THE

WORKS

OF

DANIEL WEBSTER.

VOLUME I.

EIGHTH EDITION

BOSTON:

LITTLE, BROWN AND COMPANY.

1854.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1851, by

George W. Gordon and James W. Paige,

in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

CAMBRIDGE:

STEREOTYPED BY METCALF AND COMPANY,

PRINTERS TO THE UNIVERSITY.

PRINTED AT HOUGHTON AND HAYWOOD

DEDICATION

OF THE FIRST VOLUME.

TO MY NIECES,

MRS. ALICE BRIDGE WHIPPLE,

AND

MRS. MARY ANN SANBORN:

Many of the Speeches contained in this volume were delivered

and printed in the lifetime of your father whose fraternal affection led him

to speak of them with approbation.

His death, which happened when he had only just past the middle

period of life, left you without a father, and me without a brother.

I dedicate this volume to you, not only for the love I have for yourselves,

but also as a tribute of affection to his memory, and from a

desire that the name of my brother,

EZEKIEL WEBSTER,

may be associated with mine, so long as any thing written or spoken by

me shall be regarded or read.

DANIEL WEBSTER.

CONTENTS

OF THE FIRST VOLUME.

|

PAGE |

BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR. |

| Chapter I. |

xiii |

Former Editions of the Works of Mr. Webster, and Plan of this Edition.—Parentage and Birth.—First Settlements in the Interior of New Hampshire.—Establishment of his Father at Salisbury.—Scanty Opportunities of Early Education.—First Teachers, and recent Letter to Master Tappan.—Placed at Exeter Academy.—Anecdotes while there.—Dartmouth College.—Study of the Law at Salisbury.—Residence at Fryeburg in Maine, and Occupations there.—Continuance of the Study of the Law at Boston, in the Office of Hon. Christopher Gore.—Admission to the Bar of Suffolk, Massachusetts.—Commencement of Practice at Boscawen, New Hampshire.—Removal to Portsmouth.—Contemporaries in the Profession.—Increasing Practice.

|

|

|

| Chapter II. |

xxxiii |

Entrance on Public Life.—State of Parties in 1812.—Election to Congress.—Extra Session of 1813.—Foreign Relations of the Country.—Resolutions relative to the Berlin and Milan Decrees.—Naval Defence.—Reelected to Congress in 1814.—Peace with England.—Projects for a National Bank.—Mr. Webster's Course on that Question.—Battle of New Orleans.—New Questions arising on the Return of Peace.—Course of Prominent Men of Different Parties.—Mr. Webster's Opinions on the Constitutionality of the Tariff Policy.—The Resolution to restore Specie Payments moved by Mr. Webster.—Removal to Boston.

|

|

|

| Chapter III. |

xlviii |

Professional Character particularly in Reference to Constitutional Law.—The Dartmouth College Case argued at Washington in 1818.—Mr. Ticknor's Description of that Argument.—The Case of Gibbons and Ogden in 1824.—Mr. Justice Wayne's Allusion to that Case in 1847.—The Case of Ogden and Saunders in 1827.—The Case of the Proprietors of the Charles River Bridge.—The Alabama Bank Case.—The Case relative to the Boundary between Massachusetts and Rhode Island.—The Girard Will Case.—The Case of the Constitution of Rhode Island.—General Remarks on Mr. Webster's Practice in the Supreme Court of the United States.—Practice in the State Courts.—The Case of Goodridge,—and the Case of Knapp.

|

|

|

| Chapter IV. |

lx |

The Convention to revise the Constitution of Massachusetts.—John Adams a Delegate.—Mr. Webster's Share in its Proceedings.—Speeches on Oaths of Office, Basis of Senatorial Representation, and Independence of the Judiciary.—Centennial Anniversary at Plymouth on the 22d of December, 1820.—Discourse delivered by Mr. Webster.—Bunker Hill Monument, and Address by Mr. Webster on the Laying of the Corner-Stone, 17th of June, 1825.—Discourse on the Completion of the Monument, 17th of June, 1843.—Simultaneous Decease of Adams and Jefferson on the 4th of July, 1826.—Eulogy by Mr. Webster in Faneuil Hall.—Address at the Laying of the Corner-Stone of the New Wing of the Capitol.—Remarks on the Patriotic Discourses of Mr. Webster, and on the Character of his Eloquence in Efforts of this Class.

|

|

|

| Chapter V. |

lxxii |

Election to Congress from Boston.—State of Parties.—Meeting of the Eighteenth Congress.—Mr. Webster's Resolution and Speech in favor of the Greeks.—Argument in the Supreme Court in the Case of Gibbons and Ogden.—Circumstances under which it was made.—Speech on the Tariff Law of 1824.—A complete Revision of the Law for the Punishment of Crimes against the United States reported by Mr. Webster, and enacted.—The Election of Mr. Adams as President of the United States.—Meeting of the Nineteenth Congress, and State of Parties.—Congress of Panama, and Mr. Webster's Speech on that Subject.—Election as a Senator of the United States.—Revision of the Tariff Law by the Twentieth Congress.—Embarrassments of the Question.—Mr. Webster's Course and Speech on this Subject.

|

|

|

| Chapter VI. |

lxxxvii |

Election of General Jackson.—Debate on Foot's Resolution.—Subject of the Resolution, and Objects of its Mover.—Mr. Hayne's First Speech.—Mr. Webster's original Participation in the Debate unpremeditated.—His First Speech.—Reply of Mr. Hayne with increased Asperity.—Mr. Webster's Great Speech.—Its Threefold Object.—Description of the Manner of Mr. Webster in the Delivery of this Speech, from Mr. March's "Reminiscences of Congress."—Reception of his Speech throughout the Country.—The Dinner at New York.—Chancellor Kent's Remarks.—Final Disposal of Foot's Resolution.—Report of Mr. Webster's Speech.—Mr. Healey's Painting.

|

|

|

| Chapter VII. |

ci |

General Character of President Jackson's Administrations.—Speedy Discord among the Parties which had united for his Elevation.—Mr. Webster's Relations to the Administration.—Veto of the Bank.—Rise and Progress of Nullification in South Carolina.—The Force Bill, and the Reliance of General Jackson's Administration on Mr. Webster's Aid.—His Speech in Defence of the Bill, and in Opposition to Mr. Calhoun's Resolutions.—Mr. Madison's Letter on Secession.—The Removal of the Deposits.—Motives for that Measure.—The Resolution of the Senate disapproving it.—The President's Protest.—Mr. Webster's Speech on the Subject of the Protest.—Opinions of Chancellor Kent and Mr. Tazewell.—The Expunging Resolution.—Mr. Webster's Protest against it.—Mr. Van Buren's Election.—The Financial Crisis and the Extra Session of Congress.—The Government Plan of Finance supported by Mr. Calhoun and opposed by Mr. Webster.—Personalities.—Mr. Webster's Visit to Europe and distinguished Reception.—The Presidential Canvass of 1840.—Election of General Harrison.

|

|

|

| Chapter VIII. |

cxix |

Critical State of Foreign Affairs on the Accession of General Harrison.—Mr. Webster appointed to the State Department.—Death of General Harrison.—Embarrassed Relations with England.—Formation of Sir Robert Peel's Ministry, and Appointment of Lord Ashburton as Special Minister to the United States.—Course pursued by Mr. Webster in the Negotiations.—The Northeastern Boundary.—Peculiar Difficulties in its Settlement happily overcome.—Other Subjects of Negotiation.—Extradition of Fugitives from Justice.—Suppression of the Slave-Trade on the Coast of Africa.—History of that Question.—Affair of the Caroline.—Impressment.—Other Subjects connected with the Foreign Relations of the Government.—Intercourse with China.—Independence of the Sandwich Islands.—Correspondence with Mexico.—Sound Duties and the Zoll-Verein.—Importance of Mr. Webster's Services as Secretary of State.

