A WEST COUNTRY PILGRIMAGE

Eden Phillpotts

A WEST COUNTRY PILGRIMAGE

BY

EDEN PHILLPOTTS

AUTHOR OF

"DANCE OF THE MONTHS," "A SHADOW PASSES," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY A. T. BENTHALL

LONDON

LEONARD PARSONS

PORTUGAL STREET

First Published, May 1920

Leonard Parsons, Ltd.

CONTENTS

| Page | |

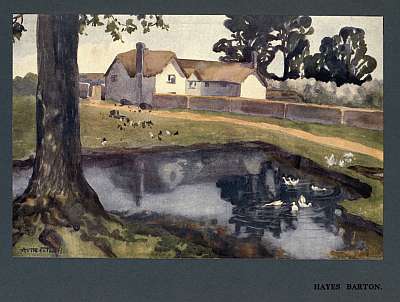

| HAYES BARTON | 7 |

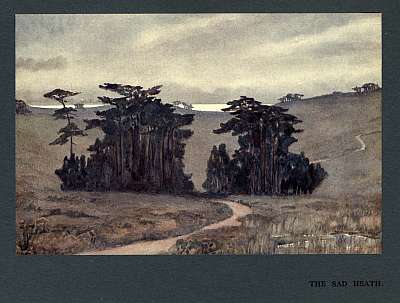

| THE SAD HEATH | 15 |

| DAWLISH WARREN | 21 |

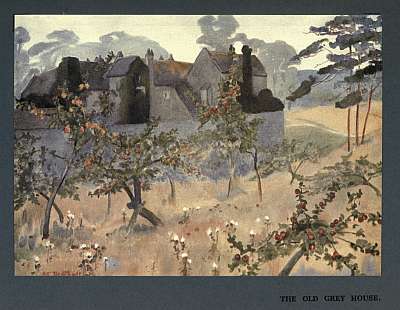

| THE OLD GREY HOUSE | 29 |

| BERRY POMEROY | 35 |

| BERRY HEAD | 41 |

| THE QUARRY AND THE BRIDGE | 47 |

| BAGTOR | 55 |

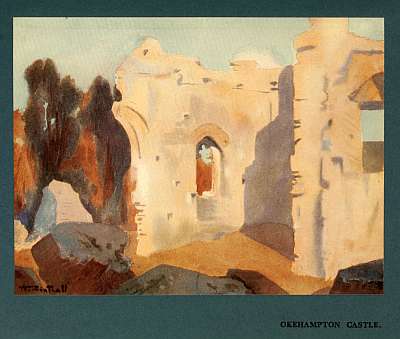

| OKEHAMPTON CASTLE | 63 |

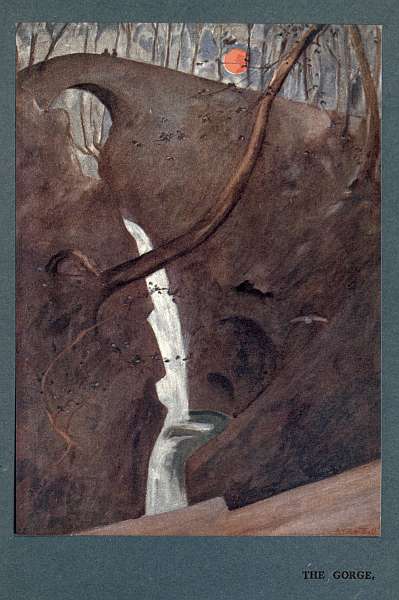

| THE GORGE | 69 |

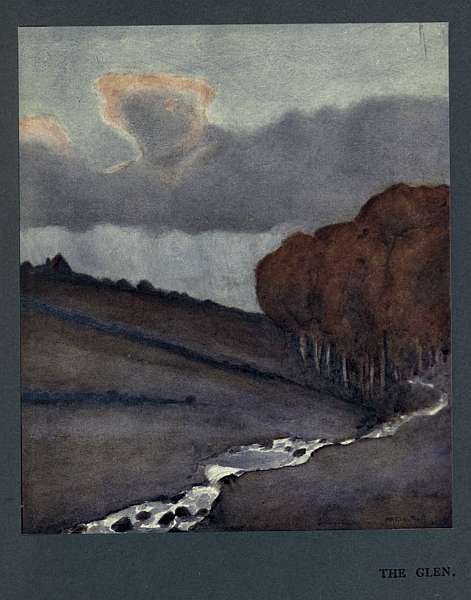

| THE GLEN | 77 |

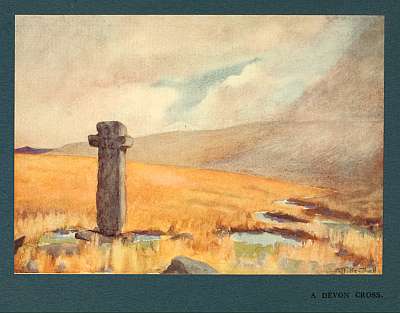

| A DEVON CROSS | 85 |

| COOMBE | 91 |

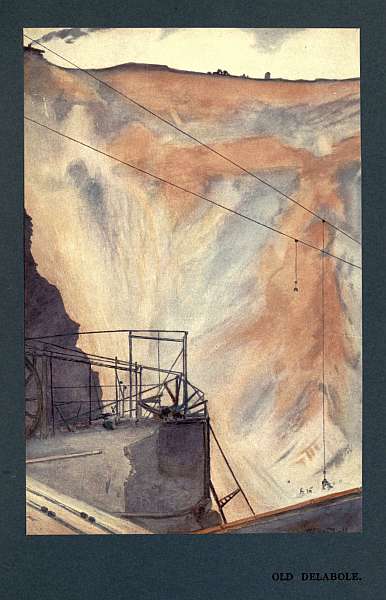

| OLD DELABOLE | 97 |

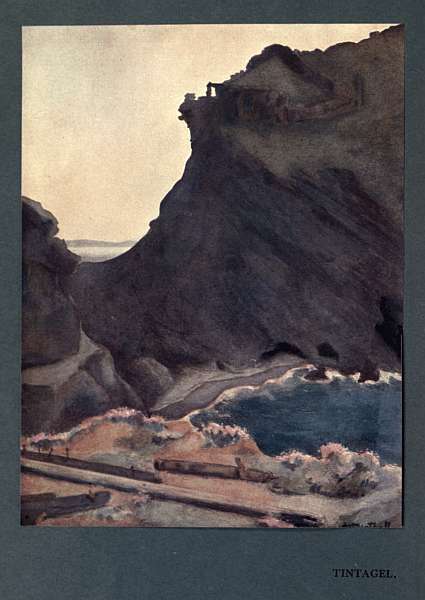

| TINTAGEL | 103 |

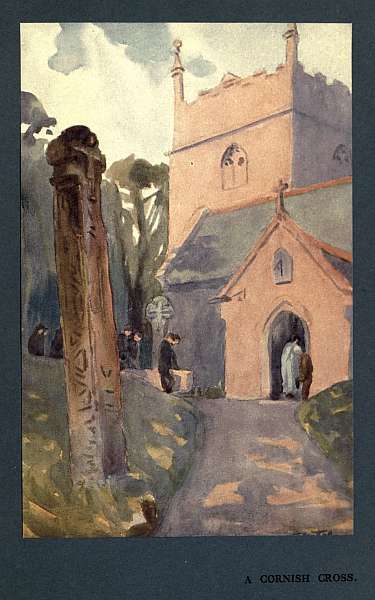

| A CORNISH CROSS | 111 |

HAYES BARTON

[9]

East of Exe River and south of those rolling heaths crowned by the encampment of Woodberry, there lies a green valley surrounded by forest and hill. Beyond it rise great bluffs that break in precipices upon the sea. They are dimmed to sky colour by a gentle wind from the east, for Eurus, however fierce his message, sweeps a fair garment about him. Out of the blue mists that hide distance the definition brightens and lesser hills range themselves, their knolls dark with pine, their bosoms rounded under forest of golden green oak and beech; while beneath them a mosaic of meadow and tilth spreads in pure sunshine. One field is brushed with crimson clover; another with dull red of sorrel through the green meadow grass; another shines daisy-clad and drops to the green of wheat. Some crofts glow with the good red earth of Devon, and no growing things sprout as yet upon them; but they hold seed of roots and their hidden wealth will soon answer the rain.

In the heart of the vale a brook twinkles and buttercups lie in pools of gold, where lambs are playing together.

Elms set bossy signets on the land and throng the hedgerows, their round tops full of sunshine; under them the hawthorns sparkle very white against the riot of the green. From the lifted spinneys and coverts, where bluebells fling[10] their amethyst at the woodland edge, pheasants are croaking, and silver-bright against the blue aloft, wheel gulls, to link the lush valley with the invisible and not far distant sea. They cry and musically mew from their high place; and beneath them the cuckoo answers.

