advantage as regards Godwin, I think I may claim in general terms that mine is the best edition of Eltzbacher for those who read both English and German.

Besides looking out for the accurate presentation of the passages quoted from Tucker, I have kept watch of the correctness of the subject-matter. Whatever seemed to me to represent Tucker's book unfairly, either by misrepresenting his doctrine or by misapplying the quotations, has been corrected by a note.[xvi] This will be useful to the reader not only by giving him a better Tucker, but also by giving a sample from which he may judge what amount of fault the followers of Kropotkin or Tolstoi or the rest would be likely to find with the chapters devoted to them. The merely popular reader will probably get the impression that Eltzbacher is really a rather unreliable man. The competent student, who knows what must be looked out for in all work of this sort, will have his confidence in Eltzbacher increased by seeing how little of serious fault appears in such a search.

The index is compiled independently for this translation. Omitting such entries as merely duplicate the utility of the table of contents, and making an effort to head every entry with the word under which the reader will actually seek it, I hope I have bettered Eltzbacher's index; and I hope the index will be not only a place-finder but a help toward the appreciation of the Anarchistic teachings.

I have not in general undertaken to criticise those features of the book which embody Eltzbacher's own opinions. Whether it was in fact right to select these seven men as the touchstone of Anarchism,—whether Eltzbacher is right in discussing the definition of the State as he does, or whether he might better simply have taken as authoritative that definition which has legal force in international law,—whether he ought to have added any other feature to his book,—are points on which the reader does not care for my judgment, nor am I eager to express a judgment. Having had to work over the book very carefully in detail, I have felt entitled to express an opinion as to how well Eltzbacher has done the work that he did choose to do; I have also told what work I as translator claim to have done; and it is time this preface ended.

Steven T. Byington.

Ballardvale, Mass., August 28, 1907.

[1] Entitled "The Ego and His Own." N. Y., Benj. R. Tucker, 1907.

[xvii]

Adler, "Handwoerterbuch" = Georg Adler, "Anarchismus," in Handwoerterbuch der Staatswissenschaften, 2d ed. (Jena 1898), vol. 1 pp. 296-327.

Adler, "Nord und Sued" = Georg Adler, "Die Lehren der Anarchisten," in Nord und Sued (Breslau) vol. 32 (1885) pp. 371-83.

Ba. "Articles" = "Articles écrits par Bakounine dans l'Egalité de 1869," in Mémoire présenté par la fédération jurassienne de l'Association internationale des travailleurs à toutes les fédérations de l'Internationale (Sonvillier, n. d.), "Pièces justificatives" pp. 68-114.

Ba. "Briefe" = "Briefe Bakunins," in Dragomanoff (see below) pp. 1-272.

Ba. "Dieu" = Michel Bakounine, Dieu et l'Etat, 2d ed. (Paris 1892).

Ba. "Dieu" Œuvres = "Dieu et l'Etat," in Michel Bakounine, Œuvres, 3d ed. (Paris 1895), pp. 261-326.

Ba. "Discours" = "Discours de Bakounine au congrès de Berne," in Mémoire présenté par la fédération jurassienne de l'Association internationale des travailleurs à toutes les fédérations de l'Internationale (Sonvillier, n. d.), "Pièces justificatives" pp. 20-38.

Ba. "Programme" = Bakounine, "Programme de la section slave à Zurich," in Dragomanoff (see below) pp. 381-3.

Ba. "Proposition" = "Fédéralisme, socialisme et antithéologisme. Proposition motivée au Comité central de la Ligue de la paix et de la liberté," in Michel Bakounine, Œuvres, 3d ed. (Paris 1895), pp. 1-205.

Ba. "Statuts" = "Statuts secrets de l'Alliance" and "Programme et règlement de l'Alliance publique," in "L'Alliance" (see below) pp. 118-35.

Ba. "Volkssache" = M. Bakunin, "Die Volkssache. Romanow, Pugatschew oder Pestel?" in Dragomanoff (see below) pp. 303-9.

Bernatzik = Bernatzik, "Der Anarchismus," in Jahrbuch fuer Gesetzgebung, Verwaltung und Volkswirtschaft im Deutschen Reich (Leipzig) vol. 19 (1895) pp. 1-20.

[xviii]

Bernstein = Eduard Bernstein, "Die soziale Doktrin des Anarchismus," in Die Neue Zeit (Stuttgart) year 10 (1891-2) vol. 1 pp. 358-65, 421-8; vol. 2 pp. 589-96, 618-26, 657-66, 772-8, 813-19.

Crispi = Francesco Crispi, "The Antidote for Anarchy," in Daily Mail (London) no. 807 (1898) p. 4.

"Der Anarchismus und seine Traeger" = Der Anarchismus und seine Traeger. Enthuellungen aus dem Lager der Anarchisten von [symbol: circle in triangle], Verfasser der Londoner Briefe in der Koelnischen Zeitung (Berlin 1887).

"Die historische Entwickelung des Anarchismus" = Die historische Entwickelung des Anarchismus (New York 1894).

Diehl = Karl Diehl, P.-J. Proudhon. Seine Lehre und sein Leben. (3 vol., Jena 1888-96.)

Dragomanoff = Michail Dragomanow, Michail Bakunins sozial-politischer Briefwechsel mit Alexander Iw. Herzen und Ogarjow, deutsch von Boris Minzès (Stuttgart 1895).

Dubois = Felix Dubois, Le Péril anarchiste (Paris 1894).

Ferri = "Discours de Ferri" in Congrès international d'anthropologie criminelle, compte rendu des travaux de la quatrième session, tenue à Genève du 24 au 29 août 1896 (Genève 1897) pp. 254-7.

Garraud = R. Garraud, L'Anarchie et la Répression (Paris 1895).

Godwin = William Godwin, An Enquiry concerning Political Justice and its Influence on General Virtue and Happiness (2 vol., London 1793). [Bracketed references are to the "First American from the second London edition, corrected," Philadelphia, 1796.]

"Hintermaenner" = Die Hintermaenner der Sozialdemokratie. Von einem Eingeweihten (Berlin 1890).

Kr. "Anarchist Communism" = Peter Kropotkine, Anarchist Communism: its Basis and Principles, 2d ed. (London 1895). [Reprinted from the Nineteenth Century.]

Kr. "Conquête" = Pierre Kropotkine, La Conquête du pain, 5th ed. (Paris 1895).