|

|

|

| Chapter IX. |

cxliii |

Mr. Webster resigns his Place in Mr. Tyler's Cabinet.—Attempts to draw public Attention to the projected Annexation of Texas.—Supports Mr. Clay's Nomination for the Presidency.—Causes of the Failure of that Nomination.—Mr. Webster returns to the Senate of the United States.—Admission of Texas to the Union.—The War with Mexico.—Mr. Webster's Course in Reference to the War.—Death of Major Webster in Mexico.—Mr. Webster's unfavorable Opinion of the Mexican Government.—Settlement of the Oregon Controversy.—Mr. Webster's Agency in effecting the Adjustment.—Revival of the Sub-Treasury System and Repeal of the Tariff Law of 1842.—Southern Tour.—Success of the Mexican War and Acquisition of the Mexican Provinces.—Efforts in Congress to organize a Territorial Government for these Provinces.—Great Exertions of Mr. Webster on the last Night of the Session.—Nomination of General Taylor, and Course of Mr. Webster in Reference to it.—A Constitution of State Government adopted by California prohibiting Slavery.—Increase of Antislavery Agitation.—Alarming State of Affairs.—Mr. Webster's Speech for the Union.—Circumstances under which it was made, and Motives by which he was influenced.—General Taylor's Death, and the Accession of Mr. Fillmore to the Presidency.—Mr. Webster called to the Department of State.

|

|

|

SPEECHES DELIVERED ON VARIOUS PUBLIC OCCASIONS. |

|

|

| First Settlement of New England |

1 |

| The Bunker Hill Monument |

55 |

| The Completion of the Bunker Hill Monument |

79 |

| Adams and Jefferson |

109 |

| The Election of 1825 |

151 |

| Dinner at Faneuil Hall |

161 |

| The Boston Mechanics’ Institution |

175 |

| Public Dinner at New York |

191 |

| The Character of Washington. |

217 |

| National Republican Convention at Worcester |

235 |

| Reception at Buffalo |

279 |

| Reception at Pittsburg |

285 |

| Reception at Bangor |

307 |

| Presentation of a Vase |

317 |

| Reception at New York |

337 |

| Reception at Wheeling |

381 |

| Reception at Madison |

395 |

| Public Dinner in Faneuil Hall |

411 |

| Royal Agricultural Society |

433 |

| The Agriculture of England |

441 |

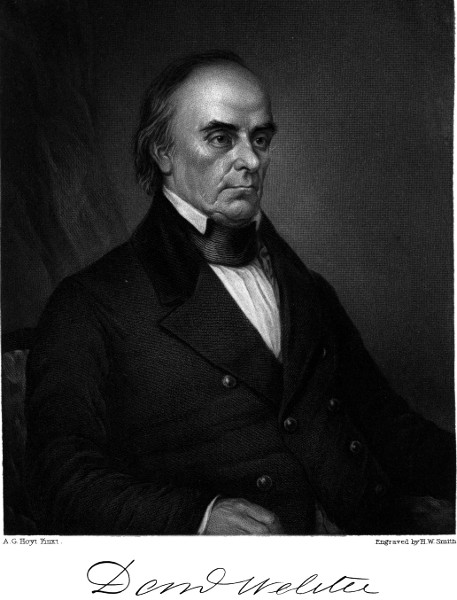

BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIR

OF THE

PUBLIC LIFE

OF

DANIEL WEBSTER.

BY

EDWARD EVERETT.

Former Editions of the Works of Mr. Webster, and Plan of this Edition.—Parentage

and Birth.—First Settlements in the Interior of New Hampshire.—Establishment

of his Father at Salisbury.—Scanty Opportunities of Early Education.—First

Teachers, and recent Letter to Master Tappan.—Placed at Exeter Academy.—Anecdotes

while there.—Dartmouth College.—Study of the Law at Salisbury.—Residence

at Fryeburg in Maine, and Occupations there.—Continuance

of the Study of the Law at Boston, in the Office of Hon. Christopher Gore.—Admission

to the Bar of Suffolk, Massachusetts.—Commencement of Practice

at Boscawen, New Hampshire.—Removal to Portsmouth.—Contemporaries in the

Profession.—Increasing Practice.

The first collection of Mr. Webster’s speeches in the Congress

of the United States and on various public occasions was

published in Boston, in one volume octavo, in 1830. This

volume was more than once reprinted, and in 1835 a second

volume was published, containing the speeches made up to that

time, and not included in the first collection. Several impressions

of these two volumes were called for by the public. In

1843 a third volume was prepared, containing a selection from

the speeches of Mr. Webster from the year 1835 till his entrance

into the cabinet of General Harrison. In the year 1848

appeared a fourth volume of diplomatic papers, containing a

portion of Mr. Webster’s official correspondence as Secretary

of State.

The great favor with which these volumes have been received

throughout the country, and the importance of the subjects

discussed in the Senate of the United States after Mr.

Webster’s return to that body in 1845, have led his friends to

think that a valuable service would be rendered to the community

xiv

by bringing together his speeches of a later date than

those contained in the third volume of the former collection,

and on political subjects arising since that time. Few periods

of our history will be entitled to be remembered by events of

greater moment, such as the admission of Texas to the Union,

the settlement of the Oregon controversy, the Mexican war, the

acquisition of California and other Mexican provinces, and the

exciting questions which have grown out of the sudden extension

of the territory of the United States. Rarely have public

discussions been carried on with greater earnestness, with

more important consequences visibly at stake, or with greater

ability. The speeches made by Mr. Webster in the Senate,

and on public occasions of various kinds, during the progress

of these controversies, are more than sufficient to fill two

new volumes. The opportunity of their collection has been

taken by the enterprising publishers, in compliance with opinions

often expressed by the most respectable individuals, and

with a manifest public demand, to bring out a new edition of

Mr. Webster’s speeches in uniform style. Such is the object

of the present publication. The first two volumes contain the

speeches delivered by him on a great variety of public occasions,

commencing with his discourse at Plymouth in December,

1820. Three succeeding volumes embrace the greater part

of the speeches delivered in the Massachusetts Convention and

in the two houses of Congress, beginning with the speech on

the Bank of the United States in 1816. The sixth and last

volume contains the legal arguments and addresses to the jury,

the diplomatic papers, and letters addressed to various persons

on important political questions.

The collection does not embrace the entire series of Mr.

Webster’s writings. Such a series would have required a larger

number of volumes than was deemed advisable with reference

to the general circulation of the work. A few juvenile performances

have accordingly been omitted, as not of sufficient importance

or maturity to be included in the collection. Of the

earlier speeches in Congress, some were either not reported at

all, or in a manner too imperfect to be preserved without doing

injustice to the author. No attempt has been made to collect

from the contemporaneous newspapers or Congressional registers

the short conversational speeches and remarks made by

xv

Mr. Webster, as by other prominent members of Congress, in

the progress of debate, and sometimes exercising greater influence

on the result than the set speeches. Of the addresses to

public meetings it has been found impossible to embrace more

than a selection, without swelling the work to an unreasonable

size. It is believed, however, that the contents of these volumes

furnish a fair specimen of Mr. Webster’s opinions and

sentiments on all the subjects treated, and of his manner of discussing

them. The responsibility of deciding what should be

omitted and what included has been left by Mr. Webster to

the friends having the charge of the publication, and his own

opinion on details of this kind has rarely been taken.

In addition to such introductory notices as were deemed expedient

relative to the occasions and subjects of the various

speeches, it has been thought advisable that the collection

should be accompanied with a Biographical Memoir, presenting

a condensed view of Mr. Webster’s public career, with a few

observations by way of commentary on the principal speeches.

