|

Transcriber’s note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE

ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

ELEVENTH EDITION

| FIRST |

edition, |

published in |

three |

volumes, |

1768-1771. |

| SECOND |

” |

” |

ten |

” |

1777-1784. |

| THIRD |

” |

” |

eighteen |

” |

1788-1797. |

| FOURTH |

” |

” |

twenty |

” |

1801-1810. |

| FIFTH |

” |

” |

twenty |

” |

1815-1817. |

| SIXTH |

” |

” |

twenty |

” |

1823-1824. |

| SEVENTH |

” |

” |

twenty-one |

” |

1830-1842. |

| EIGHTH |

” |

” |

twenty-two |

” |

1853-1860. |

| NINTH |

” |

” |

twenty-five |

” |

1875-1889. |

| TENTH |

” |

ninth edition and eleven supplementary volumes, |

1902-1903. |

| ELEVENTH |

” |

published in twenty-nine volumes, |

1910-1911. |

COPYRIGHT

in all countries subscribing to the

Bern Convention

by

THE CHANCELLOR, MASTERS AND SCHOLARS

of the

UNIVERSITY OF CAMBRIDGE

All rights reserved

THE

ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A

DICTIONARY

OF

ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL

INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME X

EVANGELICAL CHURCH to FRANCIS JOSEPH

New York

Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.

342 Madison Avenue

Copyright, in the United States of America, 1910,

by

The Encyclopædia Britannica Company.

VOLUME X SLICE I

Evangelical Church Conference to Fairbairn, Sir William

Articles in This Slice

| EVANGELICAL CHURCH CONFERENCE | EXPULSION |

| EVANGELICAL UNION | EXTENSION |

| EVANS, CHRISTMAS | EXTENUATING CIRCUMSTANCES |

| EVANS, EVAN HERBER | EXTERRITORIALITY |

| EVANS, SIR GEORGE DE LACY | EXTORTION |

| EVANS, SIR JOHN | EXTRACT |

| EVANS, OLIVER | EXTRADITION |

| EVANSON, EDWARD | EXTRADOS |

| EVANSTON | EXTREME UNCTION |

| EVANSVILLE | EYBESCHÜTZ, JONATHAN |

| EVARISTUS | EYCK, VAN |

| EVARTS, WILLIAM MAXWELL | EYE (English town) |

| EVE | EYE (organ) |

| EVECTION | EYEMOUTH |

| EVELETH | EYLAU |

| EVELYN, JOHN | EYRA |

| EVERDINGEN, ALLART VAN | EYRE, EDWARD JOHN |

| EVEREST, SIR GEORGE | EYRE, SIR JAMES |

| EVEREST, MOUNT | EYRIE |

| EVERETT, ALEXANDER HILL | EZEKIEL |

| EVERETT, CHARLES CARROLL | EZRA |

| EVERETT, EDWARD | EZRA, THIRD BOOK OF |

| EVERETT (Massachusetts, U.S.A.) | EZRA, FOURTH BOOK OF |

| EVERETT (Washington, U.S.A.) | EZRA AND NEHEMIAH, BOOKS OF |

| EVERGLADES | EZZO |

| EVERGREEN | EZZOLIED |

| EVERLASTING | F |

| EVERSLEY, CHARLES SHAW LEFEVRE | FABBRONI, ANGELO |

| EVESHAM | FABER |

| EVIDENCE | FABER, BASIL |

| EVIL EYE | FABER, FREDERICK WILLIAM |

| EVOLUTION | FABER, JACOBUS |

| EVORA | FABER, JOHANN |

| ÉVREUX | FABERT, ABRAHAM DE |

| EWALD, GEORG HEINRICH AUGUST VON | FABIAN, SAINT |

| EWALD, JOHANNES | FABIUS |

| EWART, WILLIAM | FABIUS PICTOR, QUINTUS |

| EẂE | FABLE |

| EWELL, RICHARD STODDERT | FABLIAU |

| EWING, ALEXANDER | FABRE, FERDINAND |

| EWING, JULIANA HORATIA ORR | FABRE D’ÉGLANTINE, PHILIPPE FRANÇOIS NAZAIRE |

| EWING, THOMAS | FABRETTI, RAPHAEL |

| EXAMINATIONS | FABRIANI, SEVERINO |

| EXARCH | FABRIANO |

| EXCAMBION | FABRICIUS, GAIUS LUSCINUS |

| EXCELLENCY | FABRICIUS, GEORG |

| EXCHANGE | FABRICIUS, HIERONYMUS |

| EXCHEQUER | FABRICIUS, JOHANN ALBERT |

| EXCISE | FABRICIUS, JOHANN CHRISTIAN |

| EXCOMMUNICATION | FABRIZI, NICOLA |

| EXCRETION | FABROT, CHARLES ANNIBAL |

| EXECUTION | FABYAN, ROBERT |

| EXECUTORS AND ADMINISTRATORS | FAÇADE |

| EXEDRA | FACCIOLATI, JACOPO |

| EXELMANS, RENÉ JOSEPH ISIDORE | FACE |

| EXEQUATUR | FACTION |

| EXETER, EARL, MARQUESS AND DUKE OF | FACTOR |

| EXETER (England) | FACTORY ACTS |

| EXETER (New Hampshire, U.S.A.) | FACULA |

| EXETER BOOK | FACULTY |

| EXHIBITION | FAED, THOMAS |

| EXHUMATION | FAENZA |

| EXILARCH | FAEROE |

| EXILE | FAESULAE |

| EXILI | FAFNIR |

| EXMOOR FOREST | FAGGING |

| EXMOUTH, EDWARD PELLEW | FAGGOT |

| EXMOUTH | FAGNIEZ, GUSTAVE CHARLES |

| EXODUS, BOOK OF | FAGUET, ÉMILE |

| EXODUS, THE | FA-HIEN |

| EXOGAMY | FAHLCRANTZ, CHRISTIAN ERIK |

| EXORCISM | FAHRENHEIT, GABRIEL DANIEL |

| EXORCIST | FAIDHERBE, LOUIS LÉON CÉSAR |

| EXOTIC | FAIENCE |

| EXPATRIATION | FAILLY, PIERRE LOUIS CHARLES DE |

| EXPERT | FAIN, AGATHON JEAN FRANÇOIS |

| EXPLOSIVES | FAIR |

| EXPRESS | FAIRBAIRN, ANDREW MARTIN |

| EXPROPRIATION | FAIRBAIRN, SIR WILLIAM |

INITIALS USED IN VOLUME X. TO IDENTIFY INDIVIDUAL

CONTRIBUTORS,1 WITH THE HEADINGS OF THE

ARTICLES IN THIS VOLUME SO SIGNED.

| A. B. R. |

Alfred Barton Rendle, M.A., D.Sc, F.R.S., F.L.S.

Keeper, Department of Botany, British Museum. Author of Text Book on Classification

of Flowering Plants; &c. |

Flower. |

| A. D. |

Austin Dobson, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Dobson, H. Austin. |

Fielding, Henry. |

| A. F. B. |

Aldred Farrer Barker, M.Sc.

Professor of Textile Industries at Bradford Technical College. |

Felt. |

| A. F. P. |

Albert Frederick Pollard, M.A., F.R.Hist.Soc.

Professor of English History in the University of London. Fellow of All Souls’

College, Oxford. Assistant Editor of the Dictionary of National Biography, 1893-1901.

Lothian Prizeman, Oxford, 1892; Arnold Prizeman, 1898. Author of

England under Protector Somerset; Henry VIII.; Life of Thomas Cranmer; &c. |

Ferrar, Bishop;

Fox, Edward;

Fox, Richard. |

| A. G. |

Major Arthur George Frederick Griffiths (d. 1908).

H.M. Inspector of Prisons, 1878-1896. Author of The Chronicles of Newgate;

Secrets of the Prison House; &c. |

Finger Prints. |

| A. Go.* |

Rev. Alexander Gordon, M.A.

Lecturer on Church History in the University of Manchester. |

Faber, Basil, Jacobus and Johann;

Familists; Farel, G.; Flacius. |

| A. H.-S. |

Sir A. Houtum-Schindler, C.I.E.

General in the Persian Army. Author of Eastern Persian Irak. |

Fars;

Firuzabad. |

| A. L. |

Andrew Lang.

See the biographical article: Lang, Andrew. |

Fairy;

Family. |

| A. L. B. |

Alfred Lys Baldry.

Art Critic of the Globe, 1893-1908. Author of Modern Mural Decoration and

biographies of Albert Moore, Sir H. von Herkomer, R.A., Sir J. E. Millais, P.R.A.,

Marcus Stone, R.A., and G. H. Boughton, R.A. |

Fortuny. |

| A. N. |

Alfred Newton, F.R.S.

See the biographical article: Newton, Alfred. |

Falcon; Fieldfare; Finch;

Flycatcher; Fowl. |

| A. S. |

Arthur Smithells, F.R.S.

Professor of Chemistry in the University of Leeds. Author of Scientific Papers on

Flame and Spectrum Analysis. |

Flame. |

| A. M. C. |

Agnes Mary Clerke.

See the biographical article: Clerke, A. M. |

Flamsteed. |

| A. W. |

Arthur Watson.

Secretary in the Academic Department, University of London. |

Examinations (in part). |

| A. W. R. |

Alexander Wood Renton, M.A., LL.B.

Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Ceylon. Editor of Encyclopaedia of the Laws

of England. |

Fixtures;

Flat. |

| A. W. W. |

Adolphus William Ward, D.Litt., LL.D.

