|

Transcriber’s note:

|

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. Sections in Greek will yield a transliteration

when the pointer is moved over them, and words using diacritic characters in the

Latin Extended Additional block, which may not display in some fonts or browsers, will

display an unaccented version.

Links to other EB articles: Links to articles residing in other EB volumes will

be made available when the respective volumes are introduced online.

|

THE ENCYCLOPÆDIA BRITANNICA

A DICTIONARY OF ARTS, SCIENCES, LITERATURE AND GENERAL INFORMATION

ELEVENTH EDITION

VOLUME XI SLICE V

Gassendi, Pierre to Geocentric

Articles in This Slice

| GASSENDI, PIERRE | GEFLE |

| GASTEIN | GEGENBAUR, CARL |

| GASTRIC ULCER | GEGENSCHEIN |

| GASTRITIS | GEIBEL, EMANUEL |

| GASTROPODA | GEIGE |

| GASTROTRICHA | GEIGER, ABRAHAM |

| GATAKER, THOMAS | GEIJER, ERIK GUSTAF |

| GATCHINA | GEIKIE, SIR ARCHIBALD |

| GATE | GEIKIE, JAMES |

| GATEHOUSE | GEIKIE, WALTER |

| GATES, HORATIO | GEILER VON KAISERSBERG, JOHANN |

| GATESHEAD | GEINITZ, HANS BRUNO |

| GATH | GEISHA |

| GATLING, RICHARD JORDAN | GEISLINGEN |

| GATTY, MARGARET | GEISSLER, HEINRICH |

| GAU, JOHN | GELA |

| GAUDEN, JOHN | GELADA |

| GAUDICHAUD-BEAUPRÉ, CHARLES | GELASIUS |

| GAUDRY, JEAN ALBERT | GELATI |

| GAUDY | GELATIN |

| GAUERMANN, FRIEDRICH | GELDERLAND (duchy) |

| GAUGE | GELDERLAND (province of Holland) |

| GAUHATI | GELDERN |

| GAUL, GILBERT WILLIAM | GELL, SIR WILLIAM |

| GAUL | GELLERT, CHRISTIAN FÜRCHTEGOTT |

| GAULT | GELLERT |

| GAUNTLET | GELLIUS, AULUS |

| GAUR (ruined city of India) | GELLIVARA |

| GAUR (wild ox) | GELNHAUSEN |

| GAUSS, KARL FRIEDRICH | GELO |

| GAUSSEN, FRANÇOIS SAMUEL ROBERT LOUIS | GELSEMIUM |

| GAUTIER, ÉMILE THÉODORE LÉON | GELSENKIRCHEN |

| GAUTIER, THÉOPHILE | GEM |

| GAUTIER D'ARRAS | GEM, ARTIFICIAL |

| GAUZE | GEMBLOUX |

| GAVARNI | GEMINI |

| GAVAZZI, ALESSANDRO | GEMINIANI, FRANCESCO |

| GAVELKIND | GEMISTUS PLETHO, GEORGIUS |

| GAVESTON, PIERS | GEMMI PASS |

| GAVOTTE | GENDARMERIE |

| GAWAIN | GENEALOGY |

| GAWLER | GENELLI, GIOVANNI BUONAVENTURA |

| GAY, JOHN | GENERAL |

| GAY, MARIE FRANÇOISE SOPHIE | GENERATION |

| GAY, WALTER | GENESIS |

| GAYA | GENET |

| GAYAL | GENEVA (New York, U.S.A.) |

| GAYANGOS Y ARCE, PASCUAL DE | GENEVA (Switzerland) |

| GAYARRÉ, CHARLES ÉTIENNE ARTHUR | GENEVA CONVENTION |

| GAY-LUSSAC, JOSEPH LOUIS | GENEVA, LAKE OF |

| GAZA, THEODORUS | GENEVIÈVE, ST |

| GAZA | GENEVIÈVE, OF BRABANT |

| GAZALAND | GENGA, GIROLAMO |

| GAZEBO | GENISTA |

| GAZETTE | GENIUS |

| GEAR | GENUS, STÉPHANIE-FÉLICITÉ DU CREST DE SAINT-AUBIN |

| GEBER | GENNA |

| GEBHARD TRUCHSESS VON WALDBURG | GENNADIUS II. |

| GEBWEILER | GENOA |

| GECKO | GENOVESI, ANTONIO |

| GED, WILLIAM | GENSONNÉ, ARMAND |

| GEDDES, ALEXANDER | GENTIAN |

| GEDDES, ANDREW | GENTIANACEAE |

| GEDDES, JAMES LORRAINE | GENTILE |

| GEDDES, SIR WILLIAM DUGUID | GENTILE DA FABRIANO |

| GEDYMIN | GENTILESCHI, ARTEMISIA and ORAZIO DE’ |

| GEE, THOMAS | GENTILI, ALBERICO |

| GEEL, JACOB | GENTLE |

| GEELONG | GENTLEMAN |

| GEESTEMÜNDE | GENTZ, FRIEDRICH VON |

| GEFFCKEN, FRIEDRICH HEINRICH | GEOCENTRIC |

| GEFFROY, MATHIEU AUGUSTE | |

503

GASSENDI1 [Gassend], PIERRE (1592-1655), French philosopher,

scientist and mathematician, was born of poor parents

at Champtercier, near Digne, in Provence, on the 22nd of January

1592. At a very early age he gave indications of remarkable

mental powers and was sent to the college at Digne. He showed

particular aptitude for languages and mathematics, and it is

said that at the age of sixteen he was invited to lecture on

rhetoric at the college. Soon afterwards he entered the university

of Aix, to study philosophy under P. Fesaye. In 1612 he was

called to the college of Digne to lecture on theology. Four

years later he received the degree of doctor of theology at Avignon,

and in 1617 he took holy orders. In the same year he was

called to the chair of philosophy at Aix, and seems gradually to

have withdrawn from theology. He lectured principally on the

Aristotelian philosophy, conforming as far as possible to the

orthodox methods. At the same time, however, he followed

with interest the discoveries of Galileo and Kepler, and became

more and more dissatisfied with the Peripatetic system. It was

the period of revolt against the Aristotelianism of the schools,

and Gassendi shared to the full the empirical tendencies of the

age. He, too, began to draw up objections to the Aristotelian

philosophy, but did not at first venture to publish them. In

1624, however, after he had left Aix for a canonry at Grenoble,

he printed the first part of his Exercitationes paradoxicae adversus

Aristoteleos. A fragment of the second book was published

later at La Haye (1659), but the remaining five were never

composed, Gassendi apparently thinking that after the Discussiones

Peripateticae of Francesco Patrizzi little field was left

for his labours.

After 1628 Gassendi travelled in Flanders and Holland.

During this time he wrote, at the instance of Mersenne, his

examination of the mystical philosophy of Robert Fludd (Epistolica

dissertatio in qua praecipua principia philosophiae Ro.

Fluddi deteguntur, 1631), an essay on parhelia (Epistola de

parheliis), and some valuable observations on the transit of

Mercury which had been foretold by Kepler. He returned to

France in 1631, and two years later became provost of the

cathedral church at Digne. Some years were then spent in

travelling through Provence with the duke of Angoulême,

governor of the department. The only literary work of this

period is the Life of Peiresc, which has been frequently reprinted,

and was translated into English. In 1642 he was engaged by

Mersenne in controversy with Descartes. His objections to the

fundamental propositions of Descartes were published in 1642;

they appear as the fifth in the series contained in the works

of Descartes. In these objections Gassendi’s tendency towards

the empirical school of speculation appears more pronounced

than in any of his other writings. In 1645 he accepted the chair

of mathematics in the Collège Royal at Paris, and lectured for

many years with great success. In addition to controversial

writings on physical questions, there appeared during this period

the first of the works by which he is known in the history of

philosophy. In 1647 he published the treatise De vita, moribus,

et doctrina Epicuri libri octo. The work was well received, and

two years later appeared his commentary on the tenth book of

Diogenes Laërtius, De vita, moribus, et placitis Epicuri, seu

Animadversiones in X. librum Diog. Laër. (Lyons, 1649; last

edition, 1675). In the same year the more important Syntagma

philosophiae Epicuri (Lyons, 1649; Amsterdam, 1684) was

published.

In 1648 ill-health compelled him to give up his lectures at the

Collège Royal. He travelled in the south of France, spending

nearly two years at Toulon, the climate of which suited him.

In 1653 he returned to Paris and resumed his literary work,

publishing in that year lives of Copernicus and Tycho Brahe.

The disease from which he suffered, lung complaint, had, however,

established a firm hold on him. His strength gradually

failed, and he died at Paris on the 24th of October 1655. A

bronze statue of him was erected by subscription at Digne in

1852.

His collected works, of which the most important is the Syntagma

philosophicum (Opera, i. and ii.), were published in 1658

by Montmort (6 vols., Lyons). Another edition, also in 6 folio

volumes, was published by N. Averanius in 1727. The first

two are occupied entirely with his Syntagma philosophicum;

the third contains his critical writings on Epicurus, Aristotle,

Descartes, Fludd and Lord Herbert, with some occasional

pieces on certain problems of physics; the fourth, his Institutio

astronomica, and his Commentarii de rebus celestibus; the

fifth, his commentary on the tenth book of Diogenes Laërtius,

the biographies of Epicurus, N.C.F. de Peiresc, Tycho Brahe,

Copernicus, Georg von Peuerbach, and Regiomontanus, with

some tracts on the value of ancient money, on the Roman

calendar, and on the theory of music, to all which is appended

a large and prolix piece entitled Notitia ecclesiae Diniensis;

the sixth volume contains his correspondence. The Lives,

especially those of Copernicus, Tycho and Peiresc, have been

justly admired. That of Peiresc has been repeatedly printed;

it has also been translated into English. Gassendi was one of

the first after the revival of letters who treated the literature

of philosophy in a lively way. His writings of this kind, though

too laudatory and somewhat diffuse, have great merit; they

abound in those anecdotal details, natural yet not obvious

reflections, and vivacious turns of thought, which made Gibbon

style him, with some extravagance certainly, though it was true

enough up to Gassendi’s time—“le meilleur philosophe des

littérateurs, et le meilleur littérateur des philosophes.”

Gassendi holds an honourable place in the history of physical

science. He certainly added little to the stock of human knowledge,

but the clearness of his exposition and the manner in which he, like

Bacon, urged the importance of experimental research, were of

inestimable service to the cause of science. To what extent any

place can be assigned him in the history of philosophy is more doubtful.

The Exercitationes on the whole seem to have excited more

attention than they deserved. They contain little or nothing

beyond what had been already advanced against Aristotle. The

first book expounds clearly, and with much vigour, the evil effects of

the blind acceptance of the Aristotelian dicta on physical and philosophical

study; but, as is the case with so many of the anti-Aristotelian

works of this period, the objections show the usual ignorance

of Aristotle’s own writings. The second book, which contains the

review of Aristotle’s dialectic or logic, is throughout Ramist in tone

and method. The objections to Descartes—one of which at least,

through Descartes’s statement of it in the appendix of objections

in the Meditationes has become famous—have no speculative value,

and in general are the outcome of the crudest empiricism. His

labours on Epicurus have a certain historical value, but the want of

consistency inherent in the philosophical system raised on Epicureanism

is such as to deprive it of genuine worth. Along with strong

expressions of empiricism we find him holding doctrines absolutely

irreconcilable with empiricism in any form. For while he maintains

constantly his favourite maxim “that there is nothing in the intellect

which has not been in the senses” (nihil in intellectu quod non prius

fuerit in sensu), while he contends that the imaginative faculty

(phantasia) is the counterpart of sense—that, as it has to do with

material images, it is itself, like sense, material, and essentially the

same both in men and brutes; he at the same time admits that the

intellect, which he affirms to be immaterial and immortal—the most

characteristic distinction of humanity—attains notions and truths of

which no effort of sensation or imagination can give us the slightest

apprehension (Op. ii. 383). He instances the capacity of forming

“general notions”; the very conception of universality itself (ib.

