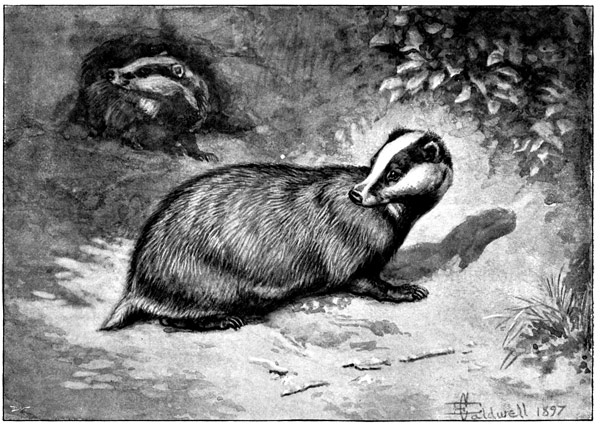

Badger. [Frontispiece.

Title: The Badger: A Monograph

Author: Sir Alfred E. Pease

Release date: July 24, 2011 [eBook #36830]

Most recently updated: January 7, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roberta Staehlin, David Garcia and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Badger. [Frontispiece.

THE BADGER

A MONOGRAPH

BY

AUTHOR OF

"THE CLEVELAND HOUNDS AS A TRENCHER-FED PACK,"

"HORSE BREEDING FOR FARMERS," ETC.

LONDON

LAWRENCE AND BULLEN, Ltd.

16, HENRIETTA STREET, COVENT GARDEN, W.C.

1898

All rights reserved

Richard Clay & Sons, Limited,

London & Bungay.

I do not know of the existence of any monograph on the Badger, ancient or modern, in English or any other language. Nor have I been able to find any adequate description in any work on natural history or British fauna of this the largest, and by no means the least interesting, of the real wild animals that still exist in England and Wales. So that, however unfitted I may be to write a scientific treatise on the last of the bear tribe that we have yet with us, I have ventured to think that my own observations and researches, with experiences of the chase of this troglodyte, may be of interest to lovers[2] of the animal world, and to not a few sportsmen.

From my boyhood all wild animals have had for me an intense fascination, and though in later years my hunting-grounds have been for the most part in other countries and continents, and among larger game, I doubt if any of the beasts whose acquaintance I have thus made has been a source of greater interest to me than the badger. The charm of an animal for man, where the sporting is the master instinct, appears to be measured by his capacity to elude observation and defy pursuit; and the badger, judged by this test, is a charming creature. I may be mistaken, but to me it appears that the chase in its widest sense is one of the best schools for studying nature. Such knowledge as I have gained of the badger has been due to the indulgence of this "brutal" instinct, as it is profanely called, and from quiet observation. If the reader will spare a little time, I will show him the manner in which my observations are made, but I warn him that there is nothing[3] scientific about them. I have no microscope and no dissecting-room.

It is June. A hot summer's day is dying, and the sun is sinking through soft clouds of glory behind the pine woods on the hill. A thousand birds in vale and woodland are singing with an ecstasy and sweetness that seem tenderly conscious that the hours of song are numbered—that the days are coming when darkness or dawn will steal over the land in silence, unheralded as it is to-day by their wild sweet notes. We wander across the pasture by the cattle, and along the side of the ripening meadow towards the wooded bank under the edge of the moor, where the badger has his home. As we near the covert, a few rabbits that have ventured far out into the field frisk up the hill, alarming their less adventurous companions, and all make for the shelter of the wood, displaying a hundred little cotton tails.

As the gate into the plantation opens a few wood-pigeons stop their cooing and fly swiftly up and out of the trees with a clean cutting slap-slap of their wings to some other[4] solitude safer from intrusion. Once in the shadow of the firs, softly treading we come up-wind to the badger "set." Here we choose a place among the larch stems which gives us a good view of the most-used entrances to the earth, some fifteen yards from the nearest hole. We turn up our coat-collars, draw our caps over our faces, and settle ourselves in such positions as will least try our patience and muscles during the hour in which we must remain immovable. In idea nothing could be more delightful than to sit in the deepening twilight of a summer's evening, with a soft breath of air stirring the feathery larch tops against the sky above, the ground carpeted with the vivid green of the opening bracken, surrounded by the music of cooing wood-pigeons, the full notes of blackbird and thrush, and listening to the pleasant sounds carried on the breeze from the distant farms.

Delightful as is the enjoyment of the confidences of Nature in her most hidden solitudes, the pleasure has its price, and the angler on a summer's eve can sympathize[5] with the man who sits over a badger earth. But he at least can protect himself to some extent against the exasperating attacks of midges in myriads, and vent his feelings aloud, and flog the waters, whilst the latter must stoically endure the torture and the plague. The most he can do is occasionally to draw his hand from his pocket, and slowly move it to his face and massacre the settlers on his nose, his ears, his neck, and carefully move it again into its hiding-place. In spite of the torment, however, he may enjoy the sights and sounds, known to but few, that these witching hours alone can give. The rabbits emerge within a yard of him, first the little ones, unconscious of his eye, then the old ones sit up and, imitating his immovability, watch him critically with their black beady eyes set, and noses palpitating; after a while old paterfamilias gives his signal of alarm or warning by a sharp pat, pat with his hind foot, telling all round that there is something in his vicinity he does not know how to account for. The cry of the startled blackbird warns that some other enemy is[6] on foot as he flies from the bur-tree to the thorn, and we see an old fox moving through the young bracken with lowered head and brush, starting off on his nightly raid. A belated squirrel throws himself from the tree above, runs close by us on the ground, up the stem of a larch, and is soon lost in the sea of green above. A numerous and dissipated family of little crested wrens, which should have settled for the night ere this, twitter with diminutive voices as they twist in and out and hang on the boughs of the spruce in front of us.

Gradually, as the daylight fades, one after another of the singers becomes silent, the sounds of day are hushed, and a perfect silence reigns in the twilight amidst the trees. Without any warning we are conscious of the clean black-and-white face of an old badger over the earthwork outside his hole, and presently he is all in view, sitting with bowed fore-legs and his head turning on his lithe outstretched neck, scenting the night air. There is nothing to excite his suspicion, so he shambles to the nearest[7] tree, puts up his fore-feet and rubs his neck, smells round the well-known trunk, and having satisfied himself that all is as usual, sits for awhile admiring the limited landscape before him. He then shuffles a few yards from the earth, scratches the soil here and there as if to keep his digging tools in order, and returns to the bottom of the tree. Another pied face appears, and more quickly than the first she trundles off to join her mate, and they bounce along one after another over the earths, round the trees, down one hole and out at another, and then rest awhile outside the earth they first emerged from. Three more come forth, and go through very much the same programme as the first, snorting and bumping along one after the other and one against the other.

Presently one takes off into the thickest covert. You can hear him bumping along, sweeping through the bracken and crackling the dead wood. Presently the others come past you, tumbling along so close that you could hit them with your stick. Probably they take no notice, but if you wink, wince,[8] or move they will shamble back to the earth and watch you for ten minutes. It is then a trial for your nerves. If you move you have seen the last of them for the night, but if you succeed in being perfectly still they will recover sufficient confidence to sally forth again, but will take off quickly in different directions for their night's ramble. Then at last we may raise our stiff limbs and turn our steps through the dark woods, leaving the fox and badger to their devices, and once more frightening the rabbits which flash past us as we wade homewards through the grass heavy and wet with dew. We have made no startling discovery on this our first night together by the badger "set," but probably we have made a better acquaintance with badgers in this hour than we could have gained in any museum of natural history, with the assistance of the most erudite Fellow of the Zoological Society.

