Title: From School to Battle-field: A Story of the War Days

Author: Charles King

Illustrator: Violet Oakley

Charles H. Stephens

Release date: October 9, 2011 [eBook #37672]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Suzanne Shell, Matthew Wheaton and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

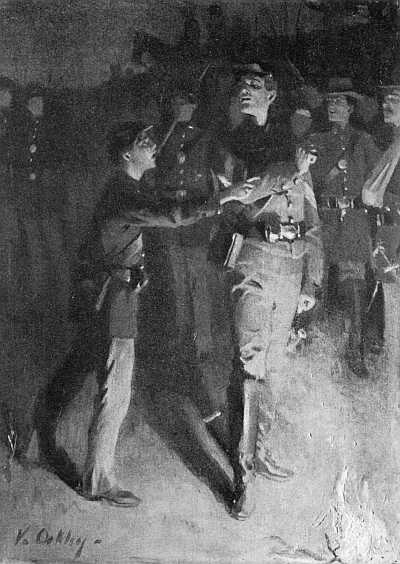

"Come down aff the top o' dthat harrse!" Page 257

A STORY OF THE WAR DAYS

BY

CAPTAIN CHARLES KING, U.S.A.

AUTHOR OF "TROOPER ROSS," ETC.

ILLUSTRATED BY

VIOLET OAKLEY AND CHARLES H. STEPHENS

PHILADELPHIA

J. B. LIPPINCOTT COMPANY

1899

Copyright, 1898,

BY

J. B. Lippincott Company.

Table of Contents

CHAPTER I.

CHAPTER II.

CHAPTER III.

CHAPTER IV.

CHAPTER V.

CHAPTER VI.

CHAPTER VII.

CHAPTER VIII.

CHAPTER IX.

CHAPTER X.

CHAPTER XI.

CHAPTER XII.

CHAPTER XIII.

CHAPTER XIV.

CHAPTER XV.

CHAPTER XVI.

CHAPTER XVII.

CHAPTER XVIII.

CHAPTER XIX.

CHAPTER XX.

CHAPTER XXI.

CHAPTER XXII.

CHAPTER XXIII.

CHAPTER XXIV.

CHAPTER XXV.

ILLUSTRATIONS

| PAGE | |

| "Come down aff the top o' dthat harrse!" | Frontispiece. |

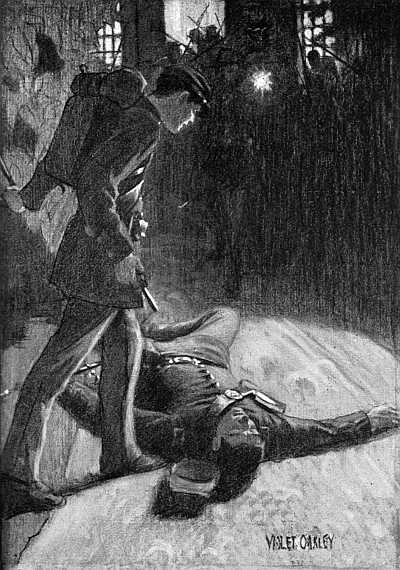

| Almost senseless, till Shorty strove to lift his bleeding head upon his knee | 30 |

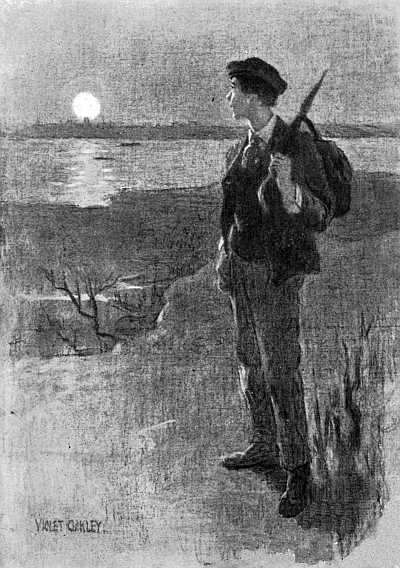

| "I couldn't stand it. I had to go" | 106 |

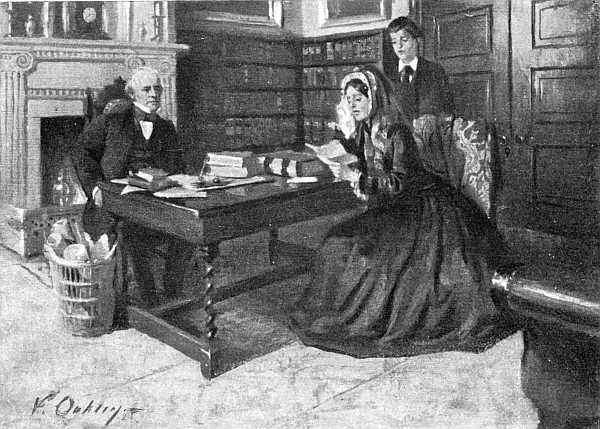

| She was permitted to read and to weep over Snipe's pathetic letter | 123 |

| First capture of the advancing arms of the Union | 221 |

| "Where'd you get that watch?" | 302 |

[9]

FROM SCHOOL TO BATTLE-FIELD.

"If there's anything I hate more than a rainy Saturday, call me a tadpole!" said the taller of two boys who, with their chins on their arms and their arms on the top of the window-sash, were gazing gloomily out over a dripping world. It was the second day of an east wind, and every boy on Manhattan Island knows what an east wind brings to New York City, or used to in days before the war, and this was one of them.

"And our nine could have lammed that Murray Hill crowd a dozen to nothing!" moaned the shorter, with disgust in every tone. "Next Saturday the 'Actives' have that ground, and there'll be no decent place to play[10]—unless we can trap them over to Hoboken. What shall we do, anyhow?"

The taller boy, a curly-headed, dark-eyed fellow of sixteen, whose long legs had led to his school name of Snipe, turned from the contemplation of an endless vista of roofs, chimneys, skylights, clothes-lines, all swimming in an atmosphere of mist, smoke, and rain, and glanced back at the book-laden table.

"There's that Virgil," he began, tentatively.

"Oh, Virgil be blowed!" broke in the other on the instant. "It's bad enough to have to work week-days. I mean what can we do for—fun?" and the blue eyes of the youngster looked up into the brown of his taller chum.

"That's all very well for you, Shorty," said Snipe. "Latin comes easy to you, but it don't to me. You've got a sure thing on exam., I haven't, and the pater's been rowing me every week over those blasted reports."

"Well-l, I'm as bad off in algebra or Greek, for that matter. 'Pop' told me last week I ought to be ashamed of myself," was the junior's answer.

And, lest it be supposed that by "Pop" he referred to the author of his being, and thereby deserves the disapproval of every right-minded reader at the start, let it be explained here and now that "Pop" was the head—the "rector"—of a school famous in the ante-bellum days of Gotham; famous indeed as was its famous head, and though they called him nicknames, the[11] boys worshipped him. Older boys, passed on into the cap and gown of Columbia (items of scholastic attire sported only, however, at examinations and the semi-annual speech-making), referred to the revered professor of the Greek language and literature as "Bull," and were no less fond of him, nor did they hold him less in reverence. Where are they now, I wonder?—those numerous works bound in calf, embellished on the back with red leather bands on which were stamped in gold ——'s Virgil, ——'s Horace, ——'s Sallust, ----'s Homer? Book after book had he, grammars of both tongues, prosodies likewise, Roman and Greek antiquities, to say nothing of the huge classical dictionary. One could cover a long shelf in one's student library without drawing upon the works of any other authority, and here in this dark little room, on the topmost floor of a brownstone house in Fourteenth Street, a school-boy table was laden at its back with at least eight of Pop's ponderous tomes to the exclusion of other classics.

