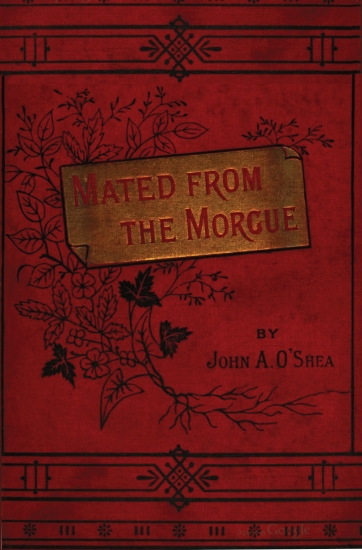

Title: Mated from the Morgue: A Tale of the Second Empire

Author: John Augustus O'Shea

Release date: November 13, 2011 [eBook #38008]

Most recently updated: December 2, 2011

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This book was

produced from scanned images of public domain material

from the Google Print project.)

A TALE OF THE SECOND EMPIRE

BY

JOHN AUGUSTUS O'SHEA

AUTHOR OF

'LEAVES FROM THE LIFE OF A SPECIAL CORRESPONDENT,' 'AN

IRON-BOUND CITY,' 'ROMANTIC SPAIN,' 'MILITARY

MOSAICS,' ETC.

'La Ville de Paris a son grand mât tout de bronze, sculpté de

victoires, et pour vigie Napoléon.'—DE BALZAC.

LONDON

SPENCER BLACKETT

[Successor to J. & R. Maxwell]

MILTON HOUSE, 35, ST. BRIDE STREET, E.C.

1889

[All rights reserved]

———

THIS tale, such as it is, has one merit. It is a study of manners, mainly made on the spot, not evolved from the shelves of the British Museum. There is in it, at least, a crude attempt at photography, a process in which sunlight and air have some part, and, therefore, liker to nature than the adumbrations of the reading-room. The localities are faithfully drawn, the persons are not dolls with stuffing of sawdust, but human animals who might have lived—and, mayhap, did live. If the volume does not kill an hour, the writer is murderer only in thought.

TO MY FRIEND,

COLONEL THE BARON CRAIGNISH,

EQUERRY TO

HIS HIGHNESS THE DUKE OF SAXE-COBURG-GOTHA,

This Little Book,

IN TARDY THANK-OFFERING FOR THAT LARGE

LEG OF MUTTON.

| CONTENTS | ||

|---|---|---|

| ——— | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | A HOUSELESS DOG | 1 |

| II. | A CRUSH AT THE MORGUE | 8 |

| III. | LE VRAI N'EST PAS TOUJOURS VRAISEMBLABLE | 20 |

| IV. | THE SONG-BIRD'S NEST | 30 |

| V. | NAPOLEONIC IDEAS | 40 |

| VI. | THE OLD BONAPARTIST'S STORY | 52 |

| VII. | FRIEZECOAT AT HOME | 65 |

| VIII. | POPPING THE QUESTION | 75 |

| IX. | A SOLDIER OF FORTUNE | 85 |

| X. | 'LA JEUNE FRANCE' | 96 |

| XI. | THE BONE OF CONTENTION | 104 |

| XII. | ORANGE BLOSSOMS | 121 |

| XIII. | THE HONEYMOON TRIP | 128 |

| XIV. | VANITAS VANITATUM | 139 |

| XV. | THE FIFTH OF MAY, 1870 | 152 |

THE scene is Paris, the Imperial Paris, but not a quarter that is fashionable, wealthy, or much frequented by the tourist. It is the wild, slovenly, buoyant quarter of the Paris of the left bank, known as le Pays Latin—the Land of Latin. The quarter of frolic and genius, of vaulting ambition and limp money-bags, of generosity and meanness, of truth and hypocrisy; the quarter which supplies the France of the future with its mighty thinkers, the France of the passing with the forlorn hopes of its revolutions, the world—and the demi monde too—very often with its most brilliant and erratic meteors.

The time is the spring of 1866. The chestnut-tree, called the Twentieth of March, in the Champs Elysées, has shown its first blossoms. But the weather is cold and damp in spite of these deceitful blossoms: the skies weep, and chill winds blow sullenly along the Seine. It is just the weather to make the blaze of a ruddy fire a cheerful sight, and the hiss of the crackling logs a cheerful sound; but there is neither fire nor, indeed, grate or stove wherein to put it, in the cabinet numbered 37, on the fifth story of the Hôtel de Suez, in the Rue du Four, into which we ask the reader to penetrate. A portmanteau, whose half-opened lid betrays 'the poverty of the land,' lies in a corner, a shabby suit of man's wearing apparel hangs carelessly on a chair, and a head, thickly covered with hair, protrudes from the blankets in a little bed in a recess, and out of the mouth in this head protrudes a Turkish pipe of exaggerated length, and out of the same mouth at regular intervals filters a slender thread of smoke. The lips contract and open again, and no smoke comes. The head is elevated, the blankets thrown back, and the shoulders and torso of the smoker appear rising gradually from the bed till they are erect; the bowl of the Turkish pipe is regarded a moment deprecatingly (as if the pipe could have been kept alight without tobacco), and the lips move again, this time to soliloquy:

'Mr. Manus O'Hara, I have a great respect for your father's son: you come of a fine proud spend-thrift old Irish family; but I tell you what, my brilliant friend, if you don't replenish the exchequer I shall be obliged to cut your society. You're not in a position to pay any more visits to that interesting elderly female acquaintance of yours, your aunt.[1] Realize your position, sir, I beg of you. You're in a most confounded state of impecuniosity; you haven't a sou left, and I'm afraid your pipe is finally extinguished. Then, that delightful lady in the den of Cerberus below, who was one long smile when you and the sack,[2] now that you are en dèche,[3] is an eternal snarl like a very dog of Hades. When you had money you had a room on the first floor at thirty francs a month; now that you are poor she stuffs you into a garret on the fourth at thirty-five. Perdition catch it, Mr. O'Hara, it's very expensive to be poor. Without cash or credit! Charming position for a young man of genius! If you had a good suit of clothes you might have a chance of getting into the hôtel des haricots,[4] but with your present raiment there is no danger of your encouraging that horrible temptation of ingenuous youth known as running into debt. It's my private opinion you wouldn't get a box of matches on your solemn oath, let alone your word, at the present crisis in your chequered career. Good heavens! How cold it is! Without cash or credit. That's the burden of the litany. Shall I pray? Bah! Who could pray with hunger gnawing his vitals? Forty-two hours without food, and still without cash or credit to procure a bite.'

The head was dipped suddenly and violently under the blankets.

A long pause.

The bed-covering billows as if stirred by some strong agitation of the form beneath.

All is quiet again.

Now a stifled sound as of sobbing comes from under the blankets. They are forcibly flung back, and a pale face, one feverish flush on each cheek, emerges. The eyes flash with a sharp fitful light amid the quick-darting big tears, and the breast heaves with convulsive sobs. At length amid the sobs rise broken words:

'Too proud to beg, and not paid for working. Must I die, then? A hound is fed; 'tis only man is let perish by his fellow-beings!'

Silence again; and suddenly and startlingly on the air to the silence succeeds a mocking, hysterical laugh. The form springs from its recumbent position on to the bare floor, and approaches a small mirror fixed against the wall.

That laugh again.

'Ha, ha! Manus, my boy, die game!' and with the expression of this advice, or rather intention, calm seems to come to the troubled spirit of our poor friend. He takes his clothes off the chair and dresses himself, keeping up a jeering comment of self-ridicule, as he puts on each shabby article of attire.

'Ha! my pretty paper collar, I must turn you. You'll never die a heretic. By Jove! paper collars were a great invention: they emancipate the lord of creation from the thraldom of the washerwoman. Better to face the free sky than to pine in this stuffy cell. Your toilette is finished, Manus, my friend, and now to pass under the Caudine forks.'

The Caudine forks was the term he applied to the passage leading by the concierge's narrow office to the open street—a humiliating passage enough, it is made, to any man of proud spirit and slim purse by the voluble Parisian concierge, the warder of the entrance to the lodging-house. The concierge is a perennial fountain of gossip, the demon of grasp personified, and is popularly supposed always to have a daughter at the Conservatory of Music. Watching his opportunity, crouched at the bottom of the dark stairs, O'Hara bolted at a mad rush through the hall, and never ceased running until he had gained the Boulevard St. Michel, after traversing the intervening Rue de l'Ecole de Médecine.

