Cover

Cover

Title: The Argus Pheasant

Author: John Charles Beecham

Illustrator: George W. Gage

Release date: August 26, 2011 [eBook #37215]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Katie Hernandez, Suzanne Shell and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Cover

Cover

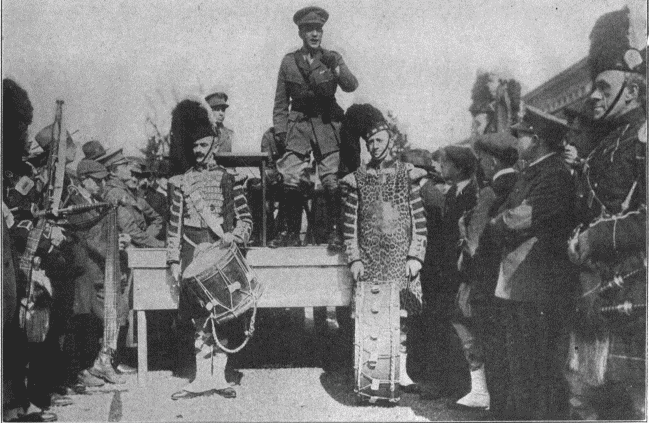

The Chinaman's laborious progress through the cane had

amused her. She knew why he stepped so carefully

The Chinaman's laborious progress through the cane had

amused her. She knew why he stepped so carefullyFrontispiece by

GEORGE W. GAGE

New York

W. J. Watt & Company

PUBLISHERS

[Pg iii]

Copyright, 1918, by

W. J. WATT & COMPANY

PRESS OF

BRAUNWORTH & CO.

BOOK MANUFACTURERS

BROOKLYN, N. Y.

[Pg iv]

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | The Omniscient Sachsen | 1 |

| II. | Ah Sing Counts His Nails | 10 |

| III. | Peter Gross is Named Resident | 25 |

| IV. | Koyola's Prayer | 35 |

| V. | Sachsen's Warning | 54 |

| VI. | The Pirate League | 73 |

| VII. | Mynheer Muller Worries | 82 |

| VIII. | Koyala's Warning | 97 |

| IX. | The Long Arm of Ah Sing | 107 |

| X. | Captain Carver Signs | 119 |

| XI. | Mynheer Muller's Dream | 125 |

| XII. | Peter Gross's Reception | 134 |

| XIII. | A Fever Antidote | 144 |

| XIV. | Koyala's Defiance | 154 |

| XV. | The Council | 165 |

| XVI. | Peter Gross's Pledge | 173 |

| XVII. | The Poisoned Arrow | 192 |

| XVIII. | A Summons to Sadong | 198 |

| XIX. | Koyala's Ultimatum | 207 |

| XX. | Lkath's Conversion | 216 |

| XXI. | Captured by Pirates | 226 |

| XXII. | In the Temple | 238 |

| XXIII. | Ah Sing's Vengeance | 245 |

| XXIV. | A Rescue | 252 |

| XXV. | The Fight on the Beach | 259 |

| XXVI. | "To Half of My Kingdom—" | 268 |

| XXVII. | A Woman Scorned | 274 |

| XXVIII. | The Attack on the Fort | 285 |

| XXIX. | A Woman's Heart | 296 |

| XXX. | The Governor's Promise | 310 |

Ah, God, for a man with a heart, head, hand,

Like some of the simple great ones gone

Forever and ever by;

One still, strong man in a blatant land,

Whatever they call him—what care I?—

Aristocrat, democrat, autocrat—one

Who can rule and dare not lie! Tennyson.

It was very apparent that his Excellency Jonkheer Adriaan Adriaanszoon Van Schouten, governor-general of the Netherlands East Indies, was in a temper. His eyes sparked like an emery-wheel biting cold steel. His thin, sharp-ridged nose rose high and the nostrils quivered. His pale, almost bloodless lips were set in rigid lines over his finely chiseled, birdlike beak with its aggressive Vandyke beard. His hair bristled straight and stiff, like the neck-feathers of a ruffled cock, over the edge of his linen collar. It was this latter evidence of the governor's unpleasant humor that[2] his military associate, General Gysbert Karel Vanden Bosch, observed with growing anxiety.

The governor took a pinch of snuff with great deliberation and glared across the big table of his cabinet-room at the general. Vanden Bosch shrank visibly.

"Then, my dear generaal," he demanded, "you say we must let these sons of Jazebel burn down my residences, behead my residents, and feed my controlleurs to the crocodiles without interference from the military?"

"Ach, no, your excellency!" General Vanden Bosch expostulated hastily. "Not that!"

"I fear I have not understood you, my dear general. What do you advise?"

The icy sweetness of the choleric Van Schouten sent a cold shiver along the commander's spine. He wriggled nervously in the capacious armchair that he filled so snugly. Quite unconsciously he mumbled to himself the clause which the pious Javanese had added to their prayers since Van Schouten's coming to Batavia: "And from the madness of the orang blanda devil at the paleis, Allah deliver us."

"Ha! generaal, what do you say?" the governor exclaimed.

Vanden Bosch coughed noisily and rallied his wits.

"Ahem, your excellency; ah-hum! It is a problem, as your excellency knows. I could send Colonel Heyns and his regiment to Bulungan, if your excellency so desires. But—ahem—as your excel[3]lency knows, all he will find is empty huts. Not a proa on the sea; not a Dyak in his field."

"You might as well send that many wooden men!" Van Schouten snapped.

The general winced. His portentously solemn features that for forty years had impressed the authorities at The Hague with his sagacity in military affairs became severely grave. Oracularly he suggested:

"Would it not be wise, your excellency, to give Mynheer Muller, the controlleur, more time? His last report was very satisfactory. Very satisfactory, indeed!" He smacked his lips at the satisfactoriness thereof.

"Donder en bliksem!" the governor swore, crashing his lean fist on the table. "More time for what? The taxes have not been paid for two years. Not a kilo of rice has been grown on our plantations. Not a liter of dammargum has been shipped here. The cane is left to rot uncut. Fire has ravaged the cinchona-groves my predecessors set with such care. Every ship brings fresh reports of piracies, of tribal wars, and head-hunting. How much longer must we possess our souls in patience while these things go on?"

The general shook his head with a brave show of regret.

"Ach! your excellency," he replied sadly; "he promised so well."

"Promises," the governor retorted, "do not pay taxes."[4]

Vanden Bosch rubbed his purple nose in perplexity.

"I suppose it is the witch-woman again," he remarked, discouragedly.

"Who else?" Van Schouten growled. "Always the witch-woman. That spawn of Satan, Koyala, is at the bottom of every uprising we have in Borneo."

"That is what we get for letting half-breeds mingle with whites in our mission schools," Vanden Bosch observed bitterly.

The governor scowled. "That folly will cost the state five hundred gulden," he remarked. "That is the price I have put on her head."

The general pricked up his ears. "H-m, that should interest Mynheer Muller," he remarked. "There is nothing he likes so well as the feel of a guilder between his fingers."

The governor snorted. "Neen, generaal," he negatived. "For once he has found a sweeter love than silver. The fool fairly grovels at Koyala's feet, Sachsen tells me."

"So?" Vanden Bosch exclaimed with quickened interest. "They say she is very fair."

"If I could get my hands on her once, the Argus Pheasant's pretty feathers would molt quickly," Van Schouten snarled. His fingers closed like an eagle's talons.

"Argus Pheasant, Bintang Burung, the Star Bird—'tis a sweet-sounding name the Malays have for her," the general remarked musingly. There was[5] a sparkle in his eye—the old warrior had not lost his fondness for a pretty face. "If I was younger," he sighed, "I might go to Bulungan myself."

The governor grunted.

"You are an old cock that has lost his tail-feathers, generaal," he growled. "This is a task for a young man."

The general's chest swelled and his chin perked up jauntily.

"I am not so old as you think, your excellency," he retorted with a trace of asperity.

"Neen, neen, generaal," the governor negatived, "I cannot let you go—not for your own good name's sake. The gossips of Amsterdam and The Hague would have a rare scandal to prate about if it became whispered around that Gysbert Vanden Bosch was scouring the jungles of Bulungan for a witch-woman with a face and form like Helen of Troy's."

The general flushed. His peccadillos had followed him to Java, and he did not like to be reminded of them.

"The argus pheasant is too shy a bird to come within gunshot, your excellency," he replied somberly. "It must be trapped."

"Ay, and so must she," the governor assented. "That is how she got her name. But you are too seasoned for bait, my dear generaal." He chuckled.

Vanden Bosch was too much impressed with his own importance to enjoy being chaffed. Ignoring the thrust, he observed dryly:

"Your excellency might try King Saul's plan."[6]

"Ha!" the governor exclaimed with interest. "What is that?"

Van Schouten prided himself on his knowledge of the Scriptures, and the general could not repress a little smirk of triumph at catching him napping.