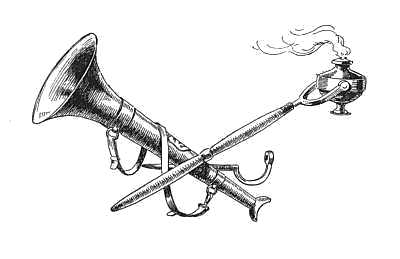

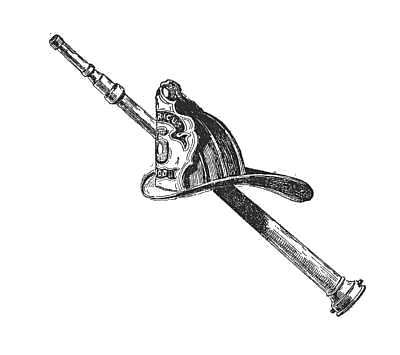

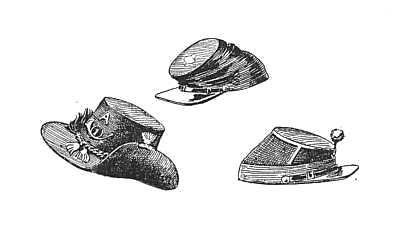

But on the shelf above were books by no means so scholarly and far more worn. There they stood in goodly array, Mayne Reid's "Boy Hunters," "Scalp Hunters," "The Desert Home," "The White Chief," flanked by a dusty "Sanford and Merton" that appeared to hold aloof from its associates. There, dingy with wear though far newer, was Thomas Hughes's inimitable "Tom Brown's School-Days at Rugby." There was what was then his latest, "The Scouring of the White Horse,"[12] which, somehow, retained the freshness of the shop. There were a few volumes of Dickens, and Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales. There on the wall were some vivid battle pictures, cut from the London Illustrated News,—the Scots Grays in the mêlée with the Russian cavalry at Balaklava; the Guards, in their tall bearskins and spike-tail coats, breasting the slopes of the Alma. There hung a battered set of boxing-gloves, and on the hooks above them a little brown rifle, muzzle-loading, of course. The white-covered bed stood against the wall on the east side of the twelve-by-eight apartment, its head to the north. At its foot were some objects at which school-boys of to-day would stare in wonderment; a pair of heavy boots stood on the floor, with a pair of trousers so adjusted to them that, in putting on the boots, one was already half-way into the trousers, and had only to pull them up and tightly belt them at the waist. On the post hung a red flannel shirt, with a black silk neckerchief sewed to the back of the broad rolling collar. On top of the post was the most curious object of all,—a ribbed helmet of glistening black leather, with a broad curving brim that opened out like a shovel at the back, while a stiff, heavy eagle's neck and head, projecting from the top, curved over them and held in its beak an emblazoned front of black patent leather that displayed in big figures of white the number 40, and in smaller letters, arching over the figures, the name, Lady Washington. It was the fire-cap of a famous engine[13] company of the old New York volunteer department,—a curious thing, indeed, to be found in a school-boy's room.

The desk, littered with its books and papers, stood in the corner between the window and the east wall. Along the west wall was a curtained clothes-press. Then came the marble-topped washstand, into which the water would flow only at night, when the demand for Gotham's supply of Croton measurably subsided. Beyond that was the door leading to the open passage toward the stairway to the lower floors. In the corner of the room were the school-boy paraphernalia of the day,—a cricket bat, very much battered, two base-ball bats that the boys of this generation would doubtless scan suspiciously, "heft" cautiously, then discard disdainfully, for they were of light willow and bigger at the bulge by full an inch than the present regulation. Beneath them in the corner lay the ball of the year 1860, very like the article now in use, but then referred to as a "ten shilling," and invariably made at an old shoe-shop at the foot of Second Avenue, whose owner, a veteran cobbler, had wisely quit half-soling and heeling for a sixpence and was coining dollars at the newly discovered trade. All the leading clubs were then his patrons,—the Atlantics, the Eckfords, the Mutuals, the Stars, even the Unions of Morrisania. All the leading junior clubs swore by him and would use no ball but his,—the champion Actives, the Alerts, the Uncas. (A "shanghai club" the boys[14] declared the last named to be when it first appeared at Hamilton Square in its natty uniform of snow-white flannel shirts and sky-blue trousers.) Base ball was in its infancy, perhaps, but what a lusty infant and how pervading! Beyond that corner and hanging midway on the northward wall was a portentous object, an old-fashioned maple shell snare-drum, with white buff leather sling and two pairs of ebony sticks, their polished heads and handles proclaiming constant use, and the marble surface of the washstand top, both sides, gave proof that when practice on the sheepskin batter head was tabooed by the household and the neighborhood, the inoffensive stone received the storm of "drags," and "flams," and "rolls." Lifting the curtain that overhung the boyish outfit of clothing, there stood revealed still further evidence of the martial tastes of the occupant, for the first items in sight were a natty scarlet shell-jacket, a pair of trim blue trousers, with broad stripe of buff, and a jaunty little forage-cap, with regimental wreath and number. Underneath the curtain, but readily hauled into view, were found screwed and bolted to heavy blocks of wood two strange-looking miniature cannon, made, as one could soon determine, by sawing off a brace of old-fashioned army muskets about a foot from the breech. Two powder-flasks and a shot-bag hung on pegs at the side of the curtained clothes-press. A little mirror was clamped to the wall above the washstand. Some old fencing foils and a weather-beaten umbrella stood[15] against the desk. An open paint-box, much besmeared, lay among the books. Some other pamphlets and magazines were stacked up on the top of the clothes-press. Two or three colored prints, one of Columbian Engine, No. 14, a very handsome Philadelphia "double-decker." Another of Ringgold Hose, No. 7, a really beautiful four-wheeler of the old, old type, with chocolate-colored running gear and a dazzling plate-glass reel, completed the ornamentation of this school-boy den. There was no room for a lounge,—there was room only for two chairs; but that diminutive apartment was one of the most popular places of resort Pop's boys seemed to know, and thereby it became the hot-bed of more mischief, the birthplace of more side-splitting school pranks than even the staid denizens of that most respectable brownstone front ever dreamed of, whatever may have been the convictions of the neighborhood, for Pop's boys, be it known, had no dormitory or school-house in common. No such luck! They lived all over Manhattan Island, all over Kings, Queens, and Westchester counties. They came from the wilds of Hoboken and the heights of Bergen. They dwelt in massive brownstone fronts on Fifth Avenue and in modest wooden, one-story cottages at Fort Washington. They wore "swell" garments in some cases and shabby in others. They were sons of statesmen, capitalists, lawyers, doctors, and small shopkeepers. They were rich and they were poor; they were high and they were low, tall and short, skinny and stout, but they[16] were all pitched, neck and crop, into Pop's hopper, treated share and share alike, and ground and polished and prodded or praised, and a more stand-on-your-own-bottom lot of young vessels ("vessels of wrath," said the congregation of a neighboring tabernacle) never had poured into them impartially the treasures of the spring of knowledge. They were of four classes, known as the first, second, third, and fourth Latin, corresponding to the four classes of Columbia and other colleges, and to be a first Latin boy at Pop's was second only to being a senior at Yale or Columbia. As a rule the youngsters "started fair" together at the bottom, and knew each other to the backbone by the time they reached the top. Few new boys came in except each September with the fourth Latin. Pop had his own way of teaching, and the boy that didn't know his methods and had not mastered his "copious notes" might know anybody else's Cæsar, Sallust, or Cicero by rote, but he couldn't know Latin. Pop had a pronunciation of the Roman tongue that only a Pop's bred boy could thoroughly appreciate. Lads who came, as come in some rare cases they did, from Eton or Harrow, from the Latin schools of Boston or the manifold academies of the East, read as they had been taught to read, and were rewarded with a fine sarcasm and the information that they had much to unlearn. Pop's school was encompassed roundabout by many another school, whose pupils took their airing under ushers' eyes, to the howling disdain of Pop's unhampered pupils,[17] who lined the opposite curb and dealt loudly in satirical comment. There was war to the knife between Pop's boys and Charlier's around the corner, to the end that the hours of recess had to be changed or both schools, said the police, would be forbidden the use of Madison Square. They had many faults, had Pop's boys, though not all the neighborhood ascribed to them, and they had at least one virtue,—they pulled well together. By the time it got to the top of the school each class was like a band of brothers, and never was there a class of which this could be more confidently asserted than the array of some twenty-seven youngsters, of whom Snipe and his smaller chum, Shorty, were prominent members, in the year of our Lord eighteen hundred and sixty.

Yet, they had their black sheep, as is to be told, and their scapegraces, as will not need to be told, and months of the oddest, maddest, merriest school life in the midst of the most vivid excitement the great city ever knew, and on the two lads wailing there at the attic window because their fates had balked the longed-for game at Hamilton Square, there were dawning days that, rain or shine, would call them shelterless into constant active, hazardous life, and that, in one at least, would try and prove and temper a brave, impatient spirit,—that should be indeed the very turning-point of his career.

