THE RAINBOW BOOK

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

LITTLEDOM CASTLE

MY SON AND I

MARGERY REDFORD

THE LOVE FAMILY

THE CHILD OF THE AIR

All rights reserved

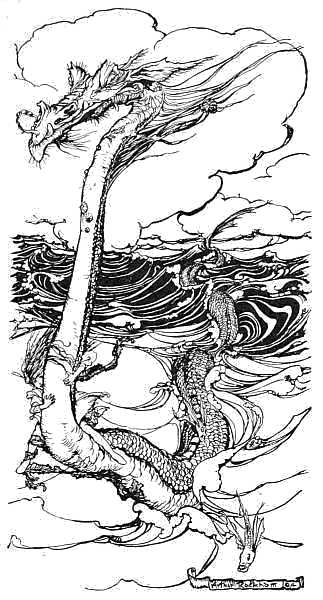

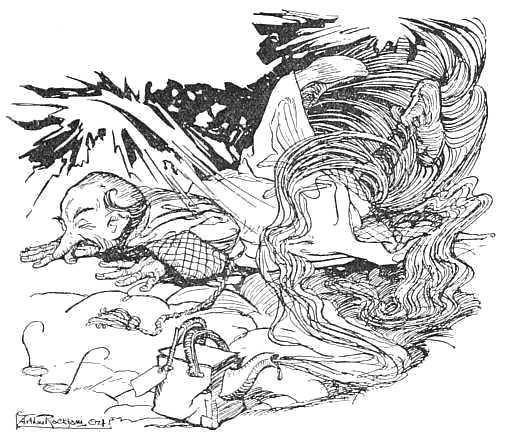

The Fish-King and the Dog-Fish

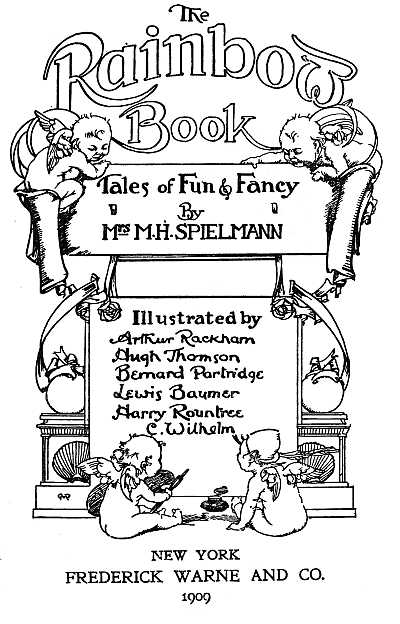

The Rainbow Book Tales of Fun & Fancy

By Mrs. M. H. SPIELMANN

Illustrated by

Arthur Rackham

Hugh Thomson

Bernard Partridge

Lewis Baumer

Harry Rountree

C. Wilhelm

NEW YORK

FREDERICK WARNE AND CO.

1909

TO

BARBARA MARY RACKHAM

WITH ALL GOOD WISHES

FOR HER FUTURE HAPPINESS

MABEL H. SPIELMANN

[v]

PREFACE

It's all very well—but you, and I, and most of us who are healthy in mind and blithe of spirit, love to give rein to our fun and fancy, and to mingle fun with our fancy and fancy with our fun.

The little Fairy-people are the favourite children of Fancy, and were born into this serious world ages and ages ago to help brighten it, and make it more graceful and dainty and prettily romantic than it was. They found the Folk-lore people already here—grave, learned people whose learning was all topsy-turvy, for it dealt with toads, and storms, and diseases, and what strange things would happen if you mixed them up together, and how the devil would flee if you did something with a herb, and how the tempest would stop suddenly, as Terence records, if you sprinkled a few drops of vinegar in front of it. No doubt, since then thousands of people have sprinkled tens of thousands of gallons of good vinegar before advancing tempests, and although tempests pay far less attention to the liquid than the troubled waters to a pint of oil, the sprinklers and their[vi] descendants have gone on believing with a touching faith. It is pretty, but not practical.

But what is pretty and practical too, is that all of us should sometimes let our fancy roam, and that we should laugh as well, even over a Fairy-story. Yet there are some serious-minded persons, very grave and very clever, who get angry if a smile so much as creeps into a Fairy-tale, and if our wonder should be disturbed by anything so worldly as a laugh. A Fairy-tale, they say, should be like an old Folk-tale, marked by sincerity and simplicity—as if humour cannot be sincere and simple too. "The true Fairy-story is not comic." Why not? Of this we may be sure—take all the true humourless Fairy-stories and take "Alice"—and "Alice" with its fun and fancy will live beside them as long as English stories are read, loved for its fancy and its fun, and hugged and treasured for its jokes and its laughter. The one objection is this: the "true Fairy-story" appeals to all children, young and old, in all lands, equally, by translation; and jokes and fun are sometimes difficult to translate. But that is on account of the shortcomings of language, and it is hard to make young readers suffer by starving them of fun, because the power of words is less absolute than the power of fancy in its merrier mood.

Some people, of course, take their Fairies very[vii] seriously indeed, and we cannot blame them, for it is a very harmless and very beautiful mental refreshment. Some, indeed, not only believe firmly in Fairies—in their existence and their exploits—but believe themselves to be actually visited by the Little People. For my part, I would rather be visited by a Fairy than by a Spook any day, or night: but when the "sincerity" of some of us drove the Fairies out, the world was left so blank and unimaginative, that the Spooks had to be invited in. The admixture of faith and imagination produces strange results, while it raises us above the commonplaceness of everyday life.

But, as I say, certain favoured people, mostly little girls, it is true, are regularly visited by Fairies even in the broad daylight, and they watch them at their pretty business, at their games and play (for Fairies, you may be sure, play and laugh, however much the Folk-lorists may frown when we are made to laugh with them). Two hundred and fifty years ago a Cornish girl declared that she had wonderful adventures with the Fairies—and she meant truly what she said. And it is only fifty years since an educated lady wrote a sincere account of her doings with Fairies and theirs with her, in an account which was reprinted in one of the most serious of papers, and which showed that the lady, like the uneducated Cornish girl two[viii] centuries before, was a true "fairy-seer." Here is a part of her story:—

"I used to spend a great deal of my time alone in our garden, and I think it must have been soon after my brother's death that I first saw (or perhaps recollect seeing) Fairies. I happened one day to break, with a little whip I had, the flower of a buttercup: a little while after, as I was resting on the grass, I heard a tiny but most beautiful voice saying, 'Buttercup, who has broken your house?' Then another voice replied, 'That little girl that is lying close by you.' I listened in great wonder, and looked about me, until I saw a daisy, in which stood a little figure not larger, certainly, than one of its petals.

"When I was between three and four years old we removed to London, and I pined sadly for my country home and friends. I saw none of them for a long time, I think because I was discontented; I did not try to make myself happy. At last I found a copy of Shakespeare in my father's study, which delighted me so much (though I don't suppose I understood much of it) that I soon forgot we were living where I could not see a tree or a flower. I used to take the book and my little chair, and sit in a paved yard we had. (I could see the sky there.) One day, as I was reading the 'Midsummer Night's Dream,' I[ix] happened to look up, and saw before me a patch of soft, green grass with the Fairy-ring upon it: whilst I was wondering how it came, my old friends appeared and acted the whole play (I suppose to amuse me). After this they often came, and did the same with the other plays."

There! what do you say to that? Do you wonder that the good folk of Blagdon, for example, still point to the hill "where the fairies come to dance," and show you the Fairy-rings, like that which Cedric saw (as is recounted in this book), with the Little People capering about? Of course, the country folk don't laugh at them, because it is all so mysterious, and, as the scientific professors declare, abnormal, if not supernormal; but do you believe for one moment, that in their joyous dance the fairies do not laugh and joke as well as play and caper? The Bird-Fairy, as appears later, was always grave and loving, and didn't laugh—but then she was an enchanted Princess, and had sad and serious business on hand, and was not quite sure, sanguine though she was, of defeating the machinations of the cunning and wicked Wizard. But look at the classic Grimm, at the tiny, dancing, capering tailors whose portraits Cruikshank drew so well in it, and say if there is not a peal of laughter in every open mouth of them, and a chuckle in every limb and joint. Not "comic,"[x] Mr. Folk-lorist? Why, they are the very spirit and personification of comedy and fun!

But then your scientist comes along and tries to explain away the Fairy-rings themselves, which have defied explanation since Fairy-rings first came among us. Once at Kinning Park at Glasgow (and thousands of times elsewhere) four Fairy-rings appeared in one night—on a cricket-ground, if you please! on which the cricketers had been continuously playing and practising; and the poets said that they were made by the Fairies dancing under the moonlight, or, when the moon went to bed, by the lamplight of a glow-worm. That, I think, must be the truth, simple and sincere. Each ring was a belt of grass darker and greener than the surrounding turf, and was eight or ten inches broad; and the largest were nine and ten feet in diameter, and the others five and six, measuring from the centre of the belt. And the circles were accurate and the advent of them quite sudden. Clearly, the Fairies must have made them. But then a learned professor arose and lectured about them before the British Association. He was a great naturalist, and said that the rings contained a great number of toad-stools. And he brought along a chemist who analysed the fungi, and said he found in them a lot of phosphoric acid and potash and peroxide of iron and sulphuric acid, and[xi] a lot of things the fairies had never heard of and certainly never brought there, and he said that that, with phosphated alkali and magnesia, accounted for the rings! And then another great professor said that they must have been years in coming, and that electricity might have something to do with it, and that small rings sometimes spread to fifty yards in diameter—which only proves the wonderful power of happy industry of the Fairies, even in their revels and in their play.

So much for the Fairies.