See the biographical article: Ward, A. W. |

Foote, Samuel;

Ford, John. |

| C. El. |

Sir Charles Norton Edgcumbe Eliot, K.C.M.G., C.B., M.A., LL.D., D.C.L.

Vice-Chancellor of Sheffield University. Formerly Fellow of Trinity College,

Oxford. H.M.’s Commissioner and Commander-in-Chief for the British East Africa

Protectorate; Agent and Consul-General at Zanzibar; Consul-General for German

East Africa, 1900-1904. |

Finno-Ugrian. |

| C. F. B. |

Charles Francis Bastable, M.A., LL.D.

Regius Professor of Laws and Professor of Political Economy in the University of

Dublin. Author of Public Finance; Commerce of Nations; Theory of International

Trade; &c. |

Finance. |

| C. F. C. |

C. F. Cross, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. F.I.C.

Analytical and Consulting Chemist. |

Fibres. |

| C. F. R. |

Charles Francis Richardson, A.M., Ph.D.

Professor of English at Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, U.S.A.

Author of A Story of English Rhyme; A History of American Literature; &c. |

Fiske, John. |

| C. H. T.* |

Crawford Howell Toy, A.M.

See the biographical article: Toy, Crawford Howell. |

Ezekiel. |

| C. J. |

Charles Johnson, M.A.

Clerk in H.M. Public Record Office. Joint Editor of the Domesday Survey for the

Victoria County History: Norfolk. |

Exchequer (in part). |

| C. J. B. M. |

Charles John Bruce Marriott, M.A.

Clare College, Cambridge. Secretary of the Rugby Football Union. |

Football: Rugby (in part). |

| C. J. N. F. |

Charles James Nicol Fleming.

H.M. Inspector of Schools, Scotch Education Department. |

Football: Rugby (in part). |

| C. L. K. |

Charles Lethbridge Kingsford, M.A., F.R.Hist.Soc., F.S.A.

Assistant Secretary to the Board of Education. Author of Life of Henry V. Editor

of Chronicles of London and Stow’s Survey of London. |

Fabyan;

Fastolf. |

| C. P. I. |

Sir Courtenay Peregrine Ilbert, K.C.B., K.C.S.I., C.I.E.

Clerk of the House of Commons. Chairman of Statute Law Committee. Parliamentary

Counsel to the Treasury, 1899-1901. Legal Member of Council of Governor-General

of India, 1882-1886; President, 1886. Fellow of the British Academy.

Formerly Fellow and Tutor of Balliol College, Oxford. Author of The Government

of India; Legislative Method and Forms. |

Evidence. |

| C. W. A. |

Charles William Alcock. (d. 1907).

Formerly Secretary of the Football Association, London. |

Football: Association (in part). |

| D. H. |

David Hannay.

Formerly British Vice-Consul at Barcelona. Author of Short History of the Royal

Navy; Life of Emilio Castelar; &c. |

First of June, Battle of the;

Fox, Charles James. |

| D. Mn. |

Rev. Dugald Macfadyen, M.A.

Minister of South Grove Congregational Church, Highgate. Director of the London

Missionary Society. |

Excommunication. |

| D. N. P. |

Diarmid Noel Paton, M.D., F.R.C.P. (Edin.).

Regius Professor of Physiology in the University of Glasgow. Formerly Superintendent

of Research Laboratory of Royal College of Physicians, Edinburgh.

Biological Fellow of Edinburgh University, 1884. Author of Essentials of Human

Physiology; &c. |

Fever. |

| D. S. M.* |

David Samuel Margoliouth, M.A., D.Litt.

Laudian Professor of Arabic, Oxford. Fellow of New College. Author of Arabic

Papyri of the Bodleian Library; Mohammed and the Rise of Islam; Cairo, Jerusalem

and Damascus. |

Fatimites. |

| E. B. |

Edward Breck, M.A., Ph.D.

Formerly Foreign Correspondent of the New York Herald and the New York Times.

Author of Fencing; Wilderness Pets; Sporting in Nova Scotia; &c. |

Foil-fencing;

Football: American (in part). |

| E. Ca. |

Egerton Castle, M.A., F.S.A.

Trinity College, Cambridge. Author of Schools and Masters of Fence; &c. |

Fencing. |

| Ed. C.* |

The Hon. Edward Evan Charteris.

Barrister-at-Law, Inner Temple. |

Fair (in part). |

| E. C. B. |

Rt. Rev. Edward Cuthbert Butler, O.S.B., M.A., D.Litt.

Abbot of Downside Abbey, Bath. Author of “The Lausiac History of Palladius,”

in Cambridge Texts and Studies, vol. vi. |

Fontevrault;

Francis of Assisi, St;

Francis of Paola, St. |

| E. C. Q. |

Edmund Crosby Quiggin, M.A.

Fellow and Lecturer in Modern Languages and Monro Lecturer in Celtic,

Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. |

Finn mac Cool. |

| E. D. R. |

Lieut.-Colonel Emilius C. Delmé Radcliffe.

Author of Falconry: Notes on the Falconidae used in India in Falconry. |

Falconry. |

| E. E. A. |

Ernest E. Austen.

Assistant in Department of Zoology, Natural History Museum, South Kensington. |

Flea. |

| E. E. H. |

Rev. Edward Everett Hale.

See the biographical article: Hale, E. E. |

Everett, Edward. |

| E. G. |

Edmund Gosse, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Gosse, Edmund. |

Ewald, Johannes; Fabliau;

Fabre, Ferdinand; Feuillet;

Finland: Literature;

FitzGerald, Edward; Flaubert;

Flemish Literature; Forssell. |

| E. H. P. |

Edward Henry Palmer, M.A.

See the biographical article: Palmer, E. H. |

Firdousi (in part). |

| E. K. |

Edmund Knecht, Ph.D., M.Sc.Tech. (Manchester), F.I.C.

Professor of Technological Chemistry, Manchester University. Head of Chemical

Department, Municipal School of Technology, Manchester. Examiner in Dyeing,

City and Guilds of London Institute. Author of A Manual of Dyeing; &c. Editor

of Journal of the Society of Dyers and Colourists. |

Finishing. |

| E. M. Ha. |

Ernest Maes Harvey.

Partner in Messrs. Allen Harvey & Ross, Bullion Brokers, London. |

Exchange. |

| E. O.* |

Edmund Owen, M.B., F.R.C.S., LL.D., D.Sc.

Consulting Surgeon to St Mary’s Hospital, London, and to the Children’s Hospital,

Great Ormond Street, London. Chevalier of the Legion of Honour. Late Examiner

in Surgery at the University of Cambridge, London and Durham. Author of A

Manual of Anatomy for Senior Students. |

Fistula. |

| E. O. S. |

Edwin Otho Sachs, F.R.S. (Edin.), A.M.Inst.M.E.

Chairman of the British Fire Prevention Committee. Vice-President, National

Fire Brigades Union. Vice-President, International Fire Service Council. Author

of Fires and Public Entertainments; &c. |

Fire and Fire Extinction. |

| E. Pr. |

Edgar Prestage.

Special Lecturer in Portuguese Literature at the University of Manchester. Commendador,

Portuguese Order of S. Thiago. Corresponding Member of Lisbon

Royal Academy of Sciences and Lisbon Geographical Society. |

Falcao;

Ferreira. |

| E. Re. |

Elisée Reclus.

See the biographical article: Reclus, J. J. E. |

Fire. |

| E. Tn. |

Rev. Ethelred Leonard Taunton, (d. 1907).

Author of The English Black Monks of St Benedict; History of the Jesuits in England. |

Feckenham;

Fisher, John. |

| E. W. H. |

Ernest William Hobson, M.A., D.Sc., F.R.S., F.R.A.S.

Fellow and Tutor in Mathematics, Christ’s College, Cambridge. Stokes Lecturer

in Mathematics in the University. |

Fourier’s Series. |

| F. C. C. |

Frederick Cornwallis Conybeare, M.A., D.Th. (Giessen).

Fellow of the British Academy. Formerly Fellow of University College, Oxford.

Author of The Ancient Armenian Texts of Aristotle; Myth, Magic and Morals; &c. |

Extreme Unction. |

| F. G. P. |

Frederick Gymer Parsons, F.R.C.S., F.Z.S., F.R.Anthrop.Inst.

Vice-President, Anatomical Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Lecturer on

Anatomy at St Thomas’s Hospital and the London School of Medicine for Women.

Formerly Hunterian Professor at the Royal College of Surgeons. |

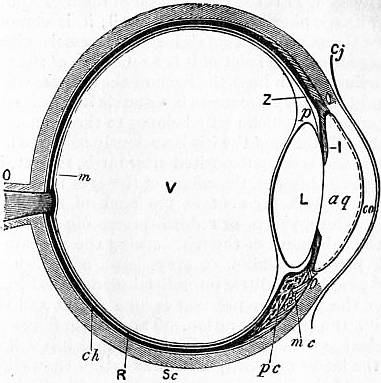

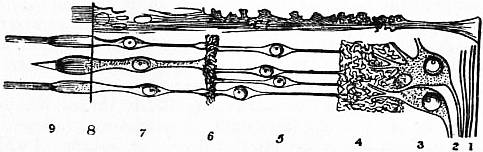

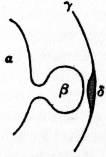

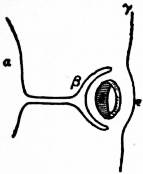

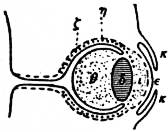

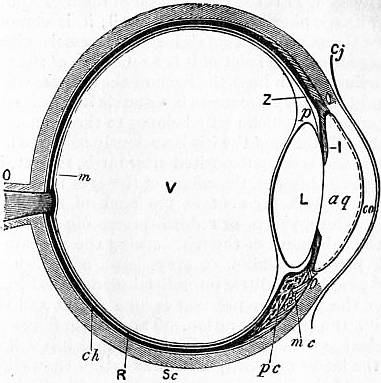

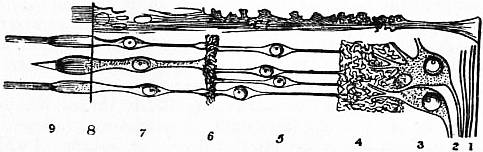

Eye: Anatomy. |

| F. J. H. |

Francis John Haverfield, M.A., LL.D., F.S.A.

