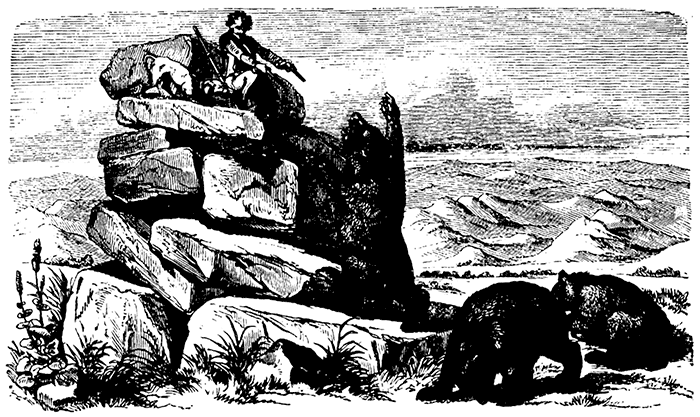

FIGHT WITH THE GRIZZLY BEARS. [p. 290.

Title: The Backwoodsman; Or, Life on the Indian Frontier

Editor: Sir Lascelles Wraxall

Release date: August 15, 2011 [eBook #37100]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Garcia, Linda Hamilton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Kentuckiana Digital Library)

THE

OR,

LONDON:

WARD, LOOK, AND TYLER,

WARWICK HOUSE, PATERNOSTER ROW.

THE

OR,

EDITED BY

SIR C. F. LASCELLES WRAXALL, Bart.

LONDON:

WARD, LOOK, AND TYLER,

WARWICK HOUSE, PATERNOSTER ROW.

LONDON:

PRINTED BY J. OGDEN AND CO.

172, ST. JOHN STREET, E.C.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | MY SETTLEMENT | 1 |

| II. | THE COMANCHES | 6 |

| III. | A FIGHT WITH THE WEICOS | 12 |

| IV. | HUNTING ADVENTURES | 19 |

| V. | THE NATURALIST | 30 |

| VI. | MR. KREGER'S FATE | 41 |

| VII. | A LONELY RIDE | 53 |

| VIII. | THE JOURNEY CONTINUED | 66 |

| IX. | HOMEWARD BOUND | 82 |

| X. | THE BEE HUNTER | 99 |

| XI. | THE WILD HORSE | 114 |

| XII. | THE PRAIRIE FIRE | 126 |

| XIII. | THE DELAWARE INDIAN | 137 |

| XIV. | IN THE MOUNTAINS | 151 |

| XV. | THE WEICOS | 162 |

| XVI. | THE BEAR HOLE | 173 |

| XVII. | THE COMANCHE CHIEF | 185 |

| XVIII. | THE NEW COLONISTS | 208 |

| XIX. | A BOLD TOUR | 224 |

| XX. | THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS | 238 |

| XXI. | LOST IN THE MOUNTAINS | 253 |

| XXII. | BEAVER HUNTERS | 267 |

| XXIII. | THE GRIZZLY BEARS | 282 |

| XXIV. | ASCENT OF THE BIGHORN | 300 |

| XXV. | ON THE PRAIRIE | 326 |

| XXVI. | THE COMANCHES | 345 |

| XXVII. | HOME AGAIN | 363 |

| XXVIII. | INDIAN BEAUTIES | 381 |

| XXIX. | THE SILVER MINE | 396 |

| XXX. | THE PURSUIT | 412 |

THE BACKWOODSMAN

MY SETTLEMENT.

My blockhouse was built at the foot of the mountain chain of the Rio Grande, on the precipitous banks of the River Leone. On three sides it was surrounded by a fourteen feet stockade of split trees standing perpendicularly. At the two front corners of the palisade were small turrets of the same material, whence the face of the wall could be held under fire in the event of an attack from hostile Indians. On the south side of the river stretched out illimitable rolling prairies, while the northern side was covered with the densest virgin forest for many miles. To the north and west I had no civilized neighbours at all, while to the south and east the nearest settlement was at least 250 miles distant. My small garrison consisted of three men, who, whenever I was absent, defended the fort, and at other times looked after the small field and garden as well as the cattle.

As I had exclusively undertaken to provide my colony with meat, I rarely stayed at home, except when there was some pressing field work to be done. Each dawn saw me leave the fort with my faithful dog Trusty, and turn my horse either toward the boundless prairie or the mountains of the Rio Grande.

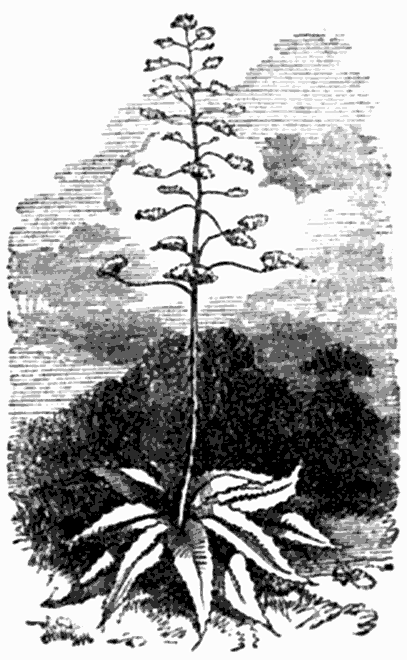

Very often hunting kept me away from home for several days, in which case I used to bivouac in the tall grass by the side of some prattling stream. Such oases, though not frequent, are found here and there on the prairies of the Far West, where the dark, lofty magnolias offer the wearied traveller refreshment beneath their thick foliage, and the stream at their base grants a cooling draught. One of these favourite spots of mine lay near the mountains, about ten miles from my abode. It was almost the only water far and wide, and here formed two ponds, whose depths I was never able to sound, although I lowered large stones fastened to upwards of a hundred yards of lasso. The small space between the two ponds was overshadowed by the most splendid magnolias, peca-nut trees, yuccas, evergreen oaks, &c., and begirt by a wall of cactuses, aloes, and other prickly plants. I often selected this place for hunting, because it always offered a large quantity of game of every description, and I was certain at any time of finding near this water hundreds of wild turkeys, which constitute a great dainty in the bill of fare of the solitary hunter.

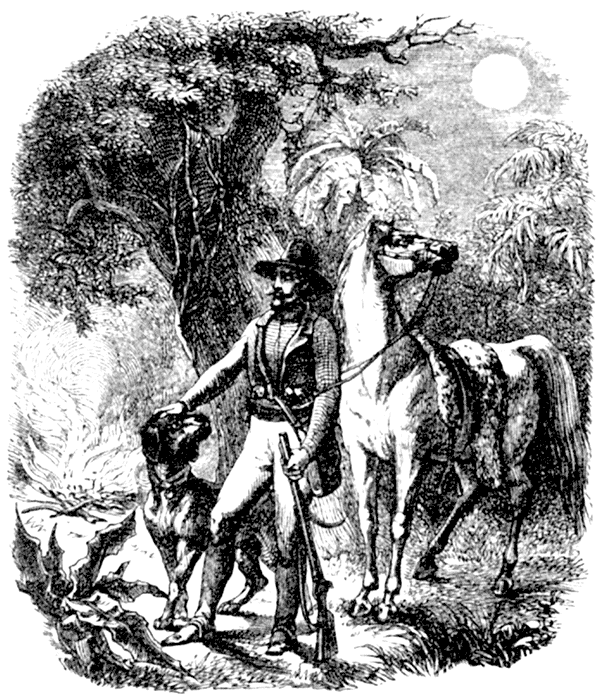

After a very hot spring day I had sought the ponds, as it was too late to ride home. The night was glorious; the magnolias and large-flowered cactuses diffused their vanilla perfume over me; myriads of fireflies continually darted over the plain, and a gallant mocking-bird poured forth its dulcet melody into the silent night above my head. The whole of nature seemed to be revelling in the beauty of this night, and thousands of insects sported round my small camp fire. It was such a night as the elves select for their gambols, and for a long time I gazed intently at the dark blue expanse above me. But, though the crystal springs incessantly bubbled up to the surface, the Lurleis would not visit me, for they have not yet strayed to America.

