My Experiences in Manipur

and

the Naga Hills

Major General Sir James Johnstone, K.C.S.I.

in

Manipur and the Naga Hills

London

Sampson Low, Marston and Company Limited

St. Dunstan’s House

Fetter Lane, Fleet Street, E.C.

1896

London:

Printed by William Clowes and Sons, Limited,

Stamford Street and Charing Cross. [5]

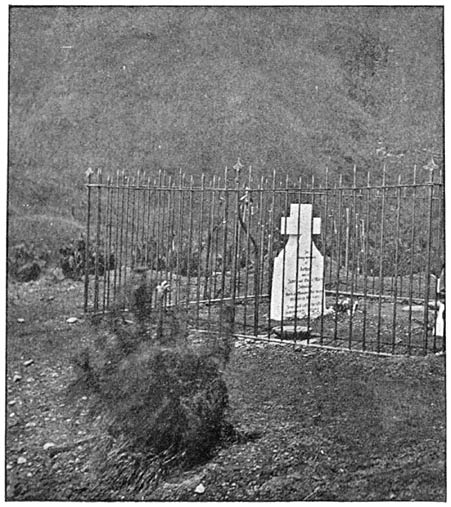

I DEDICATE

THESE PAGES TO THE MEMORY OF

My Wife,

WHO SHARED IN MANY OF MY LABOURS AND ANXIETIES

IN MANIPUR, AND THE NAGA HILLS,

AND WHOSE SPIRIT INSPIRED ME IN MY LAST ENTERPRISE,

AND WHO, HAD SHE LIVED,

WOULD HAVE WRITTEN A BETTER RECORD OF

OUR EXPERIENCES THAN I HAVE

BEEN ABLE TO DO. [vii]

Author’s Preface.

When I first brought my wife out to India in 1873, I was struck by the comments she made on things which had so long been part of my daily life. I had almost ceased to observe them. Every day she noted something new, and her diary was so interesting that I advised her to write a book on her “First Impressions of India,” and she meant to do so, but never had time. Had she lived, this would have been a pleasure to her, but it was otherwise ordained. I feel now that I am in some way carrying out her wishes, by attempting a description of our life in India, though I am fully sensible that I cannot hope to achieve the pleasant chatty style in which she excelled.

I have also striven to give a fair record of the events with which I was connected; and perhaps, as they include a description of a state of things that has passed away for ever, they may not be devoid of interest. I am one of those old-fashioned Anglo-Indians who still believe in personal government, a system by which we gained India, solidified our rule, and made ourselves fairly acceptable to the people whom we govern. I believe the machine-like [viii]system which we have introduced and are endeavouring to force into every corner of India, till all personal influence is killed out, to be ill-adapted to the requirements of these Oriental races, and blighting in its effects. Not one native chief has adopted it in its integrity, which is in itself a fair argument that it is distasteful to the native mind; and we may be assured that if we evacuated India to-morrow, personal rule would again make itself felt throughout the length and breadth of the land, and grow stronger every day. I have always striven to be a reformer, but a reformer building on the solid foundations that we already find everywhere in India. Wherever you go, if there is a semblance of native rule left, you find a system admirably adapted to the needs of the population, though very often grown over with abuses. Clear away these abuses, and add a little in the way of modern progress, but always building on the foundation you find ready to hand, and you have a system acceptable to all.

We are wonderfully timid in sweeping away real abuses, for fear of hurting the feelings of the people; at the same time we weigh them down with unnecessary, oppressive, and worrying forms, and deluge the country with paper returns, never realising that these cause far more annoyance than would be felt at our making some radical change in a matter which, after all, affects only a minority. Take, for instance, the case of suttee, or widow-burning. It was argued for years that we could not put it down without causing a rebellion. What are the facts? A governor-general, blessed with moral courage in [ix]a great degree, determined to abolish the barbarous custom, and his edict was obeyed without a murmur. So it has been in many other cases, and so it will be wherever we have the courage to do the right thing. An unpopular tax would cause more real dissatisfaction than any interference with bad old customs, only adhered to from innate conservatism. The great principle on which to act is to do what is right, and what commends itself to common sense, and to try and carry the people with you. Do not let us have more mystery than is necessary; telling the plain truth is the best course; vacillation is fatal; the strongest officer is generally the most popular, and is remembered by the people long after he is dead and gone.

