Title: Triumphs of Invention and Discovery in Art and Science

Author: J. Hamilton Fyfe

Release date: July 17, 2011 [eBook #36768]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Sharon Joiner, Jana Srna, Bill Keir, Erica

Pfister-Altschul and the Online Distributed Proofreading

Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from

images generously made available by The Internet

Archive/American Libraries.)

It is not difficult to account for the pre-eminence, generally assigned to the victories of war over the victories of peace in popular history. The noise and ostentation which attend the former, the air of romance which surrounds them,—lay firm hold of the imagination, while the directness and rapidity with which, in such transactions, the effect follows the cause, invest them with a peculiar charm for simple and superficial observers. As Schiller says,—

[Pg vi] The path of peace is long and devious, now dwindling into a mere foot-track, now lost to sight in some dense thicket; and the heroes who pursue it are often mocked at by the crowd as poor, half-witted souls, wandering either aimlessly or in foolish chase of some Jack o' lantern that ever recedes before them. The goal they aim at seems to the common eye so visionary, and their progress towards it so imperceptible,—and even when reached, it takes so long before the benefits of their achievement are generally recognised,—that it is perhaps no wonder we should be more attracted by the stirring narratives of war, than by the sad, simple histories of the great pioneers of industry and science.

Picturesque and imposing as deeds of arms appear, the victories of peace—the development of great discoveries and inventions, the performance of serene acts of beneficence, the achievements of social reform—possess a deeper interest and a truer romance for the seeing eye and the understanding heart. Wounds and death have to be encountered in the struggles of peace as well as in the contests of war; and [Pg vii] peace has her martyrs as well as her heroes. The story of the cotton-spinning invention is at once as tragic and romantic as the story of the Peninsular war. There were "forlorn hopes" of brave men in both; but in the one case they were cheered by sympathy and association, in the other the desperate pioneers had to face a world of foes, "alone, unfriended, solitary, slow."

The following pages contain sketches of some of the more momentous victories of peace, and the heroes who took part in them. The reader need hardly be reminded that this brief list does not exhaust the catalogue either of such events or persons, and that only a few of a representative character are here selected.

In the present edition the different sections have been carefully revised, and the details brought down to the latest possible date.

J. H. F.

Some Dutch writers, inspired by a not unnatural feeling of patriotism, have endeavoured to claim the honour of inventing the Art of Printing for a countryman of their own, Laurence Coster of Haarlem. Their sole reliance, however, is upon the statements of one Hadrian Junius, who was born at Horn, in North Holland, in 1511. About 1575 he wrote a work, entitled "Batavia," in which the account of Coster first appeared. And, as an unimpeachable authority has remarked, almost every succeeding advocate of Coster's pretensions has taken the liberty [Pg 14] of altering, amplifying, or contradicting the account of Junius, according as it might suit his own line of argument; but not one of them has succeeded in producing a solitary fact in confirmation of it. The accounts which are given of Coster's discovery by Junius and his successors present many contradictory features. Thus Junius says: "Walking in a neighbouring wood, as citizens are accustomed to do after dinner and on holidays, he began to cut letters of beech-bark, with which, for amusement—the letters being inverted as on a seal—he impressed short sentences on paper for the children of his son-in-law." A later writer, Scriverius, is more imaginative: "Coster," he says, "walking in the wood, picked up a small bough of a beech, or rather of an oak-tree, blown off by the wind; and after amusing himself with cutting some letters on it, wrapped it up in paper, and afterwards laid himself down to sleep. When he awoke, he perceived that the paper, by a shower of rain or some accident having got moist, had received an impression from these letters; which induced him to pursue the accidental discovery."

Not only are these accounts evidently deficient in authenticity, but it should be remarked that the earliest of them was not put before the world until Laurence Coster had been nearly a hundred and fifty years in his grave. The presumed writer of the narrative which first did justice to his memory had [Pg 15] been also twelve years dead when his book was published. His information, or rather the information brought forward under cover of his name, was derived from an old man who, when a boy, had heard it from another old man who lived with Coster at the time of the robbery, and who had heard the account of the invention from his master. For, to explain the fact of the early appearance of typography in Germany, the Dutch writers are forced to the hypothesis that an apprentice of Coster's stole all his master's types and utensils, fleeing with them first to Amsterdam, second to Cologne, and lastly to Mentz! The whole story is too improbable to be accepted by any impartial inquirer; and the best authorities are agreed in dismissing the Dutch fiction with the contempt it deserves, and in ascribing to John Gutenberg, of Mentz, the honour to which he is justly entitled.

Of the career of Gutenberg we shall speak presently, but let us first point out that the invention of typography, like all great inventions, was no sudden conception of genius—not the birth of some singularly felicitous moment of inspiration—but the result of what may be called a gradual series of causes. Printing with movable types was the natural outcome of printing with blocks. We must go back, therefore, a few years, to examine into the origin of "block books."

[Pg 16] Mr. Jackson observes that there cannot be a doubt that the principle on which wood engraving is founded—that of taking impressions on paper or parchment, with ink, from prominent lines—was known and practised in attesting documents in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries. Towards the end of the fourteenth, or about the beginning of the fifteenth century, he says, there seems reason to believe that this principle was adopted by the German card-makers for the purpose of marking the outlines of the figures on their cards, which they afterwards coloured by the practice called stencilling.

It was the Germans who first practised card-making as a trade, and as early as 1418 the name of a kartenmacher, or card-maker, occurs in the burgess-books of Augsburg. In the town-books of Nuremburg, the designation formschneider, or figure-cutter, is found in 1449; and we may presume that block books—that is, books each page of which was cut on a single block—were introduced about this time. These books were on religious subjects, and were intended, perhaps, by the monks as a kind of counterbalance against the playing-cards; "thus endeavouring to supply a remedy for the evil, and extracting from the serpent a cure for his bite."

The earliest woodcut known—one of St. Christopher—bears the date of 1432, and was found in a convent situated within about fifty miles of the city of Augsburg—the convent of Buxheim, near Mem[Pg 17]mingen. It was pasted on the inside of the right hand cover of a manuscript entitled Laus Virginis, and measures eleven and a quarter inches in height, by eight and one-eighth inches in width.

The following description of it by Jackson is interesting:—

"To the left of the engraving the artist has introduced, with a noble disregard of perspective, what Bewick would have called a 'bit of nature.' In the foreground a figure is seen driving an ass loaded with a sack towards a water-mill; while by a steep path a figure, perhaps intended for the miller, is seen carrying a full sack from the back-door of the mill towards a cottage. To the right is seen a hermit—known by the bell over the entrance to his dwelling—holding a large lantern to direct St. Christopher as he crosses the stream. The couplet at the foot of the cut,—

may be translated as follows,—

These lines allude to a superstition, once popular in all Catholic countries, that on the day they saw a figure or image of St. Christopher, they would be safe from a violent death, or from death unabsolved and unconfessed."

[Pg 18] Passing over some other woodcuts of great antiquity, in all of which the figures are accompanied by engraved letters, we come to the block books proper. Of these, the most famous are called, the Apocalypsis, seu Historia Sancti Johannis (the "Apocalypse, or History of St. John"); the Historia Virginis ex Cantico Canticorum ("Story of the Virgin, from the Song of Songs"); and the Biblia Pauperum ("Bible of the Poor"). The first is a history, pictorial and literal, of the life and revelations of St. John the Evangelist, partly derived from the book of Revelation, and partly from ecclesiastical tradition. The second is a similar biography of the Virgin Mary, as it is supposed to be typified in the Song of Solomon; and the third consists of subjects representing many of the most important passages in the Old and New Testaments, with texts to illustrate the subject, or clinch the lesson of duty it may shadow forth.