My dog and horse also played around me for a long time, until, quite tired, they lay down by the fire-side, and all three of us slept till dawn, when the gobbling of the turkeys aroused us. The morning was as lovely as the night. To the east the flat prairie bordered the horizon like a sea; the dark sky still glistened with the splendour of all its jewels, while the skirt of its garment was dipped in brilliant carmine; the night fled rapidly toward the mountains, and morn pursued it clad in his festal robes. The sun rose like a mighty ball over the prairie, and the heavy dew bowed the heads of the tender plants, as if they were offering their morning thanksgiving for the refreshment which had been granted them. I too was saturated with dew, and was obliged to hang my deerskin suit to dry at the fire; fortunately the leather had been smoked over a wood fire, which prevents it growing hard in drying. I freshened up the fire, boiled some coffee, roasted the breast of a turkey, into which I had previously rubbed pepper and salt, and finished breakfast with Trusty, while Czar, my famous white stallion, was greedily browzing on the damp grass, and turned his head away when I went up to him with the bridle. I hung up the rest of the turkey, as well as another I had shot on the previous evening, and a leg of deer meat, in the shadow of a magnolia, as I did not know whether I might not return to the spot that evening, saddled, and we were soon under weigh for the mountains, where I hoped to find buffalo.

I was riding slowly along a hollow in the prairie, when a rapidly approaching sound attracted my attention. In a few minutes a very old buffalo, covered with foam, dashed past me, and almost at the same moment a Comanche Indian pulled up his horse on the rising ground about fifty yards from me. As he had his bow ready to shoot the buffalo, the savage made his declaration of war more quickly than I, and his first arrow passed through my game bag sling, leather jacket and waistcoat to my right breast, while two others whizzed past my ear. To pluck out the arrow, seize a revolver, and dig the spurs into my horse, were but one operation; and a second later saw me within twenty yards of the Redskin, who had turned his horse round and was seeking safety in flight. After a chase of about two miles over awfully rough ground, where the slightest mistake might have broken my neck, the Indian's horse began to be winded, while Czar still held his head and tail erect. I rapidly drew nearer, in spite of the terrible blows the Redskin dealt his horse, and when about thirty paces behind the foe, I turned slightly to the left, in order, if I could, to avoid wounding his horse by my shot. I raised my revolver and fired, but at the same instant the Indian disappeared from sight, with the exception of his left foot, with which he held on to the saddle, while the rest of his body was suspended on the side away from me. With the cessation of the blows, however, the speed of his horse relaxed, and I was able to ride close up. Suddenly the Indian regained his seat and urged on his horse with the whip; I fired and missed again, for I aimed too high in my anxiety to spare the mustang. We went on thus at full gallop till we reached a very broad ravine, over which the Indian could not leap. He, therefore, dashed past my left hand, trying at the same moment to draw an arrow from the quiver over his left shoulder. I fired for the third time; with the shot the Comanche sank back on his horse's croup, hung on with his feet, and went about a hundred yards farther, when he fell motionless in the tall grass. As he passed me, I had noticed that he was bleeding from the right chest and mouth, and was probably already gone to the happy hunting-grounds. I galloped after the mustang, which soon surrendered, though with much trembling, to the pale face; I fastened its bridle to my saddle bow, led both horses into a neighbouring thicket, and reloaded my revolver.

I remained for about half-an-hour in my hiding-place, whence I could survey the landscape around, but none of the Indian's comrades made their appearance, and I, therefore, rode up to him to take his weapons. He was dead. The bullet had passed through his chest. I took his bow, quiver and buffalo hide, and sought for the arrows he had shot at me as I rode back. I resolved to pass the night at the ponds, not only to rest my animals, but also to conceal myself from the Indians who, I felt sure, were not far off. I was not alarmed about myself, but in the event of pursuit by superior numbers, I should have Trusty to protect, and might easily lose the mustang again.

I reached the springs without any impediment, turned my horses out to grass in the thicket, and rested myself in the cool shade of the trees hanging over the ponds. A calm, starry night set in, and lighted me on my ride home, which I reached after midnight. The mustang became one of my best horses. It grew much stronger, as it was only four years old when I captured it; and after being fed for awhile on maize, acquired extraordinary powers of endurance.

THE COMANCHES.

The summer passed away in hunting, farm-work, building houses, and other business, and during this period I had frequently visited the ponds. One evening I rode to them again in order to begin hunting from that point the next morning. If I shot buffaloes not too far from my house, I used to ride back, and at evening drove out with a two-wheeled cart, drawn by mules, to fetch the meat and salt it for the probable event of a siege. As I always had an ample supply of other articles for my garrison and cattle, and as I had plenty of water, I could resist an Indian attack for a long time. Large herds of buffalo always appear in the neighbourhood, so soon as the vegetation on the Rocky Mountains begins to die out, and the cold sets in. They spread over the evergreen prairies in bands of from five to eight hundred head, and I have often seen at one glance ten thousand of these relics of the primeval world. For a week past these wanderers had been moving southwards; but, though their appearance may be so agreeable to the hunter in these parts, it reminds him at the same time that his perils are greatly increased by their advent. Numerous tribes of horse Indians always follow these herds to the better pasturage and traverse the prairie in every direction, as they depend on the buffalo exclusively for food. The warmer climate during the winter also suits them better, as they more easily find forage for their large troops of horses and mules.

At a late hour I reached the ponds, after supplying myself en route with some fat venison. Before I lit my fire, I also shot two turkeys on the neighbouring trees, because at this season they are a great dainty, as they feed on the ripe oily peca-nuts. I sat till late over my small fire, cut every now and then a slice from the meat roasting on a spit, and bade my dog be quiet, who would not lie down, but constantly sniffed about with his broad nose to the ground, and growling sullenly. Czar, on the contrary, felt very jolly, had abundant food in the prairie grass, and snorted every now and then so lustily, that the old turkeys round us were startled from their sleep. It grew more and more quiet. Czar had lain down by my side, and only the unpleasant jeering too-whoot of the owl echoed through the night, and interrupted the monotonous chorus of the hunting wolves which never ceases in these parts. Trusty, my faithful watchman, was still sitting up with raised nose, when I sank back on my saddle and fell asleep. The morning was breaking when I awoke, saturated with dew; but I sprang up, shook myself, made up the fire, put meat on the spit and coffee to boil, and then leapt into the clear pond whose waters had so often refreshed me. After the bath I breakfasted, and it was not till I proceeded to saddle my horse that I noticed Trusty's great anxiety to call my attention to something. On following him, I found a great quantity of fresh Indian sign, and saw that a large number of horses had been grazing round the pond on the previous day. I examined my horse gear and weapons, opened a packet of cartridges for my double-barrelled rifle, and then rode in the direction of the Leone. I had scarce crossed the first upland and reached the prairie when Czar made an attempt to bolt, and looked round with a snort. I at once noticed a swarm of Comanches about half a mile behind me, and coming up at full speed. There was not a moment to lose in forming a resolution—I must either fly or return to my natural fortress at the springs. I decided on the latter course, as my enemies were already too near for my dog to reach the thicket or the Leone before them, for though the brave creature was remarkably powerful and swift-footed, he could not beat good horses in a long race.

I therefore turned Czar round, and flew back to the ponds. A narrow path which I had cut on my first visit through a wall of prickly plants led to the shady spot between the two ponds, which on the opposite side were joined by a broad swamp, so that I had only this narrow entrance to defend. The thicket soon received us. Czar was fastened by the bridle to a wild grape-vine; my long holster-pistols were thrust into the front of my hunting-shirt; the belt that held my revolvers was unbuckled, and I was ready for the attack of the savages. Trusty, too, had put up the stiff hair on his back, and by his growling showed that he was equally ready to do his part in the fight. The Indians had come within a few hundred yards, and were now circling round me with their frightful war-yell, swinging their buffalo-hides over their heads, and trying, by the strangest sounds and gestures, either to startle my horse or terrify me. I do not deny that, although used to such scenes, I felt an icy coldness down my back at the sight of these demons, and involuntarily thought of the operation of scalping. I remained as quiet as I could, however, and resolved not to expend a bullet in vain. The distance was gradually reduced, and the savages came within about a hundred and fifty yards, some even nearer. The boldest came within a hundred and twenty yards of me, while the others shot some dozen arrows at me, some of which wounded the sappy cactuses around me. The savages continually grew bolder, and it was time to open the ball, for attacking is half the battle when engaged with Indians.

