Title: Life of Mary Queen of Scots, Volume 2 (of 2)

Author: Henry Glassford Bell

Release date: August 13, 2011 [eBook #37059]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian

Libraries.)

Just Published, 3 Vols. post 8vo,

Price 1l. 4s. boards,

THE LAIRDS OF FIFE.

VELUTI IN SPECULUM.

PRINTED FOR CONSTABLE & CO., EDINBURGH;

AND HURST, CHANCE & CO., LONDON.

LIFE

OF

MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS.

VOL. II.

LIFE OF MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS, VOL. II.

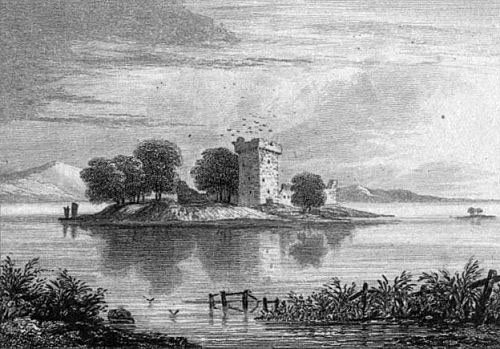

Drawn by W. Brown Engraved by W. Miller

LOCHLEVEN CASTLE.

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED FOR CONSTABLE & Co. EDINBURGH:

AND HURST, CHANCE & Co. LONDON.

1828.

LIFE

OF

MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS.

BY

HENRY GLASSFORD BELL, Esq.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. II.

| “AYEZ MEMOIRE DE L’AME ET DE L’HONNEUR DE CELLE QUI A ESTE VOTRE ROYNE.” Mary’s own Words. |

EDINBURGH:

PRINTED FOR CONSTABLE & CO. EDINBURGH;

AND HURST, CHANCE & CO. LONDON.

1828.

| PAGE | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| The Proposal of a Divorce between Mary and Darnley, and the Christening of James VI | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Occurrences immediately preceding Darnley’s Death | 19 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| The Death of Darnley | 37 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Bothwell’s Trial and Acquittal | 55 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Bothwell’s Seizure of the Queen’s Person, and subsequent Marriage to her | 77 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| The Rebellion of the Nobles, the Meeting at Carberry Hill, and its Consequences | 99 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Mary at Loch-Leven, her Abdication, and Murray’s Regency | 120 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Mary’s Escape from Loch-Leven, and the Battle of Langside | 147 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Mary’s Reception in England, and the Conferences at York and Westminster | 161 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Mary’s Eighteen Years’ Captivity | 191 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Mary’s Trial and Condemnation | 219 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Mary’s Death, and Character | 245 |

| An Examination of the Letters, Sonnets, and other Writings, adduced in Evidence against Mary Queen of Scots | 267 |

| Addendum | 335 |

ERRATA IN VOL. I.

Preface, p. v, for “eminent,” read “imminent.”

Page 104, for “On the 25th of August 1561, Mary sailed out of the harbour of Calais,” read “on the 15th of August,” &c.

Page 155, for “knapsack,” read “knapscap.”

LIFE OF MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS.

THE PROPOSAL OF A DIVORCE BETWEEN MARY AND DARNLEY, AND THE CHRISTENING OF JAMES VI.

It was in December 1566, during Mary’s residence at Craigmillar, that a proposal was made to her by her Privy Council, which deserves particular attention. It originated with the Earl of Bothwell, who was now an active Cabinet Minister and Officer of State. Murray and Darnley, the only two persons in her kingdom to whom Mary had been willing to surrender, in a great degree, the reins of government, had deceived her; and finding her interests betrayed by them, she knew not where to look for an adviser. Rizzio had been faithful to her, and to him she listened[Pg 2] with some deference; but it was impossible that he could ever have supplied the place of a Prime Minister. The Earl of Morton was not destitute of ambition sufficient to have made him aspire to that office; but he chose, unfortunately for himself, to risk his advancement in espousing Darnley’s cause, in opposition to the Queen. Both, in consequence, fell into suspicion; Morton was banished from Court, and Murray again made his appearance there. But, though she still had a partiality for her brother, Mary could not now trust him, as she had once done. Gratitude and common justice called upon her not to elevate him above those men, (particularly Huntly and Bothwell), who had enabled her to pass so successfully through her recent troubles. She made it her policy, therefore, to preserve as nice a balance of power as possible among her ministers. Bothwell’s rank and services, undoubtedly entitled him to the first place; but this the Queen did not choose to concede to him. The truth is, she had never any partiality for Bothwell. His turbulent and boisterous behaviour, soon after her return from France, gave her, at that period, a dislike to him, which she testified, by first committing him to prison, and afterwards ordering him into banishment. He had conducted himself better since his recall; but experience had taught Mary the deceitfulness of appearances; and Bothwell, though much more listened to than before, was not allowed to assume any tone of superiority in her councils. She restored Maitland to his lands and place at Court, in such direct opposition to the Earl’s wishes, that, so recently as the month of August[Pg 3] (1566), he and Murray came to very high words upon the subject in the Queen’s presence. After Rizzio’s murder, some part of Maitland’s lands had been given to Bothwell. These Murray wished him to restore; but he declared positively, that he would part with them only with his life. Murray, enraged at his obstinacy, told him, that “twenty as honest men as he should lose their lives, ere he saw Lethington robbed;” and through his influence with his sister, Maitland was pardoned, and his lands given back.[1] Thus Mary endeavoured to divide her favours and friendship among Murray, Bothwell, Maitland, Argyle the Justice-General, and Huntly the Chancellor.

It was in this state of affairs, when the contending interests of the nobility were in so accurate an equilibrium, that Bothwell’s daring spirit suggested to him, that there was an opening for one bold and ambitious enough to take advantage of it. As yet, his plans were immatured and confused; but he began to cherish the belief that a dazzling reach of power was within his grasp, were he only to lie in wait for a favourable opportunity to seize the prize. With these views, it was necessary for him to strengthen and increase his resources as much as possible. His first step was to prevail on Murray, Huntly, and Argyle, about the beginning of October, to join with him in a bond of mutual friendship and support;[2] his second was to lay aside any enmity he may have felt towards Morton, and to intimate to him, that he would himself[Pg 4] petition the Queen for his recall; his third and boldest measure, was that of arranging with the rest of the Privy Council the propriety of suggesting to Mary a divorce from her husband. Bothwell’s conscience seldom troubled him much when he had a favourite end in view. He was about to play a hazardous game; but if the risk was great, the glory of winning would be proportionate. Darnley had fallen into general neglect and odium; yet he stood directly in the path of the Earl’s ambition. He was resolved that means should be found to remove him out of it; and as there was no occasion to have recourse to violence until gentler methods had failed, a divorce was the first expedient of which he thought. He knew that the proposal would not be disagreeable to the nobility; for it had been their policy, for some time back, to endeavour to persuade the nation at large, and Mary in particular, that it was Darnley’s ill conduct that made her unhappy, and created all the differences which existed. Nor were these representations altogether unfounded; but the Queen’s unhappiness arose, not so much from her husband’s ingratitude, as from the impossibility of retaining his regard, and at the same time discharging her duty to the country. Though the nobles were determined to shut their eyes upon the fact, it was nevertheless the share which they held in the government, and the necessity under which Mary lay to avail herself of their assistance, which alone prevented her from being much more with her husband, and a great deal less with them. There were even times, when, perplexed by all the thousand cares of greatness, and grievously disappointed in the fulfilment of her most fondly [Pg 5]cherished hopes, Mary would gladly have exchanged the splendors of her palace for the thatched roof and the contentment of the peasant. It was on more than one occasion that Sir James Melville heard her “casting great sighs, and saw that she would not eat for no persuasion that my Lords of Murray and Mar could make her.” “She is in the hands of the physicians,” Le Croc writes from Craigmillar, “and is not at all well. I believe the principal part of her disease to consist in a deep grief and sorrow, which it seems impossible to make her forget. She is continually exclaiming “Would I were dead!”[3] “But, alas!” says Melville, “she had over evil company about her for the time; the Earl Bothwell had a mark of his own that he shot at.”[4]

