Title: The Story of Seville

Author: Walter M. Gallichan

Contributor: C. Gasquoine Hartley

Release date: November 13, 2011 [eBook #38009]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chuck Greif and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images available at The Internet Archive)

| [Numerous typographical errors, as well as many (but not all) of the mis-placed or missing accents of Spanish words, have been corrected. Please see the list of these at the end of this etext. (note of etext transcriber)] |

| "He who Seville has not seen, |

| Has not seen a marvel great." |

| "To whom God loves He gives a house in Seville." |

| Popular Spanish Sayings. |

Saints Justa y Rufina

From the painting by Goya

All Rights Reserved

IN the story of Seville I have endeavoured to interest the reader in the associations of the buildings and the thoroughfares of the city.

I do not claim to have written a full history of Seville, though I have sketched the salient events in its annals in the opening chapters of this book. The history of Seville is the history of Spain, and if I have omitted many matters of historical importance from my pages, it is because I wished to focus attention upon the city itself. I trust that I have succeeded in awaking here and there an echo of the past, and in bringing before the imagination the figures of Moorish potentate or sage, and of Spanish ruler, artist, priest and soldier.

Those who are acquainted with the history of Spain will appreciate the difficulty that besets the historian in the matter of chronological accuracy, and even in a narration of many of the main events. The chronicles of the Roman, Gothic and Moorish epochs are hardly accepted as reliable. Patriotic bias and religious enthusiasm are elements that frequently mislead in the making of history, though the Spaniard is not alone in the commission of error in this respect.

Seville abounds with human interest. The city may at the first glance slightly disappoint the visitor, but he cannot wander far without a growing sense of its fascination. Most of the noteworthy buildings are hidden amidst narrow alleys, for the designers of the city have shown great economy in utilising space. It is therefore difficult to gain large general views of Seville, unless one ascends the Giralda, while the obtrusion of modern dwelling-houses and stores often mars the view of fine public edifices. But the modernity of Seville seldom strikes one as wholly out of place and in sharp contrast to the ancient monuments. The plan is Morisco, and the impression conveyed is partly Moorish and partly mediæval. In a word, Seville brings us at every step closely in touch with antiquity.

For the chapters on the Artists of Seville I am indebted to C. Gasquoine Hartley (Mrs. Walter M. Gallichan), who has devoted much study to the art of Spain. The drawings by Miss Elizabeth Hartley were prepared while I was gathering material for the book in Seville, and the illustrations will be found to refer to the text. I have also to thank my brother, Mr. F. H. Gallichan, for his plan of the city.

The frontispiece photograph of Goya's picture of SS. Justa and Rufina was reproduced in the Art Journal as an illustration to an article on "Goya" by C. Gasquoine Hartley. My thanks are due to Messrs. Virtue & Company for permission to reproduce the picture in this book.

WALTER M. GALLICHAN.

THE CRIMBLES,

YOULGREAVE, BAKEWELL,

August 20, 1903.

| CONTENTS | |

|---|---|

| CHAPTER I | |

| PAGE | |

| Romans, Goths and Moors | 1 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| The City Regained | 26 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Seville under the Catholic Kings | 62 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| The Remains of the Mosque | 73 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| The Cathedral | 85 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| The Alcázar | 110 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| The Literary Associations of the City | 129 |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| The Artists of Seville | 146 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Velazquez and Murillo | 165 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| The Pictures in the Museo | 176 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| The Churches of the City | 187 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| Some Other Buildings | 201 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Seville of To-day | 213 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| The Alma Mater of Bull-fighters | 242 |

| CHAPTER XV | |

| Information for the Visitor | 262 |

| Index | 269 |

| Alterations made by the etext transcriber | |

| ILLUSTRATIONS | |

|---|---|

| PAGE | |

| SS. Justa and Rufina, from the painting by Goya (photogravure) | Frontispiece |

| Roman Amphitheatre at Italica | 1 |

| The Guadalquivir | 3 |

| Roman Walls | 8 |

| The Pillars of Hercules and Julius Cæsar | 11 |

| Moorish Fountain in the Court of Oranges | 23 |

| Roman Capital | 25 |

| Old Walls of the Alcázar | 41 |

| Sword of Isabella | 49 |

| Plaza San Francisco | 55 |

| Fountain in Bath, Alcázar | 66 |

| Puerta del Perdón | 75 |

| Stone Pulpit in Court of Oranges | 78 |

| Cuerpo de Azucenas | 79 |

| The Giralda | 84 |

| Pinnacle of the Cathedral | 87 |

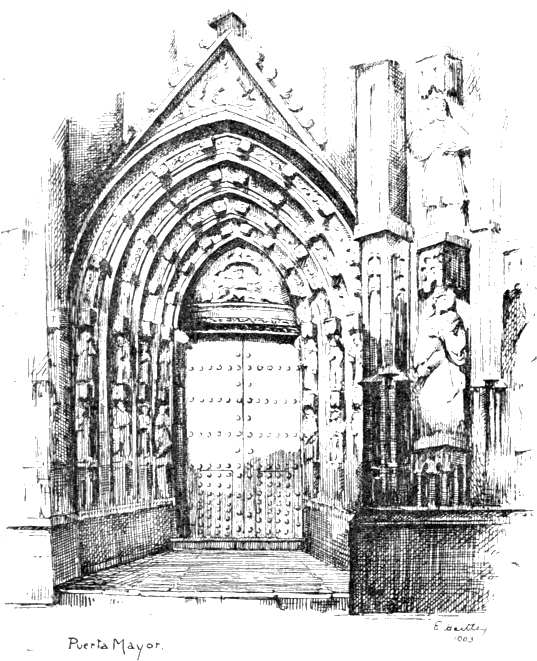

| Puerta Mayor—The Central Door of the Cathedral | 89 |

| Pinnacle of the Cathedral | 91 |

| Interior of the Cathedral | 97 |

| Patio de las Doncellas | 111 |

| In the Garden of the Alcázar | 125 |

| Cancela of the Casa Pilatos | 133 |

| The Guardian Angel (Murillo) | facing 172 |

| The Conception (Murillo) | facing 178 |

| The Road to Calvary (Valdés Leal) | facing 180 |

| Saint Hugo in the Refectory (Zurbaran) | facing 182 |

| The Crucifixion (Montañes) | facing 186 |

| Minaret of San Marcus | 190 |

| Puerta de Santa Maria | 195 |

| Patio del Casa Murillo | 203 |

| Amphora | 212 |

| Patio del Colegio, San Miguel | 215 |

| The Golden Tower | 223 |

| A Roof Garden | 238 |

| Arms of Seville | 241 |

| Plan of City (not available) | facing 268 |

| 'The sound, the sight |

| Of turban, girdle, robe, and scimitar |

| And tawny skins, awoke contending thoughts |

| Of anger, shame and anguish in the Goth.' |

| Robert Southey, Roderick. |

SEVILLE the sunny, the gem of Andalusia, is a city in the midst of a vast garden. Within its ancient walls, the vine, the orange tree, the olive, and the rose flourish in all open spaces, while every patio, or court, has its trellises whereon flowers blossom throughout the year. Spreading palms overshadow the public squares and walks, and the banks of the brown Guadalquivir are densely clothed with an Oriental verdure.

The surrounding country of the Province of Sevilla, La Tierra de Maria Santisima, is flat, and in the neighbourhood of the city sparsely wooded. On the low hills of Italica and San Juan de Aznalfarache, the Hisn-al-Faradj of the Moors, olive groves cover many thousands of acres. The plain is a parterre of wide grain fields, and meadows of rife grass, divided by straight white roads, with their trains of picturesque mule teams and waggons, and their rows of tall, straight trees. Here and there the cold grey cactus serves as a fence, but there is no other kind of hedgerow.

Far away, across the yellow wheatfields, and beyond the vine-clad slopes of the middle distance, rise the huge shoulders and purple peaks of wild sierras.

The Guadalquivir, rolling and eddying in a wide bed, takes its tint from the light soil and sand, and is always turbid, as though in spate. Below Seville, on the left bank of the river, stretch the great salt marshes, or Marismas, haunted by the stork, the heron, and innumerable wildfowl. Here, among the arms of the tidal water, the cotton plant is cultivated. Winter floods are a source of danger to Seville, especially when a south-west wind is blowing and the tide ascending the river. Then the Guadalquivir overflows its banks and deluges the town and the flat land, drowning live stock and destroying buildings. In 1595 and 1626 occurred two of the worst floods, or avenidas, on record. The flood of 1626 washed away the foundations of about three thousand houses.

