THE STRANGE STORY BOOK

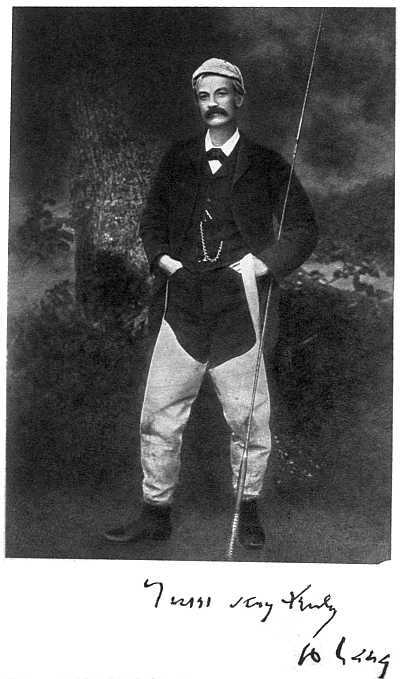

Yours Very Truly

A Lang

THE STRANGE STORY BOOK

BY MRS. LANG

EDITED BY ANDREW LANG

WITH PORTRAIT OF ANDREW LANG

AND 12 COLOURED PLATES AND

NUMEROUS OTHER ILLUSTRATIONS BY H. J. FORD

LONGMANS, GREEN, AND CO.

39 PATERNOSTER ROW, LONDON

NEW YORK, BOMBAY, AND CALCUTTA

1913

[All rights reserved]

Mrs. Andrew Lang desires to give her most grateful thanks to the Authorities of the Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology for permission to include in her Christmas book the Tlingit stories collected by Dr. John R. Swanton.

[vii]

PREFACE

TO THE CHILDREN

And now the time has come to say good-bye; and good-byes are always so sad that it is much better when we do not know that we have got to say them. It is so long since Beauty and the Beast and Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood came out to greet you in the 'Blue Fairy Book,' that some of you who wore pigtails or sailor suits in those days have little boys and girls of your own to read the stories to now, and a few may even have little baby grandchildren. Since the first giants and enchanted princes and ill-treated step-daughters made friends with you, a whole new world of wheels and wings and sharp-voiced bells has been thrown open, and children have toy motors and aeroplanes which take up all their thoughts and time. You may see them in the street bending over pictures of the last machine which has won a prize of a thousand pounds, and picturing to themselves the day when they shall invent something finer still, that will fly higher and sail faster than any of those which have gone before it.

Now as this is the very last book of all this series that began in the long long ago, perhaps you may like to hear something of the man who thought over every one of the twenty-five, for fear lest a story should creep in which he did not wish his little boys and girls to read. He was born when nobody thought of travelling in anything but a train—a very slow one—or a steamer. It took a great deal of persuasion to induce him later to get into a motor and he had not the slightest desire to go up in an aeroplane—or to possess[viii] a telephone. Somebody once told him of a little boy who, after giving a thrilling account at luncheon of how Randolph had taken Edinburgh Castle, had expressed a desire to go out and see the Museum; 'I like old things better than new,' said the child! 'I wish I knew that little boy,' observed the man. 'He would just suit me.' And that was true, for he too loved great deeds of battle and adventure as well as the curious carved and painted fragments guarded in museums which show that the lives described by Homer and the other old poets were not tales made up by them to amuse tired crowds gathered round a hall fire, but were real—real as our lives now, and much more beautiful and splendid. Very proud he was one day when he bought, in a little shop on the way to Kensington Gardens, a small object about an inch high which to his mind exactly answered to the description of the lion-gate of Mycenæ, only that now the lions have lost their heads, whereas in the plaster copy from the shop they still had eyes to look at you and mouths to eat you. His friends were all sent for to give their opinion on this wonderful discovery, but no two thought alike about it. One declared it dated from the time of Solomon or of Homer himself, and of course it would have been delightful to believe that! but then somebody else was quite certain it was no more than ten years old, while the rest made different guesses. To this day the question is undecided, and very likely always will be.

All beasts were his friends, just because they were beasts, unless they had been very badly brought up. He never could resist a cat, and cats, like beggars, tell each other these things and profit by them. A cat knew quite well that it had only to go on sitting for a few days outside the window where the man was writing, and that if it began to snow or even to rain, the window would be pushed up and the cat would spend the rest of its days stretched in front of the fire, with a saucer of milk beside it, and fish for every meal.

But life with cats was not all peace, and once a terrible thing happened when Dickon-draw-the-blade was the Puss in Possession. His master was passing through London[ix] on the way to take a journey to some beautiful old walled towns in the south of France where the English fought in the Hundred Years War, and he meant to spend a few weeks in the country along the Loire which is bound up with the memory of Joan of Arc. Unluckily, the night after he arrived from Scotland Dickon went out for a walk on the high trellis behind the house, and once there did not know how to get down again. Of course it was quite easy, and there were ropes of Virginia creeper to help, but Dickon lost his presence of mind, and instead of doing anything sensible only stood and shrieked, while his master got ladders and steps and clambered about in the dark and in the cold, till he put Dickon on the ground again. Then Dickon's master went to bed, but woke up so ill that he was obliged to do without the old towns, and go when he was better to a horrid place called Cannes, all dust and tea-parties.

Well, besides being fond of beasts, he loved cricket, and he never could be in a house with a garden for half an hour without trying to make up a cricket team out of the people who were sitting about declaring it was too hot to do anything at all; yet somehow or other, in ten minutes they were running and shouting with the rest. He would even turn a morning call to account in this way. Many years ago, a young lady who wished to introduce a new kind of dancing and thought he might be of use to her, begged a friend to invite them to meet. They did meet, but before a dozen words had been exchanged one was on the lawn and the other in the drawing-room, and there they remained to the end of the visit.

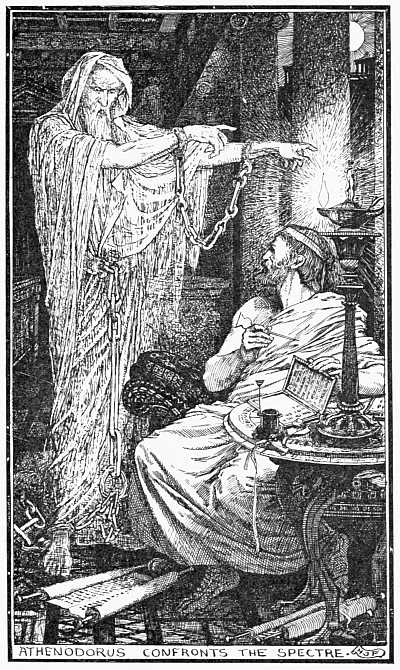

Do you love ghosts? So did he, and often and often he wanted to write you a book of the deadliest, creepiest ghost-stories he could find or invent, but he was afraid: afraid not of the children of course, but of their mothers, who were quite certain that if such a volume were known only to be in print, all kinds of dreadful things would happen to their sons and daughters. Perhaps they might have; nobody can prove that they wouldn't. At any rate, it was best to be on the safe side, so the book was never written.[x]

The books that told of wonderful deeds enthralled him too, and these he read over and over again. He could have stood a close examination of Napoleon's battles and generals, and would have told you the ground occupied by every regiment when the first shot was fired at Waterloo. As for travelling, he longed to see the places where great events had happened, but travelling tired him, and after all, when it came to the point, what was there in the world better than Scotland? As long as he could lie by a burn with a book in his pocket, watching the fish dancing in and out, he did not care so very much even about catching them. And he lay so still that two or three times a little bird came and perched on his rod—once it was a blue and green kingfisher—and he went home brimming with pride at the compliment the bird had paid him. Wherever he stayed, children were his friends, and he would tell them stories and write them plays and go on expeditions with them to ghost-haunted caves or historic castles. He would adapt himself to them and be perfectly satisfied with their company, and there is certainly one story of his own which owes its ending to a little girl, though in the Preface he was careful to speak of her as 'The Lady.'

Everything to do with the ideas and customs of savages interested him, and perhaps if some of you go away by and bye to wild parts of the world, you will make friends with the people whose stories you may have read in some of the Christmas books. But remember that savages and seers of fairyland are just like yourselves, and they will never tell their secrets to anyone who they feel will laugh at them. This man who loved fairies was paying a visit in Ireland several years ago and the girls in the house informed him that an old peasant in the hills was learned in all the wisdom and spells of the little folk. He perhaps might be persuaded to tell them a little, he did sometimes, but never if his own family were about—'they only mocked at him,' he said. It was a chance not to be missed; arrangements were made to send his daughters out of the way, and the[xi] peasant's fairy-tales were so entertaining that it was hours before the party came back.

