|

Transcriber’s note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME XI SLICE IV

G to Gaskell Elizabeth

Articles in This Slice

| G | GALLUPPI, PASQUALE |

| GABBRO | GALLUS, CORNELIUS |

| GABEL, KRISTOFFER | GALLUS, GAIUS AELIUS |

| GABELENTZ, HANS CONON VON DER | GALLUS, GAIUS CESTIUS |

| GABELLE | GALLUS, GAIUS SULPICIUS |

| GABERDINE | GALOIS, EVARISTE |

| GABES | GALSTON |

| GABII | GALT, SIR ALEXANDER TILLOCH |

| GABINIUS, AULUS | GALT, JOHN |

| GABION | GALT |

| GABLE | GALTON, SIR FRANCIS |

| GABLER, GEORG ANDREAS | GALUPPI, BALDASSARE |

| GABLER, JOHANN PHILIPP | GALVANI, LUIGI |

| GABLETS | GALVANIZED IRON |

| GABLONZ | GALVANOMETER |

| GABORIAU, ÉMILE | GALVESTON |

| GABRIEL | GALWAY (county of Ireland) |

| GABRIEL HOUNDS | GALWAY (town of Ireland) |

| GABRIELI, GIOVANNI | GAMA, VASCO DA |

| GABUN | GAMALIEL |

| GACE BRULÉ | GAMBETTA, LÉON |

| GACHARD, LOUIS PROSPER | GAMBIA (river of West Africa) |

| GAD | GAMBIA (country of West Africa) |

| GADAG | GAMBIER, JAMES GAMBIER, |

| GADARA | GAMBIER |

| GADDI | GAMBOGE |

| GADE, NIELS WILHELM | GAMBRINUS |

| GADOLINIUM | GAME |

| GADSDEN, CHRISTOPHER | GAME LAWS |

| GADSDEN, JAMES | GAMES, CLASSICAL |

| GADWALL | GAMING AND WAGERING |

| GAEKWAR | GAMUT |

| GAETA | GANDAK |

| GAETANI | GANDAMAK |

| GAETULIA | GANDERSHEIM |

| GAGE, LYMAN JUDSON | GANDHARVA |

| GAGE, THOMAS | GANDÍA |

| GAGE | GANDO |

| GAGERN, HANS CHRISTOPH ERNST | GANESA |

| GAHANBAR | GANGES |

| GAIGNIÈRES, FRANÇOIS ROGER DE | GANGOTRI |

| GAIL, JEAN BAPTISTE | GANGPUR |

| GAILLAC | GANGRENE |

| GAILLARD, GABRIEL HENRI | GANILH, CHARLES |

| GAINESVILLE (Florida, U.S.A.) | GANJAM |

| GAINESVILLE (Texas, U.S.A.) | GANNAL, JEAN NICOLAS |

| GAINSBOROUGH, THOMAS | GANNET |

| GAINSBOROUGH | GANODONTA |

| GAIRDNER, JAMES | GANS, EDUARD |

| GAIRLOCH | GÄNSBACHER, JOHANN BAPTIST |

| GAISERIC | GANTÉ |

| GAISFORD, THOMAS | GANYMEDE |

| GAIUS | GAO |

| GAIUS CAESAR | GAOL |

| GALAGO | GAON |

| GALANGAL | GAP |

| GALAPAGOS ISLANDS | GAPAN |

| GALASHIELS | GARARISH |

| GALATIA | GARASHANIN, ILIYA |

| GALATIANS, EPISTLE TO THE | GARAT, DOMINIQUE JOSEPH |

| GALATINA | GARAT, PIERRE-JEAN |

| GALATZ | GARAY, JÁNOS |

| GALAXY | GARBLE |

| GALBA, SERVIUS SULPICIUS (Roman general and orator) | GARÇÃO, PEDRO ANTONIO JOAQUIM CORRÊA |

| GALBA, SERVIUS SULPICIUS (Roman emperor) | GARCIA (DEL POPOLO VICENTO), MANOEL |

| GALBANUM | GARCÍA DE LA HUERTA, VICENTE ANTONIO |

| GALCHAS | GARCÍA DE PAREDES, DIEGO |

| GALE, THEOPHILUS | GARCÍA GUTIÉRREZ, ANTONIO |

| GALE, THOMAS | GARD |

| GALE | GARDA, LAKE OF |

| GALEN, CHRISTOPH BERNHARD | GARDANE, CLAUDE MATTHIEU |

| GALEN, CLAUDIUS | GARDELEGEN |

| GALENA (Illinois, U.S.A.) | GARDEN |

| GALENA (Kansas, U.S.A.) | GARDENIA |

| GALENA (ore of lead) | GARDINER, JAMES |

| GALEOPITHECUS | GARDINER, SAMUEL RAWSON |

| GALERIUS | GARDINER, STEPHEN |

| GALESBURG | GARDINER |

| GALGĀCUS | GARDNER, PERCY |

| GALIANI, FERDINANDO | GARDNER |

| GALICIA (crownland of Austria) | GARE-FOWL |

| GALICIA (province of Spain) | GARFIELD, JAMES ABRAM |

| GALIGNANI, GIOVANNI ANTONIO | GAR-FISH |

| GALILEE (province of Palestine) | GARGANEY |

| GALILEE (architectural term) | GARGANO, MONTE |

| GALILEE, SEA OF | GARGOYLE |

| GALILEO GALILEI | GARHWAL |

| GALION | GARIBALDI, GIUSEPPE |

| GALL, FRANZ JOSEPH | GARIN LE LOHERAIN |

| GALL | GARLAND, JOHN |

| GALLABAT | GARLIC |

| GALLAIT, LOUIS | GARNET, HENRY |

| GALLAND, ANTOINE | GARNET |

| GALLARATE | GARNETT, RICHARD |

| GALLARS, NICOLAS DES | GARNIER, CLÉMENT JOSEPH |

| GALLAS, MATTHIAS | GARNIER, GERMAIN |

| GALLAS | GARNIER, JEAN LOUIS CHARLES |

| GALLATIN, ALBERT | GARNIER, MARIE JOSEPH FRANÇOIS |

| GALLAUDET, THOMAS HOPKINS | GARNIER, ROBERT |

| GALLE | GARNIER-PAGÈS, ÉTIENNE JOSEPH LOUIS |

| GALLENGA, ANTONIO CARLO NAPOLEONE | GARNISH |

| GALLERY | GARO HILLS |

| GALLEY | GARONNE |

| GALLIA CISALPINA | GARRET |

| GALLIC ACID | GARRETT, JOÃO BAPTISTA DA SILVA LEITÃO DE ALMEIDA |

| GALLICANISM | GARRETTING |

| GALLIENI, JOSEPH SIMON | GARRICK, DAVID |

| GALLIENUS, PUBLIUS LICINIUS EGNATIUS | GARRISON, WILLIAM LLOYD |

| GALLIFFET, GASTON ALEXANDRE AUGUSTE | GARRISON |

| GALLIO, JUNIUS ANNAEUS | GARROTE |

| GALLIPOLI (Italy) | GARRUCHA |

| GALLIPOLI (Turkey) | GARSTON |

| GALLIPOLIS | GARTH, SIR SAMUEL |

| GALLITZIN, DEMETRIUS AUGUSTINE | GARTOK |

| GALLIUM | GARY |

| GALLON | GAS |

| GALLOWAY, JOSEPH | GASCOIGNE, GEORGE |

| GALLOWAY, THOMAS | GASCOIGNE, SIR WILLIAM |

| GALLOWAY | GASCONY |

| GALLOWS | GAS ENGINE |

| GALLS | GASKELL, ELIZABETH CLEGHORN |

377

G The form of this letter which is familiar to us is an

invention of the Romans, who had previously converted

the third symbol of the alphabet into a representative

of a k-sound (see C). Throughout the whole of Roman

history C remained as the symbol for G in the abbreviations

C and Cn. for the proper names Gaius and Gnaeus. According

to Plutarch (Roman Questions, 54, 59) the symbol for G was

invented by Spurius Carvilius Ruga about 293 B.C. This probably

means that he was the first person to spell his cognomen

RVGA instead of RVCA. G came to occupy the seventh place

in the Roman alphabet which had earlier been taken by Z,

because between 450 B.C. and 350 B.C. the z-sounds of Latin

passed into r, names like Papisius and Fusius in that period

becoming Papirius and Furius (see Z), so that the letter z had

become superfluous. According to the late writer Martianus

Capella z was removed from the alphabet by the censor Appius

Claudius Caecus in 312 B.C. To Claudius the insertion of G into

the alphabet is also sometimes ascribed.

In the earliest form the difference from C is very slight, the

lower lip of the crescent merely rising up in a straight line  ,

but

,

but  and

and  are found also in republican times. In the earliest

Roman inscription which was found in the Forum in 1899 the

form is

are found also in republican times. In the earliest

Roman inscription which was found in the Forum in 1899 the

form is  written from right to left, but the hollow at the bottom

lip of the crescent is an accidental pit in the stone and not a

diacritical mark. The unvoiced sound in this inscription is

represented by K. The use of the new form was not firmly

established till after the middle of the 3rd century B.C.

written from right to left, but the hollow at the bottom

lip of the crescent is an accidental pit in the stone and not a

diacritical mark. The unvoiced sound in this inscription is

represented by K. The use of the new form was not firmly

established till after the middle of the 3rd century B.C.