Nestling now upon the very heart of this wide vale a homestead lies, where the fields make a dimple and the burn comes flashing. Byres and granaries light gracious colour here, for their slate roofs are mellow with lichen of red gold, and they stand as a bright knot round which the valley opens and blossoms with many-coloured petals. The very buttercups shine pale by contrast, and the apple-blooth, its blushes hidden from this distance, masses in pure, cold grey beneath the glow of these great roofs. Cob walls stretch from the outbuildings, and their summits are protected against weather by a little penthouse of thatch. In their arms the walls hold a garden of many flowers, rich in promise of small fruits. Gooseberries and raspberries flourish amid old gnarled apple trees; there are strawberries, too, and the borders are bright with May tulips and peonies. Stocks and wallflowers blow flagrant by the pathway, murmured over by honey bees; while where the farmhouse itself stands, deep of eave under old thatch, twin yew trees make a dark splash on either side of the entrance, and a wistaria showers its mauve ringlets upon the grey and ancient front. The dormer windows are all open, and there is a glimpse of a cool darkness through the open door. Within the solid walls of this dwelling neither sunshine nor cold can penetrate, and Hayes Barton is warm in winter, in summer cool. The[11] house is shaped in the form of a great E, and it has been patched and tinkered through the centuries; but still stands, complete and sturdy in harmony of design, with unspoiled dignity from a far past. Only the colours round about it change with the painting of the seasons, for the forms of hill and valley, the modelling of the roof-tree, the walls and the great square pond outside the walls, change not. Enter, and above the dwelling-rooms you shall find a chamber with wagon roof and window facing south. It is, on tradition meet to be credited, the birthplace of Walter Ralegh.

Proof rests with Sir Walter's own assertion, and at one time the manor house of Fardel, under Dartmoor, claimed the honour; but Ralegh himself declares that he was born at Hayes, and speaks of his "natural disposition to the place" for that reason. He desired, indeed, to purchase his childhood's home and make his Devonshire seat there; but this never happened, though the old, three-gabled, Tudor dwelling has passed through many hands and many notable families.

"Probably no conceivable growth of democracy," says a writer on Ralegh's genealogy, "will make the extraction of a famous man other than a point of general interest." Ralegh's family, at least, won more lustre from him than he from them, though his mother, of the race of the Champernownes, was a mother of heroes indeed. By her first marriage she had borne Sir Walter's great half-brother, Humphrey Gilbert; and when Otho Gilbert passed, the widow wedded Walter Ralegh, and gave birth to another prodigy. The family of the Raleghs must have been a large and scattered one; but our Western historian, Prince, stoutly declares that[12] Sir Walter was descended from an ancient and noble folk, "and could have produced a much fairer pedigree than some of those who traduc'd him."

The tale of his manifold labours has been inadequately told, though Fame will blow her trumpet above his grave for ever; but among the lesser histories Prince's brief chronicle is delightful reading, and we may quote a passage or two for the pleasure of those who pursue this note.

"A new country was discovered by him in 1584," says the historian, "called in honour of the Queen, Virginia: a country that hath been since of no inconsiderable profit to our nation, it being so agreeable to our English bodies, so profitable to the Exchequer, and so fruitful in itself; an acre there yielding over forty bushels of corn; and, which is more strange, there being three harvests in a year: for their corn is sow'd, ripe and cut down in little more than two months."

I fear Virginia to-day will not corroborate these agricultural wonders.

We may quote again, for Prince, on Sir Walter's distinction, is instructive at this moment:—

"For this and other beneficial expeditions and designs, her Majesty was pleased to confer on him the honour of Knighthood; which in her reign was more esteemed; the Queen keeping the temple of honour close shut, and never open'd but to vertue and desert."

Well may democracy call for the destruction of that temple when contemplating those that are permitted entrance to-day.

Then vanished Elizabeth, and a coward king took her place.[13]

"Fourteen years Sir Walter spent in the Tower, of whom Prince Henry would say that no King but his father would keep such a bird in a cage."

But freedom followed, and the scholar turned into the soldier again. Ultimately Spain had her way with her scourge and terror. James ministered to her revenge, and Ralegh perished; "the only man left alive, of note, that had helped to beat the Spaniards in the year 1588."

The favour of the axe was his last, and being asked which way he would dispose himself upon the block, he answered, "So the heart be right, it is no matter which way the head lieth."

"Authors," adds old Prince, "are perplexed under what topick to place him, whether of statesman, seaman, soldier, chymist, or chronologer; for in all these he did excel. He could make everything he read or heard his own, and his own he would easily improve to the greatest advantage. He seemed to be born to that only which he went about, so dextrous was he in all his undertakings, in Court, camp, by sea, by land, with sword, with pen. And no wonder, for he slept but five hours; four he spent in reading and mastering the best authors; two in a select conversation and an inquisitive discourse; the rest in business."

We may say of him that not only did he write The History of the World, but helped to make it; we may hold of all Devon's mighty sons, this man the mightiest. Fair works have been inspired by his existence, but one ever regrets that Gibbon, who designed a life of Ralegh, was called to relinquish the idea before the immensity of his greater theme.[14]

In the western meadow without the boundary of Hayes Barton there lies a great pool, where a cup has been hollowed to hold the brook. Here, under oak trees, one may sit, mark a clean reflection of the farmhouse upon the water, and regard the window of the birth chamber opening on the western gable of the homestead. Thence the august infant's eyes first drew light, his lungs, the air. He has told us that dear to memory was that snug nook, and many times, while he wandered the world and wrote his name upon the golden scroll, we may guess that the hero turned his thought to these happy valleys and, in the mind, mirrored this haunt of peace.

THE SAD HEATH

[17]

Through the sad heath white roads wandered, trickling hither and thither helplessly. There was no set purpose in them; they meandered up the great hill and sometimes ran together to support each other. Then, fortified by the contact, they climbed on across the dusky upland, where it rolled and fell and lifted steadily to the crown of the land: a flat-headed clump of beech and oak with a fosse round about it. Only the roads twisting through this waste and a pool or two scattered upon it brought any light to earth; but there were flowers also, for the whins dragged a spatter of dull gold through the sere and a blackthorn hedge shivered cold and white, where fallow crept to the edge of the moors. For the rest, from the sad-coloured sky to the sentinel pines that rose in little detached clusters on every side, all was restrained and almost melancholy. The pines specially distinguished this rolling heath. They lifted their darkness in clumps, ascending to the hill-tops, spattered every acre of the land, and sprang as infant plants under the foot of the wanderer. Scarcely a hundred yards lacked them; and they ranged from the least seedling to full-grown trees that rose together and thrust with dim red branch and bough through their own darkness.[18]

There was no wind on the heath, and few signs of spring. She had passed, as it seemed, lighted the furzes, waked a thousand catkins on the dwarf sallows in the bogs, and then departed elsewhere. One felt that the deserted heath desired her return and regarded its obstinate winter robes with impatience. It was an uplifted place, and seemed to shoulder darkly out of the milder, mellower world beneath. Far below, an estuary shone through the valley welter and ran a streak of dull silver from south to north; while easterly rose up the grey horizons of the sea.

In the murk of that silent hour, a spirit of thirst seemed to animate the heather and the marshes that oozed out beneath. The secret impressed upon my conscious intelligence was one of suspense, a watchful and alert attitude—an emotion shared by the trees and the thickets, the heath and the hills. It ascended higher and higher to the frowning crest of the land, where round woods made a crown for the wilderness and marked castramentations of old time. So unchanging appeared this place that little imagination was needed to bring back the past and revive a vanished century when the legions flashed where now the great trees frowned and a hive of men, loosed from a hundred galleys, swarmed hither to dig the ditches and pile these venerable earthworks for a stronghold.

Thus the place lay in the lap of that tenebrous hour and waited for the warm rain to loose its fountains of sap and brush the loneliness with waking and welcoming green. It endured and hoped and seemed to turn blind eyes from the pond and bog upward to question the gathering clouds.

Nigh me, a persistent and inquiring thrush clamoured[19] from a pine. I could see his amber, speckled bosom shaking with his song.

"Why did he do it? Why did he do it? Why did he?"

He had asked the question a thousand times; and then a dark bird, that flapped high and heavy through the grey air, answered him.

"God knows! God knows!" croaked the carrion crow.

DAWLISH WARREN

[23]

There is a spit of land that runs across the estuary of the Exe, and as the centuries pass, the sea plays pranks with it. A few hundred years ago the tideway opened to the West, not far from the red cliffs that tower there, and then Exmouth and the Warren were one; but now it is at Exmouth that the long sands are separated from the shore and, past that little port, the ships go up the river, while the eastern end of the Warren joins the mainland. So it has stood within man's memory; but now, as though tired of this arrangement, wind and sea are modifying the place again, for the one has found a new path in the midst, and the other has blown at the sand dunes until their heads are reduced by many feet from their old altitude.

These sands are many-coloured, for over the yellow staple prevails a delicate and changing harmony of various tones, now rose, now blue, as though a million minute shining particles were reflecting the light of the sky and bringing it to earth on their tiny surfaces. But in truth these tender shades show where the sand is weathered, for if we walk upon it and break the thin crust created by the last rain, the dream tints depart, and a brighter corn colour breaks through. Coarse mat-grass binds the dunes and helps to hold them together against the forces of wind and water; but their tendency is[24] to decrease. Perhaps observation would prove that their masses shift and vanish more quickly than we guess, for the sand is the sea's toy, and she makes and unmakes her castles at will.