One of his bolts Bothwell lost no time in shooting; but it missed the mark. By undertaking to sue with them for Morton’s pardon, and by making other promises, he prevailed on Murray, Huntly, Argyle and Lethington, to join him in advising the Queen to consent to a divorce. It could have been obtained only through the interference of the Pope, and Murray at first affected to have some religious scruples; but as the suggestion was secretly agreeable to him, it was not difficult to overcome his objections. “Take you no trouble,” said Lethington to him, “we shall find the means well enough to make her quit of him, so that you and my Lord of Huntly will only behold the matter, and not be offended thereat.” The Lords[Pg 6] therefore proceeded to wait upon the Queen, and lay their proposal before her. Lethington, who had a better command of words than any among them, commenced by reminding her of the “great number of grievous and intolerable offences, the King, ungrateful for the honour received from her Majesty, had committed.” He added, that Darnley “troubled her Grace and them all;” and that, if he was allowed to remain with her Majesty, he “would not cease till he did her some other evil turn which she would find it difficult to remedy.” He then proceeded to suggest a divorce, undertaking for himself and the rest of the nobility, to obtain the consent of Parliament to it, provided she would agree to pardon the Earl of Morton, the Lords Ruthven and Lindsay, and their friends, whose aid they would require to secure a majority. But Lethington, and the rest, soon found that they had little understood Mary’s real sentiments towards her husband. She would not at first agree even to talk upon the subject at all; and it was only after “every one of them endeavoured particularly to bring her to the purpose,” that she condescended to state two objections, which, setting aside every other consideration, she regarded as insuperable. The first was, that she did not understand how the divorce could be made lawfully; and the second, that it would be to her son’s prejudice, rather than hurt whom, she declared she “would endure all torments.” Bothwell endeavoured to take up the argument, and to do away with the force of these objections, alleging, that though his father and mother had been divorced, there had never been any doubt as to his succession to his paternal estates; but his [Pg 7]illustrations and Lethington’s oratory met with the same success. Mary answered firmly, “I will that you do nothing, by which any spot may be laid on my honour and conscience; and therefore, I pray ye rather let the matter be in the estate as it is, abiding till God of his goodness put a remedy to it. That you believe would do me service, may possibly turn to my hurt and displeasure.” As to Darnley, she expressed a hope that he would soon change for the better; and, prompted by the ardent desire she felt to get rid, for a season, of her many cares, she said she would perhaps go for a time to France, and remain there till her husband acknowledged his errors. She then dismissed Bothwell and his friends, who retired to meditate new plots.[5]

[Pg 8]On the 11th of December, Mary proceeded to Stirling, to make the necessary arrangements for the baptism of her son, which she determined to celebrate with the pomp and magnificence his future prospects justified. Darnley, who had been with the Queen a week at Craigmillar Castle, and afterwards came into Edinburgh with her, had gone to Stirling two days before.[6] Ambassadors had arrived from England, France, Piedmont, and Savoy, to be present at the ceremony. The Pope also had proposed sending a nuncio into Scotland; but Mary had good sense enough to know, that her bigoted subjects would be greatly offended, were she to receive any such servant of Antichrist. It may have occurred to her, besides, that his presence might facilitate the negotiations for the divorce proposed by her nobility, but which she was determined should not take place. She, therefore, wrote to the great spiritual Head of her Church, expressing all that respect for his authority which a good Catholic was bound to feel; but she, at[Pg 9] the same time, contrived to prevent his nuncio, Cardinal Laurea, from coming further north than Paris.[7]

The splendour of Mary’s preparations for the approaching ceremony, astonished not a little the sober minds of the Presbyterians. “The excessive expenses and superfluous apparel,” says Knox, “which were prepared at that time, exceeded far all the preparations that ever had been devised or set forth before in this country.” Elizabeth, as if participating in Mary’s maternal feelings, ordered the Earl of Bedford, her ambassador, to appear at Stirling with a very gorgeous train; and sent by him as a present for Mary a font of gold, valued at upwards of 1000l. In her instructions to Bedford, she desired him to say jocularly, that it had been made as soon as she heard of the Prince’s birth, and that it was large enough then; but that, as he had now, she supposed, outgrown it, it might be kept for the next child. It was too far in the season to admit of [Pg 10]Elizabeth’s sending any of the Ladies of her own realm into Scotland; she, therefore, fixed on the Countess of Argyle to represent her as godmother, preferring that lady, because she understood her to be much esteemed by Mary. To meet the extraordinary expenditure occasioned by entertaining so many ambassadors, the Queen was permitted to levy an assessment of 12,000l. It may appear strange, how a taxation of this kind could be imposed without the consent of Parliament; but it was managed thus. The Privy Council called a meeting both of the Lords Temporal and Spiritual, and of the representatives of the boroughs, and informed them that some of the greatest princes in Christendom had requested permission to witness, through their ambassadors, the baptism of the Prince. It was therefore moved, and unanimously carried, that their Majesties should be allowed to levy a tax for “the honourable expenses requisite.” The tax was to be proportioned in this way; six thousand pounds from the spiritual estate;—four thousand from the barons and freeholders;—and two thousand from the boroughs.[8]

Till the ceremony of baptism took place, the Queen gave splendid banquets every day to the ambassadors and their suites. At one of these a slight disturbance occurred, which, as it serves to illustrate amusingly the manners of the times, is worth describing. There seems to have been some little jealousy between the English and French envoys upon matters of precedence; and Mary on the whole was inclined to favour the English, being now more connected with England than with[Pg 11] France. It happened, however, that at the banquet in question, a kind of mummery was got up, under the superintendance of one of Mary’s French servants, called Sebastian, who was a fellow of a clever wit. He contrived a piece of workmanship, in the shape of a great table; and its machinery was so ingeniously arranged, that, upon the doors of the great hall in which the feast was to be held, being thrown open, it moved in, apparently of its own accord, covered with delicacies of all sorts. A band of musicians, clothed like maidens, singing and accompanying themselves on various instruments, surrounded the pageant. It was preceded, and this was the cause of the offence, by a number of men, dressed like satyrs, with long tails, and carrying whips in their hands. These satyrs were not content to ride round the table, but they put their hands behind them to their tails, wagging them in the faces of the Englishmen, who took it into their heads that the whole was done in derision of them, “daftly apprehending that which they should not seem to have understood.” Several of the suite of the Earl of Bedford, perceiving themselves thus mocked, as they thought, and the satyrs “wagging their tails or rumples,” were so exasperated, that one of them told Sir James Melville, if it were not in the Queen’s presence, “he would put a dagger to the heart of the French knave Sebastian, whom he alleged did it for despite that the Queen made more of them than of the Frenchmen.” The Queen and Bedford, who knew that the whole was a mere jest, had some trouble in allaying the wrath of the hot-headed Southerns.

In the midst of these festivities, Mary had [Pg 12]various cares to perplex her, and various difficulties to encounter. When she first came to Stirling, she found that Darnley had not chosen to go, as usual, to the Castle, but was residing in a private house. He left it, however, upon the Queen’s arrival, and took up his residence in the Castle with her,—a fact of some consequence, and one which Murray has himself supplied.[9] But Darnley’s sentiments towards Mary’s ministers, continued unchanged; and it was impossible to prevail upon them to act and associate together, with any degree of harmony, even in presence of the ambassadors. Mary was extremely anxious to prevent her husband from exposing his weakness and waywardness to foreigners; but he was as stubborn as ever; and though he had given up thoughts of going abroad, it was only because he hoped to put into execution some new plot at home. Surrounded by gayeties, he continued sullen and discontented, shutting himself up in his own apartment, and associating with no one, except his wife and the French envoy, Le Croc, for whom he had contracted a sort of friendship. To heighten his bad humour, Elizabeth, according to Camden, had forbidden Bedford, or any of his retinue, to give him the title of King. The anger inspired by his contempt of her authority, on the occasion of his marriage, had not yet subsided; and there is not a state paper extant, in which she acknowledges Darnley in other terms than as “Henry Stuart, the Queen of Scotland’s husband.” It seems likely that this, added to the other reasons already mentioned, was the cause why Darnley refused to be present at the[Pg 13] christening of his son.[10] Mary had another cause of vexation. The baptism was to be performed after the Catholic ritual, and the greater part of her nobility, in consequence, not only refused to take any share in the ceremony, but even to be present at it. All Mary’s influence with Murray, Huntly, and Bothwell, was exerted in vain. They did not choose to risk their character with the Reformers, to gratify her. “The Queen laboured much,” says Knox, “with the noblemen, to bear the salt, grease,[Pg 14] and candles, and such other things, but all refused.”

