Title: Molly Brown's Junior Days

Author: Nell Speed

Illustrator: Charles L. Wrenn

Release date: July 12, 2011 [eBook #36717]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan, eagkw, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net)

E-text prepared by

Stephen Hutcheson, Rod Crawford, Dave Morgan, eagkw,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

BY

NELL SPEED

AUTHOR OF “MOLLY BROWN’S FRESHMAN DAYS,” “MOLLY

BROWN’S SOPHOMORE DAYS,” ETC., ETC.

WITH FOUR HALF-TONE ILLUSTRATIONS

By CHARLES L. WRENN

NEW YORK

HURST & COMPANY

PUBLISHERS

Copyright, 1912,

by

HURST & COMPANY

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Daughters of Wellington | 5 |

| II. | Minerva Higgins | 18 |

| III. | In the Cloisters | 32 |

| IV. | A Literary Evening | 44 |

| V. | Various Happenings | 57 |

| VI. | “The Best Laid Schemes” | 74 |

| VII. | A Midnight Adventure | 89 |

| VIII. | Covering Their Tracks | 105 |

| IX. | The Grave Diggers | 116 |

| X. | A Visit of State | 134 |

| XI. | A Swopping Party and a Mock Trial | 147 |

| XII. | Alarms and Discoveries | 163 |

| XIII. | “The Moving Finger Writes” | 175 |

| XIV. | An Invitation and an Apology | 187 |

| XV. | A Christmas Ghost Story That Was Never Told | 200 |

| XVI. | More Christmas Presents and a Coasting Party of Two | 212 |

| XVII. | The Wayfarers | 226 |

| XVIII. | Healing the Blind | 246 |

| XIX. | A Warning | 259 |

| XX. | The Parable of the Sun and Wind | 272 |

| XXI. | The Junior Gambol | 289 |

| Did I frighten you? I am sorry | Frontispiece |

| Page | |

| They set to work to dig a small grave for Judy’s slipper | 129 |

| “And she’s given me a pair of silk stockings,” cried Molly | 213 |

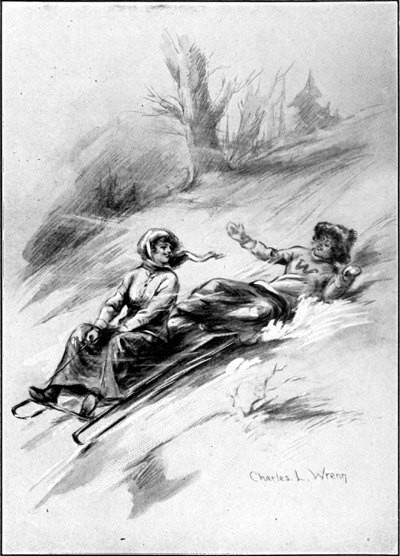

| The next thing she knew she was buried deep in a snow drift, and Judy was whizzing on alone | 224 |

No. 5 in the Quadrangle at Wellington College was in a condition of upheaval. Surprising things were happening there. The simultaneous arrival of six trunks, five express boxes and a piano had thrown the three orderly and not over-large rooms into a state of the wildest confusion.

In the midst of this mountain of luggage and scattered boxes stood a small, lonely figure dressed in brown, gazing disconsolately about.

“I feel as if I had been cast up by an earthquake with a lot of other miscellaneous things,” she remarked hopelessly.

It was Nance Oldham, back at college by an early train, and devoutly wishing she had waited for the four-ten when the others were expected.[6]

“This is too much to face alone,” she continued. “If it had been at Queen’s it never would have happened. Mrs. Markham wouldn’t have allowed six trunks and a piano and five boxes to be piled into one room. And mine at the very bottom, too. If it wasn’t a selfish act, I think I’d leave everything and go call on Mrs. McLean—but, no, that wouldn’t do on the first day.” Nance blushed. “But Andy’s there to-day.” She blushed again at this bold, outspoken thought. “I shall get the janitor to come up here and distribute these things,” she added presently, with New England determination not even to peep at a picture of pleasure behind a granite wall of duty.

The doors of No. 5 opened on a broad, high-ceiled corridor, the side walls of which were wainscoted halfway up with dark polished wood. On either side of this corridor ranged the apartments and single rooms of the Quadrangle, one row facing the campus, the other the courtyard. An occasional upholstered bench or high-backed chair stood between the frequent doors and gave[7] a home-like touch to the long gallery. They had been the gift of a rich ex-graduate.

Nance, closing the door of No. 5, paused and looked proudly down the polished vista of the hallway, which curved at the far end and continued its way on the other side of the Quadrangle.

The sound of voices and laughter floated to her through the half open doors of the other rooms. With a smile of contentment, she sat down in one of the high-backed chairs.

“Dear old Wellington,” she said softly, “other girls love their homes, but I love you.” Thus she apostrophized the classic shades of the university while her gaze lighted absently on a large laundry bag stuffed full standing just outside one of the doors. It was different from the usual Wellington laundry bag, being of a peculiar shape and of material covered with Japanese fans.

“It’s Otoyo’s. Of course, she must have been here since Monday. I heard she had spent the summer down in the village.”

She hastened along the green path of carpet[8] running down the middle of the corridor and paused at the room of the Japanese laundry bag.

“Otoyo Sen,” she called. “Why don’t you come out and meet your friends?”

The Japanese girl was seated on the floor gazing at a photograph. She rose quickly and flew to the door, thrusting the picture behind her.

“Oh, I am so deeply happee to see you again, Mees Oldham,” she exclaimed.

“She has learned the use of adverbs,” thought Nance, kissing Otoyo’s round dark cheek.

“You see I have been studying long time. I now speak the language with correctness. Do you not think so?” said Otoyo, apparently reading Nance’s thoughts.

“Perfectly,” answered Nance. “But tell me the news. Is Queen’s not to be rebuilt?”

“No, no. Queen’s is to remain flat on the ground. She will not be erected into another building.”

“And have you had a happy summer? Was it quite lonesome for you, poor child?”

“No, no,” protested Otoyo, still hiding the photograph[9] behind her. “Those who remained at Wellington were most kind to little Japanese girl.”

“And who remained, Otoyo?”

“Professor Green was here long time. I studied the English language under him. He is a great man. It is an honorable pleasure to learn from one so great.”

“He is, indeed. And who else? Any of the rest of the faculty?”

“No, no. They had all departing gone.”

Nance smiled. There was still a relic of last year’s English.

“Mrs. McLean and her family remained at Wellington through the entire summer,” went on Otoyo fluently.

“And were they nice to you, Otoyo?”

“Veree, exceedinglee.”

“Was Andy well?”

“Quite, quite,” replied the Japanese girl, backing off from Nance and slipping the photograph into a book.

Not for many a day did Nance find out that it[10] was a portrait of that youth himself, taken at the age of eight in Scotch kilties and a little black velvet hat with two streamers down the back.

Suddenly Otoyo became very voluble. She changed the subject and talked in rapid, smooth English. Could she not see the new rooms of her friends? She understood everybody was coming down on the four-ten train. It would be very crowded. She had found a new laundress whom she could highly recommend.

Nance looked at her curiously as they strolled back to the other rooms. Something was changed about the little Japanese girl. She seemed older and much less timid.

It was Miss Sen who found the man to move the trunks, and who helped Nance unpack her things and lay them in half the chest of drawers; and it was Otoyo, also, who, with the skill of an artisan, removed all the nails from the express box tops so that they might be unpacked immediately by their owners. At lunch time she led Nance into the great dining hall of the Quadrangle where more than a hundred girls ate their[11] meals three times a day. There was no attention she did not show to Nance, and all because her conscience was heavy within her on account of the one dishonorable act of her life. How could she know that among the scores of photographs taken of young Andy from his babyhood to his present age, Mrs. McLean would never miss one small, faded picture out of the pile thrust into a cabinet drawer?

At last it came time to meet the four-ten, and Nance, looking spic and span in fresh white duck and white shoes and stockings, was rather surprised to find Otoyo also attired in a pretty white dress, her face shaded with a Leghorn hat trimmed with pink roses.

“Why, Miss Sen,” she exclaimed, “how did you learn so soon to dress yourself in this charming American style?”

“At a garden party at Mrs. McLean’s I learned a very many things,” said Otoyo, “and by the purchasing agent I have obtained dresses of summer, of duckling, lining and musling; also this hat and two others very pretty.”[12]

Nance laughed.

“You mean duck, linen and muslin, child,” she said.

