THE SQUIRE'S KEEPER.

Title: The Confessions of a Poacher

Author: F.L.S. John Watson

Illustrator: active 19th century James West

Release date: August 4, 2011 [eBook #36970]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Edwards, Linda Hamilton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive)

"Poaching is one of the fine arts—how 'fine' only the initiated know."

THE SQUIRE'S KEEPER.

The Leadenhall Press,

50, Leadenhall Street, London, E.C.

T 4,463.z

poacher of these "Confessions" is no imaginary being. In the following pages I have set down nothing but what has come within his own personal experience; and, although the little book is full of strange inconsistencies, I cannot, knowing the man, call them by a harder name. Nature made old "Phil" a Poacher, but she made him a Sportsman and a Naturalist at the same time. I never met any man who was in closer sympathy with the wild creatures about him; and never dog or child came within his influence but what was permanently attracted by his personality. Although eighty years of age there is still some of the old erectness in his carriage; some of the old fire in his eyes. As a young man he was handsome, though now his features are battered out of all original conception. His silvery hair still covers a lion-like head, and his tanned cheeks are hard and firm. If his life has been a lawless one he has paid heavily for his wrong doings. Great as a poacher, he must have been great whatever he had been. In my boyhood he was the hero whom I worshipped, and I hardly know that I have gone back on my loyalty.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | The Embryo Poacher | 7 | |

| 2. | Under the Night | 19 | |

| 3. | Graduating in Woodcraft | 32 | |

| 4. | Partridge Poaching | 45 | |

| 5. | Hare Poaching | 57 | |

| 6. | Pheasant Poaching | 74 | |

| 7. | Salmon and Trout Poaching | 90 | |

| 8. | Grouse Poaching | 109 | |

| 9. | Rabbit Poaching | 123 | |

| 10. | Tricks | 135 | |

| 11. | Personal Encounters | 151 | |

THE

CONFESSIONS OF A POACHER.

not remember the time when I was not a poacher; and if I may say so, I believe our family has always had a genius for woodcraft.

I was bred on the outskirts of a sleepy town in a good game country, and my depredations were mostly when the Game Laws were less rigorously enforced than now. Our home was roughly adorned in fur and feather, and a number of gaunt lurchers always constituted part of the family. An almost passionate love of nature, summers of birds' nesting, and a life spent almost wholly out of doors constituted an admirable training for an embryo poacher. If it is true that poets are born, not made, it is equally so of poachers. The successful "moucher" must be an inborn naturalist—must have much in common with the creatures of the fields and woods around him.

There is a miniature bird and animal fauna which constitutes as important game to the young poacher as any he is likely to come across in after life. There are mice, shrews, voles, for all of which he sets some primitive snare and captures. The silky-coated moles in their runs offer more serious work, and being most successfully practised at night, offers an additional charm. Then there are the red-furred squirrels which hide among the delicate leaves of the beeches and run up their grey boles—fairy things that offer an endless subject of delight to any young savage, and their capturing draws largely upon his inventive genius. A happy hunting ground is furnished by farmers who require a lad to keep the birds from their young wheat or corn, as when their services are required the country is all like a garden. At this time the birds seem creatures born of the sun, and not only are they seen in their brightest plumage, but when indulging in all their love frolics. By being employed by the farmers the erstwhile poacher is brought right into the heart of the land, and the knowledge of woodcraft and rural life he there acquires is never forgotten. As likely as not a ditch runs by the side of the wheat fields, and here the water-hen leads out her brood. To the same spot the birds come at noon to indulge their mid-day siesta, and in the deep hole at the end of the cut a shoal of silvery roach fall and rise towards the warm sunlight. Or a brook, which is a tiny trout stream, babbles on through the meadows and pastures, and has its attractions too. A stream is always the chief artery of the land, as in it are found the life-giving elements. All the birds, all the plants, flock to its banks, and its wooded sides are hushed by the subdued hum of insects. There are tall green brackens—brackens unfurling their fronds to the light, and full of the atoms of beautiful summer. At the bend of the stream is a lime, and you may almost see its glutinous leaves unfolding to the light. Its winged flowers are infested with bees. It has a dead bough almost at the bottom of its bole, and upon it there sits a grey-brown bird. Ever and anon it darts for a moment, hovers over the stream, and then returns to its perch. A hundred times it flutters, secures its insect prey, and takes up its old position on the stump. Bronze fly, bluebottle, and droning bee are secured alike, for all serve as food to the loveable pied fly-catcher.

It is the time of the bloom of the first June rose; and here, by the margin of the wood, all the ground by fast falling blossom is littered. Every blade teems with life, and the air is instinct with the very breath of being. Birds' sounds are coming from over and under—from bough and brake, and a harmonious discord is flooded from the neighbouring copse. The oak above my head is a murmurous haunt of summer wings, and wood pigeons coo from the beeches. The air is still, and summer is on my cheek; arum, wood-sorrel, and celandine mingle at my feet. The starlings are half buried in the fresh green grass, their metallic plumage flashing in the sun. Cattle are lazily lying dotted over the meadows, and the stream is done in a setting of green and gold. Swallows, skimming the pools, dip in the cool water, and are gone—leaving a sweet commotion in ever widening circles long after they have flown. A mouse-like creeper alights at the foot of a thorn, and runs nimbly up the bark; midway it enters a hole in which is its nest. A garrulous blue-winged jay chatters from the tall oak, and purple rooks are picking among the corn. Butterflies dally through the warm air, and insects swarm among the leaves and flowers of the hedge bottoms. A crake calls, now here, now far out yonder. Bluebells carpet the wood-margin, and the bog is bright with marsh plants.

This, then, is the workshop of the young poacher, and here he receives his first impressions. Is it strange that a mighty yearning springs up within him to know more of nature's secrets? He finds himself in a fairy place, and all unconsciously drinks in its sweets. See him now deeply buried in a golden flood of marsh marigolds! See how he stands spellbound before saxifrages which cling to a dripping rock. Water avens, wild parsley, and campions crowd around him, and flags of the yellow and purple iris tower over all. He watches the doings of the reed-sparrows deep down in the flags, and sees a water-ouzel as it rummages among the pebbles at the bottom of the brook. The larvæ of caddis flies, which cover the edge of the stream, are a curious mystery to him, and he sees the kingfisher dart away as a bit of green light. Small silvery trout, which rise in the pool, tempt him to try for them with a crooked pin, and even now with success. He hears the cuckoos crying and calling as they fly from tree to tree, and quite unexpectedly finds the nest of a yellow-hammer, between a willow and the bank, containing its curiously speckled eggs.

Still the life, and the "hush," and the breath go on. Everything breathes, and moves, and has its being; the things of the day are the essence thereof. On the margin of the wood are a few young pines, their delicate plumes just touched with the loveliest green. An odour of resinous gum is wafted from them, and upon one of the slender sprays a pair of diminutive goldcrests have hung their procreant cradle. These things are enough to win any young Bohemian to their ways, and although as yet they only comprise "the country," soon their wondrous detail lures their lover on, and he seeks to satisfy the thirst within him by night as well as by day.

Endless acquaintances are to be made in the fields, and those of the most pleasurable description. Nests containing young squirrels can be found in the larch tree tops, and any domestic tabby will suckle these delightful playthings. Young cushats and cushats' eggs can be obtained from their wicker-like nests, and sold in the villages. A prickly pet may be captured in a hedgehog trotting off through the long grass, and colonies of young wild rabbits may be dug from the mounds and braes. The skin of every velvety mole is one patch nearer the accomplishment of a warm, furry vest for winter, and this, if the pests of which it is comprised are the owner's taking, is worn with pardonable pride. A moleskin vest constitutes a graduation in woodcraft so to speak. Sometimes a brace of leverets are found in a tussocky grass clump, but these are more often allowed to remain than taken. And there are almost innumerable captures to be made among the feathered as well as furred things of the fields and woods. Chaffinches are taken in nooses among the corn, as are larks and buntings. Crisp cresses from the springs constitute an important source of income, and the embrowned nuts of autumn a harvest in themselves. It is during his early days of working upon the land that the erstwhile poacher learns of the rain-bringing tides; of the time of migration of birds; of the evening gamboling of hares; of the coming together of the partridge to roost; of the spawning of salmon and trout; and a hundred other scraps of knowledge which will serve him in good stead in his subsequent protest against the Game Laws.