Many things which might otherwise fitly be said in such an

essay must, it is true, be excluded by that delicacy which

qualifies the eulogy to be awarded even to the most eminent

living worth. Much may be safely omitted, as too well known

to need repetition in this community, though otherwise pertaining

to a full survey of Mr. Webster’s career. In preparing the

following notice, free use has been made by the writer of the

biographical sketches already before the public. Justice, however,

requires that a specific acknowledgment should be made

to an article in the American Quarterly Review for June,

1831, written, with equal accuracy and elegance, by Mr. George

Ticknor, and containing a discriminating estimate of the

speeches embraced in the first collection; and also to the

highly spirited and vigorous work entitled “Reminiscences of

Congress,” by Mr. Charles W. March. To this work the present

sketch is largely indebted for the account of the parentage

and early life of Mr. Webster; as well as for a very graphic

description of the debate on Foot’s resolution.

The family of Daniel Webster has been established in America

from a very early period. It was of Scottish origin, but

passed some time in England before the final emigration.

xvi

Thomas Webster, the remotest ancestor who can be traced, was

settled at Hampton, on the coast of New Hampshire, as early

as 1636, sixteen years after the landing at Plymouth, and six

years from the arrival of Governor Winthrop in Massachusetts

Bay. The descent from Thomas Webster to Daniel can be

traced in the church and town records of Hampton, Kingston

(now East Kingston), and Salisbury. These records and the

mouldering headstones of village grave-yards are the herald’s

office of the fathers of New England. Noah Webster, the

learned author of the American Dictionary of the English Language,

was of a collateral branch of the family.

Ebenezer Webster, the father of Daniel, is still recollected in

Kingston and Salisbury. His personal appearance was striking.

He was erect, of athletic stature, six feet high, broad and

full in the chest. Long service in the wars had given him a

military air and carriage. He belonged to that intrepid border

race, which lined the whole frontier of the Anglo-American colonies,

by turns farmers, huntsmen, and soldiers, and passing

their lives in one long struggle with the hardships of an infant

settlement, on the skirts of a primeval forest. Ebenezer Webster

enlisted early in life as a common soldier, in one of those

formidable companies of rangers, which rendered such important

services under Sir Jeffrey Amherst and Wolfe in the Seven

Years’ War. He followed the former distinguished leader in

the invasion of Canada, attracted the attention and gained

the good-will of his superior officers by his brave and faithful

conduct, and rose to the rank of a captain before the end of

the war.

For the first half of the last century the settlements of New

Hampshire had made but little progress into the interior. Every

war between France and Great Britain in Europe was the

signal of an irruption of the Canadian French and their Indian

allies into New England. As late as 1755 they sacked villages

on the Connecticut River, and John Stark, while hunting on

Baker’s River, three years before, was taken a prisoner and sold

as a slave into Canada. One can scarcely believe that it is

not yet a hundred years since occurrences like these took place.

The cession of Canada to England by the treaty of 1763 entirely

changed this state of things. It opened the pathways of

the forest and the gates of the Western hills. The royal governor

xvii

of New Hampshire, Benning Wentworth, began to make grants

of land in the central parts of the State. Colonel Stevens of

Kingston, with some of his neighbors, mostly retired officers and

soldiers, obtained a grant of the town of Salisbury, which was

at first called Stevenstown, from the principal grantee. This

town is situated exactly at the point where the Merrimack River

is formed by the confluence of the Pemigewasset and Winnipiseogee.

Captain Webster was one of the settlers of the

newly granted township, and received an allotment in its northerly

portion. More adventurous than others of the company, he

cut his way deeper into the wilderness, and made the path he

could not find. At this time his nearest civilized neighbors on

the northwest were at Montreal.

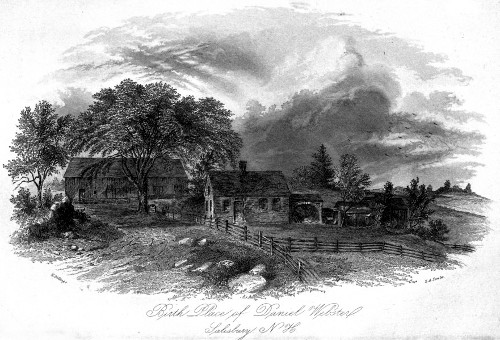

The following allusion of Mr. Webster to his birthplace will

be read with interest. It is from a speech delivered before a

great public assembly at Saratoga, in the year 1840.

“It did not happen to me to be born in a log cabin; but my elder

brothers and sisters were born in a log cabin, raised amid the snowdrifts

of New Hampshire, at a period so early that, when the smoke first

rose from its rude chimney, and curled over the frozen hills, there was

no similar evidence of a white man’s habitation between it and the settlements

on the rivers of Canada. Its remains still exist. I make to it

an annual visit. I carry my children to it to teach them the hardships endured

by the generations which have gone before them. I love to dwell

on the tender recollections, the kindred ties, the early affections, and the

touching narratives and incidents, which mingle with all I know of this

primitive family abode. I weep to think that none of those who inhabited

it are now among the living; and if ever I am ashamed of it, or if I ever

fail in affectionate veneration for HIM who reared and defended it against

savage violence and destruction, cherished all the domestic virtues beneath

its roof, and, through the fire and blood of seven years’ revolutionary

war, shrunk from no danger, no toil, no sacrifice, to serve his

country, and to raise his children to a condition better than his own,

may my name and the name of my posterity be blotted for ever from

the memory of mankind!”

Soon after his settlement in Salisbury, the first wife of Ebenezer

Webster having deceased, he married Abigail Eastman,

who became the mother of Ezekiel and Daniel Webster, the

only sons of the second marriage. Like the mothers of so many

men of eminence, she was a woman of more than ordinary intellect,

and possessed a force of character which was felt throughout

xviii

the humble circle in which she moved. She was proud of

her sons and ambitious that they should excel. Her anticipations

went beyond the narrow sphere in which their lot seemed

to be cast, and the distinction attained by both, and especially

by the younger, may well be traced in part to her early promptings

and judicious guidance.

About the time of his second marriage, Captain Ebenezer

Webster erected a frame house hard by the log cabin. He dug

a well near it and planted an elm sapling. In this house Daniel

Webster was born. It has long since disappeared, but the spot

where it stood is well known, and is covered by a house since

built. The cellar of the log cabin is still visible, though partly

filled with the accumulations of seventy years. “The well

still remains,” says Mr. March, “with water as pure, as cool,

and as limpid as when first brought to light, and will remain

in all probability for ages, to refresh hereafter the votaries of genius

who make their pilgrimage hither, to visit the cradle of

one of her greatest sons. The elm that shaded the boy still

flourishes in vigorous leaf, and may have an existence beyond

its perishable nature. Like

‘The witch-elm that guards St. Fillan’s spring,’

it may live in story long after leaf, and branch, and root have

disappeared for ever.”

The interval between the peace of 1763 and the breaking out

of the war of the Revolution was one of excitement and anxiety

throughout the Colonies. The great political questions of the

day were not only discussed in the towns and cities, but in the

villages and hamlets. Captain Webster took a deep interest

in those discussions. Like so many of the officers and soldiers

of the former war, he obeyed the first call to arms in the new

struggle. He commanded a company, chiefly composed of his

own townspeople, friends, and kindred, who followed him

through the greater portion of the war. He was at the battle

of White Plains, and was at West Point when the treason of

Arnold was discovered. He acted as a Major under Stark at

Bennington, and contributed his share to the success of that

eventful day.

In the last year of the Revolutionary war, on the 18th of

January, 1782, Daniel Webster was born, in the home which his

xix

father had established on the outskirts of civilization. If the

character and situation of the place, and the circumstances

under which he passed the first years of his life, might seem adverse

to the early cultivation of his extraordinary talent, it still

cannot be doubted that they possessed influences favorable to

elevation and strength of character. The hardships of an infant

settlement and border life, the traditions of a long series of

Indian wars, and of two mighty national contests, in which

an honored parent had borne his part, the anecdotes of Fort

William Henry, of Quebec, of Bennington, of West Point, of

Wolfe and Stark and Washington, the great Iliad and Odyssey

of American Independence,—this was the fireside entertainment

of the long winter evenings of the secluded village

home. Abroad, the uninviting landscape, the harsh and craggy

outline of the hills broken and relieved only by the funereal

hemlock and the “cloud seeking” pine, the lowlands traversed

in every direction by unbridged streams, the tall, charred

trunks in the cornfields, that told how stern had been the

struggle with the boundless woods, and, at the close of the year,

the dismal scene which presents itself in high latitudes in a

thinly settled region, when

“the snows descend; and, foul and fierce,

All winter drives along the darkened air”;—

these are circumstances to leave an abiding impression on the

mind of a thoughtful child, and induce an early maturity of

character.