It is probable that the southern kingdom of Andalusia derived its name from the Vandals, who overran the country after the Roman occupation. The region was then known as Vandalitia, or Vandalusia. Lower Andalusia has been said to be the Tarshish of the Bible. The Phœnicians called the land Tartessus, or Tartessii. Nowadays Andalusia includes the provinces of Sevilla, Huelva, Cadiz, Córdova, Jaén, Granada and Almeria, and has a population of over three millions. Seville is the capital, the seat of an archbishop, and a university town. The traveller from Northern Europe will feel the spirit of Spain upon him as he approaches Seville from Cadiz or Córdova through a semi-tropical country under a burning blue sky. He will note everywhere the influence of the Arab in the architecture of modern public buildings, churches and dwelling-houses, in the tortuous, narrow streets, in the features, language, music and garb of the people, and in many of the customs of the district. The character of the landscape is strange, the atmosphere vivid, and the distant objects show sharply against the horizon. For leagues he will traverse groves of olive, or vineyards, and pass across wastes purple with the flower of the lavender or scarlet with poppies.

Seville of to-day is white, clean and bright. Gautier noted that the shadows of the houses in the narrow thoroughfares are blue, in contrast to the white of the dazzling buildings at noon. During the siesta of the hot months, the streets are deserted daily for about four hours, shutters screen the rooms from the blinding sunshine, and awnings are drawn across the roofs of the patios. In the evening the town awakens, and the plazas and alleys are thronged and gay until two in the morning. Everyone endeavours to lead an al fresco life, and to conserve physical energy in this city of eternal sunshine. Unlike Toledo and Avila, where the houses are sombre and the doors heavy and barred, as though the towns were inhospitable, Seville opens wide the gates of its beautiful courts so that the passer-by may peep within.

'Seville is a fine town,' wrote Lord Byron, in a letter, during his stay in Spain in 1809. We may regret that he had so little to say about the fascinating capital. George Borrow, who lived for a time in the Plazuela de la Pila Seca, near the Cathedral, speaks in rapturous phrases of the view of Seville and the Guadalquivir. 'Cold, cold must the heart be which can remain insensible to the beauties of this magic scene, to do justice to which the pencil of Claude himself were barely equal. Often have I shed tears of rapture whilst I beheld it, and listened to the thrush and the nightingale piping their melodious songs in the woods, and inhaled the breeze laden with the perfume of the thousand orange gardens of Seville.'

The city is rich in antiquities, in historic buildings associated with illustrious names, in works of art and in sumptuous palaces. A great company of the spirits of famous kings, warriors, explorers, authors, painters and priests spring up in the imagination as one stands in the aisles of the splendid Cathedral, or dreams amid the roses and the tinkling fountains of the secluded gardens of the Alcázar. Here, to this prized and fertile territory of southernmost Spain, came Publius Cornelius Scipio and Cato. Trajan, Hadrian and Theodosius were born at the municipium of Italica, a few miles from modern Seville. El Begi, 'the most accomplished scholar of Spain,' spent the greater part of his life in the city.

San Isidoro and San Leandro lived here. Moorish monarchs and Christian sovereigns ruled from the palace, and in their turn attacked and defended the fair city. The figures crowd before the mind's eye—Ferdinand III., who redeemed the town from the Moriscoes, Alfonso (El Sabio) the Learned, Pedro I. the Cruel, and Ferdinand and Isabella the Catholic. We see the fair, blue-eyed Genoese youth, Christoforo Colombo, or Columbus, the maker of the modern prosperity of Seville, who, after achieving fame, was alternately petted and punished by his sovereigns. We picture the triumphant return of Hernando Pizarro to the city, with half a million pesos of gold, and a great treasure of silver.

Lope de Rueda, 'the real father of the Spanish theatre,' a gold-worker of Seville; Fernando de Herrera, the poet; the mighty Cervantes, who spent three years of his life in the Andalusian capital; Velazquez, Zurbaran, Roelas, Murillo and minor artists of note were either born in the city or closely associated with it.

For the present we must take a look back into the dim and remote period when the Phœnicians came to wrest the soil of Southern Spain from the race of mingled Celtic and Iberian blood. It is at this uncertain date that the history of Seville may be said to begin.

We learn from the historians of Phœnicia that the shrewd, practical and industrious people of that marvellous ancient civilisation were great colonisers. 'The south of Spain,' writes Professor George Rawlinson, 'was rich in metallic treasures, and yielded gold, silver, copper, iron, lead and tin.' In their quest for valuable metal, certain Phœnician explorers discovered the Peninsula of Iberia, and in the mineral-yielding region watered by the Guadalquivir they founded the colony of Tartessii. Doubt exists whether Tartessii was the name given to the plains of the Guadalquivir or to a town. Strabo, Mela and Pliny state that the Phœnicians built a town and called it Tartessus. Was this town the foundation of Seville? No one will attempt to give an authoritative answer, though it has been stated that the town was not Cadiz, the Gades of the Phœnicians. Two cities of considerable importance appear to have been the marts of the Phœnician Sephela, or plain, and it is not wholly improbable that Seville was one of them.

In the choice of new territory for the development of mining and agriculture, the enterprising colonists displayed much intelligence. They settled upon a soil that will bring forth richly without artificial stimulation.

The hill ranges produced vines and olive trees, yielding fine wine and ample oil. Tunny and other fish were plentiful in the sea, and the rivers afforded large eels.

This is all that can be known of the Phœnician colony in Southern Spain. We are beginning to tread upon firmer historic ground when Hamilcar Barca landed at Cadiz in 237 B.C., after a series of victories in Africa, and subdued Andalusia. Hasdrubal, son-in-law of the conqueror, was the founder of Cartagena, or New Carthage, the centre of Carthaginian rule in Spain, and the wealthiest city of the Peninsula.

But during the second Punic War the Romans invaded Iberia, and gained all the eastern coast from New Carthage to the Pyrenees. Plutarch says that Publius Cornelius Scipio came to Spain with eleven thousand soldiers, seized Cartagena, reduced Cadiz, and founded the city of Italica, near Seville. Hispalis was the Roman name given to the city on the Guadalquivir until Cæsar changed the name to Julia Romula. The city then became the capital of Roman Spain, a centre of industry, and a fortress. A splendid aqueduct, which has partly endured to this day, was constructed to bring a plentiful supply of water from the hills. The aqueduct was extended by the Almohades in 1172, and forms one of the interesting monuments of the Roman and Arab colonisers. Around the city were reared high walls, with watch towers, and many strong gates. It is said that the walls of Seville were five miles in length, and it has been stated that they were once ten miles long. Within the gates were palaces, temples to the honour of the Sun, Hercules, Bacchus and Venus, and other fine edifices.

Under Augustus, Spain was part of the Roman Empire. In Seville the rule of the conquerors was beneficent, and the original inhabitants were fairly governed, while the city was extended and new crafts introduced. Under the Romans, Christianity came to the Peninsula, and Seville was made the seat of a bishop. The remaining portions of the great aqueduct, the wall, the two high granite columns in the Alameda de Hercules, with the statues of Julius Cæsar and Hercules upon them, the shafts of the columns discovered in the Calle Abades, and the beautiful fragments of capitals and statues in the Museo Arqælógico are the chief vestiges of Seville in the days of the Romans. At Urbs Italica, 'the camp of the Italians,' there still exists a grass-grown, mouldered amphitheatre, the only remnant of a mighty town.

Built on the slopes once dotted with the tents of the aboriginal hamlet of Sancios, Italica lies about five miles to the west of Seville, amid olive gardens and wheatfields. The circus is a ruin; but the passages can be followed below the tiers of seats, and one may peer into the dens once tenanted by the lions and other fierce beasts. Bees hum amongst the wild thyme, lizards creep on the worn stones, and a tethered ass grazes in the arena. The glory of Rome has departed; the plaudits from those deserted and grassy seats have not been heard for centuries; and blood has ceased to redden the floor, where fragrant herbs now spring and butterflies sun themselves on fallen masonry. Here is all that is left of Italica, the home of Trajan and Hadrian, and the asylum for Scipio's aged warriors. For a period the decaying town was known as Old Seville, and tons of its masonry were removed to build Seville the New.

Rome fell, and the Silingi Vandals swarmed into the country, captured Hispalis, and made it the seat of their empire. This period in the history of Seville is dark, and beset with difficulty for the annalist. About the year 520 a great horde of Goths spread over Andalusia. They seized the Vandal capital, but afterwards established a new capital of their own at Toledo.