With respect to the engraving, we are told that the cuts are executed in the simplest manner, as there is not the least attempt at shading, by means of cross lines or hatchings, to be detected in any one of the designs. The most difficult part of the engraver's task, says Jackson, supposing the drawing to have been made by another person, would be the cutting of the letters, which, in several of the subjects, must have occupied a considerable portion of time, and have [Pg 19] demanded no small degree of perseverance, care, and skill.

These block books were followed by others in which no illustrations appeared, but in which the entire page was occupied with text. The Grammatical Primer, called the "Donatus," from the name of its supposed compiler, was thus printed, or engraved, enabling copies of it to be multiplied at a much cheaper rate than they could be produced in manuscript.

And thus we see that the art of printing—or, more correctly speaking, engraving on wood—has advanced from the production of a single figure, with merely a few words beneath it, to the impression of whole pages of text. Next, for the engraved page were to be substituted movable letters of metal, wedged together within an iron frame; and impressions, instead of being obtained by the slow and tedious process of friction, were to be secured by the swift and powerful action of the press.

About the year 1400, John Gænsfleisch, or Gutenberg, was born at Mentz. He sprung from an honourable family, and it is said that he himself was by birth a knight. He seems to have been a person of some property.

About 1434 we find him living in Strasburg, and, in partnership with a certain Andrew Drytzcher, endeavouring to perfect the art of typography. How [Pg 20] he was induced to direct his attention towards this object, and under what circumstances he began his experiments, it is impossible to say; but there can be no doubt that he was the first person who conceived the idea of movable types—an idea which is the very foundation of the art of printing.

An old German chronicler furnishes the following account of the early stages of the great printer's discovery:—

"At this time (about 1438), in the city of Mentz, on the Rhine, in Germany, and not in Italy as some persons have erroneously written, that wonderful and then unheard-of art of printing and characterizing books was invented and devised by John Gutenberger, citizen of Mentz, who, having expended most of his property in the invention of this art, on account of the difficulties which he experienced on all sides, was about to abandon it altogether; when, by the advice and through the means of John Fust, likewise a citizen of Mentz, he succeeded in bringing it to perfection. At first they formed or engraved the characters or letters in written order on blocks of wood, and in this manner they printed the vocabulary called a 'Catholicon.' But with these forms or blocks they could print nothing else, because the characters could not be transposed in these tablets, but were engraved thereon, as we have said. To this invention succeeded a more subtle one, for they found out the means of cutting the forms of all the [Pg 21] letters of the alphabet, which they called matrices, from which again they cast characters of copper or tin of sufficient hardness to resist the necessary pressure, which they had before engraved by hand."

This is a very brief and summary account of a great invention. By comparison of other authorities we are enabled to bring together a far greater number of details, though we must acknowledge that many of these have little foundation but in tradition or romance.

Let us, therefore, take a peep at the first printer, working in seclusion and solitude in the old historic city of Strasburg, and endeavouring to elaborate in practice the grand idea which has been conceived and matured by his energetic brain. Doubtlessly he knew not the full importance of this idea, or of how great a social and religious revolution it was to be the seed, and yet we cannot believe that he was altogether unconscious of its value to future generations.

Shutting himself up in his own room, seeing no one, rarely crossing the threshold, allowing himself hardly any repose, he set himself to work out the plan he had formed. With a knife and some pieces of wood he constructed a set of movable types, on one face of each of which a letter of the alphabet was carved in relief, and which were strung together, in the order of words and sentences, upon a piece of wire. By means of these he succeeded in [Pg 22] producing upon parchment a very satisfactory impression.

To be out of the way of prying eyes, he took up his quarters in the ruins of the old monastery of St. Arbogaste, outside the town, which had long been abandoned by the monks to the rats and beggars of the neighbourhood; and the better to mask his designs, as well as to procure the funds necessary for his experiments, he set up as a sort of artificer in jewellery and metal-work, setting and polishing precious stones, and preparing Venetian glass for mirrors, which he afterwards mounted in frames of metal and carved wood. These avowed labours he openly practised, along with a couple of assistants, in a public part of the monastery; but in the depths of the cloisters, in a dark secluded spot, he fitted up a little cell as the atelier of his secret operations; and there, secured by bolts and bars, and a thick oaken door, against the intrusion of any one who might penetrate so far into the interior of the ruins, he applied himself to his great work. He quickly perceived, as a man of his inventiveness was sure to perceive, the superiority of letters of metal over those of wood. He invented various coloured inks, at once oily and dry, for printing with; brushes and rollers for transferring the ink to the face of the types; "forms," or cases, for keeping together the types arranged in pages; and a press for bringing the inked types and the paper in contact.

[Pg 23] Day and night, whenever he could spare an instant from his professed occupations, he devoted himself to the development of his great design. At night he could hardly sleep for thinking of it, and his hasty snatches of slumber were disturbed by agitating dreams. Tradition has preserved the story of one of these for us as he afterwards told it to his friends. He dreamt that, as he sat feasting his eyes upon the impression of his first page of type, he heard two voices whispering at his ear—the one soft and musical, the other harsh, dull, and bitter in its tones. The one bade him rejoice at the great work he had achieved; unveiled the future, and showed the men of different generations, the peoples of distant lands, holding high converse by means of his invention; and cheered him with the hope of an immortal fame. "Ay," put in the other voice, "immortal he might be, but at what a price! Man, more often perverse and wicked than wise and good, would profane the new faculty this art created, and the ages, instead of blessing, would have cause to curse the man who gave it to the world. Therefore let him regard his invention as a seductive but fatal dream, which, if fulfilled, would place in the hands of man, sinful and erring as he was, only another instrument of evil." Gutenberg, whom the first voice had thrown into an ecstasy of delight, now shuddered at the thought of the fearful power to corrupt and to debase his art would give to wicked men, and [Pg 24] awoke in an agony of doubt. He seized his mallet, and had almost broken up his types and press, when he paused to reflect that, after all, God's gifts, although sometimes perilous and capable of abuse, were never evil in themselves, and that to give another means of utterance to the piety and reason of mankind was to promote the spread of virtue and intelligence, which were both divine. So he closed his ears to the suggestions of the tempter, and persisted in his work.

Gutenberg had scarcely completed his printing machine, and got it into working order, when the jealousy and distrust of his associates in the nominal business he carried on, brought him into trouble with the authorities of Strasburg. He could have saved himself by the disclosure of all the secrets of his invention; but this he refused to do. His goods were confiscated; and he returned penniless, with a heavy heart, to his native town Mentz. There, in partnership with a wealthy goldsmith named John Fust, and his son-in-law Schoeffer, he started a printing office; from which he sent out many works, mostly of a religious character. The enterprise throve; but misfortune was ever dogging Gutenberg's steps, and he had but a brief taste of prosperity. The priests looked with suspicion upon the new art, which enabled people to read for themselves what before they had to take on trust from them. The transcribers of books,—a large and influential [Pg 25] guild,—were also hostile to the invention, which threatened to deprive them of their livelihood. These two bodies formed a league against the printers; and upon the head of poor Gutenberg were emptied all the vials of their wrath. Fust and Schoeffer, with crafty adroitness, managed to conciliate their opponents, and to offer up their partner as a sacrifice for themselves. By the zeal of his enemies, and the treachery of his friends, Gutenberg was driven out of Mentz. After wandering about for some time in poverty and neglect, Adolphus, the Elector of Nassau, became his patron; and at his court Gutenberg set up a press, and printed a number of works with his own hands. Though poor, his last years were spent in peace; and when he died, he had only a few copies of the productions of his press to leave to his sister.

Meanwhile, at Strasburg, some of his former associates pieced together the revelations that had fallen from him, while at the old monastery, as to his invention; and not only worked it with success, but claimed all the credit of its origin. In the same way, Fust and Schoeffer, at Mentz, grew rich through the invention of the man they had betrayed, and tried to rob of his fame.