Mr. March has described an incident of Mr. Webster’s earliest

youth in a manner so graphical, that we are tempted to repeat

it in his own words:—

“In Mr. Webster’s earliest youth an occurrence of such a nature took

place, which affected him deeply at the time, and has dwelt in his memory

ever since. There was a sudden and extraordinary rise in the Merrimack

River, in a spring thaw. A deluge of rain for two whole days

poured down upon the houses. A mass of mingled water and snow

rushed madly from the hills, inundating the fields far and wide. The

highways were broken up, and rendered undistinguishable. There was

no way for neighbors to interchange visits of condolence or necessity,

save by boats, which came up to the very door-steps of the houses.

“Many things of value were swept away, even things of bulk. A

large barn, full fifty feet by twenty, crowded with hay and grain, sheep,

xx

chickens, and turkeys, sailed majestically down the river, before the

eyes of the astonished inhabitants; who, no little frightened, got ready

to fly to the mountains, or construct another ark.

“The roar of waters, as they rushed over precipices, casting the

foam and spray far above, the crashing of the forest-trees as the storm

broke through them, the immense sea everywhere in range of the eye,

the sublimity, even danger, of the scene, made an indelible impression

upon the mind of the youthful observer.

“Occurrences and scenes like these excite the imaginative faculty,

furnish material for proper thought, call into existence new emotions,

give decision to character, and a purpose to action.”—pp. 7, 8.

It may well be supposed that Mr. Webster’s early opportunities

for education were very scanty. It is indeed correctly

remarked by Mr. Ticknor, in reference to this point, that “in

New England, ever since the first free school was established

amidst the woods that covered the peninsula of Boston in 1636,

the schoolmaster has been found on the border line between

savage and civilized life, often indeed with an axe to open his

own path, but always looked up to with respect, and always

carrying with him a valuable and preponderating influence.”

Still, however, compared with any thing that would be called a

good school in this region and at the present time, the schools

which existed on the frontier sixty years ago were sadly defective.

Many of our district schools even now are below their

reputation. The Swedish Chancellor’s exclamation of wonder

at the little wisdom with which the world is governed, might

well be repeated at the little learning and skill with which the

scholastic world in too many parts of our country is still taught.

In Mr. Webster’s boyhood it was much worse. Something that

was called a school was kept for two or three months in the

winter, frequently by an itinerant, too often a pretender, claiming

only to teach a little reading, writing, and ciphering, and wholly

incompetent to give any valuable assistance to a clever youth

in learning either.

Such as the village school was, Mr. Webster enjoyed its

advantages, if they could be called by that name. It was,

however, of a migratory character. When it was near his

father’s residence it was easy to attend; but it was sometimes

in a distant part of the town, and sometimes in another town.

While he was quite young, he was daily sent two miles and a

xxi

half or three miles to school in mid-winter and on foot. If the

school-house lay in the same direction with the miller or the

blacksmith, an occasional ride might be hoped for. If the

school was removed to a still greater distance, he was boarded

at a neighbor’s. Poor as these opportunities of education were,

they were bestowed on Mr. Webster more liberally than on his

brothers. He showed a greater eagerness for learning; and he

was thought of too frail a constitution for any robust pursuit.

An older half-brother good-humoredly said, that “Dan was sent

to school that he might get to know as much as the other boys.”

It is probable that the best part of his education was derived from

the judicious and experienced father, and the strong-minded,

affectionate, and ambitious mother.

Mr. Webster’s first master was Thomas Chase. He could

read tolerably well, and wrote a fair hand; but spelling was not

his forte. His second master was James Tappan, now living

at an advanced age in Gloucester, Massachusetts. His qualifications

as a teacher far exceeded those of Master Chase. The

worthy veteran, now dignified with the title of Colonel, feels a

pride, it may well be supposed, in the fame of his quondam

pupil. He lately addressed a letter to him, recounting some of

the incidents of his own life since he taught school at Salisbury.

This unexpected communication from his aged teacher

drew from Mr. Webster the following answer, in which a handsome

gratuity was inclosed, more, probably, than the old gentleman

ever received for a winter’s teaching at “New Salisbury.”[1]

“Washington, February 26, 1851.

“Master Tappan,—I thank you for your letter, and am rejoiced to

know that you are among the living. I remember you perfectly well as

a teacher of my infant years. I suppose my mother must have taught

me to read very early, as I have never been able to recollect the time

when I could not read the Bible. I think Master Chase was my earliest

schoolmaster, probably when I was three or four years old. Then came

Master Tappan. You boarded at our house, and sometimes, I think, in

the family of Mr. Benjamin Sanborn, our neighbor, the lame man.

Most of those whom you knew in ‘New Salisbury’ have gone to their

graves. Mr. John Sanborn, the son of Benjamin, is yet living, and is

xxii

about your age. Mr. John Colby, who married my oldest sister, Susannah,

is also living. On the ‘North Road’ is Mr. Benjamin Hunton,

and on the ‘South Road’ is Mr. Benjamin Pettengil. I think of none

else among the living whom you would probably remember.

“You have indeed lived a checkered life. I hope you have been

able to bear prosperity with meekness, and adversity with patience.

These things are all ordered for us far better than we could order them

for ourselves. We may pray for our daily bread; we may pray for

the forgiveness of sins; we may pray to be kept from temptation, and

that the kingdom of God may come, in us, and in all men, and his will

everywhere be done. Beyond this, we hardly know for what good to

supplicate the Divine Mercy. Our Heavenly Father knoweth what we

have need of better than we know ourselves, and we are sure that his

eye and his loving-kindness are upon us and around us every moment.

“I thank you again my good old schoolmaster, for your kind letter,

which has awakened many sleeping recollections; and, with all good

wishes, I remain your friend and pupil,

“Daniel Webster.

To “Mr. James Tappan.”

He derived, also, no small benefit from the little social library,

which, chiefly by the exertions of Mr. Thompson (the intelligent

lawyer of the place), the clergyman, and Mr. Webster’s

father, had been founded in Salisbury. The attention of the

people of New Hampshire had been called to this mode of promoting

general and popular education by Dr. Belknap. In the

patriotic address to the people of New Hampshire, at the close

of his excellent History, he says:—

“This (the establishment of social libraries) is the easiest, the cheapest,

and the most effectual mode of diffusing knowledge among the

people. For the sum of six or eight dollars at once, and a small annual

payment besides, a man may be supplied with the means of literary improvement

during his life, and his children may inherit the blessing.”[2]

From the village library at Salisbury, founded on recommendations

like these, Mr. Webster was able to obtain a moderate

supply of good reading. It is quite worth noticing, that his

attention, like that of Franklin, was in early boyhood attracted

to the Spectator. Franklin, as is well known, studiously formed

his style on that of Addison;—and a considerable resemblance

may be traced between them. There is no such resemblance

xxiii

between Mr. Webster’s style and that of Addison, unless it be

the negative merit of freedom from balanced sentences, hard

words, and inversions. It may, no doubt, have been partly

owing to his early familiarity with the Spectator, that he escaped

in youth from the turgidity and pomp of the Johnsonian school,

and grew up to the mastery of that direct and forcible, but not

harsh and affected sententiousness, that masculine simplicity,

with which his speeches and writings are so strongly marked.

The year before Mr. Webster was born was rendered memorable

in New Hampshire by the foundation of the Academy

at Exeter, through the munificence of the Honorable John Phillips.