Kr. "L'Anarchie dans l'évolution socialiste" = Pierre Kropotkine, L'Anarchie dans l'évolution socialiste (Paris 1892).

Kr. "L'Anarchie. Sa philosophie—son idéal" = Pierre Kropotkine, L'Anarchie. Sa philosophie—son idéal (Paris 1896).

Kr. "Morale" = Pierre Kropotkine, La Morale anarchiste (Paris 1891).

Kr. "Paroles" = Pierre Kropotkine, Paroles d'un révolté, ouvrage publié par Elisée Réclus, nouv. éd. (Paris, n. d.)

[xix]

Kr. "Prisons" = Pierre Kropotkine, Les Prisons (Paris 1890).

Kr. "Siècle" = Pierre Kropotkine, Un siècle d'attente. 1789-1889 (Paris 1893).

Kr. "Studies" = Revolutionary Studies, translated from "La Révolte" and reprinted from "The Commonweal" (London 1892).

Kr. "Temps nouveaux" = Pierre Kropotkine, Les Temps nouveaux (conférence faite à Londres) (Paris 1894).

"L'Alliance" = L'Alliance de la démocratie socialiste et l'Association internationale des travailleurs (Londres et Hambourg 1873).

Lenz = Adolf Lenz, Der Anarchismus und das Strafrecht. Sonderabdruck aus der Zeitschrift fuer die gesamte Strafrechtswissenschaft, Bd. 16, Heft 1 (Berlin, n. d.).

Lombroso = C. Lombroso, Gli Anarchici, 2d ed. (Torino 1895).

Mackay, "Anarchisten" = John Henry Mackay, Die Anarchisten. Kulturgemaelde aus dem Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts. Volksausgabe (Berlin 1893).

Mackay, "Magazin" = John Henry Mackay, "Der individualistische Anarchismus: ein Gegner der Propaganda der That," in Das Magazin fuer Litteratur (Berlin und Weimar) vol. 67 (1898) pp. 913-15.

Mackay, "Stirner" = John Henry Mackay, Max Stirner. Sein Leben und sein Werk (Berlin 1898).

Merlino = F. S. Merlino, L'Individualismo nell'anarchismo (Roma 1895).

Pfau = "Proudhon und die Franzosen," in Ludwig Pfau, Kunst und Kritik, vol. 6 of Aesthetische Schriften, 2d ed. (Stuttgart, Leipzig, Berlin, 1888), pp. 183-236.

Plechanow = Georg Plechanow, Anarchismus und Sozialismus (Berlin 1894).

Pr. "Banque" = P.-J. Proudhon, Banque du peuple, suivie du rapport de la commission des délégués du Luxembourg (Paris 1849). (In Proudhon's Œuvres complètes, Paris 1866-83, this forms part of the volume "Solution.")

Pr. "Contradictions" = P.-J. Proudhon, Système des contradictions économiques, ou philosophie de la misère (2 vol., Paris 1846).

Pr. "Confessions" = P.-J. Proudhon, Les Confessions d'un révolutionnaire, pour servir à l'histoire de la révolution de février (Paris 1849).

Pr. "Droit" = P.-J. Proudhon, Le Droit au travail et le Droit de propriété (Paris 1848). (In the Œuvres this forms part of the volume "La Révolution sociale.")

[xx]

Pr. "Idée" = P.-J. Proudhon, Idée générate de la révolution au XIXe siècle (choix d'études sur la pratique révolutionnaire et industrielle) (Paris 1851).

Pr. "Justice" = P.-J. Proudhon, De la justice dans la révolution et dans l'Eglise. Nouveaux principes de philosophie pratique (3 vol., Paris 1858).

Pr. "Organisation" = P.-J. Proudhon, Organisation du crédit et de la circulation, et solution du problème social (Paris 1848). (In the Œuvres this forms part of the volume "Solution.")

Pr. "Principe" = P.-J. Proudhon, Du principe fédératif et de la nécessité de reconstituer le parti de la révolution (Paris 1863).

Pr. "Propriété" = P.-J. Proudhon, Qu'est-ce que la propriété? ou recherches sur le principe du droit et du gouvernement. Premier mémoire (Paris 1841).

Pr. "Solution" = P.-J. Proudhon, Solution du problème social (Paris 1848).

Proal = Louis Proal, La Criminalité politique (Paris 1895).

Reichesberg = Naum Reichesberg, Sozialismus und Anarchismus (Bern und Leipzig 1895).

Rienzi = Rienzi, L'Anarchisme, traduit du néerlandais par August Dewinne (Bruxelles 1893).

Sernicoli = E. Sernicoli, L'Anarchia e gli Anarchici. Studio storico e politico di E. Sernicoli (2 vol., Milano 1894).

Shaw = George Bernard Shaw, The Impossibilities of Anarchism (London 1895).

Silio = Cesar Silio, "El Anarquismo y la Defensa Social," in La Espana Moderna (Madrid) vol. 61 (1894) pp. 141-8.

Stammler = Rudolf Stammler, Die Theorie des Anarchismus (Berlin 1894).

Stirner = Max Stirner, Der Einzige und sein Eigentum (Leipzig 1845).

Stirner "Vierteljahrsschrift" = M. St., "Rezensenten Stirners," in Wigands Vierteljahrsschrift (Leipzig) vol. 3 (1845) pp. 147-94.

To. "Confession" = Graf Leo Tolstoj, Bekenntnisse. Was sollen wir denn thun? deutsch von H. von Samson-Himmelstjerna (Leipzig 1886), pp. 1-102.

To. "Gospel" = Graf Leo N. Tolstoj, Kurze Darlegung des Evangeliums, deutsch von Paul Lauterbach (Leipzig, n. d.).

To. "Kernel" = "Das Korn," in Graf Leo N. Tolstoj, Volkserzaehlungen, deutsch von Wilhelm Goldschmidt (Leipzig, n. d.), pp. 87-9.

To. "Kingdom" = Leo N. Tolstoj, Das Reich Gottes ist in[xxi] euch, oder das Christentum als eine neue Lebensauffassung, nicht als mystische Lehre, deutsch von R. Loewenfeld (Stuttgart, Leipzig, Berlin, Wien, 1894).

To. "Linen-Measurer" = "Leinwandmesser. Die Geschichte eines Pferdes," in Leo N. Tolstoj, Gesammelte Werke, deutsch herausgegeben von Raphael Loewenfeld, vol. 3 (Berlin 1893) pp. 573-631.