There is a curious, but not very well authenticated story about a visit Fust made to Paris to push the sale of his Bibles. "The tradition of the Devil and Dr. Faustus," writes D'Israeli in the "Curiosities of Litera[Pg 26]ture," "was said to have been derived from the odd circumstances in which the Bibles of the first printer, Fust, appeared to the world. When Fust had discovered this new art, and printed off a considerable number of copies of the Bible to imitate those which were commonly sold as MSS., he undertook the sale of them at Paris. It was his interest to conceal this discovery and to pass off his printed copies for MSS. But, enabled to sell his Bibles at sixty crowns, while the other scribes demanded five hundred, this raised universal astonishment; and still more when he produced copies as fast as they were wanted, and even lowered his price. The uniformity of the copies increased the wonder. Informations were given in to the magistrates against him as a magician; and on searching his lodgings, a great number of copies were found. The red ink, and Fust's red ink is peculiarly brilliant, which embellished his copies, was said to be his blood; and it was solemnly adjudged that he was in league with the Infernal. Fust at length was obliged, to save himself from a bonfire, to reveal his art to the Parliament of Paris, who discharged him from all prosecution in consideration of the wonderful invention."

The edition of the Bible, which was one of the very first productions of Gutenberg and Fust's press, is called the Mazarin, in consequence of the first known copy having been discovered in the famous library formed by Cardinal Mazarin. It seems to [Pg 27] have been printed as early as August 1456, and is a truly admirable specimen of typography; the characters being very clear and distinct, and the uniformity of the printing perfectly remarkable. A copy in the Royal Library at Paris is bound in two volumes, and every complete page consists of two columns, each containing forty-two lines. The reader will recognize the appropriateness of the fact that from the first printing press the first important work produced should be a copy of God's Word. It sanctified the new art which was to be so fruitful of good and evil results—the good superabounding, and clearly visible—the evil little, and destined, perhaps, to be directed eventually to good—for successive generations of mankind. It was a fitting forerunner of the long generation of books which have since issued so ceaselessly from the printing press; books, of the majority of which we may say, with Milton, that "they contain a potency of life in them to be as active as those souls were whose progeny they are; to preserve, as in a vial, the purest efficacy and extraction of the living intellects that feed them."

Gutenberg's career was dashed with many lights and shadows, but it closed in peace. In 1465, the Archbishop-elector of Mentz appointed him one of his courtiers, with the same allowance of clothing as the remainder of the nobles attending his court, and all other privileges and exemptions. It is pro[Pg 28]bable that from this time he abandoned the practice of his new invention. The date of his death is uncertain; but there is documentary evidence extant which proves that it occurred before February 24, 1468. He was interred in the church of the Recollets at Mentz, and the following epitaph was composed by his kinsman Adam Gelthaus:—

"Joanni Gesnyfleisch, artis impressoriae repertori, de omni natione et lingua optime merito, in nominis sui memoriam immortalem Adam Gelthaus posuit. Ossa ejus in ecclesia D. Francisci Moguntina feliciter cubant."

During the last thirty or forty years of the fifteenth century, while printing was becoming gradually more and more practised on the Continent, and the presses of Mentz, Bamberg, Cologne, Strasburg, Augsburg, Rome, Venice, and Milan, were sending forth numbers of Bibles, and various learned and theological works, chiefly in Latin, an English merchant, a man of substance and of no little note in Chepe, appeared at the court of the Duke of Burgundy at Bruges, to negotiate a commercial treaty between that sovereign and the king of England; which accomplished, the worthy ambassador seems to have liked the place and the people so well, and to have been so much liked in return, that for some years afterwards he took up his residence there, holding some honourable, easy [Pg 29] appointment in the household of the Duchess of Burgundy. This was William Caxton, who here ripened, if he did not acquire, his love of literature and scholarship, and began, from hatred of idleness, to take pen in hand himself.

"When I remember," says he, in his preface to his first work, a translation of a fanciful "Recueil des Histoires de Troye," "that every man is bounden by the commandment and counsel of the wise man to eschew sloth and idleness, which is mother and nourisher of vices, and ought to put himself into virtuous occupation and business, then I, having no great charge or occupation, following the said counsel, took a French book, and read therein many strange marvellous histories. And for so much as this book was new and late made, and drawn into French, and never seen in our English tongue, I thought in myself, it should be a good business to translate it into our English, to the end that it might be had as well in the royaume of England as in other lands, and also to pass therewith the time; and thus concluded in myself to begin this said work, and forthwith took pen and ink, and began boldly to run forth, as blind Bayard, in this present work."

While at work upon this translation, Caxton found leisure to visit several of the German towns where printing presses were established, and to get an insight into the mysteries of the art, so that by the time he had finished the volume, he was able to [Pg 30] print it. At the close of the third book of the "Recuyell," he says: "Thus end I this book which I have translated after mine author, as nigh as God hath given me cunning, to whom be given the laud and praise. And for as much as in the writing of the same my pen is worn, mine hand weary and not steadfast, mine eyen dimmed with overmuch looking on the white paper, and my courage not so prone and ready to labour as it hath been, and that age creepeth on me daily, and feebleth all the body; and also because I have promised to divers gentlemen and to my friends, to address to them as hastily as I might, this said book, therefore I have practised and learned, at my great charge and dispense, to ordain this said book in print, after the manner and form you may here see; and is not written with pen and ink as other books are, to the end that every man may have them at once. For all the books of this story, named the "Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye," thus imprinted as ye here see, were begun in one day, and also finished in one day" (that is, in the same space of time).

By the year 1477, Caxton had returned to London, and set up a printing establishment within the precincts of Westminster Abbey; had given to the world the three first books ever printed in England,—"The Game and Play of the Chesse" (March 1474); "A boke of the hoole Lyf of Jason" (1475); and "The Dictes and Notable Wyse Sayenges of the [Pg 31] Phylosophers" (1477),—and was fairly started in the great work of supplying printed books to his countrymen, which, as a placard in his largest type sets forth, if any one wanted, "emprynted after the forme of this present lettre whiche ben well and truly correct, late hym come to Westmonster, in to the Almonesrye, at the reed pale, and he shal have them good chepe." From the situation of the first printing office, the term chapel is applied to such establishments to this day.

Caxton published between sixty and seventy different works during the seventeen years of his career as a printer, all of them in what is called black letter, and the bulk of them in English. He had always a view to the improvement of the people in the works he published, and though many of his productions may seem to us to be of an unprofitable kind, it is clear that in the issue of chivalrous narratives, and of Chaucer's poems (to whom, says the old printer, "ought to be given great laud and praising for his noble making and writing"), he was aiming at the diffusion of a nobler spirit, and a higher taste than then prevailed.

In 1490, Caxton, an old, worn man, verging on fourscore years of age, wrote, "Every man ought to intend in such wise to live in this world, by keeping the commandments of God, that he may come to a good end; and then, out of this world full of wretchedness and tribulation, he may go to heaven, [Pg 32] unto God and his saints, unto joy perdurable;" and passed away, still labouring at his post. He died while writing, "The most virtuous history of the devout and right renouned Lives of Holy Fathers living in the desert, worthy of remembrance to all well-disposed persons."

Wynkyne de Worde filled his master's place in the almonry of Westminster; and the guild of printers gradually waxed strong in numbers and influence. In Germany they were privileged to wear robes trimmed with gold and silver, such as the nobles themselves appeared in; and to display on their escutcheon, an eagle with wings outstretched over the globe,—a symbol of the flight of thought and words throughout the world. In our own country, the printers were men of erudition and literary acquirements; and were honoured as became their mission.

