Museum of Natural History

Lawrence

1959

Editors: E. Raymond Hall, Chairman, Henry S. Fitch,

Robert W. Wilson

Volume 11, No. 7, pp. 401-442, 2 plates, 4 figs. in text, 5 tables

Published May 8, 1959

University of Kansas

Lawrence, Kansas

A Contribution From

The State Biological Survey of Kansas

THE STATE PRINTING PLANT

TOPEKA, KANSAS

1959

27-7080

Kansas

The Big Blue River in northeastern Kansas will soon be impounded by the Tuttle Creek Dam, located about five miles north of Manhattan, Kansas. Since the inception of this project by the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers much argument has arisen as to the values of the dam and reservoir as opposed to the values of farmland and cultural establishments to be inundated (Schoewe, 1953; Monfort, 1956; and Van Orman, 1956). Also, there has been some concern about the possible effects of impoundment on the fish-resources of the area, which supports "a catfish fishery that is notable throughout most of the State of Kansas and in some neighboring states (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1953:9)." The objectives of my study, conducted from March 30, 1957, to [404] August 9, 1958, were to record the species of fish present and their relative abundance in the stream system, and to obtain a measure of angler success prior to closure of the dam. These data may be used as a basis for future studies on the fish and fishing in the Big Blue River Basin, Kansas.

I thank Messrs. J. E. Deacon, D. A. Distler, Wallace Ferrel, D. L. Hoyt, F. E. Maendele, C. O. Minckley, B. C. Nelson, and J. C. Tash for assistance in the field and for valuable suggestions. Dr. J. B. Elder, Kansas State College, arranged for loan of specimens, and Mr. B. C. Nelson supplied data on Notropis deliciosus (Girard) in Kansas, and on specimens in the University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

I thank the many landowners who allowed me access to streams in the Big Blue River Basin. The U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Kansas City District, also allowed access in the reservoir area, and furnished information and some photographs. Mr. J. C. Tash did chemical determinations on my water samples.

Dr. Frank B. Cross guided me in this study and in preparation of this report. Drs. E. Raymond Hall and K. B. Armitage offered valuable suggestions on the manuscript. Equipment and funds for my study were furnished by the State Biological Survey of Kansas, and the Kansas Forestry, Fish and Game Commission granted necessary permits.

The data on Tuttle Creek Dam and Reservoir that follow were furnished by Mr. Donald D. Poole, U. S. Army Corps of Engineers, Kansas City District. The dam, an earth-fill structure, will be 7,500 feet in length, with a maximum height of 157 feet above the valley floor. Release of water will be from beneath the west end of the dam, through two tunnels 20 feet in diameter that have a capacity of 45,000 cubic feet per second; however, releases exceeding 25,000 c. f. s. are not planned. The gated spillway is located at the east end of the dam. Freeboard will be 23 feet at the top of flood-control pool.

The reservoir will have a maximum pool of 2,280,000 acre-feet capacity, a 53,500-acre surface area, and 368 miles of shoreline. The present operational plan provides for a conservation pool having a surface area of 15,700 acres, a shoreline of 112 miles, and a length of 20 miles.

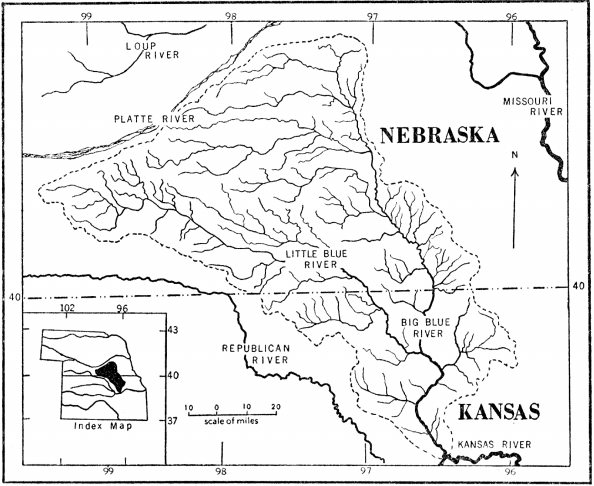

Big Blue River and its tributaries, a sub-basin of the Kansas River System, drain approximately 9,600 square miles, of which 2,484 miles are in Kansas (Colby, et al., 1956:44). The headwaters [405] of the Big Blue River are in central Hamilton County, Nebraska, near the Platte River (Fig. 1). The stream flows generally south and east for 283 miles to its confluence with the Kansas River near Manhattan, Kansas. Little Blue River, the largest tributary to the Big Blue, rises in eastern Kearney and western Adams counties, Nebraska, and flows southeast for 208 miles to join the Big Blue near Blue Rapids, Kansas (Nebraska State Planning Board, 1936:628). The Big Blue River Basin varies in width from 129 miles in the northwest, to approximately ten miles near the mouth (Colby, et al., 1956:44).

Fig. 1. Big Blue River Basin, Kansas and Nebraska.

In Kansas, outcrops of Pennsylvanian and Cretaceous age occur along the extreme eastern and western sides of the Big Blue River Basin, respectively, whereas Permian beds (overlain by Pleistocene deposits) occur throughout most of the remainder of the watershed (see Moore and Landes, 1937). The Big Blue and Little Blue rivers and their tributaries have deeply incised the Permian beds of the Flint Hills in Kansas, exposing limestones and shales [406] of the Admire, Council Grove, Chase, and Sumner groups (Wolfcampian and Leonardian series) (Walters, 1954:41-44). Pleistocene deposits in the Big Blue Basin in Kansas consist of alluvium, glacial till, and glacial outwash from the Kansan glacial stage, overlain by loess deposits of Wisconsin and Recent stages (Frye and Leonard, 1952: pl. 1).

The Big Blue River was formed "in part on the till plain surface and in part by integration of spillway channels," in the latter portion of the Kansan glaciation (Frye and Leonard, 1952:192). This stream, and the Republican River to the west, carried waters from the areas that are now the Platte, Niobrara, and upper Missouri River basins (Lugn, 1935:153). Drainage was southward, through Oklahoma, until establishment of the east-flowing Kansas River (Frye and Leonard, 1952:189-190). As Kansan ice receded the Blue and Republican rivers retained what is now the Platte River Basin. The lower Platte River developed and the surface drainage became distinct in the Iowan (Tazwellian) portion of the Wisconsin glacial stage (Lugn, 1935:152-153). However, according to Lugn (1935:203) the Platte River Basin contributes about 300,000 acre-feet of water per year to the Big Blue and Republican rivers by percolation through sands and gravels underlying the uplands that now separate the basins.

Climate of the Big Blue River Basin is of the subhumid continental type, with an average annual precipitation of 22 inches in the northwest and 30 inches in the southeast. The mean annual evaporation from water surfaces exceeds annual precipitation by approximately 30 inches (Colby, et al., 1956:32-33).

The average annual temperature for the basin is 53° F. (Flora, 1948:148). According to Kincer (1941:704-705) the average temperature in July, the warmest month, is 78° F., and the coolest month, January, averages 28° F. Periods of extreme cold and heat are sometimes of long duration. Length of the growing season varies from less than 160 days in the northwest to 180 days in the southeast (Kincer, loc. cit.).

The human population of the Big Blue Basin varies from about 90 persons per square mile in one Nebraska county in the northwest and one Kansas county in the southeast, to as few as six persons per square mile in some northeastern counties. The population is most dense along the eastern border of the basin, decreasing toward the west. This decrease in population is correlated [407] with the decrease in average annual precipitation from east to west (Colby, et al., 1956:80).

The principal land-use in the Big Blue Watershed is tilled crops, with wheat, sorghums, and corn being most important. Beef cattle are important in some portions of the basin. Colby, et al. (1956:24) reported that in 1954 as much as 55 per cent of the land in some counties near the mouth of the Big Blue River was in pasture. Only one Nebraska county had less than 15 per cent in pastureland.

Streams of the Big Blue River Basin are of three kinds: turbid, sandy-bottomed streams, usually 150 to 300 feet in width; relatively clear, mud-bottomed streams, ten to 60 feet in width; and clear, deeply incised, gravel-bottomed streams, usually five to 30 feet in width.

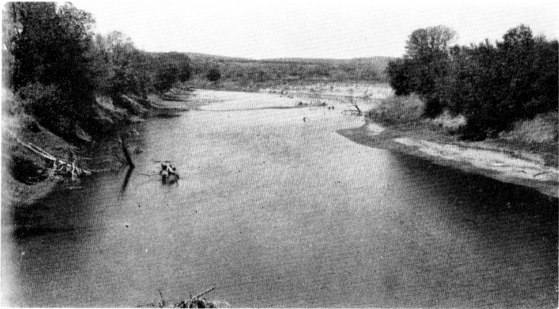

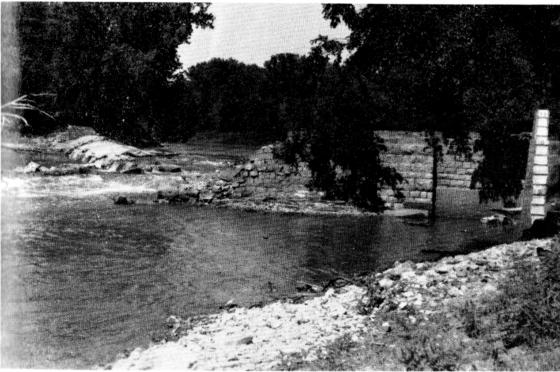

Sand-bottomed Streams.—The Big Blue and Little Blue rivers represent this kind of stream. The bottoms of these rivers consist almost entirely of fine sand; nevertheless, their channels are primarily deep and fairly uniform in width, rather than broad, shallow, and braided as in the larger Kansas and Arkansas rivers in Kansas (Plate 11, Fig. 1). In the Big Blue River, gravel occurs rarely on riffles, and gravel-rubble bottoms are found below dams (Plate 11, Fig. 2). The Big Blue flows over a larger proportion of gravelly bottom than does the Little Blue.

Big Blue River rises at about 1,800 feet above mean sea level and joins the Kansas River at an elevation of 1,000 feet above m. s. l. The average gradient is 2.8 feet per mile. Little Blue River, originating at 2,200 feet, has an average gradient of 5.3 feet per mile, entering the Big Blue at 1,100 feet above mean sea level (Nebraska State Planning Board, 1936:628, 637). The Little Blue is the shallower stream, possibly because of the greater amount of sandy glacial deposits in its watershed and the swift flow that may cause lateral cutting, increased movement, and "drifting" of the sandy bottom.

