MARIE SALTUS

MARIE SALTUS

Title: Edgar Saltus: The Man

Author: Marie Saltus

Release date: September 11, 2011 [eBook #37398]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Adam Buchbinder, Josephine Paolucci, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

E-text prepared by Adam Buchbinder, Josephine Paolucci,

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

(http://www.pgdp.net)

MARIE SALTUS

MARIE SALTUS

EDGAR SALTUS

EDGAR SALTUS

... "even the weariest river

Winds somewhere safe to sea."

1925

PASCAL COVICI · Publisher

CHICAGO

Copyright 1925

PASCAL COVICI · Publisher

CHICAGO

To the Ego using the personality,

EDGAR SALTUS

Peace and Progress.

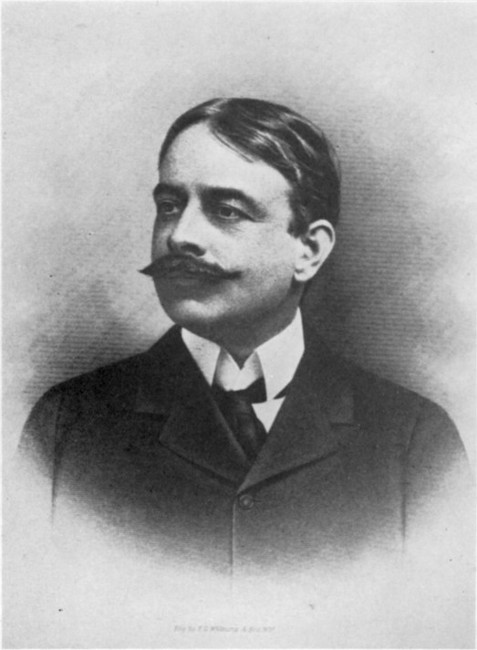

Marie Saltus, Edgar Saltus Frontispiece

Facing Page

Francis Henry Saltus 6

Father of Edgar Saltus.

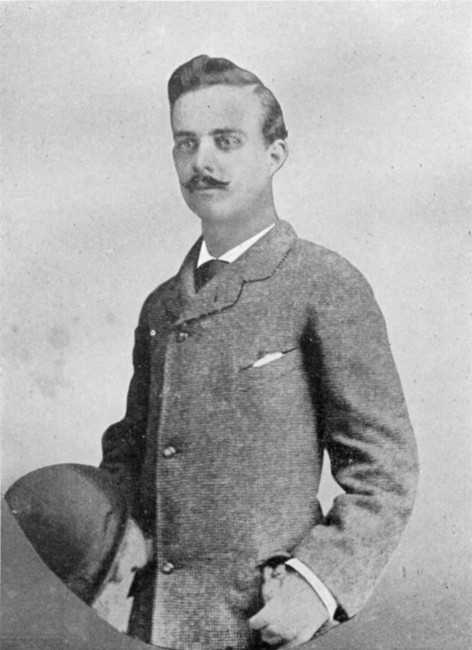

Edgar Saltus 10

At Two Years of Age, sitting on the Lap of His

Mother, Eliza Evertson Saltus.

Edgar Saltus 12

Sixteen Years of Age.

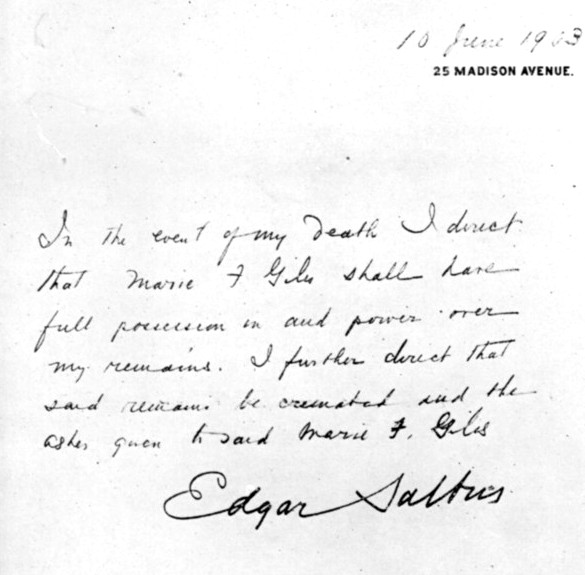

Fac-simile of Document given to Marie Saltus 116

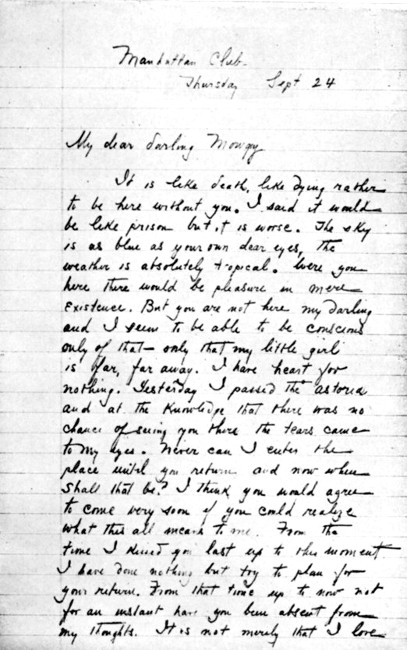

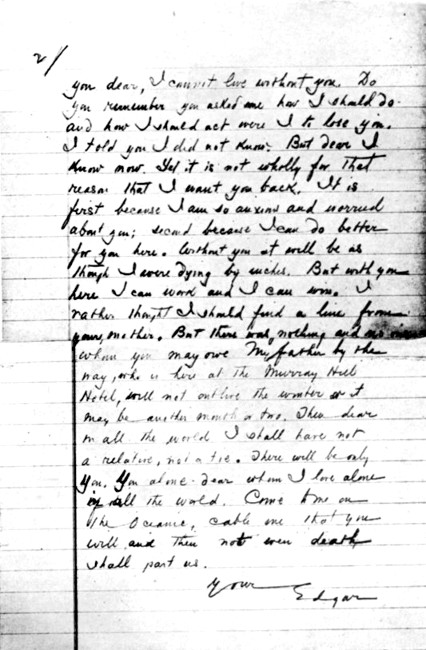

Fac-simile of Letter sent to Marie Saltus 128

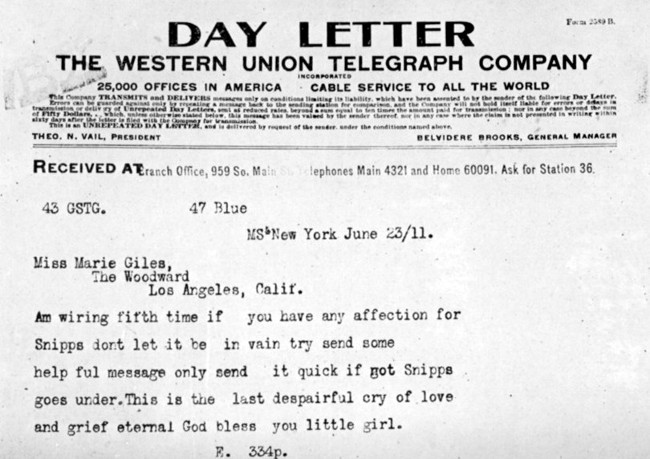

Fac-simile of Telegram sent to Marie Saltus 214

Mrs. J. Theus Munds 270

The Daughter of Edgar Saltus, and Her Little Son.

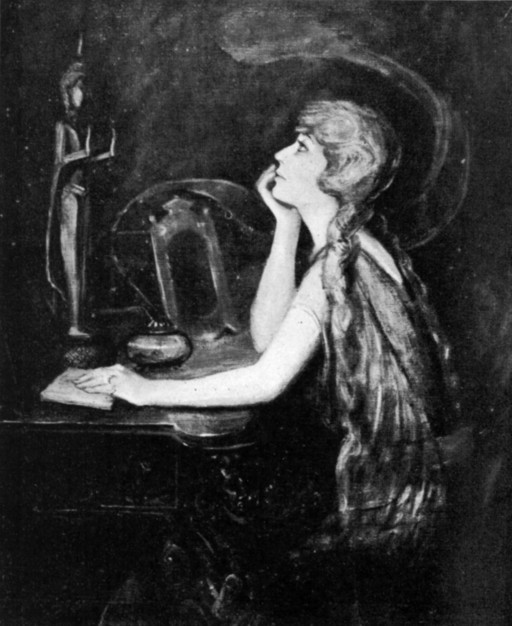

Marie Saltus 310

Sitting at the Table on which her Husband wrote

his Books, burning Incense before a Siamese Buddha,

and meditating on a Stanza from the Bhagavad-Gitâ.

Without the explanation of reincarnation, the riddle of Edgar Saltus would rival that of the Sphinx. Super-developed in some things, correspondingly deficient in others, he presented an exterior having the defects of his finest qualities, suffused with complexes and contradictions.

Amusements and interests looked upon as pleasurable by the many, bored him in the extreme. With likes and dislikes shared and understood by few, he lived in a world of his own. This world was inhabited by creatures of the imagination—delightful beings—too delightful to be real, who, having the merit of being extinguishable at will, never remained to bore him.