He stopped a minute, laughed, tightened the belt which supported his trousers, cried in a light voice, 'Blockade safely run!' and resumed his way rapidly along the boulevard till he came to the quay, then turned to the right, past Notre Dame, until he reached the Pont d'Archevêche, whereat he stopped. The Morgue was near—gloomy receptacle of the unclaimed dead, sent to their God before their time by crime, starvation, or despair, or by some of the accidents which often-times cut short the span of the happiest human life. He looked at it with a desperate, desponding, forlorn look for a little time, and then broke out as if in sequence of some train of thought:

'No; it's no use thinking of it. I couldn't do it. If it weren't for the immortality of the soul, and that inconvenient religious training I've got! Now if I were a Pagan, I could freely end my woes in that silent river; but I'm a Christian, and must suffer them, and curse my kind.'

A mournful yet affectionate whine at his feet attracted his attention. He looked down. A lank, ugly cur, of unassignable breed, but unmistakably currish—a rank, unmitigated cur, with melancholy visage and moist eyes—returned the look.

'Poor dog, you, too, have hunger in your face. The world has deserted you!'

The dog whined again, and rubbed his thin sides familiarly and confidently against the bottom of O'Hara's trousers.

'Alas! friend, I am like yourself—a wretched, friendless dog. Your imploring looks are lost on me, though, Heaven knows, I would relieve you if I could. Haud ignara mali miseris succurrere disco. Faith! the gender is wrong there. My grammar is going with everything else. I suppose I should have said ignarus.'

He faintly smiled at the notion.

'But I have nothing—absolutely nothing,' running his hand expressively across his waistcoat-pockets. It stopped—his face lit up joyfully; then fell. 'Blessed,' continued he, 'are those who expect nothing, for they shall not be disappointed,' and slowly putting his hand into the pocket he extracted, with difficulty, a silver piece of ten sous. He looked at it steadily, almost incredulously, then at the dog. 'Come, my friend,' he cried, 'companion in misfortune, you must share my luck.' And five minutes afterwards O'Hara and his dumb acquaintance might be seen in the nearest crêmerie, O'Hara munching a roll of bread and the houseless dog greedily lapping a bowl of hot milk.

And both of them looked very happy dogs.

WHEN the stray dog had finished his welcome repast, licking the sides of the bowl which had contained it with a gusto which many a dyspeptic favourite, fondled on the velvet cushion of my lady, and carried about by my lady's footman, would have envied, O'Hara began to talk with him; yes, to talk with him—and the dog answered him, as far as eyes and tail could speak.

'Well, my poor fellow, you seem to like that!'

The dog curled his tail and licked his lips.

'What's your name? You don't know, nor where you were born. You're as ignorant as Topsy.'

The dog sought the ground with his eyes.

'I must give you a name. Suppose I call you Chance, to mark how I found you; or Bran, like the dog in Ossian; or Hector—no, that's too bumptious a name, and you're no bully.'

The dog wisely shook his head, as if he looked on the idea of bullyism with pity.

'Let me see; egad, I'll naturalize you! I think you have a very Irish face—an honest, open, grateful face—and I'll call you Pat.'

The dog wagged his tail joyfully, stood on his hind legs, and stretched out a paw.

'Wonderful creature! can it be that I have hit on your name? Well, Pat'—again the tail wagged—'if you belonged to a rich family you would be housed, perhaps, in that hospital for indisposed gentlemen of your breed I see advertised on a kiosk near the Palais Royal; but, because you really want a friend and a crust, you are left without either. That's the way with the world, Pat,[5] and you're a vagabond, though goodness knows you're ugly enough to be a pet. I declare you're as ill-favoured as any pug I ever met sitting on a Brussels hearthrug, if it were not for that face.'

The dog gave an assenting bark.

'But we mustn't be stopping here too long, Pat, though our time isn't very precious. George Francis Train says the next best thing to money is the suspicion of money, and I say the next best thing to occupation is the suspicion of occupation; and, by my word, they lock you up for having no occupation in England, though you may be wearing the soles off your feet to get one. In the great world they go to the theatre or the opera or the circus after dinner to promote digestion, and I think I know where we can enjoy ourselves cheaply after our banquet. Hi! Pat, come along.'

And, rising, our friend retraced his steps towards the bridge, stopping for a moment at a tobacco-shop, where he purchased and lit a cigar at a sou, at the same time giving loud expression to his regret that he had forgotten his Turkish pipe.

'We must be economic, you know, and tobacco goes farther than a weed,' and seeming mentally to calculate the state of his finances—'three sous for milk and two for bread, five, that leaves five'—previous to hazarding the investment.

The open space in front of the Morgue is a favourite 'pitch' of the mountebanks who earn their livelihood on Paris streets. At the time our pair made their appearance, it was occupied by a number of the tribe in full swing. In one corner a low-sized, deformed figure, recalling the Quasimodo whom Victor Hugo's genius has made historic in connection with the neighbouring church of Notre Dame, was appealing to a crowd of bystanders to jerk ten sous more into the ring, and he would transfer the hump on his back to his breast. O'Hara did not wait for the tardy money to come in; he had no taste for the crooked talents of the posture-master.

A group in another corner surrounded a tanned fellow, with long hair and an eye like an onyx, who beat time on a drum, as he chanted a merry skit on a Paris by-word of the season—'Avez-vous vu Lambert?' to the air of 'Maman, le mal que j'ai,' while the woman who accompanied him sold copies of it by the sheaf to laughing workmen, soldiers, and nursery-maids.

But by far the largest assemblage was drawn to a stout acrobat in faded tights, which might have been washed at some remote era, bedizened with spangles that revealed a faint tradition of glitter. He had an amazing flow of impudent 'patter,' this acrobat, and let it spout uninterruptedly as he flung up little metal rings, in quick succession, high in the air, catching them as they fell on a tin cone, strapped to his forehead, in the fashion of a unicorn's horn. Sometimes he missed them, and they slapped with a crack on his skull, and rolled off behind by a bald channel, which frequent misadventure of the kind had worn in his hair. But the spectators were as highly amused when he failed as when he succeeded—indeed, more so, if the truth must be told—for had they not a hit and a miss together? When the cone was encircled with rings, he flung up a monster potato, impaling it on the spike as it descended, amid the acclamations of his admirers.

'Come along, Pat,' said O'Hara; 'here is something more in our line,' as he passed to another group, before which the owner of a troop of educated dogs and cats was performing.

'This is M'sieu Rigolo,' cried the showman, as he placed one chair reversed on another, and taking a poor cat, that looked as if it couldn't get up an emotion at a family of mice round a Stilton cheese, balanced its claws consecutively lengthwise and crosswise on the upstanding legs. When the cat had been sufficiently tortured it was dismissed, to its evident satisfaction, to the basket which served as green-room to the perambulating theatre.

'Present yourself, M'sieu Romulus,' cried the showman, and a poodle of remarkably subdued mien reluctantly entered the arena, much as a slave who was devoted to the lions might have done in the old Roman times. M'sieu Romulus had not the boldness of his illustrious namesake of antiquity, but he had more than his sagacity. His strong point lay in detecting the most amorous man, the most beautiful lady, the greatest idler and so-forth in the surrounding company. The showman, putting a card in his mouth, asked him to point out such a one. Romulus stood up in the attitude dogs are wont when asked to beg, moved carefully round and finally trotted off in the way he should go, and dropped the card at the feet of the chosen person.

Romulus was dismissed in his turn to the green-room, and the showman called for Mademoiselle. The call was responded to by one of the saddest short-eared dogs ever seen, girt round the middle with a miniature crinoline which made the creature a grotesque caricature of a woman in the prevailing fashion as she hopped into the circle painfully on her hind-legs.

'Salut, Ma'amselle!' said the showman; 'we want to see you dance a minuet,' and he commenced playing on a pandean pipe. But Ma'amselle did not dance long. Pat, who had been watching the whole performance with canine amazement from between O'Hara's legs, suddenly rushed in, extended his paws and lowered his head in front of the disguised member of his species, and barked a good-natured bark. Ma'amselle dropped on all fours, and looked up inquisitively at the showman's face. The showman flung his pandean pipe at Pat's snout, and the poor intruder ran howling round the amused throng. No one would make room for him to escape, until at last a short thickset man, in a long frieze coat caught him, pulled him to himself, and cried to the showman, in a foreign accent, 'It is not French to strike a dog for gallantry; he simply entered because he didn't like to see Ma'amselle dance without a partner. Didn't you see him make his bow?'

'Pardon me, sir,' said O'Hara, who had been shut out from the inner circle by the forward rush, as he made his way to the friendly stranger; 'but I believe I am the next of kin to this unfortunate animal.'

'Have him, sir, and welcome,' said he in the frieze. 'I never like to see an animal struck that can't strike back for itself.'

'Thanks, sir,' said O'Hara, and then, turning to Pat, he continued, speaking this time in English, 'Come, my companion, we'll leave that brute of a showman: every dog has his day, and perhaps you'll have yours yet.'