For approximately a 50-year period, stream-flow in the Big Blue River at its point of entry into Kansas (Barnston, Nebraska) averaged 603 cubic feet per second, with maximum and minimum instantaneous flows of 57,700 c. f. s. and one c. f. s. The Little Blue River at Waterville, Kansas, averaged a daily discharge of 601 c. f. s. (maximum 50,400, minimum 28). Below the confluence of the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers, at Randolph, Kansas, the [408] average daily discharge was 1,690 c.f.s. (maximum 98,000, minimum 31) (Kansas Water Resources Fact-finding and Research Committee, 1955:27).

The turbidity of the Big Blue River, as determined by use of a Jackson turbidimeter, varied from 27 parts per million in winter (January 10, 1958) to as high as 14,000 p.p.m. (July 12, 1958). The Little Blue River has similar turbidities, with high readings being frequent. In the summer of 1957, pH ranged from 7.2 to 8.4 in the Big Blue River Basin—values that correspond closely with those of Canfield and Wiebe (1931:3) who made 25 determinations ranging from 7.3 to 8.3 in the streams of the Nebraskan portion of this basin in July, 1930. Surface temperatures at various stations varied from 38° F. on January 10, 1958, to 90° F. in backwater-areas on July 19, 1957. The average surface temperature at mid-day in July and August, 1957, was approximately 86.5° F.

Chemical determinations were made on water-samples from my Station 4-S on the Big Blue River, and Station 50-S on the Little Blue (Table 1). These samples were taken from the surface in strong current. Determinations were made by methods described in Standard Methods for the Examination of Water and Sewage, 10th edition, 1955.

| Station and Date |

Phenolphthalein alkalinity | Methyl-orange alkalinity | Chlorides | Sulphates | Nitrates | Nitrites | Ammonia | Phosphate |

| 4-S August 9........ |

0.0 | 154 | 16 | 28 | 3.5 | .083 | .250 | .225 |

| 50-S August 9........ |

0.0 | 125 | 24 | 20 | 2.5 | .669 | .427 | .240 |

| 35-M August 9........ |

0.0 | 366 | 15 | 108 | 9.4 | .220 | .750 | .080 |

| 11-G July 8........ |

0.0 | 272 | 15 | 60 | 4.5 | .060 | .625 | .140 |

| 18-G July 22........ |

0.0 | 183 | 10 | 60 | 1.6 | .938 | .293 | .240 |

The banks of both the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers support narrow riparian forests comprised primarily of elm, Ulmus americanus, cottonwood, Populus deltoides, sycamore, Platanus occidentalis, and willow, Salix spp. Maple, Acer sp., oak, Quercus spp., and ash, Fraxinus sp. occur where the rivers flow near steep, rocky hillsides. Many of the hills are virgin bluestem prairies (Andropogon spp.), but the floodplains are heavily cultivated.

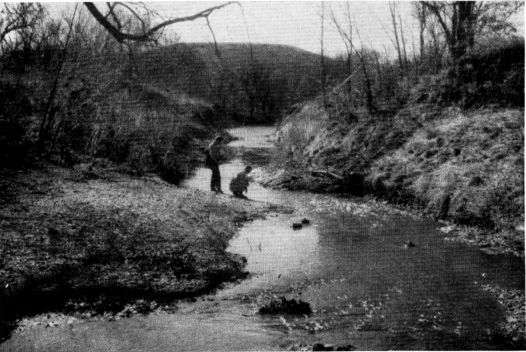

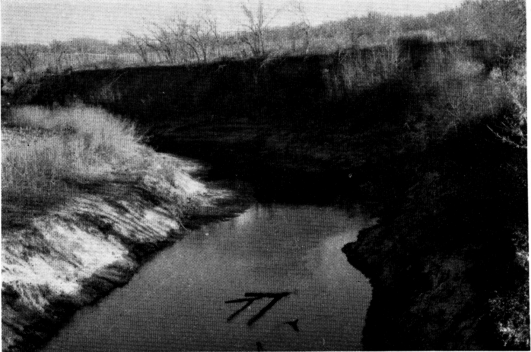

Mud-bottomed Streams.—Streams of this kind are present in the watershed of the Black Vermillion River that enters Big Blue River from the east. The area east of the Big Blue River and north of the Black Vermillion River is till plains, where relief seldom exceeds 100 feet (Walters, 1954:12). Streams in this portion of the basin, and streams entering the Little Blue River from the west (Mill Creek and Horseshoe Creek systems), tend to have V-shaped channels, fewer riffles than the Little Blue and Big Blue rivers and in the gravelly streams (to be described later), and have bottoms of mud or clay, with few rocks (Plate 12, Fig. 1). However, in the extreme headwaters of most western tributaries of the Little Blue River (in Washington and Republic counties) sandy bottoms predominate. The Black Vermillion River flows on a broad floodplain and is a mud-bottomed, sluggish stream, with an average gradient of approximately one foot per mile. Fringe-forests of elm, cottonwood, sycamore, and willow persist along most of these stream-courses.

Notwithstanding the mud bottoms, the water in this kind of stream in the Big Blue Basin remains clearer than that of the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers. Heavy algal blooms were noted in the Black Vermillion River and Mill Creek, Washington County, in 1957 and 1958. Temperatures at Stations 45-M and 46-M on Mill Creek, Washington County, averaged 85.5° F. on July 31, 1957. Chemical characteristics of a water-sample from Station 35-M, Black Vermillion River, are in Table 1.

Gravel-bottomed Streams.—Most streams of this kind are tributary to the Big Blue River; however, streams entering Black Vermillion River from the south are also of this type (Plate 12, Fig. 2). The streams are "characteristically a series of large pools (to 100 feet in length and more than two feet in depth) connected by short riffles and smaller pools" (Minckley and Cross, in press). The average gradients are high: Carnahan Creek, 33 feet per mile; Mill Creek, Riley County, 21 feet; Clear Creek, 16 feet per mile. Stream-flow is usually less than five cubic feet per second. In summer, these streams may become intermittent, but springs and [410] subsurface percolation maintain pool-levels (Minckley and Cross, loc. cit.).

The average temperatures of these small streams (79.5° to 81.0° F. in July and August, 1957) were lower than temperatures in stream-types previously described. Turbidities were usually less than 25 p.p.m. The chemical properties of water-samples from two of these streams (Stations 11-G and 18-G) are listed in Table 1.

The earliest records of fishes from the Big Blue River Basin are those of Cragin (1885) and Graham (1885) in independently published lists of the fishes of Kansas. Meek (1895) recorded fishes collected in 1891 "from both branches of the Blue River, a few miles west of Crete, Nebraska." Evermann and Cox (1896) reported five collections from the Nebraskan part of the basin. Their collections were made in October, 1892, and August, 1893, and the stations were: in 1892, Big Blue River at Crete; in 1893, Big Blue River at Seward, Lincoln Creek at Seward and York, and Beaver Creek at York.

Canfield and Wiebe (1931) obtained fish from 18 localities in Nebraska in July, 1930; however, their major concern was determination of water quality. Their stations were: Big Blue River at Stromsburg, Polk Co.; Surprise and Ulysses, Butler Co.; Staplehurst, Seward, and Milford, Seward Co.; Crete and Wilber, Saline Co.; Beatrice, Blue Springs, and Barnston, Gage Co.; Little Blue River at Fairbury, Jefferson Co.; Hebron, Thayer Co.; Sandy Creek at Alexandria, Thayer Co.; West Fork of Big Blue River at Stockham, Hamilton Co.; McCool Junction, York Co.; Beaver Crossing, Seward Co.; and Beaver Creek at York, York Co.

Breukelman (1940) and Jennings (1942) listed fishes from the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History and the Kansas State College Museum, respectively, including some specimens collected from the Big Blue River System in Kansas. Because records in these two papers pertain to collections that were widely spaced in the basin and in time, the specific localities are not given herein. One of Jennings' (loc. cit.) records, Scaphirhynchus platorynchus (Rafinesque), was cited by Bailey and Cross (1954:191). More recently, Minckley and Cross (in press) recorded several localities, and cited some papers mentioned above, in a publication dealing with Notropis topeka (Gilbert) in Kansas.

Information on the fishes of the Nebraskan portion of the Big Blue River Basin was compiled, and additional localities were reported, in a doctoral thesis by Dr. Raymond E. Johnson, entitled The Distribution of Nebraska Fishes, 1942, at the University of Michigan.

The gear and techniques used are listed below:

Entrapment Devices.—Hoop and fyke nets and wire traps were used for 288 trap/net hours in 1957. The nets were not baited, and were set parallel to the current, with the mouths downstream. Hoop nets were 1½ to three feet in diameter at the first hoop, with a pot-mesh of one inch; fyke nets [411] were three feet at the first hoop, pot-mesh of one inch; wire traps, with an opening at each end, were 2½ feet in diameter and covered with one-inch-mesh, galvanized chicken wire.

Gill Nets.—Experimental gill nets were set on three occasions in areas with little current. These nets were 125 feet in length, with ¾ to two inch bar-mesh in 25-foot sections.

Seines.—Seining was used more than other methods. An attempt was made to seine all habitats at each station. In swift water, seine-hauls were usually made downstream, but in quiet areas seining was done randomly. Haul-seines six to 60 feet in length, three to eight feet in depth, and with meshes of ⅛ to ½ inch were used. For collection of riffle-fishes, the seine was planted below a selected area and the bottom was kicked violently by one member of the party, while one or two persons held the seine, raising it when the area had been thoroughly disturbed. Seining on riffles was done with a four-foot by four-foot bobbinet seine.

Rotenone.—Rotenone was used in pools of smaller streams, mouths of creeks, borrow-pits, and cut-off areas. Both powdered and emulsifiable rotenone were used. The rotenone was mixed with water and applied by hand, or into the backwash of an outboard motor.

Electric Shocker.—The electrical unit used in this study generated 115 volts and 600 to 700 watts, alternating current. The shocking unit consisted of two booms, each with two electrodes, mounted on and operated from a slowly moving boat. Fish were recovered in scape nets, or in many cases were identified as they lay stunned and were not collected.

Data on relative abundance of fishes were obtained by counts of seine hauls at 29 of the 59 stations, counts of rotenoned fish at seven stations, and results with the electric shocker at nine stations. Counts were usually made in the field; however, in some collections all fish were preserved and counted in the laboratory. Some fish (or "swirls" presumed to be fish) observed while shocking were not identified and are not included in the calculations. However, all fish positively identified while shocking are included.