To write a proper biography one should have perspective. It is lacking here. That in itself makes the writing difficult. Many of those associated [Pg xii]with Mr. Saltus' life are incarnate, and not all of them are willing to be dragged into the limelight of publicity by the point of the pen.

Where it will not offend, names are given. Where the possibility of annoyance suggests itself, initials only are used. It circumscribes one more than a little.

A brief hundred years should elapse between the passing of an interesting personality and the putting into print of his life. It would follow here, but for the fact that so many mythical and malicious tales have been circulated about Edgar Saltus since his death that the necessity for giving the facts, good, bad, and indifferent, and putting an end to the weird, wild, and fantastic stories seems urgent.

From an article published in The Bookman one would believe the astonishing fact that Mr. Saltus made a practice of sitting "on a sort of baldachined throne dispersing cigarettes ten inches long and reading Chinese poetry." From the same source it was stated that he had a "salon, and was attended by some lady of his choice—not necessarily the same." As a final kick it was stated that he dyed his moustache.[Pg xiii]

Every newspaper in the country reprinted the article. What they did not reprint was a letter from me (in The Bookman also) denying the fabrications and giving the truth.

In a foreword of appreciation to a bibliography of Mr. Saltus' books, I was fortunately able to blue pencil the following, before it saw the darkness of print: "Edgar Saltus, neglected and alone, died in an obscure lodging-house in the East Side of New York." The author is a delightful man writing out of the fulness of his admiration. He put in only what he had been told.

Every day brings in new and wilder tales than the preceding one. They are so fantastic they would be amusing, were they not tragic.

If the public is sufficiently interested to pass along and embellish these grotesque stories, will they not be equally interested to know the truth?

When the writing of this biography was first attempted, an effort was made to give the life of Edgar Saltus without using the uninteresting "I" and "me." The effort failed. So[Pg xiv] much of his life had been silhouetted against my own for over twenty years, that any attempt to remove the background injured the picture, and it was reluctantly put back there.

In giving many of the high lights and incidents of Mr. Saltus' later life, the desire has been to speak only of those in which he was the dominating figure. Many amusing events in which he was somewhat subsidiary, have been in consequence omitted.

With the desire to keep my personality in the background as much as possible, it is brought forward only when needed to throw some incident or characteristic of Mr. Saltus into relief.

It is a painful process to tear the veil from one's life and write fully and freely—almost brutally at times, with the heart's blood. Less would be useless. One must tell all or nothing.

A few years ago we had skeletons. Every respectable family had one—sometimes two. They were locked in cupboards, or carefully put away in bureau drawers with lavender and old laces. When spoken of, it was in whispers[Pg xv] and with profound respect. All that has changed. With the new psychology nothing is hidden. Everything must be aired in the light. One may be behind anything but the times. That is fatal.

That Edgar Saltus was unable to hit it off with two charming and cultured wives does not reflect on either of them. On the contrary. No normal woman could live with him for a week without friction. By normal, I refer to the woman who as a rule does the things that are expected of her, leaves undone those she is not expected to do, and has plenty of health in her.

The very fact that a woman was in the main like others, irritated Mr. Saltus. It was enough for any one to say to him, "It is considered the proper thing to do this or that," to send him into a rage. No act was too erratic or too independent to please him, provided it revealed and developed the individuality of the doer.

As he looked upon sports of all kinds as outlets for primitive egos, amusements also, unless draped with interesting psychological problems,[Pg xvi] and gatherings of humans as an abomination and a stench to his nostrils, most women, in spite of the charm of his manner and the brilliance of his mind, would find little in common with him.

A boy at heart, adoring tricks, games and fairy stories, he did not want to be recalled to the things of earth. Impractical as he was, he could not endure practical people, accepting the blunders and forgetfulness of one even less so than himself with patience and grace. If five minutes before the dinner hour I would rush home and say:

"Too sorry dear, but I forgot to order anything for dinner. There is nothing in the house" (it happened more than once, but his reply was always the same)—

"Never mind, little puss. Thank God your mind is in the clouds—not in the kitchen. Let's go around the corner."

"Around the corner" meant to a tiny place called the Cozy frequented by Columbia students. Fortunately it was only a few yards from our home.[Pg xvii]

What he could not forgive was stupidity, and the desire to please Mrs. Smith and Mr. Jones and wonder what the neighbors would or would not think about things. This, however, he was never called upon to endure.

Only a person fundamentally the same and sharing his peculiar dislikes could have had a chance of success. A woman less temperamental and high-strung than himself would yield anything for peace. Yielding to Mr. Saltus was fatal. A mental ascendency on his part, no matter what the circumstances, and the beginning of the end was in sight.

There is a rather pathetic side to his biography. During the writing of it, Mr. Saltus seems to have been at my elbow all the time, a highly amused and almost disinterested critic. The writing of a biography had been a joke between us.

Asked by him once if I felt I had been in any way the gainer for my experiences of life with him, and what I would do in the future to keep my mind occupied if he passed on, I answered:[Pg xviii]

"Enormously the gainer. I could start a home."

"Would you make it into a training house for husbands—or turn it into a zoo?" he inquired.

"Neither. 'The Saltus Shelter for Scoundrels' would be the result. A sign in the window would inform the world that the superintendent, Marie Saltus, was a post-graduate on scoundrels." (It was a sobriquet Mr. Saltus was fond of applying to himself.) "It will be a wonderful home. Here is the first rule. 'Do all the things you ought not to do. Leave undone all the things you should do. All the comforts of home assured.'"

Mr. Saltus laughed, and added:

"Never pick up anything. Drop cigars and cigarettes on the floor. It will improve the carpets. Find fault with everything. Swear and make a row whenever you can."

To that I added that the waiting-list would be so long that the old scoundrels would be fighting among themselves to get in. The idea amused Mr. Saltus very much. Every day or[Pg xix] two he would come up with a new suggestion.

"See here, Mowgy, I have another rule for the old scoundrels. Having served such an apprenticeship with me," he said, "you will have the home overflowing in a week. Draw the line. Take no one under seventy-five and have tea with them only on Sundays in August."

The Saltus Shelter for Scoundrels became a pet theme. A diet was drawn up for the inmates by Mr. Saltus, and a course of reading outlined. The by-laws grew and were embellished.

This was during the last winter of his life, when failing health kept him indoors much of the time. To take him out of himself, it became necessary to supply food for the imagination.

"Suppose you became ill and you had to leave the old scoundrels to their fate? What then?" he inquired one day.

"That is provided for. If the Saltus Shelter is shattered, I will sit down and write your biography."

"That will fall flatter. No one will read it," he said.[Pg xx]

"Yes, they will. I will call it. 'The Annals of Ananias.' It will be your punishment for having written 'Madame Sapphira,' and people will fall over themselves to read it, for I will tell the worst."

He took notice of that.

"Wow! Wow! Will you tell about the time I got a piece of chocolate when I thought I was securing an opera glass, and how I threw it away, hitting a bald man on the head?"

"Of course. Didn't I say the worst?"

"Surely you won't mention the time I kicked the dog and smashed up the cut-glass?"

"Yes, I will, and how you played the hose on poor Jean, and all the other demoniacal things you have done."

At that he would say, "Wow—Wow," again, but the idea amused him, and scarcely a day passed without inquiries about the biography.

"You won't tell the worst really, will you, Mowgy? You will not mention the time I got squiffy, or the time I pretended I was a crazy man and miawed in the trolley car?"[Pg xxi]

"When I say everything, I mean everything."

"Then you must tell about the time in Paris when you tried to murder me, and when, mistaking a strange man for me, you wrote him such a villainous letter."

"Concerning these you are safe. There is too much about myself in those incidents to interest people. Like Cæsar, the good will be interred with your bones."

"No one will believe there could have been such a demon. They will say the remarkable thing about it is that you have survived."

We joked about it a great deal during the winter, Mr. Saltus suggesting incidents to be included or omitted.

When after his death one publisher after another urged me to give them a biography, I did not know whether to laugh or to weep.

Could I? The words we had said repeated themselves. His wistful spirit seemed to stand at my side—laughing. He could take a joke on himself so well.

During the writing of it he has seemed to[Pg xxii] be beside me—amused, but caring less, if anything, what any one might say or think about it. It was all trivial.

When engaged in writing a book it was Mr. Saltus' custom to sharpen dozens of pencils and have them at hand. Writing rapidly, he would discard one after another as they became dull, till the last was reached. These he sharpened again, and started in to repeat the process. After his death I collected a box full and kept them. It is with the same pencils that these words are being written. They have come straight from his hand to mine. His emanations seem to have permeated them.

It has not been an easy task, but it is truthful. The worst, as well as the best, has been given. His friends will find that the eager and aspiring spirit they admired was even bigger than they knew.

