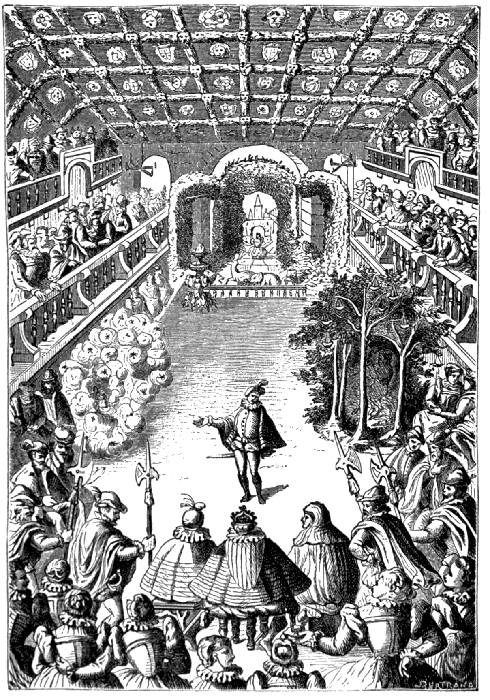

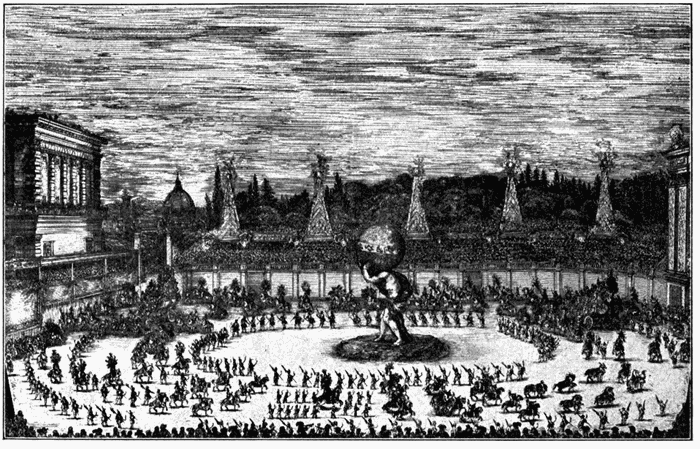

LE BALLET DE LA REINE

A FRENCH COURT BALLET IN

THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH

CENTURY

Title: A Book About the Theater

Author: Brander Matthews

Release date: July 20, 2011 [eBook #36790]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow, Ernest Schaal, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

Books by Brander Matthews

Biographies

Shakspere as a Playwright

Molière, His Life and His Works

Essays and Criticisms

French Dramatists of the 19th Century

Pen and Ink, Essays on subjects of more or less importance

Aspects of Fiction, and other Essays

The Historical Novel, and other Essays

Parts of Speech, Essays on English

The Development of the Drama

Inquiries and Opinions

The American of the Future, and other Essays

Gateways to Literature, and other Essays

On Acting

A Book About the Theater

A BOOK

ABOUT THE THEATER

BY

BRANDER MATTHEWS

PROFESSOR OF DRAMATIC LITERATURE IN COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY; MEMBER

OF THE AMERICAN ACADEMY OF ARTS AND LETTERS

NEW YORK

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

1916

Copyright, 1916, by

CHARLES SCRIBNER'S SONS

Published October, 1916

My Dear Augustus:

Let me begin by confessing my regret that I cannot overhear your first remark when you receive this sheaf of essays, many of which are devoted to the subordinate subdivisions of the art of the stage. As it is, I can only imagine your surprise at discovering that this book, which contains papers dealing with certain aspects of the theater rarely considered to be worthy of criticism, is signed by the occupant of the earliest chair to be established in any American university specifically for the study of dramatic literature. I fancy I can hear the expression of your wonder that a sexagenarian professor should turn aside from his austere analysis of the genius of Sophocles and of Shakspere, of Molière and of Ibsen, to discuss the minor arts of the dancer and the acrobat, to chatter about the conjurer and the negro minstrel, to consider the principles of pantomime and the development of scene-painting. But I am emboldened to hope that your surprise will be only momentary, and that you will be moved to acknowledge that perhaps there may be some advantage to be derived from these deviations into the by-paths of stage history.

You are rather multifarious yourself; "like Cerberus, you are three gentlemen at once"; you have been a reporter, you have published a novel, you have painted pictures, you have delivered addresses—and you write plays, too. I think that you, at least, will readily understand how a student of the stage may like to stray now and again from the main road and to ramble away from the lofty temple of dramatic art to loiter for a little while in one or another of its lesser chapels. And you, again, will appreciate my conviction that these loiterings and these strollings may be as profitable as that casual browsing about in a library which is likely to enrich our memories with not a little interesting information that we might never have captured had we adhered to a rigorous and rigid course of study. You will see what I mean when I declare my belief that I have come back from these wanderings with an increased understanding of the theory of the theater, and with an enlarged acquaintance with its manifold manifestations.

Perhaps I ought to explain, furthermore, that these excursions into the purlieus of the playhouse began long, long ago. I gave a Punch and Judy show before I was sixteen; I performed experiments in magic, I blacked up as Tambo, I whitened myself as Clown, I played the low-comedy part in a farce, and I attempted the flying trapeze before I was twenty; and I was not encouraged by the result of these early experiences to repeat any of the experiments after I came of age. I think it was as a spinner of hats and as the underman of a "brothers' act" that I came nearest to success; at least I infer this from the fact—may I mention it without seeming to boast?—that with my partners in this brothers' act, I was asked if I would care to accept an engagement with a circus for the summer. As to the merits of the other efforts I need say nothing now; the rest is silence. When the cynic declared that the critics were those who had failed in literature and art, he overstated his case, as is the custom of cynics. But it is an indisputable advantage for any critic to have adventured himself in the practise of the art to the discussion of which he is to devote himself; he may have failed, or at least he may not have succeeded as he could wish; but he ought to have gained a firmer grasp on the principles of the art than he would have had if he had never risked himself in the vain effort.

With this brief word of personal explanation I step down from the platform of the preface to let these various essays speak for themselves. If they have any message of any value, I feel assured in advance that your friendly ear will be the first to interpret it. And I remain,

Ever yours,

Brander Matthews

Columbia University,

in the City of New York.

CONTENTS

PAGE

Le ballet de la reine Frontispiece

FACING PAGE

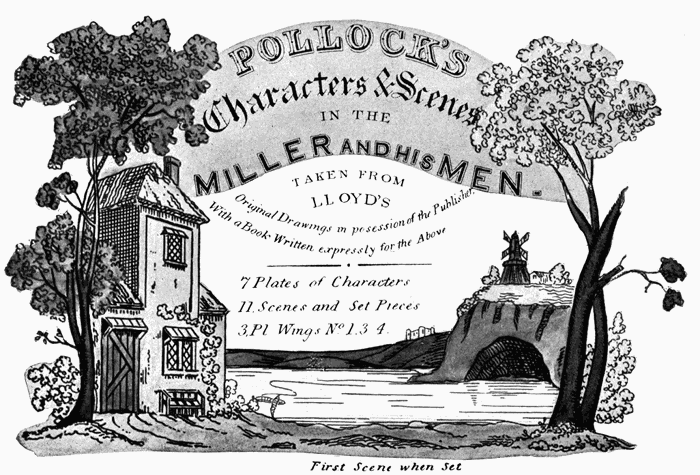

Upper half of Plate No. 1, the 'Miller and His Men' 40

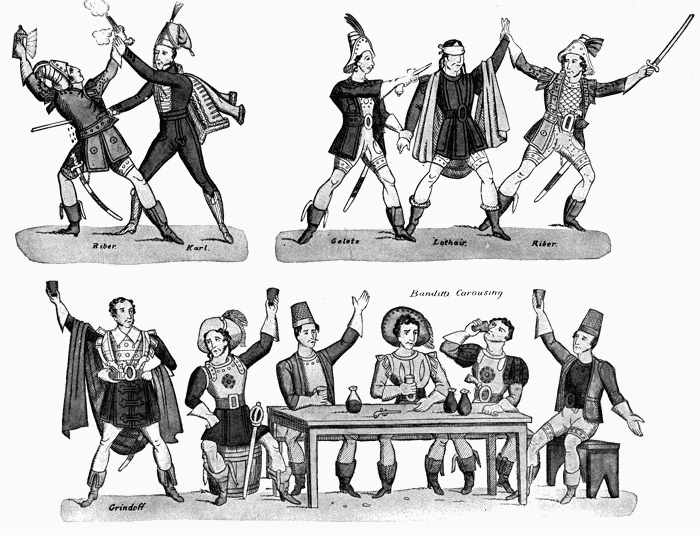

A group of the principal characters from

Pollock's juvenile drama, the 'Miller and His Men' 42

Explosion of the mill. A back drop in the 'Miller and His Men' 46

Plate No. 7, the 'Miller and His Men' 48

Lower half of Plate No. 5, the 'Miller and His Men' 52

The Roman Theater at Orange 134

The multiple set of the French medieval stage 134

The set of the Italian comedy of masks 134

An outdoor entertainment in the gardens of

the Pitti Palace in Florence in the early sixteenth century 136

The set for the opera of 'Persée' (as

performed at the Opéra in Paris in the seventeenth century) 140

A prison (designed by Bibiena in Italy in the eighteenth century) 140

The screen scene of the 'School for Scandal'