384), to which he says brutes, who partake as truly as men in the

faculty called phantasia, never attain; the notion of God, whom he

says we may imagine to be corporeal, but understand to be incorporeal;

and lastly, the reflex action by which the mind makes its

own phenomena and operations the objects of attention.

The Syntagma philosophicum, in fact, is one of those eclectic

systems which unite, or rather place in juxtaposition, irreconcilable

dogmas from various schools of thought. It is divided, according to

the usual fashion of the Epicureans, into logic (which, with Gassendi

as with Epicurus, is truly canonic), physics and ethics. The logic,

which contains at least one praiseworthy portion, a sketch of the

history of the science, is divided into theory of right apprehension

(bene imaginari), theory of right judgment (bene proponere), theory

of right inference (bene colligere), theory of right method (bene

ordinare). The first part contains the specially empirical positions

which Gassendi afterwards neglects or leaves out of account. The

senses, the sole source of knowledge, are supposed to yield us immediately

cognition of individual things; phantasy (which Gassendi

504

takes to be material in nature) reproduces these ideas; understanding

compares these ideas, which are particular, and frames

general ideas. Nevertheless, he at the same time admits that the

senses yield knowledge—not of things—but of qualities only, and

holds that we arrive at the idea of thing or substance by induction.

He holds that the true method of research is the analytic, rising from

lower to higher notions; yet he sees clearly, and admits, that inductive

reasoning, as conceived by Bacon, rests on a general proposition

not itself proved by induction. He ought to hold, and in

disputing with Descartes he did apparently hold, that the evidence

of the senses is the only convincing evidence; yet he maintains, and

from his special mathematical training it was natural he should

maintain, that the evidence of reason is absolutely satisfactory.

The whole doctrine of judgment, syllogism and method is a mixture

of Aristotelian and Ramist notions.

In the second part of the Syntagma, the physics, there is more

that deserves attention; but here, too, appears in the most glaring

manner the inner contradiction between Gassendi’s fundamental

principles. While approving of the Epicurean physics, he rejects

altogether the Epicurean negation of God and particular providence.

He states the various proofs for the existence of an immaterial,

infinite, supreme Being, asserts that this Being is the author of the

visible universe, and strongly defends the doctrine of the foreknowledge

and particular providence of God. At the same time he

holds, in opposition to Epicureanism, the doctrine of an immaterial

rational soul, endowed with immortality and capable of free determination.

It is altogether impossible to assent to the supposition

of Lange (Gesch. des Materialismus, 3rd ed., i. 233), that all this

portion of Gassendi’s system contains nothing of his own opinions,

but is introduced solely from motives of self-defence. The positive

exposition of atomism has much that is attractive, but the hypothesis

of the calor vitalis (vital heat), a species of anima mundi (world-soul)

which is introduced as physical explanation of physical phenomena,

does not seem to throw much light on the special problems which

it is invoked to solve. Nor is his theory of the weight essential

to atoms as being due to an inner force impelling them to motion

in any way reconcilable with his general doctrine of mechanical

causes.

In the third part, the ethics, over and above the discussion on

freedom, which on the whole is indefinite, there is little beyond

a milder statement of the Epicurean moral code. The final end of

life is happiness, and happiness is harmony of soul and body

(tranquillitas animi et indolentia corporis). Probably, Gassendi

thinks, perfect happiness is not attainable in this life, but it may

be in the life to come.

The Syntagma is thus an essentially unsystematic work, and

clearly exhibits the main characteristics of Gassendi’s genius. He

was critical rather than constructive, widely read and trained

thoroughly both in languages and in science, but deficient in speculative

power and original force. Even in the department of natural

science he shows the same inability steadfastly to retain principles

and to work from them; he wavers between the systems of Brahe

and Copernicus. That his revival of Epicureanism had an important

influence on the general thinking of the 17th century may be admitted;

that it has any real importance in the history of philosophy

cannot be granted.

Authorities.—Gassendi’s life is given by Sorbière in the first

collected edition of the works, by Bugerel, Vie de Gassendi (1737;

2nd ed., 1770), and by Damiron, Mémoire sur Gassendi (1839). An

abridgment of his philosophy was given by his friend, the celebrated

traveller, Bernier (Abrégé de la philosophie de Gassendi, 8 vols., 1678;

2nd ed., 7 vols., 1684). The most complete surveys of his work are

those of G.S. Brett (Philosophy of Gassendi, London, 1908), Buhle

(Geschichte der neuern Philosophie, iii. 1, 87-222), Damiron (Mémoires

pour servir à l’histoire de philosophie au XVIIe siècle), and P.F. Thomas

(La Philosophie de Gassendi, Paris, 1889). See also Ritter, Geschichte

der Philosophie, x. 543-571; Feuerbach, Gesch. d. neu. Phil. von

Bacon bis Spinoza, 127-150; F.X. Kiefl, P. Gassendis Erkenntnistheorie

und seine Stellung zum Materialismus (1893) and “Gassendi’s

Skepticismus” in Philos. Jahrb. vi. (1893); C. Güttler, “Gassend

oder Gassendi?” in Archiv f. Gesch. d. Philos. x. (1897), pp.

238-242.

(R. Ad.; X.)

1 It was formerly thought that Gassendi was really the genitive

of the Latin form Gassendus. C. Güttler, however, holds that it is

a modernized form of the O. Fr. Gassendy (see paper quoted in

bibliography).

GASTEIN, in the duchy of Salzburg, Austria, a side valley of

the Pongau or Upper Salzach, about 25 m. long and 1¼ m.

broad, renowned for its mineral springs. It has an elevation

of between 3000 and 3500 ft. Behind it, to the S., tower the

mountains Mallnitz or Nassfeld-Tauern (7907 ft.) and Ankogel

(10,673 ft.), and from the right and left of these mountains two

smaller ranges run northwards forming its two side walls. The

river Ache traverses the valley, and near Wildbad-Gastein forms

two magnificent waterfalls, the upper, the Kesselfall (196 ft.),

and the lower, the Bärenfall (296 ft.). Near these falls is the

Schleierfall (250 ft.), formed by the stream which drains the

Bockhart-see. The valley is also traversed by the so-called

Tauern railway (opened up to Wildbad-Gastein in September

1905), which goes to Mallnitz, piercing the Tauern range by a

tunnel 9260 yds. in length. The principal villages of the valley

are Hof-Gastein, Wildbad-Gastein and Böckstein.

Hof-Gastein, pop. (1900) 840, the capital of the valley, is

also a watering-place, the thermal waters being conveyed here

from Wildbad-Gastein by a conduit 5 m. long, constructed in

1828 by the emperor Francis I. of Austria. Hof-Gastein was,

after Salzburg, the richest place in the duchy, owing to its gold

and silver mines, which were already worked during the Roman

period. During the 16th century these mines were yielding

annually 1180 ℔ of gold and 9500 ℔ of silver, but since the

17th century they have been much neglected and many of them

are now covered by glaciers.

Wildbad-Gastein, commonly called Bad-Gastein, one of

the most celebrated watering-places in Europe, is picturesquely

situated in the narrow valley of the Gasteiner Ache, at an

altitude of 3480 ft. The thermal springs, which issue from

the granite mountains, have a temperature of 77°-120° F., and

yield about 880,000 gallons of water daily. The water contains

only 0.35 to 1000 of mineral ingredients and is used for bathing

purposes. The springs are resorted to in cases of nervous

affections, senile and general debility, skin diseases, gout and

rheumatism. Wildbad-Gastein is annually visited by over

8500 guests. The springs were known as early as the 7th century,

but first came into fame by a successful visit paid to them by

Duke Frederick of Austria in 1436. Gastein was a favourite

resort of William I. of Prussia and of the Austrian imperial

family, and it was here that, on the 14th of August 1865, was

signed the agreement known as the Gastein Convention, which

by dividing the administration of the conquered provinces of

Schleswig and Holstein between Austria and Prussia postponed

for a while the outbreak of war between the two powers. It

was also here (August-September 1879) that Prince Bismarck

negotiated with Count Julius Andrássy the Austro-German

treaty, which resulted in the formation of the Triple Alliance.

See Pröll, Gastein, Its Springs and Climate (Vienna, 5th ed.,

1893).

GASTRIC ULCER (ulcer of the stomach), a disease of much

gravity, commonest in females, and especially in anaemic

domestic servants. It is connected in many instances with

impairment of the circulation in the stomach and the formation

of a clot in a small blood-vessel (thrombosis). It may be due

to an impoverished state of the blood (anaemia), but it may also

arise from disease of the blood-vessels, the result of long-continued

indigestion and gastric catarrh.

When clotting takes place in a blood-vessel the nutrition of

that limited area of the stomach is cut off, and the patch undergoes

digestion by the unresisted action of the gastric juices, an

ulcer being formed. The ulcer is usually of the size of a silver

threepence or sixpence, round or oval, and, eating deeply, is apt

to make a hole right through the coats of the stomach. Its

usual site is upon the posterior wall of the upper curvature, near

to the pyloric orifice. It may undergo a healing process at any

stage, in which case it may leave but little trace of its existence;

while, on the other hand, it may in the course of cicatrizing

produce such an amount of contraction as to lead to stricture

of the pylorus, or to a peculiar hour-glass deformity of the stomach.

Perforation is in most cases quickly fatal, unless previously

the stomach has become adherent to some neighbouring organ,

by which the dangerous effects of this occurrence may be averted,

or unless the condition has been promptly recognized and an

operation has been quickly done. Usually there is but one ulcer,

but sometimes there are several ulcers.

The symptoms of ulcer of the stomach are often indefinite and

obscure, and in some cases the diagnosis has been first made on

the occurrence of a fatal perforation. First among the symptoms

is pain, which is present at all times, but is markedly increased

after food. The pain is situated either at the lower end of the

breast-bone or about the middle of the back. Sometimes it is

felt in the sides. It is often extremely severe, and is usually

accompanied with localized tenderness and also with a sense of

oppression, and by an inability to wear tight clothing. The pain

is due to the movements of the stomach set up by the presence

505

of the food, as well as to the irritation of the inflamed nerve

filaments in the floor of the ulcer. Vomiting is a usual symptom.

It occurs either soon after the food is swallowed or at a later

period, and generally relieves the pain and discomfort. Vomiting

of blood (haematemesis) is a frequent and important symptom.

The blood may show itself in the form of a brown or coffee-like

mixture, or as pure blood of dark colour and containing clots.

It comes from some vessel or vessels which the ulcerative process

has ruptured. Blood is also found mixed with the discharges

from the bowels, rendering them dark or tarry-looking. The

general condition of the patient with gastric ulcer is, as a rule,

that of extreme ill-health, with pallor, emaciation and debility.

The tongue is red, and there is usually constipation. In most

of the cases the disease is chronic, lasting for months or years;

and in those cases where the ulcers are large or multiple, incomplete

healing may take place, relapses occurring from time

to time. But the ulcers may give rise to no marked symptoms,

and there have been instances where fatal perforation suddenly

took place, and where post-mortem examination revealed the

existence of long-standing ulcers which had given rise to no

suggestive symptoms. While gastric ulcer is to be regarded as

dangerous, its termination, in the great majority of cases, is

in recovery. It frequently, however, leaves the stomach in a

delicate condition, necessitating the utmost care as regards diet.