"King Saul tied David's hands by giving him his daughter to wife," he explained. "In the same way, your excellency might clip the Argus Pheasant's wings by marrying her to one of our loyal servants. It might be managed most satisfactorily. A proper marriage would cause her to forget the brown blood that she hates so bitterly."

"It is not her brown blood that she hates, it is her white blood," Van Schouten contradicted. "But who would be the man?"

"Why not Mynheer Muller, the controlleur!" Vanden Bosch asked. "From what your excellency says, he would not be unwilling. Then our troubles in Bulungan would be over."

Van Schouten scowled thoughtfully.

"It would be a good match," the general urged. "He is only common blood—a Marken herring-fisher's son by a Celebes woman. And she"—he shrugged his shoulders—"for all her pretty face and plump body she is Leveque, the French trader's daughter, by a Dyak woman."

He licked his lips in relish of the plan.

Van Schouten shook his head.

"No, I cannot do it," he said. "I could send her to the coffee-plantations—that would be just punishment for her transgressions. But God keep me from sentencing any woman to marry."[7]

"But, your excellency," Vanden Bosch entreated.

"It is ridiculous, generaal," the governor cut in autocratically. "The argus pheasant does not mate with the vulture."

Vanden Bosch's face fell. "Then your excellency must appoint another resident," he said, in evident disappointment. "It will take a strong man to bring those Dyaks to time."

Van Schouten looked at him fixedly for several moments. A miserable sensation of having said too much crept over the general.

"Ha!" Van Schouten exclaimed. "You say we must have a new resident. That has been my idea, too. What bush-fighter have you that can lead two hundred cut-throats like himself and harry these tigers out of their lairs till they crawl on their bellies to beg for peace?"

Inwardly cursing himself for his folly in ceasing to advocate Muller, the general twiddled his thumbs and said nothing.

"Well, generaal?" Van Schouten rasped irascibly.

"Ahem—you know what troops I have, your excellency. Mostly raw recruits, here scarce three months. There is not a man among them I would trust alone in the bush. After all, it might be wisest to give Mynheer Muller another chance." His cheeks puffed till they were purple.

Van Schouten's face flamed.

"Enough! Enough!" he roared. "If the military cannot keep our house in order, Sachsen and I will find a man. That is all, generaal. Goedendag!"[8]

Vanden Bosch made a hasty and none too dignified exit, damning under his breath the administration that had transferred him from a highly ornamental post in Amsterdam to live with this pepper-pot. He was hardly out of the door before the governor shouted:

"Sachsen! Hola, Sachsen!"

The sound of the governor's voice had scarcely died in the marbled corridors when Sachsen, the omniscient, the indispensable secretary, bustled into the sanctum. His stooped shoulders were crooked in a perpetual obeisance, and his damp, gray hair was plastered thinly over his ruddy scalp; but the shrewd twinkle in his eyes and the hawklike cast of his nose and chin belied the air of humility he affected.

"Sachsen," the governor demanded, the eagle gleaming in his lean, Cæsarian face, "where can I find a man that will bring peace to Bulungan?"

The wrinkled features of the all-knowing Sachsen crinkled with a smile of inspiration.

"Your excellency," he murmured, bowing low, "there is Peter Gross, freeholder of Batavia."

"Peter Gross, Pieter Gross," Van Schouten mused, his brow puckered with a thoughtful frown. "The name seems to have slipped my memory. What has Peter Gross, freeholder of Batavia, done to merit such an appointment at our hands, Sachsen?"

The secretary bowed again, punctiliously.

"Your excellency perhaps remembers," he reminded, "that it was Peter Gross who rescued Lieu[9]tenant Hendrik de Koren and twelve men from the pirates of Lombock."

"Ha!" the governor exclaimed, his stern features relaxing a trifle. "Now, Sachsen, answer me truthfully, has this Peter Gross an eye for women?"

The secretary bent low.

"Your excellency, the fairest flowers of Batavia are his to pick and choose. The good God has given him a brave heart, a comely face, and plenty of flesh to cover his bones. But his only mistress is the sea."

"If I should send him to Bulungan, would that she-devil, Koyala, make the same fool of him that she has of Muller?" the governor demanded sharply.

"Your excellency, the angels above would fail sooner than he."

The governor's fist crashed on the table with a resounding thwack.

"Then he is the man we need!" he exclaimed. "Where shall I find this Peter Gross, Sachsen?"

"Your excellency, he is now serving as first mate of the Yankee barkentine, Coryander, anchored in this port. He was here at the paleis only a moment ago, inquiring for news of three of his crew who had exceeded their shore leave. I think he has gone to Ah Sing's rumah makan, in the Chinese campong."

Van Schouten sprang from his great chair of state like a cockerel fluttering from a roost. He licked his thin lips and curved them into a smile.

"Sachsen," he said, "except myself, you are the only man in Java that knows anything. My hat and coat, Sachsen, and my cane!"[10]

Captain Threthaway, of the barkentine, Coryander, of Boston, should have heeded the warning he received from his first mate, Peter Gross, to keep away from the roadstead of Batavia. He had no particular business in that port. But an equatorial sun, hot enough to melt the marrow in a man's bones, made the Coryander's deck a blistering griddle; there was no ice on board, and the water in the casks tasted foul as bilge. So the captain let his longing for iced tea and the cool depths of a palm-grove get the better of his judgment.

Passing Timor, Floris, and the other links in the Malayan chain, Captain Threthaway looked longingly at the deeply shaded depths of the mangrove jungles. The lofty tops of the cane swayed gently to a breeze scarcely perceptible on the Coryander's sizzling deck. When the barkentine rounded Cape Karawang, he saw a bediamonded rivulet leap sheer off a lofty cliff and lose itself in the liana below. It was the last straw; the captain felt he had to land and taste ice on his tongue again or die. Calling his first mate, he asked abruptly:[11]

"Can we victual at Batavia as cheaply as at Singapore, Mr. Gross?"

Peter Gross looked at the shore-line thoughtfully.

"One place is as cheap as the other, Mr. Threthaway; but if it's my opinion you want, I advise against stopping at Batavia."

The captain frowned.

"Why, Mr. Gross?" he asked sharply.

"Because we'd lose our crew, and Batavia's a bad place to pick up another one. That gang for'ard isn't to be trusted where there's liquor to be got. 'Twouldn't be so bad to lose a few of them at Singapore—there's always English-speaking sailors there waiting for a ship to get home on; but Batavia's Dutch. We might have to lay around a week."

"I don't think there's the slightest danger of desertions," Captain Threthaway replied testily. "What possible reason could any of our crew have to leave?"

"The pay is all right, and the grub is all right; there's no kicking on those lines," Peter Gross said, speaking guardedly. "But most of this crew are drinking men. They're used to their rations of grog regular. They've been without liquor since we left Frisco, except what they got at Melbourne, and that was precious little. Since the water fouled on us, they're ready for anything up to murder and mutiny. There'll be no holding them once we make port."

Captain Threthaway flushed angrily. His thin,[12] ascetic jaw set with Puritan stubbornness as he retorted:

"When I can't sail a ship without supplying liquor to the crew, I'll retire, Mr. Gross."

"Don't misunderstand me, captain," Peter Gross replied, with quiet patience.

"I'm not disagreeing with your teetotaler principles. They improve a crew if you've got the right stock to work with. But when you take grog away from such dock-sweepings as Smith and Jacobson and that little Frenchman, Le Beouf, you take away the one thing on earth they're willing to work for. We had all we could do to hold them in hand at Melbourne, and after the contrary trades we've bucked the past week, and the heat, their tongues are hanging out for a drop of liquor."

"Let them dare come back drunk," the captain snapped angrily. "I know what will cure them."

"They won't come back," Peter Gross asserted calmly.

"Then we'll go out and get them," Captain Threthaway said grimly.

"They'll be where they can't be found," Peter Gross replied.

Captain Threthaway snorted impatiently.

"Look here, captain!" Peter Gross exclaimed, facing his skipper squarely. "Batavia is my home when I'm not at sea. I know its ins and outs. Knowing the town, and knowing the crew we've got, I'm sure a stop there will be a mighty unpleasant experience all around. There's a Chinaman there,[13] Ah Sing, a public-house proprietor and a crimp, that has runners to meet every boat. Once a man goes into his rumah makan, he's as good as lost until the next skipper comes along short-handed and puts up the price."

Captain Threthaway smiled confidently.

"Poor as the crew is, Mr. Gross, there's no member of it will prefer lodging in a Chinese crimp's public house ten thousand miles from home to his berth here."

"They'll forget his color when they taste his hot rum," Peter Gross returned bruskly. "And once they drink it, they'll forget everything else. Ah Sing is the smoothest article that ever plaited a queue, and they don't make them any slicker than they do in China."

Captain Threthaway's lips pinched together in irritation.

"There are always the authorities," he remarked pettishly, to end the controversy.

Peter Gross restrained a look of disgust with difficulty.