Fish from selected size-groups were aged in this study. Scales for age-determinations were removed from positions recommended by Lagler (1952:108). Scales were placed in water between glass slides and were read on a standard scale-projection device.

Pectoral spines of catfish were removed from one or both sides, sectioned, and read by methods described by Marzolf (1955:243-244).

Calculation of length at the last annulus for both scale-fish and catfish was made by direct proportion. All measurements are of total length to the nearest tenth of an inch unless specified otherwise.

From April 6 to May 28, 1957, a creel census was taken below Turtle Creek Dam. From June 16 to July 24, 1958, I periodically visited the main points of access to the Big Blue River, beginning approximately eight miles downstream from Tuttle Creek Dam and ending six miles upstream from the maximal extension [412] of the reservoir at capacity level. Access-points consisted of 11 bridges, two power dams, and three areas where county roads approached the river. Eleven eight-hour days were spent in the 1957 census and 22 checks in 15 days were made in 1958. An equal number of morning (6:00 a.m. to 12:00 noon) and afternoon (12:00 noon to 8:30 p.m.) checks were made.

Fishermen contacted were asked the following questions: home address (or residence at the time of the fishing trip); time they started fishing; kind of fish sought; number and kinds of fish in possession; and baits used. Also, the number of poles and type of fishing (from the bank, from boat, etc.) were recorded. Fishes caught were examined to confirm identifications. About 80 per cent of all fishermen seen were contacted.

Fish per man-hour, as used in this report, refers to the average number of fish of all species caught by one fisherman in one hour. Fisherman-day is the average time spent fishing in one day by one person. Because some fishermen used more than one pole, the data are also expressed as catch per pole-hour.

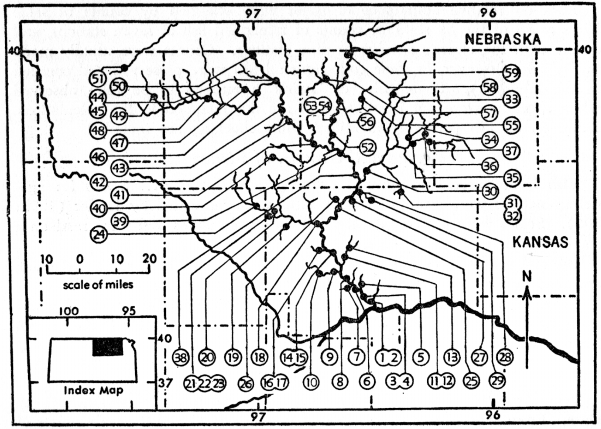

In the list that follows, stations are numbered consecutively from the mouth of the Big Blue River, listing stations on each tributary as it is ascended. The letters following station-numbers indicate the general type of stream: S = sandy; M = muddy; and G = gravelly. The Big Blue River is the boundary between Riley and Pottawatomie counties, Kansas, along part of its length. Stations in this area have been designated Riley County. The legal description of each station is followed by the date(s) of collection, and each station is plotted in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Collection stations in the Big Blue River Basin, Kansas, 1957 and 1958.

Fig. 2. Big Blue River at Oketo, Marshall County, Kansas. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, photograph No. 67516.

Fig. 1. Black Vermillion River, approximately one mile upstream from its mouth. Photograph by Robert G. Webb.

Forty-eight species were obtained in this survey and five others have been recorded in literature or are deposited in museums: KSC = Kansas State College Museum; and UMMZ = University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Specimens, unless designated otherwise, are in the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History (KU).

In this list, the scientific name of each species is followed by the common name, citations of previous records, and the stations where the species was obtained. I follow Bailey (1956:328-329) in treating Lepisosteus osseus (Linnaeus), Catostomus commersonnii (Lacépède), Semotilus atromaculatus (Mitchill), Notropis lutrensis (Baird and Girard), Pimephales promelas Rafinesque, Ictalurus melas (Rafinesque), Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque), and Lepomis macrochirus Rafinesque, in binomial form only.

Scaphirhynchus platorynchus (Rafinesque), shovelnose sturgeon: [415] Jennings (1942:364) as Scaphirhynchus platorhynchus (Rafinesque); Bailey and Cross (1954:191). Stations 3-S and 4-S.

Shovelnose sturgeon were found only in the lower portion of the Big Blue River. On April 20, 1957, many were seen in fishermen's creels at Stations 3-S and 4-S. One male and two females that I examined on that date were ripe or nearly so; eggs seemed well developed and milt flowed freely from the male. After April, 1957, none was collected or observed until April 26, 1958, when one specimen was obtained while shocking. Forbes and Richardson (1920:27) reported that shovelnose sturgeon spawn in Illinois between April and June, and Eddy and Surber (1947:80) reported spawning in May and early June in Wisconsin and Minnesota.

Lepisosteus platostomus Rafinesque, shortnose gar: Jennings (1942:364). Stations 3-S and 4-S.

I saw shortnose gar at various times in 1956 and 1957 at Rocky Ford Dam on the Big Blue River (Station 4-S). One was seen while shocking at Station 3-S on December 26, 1957.

Lepisosteus osseus (Linnaeus), longnose gar: Jennings (1942:364) as Lepisosteus osseus oxyurus Rafinesque. Stations 1-S, 2-S, 3-S, 4-S, 6-S, 8-S, 9-G, 15-S, 18-G, 25-S, 41-S, 44-S, 52-S, and 53-S.

Longnose gar were abundant in the mainstream of the Big Blue River but usually evaded capture. This species, and the shortnose gar, resided in the larger rivers, with L. osseus being taken in only two creeks near their mouths. In periods of high water, gar moved into the flooded creeks, but returned to the river as stream-levels subsided.

Young-of-the-year L. osseus, averaging 21.5 mm. in total length (range 13 to 30 mm.), were taken on June 14, 1957, and larger young (estimated 60 to 70 mm. total length) were taken on June 27, 1958.

Dorosoma cepedianum (LeSueur), gizzard shad: Jennings (1942:364). Stations 1-S, 3-S, 4-S, 6-S, 8-S, 44-S, 45-M, and 53-S.

Most gizzard shad were young-of-the-year, taken on July 16 and 17, 1957, at Stations 3-S and 4-S. Twenty specimens from Station 6-S that were in their second summer of life were from 3.8 to 5.9 inches total length at the last annulus (average 4.3). This species was usually found in quiet water and was most abundant near the mouth of the Big Blue River.

Hiodon alosoides (Rafinesque), goldeye. Stations 3-S, 4-S, and 53-S.

I caught five specimens of H. alosoides from the Big Blue River, [416] and another specimen, obtained by Dr. R. B. Moorman in 1954, is at Kansas State College (KSC 4984).

One goldeye that I caught on April 20, 1956, prior to the beginning of my study, was a ripe female measuring 15.5 inches total length. The fish was beginning its seventh summer of life.

Cycleptus elongatus LeSueur, blue sucker. The blue sucker is included on the basis of a single specimen (KSC 2917) collected by I. D. Graham and labeled "Blue River." No other data are with the specimen; however, most fishes deposited at Kansas State College by Graham are dated "1885" or "1886" and were caught near "Manhattan" (Riley County).

Ictiobus cyprinella (Valenciennes), bigmouth buffalo. Stations 3-S, 6-S, and 30-M.

Bigmouth buffalo were rare, and were taken only in quiet parts of larger streams, and in the borrow-pit at Station 6-S.

Ictiobus niger (Rafinesque), black buffalo. Stations 3-S, 41-S, and 53-S.

Only four individuals of I. niger were taken. All were large adults (more than 20 inches in total length), and all were shocked in the deeper, swifter areas, where the channel narrowed.

Ictiobus bubalus (Rafinesque), smallmouth buffalo. Stations 1-S, 3-S, 6-S, 7-G, 18-G, 38-S, 41-S, 43-S, 46-M, and 53-S.

This species was found in relatively quiet waters in the main channel, in cut-off areas, and in creek-mouths. The ages and total lengths of 30 individuals obtained at Station 6-S were (average followed by number of fish in parentheses): I, 2.4 (11); II, 4.4 (14); and III, 6.6 (5).

Canfield and Wiebe (1931:6-7, 10) recorded "buffalo-fish" and "buffalo" from the Big Blue Basin in Nebraska; however, no specific designation was given.

Carpiodes forbesi Hubbs, plains carpsucker. Station 3-S.

This represents the first record known to me of the plains carpsucker from Kansas. The specimen (KU 4180), 430 mm. in standard length, has the following characters: lower lip without a median, nipple-like projection; dorsal fin-rays, 25; lateral-line scales, 38; diameter of orbit into distance from anterior nostril to tip of snout, 1.1; body-depth into standard length, 3.3; and head-length into standard length, 3.9. The specimen was taken while shocking a wide, shallow channel, over sand bottom.

Carpiodes carpio carpio (Rafinesque), river carpsucker: Jennings (1942:364). Stations 1-S, 2-S, 3-S, 4-S, 5-G, 6-S, 7-G, 8-S, [417] 9-G, 11-G, 14-S, 15-S, 18-G, 19-G, 23-G, 25-S, 27-G, 28-G, 30-M, 38-S, 39-S, 41-S, 42-S, 43-S, 44-S, 45-M, 50-S, 52-S, and 53-S.

The river carpsucker occurred at most stations on the larger streams, and in many of the smaller tributaries. In smaller streams C. c. carpio frequented the largest pools, in or near the floodplains of larger streams. A marked preference for still water, soft, silty bottoms, and areas with drift or other cover was apparent; however, the species also occurred in open waters with moderate to swift currents.

The sizes attained by the river carpsucker at different ages were (averages followed by number of fish in parentheses): I, 1.9 (10); II, 3.9 (5); III, 5.3 (8); IV, 7.7 (5); V, 11.9 (2); VI, 11.6 (7); VII, 12.8 (6); VIII, 13.1 (1); IX, 14.9 (2); X, 15.8 (8); and XI, 17.6 (1). These averages are significantly less than those reported by Buchholz (1957:594) for the river carpsucker in the Des Moines River, Iowa.

Examination of the gonads of river carpsucker in summer, 1957, indicated that spawning occurred in late July. Young-of-the-year, averaging 21 mm. in total length, first appeared in my collections on July 30, 1957.

Carpiodes velifer (Rafinesque), highfin carpsucker: Meek (1895:135); Evermann and Cox (1896:389).

