Somers and the Admiral. Page 202.

BRAVE OLD SALT.

Oliver Optic.

LEE & SHEPARD.

BOSTON.

BRAVE OLD SALT;

OR,

LIFE ON THE QUARTER DECK.

A Story of the Great Rebellion.

BY

OLIVER OPTIC,

Author of "THE SOLDIER BOY," "THE SAILOR BOY," "THE YOUNG LIEUTENANT," "THE YANKEE MIDDY," "FIGHTING JOE," "THE WOODVILLE STORIES," "THE RIVERDALE STORY BOOKS," ETC., ETC.

BOSTON:

LEE AND SHEPARD,

SUCCESSORS TO PHILLIPS, SAMPSON & CO.

1866.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1866, by

WILLIAM T. ADAMS,

In the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts.

ELECTROTYPED AT THE

Boston Stereotype Foundry,

No. 4 Spring Lane.

TO

SAMUEL C. PERKINS, ESQ.,

This Book

IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED,

BY HIS FRIEND

WILLIAM T. ADAMS.

[5]

PREFACE.

This volume, the sixth and last of "The Army and Navy Stories," is a record of "Life on the Quarter Deck," mostly in the squadron of Vice Admiral Farragut, one of whose familiar appellations, used in the ward-room and on the berth deck, has furnished the leading title of the book. The terrible war which devastated our country for four years has given to history two generals, Grant and Sherman, and one admiral, Farragut, whose achievements are unsurpassed, if they are equalled, in the annals of military and naval warfare; but while the author, in this work, has gratefully rendered his tribute of admiration to the distinguished naval commander, he has not attempted to present a complete biography of him.

Those who have read the preceding volumes of this series need hardly be told that this is a book of adventure—of personal experience in the great struggle of the nineteenth century. Jack Somers, "The Sailor Boy," Mr. Somers, "The Yankee Middy," and Captain Somers, Lieutenant Commanding, are the same person; though often as he changes his official position, he is still the same honest, true, and Christian young man.

In our completed sixth volume we take leave of the Somers[6] family with many regrets. If our young friends in the army and navy had been less true, noble, and Christian, we could have parted with less sorrow. Yet the army and navy, as they crushed the Rebellion, have given us many young men just as true, just as noble and Christian. Let us gratefully cherish these living heroes, and they will not pass away from us "like a tale that is told."

To the readers, young and old, who have perseveringly followed my heroes through the two thousand pages of this series, I am even more than grateful; for I feel that they have sympathized with me in my desire to present a lofty ideal to the young man of to-day—one who will be true to God, true to himself, and true to his country, in whatever sphere his lot may be cast, whether on the forecastle or the quarter deck; as a private or an officer, in the great army which must ever battle with life's trials and temptations till the crown immortal be won.

Harrison Square, Mass., March 13, 1866.

CONTENTS.

[7]| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Lieutenant Pillgrim. | 11 |

| II. | Waiting for the Ship. | 23 |

| III. | The Wounded Sailor. | 33 |

| IV. | The Front Chamber. | 44 |

| V. | Somers comes to his Senses. | 55 |

| VI. | Lieutenant Wynkoop, R. N. | 66 |

| VII. | Langdon's Letters. | 77 |

| VIII. | The United States Steamer Chatauqua. | 87 |

| IX. | In the State-Room. | 97 |

| X. | The Chief Conspirator. | 108 |

| XI. | After General Quarters. | 119 |

| XII. | The Ben Nevis. | 130 |

| XIII. | A Conflict of Authority. | 140 |

| XIV. | The Prize Steamer. | 150 |

| XV. | The Prisoner in the Cabin. | 160 |

| XVI. | Captain Walmsley. | 170 |

| XVII. | Off Mobile Bay. | 180 |

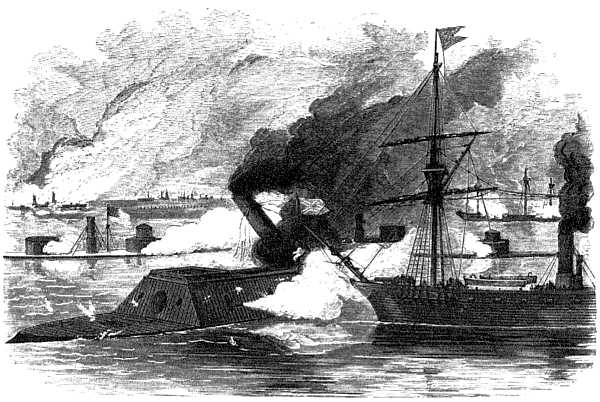

| XVIII. | Brave Old Salt. | 190 |

| XIX. | The Boat Expedition. | 200 |

| XX. | The Picket Boat. | 211 |

| XXI. | The Ben Lomond. | 222 |

| XXII. | Running the Blockade.[8] | 233 |

| XXIII. | A Yankee Trick. | 244 |

| XXIV. | Pillgrim and Langdon. | 254 |

| XXV. | The Battle of Mobile Bay. | 264 |

| XXVI. | In the Hospital. | 274 |

| XXVII. | Miss Portington not at Home. | 284 |

| XXVIII. | The Ben Ledi. | 294 |

| XXIX. | A Long Chase. | 303 |

| XXX. | The End of the Rebellion. | 318 |

[10]

BRAVE OLD SALT.

[11]

BRAVE OLD SALT;

OR,

LIFE ON THE QUARTER DECK.

CHAPTER I.

LIEUTENANT PILLGRIM.

"Well, Prodigy, I congratulate you on your promotion. I even agree with your enthusiastic admirers, who say that no young man better deserves his advancement than you," said Miss Kate Portington, standing in the entry of her father's house at Newport, holding Mr. Ensign John Somers by the hand.

"Thank you, Miss Portington," replied the young officer, with a blush caused as much by the excitement of that happy moment, as by the handsome compliment paid by the fair girl, who, we are compelled to acknowledge, had formed no inconsiderable portion of the young man's thoughts, hopes, and aspirations during the preceding year.[12]

John Somers had been examined by the board of naval officers appointed for the purpose, had been triumphantly passed, and promoted to the rank he now held. A short furlough had been granted to him, and he had just come from Pinchbrook, where he had spent a week. A visit to Newport was now almost as indispensable as one to the home of his childhood, and on his way to join the ship to which he had been ordered, he paused to discharge this pleasing duty.

Ensign Somers was dressed in a new uniform, and a certain boyish look, for which he was partly indebted to the short jacket he had worn as a midshipman, had vanished. Perhaps Miss Portington felt that the pertness, not to say impudence, with which she had formerly treated him, though allowable, under a liberal toleration, towards a boy, would hardly be justifiable in her intercourse with a young man. Though, from the force of habit, she called him "Prodigy," there was a certain maidenly reserve in her manner, which rather puzzled Somers, and he could not help asking himself what he had done to cause this slight chill in her tones and actions.

Undoubtedly it was the frock coat which produced this refrigerating effect; but it was a very elegant and well-fashioned garment, having the shoulder straps on which glistened the "foul anchor," indicating his new rank, and each sleeve being adorned with a single gold band on[13] the cuff, also indicative of his new position. The cap, which he now held in his hand, was decorated with a band of gold lace, and bore on its front the appropriate naval emblem. In strict accordance with the traditions of the navy, he wore kid gloves, without which a naval officer, on a ceremonial occasion, would be as incomplete as a ship without a rudder.

We have no means of knowing what Mr. Ensign Somers thought of himself in his "new rig," which certainly fitted with admirable nicety, and gave him an appearance of maturity which he did not possess when we last saw him on the quarter deck of the Rosalie. We will venture to assert, however, that he felt like a man, and fully believed that he was one—a commendable sentiment in a person of his years, inasmuch as, if he feels like a man, he is the more likely to act like one. As we can hardly suppose he soared above all the vanities of his impressible period of life, it is more than probable that he regarded himself as a very good looking young fellow; which brilliant suggestion was, no doubt, wholly or in part due to the new uniform he wore.

If not wholly above the weakness of a young man of twenty, possibly he had a great deal of confidence in his own knowledge and ability, regarded some of the veterans of the navy as "old fogies," and looked upon his own father as "a slow coach." But we must do Mr. Somers the justice to say that he tried to be humble in[14] his estimate of himself, and to bear the honors he had won with meekness; that he endeavored to crush down and mortify that overweening self-sufficiency which distorts and disfigures the character of many estimable young men. His native bashfulness had, in some measure, been overcome by his intercourse with the world, and the humility of his nature, though occasionally assaulted by the accident of a new coat and an extra supply of gold lace, or by the hearty commendations of his superiors, was genuine, and, in the main, saved him from the besetting sin of his years.

