LA FAVORITA.

LA FAVORITA.

Title: Lippincott's Magazine of Popular Literature and Science, Volume 20. December, 1877

Author: Various

Release date: November 7, 2011 [eBook #37946]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Juliet Sutherland, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net.

Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1877, by J. B. Lippincott & Co., in the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington.

Transcriber's notes: Minor typos have been corrected. Table of contents has been generated for HTML version.

A MONTH IN SICILY.

"FOR PERCIVAL."

CAPTURED BY COSSACKS.

A PORTRAIT.

"GOD'S POOR."

DAYS OF MY YOUTH.

A LAW UNTO HERSELF.

OUIDA'S NOVELS.

A KENTUCKY DUEL.

FOLK-LORE OF THE SOUTHERN NEGROES.

SELIM.

ENGLISH DOMESTICS AND THEIR WAYS.

OUR MONTHLY GOSSIP.

LITERATURE OF THE DAY.

BOOKS RECEIVED.

LA FAVORITA.

LA FAVORITA.

Early on the morning of the first of February we stood on the deck of the steamer for Palermo, watching the sun rise over the water. Far away in the south the blue edge of the sea began to grow bluer with the rising of the distant land. A fresh breeze blew from the shore—not a pleasant feature in February weather at home, but suggesting comparisons with the warmest morning of a New England May. With the swift advance of the steamer the [Pg 650]blue line in the south rapidly rose above the level of the sea into the definite shape of a rugged mountain-range: gradually the blueness of distance changed to rich shades of brown and red on the jagged, treeless summits, and to deepest green where long orange-farms border the bases of the mountains.

Who has not longed to see Sicily? Every one who loves poetry, romance or the history of ancient civilization must often turn in thought to this beautiful and famous Mediterranean island. To the most ancient poets it was a mysterious land, where dwelt the monster Charybdis and the bloody Læstrigones; where Ulysses met the Cyclops; where the immortal gods waged battles with the giant sons of Earth, and bound Enceladus in his eternal prison. No doubt it was the terrific natural phenomena of Sicily—the earthquakes and the outbursts of Etna—which rendered it so much a land of horrors to the early Greek imagination. But in that far-distant age it was not only the terrors of the place that had worked upon the imaginative Greeks: the almost tropical luxuriance of the country, the unrivalled scenery, the brilliancy of the sky, made it a fitting ground for the adventures of nymphs, heroes and gods. In the fountain of Sicilian Ortygia dwelt Arethusa, the nymph dear to the poets; beside the Lake of Enna, where rich vegetation overran the lips of the extinct volcano, was the spot called in mythology the meeting-place of Pluto and Proserpine—the power of darkness and the springing plant personified; and so through all the country places were found made sacred by the presence of the great divinities, and temples were erected in their honor.

When the age of fable had passed away, far back in the early dawn of European history begins authentic knowledge about Sicily. While wicked Ahaz reigned in the kingdom of Judah, and Isaiah had not ceased to utter his prophecies, the Greek colonization of Sicily began. Seven hundred and thirty-five years before Christ, Theocles with his band of Greeks from Eubœa founded Naxos on the coast, hard by the fertile slopes of Etna. Within three centuries from that time the whole Sicilian coast had been studded with Greek cities, and to such wealth, power and splendor of art had they attained that all succeeding epochs of the island's history seem degenerate times when compared with that early golden age.

It has been truly said that "there is not a nation which has materially influenced the destinies of European civilization that has not left distinct traces of its activity in this island." Phœnicians, Greeks, Romans, Saracens, Normans, Spaniards, French and English have successively occupied the island, and noble monuments of the varied civilizations are standing to this day. Scattered through the island, their architectural remains crown the mountain-tops or lie in confusion along the Mediterranean shore, a series of ruins extending through twenty-five centuries, unmatched in any other country for variety of age and style.

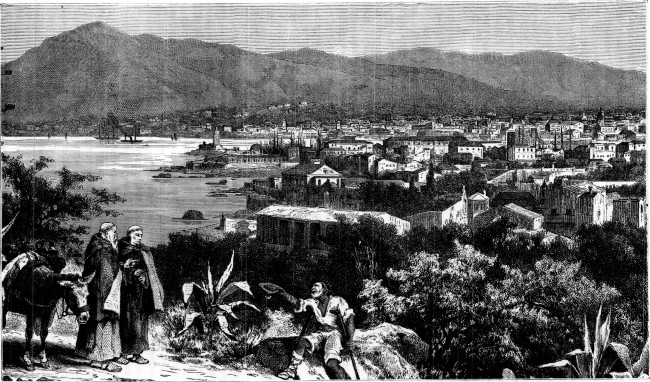

At ten o'clock our steamer entered the Gulf of Palermo, passing near the base of Monte Pellegrino, a wild promontory which towers up two thousand feet from the sea. On the day before I had entered for the first time the famous Bay of Naples, but with less delight than I now looked upon the beauties of this Sicilian gulf. Flanked with lofty mountains, colored with the matchless blue of the Mediterranean, studded with picturesque lateen sails, the bay is a fitting entrance to this fair historic island: a more beautiful approach could hardly be imagined even to the Islands of the Blessed.

The Italians call Palermo la felice ("the happy"). It is most happy in its climate, its situation and its noble streets and gardens. Below the city lies the lovely bay: behind it stretches back for miles, between converging mountain-chains, the fruit-producing level of the Golden Shell (La Conca d'Oro). The plain is one vast orchard of oranges and lemons which every year distributes its huge crop over half the habitable globe. The city is worthy of its position. The chief streets are broad, clean and handsomely built—a contrast to the universal shabbiness and squalor we had [Pg 651]found in Naples.

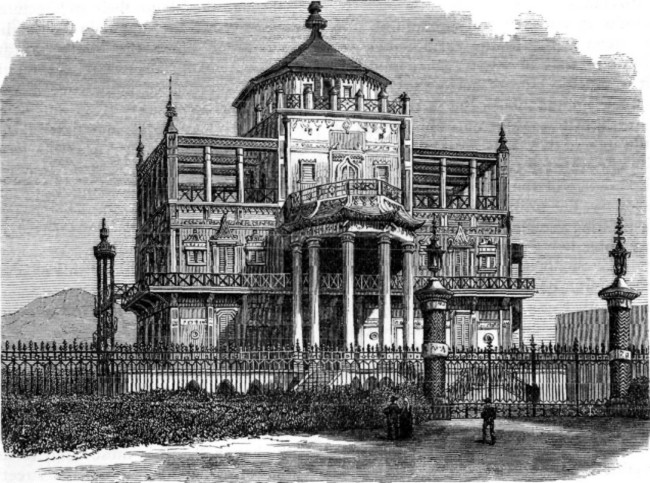

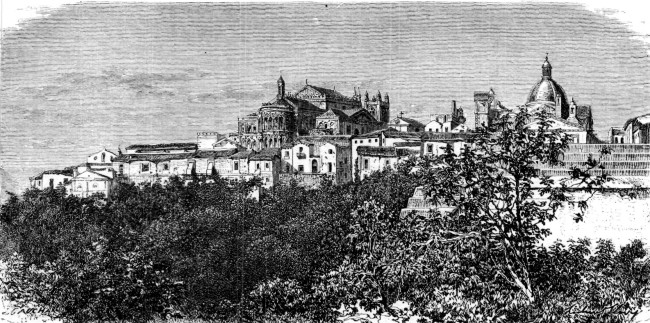

CATHEDRAL OF PALERMO.

CATHEDRAL OF PALERMO.

A traveller is sure to be put in a good humor with the place by the many and unusual comforts which he meets in the great sea-fronting hotel; and the first look from the windows of his apartment confirms the opinion that Palermo is the fairest of Southern cities. The outlook is upon the grand seashore drive, the Marina, as gay and pretty a sight as can be found in any European capital. The broad, tree-shaded avenue, bordered on one side by hotels and palaces, on the other by the waters of the bay, is thronged with private carriages. Beginning at the sea-facing gate of the city, the road commands through all its length a view of the mountains, the bay and the open sea: at its terminus lie the public flower-gardens—acres of our choicest hothouse plants growing in tropical profusion.

In Palermo, as in so many European towns, the cathedral is the chief architectural attraction. To approach it from the bay the whole length of the city must be traversed on the Corso Vittorio Emmanuele, the chief business street. This corso is crossed at the centre of the town by another of equal width, which also commemorates by its name Italian unity—the Corso Garibaldi. There is one other broad and important street which no American can enter without remembering that even in this distant land the interest and sympathy of the people have been with our country in its struggles and successes: it is the Via Lincoln.

The drive up the Corso gives an opportunity for seeing a remarkably handsome street lined with gay shops, and for studying the peculiar and often fine faces of the Sicilian people; but nothing of striking interest appears until, near the centre of the town, a street opening on the left discloses a vista ending in a small forest of white marble statues. On a nearer view it is found that the statues belong to the immense fountain of the Piazza Pretoria, a work erected about a. d. 1550 by command of the senate of Palermo. It is perhaps the largest and most elaborate fountain in Europe, and, though it is easy to criticise the countless sculptures that adorn it, the whole effect of their combination into an architectural unit is most imposing.