at Drury Lane in 1778 144

A landscape set 146

A set for the opera of 'Robert le Diable' 146

The set of the last act of the 'Garden of Allah' 148

A set for 'Medea' 148

The set of 'Œdipe-Roi' (at the Théâtre Français) 150

The set of the 'Return of Peter Grimm' 150

Scenes from Punch and Judy 274

Scenes from Punch and Judy (continued) 276

Roman puppets. Greek and Roman puppets. Puppet of Java. 290

A Sicilian marionette show 292

A Belgian puppet. A Chinese puppet theater.

Puppet figure representing the younger Coquelin 294

Puppets in Burma 296

The puppet play of Master Peter (Italian) 296

A Neapolitan Punchinella 300

The broken bridge. Plan showing the construction of a

shadow-picture theater. A Hungarian dancer (a shadow picture) 308

Shadow Pictures. The return from the Bois de

Boulogne. The ballet. A regiment of French soldiers 310

Shadow Picture. The Sphinx I: Pharaoh passing in triumph 312

Shadow Picture. The Sphinx II: Moses leading his people out of Egypt 314

Shadow Picture. The Sphinx III: Roman warriors in Egypt 316

Shadow Picture. The Sphinx IV: The British troops to-day 318

THE SHOW BUSINESS

I

At an interesting moment in Disraeli's picturesque career in British politics he indulged in one of his strikingly spectacular effects, in accord with his characteristic method of boldly startling the somewhat sluggish imagination of his insular countrymen; and in the next week's issue of Punch there was a cartoon by Tenniel reflecting the general opinion in regard to his theatrical audacity. He was represented as Artemus Ward, frankly confessing that "I have no principles; I'm in the show business."

The cartoon was good-humored enough, as Punch's cartoons usually are; but it was not exactly complimentary. It was intended to voice the vague distrust felt by the British people toward a leader who did not scrupulously avoid every possible opportunity to be dramatic. And yet every statesman who was himself possessed of constructive imagination, and who was therefore anxious to stir the imaginations of those he was leading, has laid himself open to the same charge. Burke, for one, was accused of being frankly theatrical; and Napoleon, the child of that French Revolution which Burke combated with undying vigor, never hesitated to employ kindred devices. When Napoleon took the Imperial Crown from the hands of the Pope to place it on his own head, and when Burke cast the daggers on the floor of the House of Commons, they were both proving that they were in the show business. So was Julius Cæsar when he thrice thrust aside the kingly crown; and so was Frederick on more than one occasion. Even Luther did not shrink from the spectacular if that could serve his purpose, as when he nailed his theses to the door of the church.

If the statesmen have now and again acted as tho they were in the show business, we need not be surprised to discover that the dramatists have done it even more often, in accord with their more intimate relation to the theater. No one would deny that Sardou and Boucicault were showmen, with a perfect mastery of every trick of the showman's trade. But this is almost equally true of the supreme leaders of dramatic art, Sophocles, Shakspere, and Molière. The great Greek, the great Englishman, and the great Frenchman, however much they might differ in their aims and in their accomplishments, were alike in the avidity with which they availed themselves of every spectacular device possible to their respective theaters. The opening passage of 'Œdipus the King,' when the chorus appeals to the sovran to remove the curse that hangs over the city, is as potent on the eye as on the ear. The witches and the ghost in 'Macbeth,' the single combats and the bloody battles that embellish many of Shakspere's plays are utilizations of the spectacular possibilities existing in that Elizabethan playhouse, which has seemed to some historians of the drama to be necessarily bare of all appeal to the senses. And in his 'Amphitryon' Molière has a succession of purely mechanical effects (a god riding upon an eagle, for example, and descending from the sky) which are anticipations of the more elaborate and complicated transformation scenes of the 'Black Crook' and the 'White Fawn.'

At the end of the nineteenth century the two masters of the stage were Ibsen and Wagner, and both of them were in the show business—Wagner more openly and more frequently than Ibsen. Yet the stern Scandinavian did not disdain to employ an avalanche in 'When We Dead Awaken,' and to introduce a highly pictorial shawl dance for the heroine of his 'Doll's House.' As for Wagner, he was incessant in his search for the spectacular, insisting that the music-drama was the "art-work of the future," since the librettist-composer could call to his aid all the other arts, and could make these arts contribute to the total effect of the opera. He conformed his practise to his principles, and as a result there is scarcely any one of his music-dramas which is not enriched by a most elaborate scenic accompaniment. The forging of the sword, the ride of the Valkyries, the swimming of the singing Rhinemaidens, are only a few of the novel and startling effects which he introduced into his operas; and in his last work, 'Parsival,' the purely spectacular element is at least as ample and as varied as any that can be found in a Parisian fairy-play or in a London Christmas pantomime. And what is the 'Blue Bird' of M. Maeterlinck, the philosopher-poet, who is also a playwright, but a fairy-play on the model of those long popular in Paris, the 'Pied de Mouton,' and the 'Biche au Bois'? It has a meaning and a purpose lacking in its emptier predecessors; but its method is the same as that of the uninspired manufacturers of these spectacular pieces.

II

It is not without significance that our newspapers, which have a keen understanding of the public taste, are in the habit of commenting upon entertainments of the most diverse nature under the general heading of "Amusements." It matters not whether this entertainment is proffered by Barnum and Bailey, or by Weber and Fields, by Sophocles or by Ibsen, by Shakspere or by Molière, by Wagner or by Gilbert and Sullivan, it is grouped with the rest of the amusements. And this is not so illogical as it may seem, since the primary purpose of all the arts is to entertain, even if every art has also to achieve its own secondary aim. Some of these entertainments make their appeal to the intellect, some to the emotions, and some only to the nerves, to our relish for sheer excitement and for brute sensation; but each of them in its own way seeks, first of all, to entertain. They are, every one of them, to be included in the show business.

This is a point of view which is rarely taken by those who are accustomed to consider the drama only in its literary aspects, and who like to think of the dramatic poet as a remote and secluded artist, scornful of all adventitious assistance, seeking to express his own vision of the universe, and intent chiefly, if not solely, on portraying the human soul. And yet this point of view needs to be taken by every one who wishes to understand the drama as an art, for the drama is inextricably bound up with the show business, and to separate the two is simply impossible. The theater is almost infinitely various, and the different kinds of entertainment possible in it cannot be sharply distinguished, since they shade into each other by almost imperceptible gradations. Only now and again can we seize a specimen that completely conforms to any one of the several types into which we theoretically classify the multiple manifestations of the drama.

Buffalo Bill's Wild West and Barnum and Bailey's Greatest Show on Earth might seem, at first sight, to stand absolutely outside the theater. But it is impossible not to perceive the close kinship between the program of the Barnum and Bailey show and the program of the New York Hippodrome, since they have the circus in common. At the Hippodrome, however, we have at least a rudimentary play with actual dialog and with abundant songs and dances executed by a charging squadron of chorus-girls; and in this aspect its spectacle is curiously similar to the nondescript medley which is popularly designated as a "summer song-show." Now, the summer song-show is first cousin to the so-called American "comic opera"—so different from the French opéra comique. Even if it has now fallen upon evil days, this American comic opera is a younger sister of the sparkling ballad-opera of Gilbert and Sullivan, and of the exhilarating opéra bouffe of Offenbach, with its libretto by Meilhac and Halévy.