Standing in the presence of Miss Kate Portington, after an absence of several months, wearing a new coat glittering with the laurels he had won on the bloodstained decks of the nation's ships, he would have been more than human if he had not felt proud of what he was, and what he had done—proud, not vain. He was happy, holding the hand of her who had occupied so large a place in his thoughts, and whose image had fringed with roseate hues his brightest hopes and strongest aspirations.

Kate was not so free with him as she had been, and her reserve annoyed and perplexed him. He had anticipated a much warmer welcome than that which greeted him on his arrival. He was slightly disappointed, though there was nothing in her manner for which he could have reproached her, even if their relations had[15] been more intimate than they were. She was less stormy, but still gentle and kind; a little more distant in manner, though her looks and words assured him she regarded him with undiminished interest. Had he known that the elegant frock coat he wore produced the chill in the lady which so vexed and disconcerted him, he would willingly have exchanged it for the short jacket in which he had won his promotion.

They were standing in the entry. When the servant admitted Mr. Somers, Kate had heard his voice, and perhaps from prudential motives—for there was a visitor in the parlor—she had preferred to meet him in the hall.

"You have been very fortunate, Mr. Somers," added she, gently releasing her hand from that of the ensign.

Mr. Somers, instead of "Prodigy"!

"I have. I don't deserve my promotion, I know; but I could not help taking it when it was within my reach," replied Somers; and her words, though so slightly chilled that the frigid tone could not have been noticed by any one who did not expect an unreasonable warmth, took half the conceit out of him, and let him down a long reach from the high hopes and brilliant expectations with which he had looked forward to this meeting.

"On the contrary, Mr. Somers, I think you deserve even more than you have received."

"Thank you, Miss Portington; you were always more lavish of kind words than I deserved."[16]

"Why, Prodigy—"

She suddenly checked herself. It was evident to Somers that she intended to say something pert or saucy. Perhaps she choked down the impertinent words from the fear that the honorable secretary of the navy, if such wild and wayward young ladies as herself were permitted to contaminate the plushy air of Newport society, would remove the Naval Academy back to Annapolis, where it is better to be "proper" than to be loyal.

"You were about to say something, Miss Portington," said Somers.

"I was, but it was saucy."

"I am sorry you did not say it."

"I am glad I did not, for you must know, Mr. Somers, that mother has scolded me so much for being saucy, that I have solemnly resolved to be proper in all things henceforth and forevermore."

"I am sorry for it," answered Somers, with unaffected earnestness.

"Sorry, you wretch?"

Somers laughed.

"There's another slip. I have done my best to reform my life. I am afraid I shall never succeed. Now, Prodigy—"

Somers laughed again.

"Again!" exclaimed Kate.

"I wish to ask one favor of you, Miss Portington."[17]

"It would afford me more pleasure to grant it, than it does you to ask it. Name it."

"That you will never call me Prodigy again."

"I had firmly resolved before you came never to do it," laughed she.

"Well, I only asked it in order to help along your good resolutions."

"Then you are making fun of me?"

"Like yourself, I am very serious."

"But I am in earnest, Mr. Somers; I mean to reform. Now, father and mother will be very glad to see you, Mr. Somers."

"Your father?"

"He was temporarily relieved to attend a court martial. He is going away again to-morrow."

"You have other visitors?"

"Only Lieutenant Pillgrim."

"I have not the pleasure of his acquaintance."

"He is a Virginian, I believe; at any rate he is from the South, and has just been restored to his rank in the navy."

Kate led the way into the parlor, where he was first welcomed by her mother.

"Mr. Somers, I am glad to see you, and to congratulate you on your promotion," said the commodore, as he grasped the hand of the young officer.

"Thank you, sir," replied Somers. "The only ungratified[18] wish I had was that I might be appointed to your ship."

"My ship!"

"I should have been glad to serve under so able and distinguished a commander."

"I wouldn't have you in my ship," promptly returned the commodore, shaking his head energetically.

Somers looked abashed, and Kate wore a troubled expression.

"I should endeavor to do my duty," he added.

"I have no doubt of it, but I wouldn't have you in my ship."

"Your remark is not very complimentary," said Somers, his face beginning to flush with indignation at what seemed to be an assault upon his professional character.

"It is the most complimentary thing I could say to you. And I mean what I say: I wouldn't have you in my ship."

"Why not, father?" demanded Kate.

"Because I like the young dog, and because I believe in discipline. I never indulge in partiality on board my ship, and it is better to keep out of temptation. I am under obligations to you, Mr. Somers; I am happy to acknowledge them, but they must not come between me and duty. Mr. Somers, Lieutenant Pillgrim," continued Commodore Portington, turning to the visitor.

Somers looked at the officer thus indicated, and as his[19] eyes rested upon him, he started back with a momentary astonishment, for the face had a strange look of familiarity to him.

"Mr. Somers, I am happy to meet and to know you. Your name and reputation are already familiar to me."

"I am glad to know you, sir," replied Somers, with some confusion. "Your face looks so familiar to me, that I think we must have met before."

"Never, to my knowledge," answered the lieutenant, with easy self-possession.

"I was quite sure I had seen you before."

"Possibly; I do not remember it, however."

"If I had met you without the favor of an introduction, I should certainly have claimed the honor of your acquaintance."

"I should have been proud to be so claimed, but I must confess you would have had the advantage of me."

"Of course, I must be mistaken, as you suggest."

"It is not unlikely that we have met in some ante-room where we were dancing attendance on the powers that be, in search of employment; but I am quite sure, Mr. Somers, that I should have been proud and happy to number you among my friends."

"It is not too late now," said the commodore.

"Certainly not. I should be but too happy to have as my friend one who has served his country so faithfully," added Mr. Pillgrim, as he bowed gracefully to[20] Somers, "especially as I understand we are appointed to the same ship."

"Indeed!"

"I am ordered to the Chatauqua."

"So am I."

"Then, Mr. Pillgrim, you will take care of our Prodigy; you will be excellent friends, I trust," said Kate, beginning very impulsively in her old way, and suddenly checking herself when her resolution to be "proper" interposed itself.

"What is the matter, Kate? Have you and Mr. Somers had a falling out?" demanded the commodore.

"O, no, father."

"You talk as though you had had a quarrel, and for a moment had forgotten to be savage."

"We have had no quarrel, pa," replied Kate, blushing. "I was going to be saucy, but ma says I must not be saucy, and I shall not be saucy any more. I only hoped the two gentlemen who are going to live together in the same ship would be good friends."

"Of course they will. Officers never quarrel."

"Perhaps they don't; but they are not always as good friends as I hope these gentlemen will be," laughed Kate.

"Perhaps he will be my friend for your sake, if he is not for mine," added Pillgrim.

"I do not wish that. I don't like to have anybody do anything for my sake, unless it be to take paregoric when I am sick."[21]

"I trust I shall not be paregoric to him," said Pillgrim.

"Then he will not take you for my sake."

"As Lieutenant Pillgrim is my superior officer, I should be likely to court his good will, and prize his friendship very highly. If we are not friends, I am sure it will not be my fault."

At this moment the dinner bell rang; and although Somers did not feel intimate enough with the family to invite himself to dine, he was easily prevailed upon to remain, and gallantly gave his arm to Mrs. Portington, as Kate, for some wayward reason of her own, had already seized upon that of Lieutenant Pillgrim.

At the table Somers sat opposite the lieutenant, and he found it impossible to avoid looking upon him with a strange and undefinable interest. Since his first glance at the commodore's visitor, who seemed to be on the best of terms with the family, he had been perplexed by some strange misgivings. He could not banish from his mind an assurance that he had seen him before; that he had talked with him, and even been, to some extent, intimate with him.

The thought that Kate was somewhat changed in her demeanor towards him did not contribute to increase his satisfaction. She had contrived to take the lieutenant's arm instead of his own, and perhaps he had come as the successor of Phil Kennedy, who had been reputed to[22] be high in her good graces. But Mr. Pillgrim was a gentleman of thirty-five, at least, and this was not probable, in his view of the matter. Somers, being disinterested, was more worried to know when, where, and under what circumstances he had met the lieutenant.