Well, there does not seem much more to add except to place at the end of these pages a poem which should have gone into the very first Fairy Book, but by some accident was left out. It is only those who know how to shake off the fetters of the outside world, and to sever themselves from its noise and scramble, that can catch the sound of a fairy horn or the rush of fairy feet. The little girl in the poem had many friends in fairyland as well as pets among the wood folk, and she has grown up among the books year by year, sometimes writing stories herself of the birds and beasts she has tamed, and being throughout her life the dearest friend of the man who planned the Christmas books twenty-five years ago.

TO ELSPETH ANGELA CAMPBELL

Too late they come, too late for you,

These old friends that are ever new,

Enchanted in our volume blue.

For you ere now have wandered o'er

A world of tales untold of yore,

And learned the later fairy lore!

Nay, as within her briery brake,

The Sleeping Beauty did awake,

Old tales may rouse them for your sake.

And you once more may voyage through

The forests that of old we knew,

The fairy forests deep in dew,

Where you, resuming childish things,

Shall listen when the Blue Bird sings,

And sit at feasts with fairy kings,

[xii]And taste their wine, ere all be done,

And face more welcome shall be none

Among the guests of Oberon.

Ay, of that feast shall tales be told,

The marvels of that world of gold

To children young, when you are old.

When you are old! Ah, dateless when,

For youth shall perish among men,

And Spring herself be ancient then.

A. L.

1889.

[xiii]

CONTENTS

[xv]

ILLUSTRATIONS

[1]

THE DROWNED BUCCANEER

The story of Wolfert Webber was said by Louis Stevenson to be one of the finest treasure-seeking stories in the world; and as Stevenson was a very good judge, I am going to tell it to you.

Wolfert's ancestor, Cobus Webber, was one of the original settlers who came over from Holland and established themselves on the coast of what is now the State of New York. Like most of his countrymen, Cobus was a great gardener, and devoted himself especially to cabbages, and it was agreed on all sides that none so large or so sweet had ever been eaten by anybody.

Webber's house was built after the Dutch pattern, and was large and comfortable. Birds built their nests under the eaves and filled the air with their singing, and a button-wood tree, which was nothing but a sapling when Cobus planted his first cabbage, had become a monster overshadowing half the garden in the days of his descendant Wolfert early in the eighteenth century.

The button-wood tree was not the only thing that had grown during those years. The city known at first as 'New Amsterdam,' and later as 'New York,' had grown also, and surrounded the house of the Webbers. But if the family could no longer look from the windows at the beautiful woods and rivers of the countryside, as their forefathers had done, there was no reason to drive a cart about from one village to another to see who wanted cabbages, for now the housewives came to Wolfert to choose their own, which saved a great deal of trouble.

Yet, though Wolfert sold all the cabbages he could raise,[2] he did not become rich as fast as he wished, and at length he began to wonder if he was becoming rich at all. Food was dearer than when he was a boy, and other people besides himself had taken to cabbage-growing. His daughter was nearly a woman, and would want a portion if she married. Was there no way by which he could make the money that would be so badly needed by and bye?

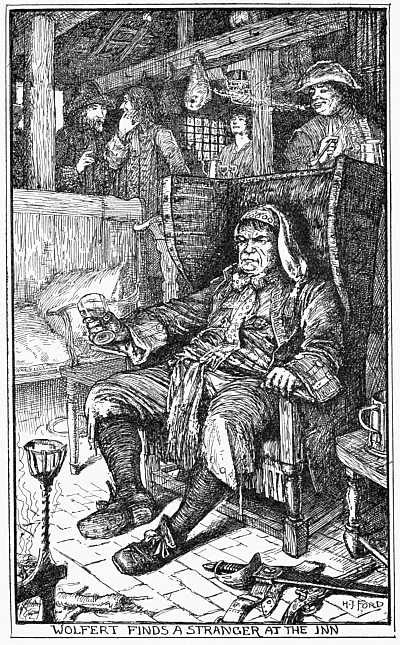

Thinking of those things, Wolfert walked out one blustering Saturday afternoon in the autumn to a country inn near the sea, much frequented by the Dutchmen who lived within reach. The usual guests were gathered round the hearth, and in a great leather armchair sat Ramm Rapelye, a wealthy and important person, and the first white child born in the State. Wolfert drew up a chair and stared moodily into the fire till he was startled by a remark of the landlord's, which seemed to chime in exactly with his thoughts.

'This will be a rough night for the money-diggers,' said he.

'What! are they at their works again?' asked a one-eyed English captain.

'Ay, indeed,' answered the landlord; 'they have had great luck of late. They say a great pot of gold has been dug up just behind Stuyvesant's orchard. It must have been buried there in time of war by old Stuyvesant, the governor.'

'Yes,' said Peechy Prauw, another of the group. 'Money has been dug up all over the island from time to time. The lucky man has always dreamt of the treasure three times beforehand, and, what is more wonderful still, nobody has ever found it who does not come from the old Dutch settlers—a sure proof that it was a Dutchman that buried it.'

That evening Wolfert went home feeling as if he was walking on air. The soil of the place must be full of gold, and how strange it was that so little of it should yet be upturned! He was so excited that he never listened to a word his wife said, and went to bed with his mind full of the talk he had heard.

His dreams carried on his last waking thoughts. He was[3] digging in his garden, and every spadeful of mould that he threw up laid bare handfuls of golden coins or sparkling stones. Sometimes he even lighted on bags of money or heavy treasure-chests.

When he woke, his one wish was to know if his dream would be repeated the next two nights, for that, according to Peechy Prauw, was needful before you could expect to discover the treasure.

On the third morning he jumped up almost mad with delight, for he had had the three dreams, and never doubted that he could become rich merely by stretching out his hand. But even so, great caution was necessary, or other people might suspect and rob him of his wealth before he had time to place it in safety. So as soon as he thought his wife and daughter were sound asleep, he got softly out of bed and, taking his spade and a pickaxe, began to dig in the part of the garden furthest from the road. The cabbages he left lying about, not thinking it was worth while for such a rich man to trouble about them.

Of course, his wife and daughter quickly perceived what he was doing, but he would explain nothing, and grew so cross when they ventured to put him a question that they feared he was going out of his mind.

Then the frosts began and the ground for many weeks was too hard to dig. All day long he sat gazing into the fire and dreaming dreams, and his wife saw their savings slowly dwindling.

At last spring came—surely the winter had never before been so long!—and Wolfert went gaily back to his digging; but not so much as a silver penny rewarded his labours. As the months passed by his energy became feverish, and his body thinner and thinner. His friends, one by one, ceased to come to his house, and at length his only visitor was a young man—Dick Waldron by name—whom he had rejected as a husband for his daughter on account of his poverty.

On a Saturday afternoon Wolfert left the house not knowing or caring where he was going, when suddenly he found himself close to the old inn by the sea-shore. It was a[4] year since he had entered it, and several of the usual customers were now present, though in the great armchair once occupied by Ramm Rapelye a stranger was seated. He was an odd and forbidding-looking person, short, bow-legged, and very strong, with a scar across his face; while his clothes were such a jumble of curious garments that they might have been picked out of dust-heaps at various times. Wolfert did not know what to make of him, and turned to inquire of Peechy Prauw, who took him into a corner of the large hall and explained how the man came there. As to who he was, no one knew; but one night a great shouting had been heard from the water-side, and when the landlord went down with his negro servant he found the stranger seated on a huge oak sea-chest. No ship was in sight, nor boat of any kind. With great difficulty his chest was moved to the inn and put in the small room which he had taken, and there he had remained ever since, paying his bill every night and spending all day at the window, watching with his telescope the ships that went by. And if anyone had been there to notice, they would have seen that it was the little vessels and not the big ones that he examined most attentively.

By and bye, however, there was a change in the stranger's habits. He spent less time in his room and more downstairs with the rest of the company, telling them wonderful stories of the pirates in the Spanish Main. Indeed, so well did he describe the adventures that his listeners were not slow in guessing that he had himself taken a chief part in them.

One evening the talk happened to turn on the famous Captain Kidd, most celebrated of buccaneers. The Englishman was relating, as he often did, all the traditions belonging to this hero, and the stranger who liked no one to speak but himself, could hardly conceal his impatience. At length the Englishman made some allusion to a voyage of Kidd's up the Hudson river in order to bury his plunder in a secret place, and at these words the stranger could contain himself no longer.

'Kidd up the Hudson?' he exclaimed; 'Kidd was never up the Hudson.'

[7]'I tell you he was,' cried the other; 'and they say he buried a quantity of treasure in the little flat called the Devil's Hammer that runs out into the river.'

'It is a lie,' returned the stranger; 'Kidd was never up the Hudson! What the plague do you know of him and his haunts?'