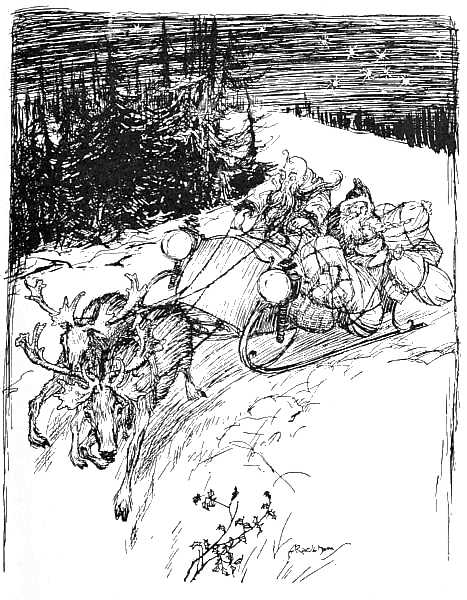

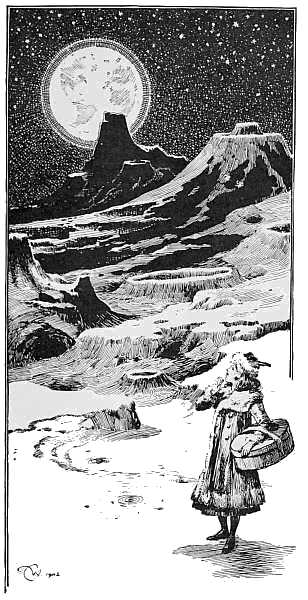

But everybody is not in love with Fairies; some people don't care for them, some (as we have seen) don't even believe in them! Many don't care to read about them, being insensible to their grace and pretty elegance, their exquisite dignity, and their ever-present youth. Who ever heard of a middle-aged fairy? Such folk, be their age what it may, generally prefer fun; especially do they love what Charles Dickens once for all defined and established as the Spirit of Christmas. Well, here they may find Father Christmas at home, and on his rounds. Here they will find revealed and laid bare the whole secret and mystery of Santa Claus—where the presents come from, and where they are stored—how they are packed and how delivered while we are all asleep in our beds, delivered from the waits. Here, too, the "old-fangled[xii] father" is justified in the eyes of his "new-fangled sons," who recognise that fundamental truths—and such truths!—are not shaken by the on-coming tide of Time. And here, besides, you may learn what goes on on that other side of the moon which we never see, and what is its service to Man, and to Woman and Child as well. And for the first time in the history of romance we discover what it was that the Sleeping Beauty dreamt. And there are stories of other kinds—with a touch of pathos, too.

Story-telling is the oldest of the arts—the art of which we never tire—the art which will be out-lived by none other, however fascinating, however beautiful, however perfect. It may deal with human thought and human passion; it may appeal to the highest intellect and the profoundest sentiments of men; or just to the brightest and dreamiest fancy of the young. Be it but well told, even though it does not stir our emotions, the little story delights the imagination, and makes us grateful to the teller for an hour well spent or pleasantly whiled away. That is the greatest reward of the writer, as it is the sole ambition of the author of these little tales.

CONTENTS

| Adventures in Wizard-land— | PAGE | |

| Illustrated by Arthur Rackham, A.R.W.S. | ||

| I. | A Knock at the Red Door | 1 |

| II. | The Wizard at Home | 8 |

| III. | The Bird-Fairy Speaks | 18 |

| IV. | The Lost Catseye | 26 |

| V. | In the Fish-King's Realm | 45 |

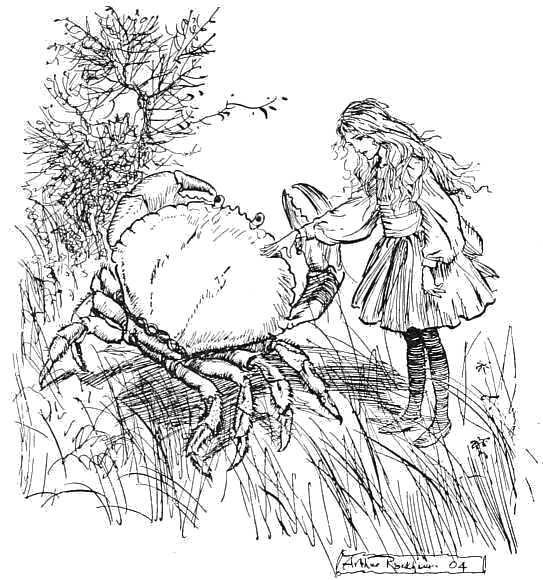

| VI. | The Mystery of the Crab | 67 |

| VII. | The Magic Bracelets | 76 |

| VIII. | The Spell—and how it Worked | 83 |

| The Old-Fangled Father and his New-Fangled Sons | 91 | |

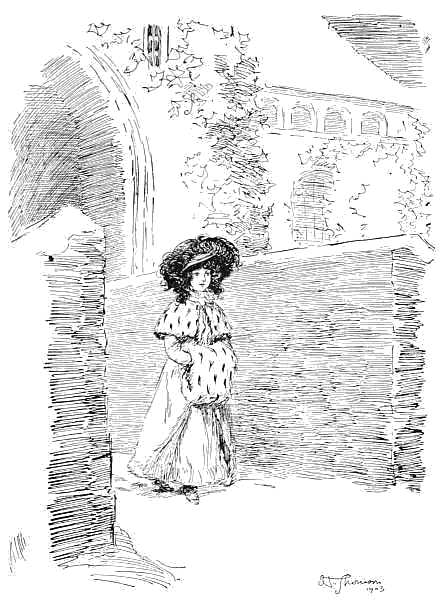

| The Little Picture Girl | 103 | |

| Illustrated by Hugh Thomson, R.I. | ||

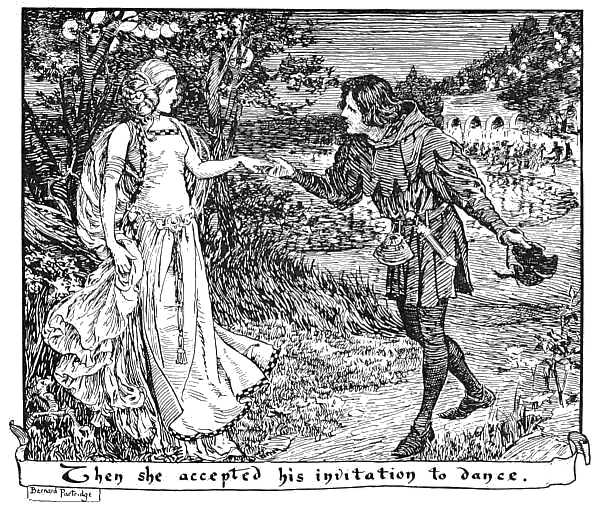

| The Sleeping Beauty's Dream | 117 | |

| Illustrated by Bernard Partridge, R.I. | ||

| The Gamekeeper's Daughter | 123 | |

| Illustrated by Lewis Baumer | ||

| All on a Fifth of November | 139 | |

| Father Christmas at Home | 150 | |

| Illustrated by Arthur Rackham, A.R.W.S. | ||

| [xiv] | ||

| A Birthday Story | 168 | |

| Little Starry | 178 | |

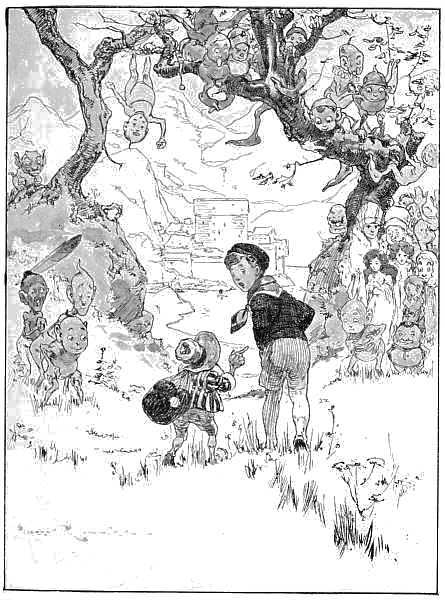

| Cedric's Unaccountable Adventure | 187 | |

| Illustrated by Harry Rountree | ||

| Rosella | 206 | |

| The Cuckoo that Lived in the Clock-House | 220 | |

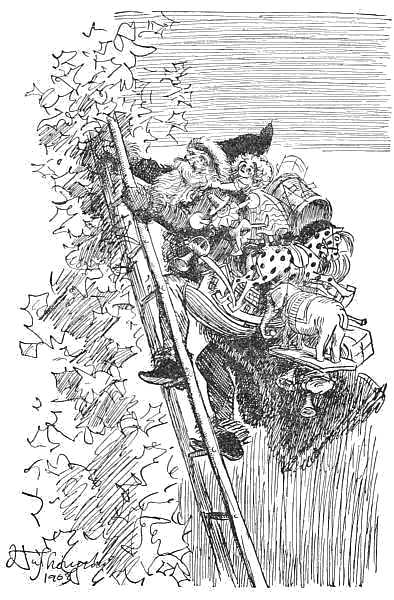

| Christmas at the Court of King Jorum | 229 | |

| Illustrated by Hugh Thomson, R.I. | ||

| One April Day | 247 | |

| The Storm the Teapot Brewed | 259 | |

| Monica the Moon Child | 268 | |

| Illustrated by C. Wilhelm[xv] | ||

ILLUSTRATIONS

[xvi]

ILLUSTRATIONS IN THE TEXT

The Title-page and End-papers are by Mr. Carton Moore Park.

[1]

CHAPTER I

A KNOCK AT THE RED DOOR

"It's a shame, Dulcie. We mayn't go out just because it's raining a few drops," said the boy at the nursery window.

"Yes, a fearful shame," replied his sister. She always sympathised with him and gave in to him, right or wrong. She carefully propped her doll bolt upright on a chair and came to where he stood. "Never mind, Cyril. Let's play at something."

"Yes, but I do mind. It's too bad! It's always 'you mustn't' this, 'you mustn't' that. It would be a saving of breath if they'd just say the few things that we might do. Are you willing to go on putting up with it? I suppose you are, as you're only a girl."[2]

"No, I don't want to, but I've got to. Mother says it is for our good, and we are spoilt."

