Title: Sketch of the life of Abraham Lincoln

Author: Isaac N. Arnold

Release date: October 22, 2011 [eBook #37818]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roberta Staehlin, David Garcia, Matthew Wheaton

and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive/American

Libraries.)

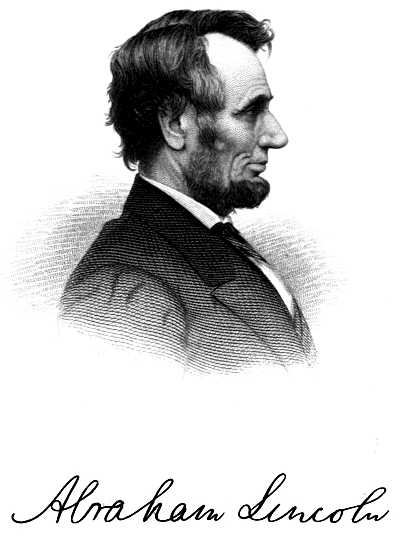

ABRAHAM LINCOLN, PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA.

Engd by H. B. Hall Jr. from a Photo by Brady & Co.

Published by Jno. B. Bachelder.

NEW YORK.

COMPILED IN MOST PART

FROM THE

History of Abraham Lincoln, and the Overthrow of Slavery.

PUBLISHED BY MESSRS. CLARK AND CO., CHICAGO.

BY

ISAAC N. ARNOLD

JOHN B. BACHELDER, PUBLISHER,

59 BEEKMAN STREET, NEW YORK.

1869.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1868, by

JOHN B. BACHELDER,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the United States for the Southern

District of New York.

ALVORD, PRINTER.

Time out of mind, words prefatory have been considered indispensable to the successful publication of a book. This sketch of the Life and Death of Abraham Lincoln is intended as an accompaniment to the Historical Painting which has rescued from oblivion, and, with almost perfect fidelity, transmitted to futurity, "The Last Hours of Lincoln." In its preparation has been invoked the aid of one who in life was near the heart of Mr. Lincoln, and at death was a witness to that last sad scene, so accurately delineated by the painter's art—the Hon. Isaac N. Arnold. His intimate and social relations with Mr. Lincoln, his unbounded admiration of the goodness and sincerity of the Great Emancipator, renders this invocation eminently appropriate. This sketch contains subject-matter never before made public, presented in the full dress of the author's happiest style.

In confident reliance upon the affection of the people for the great Apostle of Liberty—the Martyr—who in his blood wrote his belief "that all men everywhere should be free," this sketch is submitted.

January 1, 1869.

CONTENTS.

| PAGE | |

| Sketch of the Life of Abraham Lincoln, | 9 |

| Lincoln Ancestry, | 10 |

| Boyhood of Lincoln, | 11 |

| Youthful Duties and Amusements, | 11 |

| Early Education, | 13 |

| Elected Captain—Black Hawk War, | 14 |

| Nomination for Legislature, | 14 |

| Member of the Legislature, | 15 |

| Admitted to the Bar, | 15 |

| Practice at the Bar, | 15 |

| Professional Bearing, | 17 |

| Retirement from the Legislature, | 18 |

| Anti-Slavery Proclivities, | 18 |

| Marriage, | 19 |

| Mary Todd, | 19 |

| Children, | 19 |

| In Congress, | 20 |

| Stephen A. Douglas, | 20 |

| Abolition of Slavery at Washington, | 20 |

| Successor in Congress—E. D. Baker, | 20 |

| Beginning of the End of Slavery, | 20 |

| Lincoln in the Kansas Struggle, | 21 |

| [6]Lincoln and Douglas Debate, | 23 |

| Early Acquaintance of Lincoln and Douglas, | 23 |

| Douglas as a Debater, | 24 |

| Douglas—Lincoln—Personal Description, | 25 |

| Douglas—Lincoln—Personal Description continued, | 25 |

| Cooper Institute Address | 27 |

| Chicago Convention—Nomination to Presidency, | 28 |

| Popular Vote—Election, | 28 |

| Journey To Washington, | 29 |

| Arrival at Washington, | 30 |

| Reception, | 30 |

| First Inauguration, | 31 |

| Civil War, | 31 |

| Thirty-seventh Congress, | 32 |

| Calling Out Troops, | 32 |

| Regular Session of Congress, December, 1861, | 33 |

| Slavery Laws Passed, | 33 |

| Emancipation Proclamation, | 34 |

| Owen Lovejoy, | 34 |

| Proclamation Issued—January 1, 1863, | 36 |

| Gettysburg—Consecration, | 39 |

| New Year—1864, | 40 |

| Lieutenant-General—nomination of Ulysses S. Grant, | 41 |

| Constitutional Amendment abolishing Slavery, | 42 |

| Second Inauguration, | 42 |

| Visit to Army Head-quarters—City Point, | 44 |

| Lincoln—Grant—Sherman—Personal Appearance, | 45 |

| Union Troops enter Richmond, | 46 |

| Visit to Richmond, | 46 |

| Return to Washington, | 47 |

| Review of the Army, | 47 |

| Last Days of Lincoln, | 48 |

| Assassination, | 49 |

| Visit to Ford's Theater, | 50 |

| John Wilkes Booth, | 50 |

| Details of the Assassination, | 51 |

| President removed from the Theater, | 51 |

| [7]Death of Lincoln | 51 |

| Scenes in Washington | 52 |

| Death of Booth | 52 |

| Attempted Assassination of Secretary Seward | 52 |

| Reception of Mr. Lincoln's Death Throughout the Country | 53 |

| Meeting of Members of Congress | 54 |

| Committee To Attend the Remains To Illinois | 54 |

| Funeral Ceremonies | 54 |

| Funeral Cortege.—Washington, Philadelphia, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Indiana, Illinois | 54 |

| Personal Sketches | 56 |

| Fondness for Reading | 59 |

| Last Sunday of His Life | 59 |

| Conversational Powers | 60 |

| Public Speaker | 60 |

| The Words of Lincoln | 61 |

| Habitual Manner of Transacting Business at the White House | 65 |

| Description of Rooms and Furniture | 66 |

| Etiquette of Business Reception | 67 |

| Greatness of His Services | 69 |

| The Most Democratic President | 71 |

| Religious Creed | 71 |

| Belief in a God | 73 |

Modern history furnishes no life more eventful and important, terminated by a death so dramatic, as that of the Martyr President. Poetry and painting, sculpture and eloquence, have all sought to illustrate his career, but the grand epic poem of his life has yet to be written. We are too near him in point of time, fully to comprehend and appreciate his greatness and the vast influence he is to exert upon the world. The storms which marked his tempestuous political career have not yet entirely subsided, and the shock of his fearfully tragic death is still felt; but as the dust and smoke of war pass away, and the mists of prejudice which filled the air during the great conflict clear up, his character will stand out in bolder relief and more perfect outline.

The ablest and most sincere apostle of liberty the world has ever seen was Abraham Lincoln. He was a Christian statesman, with faith in God and man. The two men, whose pre-eminence in American history the world[10] will ever recognize, are Washington and Lincoln. The Republic which the first founded and the latter saved, has already crowned them as models for her children.

Abraham Lincoln was born, February 12th, 1809, in Hardin County, in the Slave State of Kentucky.[1]

[1] When the compiler of the Annals of Congress asked Mr. Lincoln to furnish him with data from which to compile a sketch of his life, the following brief, characteristic statement was given. It contrasts very strikingly with the voluminous biographies furnished by some small great men who have been in Congress:—

"Born, February 12th, 1809, in Hardin County, Kentucky.

"Education defective.

"Profession, a Lawyer.

"Have been a Captain of Volunteers in Black Hawk War.

"Postmaster at a very small office.

"Four times a member of the Illinois Legislature, and was a member of the Lower House of Congress.