On the 19th of December 1566, the baptism, for which so many preparations had been made, took place.[11] The ceremony was performed between five and six in the afternoon. The Earls of Athol and Eglinton, and the Lords Semple and Ross, being of the Catholic persuasion, carried the instruments. The Archbishop of St Andrews, assisted by the Bishops of Dumblane, Dunkeld, and Ross, received the Prince at the door of the chapel. The Countess of Argyle held the infant at the font, and the Archbishop baptized him by the name of Charles James, James Charles, Prince and Steward of Scotland, Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Lord of the Isles, and Baron of Renfrew; and these names and titles were proclaimed three times by heralds, with sound of trumpet. Mary called her son Charles, in compliment to the King of France, her brother-in-law; but she gave him also the name of James, because, as she said, her father, and all the good kings of Scotland, his predecessors, had been called by that name. The Scottish nobles of the Protestant persuasion, together with the Earl of Bedford, remained at the door of the chapel; and the Countess of Argyle had afterwards to do penance for the share she took in the business of the day,—a circumstance which shows very forcibly the power of the clergy at this time, who were able to triumph over a Queen’s representative, a King’s daughter, and their Sovereign’s sister. It is also worthy of [Pg 15]notice, that of the twelve Earls, and numerous Lords then in the castle, only two of the former, and three of the latter, ventured to cross the threshold of a Catholic chapel.[12]

Elizabeth was probably not far wrong, in supposing that her font had grown too small for the infant James. He was a remarkably stout and healthy child, and as Le Croc says, he made his gossips feel his weight in their arms. Mary was very proud of her son, and from his earliest infancy, the establishment of his household was on the most princely scale. The Lady Mar was his governess. A certain Mistress Margaret Little, the spouse of Alexander Gray, Burgess of Edinburgh, was his head-nurse; and for her good services, there was granted to her and her husband, in February 1567, part of the lands of Kingsbarns in Fife, during their lives. The chief nurse had four or five women under her, “Keepers of the King’s clothes,” &c. Five ladies of distinction were appointed to the honourable office of “Rockers” of the Prince’s cradle. For his kitchen, James, at the same early age, had a master-cook, a foreman, and three other servitors, and one for his pantry, one for his wine, and two for his ale-cellar. He had three “chalmer-chields,” one “furnisher of coals,” and one pastry-cook or confectioner. Five musicians or “violars,” as they are called, completed the number of his household. To fill so many mouths, there was a fixed allowance of provisions, consisting of bread, beef, veal, mutton, capons, chickens, pigeons, fish,[Pg 16] pottages, wine and ale. Thus, upon the life of the infant, the comfortable support of a reasonable number of his subjects depended.[13]

The captivating grace and affability of Mary’s manners, won for her, upon the baptismal occasion, universal admiration. She sent home the ambassadors with the most favourable impressions, which were not less loudly proclaimed, because she enriched them, before they went, with gifts of value. To Bedford, in particular, she gave a chain of diamonds, worth about six or seven hundred pounds. To other individuals of his suite, she gave chains of pearl, rings, and pictures.[14] But she was all the time making an effort to appear happier and more contented than she really was. “She showed so much earnestness,” says Le Croc, “to entertain all the goodly company, in the best manner, that this made her forget, in a good measure, her former ailments. But I am of the mind, however, that she will give us some trouble as yet; nor can I be brought to think otherwise, so long as she continues to be so pensive and melancholy. She sent for me yesterday, and I found her laid on the bed weeping sore. I am much grieved for the many troubles and vexations she meets with.” Mary did not weep without cause. One source of uneasiness, at the present moment, was the determination of her ministers to force from her a pardon for the Earl of Morton, and seventy-five of his accomplices. As some one has remarked, her whole reign was made up of plots and pardons. Her chief failing indeed, was the facility with which she allowed herself to be persuaded to[Pg 17] forgive the deadliest injuries which could be offered to her. Murray, from the representations he had made through Cecil, had induced Elizabeth to desire Bedford to join his influence to that of Mary’s Privy Council in behalf of Morton. The consequence was, that the Queen could no longer resist their united importunities, and, with two exceptions, all the conspirators against Rizzio were pardoned. These exceptions were, George Douglas, who had seized the King’s dagger, and struck Rizzio the first blow; and Andrew Kerr, who, in the affray, had threatened to shoot the Queen herself. Robertson, with great inaccuracy, has said, that it was to the solicitations of Bothwell alone that these criminals were indebted for their recall. It would have been long before Bothwell, whose weight with Mary was never considerable, could have obtained, unassisted, her consent to such a measure; and the truth of this assertion is proved by the clearest and directest testimony. In a letter which Bedford wrote to Cecil on the 30th of December, we meet with the following passage:—“The Queen here hath now granted to the Earl of Morton, to the Lords Ruthven and Lindsay, their relaxation and pardon.[15] The Earl of Murray hath done very friendly towards the Queen for them, so have I, according to your advice; the Earls Bothwell and Athol, and all other Lords helped therein, or else such pardons could not so soon have been gotten.”[16] It is no doubt true, that Bothwell was glad of this opportunity to [Pg 18]ingratiate himself with Morton, and that, in the words of Melville, he “packed up a quiet friendship with him;”—but it is strange that Robertson should have been so ignorant of the real influence which secured a remission of their offences from Mary.

Darnley was of course greatly offended that any of his former accomplices should be received again into favour. They would return only to force him a few steps farther down the ladder, to the top of which he had so eagerly desired to climb. They were recalled too at the very time when he had it in contemplation, according to common report, to seize on the person of the young Prince, and, after crowning him, to take upon himself the government as his father. Whether this report was true or not, (and perhaps it was a belief in it which induced the Queen to remove shortly afterwards from Stirling to Edinburgh), it is certain that Darnley declared he “could not bear with some of the noblemen that were attending in the Court, and that either he or they behoved to leave the same.”[17] He accordingly left Stirling on the 24th of December, the very day on which Morton’s pardon was signed, to visit his father at Glasgow. But it was not with Mary he had quarrelled, with whom he had been living for the last ten days, and whom he intended rejoining in Edinburgh, as soon as she had paid some Christmas visits in the neighbourhood of Stirling.[18]

OCCURRENCES IMMEDIATELY PRECEDING DARNLEY’S DEATH.

We are now about to enter upon a part of Mary’s history, more important in its results, and more interesting in its details, than all that has gone before. A deed had been determined on, which, for audacity and villany, has but few parallels in either ancient or modern story. The manner of its perpetration, and the consequences which ensued, not only threw Scotland into a ferment, but astonished the whole of Europe; and, even to this day, the amazement and horror it excited, continue to be felt, whenever that page of our national history is perused which records the event. Ambition has led to the commission of many crimes; but, fortunately for the great interests of society, it is only in a few instances, of which the present is one of the most conspicuous, that it has been able to involve in misery, the innocent as well as the guilty. But, even where this is the case, time rescues the virtuous from unmerited disgrace, and, causing the mantle of mystery to moulder away, enables us to point out, on one hand, those who have been unjustly accused, and, on the other, those who were both[Pg 20] the passive conspirators and the active murderers. A plain narrative of facts, told without violence or party-spirit, is that upon which most reliance will be placed, and which will be most likely to advance the cause of truth by correcting the mistakes of the careless, and exposing the falsehoods of the calumnious.