In the Latin alphabet the sound was always the voiced stop

(as in gig) in classical times. Later, before e, g passed into a

sound like the English y, so that words begin indifferently with

g or j; hence from the Lat. generum (accusative) and Ianuarium

we have in Ital. genero and Gennajo, Fr. gendre and janvier.

In the ancient Umbrian dialect g had made this change between

vowels before the Christian era, the inhabitant of Iguvium (the

modern Gubbio) being in the later form of his native speech

Iuvins, Lat. Iguvinus. In most cases in Mid. Eng. also g passed

into a y sound; hence the old prefix ge of the past participle

appears only as y in yclept and the like. But ng and gg

took a different course, the g becoming an affricate dẓ (dzh), as

in singe, ridge, sedge, which in English before 1500 were senge,

rigge, segge, and in Scotch are still pronounced sing, rig, seg.

The affricate in words like gaol is of French origin (geôle),

from a Late Lat. gabiola, out of caveola, a diminutive of the

Lat. cavea.

The composite origin of English makes it impossible to lay

down rules for the pronunciation of English g; thus there are

in the language five words Gill, three of which have the g hard,

while two have it soft: viz. (1) gill of a fish, (2) gill, a ravine,

both of which are Norse, and (3) Gill, the surname, which is

mostly Gaelic = White; and (4) gill a liquid measure, from

O. Fr. gelle, Late Lat. gella in the same sense, and (5) Gill, a

girl’s name, shortened from Gillian, Juliana (see Skeat’s Etymological

Dictionary). No one of these words is of native origin;

otherwise the initial g would have changed to y, as in Eng.

yell from the O. Eng. gellan, giellan.

(P. Gi.)

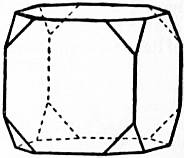

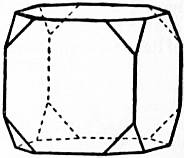

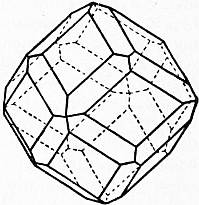

GABBRO, in petrology, a group of plutonic basic rocks,

holocrystalline and usually rather coarse-grained, consisting

essentially of a basic plagioclase felspar and one or more ferromagnesian

minerals (such as augite, hornblende, hypersthene

and olivine). The name was given originally in north Italy to

certain coarsely crystalline dark green rocks, some of which are

true gabbros, while others are serpentines. The gabbros are the

plutonic or deep-seated representatives of the dolerites, basalts

and diabases (also of some varieties of andesite) with which they

agree closely in mineral composition, but not in minute structure.

Of their minerals felspar Is usually the most abundant, and is

principally labradorite and bytownite, though anorthite occurs

in some, while oligoclase and orthoclase have been found in others.

The felspar is sometimes very clear and fresh, its crystals being

for the most part short and broad, with rather irregular or

rounded outlines. Albite twinning is very frequent, but in these

rocks it is often accompanied by pericline twinning by which the

broad or narrow albite plates are cut transversely by many thin,

bright and dark bars as seen in polarized light. Equally

characteristic of the gabbros is the alteration of the felspars to

cloudy, semi-opaque masses of saussurite. These are compact,

tough, devoid of cleavage, and have a waxy lustre and usually a

greenish-white colour. When this substance can be resolved by

the microscope it proves to consist usually of zoisite or epidote,

with garnet and albite, but mixed with it are also chlorite,

amphibole, serpentine, prehnite, sericite and other minerals.

The augite is usually brown, but greenish, violet and colourless

varieties may occur. Hypersthene, when present, is often strikingly

pleochroic in colours varying from pink to bright green.

It weathers readily to platy-pseudomorphs of bastite which are

soft and yield low polarization colours. The olivine is colourless

in itself, but in most cases is altered to green or yellow serpentine,

often with bands of dark magnetite granules along its cleavages

and cracks. Hornblende when primary is often brown, and may

surround augite or be perthitically intergrown with it; original

green hornblende probably occurs also, though it is more

frequently secondary. Dark-brown biotite, although by no

means an important constituent of these rocks, occurs in many

of them. Quartz is rare, but is occasionally seen intergrown

with felspar as micropegmatite. Among the accessory minerals

may be mentioned apatite, magnetite, ilmenite, picotite and

garnet.

A peculiar feature, repeated so constantly in many of the

minerals of these rocks as to be almost typical of them, is the

occurrence of small black or dark brown enclosures often regularly

arranged parallel to certain crystallographic planes. Reflection

of light from the surfaces of these minute enclosures produces a

shimmering or Schiller. In augite or hypersthene the effect is

that the surface of the mineral has a bronzy sub-metallic appearance,

and polished plates seen at a definite angle yield a bright

coppery-red reflection, but polished sections of the felspars may

exhibit a brilliant play of colours, as is well seen in the Labrador

spar, which is used as an ornamental or semi-precious stone.

In olivine the black enclosures are not thin laminae, but branching

growths resembling pieces of moss. The phenomenon is known as

“schillerization”; its origin has been much discussed, some

holding that it is secondary, while others regard these enclosures

as original.

In many gabbros there is a tendency to a centric arrangement

of the minerals, the first crystallized forming nuclei around which

the others grow. Thus magnetite, apatite and picotite, with

olivine, may be enclosed in augite, hornblende, and hypersthene,

sometimes with a later growth of biotite, while the felspars

occupy the interspaces between the clusters of ferromagnesian

minerals. In some cases there are borders around olivine consisting

of fibrous hornblende or tremolite and rhombic pyroxene

(kelyphitic or ocellar structures); spinels and garnet may

occur in this zone, and as it is developed most frequently where

olivine is in contact with felspar it may be due to a chemical

resorption at a late stage in the solidification of the rock. In

some gabbros and norites reaction rims of fibrous hornblende

are found around both hypersthene and diallage where these

are in contact with felspar. Typical orbicular structure such

as characterizes some granites and diorites is rare in the

gabbros, though it has been observed in a few instances in

Norway, California, &c.

In a very large number of the rocks of this group the plagioclase

felspar has crystallized in large measure before the pyroxene, and is

enveloped by it in ophitic manner exactly as occurs in the diabases.

When these rocks become fine-grained they pass gradually into

ophitic diabase and dolerite; only very rarely does olivine enclose

378

felspar in this way. A fluxion structure or flow banding also can

be observed in some of the rocks of this series, and is characterized

by the occurrence of parallel sinuous bands of dark colour, rich in

ferromagnesian minerals, and of lighter shades in which felspars

predominate.

These basic holocrystalline rocks form a large and numerous class

which can be subdivided into many groups according to their mineral

composition; if we take it that typical gabbro consists of plagioclase

and augites or diallage, norite of plagioclase and

hypersthene, and troctolite of plagioclase and olivine,

we must add to these olivine-gabbro and olivine-norite

in which that mineral occurs in addition to

those enumerated above. Hornblende-gabbros are

distinctly rare, except when the hornblende has been

developed from pyroxene by pressure and shearing,

but many rocks may be described as hornblende- or

biotite-bearing gabbro and norite, when they contain

these ingredients in addition to the normal minerals plagioclase,

augite and hypersthene. We may recognize also quartz-gabbro

and quartz-norite (containing primary quartz or micropegmatite)

and orthoclase-gabbro (with a little orthoclase). The name eucrite

has been given to gabbros in which the felspar is mainly anorthite;

many of them also contain hypersthene or enstatite and olivine, while

allivalites are anorthite-olivine rocks in which the two minerals

occur in nearly equal proportions; harrisites have preponderating

olivine, anorthite felspar and a little pyroxene. In areas of gabbro

there are often masses consisting nearly entirely of a single mineral,

for example, felspar rocks (anorthosites), augite or hornblende rocks

(pyroxenites and hornblendites) and olivine rocks (dunites or peridotites).

Segregations of iron ores, such as ilmenite, usually with

pyroxene or olivine, occur in association with some gabbro and

anorthosite masses.

Some gabbros are exceedingly coarse-grained and consist of individual

crystals several inches in length; such a type often form

dikes or veins in serpentine or gabbro, and may be called gabbro-pegmatite.

Very fine-grained gabbros, on the other hand, have been

distinguished as beerbachites. Still more common is the occurrence

of sheared, foliated or schistose forms of gabbro. In these the

minerals have a parallel arrangement, the felspars are often broken

down by pressure into a mosaic of irregular grains, while greenish

fibrous or bladed amphibole takes the place of pyroxene and olivine.

The diallage may be present as rounded or oval crystals around

which the crushed felspar has flowed (augen-gabbro); or the whole

rock may have a well-foliated structure (hornblende-schists and

amphibolites). Very often a mass of normal gabbro with typical

igneous character passes at its margins or along localized zones into

foliated rocks of this kind, and every transition can be found between

the different types. Some authors believe that the development of

saussurite from felspar is also dependent on pressure rather than on

weathering, and an analogous change may affect the olivine, replacing

it by talc, chlorite, actinolite and garnet. Rocks showing changes

of the latter type have been described from Switzerland under the

name allalinites.

Rocks of the gabbro group, though perhaps not so common nor

occurring in so great masses as granites, are exceedingly widespread.