Continuing the drive up the Corso, a broad piazza suddenly opens on the right, flanked by the cathedral. The abruptness of the transition from between the dark lines of buildings into the sunlight of the square adds to the first strong impression produced by the beauty of the vast duomo. In its external architecture the church is unique: the charm of it to one who has been travelling through Italy is its utter dissimilarity to all the Italian churches. Architectural writers call it a building of the "Sicilian Gothic style;" and, though the expression does not convey a vivid image except to the student of art, any one can see its essential difference from the style of the North, and can recognize the rare grandeur and beauty of the church. The form is simple, but the dimensions are grand. Without the boldness of outline of true Gothic churches, the walls are so covered with ornaments of interlacing arches, cornices and arabesque slightly raised on the masonry as to produce an effect of wonderful richness. The style is peculiarly Sicilian, yet every observer of mediæval churches will at once detect the Norman, Italian and Saracenic influences blended in an exquisite harmony. Connected with the church by light arches, but separated from it by a street, stands the campanile, a mass of enormous solidity, terminating in many pinnacles and one slender and graceful tower rising above them all. Four other lofty towers, springing from the corners of the church, give additional lightness to its elegant design: they were added to the building nearly three centuries after the Norman conquest of Sicily, and yet their minaret-like form and pointed panel ornaments show how strong and lasting had been the influence of Arabian art upon the mediæval architects of Sicily.[Pg 653]

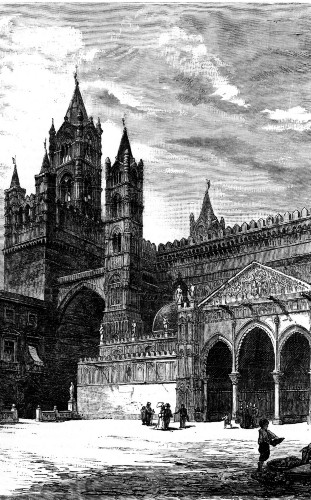

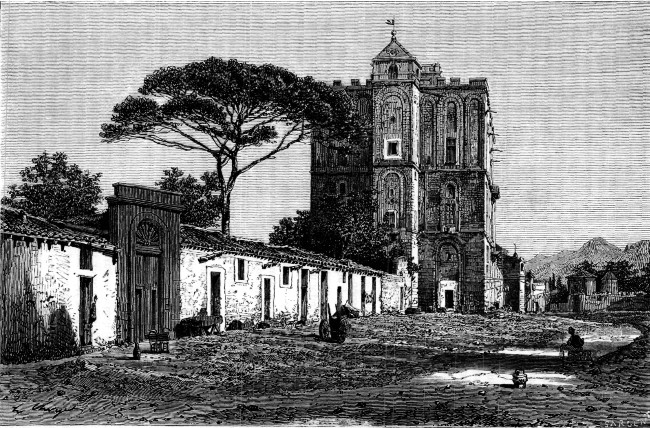

GROTTO OF SANTA ROSALIA.

GROTTO OF SANTA ROSALIA.

It is seven hundred years since the foundations of the duomo were laid. In that distant age, and in a land so remote, it is a curious circumstance that its founder was an Englishman: Gualterio Offamilio is the amusing Italian corruption by which the name of Walter of the Mill was suited to the Southern tongue. After Roger and his Normans had driven from Sicily the Arab power which had held the land for more than two centuries, and when Christianity had succeeded the Mohammedan religion throughout the island, Archbishop Walter assumed spiritual sovereignty in Palermo, and founded this cathedral on the site of an[Pg 654] ancient mosque. Only a part of the original building remains in the crypt and two walls of the present church. All subsequent ages have changed and added to its original simple form, but often have taken from its beauty. Within the church only a part of the south aisle commands close attention: there in canopied sarcophagi of porphyry reposes the dust of Roger, king of Sicily (1154), of Henry VI., emperor of Germany, and of Frederick II., Roger's most illustrious grandson, king of Sicily, king of Jerusalem and emperor of Germany. In a chapel at the right of the high altar, sacred to Santa Rosalia, rest the bones of the saint enshrined in a sarcophagus of silver. Thirteen hundred pounds of the precious metal are wrought into the shrine, and the whole chapel is sumptuous with marble frescoes and gilding, for to the pious souls of Palermo this is the very holy of holies. The cathedral is dedicated to Rosalia, and almost divine honors are paid to her by the city from which she fled in horror at its wickedness.

Every summer a festival of three days is held in honor of this favorite saint; and again in September a day is kept to commemorate her death, when a vast concourse of people from Palermo climb the side of the neighboring Monte Pellegrino to worship at the grotto of St. Rosalia, a natural cavern situated under an overhanging crag of the summit. Here the faithful Sicilians believe that the holy maiden dwelt in solitude for many years; and here were found in 1624 the bones of the saint, which put a stop to the plague then raging in Palermo. The cave has been made a church by building a porch at the entrance. Twisted columns of alabaster support the roof of the vestibule, but within the cavern the walls are of the natural rock, contrasting strangely with the magnificent workmanship of the high altar, beneath which lies the marble statue of the saint overlaid with a robe of gold, while about the recumbent figure are placed a book and skull and other objects of pure gold. It is a figure of a fair young girl, represented by the artist as dying, with her head at rest upon one hand. Though the statue is the work of no very famous artist, Goethe in the narrative of his Sicilian travel has truly said of it, "The head and hands of white marble are, if not faultless in style, at least so pleasing and natural that one cannot help expecting to see them move."

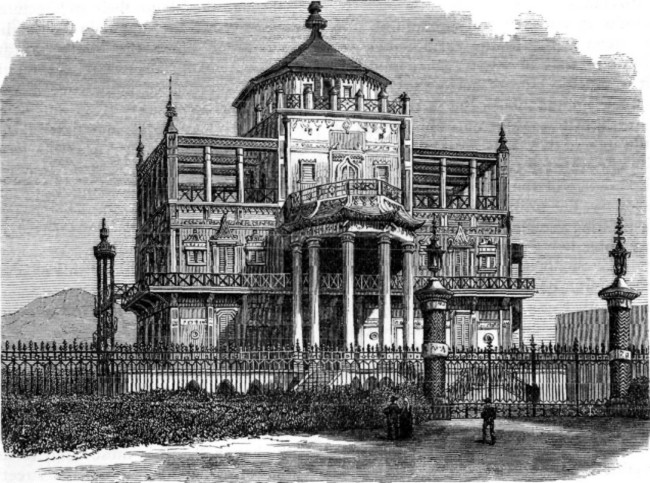

Under the southern precipices of this Mountain of the Pilgrim lies a royal park, and in the midst of it stands a gaudy and fantastic villa called La Favorita. The house is worth a visit for the sake of seeing what a half-crazy fancy will produce when united with royal wealth. King Ferdinand I., during his stay in Sicily early in this century, amused himself by building this country palace in the style of a Chinese villa, and adorned it with innumerable little bells, to be rung by every movement of the wind.

It was in the Favorita that the old king found himself cornered by Lord William Bentinck and his army during the British occupation of the island in 1812. It is said that his faithful subjects from Palermo encamped by thousands in the neighborhood—not, however, for the sake of defending their aged monarch, but to enjoy the fun of witnessing a fight in which both sides were hated by them with equal cordiality.

To an enterprising traveller some of the pleasantest hours of a long tour are those when, cutting loose from all guides and books, he wanders alone through the streets of an old city, enjoying with a sense of discovery the scraps of antiquity not described in any book which he is sure to meet with. Palermo and its neighborhood afford a most fertile field for such researches. The Saracenic villas of the suburbs and the early Norman buildings of the town will repay considerable patience spent in looking up the beauties to be found in the details of their construction. For instance, in the plain old church of S. Agostino there is a doorway and wheel window one sight of which is an ample reward for much wandering and searching.[Pg 655]

MONREALE

MONREALE

On a morning too fresh and beautiful for staying in the city we rendered a vivacious cabman ecstatically happy by an engagement to drive us to Monreale. A brisk drive past the royal palace, out of the southern gate and five miles across the orange-covered plain brought us to the foot of an abrupt mountain. Not a half mile away, but far above, on the seemingly unapproachable heights, was perched the quaint village which was our destination: its ancient towering buildings glittered white and hot in the February sun under the canopy of cloudless blue. Ascending for half an hour on the well-constructed zigzag road, we stopped at the gate in the town-wall to buy the luscious-looking fruit of the cactus from a road-side vender, one of those ideal hags, apparently preserved by desiccation under the torrid sun, whom only Italy can produce in perfection. Then onward and upward we pushed through the village street—a street characteristic of these Southern walled villages, narrow, dark, festooned above with interminable lines of drying macaroni, covered below with abundant filth, and bordered by house-walls of enormous thickness, built for resisting heat. At every house-door or on the pavement in front sits the man of the house plying his trade, that all the world may know whether his goods are well made or ill. Up and down the street flow the lines of dark-eyed,[Pg 656] swarthy people—women robed in rags, occasionally set off by a bit of striking color; children who in their astonishment become rigid at the sight of a foreigner; here and there an officer of the Italian army carefully picking his way through the mud; and everywhere produce-laden asses driven toward Palermo by the most picturesque of cut-throats, for without its ever-present force of soldiers Monreale would at once relapse into a hotbed of brigandage, as its recent history shows.