The highfin carpsucker was not taken in my survey. Meek (1895:135) reported "this small sucker [C. velifer] ... common in Blue River at Crete," characterizing the specimens as having "Dorsal rays, 24 to 30; scales in the lateral-line, 36 to 41; head 3¾ to 4; and depth 2½ to 3." The ranges in the number of dorsal rays and the number of scales in the lateral-line are higher than usual in C. velifer, or in C. c. carpio, which is now common in the Big Blue River Basin. Both species normally have 33 to 37 lateral-line scales and 27 or fewer dorsal rays (Bailey, 1956:352-353; Moore, 1957:79; and Trautman, 1957:81-82). The other characters listed by Meek would fit the young and some adults of either species, or possibly a composite including C. forbesi.

Graham (1885:72) and Cragin (1885:107) reported Ictiobus velifer (= Carpiodes velifer) from "Eureka Lake," Riley County, Kansas. This lake, which no longer exists, was in the Kansas River Valley, about ten miles upstream from the mouth of the Big Blue River. Other, more recent records from the Kansas River Basin, in the vicinity of the Big Blue River, are: Maple Leaf Lake, Riley [418] Co., Oct. 4, 1925; Deep Creek, Riley Co., no date; Wildcat Creek, Riley Co., Sept. 7, 1923; and Wildcat Creek, Riley Co., Sept. 29, 1925 (UMMZ 122187-90). Most of the collections were made by Minna E. Jewell (Nelson, personal communication).

Moxostoma aureolum (LeSueur), northern redhorse: Cragin (1885:108) as Moxostoma macrolepidotum LeSueur; Meek (1895:136) as Moxostoma macrolepidotum duquesnei (LeSueur); Evermann and Cox (1896:394-395); and Jennings (1942:364) as Moxostoma erythrurum (Rafinesque). Stations 41-S, 43-S, 44-S, and 53-S.

I collected three northern redhorse from the Big Blue River Basin, and another specimen was seined in the mouth of Mill Creek, Riley County (my present Station 9-G) by the Kansas State College class in fisheries management in 1954 (KSC 5068). I reidentify as M. aureolum the two specimens recorded by Jennings (loc. cit.) as M. erythrurum.

The subspecific status of M. aureolum in the Kansas River Basin is to be the subject of another paper.

Catostomus commersonnii (Lacépède), white sucker: Canfield and Wiebe (1931:8) as "common suckers"; and Breukelman (1940:380). Stations 7-G, 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 16-G, 18-G, 19-G, 23-G, 29-G, 31-G, 53-S, 57-M, and 58-G.

The white sucker occurred primarily in upland streams of the Flint Hills, with one occurrence in muddy habitat, and one in the main stream of the Big Blue River. Young C. commersonnii were often taken in riffles, but adults were in the larger, deeper pools. The ages and total lengths at the last annulus for 12 white suckers were: I, 2.8 (4); II, 3.9 (6); III, 8.2 (1); and IV, 9.2 (1).

Cyprinus carpio Linnaeus, carp: Canfield and Wiebe (1931:5-8, 10) as "carp." Stations 1-S, 2-S, 3-S, 4-S, 6-S, 7-G, 8-S, 15-S, 16-G, 18-G, 23-G, 24-G, 25-S, 27-G, 30-M, 35-M, 38-S, 41-S, 42-S, 43-S, 44-S, 45-M, 52-S, 53-S, and 56-S.

Carp occurred throughout the basin. The habitat of this species closely approximated that of the river carpsucker; however, carp were more often taken in moderate to swift water than were C. c. carpio.

The ages and average lengths at the last annulus for 40 carp from the Big Blue River Basin were: I, 2.3 (4); II, 4.7 (10); III, 7.0 (10); IV, 9.0 (3); V, 11.3 (4); VI, 18.6 (1); VII, 18.9 (3); VIII, no fish; IX, 20.6 (3); X, 19.1 (2); XI, 21.1 (1); XII, 22.0 (1); and XIII, 24.1 (2).

Carassius auratus (Linnaeus), goldfish. Station 4-S. [419]

I saw goldfish seined from Station 4-S by anglers obtaining bait on April 20, 1957. Goldfish were commonly used for bait at Stations 4-S and 54-S.

Semotilus atromaculatus (Mitchill), creek chub: Evermann and Cox (1896:399); and Jennings (1942:364) as Semotilus atromaculatus atromaculatus (Mitchill). Stations 5-G, 7-G, 10-G, 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 16-G, 17-G, 18-G, 23-G, 24-G, 27-G, 28-G, 29-G, 31-G, 32-G, 33-M, 34-M, 36-M, 37-M, 40-M, 46-M, 47-M, 48-M, 49-M, 50-S, 53-S, 54-G, 55-M, 56-S, 57-M, 58-G, and 59-G.

Creek chubs were found in all habitats in the Big Blue River Basin, but were abundant only in the headwaters of muddy streams and in clear upland creeks.

Chrosomus erythrogaster (Rafinesque), southern redbelly dace: Jennings (1942:365). Stations 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 16-G, 27-G, 29-G, and 53-S.

This colorful species occupied the headwaters of the clear, spring-fed creeks where it was abundant. Only one specimen was taken in muddy or sandy habitat (at the mouth of a small creek at Station 53-S), where it may have been washed by floods just prior to my collecting.

Hybopsis storeriana (Kirtland), silver chub. Station 3-S.

One specimen of H. storeriana (KU 3810) was seined in swift water near a sandbar on April 6, 1957, and another was taken at the same locality on April 26, 1958.

Hybopsis aestivalis (Girard), speckled chub: Meek (1895:137); and Evermann and Cox (1896:409), both as Hybopsis hyostomus Gilbert. Stations 3-S, 4-S, 14-S, 25-S, 38-S, 39-S, 50-S, and 56-S.

This species was restricted to wide, swift parts of the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers, and was found over clean, sometimes shifting, sand bottoms. On May 29, 1958, three males in breeding condition were collected and on June 16, 1958, a large series of both male and female H. aestivalis, all with well-developed gonads, was collected. The water temperature was 77.0° F. Hubbs and Ortenburger (1929:25-26) reported that Extrarius tetranemus (Gilbert) (= Hybopsis aestivalis tetranemus) spawns in summer especially in early July. Cross (1950:135) reported a single pair of H. a. tetranemus that he considered in breeding condition on June 9, 1948.

Breukelman (1940:380) recorded speckled chubs in the Kansas River Basin as Extrarius (= Hybopsis) aestivalis: sesquialis × tetranemus; however, the name sesquialis is a nomen nudum, and [420] the status of this species in the Kansas River Basin is yet to be elucidated.

Phenacobius mirabilis (Girard), plains suckermouth minnow: Meek (1895:136); and Evermann and Cox (1896:408). Stations 2-S, 3-S, 4-S, 5-G, 6-S, 7-G, 8-S, 9-G, 11-G, 16-G, 18-G, 25-S, 26-G, 27-G, 35-M, 38-S, 39-S, 40-M, 42-S, 47-M, 50-S, 52-S, 53-S, 54-G, and 56-S.

Phenacobius mirabilis was widespread in the basin, occurring most frequently on riffles over bottoms of clean sand or gravel. Young-of-the-year were usually taken in backwaters.

Notropis percobromus (Cope), plains shiner. Stations 3-S and 4-S.

The plains shiner occurred only in the lower part of the main stream of the Big Blue River.

Notropis rubellus (Agassiz), rosyface shiner. Station 5-G.

One rosyface shiner (KU 4195) was taken. This species was previously reported from only two localities in the Kansas River Basin: in the Mill Creek Watershed, Wabaunsee County, and Blacksmith Creek, Shawnee County as Notropis rubrifrons (Cope) (Gilbert, 1886:208). Mill Creek and Blacksmith Creek are northward-flowing tributaries of the Kansas River that arise in the Flint Hills. Graham (1885:73) also recorded N. rubellus (as N. rubrifrons) from the "Kansas and Missouri Rivers"; however, I suspect that his specimens were Notropis percobromus, a species not generally recognized in Graham's time (see Hubbs, 1945:16-17). Notropis rubellus is now abundant in the Mill Creek Watershed (Wabaunsee County), but, except for my specimen No. 4195, has not been taken recently in other streams in the Kansas River Basin.

Notropis umbratilis umbratilis (Girard), redfin shiner. Station 3-S.

One specimen of N. u. umbratilis was captured near a sandbar on March 26, 1958. The absence of this species in Flint Hills streams of the Big Blue River Basin is unexplained; redfin shiners occur commonly in southern tributaries of the Kansas River both upstream and downstream from the mouth of the Big Blue River. In Kansas this species is usually associated with the larger pools of clear, upland streams.

Canfield and Wiebe (1931:6-8) may have referred to this species in recording "black-fin minnows" from the Nebraskan portion of the Big Blue River Basin.

Notropis cornutus frontalis (Agassiz), common shiner. Stations [421] 4-S, 5-G, 7-G, 10-G, 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 18-G, 22-G, 26-G, 27-G, 28-G, 29-G, 31-G, 32-G, and 59-G.

Common shiners were most abundant in middle sections of the clear, gravelly creeks.

Notropis lutrensis (Baird and Girard), red shiner: Meek (1895:136); and Evermann and Cox (1896:404-405). All stations excepting 1-S, 17-G, 30-M, and 51-M.

Red shiners were the most widespread species taken in my survey, occurring in all habitats, and in all kinds of streams. On two occasions I observed what apparently was spawning behavior of this species. Both times the specimens collected were in the height of breeding condition, stripping in the hand easily, and often without pressure. At the first locality (Station 29-G) no attempt was made to obtain eggs, but by disturbing the bottom at the second (55-M) I found eggs that were thought to be those of red shiners. The eggs were slightly adhesive, clinging to the hand and to the bobbinet seine.

On June 29, 1958, at Station 29-G, red shiners appeared to be spawning in an open-water area measuring about 15 by 15 feet, over nests of Lepomis cyanellus Rafinesque and L. humilis (Girard). No interspecific activity was noted between the sunfish and the red shiners. Water temperature at this station was 73.4° F., and the bottom was gravel, sand, and mud. Observations were made from a high cut-bank, by naked eye and by use of 7-X binoculars.