Almost every young rustic who develops into a poacher has some such outdoor education as that sketched above. He has about him much ready animal ingenuity, and is capable of almost infinite resource. His snares and lines are constructed with his pocket knife, out of material he finds ready to hand in the woods. He early learns to imitate the call of the game birds, so accurately as to deceive even the birds themselves; and his weather-stained clothes seem to take on themselves the duns and browns and olives of the woods. A child brought up in the lap of Nature is invariably deeply marked with her impress, and we shall see to what end she has taught him.

the embryo poacher has once tasted the forbidden fruits of the land—and it matters not if his game be but field-mice and squirrels—there is only one thing wanting to win him completely to Nature's ways. This is that he shall see her sights and hear her sounds under the night. There is a charm about the night side of nature that the town dweller can never know. I have been once in London, and well remember what, as a country lad, impressed me most. It was the fact that I had, during the small hours of the morning, stood alone on London Bridge. The great artery of life was still; the pulse of the city had ceased to beat. Not a moving object was visible. Although bred among the lonely hills, I felt for the first time that this was to be alone; that this was solitude. I felt such a sense as Macaulay's New Zealander may experience when he sits upon the ruins of the same stupendous structure; and it was then for the first time I knew whence the inspiration, and felt the full force and realism of a line I had heard, "O God! the very houses seemed to sleep." I could detect no definite sound, only that vague and distant hum that for ever haunts and hangs over a great city. Then my thoughts flew homeward (to the fells and upland fields, to the cold mists by the river, to the deep and sombre woods). I had never observed such a time of quiet there; no absolute and general period of repose. There was always something abroad, some creature of the fields or woods, which by its voice or movements was betrayed. Just as in an old rambling house there are always strange noises that cannot be accounted for, so in the night-paths of nature there are innumerable sounds which can never be localised. To those, however, who pursue night avocations in the country, there are always calls and cries which bespeak life as animate under the night as that of the day. This is attributable to various animals and birds, to beetles, to night-flying insects, even to fish; and part of the education of the young poacher is to track these sounds to their source.

I have said that our family was a family of poachers. The old instinct was in us all, though I believe that the same wild spirit which drove us to the moor and covert at night was only the same as was strongly implanted in the breast of Lord ——, our neighbour, who was a legitimate sportsman and a Justice of the Peace. If we were not allowed to see much real poaching when we were young we saw a good deal of the preparations for it. As the leaves began to turn in autumn there was great activity in our old home among nets and snares. When wind and feather were favourable, late afternoon brought home my father, and his wires and nets were already spread on the clean sanded floor. There was a peg to sharpen, or a broken mesh to mend. Every now and then he would look out on the darkening night, always directing his glance upward. The two dogs would whine impatiently to be gone, and in an hour, with bulky pockets, he would start, striking right across the land and away from the high road. The dogs would prick out their ears on the track, but stuck doggedly to his heels; and then, as we watched, the darkness would blot him out of the landscape, and we turned with our mother to the fireside. In summer we saw little but the "breaking" of the lurchers. These dogs take long to train, but, when perfected, are invaluable. All the best lurchers are the produce of a cross between the sheep-dog and greyhound, a combination which secures the speed and silence of the one, and the "nose" of the other. From the batches of puppies we always saved such as were rough-coated, as these were better able to stand the exposure of long, cold nights. In colour the best are fawn or brown—some shade which assimilates well to the duns and browns and yellows of the fields and woods; but our extended knowledge of the dogs came in after years.

The oak gun-rack in our old home contained a motley collection of fowling pieces, mostly with the barrels filed down. This was that the pieces might be more conveniently stowed away in the pocket until it was policy to have them out. The guns showed every graduation in age, size, and make, and among them was an old flint-lock which had been in the family for generations. This heirloom was often surreptitiously stolen away, and then we were able to bring down larger game. Wood pigeons were waited for in the larches, and shot as they came to roost. The crakes were called by the aid of a small "crank," and shot as they emerged from the lush summer grass. Large numbers of green plover were bagged from time to time, and often in winter we had a chance at their grey cousins, the whistling species. Both these fed in the water-meadows through winter, and the former were always abundant. In spring, "trips" of rare dotterel often led us about the higher hills for days, and sometimes we had to stay all night on the mountain. Then we were up with the first gray light in the morning, and generally managed to bring down a few birds. The feathers of these are extremely valuable for fishing, and my father invariably supplied them to the county justices who lived near us. He trained a dog to hunt dotterel, and so find their nests, and in this was most successful—more so than an eminent naturalist who spent five consecutive summers about the summits of our highest mountains, though without ever coming across a nest or seeing the birds. Sometimes we bagged a gaunt heron as it flapped heavily from a ditch—a greater fish poacher than any in the country side. One of our great resorts on winter evenings was to an island which bordered a disused mill-dam. This was thickly covered with aquatic vegetation, and to it came teal, mallard, and poachard. All through the summer we had worked assiduously at a small "dug-out," and in this we waited, snugly stowed away behind a willow root. When the ducks appeared on the sky-line the old flint-lock was out, a sharp report tore the darkness, and a brace of teal or mallard floated down stream, and on to the mill island. In this way half a dozen ducks would be bagged, and, dead or dying, they were left where they fell, and retrieved next morning. Sometimes big game was obtained in the shape of a brace of geese, which proved themselves the least wary of a flock; but these only came in the severest weather.

Cutting the coppice, assisting the charcoal burners, or helping the old woodman—all gave facilities for observing the habits of game, and none of these opportunities were missed. In this way we were brought right into the heart of the land, and our evil genius was hardly suspected. An early incident in the woods is worth recording. I have already said that we took snipe and woodcock by means of "gins" and "springes," and one morning on going to examine a snare, we discovered a large buzzard near one which was "struck." The bird endeavoured to escape, but, being evidently held fast, could not. A woodcock had been taken in one of our snares, which, while fluttering, had been seen and attacked by the buzzard. Not content, however, with the body of the woodcock, it had swallowed a leg also, around which the nooze was drawn, and the limb was so securely lodged in its stomach that no force which the bird could exert could withdraw it. The gamekeepers would employ us to take hedgehogs, which we did in steel traps baited with eggs. These prickly little animals were justly blamed for robbing pheasants' nests, and many a one paid the penalty for so doing. We received so much per head for the capture of these, as also for moles which tunnelled the banks of the water meadows. Being injurious to the stream sides and the young larches, the farmers were anxious to rid these; and one summer we received a commission to exercise our knowledge of field-craft against them. But in the early days our greatest successes were among the sea ducks and wildfowl which haunted the marram-covered flats and ooze banks of an inland bay a few miles from our home. Mention of our capturing the sea birds brings to mind some very early rabbit poaching. At dusk the rabbits used to come down from the woods, and on to the sandy saline tracts to nibble the short sea grass. As twilight came we used to lie quiet among the rocks and boulders, and, armed with the old flint-lock, knock over the rabbits as soon as they had settled to feed. But this was only tasting the delights of that first experience in "fur" which was to become so widely developed in future years. Working a duck decoy—when we knew where we had the decoyman—was another profitable night adventure, which sometimes produced dozens of delicate teal, mallard and widgeon. Another successful method of taking seafowl was by the "fly" or "ring" net. When there was but little or no moon these were set across the banks last covered by the tide. The nets were made of fine thread, and hung on poles from ten to twenty yards apart. Care had to be taken to do this loosely, so as to give the nets plenty of "bag." Sometimes we had these nets hung for half a mile along the mud flats, and curfew, whimbrel, geese, ducks, and various shore-haunting birds were taken in them. Sometimes a bunch of teal, flying down wind, would break right through the net and escape. This, however, was not a frequent occurrence.

