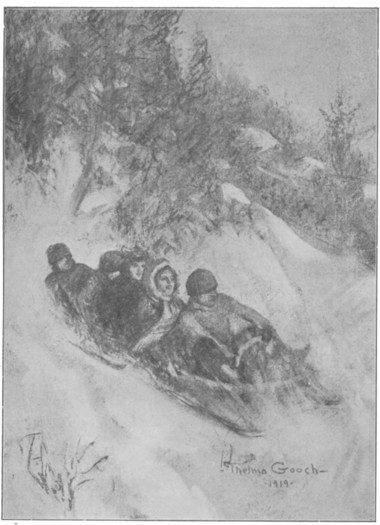

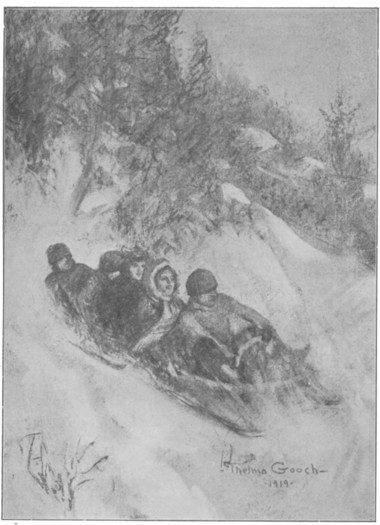

“The bobsled bumped over these hammocks, gathering speed.”

Title: The Corner House Girls Snowbound

Author: Grace Brooks Hill

Illustrator: Thelma Gooch

Release date: December 28, 2011 [eBook #38431]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

“The bobsled bumped over these hammocks, gathering speed.”

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS SNOWBOUND

|

HOW THEY WENT AWAY WHAT THEY DISCOVERED AND HOW IT ENDED |

BY GRACE BROOKS HILL

Author of “The Corner House Girls,” “The Corner

House Girls on a Tour,” Etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY THELMA GOOCH

NEW YORK

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

By Grace Brooks Hill

The Corner House Girls Series

12mo. Cloth. Illustrated.

|

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS AT SCHOOL THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS UNDER CANVAS THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS IN A PLAY THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS’ ODD FIND THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS ON A TOUR THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS GROWING UP THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS SNOWBOUND |

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS—NEW YORK

Copyright, 1919, by Barse & Hopkins

The Corner House Girls Snowbound

Printed in U. S. A.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS SNOWBOUND

There was a vast amount of tramping up and down stairs, and little feet, well shod, are noisy. This padding up and down was by the two flights of back stairs from the entry off the kitchen porch to the big heated room that was called by the older folks who lived in the old Corner House, “the nursery.”

“But it isn’t a nursery,” objected Dot Kenway, who really was not yet big enough to fit the name of “Dorothy.” “We never had a nurse, did we, Tess? Ruthie helped bring us up after our own truly mamma died. And, then, ‘nursery’ sounds so little.”

“Just as though you were kids,” put in Master Sammy Pinkney, who lived in the house across the street, and nearest, on Willow Street, from the Kenway sisters’ beautiful home in Milton, but who felt that he, too, “belonged” in the old Corner House.

“No. It should be called ‘the playroom,’” agreed Tess, who was older than Dot, and considerably bigger, yet who no more fitted the name she was christened with than the fairylike Dot fitted hers. Nobody but Aunt Sarah Maltby—and she only when she was in a most severe mood—called the next-to-the-youngest Corner House girl “Theresa.”

It was Saturday morning, and it had begun to snow; at first in a desultory fashion before Tess and Dot—or even Sammy Pinkney—were out of bed. Of course, they had hailed the fleecy, drifting snow with delight; it looked to be the first real snowstorm of the season.

But by the time breakfast was well over (and breakfast on Saturday morning at the old Corner House was a “movable feast,” for the Kenway sisters did not all get up so promptly as they did on school days) Sammy Pinkney waded almost to the top of his rubber boots in coming from his house to play with the two younger Kenway sisters.

Of course, Sammy had picked out the deepest places to wade in; but the snow really was gathering very fast. Mrs. MacCall, the Kenways’ dear friend and housekeeper, declared that it was gathering and drifting as fast as ever she had seen it as a child “at home in the Hielands,” as she expressed it.

“’Tis stay-in-the-hoose weather,” the old Scotch woman declared. “Roughs and toughs, like this Sammy Pinkney boy, can roll in the snow like porpoises in the sea; but little girls would much better stay indoor and dance ‘Katie Beardie.’”

“Oh, Mrs. Mac!” cried Dot, “what is ‘dancing Katie Beardie’?”

So the housekeeper stopped long enough in her oversight of Linda, the Finnish girl, to repeat the old rhyme one hears to this day amid the clatter of little clogs upon the pavements of Edinburgh.

“‘Katie Beardie had a grice,

It could skate upon the ice;

Wasna that a dainty grice?

Dance, Katie Beardie!

Katie Beardie had a hen,

Cackled but and cackled ben;

Wasna that a dainty hen?

Dance, Katie Beardie!’

“and you little ones have been ‘cackling but and cackling ben’ ever since breakfast time. Do, children, go upstairs, like good bairns, and stay awhile.”

Tess and Dot understood a good deal of Mrs. MacCall’s Scotch, for they heard it daily. But now she had to explain that a “grice” was a pig and that “but” and “ben” meant in and out. But even Sammy knew how to “count out” in Scotch, for they had long since learned Mrs. MacCall’s doggerel for games.

Now they played hide and seek, using one of the counting-out rhymes the housekeeper had taught them:

Eenerty, feenerty, fickerty, faig,

Ell, dell, domen, aig.

Irky, birky, story, rock,

Ann, tan, touzelt Jock.

And then Sammy disappeared! It was Dot’s turn to be “it,” and she counted one hundred five times by the method approved, saying very rapidly: “Ten, ten, double-ten, forty-five and fifteen!” Then she began to hunt.

She found Tess in the wardrobe in the hall which led to the other ell of the big house. But Sammy! Why, it was just as though he had flown right out of existence!

Tess was soon curious, too, and aided her sister in the search, and they hunted the three floors of the old Corner House, and it did not seem as though any small boy could be small enough to hide in half the places into which the girls looked for Sammy Pinkney!

Dot was a persistent and faithful searcher after more things than one. If there was anything she really wanted, or wanted to know, she always stuck to it until she had accomplished her end—or driven everybody else in the house, as Agnes said, into spasms.

With her Alice-doll hugged in the crook of one arm—the Alice-doll was her chiefest treasure—Dot hunted high and low for the elusive Sammy Pinkney. Of course, occasional household happenings interfered with the search; but Dot took up the quest again as soon as these little happenings were over, for Sammy still remained in hiding.

For instance, Alfredia Blossom and one of her brothers came with the family wash in a big basket with which they had struggled through the snowdrifts. Of course they had to be taken into the kitchen and warmed and fed on seed cookies. The little boy began to play with Mainsheet, one of the cats, but Alfredia, the little girls took upstairs with them in their continued hunt for Sammy.

“Wha’ fur all dis traipsin’ an’ traipsin’ up dese stairs?” demanded a deep and unctuous voice from the dark end of the hall where the uncarpeted stairs rose to the garret landing.

“Oh, Uncle Rufus!” chorused the little white girls, and:

“Howdy, Gran’pop?” said Alfredia, her face one broad grin.

“Well, if dat ain’ de beatenes’!” declared the aged negro who was the Kenways’ man-of-all-work. “Heah you chillen is behin’ me, an’ I sho’ thought yo’ all mus’ be on ahaid of me. I sho’ did!”

“Why, no, Uncle Rufus; here we are,” said Dot.

“I see yo’ is, honey. I see yo’,” he returned, chuckling gleefully. “How’s Pechunia, Alfredia? Spry?”

“Yes, sir,” said his grandchild, bobbing her head on which the tightly braided “pigtails” stood out like the rays of a very black sun. “Mammy’s all right.”

“But who’s been trackin’ up all dese stairs, if ’twasn’t yo’ chillen?” demanded the negro, returning to the source of his complaint. “Snow jes’ eberywhere! Wha’s dat Sam Pinkney?” he added suddenly.

“We don’t know, Uncle Rufus,” said Tess slowly.

“Sammy went and hid from us, and we can’t find him,” explained Dot.

Uncle Rufus pointed a gnarled finger dramatically at a blob of snow on the carpet at the foot of the garret stairs.

“Dah he is!” he exclaimed.

“Oh!” gasped Tess.

“Where, Uncle Rufus?” begged Dorothy, somewhat startled.

“Fo’ de lan’s sake!” murmured Alfredia, her eyes shining. “He mus’ a done melted most away.”

“Dah’s his feetsteps, chillen,” declared the old man. “An’ dey come all de way up de two flights from de back do’. I been gadderin’ up lumps o’ snow in dis here shovel—”

He halted with a sharp intake of breath, and raised his head to look up the garret stairs. It was very dark up there, for the door that opened into the great, open room extending the full width of the main part of the old Corner House was closed. In winter the children seldom went up there to play; and Uncle Rufus never mounted to the garret at all if he could help it.

“What’s dat?” he suddenly whispered.

“Tap, tap, tap; tap, tap, tap!” went the sound that had caught the old man’s attention. It receded, then drew nearer, then receded. Uncle Rufus turned a face that had suddenly become gray toward the three little girls.