Personal rule is doomed, and men born to be personal rulers and a blessing to the governed, are now harassed by the authorities till they give up in despair, and swim with the stream.

The machine system did not gain India, and will not keep it for us; we must go back to a better system, or be prepared to relax our grasp, and give up the grandest work any nation ever undertook—the regeneration of an empire!

The House of Commons has to answer for much. No Indian administration is safe from the interference of theorists. To-day it is opium that is attacked by self-righteous individuals, who see in the usual, and in most cases harmless, stimulant of millions, a crying evil; while they view with apparent complacency the expenditure of £120,000,000 per annum on intoxicating liquors in England, and long columns in almost every newspaper recording [x]brutal outrages on helpless women and children as the result.

Then the military administration is attacked, and in pursuance of another chimera, an iniquitous bill is forced on the Government of India calculated to produce results, which will probably sap the efficiency of our army at a critical moment. So it goes on, and it is hardly to be wondered at that the authorities in India give up resistance in sheer disgust, knowing all the while that, as the French say, le deluge must come after them.

It may be said, “What has all this to do with Manipur and the Naga Hills?” Nothing perhaps directly, but indirectly a great deal. The system which I decry carries its evil influence everywhere, and Manipur has suffered from it. I describe the Naga Hills and Manipur as they were in old days. I strove hard for years to hold the floods back from this little State and to preserve it intact, while doing all I could to introduce reforms. Now the floods have overwhelmed it, and if it rises again above them it will not be the Manipur that I knew and loved. May it, in spite of my doubts and fears, be a better Manipur. [xi]

Contents

Page

Introduction xix

Arrival in India—Hospitable friends—The Lieut.-Governor—Journey to the Naga Hills—Nigriting—Golaghat—A panther reminiscence—Hot springs—A village dance—Dimapur—My new abode 1

Samagudting—Unhealthy quarters—A callous widower—Want of water—Inhabitants of the Naga Hills—Captain Butler—Other officials—Our life in the wilds—A tiger carries off the postman—An Indian forest—Encouragement 12

Historical events connected with Manipur and the Naga Hills—Different tribes—Their religion—Food and customs 22

Value of keeping a promise—Episode of Sallajee—Protection given to small villages, and the large one defied—“Thorough” Government of India’s views—A plea for Christian education in the Naga Hills 37

Visit Dimapur—A terrible storm—Cultivation—Aggression by Konoma—My ultimatum—Konoma submits—Birth of a son—Forest flowers—A fever patient—Proposed change of station—Leave Naga Hills—March through the forest—Depredation by tigers—Calcutta—Return to England 45 [xii]

Return to India—Attached to Foreign Office—Imperial assemblage at Delhi—Almorah—Appointed to Manipur—Journey to Shillong—Cherra Poojee—Colonel McCulloch—Question of ceremony 54

Start for Manipur—March over the hills—Lovely scenery—View of the valley—State reception—The Residency—Visitors 60