[23]

CHAPTER II.

WAITING FOR THE SHIP.

Somers was utterly unable to satisfy himself in regard to Lieutenant Pillgrim. The face was certainly familiar to him, not as a combination of remembered features, but rather as an expression. To him the eye seemed to be the whole of the man, and its gaze would haunt him, though his memory refused to identify it with any time, place, or circumstances. Though his reason compelled him to believe that he was mistaken, and that Mr. Pillgrim was actually a stranger, his consciousness of having seen, and even of having been intimate with, the gentleman, most obstinately refused to be shaken.

"Of course, gentlemen, you have no idea to what point the Chatauqua has been ordered?" said the commodore.

"I have not," replied Mr. Pillgrim.

"I have heard it said that she was going to the Gulf," added Somers.

"Very likely; there are two points where extensive naval operations are likely to be undertaken—at Mobile[24] and at Wilmington. The rebellion has had so many hard knocks that the bottom must drop out before many months."

"I am afraid the end is farther off than most people at the North are willing to believe," said Mr. Pillgrim.

"Every thing looks hopeful. If we can contrive to batter down Fort Fisher, and open Mobile Bay, the rebels may count the months of their Confederacy on their fingers."

"I think there is greater power of resistance left in the South, than we give it the credit for."

"The rebels have fought well; what of it?" continued the commodore, who did not seem to be pleased with the style of the lieutenant's remarks.

"As fighting men, we can hardly fail to respect those who have fought so bravely as the people of the South."

"People of the South!" sneered the commodore. "Why don't you call them rebels?"

"Of course that is what I mean," answered Mr. Pillgrim, a slight flush visible on his cheek.

"If you mean it, why don't you say it? Call things by their right names. The people of the South are not all rebels. Why, confound it, Farragut is a Southerner; so is General Anderson; so are a hundred men, who have distinguished themselves in putting down treason. It's an insult to these men to talk about the people of the South as rebels."[25]

"I agree with you, Commodore Portington, and what I said was only a form of expression."

"It's a very bad form of expression. Why, man, you are a Southerner yourself."

"I am; and I suppose that is what makes me so proud of the good fighting the people of the South—I mean the rebels—have done. We can't help respecting men who have behaved with so much gallantry."

"Can't we?" exclaimed the commodore, with a sneer so wholesome and honest, that Lieutenant Pillgrim withered under it. "I can help it. I have no respect for rebels and traitors under any circumstances."

"Nor I, as rebels and traitors," replied Pillgrim, mildly.

"As rebels and traitors! I don't like these fine-spun distinctions. If a man is a traitor, call him so, and swing him up on the fore-yard arm, where he belongs."

"You are willing to acknowledge that the rebels have fought well in this war?" added the lieutenant.

"They have fought well: I don't deny it."

"And you appreciate gallant conduct?"

"That depends on the cause. No, sir! I don't appreciate gallant conduct on the part of rebels and traitors. It is not gallant conduct; and the better they fight, the more wicked they are."

"I can hardly take your view of the case."

"Can't you? The best fighting I ever saw in my life[26] was on the deck of a pirate ship. The black-hearted villains fought like demons. Not a man of them would yield the breadth of a hair. We had to cut them down like dogs. Is piracy respectable because these men fought well?"

"Certainly not; but the bravery of such men—"

"Nonsense! I know what you are going to say; but you can't separate the pirate from his piracy, nor the traitor from his treason," replied the commodore, warmly. "The other day I saw a little dirty urchin fighting with his mother. The young cub had run away, I suppose, and the woman was dragging him back to the house. He was not more than six years old, but he displayed a power of resistance which rather astonished me. He kicked, bit, scratched, and yelled like a young tiger. He called his mother everything but a lady. The poor woman tugged at him with all her strength, but the little rascal was almost a match for her. I wanted to take him by the nape of the neck, and shake the ugly out of him: nothing but my fixed principles of neutrality prevented me from doing so. I suppose, Mr. Pillgrim, you would have sympathized with the brat, because he fought bravely."

"Hardly," replied the lieutenant, laughing at the simile.

"But he fought like a tiger, and displayed no mean strategy in his rebellious warfare. Of course he was worthy of your admiration," sneered the commodore.[27]

"That's hardly a fair comparison."

"The fairest in the world. The rebels have insulted their own mother—the parent that fostered, protected, and loved them. They undertook to run away from her; and when she attempts to bring them back to their duty, they kick, and scratch, and bite; and you admire them because they fight well."

"I stand convicted, Commodore Portington. I never took this view of the matter; I acknowledge that you are right," said Mr. Pillgrim.

Somers, who had been an attentive listener to the conversation, thought the lieutenant yielded very gracefully, and much more readily than could have been expected; but then the logician was a commodore, and perhaps it was prudence and politeness on his part to agree with his powerful superior.

After dinner the party took a ride to the beach and to the Glen; and after an early tea, Somers and Pillgrim, who were to be fellow-passengers to Philadelphia, where the Chatauqua was fitting out, began to demonstrate in the direction of their departure. Kate, though she had been tolerably playful during the afternoon, had, in the main, carried out her good resolution to be proper. She had not been impudent—hardly pert; and deprived of this convenient mask for whatever kindness she might have entertained towards the young ensign, she seemed to be very cold and indifferent to him. She was more[28] thoughtful, serious, and earnest than when they had met on former occasions. He could not help asking himself what he had done to produce this marked change in her conduct.

"Good by, Miss Portington," said he, when he had taken leave of her father and mother.

"Good by, Mr. Somers. Shall I hear from you when you reach your station?" she asked, presenting her hand.

"If you desire it."

"If I desire it! Why, Mr. Somers, you forget that I am deeply interested in your success."

"Perhaps, if I do anything of which you would care to learn, the newspapers may inform you of the fact," replied Somers, with a kind of grim smile, which seemed actually to alarm poor Kate.

"I would rather hear it from you."

"I judge that you are more interested in my success than you are in me."

"Ah, Mr. Somers, you cannot separate the pirate from his piracy, pa said; nor the hero from his heroism, let me add."

"Thank you, Miss Portington."

"I cannot forget how deeply indebted we are to you, Mr. Somers."

"I wish you could."

"Why do you wish so?" demanded the astonished maiden; more astonished at his manner than his words.[29]

"I am sorry to have you burdened with such a weight of obligation."

"I think you mean to quarrel with me, Mr. Somers. I beg you will not be so savage just as you are going away," laughed Kate, though there was a troubled expression on her fair face. "I asked you if I should hear from you, Mr. Somers."

"Certainly, if you desire."

"Why do you qualify your words? I should be just as glad to hear from you as I ever was."

"Then you shall, at every opportunity."

"Thank you, Mr. Somers. That sounds hearty and honest, as father would say."

"I do not wish you to feel an interest in me from a sense of duty. I shall not write any letters from a sense of duty, or even because I have promised to do so. I shall write to you because—because I can't help it," stammered Somers, almost overcome by the violence of his exertions.

"I thank you, Mr. Somers, and I am sure your letters will be all the more welcome from my knowledge of the fact."

"Good by," said he, gently pressing the little hand he held.

"Good by," she replied; and to his great satisfaction and delight, the pressure was returned—a kind of telegraphic[30] signal, infinitely more expressive than all the words in the spelling-book, strung into sentences, could have been to a young man in his desperate condition.

Mr. Ensign Somers was now entirely satisfied. That gentle pressure of the hand had atoned for all her reserve and coldness, real or imaginary, and made the future bright and pleasant to look upon. Undoubtedly Mr. Somers was a silly young fellow; but there is some consolation in believing that he was just like all young men under similar circumstances.

Mr. Pillgrim followed him out of the house, and they hastened down to the wharf to take the steamer for New York. On the passage the two officers treated each other with courtesy and consideration, but there appeared to be no strong sympathy of thought or feeling between them, and they were not drawn so closely together as they might have been under similar circumstances, if there had been more of opinion and sentiment common between them.

On their arrival at Philadelphia, they found the Chatauqua was still in the hands of the workmen, and would not go into commission for a week or ten days. They reported to the commandant of the navy yard, and took up their quarters at the "Continental," where Somers found his old friend Mr. Waldron, who had been detached from the Rosalie at his own request, and ordered to the Chatauqua, in which he was to serve as executive[31] officer. This was splendid news to Somers, for he regarded Mr. Waldron as a true and trusty friend, in whom he could with safety confide.