Patter, patter, patter! drip, drip, drip! the rain came pelting in steady shower. The gusty wind blew the[18] chimney smoke down into the hollow of the long quadrilateral of red brick house backs. Three, four, and five stories high, they hemmed in, without a break, a "plant" of rectangular back-yards, each with its flag-stone walk, each with its square patch of turf, each with its flower-beds at the foot of the high, spike-topped boundary fence, few with visible shrubs, fewer still diversified by grape arbors, most of them criss-crossed with clothes-lines, several ornamented with whirligigs, all on this moist November afternoon wringing wet from the steady downpour that came on with the dawn and broke the boys' hearts, for this was to have been the match day between the Uncas and the Murray Hills, and Pop's school was backing the Indians to a man. One more week and winter might be upon them and the ball season at an end. Verily, it was indeed too bad!

With a yawn of disgust, the shorter boy at the open-topped window threw up his hands and whirled about. There on the bed lay the precious base-ball uniform in which he was wont to figure as shortstop. There, too, lay Snipe's, longer in the legs by nearly a foot. "There's nothing in-doors but books, Snipy. There's only one thing to tempt a fellow out in the wet,—a fire, and small chance of that on such a day. We might take the guns up on the roof and shoot a few skylights or something——"

"Shut up!" said Snipe, at this juncture, suddenly,[19] impetuously throwing up his hand. "Twenty-third Street!"

Shorty sprang to the window and levelled an old opera-glass at the summit of an odd white tower that loomed, dim and ghost-like, through the mist above the housetops quarter of a mile away. Both boys' eyes were kindling, their lips parting in excitement. Both were on tiptoe.

"Right! Down comes the lever!" was the next announcement. "Upper Fifth, I'll bet a bat! Listen!"

Suddenly there pealed on the heavy air, solemn and slow, the deep, mellow tones of a great bell. Even as he counted the strokes each boy reached for his cap. One—two—three—four!

"Fourth!" cried Shorty. "Come on!" And, light as kittens, away scurried the two, skimming down three flights of stairs, nearly capsizing a sedate old butler, snatching their top-coats in the hall, letting themselves out with a bang, leaping down the broad flight of brownstone steps to the broader walk below, then spurting away for Union Square, fast as light-heeled, light-hearted lads could run.

[20]

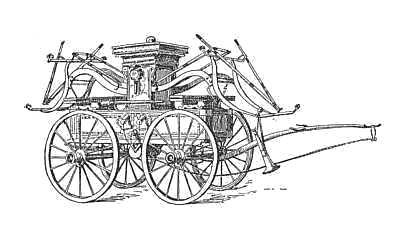

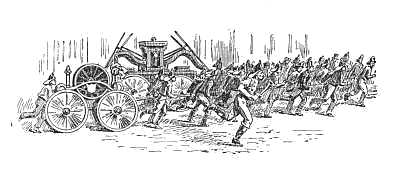

A curious thing to look back upon is the old volunteer fire department of New York as it was forty years ago. No horses, no fire-boats, few steamers, no telegraph alarm-boxes, only a great array of practically go-as-you-please companies, averaging forty or fifty men apiece, scattered all over the inhabited parts of the island from Harlem to the Battery. Sixty of these organizations, there or thereabouts, were hose companies, each manning a light, high-wheeled, fancifully painted carriage with its hose-reel perched gracefully above the running-gear, decked out with fancy lamps and jangling bells,—a carriage so light that a boy could start it on the level and a dozen athletic men could make it fairly spin over the paved streets. Then there were fifty engine companies, all but two or three specially favored bands "tooling" hand machines, some of the old "double-deck" Philadelphia pattern, some with long side levers,[21] "brakes" they called them; others still with strange, uncouth shapes, built by some local expert with the idea of out-squirting all competitors. Down in Centre Street was the heavy apparatus of the Exempt Company, only called upon in case of fires of unusual magnitude. Near by, too, was stored a brace of what were then considered powerful steamers, brought out only on such occasions; but two companies that wielded strong political influence proudly drew at the end of their ropes light-running and handsome steam fireengines, and these two companies, Americus 6,—"Big Six" as they called her,—and her bitter rivals of Manhattan 8, were the envied of all the department. Add to these some nineteen hook and ladder companies that ran long, light, prettily ornamented trucks, and you have the New York fire department as it was just before the war. Famous men were its chiefs in those days, and the names of Harry Howard and John Decker, of Carson and Cregier, were household words among the boys at Pop's, most of whom were strong partisans of some company on whose speed and prowess they pinned their faith. Strange, indeed, to-day seems the system by which fire alarms were communicated. There were no electric bells, no gongs, no telephones in the various engine-houses, which were scattered all over the town, generally in groups of two, an engine and a hose company being "located" side by side, though a large number occupied single houses. On the roof of the old[22] post-office at Nassau Street, in a huge frame-work at the rear of the City Hall, and in tall observation-towers of iron tubing or wooden frame, placed at convenient points about the city, were hung big, heavy, deep-toned bells that struck the hour at noon and nine at night, but otherwise were used exclusively for the purpose of giving alarms of fire. The city was divided into eight districts, and the sounding of the tower bells of any number from one to eight, inclusive, meant that a fire had been discovered within the limits of that district, and all companies designated for service therein must hunt it up and put it out. The seventh and eighth districts divided the lower part of the city, a little below Canal Street, evenly between them. Then, as the city broadened there, the great, far-spreading space between the East and North Rivers, south of Twenty-second Street, was parcelled off into the third, fourth, fifth, and sixth districts, beginning from the west. These were quite narrow at the south, but flared out north and eastward. Above them, on the east and west sides of the city respectively, lay the first and second districts, the former extending almost to Harlem, which had on Mount Morris its own bell-tower and at its foot a little department of its own. Night and day a single watcher was perched in the glass-enclosed lookout at the summit of each lofty tower, his sole communication with the world below being a speaking-tube to the engine-house at the base and a single wire that connected his[23] "circuit" with the main office at the City Hall, a circuit so limited in its possibilities that it could only administer a single tap at a time upon the tiny gong-bell over the watcher's desk, and finally the big, booming bell that, hanging midway down in the lofty structure, was yet so high above the neighboring roofs and walls that its sound bellowed forth in unimpeded volume. It was struck by a massive swinging hammer, worked by a long steel lever aloft in the watch-tower, the entire apparatus being the design, as were some of the strange-looking engines, of ex-Chief Carson, and one of the greatest treats that Pop's boys could possibly have was to be piloted of a wintry Saturday afternoon or summer evening, by one of their number who had the open sesame, up, up the winding stairway, up past the huge, silent monster that hung midway. (You may venture to bet they wasted no time there, but scurried past him, full tilt, lest an alarm should come at the instant and he should suddenly boom forth and stun them with his clamor.) Once well past him, they breathed freer, if harder, for the climb was long, and at last, tapping on a little trap-door, were admitted to the sanctum at the summit, and could gaze in delight and wonderment about them and over the busy, bustling world far, far beneath. Once well above the low ground of Canal Street, the city rose, and from the Hudson to the East River, along about the line of Spring Street, the ground was high, and here was established the inner row of[24] Gotham's picket guards against fire: three tall towers, one away over at Essex Market, on the far east side, guarding the sixth district; one on Marion Street, guarding the lower fourth and fifth; one over at McDougal Street, guarding the lower third. The next post to the northward was at Jefferson Market, on Sixth Avenue, a tall white wooden shaft that seemed to pierce the skies, so low were all the surrounding buildings, and from his eerie at its summit Jefferson's ringer watched over the upper third and fourth districts. The next tower was Twenty-third Street, near First Avenue, an open affair of iron, like that at McDougal, and here the guardian looked out over all the lower first and upper fifth districts, as well as having an eye on the northeastern part of the fourth. Then came Thirty-second Street, far over near Ninth Avenue, another open cage; and in the cozy, stove-warmed roost at the top of each, snugly closed against wind and weather, day and night, as has been said, and only one man at a time, the ringer kept his ceaseless vigil. It was his duty to be ever on the alert, ever moving about and spying over the city. If an unusual smoke or blaze manifested itself anywhere, he would at once unsling his spy-glass and examine it. If it lay long blocks or miles away and closer to some other tower, the unwritten law or etiquette of the craft demanded that he should touch the key of his telegraph. This instantly sounded the little bell in the other towers on his circuit, and called upon his fellows to look about[25] them. At no time could he sit and read. He must pace about the narrow confines of his rounded den, or on the encircling gallery outside, and watch, watch, watch. Whenever he discovered a fire, the first thing was to let down his lever and strike one round of the district in which it lay,—fast if the fire was near, slow if at a distance. This was all the neighboring companies had to judge by, as the first arrivals at the engine-house, or the loungers generally sitting about the stove back of the apparatus, or the bunkers who slept there at night, sprang for their fire-caps, raced for the trumpet that stood on the floor at the end of the tongue, threw open their doors, manned the drag-rope, and "rolled" for the street. No company could speed far on its route before meeting some runner or partisan who could tell the exact or approximate location of the fire. The first round from the tower would start every machine in its neighborhood. Then the ringer would spring to his telegraph and rapidly signal to the City Hall two rounds of the district, then add the number of his tower. Then back he would go to his lever and bang another round. If the fire was trivial four rounds would suffice; if a great conflagration ensued he would keep on ringing for half an hour, and if it proved so great that the chief engineer deemed it necessary to call out his entire force, word would be sent to the nearest tower, and a general alarm would result,—a continuous tolling until signalled from the City Hall to cease. Well did Pop's boys remember[26] the one general alarm of 1859, when the magnificent Crystal Palace at Sixth Avenue and Forty-second Street went up in smoke; and all in half an hour! And thrilling and interesting it was to the favored few of their number permitted sometimes to stand watch of an evening with the ringer, and to peer down on the gaslights of the bustling streets and over dim roofs and spires and into many an open window long blocks away! It was joy to be allowed to man the lever with the silent, mysterious hermit of the tower and help him bang the big bell when the last click of the telegraph from the City Hall announced that the second-hand of the regulator at the main office had just reached the mark at nine o'clock. It was simply thrilling to sit and watch the keen-eyed sentinel as he suddenly and intently scanned a growing light about some distant dormer window, reached for his glass, peered through it one instant, then clapped it into its frame, sprang for the lever, and in another moment three or four or five deep, clanging notes boomed out on the night air from below. It was wild delight to lean from the gallery without and watch the rush and excitement in the streets,—to hear the jangle of the bells of the white hose carriage as "she" shot suddenly into view and, with a dozen active dots on the drag-rope, went spinning down the street, closely followed by her next-door neighbor, the engine, with a rapidly growing crew. It was keen excitement to watch the bursting of the blaze, the roll of the smoke from the[27] upper windows, to see it wax and spread and light up the neighboring roofs and chimneys with its glare, to mark from on high the swiftly gathering throngs on the broad avenue, and under the gaslight to see company after company come trotting out from the side streets, curving round into the car-tracks, and the moment the broad tires of their engine, truck, or carriage struck the flat of the rails, up would rise a yell from every throat and away they would go at racing speed. It was thrilling, indeed, to see two rival companies reach the avenue at the same point and turn at once into the tracks. Then to the stirring peal of the alarm the fiercely contending bands would seem fairly to spurn the stones beneath their flying feet, and carts, carriages, "busses," everything except the railway-cars themselves, would clear the track for the rival racers, and the air would resound with their rallying-cries. Time and again, it must be owned, so fierce was the strain for supremacy, that furious rows broke forth between the contestants, and that between many companies there were for months and years bitter feuds that often led to war to the knife, and a fire was sometimes left to look out for itself while the firemen settled their quarrel with fists, stones, and "spanners." As a rule, though, there were so many companies at each fire that there were more than enough to fight the flames, for every company had to run to two districts as well as cover its own neighborhood. Rowdyism was rampant in some of the organizations,[28] but then a benignant "Tammany" guarded the interests of a force so strong in numbers, so potent a factor in politics, and only when a company had become repeatedly and notoriously negligent of its proper duties in order to indulge its love for fight was it actually disbanded. Compared with the system of to-day it was almost grotesque; but in the years when Pop's boys were in their glory the old volunteer fire department was on its last legs, yet was as ignorant of its coming dissolution as of the approach of the great war that should summon so many of its members to meet a foe far harder to down than the hottest fire they had ever tackled. They were still monarchs of all they surveyed, those red-shirted, big-hearted roughs, and many a company had a jolly word of welcome for Pop's boys, who more than once had given some favorite company first notice—"a still alarm"—of a blaze, and thereby enabled the "Zephyrs" of 61 Hose or the "Pacifics" of 28 Engine to be first at the fire, getting a "scoop" on their nearest neighbors of the "Lexington" or the "Metamoras," for every company besides its number had its name, and every company, high or low, its swarm of boy admirers, adherents, and followers, most of them, it must be admitted, street gamins.