"Yes, there are always the authorities," he conceded. "But in the Chinese campong they're about as much use as a landlubber aloft in a blow. The campong is a little republic in itself, and Ah Sing is the man that runs it. If the truth was known, I guess he's the boss Chinaman of the East Indies—pirate, trader, politician—anything he can make a guilder at. From his rum-shop warrens run into every section of Chinatown, and they're so well hid[14] that the governor, though he's sharp as a weasel and by all odds the best man the Dutch ever had here, can't find them. It's the real port of missing men."

Captain Threthaway looked shoreward, where dusky, breech-clouted natives were resting in the cool shade of the heavy-leafed mangroves. A bit of breeze stirred just then, bringing with it the rich spice-grove and jungle scents of the thickly wooded island. A fierce longing for the shore seized the captain. He squared his shoulders with decision.

"I'll take the chance, Mr. Gross," he said. "This heat is killing me. You may figure on twenty-four hours in port."

Twelve hours after the Coryander cast anchor in Batavia harbor, Smith, Jacobson, and Le Beouf were reported missing. When Captain Threthaway, for all his Boston upbringing, had exhausted a prolific vocabulary, he called his first mate.

"Mr. Gross," he said, "the damned renegades are gone. Do you think you can find them?"

Long experience in the vicissitudes of life, acquired in that best school of all, the forecastle, had taught Peter Gross the folly of saying, "I told you so." Therefore he merely replied:

"I'll try, sir."

So it befell that he sought news of the missing ones at the great white stadhuis, where the Heer Sachsen, always his friend, met him and conceived the inspiration for his prompt recommendation to the governor-general.[15]

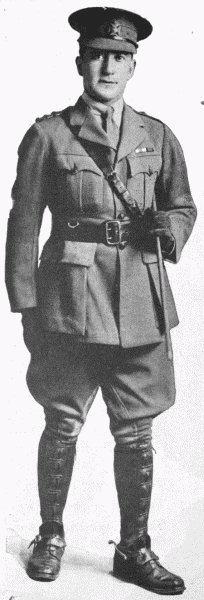

Peter Gross ambled on toward Ah Sing's rumah makan without the slightest suspicion he was being followed. On his part, Governor-General Van Schouten was content to let his quarry walk on unconscious of observation while he measured the man.

"God in Israel, what a man!" his excellency exclaimed admiringly, noting Peter Gross's broad shoulders and stalwart thighs. "If he packs as much brains inside his skull as he does meat on his bones, there are some busy days ahead for my Dyaks." He smacked his lips in happy anticipation.

Ah Sing's grog-shop, with its colonnades and porticoes and fussy gables and fantastic cornices terminating in pigtail curlicues, was a squalid place for all the ornamentation cluttered on it. Peter Gross observed its rubbishy surroundings with ill-concealed disgust.

"'Twould be a better Batavia if some one set fire to the place," he muttered to himself. "Yet the law would call it arson."

Looking up, he saw Ah Sing seated in one of the porticoes, and quickly masked his face to a smile of cordial greeting, but not before the Chinaman had detected his ill humor.

There was a touch of three continents in Ah Sing's appearance. He sat beside a table, in the American fashion; he smoked a long-stemmed hookah, after the Turkish fashion, and he wore his clothes after the Chinese fashion. The bland innocence of his[16] pudgy face and the seraphic mildness of his unblinking almond eyes that peeped through slits no wider than the streak of a charcoal-pencil were as the guilelessness of Mother Eve in the garden. Motionless as a Buddha idol he sat, except for occasional pulls at the hookah.

"Good-morning, Ah Sing," Peter Gross remarked happily, as he mounted the colonnade.

The tiny slits through which Ah Sing beheld the pageantry of a sun-baked world opened a trifle wider.

"May Allah bless thee, Mr. Gross," he greeted impassively.

Peter Gross pulled a chair away from one of the other tables and placed it across the board from Ah Sing. Then he succumbed to it with a sigh of gentle ease.

"A hot day," he panted, and fanned himself as though he found the humidity unbearable.

"Belly hot," Ah Sing gravely agreed in a guttural voice that sounded from unfathomable abysses.

"A hot day for a man that's tasted no liquor for nigh three months," Peter Gross amended.

"You makee long trip?" Ah Sing inquired politely.

Peter Gross's features molded themselves into an expression eloquently appreciative of his past miseries.

"That's altogether how you take it, Ah Sing," he replied. "From Frisco to Melbourne to Batavia isn't such a thunderin' long ways, not to a man that's done the full circle three times. But when you[17] make the voyage with a Methodist captain who doesn't believe in grog, it's the longest since Captain Cook's. Ah Sing, my throat's dryer than a sou'east monsoon. Hot toddy for two."

Ah Sing clapped his hands and uttered a magic word or two in Chinese. A Cantonese waiter paddled swiftly outside, bearing a lacquered tray and two steaming glasses. One he placed before Ah Sing and the other before Peter Gross, who tossed a coin on the table.

"Pledge your health, sir," Peter Gross remarked and reached across the board to clink glasses with his Chinese friend. Ah Sing lifted his glass to meet the sailor's and suddenly found it snaked out of his hands by a deft motion of Peter Gross's middle finger. Gross slid his own glass across the table toward Ah Sing.

"If you don't mind," he remarked pleasantly. "Your waiter might have mistaken me for a plain A. B., and I've got to get back to my ship to-night."

Ah Sing's bland and placid face remained expressionless as a carved god's. But he left the glass stand, untasted, beside him.

The Coryander's mate sipped his liquor and sank deeper into his chair. He studied with an air of affectionate interest the long lane of quaintly colonnaded buildings that edged the city within a city, the Chinese campong. Pigtailed Orientals, unmindful of the steaming heat, squirmed across the scenery. Ten thousand stenches were compounded into one, in which the flavor of garlic predominated.[18] Peter Gross breathed the heavy air with a smile of reminiscent pleasure and dropped another notch into the chair.

"It feels good to be back ashore again for a spell, Ah Sing," he remarked. "A nice, cool spot like this, with nothing to do and some of your grog under the belt, skins a blistery deck any day. I don't wonder so many salts put up here."

Back of the curtain of fat through which they peered, Ah Sing's oblique eyes quivered a trifle as they watched the sailor keenly.

"By the way," Peter Gross observed, stretching his long legs out to the limit of their reach, "you haven't seen any of my men, have you? Smith, he's pock-marked and has a cut over his right eye; Jacobson, a tall Swede, and Le Beouf, a little Frenchman with a close-clipped black mustache and beard?"

Ah Sing gravely cudgeled his memory.

"None of your men," he assured, "was here."

Peter Gross's face fell.

"That's too bad!" he exclaimed in evident disappointment. "I thought sure I'd find 'em here. You're sure you haven't overlooked them? That Frenchie might call for a hop; we picked him out of a hop-joint at Frisco."

"None your men here," Ah Sing repeated gutturally.

Peter Gross rumpled his tousled hair in perplexity.

"We-el," he drawled unhappily, "if those chaps[19] don't get back on shipboard by nightfall I'll have to buy some men from you, Ah Sing. Have y' got three good hands that know one rope from another?"

"Two men off schooner Marianna," Ah Sing replied in his same thick monotone. "One man, steamer Callee-opie. Good strong man. Work hard."

"You stole 'em, I s'pose?" Peter Gross asked pleasantly.

Ah Sing's heavy jowls waggled in gentle negation.

"No stealum man," he denied quietly. "Him belly sick. Come here, get well. Allie big, strong man."

"How much a head?"

"Twlenty dlolla."

"F. O. B. the Coryander and no extra charges?"

Ah Sing's inscrutable face screwed itself into a maze of unreadable wrinkles and lines.

"Him eat heap," he announced. "Five dlolla more for board."

"You go to blazes," Peter Gross replied cheerfully. "I'll look up a couple of men somewhere else or go short-handed if I have to."

Ah Sing made no reply and his impassive face did not alter its expressionless fixity. Peter Gross lazily pulled himself up in his chair and extended his right hand across the table. A ring with a big bloodstone in the center, a bloodstone cunningly chiseled and marked, rested on the middle finger.

"See that ring, Ah Sing?" he asked. "I got that down to Mauritius. What d'ye think it's worth?"[20]

Ah Sing's long, claw-like fingers groped avariciously toward the ring. His tiny, fat-encased eyes gleamed with cupidity.

With a quick, cat-like movement, Peter Gross gripped one of the Chinaman's hands.

"Don't pull," he cautioned quickly as Ah Sing tried to draw his hand away. "I was going to tell you that there's a drop of adder's poison inside the bloodstone that runs down a little hollow pin if you press the stone just so—" He moved to illustrate.

"No! No!" Ah Sing shrieked pig-like squeals of terror.

"Just send one of your boys for my salts, will you?" Peter Gross requested pleasantly. "I understand they got here yesterday morning and haven't been seen to leave. Talk English—no China talk, savvy?"