There is one kind of poaching, which, as a lad, I was forbidden, and I have never indulged in it from that day to this. This was egg poaching. In our own district it was carried on to a large extent, though I never heard of it until the artificial rearing of game came in. The squire's keeper will give sixpence each for pheasants' eggs, and fourpence for those of partridges. I know for certain that he often buys eggs (unknowingly, of course) from his master's preserves as well as those of his neighbours. In the hedge bottom, along the covert side, or among broom and gorse, the farm labourer notices a pair of partridges roaming morning after morning. Soon he finds their oak-leaf nest and olive eggs. These the keeper readily buys, winking at what he knows to be dishonest. Ploughboys and farm labourers have peculiarly favourable opportunities for egg poaching. As to pheasants' eggs, if the keeper be an honest man and refuses to buy, there are always large town dealers who will. Once in the coverts pheasants' eggs are easily found. The birds get up heavily from their nests, and go away with a loud whirring of wings. In this species of poaching women and children are largely employed, and at the time the former are ostensibly gathering sticks, the latter wild flowers. I have known the owner of the "smithy," who was the receiver in our village, send to London in the course of a week a thousand eggs, every one of them gathered off the neighbouring estates.

When I say that I never indulged in egg poaching I do not set up for being any better than my neighbours. I had been forbidden to do it as a lad because my father give it the ugly name of thieving, and it had never tempted me aside. It was tame work at best, and there was none of the exhilarating fascination about it that I found in going after the game birds themselves.

as the sportsman loves "rough shooting," so the poacher invariably chooses wild ground for his depredations. There is hardly a sea-parish in the country which has not its shore shooter, its poacher, and its fowler. Fortunately for my graduation in woodcraft I fell in with one of the latter at the very time I most needed his instructions. As the "Snig," as I was generally called, was so passionately fond of "live" things, old "Kittiwake" was quite prepared to be companionable. Although nearly three score years and ten divided our lives, there was something in common between us. Love of being abroad beneath the moon and stars; of wild wintry skies; of the weird cries that came from out the darkness—love of everything indeed that pertained to the night side of nature. What terrible tales of the sands and marshes the old man would tell as we sat in his turf-covered cottage, listening to the lashing storm and driving water without. Occasionally we heard sounds of the Demon Huntsman and his Wish-hounds as they crossed the wintry skies. If Kittiwake knew, he would never admit that these were the wild swans coming from the north, which chose the darkest nights for their migration. When my old tutor saw that I was already skilled in the use of "gins" and "springes," and sometimes brought in a snipe or woodcock, his old eyes glistened as he looked upon the marsh-birds. It was on one such occasion, pleased at my success, that he offered what he had never offered to mortal—to teach me the whole art of fowling. I remember the old man as he lay on his heather bench when he made this magnanimous offer. In appearance he was a splendid type of a northern yeoman, his face fringed with silvery hair, and cut in the finest features. One eye was bright and clear even at his great age, though the other was rheumy, and almost blotted out. He rarely undressed at nights, his outward garb seemed more a production of nature than of art, and was changed, when, like the outer cuticle of the marsh vipers, it sloughed off. It was only in winter that the old man lived his lonely life on the mosses and marshes, for during the summer he turned from fowler to fisher, or assisted in the game preserves. The haunts and habits of the marsh and shore birds he knew by heart, and his great success in taking them lay in the fact that he was a close and accurate observer. He would watch the fowl, then set his nets and noozes by the light of his acquired knowledge. These things he had always known, but it was in summer, when he was assisting at pheasant rearing, that he got to know all about game in fur and feather. He noted that the handsome cock pheasants always crowed before they flew up to roost; that in the evening the partridges called as they came together in the grass lands; and he watched the ways of the hares as they skipped in the moonlight. These things we were wont to discuss when wild weather prevented our leaving the hut; and all our plans were tested by experiment before they were put into practice. It was upon these occasions, too, that the garrulous old man would tell of his early life. That was the time for fowl; but now the plough had invaded the sea-birds' haunt. He would tell of immense flocks of widgeon, of banks of brent geese, and clouds of dunlin. Bitterns used to boom and breed in the bog, and once, though only once, a great bustard was shot. In his young days Kittiwake had worked a decoy, as had his father and grandfather before him; and when any stray fowler or shore-shooter told of the effect of a single shot of their big punt-guns, he would cap their stories by going back to the days of decoying. Although decoying had almost gone out, this was the only subject that the old man was reticent upon, and he surrounded the craft with all the mystery he was able to conjure up. The site of his once famous decoy was now drained, and in summer ruddy corn waved above it. Besides myself, Kittiwake's sole companion on the mosses was an old shaggy galloway, and it was almost as eccentric and knowing as its master. So great was the number of gulls and terns that bred on the mosses, that for two months during the breeding season the old horse was fed upon their eggs. Morning and evening a basketful was collected, and so long as these lasted Dobbin's coat continued sleek and soft.

In August and September we would capture immense numbers of "flappers"—plump wild ducks—but, as yet, unable to fly. These were either caught in the pools, or chased into nets which we set to intercept them. As I now took more than my share of the work, and made all the gins, springes, and noozes which we used, a rough kind of partnership sprung up between us. The young ducks brought us good prices, and there was another source of income which paid well, but was not of long duration. There is a short period in each year when even the matured wild ducks are quite unable to fly. The male of the common wild duck is called the mallard, and soon after his brown duck begins to sit the drake moults the whole of its flight feathers. So sudden and simultaneous is this process that for six weeks in summer the usually handsome drake is quite incapable of flight, and it is probably at this period of its ground existence that the assumption of the duck's plumage is such an aid to protection. Quite the handsomest of the wildfowl on the marsh were a colony of sheldrakes which occupied a number of disused rabbit-burrows on a raised plateau overlooking the bay. The ducks were bright chestnut, white, and purple, and in May laid from nine to a dozen creamy eggs. As these birds brought high prices for stocking ornamental waters, we used to collect the eggs and hatch them out under hens in the turf cottage. This was a quite successful experiment up to a certain point; but the young fowl, immediately they were hatched, seemed to be able to smell the salt water, and would cover miles to gain the creek. With all our combined watchfulness the downy ducklings sometimes succeeded in reaching their loved briny element, and once in the sea were never seen again. The pretty sea swallows used to breed on the marsh, and the curious ruffs and reeves. These indulged in the strangest flights at breeding time, and it was then that we used to capture the greatest numbers. We took them alive in nets, and then fattened them on soaked wheat. The birds were sent all the way to London, and brought good prices. By being kept closely confined and frequently fed, in a fortnight they became so plump as to resemble balls of fat, and then brought as much as a florin a piece. If care were not taken to kill the birds just when they attained to their greatest degree of fatness they fell rapidly in condition, and were nearly worthless. To kill them we were wont to pinch off the head, and when all the blood had exuded the flesh remained white and delicate. Greater delicacies even than ruffs and reeves were godwits, which were fatted in like manner for the table. Experiments in fattening were upon one occasion successfully tried with a brood of greylag geese which we discovered on the marshes. As this is the species from which the domestic stock is descended, we found little difficulty in herding, though we were always careful to house them at night, and pinioned them as the time of the autumnal migration came round. We well knew that the skeins of wild geese which at this time nightly cross the sky, calling as they fly, would soon have robbed us of our little flock.

In winter, snipe were always numerous on the mosses, and were among the first birds to be affected by severe weather. If on elevated ground when the frost set in, they immediately betake themselves to the lowlands, and at these times we used to take them in pantles made of twisted horsehair. In preparing these we trampled a strip of oozy ground until, in the darkness, it had the appearance of a narrow plash of water. The snipe were taken as they came to feed on ground presumably containing food of which they were fond. As well as woodcock and snipe, we took larks by thousands. The pantles for these we set somewhat differently than those intended for the minor game birds. A main line, sometimes as much as a hundred yards in length, was set along the marsh; and to this at short intervals were attached a great number of loops of horsehair in which the birds were strangled. During the migratory season, or in winter when larks are flocked, sometimes a hundred bunches of a dozen each would be taken in a single day.