When the four-ten train to Wellington pulled into the station it seemed as if every student in the university must be crowded inside. They leaned from the windows and packed the doorways, overflowing onto the platforms.

The air vibrated with high feminine shrieks of joy. Only the poor little freshies were silent in all this jubilation of reunions. Suddenly Nance, spying Molly Brown and Judy Kean, rushed to meet them, Otoyo following at her heels like a toy spaniel after a larger dog. There was a long triangular embrace.

“Well, here we are, and juniors,” was Judy’s first comment. “Nance, you’re looking fine as silk. No sign of travel on that snowy gown.”

“There oughtn’t to be,” said Nance. “I just put it on half an hour ago.”

“And look at our little Jap,” cried Molly, hugging Otoyo. “Look at little Miss Sen, all dressed up in a beautiful linen.”[13]

“Little Miss Sen has been learning a thing or two,” said Nance. “She’s been to parties, she’s been studying English under a famous professor; she’s been buying duckling, lining and musling dresses through a purchasing agent with very good taste, and she’s got a photograph she looks at in private and hides away when any one comes into the room. Oh, you needn’t think I didn’t see you!”

Otoyo blushed scarlet and hung her head.

“Oh, thou crafty one,” Judy was saying, when four of the old Queen’s girls pounced on them with suit cases and satchels. “Why, here are the Gemini,” Judy continued, embracing the Williams sisters. “Burned to a mahogany brown, too. Where did you get that tan? You look like a pair of—hum—Filipinos.”

“Don’t be making invidious remarks, Judy,” put in Katherine. “Learn to see the beautiful in all things, even complexions.”

In the meantime Margaret Wakefield, looking five years older than her real age because of her matured figure and self-possessed air, was shaking[14] hands all around, making an appropriate remark with each greeting, like the politician she was; and Jessie Lynch was crying in heartbroken tones:

“I left a box of candy and a bunch of violets and two new magazines on the train!”

“Where’s my little freshman?” Molly demanded of the other girls above the din and racket.

“There she is,” Judy pointed out. “But there is no hurry. Every bus is jammed full.”

The lonely freshman was standing pressed against the wall of the waiting room looking hopelessly on while the usual mob besieged Mr. Murphy, baggage master.

“Why, the poor little thing,” cried Molly, rushing to take the girl under her wing.

“It’s astonishing how one good deed starts another,” thought Nance, looking about her for other stranded freshies; and both the Williamses were doing the same thing.

There were several such lonely souls wandering about like lost spirits. They had been jostled[15] and pushed this way and that in the crowd, and one little girl was on the point of shedding tears.

“I can always tell a new girl by the wild light in her eye,” observed Edith Williams, making for an unhappy looking young person who had given up in despair and was sitting on her suit case.

At last they were all bundled into one of the larger buses from the livery stable. The older girls were thrilled with expectant joy while they watched eagerly for the first glimpse of the twin gray towers; the new girls, most of them, gazed sadly the other way, as if home lay behind them.

“It isn’t a case of ‘abandon hope all ye who enter here,’” observed Judy to a dejected freshman who in five minutes had lost all interest in her college career. “Look at us blooming creatures and you’ll see what it can do. There’s no end to the fun of it and no end to the things you’ll learn besides mere book knowledge.”

“I suppose so,” said the girl, struggling to[16] keep back her tears, “but it’s a little lonesome at first.”

“Poor little souls,” thought Molly, who had overheard with much pride Judy’s eulogy of college, “how can we explain it to them? They’ll just have to find it out themselves as we did before them.”

The truth is, our new juniors felt quite motherly and old.

A hushed silence fell over the Queen’s girls when the bus drove by the grass-grown plot where once had stood their college home.

“If a dear friend had been buried there, we couldn’t have felt more solemn,” Molly wrote her sister that night.

But the prestige felt in alighting finally at the great arched entrance to the Quadrangle drove away all sad thoughts, and when they hastened down the long polished corridor to their rooms, they could not quench the pride which rose in their breasts. It was the real thing at last. Queen’s and O’Reilly’s had been great fun, but this was college. They were the true daughters[17] of Wellington now, and that night when the gates clicked together at ten, they would sleep for the first time behind her gray stone walls.

At that moment the voices of a hundred-odd other daughters hummed through the halls, but it was all a part of the college atmosphere, as Judy said.

Their bedrooms were not quite as large as the old Queen’s rooms, but oh, the sitting room! They viewed it with pride. Each of the three had contributed something toward additional furniture. The piano was Judy’s; the divan, Nance’s; and the cushions, yet to be unpacked, Molly’s. There was another contribution not made by any of the three. It was the beautiful Botticelli photograph left for Molly by Mary Stewart, who had gone to Europe for the winter.

“How glad I am the walls are pale yellow and the woodwork white!” exclaimed Judy joyfully.

“How glad I am there’s plenty of room on these shelves for everybody’s books,” said Nance.

“And how glad I am to be a junior and back at old Wellington,” finished Molly, squeezing a hand of each friend.

“There’s only one thing worse than a faculty call-down and that’s a Beta Phi freeze-out,” remarked Judy Kean one Saturday afternoon a few weeks after the opening day of college.

“Why do you bring up disagreeable subjects, Judy? Have you been getting a call-down?” asked Katherine Williams.

“Not your old Aunty Judy,” replied the other. “I’m far too wise for that after two years’ experience, but I saw some one else get one of the most flattening, extinguishing, crushing call-downs ever received by an inmate of this asylum for young ladies. And they do tell me it was followed soon after by another one.”

“Do tell,” exclaimed an interested chorus.

“It was that fresh Miss Higgins from Ohio,” continued Judy, with some enjoyment of the curiosity[19] she was exciting. “You know she’s always trying to attract the attention of the masses——”

“We being the masses,” interrupted Edith.

“And stand in the limelight. She’s bright, I hear, very bright, but she knows it.”

“I recognized her type almost immediately,” said Katherine. “She’s one of those brightest-girls-in-the-high-school-pride-of-the-town kind.”

“Exactly,” answered Judy. “She has been regarded as a prodigy for so long that she doesn’t understand the relative difference between a freshman and a senior. I honestly believe she thought everybody in Wellington knew all about her, and she wears as many gold medals on her chest as a field marshal on dress parade.”

“We saw the gold medals on Sunday,” interposed Molly. “I think it’s rather pathetic, myself. She is more to be pitied than scorned, because of course she doesn’t know any better.”

“She’ll have to live and learn, then,” said Judy.

“Get to the point of your story, Judy. Who extinguished her?” ejaculated Margaret Wakefield, impatient of such slipshod methods of narration.[20]

“How can I tell a tale when I’m interrupted by forty people at once?” exclaimed Judy. “Besides, I haven’t the gift of language like you, old suffragette.”

Margaret laughed. She was entirely good-natured over the jibes of her friends about her passion for universal suffrage.

“Well, the Beta Phi crowd of seniors,” went on Judy, “were walking across the campus in a row. I don’t suppose Miss Higgins had any way to know this soon in the game that they represented the triple extract of concentrated exclusiveness at Wellington. Anyhow, she knows it now. She came rushing up behind them and gave Rosomond a light, friendly slap on the back. If you could have seen Rosomond’s face! But Miss Higgins was entirely dense. She began something about ‘Hello, girls, have you heard the news about Prexy——’ but she never got any further. Rosomond gave her the most freezing look I ever saw from a human eye.”

“What did she say?”

“That was it. She never said anything. Nobody[21] said anything. Eloise Blair carries tortoise-shell lorgnettes——”

“She doesn’t need them,” broke in Nance.

“She only does it to make herself more haughty.”

“Anyway, Eloise raised the lorgnettes.”

“Poor Miss Higgins,” cried Molly.

“There was perfect silence for about a minute. Then they all walked on, leaving little Higgins standing alone in the middle of the campus.”

“And where were you?” asked Margaret.

“Oh, I was with the seniors,” answered Judy, flushing slightly. “I had been over to Beta Phi to see Rosomond about something.”

It was impossible for Judy’s friends not to make an amiable unspoken guess as to why she had visited the Beta Phi circle. It had been evident for some time that she was working to get into the “Shakespeareans,” the most exclusive dramatic club in college. There was an awkward silence as this thought flashed through their minds. Molly felt embarrassed for her chum. After all, she was no worse than Margaret Wakefield, who had managed to get herself elected[22] three years in succession as president of her class.

“What was the other extinguisher Miss Higgins had, Judy?” asked Molly.