I therefore aimed at the nearest man—a powerful, stout, rather elderly savage, mounted on a very fast golden-brown stallion—and at once saw that the bullet struck him: in his fall he pulled his horse round towards me, and dashed past within forty yards, which enabled me to see that the bullet had passed through his body, and he did not need a second. About one hundred yards farther on he kissed the ground. After the shot the band dashed off, and their yell was augmented to a roar more like that of a wounded buffalo than human voices. They assembled about half a mile distant, held a short consultation, and then returned like a whirlwind towards me with renewed yells. The attack was now seriously meant, although the sole peril I incurred was from arrows shot close to me. I led Czar a few paces in the rear behind a widely-spreading yucca, ordered Trusty to lie down under the cactuses, reloaded my gun, and, being a bit of Indian myself, I disappeared among the huge aloes in front of me, pulling my stout beaver hat over my eyes. I allowed the tornado to come within a hundred and sixty paces, when I raised my good rifle between the aloes, pulled the trigger, and saw through the smoke a Redskin bound in the air, and fall among the horses' hoofs. A dense dust concealed the band from sight, but a repetition of the yells reached my ear, and I soon saw the savages going away from me, whereon I gave them the contents of the second barrel, which had a good effect in spite of the distance, as I recognised in the fresh yells raised and the dispersion of the band. The Indians, ere long, halted a long way off; but after awhile continued their retreat. I understood these movements perfectly well: they wanted to give me time to leave my hiding-place, and then ride me down on the plain. Hence I waited till the Comanches were nearly two miles off, and watched them through my glass as they halted from time to time, and looked round at me. I was certain that we now had a sufficient start to reach the forest on the Leone without risk. My rifle was reloaded, and my pistols were placed in the holsters. I stepped out of my hiding-place and mounted my horse, which bore me at a rapid pace towards my home. The enemy scarce noticed my flight ere they dashed down from the heights after me like a storm-cloud. I did not hurry, however, for fear of fatiguing Trusty; but selected the buffalo paths corresponding with my direction, thousands of which intersect the prairies like a net, and at the end of the first mile felt convinced that we should reach the forest all right, which now rose more distinctly out of the sea of grass. So it was: we dashed into the first bushes only pursued by five Indians, where I rode behind some dwarf chestnuts, dismounted, and prepared to receive my enemies. They remained out of range, however, and in a short time retired again.

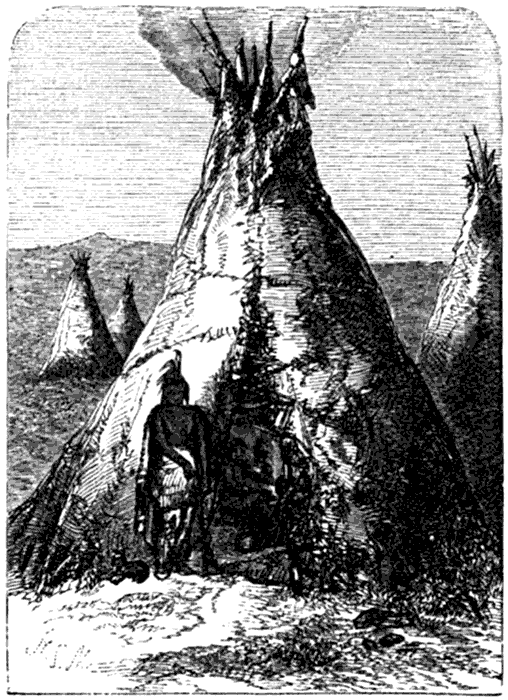

My readers will naturally ask why some thirty Indians allowed a single hunter to emerge from his hiding-place, and why they did not compel him to surrender by a short siege? The Comanches are horse Indians, who can only effect anything when mounted, and hence never continue a pursuit into a thicket. They never undertake any martial exploit by night; and, moreover, the Indian, when he goes into action, has very different ideas from a white man; for while the latter always thinks he will be the last to fall, every Redskin believes that he will be the first to be hit. At the same time, these tribes set a far higher value on the life of one of their warriors than we white men do, and they often told me that we pale-faces grew out of the ground like mushrooms, while it took them eighteen years to produce a warrior. The tribes are not large; they consist of only one hundred and fifty to three hundred men; they have their chief and are quite independent of the other clans, although belonging to the same nations. The Comanches, for instance, reckon thirty thousand souls, spread over the whole of the Far West. In consequence of the many sanguinary wars which the different tribes wage together, it is frequently of great consequence to a clan, whether it counts ten men more or less, and hence the anxiety felt by the savages about the life of their warriors. The Northern Indians have assumed many of the habits of the white men, and are advancing gradually towards civilization; they nearly all carry fire-arms, wear clothes, till the ground, and their squaws, children, and old men, live in villages together. Our Southern Indians are all at the lowest stage of civilization, are generally cannibals, have no home, follow the buffalo, on whose flesh they live, and have assumed none of our customs. At times they may get hold of a horse-cloth or a bit, which they have taken from a hunter or stolen from a border settlement, but in other respects they are children of nature; they go about almost naked, and only carry weapons of their own manufacture. Their long lance is a very dangerous weapon, owing to the skill with which they use it; and the same is the case with their bows, from which they discharge arrows at a distance of fifty yards, with such accuracy and force, as to pierce the largest buffalo. The lasso (a plaited rope of leather) is another weapon which they employ with extraordinary skill; they throw the noose at one end over the head of an enemy, then gallop off in the opposite direction, and drag their captive to death. There are but very few foot Indians in the South; they generally live in the mountains, as they are always at war with the horse savages, and would be at a disadvantage on the plains; but they are by far the most dangerous denizens of these parts, as the most of them are supplied with fire-arms, and try to overpower their enemy treacherously at night. The Weicos form the chief tribe of these foot Indians, and are pursued both by the mounted Redskins and the white borderers like the most dangerous of wild beasts: on their account I have often spent the night without fire, and have been startled from my sleep by the whoot of the owl, which they imitate admirably, as a distant signal to one another. In the conduct of the horse Indians there is something open and chivalrous, and I never hated them for chasing me; we contended for the possession of the land, which they certainly held first, but which nature assuredly created for a better object than that a few wild hordes should use it for their hunting and war forages. It always seemed to me an honourable contest between civilization and savageness when I was attacked by these steppe-horsemen, and I never felt that blood-thirsty hatred which beset me when I noticed the Weicos and Tonkaways creeping about like vipers. I more than once all but fell victim to their cunning, and it is always a pleasant memory that I frequently punished them severely for it.

A FIGHT WITH THE WEICOS.

As I mentioned, my fort stood on the south side of the Leone river, and in front of it lay one of the richest and most fertile prairies, which ran to the bank of Mustang Creek, a small stream running parallel to the Leone, beneath the shade of lofty peca-nut trees, magnolias, cypresses, and oaks, to join the Rio Grande. The prairie between the Leone and this stream was about five miles broad; and often, when I had spent the day at home, I rode off to pass the night there, in order to shoot at daybreak as much game as my horse could comfortably carry, and be back to breakfast. I had found, in a coppice close to the stream, a small grassy clearing, where Czar was always comfortable. Around it stood colossal primæval oaks and magnolias, in whose shade many varieties of evergreen bushes, such as myrtle, laurel, and rhododendron, formed an impenetrable thicket, as they were intertwined with pendant llianas and vines the thickness of my body. In this thicket I had built a sort of hut of buffalo hides, in which I hid away a frying-pan, an old axe, and a coffee-pot. At this spot I passed many a hot summer night, for I found there a cool, quiet bed, which the sun never reached, for myself and my faithful companions, and ran no risk of being betrayed by my camp-fire and disturbed by the Indians.

After one of these hot days, I rode Czar out of the fort, and Trusty, released from the chain, sprang joyfully at my horse's head, delighted at getting into the open country again, and the prospect of fresh deer or buffalo kidneys. We went slowly toward the thickly-wooded bank of the creek, which bordered the prairie ahead of us like a purple strip, through large gay fields of flowers, with which the prairie is adorned. Blue, yellow, red, and white beds, in the most varied hues, succeeded each other, and filled the air with the sweetest and most fragrant perfumes. Wherever the eye turned it fell on herds of deer, that were sheltering themselves from the burning sun under isolated elms and mosquito trees, and rose on our approach to be ready for flight. Further on grazed many herds of migratory buffaloes, from which the prairies at this season are never quite free, and, here and there, antelopes were flying over the heaving sea of grass and flowers. As I rode along, my eye was certainly rejoiced by this abundance of game, but I did not change my direction on that account, because I was not any great distance from the thickets in advance of the forest on Mustang Creek, where I could approach the game with much less trouble. These wooded intervals, which run for about a mile into the prairie, consist of dwarf plum-trees, four feet in height, partly separate, partly in clumps, which are closely interlaced with wild vines, but always leave small openings between, and here and there are overshadowed by a densely-foliaged elm. You are obliged to wind between these clumps till you reach a broad open grassy clearing, which extends between these thickets and the high woods on Mustang Creek.