Almost at the summit of the town, facing a broad, paved square, stands the cathedral and its adjacent Benedictine monastery, both built upon the brink of the precipitous mountain, and both in external appearance severely plain, almost to shabbiness.

William II., king of Sicily, called the Good, founded on this Royal Mount a monastery for the Benedictine friars, and built it up with all the strength of a fortress and the magnificence of a palace. Little is left of that original building, which was finished in 1174, but in its few remains have fortunately been preserved the most splendid of cloisters. This scene of centuries of Benedictine meditations is a large quadrangle surrounded by an arcade of multitudinous small pointed arches resting upon pairs of slender white marble columns, like stalks of snow-white lilies in their grace and lightness. Some of the marble shafts are wrought with reliefs of flowers and trailing vines, while most of them were inlaid in bands or spirals of mosaic in gold and colors, now injured by age. The capitals which crown these shafts are exquisitely carved, and all mythology, the legends of the Church and the book of Nature have been ransacked to furnish subjects for the designs; so that out of two hundred or more no two are similar. All the decaying magnificence of the great building is pervaded by an oppressive silence, for it is one of the innumerable religious houses suppressed by the Italian government.

From the monastery to the cathedral is a walk of but a few steps. All disappointment at the external plainness is forgotten in approaching the chief entrance of the church. Michael Angelo said of Ghiberti's doors at Florence that "they were worthy to be the entrance to Paradise." They have rightly become famous through all the world, and yet these doors of Monreale leave on the mind of the beholder a strong impression of their beauty not less lasting than the Baptistery gates at Florence. In the execution of the biblical reliefs which completely encrust the massive leaves of bronze they must yield, of course, to the mature art of Ghiberti's later age; but the stately height of the solid metal doors, the alternate bands of mosaic and wrought-stone arabesques which flank them and surround over head the Arabian arch, and, above all, the sense that they conceal from view unparalleled splendors beyond, leave on the mind an impression which cannot be effaced.

Perhaps no other building deserves the epithet "splendid" so exactly as the cathedral of Monreale: the whole interior is radiant from the vast extent of its pictured walls. All the walls and vaulting of the nave and aisles, transepts and tribune, are overspread with ancient mosaics on a golden ground. It is natural to compare St. Mark's cathedral at Venice with this church, on account of its immense mosaic-covered surface: its sumptuous interior delights every beholder with the satisfying completeness which belongs to it; yet in all the Oriental splendor of the Venetian church nothing can equal in impressiveness a glance down the nave of Monreale. Wherever the eye turns it rests upon the glowing colors of some sacred picture—scenes from the Old Testament history, bright-robed figures of flying angels, haloed saints in the quaint Byzantine style, apostles and martyrs, patriarchs and prophets, and, high above them all, from a great picture in the vaulting of the apse, a startling face of Christ looking solemnly down through the length of the cathedral. Half the stiffness which characterizes these early mosaics seems to have been cast aside in treating this supreme subject. The colossal size of the figure, the hand raised in blessing[Pg 657] the multitude, the sad but awful expression of the countenance, make it an all-pervading presence in the church. Amid all the glittering splendor of the building, while the gorgeous pomp of a holiday mass progressed and rippling strains of organ-music ran echoing through the arches, through all the bewildering brightness of the spectacle, the majesty of that Presence could not for a moment be forgotten, nor could the eyes avoid straying off from the glitter below to answer again and again to that solemn gaze above.

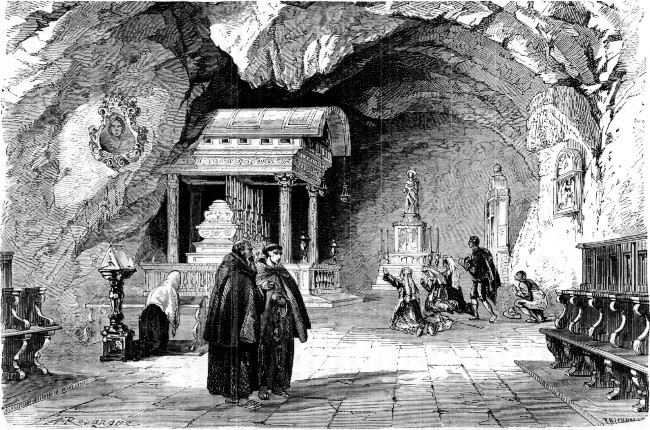

LA ZIZA.

LA ZIZA.

It is impossible, in any ordinary picture, to convey more than a very faint idea of this building, in which the peculiar beauties are dependent upon color, unlike the Gothic churches of the North: nothing but an oil painting of minute details could render the effects produced by the bars of sunshine descending through the twilight of the church and striking on the glowing, pictured walls. The extent of surface covered by the mosaics is said to be more than sixty thousand square feet.

By the bounty of the same pious monarch who endowed the neighboring monastery the cathedral was completed just seven hundred years ago. His body lies entombed in the transept: his monument is the wonderful pile whose construction has made his name to be remembered by succeeding ages more than all his other deeds.

Outside the cathedral, adjoining the monastery-wall, a commanding terrace is built upon the verge of the precipice. Leaning from its edge, we gazed almost vertically into the orange-groves below, where the ripe fruit glowed with the brightness of a flame contrasted with the darkness of the foliage. Far and wide were spread the fruit-gardens over the plain, to where the mountains towered up in the east, and northward to the city and the sea. It is one of those bright and satisfying scenes from which a traveller can hardly turn away without a tinge of bitterness in the thought of never seeing them again.

The drive back to the town was pleasantly varied by a détour which brought us to the Capuchin monastery and the Saracenic villa of La Ziza. The vaults of the monastery are mentioned as one of the interesting sights, but it must be a very ghoulish soul that would take pleasure in them. The horrors of the more famous Capuchin vaults at Rome are tame in comparison with these. There the ornaments are skulls and skeletons in a tolerable state of cleanliness: here the departed brethren have been subjected to some mummifying process, and as they lie piled in hideous confusion their withered faces stare horribly in the twilight of the cellar. Numerous fiery-eyed cats run about with much scratching and scrabbling over the dry bodies, making the place none the pleasanter with their uncanny wails. A very brief visit is sufficient.

La Ziza, the only Saracenic house of this region which is still inhabited, is simply a massive, battlemented tower of unmistakably Arabian appearance. The outside walls are adorned with the depressed panels characteristic of the Saracenic style, but within the Oriental look has almost vanished under the repairs and decorations of many centuries. Only the lofty hallway, arched above with a kind of honeycomb vaulting and cooled by a little cascade of water rushing through it, retains much of the Oriental beauty, and seems like a hall of the Alhambra. Along a wall of the vestibule runs an inscription in Arabic which has been a puzzle to Orientalists, and of which no undisputed interpretation is given. The palace was built as a country pleasure-house by one of the Saracenic princes of Palermo, and can be little less than a thousand years old; indeed, an inscription on its walls, inscribed by one of the Spanish proprietors, claims for the house an antiquity of eleven hundred years.

From the battlements of La Ziza one has the loveliest near view of Palermo and the plain of the Golden Shell. An enthusiastic verse, written over the doorway of the palace, declares it to be the most beautiful scene upon our planet, and while the eyes are resting on the view it is easy to believe the poet; but many of the mountain-views about the city surpass it.

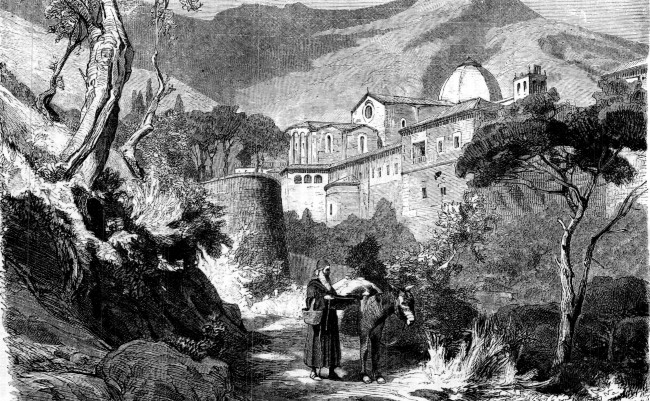

One of the most attractive of the mountain-excursions from Palermo is that to the monastery of San Martino. At a height of seventeen hundred feet above the city, in a lonely spot, the monastery stands on another flank of the mountain on which Monreale is also perched. The mule-path from the suburban village of Boccadifalco to San Martino would be worth traversing for its own wild beauty alone. It first enters a gorge between grand cliffs: then, climbing a rocky ascent which commands a superb view of the plain, it runs through a fruitful valley, where the monastery suddenly appears in the front.[Pg 659]

Palermo.

Palermo.