“Dat’s—dat’s de same noise used to be up in dat garret befo’ your Unc’ Stower die, chillen. Ma mercy me!”

“Oh!” squealed Alfredia, turning to run. “Dat’s de garret ghos’! I’s heard ma mammy tell ’bout dat ol’ ha’nt.”

But Tess seized her and would not let her go.

“That is perfect nonsense, Alfredia!” she said very sternly. “There is no such thing as a ghost.”

“Don’ you be too uppity, chile!” murmured Uncle Rufus.

“A ghost!” cried Dot, coming nearer to the attic stairs. “Oh, my! What I thought was a goat when I was a very little girl? I remember!”

“Dat’s jest de same noise,” murmured Uncle Rufus, as the tapping sound was repeated.

“But Ruthie laid that old ghost,” said Tess with scorn. “And it wasn’t anything—much. But this—”

Dot, who had examined the wet marks and lumps of snow on the lower treads of the garret stairs, suddenly squealed:

“Oh, looky here! ’Tisn’t a ghost, but ’tis a goat! Those are Billy Bumps’ footsteps! Of course they are!”

“Sammy Pinkney!” was the chorus of voices, even Uncle Rufus joining in. Then he added:

“Dat boy is de beatenes’! How come he make dat goat climb all dese stairs?”

“Why,” said Dot, “Billy Bumps can climb right up on the roof of the hen houses. He can climb just like a—a—well, just like a goat! Coming upstairs isn’t anything hard for Billy Bumps.”

“Sammy Pinkney, you come down from there with that goat!” commanded Tess sternly. “What do you suppose Ruthie or Mrs. MacCall will say?”

The door swung open above, and the wan daylight which entered by the small garret windows revealed Sammy Pinkney, plump, sturdy and freckled, stooping to look down at the startled group at the top of the stairs.

“I spy Sammy!” cried Dot shrilly, just remembering that they were playing hide and seek—or had been.

But somebody else spied Sammy at that moment, too. The mischievous boy had led Billy Bumps, the goat, up three long flights of stairs and turned him loose to go tap, tap, tapping about the bare attic floor on his hard little hoofs.

Billy spied Sammy as the youth stooped to grin down the stairs at Uncle Rufus and the little girls. Billy had a hair-trigger temper. He did not recognize Sammy from the rear, and he instantly charged.

Just as Sammy was going to tell those below how happy he was because he had startled them, Billy Bumps dashed out of the garret and butted the unsuspicious boy. Sammy sailed right into the air, arms and legs spread like a jumping frog, and dived down the stairway, while Billy stood blatting and shaking his horns at the head of the flight.

Uncle Rufus and Alfredia had fallen back from the foot of the stairs under the impression that it was the garret ghost, rather than the garret goat, that was charging the mischievous Sammy Pinkney. And the two smallest Corner House girls were much too small to catch Sammy in full flight.

So it certainly would have gone hard with that youngster had not other and more able hands intervened. There was a shout from behind Uncle Rufus, an echoing bark, and a lean boy with a big dog dashed into the forefront of this exciting adventure.

The boy, if tall and slender, was muscular enough. Indeed, Neale O’Neil was a trained athlete, having begun his training very young indeed with his uncle, Mr. William Sorber, of Twomley and Sorber’s Herculean Circus and Menagerie. As the big Newfoundland dog charged upstairs to hold back the goat, Neale, with outspread arms, met Sammy in mid-air.

Neale staggered back, clutching the small boy, and finally tripped and fell on the carpet of the hall. But he was not hurt, nor was Sammy.

“Fo’ de good lan’ sake!” gasped Uncle Rufus, “what is we a-comin’ to? A goat in de attic, an’—Tessie! yo’ call off dat dog or he’ll eat Billy Bumps, complete an’ a-plenty!”

The big dog was barking vociferously, while the goat stamped his hoofs and shook his horns threateningly at the head of the flight of stairs. Tom Jonah and Billy Bumps never had been friends.

Tess called the old dog down while Sammy and Neale O’Neil scrambled up from the hall floor. Two older girls appeared, running from the front of the house—a blonde beauty with fluffy, braided hair, and a more sedate brunette who was older than her sister by two years or more.

“What is the matter?” demanded the blonde girl. “If this Corner House isn’t the noisiest place in Milton—Ruth, see that goat!”

“Well, Sammy!” exclaimed Ruth Kenway, severely, “why didn’t you bring Scalawag, the pony, into the house as well? That goat!”

“I was goin’ to,” confessed the rather abashed Sammy. “But I didn’t have time.”

“Don’t you ever do such a thing again, Sammy Pinkney!” ordered Ruth, severely.

She had to be severe. Otherwise the younger ones would have completely overrun the old Corner House and made it unlivable for more sedate and quiet folk.

The responsibility for the welfare of her three sisters and that of Aunt Sarah Maltby, who lived with them, had early fallen on Ruth Kenway’s shoulders. In a much larger city than Milton the Kenways had lived in a very poor tenement and had had a hard struggle to get along on a small pension, their mother and father both being dead, until Mr. Howbridge, administrator of Uncle Peter Stower’s estate, had looked the sisters up.

At that time there was some uncertainty as to whom the old Corner House, standing opposite the Parade Ground in Milton, and the rest of the Stower property belonged; for Uncle Peter Stower had died, and his will could not be found. That there was a will, Mr. Howbridge knew, for he had drawn it for the miserly old man who had lived alone with his colored servant, Uncle Rufus, in the old Corner House for so long.

The surrogate, however, finally allowed the guardian of the Kenway sisters to place them in the roomy old house, with their aunt and with Mrs. MacCall as housekeeper, while the court tangle was straightened out. This last was satisfactorily arranged, as related in the first book of this series, entitled “The Corner House Girls.”

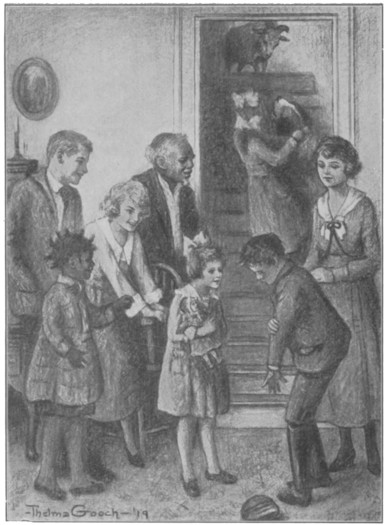

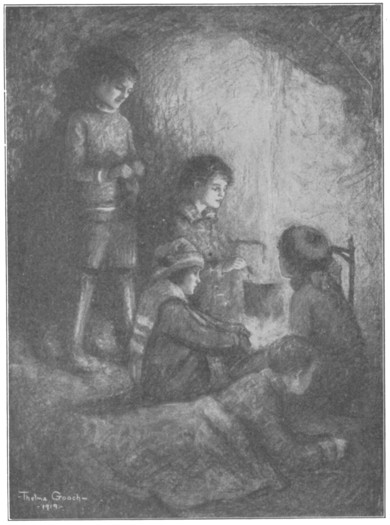

“Even Ruth could scarcely keep a sober face.”

In successive volumes are related in detail the adventures of the four sisters and their friends since their establishment in the old Corner House, telling of their adventures at school, in a summer camp at the seashore, of their taking part in a school play, of the odd find made in the old Corner House garret, and on an automobile tour through the State.

In that sixth volume of the series the Kenways met Luke and Cecile Shepard, brother and sister, who prove to be delightful friends, especially to Ruth. Agnes, the second Kenway, already had a faithful chum and companion in Neale O’Neil. But in Luke, Ruth found a most charming acquaintance, and in the seventh book, “The Corner House Girls Growing Up,” the friendship of Ruth and Luke is cemented by a series of incidents that try both of their characters.

Of course, each month saw the four sisters that many days older. They were actually growing up—“growing out of aye ken!” Mrs. MacCall often said. Just the same, they still liked fun and frolic and, especially the younger ones, were just as likely to play pranks as ever.

Even Ruth could scarcely keep a sober face when she looked now from Sammy Pinkney’s rueful countenance to the goat shaking his head at the top of the garret stairs.

“Now,” she said as severely as possible, “I would like to know how you intend to get him down again.”

“More than that, Sam,” said Neale: “How did you ever get him up there?”

“Oh, that was easy!” declared the small boy, his confident grin returning to his freckled face. “I got a stick and tied to it one of those old cabbages that Uncle Rufus has got packed away under the shed. Then,” went on the inventive genius, “I went behind Billy and pushed, holding the cabbage ahead of his nose. Say, that goat would walk up the side of a house, let alone three flights of stairs, for a cabbage!”

“Can you beat him?” murmured Neale, vastly delighted by this confession.

“I feel sometimes as though I would like to beat him,” answered Ruth. “See if you can get Billy Bumps out to his proper quarters, Neale.”

But that was not easy, and it took an hour’s work and finally the tying of Billy Bumps “hand and foot” before the sturdy goat was overcome and returned to his pen.

By this time, however, the snow had stopped. Lunch was served in the big Corner House dining-room, Neale and Sammy being guests.

It was an hilarious meal, of course. With such a crowd of young folks about the table—and on Saturday, too!—a sedate time was not possible. But Ruth tried to keep the younger ones from talking too loud or being too careless in their table manners.

Aunt Sarah Maltby, sitting at one end of the table, shook her head solemnly about midway of the meal at Sammy Pinkney.