Amalaric was the first of the Gothic monarchs who sat on the throne in Seville. He reigned probably from about the year 522. Theudis ruled in Seville (531 to 548), and we read that he was murdered there after an attempt to expel the Byzantine troops of Justinian from Africa. Theudisel, or Theudigisel, was general to Theudis, whom he succeeded as ruler at Seville. Theudisel shared the fate of his predecessor on the throne. After a reign of eighteen months, he was killed by the sword-thrusts of a dozen nobles of his retinue, while taking supper in his palace. This 'monster of licentiousness' was wont to kill all women who repelled his addresses, and his assassination was a work of vengeance on the part of outraged fathers and husbands among his courtiers.

Schlegel says the Goths were ready converts to Christianity, but 'in the Arian form.' At a later period of their supremacy in Spain there came a wider adherence to orthodox Catholicism, and the civil power was largely in the hands of the bishops and clergy. The most influential bishop of this day was Saint Isidore (San Isidoro) who held office in Seville. His brothers, Leander and Fulgentius, were also prelates, and his sister, Florentina, was made a saint. Saint Leander was the elder brother of Isidore, and through him the youth received his education after the death of his parents. The pupil was earnest and diligent in his studies, and as he grew to manhood he zealously assisted his brother, who then held the See of Seville, in converting the Goths from the heresy of Arius.

Dissensions between the orthodox and the Arians caused great strife and family bitterness among the ruling class. During the reign of King Leovigild rebellions broke out in Castile and León. The leader of the rebels was Leovigild's own son, Ermenigild, who had married Ingunda, daughter of Brunichilda and of Sigebert. Ingunda professed the orthodox faith, while Gosvinda, the second wife of Leovigild, was of the Arian sect. A rivalry arose between the two dames. According to Gregory of Tours, Gosvinda determined that Ingunda should be compelled to embrace the heterodox creed. One day when the two disputants were together, engaged in hot controversy, the fanatical Gosvinda gripped Ingunda by the hair of her head, threw her to the ground, trod upon her, and bade an Arian priest baptize the prostrate woman.

This incident not unnaturally brought about a quarrel between Leovigild and his son. Ermenigild was then ruling in Seville, while Leovigild maintained his court at Toledo. The trouble grew when Leander, the uncle of Ermenigild, persuaded the young man to forsake Arianism. His father was deeply angered, and vowed that the Gothic crown should never come to an apostate. The Archbishop of Tours states that the father was the first to take up arms after the rupture, but other historians suppose that the turbulent Ermenigild began the hostilities.

This domestic difference led to serious warfare. Ermenigild was besieged in Seville by his father's forces, after begging aid from Mir, King of the Suevi, in Galicia. Mir started with an army to assist the rebellious prince, but on the way he was defeated by Leovigild, and forced to aid the monarch. For a year Ermenigild resisted the siege of Seville. The people were on the point of starvation when he resolved upon capitulation. Nothing remained but flight, and the prince made his escape from the city and reached Córdova. There he was captured, divested of his regal garments and authority, and banished to Valencia. Very soon the strife was renewed. Ermenigild, panting for a reprisal, solicited aid from the Greeks and rebels of the east coast, and invaded Estremadura. His father went to meet him with a force of his bravest men. The attack was made by Leovigild, who drove his son's army from Merida into Valencia, and took the young man a prisoner.

The King was stern, but he could not act ungenerously towards his foe and son. He offered Ermenigild pardon and favour on condition that he would reject his heretical faith. The rebel refused the terms; he would rather remain in his dungeon than practise hypocrisy. Again the father besought the son, through an Arian priest, to renounce his false doctrine, and again Ermenigild was resolute. In a passion, he cursed the cleric, crying: 'As the minister of the devil, thou canst only guide to hell! Begone, wretch, to the punishments which are prepared for thee!' This was more than Leovigild could bear. He immediately sentenced his son to death. The legend of Ermenigild's last days relates that on the night of his execution a light from Paradise shone in his cell, and that angels watched over the grave, singing hymns in his praise. Ermenigild was sainted, and one of his bones is at Zaragoza.

It was in this time of religious stress and civil discord that Saint Isidore of Seville began his labours. For about thirty-six years he ruled as governor of the church in the city. His hand was open towards the poor, and he preached with fervid eloquence. It is to the industry of Isidore that Spain owes respect, for his writings are the only basis for a history of the chief events during the Gothic epoch. He wrote the Historia de Regibus Gothorum, Wandalorum et Suevorum, and one of the celebrated books of study of mediævalism, The Etymologies or Origins of Things.

San Isidore's philosophy was Platonic and Aristotelian. In theology he followed the teaching of St. Gregory the Great. He was a puritan in his attitude towards the play.

'What connection,' he writes, 'can a Christian have with the folly of the circus games, with the indecency of the theatre, with the cruelty of the amphitheatre, with the wickedness of the arena, or with the lasciviousness of the plays? They who enjoy such spectacles deny God, and, as backsliders in the faith, hunger after that which they renounced at their baptism, enslaving themselves to the devil with his pomps and vanities.'

The gift of oratory possessed by Saint Isidore was predicted in his infancy by the issue of a swarm of bees from his mouth. His body was laid to rest, in 636, in Seville.

When King Fernando decided to collect all the bones of martyrs and saints that he could find in the cathedrals and burial grounds, he raised an army and came to Seville, which was then under the Moors. Ibn Obeid, the chief of the Moriscoes, favoured Fernando's scheme, and allowed the King to enter the city to search for the remains of Justus. These bones could not be found; but while the seekers were at their task the spirit of Saint Isidore appeared to them, and said that the remains of Justus could not be discovered, as it was ordained that they should rest at Seville. Saint Isidore then offered his own remains for removal, and his embalmed corpse was taken to the Church of John the Baptist, in León, in 1063.

Until the time of Recared I. the Goths in Spain remained Arians. When they forsook their early faith, they adopted a ritual which differed from that of the Catholics. It was not until the reign of Alfonso VI. that the Roman service was used throughout the land. The civil law of the Goths was founded on the Forum Judicum of the Romans. This lengthy code became later the Fuero Juzgo, and was eventually adapted to the community by Alfonso X. in 1258, and known as the Siete Partidas, or Seven Sections. Under the Gothic code slavery was permitted, and great power was vested in the hands of the nobility.

'The old Roman civilisation,' writes Mr. H. E. Watts, in his Spain, 'which the Celtiberians had been so quick to adopt, sat awkwardly on these newer barbarians. It was a heritage to which they had not succeeded of nature, and a burden too great for them to support? The Romans had made one nation of Spain. The Visigoths were not much more than an encampment.' When the Berbers, new converts to Mohammedanism, began to cast envious eyes upon lovely Andalusia, the Goths were demoralised through easy living in a southern clime. Spain had become a nation of lords and serfs, and the slaves, the mass of the people, had no heart to fight for the land that had been wrested from them.

When Tarik, lieutenant of Musa, came with a force of seven thousand Berbers to battle for the Prophet and to conquer Spain, the Gothic King, Roderic, hastily collected an army of defence and advanced towards Xeres. Theodomir, Governor of Andalusia, had learned that the invaders were marching from Algeciras, where they landed on the 30th of April 711. The Berbers had many horsemen, well-equipped and valiant, while Roderic possessed only a small number of mounted men.

It was not until 19th July that the decisive and memorable battle was fought. The Gothic King met his foes on the banks of the Guadalete (Wad-el-leded) 'the river of delight.' It is said that the combat lasted for seven days. The Goths, though enervated, had not wholly lost their prowess, and they strove desperately with the fierce host of Tarik. So bravely fought the defenders that the Moors grew disheartened; but their leader, sword in hand, and calling upon Allah, told his troops that they had no vessels with which to escape from the country. The Berbers must win or perish. Spurring his steed, Tarik dashed into the Gothic ranks, cleaving a way as he rode, and inspiring his followers to a supreme effort. Roderic also rallied his soldiers to a last stand. His army numbered more than that of the Berber general, but the men were ill-trained, and no match for the desperate enemies who had battled in many campaigns.

Some Spanish historians assert that the sons of Witiza, the King dethroned by Roderic and sentenced to death, aided by other traitors, deserted their companies and joined the Berbers. It has also been recorded that Count Julian, whose daughter was dishonoured by Roderic, had allied himself with the foe in Africa. These stories have not, however, been accepted by later chroniclers.

