Title: Poultry

Author: Hugh Piper

Release date: January 18, 2012 [eBook #38606]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive)

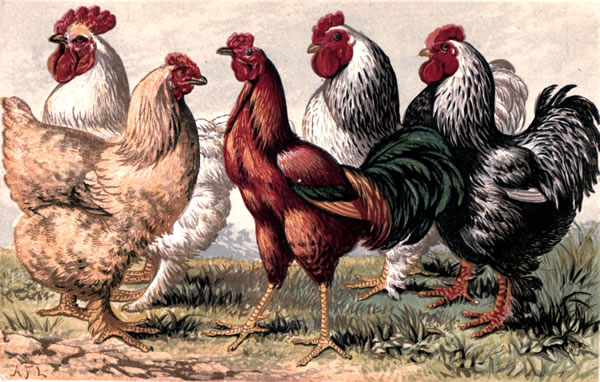

White Dorking Cock. Coloured Dorkings. Duck-winged and Black-breasted Red Game.

White Dorking Cock. Coloured Dorkings. Duck-winged and Black-breasted Red Game. This work is intended as a practical guide to those about to commence Poultry keeping, and to provide those who already have experience on the subject with the most trustworthy information compiled from the best authorities of all ages, and the most recent improvements in Poultry Breeding and Management. The Author believes that he has presented his readers with a greater amount of valuable information and practical directions on the various points treated than will be found in most similar works. The book is not the result of the Author's own experience solely, and he acknowledges the assistance he has received from other authorities. Among those whom he has consulted he desires specially to acknowledge his obligations to Mr. Tegetmeier, whose "Poultry Book" (published by Messrs. Routledge & Sons, London) contains his especial knowledge of the Diseases of Poultry; and to Mr. L. Wright, whose excellent and practical Treatise, entitled "The Practical Poultry Keeper" (published by Messrs. Cassell, Petter & Galpin, London), cannot be too highly commended.

| PAGE | |||

| CHAPTER I.—Introduction | 1 | ||

| Neglect of Poultry-breeding—Profit of Poultry-keeping—Value to the Farmer—Poultry Shows—Cottage Poultry. | |||

| CHAPTER II.—The Fowl-House | 6 | ||

| Size of the House—Brick and Wood—Cheap Houses—The Roof—Ventilation—Light—Warmth—The Flooring—Perches—Movable Frame—Roosts for Cochin-Chinas and Brahma-Pootras—Nests for laying—Cleanliness—Fowls' Dung—Doors and Entrance-holes—Lime-washing—Fumigating—Raising Chickens under Glass. | |||

| CHAPTER III.—The Fowl-Yard | 18 | ||

| Soil—Situation—Covered Run—Pulverised Earth for deodorising—Diet for confined Fowls—Height of Wall, &c.—Preventing Fowls from flying—The Dust-heap—Material for Shells—Gravel—The Gizzard—The Grass Run. | |||

| CHAPTER IV.—Food | 27 | ||

| Table of relative constituents and qualities of Food—Barley—Wheat—Oats—Meal—Refuse Corn—Boiling Grain—Indian Corn, or Maize—Buckwheat—Peas, Beans and Tares—Rice—Hempseed—Linseed—Potatoes—Roots—Soft Food—Variety of Food—Quantity—Mode of Feeding—Number of Meals—Grass and [vi]Vegetables—Insects—Worms—Snails and Slugs—Animal Food—Water—Fountains. | |||

| CHAPTER V.—Eggs | 40 | ||

| Eggs all the Year round—Warmth essential to laying—Forcing Eggs—Soft Shells—Shape and Colour of Eggs—The Air-bag—Preserving Eggs—Keeping and Choosing Eggs for setting—Sex of Eggs—Packing Setting-eggs for travelling. | |||

| CHAPTER VI.—The Sitting Hen | 48 | ||

| Evil of restraining a Hen from sitting—Checking the Desire—A separate House and Run—Nests for sitting in—Damping Eggs—Filling for Nests—Choosing their own Nests—Choosing a Hen for sitting—Number and Age of Eggs—Food and Exercise—Absence from the Nest—Examining the Eggs—Setting two Hens on the same day—Time of Incubation—The "tapping" sound—Breaking the Shell—Emerging from the Shell—Assisting the Chicken—Artificial Mothers—Artificial Incubation. | |||

| CHAPTER VII.—Rearing and Fattening Fowls | 63 | ||

| The Chicken's first Food—Cooping the Brood—Basket and Wooden Coops—Feeding Chickens—Age for Fattening—Barn-door Fattening—Fattening-Houses—Fattening-Coops—Food—"Cramming"—Capons and Poulardes—Killing Poultry—Plucking and packing Fowls—Preserving Feathers. | |||

| CHAPTER VIII.—Stock, Breeding, and Crossing | 75 | ||

| Well-bred Fowls—Choice of Breed—Signs of Age—Breeding in-and-in—Number of Hens to one Cock—Choice of a Cock—To prevent Cocks from fighting—Choice of a Hen—Improved Breeds—Origin of Breeds—Crossing—Choice of Breeding Stock—Keeping a Breed pure. | |||

| CHAPTER IX.—Poultry Shows | 83 | ||

| The first Show—The first Birmingham Show—Influence of Shows—Exhibition Rules—Hatching for Summer and Winter Shows—Weight—Exhibition Fowls sitting—Matching Fowls—Imparting lustre to the Plumage—Washing Fowls—Hampers—Travelling—Treatment on Return—Washing the Hampers and Linings—Exhibition Points—Technical Terms. | |||

| CHAPTER | X.— | Cochin-Chinas, or Shanghaes | 93 |

| CHAPTER | XI.— | Brahma-Pootras | 101 |

| CHAPTER | XII.— | Malays | 105 |

| CHAPTER | XIII.— | Game | 108 |

| CHAPTER | XIV.— | Dorkings | 112 |

| CHAPTER | XV.— | Spanish | 115 |

| CHAPTER | XVI.— | Hamburgs | 118 |

| CHAPTER | XVII.— | Polands | 121 |

| CHAPTER | XVIII.— | Bantams | 124 |

| CHAPTER | XIX.— | French and Various | 128 |

| CHAPTER | XX.— | Turkeys | 132 |

| CHAPTER | XXI.— | Guinea-Fowls | 139 |

| CHAPTER | XXII.— | Ducks | 142 |

| CHAPTER | XXIII.— | Geese | 147 |

| CHAPTER | XXIV.— | Diseases | 150 |

| PAGE | ||

| PLATE I.—Facing the Title-page. | ||

| White Dorking Cock—Coloured Dorkings—Duck-winged and Black-breasted Red Game. | ||

| PLATE II. | 93 | |

| White and Buff Cochin-China—Malay Cock—Light and Dark Brahma-Pootras. | ||

| PLATE III. | 115 | |

| Golden-pencilled and Silver-spangled Hamburgs—Black Spanish. | ||

| PLATE IV. | 121 | |

| White-crested Black Polish—Golden and Silver-spangled Polish. | ||

| PLATE V. | 124 | |

| White and Black Bantams—Gold and Silver-laced or Sebright Bantams—Game Bantams. | ||