"Do you know Lieutenant Pillgrim?" asked Somers, after they had discussed their joint information in regard to the new ship.

"I am not personally acquainted with him, though I have heard his name mentioned. He is a Virginian, I think."

"Yes."

"If I mistake not, there were some doubts about his loyalty, though he never tendered his resignation; he has been kept in the background."

"He seems to be a loyal and true man."

"No doubt of it, or he would not have been appointed to the Chatauqua."

"He has some respect for the rebels, but no sympathy."

"I think he has frequently applied for employment, but has not obtained it until the present time. I have no doubt he is a good fellow and a good officer. He ranks next to me. But, Somers, I leave town in half an hour," continued Mr. Waldron, consulting his watch. "I am going to run home for a few days, till the ship goes into commission. I will see you here on my return."

Somers walked to the railroad station with his late commander, and parted with him as the train started. During the three succeeding days, he visited the museums,[32] libraries, and other places of resort, interesting to a young man of his tastes. He went to the navy yard every day, and, with his usual zeal, learned what he could of the build, rig, and armament of the Chatauqua, and gathered such other information relating to his profession as would be useful to him in the future.

Lieutenant Pillgrim passed his time in a different manner. Though he was not what the world would call an intemperate or an immoral man, he spent many of his hours in bar-rooms, billiard-saloons, and places of public amusement. He several times invited Somers to "join" him at the bar, to play at billiards, and to visit the theatre, and other places of more questionable morality. The young officer was not a prude, but he never drank, did not know how to play billiards, and never visited a gambling resort. He went to the theatre two or three times; but this was the limit of his indulgence.

Mr. Pillgrim was courteous and gentlemanly; he did not press his invitations. He treated his brother officer with the utmost kindness and consideration; was always ready, and even forward, to serve him; and their relations were of the pleasantest character.

One evening, when Somers called at the office for the key of his room, after his return from the navy yard, a letter was handed to him. The writing was an unfamiliar hand, scrawling and hardly legible. It was evidently the production of an illiterate person. On reaching his room he opened it.

[33]

CHAPTER III.

THE WOUNDED SAILOR.

The curiosity of Somers was not a little excited before he opened the uncouth letter in his hand. It was postmarked Philadelphia, which made its reception all the more strange, for he had no friends or acquaintances residing in the city. He tore open the dirty epistle, which was not even enclosed in an envelope, and read as follows:—

Mr. John Somers Esq. Sir. I been wounded in the leg up the Missippi and can not do nothing more. I been in your division aboard the Rosalie, and I know you was a good man and I know you was a good officer, I hope you be in good helth, as I am not at this present writen. my Leg is very bad, and don't git no better. This is to inform you that I am the only son of a poor widdow, who has no other Son, and she can not do nothing for me, nor I can't do nothing for her. I have Fout for my countrey and have been woundded in the servis.[34] If you could git a penshin for me. it would be a grate help to me Sorrowin condition. I live No — Front Street. If I might make bold to ask you to come and see a old Sailor, thrown on the beam ends of missfortune, I would be very thankful to you.

N. B. The doctor says he thinks my Leg will have to come off.

Tom Longstone knows me, and you ask him, he will tell you all About me.

"Thomas Barron," mused Somers, as he folded the letter. "I don't remember him. There were two or three Toms on board the Rosalie. At any rate, I have nothing better to do than call upon him. He is an old sailor, and that is enough for me."

It was already after dark; but he decided to visit the sufferer that night, and after tea he left the house for this purpose. He was sufficiently acquainted with the streets of this systematic city to make his way without assistance. Of course he did not expect to find the home of the old sailor in a wealthy and aristocratic portion of the city; but if he had understood the character of the section to which the direction led him, he would probably have deferred his charitable mission till the following day. On reaching the vicinity of the place indicated, he[35] found himself in a vile locality, surrounded by the lowest and most depraved of the population.

With considerable difficulty he found the number mentioned in the letter. The lower story of the building was occupied as a liquor shop, and a further examination of the premises assured him the place was a sailor's boarding-house. As this fact was not inconsistent with the character of Tom Barron, he entered the shop. Half a dozen vagabonds had possession; and as Somers entered, the attention of the whole group was directed to him.

"Is there a sailor by the name of Thomas Barron in this house?" asked Somers of the greasy, corpulent woman, who stood behind about four feet of counter, forming the bar, on which were displayed several bottles and decanters.

"Yes, sir; and very bad he is too," replied the woman, civilly enough, though the young officer could hardly help shuddering in her presence.

"Could I see him?"

"I 'spect you can, if you be the officer Tom says is comin' to see him."

"I am the person."

"Tom's very bad."

"So he says in his letter."

"He hain't had a minute's peace or comfort with that leg sence he come home from the war. Be you any relation of his?"[36]

"I am not."

"Mebbe you're his friend."

"He served under me in the Rosalie."

"Tom hain't paid no board for two months, which comes hard on a poor woman like me, takin' care of him, and his mother too, that come here to nuss him."

"Perhaps something can be done for him."

"Well, I hope so. I don't see how I can keep him any longer. He owes me forty dollars. If any body'll pay half on't, I'd keep on doin' for him."

"I will see what can be done for him. Why was he not sent to the hospital?"

"He's too bad to be sent, and he don't want to go, nuther. He says the doctors try speriments on poor fellers like him, and he don't want to be cut up afore he's dead."

"Well, I will endeavor to have something done for him. I am entirely willing to help him as much as I can."

"Perhaps you'd be willin' to do sunthin' towards payin' my bill, then."

"Perhaps I will; but I wish to see the man before I do anything. Will you show me to his room?"

"I don't go up and down stairs none now. Here, Childs, you show this gentleman up to the front room," said the landlady to one of the vagabonds before her. "Then go and tell Tom his officer has come. I suppose[37] they'll want to slick up a little, afore they let you in; but Miss Barron will tell you when she is ready."

Somers followed the man up a flight of rickety stairs, and was ushered into the front room. It was a bedchamber, supplied with the rudest and coarsest furniture. The visitor sat down, after telling Childs that the sailor's mother need not stop to "slick up" before he was admitted. He did not like the surroundings, even independent of the villainous odors that rose from the groggery, and those that were engendered in the apartment where he sat. Slush and tar were agreeable perfumes, compared with those which assaulted his sense in this chamber; and he hoped Mrs. Barron would humiliate her pride to an extent which would permit him to make a speedy exit from the house.

Mrs. Barron, however, appeared not to be in a hurry, and Somers waited ten minutes by his watch, which seemed to expand into a full hour before he heard a sound to disturb the monotony of the chamber's quiet. But when it was disturbed, it was in such a manner that he forgot all about the place and the odors, the hour and the occasion, and even the poor sailor, who had so piteously appealed to him for assistance.

In the rear of the room in which Somers sat, there was a door communicating with another apartment. The house was old and out of repair; and this door, never very nicely adjusted, was now warped and thrown[38] out of place, so that great cracks yawned around the edges, and whatever was said or done in one room, of which any knowledge could be obtained by the sense of hearing, was immediately patent to the occupants of the other. Somers heard footsteps in the rear room, though the parties appeared not to have come up the stairs by which he had ascended. The rattling of chairs and of glass ware next saluted his ears; but as yet Somers had not the slightest interest in the business of the adjoining apartment, and only wished that Mrs. Barron would speedily complete the preparations for his reception.

"It's dangerous business," said one of the men in the rear room; which remark followed a smack of the lips, and a rude depositing of the glass on the table, indicating that the speaker had just swallowed his dram.

The man uttered his remark in a loud tone, exhibiting a strange carelessness, if the matter in hand was as dangerous as the words implied.

"I know it is dangerous, Langdon," said another person, in a voice which instantly riveted the attention of the listener.

Somers heard the voice. It startled him, and he had no eye, ear, or thought for anything but the individual who had last spoken. If he had considered his position at all, it would only have been to wish that Mrs. Barron might be as proud as a Chestnut Street belle, in order to[39] afford him time to inform himself in relation to the business of the men who occupied the other room.

"You have been shut up in Fort Lafayette once," added the first speaker.

"In a good cause I am willing to go again," replied the voice so familiar to the ears of Somers. "I lost eighty thousand dollars in a venture just like this. I must get my money back."

"If you can, Coles."