The battle was to the Moors. Roderic was either killed on the field by Tarik himself, or taken prisoner and released to spend the rest of his days in a monastery. One account states that Tarik slew his opponent, and sent the head to Musa, who had it conveyed to the Court at Damascus. The beaten Goths retreated rapidly before the advancing army. Some followed Theodomir into Murcia, others went to the Asturian mountains. The band of the Andalusian Governor was pursued by the enemy and routed; and Theodomir was compelled to surrender and to confess fealty to the Khalif. Upon this condition the Governor was allowed to possess Murcia and parts of Valencia and Granada, his territory being known as Tadmir.

Seville was soon in a state of siege. Envious of the good fortune of his lieutenant, Musa came to Andalusia with eighteen thousand Arabs of valour. He was assisted in command by his sons Abdelola and Meruan. His eldest son, Abdelasis, remained in authority in Africa. The Sevillians made a valiant defence of their beautiful city; but after several weeks of siege Musa led his army through the gates. From that hour, until its capture by Fernando III., the Andalusian capital was in the hands of the Moors. Carmona and neighbouring towns were also seized by Musa.

After the subjection of Seville, the Arab general started upon a campaign. It appears that Musa had not left an efficient force within the city walls, for the inhabitants rose and attempted to expel their victors. Hearing of the trouble, Musa sent his son Abdelasis into Spain to quell the revolt in Seville. Abdelasis used suasion first; but the natives were in arms and ardent to regain the city. They prepared for a second siege. With much slaughter, the son of Musa put down the rebellion of the newly-conquered citizens, and proceeded through the south of Spain, winning battles everywhere. Musa was so gratified by his son's successes that he appointed him ruler of the annexed territory.

Abdelasis had a reputation for humane conduct towards the vanquished people. He fell in love with Egilona, widow of the unfortunate Roderic, and made her first a member of his harem and afterwards his wife. That he respected her is shown by the fact that her counsel was always sought in affairs of government.

The Berber King of Seville was to learn that the throne is not the most peaceful resting-place after war's alarms. Scandal was set abroad that Abdelasis was scheming to become sole ruler of the Berber dominion, and this report reached the ears of Suleyman, brother and heir of the Khalif. There is no doubt that Suleyman resented the favour shown to Musa and his sons, while he feared that Abdelasis might one day contest with him for sovereignty. Seized by this fear, the heir to the crown gave secret orders for the killing of the three sons of the great commander, Musa.

One day, while Abdelasis was taking part in the devotions within the Mosque of Seville, hired murderers crept up to him and stabbed him to death. The two brothers of Abdelasis shared the like fate. The head of the King was sent to the Khalif at Damascus, who caused it to be shown to Musa. Then the brave general, gazing in anger upon his sovereign, cried aloud: 'Cursed be he who has destroyed a better man than himself!' The distracted Musa fell sick through grief, and soon died.

There is another account of the death of Musa. His jealousy of Tarik, who conducted the first successful campaign in the Peninsula, led the general to treat his inferior officer with indignity. The friends of Tarik at Damascus, in the Court of the Khalif, breathed vengeance upon Musa, and prevailed upon the monarch to punish his commander-in-chief. A party of arrest seized Musa in his camp, and brought him before the Khalif, who commanded that he should be degraded and publicly beaten. The disgrace broke Musa's heart and caused his death.

Abdelasis was succeeded by Ayub, who acted as Viceroy of the Khalif. The new ruler preferred Córdova to Seville, and thither he removed with his retinue. For a long period the city was one of lesser importance; but it gained greatness and independence under Abul Kâsein Mohammed in 1021. In the time of Abbad and Al-Motamid II. the population of the town rose to four hundred thousand, and the grandeur of the place rivalled, if it did not exceed, that of Córdova. In 1078 proud Córdova was subject to Seville, and the ancient metropolis of the Moors in Spain was falling into decay, while 'the pearl of Andalusia' was shining in its chief splendour.

Abderahman I., Emir of Córdova, in 777, made a bold stroke by proclaiming himself Khalif and sole ruler of Spain. It is not necessary to recount the victories of Abderahman. He came in triumph to Seville and was bade welcome. 'His appearance, his station, his majestic mien, his open countenance,' writes Dunham, 'won the multitude even more perhaps than the prospect of the blessings which he was believed to have in store for them.' Abderahman's rule in Seville laid the foundation of the city's prosperity. He narrowed the channel of the Guadalquivir, and made the river navigable; he built residences, and laid out gardens, and transplanted the palm tree into Spain. We read that the Moorish King was honourable, bold and generous, and possessed of a fine sense of justice. He encouraged letters, and was a benefactor of educational institutions. The King was also a poet, and loved the society of intellectual men.

Although the peaceful arts flourished in Seville at this period, the city was frequently the scene of battle. Conspiracies, factions and revolts constantly disturbed Spain, and during the reign of Abderahman several rival chiefs made assault upon Seville. One of these was Yusuf, who raised troops, took the fort of Almodovar, and moved towards Lorca. There he was met by Abdelmelic, general of Abderahman, who overcame the rebel force, killed the leader, and sent his head, after the Oriental manner, to the King. The trophy was displayed at Córdova. But the rebellion was not quelled by Abdelmelic's victory. Yusuf's three sons gathered an army and made attacks upon Toledo, Sidonia, and Seville. Another insurrection broke out at Toledo, under one of Yusuf's relatives, Hixem ben Adri el Fehri.

Upon the advice of Abderahman's first minister, the King proposed an amnesty, to last for three days. Hixem accepted the terms, and gained pardon. But he abused the King's clemency at a later date, and came with a body of troops to the gates of Seville. There was hard fighting, but the Governor, Abdelmelic, preserved the city and drove away the foe. Strife was again caused by the Wali of Mequinez, one Abdelgafar, who came bent upon the capture of Seville. The Wali was encountered by Cassim, young son of Abdelmelic. Fear seized the youthful officer, and he fled with his soldiers. He was met by his father, who drew his dagger and killed the young man, saying: 'Die, coward! thou art not my son, nor dost thou belong to the noble race of Meruan!' The Governor then pursued the enemy, but they escaped him, and came near again to Seville. Abdelmelic hurried to the Guadalquivir, and in a night fight he was overcome and received a wound. The troops of the Wali poured into the city. But in spite of his injury the Governor entered Seville, and after a furious combat expelled the host of Abdelgafar. The Wali was afterwards caught and killed on the bank of the Xenil. In reward for his bravery, the King made Abdelmelic Governor of Eastern Spain.

It is stated that, in 843, a fleet of ships, manned by Norman pirates, sailed up the Guadalquivir. The pirates made a sudden raid upon Seville. The inhabitants were taken by surprise, the town was robbed, and the thieves made good their escape to the river.

Seville in the days of Moorish might was one of the fairest cities on earth. Beautiful palaces were built upon the sites of the Roman halls, gardens were shady with palms, and odorous with the blossom of orange trees, and there were hundreds of public baths. The streets were paved and lighted. In winter the houses were warmed, and in summer cooled by scented air brought by pipes from beds of flowers.

Poetry, music and the arts were cultivated; the philosopher and the artist were held in respect. There were halls of learning and great libraries, which were visited by scholars from all parts of Europe.

The Alcázar, the Mosque, the lordly Giralda Tower and other remains testify to the ancient splendour of Seville. It was the Moor who applied the method of science to the cultivation of the plains, who bred the cattle, introduced the orange tree, and planted the palm in the city. Granada and Seville were centres of silk-growing. Here were manufactured the damascened swords and other weapons, and beautiful metal work of divers kinds, which was in demand all over Spain for centuries. Moorish civilisation was unsurpassed for its handicrafts and architectural decorations. Long after the Christian reclamation of Seville, the Mudéjar, or Moor, living under the new rule, was employed by the State to construct bridges and to build castles, to design houses, and to decorate them with the wonderful glazed tiles and imperishable colours.

Among the learned Moors of Seville the most eminent was Abu Omar Ahmed Ben Abdallah, known as El Begi. Abu Omar's father had spared no cost in providing for his son's education. He employed as tutors the greatest scholars of the time, and sent the lad to Africa, Syria, Egypt and Khorassan in order to confer with sage men and doctors of repute. At the age of eighteen years Abu Omar was wonderfully cultured, and as he grew to middle age there was no man who could surpass him in knowledge of arts and sciences. 'Even in his earliest youth, the Cadi of that city, Aben Faweris,' says Condé, 'very frequently consulted him in affairs of the highest importance.' El Begi, the Sage, was born in Seville and lived there during most of his life.