To. "Money" = Graf Leo Tolstoj, Geld! Soziale Betrachtungen, deutsch von August Scholz (Berlin 1891).

To. "Morning" = "Der Morgen des Gutsherrn," in Leo N. Tolstoj, Gesammelte Werke, deutsch herausgegeben von Raphael Loewenfeld, vol. 2, 2d ed. (Leipzig, n. d.), pp. 1-81.

To. "On Life" = Graf Leo Tolstoj, Ueber das Leben, deutsch von Sophie Behr (Leipzig 1889).

To. "Patriotism" = Graf Leo N. Tolstoj, Christentum und Vaterlandsliebe, deutsch von L. A. Hauff (Berlin n. d.).

To. "Persecutions" = Russische Christenverfolgungen im Kaukasus. Mit einem Vor- und Nachwort von Leo Tolstoj (Dresden und Leipzig 1896) pp. 7-8, 38-48.

To. "Reason and Dogma" = Graf Leo N. Tolstoj, Vernunft und Dogma. Eine Kritik der Glaubenslehre, deutsch von L. A. Hauff (Berlin n. d.).

To. "Religion and Morality" = Graf Leo Tolstoj, Religion und Moral. Antwort auf eine in der "Ethischen Kultur" gestellte Frage, deutsch von Sophie Behr (Berlin 1894).

To. "What I Believe" = Graf Leo Tolstoj, Worin besteht mein Glaube? Eine Studie, deutsch von Sophie Behr (Leipzig 1885).

To. "What Shall We Do" = Graf Leo Tolstoj, Was sollen wir also thun? deutsch von August Scholz (Berlin 1891).

Tripels = "Discours de Tripels," in Congrès international d'anthropologie criminelle, compte rendu des travaux de la quatrième session, tenue à Genève du 24 au 29 août 1896 (Genève 1897) pp. 253-4.

Tucker = Benj. R. Tucker, Instead of a Book. By a Man Too Busy to Write One. A fragmentary exposition of philosophical Anarchism (New York 1893).

Van Hamel = Van Hamel, "L'Anarchisme et le Combat contre l'anarchisme au point de vue de l'anthropologie criminelle," in Congrès international d'anthropologie criminelle, compte rendu des travaux de la quatrième session, tenue à Genève du 24 au 29 août 1896 (Genève 1897) pp. 254-7.

Zenker = E. V. Zenker, Der Anarchismus. Kritische Geschichte der anarchistischen Theorie (Jena 1895).

[2]

[3]

1. We want to know Anarchism scientifically, for reasons both personal and external.

We wish to penetrate the essence of a movement that dares to question what is undoubted and to deny what is venerable, and nevertheless takes hold of wider and wider circles.

Besides, we wish to make up our minds whether it is not necessary to meet such a movement with force, to protect the established order or at least its quiet progressive development, and, by ruthless measures, to guard against greater evils.

2. At present there is the greatest lack of clear ideas about Anarchism, and that not only among the masses but among scholars and statesmen.

Now it is a historic law of evolution[2] that is described as the supreme law of Anarchism, now it is the happiness of the individual,[3] now justice.[4]

Now they say that Anarchism culminates in the negation of every programme,[5] that it has only a negative aim;[6] now, again, that its negating and destroying side is balanced by a side that is affirmative and creative;[7] now, to conclude, that what is original in Anarchism is to be found exclusively in its utterances about the ideal society,[8] that its real, true essence consists in its positive efforts.[9]

[4]

Now it is said that Anarchism rejects law,[10] now that it rejects society,[11] now that it rejects only the State.[12]

Now it is declared that in the future society of Anarchism there is no tie of contract binding persons together;[13] now, again, that Anarchism aims to have all public affairs arranged for by contracts between federally constituted communes and societies.[14]

Now it is said in general that Anarchism rejects property,[15] or at least private property;[16] now a distinction is made between Communistic and Individualistic,[17] or even between Communistic, Collectivistic, and Individualistic Anarchism.[18]

Now it is asserted that Anarchism conceives of its realization as taking place through crime,[19] especially through a violent revolution[20] and by the help of the propaganda of deed;[21] now, again, that Anarchism rejects violent tactics and the propaganda of deed,[22] or that these are at least not necessary constituents of Anarchism.[23]

3. Two demands must be made of everybody who undertakes to produce a scientific work on Anarchism.

First, he must be acquainted with the most important Anarchistic writings. Here, to be sure, one[5] meets great difficulties. Anarchistic writings are very scantily represented in our public libraries. They are in part so rare that it is extremely difficult for an individual to acquire even the most prominent of them. So it is not strange that of all works on Anarchism only one is based on a comprehensive knowledge of the sources. This is a pamphlet which appeared anonymously in New York in 1894, "Die historische Entwickelung des Anarchismus" which in sixteen pages gives a concise presentation that attests an astonishing acquaintance with the most various Anarchistic writings. The two large works, "L'anarchia e gli anarchici, studio storico e politico di E. Sernicoli" 2 vol., Milano, 1894, and "Der Anarchismus, kritische Geschichte der anarchistischen Theorie von E. V. Zenker," Jena, 1895, are at least in part founded on a knowledge of Anarchistic writings.

Second, he who would produce a scientific work on Anarchism must be equally at home in jurisprudence, in economics, and in philosophy. Anarchism judges juridical institutions with reference to their economic effects, and from the standpoint of some philosophy or other. Therefore, to penetrate its essence and not fall a victim to all possible misunderstandings, one must be familiar with those concepts of philosophy, jurisprudence, and economics which it applies or has a relation to. This demand is best met, among all works on Anarchism, by Rudolf Stammler's pamphlet, "Die Theorie des Anarchismus," Berlin, 1894.

[2] "Der Anarchismus und seine Traeger" pp. 124, 125, 127; Reichesberg p. 27.

[3] Lenz p. 3.

[4] Bernatzik pp. 2, 3.

[5] Lenz p. 5.

[6] Crispi.

[7] Van Hamel p. 112.

[8] Adler p. 321.

[9] Reichesberg p. 13.

[10] Stammler pp. 2, 4, 34, 36; Lenz pp. 1, 4.

[11] Silió p. 145; Garraud p. 12; Reichesberg p. 16; Tripels p. 253.

[12] Bernstein p. 359; Bernatzik p. 3.

[13] Reichesberg p. 30.

[14] Lombroso p. 31.

[15] Silió p. 145; Dubois p. 213.