I had hardly reached these advance woods, ere I saw a very large stag standing in the shadow of an old elm-tree, driving away the flies with its antlers, and feeding on the fine, sweet mosquito grass, which is much more tender in the shade than when it is exposed to the burning sunbeams. The beautiful creature was hardly sixty paces from me, and I seized my rifle, which was lying across the saddle in front of me. In a moment Czar, who was well acquainted with this movement, halted, buried his small head in the grass, and began seeking the green young shoots which are covered by the dry withered stalks. I shot the deer, and as I saw that it could not go far I allowed Trusty to catch it, which always afforded him great delight. I rode up, threw the bridle before dismounting over the end of a long pendant branch, and then dragged the deer into the shade to break it up, and cut off the meat I intended to take with me. I had knelt down by the deer and just thrust in my bowie knife, when Trusty, who was sitting not far from me, began growling, and on my inquiring what was the matter, growled still more loudly, while looking in the direction behind me. I knew the faithful creature so well that I only needed to look in his large eyes to read what he wished to tell me. They had turned red, a sure sign of his rising anger: but I believed that wolves were at hand, which were his most deadly enemies, because he had fared badly from their claws now and then before I could get up to free him from his tormentors. I ordered Trusty to be quiet, as I heeded the dangers which had beset me for years much less than I had done at the beginning of my border-life, and bent down again over the deer, when Trusty sprang, with furious barks, toward the quarter where he had been looking. I quickly rose, and on turning round saw two perfectly naked Indians, armed with guns, leap out of the tall grass about sixty yards from me, and dash away like antelopes. My first step was to seize my rifle, which was leaning against the tree, but the savages took an enormous bound over one of the clumps of plum-trees, and disappeared from sight. In a few minutes I had unfastened Czar, and rushed after the Indians through the many windings between the close-grown bushes. They had gained a great start, and had increased it by leaping over clumps, which I was compelled to ride round; still I kept them pretty constantly in sight, and reached the open prairie in front of the creek, at the moment when the savages had crossed about half of it. I gave Czar a slight touch of the spur, and urged him on with the usual pat on his powerful hard neck; he leaped through the grass as if he hardly touched the ground, and I was obliged to set my hat tightly on my head for fear of losing it, for the pressure of the atmosphere was so great that I could hardly breathe. The Indians ran like deer, but the distance between us was speedily lessened, and I was only sixty yards behind them, when they were still fifty from the forest. I stopped my horse, leaped off, aimed with my right-hand barrel at the savage furthest ahead, and dropped him. In the meanwhile the other Indian reached the skirt of the wood, and sprang into the shade of an old oak, at the moment when the bead of my rifle covered him. I fired and saw him turn head over heels. At this moment Trusty came panting over the prairie, who had remained behind as I had leapt over some clumps which he was obliged to skirt; he saw the first Indian leap out of the grass, like a hare which has been shot through the head, and his legs seemed too slow for his growing fury; a loud shout urged him on still more, and in a few seconds he and the savage disappeared in the tall grass. A frightfully shrill yell, which echoed far and wide through the forest, proved that the Indian was feeling Trusty's teeth, and the heaving grass over them showed that it was a struggle for life or death. Loading my rifle detained me for a few minutes at the spot whence I had fired; then I ran up to Czar, who had strayed a little distance, and rode to the battle-field. The contest was over; the savage was dead, and Trusty's handsome shaggy coat was spotted with blood. He was standing with his fore paws on his enemy, and tearing out his throat. A dog like Trusty was invaluable to me, and for my own preservation I dared not assuage the creature's savageness; besides, the man was dead, and it was a matter of indifference whether the buzzards devoured his body or Trusty tore it piece-meal. In the meanwhile I fastened the dead man's short Mexican escopeta, hunting-pouch, and necklace to my saddle; then I called Trusty off, mounted Czar, and rode back to my deer, as I did not dare venture into the forest, where a large number of these Weicos were very probably lying in ambush. The two had come down from the mountains to the banks of Mustang Creek, whither the great quantity of game of all descriptions had attracted them; on hearing my shot, they crept up unnoticed, had got within distance of me, and in a few seconds would doubtless have settled me, had not my faithful watcher scented them, or remarked their movements in the grass.

On coming within sight of my deer, I saw that a dozen buzzards had collected, some on the trees, others circling slowly in the air, and watching with envious glances three wolves, which had already begun greedily to share my deer. Although I hardly ever expended a bullet on these tormentors, I was annoyed at their impudence, for though they saw me coming, they did not interrupt their banquet. I shot one of them, a very old red she-wolf, took the loins and legs of the deer, hung them to my saddle, and rode home to pass the night.

My dogs inside the fort announced to the garrison the arrival of a stranger, and they were no little surprised to see me return at so unusual an hour. The gate was opened, and after Czar had been relieved of his rather heavy burden, I led him once more into the grass to let him have a good roll; and after he had been put into the stable with a feed of Indian corn, I described the events of the day at the supper-table. My news aroused the apprehensions of my men, for they knew the vengeful spirit of these Weicos, and we therefore resolved to keep watch during the night. We were still smoking and talking at midnight, when the dogs, of which I had fourteen, began making a tremendous row. They all ran out through the small apertures left for the purpose in the stockade, and stood barking on the river bank at some foe on the other side, at the spot where my maize field in the forest joined the river. It was a pitch dark and calm night. We listened attentively, and could distinctly hear the trampling of dry brushwood in the field. It might be occasioned by buffalo, which had broken through the fence, and were regaling on my maize. But these animals rarely move at night, and there was a much greater probability of Indians being there. We gently opened the gate. I took my large duck gun, which held sixteen pistol bullets in each barrel, and crawled down on my stomach to the river bank, where I lay perfectly quiet. When I arrived there, one of my dogs was yelping, and I distinctly heard the twang of a bow-string. I noticed the quarter very carefully; the river was only forty yards across, and the direction was shown me still more plainly by the crackling of brushwood. I shot one barrel there, upon which human cries and a hurried flight were audible; then I sent the second after it, and fresh groans echoed through the quiet forest and mingled with the roar of my two shots. I remained lying in the grass, as I might be easily seen against the starry sky from the other bank, which was thirty feet lower. The leaping and running through the maize retired farther and farther toward the wood, and scarce reached my ear, when suddenly a wild war yell resounded in the forest, which was answered by countless wolf howls on the prairie behind me. This was the last outbreak of fury on the part of the Indians, of whom I never saw anything more beyond the various bloody traces which they left in the field. We found several arrows sticking in the river bank, whose form led me to conclude that the assailants were Cato Indians. The damage I received from this nocturnal visit only consisted in the trampled maize and a harmless wound which one of my dogs had received from an arrow in the leg. The morning was spent in following the trail of the savages to the prairie on the other side of the forest, where a number of horses had awaited these night-wanderers and borne them away. In the afternoon I rode again to Mustang Creek with one of my people—to the spot where the second Indian had disappeared on the previous day. The entrance into the wood and the roots of the old oak were covered with blood. I sent Trusty on ahead to see whether the road was clear, and if we could penetrate into the gloom of the forest without danger. We cautiously followed the dog, who kept the blood-marked trail and reached the river, on whose bank the Weico was sleeping the last sleep. He was cold and stiff my bullet had passed through his brown sides. The wounds were stopped with grass, and his escopeta lay ready cocked close to him. He was a very young and handsome man, and death had chosen him a glorious resting-place under the dark arbour of leaves. The rapid, crystalline, icy stream laved his small, handsomely-shaped feet, and on a pillow of large ferns reposed his head, round which his raven silky hair fell, while the mossy bed beneath him was dyed by his blood, till it resembled the purple velvet of a lying-in-state.

We stood silently before this painfully-beautiful picture, and even Trusty seemed to feel that this was no longer an object for wild passion, for he lay down quietly in the grass. Death had reconciled us: the dice had fallen in my favour, and if they had been against me, I should not have found such an exquisite grave: my bones would have been bleached for years by the sun on the open prairie, and greeted with shouts of joy by passing Indians. Feelings which are rarely carried into these solitudes, and still more rarely retained there, gained the mastery over me. I could not leave this noble creation of nature to the wolves and buzzards. We therefore fastened a heavy stone round his feet, and another round his neck, and gently let him down into the clear water, where he found his last solitary resting-place between two large rocks. Taking his few traps, more as a reminiscence than as a booty, we returned to our horses, which we had left in the first thicket. They greeted us with their friendly neighing and impatient stamping while still a long distance off, and away we galloped over the open prairie, up hill and down hill, after a flying herd of buffalo, at one moment leaping across broad watercourses, at another over aged trees uprooted by storms, until several of these primæval monsters had kissed the blood-stained ground. Our melancholy thoughts had been dispersed by the light prairie breeze, and, merry and independent, like the vultures in the blue sky overhead, we returned heavily laden to our fort, whose inhabitants, down to the dogs, gave us a most hearty welcome.

HUNTING ADVENTURES.