| PLATE VI. | 128 | |

| French: Houdans—La Flêche Cock—Crêve-Cœur Hen. | ||

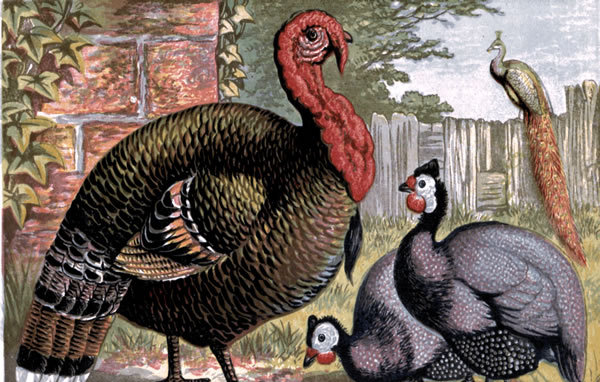

| PLATE VII. | 132 | |

| Turkey—Guinea-Fowls. | ||

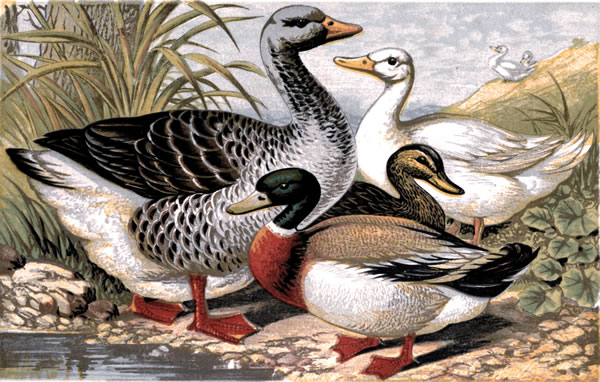

| PLATE VIII. | 142 | |

| Toulouse Goose—Rouen Ducks—Aylesbury Ducks. | ||

Until of late years the breeding of poultry has been almost generally neglected in Great Britain. Any kind of mongrel fowl would do for a farmer's stock, although he fully appreciated the importance of breeding in respect of his cattle and pigs, and the value of improved seeds. Had he thought at all upon the subject, it must have occurred to him that poultry might be improved by breeding from select specimens as much as any other kind of live stock. The French produce a very much greater number of fowls and far finer ones for market than we do. In France, Bonington Mowbray observes, "poultry forms an important part of the live stock of the farmer, and the poultry-yards supply more animal food to the great mass of the community than the butchers' shops"; while in Egypt, and some other countries of the East, from time immemorial, vast numbers of chickens have been hatched in ovens by artificial heat to supply the demand for poultry; but in Great Britain poultry-keeping has been generally neglected, eggs are dear, and all kinds of poultry so great a luxury that the lower classes and a large number of the middle seldom, if ever, taste it, except perhaps once a year in the form of a Christmas goose, while hundreds of thousands cannot afford even this. It is computed that a million of eggs are eaten daily in London and its suburbs[2] alone; yet this vast number only gives one egg to every three mouths. "It is a national waste," says Mr. Edwards, "importing eggs by the hundreds of millions, and poultry by tens of thousands, when we are feeding our cattle upon corn, and grudging it to our poultry; although the return made from the former, it is generally admitted, is not five per cent. beyond the value of the corn consumed, whereas an immense percentage can be realised by feeding poultry." A writer in the Times, of February 1, 1853, states that, while it will take five years to fatten an ox to the weight of sixty stone, which will produce a profit of £30, the same sum may be realised in five months by feeding an equal weight of poultry for the table.

Although fowls are so commonly kept, the proportion to the population is still very small, and the number of those who rear and manage them profitably still smaller, chiefly because most people keep them without system or order, and have not given the slightest attention to the subject. Nevertheless, it costs no more trouble and much less expense to keep fowls successfully and profitably, for neglected fowls are always falling sick, or getting into mischief and causing annoyance, and often expense and loss. "A man," says Mr. Edwards, "who expects a good return of flesh and eggs from fowls insufficiently fed and cared for, is like a miller expecting to get meal from a neglected mill, to which he does not supply grain."

The antiquated idea that fowls on a farm did mischief to the crops has been proved to be false; for if the grain is sown as deeply as it should be, they cannot reach it by scratching; and, besides, they greatly prefer worms and insects. Mr. Mechi says, "commend me to poultry as the farmer's best friend," and considers the value of fowls, in destroying the vast number of worms, grubs, flies, beetles, insects, larvæ, &c., which they devour, as incalculable; and the same may be said as to their destruction of the seeds of weeds. They also consume large quantities of kitchen and table refuse, which is generally otherwise wasted, and often allowed to decay and become a source of disease, or at least of impurity.

The enormous prices paid at the poultry shows of 1852 and 1853 for fancy fowls gave a new impulse to poultry-keeping; and many persons who formerly thought the management of poultry beneath their attention, now superintend their yards. Mrs. Ferguson Blair, now the Hon. Mrs. Arbuthnot, the authoress of the "Henwife," whose experience may be judged by the fact that she gained in four years upwards of 460 prizes in England and Scotland, and personally superintended the management of forty separate yards, in which above 1,000 chickens were hatched annually, says:—

"I began to breed poultry for amusement only, then for exhibition, and lastly, was glad to take the trouble to make it pay, and do not like my poultry-yard less because it is not a loss. It is impossible to imagine any occupation more suited to a lady, living in the country, than that of poultry rearing. If she has any superfluous affection to bestow, let it be on her chicken-kind and it will be returned cent. per cent. Are you a lover of nature? come with me and view, with delighted gaze, her chosen dyes. Are you a utilitarian? rejoice in such an increase of the people's food. Are you a philanthropist? be grateful that yours has been the privilege to afford a possible pleasure to the poor man, to whom so many are impossible. Such we often find fond of poultry—no mean judges of it, and frequently successful in exhibition. A poor man's pleasure in victory is, at least, as great as that of his richer brother. Let him, then, have the field whereon to fight for it. Encourage village poultry-shows, not only by your patronage, but also by your presence. A taste for such may save many from dissipation and much evil; no man can win poultry honours and haunt the taproom too."

For those who desire to encourage a taste for poultry keeping in young people, and their humbler neighbours, we would recommend our smaller work on the subject as a suitable present.[1]

"It becomes," says Miss Harriet Martineau, "an interesting wonder every year why the rural cottagers of the United Kingdom do not rear fowls almost universally, seeing how little the cost would be and how great the demand. We import many millions of eggs annually. Why should we import any? Wherever there is a cottage family living on potatoes or better fare, and grass growing anywhere near them, it would be worth while to nail up a little penthouse, and make nests of clean straw, and go in for a speculation in eggs and chickens. Seeds, worms, and insects go a great way in feeding poultry in such places; and then there are the small and refuse potatoes from the heap, and the outside cabbage leaves, and the scraps of all sorts. Very small purchases of broken rice (which is extremely cheap), inferior grain, and mixed meal, would do all else that is necessary. There would be probably larger losses from vermin than in better guarded places; but these could be well afforded as a mere deduction from considerable gains. It is understood that the keeping of poultry is largely on the increase in the country generally, and even among cottagers; but the prevailing idea is of competition as to races and specimens for the poultry-yard, rather than of meeting the demand for eggs and fowls for the table."

With the exception of prizes for Dorkings, which are chiefly bred for market, our poultry-shows have always looked upon fowls as if they were merely ornamental birds, and have framed their standards of excellence accordingly, and not with any regard to the production of profitable poultry, which is much to be regretted.

Martin Doyle, the cottage economist of Ireland, in his 'Hints to Small Holders,' observes that "a few cocks and hens, if they be prevented from scratching in the garden, are a useful and appropriate stock about a cottage, the warmth of which causes them to lay eggs in winter—no trifling advantage to the children when milk is scarce. The French, who are extremely fond of eggs, and contrive to have them in great abundance, feed the fowls so well on curds and buckwheat, and keep them so warm, that they have plenty of eggs even in winter. Now, in our country[5] (Ireland), especially in a gentleman's fowl yard, there is not an egg to be had in cold weather; but the warmth of the poor man's cabin insures him an egg even in the most ungenial season."

Such fowls obtain fresh air, fresh grass, and fresh ground to scratch in, and prosper in spite of the most miserable, puny, mongrel stock, deteriorating year after year from breeding in and in, without the introduction of fresh blood even of the same indifferent description. Many an honest cottager might keep himself and family from the parish by the aid of a small stock of poultry, if some kind poultry-keeper would present him with two or three good fowls to begin with, for the cottager has seldom capital even for so small a purchase.

Considerable profit may be made by the sale of eggs for hatching and surplus stock, if the breeds kept are good, and the stock known to be pure and vigorous. The 'Henwife' says: "You may reduce your expenses by selling eggs for setting, at a remunerative price. No one should be ashamed to own what he is not ashamed to do; therefore, boldly announce your superfluous eggs for sale, at such a price as you think the public will pay for them." This is now done extensively by breeders of rank and eminence, especially through the London Field and agricultural papers. But, "beware of sending such eggs to market. Every one would be set, and you might find yourself beaten by your own stock, very likely in your own local show, and at small cost to the exhibitor."

The great secret of success in keeping fowls profitably is to hatch chiefly in March and April; encourage the pullets by proper feeding to lay at the age of six months; and fatten and dispose of them when about nineteen months old, just before their first adult moult; and never to allow a cockerel to exceed the age of fourteen weeks before it is fattened and disposed of.