Between the rude screw-press of Gutenberg or Caxton, slow and laboured in its working, to the first-class printing machine of our own day, throwing off its fifteen or eighteen thousand copies of a large four-page journal in an hour, what a stride has been taken in the noble art! Step by step, slowly but surely, has the advance been made,—one improvement suggested after another at long intervals, and by various minds. With the perfection of the [Pg 33] printing press, the name of Earl Stanhope is chiefly associated; but, although when he had put the finishing touches to its construction, immensely superior to all former machines, it was unavailable for rapid printing. In relation to the demand for literature and the means of supplying it, the world had, half a century ago, reached much the same deadlock as in the days when the production of books depended solely on the swiftness of the transcriber's pen, and when the printing press existed only in the fervid brain and quick imagination of a young German student. Not only the growth, but the spread of literature, was restricted by the labour, expense, and delay incident to the multiplication of copies; and the popular appetite for reading was in that transition state when an increased supply would develop it beyond all bounds or calculation, while a continuance of the starvation supply would in all likelihood throw it into a decline from want of exercise.

Such was the state of things when a revolution in the art of printing was effected which, in importance, can be compared only to the original discovery of printing. In fact, since the days of Gutenberg to the present hour, there has been only one great revolution in the art, and that was the introduction of steam printing in 1814. The neat and elegant, but slow-moving Stanhope press, was after all but little in advance of its rude prototype [Pg 34] of the fifteenth century, the chief features of which it preserved almost without alteration. The steam printing machine took a leap ahead that placed it at such a distance from the printing press, that they are hardly to be recognised as the offspring of the same common stock. All family resemblance has died out, although the printing machine is certainly a development of the little screw press.

Of the revolution of 1814, which placed the printing machine in the seat of power, vice the press given over to subordinate employment, Mr. John Walter of the Times was the prominent and leading agent. But for his foresight, enterprise, and perseverance, the steam machine might have been even now in earliest infancy, if not unborn.

Familiar as the invention of the steam printing machine is now, in the beginning of the present century it shared the ridicule which was thrown upon the project of sailing steam ships upon the sea, and driving steam carriages upon land. It seemed as mad and preposterous an idea to print off 5000 impressions of a paper like the Times in one hour, as, in the same time, to paddle a ship fifteen miles against wind and tide, or to propel a heavily laden train of carriages fifty miles. Mr. Walter, however, was convinced that the thing could be done, and lost no time in attempting it. Some notion of the difficulties he had to overcome, and the disappointments he had to endure, while engaged in this enter[Pg 35]prise, may be gathered from the following extracts from the biography of Mr. Walter, which appeared in the Times at the time of his death in July 1847:—

"As early as the year 1804, an ingenious compositor, named Thomas Martyn, had invented a self-acting machine for working the press, and had produced a model which satisfied Mr. Walter of the feasibility of the scheme. Being assisted by Mr. Walter with the necessary funds, he made considerable progress towards the completion of his work, in the course of which he was exposed to much personal danger from the hostility of the pressmen, who vowed vengeance against the man whose inventions threatened destruction to their craft. To such a length was their opposition carried, that it was found necessary to introduce the various pieces of the machine into the premises with the utmost possible secresy, while Martyn himself was obliged to shelter himself under various disguises in order to escape their fury. Mr. Walter, however, was not yet permitted to reap the fruits of his enterprise. On the very eve of success he was doomed to bitter disappointment. He had exhausted his own funds in the attempt, and his father, who had hitherto assisted him, became disheartened, and refused him any further aid. The project was, therefore, for the time abandoned.

"Mr. Walter, however, was not the man to be deterred from what he had once resolved to do. He [Pg 36] gave his mind incessantly to the subject, and courted aid from all quarters, with his usual munificence. In the year 1814 he was induced by a clerical friend, in whose judgment he confided, to make a fresh experiment; and, accordingly, the machinery of the amiable and ingenious Kœnig, assisted by his young friend Bower, was introduced—not, indeed, at first into the Times office, but into the adjoining premises, such caution being thought necessary upon the threatened violence of the pressmen. Here the work advanced, under the frequent inspection and advice of the friend alluded to. At one period these two able mechanics suspended their anxious toil, and left the premises in disgust. After the lapse, however, of about three days, the same gentleman discovered their retreat, induced them to return, showed them, to their surprise, their difficulty conquered, and the work still in progress. The night on which this curious machine was first brought into use in its new abode was one of great anxiety, and even alarm. The suspicious pressmen had threatened destruction to any one whose inventions might suspend their employment. 'Destruction to him and his traps.' They were directed to wait for expected news from the Continent. It was about six o'clock in the morning when Mr. Walter went into the press-room, and astonished its occupants by telling them that 'The Times was already printed by steam! That if they attempted violence, there was a force ready [Pg 37] to suppress it; but that if they were peaceable, their wages should be continued to every one of them till similar employment could be procured,'—a promise which was, no doubt, faithfully performed; and having so said, he distributed several copies among them. Thus was this most hazardous enterprise undertaken and successfully carried through, and printing by steam on an almost gigantic scale given to the world."

On that memorable day, the 29th of November 1814, appeared the following announcement,—"Our journal of this day presents to the public the practical result of the greatest improvement connected with printing since the discovery of the art itself. The reader now holds in his hands one of the many thousand impressions of the Times newspaper which were taken off last night by a mechanical apparatus. That the magnitude of the invention may be justly appreciated by its effects, we shall inform the public that after the letters are placed by the compositors, and enclosed in what is called a form, little more remains for man to do than to attend and watch this unconscious agent in its operations. The machine is then merely supplied with paper; itself places the form, inks it, adjusts the paper to the form newly inked, stamps the sheet, and gives it forth to the hands of the attendant, at the same time withdrawing the form for a fresh coat of ink, which itself again distributes, to meet the ensuing sheet, now [Pg 38] advancing for impression; and the whole of these complicated acts is performed with such a velocity and simultaneousness of movement, that no less than 1100 sheets are impressed in one hour."

Kœnig's machine was, however, very complicated, and before long, it was supplanted by that of Applegath and Cowper, which was much simpler in construction, and required only two boys to attend it—one to lay on, and the other to take off the sheets. The vertical machine which Mr. Applegath subsequently invented, far excelled his former achievement; but it has in turn been superseded by the machine of Messrs. Hoe of New York. All these machines were first brought into use in the Times' printing office; and to the encouragement the proprietors of that establishment have always afforded to inventive talent, the readiness with which they have given a trial to new machines, and the princely liberality with which they have rewarded improvements, is greatly due the present advanced state of the noble craft and mystery.

The printing-house of the Times, near Blackfriars Bridge, forms a companion picture to Gutenberg's printing-room in the old abbey at Strasburg, and illustrates not only the development of the art, but the progress of the world during the intervening centuries. Visit Printing-House Square in the day-time, and you find it a quiet, sleepy place, with hardly any signs of life or movement about it, except [Pg 39] in the advertisement office in the corner, where people are continually going out and in, and the clerks have a busy time of it, shovelling money into the till all day long. But come back in the evening, and the place will wear a very different aspect. All signs of drowsiness have disappeared, and the office is all lighted up, and instinct with bustle and activity. Messengers are rushing out and in, telegraph boys, railway porters, and "devils" of all sorts and sizes. Cabs are driving up every few minutes, and depositing reporters, hot from the gallery of the House of Commons or the House of Lords, each with his budget of short-hand notes to decipher and transcribe. Up stairs in his sanctum the editor and his deputies are busy preparing or selecting the articles and reports which are to appear in the next day's paper. In another part of the building the compositors are hard at work, picking up types, and arranging them in "stick-fulls," which being emptied out into "galleys," are firmly fixed therein by little wedges of wood, in order that "proofs" may be taken of them. The proofs pass into the hands of the various sets of readers, who compare them with the "copy" from which they were set up, and mark any errors on the margin of the slips, which then find their way back to the compositors, who correct the types according to the marks. The "galleys" are next seized by the persons charged with the "making-up" of the paper, who divide them into [Pg 40] columns of equal length. An ordinary Times newspaper, with a single inside sheet of advertisements, contains seventy-two columns, or 17,500 lines, made up of upwards of a million pieces of types, of which matter about two-fifths are often written, composed, and corrected after seven o'clock in the evening. If the advertisement sheet be double, as it frequently is, the paper will contain ninety-six columns. The types set up by the compositors are not sent to the machine. A mould is taken of them in a composition of brown paper, by means of which a "stereotype" is cast in metal, and from this the paper is printed. The advertisement sheet, single or double, as the case may be, is generally ready for the press between seven or eight o'clock at night. The rest of the paper is divided into two "forms,"—that is, columns arranged in pages and bound together by an iron frame, one for each side of the sheet. Into the first of these the person who "makes up" the paper endeavours to place all the early news, and it is ready for press usually about four o'clock. The other "form" is reserved for the leading articles, telegrams, and all the latest intelligence, and does not reach the press till near five o'clock.