The stranger looked after the pair sharply as they turned towards a crowd where a little old man was expatiating on the marvellous abilities of Madame La Blague, the celebrated clairvoyante, and muttered something between his teeth. The celebrated clairvoyante was seated on a chair in the centre of a crowd, her eyes bandaged like those of the figure of Justice, and her hands crossed on her lap in the attitude of Patience on the monument.

'Now then, messieurs,' said the little old man, 'take a ticket and have your fortune told. Only ten centimes. Tell me your hopes, your fears, your desires, and madame will at once read the answer in the Book of Fate when I ask her.'

'Hark you, friend, I want my fortune told.'

It was the man in frieze who spoke. He had moved up after O'Hara and the dog.

'Take a ticket, sir, and wait your turn,' squeaked the little old man.

'Is it so? That's a thing I never do. Ten centimes, you charge; now I'll give ten francs—that's a thousand centimes—if madame is able to return me a single true answer to five plain questions I'll put to her myself.'

'I'll try, at all events, sir,' said the woman with bandaged eyes.

'I like that. To start—how old am I?'

'Forty-four,' answered the woman, after a pause.

'You don't flatter. I'm between the thirties and the forties still. Guess again—what's my disposition?'

'Impatient,' was the immediate answer.

'You've got to earn the money yet. My profession?'

'Soldier.'

'What regiment?'

'The Foreign Legion.'

'Ha! Then you've found out I'm a foreigner. From what country, pray?'

'From Ireland.'

The stranger in frieze started, gave an ejaculation of surprise, and, taking out a ten-franc piece, advanced towards the woman, and said he could understand her guessing he was a military man from his tone of voice, and the further fact that he had served in the Legion from his foreign accent; but he demanded in a puzzled tone that she would explain how she had discovered his country before he redeemed his promise.

'We show-folk travel a great deal, sir,' she said in a low voice. 'I have been in Ireland, and I recognised the accent.'

'That explains the mystery. Like Columbus's egg, all things are easy when they're known. Well, madame,' he continued aloud with a chuckle, 'if you've been in Ireland you know us. When we promise France we give the Isle of St. Louis.[6] Here is a ten-sous bit for you.'

Her countenance fell until her delicate fingers conveyed to her senses that it was, indeed, ten francs she possessed. The crowd applauded, said he was as witty as he was generous, and the man in frieze turned on his heel. He looked curiously towards the neat white one-storied structure beside the footpath from the Pont d'Archevêche to the Pont St. Louis, into which a stream of wayfarers was continually flowing, and finally directed his steps thitherward too. It was a cheerful-looking building that, which drew so many visitors, but, nevertheless, it was the Morgue—half-way house between untimely death and the outcast's grave. The stranger entered the wide door—a tall partition divided what was inside from his view; he passed around it and was within the grisly hall. O'Hara mechanically followed; he had no curiosity to scan the lineaments of the naked corpses which awaited recognition within—he was rather blasé of sights of the kind, and regarded a body on a Morgue slab as he would a carcase on a butcher's stall; but he felt a something impelling him towards this stranger who had discovered himself to be a countryman. As he entered, reading, perhaps for the hundredth time, the inscriptions on the wall, which told friends who identified the deceased that they could establish their identity with the greffier free of charge, he caught an exclamation of surprise in English in the brusque voice of the man in frieze.

'Hah! so you've shuffled off this mortal coil, Marguerite.'

O'Hara turned in the direction from which the voice came; he distinguished his compatriot in the middle of an unusually excited mass which pressed against the bars of this loathsome cage of mysterious horrors, a grim smile twisting his features. He could not see any of the twelve sloping tables on which the bodies were laid out in their last toilette—their stiff limbs stretched, hair combed back, hands fixed by their cold sides, and squares of black boarding covering the stomach and thighs—because of the intervening crowd. The clothing of the unclaimed dead, hats, jackets, and blouses, suspended from racks overhead, alone was visible.

'What's the excitement?' he asked of a grizzled soldier, who edged his way back from the bars.

'Oh, it's only a cocotte of the quarter, who's been fool enough to go to the devil before the devil came to her. Sapristi! but she's been a well-favoured wench, and's got a well-turned leg even on her calafaque.'[7]

'Marguerite, Marguerite,' said O'Hara, as if recalling some train of thought.

'Yes, that's what's yonder individual, who pretends that he knew her, denominated her; but I inflect he's a joker.'

'Tall, with an Italian face and black hair?' asked O'Hara eagerly.

'Ay, ay, tall, with a handsome, despising face, and long hair, as black as a grenadier's bearskin.'

'I, too, think I know her—if it be the same.'

'If it be the same! It strikes me, jokers are consolidating in the Morgue to-day. Good-morning, bourgeois, I'm an old soldier,' and away marched the veteran.

A pretty little girl, coquettishly clad in the costume of the grisette, a well-fitting robe of gray, relieved by a tidy patent leather belt with clasp, setting off her figure, and large imitation coral drops glistening under her bright chestnut hair, entered at the moment, a basket on her arm, as if returning from her work.

'Have you seen the bodies yet, please, sir?' she said to O'Hara.

'Not yet, mademoiselle,' he replied graciously; 'but if you wait a little, I shall get a place for both to see them.'

She smiled her thanks.

'Now, then, forward. It's the first time I have ever seen a crush at the Morgue;' and they perseveringly made their way to the front.

On a black slab lay extended the nude limbs of a woman who had been taken from life before she had reached its noon, whilst she might have been full of strength and lusty joy. They were bloodless to the view, but round and beautiful of proportion, and clean of colour as a statue of purest marble by a master hand. The head was pillowed on a luxuriant mass of wet, matted raven hair. There was a smile on the face (which was wickedly handsome, as the soldier had described it), even in death, and a proud, disdainful curl had left its unchangeable impress on the mouth.

'By Jove, it is Marguerite!' cried O'Hara involuntarily.

At the same instant the little grisette, whom he had helped to a place, turned pale and trembled, and falling back in a faint, sank into his arms as she murmured from between her white lips, 'Merciful God! Caroline, poor Caroline!'

THE crowd immediately gathered round the fainting grisette as she lay in the arms of our friend, forgetting, in their eagerness for this fresh excitement, the morbid spectacle on the slab. With the same idle gaze of curiosity which they had bestowed on the dead girl they turned to the inanimate form of the living. O'Hara gently permitted the body to lapse on the ground, and quickly divesting himself of his coat, folded it in the shape of a bolster under her head—and then looked at her and felt embarrassed how further to act. Above all things he abhorred a 'scene' and here he was fairly constrained to sit for one of the leading figures in the picture. He lost his presence of mind amid the multifarious inquiries and suggestions and proffers of help of the craning spectators who pressed upon him and his breathless charge; and, to complete his humiliation, he awoke to the fact that he had a piece of canvas sewed on where the back ought to have been in the waistcoat he exposed, just as a well-dressed lady put a bottle of eau de Cologne into his hand, telling him to apply it to the lips of the sufferer. How soon he might himself be in a condition to require a restorative we might have to tell, had not an imperious voice commanded the crowd to make way, and a man, following it into the centre of the group, proceeded to put his orders into force by a vigorous and skilful application of his elbows.

'Stand back,' he cried; 'all the creature wants is air, and ye're getting up a competition to smother her.'

Turning to one of the busiest on-lookers, he urged him towards the door of the greffier's office, directing him, as he was a smart fellow, to fetch a carafe of cold water in a hurry; and then, leaning over O'Hara, as he held the pungent bottle to the girl's nostrils, he said in English, accompanying his words with an impatient gesture, 'Drat that stuff; here's what'll revive her!' at the same time producing a brandy-flask.

O'Hara looked up and recognised the sturdy stranger of the frieze coat.

'Well, how long will you keep staring at me? Ay, boy, that's right with the water—see, she opens her eyes. Now to slip a little of the water of life down her throat. Keep her mouth open with your penknife. Ho, ho! she'll come round in a jiffy. See here, mister, you with your coat off, will you help me to trundle my sister out of this infernal hole? Catch up her legs, man. Hang it! one would think you were handling glass marked "This side uppermost."'

Partly in obedience to this torrent of words, and partly because he had, for the time being, no will of his own, his self-possession completely gone, O'Hara obeyed the stranger, and between them the girl, still pale and prostrate, was lifted to the door. The stranger hailed a hackney carriage which was passing, and, helping the grisette in and pushing O'Hara after her, he mounted beside the coachman, and drove in the direction of the Place before the gate of Notre Dame.

When they had arrived opposite the Hôtel Dieu, he stopped the carriage, dismounted, looked in at the window, and burst into a roar of laughter.