To the verdict of any human he was—and still must be—indifferent. It did not touch him in the flesh. It cannot reach him in the spirit. To him at the last one thing alone mattered, through the sum total of his life's experiences—the ability to know himself, and knowing[Pg xxiii] that self to co-operate with his evolution. To turn from the illusory to the illimitable, seeking only the way; that was what mattered.

Realizing at the last that all the wisdom of the world could be epitomized in a single sentence, he found strength in that. "He attaineth peace into whom all desires flow as rivers into an ocean, which, being full, remaineth unaffected by any."

From the very beginning Edgar Saltus was none of the things that he appeared to be and a hundred that no one ever suspected. Having a nature with a curious complex of the super-feminine, Edgar Saltus took unto himself a prerogative usually assigned to it, and, snipping off a few years, gave the date of his birth to "Who's Who," as 1868.

Late in life, when confronted with the family Bible in which the date had been correctly set down, and with a photograph of himself as a baby on which his mother had proudly recorded the same, he admitted, reluctantly it must be confessed, that he had juggled things a bit. In those days births were not recorded as they now are.

His irritation at the detection being construed[Pg 4] as shame over his act, he laughed. The annoyance was at himself for omitting, when he had the chance, to knock off a few more objectionable years. The glorious gift of seeming as young as he looked had been offered by fate, and lost.

As a matter of fact Edgar Saltus was born in New York City, some time during the night of October 8, 1855.

When, later in life, he became interested in occultism, and the possibility of having an astrological chart was suggested, there was no one living who could tell him the exact hour. Trivial as it may seem, he would have given much to ascertain it. The Libra qualities assigned to those born in October were all his. This fact made him keen to know how they would be modified or increased by that of the sign rising at the hour of his birth.

It delighted him to brush aside many annoying happenings with the remark that all Libra people were volatile, evanescent, and often irritable; were born so, and could not escape their[Pg 5] limitations. Upon these occasions he would end up with the statement that however objectionable the sign, it was less so than that of Scorpio rising with the Sun in Taurus (which was mine). That, he declared, only a philosopher could understand and hit it off with. He had a splendid ally in the stars.

Edgar Saltus had the good fortune, or the bad luck, as one looks at it, to be born the son of a brilliant father. Francis Henry Saltus not only brought into being the first rifled steel cannon ever made, but perfected a number of other inventions as well. For this he was decorated by almost all the crowned heads of Europe. Queen Victoria knighted him and presented his wife with a marvelous Indian shawl. He was given the Legion of Honour of France, the Order of Isabella the Catholic, of Spain—the Order of Gustavus Vasa of Sweden, and the Order of Christ of Portugal. For having chartered a ship, loading it with provisions and sending it to the starving people of the Canary Islands during a famine, he was[Pg 6] given the inheritable title of Marquise de Casa Besa by the King of Portugal as well. The title, however, he never used.

From Solomon Saltus back to the time of the Emperor Tiberius, the men of the Saltus family appear to have left a mark either of gore or glory upon their generation. Francis Henry Saltus did not purpose to do less. An omnivorous reader, a student and a philosopher, with some queer twists to his curious mentality, he passed on the lot—twists included—not only to his son by a former wife, Francis Saltus Saltus, named after himself, but to the little Edgar as well.

Concerning Francis Saltus Saltus, volumes might be written. A genius, and ambidextrous, he could write sonnets with one hand and compose operas with the other. Without instruction he could improvise on any musical instrument and learn any language with equal facility.

He did all this as a bird sings, joyously, and with so little effort that one was appalled at his genius. A clearer case of subconscious memory never existed. He learned nothing, but he remembered everything. To know where he had acquired it and how would be interesting.

FRANCIS HENRY SALTUS

FRANCIS HENRY SALTUSHis ability was supernormal, yet anything once written (he never made a revised copy) was tossed aside—fait accompli. A new thought or a fleeting melody called him elsewhere.

What he lacked was the concentration, the patience, the sustained interest in his creation, to go over his work, rearrange, polish and put it into shape to live. Details were deadly. What he had written—he had written. With an indifference proportionate to his genius, he yawned—and lighted a cigarette.

That lack was tragic. It meant a niche in the gallery of "might have beens" instead of the high place in the Hall of Fame, where he really belonged, and where, had he but condescended to care, he could have flamed as a volcano in active eruption.

Frank was in his sixth year when little Edgar made his début. These four, Francis Senior and[Pg 8] Junior, with Edgar and his mother, constituted the family.

A descendant of a line of illustrious Dutch admirals, Eliza Evertson, after two rather unhappy love affairs, married Francis Saltus. She had passed her first youth. Brave she must have been, to risk her happiness with a brilliantly eccentric husband, and take upon herself the upbringing of his even more erratic son.

Until Edgar was seven the experiment was fairly successful. Eliza Saltus, witty, quick at repartee, and interestingly sarcastic, took her place in the "family party" which constituted the social set in those days. New York was a small place. Everybody who was anybody, knew everybody else.

Tall, fair, and distinguished looking, wearing his honors and decorations as lightly as a boutonniere, Francis Saltus was a splendid foil for the brunette beauty and vivacious spirits of his wife. During these early years together they traveled a great deal, and the problem of peace did not present itself. Eliza Evertson was a person[Pg 9] not easily submerged. In a large home in West Seventeenth Street, none too cheerful at best, filled with massive Italian furniture of carved olive wood, these four struggled for a time to keep together and form a family.

Of those early years Mr. Saltus always told with sadness—how his mother fought against the influence of Frank, who, even at pre-adolescence, evinced many of the peculiarities and angles which developed rapidly with the years.

Resentful over the father's preference for his first-born, the little Edgar became the idol of his mother's heart, giving to her his deepest affection in return. Francis Saltus' pride in the elder son outweighing every other sentiment, he could see no fault in him, in spite of his habit of getting up when he pleased, eating at odd times, composing on the piano at two a. m., or bringing all kinds of queer people to the house at any hour of the day or night.

Whether or not the stepmother exercised the tact which would have oiled the machinery of things, one cannot know. Good mothers[Pg 10] are seldom philosophers. The fact that Frank was over-indulged and given plenty of money by an adoring father, who scarcely noticed her own small son, must have hurt her independence and pride. That she could see only his faults, and nothing of his genius, cemented the bond between the father and Frank as nothing else could have done. Blond, handsome, debonair, Frank Saltus charmed as he breathed. Only his stepmother was impervious to his fascinations.

The little Edgar combined the Greek features of his father and half-brother with the dark eyes and olive coloring of his mother. High-strung, timid, and so nervous that a slight hesitancy marred his speech at times, the child lived in fear of offending his father by a refusal to repeat his mother's warnings against Frank, and the fear of enraging his mother by his unwillingness to repeat his father's comments.

EDGAR SALTUS

EDGAR SALTUSThe battle-ground of a ceaseless conflict between his parents, the boy developed a quality negative in one sense, dangerous in another. He was afraid to repeat anything of a disagreeable nature or admit an unpleasant truth. Forced to the wall he avoided truth,—made a jest of it if he could, or, as a last resource, denied it pointblank. It is the fear of danger and discord and the hanging back from it that injures. On the firing-line death may be in waiting, but fear has fled.

To get the right slant on Edgar Saltus' life as a whole, this early training—or lack of it—must be taken into consideration. This almost physical disability to tell the truth, if that truth were disagreeable, was equaled by his inability to bear pain. At any excess of it he fainted. It followed him throughout life. Rarely did he get into a dentist's chair without fainting.

With so many charming and endearing qualities, an understanding needing no words, a tenderness greater by far than that possessed by most women, one can but speculate as to what a rare and radiant being he would have been minus the handicap concerning truth, which, with all its ramifications, penetrated and[Pg 12] disintegrated much of his life and the lives closest to him.

Unable to make a go of it as a family, divorce in those days being looked upon as disgraceful, Francis Saltus took his first-born abroad, while Edgar was sent to St. Paul's School at Concord, New Hampshire. Never again did they attempt to live as a family. During vacations young Edgar went to his mother. An occasional call on his father was all that was required of him.

According to his own account he was always at the foot of his class and not popular. Uninterested in sports, abhorring all forms of "get together" societies, living very much in a world of his own imagining, he was as inconspicuous as he was unhappy. Slightly undersized, slim, straight, and well-proportioned, with his clear-cut features, dark oriental eyes, and olive skin, he looked and felt out of place in a western world,—as perhaps he was.

EDGAR SALTUS

EDGAR SALTUSGirls took to him on sight, wrote to him, sent him locks of their hair, and suggested meeting him. His first flirtation was with a girl from New Haven. That her name was Nellie was all he remembered of the episode.

During the summer vacations he had a succession of flirtations. A dip into them would be like turning a page of "Who Was Who" a generation ago. One irate father, thinking he had called too often upon his young daughter, put it to him straight.

"Young man, you have made yourself very much at home in this house. What are your intentions?"

"To leave," he replied quickly, as he made for the door.