The first sight of Hoe's machine, by several of which the Times is now printed, fills the beholder with bewilderment and awe. You see before you a huge pile of iron cylinders, wheels, cranks, and levers, whirling away at a rate that makes you [Pg 41] giddy to look at, and with a grinding and gnashing of teeth that almost drives you deaf to listen to. With insatiable appetite the furious monster devours ream after ream of snowy sheets of paper, placed in its many gaping jaws by the slaves who wait on it, but seems to find none to its taste or suitable to its digestion, for back come all the sheets again, each with the mark of this strange beast printed on one side. Its hunger never is appeased,—it is always swallowing and always disgorging, and it is as much as the little "devils" who wait on it can do, to put the paper between its lips and take it out again. But a bell rings suddenly, the monster gives a gasp, and is straightway still, and dead to all appearance. Upon a closer inspection, now that it is at rest, and with some explanation from the foreman you begin to have some idea of the process that has been going on before your astonished eyes.

The core of the machine consists of a large drum, turning on a horizontal axis, round which revolve ten smaller cylinders, also on horizontal axes, in close proximity to the drum. The stereotyped matter is bound, like a malefactor on the wheel, to the central drum, and round each cylinder a sheet of paper is constantly being passed. It is obvious, therefore, that if the type be inked, and each of the cylinders be kept properly supplied with a sheet of paper, a single revolution of the drum will cause the ten cylinders to revolve likewise, and produce an impression on one [Pg 42] side of each of the sheets of paper. For this purpose it is necessary to have the type inked ten times during every revolution of the drum; and this is managed by a very ingenious contrivance, which, however, is too complicated for description here. The feeding of the cylinders is provided for in this way. Over each cylinder is a sloping desk, upon which rests a heap of sheets of white paper. A lad—the "layer-on"—stands by the side of the desk and pushes forward the paper, a sheet at a time, towards the tape fingers of the machine, which, clutching hold of it, drag it into the interior, where it is passed round the cylinders, and printed on the outer side by pressure against the types on the drum. The sheet is then laid hold of by another set of tapes, carried to the other end of the machine from that at which it entered, and there laid down on a desk by a projecting flapper of lath-work. Another lad—the "taker-off"—is in attendance to remove the printed sheets, at certain intervals. The drum revolves in less than two seconds; and in that time therefore ten sheets—for the same operation is performed simultaneously by the ten cylinders—are sucked in at one end and disgorged at the other printed on one side, thus giving about 20,000 impressions in an hour.

Such is the latest marvel of the "noble craft and mystery" of printing; but it is not to be supposed that the limits of production have even now been reached. The greater the supply the greater has [Pg 43] grown the demand; the more people read, the more they want to read; and past experience assures us that ingenuity and enterprise will not fail to expand and multiply the powers of the press, so that the increasing appetite for literature may be fully met.

We have briefly alluded to stereotyping; but some fuller notice seems requisite of a process so valuable and important, without which, indeed, the rapid multiplication of copies of a newspaper, even by a Hoe's six-cylinder machine, would be impossible. If stereotyping had not been invented, the printer would require to "set up" as many "forms" of type as there are cylinders in the machine he uses; an expensive and time-consuming operation which is now dispensed with, because he can resort to "casts." There is yet another advantage gained by the process; "casts" of the different sheets of a book can be preserved for any length of time; and when additional copies or new editions are needed, these "casts" can at once be sent to the machine, and the publisher is saved the great expense of "re-setting."

The reader is well aware that while many books disappear with the day which called them forth, so there are others for which the demand is constant. This was found to be the case soon after the invention of printing, and the plan then adopted was the expensive and cumbrous one of setting up the whole [Pg 44] of the book in request, and to keep the type standing for future editions. The disadvantages of this plan were obvious—a large outlay for type, the amount of space occupied by a constantly increasing number of "forms," and the liability to injury from the falling out of letters, from blows, and other accidents. As early as the eighteenth century attempts seem to have been made to remedy these inconveniences by cementing the types together at the bottom with lead or solder to effect their greater preservation. Canius, a French historian of printing, states that in June 1801 he received a letter from certain booksellers of Leyden, with a copy of their stereotype Bible, the plates for which were formed by soldering together the bottom of common types with some melted substance to the thickness of about three quires of writing-paper; and, it is added, "These plates were made about the beginning of the last century by an artist named Van du Mey."

This, however, was not true stereotyping; whose leading principle is to dispense with the movable types—to set them again, as it were, at liberty—by making up perfect fac-similes in type-metal of the various combinations into which they may have entered. These fac-similes being made, the type is set free, and may be distributed, and used for making up fresh pages; which may once more furnish, so to speak, the punches to the mould into which the type-metal is poured for the purpose of effecting the fac-simile.

[Pg 45] The inventor of this ingenious process of casting plates from pages of type was William Ged, a goldsmith of Edinburgh, in 1735. Not possessing sufficient capital to carry out his invention, he visited London, and sought the assistance of the London stationers; from whom he received the most encouraging words, but no pecuniary assistance. But Ged was a man not readily discomfited, and applying at length to the Universities and the King's printer, he obtained the effective patronage he needed. He "stereotyped" some Bibles and Prayer-books, and the sheets worked off from his plates were admitted equal in point of appearance and accuracy to those printed from the type itself.

But every benefactor of his kind is doomed to meet with the opposition of the envious, the ignorant, or the prejudiced. "The argument used by the idol-makers of old, 'Sirs, ye know that by this craft we have our wealth,' and, 'This our craft is in danger to be set at nought,' was, as is usual in such cases, urged against this most useful and important invention. The compositors refused to set up works for stereotyping, and even those which were set up, however carefully read and corrected, were found to be full of gross errors. The fact was, that when the pages were sent to be cast, the compositors or pressmen, bribed, it is said, by a typefounder, disturbed the type, and introduced false letters and [Pg 46] words. Poor Ged died, and left the dangerous secret of his art (which he did not disclose during his life-time) to his son, who, after many struggles for success, failed as his father had done before him." There is a tradition current, however, that he joined the Jacobite rebellion, was arrested, imprisoned, tried, and sentenced, but was eventually spared in consideration of the value of his father's admirable invention.

That invention, after being forgotten for nearly half a century, was revived by a Dr. Tilloch, and taken up, improved, and extended by the ingenious Earl Stanhope. It is now practised in the following manner:—

The type employed differs slightly from that in common use. The letter should have no shoulder, but should rise in a straight line from the foot; the spaces, leads, and quadrats are of the same height as the stem of the letter; the object being to diminish the number and depth of the cavities in the page, and thus lessen the chances of the mould breaking off and remaining in the form. Each page is corrected with the utmost care, and "imposed" in a small "chase" with metal furniture (or frame-work), which rises to a level with the type. Of course the number of pages in the form will vary according to the size of the book; a sheet being folded into sixteen leaves, twelve, eight, four, or two for 16mo, 12mo, 8vo, quarto, or folio.