“Oh, yes. That was even worse. It came from your particular friend, Professor Green. She interrupted him in the middle of a lecture with one of those unnecessary questions new girls ask to show how much they know. And then she said something about methods at Mill Town High School.”

“Really?” chorused the voices. “And what did he say?”

“He looked very much bored and replied that they were not interested in Mill Town High School, and he would be obliged if she would pay attention to the lecture. It was a public rebuke, nothing more nor less.”

“The mean thing,” exclaimed Molly.

“Now, Molly,” interposed Margaret, “you know very well that girls of that type ought to be taken down. They are never tolerated at college. A conceited boy at college is always thoroughly[23] hazed until there’s not a drop of conceit left, and it does him good. And since we can’t haze, we simply have to extinguish a fresh freshie. Miss Higgins may develop into a very nice girl in a year or two, but at present she’s the veriest little upstart——”

“Do be careful,” said Molly cautiously. “I’ve invited her this afternoon to drink tea——”

“Molly Brown,” they cried, pummeling her with sofa cushions and beating her with her own slippers.

“Really, Molly, you must restrain your inviting habits,” said Judy.

“I’m sorry,” apologized poor Molly.

“Why did you do it, pray? You know perfectly well no one here wants her.”

“I know it, but I was sorry for her. She seemed so brash and lonesome at the same time. I thought it might help her some to mingle with a few fine, intelligent, well-bred girls like you——”

“Here, here! Don’t try to get out of it that way.”[24]

“She appears to be very learned,” continued Molly, turning her blue eyes innocently from one to the other. “I thought it would be nice to pit her against Margaret and Edith. She discusses deep subjects and uses big words I can only dimly guess the meaning of——” There was a tap at the door. “Now, be nice, please.”

“Come in,” called Nance, in a tone of authority, and Minerva Higgins appeared in their midst.

She had done honor to the occasion by putting on a taffeta silk of indigo blue, and by pinning on some of her most conspicuous gold medals acquired at intervals during her early education.

Judy shook her head over the indigo blue.

“Only certain minds could wear it,” she thought.

Molly rose, but before she could frame a cordial greeting, the new guest was saying:

“How do you do, Molly? Awfully nice of you to ask me. You don’t mind my calling you by your first name, do you? My name is Minerva[25] but the girls at Mill Town High School called me ‘Minnie.’ I hope you’ll do the same.”

“I shall be glad to,” answered Molly, rather taken back by this sudden intimacy.

After she had performed all necessary introductions, wicked Katherine Williams remarked:

“Minnie is a very charming name, but I insist on calling you ‘Minerva’ after the Goddess of Wisdom. She never wore gold medals, but then it wasn’t the fashion among the early Greeks.”

Minerva’s face was the picture of complacency.

“In Greece she would have been ‘Athene,’” she observed.

There was a loud clearing of throats and Judy, as usual, was seized with a violent fit of coughing.

“Sit down here, Miss Higgins—I mean Minnie,” said Molly hastily. “The tea will be ready in a minute.”

“You have been to college before, Minerva?” asked Edith Williams solemnly.

Minerva looked somewhat surprised.

“Oh, no. Not college. I am just out of High[26] School. Mill Town High School is a very wonderful educational institution, you know. Perhaps you have heard of it. A diploma from there will admit a girl into any of the best colleges in the country. I could have gone to a private school. My father is professor of Greek at the Academy in Mill Town, but I preferred to take advantage of the high standards of the High School, which are even higher than those of the Academy.”

“I suppose your father’s taste in Greek caused him to name you Minerva,” observed Judy.

“But Minerva isn’t Greek, Julia,” admonished Katherine.

Again Molly interceded. It was cruel to make fun of the poor girl, although there was no denying that Minerva had a high opinion of herself.

“Have a sandwich,” she said soothingly.

There was a long interval of silence while Minerva crunched her sandwich.

“Your life at Mill Town High School must have been one grand triumphal progress, judging[27] from your medals, Miss Higgins,” said Edith Williams finally.

Minerva glanced proudly down at the awards of merit.

“There are a good many of them,” she observed, with a smile that was almost more than they could stand. “And there are more of them still. I’ve won one or two medals each year ever since I started to school. But I don’t like to wear them all at once.”

“That’s very modest of you.”

“Are you going to specialize on any subjects, Miss Higgins?” asked Margaret Wakefield, really meaning to be kind and lead the girl away from topics which made her appear ridiculous.

“Biology, I think. But I am interested in Comparative Philology, too, and after I skim through a little Greek and Latin, I intend to take up some of the ancient languages, Sanskrit and Hebrew.”

Was it possible that Minerva was making game of them? They regarded her suspiciously, but she seemed sublimely unconscious.[28]

“Why not study also the ancient tongue of the Basques?” asked Edith, quite gravely.

“That would be interesting,” replied Minerva, “but I want to get through this little college course first.”

Molly batted her heavenly eyes and suddenly burst out laughing.

“Excuse me,” she said. “I didn’t mean to be rude, but the course at Wellington doesn’t seem so small to us. We have to study all the time and then just barely pull through. I’ve almost flunked twice in mathematics. I wish I could call it a little course.”

“Ah, well, we are not all Minervas,” observed Margaret. “Some of us are just ordinary school girls learning the rudiments of education. We have not had the advantages of Mill Town High School, and if any of us have won gold medals we never show them.”

This measured rebuff, however, had no more effect on Minerva’s impervious vanity than a cup of water dashed against a granite boulder. She was already up, wandering about the room,[29] boldly examining the girls’ belongings, ostentatiously reading the titles of books aloud.

“Plays by Molière. Oh, yes, I read them in the original two years ago. They’re easy. ‘Green’s Short History of the English People,’ very interesting book. ‘The Broad Highway.’ I never read fiction. Only biography and history——”

Edith Williams, stretched at her ease on the divan, gave an inaudible groan and turned her face to the wall.

Molly glanced helplessly about her.

“‘The Primavera,’ that’s by Botticelli,” went on the girl, infatuated by her own intelligence. “Good artist, but I don’t care for the old masters as a general thing. They are always out of drawing.”

Katherine rolled her eyes up into her head until only the whites could be seen, which gave her the horrible aspect of a corpse.

There was a long and eloquent silence. Presently Minerva took her departure, and Molly, hospitable to the last gasp, saw her to the door and invited her to come again.[30]

With the door safely locked and Minerva out of earshot, there was a general collapse. Nobody laughed, but the room was filled with painful sounds, moans and groans. Judy pretended to faint on top of Edith, and Molly sat in a remote corner of the room.

Somehow, they felt beaten, vanquished.

“I am sore all over with repressed emotions,” cried Judy. “I couldn’t stand another séance like that.”

“Does she know as much as she claims?” asked Nance.

“Of course not,” exclaimed Margaret irritably. “If she really knew she wouldn’t claim anything. It’s only ignorant people who boast of knowledge. I suppose she has been looked up to for so long that she regards herself as a fountain of wisdom.”

“She must be taken down,” said Edith firmly. “This mustn’t be allowed to go on at Wellington.”

“But hazing isn’t allowed,” put in Molly.

“Not by hazing, goosie. By some homely little[31] practical joke that will show herself to herself as others see her.”

“All right,” consented Molly. She felt indeed that something should be done to save poor Minerva Higgins from eternal ridicule.

“If anybody has suggestions to make,” here announced Margaret Wakefield, self-constituted chairman of all committees, impromptu or otherwise, “they may be stated in writing or announced by word of mouth to-morrow night in our rooms at a fudge party.”

“Accepted,” they cried in one breath.

In the meantime, Minerva Higgins was writing home to her mother that she had been, if not the guest of honor, almost that, at a junior tea, and had found the girls rather interesting though poor talkers. In fact, it was necessary to do almost all the talking herself.

Life in the Quadrangle hummed busily on. The girls found themselves in the very heart of college affairs. As a matter of fact the old Queen’s circle had been somewhat restricted, having narrowed down to less than a dozen; whereas now, they associated with many times that number and were invited to a bewildering succession of teas and fudge parties.

Also they were nearer to the library, the gymnasium, the classrooms and the cloisters. Here, during the warm, hazy days of Indian summer Molly loved to walk. It was not such a popular place as she had imagined with the Quadrangle girls, and often she was quite alone in the arcade, bordered now with hydrangeas turning a delicate pink under the autumn suns.