The red shiners moved rapidly at the surface of the water, with one male (rarely two or more) following one female. The male followed closely, passing the female and causing her to change direction. At the moment of the female's hesitation, prior to her turn, the male would erect his fins in display, at the side and a little in front of the female. After brief display, usually less than two seconds, the male resumed the chase, swimming behind and around the female in a spiral fashion. After a chase of two to three feet, the female would sometimes allow the male to approach closely on her left side. The male nudged the female on the caudal peduncle and in the anal region, moving alongside with his head near the lower edge of the left operculum of the female, thus placing his genital pore about a head-length behind and below that of the female. At this time spawning must have occurred; however, possibly because of the speed of the chase, I observed no vibration of the fish as described for other species of Notropis at the culmination [422] of spawning (Pfeiffer, 1955:98; Raney, 1947:106; and others). While the spawning act presumably occurred the pair was in forward motion in a straight course, for three to five feet, at the end of which the male moved rapidly away, gyrating to the side and down. The female then swam away at a slower rate. In instances when the female failed to allow the male to move alongside, the male sometimes increased his speed, striking the female, and often causing her to jump from the water.

Some conflict between males was observed, usually when two or more followed one female. The males would leave the female, swerve to one side, and stop, facing each other or side by side. At this moment the fins were greatly elevated in display. There was usually a rush on the part of one male, resulting in the flight of the other, and the aggressive male would pursue for about two feet. Many times the pursued male jumped from the water.

At Station 55-M, on July 9, 1958, activity similar to that described above was observed in a small pool near a mass of debris. At this station I watched from the bank, three feet from the spawning shiners. Water temperature was not recorded.

The minnows performed the same types of chase and display, all in open water, as described for Station 29-G, However, at Station 55-M, much activity of males occurred near the small deposit of debris. It seemed that conflict was taking place, with males behaving as described above, and milling violently about. Examination of the area revealed nests of L. cyanellus near the debris, and some of the activity by the shiners may have been raids on nests of the sunfish. However, females nearing the group of males were immediately chased by one to four individual males, with one usually continuing pursuit after a short chase by the group. The male again moved into position at the lower left edge of the operculum of the female as at Station 29-G.

Another kind of behavior was observed also, in which the female sometimes stopped. The male approached, erecting his fins and arching his body to the left. The female also assumed this arch to the left, and the pair moved in a tight, counter-clockwise circle, with the male on the inside. After a short period in this position, the male moved aside in display, and gyrated to the side and down. Females at both stations moved about slowly, usually remaining in the immediate vicinity of activity by males, and returning to the area even when pursued and deserted some distance away.

Notropis deliciosus (Girard), sand shiner: Meek (1895:136); [423] Evermann and Cox (1896:402), both as Notropis blennius (Girard); and Jennings (1942:365) as Notropis deliciosus missuriensis (Cope). All stations excepting 1-S, 10-G, 12-G, 17-G, 20-G, 21-G, 22-G, 24-G, 29-G, 30-M, 31-G, 32-G, 33-M, 35-M, 51-M, 55-M, 57-M, 58-G, and 59-G.

Nelson (personal communication) has studied the sand shiner in Kansas, and has found that the Big Blue River is an area of intergradation between the southwestern subspecies (deliciosus) and the plains subspecies (missuriensis). Notropis d. deliciosus prefers cool, rocky habitat, and occurs in small streams of the Flint Hills, whereas N. d. missuriensis occupies the sandy, turbid Big Blue and Little Blue rivers. Intergrades occur most frequently in the Big Blue River, but are found in all habitats.

Notropis topeka (Gilbert), Topeka shiner: Meek (1895:136); Evermann and Cox (1896:403); and Minckley and Cross (in press). Stations 10-G, 11-G, 12-G, 19-G, 31-G, and 32-G.

This species was common locally in the upland streams. Female Topeka shiners stripped easily at Station 11-G on July 8, 1958, and adult N. topeka in high breeding condition were collected at Station 31-G on July 14, 1958. The water temperature at both stations was 77.5° F. Evermann and Cox (1896:403-404) recorded female Topeka shiners "nearly ripe" on June 29, 1893.

Notropis buchanani Meek, ghost shiner. Stations 3-S and 4-S. Only two specimens of N. buchanani were taken, both on August 14, 1957. These specimens (KU 3833), a female with well-developed ova, and a tuberculate male, were near a sandbar in the main channel. To my knowledge, this is the first published record of the ghost shiner from the Kansas River Basin. Mr. James Booth, State Biological Survey, collected N. buchanani from two stations on Mill Creek, Wabaunsee County, Kansas, 1953.

Hybognathus nuchalis Agassiz, silvery minnow. Stations 2-S, 3-S, 4-S, 7-G, 8-S, and 16-G.

This species was taken sporadically, but sometimes abundantly, in the Big Blue River. At Stations 7-G and 16-G a few young-of-the-year were found.

Bailey (1956:333) does not consider the southwestern Hybognathus placita (Girard) specifically distinct from the northeastern H. nuchalis, but little evidence of intergradation has been published. In Table 2, I have compared measurements and counts of 50 specimens of Hybognathus from the Big Blue River, 50 H. n. placita from the Walnut River, Kansas (Arkansas River Basin), and 50 H. n. nuchalis from Wisconsin. Measurements and counts were made by methods described by Hubbs and Lagler (1947:8-15) and measurements are expressed as thousandths of standard length.

| Count or Proportional Measurement | Walnut River, Kansas H. n. placita, KU 3869 |

Big Blue River, Kansas KU 3812 |

Chippewa River, H. n. nuchalis, KU 2012 |

||||||

| X | σ | 2 σm | X | σ | 2 σm | X | σ | 2 σm | |

| Lateral-line scales | 38.9 (37-41) |

1.1 | 0.4 | 37.2 (35-39) |

1.1 | 0.4 | 37.3 (35-39) |

1.0 | 0.2 |

| Predorsal scale-rows | 16.8 (15-19) |

0.9 | 0.7 | 15.9 (14-17) |

0.8 | 0.2 | 15.1 (14-17) |

0.5 | 0.1 |

| Scale-rows below lateral-line | 15.6 (13-18) |

1.2 | 0.3 | 14.9 (12-16) |

1.0 | 0.3 | 12.9 (12-15) |

0.7 | 0.2 |

| Scale-rows around caudal peduncle | 16.2 (15-19) |

1.1 | 0.3 | 15.8 (14-18) |

0.8 | 0.2 | 13.8 (12-15) |

0.6 | 0.2 |

| Orbit ÷ standard length | .051 (044-61) |

.0035 | .0010 | .059 (047-71) |

.0047 | .0013 | .068 (059-77) |

.0044 | .0013 [425] |

| Gape-width ÷ standard length | .066 (055-75) |

.0046 | .0013 | .064 (055-74) |

.0044 | .0013 | .056 (046-64) |

.0038 | .0011 |

| Orbit ÷ gape-width | .776 (647-945) |

.0083 | .0024 | .907 (712-1.067) |

.0080 | .0023 | 1.223 (953-1.566) |

.0119 | .0034 |

Hybognathus from the Big Blue River tend to have fewer, larger scales than H. n. placita from the Walnut River, Kansas, but more and smaller scales than H. n. nuchalis from Wisconsin. In specimens from the Blue River, the size of the orbit divided by standard length, and the width of gape divided by standard length and width of orbit, are also intermediate between the Walnut River and Wisconsin specimens, but tend toward the former. Specimens from the Big Blue River resemble H. n. placita from the Walnut River in body shape, robustness, and in the embedding of scales on the nape.

Pimephales notatus (Rafinesque), bluntnose minnow: Meek (1895:136); and Evermann and Cox (1896:399). Stations 2-S, 3-S, 5-G, 6-S, 8-S, 9-G, 10-G, 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 16-G, 19-G, 27-G, 29-G, 53-S, 54-G, and 58-G.

The bluntnose minnow preferred the clearer creeks, with gravel or gravel-silt bottoms, but occurred rarely in the mainstream of the Big Blue River. Males and females in high breeding condition were taken on July 14, 1958. The temperature of the water was 75.5° F.

Pimephales promelas Rafinesque, fathead minnow: Meek (1895: 136); and Evermann and Cox (1896:397-398). All stations excepting 1-S, 4-S, 12-G, 30-M, 43-S, 44-S, and 56-S.

Small muddy streams were preferred by P. promelas; however, the fathead minnow was taken in all habitats, and in association with most other species.

Canfield and Wiebe (1931:6-7) may have recorded P. promelas from the Big Blue River Basin, Nebraska, as "blackhead minnows."

Campostoma anomalum plumbeum (Girard), stoneroller. All stations excepting 1-S, 2-S, 3-S, 14-S, 15-S, 21-G, 22-G, 28-G, 30-M, 33-M, 34-M, 35-M, 36-M, 37-M, 38-S, 41-S, 44-S, 45-M, 51-M, 52-S, and 55-M.

Stonerollers were usually taken in riffles with gravel-rubble bottoms. Those individuals collected in areas with mud or sand bottoms were almost invariably in the current, or in the edge of currents.

Specimens from the Big Blue River Basin have an average of 47.4 scale-rows around the body (range 42-54).

Ictalurus melas (Rafinesque), black bullhead: Evermann and [427] Cox (1896:387) as Ameiurus melas (Rafinesque); and Canfield and Wiebe (1931:5-7, 10) as "bullheads." Stations 2-S, 6-S, 7-G, 11-G, 16-G, 20-G, 22-G, 23-G, 24-G, 28-G, 35-M, 40-M, 51-M, 53-S, 55-M, 56-S, 57-M, and 58-G.

Black bullhead occurred in all habitats, but were less commonly taken in the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers than in other streams.

Ictalurus natalis (LeSueur), yellow bullhead. Stations 7-G, 9-G, 10-G, 11-G, 17-G, 18-G, 19-G, 34-M, 35-M, 36-M, 37-M, 40-M, 47-M, 48-M, 53-S, and 55-M.

The yellow bullhead inhabited the muddy-bottomed streams and the upland, gravelly creeks, usually occurring in the headwaters. I obtained only one I. natalis in the sandy Big Blue River.

Ictalurus punctatus (Rafinesque), channel catfish: Cragin (1885:107); Meek (1895:135); Evermann and Cox (1896:386); and Canfield and Wiebe (1931:6-7, 10) as "channel catfish." Stations 1-S, 2-S, 3-S, 4-S, 5-G, 6-S, 7-G, 8-S, 9-G, 11-G, 14-S, 15-S, 16-G, 18-G, 25-S, 27-G, 30-M, 35-M, 38-S, 39-S, 41-S, 42-S, 43-S, 44-S, 46-M, 50-S, 51-M, 52-S, 53-S, and 56-S.

Channel catfish were most common in the larger, sandy streams, but occurred in other kinds of streams. The ages and calculated total lengths at the last annulus for 40 channel catfish were: I, no fish; II, 7.3 (16); III, 10.6 (5); IV, 12.3 (5); V, 13.3 (6); VI, 15.5 (4); VII, 18.0 (3); and VIII, 21.9 (1). These lengths are slightly lower than averages reported by Finnell and Jenkins (1954:5) in Oklahoma impoundments.