Coles! But Somers did not need to have his identity confirmed by the use of his name. He knew Coles's voice. At Newport he had lain in the fore-sheets of the academy boat, and heard Coles and Phil Kennedy mature their plan to place the Snowden on the ocean, as a Confederate cruiser. He had listened to the whole conversation on that occasion, and the knowledge he had thus obtained enabled the government to capture the steamer, and defeat the intentions of the conspirators.

The last Somers had known of Coles, he was a prisoner in Fort Lafayette. Probably he had been released by the same influence which set Phil Kennedy at liberty, and permitted him to continue his career of treason and plunder. Coles had lost eighty thousand dollars by his speculation in the Snowden, for one half of which Kennedy was holden to him; but the bond had been effectually cancelled by the death of the principal. Coles wanted his money back. It was a very natural desire;[40] but Somers could not help considering it as a very extravagant one, under present circumstances.

The listener could not help regarding it as a most remarkable thing, that he should again be within hearing of Coles, engaged in plotting treason. Such an event might happen once; but that it should occur a second time was absolutely marvellous. If our readers are of the opinion that the writer is too severely taxing their credulity in imposing the situation just described upon them, he begs they will suspend their judgment till the sequel justifies him.

It was so strange to Somers, that he could not help thinking he had been brought there by some mysterious power to listen to and defeat the intentions of the conspirators. He was not so far wrong as he might have been. It was Coles who spoke; it was Coles who had been in Fort Lafayette; and it was Coles who had lost eighty thousand dollars by the Snowden. All these things were real, and Somers had no suspicion that he had inhaled some of the vile compounds in the bar below, which might have thrown him into a stupor wherein he dreamed the astounding situation in which he was actually placed.

Somers listened, and when Coles had mixed and drank his dram, he spoke again.

"I can and will get my money back," said he, with an oath which froze the blood of the listener.[41]

"Don't believe it, Coles."

"You know me, Langdon," added the plotter, with a peculiar emphasis.

Langdon acknowledged that he did know him; and as there was, therefore, no need of an introduction, Coles proceeded.

"You know me, Langdon; I don't make any mistakes myself."

Perhaps Langdon knew it; but Somers had some doubts, which, however, he did not purpose to urge on this occasion.

"Phil Kennedy was a fool," added Coles, with another oath. "He spoiled all my plans before, and I was glad when I heard that he was killed, though I lost forty thousand dollars when he slipped out. He spilt the milk for me."

Somers thought not.

"Phil was smart about some things; but he couldn't keep a hotel. Why, that young pup that finally gave him his quietus, twirled him around his fingers, like he had been a school girl."

"Thank you, Mr. Coles; but I shall have the pleasure of serving you in the same way before many weeks," thought Somers, flattered by this warm and disinterested tribute to his strategetic ability.

"You mean Somers?" said Langdon.

"I mean Somers. The young pup isn't twenty-one[42] yet, but he is the smartest man in the old navy, by all odds, whether the others be admirals, commodores, lieutenants, or what not."

"That's high praise, Coles."

"It's true. If he wasn't an imfernal Yankee, I would drink his health in this old Bourbon. Good liquor—isn't it, Langdon?"

"Like the juice of a diamond."

"I would give more for this Somers than I would for any four rear admirals. He has just been appointed to the Chatauqua; but he will be in command of some small craft down South, before many months, doing more mischief to us than any four first-class steamers in the service. He is as brave as a young lion; knows a ship from keel to truck, and is as familiar with every bolt and pin of an engine as though he had been a machinist all his life."

"Big thing, eh, Coles?"

"If I had this Somers, I could make his fortune and mine in a year, and have a million surplus besides."

"What would you do with him?"

"I would give him the command of my steamer. I would rather have him in that place than all the old grannies in the Confederate navy."

Somers thought Mr. Coles was rather extravagant. He had no idea that Mr. Ensign Somers was one tenth part of the man which the amiable and patronizing Mr.[43] Coles declared he was; and he was impatient to have the speaker announce his intentions, rather than waste any more time in such unwarrantable commendation.

But instead of telling what he intended to do, he confined himself most provokingly to what he had failed to do, giving Langdon minute details of the capture of the Theban and the Snowden, dwelling with peculiar emphasis on the agency of Somers in the work. This was not interesting to the listener, but something better soon followed.

[44]

CHAPTER IV.

THE FRONT CHAMBER.

"But I am going to get back the money I lost, and make a pile besides," said Coles, when he had fully detailed the events attending the loss of the Snowden.

"If you can," added the sceptical Langdon.

"Of course there is some risk, but my plans are so well laid that a failure is hardly possible," continued Coles.

"It was possible before."

"Nothing but an accident could have defeated my plan before. Everything worked to my satisfaction, and I was sure of success."

"But you failed."

"I shall not fail again."

"I hope not."

"Then believe I shall not," retorted Coles, apparently irritated by the doubts and fears of his companion.

"It is not safe to believe too much," added Langdon, with a kind of chuckle, whose force Somers could hardly understand; "you believed too much before."[45]

"I have been more cautious this time, and I wouldn't give anybody five per cent. to insure the venture."

Somers was becoming very impatient to hear the particulars of the plan, for he was in momentary fear of being summoned to the bedside of the wounded sailor. Coles was most provokingly deliberate in the discussion of his treasonable project; but when the naval officer considered that the conversation was not especially intended for him, he did not very severely censure the conspirators for their tardiness.

"I don't understand what your plan is," said Langdon.

"Nor I either," was Somers's facetious thought.

"I will tell you all about it. Are there any ears within hail of us?"

"Not an ear."

"Is there anybody in the front room?"

"No."

"Are you sure?"

"The old woman told me the front room was not occupied. She sent in there an officer who wanted to see a sick sailor upstairs; but he is gone before this time."

"Perhaps not; make sure on this point before I open my mouth. I have no idea of being tripped up this time," said the cautious Coles.

"I will look into the front room," added Langdon, "though I know there is no one there."[46]

Somers was rather annoyed at this demonstration of prudence; but it was quite natural, and he was all the more interested to hear the rest of the conference. Dismissing for a moment the dignity of the quarter deck, he dropped hastily on the floor, and crawled under the bed, concluding that Langdon, who was already fully satisfied the front room was empty, would not push his investigations to an unreasonable extent. But he had already prepared himself for the worst, and if his presence were detected, he resolved to take advantage of the high estimation in which he was held, and, for his country's good, proposed to offer his valuable services in getting the piratical ship to sea. He could thus obtain the secret, and defeat the purposes of the conspirators.

He fortunately avoided the necessity of resorting to this disagreeable course, for Langdon only opened the door, and glanced into the chamber he occupied.

"The room is empty," he reported to Coles, on his return.

"There are cracks around this door big enough to crawl through. Somebody may go into that room without being heard, and listen to all I say."

"There is no danger."

"But there is danger; and I will not leave the ghost of a chance to be discovered. Langdon, lock that front room, and put the key in your pocket. I must have things perfectly secure before I open my mouth."[47]

Langdon complied with the request of his principal; the door was locked, and Somers, without much doubt or distrust, found his retreat cut off for the present. But, at last, everything was fixed to the entire satisfaction of Coles. The glasses clinked again, indicating that the worthies had fortified themselves with another dose from the bottle. Somers crawled out from under the bed, and heedless of the dust which whitened his new uniform, placed himself in a comfortable position, where he could hear all that was said by the confederates.