In Great Britain, for example, there are areas of gabbro in Shetland,

Aberdeenshire, and other parts of the Highlands, Ayrshire, the

Lizard (Cornwall), Carrock Fell (Cumberland) and St David’s

(Wales). Most of these occur along with troctolites, norites, serpentine

and peridotite. In Skye an interesting group of fresh olivine-gabbros

is found in the Cuillin Hills; here also peridotites occur

and there are sills and dikes of olivine-dolerite, while a great series

of basaltic lavas and ash beds marks the site of volcanic outbursts

in early Tertiary time. In this case it is clearly seen that the gabbros

are the deep-seated and slowly crystallized representatives of the

basalts which were poured out at the surfaces, and the dolerites

which consolidated in fissures. The older gabbros of Britain, such

as those of the Lizard, Aberdeenshire and Ayrshire, are often more

or less foliated and show a tendency to pass into hornblende-schists

and amphibolites. In Germany gabbros are well known in the

Harz Mountains, Saxony, the Odenwald and the Black Forest.

Many outcrops of similar rocks have been traced in the northern

zones of the Alps, often with serpentine and hornblende-schist.

They occupy considerable tracts of country in Norway and Sweden,

as for instance in the vicinity of Bergen. The Pyrenees, Ligurian

Alps, Dauphiné and Tuscany are other European localities for gabbro.

In Canada great portions of the eastern portion of the Dominion are

formed of gabbros, norite, anorthosite and allied rock types. In

the United States gabbros and norites occur near Baltimore and near

Peekskill on the Hudson river. As a rule each of these occurrences

contains a diversity of petrographical types, which appear also in

certain of the others; but there is often a well-marked individuality

about the rocks of the various districts in which gabbros are

found.

From an economic standpoint gabbros are not of great importance.

They are used locally for building and for road-metal, but are too

dark in colour, too tough and difficult to dress, to be popular as

building stones, and, though occasionally polished, are not to be

compared for beauty with the serpentines and the granites. Segregations

of iron ores are found in connexion with many of them

(Norway and Sweden) and are sometimes mined as sources of the

metal.

Chemically the gabbros are typical rocks of the basic subdivision

and show the characters of that group in the clearest way. They

have low silica, much iron and magnesia, and the abundance of lime

distinguishes them in a marked fashion from both the granites and

the peridotites. A few analyses of well-known gabbros are cited

here.

| | SiO2 | TiO2 | Ab2O3 | FeO | Fe2O3 | MgO | CaO | Na2O | K2O | H2O |

| I. | 49.63 | 1.75 | 16.18 | 12.03 | 1.92 | 5.38 | 9.33 | 1.89 | 0.81 | 0.55 |

| II. | 49.90 | .. | 16.04 | .. | 7.81 | 10.08 | 14.48 | 1.69 | 0.55 | 1.46 |

| III. | 45.73 | .. | 22.10 | 3.51 | 0.71 | 11.16 | 9.26 | 2.54 | 0.34 | 4.38 |

| IV. | 46.24 | .. | 29.85 | 2.12 | 1.30 | 2.41 | 16.24 | 1.98 | 0.18 | .. |

I. Gabbro, Radanthal, Harzburg; II. Gabbro, Penig, Saxony;

III. Troctolite, Coverack, Cornwall; IV. Anorthosite, mouth of the

Seine river, Bad Vermilion lake, Ontario, Canada.

(J. S. F.)

GABEL, KRISTOFFER (1617-1673), Danish statesman, was

born at Glückstadt, on the 6th of January 1617. His father,

Wulbern, originally a landscape painter and subsequently

recorder of Glückstadt, was killed at the siege of that fortress

by the Imperialists in 1628. Kristoffer is first heard of in 1639,

as overseer and accountant at the court of Duke Frederick.

When the duke ascended the Danish throne as Frederick III.,

Gabel followed him to Copenhagen as his private secretary and

man of business. Gabel, who veiled under a mysterious reticence

considerable financial ability and uncommon shrewdness, had

great influence over the irresolute king. During the brief interval

between King Charles X.’s first and second attack upon Denmark,

Gabel was employed in several secret missions to Sweden; and he

took a part in the intrigues which resulted in the autocratic

revolution of 1660 (see Denmark: History). His services on

this occasion have certainly been exaggerated; but if not the

originator of the revolution, he was certainly the chief intermediary

between Frederick III. and the conjoined Estates in

the mysterious conspiracy which established absolutism in

Denmark. His activity on this occasion won the king’s lifelong

gratitude. He was enriched, ennobled, and in 1664 made governor

of Copenhagen. From this year must be dated his open and

official influence and power, and from 1660 to 1670 he was the

most considerable personage at court, and very largely employed

in financial and diplomatic affairs. When Frederick III. died,

in February 1670, Gabel’s power was at an end. The new ruler,

Christian V., hated him, and accusations against him poured in

from every quarter. When, on the 18th of April 1670, he was

dismissed, nobody sympathized with the man who had grown

wealthy at a time when other people found it hard to live. He

died on the 13th of October 1673.

See Carl Frederik Bricka, Dansk. Biograf. Lex. art “Gabel”

(Copenhagen, 1887, &c.); Danmarks Riges Historie (Copenhagen,

1897-19051905), vol. v.

GABELENTZ, HANS CONON VON DER (1807-1874), German

linguist and ethnologist, born at Altenburg on the 13th of

October 1807, was the only son of Hans Karl Leopold von der

Gabelentz, chancellor and privy-councillor of the duchy of

Altenburg. From 1821 to 1825 he attended the gymnasium of

his native town, where he had Matthiae (the eminent Greek

scholar) for teacher, and Hermann Brockhaus and Julius Löbe

for schoolfellows. Here, in addition to ordinary school-work,

he carried on the private study of Arabic and Chinese; and the

latter language continued especially to engage his attention

during his undergraduate course, from 1825 to 1828, at the

universities of Leipzig and Göttingen. In 1830 he entered the

public service of the duchy of Altenburg, where he attained to the

rank of privy-councillor in 1843. Four years later he was chosen

to fill the post of Landmarschall in the grand-duchy of Weimar,

and in 1848 he attended the Frankfort parliament, and represented

the Saxon duchies on the commission for drafting an

imperial constitution for Germany. In November of the same year

he became president of the Altenburg ministry, but he resigned

office in the following August. From 1851 to 1868 he was

president of the second chamber of the duchy of Altenburg; but

in the latter year he withdrew entirely from public life, that he

379

might give undivided attention to his learned researches. He

died on his estate of Lemnitz, in Saxe-Weimar, on the 3rd of

September 1874.

In the course of his life he is said to have learned no fewer than

eighty languages, thirty of which he spoke with fluency and

elegance. But he was less remarkable for his power of acquisition

than for the higher talent which enabled him to turn his knowledge

to the genuine advancement of linguistic science. Immediately

after quitting the university, he followed up his Chinese

researches by a study of the Finno-Ugrian languages, which

resulted in the publication of his Éléments de la grammaire

mandchoue in 1832. In 1837 he became one of the promoters,

and a joint-editor, of the Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes,

and through this medium he gave to the world his

Versuch einer mordwinischen Grammatik and other valuable contributions.

His Grundzüge der syrjänischen Grammatik appeared

in 1841. In conjunction with his old school friend, Julius Löbe,

he brought out a complete edition, with translation, glossary

and grammar, of Ulfilas’s Gothic version of the Bible (1843-1846);

and from 1847 he began to contribute to the Zeitschrift der

deutschen morgenländischen Gesellschaft the fruits of his researches

into the languages of the Swahilis, the Samoyedes, the Hazaras,

the Aimaks, the Formosans and other widely-separated tribes.

The Beiträge zur Sprachenkunde (1852) contain Dyak, Dakota,

and Kiriri grammars; to these were added in 1857 a Grammatik

u. Wörterbuch der Kassiasprache, and in 1860 a treatise in universal

grammar (Über das Passivum). In 1864 he edited the Manchu

translations of the Chinese Sse-shu, Shu-king and Shi-king,

along with a dictionary; and in 1873 he completed the work

which constitutes his most important contribution to philology,

Die melanesischen Sprachen nach ihrem grammatischen Bau

und ihrer Verwandschaft unter sich und mit den malaiisch-polynesischen

Sprachen untersucht (1860-1873). It treats of the

language of the Fiji Islands, New Hebrides, Loyalty Islands,

New Caledonia, &c., and shows their radical affinity with the

Polynesian class. He also contributed most of the linguistic

articles in Pierer’s Conversations-Lexicon.

GABELLE (French, from the Med. Lat. gabulum, gablum,

a tax, for the origin of which see Gavelkind), a term which,

in France, was originally applied to taxes on all commodities,

but was gradually limited to the tax on salt. In process of time

it became one of the most hated and most grossly unequal

taxes in the country, but, though condemned by all supporters

of reform, it was not abolished until 1790. First imposed in 1286,

in the reign of Philip IV., as a temporary expedient, it was made

a permanent tax by Charles V. Repressive as a state monopoly,

it was made doubly so from the fact that the government obliged

every individual above the age of eight years to purchase weekly a

minimum amount of salt at a fixed price. When first instituted,

it was levied uniformly on all the provinces in France, but for the

greater part of its history the price varied in different provinces.