Another occasion was more complicated. This time it was the girl herself, a girl he had vowed to work and wait for forever if necessary. Suggesting that they omit the waiting and do the working upon their respective parents, the girl persuaded him to elope, very much against his will. It was the last thing he wanted. To love and run was far more to his fancy. Letting drop the fact of what they contemplated[Pg 14] where it would percolate quickly, he drove off with the bride-to-be in a dog-cart.

During this drive his wits got to working. At one parsonage after another they stopped, young Edgar getting out and inquiring at the door, only to drive on again. After an hour or so the girl's father overtook them. The elopement was off; the would-be bride in tears. Instead of inquiring for a clergyman to marry them, he had very politely inquired the way to the next village.

A danger escaped is always a ready theme for conversation, and it amused him more than a little to tell of this episode with the comment:

"No woman could drag me to the altar, I could slide like water through a crack and vanish."

So he could. A more ingenious man at evading anything he disliked never existed. While agreeing with every appearance of delight, he was concocting a clever escape. He always managed to slip through, as he said.

Of his father and brother he saw but little[Pg 15] during these years. The latter had to his credit a volume of verse, "Honey and Gall," and half a dozen operas, one of which he had conducted himself.

On the table near my hand is a copy of "Honey and Gall," an original, bound in green. On the fly-leaf in Frank's characteristic hand is written:

EDGAR E. SALTUS

With the love and good wishes of his most affectionate brother,

F. S. SALTUS.

No resentment there. A spirit of love, tolerance, and interest is exhaled. In the book are many marginal notes in the same handwriting. Changes, interpolations, and corrections emphasise the beauty of the lines. The pity of it is that they were put there too late, but the soul of the author stares one in the face. Between the pages pressed flowers rest, souvenirs of shadow or sunshine. During the years the paper has not only become discolored but has reproduced the outline of the blossoms. The[Pg 16] book is like a living thing, so close does it bring the author. Emanations of his personality rise from the pages like perfume, compelling the sympathy and understanding he needed so uniquely.

One poem especially—"Pantheism"—tears the veil from his Greek features, revealing an Oriental in masquerade. Neither pagan nor Christian in the accepted sense, the musk-scented mysticism of eastern philosophy rises from it like incense. Out of place in the conventional environment of New York,—subconscious memory rising to the surface of his waking consciousness, he writes of other lives and loves, and anterior experiences,—putting his deepest and most profound beliefs into words. No other poem in the book strikes the same chord, or has as many marginal notes by the author.

Too handsome, too much sought after by women, too well supplied with money to have an incentive to work, he sank into something of a psychic stupor. He knew nothing of the[Pg 17] feminine as revealed by mother, sister or wife. To him, alone and misunderstood, Silence offered her arm. Silence is a dynamic force but it offers peace. One can but hope that he was given his full share.

Brilliant, handsome, with a manner irresistible to women, Frank Saltus was reaching the high noon of his life. So facile was his pen, so limitless the scope of his erratic genius, that young Edgar sank into the shadow of him. Tragically pathetic is the fact, that, despite the superabundance of his gifts, he failed to bring any one of them to the perfection that could have made him immortal. There may have been philosophy even in this.

Among the other poems in the volume is one to his most intimate friend,—Edgar Fawcett. This friendship not only lasted his lifetime, but was stretched to include the younger Edgar, whose close association with the poet continued until the latter's death.

In spite of their real admiration and regard for Fawcett, both Edgar and Frank Saltus[Pg 18] enjoyed teasing and tormenting him enormously. His vulnerable places were so much exposed. Though timid with women, nevertheless he fancied they were in love with him. With inimitable skill, Frank Saltus composed letters purporting to come from passionate young heiresses who were in love with him. One especially wrote frequently and at length. Fawcett not only answered them, but, rushing to his rooms, read them aloud to Frank. More letters followed.

"What am I to do," he asked, "when women persecute me like this? Even you have not received such letters as mine."

The brothers agreed with him. While pretending to be annoyed by them Fawcett was really living in rapture. Nothing like it had brushed against his life before. As fast as the letters were sent out, did Fawcett come in to read them to their creator. It began to pall. One could not keep on writing them indefinitely. Something had to be done. The heiress who could not live without him threw out[Pg 19] vague hints of suicide. Hectic and harrowed, Fawcett came to Frank's rooms and burst into tears. After that the letters ceased. Fawcett could not be comforted. Some helpless and beautiful being had died for love of him. This incident became the episode of his life, and he passed over without knowing the truth.

According to Mr. Saltus, there was something charming and childlike about Edgar Fawcett. A rejected manuscript sent him into hysterics. He kept an account book, alphabetically arranged. If you offended him, a black mark went against your name. If you pleased him, a mark of merit was substituted.

From an old note-book of Mr. Saltus is copied the following: "Edgar Fawcett has to pay higher wages to his valet than anyone else, because he reads his poems to him." In another place is written: "Idleness is necessary to the artist. It is the quality in which he shines the best. Be idle, Fawcett. Let others toil. Be idle and give us a rest."[Pg 20]

None the less the brothers had an affectionate admiration for him. Edgar Saltus dedicated "Love and Lore"

His school days in the States over, Edgar Saltus went abroad with his mother for an indefinite time. Europe became their headquarters during what must have been the most constructively interesting part of his early life. Heidelberg, Munich, the Sorbonne, and an elderly professor supplementing certain studies did their best for him. At an age when the world seemed his for the taking, with brilliant mind, unusual physical attractiveness, the ability to charm without effort, and sufficient means, his path was if anything too rosy.

The pampered only child of an adoring mother, he had only to express a wish to have it gratified. He became selfish and self-centered as the result. His motto was "Carpe diem," and he carefully contrived to live down to it.

During a summer in Switzerland without his mother Mr. Saltus met a charming young girl[Pg 22] of semi-royal birth, whom we will call Marie C——, and eloped with her. Her furious family followed, overtaking them in Venice. As she was unable, because of her exalted station, to be married by a priest without credentials and permission, the ceremony had been omitted for the moment. That complicated matters. Marie was whisked off to a convent, where, the year following, she died. As usual the woman paid. Meanwhile, a young and charming Venetian countess did her best to console the explorer in hearts.

On the heels of this episode came his mother. Funds were stopped, and to the chagrin of the countess who had braved disgrace, her charmer was taken back to Heidelberg.

With an insight and interest almost paternal, the old professor who had tutored him at times gave Mr. Saltus a lesson he never forgot. Realizing as he must have that the youth had a quality of fascination seldom encountered, a quality likely to lead to his early ruin if not circumscribed, he assigned himself the job. Taking[Pg 23] him to an exhibit where wax figures representing parts of the human body in different stages of disease were set up for a clinic, he let it do its work.

Illness, ugliness, unsightliness of any kind, had a horror for Mr. Saltus. It was an intrinsic part of his inner essence. That exhibit nearly did for him. It made him ill for a week,—the most profitable illness he ever had in his life. Never in his wildest and least responsible moments did he have an affair with any woman other than of his own class.

A student of the classics, with Flaubert sitting on the lotus leaf of perfection before his eyes, it soon became the desire of his heart to meet some of the great ones of letters. Even then the young Edgar was trying his hand at it.

Through the friendship of Stuart Merrill, a young American poet living in Paris, he had the supreme bliss of being presented to Victor Hugo. The anticipation of it alone made him tremble. It was to him like meeting the Dalai Lama in person. Reverently he approached the[Pg 24] great one repeating, as he did so, the Byzantine formula, "May I speak and live?"

The magnificent one condescended to permit it. From a great chair which resembled a shrine and in which he looked like an old idol, he deigned to speak to his admirer. Mr. Saltus left his presence with winged feet.

The author of "Poèmes Antiques," Leconte de Lisle, was another to whom the youthful aspirant was on his knees. Through Stuart Merrill again he was admitted to Olympus.

"You are a church. You have your worshipers," he told the poet. Leconte de Lisle listened, or pretended to listen, with indifference. That attitude of his appealed as much to Mr. Saltus as his poems. It was the way genius should act, he reflected.

Another meteor crossing his orbit was Verlaine. It was at the Café François Premier that they met. Shabby, dirty, and a little drunk, he talked delightfully as only poets and madmen can. He talked of his "prisons" and of his "charity hospitals," quite unaffectedly and as[Pg 25] a landed proprietor speaks of his estates. One of these Edgar Saltus visited. It was an enclosure at the back of a shop in a blind alley, where he had a cot that stood not on the floor, for there was no floor, but on the earth.

Of Oscar Wilde and Owen Meredith, he had at that time only a peep in passing. His particular chums were the Duke of Newcastle and Lord Francis Hope. Among the interesting personalities with whom he became friends was the Baron Harden Hickey. In what way he became a Baron was never elucidated to Mr. Saltus' satisfaction. Poet, scholar, and crack duelist, his sword was as mighty as his pen. At my hand is a book of his called "Euthanasia," and inscribed in his writing are the words:

Harden Hickey had ambitions. One of them was to found a monarchy at Trinidad and rule there. He was nothing if not original. The[Pg 26] post of Poet Laureate he offered to Edgar Saltus. Owing to the intervention of the Powers, the project failed. Harden Hickey killed himself. Such friends in any event were not commonplace.