The Earl of Bothwell was now irrevocably resolved to push his fortunes to the utmost. He acted, for the time, in conjunction with the Earl of Murray, though independently of him, using his name and authority to strengthen his own influence, but communicating to the scarcely less ambitious Murray only as much of his plans as he thought he might disclose with safety. Bothwell was probably the only Scottish baron of the age over whom Murray does not appear ever to have had any control. His character, indeed, was not one which would have brooked control. On Mary’s return home, so soon as he perceived the ascendancy which her brother possessed over her, he entered into a conspiracy with Huntly and others, to remove him. The conspiracy failed, and Bothwell left the kingdom. He was not recalled till Murray had fallen into disgrace; and though the Earl was subsequently pardoned, he never regained that superiority in Mary’s councils he had once enjoyed. But Bothwell hoped to secure the distinction for himself; and, that he might not lose it as Murray had done, after it was once gained, he daringly aimed at becoming not merely a prime minister, but a king. The historians, therefore, (among whom are to be included many of Mary’s most zealous defenders), who speak of Bothwell as only a “cat’s-paw” in the hands of Murray[Pg 21] and his party, evidently mistake both the character of the men, and the positions they relatively held. Murray and Bothwell had both considerable influence at Court; but there was no yielding on the part of either to the higher authority of the other, and the Queen herself endeavoured, upon all occasions, to act impartially between them. We have found her frequently granting the requests of Murray in opposition to the advice of Bothwell; and there is no reason to suppose, that, when she saw cause, she may not have followed the advice of her Lord High Admiral, in preference to that of her brother. A circumstance which occurred only a few days after the baptism of James VI., strikingly illustrates the justice of these observations. It is the more deserving of attention, as the spirit of partiality, which has been unfortunately so busy in giving an erroneous colouring even to Mary’s most trifling transactions, has not forgotten to misrepresent that to which we now refer.

Darnley’s death being resolved, Bothwell began to consider how he was to act after it had taken place. He probably made arrangements for various contingencies, and trusted to the chapter of accidents, or his own ingenuity, to assist him in others. But there was one thing certain, that he could never become the legal husband of Mary, so long as he continued united to his own wife, the Lady Jane Gordon. Anticipating, therefore, the necessity of a divorce, and aware that the emergency of the occasion might not permit of his waiting for all the ordinary forms of law, he used his interest with the Queen at a time when his real motives were little suspected, to revive the ancient[Pg 22] jurisdiction of the Catholic Consistorial Courts, which had been abolished by the Reformed Parliament of 1560, and the ordinary civil judges of Commissary Courts established in their place. In accordance with his request, Mary restored the Archbishop of St Andrews, the Primate of Scotland, to the ancient Consistorial Jurisdiction, granted him by the Canon laws, and discharged the Commissaries from the further exercise of their offices. Thus, Bothwell not only won the friendship of the Archbishop, but secured for himself a court, where the Catholic plea of consanguinity might be advanced,—the only plausible pretext he could make use of for annulling his former marriage. This proceeding, however, in favour of the Archbishop and the old faith, gave great offence to the Reformed party; and when the Primate came from St Andrews to Edinburgh, at the beginning of January, for the purpose of holding his court, his authority was very strenuously resisted. The Earl of Murray took up the subject, and represented to Mary the injury she had done to the true religion. Bothwell, of course, used every effort to counteract the force of such a representation; but he was unsuccessful. By a letter which the Earl of Bedford wrote to Cecil from Berwick, on the 9th of January 1567, we learn that the Archbishop was not allowed to proceed to the hearing of cases, and that “because it was found to be contrary to the religion, and therefore not liked of by the townsmen; at the suit of my Lord of Murray, the Queen was pleased to revoke that which she had before granted to the said bishop.” Probably the grant of jurisdiction was not “revoked,” but only suspended, as Bothwell subsequently availed himself of it; but[Pg 23] even its suspension sufficiently testifies, that Mary, at this period, listened implicitly and exclusively neither to one nor other of her counsellors.[19]

In the meantime, Darnley, who, as we have seen, left Stirling for Glasgow on the 24th of December, had been taken dangerously ill. Historians differ a good deal concerning the nature of his illness, which is by some confidently asserted to have been occasioned by poison, administered to him either before he left Stirling, or on the road, by servants, who had been bribed by Bothwell; and by others is as confidently affirmed to have been the small-pox, a complaint then prevalent in Glasgow. On the whole, the latter opinion seems[Pg 24] to be the best supported, as it is confirmed by the authority both of the English ambassador, and of the cotemporary historians, Lesley and Blackwood. Knox, Buchanan, Melville, Crawford, Birrell and others, mention, on the other hand, that the belief was prevalent, that the King’s sickness was the effect of poison. But as the only evidence offered in support of this popular rumour is, that “blisters broke out of a bluish colour over every part of his body,” and as this may have been the symptoms of small-pox as well as of poison, the story does not seem well authenticated. Besides, in the letter which Mary is alleged to have written a week or two afterwards to Bothwell from Glasgow, she is made to say that Darnley told her he was ill of the small-pox. Whether the letter be a forgery or not, this paragraph would not have been introduced, unless it had contained what was then known to be the fact.

Be this matter as it may, it is of more importance to correct a mistake into which Robertson has not unwillingly fallen, regarding the neglect and indifference with which he maintains Mary treated her husband, during the earlier part of his sickness. We learn, in the first place, by Bedford’s letter to Cecil, already mentioned, that as soon as Mary heard of Darnley’s illness, she sent her own physician to attend him.[20] And, in the second place, it appears, that it was some time before Darnley’s complaint assumed a serious complexion; but that, whenever Mary understood he was considered in danger, she immediately set out to visit him. “The Queen,” says Crawford, “was no sooner informed of his danger, than she hasted after [Pg 25]him.”—“As soon as the rumour of his sickness gained strength,” says Turner (or Barnestaple), “the Queen flew to him, thinking more of the person to whom she flew, than of the danger which she herself incurred.”—“Being advertised,” observes Lesley, “that Darnley was repentant and sorrowful, she without delay, thereby to renew, quicken, and refresh his spirits, and to comfort his heart to the amendment and repairing of his health, lately by sickness sore impaired, hasted with such speed as she conveniently might, to see and visit him at Glasgow.” Thus, Robertson’s insinuation falls innocuous to the ground.

It was on the 13th of January 1567 that Mary returned from Stirling to Edinburgh, having spent the intermediate time, from the 27th of December, in paying visits to Sir William Murray, the Comptroller of her household, at Tullibardin, and to Lord Drummond at Drummond Castle. As is somewhere remarked, “every moment now begins to be critical, and every minuteness and specific caution becomes necessary for ascertaining the truth, and guarding against slander.” The probability is, that Bothwell was not with Mary either at Tullibardin or Drummond Castle. Meetings of her Privy Council were held by her on the 2d and 10th of January; and it appears by the Register, that Bothwell was not present at any of them. Chalmers is of opinion, that, during the early part of January he must have been at Dunbar, making his preparations, and arranging a meeting with Morton. When the Queen arrived at Edinburgh on the 13th, she lodged her son, whom she brought with her, in Holyroodhouse. A few days [Pg 26]afterwards, she set out for Glasgow to see her husband. Her calumniators, on the supposition that she had previously quarrelled with Darnley, affect to discover something very forced and unnatural in this visit. But Mary had never quarrelled with Darnley. He had quarrelled with her ministers, and had been enraged at the failure of his own schemes of boyish ambition, but against his wife he had himself frequently declared he had no cause of complaint. Mary, on her part, had always shown herself more grieved by Darnley’s waywardness than angry at it. Only a day or two before going to Glasgow, she said solemnly, in a letter she wrote to her ambassador at Paris,—“As for the King, our husband, God knows always our part towards him.”—“God willing, our doings shall be always such as none shall have occasion to be offended with them, or to report of us any way but honourably.”[21] So far, therefore, from there being any thing uncommon or forced in her journey to Glasgow, nothing could be more natural, or more likely to have taken place. “Darnley’s danger,” observes Dr Gilbert Stuart, with the simple eloquence of truth, “awakened all the gentleness of her nature, and she forgot the wrongs she had endured. Time had abated the vivacity of her resentment, and after its paroxysm was past, she was more disposed to weep over her afflictions, than to indulge herself in revenge. The softness of grief prepared her for a returning tenderness. His distresses effected it. Her memory shut itself to his errors and imperfections, and was only open to his better qualities and accomplishments. He [Pg 27]himself, affected with the near prospect of death, thought, with sorrow, of the injuries he had committed against her. The news of his repentance was sent to her. She recollected the ardour of that affection he had lighted up in her bosom, and the happiness with which she had surrendered herself to him in the bloom and ripeness of her beauty. Her infant son, the pledge of their love, being continually in her sight, inspirited her sensibilities. The plan of lenity which she had previously adopted with regard to him; her design to excite even the approbation of her enemies by the propriety of her conduct; the advices of Elizabeth by the Earl of Bedford to entertain him with respect; the apprehension lest the royal dignity might suffer any diminution by the universal distaste with which he was beheld by her subjects, and her certainty and knowledge of the angry passions which her chief counsellors had fostered against him—all concurred to divest her heart of every sentiment of bitterness, and to melt it down in sympathy and sorrow. Yielding to tender and anxious emotions, she left her capital and her palace, in the severest season of the year, to wait upon him. Her assiduities and kindnesses communicated to him the most flattering solacement; and while she lingered about his person with a fond solicitude, and a delicate attention, he felt that the sickness of his mind and the virulence of his disease were diminished.”