In this work we shall consider the accommodation and requisites for keeping fowls successfully on a moderate scale, and the reader must adapt them to his own premises, circumstances, and requirements. Everywhere there must be some alterations, omissions, or compromises. We shall state the essentials for their proper accommodation, and describe the mode of constructing houses, sheds, and arranging runs, and the reader must then form his plan according to his own wishes, resources, and the capabilities of the place. The climate of Great Britain being so very variable in itself, and differing in its temperature so much in different parts, no one manner or material for building the fowl-house can be recommended for all cases.

Plans for poultry establishments on large scales for the hatching, rearing, and fattening of fowls, turkeys, ducks, and geese, are given in our smaller work on Poultry, referred to on page 3.

The best aspects for the fowl-house are south and south-east, and sloping ground is preferable to flat.

"It is only of late years," says Mr. Baily, "poultry-houses have been much thought of. In large farmyards, where there are cart-houses, calf-pens, pig-styes, cattle-sheds, shelter under the eaves of barns, and numerous other roosting-places, not omitting the trees in the immediate vicinity, they are little required—fowls will generally do better by choosing for themselves; and it is beyond a doubt healthier for them to be spread about in this manner, than to be confined to one place. But a love of order, on the one hand, and a dread of thieves or foxes on the other, will sometimes make it desirable to have a proper poultry-house."

Each family of fowls should, if possible, have a house and run; and if they are kept as breeding stock, and the breeds are to be preserved pure, this is essential. And where many kinds are kept, the various houses must be adapted to the peculiarities of the different breeds, in order to do justice to them all, and to attain success in each.

The size of the house and the extent of the yard or run should be proportioned to the number of fowls kept; but it is better for the house to be too small than too large, particularly in winter, for the mutual imparting of animal heat. It is found by experience that when fowls are crowded into a small space, their desire for laying continues even in winter; and there is no fear of engendering disease by crowding if the house is properly ventilated, and thoroughly cleansed every day. Mr. Baily kept for years a cock and four hens in a portable wooden house six feet square, and six feet high in the centre, the sides being somewhat shorter, and says such a house would hold six hens as well as four. Ventilating holes were made near the top. It had no floor, being placed upon the ground, and could be moved at pleasure by means of two poles placed through two staples fixed at the end of each side. A few Cochin-Chinas may be kept where there is no other convenience than an outhouse six feet square to serve for their roosting, laying, and sitting, with a yard of twice that size attached. Mr. Wright "once knew a young man who kept fowls most profitably, with only a house of his own construction, not more than three feet square, and a run of the same width, under twelve feet long." The French breeders keep their fowls in as small a space as possible, in order to generate and preserve the warmth that will induce them to lay; while the English breeders allow more space for exercise, larger houses, and free circulation of air. The French mode, is very likely the best for the winter and the English for the summer, but the two opposite methods may be made available by having one or more extra houses and runs into which the fowls can be distributed in the summer. A close, warm roosting-place will cause the production of more eggs in winter,[8] when they are scarcest and most valuable, while air and exercise are necessary to rear superior fowls for the table; and if they can have the run of a farmyard or good fields in which to pick up grain or insects, their flesh will be far superior in flavour to that of fowls kept in confinement, or crammed in coops.

Almost any outbuilding, shed, or lean-to, may be easily and cheaply converted into a good fowl-house by the exercise of a little thought and ingenuity.

The best material to build a house with is brick, but the cheapest to be durable is board, with the roof also of wood, covered with patent felt. One objection to timber houses is their being combustible, and easily ignited, and houses had better be built of a single brick in thickness, unless cheapness is a great object.

A lean-to fowl-house may be constructed for a very small sum, with boards an inch thick, against the west or south side of any wall. Whenever wood is employed it should be tongued, which is a very cheap method of providing against warping by heat, or admitting wind or rain; lying flat against the uprights, it saves material and has an external appearance far superior to any other method of boarding. If the second coat of paint is rough cast over with sand, it will greatly improve the appearance, and the house will not be unsightly even in the ornamental part of a gentleman's grounds.

A house may be built very cheaply by driving poles into the ground at equal distances, and nailing weather-boarding upon their outside. If it is to be square, one pole should be placed at each corner, and two more will be required for the door-posts. The house may be made with five, six, or more sides, as many poles being used as there are sides, and the door may occupy one side if the house be small and the side narrow, otherwise two door-posts will be required. If the boards are not tongued together, the chinks between them must be well caulked by driving in string or tow with a blunt chisel, for it is not only necessary to keep out the rain but also to keep out the wind, which has great influence on the health and laying of the fowls.

Where double boarding is employed for the sides, the house may be made much warmer by filling up the space with straw, or still better with marsh reeds, so durable for thatching. This plan, unfortunately, affords a shelter for rats, mice, and insects, and therefore, if adopted, it will be highly advantageous to form the inside boarding in panels, so as to be removable at pleasure for examination and cleansing.

For the roof, tiles or slates alone are not sufficient, but, if used, must have a boarding or ceiling under them; otherwise all the heat generated by the fowls will escape through the numerous interstices, and it will be next to impossible to keep the house warm in winter. A corrugated roof of galvanised iron may be used instead, but a ceiling also will be absolutely necessary for the sake of warmth. A rough ceiling of lath and plaster not only preserves the warmth generated by the fowls and keeps out the cold, but has the great advantage of being easily lime-washed, an operation that should be performed at least four or five times a year. Boards alone make a very good and cheap roof. They may be laid either horizontally, one plank overlapping the other, and the whole well tarred two or three times, and once every autumn afterwards; or they may be laid perpendicularly side by side, fitting closely, in which case they should be well tarred, then covered with old sheeting, waste calico, or thick brown paper tightly stretched over it, and afterwards brushed over with hot tar, or a mixture of tar boiled with a little lime, and applied while hot; this, soaking through the calico, cements it to the roof, and makes it waterproof. But board covered with patent felt, and tarred once a year, is the best. The roof ought to project considerably beyond the walls, in order to prevent the rain from dripping down them.

Ventilation is most important, and the house should be high, especially if there are many fowls, for by having it lofty a current of air can pass through it far above the level of the fowls, and purify the atmosphere without causing a draught near them. They very much dislike a draught, and will alter their positions to avoid it, and if[10] unable to do so, will seek another roosting-place. Ventilation may be obtained by leaving out some bricks in the wall or making holes in the boarding; and when there is a shed at the side of the fowl-house, by boring a few holes near the top of the wall next to the shed; all ventilators should be considerably above the perches, in order to avoid a draught near to the fowls; and should be entirely closed at night in severe weather. The best method of ventilation for a fowl-house of sufficient size and height, is by means of an opening in the highest part of the roof, covered with a lantern of laths or narrow boards, placed one over the other in a slanting position, with a small space between them like Venetian blinds.

Light is essential, not only for the health of the fowls, but in order that the state of the house may be seen, and the floor and perches may be well cleansed. It may be admitted either through a common window, a pane or two of thick glass placed in the sides, or glass tiles in the roof. It also induces them to take shelter there in rough weather.

Warmth is the most important point of all. Fowls that roost in cold houses and exposed places require more food and produce fewer eggs; and pullets which are usually forward in laying will not easily be induced to do so in severe weather if their house is not kept warm. It is a great advantage when the house backs a fire-place or stable. A gentleman told Mr. Baily that he "had been very successful in raising early chickens in the north of Scotland, and he attributed much of it to the following arrangements. He had always from twenty to thirty oxen or other cattle fattening in a long building; he made his poultry-house to join this, and had ventilators and openings made in the partition, so that the heat of the cattle-shed passed into the fowl-house. Little good has resulted from the use of stoves, or hot-water pipes, for poultry; but by skilfully taking advantage of every circumstance like that above mentioned, and by consulting aspect and position, many valuable helps are obtained."

A house built of wood in the north of England and[11] Scotland must be lined, unless artificially warmed. Felt is the best material, as its strong smell of tar will keep away most insects. Matting is frequently used, and will make the house sufficiently warm, but it harbours vermin, and therefore, if used, should be only slightly fastened to the walls, so that it can be often taken down and well beaten, and, if necessary, fumigated.