To understand and appreciate all sides of the badger's character you must see him in war as well as at peace; and such knowledge has to be purchased by great labour and[9] bodily fatigue. In the name of sport, as in the name of liberty, great crimes are often committed. There are those who look upon hunting of all sorts as cruel and degrading, and cannot understand the pleasures of a chase involving the distress of pursuit or pain to any animal. I have a certain sympathy for such sentiments, and yet, paradoxical as it may appear, my very love of animals increases my passion for hunting them. Besides the longing to come to close quarters with them, the desire to possess or to handle them, there is the natural ambition to be even with them. There is an unwritten code of honour in the field which, if followed, makes the struggle of wits and strength, of skill and endurance, a fair one, and one in which alone many a valuable lesson out of Nature's book can be taught. To relieve any tender consciences amongst my readers I may here declare, without wishing to reflect on brother sportsmen whose methods are more Cromwellian, that when victorious in the war with a badger, when, after many a hard-fought battle in his subterranean[10] fortress—when mine and counter-mine, tunnel, shaft, and trench have driven him fighting to his last stand in his deepest and innermost citadel, and he has been forced to capitulate—I have never abandoned him to a victorious soldiery howling for blood, but have always given him honourable terms. I have never willingly or wantonly killed a badger; he has invariably become a pampered prisoner, or been transported to some new home, where some one whom I had interested in his species was prepared to give him protection, and a new start in life. Among those who have given my badgers protection I may name Mr. Edward North Buxton, who has done so much to maintain the natural beauty of Epping Forest, and to protect wild life within its borders. I know of several thriving colonies of badgers within the forest precincts descended from my prisoners of war.

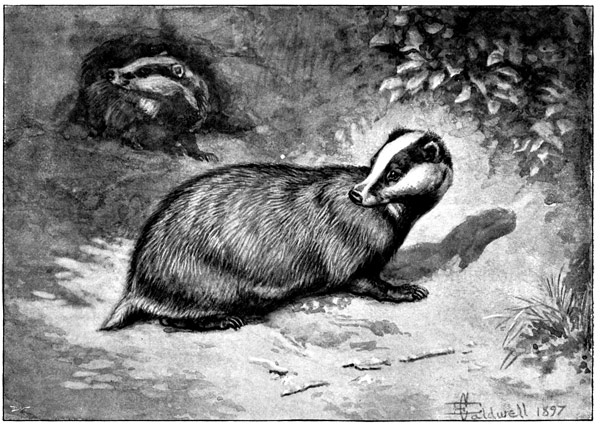

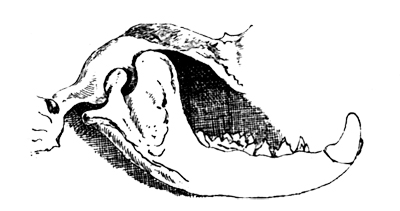

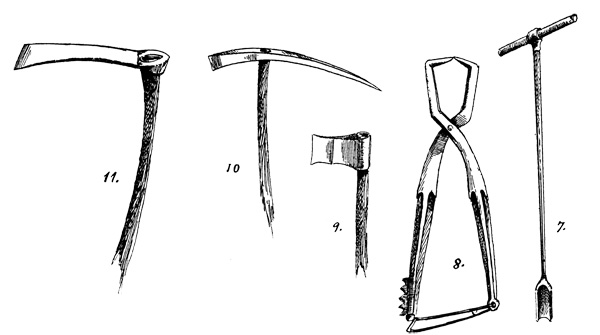

I have kept many badgers in confinement, but never to "try" my dogs, and all my terriers learnt their trade in legitimate fashion. Badger-baiting I unreservedly condemn—it[11] is as much a profanation of sport as coursing bagged hares in enclosed grounds. There are degrees of wickedness, and when a badger is placed in a properly-constructed badger-box there are few terriers that would not be vanquished in the encounter. The figure below illustrates the correct box.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

One of the atrocious methods by which the badger was baited in the last century is described and denounced in volume xii. of the Sporting Magazine, 1788. "They dig a place in the earth about a yard long, so that one end is four feet deep. At this end a strong stake is driven down. Then the badger's tail is split, a chain put through it, and fastened to the stake with such ability that the badger can come up to the other[12] end of the place. The dogs are brought and set upon the poor animal, who sometimes destroys several dogs before it is killed."

Badger-baiting, it seems, was the price the race had to pay for its existence, and with the happy disuse of a brutal sport the harmless badger has been doomed to extinction. The only method by which any British wild animal can be preserved from extinction in this age of what is termed progress, is to hunt it. Who can doubt, that if fox-hunting and otter-hunting were stopped to-day, both these creatures would be extinct within the next few years? It may be a hard bargain to make with them, but considering their own crimes of violence, and their incompatibility with "civilization," it does not seem to be a too severe condition to impose on the fox and the otter, that if they are permitted to live they must at least submit to the risks and fortunes of the chase. Not being able to do more than speculate on the intellectual and nervous capacity of animals, we are apt to assign to them some measure of human[13] powers of thought and feeling. Undoubtedly they are physically less sensitive, and we probably err when we ascribe to them more than a slight ability to anticipate, or credit them with such sentiments as anxiety, mental distress, and those thoughts and sensations that in the main make pain intolerable. Those species that have long been associated with man have, I think, a greater capacity for suffering. The individuality of each domestic race has been developed; the difference of temperament and character of each individual becomes more marked, and more or less humanized, according to the influences by which it is surrounded. There is a more uniform character and greater similarity of temperament among wild animals, and the more refined the civilization and the more cultivated the senses, the more sensitive will the whole animal become. This may be seen in the most common of Nature's operations. The wild beast produces its young with ease and without pain. With woman, raised amidst the refinements of civilization, the same operation is with every[14] precaution and assistance sometimes a dangerous, always an agonizing ordeal.

No, the terms are not hard. Take the case of a fox, the most hunted of animals. The ordinary lot of a fox compared with that of any other creature, wild or domestic, or even with man himself, is not an unenviable one. Unlike the domestic animals, he is not born into servitude or to die in early life by the butcher's knife or axe. Happier than man, he lives his life, whether longer or shorter, free from the worries, cares, and the thousand ills which flesh is heir to. The fox's life is free as air. Protected for the most part from the natural consequences of his marauding disposition, fair play is given to him to avoid the punishment he deserves by the exercise of that strategy, activity, and endurance with which he is so abundantly endowed. Two or three days in the three hundred and sixty-five he may have to exert himself more or less to save his brush, or the end may come swiftly and suddenly after a long run; but even so, are there not many of us who would[15] be glad to know that our death would come as swiftly and painlessly to us as to the fox, who, flying for forty minutes before the pack, confident, perhaps, to the last that he is a match for his pursuers, is rolled over in his stride? The sportsman may pity the sinking fox, with every desire to see the victory of the straining pack, in the moment when, after gallantly standing up before hounds, a straight-necked veteran finds he has shot his last bolt, and turns with fire yet in his eye to meet death in its swiftest form.

There is something strange in the mixture of pain with pleasure. My little son comes out cub-hunting with me in the early morning of a September day. He is the picture of delight, sitting on his pony among the hounds, the effigy of enjoyment as he follows them with his and his pony's head just above the high bracken, the incarnation of satisfaction as he receives his first brush and is blooded. He is none the less a little sportsman for sobbing himself to sleep at night with his brush hugged under the bedclothes, because of the thought that the bright little[16] cubs he saw killed will never again run in and out of the wood on the hillside as of yore. I look into his room the following day, and find him in his night-shirt busy extracting the tail-bone from his trophy, and he stops in his work only to ask when the hounds will be out again.

The power of enjoying hunting of any sort is no evidence of want of tenderer feelings. It may be that the days of sport are numbered by the exigencies of what is termed the progress of civilization; but whether men's hearts will be braver, their bodies and minds healthier, or their natures kindlier and happier for the change, only time may show. All this is something in the nature of apology; but, excuse or none, thousands are conscious that the nearest approach to pure unmixed pleasure that they have known has been derived from the chase, where cares are forgotten, pulses quickened, eyes brightened, and the mind refreshed. About conscious or unconscious vicarious sacrifice with regard to the badger I will not say more than this, that the baiting of[17] an animal in confinement, even though he be but the scapegoat for a thousand of his kind, is so repugnant to humanity, and so likely to breed cruelty, that though I lament his imminent extinction I would say, "perish Meles taxus" rather than let him pay this price for the continuance of his race, and, whatever view he might have himself, I would refuse him the option.