We cannot fail to perceive that the librettos of Gilbert and of Meilhac and Halévy are admirable in themselves, that they would please even without the music of Sullivan and Offenbach, and that they are truly comedies of a kind. That is to say, the books of 'Patience' and 'Pinafore' do not differ widely in method or in purpose from Gilbert's non-musical play 'Engaged'; and the books of the 'Vie Parisienne' and the 'Diva' do not differ widely from Meilhac and Halévy's non-musical play, 'Tricoche et Cacolet.' 'Engaged' and 'Tricoche et Cacolet' are farces or light comedies, and we find that it is not easy to draw a strict line of demarcation between light comedies of this sort and comedies of a more elevated type. Gilbert was also the author of 'Sweethearts,' and of 'Charity,' and Meilhac and Halévy were also the authors of 'Froufrou.' Still more difficult would it be to separate sharply plays like 'Charity' and 'Froufrou' from the social dramas of Pinero and Ibsen, the 'Benefit of the Doubt,' for instance, and the 'Doll's House.' Sometimes these social dramas stiffen into actual tragedy, the 'Second Mrs. Tanqueray,' for example, and 'Ghosts.' And more than one critic has dwelt upon the structural likeness of the somber and austere 'Ghosts' of Ibsen to the elevated and noble 'Œdipus the King' of Sophocles, even if the Greek play is full of a serener poetry and charged with a deeper message.

It is a far cry from Buffalo Bill's Wild West to the 'Œdipus' of Sophocles; but they are only opposite ends of a long chain which binds together the heterogeneous medley of so-called "amusements." In the eyes of every observer with insight into actual conditions, the show business bears an obvious resemblance to the United States, in that it is a vast territory divided into contiguous States, often difficult to bound with precision; and, like the United States, the show business is, in the words of Webster, "one and indivisible, now and forever." There is indisputable profit for every student of the art of the stage in a frank recognition of the fact that dramatic literature is inextricably associated with the show business, and the wider and deeper his acquaintance with the ramifications of the show business, the better fitted he is to understand certain characteristics of the masterpieces of dramatic literature. Any consideration of dramatic literature, apart from the actual conditions of performance, apart from the special theater for which any given play was composed, and to the conditions of which it had, perforce, to conform, is bound to be one-sided, not to say sterile. The masterpieces of dramatic literature were all of them written to be performed by actors, in a theater, and before an audience. And these masterpieces of dramatic literature which we now analyze with reverence, were all of them immediately successful when represented by the performers for whom they were written, and in the playhouses to the conditions of which they had been adjusted.

It is painfully difficult for the purely literary critic to recognize the inexorable fact that there are no truly great plays which failed to please the contemporary spectators for whose delight they were devised. Many of the plays which win success from time to time, indeed, most of them, achieve only a fleeting vogue; they lack the element of permanence; they have only theatrical effectiveness; and they are devoid of abiding dramatic value. But the truly great dramas established themselves first on the stage; and afterward they also revealed the solid qualities which we demand in the study. They withstood, first of all, the ordeal by fire before the footlights of the theater, and they were able thereafter also to resist the touchstone of time in the library.

When an academic investigator into the arid annals of dogmatic disquisition about the drama was rash enough to assert that, "from the standpoint of the history of culture, the theater is only one, and a very insignificant one, of all the influences that have gone to make up dramatic literature," Mr. William Archer promptly pointed out that this was "just about as reasonable as to declare that the sea is only one, and a very insignificant one, among the influences that have gone to the making of ships." It is true, Mr. Archer admitted, that there are "model ships and ships built for training purposes on dry land; but they all more or less closely imitate sea-going vessels, and if they did not, we should not call them ships at all.... The ship-builder, in planning his craft, must know what depths of water—be it river, lake, or ocean—she will have to ply in, what conditions of wind and weather she may reckon upon encountering, and what speed will be demanded of her if she is to fulfil the purpose for which she is destined.... The theater—the actual building, with its dimensions, structure, and scenic appliances—is the dramatist's sea. And the audience provides the weather."

III

Since the drama is irrevocably related to the theater, all the varied ramifications of the show business have their interest and their significance for students of the stage. It is not too much to say that there is no form of entertainment, however humble and however remote from literature, which may not supply a useful hint or two, now and again, to the historian of the drama. For example, few things would seem farther apart than the lamentable tragedy of Punch and Judy and the soul-stirring plays of the Athenian dramatic poets; and yet there is more than one point of contact between these two performances. An alert observer of a Punch-and-Judy show in the streets of London can get help from it for the elucidation of a problem or two which may have puzzled him in his effort to understand the peculiarities of Attic tragedy. Mr. Punch's wooden head, for example, has the same unchanging expression which characterized the towering masks worn by the Athenian performers. In like manner a nondescript hodgepodge of funny episodes, interspersed with songs and dances, such as Weber and Fields used to present in New York, may be utilized to shed light on the lyrical-burlesques of Aristophanes as these were performed in Athens more than two thousand years ago.

Perhaps even a third instance of this possibility of explaining the glorious past by the humble present may not be out of place. A few years ago Edward Harrigan put together a variety-show sketch, called the 'Mulligan Guards,' and its success encouraged him to develop it into a little comic drama called the 'Mulligan Guards' Picnic,' which was the earliest of a succession of farcical studies of tenement-house life in New York, culminating at last in a three-act comedy, entitled 'Squatter Sovereignty.' In this series of humorous pieces Harrigan set before us a wide variety of types of character, Irishmen of all sorts, Germans and Italians, negroes and Chinamen, as these are commingled in the melting-pot of the cosmopolitan metropolis. These humorous pieces were the result of a spontaneous evolution, and their author was wholly innocent of any acquaintance with the Latin drama. And yet, as it happened, Harrigan was doing for the tenement-house population of New York very much what Plautus had done for the tenement-house population of Rome. A familiarity with the plays of the Latin playwright could not but increase our appreciation of the amusing pieces of the Irish-American sketch-writer; and a familiarity with the comic dramas of Harrigan could not fail to be of immediate assistance to us in our desire to understand the remote life which Plautus was dealing with.

The plays of the Roman dramatist were deliberately adapted from the Greek, and they therefore had an avowedly literary source, whereas the immediate origin of the plays performed in New York was only an unpretending sketch for a variety-show; but both of these groups had the same flavor of veracity in their reproduction of the teeming life of the tenements. Humble as is the beginning of the 'Mulligan Guard' series, at least as humble is the beginning of the improvised pieces of the Italians, the comedy of masks, which Molière lifted into literature in his 'Etourdi,' and in his 'Fourberies de Scapin.' In the hands of the Italians the comedy of masks was absolutely unliterary, since it was not even written, and its performers were not only comedians, but acrobats also. And here the drama is seen to be impinging on the special sphere of the circus—just as it does again in the plays prepared for the New York Hippodrome. It is more than probable that this improvised comedy of the Italians is the long development of a primitive semi-gymnastic, semi-dramatic entertainment, given by a little group of strollers, performing in the open market-place to please the casual crowd that might collect.

Equally unpretending was the origin of the French melodrama, which Victor Hugo lifted into literature in his 'Hernani' and 'Ruy Blas.' It began in the temporary theaters erected for a brief season in one or the other of the fairs held annually in different parts of Paris. The performances in these playhouses were almost exactly equivalent to those in our variety-shows; they were medleys of song and dance, of acrobatic feats and of exhibitions of trained animals. As in our own variety-shows, again, there were also little plays performed from time to time, at first scarcely more than a framework on which to hang songs and dances, but at last taking on a solider substance, until finally they stiffened themselves into pathetic pieces in three or more acts, capable of providing pleasure for a whole evening. The humor was direct, and the characters were painted in the primary colors; the passions were violent, and the plots were arbitrary; but the playwrights had discovered how to hold the interest of their simple-minded spectators, and how to draw tears and laughter at will.

In fact, the more minutely the history of the stage is studied, the more clearly do we perceive that the beginnings of every form of the drama are strangely unpretentious, and that literary merit is attained only in the final stages of its development. Dramatic literature is but the ultimate evolution of that which in the beginning was only an insignificant and unimportant experiment in the show business; and it must always remain intimately related to the show business, even when it climbs to the lonely peaks of the poetic drama. Whatever its value, and however weighty its message, it is still to be commented upon under the head of "amusements," for if it does not succeed in amusing, it ceases to exist except in the library, and even there only for special students. It lives by its immediate theatrical effectiveness alone, even if it can survive solely by its literary quality.