There were five distinct groups of provinces, classified as follows:

(a) the Pays de grandes gabelles, in which the tax was heaviest;

(b) the Pays de petites gabelles, which paid a tax of about half

the rate of the former; (c) the Pays de salines, in which the tax

was levied on the salt extracted from the salt marshes; (d) the

Pays rédimés, which had purchased redemption in 1549; and

(e) the Pays exempts, which had stipulated for exemption on

entering into union with the kingdom of France. Greniers

à sel (dating from 1342) were established in each province, and to

these all salt had to be taken by the producer on penalty of

confiscation. The grenier fixed the price which it paid for the

salt and then sold it to retail dealers at a higher rate.

See J.J. Clamagéran, Histoire de l’impôt en France (1876); A.

Gasquet, Précis des institutions politiques de l’ancienne France (1885);

Necker, Compte rendu (1781).

GABERDINE, or Gabardine, any long, loose over-garment,

reaching to the feet and girt round the waist. It was, when made

of coarse material, commonly worn in the middle ages by pilgrims,

beggars and almsmen. The Jews, conservatively attached to

the loose and flowing garments of the East, continued to wear

the long upper garment to which the name “gaberdine” could

be applied, long after it had ceased to be a common form as worn

by non-Jews, and to this day in some parts of Europe, e.g. in

Poland, it is still worn, while the tendency to wear the frock-coat

very long and loose is a marked characteristic of the race.

The fact that in the middle ages the Jews were forbidden to

engage in handicrafts also, no doubt, tended to stereotype a form

of dress unfitted for manual labour. The idea of the “gaberdine”

being enforced by law upon the Jews as a distinctive garment

is probably due to Shakespeare’s use in the Merchant of Venice,

I. iii. 113. The mark that the Jews were obliged to wear generally

on the outer garment was the badge. This was first enforced

by the fourth Lateran Council of 1215. The “badge” (Lat.

rota; Fr. rouelle, wheel) took generally the shape of a circle of

cloth worn on the breast. It varied in colour at different times.

In France it was of yellow, later of red and white; in England it

took the form of two bands or stripes, first of white, then of

yellow. In Edward I.’s reign it was made in the shape of the

Tables of the Law (see the Jewish Encyclopedia, s.v. “Costume”

and “Badge”). The derivation of the word is obscure. It

apparently occurs first in O. Fr. in the forms gauverdine, galvardine,

and thence into Ital. as gavardina, and Span. gabardina,

a form which has influenced the English word. The New English

Dictionary suggests a connexion with the O.H. Ger. wallevart,

pilgrimage. Skeat (Etym. Dict., 1898) refers it to Span. gaban,

coat, cloak; cabaña, hut, cabin.

GABES, a town of Tunisia, at the head of the gulf of the same

name, and 70 m. by sea S.W. of Sfax. It occupies the site of the

Tacape of the Romans and consists of an open port and European

quarter and several small Arab towns built in an oasis of date

palms. This oasis is copiously watered by a stream called the

Wad Gabes. The European quarter is situated on the right bank

of the Wad near its mouth, and adjacent are the Arab towns

of Jara and Menzel. The houses of the native towns are built

largely of dressed stones and broken columns from the ruins

of Tacape. Gabes is the military headquarters for southern

Tunisia. The population of the oasis is about 20,000, including

some 1500 Europeans. There is a considerable export trade in

dates.

Gabes lies at the head of the shat country of Tunisia and is

intimately connected with the scheme of Commandant Roudaire

to create a Saharan sea by making a channel from the Mediterranean

to these shats (large salt lakes below the level of the sea).

Roudaire proposed to cut a canal through the belt of high ground

between Gabes and the shats, and fixed on Wad Melah, a spot

10 m. N. of Gabes, for the sea end of the channel (see Sahara).

The company formed to execute his project became simply an

agricultural concern and by the sinking of artesian wells created

an oasis of olive and palm trees.

The Gulf of Gabes, the Syrtis Minor of the ancients, is a semi-circular

shallow indentation of the Mediterranean, about 50 m.

across from the Kerkenna Islands, opposite Sfax on its northern

shore, to Jerba Island, which lies at its southern end. The

waters of the gulf abound in fish and sponge.

GABII, an ancient city of Latium, between 12 and 13 m. E. of

Rome, on the Via Praenestina, which was in early times known

as the Via Gabina. The part played by it in the story of the

expulsion of the Tarquins is well known; but its importance

in the earliest history of Rome rests upon other evidence—the

continuance of certain ancient usages which imply a period of

hostility between the two cities, such as the adoption of the

cinctus Gabinus by the consul when war was to be declared.

We hear of a treaty of alliance with Rome in the time of Tarquinius

Superbus, the original text of which, written on a bullock’s

skin, was said by Dionysius of Halicarnassus to be still extant

in his day. Its subsequent history is obscure, and we only hear

of it again in the 1st century B.C. as a small and insignificant

place, though its desolation is no doubt exaggerated by the poets.

From inscriptions we learn that from the time of Augustus or

Tiberius onwards it enjoyed a municipal organization. Its baths

were well known, and Hadrian, who was responsible for much of

the renewed prosperity of the small towns of Latium, appears to

have been a very liberal patron, building a senate-house (Curia

380

Aelia Augusta) and an aqueduct. After the 3rd century Gabii

practically disappears from history, though its bishops continue to

be mentioned in ecclesiastical documents till the close of the 9th.

The primitive city occupied the eastern bank of the lake, the

citadel being now marked by the ruins of the medieval fortress of

Castiglione, while the Roman town extended farther to the south.

The most conspicuous relic of the latter is a ruined temple,

generally attributed to Juno, which had six columns in the front

and six on each side. The plan is interesting, but the style of

architecture was apparently mixed. To the east of the temple

lay the Forum, where excavations were made by Gavin Hamilton

in 1792. All the objects found were placed in the Villa Borghese,

but many of them were carried off to Paris by Napoleon, and

still remain in the Louvre. The statues and busts are especially

numerous and interesting; besides the deities Venus, Diana,

Nemesis, &c., they comprise Agrippa, Tiberius, Germanicus,

Caligula, Claudius, Nero, Trajan and Plotina, Hadrian and

Sabina, M. Aurelius, Septimius Severus, Geta, Gordianus Pius

and others. The inscriptions relate mainly to local and municipal

matters.

See E.Q. Visconti, Monumenti Gabini della Villa Pinciana

(Rome, 1797, and Milan, 1835); T. Ashby in Papers of the British

School at Rome, i. 180 seq.; G. Pinza in Bull. Com. (1903),

321 seq.

(T. As.)

GABINIUS, AULUS, Roman statesman and general, and

supporter of Pompey, a prominent figure in the later days of the

Roman republic. In 67 B.C., when tribune of the people, he

brought forward the famous law (Lex Gabinia) conferring upon

Pompey the command in the war against the Mediterranean

pirates, with extensive powers which gave him absolute control

over that sea and the coasts for 50 m. inland. By two other

measures of Gabinius loans of money to foreign ambassadors

in Rome were made non-actionable (as a check on the corruption

of the senate) and the senate was ordered to give audience to

foreign envoys on certain fixed days (1st of Feb.-1st of March).

In 61 Gabinius, then praetor, endeavoured to win the public

favour by providing games on a scale of unusual splendour,

and in 58 managed to secure the consulship, not without suspicion

of bribery. During his term of office he aided Publius Clodius

in bringing about the exile of Cicero. In 57 Gabinius went

as proconsul to Syria. On his arrival he reinstated Hyrcanus

in the high-priesthood at Jerusalem, suppressed revolts, introduced

important changes in the government of Judaea, and

rebuilt several towns. During his absence in Egypt, whither he

had been sent by Pompey, without the consent of the senate,

to restore Ptolemy Auletes to his kingdom, Syria had been

devastated by robbers, and Alexander, son of Aristobulus, had

again taken up arms with the object of depriving Hyrcanus of the

high-priesthood. With some difficulty Gabinius restored order,

and in 54 handed over the province to his successor, M. Licinius

Crassus. The knights, who as farmers of the taxes had suffered

heavy losses during the disturbances in Syria, were greatly

embittered against Gabinius, and, when he appeared in the senate

to give an account of his governorship, he was brought to trial

on three counts, all involving a capital offence. On the charge

of majestas (high treason) incurred by having left his province for

Egypt without the consent of the senate and in defiance of the

Sibylline books, he was acquitted; it is said that the judges were

bribed, and even Cicero, who had recently attacked Gabinius

with the utmost virulence, was persuaded by Pompey to say as

little as he could in his evidence to damage his former enemy.

On the second charge, that of repetundae (extortion during the

administration of his province), with especial reference to the

10,000 talents paid by Ptolemy for his restoration, he was found

guilty, in spite of evidence offered on his behalf by Pompey and

witnesses from Alexandria and the eloquence of Cicero, who had

been induced to plead his cause. Nothing but Cicero’s wish to

do a favour to Pompey could have induced him to take up what

must have been a distasteful task; indeed, it is hinted that the

half-heartedness of the defence materially contributed to

Gabinius’s condemnation. The third charge, that of ambitus

(illegalities committed during his canvass for the consulship),

was consequently dropped; Gabinius went into exile, and his

property was confiscated. After the outbreak of the civil war,

he was recalled by Caesar in 49, and entered his service, but took

no active part against his old patron Pompey. After the battle

of Pharsalus, he was commissioned to transport some recently

levied troops to Illyricum. On his way thither by land, he was

attacked by the Dalmatians and with difficulty made his way

to Salonae (Dalmatia). Here he bravely defended himself

against the attacks of the Pompeian commander, Marcus

Octavius, but in a few months died of illness (48 or the beginning

of 47).