The badger has made a wonderful struggle for existence, and may linger on for many years yet in the more secluded corners of England and Wales (in Scotland he is almost extinct), but he owes all to his own mysterious silent ways, and nothing to man's mercy in the matter. The intelligent and unprejudiced wearers of velveteen, who, with the tacit consent of their masters, have by means of the steel trap, flag-trap, and gun, exterminated and banished for ever the most interesting of our animals and the most beautiful of our birds, have hitherto failed in their ruthless attempt to rid earth and heaven of everything but furred and feathered game, so far as the badger is concerned. In many[18] English counties, however, the badger has given in before ceaseless digging, snaring, and shooting, and the silent covert where he had his earth, where he dug and delved and made his wonderful subterranean stronghold, knows him no more. He has gone with the polecat, the pine marten, the wild cat, the harriers, the buzzards, and a host of the brightest and loveliest of our birds. Guiltless of the crimes of his fellow-victims against game, he was and is still ignorantly classed under that all-embracing word of the keeper, "vermin." There are few who lament his disappearance save perhaps the makers of shaving-brushes, and the old people whose faith in the efficacy of "badger-grease" can no longer find the opportunity of exercising the same. This faith is an old one. I read in the Sporting Magazine, 1800, volume xvii.—"The flesh, blood, and grease of the badger are very useful for oils, ointments, salves, and powders, for shortness of breath, the cough of the lungs, for the stone, sprained sinews, coll-achs, etc. The skin, being well dressed, is very warm and comfortable[19] for ancient people who are troubled with paralytic disorders." Evidently a few badgers in the good old days supplied the place of the country doctor. About the fancied or really mischievous habits of the badger I shall have something to say later on.

The badger (Meles taxus, or Ursus meles) is known under various aliases, viz. the Brock (Danish Broc, Erse Broc, Welsh Brock), the Pate, and the Grey. Of these the Brock is perhaps the commonest, and is the name most used in the north of England. There is an expression common in the north that would lead the ignorant to believe that a badger perspires, or sweats, viz. "sweating like a brock." In Yorkshire I often hear a man say, "Ah sweats like a brock," and the user of this elegant metaphor innocently imagines he is perspiring like a badger. But "brock" is the old north-country word for the insect known as "cuckoo-spit" (Aphrophora spumaria), which covers itself in the larval state with froth and foam (cf. Welsh broch,[21] foam)—vide Atkinson's Dictionary of the Cleveland Dialect. In parts of Cornwall and Wales the word "Grey" may be in use, but I myself have only come across it in books, more especially old ones. Though able to boast these several titles, there is but one species known in Europe, and in general appearance he is the same animal, though varying locally in size and shade of colour. He has been classed as belonging to the bear tribe, but the badger is really a single species and a sub-genus in itself. The dentition of a badger is half tuberculous and half carnivorous, and in this respect approaches the martens.

About few animals has there been more nonsense written in regard to habits and anatomy, and for many of the popular notions concerning the badger there is no foundation whatever. In the ancient books descriptive of sport and wild animals we read that there were in England two kinds of badger—the one as we know it, and the other a "pig-badger," with cloven hoofs and other attributes of the porker. It is astonishing how[22] these old authors drew upon their imagination, and where they found suggestions for their errors. In this case it may be they were misled by the custom, which still continues, of distinguishing between the dog and bitch, or male and female badger, by using the terms boar and sow; or it may be the idea dawned whilst they ate their rasher from a badger ham!

There are altogether not more than five (or perhaps six) kinds of badger known throughout the world, so far as I know.[1]

1. The European badger, known over almost the whole of Europe and Asia. 2. A larger species, confined to the high steppes of Eastern Siberia. 3. The North American mistonusk, or chocaratouch (Meles labradorica or hudsonius). 4. The Mexican badger, found south of latitude 35 degrees. 5. The Japanese badger. 6. The Indian badger (Meles indica) might be added perhaps, though it has a pig's snout, long legs, and long tail. Its native name is bhalloo-soor, i.e. the bear pig.

[23]Nos. 3 and 4, the chocaratouch and Mexican, differ so distinctly from the others in dentition, though in appearance similar to the European species, that a new genus, Taxidea, has been established for their reception.[2]

Popular error, and old writers, describe the badger as having his legs shorter on one side than the other, and the latter, with philosophical ingenuity, have discovered therein a wonderful provision of nature; for, says Nicholas Cox, "He hath very sharp Teeth, and therefore is accounted a deep-biting beast; his back is broad, and his legs are longer on the right side than the left, and therefore he runneth best when he gets on the side of an Hill or a Cart roadway." The same author also states—"Her manner [24]is to fight on her back, using thereby both her Teeth and her Nails, and by blowing up her Skin after a strange and wonderful manner she defendeth herself against any blow and teeth of Dogs. Only a small stroke on her Nose will dispatch her presently. You may thrash your heart weary on her back, which she values as a matter of nothing." If such a provision in the matter of legs did exist, one can realize the comfort of the uneven legs on a hill-side, but what gravels us is the discomfort of the return journey! The rolling, shambling gait that characterizes the badger is doubtless the origin of this absurd theory, which might be equally applied to any other member of the bear family. The European badger, as we find him in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, stands about ten to twelve inches from the ground, has a long, stout body, with the belly near the earth. He has a coat so long and dense, and legs so short, that he appears to travel very nearly ventre à terre. The male is somewhat larger than the female, and weighs more. The weight of a male is[25] about 25 lbs., that of a female about 22 lbs. When they are fat, or in grease in September, they will scale more. Badgers have been known to weigh up to about 40 lbs.; the largest I ever dug out and weighed was an old lean dog badger that scaled over 35 lbs.

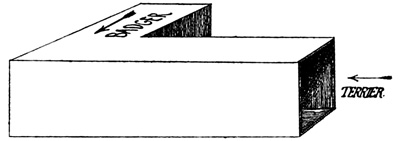

The head of the badger is wedge-shaped in general conformation, the back of the head large, the cheek-bones well sprung, and the muzzle fine and long. The nose or snout is black in colour, long and full; the eyes small, black, or black-blue; and the ears small, round, close-set, and neat. The strength of a badger's legs is most remarkable, and for his size (the animal only weighs from 19 lbs. to 35 lbs.) he possesses a most wonderful combination of bone and muscle. The legs are very short and the joints large; the feet, like the legs, are nearly black, and are large and long. The badger is a plantigrade, that is, when travelling he puts down the whole of his foot, including the heel, flat on the ground. His fore-feet are larger, longer, and better equipped for digging than[26] his hind, but all are armed with long, sharp claws, and it is prodigious what he can effect with them. There is no mistaking his tracks—no animal's footprint is in the least like his. His heel is large and wide; this, and his four round, plump toes, leave an impression in sand, mud, or snow that cannot be confounded with any other. If the mud is deep, or there is snow on the ground, he also leaves the mark of his claws, but as a rule these are not observable, as he puts his weight on the sole of his foot—his tracks are usually almost in a line. The badger is cut out for a miner. His wedge-shaped head is capable of forcing a passage through sand and soft strata, whilst his armour-tipped diggers are worked by machinery that rivals in power the steam navvy; and whilst his fore-feet are going like an engine, throwing stones, bits of rock, sand, clay, and all that he comes in contact with between his fore-legs (which are set wide apart, leaving plenty of room under the chest), his powerful hams are working his hind-legs and feet like little demons, throwing back all that the fore-feet[27] throw under his belly. And this is not all. His powerful jaw and teeth will cut, break, and tear all roots that obstruct his passage onwards, and it is most entertaining to see him going through earth, shale, and stone with the rapidity and sustained energy of a machine. No one who has not seen it would credit what one of these animals can do. I have often been defeated by their being able to penetrate more quickly than even a gang of men with pick-axe, spade, shovels, and crowbar could follow. And it is safe to say that as long as a terrier is not up to the badger, the badger is not only advancing quicker than the men (if his earth is on a hill-side), but has also, in nine cases out of ten, barricaded his retreat and scored a victory. I have known a badger, left for awhile by the terrier, bore his way straight up out to daylight and escape. The badger is covered with a thick, long-haired coat, which with a loose skin of extraordinary density and toughness forms a complete and effective armour. The hair on his head is short and smooth, and the sharp, clean black-and-white markings[28] of his head give a very pretty and effective appearance to it. The general appearance in colour of a badger is a sort of silvery-grey, turning to black on the throat, breast, belly, and legs. Inverting the usual colouring of other animals, which is generally dark on the back, with lighter colouring on the belly and under the arms and thighs, the badger is lighter on the back and black underneath. Not only is this colouring peculiar to the badger, but his hair is unlike that of any other creature known to me, being light at the root and darker above.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The colour of a badger alters with age. The little cubs, till they are seven or eight months old, are a clean, bright, light silvery-grey; they then become yellower in their coats, a colour which they keep sometimes permanently, but which they generally change[29] after two years for a suit of darker, purer grey. The badger's tail is about five inches long, covered with long, coarse, lighter-coloured hair than that on his body, and is of a yellowish-brown colour.