IV

Those who are in the habit of gaging the drama by this literary quality only are prone to deplore the bad taste of the public which flocks to purely spectacular pieces. But this again is no new thing, and it does not disclose any decline in the ability to appreciate the best. A century ago in London, when Sarah Siddons and John Philip Kemble were in the full plenitude of their powers, and when they were performing the noblest plays of Shakspere, they were thrust aside for a season or two while the theater was given up to empty melodramatic spectacles like 'Castle Specter' and the 'Cataract of the Ganges.' It was horrifying to the lovers of the drama that these great actors in those great plays should have to give way to the attraction exerted on the public by a trained elephant, or by an imitation waterfall; but it is equally horrifying to be informed that the theater in London for which Shakspere wrote his masterpieces, and in which he himself appeared as an actor, was also used for fencing-matches, and for bull-baitings and bear-baitings, and that the theater in Athens for which Sophocles wrote his masterpieces, and in which he may have appeared as an actor, was also used for the annual cock-fight.

So strong is the popular appreciation of spectacle that the drama, the true theater as distinguished from the mere show business, has always to fight for its right to exist, and to hold its place in competition with less intellectual and more sensational entertainments. The playhouses of any American city are likely to have a lean week whenever the circus comes to town, and perhaps the chief reason why the most of them now close in summer is to be sought not so much in the frequent hot spells, as in the irresistible attraction exerted by the base-ball games. The drama in Spain, which flourished superbly in the days of Lope de Vega and Calderon, sank into a sad decline when it had to compete with the fiercer delights of the bullfight; and the drama in Rome was actually killed out by the overpowering rivalry of the sports of the arena, the combats of gladiators, and the matching of men with wild beasts. What is known to the economists as Gresham's Law, according to which an inferior currency always tends to drive out a superior, seems to have an analog in the show business.

(1912.)

II

THE LIMITATIONS OF THE STAGE

THE LIMITATIONS OF THE STAGE

I

Few competent critics would dispute the assertion that the drama, if not actually the noblest of the arts, is at all events the most comprehensive, since it can invoke the aid of all the others without impairing its own individuality or surrendering its right to be considered the senior partner in any alliance it may make. Poetry, oratory, and music, painting, sculpture, and architecture, these the drama can take into its service, with no danger to its own control. Yet even if the drama may have the widest range of any of the arts, none the less are its boundaries clearly defined. What it can do, it does with a sharpness of effect and with a cogency of appeal no other art can rival. But there are many things it cannot do; and there are not a few things that it can attempt only at its peril. Some of these impossibilities and inexpediencies are psychologic subtleties of character and of sentiment too delicate and too minute for the magnifying lens of the theater itself; and some of them are physical, too large in themselves to be compressed into the rigid area of the stage. In advance of actual experiment, it is not always possible for even the most experienced of theatrical experts to decide the question with certainty.

Moreover, there is always the audience to be reckoned with, and even old stagers like Henry Irving and Victorien Sardou cannot foresee the way in which the many-headed monster will take what is set before it. When Percy Fitzgerald and W. G. Wills were preparing an adaptation of the 'Flying Dutchman' for Henry Irving, the actor made a suggestion which the authors immediately adopted. The romantic legend has for its hero a sea-captain condemned to eternal life until he can find a maiden willing to share his lot; and when at last he meets the heroine she has another lover, who is naturally jealous of the new aspirant to her hand. The young rival challenges Vanderdecken to a duel, and what Irving proposed was that the survivor of the fight should agree to throw the body of his rival into the sea, and that the waves should cast up the condemned Vanderdecken on the shore, since the ill-fated sailor could not avoid his doom by death at the hand of man. This was an appropriate development of the tale; it was really imaginative; and it would have been strangely moving if it had introduced into it a ballad on the old theme. But in a play performed before us in a theater its effect was not altogether what its proposer had hoped for, altho he presented it with all his marvelous command of theatrical artifice.

The stage-setting Irving bestowed upon this episode was perfectly in keeping with its tone. The spectators saw the sandy beach of a little cove shut in by cliffs, with the placid ocean bathed in the sunset glow. The two men crossed swords on the strand; Vanderdecken let himself be killed, and the victorious lover carried his rival's body up the rocks and hurled it into the ocean. Then he departed, and for a moment all was silence. A shuddering sigh soon swept over the face of the waters, and a ripple lapped the sand. Then a little wave broke on the beach, and withdrew, rasping over the stones. At last a huge roller crashed forward and the sea gave up its dead. Vanderdecken lay high and dry on the shore, and in a moment he staggered to his feet, none the worse for his wounds. But unfortunately the several devices for accomplishing this result, admirable as they were, drew attention each of them to itself. The audience could not help wondering how the trick of the waves was being worked, and when the Flying Dutchman was washed up by the water, it was not the mighty deep rejecting Vanderdecken, again cursed with life, that the spectators perceived, but rather the dignified Henry Irving himself, unworthily tumbled about on the dust of his own stage. In the effort to make visible this imaginative embellishment of the strange story, its magic potency vanished. The poetry of the striking improvement on the old tale had been betrayed by its translation into the material realities of the theater, since the concrete presentation necessarily contradicted the abstract beauty of the idea.

Here we find ourselves face to face with one of the most obvious limitations of the stage—that its power of suggestion is often greater than its power of actual presentation. There are many things, poetic and imaginative, which the theater can accomplish, after a fashion, but which it ventures upon only at imminent peril of failure. Many things which are startlingly effective in the telling are ineffective in the actual seeing. The mere mechanism needed to represent them will often be contradictory, and sometimes even destructive. Perhaps it may be advisable to cite another example, not quite so cogent as Irving's 'Vanderdecken,' and yet carrying the same moral. This other example will be found in a piece by Sardou, a man who knew all the possibilities of the theater as intimately as Irving himself, and who was wont to utilize them with indefatigable skill. Indeed, so frequently did the French playwright avail himself of stage devices, and so often was he willing to rely upon them, that not a few critics of our latter-day drama have been inclined to dismiss him as merely a supremely adroit theatrical trickster.

In his sincerest play, 'Patrie,' the piece which he dedicated to Motley, and which he seems himself to have been proudest of, Sardou invented a most picturesque episode. The Spaniards are in possession of Brussels; the citizens are ready to rise, and William of Orange is coming to their assistance. The chiefs of the revolt leave the city secretly and meet William at night in the frozen moat of an outlying fort. A Spanish patrol interrupts their consultation, and forces them to conceal themselves. A little later a second patrol is heard approaching, just when the return of the first patrol is impending. For the moment it looks as tho the patriots would be caught between the two Spanish companies. But William of Orange rises to the occasion. He calls on his "sea-wolves"; and when the second patrol appears, marching in single file, there suddenly spring out of the darkness upon every Spanish soldier two fur-clad creatures, who throttle him, bind him, and throw him into a hole in the ice of the moat. Then they swiftly fill in this gaping cavity with blocks of snow, and trample the path level above it. And almost immediately after the sea-wolves have done their deadly work and withdrawn again into hiding, the first patrol returns, and passes all unsuspecting over the bodies of their comrades—a very practical example of dramatic irony.

As it happened, I had read 'Patrie' some years before I had an opportunity to see it on the stage, and this picturesque scene had lingered in my memory so that in the theater I eagerly awaited its coming. When it arrived at last I was sadly disappointed. The sea-wolves belied their appetizing name; they irresistibly suggested a group of trained acrobats, and I found myself carelessly noting the artifices by the aid of which the imitation snowballs were made to fill the trapdoor of the stage which represented the yawning hole in the ice of the frozen moat. The thing told was picturesque, but the thing seen was curiously unmoving; and I have noted without surprise that in the latest revival of 'Patrie' the attempt to make this episode effective was finally abandoned, the sea-wolves being cut out of the play.

II

In 'Patrie' as in 'Vanderdecken' the real reason for the failure of these mechanical devices is that the plays were themselves on a superior level to those stage-tricks; the themes were poetic, and any theatrical effect which drew attention to itself interrupted the current of emotional sympathy. It disclosed itself instantly as incongruous, as out of keeping with the elevation of the legend—in a word, as inartistic. A similar effect, perhaps even more frankly mechanical, would not be inartistic in a play of a lower type, and it might possibly be helpful in a frankly spectacular piece, even if this happened also to be poetic in intent. In a fairy-play, a féerie, as the French term it, we expect to behold all sorts of startling ingenuities of stage-mechanism, whether the theme is delightfully imaginative, as in Maeterlinck's beautiful 'Blue Bird,' or crassly prosaic, as in the 'Black Crook' and the 'White Fawn.'