Occasionally the disease proves fatal by sudden haemorrhage,

but a fatal result is more frequently due to perforation and the

escape of the contents of the stomach into the peritoneal cavity,

in which case death usually occurs in from twelve to forty-eight

hours, either from shock or from peritonitis. Should the stomach

become adherent to another organ, and fatal perforation be

thus prevented, chronic “indigestion” may persist, owing to

interference with the natural movements of the stomach.

Stricture of the pylorus and consequent dilatation of the stomach

may be caused by the cicatrization of an ulcer.

The patient should at once be sent to bed and kept there, and

allowed for a while nothing stronger than milk and water or

milk and lime water. But if bleeding has recently taken place

no food whatever should be allowed by the stomach, and the

feeding should be by nutrient enemata. As the symptoms

quiet down, eggs may be given beaten up with milk, and later,

bread and milk and home-made broths and soups. Thus the

diet advances to chicken and vegetables rubbed through a

sieve, to custard pudding and bread and butter. As regards

medicines, iron is the most useful, but no pills of any sort should

be given. Under the influence of rest and diet most gastric

ulcers get well. The presence of healthy-looking scars upon the

surface of the stomach, which are constantly found in operating

upon the interior of the abdomen, or as revealed in post-mortem

examinations, are evidence of the truth of this statement. It

is unlikely that under the treatment just described perforation

of the stomach will take place, and if the surgeon is called in

to assist he will probably advise that operation is inadvisable.

Moreover, he knows that if he should open the abdomen to search

for an ulcer of the stomach he might fail to find it; more than

that, his search might also be in vain if he opened the stomach

itself and examined the interior. Serious haemorrhages, however,

may make it necessary that a prompt and thorough search should

be made in order that the surgeon may endeavour to locate the

ulcer, and, having found it, secure the damaged vessel and save

the patient from death by bleeding.

Perforation of a gastric ulcer having taken place, the septic

germs, which were harmless whilst in the stomach, escape with

the rest of the contents of the stomach into the general peritoneal

cavity. The immediate effects of this leakage are sudden and

severe pain in the upper part of the abdomen and a great shock

to the system (collapse). The muscles of the abdominal wall

become hard and resisting, and as peritonitis appears and

the intestines are distended with gas, the abdomen is distended

and becomes greatly increased in size and ceases to move,

the respiratory movements being short and quick. At first,

most likely, the temperature drops below normal, and the

pulse quickens. Later, the temperature rises. If nothing is

done, death from the septic poisoning of peritonitis is almost

certain.

The treatment of ruptured gastric ulcer demands immediate

operation. An incision should be made in the upper part of

the middle line of the abdomen, and the perforation should be

looked for. There is not, as a rule, much difficulty in finding it,

as there are generally deposits of lymph near the spot, and other

signs of local inflammation; moreover, the contents of the

stomach may be seen escaping from the opening. The ulcer is

to be closed by running a “purse-string” suture in the healthy

tissue around it, and the place is then buried in the stomach by

picking up small folds of the stomach-wall above and below it

and fixing them together by suturing. This being done, the

surface of the stomach, and the neighbouring viscera which have

been soiled by the leakage, are wiped clean and the abdominal

wound is closed, provision being made for efficient drainage. A

large proportion of cases of perforated gastric ulcer thus treated

recover.

(E. O.*)

GASTRITIS (Gr. γαστήρ, stomach), an inflammatory affection

of the stomach, of which the condition of catarrh, or irritation of

its mucous membrane, is the most frequent and most readily

recognized. This may exist in an acute or a chronic form, and

depends upon some condition, either local or general, which produces

a congested state of the circulation in the walls of the

stomach (see Digestive Organs: Pathology).

Acute Gastritis may arise from various causes. The most

intense forms of inflammation of the stomach are the toxic

conditions which follow the swallowing of corrosive poisons,

such as strong mineral acids of alkalis which may extensively

destroy the mucous membrane. Other non-corrosive poisons

cause acute degeneration of the stomach wall (see Poisons).

Acute inflammatory conditions may be secondary to zymotic

diseases such as diphtheria, pyaemia, typhus fever and others.

Gastritis is also caused by the ingestion of food which has begun

to decompose, or may result from eating unsuitable articles

which themselves remain undigested and so excite acute catarrhal

conditions. These give rise to the symptoms well known as

characterizing an acute “bilious attack,” consisting in loss of

appetite, sickness or nausea, and headache, frontal or occipital,

often accompanied with giddiness. The tongue is furred, the

breath foetid, and there is pain or discomfort in the region of the

stomach, with sour eructations, and frequently vomiting, first of

food and then of bilious matter. An attack of this kind tends to

subside in a few days, especially if the exciting cause be removed.

Sometimes, however, the symptoms recur with such frequency

as to lead to the more serious chronic form of the disease.

The treatment bears reference, in the first place, to any known

source of irritation, which, if it exist, may be expelled by an

emetic or purgative (except in cases due to poisoning). This,

however, is seldom necessary, since vomiting is usually present.

For the relief of sickness and pain the sucking of ice and counter-irritation

over the region of the stomach are of service. Further,

remedies which exercise a soothing effect upon an irritable

mucous membrane, such as bismuth or weak alkaline fluids, and

along with these the use of a light milk diet, are usually sufficient

to remove the symptoms.

Chronic Gastric Catarrh may result from the acute or may arise

independently. It is not infrequently connected with antecedent

disease in other organs, such as the lungs, heart, liver or kidneys,

and it is especially common in persons addicted to alcoholic

excess. In this form the texture of the stomach is more altered

than in the acute form, except in the toxic and febrile forms above

referred to. It is permanently in a state of congestion, and its

mucous membrane and muscular coat undergo thickening and

other changes, which markedly affect the function of digestion.

The symptoms are those of dyspepsia in an aggravated form

(see Dyspepsia), of which discomfort and pain after food, with

distension and frequently vomiting, are the chief; and the

treatment must be conducted in reference to the causes giving

rise to it. The careful regulation of the diet, alike as to the

amount, the quality, and the intervals between meals, demands

special attention. Feeding on artificially soured milk may in

506

many cases be useful. Lavage or washing out of the stomach

with weak alkaline solutions has been used with marked success in

the treatment of chronic gastritis. Of medicinal agents, bismuth,

arsenic, nux vomica, and the mineral acids are all of acknowledged

efficacy, as are also preparations of pepsin.

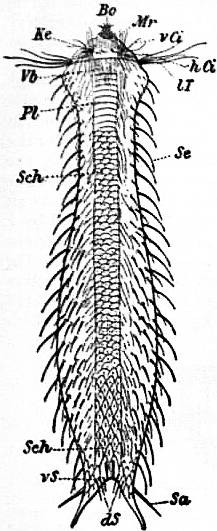

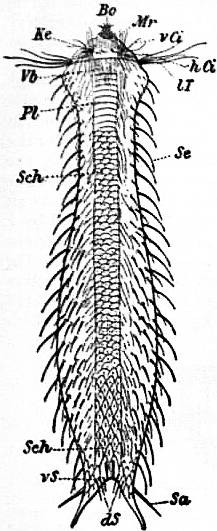

GASTROPODA, the second of the five classes of animals

constituting the phylum Mollusca. For a discussion of the relationship

of the Gastropoda to the remaining classes of the

phylum, see Mollusca.

The Gastropoda are mainly characterized by a loss of symmetry,

produced by torsion of the visceral sac. This torsion may be resolved

into two successive movements. The first is a ventral flexure

in the antero-posterior or sagittal plane; the result of this is to

approximate the two ends of the alimentary canal. In development,

the openings of the mantle-cavity and the anus are always

originally posterior; later they are brought forward ventrally.

During this first movement flexure is also produced by the coiling

of the visceral sac and shell; primitively the latter was bowl-shaped;

but the ventral flexure, which brings together the two extremities

of the digestive tube, gives the visceral sac the outline of a more or

less acute cone. The shell necessarily takes this form also, and then

becomes coiled in a dorsal or anterior plane—that is to say, it

becomes exogastric. This condition may be seen in embryonic

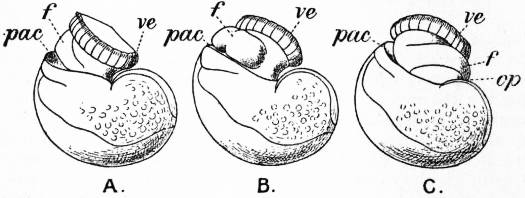

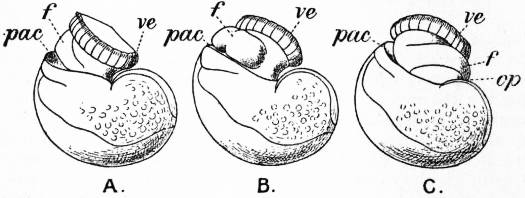

Patellidae, Fissurellidae and Trochidae (fig. 1, A), and agrees with

the method of coiling of a mollusc without lateral torsion, such as

Nautilus. But ultimately the coil becomes ventral or endogastric,

in consequence of the second torsion movement then apparent.

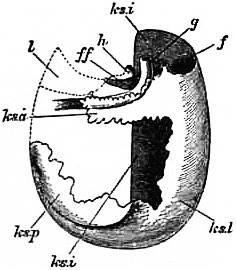

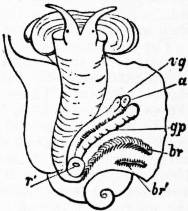

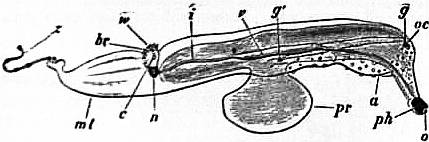

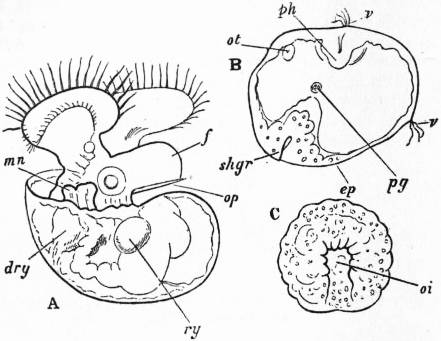

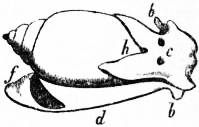

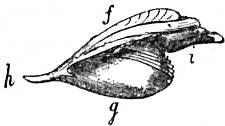

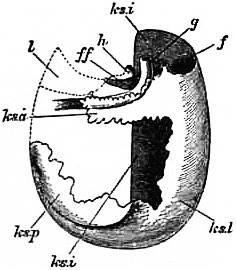

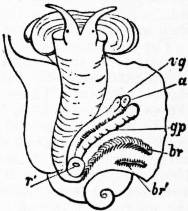

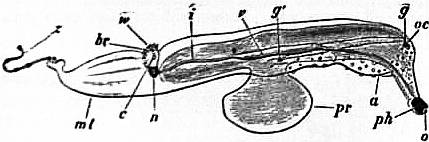

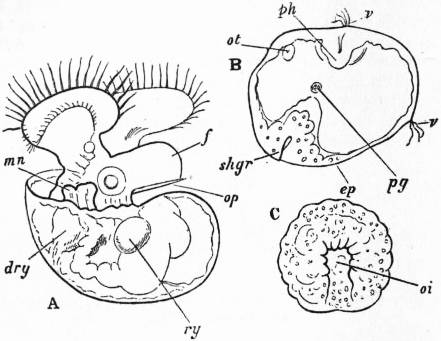

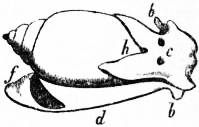

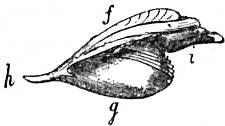

|

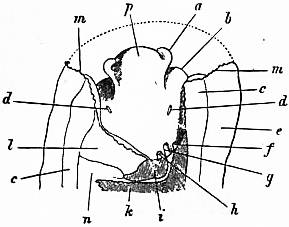

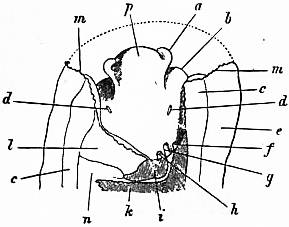

| From Lankester’s Treatise on Zoology. |

| Fig. 1.—Three stages in the development of Trochus, during the

process of torsion. (After Robert.) |

|

A, Nearly symmetrical larva (veliger).