During the rigour of winter great flocks of migratory ducks and geese came to the bay, and prominent among them were immense flocks of scoters. Often from behind an ooze bank did we watch parties of these playing and chasing each other over the crests of the waves, seeming indifferent to the roughest seas. The coming of the scoter brought flush times, and in hard weather our takes were tremendous. Another of the wild ducks which visited us was the pochard or dunbird. We mostly called it "poker" and "redhead," owing to the bright chestnut of its neck and head. It is somewhat heavily made, swims low in the water, and from its legs being placed far behind for diving it is very awkward on land. In winter the pochard was abundant on the coast, but as it was one of the shyest of fowl it was always difficult to approach. If alarmed it paddles rapidly away, turning its head, and always keeping an eye to the rear. On account of its wariness it is oftener netted than shot. The shore-shooters hardly ever get a chance at it. We used to take it in the creeks on the marsh, and, as the matter is difficult to explain, I will let the following quotation tell how it was done:

"The water was surrounded with huge nets, fastened with poles laid flat on the ground when ready for action, each net being, perhaps, sixty feet long and twenty feet deep. When all was ready the pochards were frightened off the water. Like all diving ducks they were obliged to fly low for some distance, and also to head the wind before rising. Just as the mass of birds reached the side of the pool, one of the immense nets, previously regulated by weights and springs, rose upright as it was freed from its fastenings by the fowler from a distance with a long rope. If this were done at the right moment the ducks were met full in the face by a wall of net, and thrown helpless into a deep ditch dug at its foot for their reception."

In addition to our nets and snares we had a primitive fowling-piece, though we only used it when other methods failed. It was an ancient flint-lock, with tremendously long barrels. Sometimes it went off; oftener it did not. I well remember with what desperation I, upon one occasion, clung to this murderous weapon whilst it meditated, so to speak. It is true that it brought down quite a wisp of dunlins, but then there was almost a cloud of them to fire at. These and golden plover were mainly the game for the flint-lock, and with them we were peculiarly successful. If we had not been out all night we were invariably abroad at dawn, when golden plover fly and feed in close bodies. Upon these occasions sometimes a dozen birds were bagged at a shot, though, after all, the chief product of our days were obtained in the cymbal nets. We invariably used a decoy, and when the wild birds were brought down, and came within the workings of the net, it was rapidly pulled over and the game secured. For the most part, however, only the smaller birds were taken in this way. Coots came round in their season, and although they yielded a good harvest, netting them was not very profitable, for as their flesh was dark and fishy only the villagers and fisher-folk would buy them.

A curious little bird, the grebe or dabchick, used to haunt the pools and ditches of the marsh, and we not unfrequently caught them in the nets whilst drawing for salmon which ran up the creek to spawn. They had curious feet, lobed like chestnut leaves, and hardly any wing. This last was more like a flipper, and upon one occasion, when no less than three had caught in the meshes, a dispute arose between us as to whether they were able to fly. Kittiwake and I argued that whilst they were resident and bred in the marshes, yet their numbers were greatly augmented in autumn by other birds which came to spend the winter. Whilst I contended that they flew, Kittiwake said that their tiny wings could never support them, and certainly neither of us had ever seen them on their journeyings. Two of the birds we took a mile from the water, and then threw them into the air, when they darted off straight and swift for the mosses which lay stretched at our feet a mile below.

bloom on the brambles; the ripening of the nuts; and the ruddiness of the corn all acted as reminders that the "fence" time was rapidly drawing to a close. So much did the first frosts quicken us that it was difficult to resist throwing up our farm work before the game season was fairly upon us. There was only one way in which we could curb the wild impulse within. We stood up to the golden corn and smote it from the rising to the going down of the sun. The hunters' moon tried hard to win us to the old hard life of sport; but still the land must be cleared. There was a double pleasure in the ruddy sheaves, for they told of golden guineas, and until the last load was carried neither nets, gins, nor the old duck-gun were of any use. The harvest housed the game could begin, and then the sweet clover, which the hares loved, first pushed their shoots between the stubble stalks. But neither the hares on the fallows, the grouse on the moor, nor the pheasants on the bare branches brought us so much pleasure as the partridge. A whole army of shooters love the little brown birds, and we are quite of their way of thinking.

A long life of poaching has not cooled our ardour for this phase of woodcraft. At the outset we may state that we have almost invariably observed close times, and have rarely killed a hare or game-bird out of season. The man who excels in poaching must be country bred. He must not only know the land, but the ways of the game by heart. Every sign of wind and weather must be observed, as all help in the silent trade. Then there is the rise and wane of the moon, the rain-bringing tides, and the shifting of the birds with the seasons. These and a hundred other things must be kept in an unwritten calendar, and only the poacher can keep it. Speaking from hard experience, his out-door life will make him quick; will endow him with much ready animal ingenuity. He will take in an immense amount of knowledge of the life of the fields and woods; and it is this teaching which will ultimately give him accuracy of eye and judgment sufficient to interpret what he sees aright. To succeed the poacher must be a specialist. It is better if he directs his attention to "fur," or to "feather" alone; but it is terribly hard to resist going in for both. There is less scope for field ingenuity in taking game birds; but at the same time there is always the probability of more wholesale destruction. This arises from the fact of the birds being gregarious. Both grouse and partridge go in coveys, and pheasants are found in the company of their own kind. Partridges roost on the ground, and sleep with tails tucked together and heads outwards. Examine the fallow after they have left it in a morning, and this will be at once apparent. A covey in this position represents little more than a mass of feathers. It is for protective reasons that partridges always spend their nights in the open. Birds which do not perch would soon become extinct were they to seek the protection of woods and hedge-bottoms by night. Such ground generally affords cover for vermin—weazels, polecats, and stoats. Although partridges roam far by day, they invariably come together at night, being partial to the same fields and fallows. They run much, and rarely fly, except when passing from one feeding ground to another. In coming together in the evening their calls may be heard to some distance. These were the sounds we listened for, and marked. We remembered the gorse bushes, and knew that the coveys would not be far from them.