His father Thomas and his grandfather Abraham were born in Rockingham County, Virginia. His ancestors were from Pennsylvania, and were Friends or Quakers. The grandfather after whom he was named, went early to Kentucky, and was murdered by the Indians, while at work upon his farm. The early and fearful conflicts in the dense forests of Kentucky, between the settlers and the Indians, gave to a portion of that beautiful State the name of the "dark and bloody ground." The subject of this sketch was the son, the grandson, and the great grandson of a pioneer. His ancestors had settled on the border, first in Pennsylvania, then in Virginia, and from thence to Kentucky. His grandfather had four sons and two daughters. Thomas the youngest son was the father of Abraham, and his life was a struggle with poverty, a hard-working man with very limited education. He could barely sign his name. In the twenty-eighth year of his age he married Nancy Hanks, a native of Virginia, [11]she was one of those plain, dignified matrons, possessing a strong physical organization, and great common sense, with deep religious feeling, and the utmost devotion to her family and children, such as are not unusual in the early settlements of our country. Reared on the frontier, where life was a struggle, she could use the rifle and the implements of agriculture as well as the distaff and spinning-wheel. She was one of those strong, self-reliant characters, yet gentle in manners, often found in the humbler walks of life, fitted as well to command the respect, as the love of all to whom she was known. Abraham had a brother older, and a sister younger than himself, but both died many years before he reached distinction.

In 1816, when he was only eight years old, the family removed to Spenser County, Indiana. The first tool the boy of the backwoods learns to use is the ax. This, young Lincoln, strong and athletic beyond his years, had learned to handle with some effect, even at that early age, and he began from this period to be of important service to his parents in cutting their way to, and building up, a home in the forests.

A feat with the rifle soon after this period shows that he was not unaccustomed to its use: seeing a flock of wild turkeys approaching, the lad seized his father's rifle and succeeded in shooting one through a crack of his father's cabin.

In the autumn of 1818 his mother died. Her death was to her family, and especially her favorite son Abraham, an irreparable loss. Although she died when in his tenth year, she had already deeply impressed upon him those elements of character which were the foundation of his greatness;[12] perfect truthfulness, inflexible honesty, love of justice and respect for age, and reverence for God. He ever spoke of her with the most touching affection. "All that I am, or hope to be," said he, "I owe to my angel mother."

It was his mother who taught him to read and write; from her he learned to read the Bible, and this book he read and re-read in youth, because he had little else to read, and later in life because he believed it was the word of God, and the best guide of human conduct. It was very rare to find, even among clergymen, any so familiar with it as he, and few could so readily and accurately quote its text.

There is something very affecting in the incident that this boy—whom his mother had found time amidst her weary toil and the hard struggle of her rude life, to teach to write legibly, should find the first occasion of putting his knowledge of the pen to practical use, was in writing a letter to a traveling preacher, imploring him to come and perform religious services over his mother's grave. The preacher, a Mr. Elkin, came, though not immediately, traveling many miles on horseback through the wild forests; and some months after her death the family and neighbors gathered around the tree beneath which they had laid her, to perform the simple, solemn funeral rites. Hymns were sung, prayers said, and an address pronounced over her grave. The impression made upon young Lincoln by his mother was as lasting as life. Love of truth, reverence for religion, perfect integrity, were ever associated in his mind with the tenderest love and respect for her. His father subsequently married Mrs. Sally Johnson, of Kentucky, a widow with three children.

In March, 1830, the family removed to Illinois, and settled in Macon County, near Decatur. Here he assisted his father to build a log-cabin; clear, fence, and plant, a few acres of[13] land; and then, being now twenty-one years of age, he asked permission to seek his own fortune. He began by going out to work by the month, breaking up the prairie, splitting and chopping cord wood, and any thing he could find to do. His father not long afterward removed to Coles County, Illinois, where he lived until 1851, dying at the age of seventy-three. He lived to see his son Abraham one of the most distinguished men in the State, and received from him many memorials of his affection and kindness. His son often sent money to his father and other members of his family, and always treated them, however poor and illiterate, with the kindest consideration.

It is clear from his own declarations that he early cherished an ambition, probably under the inspiration of his mother, to rise to a higher position. He had in all less than one year's attendance at school, but his mother having taught him to read and write, with an industry, application, and perseverance untiring, he applied himself to all the means of improvement within his reach. Fortunately, providentially, the Bible has been everywhere and always present in every cabin and home in the land. The influence of this book formed his character; he was able to obtain in addition to the Bible, Æsop's Fables, Bunyan's Pilgrim's Progress, Weems' Life of Washington, and Burns' Poems. These constituted nearly all he read before he reached the age of nineteen. Living on the frontier, mingling with the rude, hard-working, honest, and virtuous backwoodsmen, he became expert in the use of every implement of agriculture and woodcraft, and as an ax-man he had no superior.

His days were spent in hard manual labor, and his evenings in study; he grew up free from idleness, and contracted no stain of intemperance, profanity, or vice; he[14] drank no intoxicating liquors, nor did he use tobacco in any form.

There is a tradition that while residing at New Salem, Mr. Lincoln entertained a boy's fancy for a prairie beauty named Ann Rutledge. Mr. Irving, in his life of Washington, says: "Before he (Washington) was fifteen years of age, he had conceived a passion for some unknown beauty, so serious as to disturb his otherwise well-regulated mind, and to make him really unhappy." Some romance has been published in regard to this early attachment of Lincoln, and gossip and imagination have converted a simple, boyish fancy, such as few reach manhood without having passed through, into a "grand passion." It has been produced in a form altogether too dramatic and highly-colored for the truth. The idea that this fancy had any permanent influence upon his life and character is purely imaginary. No man was ever a more devoted and affectionate husband and father than he.

In the spring of 1832 Lincoln volunteered as a private in a company of soldiers raised by the Governor of Illinois, for what is known as the Black Hawk War. He was elected captain of the company, and served during the campaign, but had no opportunity of meeting the enemy.

Soon after his return he was nominated for the State Legislature, and in the precinct in which he resided, out of 284 votes received all but seven. It was while a resident of New Salem that he became a practical surveyor.

Up to this period the life of Lincoln had been one of labor, hardship, and struggle: his shelter had been the log-cabin; his food, the "corn dodger and common doings,"[2] the [15]game of the forests and the prairie, and the products of the farm; his dress, the Kentucky jean and buckskin of the frontier; the tools with which he labored, the ax, the hoe, and the plow. He had made two trips to New Orleans; these and his soldiering in the Black Hawk War showed his fondness for adventure.

[2] The settlers have an expression, "Corn dodger and common doin's," as contradistinguished from "Wheat bread and chickin fixin's."

Thus far he had been a backwoodsman, a rail-splitter, a flatboatman, a clerk, a captain of volunteers, a surveyor. In 1834 he was elected to the Legislature of Illinois, receiving the highest vote of any one on the ticket. He was re-elected in 1836 (the term being for two years). At this session he met, as a fellow-member, Stephen A. Douglas, then representing Morgan County.

He remained a member of the Legislature for eight years, and then declined being again a candidate.

He was admitted to the bar of the Supreme Court of Illinois in the autumn of 1836, and his name first appears on the roll of attorneys in 1837.

In April of this year he removed to Springfield, and soon after entered into partnership with his friend, John T. Stewart. As a lawyer he early manifested, in a wonderful degree, the power of simplifying and making clear to the common understanding the most difficult and abstruse questions.

The circuit practice—"riding the circuit" it was called—as conducted in Illinois thirty years ago, was admirably adapted to educate, develop, and discipline all there was in a man of intellect and character. Few books could be obtained upon the circuit, and no large libraries for consultation could be found anywhere. A mere case lawyer was a helpless child in the hands of the intellectual giants produced by these circuit-court contests, where novel questions[16] were constantly arising, and must be immediately settled upon principle and analogy.[3]

[3] Vide "History of Abraham Lincoln and the Overthrow of Slavery," p. 76.