'What do I know?' echoed the Englishman. 'Why, I was in London at the time of his trouble and saw him hanged.'

'Then, sir, let me tell you that you saw as pretty a fellow hanged as ever trod shoe-leather, and there was many a landlubber looking on that had better have swung in his stead.'

Here Peechy Prauw struck in, thinking the discussion had gone far enough.

'The gentleman is quite right,' said he; 'Kidd never did bury money up the Hudson, nor in any of these parts. It was Bradish and some of his buccaneers who buried money round here, though no one quite knew where: Long Island, it was said, or Turtle Bay, or in the rocks about Hellgate. I remember an adventure of old Sam, the negro fisherman, when he was a young man, which sounded as if it might have to do with the buccaneers. It was on a dark night many years ago, when Black Sam was returning from fishing in Hellgate—' but Peechy got no further, for at this point the stranger broke in:

'Hark'ee, neighbour,' he cried; 'you'd better let the buccaneers and their money alone,' and with that the man rose from his seat and walked up to his room, leaving dead silence behind him. The spell was broken by a peal of thunder, and Peechy was begged to go on with his story, and this was it:—

Fifty years before, Black Sam had a little hut so far down among the rocks of the Sound that it seemed as if every high tide must wash it away. He was a hard-working young man, as active as a cat, and was a labourer at a farm on the island. In the summer evenings, when his work was done, he would hasten down to the shore and remove his light boat and go out to fish, and there was not a corner of the Sound that he did not know, from the Hen and Chickens to the Hog's Back,[8] from the Hog's Back to the Pot, and from the Pot to the Frying Pan.

On this particular evening Sam had tried in turn all these fishing-grounds, and was so eager to fill his basket that he never noticed that the tide was ebbing fast, and that he might be cast by the currents on to some of the sharp rocks. When at length he looked up and saw where he was, he lost no time in steering his skiff to the point of Blackwell's Island. Here he cast anchor, and waited patiently till the tide should flow again and he could get back safely. But as the night drew on, a great storm blew up and the lightning played over the shore. So before it grew too dark, Sam quickly changed his position and found complete shelter under a jutting rock on Manhattan Island, where a tree which had rooted itself in a cleft spread its thick branches over the sea.

'I shan't get wet, anyhow,' thought Sam, who did not like rain, and, making his boat fast, he laid himself flat in the bottom and went to sleep.

When he awoke the storm had passed, and all that remained of it was a pale flash of lightning now and then. By the light of these flashes—for there was no moon—Sam was able to see how far the tide had advanced, and judged it must be near midnight. He was just about to loose the moorings of his skiff, as it was now safe to venture out to sea, when a glimmer on the water made him pause. What could it be? Not lightning certainly, but whatever it was, it was rapidly approaching him, and soon he perceived a boat gliding along in the shadow, with a lantern at the prow. Sam instantly crouched still farther into the shadow, and held his breath as a boat passed by, and pulled up in a small cave just beyond. Then a man jumped on shore, and, taking the lantern, examined all the rocks.

'I've got it!' he exclaimed to the rest. 'Here is the iron ring,' and, returning to the boat, he and the five others proceeded to lift out something very heavy, and staggered with it a little distance, when they paused to take breath. By the light of the lantern which one of them held on high, Sam perceived that five wore red woollen caps, while the man who had found[9] the iron ring had on a three-cornered hat. All were armed with pistols, knives, and cutlasses, and some carried, besides, spades and pickaxes.

Slowly they climbed upwards towards a clump of thick bushes, and Sam silently followed them and scaled a rock which overlooked the path. At a sign from their leader they stopped, while he bent forward with the lantern, and seemed to be searching for something in the bushes.

'Bring the spades,' he said at last, and two men joined him and set to work on a piece of open ground.

'We must dig deep, so that we shall run no risks,' remarked one of the men, and Sam shivered, for he made sure that he saw before him a gang of murderers about to bury their victim. In his fright he had started, and the branches of the tree to which he was clinging rustled loudly.

'What's that?' cried the leader. 'There's someone watching us,' and the lantern was held up in the direction of the sound and Sam heard the cock of a pistol. Luckily his black face did not show in the surrounding dark, and the man lowered the lantern.

'It was only some beast or other,' he said, 'and surely you are not going to fire a pistol and alarm the country?'

So the pistol was uncocked and the digging resumed, while the rest of the party bore their burden slowly up the bank. It was not until they were out of sight that Sam ventured to move as much as an eyelid; but great as his fear was, his curiosity was greater still, and instead of creeping back to his boat and returning home, he resolved to remain a little longer.

The sound of spades could now be heard, and as the men would all be busy digging the grave, Sam thought he might venture a little nearer.

Guided by the noise of the strokes he crawled upwards, till only a steep rock divided him from the diggers. As silently as before he raised himself to the top, feeling every ledge with his toes before he put his feet on it, lest he should dislodge a loose stone which might betray him. Then he peered over the edge and saw that the men were immediately below him—and far closer than he had any idea of. Indeed, they were so[10] near that it seemed as if it were safer to keep his head where it was than to withdraw it.

By this time the turf was carefully being replaced over the grave, and dry leaves scattered above it.

'I defy anybody to find it out!' cried the leader at last, and Sam, forgetting everything, except his horror of their cruelty, exclaimed:

'The murderers!' but he did not know he had spoken aloud till he beheld the eyes of the whole gang fixed upon him.

'Down with him,' shouted they; and Sam waited for no more, but the next instant was flying for his life. Now he was crashing through undergrowth, now he was rolling down banks, now he was scaling rocks like a mountain goat; but when at length he came to the ridge at the back, where the river ran into the sea, one of the pirates was close behind him.

The chase appeared to be over; a steep wall of rock lay between Sam and safety, and in fancy he already heard the whiz of a bullet. At this moment he noticed a tough creeper climbing up the rock, and, seizing it with both hands, managed to swing himself up the smooth surface. On the summit he paused for an instant to take breath, and in the light of the dawn he was clearly visible to the pirate below. This time the whiz of the bullet was a reality, and it passed by his ear. In a flash he saw his chance of deceiving his pursuers and, uttering a loud yell, he threw himself on the ground and kicked a large stone lying on the edge into the river.

'We've done for him now I think,' remarked the leader, as his companions came panting up. 'He'll tell no tales; but we must go back and collect our booty, so that it shan't tell tales either,' and when their footsteps died away Sam clambered down from the rock and made his way to the skiff, which he pushed off into the current, for he did not dare to use the oars till he had gone some distance. In his fright he forgot all about the whirlpools of Pot and Frying Pan, or the dangers of the group of rocks right in the middle of Hellgate, known as the Hen and Chickens. Somehow or other he got safely home, and hid himself snugly for the rest of the day in the farmhouse where he worked.[11]

This was the story told by Peechy Prauw, which had been listened to in dead silence by the men round the fire.

'Is that all?' asked one of them when Peechy stopped.

'All that belongs to the story,' answered he.

'And did Sam never find out what they buried?' inquired Wolfert.

'Not that I know of,' replied Peechy; 'he was kept pretty hard at work after that, and, to tell the truth, I don't think he had any fancy for another meeting with those gentlemen. Besides, places look so different by daylight that I doubt if he could have found the spot where they had dug the grave. And after all, what is the use of troubling about a dead body, if you cannot hang the murderers?'

'But was it a dead body that was buried?' said Wolfert.

'To be sure,' cried Peechy. 'Why, it haunts the place to this day!'

'Haunts!' repeated some of the men, drawing their chairs nearer together.

'Ay, haunts,' said Peechy again. 'Have none of you heard of Father Redcap that haunts the old farmhouse in the woods near Hellgate?'

'Yes,' replied one; 'I've heard some talk of that, but I always took it for an old wives' tale.'

'Old wives' tale or not,' answered Peechy, 'it stands not far from that very spot—and a lonely one it is, and nobody has ever been known to live in it. Lights are seen from time to time about the wood at night, and some say an old man in a red cap appears at the windows and that he is the ghost of the man who was buried in the bushes. Once—so my mother told me when I was a child—three soldiers took shelter there, and when daylight came they searched the house through from top to bottom and found old Father Red Cap in the cellar outside on a cider-barrel, with a jug in one hand and a goblet in the other. He offered them a drink, but just as one of the soldiers held out his hand for the goblet, a flash of lightning blinded them all three for several minutes, and when they could see again, Red Cap had vanished, and nothing but the cider-barrel remained.'[12]

'That's all nonsense!' exclaimed the Englishman.

'Well, I don't know that I don't agree with you,' answered Peechy; 'but everybody knows there is something queer about the house. Still, as to that story of Black Sam's, I believe it just as well as if it had happened to myself.'