It is scarce possible to form an idea of the abundance of game with which the country near me was blessed in those days. It really seemed to be augmented with every year of my residence, for which I may account by the fact that the several vagabond hordes of Indians—who prefer the flesh of deer, antelopes, and turkey to that of buffaloes, whose enormous mass they cannot devour at once, while the smaller descriptions of game could be killed in the forests and coppices, without revealing themselves to the enemy on the wide prairie—that these Indians, I say, more or less avoided my neighbourhood, while, for my part, I had greatly reduced the number of wild beasts, especially of the larger sort. I consumed a great quantity of meat in my household, owing to the number of dogs I kept, but I really procured it as if only amusing myself. There were certainly days on which I shot nothing. At times I did not get sight of a buffalo for a week, or the prairie grass was burnt down to the roots, which rendered it extremely difficult to stalk the game, while just at this period, when the first green shoots spring up, the animals principally visit the open plains, whence they can see their pursuers for a long distance. For all that, though we had generally a superabundance of meat, and too often behaved with unpardonable extravagance, I have frequently killed five or six buffaloes, each weighing from a thousand to fifteen hundred pounds, in one chase, lasting perhaps half-an-hour, and then merely carried off their tongues and marrow-bones. Often, too, I have shot one or two bears, weighing from five to eight hundred pounds, and only taken home their paws and a few ribs, because the distance was too great to burden my horse with a large supply of meat. I could always supply our stock in the vicinity of my fort, although at times we were compelled to put up with turkeys, or fish and turtle, with which our river literally swarmed.

Bear-meat formed an important item in our larder—or, more correctly speaking, bear's-grease—which was of service in a great many ways. We employed it to fry our food, for which buffalo or deer fat was not so good; we used it to burn in our lamps, to rub all our leather with, and keep it supple; we drank it as a medicine—in a word, it answered a thousand demands in our small household. This is the sole fatty substance, an immoderate use of which does not turn the stomach or entail any serious consequences. The transport of this article, though, was at times rather difficult, especially on a warm day; as this fat easily becomes liquid, and will even melt in the hunter's hand while he is paunching a bear. This is chiefly the case with the stomach fat, which is the finest and best; that on the back and the rest of the body, which at the fatting season is a good six inches thick, is harder and requires to be melted over a slow fire before it can be used in lamps.

These animals were very numerous in my neighbourhood. In spring and summer they visited the woods, where with their cubs they regaled upon wild plums, grapes, honey, and young game of all sorts, and at times played the deuce in my maize-field. In autumn the rich crop of peca-nuts, walnuts, acorns, chestnuts, and similar fruits, kept them in our forests; and in winter they sought rocky ravines and caves, where they hybernated. Very many took up their quarters in old hollow trees, so that at this season I had hardly any difficulty in finding a bear in my neighbourhood. Trusty was a first-rate hand at this, for he found a track, and kept to it as long as I pleased; and at the same time possessed the great advantage that he never required a leash, never went farther than I ordered him, and never followed game without my permission. When a bear rose before me it rarely got fifty paces away, unless it was in thorny bushes, where the dog could not escape its attack; for, so soon as the bear bolted, Trusty dug his teeth so furiously into its legs, and slipped away with such agility, that the bear soon gave up all attempts at flight, and stood at bay. It was laughable to see the trouble the bear was in when I came up; how it danced round Trusty, and with the most ridiculous entrechats upbraided his impudence; while Trusty continually sprang away, lay down before Bruin, and made the woods ring with his bass voice. Frequently, however, the honest dog incurred great peril during this sport, and his life more than once depended on my opportune arrival.

In this way I followed one warm autumn day a remarkably broad bear trail on the mountains of the Rio Grande. Trusty halting fifty yards ahead of me, showed me that it stopped at a small torrent, where the bear had watered on the previous night. I dismounted, examined the trail carefully, and saw that it was made by a very old fat bear; it was in the fatting season, when the bear frequently interrupts its sleep and pays a nocturnal visit to the water. At this season these animals are very clumsy and slow, and cannot run far, as they soon grow scant of breath; they soon stop, and can be easily killed by the hunter—always supposing that he can trust to his dog and horse, for any mistake might expose the rider to great danger. I ordered Trusty to follow the trail; it ran for some distance up the ravine, then went up the bare hill-side, which was covered with loose boulders and large masses of rock, into the valley on the opposite side, in the middle of which was a broad but very swampy pool, girdled by thick thorny bushes. Trusty halted in front of this thicket, looked round to me, and then again at the bushes, while wagging his long tail. I knew the meaning of this signal, and that the bear was not far off. I ordered the dog on, and drew a revolver from my belt; feeling assured that the bear would soon leave the underwood and seek safety in flight. Trusty disappeared in the bushes, and his powerful bark soon resounded through the narrow valley. It was an impossibility for me to ride through the thicket, hence I galloped to the end of the coppice, and saw there the bear going at a rapid pace up the opposite steep hill, with Trusty close at its heels. I tried to cross the swamp, but Czar retreated with a snort, as if to show me the danger of the enterprise. By this time Trusty had caught up to the bear at the top of the hill, and furiously attacked it in the rear. The bear darted round with extraordinary agility, and was within an ace of seizing Trusty, but after making a few springs at the dog, it continued its hurried flight, and disappeared with Trusty over the hill-top. I had ridden farther up the water when I heard my dog baying; I drove the spurs into my horse, and with one immense leap, we were both in the middle of the swamp up to the girths; then, with an indescribable effort, Czar gave three tremendous leaps, which sent black mud flying round us, and reached the opposite firm ground with his fore feet, while his hind quarters sunk in the quivering morass; with one spring I was over his head, when I sank in up to the knees, and after several tremendous exertions, the noble fellow sprang ashore, trembling all over. Trusty's barking, as if for help, continually reached me as I galloped up the steep hill-side; I arrived on the summit at the moment when the bear sprang at Trusty, and buried him beneath its enormous weight. My alarm for the faithful dog—my best friend in these solitudes, made me urge Czar on; he bounded like a cat over the remaining rocks, and I saw Trusty slip out from under the bear in some miraculous way, and attack it again on the flank. I halted about ten paces from the scene of action, held my rifle between the little red fiery eyes of the bright black monster, and laid it lifeless on the bare rocks. The greatest peril for dogs is at the moment when the bear is shot, for they are apt to attack it as it falls, and get crushed in its last convulsive throes. I leapt off Czar, who was greatly excited by the sharp ride, went up to Trusty, who was venting his fury on Bruin's throat, examined him, and found that he had received three very serious wounds, two on the back and one over the left shoulderblade, which were bleeding profusely, though in his fury he did not seem to notice them. I took my case from the holster and sewed up his wounds, during which operation he lay very patiently before me, and looked at me with his large eyes, as if asking whether this were necessary. Then I took off my jacket and set to work on the bear, stripped it, and put the hide as well as a hundred pounds' weight of the flesh on Czar's back. If my readers will bear in mind that the sun was shining on my back furiously, and that I was on a bare blazing rock, they will understand that I was worn out, and longed for a cool resting-place. The bear weighed at least 800 lbs., and it requires a great effort to turn such an animal over.

I was a good hour's ride from the shade of the Leone, and only half that distance to the mountain springs I have already described. I therefore selected the latter, although they took me rather farther from home. I walked, although I made Czar carry my jacket, weapons, and pouch, and reached my destination in the afternoon, with my two faithful companions at my heels. Czar had a hearty meal after I had bathed him in the pond, and poor Trusty, whose wounds had dried in the sun, and pained him terribly, felt comfortable in the cool grass, and did not disturb the linen rag which I moistened every now and then. Nor did I forget myself; I rested, bathed, and after awhile enjoyed the liver and tongue of the old vagabond, until the evening breeze had cooled the air, and I reached home partly on foot, partly on horseback.