O'Hara turned from the girl, who was leaning back in a corner, her eyes open in a wide, wondering way, and confronted the stranger with a fierce yet perplexed look. But he only renewed his laughter.

'Is it at me or your sister you're laughing, sir?' O'Hara found words at length to say.

'My sister! Ha, ha! never saw her in my life before,' and he resumed his guffaw.

'Open the door,' cried O'Hara, at last thoroughly roused.

'Who's your tailor?' said the irrepressible man in the frieze coat.

The pride of the poverty-stricken Irish gentleman was touched; his shame overcame his anger, and, foolish fellow! he blushed for that of which he had no need to be ashamed.

'That's the loudest thing in vestings I know; you've got the falls of Niagara on your back, man.'

O'Hara, removing his waistcoat in a flurry of confusion, discovered that the painted side of the old canvas, the remains of some artist friend, had been, indeed, turned outwards when he had put it for a patch to his waistcoat a few days before in his blundering amateur tailor fashion.[8] Looking at it, he could not help laughing himself.

'When a man wears that pattern of waistcoat, he shouldn't forget his coat after him.'

To heighten his difficulties, O'Hara now discovered for the first time that he had left his coat behind him at the Morgue.

'Can't go back,' said the stranger. 'Here, coachman, to la Belle Jardinière.' (This was the name of a famous clothing warehouse in the quarter.)

'But I've no money, sir, to buy a coat, if that be what you mean by going there,' said O'Hara.

'Tell me something I don't know; you're a poor devil!'

'Ah! you've discovered that,' exclaimed O'Hara, nettled.

'Knew it by intuition—been one myself.'

'But I am not a mendicant.'

'Who said you were?'

'I have money coming to me—I'll have it—in a few days.'

'I know it, and I'll lend you the price of a coat in the meanwhile.'

'Thanks,' cried O'Hara, with effusion, for he couldn't help feeling the terrible awkwardness of his loss, and he began to see that his new acquaintance was a humorist. 'What might your name be, sir?'

'What might it be! It might be Beelzebub, but it isn't.'

'What is it, then, if that pleases you better?'

'What's in a name?'

O'Hara paused a moment. 'Right!' he answered at last; 'a name is nothing without money behind it.'

'Ay, ay, my lad; "what's in a name?" as the divine Williams says: it's nothing, as you remark—just about as much as your purse holds at present. Don't be angry with me; been that way myself. Know Goldsmith?—

| '"Ill fares the cove, to hastening duns a prey, |

| Whose bills accumulate and bobs decay." |

'Ha, ha!—see the point—Bills and Bobs. But look to the lassie; she's going off again, I fear;' and the queer stranger handed him the brandy-flask in which he had such faith.

'Caroline,' the grisette again murmured, and dropped off with glassy eyes into a tranced sleep, irregularly punctuated with sighs.

'Here you are, sir,' cried the coachman—'la Belle Jardinière.'

'Stay where you are,' said the stranger. 'I'll fetch you out a fifty-franc coat; can size you at a glance. Shake up that girl;' and he disappeared rapidly.

The girl, fully roused by the sudden stoppage of the vehicle, gazed round her with a lost look, as if to collect her scattered senses, and vainly endeavoured to realize how and why she found herself in a state of exhaustion in a carriage with a strange man. At last, under the influence of O'Hara's kindly reassuring face, she began to recall what had happened. The slab in the Morgue, with its burden, which had robbed her of her senses and strength, rose before her eyes, and she shuddered.

'Courage, my dear,' cried O'Hara firmly; 'drink,' pressing the flask of brandy to her lips; 'you are with friends!'

The girl did as desired, and looked her thanks. O'Hara commenced chafing her hands. She smiled faintly, uttered a few gracious words, in which the magic syllable 'home,' a spell in every land, alone could be distinguished.

'Ha! you want to get home, my pretty one; we'll take you,' said the rough yet good-natured stranger, popping in his head at the window. 'What's the neighbourhood?'

'Place du Panthéon,' whispered the girl.

'All right, catch your coat and I'll follow it,' flinging the purchase on O'Hara's lap, then turning to the coachman to give him his directions before entering, he exclaimed, 'Hallo! What's the row?'

The coachman either didn't hear him or was so busy with some object at the other side of the carriage, which he was endeavouring to reach with the lash of his whip, that he didn't mind him.

'I'll put a flea in your ear,' and with the expression of this benevolent intention, he jumped on the box, doubled his fist, and was about to apply it to the side of the unconscious Jehu's head, when he suddenly arrested it in its progress, snatched the whip out of the uplifted hand before him instead, and broke into a hearty laugh.

O'Hara felt more and more puzzled at the extraordinary conduct of this extraordinary person, and couldn't help looking out after him, when he heard the unexpected merriment. The stranger was descending and encountered his bewildered stare.

'Look out of the other window,' cried he; 'blessed if it ain't that inquisitive dog!'

O'Hara complied, and discovered the cause of all the commotion.

It was Pat, the foundling dog, who was panting on the pavement, the threadbare coat of the man who had befriended him held between his teeth![9]

The faithful creature was at once, of course, received into the carriage, and the driver was ordered to proceed rapidly to the Place du Panthéon, taking the Boulevard St. Michel on his way.

'We shall call into la Jeune France on the route,' said the stranger, 'and get this poor little wench something to revive her.'

The girl caught the words and made signs of dissent at the mention of la Jeune France, which is a famous coffee-house much affected by roystering students and the frail partners of their revels. As soon as she could find language, she uttered a feeble but emphatic 'No.'

'What! You turn up your nose at la Jeune France. Well, we'll cut it. Driver, straight to the Panthéon. Nevertheless, my child, it was there I met your dead friend first!'

'No, never,' cried the girl with gathering energy. 'Poor Caroline!' and she burst into a comforting flood of tears.

'Poor Caroline, indeed! How many aliases had she? When I knew her last she was called Marguerite la modiste,[10] and that was no later than last night.'

'You met her last night?' inquired the girl in excited tones.

'I danced with her at the Closerie des Lilas!'

'Oh no! Say you didn't. Caroline never frequented such a place,' pleaded the poor girl in the beseeching tone of one praying for mercy from a threatened weapon.

'It was there I made her acquaintance, too,' remarked O'Hara.

'There must be some mystery here,' said the stranger, pausing; 'you call your friend Caroline. I call her Marguerite, and she's known to the entire quarter by that name. We shan't speak about her reputation.' With a wink at O'Hara, 'De mortuis nil nisi bonum, with Swift's translation. Not meaning any compliment, she was more beloved than respected.'

'I don't understand you, monsieur, but I'm grateful to you both for your kindness. I'll thank you to let me alight as we arrive at the Place du Panthéon.'

The girl arose, but the effort was too much for her strength, and she tottered back helpless to the seat, crying:

'Oh, I am so weak! My head is on fire!'

'Rest where you are; we'll see you to your own door, and I'll have a doctor by your bedside in five minutes,' insisted the stranger with gentle violence. 'What's your street and number?'

'Rue de la Vieille Estrapade, thirty.'

The carriage was quickly driven to the street indicated, which runs quite near, in close parallel with the temple of St. Geneviève on its southern side, and the Jehu, with a crack of his whip, drew up before number thirty—a tall, substantial, square-built house.

'Now, my child, take my arm,' said the stranger in the frieze coat, rising and assisting his wearied charge to the door.

No sooner had the faltering creature reached the steps of the carriage, than a blithe female voice rang out from a window on the third story:

'Welcome, Berthe—welcome, our little song-bird.'

The girl raised her eyes in a stupefied daze, her frame quivered, the blood fled from her cheeks, and for the second time she sank into the arms of our friend, who stood luckily behind her, in a profound swoon; but this time it was a swoon of joy.

JOY seldom kills. Before the female figure, whose apparition at the window had thrown the girl, so strangely fallen under O'Hara's protection, into her second swoon, had time to trip down the stairs, the attack had spent itself, even without the intervention of the brandy-flask of him whose name was not Beelzebub. The sensitive creature was smothered with kisses by her friend, the while the two male observers of the situation looked on and at each other with a comical stare of envy. The newcomer was a slender, willowy woman, of a meridional cast of countenance—hair rich and dark in hue, features proud and delicately chiselled, and complexion swarthy. She was tall in stature and gracefully built, but rather inclined to the meagre, and seemed as if she had aged before her time. She might not have been more than twenty-three, but she looked as if verging on thirty, and yet there was quite a youthful impetuosity in her manner, and springiness in her movements, as she literally devoured her little friend in her embraces. In the middle of this tantalizing greeting, he whom we shall call Friezecoat, for want of an introduction, called out in his rough and ready voice:

'Ho, ho, my pets! I protest against this, unless we lords of creation are admitted into the arrangement.'