And all this explanation as our two youngsters are scooting through the dripping rain for Union Square.

As they sped across Fifth Avenue a long white seam flashed into view just beyond the Washington statue,[29] and went like a dim streak sailing away up Fourth Avenue.

"There goes Twelve Truck!" panted Shorty, already half-winded in the fierce effort to keep up with Snipe's giant strides. "Seven Hose must be just ahead. Look out for Twenty-three now!"

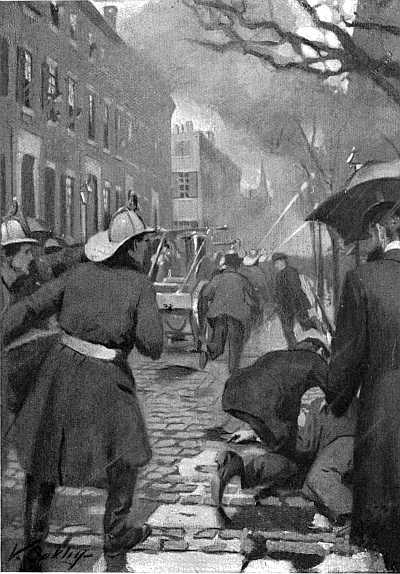

Yes, out from Broadway, as he spoke, a little swarm of men and boys on the drag-ropes, another company came, hauling a bulky little red hand-engine, and went tugging in chase of the lighter hook and ladder. A minute's swift run brought the youngsters to the open square, another around to the broad space in front of the Everett, and there the misty atmosphere grew heavy and thick, and the swarm of scurrying men and boys breathed harder as they plunged into a dense drift of smoke. Just as our youngsters noted that the crowds were running eastward through Nineteenth Street, the old rallying cry of another company was heard, and a light hose carriage came bounding across the car-tracks from the direction of Broadway. Snipe by this time was a dozen yards ahead, and could not hear or would not heed the half-choking, warning cry of puffing little Shorty.

"Lay low, Snipe; that's the Metamora. Look out—look out for the——"

Too late! Half a dozen young fellows were sprinting along beside their pet hose carriage. No more were needed on the ropes, and as Shorty rounded the corner[30] into Nineteenth Street and saw the flames bursting from the roof of a stable close to Lexington Avenue, he saw, too, with bursting heart, three of those young flankers spring up on the sidewalk in chase of long-limbed Snipe, saw one of them overtake him, lay sudden hand on his shoulder on one side and hurl him violently to the left, just in time to be tripped over the tangling foot of another and tumbled headlong into the reeking gutter, there to lie, stunned and almost senseless, till Shorty, raging, yet breathless and helpless, strove to lift his bleeding head upon his knee.

Almost senseless, till Shorty strove to lift his bleeding head upon his knee.

[31]

Bigger crowds ran to fires, big or little, in those days than now. The blaze which had well-nigh destroyed an old frame stable in Nineteenth Street that rainy Saturday afternoon before a single fire company reached the scene, and that drew to the spot in the course of half an hour at least twenty companies,—engine, hose, or hook and ladder,—would be handled now by one compact little battalion with one-tenth the loss, with no more than forty men, without an unnecessary sound, and in much less than half the time. Although aided by sympathizing hands, Shorty had barely time to get Snipe on his shaky legs and in the lee of a sheltering tree-box when another company came tearing around from upper Fourth Avenue,—their old friends of Zephyr Hose,—close followed by Engine 28, and Shorty lifted up his voice in a yodel that instantly brought two or three panting young fellows to his side,—big boys who[32] had run with their pet company the half-mile from Twenty-eighth Street. Instant suspicion, mingled with wrath, gleamed in their eyes at sight of Snipe's pale face and bleeding temple. "Yes, the Hulker fellows!" sobbed Shorty, now half mad with indignation and excitement. "I saw just the two that did it. One of them belongs to the first nine of the Metamoras,—the juniors,—and had a row with Snipe the day of the match. Briggs was with them. Wait till we tend to Snipe, then we can fix him."