“Young man,” she said in her severest way, “what do you suppose will become of you? You are the most mischievous boy I have ever seen—and I have seen a good many in my time.”

“Yes’m,” said Sammy, hanging his head, for he was afraid of Aunt Sarah.

“You should think of the future,” admonished the old lady. “There is something besides fun in this world.”

“Yes’m,” again came from the abashed, if not repentant, Sammy.

“Think what you might make of yourself, young man, if you desired. Do you realize that every boy born in this country has a chance to be president?”

“Huh!” ejaculated Sammy, suddenly looking up. “Be president, Miss Maltby? Huh! I tell you what: I’ll sell you my chance for a quarter.”

The irrepressible laugh from the other young folks that followed might have offended Aunt Sarah had not the front door bell rung at that very moment. Agnes, who was nearest, and much quicker than rheumatic Uncle Rufus, ran to answer the summons.

“Oh, Ruthie!” her clear voice instantly sounded as far as the dining-room, “here’s Mr. Howbridge’s man, and he’s got a great big sleigh at the gate, and—Why, there’s Mr. Howbridge himself!”

Not only the oldest Kenway ran to join her sister at the door, but all the other young folks trooped out. They forgot their plates at the announcement of the appearance of the girls’ guardian.

“Did you e’er see such bairns before?” demanded the housekeeper of Aunt Sarah. “They have neither appetite nor manners on a Saturday!”

In the big front hall the girls and boys were delightedly greeting Mr. Howbridge, while the coach-man plowed back to the gate through the snow to hold the frisky pair of bay horses harnessed to the big pung. Bits of straw clung to the lawyer’s clothing, and he was rosy and smiling.

“I did not know but what you would already be out, young folks,” Mr. Howbridge announced. “Although I had John harness up just as soon as the weather broke.”

“Oh, Mr. Howbridge,” Ruth said, remembering her “manners” after all, “won’t you come in?”

“Won’t you come out, Miss Ruth?” responded the man, laughing.

“Oh! Oh! OH!” cried Tess, in crescendo, peering out of the open door. “That sleigh of Mr. Howbridge’s is full of straw.”

“A straw-ride!” gasped Agnes, clasping her hands. “Oh, Mr. Howbridge! have you come to take us out?”

“Of course. All of you. The more the merrier,” said their guardian, who was very fond indeed of his wards and their young friends, and missed no chance to give them pleasure.

At that statement there was a perfect rout while the young people ran for their wraps and overshoes. The dessert was forgotten, although it was Mrs. MacCall’s famous “whangdoodle pudding and lallygag sauce.”

“Never mind the eats now, Mrs. Mac!” cried Agnes, struggling into her warm coat. “Have an extra big dinner. We’ll come home tonight as hungry as crows—see if we don’t!”

In ten minutes the whole party, the four Kenway sisters, Neale, and Sammy, and Tom Jonah, had tumbled into the body of the big sleigh which was so heaped with clean straw that they burrowed right into it just like mice! The big bay horses were eager to start, and tossed their heads and made the little silver bells on the harness jingle to a merry tune indeed.

Mr. Howbridge and Ruth sat up on the wide front seat—the only seat—with the driver, John. The guardian wished to talk in private with the oldest Kenway girl. He considered her a very bright girl, with a very well-balanced mind.

While the younger folks shouted and joked and snowballed each other as the horses sped along the almost unbroken track, Ruth and her guardian were quite seriously engaged in conversation.

“I want to get some good advice from you, Miss Ruth Kenway,” said the lawyer, smiling sideways at her. “I know that you have an abundant supply.”

“You are a flatterer,” declared the girl, her eyes sparkling nevertheless. She was always proud to be taken into his confidence. “Is it something about the estate?”

“No, my dear. Nothing about the Stower estate.”

“I was afraid we might be spending too much money,” said the girl, laughing. “You know, I do think we are extravagant.”

“Not in your personal expenditures,” answered their guardian. “Only in the Kenways’ charities do I sometimes feel like putting on the brake. But this,” he added, “is something different.”

“What is it, Mr. Howbridge? I am sure I shall be glad to help you if I can,” Ruth said earnestly.

“Well, now, Miss Ruth,” said the lawyer, a quizzical smile wreathing his lips. “What would you do, for instance, if a pair of twins had been left to you?”

Sometimes Mr. Howbridge called her “Martha,” because she was so cumbered with family cares. Sometimes he called her “Minerva,” and acclaimed her to be wise. He so frequently joked with her in this way that Ruth Kenway was not at all sure the lawyer was in earnest on this occasion.

“Twins?” she repeated, smiling up at him over the top of her muff. “Twin what? Twin puppies, or kittens, or even fish? I suppose there are twin fish?”

“You joke me, and I am serious,” he said, while the younger ones shouted and sang amid the straw behind. “I really have had a pair of twins given to me. I am their guardian, the administrator of their estate, just as I was made administrator of the Stower estate and guardian of you girls. It is no joke, I assure you,” and he finished rather ruefully.

“Goodness me! you don’t mean it?” cried Ruth.

“Yes, I do. I mean it very much. I do, indeed, think it rather mean. If all my friends who die and go to a better world leave me their children to take care of, I shall be in a worse pickle than the Little Old Woman Who Lived in the Shoe.”

“Like old Mrs. Bobster at Pleasant Cove,” laughed Ruth. “But even she did not have twins. And if your new family is as troublesome as the Corner House crowd, what will you ever do?”

“That is what I am asking you, Minerva,” he said seriously. “What would you do if you had had twins left to you?”

“What are they, Mr. Howbridge? Boys or girls?”

“Both.”

“Both? Oh! You mean one is a boy and one is a girl.”

“Ralph and Rowena Birdsall.”

“That is better than having two of either sex, I should say,” Ruth observed with more gravity. “They sort of—sort of balance each other.”

“I guess they are ‘some kids,’ as our friend Neale would say,” suddenly laughed Mr. Howbridge. “I knew Birdsall very well. I might say we were very close friends, both socially and in business. Poor fellow! The last two years of his life were very sad indeed.”

“Has he left plenty for the twins?” asked Ruth.

“More than ‘plenty,’” said Mr. Howbridge. “He was very, very wealthy. Ralph and Rowena will come into very large fortunes when they are of age. The money is well invested.”

“Then you need not worry about that,” Ruth said sedately.

“No? The more money, the more worry for the administrator and guardian,” Mr. Howbridge said succinctly. “I can assure you that is true. But it is what to do for, and with, the twins themselves that bothers me most just at first.”

“How old are they?”

“About twelve. Nice age! All legs and arms and imagination.”

“Dear me! Do you know them well?”

“Haven’t seen them since they were two little red mites in their cradle.”

“Then you merely imagine they are so very terrible.”

“I heard enough about them from Frank, Frank Birdsall. That was their father’s name. He used to be very fond of talking about them. Proud as Lucifer, he was, of Ralph and Rowena. And his wife—”

“Oh! Of course, the mother is dead, too.”

“That was what killed Frank, I verily believe,” said Mr. Howbridge gravely. “She died two years ago at a camp he owned up near the Canadian border. Red Deer Lodge it is called. Mrs. Birdsall was flung from her horse.

“It crushed her husband. He brought the children away from there (they had spent much of their time up in the wilderness, for they loved it) and never went back again.

“That’s another piece of work he’s left me. Because he did not want ever to see the Lodge again, I have to go up there—now, in mid-winter—and attend to something that’s been hanging fire too long already. It is a nuisance.”

“A camp in the woods in mid-winter must be an enjoyable place,” Ruth said thoughtfully. “You can take your guns; and you can snowshoe; can skate; maybe—”

“And, as our good Mrs. Mac would say, eat fried snowballs and icicle soup!” finished Mr. Howbridge. “Ugh! It’s a fine place, Red Deer Lodge, but I shall take only my man and we’ll have to depend on some old guide or trapper to do for us. No, I look forward to no pleasant time at Red Deer Lodge, I assure you.”

This conversation was not carried on in sequence. The party in the body of the sleigh frequently interrupted. Sammy managed to dance all over the sleigh, and half a dozen times he was on the point of pitching out into the drifts.

“Let him!” snapped Agnes at last. “Let him be buried in the snow, and we won’t stop for him—not until we come back.”

“The poor kid would be an icicle then,” objected Neale O’Neil.

“And he’d miss the nice hot chocolate and buns Mr. Howbridge says we are to have at Crowder’s Inn,” put in Tess, the thoughtful.

Dot squeezed her Alice-doll close to her little bosom and made up her mind that that precious possession should not pop out by accident into a drift and be left behind.

“I don’t suppose I should have brought her,” Dot confessed to Tess. “I should have given the sailor-boy baby an airing instead.”

“Oh, yes! Nosmo King Kenway,” murmured her sister.

Dot hurried on, ignoring the suggestive name of the sailor-boy baby who had been inadvertently christened after a sign on a barn door.

“You know,” the smallest Corner House girl said, “Alice’s complexion is so delicate. Of course, Neale had her all made over in the doll’s hospital; but I am always afraid that the wind will crack it.”

“I wouldn’t worry so about her, Dot,” advised Tess.

“You would if Alice were your baby,” declared Dot. “And you know she is delicate. She’s never been the same since Lillie Treble buried her with the dried apples in our back yard.”

Meanwhile Neale O’Neil had caught a sentence or two flung back by the wind from the high front seat. He bobbed up between Mr. Howbridge and Ruth.