B, A stage 1½ hours later than A.

C, A stage 3½ hours later than B.

f, Foot. |

op, Operculum.

pac, Pallial cavity.

ve, Velum. |

The shell is represented as fixed, while the head and foot rotate

from left to right. In reality the head and foot are fixed and the

shell rotates from right to left.

The second movement is a lateral torsion of the visceral mass, the

foot remaining a fixed point; this torsion occurs in a plane approximately

at right angles to that of the first movement, and carries the

pallial aperture and the anus from behind forwards. If, at this

moment, the animal were placed with mouth and ventral surface

turned towards the observer, this torsion carries the circumanal

complex in a clockwise direction (along the right side in dextral

forms) through 180° as compared with its primitive condition. The

(primitively) right-hand organs of the complex thus become left-hand,

and vice versa. The visceral commissure, while still surrounding

the digestive tract, becomes looped; its right half, with its

proper ganglion, passes to the left side over the dorsal face of the

alimentary canal (whence the name supra-intestinal), while the left

half passes below towards the right side, thus originating the name

infra-intestinal given to this half and to its ganglion. Next, the

shell, the coil of which was at first exogastric, being also included

in this rotation through 180°, exhibits an endogastric coiling (fig. 1,

B, C). This, however, is not generally retained in one plane, and the

spire projects, little by little, on the side which was originally left,

but finally becomes right (in dextral forms, with a clockwise direction,

if viewed from the side of the spire; but counter-clockwise in sinistral

forms). Finally, the original symmetry of the circumanal complex

vanishes; the anus leaves the centre of the pallial cavity and passes

towards the right side (left side in sinistral forms); the organs of this

side become atrophied and disappear. The essential feature of the

asymmetry of Gastropoda is the atrophy or disappearance of the

primitively left half of the circumanal complex (the right half in

sinistral forms), including the gill, the auricle, the osphradium, the

hypobranchial gland and the kidney.

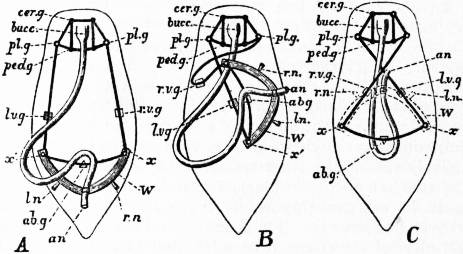

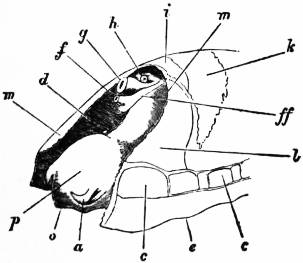

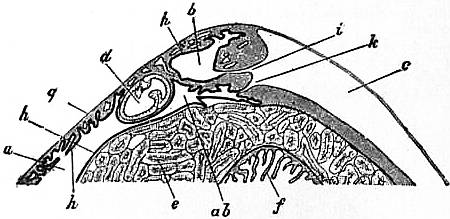

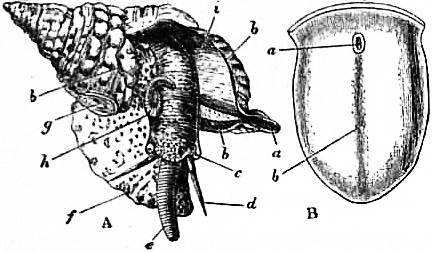

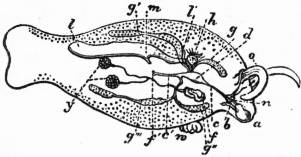

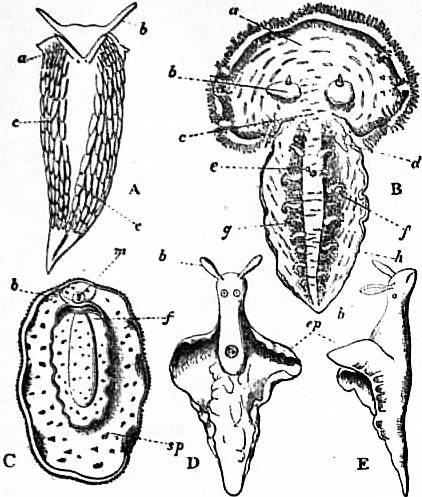

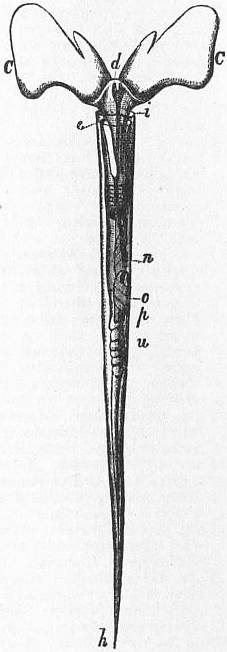

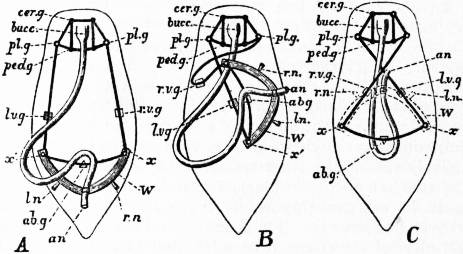

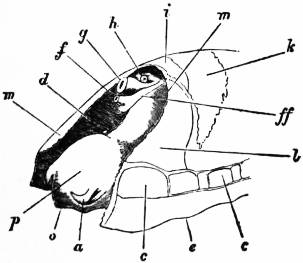

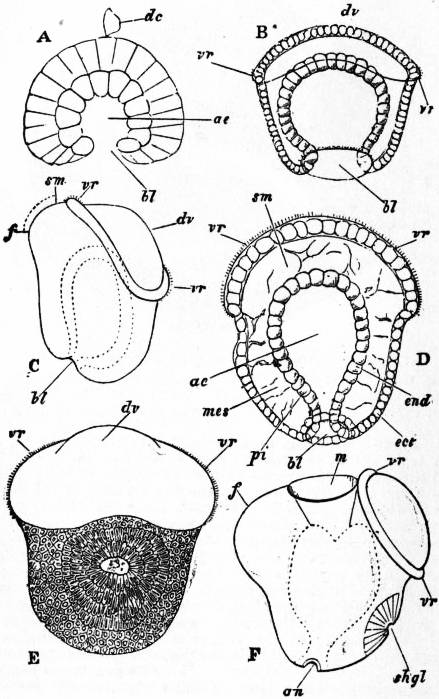

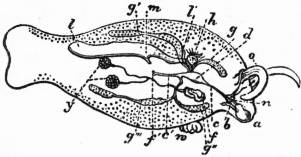

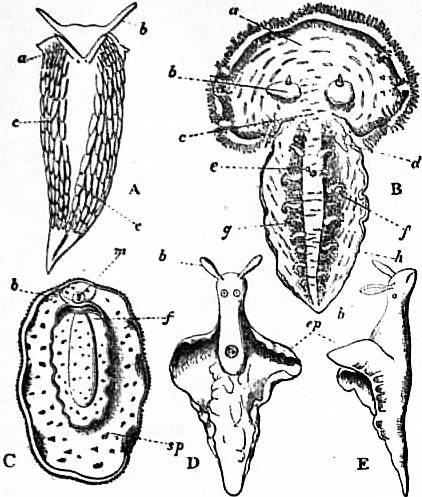

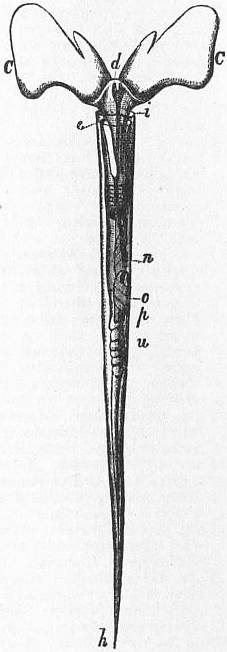

|

| From Lankester’s Treatise on Zoology. |

| Fig. 2.—Four stages in the

development of a Gastropod

showing the process of body

torsion. (After Robert.) |

|

A, Embryo without flexure.

B, Embryo with ventral flexure of the intestine.

C, Embryo with ventral flexure and exogastric shell.

D, Embryo with lateral torsion and an endogastric shell.

a, Anus.

f, Foot.

m, Mouth.

pa, Mantle.

pac, Pallial cavity.

ve, Velum. |

In dextral Gastropods the only structure found on the topographically

right side of the rectum is the genital duct. But this is

not part of the primitive complex. It is absent in the most primitive

and symmetrical forms, such as Haliotis and Pleurotomaria. Originally

the gonads opened into the kidneys. In the most primitive

existing Gastropods the gonad opens into the right kidney (Patellidae,

Trochidae, Fissurellidae). The gonaduct, therefore, is derived from

the topographically right kidney. The transformation has been

actually shown to take place in the development of Paludina. In

a dextral Gastropod the shell is coiled in a right-handed spiral from

apex to mouth, and the spiral also

projects to the right of the median

plane of the animal.

When the shell is sinistral the

asymmetry of the organs is usually

reversed, and there is a complete situs

inversus viscerum, the direction of the

spiral of the shell corresponding to

the position of the organs of the

body. Triforis, Physa, Clausilia are

examples of sinistral Gastropods, but

reversal also occurs as an individual

variation among forms normally dextral.

But there are forms in which

the involution is “hyperstrophic,”

that is to say, the turns of the spire

projecting but slightly, the spire,

after flattening out gradually, finally

becomes re-entrant and transformed

into a false umbilicus; at the same

time that part which corresponds to

the umbilicus of forms with a normal

coil projects and constitutes a false

spire; the coil thus appears to be

sinistral, although the asymmetry

remains dextral, and the coil of the

operculum (always the opposite to

that of the shell) sinistral (e.g.

Lanistes among Streptoneura, Limacinidae

among Opisthobranchia). The

same, mutatis mutandis, may occur

in sinistral shells.

The problem of the causes of the

torsion of the Gastropod body has

been much discussed. E.R. Lankester

in the ninth edition of this

work attributed it to the pressure of the shell and visceral hump

towards the right side. He referred also to the nautiloid shell of

the larva falling to one side. But these are two distinct processes.