One afternoon, a few days after Margaret’s[33] fudge party to discuss the question of Minerva Higgins, Molly sought a few quiet moments in the cloistered walk. It was a half hour before closing-up time, but she would not miss the six strokes of the tower clock again, as she had on her first day at college two years before.

She usually confined her walks to the far side of the arcade, keeping well away from the side of the cloisters on which the studies of some of the faculty opened. That afternoon she carried her volume of Rossetti with her, and pacing slowly up and down, she read in a low musical voice to herself:

Waves of rhythm ran through Molly’s head, and when she reached the end of the walk she[34] turned mechanically and went the other way without pausing in her reading.

Many girls studied in this way in the cloisters and it was not an unusual sight, but Molly made a picture not soon to be forgotten by any one who might chance to wander in the arcade at that hour. She was still spare and undeveloped, but the grace that was to come revealed itself in the girlish lines of her figure. Her eyes seemed never more serenely, deeply blue than now, and her hair, disordered from the tam o’shanter she had pulled off and tossed onto a stone bench, made a fluffy auburn frame about her face. Molly was by no means beautiful from the standpoint of perfection. Her eyebrows and lashes should have been darker; her chin was too pointed and her mouth a shade too large. But few people took the trouble to pick out flaws in her face or figure. Those who loved her thought her beautiful, and the few who did not could not deny her charm.

Presently she sat down on a bench, continuing to declaim the poem out aloud, making a gesture[35] occasionally with her unoccupied hand. After reading a verse, she closed her eyes and repeated it to herself. Opening her eyes between verses, she encountered the amused gaze of Professor Edwin Green who, having seen her in the distance, had cut across the grassy court and now stood as still as a statue leaning against a stone pillar.

“Oh,” exclaimed Molly, with a nervous start.

“Did I frighten you? I am sorry. I should have walked more heavily. It’s unkind to steal up on people who are reading poetry aloud.”

“I was learning the—something by heart,” she said, blushing a little as if she had been detected in a guilty act. After all, it was the professor who had introduced her to that poem and given her the book last Christmas, but that, of course, was not the reason why she was so fond of the poem she was studying.

“How do you like the Quadrangle?” he asked. “Are you comfortable and happy?”

Molly clasped her hands in the excess of her enthusiasm.[36]

“I was never so happy in all my life,” she cried. “It is perfect. Our rooms are beautiful, and a sitting room, too. Think of that, with yellow walls and a piano!”

The professor looked vastly pleased. For an instant his face was lighted by a beaming, radiant smile. Then he thrust his hands into his pockets and pressed his lips together in a thin line of determination.

“I feel as if I were one of the workers inside the hive now,” Molly continued.

“And all the difficulties about tuition have been settled?” he asked. “Forgive my mentioning it, but I felt an interest on account of my close relationship to the Blounts.”

“Oh, yes. The money from the two acres of orchard settled that. You see, whoever bought it, whether it was an old man or a company—for some reason the name is still a secret with the agent—paid cash. They rarely do, mother says, and the money is usually spent in driblets before you realize it. Mr. Richard Blount expects to settle with his father’s creditors in a few[37] months. My sisters are working. They say they enjoy it, but they are both engaged to be married,” she added, smiling.

“Did the orchard yield a good crop this year?” asked the professor irrelevantly.

“Oh, splendid. The apples were packed in barrels and sent away. Several of them were sent to mother as a present. Very nice of the owner, wasn’t it?”

“Very,” replied the professor, fingering something in his pocket absently.

“The owner of the orchard has it kept in fine condition. The trees have been trimmed and the ground cleared. Mother says she’s ashamed of her own shiftlessness whenever she looks at it. The grass was as smooth as velvet all summer until the drought came and dried it brown. I used to go there summer mornings and lie in a hammock and read. I didn’t think any one would care. There’s no harm in attaching a hammock to two trees. Mother says I don’t seem to remember that we are no longer the owners of the orchard. I have played in it and lived in it so[38] much of my life that I’ve got the habit, I suppose.”

The professor cleared his throat.

“You said the ground sloped slightly, did you not?”

“Yes, just a gradual slope to a little brook at the bottom of the hill. The water seems to cool the air in summer. It never goes dry and there is a little basin in one place we used to call ‘the birds’ bath tub.’ Such birds you never imagined! They are attracted by the apples, I suppose. But there are hundreds of them. They sing from morning to night.”

“You paint a very attractive picture, Miss Brown. It must have been hard to give up this charming property.”

“But you see we haven’t given it up exactly. It’s there right against us. We can still look at it and even walk under the trees. No one minds. And see what I have for it! Nothing could ever take the place of college—not even an apple orchard.”[39]

A sharp voice broke in on this pleasant conversation.

“Cousin Edwin, I’ve been looking for you everywhere.”

Judith Blount appeared hastening down the walk.

The professor watched the advancing figure calmly.

“Well, now you have found me, what do you want?” he asked.

Molly detected a slight note of annoyance in his voice. She had a notion that Judith was one of the trials of his life.

“I have rewritten the short story you criticized for me last week, and I want you to look it over again.”

He took the roll of paper without a word and thrust it into his coat pocket.

Molly rose.

“I must be going,” she said. “It must be nearly six o’clock.”

Judith promptly sat down on the bench facing[40] her cousin, who still leaned against the stone pillar.

“Don’t you think it’s a little chilly to be lingering here, Judith?” he remarked politely, as he joined Molly.

“It wasn’t too chilly for you a moment ago,” answered Judith hotly.

But she rose and walked on the other side of the professor.

“How do you like your rooms?” he asked presently.

“I hate them,” she replied, with such fierce resentment that Molly was sure that Judith was glad to have something on which to vent her angry mood. “Thank heavens, this is my last year. I detest Wellington. I have never been happy here. It’s brought shame and misfortune on me. It’s a horrid old place.”

“Oh, Judith,” protested Molly, unable to endure this libel on her beloved college.

“My dear child, you can’t blame Wellington for your misfortunes,” interposed the professor,[41] who himself cherished a deep affection for the two gray towers.

“It is hard to live in the village instead of at college,” said Molly, feeling suddenly very sorry for the unhappy Judith.

But Judith was in no state to be sympathized with. All day she had been nursing a grievance. One of her friends in prosperity at the Beta Phi House had turned a cold shoulder on her that morning; and Judith was so enraged by the slight that her feelings were like an open sore.

She turned on Molly angrily.

“You ought to know,” she said. “You had to do it long enough.”

“Judith, Judith,” remonstrated the professor. “Can’t you understand that you gain nothing, and always lose something, by giving way like this? Denouncing and hating make the object you are working for recede. You’ll never get it that way.”

“How do you know what I’m working for?” she demanded, more quietly.[42]

“We are all of us working for the same thing,” he answered. “Happiness. None of us proposes to get it in the same way, but all of us propose to reach the same goal. What would give me happiness no doubt would never satisfy you.”

“You don’t know that, either. What would give you happiness?” Judith asked, with some curiosity.

The professor paused a moment, then he said calmly:

“A little home of my own in a shady quiet place with plenty of old trees, where I could work in peace. I have always fancied an old orchard. There might be a brook at one end——”

Molly smiled.

“He’s thinking of my orchard,” she thought.

“There must be hundreds of birds in my orchard,” went on the professor, “and the grass must always be thick and green, except perhaps when the drought comes and it can’t help itself——”

The six o’clock bell boomed out.[43]

“Have an apple,” he said, taking two red apples from his pocket and giving one to each of the girls.

Then he opened the small oak door and stood politely aside while they passed out.

The entertainment designed to bring Miss Minerva Higgins to a true understanding of her position as a freshman took place one Friday evening in the rooms of Margaret and Jessie. It was called on the invitation “A Literary Evening,” and was to be in the nature of a spread and fudge affair. There had been two rehearsals beforehand, and the girls were now prepared to enjoy themselves thoroughly.

Molly was loath to take part in the literary evening.

“I can’t bear to see anybody humiliated even when she ought to be,” she said, but she consented to come and to give a recitation.

Several study tables had been united for the supper, the cracks concealed by Japanese towelling contributed by Otoyo. There was no Mrs.[45] Murphy in the Quadrangle from whom to borrow tablecloths. All the chairs from the other rooms were brought in to seat the company, who appeared grave and subdued. Most of the girls were dressed to resemble famous poets and authors. Judy was Byron; Margaret Wakefield, George Eliot; Nance, Charlotte Bronté; Edith Williams, Edgar Allan Poe; and Molly was Shelley. Shakespeare, Voltaire and Charles Dickens were in the company, and “The Duchess,” impersonated by Jessie Lynch.