As a lad, I very well remember the silvery hills towering to little mountains above my head; and again I can hear the gentle tinkle of the sand for ever rustling about me where I basked like a lizard in some sun-baked nook. I remember the horrent couch grass that waved its ragged tresses above me, and how I told myself that the range of the sand dunes were great lions with bristling manes marching along to Exmouth. Presently they would swim across to the shore and eat up everybody, as soon as they had landed and shaken themselves. And the mud-flats I loved well also, where the sea-lavender spread its purple on sound land above the network of mud. I flushed summer snipe there and often lay motionless to watch sea-birds fishing. Many wild flowers flourished and the glass-wort made the flats as red as blood in autumn. It was a dreamland of wonders for me, and now I was seeking mermaids' purses in the tide-fringe and sorrowing to find them empty; now I was after treasure-trove flung overboard from pirate ships, now hunting for the secret hiding-places of buccaneers in the dunes.

The ships go by still; but not the ships I knew; the flowers still sparkle in the hollows and brakes; but their wonder has waned a little. No more shall I weave the soldanella and sea-rocket and grey-green wheat grass into crowns for the sea-nymphs to find when they come up from the waves in the moonlight.[25]

It is a place of sweet air and wonderful sunshine. On a sunny day, with the sand ablaze against the blue sky, one might think oneself in some desert region of the East; but then green spaces, scarlet flags and a warning "fore!" tell a different story. For golfers have found the Warren now. Where once I roamed with only the gulls above and rabbits below for company, and for music the sigh of the wind in the bents and the song of the sea, half a hundred little houses have sprung up, and bungalows, red and white and green, throng the Warren. At hand is a railway-station, whence hundreds descend to take their pleasure, while easterly this once peaceful region is most populous and the Exmouth boats cross the estuary and land their passengers.

One does not grudge the joy of the place to townsfolk or golfers; one only remembers the old haunt of peace, now peaceful no more, the old beauties that have vanished under the little dwellings and little flagstaffs, the former fine distinction that has departed.

Dawlish Warren now gives pleasure to hundreds, where once only the dreamer or sportsman wandered through its mazes; and that is well; but we of the old brigade, who remember its far-flung loneliness, its rare wild flowers, its unique contours, its isolation and peculiar charm, may be forgiven if we forget the twentieth century for a season and conjure back the old time before us.

Topsham, in the estuary, wakens thoughts of the Danes and their sword and fire, when Hungar and Hubba brought their Viking ships up the river, destroyed the busy little port, and, pushing on, defeated St. Edmond, King of the East[26] Angles. The pagans scourged this Christian monarch with whips, then bound him to a tree and slew him.

Yet arrows did not fail.

These furious wretches still let fly

Thicker than winter's hail.

So writes the old poet quoted by Risdon, who adds that the Danes, cutting off St. Edmond's head, "contumeliously threw it in a bush."

But Topsham in Tudor times was a place of importance, a naval port, a mart and road for ships. Thanks to weirs built across the waterway by the Earls of Devon, Exeter began to lose its old-time trade, when the tide was wont to ascend to the city. Therefore Exeter fought the earls, and in the reign of Henry VIII. the city obtained a grant to cut a canal from Topsham. Thus vessels of fifteen tons burthen could ascend to the capital, and Topsham sank under the blow and lost its old importance.

Exmouth also figures in the reign of Edward I. as a naval port. In 1298 she contributed a fighting ship to the Fleet, and in 1347 sent ten vessels to aid the third Edward's expedition against Calais. From Exmouth, too, Edward IV. and Warwick, "the King Maker," embarked for the Continent.

Risdon also makes mention of Lympston, another village in the estuary, aforetime in the lordship of the Dynhams, "of which family John Dynham, a valiant esquire siding with the Earl of March, took the Lord Rivers and Sir Anthony his son at Sandwich in their beds, when he was hurt in the leg, the 37th Henry 6."[27]

The villages are worth a visit still, but Exmouth is best known to those who visit Dawlish Warren now. For the open sea welcomes all who come hither, and the little holiday homes that stand on either side of the tidal stream are too few for those who would dwell here in July and August if they could.

I have seen dawn upon the Exe, and watched the mists rise upon these heron-haunted flats to meet the morning. Then the villages twinkle out over the water, and a land breeze wakens the sleepy dunes, ruffles the still waters and fills the red sails of little fishers that come down to the sea.

THE OLD GREY HOUSE

[31]

Among the ancient, fortified manors of the West Country there is a pleasant ruin whose history is innocent of event, yet glorified with a noble name or two that rings down through the centuries harmoniously. You shall find Compton Castle where the hamlet of Lower Marldon straggles through a deep and fertile valley not many miles from Torbay.

Compton's time-stained face and crown of ivy rise now above a plat of flowers. Trim borders of familiar things blossom within their box-hedges before the entrance, and at this autumn hour fat dahlias, spiring hollyhocks, and rainbows of asters and pansies wind a girdle beneath the walls.

It is a ruin of wide roofs and noble frontage. Above its windows sinister bartizans frown grimly; the portals yawn vast and deep; only the chapel-windows open frankly upon the face of the dwelling; but above, all apertures are narrow, up to the embattled towers.

In the lap of many an enfolding hill Compton huddles its aged fabric, and, despite certain warlike additions, can have risen for no purpose of offence, for the land rakes it on every side; it stands at the bottom of a great green cup, whose slopes are crowned with fir and beech, whose sides now glimmer under stubble of corn, green of roots, and wealth of wide orchards, bright with the ripening harvest. Close at hand men make[32] ready the cider-presses again, and the cooper's mallet echoes among his barrels.

Much of the castle still stands, and the entrance hall, chapel, priest's chamber, and kitchen, with its gigantic hearth and double chimney, are almost intact. A mouldering roof of lichened slates still covers more than half of the ruin; but the banqueting hall has vanished, and many a tower and turret, under their weight of ivy, lift ragged and broken to the sky. Where now jackdaws chiefly dwell and bats sidle through the naked windows at call of dusk; where wind and rain find free entrance and pellitory-of-the-wall hangs its foliage for tapestry, with toadflax and blue speedwell; where Nature labours unceasing from fern-crowned battlement to mossy plinth, there dwelt of old the family of Gilbert.

One Joan Compton conveyed the manor for her partage in the second Edward's reign; and of their posterity are justly remembered and revered the sons of Otho Gilbert, whose lady—a maiden of the Champernownes—bore not only Humphrey, the adventurer, who discovered Gilbert's Straits and founded the first British settlement of Newfoundland; but also his more famous uterine brother, Walter Ralegh. For upon Otho Gilbert's passing, his dame mated with Walter Ralegh of Fardel, and by him brought into the world the poet, statesman, soldier, courtier, explorer, and master-jewel of Elizabeth's Court. A noble matron surely must have been that Katherine, mother of two such sons; and less only in honour to these knights were Sir Humphrey's brothers, of whom Sir John, his senior, rendered himself acceptable to God and man by manifold charities and virtues; while Adrian[33] Gilbert is declared a gentleman very eminent for his skill in mines and matters of engineering and science.

Within these walls tradition brings Sir Walter and Sir Humphrey together. We may reasonably see them here discussing their far-reaching projects, while still the world smiled and both basked in the sunshine of Royal favour. Yet, at the end of their triumphs, from our standpoint in time, we can mark, stealing along the avenue of years, the shadow, hideous in one case and violent in both, destined presently to put a period to each great life.

When the little Squirrel, a vessel of but ten tons burthen, was bearing Sir Humphrey upon his last voyage from Newfoundland, before his vision there took shape the spectre of a mighty lion gliding over the sea, "yawning and gaping wide as he went." Upon which portent there rose the storm whereby he perished. Yet the knight's memory is green, and his golden anchor, with pearl at peak, badge of a Sovereign's grace, is not forgot; nor his crest of a squirrel, whose living prototype still haunts the fir trees beside the castle; nor his motto, worthy of so righteous a genius and steadfast a man: "Malem mori, quam mutare."

The navigator passed to his restless resting-place in 1584; his half-brother, still busy with the colonisation of Virginia, did not kneel at Westminster and brush his grey hair from the path of the axe until Fate had juggled with him for further four-and-thirty years. Then his sword and pen were laid down; his wise head fell low; and the portion of the great: well-doing, ill report, was won.

At gloaming time, when the jackdaws make an end; when[34] the owl glides out from his tower to the trees and the beetles boom, twilight shadows begin to move and the old grey house broods, like a sentient thing, upon the past; but no unhappy spirits haunt its desolation, and the mighty dead, despite their taking off, revisit these glimpses of the moon to clasp pale hands no more. Abundant life flows to the gate and circles the walls. Arable land ascends the hills, and the clank of plough and cry of man to his horses will soon be heard in the stubble of the corn. The orchards flash ruddy and gold; to-morrow they will be naked and grey; and then again they will foam with flowers and roll in a white sea to the castle walls. Time rings his rounds and forgets not this sequestered hollow. Today, beside the entrance-gate of Compton, the husbandman mounts his nag from that same "upping-stock" whence a Gilbert and a Ralegh leapt to horse in England's age of gold.