Various materials are recommended for the flooring. Boards are warm, but they soon become foul. Beaten earth, with loose dust scattered over it some inches deep, is excellent for the feet of the birds, but is a harbour for the minute vermin which are often so troublesome, and even destructive, to domestic fowls. Mowbray recommends a floor of "well-rammed chalk or earth, that its surface, being smooth, may present no impediment to being swept perfectly clean." Chalk laid on dry coal-ashes to absorb the moisture is excellent. A mixture of cow-dung and water, about the consistency of paint, put on the surface of the floor, no thicker than paint, gives it a hard surface which will bear sweeping down. It is used by the natives of India, not only for the floors, but often for the walls of their houses, and is supposed to be healthy in its application, and to keep away vermin. Miss Watts says: "Dig out the floor to about a foot deep, and fill in with burnt clay, like that used extensively on railways, the strong gravel which is called 'metal' in road-making, or any loose dry material of the kind. Let this be well rammed down, and then lay over it, with a bricklayer's trowel, a flooring of a compost of cinder-ashes, gravel, quick-lime, and water. This flooring is without the objections due to those which are cold and damp, and those which imbibe foul moisture. Stone is too cold for a flooring; beaten earth or wood becomes foul when the place is inhabited by living animals; and a flooring of bricks possesses both these bad qualities united." Bricks are the worst of all materials; they retain moisture, whether atmospheric or arising from insufficient drainage; and thus the temperature is kept low, and disease too often follows, especially rheumatic attacks of the feet and legs. However, trodden earth makes a very good[12] flooring, and it or other materials may easily be kept clean by placing moveable boards beneath the perches to receive the fowl-droppings. The floor should slope from every direction towards the door, to facilitate its cleansing, and to keep it dry.

Perches are generally placed too high, probably because it was noticed that fowls in their natural state, or when at large, usually roost upon high branches; but it should be observed that, in descending from lofty branches, they have a considerable distance to fly, and therefore alight on the ground gently, while in a confined fowl-house the bird flutters down almost perpendicularly, coming into contact with the floor forcibly, by which the keel of the breast-bone is often broken, and bumble-foot in Dorkings and corns are caused.

Some writers do not object to lofty perches, provided the fowls have a board with cross-pieces of wood fastened on to it reaching from the ground to the perch; but this does not obviate the evil, for they will only use it for ascent, and not for descent. The air, too, at the upper part of any dwelling-room, or house for animals, is much more impure than nearer the floor, because the air that has been breathed, and vapours from the body, are lighter than pure air, and consequently ascend to the top. The perches should therefore not be more than eighteen inches from the ground, unless the breed is very small and light. Perches are also generally made too small and round. When they are too small in proportion to the size of the birds, they are apt to cause the breast-bone of heavy fowls to grow crooked, which is a great defect, and very unsightly in a table-fowl. Those for heavy fowls should not be less than three inches in diameter. Capital perches may be formed of fir or larch poles, about three inches in diameter, split into two, the round side being placed uppermost; the birds' claws cling to it easily, and the bark is not so hard as planed wood. The perches, if made of timber, should be nearly square, with only the corners rounded off, as the feet of fowls are not formed for clasping smooth round poles. Those for chickens should not be thicker[13] than their claws can easily grasp, and neither too sharp nor too round.

When more than one row of perches is required they should be ranged obliquely—that is, one above and behind the other; by which arrangement each perch forms a step to the next higher one, and an equal convenience in descending, and the birds do not void their dung over each other. They should be placed two feet apart, and supported on bars of wood fixed to the walls at each end; and in order that they may be taken out to be cleaned, they should not be nailed to the supporter, but securely placed in niches cut in the bar, or by pieces of wood nailed to it like the rowlocks of a boat. If the wall space at the sides is required for laying-boxes, the perches must be shorter than the house, and the oblique bars which support them must be securely fastened to the back of the house, and, if necessary, have an upright placed beneath the upper end of each.

Some breeders prefer a moveable frame for roosting, formed of two poles of the required length, joined at each end by two narrow pieces; the frame being supported upon four or more legs, according to its length and the weight of the fowls. If necessary it should be strengthened by rails—connecting the bottoms of the legs, and by pieces crossing from each angle of the sides and ends. These frames can conveniently be moved out of the house when they require cleansing. Or it may be made of one pole supported at each end by two legs spread out widely apart, like two sides of an equilateral or equal-sided triangle. The perch may be made more secure for heavy fowls by a rail at each side fastened to each leg, about three inches from the foot.

Mr. Baily says: "I had some fowls in a large outhouse, where they were well provided with perches; as there was plenty of room, I put some small faggots, cut for firing, at one extremity, and I found many of the fowls deserted their perches to roost on the faggots, which they evidently preferred."

Cochin-Chinas and Brahma Pootras do not require[14] perches, but roost comfortably on a floor littered down warmly with straw. It should be gathered up every morning, and the floor cleaned and kept uncovered till night, when the straw, if clean, should be again laid down. It must be often changed. A bed of sand is also used, and a latticed floor even without straw, and some use latticed benches raised about six inches from the floor. But we should think that latticed roosting-places must be uncomfortable to fowls, and the dung which falls through is often unseen, and, consequently, liable to remain for too long a time, while a portion will stick to the sides of the lattice-work, and be not only difficult to see, but also to remove when seen. The "Henwife" finds, however, "that if there are nests, there the Cochins will roost, in spite of all attempts to make them do otherwise." It is a good plan, in warm weather, occasionally to sprinkle water over and about the perches, and scatter a little powdered sulphur over the wetted parts, which will greatly tend to keep the fowls free from insect parasites.

The nests for laying in are usually made on the ground, or in a kind of trough, a little raised; but some use boxes or wicker-baskets, which are preferable, as they can be removed separately from time to time, and thoroughly cleansed from dust and vermin, and can also be kept a little apart from each other. These boxes or troughs should be placed against the sides of the house, and a board sloping forwards should be fixed above, to prevent the fowls from roosting upon the edges. If required, a row of laying-boxes or troughs may be placed on the ground, and another about a foot or eighteen inches above the floor. The nest should be made of wheaten, rye, or oaten straw, but never of hay, which is too hot, and favourable besides to the increase of vermin. Heath cut into short pieces forms excellent material for nests, but it cannot always be had. The material must be changed whenever it smells foul or musty, for if it is allowed to become offensive, the hens will often drop their eggs upon the ground sooner than go to the nest. When the fowl-house adjoins a passage, or it can be otherwise so contrived,[15] it is an excellent plan to have a wooden flap made to open just above the back of the nests, so that the eggs can be removed without your going into the roosting-house, treading the dung about, and disturbing any birds that may be there, or about to enter to lay. Where possible the nests in the roosting-houses should be used for laying in only; and a separate house should be set apart for sitting hens. Where there are but a few fowls and only one house, if a hen is allowed to sit, a separate nest must be made as quiet as possible for her.—See Chapter VI.

Cleanliness must be maintained. The Canada Farmer suggested an admirable plan for keeping the roosting-house clean. A broad shelf, securely fastened, but moveable, is fixed at the back of the house, eighteen inches from the ground, and the perch placed four or five inches above it, a foot from the wall. The nests are placed on the ground beneath the board, which preserves them from the roosting fowl's droppings, and keeps them well shaded for the laying or sitting hen, if the latter is obliged to incubate in the same house, and the nests do not need a top. The shelf can be easily scraped clean every morning, and should be lightly sanded afterwards. Thus the floor of the house is never soiled by the roosting birds, and the broad board at the same time protects them from upward draughts of air. Where the nests and perches are not so arranged, the idea may be followed by placing a loose board below each perch, upon which the dung will fall, and the board can be taken up every morning and the dung removed. With proper tools, a properly constructed fowl-house can be kept perfectly clean, and all the details of management well carried out without scarcely soiling your hands. A birch broom is the best implement with which to clean the house if the floor is as hard as it ought to be. A handful of ashes or sand, sprinkled over the places from which dung has been removed, will absorb any remaining impurity.