"I don't think so at all. It's very hard lines," growled Cyril. "I'm sure the garden isn't a bit wet, and the rocks have only a sprinkle."

Certainly the window panes had more than a sprinkle trickling down them. But the birds were twittering fussily in the bushes and amongst the ivy, and the garden was looking its best in the summer shower. Fitful gleams of sunshine cast loving touches here and there on the roses and the sweet honeysuckle; and the tall white lilies never looked fresher or smarter. Beyond, were those tempting rocks, with their surroundings of sand, which rose so strangely in that part of inland Kent, telling of former ages and of the vagaries of the sea and river. The rocks were the happy playground of these lucky Twins, who lived in the fine solitary house close by, and who were now peering so disconsolately through the window, flattening their noses against the glass blurred with the pattering rain.

They were exactly the same height; they resembled one another in feature, and, being twins, were both nine years old; and there the likeness ended, for his dark hair was short and thick, and hers was fair and very long. She was timid and gentle though her bright face was very happy; he, what is termed "a handful."[3]

"I know!" exclaimed Dulcie after a moment's silence, drawing her brother away from the melancholy amusement of tracing down the trailing drops with his finger until they disappeared mysteriously at the bottom of the glass. "I know! Let's play 'Birds, Beasts, and Fishes.'"

Cyril cast a lingering look at the tiresome dark clouds, then with a sigh and a frown turned round in token of consent, graciously suffered himself to be settled at the table with paper and pencil, and was soon excitedly trying to guess what Dulcie's Bird could be that began with the letter c, had four between, and ended with an e.

"It's very easy, really," pleaded Dulcie, burning to tell. "Do you give it up?"

Cyril wasn't so easily beaten as that, and thought till he grew impatient.

"Shall I tell you?—Let me tell you!" urged his sister.

"If you like," he replied magnanimously.

"Canare!"

"I'm sure it's spelt with a y," he said, as if he weren't quite certain in spite of his words.

They argued who should score the mark, and settled the point by counting it a draw. She followed it up with a Fish, which was s, two between, and an l, which puzzled Cyril until he found, of course, that it was "soul."[4]

Believing he had lost again, he allowed his interest in the game to flag, and still restless, he ran to the window.

"Hooray! it's fine now," he cried. "Come along, we don't want hats!"

"Ought we to go, do you think, Cyril, without asking?"

"I'm not going to ask, not if I know it. We would be sure to be 'don't'-ed. I'm going out. It's so stuffy here. You can do as you like."

"If you go, I shall go too," she replied quickly, following him and taking his hand. He didn't quite like that, but he felt, as she was "only a woman," he would let her.

Away they ran lightly, out into the sunshine, happy to be in the warm, scented air, through the garden, off to the dear old rocks which were already drying nicely, and at once a fine game of hide-and-seek was in full swing.

Dulcie had gone again to hide, and Cyril had his face buried in his hands, waiting for the familiar "Cuckoo!" when he was startled instead by a faint cry of surprise, followed by "Cyril, come quick! Quick!"

"It must be a beetle or a toad, or something," he said to himself as he hurried to the spot from which her voice seemed to come; but it was only after she had repeated her excited cries that he found her at last.[5]

She had found a passage through the rocks which they had never noticed before!

"Come along!" cried Cyril joyously at the sight of it. "Come along! we'll go on a voyage of discovery!"

Down the passage they went, far and carefully, for there was only a glimmer of light in a thin streak peeping through, because the rocks all but joined at the top, and the ground was uneven and slippery. But in spite of their caution they got a sudden start, for they became aware of a silent brook flowing deep and swiftly by, at their feet: another step and they would have been in it. The Twins, rather startled, looked at one another, and then without further thought they just jumped across. Jumped into an open space—into Moonlight. There was actually a full moon overhead, but with such seams and lines about it that it bore the appearance of being pieced together like a geographical puzzle.

"Cyril, look there!" whispered Dulcie, pressing close up to him, as soon as she found words.

In the white light there stood an immense rock. In it there was a wooden door with hewn-out steps leading up to it. A nice red door it was, with a green knocker upon it in the shape of a mouth smiling a welcome. Of course they went up to it, climbed the steps, which were high and difficult, and[6] stared at the neatly engraved brass plate below it, which bore the words:

If not, why?

"I'm going to knock," said Cyril.

"Oh no, we don't want any answer," said Dulcie, "so why do it?"

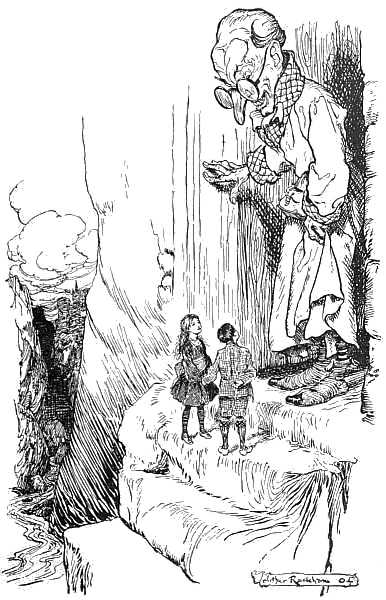

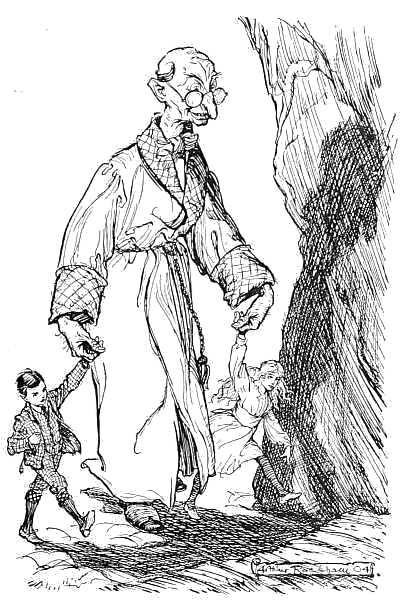

A backward glance at the steps puzzled her, for they had grown steeper than before and impossible to climb down again, or up, for the matter of that, and the door before which they stood was now at such a height from the ground as to make her feel giddy to look below. She hardly had time to think about it when Cyril raised the knocker and let it go. Instead of the usual sound a knocker makes, a loud laugh rang out, discordant and disconcerting. "You needn't be frightened," he remarked, for his little sister hung back and tightened her grasp of his arm. The next moment the door swung open and there stood on the threshold a very tall man with an enormous bald head. He was clad in a yellow satin dressing-gown, and wore great smoke-coloured spectacles.

"So you've come to see the Wizard," he said blandly. "Pray walk in!"

"So you've come to see the Wizard," he said

[7]

"I—I think we'd—we'd rather not, thank you very much," stammered Cyril, very red, whilst Dulcie looked up, pale and wondering. "We're not dressed for visiting," she urged in a loud whisper in her brother's ear.

"But you require an answer, or why knock?" retorted the strange man. "Pray walk in," he repeated. He was so polite.

The door swung behind them, and the trembling twins found themselves alone with the Wizard in a very large cave, where the walls glowed with phosphorescent light, while the further end was hidden in deep gloom.

[8]

CHAPTER II

THE WIZARD AT HOME

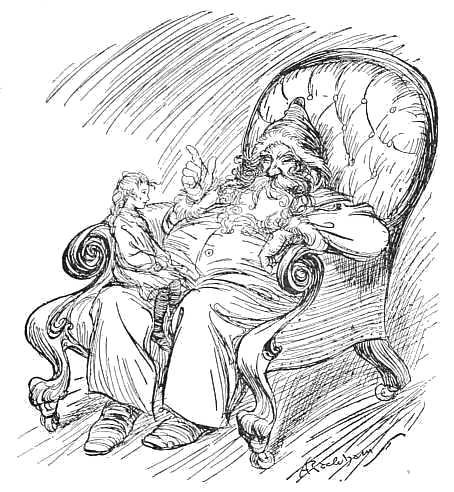

"How do you do?" said the Wizard, as if he remembered he had forgotten to ask. The Twins shyly shook hands with him and said they were quite well, thank him. They didn't want to a bit, but he seemed to expect it. "Let's talk matters over," he added with a smile. It was such a winning smile that the children began to feel less uncomfortable. "You're not always quite content, I believe," and he rubbed his hands cheerfully together. "That mother of yours interferes rather too much, eh?" With a rapid movement he pushed his spectacles away on to the top of his bumpy baldness, revealing a pair of small eyes with a red, slumbering glow in them.

As Cyril didn't reply Dulcie ventured to remark, "If you please, my brother thinks she says 'don't' too often."

"But how do you know that?" interrupted Cyril, who, though surprised, took a more practical view of the situation.[9]

"Because," slowly replied the Wizard, taking off his spectacles and scratching his big nose with them—"because I was an optician in my youth and made these glasses, through which I have only to look to see people as they really are and not what they appear to be. ["How clever!" broke in Dulcie under her breath.] I found out at a glance that you are discontented with your lot, and prefer to be free. You are tired of control, eh? Isn't that the state of Home Affairs?"

"Yes," said Cyril, once more full of his wrongs. "It's only children who are not allowed to do what they want. Grown-ups do as they like; so does our dog; he goes out and comes in when he likes, eats when he wants, leaves what he likes—or rather, what he doesn't like; so does our cat. You see," he continued, growing quite chummy, "we are never allowed to do this, that, and the other, like other people—animals, I mean—and they are free and happy, and they needn't bother with lessons. It's so stupid being a child!" he concluded plaintively, and Dulcie nodded a similar opinion.

"Just as I thought. Well, I shouldn't put up with it if I were you," replied their new friend, smiling again, and scratching his nose with his spectacles in his thoughtful, insinuating manner. "I should advise you to go your own way, seek[10] your own fortunes, and find your own happiness for yourselves. We must see what we can do to help you to freedom. Eh?"