Many philosophers must have mused in this cultured age amid the orange trees of the court of the magnificent mosque. From the summit of the Giralda, astronomers surveyed the spangled sky, making observations for the construction of astronomical tables. Chemists questioned nature in the laboratories by means of careful experiments, and mathematicians taught in the schools. There were seventy public libraries in Andalusia; the library of the State contained six hundred thousand volumes, and the catalogue included forty-four tomes. Scholars also possessed large private libraries. There was no censorship, no meddling with the works of genius. Men of science were encouraged to investigate every problem of human existence. Abu Abdallah wrote an encyclopædia of the sciences. The theory of the evolution of species was part of the Arab education. Moorish thought was destined to influence Spain for ages. The discovery of the New World was due to the Mohammedan teaching of the sphericity of the earth, and it was the work of Averroes that set Christopher Columbus thinking upon his voyage of exploration.

The Moors in Seville were not only a cultured and devout community. They were commercial and manufacturing, weavers of cotton, silk and wool, makers of leather and paper, and growers of grain. In their hours of recreation they played chess, sang and danced. Their dances have survived to this day in the south of Spain, and may be witnessed in the cafés of Seville and Malaga.

'All the intellect of the country which was not employed in the service of the church was devoted to the profession of arms.'

Buckle, History of Civilisation.

IN 1023 Abu el Kásim Mohammed, then Cadi of Seville, raised a revolt against the Berber rulers of Andalusia. The rising was successful, and the town once more became a capital. Under the Abbadid dynasty, and the rule of Motadid and Motamid, Seville was secure and peaceful. Stirring days came with the rise of the Almoravides in the eleventh century. In Morocco, Yussuf, son of Tashfin, had been inspired to wage battle in the name of a reformed religion. The Almoravides, or Mourabitins, i.e., 'those who are consecrated to the service of God,' were a fanatical sect led by an intrepid warrior. They had made havoc in Northern Africa, deposing sovereigns and seizing territory. Now they were to make history in Spain.

Under Alfonso III. the Spaniards of the northern and central parts of the Peninsula had prospered in their arduous task of stemming the advance of the Moors northwards. Spain had won back Asturias, Galicia, and part of Navarre, and in time León and Castile were restored to Christian rule. But under Almanzor, a most redoubtable commander, León fell, and the whole population of its capital was slaughtered. The death of Almanzor, in 1002, brought about vast changes for the Moorish kingdom in the south of Spain. There was no great leader to control the fortunes of Islam. The territorial governors were in constant dispute, and often at war one with the other. It was a golden opportunity for the soldiers of the Cross.

In 1054 Fernando I., a sagacious ruler of León and Castile, made a crusade against the Moors of Portugal, and brought the King of Toledo to his knees. He besieged Valencia and brought his troops into Andalusia. Under Alfonso VI., Toledo was recovered, amid the rejoicings of the Christian host, who anticipated a speedy delivery from the Morisco domination. The coming of Yussuf and his fierce Almoravides dashed the hopes of Alfonso's army. Finding themselves encompassed with growing dangers, the Moors of Spain begged the assistance of the powerful Almoravides. A conference of the Moorish rulers was held at Seville, and a message sent to Yussuf. The Almoravide King was astute. At first he displayed but little sympathy for his brethren in Spain. But the offer of Algeciras induced him to promise aid, and he came with a strong army of Moors and Berbers. Alfonso was informed that a profession of belief in the creed of Mahomet would spare him from certain death. The Christian sovereign replied by allying himself with Sancho of Navarre, and bringing a force to meet Yussuf. Between Badajoz and Merida the armies met in a terrible conflict. Alfonso was forced to retreat, and for the present Yussuf offered no further demonstration of his military skill.

Next year the King of Morocco returned to Spain with his army, and exhorted the Moors of Andalusia to unite with him in a war of extinction. The petty sovereigns showed but little enthusiasm for a campaign. Probably they distrusted Yussuf's motives. Such suspicion was not without a basis, for when the Almoravides came for the third time, the monarch plainly stated that he purposed to annex all the remaining Mohammedan region. With a hundred thousand men, Yussuf took Seville and Granada. Alfonso came to the assistance of the Sevillians with a force of twenty thousand; but the Almoravides seized the city, and held it until the days of the Almohades in 1147.

Alfonso then sought the alliance of France to assist his nation in expelling the African invaders. But the power of the Almoravides grew. Córdova was their seat of government, and Seville was one of their most important cities. The Moriscoes in Spain were no longer an independent race, but under the sway of Morocco. Motamid II. doubtless rued the hour when he sought aid from Yussuf. Fair Seville had passed out of his hands.

At this time there arose the famous Cid, the revered warrior and type of Spanish chivalry. Many are the legends and ballads extolling the bravery of this champion of Christendom. Some of the stories of his deeds are so improbable that certain historians of Spain have regarded the hero as a character of fable; but Professor Dozy has investigated the old chronicles, both Spanish and Moorish, and reached the conclusion that there was a Cid, a mighty soldier and a devout Catholic, named Rodrigo Diez de Bivar. There is no doubt that the Cid loved the field of battle from his youth, and that he was ever ready to fight, sometimes for the Christians, and sometimes for Moorish chieftains at war with one another. In the end he became a valorous freebooter, with a following of the sons of noble families. The Cid came at least on one occasion to Seville as an emissary of King Alfonso to Motamid, to collect sums due from the Arab ruler. Motamid was then at strife with Abdallah, King of Granada, who was assisted by certain Christian caballeros, including Garci Ordoñez, formerly standard-bearer to Fernando. The Cid endeavoured to restrain the King of Granada from making war upon Motamid's city, but Abdallah was not to be influenced for peace. He went forth and was met by the combined armies of the Cid and Motamid of Seville, and defeated with much loss. Ordoñez and the Christian cavaliers were taken prisoners. The Cid took his tribute, and certain costly gifts for Alfonso from Motamid, and departed. Soon after this episode in Andalusia, Alfonso heard that Rodrigo, the Cid, had retained some of the presents sent by the King of Seville. This report was set going by Garci Ordoñez in revenge for his defeat at the hands of the Cid and Motamid, and the tale was credited by King Alfonso. There was already prejudice against the Cid in the royal mind, and Alfonso was still further displeased when his general went to attack Abdallah without permission. When he heard that, to crown all, the Cid had exhibited dishonesty, Alfonso was wroth, and banished Rodrigo from the kingdom. But the Cid gained immense power and homage as an independent sovereign, and when Alfonso was in sore need of a general to fight for him against the Almoravides, he approached the gallant Rodrigo with assurances of friendliness, and solicited his aid. Perhaps the missive of Alfonso went astray; at anyrate, the Cid did not at once respond to the King's call for help. This apparent apathy incensed Alfonso. Again he sought to punish the Cid, confiscating his estates and imprisoning his wife and children. And again the invincible Rodrigo proclaimed himself a king on his own account. He died in 1099, and at his death his territory was taken by Yussuf, the Almoravide. The Cid's bridle, worn by his steed, Babieca, hangs in the Capilla de la Granada, in the south-east corner of the Court of the Oranges at Seville.

The Almoravides appear to have been an exceedingly energetic and turbulent race. They were, indeed, too fond of warfare, for they were constantly fighting amongst themselves when they were not at war with the Christians. Under their dominion every ruler of a city who could raise troops called himself sovereign, and made attack upon the governor of the nearest wealthy centre. The Almoravide rule was not so just and prudent as that of the Moors who preceded them, and the people groaned under its despotism. Conquest by the Almohades came as a redemption from the tyranny of the Almoravides.

In Northern Africa, the land of prophets and of new sects, Mohammed, son of Abdalla, proclaimed himself the Mehdi, and gained the adherence of a great horde of devotees. These Unitarians were even more fervent in piety than the Almoravides. The Mehdi's general, Abdelmumen, soon became the victor of Moorish Spain. Seville was secured by the invaders in 1147, and remained under the Almohade rule till 1248. The Almohades built the great mosque, with its high minaret, part of the structure being formed of stonework of the Roman period; the Alcázar, a huge palace, which extended as far as the bank of the Guadalquivir to the Golden Tower, and many other magnificent edifices. The palace of the Moorish sovereigns at Seville was erected in the form of a triangle, with the chief gate at the Torre de la Plata (Silver Tower), which stood in the Calle de Ataranzas until 1821, when it was taken down.

Trade revived in the city after its capture by the Almohades; the weavers, the metal-workers, and the builders and the decorators of houses found constant employment under the new ruler, Abu Yakub Yussuf. The Christian Spaniards saw a revival of the Mohammedan fortunes, and lamented the influx of this vigorous infidel host. Earnest prayers were addressed to the knights of the Cross in all the nations of Europe beseeching succour for the faithful in Spain. Pope Innocent III. declared a crusade, and called upon foreign Christian rulers to aid the Spaniards, with the result that a number of French and English crusaders travelled to Spain. A memorable battle was fought in the Sierra Morena, the range dividing Castile from Andalusia, and the Almohade army was almost destroyed. After this repulse the Moors never made a military demonstration of any importance in Castile, but remained in Andalusia and the southern districts. Seville and Córdova each had a different governor; the Almohade unity was ruptured, and the empire was crumbling.