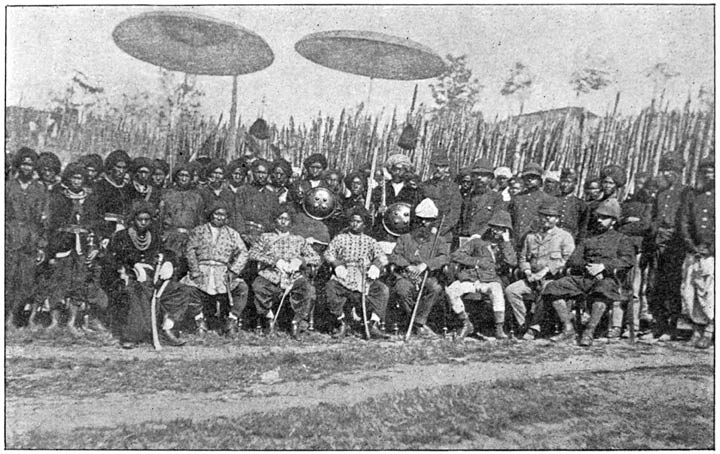

Visit the Maharajah—His ministers—Former revolutions—Thangal Major 69

Manipur—Early history—Our connection with it—Ghumbeer Singh—Burmese war 78

Ghumbeer Singh and our treatment of him—Nur Singh and attempt on his life—McCulloch—His wisdom and generosity—My establishment—Settlement of frontier dispute 88

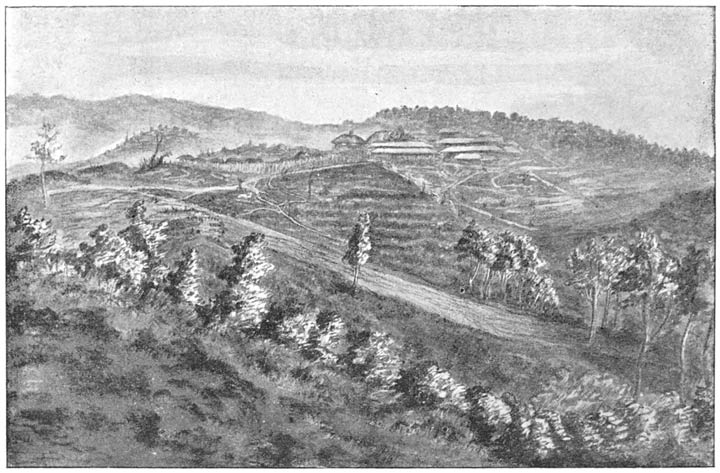

My early days in Manipur—The capital—The inhabitants—Good qualities of Manipuris—Origin of valley of Manipur—Expedition to the Naga Hills—Lovely scenery—Attack on Kongal Tannah by Burmese—Return from Naga Hills—Visit Kongal Tannah 95

Discussions as to new Residency—Its completion—Annual boat-races—Kang-joop-kool—Daily work—Dealings with the Durbar 104

Violent conduct of Prince Koireng—A rebuke—Service payment—Advantages of Manipuri system—Customs duties—Slavery—Releasing slaves—Chowbas’ fidelity—Sepoy’s kindness to children—Visit to the Yoma range 112 [xiii]

An old acquaintance—Monetary crisis—A cure for breaking crockery—Rumour of human sacrifices—Improved postal system—Apricots—Mulberries—A snake story—Search after treasure—Another snake story—Visit to Calcutta—Athletics—Ball practice—A near shave 122

Spring in Manipur—Visit Kombang—Manipuri orderlies—Parade of the Maharajah’s Guards—Birth of a daughter—An evening walk in the capital—Polo—Visit to Cachar 131

Punishment of female criminals—A man saved from execution—A Kuki executed—Old customs abolished—Anecdote of Ghumbeer Singh—The Manipuri army—Effort to re-organise Manipur Levy—System of rewards—“Nothing for nothing”—An English school—Hindoo festivals—Rainbows—View from Kang-joop-kool 138

Mr. Damant and the Naga Hills—Rumours on which I act—News of revolt in Naga Hills and Mr. Damant’s murder—Maharajah’s loyalty—March to the relief of Kohima—Relief of Kohima—Incidents of siege—Heroism of ladies—A noble defence 147

Restoring order and confidence—Arrival of Major Evans—Arrival of Major Williamson—Keeping open communication—Attack on Phesama—Visit to Manipur—General Nation arrives—Join him at Suchema—Prepare to attack Konoma—Assault of Konoma 161

Konoma evacuated—Journey to Suchema for provisions and ammunition, and return—We march to Suchema with General—Visit Manipur—Very ill—Meet Sir Steuart Bayley in Cachar—His visit to Manipur—Grand reception—Star of India—Chussad attack on Chingsow—March to Kohima and back—Reflections on Maharajah’s services—Naga Hills campaign overshadowed by Afghan war 175 [xiv]

Visit Chingsow to investigate Chussad outrage—Interesting country—Rhododendrons—Splendid forest—Chingsow and the murders—Chattik—March back across the hills 182

Saving a criminal from execution—Konoma men visit me—A terrible earthquake—Destruction wrought in the capital—Illness of the Maharajah—Question as to the succession—Arrival of the Queen’s warrant—Reception by the Maharajah—The Burmese question 190

March to Mao and improvement of the road—Lieutenant Raban—Constant troubles with Burmah—Visit to Mr. Elliott at Kohima—A tiger hunt made easy—A perilous adventure—Rose bushes—Brutal conduct of Prince Koireng—We leave Manipur for England 198

Return to Manipur—Revolution in my absence—Arrangements for boundary—Survey and settlement—Start for Kongal—Burmese will not act—We settle boundary—Report to Government—Return to England 208

Return to India—Visit to Shillong—Manipur again—Cordial reception—Trouble with Thangal Major—New arts introduced 216

A friend in need—Tour round the valley—Meet the Chief Commissioner—March to Cachar—Tour through the Tankhool country—Metomi Saraméttie—Somrah—Terrace cultivators—A dislocation—Old quarters at Kongal Tannah—Return to the valley—A sad parting 223 [xv]

More trouble with Thangal Major—Tit-for-tat—Visit to the Kubo valley—A new Aya Pooiel—Journey to Shillong—War is declared—A message to Kendat to the Bombay-Burmah Corporation agents—Anxiety as to their fate—March to Mao 236

News from Kendat—Mr. Morgan and his people safe—I determine to march to Moreh Tannah—March to Kendat—Arrive in time to save the Bombay-Burmah Corporation Agents—Visit of the Woon—Visit to the Woon 244

People fairly friendly—Crucifixion—Carelessness of Manipuris—I cross the Chindwin—Recross the Chindwin—Collect provisions—Erect stockades and fortify our position—Revolt at Kendat—We assume the offensive—Capture boats and small stockades—Revolt put down—Woon and Ruckstuhl rescued—Steamers arrive and leave 251

Mischief done by departure of steamers—Determine to establish the Woon at Tamu—The country quieting down—Recovery of mails—Letter from the Viceroy—Arrive at Manipur—Bad news—I return to Tamu—Night march to Pot-thâ—An engagement—Wounded—Return to Manipur—Farewell—Leave for England 260

Conclusion.

The events of 1890–1 271

Introductory Memoir.

These experiences were written in brief intervals of leisure, during the last few months of the author’s busy life, which was brought to a sudden close before they were finally revised. Only last March when his nearest relations met at Fulford Hall to take leave of the eldest son of the house, before he sailed for India, the manuscript was still incomplete, and Sir James read some part of it aloud. His health had suffered greatly from over-fatigue in the unhealthy parts of India, in which his lot had been chiefly cast, but it was now quite restored and a prolonged period of usefulness seemed before him.

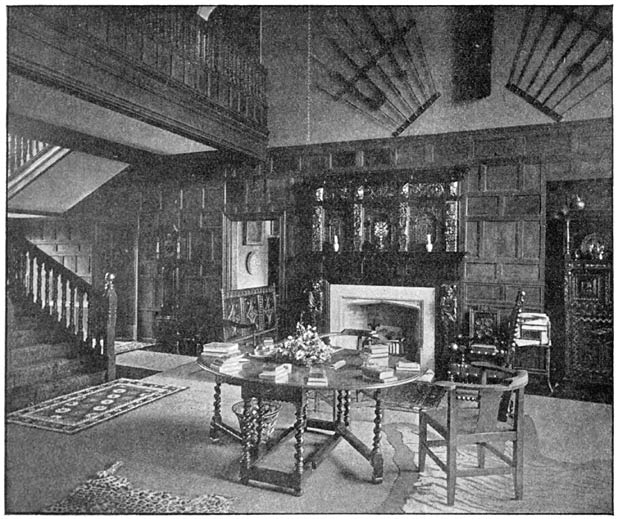

Improvements on the farms on his estate, a church within reach of his cottagers, to be built as a memorial to his late wife, and the hope of being once more employed abroad, probably as a colonial governor, were all plans for the immediate future, while the present was occupied with the magisterial and other business (including lectures on history in village institutes), which fill up so much of an English country gentleman’s life. He had saved nothing in India. What the Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal wrote in 1872 of his early work at [xx]Keonjhur, applied to everything else he subsequently undertook: “Captain Johnstone’s schools, twenty in number, continue to flourish, attracting an average attendance of 665 children. Captain Johnstone’s efforts to improve the crops and cattle of Keonjhur have before been remarked by the Lieutenant-Governor. His sacrifices for this end and for his charge generally, are, His Honour believes, almost unique.”1 But in 1881 by the death of his late father’s elder brother, he inherited the Fulford estate on the boundaries of Worcestershire and Warwickshire, as well as Dunsley Manor in Staffordshire. The old Hall at Fulford, a strongly built, black and white, half-timbered erection of some centuries back, had been pulled down a few years before, and Sir James built the present house close to the old site. It was here that he was brought back in a dying state on June 13th, 1895, about 10 A.M., after riding out of the grounds only ten minutes before, full of life and energy. No one witnessed what occurred; he was a splendid horseman, but there was evidence that the horse, always inclined to be restive, had taken fright on passing a cottager’s gate and tried to turn back, and that, as its master’s whip was still firmly grasped in his hand, there had been a struggle.

He was engaged to assist the next day at the annual meeting of the Conservative and Unionist Association at Stratford-on-Avon. The Marquis of Hertford, who presided, when announcing the catastrophe in very feeling terms, spoke of the excellent work that Sir James Johnstone had done for [xxi]the Unionist cause in Warwickshire. At Wythall Church (of which he was warden) the Vicar alluded, the following Sunday, to “the striking example he had set of a devout and attentive worshipper.”

A retired official who had been acquainted with him in India for over thirty years, wrote on the same occasion to Captain Charles Johnstone, R.N.: “Your brother was a type of character not at all common, high-principled, fearless, just, with an overwhelming sense of duty, and restless spirit of adventure. It is by characters of his type, that our great empire has been created, and it is only if such types continue that we may look forward and hope that it will be maintained and extended.”

Although the family from which Sir James Johnstone sprang is of Scottish origin, his own branch of it had lived in Worcestershire and Warwickshire for nearly a century and a half. “It has taken a prominent part in the social and public life of the Midlands, and has produced several eminent physicians.”2 He was the eleventh in direct male descent from William Johnstone of Graitney, who received a charter of the barony of Newbie for “distinguished services” to the Scottish crown in 1541. A remnant of the old Scottish estates was inherited by his great-grandfather, Dr. James Johnstone, who died at Worcester in 1802, and who, being the fourth son of his parents, had left Annandale at the age of twenty-one to settle in Worcestershire as a physician, but who always kept up his relations with Scotland, and meant to return there in his old age. His anxiety to secure this estate—Galabank—in the male [xxii]line, really defeated his purpose; for he bequeathed it to his then unmarried younger son, the late Dr. John Johnstone, F.R.S., whose daughter now possesses it, to the exclusion of his elder sons who seemed likely to leave nothing but daughters. One of these elder sons was Sir James’s grandfather, the late Dr. Edward Johnstone of Edgbaston Hall, who had married the heiress of Fulford, but was left a widower in 1800. Dr. Edward Johnstone was remarried in 1802 to Miss Pearson of Tettenhall, and of their two sons, the younger, James, born in 1806, practised for many years as a physician, and was President of the British Medical Association when it met in Birmingham in 1856. His eldest son, the subject of this notice, was born in a house now pulled down in the Old Square, Birmingham, on February 9th, 1841. Brought up in the midst of the large family of brothers and sisters, whose childhood was passed between their home in the Old Square and their grandfather’s residence at Edgbaston Hall, where they spent the summer and autumn: he used also to look back with particular pleasure on his visits to his maternal grandfather’s country house, where he first mounted a pony. His mother was his instructor, except occasional lessons from the Rev. T. Price, till at the age of nine he entered King Edward’s Classical School, of which his father was a governor. The head master at that time (1850), was the Rev. (now Archdeacon) E. H. Gifford, D.D., and in the school list for 1852, Johnstone senior is placed next in the same class to Mackenzie (now Sir Alex.), the present Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal. [xxiii]

In 1855, young James Johnstone went to a military college in Paris, which was swept away before 1870, with a great part of the older portion of the city. After a year and a half in Paris he was transferred to the Royal Naval and Military Academy, Gosport, and a few months later qualified for one of the last cadetships given under the old East India Company. Without delay he proceeded to India, which was at that period distracted by the Indian Mutiny, so that his regiment the 68th Bengal Native Infantry, consisted only of officers attached to different European regiments, or acting in a civil capacity. With the 73rd (Queen’s Regiment) he marched through the country, and was actively employed in the suppression of the insurgents, after which he was stationed for some time in Assam where he also saw active service. There, in 1862, he met with the accident he alludes to on pp. 3 and 20. It came in the course of his duty, as the population of a village which had been disarmed had sent to the nearest military post to ask for assistance against a tiger (panther), causing destruction in the neighbourhood; but he was very much hurt, and the weakening effects of this accident, seem to have predisposed him to attacks of the malaria fever of the district, from which he frequently suffered afterwards.

His next post was at Keonjhur, where there had been an outbreak against the Rajah by some of the hill-tribes and the chief insurgent had been executed. Lieutenant Johnstone was appointed special assistant to the superintendent of the Tributary Mehals at Cuttack, in whose official district Keonjhur lies. The [xxiv]Superintendent wrote to the Lieutenant-Governor (Sir William Grey) of Bengal in 1869: “Captain Johnstone has acquired their full confidence, and hopes very shortly to be able to dispense with the greater part of the Special Police Force posted at Keonjhur. He appears to take very great interest in his work, and is sanguine of success.” The same official when enclosing Captain Johnstone’s first report, wrote: “It contains much interesting matter regarding the people, and shows that he has taken great pains in bringing them into the present peaceable and apparently loyal condition,” and a little further on, when describing an interview he had with the Rajah: “From the manner in which he spoke of Captain Johnstone, I was exceedingly glad to find that the most good feeling exists between them.” He also adds, apropos of a recommendation that the Government should pay half the expense of the special commission instead of charging it all on the native state: “Nearly one half of Captain Johnstone’s time has been occupied in Khedda (catching wild elephants) operations, which have been successful and profitable to Government, and totally unconnected with that officer’s duty in Keonjhur.”3

A year later the superintendent (T. E. Ravenshaw, Esq.) reports: “Captain Johnstone, with his usual liberality and tact, has clothed two thousand naked savages, and has succeeded in inducing them to wear the garments;” and again, “Captain Johnstone’s success in establishing schools has been most marked, and there are now nine hundred children receiving a rudimentary education.... Captain Johnstone [xxv]has very correctly estimated the political importance of education and enlightenment among the hill people, and it is evident that he has worked most judiciously and successfully in this direction.” And again: “In the matter of improvement of breed of cattle, Captain Johnstone has, at his own expense, formed a valuable herd of sixty cows and several young bulls ready to extend the experiment.... Captain Johnstone’s experiments on rice and flax cultivation have been very successful” (two years later this is attributed to his having superintended them himself). The official report sums up, “Of Captain Johnstone I cannot speak too highly; his management has been efficient, and he has exercised careful and constant supervision over the Rajah and his estate, in a manner which has resulted in material improvement to both.”

Subsequently, when Captain Johnstone was on leave in England, the Keonjhur despatches show that he sent directions that the increase of his herd of cattle should be distributed gratis among the natives. They were at first afraid to accept them, hardly believing in the gift.

“Keonjhur,” says the Government report of India for 1870–1, “continues under the able administration of Captain Johnstone, who, it will be remembered, was mainly instrumental in restoring the country to quiet three years ago.”

Captain Johnstone was too good a classic not to remember the Roman method of conquering and subduing a province; and as far as funds would permit, he opened out roads and cleared away jungle. But he suffered again from the malaria so prevalent [xxvi]in the forest districts of India, and took three months’ furlough in 1871, which meant just one month in England. Although he had lost his father in May, 1869, and his absence from home that year gave him some extra legal expense, he would not quit his work till he could leave it in a satisfactory state; yet the Lieut.-Governor of Bengal (Sir George Campbell) twice referred to this furlough as being “most unfortunate,” particularly as it had to be repeated within a few months. The superintendent wrote from Cuttack in his yearly report to the Lieut.-Governor: “Captain Johnstone’s serious and alarming illness necessitated his taking sick leave to England in August, 1871. He had only a short time previously returned from furlough, and with health half restored, over-tasked his strength in carrying out elephant Khedda work in the deadly jungles of Moburdhunj.”

In the spring of 1872, Captain Johnstone was married to Emma Mary Lloyd, with whose family his own had a hereditary friendship of three generations. Her father was at that time M.P. for Plymouth, and living at Moor Hall in Warwickshire. Their first child, James, died of bronchitis when six months old, and they returned to India a short time afterwards, at which point the experiences begin. Their second child, Richard, was born at Samagudting, and is now a junior officer in the battalion of the 60th King’s Own Royal Rifles, quartered in India. The third son, Edward, was born at Dunsley Manor, and two younger children in Manipur.

Manipur, to which Colonel Johnstone was appointed [xxvii]in 1877, was called by one of the Indian secretaries the Cinderella among political agencies. “They’ll never,” he said, “get a good man to take it.” “Well,” was the reply, “a good man has taken it now.” The loneliness, the surrounding savages, and the ill-feeling excited by the Kubo valley (which so late as 1852 is placed in Manipur, in maps published in Calcutta) having been made over to Burmah, were among the reasons of its unpopularity. Colonel Johnstone’s predecessor, Captain Durand (now Sir Edward) draws a very glaring picture in his official report for 1877, of the Maharajah’s misgovernment; the wretched condition of the people, and the most unpleasant position of the Political Agent, whom he described as “in fact a British officer under Manipur surveillance.... He is surrounded by spies.... If the Maharajah is not pleased with the Political Agent he cannot get anything—he is ostracised. From bad coarse black atta, which the Maharajah sells him as a favour, to the dhoby who washes his clothes, and the Nagas who work in his garden, he cannot purchase anything.” Yet, well knowing all this, Colonel Johnstone readily accepted the post, confident that with his great knowledge of Eastern languages, and of Eastern customs and modes of thought, he should be able to bring about a better state of things, both as regarded the oppressed inhabitants and the permanent influence of the representative of the British Government. Whether this confidence was justified, the following pages will show.

Editor. [1]