The unfortunate Minerva was a little disconcerted at first when she found herself the only girl at the feast in her own character.

“Why didn’t you tell me, so that I could have come in costume, too?” she asked Margaret.

“But you had your medals,” was Margaret’s enigmatic answer.

Minerva looked puzzled. Then her gaze fell to the shining breastplate of silver and gold trophies. She had worn them all this evening. The temptation had been too great. The medals gleamed like so many solemn eyes. She wondered[46] if the others could read what was inscribed on them, or if it would be necessary to call attention to the most choice ones: “THE HIGHEST GENERAL AVERAGE FOR FOUR YEARS”; “REGULAR ATTENDANCE”; “MATHEMATICS”; “THE BEST HISTORICAL ESSAY”; “ENGLISH AND COMPOSITION.”

Edith opened the evening by delivering a speech in Latin which was really one of Virgil’s eclogues mixed up with whatever she could recall of Livy and Horace, and filled out occasionally with Latin prose composition. It was so excruciatingly funny that Judy sputtered in her tea and was well kicked on her shins under the table.

Minerva, however, appeared to be profoundly impressed, and the company murmured subdued approvals when, at last, the speaker took breath and sat down, gazing solemnly around her with dark, melancholy eyes very much blacked around the lids.

Margaret then delivered a learned discourse[47] on “Poise of Body and Poise of Mind,” which was skillfully expressed in such deep and intricate language that nobody could understand what she was talking about.

“Very, very interesting, indeed,” observed Edith.

“Remarkable; wonderful; so clearly put,” came from the others.

Minerva rubbed her eyes and frowned.

Nance recited “The Raven,” translated into very bad French. This was almost more than their gravity could endure, and when she ended each verse with “Dit le corbeau: jamais plus,” many of the girls stooped under the table for lost handkerchiefs and Japanese napkins.

But it was not until Judy had sung a lullaby in Sanskrit—so called—that Minerva became at all suspicious. Even then it was the wrong kind of suspicion. She thought that perhaps she should have laughed, and the others had politely refrained because she hadn’t.

After a great deal of learned talk, Molly stood[48] on a soap box and recited “Curfew Shall Not Ring To-night.”

This was the crowning joy of that famous evening, but still Minerva appeared seriously impressed.

“I recited that once at Mill Town High School,” she remarked.

“Can’t you give us something to-night?” asked Molly kindly, feeling that in some way the unfortunate Minerva ought to be allowed to join in.

“I don’t know that I ought to give another poem by the same man,” she replied, “except that Miss Oldham gave ‘The Raven’ in French.”

“Don’t tell us you know ‘The Bells’?” demanded Edith Williams, in a trembling whisper.

“Oh, yes. I’ve given it at lots of school entertainments.”

“We had better turn down the lights,” said Margaret. “The room should be in darkness except the side light where Miss Higgins will stand. That will be the spot light.”

This was a fortunate arrangement because, while Minerva recited “The Bells,” with all[49] proper gestures, intonations and echoes, according to Cleveland’s recitation book, the girls silently collapsed. When she had finished, they were reduced to that exhausted state that arrives after a supreme effort not to laugh.

At last the entertainment came to an end. Minerva departed with some of the others, while those who lived close by remained to chat for a few minutes.

“I give up,” exclaimed Margaret Wakefield. “Minerva is beyond teaching. She must remain forever the smartest girl in Mill Town High School.”

“The only pity of it is that it was all wasted on one humorless person. We really furnished her with a most delightful entertainment and she never even guessed it,” declared Nance.

“I’m glad she didn’t,” remarked Molly. “It was cruel, I think. Suppose she had caught on? Do you think it would have helped her? And we would have been uncomfortable.”

“Suppose she did understand and pretended[50] not to. The joke would have been decidedly on us,” put in Katherine.

Later events of that evening would seem to bear out this suggestion, although just how deeply, if at all, Minerva was implicated in what followed no one could possibly tell. It was a question long afterwards in dispute whether one person had managed the sequel to the Literary Evening, or whether there had been a confederate. Certainly it seemed that every imp in Bedlam had been set free to do mischief, and if Minerva, as arch-imp, was looking for revenge, she found it.

“I don’t like to appear inhospitable, girls, but it’s five minutes of ten and I think you’d better chase along,” said Margaret Wakefield.

But when Judy laid hold of the knob and tried to open the door, it would not budge.

“It won’t open,” she exclaimed. “What’s to be done?”

What was to be done? They pulled and jerked and endeavored to pry it open with a silver shoe horn and a pair of scissors, and at last Jessie, as[51] the smallest, was chosen to climb over the transom and go for help. It was five minutes past ten, and they prudently turned out the lights.

“Let me get at that knob just once before we work the transom scheme,” ejaculated Margaret, who was very strong and athletic.

“People always think they can open tin cans and doors and pull stoppers when other people can’t,” observed Judy sarcastically.

Margaret treated this remark with contemptuous indifference. Seizing the knob with both hands, she turned it and, putting her knee to the jamb, pulled with all her force. The arch fiend on the other side must have turned the key at this critical moment, for the door flew open and the president tumbled back as if she had been shot from a catapult, knocking a number of surprised poets and authors into a tumbled heap. They were all considerably bruised and battered, and Margaret bit her tongue; a severe punishment for one whose oratory was the pride of the class.

“Hush,” whispered Jessie, who alone had escaped[52] the tumble, “here comes the house matron.”

Softly she closed the door, and the girls waited until the danger was over. Then Margaret hastened to examine the keyhole.

“There’s no key in it,” she whispered, speaking with difficulty, because her tongue was bleeding from the marks of two teeth.

Whoever played the trick must have unlocked the door, jerked the key out and fled the instant the matron appeared at the end of the corridor. There was no time to discuss the mystery, however. She would be coming back in two minutes. Again they waited in silence until they heard the swish of her dress as she went past the door, now left open a crack in order that Judy, lying flat on her stomach on the floor, and enjoying herself immensely, might be on the lookout.

“Come on,” she hissed, as the large, rotund figure of Mrs. Pelham was lost in the darkness, and out they scuttled like a lot of mice loosed from the trap.

But the evening’s adventures were not over.

As Judy, in advance of Molly and Nance,[53] pushed open their door, already ajar, a small pail of water, placed on the top of the door by the arch-imp, whoever she was, fell on Judy’s head and deluged her. It contained hardly a quart of water, but it might have been a gallon for the wreck it made of Judy’s clothes and the room.

“Oh, but I’ll get even with somebody,” exclaimed that enraged young woman.

They turned on the green-shaded student’s lamp and drew the blinds, the night watchman being very vigilant at the dormitories, and began silently mopping up the floor with towels.

Judy removed her wet clothes, and unbound her long hair, light in color and fine as silk in quality.

“I can’t go to bed,” she announced, “until I find out what’s happened to the Gemini,” and without another word she crept into the corridor.

“Nance,” whispered Molly, when they were alone, “if Minerva Higgins did this, she’s about the boldest freshman alive to-day. But, after all, we can’t exactly blame her, considering what we did to her.”[54]

“She is taking great chances,” replied Nance, who had a thorough respect for college etiquette and class caste. “Every pert freshman must be prepared for a call-down; and if she doesn’t take it like a lamb, she’ll just have to expect a freeze-out. It’s much better for her in the end. If Minerva were allowed to keep this up for four years, she would be entirely insufferable. She’s almost that now.”

“Don’t you think she could find it out without such severe methods?”

“Severe methods, indeed,” answered Nance indignantly. “Do you call it severe to be asked to sup with the brightest girls in Wellington? Margaret’s speech alone was worth all the humiliation Minerva might have felt; but she didn’t feel any. Do you consider that rough, crude jokes like this are going to be tolerated?”

“But we don’t know that Minerva played them, yet,” pleaded Molly. “I do admit, though, that it must have been a very ordinary person who could think of them. Margaret might have been[55] badly hurt if she hadn’t fallen on top of the rest of us.”

Presently Judy came stalking into their bedroom.

“It’s just as I expected,” she announced. “The Williamses’ bed was full of carpet tacks and Mabel Hinton fell over a cord stretched across her door and sprained her wrist. She has it bound with arnica now.”

“I don’t see how Minerva could have had time to do all those things,” broke in Molly.

There are some rare and very just natures—and Molly’s was one of them—which will not be convinced by circumstantial evidence alone.