In the larva a nautiloid shell is developed which is coiled exogastrically,

that is, dorsally, and the pallial cavity is posterior or

ventral (fig. 2, C): the larva therefore resembles Nautilus in the

relations of body and shell. The shell then rotates towards the left

side through 180°, so that it becomes ventral or endogastric (fig. 2,

D). The pallial cavity, with its organs, is by this torsion moved

up the right side of the larva to the dorsal surface, and thus the left

organs become right and vice versa. In the subsequent growth of

the shell the spire comes to project on the right side, which was

originally the left. Neither the rotation of the shell as a whole nor

its helicoid spiral coiling is the immediate cause of the torsion of the

body in the individual, for the direction of the torsion is indicated

in the segmentation of the ovum, in which there is a complete

507

reversal of the cleavage planes in sinistral as compared with dextral

forms. The facts, however, strongly suggest that the original cause

of the torsion was the weight of the exogastric shell and visceral

hump, which in an animal creeping on its ventral surface necessarily

fell over to one side. It is not certain that the projection of the spire

to the originally left side of the shell has anything to do with the

falling over of the shell to that side. The facts do not support such

a suggestion. In the larva there is no projection at the time the

torsion takes place. In some forms the coiling disappears in the

adult, leaving the shell simply conical as in Patellidae, Fissurellidae,

&c., and in some cases the shell is coiled in one plane, e.g. Planorbis. In

all these cases the torsion and asymmetry of the body are unaffected.

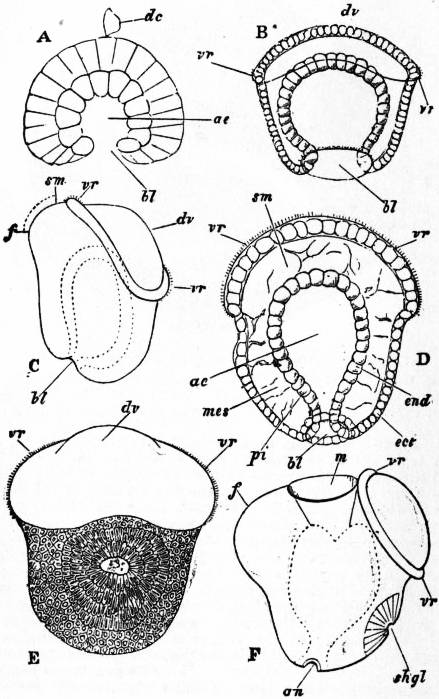

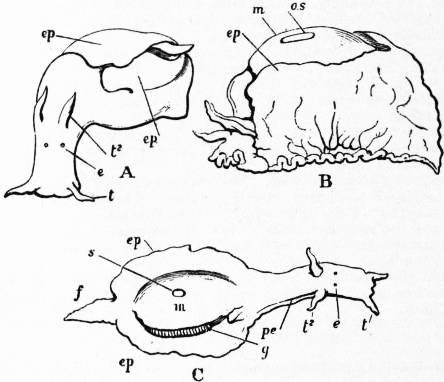

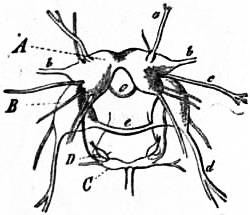

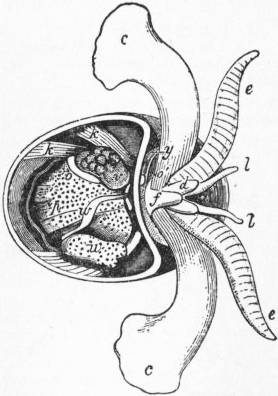

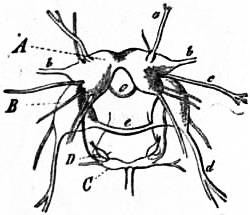

|

| Fig 3.—Sketch of a model designed so as to show the effect of

torsion or rotation of the visceral hump in Streptoneurous Gastropoda. |

|

A, Unrotated ancestral condition.

B, Quarter-rotation.

C, Complete semi-rotation (the limit).

an, Anus.

ln, rn, Primarily left nephridium and primarily right nephridium.

lvg, Primarily left (subsequently the sub-intestinal) visceral ganglion.

rvg, Primarily right (subsequently the sub-intestinal) visceral ganglion. |

cerg, Cerebral ganglion.

plg, Pleural ganglion.

pedg, Pedal ganglion.

abg, Abdominal ganglion.

bucc, Buccal mass.

W, Wooden arc representing the base-line of the wall of the visceral hump.

x, x′, Pins fastening the elastic cord (representing the visceral nerve loop) to W. |

The characteristic torsion attains its maximum effect among the

majority of the Streptoneura. It is followed in some specialized

Heteropoda and in the Euthyneura by a torsion in the opposite

direction, or detorsion, which brings the anus farther back and untwists

the visceral commissure (see Euthyneura, below). This conclusion

has shown that the Euthyneura do not represent an archaic

form of Gastropoda, but are themselves derived from streptoneurous

forms. The difference between the two sub-classes has been shown

to be slight; certain of the more archaic Tectibranchia (Actaeon)

and Pulmonata (Chilina) still have the visceral commissure long

and not untwisted. The fact that all the Euthyneura are hermaphrodite

is not a fundamental difference; several Streptoneura are so,

likewise Valvata, Oncidiopsis, Marsenina, Odostomia, Bathysciadium,

Entoconcha.

Classification.—The class Gastropoda is subdivided as follows:

| Sub-class I. Streptoneura. |

| Order 1. Aspidobranchia. |

| Sub-order | 1. Docoglossa. |

| ” | 2. Rhipidoglossa. |

| Order 2. Pectinibranchia. |

| Sub-order | 1. Taenioglossa. |

| Tribe | 1. Platypoda. |

| ” | 2. Heteropoda. |

| Sub-order | 2. Stenoglossa. |

| Tribe | 1. Rachiglossa. |

| ” | 2. Toxiglossa. |

| Sub-class II. Euthyneura. |

| Order 1. Opisthobranchia. |

| Sub-order | 1. Tectibranchia. |

| Tribe | 1. Bullomorpha. |

| ” | 2. Aplysiomorpha. |

| ” | 3. Pleurobranchomorpha. |

| Sub-order | 2. Nudibranchia. |

| Tribe | 1. Tritoniomorpha. |

| ” | 2. Doridomorpha. |

| ” | 3. Eolidomorpha. |

| ” | 4. Elysiomorpha. |

| Order 2. Pulmonata. |

| Sub-order | 1. Basommatophora. |

| ” | 2. Stylommatophora. |

| Tribe | 1. Holognatha. |

| ” | 2. Agnatha. |

| ” | 3. Elasmognatha. |

| ” | 4. Ditremata. |

Sub-Class I.—Streptoneura

In this division the torsion of the visceral mass and visceral

commissure is at its maximum, the latter being twisted into a

figure of eight. The right half of the commissure with its ganglion

is supra-intestinal, the left half with its ganglion infra-intestinal.

In some cases each pleural ganglion is connected with the opposite

branch of the visceral commissure by anastomosis with the

pallial nerve, a condition which is called dialyneury; or there

may be a direct connective from the pleural ganglion to the

visceral ganglion of the opposite side, which is called zygoneury.

The head bears only one pair of tentacles. The radular teeth are

of several different kinds in each transverse row. The heart is

usually posterior to the branchia (proso-branchiate). The sexes

are usually separate.

The old division into Zygobranchia and Azygobranchia must

be abandoned, for the Azygobranchiate Rhipidoglossa have

much greater affinity to the Zygobranchiate Haliotidae and

Fissurellidae than to the Azygobranchia in general. This is

shown by the labial commissure and pedal cords of the nervous

system, by the opening of the gonad into the right kidney, and by

other points. Further, the Pleurotomariidae have been discovered

to possess two branchiae. The sub-class is now divided into two

orders: the Aspidobranchia in which the branchia or ctenidium

is bipectinate and attached only at its base, and the Pectinibranchia

in which the ctenidium is monopectinate and attached

to the mantle throughout its length.

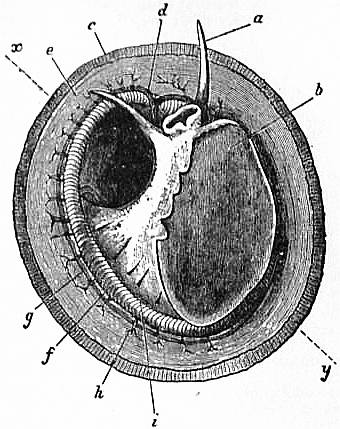

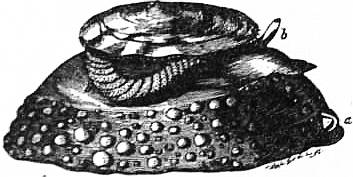

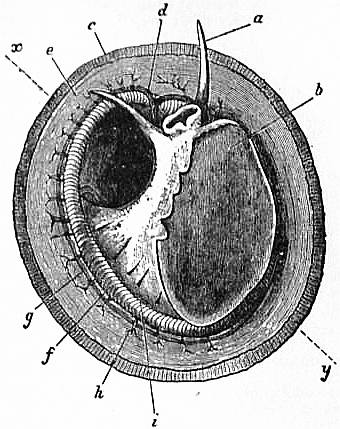

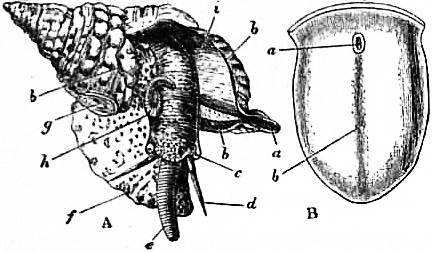

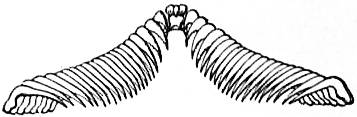

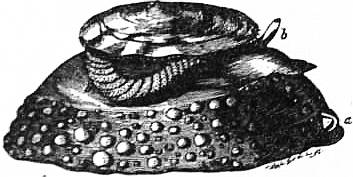

|

| Fig. 4.—The Common Limpet (Patella vulgata) in its shell, seen from

the pedal surface. (Lankester.) |

|

x, y, The median antero-posterior axis.

a, Cephalic tentacle.

b, Plantar surface of the foot.

c, Free edge of the shell.

d, The branchial efferent vessel carrying aerated blood to the

auricle, and here interrupting the circlet of gill lamellae. |

e, Margin of the mantle-skirt.

f, Gill lamellae (not ctenidia, but special pallial growths, comparable

with those of Pleurophyllidia).

g, The branchial efferent vessel.

h, Factor of the branchial advehent vessel.

i, Interspaces between the muscular bundles of the root of

the foot, causing the separate areae seen in fig. 5, c. |

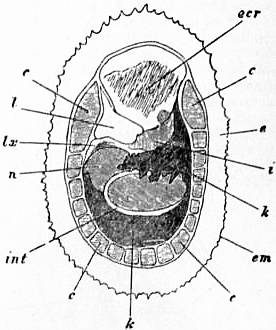

|

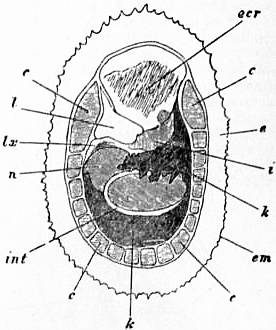

| Fig. 5.—Dorsal surface of the

Limpet removed from its shell and deprived of its black pigmented epithelium;

the internal organs are seen through the transparent body-wall. (Lankester.) |

c, Muscular bundles forming the root of the foot, and adherent to the shell.

e, Free mantle-skirt.

em, Tentaculiferous margin of the same.

i, Smaller (left) nephridium.

k, Larger (right) nephridium.

l, Pericardium.

lx, Fibrous septum, behind the pericardium.

n, Liver.

int, Intestine.

ecr, Anterior area of the mantle-skirt over-hanging the head (cephalic hood). |

Order I. Aspidobranchia.—These are the most primitive Gastropods,

retaining to a great degree the original symmetry of the

organs of the pallial complex, having two kidneys, in some cases

two branchiae, and two auricles. The gonad has no accessory

organs and except in Neritidae

no duct, but discharges

into the right kidney.