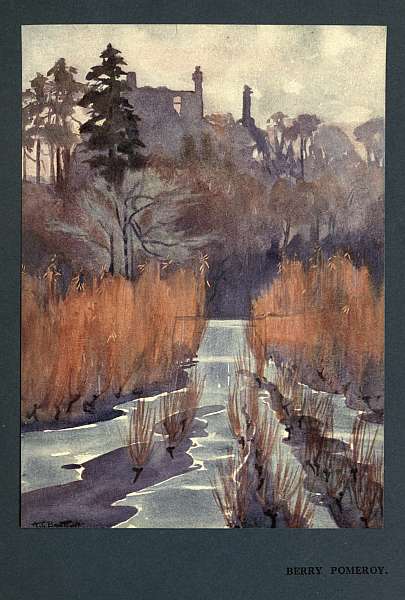

BERRY POMEROY

[37]

Hither, a thousand years and more ago, rode Radulphus de la Pomerio, lord of the Norman Castle of the Orchard; for William I. was generous to those who helped his conquests. Radulphus, as the result of a hero's achievements at Hastings, won eight-and-fifty Devon lordships, and of these he chose Beri, "the Walled town," for his barony, or honour.

Forward we may imagine him pressing with his cavalcade, through the wooded hills and dales, until this limestone crag and plateau in the forest suddenly opened upon his view, and the Norman eagle, judging the strength of such a position, quickly determined that here should his eyrie be built. For it was a stronghold impregnable before the days of gunpowder.

So the banner with the Pomeroy lion upon it was set aloft on the bluff, and soon the sleep of the woods departed to the strenuous labour of a thousand men. There is a great gap in the hill close at hand that shows whence came these time-worn stones, when a feudal multitude of workers were set upon their task. Then, grim, squat and stern, with a hundred eyes from which the cross-bow's bolts might leap, arose another Norman castle, its watch-towers and great ramparts wedged into the woods and beetling over[38] the valley beneath. It sprang from the solid rock, dominated a gorge, and so stood for many hundred years, during which time the descendants of Ralph exercised baronial rights and enjoyed the favour of their princes. The family, indeed, continued to prosper until 1549, but then disaster overtook them and they disappeared, disgraced. It was during this year that Devon opposed the "Act for Reforming the Church Service." Tooth and nail she resented the proposed changes; and among the malcontents there figured a soldier Pomeroy, now head of his house, who had fought with distinction in France during the reign of Henry VIII. Like many another military veteran since his time, he assumed an exceedingly definite attitude on matters of religion, and held tolerance a doubtful virtue where dogma was involved. Him, therefore, the discontented gentlemen of the West elected their leader, and, after preliminary successes, the baron lost the day at Clist Heath, nigh Exeter. He was captured, and only escaped with his life. He kept his head on his shoulders, but Berry Pomeroy became sequestrated to the Crown.

By purchase, the old castle now owned new masters, for the Seymours followed the founders in their heritage, and the great Elizabethan ruin, that lies in the midst of the Norman work and towers above it, is of their creation.

Sir Edward—a descendant of the Protector—it was who, when William III. remarked to him, "I believe you are of the family of the Duke of Somerset?" made instant reply, "Pardon, sir; the Duke of Somerset is of my family." This haughty gentleman was the last of his race to dwell at Berry Pomeroy; but to his descendants the castle still belongs, and[39] it can utter this unique boast: that since the Conquest it has changed hands but once.

The fabric of Seymour's mansion was, it is said, never completed, but enough still stands to make an imposing ruin; while the earlier fragments of the original fortress, including the southern gateway, the pillared chamber above it and the north wing of the quadrangle, complete a spectacle sufficiently splendid in its habiliments of grey and green.

Nature had played with it and rendered it beautiful. Ivy crowns every turret and shattered wall; its limbs writhe like hydras in and out of the ruined windows, and twist their fingers into the rotting mortar; while along the tattered battlements and archways, grass and wild flowers grow rankly together and many saplings of oak and ash and thorn find foothold aloft. Over all the jackdaws chime and chatter, for it is their home now, and they share it with the owl and the flittermouse.

Seen from beyond the stew ponds in the valley below, the ruins of Berry still present a noble vision piled among the tree-tops into the sky, and never can it more attract than at autumn time, when the wealth of the woods is scattered and only spruce and pine trail their green upon the grey and amber of the naked forest. Then, against the low, lemon light of a clear sunset, Berry's ragged crown ascends like a haunted castle in a fairy story; while beneath the evening glow, the still water casts many a crooked reflection from the overhanging branches, and the last leaves hanging on the osiers splash gold against the gloom of the banks. The hour is very still after wind and rain; twilight broods[40] under gathering vapours, while another night gently obscures detail and renders all formless and vast as the darkness falls. The castle is swallowed up in the woods; the first owl hoots; then there is a rush overhead and a splash and scutter below, as the wild duck come down from above, and, for a little while, break the peace with their noise. Their flurry on the water sets up wavelets, that catch the last of the light and run to bank with a little sigh. Then all is silent and stars begin to twinkle through the network of boughs at forest edge.

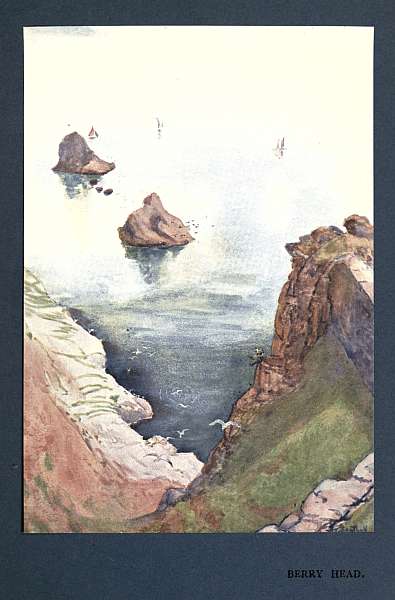

BERRY HEAD

[43]

Upon this seaward-facing headland the great cliffs slope outward like the sides of an old "three-decker." They bulge upon the sea, and the flower-clad scales of the limestone are full of lustrous light and colour, shining radiantly upon the still tide that flows at their feet. For, on this breathless August day, the very sea is weary; not a ripple of foam marks juncture of rock and water.

The cliffs are spattered with green, where scurvy-grass and samphire, thrift and stonecrop find foothold in every cleft; but the flowers are nearly gone; the rare, white rock rose which haunts these crags has shed her last petal and the little cathartic flax and centaury; the snowy dropwort, storks-bill and carline thistles have all been scorched away by days of sunshine and dewless nights. Only the sea lavender still brushes the great, glaring planes of stone with cool colour, and a wild mallow lolls here and there out of a crevice.

By the coastguard path holiday folk tramp with hot faces, but, save for the gulls, there is little sound or movement, for land and sea are swooning in the heavy noontide hour. The birds are everywhere—cresting the finials of the rocks, swooping over the sea, busy teaching the little grey "squabs" to use their wings and trust the air. Now and then a coney thrusts his ears from a burrow, likes not the heat, and pops[44] back again to his cool, dark parlour. Brown hawks hang above the brown sward. Life seems to be retreating before the pitiless sun, yet the sear, scorched grasses will be green again in a few weeks when the cisterns of the autumn rains open upon them. Already tiny, blue scilla autumnalis is pressing her head through the turf.

Islets lie off-shore, so full of light that they glow like bubbles blown of air and seem to float on the surface of the sea. Their shadows fall in delicious purple on the aquamarine waters and warm hues percolate their ragged, silver faces, while the gulls cluster in myriads upon them, and, black and silent among the noisy sea-fowl, stand dusky cormorants with long necks lifted. Like pale blue silk, shot and streamed over with pure light, the Channel rises to the mists of the horizon. Light penetrates air and water and earth, so that the weight of land and water are lifted off them and lost; indeed the scene appears to be composed of imponderable hazes and vapours merging into each other; it is wrought in planes of light—a gorgeous, unsubstantial illumination as though the clouds were come to earth. The eternal melody of the gulls pierces the picture with sound, hard and metallic, until their din and racket seem of heavier substance and reality than the mighty cliffs and sea from which it pours. Yet the birds themselves, in their floatings and their wheelings, are lighter than feathers. They make the only movement save for fisher craft with tan-red sails now streaming in line round the Head to sea. For the Scruff they are bound—a great, sandy bottom where sole and turbot dwell ten sea-miles off-shore.

Inland gleam cornfields of heavy grain ripe for harvest[45]—pale yellow of oats and golden brown of wheat, where the poppies stir with the gipsy rose; and flung up upon the cliff-edge rise lofty ramparts, ribbed with granite and bored by portholes for cannon. A modern gun a league out at sea would crumble these masonries like sponge-cake; but they were lifted in haste a hundred years ago, when England quaked at the threatened advent of "Boney," whose ordnance could not have destroyed them. The great fortresses were piled by many thousands of busy hands, yet time sped quicker than the engineers, and before the forts were completed, Napoleon, from the deck of the Bellerophon in the bay beneath, had looked his last on Europe.

Still the unfinished work sprawls over the cliffs, and whence cannon were meant to stare, now thrust the blackberry, brier and eagle-fern through the embrasures, and stunted black-thorns and white-thorns shine green against the grey.

One clambers among them to seek the gift of a patch of shade, and wonders what the first Napoleon would have thought of the hydroplane purring out to sea half a mile overhead.

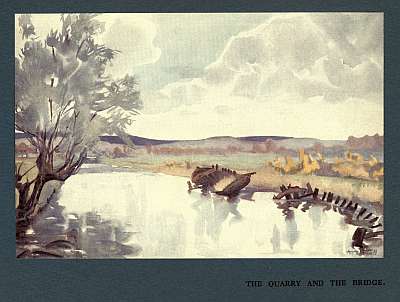

THE QUARRY AND THE BRIDGE

[49]

Lastrea and athyrium, their foliage gone, cling in silky russet knobs under the granite ledges, warm the iron-grey stone with brown and agate brightness, and promise many a beauty of unfolding frond when spring shall come again. For their jewels will be unfolding presently, to soften the cleft granite with misty green and bring the vernal time to these silent cliffs.