In picturesque melodrama also, in the dramatization of 'Ben Hur,' for example, we should be disappointed if we were bereft of the wreck of the Roman galley, and if we were deprived of the chariot race. These episodes can be presented in the theater only by the aid of mechanisms far more elaborate than those needed for the scenes in 'Vanderdecken' and 'Patrie'; but in 'Ben Hur' these mechanisms are not incongruous and distracting as were the simpler devices of 'Vanderdecken' and 'Patrie,' because the dramatization of the romanticist historical novel is less lofty in its ambition, less imaginative, less ethereally poetic. In 'Vanderdecken' and in 'Patrie' the tricks seemed to obtrude themselves, whereas in 'Ben Hur' they were almost obligatory. In certain melodramas with more modern stories—in the amusing piece called the 'Round Up,' for example—the scenery is the main attraction. The scene-painter is the real star of the show. And there is no difficulty in understanding the wail of the performer of the principal part in a piece of this sort, when he complained that he was engaged to support forty tons of scenery. "It's only when the stage-carpenters have to rest and get their breath that I have a chance to come down to the footlights and bark for a minute or two."

A moment's consideration shows that this plaintive protest is unreasonable, however natural it may be. In melodramas like the 'Round Up' and 'Ben Hur,' as in fairy-plays like the 'Blue Bird,' the acting is properly subordinated to the spectacular splendor of the whole performance. When we enter a theater to behold a play of either of these types, we expect the acting to be adequate, no doubt, but we do not demand the highest type of histrionic excellence. What we do anticipate, however, is a spectacle pleasing to the eye and stimulating to the nerves. In plays of these two classes the appeal is sensuous rather than intellectual; and it is only when the appeal of the play is to the mind rather than to the senses that merely mechanical effects are likely to be disconcerting.

Mr. William Archer has pointed out that Ibsen in 'Little Eyolf,' has for once failed to perceive the strict limitation of the stage when he introduced a flagstaff, with the flag at first at half-mast, and a little later run up to the peak. Now, there are no natural breezes in the theater to flutter the folds of the flag, and every audience is aware of the fact. This, then, is the dilemma: either the flag hangs limp and lifeless against the pole, which is a flat spectacle, or else its folds are made to flutter by some concealed pneumatic blast or electric fan, which instantly arouses the inquiring curiosity of the audience. Here we find added evidence in support of Herbert Spencer's invaluable principle of Economy of Attention, which he himself applied only to rhetoric, but which is capable of extension to all the other arts—and to no one of them more usefully than to the drama. At any given moment a spectator in the theater has only so much attention to bestow upon the play being presented before his eyes, and if any portion of his attention is unduly distracted by some detail—like either the limpness or the fluttering of a flag—then he has just so much less to give to the play itself.

Very rarely, indeed, can we catch Ibsen at fault in a technical detail of stage-management; he was extraordinarily meticulous in his artful adjustment of the action of his social dramas to the picture-frame stage of our modern cosmopolitan theater. He was marvelously skilful in endowing each of his acts with a background harmonious for his characters; and nearly always was he careful to refrain from the employment of any scenic device which might attract attention to itself. He eschewed altogether the more violent spectacular effects, altho he did call upon the stage manager to supply an avalanche in the final act of 'When the Dead Awaken'; but even this bold convulsion of nature was less incongruous than might be expected, since it was not exhibited until the action of the play itself was complete. In fact, the avalanche might be described as only a pictorial epilog.

III

The principle of sternly economizing the attention of the audience can be violated by distractions far less extraneous and far less extravagant than avalanches. When Marmontel's forgotten tragedy of 'Cleopatra' was produced in the eighteenth century at the Théâtre Français, the misguided poet prevailed upon Vaucanson to make an artificial asp, which the Egyptian queen coiled about her arm at the end of the play, thereby releasing a spring, whereupon the beast raised its head angrily and emitted a shrill hiss before sinking its fangs into Cleopatra's flesh. At the first performance a spectator, bored by the tediousness of the tragedy, rose to his feet when he heard the hiss of the tiny serpent: "I agree with the asp!" he cried, as he made his way to the door.

But even if Vaucanson's skilful automaton had not given occasion for this disastrous gibe, whatever attention the audience might pay to the mechanical means of Cleopatra's suicide was necessarily subtracted from that available for the sad fate of Cleopatra herself. If at that moment the spectators noted at all the hissing snake, then they were not really in a fit mood to feel the tragic death-struggle of "the serpent of old Nile." A kindred blunder was manifest in a recent sumptuously spectacular revival of 'Macbeth,' when the three witches flew here and there thru the dim twilight across the blasted heath, finally vanishing into empty air. These mysterious flittings and disappearances were achieved by attaching the performers of the weird sisters to invisible wires, whereby they could be swung aloft; the trick had been exploited earlier in the so-called Flying Ballet, wherein it was a graceful and amusing adjunct of the terpsichorean revels. But in 'Macbeth' it emptied Shakspere's scene of its dramatic significance, since the spectator waited for and watched the startling flights of the witches, and admired the dexterity with which their aerial voyages were controlled; and as a result he failed to feel the emotional importance of the interview between Macbeth and the withered croons, whose untoward greetings were to start the villain-hero on his downward career of crime.

In this same revival of 'Macbeth' an equally misplaced ingenuity was lavished on the apparition of Banquo's ghost at the banquet. The gruesome specter was made mysteriously visible thru the temporarily transparent walls of the palace, until at last he emerged to take his seat on Macbeth's chair. The effect was excellent in itself, and the spectators followed all the movements of the ghost with pleased attention, more or less forgetting Macbeth, and failing to note the maddening effect of the apparition upon the seared countenance of the assassin-king. In this revival of 'Macbeth' no opportunity was neglected to adorn the course of the play with every possible scenic and mechanic accompaniment; and the total result of these accumulated artificialities of presentation was to rob one of Shakspere's most poetic tragedies of nearly all its poetry, and to reduce this imaginative masterpiece to the prosaic level of a spectacular melodrama.

Another of Shakspere's tragedies has become almost impossible in our modern playhouses, because the stage-manager does not dare to do without the spectacular effects that the story seems to demand. Shakspere composed 'King Lear' for the bare platform-stage of the Globe Theater, devoid of all scenery, and supplied with only the most primitive appliances for suggesting rain and thunder; and he introduced three successive storm scenes, each intenser in interest than the one that went before, until the culmination comes in perhaps the sublimest and most pitiful episode in all tragedy, when the mad king and his follower, who is pretending to be insane, and his faithful fool are together out in the tempest. At the original production, three centuries ago, the three storms may have increased in violence as they followed one another; but at best the fierceness of the contending elements could then be only suggested, and the rain and the thunder were not allowed to divert attention away from the agonized plight of the mad monarch. But to-day the three storm scenes are rolled into one, and the stage-manager sets out to manufacture a realistic tempest in rivalry with nature. The mimic artillery of heaven and the simulated deluge from the skies which the producer now provides may excite our artistic admiration for his skill, but they distract our attention from the coming together of the characters so strangely met in the midst of the storm. The more realistically the tempest is reproduced the worse it is for the tragedy itself; and in most recent revivals the full effect of the painful story has been smothered by the sound and fury of the man-made storm.

The counterweighted wires which permit the figures of the Flying Ballet to soar over the stage and to float aloft in the air, disturb the current of our sympathy when they are employed to lend lightness to intangible creatures like the weird sisters of Shakspere's tragedy; but they have been more artistically utilized in two of Shakspere's comedies to suggest the ethereality of Puck and of Ariel. The action of the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' takes place in fairy-land, and that of the 'Tempest' passes in an enchanted island, and even if we wonder for a moment how the levitation of these airy spirits is achieved, this temporary distraction of our attention is negligible in playful comedies like these with all their scenes laid in a land of make-believe. And yet it may be doubted whether even the 'Midsummer Night's Dream' and the 'Tempest,' fairy-plays as they are, do not on the whole lose more than they gain from elaborate scenic and mechanical adjuncts. They are of poetry all compact, and the more simply they are presented, the less obtrusive the scenery and the less protruded the needful effects, the more the effort of the producer is centered upon preserving the ethereal atmosphere wherein the characters live, move, and have their being, the more harmonious the performance is with the pure fancy which inspired these two delightful pieces, then the more truly successful is the achievement of the stage-manager.

IV

On the other hand, of course, the scenic accompaniment of a poetic play, whether tragic or romantic or comic, must never be so scant or so barren as to disappoint the spectators. The stage-accessories must be adequate and yet subordinate; they ought to resemble the clothes of a truly well-dressed woman, in that they never call attention to themselves altho they can withstand and even reward intimate inspection. This delicate ideal of artistic stage-setting, esthetically satisfying, and yet never flamboyant, was completely attained in the production of 'Sister Beatrice,' at the New Theater, due to the skill and taste of Mr. Hamilton Bell. The several manifestations of the supernatural might easily have been over-emphasized; but a fine restraint resulted in a unity of tone and of atmosphere, so subtly achieved that the average spectator carried away the memory of more than one lovely picture without having let his thoughts wander away to consider by what means he had been made to feel the presence of a miracle.