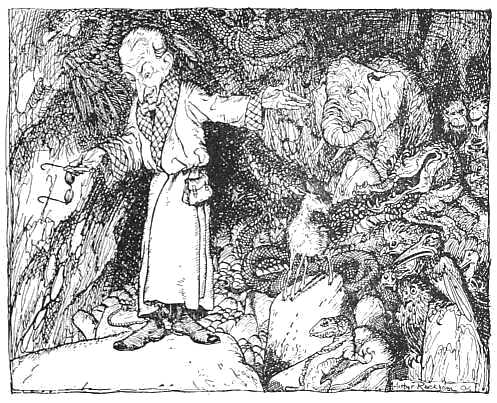

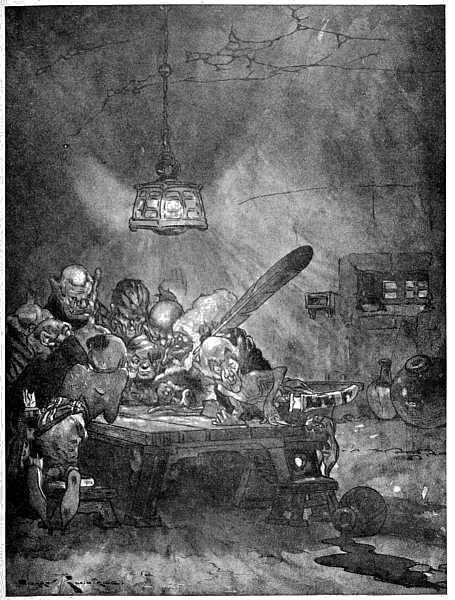

The little guests did not think to thank him, for their eyes had begun to roam with curiosity over the strange things that were all about. The cave dwelling was queerly furnished, if it could be called furniture. There were animals of all sizes and shapes, standing around stuffed, staring, and immovable. Snakes, fish, small birds; an elephant just like life standing rigidly next to a number of grinning stuffed monkeys; while a crocodile with open jaws looked snaps at a startled fawn with wide-set eyes. It was like a frozen Zoological Gardens.

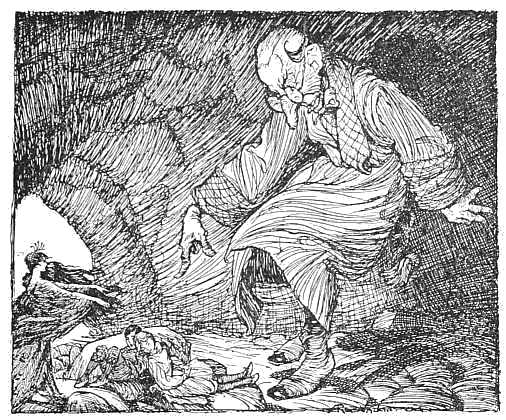

"Once upon a time," remarked the Wizard, following the children's source of interest, "all those poor creatures were children like you. Ah! their end was sad, very sad; very sad indeed!"

The Twins didn't like that remark at all, nor did they relish the winning smile this time that accompanied it. Then bursting out laughing he exclaimed—

"Now I'll show you something funny," and he brought out from a corner what looked like a cinematograph. "Look!" he said as he touched a spring and set it going.

There was a hissing sound, and the gloom at the[11] end of the cave passed away, and there marched along in living procession all the inhabitants of their Noah's Ark.

Dulcie and Cyril were transfixed with delight at this charming entertainment.

"All those poor creatures were children"

"And we don't pay anything to come in!" remarked Cyril softly to his sister. "It can't pay him. They're all going in for safety, you see—all the birds, all the beasts——"

"Where are the fishes?" anxiously interrupted his little sister in a whisper.[12]

"Don't be such a Billy," retorted Cyril with a frown; "the fishes are used to being drowned."

After Noah went into the Ark and had shut the door, the gloom reappeared. The show was over.

"That's a little idea of my own," remarked the Wizard as he put the machine away. "Amusing, isn't it?"

The Twins nodded. Then he invited the children to look through a hole in the wall of the cave, and they saw a small room.

"That's my hospitable bedroom," he said, "that I've endowed myself with. When I'm down in the mumps from being crouped up here so long, I go there and wrap myself up in thoughts all nice and smug. It is fitted with the epileptic light, rheumatic bells, and all the latest infections.

"Now, what were we talking about before? Ah yes! My inventions. None of your modern up-to-date rubbish, only inventions of the future for me. None of your wireless telephony and wireless telegraphy for me. Listen to this." He called out—

"Number A. 1. Sea Power! Have you been successful in that last little financial venture, Sire?"

There were rushing sounds, as of waves, at the far end of the cave, and a muffled voice replied—

"No, Cabalistic One, I have lost again. Just[13] my luck! Dash—sh—sh—" which resolved itself into the swish-swish of rolling surf. Then all was quiet again.

"The reply of a friend of mine residing far away at a place called 'The Billows,'" explained the Wizard in an offhand way. "I help him in his little transactions, which are sometimes rather—in fact very—!" and raising his arm he smothered a laugh in his yellow satin sleeve which was not pleasant to hear. "I always like to laugh up there," he explained, as the children looked surprised.

Dulcie's hand stole into her brother's and she whispered him to "Come away, come away, do, quick, and let's go home."

"But you haven't seen any of my marvellous jewellery yet," replied their host, as though she had spoken aloud.

"Don't be timid"—he was looking at them through those horrid spectacles again, which laid bare all their thoughts. "You know I am only answering that knock of yours. Had you not required an answer, there would have been no information forthcoming. I should just like to show you these bracelets I have here." He pushed his glasses across his baldness and took two jewelled golden circlets out of a satchel which hung from the cord of his gown. "Other children have taken great interest in them," said the Wizard slowly[14]—"in fact have worn all the gems out. But I've often had them done up again; and you are both welcome to them—very welcome to them, if you like. You see, they are able to inform their wearers how to play at 'Birds, Beasts, and Fishes' properly."

He took two jewelled circlets out of a satchel

"We know already," replied the boy and girl together, now restlessly impatient to be gone.

"I don't mean that tiresome educational game you were playing when you were waiting in because of those few drops of rain. I mean the real thing—to be actually the real[15] animals themselves in the realms of the Birds, Beasts, and Fishes. Only in that way can children realise how much nicer it is to be one of them, and to live a life free from the 'don'ts' and vexatious care of their elders. Ah! Now you're interested!"

The Twins were staring at him open-mouthed.

"These bracelets," continued the Wizard, whilst the ten catseye gems in each of them gleamed curiously as he spoke—"see—aren't they beautiful—

"These Bracelets will empower the wearers to become Bird, Beast, or Fish, at each wish; to regain his shape, or her shape, at will, and to live in any atmosphere—or in none! At every change of form a catseye will disappear and return to me. With the last wish the wonderful adventures will be over, and the shape last chosen will remain to the end of existence. All these silly animals in my dwelling came at the last to seek my help as they were dissatisfied. I did what I could, which wasn't much. Of course I don't want so many of them here," he added carelessly, scratching his nose with his glasses, "though they do help with my experiments—they do that—oh yes—but I always advise getting experience first. They somehow got to know that as children under ten they could only pass into my Moonlight and never out of it; and[16] that my faithful Brook would not see them twice. So they came for help in their last shapes as animals. Oh!" he added, pulling himself up with evident pretence, "I helped them right enough! They should have kept a pair of catseyes—I warned them—and they might have crossed my Brook in some other shape than their own and changed to themselves the other side. But somehow they were not fortunate enough to manage that. Some people are so thoughtless. Pray excuse me, my dears, there's some one at the knocker," and throwing the bracelets into a corner where they glittered strangely, the Wizard vanished.

"Come away, do come away," implored Dulcie, plucking at her brother's sleeve. "I'm so frightened," she whimpered. "Don't touch them. Oh! I want to go home."

"But, sis, you heard what he said. We can't cross his horrid brook twice whilst we are under ten. Crying won't help," replied the boy sturdily. Nevertheless, he looked terribly frightened himself, although he patted her shoulder comfortingly. "I feel I must!" he muttered; "besides, it's our only way out of here, and get out of here we must, and escape in some other shape."

Cyril hastily picked up the bracelets, put one on his wrist and the other on Dulcie's, and taking her by the hand dragged her right into the gloomy[17] part of the cavern farther and farther away from the hateful dwelling and its awful master. He couldn't tell where he was leading her, but he ran blindly on until at last there was daylight in the distance. And the Twins found themselves surrounded by haystacks, windmills, and other country objects.

"Ah!" exclaimed Cyril with delight, "see how I've saved you, Dulcie!"

"And a good job too," she replied with conviction.

So they wandered gaily on, laughing at anything and everything in the happiness of their escape. They were happy, anyhow; happy in their absolute freedom. And were they not in the possession, too, of the precious bracelets which were going to lead them into all sorts of delightful adventures as soon as they chose! They could talk of nothing else—and babbled on of how they would cross the brook as animals, and how they would be wiser than all the other poor creatures, by keeping a gem in reserve and change to themselves on the other side.

Little could they guess of the troubles and adventures that awaited them![18]

CHAPTER III

THE BIRD-FAIRY SPEAKS

The children had been so busy chattering of fun to come, that it was all of a sudden they realised they were in a glade which looked quite enchanting, and with so many daisies about that Dulcie wanted to sit down and weave those they gathered into a chain.

"Don't wait for that," said Cyril; "carry them in my handkerchief."

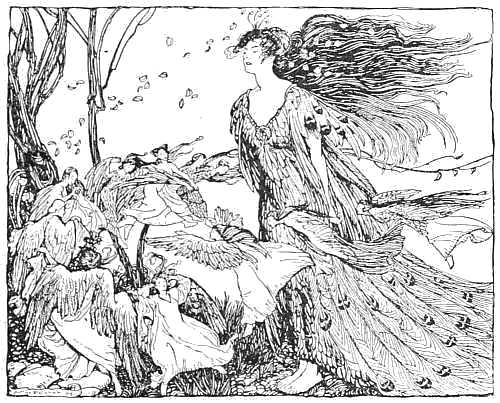

But when he felt in his pockets the handkerchief was not there. He must have dropped it. Dulcie proposed that they should retrace their steps, but sweet sounds of innumerable birds came from the high trees around and filled the air—and they stayed to listen to the concert of trills, chirrups, gentle call-notes, cadences, and bursts of tremulous song. And now, against the deep blue sky hovered what looked like a cloud which suddenly separated and descended, and the Twins found themselves face to face with a most lovely being, surrounded by a ring of exquisite little creatures, who danced to the continuous music of the Wood[19].