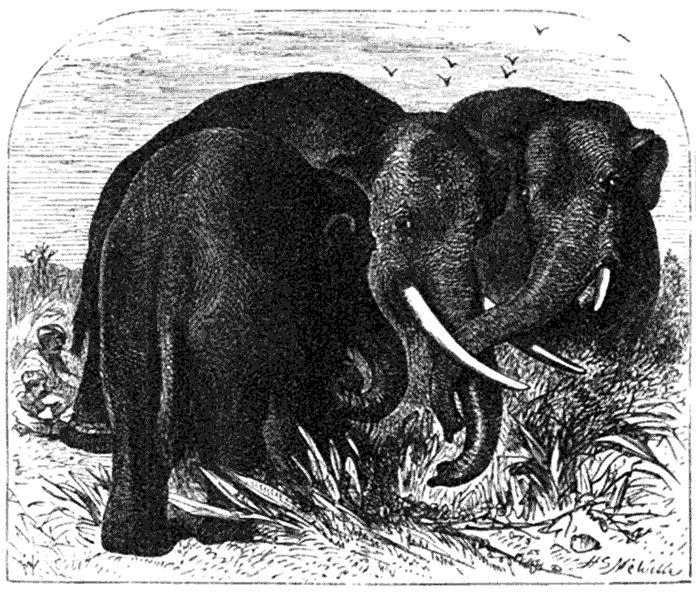

Nature seems to have selected the buffalo before all varieties of game for the purpose of bringing to the door of the man who first dares to carry civilization into the desert, abundant food for him and his during the first years, so that he may have time to complete the works connected with his settlement, and have no trouble in procuring provisions. When this time is passed, nature withdraws this liberal support from him; in the course of a few years he must go a long distance to obtain this food as a dainty, which he grew quite tired of in the early years, for the buffalo is not frightened by the pioneer's solitary house and field, but as soon as several appear, the animals depart and are only seen as stragglers.

The woolly hides of the buffaloes supply the new-comer in the desert with the most splendid and comfortable beds. When laid over the roof they protect his unfinished house from rain and storm; he uses their leather for saddles, boot-soles, making ropes of all sorts, traces, &c.; its meat, one of the most luxurious sorts that nature offers man, seems to be given to the borderer as a compensation for the countless privations and thousand dangers to which he subjects himself. Buffalo's marrow is a great delicacy, and very strengthening. The fat can be used in many ways, and the horns converted into drinking cups, powder flasks, &c.; in a word, the whole of the buffalo is turned to account in the settler's housekeeping.

These animals are hunted in several ways. With an enduring, well-trained horse, you ride up to them and shoot them with pistols or a rifle, for a horse accustomed to this chase always keeps a short distance from the buffalo, and requires no guidance with the reins; but this mode of hunting can only be employed on the plains, for in the mountainous regions the buffalo has a great advantage in its sure footing over a horse that has to carry a rider. In such regions, and in wooded districts, you stalk the animals, which is not difficult, and if you keep yourself concealed you may kill several with ease, as they are not startled by the mere report of a rifle. On the prairies, too, where the grass is rather high, you can creep up to them through it, and if it be not sufficiently tall to hide you, you make use of some large skin, such as a wolf's, and covered with this, crawl up within range. This, however, is always a dangerous plan, for if you are noticed by a wounded buffalo, you run a great risk of being trampled to death by it. On these crawling hunts, I always had Trusty a short distance behind me, who moved through the grass quite as cautiously as myself, and when it was necessary, I set him on, and had time to run to my horse, while Trusty attacked the buffalo and pinned it to the spot.

I always preferred riding after buffaloes, for this is one of the most exciting modes of hunting I am acquainted with, as it demands much skill from the rider and agility and training on the part of the horse. Horses that have been used to the sport for any time are extremely fond of it, and at the sight of the buffalo become so excited that there is a difficulty in holding them in. The revolver is the best weapon to use. You have the great advantage with it of firing several shots without reloading. I always carried two in my belt, which gave twelve shots, and also two spare cylinders. I also had my double rifle with me, which lay unfastened between me and the saddle cloth. The American revolvers are admirably made, and carry their bullets very accurately for a hundred yards; but at longer distances they cannot be depended on, as it is difficult to take aim with them. It requires considerable practice to kill a buffalo at a gallop, for you may send a dozen bullets into it, and yet not prevent it from continuing its clumsy-looking though very rapid progress. The buffalo's heart lies very deep in the chest behind the shoulder-blades; it can be easily missed through the eye being caught by the hump on the back; and besides, it requires very great practice to hit with a pistol when going at full speed. If you shoot the buffalo at the right spot, it drops at once, and frequently turns head over heels. The animal is in the best condition in spring, when it has changed its coat. At this season its head is adorned with long dark brown locks, and its hind-quarters are covered with shining black hair. So long as old tufts bleached by the sun are hanging about it it is not in prime condition, and the experienced hunter never selects such a quarry.

On a spring morning—I need not add a fine one, for at this season the blue sky rarely deserts us for more than a few hours—I rode at daybreak down the river toward the mountains; a cold, refreshing breeze was blowing, which had an invigorating effect upon both men and animals. Czar was full of playfulness. He often pretended to kick at Trusty, his dearest friend, who was trotting by his side, shook his broad neck, and could hardly be held in. Trusty ran ahead, every now and then rolled in the tall grass, kicked up the earth behind him, and then looked up at me with a loud bark of delight. I too was in an excellent humour; the small birds-of-paradise, with their long black and white tails and crimson breasts, fluttered from bush to bush. The humming birds darted past me like live coals, and suddenly stopped as if spell-bound in front of some flowers, whence they sucked the honey for a few seconds with their beaks, and then hummed off to another fragrant blossom. Countless vultures described their regular circles over my head; above them gleamed against the ultramarine sky the brilliant white plumage of a silver heron, or the splendid pink of a flamingo; whilst high up in ether the royal eagles were bathing in the sunshine. The prairie was more beautiful this day than I had ever seen it; it was adorned by every designation of bulbous plants, the prevailing flora in the spring.

Lost in admiration of these natural beauties, which words are powerless to describe, I reached the hilly ground near the mountain springs; and first learned from Czar's tugging at the bridle, and his repeated bounds, that I had come in sight of a herd of about forty buffaloes, that did not appear to notice me yet. Probably they were engaged with that portion of the beauties of nature which most interested them; for, at any rate, they all had their huge shaggy heads buried in the fresh young grass. I was never better inclined to have a jolly chase than on this day, and the same was the case with Czar and Trusty. I let loose the reins, drew a revolver, and dashed among the astounded herd, looking for a plump bull. Surprised and disturbed, these philosophers turned their heads towards the mountains, raised their tails erect, and started in their awkward gallop, with the exception of one old fellow, the very one I had selected for the attack. He looked after the fugitives for awhile, as if reproaching them with their cowardice; shook his wild shaggy mane several times, and then dashed furiously at me with his head down. I was so surprised at this unexpected attack that I did not fire, but turned my horse to fly. The buffalo pursued me some thousand yards, keeping rather close, while his companions halted, and seemed to be admiring the chivalric deed of their knight. At length he stopped, as he had convinced himself that he could not catch up to me, and stamped with his long-haired front legs till the dust flew up in a cloud around him. I turned my horse and raised my rifle, to make more sure of hitting the bull, as his determined conduct had imbued me with some degree of respect. I fired, and wounded him in the side a little too far back; at the same instant he dashed ahead again, but then thought better of it, and tried to rejoin the flying herd. I now set Trusty on him, who soon brought him at bay, and I gave him a bullet from the revolver. Again he rushed at me, and again fled. In this way, pursuing and pursued in turn, I had given him five bullets, when he left the herd in a perfect state of mania, and dashed after me. I made a short turn with my horse; the bull rushed past; I turned Czar again towards the buffalo; and as I passed I put a bullet through his heart at the distance of three yards. The monster fell to the ground in a cloud of dust, and raised up a heap of loose sand which it stained with its dark blood.

To my surprise I noticed that Trusty did not come up to the fallen buffalo, but rushed past it, loudly barking, to the thicket at the springs, whence I saw an immense panther leap through the prickly plants. I galloped round the ponds and saw the royal brute making enormous leaps through the tall prairie grass toward the mountains. Trusty was not idle either, and was close behind it. I spurred Czar, and kept rather nearer the mountains, so as to cut off the fugitive's retreat and drive it farther out on the plains, while my hunting cry incessantly rang in its ears. It had galloped about a mile, when we got rather close to it; it altered its course once more, and climbed up an old evergreen live oak, among whose leafy branches it disappeared. I called Trusty to heel, stopped about fifty yards from the oak to reload my right-hand barrel, and then rode slowly round, looking for a gap in the foliage through which to catch a glimpse of this most dangerous animal. The leaves were very close, and I had ridden nearly round, when I suddenly saw its eyes glaring at me from one of the main branches in the middle of the tree. I must shoot it dead, or else it would be a very risky enterprise; and Czar's breathing was too violent for me to fire from his back with any certainty. I cautiously dismounted, keeping my eye on the panther, held a revolver in my left hand, brought the bead of my rifle to bear right between the eyes of the king of these solitudes—and fired. With a heavy bump the panther fell from branch to branch, and lay motionless on the ground. I kept Trusty back, waited a few moments to see whether the jaguar was really dead, as I did not wish to injure the beautiful skin by a second bullet unnecessarily, then walked up and found that the bullet had passed through the left eye into the brain. It had one of the handsomest skins I ever took; it is so large that I can quite wrap myself up in it, and now forms my bed coverlet. When I had finished skinning it and cut out the tusks with the small axe I always carried in a leathern case, I rode back to my buffalo, with the skin proudly hanging down on either side of my horse. On getting there I led Czar through the narrow entrance into the thicket, where I came upon a freshly killed, large deer, one of whose legs was half eaten away. It was the last meal of the savage beast of prey, and I was surprised it had left its quarry. The noise of the buffalo and the horse galloping, Trusty's bass voice, and the crack of the revolver in such close vicinity, must have appeared dangerous to it, and it had fancied it could slip off unnoticed.