A flash of malevolent fury broke Ah Sing's mask of impassivity. The rage his face expressed caused Peter Gross to grip his hand the harder and look quickly around for a possible danger from behind. They were alone. Peter Gross moved a finger toward the stone, and Ah Sing capitulated. At his shrill cry there was a hurried rustle from within. Peter Gross kept close grip on the Chinaman's hand until he heard the shuffling tramp of sailor feet. Smith, Jacobson and Le Beouf, blinking sleepily, were herded on the portico by two giant Thibetans.[21]

Peter Gross shoved the table and Ah Sing violently back and leaped to his feet.

"You'll—desert—will you?" he exclaimed. Each word was punctuated by a swift punch on the chin of one of the unlucky sailors and an echoing thud on the floor. Smith, Jacobson, and Le Beouf lay neatly cross-piled on one of Ah Sing's broken chairs.

"I'll pay for the chair," Peter Gross declared, jerking his men to their feet and shoving them down the steps.

Ah Sing shrilled an order in Chinese. The Thibetan giants leaped for Peter Gross, who sprang out of their reach and put his back to the wall. In his right hand a gun flashed.

"Ah Sing, I'll take you first," he shouted.

The screen separating them from the adjoining portico was violently pushed aside.

"Ah Sing!" exclaimed a sharp, authoritative voice.

Ah Sing looked about, startled. The purpled fury his face expressed sickened to a mottled gray. Adriaan Adriaanszoon Van Schouten, governor-general of Java, leaning lightly on his cane, frowned sternly at the scene of disorder. At a cry from their master the two Thibetans backed away from Peter Gross, who lowered his weapon.

"Is it thus you observe our laws, Ah Sing?" Van Schouten demanded coldly.

Ah Sing licked his lips. "Light of the sun—" he began, but the governor interrupted shortly:

"The magistrate will hear your explanations."[22] His eagle eyes looked penetratingly upon Peter Gross, who looked steadfastly back.

"Sailor, you threatened to poison this man," the governor accused harshly, indicating Ah Sing.

"Your excellency, that was bluff," Peter Gross replied. "The ring is as harmless as your excellency's own."

Van Schouten's eyes twinkled.

"What is your name, sailor, and your ship?" he demanded.

"Peter Gross, your excellency, first mate of the barkentine Coryander of Boston, now lying in your excellency's harbor of Batavia."

"Ah Sing," Van Schouten rasped sternly, "if these drunken louts are not aboard their ship by nightfall, you go to the coffee-fields."

Ah Sing's gimlet eyes shrank to pin-points. His face was expressionless, but his whole body seemed to shake with suppressed emotion as he choked in guttural Dutch:

"Your excellency shall be obeyed." He salaamed to the ground.

Van Schouten glared at Peter Gross.

"Mynheer Gross, the good name of our fair city is very dear to us," he said sternly. "Scenes of violence like this do it much damage. I would have further discourse with you. Be at the paleis within the hour."

"I shall be there, your excellency," Peter Gross promised.

The governor shifted his frown to Ah Sing.[23]

"As for you, Ah Sing, I have heard many evil reports of this place," he said. "Let me hear no more."

While Ah Sing salaamed again, the governor strode pompously away, followed at a respectful distance by Peter Gross. It was not until they had disappeared beyond a curve in the road that Ah Sing let his face show his feelings. Then an expression of malignant fury before which even the two Thibetans quailed, crossed it.

He uttered a harsh command to have the débris removed. The Thibetans jumped forward in trembling alacrity. Without giving them another glance he waddled into the building, into a little den screened off for his own use. From a patent steel safe of American make he took an ebony box, quaintly carved and colored in glorious pinks and yellows with a flower design. Opening this, he exposed a row of glass vials resting on beds of cotton. Each vial contained some nail parings.

He took out the vials one by one, looked at their labels inscribed in Chinese characters, and placed them on an ivory tray. As he read each label a curious smile of satisfaction spread over his features.

When he had removed the last vial he sat at his desk, dipped a pen into India ink, and wrote two more labels in similar Chinese characters. When the ink had dried he placed these on two empty vials taken from a receptacle on his desk. The vials were placed with the others in the ebony box and locked in the safe.[24]

The inscriptions he read on the labels were the names of men who had died sudden and violent deaths in the East Indies while he had lived at Batavia. The labels he filled out carried the names of Adriaan Adriaanszoon Van Schouten and Peter Gross.[25]

"Sailor, the penalty for threatening the life of any citizen is penal servitude on the state's coffee-plantations."

The governor's voice rang harshly, and he scowled across the big table in his cabinet-room at the Coryander's mate sitting opposite him. His hooked nose and sharp-pointed chin with its finely trimmed Van Dyke beard jutted forward rakishly.

"I ask no other justice than your excellency's own sense of equity suggests," Peter Gross replied quietly.

"H'mm!" the governor hummed. He looked at the Coryander's mate keenly for a few moments through half-closed lids. Suddenly he said:

"And what if I should appoint you a resident, sailor?"

Peter Gross's lips pressed together tightly, but otherwise he gave no sign of his profound astonishment at the governor's astounding proposal. Sinking deeper into his chair until his head sagged on his breast, he deliberated before replying.

"Your excellency is in earnest?"

"I do not jest on affairs of state, Mynheer Gross. What is your answer?"[26]

Peter Gross paused. "Your excellency overwhelms me—" he began, but Van Schouten cut him short.

"Enough! When I have work to do I choose the man who I think can do it. Then you accept?"

"Your excellency, to my deep regret I must most respectfully decline."

A look of blank amazement spread over the governor's face. Then his eyes blazed ominously.

"Decline! Why?" he roared.

"For several reasons," Peter Gross replied with disarming mildness. "In the first place I am under contract with Captain Threthaway of the Coryander—"

"I will arrange that with your captain," the governor broke in.

"In the second place I am neither a soldier nor a politician—"

"That is for me to consider," the governor retorted.

"In the third place, I am a citizen of the United States and therefore not eligible to any civil appointment from the government of the Netherlands."

"Donder en bliksem!" the governor exclaimed. "I thought you were a freeholder here."

"I am," Peter Gross admitted. "The land I won is at Riswyk. I expect to make it my home when I retire from the sea."

"How long have you owned that land?"

"For nearly seven years."

The governor stroked his beard. "You talk[27] Holland like a Hollander, Mynheer Gross," he observed.

"My mother was of Dutch descent," Peter Gross explained. "I learned the language from her."

"Good!" Van Schouten inclined his head with a curt nod of satisfaction. "Half Holland is all Holland. We can take steps to make you a citizen at once."

"I don't care to surrender my birthright." Peter Gross negatived quietly.

"What!" Van Schouten shouted. "Not for a resident's post? And eight thousand guilders a year? And a land grant in Java that will make you rich for life if you make those hill tribes stick to their plantations? What say you to this, Mynheer Gross?" His lips curved with a smile of anticipation.

"The offer is tempting and the honor great," Peter Gross acknowledged quietly. "But I can not forget I was born an American."

Van Schouten leaned back in his chair with a look of astonishment.

"You refuse?" he asked incredulously.

"I am sorry, your excellency!" Peter Gross's tone was unmistakably firm.

"You refuse?" the governor repeated, still unbelieving. "Eight—thousand—guilders! And a land grant that will make you rich for life!"

"I am an American, and American I shall stay."

The governor's eyes sparkled with admiration.

"By the beard of Orange!" he exclaimed, "it is no wonder you Yankees have sucked the best blood[28] of the world into your country." He leaned forward confidentially.

"Mynheer Gross, I cannot appoint you resident if you refuse to take the oath of allegiance to the queen. But I can make you special agent of the gouverneur-generaal. I can make you a resident in fact, if not in name, of a country larger than half the Netherlands, larger than many of your own American States. I can give you the rewards I have pledged you, a fixed salary and the choice of a thousand hectares of our fairest state lands in Java. What do you say?"

He leaned forward belligerently. In that posture his long, coarse hair rose bristly above his neck, giving him something of the appearance of a gamecock with feathers ruffled. It was this peculiarity that first suggested the name he was universally known by throughout the Sundas, "De Kemphaan" (The Gamecock).

"To what province would you appoint me?" Peter Gross asked slowly.

The governor hesitated. With the air of a poker player forced to show his hand he confessed:

"It is a difficult post, mynheer, and needs a strong man as resident. It is the residency of Bulungan, Borneo."

There was the faintest flicker in Peter Gross's eyes. Van Schouten watched him narrowly. In the utter stillness that followed the governor could hear his watch tick.

Peter Gross rose abruptly, leaped for the door,[29] and threw it open. He looked straight into the serene, imperturbable face of Chi Wung Lo, autocrat of the governor's domestic establishment. Chi Wung bore a delicately lacquered tray of Oriental design on which were standing two long, thin, daintily cut glasses containing cooling limes that bubbled fragrantly. Without a word he swept grandly in and placed the glasses on the table, one before the governor, and the other before Peter Gross's vacant chair.