Camden Professor of Ancient History in the University of Oxford. Fellow of

Brasenose College. Ford’s Lecturer, 1906-1907. Fellow of the British Academy.

Author of Monographs on Roman History, especially Roman Britain; &c. |

Fosse. |

| F. J. W. |

Frederick Joseph Wall, F.C.S.

Secretary to the Football Association. |

Football: Association (in part). |

| F. R. C. |

Frank R. Cana.

Author of South Africa from the Great Trek to the Union. |

France: Colonies. |

| F. S. |

Francis Storr, M.A.

Editor of the Journal of Education, London. Officier d’Académie, Paris. |

Fable. |

| G. A. B. |

George A. Boulenger, D.Sc., Ph.D., F.R.S.

In charge of the Collections of Reptiles and Fishes, Department of Zoology, British

Museum. Vice-President of the Zoological Society of London. |

Flat-fish. |

| G. A. Be. |

George Andreas Berry, M.B., F.R.C.S., F.R.S. (Edin.).

Hon. Surgeon Oculist to His Majesty in Scotland. Formerly Senior Ophthalmic

Surgeon, Edinburgh Royal Infirmary, and Lecturer on Ophthalmology in the University

of Edinburgh. Vice-President, Ophthalmological Society. Author of

Diseases of the Eye; The Elements of Ophthalmoscopic Diagnosis; Subjective

Symptoms in Eye Diseases; &c. |

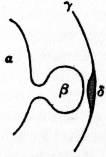

Eye: Diseases. |

| G. B. A. |

George Burton Adams, A.M., B.D., Ph.D., Litt.D.

Professor of History, Yale University. Editor of American Historical Review.

Author of Civilization during the Middle Ages; Political History of England,

1066-1216; &c. |

Feudalism. |

| G. C. L. |

George Collins Levey, C.M.G.

Member of Board of Advice to Agent-General of Victoria. Formerly Editor and

Proprietor of the Melbourne Herald. Secretary, Colonial Committee of Royal

Commission to Paris Exhibition, 1900. Secretary, Adelaide Exhibition, 1887.

Secretary, Royal Commission, Hobart Exhibition, 1894-1895. Secretary to Commissioners

for Victoria at the Exhibitions in London, Paris, Vienna, Philadelphia

and Melbourne, 1873, 1876, 1878, 1880-1881. |

Exhibition. |

| G. E. |

Rev. George Edmundson, M.A., F.R.Hist.S.

Formerly Fellow and Tutor of Brasenose College, Oxford. Ford’s Lecturer, 1909.

Hon. Member, Dutch Historical Society, and Foreign Member, Netherlands Association

of Literature. |

Flanders. |

| G. F. Z. |

George Frederick Zimmer, A.M.Inst.C.E.

Author of Mechanical Handling of Material. |

Flour and Flour Manufacture. |

| G. G. P.* |

George Grenville Phillimore, M.A., B.C.L.

Christ Church, Oxford. Barrister-at-Law, Middle Temple. |

Fishery, Law of. |

| G. P. |

Gifford Pinchot, A.M., D.Sc., LL.D.

Professor of Forestry, Yale University. Formerly Chief Forester, U.S.A. President

of the National Conservation Association. Member of the Society of American

Foresters, Royal English Arboricultural Society, &c. Author of The White Pine;

A Primer of Forestry; &c. |

Forests and Forestry: United States. |

| G. W. T. |

Rev. Griffiths Wheeler Thatcher, M.A., B.D.

Warden of Camden College, Sydney, N.S.W. Formerly Tutor in Hebrew and Old

Testament History at Mansfield College, Oxford. |

Fairūzābādī;

Fakhr ud-Dīn Rāzi;

Fārābī; Farazdaq. |

| H. B. S. |

Rev. Henry Barclay Swete, M.A., D.D., Litt.D.

Regius Professor of Divinity, Cambridge University. Fellow of Gonville and Caius

College, Cambridge. Fellow of King’s College, London. Fellow of British Academy.

Hon. Canon of Ely Cathedral. Author of The Holy Spirit in the New Testament; &c. |

Fathers of the Church. |

| H. Ch. |

Hugh Chisholm, M.A.

Formerly Scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford. Editor of the 11th Edition

of the Encyclopaedia Britannica; Co-Editor of the 10th edition. |

Forster. |

| H. De. |

Hippolyte Delehaye, S.J.

Assistant in the compilation of the Bollandist publications: Analecta Bollandiana

and Acta Sanctorum. |

Fiacre, Saint;

Florian, Saint. |

| H. F. G. |

Hans Friedrich Gadow, F.R.S., Ph.D.

Strickland Curator and Lecturer on Zoology in the University of Cambridge.

Author of “Amphibia and Reptiles,” in the Cambridge Natural History. |

Flamingo. |

| H. L. S. |

H. Lawrence Swinburne (d. 1909). |

Flag. |

| H. St. |

Henry Sturt, M.A.

Author of Idola Theatri; The Idea of a Free Church; Personal Idealism. |

Fechner;

Feuerbach, Ludwig A. |

| H. W. C. D. |

Henry William Carless Davis, M.A.

Fellow and Tutor of Balliol College, Oxford. Fellow of All Souls’ College, Oxford,

1895-1902. Author of England under the Normans and Angevins; Charlemagne. |

Fitz Neal;

Fitz Peter, Geoffrey;

Fitz Stephen, William;

Fitz Thedmar; Flambard;

Florence of Worcester. |

| H. W. S. |

H. Wickham Steed.

Correspondent of The Times at Vienna. Correspondent of The Times at Rome,

1897-1902. |

Fabrizi. |

| I. A. |

Israel Abrahams, M.A.

Reader in Talmudic and Rabbinic Literature, University of Cambridge. President,

Jewish Historical Society of England. Author of A Short History of Jewish Literature;

Jewish Life in the Middle Ages. |

Exilarch;

Eybeschutz. |

| J. A. C. |

Sir Joseph Archer Crowe, K.C.M.G.

See the biographical article: Crowe, Sir Joseph A. |

Eyck, Van. |

| J. A. H. |

John Allen Howe, B.Sc.

Curator and Librarian of the Museum of Practical Geology, London. Author of

The Geology of Building Stones. |

France: Geology. |

| J. A. S. |

John Addington Symonds, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Symonds, John A. |

Ficino;

Filelfo. |

| J. B.* |

Joseph Burton.

Partner in Pilkington’s Tile and Pottery Co., Clifton Junction, Manchester. |

Firebrick (in part). |

| J. B. P. |

James Bell Pettigrew, M.D., LL.D., F.R.S., F.R.C.P. (Edin.) (1834-1908).

Chandos Professor of Medicine and Anatomy, University of St Andrews, 1875-1908.

Author of Animal Locomotion; &c. |

Flight and Flying (in part). |

| J. Bt. |

James Bartlett.

Lecturer on Construction, Architecture, Sanitation, Quantities, &c., at King’s

College, London. Member of Society of Architects. Member of Institute of

Junior Engineers. |

Foundations. |

| J. C. M. |

James Clerk Maxwell, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Maxwell, James Clerk. |

Faraday. |

| J. E. C. B. |

John Edward Courtenay Bodley, M.A.

Balliol College, Oxford. Corresponding Member of the Institute of France. Author

of France; The Coronation of Edward VII.; &c. |

France: History, 1870-1910. |

| J. E. P. W. |

John Edward Power Wallis, M.A.

Puisne Judge, Madras. Vice-Chancellor of Madras University. Inns of Court

Reader in Constitutional Law, 1892-1897. Formerly Editor of State Trials. |

Extradition. |

| J. F. St. |

John Frederick Stenning, M.A.

Dean and Fellow of Wadham College, Oxford. University Lecturer in Aramaic.

Lecturer in Divinity and Hebrew at Wadham College. |

Exodus, Book of. |

| J. G. H. |

Joseph G. Horner, A.M.I.Mech.E.

Author of Plating and Boiler Making; Practical Metal Turning; &c. |

Forging;

Founding. |

| J. G. R. |

John George Robertson, M.A., Ph.D.

Professor of German at the University of London. Formerly Lecturer on the

English Language, Strassburg University. Author of History of German Literature;

&c. |

Fouqué, Baron. |

| J. H. P.* |

John Hungerford Pollen, M.A. (d. 1908).

Formerly Professor of Fine Arts in Catholic University of Dublin. Fellow of

Merton College, Oxford. Cantor Lecturer, Society of Arts, 1885. Author of

Ancient and Modern Furniture and Woodwork; Ancient and Modern Gold and

Silversmith’s Work; The Trajan Column; &c. |

Fan. |

| J. Hl. R. |

John Holland Rose, M.A., Litt.D.

Lecturer on Modern History to the Cambridge University Local Lectures Syndicate.