[16] Lombroso p. 31; Proal p. 50.

[17] Rienzi p. 9; Stammler pp. 28-31; Merlino pp. 18, 27; Shaw p. 23.

[18] "Die historische Entwickelung des Anarchismus" p. 16; Zenker p. 161.

[19] Garraud p. 6; Lenz p. 5.

[20] Sernicoli vol. 2 p. 116; Garraud p. 2; Reichesberg p. 38; Van Hamel p. 113.

[21] Garraud pp. 10, 11; Lombroso p. 34; Ferri p. 257.

[22] Mackay "Magazin" pp. 913-915; "Anarchisten" pp. 239-243.

[23] Zenker pp. 203, 204.

[6]

The problem for our study is, to get determinate concepts of Anarchism and its species. As soon as such determinate concepts are attained, Anarchism is scientifically known. For their determination is not only conditioned on a comprehensive view of all the individual phenomena of Anarchism; it also brings together the results of this comprehensive view, and assigns to them a place in the totality of our knowledge.

The problem of getting determinate concepts of Anarchism and its species seems at a first glance perfectly clear. But the apparent clearness vanishes on closer examination.

For there rises first the question, what shall be the starting-point of our study? The answer will be given, "Anarchistic teachings." But there is by no means an agreement as to what teachings are Anarchistic; one man designates as "Anarchistic" these teachings, another those; and of the teachings themselves a part designate themselves as Anarchistic, a part do not. How can one take any of them as Anarchistic teachings for a starting-point, without applying that very concept of Anarchism which he has yet to determine?

Then rises the further question, what is the goal of the study? The answer will be given, "the concepts[7] of Anarchism and its species." But we see daily that different men define in quite different ways the concept of an object which they yet conceive in the same way. One says that law is the general will; another, that it is a mass of precepts which limit a man's natural liberty for other men's sake; a third, that it is the ordering of the life of the nation (or of the community of nations) to maintain God's order of the world. They all know that a definition should state the proximate genus and the distinctive marks of the species, but this knowledge does them little good. So it seems that the goal of the study does still require elucidation.

Lastly rises the question, what is the way to this goal? Any one who has ever observed the conflict of opinions in the intellectual sciences knows well, on the one hand, how utterly we lack a recognized method for the solution of problems; and, on the other hand, how necessary it is in any study to get clearly in mind the method that is to be used.

2. Our study can come to a more precise specification of its problem. The problem is to put concepts in the place of non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species.

Every concept-determining study faces the problem of comprehending conceptually an object that was first comprehended non-conceptually, and therefore of putting a concept in the place of non-conceptual notions of an object. This problem finds a specially clear expression in the concept-determining judgment (the definition), which puts in immediate juxtaposition, in its subject some non-conceptual notion of an object,[8] and in its predicate a conceptual notion of the same object.

Accordingly, the study that is to determine the concepts of Anarchism and its species has for its problem to comprehend conceptually objects that are first comprehended in non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species; and therefore, to put concepts in the place of these non-conceptual notions.

3. But our study may specify its problem still more precisely, though at first only on the negative side. The problem is not to put concepts in the place of all notions that appear as non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species.

Any concept can comprehend conceptually only one object, not another object together with this. The concept of health cannot be at the same time the concept of life, nor the concept of the horse that of the mammal.

But in the non-conceptual notions that appear as notions of Anarchism and its species there are comprehended very different objects. To be sure, the object of all these notions is on the one hand a genus that is formed by the common qualities of certain teachings, and on the other hand the species of this genus, which are formed by the addition of sundry peculiarities to these common qualities. But still these notions have in view very different groups of teachings with their common and special qualities, some perhaps only the teachings of Kropotkin and Most, others only the teachings of Stirner, Tucker, and Mackay, others again the teachings of both sets of authors.

[9]

If one proposed to put concepts in the place of all the non-conceptual notions which appear as notions of Anarchism and its species, these concepts would have to comprehend at once the common and special qualities of quite different groups of teachings, of which groups one might embrace only the teachings of Kropotkin and Most, another only those of Stirner, Tucker, and Mackay, a third both. But this is impossible: the concepts of Anarchism and its species can comprehend only the common and special qualities of a single group of teachings; therefore our study cannot put concepts in the place of all the notions that appear as notions of Anarchism and its species.

4. By completing on the affirmative side this negative specification of its problem, our study can arrive at a still more precise specification of this problem. The problem is to put concepts in the place of those non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species, having in view one and the same group of teachings, which are most widely diffused among the men who at present are scientifically concerned with Anarchism.

Because the only possible problem for our study is to put concepts in the place of part of the notions that appear as non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species,—to wit, only in the place of such notions as have in view one and the same group of teachings with its common and special qualities,—therefore we must divide into classes, according to the groups of teachings that they severally have in view, the notions that appear as notions of Anarchism and its species, and we must choose the class whose notions[10] are to be replaced by concepts.

The choice of the class must depend on the kind of men for whom the study is meant. For the study of a concept is of value only for those who non-conceptually apprehend the object of the concept, since the concept takes the place of their notions only. For those who form a non-conceptual notion of space, the concept of morality is so far meaningless; and just as meaningless, for those who mean by Anarchism what the teachings of Proudhon and Stirner have in common, is the concept of what is common to the teachings of Proudhon, Stirner, Bakunin, and Kropotkin.

But the men for whom this study is meant are those who at present are scientifically concerned with Anarchism. If all these, in their notions of Anarchism and its species, had in view one and the same group of teachings, then the problem for our study would be to put concepts in the place of this set of notions. Since this is not the case, the only possible problem for our study is to put concepts in the place of that set of notions which has in view a group of teachings that the greatest possible number of the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism have in view in their non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species.

In accordance with what has been said, the starting-point of our study must be those non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species, having in view one and the same group of teachings, which are most widely diffused among the men who at present are[11] scientifically concerned with Anarchism.

1. How can it be known what group of teachings the non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species most widely diffused among the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism have in view?

First and foremost, this may be seen from utterances regarding particular Anarchistic teachings, and from lists and descriptions of such teachings.

We may assume that a man regards as Anarchistic those teachings which he designates as Anarchistic, and, further, those teachings which are likewise characterized by the common qualities of these. We may further assume that a man does not regard as Anarchistic those teachings which he in any form contrasts with the Anarchistic teachings, nor, if he undertakes to catalogue or describe the whole body of Anarchistic teachings, those teachings unknown to him which are not characterized by the common qualities of the teachings he catalogues or describes.