The youngster's heart was beating hard and savagely, for the outrage was brutal. There had been angry words between the rival clubs, the Uncas and the Metamora, the day of their great game, and hosts of other juniors had gathered about the wrangling nines, not utterly displeased at the idea of a falling out between two of the strongest and, as juniors went in those days, "swellest" organizations on the list. Then, as luck would have it, several of the older boys of both clubs were devoted followers, even "runners," of two rival hose companies, the Uncas almost to a man pinning their fortunes on the white Zephyr, whose home was but three short blocks above Pop's school, and one of whose active members, the son of a Fifth Avenue millionaire, was the biggest and oldest—and stupidest—of Pop's pupils, though not in the classical department. The Metamoras, in like manner, swore by the swell hose company of that name, whose carriage was housed on[33] Fifth Avenue itself, diagonally over across the way from the impressively dignified and aristocratic brownstone mansion of the Union Club. And what Pop's boys, the First Latin, at least, were well-nigh a unit in condemning was that just two of their own number, residents of that immediate neighborhood, were known to be in league with the Metamora crowd, even to the extent, it was whispered, of secretly associating with the Hulkers, and by the Hulkers was meant a little clique led by two brothers of that name, big, burly young fellows of nineteen and eighteen respectively, sons of a wealthy widow, who let them run the road to ruin and bountifully paid their way,—two young scapegraces who were not only vicious and well-nigh worthless themselves, but were leading astray half a score of others who were fit for better things. No wonder the hearts of the Uncas were hot against them.

Into the area doorway of a neighboring dwelling, with faces of gloom, they had led their wounded comrade. Sympathizing, kind-hearted women bathed his forehead and smoothly bandaged it, even as the uproar without increased, and companies from far down-town kept pouring into the crowded street. By this time half a dozen streams were on the blaze and the black smoke had turned to white steam, but still they came, Gulick and Guardian, hose and engine, from under the Jefferson tower, and natty 55 Hose,—the "Harry Howards,"—from away over near the Christopher ferry, and their[34] swell rivals of 38, from Amity Street, close at the heels of Niagara 4, with her handsome Philadelphia double-deck engine, and "3 Truck," from Fireman's Hall, in Mercer Street, and another big double-decker, 11, from away down below the Metropolitan Hotel, raced every inch of the mile run up Broadway by her east side rival, Marion 9. Fancy the hundreds of shouting, struggling, excited men blocking Lexington Avenue and Eighteenth Street for two hundred yards in every direction from what we would call to-day a "two-hundred-dollar fire," and you can form an idea of the waste of time, money, material, and energy, the access of uproar, confusion, and, ofttimes, rowdyism, that accompanied an alarm in the days before the war. Remember that all this, too, might result from the mere burning out of a chimney or the ignition of a curtain in a garret window, and you can readily see why tax-payers, thinking men, and insurance companies finally decided that the old volunteer department must be abolished.

But until the war came on there was nothing half so full of excitement in the eyes of young New York, and Pop's boys, many of them at least, thought it the biggest kind of fun outside of school, where they had fun of their own such as few other boys saw the like of.

It was inside the school, however, on the following Monday morning, that the young faces were grave and full of import, for Snipe was there, still bandaged and a trifle pale, and Shorty, scant of breath but full of vim[35] and descriptives, and time and again had he to tell the story of the Hulkers' attack to classmates who listened with puckered brows and compressed lips, all the while keeping an eye on two black sheep, who followed with furtive glances Snipe and Shorty wherever they went; and one of these two was the Pariah of the school.

The only son of a wealthy broker, Leonard Hoover at eighteen years of age had every advantage that the social position of his parents and a big allowance could give him, but he stood in Pop's school that saddest of sights,—a friendless boy. Always immaculately dressed and booted and gloved, he was a dullard in studies, a braggart in everything, and a success in nothing. For healthful sports and pastimes he had no use whatever. Books were his bane, and at eighteen he knew less of Latin than boys in the fourth form, but Pop had carried him along for years, dropping him back thrice, it was said in school traditions, until at last he had to float him with the First Latin, where he sat week after week at the foot of the class. It was said that between the revered rector of the school and the astute head of the firm of Hoover, Hope & Co. a strong friendship existed, but whatever regard "the Doctor" entertained for the father he denied the son. Long years of observation of the young fellow's character had convinced this shrewd student of boy nature that here was a case well-nigh without redeeming feature. Lazy, shifty, lying, malevolent, without a good word or kind thought for a[36] human being, without a spark of gratitude to the father who had pulled him through one disgrace after another, and who strove to buy him a way through life, young Hoover was, if truth were confessed, about as abhorrent to the Doctor as he was obnoxious to the school. A plague, a bully, a tyrant to the little fellows in the lower classes, a cheat and coward among his fellows, filled with mean jealousy of the lads who year after year stepped over his head to the upper forms, stingy though his pockets were lined with silver, sneaking, for he was never known to do or say a straightforward thing in his life, it had come to pass by the time he spent his sixth year with Pop that Hoover was the school-boy synonym for everything disreputable or mean. And, as though the Providence that had endowed him through his father with everything that wealth and influence could command was yet determined to strike a balance somewhere, "Len" Hoover had been given a face almost as repellent as his nature. His little black eyes were glittering and beady, which was bad enough, but in addition were so sadly and singularly crossed that the effect was to distort their true dimensions and make the right optic appear larger and fuller than the left, which at times was almost lost sight of,—a strange defect that even Pop had had the weakness to satirize, and, well knowing that Hoover would never understand the meaning, had in a moment of unusual exasperation referred to him as "Cyclops," or Polyphemus, a name[37] that would have held among the boys had it not been too classical and not sufficiently contemptuous. An ugly red birth-mark added to his facial deformity, but what more than anything else gave it its baleful expression was the sneer that never seemed to leave his mouth. The grin that sometimes, when tormenting a little boy, distended that feature could never by any possibility be mistaken for a smile. Hoover's white, slender, shapely hands were twitching and tremulous. New boys, who perhaps had to shake hands with him, said they were cold and clammy. He walked in his high-heeled boots in a rickety way that baffled imitation. He never ran. He never took part in any sport or game. He never subscribed a cent to any school enterprise,—base ball, cricket, excursion, or debate. He never even took part in the customary Christmas gifts to the teachers, for in the days of this class of Snipe's and Shorty's and others whose scholarly attainments should have won them first mention, there were some beloved men whom even mischief-loving lads delighted to remember in that way. One Christmas-tide Hoover had appeared just before the holiday break-up, followed by a servant in dark livery, a thing seldom seen before the war, and that servant solemnly bore half a dozen packages of which Hoover relieved him one at a time, and personally took to the desk of the master in each one of the five rooms, left it there without a word of explanation, but with an indescribable grin, bade the servant hand the sixth to the[38] open-mouthed janitor, and disappeared. A perplexed lot were Pop's several assistants when school closed that afternoon. John, the janitor aforesaid, declared they held an informal caucus in the senior master's room (Othello was the pet name borne at the time by this gifted teacher and later distinguished divine), and that three of the number, who had smilingly and gracefully thanked the boys for the hearty little tribute of remembrance and good will with which the spokesman of the class had wished each master a Merry Christmas, declared they could accept no individual gift from any pupil, much less Hoover, and that he, John, believed the packages had been returned unopened.

And this was the state of feeling at the old school towards its oldest scholar, in point of years spent beneath its roof, on the bleak November morning following Snipe's and Shorty's disastrous run to the fire, when at twelve o'clock the First Latin came tumbling down-stairs for recess. Ordinarily they went with a rush, bounding and jostling and playing all manner of pranks on each other and making no end of noise, then racing for doughnuts at Duncan's, two blocks away. But this time there was gravity and deliberation, an ominous silence that was sufficient in itself to tell the head-master, even before he noted the fact that Hoover was lingering in the school-room instead of sneaking off solus for a smoke at a neighboring stable, that something of an unusual nature was in the wind.[39]

"Why don't you go out to recess, Hoover?" said he, shortly. "If any lad needs fresh air, it's you."