[Pg 47] Having our pages of type in complete order, we now proceed to rub the surface with a soft brush which has been lightly dipped into a very thin oil. Plumbago is sometimes preferred. A brass rectangular frame of three sides, with bevelled borders adapted to the size of the pages, is placed upon the chase so as to enclose three sides of the type, the fourth side being formed by a single brass edge, having the same inward sloping level as the other three sides. The use of this frame is to determine the size and thickness of the cast, which is next taken in plaster-of-paris—two kinds of the said plaster being used; the finer is mixed, poured over the surface of the type, and gently worked in with a brush so as to insure its close adhesion to the exclusion of bubbles of air; the coarser, after being mixed with water, is simply poured and spread over the previous and finer stratum.

The superfluous plaster is next cleared away; the mould soon sets; the frame is raised; and the mould comes off from the surface of the type, on which it has been prevented from encrusting itself by the thin film of oil or plumbago.

The next step is to dress and smoothen the plaster-mould, and set it on its edge in one of the compartments of a sheet-iron rack contained in an oven, and exposed, until perfectly dry, to a temperature of about 400°. This occupies about two hours. A good workman, it is said, will mould ten octavo [Pg 48] sheets, or one hundred and sixty pages in a day: each mould generally contains a couple of octavo pages.

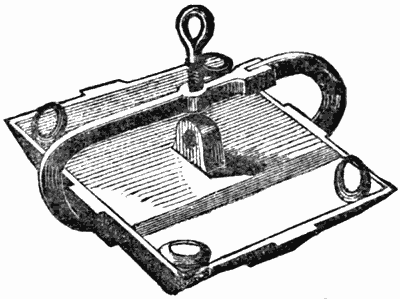

In the state to which it is now brought, the mould is exceedingly friable, and requires to be handled with becoming care. With the face downwards it is placed upon the flat cast-iron floating-plate, which, in its turn, is set at the bottom of a square cast-iron tray, with upright edges sloping outwards, called the "dipping pan." It has a cast-iron lid, secured by a screw and shackles, not unlike a copying machine. This pan having been heated to 400°, it is plunged into an iron pot containing the melted alloy, which hangs over a furnace, the pan being slightly inclined so as to permit the escape of the air. A small space is left between the back or upper surface of the mould, and the lid of the dipping-pan, and the fluid metal on entering into the pan through the corner openings, floats up the plaster together with the iron plate (hence called the floating-plate) on which the mould is set, with this effect, that the metal flows through the notches cut in the edge of the mould, and fills up every part of it, forming a layer of metal on its face corresponding to the depth of [Pg 49] the border, while on the back is left merely a thin metallic film.

The dipping-pan, says Tomlinson, is suspended, plunged in the metal, and removed by means of a crane; and when taken out, is set in a cistern of water upon supports so arranged that only the bottom of the pan comes in contact with the surface of the water. The metal thus sets, or solidifies, from below, and containing fluid above, maintains a fluid pressure during the contraction which accompanies the cooling.

As it thus shrinks in dimensions, molten metal is poured into the corners of the pan for the purpose of maintaining the fluid pressure on the mould, and thus securing a good and solid cast. For if the pan were allowed to cool more slowly, the thin metallic film at the back of the inverted plaster mould would probably solidify first, and thus prevent the fluid pressure which is necessary for filling up all the lines of the mould.

Tomlinson concludes his description of these interesting processes by informing us that an experienced and skilled workman will make five dips, each containing two octavo pages, in the course of an hour, or, as already stated, at the rate of nearly ten octavo sheets a day.

When the pan is opened, the cake of metal and plaster is removed, and beaten upon its edges with a mallet, to clear away all superfluous metal. The [Pg 50] stereotype plate is then taken by the picker, who planes its edges square, "turns" its back flat upon a lathe until the proper thickness is obtained, and removes any minute imperfections arising from specks of dirt and air-bubbles left among the letters in casting the mould. Damaged letters are cut out, and separate types soldered in as substitutes. After all this anxious care to obtain perfection, the plate is pronounced ready for working, and when made up with the other plates into the proper form, it may be worked either at the hand-press or by machine.

Other modes of stereotyping have been introduced, but not one has attained to the popularity of the method we have just described.

"It is said that ideas produce revolutions and truly they do—not spiritual ideas only, but even mechanical."—Carlyle.

As the last century was drawing to its close, two great revolutions were in progress, both of which were destined to exercise a mighty influence upon the years to come,—the one calm, silent, peaceful, the other full of sound and fury, bathed in blood, and crowned with thorns,—the one the fruit of long years of patient thought and work, the other the outcome of long years of oppression, suffering, and sin,—the one was Watt's invention of the steam engine, the other the great popular revolt in France. These are the two great events which set their mark upon our century, gave form and colour to its character, and direction to its aims and aspirations. In the pages of conventional history, of course, the French revolution, with its wild phantasmagoria of retribution, its massacres and martyrdoms, will no doubt have assigned to it the foremost rank as the great feature of the era,—

[Pg 54] But those who can look below the mere surface of events, and whose fancy is not captivated by the melo-drama of rebellion, and the pageantry of war, will find that Watt's steam machine worked the greatest revolution of modern times, and exercised the deepest, as well as widest and most permanent influence over the whole civilized world.

Like all great discoveries, that of the motive power of steam, and the important uses to which it might be applied, was the work, not of any one mind, but of several minds, each borrowing something from its predecessor, until at last the first vague and uncertain Idea was developed into a practical Reality. Known dimly to the ancients, and probably employed by the priests in their juggleries and pretended miracles, it was not till within the last three centuries that any systematic attempt was made to turn it to useful account.

But before we turn our attention to the persons who made, and, after many failures and discouragements, successfully made this attempt, it will be advisable we should say something as to the principle on which their invention is founded.

The reader knows that gases and vapours, when imprisoned within a narrow space, do struggle as resolutely to escape as did Sterne's starling from his cage. Their force of pressure is enormous, and if confined in a closed vessel, they would speedily rend it into fragments. Let some water boil in a [Pg 55] pipkin whose lid fits very tightly; in a few minutes the vapour or steam arising from the boiling water, overcoming the resistance of the lid, raises it, and rushes forth into the atmosphere.

Take a small quantity of water, and pour it into the hollow of a ball of metal. Then with the aid of a cork, worked by a metallic screw, close the opening of the ball hermetically, and place the ball in the heart of a glowing fire. The steam formed by the boiling water in the inside of the metallic bomb, finding no channel of escape, will burst through the bonds that sought to confine it, and hurl afar the fragments with a loud and dangerous explosion.

These well-known facts we adduce simply as a proof of the immense mechanical power possessed by steam when enclosed within a limited area. Now, the questions must have occurred to many, though they were themselves unable to answer them,—Why should all this force be wasted? Can it not be directed to the service and uses of man? In the course of time, however, human intelligence did discover a sufficient reply, and did contrive to utilize this astonishing power by means of the machine now so famous as the Steam Engine.

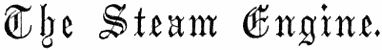

Let us take a boiler full of water, and bring it up to boiling point by means of a furnace. Attach to this boiler a tube, which guides the steam of the boiler into a hollow metallic cylinder, tra[Pg 56]versed by a piston rising and sinking in its interior. It is evident that the steam rushing through the tube into the lower part of the cylinder, and underneath the piston, will force the piston, by its pressure, to rise to the top of the cylinder. Now let us check for a moment the influx of the steam below the piston, and turning the stopcock, allow the steam which fills that space to escape outside; and, at the same time, by opening a second tube, let in a supply of steam above the piston: the pressure of the steam, now exercised in a downward direction, will force the piston to the bottom of its course, because there will exist beneath it no resistance capable of opposing the pressure of the steam. If we constantly keep up this alternating motion, the piston now rising and now falling, we are in a position to profit by the force of steam. For if the lever, attached to the rod of the piston at its lower end, is fixed by its upper to a crank of the rotating axle of a workshop or factory, is it not clear that the continuous action of the steam will give this axle a continuous rotatory movement? And this movement may be transmitted, by means of bands and pulleys, to a number of different machines or engines all kept at work by the power of a solitary engine.