The quarry lies like a gash in the slope of the hills. To the dizzy edges of it creep heather and the bracken; beneath, upon its precipices, a stout rowan or two rises, and everywhere Nature has fought and laboured to hide this wound driven so deep into her mountain-side by man. A cicatrix of moss and fern and many grasses conceal the scars of pick and gunpowder; time has weathered the harsh edges of the riven stone; the depths of the quarry are covered by pools of clear water, for it is nearly a hundred years since the place yielded its stores.

One great silence is the quarry now—an amphitheatre of peace and quiet hemmed by the broken abutments of granite, and opening upon the hillside. The heather extends over wide, dun spaces to a blue distance, where evening lies dim upon the plains beneath; round about a minor music of dripping water tinkles from the sides of the quarry; a current of air brushes the pools and for a moment frets their pale [50] surfaces; the dead rushes murmur and then are silent; here and there, along the steps and steep places flash the white scuts of the rabbits. A pebble is dislodged by one of them, and, falling to the water beneath, sets rings of light widening out upon it and raises a little sound.

In the midst, casting its jagged shadow upon the water, springs a great, ancient crane from which long threads of iron still stretch round about to the cliffs. It stands stoutly yet and marks the meaning of all around it.

At time of twilight it is good to be here, for then one may measure the profundity of such peace and contrast this matrix of vanished granite with the scene of its present disposal; one may drink from this cup all the mystery that fills a deserted theatre of man's work and feel that loneliness which only human ruins tell; and then one may open the eye of the mind upon another vision, and suffer the ear of imagination to throb with its full-toned roar.

For hence came London Bridge; the mighty masses of granite riven from this solitude span Thames.

Away in the heath and winding onward by many a curve may yet be traced the first railroad in the West Country. It started here, upon the frontier hills of Dartmoor, and sank mile upon mile to the valleys beneath. But of granite were wrought the lines, and over them ran ponderous wagons. Many thousand feet of stone were first cut for the railway, before those greater masses destined for London set forth upon it to their destination.

Like the empty quarry this deserted railway now lies silent, and the place of its passing on the hills and through the forest[51] beneath is at peace again. From the Moor the tramway drops into the woods of Yarner, and here, between a heathery hillside and the fringes of the forest, the broken track may still be found, its semi-grooved lengths of granite scattered and clad in emerald moss, where once the great wheels were wont to grind it. The line passes under interlacing boughs of beeches and winds this way and that, like a grey snake, through the copper brightness of the fallen leaves; it turns and twists, dropping ever, and ceases at last at the mouth of a little canal in the valley, where barges waited of old to carry the stone to the sea.

Here also is stagnation now, but picturesque wrecks of the ancient boats may still be seen at Teigngrace in the forgotten waterway. They lie foundered upon the canal with bulging sides and broken ribs. Their shapes are outlined in grasses and flowers; sallows leap silvery from the old bulwarks and alders find foothold there; briar and kingcups flourish upon their decay; moss and ferns conceal their wounds; in summer purple spires of loosestrife man their water-logged decks, and the vole swims to and from his hidden nest therein.

Here came the Hey Tor granite, after dropping twelve hundred feet from the Moor above. Leaving the great wains, it was shipped upon the Stover Canal and despatched down the estuary of Teign to Teignmouth, whence larger vessels bore it away to London for its final purpose.

It came to supersede that bridge of houses familiar in the old pictures, the bridge that was a street; the bridge that in its turn had taken the place of older bridges built with wood:[52] those mediæval structures that perished each in turn by flood or fire.

It was in 1756 that the Corporation of London obtained an order to rebuild London Bridge; but things must have moved slowly, for not until fifty years later was the announcement made of a new bridge to pass from Bankside, Southwark, to Queen Street, Cheapside. The public was invited to invest in the enterprise, and doubtless proved willing enough to do so. The ancient structure, long a danger to the navigation of the river, vanished, and in 1825, with great pomp and ceremony, the foundation-stone of the "New London Bridge" sank to its place. A recent writer in The Academy has given a graphic picture of the event, and described the immense significance attached to the occasion. From the earliest dawn of that June morning, London flocked to waterside and thronged each point of vantage. Before noon the roofs of Fishmongers' Hall, of St. Saviour's Church, and every building that offered a glimpse of the ceremony were crowded; the river was alive with craft of all descriptions; the cofferdam for the erection of the first pier served the purpose of a private enclosure, where notable folk sat in four tiers of galleries under flags and awnings.

At four o'clock, by which time the great company must have been weary of waiting, two six-pounder guns at the Old Swan Stairs announced the approach of the Civic and State authorities. The City Marshal, the Bargemasters, the Watermen, the members of the Royal Society, the Goldsmiths, the Under-Sheriffs, the Lord Mayor and the Duke of York appeared.

"His Lordship, who was in full robes," so says an eye-witness[53] of the event, "offered the chair to his Royal Highness, which was positively declined on his part. The Mayor, therefore, seated himself; the Lady Mayoress, with her daughters in elegant dresses, sat near his Lordship, accompanied by two fine-looking, intelligent boys, her sons; near them were the two lovely daughters of Lord Suffolk, and many other fashionable ladies."

Then followed the ceremony. Coins in a cut-glass bottle were placed beneath a copper plate, and upon them descended a mighty block of Dartmoor granite. "The City sword and mace were placed upon it crossways, the foundation of the new bridge was declared to be laid, the music struck up 'God save the King,' and three times three excessive cheers broke forth from the company, the guns of the Honourable Artillery Company on the Old Swan Wharf fired a salute, and every face wore smiles of gratulation. Three cheers were afterwards given for the Duke of York, three for Old England, and three for the architect, Mr. Rennie."

Then did a journalist with imagination dance a hornpipe upon the foundation-stone—for England would not take its pleasure sadly on that great day—and subsequently many ladies stood upon it, and "departed with the satisfaction of being enabled to relate an achievement honourable to their feelings!"

And still the noble bridge remains, though the delicate feet that rested on its foundation-stone have all tripped to the shades. The bridge remains, and its five simple spans—the central one of a hundred and fifty-two feet—make a startling contrast with the nineteen little arches and huge pedestals of the ancient structure. New London Bridge is[54] more than a thousand feet long; its width is fifty-six feet; its height, above low water, sixty feet. The central piers are twenty-four feet thick, and the voussoirs of the central arch four feet nine inches deep at the crown and nine feet at the springing. The foundations lie twenty-nine feet, six inches beneath low water; the exterior stones are all of granite; while the interior mass of the fabric came half from Bramley Fall and half from Derbyshire.

More than seven years did London Bridge take a-building, and it was opened in 1831. The total costs were something under a million and a half of money—less than is needed for a modern battleship.

And already, before it is one hundred years old, there comes a cry that London's heart finds this great artery too small for the stream of life that flows for ever upon it. One may hope, however, that when the necessity arrives, this notable bridge will not be spoiled, but another created hard by, if needs must, to fulfil the demands of traffic. Perhaps a second tunnel may solve the problem, since metropolitan man is turning so rapidly into a mole.

From quarry to bridge is a far cry, yet he who has seen both may dream sometimes among the dripping ferns, silent cliff-faces and unruffled pools, of the city's roar and riot and the ceaseless thunder of man's march from dawn till even; while there—in the full throb and hurtle of London town, swept this way and that amid the multitudes that traverse Thames—it is pleasant to glimpse, through the reek and storm, the cradle of this city-stained granite, lying silent at peace in the far-away West Country.

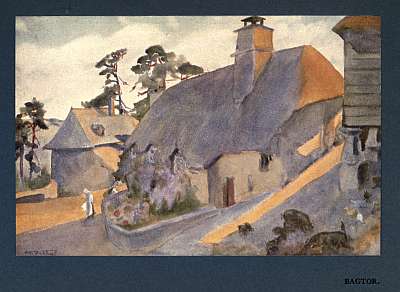

BAGTOR

[57]

From the little southern salient of Bagtor at Dartmoor edge, there falls a slope to the "in country" beneath. Thereon Bagtor woods extend in many a shining plane—from wind-swept hill-crowns of beech and fir, to dingles and snug coombs in the valley bottom a thousand feet beneath.

On a summer day one loiters in the dappled wood, for here is welcome shade after miles of hot sunshine on the heather above. Music of water splashes pleasantly through the trees, where a streamlet falls from step to step; the last of the bluebells still linger by the way, and above them great beech-boles rise, all chequered with sun splashes. On the earth dead leaves make a russet warmth, brighter by contrast with the young green round about, and brilliant where sunlight winnows through. There, in the direct beam, flash little flies, which hang suspended upon the light like golden beads; while through the glades, young fern is spread for pleasant resting-places. Pigeons murmur aloft unseen, and many a grey-bird and black-bird sing beside their hidden homes.

At last the woodlands make an end, old orchards spread in a clearing, and the sun, now turning west, has left the apple trees, so that their blossom hangs cool and shaded on the boughs. Behind—a background for the orchard—there rise the walls of an ancient house, weathered and worn—a mass of picturesque gables and tar-pitched roofs with red-brick[58] chimneys ascending above them. No great dignity or style marks this dwelling. It is a thing of patches and additions. Here the sun still burns radiantly, makes the roof golden, and flashes on the snow-white "fan-tails" that strut up and down upon it.