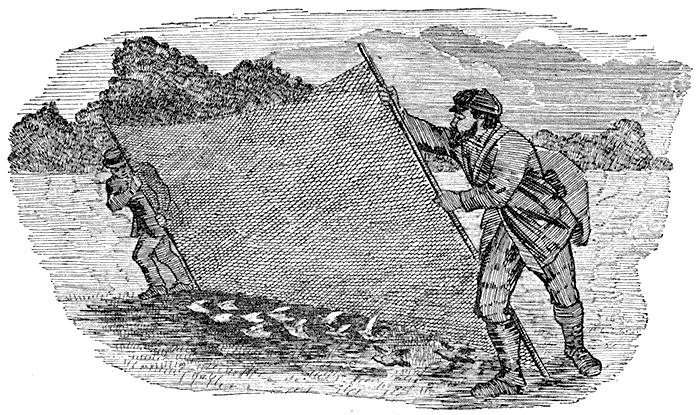

We always considered partridge good game, and sometimes were watching a dozen coveys at the same time. September once in, there was never a sun-down that did not see one of us on our rounds making mental notes. It was not often, however, that more than three coveys were marked for a night's work. One of these, perhaps, would be in turnips, another among stubble, and the third on grass. According to the nature of the crop, the lay of the land, wind, &c., so we varied our tactics. Netting partridges always requires two persons, though a third to walk after the net is helpful. If the birds have been carefully marked down, a narrow net is used; if their roosting-place is uncertain a wider net is better. When all is ready this is slowly dragged along the ground, and is thrown down immediately the whirr of wings is heard. If neatly and silently done, the whole covey is bagged. There is a terrible flutter, a cloud of brown feathers, and all is over. It is not always, however, that the draw is so successful. In view of preventing this method of poaching, especially on land where many partridges roost, keepers plant low scrubby thorns at intervals. These so far interfere with the working of the net as to allow the birds time to escape. We were never much troubled, however, in this way. As opportunity offered the quick-thorns were torn up, and a dead black-thorn bough took their place. As the thorns were low the difference was never noticed, even by the keepers, and, of course, they were carefully removed before, and replaced after, netting. Even when the dodge was detected the fields and fallows had been pretty much stripped of the birds. This method is impracticable now, as the modern method of reaping leaves the brittle stubble as bare as the squire's lawn. We had always a great objection to use a wide net where a narrow one would suit the purpose. Among turnips, and where large numbers of birds were supposed to lie, a number of rows or "riggs" were taken at a time, until the whole of the ground had been traversed. This last method is one that requires time and a knowledge of the keeper's beat. On rough ground the catching of the net may be obviated by having about eighteen inches of smooth glazed material bordering the lowest and trailing part of it. Some of the small farmers were as fond of poaching as ourselves, and here is a trick which one of them successfully employed whenever he heard the birds in his land. He scattered a train of grain from the field in which the partridge roosted, each morning bringing it nearer and nearer to the stack-yard. After a time the birds became accustomed to this mode of feeding, and as they grew bolder the grain-train was continued inside the barn. When they saw the golden feast invitingly spread, they were not slow to enter, and the doors were quickly closed upon them. Then the farmer entered with a bright light and felled the birds with a stick.

In the dusk of a late autumn afternoon a splendid "pot" shot was sometimes had at a bunch of partridges just gathered for the night. I remember a score such. The call of the partridge is less deceptive than any other game bird, and the movements of a covey are easily watched. This tracking is greatly aided if the field in which the birds are is bounded by stone walls. As dusk deepens and draws to dark, they run and call less, and soon all is still. The closely-packed covey is easy to detect against the yellow stubble, and resting the gun on the wall, a charge of heavy shot fired into their midst usually picks off the lot. If in five minutes the shot brings up the keeper it matters little, as then you are far over the land.

Partridges feed in the early morning—as soon as day breaks, in fact. They resort to one spot, and are constant in their coming, especially if encouraged. This fact I well knew, and laid my plans accordingly. By the aid of the moon a train of grain was laid straight as a hazel wand. Upon these occasions I never went abroad without an old duck-gun, the barrels of which had been filed down. This enabled me to carry the gun-stock in one pocket, the barrels in the other. The shortness of the latter in nowise told against the shooting, as the gun was only required to use at short distances. The weapon was old, thick at the muzzle, and into it I crammed a heavy charge of powder and shot. Ensconced in the scrub I had only now to wait for the dawn. Almost before it was fully light the covey would come with a loud whirring of wings, and settle to feed immediately. This was the critical moment. Firing along the line a single shot strewed the ground with dead and dying; and in ten minutes, always keeping clear of the roads, I was a mile from the spot.

I had yet another and a more successful method of taking partridges. When, from the watchfulness or cleverness of keepers (they are not intelligent men as a rule), both netting and shooting proved impracticable, I soaked grain until it became swollen, and then steeped it in the strongest spirit. This, as before, was strewn in the morning paths of the partridge, and, soon taking effect, the naturally pugnacious birds were presently staggering and fighting desperately. Then I bided my time, and as opportunity offered, knocked the incapacitated birds on the head.

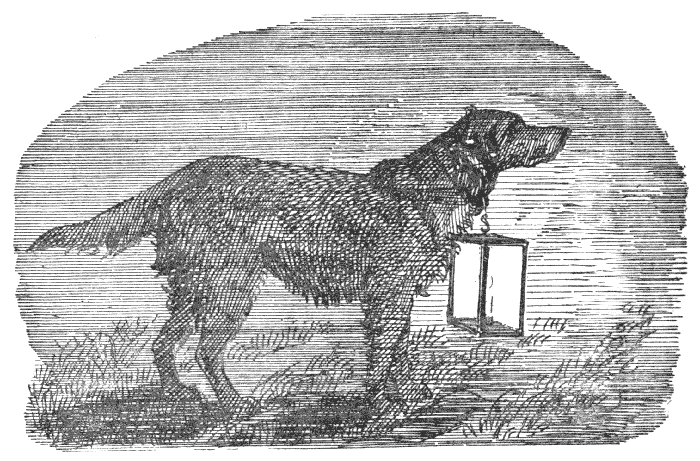

One of the most ingenious and frequently successful methods I employed for bagging partridge was by the aid of an old setter bitch having a lantern tied to her neck. Being somewhat risky, I only employed it when other plans failed, and when I had a good notion of the keeper's whereabouts. The lantern was made from an old salmon canister stripped of its sides, and contained a bit of candle. When the bitch was put off into seeds or stubble she would range quietly until she found the birds, then stand as stiffly as though done in marble. This shewed me just where the covey lay, and as the light either dazzled or frightened the birds, it was not difficult to clap the net over them. It sometimes happened that others besides myself were watching this strange luminous light, and it was probably set down as some phenomenon of the night-side of nature. Once, however, I lost my long silk net, and as there was everything to be gained by running, and much to be lost by staying, I ran desperately. Only an old, slow dog can be used in this species of poaching, and it is marvellous to see with what spirit and seeming understanding it enters into the work.

hare season generally began with partridge poaching, so that the coming of the hunter's moon was always an interesting autumnal event. By its aid the first big bag of the season was made. When a field is sown down, which it is intended to bring back to grass, clover is invariably sown with the grain. This springs between the corn stalks, and by the time the golden sheaves are carried, has swathed the stubble with mantling green. This, before all others, is the crop which hares love.

Poaching is one of the fine arts, and the man who would succeed must be a specialist. If he has sufficient strength to refrain from general "mouching," he will succeed best by selecting one particular kind of game, and directing his whole knowledge of woodcraft against it. In spring and summer I was wont to closely scan the fields, and as embrowned September drew near, knew the whereabouts of every hare in the parish—not only the field where it lay, but the very clump of rushes in which was its form. As puss went away from the gorse, or raced down the turnip-rigg, I took in every twist and double down to the minutest detail.

Then I scanned the "smoots" and gates through which she passed, and was always careful to approach these laterally. I left no trace of hand nor print of foot, nor disturbed the rough herbage. Late afternoon brought me home, and upon the hearth the wires and nets were spread for inspection. When all was ready, and the dogs whined impatiently to be gone, I would strike right into the heart of the land, and away from the high-road.

Mention of the dogs brings me to my fastest friends. Without them poaching for fur would be almost impossible. I invariably used bitches, and as success depended almost wholly upon them, I was bound to keep only the best. Lurchers take long to train, but when perfected are invaluable. I have had, maybe, a dozen dogs in all, the best being the result of a pure cross between greyhound and sheepdog. In night work silence is essential to success, and such dogs never bark; they have the good nose of the one, and the speed of the other. In selecting puppies it is best to choose rough-coated ones, as they are better able to stand the exposure of cold, rough nights. Shades of brown and fawn are preferable for colour, as these best assimilate to the duns and browns of the fields and woods. The process of training would take long to describe; but it is wonderful how soon the dog takes on the habits of its master. They soon learn to slink along by hedge and ditch, and but rarely shew in the open. They know every field-cut and by-path for miles, and are as much aware as their masters that county constables have a nasty habit of loitering about unfrequented lanes at daybreak.