We have now reached the last days of the Morisco rule in Seville. The deliverer, Fernando III., the adored Saint Fernando, came to the throne at an auspicious hour, and upon his accession made ready for war upon the Mohammedans. In 1235 Córdova was taken by Fernando, and Jaén and other towns fell into his hands. Assisted by Aben Alhamar, King of Granada, who had been compelled to yield allegiance to the victorious Fernando, the Christian monarch marched upon Seville. The inhabitants prepared for a stubborn defence. A Moorish fleet guarded the mouth of the Guadalquivir, while the troops of the Almohades awaited attack within the city. Fernando sent war vessels from the Biscayan coast to San Lucar to attack the Moorish fleet. The navy was in the command of Admiral Raymond Boniface (Ramon Bonifaz), and in an engagement the Moorish ships were driven from their position. Bonifaz lived in Seville after the capture of the town. On the front of a house in Placentines, now the shop of a dealer in antiquities, there is this inscription in Spanish and French: 'Esta casa fué cedida por el Santo Rey D. Fernando III. à su almirante D. Ramon Bonifaz cuando conquesto à Sevilla libertando del dominio Sarraceno.'

The infidels next made a stand on land, but failed to overcome the army of Fernando. For fifteen months Seville was besieged. Provisions were brought into the town from the surrounding district of Axarafa, thirty miles long, on the right bank of the Guadalquivir. This highly-cultivated region is said to have contained a hundred fertile farms. Seville was connected with the suburb of Triana (the town of Trajan) by a bridge of boats and a chain bridge. The boat-bridge was broken by Fernando during the siege by launching heavy vessels upon it. But still the defenders held out behind their high, broad walls, driving back the charges of the Christians against the sturdy gates, and raining missiles from the towers. At length, when Triana and Alfarache were in the hold of Fernando's force, and all food supplies cut off, the defenders were forced to yield. On 23rd November Fernando made a triumphal entry. The vanquished ruler, Abdul Hassan, who had proved a most courageous defender, was offered territory and money if he would continue to live in Seville, or in a city of the kingdom of Castile, as a dependent officer of the King. The Moor proudly rejected these terms; he preferred to leave the scene of his defeat, and with thousands of his people he departed for Africa. It is stated that three or four hundred thousand Moors had quitted Seville before its capture. If this is true, only a few Almohades remained in the place. Those who elected to stay were bade to render the same tribute to Fernando as they had been in the habit of paying to their princes. Such as desired to return to their country were offered the means of travelling and protection.

The triumphant King, escorted by his troops, the loyal inhabitants and the clergy, proceeded to the mosque. Christian bishops purified the temple, and dedicated it to the service of God and the Virgin, and a high and imposing Mass was celebrated. Amid festivities and ceremonies, Fernando took possession of Seville and all its rich treasure. He occupied the Alcázar, then in its pristine splendour, and divided the houses and land around the city among his knights.

The Christian King was brave, and his treatment of the conquered shows that he had a strain of mercy in his nature. He was, however, an intensely bigoted pietist, for at Palencia he set fire with his own hands to the faggots to burn heretics. His austerities were excessive, and fasting is said to have weakened his body. Fernando died from dropsy at Seville, four years after his conquest of the town. On his deathbed he called his son Alfonso, bade him farewell, and exhorted him to follow justice and clemency. Then, amid deep sorrow in the city, the King took the Mass, and passed away. In 1671 Fernando III. was canonised by Pope Clement X.

The keys of Seville, which were given up by the Governor at the surrender of the city, may be seen in the cathedral. One key is of silver, and bears the inscription: 'May Allah grant that Islam may rule for ever in this city.' The other key is made of iron-gilt, and is of Mudéjar workmanship. It is lettered: 'The King of Kings will open; the King of the Earth will enter.' San Fernando's shrine is on view in the cathedral on May 30, August 22 and November 23, when honour is paid to the body of the sainted monarch by the soldiers of the Seville garrison, who march past with the colours lowered.

In the collection of paintings in the house of Señor Don Joaquin Fernandez Pereyra, 86, Calle Betis, Triana, there is a picture attributed to Velazquez, and said to have been painted by him at the age of twenty-eight, representing the Sultan of Seville handing the keys of the city to San Fernando.[A] It is said that Velazquez painted himself as model of the King. If the work is not that of the master, it is by an artist of parts. The colour is good, and the horse well drawn and painted.

Fernando III. was succeeded by his son Alfonzo X., El Sabio, 'the Learned.' He occupied the Palace of the Alcázar, and devoted his leisure to the study of geometry, ancient laws, history and poetry. The King wrote verse to the Virgin in the Galician dialect, which resembles the Portuguese tongue, and was, for his age, a versatile and accomplished scholar. His ambition was great, and though he was called 'the Learned,' he was prone to serious error in the conduct of the affairs of government. He attempted to take Gascony, which was then in the possession of Henry III. of England, and governed by Simon de Montfort. The King's military enterprises were costly, and as they failed, the people resented the increase of taxes, and especially the measure of direct taxation. When Alfonso presented Algarve to the King of Portugal, with his natural daughter, Beatrice de Guzman, the nobles rebelled under the King's brother, Felipe, and were aided by the King of Granada. Alfonso invited the malcontent party to a conference of arbitration at Burgos. The knights were appeased; but the King was forced to yield his ground, and to make many concessions. Upon the death of Alfonso's eldest son, Fernando, a dispute arose concerning the heir to the crown. Fernando left two sons, born to him by Blanche, sister of Philip IV. of France. The second son of Alfonso, Sancho, was announced as rightful successor, but this proclamation was a cause of offence to Philip IV., who claimed that the eldest child of his sister was the lawful heir to the throne of Castile. The King of France demanded that Alfonso should restore the dowry to Blanche, and allow her and the children to come to France. Alfonso refused the request. War was then declared by Philip of France; and further anxiety was caused by the disloyalty of Sancho, who took the lead of the discontented party, and laid siege to Toledo, Córdova, and other towns. The King was at his wit's end. He begged aid from Morocco, from the infidels, while, at the same time, he desired the Pope to excommunicate Sancho. Eventually the quarrel between King and Prince was patched up. Alfonso appears to have cherished affection for his unruly son, for upon hearing, soon after the reconciliation, that Sancho was seriously ill, the King died of grief.

So closed the troubled career of Alfonso el Sabio. He was a type of the bookish student, a great reader, but without a knowledge of human nature, and devoid of aptitude for governing a nation. In his fondness for book-learning, and his incapacity for ruling, Alfonso may be compared to James I. of England. It is claimed to the credit of the learned monarch that he encouraged the arts and education in the royal city of Seville, and founded the university. He loved the retirement of his study in the beautiful Alcázar rather than the council seat; but, at the same time, he had a craving for power and wished to extend his realm. Alfonso the Learned presented a reliquary to the chapter of the cathedral, which may be seen among the treasures. His body rests in the Capilla Real (Royal Chapel), where it was interred in 1284.

There is but little of interest to record in the annals of Seville until the time of Pedro I. Under Alfonso XI., a great council was held in the city to discuss plans for defending Andalusia from the Emperor of Morocco, who had landed in Spain with a powerful army. The King of Portugal attended the conference and promised his support, and in a battle fought near Tarifa the invading force was driven back. During the reign of Alfonso XI., the Earl of Derby and the Earl of Salisbury came to Spain, to fight for Christianity, and to offer amity to the martial King.

With the death of Alfonso XI., we come to the days of his son, Pedro I., the most renowned of all the Christian sovereigns who made court at the capital of Andalusia. The reign of Pedro el Cruel abounds with so much 'incident' from the story-teller's point of view, that many tales, ballads and plays of Spain are concerned with the exploits of this remarkable King. In some of the narratives he is portrayed as a veritable monster of cruelty and perfidy; in others he is represented as a severe, but just, monarch, with sympathy for the lower classes. Pedro was sixteen when he came to the throne. Fearing an attempt on the part of Enrique (son of Alfonso XI. by his mistress, Leonora de Guzman) to seize the crown, Pedro contrived to lure Leonora to Seville, and to imprison her in the Alcázar. From this dungeon the wretched woman was sent to other prisons, until she was done to death. There was no limit to Pedro's ferocity when his malignity was aroused. His deeds suggest an insane lust for bloodshed, and a delight in the infliction of suffering. He killed with his own hand, or by the aid of bravoes, all relatives, rivals and dangerous persons who came within his power. His first wife was Blanche of Bourbon, niece of King John of France; but he deserted her in two days, to return to his mistress, the lovely Maria de Padilla. When Pedro's fancy fell upon the handsome Juana de Castro, he declared that his union with Blanche was invalid, and induced the Bishops of Salamanca and Avila to perform a marriage service. Soon after the wedding Pedro left his bride, and insolently avowed that he had only experienced a passing passion for her.