My buffalo was very plump; it supplied me and Trusty with an excellent dinner, and for dessert I had the marrow-bones, roasted on the fire and split open with my axe, which, when peppered and salted, are a great delicacy. A little old brandy from my flask, mixed with the cold spring water, was a substitute for champagne; my sofa was the body of the deer, covered with the skin of its assassin.

THE NATURALIST.

Years had passed since the first establishment of my settlement, but it was still the greatest rarity to see a strange white face among us; and though I visited the nearest town more frequently than at the outset, it led to no settled intercourse. I rode there several times a year, taking to market on mules my stock of hides, wax, tallow, &c., and brought back provisions, tools, powder, and lead. On these occasions I received the letters which had arrived for me in the interval, posted my own, took my packets of books forwarded from New York, and then my intercourse with the world was at an end for six months. The mules and horses certainly left traces during these rides in the clayey soil, but they were soon destroyed by heavy rains or trampled by herds of passing buffaloes, and thus hidden from the most acute eyes. Moreover, on these journeys I never kept the same road, as I always guided myself by the compass, and altered my course according to the seasons, as I had to pass spots which were inundated at certain periods, and others where water at times was very scarce. The first two-thirds of the country was a wretched sandy region, without grass, on which stunted oaks grew here and there, very mountainous and dry, where no one would dream of settling or undergoing the perils of a pioneer for the sake of the land. Nearer to me no one ventured to come, as many attempts had been made to settle on this fertile soil, but had all turned out unhappily; the last of them entailing the destruction of a family of nineteen persons: on my hunting expeditions I often saw their bones bleaching in the sun. As I said, no change had occurred in my position, save that my mode of life was safer and more comfortable; the country alone still remained a solitude, which no isolated visitor could enter without staking his scalp.

Hence I was greatly surprised one morning when the sentry came into my house and informed me that a white man was riding alone along the river, mounted on a mule, which is the most unsuitable of animals in the Indian country. I ran with a telescope to the turret at the south-east end of the fort, and not only found the watchman's statement confirmed, but also that the man had not even a weapon; unless it was hidden in two enormous packs which dangled on each side of his mule. The rider drew nearer, at one moment emerging on the ridges, and then disappearing again in the hollows. At length our growing curiosity was satisfied, and a white man, a German, saluted us with an innocently calm smile. On my asking how he had come here alone and unarmed, he said cheerfully:—"Well, from the settlement. I was able to find your mule-track quite easily. Mr. Jones accompanied me for a whole day, and during the last four I have seen nobody." It soon came out that his name was Kreger, and that he was a botanist who had come to examine the Flora about us, which had not yet been collected. For this purpose he brought with him two enormous bundles of blotting-paper, which hung on his Lizzy—so he called his gallant charger—and, like woolbags in a battery, might have protected him against Indian arrows, if he had had any missiles to reply with; but he only had a pistol in his trowsers' pocket, which would not go off, in spite of all the experiments we made with it. Everybody had warned him of the danger to which he exposed himself on his journey to me; and the last pioneer he passed, a Mr. Jones, had tried to keep him back by force, but he had merely laughed, and declared that an Indian could not touch him on his Lizzy.

There are men who wantonly rush into perils because danger has something attractive for them, and who seek them in order to have an opportunity of expending the energy they feel within them; there are others who incur danger in order to display themselves to the world as heroes, though their courage is not very genuine; lastly, there are men who expose themselves calmly and delightedly to great dangers, because they are entirely ignorant of them, and cannot be persuaded of their existence till they are surprised and destroyed by them. Such a man was our new acquaintance, Mr. Kreger: we all tried to make him understand how madly he had behaved, and that it was only by a miracle he had escaped the notice of the Redskins, which must have entailed his inevitable death, during his long solitary journey to us, and while sleeping at night by a large fire. He merely smiled at it all, and said that it could not be quite so bad, while making repeated applications to his snuff-box. As regarded his intentions of making his excursions from my house, I told him it was impossible; because when I went out hunting I did not waste my time over plants, and he, as no sportsman, would be a nuisance to me; on the other hand, we could not think of letting him wander about alone, the danger of which I confirmed by telling him various adventures of mine. For all this, I received him hospitably; gave him a place to sleep in, and a seat at table; showed him where to find corn for Lizzy, where he could wash his sheets—in a word, made him as comfortable as lay in my power.

I had long intended to explore more distant countries than those I had visited during my sporting excursions, especially the continuation of our plateaux to the north, and had made my arrangements for this tour, when Mr. Kreger surprised us by his advent. On the day after his arrival we took a walk round the fort and the garden, during which he broke off the conversation every moment, and plucked some rare plant to put in his herbal, which he called his cannon; and laughed at the revolver in my belt and the rifle I carried. I told him that I intended to make a journey, in which, if he liked to accompany me, he would be able to make his researches, as my hunting on this trip would be restricted to my meat supply. He was delighted, and agreed to come with me; to which I consented on condition of his riding one of my horses, and I recommended the mustang, whose powers of endurance I knew and tried to prove by telling him how it came into my possession. But it was of no avail, for none of my cattle possessed the qualities of his Lizzy; and he offered a bet that no one could catch her. For the sake of the joke, the mustang and the mule were soon saddled; a mosquito tree on the prairie, about half a mile from the fort, was selected as the goal; and away we started through the tall grass. It was really surprising how fast Lizzy went, cocking up her rat-like tail and long ears; she accepted with pleasure the shower of blows that fell on her, and reached the goal only twenty yards behind me. I laughed most heartily at the amusing appearance of our naturalist, and expressed my admiration at his mule's pace; but remarked at the same time, that for no consideration in the world would I ride her in the country I intended visiting, because I was well acquainted with the obstinacy of mules, and knew that when called on to show their speed they refuse to do so, and neither fire nor sword could induce them. All such remarks, however, produced no change in Kreger's invincible faith in his favourite; and, as if he had assumed a portion of Lizzy's obstinacy through his long friendly relations with her, he irrevocably adhered to his resolution of only entrusting his carcass to her during the impending excursion.

Our preparations, which were very simple, occupied us about a week; they consisted in removing Czar's shoes, and rubbing his hoofs frequently with bear's grease, for the Indians follow the track of a shoed horse as wolves do a deer's bleeding trail; in grinding coffee, and forcing it into bladders, and in plaiting two new lassos, for which I fetched two new buffalo hides, in which chase the botanist accompanied me, and felt a pride in having given me an indubitable proof of his Lizzy's powers, for she followed close at Czar's tail during the entire hunt. Mr. Kreger assisted me in making the lassos. The hide is fastened tight on the ground with wooden pegs, a very sharp knife is thrust into the centre, and a strip about the breadth of a finger is cut, until the whole hide is transferred into one very long line, which, though not so long as the one with which Dido measured the ground to build Carthage on, attained a very great length. This strip was then fastened between trees, the hair shaved off with a knife, after which it was cut into five equal lengths, and these were plaited into a lasso about forty feet long, which was once more fastened between trees, with heavy weights attached to it, and thus stretched to its fullest extent. When such a line has been dried in the open air, it is rubbed with bear's grease, through which it always remains soft and supple, and will resist a tremendous pull. The one made by Mr. Kreger, though not plaited so smoothly and regularly, was useful, and afforded him great pleasure as a perfection of his Lizzy's equipment. One end of this lasso is fastened round the horse's neck; it is rolled up, fastened by a loop to the saddle, undone when the animal is grazing, and bound round a tree or bush.