"Ha!" Van Schouten exclaimed, smacking his lips. "Chi Wung, you peerless, priceless servant, how did you guess our needs?"

With a bland bow and never a glance at Peter Gross, Chi Wung strutted out in Oriental dignity, carrying his empty tray. Peter Gross closed the door carefully, and walked slowly back.

"I was about to say, your excellency," he murmured, "that Bulungan has not a happy reputation."

"It needs a strong man to rule it," the governor acknowledged, running his glance across Peter Gross's broad shoulders in subtle compliment.

"Those who have held the post of resident there found early graves."

"You are young, vigorous. You have lived here long enough to know how to escape the fevers."

"There are worse enemies in Bulungan than the fevers," Peter Gross replied. "It is not for nothing that Bulungan is known as the graveyard of Borneo."

The governor glanced at Peter Gross's strong face and stalwart form regretfully.[30]

"Your refusal is final?" he asked.

"On the contrary, if your excellency will meet one condition, I accept," Peter Gross replied.

The governor put his glass down sharply and stared at the sailor.

"You accept this post?" he demanded.

"Upon one condition, yes!"

"What is that condition?"

"That I be allowed a free hand."

"H'mm!" Van Schouten drew a deep breath and leaned back in his chair. The sharp, Julian cast of countenance was never more pronounced, and the eagle eyes gleamed inquiringly, calculatingly. Peter Gross looked steadily back. The minutes passed and neither spoke.

"Why do you want to go there?" the governor exclaimed suddenly. He leaned forward in his chair till his eyes burned across a narrow two feet into Peter Gross's own.

The strong, firm line of Peter Gross's lips tightened. He rested one elbow on the table and drew nearer the governor. His voice was little more than a murmur as he said:

"Your excellency, let me tell you the story of Bulungan."

The governor's face showed surprise. "Proceed," he directed.

"Six years ago, when your excellency was appointed governor-general of the Netherlands East Indies," Peter Gross began, "Bulungan was a No Man's land, although nominally under the Dutch[31] flag. The pirates that infested the Celebes sea and the straits of Macassar found ports of refuge in its jungle-banked rivers and marsh mazes where no gun-boat could find them. The English told your government that if it did not stamp out piracy and subjugate the Dyaks, it would. That meant loss of the province to the Dutch crown. Accordingly you sent General Van Heemkerken there with eight hundred men who marched from the lowlands to the highlands and back again, burning every village they found, but meeting no Dyaks except old men and women too helpless to move. General Van Heemkerken reported to you that he had pacified the country. On his report you sent Mynheer Van Scheltema there as resident, and Cupido as controlleur. Within six months Van Scheltema was bitten by an adder placed in his bedroom and Cupido was assassinated by a hill Dyak, who threw him out of a dugout into a river swarming with crocodiles.

"Lieve hemel, no!" Van Schouten cried. "Van Scheltema and Cupido died of the fevers."

"So it was reported to your excellency," Peter Gross replied gravely. "I tell you the facts."

The governor's thin, spiked jaw shot out like a vicious thorn and his teeth clicked.

"Go on," he directed sharply.

"For a year there was neither resident nor controlleur at Bulungan. Then the pirates became so bold that you again took steps to repress them. The stockade at the village of Bulungan was enlarged and the garrison was increased to fifty men. Lieu[32]tenant Van Slyck, the commandant, was promoted to captain. A new resident was appointed, Mynheer de Jonge, a very dear friend of your excellency. He was an old man, estimable and honest, but ill-fitted for such a post, a failure in business, and a failure as a resident. Time after time your excellency wrote him concerning piracies, hillmen raids, and head-hunting committed in his residency or the adjoining seas. Each time he replied that your excellency must be mistaken, that the pirates and head-hunters came from other districts."

The governor's eyes popped in amazement. "How do you know this?" he exclaimed, but Peter Gross ignored the question.

"Finally about two years ago Mynheer de Jonge, through an accident, learned that he had been deceived by those he had trusted, had a right to trust. A remark made by a drunken native opened his eyes. One night he called out Captain Van Slyck and the latter's commando and made a flying raid. He all but surprised a band of pirates looting a captured schooner and might have taken them had they not received a warning of his coming. That raid made him a marked man. Within two weeks he was poisoned by being pricked as he slept with a thorn dipped in the juice of the deadly upas tree."

"He was a suicide!" the governor exclaimed, his face ashen. "They brought me a note in his own handwriting."

"In which it was stated that he killed himself[33] because he felt he had lost your excellency's confidence?"

"You know that, too?" Van Schouten whispered huskily.

"Your excellency has suffered remorse without cause," Peter Gross declared quietly. "The note is a forgery."

The governor's hands gripped the edge of the table.

"You can prove that?" he cried.

"For the present your excellency must be satisfied with my word. As resident of Bulungan I hope to secure proofs that will satisfy a court of justice."

The governor gazed at Peter Gross intently. A conflict of emotions, amazement, unbelief, and hope were expressed on his face.

"Why should I believe you?" he demanded fiercely.

Peter Gross's face hardened. The sternness of the magistrate was on his brow as he replied:

"Your excellency remembers the schooner Tetrina, attacked by Chinese and Dyak pirates off the coast of Celebes three years ago? All her crew were butchered except two left on the deck that night for dead. I was one of the two, your excellency. My dead comrades have left me a big debt to pay. That is why I will go to Bulungan."

The governor rose. Decision was written on his brow.

"Meet us here to-night, Mynheer Gross," he said. "There is much to discuss with Mynheer Sachsen[34] before you leave. God grant you may be the instrument of His eternal justice." Peter Gross raised a hand of warning.

"Sometimes the very walls have ears, your excellency," he cautioned. "If I am to be resident of Bulungan no word of the appointment must leak out until I arrive there."[35]

It was a blistering hot day in Bulungan. The heavens were molten incandescence. The muddy river that bisected the town wallowed through its estuary, a steaming tea-kettle. The black muck-fields baked and flaked under the torrid heat. The glassy surface of the bay, lying within the protecting crook of a curling tail of coral reef, quivered under the impact of the sun's rays like some sentient thing.

In the village that nestled where fresh and salt water met, the streets were deserted, almost lifeless. Gaunt pariah dogs, driven by the acid-sharp pangs of a never-satiated hunger, sniffed among the shadows of the bamboo and palmleaf huts, their backs arched and their tails slinking between their legs. Too weak to grab their share of the spoil in the hurly-burly, they scavenged in these hours of universal inanity. The doors of the huts were tightly closed—barricaded against the heat. The merchant in his dingy shop, the fisherman in his house on stilts, and the fashioner of metals in his thatched cottage in the outskirts slept under their mats. Apoplexy was the swift and sure fate of those who dared the awful torridity.[36]

Dawn had foretold the heat. The sun shot above the purple and orange waters of the bay like a conflagration. The miasmal vapors that clustered thickly about the flats by night gathered their linen and fled like the hunted. They were scurrying upstream when Bogoru, the fisherman, walked out on his sampan landing. He looked at the unruffled surface of the bay, and then looked upward quickly at the lane of tall kenari trees between the stockade and government buildings on an elevation a short distance back of the town. The spindly tops of the trees pointed heavenward with the rigidity of church spires.

"There will be no chaetodon sold at the visschersmarkt (fishmart) to-day," he observed. "Kismet!"

With a patient shrug of his shoulders he went back to his hut and made sure there was a plentiful supply of sirih and cooling limes on hand.

In the fruit-market Tagotu, the fruiterer, set out a tempting display of mangosteen, durian, dookoo, and rambootan, pineapples, and pomegranates, jars of agar-agar, bowls of rice, freshly cooked, and pitchers of milk.

The square was damp from the heavy night dew when he set out the first basket, it was dry as a fresh-baked brick when he put out the last. The heavy dust began to flood inward. Tagotu noticed with dismay how thin the crowd was that straggled about the market-place. Chepang, his neighbor, came out of his stall and observed:[37]

"The monsoon has failed again. Bunungan will stay in his huts to-day."

"It is the will of Allah," Tagotu replied patiently. Putting aside his offerings, he lowered the shades of his shop and composed himself for a siesta.

On the hill above the town, where the rude fort and the government buildings gravely faced the sea, the heat also made itself felt. The green blinds of the milk-white residency building, that was patterned as closely as tropical conditions would permit after the quaint architecture of rural Overysel, were tightly closed. The little cluster of residences around it, the controlleur's house and the homes of Marinus Blauwpot and Wang Fu, the leading merchants of the place, were similarly barricaded. For "Amsterdam," the fashionable residential suburb of Bulungan village, was fighting the same enemy as "Rotterdam," the town below, an enemy more terrible than Dyak blow-pipes and Dyak poisoned arrows, the Bornean sun.