What group of teachings those non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species which are most widely diffused among the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism have in view, may be seen secondly from the definitions of Anarchism and from other utterances about it. We may doubtingly assume that a man regards as Anarchistic those teachings which come under his definition of Anarchism, or for which his utterances about Anarchism hold good; and, on the contrary, that he does not regard as Anarchistic those teachings which do not come under that definition, or for which these utterances do not hold good.

[12]

When these two means of knowledge lead to contradictions, the former must be decisive. For, if a man so defines Anarchism, or so speaks of Anarchism, that on this basis teachings which he declares non-Anarchistic manifest themselves to be Anarchistic,—and perhaps other teachings, which he counts among the Anarchistic, to be non-Anarchistic,—this can be due only to his not being conscious of the scope of his general pronouncements; therefore it is only from his treatment of the individual teachings that one can find out his opinion of these.

2. These means of knowledge inform us what group of teachings the non-conceptual notions of Anarchism and its species most widely diffused among the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism have in view.

We learn, first, that the teachings of certain particular men are recognized as Anarchistic teachings by the greater part of those who at present are scientifically concerned with Anarchism.

We learn, second, that by the greater part of those who at present are scientifically concerned with Anarchism the teachings of these men are recognized as Anarchistic teachings only in so far as they relate to law, the State, and property; but not in so far as they may be concerned with the law, State, or property of a particular legal system or a particular group of legal systems, nor in so far as they regard other objects, such as religion, the family, art.

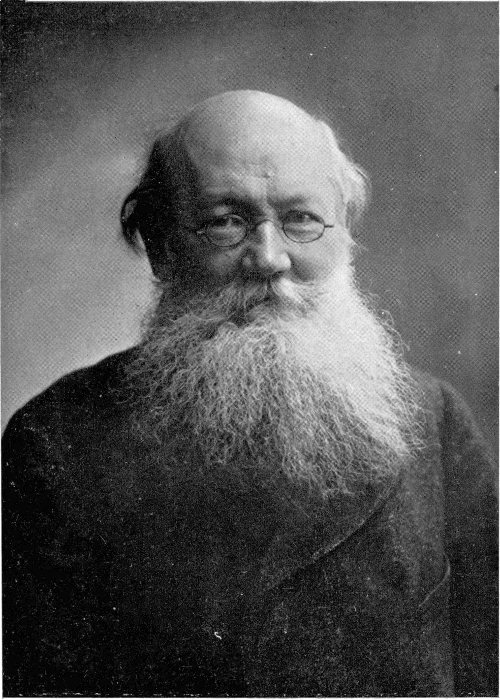

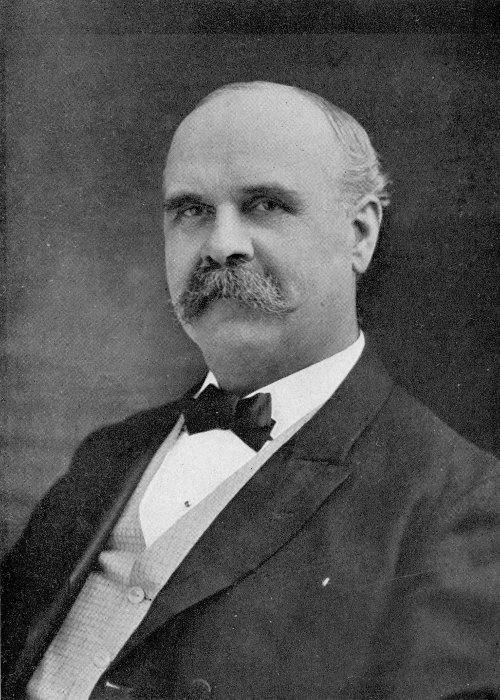

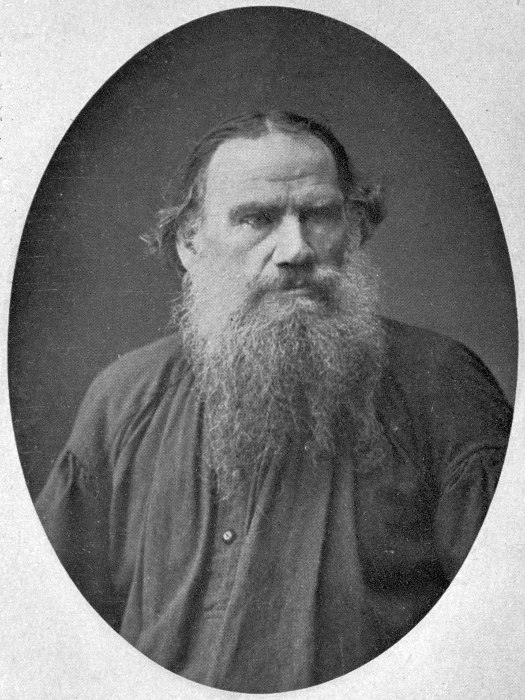

Among the recognized Anarchistic teachings seven are particularly prominent: to wit, the teachings of Godwin, Proudhon, Stirner, Bakunin, Kropotkin,[13] Tucker, and Tolstoi. They all manifest themselves to be Anarchistic teachings according to the greater part of the definitions of Anarchism, and of other scientific utterances about it. They all display the qualities that are common to the doctrines treated of in most descriptions of Anarchism. Some of them, be it one or another, are put in the foreground in almost every work on Anarchism. Of no one of them is it denied, to an extent worth mentioning, that it is an Anarchistic teaching.

In accordance with what has been said, the goal of our study must be to determine, first, the concept of the genus which is constituted by the common qualities of those teachings which the greater part of the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism recognize as Anarchistic teachings; second, the concepts of the species of this genus, which are formed by the accession of any specialties to those common qualities.

1. The first thing toward a concept is that an object be apprehended as clearly and purely as possible.

In non-conceptual notions an object is not apprehended with all possible clearness. In our non-conceptual notions of gold we most commonly make clear to ourselves only a few qualities of gold; one of us, perhaps, thinks mainly of the color and the lustre, another of the color and malleability, a third of some other qualities. But in the concept of gold color, lustre, malleability, hardness, solubility, fusibility, specific gravity, atomic weight, and all other qualities of gold, must be apprehended as clearly as possible.