“What’s all this about red deer, and snowshoes, and eating icicle soup?” he asked. “Sounds awfully interesting. Are you planning to go hunting, Mr. Howbridge?”

“I’ve got to go to a hunting lodge, clear up state, my boy,” said the lawyer. “And I dread it just as much as you young folks would enjoy it.”

“It would be fine, I think,” murmured Ruth.

“Oh, bully!” shouted Agnes, suddenly standing up in the straw and clinging to Neale for support. “To a regular, sure-enough winter camp? Then Carrie and Lucy Poole, and Trix Severn can’t crow over us any more! They went, last year, to Letterbeg Camp, up beyond Hoosac.”

“But, goodness, Agnes, wait till we are asked, do!” admonished Ruth. “I never saw or heard of such precipitate young ones.”

“Young one yourself!” grumbled Agnes.

“It’s my fault,” said the good-natured Neale. “Aggie misunderstood what I said.”

“No need to worry about it,” said Mr. Howbridge cheerfully. “If you young folks really want to come with me—”

“Oh, Mr. Howbridge!” exclaimed Ruth, in a tone that showed she, herself, had been much taken with the idea.

“Why, I hate to go alone. I can send up some servants to open the Lodge. Frank was always begging me to make use of it. After Mrs. Birdsall was killed he never would go near the place, as I said. Though I believe the twins, Ralph and Rowena, have been up there with a caretaker and a governess, or somebody to look out for them.”

“Where are they now?” asked Ruth.

“The Birdsall place in Arlington was closed soon after Frank died, three months ago. His old butler and his wife live in a nice home near by, and they have the children and their governess with them.”

“With just servants?” murmured Ruth.

“They are very suitable people,” declared Mr. Howbridge, as though he felt the faint criticism in the girl’s words. “I went myself and saw Rodgers and Mrs. Rodgers. The governess and the twins were out for a drive, so I did not see them.”

“The poor things!” sighed Ruth.

“My!” exclaimed Agnes, “those children are worse off than we Kenways were. They haven’t got anybody like Ruth, Mr. Howbridge.”

“That is true,” agreed the lawyer. “But what am I to do? Separate them? Send them to boarding school—the boy one way and the girl another?”

“Gee! that would be tough, Mr. Howbridge,” declared Neale O’Neil, with considerable feeling for the unfortunate twins.

“I don’t see what I’m to do,” complained the lawyer.

“They should have a real home,” Ruth stated, with some severity. “Sending them to boarding school is dodging the issue. So is leaving them wholly in the care of servants.”

“Who would take in two tearing and wearing children, twelve years old?” demanded Mr. Howbridge, on the defensive.

“Perhaps the fault does go back to the parents—to the father, at least,” admitted Ruth. “He should have made provision for his children before he died.”

“I suppose you think the duty devolves upon me,” said Mr. Howbridge, rather grumpily. “Should I take them into my house? Should I break up the habits of years for two half-wild children?”

“Oh, I don’t know that,” Ruth told him brightly. “It’s one of those things one must decide for oneself, isn’t it?”

There was not much more said after that during the ride about the twins, Ralph and Rowena Birdsall. But Red Deer Lodge!

The idea of going to a real camp in winter was taken up by everybody in the party, for even Tom Jonah barked. In the depths of the wilderness, with wild woods, and wild animals, and perhaps wild men! (this in Sammy’s mind) all about the Lodge! The freckled boy considered the idea even superior to his long cherished desire to run away to be a pirate.

“I’ll get me a bow-arrer and learn to shoot before we start,” Sammy declared, deluding himself, as he always did, with the idea that he was to be a member of the party in any case.

“But you don’t even know if your mother’ll let you go, Sammy Pinkney!” cried Tess.

“She’ll let me go if Aggie says I may,” declared Sammy. “I can, can’t I, Aggie?” grabbing her by her plaid skirt and almost pulling her over backwards.

“Stop! You can can that!” declared the next-to-the-oldest Corner House girl slangily. “What do you think I am—a bell rope, that you yank me that way?”

“I can go to that Red Deer Lodge, can’t I?” insisted the youngster.

“You can start right now, for all I care,” said Agnes, rather grumpily, and giving Sammy no further attention.

But that was enough for Sammy Pinkney. He considered that he had a particular invitation to accompany the party into the woods, and he would tell his mother so when he reached home.

But Dot began to be worried.

“Just see here, Tess Kenway!” she exclaimed suddenly. “Do you suppose my Alice-doll—or any of the other dollies—can stand it?”

“Stand what?” her sister, quite excited, asked.

“Living in tents in winter?”

“In what tents?” asked the amazed Tess.

“Up there at Red Darling Camp—”

“Red Deer!”

“Well, I knew it was some nice word,” Dot, undisturbed, said. “But Alice is so delicate.”

“Why, Dot Kenway! we won’t have to live in tents,” said Tess.

“We did in that other camp we went to,” said the smaller girl. “Don’t you ’member? And the tent ’most blowed over one night, and you and I and Tom Jonah went sailing in a boat? And that clam man—”

“But, Dot!” cried Tess, “that was a summer camp. This is a winter one. And it’s all made of logs, and there are doors and windows and fireplaces and—and everything!”

“Oh!” murmured Dot. “I wondered how they’d keep Jack Frost out. And he’s stinging my ears right now, Tess Kenway.”

The roadside inn was in sight now, and presently the big sleigh pulled up before it with the bells jangling and the horses steaming, as Dot remarked, “just as though they had boiling water in ’em and the smoke was leaking out.”

The whole party ran into the grillroom and chased Jack Frost away with hot chocolate and cakes. There the idea of going to Red Deer Lodge for the Christmas holidays was well thrashed out.

“Of course, I will send up my own servants and supplies. Being administrator of the estate, there will be no question of my using the Lodge as I see fit,” Mr. Howbridge said cheerfully. “And I shall be delighted to have you young folks with me.

“I am really going to confer with an old timber cruiser about the standing timber contracted for by the Neven Lumber Company before Frank Birdsall died. This timber cruiser—”

“It sounds like a sea-story!” interrupted Agnes, roguishly.

“What is a timber cruiser?” demanded Ruth, quite as puzzled as her sister.

“It is not a ‘what’ but a ‘who,’” laughed Mr. Howbridge. “In his way, Ike M’Graw is quite a famous character up there. A timber cruiser is a man who knows timber so well that just by walking through a wood lot and looking he can number and mark down the trees that are sound and will make good timber.

“Ike has written me through a friend (for the old man cannot use a pen himself, save to make his cross) that he has been over the entire Birdsall estate and that his figures and the figures of the Nevens people are too far apart. I fear that the lumber company is trying to put something over on me, and as administrator of the estate I must look out for the twins’ interests.”

“You are more careful of their money, Mr. Howbridge, than you are of the twins themselves, are you not?” Ruth suggested, in a low voice.

“Now, don’t tell me that!” he cried. “I really cannot take those children into my house.”

“Well, you know,” she told him, smiling, “you brought this on yourself by asking my advice. And you intend to fill that Lodge up there with us ‘young ones.’”

“But I shall have you to manage for me, Miss Ruth,” declared the lawyer. “That is different.”

“Perhaps we might take the twins along with us, and you’d get used to them,” Ruth said. “You say they like it up there in the wilderness.”

“Frank said they were crazy about it.”

“Well?”

“You don’t know what you are letting yourselves in for. Ralph and Rowena are young savages.”

“Can’t be much worse than Sammy, yonder,” chuckled Neale, who, with Agnes, was much interested in this part of the planning.

“Oh, Ruthie!” exclaimed the second Kenway sister suddenly, clasping her hands. “There’s Cecile and Luke!”

“Where—what—?”

“I mean we invited them to come to the Corner House for the holidays.”

“Ah-ha!” exclaimed Mr. Howbridge promptly. “The Shepards? Of course! I had already included them—in my mind.”

“Mr. Howbridge! It will be more than a party. It will be a convention,” gasped Ruth.

“It’s such a lonely place that we’ll need a big crowd to make it worth while going at all,” the lawyer laughed. “Yes. Cecile and Luke are invited. I will have them written to at once—in addition to your own invitation to them, Miss Ruth.”

“Dear me! you are just the best guardian, Mr. Howbridge,” sighed Agnes ecstatically.

“And I think,” Ruth added, “that you ought to think seriously of taking the Birdsall twins with us.”

That was not decided at that time, however. And when the party got back to the old Corner House, just across from the Parade Ground at the head of Main Street, Mr. Howbridge was met with a piece of news that shocked him much more than had the thought of the twins making their home with him in his quiet bachelor residence.

A clerk from the lawyer’s office awaited Mr. Howbridge. There was a telegram from Rodgers, the Birdsalls’ ex-butler. It read:

“Ralph and Rowena away since yesterday noon. Hospitals searched. Cannot have pond dragged. Two feet of ice. Wire instructions.

—Rodgers.”

Mr. Howbridge, before he hurried away to his office, asked Ruth:

“What do you think of that? And you suggest my keeping those twins—those two wild youngsters—in my home!”

“I will tell you what I think of that telegram,” said the oldest Kenway girl, handing the yellow sheet of paper back to him. “I think that man Rodgers is not a fit person to have charge of the boy and girl.”

“Why not?” he asked in surprise.

“Imagine thinking of dragging a pond in mid-winter—or at any other time of the year—for two healthy children! First idea the man seems to have. I guess the twins had reason for running away.”

“Hear! Hear!” cried Agnes, who deliberately listened.