In the silence that followed this discussion, the roar of the storm might plainly be heard, and the thunder grew louder and louder every moment. It was accompanied by the sound of guns coming up from the sea and by a loud shout, yet it was strange that, though the whole strait was constantly lit up by lightning, not a creature was to be seen.

Suddenly another noise was added to the rest. The window of the room above was thrown up, and the voice of the stranger was heard answering the shout from the sea. After a few words uttered in a language unknown to anyone present, there was a great commotion overhead, as if someone were dragging heavy furniture about. The negro servant was next called upstairs, and soon he appeared holding one handle of the great sea-chest, while the stranger clung to the other.

'What!' cried the landlord, stepping forward in surprise, and raising his lantern. 'Are you going to sea in such a storm?'

'Storm!' repeated the stranger. 'Do you call this sputter of weather a storm? Don't preach about storms to a man whose life has been spent amongst whirlwinds and tornadoes,' and as he spoke, the voice from the water rang out, calling impatiently.

'Put out the light,' it said. 'No one wants lights here,' and the stranger turned instantly and ordered the bystanders who had followed from curiosity, back to the inn.

But although they retired to a little distance, under the shadow of some rocks, they had no intention of going any further. By help of the lightning they soon discovered a boat filled with men, heading up and down under a rocky point close by, and kept in position with great difficulty by a boat-[13]hook, for just there the current was strong. One of the crew reached forward to seize a handle of the stranger's heavy sea-chest and assist the owner to place it on board. But his movement caused the boat to drift into the current, the chest slipped from the gunwale and fell into the sea, dragging the stranger with it, and in that pitch darkness and amidst those huge waves, no aid was possible. One flash, indeed, showed for an instant a pair of outstretched hands; but when the next one came, nothing was to be seen or heard but the roaring waters.

The storm passed at midnight, the men were able to return to their homes, casting, as they went along, fearful glances towards the sea. But the events of the evening, and the tales he had listened to, made a deep impression on the mind of Wolfert, and he wondered afresh if he were not the person destined to find the hidden treasure of Black Sam's adventure. It was no dead body, he felt sure, that the pirates had buried on the island, but gold and, perhaps, jewels; and the next morning he lost no time in going over to the place and making cautious inquiries of the people who lived nearest to it.

'Oh! yes,' he was told, 'he had heard quite right. Black Sam's story had filtered out somehow, and many were the visits which had been paid to the wood by experienced money-diggers, though never once had they met with success. And more, it had been remarked that for ever after, the diggers had in every case been dogged by ill-luck.' (This, thought Wolfert to himself, was because they had neglected some of the proper ceremonies necessary to be performed by every hunter after treasure.) 'Why, the very last man who had dug there,' went on the speakers, 'had worked the whole night, in spite of two handfuls of earth being thrown in for one which he threw out. However, he persevered and managed to uncover an iron chest when, with a roar that might have been heard across the Sound, a crowd of strange figures sprang out of the hole and dealt him such blows that he was fain to betake himself to his boat as fast as his legs could[14] carry him. This story the man told on his death-bed, so no doubt it was true.'

Now every tale of the sort only went to prove to Wolfert that Sam had actually seen the pirates burying the treasure, and he was quite determined to make an effort to obtain it for himself. The first thing to be done was to get Sam to serve as his guide, for many years had passed since his adventure, and the trees and bushes would have grown thickly about the hole.

The negro was getting old by this time, but he perfectly recollected all that had happened, though his tale was not quite the same as the one told by Peechy Prauw. But, he was an active man yet, and readily agreed to go with Wolfert for a couple of dollars. As to being afraid of ghosts or pirates, Sam had long forgotten that he had feared either.

This time the two made their expedition mostly on foot, and after walking five or six miles they reached a wood which covered the eastern part of the island. Here they struck into a deep dark lane overgrown with brambles and overshadowed by creepers, showing that it was seldom indeed that anybody went that way. The lane ended at the shore of the Sound, and just there were traces of a gap surrounded by trees that had become tall since the days when Sam last saw them. Near by stood the ruins of a house—hardly more than a heap of stones, which Wolfert guessed to be the one in Peechy Prauw's story.

It was getting late, and there was something in the loneliness and desolation of the place which caused even Wolfert to feel uncomfortable. Not that he was specially brave, but his soul was so possessed with the idea of money-getting—or, rather, money-finding—that he had no thoughts to spare for other matters. He clung to Sam closely, scrambling along the edges of rocks which overhung the sea, till they came to a small cave. Then Sam paused and looked round; next he pointed to a large iron ring fastened to a sort of table-rock.

Wolfert's eyes followed him, and glistened brightly and greedily. This was the ring of Peechy Prauw's tale, and[15] when the negro stooped to examine the rock more carefully, Wolfert fell on his knees beside him and was able to make out just above the ring three little crosses cut in the stone.

Starting from this point, Sam tried to remember the exact path that the pirates had taken, and after losing his way two or three times came to the ridge of rock from which he had overlooked the diggers. On the face of it also were cut three crosses, but if you had not known where to look you would never have found them, for they were nearly filled up with moss. It was plain that the diggers had left this mark for their guidance, but what was not so plain was where they had buried their treasure, for fifty years change many things. Sam fixed first on one spot and then on another—it must have been under that mulberry tree, he declared. Or stay, was it not beside that big white stone, or beneath that small green knoll? At length Wolfert saw that Sam could be certain of nothing, and as he had brought neither spade nor pickaxe nor lantern with him, decided that he had better content himself with taking notes of the place, and return to dig some other day.

On their way back Wolfert's fancy began to play him strange tricks, as it has a way of doing when people are excited or very tired. He seemed to behold pirates hanging from every tree, and the fall of a nut or the rustling of a leaf caused him to jump and to feel for his companion. As they approached the garden of the ruined house, they saw a figure advancing along a mossy path with a heavy burden on his shoulders. On his head was a red cap, and he passed on slowly until he stopped at the door of what looked to be a burying-vault. Then he turned and shook his fist at them, and as Wolfert saw his face he recognised with horror the drowned buccaneer.

Wolfert did not need to look twice, but rushed away helter-skelter with Sam behind him, running nearly as fast as he had done fifty years before. Every stone they stumbled over they imagined to be the pirate's foot stretched out to trip them up; every bramble that caught them to be his hands grasping at[16] their clothes. They only breathed fully when Wolfert's home was in sight.

It was several days before he recovered from the shock and the run combined, and all that time he behaved in such a strange manner that his wife and daughter were convinced that he was rapidly going mad. He would sit for hours together staring before him, and if a question was put to him, seldom gave a sensible answer. He scarcely ate any food, and if he did fall asleep, he talked about money-bags, and flung the blankets right and left, imagining that he was digging the earth out of the hole.

In this extremity the poor woman felt that the matter was beyond her skill, and she hastened to consult a German doctor famous for his learning. But the result was very different from what she had expected. At the doctor's first interview with Wolfert he questioned the patient closely as to all that he had seen and heard of the treasure, and at length told him that if he was ever to find it, it was necessary to proceed with the utmost caution and to observe certain ceremonies.

'You can never dig for money except at night,' ended the doctor, 'and then you must have the help of a divining rod. As I have some experience in these matters, you had better let me join in the search. If you agree to this, you can leave all preparations to me. In three days everything will be ready.'

Wolfert was delighted at this offer. Now, he thought, he was sure of success, and though he neglected his work as much as ever, he was so much brighter and happier than before that his wife congratulated herself on her wisdom in sending him to the doctor.

When the appointed night arrived Wolfert bade his women-kind go to bed and not to feel frightened if he should be out till daylight; and dressed in his wife's long, red cloak, with his wide felt hat tied down by his daughter's handkerchief, he set gaily out on his adventure.

The doctor was awaiting him, with a thick book studded with clasps under his arm, a basket of dried herbs and drugs[17] in one hand, and the divining rod in the other. It was barely ten o'clock, but the whole village was fast asleep, and nothing was to be heard save the sound of their own footsteps. Yet, now and then it seemed to Wolfert that a third step mingled with theirs, and as he glanced round he fancied he saw a figure moving after them, keeping always in the shadow but stopping when they stopped, and proceeding when they proceeded.

Sam was ready for them and had put the spades and pickaxes in the bottom of his boat, together with a dark lantern. The tide was in their favour running fast up the Sound, so that oars were hardly needed. Very shortly they were passing the little inn where these strange adventures had begun; it was dark and still now, yet Wolfert thought he saw a boat lurking in the very place where he had beheld it on the night of the storm, but the shadow of the rocks lay so far over the water that he could be sure of nothing. Still, in a few minutes he was distinctly aware of the noise of oars, apparently coming from a long way off, and though both his companions were silent, it was evident from the stronger strokes instantly pulled by Sam that he had heard it also. In half an hour the negro shot his skiff into the little cave, and made it fast to the iron ring.