The monastery of San Martino has been the wealthiest in Sicily. The entrance-hall is on a scale of regal magnificence, adorned with many-colored marbles. The brethren were all of noble extraction. Though the external architecture of the building is not in the best taste, the grand scale on which it is built, and still more the wild, picturesque site, give to the monastery a beauty which even an Italian architect of the last century could not disfigure. Ascending a grand staircase with balustrades of purple marble, an upper hall is reached, from which the wonderful view may be seen to the best advantage. Turning the eye to the north and east across the savage-looking mountains, a short reach of the coast is seen, and beyond is the boundless expanse of sea, dotted on the horizon by the volcanoes of the Æolian Islands, which lie more than a hundred miles away. The abbey abounds in pictures by masters of the seventeenth century, and there is also a museum of Greek and Saracenic remains, but nothing within the walls compares with the interest of the window-views.

Attractive as are the sights of Palermo, most of them must be passed over or very hastily visited if the tour of the island is to be made in a month, for the Greek cities beyond demand a greater share of time by reason of their immense antiquity and the grandeur of their remains.

Being well prepared for the inland journey, and eager to see antiquities so little known to the outer world, one question arose to give us pause—a question which every year keeps thousands of prudent tourists from exploring a country as full of glorious scenery as Switzerland, possessing more of Greek antiquities than Greece itself, and a far lovelier winter climate than Italy—"Is it safe?" The doubtful question whether this rarely-attempted journey should be accomplished was settled by the friendly advice of the courteous consul of the United States at Palermo. That advice may be of use to travellers in the future: it was to the effect that for two American gentlemen travelling alone and without ostentation through Sicily there is no more danger of capture or violent death than in any civilized country. It is admitted that highway robbery is not impossible, as in many places nearer home, but the simple preventive is to carry as little ready money as possible over the short spaces of unsettled country, and to forward superfluous baggage by steamer. That there are banditti in certain districts of the island no one denies, but their object is the capture of wealthy Sicilians, whose ransom is sure and ample, while that of a foreigner is uncertain and necessarily long delayed.

A dark afternoon found us comfortably established in the best seats of an old-fashioned stage-coach in front of the general post-office of Palermo, whence the stage-lines radiate to the various parts of the island. After the long deliberation which seems to characterize all business (especially official business) transacted outside of England and America, the mail-bags were delivered, and our journey began in the midst of a shower descending with all the tremendous impetuosity of a semi-tropical rainy season. The cumbersome vehicle dashed on with considerable spirit through streets almost emptied by the violence of the shower, and out through the broad arch of the stately Porta Nuova crowded by multitudes seeking shelter from the storm. Late twilight found us at the end of the first stage in Monreale. From thence onward the journey continued for a while through pitchy darkness. The broad highway is engineered with admirable skill along the sides of mountains and over deep ravines, through a region of most uncommon beauty, it is said, but now hidden from us by the impenetrable gloom. However, as the night advanced the clouds rolled away with surprising suddenness, and left a bright moon rising over the mountains. We began to see[Pg 661] something of the beautifully varied country, though viewing it at a disadvantage through the narrow window of a covered coach. Wherever the rugged nature of the country permitted every rood of ground was under exquisite cultivation, and already had its first soft covering of springing vegetation. The night-air was sweet with the spring-like odors of freshly-turned earth and of wild-flowers: from time to time white masses of flower-laden almond trees flashed past the window, looking in the moonlight wonderfully like the snow-drifts which at this season line the roads in New England.

CONVENT OF SAN MARINO, NEAR PALERMO.

CONVENT OF SAN MARINO, NEAR PALERMO.

After nightfall the surface of the rich and well-cultivated country seemed as solitary as a wilderness: not a creature was stirring along the road. The intense silence of the night was broken only by the hum of our coach-wheels and the sharp snap of hoofs from our cavalry guard. How unlike were all the surroundings to those of an ordinary modern night-journey over the mail-routes of Europe! The primitive conveyance, the quiet of the lonely road, the arms of the attendant troop of horsemen flashing in the light of the moon,—all the concomitants of an old-time night-journey seemed to carry us back from the age of railroads to an earlier time.

Eleven drowsy hours of staging, and then a long, slow ascent, brought us up to the hilltop where stands the village of Calatafimi. The chief inn of the town is probably not surpassed in Europe in the number of its small discomforts, animate and inanimate, but it must be made the base of operations for visiting the ruins of Segesta. The remnant of the night spent in sleep prepared us for our investigations on the following day. It was pleasant, rising in the cool early morning, to step out from the comfortless interior of the tavern to enjoy on a southern balcony the temperate warmth of the low sun and to look down on the lovely landscape. Before us lay a fertile rolling country clad with verdure, and rising gradually upward toward the south to an elevation deserving to be called a mountain from its great height, yet from its gentle slope and cultivated sides rather to be called a hill. A field near the crest of that distant hill, marked only by a few white crosses, is a spot memorable in Sicilian history, for there lie the heroes who fell fighting with Garibaldi for the unity of Italy on May 15, 1860. Sicily has in all ages been a battle-ground for the contending races of two continents: on Sicilian soil Athens received her most disabling blow, and here too the Punic power was broken; yet there is hardly one among the battlefields of Sicily upon which greater destinies have been settled than on this field of Calatafimi.

Before the morning was far advanced we started out in search of the village curé, the unfailing friend of strangers, that we might inquire of him about the safety of visiting the ruin and in regard to the pleasantest way of reaching it. Picking our way about through the mud of the squalid village, we at length found the old gentleman just coming from his little church on the side of the castle hill at the end of the town. Filled with unfeigned delight that the monotony of his existence should be broken by the advent of two foreigners, especially such living wonders as Americans, the benign priest took a lively interest in our case, gave us the information for which we had asked, vouching for the safety of the country, and begged us to walk on with him. For five minutes we followed on together the road cut in the hillside beneath the walls of the Saracenic citadel, our companion all the while talking vehemently, and helping out our lame knowledge of the language with gestures so dramatic that an understanding of his words was hardly needed. Suddenly the road curved round the side of the hill; we stood on the floor of a deserted quarry; the old man ceased speaking and pointed forward: "Ecco!" Before us the hill dropped abruptly down in a precipice: far below a deep valley spread out before our eyes, "fair as the garden of the Lord." As the light of the morning sun streamed down through its length, bringing out in great brilliancy the fresh green of spring, it looked like a paradise of luxuriant vegetation. The gray of olive trees and the darkness of orange-groves contrasted with the color of springing plants, and everywhere were scattered the pink-and-white plumes of the blossoming almonds. Beyond the valley a[Pg 663] rugged, saddle-shaped mountain rose to an imposing height, and upon the summit line stood in solitary majesty the Doric temple of Segesta, each column in clear relief against the blue of the sky. It is so far removed from all abodes of men, standing alone for thousands of years in the region of the clouds—so grand in its severe and noble outlines—so venerable in its mysterious antiquity—so blended with the natural beauties of the place,—that it seems rather to belong to the power that raised the mountains than to any workmanship of man. The world cannot show a more wonderful example of art exquisitely harmonized with the grandeur of natural scenery.

Eager for a closer view of the temple, we returned immediately to the town, and, being provided with a guide and a beast, were soon on the way down the winding road to the valley. A bridle-path diverged from the main road: an avenue of over-arching olive trees shaded the way, and on all sides here, as everywhere through the country, the orange-crop loaded the trees almost to breaking—the most beautiful of all crops as the fruit hangs upon the branches. As we passed the lower slopes dotted with browsing sheep, and began the rugged ascent of the mountain on which the temple stands, the pathway crept up the edge of a profound gorge: it was a perilous way, clinging close to the edge of the bank, and at some points, where we could look down a thousand feet to the torrent below, the path was so narrow and broken that even our sure-footed mountain-donkeys hesitated to advance. The picturesque but hard climb at length came to an end at the edge of the broad, flattened summit of the mountain. Again the temple suddenly came in sight, but now near at hand. The mountain-shepherds have planted with wheat the level of the summit, and the pale yellow of the volcanic rock from which the temple is built harmonizes well with the color of its surroundings. It cannot be called a ruin. It stands as the builders left it in the fifth century before Christ. Not a column is broken, not a stone has fallen. The interior was never finished, but the outside is perfect.

The pure outlines of a Doric temple are beautiful in any situation, but the impression which this one made upon us in the bright morning sunlight, standing in the midst of verdure and flowers on the brink of that stupendous chasm and overlooking that glorious country, is not a thing to be conveyed in words.