See Dio Cassius xxxvi. 23-36, xxxviii. 13. 30, xxxix. 55-63;

Plutarch, Pompey, 25. 48; Josephus, Antiq. xiv. 4-6; Appian,

Illyrica, 12, Bell. Civ. ii. 24. 59; Cicero, ad Att. vi. 2, ad Q. Fratrem,

ii. 13, Post reditum in senatu, 4-8, Pro lege Manilia, 17, 18, 19;

exhaustive article by Bähr in Ersch and Gruber’s Allgemeine

Encyclopädie; and monograph by G. Stocchi, Aulo Gabinio e i suoi

processi (1892).

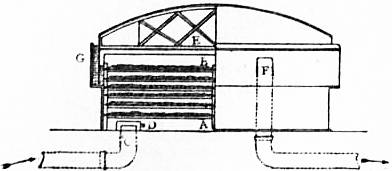

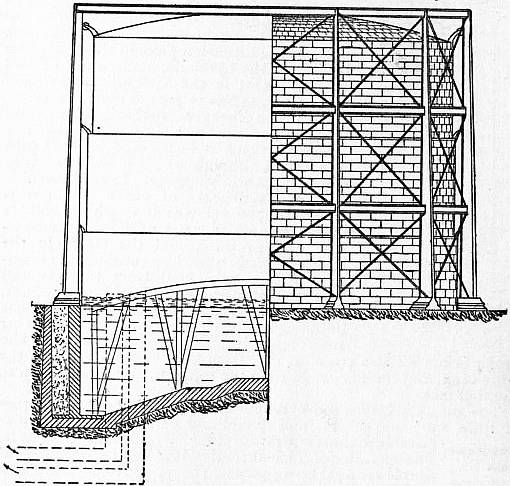

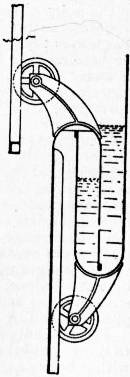

GABION (a French word derived through Ital. gabbione,

gabbia, from Lat. cavea, a cage), a cylindrical basket without

top or bottom, used in revetting fortifications and for numerous

other purposes of military engineering. The gabion is filled

with earth when in position. The ordinary brushwood gabion in

the British service has a diameter of 2 ft. and a height of 2 ft. 9 in.

There are several forms of gabion in use, the best known being

the Willesden paper band gabion and the Jones iron or steel

band gabion.

GABLE, in architecture, the upper portion of a wall from the

level of the eaves or gutter to the ridge of the roof. The word is

a southern English form of the Scottish gāvel, or of an O. Fr.

word gable or jable, both ultimately derived from O. Norwegian

gafl. In other Teutonic languages, similar words, such as

Ger. Gabel and Dutch gaffel, mean “fork,” cf. Lat. gabalus,

gallows, which is Teutonic in origin; “gable” is represented

by such forms as Ger. Giebel and Dutch gevel. According to the

New English Dictionary the primary meaning of all these words

is probably “top” or “head,” cf. Gr. κεφαλή, and refers to the

forking timbers at the end of a roof. The gable corresponds to

the pediment in classic buildings where the roof was of low pitch.

If the roof is carried across on the top of the wall so that the

purlins project beyond its face, they are masked or hidden by a

“barge board,” but as a rule the roof butts up against the back of

the wall which is raised so as to form a parapet. In the middle

ages the gable end was invariably parallel to the roof and was

crowned by coping stones properly weathered on both sides to

throw off the rain. In the 16th century in England variety was

given to the outline of the gable by a series of alternating semi-circular

and ogee curves. In Holland, Belgium and Scotland a

succession of steps was employed, which in the latter country are

known as crow gables or corbie steps. In Germany and the

Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries the step gables

assume very elaborate forms of an extremely rococo character,

and they are sometimes of immense size, with windows in two or

three storeys. Designs of a similar rococo character are found in

England, but only in crestings such as those which surmount the

towers of Wollaton and the gatehouse of Hardwick Hall.

Gabled Towers, in architecture, are those towers which are

finished with gables instead of parapets, as at Sompting, Sussex.

Many of the German Romanesque towers are gabled.

GABLER, GEORG ANDREAS (1786-1853), German Hegelian

philosopher, son of J.P. Gabler (below), was born on the 30th

of July 1786, at Altdorf in Bavaria. In 1804 he accompanied

his father to Jena, where he completed his studies in philosophy

and law, and became an enthusiastic disciple of Hegel. After

holding various educational appointments, he was in 1821

appointed rector of the Bayreuth gymnasium, and in 1830

general superintendent of schools. In 1835 he succeeded Hegel

in the Berlin chair. He died at Teplitz on the 13th of September

1853. His works include Lehrbuch d. philos. Propädeutik (1st

vol., Erlangen, 1827), a popular exposition of the Hegelian

system; De verae philosophiae erga religionem Christianam pietate

(Berlin, 1836), and Die Hegel’sche Philosophie (ib., 1843), a

defence of the Hegelian philosophy against Trendelenburg.

381

GABLER, JOHANN PHILIPP (1753-1826), German Protestant

theologian of the school of J.J. Griesbach and J.G. Eichhorn,

was born at Frankfort-on-Main on the 4th of June 1753. In

1772 he entered the university of Jena as a theological student.

In 1776 he was on the point of abandoning theological pursuits,

when the arrival of Griesbach inspired him with new ardour.

After having been successively Repetent in Göttingen and teacher

in the public schools of Dortmund (Westphalia) and Altdorf

(Bavaria), he was, in 1785, appointed second professor of theology

in the university of Altdorf, whence he was translated to a chair

in Jena in 1804, where he succeeded Griesbach in 1812. Here he

died on the 17th of February 1826. At Altdorf Gabler published

(1791-1793) a new edition, with introduction and notes, of

Eichhorn’s Urgeschichte; this was followed, two years afterwards,

by a supplement entitled Neuer Versuch über die mosaische

Schöpfungsgeschichte. He was also the author of many essays

which were characterized by much critical acumen, and which had

considerable influence on the course of German thought on

theological and Biblical questions. From 1798 to 1800 he was

editor of the Neuestes theologisches Journal, first conjointly with

H.K.A. Hänlein (1762-1829), C.F. von Ammon (1766-1850)

and H.E.G. Paulus, and afterwards unassisted; from 1801 to

1804 of the Journal für theologische Litteratur; and from 1805

to 1811 of the Journal für auserlesene theologische Litteratur.

Some of his essays were published by his sons (2 vols., 1831); and

a memoir appeared in 1827 by W. Schröter.

GABLETS (diminutive of “gable”), in architecture, triangular

terminations to buttresses, much in use in the Early English

and Decorated periods, after which the buttresses generally

terminated in pinnacles. The Early English gablets are generally

plain, and very sharp in pitch. In the Decorated period they

are often enriched with panelling and crockets. They are

sometimes finished with small crosses, but of oftener with finials.

GABLONZ (Czech, Jablonec), a town of Bohemia, Austria,

94 m. N.E. of Prague by rail. Pop. (1900) 21,086, mostly

German. It is the chief seat of the glass pearl and imitation

jewelry manufacture, and has also an important textile industry,

and produces large quantities of hardware, papier mâché and

other paper goods.

GABORIAU, ÉMILE (1833-1873), French novelist, was born

at Saujon (Charente Inférieure) on the 9th of November 1833.

He became secretary to Paul Féval, and, after publishing some

novels and miscellaneous writings, found his real gift in L’Affaire

Lerouge (1866), a detective novel which was published in the

Pays and at once made his reputation. The story was produced

on the stage in 1872. A long series of novels dealing with the

annals of the police court followed, and proved very popular.

Among them are: Le Crime d’Orcival (1867), Monsieur Lecoq

(1869), La Vie infernale (1870), Les Esclaves de Paris (1869),

L’Argent des autres (1874). Gaboriau died in Paris on the 28th

of September 1873.

GABRIEL (Heb. גבריאל, man of God), in the Bible, the

heavenly messenger (see Angel) sent to Daniel to explain the

vision of the ram and the he-goat, and to communicate the prediction

of the Seventy Weeks (Dan. viii. 16, ix. 21). He was also

employed to announce the birth of John the Baptist to Zacharias,

and that of the Messiah to the Virgin Mary (Luke i. 19, 26).