Like Bogoru, the fisherman, and Tagotu, the fruit-vender, Cho Seng, Mynheer Muller's valet and cook, had seen the threat the sunrise brought. The sun's copper disc was dyeing the purple and blue waters of the bay with vermilion and magentas when he pad-padded out on the veranda of the controlleur's house. He was clad in the meticulously neat brown jeans that he wore at all times and occasions except funeral festivals, and in wicker sandals. With a single sweep of his eyes he took in the kenari[38]-tree-lined land that ran to the gate of the stockade where a sleepy sentinel, hunched against a pert brass cannon, nodded his head drowsily. The road was tenantless. He shot another glance down the winding pathway that led by the houses of Marinus Blauwpot and Wang Fu to the town below. That also was unoccupied. Stepping off the veranda, he crossed over to an unshaded spot directly in front of the house and looked intently seaward to where a junk lay at anchor. The brown jeans against the milk-white paint of the house threw his figure in sharp relief.

Cho Seng waited until a figure showed itself on the deck of the junk. Then he shaded his eye with his arm. The Chinaman on the deck of the junk must have observed the figure of his fellow countryman on the hill, for he also shaded his eyes with his arm.

Cho Seng looked quickly to the right—to the left. There was no one stirring. The sentinel at the gate drowsed against the carriage of the saucy brass cannon. Shading his eyes once more with a quick gesture, Cho Seng walked ten paces ahead. Then he walked back five paces. Making a sharp angle he walked five paces to one side. Then he turned abruptly and faced the jungle.

The watcher on the junk gave no sign that he had seen this curious performance. But as Cho Seng scuttled back into the house, he disappeared into the bowels of the ugly hulk.

An hour passed before Cho Seng reappeared on[39] the veranda. He cast only a casual glance at the junk and saw that it was being provisioned. After listening for a moment to the rhythmic snoring that came from the chamber above—Mynheer Muller's apartment—he turned the corner of the house and set off at a leisurely pace toward the tangle of mangroves, banyan, bamboo cane, and ferns that lay a quarter of a mile inland on the same elevation on which the settlement and stockade stood.

There was nothing in his walk to indicate that he had a definite objective. He strolled along in apparent aimlessness, as though taking a morning's constitutional. Overhead hundreds of birds created a terrific din; green and blue-billed gapers shrilled noisily; lories piped their matin lays, and the hoarse cawing of the trogons mingled discordantly with the mellow notes of the mild cuckoos. A myriad insect life buzzed and hummed around him, and scurried across his pathway. Pale white flowers of the night that lined the wall shrank modestly into their green cloisters before the bold eye of day. But Cho Seng passed them by unseeing, and unhearing. Nature had no existence for him except as it ministered unto his physical needs. Only once did he turn aside—a quick, panicky jump—and that was when a little spotted snake glided in front of him and disappeared into the underbrush.

When he was well within the shadows of the mangroves, Cho Seng suddenly brightened and began to look about him keenly. Following a faintly defined path, he walked along in a circuitous[40] route until he came to a clearing under the shade of a huge banyan tree whose aërial roots rose over his head. After peering furtively about and seeing no one he uttered a hoarse, guttural call, the call the great bird of paradise utters to welcome the sunrise—"Wowk, wowk, wowk."

There was an immediate answer—the shrill note of the argus pheasant. It sounded from the right, near by, on the other side of a thick tangle of cane and creeper growth. Cho Seng paused in apparent disquietude at the border of the thicket, but as he hesitated, the call was repeated more urgently. Wrenching the cane apart, he stepped carefully into the underbrush.

His progress through it was slow. At each step he bent low to make certain where his foot fell. He had a mortal fear of snakes—his nightmares were ghastly dreams of a loathsome death from a serpent's bite.

There was a low ripple of laughter—girlish laughter. Cho Seng straightened quickly. To his right was another clearing, and in that clearing there was a woman, a young woman just coming into the bloom of a glorious beauty. She was seated on a gnarled aërial root. One leg was negligently thrown over the other, a slender, shapely arm reached gracefully upward to grasp a spur from another root, a coil of silky black hair, black as tropic night, lay over her gleaming shoulder. Her sarong, spotlessly white, hung loosely about her wondrous form and was caught with a cluster of rubies above her breasts.[41] A sandal-covered foot, dainty, delicately tapering, its whiteness tanned with a faint tint of harvest brown, was thrust from the folds of the gown. At her side, in a silken scabbard, hung a light, skilfully wrought kris. The handle was studded with gems.

"Good-morning, Cho Seng," the woman greeted demurely.

Cho Seng, making no reply, snapped the cane aside and leaped through. Koyala laughed again, her voice tinkling like silver bells. The Chinaman's laborious progress through the cane had amused her. She knew why he stepped so carefully.

"Good-morning, Cho Seng," Koyala repeated. Her mocking dark brown eyes tried to meet his, but Cho Seng looked studiedly at the ground, in the affected humility of Oriental races.

"Cho Seng here," he announced. "What for um you wantee me?" He spoke huskily; a physician would instantly have suspected he was tubercular.

Koyala's eyes twinkled. A woman, she knew she was beautiful. Wherever she went, among whites or Malays, Chinese, or Papuans, she was admired. But from this stolid, unfathomable, menial Chinaman she had never been able to evoke the one tribute that every pretty woman, no manner how good, demands from man—a glance of admiration.

"Cho Seng," she pouted, "you have not even looked at me. Am I so ugly that you cannot bear to see me?"

"What for um you wantee me?" Cho Seng reit[42]erated. His neck was crooked humbly so that his eyes did not rise above the hem of her sarong, and his hands were tucked inside the wide sleeves of his jacket. His voice was as meek and mild and inoffensive as his manner.

Koyala laughed mischievously.

"I asked you a question, Cho Seng," she pointed out.

The Chinaman salaamed again, even lower than before. His face was imperturbable as he repeated in the same mild, disarming accents:

"What for um you wantee me?"

Koyala made a moue.

"That isn't what I asked you, Cho Seng," she exclaimed petulantly.

The Chinaman did not move a muscle. Silent, calm as a deep-sea bottom, his glance fixed unwaveringly on a little spot of black earth near Koyala's foot, he awaited her reply.

Leveque's daughter shrugged her shoulders in hopeless resignation. Ever since she had known him she had tried to surprise him into expressing some emotion. Admiration, fear, grief, vanity, cupidity—on all these chords she had played without producing response. His imperturbability roused her curiosity, his indifference to her beauty piqued her, and, womanlike, she exerted herself to rouse his interest that she might punish him. So far she had been unsuccessful, but that only gave keener zest to the game. Koyala was half Dyak, she had in her veins the blood of the little brown[43] brother who follows his enemy for months, sometimes years, until he brings home another dripping head to set on his lodge-pole. Patience was therefore her birthright.

"Very well, Cho Seng, if you think I am ugly—" She paused and arched an eyebrow to see the effect of her words. Cho Seng's face was as rigid as though carved out of rock. When she saw he did not intend to dispute her, Koyala flushed and concluded sharply:

"—then we will talk of other things. What has happened at the residency during the past week?"

Cho Seng shot a furtive glance upward. "What for um?" he asked cautiously.

"Oh, everything." Koyala spoke with pretended indifference. "Tell me, does your baas, the mynheer, ever mention me?"

"Mynheer Muller belly much mad, belly much drink jenever (gin), belly much say 'damn-damn, Cho Seng,'" the Chinaman grunted.

Koyala's laughter rang out merrily in delicious peals that started the rain-birds and the gapers to vain emulation. Cho Seng hissed a warning and cast apprehensive glances about the jungle, but Koyala, mocking the birds, provoked a hubbub of furious scolding overhead and laughed again.

"There's nobody near to hear us," she asserted lightly.

"Mebbe him in bush," Cho Seng warned.

"Not when the southeast monsoon ceases to blow," Koyala negatived. "Mynheer Muller loves his[44] bed too well when our Bornean sun scorches us like to-day. But tell me what your master has been doing?"

She snuggled into a more comfortable position on the root. Cho Seng folded his hands over his stomach.

"Morning him sleep," he related laconically. "Him eat. Him speakee orang kaya, Wobanguli, drink jenever. Him speakee Kapitein Van Slyck, drink jenever. Him sleep some more. Bimeby when sun so-so—" Cho Seng indicated the position of the sun in late afternoon—" him go speakee Mynheer Blauwpot, eat some more. Bimeby come home, sleep. Plenty say 'damn-damn, Cho Seng.'"

"Does he ever mention me?" Koyala asked. Her eyes twinkled coquettishly.

"Plenty say nothing," Cho Seng replied.

Koyala's face fell. "He doesn't speak of me at all?"

Cho Seng shot a sidelong glance at her.

"Him no speakee Koyala, him plenty drink jenever, plenty say 'damn-damn, Cho Seng.'" He looked up stealthily to see the effect of his words.

Koyala crushed a fern underfoot with a vicious dab of her sandaled toes. Something like the ghost of a grin crossed the Chinaman's face, but it was too well hidden for Koyala to see it.

"How about Kapitein Van Slyck? Has he missed me?" Koyala asked. "It is a week since I have been at the residency. He must have noticed it."[45]

"Kapitein Van Slyck him no speakee Koyala," the Chinaman declared.