The length-frequency distribution of 438 channel catfish, collected by rotenone on August 5 and 7, 1958, indicated that two age-groups were represented. Without examination of spines, I assigned 265 fish to age-group O (1.3 to 2.9 inches, average 2.5) and 173 fish to age-group I (3.1 to 5.8 inches, average 4.5). The average total length of age group I (4.5 inches) is only slightly higher than the total length at the first annulus reported as average for Oklahoma (4.0 inches, Finnell and Jenkins, loc. cit.). It seems unlikely that my yearling fish taken in August, 1958, would have reached the length at the second annulus recorded in my study of spines (7.3 inches) by the end of the 1958 growing season.

From 1952 to 1956, severe drought was prevalent in Kansas, probably causing streams to flow less than at any previously recorded time (Minckley and Cross, in press). This drought must have resulted in reduced populations of fishes in the streams. The channel catfish hatched in 1956 were therefore subjected to low [428] competition for food and space when normal flow was resumed in 1957, and grew rapidly, reaching an average total length of 7.3 inches at the second annulus, while channel catfish that were members of the large 1957 and 1958 hatches suffered more competition and grew more slowly.

Noturus flavus Rafinesque, stonecat: Jennings (1942:365). Stations 3-S, 4-S, 6-S, 16-G, 25-S, 28-G, 38-S, 41-S, 42-S, 43-S, 52-S, 53-S, and 56-S.

Noturus flavus frequented riffles and swift currents along sandbars in the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers. Cross (1954:311) reported that "the shale-strewn riffles of the South Fork [of the Cottonwood River, Kansas] provide ideal habitat for the stonecat." In my study-area, this species was found not only on rubble-bottomed riffles, but occurred along both stationary and shifting sandbars where no cover was apparent.

Pylodictis olivaris (Rafinesque), flathead catfish: Canfield and Wiebe (1931:7) as "yellow catfish." Stations 3-S, 4-S, 6-S, 8-S, 15-S, 25-S, 38-S, 41-S, 43-S, 44-S, 53-S, and 56-S.

Flathead catfish were found only in the larger rivers. The species was taken rarely by seine, but was readily obtained by electric shocker. Data on the age and growth and food-habits of this species are to be the subject of another paper.

Anguilla bostoniensis (LeSueur), American eel: Jennings (1942:365).

American eels are now rare in Kansas, and none was taken in my survey. The specimen reported by Jennings (loc. cit.) is at Kansas State College (KSC 2916), and was taken by I. D. Graham from the Big Blue River, Riley County, 1885.

Fundulus kansae Garman, plains killifish. Station 42-S.

The plains killifish was collected by me only at Station 42-S. Specimens were collected from my Station 4-S by the Kansas State College class in fisheries management in 1954 (KSC 4985). My specimens were 11 to 13 mm. in total length.

Roccus chrysops (Rafinesque), white bass. Station 3-S.

That the white bass is indigenous to Kansas is evidenced by records of Graham (1885:77) and Cragin (1885:111); however, since that time, and prior to the introduction of this species into reservoirs in the State, R. chrysops has rarely been recorded in Kansas. I collected young white bass at Station 3-S in both 1957 and 1958, and I collected them also in an oxbow of the Kansas River four miles west of Manhattan, Riley County, Kansas, in the mouth [429] of McDowell's Creek, Riley County, and in Deep Creek, Wabaunsee County, and I saw other specimens from an oxbow of the Kansas River on the Fort Riley Military Reservation, Riley County, Kansas. The apparent increase in abundance of white bass in the Kansas River Basin must be attributable to introductions in reservoirs, with subsequent escape and establishment in the streams.

Micropterus salmoides salmoides (Lacépède), largemouth bass. Stations 6-S, 11-G, 43-S, and 45-M.

Four largemouth bass were taken. This species has been widely stocked in farm-ponds and other impoundments in Kansas.

Lepomis cyanellus Rafinesque, green sunfish: Breukelman (1940:382); and Canfield and Wiebe (1931:5, 7-8, 10) as "green sunfish." All stations excepting 1-S, 2-S, 4-S, 8-S, 9-G, 15-S, 22-G, 25-S, 30-M, 32-G, 34-M, 38-S, 39-S, 41-S, 42-S, 43-S, 44-S, 45-M, 46-M, 47-M, 50-S, and 52-S.

Green sunfish occurred primarily in the muddy streams. The ages and total lengths at the last annulus for 25 specimens are as follows: I, 1.1 (9); II, 2.2 (4); III, 3.1 (7); IV, 5.4 (4); and V, 6.0 (1). Male green sunfish were seen on nests on June 29, July 1, and July 9, 1958.

Lepomis humilis (Girard), orangespotted sunfish: Meek (1895:137); Evermann and Cox (1896:418); Canfield and Wiebe (1931:6) as "orange spots"; and Breukelman (1940:382). All stations excepting 1-S, 9-G, 13-G, 15-G, 17-G, 21-G, 26-G, 34-M, 36-M, 38-M, 43-M, 44-S, 47-M, 50-S, and 52-S.

Lepomis humilis was most common over sand-silt bottoms. Only two age-groups were found; their calculated total lengths were I, 1.7 (15); and II, 2.4 (10). Orangespotted sunfish were seen nesting on the same dates as Lepomis cyanellus.

Lepomis macrochirus Rafinesque, bluegill. Stations 7-G, 13-G, 16-G, 24-G, and 59-G.

This species has been widely stocked in Kansas. Only young-of-the-year and sub-adults were taken, and these were rare.

Pomoxis annularis Rafinesque, white crappie: Canfield and Wiebe (1931:5-8, 10) as "white crappie." Stations 3-S, 6-S, 8-S, 12-G, 42-S, and 53-S.

White crappie were rare, except in a borrow-pit at Station 6-S. Ages and calculated total lengths at the last annulus for 50 specimens from 6-S are as follows: I, 3.6 (22); II, 5.0 (14); III, 7.1 (5); IV, 8.3 (7); and V, 10.7 (2).

Pomoxis nigromaculatus (LeSueur), black crappie. Station 6-S.

One black crappie (KU 4174) was taken. Canfield and Wiebe [430] (1931:10) noted: "The Black Crappie has been planted here [Big Blue River Basin in Nebraska] by the State, but, apparently, is not propagating itself."

Stizostedion canadense (Smith), sauger. Station 56-S.

Mr. Larry Stallbaumer, of Marysville, Kansas, obtained a sauger (KU 4179) while angling on May 25, 1958.

Stizostedion vitreum (Mitchill), walleye.

Though I failed to obtain the walleye in my survey, Dr. Raymond E. Johnson (personal communication) reported that the species occurred in the Nebraskan portion of the Big Blue River in recent years. Canfield and Wiebe (1931:6, 10) reported that "yellow pike are taken at Crete [Nebraska]," but may have referred to either the walleye or the sauger.

Perca flavescens (Mitchill), yellow perch: Canfield and Wiebe (1931:5-6, 10) as "ring perch" and "yellow perch."

This fish was not taken in my survey. Canfield and Wiebe (loc. cit.) reported that the yellow perch "had been planted by the State [Nebraska]."

Etheostoma nigrum nigrum Rafinesque, johnny darter: Jennings (1942:365) as Boleosoma nigrum nigrum (Rafinesque). Stations 10-G, 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 16-G, 29-G, 40-M, 53-S, and 54-G.

The larger pools of gravelly streams were preferred by johnny darters, but one specimen was taken from the main stream of the Big Blue River, and the species was abundant in one stream over hard, sand-silt bottom.

Etheostoma spectabile pulchellum (Girard), orangethroat darter: Jennings (1942:365) as Poecilichthys spectabilis pulchellus (Girard). Stations 5-G, 7-G, 10-G, 11-G, 12-G, 13-G, 16-G, 17-G, 18-G, 21-G, 23-G, 27-G, 28-G, 29-G, 33-M, 40-M, 49-M, 53-S, 54-G, and 59-G.

The orangethroat darter was less restricted in habitat than the johnny darter, occurring in all stream-types, but most often in the riffles of gravelly streams. Most specimens from muddy or sandy streams were small.

Aplodinotus grunniens Rafinesque, freshwater drum. Stations 3-S, 4-S, 6-S, 7-G, 8-S, 15-S, 38-S, 39-S, 53-S, and 56-S.

The ages and calculated total lengths at the last annulus for 42 freshwater drum from the Big Blue River were: I, 3.0 (10); II, 5.7 (6); III, 9.4 (7); IV, 12.1 (13); V, 14.0 (3); VI, 15.1 (2); and VII, 16.3 (1).

I obtained two hybrid fishes in my study-area. One specimen of Notropis cornutus frontalis × Chrosomus erythrogaster was taken at Station 29-G. This combination was recorded by Trautman (1957:114) in Ohio. The other hybrid was Lepomis cyanellus × Lepomis humilis, captured at Station 24-G. This combination was first recorded by Hubbs and Ortenburger (1929:42).

Hubbs and Bailey (1952:144) recorded another hybrid combination from my area of study: Campostoma anomalum plumbeum × Chrosomus erythrogaster, UMMZ 103132, from a "spring-fed creek on 'Doc' Wagner's farm, Riley County, Kansas; September 21, 1927; L. O. Nolf [collector]."

The relative abundance of different species was estimated by combining counts of individual fishes taken in 290 seine-hauls, 26 hours and 15 minutes of shocking, and seven samples obtained with rotenone. At some stations all seine-hauls were counted. At other stations the seine-hauls in which complete counts were recorded had been selected randomly in advance; that is to say, prior to collecting at each station. I selected those hauls to be counted from a table of random numbers (Snedecor, 1956:10-13). I did not use the frequency-of-occurrence method as proposed by Starrett (1950:114), in which the species taken and not the total number of individuals are recorded for all seine-hauls. However, the frequency of occurrence of each species is indicated by the number of stations at which it was found, and those stations are listed in the previous accounts. Table 3 shows the percentage of the total number of fish that each species comprised in three kinds of streams: sandy (Big Blue and Little Blue rivers), muddy, and gravelly streams.