Because he stood in the divine presence (see Luke i. 19; Rev.

viii. 2; and cf. Tobit xii. 15), both Jewish and Christian writers

generally speak of him as an archangel. In the Book of Enoch

“the four great archangels” are Michael, Uriel, Suriel or Raphael,

and Gabriel, who is set over “all the powers” and shares the

work of intercession. His name frequently occurs in the Jewish

literature of the later post-Biblical period. Thus, according to

the Targum Pseudo-Jonathan, he was the man who showed the

way to Joseph (Gen. xxxvii. 15); and in Deut. xxxiv. 6 it is

affirmed that he, along with Michael, Uriel, Jophiel, Jephephiah

and the Metatron, buried the body of Moses. In the Targum on

2 Chron. xxxii. 21 he is named as the angel who destroyed the

host of Sennacherib; and in similar writings of a still later period

he is spoken of as the spirit who presides over fire, thunder, the

ripening of the fruits of the earth and similar processes. In the

Koran great prominence is given to his function as the medium

of divine revelation, and, according to the Mahommedan interpreters,

he it is who is referred to by the appellations “Holy

Spirit” and “Spirit of Truth.” He is specially commemorated

in the calendars of the Greek, Coptic and Armenian churches.

GABRIEL HOUNDS, a spectral pack supposed in the North of

England to foretell death by their yelping at night. The legend

is that they are the souls of unbaptized children wandering

through the air till the day of judgment. They are also sometimes

called Gabriel or Gabble Ratchet. A very prosaic explanation

of this nocturnal noise is given by J.C. Atkinson in

his Cleveland Glossary (1868). “This,” he writes, “is the name

for a yelping sound heard at night, more or less resembling

the cry of hounds or yelping of dogs, probably due to large

flocks of wild geese which chance to be flying by night.”

See further Joseph Lucas, Studies in Nidderdale (1882), pp.

156-157.

GABRIELI, GIOVANNI (1557-1612?), Italian musical composer,

was born at Venice in 1557, and was a pupil of his uncle

Andrea, a distinguished musician of the contrapuntal school

and organist of St Mark’s. He succeeded Claudio Merulo as

first organist of the same church in 1585, and died at Venice

either in 1612 or 1613. He was remarkable for his compositions

for several choirs, writing frequently for 12 or 16 voices, and is

important as an early experimenter in chromatic harmony.

It was probably for this reason that he made a special point of

combining voices with instruments, being thus one of the founders

of choral and orchestral composition. Among his pupils was

Heinrich Schütz; and the church of St Mark, from the time of

the Gabrielis onwards down to that of Lotti, became one of the

most important musical schools in Europe.

See also Winterfeld, Johann Gabrieli und seine Zeit (1834).

GABUN, a district on the west coast of Africa, one of the

colonies forming French Congo (q.v.). It derives its designation

from the settlements on the Gabun river or Rio de Gabão. The

Gabun, in reality an estuary of the sea, lies immediately north of

the equator. At the entrance, between Cape Joinville or Santa

Clara on the N. and Cape Pangara or Sandy Point on the S., it

has a width of about 10 m. It maintains a breadth of some 7 m.

for a distance of 40 m. inland, when it contracts into what is

known as the Rio Olambo, which is not more than 2 or 3 m.

from bank to bank. Several rivers, of which the Komo is

the chief, discharge their waters into the estuary. The Gabun

was discovered by Portuguese navigators towards the close of the

15th century, and was named from its fanciful resemblance to a

gabão or cabin. On the small island of Koniké, which lies about

the centre of the estuary, scanty remains of a Portuguese fort have

been discovered. The three principal tribes in the Gabun are the

Mpongwe, the Fang and the Bakalai.

GACE BRULÉ (d. c. 1220), French trouvère, was a native of

Champagne. It has generally been asserted that he taught

Thibaut of Champagne the art of verse, an assumption which is

based on a statement in the Chroniques de Saint-Denis: “Si

fist entre lui [Thibaut] et Gace Brulé les plus belles chançons et

les plus délitables et melodieuses qui onque fussent oïes.” This

has been taken as evidence of collaboration between the two

poets. The passage will bear the interpretation that with those

of Gace the songs of Thibaut were the best hitherto known.

Paulin Paris, in the Histoire littéraire de la France (vol. xxiii.),

quotes a number of facts that fix an earlier date for Gace’s songs.

Gace is the author of the earliest known jeu parti. The interlocutors

are Gace and a count of Brittany who is identified with

Geoffrey of Brittany, son of Henry II. of England. Gace appears

to have been banished from Champagne and to have found

refuge in Brittany. A deed dated 1212 attests a contract between

Gatho Bruslé (Gace Brulé) and the Templars for a piece of land

in Dreux. It seems most probable that Gace died before 1220, at

the latest in 1225.

See Gédéon Busken Huet, Chansons de Gace Brulé, edited for the

Société des anciens textes français (1902), with an exhaustive introduction.

Dante quotes a song by Gace, Ire d’amor qui en mon cuer

repaire, which he attributes erroneously to Thibaut of Navarre

(De vulgari eloquentia, p. 151, ed. P. Rajna, Florence, 1895).

382

GACHARD, LOUIS PROSPER (1800-1885), Belgian man of

letters, was born in Paris on the 12th of March 1800. He entered

the administration of the royal archives in 1826, and was appointed

director-general, a post which he held for fifty-five years.

During this long period he reorganized the service, added to the

records by copies taken in other European collections, travelled

for purposes of study, and carried on a wide correspondence

with other keepers of records, and with historical scholars. He

also edited and published many valuable collections of state

papers; a full list of his various publications was printed in the

Annuaire de l’académie royale de Belgique by Ch. Piot in 1888,

pp. 220-236. It includes 246 entries. He was the author of

several historical writings, of which the best known are Don

Carlos et Philippe II (1867), Études et notices historiques concernant

l’histoire des Pays-Bas (1863), Histoire de la Belgique

au commencement du XVIIIe siècle (1880), Histoire politique et

diplomatique de P.P. Rubens (1877), all published at Brussels.

His chief editorial works are the Actes des états généraux des

Pays-Bas 1576-1585 (Brussels, 1861-1866), Collection de documents

inédits concernant l’histoire de la Belgique (Brussels, 1833-1835),

and the Relations des ambassadeurs Vénitiens sur Charles

V et Philippe II (Brussels, 1855). Gachard died in Brussels

on the 24th of December 1885.

GAD, in the Bible. 1. A prophet or rather a “seer” (cp.

1 Sam. ix. 9), who was a companion of David from his early days.

He is first mentioned in 1 Sam. xxii. 5 as having warned David

to take refuge in Judah, and appears again in 2 Sam. xxiv. 11 seq.

to make known Yahweh’s displeasure at the numbering of the

people. Together with Nathan he is represented in post-exilic

tradition as assisting to organize the musical service of the temple

(2 Chron. xxix. 25), and like Nathan and Samuel he is said to have

written an account of David’s deeds (1 Chron. xxix. 29); a

history of David in accordance with later tradition and upon the

lines of later prophetic ideas is far from improbable.

2. Son of Jacob, by Zilpah, Leah’s maid; a tribe of Israel

(Gen. xxx. 11). The name is that of the god of “luck” or

fortune, mentioned in Isa. lxv. 11 (R.V. mg.), and in several

names of places, e.g. Baal-Gad (Josh. xi. 17, xii. 7), and

possibly also in Dibon-Gad, Migdol-Gad and Nahal-Gad.1

There is another etymology in Gen. xlix. 19, where the name

is played on: “Gad, a plundering troop (gĕdûd) shall plunder him

(yegudennu), but he shall plunder at their heels.” There are no

traditions of the personal history of Gad. One of the earliest

references to the name is the statement on the inscription of

Mesha, king of Moab (about 850 B.C.), that the “men of Gad”

had occupied Ataroth (E. of Dead Sea) from of old, and that the

king of Israel had fortified the city. This is in the district

ascribed to Reuben, with which tribe the fortunes of Gad were

very closely connected. In Numbers xxxii. 34 sqq., the cities

of Gad appear to lie chiefly to the south of Heshbon; in Joshua

xiii. 24-28 they lie almost wholly to the north; while other texts

present discrepancies which are not easily reconciled with either

passage. Possibly some cities were common to both Reuben and

Gad, and perhaps others more than once changed hands. That

Gad, at one time at least, held territory as far south as Pisgah

and Nebo would follow from Deut. xxxiii. 21, if the rendering of

the Targums be accepted, “and he looked out the first part for

himself, because there was the portion of the buried law-giver.”

It is certain, however, that, at a late period, this tribe was localized

chiefly in Gilead, in the district which now goes by the name of

Jebel Jil‘ād. The traditions encircling this district point, it

would seem, to the tribe having been of Aramaean origin (see the

story of Jacob); at all events its position was extremely exposed,

and its population at the best must have been a mixed one.

Its richness and fertility made it a prey to the marauding nomads

of the desert; but the allusion in the Blessing of Jacob gives the

tribe a character for bravery, and David’s men of Gad (1 Chron.

xii. 8) were famous in tradition. Although rarely mentioned by

name (the geographical term Gilead is usual), the history of Gad

enters into the lives of Jephthah and Saul, and in the wars of

Ammon and Moab it must have played some part. It followed

Jeroboam in the great revolt against the house of David, and its

later fortunes until 734 B.C. (1 Chron. v. 26) would be those of

the northern kingdom.

See, for a critical discussion of the data, H.W. Hogg, Ency. Bib.

cols. 1579 sqq.; also Gilead; Manasseh; Reuben.