One day Abu Said, King of Granada, wrote to Pedro of Seville, begging an audience of him that he might seek his help in resisting an enemy, Mahommed-ibn-Yussuff. To this request Pedro acceded. Abu Said, escorted by three hundred of his court, and a number of menials, journeyed to Seville, and was received most graciously by the King, who gave orders that the visitor and his retinue should be well cared for in the Alcázar. The Red King, Abu Said, possessed a splendid treasure of jewels. Among the precious stones was the famous ruby which now decorates the royal crown of England. It is possible that the Moorish King intended to present certain of his gems to Pedro, for we read that he brought his treasure with him to Seville. But his host, hearing how fine a store of jewels lay within his reach, commanded a number of hired murderers to purloin the treasures by force. The guest and his nobles were surprised in their apartments; they were stripped of their valuables and money, while the Red King was deprived of the very clothes that he wore. Dressed in common raiment, and seated upon a donkey, the unfortunate Abu was taken, amid the derision of the rabble, to a field without Seville, and there executed with thirty-six of his courtiers. Pedro's excuse for his treachery and cruelty was that the King of Granada had betrayed him in his war with Aragon, a charge that could not be founded.

Among the beauties of Seville of that date was the Señora Urraca Osorio. When Pedro saw her, he vowed to bring her within his power. At first he paid her compliments and endeavoured to win her favour by flattery and gifts. Urraca was a proud woman. In all likelihood she recoiled from this brutal flatterer and deceiver of women, and not even his kingly rank could induce her to pay the least heed to his addresses. No one dared to foil Pedro; the señora doubtless surmised the revenge that the King would plan against her. Yet she bravely refused to lend her ear to his proposal, preferring death to the forfeiture of her self-respect. Then Pedro threatened a terrible punishment. Urraca still refused. Faggots were piled in the market square of the town, and the persecuted lady was led forth and burned to death in public.

The people of Seville seem to have been hypnotised by their cruel sovereign. For these horrible deeds they even offered pleas of extenuation, and, according to some Spanish historians, Pedro was one of the most popular of the kings that lived in the city after its restoration to the Christians. A certain Bohemian strain in the King's character no doubt appealed to a mass of his subjects. He was credited with sympathy for the labouring class and a desire to protect the people against the tyranny of the nobles. Where his own personal interests were not concerned, Pedro the Cruel sometimes evinced that sense of equity that led Felipe II. to describe him as 'the Just.' But in private matters Pedro displayed no trait of justice and no hint of magnanimity.

Now and then Pedro would muffle himself in his capa, don his sword, and wander from the palace after dark to the low quarters of Seville. He liked to study the life of the Mudéjares, the Jews, and the artisans, and to rub shoulders with his subjects when they were scarcely likely to recognise him. One night the King was roaming in the alleys of the city, keeping an eye upon all who passed by, and probably hoping that he might find an unlucky watchman off his guard and neglecting his duty. Suddenly a passing hidalgo pushed against the King. Pedro abused the stranger; there was an altercation, and swords were whipped out of their sheaths. In the dim light of the thoroughfare the combatants clashed blades, and engaged in a duel to the death. Presently the King's opponent received a thrust in a vital part of the body, and falling to the pavement, he lay bleeding to death. A few weeks before this night's encounter Pedro had forbidden street-fighting, on penalty of capital punishment for the unwary custodians of order in the city.

With a grim smile, the King sheathed his weapon and went home to the Alcázar, musing upon the consternation of the authorities when the corpse of the caballero was discovered. Next morning he sent for the Alcalde, or Mayor of the city. 'Sir,' said Pedro, 'you fully understand that I hold you accountable for any breach of the peace that occurs in the streets of Seville?' The Mayor humbly responded that he knew the fresh regulation which his majesty had been pleased to enforce. At that moment a page brought word to the King that the dead body of a hidalgo had been found, early that morning, in the plaza near where the Casa Pilatos now stands. 'What means this?' demanded Pedro, turning to the affrighted Alcalde. 'If the murderer of this gentleman is not found in two days, understand that you will be hanged.' The Mayor's face was white as he bowed himself from the royal chamber. With a sinking heart he prepared himself for his fate. There was scarcely any hope of tracking the assassin in forty-eight hours.

The wretched Mayor sat down in his room to meditate upon the best means of tracing the criminal. Meanwhile the story of the murder was abroad, and people were talking of the affair. The gossip reached the ears of an old woman, who went at once to the Alcalde, telling him that she had seen a fight from her bedroom window late during the previous night. The combatants appeared to be gentlemen, but to make sure, she lit a candle and leaned out of the window. One man had his back towards her, and she could not see his face. But of the identity of his opponent she was quite certain: it was his majesty the King, and no other. When she saw, beyond a doubt, that it was the King who plunged his blade into the hidalgo's breast, she felt terrified, blew out the candle, and withdrew her head from the window.

'Thank God!' cried the Mayor, seizing the old woman's hand. Then he hurried to the Alcázar, sought a hearing from the sovereign, and said that he had found the murderer of the hidalgo. The King smiled. 'Indeed, your majesty,' said the Alcalde, 'I can let you look him in the face when he hangs on the gallows.' 'Good!' replied Pedro, still smiling incredulously.

Hastening to the quarter of the Moorish artisans, the Mayor ordered them to make a cunning effigy of the King, and to bring it to him without delay. A few days after, the Alcalde requested his majesty to attend the hanging of the criminal in the Plaza de San Francisco. Greatly curious, Pedro came to the place of execution. And there, upon the gibbet, he saw a dummy of himself dangling from the rope. Struck with the humour and ingenuity of the Mayor's device, the King said: 'Justice has been done. I am satisfied.' The street where Pedro fought with the hidalgo is called the Calle della Cabeza del Rey Don Pedro, and the alley where the old woman lived is known as the Calle del Candilejo, or 'street of the candlestick.'

In visiting the Alcázar we shall have more to recall of the career of Pedro the Cruel. The palace is haunted with memories of the King and of Maria de Padilla. Pedro was fond of Seville and preferred the Alcázar to any other residence. He made many alterations in the palace, built the rooms around the Patio de la Monteria, and brought material for their construction from the remains of Moorish edifices in Seville, Córdova, and other places.

When Pedro caused his unfortunate wife, Blanche, to die in prison, from the dagger, or by poison, his subjects were at length aroused to indignation. The insensate ruler was bringing the nation to the verge of ruin by his misdeeds. France resented the dastardly murder of Blanche of Bourbon, and the King vowed revenge on Pedro. Enrique, brother of Pedro, was fighting for the crown, and had been proclaimed Sovereign at Toledo; while the Sevillians, who had long endured their King's severities and condoned his cruelties, were up in arms and threatening the royal palace. Pedro fled from Seville, and came eventually into Aquitaine, to the court of the English Black Prince at Bordeaux. The chivalrous Black Prince espoused the cause of Pedro against Enrique, pitying the fugitive King who had been forced to leave his country. In return for his support, Pedro offered his English ally a large sum of gold, and the great ruby stolen from Abu Said in the Alcázar of Seville.

The campaign was decided in favour of the King of Spain, but its hardships cost the Black Prince his life. Pedro was again acknowledged King. His downfall was, however, fast approaching. Enrique conquered his brother, soon after the departure of the English army, and came to see him at Montiel in La Mancha. It is said that Pedro was treacherously drawn into a trap. In any case, he fell by the dagger of his brother Enrique; and so ended violently the life of one who had lived in violence and bloodshed.

As our story is more concerned with the city of Seville than with the fortunes of the rulers of Spain, we may resume the narration at the time of Isabella and Fernando. No incidents of signal importance occurred in Seville between the death of Pedro I. and the accession of the famous Catholic Queen. With the reign of Isabella, the city became the theatre of events that influenced the whole of the nation, and indeed the whole of Christendom.