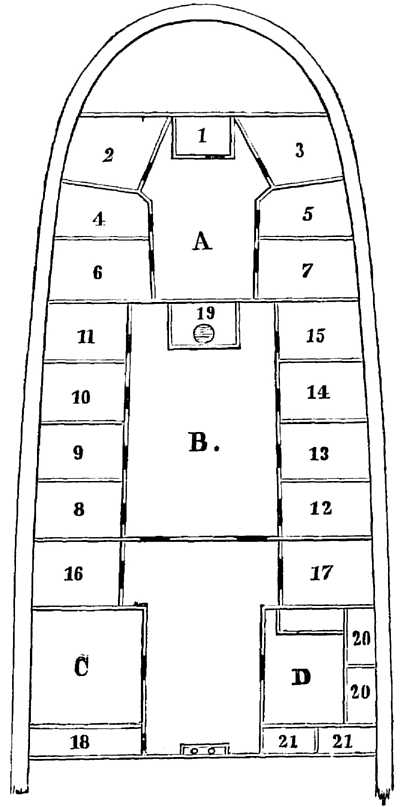

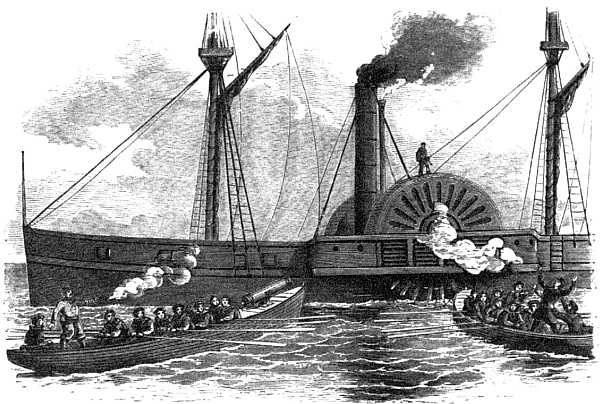

Coles now told his story in a straightforward, direct manner, and Somers made memoranda on the back of a letter of the principal facts in the statement. The arch conspirator had just purchased a fine iron side-wheel steamer, captured on the blockade, called the Ben Nevis. She was about four hundred tons burden, and under favorable circumstances had often made sixteen knots an hour. It had already been announced in the newspapers that the Ben Nevis would run regularly between New York and St. John. Coles intended to clear her properly for her destined port, where she could, by an arrangement already made, be supplied with guns, ammunition, and a crew. She was to clear regularly for New York, but instead of proceeding there was to commence her piratical course on the ocean.

This was the plan of the worthy Mr. Coles, which Langdon permitted him to develop without a single[48] interruption. But the prudent, or rather critical, confederate raised many objections, which were discussed at great length—so great that Somers, possessed of the principal facts, would have left the room, if the door had not been locked, and escaped from the house, so as to avoid the possibility of being discovered. The wounded sailor could be attended to on the following day.

"But one thing we lack," continued Coles, after he had removed all the objections of his companion.

"More than one, I fear," said the doubtful Langdon.

"Well, one thing more than all others."

"What is that?"

"A naval officer to command her."

"There are plenty of them."

"No doubt of it; but they are not the kind I want. I need a man who will play into my hand, as well as grind up the Yankees. I have no idea of burning all the property captured by my vessel."

"Why don't you take command yourself?"

"I have other business to do."

"There are scores of Confederate naval officers in Canada and New Brunswick," suggested Langdon.

"I know them all, and I wouldn't trust them to command a mud-scow. In a word, Langdon, I want this Somers, and I must have him."

"But he is a northern Yankee. He would sooner cut his own throat than engage in such an enterprise."[49]

"Thank you for that," said Somers to himself. "If you had known me all my lifetime, you couldn't have said a better or a truer thing of me."

"I know he is actually reeking with what he calls loyalty. He will be a hard subject, but I think he can be brought over."

"Perhaps he can."

"It must be done; that is the view we must take of the matter."

"It will be easier to believe it than to do it."

"This is to be your share of the enterprise."

"Mine?"

"Yes."

"Well, I think you have given me the biggest job in the work."

"It can be done," said Coles, confidently. "Somers is a mere boy in years, though he is smarter and knows more than any man in the navy in the prime of life."

"I'm afraid he is too smart, and knows too much to be caught in such a scrape."

"No; he is young and ambitious. Offer him a commission as a commander in the Confederate navy, to begin with. I have the commission duly signed by the president of the Confederacy, countersigned by the secretary of the navy, with a blank for the name of the man who receives it, which I am authorized to fill up as I think best. Somers must have this commission."[50]

"If he will take it."

"He will take it. In the old navy he is nothing but a paltry ensign. He has been kept back. His merit has been ignored. He must stand out of the way for numskulls and old fogies. Even if the war should last ten years longer, he could not reach the rank, in that time, which I now tender him. He will at once be offered the command of a fine steamer, and may walk the quarter deck like a king. He is ambitious, and if you approach him in the right way, you can win him over."

Somers listened with interest to this precious scheme. He did not even feel complimented by the exalted opinion which such a man as Coles entertained of him. It would be a pleasant thing for a young man like him to be a commander, and have a fine steamer; but as he could regard only with horror the idea of firing a gun at a vessel bearing the stars and stripes, he was not even tempted by the bait; and he turned his thoughts from it without the necessity of a "Get thee behind me, Satan," in dismissing it.

"Where is this Somers?" asked Langdon.

"He is at the Continental," replied Coles. "He has been appointed fourth lieutenant of the Chatauqua; but what a position for a man of his abilities! He is better qualified to command the ship than the numskull to whom she has been given. Waldron, the first lieutenant, is smart: he ought to be commander; though I think[51] Somers did all the hard work in Doboy Sound, for which Waldron got the credit, and for which he was promoted. Pillgrim, the second lieutenant, is a renegade Virginian."

"We had some hopes of him, at one time," said Langdon.

"He is worse than a Vermont Yankee now—has been all along, for that matter. I tried to do something with him, but he talked about the old flag, and other bosh of that sort."

"Let him go," added Langdon, with becoming resignation.

"Let him go! He never went. He has always been a Yankee at heart. If the navy department wouldn't trust him, it was their fault, not his, for the South has not had a worse enemy than he since the first gun was fired at Sumter. He is none the better, and all the more dangerous to us, because he gives the South credit for skill and bravery."

Somers was pleased to hear this good account of Lieutenant Pillgrim; not because he had any doubt in regard to his loyalty, but because it confirmed the good impression he had received of his travelling companion. If the conspirators would only have graciously condescended to resolve the doubts in his mind in regard to some indefinite previous acquaintance he had had with the second lieutenant of the Chatauqua, he would have been greatly obliged to them. They did not do this, and Somers[52] was still annoyed and puzzled by the belief, patent to his consciousness, that he had somewhere been intimate with the "renegade Virginian," before they met at the house of Commodore Portington.

"Now, Langdon, you must contrive to meet Somers, sound him, and bring him over. You must be cautious with him. He is a young man of good morals—never drinks, gambles, or goes to bad places. He is a perfect gentleman in his manners, never swears, and is the pet of the chaplains."

"I think I can manage him."

"I know you can; I have picked you out of a hundred smart fellows for this work."

"How will it do for me to put on a white choker, and approach him as a doctor of divinity."

"You can't humbug him."

"If I can't, why should I try?"

"If you should pretend to be a clergyman, and he smelt the whiskey in your breath, he would set you down as a hypocrite at once."

"That's so," thought Somers.

"He wouldn't listen to a preacher who drank whiskey. He is a fanatic on these points."

Somers could not imagine where Coles had obtained such an intimate knowledge of his views and principles; though, if he wanted his services in the Confederate navy, it was probable he had made diligent inquiries in regard to his opinions and habits.[53]

"I think I could blind him as a D.D., but I am not strenuous."

"You had better get acquainted with him in some other capacity."

"As you please; I will think over the matter, and be ready to make a strike to-morrow morning. What time is it?"

"Quarter past ten."

"So late! I must be off at once."

Somers heard the clatter of glass-ware again, as the conspirators took the parting libation. He listened to their retreating footsteps, heard Langdon return the key, and then began to wonder what had become of Tom Barron and his mother. He had waited more than two hours in the front room, and no summons had come for him to see the wounded sailor. It was very singular, to say the least; but while he was deliberating on the point, a hand was placed on the door of the chamber. The key turned, and a person entered.

Now, Somers had a very strong objection to being seen after what had occurred. If discovered in this room, Coles might see him, and finding his plans discovered, might change them so as to defeat the ends of justice. And the listener felt that, if detected in this apartment by the conspirators, they would not scruple to take his life in order to save themselves and their schemes.[54]

For these reasons Somers decided not to be seen. The person who entered the room was a rough, seafaring man, and evidently intended to sleep there, which Somers was entirely willing he should do, if it could be done without imperilling his personal safety. He therefore crawled under the bed again, as quietly as possible. Unfortunately it was not quietly enough to escape the observation of the lodger, who, not being of the timid sort, seized him by the leg, dragged him out, and with a volley of marine oaths, began to kick him with his heavy boot.

Somers sprang to his feet, and attempted to explain; but the indignant seaman struck him a heavy blow on the head, which felled him senseless on the floor.

[55]

CHAPTER V.

SOMERS COMES TO HIS SENSES.