Forms adapted to terrestrial

life and to aerial respiration

occur in various

divisions of Gastropods, and

do not constitute a single

homogeneous group. Thus

the Helicinidae, which are

terrestrial, are now placed

among the Aspidobranchia.

In these there are neither

branchia nor osphradium,

and the pallial chamber

which retains its large opening

serves as a lung. Degeneration

of the shell

occurs in some members of

the order. It is largely

covered by the mantle in

some Fissurellidae, is entirely

internal in Pupilia

and absent in Titiscaniidae.

The common limpet is a

specially interesting and

abundant example of the

more primitive Aspidobranchia.

The foot of the

limpet is a nearly circular

disk of muscular tissue; in

front, projecting from and

raised above it, are the head

and neck (figs. 4, 13). The

visceral hump forms a low

conical dome above the sub-circular

foot, and standing

out all round the base of this

dome so as completely to

overlap the head and foot,

is the circular mantle-skirt.

The depth of free mantle-skirt

is greatest in front, where the head and neck are covered

in by it. Upon the surface of the visceral dome, and extending

508

to the edge of the free mantle-skirt, is the conical shell. When

the shell is taken away (best effected by immersion in hot

water) the surface of the visceral dome is found to be covered by a

black-coloured epithelium, which may be removed, enabling the

observer to note the position

of some organs lying

below the transparent integument

(fig. 5). The

muscular columns (c) attaching

the foot to the

shell form a ring incomplete

in front, external to

which is the free mantle-skirt.

The limits of the

large area formed by the

flap over the head and

neck (ecr) can be traced,

and we note the anal

papilla showing through

and opening on the right

shoulder, so to speak, of

the animal into the large

anterior region of the

sub-pallial space. Close

to this the small renal

organ (i, mediad) and the

larger renal organ (k, to

the right and posteriorly)

are seen, also the pericardium

(l) and a coil of

the intestine (int) embedded

in the compact

liver.

|

| Fig. 6.—Anterior portion of the same

Limpet, with the overhanging cephalic

hood removed. (Lankester.) |

|

a, Cephalic tentacle.

b, Foot.

c, Muscular substance forming the root of the foot.

d, The capito-pedal organs of Lankester (= rudimentary ctenidia).

e, Mantle-skirt.

f, Papilla of the larger nephridium.

g, Anus. |

h, Papilla of the smaller nephridium.

i, Smaller nephridium.

k, Larger nephridium.

l, Pericardium.

m, Cut edge of the mantle-skirt.

n, Liver.

p, Snout. |

|

| Fig. 7.—The same specimen viewed

from the left front, so as to show the sub-anal tract (ff) of the larger nephridium,

by which it communicates with the pericardium. o, Mouth; other letters as in fig. 6. |

On cutting away the

anterior part of the

mantle-skirt so as to

expose the sub-pallial

chamber in the region

of the neck, we find the

right and left renal papillae (discovered by Lankester in 1867) on

either side of the anal papilla (fig. 6), but no gills. If a similar

examination be made of the allied genus Fissurella (fig. 17, d), we

find right and left of the two renal apertures a right and left gill-plume

or ctenidium, which here as in Haliotis and Pleurotomaria

retain their original paired condition. In Patella no such plumes

exist, but right and left of the neck are seen a pair of minute oblong

yellow bodies (fig. 6, d), which were originally described by Lankester

as orifices possibly connected with the evacuation of the generative

products. On account of their position they were termed by him

the “capito-pedal orifices,” being placed near the junction of head

and foot. J.W. Spengel has, however, in a most ingenious way

shown that these bodies are the representatives of the typical pair

of ctenidia, here reduced to a mere rudiment. Near to each rudimentary

ctenidium Spengel has discovered an olfactory patch or

osphradium (consisting of modified epithelium) and an olfactory

nerve-ganglion (fig. 8). It will be remembered that, according to

Spengel, the osphradium of mollusca is definitely and intimately

related to the gill-plume or ctenidium, being always placed near the

base of that organ; further,

Spengel has shown

that the nerve-supply of

this olfactory organ is

always derived from the

visceral loop. Accordingly,

the nerve-supply

affords a means of testing

the conclusion that

we have in Lankester’s

capito-pedal bodies the

rudimentary ctenidia.

The accompanying diagrams

(figs. 9, 10) of

the nervous systems of

Patella and of Haliotis,

as determined by

Spengel, show the identity

in the origin of the

nerves passing from the

visceral loop to Spengel’s

olfactory ganglion of the

Limpet, and that of the

nerves which pass from

the visceral loop of Haliotis to the olfactory patch or osphradium,

which lies in immediate relation on the right and on the left side

to the right and left gill-plumes (ctenidia) respectively. The same

diagrams serve to demonstrate the streptoneurous condition of the

visceral loop in Aspidobranchia.

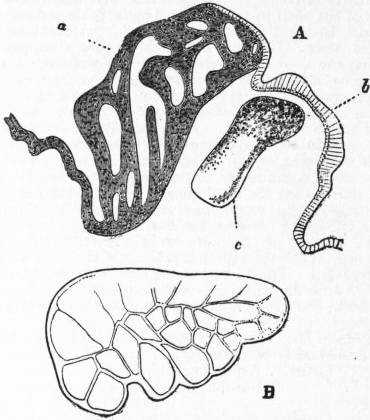

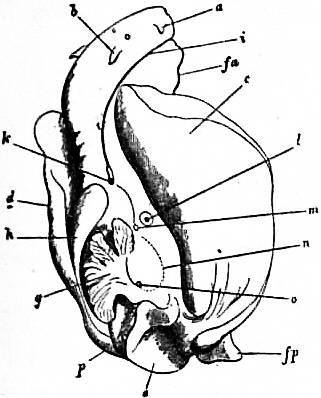

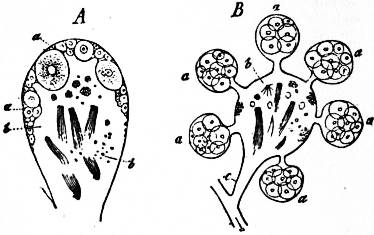

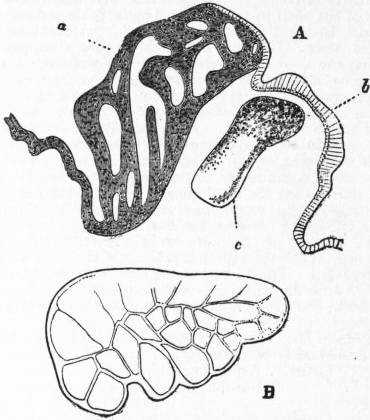

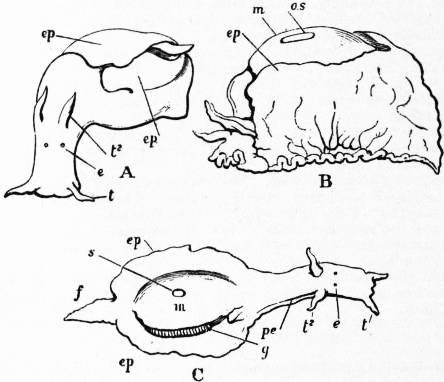

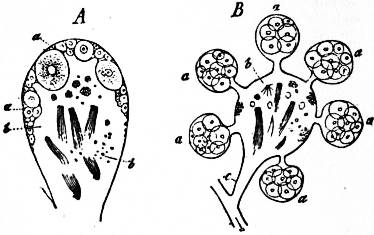

|

| Fig. 8.—A, Section in a plane vertical to the surface of the neck

of Patella through a, the rudimentary ctenidium (Lankester’s organ),

and b, the olfactory epithelium (osphradium); c, the olfactory

(osphradial) ganglion. (After Spengel.) |

B, Surface view of a rudimentary ctenidium of Patella excised

and viewed as a transparent object. (Lankester.) |

|

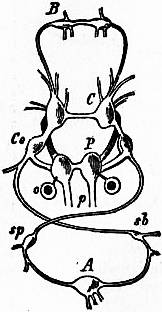

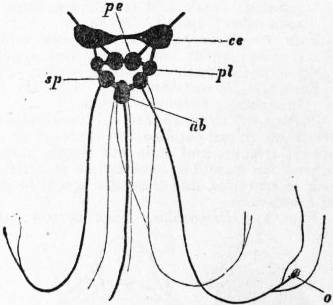

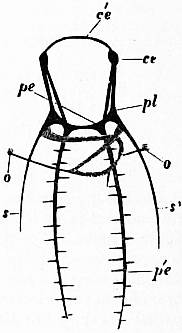

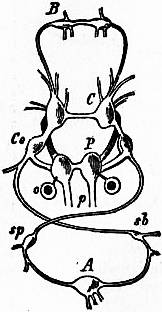

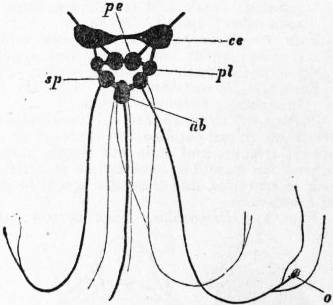

| Fig. 9.—Nervous system

of Patella; the visceral loop is lightly shaded; the buccal ganglia are omitted. (After Spengel.) |

|

ce, Cerebral ganglia.

c’e, Cerebral commissure.

pl, Pleural ganglion.

pe, Pedal ganglion.

p′e, Pedal nerve.

s, s′, Nerves (right and left) to the mantle.

o, Olfactory ganglion, connected by nerve to the streptoneurous visceral loop. |

Thus, then, we find that the limpet possesses a symmetrically

disposed pair of ctenidia in a rudimentary condition, and justifies

its position among Aspidobranchia. At the same time it possesses

a totally distinct series of functional gills, which are not derived

from the modification of the typical molluscan ctenidium. These gills

are in the form of delicate lamellae (fig. 4, f), which form a series

extending completely round the inner face of the depending mantle-skirt.

This circlet of gill-lamellae led Cuvier to class the limpets

as Cyclobranchiata, and, by erroneous identification of them with

the series of metamerically repeated ctenidia of Chiton, to associate

the latter mollusc with the former. The gill-lamellae of Patella are

processes of the mantle comparable with the plait-like folds often

observed on the roof of the branchial chamber in other Gastropoda

(e.g. Buccinum and Haliotis). They are

termed pallial gills. The only other molluscs

in which they are exactly represented

are the curious Opisthobranchs

Phyllidia and Pleurophyllidia (fig. 55).

In these, as in Patella, the typical ctenidia

are aborted, and the branchial function is

assumed by close-set lamelliform processes

arranged in a series beneath the

mantle-skirt on either side of the foot. In

fig. 4, d, the large branchial vein of Patella

bringing blood from the gill-series to the

heart is seen; where it crosses the series

of lamellae there is a short interval devoid

of lamellae.

The heart in Patella consists of a single

auricle (not two as in Haliotis and

Fissurella) and a ventricle; the former

receives the blood from the branchial

vein, the latter distributes it through a

large aorta which soon leads into irregular

blood-lacunae.

The existence of two renal organs in

Patella, and their relation to the pericardium

(a portion of the coelom), is

important. Each renal organ is a sac

lined with glandular epithelium (ciliated

cell, with concretions) communicating

with the exterior by its papilla, and by

a narrow passage with the pericardium.