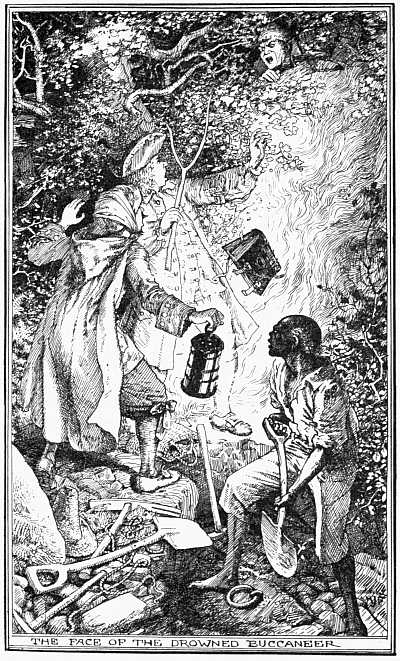

Even with the help of the notes he had taken, it was some time before Wolfert managed to hit on the exact spot where the treasure had been buried. After losing their way twice or thrice they reached the ledge of rock with the crosses on it, and at a sign from Wolfert the doctor produced the divining rod. This was a forked twig, and each of the forks was grasped in his hand, while the stem pointed straight upwards. The doctor held it at a certain distance above the ground, and frequently changed his position, and Wolfert kept the light of the lantern full on the twig, but it never stirred. Their hopes and their patience were nearly exhausted when the rod began slowly to turn, and went on turning until the stem pointed straight to the earth.

'The treasure lies here,' said the doctor.

'Shall I dig?' asked Sam.[18]

'No! no! not yet. And do not speak, whatever you see me do,' and the doctor drew a circle round them and made a fire of dry branches and dead leaves. On this he threw the herbs and drugs he had brought with him, which created a thick smoke, and finished by reading some sentences out of the clasped book. His companions, nearly choked and blinded by the dense vapour, understood nothing of what was going on, and it is quite possible that there was not anything to understand, but the doctor thought that these ceremonies were necessary to the right beginning of any important adventure. At last he shut the book.

'You can dig now,' he said to Sam.

So the negro struck his pickaxe into the soil, which gave signs of not having been disturbed for many a long day. He very soon came to a bed of sand and gravel, and had just thrust his spade into it, when a cry came from Wolfert.

'What is that?' he whispered. 'I fancied I heard a trampling among the dry leaves and a rustling through the bushes.' Sam paused, and for a moment there was no sound to break the stillness. Then a bat flitted by, and a bird flew above the flames of the fire.

Sam continued to dig, till at length his spade struck upon something that gave out a hollow ring. He struck a second time, and turned to his companions.

'It is a chest,' he cried.

'And full of gold, I'll warrant,' exclaimed Wolfert, raising his eyes to the doctor, who stood behind him. But beyond the doctor who was that? By the dying light of the lantern, peering over the rock, was the face of the drowned buccaneer.

With a shriek of terror he let fall the lantern, which fizzled out. His companions looked up, and, seeing what he saw, were seized with a fear as great as his. The negro leaped out of the hole, the doctor dropped his book and basket, and they all fled in different directions, thinking that a legion of hobgoblins were after them. Wolfert made a dash for the water-side and the boat, but, swiftly as he ran, someone behind him ran more swiftly still. He gave himself up for lost, when a hand clutched at his cloak; then suddenly a third person seemed to gain on them, and to attack his pursuer. Pistol shots were fired in the fierceness of the fight, the combatants fell, and rolled on the ground together.

[21]Wolfert would thankfully have disappeared during the struggle, but a precipice lay at his feet, and in the pitch darkness he knew not where he could turn in safety. So he crouched low under a clump of bushes and waited.

Now the two men were standing again and had each other by the waist, straining and dragging and pulling towards the brink of the precipice. This much Wolfert could guess from the panting sounds that reached him, and at last a gasp of relief smote upon his ears followed instantaneously by a shriek and then a plunge.

One of them had gone, but what about the other? Was he friend or foe? The question was soon answered, for climbing over a group of rocks which rose against the sky was the buccaneer. Yes; he was sure of it.

All his terrors revived at the sight, and he had much ado to keep his teeth from chattering. Yet, even if his legs would carry him, where could he go? A precipice was on one side of him and a murderer on the other. But as the pirate drew a few steps nearer, Wolfert's fears were lashed into frenzy, and he cast himself over the edge of the cliff, his feet casting about for a ledge to rest on. Then his cloak got caught in a thorn tree and he felt himself hanging in the air, half-choking. Luckily the string broke and he dropped down, rolling from bank to bank till he lost consciousness.

It was long before he came to himself. When he did, he was lying at the bottom of a boat, with the morning sun shining upon him.

'Lie still,' said a voice, and with a leap of the heart he knew it to be that of Dick Waldron, his daughter's sweetheart.

Dame Webber, not trusting her husband in the strange condition he had been in for months, had begged the young man to follow him, and though Dick had started too late to overtake the party, he had arrived in time to save Wolfert from his enemy.[22]

The story of the midnight adventure soon spread through the town, and many were the citizens who went out to hunt for the treasure. Nothing, however, was found by any of the seekers; and whether any treasure had been buried there at all, no one could tell, any more than they knew who the strange buccaneer was, and if he had been drowned or not. Only one thing was curious about the whole affair, and that was the presence in the Sound at that very time of a brig looking like a privateer which, after hanging about for several days, was seen standing out to sea the morning after the search of the money-diggers.

Yet, though Wolfert missed one fortune, he found another, for the citizens of Manhattan desired to cut a street right through his garden, and offered to buy the ground for a large sum. So he grew to be a rich man after all, and might be seen any day driving about his native town in a large yellow carriage drawn by two big black Flanders mares.[23]

THE PERPLEXITY OF ZADIG

On the banks of the river Euphrates there once lived a man called Zadig, who spent all his days watching the animals he saw about him and in learning their ways, and in studying the plants that grew near his hut. And the more he knew of them, the more he was struck with the differences he discovered even in the beasts or flowers which he thought when he first saw them were exactly alike.

One morning as he was walking through a little wood there came running towards him an officer of the queen's household, followed by several of her attendants. Zadig noticed that one and all seemed in the greatest anxiety and glanced from side to side with wild eyes as if they had lost something they held to be very precious, and hoped against hope that it might be lurking in some quite impossible place.

On catching sight of Zadig, the first of the band stopped suddenly.

'Young man,' he said, panting for breath, 'have you seen the queen's pet dog?'

'It is a tiny spaniel, is it not?' answered Zadig, 'which limps on the left fore-paw, and has very long ears?'

'Ah then, you have seen it!' exclaimed the steward joyfully, thinking that his search was at an end and his head was safe, for he knew of many men who had lost theirs for less reason.

'No,' replied Zadig, 'I have never seen it. Indeed, I did not so much as know that the queen had a dog.'

At these words the faces of the whole band fell, and with sighs of disappointment they hurried on twice as fast as before, to make up for lost time.[24]

Strange to say, it had happened that the finest horse in the king's stable had broken away from its groom and galloped off no one knew where, over the boundless plains of Babylon. The chief huntsman and all the other officials pursued it with the same eagerness that the officers of the household had displayed in running after the queen's dog and, like them, met with Zadig who was lying on the ground watching the movements of some ants.

'Has the king's favourite horse passed by here?' inquired the great huntsman, drawing rein.

'You mean a wonderful galloper fifteen hands high, shod with very small shoes, and with a tail three feet and a half long? The ornaments of his bit are of gold and he is shod with silver?'

'Yes, yes, that is the runaway,' cried the chief huntsman; 'which way did he go?'

'The horse? But I have not seen him,' answered Zadig, 'and I never even heard of him before.'

Now Zadig had described both the horse and the dog so exactly that both the steward and the chief huntsman did not doubt for a moment that they had been stolen by him.

The chief huntsman said no more, but ordered his men to seize the thief and to bring him before the supreme court, where he was condemned to be flogged and to pass the rest of his life in exile. Scarcely, however, had the sentence been passed than the horse and dog were discovered and brought back to their master and mistress, who welcomed them with transports of delight. But as no one would have respected the judges any longer if they had once admitted that they had been altogether mistaken, they informed Zadig that, although he was to be spared the flogging and would not be banished from the country, he must pay four hundred ounces of gold for having declared he had not seen what he plainly had seen.

With some difficulty Zadig raised the money, and when he had paid it into court, he asked permission to say a few words of explanation.