The difficulty lies not so much in obtaining game as in getting it home safely; but for all that I was but rarely surprised with game upon me in this way. Disused buildings, stacks, and dry ditches are made to contain the "haul" until it can be sent for—an office which I usually got some of the field-women to perform for me. Failing these, country carriers and early morning milk-carts were useful. When I was night poaching, it was important that I should have the earliest intimation of the approach of a possible enemy, and to secure this the dogs were always trained to run on a few hundred yards in advance. A well-trained lurcher is almost infallible in detecting a foe, and upon meeting one he runs back to his master under cover of the far side of a fence. When the dog came back to me in this way I lost not a second in accepting the shelter of the nearest hedge or deepest ditch till the danger was past. If suddenly surprised and without means of hiding, myself and the dog would make off in different directions. Then there were times when it was inconvenient that we should know each other, and upon such occasions the dogs would not recognise me even upon the strongest provocation.

My best lurchers knew as much of the habits of game as I did. According to the class of land to be worked they were aware whether hares, partridges, or rabbits were to constitute the game for the night. They judged to a nicety the speed at which a hare should be driven to make a snare effective, and acted accordingly. At night the piercing scream of a netted hare can be heard to a great distance, and no sound sooner puts the keeper on the alert.

Consequently, when "puss" puts her neck into a wire, or madly jumps into a gate-net, the dog is on her in an instant, and quickly stops her piteous squeal. In field-netting rabbits, lurchers are equally quick, seeming quite to appreciate the danger of noise. Once only have I heard a lurcher give mouth. "Rough" was a powerful, deep-chested bitch, but upon one occasion she failed to jump a stiff, stone fence, with a nine-pound hare in her mouth. She did not bark, however, until she had several times failed at the fence, and when she thought her whereabouts were unknown. Hares and partridges invariably squat on the fallow or in the stubble when alarmed, and remain absolutely still till the danger is passed. This act is much more likely to be observed by the dog than its master, and in such cases the lurchers gently rubbed my shins to apprise me of the fact. Then I moved more cautiously. Out-lying pheasants, rabbits in the clumps, red grouse on the heather—the old dog missed none of them. Every movement was noted, and each came to the capacious pocket in turn. The only serious fights I ever had were when keepers threatened to shoot the dogs. This was a serious matter. Lurchers take long to train, and a keeper's summary proceeding often stops a whole winter's work, as the best dogs cannot easily be replaced. Many a one of our craft would as soon have been shot himself as seen his dog destroyed; and there are few good dogs which have not, at one time or other, been riddled with pellets during their lawless (save the mark!) career. If a hare happens to be seen, the dog sometimes works it so cleverly as to "chop" it in its "form"; and both hares and rabbits are not unfrequently snapped up without being run at all. In fact, depredations in fur would be exceedingly limited without the aid of dogs; and one country squire saved his ground game for a season by buying my best brace of lurchers at a very fancy price; while upon another occasion a bench of magistrates demanded to see the dogs of whose doings they had heard so much. In short, my lurchers at night embodied all my senses.

Whilst preparing my nets and wires, the dogs would whine impatiently to be gone. Soon their ears were pricked out on the track, though until told to leave they stuck doggedly to heel. Soon the darkness would blot out even the forms of surrounding objects, and our movements were made more cautiously. A couple of snares are set in gaps in an old thorn fence not more than a yard apart. These are delicately manipulated, as we know from previous knowledge that the hare will take one of them. The black dog is sent over, the younger fawn bitch staying behind. The former slinks slowly down the field, sticking close to the cover of a fence running at right angles to the one in which the wires are set. I have arranged that the wind shall blow from the dog and across to the hare's seat when the former shall come opposite. The ruse acts; "puss" is alarmed, but not terrified; she gets up and goes quietly away for the hedge. The dog is crouched, anxiously watching; she is making right for the snare, though something must be added to her speed to make the wire effective. As the dog closes in, I wait, bowed, with hands on knees, still as death, for her coming. I hear the brush of the grass, the trip, trip, trip, as the herbage is brushed. There is a rustle among the dead leaves, a desperate rush, a momentary squeal—and the wire has tightened round her throat.

Again we trudge silently along the lane, but soon stop to listen. Then we disperse, but to any on-looker would seem to have dissolved. This dry ditch is capacious, and its dead herbage tall and tangled. A heavy foot, with regular beat, approaches along the road, and dies slowly away in the distance.

Hares love green cornstalks, and a field of young wheat is at hand; I spread a net, twelve feet by six, at the gate, and at a sign the dogs depart different ways. Their paths soon converge, for the night is torn by a piteous cry; the road is enveloped in a cloud of dust; and in the midst of the confusion the dogs dash over the fence. They must have found their game near the middle of the field, and driven the hares—for there are two—so hard that they carried the net right before them; every struggle wraps another mesh about them, and, in a moment, their screams are quieted. By a quick movement I wrap the long net about my arm, and, taking the noiseless sward, get hastily away from the spot.

In March, when hares are pairing, four or five may frequently be found together in one field. Although wild, they seem to lose much of their natural timidity, and during this month I usually reaped a rich harvest. I was always careful to set my wires and snares on the side opposite to that from which the game would come, for this reason—that hares approach any place through which they are about to pass in a zig-zag manner. They come on, playing and frisking, stopping now and then to nibble the herbage. Then they canter, making wide leaps at right angles to their path, and sit listening upon their haunches. A freshly impressed footmark, the scent of dog or man, almost invariably turns them back. Of course these traces are certain to be left if the snare be set on the near side of the gate or fence, and then a hare will refuse to take it, even when hard pressed. Now here is a wrinkle to any keeper who cares to accept it. Where poaching is prevalent and hares abundant, every hare on the estate should be netted, for it is a fact well known to every poacher versed in his craft, that an escaped hare that has once been netted can never be retaken. The process, however, will effectually frighten a small percentage of hares off the land altogether.

The human scent left at gaps and gateways by ploughmen, shepherds, and mouchers, the wary poacher will obliterate by driving sheep over the spot before he begins operations. On the sides of fells and uplands hares are difficult to kill. This can only be accomplished by swift dogs, which are taken above the game. Puss is made to run down-hill, when, from her peculiar formation, she goes at a disadvantage.

Audacity almost invariably stands the poacher in good stead. Here is an actual incident. I knew of a certain field of young wheat in which was several hares—a fact observed during the day. This was hard by the keeper's cottage, and surrounded by a high fence of loose stones. It will be seen that the situation was somewhat critical, but that night my nets were set at the gates through which the hares always made. To drive them the dog was to range the field, entering it at a point furthest away from the gate. I bent my back in the road a yard from the wall to aid the dog. It retired, took a mighty spring, and barely touching my shoulders, bounded over the fence. The risk was justified by the haul, for that night I bagged nine good hares.

Owing to the scarcity of game, hare-poaching is now hardly worth following, and I believe that what is known as the Ground Game Act is mainly responsible for this. A country Justice, who has often been my friend when I was sadly in need of one, asked me why I thought the Hares and Rabbits Act had made both kinds of fur scarcer. I told him that the hare would become abundant again if it were not beset by so many enemies. Since 1880 it has had no protection, and the numbers have gone down amazingly. A shy and timid animal, it is worried through every month of the year. It does not burrow, and has not the protection of the rabbit. Although the colour of its fur resembles that of the dead grass and herbage among which it lies, yet it starts from its "form" at the approach of danger, and from its size makes an easy mark. It is not unfrequently "chopped" by sheep-dogs, and in certain months hundreds of leverets perish in this way. Hares are destroyed wholesale during the mowing of the grass and the reaping of the corn. For a time in summer, leverets especially seek this kind of cover, and farmers and farm-labourers kill numbers with dog and gun—and this at a time when they are quite unfit for food. In addition to these causes of scarcity there are others well known to sportsmen. When harriers hunt late in the season—as they invariably do now-a-days—many leverets are "chopped," and for every hare that goes away three are killed in the manner indicated. At least, that is my experience while mouching in the wake of the hounds. When hunting continues through March, master and huntsman assert that this havoc is necessary in order to kill off superabundant jack-hares, and so preserve the balance of stock. Doubtless there was reason in this argument before the present scarcity, but now there is none. March, too, is a general breeding month, and the hunting of doe-hares entails the grossest cruelty. Coursing is confined within no fixed limits, and is prolonged far too late in the season. What has been said of hunting applies to coursing, and these things sportsmen can remedy if they wish. There is more unwritten law in connection with British field-sports than any other pastime; but obviously it might be added to with advantage. If something is not done the hare will assuredly become extinct. To prevent this a "close time" is, in the opinion of those best versed in woodcraft, absolutely necessary. The dates between which the hare would best be protected are the first of March and the first of August. Then we would gain all round. The recent relaxation of the law has done something to encourage poaching, and poachers now find pretexts for being on or about land which before were of no avail, and to the moucher accurate observation by day is one of the essentials to success.