No answer for a moment. Hoover stood shuffling uneasily at the long window looking out on Fourth Avenue, every now and then peering up and down the street.

Impatiently the master repeated his question, and then, sullen and scowling, Hoover answered,—

"I can have trouble enough—here."

"What do you mean?" asked Othello.

"They're layin' for me,—at least Snipe is."

"By Snipe you mean Lawton, I suppose. What's the trouble between you?" and the master sat grimly eying the ill-favored fellow.

"It's not a thing—I want to speak of," was the answer. "He knows that I know things that he can't afford to have get out,—that's all." Then, turning suddenly, "Mr. Halsey," said he, "there's things going on in this school the Doctor ought to know. I can't tell him or tell you, but you—you ask John where Joy's watch went and how it got there."

The master started, and his dark face grew darker still. That business of Joy's watch had been the scandal of the school all October. Joy was one of the leaders of the First Latin, a member of one of the oldest families of Gotham, and this watch was a beautiful and costly thing that had been given him on his birthday the year before. One hot Friday noon when[40] the school went out to recess, Joy came running back up the stairs from the street below and began searching eagerly about the bookcases at the back of the long school-room. A pale-faced junior master sat mopping the sweat from his forehead, for the First Latin had executed its famous charge but two minutes before, and he had striven in vain to quell the tumult.

"What's the matter, Joy?" he asked. "I beg pardon. Mr. Joy, I should say. I wonder that I am so forgetful as to speak to a young gentleman in the First Latin as I would to boys in the other forms in the school."

At other times when the weakling who had so spoken gave voice to this sentiment it was the conventional thing for the First Latin to gaze stolidly at him and, by way of acknowledgment of the sentiment, to utter a low, moaning sound, like that of a beast in pain, gradually rising to a dull roar, then dying away to a murmur again, accentuated occasionally here and there by deep gutturals, "Hoi! hoi! hoi!" and in this inarticulate chorus was Joy ever the fugleman. But now, with troubled eyes, he stared at the master.

"My watch is gone, sir!"

"Gone, Mr. Joy? You terrify me!" said Mr. Meeker, whose habit it was to use exaggerated speech. "When—and how?"

"While we were—having that scrimmage just now," answered Joy, searching about the floor and the benches. "I had it—looked at it—not two minutes before the bell[41] struck. You may remember, sir, you bade me put it up."

"I do remember. And when did you first miss it?"

"Before we got across Twenty-fifth Street, sir."

By this time, with sympathetic faces, back came Carey and Doremus and Bertram and others of the First Latin, and John, the janitor, stood at the door and looked on with puzzled eyes. It was not good for him that valuables should be lost at any time about the school. All four young fellows searched, but there was no sign. From that day to this Joy had seen no more of his beautiful watch. Detectives had sought in vain. Pawn-shops were ransacked. The Doctor had offered reward and Mr. Meeker, the master, his resignation, but neither was accepted.

And now Hoover, the uncanny, had declared he had information. It was still over an hour before the Doctor could be expected down from his morning's work at Columbia. The head-master felt his fingers tingling and his pulses quicken. He himself had had a theory—a most unpleasant one—with regard to the disappearance of that precious watch. He knew his face was paling as he rose and backed the downcast, slant-eyed youth against the window-casing.

"Hoover," said he, "I've known you seven years, and will have no dodging. Tell me what you know."

"I—I—don't know anything, sir," was the answer, "but you ask John. He does."[42]

"Stay where you are!" cried the master, as he stepped to his desk and banged the gong-bell that stood thereon. A lumbering tread was heard on the stairway, and a red-faced, shock-headed young man came clumsily into the room. Mr. Halsey collared him without ado and shoved him up alongside Hoover. He had scant reverence for family rank and name, had Halsey. In his eyes hulking John and sullen Hoover were about on a par, with any appreciable odds in favor of the janitor.

"Hoover tells me you know where Joy's watch went and who took it. Out with the story!" demanded he.

"I d-don't," mumbled John, in alarm and distress. "I—I only said that—there was more'n one could tell where it went." And then, to Mr. Halsey's amaze and disgust, the janitor fairly burst into tears. For two or three minutes his uncouth shape was shaken by sobs of unmistakable distress. Halsey vainly tried to check him, and angrily demanded explanation of this womanish conduct. At last John seemed about to speak, but at that moment Hoover, with shaking hand, grabbed the master's arm and muttered, "Mr. Halsey,—not now!"

Following the frightened glance of those shifting eyes, Halsey whirled and looked towards the stairs. Then, with almost indignant question quivering on his lips, turned angrily on the pair. With a queer expression on his white and bandaged face, Snipe Lawton stood gazing at them from the doorway.

[43]

That famous charge of the First Latin is something that must be explained before this school story can go much further. To begin with, one has to understand the "lay of the land," or rather the plan of the school-room. Almost every boy knows how these buildings facing on a broad business thoroughfare are arranged:—four or five stories high, thirty or forty or fifty feet front, according to the size of the lot, perhaps one hundred to two hundred deep, with the rooms from basement to attic all about of a size unless partitioned off on different lines. In the days whereof we write Pop had his famous school in the second and third floors of one of these stereotyped blocks. Two-thirds of the second floor front was given up to one big room. A high wooden partition, glazed at the top and pierced with two doors, divided this, the main school-room, from two smaller ones where the Third and Fourth Latin wrestled with their verbs and declensions and gazed out through the long rear[44] windows over a block of back-yards and fences. Aloft on the third floor were the rooms of the masters of the junior forms in English, mathematics, writing, etc. But it is with the second, the main floor and the main room on that floor, that we have to do. This was the home of the First Latin. It was bare as any school-room seen abroad, very nearly. Its furniture was inexpensive, but sufficient. A big stove stood in the centre of the long apartment, and some glazed bookcases between the west windows and against the south wall at the west end. A closet, sacred to Pop, was built against the north wall west of the stairway, which was shut off by a high wooden partition, reaching to the ceiling. A huge coat-rack stood in the southeast corner. A big open bookcase, divided off into foot square boxes for each boy's books, occupied the northeast corner, with its back against the northward wall. Six or seven benches abutting nearly end to end were strung along the south side, extending from the west windows almost to the coat-rack, the farthermost bench being at an obtuse angle. The bookbox, doors, and partitions were painted a cheerful lead color, the benches a deep dark green. So much for the accommodation of the lads. Now for their masters. On a square wooden dais, back to the light, was perched the stained pine desk at which from one-thirty to three each afternoon sat glorified Pop. Boy nor man ventured to assume that seat at other time, save when that front, like Jove, gleamed above the desk to threaten and command,[45] and the massive proportions, clad in glossy broadcloth of scholarly black, settled into the capacious depths of that wicker-bottomed chair. In front of the desk, six feet away, the low stove, so often seasoned with Cayenne pepper, warmed the apartment, but obstructed not his view. At an equal distance beyond the stove was the table at which from nine A.M. to three P.M. sat the master in charge of the room, and thereby hung many and many a tale. It was a great big, flat-topped table, covered with shiny black oilcloth, slightly padded, and was so hollowed out on the master's side that it encompassed him round about like some modern boom defence against torpedo attack, and many a time that defence was needed. From the instant of the Doctor's ponderous appearance at the door law and disciplined order prevailed within this scholastic sanctuary, but of all the bear-gardens ever celebrated in profane history it was the worst during the one hour in which, each day from eleven to twelve, Mr. Meeker imparted to the First Latin his knowledge of the higher mathematics and endeavored to ascertain what, if any, portion thereof lodged long enough to make even a passing impression on the minds of that graceless assembly. There were other hours during which the spirit of mischief had its sway. There were other masters who found that First Latin an assemblage of youths who made them wonder why the Doctor had, after long, long years of observance, finally banished forever the system of punishment which was of the breech—the vis a tergo[46] order, that was the mainstay of grammar-school discipline in Columbia's proud past; but it was left to Mr. Meeker to enjoy as did no other man the full development of a capacity for devilment, a rapacity for mischief never equalled in the annals of the school.