Great Scotch firs tower to the south, and the light burns redly in their boughs against the blue sky above them. A farmhouse nestles beside the old mansion under a roof of ancient thatch, that falls low over the dawn-facing front, and makes ragged eyelashes for the little windows. The face of the farm is nearly hidden in green things, and a colour note of mauve dominates the foliage where wistaria showers. There are climbing roses too, a Japanese quince, and wallflowers and columbines in the garden plot that subtends the dwelling. Mossy walls enclose the garden, and beneath them spreads the farmyard—a dust-dry place to-day wherein a litter of black piglets gambol round their mother. Poultry cluck and scratch everywhere, and a company of red calves cluster together in one corner. A ploughman brings in his horses. From a byre comes the purr of milk falling into a pail.

On still evenings bell music trickles up to this holt of ancient peace from a church tower three miles away; for we stand in the parish of Ilsington on the shoulder of Dartmoor, and the home of the silver "fan-tails" is Bagtor House—a spot sanctified to all book-lovers. Here, a very mighty personage first saw the light and began his pilgrimage; at Bagtor was John Ford born, the first great decadent of English letters, the tragedian whose sombre works belong to the sunset time of the spacious days.[59]

In April of 1586 the infant John received baptism at Ilsington church; while, sixteen years later, he was apprenticed to his profession and became a member of the Middle Temple. At eighteen John Ford, who wrote out of his own desire and under an artist's compulsion only, first tempted fortune; and over his earliest effort, Fame's Memorial, a veil may be drawn; while of subsequent collaborations with Webster and Decker, part perished unprinted and Mr. Warburton's cook "used up" his comedies. Probably they are no great loss, for a master with less sense of humour never lived. But The Witch of Edmonton in Swinburne's judgment embodies much of Ford's best, and his greatest plays all endure.

The man who wrote The Lover's Melancholy, 'Tis Pity She's a Whore, The Broken Heart and Love's Sacrifice was born in this sylvan scene and his cradle rocked to the murmur of wood doves. True he vanished early from Devonshire, and though uncertain tradition declares his return, asserting that, while still in prime and vigour, he laid by his gown and pen and came back to Bagtor, to end his days where he was born, and mellow his stormy heart before he died, no proof that he did so exists. His life's history has been obliterated and contemporary records of him have yet to appear.

As an artist he must surely have loved horror for horror's sake, and, too often, our terror arouses not that pity to which tragedy should lift man's heart, but rather generates disgust before his extraordinary plots and the unattractive and inhuman characters which unravel them. One salutes the intellectual power of him, but merely[60] shudders, without being enchained or uplifted by the nature of his themes. It has been well said of Ford that he "abhorred vice and admired virtue; but ordinary vice or modern virtue were to him as light wine to a dram drinker.... Passion must be incestuous or adulterous; grief must be something more than martyrdom, before he could make them big enough to be seen."

There is a little of Michaelangelo about Ford—something excruciating, tortured. The tormented marble of the one is reflected in the wracked and writhing characters of the other; but whether Ford felt for the sorrow of earth as the Florentine; whether he shared that mightier man's fiery patriotism, enthusiasm of humanity and tragic griefs before the suffering of mankind, we know not. One picture we have of him from old time, and it offers a gloomy, aloof figure, little caring to win friendship, or court understanding from his fellows:—

With folded arms and melancholy hat.

So depicted the gloomy artist might serve for tragedy's self—arms crossed, brows drawn, eyes darkling under the broad-brimmed beaver, with the plotter's night-black cloak swept round his person. Or to a vision of Michaelangelo's "Il Penseroso" we may exalt the poet, and see him in that solemn and stately stone, finally at peace, his last word written and the finger of silence upon his gloomy lips.

Hazlitt finds John Ford finical and fastidious. He certainly is so, and one often wonders how this mind and pen should have welcomed such appalling subjects. He plays[61] with edged tools and too well knows the use of poisoned weapons, says Hazlitt; and the criticism is just in the opinion of those who, with him, account it an artist's glory that he shall not tamper with foul and "unfair" subjects, or sink his genius to the kennel and gutter. That, however, is the old-world, vanished attitude, for artists recognise no "unfair" subjects to-day.

Indeed, Ford can be not seldom beautiful and tender and touched to emotion of pity; but by the time of Charles, the golden galaxies were gone; their forces were spent; their inspiration had perished; England, merry no more, began to shiver in the shadow of coming puritan eclipse; and that twilight seems to have cast by anticipation its penumbra about Ford.

There is in him little of the rollicking, superficial coarseness of the Elizabethans; the stain is in web and woof. His great moments are few; he is mostly ferocious, or absurdly sentimental, and one confesses that the bulk of his best work, judged against the highest of ancient or modern tragedy, rings feebly with a note of too transparent artifice. He is moved by intellectual interest rather than creative inspiration; there is far more brain than heart in his writings.

Perhaps he knew it and convinced himself, while still at the noon of intelligence, that he was no creator. Perhaps he abandoned art, through failure to satisfy his own ideals. At any rate it would seem that he stopped writing at a time when most men have still much to give.

One would like at least to believe that he found in his birthplace the distinguished privacy he desired and an abode[62] of physical and mental peace. He may, indeed, have come home again to Devon when his work was ended; he may have passed the uncertain residue of life in seclusion with wife and family at this estate of his ancestors; his dust may lie unhonoured and unrecorded at Ilsington, as Herrick's amid the green graves not far distant at Dean Prior.

It is all guesswork, and the truth of John Ford's life, as of his death, may be forever hidden. One sees him a notable, silent, subtle man, prone to pessimism as a gift of heredity—a man disappointed in his achievement, soured by inner criticism and comparison with those who were greater than he.

So, weary of cities and the company of wits and poets, he came back to the country, that he might heal his disappointments and soothe his pains. His life, to the unseeing eyes around him, doubtless loomed prosperous and complete; to himself, perchance, all was dust and ashes of thwarted ambition. Again he roamed the woods where he had learned to walk; won to the love of nature; underwent the thousand new experiences and fancied discoveries of a townsman fresh in the country; and, through these channels, came to contentment and sunshine of mind, bright enough to pierce the night of his thoughts and sweeten the dark currents of his imagination. It may be so.

OKEHAMPTON CASTLE

[65]

A high wind roared over the tree-tops and sent the leaf flying—blood-red from the cherry, russet from the oak, and yellow from the elm. Rain and sunshine followed swiftly upon each other, and the storms hurtled over the forest, hissed in the river below and took fire through their falling sheets, as the November sun scattered the rear-guard of the rain and the cloud purple broke to blue. A great wind struck the larches, where they misted in fading brightness against the inner gloom of the woods, and at each buffet, their needles were scattered like golden smoke. Only the ash trees had lost all their leaves, for a starry sparkle of foliage still clung to every other deciduous thing. The low light, striking upon a knoll and falling on dripping surfaces of stone and tree trunk, made a mighty flash and glitter of it, so that the trees and the scattered masonry, that ascended in crooked crags above their highest boughs, were lighted with rare colour and blazed against the cloud masses now lumbering storm-laden from the West.

The mediæval ruin, that these woods had almost concealed in summer, now loomed amid them well defined. Viewed from aloft the ground plan of the castle might be distinctly traced, and it needed no great knowledge to follow the architectural design of it. The sockets of the pillars that sprang to a groined[66] entrance still remained, and within, to right and left of the courtyard, there towered the roofless walls of a state chamber, or banqueting hall, on the one hand, a chapel, oratory and guard-room on the other. The chapel had a piscina in the southern wall; the main hall was remarkable for its mighty chimney. Without, the ruins of the kitchens were revealed, and they embraced an oven large enough to bake bread for a village. Round about there gaped the foundations of other apartments, and opened deep eyelet windows in the thickness of the walls. The mass was so linked up and knit together that of old it must have presented one great congeries of chambers fortified by a circlet of masonry; but now the keep towered on a separate hillock to the south-west of the ruin, and stood alone. It faced foursquare, dominated the valley, and presented a front impregnable to all approach.

This is the keep that Turner drew, and set behind it a sky of mottled white and azure specially beloved by Ruskin; but the wizard took large liberties with his subject, flung up his castle on a lofty scarp, and from his vantage point at stream-side beneath, suggested a nobler and a mightier ruin than in reality exists. One may suppose that steps or secret passages communicated with the keep, and that in Tudor times no trees sprang to smother the little hill and obscure the views of the distant approaches—from Dartmoor above and the valleys beneath. Now they throng close, where oak and ash cling to the sides of the hillock and circle the stones that tower to ragged turrets in their midst.

Far below bright Okement loops the mount with a brown[67] girdle of foaming waters that threads the meadows; and beyond, now dark, now wanly streaked with sunshine, ascends Dartmoor to her border heights of Yes Tor and High Willhayes. Westerly the land climbs again and the last fires of autumn flicker over a forest.

I saw the place happily between wild storms, at a moment when the walls, warmed by a shaft of sunlight, took on most delicious colour and, chiming with the gold of the flying leaves, towered bright as a dream upon the November blue.