A few elementary books, such as Blackstone's and Kent's Commentaries, Chitty's Pleadings, and Starkie's Evidence, could sometimes be found, or an odd volume would be carried along with the scanty wardrobe of the attorney in his saddle-bags. These were studied until the text was as familiar as the alphabet. By such aid as these afforded, and the application of principles, were all the complex questions which arose settled. Thirty years ago it was the practice of the leading members of the bar to follow the judge from county to county. The court-houses were rude log buildings, with slab benches for seats, and the roughest pine tables. In these, when courts were in session, Lincoln could be always found, dressed in Kentucky jean, and always surrounded by a circle of admiring friends—always personally popular with the judges, the lawyers, the jury, and the spectators. His wit and humor, his power of illustration by apt comparison and anecdote, his power to ridicule by ludicrous stories and illustrations, were inexhaustible.

He always aided by his advice and counsel the young members of the bar. No embarrassed tyro in the profession ever sought his assistance in vain, and it was not unusual for him, if his adversary was young and inexperienced, kindly to point out to him formal errors in his pleadings and practice. His manner of conducting jury trials was very effective.

He was familiar, frequently colloquial: at the summer terms of the courts, he would often take off his coat, and leaning carelessly on the rail of the jury box, would [17]single out and address a leading juryman, in a conversational way, and with his invariable candor and fairness would proceed to reason the case. When he was satisfied that he had secured the favorable judgment of the juryman so addressed, he would turn to another, and address him in the same manner, until he was convinced the jury were with him. There were times when aroused by injustice, fraud, or some great wrong or falsehood, when his denunciation was so crushing that the object of it was driven from the court-room.

There was a latent power in him which when aroused was literally overwhelming. This power was sometimes exhibited in political debate, and there were occasions when it utterly paralyzed his opponent. His replies to Douglas, at Springfield and Peoria, in 1858, were illustrations of this power. His examination and cross-examination of witnesses were very happy and effective. He always treated those who were disposed to be truthful with respect.

Mr. Lincoln's professional bearing was so high, he was so courteous and fair that no man ever questioned his truthfulness or his honor. No one who watched him for half an hour in court in an important case ever doubted his ability. He understood human nature well; and read the character of party, jury, witnesses, and attorneys, and knew how to address and influence them. Probably as a jury lawyer, on the right side, he has never had his superior.

Such was Mr. Lincoln at the bar, a fair, honest, able lawyer, on the right side irresistible, on the wrong comparatively weak.[18]

A friend and associate of Mr. Lincoln, speaking of him, as he was in 1840, says: "They mistake greatly who regard him as an uneducated man. In the physical sciences he was remarkably well read. In scientific mechanics, and all inventions and labor-saving machinery, he was thoroughly informed. He was one of the best practical surveyors in the State. He understood the general principles of botany, geology, and astronomy, and had a great treasury of practical useful knowledge."

He continued to acquire knowledge and to grow intellectually until his death, and became one of the most intelligent and best-informed men in public life.

Early in life he became an anti-slavery man, as well from the impulses of his heart as the convictions of his reason. He always had an intense hatred of oppression in every form, and an honest, earnest faith in the common people, and his sympathies were ever with the oppressed. The most conspicuous traits of his character were love of justice and love[19] of truth. It is false, very arrogant, and to those who knew Lincoln in his earlier years, it is very amusing, for any man or set of men to assume to himself or themselves the credit of having inspired him with hatred of slavery. No man was less influenced by others in coming to his conclusions than he; and this was especially true in regard to questions involving right and justice. His own heart, his own observation, his own clear intellect led him to become an anti-slavery man. Long before he plead the cause of the slave before the American people, he said to a friend,[4] "It is strange that while our courts decide that a man does not lose his title to his property by its being stolen, but he may reclaim it whenever he can find it, yet if he himself is stolen he instantly loses his right to himself!"

[4] Hon. Jos. Gillespie.

In November, 1842, he was married to Miss Mary Todd, daughter of the Hon. Robert S. Todd, of Kentucky. The mother of Mrs. Lincoln died when she was young. She had sisters living at Springfield, Illinois. Visiting them, she made the acquaintance and won the heart of Mr. Lincoln. They had four children, Robert, Edward (who died in infancy), William, and Thomas. Robert and Thomas survive. William, a beautiful and promising boy, died at Washington, during his father's presidency. Mr. Lincoln was a most fond, tender, and affectionate husband and father. No man was ever more faithful and true in his domestic relations.

On the 6th of December, 1847, Mr. Lincoln took his seat in Congress. Mr. Douglas, who had already run a brilliant career in the lower House of Congress, at this same session took his seat in the Senate. Mr. Lincoln distinguished himself by able speeches upon the Mexican War, upon Internal Improvements, and by one of the most effective campaign speeches of that Congress in favor of the election of General Taylor to the Presidency. He proposed a bill for the abolition of slavery at the National capital. He declined a re-election, and was succeeded by his friend, the eloquent E. D. Baker, who was killed at Ball's Bluff.

In 1852, he lead the electoral ticket of Illinois in favor of General Scott for President. Franklin Pierce was elected, and Mr. Lincoln remained quietly engaged in his professional pursuits until the repeal of the Missouri Compromise in 1854. This event was the beginning of the end of slavery. "It thoroughly roused the people of the Free States to a realization of the progress and encroachments of the slave power, and the necessity of preserving 'the jewel of freedom.'" From that hour the conflict went on between freedom and slavery, first by the ballot, and all the agencies by which public opinion is influenced, and then the slave-holders, seeing that their supremacy was departing, sought by arms to overthrow the government which they could no longer control.

Mr. Lincoln, while a strong opponent of slavery, had up to this time rested in the hope that by peaceful agencies it was[21] in the course of ultimate extinction. But now seeing the vast strides it was making, he became convinced its progress must be arrested or that it would dominate over the republic, and Slavery would become "lawful in all the States." From this time he gave himself with solemn earnestness to the cause of liberty and his country. He forgot himself in his great cause. He did not seek place, if the great cause could be better advanced by the promotion of another; hence his promotion of the election of Trumbull to the United States Senate.

This unselfish devotion to principle was a great source of his power. Placing himself at the head of those who opposed the extension of, and who believed in the moral wrong of slavery, he entered upon his great mission with a singleness of purpose, an eloquence and power, which made him as the advocate of freedom, the most effective and influential speaker who ever addressed the American people.

He brought to the tremendous struggle between freedom and slavery physical strength and endurance almost superhuman. Notwithstanding his modesty and the absence of all self-assertion, when we review the conflict from 1854 to 1865, when the struggle closed by the adoption of the constitutional amendment abolishing and prohibiting slavery forever throughout the republic, it is clear that Lincoln's speeches and writings did more to accomplish this result than any other agency.

Following the repeal of the Missouri Compromise came the Kansas struggle, and the organization of a great party to resist the encroachments and aggressions of slavery. The people instinctively found the leader of such a party in Lincoln.

Looking over the whole ground, with the sagacity[22] which marked his far-seeing mind, he saw that the basis upon which to build were the grand principles of the Declaration of Independence. This foundation was broad enough to include old-fashioned Democrats who sympathized with Jefferson in his hatred of slavery; Whigs who had learned their love of liberty from the utterances of the Adamses and Channings, and the earlier speeches of Webster; and anti-slavery men, who recognized Chase and Sumner as their leaders.

He now addressed himself to the work of consolidating out of all these elements a party, the distinctive characteristics of which should be the full recognition of the principles of the Declaration of Independence and hostility to the extension of Slavery. This was the party which in 1856 gave John C. Fremont 114 electoral votes for President, and in 1860, elected Lincoln to the executive chair.

In the midsummer of 1858, Senator Douglas, whose term approached its close, came home to canvass for re-election. It was in the midst of the Kansas struggle, and although he had broken with the administration of Buchanan, because he resisted the admission of Kansas into the Union, under the fraudulent Lecompton Constitution, and insisted that the people of that State, should enjoy the right by a fair vote, of deciding upon the character of their Constitution,[5] yet the people of Illinois did not forget that he was chiefly responsible for the repeal of the Missouri Compromise, and that he had indorsed the Dred Scott decision. On the 17th of June, 1858, the Republican State Convention of Illinois met and by acclamation nominated Mr. Lincoln for the Senate. He was unquestionably more indebted to Douglas for his greatness than to any other person.