The badger has another peculiar distinction that is somewhat mysterious, viz. a pouch, the vent of which is close under the root of the tail, and contains an oily fœtid matter which he has the power of emitting. Different uses have been ascribed to this provision, such as that which ferrets and polecats have. I have never noticed a badger use it as has been suggested, as a mode of defence or annoyance, and am sure that this is not its purpose. But there is no doubt the badger sucks and licks this substance, whether by way of taking a tonic, a cooling draught, a stimulant, or other physic I cannot say. I am, however, inclined to believe, that from this source he is able to maintain his health and support life during those periods of seclusion and total retirement in his "earth" which have led naturalists to describe him as a hibernating animal.

[30] In this theory I am strengthened by a French author, Edmond Le Masson, who writes—"The badger does not always give evidence of his presence in his woody retreat.... There, should one go to see him, he may, from pure idleness, remain shut up, it being easy for him to support himself during the longest period of retirement by licking the secretion which oozes from the pouch under his tail." The author goes on to give an account which was sent to the French papers by M. Récopé, Garde Général at Marly-le-Roi, of a badger that was shut in a culvert without any food whatever for forty-five days, walled in on every side, and where no tree root could penetrate. A gamekeeper, a noted trapper, had blocked the exit, and tried in every way he could devise to trap him, from February 18, 1853, to April 4, and when at last he succumbed to a ruse of the keeper's he was quite lively, and weighed nearly 19 lbs. It appears that however carefully his traps were set in the mouth of the exit, the badger came every night and rolled on them and struck them, as they will do[31] when they suspect any human infernal machine. That he will remain for a week or two at a time without issuing from his "earth" is certain, but the most casual observer will see badger tracks in the snow in the severest weather, and I have never been able to find that there were no tracks in the snow issuing from the "earths" in winter for more than a week or two at a time. The badger is less active, eats less, goes fewer and shorter journeys in winter, and has a hibernating tendency; but the idea that the British species shuts himself up and takes to his bed through the winter months, and never comes forth till spring, is a fallacy.

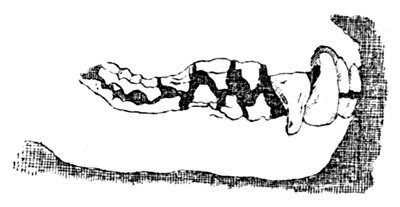

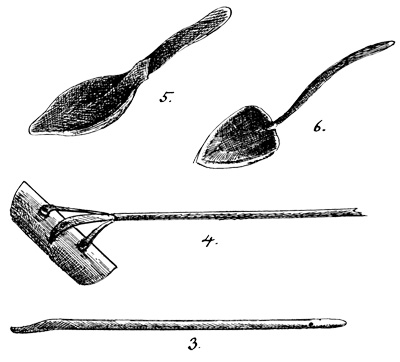

Fig. 3. Lower Jaw of Badger.

Fig. 3. Lower Jaw of Badger.

Fig. 4. Dovetailed Jaws.

Fig. 4. Dovetailed Jaws.

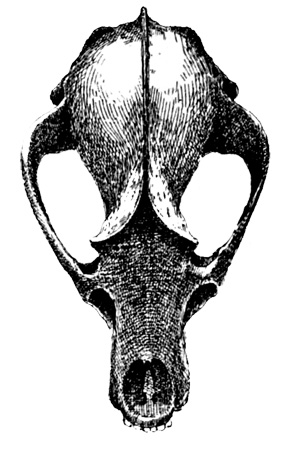

Fig. 5. Skull of Badger—front view.

Fig. 5. Skull of Badger—front view.

Having attempted a slight description of the badger as far as his exterior is concerned, I shall leave to "Dryasdust" the description and nomenclature of the badger's interior economy, as well as the enumeration, weights, and measurements of his bones and muscles. He possesses, however, one or two structural peculiarities that deserve a little attention. There is much similarity in the general[32] conformation of the badger's and bear's skull, but the protecting ridge on the head is absent in the bear. What gives to the badger's jaw its proverbial and terrific force? To witness its work is to know that its power of biting, crushing, and holding must be the result of some peculiarly strong mechanical as well as muscular construction. The examination of the skull helps in the solution of the mystery. The conformation of the jaw is strong, and the muscles attached to it powerful; but besides this he has two distinguishing structural additions that give his jaws, furnished with his formidable teeth, the strength and retentive power of an iron vice. The first is that his lower jaws are locked into sockets in the skull, and are thereby made—unlike those of all other animals I know of—impossible[33] of dislocation.[3] His head or skull, when stripped of flesh and bare, still retains the lower jaws in such a way that they cannot be displaced without fracturing the massive bones of the head or jaw. The teeth of a badger require respectful attention. There are eighteen teeth in the lower and sixteen in the upper jaw, in all thirty-four. The four big molars, two above and two below, are large and strong, the upper being much the larger and wider ones, the lower being longer and fitting within the upper, as do all the lower teeth. The four canines are large, thick, round, long and formidable, and are his chief weapons. The lower canines dovetail when the jaws close with the upper,[34] but all the four points or ends turn outward and backward.

Fig. 6. Skull—side view.

Fig. 6. Skull—side view.

The second peculiarity arises from a high ridge of bone, standing straight up and running from the base of the skull to between the ears, giving a firm hold to the ligaments and tendons, and an additional leverage and length, which are again rendered more effective by passing over the high cheek-bones as over a pulley before reaching the jaws. There is a saying that "a badger never leaves go till he makes his teeth meet," and there is a foundation of truth in[35] it. The length of time he will hold on to the limb of an enemy is certainly fearful, and the way in which his thick strong canines go through the bone. On one occasion, in Wales, a keeper residing near the place I was staying at thought he saw the badger's tail at the end of a badger-digging, and laid hold of it to draw him. He had made a terrible mistake, and had got hold of a hind-foot. The badger held him by the wrist for ten minutes with his arm stretched up the hole; when he let go his hold the hand was hanging by a few shreds, and had, of course, to be amputated. I have always[36] drawn a badger when possible by the tail, as the use of the tongs is sometimes difficult, especially in certain holes and at great depths, and there is a liability for the tongs to give way, and then the badger charges in your face or through your legs. I have seen a badger's teeth break and fly off in chips from iron tongs, a sight and sound that is not pleasant. To one who knows how to do it, drawing by the tail is a simple, quiet, and effective way of "taking the brock."

A badger has the proverbial nine lives that John Chinaman attributes to women and we to cats. You cannot kill a badger by a blow on the head, the structure is so dense. His brain is so well protected by the ridges of bone along his skull and over his eye-sockets, and by the strength and projection of his cheek-bones, as to make him all but invulnerable in that quarter. His skin is so thick and tough, and his coat so heavy and coarse, that shot will scarcely penetrate it; but he has one place as tender as a nigger's shins, and that is his nose, where, if he is struck once, he is instantly[37] dispatched. I was witness of a scene in the hunting field with the Cleveland hounds during the mastership of the late Mr. Henry Turner Newcomen, which, however disgusting, illustrated the vitality of the badger. We thought we had run a fox to ground in a drain. The terriers were sent for, one was put in to bolt him, but after a quarter of an hour's attempt he came out, having given it up, with severe marks of punishment. One that could be depended on was then dispatched to ground, and digging operations commenced. As time went on we thought from the sound that it could not be a fox, and presently there was a charge down the drain, and a badger came bouncing and floundering out among the crowd of bystanders, the terrier holding on to him. The other terriers, barking furiously to join in the fray, excited the hounds in an adjoining field; they broke out past the whips, and nineteen couple were soon at the badger, who was entirely lost to view in the struggling and worrying mass. But he was plying his jaws all the time, as was evidenced by the howls[38] of pain from the wounded hounds as they withdrew from this unaccustomed entertainment. The whips and others did their best to flog the hounds off, but this was not accomplished for at least ten minutes. After much bloodshed, and when the last hound had been choked off, the badger showed neither scratch nor wound, and looked as fresh as possible. Mr. Newcomen ordered a whip to despatch him and end the tragedy. The whip clubbed a weighted hunting-stock, striking him several smashing blows on the head, and left him apparently dead. A farmer having asked if he might have him to stuff, put him in a sack and carried him off. A few days later I met the farmer, Mr. R. Brunton, of Marton, and he told me that when he got home the badger was as lively as ever, so he put him on a collar and chain and fastened him to a kennel. The day following he thought, from the appearance of the badger, that he was hurt about the head, and with some difficulty examined him, and found that the lower jaw was injured. He thereupon got a revolver and fired a[39] shot into his ear, and then he assured me the badger only shook his head. He was so taken aback that for a moment or two he thought of giving up the attempt to kill him, but firing a second ball into him behind the shoulder he put an end at once to the poor brute's sufferings.