On arriving at Glasgow, Mary found her husband convalescent, though weak and much reduced. She lodged in the same house with him; but his disease being considered infectious, they had separate apartments. Finding that his recent[Pg 28] approach to the very brink of the grave had exercised a salutary influence over his mind and dispositions, and hoping to regain his entire confidence, by carefully and affectionately nursing him during his recovery, she gladly acceded to the proposal made by Darnley, that she should take him back with her to Edinburgh or its vicinity. She suggested that he should reside at Craigmillar Castle, as the situation was open and salubrious; but for some reason or other, which does not appear, he objected to Craigmillar, and the Queen therefore wrote to Secretary Maitland to procure convenient accommodation for her husband, in the town of Edinburgh.[22] Darnley disliked the Lords of the Privy Council too much to think of living at Holyrood; and besides, it was the opinion of the physicians, that the young Prince, even though he should not be brought into his father’s presence, might catch the infection from the servants who would be about the persons of both. But when Mary wrote to Maitland, she little knew that she was addressing an accomplice of her husband’s future murderer. The Secretary showed her letter to Bothwell, and they mutually determined on recommending to Darnley the house of the Kirk-of-Field, which stood on an airy and healthy situation to the south of the town, and which, therefore, appeared well suited for an invalid, although they preferred it because it stood by itself, in a comparatively solitary part of the town.[23] On Monday, January 27th, Mary and Darnley left Glasgow. They appear to have travelled in a wheeled[Pg 29] carriage, and came by slow and easy stages to Edinburgh. They slept on Monday night at Callander. They came on Tuesday to Linlithgow, where they remained over Wednesday, and arrived in Edinburgh on Thursday.

The Kirk-of-Field, in which, says Melville, “the King was lodged, as a place of good air, where he might best recover his health,” belonged to Robert Balfour, the Provost or head prebendary of the collegiate church of St Mary-in-the-Field, so called because it was beyond the city wall when first built. When the wall was afterwards extended, it enclosed the Kirk-of-Field, as well as the house of the Provost and Prebendaries. The Kirk-of-Field with the grounds pertaining to it, occupied the site of the present College, and of those buildings which stand between Infirmary and Drummond Street. In the extended line of wall, what was afterwards called the Potter-row Port, was at first denominated the Kirk-of-Field Port, from its vicinity to the church of that name. The wall ran east from this port along the south side of the present College, and the north side of Drummond Street, where a part of it is still to be seen in its original state. The house stood at some distance from the Kirk, and the latter, from the period of the Reformation, had fallen into decay. The city had not yet stretched in this direction much farther than the Cowgate. Between that street and the town wall, were the Dominican Convent of the Blackfriars, with its alms-houses for the poor, and gardens, covering the site of the present High School and Royal Infirmary,—and the Kirk-of-Field and its Provost’s[Pg 30] residence. The house nearest to it of any note was Hamilton House, which belonged to the Duke of Chatelherault, and some part of which is still standing in College Wynd.[24] It was at first supposed, that Darnley would have taken up his abode there; but the families of Lennox and Hamilton were never on such terms as would have elicited this mark of friendship from the King. The Kirk-of-Field House stood very nearly on the site of the present north-west corner of Drummond Street. It fronted the west, having its southern gavel so close upon the town-wall, that a little postern door entered immediately through the wall into the kitchen. It contained only four apartments; but these were commodious, and were fitted up with great care. Below, a small passage went through from the front door to the back of the house; upon the right hand of which was the kitchen, and upon the left, a room furnished as a bedroom, for the Queen, when she chose to remain all night. Passing out at the back-door, there was a turnpike stair behind, which, after the old fashion of Scottish houses, led up to the second story. Above, there were two rooms corresponding with those below. Darnley’s chamber was immediately over Mary’s; and on the other side of the lobby, above the kitchen, a “garde-robe” or “little-gallery,” which was used as a servant’s room, and which had a window in the gavel, looking through the town-wall, and corresponding with the postern door below. Immediately beyond this wall, was a lane shut in by [Pg 31]another wall, to the south of which were extensive gardens.[25]

During the ten days which Darnley spent in his new residence, Mary was a great deal with him, and slept several nights in the room we have described below her husband’s, this being more agreeable to her, than returning at a late hour to Holyrood Palace. Darnley was still much of an invalid, and his constitution had received so severe a shock, that every attention was necessary during his convalescence. A bath was put up for him, in his own room, and he appears to have used it frequently. He had been long extremely unpopular, as has been seen, among the nobles; but following the example which Mary set them, some were disposed to forget their former disagreements, and used to call upon him occasionally, and among others, Hamilton, the Archbishop of St Andrews, who came to Edinburgh about this time, and lodged hard by in Hamilton house. Mary herself, after sitting for hours in her husband’s sick-chamber, used sometimes to breathe the air in the [Pg 32]neighbouring gardens of the Dominican convent; and she sometimes brought up from Holyrood her band of musicians, who played and sung to her and Darnley. Thus, every thing went on so smoothly, that neither the victim nor his friends could in the least suspect that they were all treading the brink of a precipice.

Bothwell had taken advantage of Mary’s visit to Glasgow, to proceed to Whittingham, in the neighbourhood of Dunbar, where he met the Earl of Morton, and obtained his consent to Darnley’s murder. To conceal his real purpose, Bothwell gave out at Edinburgh, that he was going on a journey to Liddesdale; but, accompanied by Secretary Maitland, whom he had by this time won over to his designs, and the notorious Archibald Douglas, a creature of his own, and a relation of Morton, he went direct to Whittingham. There, the trio met Morton, who had only recently returned from England, and opened to him their plot. Morton heard of the intended murder without any desire to prevent its perpetration; but before he would agree to take an active share in it, he insisted upon being satisfied that the Queen, as Bothwell had the audacity to assert, was willing that Darnley should be removed. “I desired the Earl Bothwell,” says Morton in his subsequent confession, “to bring me the Queen’s hand write of this matter for a warrant, and then I should give him an answer; otherwise, I would not mell (intermeddle) therewith;—which warrant he never purchased (procured) unto me.”[26] But though[Pg 33] Morton, refused to risk an active, he had no objections to take a passive part in this conspiracy. Bothwell, Maitland, and Douglas, returned to Edinburgh, and he proceeded to St Andrews, with the understanding, that Bothwell was to communicate with him, and inform him of the progress of the plot. Accordingly, a day or two before the murder was committed, Douglas was sent to St Andrews, to let Morton know that the affair was near its conclusion. Bothwell, however, was well aware that what he had told the Earl regarding the wishes of the Queen, was equally false and calumnious. Of all persons in existence, it was from her that he most wished to conceal his design; and as for a written approval of it, he knew that he might just as well have applied to Darnley himself. Douglas was, therefore, commanded to say to Morton, evasively, “that the Queen would bear no speech of the matter appointed to him.” Morton, in consequence, remained quietly in the neighbourhood of St Andrews till the deed was done.[27]