[5] That they "should be perfectly free to form and regulate their domestic institutions in their own way."

In 1856 Lincoln said, "Twenty years ago Judge Douglas and I first became acquainted; we were both young then, he a trifle younger than I. Even then we were both ambitious, I perhaps quite as much as he. With me the race of ambition has proved a flat failure; with him it has been one of splendid success. His name fills the nation, and it is not unknown in foreign lands. I affect no contempt for the high eminence he has reached; so reached that the oppressed of my species might have [24]shared with me in the elevation, I would rather stand on that eminence than wear the richest crown that ever pressed a monarch's brow."

Ten years had not gone by, before the modest Lincoln, then so humbly expressing this noble sentiment, and to whom at that moment "The race of ambition seemed a flat failure;" ten years had not passed, ere he had reached an eminence on which his name filled, not a nation only, but the world; and he had indeed so reached it, that the oppressed did share with him in the elevation; and so far had he passed his then great rival, that the name of Douglas will be carried down to posterity, chiefly because of its association as a competitor with Lincoln.

But in many particulars Douglas was not an unworthy competitor. The contest between these two champions was perhaps the most remarkable in American history. They were the acknowledged leaders, each of his party. Douglas had been a prominent candidate for the presidency, was well known and personally popular, not only in the West, but throughout the Union. Both were men of great and marked individuality of character. The immediate prize was the Senatorship of the great State of Illinois, and, in the future, the presidency. The result would largely influence the struggle for freedom in Kansas, and the question of slavery throughout the Union. The canvass attracted the attention of the people everywhere, and the speeches were reported and published, not only in the leading papers in the State, but reporters were sent from most of the large cities, to report the incidents of the debates, and describe the conflict.

Douglas was at this time unquestionably the leading debater in the United States Senate. For years he had[25] been accustomed to meet the great leaders of the nation in Congress, and he had rarely been discomfited. He had contended with Jefferson Davis, and Toombs, and Hunter, and with Chase, and Sumner, and Seward; and his friends claimed that he was the equal, if not the superior, of the ablest. He was fertile in resources, severe in denunciation, familiar with political history, and had participated so many years in Congressional debate, that he handled with readiness and facility all the weapons of political controversy. Of indomitable physical and moral courage, he was certainly among the most formidable men in the nation on the stump. In Illinois, where he had hosts of friends and enthusiastic followers, he possessed a power over the masses unequaled by any other man, a most striking exhibition of which was exhibited in this canvass, in which he held to himself the whole Democratic party of the State. The administration of Buchanan, with all its patronage wielded by the wily and unscrupulous Slidell, and running a separate ticket, was able to detach only 5,000 out of 126,000 votes from him. There was something exciting, something which stirred the blood, in the boldness with which he threw himself into the conflict, and dealt his blows right and left against the Republican party on one side, and the administration of Buchanan, which sought his defeat, on the other.

Two men presenting more striking contrasts, physically, intellectually, and morally, could not anywhere be found. Douglas was a short, sturdy, resolute man, with large head and chest, and short legs; his ability had gained for him the appellation of "The little giant of Illinois."

Lincoln was of the Kentucky type of men, very tall, long-limbed, angular, awkward in gait and attitude, physically a real giant, large-featured, his eyes deep-set under[26] heavy eyebrows, his forehead high and retreating, with heavy, dark hair.

Their style of speaking, like every thing about them, was in striking contrast. Douglas, skilled by a thousand conflicts in all the strategy of a face to face encounter, stepped upon the platform and faced the thousands of friends and foes around him with an air of conscious power. There was an air of indomitable pluck, sometimes something approaching impudence in his manner, when he looked out on the immense throngs which surged and struggled before him. Lincoln was modest, but always self-possessed, with no self-consciousness, his whole mind evidently absorbed in his great theme, always candid, truthful, cool, logical, accurate; at times, inspired by his subject, rising to great dignity and wonderful power. The impression made by Douglas, upon a stranger who saw him for the first time on the platform, would be—"that is a bold, audacious, ready debater, an ugly opponent." Of Lincoln—"There is a candid, truthful, sincere man, who, whether right or wrong, believes he is right." Lincoln argued the side of freedom, with the most thorough conviction that on its triumph depended the fate of the Republic. An idea of the impression made by Lincoln in these discussions may be inferred from a remark made by a plain old Quaker, who, at the close of the Ottawa debate, said: "Friend, doubtless God Almighty might have made an honester man than Abe Lincoln, but doubtless he never did." It is curious that the cause of freedom was plead by a Kentuckian, and that of slavery by a native of Vermont. Forgetful of the ancestral hatred of slavery to which he had been born, Douglas had, by marriage, become a slave-holder. Lincoln had one great advantage[27] over his antagonist—he was always good-humored; while Douglas sometimes lost his temper, Lincoln never lost his.

The great champions in these debates, and their discussions, have passed into history, and the world has ratified the popular verdict of the day—that Lincoln was the victor. It should be remembered, in justice to the intellectual power of Douglas, that Lincoln spoke for liberty, and he was the organ of a new and vigorous party, with a full consciousness of being in the right. Douglas was looking to the presidency as well as the senatorship, and must keep one eye on the slave-holder and the other on the citizens of Illinois.

The debates in the old Continental Congress, and those on the Missouri question of 1820-1, those of Webster and Hayne, and Webster and Calhoun, are all historical; but it may be doubted if either were more important than these of Lincoln and Douglas.

Mr. Lincoln, although his party received a majority of the popular vote was defeated for Senator, because certain Democratic Senators held over from certain Republican districts.

On the 27th of February, 1860, Mr. Lincoln delivered his celebrated Cooper Institute address. Many went to hear the prairie orator, expecting to be entertained with noisy declamation, extravagant and verbose, and with plenty of amusing stories. The speech was so dignified, so exact in language and statement, so replete with historical learning, it exhibited such strength and grasp of thought and was so elevated in tone, that the intelligent audience were astonished and delighted. The closing sentence is characteristic, and should never be forgotten by those who advocate the right. "Let us have faith that right makes might, and in that faith let us to the end dare to do our duty as we understand it."

When the National Convention met at Chicago in the June following, to nominate a candidate for President, while a majority of the delegates were divided among Messrs. Seward, Chase, Cameron, and Bates, Mr. Lincoln was the first choice of a large plurality, and the second choice of all; besides he was personally so popular with the people, his sobriquet of "Honest old Abe," "The Illinois Rail-splitter," satisfied the shrewd men who were studying the best means of securing success, that he was the most available man to head the ticket. These considerations made his nomination a certainty from the beginning.

The nomination was hailed with enthusiasm throughout the Union. Never did a party enter upon a canvass with more zeal and energy. With the usual motives which actuate political parties there were in this canvass mingled a love of country, a devotion to liberty, a keen sense of the wrongs and outrages inflicted upon the Free State men of Kansas, which fired all hearts with enthusiasm. Mr. Lincoln received one hundred and eighty electoral votes, Douglas twelve, Breckinridge seventy-two, and John Bell of Tennessee, thirty-nine. Mr. Lincoln received of the popular vote 1,866,452, a plurality, but not a majority of the whole.

By the election of Mr. Lincoln the executive power of the republic passed from the slave-holders. Mr. Lincoln and the great party who elected him contemplated no interference with slavery in the States. They meant to prevent its[29] further extension, but the slave-holders instinctively felt that with the government in the hands of those who believed slavery morally wrong, the end of slavery was a mere question of time. Rather than yield, the slave aristocracy resolved "to take up the sword," and hence the terrible civil war.