[14]

Nor is an object apprehended in all possible purity in our non-conceptual notions. We introduce into our non-conceptual notions of gold many things that do not belong among the qualities of gold; one, perhaps, thinks of the present value of gold, another of golden dishes, a third of some sort of gold coin. But all these alien adjuncts must be kept away from the concept of gold.

So the first goal of our study is to describe as clearly as possible on the one side, and as purely as possible on the other, the common qualities of those teachings which the greater part of the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism recognize as Anarchistic teachings, and the specialties of all the teachings which display these common qualities.

2. It is further requisite for a concept that an object should have its place assigned as well as possible in the total realm of our experience,—that is, in a system of species and genera which embraces our total experience.

In non-conceptual notions an object does not have its place assigned in the total realm of our experience, but arbitrarily in one of the many genera in which it can be placed according to its various qualities. One of us, perhaps, thinks of gold as a species of the genus "yellow bodies," another as a species of the genus "malleable bodies," a third as a species of some other genus. But the concept of gold must assign it a place in a system of species and genera that embraces our whole experience,—a place in the genus "metals."

So a further goal of our study is to assign a place as well as possible in the total realm of our experience[15] (that is, in a system of species and genera which embraces our total experience) for the common qualities of those teachings which the greater part of the men at present scientifically concerned with Anarchism recognize as Anarchistic teachings, and for the specialties of all the teachings that display these common qualities.

In accordance with what has been said, the way that our study must take to go from its starting-point to its goal will be in three parts. First, the concepts of law, the State, and property must be determined. Next, it must be ascertained what the Anarchistic teachings assert about law, the State, and property. Finally, after removing some errors, we must get determinate concepts of Anarchism and its species.

1. First, we must get determinate concepts of law, the State, and property; and this must be of law, the State, and property in general, not of the law, State, or property of a particular legal system or a particular family of legal systems.

Law, the State, and property, in this sense, are the objects about which the doctrines which are to be examined in their common and special qualities make assertions. Before the fact of any assertions about an object can be ascertained,—not to say, before the common and special qualities of these assertions can be brought out and assigned to a place in the total realm of our experience,—we must get a determinate concept of this object itself. Hence the first thing that must be done is to determine the concepts of law, the State, and property (chapter II).

[16]

2. Next, it must be ascertained what the Anarchistic teachings assert about law, the State, and property;—that is, the recognized Anarchistic teachings, and also those teachings which likewise display the qualities common to these.

What the recognized Anarchistic teachings say, must be ascertained in order to determine the concept of Anarchism. What all the teachings that display the common qualities of the recognized Anarchistic teachings say, must be ascertained in order that we may get determinate concepts of the species of Anarchism.

So each of these teachings must be questioned regarding its relation to law, the State, and property. These questions must be preceded by the question on what foundation the teaching rests, and must be followed by the question how it conceives the process of its realization.

It is impossible to present here all recognized Anarchistic teachings, not to say all Anarchistic teachings. Therefore our study limits itself to the presentation of seven especially prominent teachings (chapters III to IX), and then, from this standpoint, seeks to get a view of the totality of recognized Anarchistic teachings and of all Anarchistic teachings (chapter X).

The teachings presented are presented in their own words,[24] but according to a uniform system: the first, for security against the importation of alien thoughts; the second, to avoid the uncomparable juxtaposition[17] of fundamentally different courses of thought. They have been compelled to give definite replies to definite questions; it was indeed necessary in many cases to bring the answers together in tiny fragments from the most various writings, to sift them so far as they contradicted each other, and to explain them so far as they deviated from ordinary language. Thus Tolstoi's strictly logical structure of thought and Bakunin's confused talk, Kropotkin's discussions full of glowing philanthropy and Stirner's self-pleasing smartness, come before our eyes directly and yet in comparable form.

3. Finally, after removing widely diffused errors, we are to get determinate concepts of Anarchism and its species.

We must, therefore, on the basis of that knowledge of the Anarchistic teachings which we have acquired, clear away the most important errors about Anarchism and its species; and then we must determine what the Anarchistic teachings have in common, and what specialties are represented among them, and assign to both a place in the total realm of our experience. Then we have the concepts of Anarchism and its species (chapter XI).

[24] Russian writings are cited from translations, which are cautiously revised where they seem too harsh.

[18]

In this discussion we are to get determinate concepts of law, the State, and property in general, not of the law, State, and property of a particular legal system or of a particular family of legal systems. The concepts of law, State, and property are therefore to be determined as concepts of general jurisprudence, not as concepts of any particular jurisprudence.

1. By the concepts of law, State, and property one may understand, first, the concepts of law, State, and property in the science of a particular legal system.

These concepts of law, State, and property contain all the characteristics that belong to the substance of a particular legal system. They embrace only the substance of this system. They may, therefore, be called concepts of the science of this system. For we may designate as the science of a particular legal system that part of jurisprudence which concerns itself exclusively with the norms of a particular legal system.

The concepts of law, State, and property in the science of a legal system are distinguished from the concepts of law, State, and property in the sciences of other legal systems by this characteristic,—that they are concepts of norms of this particular system. From this characteristic we may deduce all the characteristics that result from the special substance of this system of law in contrast to other such systems. The[19] concepts of property in the present laws of the German empire, of France, and of England are distinguished by the fact that they are concepts of norms of these three different legal systems. Consequently they are as different as are the norms of the present imperial-German, French, and English law on the subject of property. The concepts of law, State, and property in different legal systems are to each other as species-concepts which are subordinate to one and the same generic concept.

2. Second, one may understand by the concepts of law, State, and property the concepts of law, State, and property in the science of a particular family of laws.

These concepts of law, State, and property contain all the characteristics that belong to the common substance of the different legal systems of this family. They embrace only the common substance of the different systems of this family. They may, therefore, be called concepts of the science of this family of laws. For we may designate as the science of a particular family of laws that part of jurisprudence which deals exclusively with the norms of a particular family of legal systems, so far as these are not already dealt with by the sciences of the particular legal systems of this family.

The concepts of law, State, and property in the science of a family of laws are distinguished from the concepts of law, State, and property in the sciences of the legal systems that form the family by lacking the characteristic of being concepts of norms of these systems, and consequently lacking also all the [20]characteristics which may be deduced from this characteristic according to the special substance of one or another legal system. The concept of the State in the science of present European law is distinguished from the concepts of the State in the sciences of present German, Russian, and Belgian law by not being a concept of norms of any one of these systems, and consequently by lacking all the characteristics that result from the special substance of the constitutional norms in force in Germany, Russia, and Belgium. Its relation to the concepts of the State in the science of these systems is that of a generic concept to subordinate species-concepts.