“She would have had plenty of time,” argued Judy. “It would hardly have taken five minutes provided she had planned it all out beforehand. Besides, it’s easy for you to talk, Molly. You didn’t bite your tongue, or sprain your wrist, or get a ducking; or undress in the dark and get into a bedful of tacks. You escaped.”

“Disgusting!” came Nance’s muffled voice from the covers.[56]

“It is horrid,” admitted Molly. “Whoever did it——”

“Minerva!” broke in Judy.

“—must have a very mistaken idea of college and the sorts of amusement that are customary.”

So the argument ended for the night.

Guilty or innocent, Minerva Higgins displayed an inscrutable face next day, and the juniors, lacking all necessary evidence, were obliged to admit themselves outwitted; but they let it be known that jokes of that class were distinctly foreign to Wellington notions, and woe be to the author of them if her identity was ever disclosed.

In the meantime, Molly was busy with many things. As usual she was very hard up for clothes, and was concocting a scheme in her mind for saving up money enough to buy a new dress for the Junior Prom. in February. She bought a china pig in the village, large enough to hold a good deal of small change, and from time to time dropped silver through the slit in his back.[58]

“He’s a safe bank,” she observed to her friends, “because the only way you can get money out of him is to smash him.”

The pig came to assume a real personality in the circle. For some unknown reason he had been christened “Martin Luther.” The girls used to shake him and guess the amount of money he contained. Sometimes they wrote jingles about him, and Judy invented a dialogue between Martin Luther and herself which was so amusing that its fame spread abroad and she was invited to give it many times at spreads and fudge parties.

The scheme that had been working in Molly’s mind for some weeks at last sprung into life as an idea, and seizing a pencil and paper one day she sketched out her notion of the plot of a short story. It was not what she herself really cared for, but what she considered might please the editor who was to buy it as a complete story, and the public who would read it. There were mystery and love, beauty and riches in Molly’s first attempt. Then she began to write. But[59] it was slow work. The ideas would not flow as they did for letters home and for class themes. She found great difficulty in expressing herself. Her conversations were stilted and the plot would not hang together.

“I never thought it would be so hard,” she said to herself when she had finished the tale and copied it out on legal cap paper. “And now for the boldest act of my life.”

With a triumphant flourish of the pen, she rolled up the manuscript and marched across the courtyard to the office of Professor Green.

“Come in,” he called, quite gruffly, in answer to her knock. But when she entered, he rose politely and offered her a seat. Sitting down again in his revolving desk chair, he looked at her very hard.

“I know you will think I have the most colossal nerve,” she began, “when you hear why I have called; but I really need advice and you’ve been so kind—so interested, always.”

“What is it this time?” he interrupted kindly. “More money troubles?”[60]

“No, not exactly. Although, of course, I am always anxious to earn money. Who isn’t? But I have a writing bee in my head. I’ve had it ever since last winter, although I confined myself mostly to verse——”

Molly paused and blushed. She felt ashamed to discuss her poor rhymes with this learned man nearly a dozen years older than she was.

“There’s no money in poetry,” she went on, “and I thought I would switch off to prose. I have written a short story and—I hope you won’t be angry—I’ve brought it over for you to look at. I knew you looked over some of Judith’s stories.”

“Of course I shan’t be angry, child. I’m glad to help you, although I am not a fiction writer and therefore might hardly be thought competent to judge. Let’s see what you have.” He held out his hand for the manuscript. “On second thought,” he continued, “suppose you read it aloud to me. Girls’ handwriting is generally much alike—hard to make out.”

Molly, trembling with stage fright, her face[61] crimson, began to read. The professor, resting his chin on his interlocked fingers, turned his whimsical brown eyes full upon her and never shifted his gaze once during the entire reading, which lasted some twenty-five minutes. When she had finished, Molly dropped the papers in her lap and waited.

“Well, what do you think of it? Please don’t mince matters. Tell me the truth.”

The professor came back to life with a start. She knew at once that he had not heard a word.

“Oh, er—I beg your pardon,” he said. “Very good. Very good, indeed. Suppose you leave the manuscript with me. I’ll look it over again to-night.”

She rose to go. After all she had no right to complain, since she had asked this favor of a very busy man; but she did wish he had paid attention.

“Wait a moment, Miss Brown, there was something I wanted to say. What was it now?” He rubbed his head, and then thrust his hands into his pockets. “Oh, yes. This is what I wanted[62] to say—have an apple?” A flat Japanese basket on the table was filled with apples. “Excuse my not passing the basket, but they roll over. Take several. Help yourself.”

He made Molly take three, one for Nance, one for Judy and one for herself. Then he saw her to the outer door, bowing silently, all the time like a man in a dream.

The next morning the manuscript was returned to Molly by the professor after the class in Literature. It was folded into a big envelope and contained a note. The note had no beginning and was signed “E. G.” This is what it said:

“Since you wish my true opinion of this story, I will tell you frankly that it is decidedly amateurish. The style is heavy and labored and the plot mawkishly sentimental and mock heroic.

“Try to think up some simple story and write it out in simple language. Do not employ words that you are not in the habit of using. Be natural and express yourself as you would if you were writing a letter to your mother. Write about real people and real happenings; not about[63] impossibly beautiful and rich goddesses and superbly handsome, fearless gods. Such people do not really exist, you know, and you are supposed to be painting a word picture of life.

“You have talent, but you must be willing to work very hard. Good writing does not come in a day any more than good piano playing or painting. I would add: be yourself—unaffected—sincere—and your style will be perfect.”

Molly wept a little over this frank expression of criticism, although there did seem to be an implied compliment in the last line. She reread the story and blushed for her commonplaceness. Surely there never had been written anything so inane and silly.

For a long time she sat gazing at the white peak of Fujiyama on the Japanese scroll.

“Simple and natural, indeed,” she exclaimed. “It’s much harder than the other way. Unaffected and sincere! That’s not easy, either.” She sighed and tore the story into little bits, casting it into the waste-paper basket. “That’s the best place for you,” she continued, apostrophizing her first attempt at fiction. “Nobody would ever have[64] laughed or cried over you. Nobody would even have noticed you. My trouble is that I try too hard. I am always straining my mind for words and ideas. Now, when I write letters, how do I do? I let go. I never worry. Can a story be written in that way?”

“How now, Mistress Molly,” called Judy, bursting into the room. “Why are you lingering here in the house when all the world’s afield? Get thee up and go hence with me unto the green woods where we are to have tea, probably for the last time before the winter’s call.”

“Who’s ‘we’?” asked Molly.

“Why, the usual crowd, and a few others from Beta Phi House.”

“But you’ll never have enough teacups to go around, child,” objected Molly.

“Oh, yes, we shall. There are two other tea baskets coming from Beta Phi. There will be plenty and some over besides. Rosomond Chase and Millicent Porter were so taken with my basket last year that they each bought one. Of[65] course Millicent’s is much finer than mine or Rosomond’s.”

“I dare say. But I don’t think I want to go, Judy.”

The truth was Molly never felt in sympathy with those two Beta Phi girls, who represented an element in college she did not like. They dressed a great deal, for one thing, especially Millicent Porter, the girl who had sub-let Judith Blount’s apartment the year before.

“Now, Molly, I think you’re unkind,” burst out Judy. She never could endure even small disappointments. “They are awfully nice girls and they want to know you better. They said they did.”

“Well, why don’t they come and see me? That’s easy.”

Judy did not reply. She was pulling down all the clothes in the closet in a search for Molly’s tam and sweater. She was in one of her queer, excited moods. Could it be that Judy thought the sparkling coterie from Queen’s was being honored by these two rich young persons from[66] Beta Phi? Molly rejected the suspicion almost as soon as it entered her mind. No, it was simply that poor old Judy was obsessed with a desire to get into the “Shakespeareans,” and by courting the most influential members she thought she could make it.

Molly pulled her slender length from the depths of the Morris chair where she had been lolling.

“Very well,” she said resignedly. “I was meditating on my ambitions when you broke in on me. You are a very demoralizing young person, Judy.”

Judy laughed. She made a charming picture in her scarlet tam and sweater.

“Come along,” she cried, “and ambitions be hanged.” She seized her tea basket under one arm and a box of ginger snaps under the other.

“Why, Judy, I am really shocked at you,” exclaimed Molly. “I think I’ll have to give you another shaking up before long. You’re getting lax and lazy.”

“Nothing of the sort. I only want to enjoy[67] life while the weather is good. It’s lots easier to think of ambitions on rainy days.”