Fowls' dung is a very valuable manure, being strong, stimulating, and nitrogenous, possessing great power in forcing the growth of vegetables, particularly those of the[16] cabbage tribe, and is excellent for growing strawberries, or indeed almost any plants, if sufficiently diluted; for, being very strong, it should always be mixed with earth. A fowl, according to Stevens, will void at least one ounce of dry dung in twenty-four hours, which is worth at least seven shillings a cwt.

The door should fit closely, a slight space only being left at the bottom to admit air. It should have a square hole, which is usually placed either at the top or bottom, for the poultry to enter to roost. A hole at the top is generally preferred, as it is inaccessible to vermin. The fowls ascend by means of a ladder formed of a slanting board, with strips of wood nailed across to assist their feet; a similar ladder should be placed inside to enable them to descend, if they are heavy fowls; but the evil is that, even with this precaution, they are inclined to fly down, as they do from high perches, without using the ladder, and thus injure their feet. A hole in the middle of the door would be preferable to either, and obviate the defects of both. These holes should be fitted with sliding panels on the inside, so that they can be closed in order to keep the fowls out while cleaning the house, or to keep them in until they have laid their eggs, or it may be safe to let them out in the morning in any neighbourhood or place where they would else be liable to be stolen. Every day, after the fowls have left their roosts, the doors and windows should be opened, and a thorough draught created to purify the house. During the winter months all the entrance holes should be closed from sunset to sunrise, unless in mild localities. Where there are many houses, they should, if possible, communicate with each other by doors, so that they may be cleaned from end to end, or inspected without the necessity of passing through the yards, which is especially unpleasant in wet weather. The doors should be capable of being fastened on either side, to avoid the chance of the different breeds intermingling while your attention is occupied in arranging the nests, collecting eggs, &c. See that your fowls are securely locked in at night, for they are more easily stolen than any other kind of domestic animals.[17] A good dog in the yard or adjoining house or stable is an excellent protection.

Every poultry-house should be lime-washed at least four or five times a year, and oftener if convenient. Vermin of any kind can be effectually destroyed by fumigating the place with sulphur. In this operation a little care is requisite; it should be commenced early in the morning, by first closing the lattices, and stopping up every crevice through which air can enter; then place on the ground a pan of lighted charcoal, and throw on it some brimstone broken into small pieces. Directly this is done the room should be left, the door kept shut and airtight for some hours; care too should be taken that the lattices are first opened, and time given for the vapour to thoroughly disperse before any one again enters, when every creature within the building will be found destroyed.

It is said that a pair of caged guinea-pigs in the fowl-house will keep away rats.

In a large establishment, and in a moderate one, if the outlay is not an object, the pens for the chickens and the passages between the various houses may be profitably covered with glass, and grapes grown on the rafters. Raising chickens under glass has been tried with great success.

The scarcity of poultry in this country partly arises from all gallinaceous birds requiring warmth and dryness to keep them in perfect health, while the climate of Great Britain is naturally moist and cold.

"The warmest and driest soils," says Mowbray, "are the best adapted to the breeding and rearing of gallinaceous fowls, more particularly chickens. A wet soil is the worst, since, however ill affected fowls are by cold, they endure it better than moisture. Land proper for sheep is generally also adapted to the successful keeping of poultry and rabbits."

But poultry may be reared and kept successfully even on bad soils with good drainage and attention. The "Henwife" says: "I do not consider any one soil necessary for success in rearing poultry. Some think a chalk soil essential for Dorkings, but I have proved the fallacy of this opinion by bringing up, during three years, many hundreds of these soi disant delicate birds on the strong blue clay of the Carse of Gowrie, doubtless thoroughly drained, that system being well understood and universally practised by the farmers of the district. A coating of gravel and sand once a year is all that is requisite to secure the necessary dryness in the runs." The best soil for a poultry-yard is gravel, or sand resting on chalk or gravel. When the soil is clayey, or damp from any other cause, it should be thoroughly drained, and the whole or a good portion of the ground should be raised by the addition of twelve inches of chalk, or bricklayer's rubbish, over which should be spread a few inches of sand. Cramp, roup, and some other diseases, more frequently arise from stagnant wet in the soil than from any other cause.

The yard should be sheltered from the north and east winds, and where this is effected by the position of a shrubbery or plantation in which the fowls may be allowed to run, it will afford the advantage of protection, not only from wind and cold, but also shelter from the rain and the burning sun. It also furnishes harbourage for insects, which will find them both food and exercise in picking up. Indeed, for all these purposes a few bushes may be advantageously planted in or adjoining any poultry-yard. When a tree can be enclosed in a run, it forms an agreeable object for the eye, and affords shelter to the fowls.

A covered run or shed for shelter in wet or hot weather is a great advantage, especially if chickens are reared. It may be constructed with a few rough poles supporting a roof of patent felt, thatch, or rough board, plain or painted for preservation, and may be made of any length and width, from four feet upwards, and of any height from four feet at the back and three feet in the front, to eight feet at the back and six feet in the front. The shed should, if possible, adjoin the fowl-house. It should be wholly or partly enclosed with wire-work, which should be boarded for a foot from the ground to keep out the wet and snow, and to keep in small chickens. The roof should project a foot beyond the uprights which support it, in order to throw the rain well off, and have a gutter-shoot to carry it away and prevent it from being blown in upon the enclosed space. The floor should be a little higher than the level of the yard, both in order to keep it dry and the easier to keep it clean; and it should be higher at the back than in the front, which will keep it drained if any wet should be blown in or water upset. If preferred, moveable netting may be used, so that the fowls can be allowed their liberty in fine weather, and be confined in wet weather. But the boarding must be retained to keep out the wet. The ground may be left in its natural state for the fowls to scratch in, in which case the surface should be dug up from time to time and replaced with fresh earth pressed down moderately hard. If the house is large and has a good window, a shed is not absolutely necessary, especially for a few fowls only, but it is a valuable addition,[20] and is also very useful to shelter the coops of the mother hens and their young birds in wet, windy, or hot weather.

By daily attention to cleanliness, a few fowls may be kept in such a covered shed, without having any open run, by employing a thick layer of dry pulverised earth as a deodoriser, which is to be turned over with a rake every day, and replaced with fresh dry pulverised earth once a week. The dry earth entirely absorbs all odour. In a run of this kind, six square feet should be allowed to each fowl kept, for a smaller surface of the dry earth becomes moist and will then no longer deodorise the dung. Sifted ashes spread an inch deep over the floor of the whole shed will be a good substitute if the dry earth cannot be had. They should be raked over every other morning, and renewed at least every fortnight, or oftener if possible. The ground should be dug and turned over whenever it looks sodden, or gives out any offensive smell; and three or four times a year the polluted soil below the layer, that is, the earth to the depth of three or four inches, should be removed and replaced with fresh earth, gravel, chalk, or ashes.[2] The shed must be so contrived that the sun can shine upon the fowls during some part of the day, or they will not continue in health for any length of time, and it is almost impossible to rear healthy chickens without its light and warmth; and it will be a great improvement if part of the run is open. Another shed will be required if chickens are to be reared.

Fowls that are kept in small spaces or under covered runs will require a different diet to those that are allowed to roam in fields and pick up insects, grass, &c., and must be provided with green food, animal food in place of insects, and be well supplied with mortar rubbish and gravel.

The height of the wall, paling, or fencing that surrounds the yard, and of the partitions, if the yard is divided into compartments for the purpose of keeping two or more breeds separate and pure, must be according to the nature of the breed. Three feet in height will be sufficient to retain Cochins and Brahmas; six feet will be required for moderate-sized fowls; and eight or nine feet will be necessary[21] to confine the Game, Hamburg, and Bantam breeds. Galvanised iron wire-netting is the best material, as it does not rust, and will not need painting for a long time. It is made of various degrees of strength, and in different forms, and may be had with meshes varying from three-fourths of an inch to two inches or more; with very small meshes at the lower part only, to keep out rats and to keep in chickens; with spikes upon the top, or with scoloped wire-work, which gives it a neat and finished appearance; with doors, and with iron standards terminating in double spikes to fix in the ground, by which wooden posts are divided, while it can be easily fixed and removed. The meshes should not be more than two inches wide, and if the meshes of the lower part are not very small, it should be boarded to about two feet six inches from the ground, in order to keep out rats, keep in chickens, and to prevent the cocks fighting through the wire, which fighting is more dangerous than in the open, for the birds are very liable to injure themselves in the meshes, and, Dorkings especially, to tear their combs and toes in them. If iron standards are not attached to the netting, it should be stretched to stout posts, well fixed in the ground, eight feet apart, and fastened by galvanised iron staples. A rail at the top gives a neater appearance, but induces the fowls to perch upon it, which may tempt them to fly over.