Author of Life of Napoleon I.; Napoleonic Studies; The Development of the European

Nations; The Life of Pitt; chapters in the Cambridge Modern History. |

Fouché. |

| J. H. R. |

John Horace Round, M.A., LL.D. (Edin.).

Author of Feudal England; Studies in Peerage and Family History; Peerage and

Pedigree; &c. |

Ferrers: Family;

Fitzgerald: Family. |

| J. I. |

Jules Isaac.

Professor of History at the Lycée of Lyons. |

Francis I. of France. |

| J. K. L. |

Sir John Knox Laughton, M.A., Litt.D.

Professor of Modern History, King’s College, London. Secretary of the Navy

Records Society. Served in the Baltic, 1854-1855; in China, 1856-1859. Mathematical

and Naval Instructor, Royal Naval College, Portsmouth, 1866-1873;

Greenwich, 1873-1885. President, Royal Meteorological Society, 1882-1884.

Honorary Fellow, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Fellow, King’s College,

London. Author of Physical Geography in its Relation to the Prevailing Winds and

Currents; Studies in Naval History; Sea Fights and Adventures; &c. |

Farragut;

Fitzroy. |

| J. L. B. |

Julian Levett Baker, F.I.C.

Analytical and Consulting Chemist. Examiner in Brewing to the City and Guilds

of London Institute, Department of Technology. Hon. Secretary of the Institute

of Brewing. Author of The Brewing Industry; &c. |

Fermentation. |

| J. Ma. |

John Macdonald.

|

Fair (in part). |

| J. M. S. |

James Montgomery Stuart.

Author of The History of Free Trade in Tuscany; Reminiscences and Essays. |

Foscolo. |

| J. Pa. |

James Paton, F.L.S.

Superintendent of Museums and Art Galleries of Corporation of Glasgow. Assistant

in Museum of Science and Art, Edinburgh, 1861-1876. President of Museums

Association of United Kingdom, 1896. Editor and part-author of Scottish National

Memorials, 1890. |

Feather (in part). |

| J. P. E. |

Jean Paul Hippolyte Emmanuel Adhémar Esmein.

Professor of Law in the University of Paris. Officer of the Legion of Honour.

Member of the Institute of France. Author of Cours élémentaire d’histoire du droit

français; &c. |

France: Law and Institutions. |

| J. R. C. |

Joseph Rogerson Cotter, M.A.

Assistant to the Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy, Trinity College,

Dublin. Editor of 2nd edition of Preston’s Theory of Heat. |

Fluorescence. |

| J. R. F.* |

Joseph R. Fisher.

Editor of the Northern Whig, Belfast. Author of Finland and the Tsars; Law of

the Press; &c. |

Finland. |

| J. R. J. J. |

Julian Robert John Jocelyn.

Colonel, R.A. Formerly Commandant, Ordnance College; Member of Ordnance

Committee; Commandant, Schools of Gunnery. |

Fireworks: History. |

| J. S. Bl. |

Rev. John Sutherland Black, M.A., LL.D.

Assistant Editor, 9th edition, Encyclopaedia Britannica. Joint Editor of the

Encyclopaedia Biblica. Translated Ritschl’s Critical History of the Christian

Doctrine of Justification and Reconciliation. |

Fasting;

Feasts and Festivals. |

| J. S. F. |

John Smith Flett, D.Sc, F.G.S.

Petrographer to the Geological Survey. Formerly Lecturer on Petrology in Edinburgh

University. Neill Medallist of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. Bigsby

Medallist of the Geological Society of London. |

Felsite;

Flint. |

| J. S. K. |

John Scott Keltie, LL.D., F.S.S.. F.S.A. (Scot.).

Secretary, Royal Geographical Society. Knight of Swedish Order of North Star.

Commander of the Norwegian Order of St Olaf. Hon. Member, Geographical

Societies of Paris, Berlin, Rome, &c. Editor of Statesman’s Year Book. Editor of

the Geographical Journal. |

Finland (in part);

Flinders. |

| J. T. Be. |

John T. Bealby.

Joint Author of Stanford’s Europe. Formerly Editor of the Scottish Geographical

Magazine. Translator of Sven Hedin’s Through Asia, Central Asia and Tibet; &c. |

Fens;

Ferghana (in part). |

| K. S. |

Kathleen Schlesinger.

Author of The Instruments of the Orchestra. |

Fiddle; Fife; Flageolet;

Flute (in part). |

| L. D.* |

Louis Duchesne.

See the biographical article: Duchesne, L. M. O. |

Formosus. |

| L. F. S. |

Leslie Frederic Scott, M.A., K.C.C.

Barrister-at-Law, Inner Temple. |

Factor. |

| L. J. |

Lieut.-Colonel Louis Charles Jackson, R.E., C.M.G.

Assistant Director of Fortifications and Works, War Office. Formerly Instructor

in Fortification, R.M.A., Woolwich. Instructor in Fortification and Military

Engineering, School of Military Engineering, Chatham |

Fortification and Siegecraft. |

| L. V.* |

Luigi Villari.

Italian Foreign Office (Emigration Dept.). Formerly Newspaper Correspondent

in east of Europe. Italian Vice-Consul in New Orleans, 1906; Philadelphia, 1907;

Boston, U.S.A., 1907-1910. Author of Italian Life in Town and Country; Fire and

Sword in the Caucasus; &c. |

Faliero; Fanti, Manfredo;

Farini, Luigi Carlo;

Farnese: Family;

Ferdinand I. and IV. of Naples;

Ferdinand II. of the Two Sicilies;

Fiesco; Filangieri, C.;

Florence; Foscari;

Fossombroni;

Francis II. of the Two Sicilies;

Francis IV. and V. of Modena. |

| M. Ha. |

Marcus Hartog, M.A., D.Sc, F.L.S.

Professor of Zoology, University College, Cork. Author of "“Protozoa,” in Cambridge

Natural History; and papers for various scientific journals. |

Flagellate; Foraminifera. |

| N. W. T. |

Northcote Whitbridge Thomas, M.A.

Government Anthropologist to Southern Nigeria. Corresponding Member of the

Société d’Anthropologie de Paris. Author of Thought Transference; Kinship and

Marriage in Australia; &c. |

Faith Healing;

Fetishism;

Folklore. |

| O. H.* |

Otto Hehner, F.I.C., F.C.S.

Public Analyst. Formerly President of Society of Public Analysts. Vice-President

of Institute of Chemistry of Great Britain and Ireland. Author of works on Butter

Analysis; Alcohol Tables; &c. |

Food Preservation. |

| O. M. |

David Orme Masson, M.A., D.Sc, F.R.S.

Professor of Chemistry, Melbourne University. Author of papers on chemistry in

the transactions of various learned societies. |

Fireworks: Modern. |

| P. A. |

Paul Daniel Alphandéry.

Professor of the History of Dogma, École Pratique des Hautes Études, Sorbonne,

Paris. Author of Les Idées morales chez les hétérodoxes latines au début du XIII^e

siècle. |

Flagellants. |

| P. A. K. |

Prince Peter Alexeivitch Kropotkin.

See the biographical article: Kropotkin, P. A. |

Ferghana (in part);

Finland (in part). |

| P. C. Y. |

Philip Chesney Yorke, M.A.

Magdalen College, Oxford. |

Falkland; Fanshaw;

Fawkes, Guy; Fell, John;

Fortescue, Sir John. |

| P. C. M. |

Peter Chalmers Mitchell, F.R.S., F.Z.S., D.Sc, LL.D.

Secretary to the Zoological Society of London. University Demonstrator in Comparative

Anatomy and Assistant to Linacre Professor at Oxford, 1881-1891.

Examiner in Zoology to the University of London, 1903. Author of Outlines of

Biology; &c. |

Evolution. |

| P. G. K. |

Paul George Konody.

Art Critic of the Observer and the Daily Mail. Formerly Editor of The Artist.

Author of The Art of Walter Crane; Velasquez, Life and Work; &c. |

Fiorenzo di Lorenzo;

Fragonard. |

| P. J. H. |

Philip Joseph Hartog, M.A., L. ès Sc. (Paris).

Academic Registrar of the University of London. Author of The Writing of English,

and articles in the Special Reports on educational subjects of the Board of Education. |

Examinations (in part). |

| P. W. |

Paul Wiriath.

Director of the École Supérieure Pratique de Commerce et d’Industrie, Paris. |

France: History to 1870. |

| R. Ad. |

Robert Adamson, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Adamson, R. |

Fichte;

Fourier, F. C. M. |

| R. A. S. M. |

Robert Alexander Stewart Macalister, M.A., F.S.A.

St John’s College, Cambridge. Director of Excavations for the Palestine Exploration

Fund. |

Font. |

| R. H. C. |

Rev. Robert Henry Charles, M.A., D.D., D.Litt. (Oxon.).

Grinfield Lecturer and Lecturer in Biblical Studies, Oxford. Fellow of the British

Academy. Formerly Senior Moderator of Trinity College, Dublin. Author and

Editor of Book of Enoch; Book of Jubilees; Apocalypse of Baruch; Assumption of

Moses; Ascension of Isaiah; Testaments of the XII. Patriarchs; &c. |

Ezra: Third and Fourth Books of. |

| R. J. M. |

Ronald John McNeill, M.A.

Christ Church, Oxford. Barrister-at-Law. Formerly Editor of the St James’s

Gazette, London. |

Fenians;

Fitzgerald, Lord Edward;

Flood, Henry. |

| R. L.* |

Richard Lydekker, F.R.S., F.G.S., F.Z.S.