The other girls were waiting on the campus: the Williamses, Margaret and Jessie, Nance and presently the two Beta Phi girls. Rosomond Chase was a plump, rather heavy blonde type, always dressed to perfection and bright enough when she felt inclined to exert her mind. Millicent Porter was quite the opposite in appearance; small, wiry, with a prominent, sharp-featured face; prominent nose, prominent teeth and rather bulging eyes. She talked a great deal in a highly pompous tone, and her voice always slurred over from one statement to another as if to ward off interruption. She seemed much amused at this little escapade in the woods, quite Bohemian and informal.

The Queen’s girls could hardly explain why she appeared so patronizing. It was her manner more than what she said; although Margaret insisted that it was because she monopolized the conversation.

“We didn’t go to listen to a monologue,” Margaret[68] thundered later when they were discussing the tea party. “We came to hear ourselves talk.”

What surprised Molly was the attention that the young person of unlimited wealth bestowed upon her.

“Come and sit beside me, Miss Brown, and tell me about Kentucky,” she ordered.

“I am afraid I haven’t the gift of language,” replied Molly, without budging from her seat on a log. “Ask Margaret Wakefield. She’s the only conversationalist in the crowd.”

“I suppose Mahomet must go to the mountain, then,” observed Miss Porter, and she moved graciously over to the log, where she regaled Molly with a great deal of wordy talk.

“If she’s going to do all the conversing, it might as well be on something interesting,” thought Molly, and she started Millicent on the topic of silver work. This young woman, rich beyond calculation, had an unusual talent which had not been neglected. She worked in silver.

“Her natural medium,” Edith had observed when she heard of it.[69]

She could beat out chains and necklaces, rings of antique patterns, beautiful platters with enameled centers with all the skill of a real silversmith.

Molly listened with polite interest to Millicent’s lengthy description of her art. There was often an unconscious flattery in the sympathetic attention Molly gave to other people’s talk. It had the effect of loosening tongues and brought forth confidences and heart secrets. She was a good listener and the repository of many a hidden thought.

“I am only going to college, you know, to please papa,” Millicent was saying. “He thinks I should be finished off like a piece of statuary or a new house. I would much rather do things with my hands. I can’t see how I am to be benefited by all these classics. In the sort of life I shall lead they won’t do me any good. Society people never quote Latin and Greek or make learned references to early Roman history and things of that sort. It isn’t considered good form. Modern novels are the only things people[70] read nowadays, but papa is determined. Now, with silver work, it’s quite different. I love it. I love to make beautiful things. I have just finished a grape-vine chain. The workmanship is exquisite. My sitting room is my studio, you know, and I work there when I am not busy with stupid books. You seem interested. Do you know anything about silver work?”

Molly admitted her ignorance on the subject, but Millicent did not pause to listen. Her voice slurred over from the question to her next outburst.

“I like beautiful rich colors. I intend to design all the costumes for the next Shakespearean performance. If I had been born in a different sphere in life, I should have divided my time between silver work and costuming. I can draw, too, but it’s more designing than anything else.”

Then Millicent, encouraged by Molly’s sympathetic blue eyes, lowered her voice and plunged into confidences.

“The truth is,” she said, “we were not so—er—well-to-do two generations ago. My great-grandfather[71] was an Italian silversmith. Isn’t it interesting? He was really an artist in his way, and made wonderful vessels for the church, crucifixes, and things like that. I tell mamma I believe her grandfather’s soul has entered into my body. But that isn’t all. Now, if I tell you this, will you promise never to breathe it? It’s really a family secret, but it accounts for my love of rich, beautiful things. I can sew, you know. I adore to embroider. If I had to, I could easily make all my own clothes——”

“But that’s nothing to be ashamed of,” broke in Molly.

“No, no. That isn’t the secret. The secret is where I got the taste for such things. You promise not to mention this?”

“I promise,” replied Molly gravely, repressing the smile that for an instant hovered on her lips.

“The silversmith grandfather had a brother who was a merchant. He had a shop in Florence where he sold all sorts of beautiful fabrics, velvets and brocades and lots of antique things.”[72]

“No doubt it was an antique shop,” thought Molly.

“Mamma remembers it well, and the shop is still there to-day, but it’s in other hands.”

Molly felt much amusement at this explanation of heredity. It would not be difficult to add a few lines to Millicent’s small, thin face and place it on the shoulders of the old silversmith or of his brother, the dealer in antiques. How would they feel if they could hear this granddaughter conversing about society and the classics?

“But I have rattled on. Here I have told you two family secrets. But of course they will go no farther. You know more about me than any girl in Wellington. Won’t you come over to dinner with me Saturday evening and see my studio?”

“I am so sorry,” said Molly, “but I have an engagement,”—to try to write a sincere, natural, simple short story, she added, in her mind.

“Oh, dear, what a nuisance! Can you come[73] Sunday? They have horrid early dinners Sunday, but no matter.”

Molly was obliged to accept, anxious as she was to keep out of the Beta Phi crowd.

“By the way, do you act?” asked Millicent abruptly.

“A little,” answered Molly, and that ended the tea party.

In the evening Judy was slightly cold to Molly. It was almost imperceptible, so subtle was the change, and Molly herself was hardly aware of it until her friend, stretched on the couch reading, suddenly closed her book with a snap and remarked:

“Considering you dislike the Beta Phi girls, you certainly managed to monopolize one of them.”

“Judy!” remonstrated Nance, shocked at this unaccountable exhibition of temperament.

Molly said nothing whatever, and presently she slipped off to bed.

“We’ve all got our faults,” she kept saying to herself, but she was bitterly hurt, nevertheless.

Judy did have her failings, the faults of an only child spoiled by indulgent parents. But they were only on the surface, impulsive flashes of irritability that never failed to be followed by deep, poignant regret when the tempest had passed.

The next morning Molly was wakened by the fragrance of violets, and, opening her eyes, she looked straight into the heart of a big bunch of those flowers lying on her chest.

“Goodness, I feel like a corpse,” she exclaimed.

Scrawled on a card pinned to the purple tissue ribbon around the stems of the violets was the following inscription:

“For dearest Molly from her devoted and loving Judy.”

“The poor child must have got up early this morning and gone down to the village for them,” she said to Nance. “And she does hate getting up early, too.”

Thus the coldness between the two girls came to a temporary end. Molly did not go to the Beta Phi House to dinner on Sunday. Millicent sent word that she was ill with a headache and would like to postpone the visit. Some of the Shakespeareans came to the apartment of the three girls to call one evening, but they were Judy’s friends, invited by her to drop in and have fudge, and Molly and Nance kept quiet and remained in the background. If Judy was working to get into the Shakespeareans, she should have the field to herself. The three visitors, seniors all of them, left early, but in some mysterious way the news of their call spread through the Quadrangle.

“Which of you is boning for the ‘Shakespeareans’?” Minerva Higgins demanded of Nance next day.

This irrepressible young person had already[76] acquired a smattering of college slang and college gossip. But still she had not learned the difference between a freshman and a junior.

Nance drew herself up haughtily.

“Miss Higgins,” she said, “there are some things at Wellington that are never discussed.”

“Excuse me,” said Minerva, making an elaborate bow.

But Nance did not even notice the bow. She had gone on her way like an injured dignitary.

The air was certainly full of rumors, however. Everybody, even the faculty, wondered upon whose shoulders the Shakespeareans’ highly coveted honors would fall. The new members of this distinguished body were always chosen after the junior play, preparations for which were now under way. There had been first a stormy meeting of the class. It was quite natural for President Wakefield to want all her particular friends to form the committee to choose a play and select the actors, and it was equally human of the Caroline Brinton forces to resent the old clique rule. But Margaret was a[77] mighty leader and would brook no interference. So the Queen’s girls were the ruling spirits of the entertainment. Judy was chairman of the committee, and was to have the principal part in the play, it being tacitly understood that she wanted to show the Shakespeareans what she could do.

It was like the scholarly group to give a wide berth to the modern comedies and melodramas usually selected by juniors for this performance, and to settle on “Twelfth Night.”

“We can never do it,” Caroline Brinton had announced in great vexation. “We haven’t time and we have no coach.”

But she had been calmly overruled and “Twelfth Night” it was to be, with daily rehearsals except on Saturdays, when there were two.