Where it is not convenient to fix a fence sufficiently high, or when a hen just out with her brood has to be kept in, a fowl may be prevented from flying over fences by stripping off the vanes or side shoots from the first-flight feathers of one wing, usually ten in number, which will effectually prevent the bird from flying, and will not be unsightly, as the primary quills are always tucked under the others when not used for flying. This method answers much better than clipping the quills of each wing, as the cut points are liable to inflict injuries and cause irritation in moulting.

The openness of the feathers of fowls which do not throw off the water well, like those of most birds, enables them to cleanse themselves easier from insects and dirt, by dusting their feathers, and then shaking off the dirt and these[22] minute pests with the dust. For this purpose one or more ample heaps of sifted ashes, or very dry sand or earth, for them to roll in, must be placed in the sun, and, if possible, under shelter, so as to be warm and perfectly dry. Wood ashes are the best. This dust-heap is as necessary to fowls as water for washing is to human beings. It cleanses their feathers and skin from vermin and impurities, promotes the cuticular or skin excretion, and is materially instrumental in preserving their health. If they should be much troubled with insects, mix in the heap plenty of wood ashes and a little flour of sulphur.

A good supply of old mortar-rubbish, or similar substance, must be kept under the shed, or in a dry place, to provide material for the eggshells, or the hens will be liable to lay soft-shelled eggs. Burnt oyster-shells are an excellent substitute for common lime, and should be prepared for use by being heated red-hot, and when cold broken into small pieces with the fingers, but not powdered. Some give chopped or ground bones, or a lump of chalky marl. Eggshells roughly crushed are also good, and are greedily devoured by the hens.

A good supply of gravel is also essential, the small stones which the fowls swallow being necessary to enable them to digest their hard food. Fowls swallow all grain whole, their bills not being adapted for crushing it like the teeth of the rabbit or the horse, and it is prepared for digestion by the action of a strong and muscular gizzard, lined with a tough leathery membrane, which forms a remarkable peculiarity in the internal structure of fowls and turkeys. "By the action," says Mr. W. H. L. Martin, "of the two thick muscular sides of this gizzard on each other, the seeds and grains swallowed (and previously macerated in the crop, and there softened by a peculiar secretion oozing from glandular pores) are ground up, or triturated in order that their due digestion may take place. It is a remarkable fact that these birds are in the habit of swallowing small pebbles, bits of gravel, and similar substances, which it would seem are essential to their health. The definite use of these substances, which are certainly ground down by[23] the mill-like action of the gizzard, has been a matter of difference among various physiologists, and many experiments, with a view to elucidate the subject, have been undertaken. It was sufficiently proved by Spallanzani that the digestive fluid was incapable of dissolving grains of barley, &c., in their unbruised state; and this he ascertained by filling small hollow and perforated balls and tubes of metal or glass with grain, and causing them to be swallowed by turkeys and other fowls; when examined, after twenty-four and forty-eight hours, the grains were found to be unaffected by the gastric fluid; but when he filled similar balls and tubes with bruised grains, and caused them to be swallowed, he found, after a lapse of the same number of hours, that they were more or less dissolved by the action of the gastric juice. In other experiments, he found that metallic tubes introduced into the gizzard of common fowls and turkeys, were bruised, crushed, and distorted, and even that sharp-cutting instruments were broken up into blunt fragments without having produced the slightest injury to the gizzard. But these experiments go rather to prove the extraordinary force and grinding powers of the gizzard, than to throw light upon the positive use of the pebbles swallowed; which, after all, Spallanzani thought were swallowed without any definite object, but from mere stupidity. Blumenbach and Dr. Bostock aver that fowls, however well supplied with food, grow lean without them, and to this we can bear our own testimony. Yet the question, what is their precise effect? remains to be answered. Boerhave thought it probable that they might act as absorbents to superabundant acid; others have regarded them as irritants or stimulants to digestion; and Borelli supposed that they might really contribute some degree of nutriment."

Sir Everard Home, in his "Comparative Anatomy," says: "When the external form of this organ is first attentively examined, viewing that side which is anterior in the living bird, and on which the two bellies of the muscle and middle are more distinct, there being no other part to obstruct the view, the belly of the muscle on the left side is[24] seen to be larger than on the right. This appears, on reflection, to be of great advantage in producing the necessary motion; for if the two muscles were of equal strength, they must keep a greater degree of exertion than is necessary; while, in the present case, the principal effect is produced by that of the left side, and a smaller force is used by that on the right to bring the parts back again. The two bellies of the muscle, by their alternate action, produce two effects—the one a constant friction on the contents of the cavity; the other, a pressure on them. This last arises from a swelling of the muscle inwards, which readily explains all the instances which have been given by Spallanzani and others, of the force of the gizzard upon substances introduced into it—a force which is found by their experiments always to act in an oblique direction. The internal cavity, when opened in this distended state, is found to be of an oval form, the long diameter being in the line of the body; its capacity nearly equal to the size of a pullet's egg; and on the sides there are ridges in their horny coat (lining membrane) in the long direction of the oval. When the horny coat is examined in its internal structure, the fibres of which it is formed are not found in a direction perpendicular to the ligamentous substance behind it; but in the upper portion of the cavity it is obliquely upwards. From this form of cavity it is evident that no part of the sides is ever intended to be brought in contact, and that the food is triturated by being mixed with hard bodies, and acted on by the powerful muscles which form the gizzard."

The experiments of Spallanzani show that the muscular action of the gizzard is equally powerful whether the small stones are present or not; and that they are not at all necessary to the trituration of the firmest food, or the hardest foreign substances; but it is also quite clear that when these small stones are put in motion by the muscles of the gizzard they assist in crushing the grain, and at the same time prevent it from consolidating into a thick, heavy, compacted mass, which would take a far longer time in undergoing the digestive process than when separated and intermingled with the pebbles.

This was the opinion of the great physiologist, John Hunter, who, in his treatise "On the Animal Economy," after noticing the grinding powers of the gizzard, says, in reference to the pebbles swallowed, "We are not, however, to conclude that stones are entirely useless; for if we compare the strength of the muscles of the jaws of animals which masticate their food with those of birds who do not, we shall say that the parts are well calculated for the purpose of mastication; yet we are not thence to infer that the teeth in such jaws are useless, even although we have proof that the gums do the business when the teeth are gone. If pebbles are of use, which we may reasonably conclude they are, birds have an advantage over animals having teeth, so far as pebbles are always to be found, while the teeth are not renewed. If we constantly find in an organ substances which can only be subservient to the functions of that organ, should we deny their use, although the part can do its office without them? The stones assist in grinding down the grain, and, by separating its parts, allow the gastric juice to come more readily in contact with it."

When a paddock is used as a run for a large number of poultry, it should be enclosed either by a wall or paling, but not by a hedge, as the fowls can get through it, and will also lay their eggs under the hedge. The paddock should be well drained, and it will be a great advantage if it contains a pond, or has a stream of water running through or by it. Mowbray advises that the grass run should be sown "with common trefoil or wild clover, with a mixture of burnet, spurry, or storgrass," which last two kinds "are particularly salubrious to poultry." If the grass is well rooted before the fowls are allowed to run on it, they may range there for several hours daily, according to its extent and their number, but it should be renewed in the spring by sowing where it has become bare or thin. A dry common, or pasture fields, in which they may freely wander and pick up grubs, insects, ants' eggs, worms, and leaves of plants, is a great advantage, and they may be accustomed to return from it at a call. Where there is a cropped[26] field, orchard, or garden, in which fowls may roam at certain seasons, when the crops are safe from injury, each brood should be allowed to wander in it separately for a few hours daily, or on different days, as may be most convenient. "A garden dung-heap," says Mr. Baily, "overgrown with artichokes, mallows, &c., is an excellent covert for chickens, especially in hot weather. They find shelter and meet with many insects there." When horse-dung is procured for the garden, or supplied from your stables, some should be placed in a small trench, and frequently renewed, in which the fowls will amuse themselves, particularly in winter, by scraping for corn and worms. When fowls have not the advantage of a grass run they should be indulged with a square or two of fresh turf, as often as it can be obtained, on which they will feed and amuse themselves. It should be heavy enough to enable them to tear off the grass, without being obliged to drag the turf about with them.