The Earl of Murray was another powerful nobleman, who, when the last act of this tragedy was about to be performed, withdrew to a careful distance from the scene. It is impossible to say whether Murray was all along acquainted with Bothwell’s intention; there is certainly no direct evidence that he was; but there are very considerable probabilities. When a divorce was proposed to Mary at Craigmillar, she was told that Murray would look through his fingers at it; and this design being frustrated, by the Queen’s refusal to agree to it, there is every[Pg 34] likelihood that Bothwell would not conceal from the cabal he had then formed, his subsequent determination. That he disclosed it to Morton and Maitland, is beyond a doubt; and that Murray again consented “to look through his fingers,” is all but proved. It is true he was far too cautious and wily a politician, to plunge recklessly, like Bothwell, into such a sea of dangers and difficulties; but he was no friend to Darnley,—having lost through him much of his former power; and however the matter now ended, if he remained quiet, he could not suffer any injury, and might gain much benefit. If Bothwell prospered, they would unite their interests,—if he failed, then Murray would rise upon his ruin. Only three days before the murder, the Lord Robert Stuart, Murray’s brother, having heard, as Buchanan affirms of the designs entertained against Darnley’s life, mentioned them to the King. Darnley immediately informed Mary, who sent for Lord Robert, and in the presence of her husband and the Earl of Murray, questioned him on the subject. Lord Robert, afraid of involving himself in danger, retracted what he had formerly said, and denied that he had ever repeated to Darnley any such report. High words ensued in consequence; and even supposing that Murray had before been ignorant of Bothwell’s schemes, his suspicions must now have been roused. Perceiving that the matter was about to be brought to a crisis, he left town abruptly upon Sunday, the very last day of Darnley’s life, alleging his wife’s illness at St Andrews, as the cause of his departure. The fact mentioned by Lesley, in his “Defence of Queen Mary’s Honour,” that on the evening of[Pg 35] this day, Murray said, when riding through Fife, to one of his most trusty servants,—“This night, ere morning, the Lord Darnley shall lose his life,” is a strong corroboration of the supposition that he was well informed upon the subject.[28]

There were others, as has been said, whom Bothwell either won over to assist him, or persuaded to remain quiet. One of his inferior accomplices afterwards declared, that the Earl showed him a bond, to which were affixed the signatures of Huntly, Argyle, Maitland, and Sir James Balfour, and that the words of the bond were to this effect:—“That for as much as it was thought expedient and most profitable for the commonwealth, by the whole nobility and Lords undersubscribed, that such a young fool and proud tyrant should not reign, nor bear rule over them, for diverse causes, therefore, these all had concluded, that he should be put off by one way or other, and who-soever should take the deed in hand, or do it, they should defend and fortify it as themselves, for it should be every one of their own, reckoned and holden done by themselves.”[29] To another of his accomplices, Bothwell declared that Argyle, Huntly, Morton, Maitland, Ruthven, and Lindsay, had promised to support him; and when he was asked what part the Earl of Murray would take, his answer was,—“He does not wish to intermeddle with it; he does not mean either to aid or hinder us.”[30]

[Pg 36]But whoever his assistants were, it was Bothwell’s own lawless ambition that suggested the whole plan of proceeding, and whose daring hand was to strike the final and decisive blow. Everything was now arranged. His retainers were collected round him;—four or five of the most powerful ministers of the crown knew of his design, and did not disapprove of it;—the nobles then at court were disposed to befriend him, from motives either of political interest or personal apprehension;—Darnley and the Queen were unsuspicious and unprotected. A kingly crown glittered almost within his grasp; he had only to venture across the Rubicon of guilt, to place it on his brow.

THE DEATH OF DARNLEY.

It was on Sunday, the 9th of February 1567, that the final preparations for the murder of Darnley were made. To execute the guilty deed, Bothwell was obliged to avail himself of the assistance of those ready ministers of crime, who are always to be found at the beck of a wealthy and depraved patron. There were eight unfortunate men whom he thus used as tools with which to work his purpose. Four of these were merely menial servants;—their names were, Dalgleish, Wilson, Powrie, and Nicolas Haubert, more commonly known by the sobriquet of French Paris. He was a native of France, and had been a long while in the service of the Earl of Bothwell; but on his master’s recommendation, who foresaw the advantages he might reap from the change, he was taken into the Queen’s service shortly before her husband’s death. Bothwell was thus able to obtain the keys of some of the doors of the Kirk-of-Field house, of which he caused counterfeit impressions to be taken.[31] The other four who were at the “deed-doing,”[Pg 38] were persons of somewhat more consequence. They were small landed proprietors or lairds, who had squandered their patrimony in idleness and dissipation, and were willing to run the chance of retrieving their ruined fortunes at any risk. They were the Laird of Ormiston, Hob Ormiston his uncle, “or father’s brother,” as he is called, John Hepburn of Bolton, and John Hay of Tallo. Bothwell wished Maitland, Morton, and one or two others, to send some of their servants also to assist in the enterprise; but if they ever promised to do so, it does not appear that they kept their word. Archibald Douglas, however, who had linked himself to the fortunes of Bothwell, was in the immediate neighbourhood with two servants, when the crime was perpetrated.[32]

Till within two days of the murder, Bothwell had not made up his mind how the King was to be killed. He held various secret meetings with his four principal accomplices, at which the plan first proposed was to attack Darnley when walking in the gardens adjoining the Kirk-of-Field, which his returning health enabled him to visit occasionally when the weather was favourable. But the success of this scheme was uncertain, and there was every probability that the assassins would be discovered.[33] It was next suggested that the house might easily be entered at midnight, and the King stabbed in bed. But a servant commonly lay in the same apartment with him, and there were always one or two in the adjoining room, who might have resisted or escaped, and afterwards have been[Pg 39] able to identify the criminals. After much deliberation, it at length occurred that gunpowder might be used with effect; and that, if the whole premises were blown up, they were likely to bury in their ruins every thing that could fix the suspicion on the parties concerned. Powder was therefore secretly brought into Edinburgh from the Castle of Dunbar, of which Bothwell had the lordship, and was carried to his own lodgings in the immediate vicinity of Holyrood Palace.[34] It then became necessary to ascertain on what night the house could be blown up, without endangering the safety of the Queen, whom Bothwell had no desire should share the fate of her husband. She frequently slept at the Kirk-of-Field; and it was difficult to ascertain precisely when she would pass the night at Holyrood.[35] In his confession, Hay mentions, that “the purpose should have been put in execution upon the Saturday night; but the matter failed, because all things were not in readiness.” It is not in the least unlikely that this delay was owing to Mary’s remaining with her husband that evening.

On Sunday, Bothwell learned that the Queen intended honouring with her presence a masque which was to be given in the Palace, at a late hour, on the occasion of the marriage of her French servant Sebastian, to Margaret Carwood, one of her waiting-maids. He knew therefore that she could not sleep at the Kirk-of-Field that night, and took his measures accordingly. At dusk he assembled his accomplices, and told them that the time was come when he should have occasion[Pg 40] for their services.[36] He was himself to sup between seven and eight at a banquet given to the Queen by the Bishop of Argyle, but he desired them to be in readiness as soon as the company should break up, when he promised to join them.[37] The Queen dined at Holyrood, and went from thence to the house of Mr John Balfour, where the Bishop lodged. She rose from the supper-table about nine o’clock, and, accompanied by the Earls of Argyle, Huntly, and Cassils, she went to visit her husband at the Kirk-of-Field. Bothwell, on the contrary, having called Paris aside, who was in waiting on the Queen, took him with him to the lodgings of the Laird of Ormiston.[38] There he met Hay and Hepburn, and they passed down the Blackfriars Wynd together. The wall which surrounded the gardens of the Dominican monastery ran near the foot of this wynd. They passed through a gate in the wall, which Bothwell had contrived to open by stealth, and, crossing the gardens, came to another wall immediately behind Darnley’s house.[39]