At the Conquest, Baldwin de Redvers received no fewer than one hundred and eighty-one manors in Devon alone, for William rewarded his strong men according to their strength. We may take it, therefore, that this Baldwin de Redvers, or Baldwin de Brionys, was a powerful lieutenant to the Conqueror—a man of his hands and stout enough to hold the West Country for his master. From his new possessions the Baron chose Ochementone[1] for his perch; indeed, he may be said to have created the township. With military eye he marked a little spur of the hills that commanded the passes of the Moor and the highway to Cornwall and the Severn Sea; and there built his stronghold,—the sole castle in Devon named in Domesday. But of this edifice no stone now stands upon another. It has vanished into the night of time past, and its squat, square, Norman keep scowls down upon the valleys no more.

[1] "Okehampton" is a word which has no historic or philological excuse.

The present ruins belong to the Perpendicular period of [68]later centuries, and until a recent date the second castle threatened swiftly to pass after the first; but a new lease of life has lately been given to these fragments; they have been cleaned and excavated, the conquering ivy has been stripped from their walls, and a certain measure of work accomplished to weld and strengthen the crumbling masonry. Thus a lengthened existence has been assured to the castle. "Time, which antiquates antiquities," is challenged, and will need reinforcement of many years wherein again to lift his scaling ladders of ivy, loose his lightnings from the cloud, and marshal his fighting legions of rain and tempest, frost and snow.

THE GORGE

[71]

Reflection swiftly reveals the significance of a river gorge, for it is upon such a point that the interest of early man is seen to centre. The shallow, too, attracts him, though its value varies; it must ever be a doubtful thing, because the shallow depends upon the moods of a river, and a ford is not always fordable. But to the gorge no flood can reach. There the river's banks are highest, the aperture between them most trifling; there man from olden time has found the obvious place of crossing and thrown his permanent bridge to span the waterway. At a gorge is the natural point of passage, and Pontifex, the bridge-builder, seeking that site, bends road to river where his work may be most easily performed, most securely founded. But while the bridge, its arch springing from the live rock, is safe enough, the waters beneath are like to be dangerous, and if a river is navigable at all, at her gorges, where the restricted volume races and deepens, do the greatest dangers lie. In Italy this fact gave birth to a tutelary genius, or shadowy saint, whose special care was the raft-men of Arno and other rivers. Their dangerous business took these foderatore amid strange hazards, and one may imagine them on semi-submerged timbers, swirling and crashing over many a rocky rapid, in the throats of the hills, where twilight homed[72] and death was ever ready to snatch them from return to smooth waters and sunshine. So a new guardian arose to meet these perils, and the boldest navigator lifted his thoughts to Heaven and commended his soul to the keeping of San Gorgone.

Sublimity haunts these places; be they great as the Grand Cañon of Arizona and the mountain rifts of Italy and France, or trifling as this dimple on Devon's face of which I tell to-day, they reveal similar characteristics and alike challenge the mind of the intelligent being who may enter them.

Here, under the roof of Devon, through the measures that press up to the Dartmoor granite and are changed by the vanished heat thereof, a little Dartmoor stream, in her age-long battle with earth, has cut a right gorge, and so rendered herself immortal. There came a region in her downward progress when she found barriers of stone uplifted between her and her goal; whereupon, without avoiding the encounter, she cast herself boldly upon the work and set out to cleave and to carve. Now this glyptic business, begun long before the first palæolithic man trod earth, is far advanced; the river has sunk a gulley of near two hundred feet through the solid rock, and still pursues her way in the nether darkness, gnawing ceaselessly at the stone and leaving the marks of her earlier labours high up on either side of the present channel. There, written on the dark Devonian rock, is a record of erosion set down ages before human eye can have marked it; for fifty feet above the present bed are clean-scooped pot-holes, round and true, left by those prehistoric waters. But the sides of the gorge are mostly broken and sloping; and upon the shelves[73] of it dwell trees that fling their branches together with amazing intricacies of foliage in summer-time and lace-like ramage in winter. Now bright sunshine flashes down the pillars of them and falls from ledge to ledge of each steep precipice; it brightens great ivy banks and illuminates a thousand ferns, that stud each little separate knoll in the great declivities, or loll from clefts and crannies to break the purple shadows with their fronds. The buckler and the shield fern leap spritely where there is most light; the polypody loves the limb of the oak; the hart's tongue haunts the coolest, darkest crevices and hides the beauty of silvery mosses and filmy ferns under cover of each crinkled leaf. And secret waters twinkle out by many a hidden channel to them, bedewing their foliage with grey moisture.

On a cloudy day night never departs from the deepest caverns of this gorge, and only the foam-light reveals each polished rib and buttress. The air is full of mist from a waterfall that thunders through the darkness, and chance of season and weather seldom permit the westering sun to thrust a red-gold shaft into the gloom. But that rare moment is worth pilgrimage, for then the place awakens and a thousand magic passages of brightness pierce the gorge to reveal its secrets. In such moments shall be seen the glittering concavities, the fair pillars and arches carved by the water, and the hidden forms of delicate life that thrive upon them, dwelling in darkness and drinking of the foam. Most notable is a crimson fungus that clings to the dripping precipices like a robe, so that they seem made of polished bloodstone, and hint the horror of some tragedy in these loud shouting caves.[74] Below the mass of the river, very dark under its creaming veil of foam, shouts and hastens; above, there slope upwards the cliff-masses to a mere ribbon of golden-green, high aloft where the trees admit rare flashes from the azure above them. Beech and ash spring horizontally from the precipices, and great must be the bedded strength of the roots that hold their trunks hanging there. With the dark forces of the gorge dragging them downward and the sunshine drawing them triumphantly up—between gravitation and light—they poise, destruction beneath and life beckoning from above. They nourish thus above their ultimate graves, since they, too, must fall at last and join those dead tree skeletons whose bones are glimmering amid the rocks below.

Here light and darkness so cunningly blend that size is forgotten, as always happens before a thing inherently fine. The small gorge wrought of a little river grows great and bulks large to imagination. The soaring sides of it, the shadow-loving things beneath, the torture of the trees above, and the living water, busy as of yore in levelling its ancient bed to the sea, waken wonder at such conquest over these fire-baked rocks. The heart goes out to the river and takes pleasure to follow her from the darkness of her battle into the light again, where, flower-crowned, she emerges between green banks that shelve gently, hung with wood-rush and meadow-sweet, angelica and golden saxifrage. Here through a great canopy of translucent foliage shines the noon sunlight, celebrating peace. Into the river, where she spreads upon a smooth pool, and trout dart shadowy through the crystal, the brightness burns, until the stream bed sparkles with amber and agate and flashes up in[75] sweet reflections beneath each brier and arched fern-frond bending at the brink.

Nor does the rivulet lack correspondence with greater streams in its human relation; she is complete in every particular, for man has found her also; and dimly seen, amid the very tree-tops, where the gorge opens, and great rocks come kissing close, an arch of stone carries his little road from hamlet to hamlet.

THE GLEN

[79]

There is a glen above West Dart whence a lesser stream after brief journeying comes down to join the river. By many reaches, broken with little falls, the waters descend upon the glen from the Moor; but barriers of granite first confront them, and before the lands break up and hollow, a mass of boulders, piled in splendid disorder and crowned with willow and rowan, crosses the pathway of the torrent. Therefore the little river divides and leaps and tumbles foaming over the mossy granite, or creeps beneath the boulders by invisible ways. Into fingers and tresses the running waters dislimn, and then, that great obstacle passed, their hundred rillets run together again and go on their way with music. By a descent that becomes swiftly steeper, the burn falls upon fresh rocks, is led into fresh channels and broken to the right and left where mossy islets stand knee-deep in fern and bilberry. Here spring up the beginnings of the wood, for the glen is full of trees. Beech and alder, with scrub of dwarf willow at their feet, cluster on the islets and climb the deepening valley westward; but in the glen stand aged trees, and on the crest of the slope haggard spruce firs still fight for life and mark, in their twisted and decaying timbers and perishing boughs, the torment of the unsleeping wind. Great is the contrast between these stricken ruins with death in their high tops,[80] and the sylva beneath sheltered by the granite hill. There beech and pine are prosperous and sleek compared with the unhappy, time-foundered wights above them; but if the spruces perish, they rule. The lesser things are at their feet and the sublimity of their struggle—their mournful but magnificent protest against destiny—makes one ignore the sequestered woodland, where there is neither battle nor victory, but comfortable, ignoble shelter and repose. The river kisses the feet of these happy nonentities; they make many a stately arch and pillar along the water; in spring the pigeon and the storm-thrush nest among their branches; and they gleam with newly-opened foliage and shower their silky shards upon the earth; in autumn they fling a harvest of sweet beech mast around their feet. The seed germinates and thousands of cotyledon leaves appear like fairy umbrellas, from the waste of the dead leaves. The larger number of these seedlings perish, but some survive to take their places in fulness of time.

By falls and rapids, by flashing stickles and reaches of stillness, the little river sinks to the heart of the glen; but first there is a water-meadow under the hills where an old clapper-bridge flings its rough span from side to side. This is of ancient date and has been more than once restored against the ravages of flood since pack-horses tramped that way in Tudor times. Here the streamlet rests awhile before plunging down the steeps beyond and entering the true glen—a place of shelving banks and many trees.