The following table, which first appeared in the "Poultry Diary," will show at a glance the relative constituents and qualities of the different kinds of food, and may be consulted with great advantage by the poultry-keeper, as it will enable him to proportion mixed food correctly, and to change it according to the production of growth, flesh, or fat that may be desired, and according to the temperature of the season. These proportions, of course, are not absolutely invariable, for the relative proportions of the constituents of the grain will vary with the soil, manure used, and the growing and ripening characteristics of the season.

| There is in every 100 lbs. of |

Flesh- forming Food. |

Warmth-giving Food. |

Bone- making Food. |

Husk or Fibre. |

Water. | |

| Gluten, &c. |

Fat or Oil. |

Starch, &c. |

Mineral Substance |

|||

| Oats | 15 | 6 | 47 | 2 | 20 | 10 |

| Oatmeal | 18 | 6 | 63 | 2 | 2 | 9 |

| Middlings or fine Sharps | 18 | 6 | 53 | 5 | 4 | 14 |

| Wheat | 12 | 3 | 70 | 2 | 1 | 12 |

| Barley | 11 | 2 | 60 | 2 | 14 | 1 |

| Indian Corn | 11 | 8 | 65 | 1 | 5 | 10 |

| Rice | 7 | a trace | 80 | a trace | -- | 13 |

| Beans and Peas | 25 | 2 | 48 | 2 | 8 | 15 |

| Milk | 4½ | 3 | 5 | ¾ | -- | 86¾ |

Barley is more generally used than any other grain, and, reckoned by weight, is cheaper than wheat or oats; but, unless in the form of meal, should not be the only grain given, for fowls do not fatten upon it, as, though possessing a very fair proportion of flesh-forming substances, it contains a lesser amount of fatty matters than other varieties of corn. In Surrey barley is the usual grain given, excepting during the time of incubation, when the sitting hens have oats, as being less heating to the system than the former. Barley-meal contains the same component parts as the whole grain, being ground with the husk, but only inferior barley is made into meal.

Wheat of the best description is dearer than barley, both by weight and measure, and possesses but about one-twelfth part more flesh-forming material, but it is fortunate that the small cheap wheat is the best for poultry, for Professor Johnston says, "the small or tail corn which the farmer separates before bringing his grain to market is richer in gluten (flesh-forming food) than the full-grown grain, and is therefore more nutritious." The "Henwife" finds "light wheats or tailings the best grain for daily use, and next to that barley."

Oats are dearer than barley by weight. The heaviest should be bought, as they contain very little more husk than the lightest, and are therefore cheaper in proportion. Oats and oatmeal contain much more flesh-forming material than any other kind of grain, and double the amount of fatty material than wheat, and three times as much as barley. Mowbray says oats are apt to cause scouring, and chickens become tired of them; but they are recommended by many for promoting laying, and in Kent, Sussex, and Surrey for fattening. Fowls frequently refuse the lighter samples of oats, but if soaked in water for a few hours so as to swell the kernel, they will not refuse them. The meal contains more flesh-forming material than the whole grain.

The meal of wheat and barley are much the same as the whole grain, but oatmeal is drier and separated from a large portion of the husk, which makes it too dear except[29] for fattening fowls and feeding the youngest chickens, for which it is the very best food. Fine "middlings," also termed "sharps" and "thirds," and in London coarse country flour, are much like oatmeal, but cheaper than the best, and may be cheaply and advantageously employed instead of oatmeal, or mixed with boiled or steamed small potatoes or roots.

Many writers recommend refuse corn for fowls, and the greater number of poultry-keepers on a small scale perhaps think such light common grain the cheapest food; but this is a great mistake, as, though young fowls may be fed on offal and refuse, it is the best economy to give the older birds the finest kind of grain, both for fattening and laying, and even the young fowls should be fed upon the best if fine birds for breeding or exhibition are desired. "Instead of giving ordinary or tail corn to my fattening or breeding poultry," says Mowbray, "I have always found it most advantageous to allow the heaviest and the best; thus putting the confined fowls on a level with those at the barn-door, where they are sure to get their share of the weightiest and finest corn. This high feeding shows itself not only in the size and flesh of the fowls, but in the size, weight, and substantial goodness of their eggs, which, in these valuable particulars, will prove far superior to the eggs of fowls fed upon ordinary corn or washy potatoes; two eggs of the former going further in domestic use than three of the latter." "Sweepings" sometimes contain poisonous or hurtful substances, and are always dearer, weight for weight, than sound grain.

Some poultry-keepers recommend that the grain should be boiled, which makes it swell greatly, and consequently fills the fowl's crop with a smaller quantity, and the bird is satisfied with less than if dry grain be given; but others say that the fowls derive more nutriment from the same quantity of grain unboiled. Indeed, it seems evident that a portion of the nutriment must pass into the water, and also evaporate in steam. The fowl's gizzard being a powerful grinding mill, evidently designed by Providence for the purpose of crushing the grain into meal, it is clear[30] that whole grain is the natural diet of fowls, and that softer kinds of food are chiefly to be used for the first or morning meal for fowls confined in houses (see p. 34), and for those being fattened artificially in coops, where it is desired to help the fowl's digestive powers, and to convert the food into flesh as quickly as possible.

Indian corn or maize, either whole or in meal, must not be given in too great a proportion, as it is very fattening from the large quantity of oil it contains; but mixed with barley or barley-meal, it is a most economical and useful food. It is useful for a change, but is not a good food by itself. It may be given once or twice a week, especially in the winter, with advantage. From its size small birds cannot eat it and rob the fowls. Whether whole or in meal, the maize should be scalded, that the swelling may be done before it is eaten. The yellow-coloured maize is not so good as that which is reddish or rather reddish-brown.

Buckwheat is about equal to barley in flesh-forming food, and is very much used on the Continent. Mr. Wright has "a strong opinion that the enormous production of eggs and fowls in France is to some extent connected with the almost universal use of buckwheat by French poultry-keepers." It is not often to be had cheap in this country, but is hardy and may be grown anywhere at little cost. Mr. Edwards says, he "obtained (without manure) forty bushels to the acre, on very poor sandy soil, that would not have produced eighteen bushels of oats. The seed is angular in form, not unlike hempseed; and is stimulating, from the quantity of spirit it contains."

Peas, beans, and tares contain an extraordinary quantity of flesh-forming material, and very little of fat-forming, but are too stimulating for general use, and would harden the muscular fibres and give too great firmness of flesh to fowls that are being fattened, but where tares are at a low price, or peas or beans plentiful, stock fowls may be advantageously fed upon any of these, and they may be given occasionally to fowls that are being fattened. It is better to give them boiled than in a raw state, especially if they are hard and dry, and the beans in particular may[31] be too large for the fowls to swallow comfortably. Near Geneva fowls are fed chiefly upon tares. Poultry reject the wild tares of which pigeons are so fond.

Rice is not a cheap food. When boiled it absorbs a great quantity of water and forms a large substance, but, of course, only contains the original quantity of grain which is of inferior value, especially for growing chickens, as it consists almost entirely of starch, and does not contain quite half the amount of flesh-forming materials as oats. When broken or slightly damaged it may be had much cheaper, and will do as well as the finest. Boil it for half an hour in skim-milk or water, and then let it stand in the water till cold, when it will have swollen greatly, and be so firm that it can be taken out in lumps, and easily broken into pieces. In addition to its strengthening and fattening qualities rice is considered to improve the delicacy of the flesh. Fowls are especially fond of it at first, but soon grow tired of this food. If mixed with less cloying food, such as bran, they would probably continue to relish it.

Hempseed is most strengthening during moulting time, and should then be given freely, especially in cold localities.

Linseed steeped is occasionally given, chiefly to birds intended for exhibition, to increase the secretion of oil, and give lustre to their plumage.