Deciding at last that he must have some kind of an occupation, his mother having on his account drawn liberally from her principal, Mr. Saltus decided to return to the United States. Once there he entered Columbia Law School. Terse, clear, and versatile with his pen, the law seemed more or less to beckon. Plead he could not; owing to his acute nervousness and his slight hesitancy of speech that was out of the question. The uninteresting but necessary technical side of the law could alone be his. In some climates and altitudes Mr. Saltus' speech became almost a stammer. In others it vanished. Never was it unpleasant, and many thought it rather fascinating. People affected him in this way. Most of them got on his nerves, and the peculiar hesitancy followed, while with those to whom he was accustomed,[Pg 27] he could talk for hours without a trace of it. Even as a youth his disinclination to meet people, his horror of crowds, and his desire to be alone a great deal were becoming marked characteristics. So also was the quality he had developed as a child, the increasing inability to face a disagreeable issue.

During his life in Germany, Schopenhauer had been his daily food. From his angle religions were superstitions for the ignorant and credulous. They offered nothing. With Schopenhauer came Spinoza. Between them the Columbia student became saturated like a sponge.

At intervals Mr. Saltus had tried his hand at verse as well as prose. A sonnet written in Venice and published afterward under the title of "History" was among his first. Timidly, almost apologetically, he took it to his brother Frank.

"Splendid! Better than anything I ever did," was the unexpected praise. "I write more easily, but it is too much fag for me to polish[Pg 28] my work. You are slower, but you scintillate. Go in for letters. It is your place in the scheme of things."

Thus encouraged, and by the brother who was the flame of the family, Edgar Saltus took up his pencil in earnest. Fundamentally, both Edgar and Frank Saltus were alike. They seemed to be oriental souls functioning for a life in occidental bodies, and the clothes pinched. Neither could endure routine, nor could they tolerate the prescribed and circumscribed existence of the western world. It was difficult to internalize in an environment both objective and external. They were subtle, indolent, exotic, living in worlds of their own, as far removed from those with whom they brushed elbows as is the fourth dimension.

Frank let himself go the way of least resistance, without effort or desire to fit in with his environment. Having traveled everywhere, and exhausted to its limit every emotion and experience, bored to tears with the world outside of his imagination and finally even with[Pg 29] that within, he stimulated what remained with alcohol and drugs. As the mood took him he composed, tossing off sonnets and serenades like champagne, carelessly and without effort, a Titan with the indifference of a pigmy. What he might have been, had he forced his furtive and fertile fancy to grapple with the tedium of sandpaper and polish, only an extension of consciousness could reveal.

Writing of him in those days James Huneker said:

"He had the look of a Greek god gone to ruin. He was fond of absinthe and I never saw him without a cigarette in his mouth. He carved sonnets out of solid wood and compiled epigrams for Town Topics as a pastime. He composed feuilletons that would have made the fortune of a boulevardier. He was a ruin, but he was a gentleman. Edgar Saltus was handsome in a different way, dark, petit maitre."

Of Frank Saltus' multiple love affairs one alone cut deep enough to leave an imprint.[Pg 30] Under the title "To Marie B—," he wrote one of his best poems.

Curiously enough, the name Marie had been that of Edgar's first and unfortunate love. So convinced was he that no one with that name could survive close association with a Saltus, that from the first hour of our acquaintance he refused to call me by it, using a contraction I had lisped as an infant in trying to pronounce Marie, Mowgy. It was the last word he spoke on earth.

The son of a brilliant father and brother of a genius, Edgar Saltus was made conscious of his supposed inferiority by the world at large. To his mother, in spite of her indulgent idolatry of him, must be given the credit that he, too, did not sink into an apathy and dream his life away. The worst side of his brother's character was held always before him, as well as his inability to earn anything with all his talents, and the fact that he, Edgar, was an Evertson as well as a Saltus was used effectively. As far as she could she fought the soft, sensual[Pg 31] streak in his nature, the oriental under its mask. Too late to grapple with his fixed habit of avoiding the ugly, unpleasant, and the irksome, she hammered in the lesson of dissipated talents and a wasted life. So well was this done that Edgar Saltus, to use his own words, "By the grace of God and absent-minded professors," managed to take his degree as a Doctor of Law.

With that in one pocket and a sonnet in the other, he cut loose to have a little fling before starting in for a career at the bar. That career never materialized.

With a mother always a part of the upper ten, he was soon submerged by balls, receptions, and festivities. His ability to fraternize being limited and superficial and the necessity for a great deal of solitude fundamental, it was not long before the desire to express himself with his pen reasserted itself, and a number of sonnets was the result. Few knew anything of the hours he put in pruning, polishing, and sandpapering them. Albert Edwin Shroeder,[Pg 32] a friend reaching back to the Heidelberg days, knew the most, but even with him Edgar Saltus was reticent about his work. It may be mentioned in passing that Shroeder was an intimate friend of Frank Saltus, as well. His admiration for the brothers expressed itself in many ways. Among Mr. Saltus' effects are letters from him and some books. On the fly-leaf of one is written, "To the Master from his servant A. Shroeder." On another, "To the unique, from one who admires him uniquely." This friendship lasted until Mr. Shroeder's death.

Other intimate friends were Clarence and Walter Andrews. Of his escapades with them Mr. Saltus was never weary of telling, the tendrils of their friendship being long and strong. Of those who knew him in these halcyon days Walter Andrews alone survives. Sitting at my side, as he very graciously offered to do, he drove with Mr. Saltus' only child, his daughter, Mrs. J. Theus Munds, and myself, to Sleepy[Pg 33] Hollow Cemetery and saw the ashes of his oldest friend returned to the earth.

Not fitted by nature for the cut and dried, the literal and the precise, longing more and more to express himself in writing, he let the law linger. Having already several stories to his credit, the possibility of making letters his profession appealed strongly to Mr. Saltus. Money in itself meant nothing to him. It went through his hands as through a sieve. To be free from rules and routine, free to express himself, that alone mattered, and that, despite the inroads made into their capital, he could do.

Law books were consigned to the trash baskets. Paper and pencils took their place, and it was not long before the results took on a golden hue.

At that epoch, his star rising to the ascendent and Fame flitting before him as a will-o'-the-wisp urging him on, he met one of New York's most beautiful young matrons—Mme. C——. An American herself of old Knickerbocker[Pg 34] stock, married to a nobleman, she represented youth, beauty, charm, and position, added to which she had a brilliant mind.

A serious love affair resulted. Vainly did Mrs. Saltus urge her son to marry and settle down. Vainly did the family of Mme. C——warn her of possible perils ahead. So handsome in those days that the papers referred to him as the "Pocket Apollo," so popular that girls fought for his favor, Mr. Saltus had a triumphal sail through a social sea as heady as champagne.

From his own account and a diary of Mme. C——'s found after his death, the affair must have cut deep. Quoting from it one reads:

"Edgar called to-day. There is no one like him in the world. He is the unique. I adore him to madness."

Again one reads:

"Edgar is the center of my being. Never can I cease to love him. That is certain. But should he ever cease to love me—? It is unthinkable. I cannot contemplate it—and live."[Pg 35]

Once again:

"They tell me that this cannot go on. I have children. Oh, my God! Can I tear him out of my heart—and live?"

There is no doubt whatever but that the devotion was very sincere on both sides. It ended, nevertheless, owing no doubt to the fine qualities of Mme. C——, who, putting the happiness of others before her own, went abroad and lost herself there for a time.

Proud, arrogant, accustomed to having his own way at any cost, selfish and self-centered as the result of his indulgent childhood, during which he had never exercised the least self-control, it was a new experience to Edgar Saltus. Taking what he wanted when he wanted it and because he wanted it, without the least thought of others, save perhaps his mother, he had built up on his weaknesses, in ignorance of, and not recognizing, his strength. The affair of Mme. C—— hurt.

Little wonder it was that when a pretty and petite blonde girl swam into the maelstrom of[Pg 36] his environment, he made a grab for her. Pert and piquant, her face upturned in the waltz, he whispered the lines beginning: "Helen, thy beauty is to me" ... following it up as only he could. In addition to her own attractiveness, Helen Read had a father who was a partner of J. Pierpont Morgan. She was no small catch, and there were many out with fishing tackle and bait.

On the surface it looked like an ideal match. All the gifts of the gods were divided between them. Besides, every one approved of it. That in itself should have warned them of disaster.

The year 1883 turned a new page, Edgar Saltus breaking into matrimony and into print almost simultaneously. Houghton, Mifflin and Company having agreed to bring out his translation of Balzac, the horizon opened like a fan. The microbe of ink having entered into his blood, he conceived the idea of putting Schopenhauer and Spinoza before the public in condensed and epigrammatic form. To their philosophy he determined to add his own. "The[Pg 37] Philosophy of Disenchantment" and "The Anatomy of Negation" began brewing in the caldron of his mind.