The badger, as I have said, is becoming very scarce in England, and is decreasing in numbers in France and other countries as well. There are, however, several English and Welsh counties where in woodlands he still is to be found in considerable numbers, and some districts where they are common enough. The badger is fairly plentiful in many parts of Cornwall, Devon, Dorset, Somerset, Hants, and Gloucestershire, along the Welsh border, and in Mid and South Wales. It is to be found also in Sussex, Wilts, occasionally in Surrey and Kent, and here and there through the Midland and home counties. It is becoming rare in the north of England, but still lingers in the North Riding of Yorkshire, chiefly in the districts of the hills and moors between[40] Scarborough and York. In Lincolnshire it is to be found in places; it is extinct in Durham, and practically so in Northumberland, where within fifty years it was common enough.

A Northumberland gamekeeper of my father's has told me he knew it in the Kyloe Craggs and the Howick Woods, and remembered his father taking him to see their dog tried at a badger near Belford. In none of these places are they to be found now. In my own district of Cleveland they were in 1874 all but extinct. I remember as a boy two were caught in our neighbourhood, one in Kildale and one at Ayton; but in 1874 I had three young badgers sent me from Cornwall, dug out by one of my uncles, and these I turned out in my father's coverts, and secured for them the keeper's protection. Since then they have, with a few later introductions, held their own, and a few years ago I knew of nine badger "sets" in the vicinity, and some five on our own ground; but I regret that the hands of neighbours are against them.

[41] In Scotland the badger is now rare. In the north-eastern counties, where till recently he was to be met with in every wild woodland and forest district, he has entirely vanished. In Ross-shire and in the west he is occasionally found in places where the wild cat and marten are making their last stand against the keeper and his exterminating engine, the steel trap. In Ireland the badger is still found in the Wild West. I have come upon him in Connemara, near the Killery harbour, and have heard of him in Kerry and other counties.

As to the distribution of the badger in Ireland I quote the following interesting letters from the Field:—

"'Lepus Hibernicus' may be glad to know that the badger is still fairly common in the neighbourhood of Clonmel. The country people, who know them better under the name of 'earth-dogs,' in distinction to 'water-dogs,' or otters, not unfrequently catch them in one way or another, and offer them for sale. Fortunately for the badger the demand is extremely limited."—Badger (Clonmel).[42] "Permit me to coincide with 'Lepus Hibernicus' respecting the plentifulness of the badger in Ireland. Some years since I was on a large estate in Co. Clare, and badgers were abundant on the domain and the adjoining property; I also found them numerous in the wilds of Galway. I have found and killed them in many parts of England and Wales, but have seen and trapped far more in the west of Ireland."—J. J. M. "Your correspondent, 'Lepus Hibernicus,' in the Field of November 5, mentions that badgers are by no means uncommon in Ireland. I am in the west of Cornwall, and there are any amount here, a great deal too plentiful to please me, as I am sure they do a lot of harm to rabbits and game. I found the parts of a fowl in a field, evidently killed by a badger, as there was a trail not a foot away, and also a hole scratched, which could be the work of none other than a badger. I had two very big ones brought to me alive last week. They were caught by setting a noose of thin rope in their run. I should like to know a good way to exterminate[43] them, as, though I shoot over a great deal of ground, I have never seen one out in daytime, but their trail is everywhere."—H. J. W. "The badger is by no means rare in the west of Clare, where I have trapped several."—A. H. G. "I beg to inform 'Lepus Hibernicus' that badgers are by no means scarce in this place."—A. R. Warren, Warren's Court, Lisarda, Cork. "The badger in this part of the Co. Cork is certainly not rare—Owen, Sheehy, Coosane, and Goulacullen mountains, with the adjoining ranges, afford shelter to a goodly number. Farm hands occasionally capture unwary ones, and offer them for sale as pets, or to test the mettle of the national terrier, or to be converted into bacon. A badger's ham is often seen suspended from the rafter of a farmer's kitchen."—J. Wagner (Dunmanway, Co. Cork).

The counties in which I have had most acquaintance with the badger have been Radnorshire, Yorkshire, Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, and Cornwall, but perhaps most of my experience has been gained in the[44] last-named county, as far as digging for him is concerned; whilst it is at home in Cleveland that I have watched him for nearly twenty years, and gained some knowledge of his mode of life and habits. I am not sure whether there are not a few still left in the Cheviots and the districts of the Upper Tyne and Tweed. Up till about 1850 they were to be found on the Cleveland hills, or rather on their wooded sides and in the "gills." The last place where I heard of them being hunted was in the ravine and woods of Kilton.

A badger's earth or warren is properly and generally called a "set" or "cete." They vary in respect of size, number of entrances, depth of galleries, and choice of site almost as much as rabbit-holes. Sometimes badgers will find sufficient room in rocks to make a home, and it is extraordinary the excavations they occasionally make in apparently solid rock. Usually, however, they select some softer material in which to make their underground passages and chambers. They will choose a quiet hillside away from man's[45] habitation, amongst the whin bushes, or in the woods near a stream or small runner of water. Such a "set," if long established, will penetrate through earth, clay, and sub-soil, to some stratum of shale, or sand, or loose rock. Some of the galleries and chambers will be at a great distance from the surface, and some at an enormous depth. When a new earth is made I have always found the badger appropriate the holes of rabbits, and proceed to excavate, enlarge, and open them out. This operation of opening a new earth takes place constantly in the spring-time, great masses of material being thrown out; but as often as not the new house is abandoned before completed, and the subsequent labours of the family are devoted to repairing, enlarging, and making new front or back doors to the old place. In Cornwall I once tried my hand with my brother, some strong Cornishmen, and a team of terriers, at a very innocent-looking badger "set" situated in a level field. There were but three holes, and these not very far apart. The farmer told us that there had[46] been badgers there all his life, and no one had ever been able to dig one out. This rather stimulated us than otherwise, and we had in the course of a few hours dug a trench some six feet deep, and were nearing the sounds of the subterranean conflict, which had been sustained by the terriers, when suddenly we found that we were above the sound, and we sank a shaft down three feet from the bottom of our trench, to find galleries and chambers in all directions. The battle had by this time moved, and we were in despair at the prospect of following on the level with a depth of nine feet of surface soil to be lifted in every direction we turned. I was listening at the bottom of the trench, having penetrated to the third storey of this underground barrack, when I distinctly heard the "bump-bump" of the badger below me. My companions came down and listened too, and there was not the slightest doubt that there was a fourth storey and labyrinth of passages some three or four feet below us, and for anything we knew another beyond. The day was far spent, the task was impossible,[47] and the rest of our time was devoted to getting the terriers out, and making as good a retreat as we could before the victorious enemy.

I should think this "set" was hundreds of years old, and some of the passages, the farmer told us, were a hundred yards long! As a rule a badger's hole descends rapidly at first, and then may branch into any number of by-ways and subterranean galleries. Whichever route you follow, however, you invariably come to a chamber or "oven," which is generally a sort of vaulted hall, where four ways meet, and which is, or has been, the living-room of the family at some previous time. Where there is an old-established "set" it is difficult to drive the badgers permanently away from it. They may leave it for a while from fancy, or because of disturbance, but they will certainly return.

The badger and his wife have a regular spring cleaning after the winter is over, and about March and April a cart-load of winter bedding, rubbish, earth, and sweepings will be thrown in a few nights outside the front[48] door. There is generally the old bedding left in one or two of the big chambers for the lady who is to be brought to bed in February, March, or April; and there is another turn-out after this interesting event has been accomplished. About the middle of June, in July and August, and as late as October and November, an extraordinary amount of fresh bedding will be taken in. On summer evenings I have watched the badgers at work, but regret that I cannot substantiate the following description:—"Badgers when they Earth, after by digging they have entered a good depth, for the clearing of the Earth out, one of them falleth on the back, and the other layeth Earth on the belly, and so taking his hinder feet in the mouth draweth the Belly-laden Badger out of the Hole or Cave; and having disburdened herself, re-enters and doth the like till all be finished."