Naturalists ought to know best; but there has been more unnatural history written concerning hares than any other British animal. It is said to produce two young ones at a birth, but observant poachers know that from three to five leverets are not unfrequently found: then it is stated that hares breed twice, or at most thrice, a year. Anyone, however, who has daily observed their habits, knows that there are but few months in which leverets are not born. In mild winters young ones are found in January and February, whilst in March they have become common. They may be seen right on through summer and autumn, and last December I saw a brace of leverets a month old. Does shot in October are sometimes found to be giving milk, and in November old hares are not unfrequently noticed in the same patch of cover. These facts would seem to point to the conclusion that the hare propagates its species almost the whole year round—a startling piece of evidence to the older naturalists. Add to this that hares pair when a year old, that gestation lasts only thirty days, and it will be seen what a possibly prolific animal the hare may be. The young are born covered with fur, and after a month leave their mother to seek their own subsistence.

late summer and autumn the poacher's thoughts go out to the early weeks of October. Neither the last load of ruddy corn, nor the actual netting of the partridge gladden his heart as do the first signs of the dying year. There are certain sections of the Game Laws which he never breaks, and only some rare circumstance tempts him to take immature birds. But by the third week of October the yellow and sere of the year has come. The duns and browns are over the woods, and the leaves come fitfully flickering down. Everything out of doors testifies that autumn is waning, and that winter will soon be upon us. The colours of the few remaining flowers are fading, and nature is beginning to have a washed-out appearance. The feathery plumes of the ash are everywhere strewn beneath the trees, for, just as the ash is the first to burst into leaf, so it is the first to go. The foliage of the oak is already assuming a bright chestnut, though the leaves will remain throughout the year. In the oak avenues the acorns are lying in great quantities, though oak mast is not now the important product it once was, cheap grain having relegated it almost exclusively to the use of the birds. And now immense flocks of wood pigeons flutter in the trees or pick up the food from beneath. The garnering of the grain, the flocking of migratory birds, the wild clanging of fowl in the night sky—these are the sights and sounds that set the poacher's thoughts off in the old grooves.

Of all species of poaching, that which ensures a good haul of pheasants is most beset with difficulty. Nevertheless there are silent ways and means which prove as successful in the end as the squire's guns, and these without breaking the woodland silence with a sound. The most successful of these I intend to set down, and only such will be mentioned as have stood me in good stead in actual night work. Among southern woods and coverts the pheasant poacher is usually a desperate character; not so in the north. Here the poachers are more skilled in woodcraft, and are rarely surprised. If the worst comes to the worst it is a fair stand-up fight with fists, and is usually bloodless. There is little greed of gain in the night enterprise, and liberty by flight is the first thing resorted to.

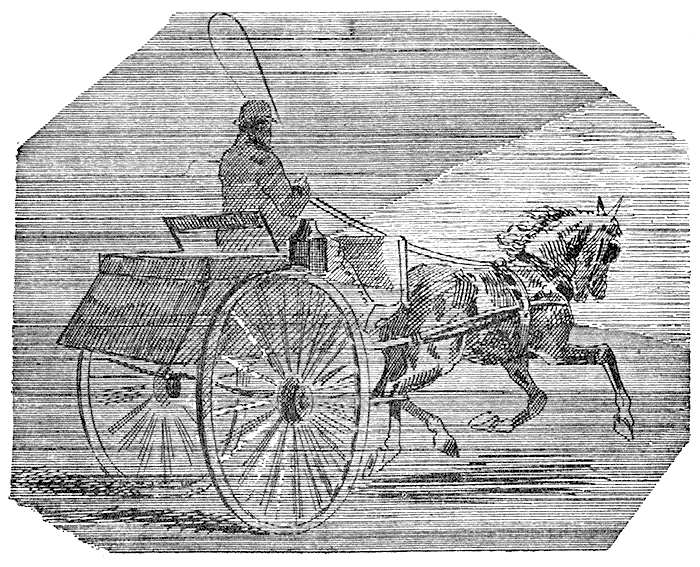

It is well for the poacher, and well for his methods, that the pheasant is rather a stupid bird. There is no gainsaying its beauty, however, and a brace of birds, with all the old excitement thrown in, are well worth winning, even at considerable risk. In a long life of poaching I have noticed that the pheasant has one great characteristic. It is fond of wandering; and this cannot be prevented. Watch the birds: even when fed daily, and with the daintiest food, they wander off, singly or in pairs, far from the home coverts. This fact I knew well, and was not slow to use my knowledge. When October came round they were the very first birds to which I directed my attention. Every poacher observes, year by year (even leaving his own predaceous paws out of the question), that it by no means follows that the man who rears the pheasants will have the privilege of shooting them. There is a very certain time in the life of the bird when it disdains the scattered corn of the keeper, and begins to anticipate the fall of beech and oak mast. In search of this the pheasants make daily journeys, and consume great quantities. They feed principally in the morning; dust themselves in the roads or turnip-fields at mid-day, and ramble through the woods in the afternoon. And one thing is certain: That when wandered birds find themselves in outlying copses in the evening they are apt to roost there. As already stated, these were the birds to which I paid my best attention. When wholesale pheasant poaching is prosecuted by gangs, it is in winter, when the trees are bare. Guns, with the barrels filed down, are taken in sacks, and the pheasants are shot where they roost. Their bulky forms stand sharply outlined against the sky, and they are invariably on the lower branches. If the firing does not immediately bring up the keepers, the game is quickly deposited in bags, and the gang makes off. And it is generally arranged that a light cart is waiting at some remote lane end, so that possible pursuers may be quickly outpaced. The great risk incurred by this method will be seen, when it is stated that pheasants are generally reared close by the keeper's cottage, and that their coverts immediately surround it. It is mostly armed mouchers who enter these, and not the more gifted (save the mark!) country poacher. And there are reasons for this. Opposition must always be anticipated, for, speaking for the nonce from the game-keeper's standpoint, the covert never should be, and rarely is, unwatched. Then there are the certain results of possible capture to be taken into account. This affected, and with birds in one's possession, the poacher is liable to be indicted upon so many concurrent charges, each and all having heavy penalties. Than this I obtained my game in a different and quieter way. My custom was to carefully eschew the preserves, and look up all outlying birds. I never went abroad without a pocketful of corn, and day by day enticed the wandered birds further and further away. This accomplished, pheasants may be snared with hair nooses, or taken in spring traps. One of my commonest and most successful methods with wandered birds was to light brimstone beneath the trees in which they roosted. The powerful fumes soon overpowered them, and they came flopping down the trees one by one. This method has the advantage of silence, and if the night be dead and still, is rarely detected. Away from the preserves, time was never taken into account in my plans, and I could work systematically. I was content with a brace of birds at a time, and usually got most in the end, with least chance of capture.

I have already spoken at some length of my education in field and wood-craft. An important (though at the time unconscious) part of this was minute observation of the haunts and habits of all kinds of game; and this knowledge was put to good use in my actual poaching raids. Here is an instance of what I mean: I had noticed the great pugnacity of the pheasant, and out of this made capital. After first finding out the whereabouts of the keeper, I fitted a trained game-cock with artificial spurs, and then took it to the covert side. The artificial spurs were fitted to the natural ones, were sharp as needles, and the plucky bird already knew how to use them. Upon his crowing, one or more cock pheasants would immediately respond, and advance to meet the adversary. A single blow usually sufficed to lay low the pride of the pheasant, and in this way half-a-dozen birds were bagged, whilst my own representative remained unhurt.