Cyril and Dulcie gazed at their beautiful companion, who stepped towards them smiling graciously. She looked like a lovely young girl. Draped about her was a wondrous garment of feathers of every hue. But she was strange indeed, for her hands, clasped behind her, drew close together two enormous wings which sprouted from her shoulders and formed part of her white arms; whilst upon her shapely head among her black tresses was the aigrette of the peacock. Her attendants had no aigrette, and their feathered[20] draperies were of sober brown. They were much smaller too, smaller even than the Twins.

"I am the Bird-Fairy," she said in cooing tones, "and you are in need of advice. I can——"

"I am the Bird-Fairy," she said

"Not exactly, thanks. You are pretty!" stammered Cyril, interrupting. "It's because—we want to go our own way—at home we—" he stopped in order to shake off Dulcie, who was tugging at his jacket.

"If you please," asked Dulcie shyly, "what advice?"

"It would be exactly contrary to the Wizard's," and the Fairy looked serious.

"Thanks very much," interrupted Cyril; "but we do want to seek our fortunes—to go on our adventures. It's a grand thing to do," he explained, "specially for her—she's a girl. Besides, we can't cross the Brook as children."

"Don't use those catseyes and it might be possible; that is, if you are willing. Be warned! Let me carry you quickly to the other side and then run home," said the Bird-Fairy anxiously.

Cyril shook his head, so Dulcie shook hers.

"It's always 'don't,'" he muttered. "It's sure to be all right, Dulcie," he said turning to her.

"Are you sure?" she inquired vaguely, with a lingering glance at the Fairy, who had turned away sadly.[21]

"It must be if we keep that last change as we arranged."

From the trees now issued forth sweet wood-birds of many kinds—the air was thick with them; they circled three times round the fairy ring and then all flew away, and the children were once more alone.

"Wasn't that beautiful? Ah!" sighed Dulcie, looking after them, "I wish I could be one of them and sing like them."

Hardly were the words out of her mouth when Cyril began to stare about in amazement. His sister was nowhere to be seen. Her disappearance was so rapid that the earth might have swallowed her up.

"Dulcie, Dulcie," he cried. "Wherever are you? Come back at once when I tell you!"

Nothing stirred in the stillness except the waving branches of the tall trees—and a little bird that came and perched upon his shoulder and began softly to trill into his ear what meant nothing to him. He stroked its smooth plumage. His hand touched something hard around its throat. He parted the feathers and found—a golden circlet set with catseyes, one of which was missing.

"Oh!" he exclaimed. "It's her!"

He was too flustered to talk grammar. "How fearfully quick the change came about—only just[22] a slight hint like that! I say! We shall have to look out! I wonder how you like it, you pretty little bird! I wish I could understand those chirping sounds!"

Instantly he became like her—a lark. He understood her at once, and the pair flew away, singing gaily as they rose together, fluttering up and up, soaring high and ever higher into the blue azure of the cloudless sky.

Never was there such a blissful sensation as that, flying heavenwards to the music of their own making. Dancing at a party to the accompaniment of a piano was mere ordinary child's play compared to the invigorating delight of this new experience. The earth looked like a map, and they realised now what was meant by a "bird's-eye view." After a time, still singing, they dropped quickly down to earth. Then Cyril led the way into the Wood, where they perched in one of the highest trees; and they hopped about, scanning their surroundings, and awaiting the visits of other little feathered inhabitants whose acquaintance they expected to make. In the meantime they gleaned various scraps of news from certain twitterings in the adjoining branches, some of which they clearly overheard.

And it came as a shock that these twitterings were mostly complaints about the scarcity of provisions;[23] about starvation among the weak birds who could not compete against the strong; about the unfair scrambling for tit-bits which caused grievous bodily hurt. Then a painful rumour was discussed about poor little Mother Starling, who had been taken unawares by a wild beast with terrible whiskers who was seen to pounce upon her and carry her off—and her husband, who still went about vainly calling his mate and would not be comforted. They heard how, in the hospitals under the hedges, things were in a bad way—how one patient was down with a broken wing, with no hope of getting well in time to migrate; and of others incurable, and resigned.

All this so depressed the two joyous young larks that they flew some distance away, when through the leaves they discovered in the tree next to them nothing less than the beautiful Bird-Fairy reclining asleep in the branches with her retinue of little sprites in various attitudes all around her, their shining eyes wide open, on guard.

The absolute silence proved too monotonous for our lively pair. So away they flew again—miles and miles away into the open country, enjoying to the fullest freedom found at last, feeding in the sun-gilded fields, drinking from the pools, bathing in the sandy roads, and flying for all they were worth in their youthful spirits. Life like this was life indeed![24]

Their happiness seemed complete, when a sudden sense of horror struck them both at the same moment, and hardly had they realised it when they noticed something very large which had been poised above swooping towards them, striking terror into their souls as it came. It was a sparrow-hawk, and death was upon them. Instinctively they swerved out of its terrible course, and commenced a series of short, zig-zag flights, their eyes starting nearly out of their little heads with fright. The enemy was strong on the wing and remorseless in purpose. The poor larks, with hearts fluttering wildly, were becoming feeble and less alert. The next second the hawk would seize one of its prey. The little bird gave an agonised chirp, dropped like a stone to the ground, and changed into Dulcie, affrighted and panting for breath. She looked anxiously upwards. Her pursuer, baulked, turned and darted upon its second quarry. Too late! Cyril had taken the strong hint, had also Wished, and now stood in safety on the ground beside her.

"Come on!" he shouted to the surprised and baffled enemy. "Come on now, and I'll wring your ugly neck!"

But the bird didn't wait to accept his polite invitation; and a moment later it was out of sight, and out of mind, and the children[25] found they were again alone in the beautiful glade.

"I don't want to be a bird any more," said Dulcie when she had recovered her composure.

"No, it's too risky," admitted her brother. "When that big dark thing came in sight there was so little time to think what to do. That second, too," he added with a shudder, "when I thought the brute had got you, was too awful!"

She felt quite important now at having gone through such peril.

"I could never have imagined that birds had such a lot to put up with," mused Cyril as they walked on—"hunger and suffering, with the risk any moment of being gobbled up!"

"There ought to be some one to take care of the poor things," remarked Dulcie. "If it hadn't been for the catseyes we should have been eaten up and ended like that." She glanced at the bracelet on her wrist and added, with a timid look at her brother, "It seems safer as we are."

"Bosh!" he rejoined. "We want adventures. That's what we're going for—and freedom. We had a ripping time as larks—till the end. It certainly wasn't very comfortable then."

[26]

CHAPTER IV

THE LOST CATSEYE

Something was in their path; the Twins stooped to examine it and found it to be a Hedgehog standing on its hind legs, motionless, as though waiting for somebody, and a smile was upon the face of that Hedgehog. All at once a Porcupine sprung up beside it, as if out of the earth, and the two appeared on the very best of terms.

"I must get to know what they are talking about," exclaimed Dulcie. "They seem to me to be arguing about something interesting. Oh, I do wish I could be all ears and understand them! If only I were something as small as a mole!" Before Cyril could remonstrate a mole she was, went off blindly, and was quickly lost to view amongst the thick brushwood.

"I say! I do call that mean," he complained. "Without even so much as asking my advice or saying good-bye. It's silly to become a stupid mole; it's a waste of a catseye. And all on account of a beastly spikey hedgehog and a beastly[27] prickly porcupine. Halloa! Wherever have you all got to?"

Out of humour, he looked right and left. They were nowhere to be seen. "I hope she will soon come to her senses!" he muttered. "It isn't much fun being left like this."

He lay down on his back to await her, and kicked up his legs in the air as a pastime, whilst the tall trees above him waved their upper branches in the breeze. His glittering bracelet caught his attention, causing his thoughts to drift on adventures past and to come. He looked harder at it, and becoming concerned he carefully counted the missing catseyes. He had only wished to be a lark, and to be himself. Yet THREE were gone! The two first—and the last one! "Could this," he asked himself, "be some dreadful trick of the Wizard's—likely to occur at the last?" Cyril turned pale at the possibility. "Or could that last one have become loose and got lost?" he pondered. If so, he realised that it must be found. The thought about the Wizard worried him. He was uneasy, too, about Dulcie, and sat up eagerly listening for her coming, and wondering what he had better do.

Meanwhile, our little mole had groped its way to a hole whence could be heard sounds of a quaint voice. It was that of the Porcupine saying pretty[28] poetry softly to the accompaniment of a slow musical titter.

Strong, elegant, and dandy;

And you a Hedgehog, bright as wine,

And sweet as sugar-candy.

Dear Hedgehog fair, say you'll be mine

And wed the dandy Porcupine!

Dear Hedgehog—bright as currant-wine,

Take me—as strong as brandy,

Be Mrs. Porcupine, I pray—

I've begged so often—don't say nay—

Be Mrs. Porky, sweet and jolly.

Nay—titter not,

Or off I'll trot

And straightway marry Molly."

"Ah!" he observed after a long pause, during which the Hedgehog had remained silent and had never moved a quill in response, "There goes Molly the Mole!"

Molly the Mole, who had distracted his attention, heeded him not, but went and struck up an acquaintance with the little stranger in the hole close by. For some time they remained in close conversation. It was not at all an amusing conversation, as Dulcie explained later, and she was not sorry when the danger of a horse's hoofs galloping nearly on top of them caused them to run off. They got separated, and Dulcie was glad to bring herself again into the[29] possession of her own five senses. Peeping from behind a tree, she saw Molly and the Hedgehog walking off together, leaving the Porcupine disconsolate. And then she beheld a young girl with short red hair dismount from her horse, walk back rapidly towards some glittering object, and pick it up.