1 See G.B. Gray, Heb. Proper Names, pp. 134 seq., 145.

GADAG, or Garag, a town of British India, in the Dharwar

district of Bombay, 43 m. E. of Dharwar town. Pop. (1901)

30,652. It is an important railway junction on the Southern

Mahratta system, with a growing trade in raw cotton, and also

in the weaving of cotton and silk. There are factories for

ginning and pressing cotton, and a spinning mill. The town

contains remains of a number of temples, some of which exhibit

fine carving, while inscriptions in them indicate the existence

of Gadag as early as the 10th century.

GADARA, an ancient town of the Syrian Decapolis, the capital

of Peraea, and the political centre of the small district of Gadaris.

It was a Greek city, probably entirely non-Syrian in origin.

The earliest recorded event in its history is its capture by

Antiochus III. of Syria in 218 B.C.; how long it may have

existed before this date is unknown. About twenty years later

it was besieged for ten months by Alexander Jannaeus. It was

restored by Pompey, and in 30 B.C. was presented by Augustus

to Herod the Great; on Herod’s death it was reunited to Syria.

The coins of the place bear Greek legends, and such inscriptions

as have been found on its site are Greek. Its governing and

wealthy classes were probably Greek, the common people being

Hellenized and Judaized Aramaeans. The community was

Hellenistically organized, and though dependent on Syria and

acknowledging the supremacy of Rome it was governed by a

democratic senate and managed its own internal affairs. In the

Jewish war it surrendered to Vespasian, but in the Byzantine

period it again flourished and was the seat of a bishop. It was

renowned for its hot sulphur baths; the springs still exist and

show the remains of bath-houses. The temperature of the

springs is 110° F. This town was the birthplace of Meleager the

anthologist. There is a confusion in the narrative of the healing

of the demoniac between the very similar names Gadara, Gerasa

and Gergesa; but the probabilities, both textual and geographical,

are in favour of the reading of Mark (Gerasenes, ch. v. 1, revised

version); and that the miracle has nothing to do with Gadara,

but took place at Kersa, on the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

Gadara is now represented by Umm Kais, a group of ruins

about 6 m. S.E. of the Sea of Galilee, and 1194 ft. above the

sea-level. There are very fine tombs with carved sarcophagi in

the neighbourhood. There are the remains of two theatres and

(probably) a temple, and many heaps of carved stones, representing

ancient buildings of various kinds. The walls are, or were,

traceable for a circuit of 2 m., and there are also the remains of

a street of columns. The natives are rapidly destroying the ruins

by quarrying building material out of them.

(R. A. S. M.)

GADDI. Four painters of the early Florentine school—father,

son and two grandsons—bore this name.

1. Gaddo Gaddi was, according to Vasari, an intimate friend

of Cimabue, and afterwards of Giotto. The dates of birth and

death have been given as 1239 and about 1312; these are probably

too early; he may have been born towards 1260, and may have

died in or about 1333. He was a painter and mosaicist, is said

to have executed the great mosaic inside the portal of the

cathedral of Florence, representing the coronation of the Virgin,

and may with more certainty be credited with the mosaics inside

the portico of the basilica of S. Maria Maggiore, Rome, relating to

the legend of the foundation of that church; their date is probably

1308. In the original cathedral of St Peter in Rome he also

executed the mosaics of the choir, and those of the front representing

on a colossal scale God the Father, with many other

figures; likewise an altarpiece in the church of S. Maria Novella,

Florence; these works no longer exist. It is ordinarily held that

no picture (as distinct from mosaics) by Gaddo Gaddi is now

extant. Messrs Crowe & Cavalcaselle, however, consider that

the mosaics of S. Maria Maggiore bear so strong a resemblance

in style to four of the frescoes in the upper church of Assisi,

representing incidents in the life of St Francis (frescoes 2, 3, 4

383

and especially 5, which shows Francis stripping himself, and

protected by the bishop), that those frescoes likewise may, with

considerable confidence, be ascribed to Gaddi. Some other extant

mosaics are attributed to him, but without full authentication.

This artist laid the foundation of a very large fortune, which

continued increasing, and placed his progeny in a highly distinguished

worldly position.

2. Taddeo Gaddi (about 1300-1366, or later), son of Gaddo,

was born in Florence, and is usually said to have been one of

Giotto’s most industrious assistants for a period of 24 years.

This can hardly be other than an exaggeration; it is probable

that he began painting on his own account towards 1330, when

Giotto went to Naples. Taddeo also traded as a merchant, and

had a branch establishment in Venice. He was a painter,

mosaicist and architect. He executed in fresco, in the Baroncelli

(now Giugni) chapel, in the Florentine church of S. Croce, the

“Virgin and Child between Four Prophets,” on the funeral

monument at the entrance, and on the walls various incidents in

the legend of the Virgin, from the expulsion of Joachim from the

Temple up to the Nativity. In the subject of the “Presentation

of the Virgin in the Temple” are the two heads traditionally

accepted as portraits of Gaddo Gaddi and Andrea Tafi; they, at

any rate, are not likely to be portraits of those artists from the

life. On the ceiling of the same chapel are the “Eight Virtues.”

In the museum of Berlin is an altarpiece by Taddeo, the “Virgin

and Child,” and some other subjects, dated 1334; in the Naples

gallery, a triptych, dated 1336, of the “Virgin enthroned along

with Four Saints,” the “Baptism of Jesus,” and his “Deposition

from the Cross”; in the sacristy of S. Pietro a Megognano, near

Poggibonsi, an altarpiece dated 1355, the “Virgin and Child

enthroned amid Angels.” A series of paintings, partly from the

life of St Francis, which Taddeo executed for the presses in S.

Croce, are now divided between the Florentine Academy and the

Berlin Museum; the compositions are taken from or founded

on Giotto, to whom, indeed, the Berlin authorities have ascribed

their examples. Taddeo also painted some frescoes still extant

in Pisa, besides many in S. Croce and other Florentine buildings,

which have perished. He deservedly ranks as one of the most

eminent successors of Giotto; it may be said that he continued

working up the material furnished by that great painter, with

comparatively feeble inspiration of his own. His figures are

vehement in action, long and slender in form; his execution

rapid and somewhat conventional. To Taddeo are generally

ascribed the celebrated frescoes—those of the ceiling and left

or western wall—in the Cappella degli Spagnuoli, in the church

of S. Maria Novella, Florence; this is, however, open to considerable

doubt, although it may perhaps be conceded that the

designs for the ceiling were furnished by Taddeo. Dubious also

are the three pictures ascribed to him in the National Gallery,

London. In mosaic he has left some work in the baptistery of

Florence. As an architect he supplied in 1336 the plans for the

present Ponte Vecchio, and those for the original (not the present)

Ponte S. Trinita; in 1337 he was engaged on the church of

Or San Michele; and he carried on after Giotto’s death the work

of the unrivalled Campanile.

3. Agnolo Gaddi, born in Florence, was the son of Taddeo;

the date of his birth has been given as 1326, but possibly 1350

is nearer the mark. He was a painter and mosaicist, trained by

his father, and a merchant as well; in middle age he settled down

to commercial life in Venice, and he added greatly to the family

wealth. He died in Florence in October 1396. His paintings

show much early promise, hardly sustained as he advanced

in life. One of the earliest, at S. Jacopo tra’ Fossi, Florence,

represents the “Resurrection of Lazarus.” Another probably

youthful performance is the series of frescoes of the Pieve di

Prato—legends of the Virgin and of her Sacred Girdle, bestowed

upon St Thomas, and brought to Prato in the 11th century by

Michele dei Dagomari; the “Marriage of Mary” is one of the

best of this series, the later compositions in which have suffered

much by renewals. In S. Croce he painted, in eight frescoes,

the legend of the Cross, beginning with the archangel Michael

giving Seth a branch from the tree of knowledge, and ending

with the emperor Heraclius carrying the Cross as he enters

Jerusalem; in this picture is a portrait of the painter himself.

Agnolo composed his subjects better than Taddeo; he had more

dignity and individuality in the figures, and was a clear and bold

colourist; the general effect is laudably decorative, but the

drawing is poor, and the works show best from a distance.

Various other productions of this master exist, and many have

perished. Cennino Cennini, the author of the celebrated treatise

on painting, was one of his pupils.

4. Giovanni Gaddi, brother of Agnolo, was also a painter of

promise. He died young in 1383.

Vasari, and Crowe and Cavelcaselle can be consulted as

to the Gaddi. Other notices appear here and there—such as

La Cappella de’ Rinuccini in S. Croce di Firenze, by G. Ajazzi

(1845).

(W. M. R.)

GADE, NIELS WILHELM (1817-1890), Danish composer,

was born at Copenhagen, on the 22nd of February 1817, his father

being a musical instrument maker. He was intended for his

father’s trade, but his passion for a musician’s career, made

evident by the ease and skill with which he learnt to play upon

a number of instruments, was not to be denied. Though he

became proficient on the violin under Wexschall, and in the

elements of theory under Weyse and Berggreen, he was to a great

extent self-taught. His opportunities of hearing and playing in

the great masterpieces were many, since he was a member of the

court band. In 1840 his Aladdin and his overture of Ossian

attracted attention, and in 1841 his Nachklänge aus Ossian

overture gained the local musical society’s prize, the judges

being Spohr and Schneider. This work also attracted the notice

of the king, who gave the composer a stipend which enabled him

to go to Leipzig and Italy. In 1844 Gade conducted the Gewandhaus

concerts in Leipzig during Mendelssohn’s absence, and on

the latter’s death became chief conductor. In 1848, on the

outbreak of the Holstein War, he returned to Copenhagen, where

he was appointed organist and conductor of the Musik-Verein.