The special merit of this production of 'Sister Beatrice' lay in the delicate art by which more was suggested than could well be shown. In the theater, more often than not, the half is greater than the whole, and what is unseen is frequently more powerful than what is made visible. In Mr. Belasco's 'Darling of the Gods,' a singularly beautiful spectacle, touched at times with a pathetic poetry, the defeated samurais are at last reduced to commit hara-kiri. But we were not made spectators of these several self-murders; we were permitted to behold only the dim cane-brake into which these brave men had withdrawn, and to overhear each of them call out his farewell greetings to his friends before he dealt himself the deadly thrust. If we had been made witnesses of this accumulated self-slaughter we might have been revolted by the brutality of it. Transmitted to us out of a vague distance by a few scattered cries, it moved us like the inevitable close of a truly tragic tale.

In the 'Aiglon' of M. Rostand, Napoleon's feeble son finds himself alone with an old soldier of his father's on the battle-field of Wagram; and in the darkness of the night, and in the turmoil of a wind-storm the hysteric lad almost persuades himself that he is actually present at the famous fight, that he can hear the shrieks of the wounded, and the groans of the dying, and that he can see the hands and arms of the dead stretched up from the ground. This is all in the sickly boy's fancy, of course, and yet in Paris the author had voices heard, and caused hands and arms to be extended upward from the edge of the back drop, thus vulgarizing his own imaginative episode by the presentation of a concrete reality. Not quite so inartistic as this, and yet frankly freakish was the arrangement of the closet scene between Hamlet and his mother, when Sarah-Bernhardt made her misguided effort to impersonate the Prince of Denmark. On the walls of the room where Hamlet talks daggers to the queen there were full-length, life-sized portraits of her two successive husbands, and when Hamlet bids her look on this picture, and on this, the portrait of Hamlet's father became transparent, and in its frame the spectators suddenly perceived the ghost. This is an admirable example of misplaced cleverness, of the search for novelty for its own sake, of the sacrifice of the totality of impression to a mere trick.

'Hamlet' is the most poetic of plays, and the 'Aiglon' does its best to be poetic, and therefore the less overt spectacle there may be in the performance of these dramas the easier it will be for the spectator to focus his attention on the poetry itself. Even more pretentiously poetic than the 'Aiglon' is 'Chantecler,' upon which the ambitious author has also lavished a great variety of stage-effects—as tho he were not quite willing to rely for success upon his lyrical exuberance. In M. Rostand's 'Aiglon' and 'Chantecler,' as in Sarah-Bernhardt's 'Hamlet,' there was to be observed a frequent confusion of the merely theatric with the purely dramatic—a confusion to be found forty years ago in Fechter's 'Hamlet.' That picturesque French actor made over the English tragedy into a French romantic melodrama; he kept the naked plot, and he cut out all the poetry. He lowered Shakspere's play to the level of the other melodramas in which he had won success—for instance, 'No Thorofare,' due to the collaboration of Dickens and Wilkie Collins, or the earlier 'Fils de la Nuit,' acted in Paris long before Fechter appeared on the English-speaking stage.

The 'Son of the Night' was a pirate bold, personated, of course, by Fechter, and in one act his long, low, rakish craft with its black flag flying, skimmed across the stage, cutting the waves, and dropping anchor close to the footlights. The surface of the sea was represented by a huge cloth, and the incessant motion of the waves was due to the concealed activities of a dozen boys. The play had so long a run that the sea-cloth was worn dangerously thin. At last at one performance, a rent spread suddenly and disclosed a disgusted boy, just as the pirate ship with the Son of the Night on its deck was preparing to come about. Fechter was equal to the emergency. "Man overboard!" he cried, and, leaning over the bow of the boat, he grabbed the boy by the collar and pulled him on deck. Probably very few of the spectators noticed the mishap, and if they had all observed it, what matter? A laugh or two, more or less, during the performance of a prosaic melodrama, is of little or no consequence. A disconcerting accident like this in a play like the 'Son of the Night' does not cut any vital current of sympathy, for this is a quality to which the piece could make no claim. But in a truly poetic play a mishap of this sort would be a misfortune in that it might precipitate the interest and interrupt the harmony of attention demanded by the imaginative drama itself.

(1912.)

A MORAL FROM A TOY THEATER

I

In 1881, when William Ernest Henley was hard put to it to make a living, Sir Sidney Colvin kindly recommended him for the editorship of the monthly Magazine of Art. Among the contributors whom the new editor called to his aid was Robert Louis Stevenson, and among the contributions the latter made to the former's magazine was the highly characteristic and self-revelatory essay, entitled 'A Penny Plain and Two Pence Colored,' now included in the volume called 'Memories and Portraits.' In this playful paper Stevenson makes one of his many returns to his boyhood, whose moods he could always recapture at will with the assistance of that imaginative memory which was one of his special gifts, and he was able to replevin from the dim limbo of things half forgotten his longing delight in the toy theater, the scenes for which and the necessary properties and the several characters themselves in their successive dresses were to be procured printed on very thin cardboard, so that the proud possessor might cut them out at will. If the youthful capitalist had accumulated twopence, he could acquire these treasures already resplendent in their glowing hues; and yet Stevenson held that the lad was happier who parted with only a single penny, reserving the half of his fortune for the purchase of the paints wherewith he might himself vivify this scenery and these properties, and so cause his characters to start to life, emblazoned in the bold colors which please the puerile mind.

These sheets of thin cardboard, with thin little pamphlets containing the text of the pieces to be performed in the toy theater, were originally known as Skelt's Juvenile Drama; and one Skelt seems to have been its originator, probably in the early part of the nineteenth century. Apparently he parted with his precious stock in trade to one Park, who passed it on in due season to one Webb, who transmitted it to one Redington, until at last it descended to its present owner, one B. Pollock, of 73 Hoxton Street, London, N. Stevenson affected to think that Skelt's Juvenile Drama had "become, for the most part, a memory"; yet it survives now in the second decade of the twentieth century as Pollock's Juvenile Drama, and Mr. Pollock proclaims that he has republished some score plays, and that he keeps them always in print, plain and colored. He offers, furthermore, to supply "Drop Scenes, Top Drops, Orchestras, Foot and Water Pieces, Single Portraits, Combats—Fours, Sixes, Twelves, Sixteens—Fairies, Horse Soldiers, Clowns, Rifles, Animals, Birds, Butterflies, Houses, Views, Ships, &c., plain and colored, 1/2d sheet plain, 1d sheet colored."

It is from the covers of "the book of the words" of the 'Miller and His Men' that this enticing proclamation is taken—the 'Miller and His Men,' "adapted only for Pollock's characters and scenes," and accompanied by "7 Plates characters, 11 Scenes, 3 Wings, Total 21 Plates." The persons of the drama and the scenes wherein that drama is played out to its fiery end, are all in the bolder manner of the Old Masters, who sought the broadest effects, and who willingly neglected petty details. How bold and how broad the manner and the effects can best be judged by an honest transcription from the final page of the book of words, wherein the terse and tense dialog, single speech clashing with single speech, is accompanied by stage directions for the instruction of the Young Masters who are about to produce the sublime spectacle:

Enter Grindorf left hand, plate 4.

Enter Karl and Friberg, swords drawn, plate 4, followed by the Troops, right hand, plate 7.

Grindorf: Ha! ha! I have escaped you, have I?

Karl: But you are caught in your own trap.

Grindorf: Spiller!—Golotz! Golotz! I say!

Count: Villain! you cannot escape us now! Surrender, or instantly meet thy fate!

Grindorf: Surrender! I have sworn never to descend from this place alive!

Enter Lothair, as Spiller, 3rd dress, left hand, plate 7.

Grindorf: Spiller, let my bride appear.

Exit Lothair.

Enter Kehnar, right hand, plate 1.

Enter Ravina with torch, plate 7.

Ravina: Before it is too late, restore Claudine to her father's arms!

Grindorf: Never!

Ravina: Then I know my course!

Enter Lothair with Claudine, left hand, plate 6.

Kehnar: My child! Ah, Grindorf, spare her!

Grindorf: Hear me, Count Friberg; if you do not withdraw your followers, by my hand she dies!

Count: Never, till thou art yielded to justice!

Grindorf: No more—this to her heart!

Lothair: And this to thine!

Exit Lothair and Claudine, and Grindorf.

Re-enter Grindorf and Lothair fighting, plate 6, fight and exit.

Grindorf to be put on wounded, plate 7.