'Moons of justice and mirrors of truth,' he began. 'I [25]swear to you by the powers of earth and of air that never have I beheld the dog of the queen nor the horse of the king. And if this august assembly will deign to listen to me for a moment, I will inform them exactly what happened. Before I met with the officers of the queen's household I had noticed on the sand the marks of an animal's paws, which I instantly recognised to be those of a small dog; and as the marks were invariably fainter on one side than on the three others, it was easy to guess that the dog limped on one paw. Besides this, the sand on each side of the front paw-marks was ruffled on the surface, showing that the ears were very long and touched the ground.

'As to the horse, I had perceived along the road the traces of shoes, always at equal distances, which proved to me that the animal was a perfect galloper. I then detected on closer examination, that though the road was only seven feet wide, the dust on the trees both on the right hand and on the left had been swept to a height of three and a half feet, and from that I concluded the horse's tail, which had switched off the dust, must be three and a half feet long. Next, five feet from the ground I noticed that twig and leaves had been torn off the trees, so evidently he was fifteen hands high. As to the ornaments on his bit, he had scraped one of them against a rock on turning a corner too sharply, and some traces of gold remained on it, while the light marks left on the soil showed that his shoes were not of iron but of a less heavy metal, which could only be silver.'

Great was the amazement of the judges and of everybody else at the perception and reasoning of Zadig. At court, no one talked of anything else; and though many of the wise men declared that Zadig should be burnt as a wizard, the king commanded that the four hundred ounces of gold, which he had paid as a fine, should be restored to him. In obedience to this order, the clerk of the court and the ushers came in state to Zadig's hut, bringing with them the four hundred ounces; but, when they arrived, they told Zadig that three hundred and ninety-eight of them were due for law expenses, so he was not much better off than before.

Zadig said nothing, but let them keep the money. He had[26] learned how dangerous it is to be wiser than your neighbours, and resolved never again to give any information to anybody, or to say what he had seen.

He had very speedily a chance of putting this determination into practice. A prisoner of state escaped from the great gaol of Babylon, and in his flight happened to pass beneath the window of Zadig's hut. Not long after, the warders, of the gaol discovered which way he had gone, and cross-questioned Zadig closely. Zadig, warned by experience, kept silence; but notwithstanding, it was proved—or at least, they said so—that Zadig had been looking out of the window when the man went by, and for this crime he was sentenced by the judges to pay five hundred ounces of gold.

'Good gracious!' he murmured to himself as, according to the custom of Babylon, he thanked the court for its indulgence. 'What is one to do? It is dangerous to stand at your own window, or to be in a wood which the king's horse and the queen's dog have passed through. How hard it is to live happily in this life!'[27]

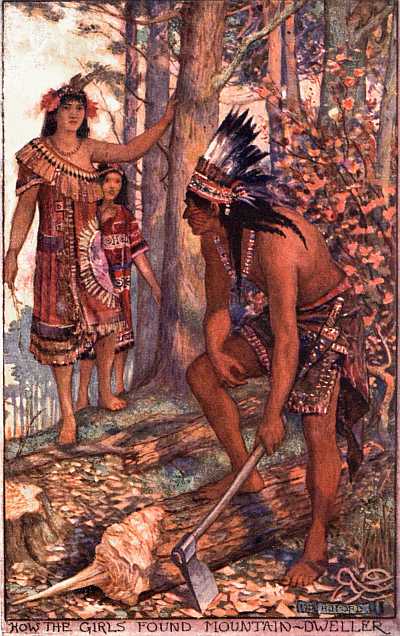

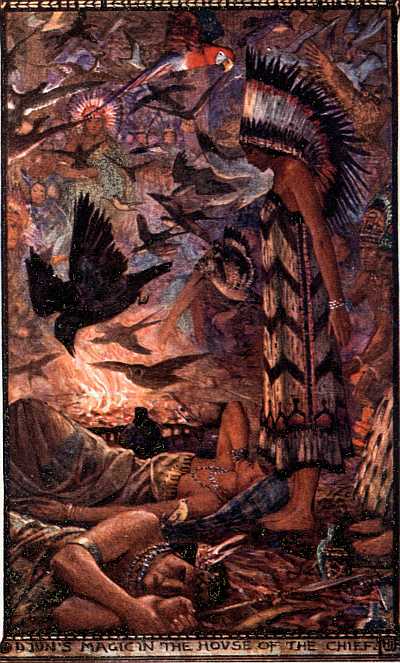

THE RETURN OF THE DEAD WIFE

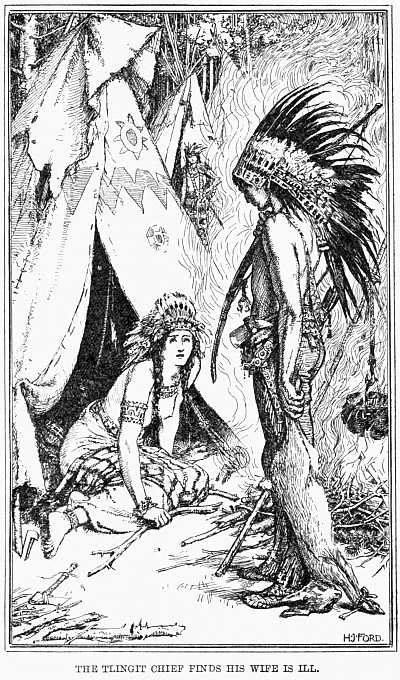

Once upon a time there lived in Alaska a chief of the Tlingit tribe who had one son. When the boy grew to be a man, he saw a girl who seemed to him prettier and cleverer than any other girl of the tribe, and his heart went out to her, and he told his father. Then the chief spoke to the father and the mother of the girl, and they agreed to give her to the young man for a wife. So the two were married, and for a few months all went well with them and they were very happy.

But one day the husband came home from hunting and found his wife sitting crouched over the fire—her eyes dull and her head heavy.

'You are ill,' he said, 'I will go for the shaman,' but the girl answered:

'No, not now. I will sleep, and in the morning the pains will have gone from me.'

But in the morning she was dead, and the young man grieved bitterly and would eat nothing, and he lay awake all that night thinking of his wife, and the next night also.

'Perhaps if I went out into the forest and walked till I was tired, I might sleep and forget my pain,' thought he. But, after all, he could not bear to leave the house while his dead wife was in it, so he waited till her body was taken away that evening for burial. Then, very early next morning, he put on his leggings and set off into the forest and walked through that day and the following night. Sunrise on the second morning found him in a wide valley covered with thick trees. Before him stretched a plain which had once been full of water, but it was now dried up.

He paused for a moment and looked about him, and as he[28] looked he seemed to hear voices speaking a long way off. But he could see nobody, and walked on again till he beheld a light shining through the branches of the trees and noticed a flat stone on the edge of a lake. Here the road stopped; for it was the death road along which he had come, though he did not know it.

The lake was narrow, and on the other side were houses and people going in and out of them.

'Come over and fetch me,' he shouted, but nobody heard him, though he cried till he was hoarse.

'It is very odd that nobody hears me,' whispered the youth after he had shouted for some time longer; and at that minute a person standing at the door of one of the houses across the lake cried out:

'Someone is shouting'; for they could hear him when he whispered, but not when he made a great noise.

'It is somebody who has come from dreamland,' continued the voice. 'Let a canoe go and bring him over.' So a canoe shot out from the shore, and the young man got into it and was paddled across, and as soon as he stepped out he saw his dead wife.

Joy rushed into his heart at the sight of her; her eyes were red as though she had been crying; and he held out his hands. As he did so the people in the house said to him:

'You must have come from far; sit down, and we will give you food,' and they spread food before him, at which he felt glad, for he was hungry.

'Don't eat that,' whispered his wife, 'if you do, you will never get back again'; and he listened to her and did not eat it.

Then his wife said again:

'It is not good for you to stay here. Let us depart at once,' and they hastened to the edge of the water and got into the canoe, which is called the Ghost's Canoe, and is the only one on the lake. They were soon across and they landed at the flat stone where the young man had stood when he was shouting, and the name of that stone is the Ghost's Rock. Down they went along the road that he had come, and on the second night they reached the youth's house.

[31]

'Stay here,' he said, 'and I will go in and tell my father.' So he entered and said to his father:

'I have brought my wife back.'

'Well, why don't you bring her in?' asked the chief, and he took a fur robe and laid it on top of a mat for her to sit on. After that the young man led his wife into the house, but the people inside could not see her enter, but only her husband; yet when he came quite close, they noticed a deep shadow behind him. The young man bade his wife sit down on the mat they had prepared for her, and a robe of marten skins was placed over her shoulders, and it hung upon her as if she had been a real woman and not a ghost. Then they put food before her, and, as she ate, they beheld her arms, and the spoon moving up and down. But the shadow of her hands they did not see, and it seemed strange to them.