A note-book in which is condensed material for writing these books is perhaps the most interesting bit of intimate work Mr. Saltus left behind him, revealing as it does an Edgar Saltus unknown and unsuspected by the world. In it is no man giving out savories and soufflés with both hands, taking the world as a jest, a game, and an amusement. It reveals the serious and sober student, hiding behind a mask of smiles, subtleties, and cynicism; the soul of a seeker, a soul very like that of his brother Frank. So out of tune was it with its environment, so little understood, and so little expecting to be, that wrapping itself in a mantle of impenetrability and adjusting its mask, no one knew what existed behind it.

The note-book itself is most characteristic of Mr. Saltus. In it are sonnets many of which have been published,—notes for his work,—drafts of letters he expected to write,—quotations[Pg 38] from various sources and epigrams of his own and others jumbled together. Some of these are written with his almost copper-plate precision, and the rest jotted down late at night, perhaps after he had dined and wined well. These are mere scratches, which only one familiar with his hand could decipher.

Youth flames from a leaf on which he has written:

The pomposity of this amused him very much during his later years. The following quotations reveal what has been referred to as his oriental soul floundering in the dark, seeking expression in a language new to his tongue. Taken at random a few of the quotations are as follows:

"There are verses in the Vedas which when repeated are said to charm the birds and beasts."

"All that we are is the result of what we have thought."[Pg 39]

"Having pervaded the Universe with a fragment of Myself,—I remain."

"Near to renunciation,—very near,—dwelleth eternal peace."

As material for a book on agnosticism it is amusing,—his agnosticism being in reality only his inability to accept creed-bound faiths. The quotations are proof, however, that germinal somewhere was an aspiration for the verities of things. Unable to find them, the ego drew in upon itself, closing the door. Behind that door however it was watching and waiting with a wistful yearning. Years later, after reading one stanza from the Book of Dzyan, it flung open the door and emerged, to bathe in the sunlight it had been seeking so long.

At the bottom of the page of quotations from the Gitâ is a footnote: "True perhaps but utterly unintelligible to the rabble."

It was not long after his marriage that turning a corner he saw Fame flitting ahead of him, smiling over her shoulder. The newspapers began to quote his witticisms, as for example:[Pg 40]

Hostess—"Mr. Saltus, what character in fiction do you admire most?"

Saltus—"God."

His books, considered outrageous to a degree, began to sell like hot cakes. To quote again from a newspaper clipping of that day:

Depraved Customer—"Do you sell the books of Edgar Saltus?"

Virtuous Bookseller—"Sir, I keep Guy de Maupassant's, The Heptameron, and Zola's, but Saltus—never."

Edgar Saltus was made.

To go back a little. It was shortly after his marriage to Helen Read that the conventional trip to Europe followed. Added to the selfishness which the circumstances of his life had fostered abundantly, Edgar Saltus had a number of odd and well developed twists. Illness in any form was abhorrent to him, contact with it unthinkable, and even to hear about it objectionable. When his young wife suffered from neuralgia—a thing which not infrequently happened—he put on his hat and walked out. The idea of schooling himself to bear anything he disliked was as foreign as Choctaw.

High-tempered, moody, impatient to a degree seldom encountered, and with the preconceived idea that he was entirely right in everything, he set sail on the matrimonial sea. Two episodes will make clear why the shoals[Pg 42] were encountered so soon. Realizing then how oblique had been his angle, the story of his life must be thrown forward, as they say in filmdom, to 1912 and then back again to the earlier episode.

We were traveling in a wagon-lit from Germany to Paris. After he had tucked me in for the night I noticed that Mr. Saltus had removed only his coat and his shoes, and was going to bed practically clothed. That alone made me take notice. We had not been married long at the time, but I was acquainted with his habits. Better than any human I ever knew, he loved to be en negligée. He could slide out of his clothes and into a dressing-gown like an eel.

This extraordinary behavior was further emphasized when, in spite of his hatred of speaking to people, servants especially, I heard him whispering at the door to the guard. At such radical conduct, I asked what it was all about. His reluctance to answer made me even more insistent. With his cleverness at evasions[Pg 43] and his agility at inventing explanations off the bat, he put me aside with the suggestion that he had asked for more covering. Knowing his ways and his wiles backward and forward, I laughed. Explain he must. Then he said that we would be crossing the frontier in the early hours of the morning, and, as it would be necessary for him to get out and open our luggage for inspection, he had remained dressed. Realizing that it was difficult for me to sleep under any conditions, and fearful lest I be annoyed by it, he had told the man not to knock, but to come in quietly and touch him instead. It was consideration for me, nothing else.

The explanation apparently covered everything. Drawing up his blankets he said, "Good-night."

Instead, however, of the usual deep breathing to follow, presently I heard him laughing, laughing heartily, and trying to suppress it. When questioned he could only say:

"If Helen could see me now! Good Lord!"[Pg 44]

When he had repeated it three or four times, I sat up and told him he could tell the worst. This is what he said:

"When Helen and I were traveling this same route and we realized that the frontier meant getting up in the night and the horrors of the customs, I suggested that she be a sport, and toss up a coin to see which of us should take on the job."

"Horrors!" I interjected. "How could you even think of such a thing?"

"How could I? There you have it. How could I? I did, all the same. We were both young and healthy. I didn't see why my sex should be penalized. We threw, and it fell to her."

Another "Horrors" came from the opposite bed. "But of course you did not let her when it came to the scratch? You remembered that you were supposed to take care of her?"

"What I remember only too well is that I did let her do it. She spoke French beautifully and she did it quite uncomplainingly. What a[Pg 45] brute I was! I cannot believe that I was ever that sort of being."

"Suppose we toss up now?" I suggested.

Mr. Saltus laughed. "You! Why, little Puss, I would sit up all night with joy, rather than have you wakened. You go out and attend to the customs!" He laughed again. "If Helen could see me now! What a hell of a life I must have led her!"

The other episode occurred during the last years of his life, when we were living in the apartments where Mr. Saltus died. His bed-room and study were at the end of a long hall, removed from the noise of the front door, the elevator, and the telephone, where he could work in quiet.

Uninterrupted quiet was a vital essential to him. Distractions of any kind, no matter how well meant or accidental, sent him into hysterics and ended his work for the day, and he begged me never to speak to him unless the house was on fire. Sometimes through carelessness I did interrupt him as he went from[Pg 46] his study to his bed-room, asking him a question or telling him of something which had occurred, but when working in his study he was left in peace.

One morning, however (it was while he was writing on "The Imperial Orgy"), something happened which at the moment seemed so vital, that, impulsively and without realizing what the effect would be, I burst into his study without warning and started to tell him.

The effect on him was of such a nature that the errand was forgotten. With a yell like that of a maniac, Mr. Saltus grabbed his hair, pulling it out where it would give way. Still screaming, he batted his head against the walls and the furniture; and finally giving way utterly, he got down and hit his head on the floor.

None of it was directed against me—the offender, yet no woman could have been blamed for running out of the house. Ten minutes later, when he had been put to bed like a small boy, given a warm drink, and had an electric pad applied to his solar plexus, his[Pg 47] one request was that I sit beside him and read extracts from the "Gitâ."

His action was pitiful, tragic.

"Poor child! No one but yourself could understand and put up with such a demon," he said. "I should be taken to the lethal chamber and put out of the way. And yet I could not help it."

The realization that he, an old man then, a student of Theosophy, the first precept of which is self-restraint, could have given way as he had, hurt him cruelly. Understanding and sympathy brought him to himself rapidly. Otherwise he would have been ill.

Mr. Saltus was an unconscious psychic. With those he loved he needed no explanation of anything. He understood even to the extent of answering one's unspoken thoughts many times. So psychic was he, that his disinclination to be in crowds or meet many people came from the fact that they devitalized him, leaving him limp as a rag. When writing a book, as he himself often expressed it, he[Pg 48] was in a state of "high hallucinatory fever," giving out of his ectoplasm very much as a materializing medium gives it out in a séance, to build up a temporary body for the spirit.

It is a well-known scientific fact that any interruption during the process of materialization causes repercussion on the body of the medium, the velocity being such that illness, if not insanity, may result.

While creating a book, Mr. Saltus was in very much the same condition, the finer forces of his etheric body being semi-detached from the physical. He could not help it any more than he could help the color of his eyes. Lacking discipline and self-control from his youth, he could not, after his formative years, coordinate his forces so as to grapple with this limitation effectively.

During an interval of reading the "Gitâ" on this occasion he told me the following:

"In the early days when I was first married to Helen Read, I was writing on a novel. She had no idea how interruptions affected me—nor[Pg 49] did I realize myself how acute anything of the kind could become. I was in the middle of an intricate plot. Helen, who out of the kindness of her heart was bringing me a present, opened the door of my study and came in more quietly than you did. Before she could open her mouth to say a word, I began to scream and pull at my hair. Rushing to an open window I tore the manuscript, on which I had been working so long, into fragments and threw them into the street. Whether she thought I had gone suddenly insane and intended to kill her, she did not stop to say. When I looked around she had fled."