The connexion with the pericardium of

the smaller of the two renal organs was

demonstrated by Lankester in 1867, at a

time when the fact that the renal organ

of the Mollusca, as a rule, opens into the

pericardium, and is therefore a typical

nephridium, was not known. Subsequent

investigations carried on under the direction

of the same naturalist have shown

that the larger as well as the smaller renal

sac is in communication with the pericardium. The walls of the renal

sacs are deeply plaited and thrown into ridges. Below the surface these

walls are excavated with blood-vessels, so that the sac is practically

a series of blood-vessels covered with renal epithelium, and forming

509

a meshwork within a space communicating with the exterior. The

larger renal sac (remarkably enough, that which is aborted in other

Anisopleura) extends between the liver and the integument of the

visceral dome very widely. It also bends round the liver as shown

in fig. 12, and forms a large sac on half of the upper surface of the

muscular mass of the foot. Here it lies close upon the genital body

(ovary or testis), and in such intimate relationship with it that,

when ripe, the gonad bursts into the renal sac, and its products are

carried to the exterior by the papilla on the right side of the anus

(Robin, Dall). This fact led Cuvier erroneously to the belief that a

duct existed leading from the gonad to this papilla. The position

of the gonad, best seen in the diagrammatic section (fig. 13), is, as

in other Aspidobranchia, devoid of a special duct communicating

with the exterior. This condition, probably an archaic one, distinguishes

the Aspidobranchia from other Gastropoda.

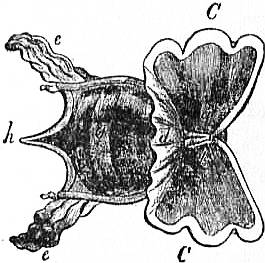

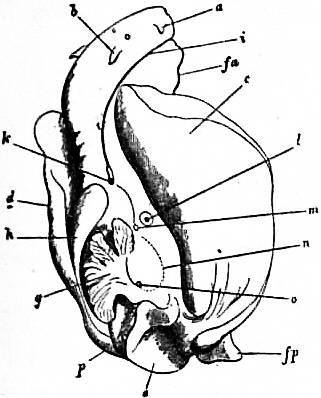

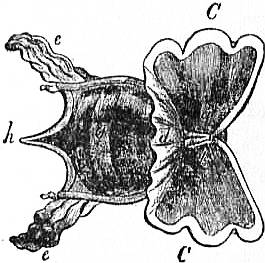

|

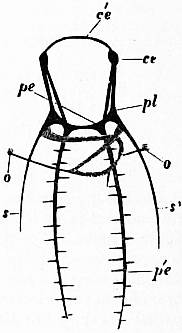

| Fig. 10.—Nervous system of Haliotis; the visceral loop is lightly

shaded; the buccal ganglia are omitted. (After Spengel.) |

ce, Cerebral ganglion.

pl.pe, The fused pleural and pedal ganglia.

pe, The right pedal nerve.

ce.pl, The cerebro-pleural connective. |

ce.pe, The cerebro-pedal connective.

s, s′, Right and left mantle nerves.

ab, Abdominal ganglion or site of same.

o, o, Right and left olfactory ganglia and osphardia receiving nerve from visceral loop. |

|

| Fig. 11.—Nervous system of

Fissurella. (From Gegenbaur, after Jhering.) |

pl, Pallial nerve.

p, Pedal nerve.

A, Abdominal ganglia in the streptoneurous visceral commissure, with supra- and sub-intestine

ganglion on each side.

B, Buccal ganglia.

C, C, Cerebral ganglia.

es, Cerebral commissure.

o, Otocysts attached to the cerebro-pedal connectives. |

|

|

| Fig. 12.—Diagram of the two

renal organs (nephridia), to show their relation to the rectum and

to the pericardium. (Lankester.) |

f, Papilla of the larger nephridium.

g, Anal papilla with rectum leading from it.

h, Papilla of the smaller nephridium, which is only represented by dotted outlines.

l, Pericardium indicated by a dotted outline—at its right

side are seen the two reno-pericardial pores.

ff, The sub-anal tract of the large nephridium given off near its

papilla and seen through the unshaded smaller nephridium.

ks.a, Anterior superior lobe of the large nephridium.

ks.l, Left lobe of same.

ks.p, Posterior lobe of same.

ks.i, Inferior sub-visceral lobe of same. |

|

|

| Fig. 13.—Diagram of a vertical antero-postero median section

of a Limpet. Letters as in figs. 6, 7, with following additions.

(Lankester.) |

q, Intestine in transverse section.

r, Lingual sac (radular sac).

rd, Radula.

s, Lamellated stomach.

t, Salivary gland.

u, Duct of same.

v, Buccal cavity |

w, Gonad.

br.a, Branchial advehent vessel (artery).

br.v, Branchial efferent vessel (vein).

bv, Blood-vessel.

odm, Muscles and cartilage of the odontophore.

cor, Heart within the pericardium. |

|

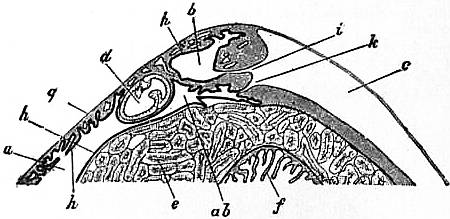

| Fig. 14.—Vertical section in a plane running right and left through

the anterior part of the visceral hump of Patella to show the two renal

organs and their openings into the pericardium. (J.T. Cunningham.) |

a, Large or external or right renal organ.

ab, Narrow process of the same running below the intestine and leading by k into the pericardium.

b, Small or median renal organ.

c, Pericardium.

d, Rectum.

e, Liver. |

f, Manyplies.

g, Epithelium of the dorsal surface.

h, Renal epithelium lining the renal sacs.

i, Aperture connecting the small sac with the pericardium.

k, Aperture connecting the large sac with the pericardium. |

The digestive tract of Patella offers some interesting features.

The odontophore is powerfully developed; the radular sac is extraordinarily

long, lying coiled in a space between the mass of the liver

and the muscular foot. The radula has 160 rows of teeth with twelve

teeth in each row. Two pairs of salivary ducts, each leading from a

salivary gland, open into the buccal chamber. The oesophagus leads

into a remarkable stomach, plaited like the manyplies of a sheep,

and after this the intestine takes a very large number of turns embedded

in the yellow liver, until at last it passes between the

two renal sacs to the anal papilla. A curious ridge (spiral? valve)

which secretes a slimy cord is found upon the inner wall of the intestine.

The general structure of the Molluscan intestine has not been

sufficiently investigated to render any comparison of this structure

of Patella with that of other Mollusca possible. The eyes of the

limpet deserve mention as examples of the most primitive kind of

eye in the Molluscan series. They are found one on each cephalic

tentacle, and are simply minute open pits or depressions of the

epidermis, the epidermic cells lining them being pigmented and

connected with nerves (compare fig. 14, art. Cephalopoda).

510

The limpet breeds upon the southern English coast in the early

part of April, but its development has not been followed. It has

simply been traced as far as the formation of a diblastula which

acquires a ciliated band, and becomes a nearly spherical trochosphere.

It is probable that the limpet takes several years to attain full

growth, and during that period it frequents the same spot, which

becomes gradually sunk below the surrounding surface, especially

if the rock be carbonate of lime. At low tide the limpet (being a

strictly intertidal organism) is exposed to the air, and (according to

trustworthy observers) quits its attachment and walks away in

search of food (minute encrusting algae), and then once more returns

to the identical spot, not an inch in diameter, which belongs, as it

were, to it. Several million limpets—twelve million in Berwickshire

alone—are annually used on the east coast of Britain as bait.

Sub-order 1. Docoglossa.—Nervous system without dialyneury.

Eyes are open invaginations without crystalline lens. Two osphradia

present but no hypobranchial glands nor operculum. Teeth of radula

beam-like, and at most three marginal teeth on each side. Heart

has only a single auricle, neither heart nor pericardium traversed

by rectum. Shell conical without spire.

Fam. 1.—Acmaeidae. A single bipectinate ctenidium on left side.

Acmaea, without pallial branchiae, British. Scurria, with

pallial branchiae in a circle beneath the mantle.

Fam. 2.—Tryblidiidae. Muscle scar divided into numerous

impressions. Tryblidium, Silurian.

Fam. 3.—Patellidae. No ctenidia but pallial branchiae in a circle

between mantle and foot. Patella, pallial branchiae forming

a complete circle, no epipodial tentacles, British. Ancistromesus,

radula with median central tooth. Nacella, epipodial

tentacles present. Helcion, circlet of branchiae interrupted

anteriorly, British.

Fam. 4.—Lepetidae. Neither ctenidia nor pallial branchiae.

Lepeta, without eyes. Pilidium. Propilidium.

Fam. 5.—Bathysciadidae. Hermaphrodite; head with appendage

on right side; radula without central tooth. Bathysciadium,

abyssal.

Sub-order 2. Rhipidoglossa.—Aspidobranchia with a palliovisceral

anastomosis (dialyneurous); eye-vesicle closed, with

crystalline lens; ctenidia, osphradia and hypobranchial glands

paired or single. Radula with very numerous marginal teeth arranged

like the rays of a fan. Heart with two auricles; ventricle

traversed by the rectum, except in the Helicinidae. An epipodial

ridge on each side of the foot and cephalic expansions between the

tentacles often present.

Fam. 1.—Pleurotomariidae. Shell spiral; mantle and shell with

an anterior fissure; two ctenidia; a horny operculum. Pleurotomaria,

epipodium without tentacles. Genus includes several

hundred extinct species ranging from the Silurian to the Tertiary.

Five living species from the Antilles, Japan and the

Moluccas. Moluccan species is 19 cm. in height.

Fam. 2.—Bellerophontidae. 300 species, all fossil, from Cambrian

to Trias.

Fam. 3.—Euomphalidae. Also extinct, from Cambrian to Cretaceous.

Fam. 4.—Haliotidae. Spire of shell much reduced; two bipectinate

ctenidia, the right being the smaller; no operculum.

Haliotis.

Fam. 5.—Velainiellidae, an extinct family from the Eocene.

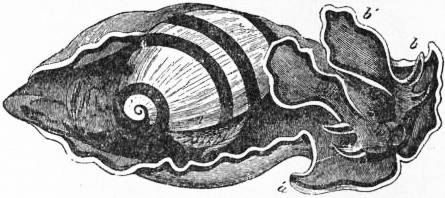

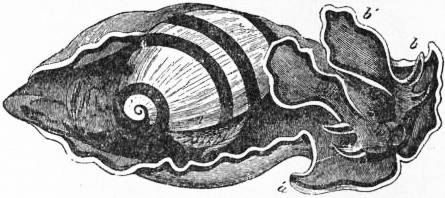

|

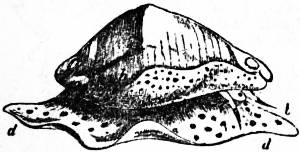

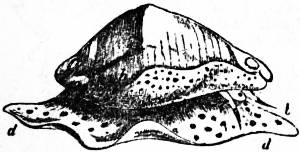

| Fig. 15.—Halio tistuberculata. d, Foot; i, tentacular processes

of the mantle. (From Owen, after Cuvier.) |

Fam. 6.—Fissurellidae. Shell conical; slit or hole in anterior

part of mantle; two symmetrical ctenidia; no operculum.

Emarginula, mantle and shell with a slit, British. Scutum,

mantle split anteriorly and reflected over shell, which has no

slit. Puncturella, mantle and shell with a foramen in front of

the apex, British. Fissurella, mantle and shell perforated at

apex, British.

Fam. 7.—Cocculinidae. Shell conical, symmetrical, without slit

or perforation. Cocculina, abyssal.