On the 11th of February, 1861, Mr. Lincoln left his quiet happy home at Springfield to enter upon that tempestuous political career which was to lead him through a martyr's grave to a deathless fame among the greatest and noblest patriots and benefactors of mankind. With a dim, mysterious foreshadowing of the future, he uttered to his friends and neighbors who gathered around him to say good-bye, his farewell. He seemed conscious that he might see the place which had been his home for "a quarter of a century, and where his children were born, and where one of them lay buried" no more. Weighed down with the consciousness of the great duties which devolved upon him, greater than those devolving upon any President since Washington, he humbly expressed his reliance upon Divine Providence, and asked his friends to pray that he might receive the assistance of "Almighty God." As he journeyed toward the capital, received everywhere with the earnest sympathies of the people, the loyal men of all parties assuring him of their support, his spirits rose, and when he passed the State line of his own State his hopefulness found expression in the words "behind the cloud the sun is shining still." And on he sped through the great Free States of the North. While on his way to the capital the people were everywhere deeply impressed by his modest yet firm reliance upon Providence. He went forth not leaning on his own strength, but resting on Almighty God.[30]

In the early gray of the morning of the 23d of February, 1861, he came in sight of the dome of the Capitol, then filled with traitors plotting his death and the overthrow of the Government. By anticipating the train, by which it had been publicly announced that he would pass through Baltimore, and passing through that city at night he escaped a deeply-laid conspiracy, which would otherwise have anticipated the crime of Booth. None who witnessed will ever forget the scene of his first inauguration.

The veteran Scott had gathered a few soldiers of the Regular Army to preserve order and security; many Northern citizens thronged the streets, few of them conscious of the volcano of treason and murder seething beneath them. The departments and public offices were full of plotting traitors. Many of the rebel generals held commissions under the Government they were about to desert and betray. The ceremony of inauguration is always imposing; on this occasion it was especially so. Buchanan, sad, dejected, bowed with a seeming consciousness of duties unperformed, rode with the President-elect to the Capitol.

There were gathered the Justices of the Supreme Court, both Houses of Congress, the representatives of foreign nations, and a vast concourse of citizens from all sections of the Union. There were Chase, and Seward, and Sumner, and Breckinridge, and Douglas, who was near the President, and was observed eagerly looking over the crowd, not unconscious of the personal danger of his great and successful rival. Mr. Lincoln was so absorbed with the gravity of the occasion and the condition of his country, that he utterly forgot himself, and there was observed a dignity, which sprung from a mind entirely engrossed with public duties.[31]

He was perfectly cool, and stepping to the eastern colonnade of the Capitol, that voice, which had been often heard by tens of thousands on the prairies of the West, now read in clear and ringing tones his inaugural. On the threshold of war, he made a last appeal for peace. He declared his fixed resolve, firm as the everlasting rocks: "I shall take care that the laws of the Union be faithfully executed in every State."

Yet his great, kind heart yearned for peace, and as he approached the close, his voice faltered with emotion. "I am loath to close," said he; "we are not enemies, but friends; we must not be enemies. Though passion may have strained, it must not break the bonds of affection. The mystic cords of memory, stretching from every battle-field and patriot's grave, to every living heart and hearthstone over all this broad land, will yet swell with the chorus of the Union, when again touched, as surely they will be, by the better angels of our nature."

Alas! these appeals for peace were received by those to whom they were addressed with coarse ribaldry, with sneers and jeers, and all the savage and barbarous passions which riot in blood. Lincoln was somewhat slow to learn that it was to force only—stern, unflinching force—that treason would yield.

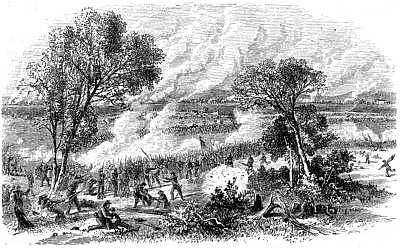

And now opened that terrible civil war which has no parallel in history. Space will not permit me to follow the President through those long and terrible days of victory and defeat, to final triumph. Through all, Lincoln was firm, constant, hopeful, sagacious, wise, confiding always in God, and in the people.

The special session of the Thirty-seventh Congress met on the 4th of July, 1861, agreeably to the call of the President. Many vacant chairs in the National Council impressed the spectator with the magnitude of the impending struggle. The old chiefs of the slave party were nearly all absent, some of them as members of a rebel government at Richmond, others in arms against their country. The President calmly, clearly, sadly reviewed the facts which compelled him to call into action the war powers of the Government, and constrained him, as the Chief Magistrate, "to accept war." He asked Congress to confer upon him the power to make the war short and decisive. He asked for 400,000 men and 400 millions of money. With hearty appreciation of the fidelity of the common people, he proudly points to the fact that, while large numbers of the officers of the Army and Navy had been guilty of the infamous crime of desertion, "not one common soldier or sailor is known to have deserted his flag."

Congress responded promptly to this call, voting 500,000 men and 500 millions of dollars to suppress the rebellion. From the beginning of the contest, the slaves flocked to the Union army as a place of security from their masters. They seemed to feel instinctively that freedom was to be found within its picket-lines and under the folds of its flag. They were ready to act as guides, as servants, to work, dig, and to fight for their liberty. And yet early in the war some officers[33] permitted masters and agents to follow the blacks into the Union lines and carry away fugitive slaves. This action was rebuked by a resolution of Congress. At this session a law was passed giving freedom to all slaves employed in aiding the rebellion. In October, 1861, the military was authorized by the Secretary of War to avail itself of the services of "fugitives from labor," in such way as might be most beneficial to the service.

The regular session of Congress assembled on the 2d of December, 1861. Great armies confronted each other in the field; and great conflicts were going on in the public mind, but the way to victory through emancipation was not yet clearly opened. The President was feeling his way, watching the progress of public opinion; striving to secure to the Union the Border States of Maryland, Kentucky, and Missouri. On the subject of Emancipation, he said in his message: "the Union must be preserved, and all indispensable means must be used," but he wisely waited until the public sentiment should consolidate, and all other means of maintaining the integrity of the nation should have been exhausted. During this session the way was prepared for the great edict of Emancipation; Slavery was abolished at the National Capital, prohibited forever in all the Territories, the slaves of rebels declared free, and the Government authorized to employ slaves as soldiers, and every person in the military or naval service of the Republic prohibited from aiding in the arrest of any fugitive slave. These measures were all urged by the personal and political friends of the President, and became laws with his sanction and hearty assent. They prepared the way for the final overthrow of slavery.

In April, 1862, it was known at Washington that the President was considering the subject of emancipating the slaves as a war measure. The Border States selected their ablest man, the venerable John J. Crittenden, from Mr. Lincoln's native State, to make a public appeal to him to stay his hand. The eloquent Kentuckian discharged the part assigned him well. Never shall I forget the scene when, with great emotion before Congress he said, that although he had voted against and opposed Mr. Lincoln, he had been won to his side. "And now," said he, "there is a niche near to Washington which should be occupied by him who shall save his country. Mr. Lincoln has a mighty destiny! * * * He is no coward, he may be President of all the people and fill that niche, but if he chooses to be in these times a mere sectarian and party man, that place will be reserved for some future and better patriot." "It is in his power to occupy a place next to Washington, the founder and preserver side by side." It was understood the Border State men everywhere were ready to crown him the peer of Washington if he would not touch slavery.

It was Owen Lovejoy, the early abolitionist, who made an instantaneous, impromptu reply, a reply the eloquence of which thrilled Congress and the country, and is in my judgment among the finest specimens of American eloquence.

Said he, "Let Abraham Lincoln make himself, as I[35] trust he will, the Emancipator, the liberator of a race, and his name shall not only be enrolled in this earthly temple, but it will be traced on the living stones of that Temple, which rears itself amidst the thrones of Heaven." Alluding to what Crittenden had said, he added, "There is a niche for Abraham Lincoln in Freedom's holy fane. In that niche he shall stand proudly, gloriously, with shattered fetters, and broken chains and slave-whips beneath his feet. * * This is a fame worth living for; ay, more, it is a fame worth dying for, even though (said he with prophetic prescience) that death led through the blood of Gethsemane and the agony of the accursed tree."