Member of the Staff of the Geological Survey of India, 1874-1882. Author of

Catalogue of Fossil Mammals, Reptiles and Birds in British Museum; The Deer

of all Lands; The Game Animals of Africa; &c. |

Flying-Squirrel; Fox. |

| R. N. B. |

Robert Nisbet Bain (d. 1909).

Assistant Librarian, British Museum, 1883-1909. Author of Scandinavia: the

Political History of Denmark, Norway and Sweden, 1513-1900; The First Romanovs,

1613-1725; Slavonic Europe: the Political History of Poland and Russia from 1469

to 1796; &c. |

Fersen, Counts von. |

| R. Po. |

René Poupardin, D. ès L.

Secretary of the École des Chartes. Honorary Librarian at the Bibliothèque

Nationale, Paris. Author of Le Royaume de Provence sous les Carolingiens; Recueil

des chartes de Saint-Germain; &c. |

Franche-Comté. |

| R. P. S. |

R. Phené Spiers, F.S.A., F.R.I.B.A.

Formerly Master of the Architectural School, Royal Academy, London. Past

President of Architectural Association. Associate and Fellow of King’s College,

London. Corresponding Member of the Institute of France. Editor of Fergusson’s

History of Architecture. Author of Architecture: East and West; &c. |

Flute: Architecture. |

| R. S. C. |

Robert Seymour Conway, M.A., D.Litt. (Cantab.).

Professor of Latin and Indo-European Philology in the University of Manchester.

Formerly Professor of Latin in University College, Cardiff; and Fellow of Gonville

and Caius College, Cambridge. Author of The Italic Dialects. |

Falisci. |

| R. Tr. |

Roland Truslove, M.A.

Formerly Scholar of Christ Church, Oxford. Fellow, Dean and Lecturer in Classics

at Worcester College, Oxford. |

France: Statistics. |

| S. A. C. |

Stanley Arthur Cook, M.A.

Editor for Palestine Exploration Fund. Lecturer in Hebrew and Syriac, and

formerly Fellow, Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge. Examiner in Hebrew and

Aramaic, London University, 1904-1908. Author of Glossary of Aramaic Inscriptions;

The Laws of Moses and the Code of Hammurabi; Critical Notes on Old Testament

History; Religion of Ancient Palestine; &c. |

Exodus, The;

Ezra and Nehemiah, Books of. |

| S. C. |

Sidney Colvin, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Colvin, S. |

Fine Arts; Finiguerra;

Flaxman. |

| St C. |

Viscount St Cyres.

See the biographical article: Iddesleigh, 1st Earl of |

Fénelon. |

| S. E. B. |

Hon. Simeon Eben Baldwin, M.A., LL.D.

Professor of Constitutional and Private International Law in Yale University.

Director of the Bureau of Comparative Law of the American Bar Association.

Formerly Chief Justice of Connecticut. Author of Modern Political Institutions;

American Railroad Law; &c. |

Extradition: U.S.A. |

| S. E. S.-R. |

Stephen Edward Spring-Rice, M.A., C.B. (1856-1902).

Formerly Principal Clerk, H.M. Treasury, and Auditor of the Civil List. Fellow of

Trinity College, Cambridge. |

Exchequer (in part). |

| T. A. I. |

Thomas Allan Ingram, M.A., LL.D.

Trinity College, Dublin. |

Explosives: Law. |

| T. As. |

Thomas Ashby, M.A., D.Litt. (Oxon.), F.S.A.

Director of British School of Archaeology at Rome. Formerly Scholar of Christ

Church, Oxford. Craven Fellow, 1897. Corresponding Member of the Imperial

German Archaeological Institute. Author of the Classical Topography of the Roman

Campagna; &c. |

Faesulae; Falerii; Falerio;

Fanum Fortunae;

Ferentino; Fermo;

Flaminia Via;

Florence: Early History;

Fondi; Fonni; Forum Appii. |

| T. Ba. |

Sir Thomas Barclay, M.P.

Member of the Institute of International Law. Member of the Supreme Council of

the Congo Free State. Officer of the Legion of Honour. Author of Problems of

International Practice and Diplomacy; &c. M.P. for Blackburn, 1910. |

Exterritoriality. |

| T. H. H.* |

Sir Thomas Hungerford Holdich, K.C.M.G., K.C.I.E., D.Sc., F.R.G.S.

Colonel in the Royal Engineers. Superintendent, Frontier Surveys, India, 1892-1898.

Gold Medallist, R.G.S., London, 1887. H.M. Commissioner for the

Persia-Beluch Boundary, 1896. Author of The Indian Borderland; The Gates of

India; &c. |

Everest, Mount. |

| T. K. C. |

Rev. Thomas Kelly Cheyne, D.D.

See the biographical article: Cheyne, T. K. |

Eve (in part). |

| T. Se. |

Thomas Seccombe, M.A.

Lecturer in History, East London and Birkbeck Colleges, University of London.

Stanhope Prizeman, Oxford, 1887. Formerly Assistant Editor of Dictionary of

National Biography, 1891-1901. Joint-author of The Bookman History of English

Literature. Author of The Age of Johnson; &c. |

Fawcett, Henry. |

| T. Wo. |

Thomas Woodhouse.

Head of Weaving and Textile Designing Department, Technical College, Dundee. |

Flax. |

| V. M. |

Victor Charles Mahillon.

Principal of the Conservatoire Royal de Musique at Brussels. Chevalier of the Legion

of Honour. |

Flute (in part). |

| W. A. B. C. |

Rev. William Augustus Brevoort Coolidge, M.A., F.R.G.S., Ph.D. (Bern).

Fellow of Magdalen College, Oxford. Professor of English History, St David’s

College, Lampeter, 1880-1881. Author of Guide to Switzerland; The Alps in

Nature and in History; &c. Editor of the Alpine Journal, 1880-1889. |

Feldkirch. |

| W. A. P. |

Walter Alison Phillips, M.A.

Formerly Exhibitioner of Merton College and Senior Scholar of St John’s College,

Oxford. Author of Modern Europe; &c. |

Excellency; Faust;

Febronianism. |

| W. B.* |

William Burton, M.A., F.C.S.

Chairman, Joint Committee of Pottery Manufacturers of Great Britain. Author of

English Stoneware and Earthenware; &c. |

Firebrick (in part). |

| W. Ca. |

Walter Camp, A.M.

Member of Yale University Council. Author of American Football; Football Facts

and Figures; &c. |

Football: American (in part). |

| W. Ga. |

Walter Garstang, M.A., D.Sc.

Professor of Zoology at the University of Leeds. Scientific Adviser to H.M.

Delegates on the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, 1901-1907.

Formerly Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford. Author of The Races and Migrations

of the Mackerel; The Impoverishment of the Sea; &c. |

Fisheries. |

| W. He. |

Walter Hepworth.

Formerly Commissioner of the Council of Education, Science and Art Department,

South Kensington. |

Fool. |

| W. M. R. |

William Michael Rossetti.

See the biographical article: Rossetti, Dante G. |

Ferrari, Gaudenzio;

Fielding, Copley;

Franceschi, Piero; Francia. |

| W. P. P. |

William Plane Pycraft, F.Z.S.

Assistant in the Zoological Department, British Museum. Formerly Assistant

Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy, Oxford. Vice-President of the

Selborne Society. Author of A History of Birds; &c. |

Feather (in part). |

| W. N. S. |

William Napier Shaw, M.A., LL.D., D.Sc, F.R.S.

Director of the Meteorological Office. Reader in Meteorology in the University of

London. President of Permanent International Meteorological Committee.

Member of Meteorological Council, 1897-1905. Hon. Fellow of Emmanuel College,

Cambridge. Fellow of Emmanuel College, 1877-1899; Senior Tutor, 1890-1899.

Joint Author of Text Book of Practical Physics; &c. |

Fog. |

| W. P. R. |

Hon. William Pember Reeves.

Director of London School of Economics. Agent-General and High Commissioner

for New Zealand, 1896-1909. Minister of Education, Labour and Justice, New

Zealand, 1891-1896. Author of The Long White Cloud, a History of New Zealand;

&c. |

Fox, Sir William. |

| W. R. S. |

William Robertson Smith, LL.D.

See the biographical article: Smith, W. R. |

Eve (in part). |

| W. R. E. H. |

William Richard Eaton Hodgkinson, Ph.D., F.R.S.

Professor of Chemistry and Physics, Ordnance College, Woolwich. Formerly

Professor of Chemistry and Physics, R.M.A., Woolwich. Part Author of Valentin-Hodgkinson’s

Practical Chemistry; &c. |

Explosives. |

| W. Sch. |

Sir Wilhelm Schlich, K.C.I.E., M.A., Ph.D., F.R.S., F.L.S.

Professor of Forestry at the University of Oxford. Hon. Fellow of St John’s College.

Author of A Manual of Forestry; Forestry in the United Kingdom; The Outlook of

the World’s Timber Supply; &c. |

Forests and Forestry. |

| W. W. F.* |

William Warde Fowler, M.A.

Fellow of Lincoln College, Oxford. Sub-rector, 1881-1904. Gifford Lecturer,

Edinburgh University, 1908. Author of The City-State of the Greeks and Romans;

The Roman Festivals of the Republican Period; &c. |

Fortuna. |

| W. W. R.* |

William Walker Rockwell, Lic. Theol.

Assistant Professor of Church History, Union Theological Seminary, New York.

Author of Die Doppelehe des Landgrafen Philipp von Hessen. |

Ferrara-Florence, Council of. |

A complete list, showing all individual contributors, appears in

the final volume.