Dulcie recognised at once the curious colouring of a catseye. She glanced at the bracelet on her wrist; all was in order there. Could it possibly belong to Cyril? The thought became a certainty. "Stop!" she called out loudly.

Too late—horse and rider were off.

"Stop! Stop thief!" shouted Dulcie as she ran after them as fast as she could.

Now Cyril, who was not the soul of patience at any time, had come to the conclusion that it was of no use waiting any longer, and that it would be better to be up and doing. So he got up and pondered again and again what to do.

"Any way I'd better risk it and become a cat," he decided, "for like that I've more chance of finding Dulcie, and of finding my catseye. It would be useful to be able to see in dark corners. But I'll search about as I am first."

He spent some time peering and searching in the Wood. But without success. Neither Dulcie nor the catseye was to be found.[30]

Just then he heard a noise. He stepped behind a tree, and peering round from behind it he beheld not far off a young lady dismount from her horse and pick up something. Cyril recognised it as his catseye. He approached timidly to claim it, when she leapt up and cantered off, evidently not seeing or hearing the boy who was running, shouting with lusty lungs: "Stop! Hi! Stop thief!"

Little did he know that his little sister, almost exhausted, was further behind gasping out the same cry—while big tears from helplessness and anxiety were coursing down her hot cheeks. For the trees hid the children from view at the distance they were apart, as well as from the rider; and shout as they would, their cries could not be heard by one another.

Cyril soon lost sight of the new owner of the gem, and didn't know what to do, or where to trace it, or, still worse, what had become of Dulcie. As he came to a narrow footpath which branched off from the main track, he went quickly along it in the hope that it might prove to be a short cut to somewhere. As it turned out he was lucky, for it proved to be a short cut to a Town, and hardly had he entered one of the streets than at the other end he saw entering it the rider on her horse. He ran towards her, but only arrived just as the girl with red hair disappeared through the door of a large white house, and the horse was being ridden off by her groom.[31]

So Cyril sauntered on, anxiously meditating how to get his belonging back. The present possessor would never believe his tale, or if she did the less likely would she be to part with a thing so valuable—and then perhaps only for a hundred pounds. He concluded he must take it—it was his—at least it was more his than hers, and his life might depend upon it. So he decided that the best thing he could do was to change into a monkey, climb into the house by one of the open windows, grab the gem as soon as found, and escape as quickly as he could.

But no sooner did the quaint little monkey stand there than it was pounced upon by a dirty brown hand, whilst a foreign voice exclaimed—

"Ah, ha! So dere you are, my leetle friend! You shall not escape from me again so soon, Jacko. Ah no!"

It was a ragged boy with a hurdy-gurdy, who had caught hold of the little twisting, mouthing creature and was already getting it into a miniature soldier's coat with brass buttons. A ludicrous doll's hat with a long feather upstanding was quickly produced from his pocket, put on its head, and the elastic slipped under its chin. A long cord was whipped out, fixed to the red coat, and a sudden jerk hitched up the whole arrangement on to the barrel-organ in a twinkling.[32]

Now Dulcie had also taken the short cut into the Town, and was just going to enter a large garden in order to rest her weary limbs after her useless chase, when the boy and monkey attracted her attention and she stopped. She would have laughed, so comic was the sight, but filled with concern at a rough jerk she cried: "Oh, please don't. You'll hurt it. Do let it go!"

"Let go, signorina? Ah no! Me take care never risk no more. No Jacko, then poor Pietro starve. Just you watch him, then give poor Pietro penny. Now, Jacko, we're 'ungry."

Had Dulcie only known the monkey was not Jacko, but Cyril, she would have been still more concerned. The lad turned the handle of the instrument, and to its cracked tune she was amused to see the monkey take off its hat with a jerky movement, replace it, dance about, salute, and perform other antics in the most approved and undignified manner.

The boy pulled his forelock. After much fumbling Dulcie found a penny and gave it to him. A sunny smile was on his swarthy face as he said "Grazia!" He kissed the monkey affectionately, and putting it in the inner pocket of his ragged coat, moved away.

And the monkey, peering out of that pocket, blinked twice so meaningly at Dulcie that she[33] stood there and gazed after it, puzzled, whilst the boy trudged off whistling. Dulcie then found a shady seat, and having nothing better or more hopeful to do, determined to rest there. Now, however, that she had leisure to think it over, she didn't at all like the loss of that gem. Supposing by some trick or other of that horrid Wizard all the rest should drop out and not be found—at some dreadfully awkward moment! What would poor Cyril do? And she also might come to be in the same plight! These thoughts were too horrible! So she began saying some poetry she had learnt in order to keep her mind on other matters.

She wasn't enjoying herself very much. The time seemed endless, and a neighbouring clock which chimed the quarters didn't help it to pass any faster; and the longer Dulcie waited, the more anxious she became. She gave up reciting poetry, or what stood for poetry, and her only thought became: "If only Cyril would come back!" In her fear she began to give up hope of his ever coming back at all, and decided to try and discover if there were such a thing as a policeman about, to whom she might confide her troubles.

Suddenly there arose a hullabaloo. Such a barking and rushing, and the next moment a large[34] black cat sprang on the seat beside her, frightening her very much. There was a terrified shriek—a gratified Wish—and Cyril found himself on a bench next Dulcie with a great hound clinging to his sailor collar at the back.

With a cry of fear she helped him in his struggles to get free; the animal, astonished and abashed, slunk away with its tail between its legs, and the brother and sister fell into one another's arms. Never before had they known how fond they were of one another—for never had they been so pleased to meet again.

"I waited so patiently," said Dulcie; she didn't add anything about thoughts of a friendly policeman, but inquired quickly—

"Do you know you've lost your catseye?"

He nodded and grinned.

"Have you got it?"

He parted his lips. It was between his teeth. He pressed it back into the empty setting of his bracelet, saying—

"I'd no time to wish sooner. I'll never set Towser to chase our poor little Miranda again, you bet! How horrid it must be to be a permanent cat!"

"However did you get it back?"

"Hallo! Hi!" was all she got in answer, and the next moment he was pommelling into, and being pommelled by, a lanky youth.[35]

"I'll teach you—to shy stones—at a—poor defenceless—cat," gasped Cyril, hitting out right and left, his face scarlet, and his hair all ruffled. How they did go for one another! First one was down and the other on top; then the pair, all legs and arms, were the other way up; then they rolled together over and over, till at last Cyril had won a brilliant victory before he allowed Dulcie to drag him away from the defeated adversary, who, as soon as he was free, slunk off miserably, with one hand to his eye and his handkerchief to his nose.

"I'm all right," exclaimed Cyril, in answer to her anxious inquiry, shaking himself into order. "That was a lark! No—I'm not hurt, not really. Served him jolly!"

Dulcie noticed that he had a lump on his forehead from the fray.

"I'm glad you won the fight with that boy, but I don't know what it was about one little bit. And, Cyril, aren't these adventures rather too—too dangerous, don't you think?"

"Of course they're not, they're awfully jolly."

"Now tell me all about it from the very beginning," said his sister as they strolled off together. So Cyril gave her a spirited record of his adventures whilst she listened eagerly, anxious not to miss a single word.[36]

"I'll begin at the beginning," he said. "Well, the funny monkey—me, you know——"

"You, Cyril?" and Dulcie gasped with surprise.

"Yes; don't interrupt, there's a dear. I quite enjoyed my little performance on the organ before you. But by the second and third time I had to do it I got sick and tired of it. The weather seemed to turn cold and made me shiver. Then I got fearfully hungry—coppers were given me, but no food did I get, and I felt I had had enough of the business. The boy's pocket, too, was draughty—there was a hole in it—besides which I got the cramp. It wouldn't have been much use trying to escape. Besides, the monkey idea was all wrong, for people were passing all the time, and, had they noticed a free monkey on the track of a catseye, a crowd would have collected, and perhaps that grinning idiot might have gone for me again. I couldn't very well change to myself inside of his jacket, nor during a performance in public, as it might have attracted attention. So I was obliged to wait for my chance, which came at last when he picked up an end of a cigarette and after begging a match was busy lighting it at a sheltered corner. I was on the pavement in a minute, managed to slip out of my idiotic red coat to which the cord was attached, flung off that absurd hat, and remembering[37] my first idea I changed into a cat, calmly sat down on the inner side of some area railings, and peered through to watch the fun."

"Yes, and what happened then?" interrupted Dulcie excitedly.

"Well, you never saw such a face as that boy's when he found the monkey's coat and hat on the ground without any monkey inside of them! He said some foreign words and commenced running about hunting for me everywhere, whilst I trotted off before his very eyes. Ha, ha, ha!"

His sister pealed with laughter and delight.

"As quickly as possible I reached the big house where I had seen the girl with the red hair go in after she had picked up my catseye."

"I saw her pick it up, too," broke in Dulcie.

But Cyril went on: "The windows were still open. I jumped up from the balcony on to a stone ledge, and then by good luck right into the bedroom of that bothersome young lady. She was reading a book. We did startle one another!

"'Oh, you darling sweet pussikins!' she said. 'Ah,' I thought, 'not so darling as all that.' And the next moment I was lifted clumsily on to her lap and stroked and patted, whilst I looked anxiously around for my catseye in the intervals—when she wasn't kissing my nose, which was disturbing and uncomfortable, and girls do like kissing[38] so. Then I saw it gleaming on the dressing-table close to the window all the time, and I became impatient. The stupid baby language and kisses bothered me, so I stopped it by giving her face an ugly scratch."

"Oh, how rude!" exclaimed Dulcie, shocked.