Fam. 8.—Trochidae. Shell spirally coiled; a single ctenidium;

eyes perforated; a horny operculum; lobes between the

tentacles. Trochus, shell umbilicated, spire pointed and prominent,

British. Monodonta, no jaws, spire not prominent,

no umbilicus, columella toothed. Gibbula, with jaws, three

pairs of epipodial cirri without pigment spots at their bases,

British. Margarita, five to seven pairs of epipodial cirri with a

pigment spot at base of each.

|

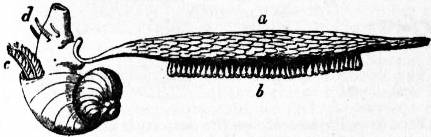

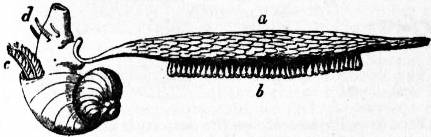

| Fig. 16.—Scutum,

seen from the pedal surface. (Lankester.) |

o, Mouth.

T, Cephalic tentacle.

br, One of the two symmetrical gills placed on the neck. | |

|

| Fig. 17.—Dorsal aspect of a specimen of Fissurella from

which the shell has been removed, whilst the anterior area of the mantle-skirt has

been longitudinally slit and its sides reflected. (Lankester.) |

a, Cephalic tentacle.

b, Foot.

d, Left (archaic right) gill-plume.

e, Reflected mantle-flap.

fi, The fissure or hole in the mantle-flap traversed by the longitudinal incision.

f, Right (archaic left) nephridium’s aperture.

g, Anus.

h, Left (archaic right) aperture of nephridium.

p, Snout. |

|

Fam. 9.—Stomatellidae. Spire of shell much reduced; a single

ctenidium. Stomatella, foot truncated posteriorly, an operculum

present, no epipodial tentacles. Gena, foot elongated

posteriorly, no operculum.

Fam. 10.—Delphinulidae. Shell spirally coiled; operculum

horny; intertentacular lobes absent. Delphinula.

Fam. 11.—Liotiidae, shell globular, margin of aperture thickened.

Liotia.

Fam. 12.—Cyclostrematidae. Shell flattened, umbilicated; foot

anteriorly truncated with angles produced into lobes. Cyclostrema.

Teinostoma.

Fam. 13.—Trochonematidae. All extinct, Cambrian to Cretaceous.

Fam. 14.—Turbinidae. Shell spirally coiled; epipodial tentacles

present; operculum thick and calcareous. Turbo. Astralium.

Molleria. Cyclonema.

Fam. 15.—Phasianellidae. Shell not nacreous, without umbilicus,

with prominent spire and polished surface. Phasianella.

Fam. 16.—Umboniidae. Shell flattened, not umbilicated, generally

smooth; operculum horny. Umbonium. Isanda.

Fam. 17.—Neritopsidae. Shell semi-globular, with short spire;

operculum calcareous, not spiral. Neritopsis. Naticopsis, extinct.

Fam. 18.—Macluritidae. Extinct, Cambrian and Silurian.

Fam. 19.—Neritidae. Shell with very low spire, without umbilicus,

internal partitions frequently absorbed; a single

ctenidium; a cephalic penis present. Nerita, marine. Neritina,

freshwater, British. Septaria, shell boat-shaped.

Fam. 20.—Titiscaniidae. Without shell and operculum, but

with pallial cavity and ctenidium. Titiscania, Pacific.

Fam. 21.—Helicinidae. No ctenidium, but a pulmonary cavity;

heart with a single auricle, not traversed by the rectum. Helicina.

Eutrochatella. Stoastoma. Bourceria.

Fam. 22.—Hydrocenidae. No ctenidium, but a pulmonary

cavity; operculum with an apophysis. Hydrocena, Dalmatia.

Fam. 23.—Proserpinidae. No operculum. Proserpina, Central

America.

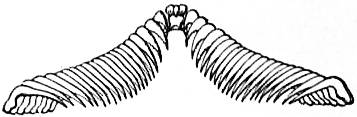

Order 2. Pectinibranchia.—In this order there is no longer any

trace of bilateral symmetry in the circulatory, respiratory and

excretory organs, the topographically right half of the pallial complex

having completely disappeared, except the right kidney, which is

511

represented by the genital duct. There is usually a penis in the male.

The ctenidium is monopectinate and attached to the mantle along

its whole length, except in Adeorbis and Valvata; in the latter alone

it is bipectinate. There is a single well-developed, often pectinated

osphradium. The eye is always a closed vesicle, and the internal

cornea is extensive. In the radula there is a single central tooth or

none.

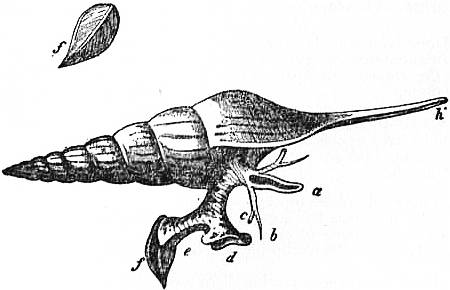

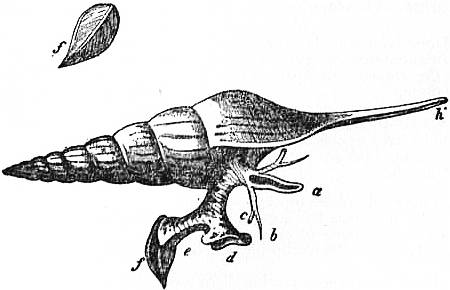

|

| Fig. 18.—Animal and shell of Pyrula laevigata. (From Owen.) |

a, Siphon.

b, Head-tentacles.

C, Head, the letter placed near the right eye. |

d, The foot, expanded as in crawling.

h, The mantle-skirt reflected over the sides of the shell. |

The former classification into Holochlamyda, Pneumochlamyda

and Siphonochlamyda has been abandoned, as it was founded on

adaptive characters not always indicative of true affinities. The

order is now divided into two sub-orders: the Taenioglossa, in

which there are three teeth on each side of the median tooth of the

radula, and the Stenoglossa, in which there is only one tooth on each

side of the median tooth. In the latter a pallial siphon, a well-developed

proboscis and an unpaired oesophageal gland are always

present, in the former they are usually absent. The siphon is an

incompletely tubular outgrowth of the mantle margin on the left

side, contained in a corresponding outgrowth of the edge of the

shell-mouth, and serving to conduct water to the respiratory cavity.

The condition usually spoken of as a “proboscis” appears to be

derived from the condition of a simple rostrum (having the mouth

at its extremity) by the process of incomplete introversion of that

simple rostrum. There is no reason in the actual significance of

the word why the term “proboscis” should be applied to an alternately

introversible and eversible tube connected with an animal’s

body, and yet such is a very customary use of the term. The introversible

tube may be completely closed, as in the “proboscis” of

Nemertine worms, or it may have a passage in it leading into a

non-eversible oesophagus, as in the present case, and in the case of

the eversible pharynx of the predatory Chaetopod worms. The

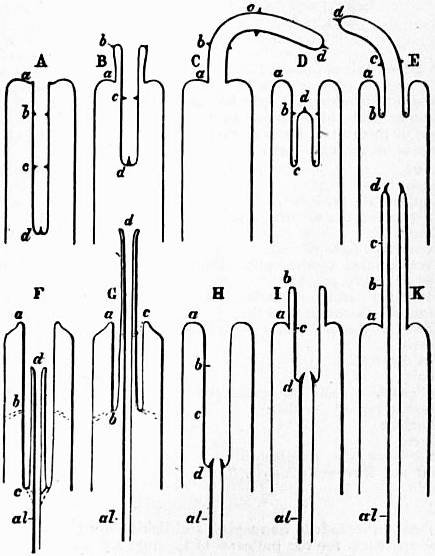

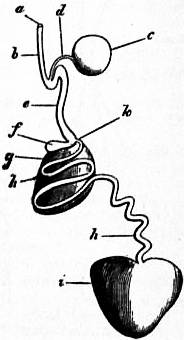

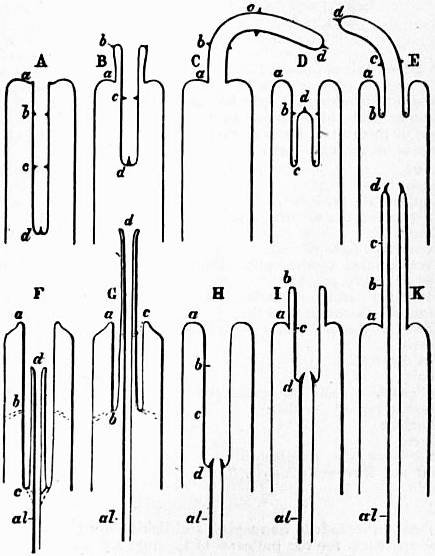

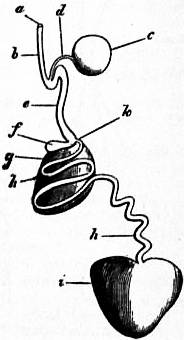

diagrams here introduced (fig. 19) are intended to show certain

important distinctions which obtain amongst the various “introverts,”

or intro- and e-versible tubes so frequently met with in animal

bodies. Supposing the tube to be completely introverted and to

commence its eversion, we then find that eversion may take place,

either by a forward movement of the side of the tube near its attached

base, as in the proboscis of the Nemertine worms, the pharynx

of Chaetopods and the eye-tentacle of Gastropods, or by a forward

movement of the inverted apex of the tube, as in the proboscis of

the Rhabdocoel Planarians, and in that of Gastropods here under

consideration. The former case we call “pleurecbolic” (fig. 19,

A, B, C, H, I, K), the latter “acrecbolic” tubes or introverts (fig.

19, D, E, F, G). It is clear that, if we start from the condition of

full eversion of the tube and watch the process of introversion, we

shall find that the pleurecbolic variety is introverted by the apex

of the tube sinking inwards; it may be called acrembolic, whilst

conversely the acrecbolic tubes are pleurembolic. Further, it is

obvious enough that the process either of introversion or of eversion

of the tube may be arrested at any point, by the development of

fibres connecting the wall of the introverted tube with the wall of

the body, or with an axial structure such as the oesophagus; on

the other hand, the range of movement of the tubular introvert may

be unlimited or complete. The acrembolic proboscis or frontal

introvert of the Nemertine worms has a complete range. So has the

acrembolic pharynx of Chaetopods, if we consider the organ as terminating

at that point where the jaws are placed and the oesophagus

commences. So too the acrembolic eye-tentacle of the snail has a

complete range of movement, and also the pleurembolic proboscis of

the Rhabdocoel prostoma. The introverted rostrum of the Pectinibranch

Gastropods presents in contrast to these a limited range of

movement. The “introvert” in these Gastropods is not the pharynx

as in the Chaetopod worms, but a prae-oral structure, its apical

limit being formed by the true lips and jaws,

whilst the apical limit of the Chaetopod’s

introvert is formed by the jaws placed at the

junction of pharynx and oesophagus, so that

the Chaetopod’s introvert is part of the stomodaeum

or fore-gut, whilst that of the Gastropod

is external to the alimentary canal altogether,

being in front of the mouth, not behind it, as

is the Chaetopod’s. Further, the Gastropod’s

introvert is pleurembolic (and therefore acrecbolic),

and is limited both in eversion and in

introversion; it cannot be completely everted

owing to the muscular bands (fig. 19, G), nor

can it be fully introverted owing to the bands

(fig. 19, F) which tie the axial pharynx to the

adjacent wall of the apical part of the introvert.

As in all such intro- and e-versible

organs, eversion of the Gastropod proboscis is

effected by pressure communicated by the

muscular body-wall to the liquid contents

(blood) of the body-space, accompanied by

the relaxation of the muscles which directly

pull upon either the sides or the apex of the

tubular organ. The inversion of the proboscis

is effected directly by the contraction of these

muscles. In various members of the Pectinibranchia

the mouth-bearing cylinder is introversible