The brunette turned a look of chilling surprise at him, as if questioning who was this intruder who spoke so familiarly. Then, holding the little girl of the chestnut hair, whom she saluted as Song-bird, at arm's-length, as if to examine the Song-bird's plumage, she exclaimed:

'Berthe, you little fool, why did you faint? How do you account for coming home thus?'

The only answer Berthe made was to lean her head forward on her friend's breast and burst into tears.

'How like that woman is to Marguerite la modiste!' whispered O'Hara to Friezecoat. 'I'm not astonished at her she calls Berthe having mistaken the body in the Morgue.'

'Oh, Caroline dear, then you are alive!' said little Berthe, at length finding words amid her sobs.

'Alive!—yes, really alive, ma mignonne, and I shall be chastising you presently to prove it, if you don't dry those tears. Why do you weep?'

'I went into the Morgue to see the body of a girl who had drowned herself, and, oh! it was so like you; and then, you know, Caroline, you've been away those three days.'

'And have I never been at Choisy-le-Roi for three days before? Giddy—giddy girl, you've been to the Morgue. Don't tell this to the grand-père.'

'Yes, and I have had such a fright. Don't frown, Caroline. I thought 'twas you I saw laid out, and when I awoke I was in a carriage with those gentlemen, who have been very kind to me and brought me home.'

The brunette bowed graciously to Friezecoat and O'Hara, and said:

'I thank you infinitely, messieurs, for your kindness to my young friend; and if you'll have the goodness to wait a little, I'll call my grandfather, and he will thank you too, and pay for this vehicle.'

'Madame, you offend me,' said Friezecoat gruffly.

'Pardon,' said the brunette, colouring a deep red; 'I see I have made a mistake. At least, gentlemen'—with an emphasis on the latter word—'you will step up to our apartment until grandfather returns you thanks in person.'

The four mounted by broad stairs to the third story, and entered a small, lightsome chamber, neatly furnished. The scent of violets was in the air. The window was draped with white curtains, the walls were hung with engravings of military subjects, a cottage pianoforte lay open at one side of the window, a comfortable armchair was set at the other, while high in a wicker-cage a throstle fluttered in the rosy light between. Plaster busts of the first and third Napoleons were set on brackets, and flanked a large print of the Imperial House, from its founder and Josephine, Marie Louise, the King of Rome, and Hortense Beauharnais, down to the youthful Prince Imperial, in his uniform as corporal of Grenadiers of the Guard.

After motioning them to seats, the girls disappeared into an inner room, and almost immediately a tall, old man, with head held erect, white hair and moustaches lending him a venerable appearance, the chocolate-coloured ribbon of the St. Helena medal in his button-hole, stood in its doorway.

'Messieurs,' said the old man, advancing stiffly, 'you have been kind to my grand-daughter, and I, Victor Chauvin, officer of the First Empire, thank you. I am at your service for any duty you can ask me in return;' and the rigid body was bent with soldierly angularity in what was intended to be a very ceremonious bow.

'And we—that is, the men of our country—are always at the service of distressed females without expecting or asking any return,' said Friezecoat as formally.

'What countryman are you, sir?'

'We are Irish.'

O'Hara regarded Friezecoat with surprise. How had this bizarre personage discovered his nationality? He forgot that he had heard him speak.

'Ah! lusty comrades as ever I met at assault on battery or bottle. I knew some of them in the Legion in the Man's time,' said the old soldier.

'The man—who was he?'

'Who was he? There was only one man in this century, and his name was Napoleon. Sir, I'm afraid you've learned history from Père Loriquet;' and the old soldier smiled.

'Yes, he was a man.'

'Sir, shake hands with me for that,' said Victor Chauvin, evidently flattered. 'But you must let the old soldier show his gratitude for your kindness to his child. I insist on it.'

'Well, if you will have it so, tell us why your grand-daughter is called the Song-bird, and we're repaid?'

'Because she sings like the nightingale; no, that's too sad. Like a canary; but that's a prisoner. I have it—like the morning-lark, for its song, fresh and pure, goes up to God's gates! Berthe, enter.'

At the call, our young acquaintance, the traces of her recent infirmities entirely removed, came radiantly into the room, smiling with an arch smile.

'Berthe, my Song-bird, treat those gentlemen, who, you have told me, have been so good to you, to a sample of your voice.'

'What shall I sing?' asked Berthe, approaching the piano.

'Sing the romance that friend Bénic wrote for you—le Vieil Irlandais—for these gentlemen are from that brave and faithful land; ay, brave and faithful, for it has known how to carry the sword without taking the cross from its hilt.'

The girl skilfully passed her fingers over the instrument, executing a tremulous prelude, and in a soft, sweet voice, trilled, to a pathetic air, the following touching verses, the old soldier joining in at the refrain which ended each:

| Mon fils, écoute un vieillard centenaire. |

| Tu nais à peine et moi je vais mourir, |

| Fuis, sans retour, par l'exil volontaire, |

| Le sol ingrat qui ne peut te nourrir. |

| Sur ce navire, où la foule s'élance, |

| Tu vas vogeur vers les États-Unis; |

| Dans ces climats, au sein de l'abondance, |

| Vivent heureux vingt peuples réunis. |

| Des flots de l'Atlantique |

| Ne crains pas le courroux; |

| Émigré en Amérique, |

| Ton sort sera plus doux. |

| Au jour naissant tu commençais l'ouvrage, |

| Sous un ciel gris, pendant un rude hiver; |

| J'ai vu faiblir ta force et ton courage |

| A défricher les champs d'un duc et pair. |

| Jamais ses pas n'ont foulé son domaine, |

| Loin de l'Irlande il voyage en seigneur. |

| Infortuné, la disette est prochaine, |

| Quitte à jamais ce séjour du malheur. |

| Des flots, etc. |

| En cultivant des savanes fertiles, |

| Garde ta foi, si tu veux prospérer; |

| Fais tes adieux a nos sillons stériles; |

| Sans espérance il faut nous séparer. |

| Prends cet argent, fruit de longs sacrifices, |

| Au centenaire un peu de pain suffit, |

| La mer est belle, et les vents sont propices; |

| Pars, mon enfant, ton aiëul te bénit. |

| Des flots, etc.[11] |

There were tears in the woman's soft voice, and when she finished there were tears in the eyes of at least one of her listeners.

'Thanks, mademoiselle,' cried O'Hara, with emotion; 'thanks for that little tribute to the sorrows and affection of poor Ireland. He who wrote it knew the land, at least, in spirit.'

'He has never been there, sir, has not my friend, Laurent Bénic; he is but a humble carpenter, but he has learned to love the green Erin, the younger sister of our France, as I have.'

'Is that the Bénic who wrote "Robert Surcouf," a rattling corsair ballad?' demanded Friezecoat.

'The same, sir.'

'Will you ask Mademoiselle Berthe to make me a copy of it, words and music, and will you allow me to send her a present of some of our Irish music in return?'

'Certainly; shall we not, Berthe?' Berthe smiled happily. 'And I'll ask you, sir, to come to hear her play your country's music. He who has been kind to the old soldier's grand-daughter is welcome to the old soldier's hearth.'

Shortly afterwards the two Irishmen, who had made such a rare rencontre, bade their farewells to the Frenchman and his grand-daughter, and left.

'He's a regular old brick, that Chauvin,' said Friezecoat on the doorstep, 'and I'll remember that song to his grand-daughter. If she wasn't my sister to-day, she may be something nearer some day. Good-night.'

'You're going, and you've not told me——'

'Not to-night. Search the side-pocket of that coat, and you'll find fifty francs in it. Au revoir.'

And this strangest of strange characters jumped into the hackney-carriage and disappeared by a street leading to the Panthéon, leaving O'Hara in a brown study in the brown shadows of the Rue de la Vieille Estrapade.

He was roused from his reverie by an affectionate whine, now become familiar. It was the dog, forgotten when they entered the house, and who had been lying patiently by its threshold. He returned the creature's welcome with a caress, and determined, as he had fallen in with him so curiously, and as he had shown so lively a sense of gratitude and fidelity—much more than humanity usually permits itself to be betrayed into—to take Pat back to his lodgings and adopt him. He did not fear the Caudine forks now, for he had the grand passport, the jingling gold, in his pocket, and the old pride returned to his port and the jovial defiance to his eye. Gaily he strode down by the Rue Soufflot to the Boulevard St. Michel—we believe he might even have been heard whistling 'Rory O'More,' to the huge delight of the dog, who capered at his heels—until he reached the café of la Jeune France, where he came to a dead stop on the pavement, as if debating something in his mind.