“Why, they have known Rodgers all their lives!”

“Perhaps that is why they have run away,” said Ruth, smiling. “Rodgers sounds to me—from his telegram—as though he had one awful lack.”

“You frighten me. What lack?”

“Lack of a sense of humor. And that is fatal in the character of anybody who has a pair of twins on his hands.”

Mr. Howbridge threw up his own hands in amazement. “I must lack that myself,” he said. “I see nothing funny, at least, in the idea of having Ralph and Rowena Birdsall in my house.”

“It helps,” said Ruth. “A sense of humor is what has kept me going all these years,” she added demurely. “If you think a pair of twins can be compared to Tess and Dot and Sammy Pinkney—to say nothing of Aggie and Neale—”

“Oh! Oh!” shouted the two latter in chorus.

“You have a mean mind, Ruthie Kenway,” declared the blonde beauty.

“I knew I wasn’t much liked,” admitted Neale O’Neil. “But that is the unkindest cut of all.”

“You have had experience, I grant you,” said Mr. Howbridge, about to take his departure. “But I foresee much trouble in the case of these Birdsall twins.”

And he was a true prophet there. The twins had utterly disappeared. The Arlington police—indeed, all the county officers together—could find no trace of the orphaned brother and sister.

Mr. Howbridge put private detectives on the case. The twins seemed to have disappeared as utterly as though they really were under the two feet of ice on Arlington Pond.

The lawyer searched personally, advertised in the newspapers, and even offered a reward for the apprehension of the children. A fortnight passed without success.

The governess, Miss Mason, was discharged, for it seemed unnecessary to pay her salary when there were no children for her to teach. Rodgers and his wife could give no aid in the search. They were rather relieved, if the truth were told, to be free of the twins.

“Master Ralph was hard enough to get along with,” the ex-butler admitted. “But Miss Rowena was worse. They wanted to go back into their own house to live. They could not understand why it was shut up, sir,” and the old serving man shook his head.

“They seemed to have taken a dislike to you, sir,” he added to Mr. Howbridge. “They said you ‘hadn’t any right to boss.’ That is the way they put it.”

“But I never even saw them,” returned the lawyer. “I didn’t try ‘to boss’ them.”

“Well, you know, sir,” Rodgers explained, “I had to give ’em reasons for things. You have to with children like Master Ralph and Miss Rowena. So I had to tell ’em you said they were to do this and that.”

“Oh! Ah! I see!” muttered the guardian.

He began to believe that perhaps Ruth Kenway was right. He should have taken more of a personal interest in Ralph and Rowena. They had evidently gained from the ex-butler an entirely wrong impression of what a guardian was.

But the disappearance of the Birdsall twins did not make any change in the plans for the mid-winter visit to Red Deer Lodge. Mr. Howbridge had to go there in any case, and he would not disappoint the Kenways and their friends.

As it chanced, full three weeks were given the Milton schools at the Christmas Holiday time. There were repairs to make in the heating arrangements of both high and grammar school buildings. The schools would close the week before Christmas and not open again until the week following New Year’s Day.

If Sammy Pinkney had had his way, the schools would never have opened again!

“I don’t see what they have to learn you things for, anyway,” complained the youngster. “You can find things out for yourself.”

“That’s rather an expensive way to learn, I’ve always heard,” said Ruth, admonishingly.

“Huh!” grumbled Sammy, “teachers don’t know much, anyway. Look! There’s what Miss Grimsby told us in physics the other day—all about what you’re made of, and how you’re made, and the names you can call yourself—if you want to.

“You know: Your legs and arms are limbs—and all that. She told us the middle part of our bodies is the trunk, and she asked us all if we understood that. Some said ‘yes,’ and some didn’t say nothing,” went on the excited boy.

“‘Don’t you know the middle of the body is the trunk?’ she asked Patsy Roach. And what do you suppose he told Miss Grimsby?”

“I can’t imagine,” said Agnes, for this was in the evening and the young people were gathered about the sitting-room table with their lesson books.

“He told her: ‘You ought to go to the circus, Miss Grimsby, and see the elephant,’” giggled Sammy. “And I guess Patsy was right. Huh! Trunk!” he added with scorn.

“Association of ideas,” chuckled Neale O’Neil, who was likewise present as usual during home study hour. “I heard that one of the kids in Dot’s grade gave Miss Andrews an extremely bright answer the other day.”

“What was that, Neale?” asked Agnes, who would rather talk than study at any time.

“History. Miss Andrews asked one little girl who discovered America, and the answer was, ‘Ohio’!”

“Oh! Oh!” murmured Agnes, while even Ruth smiled.

“Yes,” chuckled Neale. “Miss Andrews said, ‘No; Columbus discovered America,’ and the kid said: ‘Yes’m. That was his first name.’”

“She got her geography and history mixed,” said Ruth, smiling.

“That was Sadie Goronofsky’s half-sister, Becky,” explained Dot. “She isn’t very bright.”

“You bet she isn’t bright!” snorted Sammy Pinkney. “Her pop’s got a little tailor shop with another man down on Meadow Street, and they are always fighting.”

“Who are always fighting?” asked Neale quizzically. “Becky and her father or Becky and her father’s partner?”

“Smartie! Becky’s pop and the other man,” answered Sammy. “And their landlord was putting in a new store-front, and Becky’s father put out a sign telling folks they were still working—you know. Becky said it read: ‘Business going on during altercations,’ instead of ‘alterations.’ And ‘altercations’ means fights,” concluded the wise Sammy.

“Just see,” remarked Ruth quietly, “how satisfied you children should be that you know so much more than your little mates. You so frequently bring home tales about them.”

“Aw, now, Ruth,” mumbled Sammy, who was bright enough to note her characteristic criticism.

“I would try,” the oldest Kenway said admonishingly, “to bring home only the pleasant stories about my little school friends.”

“Oh! I know a nice story about Allie Newman’s little brother,” declared Dot eagerly.

“That little terror!” murmured Agnes.

“He is one tough little kid,” admitted Neale O’Neil, in an undertone.

“What about the little Newman boy?” asked Ruth indulgently. “And then we must all study.”

“Why,” said Dot, big-eyed and very much in earnest, “you know Robbie Newman doesn’t go to school yet; and he’s an awful trial to his mother.”

“That is gossip, Dot,” Tess interposed severely.

But the smallest Corner House girl was not to be derailed from the main line of her story, and went right on:

“He was naughty the other day and his mamma told him she’d shut him up somewhere all by himself. ‘If you do, Mamma,’ he said, ‘I’ll just smash ev’rything in the room.’”

“Oh-oo!” gasped Tess, proving herself to be quite as much interested in the “gossip” as the others around the evening lamp. “What a wicked boy!”

“But he didn’t smash anything,” Dot was quick to explain. “For his mother put him right out in the henhouse.”

“The henhouse! Fancy!” said Agnes.

“There wasn’t anything for him to smash there,” said Dot. “But when she had locked him in, Robbie put his head out of the little door where the hens go in and out, and he called after her:

“‘Mamma, you can lock me in here all you want to; but I won’t lay any eggs!’”

“I am not sure that it isn’t gossip,” chuckled Agnes, when the general laugh had subsided.

“That will be all now,” Ruth said with severity. “Study time is here.”

But there was another and more important subject in all their minds than either school happenings, the eccentricities of their friends, or the lesson books themselves.

The holidays! The thought of going to Red Deer Lodge! A winter vacation in the deep woods, and to live in “picnic” fashion, as they supposed, lent a charm to the plan that delighted every member of the Corner House party.

Ruth and Agnes wrote to the Shepards—to Cecile at home with her Aunt Lorena, and to Luke at college—and they were immediately enamored of the plan and returned enthusiastic acceptances of the invitation, thanking Mr. Howbridge, of course, as well.

The lawyer was having a great deal to do at this time, and he came to the old Corner House more than once to talk about the Birdsall twins to Ruth and the others. As he said, it gave him comfort to talk over something he did not know anything about with the oldest Corner House sister.

He sat one stormy day in the cozy sitting-room, with Dot and the Alice-doll on one knee and Tess and Almira, who was now a quite grown-up cat and had kittens of her own, on his other knee. All the Corner House cats were pets, no matter how grown-up they were.

“It is worrying me a great deal, Ruthie,” he said to the sympathetic girl. “Look at a day like this. We don’t know where those poor children are. Rodgers says they could have had but little money. In fact, they scarcely knew what money was for, having always had everything needful supplied them.”

“Twelve-year-old children nowadays, Mr. Howbridge,” said Ruth, “are usually quite capable of looking after themselves.”

“You think so?” queried the worried guardian.

“You remember what Agnes was at twelve. And look at our Tess.”

The lawyer pinched Tess’ cheek. “I see what she is. And she is going to be twelve some day, I suppose,” he agreed. “But what would she and—say—Sammy Pinkney do, turned out alone into the world?”

“Oh!” cried Dot, the little pitcher with the big ears, “Sammy and I went off alone to be pirates. And I’m younger than Tess.”

“I hope I shouldn’t run away with Sammy!” said Tess, in some disdain.

“Why,” Dot put in, “suppose Sammy was your brother? I felt quite sisterly to him that time we were hid in the canalboat.”

“I guess that we all feel ‘sisterly’ to Sammy,” laughed Ruth. “And I am sure, Tess, you would know what to do if you were away from home with him.”

“I guess I would,” agreed Tess severely. “I’d march him right back again.”