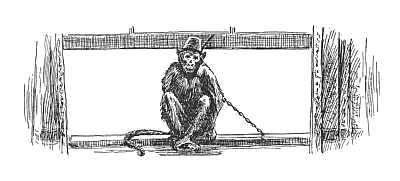

Whenever the class was formed for recitation it took seats on those northward-facing benches, the head of the class in a chair, with his back to the avenue window, close by the westernmost bench. The others of the "Sacred Band," as that guileful First Latin had once been derisively named, strung out in the order of their class rank along the benches, with Hoover, nine times out of ten, alone at the bottom. The system of recitation was peculiar to the school, and proved that the "copious notes," so often scornfully, yet enviously, referred to by outsiders, were only blessings in disguise. It might be that Virgil was the subject of the hour, the lesson say some fifty lines in the third book, and in this event Beach, not Meeker, was in the chair, a man of firmer mould, yet not invulnerable. One after another, haphazard, the youngsters were called upon to read, scan, translate, and at the very first slip in quantity, error in scanning, mistake of a word in translation, the master would cry "Next," and the first boy below who could point out the error and indicate the correction stepped up and took his place above the fellow at fault. A perfect recitation was a rarity except among the keen leaders at the head, for no error, big or little, was ever[47] let pass. It was no easy thing for the average boy to read three lines of the resounding dactylic hexameters of "P. Virgilius Maro" according to the Columbia system of the day without a slip in quantity. Scanning, too, was an art full of traps for the unwary, but hardest of all for one of Pop's boys was it to translate. No matter how easy it might be by the aid of the oft-consulted "pony" to turn the Latin into English, it was the rule of the school that the Doctor's own beautiful rendition should be memorized word for word wherever it occurred, and the instances, like the notes, were all too copious. At the word "Enough" that checked his scanning the boy began to translate, and having given the poetic and flowery version of the great translator, then turned to and, word by word, followed with the literal meaning. Then came the prodding questions as to root, verb, subject, etc., and lucky was the youngster who, when he took his seat, found himself no more than half a dozen places below where he started. At the end of the hour the marks were totted up, and he who had the highest number marched to the head of the class, the others being assigned according to their score. It was all plain sailing when the Doctor himself was in the chair. Few boys ventured on fun with him. On the other hand, few other masters could maintain order on a system that gave such illimitable possibilities for devilment. To illustrate: It is a brisk October morning. School has "been in" an hour. The First Latin is arrayed[48] for recitation in the Æneid, and the boys have easily induced an Italian organ-grinder to come, monkey and all, to serenade them, and to the lively notes of "Patrick's Day in the Morning" one of the confirmed scamps of the class is called upon to begin. He himself was the heaviest subscriber to the fund which secured the services of the dark-eyed exile and his agile monkey. Bliss knows nothing whatever of the lesson and is praying for the appearance of the red-capped simian at the window. The janitor has been sent down to bid the organ-grinder go away, but the boys have blocked that game by bidding higher, and the Italian is warned to pay no attention to such orders, but to hold his ground,—the neighborhood approves of him and he'll be short a quarter if he goes. John comes panting up-stairs to report his ill success, and meantime the recitation cannot go on. Bliss is finally told to pay no attention to "Patrick's Day" and to push ahead on the most beautiful lines in the book,

"Non ignara mali, miseris succerere disco,"

and Bliss slips on the quantity of the first syllable of the third word, is promptly snapped up by Doremus, next below, who tallies one on his score and jumps above him. Bliss shuts his book despairingly. "Mr. Beach," he begins, in tones of deepest injury, "I know that just as well as anybody else; but I protest, sir, I'm so distracted by that grinding I can't do myself justice—or the[49] subject either." And if the astute Beach had any lingering doubt as to whether the boys worked that game themselves or not the doubt is banished now. Bertram, Doremus, Snipe, Shorty, all are on their feet and pleading with the master to have that impudent music stopped. Mr. Beach vainly warns them to their seats and commands silence.

"Mr. Beach, let me go down and drive him away,—I can do it," implores Beekman, the pigmy Gothamite. It is three minutes before the master can compel silence in the class, so great is its sense of the outrage upon its peace and dignity.

"Mr. Beach, let me fetch a policeman," cries Shorty, who knows there isn't a blue-coat nearer than the Harlem depot at Twenty-sixth Street, and is spoiling for a chance to get out-of-doors.

"The next boy who speaks until bidden will have five marks struck off," says Beach, and with one accord the First Latin opens its twenty-seven mouths, even Hoover swelling the chorus, and, as though so many representatives in Congress assembled were hailing the chair, the twenty-seven ejaculate, "Mr. Beach, nobody's got five yet." Then little Post jumps up, in affected horror, and runs from his seat half-way to the master's table. "Mr. Beach!" he cries, "the monkey!"

"Aw, sit down, Post," protests Joy, in the interest of school discipline and harmony. "You ought to be ashamed of yourself making such a fuss about a monkey."[50] Snipe and Carey seize the first weapons obtainable—the sacred ruler and the Japan tray on the Doctor's desk—and make a lunge for the windows.

"Lawton—Carey! Back to your seats!" orders Beach.

"We only want to drive the monkey away, sir," protests Snipe, with imploring eyes. "Post'll have a fit, sir, if you let the monkey stay. He's subject to 'em. Ain't you, Post?"

"Yes, sir," eagerly protests Post, on the swear-to-anything principle when it's a case of school devilment, and two minutes more are consumed in getting those scamps back to their places and recording their fines, "Ten marks apiece," which means that when the day's reckoning is made ten units will be deducted from their total score. The settlement, too, is prolonged and complicated through the ingenuity of Snipe and the connivance of Bagshot and Bertram, who have promptly moved up and occupied the place vacated by their long-legged, curly-pated, brown-eyed comrade, and who now sturdily maintain that Snipe doesn't know where he belongs. As a matter of fact, Snipe doesn't; neither does he greatly care. He's merely insisting on the customary frolic before the class settles down to business, but to see the fine indignation in his handsome face and listen to the volume of protest on his tongue you would fancy his whole nature was enlisted in the vehement assertion of his rights.[51]

Mr. Beach fines Snipe another five for losing his place, and then stultifies himself by ordering Bertram and Bagshot back to their original station, thus permitting Snipe to resume his seat, whereupon he promptly claims the remission of the fine on the ground that he himself had found it, and Bertram, a youth of much dignity of demeanor, gravely addresses Mr. Beach, and protests that in the interests of decency and discipline Lawton should forfeit his place, and to prove his entire innocence of selfish motive offers to leave it to the class, and go to the foot himself if they decide against him, and the class shouts approval and urges the distracted Beach to put Snipe out forthwith. Then somebody signals "Hush!" for Halsey, the head-master, the dark Othello, has scented mischief from afar, and is heard coming swiftly down from the floor above, and Halsey is a man who has his own joke but allows no others. Bliss is the only boy on his feet as the stern first officer enters and glances quickly and suspiciously about him.

"Go on with the recitation, Mr. Beach," he says. "That Italian was doubtless hired by these young gentlemen. Let them dance to their own music now, the eloquent Bliss in the lead. Go on with your lines, Bliss."

And as this is just what Bliss can't do, Bliss is promptly "flunked" and sent to the foot, where Hoover grins sardonically. He's ahead of one fellow anyhow. Just so long now as that organ-grinder does must Halsey[52] stay—and supervise, and scorch even the best scholars in the class, for well he knows the First Latin and they him, and their respect for him is deeper than his for them, despite the known fact that Pop himself looks upon them with more than partial eyes. The class is getting the worst of it when in comes an opportune small boy. "Mr. Meeker says will Mr. Halsey please step into the Fourth Latin room a minute," and Halsey has to go.

"If those young gentlemen give you any trouble, Mr. Beach, keep the whole class in at recess," he says, and thereupon, with eyes of saddest reproach, the class follows him to the door, as though to say, How can such injustice live in mind so noble? But the moment Halsey vanishes the gloom goes with him. Beach's eyes are on the boys at the foot of the class, and with a batter and bang the Japan tray on the Doctor's desk comes settling to the floor, while Joy, who dislodged it, looks straight into the master's startled eyes with a gaze in which conscious innocence, earnest appeal, utter disapprobation of such silly pranks, all are pictured. Joy can whip the bell out from under the master's nose and over the master's table and all the time look imploringly into the master's eyes, as though to say, "Just heaven! do you believe me capable of such disrespect as that?" Three boys precipitate themselves upon the precious waiter, eager to restore it to its place, and bang their heads together in the effort. Five marks off for Shorty, Snipe,[53] and Post. Bagshot is on the floor, and announces as the sense of the First Latin that a boy who would do such a thing should be expelled. Mr. Beach says the First Latin hasn't any sense to speak of, and tells Bagshot to begin where he left off. Bagshot thereupon declares he can't remember. It's getting near the "business end" of the hour, and the whole class has to look to its marks, so it can't all be fun. Thereupon Beach, who is nothing if not classical, refers to Bagshot's lack of acquaintance with the Goddess of Memory. "Who was she, Bagshot?" "Mnemosyne." "Very good; yes, sir." ("Thought it was Bacchante!" shouts little Beekman. "No, sir. Five marks off, Beekman. No more from you, sir.") "Now, Bagshot, you should be higher than ten in your class to-day, and would be but for misbehavior. What was the color of Mnemosyne's hair?" Bagshot glares about him irresolute, and tries the doctrine of probability.