The habitat preferences of some species affect their abundance in different stream-types. Notropis lutrensis and P. mirabilis seemed almost ubiquitous. Notropis deliciosus also occurred in all kinds of streams (rarely in muddy streams); however, this species was represented by the sand-loving N. d. missuriensis in the Big Blue and Little Blue rivers, and N. d. deliciosus in the clear, gravelly, upland creeks (Nelson, personal communication). Because of its widespread occurrence, and for purposes of later discussion, I refer to this minnow also as an ubiquitous species in the Big Blue River Basin.

| Species | Sandy streams | Muddy streams | Gravelly streams | |

| Big Blue River | Little Blue River | |||

| N. lutrensis | 43.5 | 55.9 | 27.6 | 56.0 |

| I. punctatus | 14.0 | 7.0 | 1.2 | 4.2 |

| Carpiodes carpio | 11.9 | 2.0 | 5.0 | 0.5 |

| N. deliciosus | 8.2 | 28.2 | 3.1 | 11.1 |

| I. melas | 2.5 | — | 1.3 | 0.5 |

| Cyprinus carpio | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.7 | 0.2 |

| P. olivaris | 1.8 | 0.8 | — | — |

| L. humilis | 1.7 | — | 9.0 | 5.1 |

| I. bubalus | 1.4 | 0.1 | — | Tr. |

| P. mirabilis | 1.3 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 1.3 |

| H. nuchalis | 1.2 | — | — | Tr. |

| P. promelas | 0.8 | 1.0 | 28.7 | 4.0 |

| H. aestivalis | 0.7 | 0.2 | — | — |

| A. grunniens | 0.5 | — | — | 0.2 |

| L. osseus | 0.5 | 1.0 | — | — |

| C. anomalum | 0.4 | 0.2 | 2.7 | 4.6 |

| C. commersonnii | 0.4 | — | — | 0.7 |

| D. cepedianum | 0.4 | Tr. | 0.1 | — |

| N. percobromus | 0.3 | — | — | — |

| P. annularis | 0.3 | Tr. | — | — |

| N. flavus | 0.2 | 0.4 | — | Tr. |

| S. atromaculatus | 0.2 | 0.1 | 12.2 | 1.7 |

| M. aureolum | 0.1 | 0.2 | — | — |

| I. cyprinella | 0.1 | — | 0.1 | — |

| P. notatus | 0.1 | — | — | 2.2 |

| I. niger | 0.1 | 0.1 | — | — |

| H. alosoides | 0.1 | — | — | — |

| E. spectabile | 0.1 | — | 1.4 | 1.6 |

| R. chrysops | 0.1 | — | — | — |

| L. cyanellus | 0.1 | — | 3.5 | Tr. |

| H. storeriana | Tr. | — | — | — |

| L. platostomus | Tr. | — | — | — |

| M. salmoides | Tr. | — | — | — |

| P. nigromaculatus | Tr. | — | — | — |

| I. natalis | Tr. | — | 1.0 | Tr. |

| N. umbratilis | Tr. | — | — | — |

| C. forbesi | Tr. | — | — | — |

| S. platorynchus | Tr. | — | — | — |

| F. kansae | — | Tr. | — | — |

| E. nigrum | Tr. | — | 0.1 | 0.2 |

| N. rubellus | — | — | — | Tr. |

| N. topeka | — | — | — | 1.0 |

| N. cornutus | — | — | — | 1.0 |

| C. erythrogaster | — | — | — | 1.0 |

| L. macrochirus | — | — | — | 1.0 |

Carpiodes carpio, Cyprinus carpio, I. punctatus, I. melas, and L. humilis were widespread, but each was absent or rare in one of the kinds of streams (Table 3). Carpiodes carpio, Cyprinus carpio, and I. punctatus occurred most frequently in the sandy streams, whereas L. humilis was most common in muddy streams. The high per cent of I. melas in collections from the Big Blue River is a direct result of one large population that was taken with rotenone in a borrow-pit at Station 6-S. In my opinion, this species actually was most abundant in the muddy streams.

Some fish were almost restricted to the sandy streams, apparently because of preference for larger waters, or sandy stream-bottoms: P. olivaris, I. bubalus, H. nuchalis, H. aestivalis, A. grunniens, L. osseus, D. cepedianum, N. percobromus, P. annularis, N. flavus, M. aureolum, I. niger, H. alosiodes, and R. chrysops. Other species that were taken only in the larger rivers, and that are sometimes associated with streams even larger (or more sandy) than the Big Blue River are H. storeriana, L. platostomus, M. salmoides, P. nigromaculatus, C. forbesi, S. platorynchus, F. kansae, N. buchanani, S. canadense, and C. auratus. Ictiobus cyprinella also occurred more frequently in the larger streams.

The muddy-bottomed streams supported populations composed primarily of P. promelas, N. lutrensis, and S. atromaculatus. No species was restricted to this habitat, but the following were characteristic there: P. promelas, S. atromaculatus, L. humilis, L. cyanellus, and I. natalis. Carpiodes carpio, Cyprinus carpio, C. anomalum, E. spectabile, and E. nigrum were locally common in muddy streams, but the first two were most frequent in larger, sandy streams, and the last three in gravelly streams.

In gravel-bottomed, upland streams, N. cornutus, N. rubellus, N. topeka, and C. erythrogaster characteristically occurred; with the exception of N. rubellus (only one specimen taken), all were common at some stations. Other species in gravelly creeks were N. lutrensis, C. anomalum, C. commersonnii, P. notatus, L. macrochirus, E. spectabile, and E. nigrum. Although the one specimen of N. umbratilis taken in this survey was from the Big Blue River, this species is more characteristic of the clearer creeks in Kansas.

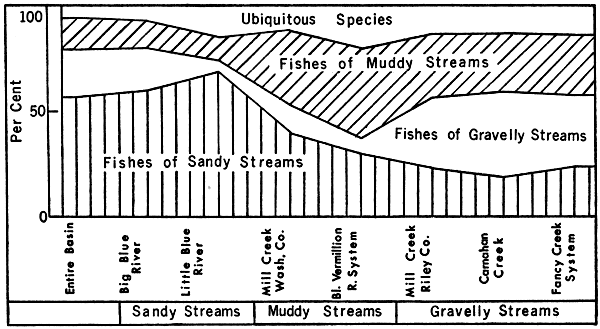

In order to illustrate the composition of the fauna in some specific streams in the Big Blue River Basin, I segregated the fishes into ecological groups, as in the above discussion: ubiquitous types; species of larger, sandy streams; fishes of muddy streams; and fishes of clear, gravelly creeks.

The total number of species taken in each of the streams was [434] divided into the number of species from that stream that were in each of these units, to give a percentage. The resultant data are presented graphically in Figure 3.

Fig. 3. Composition of the fauna of the entire Big Blue River Basin, and of seven streams or stream systems in that basin. "Mill Creek, Wash. Co." refers to all streams in the Mill Creek System, Washington and Republic counties. "Bl. Vermillion R. System" includes all streams in that watershed excepting Clear Creek and one of its tributaries (Stations 31-G and 32-G).

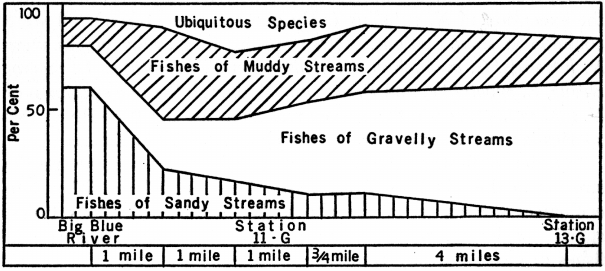

Fig. 4. Composition of the fauna of the Big Blue River, and of five collecting-sites on Carnahan Creek, Pottawatomie County. Lowermost sites are at the left of the figure.

Figure 3 gives a generalized picture of the faunal composition in different kinds of streams. However, the fauna of a small tributary becomes more distinct from the fauna of the larger stream into which the small stream flows as one moves toward the headwaters (Metcalf, 1957:92, 95-100). Figure 4 illustrates this in Carnahan [435] Creek. Station 11-G included four sampling-sites, which were approximately one, two, three, and four miles upstream from the mouth of Carnahan Creek. Station 13-G (one collection) was about four miles upstream from the closest sampling-site of Station 11-G. Applying the same methods as for Figure 3, my findings show a gradual decline in the per cent of the fauna represented by the "large-river-fishes," and an increase in the segment classified as "upland-fishes," from downstream to upstream.

Fifty-three fishermen were interviewed in the 1957 creel census period, and 152 in 1958. Only those fishermen using pole and line were interviewed. In the area censused, much additional fishing is done with set-lines, that are checked periodically by the owners.

In the 1958 census, 22 checks along approximately 80 miles of river were made, and seven of these trips were made without seeing one fisherman. The average fishing pressure for the entire area was estimated at one fisherman per 7.9 miles of stream, or one fisherman per 15.7 miles of shoreline.

Seven species of fish were identified from fishermen's creels in 1957 and 1958. These, in order of abundance were: channel catfish; carp; freshwater drum; flathead catfish; shovelnose sturgeon; smallmouth buffalo; and river carpsucker. Shovelnose sturgeon occurred in fishermen's creels only in April, 1957, and freshwater drum occurred more frequently in the spring-census of 1957 than in the summer of 1958.

Sixty-two of the fishermen interviewed in 1958 were fishing for "anything they could catch," 68 were fishing specifically for catfish, and 22 sought species other than catfish. The order of preference was as follows: channel catfish, 21.1 per cent; flathead catfish, 15.1 per cent; unspecified catfish, 12.5 per cent; carp, 9.2 per cent; freshwater drum, 1.3 per cent; and unspecified, 40.8 per cent. The kinds of fish desired by those fishermen checked in 1957 were not ascertained.

Of all fishermen checked in 1957 and 1958, 165 were men, 17 were women, and 24 were children. Ninety-three per cent were fishing from the bank, five per cent were fishing from bridges, and two per cent were wading. All but two per cent of those checked were fishing "tightline"; the remainder fished with a cork.

The ten baits most commonly used, in order of frequency, were worms, doughballs, minnows, liver, beef-spleen, chicken-entrails, coagulated blood, crayfish, shrimp, and corn.

For purposes of later comparison the data on angler success [436] (Table 4) have been divided according to areas: Area I, below Tuttle Creek Dam; Area II, in the Tuttle Creek Reservoir area; and Area III, above the reservoir. Areas I and III received the most fishing pressure, especially Station 4-S (in Area I), and Station 56-S (in Area III).