The lawyer joined in the laugh. But he was none the less anxious about Ralph and Rowena Birdsall. There was an undercurrent of feeling in his mind, too, that he had been derelict in his duty toward his wards.

“Three months after their father died, and I had not seen them,” he said more than once. “I blame myself. As you say, Ruth, I should have won their confidence in that time.”

“Oh, Mr. Howbridge, you are not to blame for that! You are unused to children, anyway.”

“But it was selfishness on my part—arrant selfishness, Frank’s children should have been my personal care. But, twins!” and he groaned.

One might have been amused by his bachelor horror of the thought of two children in his quiet home; only the situation was really too serious to breed laughter. Two twelve-year-old children striking out into the world for themselves might get into all sorts of mischief and trouble.

The lawyer had done all he could, however, toward recovering the runaways. The police of two States were on the watch for them, and private detectives were likewise hunting for them. The advertisements Mr. Howbridge put in the papers brought no helpful replies. There seemed to be many children wandering about the country, singly and in pairs, but none of them answered at all the description of the Birdsall twins.

Meanwhile the Christmas holidays were approaching. Cecile Shepard arrived at the old Corner House a week ahead of the date set for the closing of school. Luke, however, would join the party at Culberton, at the foot of Long Lake, nearly at the far end of which, and deep in the woods, was Red Deer Lodge.

Cecile was a very pretty girl, as dark as Agnes was light. She went to school every day with Agnes and sat beside her as a “visitor” during the remainder of the term.

Of course, there was much to do to prepare for this mid-winter venture into the woods. And, too, there were certain plans for Christmas to be carried out by the Corner House girls, whether they were to be at home on Christmas Day or not.

The Stower estate tenants on Meadow Street must not be forgotten.

Uncle Peter Stower, in dying and leaving his four grandnieces the Milton property, had left them, in addition (or so Ruth Kenway and her sisters concluded), the duty of overlooking the welfare of certain poor people who occupied the Stower tenements on Meadow Street, over toward the canal.

These tenants were mostly poor people; but Mrs. Kranz, who kept a delicatessen store and grocery, and Joe Maroni, whom Dot said was “both an ice man and a nice man” were two of the tenants who were well-to-do.

Joe Maroni, whose family lived in the corner cellar under Mrs. Kranz’s store, sold coal and wood, as well as ice, and had a vegetable and fruit stand on the sidewalk. Mrs. Kranz, the large German woman, was one of the Kenway girls’ staunchest friends. Both these shopkeepers were sure to aid the Corner House sisters in their plans for Christmas.

The year before the children of the Stower estate tenants had appeared under the bedroom windows of the old Corner House early on Christmas morning and sung Christmas chants.

“Agnes said, just as though it was in old fuel times,” Dot eagerly told Cecile Shepard. “And Aggie wanted to throw large yeast cakes among ’em. You know, like Lady Bountiful did, and—”

“Oh! Oh! OH!” gasped Tess, in horror and amazement. “Why will you, Dot, mix up your words so? It wasn’t fuel times, it was feudal times.”

“And why throw away the yeast cakes?” demanded Cecile, in amused wonder.

“Dear me!” exclaimed Tess, with vast disdain. “She means largess. That means gifts. Dot thought it was ‘large yeast.’ I never did hear of such a child!”

“Well, I don’t care!” wailed Dot, who did not like to be taken to task for mispronouncing words, or for other mistakes in English. “I don’t think you are at all polite, Tessie Kenway, and I’m going to tell Ruth—so now!”

Which proved that even the little Corner House girls had their little spats. Everything did not always go smoothly.

However, the plans for the entertainment of the Meadow Street families were made without any trouble. It was decided to have a great tree for the whole crowd, and to set it up in a small hall on Meadow Street, where certain lodges held their meetings, the date set for the entertainment being a week in advance of Christmas Eve—the night before the Corner House party was to start for Red Deer Lodge.

Mrs. Kranz took charge of the dressing of the tree, for when she was a child in the old country a Christmas tree was the great annual feast. Not a child among those belonging in the Stower tenements was forgotten—nor the grown folk, either, for that matter.

Tess and Dot did their share in the purchasing of the presents and preparing them for the tree. They both delighted in shopping, and their favorite mart of trade was the five and ten cent store on Main Street.

Such a jumble of things as they bought! The beauty of buying in the five and ten cent store is (or so the children declared) that one can get so much for a dollar.

Every afternoon for a week before the day set for the pre-Christmas celebration, the little folks trudged down to their favorite emporium and came back with their arms laden with a variety of articles to delight the hearts and eyes of the Meadow Street children.

Dolls and dolls’ toys were of course Dot’s favorite purchases. Tess went in for the more practical things—some to be hung on the tree marked with her own private card for the grown-up members of the expected audience.

In any case, and altogether, there was gathered at the old Corner House to be hung on the Christmas tree for the Meadow Street people a two-bushel basket of little packages, mostly from the five and ten cent store.

Ruth and Agnes saw to it that there were plenty of practical things for the poor children, too: warm coats, caps, leggings, shoes, mittens—a dozen other useful things which would be needed by the younger Goronofskys, the Pedermans, the O’Harras, and all the rest of the conglomerate crew occupying the Stower tenements.

And they had four “Santa Clauses”! Although, more properly speaking, they were “the Misses Santa Claus.” The Kenway sisters, in the prescribed uniforms of the good St. Nicholas, presided over the distribution of the presents from the illuminated tree.

Dot had every faith in the reality of Santa Claus, nor would her sisters disabuse her of that cheerful belief.

“But, of course,” the smallest Corner House girl said, “I know Santa can’t be everywhere at once. And this is a week too early for him, anyway. And on Christmas Eve he does have to rush around so to get to everybody’s house!

“We’re just going to make believe to be Santa, Sammy,” she explained to that small boy. “And we’re not going to be like you were last Christmas, Sammy, and fall down the chimney and frighten everybody so.”

“Huh!” grumbled Sammy, to whom his fiasco as a Santa Claus in the old Corner House chimney was a sore subject. “If that old brick hadn’t fallen I wouldn’t have come down so sudden. And my mom burned my Santa Claus suit up in the furnace because it was all over soot.”

This night in the Meadow Street hall was long to be remembered. Mr. Howbridge made a speech. It was a winter when work was hard to get, and at Ruth’s personal request he announced that a dollar a month would be taken off every tenant’s rent during the “hard times.”

Mrs. Kranz and Joe Maroni, being in so much better circumstances than the majority of the Stower estate tenants, gave many things for the Christmas tree, too. There was candy, and cakes, and popcorn, and nuts for the little folk, and hot drinks and cake and sandwiches for the adults.

Altogether it was a night long to be remembered by the Corner House girls. Even the little ones had begun to understand their duty toward these poor people who helped swell the Kenway family bank account. The estate might not now draw down the fifteen per cent. that Uncle Peter Stower always demanded; but the income from the Meadow Street tenements was considerable, and the tenants were now happier and more content.

“It must be lovely,” Cecile Shepard confessed to Ruth and Agnes, “to have so many folks to look out for, and be kind to, and who like you. And Ruthie has such a way with her. I can see the women all admire her.”

Agnes began to giggle. “Who wouldn’t admire her?” she said. “Ruth believes in helping folks just the way they want to be helped. She doesn’t furnish only flannels and cough sirup to the poor. Oh, no!”

“Now, Agnes!” admonished the older girl, blushing.

“I don’t care! It’s too good a joke, and it shows just why those people over on Meadow Street worship Ruth,” went on the younger sister. “Did you see that biggest Pederman girl? Olga, the one with the white eyebrows and no lashes?”

“Yes,” said Cecile. “Her face looks almost like a blank wall.”

“And a white-washed wall at that,” went on Agnes. “She’s a grown woman, but she hasn’t any too much intelligence. She was awfully sick with diphtheria last spring, and Ruth went to see her—carrying gifts, of course.”

“Things to eat don’t much appeal to you when you have diphtheria and can’t swallow,” put in Ruth.

“I know that,” chuckled Agnes. “And what do you think, Cecile? Ruthie asked Olga what she would like to have—if she could get her anything special?

“‘Yes, Miss Wuth,’ she croaked. Olga can’t pronounce her ‘R’s’ very well. ‘Yes, Miss Wuth, I’ve been wantin’ a pair of them dangly jet eawin’s for so long!’ And what do you suppose?” Agnes exploded in conclusion. “Ruth went and bought them for her! She had them on tonight.”

“I don’t care,” Ruth said, with conviction. “The earrings came nearer to curing Olga than all Dr. Forsyth’s medicine. He said so himself.”

“What do you think of that?” giggled Agnes.

“I think it was awfully sweet of our Ruth,” declared Cecile, hugging the oldest Kenway sister.

Mrs. MacCall, for her part, was not at all sure that the Kenway sisters did not “encourage pauperism” in thus helping their tenants. Mrs. MacCall was conservative in the extreme.

“No,” Ruth said earnestly, “the dear little babies, and the little folks with empty ‘tummies,’ are not paupers, Mrs. MacCall. Nor are their parents such. We haven’t a lazy tenant family in the Stower houses.”

“That may be as may be,” said the housekeeper, shaking her head. “But they are too frequently out o’ work to suit me. And guidness knows there’s plenty to do in the world.”

“They’re just unfortunate,” reiterated Ruth. “We have been lucky. We never did a thing, we Kenways, to get Uncle Peter’s wealth. We’ve had better luck than the Pedermans and Goronofskys.”