"Whereupon she gave me an angry slap, which I didn't feel a bit through the fur, and pushed me down roughly on the floor, looked at her face in the glass, and then I heard her bathing it in the dressing-room. I say! had I changed then, wouldn't she have been jolly surprised to find a strange boy in there! So, remaining her darling pussikins," he continued with a smile, "I just jumped on the table, took hold of my catseye in my mouth, and escaped by the window before she returned, and waved my tail in good-bye—stupid things, tails!" With a laugh, which was echoed by Dulcie, Cyril, grown serious again, went on with his narrative:

"But just as I alighted on the ground a boy began shying stones at me, which it was awfully difficult to dodge. One of them caught me such a whack on the side, and he laughed and shouted 'Hurrah, got him!'—Wasn't I glad when I saw him just now!—Well, I was just going to change then, when there was a great barking, and a whole lot of dogs seemed to be bearing down on me. I[39] thought I'd make myself scarce, so I tore off, and as they were on my track I simply cut. I flew along the muddy streets with the whole pack at my heels, with shouts and laughter ringing in my ears, scampering past them, past houses, past traffic, whizzing along for my life with the barking din and the pattering feet always following. At last, as a last hope, I dodged round, doubled back, the noise stopped, and I took refuge in a quiet garden, awfully puffed, and jumped on a seat next some one resting there."

"Me," said Dulcie, with a sigh of relief.

"Yes, I found it was you, Sis. I Wished, and you're a trump, for I was tired, and you rid me of that big dog." Dulcie glowed with pride and pleasure at that. "I never knew, though, that that brute was following me. Fortunately for me he gripped hold of the bracelet round my neck."

"How well you tell a story, Cyril," she said simply.

Cyril smiled contentedly. "That's nothing."

Then she inquired anxiously: "Do you think it was the Wizard's trick, that losing of the stone?"

"P'raps," replied Cyril musingly. "He's quite ugly enough for anything. But I don't think so," he added reassuringly; "it must have been an accident—got loose, or something."

Dulcie's mind being eased, she then told her own story as a mole. She couldn't remember the[40] Porcupine's verses exactly, but she repeated what she could, and they had a good laugh over them;—before, she had been blind to the fun in them. "I repeated them to Molly," continued Dulcie, rippling over with fun, "and she was so offended she vowed she'd never marry him. So I cured him of his vanity—and serve him right!"

"But why did the Hedgehog titter? That was what you wanted to find out, wasn't it?" asked Cyril.

"I suppose it was expecting the Porcupine's verses."

"Suppose?"

"I forgot to ask."

Cyril expressed his opinion that she had been a softy, that those creatures weren't worth while chumming up with, and they couldn't have much sense, and it didn't matter, after all, what they thought or did.

"I shan't tell you any more, then," replied Dulcie, offended.

"Yes, do," begged Cyril, curious to know the end. So after he had begged three times, she gave way, and informed him she was glad never to have been born a mole, for Molly was in terribly low spirits and had apologised for them, but the reason was because all her family's skins had been taken off their backs in order to keep fashionable ladies[41] from taking cold—as these ladies seemed to think that it was a prettier and warmer skin than their own. And Molly hourly expected each moment to be her last—and advised her new-found friend to prepare for the same fate—which was all very terrifying. "So I made haste to wish to be my own self again," concluded Dulcie.

Cyril made her promise faithfully never again to run off like a mole or anything else, which—being only too anxious to avoid another separation—she willingly did.

"The poor animals," she remarked earnestly, "all seem so helpless. There's no one ever to take their part or help them."

"Ah, you think that because we've not yet changed into something really great," answered Cyril with conviction.

"What a gloomy looking place we've come to! I was so interested listening and talking, I didn't notice the way we've come," broke in his sister, gazing at what appeared like a Jungle in front of them. "Surprising how we got here, isn't it?"

"I never noticed either, but it'll do beautifully," replied the boy, quite satisfied.

"But it doesn't seem very nice to be a Beast," argued Dulcie reflectively, her thoughts harking back; "somehow it's so unpeaceful."

"I tell you that's because we haven't tried[42] anything great," repeated her brother with an emphatic movement of his hand and a decided toss of his head. "If," he said, and hesitated—"if we were lions" (he waited, then finding they were both as they were he went on, reassured), "then we would know what it is to rule everybody, keep our friends in order, and eat up our enemies."

"But I don't want to eat up any one," protested Dulcie. "I think it would be very disagreeable."

"I should think it must taste rather nice—they like it. Besides, one never knows till one tries," remarked her brother. "I want to be a lion!!"

At once the King of Beasts confronted Dulcie. With a shriek she tore away as fast as her small feet could scamper. Then she changed her mind. And as a lioness, full of courage, she rejoined him.

Grand beasts they were as they bounded into the Jungle with a mighty roar. Startled creatures hurried out of their path, and the very landscape appeared insignificant in their presence. Monarchs of all they surveyed! This at last was splendid freedom.

At a river, sparkling like glass in the burning sun, they stopped and slaked their thirst, lapping up the water greedily. Then they turned again into the tangle of vegetation and laid themselves down to rest.

Purring with delight in the hot sunshine, they[43] lazily lashed their tails. The lion was just dozing when he was roused by something heavy and strong winding itself in great coils around his limbs and body. He gave forth a roar half of anger, half of fear. Struggle as he would he could not free himself; it was a huge boa-constrictor that was closing about him like bands of iron, and was just about to crush him to death when the lion disappeared and a little boy in a blue serge suit wriggled away, sobbing out: "Oh, Mother! Dulcie!"

Just then Cyril's eye caught sight of a rifle pointed from a neighbouring tree. To his horror it was aimed straight at the recumbent, lazily-blinking lioness. His heart stood still with terror. He could neither scream nor stir. Quite forgotten was the huge reptile, which had jerked back its head in astonishment at the remarkable disappearance of its quarry, with an undulating movement of surprise in that part of its anatomy which might be termed its neck. But now the creature was quite close to the lad and rearing itself up to strike at him when—crack! crack! crack! Bullets were whizzing all around. Cyril, bewildered, stumbled over the dead body of the reptile and fell to the ground. The next moment he felt Dulcie's hair over his face as she pulled him on to his feet.[44]

"Great snakes!" exclaimed Lord Algy. Captain Waring, who was eagerly peering through the branches of another tree close by, laughed as he rejoined, "Only one, my friend."

"Eh, what? Well I'm—" drawled his lordship, craning his neck and letting his eyeglass drop and dangle—he had stopped short in his sentence, not seeming quite to realise what he was. "By Jove!" he now added, "I certainly thought I hit one of those two fine brutes; most remarkable thing I ever saw in my life."

"Didn't see, you mean, my dear Algy," replied the Captain coolly and not without vexation. "I've seen a dead serpent before. Where have they moved to? that's the question: we shall have to track them again. A dead snake in the grass is not worth two fine lions in the Jungle."

"No, my dear fellow, I don't think so either—I agree with you there—it's quite the contrary, of course," remarked his lordship with a certain amount of energy.

Meanwhile, Dulcie and Cyril, with white, scared faces, were fleeing hand in hand like pixies among the trees.

[45]

CHAPTER V

IN THE FISH-KING'S REALM

It was only when they reached a meadow full of wild flowers, and the Twins, worn out with their long run, lay down to rest, that Dulcie remarked with a sigh of relief—

"We never do seem to be so safe as when we are us!"

"We won't be Birds nor Beasts any more," replied Cyril. "Hark! What's that snoring so loud?"

"It's not snoring. I believe it's the waves!" Saying which Dulcie jumped up and Cyril did the same. The children found the meadow they were in was on a cliff, and that below were far-reaching sands, and in the distance heaved the glorious deep blue sea.

They clapped their hands and danced with delight, and when that performance was over they carefully descended the steps cut in the face of the cliff which led down to the shore.

Very soon their shoes and stockings were slung round their necks, and they were running over the[46] hot sand to where the wavelets came rippling to meet their little feet.

So immersed were they in paddling that it was a little time before they noticed some one sitting amongst the rocks which peeped out of the surface of the ocean a short distance away. A hand was beckoning to them, and thinking it might be some one who wanted help, Cyril declared he would go to the rescue, and began to wade towards the spot.

Dulcie, fearful of his going alone, and not wishing to be left behind in the adventure, hurried next to him. The current was rather strong and the water got deeper as they went; but they didn't think of their clothes (which were no longer wholly dry), but only of the rescue. When they reached the rocks they found to their surprise a very quaint figure calmly seated there, who motioned them in a very grand manner to a place on each side of him. "Pray be seated. Good morning!"

"Good morning!" exclaimed the visitors politely, taking the places indicated.

"Good afternoon!" said the Fish-King. "Do you mind holding my crown one moment, my dear?"

Dulcie took it with awe. He was a very fine gentleman indeed, and the two children couldn't[47] help staring at him as he smoothed his hair in silence. He was short and stout, in a costume not unlike that of Harlequin in the pantomime, only the colouring was green and blue. His goggle green eyes and wide, down-drawn mouth made him look comically like a carp, whilst the pointed wisp of white beard on his chin and the four long white hairs he was winding round his bald head were not really an improvement to his appearance.

"Thank you kindly, my dear," he said as he took his crown and put it on. It was beautifully made, entirely of the loveliest small shells, and when he wore it he looked every inch just what he happened to be.

In spite of his queer face, the two visitors felt quite at ease with him, and were sure that with such a pleasant voice, too, he must be very nice indeed.

"What are you King of?" inquired Dulcie with a friendly smile.

"Of the fish," he answered, patting her cheek. "I'm right glad to see you."

Suddenly remembering, the little couple at once donned their shoes and stockings as a sign of respect.

"It's very healthy, I suppose," remarked Dulcie, "living out at sea like this?"

"I suppose so, my lady," answered the Fish-King[48] drily. Dulcie liked being called "my lady." "Except," he continued thoughtfully, "for an occasional attack of shingles I don't ail much." Then turning to Cyril he asked: "How's that old rascal of a Wizard? laughing in his dressing-gown, eh?"

"I'm sorry I don't know, your Majesty," replied the boy, surprised at the question and the way it was put.

"You will soon get to know me. I only hope you may not be disappointed. You certainly wouldn't have been disappointed with my ancestor."

"Who's your ancestor?" asked Dulcie bluntly. "Was he a King-fisher too?"

"Not at all. He was Neptune."

"Where did he live?"

"In Imagination."