I had another ingenious plan (if I may say so) in connection with pheasants, and, perhaps, the most successful. I may say at once that there is nothing sportsmanlike about it; but then that is in keeping with most of what I have set down. If time and opportunity offer there is hardly any limit to the depredation which it allows. Here it is: A number of dried peas are taken and steeped in boiling water; a hole is then made through the centre, and through this again a stiff bristle is threaded. The ends are then cut off short, leaving only about a quarter of an inch of bristle projecting on each side. With these the birds are fed, and they are greedily eaten. In passing down the gullet, however, a violent irritation is set up, and the pheasant is finally choked. In a dying condition the birds are picked up beneath the hedges, to the shelter of which they almost always run. The way is a quiet one; it may be adopted in roads and lanes where the birds dust themselves, and does not require trespass.

In this connection I may say that I only used a gun when every other method failed. Game-keepers sometimes try to outwit poachers by a device which is now of old standing. Usually knowing from what quarter the latter will enter the covert, wooden blocks representing roosting birds are nailed to the branches of the open beeches. I was never entrapped into firing at these dummies, and it is only with the casual that the ruse acts. He fires, brings the keepers from their hiding places, and is caught. Still another method of bagging "long-tails," though one somewhat similar to that already set down: It requires two persons, and the exact position of the birds must be known. A black night is necessary; a stiff bamboo rod, and a dark lantern. One man flashes the concentrated light upon the bare branches, when immediately half a dozen necks are stretched out to view the apparition. Just then the "angler" slips a wire nooze over the craned neck nearest him, and it is jerked down as quickly, though as silently as possible. Number two is served in like manner, then a third, a fourth, and a fifth. This method has the advantage of silence, though, if unskilfully managed, sometimes only a single bird is secured, and the rest flutter wildly off into the darkness.

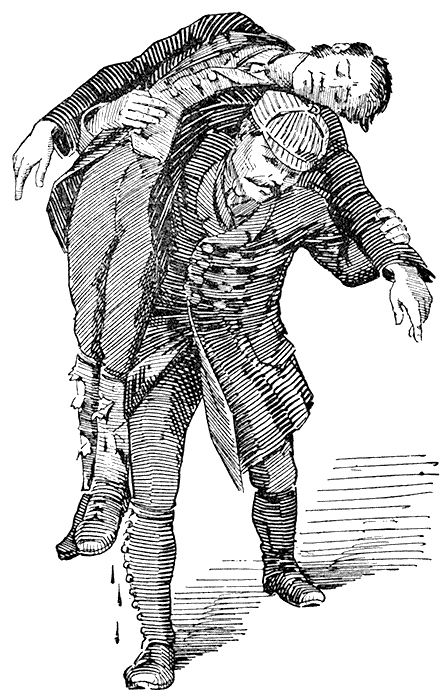

Poachers often come to untimely ends. Here is an actual incident which befell one of my companions—as clever a poacher, and as decent and quiet a man as need be. I saw him on the night previous to the morning of his death, though he did not see me. It was a night at the end of October. The winds had stripped the leaves from the trees, and the dripping branches stood starkly against the sky. I was on the high road with a vehicle, when plashes of rain began to descend, and a low muttering came from out the dull leaden clouds. As the darkness increased, occasional flashes tore zig-zag across the sky, and the rain set to a dead pour. The lightning only served to increase the darkness. I could just see the mare's steaming shoulders butting away in front, and her sensitive ears alternately pricked out on the track. The pitchy darkness increased, I gave the mare her head, and let the reins hang loosely on her neck. The lightning was terrible, the thunder almost continuous, when the mare came to a dead stop. I got down from the trap and found her trembling violently, with perspiration pouring down her flanks. All her gear was white with lather, and I thought it best to lead her on to where I knew was a chestnut tree, and there wait for a lull in the storm. As I stood waiting, a black lurcher slunk along under the sodden hedge, and seeing the trap, immediately stopped and turned in its tracks. Having warned its master, the two reconnoitered and then came on together. The "Otter" (for it was he), bade a gruff "good-night" to the enshrouded vehicle and passed on into the darkness. He slouched rapidly under the rain, and went in the direction of extensive woods and coverts. Hundreds of pheasants had taken to the tall trees, and, from beneath, were visible against the sky. Hares abounded on the fallows, and rabbits swarmed everywhere. The storm had driven the keepers to their cosy hearths, and the prospect was a poacher's paradise. Just what occurred next can only be surmised. Doubtless the "Otter" worked long and earnestly through that terrible night, and at dawn staggered from the ground under a heavy load.

Just at dawn the poacher's wife emerged from a poor cottage at the junction of the roads, and after looking about her as a hunted animal might look, made quietly off over the land. Creeping closely by the fences she covered a couple of miles, and then entered a disused, barn-like building. Soon she emerged under a heavy load, her basket, as of old, covered with crisp, green cresses. These she had kept from last evening, when she plucked them in readiness, from the spring. After two or three journeys she had removed the "plant," and as she eyed the game her eyes glistened, and she waited now only for him. As yet she knew not that he would never more come—that soon she would be a lone and heart-broken creature. For, although his life was one long warfare against the Game Laws, he had always been good and kind to her. His end had come as it almost inevitably must. The sound of a heavy unknown footstep on his way home, had turned him from his path. He had then made back for the lime-kiln to obtain warmth and to dry his sodden clothes. Once on the margin he was soon asleep. The fumes dulled his senses, and in his restless sleep he had rolled on to the stones. In the morning the Limestone Burner coming to work found a handful of pure white ashes. A few articles were scattered about, and he guessed the rest.

And so the "Otter" went to God.... The storm cleared, and the heavens were calm. In the sky, on the air, in the blades of grass were signs of awakening life. Morning came bright and fair, birds flew hither and thither, and the autumn flowers stood out to the sun. All things were glad and free, but one wretched stricken thing.

country poachers begin by loving Nature and end by hating the Game Laws. Whilst many a man is willing to recognize "property" in hares and pheasants, there are few who will do so with regard to salmon and trout. And this is why fish poachers have always swarmed. A sea-salmon is in the domain of the whole world one day; in a trickling runner among the hills the next. Yesterday it belonged to anybody; and the poacher, rightly or wrongly, thinks it belongs to him if only he can snatch it. There are few fish poachers who in their time have not been anglers; and anglers are of two kinds: there are those who fish fair, and those who fish foul. The first set are philosophical and cultivate patience: the second are predatory and catch fish, fairly if they can—but they catch fish.

Just as redwings and field-fares constitute the first game of young gunners, so the loach, the minnow, and the stickleback, are the prey of the young poacher. If these things are small, they are by no means to be despised, for there is a tide in the affairs of men when these "small fry" of the waters afford as much sport on their pebbly shallows as do the silvery-sided salmon in the pools of Strathspay. As yet there is no knowledge of gaff or click hook—only of a willow wand, a bit of string, and a crooked pin. The average country urchin has always a considerable dash of the savage in his composition, and this first comes out in relation to fish rather than fowl. See him during summer as he wantons in the stream like a dace. Watch where his brown legs carry him; observe his stealthy movements as he raises the likely stones; and note the primitive poaching weapon in his hand. That old pronged fork is every whit as formidable to the loach and bullhead as is the lister of the man-poacher to salmon and trout—and the wader uses it almost as skillfully. He has a bottle on the bank, and into this he pours the fish unhurt which he captures with his hands. Examine his aquarium, and hidden among the weeds you will find three or four species of small fry. The loach, the minnow, and the bullhead are sure to be there, with perhaps a tiny stickleback, and somewhere, outside the bottle—stuffed in cap or breeches pocket—crayfish of every age and size. During a long life I have watched the process, and this is the stuff out of which fish-poachers are made.