Koyala looked at him sternly. "I cannot believe that, Cho Seng," she said. "The captain must surely have noticed that I have not been in Amsterdam. You are not telling me an untruth, are you, Cho Seng?"

The Chinaman was meekness incarnate as he reiterated:

"Him no speakee Koyala."

Displeasure gathered on Koyala's face like a storm-cloud. She leaped suddenly from the aërial root and drew herself upright. At the same moment she seemed to undergo a curious transformation. The light, coquettish mood passed away like dabs of sunlight under a fitful April sky, an imperious light gleamed in her eyes and her voice rang with authority as she said:

"Cho Seng, you are the eyes and the ears of Ah Sing in Bulungan—"

The Chinaman interrupted her with a sibilant hiss. His mask of humility fell from him and he darted keen and angry glances about the cane.

"When Koyala Bintang Burung speaks it is your place to listen, Cho Seng," Koyala asserted sternly. Her voice rang with authority. Under her steady glance the Chinaman's furtive eyes bushed themselves in his customary pose of irreproachable meekness.

"You are the eyes and ears of Ah Sing in Bulun[46]gan," Koyala reaffirmed, speaking deliberately and with emphasis. "You know that there is a covenant between your master, your master in Batavia, and the council of the orang kayas of the sea Dyaks of Bulungan, whereby the children of the sea sail in the proas of Ah Sing when the Hanu Token come to Koyala on the night winds and tell her to bid them go."

The Chinaman glanced anxiously about the jungle, fearful that a swaying cluster of cane might reveal the presence of an eavesdropper.

"S-ss-st," he hissed.

Koyala's voice hardened. "Tell your master this," she said. "The spirits of the highlands speak no more through the mouth of the Bintang Burung till the eyes and ears of Ah Sing become her eyes and ears, too."

There was a significant pause. Cho Seng's face shifted and he looked at her slantwise to see how seriously he should take the declaration. What he saw undoubtedly impressed him with the need of promptly placating her, for he announced:

"Cho Seng tellee Mynheer Muller Koyala go hide in bush—big baas in Batavia say muchee damn-damn, give muchee gold for Koyala."

The displeasure in Koyala's flushed face mounted to anger.

"No, you cannot take credit for that, Cho Seng," she exclaimed sharply. "Word came to Mynheer Muller from the governor direct that a price of many guilders was put on my head."[47]

Her chin tilted scornfully. "Did you think Koyala was so blind that she did not see the gun-boat in Bulungan harbor a week ago to-day?"

Cho Seng met her heat with Oriental calm.

"Bang-bang boat, him come six-seven day ago," he declared. "Cho Seng, him speakee Mynheer Muller Koyala go hide in bush eight-nine day."

"The gun-boat was in the harbor the morning Mynheer Muller told me," Koyala retorted, and stopped in sudden recollection. A tiny flash of triumph lit the Chinaman's otherwise impassive face as he put her unspoken thought into words:

"Kapitein him bang-bang boat come see Mynheer Muller namiddag," (afternoon) he said, indicating the sun's position an hour before sunset. "Mynheer Muller tellee Koyala voormiddag" (forenoon). He pointed to the sun's morning position in the eastern sky.

"That is true," Koyala assented thoughtfully, and paused. "How did you hear of it?"

Cho Seng tucked his hands inside his sleeves and folded them over his paunch. His neck was bent forward and his eyes lowered humbly. Koyala knew what the pose portended; it was the Chinaman's refuge in a silence that neither plea nor threat could break. She rapidly recalled the events of that week.

"There was a junk from Macassar in Bulungan harbor two weeks—no, eleven days ago," she exclaimed. "Did that bring a message from Ah Sing?"

A startled lift of the Chinaman's chin assured her[48] that her guess was correct. Another thought followed swift on the heels of the first.

"The same junk is in the harbor to-day—came here just before sundown last night," she exclaimed. "What message did it bring, Cho Seng?"

The Chinaman's face was like a mask. His lips were compressed tightly—it was as though he defied her to wedge them open and to force him to reveal his secret. An angry sparkle lit Koyala's eyes for a moment, she stepped a pace toward him and her hand dropped to the hilt of the jeweled kris, then she stopped short. A fleeting look of cunning replaced the angry gleam; a half-smile came and vanished on her lips almost in the same instant.

Her face lifted suddenly toward the leafy canopy. Her arms were flung upward in a supplicating gesture. The Chinaman, watching her from beneath his lowered brow, looked up in startled surprise. Koyala's form became rigid, a Galatea turned back to marble. Her breath seemed to cease, as though she was in a trance. The color left her face, left even her lips. Strangely enough, her very paleness made the Dyak umber in her cheeks more pronounced.

Her lips parted. A low crooning came forth. The Chinaman's knees quaked and gave way as he heard the sound. His body bent from the waist till his head almost touched the ground.

The crooning gradually took the form of words. It was the Malay tongue she spoke—a language Cho Seng knew. The rhythmic beating of his head[49] against his knees ceased and he listened eagerly, with face half-lifted.

"Hanu Token, Hanu Token, spirits of the highlands, whither are you taking me?" Koyala cried. She paused, and a deathlike silence followed. Suddenly she began speaking again, her figure swaying like a tall lily stalk in a spring breeze, her voice low-pitched and musically mystic like the voice of one speaking from a far distance.

"I see the jungle, the jungle where the mother of rivers gushes out of the great smoking mountain. I see the pit of serpents in the jungle—"

A trembling seized Cho Seng.

"The serpents are hungry, they have not been fed, they clamor for the blood of a man. I see him whose foot is over the edge of the pit, he slips, he falls, he tries to catch himself, but the bamboo slips out of his clutching fingers—I see his face—it is the face of him whose tongue speaks double, it is the face of—"

A horrible groan burst from the Chinaman. He staggered to his feet.

"Neen, neen, neen, neen," he cried hoarsely in an agonized negative. "Cho Seng tellee Bintang Burung—"

A tremulous sigh escaped from Koyala's lips. Her body shook as though swayed by the wind. Her eyes opened slowly, vacantly, as though she was awakening from a deep sleep. She looked at Cho Seng with an absent stare, seeming to wonder why[50] he was there, why she was where she was. The Chinaman, made voluble through fear, chattered:

"Him junk say big baas gouverneur speakee muchee damn-damn; no gambir, no rice, no copra, no coffee from Bulungan one-two year; sendee new resident bimeby belly quick."

Koyala's face paled.

"Send a new resident?" she asked incredulously. "What of Mynheer Muller?"

The look of fear left Cho Seng's face. Involuntarily his neck bent and his fingers sought each other inside the sleeves. There was cunning mingled with malice in his eyes as he looked up furtively and feasted on her manifest distress.

"Him chop-chop," he announced laconically.

"They will kill him?" Koyala cried.

The Chinaman had said his word. None knew better than he the value of silence. He stood before her in all humbleness and calmly awaited her next word. All the while his eyes played on her in quick, cleverly concealed glances.

Koyala fingered the handle of the kris as she considered what the news portended. Her face slowly hardened—there was a look in it of the tigress brought to bay.

"Koyala bimeby mally him—Mynheer Muller, go hide in bush?" Cho Seng ventured. The question was asked with such an air of simple innocence and friendly interest that none could take offense.

Koyala flushed hotly. Then her nose and chin rose high with pride.[51]

"The Bintang Burung will wed no man, Cho Seng," she declared haughtily. "The blood of Chawatangi dies in me, but not till Bulungan is purged of the orang blanda" (white race). She whipped the jeweled kris out of its silken scabbard. "When the last white man spills his heart on the coral shore and the wrongs done Chawatangi's daughter, my mother, have been avenged, then Koyala will go to join the Hanu Token that call her, call her—"

She thrust the point of the kris against her breast and looked upward toward the far-distant hills and the smoking mountain. A look of longing came into her eyes, the light of great desire, almost it seemed as if she would drive the blade home and join the spirits she invoked.

With a sigh she lowered the point of the kris and slipped it back into its sheath.

"No, Cho Seng," she said, "Mynheer Muller is nothing to me. No man will ever be anything to me. But your master has been a kind elder brother to Koyala. And like me, he has had to endure the shame of an unhappy birth." Her voice sank to a whisper. "For his mother, Cho Seng, as you know, was a woman of Celebes."

She turned swiftly away that he might not see her face. After a moment she said in a voice warm with womanly kindness and sympathy:

"Therefore you and I must take care of him, Cho Seng. He is weak, he is untruthful, he has made a wicked bargain with your master, Ah Sing, which the spirits of the hills tell me he shall suffer for, but he is[52] only what his white father made him, and the orang blanda must pay!" Her lips contracted grimly. "Ay, pay to the last drop of blood! You will be true to him, Cho Seng?"

The Chinaman cast a furtive glance upward and found her mellow dark-brown eyes looking at him earnestly. The eyes seemed to search his very soul.