When Somers opened his eyes, about half an hour after the striking event just narrated, and became conscious that he was still in the land of the living, he was lying on the bed in his chamber at the Continental. By his side stood Lieutenant Pillgrim and a surgeon.

"Where am I?" asked the young officer, using the original expression made and provided for occasions of this kind.

"You are here, my dear fellow," replied the lieutenant.

This valuable information seemed to afford the injured party a great deal of consolation, for he looked around the apartment, not wildly, as he would have done if this book were a novel, but with a look of perplexity and dissatisfaction. As Mr. Ensign Somers was eminently a fighting man on all proper occasions, he probably felt displeased with himself to think he had given the stalwart seaman so easy a victory; for he distinctly remembered the affair in which he had been so rudely treated,[56] though there was a great gulf between the past and the present in his recollection.

"How do you feel, Mr. Somers?" asked the surgeon.

"The fact that I feel at all is quite enough for me at the present time, without going into the question as to how I feel," replied the patient, with a sickly smile. "I don't exactly know how I do feel. My ideas are rather confused."

"I should think they might be," added the surgeon. "You have had a hard rap on the head."

"So I should judge, for my brain is rather muddled."

"Does your head pain you?" asked the medical gentleman, placing his hand on the injured part.

"It does not exactly pain me, but it feels rather sore. I think I will get up, and see how that affects me."

Somers got up, and immediately came to the conclusion that he was not very badly damaged; and the surgeon was happy to corroborate his opinion. With the exception of a soreness over the left temple, he felt pretty well. The blow from the iron fist of the burly seaman had stunned him; and the kicks received from the big boots of the assailant had produced sundry black and blue places on his body, which a man not accustomed to hard knocks might have looked upon with suspicion, but to which Somers paid no attention.

The surgeon had carefully examined him before his consciousness returned, and was fully satisfied that he[57] had not been seriously injured. Somers walked across the room two or three times, and bathed his head with cold water, which in a great measure restored the consistency of his ideas. He felt a little sore, but he soon became as chipper and as cheerful as an early robin. His first thought was, that he had escaped being murdered, and he was devoutly thankful to God for the mercy which had again spared his life.

The doctor, after giving him some directions in regard to his head, and the black and blue spots on his body, left the room. He was a naval surgeon, a guest in the hotel, and promised to see his patient again in the morning.

"How do you feel, Somers?" asked Lieutenant Pillgrim, who sat on the bed, gazing with interest, not unmixed with anxiety, at his companion.

"I feel pretty well, considering the hard rap I got on the head."

"You have a hard head, Somers."

"Why so?"

"If you had not, you would have been a dead man. The fellow pounded you with his fist, which is about as heavy as an anvil, and kicked you with his boots, which are large enough and stout enough to make two very respectable gunboats."

"Things are rather mixed in my mind," added Somers, rubbing his head again, as if to explain how a[58] strong-minded young man like himself should be troubled in his upper works.

"I am not surprised at that. You have remained insensible more than half an hour. I was afraid, before the surgeon saw you, that your pipe was out, and you had become a D.D. without taking orders."

"I think I had a narrow escape. What a tiger the fellow was that pitched into me!"

"It was all a mistake on his part."

"Perhaps it was; but that don't make my head feel any better. Who is he, and what is he?"

"He is the captain of a coaster. He had considerable money in his pocket, and he thought you had concealed yourself in his room for the purpose of robbing him. When he saw that you were an officer in the navy, he was overwhelmed with confusion, and really felt very bad about it."

"I don't know that I blame him for what he did, under the circumstances. His conclusion was not a very unnatural one. I don't exactly comprehend how I happen to be in the Continental House, after these stunning events."

"Don't you?" said Pillgrim, with a smile.

"If I had been in condition to expect anything, I should naturally have expected to find myself, on coming to my senses, in the low groggery where I received the blows."[59]

"That is very easily accounted for. I happened to be at the house when you were struck down. I was in the lower room, and heard the row. With others I went up to see what the matter was. I had a carriage in the street, and when I recognized you, the captain of the coaster, at my request, took you up in his arms like a baby, carried you down into the street, and put you into the vehicle, and you were brought here. I presume this will fill up the entire gap in your recollection."

"It is all as clear as mud now," laughed Somers. "Mr. Pillgrim, I am very grateful to you for the kind offices you rendered me."

"Don't mention it, my dear fellow. I should have been worse than a brute if I had done any less than I did."

"That may be; but my gratitude is none the less earnest on that account. Those are villainous people in that house, and I might have been butchered and cut up, if I had been left there."

"I think not. The captain of the coaster is evidently an honest man; at any rate he is very sorry for what he did. But, Somers, my dear fellow,—you will pardon me if I seem impertinent,—how did you happen to be in such a place?" continued Mr. Pillgrim, with a certain affectation of slyness in his look, as though he had caught the exemplary young man in a house where he would not have been willing to be seen.[60]

"How did you happen to be there?" demanded Somers.

"I don't profess to be a very proper person. I take my whiskey when I want it."

"So do I; and the only difference between us is, that I never happen to want it."

"I did not go into that house for my whiskey, though. It is rather strange that we should both happen into such a place at the same time."

"Rather strange."

"But I will tell you why I was there," added Pillgrim. "I received a letter from a wounded sailor, asking me to call upon him, and assist him in obtaining a pension."

"Did you, indeed!" exclaimed Somers, amazed at this explanation. "You have also told how I happened to be there."

"How was that?"

"I received just such a letter as that you describe," replied Somers, taking the dirty epistle from his pocket, which he opened and exhibited to his brother officer.

"The handwriting is the same, and the substance of both letters is essentially the same. That's odd—isn't it?" continued the lieutenant, as he drew the epistle he had received from his pocket. "I got mine when I came in, about ten o'clock; and thinking I might go to New York in the morning for a couple of days, I thought I would attend to the matter at once."[61]

Somers took the letters, and compared them. They were written by the same person, on the same kind of paper, and were both mailed on the same day.

"This looks rather suspicious to me," added Pillgrim, reflecting on the circumstances.

"Why suspicious?"

"Why should both of us have been called? Tom Barron claims to have served with me, as he did with you. I don't remember any such person."

"Neither do I."

"Did you find out whether there was any such person at the house as Tom Barron?"

"The woman at the bar told me there was a wounded sailor there whose description answered to that contained in the letter."

"So she told me. Did you see him?"

"No."

"I did not; and between you and me, I don't believe there is any Tom Barron there, or anywhere else. This business must be investigated," said Pillgrim, very decidedly.

Somers did not wish it to be investigated. He was utterly opposed to an investigation, for he was fearful, if the matter should be "ventilated," that more would be shown than he was willing to have exhibited at the present time; in other words, Coles would find out that his enterprising scheme had been exposed to a third person.[62]

"I don't care to be mixed up in any revelations of low life, Mr. Pillgrim; and, as I have lost nothing, and the hard knocks I received were given under a mistake, I think I would rather let the matter rest just where it is."

"Very natural for a young man of your style," laughed the lieutenant. "You are afraid the people of Pinchbrook will read in the papers that Mr. Somers has been in bad places."

"They might put a wrong construction on the case," replied Somers, willing to have his reasons for avoiding an investigation as strong as possible.

"I can hand these letters over to the police, and let the officers inquire into the matter," added Pillgrim. "They need not call any names."

"I would rather not stir up the dirty pool. Besides, Tom Barron and his mother may be in the house, after all. There is no evidence to the contrary."

"I shall satisfy myself on that point by another visit to the house. If I find there is such a person there, I shall be satisfied."

"That will be the better way."

Just then it occurred to Somers that Coles might have seen him while he was insensible, and was already aware that his scheme had miscarried. He questioned Pillgrim, therefore, in regard to the persons in the bar-room when he entered. From the answers received he satisfied[63] himself that the conspirators had departed before the "row" in the front room occurred.

"Now, Somers, I am going down to that house again before I sleep," said the lieutenant. "This time, I shall take my revolver. Will you go with me?"

"I don't feel exactly able to go out again to-night. My head doesn't feel just right," replied Somers, who, however, had other reasons for keeping his room, the principal of which was the fear that he might meet Coles there, and that, by some accident, his presence in the front room during the conference might be disclosed.

"I think you are right, Somers. You had better keep still to-night," said Pillgrim. "Shall I send you up anything?"

"Thank you; I don't need anything."

"A glass of Bourbon whiskey would do you good. It would quiet your nerves, and put you to sleep."