'No,' he said at last, 'I shan't go in; I'll see, for once, if I can keep a good resolution when I have the means of breaking it. Egad, this is a day of adventures for me. If half these things were written down in a story, the world would say the author was a lunatic, or imagined he was writing for fools!'

Not the least grateful surprise awaited him at his hotel in the Rue du Four when he re-entered. It was a letter of credit for twenty pounds from a debtor in Ireland, which the concierge, who knew the handwriting, smilingly slipped into his fingers.

FEW who saw the miserable despairing lodger in the Hôtel de Suez, who looked out sadly from his thin blankets on the prospect of hope vanishing with the last vapour of his pipe, would have recognised the same entity a week afterwards in the gay, buoyant, flushed youth seated, choice Havana idly turned between his lips, deep in an armchair, soft dressing-gown falling around in showy folds, and his feet cased in embroidered slippers, resting, American-wise, on the marble top of a stove wherein the live logs cheerily hissed and blazed. The man was the same; that is the form, the cubic extent of flesh and blood and bone—but money had effected the grand transformation; money had made out of the wretch, fearful of the shadow of a sharp-tongued concierge, a very cavalier in lightsome spirit, airy courage, and happy way of looking at life in general. Twenty pounds had done this; gold had done it—the true philosopher's stone, whereat we be tempted to moralize much, to ask was not this human being as much entitled to human respect and more to human sympathy when he was forlorn? and all that sort of thing, and to put on our grave censor's cap and reproach the world. But we resist the temptation. For, indeed, is not money truly great? is it not the outward and visible representation of intrinsic worth always, and is not the man who has made it by trafficking in cloth or herrings, or some other articles for the good of society over a counter, infinitely to be preferred to him who thinks, and feels, and dreams much, and does not make money? Is he not of vastly more value to his kind than the mere scholar or martyr, the doer of high deeds or utterer of high thoughts? Is not the alderman—the Lord Mayor, perhaps, of next year—riding in his gilt chariot, more worthy much than Samuel Johnson in the attic vegetating on fourpence-halfpenny a day? For what is the worth of anything but its money value in the market?

But let us cease this teasing worn-out cynicism, which all will applaud in theory, and in practice all will repudiate, and return to our friend, O'Hara.

He sat, gay as he looked, surrounded by lights and such flowers as the early season furnished; a burning pastille poured out a thick unctuous stream of perfume; fruits were on the table by his elbow, and in companionship beside them slender bottles of sparkling wine. He had a sensuous appreciation of the beautiful, had our friend; but not a selfish, for he did not sit alone. At his feet, curled like a hedgehog on a luxurious mat, snored Pat, the foundling dog, a half-eaten bone held between his paws. Pat had evidently fallen upon pleasant lines; he was plump and sleek as an incipient alderman after his seven days' good treatment, and now, as aspirants to the dignity of the fur collar and the rapture of turtle-soup are wont, he was enjoying the snooze of satisfaction after the repast of repletion. Then, again, another of our acquaintances was present. Stiff and stately, as a bare old oak in winter, on the opposite side of the fire, sat Captain Chauvin—white-bearded, the chocolate-coloured ribbon on his breast, his stick held bolt upright between his legs—a figure of dignity and firmness in the frivolous air of this bachelor-chamber in gala; yet, somehow, he did not look out of place. There was sweetness in the old man's face, and benevolence and truth, which is beautiful everywhere.

'You do not smoke, captain—you a militaire of the First Empire. I wonder at that,' said O'Hara, languidly puffing the light cloud upwards in fantastic wreath from his Havana.

'No, mon enfant; there is a reason for it,' and the captain sighed.

O'Hara finished his cigar in peace—not that he did not notice the sigh of his guest, but he had too much delicacy to seek to fathom its cause.

'At least,' he said when he resumed conversation, 'you will not refuse to join me in a bumper.'

The captain shook his head.

'It is the first time I've caught you at my fireside, Captain Chauvin, and in my land we account it the reverse of good-fellowship not to hobnob at such a meeting. We shall drink together, as the Arabs break bread, to friendship and better knowledge of each other.'

The captain smiled—how charming is a smile on the face of manly masculine age!—and bowed.

'As it is the custom of your land, and as it is to be a gage of friendship, I even will,' said he, at the same time proffering a worn snuff-box, rudely wrought of horn, which he drew out of a gold case. 'Mon enfant, a pinch.'

O'Hara took of the snuff, though he found some difficulty in performing the operation of conveying the dust to his nostrils, sniffing it and afterwards sneezing. To tell the truth, he did not take snuff, considering it a dirty habit; but he felt constrained to do much to gratify the old man.

'Hola, you sneeze!' remarked the captain, surprised. 'It's rare fine snuff.'

'And that's a rare fine box you have it in; not the box, I mean, but the casket which holds it,' answered O'Hara, taking the gold case in his hands.

'What's this? The bees which the Bonapartes brought from Corsica, the eagle with the thunder-bolt in his talons, and the Imperial cipher. I'm not a judge of goldsmith's work, but I should say that's a piece of some value.'

'And the horn box—the box for which all this finery is the covering. What d'ye think of that?'

'It is not valuable in material nor artistically, and yet it may be valuable as a souvenir,' said O'Hara, after regarding it.

'Ah! I would not give that box for ten—what?—a thousand times its weight in gems,' said the old man, kissing it reverently. 'There's a story attached to it.'

'Yes, yes, how we do cling to the relic of what has passed from us, and each day, as we look upon it, it becomes more precious in our sight!' said O'Hara, half in soliloquy, drawing a little parcel from his breast. 'Here it is now, only a lock of woman's hair, faded, flattened out of curl, and she—where is she?—what does she? Does she ever think of me? Bah!'—with a violent jerk thrusting back the parcel to its resting-place; 'you're a fool, O'Hara! Come, captain, let me fill you a bumper of the grape-juice.'

The captain had been watching the by-play with the tress of woman's hair with an amiable, almost sympathizing, eye. 'Young friend,' said he, 'you've loved and been disappointed, I take it; but do not despair.' O'Hara blushed. 'At your time of life,' continued the captain, 'one does not die of those crosses. I know them. Do not blush; I, too, have been disappointed in what my heart had set its affections upon, and, alas! it has coloured my whole existence.'

'A good blood-colour, I fancy,' said O'Hara with a sardonic humour.

'Ah! you are disposed to take a cynical view of the sex. That is too soon. Life for you should be a comedy, as yet violet-crowned; a toying with honey goblets and rose-leaves; it is too soon to bring in the daggers and the cups of gall and the cypress-wreaths.'

'Life violet-crowned for me!' said O'Hara mockingly. 'It is a vile, malodorous sham; there is nothing true, nothing sincere in it but sin and death. The world is a mercenary, peddling world—the one only trade which is not meanness and fraud is the soldier's trade, where man is paid for cutting the throat of his fellow-man.'

'Let us drink,' said the captain, perceiving that the better way to alter his young friend's mood was to steal him away on other paths, not to dip into deep reasoning with him.

'Ay, ay, mon ami,' cried O'Hara with a return of the reckless spirit we remarked in his character when he lay seemingly without a sou in his pocket on his bed of bitterness, 'that is the disappointed man's friend. We will drink, drink, not to woman who drove Adam out of Paradise and your humble servant out of Ireland, but to man, to the real practical man, the man who tramples humbug and pretence under foot, and believes in himself alone, the solid, hard-hitting, clear-seeing man. Captain, here's to his health!'

'To his memory, rather,' said the captain, rising and touching the outstretched glass of his host with his own, 'for his soul is lost to us these five-and-forty years. Here's to Napoleon!'

'Yes, to Napoleon!' and they both drained their glasses to the lees. The captain resumed his seat as stiffly as ever; O'Hara took a cordial glance at the bottle, and replenishing his glass, cried as he held it aloft between him and the light, and watched the amber beads frothing in creamy tumult on its surface, 'Beautiful to the sight and to the taste, strange that that liquid should be the one sure friend to whom we can fly for the means to forget the world and its sorrows, our only certain refuge——'

'My young friend,' said the old man gravely, 'it seems to me you forget God!'

The tone in which these words were spoken was gentle rather than monitory. They fell on our friend's troubled soul like the rain which refreshes, not as advice too often does, and too often is meant to fall, like blistering drops of hot wax.

The youth, who had been contemplating the sparkling liquor as an artist might a great artist creation of beauty, looked at it a moment longer, then slowly lowering it, he said, in the calm voice of conviction, to his aged guest:

'You are right; God is the refuge; we should not forget Him,' and the spirit of the grape blazed vividly up as it was spilt on the burning logs. 'I was wrong, we were both wrong, even in drinking to the memory of Napoleon.'