His original endowment is estimated by Dr. Belknap at

nearly ten thousand pounds, which, in the comparative scarcity

of money in 1781, cannot be considered as less than three times

that amount at the present day. Few events are more likely to

be regarded as eras in the history of that State. In the year

1788, Dr. Benjamin Abbot, soon afterwards its principal, became

connected with the Academy as an instructor, and from that

time it assumed the rank which it still maintains among the

schools of the country. To this Academy Mr. Webster was

taken by his father in May, 1796. He enjoyed the advantage

of only a few months’ instruction in this excellent school; but,

short as the period was, his mind appears to have received an

impulse of a most genial and quickening character. Nothing

could be more graceful or honorable to both parties than the

tribute paid by Mr. Webster to his ancient instructor, at the festival

at Exeter, in 1838, in honor of Dr. Abbot’s jubilee. While

at the Academy, his studies were aided and his efforts encouraged

by a pupil younger than himself, but who, having enjoyed

better advantages of education in boyhood, was now in the senior

class at Exeter, the early celebrated and lamented Joseph

Stevens Buckminster. The following anecdote from Mr. March’s

work will not be thought out of place in this connection:—

“It may appear somewhat singular that the greatest orator of modern

times should have evinced in his boyhood the strongest antipathy to

public declamation. This fact, however, is established by his own

words, which have recently appeared in print. ‘I believe,’ says Mr.

Webster, ‘I made tolerable progress in most branches which I attended

to while in this school; but there was one thing I could not do. I could

not make a declamation. I could not speak before the school. The

xxiv

kind and excellent Buckminster sought especially to persuade me to perform

the exercise of declamation, like other boys, but I could not do it.

Many a piece did I commit to memory, and recite and rehearse in my

own room, over and over again; yet when the day came, when the

school collected to hear declamations, when my name was called, and I

saw all eyes turned to my seat, I could not raise myself from it.

Sometimes the instructors frowned, sometimes they smiled. Mr. Buckminster

always pressed and entreated, most winningly, that I would venture.

But I never could command sufficient resolution.’ Such diffidence

of its own powers may be natural to genius, nervously fearful of

being unable to reach that ideal which it proposes as the only full consummation

of its wishes. It is fortunate, however, for the age, fortunate

for all ages, that Mr. Webster by determined will and frequent trial

overcame this moral incapacity, as his great prototype, the Grecian

orator, subdued his physical defect.”—pp. 12, 13.

The effect produced, even at that early period of Mr. Webster’s

life, on the mind of a close observer of his mental powers,

is strikingly illustrated by the following anecdote. Mr. Nicholas

Emery, afterwards a distinguished lawyer and judge, and

now living in Portland, was temporarily employed, at that

time, as an usher in the Academy. On entering the Academy,

Mr. Webster was placed in the lowest class, which consisted

of half a dozen boys, of no remarkable brightness of intellect.

Mr. Emery was the instructor of this class, among others.

At the end of a month, after morning recitations, “Webster,”

said Mr. Emery, “you will pass into the other room and join a

higher class”; and added, “Boys, you will take your final leave

of Webster, you will never see him again.”

After a few months well spent at Exeter, Mr. Webster returned

home, and in February, 1797, was placed by his father

under the Rev. Samuel Wood, the minister of the neighboring

town of Boscawen. He lived in Mr. Wood’s family, and for

board and instruction the entire charge was one dollar per week.

On their way to Mr. Wood’s, Mr. Webster’s father first

opened to his son, now fifteen years old, the design of sending

him to college, the thought of which had never before entered

his mind. The advantages of a college education were a

privilege to which he had never aspired in his most ambitious

dreams. “I remember,” says Mr. Webster, in an autobiographical

memorandum of his boyhood, “the very hill which we

xxv

were ascending, through deep snows, in a New England sleigh,

when my father made known this purpose to me. I could not

speak. How could he, I thought, with so large a family and in

such narrow circumstances, think of incurring so great an expense

for me. A warm glow ran all over me, and I laid my

head on my father’s shoulder and wept.”

In truth, a college education was a far different affair fifty

years ago from what it has since become, by the multiplication

of collegiate institutions, and the establishment of public funds

in aid of those who need assistance. It constituted a person at

once a member of an intellectual aristocracy. In many cases it

really conferred qualifications, and in all was supposed to do so,

without which professional and public life could not be entered

upon with any hope of success. In New England, at

that time, it was not a common occurrence that any one attained

a respectable position in either of the professions without

this advantage. In selecting the member of the family who

should enjoy this privilege, the choice not unfrequently fell upon

the son whose slender frame and early indications of disease unfitted

him for the laborious life of our New England yeomanry.

From February till August, 1797, Mr. Webster remained under

the instruction of Mr. Wood, at Boscawen, and completed

his preparation for college. It is hardly necessary to say, that

the preparation was imperfect. There is probably no period in

the history of the country at which the standard of classical

literature stood lower than it did at the close of the last century.

The knowledge of Greek and Latin brought by our

forefathers from England had almost run out in the lapse of

nearly two centuries, and the signal revival which has taken

place within the last thirty years had not yet begun. Still,

however, when we hear of a youth of fifteen preparing himself

for college by a year’s study of Greek and Latin, we must recollect

that the attainments which may be made in that time by a

young man of distinguished talent, at the period of life when

the faculties develop themselves with the greatest energy, studying

night and day, summer and winter, under the master influence

of hope, ambition, and necessity, are not to be measured

by the tardy progress of the thoughtless or languid children of

prosperity, sent to school from the time they are able to go

alone, and carried along by routine and discipline from year to

xxvi

year, in the majority of cases without strong personal motives to

diligence. Besides this, it is to be considered that the studies

which occupy this usually prolonged novitiate are those which

are required for the acquisition of grammatical and metrical

niceties, the elegancies and the luxuries of scholarship. Short

as was his period of preparation, it enabled Mr. Webster to lay

the foundation of a knowledge of the classical writers, especially

the Latin, which was greatly increased in college, and

which has been kept up by constant recurrence to the great models

of antiquity, during the busiest periods of active life. The

happiness of Mr. Webster’s occasional citations from the Latin

classics is a striking feature of his oratory.

Mr. Webster entered college in 1797, and passed the four

academic years in assiduous study. He was not only distinguished

for his attention to the prescribed studies, but devoted

himself to general reading, especially to English history and literature.

He took part in the publication of a little weekly

newspaper, furnishing selections from books and magazines, with

an occasional article from his own pen. He delivered addresses,

also, before the college societies, some of which were published.

The winter vacations brought no relaxation. Like those of so

many of the meritorious students at our places of education,

they were employed in teaching school, for the purpose of eking

out his own frugal means and aiding his brother to prepare himself

for college. The attachment between the two brothers was

of the most affectionate kind, and it was by the persuasion of

Daniel that the father had been induced to extend to Ezekiel

also the benefits of a college education.

The genial and companionable spirit of Mr. Webster is still

remembered by his classmates, and by the close of his first college

year he had given proof of powers and aspirations which

placed him far above rivalry among his associates. “It is

known,” says Mr. Ticknor, “in many ways, that, by those

who were acquainted with him at this period of life, he was already

regarded as a marked man, and that to the more sagacious

of them the honors of his subsequent career have not

been unexpected.”

Mr. Webster completed his college course in August, 1801,

and immediately entered the office of Mr. Thompson, the next-door

neighbor of his father, as a student of law. Mr. Thompson

xxvii

was a gentleman of education and intelligence, and, at a

later period, a respectable member, successively, of the House

of Representatives and Senate of the United States. He

maintained a high character till his death. Mr. Webster remained

in his office as a student till, in the words of Mr.

March, “he felt it necessary to go somewhere and do something

to earn a little money.” In this emergency, application

was made to him to take charge of an academy at Fryeburg in

Maine, upon a salary of about one dollar per diem, being what

is now paid for the coarsest kind of unskilled manual labor.