These two speeches were read to Mr. Lincoln in his library at the White House, a room to which he sometimes retired. He was moved by the picture which Lovejoy drew. The tremendous responsibilities growing out of the slavery question, how he ought to treat those sons of "unrequited toil," were questions sinking deeper and deeper into his heart. With a purpose firmly to follow the path of duty, as God should give him to see his duty, he earnestly sought the divine guidance.

Speaking afterward of Emancipation, Mr. Lincoln said: "When, in March, May, and July, 1862, I made earnest and successive appeals to the Border States to favor compensated emancipation, I believed the indispensable necessity for military emancipation and arming the blacks would come, unless averted by that measure. They declined the proposition and I was in my best judgment driven to the alternative of either surrendering the Union or issuing the Emancipation Proclamation."[6]

[6] See Letter of the President to A. G. Hodges, dated April 4, 1864.

Before issuing the proclamation, he had appealed to the [36]Border States to adopt gradual emancipation. His appeal is one of the most earnest and eloquent papers in all history. "Our country," said he, "is in great peril, demanding the loftiest views and boldest action to bring a speedy relief; once relieved, its form of government is saved to the world, its beloved history and cherished memories are vindicated, and its future fully assured and rendered inconceivably grand."

The appeal was received by some with apathy, by others with caviling and opposition, and was followed by action on the part of none. Meanwhile his friends urged emancipation. They declared there could be no permanent peace while slavery lived. "Seize," cried they, "the thunderbolt of Liberty, and shatter Slavery to atoms, and then the Republic will live." After the great battle of Antietam, the President called his cabinet together, and announced to them that "in obedience to a solemn vow to God," he was about to issue the edict of Freedom.

The proclamation came, modestly, sublimely, reverently the great act was done. "Sincerely believing it to be an act of justice, warranted by the Constitution, upon military necessity, he invoked upon it the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favor of Almighty God."

On the first of January, 1863, the Executive mansion, as is usual on New Year's Day, was crowded with the officials, foreign and domestic, of the National Capital; the men of mark of the army and navy and from civil life crowded around the care-worn President, to express their kind wishes for him personally, and their prayers for the future of the country.

During the reception, after he had been shaking hands with hundreds, a secretary hastily entered and told him the[37] Proclamation (the final proclamation) was ready for his signature. Leaving the crowd, he went to his office, taking up a pen, attempting to write, and was astonished to find he could not control the muscles of his hand and arm sufficiently to write his name. He said to me, "I paused, and a feeling of superstition, a sense of the vast responsibility of the act, came over me; then, remembering that my arm had been well-nigh paralyzed by two hours' of hand-shaking, I smiled at my superstitious feeling, and wrote my name."

This Proclamation, the Declaration of Independence, and Magna Charta, these be great landmarks, each indicating an advance to a higher and more Christian civilization. Upon these will the historian linger, as the stepping-stones toward a higher plane of existence. From this time the war meant universal liberty. When, in June, 1858, at his home in Springfield, Lincoln startled the country by the announcement, "this nation can not endure half slave, and half free," and when he concluded that remarkable speech by declaring, with uplifted eye and the inspired voice of a prophet, "we shall not fail if we stand firm, we shall not fail, wise councils may accelerate or mistakes delay, but sooner or later the victory is sure to come," he looked to years of peaceful controversy and final triumph through the ballot-box. He anticipated no war, and he did not foresee, unless in those mysterious, dim shadows, which sometimes startle by half revealing the future, his own elevation to the presidency; he little dreamed that he was to be the instrument in the hands of God to speak those words which should emancipate a race and free his country!

I have not space to follow the movements of the armies; the long, sad campaigns of the grand army of the Potomac under McClellan, Pope, Burnside, Hooker, Meade; nor the[38] varying fortunes of war in the great Valley of the Mississippi under Freemont, and Halleck, and Buell. Armies had not only to be organized, but educated and trained, and especially did the President have to search for and find those fitted for high command.

Ultimately he found such and placed them at the head of the armies. Up to 1863, there had been vast expenditures of blood and treasure, and, although great successes had been achieved and progress made, yet there had been so many disasters and grievous failures, that the hopes of the insurgents of final success were still confident. With all the great victories in the South, and Southwest, by land and on the sea, the Mississippi was still closed. The President opened the campaign of 1863 with the determination of accomplishing two great objects, first to get control of and open the Mississippi; second to destroy the army of Virginia under Lee, and seize upon the rebel capital. By the capture of Vicksburg, and the fall of Port Hudson, the first and primary object of the campaign was realized.

"The 'Father of Waters' again went unvexed to the sea. Thanks to the great Northwest for it, nor yet wholly to them. Three hundred miles up they met New England, Empire, Keystone, and Jersey, hewing their way right and left. The army South, too, in more colors than one, lent a helping hand."[7] While the gallant armies of the West were achieving these victories, operations in the East were crowned by the decisively important triumph at Gettysburg. Let us pass over the scenes of conflict, on the sea and on the land, at the East and at the West, and come to that touching incident in the life of Lincoln, the consecration of the battle-field of Gettysburg as a National cemetery.

[7] See letter of Mr. Lincoln to State Convention of Illinois.

Here, late in the autumn of that year of battles, a portion of that battle-ground was to be consecrated as the last resting-place of those who there gave their lives that the Republic might live.

There were gathered there the President, his Cabinet, members of Congress, Governors of States, and a vast and brilliant assemblage of officers, soldiers, and citizens, with solemn and impressive ceremonies to consecrate the earth to its pious purpose. New England's most distinguished orator and scholar was selected to pronounce the oration. The address of Everett was worthy of the occasion. When the elaborate oration was finished, the tall, homely form of Lincoln arose; simple, rude, majestic, slowly he stepped to the front of the stage, drew from his pocket a manuscript, and commenced reading that wonderful address, which an English scholar and statesman has pronounced the finest in the English language. The polished periods of Everett had fallen somewhat coldly upon the ear, but Lincoln had not finished the first sentence before the magnetic influence of a grand idea eloquently uttered by a sympathetic nature, pervaded the vast assemblage. He said:—

"Fourscore and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.

"Now we are engaged in a great civil war, testing whether that nation, or any nation, so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battle-field of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field as a final resting-place for those who here gave their lives that that[40] nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.

"But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us, the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced.

"It is, rather, for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us, that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion, that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain: that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom: and that government of the people, by the people, and for the people, shall not perish from the earth."

He was so absorbed with the heroic sacrifices of the soldiers as to be utterly unconscious that he was the great actor in the drama, and that his simple words would live as long as the memory of the heroism he there commemorated.

Closing his brief address amidst the deepest emotions of the crowd, he turned to Everett and congratulated him upon his success. "Ah, Mr. Lincoln," said the orator, "I would gladly exchange my hundred pages for your twenty lines."

On the first of January, 1864, Mr. Lincoln received his friends as was usual on New Year's day, and the improved prospects of the country, made it a day of congratulation.[41] The decisive victories East and West enlivened and made buoyant and hopeful the spirits of all. One of the most devoted friends of Mr. Lincoln calling upon him, after exchanging congratulations over the progress of the Union armies during the past year, said:—

"I hope, Mr. President, one year from to-day, I may have the pleasure of congratulating you on the consummation of three events which seem now very probable."

"What are they?" said Mr. Lincoln.

"First, That the rebellion may be completely crushed. Second, That slavery may be entirely destroyed, and prohibited forever throughout the Union. Third, That Abraham Lincoln may have been triumphantly re-elected President of the United States."

"I would be very glad," said Mr. Lincoln, with a twinkle in his eye, "to compromise, by securing the success of the first two propositions."