'Not in that, mon enfant; all great men such as he was, men who sink themselves into the time and mark it as theirs even as the maker does his name into the sword-blade—all such men are messengers from God.'

'And his nephew?'

'God's messages do not come by hereditary office. He is auspicious for France; it is strong and feared and full of prosperous life to-day; and he is Emperor of the French. That is enough for me.'

'The philosophy of a soldier' was the only comment of O'Hara.

'Are you of the Opposition?' queried the captain, fancying he detected a latent sneer at the ruling dynasty in the latter expression.

'Ah I my friend,' remarked O'Hara with a smile, 'that is a delicate question. How shall I answer it? Like an Irishman, by asking another. Do you not know that I am a foreigner? I love your France, but I do not meddle in its politics. If I did, I suppose I should belong to the Opposition, for I was born in the Opposition in my own country, and as the sum of evil is greater than the sum of good, and usually preponderant, I take it that it is pretty safe ground to go on that whatever is, is wrong.'

'Have another pinch of snuff,' said the captain, shaking his head and proffering the golden box with its horn enclosure.

'This great N,' said O'Hara, again examining the ornamented outer lid with curiosity—'is that for the nephew or the uncle?'

'It is for the Man,' said Monsieur Chauvin, almost offended.

'Did you not say there was a story attached to it?' continued O'Hara.

'Yes; but would you laugh at an old man?'

'Captain Chauvin!'

'Pardon, my good young friend. I will tell it you. On the day of Mont St. Jean, the 18th of June, 1815, I was a sub-lieutenant of artillery in the column of our glorious Ney—the laurel to his ashes! Ah! your Wellington let him be slain like a dog; that was not soldierly. The Emperor directed a false attack on the château of Goumont; while the Englishman was gathering the best of his forces to its defence, the Man stood, pale and weary, with the same quiet, steady gaze, a smile fixed into the earnestness of a frown, which my comrades told me he had worn at Austerlitz, hands behind his back, and his gray great-coat lying moist over his boots. My battery was near, and I was on its right, quite close to the staff. "Messieurs," said he, as he saw the scarlet masses pressing around Goumont, "we make our game. Where is Ney?" An aide-de-camp galloped off for the Marshal, who was close at hand. The Man, surveying Goumont with his glass, and occasionally looking intently at La Haie-Sainte, gradually approached to where I stood. A soldier of the battery lay dead on the ground before me—a veteran whom we all loved. Feeling that we should shortly get the order to advance, I resolved to secure some souvenir of Tampon, as we called him. I found a horn snuff-box in his hand, clenched in death. The Man happened to turn towards me, and observed the act.

'"Comrade, a pinch," he said, and I handed him the box—that box; look at it,' and the old soldier, the fire of foughten fields in his eyes, hung over it with tenderness as over a loved living object—'that box was in his fingers—out of it he took a pinch of snuff on the day of Mont St. Jean.'

'Did you see him after?'

'Not that day. We advanced on La Haie-Sainte ten minutes after and gave them a hail of hell-fire. Our heavy artillery crashed through their ranks like bolts of thunder. They shook; Ney seized the moment to bring our guns right into the enemy's position, but we had a ravine to traverse; our pieces of twelve settled down in the muddy rye, a regiment of infantry came up from the rear to cover us, but Wellington was quicker. He saw our difficulty and poured a host of dragoons in on us in the valley. They cut our traces, overturned our guns, sabred our men. But, sapristi! they paid for it—paid for it dearly. Our cuirassiers rushed to the rescue like a whirlwind and swept them from earth to the last man. Brave fellows they were! No, I did not see him after, until all Paris turned out, six-and-twenty years ago, to welcome his remains to the Church of the Invalides. You know his will, Monsieur O'Hara: "I desire that my dust may rest on the banks of the Seine, in the midst of the French people whom I loved so well."'

The enthusiastic young Irishman could not but be affected at this reminiscence of an era which appeals to all that is romantic in our nature, told, too, by one who was an actor in it, and who carried in his heart, still vivid and strong, the proud affection for Napoleon with which that genius of war inspired his followers to the humblest. Nor was his sole motive that of gratifying the captain when he demanded the horn-box for another pinch, and, to the exuberant delight of the old man, with it in his hand sung Les Souvenirs du Peuple of Béranger.

'Thanks, thanks, my young friend!' cried the captain, the tears streaming down his cheeks; 'what a happy evening!'

'But, captain, you don't enjoy yourself; you don't drink, you won't smoke. True, you told me there was a reason for it.'

'Yes, and as we are together in free friendship, I'll tell you, my dear child, you who have sung such a beautiful song for the old soldier.'

But we must reserve the captain's story for another chapter.

'WHEN I was young like you,' began the captain, 'I had my illusions. I came of a royalist family which had suffered much by the Revolution, and had stood up for the cause of the king as long as La Vendée was able to keep a square league of ground to itself or a square inch of its flag flying. But we had to give way; we could not conquer impossibilities: Fortune always sides with the big battalions, as the Man used to say. The domain passed from the hands of the Chauvins, and I, the heir of the house, was obliged to take service with those who had helped to uproot the family tree. I had no other alternative; my parents were dead; I, the only scion of the ancient stock left, owed my life to the care of my nurse, a brave peasant woman, who was married to a burly grenadier of the Republic. They were kind in their way to the young aristocrat, and they loved France. Poor Céline, to-day I could drop a tear over your quiet grass-covered grave down in Burgundy: and Tricot, too, he was a thorough soldier. He died on the retreat from Moscow the same day that Schramm—you know Schramm, who is president of an army commission here now—was made brigadier-general.

'Did you ever hear the story of his promotion?

'He was a colonel when we made that fatal invasion, and in one of the bloody fights on our retrograde march, fell, pierced by a bullet. The blood bubbled in hot gouts from his wound, but the tears came faster from his eyes. The Man saw him.

'"What, weeping!" he said. "Why do you cry?"

'"Because I'm going to die only a colonel," said Schramm.

'"We'll settle that," said Napoleon, and made him a brigadier-general on the spot. Schramm has not died since.

'But to return to myself. I showed a mathematical taste, and early was sent, at the expense of the commune in which Céline lived, to the Polytechnic School. They did not keep us long over our course in those times, and I was shortly appointed to a corps on active service. It was there I learned to love the Man who was then leading France to a higher eminence on the path of glory than she had ever reached. He was the idol of the army. I had my ambition, and I often recollected with a thrill of pride and hope that he, too, was a mathematician, and commenced his career as a subaltern of artillery. But, as I told you, I was only sub-lieutenant at Mont St. Jean, and that day finished the soldier's chances for that era in France—put a quencher on his aspirations. To one passion succeeds another. Our life is a series of agitations, coming changeful in aspect but regular in period as the tides of the sea—sometimes smooth and glistening under a bright sun, sometimes restless, sullen, heaving under the strong breath of the storm. To glory, in my breast, followed love. I had met the daughter of another Vendéan family in Paris, where she supported herself by giving lessons in music. Her mother received me (she had known my mother), and encouraged my little attentions to Caroline with her smiles. Alas; had I been rich, at that time, what happiness might not have been mine, what sorrows might not have been spared to her and me!'

Here the aged officer stopped and busied himself with his handkerchief about the region of the eyes.

'But, sir, an officer with us who has to live on his pay cannot afford himself the luxury of a wife. Caroline had no dowry, and I had no position. If we had espoused each other she would have had to do without a trousseau, and I certainly would not have been able to present her with a corbeille. We loved each other, and we parted—not without some sighing, and many wishes for our meeting again under happier circumstances. I was very fond of my cigar, and Caroline's mother detested smoking. It was a mania with her. She had an unaccountable, almost diseased, aversion to the habit. One evening, Caroline, out of play, induced me to light a cigar in the chamber while she was looking out of the window. I can never forget the fierce, pallid face with which her mother turned on me and ordered me to leave the room on the instant. It was only by a plentiful sprinkling of tears from Caroline that her heart was softened to accept my excuses.

'"It is his first fault, and I tempted him," said Caroline; "will you not give him absolution, mamma?"