Re-enter Lothair with Claudine, plate 6.

Lothair: Ravina, fire the train!

Scene changes to explosion, Scene 11, No. 9.

The words are striking and the actions are startling, and it is no wonder that plate 7 and scene 11, No. 9, filled with joy the heart of Robert Louis Stevenson when he was a perfervid Scot of fourteen. In his manly maturity, when he had risen to an appreciation of portraits by Raeburn, and when he had sat at the feet of that inspired critic of painting, his cousin, R. A. M. Stevenson, he admitted that he had no desire to insist upon the art of Skelt's purveyors. "Those wonderful characters that once so thrilled our soul with their bold attitude, array of deadly engines and incomparable costume, to-day look somewhat pallidly," he confessed regretfully; "the extreme hard favor of the heroine strikes me, I had almost said with pain; the villain's scowl no longer thrills me like a trumpet; and the scenes themselves, those once incomparable landscapes, seem the efforts of a prentice hand. So much of fault we can find; but, on the other side, the impartial critic rejoices to remark the presence of a great unity of gusto; of those direct claptrap appeals which a man is dead and buriable when he fails to answer; of the footlight glamor, the ready-made, barefaced, transpontine picturesque, a thing not one with cold reality, but how much dearer to the mind!"

II

"Transpontine" is a Briticism for which the equivalent Americanism is "Bowery." The plays which Skelt vended for the enjoyment of romantic youth were not of his own invention, nor were they the work of his hirelings; they were artfully simplified condensations of melodramas long popular in London at the theaters on the Surrey side of the Thames, and in New York at the Bowery. In French's Standard Drama, the Acting Edition, to be obtained in yellow covers for fifteen cents, one may find "the 'Miller and His Men,' a Melo-Drama in Two Acts, by F. Pocock, Esq., author of the 'Robber's Wife,' 'John of Paris,' 'Hit or Miss,' 'Magpie and the Maid,' etc., with original casts, scene and property plots, costumes, and all the stage business." And the list of properties required for the final scene helps to elucidate what may have been cryptic in the dialog quoted from the compacted adaptation of Skelt:

Scene 4:—Slow match laid from stage in C. to mill. Lighted torch for Ravina. Red fire and explosion 3 E. L. H. Wood crash 3 E. L. H. Six stuffed figures of robbers behind mill, L. H. Eight guns, swords, and belts for hussars. Disguise cloak for Lothair. Fighting swords for Lothair and Wolf. [Wolf is evidently another name for Grindorf.]

Thus we see that the pleasant country of the Skelts stretched from the Surrey side of the Thames to the Bowery bank of the Hudson, and that the Skeltic temperament was purely melodramatic, its bass notes being transposed to adjust it to the clear treble of boyhood. It is greatly to be regretted that no inquiring scholar has yet devoted himself to the task of tracing the history of English melodrama, as Professor Thorndike has traced the history of English tragedy. Of course, there have always been melodramatic plays ever since the drama began to assert itself as an independent form of art. There is a melodramatic element in the 'Medea' of Euripides, as there is in the 'Rodogune' of Corneille; and in the Elizabethan theater the so-called tragedy of blood is nothing if not melodramatic. Yet the special form of English melodrama that flourished in the later years of the eighteenth century and the earlier years of the nineteenth deserves a more careful study than it has yet received. Apparently it was due partly to a decadence of the native type of drama represented by Lillo's 'George Barnwell,' and partly to the stimulation received first from the emotional pieces of the German Kotzebue, and afterward from the picturesque pieces of the French Pixérécourt. And not to be neglected is the influence immediately exerted on the popular plays of the latter part of the period by the romances of Scott and of Cooper.

Altho these plays were devoid of literary merit, of style, of veracity of character delineation, of sincerity of motive, they were not without theatrical effectiveness—or they could never have maintained themselves in the theater. As Sir Arthur Pinero has seen clearly, "a drama which was sufficiently popular to be transferred to the toy theaters was almost certain to have a sort of rude merit in its construction. The characterization would be hopelessly conventional, the dialog bald and despicable—but the situations would be artfully arranged, the story told adroitly and with spirit." In other words, the compounders of these melodramas were fairly skilful in devising plots likely to arouse and to sustain the interest of uncritical audiences. Probably they were unfamiliar with Voltaire's assertion that the success of a play depends mainly upon the choice of its story; and it is unlikely that they had any knowledge of Aristotle's declaration that plot is primarily more important than character; but they accomplished their humble task as well as if they had been heartened by these authorities. These ingenious and ingenuous pieces were none of them contributions to English dramatic literature, and they are not enshrined in its annals; but they were effective stage-plays, nevertheless, and they had, therefore, an essential quality lacking in the closet-dramas which Shelley and Byron were composing in those same years.

III

In the illuminating lecture on Stevenson as a writer of plays delivered by Sir Arthur Pinero in 1903 before the members of the Edinburgh Philosophical Institution, the confessions contained in 'A Penny Plain and Two Pence Colored' are skilfully employed to explain Stevenson's flat failure as a playwright. Many of his ardent admirers must have wondered why it was that he adventured four times into dramatic authorship, only to undergo a fourfold shipwreck. Yet Sir James Barrie and Mr. John Galsworthy, essayists and novelists at first, as Stevenson was, strayed successfully from prose fiction into the acted drama. Was not Stevenson as anxious for this theatrical triumph as any one of these? Was he not as richly dowered with dramatic power, as inventive, as responsive to opportunity, as ready to master a new craft? Why, then, did he fail where they have succeeded?

For these baffling questions Sir Arthur Pinero has an acceptable answer. Stevenson was unable to establish himself as a play-maker, first, because he did not take the art of play-making seriously; he did not put his full strength in it, mind and soul and body, contenting himself when he was a man with playing at play-making as he had played with his toy theater when he was a boy. The second cause of his disappointment as a dramatist was due to the abiding influence of this toy theater, and to the fact that the pieces he attempted were planned in rivalry with the 'Miller and His Men,' and therefore that they were hopelessly out of date before they were conceived. (There is a third reason, not mentioned by Sir Arthur, and yet suggesting itself irresistibly to any one who knew the editor of the Magazine of Art personally; all four of Stevenson's attempts at play-writing were made in collaboration with Henley, who was the least equipped by temper and by temperament for the practise of dramaturgy.)

Yet even if Stevenson had worked alone, and even if he had taken the new art seriously, he could never have won a place among the playwrights until he had fought himself free from the sinuous coils of Skeltery. In his youth he had saved his pence to purchase the accessories of Skelt's Juvenile Drama with boyish delight in the acquisition of things longed for to be possessed at last. When he had purchased plate 7 and scene 11, No. 9, he thought they were his possessions. But, of a truth, he was their possession, even if he did not know his slavery. As a man he was subdued to what he had worked in as a boy; and when he wanted to write plays of his own, he had no freedom to follow the better models of his own day; he was a bondman to Skelt, a thrall to Park, a minion to Webb, a chattel to Redington and to Pollock. "What am I?" he asked in his self-revelatory essay, humorously exaggerating, no doubt, yet subconsciously stating the exact truth; "What am I? What are life, art, letters, the world, but what my Skelt has made them? He stamped himself upon my immaturity." And the impression was then so deep that it could not be effaced in maturity. The boy in Stevenson survived, instead of dying when the man was born.

The art of play-writing, like the art of story-telling, and, indeed, like all the other arts, demands both a native gift and an acquired craft. Its basic principles are the same ever since the drama began; but its immediate methods vary at different times and in different countries. While every artist must say what it is given him to say, he can say it acceptably only by acquiring the method of speech employed by his immediate predecessors. However original he may prove himself at the end, in the beginning he can only imitate the methods and borrow the processes and avail himself of the practises which the elder craftsmen are employing successfully at the moment when he sets himself to learn their trade. He must—to use the apt term of the engineers—he must keep himself abreast of "state of the art." This is what the great dramatists have ever done; Sophocles follows in the footsteps of Æschylus, as Shakspere emulates Marlowe and Kyd, and as Molière went to school to the adroit and acrobatic Italian comedians. These great dramatists were perfectly content to begin by taking over the patterns devised by their immediate predecessors in play-making, even if they were soon to enlarge these patterns and so modify them to suit their even larger needs.