On the 22d of February, 1864, President Lincoln nominated General U. S. Grant as Lieutenant-General of all the armies of the United States, and on the 9th of March, at the White House, he, in person, presented the victorious General with his commission, and sent him forth to consummate with the armies of the East, his world-renowned successes at the West. Then followed the memorable campaign of 1864-5. Sherman's brilliant Atlanta campaign; Sheridan's glorious career in the Valley of the Shenandoah; Thomas's victories in Tennessee, the triumph at Lookout Mountain; Sherman's "Grand march to the sea," the fall of[42] Mobile, the capture of Fort Fisher, and Wilmington, indicating the near approach of peace through war. In the midst of these successes, Mr. Lincoln was triumphantly re-elected, the people thereby stamping upon his administration their grateful approval. At the session of Congress, of 1864-5, he urged the adoption of an amendment of the Constitution abolishing and prohibiting slavery forever throughout the Republic, thereby consummating his own great work of Emancipation.

As the great leader in the overthrow of slavery, he had seen his action sanctioned by an emphatic majority of the people, and now the constitutional majority of two-thirds of both branches of Congress had voted to submit to the States this amendment of the organic law.

Illinois, the home of Lincoln, as was fit, took the lead in ratifying this amendment, and other States rapidly followed, until more than the requisite number was obtained, and the amendment adopted. Meanwhile, military successes continued, until the victory over slavery and rebellion was won.

It was known, by a dispatch received at the Capitol at midnight, on the 3d of March, 1865, that Lee had sought an interview with Grant, to arrange terms of surrender. On the next day Lincoln again stood on the eastern colonnade of the Capitol, again to swear fidelity to the Republic, her Constitution, and laws; but, how changed the scene from his first inauguration.[43] No traitors now occupied high places under the Government. Crowds of citizens and soldiers who would have died for their beloved Chief Magistrate now thronged the area. Liberty loyalty, and victory had crowned the eagles of our armies. No conspirators were now mingling in the crowd, unless perchance the assassin Booth might have been lurking there. Many patriots and statesmen were in their graves. Douglas was dead, and Ellsworth, and Baker, and McPherson, and Reynolds, and Wadsworth, and a host of martyrs, had given their lives that liberty and the Republic might triumph. It was a very touching spectacle to see the long lines of invalid and wounded soldiers, from the great hospitals about Washington, some on crutches, some who had lost an arm, many pale from unhealed wounds, who gathered to witness the scene. As Lincoln ascended the platform, and his tall form, towering above all his associates, was recognized, cheers and shouts of welcome filled the air, and not until he raised his arm motioning for silence, could the acclamations be hushed. He paused a moment, looked over the scene, and still hesitated. What thronging memories passed through his mind! Here, four years before, he had stood pleading, oh, how earnestly, for peace. But, even while he pleaded, the rebels took up the sword, and he was forced to "accept war."

Now four long, bloody, weary years of devastating war had passed, and those who made the war were everywhere discomfited, and being overthrown. That barbarous institution which had caused the war, had been destroyed, and the dawn of peace already brightened the sky. Such the scene, and such the circumstances under which Lincoln pronounced his second Inaugural, a speech which has no parallel since Christ's Sermon on the Mount.

Who shall say that I am irreverent when I declare, that[44] the passage, "Fondly do we hope, fervently do we pray that this mighty scourge of war may speedily pass away! yet, if God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsmen's two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and every drop of blood drawn by the lash, shall be paid by another drawn by the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so it must be said now, that the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether," could only have been inspired by that Holy Book, which daily he read, and from which he ever sought guidance?

Where, but from the teachings of Christ, could he have learned that charity in which he so unconsciously described his own moral nature, "With malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us finish the work we are in, to bind up the nation's wounds, to care for him who hath borne the battle, and for his widow and his orphans, to do all which may achieve a just and lasting peace, among ourselves and among all nations."

And now Mr. Lincoln gave his whole attention to the movements of the armies, which, as he confidently hoped, were on the eve of final and complete triumph. On the 27th of March he visited the head-quarters of General Grant, at City Point, to concert with his most trusted military chiefs the final movements against Lee, and Johnston. Grant was still at bay before Petersburg. Sherman with his veterans, after occupying Georgia and South Carolina, had reached Goldsboro', North Carolina, on his victorious march north. It was[45] the hope and purpose of the two great leaders, whose generous friendship for each other made them ever like brothers, now and there to crush the armies of Lee and Johnston, and finish the "job."

An artist has worthily painted the scene of the meeting of Lincoln and his cabinet, when he first announced and read to them his proclamation of Emancipation. Another artist is now recording for the American people the scene of this memorable meeting of the President and the Generals, which took place in the cabin of the steamer "River Queen," lying at the dock in the James River. Three men more unlike personally and mentally, and yet of more distinguished ability, have rarely been called together. Although so entirely unlike, each was a type of American character, and all had peculiarities not only American, but Western.

Lincoln's towering form had acquired dignity by his great deeds, and the great ideas to which he had given expression. His rugged features, lately so deeply furrowed with care and responsibility, were now radiant with hope and confidence. He met the two great leaders with grateful cordiality; with clear intelligence he grasped the military situation, and listened with eager confidence to their details of the final moves which should close this terrible game of war.

Contrasting, with the giant-like stature of Lincoln, was the short, sturdy, resolute form of the hero of Fort Donelson and Vicksburg, so firm and iron-like, every feature of his face and every attitude and movement so quiet, yet all expressive of inflexible will and never faltering determination, "to fight it out on this line."

There, too, was Sherman, with his broad intellectual[46] forehead, his restless eye, his nervous energy, his sharply outlined features bronzed by that magnificent campaign from Chattanooga to Atlanta and from Atlanta to the Sea, and now fresh from the conquest of Georgia and South Carolina. On the eve of final triumph, Lincoln, with characteristic humanity deplored the necessity which all realized, of one more hard and deadly battle. They separated, Sherman hastening to his post, and Grant commenced those brilliant movements which in ten days ended the war. Now followed in rapid succession the fall of Richmond, the surrender of Lee, the capitulation of Johnston and his army, the capture of Jefferson Davis, and the final overthrow of the rebellion.

The Union troops, on the morning of the 4th of April, entered the rebel capital. Among the exulting columns which followed the eagles of the Republic, were some regiments of negro soldiers, who marched through the streets of Richmond singing their favorite song of "John Brown's soul is marching on."

On the day of its capture, President Lincoln, with Admiral Porter, visited Richmond. Leading his youngest son, a lad, by the hand, he walked from the James River landing to the house just vacated by the rebel President. From the time of the issuing of his proclamation to this, his triumphant entry into the rebel capital, he had been ever ready and anxious for peace. To all the world he had proclaimed, what he said so emphatically to the rebel emissaries at Hampton Roads. "There are just two indispensable conditions of peace, national unity, and national liberty." "The national authority must be restored through all the States, and I will never recede from my position on the slavery question." He would never violate the national faith, and now God had[47] crowned his efforts with complete success. He entered Richmond as a conqueror, but as its preserver he issued no decree of proscription or confiscation, and to all the South his policy was, "with malice toward none, with charity for all, with firmness in the right as God gave him to see the right, he sought to finish the work, and do all which should achieve and cherish a just and lasting peace."

On the 9th of April he returned to Washington, and had scarcely arrived at the White House before the news of the surrender of Lee and all his army reached him. No language can adequately describe the joy and gratitude which filled the hearts of the President and the people.

And here, before the attempt is made to sketch the darkest and most dastardly crime in all our annals, let us pause for one moment to mention that last review on the 22d and 23d of May, of these victorious citizen soldiers, who had come at the call of the President, and who, their work being done, were now to return again to their homes scattered throughout the country they had saved.

These bronzed and scarred veterans who had survived the battle-fields of four years of active war, whose field of operations had been a continent, the brave men who had marched and fought their way from New England and the Northwest, to New Orleans and Charleston; those who had withstood and repelled the terrific charges of the rebels at Gettysburg; those who had fought beneath and above the clouds at Lookout Mountain; who had taken Fort Donelson, Vicksburg, Atlanta, New Orleans, Savannah, Mobile, Petersburg, and Richmond; the triumphal entry of these heroes into the National Capital of the Republic which they had saved and redeemed, was deeply impressive. Triumphal arches, garlands, wreaths of flowers, evergreens, marked their pathway. Acting President[48] and Cabinet, Governors and Senators, ladies, children, citizens, all united to express the nation's gratitude to those by whose heroism it had been saved.