"Red!"

Beach compresses his lips. "M—n—no. That hardly describes it. Next."

"Carnation," hazards Van Kleeck.

"Next! Next! Next!" says Beach, indicating with his pencil one after another of the eager rank of boys, and, first one at a time and distinctly, then in confused tumbling over each other's syllables, the wiseacres of the class shout their various guesses.

"Vermilion!"[54]

"Scarlet!"

"Carrot color!"

"Solferino!"

"Magenta!"

"Pea-green!"

"Sky-blue!"

"Brick-red!" (This last from Turner, who makes a bolt for a place above Bagshot, and can only be driven back and convinced of the inadequacy of his answer by liberal cuttings of ten to twenty marks.) Then, at last, Beach turns to Carey, at the far head of the class, and that gifted young gentleman drawls,—

"Fl-a-a-me color."

"Right!" says the master, whereupon half a dozen contestants from below spring to their feet, with indignation in their eyes:

"Well, what did I say, sir?"

"That's exactly what I meant, sir."

"I'll leave it to Bliss if that wasn't my answer, sir."

And nothing but the reappearance of Othello puts an end to the clamor and settles the claimants. Shorty submits that his answer covered the case, that Mnemosyne herself couldn't tell carrot color from flame, and is sure the Doctor would declare his answer right, but is summarily squelched by Mr. Halsey, and he has the "nous" to make no reference to the matter when the Doctor comes. The hour is nearly over. Only three minutes are allowed them in which to stow their[55] Virgils in the big open bookcase and extract their algebras. Halsey vanishes to see to it that the Third Latin goes to the writing-room without mobbing the Fourth. The marks of the First are recorded, not without a volume of comment and chaff and protest. Then silence settles down as the master begins giving out the next day's lesson, for the word has been passed along the line of benches, "Get ready for a charge!" A moment later the janitor sounds the bell on the landing without, and twenty-six young fellows spring into air and rush for the bookcase. Not a word is spoken,—Hoover, alone, holds aloof,—but in less time than it takes to tell it, with solemnity on every face except one or two that will bubble over in excess of joy, the First Latin is jammed in a scrimmage such as one sees nowadays only on the football field. The whole living mass heaves against those stout partitions till they bend and crack. From the straining, struggling crew there rises the same moaning sound, swelling into roar and dying away into murmur, and at last the lustier fight their way out, algebras in hand, and within another five minutes order is apparently evolved from chaos.

In such a turmoil and in such a charge Joy's watch disappeared that October day, and the school had not stopped talking of it yet.

It has been said that two boys were the observed of gloomy eyes the Monday following Snipe's misfortune. One, Hoover, of course. The other a fellow who in[56] turn had sought to be everybody's chum and had ended by being nobody's. His name was Briggs. He was a big, powerful fellow, freckle-faced, sandy-haired, and gifted with illimitable effrontery. He was a boy no one liked and no one could snub, for Briggs had a skin as thick as the sole of a school-boy's boot, and needed it. One circumstance after another during the previous year had turned one boy after another from him, but Briggs kept up every appearance of cordial relations, even with those who cold-shouldered him and would have naught to do with him. During the previous school-year he had several times followed Snipe, Shorty, and their particular set, only to find that they would scatter sooner than have him one of the party. He had been denied admission to the houses of most of the class. He had been twice blackballed by the Uncas, and it was said by many of the school when Briggs began to consort with Hoover that he had at last found his proper level. One allegation at his expense the previous year had been that he was frequently seen at billiard-rooms or on the streets with those two Hulkers, and even Hoover had hitherto eschewed that association. Perhaps at first the Hulkers would not have Hoover. The class couldn't tell and really didn't care to know. One thing was certain: within the fortnight preceding the opening of this story Briggs and Hoover had been together more than a little and with the Hulkers more than enough.[57]

"Are you sure of what you say?" both Carey and Joy had asked Shorty that exciting Monday morning, as the eager youngster detailed for the tenth time the incidents of the assault on Snipe.

"I'm as sure of it as I am of the fire," said Shorty, positively. "Jim Briggs was with the Metamora crowd, running in the street. He looked back and laughed after he saw Snipe down."

But when confronted with this statement by the elders of the "Sacred Band" Briggs promptly and indignantly denied it.

"I never heard of it till to-day!" said he. "'Spose I'd stand by and see one of my class knocked endwise by a lot of roughs? No, sir!"

It was a question of veracity, then, between Briggs and Shorty, the class believing the latter, but being unable to prove the case. Snipe himself could say nothing. Being in the lead, he had seen none of the runners of the Metamora except the heels of a few as they bounded over him when he rolled into the street. There was an intense feeling smouldering in the class. They were indeed "laying" for Hoover as they had been for Briggs when they tumbled out for recess. The latter, with his characteristic vim and effrontery, denied all knowledge of the affair, as has been said, and challenged the class to prove a thing against him. The former, as has been told, lurked within-doors. What had he to fear? He was not at the scene of the fire and[58] the assault. He never had energy enough to run. There was some reason why he shrank from meeting or being questioned by the boys. There was some reason why Snipe Lawton should have left them and returned to the school, and was discovered standing there at the doorway, looking fixedly at the head-master's angered face as it glowered on Hoover and the tearful John. Whatever the reason, it could not well be divulged in the presence of Mr. Halsey. Hoover stood off another proposed demonstration in his honor after school at three o'clock by remaining behind, and only coming forth when he could do so under the majestic wing of the Doctor himself. Pop looked curiously at the knots of lingering First Latins, and raised his high-top hat in response to their salutations. Hoover huddled close to his side until several blocks were traversed and pursuit was abandoned. Then he shot into a street-car, leaving the Doctor to ponder on the unusual attention. And so it happened that while the class was balked for the time of its purpose, and the victim of Saturday's assault was debarred from making the queries he had planned, Mr. Halsey was enabled to pursue his bent. Just as the little group of five, gazing in disappointment up the avenue after the vanishing forms of the Doctor and Hoover, was breaking up with the consolatory promise that they'd confront Hoover with their charges first thing in the morning, the open-mouthed janitor came running.

"Oh, Lawton!" he panted, "Mr. Halsey says he[59] wishes to speak with you, and to please come right back."

"I'll wait for you, Snipe," said Shorty. "Day-day, you other fellows." And wait he did, ten, twenty minutes, and no Snipe came, and, wondering much, the smaller lad went whistling down the avenue, forgetful, in the fact that he still wore the jacket, of the dignity demanded of a lad of the First Latin and full sixteen. He wondered more when eight o'clock came that evening and without Snipe's ring at the door-bell. He wondered most when he saw Snipe's pallid, sad-eyed face on the morrow.

[60]

There was something in the friendship between those two members of the First Latin not entirely easy for the school to understand. In many ways they were antitheses,—Snipe, over-long; Shorty, under-sized; Snipe, brown-eyed and taciturn, as a rule; Shorty, blue-eyed and talkative (Loquax was Pop's pet name for him); Snipe was studious; Shorty quick to learn, but intolerant of drudgery. Both loved play, active exercise, and adventure. Both took naturally to everything connected with the fire department, but in addition the smaller boy had a decided love for the military, and was a member of the drum corps of a famous organization of the old State militia, and vastly proud of it. Snipe loved the fishing-rod, and Shorty had no use for one. Shorty loved drill, Snipe couldn't bear it. Take it all in all, they were an oddly assorted pair, but when forty-eight hours passed without their being in close communion[61] something had gone sadly amiss; and that was the case now.