Now from henceforth the young man and his wife always went everywhere together; whether he was hunting or fishing, the shadow always followed him, and he begged to have his bed made where they had first seated themselves, instead of in the room where he had slept before. And this the people in the house did gladly, for joy at having him back.

In the day, if they happened not to be away hunting or fishing, the wife was so quiet that no one would have guessed she was there, but during the night she would play games with her husband and talk to him, so that the others could hear her voice. At her first coming the chief felt silent and awkward, but after a while he grew accustomed to her and would pretend to be angry and called out: 'You had better get up now, after keeping everyone awake all night with your games,' and they could hear the shadow laugh in answer, and knew it was the laugh of the dead woman.

Thus things went on for some time, and they might have gone on longer, had not a cousin of the dead girl's who had wanted to marry her before she married the chief's son become jealous when he found that her husband had brought her back from across the lake. And he spied upon her, and listened to her when she was talking, hoping for a chance to work her[32] some ill. At last the chance came, as it commonly does, and it was in this wise:

Night after night the jealous man had hidden himself at the head of the bed, and had stolen away unperceived in the morning without having heard anything to help his wicked plans. He was beginning to think he must try something else when one evening the girl suddenly said to her husband that she was tired of being a shadow, and was going to show herself in the body that she used to have, and meant to keep it always. The husband was glad in his soul at her words, and then proposed that they should get up and play a game as usual; and, while they were playing, the man behind the curtains peeped through. As he did so, a noise as of a rattling of bones rang through the house, and when the people came running, they found the husband dead and the shadow gone, for the ghosts of both had sped back to Ghostland.

[33]

YOUNG AMAZON SNELL

When George I. was king, there lived in Worcester a man named Snell, who carried on business as a hosier and dyer. He worked hard, as indeed he had much need to do—having three sons and six daughters to provide for. The boys were sent to some kind of school, but in those days tradesmen did not trouble themselves about educating their girls, and Snell thought it quite enough for them to be able to read and to count upon their fingers. If they wanted more learning they must pick it up for themselves.

Now although Snell himself was a peaceable, stay-at-home man, his father had been a soldier, and had earned fame and a commission as captain-lieutenant, by shooting the Governor of Dunkirk in the reign of King William. Many tales did the Snell children hear in the winter evenings of their grandfather's brave deeds when he fought at Blenheim with the Welsh Fusiliers, and a thrill of excitement never failed to run through them as they listened to the story of the battle of Malplaquet, where the hero received the wound that killed him.

'Twenty-two battles!' they whispered proudly yet with awe-struck voices; 'did ever any man before fight in so many as that?' and, though the eldest boy said less than any, one morning his bed was empty, and by and bye his mother got a message to tell her that Sam had enlisted, and was to sail for Flanders with the army commanded by the Duke of Cumberland.

Poor Sam's career was not a long one. He was shot through the lungs at the battle of Fontenoy, and died in a few hours.

The old grandfather's love of a fight was in all these young[34] Snells, and one by one the boys followed Sam's example, and the girls married soldiers or sailors. Hannah, the youngest, brought up from her babyhood on talk of wars and rumours of wars, thought of nothing else.

'She would be a soldier too when she was big enough,' she told her father and mother twenty times a day, and her playfellows were so infected by her zeal, that they allowed themselves to be formed into a company, of which Hannah, needless to say, was the commander-in-chief, and meekly obeyed her orders.

In their free hours, she would drill them as her brothers had drilled her, and now and then when she decided that they knew enough not to disgrace her, she would march them through the streets of Worcester, under the admiring gaze of the shopkeepers standing at their doors.

'Young Amazon Snell's troop are coming this way. See how straight they hold themselves! and look at Hannah at the head of them,' said the women, hurrying out; and though Hannah, like a well-trained soldier, kept her eyes steadily before her, she heard it all and her little back grew stiffer than ever.

So things went on for many years, till at the end of 1740 Mr. and Mrs. Snell both died, and Hannah left Worcester to live with one of her sisters, the wife of James Gray, a carpenter, whose home was at Wapping in the east of London.

Much of Gray's work lay among the ships which drew up alongside the wharf, and sailors were continually in and out of the house in Ship Street. One of these, a Dutchman called Summs, proposed to Hannah, who married him in 1743, when she was not yet twenty.

She was a good-looking, pleasant girl, and no doubt had attracted plenty of attention. But of course she laughed at the idea of her marrying a shopkeeper who had never been outside his own parish. So, like Desdemona and many another girl before and after, she listened entranced to the marvellous stories told her by Summs, and thought herself fortunate indeed to have found such a husband.

She soon changed her opinion. Summs very quickly got tired of her; and after ill-treating her in every kind of way,[35] and even selling her clothes, deserted her, and being ill and miserable and not knowing what to do, she thankfully returned to her sister.

After some months of peace and rest, Hannah grew well and strong, and then she made up her mind to carry out a plan she had formed during her illness, which was to put on a man's dress, and go in search of the sailor who had treated her so ill. At least this was what she said to herself, but no doubt the real motive that guided her was the possibility of at last becoming a soldier or sailor, and seeing the world. It is not quite clear if she confided in her sister, but at any rate she took a suit of her brother-in-law's clothes and his name into the bargain, and it was as 'James Gray' that she enlisted in Coventry in 1745, in a regiment commanded by General Guise.

It was lucky for Hannah that, unlike most girls of her day and position, she had not been pent up at home doing needlework, as after three weeks, she with seventeen other raw recruits was ordered to join her regiment at Carlisle, so as to be ready to act, if necessary, against the Highlanders and Prince Charlie. But these three weeks had taught her much about a soldier's life which her brothers had left untold. She had learnt to talk as the men about her talked, and to drink with them if she was invited, though she always contrived to keep her head clear and her legs steady. As to her husband, of him she could hear nothing at Coventry; perhaps she might be more fortunate in the north.

In spite of a burn on her foot, which she had received after enlisting, Hannah found no difficulty in marching to Carlisle with the other recruits, and when they reached the city at the end of twenty-two days, she was as fresh as any of them. How delighted she was to find that the dream of her childhood was at last realised, and that she could make as good a soldier as the rest. But her spirits were soon dashed by the wickedness of the sergeant, who on Hannah's refusal to help him to carry out an infamous scheme on which he had set his heart, reported her to the commanding officer for neglect of duty. No inquiry as to the truth of this accusation appears to have been[36] made, and the sentence pronounced was extraordinarily heavy, even though it was thought to have been passed on a man. The prisoner was to have her hands tied to the castle gates and to receive six hundred lashes. She actually did receive five hundred, at least, so it was said, and then some officers who were present interfered, and bade them set her free.

It does not seem as if Hannah suffered much from her stripes, but very soon a fresh accident upset all her plans. The arrival of a new recruit was reported, and the youth turned out to be a young carpenter from Wapping, who had spent several days in her brother-in-law's house while she was living there. Hannah made sure that he would recognise her at once, though as a matter of fact he did nothing of the kind, and to prevent the shame of discovery, she determined to desert the regiment, and try her fortune elsewhere.

To go as far as possible from Carlisle was her one idea, and what town could be better than Portsmouth for the purpose?

But in order to travel such a long way, money was needed, and Hannah had spent all her own and did not know how to get more. She consulted a young woman whom she had helped when in great trouble, and in gratitude, the girl instantly offered enough to enable her friend to get a lift on the road when she was too tired to walk any longer.

'If you get rich, you can pay me back,' she said; 'if not, the debt is still on my side. But, oh, Master Gray, beware, I pray you! for if they catch you, they will shoot you, to a certainty.'

'No fear,' answered Hannah laughing, and very early one morning she stole out.

Taking the road south she crept along under the shade of the hedge, till about a mile from the town she noticed a heap of clothes lying on the ground, flung there by some labourers who were working at the other end of the field.

'It will be many hours yet before they will look for them,' thought she, 'and fair exchange is no robbery,' so stooping low in the ditch she slipped off her regimentals, and hiding them at the very bottom of the pile, put on an old coat and[37] trousers belonging to one of the men. Then full of hope, she started afresh.

Perhaps the commander in Carlisle never heard of the desertion of one of the garrison, or perhaps search for James Gray was made in the wrong direction. However that may be, nobody troubled the fugitive, who weary and footsore, in a month's time entered Portsmouth.

At this point a new chapter begins in Hannah Snell's history. The old desire to see the world was still strong upon her, and, after resting for a little in the house of some kind people, she enlisted afresh in a regiment of marines. A few weeks later, she was ordered to join the 'Swallow,' and to sail with Admiral Boscawen's fleet for the East Indies.