For a girl reared in an atmosphere of conventional respectability, as they were in those days, it must have been an insight into bedlam. Once again he made the remark:

"If Helen could see me now, I would seem natural to her. My next life is apt to be a busy one, paying my debts to her and to others."

In view of all this, and of the flirtations he kept up on every side, she must have had a[Pg 50] tolerance and a patience seldom encountered.

After Balzac and "The Philosophy of Disenchantment" and "The Anatomy of Negation" were off the press, novel after novel fell from his pen, and the newspaper articles quoted previously were appearing. In "A Transaction in Hearts" Mr. Saltus put some of his own experiences, but so changed that the public could not connect him with the plot. His literary bark was launched and under full sail. He could touch the garment of Fame, and the texture was soft and satisfying.

One of his novels was dedicated to E—R, his mother-in-law Emmaline Read. Another to V. A. B. was to his friend Valentine (or Vally) Blacque. E—W was to Miss Edith son, who later in life became the wife of Mr. Francis H. Wellman, a genius in his own field. Shroeder and Lorillard Ronalds were remembered as well.

During a summer abroad Mr. Saltus conceived the idea of writing "Mary Magdalen." The circumstances connected with it are interesting.[Pg 51] He was dining in the rooms of Lord Francis Hope one evening. Oscar Wilde was another guest. After their liqueurs and cigars the latter sauntered about, looking at some of the pictures he fancied. One representing Salome intrigued him more than a little. Beckoning to Mr. Saltus, he said:

"This picture calls me. I am going to write a classic—a play—'Salome.' It will be my masterpiece."

Near it was a small picture of the Magdalen.

"Do so," said Mr. Saltus, "and I will write a book—'Mary Magdalen.' We will pursue the wantons together."

Acting on the impulse, Mr. Saltus took rooms in Margaret Street, Cavendish Square, where, within walking distance of the British Museum, he could study his background for the story.

Mornings spent in research, afternoons in writing, with a bite of dinner at Pagani's in Great Portland Street, made up his days. There were interruptions, to be sure. One of[Pg 52] them was a girl named Maudie, who lived somewhere in Peckham. She joined him now and again at dinner. Asked to describe her, he said he had forgotten even her last name, but remembered that he had written of her, "She had the disposition of a sun-dial." This may have assisted to keep him in a good humor.

Many years later Mr. Saltus took me to see the rooms he had occupied during this time, with their queer old open fireplace, great four-poster bed, canopied on all sides, and the old desk at which he had spent so many happy hours. Working hours were happy hours to him, always. He had a sentiment for the place, and once when I was in London alone I stopped there, taking his old rooms for a time, and visiting the landmarks associated with that part of his life. That I should do this touched him profoundly.

During the writing of "Mary Magdalen" he met many interesting people. Among them was Owen Meredith, then British Ambassador to France. In connection with him a rather[Pg 53] amusing incident occurred. Dining one evening at the home of Lady B——, Mr. Saltus was vis-a-vis with Owen Meredith. In the course of the dinner the hostess gave the poet a novel, and asked him to translate an epigram on the fly-leaf which was written in Greek.

Looking at it he said:

"My eyes are not what they once were. Give it to our young friend here," meaning Mr. Saltus.

The passage that had stumped him stumped Mr. Saltus as well, but he refused to be caught. Glancing at it, he exclaimed:

"It is not fit to be translated in Lady B——'s presence."

At that both the rogues laughed.

In a monograph called "Parnassians Personally Encountered," Mr. Saltus tells of this episode, as also of his meeting with other celebrities of the day. Of Oscar Wilde he saw a great deal. The rapid-firing battery of his wit, his epigrams, which gushing up as a geyser confused and astounded the crowd, enchanted[Pg 54] him. At the then popular Café Royal in Regent Street, Wilde and himself, with a few congenial men, spent many an evening.

There was much in the mental companionship of Mr. Saltus and Wilde which sharpened and stimulated each, making their conversation a battle-ground of aphorisms and epigrams. According to Mr. Saltus, in spite of his abnormal life, Wilde's conversation, barring its brilliancy, was as respectable and conventional as that of a greengrocer. Neglecting to laugh at a doubtful joke tossed off by one of his admirers, he was asked somewhat sarcastically if he were shocked.

"I have lost the ability to be shocked, but not the ability to be bored," was the reply.

Vulgarity sickened him. Vice had to be perfumed, pagan, and private to intrigue him. His conversation was immaculate. Many incidents concerning Wilde are given in Mr. Saltus' monograph, "Oscar Wilde—An Idler's Impressions." They give a new slant on his[Pg 55] many-sided personality. One episode is especially illuminating.

With Mr. Saltus, Wilde was driving to his home in Chelsea on a bleak and bitter night. Upon alighting a man came up to them. He wore a short jacket which he opened. From neck to waist he was bare. At the sight Mr. Saltus gave him a gold piece, but Wilde, with entire simplicity, took off his own coat and put it about the man. It was a lesson Mr. Saltus never forgot.

The next vital experience in Mr. Saltus' life was his divorce from Helen Read. Hopelessly unsuited to be the husband of any woman who expected to find a normal, conventional and altogether rational being, his marriage with her was doomed to failure from the first.

From his rooms on Fifth Avenue, at a large Italian table of carved olive wood (the same table on which I am writing these lines), he turned out novels like flapjacks, entertaining his acquaintances in the intervals.

Among the friends of the first Mrs. Saltus was a girl belonging to one of the oldest and best families in the country. Spanish in colouring, high bred in features, a champion at sports and a belle at the balls, she was sufficiently attractive to arrest the attention of a connoisseur. Owing to her friendship with his wife, she saw a great deal of Mr. Saltus also. Their[Pg 57] acquaintance, however, had begun many years before, when as a youth in Germany he had met the girl and her family. Too young at that time to think of marriage they had been semi-sweethearts.

It was only to be expected, then, that his side of the story was put forward with all the cleverness of a master of his craft, and what man, no matter how much in the wrong, does not consider himself much abused? In this case, he gained not only a sympathetic listener, but an ally.

Tea in his rooms perhaps,—a luncheon in some quiet and secluded restaurant to talk it over, and tongues began to wag. That wagging was more easily started than stopped. It gained momentum. Before it reached its height, Mrs. Saltus brought an action for divorce, naming her one-time friend as one of the co-respondents. Willing to agree to the divorce, provided the name of the girl was omitted, Mr. Saltus struck the first opposition of his life. Bitter over her friend's "taking ways",—forgetting[Pg 58] perhaps that even in court circles the American habit of souvenir hunting had become the fashion,—she may have thought a husband superior to a bit of stone from an historic ruin, or a piece of silver from a sanctuary. Possibly in those days they were.

Many years later, when asked by Mr. Saltus as a joke, what I would do, in case some woman lured him from our fireside, I read him the account of a Denver woman, who, hearing that her husband was about to elope with his typist, appeared at the office. She was on the lookout for bargains. Facing the offenders she agreed to let them go in peace with her blessing, if the typist would promise to provide her with a new hat. Hats were scarce and expensive. Husbands, cheap and plentiful, were not much in exchange. Commenting on it the paper said, "The woman who got the hat, was in luck."

This episode and the newspaper article about it occurring many years later, there was nothing to suggest the idea to the first incumbent. Besides, being the daughter of a many[Pg 59] times millionaire, she was probably well supplied with hats.

At this time, Edgar Saltus was at the height of his fame. The newspapers reeked with the scandal. There were editions after editions in which his name appeared in large type. To protect the name of the alleged co-respondent Mr. Saltus fought tooth and nail. However much he had been at fault in his treatment of Helen Read, his intentions now were to be chivalrous in the extreme, to protect the girl who had been dragged into such a maelstrom.

Every witticism he had sent out was used against him. His amusing reply "God", spoken of previously, became a boomerang. Having once been asked what books had helped him most, he replied "My own." From that joke a colossus of conceit arose.

The history of that suit was so written up and down and then rewritten, as to be boring in the extreme. After a great deal of delay, of mud-throwing, and heart-breaking, the name of her one-time friend having been withdrawn,[Pg 60] and all suggestion of indiscretion retracted, a divorce was given to Helen Read. She was a free woman again,—free to forget, if she could, the hectic experience of marriage with a man fundamentally different from those who had entered her life.

After the divorce Mr. Saltus threw himself into his work. "Mme. Sapphira" was the immediate result. Aimed at his first wife, in an attempt to vindicate himself,—with a thin plot, and written as it was with a purpose, it not only failed to interest, but reacted rather unpleasantly upon himself. His object in writing it was too obvious.

It was his custom in those days to begin writing immediately after his coffee in the morning. That alone constituted his breakfast,—a pot of coffee and a large pitcher of milk, with a roll or two or a few thin slices of toast. Cream and sugar he detested. Accustomed to this breakfast during his life abroad, it was a habit he never changed. The same breakfast[Pg 61] in the same proportions, was served to him until his last day.