The day for our start arrived, and the morning was spent in saddling our horses and arranging our baggage in the most suitable way for both horse and rider, a most important thing in these hot regions, for the horse's back is easily galled, and then you are compelled to go on foot, which is very wearisome and fatiguing in a country where there are no roads. The naturalist at length completed his equipment of Lizzy, who looked more like a rhinoceros than a cross between a horse and a donkey. In front of the saddle hung the two bales of blotting paper over the large bearskin holsters, which, in addition to two pistols I had supplied, were crammed with biscuit, coffee, pepper and salt, snuff, &c. Over the saddle hung two leathern bags, fastened together by a strap, on which the rider had his seat. Behind the saddle, a frying-pan, coffee-pot, and tin mug, produced a far from pleasing harmony at every movement of the animal. Over the whole of this a gigantic buffalo hide was stretched, and fastened with a surcingle round Lizzy's stout body, so that, like a tortoise, she only displayed her head and tail, and caused a spectator the greatest doubt as to what genus of quadruped she belonged. In order to complete the picture, Lizzy had two enormous bushes of a summer plant, which we call "Spanish mulberry," stuck behind her ears, as a first-rate specific to keep the flies off. I had repeatedly told Kreger of the absurdity of covering Lizzy with this coat of mail, in which she would melt away. But he said that I too had a skin over my saddle, and he wanted his to protect him at night against rain and dew. On the back of this monster our naturalist mounted, dressed in a long reddish homespun coat, trowsers of the same material, though rather more faded, with Mexican spurs on his heels with wheels the size of a dollar, and a broad-brimmed felt hat, under which his long face with the large light-blue eyes and eternally-smiling mouth peeped out. Over his right shoulder hung his huge botanizing case, and over his left a double-barrelled gun of mine loaded with slugs; his hat Mr. Kreger had also adorned with a green bush, and sitting erect in his wooden Mexican stirrups, he swung his whip, and declared his readiness to start. I rode Czar, and the only difference from my ordinary equipment was that I had a bag full of provisions hung on the saddle behind me; this and a little more powder and lead than usual, was all the extra weight Czar had to carry, and too insignificant for him to feel. With a truly heavy heart I bade good-bye to Trusty, and most earnestly commended him to the care of my men. I could not take him with me to an unknown country, where I might feel certain of getting into situations where I must trust to the speed of my horse, and Trusty might easily get into trouble. The firearms I left at the service of my garrison, and consisting of nearly fifty rifles and fowling pieces, were carefully inspected. We then rode off, and soon heard the gate of the fort bolted after us.

It was the afternoon when we rode down to the river-side and waded through the stream. For the stranger this river is most beautiful and charming, for at its greatest depth it is so clear, that, were it not for its motion and the leaves, brushwood, &c., floating on it, it would be doubtful to say whether it contained any water or not. This is noticed more especially with horses which have to cross such a stream for the first time; generally they object, and look down at the water, whose depth they are unable to gauge. You see the stones at the bottom as clearly as if there were no water, and can distinctly watch the slightest movements of the countless fish and turtle with which the streams in my neighbourhood swarm. At the same time the banks are covered with the most luxurious vegetation, and the gigantic vines cross it from the tops of the trees, and are in their turn intertwined with other creepers so as to form a hanging wood over the darting waters. Most of these creepers adorn the woods with a magnificent show of flowers, and some trees are so overgrown with them, that none of their own foliage is visible. The stream in these rivers is so violent that it is very dangerous to ride through them, especially at spots where the water is deep enough to reach the horse's girths, and the danger is heightened by the extremely slippery soap stones which cover the bottom.

I rode first into the river, and Lizzy followed obediently after me, though it cost some persuasion to make my companion refrain from riding a few yards lower down in order to pluck some specimens of the beautiful aquatic plants growing on the surface, for he fancied it was no depth, while he and his Lizzy, heavily laden as they were, would have sunk, and never reached the bank again alive. I remember, while hunting, swimming on horseback through places where the current was extremely violent, and carried away my dog, which reached the bank eventually, bruised by the rocks and bleeding terribly. We reached the opposite side without any difficulty, and followed a deep-trodden buffalo path into the forest; which runs with a breadth of several miles along the river. After you have been riding ever so short a time in the sun, you feel the benefit of the gloomy and impenetrable shade of such a forest in an extraordinary degree; the air beneath the leafy aisles seems quite different; it is not only cool and refreshing, but appears to have been purified in its passage through the leaves, for these forests grow on elevated ground, where no swamps or standing waters poison the air with the exhalations of putrified vegetable matter, as is the case on the banks of the Mississippi and other eastern rivers of America. There is not a more majestic or imposing sight than such a forest; trees of the most gigantic size grow in the wildest confusion, strangest shapes, and most varied hues, so closely together that you cannot understand where all their roots find room. You see, perhaps, twenty varieties of the oak, among which the burrel oak is the handsomest and largest; it is eight feet in diameter, and its stem measures forty feet to the first branches, while its crown attains a height of one hundred and fifty to two hundred feet. On the river banks cypresses stand side by side for miles, so close together that there is hardly room for a man to pass between them. The black walnut, the tulip tree, the peca-nut, several sorts of elms, the mulberry, maples, ashes, planes, poplars, &c., press against each other, and wherever death makes a gap and restores one of these giant trees to the earth, young shoots start up from its dust in the opening through which the blue sky is visible, and soon fill up the room. Countless varieties of smaller trees flourish in this gloom, and force their way between the colossi of vegetation, for instance, the wild cherry, wild plum, a small chestnut, and several species of nut trees; beneath these the bushes and cactuses spread with an incredible variety, and relieve the gloom with their magnificently coloured perfumed flowers, which seem to maintain an eternal rivalry with the blossoms of the llianas swinging from tree to tree in the airy height. Finally, the earth itself, beneath the darkest bushes, is covered with a dense carpet of delicate plants, which, although hidden from every sunbeam, are not the less worthy of being sought by the fervent admirer of the masterpieces of nature; they gleam like subterranean fires in the shade, and diffuse their perfume far around in this palace of foliage.

The queen of the whole virgin forest, however, is the magnolia. It raises its haughty head one hundred and fifty feet above a silver grey, smooth trunk, spreads its branches regularly far around, and is so closely covered with its broad, dark green, smooth and shining leaves, that its branches are rarely illumined by a sunbeam. Among this dark mass of foliage, which is unchanged throughout the year, it puts forth in spring its large snow-white roses, with orange petals, in such profusion that you can hardly see whether white or green is the fundamental colour. Far around it spreads a perfume of vanilla which is so strong that it is dangerous to sleep under the tree unless a breeze be blowing. The flowers last a long time, and as the pearls fall one by one on the ground, their place is taken by a bunch of berries, redder and more fiery than any colour on an artist's palette. They gleam far and wide through the majestic forest like candelabra in a cathedral.

Our path ran with a hundred windings through the solemn silence; it seemed as if every living creature that had sought this sanctuary, or fled from the heated plain, were silently revelling in its beauty and gratefully reposing in its coolness; not a bird or insect could be heard, not even the sound of a falling leaf interrupted the tranquillity, and only the footfalls of our animals and the snorting of Czar echoed through the forest. Too soon for us, too soon for our horses, we reached the end of our path, where it entered the prairie on the other side, after we had walked the greater part of the distance, because the crossing creepers frequently compelled us to bow our heads under them, as the makers of the path did, for we saw their brown shaggy hair floating in all directions. We followed the path into the prairie, which begins about two miles from the forest. On either side of the path deer sprang out of the bushes, and flocks of turkeys darted backwards and forwards with long, quick steps in front of us. The former I left undisturbed, but I shot one old fat turkey-cock, and hung it on the saddle behind me.

The sun was rather low when we rode through the wide prairie, and we could only advance slowly because the grass at many spots came up to my horse's back; our cattle were very worn, and poor Lizzy panted painfully under her harness, while the perspiration poured from her in streams. The sun was setting when we reached a small affluent of the Leone, where I knew of a good camping place, at which I determined to spend the night. We unloaded our animals, which I soon completed, as I merely undid the belly-band, pulled saddle and all over Czar's croupe, removed the bit, and then gave him a few taps on his damp back, as a sign that he could go wherever he pleased. My companion was much longer in removing all the articles of his household from Lizzy's back; and when he had finished she was a gruesome sight. White foam and dust had matted her long hair, her ears hung down and almost touched the ground, and her generally melancholy face was rendered still more so by the bushes waving over it. I really felt sorry for the poor wretch, and bluntly told Mr. Kreger that I would not ride a step farther with him unless he left the buffalo hide here. He was also convinced by his Lizzy's wretched appearance, that she could not carry this weight for long, and we agreed, that I should tan the hide of the first deer I shot, and let him use it. Lizzy was led into the grass and tied to a bush, and we arranged our bivouac for the night. Kreger fetched dry wood and water. I lit the fire, set coffee to boil, spitted strips of the turkey breast and liver, rubbed the meat in with pepper and salt, and put it to roast. Then I laid my horse-rug on the grass, with the saddle, holsters, and saddle-bag on it, hung the bridle and lasso on a branch, and took my seat in front of the fire on my tiger skin, while watching the naturalist, who was making a thousand arrangements, as if we were going to remain at least a month here.