PRINCIPAL UNSIGNED ARTICLES

|

Evil Eye.

Excise.

Execution.

Executors and Administrators.

Exeter.

Exile.

Eylau.

Famine.

Fault.

Federal Government.

Federalist Party.

Fehmic Courts. |

Felony.

Fez.

Fezzan.

Fictions.

Fife.

Fig.

Filigree.

Fir.

Fives.

Fleurus.

Florida. |

Foix.

Fold.

Fontenelle.

Fontenoy.

Foot and Mouth Disease.

Forest Laws.

Forfarshire.

Forgery.

Formosa.

Foundling Hospitals.

Fountain. |

1

EVANGELICAL CHURCH CONFERENCE, a convention of

delegates from the different Protestant churches of Germany.

The conference originated in 1848, when the general desire for

political unity made itself felt in the ecclesiastical sphere as well.

A preliminary meeting was held at Sandhof near Frankfort in

June of that year, and on the 21st of September some five

hundred delegates representing the Lutheran, the Reformed, the

United and the Moravian churches assembled at Wittenberg.

The gathering was known as Kirchentag (church diet), and,

while leaving each denomination free in respect of constitution,

ritual, doctrine and attitude towards the state, agreed to act

unitedly in bearing witness against the non-evangelical churches

and in defending the rights and liberties of the churches in the

federation. The organization thus closely resembles that of the

Free Church Federation in England. The movement exercised

considerable influence during the middle of the 19th century.

Though no Kirchentag, as such, has been convened since 1871,

its place has been taken by the Kongress für innere Mission,

which holds annual meetings in different towns. There is also

a biennial conference of the evangelical churches held at Eisenach

to discuss matters of general interest. Its decisions have no

legislative force.

EVANGELICAL UNION, a religious denomination which

originated in the suspension of the Rev. James Morison (1816-1893),

minister of a United Secession congregation in Kilmarnock,

Scotland, for certain views regarding faith, the work of the Holy

Spirit in salvation, and the extent of the atonement, which were

regarded by the supreme court of his church as anti-Calvinistic

and heretical. Morison was suspended by the presbytery in

1841 and thereupon definitely withdrew from the Secession

Church. His father, who was minister at Bathgate, and two

other ministers, being deposed not long afterwards for similar

opinions, the four met at Kilmarnock on the 16th of May 1843

(two days before the “Disruption” of the Free Church), and,

on the basis of certain doctrinal principles, formed themselves

into an association under the name of the Evangelical Union,

“for the purpose of countenancing, counselling and otherwise

aiding one another, and also for the purpose of training up

spiritual and devoted young men to carry forward the work and

‘pleasure of the Lord.’” The doctrinal views of the new denomination

gradually assumed a more decidedly anti-Calvinistic

form, and they began also to find many sympathizers among

the Congregationalists of Scotland. Nine students were expelled

from the Congregational Academy for holding “Morisonian”

doctrines, and in 1845 eight churches were disjoined from the

Congregational Union of Scotland and formed a connexion with

the Evangelical Union. The Union exercised no jurisdiction

over the individual churches connected with it, and in this respect

adhered to the Independent or Congregational form of church

government; but those congregations which originally were Presbyterian

vested their government in a body of elders. In 1889

the denomination numbered 93 churches; and in 1896, after

prolonged negotiation, the Evangelical Union was incorporated

with the Congregational Union of Scotland.

See The Evangelical Union Annual; History of the Evangelical

Union, by F. Ferguson (Glasgow, 1876); The Worthies of the E. U.

(1883); W. Adamson, Life of Dr James Morison (1898).

EVANS, CHRISTMAS (1766-1838), Welsh Nonconformist

divine, was born near the village of Llandyssul, Cardiganshire,

on the 25th of December 1766. His father, a shoemaker, died

early, and the boy grew up as an illiterate farm labourer. At

the age of seventeen, becoming servant to a Presbyterian

minister, David Davies, he was affected by a religious revival and

learned to read and write in English and Welsh. The itinerant

Calvinistic Methodist preachers and the members of the Baptist

church at Llandyssul further influenced him, and he soon joined

the latter denomination. In 1789 he went into North Wales

as a preacher and settled for two years in the desolate peninsula

of Lleyn, Carnarvonshire, whence he removed to Llangefni in

Anglesey. Here, on a stipend of £17 a year, supplemented by a

little tract-selling, he built up a strong Baptist community,

modelling his organization to some extent on that of the Calvinistic

Methodists. Many new chapels were built, the money being

collected on preaching tours which Evans undertook in South

Wales.

In 1826 Evans accepted an invitation to Caerphilly, where

he remained for two years, removing in 1828 to Cardiff.

In 1832, in response to urgent calls from the north, he settled

in Carnarvon and again undertook the old work of building and

collecting. He was taken ill on a tour in South Wales, and died

at Swansea on the 19th of July 1838. In spite of his early disadvantages

and personal disfigurement (he had lost an eye in a

2

youthful brawl), Christmas Evans was a remarkably powerful

preacher. To a natural aptitude for this calling he united a

nimble mind and an inquiring spirit; his character was simple,

his piety humble and his faith fervently evangelical. For a time

he came under Sandemanian influence, and when the Wesleyans

entered Wales he took the Calvinist side in the bitter controversies

that were frequent from 1800 to 1810. His chief characteristic

was a vivid and affluent imagination, which absorbed and

controlled all his other powers, and earned for him the name of

“the Bunyan of Wales.”

His works were edited by Owen Davies in 3 vols. (Carnarvon,

1895-1897). See the Lives by D.R. Stephens (1847) and Paxton

Hood (1883).

EVANS, EVAN HERBER (1836-1896), Welsh Nonconformist

divine, was born on the 5th of July 1836, at Pant yr Onen near

Newcastle Emlyn, Cardiganshire. As a boy he saw something

of the “Rebecca Riots,” and went to school at the neighbouring

village of Llechryd. In 1853 he went into business, first at

Pontypridd and then at Merthyr, but next year made his way to

Liverpool. He decided to enter the ministry, and studied arts

and theology respectively at the Normal College, Swansea, and

the Memorial College, Brecon, his convictions being deepened

by the religious revival of 1858-1859. In 1862 he succeeded

Thomas Jones as minister of the Congregational church at

Morriston near Swansea. In 1865 he became pastor of Salem

church, Carnarvon, a charge which he occupied for nearly thirty

years despite many invitations to English pastorates. In 1894

he became principal of the Congregational college at Bangor.

He died on the 30th of December 1896. He was chairman of

the Welsh Congregational Union in 1886 and of the Congregational

Union of England and Wales in 1892; and by his earnest

ministry, his eloquence and his literary work, especially in the

denominational paper Y Dysgedydd, he achieved a position of

great influence in his country.

See Life by H. Elvet Lewis.

EVANS, SIR GEORGE DE LACY (1787-1870), British soldier,

was born at Moig, Limerick, in 1787. He was educated at

Woolwich Academy, and entered the army in 1806 as a volunteer,

obtaining an ensigncy in the 22nd regiment in 1807. His early

service was spent in India, but he exchanged into the 3rd Light

Dragoons in order to take part in the Peninsular War, and was

present in the retreat from Burgos in 1812. In 1813 he was at

Vittoria, and was afterwards employed in making a military

survey of the passes of the Pyrenees. He took part in the campaign

of 1814, and was present at Pampeluna, the Nive and

Toulouse; and later in the year he served with great distinction

on the staff in General Ross’s Bladensburg campaign, and took

part in the capture of Washington and of Baltimore and the

operations before New Orleans. He returned to England in the

spring of 1815, in time to take part in the Waterloo campaign as

assistant quartermaster-general on Sir T. Picton’s staff. As a

member of the staff of the duke of Wellington he accompanied

the English army to Paris, and remained there during the

occupation of the city by the allies. He was still a substantive

captain in the 5th West India regiment, though a lieutenant-colonel

by brevet, when he went on half-pay in 1818. In 1830

he was elected M.P. for Rye in the Liberal interest; but in the

election of 1832 he was an unsuccessful candidate both for that

borough and for Westminster. For the latter constituency he

was, however, returned in 1833, and, except in the parliament

of 1841-1846, he continued to represent it till 1865, when he

retired from political life. His parliamentary duties did not,

however, interfere with his career as a soldier. In 1835 he went

out to Spain in command of the Spanish Legion, recruited in

England, and 9600 strong, which served for two years in the

Carlist War on the side of the queen of Spain. In spite of great

difficulties the legion won great distinction on the battlefields

of northern Spain, and Evans was able to say that no prisoners

had been taken from it in action, that it had never lost a gun

or an equipage, and that it had taken 27 guns and 1100 prisoners

from the enemy. He received several Spanish orders, and on his

return in 1839 was made a colonel and K.C.B. In 1846 he became

major-general; and in 1854, on the breaking-out of the Crimean

War, he was made lieutenant-general and appointed to command

the 2nd division of the Army of the East. At the battle of the

Alma, where he received a severe wound, his quick comprehension

of the features of the combat largely contributed to the victory.

On the 26th of October he defeated a large Russian force which

attacked his position on Mount Inkerman. Illness and fatigue

compelled him a few days after this to leave the command of his

division in the hands of General Pennefather; but he rose

from his sick-bed on the day of the battle of Inkerman, the 5th of

November, and, declining to take the command of his division

from Pennefather, aided him in the long-protracted struggle by

his advice. On his return invalided to England in the following

February, Evans received the thanks of the House of Commons.

He was made a G.C.B., and the university of Oxford conferred on

him the degree of D.C.L. In 1861 he was promoted to the full

rank of general. He died in London on the 9th of January 1870.