"Ja, ja," he pledged.

"Then go, tell the captain of the junk to sail quickly to Macassar and send word by a swift messenger to Ah Sing that he must let me know the moment a new resident is appointed. There is no wind and the sun is high; therefore the junk will still be in the harbor. Hurry, Cho Seng!"

Without a word the Chinaman wheeled and shuffled down the woodland path that led from the clearing toward the main highway. Koyala looked after him fixedly.

"If his skin were white he could not be more false," she observed bitterly. "But he is Ah Sing's slave, and Ah Sing needs me, so I need not fear him—yet."

She followed lightly after Cho Seng until she could see the prim top of the residency building gleaming white through the trees. Then she stopped short. Her face darkened as the Dyak blood gathered thickly. A look of implacable hate and passion distorted it. Her eyes sought the distant hills:

"Hanu Token, Hanu Token, send a young man here to rule Bulungan," she prayed. "Send a strong man, send a vain man, with a passion for fair women.[53] Let me dazzle him with my beauty, let me fill his heart with longing, let me make his brain reel with madness, let me make his body sick with desire. Let me make him suffer a thousand deaths before he gasps his last breath and his dripping head is brought to thy temple in the hills. For the wrongs done Chawatangi's daughter, Hanu Token, for the wrongs done me!"

With a low sob she fled inland through the cane.[54]

Electric tapers were burning dimly in Governor-General Van Schouten's sanctum at the paleis that evening as Peter Gross was ushered in. The governor was seated in a high-backed, elaborately carved mahogany chair before a highly polished mahogany table. Beside him was the omniscient, the indispensable Sachsen. The two were talking earnestly in the Dutch language. Van Schouten acknowledged Peter Gross's entrance with a curt nod and directed him to take a chair on the opposite side of the table.

At a word from his superior, Sachsen tucked the papers he had been studying into a portfolio. The governor stared intently at his visitor for a moment before he spoke.

"Mynheer Gross," he announced sharply, "your captain tells me your contract with him runs to the end of the voyage. He will not release you."

"Then I must fill my contract, your excellency," Peter Gross replied.

Van Schouten frowned with annoyance. He was not accustomed to being crossed.

"When will you be able to take over the administration of Bulungan, mynheer?"[55]

Peter Gross's brow puckered thoughtfully. "In three weeks—let us say thirty days, your excellency."

"Donder en bliksem!" the governor exclaimed. "We need you there at once."

"That is quite impossible, your excellency. I will need help, men that I can trust and who know the islands. Such men cannot be picked up in a day."

"You can have the pick of my troops."

"I should prefer to choose my own men, your excellency," Peter Gross replied.

"Eh? How so, mynheer?" The governor's eyes glinted with suspicion.

"Your excellency has been so good as to promise me a free hand," Peter Gross replied quietly. "I have a plan in mind—if your excellency desires to hear it?"

Van Schouten's face cleared.

"We shall discuss that later, mynheer. You will be ready to go the first of June, then?"

"On the first of June I shall await your excellency's pleasure here at Batavia," Peter Gross agreed.

"Nu! that is settled!" The governor gave a grunt of satisfaction and squared himself before the table. His expression became sternly autocratic.

"Mynheer Gross," he said, "you told us this afternoon some of the history of our unhappy residency of Bulungan. You demonstrated to our satisfaction a most excellent knowledge of conditions there. Some of the things you spoke of were—I may say—surprising. Some touched upon matters[56] which we thought were known only to ourselves and to our privy council. But, mynheer, you did not mention one subject that to our mind is the gravest problem that confronts our representatives in Bulungan. Perhaps you do not know there is such a problem. Or perhaps you underestimate its seriousness. At any rate, we deem it desirable to discuss this matter with you in detail, that you may thoroughly understand the difficulties before you, and our wishes in the matter. We have requested Mynheer Sachsen to speak for us."

He nodded curtly at his secretary.

"You may proceed, Sachsen."

Sachsen's white head, that had bent low over the table during the governor's rather pompous little speech, slowly lifted. His shrewd gray eyes twinkled kindly. His lips parted in a quaintly humorous and affectionate smile.

"First of all, Vrind Pieter, let me congratulate you," he said, extending a hand across the table. Peter Gross's big paw closed over it with a warm pressure.

"And let me thank you, Vrind Sachsen," he replied. "It was not hard to guess who brought my name to his excellency's attention."

"It is Holland's good fortune that you are here," Sachsen declared. "Had you not been worthy, Vrind Pieter, I should not have recommended you." He looked at the firm, strong face and the deep, broad chest and massive shoulders of his protégé with almost paternal fondness.[57]

"To have earned your good opinion is reward enough in itself," Peter Gross asserted.

Sachsen's odd smile, that seemed to find a philosophic humor in everything, deepened.

"Your reward, Vrind Pieter," he observed, "is the customary recompense of the man who proves his wisdom and his strength—a more onerous duty. Bulungan will test you severely, vrind (friend). Do you believe that?"

"Ay," Peter Gross assented soberly.

"Pray God to give you wisdom and strength," Sachsen advised gravely. He bowed his head for a moment, then stirred in his chair and sat up alertly.

"Nu! as to the work that lies before you, I need not tell you the history of this residency. For Sachsen to presume to instruct Peter Gross in what has happened in Bulungan would be folly. As great folly as to lecture a dominie on theology."

Again the quaintly humorous quirk of the lips.

"If Peter Gross knew the archipelago half so well as his good friend Sachsen he would be a lucky man," Peter Gross retorted spiritedly.

Sachsen's face became suddenly grave.

"We do not doubt your knowledge of conditions in our unhappy province, Vrind Pieter. Nor do we doubt your ability, your courage, or your sound judgment. But, Pieter—"

He paused. The clear gray eyes of Peter Gross met his questioningly.

"—You are young, Vrind Pieter."

The governor rose abruptly and plucked down[58] from the wall a long-stemmed Dutch pipe that was suspended by a gaily colored cord from a stout peg. He filled the big china bowl of the pipe with nearly a half-pound of tobacco, touched a light to the weed, and returned to his chair. There was a pregnant silence in the room meanwhile.

"How old are you, Vrind Pieter?" Sachsen asked gently.

"Twenty-five, mynheer," Peter Gross replied. There was a pronounced emphasis on the "mynheer."

"Twenty-five," Sachsen murmured fondly. "Twenty-five! Just my age when I was a student at Leyden and the gayest young scamp of them all." He shook his head. "Twenty-five is very young, Vrind Pieter."

"That is a misfortune which only time can remedy," Peter Gross replied drily.

"Yes, only time." Sachsen's eyes misted. "Time that brings the days 'when strong men shall bow themselves, and the grinders shall cease because they are few, and the grasshopper shall become a burden, and desire shall fail.' I wish you were older, Vrind Pieter."

The old man sighed. There was a far-away look in his eyes as though he were striving to pierce the future and the leagues between Batavia and Bulungan.

"Vrind Gross," he resumed softly, "we have known each other a long time. Eight years is a long time, and it is eight years since you first came to Batavia. You were a cabin-boy then, and you[59] ran away from your master because he beat you. The wharfmaster at Tanjong Priok found you, and was taking you back to your master when old Sachsen saw you. Old Sachsen got you free and put you on another ship, under a good master, who made a good man and a good zeeman (seaman) out of you. Do you remember?"

"I shall never forget!" Peter Gross's voice was vibrant with emotion.

"Old Sachsen was your friend then. He has been your friend through the years since then. He is your friend to-day. Do you believe that?"

Peter Gross impulsively reached his hand across the table. Sachsen grasped it and held it.

"Then to-night you will forgive old Sachsen if he speaks plainly to you, more plainly than you would let other men talk? You will listen, and take his words to heart, and consider them well, Pieter?"

"Speak, Sachsen!"

"I knew you would listen, Pieter." Sachsen drew a deep breath. His eyes rested fondly on his protégé, and he let go Gross's hand reluctantly as he leaned back in his chair.

"Vrind Pieter, you said a little while ago that old Sachsen knows the people who live in these kolonien (colonies). His knowledge is small—"

Peter Gross made a gesture of dissent, but Sachsen did not let him interrupt.

"Yet he has learned some things. It is something to have served the state for over two-score years in the Netherlands East Indies, first as controlleur,[60] then as resident in Celebes, in Sumatra, in Java, and finally as secretary to the gouverneur, as old Sachsen has. In those years he has seen much that goes on in the hearts of the black, and the brown, and the yellow, and the white folk that live in these sun-seared islands. Much that is wicked, but also much that is good. And he has seen much of the fevers that seize men when the sun waves hot and the blood races madly through their veins. There is the fever of hate, and the fever of revenge, the fever of greed, and the fever to grasp God. But more universal than all these is the fever of love and the fever of lust!"

Peter Gross's brow knit with a puzzled frown. "What do you mean, Sachsen?" he demanded.

Sachsen smoothed back his thinning white hair.