Dalgleish and Wilson had, in the meantime, been employed in bringing up, from Bothwell’s residence in the Abbey, the gunpowder he had lodged there. It had been divided into bags, and the bags were put into trunks, which they carried upon horses. Not being able to take it all at once, they were obliged to go twice between the Kirk-of-Field and the Palace. They were not allowed to come nearer than the Convent-gate at the[Pg 41] foot of Blackfriars Wynd, where the powder was taken from them by Ormiston, Hepburn, and Hay, who carried it up to the house. When they had conveyed the whole, they were ordered to return home; and as they passed up the Blackfriars’ Wynd, Powrie, as if suddenly conscience-struck, said to Wilson, “Jesu! whatna a gait is this we are ganging? I trow it be not good.”[40] Neither of these menials had seen Bothwell, for he kept at a distance, walking up and down the Cowgate, until the others received and deposited the powder. A large empty barrel had been concealed, by his orders, in the Convent gardens, and into it they intended to have put all the bags; and the barrel was then to have been carried in at the lower back door of Darnley’s house, and placed in the Queen’s bedroom, which, it will be remembered, was immediately under that of the King. Paris, as the Queen’s valet-de-chambre, kept the keys of the lower flat, and was now in Mary’s apartment ready to receive the powder. But some delay occurred in consequence of the barrel turning out to be so large that it could not be taken in by the back door; and it became necessary therefore to carry the bags one by one into the bedroom, where they emptied them in a heap on the floor. Bothwell, who was walking anxiously to and fro, was alarmed at this delay, and came to inquire if all was ready. He was afraid that the company up stairs, among whom was the Queen, with several of her nobility and ladies in waiting, might come suddenly out upon[Pg 42] them, and discover their proceedings. “He bade them haste,” says Hepburn, “before the Queen came forth of the King’s house; for if she came forth before they were ready, they would not find such commodity.”[41] At length, every thing being put into the state they wished, they all left the under part of the house, with the exception of Hepburn and Hay, who were locked into the room with the gunpowder, and left to keep watch there till the others should return.[42]

Bothwell, having dismissed the others, went up stairs and joined the Queen and her friends in Darnley’s apartment, as if he had that moment come to the Kirk-of-Field. Shortly afterwards, Paris also entered; and the Queen, being either reminded of, or recollecting her promise, to grace with her presence Sebastian’s entertainment, rose, about eleven at night, to take leave of her husband. It has been asserted, upon the alleged authority of Buchanan, that, before going away, she kissed him, and put upon his finger a ring, in pledge of her affection. It seems doubtful, however, whether this is Buchanan’s meaning. He certainly mentions, in his own insidious manner, that Mary endeavoured to divert all suspicions from herself, by paying frequent visits to her husband, by staying with him many hours at a time, by talking lovingly with him, by paying every attention to his health, by kissing him, and making him a present of a ring; but he does not expressly say that a kiss and ring were given upon the occasion of her parting with Darnley for the last[Pg 43] time.[43] It is not at all unlikely, that the fact may have been as Buchanan is supposed to state; but as it is not a circumstance of much importance, it is unnecessary to insist upon its being either believed or discredited so long as it is involved in any uncertainty. Buchanan mentions another little particular, which may easily be conceived to be true,—that, in the course of her conversation with her husband this evening, Mary made the remark, that “just about that time last year David Rizzio was killed.” Bothwell, at such a moment, could not have made the observation; but it may have come naturally enough from Mary, or Darnley himself.[44]

Accompanied by Bothwell, Argyle, Huntly, Cassils, and others, Mary now proceeded to the palace, going first up the Blackfriars’ Wynd, and then down the Canongate. Just as she was about to enter Holyrood House, she met one of the Earl of Bothwell’s servants (either Dalgleish or Powrie), whom she asked where he had been, that he smelt so strongly of gunpowder? The fellow made some excuse, and no further notice was taken of the circumstance.[45] The Queen proceeded immediately to the rooms where Sebastian’s friends were assembled; and Bothwell, who was very anxious to avoid any suspicion, and, above all, to prevent Mary from suspecting him, continued to attend her assiduously. Paris, who carried in his pocket the key of Mary’s bed-room at the Kirk-of-Field,[Pg 44] in which he had locked Hay and Hepburn, followed in the Earl’s train. Upon entering the apartment where the dancing and masquing was going on, this Frenchman, who had neither the courage nor the cunning necessary to carry him through such a deed of villany, retired in a melancholy mood to a corner, and stood by himself wrapt in a profound reverie. Bothwell, observing him, and fearing that his conduct might excite observation, went up to him, and angrily demanded why he looked so sad, telling him in a whisper, that if he retained that lugubrious countenance before the Queen, he should be made to suffer for it. Paris answered despondingly, that he did not care what became of himself, if he could only get permission to go home to bed, for he was ill. “No,” said Bothwell, “you must remain with me; would you leave those two gentlemen, Hay and Hepburn, locked up where they now are?”—“Alas!” answered Paris, “what more must I do this night? I have no heart for this business.” Bothwell put an end to the conversation, by ordering Paris to follow him immediately.[46] It is uncertain whether the Queen had retired to her own chamber before Bothwell quitted the Palace, or whether he left her at the masque. Buchanan, always ready to fabricate calumny, says, that the Queen and Bothwell were “in long talk together, in her own chamber after midnight.” But the falsehood of this assertion is clearly established; for Buchanan himself allows, that it was past eleven before Mary left the Kirk-of-Field, and Dalgleish and Powrie both state, that Bothwell came to his own[Pg 45] lodgings from the Palace about twelve. If, therefore, he was at the masque, as we have seen, he had no time to talk with the Queen in private; and, if he had talked with the Queen, he could not have been at the masque. It is most likely that Mary continued for some time after Bothwell’s departure at Sebastian’s wedding, for Sebastian was “in great favour with the Queen, for his skill in music and his merry jesting.”

As soon as Bothwell came to his “own lodging in the Abbey,” he exchanged his rich court dress for a more common one. Instead of a black satin doublet, bordered with silver, he put on a white canvass doublet, and wrapt himself up in his riding-cloak. Taking Paris, Powrie, Wilson and Dalgleish with him, he then went down the lane which ran along the wall of the Queen’s south gardens, and which still exists, joining the foot of the Canongate, where the gate of the outer court of the Palace formerly stood. Passing by the door of the Queen’s garden, where sentinels were always stationed, the party was challenged by one of the soldiers, who demanded, “Who goes there?” They answered, “Friends.” “What friends?” “Friends to my Lord Bothwell.” They proceeded up the Canongate till they came to the Netherbow Port, or lower gate of the city, which was shut. They called to the porter, John Galloway, and desired him to open to friends of my Lord Bothwell. Galloway was not well pleased to be raised at so late an hour, and he kept them waiting for some time. As they entered, he asked, “What they did out of their beds at that time of night?” but they gave him no answer. As soon as they got into the town,[Pg 46] they called at Ormiston’s lodgings, who lived in a house, called Bassyntine’s house, a short way up the High Street, on the south side; but they were told that he was not at home. They went without him, down a close below the Blackfriars Wynd, till they came to the gate of the Convent Gardens already mentioned. They entered, and, crossing the gardens, they stopped at the back wall, a short way behind Darnley’s residence. Here, Dalgleish, Wilson, and Powrie, were ordered to remain; and Bothwell and Paris passed in, over the wall. Having gone into the lower part of the house, they unlocked the door of the room in which they had left Hay and Hepburn, and the four together held a consultation regarding the best mode of setting fire to the gunpowder, which was lying in a great heap upon the floor. They took a piece of lint, three or four inches long, and kindling one end of it, they laid the other on the powder, knowing that it would burn slowly enough to give them time to retire to a safe distance. They then returned to the Convent gardens; and having rejoined the servants whom they had left there, the whole group stood together, anxiously waiting for the explosion.