In summer the dingle is a golden-green vision of tender light that filters through the beeches. Here and there a[81] sungleam, escaping the net of the leaf, wins down to fall on mossy boulder and bole, or plunge its shaft of brightness into a dark pool. Then the amber beam quivers through the crystal to paint each pebble at the bottom and reveal the dim, swift shades of the trout, that dart through it from darkness back to darkness again. In autumn the freshets come and the winds awaken until a storm of foliage hurtles through the glen, now pattering with shrill whispers from above and taking the water gently; now whirling in mad myriads, swirling and eddying, driven hither and thither by storm until they bank upon some hillock, find harbour among holes and the elbows of great roots, or plunge down into the turmoil of the stream. The ways of the falling leaf are manifold, and as the rock delays the river, so the trees, with trunk and bough, arrest the flying foliage, bar its hurrying volume and deflect its tide. In winter the glen is good, for then a man may escape the north wind here and, finding some snug holt among the river rocks, mark the beauty about him while snow begins to touch the tree-tops and the boughs are sighing. Then can be contrasted the purple masses of sodden leaves with the splendour of the mosses among which they lie; for now the minor vegetation gleams at this, its hour of prime. It sheets every bank in a silver-green fabric fretted with liquid jewels or ice diamonds; it builds plump knobs and cushions on the granite, and some of the mosses, now in fruit, brush their lustrous green with a wash of orange or crimson, where tiny filaments rise densely to bear the seed. Here, also, dwelling among them, flourishes that treasure of such secret nooks by stream-side, the filmy fern,[82] with transparent green vesture pressed to the moisture-laden rocks.

Man's handiwork is also manifested here; not only in the felled trees and the clapper-bridge, but uniquely and delightfully; for where the river quickens over a granite apron and hastens in a torrent of foam away, the rocks have tongues and speak. He who planted this grove and added beauty to a spot already beautiful, was followed by his son, who caused to be carved inscriptions on the boulders. You may trace them through the moss, or lichen, where the records, grown dim after nearly a hundred years, still stand. It was a minister of the Church who amused himself after this fashion; but in no religious spirit did he compose; and the scattered poetry has a pleasant, pagan ring about it proper to this haunt of Pan.

Upon one great rock in the open, with its grey face to the south-west and its feet deeply bedded in grass and sand, you shall with care decipher these words:—

Thy smiles imparadise the wild.

Beside the boulder a willow stands, its finials budding with silver; upon the north-western face of the stone is another inscription whose legend startles a wayfarer on beholding the bulk of the huge mass. "This stone was removed by a flood 17—."

On the islets and by the pathway below, sharp eyes may discover other inscribed stones, and upon one island, which the bygone poet called "The Isle of Mona," there still exist[83] inscriptions in "Bardic characters." These he derived from the Celtic Researches of Davies. Furnished with the English letters corresponding to these symbols, one may, if sufficiently curious, translate each distich as one finds it. Elsewhere, beside the glen path, a sharp-eyed, little lover of Nature, tore the coat of moss from another phrase that beat us both as we hunted through the early dusk:—

This was the complete passage, and we puzzled not a little to solve its meaning. On dipping into the past, however, I discovered that the inscription was intended to have read as follows:—

Who joined the Dryads to your train.

The rhyme was designed to honour the poet's father, who set the forest here; but accident must have stayed the stone-cutter's hand and left the distich incomplete.

And now a sudden flash of red aloft above the tree-tops told that the sun was setting. Night thickened quickly, though the lamp of a great red snow-cloud still hung above the glen long after I had left it. Beneath, the mass of the beech wood took on wonderful colour and the streamlet, emerging into meadows, flashed back the last glow of the sky.

A DEVON CROSS

[87]

There are two orders of ancient human monuments on Dartmoor—the prehistoric evidences of man's earliest occupation and the mediæval remains that date from Tudor times, or earlier. The Neolith has left his cairns and pounds and hut circles, where once his lodges clustered upon the hills. The other memorials are of a different character and chiefly mark the time of the stannators, when alluvial tin abounded and the Moor supported a larger population than it does to-day. Ruins of the smelting houses and the piled debris of old tin-streaming works may be seen on every hand, and the moulds into which molten tin was poured still lie in hollows and ruins half hidden by the herbage. Here also, scattered irregularly, the Christian symbol occurs, on wild heaths and lonely hillsides, to mark some sacred place, indicate an ancient path, or guide the wayfaring monk and friar of old on their journey by the Abbot's Way.

Of these the most notable is that venerable fragment known as Siward's Cross—a place of pilgrimage these many years.

Now, on this day of March, snow-clouds swept the desert intermittently with their grey veils and often blotted every landmark. At such times one sought the little hillocks thrown up by vanished men and hid in some hollow of the tin-streamers' digging to escape the pelt of the snow and avoid the buffet[88] of the squall that brought it. Then the sun broke up the welter of hurrying grey and for a time the wind lulled and the brief white shroud of the snow melted, save where it had banked against some obstacle.

The lonely hillock where stands Siward's Cross, or "Nun's Cross," as Moormen call it, lies at a point a little above the western end of Fox Tor Mire. The land slopes gently to it and from it; the great hills roll round about. To the east a far distance opens very blue after the last snow has fallen; to the south tower the featureless ridges of Cator's Beam with the twin turrets of Fox Tor on their proper mount beneath them. The beginnings of the famous mire are at hand—a region of shattered peat-hags and morasses—where, torn to pieces, the earth gapes in ruins and a thousand watercourses riddle it. All is dark and sere at this season, for the dead grasses make the peat blacker by contrast. It is a chaos of rent and riven earth ploughed and tunnelled by bogs and waterways; while beyond this savage wilderness the planes of the hills wind round in a semicircle and hem the cradle of the great marshes below with firm ground and good "strolls" for cattle, when spring shall send them in their thousands to the grazing lands of the Moor again.

The sky shone blue by the time I reached the old cross and weak sunlight brightened its familiar face. The relic stands seven feet high, and now it held a vanishing patch of snow on each stumpy arm. Its weathered front had made a home for flat and clinging lichens, grey as the granite for the most part, yet warming to a pale gold sometimes. Once the cross was broken and thrown in two pieces on the heath;[89] but the wall-builders spared it, for the monument had long been famous. Antiquarian interest existed for the old relic, and it was mended with clamps of iron, and lifted upon a boulder to occupy again its ancient site.

For many a year experts puzzled to learn the meaning of the inscriptions upon its face, and various conjectures concerning them had their day; but it was left for our first Dartmoor authority, William Crossing, who has said the last word on these remains, to decipher the worn inscription and indicate its significance. He finds the word "Siward," or "Syward," on the eastern side, and the word "Boc-lond," for "Buckland," on the other, set in two lines under the incised cross that distinguishes the western face of the monument.

"Siward's Cross" is mentioned in the Perambulation of 1240. "It is named," says Mr. Crossing, "in a deed of Amicia, Countess of Devon, confirming the grant of certain lands for building and supporting the Abbey of Buckland, among which were the manors of Buckland, Bickleigh and Walkhampton. The latter manor abuts on Dartmoor Forest, and the boundary line, which Siward's Cross marks at one of the points, is drawn from Mistor to the Plym. The cross, therefore, in addition to being considered a forest boundary mark, also became one to the lands of Buckland Abbey, and I am convinced that the letters on it which have been so variously interpreted simply represent the word 'Bocland.' The name, as already stated, is engraved on the western face of the cross—the side on which the monks' possessions lay."

Elsewhere he observes that Siward's Cross, "standing as[90] it does on the line of the Abbot's Way, would seem not improbably to have been set up by the monks of Tavistock as a mark to point out the direction of the track across the Moor; and were it not for the fact that it has been supposed to have obtained its name from Siward, Earl of Northumberland, who, it is said, held property near this part of the Moor in the Confessor's reign, I should have no hesitation in believing such to be the case."

No matter who first lifted it, still it stands—the largest cross on Dartmoor—like a sentinel to guard the path that extended between the religious houses of Plympton, Buckland and Tavistock. And other crosses there are beyond the Mire, where an old road descended over Ter Hill. But the Abbot's Way is tramped no more, and the princes of the Church, with their men-at-arms and their mules and pack-horses, have passed into forgotten time. Few now but the antiquary and holiday-maker wander to Siward's Cross; or the fox-hunter gallops past it; or the folk, when they tramp to the heights for purple harvest of "hurts" in summer-time. The stone that won the blessings of pious men, only comforts a heifer to-day; she rubs her side against it and leaves a strand of her red hair caught in the lichens.

The snow began to fall more heavily and the wind increased. Therefore I turned north and left that local sanctity from olden time, well pleased to have seen it once again in the stern theatre of winter. It soon shrank to a grey smudge on the waste; then snow-wreaths whirled their arms about it and the emblem vanished.

COOMBE

[93]

Life comes laden still with good days that whisper of romance, when in some haunt of old legend, our feet loiter for a little before we pass forward again. I indeed seek these places, and confess an incurable affection for romance in my thoughts if not my deeds. I would not banish her from art, or life; and though most artists of to-day will have none of her, spurn romantic and classic alike, and take only realism to their bosoms; yet who shall declare that realism is the last word, or that reality belongs to her drab categories alone?

"There is no 'reality' for us—nor for you either, ye sober ones, and we are far from being so alien to one another as ye suppose, and perhaps our goodwill to get beyond drunkenness is just as respectable as your belief that ye are altogether incapable of drunkenness."