EVANS, SIR JOHN (1823-1908), English archaeologist and

geologist, son of the Rev. Dr A.B. Evans, head master of

Market Bosworth grammar school, was born at Britwell Court,

Bucks, on the 17th of November 1823. He was for many years

head of the extensive paper manufactory of Messrs John Dickinson

at Nash Mills, Hemel Hempstead, but was especially distinguished

as an antiquary and numismatist. He was the author

of three books, standard in their respective departments: The

Coins of the Ancient Britons (1864); The Ancient Stone Implements,

Weapons and Ornaments of Great Britain (1872, 2nd ed.

1897); and The Ancient Bronze Implements, Weapons and

Ornaments of Great Britain and Ireland (1881). He also wrote a

number of separate papers on archaeological and geological subjects—notably

the papers on “Flint Implements in the Drift”

communicated in 1860 and 1862 to Archaeologia, the organ of the

Society of Antiquaries. Of that society he was president from

1885 to 1892, and he was president of the Numismatic Society

from 1874 to the time of his death. He also presided over the

Geological Society, 1874-1876; the Anthropological Institute,

1877-1879; the Society of Chemical Industry, 1892-1893;

the British Association, 1897-1898; and for twenty years (1878-1898)

he was treasurer of the Royal Society. As president of the

Society of Antiquaries he was an ex officio trustee of the British

Museum, and subsequently he became a permanent trustee.

His academic honours included honorary degrees from several

universities, and he was a corresponding member of the Institut

de France. He was created a K.C.B. in 1892. He died at

Berkhamsted on the 31st of May 1908.

His eldest son, Arthur John Evans, born in 1851, was

educated at Brasenose College, Oxford, and Göttingen. He became

fellow of Brasenose and in 1884 keeper of the Ashmolean

Museum at Oxford. He travelled in Finland and Lapland in

1873-1874, and in 1875 made a special study of archaeology

and ethnology in the Balkan States. In 1893 he began his

investigations in Crete, which have resulted in discoveries of

the utmost importance concerning the early history of Greece

and the eastern Mediterranean (see Aegean Civilization and

Crete). He is a member of all the chief archaeological societies

in Europe, holds honorary degrees at Oxford, Edinburgh and

Dublin, and is a fellow of the Royal Society. His chief publications

are: Cretan Pictographs and Prae-Phoenician Script

(1896); Further Discoveries of Cretan and Aegean Script (1898);

The Mycenaean Tree and Pillar Cult (1901); Scripta Minoa

(1909 foll.); and reports on the excavations. He also edited

with additions Freeman’s History of Sicily, vol. iv.

EVANS, OLIVER (1755-1819), American mechanician, was

born at Newport, Delaware, in 1755. He was apprenticed to a

wheelwright, and at the age of twenty-two he invented a machine

for making the card-teeth used in carding wool and cotton.

In 1780 he became partner with his brothers, who were practical

millers, and soon introduced various labour-saving appliances

which both cheapened and improved the processes of flour-milling.

Turning his attention to the steam engine, he employed

steam at a relatively high pressure, and the plans of his invention

which he sent over to England in 1787 and in 1794-1795 are said

3

to have been seen by R. Trevithick, whom in that case he

anticipated in the adoption of the high-pressure principle. He

made use of his engine for driving mill machinery; and in 1803

he constructed a steam dredging machine, which also propelled

itself on land. In 1819 a disastrous fire broke out in his factory

at Pittsburg, and he did not long survive it, dying at New York

on the 21st of April 1819.

EVANSON, EDWARD (1731-1805), English divine, was born

on the 21st of April 1731 at Warrington, Lancashire. After

graduating at Cambridge (Emmanuel College) and taking holy

orders, he officiated for several years as curate at Mitcham. In

1768 he became vicar of South Mimms near Barnet; and in

November 1769 he was presented to the rectory of Tewkesbury,

with which he held also the vicarage of Longdon in Worcestershire.

In the course of his studies he discovered what he thought

important variance between the teaching of the Church of England

and that of the Bible, and he did not conceal his convictions.

In reading the service he altered or omitted phrases which seemed

to him untrue, and in reading the Scriptures pointed out errors

in the translation. A crisis was brought on by his sermon on the

resurrection, preached at Easter 1771; and in November 1773

a prosecution was instituted against him in the consistory court

of Gloucester. He was charged with “depraving the public

worship of God contained in the liturgy of the Church of England,

asserting the same to be superstitious and unchristian, preaching,

writing and conversing against the creeds and the divinity of

our Saviour, and assuming to himself the power of making

arbitrary alterations in his performance of the public worship.”

A protest was at once signed and published by a large number

of his parishioners against the prosecution. The case was dismissed

on technical grounds, but appeals were made to the court

of arches and the court of delegates. Meanwhile Evanson had

made his views generally known by several publications. In

1772 appeared anonymously his Doctrines of a Trinity and the

Incarnation of God, examined upon the Principles of Reason and

Common Sense. This was followed in 1777 by A Letter to Dr

Hurd, Bishop of Worcester, wherein the Importance of the Prophecies

of the New Testament and the Nature of the Grand Apostasy predicted

in them are particularly and impartially considered. He also

wrote some papers on the Sabbath, which brought him into

controversy with Joseph Priestley, who published the whole

discussion (1792). In the same year appeared Evanson’s work

entitled The Dissonance of the four generally received Evangelists,

to which replies were published by Priestley and David Simpson

(1793). Evanson rejected most of the books of the New Testament

as forgeries, and of the four gospels he accepted only that

of St Luke. In his later years he ministered to a Unitarian

congregation at Lympston, Devonshire. In 1802 he published

Reflections upon the State of Religion in Christendom, in which he

attempted to explain and illustrate the mysterious foreshadowings

of the Apocalypse. This he considered the most important

of his writings. Shortly before his death at Colford, near

Crediton, Devonshire, on the 25th of September 1805, he completed

his Second Thoughts on the Trinity, in reply to a work of the

bishop of Gloucester.

His sermons (prefaced by a Life by G. Rogers) were published in

two volumes in 1807, and were the occasion of T. Falconer’s Bampton

Lectures in 1811. A narrative of the circumstances which led to the

prosecution of Evanson was published by N. Havard, the town-clerk

of Tewkesbury, in 1778.

EVANSTON, a city of Cook county, Illinois, U.S.A., on the

shore of Lake Michigan, 12 m. N. of Chicago. Pop. (1900)

19,259, of whom 4441 were foreign-born; (1910 U.S. census)

24,978. It is served by the Chicago & North-Western, and the

Chicago, Milwaukee & St Paul railways, and by two electric

lines. The city is an important residential suburb of Chicago.

In 1908 the Evanston public library had 41,430 volumes. In the

city are the College of Liberal Arts (1855), the Academy (1860),

and the schools of music (1895) and engineering (1908) of Northwestern

University, co-educational, chartered in 1851, opened in

1855, the largest school of the Methodist Episcopal Church in

America. In 1909-1910 it had productive funds amounting to

about $7,500,000, and, including all the allied schools, a faculty of

418 instructors and 4487 students; its schools of medicine (1869),

law (1859), pharmacy (1886), commerce (1908) and dentistry

(1887) are in Chicago. In 1909 its library had 114,869 volumes

and 79,000 pamphlets (exclusive of the libraries of the professional

schools in Chicago); and the Garrett Biblical Institute had a

library of 25,671 volumes and 4500 pamphlets. The university

maintains the Grand Prairie Seminary at Onarga, Iroquois

county, and the Elgin Academy at Elgin, Kane county. Enjoying

the privileges of the university, though actually independent

of it, are the Garrett Biblical Institute (Evanston Theological

Seminary), founded in 1855, situated on the university campus,

and probably the best-endowed Methodist Episcopal theological

seminary in the United States, and affiliated with the Institute,

the Norwegian Danish Theological school; and the Swedish

Theological Seminary, founded at Galesburg in 1870, removed to

Evanston in 1882, and occupying buildings on the university

campus until 1907, when it removed to Orrington Avenue and

Noyes Street. The Cumnock School of Oratory, at Evanston,

also co-operates with the university. By the charter of the

university the sale of intoxicating liquors is forbidden within

4 m. of the university campus. The manufacturing importance

of the city is slight, but is rapidly increasing. The principal

manufactures are wrought iron and steel pipe, bakers’ machinery

and bricks. In 1905 the value of the factory products was

$2,550,529, being an increase of 207.3% since 1900. In

Evanston are the publishing offices of the National Woman’s

Christian Temperance Union. Evanston was incorporated as a

town in 1863 and as a village in 1872, and was chartered

as a city in 1892. The villages of North Evanston and

South Evanston were annexed to Evanston in 1874 and 1892

respectively.

EVANSVILLE, a city and the county-seat of Vanderburg

county, Indiana, U.S.A., and a port of entry, on the N. bank of

the Ohio river, 200 m. below Louisville, Kentucky—measuring

by the windings of the river, which double the direct distance.

Pop. (1890) 50,756; (1900) 59,007; (1910 census) 69,647.

Of the total population in 1900, 5518 were negroes, 5626 were

foreign-born (including 4380 from Germany and 384 from England),

and 17,419 were of foreign parentage (both parents

foreign-born), and of these 13,910 were of German parentage.

Evansville is served by the Evansville & Terre Haute, the

Evansville & Indianapolis, the Illinois Central, the Louisville &

Nashville, the Louisville, Henderson & St Louis, and the Southern

railways, by several interurban electric lines, and by river steamboats.