As he was able, besides, to earn enough to pay for his board

and to defray his other expenses by acting as assistant to the

register of deeds for the county, his salary was all saved,—a

fund for his own professional education and to help his brother

through college.

Mr. Webster’s son and one of his friends have lately visited

Fryeburg and examined these records of deeds. They are still

preserved in two huge folio volumes, in Mr. Webster’s handwriting,

exciting wonder how so much work could be done in

the evening, after days of close confinement to the business of

the school. They looked also at the records of the trustees of

the academy and found in them a most respectful and affectionate

vote of thanks and good-will to Mr. Webster when he

took leave of the employment.[3]

These humble details need no apology. They relate to trials,

hardships, and efforts which constitute no small part of the

discipline by which a great character is formed. During his

residence at Fryeburg, Mr. Webster borrowed (he was too poor

to buy) Blackstone’s Commentaries, and read them for the first

time. “Among other mental exercises,” says Mr. March, “he

committed to memory Mr. Ames’s celebrated speech on the

British treaty.” In after life he has been heard to say, that

few things moved him more than the perusal and reperusal of

this celebrated speech.

In September, 1802, Mr. Webster returned to Salisbury, and

resumed his studies under Mr. Thompson, in whose office he

xxviii

remained for eighteen months. Mr. Thompson, though, as we

have said, a person of excellent character and a good lawyer,

yet seems not to have kept pace in his profession with the

progress of improvement. Although Blackstone’s Commentaries

had been known in this country for a full generation, Mr.

Thompson still directed the reading of his pupils on the principle

of the hardest book first. Coke’s Littleton was still the

work with which his students were broken into the study of

the profession. Mr. Webster has condemned this practice.

“A boy of twenty,” says he, “with no previous knowledge of

such subjects, cannot understand Coke. It is folly to set him

upon such an author. There are propositions in Coke so abstract,

and distinctions so nice, and doctrines embracing so

many distinctions and qualifications, that it requires an effort

not only of a mature mind, but of a mind both strong and

mature, to understand him. Why disgust and discourage a

young man by telling him he must break into his profession

through such a wall as this?” Acting upon these views, even

in his youth, Mr. Webster gave his attention to more intelligible

authors, and to titles of law of greater importance in this

country than the curious learning of tenures, many of which

are antiquated, even in England. He also gave a good deal of

time to general reading, and especially the study of the Latin

classics, English history, and the volumes of Shakespeare. In

order to obtain a wider compass of knowledge, and to learn

something of the language not to be gained from the classics,

he read through attentively Puffendorff’s Latin History of

England.

In July, 1804, he took up his residence in Boston. Before

entering upon the practice of his profession, he enjoyed the advantage

of pursuing his legal studies for six or eight months in

the office of the Hon. Christopher Gore. This was a fortunate

event for Mr. Webster. Mr. Gore, afterwards Governor of

Massachusetts, was a lawyer of eminence, a statesman and a

civilian, a gentleman of the old school of manners, and a rare

example of distinguished intellectual qualities, united with practical

good sense and judgment. He had passed several years

in England as a commissioner, under Jay’s treaty, for liquidating

the claims of citizens of the United States for seizures by

British cruisers in the early wars of the French Revolution.

xxix

His library, amply furnished with works of professional and

general literature, his large experience of men and things at

home and abroad, and his uncommon amenity of temper, combined

to make the period passed by Mr. Webster in his office

one of the pleasantest in his life. These advantages, it hardly

need be said, were not thrown away. He diligently attended

the sessions of the courts and reported their decisions. He

read with care the leading elementary works of the common

and municipal law, with the best authors on the law of nations,

some of them for a second and third time; diversifying these

professional studies with a great amount and variety of general

reading. His chief study, however, was the common law, and

more especially that part of it which relates to the now unfashionable

science of special pleading. He regarded this, not

only as a most refined and ingenious, but a highly instructive

and useful branch of the law. Besides mastering all that

could be derived from more obvious sources, he waded through

Saunders’s Reports in the original edition, and abstracted and

translated into English from the Latin and Norman French

all the pleadings contained in the two folio volumes. This

manuscript still remains.

Just as he was about to be admitted to practise in the Suffolk

Court of Common Pleas in Massachusetts, an incident occurred

which came near affecting his career for life. The place of

clerk in the Court of Common Pleas for the county of Hillsborough,

in New Hampshire, became vacant. Of this court Mr.

Webster’s father had been made one of the judges, in conformity

with a very common practice at that time, of placing on

the side bench of the lower courts men of intelligence and respectability,

though not lawyers. From regard to Judge Webster,

the vacant clerkship was offered by his colleagues to his

son. It was what the father had for some time looked forward

to and desired. The fees of the office were about fifteen hundred

dollars per annum, which in those days and in that region

was not so much a competence as a fortune. Mr. Webster

himself was disposed to accept the office. It promised an immediate

provision in lieu of a distant and doubtful prospect.

It enabled him at once to bring comfort into his father’s family,

while to refuse it was to condemn himself and them to an uncertain

and probably harassing future. He was willing to sacrifice

xxx

his hopes of professional eminence to the welfare of those

whom he held most dear. But the earnest dissuasions of Mr.

Gore, who saw in this step the certain postponement, perhaps

the final defeat, of all hopes of professional advancement, prevented

his accepting the office. His aged father was, in a personal

interview with his son, if not reconciled to the refusal, at

least induced to bury his regrets in his own bosom. The subject

was never mentioned by him again. In the spring of the

same year (1805), Mr. Webster was admitted to the practice of

the law in the Court of Common Pleas for Suffolk county,

Boston. According to the custom of that day, Mr. Gore accompanied

the motion for his admission with a brief speech in

recommendation of the candidate. The remarks of Mr. Gore

on this occasion are well remembered by those present. He

dwelt with emphasis on the remarkable attainments and uncommon

promise of his pupil, and closed with a prediction of

his future eminence.

Immediately on his admission to the bar, Mr. Webster went

to Amherst, in New Hampshire, where his father’s court was

in session; from that place he went home with his father. He

had intended to establish himself at Portsmouth, which, as the

largest town and the seat of the foreign commerce of the State,

opened the widest field for practice. But filial duty kept him

nearer home. His father was now infirm from the advance of

years, and had no other son at home. Under these circumstances

Mr. Webster opened an office at Boscawen, not far

from his father’s residence, and commenced the practice of

the law in this retired spot. Judge Webster lived but a year

after his son’s entrance upon the practice of his profession;

long enough, however, to hear his first argument in court,

and to be gratified with the confident predictions of his future

success.

In May, 1807, Mr. Webster was admitted as an attorney and

counsellor of the Superior Court in New Hampshire, and in

September of that year, relinquishing his office in Boscawen to

his brother Ezekiel, he removed to Portsmouth, in conformity

with his original intention. Here he remained in the practice

of his profession for nine successive years. They were years of

assiduous labor, and of unremitted devotion to the study and

practice of the law. He was associated with several persons

xxxi

of great eminence, citizens of New Hampshire or of Massachusetts

occasionally practising at the Portsmouth bar. Among

the latter were Samuel Dexter and Joseph Story; of the residents

of New Hampshire, Jeremiah Mason was the most distinguished.

Often opposed to each other as lawyers, a strong

personal friendship grew up between them, which ended only

with the death of Mr. Mason. Mr. Webster’s eulogy on Mr.

Mason will be found in one of the volumes of this collection,

and will descend to posterity an enduring monument of

both. Had a more active temperament led Mr. Mason to embark

earlier and continue longer in public life, he would have

achieved a distinction shared by few of his contemporaries.

Mr. Webster, in the lapse of time, was called to perform the

same melancholy office for Judge Story.

During the greater part of Mr. Webster’s practice of the law

in New Hampshire, Jeremiah Smith was Chief Justice of the

State, a learned and excellent judge, whose biography has been

written by the Rev. John H. Morison, and will well repay perusal.