After a while the mother relented, but said she would not admit me to the same position in her esteem again, unless I consented to accept the penance she would impose on me. The penance was never to smoke again. I promised. This was when the wreck of our army was being re-formed at Paris, under Louis XVIII., and the allies who had violated our capital were beginning to get confident on the news which each ship conveyed from St. Helena of the hastening end of the Man whom Sir Lowe was doing to death. There was no chance of promotion for us if he did not come back; for the soldiers who loved Him, his death would indeed be the setting of the sun of Austerlitz. I had long given up the expectation of that marshal's bâton which every conscript fancies he carries in his knapsack; but still I had the conviction that some chance of distinction would present itself, even under the pacific Restoration, that might lead me to a rank sufficient to maintain my beloved Caroline in comfort as my wife. My regiment was ordered to Metz. The night I parted from her I confided to her ear the idea that was before my mind, and she looked such a cheerful, hope-inspiring look from her large liquid eyes into mine as would have put fire into a breast of stone. It was the pure lustre of a fresh innocent love, and as earnest that I accepted it as sacred, I gave her my first and last kiss of holy affection. Her mother reminded me at the door of the promise I had made about smoking, and gave me a letter of introduction to a cousin of hers who was an officer in the garrison to which we were ordered. This cousin, as I learned from a comrade who knew him, was of a haughty, overbearing temper, and I was in no hurry to hand him my credentials. About a week after my arrival I was strolling about the fortification in the cool breezy twilight of a sultry day, thinking of my future and of my Caroline, and looking up to the stars in the mood of the poet, to whom the lover is so like. I tried to shape out, in the light clouds that were flitting across the heavens in white flakes, some clue to my fortune. There that pale star, which is so small and distant to-night, but will go on steadily increasing in brightness and size until it attains its zenith, is the star of my destiny. At the instant I gazed on it a wanton scud shut it out from view; I tried to laugh, but I couldn't help feeling as if it were a presentiment of coming gloom. Then I turned towards a bank of cloud rising fantastically on the edge of the far blue horizon, and in fancy pictured to myself that a pair of jagged peaks projecting from its surface were the epaulettes of a general which awaited me; and, still looking, until my eyes had almost got as visionary as my mind, I framed out of a loose irregular mass of fleecy vapour the beamy figure of a woman, whom I had persuaded my senses into identifying as the genius of glory.

'"It is our Napoleon who comes back to France," said I; "the soldier will have his meat to carve again."

'At the moment a tall figure passed, and recalled me from my dreaming. I walked on, but somehow I was melancholic. I couldn't shake off the impression which that star, blotted out of sight as I looked, had made on my mind. I put my hand in the pocket of my uniform and involuntarily took something out of it. It was my cigar-case. Involuntarily still, I opened it—there was one cigar left. I was depressed in spirits, thinking sadly—and smoking, you know, kills thought.

'The bribe was strong. I forgot my promise to Caroline's mother, or encouraged myself to look upon it as a mere puerile engagement to humour a woman's whim, and lit the cigar. Scarcely did the red fire take at its end, and the first puff of smoke escape from my lips, when it was pulled out of my mouth and cast on the ground, and a tall man stood frowning before me, as well as I could distinguish in the dim light. My hand immediately flew to my sword-hilt, and I put myself in an attitude of defence.

'"How dare you smoke here? don't you know the magazine is beside you?" said the stranger, in a harsh voice.

'"I did not know it," I answered; "nor will I allow any fellow to make the fact known to me in that brutal manner."

'"Fellow!" and the stranger laughed; "ma foi, that's amusing; and the cockchafer has his hand on his butter-blade. Is your honour wounded, my gallant sir?"

'"Your body will be wounded shortly if you don't endeavour to civilize your tongue," I answered, enraged.

'"I positively think," said he, coolly twirling his moustaches, "that the Gascon would fight. Does your fancy run on being impaled like a frog? If so, follow me, Sir Braggart," and he moved off.

'I followed, wrath boiling in every vein. He stopped when he came to an angle in the works, totally secure from observation from any side. The moon burst out in full splendour; he cast a look upward, made a jesting remark on the politeness of the higher powers in lighting folk to kingdom come; and, throwing off his cloak, I discovered him to be a staff-officer of rank by the uniform underneath.

'"Has your courage failed yet?" he tauntingly asked, as he dexterously detached his sword from the scabbard.

'I was too vexed to speak. I said nothing, but fixed myself in the best position I knew to receive his expected attack.

'"Ha! Is that it?" he exclaimed, "think of your maître d'armes, and recommend your soul to God, if you believe in Him."

'At the last word he sprang forward, made a feint at my left leg, but carried his weapon round in a circle in the one swing, and was bringing it down on my sword-arm. But I knew the trick of old, and instead of attempting to parry the feint, I turned my body aside to the left, and held my weapon extended with a quick lunge to the front. He ran in straight upon it with a force that made it shiver. His sword fell from his grasp; his hands were thrown up over his head; he fell back, gave one convulsive shake of the limbs, and his life's blood gushed over the lips on which the taunts that brought him to his fate were yet trembling.

'I do not know how I found my way to my quarters on that dreadful night. The next thing I recollect was rising in the morning exhausted as if after the delirium of a fever, and descending feebly to my breakfast at the café opposite. A knot of officers were eagerly conversing outside the door.

'"Chauvin," said a comrade of mine from amongst them, "have you presented that letter yet?"

'I shook my head.

'"You may spare yourself the trouble; your friend was found at daybreak in a corner of the ramparts, dead as a burst shell, run through the right lung."

'I shuddered and felt as if my spine were turned to ice. Feigning urgent private business, I sought leave of absence, and flew to Paris to acquaint the mother of her whom I looked upon as my fiancée with the dreadful secret. She heard me, never changed colour, said she believed me; his conduct was in keeping with his character, which was head-strong; she did not blame me for killing him—it was done in self-defence; but, added she in the end, this would not have happened if you had kept your promise not to smoke. "The man who cannot keep his word shall be no suitor for my daughter's hand—never again approach me or mine——"

'"But Caroline whom I love," I cried.

'"Whom you love," she said, in a cutting voice—"there, there, take your mistress to your breast," and she cast an old cigar-case at my feet as she shut the door in my face.

'I never saw Caroline again. I returned to my regiment, said nothing about the fatal duel—nay, even wore mourning for my adversary, who was not very much regretted. He left after him one pretty boy, a love-child; I was not able to adopt him myself, but I watched over him and got him admitted into the regiment as enfant de troupe—a brave, truthful, but hot-headed, passionate boy. He died a soldier's death at the taking of the Smala of Abd-el-Kader, under Lamoricière. His daughter has his candour and generosity, without his ebullitions of temper. She's somewhat giddy, perhaps, but very good-natured. Don't you think so?'

'How should I know, captain?' said O'Hara, who had been a patient listener to this moving story.

'Ah, me! How an old man's brain wanders! Do you know,' he continued, after a little hesitation, 'I feel the better for having opened my bosom to you, my young friend, and I don't care for making half-confidences. I may trust your discretion, I think,' and he smiled amiably. 'Berthe, my Song-bird, the sunbeam in my house, is the daughter of the boy, the grand-daughter of him I had the misfortune to slay at Metz. No, not to slay,' he added quickly, correcting himself, 'I did not slay him; he rushed on his own death.'

'Did Caroline's mother ever divulge the secret of your confession?' inquired O'Hara.

'Never, oh no! She was one of the old nobility, the mirror of honour. She would not look upon any casualty in an affair of the kind other than as a matter of ordinary course, even of professional necessity, in the life of a soldier.'

'And you never saw Caroline? Did she learn anything about it, do you think?'

Captain Chauvin sighed.

'Sometimes I think she did, but I am sure she forgave me if she heard all as it happened. She was too good in herself to think evil of anyone. Ah! my dear sir, she was a woman. The sex, the sex! we, soldiers and men of feeling, ought to have no commerce with it, but be let walk our ways straightly.'

O'Hara was fiddling with a certain parcel which he had stolen from his bosom.

'She married a rich politician, one of the damn—— pardon me, my dear sir, one of the bourgeoisie class, and as Louis Philippe was king, the bourgeoisie was everything, and Caroline's husband was a favourite and a great man. I think she married him out of duty to her mother, to save her declining days from poverty. When Louis Philippe was sent to the right-about, the mean bourgeois politician went to the right-about too, and his fortune with him. Poor Caroline had died in giving birth to daughters, twins. Luckily, their nurse, one of the people, had a heart; she kept a wine-shop at Choisy-le-Roi, and she took care of the two poor orphans: yes, they were orphans, for that shabby Orleans rascal, who skirted, was never a real living man, nor his master either. Damn—— pardon me, sir, but Louis Philippe was no king—he was a grocer, sir, a grocer.'

'At best he was a usurper, but a singularly mild one,' remarked O'Hara.

'We shall not talk of him, sir,' said the captain; 'but now let me complete an old man's confidences. I adopted one of those twins, she was so like her mother in manner; she is my housekeeper. If Berthe is my Song-bird, it is Caroline who keeps the nest tidy.'

'That superb brunette!'

'Ah! you think her superb,' cried the aged officer, pleased. 'Superb—that's right; she is the born image of her mother.'

'And the other,' pursued O'Hara eagerly, a dark suspicion taking hold of his imagination.