The concepts of law, State, and property in the science of a family of laws are distinguished from the concepts of law, State, and property in the sciences of other such families by this characteristic,—that they are concepts of norms of this particular family. From this characteristic we may deduce all the characteristics that are peculiar to the common substance of the different legal systems of this family in contrast to the common substance of the different legal systems of other families. The concept of the State in the science of present European law and the concept of the State in the science of European law in the year 1000 are distinguished by the fact that the one is a concept of constitutional norms that are in force in Europe to-day, the other of such as were in force in Europe then; consequently they are different in the same way as what the constitutional norms in force in Europe to-day have in common is different from what was common to the constitutional norms in force in[21] Europe then. These concepts are to each other as species-concepts which are subordinate to one and the same generic concept.

3. Third, one may understand by the concepts of law, State, and property the concepts of law, State, and property in general jurisprudence.

These concepts of law, State, and property contain all the characteristics that belong to the common substance of the most different systems and families of laws. They embrace only what the norms of the most different systems and families of laws have in common. They may, therefore, be called concepts of general jurisprudence. For that part of jurisprudence which treats of legal norms without limitation to any particular system or family of laws, so far as these norms are not already treated by the sciences of the particular systems and families, may be designated as general jurisprudence.

The concepts of law, State, and property in general jurisprudence are distinguished from the concepts of law, State, and property in the particular jurisprudences by lacking the characteristic of being concepts of norms of one of these systems or at least one of these families of systems, and consequently lacking also all the characteristics which may be deduced from this characteristic according to the special substance of some system or family of laws. The concept of law per se is distinguished from the concept of law in present European law and from the concept of law in the present law of the German empire by not being a concept of norms of that family of laws, not to say that particular system, and consequently by lacking[22] all the characteristics that might belong to any peculiarities which might be common to all legal norms at present in force in Europe or in Germany. Its relation to the concepts of law in these particular jurisprudences is that of a generic concept to subordinate species-concepts.

4. In which of the senses here distinguished the concepts of law, State, and property should be defined in a particular case, and what matters should accordingly be taken into consideration in defining them, depends on the purpose of one's study.

If, for example, the point is to describe scientifically the constitutional norms of the present law of the German empire, then the concept of the State as defined on this occasion must be a concept of the science of this particular legal system. For scientific work on the norms of a particular legal system requires that concepts be formed of the norms of just this system. Consequently the material to be taken into consideration will be only the constitutional norms of the present law of the German empire.—That the concepts defined in the scientific description of a system of law are in fact concepts of the science of this system may indeed seem obscure. For every concept of the science of any particular system of law may be defined as the concept of a species under the corresponding generic concept of general jurisprudence. We define this generic concept, say the concept of the State in general jurisprudence, and add the distinctive characteristic of the species-concept, that it is a concept of norms of this particular system of law, say of the present law of the German empire. And then we[23] often leave this additional characteristic unexpressed, where we think we may assume (as is the case in the scientific description of the norms of any particular system of law) that everybody will regard it as tacitly added. The consequence is that the definition given in the scientific description of a particular system of law looks, at a superficial glance, like the definition of a concept of general jurisprudence.

Or, if the point is to compare scientifically the norms of present European law regarding property, the concept of property as defined on this occasion must be a concept of the science of this particular family of laws. For the scientific comparison of norms of different legal systems demands that concepts of the sciences of these different legal systems be subordinately arranged under the corresponding concept of the science of the family of laws which is made up of these systems. Consequently the material to be taken into consideration will be only the norms of this family of laws.—Here again, indeed, it may seem obscure that the concepts defined are really concepts of the science of this family of laws. For the concepts that belong to the science of a family of laws may likewise be defined by defining the corresponding concepts of general jurisprudence and tacitly adding the characteristic of being concepts of norms of this particular family of laws.

Finally, if it comes to pass that the point is to compare scientifically what the norms of the most diverse systems of law have in common, the concept of law as defined on this occasion must be a concept of general jurisprudence. For the scientific comparison[24] of norms of the most diverse systems and families of laws demands that concepts which belong to the sciences of the most diverse systems and families of laws be subordinately arranged under the corresponding concept of general jurisprudence. Consequently the material to be taken into consideration will be the norms of the most diverse systems and families of laws.

Here,—where the point is to take the first step toward a scientific comprehension of teachings which pass judgment on law, the State, and property in general, not only on the law, State, or property of a particular system or family of laws,—the concepts of law, State, and property must necessarily be defined as concepts of general jurisprudence. For a scientific comprehension of teachings which deal with the common substance of the most diverse systems and families of laws demands that concepts of this common substance—consequently concepts belonging to general jurisprudence—be formed. Therefore we have to take into consideration, as our material, the norms (especially regarding the State and property) of the most diverse systems and families of laws.

Law is the body of legal norms. A legal norm is a norm which is based on the fact that men have the will to see a certain procedure generally observed within a circle which includes themselves.

1. A legal norm is a norm.

A norm is the idea of a correct procedure. A correct procedure means one that corresponds either to[25] the final purpose of all human procedure (unconditionally correct procedure,—for instance, respect for another's life), or at any rate to some accidental purpose (conditionally correct procedure,—for instance, the skilled handling of a picklock). And the idea of a correct procedure means that the unconditionally or conditionally correct procedure is to be thought of not as a fact but as a task, not as something real but as something to be realized; it does not mean that I shall in fact spare my enemy's life, but that I am to spare it—not how the thief really did use the picklock, but how he should have used it. The idea of a correct procedure is what we designate as an "ought": when I think of an "ought," I think of what has to be done in order to realize either the final purpose of all human procedure or some accidental personal purpose. All passing of judgment on past procedure is conditioned upon the idea of a correct procedure—only with regard to this idea can past procedure be described as good or bad, expedient or inexpedient; and so is all deliberation on future procedure—only with regard to this idea does one inquire whether it will be right, or at any rate expedient, to proceed in a given manner.

Every legal norm represents a procedure as correct, declares that it corresponds to a particular purpose. And it represents this correct procedure as an idea, designates it not as a fact but as a task, does not say that any one does proceed so but that one is to proceed so. Hence a legal norm is a norm.