Judge Smith was an early and warm friend of Judge

Webster, and this friendship descended to the son, and glowed

in his breast with fervor till he went to his grave.

Although dividing with Mr. Mason the best of the business

of Portsmouth, and indeed of all the eastern portion of the State,

Mr. Webster’s practice was mostly on the circuit. He followed

the Superior Court through the principal counties of the State,

and was retained in nearly every important cause. It is mentioned

by Mr. March, as a somewhat singular fact in his professional

life, that, with the exception of the occasions on which he

has been associated with the Attorney-General of the United

States for the time being, he has hardly appeared ten times as

junior counsel. Within the sphere in which he was placed,

he may be said to have risen at once to the head of his profession;

not, however, like Erskine and some other celebrated British

lawyers, by one and the same bound, at once to fame and

fortune. The American bar holds forth no such golden prizes,

certainly not in the smaller States. Mr. Webster’s practice in

New Hampshire, though probably as good as that of any of his

contemporaries, was never lucrative. Clients were not very rich,

nor the concerns litigated such as would carry heavy fees. Although

xxxii

exclusively devoted to his profession, it afforded him no

more than a bare livelihood.

But the time for which he practised at the New Hampshire bar

was probably not lost with reference to his future professional and

political eminence. His own standard of legal attainment was

high. He was associated with professional brethren fully competent

to put his powers to their best proof, and to prevent him

from settling down in early life into an easy routine of ordinary

professional practice. It was no disadvantage, under these circumstances,

(except in reference to immediate pecuniary benefit,)

to enjoy some portion of that leisure for general reading,

which is almost wholly denied to the lawyer of commanding

talents, who steps immediately into full practice in a large city.

FOOTNOTES

Entrance on Public Life.—State of Parties in 1812.—Election to Congress.—Extra

Session of 1813.—Foreign Relations of the Country.—Resolutions relative to the

Berlin and Milan Decrees.—Naval Defence.—Reelected to Congress in 1814.—Peace

with England.—Projects for a National Bank.—Mr. Webster’s Course on

that Question.—Battle of New Orleans.—New Questions arising on the Return

of Peace.—Course of Prominent Men of Different Parties.—Mr. Webster’s

Opinions on the Constitutionality of the Tariff Policy.—The Resolution to restore

Specie Payments moved by Mr. Webster.—Removal to Boston.

Mr. Webster had hitherto taken less interest in politics than

has been usual with the young men of talent, at least with the

young lawyers, of America. In fact, at the time to which the

preceding narrative refers, the politics of the country were in

such a state, that there was scarce any course which could be

pursued with entire satisfaction by a patriotic young man sagacious

enough to penetrate behind mere party names, and to

view public questions in their true light. Party spirit ran high;

errors had been committed by ardent men on both sides; and

extreme opinions had been advanced on most questions, which

no wise and well-informed person at the present day would

probably be willing to espouse. The United States, although

not actually drawn to any great depth into the vortex of the

French Revolution, were powerfully affected by it. The deadly

struggle of the two great European belligerents, in which the

neutral rights of this country were grossly violated by both,

gave a complexion to our domestic politics. A change of administration,

mainly resulting from difference of opinion in respect

to our foreign relations, had taken place in 1801. If

we may consider President Jefferson’s inaugural address as the

indication of the principles on which he intended to conduct

his administration, it was his purpose to take a new departure,

and to disregard the former party divisions. “We have,”

said he, in that eloquent state paper, “called by different names

brethren of the same principle. We are all republicans, we

are all federalists.”

At the time these significant expressions were uttered, Mr.

Webster, at the age of nineteen, was just leaving college and

preparing to embark on the voyage of life. A sentiment so

xxxiv

liberal was not only in accordance with the generous temper of

youth, but highly congenial with the spirit of enlarged patriotism

which has ever guided his public course. There is certainly

no individual who has filled a prominent place in our

political history who has shown himself more devoted to principle

and less to party. While no man has clung with greater

tenacity to the friendships which spring from agreement in

political opinion (the idem sentire de republica), no man has

been less disposed to find in these associations an instrument

of monopoly or exclusion in favor of individuals, interests, or

sections of the country.

But however catholic may have been the intentions and

wishes of Mr. Jefferson, events both at home and abroad were

too strong for him, and defeated that policy of blending the

great parties into one, which has always been a favorite, perhaps

we must add, a visionary project, with statesmen of elevated

and generous characters. The aggressions of the belligerents

on our neutral commerce still continued, and, by the joint effect

of the Berlin and Milan Decrees and the Orders in Council, it

was all but swept from the ocean. In this state of things two

courses were open to the United States, as a growing neutral

power: one, that of prompt resistance to the aggressive policy

of the belligerents; the other, that which was called “the restrictive

system,” which consisted in an embargo on our own

vessels, with a view to withdraw them from the grasp of foreign

cruisers, and in laws inhibiting commercial intercourse

with England and France. There was a division of opinion in

the cabinet of Mr. Jefferson and in the country at large. The

latter policy was finally adopted. It fell in with the general

views of Mr. Jefferson against committing the country to the

risks of foreign war. His administration was also strongly

pledged to retrenchment and economy, in the pursuit of which

a portion of our little navy had been brought to the hammer,

and a species of shore defence substituted, which can now be

thought of only with mortification and astonishment.

Although the discipline of party was sufficiently strong to

cause this system of measures to be adopted and pursued for

years, it was never cordially approved by the people of the

United States of any party. Leading Republicans both at the

South and at the North denounced it. With Mr. Jefferson’s

xxxv

retirement from office it fell rapidly into disrepute. It continued,

however, to form the basis of our party divisions till the

war of 1812. In these divisions, as has been intimated, both

parties were in a false position; the one supporting and forcing

upon the country a system of measures not cordially approved,

even by themselves; the other, a powerless minority, zealously

opposing those measures, but liable for that reason to be

thought backward in asserting the neutral rights of the country.

A few men of well-balanced minds, true patriotism, and sound

statesmanship, in all sections of the country, were able to unite

fidelity to their party associations with a comprehensive view

to the good of the country. Among these, mature beyond his

years, was Mr. Webster. As early as 1806 he had, in a public

oration, presented an impartial view of the foreign relations of

the country in reference to both belligerents, of the importance

of our commercial interests and the duty of protecting them.

“Nothing is plainer,” said he, “than this: if we will have

commerce, we must protect it. This country is commercial as

well as agricultural. Indissoluble bonds connect him who

ploughs the land with him who ploughs the sea. Nature has

placed us in a situation favorable to commercial pursuits, and

no government can alter the destination. Habits confirmed by

two centuries are not to be changed. An immense portion of

our property is on the waves. Sixty or eighty thousand of our

most useful citizens are there, and are entitled to such protection

from the government as their case requires.”

At length the foreign belligerents themselves perceived the

folly and injustice of their measures. In the strife which

should inflict the greatest injury on the other, they had paralyzed

the commerce of the world and embittered the minds

of all the neutral powers. The Berlin and Milan Decrees were

revoked, but in a manner so unsatisfactory as in a great degree

to impair the pacific tendency of the measure. The

Orders in Council were also rescinded in the summer of 1812.

War, however, justly provoked by each and both of the parties,

had meantime been declared by Congress against England,

and active hostilities had been commenced on the frontier. At

the elections next ensuing, Mr. Webster was brought forward

as a candidate for Congress of the Federal party of that day,

and, having been chosen in the month of November, 1812, he

xxxvi

took his seat at the first session of the Thirteenth Congress,

which was an extra session called in May, 1813. Although his

course of life hitherto had been in what may be called a provincial

sphere, and he had never been a member even of the legislature

of his native State, a presentiment of his ability seems

to have gone before him to Washington. He was, in the organization

of the House, placed by Mr. Clay, its Speaker, upon

the Committee of Foreign Affairs, a select committee at that

time, and of necessity the leading committee in a state of war.