This, then, is the principle on which the inventions of Papin, the Marquis of Worcester, Newcomen, and James Watt have been based.

[Pg 57] The great astronomer Huyghens conceived the idea of creating a motive machine by exploding a charge of gunpowder under a cylinder traversed by a piston: the air contained in this cylinder, dilated by the heat resulting from the combustion of the powder, escaped into the outer air through a valve, whereupon a partial void existed beneath the piston, or, rather, the air considerably rarified; and from this moment the pressure of the atmospheric air falling on the upper part of the piston, and being but imperfectly counterpoised by the rarified air beneath the piston, precipitated this piston to the bottom of the cylinder. Consequently, said Huyghens, if to the said piston were attached a chain or cord coiling around a pulley, one might raise up the weights placed at the extremity of the cord, and so produce a genuine mechanical effect.

GENERAL PRINCIPLE OF THE STEAM ENGINE.

GENERAL PRINCIPLE OF THE STEAM ENGINE.

But Experiment, the touchstone of Physical Truth, soon revealed the deficiencies of an apparatus such as Huyghens had suggested. The air beneath the piston was not sufficiently rarified; the void produced was too imperfect. Evidently gunpowder [Pg 58] was not the right agent. What was? Denis Papin answered, Steam. And the first Steam Engine ever invented was invented by this ingenious Frenchman.

Papin was born at Blois on the 22nd of August 1645. He died about 1714, but neither the exact date nor the place of his death is known. The lives of most men of genius are heavy with shadows, but Papin's career was more than ordinarily characterized by the incessant pursuit of the evil spirits of adversity and persecution. A Protestant, and devoutly loyal to his creed, he fled from France with thousands of his co-religionists, when Louis XIV. unwisely and unrighteously revoked the Edict of Nantes, which permitted the Huguenots to worship God after their own fashion. And it was abroad, in England, Italy, and Germany, that he realized the majority of his inventions, among which that of the Steam Engine is the most conspicuous.

In 1707 Papin constructed a steam engine on the principle we have already described, and placed it on board a boat provided with wheels. Embarking at Cassel on the river Fulda, he made his way to Münden in Hanover, with the design of entering the waters of the Weser, and thence repairing to England, to make known his discovery, and test its capabilities before the public. But the harsh and ignorant boatmen of the Weser would not permit him to enter the river; and when he indignantly [Pg 59] complained, they had the barbarity to break his boat in pieces. This was the crowning misfortune of Papin's life. Thenceforward he seems to have lost all heart and hope. He contrived to reach London, where the Royal Society, of which he was a member, allowed him a small pittance.

In 1690 this ingenious man had devised an engine in which atmospheric vapour instead of steam was the motive agent. At a later period, Newcomen, a native of Dartmouth in Devonshire, conceived the idea of employing the same source of power.

But, previously, the value of steam, if employed in this direction, had occurred to the Marquis of Worcester, a nobleman of great ability and a quick imagination, who, for his loyalty to the cause of Charles I., had been confined in the Tower of London as a prisoner. On one occasion, while sitting in his solitary chamber, the tight cover of a kettle full of boiling water was blown off before his eyes; for mere amusement's sake he set it on again, saw it again blown off, and then began to reflect on the capabilities of power thus accidentally revealed to him, and to speculate on its application to mechanical ends. Being of a quick, ingenious turn of mind, he was not long in discovering how it could be directed and controlled. When he published his project—"An Admirable and Most Forcible Way to Drive up Water by Fire"—he was abused [Pg 60] and laughed at as being either a madman or an impostor. He persevered, however, and actually had a little engine of some two horse power at work raising water from the Thames at Vauxhall; by means of which, he writes, "a child's force bringeth up a hundred feet high an incredible quantity of water, and I may boldly call it the most stupendous work in the whole world." There is a fervent "Ejaculatory and Extemporary Thanksgiving Prayer" of his extant, composed "when first with his corporeal eyes he did see finished a perfect trial of his water-commanding engine, delightful and useful to whomsoever hath in recommendation either knowledge, profit, or pleasure." This and the rest of his wonderful "Centenary of Inventions," only emptied instead of replenishing his purse. He was reduced to borrow paltry sums from his creditors, and received neither respect for his genius nor sympathy for his misfortunes. He was before his age, and suffered accordingly.

In 1698 his work was taken up by Thomas Savery, a miner, who, through assiduous labour and well-directed study, had become a skilful engineer. He succeeded in constructing an engine on the principle of the pressure of aqueous vapour, and this engine he employed successfully in pumping water out of coal mines. We owe to Savery the invention of a vacuum, which was suggested to him, [Pg 61] it is said, in a curious manner: he happened to throw a wine-flask, which he had just drained, upon the fire; a few drops of liquor at the bottom of the flask soon filled it with steam, and, taking it off the fire, he plunged it, mouth downwards, into a basin of cold water that was standing on the table, when, a vacuum being produced, the water immediately rushed up into the flask.

In tracing this lineage of inventive genius, we next come to Thomas Newcomen, a blacksmith, who carried out the principle of the piston in his Atmospheric Engine, for which he took out a patent in 1705. It is but just to recognize that this engine was the first which proved practically and widely useful, and was, in truth, the actual progenitor of the present steam engine. It was chiefly used for working pumps. To one end of a beam moving on a central axis was attached the rod of the pump to be worked; to the other, the rod of the piston moving in the cylinder below. Underneath this cylinder was a boiler, and the two were connected by a pipe provided with a stop-cock to regulate the supply of steam. When the pump-rod was depressed, and the piston raised to the top of the cylinder, which was effected by weights hanging to the pump-end of the beam, the stop-cock was used to cut off the steam, and a supply of cold water injected into the cylinder through a water-pipe connected with the tank or cistern. The steam in the cylinder was [Pg 62] immediately condensed; a vacuum created below the piston; the latter was then forced down by atmospheric pressure, bringing with it the end of the beam to which it was attached, and raising the other along with the pump-rod. A fresh supply of steam was admitted below the piston, which was raised by the counterpoise; and thus the motion was constantly renewed. The opening and shutting of the stop-cocks was at first managed by an attendant; but a boy named Potter, who was employed for this purpose, being fonder of play than work, contrived to save himself all trouble in the matter by fastening the handles with pieces of string to some of the cranks and levers. Subsequently, Beighton, an engineer, improved on this idea by substituting levers, acted on by pins in a rod suspended from the beam.

Properly speaking, Newcomen's engine was not a steam, but an atmospheric engine; for though steam was employed, it formed no essential feature of the contrivance, and might have been replaced by an air-pump. All the use that was made of steam was to produce a vacuum underneath the piston, which was pressed down by the weight of the atmosphere, and raised by the counterpoise of the buckets at the other end of the beam. Watt, in bringing the expansive force of steam to bear upon the working of the piston, may be said to have really invented the steam engine. Half a century before the little model came into Watt's hands, Newcomen's engine [Pg 63] had been made as complete as its capabilities admitted of; and Watt struck into an entirely new line, and invented an entirely new machine, when he produced his Condensing Engine.