Molly was cast for the part of Maria, the maid. And she was glad, chiefly because the costume was easy. Judy was to play Viola, Edith Williams, Malvolio, and the other parts were variously distributed, Margaret being Sir Toby Belch.[78]

When a college girl reaches her junior year her mind is well trained to concentrate and memorize. Two years before, perhaps only Edith Williams, whose memory was abnormal, would have trusted herself to memorize a Shakespearean part. But the girls were amazed now at their own powers. Miss Pryor, teacher of elocution, was present at many of the rehearsals, criticizing and suggesting, and hers was the only outside assistance the juniors had in their ambitious production.

It was probably through her that the accounts of their ability were noised abroad, and on the night of the play there was a great rush for seats. The president herself was there and many of the faculty. Professor Green had a front balcony seat looking straight down on the stage.

“Goodness, but I’m scared!” exclaimed Molly, peeping through the hole in the curtain at the large assembly.

“Heaven help us all,” groaned Nance, dressed as an attendant of the Duke.

“Don’t talk like that,” Judy admonished them.[79] “We must make it go off all right. Molly, don’t you forget and be too solemn. Your part calls for much merriment, as the notes in the book said.”

“Don’t you be so dictatorial,” said Nance, under her breath, hoping instantly that Judy, in a high state of nerves and excitement, had not heard her.

When the seniors began thumping on the floor with their heels and the sophomores commenced clapping, Molly’s mind became a vacuum. Not even the first line of her part could she recall.

At last the curtain went up and the play began. She had no idea how Judy had conducted herself. A girl near her said:

“She certainly had an awful case of stage fright, but she’ll be all right in the next act.”

The words had no meaning to Molly, and she sat like a frozen image in the wings until Nance touched her on the shoulder and whispered:

“Hurry up.”

Then she stepped into the glare of the footlights. Her blood ceased entirely to circulate.[80] Her hands became numb. Icy fingers seemed to clutch her throat, and when she opened her mouth to speak, no voice came. She remembered making a fervent, speechless prayer.

In an instant her blood began to flow normally. She felt a wave of crimson surge into her cheeks, and she heard her own voice speaking to Margaret, stuffed out with sofa cushions to resemble Sir Toby Belch.

When the scene was over there was a great clapping of hands. It sounded to Molly like a sudden rainstorm in summer. And, like a summer shower, it was refreshing to the young actors in the great comedy.

“Good work, Molly,” Margaret whispered. “I think we carried that off pretty well. If only Judy doesn’t get scared again the thing will go all right.”

“Did Judy have stage fright?” demanded Molly, in surprise.

“You mean to say you didn’t know? She almost ruined the scene.”[81]

“Poor old Judy,” thought Molly, “and just when she wanted to do her best, too.”

Judy did improve considerably as the play progressed, but even a friendly audience has an unrelenting way of retaining first impressions; or perhaps it was that poor Judy, sensitive and high strung, imagined the audience was cold to her and so allowed her spirit to be quenched. There were no cries for “Viola” from the people in front, and there were many for Malvolio, Sir Toby and Maria.

Again and again these three actors came forth and bowed their acknowledgment. During the intermission several of the freshmen ushers carried down bouquets of flowers. Jessie received two from admirers who appeared to keep a running account at the florist’s in the village. A splendid basket of red roses and a bunch of violets were handed over the footlights for Molly, and when she was summoned from the wings to appear and receive these floral offerings she flushed crimson and remarked to the usher:[82]

“There must be some mistake. They couldn’t be for me.”

A ripple of laughter went over the entire house. There was another burst of applause which again brought Miss Molly Brown of Kentucky into prominence through no fault of her own.

The card on the magnificent basket of roses made known to her the fact that Miss Millicent Porter had thus honored her. The card on the violets merely said: “From a crusty old critic who believes in your success.”

“I thought Millicent Porter had a big crush on you,” observed Margaret later in the green room. “There’s no doubt about it now after this noble tribute.”

“Nonsense,” said Molly. “It’s because she has so much money and likes to spend it.”

“On herself, yes, buying clothes and big lumps of silver to play with; but not on you, Molly, dear, unless she had been greatly taken with your charms.”

Molly had seen a few college crushes and considered[83] them absurd, a kind of idol worship by a young girl for an older one; but because she had been so closely with her own small circle, she had escaped a crush so far.

“I’ll never believe it,” she said. “I’m much too humble a person to be admired by such a grand young lady. She sent the roses because she had to recall her invitation to dinner.”

“Only time will prove it, Miss Molly,” answered Margaret.

The play ended with a grand storm of applause and college yells. Not in their wildest dreams had the juniors hoped for such success.

“It’s difficult to tell who was the best, they were all so excellent,” the president was reported to have said.

Finally, to satisfy the persistent multitude, each actor marched slowly in front of the curtain, and each was received with more or less enthusiasm.

“Rah-rah-rah; rah-rah-rah; Wellington—Wellington—Margaret Wakefield,” they yelled; or[84] “What’s the matter with Molly Brown? She’s all right. Molly—Molly—Molly Brown.”

In the intoxicating excitement of this fifteen minutes nobody realized that Judy had withdrawn from the group of actors and hidden herself away somewhere behind the scenery. There was some speculation in the audience as to why Viola had not filed across the stage with the others, but since Judy’s really devoted friends were all behind the scenes, there was no one to bring her out unless she chose to show herself with the others.

“Wasn’t it simply grand?” cried Jessie, the last to taste the sweets of popularity. The hall was still ringing with:

“Jessie—Jessie—she’s all right!” when she bowed herself behind the curtain and joined her classmates in the green room. Then there came cries of:

“Speech! Speech! Wakefield! Wakefield!”

Margaret, as composed as a May morning, stepped to the front of the platform and gave one of her most appropriate addresses to the joy[85] of the audience and the intense amusement of the faculty.

“Think of that child, only eighteen, and making such a speech! They are certainly a remarkable group of girls. So much individuality among them,” said Miss Walker to Miss Pomeroy, at her side.

“And rare charm in some of the individuals,” added Miss Pomeroy. “The little Brown girl, for instance, who, by the way, is as tall as I am, but so thin that she seems small, has magnetism that will carry her through many a difficulty in life. They tell me she is almost adored by her friends.”

In the meantime the juniors, entirely unconscious of these compliments from high places, and perhaps it was quite as well they were, had just missed Judy from their midst.

“Didn’t she go before the curtain with the rest of us?” some one asked.

“But how strange, when she had the leading part.”

“I thought I heard them give her the yell.”[86]

“Judy, Judy,” called Molly.

“Here I am,” answered a muffled voice from behind the scenery.

Presently Judy appeared, showing a face so white and tragic that her friends were shocked. With a tactful instinct most of the girls hurriedly gathered their things together and disappeared, leaving only the intimates in the green room.

“Why, Judy, dearest, why did you hide yourself, and you the leading lady of the company?” exclaimed Molly reproachfully, when all outsiders had departed.

“Don’t flatter me, Molly,” Judy answered, in a hard, strained voice.

“But you were,” said Molly, “and you acted beautifully.”

“I ruined the play,” said Judy angrily. “I ruined the entire business, and you made me do it.”

“Oh, Judy,” cried Molly, “you are talking wildly. What do you mean?”

“You did. You upset me completely when you said: ‘don’t be so dictatorial.’ I never heard you[87] make a speech like that before. And just as I was about to go on, too. It was cruel. It was unkind. If it had come from any one else but you——”

“Here—here,” broke in Margaret. “Really, Judy, you’re losing your temper.”

“She never said it, anyhow,” cried Nance. “I said it myself.”

“She did say it, Nance. You’re just trying to screen her,” replied Judy, who had worked herself into a nervous rage.

“Is this going to be a free fight?” asked Edith, who always enjoyed battles.

Molly was gathering up her things.

“Not as far as I am concerned,” she answered, in a trembling voice.

As she went out she looked sorrowfully back at Judy, but not another word did she say.

“Aren’t you ashamed of yourself, Judy Kean?” cried Nance. “You’re jealous and that’s the whole of it,” and she flung herself out of the door after Molly. The others quickly followed. Certainly sympathy was against Judy.[88]

And what of poor Judy left all alone in the gymnasium?

Torn with anger, remorse, jealousy and disappointment, she threw herself face downward on the empty stage.

Presently the janitor came in and switched off the lights.

Molly and Nance had little to say to each other that night as they undressed for bed. Nance was still filled with hot indignation over Judy’s “falling-off” as she called it, and Molly had no heart for conversation. The door to Judy’s bedroom at the other end of the sitting room was closed and they were not surprised when she did not call “good night” as was her custom. Nobody looked in on them. It was late and the Quadrangle was soon perfectly still.