No, this is not how it is done, though it is a curious sight to see the real thing. The badger will come out, take a look round, and sit awhile close to the mouth of the hole.[49] He will then shuffle about and get further from the hole. You will watch him descend into some bracken-covered hollow, and will see nothing more of him for awhile. Then you will hear him gently pushing and shoving and grunting, and know that he is very busy over something. He will reappear bumping along backwards, a heap of bracken and of grass or old straw, left from a pheasant feed, under his belly, and encircled by his arms and fore-feet. He will continue this most undignified and curious mode of retrogression to the earth, and will disappear tail first down his hole, still hugging and tugging at his burden.

"It is very pleasant to behold them when they gather materials for their Couch, as straw, leaves, moss, and such-like; for with their Feet and their Head they will wrap as much together as a man will carry under his arm, and will make shift to get into their Cells and Couches" (The Gentleman's Recreation).

I have not seen a badger make more than two such excursions by daylight, but have[50] no doubt that after dark a considerable number of such journeys may be accomplished. For weeks together, on any morning, you may see the litter of bracken and grass strewing the way to his home and down the various entrances.

And now let me again, with all possible respect, put some of our scientific friends right. It is not often that an amateur can; but a man who is not able to tell you everything, as these learned men do, about every living creature, may from a country life and experience be able to correct some errors in respect of one animal at least. M. Buffon, the immortal and wonderful natural historian, tells us that the badger is a solitary animal. This is the reverse of truth; he is less solitary than the fox. He is fond of company; he is monogamous, and clings closely and faithfully to his own wife. With badgers, as with the human race, the sexes are not precisely equal in numbers, and often, from the force of circumstances, a badger has to remain a celibate, but he is not a bachelor by choice. He may become a[51] widower, but in either case he will travel far to seek a partner to share his shelter and his lot. It is not altogether rare to find an old solitary dog badger, who has loved and lost, or taken in late age to a hermit's cell; but he, as often as not, when he has failed to secure the companionship of the gentler sex, has found some other male to share his home, when they can live comfortably en garçon.

Nor do the married pair shun the society of their kind. I have often seen large badger "sets" almost as full of badgers as a warren is of rabbits. One evening, near my house, I waited an hour of midge-plagued time to watch the badgers come out from a small "set," and was rewarded by seeing a procession of seven full-grown badgers emerge from a single hole, and I had them all in full view for something like twenty minutes. As this was in July they could hardly be one family. They were every one more than a year old, and a badger's family is usually two in number, sometimes three, and never more than four; and this last is exceedingly[52] rare in my experience. In no sense, therefore, is the badger solitary. Indeed I have actually known myself several instances of a badger and fox living in apparent amity in the same earth, whilst I hardly ever saw a badger "earth" that was not either itself or the immediate vicinity tenanted by rabbits. As to the consistency of any friendship that exists between badgers and foxes and rabbits, I shall have more to say later on. I have, however, taken a badger and rabbit out of the same hole lying side by side. The badger is said to be the protector of the rabbit. He does not altogether deserve this title, and the rabbit enjoys the immunity in a badger's earth chiefly from the fact that the badger cannot follow it in the smaller holes without digging, an effort which in his estimation is, as a rule, not worth the candle.

Buffon dwells on the cleanliness of the badger. He certainly is not the stinking animal he is accused of being. His house and himself are as a rule bright and cleanly looking, and it is only when in confinement,[53] and deprived of the sanitary arrangements to which he is accustomed, that he becomes offensive. Writers are not correct in saying that he never deposits his dung in his earth, but as a rule he does not, and his habit is to go some little distance from his home, dig a hole, and there leave his excrement. He will use the same hole for a few days, and then cover it up with earth and make a new one. There is a smell about a badger "earth," but it is not disagreeable, and nothing like so rank and strong as that of a fox's. He is, however, often troubled with lice and ticks, so that it is desirable when your dogs have been to ground carefully to wash them. But in this respect a badger is not worse than sheep and goats, and with such a coat as he has it is no wonder that it is sometimes tenanted. The same distinguished authority states that the badger produces its young in summer, but I have never known this happen. March is the usual month, and the rule is not earlier than February nor later than April. A naturalist at Cambridge told me that he knew of a[54] badger bitch that was many months in confinement (I think he said eighteen months), and gave birth to cubs—but I was not convinced of the accuracy of his statement that she had never had access to one of her kind. It is only fair to mention that Vyner, in his Notitia Venatica, states that "It is a fact perhaps not generally known, nevertheless curious, that badgers go twelve months with young. This fact I learned from a neighbour of mine in Warwickshire, who some years ago dug out in the spring a sow badger. She was confined in an outhouse for twelve months, at about which period she produced one young one. During her confinement it was impossible for her to have been visited by a male."

That an animal of this size should go with young for such a period is so extraordinary, and so great an exception to the ordinary provisions of nature, that the theory requires much greater support than mere hearsay evidence. If it were a fact, or if it were the rule, the evidence to support the theory of twelve months' gestation should be overwhelming,[55] considering the number of badgers that are in confinement. I have had many in confinement for long periods, and have never known them to give any evidence in support of this theory. I have kept a pair for a long period, but, like many other wild animals in confinement, they never bred. All sorts of theories exist as to the period of gestation in badgers, but I think I shall be very near the mark when I say that they go with young about nine weeks, and I conceive that the mistake made by those who have thought that they go over a year is due to the fact, which I have noticed, that a pair of badgers do not breed every year. I cannot decide whether there is any precise rule, but am inclined to think that they breed once every two years. There are so many accounts of single badgers kept in confinement bringing forth young after a much longer period of gestation that it appears possible that the female has the power known to be possessed by the Roe-deer doe of postponing the operation of parturition for a considerable time.

[56] The badger is not by nature a ferocious animal, though the female will repel with the greatest savagery any approach when she has young, but so will a hen with chickens. The temperament of the badger is a gentle, shrinking one. No animal prefers a more quiet life, loving a warm bed in a dry dark corner of earth or rocks. He loves to sleep and meditate in peace for the greater part of the twenty-four hours. He lies not far within his entrance hall during the spring and summer, and on a hot day he will sometimes come to the mouth of his hole. In the evening, in June or July, he will come outside, sit looking into the wood or shuffle round the bushes, stretch himself against the tree-stems, or have a clumsy romp with his wife and little ones; and when the daylight dies he will hurry off, rushing through the covert for his nightly ramble. In the summer months he will travel as far as six miles from home, but he is in bed again an hour before sunrise.

It is only at this time of the year that he can be hunted above ground. This can be[57] done with a few beagles or harriers on a moonlight night, when, finding him in the open, they will give a merry chase and fine cry, and a run of several miles without a check. If his earths are stopped, and he finds no other refuge, he will be brought to bay. In some districts I have known sacks put into the mouths of the most used holes of a set, the open end of each sack having a running noose pegged into the ground, thus providing an astonishing reception on his return as he charges in, disturbed or pursued in his midnight ramble. By this means he is taken alive and unhurt, being bagged and secured in his attempt to enter. At other times of the year, when the days are short and the nights longer, he comes out later in the evening, waits for a moment at the mouth of his earth, takes a preliminary sniff round, and then rushes off at the top speed into the covert.

The badger is easily domesticated if brought up by hand, and proves an interesting and charming companion. I had at one time two that I could do anything with,[58] and which followed me so closely that they would bump against my boots each step I took, and come and snuggle in under my coat when I sat down. I was very much attached to them, but having to leave for the London season, I came home after a prolonged absence to find that they had reverted to their natural disposition, and had forgotten him who had been a foster-parent to them. As I could not fondle them without a pair of hedging-gloves on, and they no longer walked at my heel, I made them a home in the woods, where the thought of their happiness has helped me to bear my loss.

Many interesting stories are told of tame badgers. Here is one taken from the Field: "A few months ago, a farmer in the Cotswolds unearthed a badger and one youngster about two months old, which were sent to Mr. Barry Burge, Northleach, who only kept the former a few weeks, when she died. The orphan was petted very much by its owner. In a short time it would follow Mr. Burge through the fields and streets, and[59] answer to the call like a dog. It is an amusing sight to see the badger along with its master riding a bicycle. A short time ago Mr. Burge had a fox cub, which he has succeeded in taming. This fox has taken a great fancy to an Irish terrier, with which she plays continually. The badger, which is now about seven months old, is loose about the house at times, but generally spends most of its time in company with the fox, to which it is greatly attached, all sleeping snugly together."—G. W. Duckett, Northleach, R.S.O., Gloucestershire.