"Where's that?"

Cyril raised his eyebrows at her lack of manners.

"You turn to the right," answered his Majesty patiently, with a gesture that way, "follow your nose, mount a hill north of the Fore Head, and there you are. See?"

The Twins couldn't think what answer to make—though he seemed to expect one—so they gave a little nervous laugh.

"Just see, there's a dear boy," said the Fish-King[49] kindly, in order to change the subject—"just see if you've got a copy of the Financial Market about you, will you? Or maybe you know what the Financial Time is? That would do quite as well. Oh, beg pardon—I see you've no watch on; pawnbroken, eh?"

"I'm afraid I don't know what you mean; I've never heard of all that," admitted Cyril.

"But you have heard there's been another slump!"

"What?" ventured Dulcie.

"In what? Why, in Seaweed, of course. Just my luck. Fishy transactions never do pay, though they always promise to. But," he added, rousing himself, dismal still, "you must both come down soon and have a cup of sea or something—it's my birthday, and there's going to be jinks below."

"Birthday! How delightful!" said Dulcie.

"Why, how old can you possibly be?" asked Cyril, "if it's not impolite to ask."

"Quite right. Let me see," said the Fish-King thoughtfully. "Ah, now I remember. I'm just several millions of years—it takes a little time to fix the number exactly—and eleven days."

"That is old, Sire," murmured Dulcie as she regained her breath, which had been taken away at the idea of so many birthdays.

"Old? Nonsense, my lady."[50]

"How can it be 'and eleven days' if it's your birthday, your Worship?" asked Cyril, thinking he'd go one better than Sire.

"Because, my Philosopher, I prefer the new-fangled Calendar which puts one on eleven days; in that way, when I'm told I don't look my age, I know it's true, and not flattery. See?"

The children were not quite satisfied with the explanation. Nevertheless, they were pleased to find it the most natural thing in the world to be getting chummy with a Fish-King.

"Now, do come below waves and have a cup of sea or something," he repeated, looking appealingly first at one and then at the other.

"Thank you very much," replied his little guests. "But," said the cautious Dulcie, "sha'n't we be drownded?"

"You both have your catseyes on, I presume?" And his Majesty stared anxiously in their faces. "Yes, I see you have. Very well, then. Sit steady! Halloa there," shouting downwards. "Lift, please!" Then muttering, "It's high time we went," he smiled. His smile was so unutterably comic that it was to a merry burst of childish laughter that all the rocks descended as quickly as the tide rose above them, and the trio, smiling still, found themselves gently deposited at the bottom of the Ocean.[51]

"Wonderful thing water pressure!" remarked the Fish-King. Then, helping them off the rocks, he added with a gracious wave of the hand, "Welcome to my Domain!" And the Twins bowed so prettily that he appeared much gratified.

"Ah!" he said, taking them by the hand and stopping still, "I see Fido. Fido, Fido!" At his call a fine dog-fish came forward at a fast swim; and its head was patted graciously, whilst its tail wagged with contentment. "Now," resumed his Majesty, "we'll go to the Revels;" and they proceeded at a smart walk as buoyantly through the clear water as through air.

The sea-scape was perfectly beautiful, but as the Fish-King once more seemed deep in melancholy, the Twins gazed silently around. They were evidently walking along the King's Road, for it was wide enough to walk three abreast; the sand was so fine and glittering that it looked like gold dust; the path was bordered by exquisite shells. On either side were gardens of variegated anemones. Here and there an old sodden boot lay about untidily, at which the Fish-King frowned and looked uneasy. They passed oyster beds, where, besides oysters, all sorts of fish, large and small, were fast asleep, breathing heavily with their mouths wide open. Now and again a squadron of lobsters or jelly-fish would confront them, and respectfully[52] divide and wait until the royal procession of three had passed through.

At last they came to a great object ahead which turned out to be a sunken ship, and the children heard the Fish-King say: "Welcome, my dears, to my home! I hope your visit to 'The Billows' will please you." They eagerly assured him it would, for they felt certain they were going to have a jolly time.

On board everything was most snug and trim; and in the large saloon he led his two little guests to one end of the long table, where they found biscuits, tinned meats, jam, and other nice things, which they enjoyed very much, whilst their host looked on with a satisfied expression.

"Now will you take a cup of something?" he asked—and seemed relieved when they declined with thanks. "I'm a seatotaller myself," he observed; "I don't drink like a fish, nor go in for cups."

"I'm glad we said 'No, thank you,'" whispered Dulcie to Cyril, who nodded assent. "Why are you so sad, Mr. Fish-King?" she asked when she had satisfied her hunger, and she stroked his great flabby hand.

He didn't answer for a moment, then trying to twist up his mouth into a smile he said as he roused himself: "I fear I'm somewhat glum for a birthday party, but I've had so many of them; besides, I'm [53]bothered about the slump! One would think Seaweed safe enough for a vested interest, surely. From all accounts, they must have been cooked—softly, too, in the bargain! Can you make it out, my dears?"

Its head was patted graciously

The Twins couldn't understand it at all, and shook their heads quite emphatically over the matter.

"Now, let's go abaft," suggested his Majesty. He rose, and looked at them with a ray of cheerfulness. "We'll watch the Water Sports. I revel in them when they are good—usually they go bad."

The children readily agreed. "It's lucky you happened to come on my birthday," he continued, "for you may be amused. Here's a list of the different Courses," and he took up a Menu from the table: "they'll race through them like old boots!"

"Do they race better than new ones?" inquired Cyril.

"They've more experience," replied his Majesty. "What is about to begin," he said quite gaily as they followed him up the gangway, "is—let me see; ah yes—'Turtle Mocked.' Now just look at Fido"—he leaned over the side, the Twins did likewise. "He's turning turtle!" And the three watched with approval the antics of the dog-fish as he turned his somersaults; and they applauded this first item on the programme.[54]

"Next Innings!" shouted his Majesty. "Fish balls bowled," he read from the Menu. And taking their plaice, a game of cricket began. "They think they can play," he whispered, "and that is the way I humour them, or they might begin to cry, and I hate anything that reminds me of blubber. But how can any one in their senses imagine plaice fielding at slip? Why, they don't know cricket from a bat—nor never will at this rate, I should think."

"Once in London, we saw such a lot of fish in the big shops there," volunteered Dulcie in a burst of confidence. The next moment she wished she hadn't spoken, for Cyril was frowning at her and shaking his head. She glanced timidly at the Fish-King. He evidently didn't mind, for he merely remarked with a sigh: "Ah dear! One of these days my poor subjects will be sucked from the sea through a 2d. tube, straight to Billingsgate—I suppose that'll be the time for slumps and no mistake!"

"I suppress the Sole and Eel Course!" he cried suddenly. There was a great stir in the water at this intimation. "It's a dance," he muttered. "Let's get on with the Cod Stakes." He put down the Menu and threw overboard some nets and fishing tackle. Then began a highly amusing exhibition by old fish showing the young ones how to nibble the bait without taking the hook, and if taken by[55] some mischance, how to get unhooked—how to avoid the nets, and other life-saving dodges which his Majesty explained to the astonished Twins.

But hardly had he finished when a fat young gurnet who was taking part in the sports did get hooked, and clumsily extricating himself went off leaving a thin red track behind him.

"The poor thing is hurt!" exclaimed Dulcie.

"Oh no," said the King; "a herring-bone stitch is all that's necessary."

"I know how to do that," replied Dulcie, "but I thought it was only used to make dress things look pretty; I never heard of it for mending fish." The excitement continued unabated.

When the revels were over, the little strangers expressed their enjoyment of the birthday party, and thought perhaps they ought to be saying good-bye. Their kind host wouldn't hear of their going yet—they hadn't even seen the Cable which he was just going to visit.

"Who's won the prizes?" asked Cyril as they got off the ship.

"I have," replied his Majesty.

"Not the winners of the races and of the sports?" said the boy, in amazement.

"They can't expect to win the races and win the prizes too. I have won the prizes."

"What have you won, your Worship?"[56]

"I forget," he answered vaguely. "I've won so many in all these years, and they get so mis-laid—for all the world like addled eggs!"

"But you've only just—" commenced Cyril.

"Don't tease," said Dulcie, pulling at her brother's sleeve. And so the matter dropped.

Whilst Cyril and the Fish-King were talking about the price the crown might fetch were he obliged to part with it on account of his recent financial losses, Dulcie was so busy admiring the beautiful creatures swimming about, that she stumbled and fell before her companions could warn her that the Cable was lying in her path. She was soon up, and it was the Fish-King now who was lying prone on the ground, but his attitude was intentional; he was listening intently. At a sign from him they did likewise. The billows overhead were lashing up the spray, and through the rushing sound could be vaguely heard: "Number A. 1. Sea Power! Has that nice little venture proved successful, Sire?"

It was the Wizard's voice. The Twins stared at one another with startled eyes.

"No, thou Cabalistic One," shouted the Fish-King, and got up with an impatient sigh, so he didn't hear what sounded like the echo of mocking laughter which the children recognised before they rejoined him. "Some one's at the bottom of[57] that business, I'll be bound," he grumbled. "I'm afraid I'm too green, and ye gods and little fishes alone know how I manage to be, for I've a fit of the blues often enough," and he glanced at the garment he wore. "Now come and inspect my Workhouse." He led them away in silence to a small lugger, also wrecked, commandeered by his Majesty.

"What a lot of residences you have, Sire," remarked Dulcie timidly, realising the situation.

"One must, if one is a royalty," he replied. "I have even more than the German Emperor. I've one for eating in. One for thinking in. One for not thinking in. And a host of others. There is one which takes me eighteen hours to reach, where I go at cradle time, where the waves hush me to sleep with their lullaby—you have heard it—'Rocked in the Cradle of the Deep,' eh?"

"Yes, yes," assented the Twins readily.

His glum face slightly relaxed, then he continued: "It's always a matter of interest to me when my ship comes home. I don't whistle for it; I squall for it. Look out for squalls, for I feel restless, and in my family carping is our form of humour."