2. A legal norm is a norm based on a human will.

A norm based on a human will is a norm by virtue[26] of which one must proceed in a certain way in order that he may not put himself in opposition to the will of some particular men, and so be apprehended by the power which is at the service of these men. Such a norm, therefore, represents a procedure only as conditionally correct; to wit, as a means to the end (which we are perhaps pursuing or perhaps despising) of remaining in harmony with the will of certain men, and so being spared by the power which serves this will.

Every legal norm tells us that we must proceed in a certain way in order that we may not contravene the will of some particular men and then suffer under their power. Therefore it represents a procedure only as conditionally correct, and instructs us not as to what is good but only as to what is prescribed. Hence a legal norm is a norm based on a human will.

3. A legal norm is a norm based on the fact that men will to have a certain procedure for themselves and others.

A norm is based on the fact that men will to have a certain procedure for themselves and others when the will on which the norm is based has reference not only to others who do not will, but also, at the same time, to the willers themselves also; when, therefore, these not only will that others be subject to the norm but also will to be subject to it themselves.

Every legal norm, and of all norms only the legal norm, has the characteristic that the will on which it is based reaches beyond those whose will it is, and yet embraces them too. The rule, "Whoever takes from another a movable thing that is not his own, with the intent to appropriate it illegally, is punished with [27]imprisonment for theft," is not only based on the will of men, but each of these men is also conscious that, while on the one hand the rule applies to other men, on the other hand it applies to himself.

Here it might be alleged that, after all, the mere fact of men's will to have a certain procedure for themselves and others does not always establish law; for example, the efforts of the Bonapartists do not establish the empire in France. But it is not when this bare will exists that law is established, but only when a norm is based on this will; that is, when it has in its service so great a power that it is competent to affect the behavior of the men to whom it relates. As soon as Bonapartism spreads so widely and in such circles that this takes place, the republic will fall and the empire will indeed become law in France.

One might further appeal to the fact that in unlimited monarchies (in Russia, for instance) the law is based solely on the will of one man, who is not himself subject to it. But Russian law is not based on the czar's will at all; the czar is a weak individual man, and his will in itself is totally unqualified to affect many millions of Russians in their procedure. Russian law is based rather on the will of all those Russians—peasants, soldiers, officials—who, for the most various reasons—patriotism, self-interest, superstition—will that what the czar wills shall be law in Russia. Their will is qualified to affect the procedure of the Russians; and, if they should ever grow so few that it would no longer have this qualification, then the czar's will would no longer be law in Russia, as the history of revolutions proves.

[28]

4. It has been asserted that legal norms have still other qualities.

It has been said, first, that it belongs to the essence of a legal norm to be enforceable, or even to be enforceable in a particular way, by judicial procedure, governmental force.

If by this we are to understand that conformity can always be enforced, we are met at once by the great number of cases in which this cannot be done. When a debtor is insolvent, or a murder has been committed, conformity to the violated legal norms cannot now be enforced after the fact, but their validity is not impaired by this.

If by enforceability we mean that conformity to a legal norm must be insured by other legal norms providing for the case of its violation, we need only go on from the insured to the insuring norms for a while, to come to norms for which conformity is not insured by any further legal norms. If one refuses to recognize these norms as legal norms, then neither can the norms which are insured by them rank as legal norms, and so, going back along the series, one has at last no legal norms left.

Only if one would understand by the enforceability of the legal norm that a will must have at its disposal a certain power in order that a legal norm may be based on it, one might certainly say in this sense that enforceability belongs to the essence of a legal norm. But this quality of the legal norm would be only such a quality as would be derivable from its quality of being a norm, and would therefore have no claim to be added as a further quality.

[29]

Again, it has been named an essential quality of a legal norm that it should be based on the will of a State. But even where we cannot speak of a State at all, among nomads for instance, there are yet legal norms. Besides, every State is itself a legal relation, established by legal norms, which consequently cannot be based on its will. And lastly, the norms of international law, which are intended to bind the will of States, cannot be based on the will of a State.

Finally, it has been asserted that it was essential to a legal norm that it should correspond to the moral law. If this were so, then among the different legal norms which to-day are in force one directly after the other in the same territory, or at the same time in different territories under the same circumstances, only one could in each case be regarded as a legal norm; for under the same circumstances there is only one moral right. Nor could one speak then of unrighteous legal norms, for if they were unrighteous they would not be legal norms. But in reality, even when legal norms determine conduct quite differently under the same circumstances, they are all nevertheless recognized as legal norms; nor is it doubted that there are bad legal norms as well as good.

5. As a norm based on the fact that men have the will to see a certain procedure generally observed within a circle which includes themselves, the legal norm is distinguished from all other objects, even from those that most resemble it.

By being based on the will of men it is distinguished from the moral law (the commandment of morality); this is not based on men's willing a certain[30] procedure, but on the fact that this procedure corresponds to the final purpose of all human procedure. The maxim, "Love your enemies, bless those who curse you, do good to those who hate you, pray for those who abuse and persecute you," is a moral law; so is the maxim, "Act so that the maxims of your will might at all times serve as the principles of a general legislation." For the correctness of such a procedure is not founded on the fact that other men will have it, but on the fact that it corresponds to the final purpose of all human procedure.

By being based on the will of men the legal norm is distinguished also from good manners; these are not based on the fact that men will a certain procedure, but on the fact that they themselves proceed in a certain way. It is manners that one goes to a ball in a dress coat and white gloves, uses his knife at table only for cutting, begs the daughter of the house for a dance or at least one round, takes leave of the master and mistress of the house, and lastly presses a tip into the servant's hand; for the correctness of such a behavior is not based on the fact that other men ask this of us,—to those who start a new fashion it is often actually unpleasant to find that the fashion is spreading to more extensive circles,—but solely on the fact that other men themselves behave so, and that we want "not to be peculiar," "not to make ourselves conspicuous," "to do like the rest," etc.

By being based on a will which relates at once to those whose will it is and to others whose will it is not, it is distinguished on the one hand from an arbitrary command, in which one's will applies only to[31] others, and on the other from a resolution, in which it applies only to himself. It is an arbitrary command when Cortes with his Spaniards commands the Mexicans to bring out their gold, or when a band of robbers forbids a frightened peasantry to betray their hiding-place; here a human will decides, indeed, but a will that relates only to other men, and not at the same time to those whose will it is. A resolution is presented when I have decided to get up at six every morning, or to leave off smoking, or to finish a piece of work within a specified time—here a human will is indeed the standard, but it relates only to him whose will it is, not at all to others.