The interest of the temple is comprised in its size, antiquity and beauty, for no mention of it is made in history. Its approximate age is inferred from the internal evidence of the structure. The subjection of the city of Segesta from b. c. 409 to the powers of Carthage and Rome successively, and the subsequent decline of its own power and wealth, render it certain that no such work as this temple would have been undertaken after that date: moreover, the purity of its simple Doric form places it in the earlier ages of Sicilian history. The Carthaginian invasion of the island was doubtless the event which arrested the building. Cicero has described a wonderful statue of Diana in bronze which the people of Segesta showed him with pride as the greatest ornament of their city: it was of colossal size and faultless beauty, belonging to the best period of Greek art. As the statue was in existence before the Carthaginian invasion, it seems to me highly improbable that the citizens of Segesta would have built so grand a temple for any other purpose than to enshrine their most admired and revered statue and to make it a place of worship for Diana. This theory may explain in part the reason why the building was arrested, for it is known that the image was stolen to adorn the city of Carthage,[A] and its loss, as well as the subsequent poverty of Segesta, would have been a sufficient reason for ceasing to build a temple to contain it. Diana's worshippers of old must have looked upon these lovely mountain-ranges as an abode dear to the queen of the nymphs and the hunter's patron deity. It seems as if nothing less than the presence of the mountain-goddess lingering round her shrine could have kept the temple in its marvellous perfection through the lapse of[Pg 664] ages in a land of wars and earthquakes. The houses of the neighboring city are indistinguishably levelled with the earth, but hardly a stone of the sacred building is displaced.

The position of the temple was outside and below the limits of the ancient city. The mountain-ridge rises near at hand to a somewhat greater height, and terminates in a peak, on the summit and sides of which the town was built. Warned by the decline of the sun, we turned from the Segestan house of worship and began to climb the slope toward the Segestan place of amusement: the Greek theatre still remains with little loss or change. The ascent was interrupted by many lingering backward looks toward the grand colonnade as it appeared at fresh points of view from above. Hardly a living creature appeared on the lonely heights, except that one wandering shepherd, seeing the dress of foreigners, came forward to offer his little stock of coins ploughed from the earth or found in ancient buildings. As usual, most of the pocketful were corroded beyond recognition, but one piece bore a noble head executed in the Greek style, and the clear inscription, ΠΑΝΟΡΜΙΤΑΛ, a coin of Panormus; which is, in modern speech, Palermo. A few coppers were accepted as an ample equivalent for a coin which will not circulate.

The scattered fragments of a fortress crown the peak; and immediately below, cut in the solid rock of the western slope, lies the theatre. It is not large as compared with buildings of its class at Athens and Syracuse, yet I believe that in its seating capacity it exceeds any opera-house of our time. Entering by a ruined stage-door and crossing the orchestra, we rested on the lower tiers of seats. The great arc, comprising two-thirds of a circle, upon which the spectators were ranged, has still its covering of fine cut-stone seats, complete except at one extremity. Every part of the desolate building gains a new interest when peopled in imagination with its ancient occupants, and when we recall to mind the vast multitudes of many generations who have watched with breathless and solemn interest the stately progress of Greek tragedy before that ruined scena.

As we lounged upon the lowest seats, whereon the high dignitaries of the town used to sit, and looked across the open space of the orchestra, there at the centre of its farther side lay the slab which supported the altar of Bacchus, where stood the chorus-leader: near it a line of stone marks the front of the stage, and beyond it is spread an expanse of stage-scenery such as no modern royal theatre can boast. The whole broad prospect commanded from the colonnade below is seen across the stage of the theatre, but widened by the greater height and finished in the foreground by the majestic presence of the temple. All the north-western mountains of the island are taken in with one glance of the eye: beneath us the valley of the little river Scamander opens a long vista northward to the Mediterranean Sea, and far away the port of Castellamare glitters, in contrast with the blue, as white as a polished shell upon the shore. Most distant among the group of peaks is Mount Eryx, the lonely rock by the sea on whose summit stood the temple of Venus Erycina, more renowned in the ancient world than all other shrines of the goddess.

We climbed to the brow of the hill in order to descend through the entire length of the city. Hardly one stone is left upon another of all the streets through which the Segestans proudly conducted Cicero. Here and there appear the circular openings of cisterns which occupied the centres of ancient courtyards. The stones once hewn and carved which are strewn over the slope are now reduced to the roughness of boulders, so that one might cross the tract and catch no sign that it was once a city. Little has been done to discover what remains lie beneath the surface, but at one point, where a small excavation has been made, a heap of fallen Ionic columns cover the fragments of a tomb built on a scale of regal magnificence; and a little lower on the mountain two rooms of a house have been exhumed, the floors of which are still covered with beautiful mosaics.

Alfred T. Bacon.

[A] The statue was restored to Segesta by Scipio.

A lady's hero generally has ample leisure. He may write novels or poems, or paint the picture or carve the statue of the season, or he is a statesman and rules the destinies of nations, or he makes money mysteriously in the city, or even, it may be, not less mysteriously on the turf; but he does it in his odd minutes. That is his characteristic. Perhaps he spends his morning in stupendous efforts to gratify a wish expressed in smiling hopelessness by the heroine; later, he calls on her or he rides with her; evening comes, he dances with her till the first gray streak of dawn has touched the eastern sky. He goes home. His pen flies along the paper—he is knee-deep in manuscript; he is possessed with burning enthusiasm and energy; her features grow in idealized loveliness beneath his chisel, or the sunny tide of daylight pours in to irradiate the finished picture as well as the exhausted artist with a golden glory. He has a talent for sitting up. He gets up very early indeed if he is in the country, but he never goes to bed early, or when would he achieve his triumphs? Some things, it is true, must be done by day, but half an hour will work wonders. The gigantic intellect is brought to bear on the confidential clerk: the latter is, as it were, wound up, and the great machine goes on. Or a hasty telegram arrives as the guests file in to dinner. "Pardon me, one moment;" and instantly something is sent off in cipher which shall change the face of Europe. Unmoved, the hero returns to the love-making which is the true business of life.

There are poetry and romance enough in many an outwardly prosaic life. How often have we been told this! Nay, we have read stories in which the hero possesses a season-ticket, and starts from his trim suburban home after an early breakfast, to return in due time to dine, perhaps to talk a little "shop" over the meal, and, it may be, even to feel somewhat sleepy in the evening. But, as far as my experience goes, the day on which the story opens is the last on which he does all this. That morning he meets the woman with the haunting eyes or the old friend who died long ago—did not the papers say so?—and whose resurrection includes a secret or two. Or he is sent for to some out-of-the-way spot in the country where there is a mysterious business of some kind to be unravelled. At any rate, he needs his season-ticket never again, but changes more or less into the hero we all know.

It is hard work for these unresting men, no doubt, yet what is to be done? Unless the double-shift system can in any way be applied for their relief, I fear they must continue to toil by night that they may appear to be idle men.

And, after all, were the hero not altogether heroic, one is tempted to doubt if this abundant leisure is quite a gain.

Addie Blake, planning some bright little scheme which needed a whole day and an unoccupied squire, said once to Godfrey Hammond, "You can't think what a comfort it is to get some one who hasn't to go to business every day. I hate the very name of business! Now, you are always at hand when you are wanted."

"Yes," he said, "we idle men have a great advantage over the busy ones, no doubt; but I think it almost more than counterbalanced by our terrible disadvantage."

"What is that?"[Pg 666]

"We are at hand when we are not wanted," said Godfrey seriously.

And I think he was right. One may have a great liking—nay, something warmer than liking—for one's companions in endless idle tête-à-têtes, but they are perilous nevertheless. Some day the pale ghost—weariness, ennui, dearth of ideas, I hardly know what its true name is—comes into the room to see if the atmosphere will suit it, and sits down between you. You cannot see the colorless spectre, but are conscious of a slight exhaustion in the air. Everything requires a little effort—to breathe, to question, to answer, to look up, to appear interested. You feel that it is your own fault, perhaps: you would gladly take all the blame if you could only take all the burden. Perhaps the failing is yours, but it is your fault only as it is the fault of an electric eel that after many shocks his power is weakened and he wants to be left alone to recover it.

Still, though there may be no fault, it is a terrible thing to feel one's heart sink suddenly when one's friend pauses for a moment in the doorway as if about to return. One thinks, If weariness cannot be kept at bay in the society of those we love, where can we be safe from the cold and subtle blight? As soon as we are conscious of it, it seems to become part of us, and we shrink from the popular idea of the Hereafter, assured of finding our spectre even in the courts of heaven.

Godfrey Hammond expressed the fear of too much companionship in speech, Percival Thorne in action. He was given to lonely walks if the weather were fine—to shutting himself in his own room with a book if it were wet. He would dream for hours, for I will frankly confess that when he was shut up with a book, his book as often as not was in that condition too.

His grandfather had complained more than once, "You don't often come to Brackenhill, Percival, except to solve the problem of how little you can see of us in a given time." He did not suspect it, but much of the strong attraction which drew him to his grandson lay in that very fact. The latter confronted him in grave independence, just touched with the courteous deference due from youth to age, but nothing more. Mr. Thorne would have thanked Heaven had the boy been a bit of a spendthrift, but Percival was too wary for that. He did not refuse his grandfather's gifts, but he never seemed in want of them. They might help him to pleasant superfluities, but his attitude said plainly enough, "I have sufficient for my needs." He was not to be bought: the very aimlessness of his life secured him from that. You cannot earn a man's gratitude by helping him onward in his course when he is drifting contentedly round and round. He was not to be bullied, being conscious of his impregnable position. He was not to be flattered in any ordinary way. It was so evident to him that the life he had chosen must appear an unwise choice to the majority of his fellow-men that he accepted any assurance to the contrary as the verdict of a small minority. Nor was he conscious of any especial power or originality, so that he could be pleased by being told that he had broken conventional trammels and was a great soul. Mr. Thorne did not know how to conquer him, and could not have enough of him.