It was at this time that the arts and letters of Spain began to revive. In Seville the year 1477 is the date of the first setting up of a printing press, by one Theodoricus el Aleman (the German). Konrad Haebler, in his work on The Early Printers of Spain and Portugal, says that for fifteen years the only printers in the city were German immigrants. One of the early important books printed in Seville was Diego de Valera's Cronica de España. In 1490 a firm of printers, under the title of Four German Companions, opened business, and in three years published nine volumes, while two years later there was a rival press owned by another German.

It was in 1493 that the city saw the return of the great Columbus from his first voyage. For a long time the blue-eyed, dreamy Genoese, Christoforo Colombo, had mused upon the scientific works of the cultivated Moors, and speculated upon the existence of other lands far away across the restless ocean. Sceptics laughed at the dreamer; the clergy frowned at his impudent theories; but a few bold adventurers were inspired by his enthusiasm.

The story of his setting forth has been often told. Let us welcome the sunburnt explorer upon his return to Seville on Palm Sunday 1493. The wondering people are all anxious to catch sight of Cristobal Colon, the Italian, who claims to have discovered a New World. He passes down the streets, a tall, brawny man, bronzed, with red hair, which became white at the age of thirty. To those who question him he replies with dignity and courtesy, becoming eloquent as he describes the marvels of the vast country beyond the sea. The whole city is talking of the great news; the foreign sailor is the hero of the hour. And now those who doubted Colon's sanity are singing his praises in all the public meeting-places of Seville. An office for the administration of this new country is instituted in the city. From the Queen and her Consort to the seller of water in the streets, everyone utters the name of the explorer with admiration. The ecclesiastics, who declared that it was impious to assert that the earth is a globe, are vexed that they have been found wrong in their arrogant statements. They continue to quote from the Pentateuch, and the writings of St. Chrysostom, St. Jerome and St. Augustine to show that pious authority was on their side.

Queen Isabel had encouraged the Genoese sailor in his project, and the wealthy Pinzon family, of Palos, had assisted him with means, some of them also accompanying the explorer on his first voyage. Columbus was made an admiral, and promised further support in his expeditions. In May 1493 he started again, having with him fifteen hundred men and a fleet of fifty vessels. The crews of these ships were made up of adventurers, gold-seekers, idlers and a sprinkling of scoundrels selected by the Government. In the company there were priests, and it was through the machinations of one of them, Father Boil, that Christopher Columbus incurred the displeasure of Isabel and Fernando. By every ship that was bound for Spain from the New World, Boil sent complaints of Columbus. Unfortunately, Isabel lent her ear to these slanders, and sent Francisco Bobadilla to dismiss Cristobal Colon, and to take his place. Bobadilla took possession of Columbus's charts and papers, put him into chains, and sent him, like a felon, in the hold of a ship to Spain.

It is pitiful to read of the degradation of this honest and brave man, whose energies built up the prosperity of Spain, and made Seville one of the busiest cities of Europe. He laid his case before the Queen and Fernando, and vowed that he had in no sense neglected his duty towards the country of his adoption. We know that he was 'forgiven,' but the insult offered to him preyed upon the sensitive mind of the explorer. Yet he again resolved to visit the land that he had discovered; and in 1503 he left Spain with four worn-out ships. A year later Columbus returned for the last time. The people of San Lucar, at the mouth of the Guadalquivir, welcomed back a captain in shattered health, and a crew wearied by hardship and exposure.

Columbus now longed to settle quietly in Seville, and to end his days there. He found that his popularity was waning, and that his rents had not been collected properly during his absence. With the death of Isabel he lost royal patronage. His last voyage had cost him much; but the people of Seville believed him to be immensely rich, whereas his income was now meagre. 'Little have I profited,' writes Columbus, in a letter, 'by twenty years of service, with such toils and perils; since, at present, I do not own a roof in Spain. If I desire to eat or sleep I have no resort but an inn; and for the most times have not wherewithal to pay my bill.'

In his last days we picture Christopher Columbus bending over the manuscripts, which may be seen in the Biblioteca Columbina, the library at Seville founded by the natural son of Columbus. One of the manuscripts treats upon biblical prophecy. It was written to appease the Inquisitors, who, to the last, suspected the discoverer of heresy. Writing of this Apologia, Washington Irving says that the title and some early pages of the book are by Fernando Columbus; 'the main body of the work is by a strange hand, probably by Friar Gaspar Gorricio, or some other brother of his convent.' There are signs in the hand-writing that Columbus was old and in poor health when he wrote the work. The characters are, however, distinct. There are passages from the Christian Fathers and the Bible, construed by the author into predictions of the discovery of the New World.

The gallant voyager was now prematurely aged, though he had led an abstemious life. Disappointment at the neglect of the world no doubt preyed upon his spirits in these last days of his career, for it is said that he possessed 'a too lively sensibility.' Upon the whole, Columbus was ill-used by Spain, though his memory is revered. It is the old, sad story of worth and genius. In 1506 Cristobal Colon died in a poor lodging at Valladolid. He left a son, born to him by his mistress, Beatrix Enriquez. In his will Columbus left money to Beatrix.

Great honour was paid to the body of the famous explorer. Columbus was buried in the parish church of Santa Maria de la Antigua. Some years later the Sevillians desired that the remains should be removed to their city, and they were then carried to the Carthusian monastery of Las Cuevas, to the Chapel of St. Ann, or of Santo Christo. The house of Las Cuevas was a fine one, celebrated for its pictures and treasures, and surrounded with orange and lemon groves. But the bones of Columbus were not to remain in Seville. They were taken, in 1536, to Hispaniola, and laid in the principal chapel of the Cathedral of San Domingo. Finally the remains were removed to Havanna.

While paying due respect to Christopher Columbus, we must not forget the great services rendered to the country generally, and to Seville, by Fernando de Magallanes, or Magellan, who embarked at that port in August 1519 with five vessels. Passing the Canary Islands and Cape Verde, the Portuguese explorer reached Brazil, and went south to Patagonia, 'the land of giants,' arriving eventually at the dangerous straits which bear his name. Magellan never returned to Spain. Only two of his ships reached the Moluccas, and of the five that started but one came back to Seville on the homeward journey.

These were the days when Seville was a bustling port of embarkation, and a great storehouse for treasure from America and the Indies. A fever of emigration seized the adventurous spirits of Andalusia; and Andrea Navigiero, a Venetian ambassador, who journeyed through Spain in 1525, says that the population of Seville was so reduced that 'the city was left almost to the women.'

The discoveries and conquests of Pizarro, who came to Seville after his first voyage, added to the enthusiasm for emigration. But Pizarro found it a hard matter to raise money for the expenses of a second expedition. He contrived, however, to man three ships, and was about to start, when the Council of the Indies sought to inquire into the state of the vessels. Fearing that he might be hindered from his scheme, the explorer set sail at San Lucar, in great haste, and made for the Canary Islands.

It was in January 1534 that Hernando, brother of Francisco Pizarro, was directed to return to Seville with a great hoard of treasure. The Custom House was filled with ingots, vases and ornaments of gold, and the inhabitants were much interested in the splendid spoil. Hernando Pizarro came later under a charge of cruelty to the subject race of South America. In his Spanish Pioneers, Mr Lummis tells us that 'Hernando was for many years imprisoned at Medina del Campo, and that he died at the age of a hundred. His brother, Francisco, who was born at Truxillo, in Estremadura, was a swineherd in his boyhood. Fired with the spirit of romance and adventure, the lad deserted his herd of pigs and ran away to Seville, where he found scope for his restless energy, and was able to influence seafaring men to accompany him on a cruise of discovery.

Seville was now at the height of its commercial prosperity. There was a constant come and go of trading vessels; the silk trade was greatly developed, and leather was made for the markets of Spain. Isabel took much interest in the improvement of the commerce of the city. When she ascended the throne, Seville was notorious for its gangs of thieves and criminals of all kinds, while the surrounding country was insecure through the numbers of bandits who waylaid and robbed traders and farmers on the roads. The Queen determined to stamp out crime by rigorous measures. She held a court in the salon of the Alcázar, and, in the Castilian custom, presided over the hearing of criminal charges. Once a week, Isabel sat in her chair of state, on a daïs covered with gold cloth. For two months she conducted a crusade against robbery in the city, recovering a great amount of stolen property, and condemning many offenders to severe penalties. Her severity struck alarm among the vagabond and thieving population, and probably terrified a number of the people who had reason to fear justice. Four thousand subjects left the town. The respectable burghers grew concerned, dreading that this depopulation would injure the city and deprive it of workmen. A deputation of citizens waited upon Isabel and begged her to relax her austerity. The Queen was therefore prevailed upon to offer an amnesty for all offenders except those convicted of heresy.