“Hush, my lassie! If you undertake to level things in this world for all, you’ve a big job cut out for you. Nae doot of that.”

Although the housekeeper was often opposed both in opinion and practice to Ruth and her sisters, the latter were eager to have Mrs. MacCall go with the vacation party as chaperone and manager. And, indeed, had Mrs. MacCall not agreed, it is doubtful if Ruth would have accepted Mr. Howbridge’s invitation to go into the North Woods to Red Deer Lodge.

Mrs. MacCall sacrificed her own desires and some comfort to accompany the young folks; but she did it cheerfully because of her love for the Corner House girls.

Aunt Sarah Maltby would remain at home to oversee things at the Corner House; and of course Linda and Uncle Rufus would be with her.

Trunks had been packed the day before the early celebration of Christmas in the Meadow Street lodge room, and had been sent on by train with the serving people that Hedden, Mr. Howbridge’s butler and factotum, had engaged to go ahead of the vacation party and prepare Red Deer Lodge for occupancy over the holidays.

Of course, Neale O’Neil and the older girls had their bags to carry with them, and Sammy Pinkney came over to the old Corner House bright and early on the morning of departure, lugging his bulging suitcase.

“And I hope,” Agnes said with severity, “that you haven’t worms in that suitcase, with a lot of other worthless truck, as you had when you went on our automobile tour, Sammy.”

“Huh! where’d I dig fishworms this time of year?” responded the boy with scorn. “Besides, mom packed this bag, and she’s left out a whole lot of things I’ll need up there in the woods. She won’t even let me take my bow-arrer and a steel trap I got down at the blacksmith shop by the canal. Of course, the latch of the trap was broke, but we might have fixed it and used it to catch wolves with.”

“Oh, my!” squealed Dot. “Wolves? Why, they are savage!”

“Course they are savage,” said Sammy.

“But—but Mr. Howbridge, our guardian, wouldn’t let any wolves stay around that Darling Lodge. They might eat my Alice-doll!”

“Sure,” agreed the boy, as Agnes was not within hearing. “Like enough the wolf pack will chase us when we are sleighing, and you’ll have to throw that doll over to pacificate ’em so we can escape with our lives. They do that in Russia. Throw the babies away to save folks’ lives.”

“Well!” exclaimed Tess, half doubting this bold statement. “Babies must be awful cheap in Russia. Cheaper than they are here. You know we can’t get a baby in this house, and we all would like to have one.”

But Dot had been stricken dumb by Sammy’s wild statement. She hugged the Alice-doll to her breast, and her eyes were wide with fear.

“Do you suppose that may happen, Tess?” she whispered.

“What may happen?”

“That we get chased by wolfs and—and have to throw somebody overboard to ’em?”

“I don’t believe so,” said Tess, after all somewhat impressed by Sammy’s assurance.

“Well, anyway,” said Dot, “I was only going to take Alice up there to that Lodge; but I’ll take the sailor-doll, too. He can stand being thrown to the wolves better than Alice. He’s tougher.”

If it had not already been decided to take Tom Jonah, the big Newfoundland, along on this winter trip, Dot might really have balked at going.

However, aside from Dot’s disturbance of mind over the trip into the deep woods where, on occasion, babies had to be flung to wolves, there was something that disturbed Ruth on this morning which almost made her doubt the advisability of starting for Red Deer Lodge.

Ruth had been up as early as Linda, the Finnish maid. There was still much to do, and the sleigh would be at the door at eight-thirty. When Linda came down, however, she stopped at Ruth’s door and said she had heard Uncle Rufus groaning most of the night. The old colored man was undoubtedly suffering from one of his recurrent rheumatic attacks.

Ruth hurried up to the third story of the house and to Uncle Rufus’ room.

“Yes’m, Missie Ruth,” groaned the old man. “Ah’s jes’ knocked right down ag’in. Ah don’ believe Ah’s goin’ to be able to git up a-tall to see yo’ off dis mawnin’.”

“Poor Uncle Rufus!” said the oldest Corner House girl, commiseratingly. “I believe I’d better telephone to Dr. Forsyth and let him come—”

“No’m. Ah don’ want dat Dr. Forsyth to come a-near me, Missie Ruth,” interrupted Uncle Rufus.

“Why, of course you do,” said the girl. “He gave you something before that helped you. Don’t you remember?”

“Ah don’ say he don’ know he’s business, Missie Ruth,” said the old man, shaking his head. “Mebbe his med’cine’s jest as good as de nex’ doctor’s med’cine. But Ah don’ want Dr. Forsyth no mo’.”

“Why not?”

“Dr. Forsyth done insulted me,” said the old man, with rising indignation. “He done talk about me.”

“Why, Uncle Rufus!”

“Sho’ has!” repeated the black man. “An’ Ah nebber did him a mite o’ harm. He done say things about me dat I can’t nebber overlook—no, ma’am!”

“Why, Uncle Rufus!” murmured the worried Ruth, “I think you must be mistaken. I can’t imagine Dr. Forsyth being unkind, or saying unkind things about one.”

“He sho’ did,” declared the obstinate old man. “And he done put it in writin’. You jes’ reach me ma best coat, Missie Ruth. It’s all set down dar on ma burial papers.”

Of course, Uncle Rufus, like most frugal colored people, belonged to a “burial association”—an insurance scheme by which one must die to win.

“What could Dr. Forsyth have said about you that you think is unkind, Uncle Rufus?” repeated Ruth, as she came into the room to get the coat.

“Ah tell yo’ what he done said!” exclaimed the old man, indignantly. “Dr. Forsyth say Ah was a drunkard an’ a joy-rider! Dat’s what he say! An’ de goodness know, Missie Ruth, I ain’t tetch a drap of gin fo’ many a long year, and I ain’t nebber step foot in even your automobile. No’m! He done insulted me befo’ de members of ma burial lodge, an’ I don’ want nothin’ mo’ to do wid dat white man—no’m!”

He spread out the insurance policy with a flourish and pointed to the examining doctor’s notation regarding Uncle Rufus’ former illness: “Autotoxication.”

“Ah’s a respectable man,” urged Uncle Rufus, evidently hurt to the quick by what he thought was Dr. Forsyth’s uncalled-for criticism. “Ah don’t get drunk in no auto—no’m! An’ I don’t go scootin’ roun’ de country in one o’ dem ’bominations. Dere is niggers w’at owns one o’ dem flivvers an’ drinks gin wid it. But not Unc’ Rufus—no’m!”

“I never would accuse you of such reprehensible habits,” Ruth assured him, having considerable difficulty in suppressing after all a desire to laugh. “Nor does Dr. Forsyth mean anything like that.”

She explained carefully to the old negro that “autotoxication” meant “self-poisoning”—the poisoning of the body by unexpelled organic matter. This poison, in the form of an acid in the blood, was the cause of Uncle Rufus’ pains and aches.

“Fo’ de lan’s sake!” murmured Uncle Rufus. “Is dat sho’ ’nough so, Missie Ruth?”

“You know I would not mislead you, Uncle Rufus.”

“Dat’s right. You would not,” agreed the old man. “An’ is dat what dat fool white doctor mean? Ah jes’ got rheumatics, like Ah always has?”

“Yes, Uncle Rufus.”

“Tell me, Missie Ruth,” he asked, “what do dem doctors want to use sech wo’ds fo’, when dere is common wo’ds to use dat a pusson kin understan’?”

“Just for that reason, I fancy,” laughed Ruth. “So the patient cannot understand. The doctors think it isn’t well for the patient to know too much about what ails him, so they call ordinary illnesses by hard names.”

“Ain’t it a fac’? Ain’t it a fac’?” repeated Uncle Rufus, shaking his head. “Ah reckon if we knowed too much, we wouldn’t want doctors a-tall, eh? Well, now, Missie Ruth, you let dat Lindy gal git ma’ medicine bottle filled down to de drug store, and Ah’ll dose up like Ah done befo’. If dat white doctor’s medicine was good fo’ one time, it ought to be good fo’ another time.”

Uncle Rufus remained in bed, however, and the little girls and Sammy, as well as Neale and Agnes, trooped up to say good-bye to him before they started for the railway station.

The north-bound express train halted at Milton at three minutes past nine, and the Corner House party were in good season for it. Mr. Howbridge joined them on the station platform. Hedden, the lawyer’s man, having gone ahead to make the path smooth for his employer and his friends, Mr. Howbridge and Neale attended to getting the tickets and to the light baggage; and they made the three older girls, Mrs. MacCall, and the children comfortable in the chair car. Tom Jonah, of course, rode in the baggage car.

It was two hundred miles and more to Culberton, at the foot of Long Lake. The train made very good time, but it was past one o’clock when they alighted at the lake city. There was a narrow gauge road here that followed the line of the lake in a northerly direction; but it was little more than a logging road and the trains were so slow, and the schedule so poor, that Mr. Howbridge had planned for other and more novel means of transportation up the lake to the small town from which they would have to strike back into the wilderness by “tote-road” to Red Deer Lodge. But this new means of transportation, he told the young people, depended entirely upon the wind.

“Goodness!” gasped Agnes, “are we going up the lake by kite?”

“In a balloon, maybe?” Cecile laughed.

“Oh!” murmured Tess, who was much interested in air traffic, “I hope it’s a big aeroplane.”

“Nothing like that,” Neale assured her. “But if we have a good wind you’ll think we’re flying, Tess.”