It is needful to note how the day after the agricultural show was spent at Brackenhill.

Godfrey Hammond left by an early train. Mrs. Middleton came down to see about his breakfast with a splitting headache. The poor old lady's suffering was evident, and Sissy's suggestion that it was due to their having walked about so much in the broiling sun the day before was unanimously accepted. Mrs. Middleton countenanced the theory, though she privately attributed it to a sleepless night which had followed a conversation with Hammond about Horace.

Percival vanished immediately after breakfast. As soon as he had ascertained that there were no especial plans for the day, he slipped quietly away with his hands in his pockets, strolled through the park, whistling dreamily as he went, and passing out into the road, crossed it and made straight for the river. He lay on the grass for half an hour or so, studying[Pg 667] the growth of willows and the habits of dragon-flies, and then sauntered along the bank. Had he gone to the left it would have led him past Langley Wood to Fordborough. He went to the right.

It was a gentle little river, which had plenty of time to spare, and amused itself with wandering here and there, tracing a bright maze of curves and unexpected turns. At times it would linger in shady pools, where, half asleep, it seemed to hesitate whether it cared to go on to the county-town at all that day. But Percival defied it to have more leisure than he had, and followed the silvery clue till all at once he found himself face to face with an artist who sat by the river-side sketching.

The young man looked up with a half smile as Percival came suddenly upon him from behind a clump of alders. A remark of some kind, were it but concerning the weather, was inevitable. It was made, and was followed by others. Young Thorne looked, admired and questioned, and they drifted into an aimless talk about the art which the painter loved. Even to an outsider, such as Percival, it was full of color and grace and a charm half understood, vaguely suggestive of a world of beauty—not far off and inaccessible, but underlying the common, every-day world of which we are at times a little weary. It was as if one should tell us of virtue new and strange in the often-turned earth of our garden-plot. Percival was rather apt to analyze his pains and pleasures, but his ideal was enjoyment which should defy analysis, and he found something of it that morning in the summer weather and his new friend's talk.

It was past noon. The young artist looked at his watch and ascertained the fact. "Do you live near here?" he asked.

Percival shook his head: "I live anywhere. I am a wanderer on the face of the earth. But my grandfather lives in that gray house over yonder, and I am free to come and go as I choose. I am staying there now."

"Brackenhill, do you mean? That fine old house on the side of the hill? I am lodging at the farm down there, and the farmer—"

"John Collins," said Percival.

"Entertains me every night with stories of its magnificence. Since we have smoked our pipes together I have learnt that Brackenhill is the eighth wonder of the world."

"Not quite," said Thorne. "But it is a good old manor-house, and, thank Heaven, my ancestors for a good many generations wasted their money, and had none to spare for restoring and beautifying. I don't mean my grandfather: he wouldn't hurt it. It's a quaint old place. Come some afternoon and look at it. He shall show you his pictures."

"Thanks," the other said, but he hesitated and looked at his unfinished work. "I should like, but I don't quite know. The fact is, when I have done for to-day I'm to have old Collins's gig and drive into Fordborough to see if there are any letters for me. I am not sure I shall not have to leave the first thing to-morrow."

"And I have made you waste your time this morning."

"Don't mention it," said the young artist with the brightest smile. "I'm not much given to bemoaning past troubles, and I shall be in a very bad way indeed before I begin to find fault with past pleasures. I may not find my letter after all, and in that case I should like very much to look you up. To-morrow?"

"Pray do." The tone was unmistakably cordial.

"Your grandfather's name is Thorne, isn't it? Shall I ask for young Mr. Thorne?"

"Percival Thorne," was the quick correction: "I have a cousin."

They shook hands, but as Thorne turned away the other called after him: "I say! is there any name to that little wood out there, looking like a dark cloud on the green?"

"Yes—Langley Wood." Percival nodded a second farewell, and went on his way pondering. And this was the subject of his thoughts: "Then, my brother, I have to go through Langley Wood to-morrow evening, and I am afraid to go alone."[Pg 668]

Of course he had not forgotten his promise to Addie, but having made his arrangements and worked it all out in his own mind, he had dismissed it from his thoughts. Now, however, it rose up before him as a slightly disagreeable puzzle.

What on earth did Addie want toward nine at night in Langley Wood? The day before, in haste to answer her request and anxiety not to betray her, he had not considered whether the service he had promised to render were pleasant to him or not. In very truth, he was willing to serve Addie, and he had professed his willingness the more eagerly that he had expected a harder task. She asked so slight a thing that only eager readiness could give the service any grace at all.

But when he came to consider it he half wished that his task had been harder if it might have been different. He liked Addie, he was ready to serve her, but he foresaw possible annoyances to them both from her hasty request. He had no confidence in her prudence.

"Some silly freak of hers," he thought while he walked along, catching at the tops of the tall flowering weeds as he went. "Some silly girlish freak. Why didn't she ask Horace? Wouldn't run any risk of getting him into trouble, I suppose."

Did Horace know? he wondered. "I'm not going to be made use of by him and her: they needn't think it!" vowed Percival in sudden anger. But next moment he smiled at his own folly: "When I have given my word, and must go if fifty Horaces had planned it! I had better save my resolutions for next time." He did not think, however, that Horace did know. "Which makes it all the worse," he reflected. "A charming complication it will be if I get into trouble with him about Addie. Suppose some one sees us? Suppose Mrs. Blake is down upon me, questioning, and I, pledged to secrecy, haven't a word to say for myself? Suppose Lottie—Oh, I say, a delightful arrangement this is and no mistake!"

He could only hope that no one would see them, and that Addie's mystery would prove a harmless one.

He got in just as they were sitting down to luncheon. Horace and Sissy had spent the morning in archery and idleness, Mrs. Middleton in nursing her headache. Mr. Thorne was not there.

"Been enjoying a little solitude?" Horace inquired.

"Not much of that," was the answer. "A good deal of talk instead."

"What! did you find a friend out in the fields?"

"Yes," said Percival, "a young artist." As he spoke he remembered that he was ignorant of his new friend's name. At least he knew it was "Alf," owing to some story the painter had told: "I heard my brother calling 'Alf! Alf!' so I," etc. Alf—probably therefore Alfred—surname unknown.

They were halfway through their meal when Mr. Thorne came noiselessly in and took his accustomed place. He was very silent, and had a curiously intent expression. Horace, who was telling Sissy some trifling story about himself (Horace's little stories generally were about himself), finished it lamely in a lowered voice. Mr. Thorne smiled.

There was a silence. Percival went steadily on with his luncheon, but Horace pushed away his plate and sipped his sherry. The birds were twittering outside in the sunshine, but there was no other sound. It was like a breathless little pause of expectation.

At last Mr. Thorne spoke, in such sweetly courteous tones that they all knew he meant mischief. "Are you particularly engaged this afternoon?" he inquired of Horace.

"Not at all engaged," said the young man. His heart gave a great throb.

"Then perhaps you could give me a few minutes in the library?"

"I shall be most—" Horace began. But he checked himself and said, "Certainly. When shall I come?"

"As soon as you have finished your luncheon, if that will suit you?"

"I have finished." He drank off his wine, and, without looking at the others, walked defiantly to the door, stood aside[Pg 669] for his grandfather to pass, and followed him out.

Mrs. Middleton and Sissy exchanged glances. "Oh, my dear!" the old lady exclaimed. "Oh, I'm so frightened! I am afraid poor Horace is in trouble. Godfrey Hammond was saying only last night—"

She paused suddenly, looking at Percival. He sat with his back to the window, and the dark face was very dark in the shadow. It was just as well perhaps, for he was thinking "Told you so!" a train of thought which seldom produces an agreeable expression.

"What did Godfrey Hammond say?" Sissy asked. But nothing was to be got out of Aunt Middleton, so they adjourned to the drawing-room to wait for Horace's return. Percival read the paper; Mrs. Middleton lay on the sofa; Sissy flitted to and fro, now taking up a book, now her work, then at the piano, playing idly with one hand or singing snatches of her favorite songs. There was a mirror in which, looking sideways, she could see herself reflected as she played and Percival as he read—as much of him, at least, as was not swallowed up in the Times. There is something ghostly about a little picture like this reflected in a glass. It is so silent and yet so real: the people stir, look up, their lips move, they have every sign of life, but there is no sound. There are noises in the room behind you, but the people in the mirror make none. The Times may be rustling and crackling elsewhere, but Percival's ghost turns a ghostly paper whence no sound proceeds. Sissy is playing a little tinkling treble tune, but at the piano yonder slim white fingers are silently wandering over the ivory keys, and the girl's eyes look strangely out from the polished surface.

Sissy gazed and mused. Perhaps some day Percival will reign at Brackenhill. And who will sit at that piano where the ghost-girl sits now, and what soundless melodies will be played in that silent room?