There were many men of uncommon ability in the Thirteenth

Congress. Rarely has so much talent been found at any one

time in the House of Representatives. It contained Clay, Calhoun,

Lowndes, Pickering, Gaston, Forsyth, in the front rank;

Macon, Benson, J. W. Taylor, Oakley, Grundy, Grosvenor, W.

R. King, Kent of Maryland, C. J. Ingersoll of Pennsylvania, Pitkin

of Connecticut, and others of scarcely inferior note. Although

among the youngest and least experienced members of

the body, Mr. Webster rose, from the first, to a position of undisputed

equality with the most distinguished. The times were

critical. The immediate business to be attended to was the

financial and military conduct of the war, a subject of difficulty

and importance. The position of Mr. Webster was not such as

to require or permit him to take a lead; but it was his steady

aim, without the sacrifice of his principles, to pursue such a

course as would tend most effectually to extricate the country

from the embarrassments of her present position, and to lead to

peace upon honorable terms.

As the repeal of the Orders in Council was nearly simultaneous

with the declaration of war, the delay of a few weeks

might have led to an amicable adjustment. Whatever regret

on the score of humanity this circumstance may now inspire,

the war must be looked upon, in reviewing the past, as a great

chapter in the progress of the country, which could not be

passed over. When we reflect on the influence of the conflict, in

its general results, upon the national character; its importance as

a demonstration to the belligerent powers of the world that the

rights of neutrals must be respected; and more especially, when

we consider the position among the nations of the earth which

the United States have been enabled to take, in consequence

of the capacity for naval achievement which the war displayed,

xxxvii

we shall readily acknowledge it to be a part of that great training,

by which the country was prepared to take the station which

she now occupies.

Mr. Webster was not a member of Congress when war was

declared, nor in any other public station. He was too deeply

read in the law of nations, and regarded that august code with

too much respect, not to contemplate with indignation its infraction

by both the belligerents. With respect to the Orders in

Council, the highest judicial magistrate in England (Lord Chief

Justice Campbell) has lately admitted that they were contrary

to the law of nations.[4] As little doubt can exist that the French

decrees were equally at variance with the public law. But

however strong his convictions of this truth, Mr. Webster’s

sagacity and practical sense pointed out the inadequacy, and

what may be called the political irrelevancy, of the restrictive

system, as a measure of defence or retaliation. He could not

but feel that it was a policy which tended at once to cripple

the national resources, and abase the public sentiment, with an

effect upon the foreign powers doubtful and at best indirect. In

the state of the military resources of the country at that time,

he discerned, in common with many independent men of all

parties, that less was to be hoped from the attempted conquest

of foreign territory, than from a gallant assault upon the fancied

supremacy of the enemy at sea. It is unnecessary to state, that

the whole course of the war confirmed the justice of these views.

They furnish the key to Mr. Webster’s course in the Thirteenth

Congress.

Early in the session, he moved a series of resolutions of inquiry,

relative to the repeal of the Berlin and Milan Decrees.

The object of these resolutions was to elicit a communication

on this subject from the executive, which would unfold the proximate

causes of the war, as far as they were to be sought in

those famous Decrees, and in the Orders in Council. On the

10th of June, 1813, Mr. Webster delivered his maiden speech on

these resolutions. No full report of this speech has been preserved.

It is known only from extremely imperfect sketches,

contained in the contemporaneous newspaper accounts of the

proceedings of Congress, from the recollection of those who heard

xxxviii

it, and from general tradition. It was a calm and statesmanlike

exposition of the objects of the resolutions; and was listened to

with profound attention by the House. It was marked by all

the characteristics of Mr. Webster’s maturest parliamentary

efforts,—moderation of tone, precision of statement, force of reasoning,

absence of ambitious rhetoric and high-flown language,

occasional bursts of true eloquence, and, pervading the whole, a

genuine and fervid patriotism. We have reason to believe that

its effect upon the House is accurately described in the following

extract from Mr. March’s work.

“The speech took the House by surprise, not so much from its eloquence

as from the vast amount of historical knowledge and illustrative

ability displayed in it. How a person, untrained to forensic contests and

unused to public affairs, could exhibit so much parliamentary tact, such

nice appreciation of the difficulties of a difficult question, and such quiet

facility in surmounting them, puzzled the mind. The age and inexperience

of the speaker had prepared the House for no such display, and

astonishment for a time subdued the expression of its admiration.

“‘No member before,’ says a person then in the House, ‘ever riveted

the attention of the House so closely, in his first speech. Members

left their seats, where they could not see the speaker face to face, and

sat down, or stood on the floor, fronting him. All listened attentively

and silently, during the whole speech; and when it was over, many

went up and warmly congratulated the orator; among whom were some,

not the most niggard of their compliments, who most dissented from the

views he had expressed.’

“Chief Justice Marshall, writing to a friend some time after this

speech, says: ‘At the time when this speech was delivered, I did not

know Mr. Webster, but I was so much struck with it, that I did not hesitate

then to state, that Mr. Webster was a very able man, and would

become one of the very first statesmen in America, and perhaps the

very first.’”—pp. 35, 36.[5]

The resolutions moved by Mr. Webster prevailed by a large

majority, and drew forth from Mr. Monroe, then Secretary of

State, an elaborate and instructive report upon the subject to

which they referred.

We have already observed, that, as early as 1806, Mr. Webster

had expressed himself in favor of the protection of our

commerce against the aggressions of both the belligerents.

Some years later, before the war was declared, but when it was

visibly impending, he had put forth some vigorous articles to

the same effect. In an oration delivered in 1812, he had said:

“A navy sufficient for the defence of our coasts and harbors,

for the convoy of important branches of our trade, and sufficient

also to give our enemies to understand, when they injure us,

that they too are vulnerable, and that we have the power of

retaliation as well as of defence, seems to be the plain, necessary,

indispensable policy of the nation. It is the dictate of

nature and common sense, that means of defence shall have

relation to the danger.” In accordance with these views, first

announced by Mr. Webster a considerable time before Hull,

Decatur, and Bainbridge had broken the spell of British naval

supremacy, he used the following language in his speech on encouraging

enlistments in 1814:—

“The humble aid which it would be in my power to render to measures

of government shall be given cheerfully, if government will pursue

measures which I can conscientiously support. If even now, failing

in an honest and sincere attempt to procure an honorable peace, it will

return to measures of defence and protection, such as reason and common

sense and the public opinion all call for, my vote shall not be

withholden from the means. Give up your futile projects of invasion.

Extinguish the fires which blaze on your inland frontiers. Establish

perfect safety and defence there by adequate force. Let every man

that sleeps on your soil sleep in security. Stop the blood that flows

from the veins of unarmed yeomanry, and women and children. Give

to the living time to bury and lament their dead, in the quietness of

private sorrow. Having performed this work of beneficence and mercy

on your inland border, turn and look with the eye of justice and compassion

on your vast population along the coast. Unclench the iron

grasp of your embargo. Take measures for that end before another

sun sets upon you. With all the war of the enemy on your commerce,

if you would cease to make war upon it yourselves, you would still

have some commerce. That commerce would give you some revenue.

Apply that revenue to the augmentation of your navy. That navy in

turn will protect your commerce. Let it no longer be said, that not one

ship of force, built by your hands since the war, yet floats upon the

ocean. Turn the current of your efforts into the channel which national

xl

sentiment has already worn broad and deep to receive it. A naval force

competent to defend your coasts against considerable armaments, to convoy

your trade, and perhaps raise the blockade of your rivers, is not a

chimera. It may be realized. If then the war must continue, go to the

ocean. If you are seriously contending for maritime rights, go to the

theatre where alone those rights can be defended. Thither every indication

of your fortune points you. There the united wishes and exertions

of the nation will go with you. Even our party divisions, acrimonious

as they are, cease at the water’s edge. They are lost in

attachment to the national character, on the element where that character

is made respectable. In protecting naval interests by naval means,

you will arm yourselves with the whole power of national sentiment,