Darnley, meantime, little aware of his impending fate, had gone to bed within an hour after the Queen had left him. His servant, William Taylor, lay, as was his wont, in the same room. Thomas Nelson, Edward Simmons, and a boy, lay in the gallery, or servant’s apartment, on the same floor, and nearer the town-wall. Bothwell must have been quite aware, that from the mode of death he had chosen for Darnley, there was every probability that his attendants would also perish. But[Pg 47] when lawless ambition once commences its work of blood, whether there be only one, or a hundred victims, seems to be a matter of indifference.[47]

The conspirators waited for upwards of a quarter of an hour without hearing any noise. Bothwell became impatient; and unless the others had interfered, and pointed out to him the danger, he would have returned and looked in at the back window of the bedroom, to see if the light was burning. It must have been a moment of intense anxiety and terror to all of them. At length, every doubt was terminated. With an explosion so tremendous, that it shook nearly the whole town, and startled the inhabitants from their sleep, the house of the Kirk-of-Field blew up into a thousand fragments, leaving scarcely a vestige standing of its former walls. Paris, who describes the noise as that of a storm of thunder condensed into one clap, fell almost senseless, through fear, with his face upon the earth. Bothwell himself, though “a bold, bad man,” confessed a momentary panic. “I have been at many important enterprises,” said he, “but I never felt before as I do now.” Without waiting to ascertain the full extent of the catastrophe, he and his accomplices left the scene of their guilt with all expedition. They went out at the Convent-gate, and, having passed down to the Cowgate, they there separated, and went up by different roads to the Netherbow-Port. They were very desirous to avoid disturbing the porter again, lest they should excite his suspicion. They therefore went down a close,[Pg 48] which still exists, on the north side of the High Street, immediately above the city gate, expecting that they would be able to drop from the wall into Leith Wynd; but Bothwell found it too high, especially as a wound he had received at Hermitage Castle, still left one of his hands weak. They were forced, therefore, to apply once more to John Galloway, who, on being told that they were friends of the Earl Bothwell, does not seem to have asked any questions. On getting into the Canongate, some people were observed coming up the street; to avoid them, Bothwell passed down St Mary’s Wynd, and went to his lodgings by the back road. The sentinels, at the door of the Queen’s garden again challenged them, and they made the usual answer, that they were friends of the Earl Bothwell, carrying despatches to him from the country. The sentinels asked,—“If they knew what noise that was they had heard a short time before?” They told them they did not.[48]

When Bothwell came home, he called for a drink; and, taking off his clothes, went to bed immediately. He had not lain there above half an hour when the news was brought him that the House of the Kirk-of-Field had been blown up, and the King slain. Exclaiming that there must be treason abroad, and affecting the utmost alarm and indignation, he rose and put on the same clothes he had worn when he was last with the Queen. The Earl of Huntly and others soon joined him, and, after hearing from them as much as was then known of the matter, it was thought[Pg 49] advisable to repair to the Palace, to inform Mary of what had happened. They found her already alarmed, and anxious to see them, some vague rumours of the accident having reached her. They disclosed the whole melancholy truth as gradually and gently as possible, attributing Darnley’s death either to the accidental explosion of some gunpowder in the neighbourhood, or to the effects of lightning. Mary’s distress knew no bounds; and seeing that it was hopeless to reason with her in the first anguish of her feelings, Bothwell and the other Lords left her just as day began to break, and proceeded to the Kirk-of-Field.[49] There they found every thing in a state of confusion;—the edifice in ruins, and the town’s-people gathered round it in dismay. Of the five persons who were in the house at the time of the explosion, one only was saved. Darnley, and his servant William Taylor, who slept in the room immediately above the gunpowder, had been most exposed to its effects, and they were accordingly carried through the air over the town wall, and across the lane on the other side, and were found lying at a short distance from each other in a garden to the south of this lane,—both in their night-dress, and with little external injury. Simmons, Nelson, and the boy, being nearer the town-wall, were only collaterally affected by the explosion. They were, however, all buried in the ruins, out of which Nelson alone had the good fortune to be taken alive. The bodies were, by[Pg 50] Bothwell’s command, removed to an adjoining house, and a guard from the Palace set over them.[50]

Darnley and his servant being found at so great a distance, and so triflingly injured, it was almost universally supposed at the time, and for long afterwards, that they had been first strangled or assassinated, and then carried out to the garden. This supposition is now proved, beyond a doubt, to have been erroneous. If Darnley had been first murdered, there would have been no occasion to have blown up the house; and if this was done, that his death might appear to be the result of accident, his body would never have been removed to such a distance as might appear to disconnect it with the previous explosion. Before the expansive force of gunpowder was sufficiently understood, it was not conceived possible that it could have acted as in the present instance; and various theories were invented, none of which were so simple or so true, as that which accords with the facts now established. It is the depositions already quoted that set the matter at rest; for, having confessed so much of the truth, there could have been no reason for concealing any other part of it. Hepburn declared expressly, that “he knew nothing but that Darnley was blown into the air, for he was handled with no men’s hands that he saw;” and Hay deponed that Bothwell, some time afterwards, said to him, “What thought ye when ye saw him blown into the air?” Hay answered,—“Alas! my Lord, why speak ye of that, for whenever I hear such a[Pg 51] thing, the words wound me to death, as they ought to do you.”[51] There is nothing wonderful in the bodies having been carried so far; for it is mentioned by a cotemporary author, that “they kindled their train of gunpowder, which inflamed the whole timber of the house, and troubled the walls thereof in such sort, that great stones of the length of ten feet, and of the breadth of four feet, were found blown from the house a far way.”[52] Besides, after the minute account, which a careful collation of the different confessions and depositions has enabled us to give, of the manner in which Bothwell spent every minute of his time, from the period of the Queen’s leaving Darnley, till the unfortunate Prince ceased to exist, it would be a work of supererogation to seek to refute, by any stronger evidence, the notion that he was strangled.

It is, however, somewhat remarkable, that, even in recent times, authors of good repute should have allowed themselves to be misled by the exploded errors of earlier writers. “The house,” says Miss Benger, “was invested with armed men, some of whom watched without, whilst others entered to achieve their barbarous purpose; these having strangled Darnley and his servant with silken cords, carried their bodies into the garden, and then blew up the house with powder.”[53] This is almost as foolish as the report mentioned by Melville, that he was taken out of his bed, and brought down to a stable, where they suffocated him by stopping a napkin into his[Pg 52] mouth; or, as that still more ridiculous story alluded to by Sanderson, that the Earl of Dunbar, and Sir Roger Aston, an Englishman, who chose to hoax his countrymen, by telling them that he lodged in the King’s chamber that night, “having smelt the fire of a match, leapt both out at a window into the garden; and that the King catching hold of his sword, and suspecting treason, not only against himself, but the Queen and the young Prince, who was then at Holyrood House with his mother, desired him (Sir Roger Aston) to make all the haste he could to acquaint her of it, and that immediately armed men, rushing into the room, seized him single and alone, and stabbed him, and then laid him in the garden, and afterwards blew up the house.”[54] Buchanan, Crawford and others, fall into similar mistakes; but Knox, or his continuator, writes more correctly, and mentions, besides, that medical men “being convened, at the Queen’s command, to view and consider the manner of Darnley’s death,” were almost unanimously of opinion that he was blown into the air, although he had no mark of fire.[55]

Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, Duke of Albany and King of Scotland, perished in the twenty-first year of his age, and the eighteenth month of his reign. The suddenness and severity of his fate excited a degree of compassion, and attached an interest to his memory, which, had he died in the ordinary course of nature, would never have been felt. He had been to Scotland only a cause of civil war,—to his nobility an object of contempt,[Pg 53] of pity, or of hatred,—and to his wife a perpetual source of sorrow and misfortune. Any praise he may deserve must be given to him almost solely on the score of his personal endowments; his mind and dispositions had been allowed to run to waste, and were under no controul but that of his own wayward feelings and fancies. Keith, in the following words, draws a judicious contrast between his animal and intellectual qualities. “He is said to have been one of the tallest and handsomest young men of the age; that he had a comely face and pleasant countenance; that he was a most dexterous horseman, and exceedingly well skilled in all genteel exercises, prompt and ready for all games and sports, much given to the diversions of hawking and hunting, to horse-racing and music, especially playing on the lute; he could speak and write well, and was bountiful and liberal enough. But, then, to balance these good natural qualifications, he was much addicted to intemperance, to base and unmanly pleasures; he was haughty and proud, and so very weak in mind, as to be a prey to all that came about him; he was inconstant, credulous, and facile, unable to abide by any resolutions, capable to be imposed upon by designing men, and could conceal no secret, let it tend ever so much to his own welfare or detriment.”[56] With all his faults, there was no one in Scotland who lamented him more sincerely than Mary. She had loved him deeply; and whilst her whole life proves that she was incapable of indulging that[Pg 54] violent and unextinguishable hatred which prompts to deeds of cruelty and revenge, it likewise proves that it was almost impossible for her to cease to esteem an object for which she had once formed an attachment. Murray must himself have allowed the truth of the first part of this statement; and for many days before his death, Darnley had himself felt the force of the latter. She had, no doubt, too much good sense to believe that Darnley, in his character of king, was a loss to the country; but the tears she shed for him, are to be put down to the account, not of the queen, but of the woman and the wife.

BOTHWELL’S TRIAL AND ACQUITTAL.