Sissy's left hand steals down to the bass, striking solemn chords. "If one could but look into the glass," she thinks, "and see the future there, as people do in stories! What eyes would look out at me instead of mine? Ah, well! If I could but see Percival there I would try to be content, even if the girl turned away her face. I would be content. I would! I would!"

She turns resolutely away from the mirror, and begins that old royalist song in which yearning for the vanished past and mourning for the dreary present cannot triumph over the hope of far-off brightness—"When the king enjoys his own again." To Mrs. Middleton, to Percival, a mere song—to Sissy a solemn renunciation of all but the one hope. Let her king enjoy his own, and the rest be as Fate wills.

The last note dies away. Moved by a sudden impulse, she lifts her eyes to the ghost Percival. He has lowered his paper a little, and is looking at her with a wondering smile. A voice behind her exclaims, "Why, Sissy!" She darts across the room to the speaker and pushes the Times away altogether. "Percival," she says in a low, breathless voice, "does Miss Lisle play?"

"Miss Lisle!" He is surprised. "Oh yes, she plays. But not as well as her brother, I believe."

"And does she sing?"

"Yes. I heard her once. But no better than you sang just now. What has come to you, Sissy? You have found the one thing that was wanting."

"What was that?"

"Earnestness, depth. You sang it as if your soul and the soul of the song were one. Now I can tell you that I fancied you only skimmed over the surface of things—like a bird over the sea. I can tell you now, since I was wrong."

Her cheeks are glowing. "And Miss Lisle?" she says.

"What, now, about Miss Lisle?" He is amused and perplexed at Sissy's persistence.

"She is one of your heroic women;" and Miss Langton nods her pretty head. "Oh, I know! Jael and Judith and Charlotte Corday."

"I don't think I said anything about Judith: surely you suggested her. And, to tell you the truth, Sissy, I looked in[Pg 670] the Apocrypha, and I thought I liked I her the least of the trio. It wasn't a swift impulse like Jael's, who suddenly saw the tyrant given into her hands, and it wanted the grace of Charlotte Corday's utter self-sacrifice and quick death. Judith had great honor, and lived to be over a hundred, didn't she? I wonder if she often talked about Holofernes when she was eighty or ninety, and about her triumph—how she was crowned with a garland and led the dance? She ran an awful risk, no doubt, but she was in awful peril: it was glory or death. Charlotte Corday had no chance of a triumph: she must have known that success, as well as failure, meant the death-cart and the guillotine. Judith seems to have played her part fairly well to the end, I allow, but don't you think the praises and the after-life spoil it rather?"

Sissy, passing lightly over Percival's views about Charlotte Corday and the widow of a hundred and five who was mourned by all Israel, pounced on a more interesting avowal: "So you looked Judith out and studied her? Oh, Percival!"

"My dear Sissy, shall I tell you how many times I have seen Miss Lisle?" He was answering her arch glance rather than her spoken question. "How few times, I should say. Twice."

"I've made up my mind about people when I've only seen them once," said Sissy, apparently addressing the carpet.

"Very likely: some people have that power," said Percival. "Besides, seeing them once may mean that you had a good long interview under favorable circumstances. Now," with a smile, "shall I tell you all that Miss Lisle and I said to each other in our two meetings?" He paused, encountering Sissy's eyes, brilliantly and wickedly full of meaning.

"What! do you remember every word? Oh, Percival!"

"Hush!" said Mrs. Middleton, lifting her head from the cushion: "listen! isn't that Horace?"

"I think so;" and Percival stooped for the Times, which had fallen on the floor. Sissy stood with her hand on his chair, making no attempt to conceal her anxiety. The old lady noted her parted lips and eager eyes. "Ah! she does care for Horace. I knew it! I knew it!" she thought.

He came in, looking white and angry: his mouth was sternly set, and there was a fierce spark in his gray eyes. Mrs. Middleton beckoned him to her sofa, and would have drawn the proud head down to her with a tender whisper of "Tell me, my dear." But the young fellow straightened himself and faced them all as he stood by her side. She clasped and fondled his passive hand. "What is the matter, Horace?" she said at last.

"As it happens, there is nothing much the matter," he replied,

"You look as if a good deal might be the matter," said Sissy.

He made no answer for the moment. Then he looked at her with a curious sort of smile: "Sissy, when we were little—when you were very little indeed—do you remember old Rover?"

"That curly dog? Oh yes."

"I used to have him in a string sometimes, and take him out: it was great fun," said Horace pensively. "I liked to feel him all alive, scampering and tugging at the end of the string. It was best of all, I think, to give him an unexpected jerk just when he was going to sniff at something, and take him pretty well off his legs: he was so astonished and disappointed. But it was very grand too, if he would but make up his mind he wanted to go one way, to pull at him and make him go just the opposite. He was obstinate, was old Rover, but that was the fun of it. I was obstinate too, and the stronger. How long has he been dead?"

"I'm sure I don't know—twelve or thirteen years. Why?"

"Is it as long as that? Well, I dare say it is. It has occurred to me to-day for the first time that perhaps it was rather hard on Rover now and then.—Aunt Harriet, why did you let me have the poor old fellow and ill-use him?"

"My dear boy, what do you mean? I don't think you were ever cruel—not really cruel, you know. Children always[Pg 671] will be heedless, but I think Rover was fond of you."

"I doubt it," said Horace.

"But what do you mean?" The old lady was fairly perplexed. "What makes you think of having poor old Rover in a string to-day? I don't understand."

"Which things are an allegory." Horace looked more kindly down at the suffering face, and attempted to smile. "It was very nice then, but to-day I'm the dog."

"String pulled tight?" said Percival.

"Jerked." He disengaged his hand. "I think I'll go and have a cigar in the park." Percival was going to rise, but Horace as he passed pressed his fingers on his shoulder: "No, old fellow! not to-day—many thanks. You lecture me, you know, and generally I don't care a rap, so you are quite welcome. But to-day I'm a little sore, rubbed up the wrong way: I might take it seriously. Another time."

And he departed, leaving his lecturer to reflect on this brilliant result of all his outpourings of wisdom.

At Brackenhill they invariably dined at six o'clock, nor was the meal a lengthy one. Mr. Thorne drank little wine, and Horace was generally only too happy to escape to the drawing-room at the earliest opportunity. Percival could very well dine at home and yet be true to his rendezvous in Langley Wood.

As the time drew near he became thoughtful and, to tell the truth, a little out of temper. He liked his dinner, and Addie Blake interfered with his quiet enjoyment of it. He would have chosen to lie on the sofa in the cool, quaint, rose-scented drawing-room, and get Sissy to sing to him. Instead of which he must tramp three miles along a dusty white road that July evening to meet a girl he didn't particularly want to see, and to hear a secret which he didn't much want to know, and which he distinctly didn't want to be bound to keep. Decidedly a bore!

It was only twenty minutes past seven when they joined the ladies. Sissy represented the latter force, Aunt Middleton having gone to lie down in the hope of being better later in the evening. Mr. Thorne fidgeted about the room for a minute, and then went off to the library, whereupon Horace stretched himself with a sigh of relief. "Come out, Sissy, and have a turn in the garden."

"But, Percival," she hesitated, "what are you going to do?"

"Don't think about me: I must go out for a little while." He left them on the terrace and started on his mysterious errand. As he let himself out into the road by a little side-gate of which he had pocketed the key, it was five-and-twenty minutes to eight. He had abundance of time. It was not three miles to the white gate into Langley Wood, a little more than three miles to the milestone beyond which he was on no account to go, and he had almost an hour to do it in. Nevertheless, he started on his walk like a man in haste.

The great Fordborough agricultural show lasted two days, and on the second the price of admission was considerably reduced. It had occurred to Percival that the roads in every direction would probably be crowded with people making their way home—people who would have had more beer than was good for them. Addie would never think of such a possibility. It was true that the road from Fordborough which led past Brackenhill would be quieter than any other, but still young Thorne was seriously uneasy as he strode along. It was also true that he met hardly any one as he went, but even that failed to reassure him. "A little too early for them to have come so far, I suppose," was his comment to himself: "at any rate, she shall not wait for me."

He passed the white gate, having encountered only a few stragglers, but before he reached the milestone he saw Addie Blake coming along the road to meet him.

She was flushed, eager, excited, and looked even handsomer than usual. Percival would never fall in love with Addie. That was very certain, but the certainty[Pg 672] did not prevent a quick thrill of admiration which tingled through his blood as she advanced in her ripe dark beauty to meet him. By it, as by a charm, the service which had been almost a weariness was transmuted to a happy privilege, and the half-reluctant squire became willing and devoted.

"You are more than punctual," was his greeting.

She smiled as she held out her hand: "I may say the same of you."

"I was anxious," he confessed. "The roads are not likely to be very quiet to-day. And after sunset—"

"Yes," said Addie. "No doubt it seems strange to you that I should choose this day and this time—"

"I hardly know what I should have done if I had seen nothing of you when I reached the milestone," he went on, interrupting her. His curiosity was awakened now that he was so close to Addie's little mystery, but he was anxious that she should not feel bound to tell him anything she would rather keep to herself—very anxious that she should understand that he would not pry into her secrets.