"Perhaps it would, but I shall lie awake on those terms."

"Don't be bigoted, my dear fellow. Of course I prescribe the whiskey as a medicine."

"You are no surgeon."

"It would quiet your nerves."

"Let them kick, if nothing but whiskey will quiet them," laughed Somers. "Seriously, Mr. Pillgrim, I am very much obliged to you for your kindness, and for your interest in me; but I think I shall be better without the whiskey than with it."[64]

"As you please, Somers. If you are up when I return, I will tell you what I find at the house."

"Thank you; I will leave my door unfastened."

Mr. Pillgrim left the room to make his perilous examination of the locality of his friend's misfortunes. Somers walked the apartment, nervous and excited, considering the events of the evening. He then seated himself, and carefully wrote out the statement of Coles in regard to the Ben Nevis, and the method by which he purposed to operate in getting her to sea as a Confederate cruiser, with extended memoranda of all the conversation to which he had listened. Before he had finished this task, Lieutenant Pillgrim returned.

"It is all right," said he, as he entered the room.

"What's all right?"

"There is such a person as Thomas Barron. The facts contained in the letters are essentially true."

"Then no investigation is necessary," replied Somers, with a feeling of relief.

"None whatever; to-morrow I will see that the poor fellow is sent to the hospital, and his mother provided for."

Mr. Pillgrim, after again recommending a glass of whiskey, took his leave, and Somers finished his paper. He went to bed, and in spite of the fact that he had drank no whiskey, his nerves were quiet, and he dropped asleep like a good Christian, with a prayer in his heart for the "loved ones at home" and elsewhere.[65]

The next morning, though he was still quite sore, and his head felt heavier than usual, he was in much better condition, physically, than could have been expected. After breakfast, as he sat in the parlor of the hotel, he was accosted by a gentleman in blue clothes, with a very small cap on his head.

"An officer of the navy, I perceive," said the stranger, courteously.

"How are you, Langdon?" was the thought, but not the reply, of Somers.

[66]

CHAPTER VI.

LIEUTENANT WYNKOOP, R. N.

The gentlemanly individual who addressed Somers wore the uniform of an English naval officer. By easy and gentle approaches, he proceeded to make himself very agreeable. He was lavish in his praise of the achievements of the "American navy," and was sure that no nation on the face of the globe had ever displayed such skill and energy in creating a war marine. Somers listened patiently to this eloquent and just tribute to the enterprise of his country; and if he had not suspected that the enthusiastic speaker was playing an assumed character, he would have ventured to suggest that the position of John Bull was rather equivocal; that a little less admiration, and a little more genuine sympathy, would be more acceptable.

"We sailors belong to the same fraternity all over the world," said the pretended Englishman. "There is something in sailors which draws them together. I never meet one without desiring to know him better. Allow me to present you my card, and beg the favor of yours in return."[67]

He handed his card to Somers, who read upon it the name of "Lieutenant Wynkoop, R. N." It was elaborately engraved, and our officer began to have some doubts in regard to his new-found acquaintance, for the card could hardly have been got up since the interview of the preceding evening. This gentleman might not be Langdon, after all; but whether he was or not, it was proper to treat him with respect and consideration. Somers wrote his name on a blank card, and gave it to him.

"Thank you, Mr. Somers: here is my hand," said Lieutenant Wynkoop, when he had read the name. "I am happy to make your acquaintance."

Somers took the offered hand, and made a courteous reply, to the salutations of the other.

"May I beg the favor of your company to dinner with me in my private parlor to-day?" continued Mr. Wynkoop. "I have a couple of bottles of fine old sherry, which have twice made the voyage to India, sent to me by an esteemed American friend residing in this city."

"Thank you, Mr. Wynkoop. To the dinner I have not the slightest objection; to the wine I have; and I'm afraid you must reserve it for some one who will appreciate it more highly than I can. I never drink wine."

"Ah, indeed?" said the presumed representative of the royal navy, as he adjusted an eye-glass to his left eye, keeping it in position by contracting the muscles above and below the visual member, which gave a peculiar[68] squint to his expression, very trying to the risibles of his auditor.

"I should be happy to dine with you, but I don't drink wine," repeated Somers, in good-natured but rather bluff tones, for he did not wish to be understood as apologizing for his total abstinence principles.

"I should be glad to meet you in my private parlor, say, at four o'clock, whether you drink wine or not, Mr. Somers."

"Four o'clock?"

"It's rar-ther early, I know. If you prefer five, say the word," drawled Mr. Wynkoop.

"I should say that would be nearer supper time than four," replied Somers, who had lately been in the habit of dining at twelve in Pinchbrook.

"Earlier if you please, then."

"Any hour that is convenient for you will suit me."

"Let it be four, then. But I must acknowledge, Mr. Somers, I am not entirely unselfish in desiring to make your acquaintance. The operations of the American navy have astonished me, and I wish to know more about it. I landed in New York only a few days since, and I improve every opportunity to make the acquaintance of American naval officers. I have not yet visited one of your dock yards."

"I am going over to look at my ship this forenoon, and I should be delighted with your company."[69]

"Thank you! thank you!" exclaimed Mr. Wynkoop. "I shall be under great obligations to you for the favor."

They went to the navy yard, visited the Chatauqua, and other vessels of war fitting out there. Mr. Wynkoop asked a thousand questions about ships, engines, and armaments; and one could hardly help regarding him as the most enthusiastic admirer of naval architecture. Though the gentleman spoke in affected tones, Somers had recognized the voice of Langdon. This was the person, without a doubt, who was to lure him into the Confederate navy, who was to crown his aspirations with a commander's commission, and reward his infidelity with the command of a fine steamer.

Somers was very impatient for the inquiring member of the royal navy to make his proposition; for, strange as it may seem to the loyal reader, he had fully resolved to accept the brilliant offers he expected to receive; to permit Coles to place the name of "John Somers" in the blank of the commander's commission which he had in his possession; and even to take his place on the quarter deck of the Ben Nevis, if it became necessary to carry proceedings to that extent.

But Lieutenant Wynkoop did not even allude to the Confederate navy, or to the Ben Nevis, and did not even attempt to sound the loyalty of his companion. Somers concluded at last that this matter was reserved for the after-dinner conversation; and as he could afford to[70] wait, he continued to give his friend every facility for prosecuting his inquiries into the secret of the marvellous success of the "American navy."

After writing out his statement of Coles's plans, he had carefully and prayerfully considered his duty in relation to the startling information he had thus accidentally obtained. Of course he had no doubt as to what he should do. He must be sure that the Ben Nevis was handed over to the government; that Coles and Langdon were put in close quarters. He only inquired how this should be done. Though the Snowden and the Theban had been captured in the former instance, both Kennedy and Coles had escaped punishment, and one of them was again engaged in the work of pulling down the government.

If he gave information at the present stage of the conspiracy, his plans might be defeated. Though Coles had mentioned no names, it was more than probable that he was aided and abetted in his treasonable projects by other persons. There were traitors in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia, men of wealth and influence, occupying high positions in society, who were engaged in just such enterprises as that which had been revealed to the young naval officer.

Somers felt, therefore, that a premature exposure might ruin himself without overthrowing the conspirators. A word from one of these influential men might lay him on the shelf, to say the least, and remove all[71] suspicion from the guilty ones. He must proceed with the utmost caution, both for his own safety and the success of his enterprise.

Besides, he felt that, if he could get "inside of the ring," he should find out who the great men were that were striking at the heart of the nation in the dark. By obtaining the confidence of the conspirators, he could the more easily baffle them, and do the country a greater service than he could render on the quarter deck of the Chatauqua.

After an earnest and careful consideration of the whole matter, he concluded that his present duty was to pay out rope enough to permit Coles and his guilty associates to hang themselves. For this purpose, he was prepared to receive Langdon with open arms, to accept the commission intended for him, and to enter into the secret councils of his country's bitterest enemies.

Somers, pure and patriotic in his motives, did not for a moment consider that he exposed himself to any risk in thus entering the councils of the wicked, or even in taking a commission in the service of the enemy. He did not intend to aid or abet in the treason of the traitors, and he did not think what might be the result if a rebel commission were found upon his person. He might be killed in battle with this damning document in his pocket. If any of the conspirators were caught, they might denounce him as one of their number. He did not think[72] of these things. He was ambitious to serve his treason-ridden country, and he forgot all about himself.