The city is situated on a plateau above the river, and

has a number of fine business and public buildings, including

the court house and city hall, the Southern Indiana hospital for

the insane, the United States marine hospital, and the Willard

library and art gallery, containing in 1908 about 30,000 volumes.

The city’s numerous railway connexions and its situation in

a coal-producing region (there are five mines within the city

limits) and on the Ohio river, which is navigable nearly all the

year, combine to make it the principal commercial and manufacturing

centre of Southern Indiana. It is in a tobacco-growing

region, is one of the largest hardwood lumber markets in the

country, and has an important shipping trade in pork, agricultural

products, dried fruits, lime and limestone, flour and tobacco.

Among its manufactures in 1905 were flour and grist mill products

(value, $2,638,914), furniture ($1,655,246), lumber and timber

products ($1,229,533), railway cars ($1,118,376), packed meats

($998,428), woollen and cotton goods, cigars and cigarettes,

malt liquors, carriages and wagons, leather and canned goods.

The value of the factory products increased from $12,167,524

in 1900 to $19,201,716 in 1905, or 57.8%, and in the latter year

Evansville ranked third among the manufacturing cities in the

state. The waterworks are owned and operated by the city.

First settled about 1812, Evansville was laid out in 1817, and

was named in honour of Robert Morgan Evans (1783-1844), one

of its founders, who was an officer under General W.H. Harrison

in the war of 1812. It soon became a thriving commercial town

with an extensive river trade, was incorporated in 1819, and

received a city charter in 1847. The completion of the Wabash

4

& Erie Canal, in 1853, from Evansville to Toledo, Ohio, a distance

of 400 m., greatly accelerated the city’s growth.

EVARISTUS, fourth pope (c. 98-105), was the immediate

successor of Clement.

EVARTS, WILLIAM MAXWELL (1818-1901), American

lawyer, was born in Boston on the 6th of February 1818. He

graduated at Yale in 1837, was admitted to the bar in New York

in 1841, and soon took high rank in his profession. In 1860 he

was chairman of the New York delegation to the Republican

national convention. In 1861 he was an unsuccessful candidate

for the United States senatorship from New York. He was chief

counsel for President Johnson during the impeachment trial,

and from July 1868 until March 1869 he was attorney-general of

the United States. In 1872 he was counsel for the United States

in the “Alabama” arbitration. During President Hayes’s administration

(1877-1881) he was secretary of state; and from

1885 to 1891 he was one of the senators from New York. As

an orator Senator Evarts stood in the foremost rank, and some

of his best speeches were published. He died in New York on

the 28th of February 1901.

EVE, the English transcription, through Lat. Eva and Gr. Εὔα,

of the Hebrew name חוה Ḥavvah, given by Adam to his wife

because she was “mother of all living,” or perhaps more strictly,

“of every group of those connected by female kinship” (see

W.R. Smith, Kinship, 2nd ed., p. 208), as if Eve were the personification

of mother-kinship, just as Adam (“man”) is the

personification of mankind.

[The abstract meaning “life” (LXX. Ζωή), once favoured by

Robertson Smith, is at any rate unsuitable in a popular story.

Wellhausen and Nöldeke would compare the Ar. ḥayyatun,

“serpent,” and the former remarks that, if this is right, the

Israelites received their first ancestress from the Ḥivvites

(Hivites), who were originally the serpent-tribe (Composition des

Hexateuchs, p. 343; cf. Reste arabischen Heidentums, 2nd ed.,

p. 154). Cheyne, too, assumes a common origin for Ḥavvah and

the Ḥivvites.]

[The account of the origin of Eve (Gen. iii. 21-23) runs thus:

“And Yahweh-Elohim caused a deep sleep to fall upon the man,

and he slept. And he took one of his ribs, and closed

up the flesh in its stead, and the rib which Yahweh-Elohim

Creation of Eve.

had taken from the man he built up into a

woman, and he brought her to the man.” Enchanted at the

sight, the man now burst out into elevated, rhythmic speech:

“This one,” he said, “at length is bone of my bone and flesh

of my flesh,” &c. ; to which the narrator adds the comment,

“Therefore doth a man forsake his father and his mother, and

cleave to his wife, and they become one flesh (body).” Whether

this comment implies the existence of the custom of beena,

marriage (W.R. Smith, Kinship, 2nd ed., p. 208), seems doubtful.

It is at least equally possible that the expression “his wife”

simply reflects the fact that among ordinary Israelites circumstances

had quite naturally brought about the prevalence of

monogamy.1 What the narrator gives is not a doctrine of

marriage, much less a precept, but an explanation of a simple

and natural phenomenon. How is it, he asks, that a man is so

irresistibly drawn towards a woman? And he answers: Because

the first woman was built up out of a rib of the first man. At the

same time it is plain that the already existing tendency towards

monogamy must have been powerfully assisted by this presentation

of Eve’s story as well as by the prophetic descriptions of

Yahweh’s relation to Israel under the figure of a monogamous

union.]

[The narrator is no rhetorician, and spares us a description of

the ideal woman. But we know that, for Adam, his strangely

produced wife was a “help (or helper) matching or

corresponding to him”; or, as the Authorized Version

New Testament application.

puts it, “a help meet for him” (ii. 18b). This does

not, of course, exclude subordination on the part of the

woman; what is excluded is that exaggeration of natural

subordination which the narrator may have found both in his

own and in the neighbouring countries, and which he may have

regarded as (together with the pains of parturition) the punishment

of the woman’s transgression (Gen. iii. 16). His own ideal

of woman seems to have made its way in Palestine by slow degrees.

An apocryphal book (Tobit viii. 6, 7) seems to contain the only

reference to the section till we come to the time of Christ, to

whom the comment in Gen. ii. 24 supplies the text for an authoritative

prohibition of divorce, which presupposes and sanctifies

monogamy (Matt. x. 7, 8; Matt. xix. 5). For other New

Testament applications of the story of Eve see 1 Cor. xi. 8, 9

(especially); 2 Cor. xi. 3; 1 Tim. ii. 13, 14; and in general cf.

Adam, and Ency. Biblica, “Adam and Eve.”]

[The seeming omissions in the Biblical narrative have been

filled up by imaginative Jewish writers.] The earliest source

which remains to us is the Book of Jubilees, or Leptogenesis,

a Palestinian work (referred by R.H. Charles

Imaginative or legendary developments.

to the century immediately preceding the Christian era;

see Apocalyptic Literature). In this book, which was

largely used by Christian writers, we find a chronology

of the lives of Adam and Eve and the names of their daughters—Avan

and Azura.2 The Targum of Jonathan informs us that Eve

was created from the thirteenth rib of Adam’s right side, thus

taking the view that Adam had a rib more than his descendants.

Some of the Jewish legends show clear marks of foreign influence.

Thus the notion that the first man was a double being, afterwards

separated into the two persons of Adam and Eve (Berachot, 61;

Erubin, 18), may be traced back to Philo (De mundi opif. §53;

cf. Quaest. in Gen. lib. i. §25), who borrows the idea, and almost

the words, of the myth related by Aristophanes in the Platonic

Symposium (189 D, 190 A), which, in extravagant form, explains

the passion of love by the legend that male and female originally

formed one body.

[A recent critic3 (F. Schwally) even holds that this notion

was originally expressed in the account of the creation of man in

Gen. i. 27. This involves a textual emendation, and one must

at least admit that the present text is not without difficulty,

and that Berossus refers to the existence of primeval monstrous

androgynous beings according to Babylonian mythology.]

There is an analogous Iranian legend of the true man, which

parted into man and woman in the Bundahish4 (the Parsí

Genesis), and an Indian legend, which, according to Spiegel,

has presumably an Iranian source.5

[It has been remarked elsewhere (Adam, §16) that though

the later Jews gathered material for thought very widely, such

guidance as they required in theological reflection was

mainly derived from Greek culture. What, for instance,

Course of Jewish and Christian interpretation.

was to be made of such a story as that in Gen.

ii.-iv.? To “minds trained under the influence of the

Jewish Haggada, in which the whole Biblical history

is freely intermixed with legendary and parabolic matter,” the

question as to the literal truth of that story could hardly be

formulated. It is otherwise when the Greek leaven begins to

work.]

Josephus, in the prologue to his Archaeology, reserves the

problem of the true meaning of the Mosaic narrative, but does

not regard everything as strictly literal. Philo, the great representative

of Alexandrian allegory, expressly argues that in the

nature of things the trees of life and knowledge cannot be taken

otherwise than symbolically. His interpretation of the creation

of Eve is, as has been already observed, plainly suggested by a

Platonic myth. The longing for reunion which love implants

in the divided halves of the original dual man is the source of

sensual pleasure (symbolized by the serpent), which in turn is

the beginning of all transgression. Eve represents the sensuous

or perceptive part of man’s nature, Adam the reason. The

serpent, therefore, does not venture to attack Adam directly.

5

It is sense which yields to pleasure, and in turn enslaves the reason

and destroys its immortal virtue. This exposition, in which

the elements of the Bible narrative become mere symbols of

the abstract notions of Greek philosophy, and are adapted to

Greek conceptions of the origin of evil in the material and sensuous

part of man, was adopted into Christian theology by Clement

and Origen, notwithstanding its obvious inconsistency with the

Pauline anthropology, and the difficulty which its supporters

felt in reconciling it with the Christian doctrine of the excellence

of the married state (Clemens Alex. Stromata, p. 174). These

difficulties had more weight with the Western church, which,

less devoted to speculative abstractions and more deeply influenced

by the Pauline anthropology, refused, especially since