M. le Masson gives a pretty account of his tame badger, which, though it loses much in translation, I give in English. "I brought up and kept for more than two years a female badger, which died at last from obesity. She had been taken from her mother when only eight days old and suckled by a Normandy bitch, which had already reared me some wolf whelps. 'Grisette,' as she was named, was, like all her kind, omnivorous; meat, beetles, fruits, certain kinds of vegetables, in fact, all and everything was welcome[60] to her healthy appetite. When out walking in the country, where she always readily followed me, she would unearth rats, moles, and young rabbits, which she could scent at the bottom of their holes. In spite of her thorough domesticity, I never succeeded in overcoming her antipathy to dogs, and more especially to cats, which she chased most viciously did they dare to enter the kitchen where she reigned as queen; and where, such was her sensitiveness to cold, she had made her bed against the wall in the chimney corner. Here in winter, buried in her furs, she slept curled up for whole days together. But which of us is without a fault? A little greedy without being actually voracious, sweet Grisette sometimes ventured on to the stone-work of the cooking-stove, and from there was able to discover from which of the saucepans was exhaled the most savoury odour, and never did she make a mistake on that score!"

Du Fouilloux states in his Venerie:—"Je ay veu aux blereaux prendre deuant moy les petis cochons de laict, lesquelz ilz tray-noient[61] tout vifz en leur terrier. C'est vne[**une?] chose certaine qu'ilz en sont plus friandz que de toutes autres chairs: car si on passe vn[**un?] carnage de porceau par dessus leurs terriers, ilz ne faudront iamais de sorter pour y aller."

The badger is credited with a special love for pork. I have seen a statement in an old volume of the Gentleman's Recreation, in which the writer refers to the taste of the badger for pork. "They love Hog's-flesh above any other; for take but a piece of Pork and train it over a badger's Burrow, if he be within, you shall quickly see him appear without."

Badgers are omnivorous. In their wild state their food is principally roots and insects—they are especially fond of beetles and such creatures as are to be found just below the surface of the ground, or under the decaying dung of cattle. The natural history books say they eat frogs. This may be true, but I have not observed it. I have tried badgers in confinement with all sorts of insects and grubs, but I never could get them to touch[62] slugs or worms. They are carnivorous, and eat mice, rats, voles, and moles. They will take a rabbit out of a trap, turn it inside out, and eat all the meat, leaving the skin behind, turned neatly with the fur inside. They are also fond of very young rabbits, and will dig a shaft through several feet of solid earth direct on to the nest. But when this has been stated, nearly all has been said with regard to their propensity to damage in game coverts. I am supported by other observers in this opinion; for instance, a recent writer in the Field who says:—"In reply to E. T. D'Egmont's inquiry about catching badgers, I have never found them do much harm to the nests of winged game; but they are death on rabbits, and much resemble a fox in finding a young one appetizing. Their skins would make good waistcoats, but, apart from that, I would not destroy them upon any property of my own, because they do so much more good than harm in divers ways. We have a small property in my family, where foxes and badgers lie up together in close proximity to a rabbit warren, upon the[63] inhabitants of which they feed. It is a spot practically unknown to the outward gaze of man, as it is difficult of access; and I should fancy that any one attempting to attack their stronghold would meet with a stubborn resistance. Badgers mostly go seeking for food during the night-time. Where they abound, one occasionally meets them walking quietly along a path, with their snout low down, and occasionally giving a kind of grunt like a mongoose. They are very fond of honey. A bag pegged back over the entrance to their holes is a good way of catching them."

They do not hunt for rabbits or game like a fox or cat, and though there are undoubtedly instances of their taking partridge and pheasant eggs, in my experience I have never known it done by those around me, nor from other places where they have ample opportunity of doing so. I have known a pheasant rear a young brood on an earth tenanted by badgers; but, curiously enough, I have known a similar case on a fox's earth, containing a vixen and cubs, and I cannot[64] defend the general character of a fox in regard to game. Still it may be taken that a badger, though occasionally eating rabbits and rarely eggs, does not hunt for game, ground or feathered, or do a hundredth part of the damage done by a fox or a cat. There have always been more rabbits, hares, and pheasants in a hollow near my house, where there is a large colony of badgers, than in any other part of the coverts. The badger has a special weakness for wild honey, and the grubs of wasps and humble bees. The wildest and most unconciliatory badgers I have ever had in confinement would come out and eat a wasp's nest, and they will hunt every bank and hedgerow in July and August, routing out every wasp's and hornet's nest in the country-side. A keeper told me that upon one occasion, when he was walking along the covert edges in summer-time about nine o'clock in the evening, his attention was arrested by a curious chapping, champing noise, and looking over the fence he saw an old badger with his head in a huge wasp's nest hanging in a bramble bush, and he was[65] crunching up and eating with the greatest gusto the wasps and grubs, quite undeterred by the thousand angry insects that covered his head and body. In truth, I must admit that while he is thus useful, he has been known to enter a garden and upset the hives and purloin the honey, being as fond of it as his larger cousins, the bears.

I must also bring another charge against him. Let me introduce this painful subject by giving the following correspondence from the Field newspaper:—

"Wilfred writes—'I shall be obliged if you will allow me to ask your readers whether they have known old badgers to kill fox cubs. Last year our M.F.H. gave a neighbouring keeper a litter of cubs. He put them into a natural empty fox-earth, and kept them shut in until they had got fairly on their feed, and were quite at home. When he opened the earth, and allowed them to come out, they played about, and all went well for two or three days, when he found one at a little distance from the mouth of the earth dead, with its skull smashed in,[66] and very much bitten about the head and neck. He lost the lot in the same way in a few days. He thought an old badger or fox killed his cubs. About this time I got five cubs, and put them into an empty artificial fox-earth. All went well with them for some time after they played out, when the keeper reported finding one about twenty yards from the earth dead, and killed after the same fashion as my neighbour's cubs, and I too lost mine. In the same artificial earth I had a natural litter this season, and the cubs played out well; but on the keeper telling me he did not think they were there now, I went to examine the earth, found the foxes gone, and the earth occupied by an old badger. I had a litter of fox cubs in the deer park here, where I live, and all went well with them until ten days ago, when one was picked up dead, killed in the same manner as those last year, and another was found dead yesterday. I feel quite certain myself that they were killed by an old badger or an old fox, for I am sure if killed by dogs they would not smash the skull and neck. I[67] shall be glad if any one can enlighten me on this subject.'"

In reply to "Wilfred" there were several letters, among which were the following:—

"Sir,—Undoubtedly; every one that they can get near, and more especially hand-reared cubs that have not got the old foxes to protect them. I was first told this by old Jem Hills, the well-known huntsman of the Heythrop, in his latter years; and subsequently I had positive proof of what he said. On one occasion a man brought a fine half-grown cub to my house which he had picked up dead in the road he came along. It was bitten most severely through and behind the shoulder, and I at once remarked to a friend that was with me, 'That is the work of a badger.' On going down to an earth where I knew there was a natural litter, we found tracks of a badger all about the place, as if he had been hunting the cubs. Having at the time eight cubs that I was hand-rearing in an artificial drain, I thought it was high time to look after them, for[68] though regularly fed, I did not always watch to see whether they all came to feed. However, I did so that evening, and only two came, and these looked very wild and scared. I then searched the plantation, and picked up four of my cubs killed quite recently, and bitten in the same savage way. A few weeks after we killed a big boar badger in the drain. Several years later, I was again rearing some hand-bred cubs, and everything went well until they were a good size, when one morning I found one of them killed, evidently by a badger; and I eventually took four more of them, and the others were all driven away. This badger beat me for some little time, but I got him at last. Though old badgers and foxes are often found in the same earth, more frequently when one of the latter has been run to ground by hounds, yet, as a rule, they give each other wide berths. If your correspondent 'Wilfred' wishes to save his cubs, let him kill every badger as soon as possible."

[69]"Sir,—Replying to 'Wilfred's' question, 'Do badgers kill fox cubs?' I cannot say they do, because there are no badgers in this district; but having at different times had young foxes killed in the way he describes, namely, bitten in the head, I can assure him that it is done by an old dog fox. Should he wish for further information, I refer him to Mr. John Douglas, Royal Hotel, Pudding Chare, Newcastle-on-Tyne, who will tell him of the experience he gained when at Clumber, under the Duke of Newcastle."