In 1852 he married a daughter of the composer J.P.E. Hartmann.

He became court conductor in 1861, and was pensioned by the

government in 1876—the year in which he visited Birmingham

to conduct his Crusaders. This work, and the Frühlingsfantasie,

the Erlkönigs Tochter, Frühlingsbotschaft and Psyche (written for

Birmingham in 1882) have enjoyed a wide popularity. Indeed,

they represent the strength and the weakness of Gade’s musical

ability quite as well as any of his eight symphonies (the best of

which are the first and fourth, while the fifth has an obbligato

pianoforte part). Gade was distinctly a romanticist, but his

music is highly polished and beautifully finished, lyrical rather

than dramatic and effective. Much of the pianoforte music,

Aquarellen, Spring Flowers, for instance, enjoyed a considerable

vogue, as did the Novelletten trio; but Gade’s opera Mariotta

has not been heard outside the Copenhagen opera house. He

died at Copenhagen on the 21st of December 1890.

GADOLINIUM (symbol Gd., atomic weight 157.3), one of the

rare earth metals (see Erbium). The element was discovered

in 1880 in the mineral samarskite by C. Marignac (Comptes

rendus, 1880, 90, p. 899; Ann. chim. phys., 1880 [5] 20, p. 535).

G. Urbain (Comptes rendus, 1905, 140, p. 583) separates the

metal by crystallizing the double nitrate of nickel and gadolinium.

The salts show absorption bands in the ultra-violet. The oxide

Gd2O3 is colourless (Lecoq de Boisbaudran).

GADSDEN, CHRISTOPHER (1724-1805), American patriot,

was born in Charleston, South Carolina, in 1724. His father,

Thomas Gadsden, was for a time the king’s collector for the

port of Charleston. Christopher went to school near Bristol, in

England, returned to America in 1741, was afterwards employed

in a counting house in Philadelphia, and became a merchant and

planter at Charleston. In 1759 he was captain of an artillery

company in an expedition against the Cherokees. He was a

member of the South Carolina legislature almost continuously

from 1760 to 1780, and represented his province in the Stamp

Act Congress of 1765 and in the Continental Congress in 1774-1776.

In February 1776 he was placed in command of all the

military forces of South Carolina, and in October of the same

384

year was commissioned a brigadier-general and was taken into

the Continental service; but on account of a dispute arising out

of a conflict between state and Federal authority resigned his

command in 1777. He was lieutenant-governor of his state in

1780, when Charleston was surrendered to the British. For about

three months following this event he was held as a prisoner on

parole within the limits of Charleston; then, because of his

influence in deterring others from exchanging their paroles for

the privileges of British subjects, he was seized, taken to St

Augustine, Florida, and there, because he would not give another

parole to those who had violated the former agreement affecting

him, he was confined for forty-two weeks in a dungeon. In

1782 Gadsden was again elected a member of his state legislature;

he was also elected governor, but declined to serve on the ground

that he was too old and infirm; in 1788 he was a member of the

convention which ratified for South Carolina the Federal constitution;

and in 1790 he was a member of the convention which

framed the new state constitution. He died in Charleston on the

28th of August 1805. From the time that Governor Thomas

Boone, in 1762, pronounced his election to the legislature

improper, and dissolved the House in consequence, Gadsden was

hostile to the British administration. He was an ardent leader

of the opposition to the Stamp Act, advocating even then a

separation of the colonies from the mother country; and in

the Continental Congress of 1774 he discussed the situation on

the basis of inalienable rights and liberties, and urged an immediate

attack on General Thomas Gage, that he might be

defeated before receiving reinforcements.

GADSDEN, JAMES (1788-1858), American soldier and diplomat,

was born at Charleston, S.C., on the 15th of May 1788, the

grandson of Christopher Gadsden. He graduated at Yale in 1806,

became a merchant in his native city, and in the war of 1812

served in the regular U.S. Army as a lieutenant of engineers.

In 1818 he served against the Seminoles, with the rank of captain,

as aide on the staff of Gen. Andrew Jackson. In October 1820

he became inspector-general of the Southern Division, with the

rank of colonel, and as such assisted in the occupation and the

establishment of posts in Florida after its acquisition. From

August 1821 to March 1822 he was adjutant-general, but, his

appointment not being confirmed by the Senate, he left the army

and became a planter in Florida. He served in the Territorial

legislature, and as Federal commissioner superintended in 1823

the removal of the Seminole Indians to South Florida. In 1832

he negotiated with the Seminoles a treaty which provided for their

removal within three years to lands in what is now the state of

Oklahoma; but the Seminoles refused to move, hostilities again

broke out, and in the second Seminole War Gadsden was

quartermaster-general of the Florida Volunteers from February

to April 1836. Returning to South Carolina he became a rice

planter, and was president of the South Carolina railway.

In 1853 President Franklin Pierce appointed him minister to

Mexico, with which country he negotiated the so-called “Gadsden

treaty” (signed the 30th of December 1853), which gave to the

United States freedom of transit for mails, merchandise and

troops across the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, and provided for a

readjustment of the boundary established by the treaty of

Guadalupe Hidalgo, the United States acquiring 45,535 sq. m.

of land, since known as the “Gadsden Purchase,” in what is

now New Mexico and Arizona. In addition, Article XI. of the

treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which bound the United States

to prevent incursions of Indians from the United States into

Mexico, and to restore Mexican prisoners captured by such

Indians, was abrogated, and for these considerations the United

States paid to Mexico the sum of $10,000,000. Ratifications of

the treaty, slightly modified by the Senate, were exchanged on the

30th of June 1854; before this, however, Gadsden had retired

from his post. The boundary line between Mexico and the

“Gadsden Purchase” was marked by joint commissions appointed

in 1855 and 1891, the second commission publishing its

report in 1899. Gadsden died at Charleston, South Carolina, on

the 25th of December 1858.

An elder brother, Christopher Edwards Gadsden (1785-1852),

was Protestant Episcopal bishop of South Carolina in

1839-1852.

GADWALL, a word of obscure origin,1 the common English

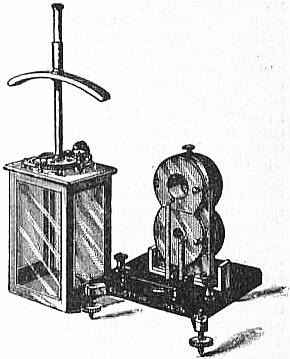

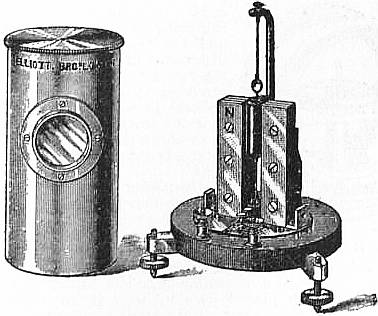

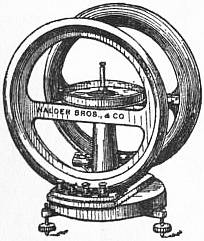

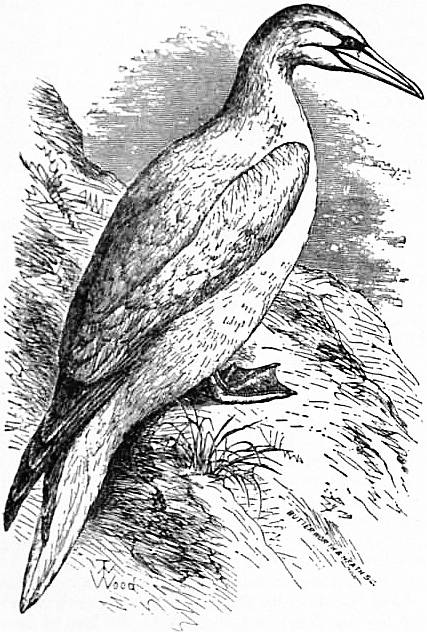

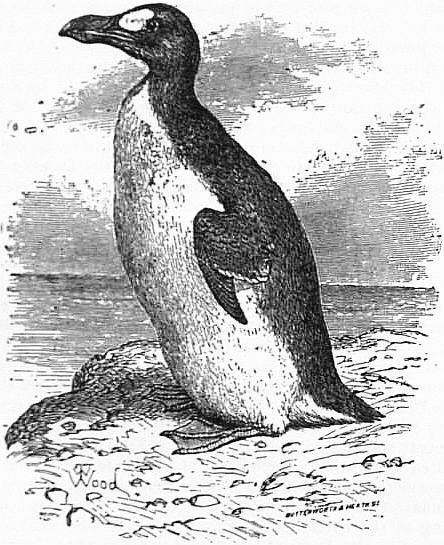

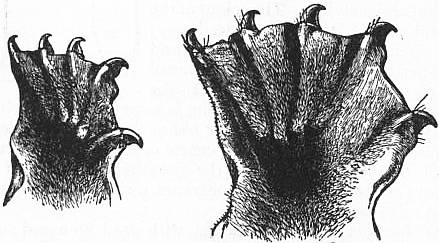

name of the duck, called by Linnaeus Anas strepera, but considered