It was Hannah's first sea-voyage, but, in spite of the roughness of the life on board ship in those days, she was happy enough. England was behind her; that was the chief thing, and who could tell what wonderful adventures lay in front? So her spirits rose, and she was so good-natured and obliging as well as so clever, that the crew one and all declared they had found a treasure. There was nothing 'James Gray' could not and would not do—wash their shirts, cook their food, mend their holes, laugh at their stories. And, as she looked a great deal younger in her men's clothes than she had done in her woman's dress, no one took her for anything but a boy, and all willingly helped to teach her the duties which would fall to her, both now and in case of war.

She kept watch for four hours in turn with the rest, and soon began to see in the dark with all the keenness of a sailor. Next she was taught how to load and unload a pistol, which pleased her very much, and was given her place on the quarter-deck, where she was at once to take up her station during an engagement. Most likely she was forced from time to time to attend drill, but this we are not told.

The 'Swallow' was not half through the Bay of Biscay when a great storm arose which blew the fleet apart, and did great damage to the vessel. Both her topmasts were lost, and it is a wonder that, in this crippled condition, the ship was able to make her way to Lisbon, where the crew remained on shore[38] till the ship was refitted, and she could join the rest of the fleet, which then set sail down the Atlantic towards the coast of India.

Except for more bad weather and a scarcity of provisions on board the 'Swallow,' nothing worthy of note occurred, till they had rounded the Cape of Good Hope and passed Madagascar.

Some fruitless attacks on a group of islands belonging to the French gave Hannah her first experience of war, and her comrades were anxious as to how 'the boy' would behave under fire. But they speedily saw that there was no danger that any cowardice of his would bring discredit on the regiment, and that 'James Gray' was as good a fighter as he was a cook. Perhaps 'James Gray,' if the truth be told, was rather relieved himself when the bugle sounded a retreat, for no one knows what may happen to him in the excitement of a first battle; or whether in the strangeness and newness of it all, he may not lose his head and run away, and be covered with shame for ever.

None of this, however, befell Hannah, and when six weeks after, they were on Indian soil, and sat down to besiege the French settlement of Pondicherry, the Worcestershire girl was given more than one chance of distinguishing herself.

Pondicherry was a very strong place and the walls which were not washed by the sea were thoroughly fortified and defended by guns, while the magazines contained ample supplies both of food and powder. Further, it was guarded by the fort of Areacopong commanding a river, and with a battery of twelve guns ready to pour forth fire on the British army. Hannah was speedily told off with some others to bring up certain stores, which had been landed by the fleet, and, after some heavy skirmishing, they succeeded in their object. Her company was then ordered to cross the river so as to be able to march, when necessary, upon Pondicherry itself, and this they did under the fire of the guns of Areacopong, with the water rising to their breasts.

At length the fort was captured and great was the rejoicing in the British lines, for the surrender of Areacopong meant the[39] removal of the chief barrier towards taking the capital of French India.

For seven nights Hannah had to be on picket duty, and was later sent to the trenches, where she constantly was obliged to dig with the water up to her waist, for the autumn rains had now begun.

But her heart and soul were bound up in the profession she had chosen, and everything else was forgotten, even her desire to revenge herself on her husband. Not a soldier in the army fought better than she, and in one of the battles under the walls of Pondicherry, she is said to have received eleven shots in her legs alone! She was carried into hospital, and when the doctors had time to attend to her, she showed them the bullet wounds down her shins, but made no mention of a ball which had entered her side, for she was resolved not to submit to any examination. This wound gave her more pain than all the rest put together, and after two days she made up her mind that in order to avoid being discovered for a woman she must extract it herself, with the help of a native who was acting as nurse.

Setting her teeth to prevent herself shrieking with the agony the slightest touch caused her, Hannah felt about till she found the exact spot where the ball was lodged, and then pressed the place until the bullet was near enough to the surface for her to pull it out with her finger and thumb. The pain of it all was such that she sank back almost fainting, but with a violent effort she roused herself, and stretching out her hand for the lint and the ointment placed within her reach by the nurse, she dressed the wound. Three months later she was as well as ever, and able to do the work of a sailor on board a ship which, at that time, was anchored in the harbour.

As soon as the fleet returned from Madras, Hannah was ordered to the 'Eltham,' but at Bombay she fell into disgrace with the first lieutenant, was put into irons for five days, spent four hours at the foretop-masthead, and received twelve lashes. She was likewise accused of stealing a shirt, but, as this was proved to be false, the charge only roused the anger of the crew, and they took the first opportunity to[40] revenge themselves on the lieutenant who had sentenced her.

It was in November 1749 that the fleet sailed for home, and the 'Eltham' was directed to steer a straight course for Lisbon, having to take on board a large sum of money, destined for some London merchants. One day when she was ashore with her mates, they turned into a public-house to have dinner. Here they happened to meet an English sailor, with whom many of the party were well acquainted. Learning that he had been lately engaged on a Dutch vessel, Hannah inquired carelessly whether he had ever come across one Jemmy Summs.

'Summs?' answered the man. 'I should think I had. I heard of him only the other day at Genoa, in prison for killing an Italian gentleman. I asked to be allowed to see him, and as he was condemned to death, they gave me leave to do so. He told me the story of his life, and how, while he was in London, he married a young woman called Hannah Snell, and then deserted her. More than six years have passed since that time, and he does not know what became of her. But he begged me, if ever I was near Wapping again, to seek her out and entreat her to forgive him. As soon as he had finished, the gaoler entered and bade us say farewell.

'That was the last we saw of him, but before I left I heard that he had been sewn up in a bag filled with stones, and thrown into the sea, which is their way of hanging.'

Hannah had listened in silence, and would gladly have quitted the place, to think over the sailor's story quietly. But she never forgot the part she was playing, and roused herself to tell the sailor that when she returned to England she would make it her business to search for the widow, and to help her if she seemed in need. Then she got up and called for the bill, and followed by her companions, rowed back to the ship.

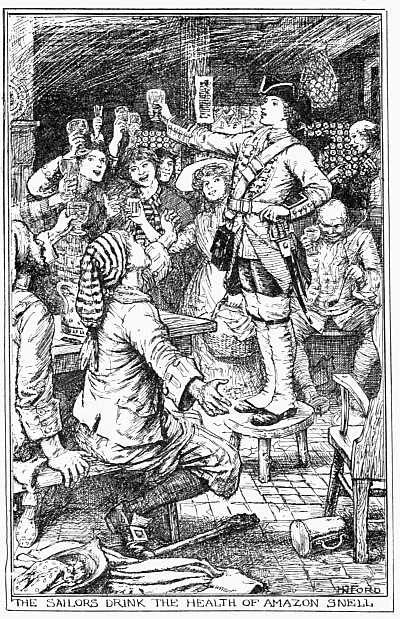

It was on June 1, 1750, that Hannah Snell landed in Portsmouth, and in the course of a few days made her way to Wapping. The rough life she had led, and even her uniform, had changed her so little that her sister recognised her at once, and flung her arms round the stranger's neck, much to the surprise of the neighbours. But Hannah, in spite of her sister's entreaties, refused to put on the dress of a woman till she had received £15 of pay due to her, and two suits; and when this was done, she invited those of the ship's crew who were then in London to drink with her at a public-house, and there revealed to them her secret.

[43]It was, however, to no purpose that she talked. These men, by whose side she had fought and drunk for so long, would believe nothing, and thought it was just 'one of Jemmy's stories.' At length she was forced to send for her sister and brother-in-law, who swore that her tale was true, and then the sailors broke out into a chorus of praise of her courage, her cleverness, and her kindness, all the time that they had known her. One, indeed, made her an offer on the spot; but Hannah had had enough of matrimony, and was not minded to tie herself to another husband.

It was not long before the wondrous story of Hannah Snell reached the ears of the Duke of Cumberland, son of George II., and Commander-in-Chief of the British Army. A petition was drawn up, setting forth her military career, and requesting the grant of a pension in consideration of her services. This petition an accident enabled her to deliver in person to the Duke as he was leaving his house in Pall Mall, and by the advice of his equerry, Colonel Napier, the pension of a shilling a day for life—£18 5s.—was bestowed on her.

It does not sound much to us, but money went a great deal further in those times.

But her fame as a female soldier was worth much more to Hannah than the scars she had won in His Majesty's service. The manager of the theatre at the New Wells, Goodman's Fields, saw clearly that the opportunity was too good to be lost, and that advertisement of 'the celebrated Mrs. Hannah Snell, who had gained twelve wounds fighting the French in India,' would earn a large fortune for him, and a small fortune for her.

So here we bid her good-bye, and listen to her for the last time—her petticoats discarded for ever—singing to the fashionable audience of Goodman's Fields the songs with which she had delighted for many months the crew of the 'Eltham.'

[44]

THE GOOD SIR JAMES