In Area I, the success ranged from 0.91 fish per fisherman-day in 1957 to 0.26 fish per fisherman-day in 1958. The 1957 census was made in April and May, when fishing in warm-water streams is considered better than in July (Harrison, 1956:203). The 1958 census was from late June through July, and stream-flow in this period was continuously above normal. Therefore, fewer people fished the river, and catches were irregular. Catches in 1958 ranged from 0.26 fish per fisherman-day in Area I to 0.44 fish per fisherman-day in Area III. In 1951, in the Republican River of Kansas and Nebraska, the average fisherman-day yielded 0.36 fish, 0.09 fish per man-hour, and 0.06 fish per pole-hour (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1952:13-14). The average fisherman-day in the Republican River study was 3.0 hours, whereas the average on the Big Blue River was 2.2 hours for all areas in 1958 (Table 4).

| Area, Year, and Number of Fishermen |

Average length of fisherman-day | Number fish per fisherman-day | Number fish per man-hour | Number fish per pole-hour [A] |

| Area I, 1957 53 fishermen |

2.7 hours | 0.91 | 0.33 | 0.23 |

| Area I, 1958 84 fishermen |

2.5 hours | 0.26 | 0.10 | 0.07 |

| Area II, 1958 27 fishermen |

1.7 hours | 0.37 | 0.22 | 0.14 |

| Area III, 1958 41 fishermen |

2.4 hours | 0.44 | 0.16 | 0.11 |

| All areas, 1958 152 fishermen |

2.2 hours | 0.33 | 0.14 | 0.09 |

[A] Fishermen used an average of 1.44 poles.

In the Big Blue River 47.7 per cent of all fishermen were successful in Area I in 1957, while only 13.1 per cent were successful in the same area in 1958 (Table 5). In the Republican River, 24 per cent of the fishing parties were successful (1.64 persons per party) (U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service, loc. cit.). The average [437] distance that each fisherman had traveled to fish in the Big Blue River was 15.7 miles. Seventy-nine per cent of the persons contacted lived within 25 miles of the spots where they fished. In the study on the Republican River, 77 per cent of the parties interviewed came less than 25 miles to fish.

| 1957 Area I | 1958 Area I | 1958 Area II | 1958 Area III | 1958 All areas | |

| Per cent of fishermen successful | 47.1 | 13.1 | 18.5 | 19.5 | 15.8 |

| Distances traveled to fish (averages in parentheses) |

0-121 (15.6) |

1-197 (20.5) |

0-124 (13.5) |

0-60 (7.4) |

0-197 (15.7) |

My primary recommendation is for continued study of the Tuttle Creek Reservoir, and the Big Blue River above and below the reservoir, to trace changes in the fish population that result from impoundment.

Probably the fishes that inhabit the backwaters, creek-mouths, and borrow-pits in the Big Blue River Basin (gars, shad, carpsucker, buffalo, carp, sunfishes, and white bass) will increase in abundance as soon as Tuttle Creek Reservoir is formed. Also, as in eastern Oklahoma reservoirs (see Finnell, et al., 1956:61-73), populations of channel and flathead catfish should increase. Because of the presence of brood-stock of the major sport-fishes of Kansas (channel and flathead catfish, bullhead, bluegill, crappie, largemouth bass, and white bass), stocking of these species would be an economic waste: exception might be made for the white bass. It may be above Tuttle Creek Dam, but was not found there.

I do recommend immediate introduction of walleye, and possibly northern pike (Esox lucius Linnaeus), the latter species having been successfully stocked in Harlan County Reservoir, Nebraska, in recent years (Mr. Donald D. Poole, personal communication). These two species probably are native to Kansas, but may have been extirpated as agricultural development progressed. Reservoirs may again provide habitats suitable for these species in the State.

If Tuttle Creek Reservoir follows the pattern found in most Oklahoma reservoirs, large populations of "coarse fish"—fishes that [438] are, however, commercially desirable—will develop (Finnell, et al., loc. cit.). To utilize this resource, and possibly to help control "coarse fish" populations for the betterment of sport-fishing, some provision for commercial harvest should be made in the reservoir.

1. The Big Blue River Basin in northeastern Kansas was studied between March 30, 1957, and August 9, 1958. The objectives were to record the species of fish present and their relative abundance in the stream, and to obtain a measure of angling success prior to closure of Tuttle Creek Dam.

2. Fifty-nine stations were sampled one or more times, using seines, hoop and fyke nets, wire traps, experimental gill nets, rotenone, and an electric fish shocker.

3. Forty-eight species of fish were obtained, and five others have been recorded in literature or found in museums. One species, Carpiodes forbesi, is recorded from Kansas for the first time.

4. Notropis lutrensis was the most abundant fish in the Big Blue River Basin, followed by Notropis deliciosus and Ictalurus punctatus. The most abundant sport-fishes were I. punctatus, I. melas, and Pylodictis olivaris, respectively.

5. The spawning behavior of Notropis lutrensis is described.

6. A creel census at major points of access to the Big Blue River, was taken in 1957 (below Tuttle Creek Dam) and in 1958 (above, in, and below the dam-site). Fishing pressure averaged one fisherman per 15.7 miles of shoreline. The average length of the fisherman-day averaged 2.2 hours, with an average of 0.33 fish per fisherman-day being caught in 1958. The average number of fish per man-hour in 1958 was 0.14 and 15.8 per cent of the fishermen were successful. Distances traveled in order to fish ranged from 0 to 197 miles (airline) and averaged 15.7 miles.

7. The primary recommendation is that studies be continued, to document changes that result from impoundment. Because brood-stock of the major sport-fishes is already present, stocking is unnecessary, except for walleye and northern pike. Also, I recommend commercial harvest of non-game food-fishes.

Transmitted December 19, 1958.

27-7080

MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

Institutional libraries interested in publications exchange may obtain this series by addressing the Exchange Librarian, University of Kansas Library, Lawrence, Kansas. Copies for individuals, persons working in a particular field of study, may be obtained by addressing instead the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas. There is no provision for sale of this series by the University Library, which meets institutional requests, or by the Museum of Natural History, which meets the requests of individuals. Nevertheless, when individuals request copies from the Museum, 25 cents should be included, for each separate number that is 100 pages or more in length, for the purpose of defraying the costs of wrapping and mailing.

* An asterisk designates those numbers of which the Museum's supply (not the Library's supply) is exhausted. Numbers published to date, in this series, are as follows:

| Vol. 1. | Nos. 1-26 and index. Pp. 1-638, 1946-1950. | |

| *Vol. 2. | (Complete) Mammals of Washington. By Walter W. Dalquest. Pp. 1-444, 140 figures in text. April 9, 1948. | |

| Vol. 3. | *1. | The avifauna of Micronesia, its origin, evolution, and distribution. By Rollin H. Baker. Pp. 1-359, 16 figures in text. June 12, 1951. |

| *2. | A quantitative study of the nocturnal migration of birds. By George H. Lowery, Jr. Pp. 361-472, 47 figures in text. June 29, 1951. | |

| 3. | Phylogeny of the waxwings and allied birds. By M. Dale Arvey. Pp. 473-530, 49 figures in text, 13 tables. October 10, 1951. | |

| 4. | Birds from the state of Veracruz, Mexico. By George H. Lowery, Jr., and Walter W. Dalquest. Pp. 531-649, 7 figures in text, 2 tables. October 10, 1951. | |

| Index. Pp. 651-681. | ||

| *Vol. 4. | (Complete) American weasels. By E. Raymond Hall. Pp. 1-466, 41 plates, 31 figures in text. December 27, 1951. | |

| Vol. 5. | Nos. 1-37 and index. Pp. 1-676, 1951-1953. | |

| *Vol. 6. | (Complete) Mammals of Utah, taxonomy and distribution. By Stephen D. Durrant. Pp. 1-549, 91 figures in text, 30 tables. August 10, 1952. | |

| Vol. 7. | *1. | Mammals of Kansas. By E. Lendell Cockrum. Pp. 1-303, 73 figures in text, 37 tables. August 25, 1952. |

| 2. | Ecology of the opossum on a natural area in northeastern Kansas. By Henry S. Fitch and Lewis L. Sandidge. Pp. 305-338, 5 figures in text. August 24, 1953. | |

| 3. | The silky pocket mice (Perognathus flavus) of Mexico. By Rollin H. Baker. Pp. 339-347, 1 figure in text. February 15, 1954. | |

| 4. | North American jumping mice (Genus Zapus). By Philip H. Krutzsch. Pp. 349-472, 47 figures in text, 4 tables. April 21, 1954. | |

| 5. | Mammals from Southeastern Alaska. By Rollin H. Baker and James S. Findley. Pp. 473-477. April 21, 1954. | |

| 6. | Distribution of Some Nebraskan Mammals. By J. Knox Jones, Jr. Pp. 479-487. April 21, 1954. | |

| 7. | Subspeciation in the montane meadow mouse, Microtus montanus, in Wyoming and Colorado. By Sydney Anderson. Pp. 489-506, 2 figures in text. July 23, 1954. | |

| 8. | A new subspecies of bat (Myotis velifer) from southeastern California and Arizona. By Terry A. Vaughn. Pp. 507-512. July 23, 1954. | |

| 9. | Mammals of the San Gabriel mountains of California. By Terry A. Vaughn. Pp. 513-582, 1 figure in text, 12 tables. November 15, 1954. | |

| 10. | A new bat (Genus Pipistrellus) from northeastern Mexico. By Rollin H. Baker. Pp. 583-586. November 15, 1954. | |

| 11. | A new subspecies of pocket mouse from Kansas. By E. Raymond Hall. Pp. 587-590. November 15, 1954. | |

| 12. | Geographic variation in the pocket gopher, Cratogeomys castanops, in Coahuila, Mexico. By Robert J. Russell and Rollin H. Baker. Pp. 591-608. March 15, 1955. | |

| 13. | A new cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus) from northeastern Mexico. By Rollin H. Baker. Pp. 609-612. April 8, 1955. | |

| 14. | Taxonomy and distribution of some American shrews. By James S. Findley. Pp. 613-618. June 10, 1955. | |

| 15. | The pigmy woodrat, Neotoma goldmani, its distribution and systematic position. By Dennis G. Rainey and Rollin H. Baker. Pp. 619-624, 2 figs. in text. June 10, 1955. | |

| Index. Pp. 625-651. | ||

| Vol. 8.[ii] | 1. | Life history and ecology of the five-lined skink, Eumeces fasciatus. By Henry S. Fitch. Pp. 1-156, 26 figs. in text. September 1, 1954. |

| 2. | Myology and serology of the Avian Family Fringillidae, a taxonomic study. By William B. Stallcup. Pp. 157-211, 23 figures in text, 4 tables. November 15, 1954. | |