"If you had gone much farther you would have missed me," she said.

"Which way did you come?"

"I did not come straight from home. Do you see that little red house? I am drinking tea there, and spending a quiet evening."

"How very pleasant!" said Percival. "And who has the privilege of entertaining you?"

"Mrs. Wardlaw. She is the widow of an officer—quite young. She is a friend of mine: she lives with an invalid aunt, an old Mrs. Watson."

"And what does Mrs. Wardlaw think of your taking a little stroll by yourself in the evening?"

"Mrs. Wardlaw asked me there on purpose. Yesterday I saw her at the show, and gave her a little note as we shook hands. This morning came an invitation to me to go and drink tea there. I told mamma and Lottie I should go—papa is out—so one of the servants walked there with me at half-past six, and will call for me again at ten or a little after."

"Very ingeniously managed," said Percival. "And the invalid aunt?"

"Went up to her room and left Mary and me to our devices," smiled Addie. "A delightful old lady. Ah, here is the wood."

"We shall probably have this part of our walk to ourselves," Percival remarked as he swung the gate open. "People going home from the show are not likely to stop to take a turn in Langley Wood."

The sound of a rattling cart and shouts of discordant laughter, mixed with what was intended for a song, came along the road they had just quitted. Addie took a few hurried steps along the path, which curved enough to hide her from observation in a moment. Safe behind a screen of leaves, she paused: "What horrible people! Is that a sample of what I may expect as I go back?"

"I fear so," said Percival. "I shall see you safe to Mrs. Wardlaw's door."

"You shall see me safe if you have good eyes," she answered. "But you will not go to the door with me."

"Ah!" he said. "Mrs. Wardlaw is only half trusted?"

Addie smiled: "What people don't know they can't let out, can they?"

"Pray understand that you are quite at liberty to apply that very wise—mark me, that very wise—discovery of yours to my case," said Thorne, looking straight at her. "You talked about good eyes just now. Mine are good or bad as it suits me." At any rate, they were earnest as they met hers.

"Don't shut them on my account," said Addie. "No, Percival: you are not like Mrs. Wardlaw. I mean to tell you all about it."

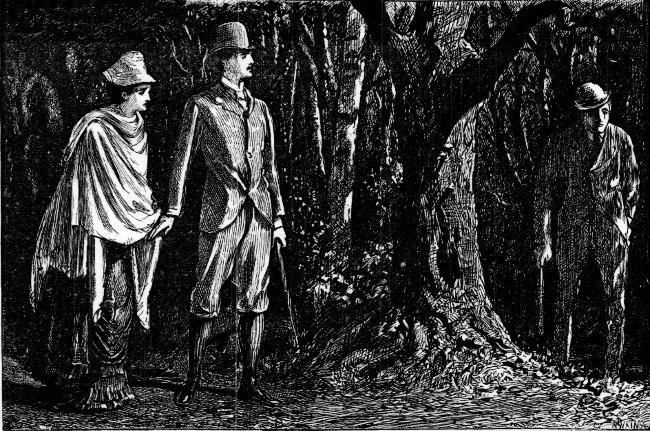

But for a moment she did not speak. They were fairly in the wood; the trees were arching high above their heads; their steps were noiseless on the turf below; outside were warmth and daylight still, but here the shadows and the coolness of the night. A leathern-winged bat flitted across their path through the gathering dusk. "They always look like ghosts," said Addie. "Doesn't it seem,[Pg 673] Percival, as if the night had come upon us unawares?"

As she spoke they reached a little open space. The path forked right and left. "Which way?" said Thorne.

"I don't know, I'm sure. There's a cottage on the farther side of the wood, toward the river—"

"Is that your destination? To the right, then." And to the right they went.

"When you promised to help me," Addie began, "do you remember what you said? I was to consider you as—" She paused, fixing her questioning eyes on him.

"As a brother. What then? Have I failed in my duty already?"

She shook her head, smiling: "Percival, what do you think that means to me?"

"Ah, that's a difficult question. Of course we who have no brothers can only imagine—we cannot know. But I have sometimes fancied that the idea we attach to the word brother is higher because no commonplace reality has ever stepped in to spoil it. For it is an evident fact that some people have brothers who are prosaic, and even disagreeable, while all the noble brothers of history and romance are ours. We may take Lord Tresham for our ideal (you remember Tresham in A Blot in the 'Scutcheon?), and declare with him—

"Stop!" said Addie. "You are going into the question much too enthusiastically and much too poetically. I don't know anything about your Tresham. And you mustn't class me with yourself, 'we who have no brothers.' I have one, Percival."

"A brother? You have one? Why, I always fancied—"

"Well, a half-brother." Addie made this concession to strict truth with something of reluctance in her tone, as if she did not like to own that her brother could possibly have been any nearer than he was. "It is my brother I am going to meet to-night."

Percival, fluent on the subject of brothers in general, was so astonished at the idea of this particular brother or half-brother that he said "Oh!"

"Papa married twice," Addie explained—"the first time when he was very young. I don't think his first wife was quite a lady," she said, lowering her voice as if the beeches might be given to gossiping.

Percival would not have been happy as a dweller in the Palace of Truth. He thought, "Then Mr. Blake's two wives were alike in one respect."

"And though Oliver was a dear boy," she went on, "he hasn't been very steady. He has had a good deal of money at one time or another, and wasted it; and he and mamma don't get on at all."

"Ah! I dare say not."

"Naturally, she thinks more about Lottie and me; and Oliver has been very tiresome. He was to be in the business with papa, but he didn't do anything, and he got terribly into debt, and then he ran away and enlisted. Papa bought him off, and found him something else to do; but mamma was dreadfully vexed: she said it was a disgrace to the family."

"Did he do better after that?"

"Not much," Addie owned. "In fact, I think he has spent most of his time since then in running away and enlisting. I really believe he has been in a dozen regiments. We were always having to write to him, 'Private Oliver Blake, Number so and so, C company, such a regiment.' It didn't look well at all."

(Addie, as she spoke, remembered how her mother used to sneer, "No doubt some day you'll meet your brother in a red jacket with a little cane, his cap very much on one side, and a tail of nursemaids wheeling their perambulators after him." Such remarks had been painful to Addie, but even then she had felt that Mrs. Blake had cause to complain.)

"He was always bought off, I suppose?" said Percival.

"Once papa declared he wouldn't. Oliver went on very quietly for a little while, and was to be a corporal. Then he wrote and said he was going to desert that day week, and he was afraid it might be very awkward for him afterward,[Pg 674] especially if he ever enlisted again, but he would take his chance sooner than stop. Papa knew he would do it, so he had to buy him off again."

"But is this going on for ever?"

"No: for the last three years Oliver has been in dreadful disgrace, I don't exactly know why, and we were not allowed to mention his name at home. But I don't care," said Addie impetuously: "if he were ever so foolish, and if he had enlisted in every regiment under the sun, he's my brother."

"And Lottie? Does she stand by him as valiantly?"

"Oliver is nothing to Lottie: he never was. He is nine years older than she is, and when she would really begin to remember him he and mamma were always quarrelling. Besides, he always petted me—not Lottie. And now she despises him because he doesn't stick to anything and get on. No—poor old Noll is my brother, only mine. No one else cares for him, except papa."

"Mr. Blake hasn't given him up, then?"

"Oh, he is angry with Oliver when they are apart, but he always forgives him when they meet. He was really angry this last time, but Oliver wrote to him, and they made it up. Only, my poor old Noll is to be sent over the sea to Canada with a man papa knows something of."

"And this is good-bye? But surely they can't mind your meeting him before he goes?"

"They do," said Addie. "Papa and mamma saw him in London ten days ago, and he was only forgiven on condition that he went away quietly and said nothing to any one. As if he wasn't sure to tell me! Mamma knows how it has been before: she thinks if papa or I saw him alone he might get round us, and then he wouldn't go. If he is steady and does well there, he is to come and see us all in two years."

"That isn't very long, is it?" said Percival cheerfully. It was evident to him that this black sheep would be much better away.

"Long! Oh no! Only, you see, Oliver won't do well unless there's something very converting in Canadian air. So I may as well say good-bye to him, mayn't I? Mind, Percival, you are not to think he's wicked. He won't do anything dreadful. He'll spend all the money he can get, and then drift away somewhere."

"A sort of Prodigal Son," Thorne suggested.

"Yes. You won't understand him—how should you? You are always wise and well-behaved, and a credit to every one—more like the son who stayed at home."

"Not an attractive character," was his reply. And he remembered Horace a few hours before: "Not to-day, old fellow: you lecture me, you know." He was startled. "Good Heavens!" he thought, "am I a prig?"

Addie laughed: "Well, I am trusting to you to understand me, at any rate. Just like Oliver!" she went on. "He came once, years ago, to stay with old Miss Hayward, who left us the house, and he knew something then of the man at this cottage; so he tells me to meet him there, without ever thinking how I should get to the place by myself at nine at night. Hush! what's that?—Oh, Noll! Noll!"