Now, the state of the art when Stevenson turned to the theater was in accord with the picture-frame stage of to-day, with a single set to the act, and without the soliloquies and the confidential asides to the audience which may then have been proper enough on the apron-stage of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Even in the lower grade of playhouse, where rude and crude melodramas were performed, the method and the manner of the 'Miller and His Men' had long departed. The pleasure that melodrama can give is perennial; but its processes vary in accord with the changing conditions of the theater. The door was open for Stevenson to write melodrama, if he preferred that species of play, and if he desired to varnish it with literature as he was to varnish the police-novel or mystery-story in the 'Wrecker.' But if he sought to do this, he was bound to inform himself as to the state of the art at the instant of composition. If he shut his eyes to the changed conditions of the theater since the 'Miller and His Men' had won a wide popularity in the playhouse, then he made an unpardonable blunder, for the battle was lost before he could deploy his forces. He might have been forewarned by the failure of Charles Lamb in a like attempt. When Lamb's Elizabethan imitation 'John Woodvil' was rejected for Drury Lane by John Philip Kemble as not "consonant with the taste of the age"; its exasperated author cried: "Hang on the age! I'll write for antiquity!" But those who write for antiquity cannot complain if they do not delight their contemporaries. It is to his contemporaries, and not to antiquity or to posterity, that every true dramatist has appealed.

IV

And as Stevenson might have taken warning from the sad fate of Lamb, so he might have found his profit in considering the happy fortune of Victor Hugo, who also had a taste for melodrama. When the leader of the French romanticists felt that it was incumbent upon him to conquer the theater which the classicists held as their last stronghold, he was swift to consider the state of the art. He sought immediate success upon the stage, and the most successful plays of that period in France were the melodramas of Pixérécourt, and of his followers, and therefore Hugo sat himself down to spy out the secrets of their craft. He made himself master of their methods, and he put together the striking and startling plots of 'Hernani' and 'Ruy Blas' in strict accord with their formulas, certain that he could varnish with literature their melodramatic actions. So glittering was his varnish, so brilliant was his metrical rhetoric, so glowing were his golden verses, that he blinded the spectators and kept the most of them from peering beneath at his arbitrary and artificial skeleton of supporting melodramatic structure. To-day, after fourscore years, we can see just what it is that Hugo did; and his plays, superb as they are in their lyric adornment, stand revealed as frank melodramas, lacking sincerity of motive and veracity of character drawing. But when Hugo wrote them they were in Kemble's phrase "consonant with the taste of the age," and the best of them have not yet worn out their welcome in the theater.

Stevenson did not heed the warning of Lamb, and he did not profit by the example of Hugo. 'Deacon Brodie' was born out of date; so was 'Admiral Guinea'; and all the varnish of literature which the two collaborators applied externally and with loving solicitude availed naught. It is due to his entanglement in the strangling coils of Skeltery that Stevenson did not take the drama seriously. He seemed to have looked at it as something to be tossed off lightly to make money in the interstices of honest work. In his stories, long and short, he strove for effect, no doubt, but he was bent also on achieving sincerity and veracity. In his plays he made little effort for either sincerity or veracity, so far at least as his plot was concerned; and he thought he could lift these concoctions to the level of literature by the polish of his dialog, and by qualities applied on the outside instead of being developed from the inside. He seems to have believed that in the drama, at least, he could attain beauty by constructing his ornament instead of by ornamenting his construction, ignoring or ignorant of the fact that in the drama, the construction, if only it be solid enough, and four square to all the winds that blow, needs no ornament and is most impressive in its stark simplicity.

In his boyhood Goethe had also played with a toy theater, and it was a puppet-show piece which first called his attention to the mighty theme of his supreme poem; but the great German poet, captivated as he may have been by his youthful experience, was able in his manhood to free himself from its shackles. He came in time to have a profound insight into the principles of dramatic art, and of the dramaturgic craft. In his old age he talked about the theater freely and frequently to Eckermann; and there are few of his utterances which do not furnish food for reflection. Here is one of them:

Writing for the stage is something peculiar; and he who does not understand it had better leave it alone. Every one thinks that an interesting fact will appear interesting on the boards—nothing of the kind! Things may be very pretty to read, and very pretty to think about; but as soon as they are put upon the stage the effect is quite different; and that which has charmed us in the closet will probably fall flat on the boards.... Writing for the stage is a trade that one must understand, and requires a talent that one must possess. Both are uncommon, and where they are not combined, we have scarcely any good result.

That Stevenson had the native gift of the dramatist is undisputable, and Sir Arthur Pinero in his lecture was able to make this clear. But "writing for the stage is also a trade that one must acquire"; and when Stevenson sought to acquire it he apprenticed himself to Skelt not to Sardou, to Redington and Pollock, not to Augier and Dumas.

(1914.)

P.S.—After the publication of this paper in Scribner's Magazine, a friendly reader in Great Britain was kind enough to copy out for me this Skeltian lyric, which appeared in the London Fun in 1868, and which was probably rimed by Henry S. Leigh:

AN EARLY STAGE

WHY FIVE ACTS?

I

In the eighteenth century, both in England and in France, every stately and ponderous tragedy and every self-respecting comedy obeyed the obligation imposed by long tradition and duly stretched itself out to the full measure of five acts, no more and no less. It felt bound thus to distend itself, even tho its theme might be far too frail for so huge a frame, and even tho the unfortunate author often found himself at his wit's end to piece out his play's end. Any one who has had occasion to read widely in the works of the eighteenth century playwrights cannot fail to feel abundant sympathy for the harassed poet who plaintively called on Parliament to pass a law abolishing fifth acts altogether. This unduly distressed dramatist was an Englishman; but about the same time a Frenchman, weary of contemplating the frequent emptiness of the contemporary tragic stage, sarcastically remarked that, after all, it must be very easy not to write a tragedy in five acts.

Yet if tragedy was to be written at all, it had to have five acts, since a smaller number would not seem proportionate to a truly tragic subject. But why five acts? Why has five the number sacred to the tragic muse? Why did even the comic muse demand it? Why does George Meredith, discussing comedy, declare that "five is dignity with a trailing robe; whereas one, or two, or three acts would be short skirts, and degrading." Why not three acts, or seven? Why was it that any other number of acts was unthinkable—or at least never thought of?

Questions like these seem to have floated before the mind of the Abbé d'Aubignac, writing in the seventeenth century, and he came very near putting to himself the query which serves as a title for this chapter. "Poets have generally agreed that all Drammas regularly should have neither more nor less than Five Acts; and the Proof of this is the general observation of it; but for the Reason, I do not know whether there be any founded in Nature. Rhetorick has this advantage over Poetry in the Parts of Oration, that the Exord, Narration, Confirmation and Peroration are founded upon a way of discoursing natural to all Men.... But for the Five Acts of the Drammatick Poem, they have not been framed upon any sound ground."

That the division of a drama into five parts was accepted in every civilized country as the only possible division, seems very strange indeed, when we consider that there is really no artistic justification for it, nor any logical necessity. Like every other work of art a play ought to have a single subject, a clearly defined topic; in other words, it ought to have Unity of Action. There is no denying that some of the greatest artists have, now and again, been tempted to deal with two themes at the same time, combining these as best they could in a single work at the risk of leaving us a little in doubt as to their intention; but in the immense majority of acknowledged masterpieces the interest is carefully centered in a single object. In these masterpieces the action is single and unswerving, sweeping forward irresistibly to its inevitable end.

If, therefore, we accept the Unity of Action as a general rule, binding upon all artists, we can hardly deny that the most obviously natural arrangement for the story is to set it forth in one act, without any intermission or subdivision whatsoever—a single action in a single act. Yet it is the play in three acts which we are bound to recognize at once as possessing the ideal form, since it enables the dramatist to set apart the three divisions, which Aristotle declared to be essential to a well-constructed tragedy—the beginning, the middle, and the end—each presented in an act of its own. To put a play into more than three acts is possible only by halving one or another of these three essential parts. In a four-act play, the beginning may be split into two acts; and in a five-act play the middle may also be subdivided.

The logic of the three-act form, and the convenience of it also, are so obvious that ever since the tyranny of the Procrustean framework in five acts was abolished in the middle years of the nineteenth century, practical playwrights of all countries have favored it more and more. The young Dumas used it in his later plays, and so did Ibsen, that consummate master of stagecraft, emancipated from empty traditions, but profiting shrewdly by every available device of his immediate predecessors. If the four-act form is also popular to-day, this seems to be because the modern dramatist, intending a play in three acts, finds himself forced by sheer press of matter, to subdivide one of the essential members, as Sir Arthur Pinero had to do in the 'Second Mrs. Tanqueray' and Mr. Henry Arthur Jones in the 'Liars.' Even the opera, which liked the larger framework of five acts when Scribe was writing librettos for Halévy and Meyerbeer, is now content with only three, since Wagner revealed his skill as a librettist.