Mr. Howbridge had taken the ex-circus boy into his confidence; but the rest of the party were so busy greeting Luke Shepard, who was waiting for them at this point, that they did not consider much how they were to get up the lake. There was no train leaving Culberton over the Lake Branch until evening. Neale disappeared immediately after greeting Luke, and took Tom Jonah with him.

In a few minutes Neale returned to the waiting room of the Culberton railroad station, and said to Mr. Howbridge:

“They are about ready. Man says the wind is good, and likely to be fresher, if anything. Favorable time. He’s making ’em ready.”

“What’s going on?” asked Luke, who was a handsome young collegian particularly interested in Ruth Kenway, and not too serious to be enthusiastic over the secret the lawyer and Neale had between them.

“Come on and we’ll show you,” Neale said, grinning.

“No, no!” exclaimed Mr. Howbridge. “Let us have lunch first. We have a long, cold ride before us.”

“In what?” Agnes asked. “We don’t take to the sleigh yet, do we?”

“Aren’t the cars on the branch line heated?” Ruth asked. “You know, we must not let the children get cold—and Mrs. MacCall.”

“Don’t mind about me, lassie,” returned the Scotchwoman. “I’ll trust myself to Mr. Howbridge.”

“We’ll go to the hotel first of all,” said the lawyer. “Hedden will have arranged for our comfort there—and other things, as well. Do not be afraid for the children, Martha.”

But “Martha” could not help being a bit worried, even if Mrs. MacCall was along. And Neale’s grin was too impish to be comforting.

“I know you men folks are cooking up something,” she sighed. “And I am not at all sure, Mr. Howbridge, that you consider the needs of small children like Tess and Dot and Sammy.”

“Huh!” grunted Sammy, who overheard this.

“I suppose if I had taken my twins home three months ago when Frank Birdsall died, you think I would have learned something about the needs and care of young persons by this time?” suggested the lawyer.

“Oh, I am sure you would have learned a great deal,” agreed Ruth, unable to suppress a smile.

“I wish I had!” groaned Mr. Howbridge.

The mystery of the disappearance of Ralph and Rowena Birdsall weighed on Mr. Howbridge’s mind continually. He did not often let the trouble come to the surface, however, being desirous of giving the young people with him a good time.

The surprise in store for them added zest to the enjoyment of the nice luncheon at the Culberton hotel. At half past two they all trooped out of the hotel, bags in hand, and instead of returning to the railway station, set off down the hill toward the docks.

“Are we going by steamer?” Agnes wanted to know. “Is there a channel open through the ice? I never did!”

“If there were two feet of ice on the Arlington Pond so that they could not drag it for the poor Birdsall twins,” Ruth said, “surely this lake must be frozen quite as thick.”

“But there’s a sailboat! I see one!” cried Tess, pointing between the buildings as they approached the waterfront.

“And there’s another,” said Sammy. “Oh, Je-ru-sa-lem! Looky, Aggie! That boat’s sailing on the ice!”

“Oh-ee!” squealed Agnes, clasping her hands and letting her bag fall to the ground. “Ice-boats! Neale! Are they really ice-boats?”

“And are we going to sail on them?” murmured Ruth.

“For mercy’s sake!” gasped the housekeeper. “Here’s a fine thing! Have you gone daft, Mr. Howbridge?”

“It will be a new experience for you and me, Mrs. MacCall,” said the lawyer calmly. “But they tell me it is very invigorating.”

“It’s the nearest thing to flying, as far as the sensation goes, that there is, I guess,” Luke Shepard put in.

“I used to have a scooter when we were in winter quarters,” said Neale O’Neil to Agnes. “Don’t be afraid, Aggie.”

“Oh, I won’t be afraid if you are along, Neale,” promptly declared the little beauty. “I know you will take care of me.”

“You bet!” responded Neale, his eyes shining.

As they came down to the big wharf the party got a better view of the lake front. There were at least a dozen ice-boats, large and small, in motion. Those farthest out from the shore had caught the full sweep of the wind and were darting about, as Mrs. MacCall said, like water-bugs on the surface of a pond.

Ruth looked around keenly as they came out on the wharf.

“Why!” she said to Mr. Howbridge, “this is the lumber company’s wharf. The company you said had bought the timber on the Birdsall Estate.”

“It is the Neven Lumber Company, as you can see by the sign over the offices yonder,” agreed their guardian. “And here comes Neven himself.”

A red-faced man with a red vest on which were small yellow dots and some grease spots, and who chewed a big and black cigar and wore his hard hat on one side of his head, approached the group as Mr. Howbridge spoke. He hailed the latter jovially.

“Hey, Howbridge! Glad to see you. So these are your folks, are they? Hope you’ll have a merry Christmas up there in the woods. Nice place, Birdsall’s Lodge.”

“Thank you,” said the lawyer quietly.

“Which of ’em’s Birdsall’s young ones?” continued the lumber dealer, staring about with very bold eyes, and especially at Ruth Kenway and Cecile Shepard.

“I am sorry to say, Mr. Neven,” said the lawyer, “that the Birdsall twins are not with us. The children have run away from their home—a home with people who have known them since they were born. It is a very strange affair, and is causing me much worry.”

“You don’t say!” exclaimed Neven. “Too bad! Too bad! But they’ll turn up. Young ’uns always do. I ran away myself when I was a kid; and look at me now,” and the lumberman puffed out his chest proudly, as though satisfied that Lem Neven was a good deal of a man.

“I reckon,” pursued the lumberman, “that you think it’s your duty to go up to the Birdsall place and look over the piece I’ve got stumpage on. But you don’t re’lly need to. My men are scientific, I tell you. I don’t hire no old has-beens like Ike M’Graw. Those old timber cruisers are a hundred years behind the times.”

“They have one very good attribute. At least, Ike has,” Mr. Howbridge said quietly.

“What’s that?” asked Neven.

“He is perfectly honest,” was the dry response. “I shall base my demands for the Birdsall estate on Ike’s report. I assure you of that now, Mr. Neven, so that you need build no false hopes upon the reports of your own cruisers. As the contract stands we can close it out and deal with another company if it seems best to do so. And some company—either yours or another—will go in there right after New Year’s and begin to cut.”

He turned promptly away from the red-faced man and followed his party along the wharf to its end. Here lay two large ice-boats. There was a boxlike cockpit on each that would hold four passengers comfortably, besides the tiller men and the boy who “trimmed ship.” A crew of two went with each boat.

“How will the other two of our party travel?” asked Ruth, when these arrangements were explained.

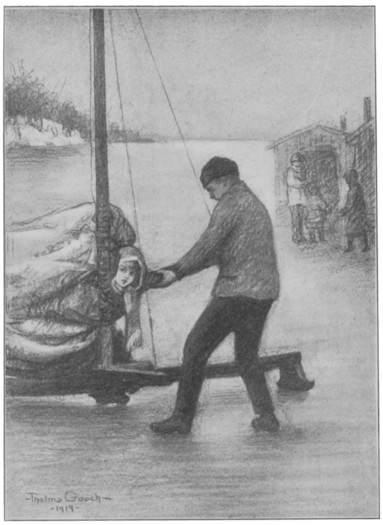

Already Neale O’Neil had beckoned Agnes to one side. There lay behind the two big boats a skeleton-like arrangement, with a seat at the stern no wider than a bobsled, and another on the “outrigger,” or crossbeam. This scooter carried a huge boom for a leg-o’-mutton sail, and it was a type of the very fastest ice-boats on the lake.

Neale helped the eager Agnes down a rude ladder to the ice. She was just reckless enough to desire to try the new means of locomotion. Her exclamations of delight drew Ruth to the edge of the wharf over their heads.

“What are you two doing down there?” asked the older girl.

“Oh, now, Ruthie!” murmured Agnes, “do let me go with Neale in this pretty boat. There isn’t room for us in the bigger boats. Do!”

Ruth knew very little about racing ice-boats. The scooter looked no more dangerous to her than did the lumbering craft that Hedden had engaged for the rest of the party.

These bigger boats, furnished with square sails rather than the leg-o’-muttons they now flaunted, were commonly used to transfer merchandise, or even logs up and down the lake. They were lumbering and slow.

“Well, if Mr. Howbridge says you can,” the oldest Corner House girl agreed, still somewhat doubtful.

Neale had already begged permission of Mr. Howbridge. The lawyer was quite as ignorant regarding ice-boating as Ruth herself. Neither of them considered that any real harm could come to Neale and Agnes in the smaller craft.

The crews of the larger ice-boats were experienced boatmen. They got their lumbering craft under way just as soon as the passengers were settled with their light baggage in the cockpits. There were bear robes and blankets in profusion. Although the wind was keen, the party did not expect that Jack Frost would trouble them.

“Isn’t this great?” cried Cecile, who was in one of the boats with Ruth, her brother, and Sammy Pinkney. “My! we always manage to have such very nice times when we are with you Corner House girls, Ruthie.”

“This is all new to me,” admitted her friend. “I hope nothing will happen to wreck us.”

“Wreck us! Fancy!” laughed Cecile.

“This wind is very strong, just the same,” said Ruth.

“Hold hard!” cried Luke, laughing. “Low bridge!”

The boom swung over, and they all stooped quickly to avoid it. The next moment the big sail filled, bulging with the force of the wind. The heavy runners began to whine over the powdered ice, and they went swiftly onward toward the middle of the lake.