Potatoes, from the large quantity of starch they contain, are not good unmixed, as regular food, but mixed with bran or meal are most conducive to good condition and laying. They contain a great proportion of nutriment, comparatively to their bulk and price; and may be advantageously and profitably given where the number of eggs produced is of more consequence than their flavour or goodness. A good morning meal of soft food for a few fowls may be provided daily almost for nothing by boiling the potato peelings till soft, and mashing them up with enough bran, slightly scalded, to make a tolerably stiff dry paste. The peelings will supply as many fowls as there are persons at the dinner table. A little salt should always be added, and in winter a slight sprinkling of pepper is good.

"It is indispensable," says Mr. Dickson, "to give the potatoes to fowls not only in a boiled state, but hot; not so hot, however, as to burn their mouths, as they are stupid enough to do if permitted. They dislike cold potatoes, and will not eat them willingly. It is likewise requisite to break all the potatoes a little, for they will not unfrequently leave a potato when thrown down unbroken, taking it, probably, for a stone, since the moment the skin is broken and the white of the interior is brought into view, they fall upon it greedily. When pieces of raw potatoes are accidentally in their way, fowls will sometimes eat them, though they are not fond of these, and it is doubtful whether they are not injurious."

Mangold-wurtzel, swedes, or other turnips, boiled with a very small quantity of water, until quite soft, and then thickened with the very best middlings or meal, is the very best soft food, especially for Dorkings.

Soft food should always be mixed rather dry and friable, and not porridgy, for they do not like sticky food, which clings round their beaks and annoys them, besides often causing diarrhœa. There should never be enough water in food to cause it to glisten in the light. If the soft food is mixed boiling hot at night and put in the oven, or covered with a cloth, it will be warm in the morning, in which state it should always be given in cold weather.

Fowls have their likes and dislikes as well as human beings, some preferring one kind of grain to all others, which grain is again disliked by other fowls. They also grow tired of the same food, and will thrive all the better for having as much variety of diet as possible, some little change in the food being made every few days. Fowls should not be forced or pressed to take food to which they show a dislike. It is most important to give them chiefly that which they like best, as it is a rule, with but few exceptions, that what is eaten with most relish agrees best and is most easily digested; but care must be taken not to give too much, for one sort of grain being more pleasing to their palate than another, induces them to eat gluttonously more than is necessary or healthy.[33] M. Réaumur made many careful experiments upon the feeding of fowls, and among them found that they were much more easily satisfied than might be supposed from the greedy voracity which they exhibit when they are fed, and that the sorts of food most easily digested by them are those of which they eat the greatest quantity.

No definite scale can be given for the quantity of food which fowls require, as it must necessarily vary with the different breeds, sizes, ages, condition, and health of the fowls; and with the seasons of the year, and the temperature of the season, much more food being necessary to keep up the proper degree of animal heat in winter than in summer; and the amount of seeds, insects, vegetables, and other food that they may pick up in a run of more or less extent. Over-feeding, whether by excess of quantity or excess of stimulating constituents, is the cause of the most general diseases, the greater proportion of these diseases, and of most of the deaths from natural causes among fowls. When fowls are neither laying well nor moulting, they should not be fed very abundantly; for in such a state over-feeding, especially with rich food, may cause them to accumulate too much fat. A fat hen ceases to lay, or nearly, while an over-fed cock becomes lazy and useless, and may die of apoplexy.

But half-fed fowls never pay whether kept for the table or to produce eggs. A fowl cannot get fat or make an egg a day upon little or poor food. A hen producing eggs will eat nearly twice as much food as at another time. In cold weather give plenty of dry bread soaked in ale.

Poultry prefer to pick their food off the ground. "No plan," says Mr. Baily, "is so extravagant or so injurious as to throw down heaps once or twice per day. They should have it scattered as far and wide as possible, that the birds may be long and healthily employed in finding it, and may not accomplish in a few minutes that which should occupy them for hours. For this reason every sort of feeder or hopper is bad. It is the nature of fowls to take a grain at a time, and to pick grass and dirt with it, which assist digestion. They should feed as pheasants, partridges,[34] grouse, and other game do in a state of nature; if, contrary to this, they are enabled to eat corn by mouthfuls, their crops are soon overfilled, and they seek relief in excessive draughts of water. Nothing is more injurious than this, and the inactivity that attends the discomfort caused by it lays the foundation of many disorders. The advantage of scattering the food is, that all then get their share; while if it is thrown only on a small space the master birds get the greater part, while the others wait around. In most poultry-yards more than half the food is wasted; the same quantity is thrown down day after day, without reference to time of year, alteration of numbers, or variation of appetite, and that which is not eaten is trodden about, or taken by small birds. Many a poultry-yard is coated with corn and meal."

If two fowls will not run after one piece, they do not want it. If a trough is used, the best kind is the simplest, being merely a long, open one, shaped like that used for pigs, but on a smaller scale. It should be placed about a foot from one of the sides of the yard, behind some round rails driven into the ground three inches apart, so that the fowls cannot get into the troughs, so as to upset them, or tread in or otherwise dirty the food. The rails should be all of the same height, and a slanting board be fixed over the trough.

Some persons give but one meal a day, and that generally in the morning; this is false economy, for the whole of the nutriment contained in the one meal is absorbed in keeping up the animal heat, and there is no material for producing eggs. "The number of meals per day," says Mr. Wright, "best consistent with real economy will vary from two to three, according to the size of the run. If it be of moderate extent, so that they can in any degree forage for themselves, two are quite sufficient, at least in summer, and should be given early in the morning and the last thing before the birds go to roost. In any case, these will be the principal meals; but when the fowls are kept in confinement they will require, in addition, a scanty feed at mid-day. The first feeding should consist of soft[35] food of some kind. The birds have passed a whole night since they were last fed; and it is important, especially in cold weather, that a fresh supply should as soon as possible be got into the system, and not merely into the crop. But if grain be given, it has to be ground in the poor bird's gizzard before it can be digested, and on a cold winter's morning the delay is anything but beneficial. But, for the very same reason, at the evening meal grain forms the best food which can be supplied; it is digested slowly, and during the long cold nights affords support and warmth to the fowls."

They should be fed at regular hours, and will then soon become accustomed to them, and not loiter about the house or kitchen door all day long, expecting food, which they will do if fed irregularly or too often, and neglect to forage about for themselves, and thus cost more for food.

Grass is of the greatest value for all kinds of poultry, and where they have no paddock, or grass-plot, fresh vegetables must be given them daily, as green food is essential to the health of all poultry, even of the very youngest chickens. Cabbage and lettuce leaves, spinach, endive, turnip-tops, turnips cut into small pieces and scattered like grain, or cut in two, radish-leaves, or any refuse, but not stale vegetables will do; but the best thing is a large sod of fresh-cut turf. They are partial to all the mild succulent weeds, such as chickweed and Chenopodium, or fat-hen, and eat the leaves of most trees and shrubs, even those of evergreens; but they reject the leaves of strawberries, celery, parsnips, carrots, potatoes, onions, and leeks. The supply of green food may be unlimited, but poultry should never be entirely fed on raw greens. Cabbage and spinach are still more relaxing when boiled than raw. They are very fond of the fruit of the mulberry and cherry trees, and will enjoy any that falls, and prevent it from being wasted.

Insect food is important to fowls, and essential for chickens and laying hens. "There is no sort of insect, perhaps," says Mr. Dickson, "which fowls will not eat. They are exceedingly fond of flies, beetles, grasshoppers, and crickets, but more particularly of every sort of grub,[36] caterpillar, and maggot, with the remarkable exception of the caterpillar moth of the magpie (Abraxas grossularia), which no bird will touch." M. Réaumur mentions the circumstance of a quantity of wheat stored in a corn-loft being much infected with the caterpillars of the small corn-moth, which spins a web and unites several grains together. A young lady devised the plan of taking some chickens to the loft to feed on the caterpillars, of which they were so fond that in a few days they devoured them all, without touching a single grain of the corn. Mr. Dickson observes, that "biscuit-dust from ships' stores, which consists of biscuit mouldered into meal, mixed with fragments still unbroken, would be an excellent food for poultry, if soaked in boiling water and given them hot. It is thus used for feeding pigs near the larger seaports, where it can sometimes be had in considerable quantity, and at a very reasonable price. It will be no detriment to this material if it be full of weevils and their grubs, of which fowls are fonder than of the biscuit itself."