Writing continuously until about two p. m., he would stop for a bite, and then go at it again until four. Hating routine and regularity above all things, his copy alone was excepted. It was his habit to write a book in the rough, jotting down the main facts and the dialogue. The next writing put it into readable form, and on this second he always worked the hardest, transforming sentences into graceful transitions,—interjecting epigrams, witticisms and clever dialogue, and penetrating the whole with his personality. The third writing (and he never wrote a book less than three times) gave it its final coat of varnish. Burnishing the finished product with untiring skill, it scintillated at last.

Poetry came more easily to him than prose. He had to school himself at first to avoid falling into it. On his knees before the spirit of Flaubert, he pruned and polished his work.

At four, it was his custom to go for a walk[Pg 62] Never interested in sports,—walking only because he recognized the necessity for keeping himself in physical trim, it was Spartan for him to do something he disliked, and to keep on doing it. Pride kept him on the job. The "Pocket Apollo" could not let himself go the way of least resistance. Shortly before this time his brother Frank, who, at the last, had become a physical wreck, had passed on. Outwardly this appeared to affect Mr. Saltus but little. In reality it touched the vital center of his hidden self. A photograph of Frank Saltus on a Shetland pony, against which the child Edgar was leaning, hung in the latter's room forever after. The likeness between them is striking. It is the only picture extant of Frank as a child.

Not long after the divorce, and while he was still much in the limelight, Mr. Saltus met at a dinner party a married woman,—a Mrs. A——. Well known, wealthy, once divorced and the heroine of many romances, she took[Pg 63] one look at the "Pocket Apollo", and decided that she had met her fate.

During this time Mr. Saltus had become engaged to Miss Elsie Smith, a talented, charming and high-bred girl belonging to one of the oldest New York families, and expecting to marry her the following year, he was not seeking an affair. Seeking or not the affair followed him, and was the cause, indirect but unmistakable, of the wrecking of what might have been a happy life with his second wife. Quoting Mr. Saltus, it began in this way.

The day after the dinner, while serving tea in his rooms to his fiancée, a knock came at the door. That was unprecedented. No one was better barricaded against intrusion than he. Not only were lift men and bell boys well paid, but instructed in a law more drastic than that of the Medes and Persians. It was to the effect, that the people he wanted to see he would arrange to have reach him. Others who called,—no matter whom or what their errand—were to be told that he was in conference with[Pg 64] an Archbishop. If they still persisted, they were to be told that he was dead.

This fancy of his continued throughout life, as attendants in the Arizona Apartments must well remember. Nothing angered him more than infringement of these rules. Unless summoned, no servant—no matter what the occasion—dared to approach him.

By what guile, subterfuge or bribe Mrs. A—— had turned the trick, Mr. Saltus had forgotten. After repeated knocking he decided to go to the door, which he did, with hell-fire in his eyes, as his fiancée stepped behind a portiere.

Determined to throttle the intruder he flung open the door. Cool and fresh as a gardenia Mrs. A—— walked in. It was an awkward moment. In that instant he no doubt remembered some of the careless compliments of the night before. Going up to him, Mrs. A—— looked into his eyes and said:—

"I love you, and I have come to tell you of it. Dine with me tonight."[Pg 65]

That was more awkward still. Even his ingenuity was taxed. Kissing her hand, telling her that she had dragged him from the heroine of a novel so abruptly that he was not normal, and promising to dine with her that evening, he bowed her out. No one else could have managed it so cleverly.

The lady of the first part then reappearing he laughed. Telling her that his promise to Mrs. A—— was the only way of sending her off, he sat down at once and wrote her a letter, saying that it would be impossible for him to dine with her after all. This he gave to his fiancée, asking her to send it by a messenger on her way home.

It was well done. Knowing that his mail was bursting with letters from love-sick women,—knowing also that no scrap-book, however large, could hold the letters, locks of hair and photographs, that poured in on him daily, and accepting it as a part of a literary man's life,—she accepted this as well. They laughed over the episode and brushed it aside.[Pg 66]

As a matter of fact Mr. Saltus played fair. He did not go to dine, but as soon as he was alone, he sent another note less formal than the first, asking Mrs. A—— to return the former note unopened, and saying that though dinner was impossible, he would give himself the pleasure of calling afterward.

This he did, and it turned the scales of his life. Questioned next day by his fiancée as to whether or not he had changed his mind and gone to dinner, he denied it vigorously. After that both ladies were invited for tea, great care being taken, however, that they should never meet again.

The following summer Mrs. A—— with a party of friends went abroad. Mr. Saltus joined them, safe in the knowledge that his fiancée was away with her family, where, being decidedly persona non grata, he could not be expected to follow. The summer passed and again he joined Mrs. A—— and her friends in Cuba. Spring saw him in New York again.[Pg 67] A year had elapsed, during which he saw his fiancée occasionally and Mrs. A—— often.

From two letters written by Mrs. A——, which, used as book-marks, were found between the leaves of an old novel after Mr. Saltus' death, a love that counted no cost—passionate and paralyzing—oozes from the pages. "How could I live if you should cease to love me?" was asked again and again.

Cease he did, however. There are those so constituted that they can drift out of an affair so gradually that it is over without any perceptible transition. It was that way with Edgar Saltus. Mercurial to a degree, easily put off by something so slight no one else would have been susceptible to it, when he was done—he was done. As he himself expressed it, he could not "relight a burnt-out cigar."

That affair over, he remembered the ring he had given and the girl to whom he was engaged. In spite of living in a social world poles apart from Mrs. A——, and in spite of absence and travel, rumors of the affair had[Pg 68] filtered to his fiancée. Straightforward herself, scorning subterfuge as weakness, she asked him to tell her the truth. With righteous indignation Mr. Saltus denied it in toto, declaring it was an invention intended to discredit him in her eyes. It was in this that he made the mistake of his life.

Talking it over with me years afterward, he admitted that had he told her the truth, loving him as she did, she would probably in the end have forgiven him. It was the streak of fear—fear of a moment's unpleasantness, which he might have faced then and there and surmounted—which was his undoing. Taking the easiest way for the time being, he reiterated his denials.

In glancing over the scenario of Edgar Saltus' life, this act, at the pinnacle of his popularity and fame, may in the region behind effects have set in motion forces which tore the peplum of popularity from him, and in spite of his genius pushed him into semi-obscurity at the last.[Pg 69]

His denials accepted, and there being no reason for delay, he married Elsie Smith in Paris in 1895. It should have been a happy marriage, the two having sufficient in common and neither being in their first youth. Its rapid failure is therefore all the more pathetic.

Going from Paris to the south of France, the first mishap was that of breaking his ankle. Unable to stand pain, Mr. Saltus fainted three times while it was being set. That rather disgusted his wife. This accident led to their first misunderstanding, when, in answering a telegram from Mrs. Saltus Sr., news of the accident was excluded. Unwilling to hear anything of an unpleasant nature himself, Mr. Saltus was equally unwilling to tell any one he loved of a disagreeable episode. The memory of his early life and training was at the bottom of this, and from one aspect it was a most lovable quality.

Asked by Mr. Saltus why she had spoken of the accident, his wife replied that she had but told the truth. At this Mr. Saltus flew into[Pg 70] a rage, declaring, as he used to put in his copy, "Truth must be pleasant, or else withheld."

The incident was slight, but that which followed was not so. He being unable because of his ankle to get about freely, and wanting some cigarettes from a trunk, Mrs. Saltus volunteered to get them. She got the shock and surprise of her life as well. Carelessness over his personal effects was a characteristic of Mr. Saltus'. That carelessness was his undoing upon this occasion. Beside the cigarettes lay a letter from Mrs. A——. His wife read it. There and then she knew she had married him as the result of a fabrication. A scene followed. Furious at his detection, Mr. Saltus upbraided her for reading a letter not intended for her eyes. It was the beginning of the end.

In one of Mr. Saltus' note books is the copy of a letter sent to his wife shortly after the episode:

Elsie:—

To be quite candid with you I cannot be candid. I cannot write to you as I used to do.[Pg 71] I no longer know what you will keep to yourself, what you will repeat, nor yet how you will distort my words. The flow of confidence is checked. An artery has been severed.... If reading has given you any idea of what a battle is, you will remember that in the excitement of danger men may be shot and slashed and not notice their wounds until the fight is at an end.

Not until I got here did I realize what you had done in telling your mother you had married me under compulsion. Then I discovered that during the fight which I had entered single handed for your sake, I had been shot—shot from behind, shot by you.

There has been a great change in the weather, from being very hot it has become quite cool. I hope you are well and enjoying yourself.

As ever,

E. S.

The letter speaks for itself. In the same note book are entries made during the same time:[Pg 72]—

May 3rd, 1896.

Problem:—"Which is harder; for a woman to live under the same roof with a man whom she detests, or for a man to live under the same roof with a woman who detests him?"

"Every day she invents some new way of being disagreeable."

"Love should have but one punishment for the wrongdoer,—that is, forgiveness."

"Injuries are writ in iron,—kindnesses scrawled in sand."

Again November 13th.

"Elsie having told me:—

1. That I can ask nothing of her.

2. That her affairs are no concern of mine.

3. That hereafter she will give no orders for me: