Title: The International Monthly, Volume 2, No. 1, December, 1850

Author: Various

Release date: October 28, 2011 [eBook #37872]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Joshua Hutchinson, Gary Rees and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by Cornell University Digital Collections)

On completing the second volume of the International Magazine, the publishers appeal to its pages with confidence for confirmation of all the promises that have been made with regard to its character. They believe the verdict of the American journals has been unanimous upon the point that the International has been the best journal of literary intelligence in the world, keeping its readers constantly advised of the intellectual activity of Great Britain, Germany, France, the other European nations, and our own country. As a journal of the fine arts, it has been the aim of the editor to render it in all respects just, and as particular as the space allotted to this department would allow. And its reproductions of the best contemporary foreign literature bear the names of Walter Savage Landor, Mazzini, Bulwer, Dickens, Thackeray, Barry Cornwall, Alfred Tennyson, R.M. Milnes, Charles Mackay, Mrs. Browning, Miss Mitford, Miss Martineau, Mrs. Hall, and others; its original translations the names of several of the leading authors of the Continent, and its anonymous selections the titles of the great Reviews, Magazines, and Journals, as well as of many of the most important new books in all departments of literature. But the International is not merely a compilation; it has embraced in the two volumes already issued, original papers, by Bishop Spencer of Jamaica, Henry Austen Layard, LL.D., the most illustrious of living travellers and antiquaries, G.P.R. James, Alfred B. Street, Bayard Taylor, A.O. Hall, R.H. Stoddard, Richard B. Kimball, Parke Godwin, William C. Richards, John E. Warren, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, Mary E. Hewitt, Alice Carey, and other authors of eminence, whose compositions have entitled it to a place in the first class of original literary periodicals. Besides the writers hitherto engaged for the International, many of distinguished reputations are pledged to contribute to its pages hereafter; and the publishers have taken measures for securing at the earliest possible day the chief productions of the European press, so that to American readers the entire Magazine will be as new and fresh as if it were all composed expressly for their pleasure.

The style of illustration which has thus far been so much approved by the readers of the International, will be continued, and among the attractions of future numbers will be admirable portraits of Irving, Cooper, Bryant, Halleck, Prescott, Ticknor, Francis, Hawthorne, Willis, Kennedy, Mitchell, Mayo, Melville, Whipple, Taylor, Dewey, Stoddard, and other authors, accompanied as frequently as may be with views of their residences, and sketches of their literary and personal character.

Indeed, every means possible will be used to render the International

Magazine to every description of persons the most valuable as well as

the most entertaining miscellany in the English language.

| Adams, John, upon Riches, | 426 |

| Ambitious Brooklet, The.—By A.O. Hall, | 477 |

| Accidents will Happen.—By C. Astor Bristed, | 81 |

| Anima Mundi.—By R.M. Milnes, | 393 |

| Astor Library, The. (Illustrated,) | 436 |

| Attempts to Discover the Northwest Passage, On the, | 166 |

| Audubon, John James.—By Rufus W. Griswold, | 469 |

| Age, Old.—By Alfred B. Street, | 474 |

| Arts, The Fine.—Munich and Schwanthaler's "Bavaria," 26.—Art in Florence, 27.—W.W. Story's Return from Italy, 27.—Les Beautes de la France, 27.—History of Art Exhibitions, 28.—Enamel Painting at Berlin, 28.—Portrait of Sir Francis Drake, 28.—The Vernets, 28.—Leutze, Powers, &c., 28.—Kaulbach, 28.—Illustrations of Homer, 28.—Old Pictures, 29.—Michael Angelo, 29.—Conversations by the Academy of Design, 29.—David's Napoleon Crossing the Alps, 29.—Gift from the Bavarian Artists to the King, 190.—Charles Eastlake, 190.—New Picture by Kaulbach, 190.—Russian Porcelain, 190.—Mr. Healey, 191.—Von Kestner on Art, 191.—Russian Music in Paris, 191.—The Goethe Inheritance, 191.—Art Unions; their True Character Considered, 191.—Waagner's "Art in the Future," 313.—Thorwaldsen, 313.—Heidel's "Illustrations of Goethe," 313.—A New Art, 313.—Albert Durer's Illustrations of the Prayer Book, 313.—Moritz Rugendus, and his Sketches of American Scenery, 314.—An Art Union in Vienna, 314.—New Picture by Kaulbach, 314.—Powers's "America," 314.—Dr. Baun's Essay on the two Chief Groups of the Friese of the Parthenon, 314.—Victor Orsel's Paintings in the Church of Notre Dame de Lorelle, 314.—Ehninger's Illustrations of Irving, 314.—Wolff's Paris, 314.—M. Leutze's "Washington Crossing the Delaware," 460.—Discovery of a Picture by Michael Angelo, 460.—The Munich Art Union, 460. Authors and Books.—A Visit to Henry Heine, 15.—Dr. Zirckel's "Sketches from and concerning the United States," 16.—Aerostation, 17.—New Works by M. Guizot, 17.—Works on the German Revolution, 18.—Dr. Zimmer's Universal History, 18.—Schlosser, 18.—MS. of Le Bel Discovered, 19.—M. Bastiat alive, and plagiarizing, 19.—Cæsarism, 19.—Songs of Carinthia, 20.—Mr. Bryant, 20.—Dr. Laing, 20.—French Reviewal of Mr. Elliot's History of Liberty, 20.—Dr. Bowring, 21.—Henry Rogers and Reviews, 21.—Rabbi Schwartz on the Holy Land, 21.—Mr. John R. Thompson, 21.—German Reviewal of "Fashion," 22.—Ruskin's New Work, 21.—Oehlenschlager's Memoirs, 22.—Planche on Lamartine, 22.—Prosper Mérimée, his Book on America, &c., 22.—Hawthorne, 22.—Matthews, the American Traveller, 23.—Professor Adler's Translation of the Iphigenia in Taurus, 23.—The Pekin Gazette, 23.—New Book by the author of "Shakespeare and his Friends," 23.—Vaulabelle's French History, 23.—Sir Edward Belcher, 23.—Guizot an Editor again, 23.—Life of Southey, 23.—Bulwer's Ears, 23.—The Count de Castelnau on South America, 23.—Diplomatic and Literary Studies of Alexis de Saint Priest, 24.—Mrs. Putnam's Review of Bowen, 24.—Herr Thaer, 24.—New Work announced in England, 24.—"Sir Roger de Coverley; by the Spectator," 25.—Memoir of Judge Story, 25.—Garland's Life of John Randolph, 25.—Sir Edgerton Brydges's edition of Milton's Poems, 25.—The Keepsake, 25.—Gray's Poems, 25.—Rev. Professor Weir, 25.—Douglas Jerrold's Complete Works, 25.—Memoirs of the Poet Wordsworth, by his Nephew, 25.—New German books on Hungary, 173.—"Polish Population in Galicia," 173.—Travels and Ethnological works of Professor Reguly, 174.—Works on Ethnology, published by the Austrian Government, 174.—Karl Gutzlow, 174.—Neandar's Library, 174.—Karl Simrock's Popular Songs, 175.—Belgian Literature, 175.—Prof. Johnston's Work on America, 175.—Literary and Scientific Works at Giessen, 175.—Beranger, 175.—The House of the "Wandering Jew," 176.—The Count de Tocqueville upon Dr. Franklin, &c., 176.—Audubon's Last Work, 176.—Book Fair at Leipsic, 176.—Baroness von Beck, 177.—Berghaus's Magazine, Albert Gallatin, &c., 177.—Auerback's Tales, 177.—Baron Sternberg, 177.—"The New Faith Taught in Art," 177.—Freiligrath, 177.—New Adventure and Discovery in Africa, 178.—French Almanacs, 178.—The Algemeine Zeitung on Literary Women, 178.—Cormenin on War, 178.—Writers of "Young France," 179.—George Sand's Last Works, 179.—New Books on the French Revolution, Mirabeau, Massena, &c., 179.—Cousin, 179.—Tomb of Godfrey of Bouillon, 179.—Maxims of Frederic the Great, 179.—New Poems by Elizabeth Barrett Browning, 180.—Rectorship of Glasgow University, 180.—Tennyson, 180.—Mayhew, D'Israeli, Leigh Hunt, The Earl of Carlisle, &c., 180.—New Work by Joseph Balmes, 180.—The late Mrs. Bell Martin, 181.—The Athenæum on Mrs. Mowatt's Novels, 181.—New work by Mrs. Southworth, 181.—Charles Mackay, sent to India, 182.—Pensions to Literary Men, 182.—German Translation of Ticknor's History of Spanish Literature, 182.—David Copperfield, 183.—D.D. Field and the English Lawyers, 183.—Louisiana Historical Collections, 183.—Elihu Burritt's Absurdities, 184.—John Mills, 184.—Dr. Latham's "Races of Men," 184.—"Homœopathic Review, 184.—Bohn's Publications, 184.—Professor Reed's Rhetoric, 185.—Mr. Bancroft's forthcoming History, 185.—Dr. Schoolcraft, 185.—MS. of Dr. Johnson's Memoirs, 185.—Literary "Discoveries," 185.—M. Girardin, 185.—Vulgar Lying of the last English Traveller in America, 186.—The Real Peace Congress, 186.—Milton, Burke, Mazzini, Webster, 187.—Sir Francis Head, 187.—Dr. Bloomfield, 187.—New Book by Mr. Cooper, 187.—Mr. Judd's "Richard Edney," 187.—E.G. Squier, Hawthorne, &c., 187.—The Author of "Olive," on the Sphere of Woman, 188.—Flemish Poems, 188.—"Lives of the Queens of Scotland," 188.—John S. Dwight, 188.—History of the Greek Revolution, 188.—New Edition of the Works of Goethe, 188.—W.G. Simms, Dr. Holmes, &c., 188.—The Songs of Pierre Dupont, 189.—Arago and Prudhon, 189.—Charles Sumner, 189.—"The Manhattaner in New Orleans," 189.—"Reveries of a Bachelor," "Vala," &c., 189.—Of Personalities, 297.—Last Work of Oersted, 298.—New Dramas, 299.—German Novels, 300.—Hungarian Literature, 301.—New German Book on America, 301.—Ruckert's "Annals of German History," 301.—Zschokke's Private Letters, 301.—Works by Bender and Burmeister, 301.—The Countess Hahn-Hahn, 302.—"Value of Goethe as a Poet," 302.—Hagen's History of [Pg vi]Recent Times, 302.—Cotta's Illustrated Bible, 302.—Wallon's History of Slavery, 302.—Translation of the Journal of the U.S. Exploring Expedition into German, 302.—Richter's Translation of Mrs. Barbauld, 302.—Bodenstet's New Book on the East, 302.—Third Part of Humboldt's "Cosmos," &c., 303.—Dr. Espe, 303.—The Works of Neander, 303.—Works of Luther, 303.—L'Universe Pittoresque, 303.—M. Nisard, 303.—French Documentary Publications, 303.—M. Ginoux, 303.—M. Veron, 304.—Eugene Sue's New Books, 304.—George Sand in the Theatre, 304.—Alphonse Karr, 304.—Various new Publications in Paris, 304.—The Catholic Church and Pius IX., 305.—Notices of Hayti, 305.—Work on Architecture, by Gailhabaud, 305.—Italian Monthly Review, 305.—Discovery of Letters by Pope, 305.—Lord Brougham, 305.—Alice Carey, 305.—Mrs. Robinson ("Talvi"), 306.—New Life of Hannah More, 306.—Professor Hackett on the Alps, 306.—Mrs. Anita George, 307.—Life and Works of Henry Wheaton, 308.—R.R. Madden, 308.—Rev. E.H. Chapin on "Woman," 308.—Discovery of Historical Documents of Quebec, 308.—Professor Andrews's Latin Lexicon, 309.—"Salander," by Mr. Shelton, 309.—Prof. Bush on Pneumatology, 309.—Satire on the Rappers, by J.R. Lowell, 309.—Henry C. Phillips on the Scenery of the Central Regions of America, 310.—Sam. Adams no Defaulter, 310.—Mr. Willis, 310.—Life of Calvin, 310.—Notes of a Howadje, 310.—Mr. Putnam's "World's Progress," 310.—Mr. Whittier, 310.—New Volume of Hildreth's History of the United States, 311.—The Memorial of Mrs. Osgood, 311.—Fortune Telling in Paris, 311.—Writings of Hartley Coleridge, 311.—New Books forthcoming in London, 312.—Mr. Cheever's "Island World of the Pacific," 312.—Works of Bishop Onderdonk, 312.—Moreau's Imitatio Christi, 312.—New German Poems, 312.—Schröder on the Jews, 312.—Arago on Ballooning, 312.—Books prohibited at Naples, 312.—Notices of Mazzini, 313.—Charles Augustus Murray, 313.—New History of Woman, 313.—Letters on Humboldt's Cosmos, 446.—German Version of the "Vestiges of Creation," 447.—Hegel's Aesthetik, 447.—New Work in France on the Origin of the Human Race, 448.—Lelewel on the Geography of the Middle Ages, 448.—More German Novels, 448.—"Man in the Mirror of Nature," 449.—Herr Kielhau, on Geology, 449.—Proposed Prize for a Defence of Absolutism, 449.—Werner's Christian Ethics, 449.—William Meinhold, 449.—Prize History of the Jews, 449.—English Version of Mrs. Robinson's Work on America, 449.—Poems by Jeanne Marie, 449.—General Gordon's Memoirs, 449.—George Sand's New Drama, 449.—Other New French Plays, 451.—M. Cobet's History of France, 451.—Rev. G.R. Gleig, 451.—Ranke's Discovery of MSS. by Richelieu, 451.—George Sand on Bad Spelling, 451.—Lola Montes, 451.—Montalembert, 451.—Glossary of the Middle Ages, 451.—A Coptic Grammar, 451.—The Italian Revolution, 452.—Italian Archæological Society, 452.—Abaddie, the French Traveller, 452.—The Vatican Library, 452.—New Ode by Piron, 452.—Posthumous Works of Rossi, 452.—Bailey, the Author of "Festus," 453.—Clinton's Fasti, 453.—Captain Cunningham, 453.—Dixon's Life of Penn, 453.—Literary Women in England, 453.—Miss Martineau's History of the Last Half Century, 453.—The Lexington Papers, 453.—Captain Medwin, 453.—John Clare, 454.—De Quincy's Writings, 454.—Bulwer's Poems, 454.—Episodes of Insect Life, 454.—Dr. Achilli, 454.—Samuel Bailey, 454.—Major Poussin, and his Work on the United States, 454.—French Collections in Political Economy, 455.—Joseph Gales, 456.—Rev. Henry T. Cheever, 456.—Job R. Tyson on Colonial History, 456.—Henry James, 456.—Torrey and Neander, 457.—Works of John C. Calhoun, 457.—Historic Certainties respecting Early America, 457.—Mr. Schoolcraft, 457.—Dr. Robert Knox, 458.—Mr. Boker's Plays, 458.—The Literary World upon a supposed Letter of Washington, 458.—Dr. Ducachet's Dictionary of the Church, 458.—Edith May's Poems, 458.—The American Philosophical Society, 458.—Professor Hows, 458.—Mr. Redfield's Publications, 458.—Rev. William W. Lord's New Poem, 450. | |

| Battle of the Churches in England, | 327 |

| Ballad of Jessie Carol.—By Alice Carey, | 230 |

| Barry Cornwall's Last Song, | 392 |

| Bereaved Mother, To a.—By Hermann, | 476 |

| Biographies, Memoirs, &c., | 425 |

| Black Pocket-Book, The, | 89 |

| Bombay, A View of.—By Peter Leicester, | 130 |

| Boswell, The Killing of Sir Alexander, | 329 |

| Brontë and her Sisters, Sketches of Miss, | 315 |

| Burke, Edmund, His Residences and Grave.—By Mrs. S.C. Hall. (Illustrated.) | 145 |

| Bunjaras, The, | 377 |

| Burlesques and Parodies, | 426 |

| Byron, Scott, and Carlyle, Goethe's Opinions of, | 461 |

| Camille Desmoulins, | 326 |

| Carey, Henry C.—By Rufus W. Griswold, | 402 |

| Castle in the Air, The.—By R.H. Stoddard, | 474 |

| Chatterton, Thomas. (Illustrated.) | 289 |

| Classical Novels, | 161 |

| Count Monte-Leone. Book Second, | 45 |

| Count Monte-Leone. Book Third, | 216 |

| Count Monte-Leone. Book Third, concluded, | 349 |

| Count Monte-Leone. Book Fourth, | 495 |

| Cow-Tree of South America, The, | 128 |

| Correspondence, Original: A Letter from Paris, | 170 |

| Cyprus and the Life Led There, | 216 |

| Davis on the Half Century: Etherization, | 317 |

| Dacier, Madame, | 332 |

| Dante.—By Walter Savage Landor, | 421 |

| Death, Phenomena of, | 425 |

| Deaths, Recent.—Hon. Samuel Young, 140.—Robinson, the Caricaturist, 140.—The Duke of Palmella, 142.—Carl Rottmann, 142.—The Marquis de Trans, 142.—Ch. Schorn, 142.—Hon. Richard M. Johnson, 142.—Wm. Blacker, 142.—Mrs. Martin Bell, 142.—Signor Baptistide, 142.—Gen. Chastel, 142.—Dr. Medicus, and others, 142.—Rev. Dr. Dwight, 195.—Count Brandenburgh, 196.—Lord Nugent, 196.—M. Fragonard, 196.—M. Droz, 197.—Professor Schorn, 197.—Gustave Schwab, 197.—Francis Xavier Michael Tomie, 427.—Governors Bell and Plumer, 427.—Birch, the Painter, 427.—Professor Sverdrup, W. Seguin, Mrs. Ogilvy, 427.—W. Howison, 428.—H. Royer-Collard, 428.—Col. Williams, 428.—William Sturgeon, 428.—J.B. Anthony, 428.—Mr. Osbaldiston, 428.—Professor Mau, 428.—Madame Junot, Mrs. Wallack, &c., 428.—Herman Kriege, 429.—Madame Schmalz, 429.—George Spence, 429.—General Lumley, 429.—Robert Roscoe, 429.—Richie, the Sculptor, 429.—Martin d'Auch, 429.—Rev. Walter Colton, 568.—Major d'Avezac, 569.—M. Asser, 569.—M. Lapie, 569.—Professor Link, 569.—General St. Martin, 570.—Frederick Bastiat, 570.—Benjamin W. Crowninshield, 571.—Professor Anstey, 571.—Donald McKenzie, 572.—Horace Everett, LL.D., 572.—James Harfield, 572.—Wm. Wilson, 572.—Professor James Wallace, 572.—Joshua Milne, 572.—General Bem, 573.—T.S. Davies, F.R.S., 573.—H.C. Schumacher, 573.—W.H. Maxwell, 573.—Alexander McDonald, 573. | |

| Dickens, To Charles.—By Walter Savage Landor, | 75 |

| Drive Round our Neighborhood, in 1850, A.—By Miss Milford, | 270 |

| Duty.—By Alfred B. Street, | 332 |

| Duchess, A Peasant, | 169 |

| Edward Layton's Reward.—By Mrs. S.C. Hall, | 201 |

| Editorial Visit, An, | 421 |

| Egypt under the Pharaohs.—By John Kinrick, | 322[Pg vii] |

| Encouragement of Literature by Governments, | 160 |

| Exclusion of Love from the Greek Drama, | 123 |

| Fountain in the Wood, The, | 129 |

| French Generals of To-Day, | 334 |

| Gateway of the Oceans, | 124 |

| Ghetto of Rome, | 393 |

| Gleanings from the Journals, | 285 |

| Grief of the Weeping Willow, | 31 |

| Haddock, Charles B., Charge d'Affaires to Portugal. (With a Portrait on steel.) | 1 |

| Hecker, Herr, described by Madame Blaze de Bury, | 30 |

| Historical Review.—The United States, 560.—Europe, 564.—Mexico, 565.—British America, 566.—The West Indies, 566.—Central America, the Isthmus, 566.—South America, 567.—Africa, 567. | |

| Hunt, Leigh, upon G.P.R. James, | 30 |

| Ireland in the Last Age: Curran, | 519 |

| Journals of Louis Philippe, | 377 |

| Kellogg's, Mr., Exploration of Mt. Sinai, | 462 |

| Kimball, Richard B., the Author of "St. Leger." (Illustrated.) | 156 |

| Layard's Recent Gifts from Nimroud. (Illustrated.) | 4 |

| Layard, Austen Henry, LL.D. (With a Portrait,) | 433 |

| Lafayette, Talleyrand, Metternich, and Napoleon.—Sketched by Lord Holland, | 465 |

| Last Case of the Supernatural, | 481 |

| Lectures, Popular, | 319 |

| Life at a Watering Place.—By C. Astor Bristed, | 240 |

| Lionne at a Watering Place, The, | 533 |

| Lost Letter, The, | 522 |

| Mazzini on Italy, | 265 |

| Mackay, Charles, Last Poems by, | 348 |

| Marvel, Andrew. (Illustrated.) | 438 |

| Mother's Last Song, The.—By Barry Cornwall, | 270 |

| Music and the Drama.—The Astor Place Opera, Parodi, 29.—Mrs. Oake Smith's New Tragedy, 30. | |

| Mystic Vial, The, Part i. | 61 |

| Mystic Vial, The, Part ii. | 249 |

| Mystic Vial, The, Part iii. | 378 |

| My Novel, Or Varieties in English Life.—By Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, Book II. Chapters i. to vi. | 109 |

| Book II. Chapters vii. to xii. | 273 |

| Book III. Chapters i. to xii. | 273 |

| Book III. Chapters xiii. to xxvii. | 273 |

| Murder Market, The, | 126 |

| New Tales by Miss Martineau—The Old Governess, | 163 |

| Novelist's Appeal for the Canadas, A, | 443 |

| Old Times in New-York, | 320 |

| Osgood, The late Mrs.—By Rufus W. Griswold, | 131 |

| Paris Fashions for December. (Illustrated.) | 144 |

| Paris Fashions for January. (Illustrated.) | 286 |

| Paris Fashions for February. (Illustrated.) | 431 |

| Paris Fashions for March. (Illustrated.) | 567 |

| Peace Society, The First, | 321 |

| Penn, (William,) and Macaulay, | 336 |

| Pleasant Story of a Swallow, | 123 |

| Poet's Lot, The.—By the author of "Festus," | 45 |

| Power's, Hiram, Greek Slave.—By Elizabeth Barret Browning, | 88 |

| Poems by S.G. Goodrich, A Biographical Review. (Illustrated.) | 153 |

| Public Libraries, Ancient and Modern, | 359 |

| Recent Deaths in the Family of Orleans, | 122 |

| Reminiscences of Paganini, | 167 |

| Responsibility of Statesmen, | 127 |

| Rossini in the Kitchen, | 321 |

| Scandalous French Dances in American Parlors, | 333 |

| Scientific Miscellany.—Hydraulic Experiments in Paris, 430.—French Populations, 430.—African Exploring Expedition, 430.—The Hungarian Academy, 430.—Gas from Water, &c., 430.—The French "Annuaire," 573.—Sittings of the Academy of Sciences, 573.—New Scientific Publications, 574.—Sir David Brewster, 574. | |

| Sir Nicholas at Marston Moor.—By Winthrop M. Praed, | 80 |

| Sliding Scale of Inconsolables. From the French, | 162 |

| Smiths, The Two Miss.—By Mrs. Crowe, | 76 |

| Song of the Season.—By Charles Mackay, | 128 |

| Sounds from Home.—By Alice G. Neal, | 332 |

| Spencer, Aubrey George, LL.D., Bishop of Jamaica, | 157 |

| Spirit of the English Annuals for 1851, | 197 |

| Stanzas.—By Alfred Tennyson, | 273 |

| Statues.—By Walter Savage Landor, | 126 |

| Story Without a Name, A.—By G.P.R. James, | 32 |

| Chapters vi. to ix. | 205 |

| Chapters x. to xiii. | 337 |

| Chapters xiv. to xvii. | 482 |

| Story of Calais, A.—By Richard B. Kimball, | 231 |

| Story of a Poet, | 88 |

| Swift, Dean, and his Amours. (Illustrated.) | 7 |

| Temper of Women, | 437 |

| Theatrical Criticism in the Last Age, | 334 |

| To a Celebrated Singer.—By R.H. Stoddard, | 86 |

| To one in Affliction.—By G.R. Thompson, | 541 |

| Troost, of Tennessee, The Late Dr. | 332 |

| Twickenham Ghost, The, | 60 |

| Valetudinarian, The Confirmed.—By Sir Edward Bulwer Lytton, | 203 |

| Vampire, The Last.—By Mrs. Crowe, | 107 |

| Voltigeur.—By W.H. Thackeray, | 197 |

| Voisenen, The Abbé de, and his Times, | 511 |

| Wane of the Year, The, | 129 |

| Webster, LL.D., Horace, and the Free Academy. (Portrait.) | 444 |

| Wearing the Beard.—Dr. Marcy, | 130 |

| Wiseman, Dr., Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster (Illustrated.) | 143 |

| Wild Sports in Algeria.—By Jules Gerard, | 121 |

| Wolf Chase, The.—By C. Whitehead, | 86 |

| Vol. II. | NEW YORK, DECEMBER 1, 1850. | No. I. |

OLD notions of diplomacy are obsolete. The plain, straightforward, and masterly manner in which Daniel Webster and Lord Ashburton managed the difficult affairs which a few years ago threatened war between this country and England have taught mankind a useful lesson on this subject. We perceive that the London Times has been engaged in a controversy whether there should be diplomatists or no diplomatists, whether, in fact, the profession should survive; arguing from this case conducted by our illustrious Secretary and Lord Ashburton, that negotiation in foreign countries is plain sailing for great men, and that common agents would do the necessary business on ordinary occasions. We are not prepared to accept the doctrine of the Times, though ready enough to admit that it is to be preferred to the employment of such persons as many whom we have sent abroad in the last twenty years—many who now in various capacities represent the United States in foreign countries. Upon this question however we do not propose now to enter. It is one which may be deferred still a long time—until the means of intercommunication shall be greater than steam and electricity have yet made them, or until the evils of unworthy representation shall have driven people to the possible dangers of an abandonment of the system without such a reason. We design in this and future numbers of the International simply to give a few brief personal sketches of the most honorably distinguished of the diplomatic servants of the United States now abroad, and we commence with the newly-appointed Charge d'Affaires to Lisbon.

Charles Brickett Haddock was born at Salisbury (now Franklin), New Hampshire, on the 20th of June, 1796. His father, William Haddock, was a native of Haverhill, Massachusetts. His paternal grandfather removed from Boston to Haverhill, and married a sister of Dr. Charles Brickett, an eminent physician of that town. The family, according to a tradition among them, are descended from Admiral Sir Richard Haddocke, one of ten sons and eleven daughters of Mr. Haddocke, of Lee, in England. Richard Haddocke was an eminent officer in the Royal Navy. He was knighted before 1678, and returned a member of Parliament the same year, and again in 1685. He died in 1713, and was buried in the family vault at Lee, where there is a gravestone, with brass plates on which are engraved portraits of his father, his father's three wives, and thirteen sons and eleven daughters.

The mother of Dr. Haddock was Abigail Webster, a favorite sister of Ezekiel and Daniel Webster, who, with Sarah, were the only children of the Hon. Ebenezer Webster by his second wife, Abigail Eastman, who survived her husband and all her daughters. Mrs. Haddock was a woman of strong character, and greatly beloved in society. She died in December, 1805, at the age of twenty-seven, leaving two sons, Charles and William, one about nine and the other seven years of age. Her last words to her husband were, "I leave you two beautiful boys: my wish is that you should educate them both." The injunction was not forgotten; both were in due time placed at a preparatory school in Salisbury, both entered Dartmouth College, and without an academic censure or reproof graduated with distinction.

The younger, having studied the profession of the law, married a daughter of Mills Olcott, of Hanover, and after a few years, rich in promise of professional eminence, died of consumption at Hanover, in 1835.

The elder, Charles B. Haddock, was born in the house in which his grandfather first lived, after he removed to the river, in Franklin; though his childhood was chiefly spent at Elms Farms, in the mansion built by his father, and now the favorite residence of his uncle, Daniel Webster,—a spot hardly equaled for picturesque and tranquil beauty in that part of New England. How much of his rural tastes and gentle feelings the professor owes to the place of his nativity it is not for us to determine. It is certain that a fitter scene to inspire the sentiments for which he is distinguished, and which he delights to refresh by[Pg 2] frequent visits to these scenes, could not well be imagined. Every hill and valley, every rock and eddy, seem to be familiar to him, and to have a legend for his heart. His earliest distinct recollections, he has often been heard to say, are the burial of a sister younger than himself, his own baptism at the bedside of his dying mother, and the death of his grandfather; and the first things that awakened a romantic emotion were the flight of the night-hawk and the note of the whippoorwill, both uncommonly numerous and noticeable there in summer evenings.

From 1807 he was in the academy during the summer months, and attended the common school in winter, until 1811, when, in his sixteenth year, he taught his own first winter school. It had been his fortune to have as instructors persons destined to unusual eminence: Mr. Richard Fletcher, now one of the justices of the Superior Court of Massachusetts; Justice Willard, of Springfield; the Rev. Edward L. Parker, of Londonderry; and Nathaniel H. Carter, the well-known poet and general writer. It was under Mr. Carter that he first felt a genuine love of learning; and he has always ascribed more of his literary tastes, to his insensible influence, as he read to him Virgil and Cicero, than to any other living teacher. His earliest Latin book was the Æneid, over the first half of which he had, summer after summer, fatigued and vexed himself, before the idea occurred to him that it was an epic poem; and that idea came to him at length not from his teachers, but from a question of his uncle, Daniel Webster, about the descent of the hero into the infernal regions. When a proper impression of its design was once formed, and some familiarity with the language was acquired, Virgil was run through with great rapidity: half a book in a day. So also with Cicero: an oration at a lesson. There was no verbal accuracy acquired or attempted; but a ready mastery of the current of discourse—a familiarity with the point and spirit of the work. In August, 1812, he was admitted a freshman in Dartmouth College. It was a small class, but remarkable from having produced a large number of eminent men, among whom we may mention George A. Simmons, a distinguished lawyer in northern New York, and one of the profoundest philosophers in this country; Dr. Absalom Peters; President Wheeler, of the University of Vermont; Governor Hubbard, of Maine; and Professor Joseph Torrey, of the University of Vermont, since so honorably known as the learned translator of Neander, and as being without a superior among American scholars in a knowledge of the profounder German literature. The late illustrious and venerated Dr. James Marsh, the editor of Coleridge, and the only pupil of that great metaphysician who was the peer of his master, was of the class below his, and was an intimate companion in study.

From the beginning of his college life it was his ambition to distinguish himself. By the general consent of his classmates, and by the appointment of the faculty, he held the first place at each public exhibition through the four years in which he was a student, and at the last commencement was complimented with having the order of the parts, according to which the Latin salutatory had hitherto been first, so changed that he might still have precedence and yet have the English valedictory. During his junior year, his mind was first decidedly turned toward religion, and with Wheeler, Torrey, Marsh, and some forty others, he made a public profession. The two years after he left college were spent at Andover, in the study of divinity. While here, with Torrey, Wheeler, Marsh, and one or two more, he joined in a critical reading of Virgil—an exercise of great value in enlarging a command of his own language, as well as his knowledge of Latin. At the close of the second year he was attacked with hemorrhage of the lungs, and advised to try a southern climate for the winter. He sailed in October, 1818, for Charleston, and spent the winter in that city and in Savannah, with occasional visits into the surrounding country. The following summer he traveled, chiefly on horseback, and in company with the Rev. Pliny Fisk, from Charleston home. To this tour he ascribes his recovery. He soon after took his master's degree, and was appointed the first Professor of Rhetoric and Belles-Lettres in Dartmouth College. From that time a change was obvious in the literary spirit of the instruction given at the institution. The department to which he was called became very soon the most attractive in the college, and some of the most distinguished orators of our country are pleased to admit that they obtained their first impressions of true eloquence and a correct style from the youthful professor. He introduced readings in the Scriptures, and in Shakspeare, Milton, and Young, with original criticisms by his pupils on particular features of the principal works of genius, as the hell of Virgil, Dante, and Milton; and the prominent characters of the best tragedies, as the Jew of Cumberland and of Shakspeare; and extemporaneous discussions of æsthetical and political questions, as upon the authenticity of Ossian, the authorship of Homer, the sincerity of Cromwell, or the expediency of the execution of Charles. He also exerted his influence in founding an association for familiar written and oral discussions in literature, in which Dr. Edward Oliver, Dr. James Marsh, Professor Fiske, Mr. Rufus Choate, Professor Chamberlain, and others, acted a prominent part.

He retained this chair until August, 1838, when he was appointed to that of Intellectual Philosophy and Political Economy, which he now holds, but, which, of course, will be occupied by another during his absence in the public service—the faculty having declined on any account to accept his resignation or to appoint a successor.

Dr. Haddock has been invited to the profes[Pg 3]sorship of rhetoric in Hamilton College, and to the presidency of that institution, the presidency and a professorship in the Auburn Theological Seminary, the presidency of Bowdoin College, and, less formally, to that of several other colleges in New England.

In public affairs, he has for four successive years been a representative in the New Hampshire Legislature, and in this period was active in introducing the present common school system of the State, and was the first commissioner of common schools, originating the course of action in that important office which has since been pursued. He was one of the fathers of the railroad system in New Hampshire, and his various speeches had the effect to change the policy of the State on this subject. He addressed the first convention called at Lebanon to consider the practicability of a road across the State, and afterward a similar convention at Montpelier. For two years he lectured every Sabbath evening to the students and to the people of the village, on the historical portions of the New Testament. For several years he held weekly meetings for the interpretation of Scripture, in which the ladies of the village met at his house. And for twenty years he has constantly preached to vacant parishes in the vicinity. He has delivered anniversary orations before the Phi Beta Kappa Societies of Dartmouth and Yale, the Rhetorical Societies of Andover and Bangor, the Religious Society of the University of Vermont, the New Hampshire Historical Society, and the New England Society of New York; numerous lyceum lectures, in Boston, Lowell, Salem, Portsmouth, Manchester, New Bedford, and other places; and of the New Hampshire Education Society he was twelve or fifteen years secretary, publishing annual reports. The principal periodicals to which he has contributed are the Biblical Repository and the Bibliotheca Sacra. A volume of his Addresses and Miscellaneous Writings was published in 1846, and he has now a work on rhetoric in preparation.

He has been twice married—the last time to a sister of Mr. Kimball, the author of "St. Leger," &c. He has three children living, and has buried seven.

In agriculture, gardening, and public improvements of all kinds, he has taken a lively interest. The rural ornaments of the town in which he lives owe much to him. He may be said to have introduced the fruit and horticulture which are now becoming so abundant as luxuries, and so remarkable as ornaments of the village.

In 1843 he received the degree of D.D. from Bowdoin College. Of Dartmouth College nearly half the graduates are his pupils. While commissioner of common schools, he published a series of letters to teachers and students which were more generally republished in the various papers of the country than anything else of the kind ever before written. Perhaps no one in this country has discussed so great a variety of subjects. His essays upon the proper standard of education for the pulpit, addresses on the utility of certain proposed lines of railway, orations on the duties of the citizen to the state, lectures before various medical societies, speeches in the New Hampshire House of Representatives, letters written while commissioner of common schools, contributions to periodicals, addresses before a great variety of literary associations, writings on agriculture and gardening, yearly reports on education, lectures on classical learning, rhetoric and belles-lettres, and sermons, delivered weekly for more than twenty years, illustrate a life of remarkable activity, and dedicated to the best interests of mankind. Unmoved by the calls of ambition, which might have tempted him to some one great and engrossing effort, his aim has been the general good of the people.

The following extract from the dedication, to his pupils, of his Addresses and Miscellaneous Writings, evinces something of his purpose:

"It is now five-and-twenty years since I adopted the resolution never to refuse to attempt anything consistent with my professional duties, in the cause of learning, or religion, which I might be invited to do. This resolution I have not at any time regretted, and perhaps I may say, I have not essentially violated it. However this may be, I have never suffered from want of something to do."

Professor Haddock's style is remarkable for purity and correctness. His sentences are all finished sentences, never subject to an injurious verbal criticism, without a mistake of any kind, or a grammatical error.

We have not written of Dr. Haddock as a politician; but he is a thoroughly informed statesman, profoundly versed in public law, and familiar with all the policy and aims of the American government. He is of course a Whig. He has been educated, politically, in the school of his illustrious uncle, and probably no man living is more thoroughly acquainted with Mr. Webster's views, or more capable of their application in affairs. It is therefore eminently suitable that he should be on the list of our representatives abroad, while the foreign department is under Mr. Webster's administration. The Whig party in New Hampshire have not been insensible of Dr. Haddock's surpassing abilities, of his sagacity, or his merits. Could they have done so, they would have made him Governor, or a senator in Congress, on any of the occasions in many years in which such officers have been chosen. Considered without reference to party, we can think of no gentleman in the country who would be likely to represent the United States more worthily at foreign courts, or who by his capacities, suavity of manner, or honorable nature, would make a more pleasing and desirable impression upon the most highly cultivated society. Those who know him well will assent to the justness of a classification which places him in the same list of intellectual diplomats which embraces Bunsen, Guizot, and our own Everett, Irving, Bancroft and Marsh.

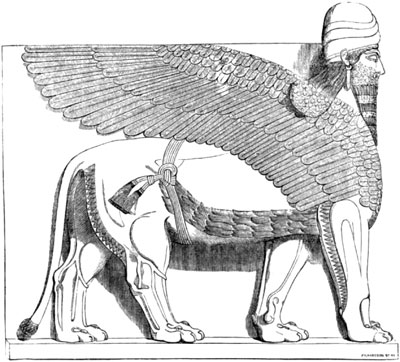

The researches of no antiquary or traveler in modern times have excited so profound an interest as those of Austen Henry Layard, who has summoned the kings and people of Nineveh through three thousand years to give their testimony against the skeptics of our age in support of the divine revelation. In a former number of The International we presented an original and very interesting letter from Dr. Layard himself, upon the nature and bearing of his discoveries. Since then he has sent to London, where they have arrived in safety, several of the most important sculptures described in his work republished here last year by Mr. Putnam. Among them are the massive and imposing statues of a human-headed bull and a human-headed lion, of which we have engravings in some of the London journals. The Illustrated London News describes these specimens of ancient art as follows:

"No. I. is the Human-Headed and Eagle-Winged Bull. This animal would seem to bear some analogy to the Egyptian sphynx, which represents the head of the King upon the body of the lion, and is held by some to be typical of the union of intellectual power with physical strength. The sphynx of the Egyptians, however, is invariably sitting, whereas the Nimroud figure is always represented standing. The apparent resemblance being so great, it is at least worthy of consideration whether the head on the winged animals of the Ninevites may not be that of the King, and the intention identical with that of the sphynx; though we think it more probable that there is no such connection, and that the intention of the Ninevites was to typify their god under the common emblems of intelligence, strength and swiftness, as signified by the additional attributes of the bird. The specimen immediately before us is of gypsum, and of colossal dimensions, the slab being ten feet square by two feet in thickness. It was situated at the entrance of a chamber, being built into the side of the door, so that one side and a front view only could be seen by the spectator. Accordingly, the Ninevite sculptor, in order to make both views perfect, has given the animal five legs. The four seen in the side view show the animal in the act of walking; while, to render the representation complete in the front view, he has repeated the right fore leg again, but in the act of standing motionless. The countenance is noble and benevolent in expression; the fea[Pg 5]tures are of true Persian type; he wears an egg-shaped cap, with three horns and a cord round the base of it. The hair at the back of the head has seven ranges of curls; and the beard, as in the portraits of the King, is divided into three ranges of curls, with intervals of wavy hair. In the ears, which are those of a bull, are pendent ear-rings. The whole of the dewlap is covered with tiers of curls, and four rows are continued beneath the ribs along the whole flank; on the back are six rows of curls, and upon the haunch a square bunch, ranged successively, and down the back of the thigh four rows. The hair at the end of the tail is curled like the beard, with intervals of wavy hair. The hair at the knee joints is likewise curled, terminating in the profile views of the limbs in a single curl of the kind (if we may use the term) called croche cœur. The elaborately sculptured wings extend over the back of the animal to the very verge of the slab. All the flat surface of the slab is covered with cuneiform inscription; there being twenty-two lines between the fore legs, twenty-one lines in the middle, nineteen lines between the hind legs, and forty-seven lines between the tail and the edge of the slab. The whole of this slab is unbroken, with the exception of the fore-feet, which arrived in a former importation, but which are now restored to their proper place.

"No. II. represents the Human-Headed and Winged Lion—nine feet long, and the same in height; and in purpose and position the same as the preceding, which, however, it does not quite equal in execution. In this relievo we have the same head, with the egg-shaped three-horned head-dress, exactly like that of the bull; but the ear is human, and not that of a lion. The beard and hair of the head are even yet more elaborately curled than the last; but the hair on the legs and sides of the animal represents that shaggy appendage of the animal. Round the loins is a succession of numerous cords, which are drawn into four separate knots; at the extremities are fringes, forming as many distinct tassels. At the end of the tail, the claw—on which we commented in a former article—is distinctly visible. The strength of both animals is admirably and characteristically conveyed. Upon the flat surface of this slab, as in the last, is a cuneiform inscription; twenty lines being between the fore legs, twenty-six in the middle, eighteen between the hind legs, and seventy-one at the back."

On the subject of Eastern languages, an[Pg 6] understanding of which is necessary to the just apprehension of these inscriptions, that most acute antiquary, Major Rawlinson, remarks:

"My own impression is that hundreds of the languages at one time current through Asia are now utterly lost; and it is not, therefore, to be expected that philologists or ethnologists will ever succeed in making out a genealogical table of language, and in affiliating all the various dialects. Coming to the Assyrian and Babylonian languages, we were first made acquainted with them as translations of the Persian and Parthian documents in the trilingual inscriptions of Persia; but lately we have had an enormous amount of historical matter brought to light in tablets of stone written in these languages alone. The languages in question I certainly consider to be Semitic. I doubt whether we could trace at present in any of the buildings or inscriptions of Assyria and Babylonia the original primitive civilization of man—that civilization which took place in the very earliest ages. I am of opinion that civilization first showed itself in Egypt after the immigration of the early tribes from Asia. I think that the human intellect first germinated on the Nile, and that then there was, in a later age, a reflux of civilization from the Nile back to Asia. I am quite satisfied that the system of writing in use on the Tigris and Euphrates was taken from the Nile; but I admit that it was carried to a much higher state of perfection in Assyria than it had ever reached in Egypt. The earliest Assyrian inscriptions were those lately discovered by Mr. Layard in the north-west Palace at Nimroud, being much earlier than anything found at Babylon. Now, the great question is the date of these inscriptions. Mr. Layard himself, when he published his book on Nineveh, believed them to be 2500 years before the Christian era; but others, and Dr. Hincks among the number, brought them down to a much later date, supposing the historical tablets to refer to the Assyrian kings mentioned in Scripture—(Shalmaneser, Sennacherib, &c.). I do not agree with either one of these calculations or the other. I am inclined to place the earliest inscriptions from Nimroud between 1350 and 1200 before the Christian era; because, in the first place, they had a limit to antiquity; for in the earliest inscriptions there was a notice of the seaports of Phœnicia, of Tyre and Sidon, of Byblus, Arcidus, &c.; and it was well known that these cities were not founded more than 1500 years before the Christian era. We have every prospect of a most important accession to our materials, for every letter I get from the countries now being explored announces fresh discoveries of the utmost importance. In Lower Chaldea, Mr. Loftus, the geologist to the commission appointed to fix the boundaries between Turkey and Persia, has visited many cities which no European had ever reached before, and has everywhere found the most extraordinary remains. At one place (Senkereh) he had come on a pavement, extending from half an acre to an acre, entirely covered with writing, which was engraved upon baked tiles, &c. At Wurka (or Ur of the Chaldees), whence Abraham came out, he had found innumerable inscriptions; they were of no great extent, but they were exceedingly interesting, giving many royal names previously unknown. Wurka (Ur or Orchoe) seemed to be a holy city, for the whole country, for miles upon miles, was nothing but a huge necropolis. In none of the excavations of Assyria had coffins ever been found, but in this city of Chaldea there were thousands upon thousands. The story of Abraham's birth at Wurka did not originate with the Arabs, as had sometimes been conjectured, but with the Jews; and the Orientals had numberless fables about Abraham and Nimroud. Mr. Layard in excavating beneath the great pyramid at Nimroud, had penetrated a mass of masonry, within which he had discovered the tomb and statue of Sardanapalus, accompanied by full annals of the monarch's reign engraved on the walls! He had also found tablets of all sorts, all of them being historical; but the crowning discovery he had yet to describe. The palace at Nineveh, or Koynupih, had evidently been destroyed by fire, but one portion of the building seemed to have escaped its influence; and Mr. Layard, in excavating in this part of the palace, had found a large room filled with what appeared to be the archives of the empire, ranged in successive tablets of terra cotta, the writings being as perfect as when the tablets were first stamped. They were piled in huge heaps from the floor to the ceiling. From the progress already made in reading the inscriptions, I believe we shall be able pretty well to understand the contents of these tablets; at all events, we shall ascertain their general purport, and thus gain much valuable information. A passage might be remembered in the book of Ezra where the Jews, having been disturbed in building the Temple, prayed that search might be made in the house of records for the edict of Cyrus permitting them to return to Jerusalem. The chamber recently found there might be presumed to be the house of records of the Assyrian kings, where copies of the royal edicts were duly deposited. When these tablets have been examined and deciphered, I believe that we shall have a better acquaintance with the history, the religion, the philosophy, and the jurisprudence of Assyria, 1500 years before the Christian era, than we have of Greece or Rome during any period of their respective histories."

Besides the gigantic figures of which we have copied engravings in the preceding pages, Dr. Layard has sent to the British Museum a large number of other sculptures, some of which are still more interesting for the light they reflect upon ancient Assyrian history. For these, as for the Grecian marbles and Egyptian antiquities, a special gallery is being fitted up.

The name of Swift is one of the most familiar in English history. Of the twenty octavo volumes in which his works are printed, only a part of one volume is read; but this part of a volume is read by everybody, and admired by everybody, though singularly enough not one in a thousand ever thinks of its real import, or appreciates it for what are and what were meant to be its highest excellences. As the author of "Gulliver's Travels," Swift is a subject of general interest; and this interest is deepened, but scarcely diffused, by the chain of enigmas which has puzzled so many of his biographers.

The most popular life of Dean Swift is Mr. Roscoe's, but since that was written several works have appeared, either upon his whole history or in elucidation of particular portions of it: one of which was a careful investigation and discussion of his madness, published about two years ago. In the last number of The International we mentioned the curious novel of "Stella and Vanessa," in which a Frenchman has this year essayed his defense against the common judgment in the matter of his amours, and we copy in the following pages an article from the London Times, which was suggested by this performance.

M. De Wailly's "Stella and Vanessa" is unquestionably a very ingenious and brilliant fiction—in every sense only a fiction—for its hypotheses are all entirely erroneous. Even Mr. Roscoe, whose Memoir has been called an elaborate apology, and who, as might have been expected from a man of so amiable and charitable a character, labors to put the best construction upon all Swift's actions,—even he shrinks from the vindication of the Dean's conduct toward Miss Vanhomrigh and Mrs. Johnson. In treating of the charges which are brought against Swift while he was alive, or that have since been urged against his reputation, the elegant historian calls to his aid every palliating circumstance; and where no palliating circumstances are to be found, seeks to enlist our[Pg 8] benevolent feelings in behalf of a man deeply unfortunate, persecuted by his enemies, neglected by his friends, and haunted all his life by the presentiment of a fearful calamity, by which at length in his extreme old age he was assaulted and overwhelmed. On some points Mr. Roscoe must be said to have succeeded in this advocacy, so honorable alike to him and to its subject; but the more serious charges against Swift remain untouched, and probably will forever remain so, by whatever ability, or eloquence, or generous partiality, combated. To speak plainly, Swift was an irredeemably bad man, devoured by vanity and selfishness, and so completely dead to every elevated and manly feeling, that he was always ready to sacrifice those most devotedly attached to him for the gratification of his unworthy passion for power and notoriety.

Swift's life, though dark and turbulent, was nevertheless romantic. He concealed the repulsive odiousness of an unfeeling heart under manners peculiarly fascinating, which conciliated not only the admiration and attachment of more than one woman, but likewise the friendship of several eminent men, who were too much dazzled by the splendor of his conversation to detect the base qualities which existed in the background. But these circumstances only enhance the interest of his life. At every page there is some discussion which strongly interests our feelings: some difficulty to be removed, some mystery to keep alive curiosity. We neither know, strictly speaking, who Swift was, what were the influences which raised him to the position he occupied, by what intricate ties he was connected with Stella, or what was the nature of that singular grief, which, in addition to the sources of sorrow to which we have alluded, preyed on him continually, and at last contributed largely to the overthrow of his reason. On this account it is not possible to proceed with indifference through the circumstances of his life, though very few careful examiners will be able to interpret them in a lenient and charitable spirit.

Mr. Roscoe appears to believe that everybody who regards unfavorably Swift's genius and morals, must be actuated by envy or party spirit, but very few of the later or earlier critics are of his opinion. In the first place, most honorable men would rather remain unknown through eternity than accept the Dean's reputation. As Savage Landor says, he was "irreverential to the great and to God: an ill-tempered, sour, supercilious man, who flattered some of the worst and maligned some of the best men that ever lived." Whatever services he performed for the party from which he apostatized, there is nothing in his more permanent writings which can be of the slightest advantage to English toryism. Indeed, in politics and in morals, he appears never to have had any fixed principles. He served the party which he thought most likely to make him a bishop, and deserted it when he discovered that it was losing ground. He studied government not as a statesman but as a partisan, as a hardy, active, and unscrupulous Swiss, who could and would do much dirty work for a minister, if he saw reason to anticipate a liberal compensation. He however always extravagantly exaggerated his own powers, and so have his biographers, and so has the writer of the following article from The Times, who seems to have accepted with too little scrutiny the estimate he made of himself. The complacency with which he frequently refers to his supposed influence over the ministers is simply ludicrous. He entirely loses sight of both his own position and theirs. Shrewd as he shows himself under other circumstances, he is here as verdant as the greenest peasant from the forest. "I use the ministers like dogs," he says in a letter to Stella, but in reality the ministers made a dog of him, employing him to fetch and carry, and bark, and growl, and show his sharp teeth to their enemies; and when the noise he had made had served their purpose,—when he had frightened away many of their assailants, and by the dirt and stench he had raised had compelled even their friends to stand aloof, they cashiered him, as they would a mastiff grown toothless and incapable of barking. With no more dirty work for him to do, they sent him over to Dublin, to be rid of his presence.

When fairly settled down in a country which he had always hitherto affected at least to detest, he began to feel perhaps some genuine attachment for its people, and on many occasions he exerted himself vigorously for their advantage; though it is possible that the real impulse was a desire to vex and embarrass the administration, which had so galled his self-conceit. Whatever the motive, however, he undoubtedly worked industriously and with great effect, for the benefit of Ireland. His style was calculated to be popular: it was simple, transparent, and though copious, pointed and energetic. His pamphlets, in the midst of their reasoning, sarcasm, and solemn banter, displayed an extent, a variety and profundity of knowledge altogether unequaled in the case of any other writer of that time. But the action of his extraordinary powers was never guided by a spark of honorable principle. The giant was as unscrupulous as the puniest and basest demagogue who coined and scattered lies for our own last election. He would seem to be the model whom half a dozen of our city editors were striving with weaker wing to imitate. He never acknowledged any merit in his antagonists, he scattered his libels right and left without mercy, threw out of sight all the charities and even decencies of private life, and affirmed the most monstrous propositions with so cool, calm and solemn an air, that in nine cases out of ten they were sure to be believed.

Without further observation we proceed[Pg 9] with the interesting article of The Times, occasioned by M. Leon de Wailly's curious and very clever romance of "Stella and Vanessa."

Greater men than Dean Swift may have lived. A more remarkable man never left his impress upon the age immortalized by his genius. To say that English history supplies no narrative more singular and original than the career of Jonathan Swift is to assert little. We doubt whether the histories of the world can furnish, for example and instruction, for wonder and pity, for admiration and scorn, for approval and condemnation, a specimen of humanity at once so illustrious and so small. Before the eyes of his contemporaries Swift stood a living enigma. To posterity he must continue forever a distressing puzzle. One hypothesis—and one alone—gathered from a close and candid perusal of all that has been transmitted to us upon this interesting subject, helps us to account for a whole life of anomaly, but not to clear up the mystery in which it is shrouded. From the beginning to the end of his days Jonathan Swift was more or less mad.

Intellectually and morally, physically and religiously, Dean Swift was a mass of contradictions. His career yields ample materials both for the biographer who would pronounce a panegyric over his tomb and for the censor whose business it is to improve one generation at the expense of another. Look at Swift with the light of intelligence shining on his brow, and you note qualities that might become an angel. Survey him under the dark cloud, and every feature is distorted into that of a fiend. If we tell the reader what he was, in the same breath we shall communicate all that he was not. His virtues were exaggerated into vices, and his vices were not without the savour of virtue. The originality of his writings is of a piece with the singularity of his character. He copied no man who preceded him. He has not been successfully imitated by any who have followed him. The compositions of Swift reveal the brilliancy of sharpened wit, yet it is recorded of the man that he was never known to laugh. His friendships were strong and his antipathies vehement and unrelenting, yet he illustrated friendship by roundly abusing his familiars and expressed hatred by bantering his foes. He was economical and saving to a fault, yet he made sacrifices to the indigent and poor sternly denied to himself. He could begrudge the food and wine consumed by a guest, yet throughout his life refuse to derive the smallest pecuniary advantage from his published works, and at his death bequeath the whole of his fortune to a charitable institution. From his youth Swift was a sufferer in body, yet his frame was vigorous, capable of great endurance, and maintained its power and vitality from the time of Charles II. until far on in the reign of the second George. No man hated Ireland more than Swift, yet he was Ireland's first and greatest patriot, bravely standing up for the rights of that kingdom when his chivalry might have cost him his head. He was eager for reward, yet he refused payment with disdain. Impatient of advancement, he preferred to the highest honors the State could confer the obscurity and ignominy of the political associates with whom he had affectionately labored until they fell disgraced. None knew better than he the stinging force of a successful lampoon, yet such missiles were hurled by hundreds at his head without in any way disturbing his bodily tranquillity. Sincerely religious, scrupulously attentive to the duties of his holy office, vigorously defending the position and privileges of his order, he positively played into the hands of infidelity by the steps he took, both in his conduct and writings, to expose the cant and hypocrisy which he detested as heartily as he admired and practiced unaffected piety. To say that Swift lacked tenderness would be to forget many passages of his unaccountable history that overflow with gentleness of spirit and mild humanity; but to deny that he exhibited inexcusable brutality where the softness of his nature ought to have been chiefly evoked—where the want of tenderness, indeed, left him a naked and irreclaimable savage—is equally impossible. If we decline to pursue the contradictory series further, it is in pity to the reader, not for want of materials at command. There is, in truth, no end to such materials.

Swift was born in the year 1667. His father, who was steward to the Society of the King's Inn, Dublin, died before his birth and left his widow penniless. The child, named Jonathan after his father, was brought up on charity. The obligation due to an uncle was one that Swift would never forget, or remember without inexcusable indignation. Because he had not been left to starve by his relatives, or because his uncle would not do more than he could, Swift conceived an eternal dislike to all who bore his name and a[Pg 10] haughty contempt for all who partook of his nature. He struggled into active life and presented himself to his fellow-men in the temper of a foe. At the age of fourteen he was admitted into Trinity College, Dublin, and four years afterward as a special grace—for his acquisitions apparently failed to earn the distinction—the degree of Bachelor of Arts was conferred upon him. In 1688, the year in which the war broke out in Ireland, Swift, in his twenty-first year, and without a sixpence in his pocket, left college. Fortunately for him, the wife of Sir William Temple was related to his mother, and upon her application to that statesman the friendless youth was provided with a home. He took up his abode with Sir William in England, and for the space of two years labored hard at his own improvement and for the amusement of his patron. How far Swift succeeded in winning the good opinion of Sir William may be learnt from the fact that when King William honored Moor Park with his presence he was permitted to take part in the interviews, and that when Sir William was unable to visit the King his protégé was commissioned to wait upon His Majesty, and to speak on the patron's authority and behalf. The lad's future promised better things than his beginning. He resolved to go into the church, since preferment stared him in the face. In 1692 he proceeded to Oxford, where he obtained his Master's degree, and in 1694, quarreling with Sir William Temple, who coldly offered him a situation worth £100 a year, he quitted his patron in disgust and went at once to Ireland to take holy orders. He was ordained, and almost immediately afterward received the living of Kilroot in the diocese of Connor, the value of the living being about equal to that of the appointment offered by Sir William Temple.

Swift, miserable in his exile, sighed for the advantages he had abandoned. Sir William Temple, lonely without his clever and keen-witted companion, pined for his return. The prebend of Kilroot was speedily resigned in favor of a poor curate for whom Swift had taken great pains to procure the presentation; and with £80 in his purse the independent clergyman proceeded once more to Moor Park. Sir William welcomed him with open arms. They resided together until 1699, when the great statesman died, leaving to Swift, in testimony of his regard, the sum of £100 and his literary remains. The remains were duly published and humbly dedicated to the King. They might have been inscribed to His Majesty's cook for any advantage that accrued to the editor. Swift was a Whig, but his politics suffered severely by the neglect of His Majesty, who derived no particular advantage from Sir William Temple's "remains."

Weary with long and vain attendance upon Court, Swift finally accepted at the hands of Lord Berkeley, one of the Lords Justices of Ireland, the rectory of Agher and the vicarages of Laracor and Rathbeggan. In the year 1700 he took possession of the living at Laracor, and his mode of entering upon his duty was thoroughly characteristic of the man. He walked down to Laracor, entered the curate's house, and announced himself "as his master." In his usual style he affected brutality, and having sufficiently alarmed his victims, gradually soothed and consoled them by evidences of undoubted friendliness and good will. "This," says Sir Walter Scott, "was the ruling trait of Swift's character to others; his praise assumed the appearance and language of complaint; his benefits were often prefaced by a prologue of a threatening nature." "The ruling trait" of Swift's character was morbid eccentricity. Much less eccentricity has saved many a murderer in our days from the gallows. We approach a period of Swift's history when we must accept this conclusion or revolt from the cold-blooded doings of a monster.

During Swift's second residence with Sir William Temple he had become acquainted with an inmate of Moor Park very different to the accomplished man to whose intellectual pleasures he so largely ministered. A young and lovely girl—half ward, half dependent in the establishment—engaged the attention and commanded the untiring services of the newly-made minister. Esther Johnson had need of education, and Swift became her tutor. He entered upon his task with avidity, condescended to the humblest instruction, and inspired his pupil with unbounded gratitude and regard. Swift was not more insensible to the simplicity and beauty of the lady than she to the kind offices of her master; but Swift would not have been Swift had he, like other men, returned everyday love with ordinary affection. Swift had felt tender impressions in his own fashion before. Once in Leicestershire he was accused by a friend of having formed an imprudent attachment, on which occasion he returned for answer, that his "cold temper and unconfined humor" would prevent all serious consequences, even if it were not true that the conduct which his friend had mistaken for gallantry had been merely the evidence "of an active and restless temper, incapable of enduring idleness, and catching at such opportunities of amusement as most readily occurred." Upon another occasion, and within four years of the Leicestershire pastime, Swift made an absolute offer of his hand to one Miss Waryng, vowing in his declaratory epistle that he would forego every prospect of interest for the sake of his "Varina," and that "the lady's love was far more fatal than her cruelty." After much and long consideration Varina consented to the suit. That was enough for Swift. He met the capitulation by charging his Varina with want of affection, by stipulating for unheard-of sacrifices, and concluding with an expression of his willingness to wed, "though she had neither fortune[Pg 11] nor beauty," provided every article of his letter was ungrudgingly agreed to. We may well tremble for Esther Johnson, with her young heart given into such wild keeping.

As soon as Swift was established at Laracor it was arranged that Esther, who possessed a small property in Ireland, should take up her abode near to her old preceptor. She came, and scandal was silenced by a stipulation insisted upon by Swift, that his lovely charge should have a matron for a constant companion, and never see him except in the presence of a third party. Esther was in her seventeenth year. The vicar of Laracor was on his road to forty. What wonder that even in Laracor the former should receive an offer of marriage, and that the latter, wayward and inconsistent from first to last, should deny another the happiness he had resolved never to enjoy himself? Esther found a lover whom Swift repulsed, to the infinite joy of the devoted girl, whose fate was already linked for good or evil to that of her teacher and friend.

Obscurity and idleness were not for Swift. Love, that gradually consumed the unoccupied girl, was not even this man's recreation. Impatient of banishment, he went to London and mixed with the wits of the age. Addison, Steele, and Arbuthnot became his friends, and he quickly proved himself worthy of their intimacy by the publication in 1704 of his Tale of a Tub. The success of the work, given to the world anonymously, was decisive. Its singular merit obtained for its author everlasting renown, and effectually prevented his rising to the highest dignity in the very church which his book labored to exalt. None but an inspired madman would have attempted to do honor to religion in a spirit which none but the infidel could heartily approve.

Politicians are not squeamish. The Whigs could see no fault in raillery and wit that might serve temporal interests with greater advantage than they had advanced interests ecclesiastical; and the friends of the Revolution welcomed so rare an adherent to their principles. With an affected ardor that subsequent events proved to be as premature as it was hollow, Swift's pen was put in harness for his allies, and worked vigorously enough until 1709, when, having assisted Steele in the establishment of the Tatler, the vicar of Laracor returned to Ireland and to the duties of a rural pastor. Not to remain, however! A change suddenly came over the spirit of the nation. Sacheverell was about to pull down by a single sermon all the popularity that Marlborough and his friends had built up by their glorious campaigns. Swift had waited in vain for promotion from the Whigs, and his suspicions were roused when the Lord-Lieutenant unexpectedly began to caress him. Escaping the damage which the marked attentions of the old Government might do him with the new, Swift started for England in 1710, in order to survey the turning of the political wheel with his own eyes, and to try his fortune in the game. The progress of events was rapid. Swift reached London on the 9th of September; on the 1st of October he had already written a lampoon upon an ancient associate; and on the 4th he was presented to Harley, the new Minister.

The career of Swift from this moment, and so long as the government of Harley lasted, was magnificent and mighty. Had he not been crotchety from his very boyhood, his head would have been turned now. Swift reigned; Swift was the Government; Swift was Queen, Lords, and Commons. There was tremendous work to do, and Swift did it all. The Tories had thrown out the Whigs and had brought in a Government in their place quite as Whiggish to do Tory work. To moderate the wishes of the people, if not to blind their eyes, was the preliminary and essential work of the Ministry. They could not perform it themselves. Swift undertook the task and accomplished it. He had intellect and courage enough for that, and more. Moreover, he had vehement passions to gratify, and they might all partake of the glory of his success; he was proud, and his pride reveled in authority; he was ambitious, and his ambition could attain no higher pitch than it found at the right hand of the Prime Minister; he was revengeful, and revenge could wish no sweeter gratification than the contortions of the great who had neglected genius and desert, when they looked to them for advancement and obtained nothing but cold neglect. Swift, single-handed, fought the Whigs. For[Pg 12] seven months he conducted a periodical paper, in which he mercilessly assailed, as none but himself could attack, all who were odious to the Government and distasteful to himself. Not an individual was spared whose sufferings could add to the tranquillity and permanence of the Government. Resistance was in vain; it was attempted, but invariably with one effect—the first wound grazed, the second killed.

The public were in ecstasies. The laughers were all on the side of the satirist, and how vast a portion of the community these are, needs not be said. But it was not in the Examiner alone that Swift offered up his victims at the shrine of universal mirth. He could write verses for the rough heart of a nation to chuckle over and delight in. Personalities to-day fly wide of the mark; then they went right home. The habits, the foibles, the moral and physical imperfections of humanity, were all fair game, provided the shaft were tipped with gall as well as venom. Short poems, longer pamphlets—whatever could help the Government and cover their foes with ridicule and scorn, Swift poured upon the town with an industry and skill that set eulogy at defiance. And because they did defy praise, Jonathan Swift never asked, and was ever too grand to accept it.

But he claimed much more. His disordered yet exquisite intellect acknowledged no superiority. He asked no thanks for his labor, he disdained pecuniary reward for his matchless and incalculable services—he did not care for fame, but he imperiously demanded to be treated by the greatest as an equal. Mr. Harley offered him money, and he quarreled with the Minister for his boldness. "If we let these great Ministers," he said, "pretend too much, there will be no governing them." The same Minister desired to make Swift his chaplain. One mistake was as great as the other. "My Lord Oxford, by a second hand, proposed my being his chaplain, which I, by a second hand, refused. I will be no man's chaplain alive." The assumption of the man was more than regal. At a later period of his life he drew up a list of his friends, ranking them respectively under the heads "Ungrateful," "Grateful," "Indifferent," and "Doubtful." Pope appears among the grateful. Queen Caroline among the ungrateful. The audacity of these distinctions is very edifying. What autocrat is here for whose mere countenance the whole world is to bow down and be "grateful!"

It is due to Swift's imperiousness, however, to state that, once acknowledged as an equal, he was prepared to make every sacrifice that could be looked for in a friend. Concede his position, and for fortune or disgrace he was equally prepared. Harley and Bolingbroke, quick to discern the weakness, called their invulnerable ally by his Christian name, but stopped short of conferring upon him any benefit whatever. The neglect made no difference to the haughty scribe, who contented himself with pulling down the barriers that had been impertinently set up to separate him from rank and worldly greatness. But, if Swift shrank from the treatment of a client, he performed no part so willingly as that of a patron. He took literature under his wing and compelled the Government to do it homage. He quarreled with Steele when he deserted the Whigs, and pursued his former friend with unflinching sarcasm and banter, but at his request Steele was maintained by the Government in an office of which he was about to be deprived. Congreve was a Whig, but Swift insisted that he should find honor at the hands of the Tories, and Harley honored him accordingly. Swift introduced Gay to Lord Bolingbroke, and secured that nobleman's weighty patronage for the poet. Rowe was recommended for office, Pope for aid. The well-to-do, by Swift's personal interest, found respect, the indigent, money for the mitigation of their pains. At Court, at Swift's instigation, the Lord Treasurer made the first advances to men of letters, and by the act made tacit confession of the power which Swift so liberally exercised, for the advantage of everybody but himself. But what worldly distinction, in truth, could add to the importance of a personage who made it a point for a Duke to pay him the first visit, and who, on one occasion, publicly sent the Prime Minister into the House of Commons to call out the First Secretary of State, whom Swift wished to inform that he would not dine with him if he meant to dine late?

A lampoon directed against the Queen's favorite, upon whose red hair Swift had been facetious, prevented the satirist's advancement in England. The see of Hereford fell vacant in 1712. Bolingbroke would now have paid the debt due from his Government to Swift, but the Duchess of Somerset, upon her knees, implored the Queen to withhold her consent from the appointment, and Swift was pronounced by Her Majesty as "too violent in party" for promotion. The most important man in the kingdom found himself in a moment the most feeble. The fountain of so much honor could not retain a drop of the precious waters for itself. Swift, it is said, laid the foundations of fortune for upward of forty families who rose to distinction by a word from his lips. What a satire upon power was the satirist's own fate! He could not advance himself in England one inch. Promotion in Ireland began and ended with his appointment to the Deanery of St. Patrick, of which he took possession, much to his disgust and vexation, in the summer of 1713.