There are few places in our country where human enterprise has effected such vast and marvellous changes within the century as the country traversed by the river Clyde. Where Glasgow now stretches far and wide, with its miles of swarming streets, its countless mills, and warehouses, and foundries, its busy ship-building yards, its harbour thronged with vessels of every size and clime, and its large and wealthy population, there was to be seen, a hundred years ago, only an insignificant little burgh, as dull and quiet as any rural market-town of our own day. There was a little quay at the Broomielaw, seldom used, and partly overgrown with broom. No boat over six tons' burden could get so high up the river, and the appearance of a masted vessel was almost an event. Tobacco was the chief trade of the town; and the tobacco merchants might be seen strutting about at the Cross in their scarlet cloaks, and looking down on the rest of the inhabitants, who got their livelihood, for the most part, by dealing in grindstones, coals, and fish—"Glasgow magistrates," as herrings are popularly called, being in as great repute then as now. There were but scanty means of intercourse [Pg 64] with other places, and what did exist were little used, except for goods, which were conveyed on the backs of pack-horses. The caravan then took two days to go to Edinburgh—you can run through now between the two cities in little more than an hour. There is hardly any trade that Glasgow does not prosecute vigorously and successfully. You may see any day you walk down to the Broomielaw, vessels of a thousand tons' burden at anchor there, and the custom duties which were in 1796 little over £100, have now reached an amount exceeding one million!

Glasgow is indebted, in a great part, for the gigantic strides which it has made, to the genius, patience, and perseverance of a man who, in his boyhood, rather more than a hundred years ago, used to be scolded by his aunt for wasting his time, taking off the lid of the kettle, putting it on again, holding now a cup, now a silver spoon over the steam as it rose from the spout, and catching and counting the drops of water it fell into. James Watt was then taking his first elementary lessons in that science, his practical application of which in after life was to revolutionize the whole system of mechanical movement, and place an almost unlimited power at the disposal of the industrial classes.

When a boy, James Watt was delicate and sickly, and so shy and sensitive that his school-days were a misery to him, and he profited but little by his attendance. At home, though, he was a great reader, [Pg 65] and picked up a great deal of knowledge for himself, rarely possessed by those of his years. One day a friend was urging his father to send James to school, and not allow him to trifle away his time at home. "Look how the boy is occupied," said his father, "before you condemn him." Though only six years old, he was trying to solve a geometrical problem on the floor with a bit of chalk. As he grew older he took to the study of optics and astronomy, his curiosity being excited by the quadrants and other instruments in his father's shop. By the age of fifteen he had twice gone through De Gravesande's Elements of Natural Philosophy, and he was also well versed in physiology, botany, mineralogy, and antiquarian lore. He was further an expert hand in using the tools in his father's workshop, and could do both carpentry and metal work. After a brief stay with an old mechanic in Glasgow, who, though he dignified himself with the name of "optician," never rose beyond mending spectacles, tuning spinets, and making fiddles and fishing tackle, Watt went at the age of eighteen to London, where he worked so hard, and lived so sparingly in order to relieve his father from the burden of maintaining him, that his health suffered, and he had to recruit it by a return to his native air. During the year spent in the metropolis, however, he managed to learn nearly all that the members of the trade there could teach, and soon showed himself a quick and skilful workman.

[Pg 66] In 1757 we find the sign of "James Watt, Mathematical Instrument Maker to the College," stuck up over the entrance to one of the stairs in the quadrangle of Glasgow College. But though under the patronage of the University, his trade was so poor, that thrifty and frugal as he was, he had a hard struggle to live by it. He was ready, however, for any work that came to hand, and would never let a job go past him. To execute an order for an organ which he accepted, he studied harmonics diligently, and though without any ear for music, turned out a capital instrument, with several improvements of his own in its action; and he also undertook the manufacture of guitars, violins, and flutes. All this while he was laying up vast stores of knowledge on all sorts of subjects, civil and military engineering, natural history, languages, literature, and art; and among the professors and students who dropped into his little shop to have a chat with him, he soon came to be regarded as one of the ablest men about the college, while his modesty, candour, and obliging disposition gained him many good friends.

Among his multifarious pursuits, Watt had experimented a little in the powers of steam; but it was not till the winter of 1763-4, when a model of Newcomen's engine was put into his hands for repair, that he took up the matter in earnest. Newcomen's engine was then about the most complete invention of its kind; but its only value was its power of pro[Pg 67]ducing a ready vacuum, by rapid condensation on the application of cold; and for practical purposes was neither cheaper nor quicker than animal power. Watt, having repaired the model, found, on setting it agoing, that it would not work satisfactorily. Had it been only a little less clumsy and imperfect, Watt might never have regarded it as more than the "fine plaything," for which he at first took it; but now the difficulties of the task roused him to further efforts. He consulted all the books he could get on the subject, to ascertain how the defects could be remedied; and that source of information exhausted, he commenced a series of experiments, and resolved to work out the problem for himself. Among other experiments, he constructed a boiler which showed by inspection the quantity of water evaporated in a given time, and thereby ascertained the quantity of steam used in every stroke of the engine. He found, to his astonishment, that a small quantity of water in the form of steam heated a large quantity of water injected into the cylinder for the purpose of cooling it; and upon further examination, he ascertained the steam heated six times its weight of well water up to the temperature of the steam itself (212°). After various ineffectual schemes, Watt was forced to the conclusion that, to make a perfect steam engine, two apparently incompatible conditions must be fulfilled—the cylinder must always be as hot as the steam that came rushing into it, and yet, at each [Pg 68] descent of the piston, the cylinder must become sufficiently cold to condense the steam. He was at his wit's end how to accomplish this task, when, as he was taking a walk one afternoon, the idea flashed across his mind that, as steam was an elastic vapour, it would expand and rush into a previously exhausted place; and that, therefore, all he had to do to meet the conditions he had laid down, was to produce a vacuum in a separate vessel, and open a communication between this vessel and the cylinder of the steam-engine at the moment when the piston was required to descend, and the steam would disseminate itself and become divided between the cylinder and the adjoining vessel. But as this vessel would be kept cold by an injection of water, the steam would be annihilated as fast as it entered, which would cause a fresh outflow of the remaining steam in the cylinder, till nearly the whole of it was condensed, without the cylinder itself being chilled in the operation. Here was the great key to the problem; and when once the idea of separate condensation was started, many other subordinate improvements, as he said himself, "followed as corollaries in rapid succession, so that in the course of one or two days the invention was thus far complete in his mind".

It cost him ten long weary years of patient speculation and experiment, to carry out the idea, with little hope to buoy him up, for to the last he used to say "his fear was always equal to his hope,"[Pg 69]—and with all the cares and embarrassments of his precarious trade to perplex and burden him. Even when he had his working model fairly completed, his worst difficulties—the difficulties which most distressed and harassed the shy, sensitive, and retiring Watt—seemed only to have commenced. To give the invention a fair practical trial required an outlay of at least £1000; and one capitalist, who had agreed to join him in the undertaking, had to give it up through some business losses. Still Watt toiled on, always keeping the great object in view,—earning bread for his family (for he was married by this time), by adding land-surveying to his mechanical labours, and, in short, turning his willing hand to any honest job that offered.

He got a patent in 1769, and began building a large engine; but the workmen were new to the task, and when completed, its action was spasmodic and unsatisfactory. "It is a sad thing," he then wrote, "for a man to have his all hanging by a single string. If I had wherewithal to pay for the loss, I don't think I should so much fear a failure; but I cannot bear the thought of other people becoming losers by my scheme, and I have the happy disposition of always painting the worst." And just then, to make matters still more gloomy, he learned that some rascally linen-draper in London was plagiarizing the great invention he had brought forth in such sore and protracted travail. "Of all things [Pg 70] in the world," cried poor Watt, sick with hope deferred, and pressed with little carking cares on every side, "there is nothing so foolish as inventing."

When nearly giving way to despair, and on the point of abandoning his invention, Watt was fortunate enough to fall in with Matthew Boulton, one of the great manufacturing potentates of Birmingham, an energetic, far-seeing man, who threw himself into the enterprise with all his spirit; and the fortune of the invention was made. An engine, on the new principle, was set up at Soho; and there Boulton and Watt sold, as the former said to Boswell, "what all the world desires to have, Power;"—the infinite power that animates those mighty engines, which—