"Sir,—I may tell 'Wilfred' that I have never known old badgers kill fox cubs, though I have studied the habits of both for nearly forty years. No doubt an old vixen, with no cubs of her own, killed his; the dog fox will not do this. Indeed, he will cater for all the cubs of his own get, but a strange vixen is very apt to kill any cubs which have no mother of their own. I have known a terrier bitch kill a litter of foxhound puppies, and one of my Irish terriers will kill puppies if she has the chance. As to the 'natural' litter[70] which 'Wilfred' found gone, they had merely been shifted by the vixen; as soon as the cubs get able to travel they are always shifted. Last year I had two tame wild ducks sitting in a hedge. A badger passed regularly within a yard of them every night, but they were undisturbed. This year a fox took one of them just before it hatched. I was sorry to read the other day in the Field an account of two old and four cub badgers having been dug out in Gloucestershire. There is surely no sport in this, and the badgers are destitute of grease now, whereas at Michaelmas they are fat enough to provide grease for all the rheumatic people in the parish. I like to catch one with my terriers when the harvest moon shines. Sometimes I get up in a convenient tree near the earth and watch the badgers feeding on the crazy roots. How fond they are of the wild bees' honey, and also of wasps' nests. Let me advise 'Wilfred' to read the exhaustive and interesting account given in a letter to the Times (October 24, 1877), and quoted in Cassell's Natural History, vol. ii. It thus concludes—'The[71] badgers and the foxes are not unfriendly, and last spring a litter of cubs was brought forth very near the badgers; but their mother removed them after they had grown familiar, as she probably thought they were showing themselves more than was prudent.' Mr. Ellis of Loughborough was the author of the letter, and he had rare opportunities of studying the habits of badgers."

I am loth to do it, but wishing to be an impartial historian, am compelled to state that the badger is capable of vulpicide. As a rule he can put up with an occasional lodger of the fox family, and live happily with him, and from his superior qualities as an architect of subterranean dwellings, he is on the whole an encourager of foxes. He often gives up his spacious apartments to a vixen in the spring, and submits to eviction. A fox will often take possession of a badger's earth, new or old; and in order to persuade foxes to take to a particular covert, no surer method can be pursued than to get badgers to make earths when they are required. But[72] even a badger's patience can be exhausted, as the following history of my own experience will show. I would premise, however, that I do not credit the oft-repeated story that the fox gets rid of the badger by leaving his evacuations in the badger's earth. Being the less and weaker animal, all a fox does is allowed on sufferance. My suspicions of a badger's capability to wage war on foxes were first aroused some years ago. The badgers had made a fine double set of earths on the north side, of a hill in a neighbouring larch wood, where no effort on my part to get foxes to breed and stay had succeeded. No sooner, however, was a colony of badgers established than foxes haunted the holes and covert. In a succession of years there was as certain to be a litter of fox cubs in the badger earth as a sunrise on the morrow.

What happened each spring was that the foxes and badgers frequented both sets indiscriminately till about March. When the vixen lay in the badgers abandoned the set of holes where she was, and restricted themselves to the other set some twenty yards[73] distant. Year after year the fox cubs prospered and grew up, till one summer the keeper found a fox cub in a field with his head bitten in two and terribly worried. I did not know how to account for it. I watched the vixen and the other cubs one evening to see that they were all right, and saw them, but found they had left the earth and were in the covert. For two years all went well and the foxes were unmolested, and then occurred something that gave me a clue to the death of the cub three years before. Two vixens lay in at the badgers' earth, and brought up their families of seven and four respectively, till they were about one-third grown. There were then to my knowledge at least four badgers and twelve foxes in these two earths. On one or two occasions the stillness of the night was broken by the veriest pandemonium at the earth, but still I did not think much of it. At the end of the hunting season, at the end of April, when the cubs were seven or eight weeks old, and a fortnight after the hounds had been through the coverts, I found the largest and finest of the vixens dead, and[74] thought that, in spite of the earths being open, she must have been chopped by the hounds. A post-mortem examination, as well as the improbability of a vixen with cubs being out in the early part of the day, convinced me that she had not been killed by hounds. She seemed to have been badly bitten through the legs and thighs but not on the body. From this time the other vixen and all the cubs left the badgers' earths and remained in the covert. It was on this occasion that an attempt to find out how many badgers there were in these earths was rewarded by seeing seven full-grown badgers emerge from a single hole. It was rough, no doubt, that the badgers should be invaded by two large families of smelling foxes, and no doubt their patience had become exhausted. Still I could not tolerate this kind of behaviour, and so I had a dig at them, took two old ones out, and transported them to Scotland. The following year there was peace and fox cubs again. The year after, however, the vixen and her cubs took off into the covert very early after another bit of Bank Holiday[75] business, at a time of night when all respectable people were quietly in bed. And yet all through the year foxes are in the earth, and this spring, as heretofore, a litter of cubs has been raised, but removed to another earth at a safe distance from the badgers. I have never heard of badgers taking the offensive against foxes; they will never molest a fox or vixen unless their earth is invaded, and in my case if I had had no badgers in this covert I should have had no foxes; and whilst it is annoying that the fox cubs and vixen should be driven out, and perhaps occasionally killed, the drawback is slight when it is considered that as long as there are badgers there will be a litter of cubs, which nine times out of ten will get safely off.

There are every now and then albino badgers reported, but I have never seen one alive. I think, however, they are more subject to albinism than most animals. I do not know of a case of melanism.

"White Badger at Overton, Hants.—While digging for badgers on April 30, we came across two dog badgers in the same[76] earth, one of which was quite white, the colour of a white ferret, with pink eyes. Unfortunately, the terriers punished him so much he had to be destroyed. I have helped to dig out a great many of these animals, but never saw nor heard of a white one before."—T. P.

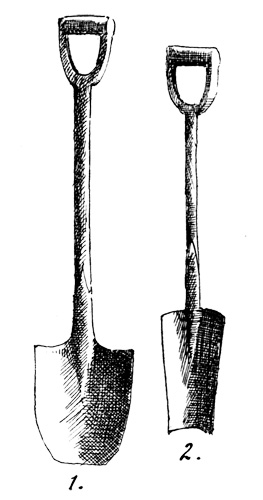

There are several methods by which the badger can be taken alive, or killed, with ease. I am familiar with several successful ways of trapping him. The reader, if he is not aware of these, must not expect me to enlighten him, as my object in writing is to arouse an interest in his preservation, not to facilitate his destruction. It may be as well to state, however, that the inhuman engine, the steel trap (by which so many of the birds and beasts that frequented the wild woods of England and Scotland have been exterminated) is an instrument that arouses the suspicion of a badger at once, and he is as clever in avoiding it as an old-fashioned rat. The badger if caught in a steel trap will frequently bite his leg or foot clean off. In[78] my opinion there are two legitimate methods of hunting the badger. First, that of a straight-forward attack on his fortress; and should it be an old-established earth, it may be the end of the longest day will not see the battle ended. There are, of course, the fortunes of war—a lucky engagement, a wrong turn on the part of the defender, a successful trench quickly cutting off his retreat—which may deliver him unexpectedly into your hands; or the enemy may outwit you altogether, conducting a masterful retreat, with gallant sorties on the dogs, and by continually changing his front drive you to abandon works, trenches, and operations that have cost great labour and time; thus you may be left with a tired and wounded pack of terriers, exhausted sappers, and the badger, having blocked and barricaded his retreat with soil, stones, and sand, is lost. The war thus made is an equal one: you attack him on his own ground in his fortress where he is acquainted with every passage, gallery, and casement; he is armed to the teeth and armour-plated, and can drive a road[79] forward, downward, or upward with extraordinary rapidity. It is true you may have many terriers, but he has an advantage over your forces. Only one of your dogs can engage at a time, and the badger has the advantage of weight, size, knowledge of the ground, and familiarity with the dark—in fact, in every respect except those of courage and endurance, which in some terriers may equal his own. The other method, less sure, depends on taking the badger off his guard, and is more in the character of an ambuscade under cover of night. When the badgers are away from home you block up their earths, placing sacks with running nooses in the mouth, in the most frequented holes. Station one of your party near the "set," and you may either take a small pack of hounds and draw the country for a few miles round, and hunt him like a fox, getting a run across country and a fine cry; or you may beat the neighbouring coverts with men and dogs of any description that are trained to hunt the badger.

In the following, taken from an article[80] which appeared in a newspaper, there is a good account of night hunting.