But there was one great shadow over the otherwise brilliant spectacle. Lincoln, their great-hearted chief, he whom all loved fondly to call their "Father Abraham;" he whose heart had been ever with them in camp, and on the march, in the storm of battle, and in the hospital; he had been murdered, stung to death, by the fang of the expiring serpent which these soldiers had crushed. There were many thousands of these gallant men in Blue, as they filed past the White House, whose weather-beaten faces were wet with tears of manly grief. How gladly, joyfully would they have given their lives to have saved his.

It has been already stated that Mr. Lincoln returned to the Capital on the 9th of April; from that day until the 14th was a scene of continued rejoicing, gratulation, and thanksgiving to Almighty God who had given to us the victory. In every city, town, village, and school district, bells rang, salutes were fired, and the Union flag, now worshiped more than ever by every loyal heart, waved from every home. The President was full of hope and happiness. The clouds were breaking away, and his genial, kindly nature was revolving plans of reconciliation and peace. How could he now bind up the wounds of his country and obliterate the scars of the war, and restore friendship and good feeling to every section? These considerations occupied his thoughts: there was no bitterness, no desire for revenge. On the morning of the 14th, Robert Lincoln, just returned from the army, where, on the staff of General Grant, he had witnessed the surrender of Lee,[49] breakfasted with his father, and the happy hour was passed in listening to details of that event. The day was occupied, first, with an interview with Speaker Colfax, then exchanging congratulations with a party of old Illinois friends, then a cabinet meeting, attended by Gen. Grant, at which all remarked his hopeful, joyous spirit, and all bear testimony that in this hour of triumph, he had no thought of vengeance, but his mind was revolving the best means of bringing back to sincere loyalty, those who had been making war upon his country. He then drove out with Mrs. Lincoln alone, and during the drive he dwelt upon the happy prospect now before them, and contrasting the gloomy and distracting days of the war with the peaceful ones now in anticipation, and looking beyond the term of his Presidency, he, in imagination, saw the time when he should return again to his prairie home, meet his old friends, and resume his old mode of life. In fancy, he was again in his old law library, and before the courts: with these were mingled visions of a prairie farm, and once more the plow and the ax should become familiar to his hand. Such were some of the incidents and fancies of the last day of the life of Abraham Lincoln.

From the time of the election of Mr. Lincoln to the Presidency, many threats, public and private, were made of his assassination. An attempt to murder him would undoubtedly have been made, in February, 1861, on his passage through Baltimore, had not the plot been discovered, and the time of his passage been anticipated. From the day of his inauguration, he began to receive[50] letters threatening assassination. He said: "The first one or two made me uncomfortable, but," said he, smiling, "there is nothing like getting used to things." He was constitutionally fearless, and came to consider these letters as idle threats, meant only to annoy him, and it was very difficult for his friends to induce him to resort to any precautions.

It was announced through the press that on the evening of the 14th of April, Mr. Lincoln and General Grant would attend Ford's Theater. The General did not attend, but Mr. Lincoln, being unwilling to disappoint the public expectation, accompanied by Mrs. Lincoln, Miss Harris, and Major Rathbone, was induced to go. The writer met him on the portico of the White House just as he was about to enter his carriage, exchanged greetings with him, and will never forget the radiant, happy expression of his countenance, and the kind, genial tones of his voice, as we parted for the night as we then thought—forever in this world, as it resulted.

The President was received, as he always was, by acclamations. When he reached the door of his box, he turned, and smiled, and bowed in acknowledgment of the hearty greeting which welcomed him, and then followed Mrs. Lincoln into the box. This was at the right hand of the stage. In the corner nearest the stage sat Miss Harris, next her Mrs. Lincoln. Mr. Lincoln sat nearest the entrance, Major Rathbone being seated on a sofa, in the back part of the box. The theater, and especially the box occupied by the President's party, was most beautifully draped with the national colors. While the play was in progress, John Wilkes Booth visited the theater behind the scenes, left a horse ready saddled in the[51] alley behind the building, leaving a door opening to this alley ready for his escape.

In the midst of the play, at the hour of 10.30, a pistol shot, sharp and clear, is heard! a man with a bloody dagger in his hand leaps from the President's box to the stage exclaiming, "Sic semper tyrannis," "the South is avenged." As the assassin struck the stage, the spur on his boot having caught in the folds of the flag, he fell to his knee. Instantly rising, he brandished his dagger, darted across the stage, out of the door he had left open, mounted his horse and galloped away. The audience, startled and stupefied with horror, were for a few seconds spell-bound. Some one cries out in the crowd, "John Wilkes Booth!" This man, an actor, familiar with the locality, after arranging for his escape, had passed round to the front of the theater, entered, passed in to the President's box, entered at the open and unguarded door, and stealing up behind the President, who was intent upon the play, placed his pistol near the back of the head of Mr. Lincoln, and fired. The ball penetrated the brain, and the President fell upon his face mortally wounded, unconscious and speechless from the first. Major Rathbone had attempted to seize Booth as he rushed past toward the stage, and received from the assassin a severe cut in the arm.

No words can describe the anguish and horror of Mrs. Lincoln. The scene was heart-rending; she prayed for death to relieve her suffering. The insensible form of the President was removed across the street to the house of a Mr. Peterson. Robert Lincoln soon reached the scene, and the members of the cabinet and personal friends crowded around the place of the fearful tragedy. And there the strong constitution of Mr. Lincoln struggled with death, until twenty-two minutes past seven the next morning, when his heart ceased to beat. The[52] scene during that long fearful night of woe, at the house of Peterson, beggars description.

News of the appalling deed spread through the city, and it was found necessary to restrain the anxious, weeping people by a double guard around the house. The surgeons from the first examination of the wound, pronounced it mortal; and the shock and the agony of that terrible night to Mrs. Lincoln was enough to distract the reason, and break the heart of the most self-controlled. Robert Lincoln sought, by manly self-mastery to control his own grief and soothe his mother, and aid her to sustain her overwhelming sorrow.

When at last, the noble heart ceased to beat, the Rev. Dr. Gurley, in the presence of the family, the household, and those friends of the President who were present, knelt down, and touchingly prayed the Almighty Father, to aid and strengthen the family and friends to bear their terrible sorrow.

I will not attempt with feeble pen to sketch the scenes of that terrible night; I leave that for the pencil of the artist!

As has been said, the name of the assassin was John Wilkes Booth! He was shot by Boston Corbett, a soldier on the 21st of April.

On the same night of the assassination of the President, an accomplice of Booth attempted to murder Mr. Seward, the Secretary of State, in his own house, while confined to his bed from severe injuries received by being thrown from his carriage. He was terribly mangled; and his life was saved by the heroic efforts of his sons and daughter and a nurse,[53] whose name was Robinson. Some of the accomplices of Booth were arrested, tried, convicted, and hung; but all were the mere tools and instruments of the Conspirators. Mystery and darkness yet hang over the chief instigators of this most cowardly murder: none can say whether the chief conspirators will ever, in this world, be dragged to light and punishment.

The terrible news of the death of Lincoln was, on the morning of the 15th, borne by telegraph to every portion of the Republic. Coming, as it did, in the midst of universal joy, no language can picture the horror and grief of the people on its reception. A whole nation wept. Persons who had not heard the news, coming into crowded cities, were struck with the strange aspect of the people. All business was suspended; gloom, sadness, grief, sat upon every face. The flag, which had everywhere, from every spire and masthead, roof, and tree, and public building, been floating in glorious triumph, was now lowered; and, as the hours of that dreary 15th of April passed on, the people, by common impulse, each family by itself, commenced draping their houses and public buildings in mourning, and before night the whole nation was shrouded in black.