The Old Testament

In the Light of

The Historical Records and Legends

of Assyria and Babylonia

By

Theophilus G. Pinches

LL.D., M.R.A.S.

Published under the direction of the Tract Committee

Third Edition—Revised, With Appendices and Notes

London:

Society For Promoting Christian Knowledge

1908

Contents

- Foreword

- Chapter I. The Early Traditions Of The Creation.

- Chapter II. The History, As Given In The Bible, From The Creation To The Flood.

- Chapter III. The Flood.

- Appendix. The Second Version Of The Flood-Story.

- Chapter IV. Assyria, Babylonia, And The Hebrews, With Reference To The So-Called Genealogical Table.

- The Tower Of Babel.

- The Patriarchs To Abraham.

- Chapter V. Babylonia At The Time Of Abraham.

- The Religious Element.

- The King.

- The People.

- “Year of Šamaš and Rimmon.”

- Chapter VI. Abraham.

- Salem.

- Chapter VII. Isaac, Jacob, And Joseph.

- Chapter VIII. The Tel-El-Amarna Tablets And The Exodus.

- Chapter IX. The Nations With Whom The Israelites Came Into Contact.

- Amorites.

- Hittites.

- Jebusites.

- Girgashites.

- Moabites.

- Chapter X. Contact Of The Hebrews With The Assyrians.

- Sennacherib.

- Esarhaddon.

- Aššur-Banî-Âpli.

- Chapter XI. Contact Of The Hebrews With The Later Babylonians.

- Chapter XII. Life At Babylon During The Captivity, With Some Reference To The Jews.

- Chapter XIII. The Decline Of Babylon.

- Appendix. The Stele Inscribed With The Laws Of Ḫammurabi.

- Appendix To The Third Edition.

- Notes And Additions.

- Index.

- Footnotes

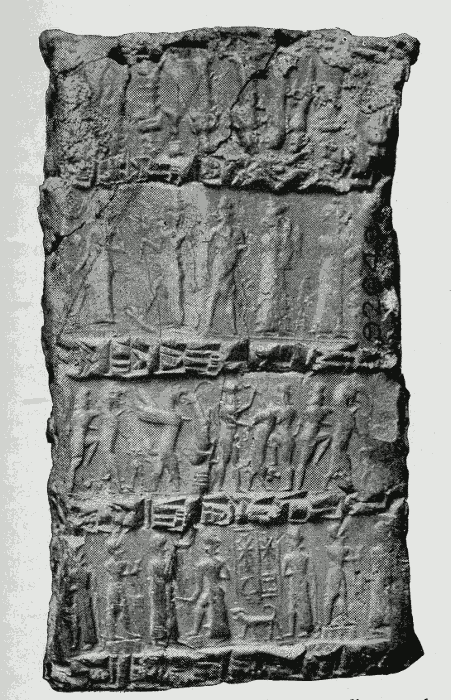

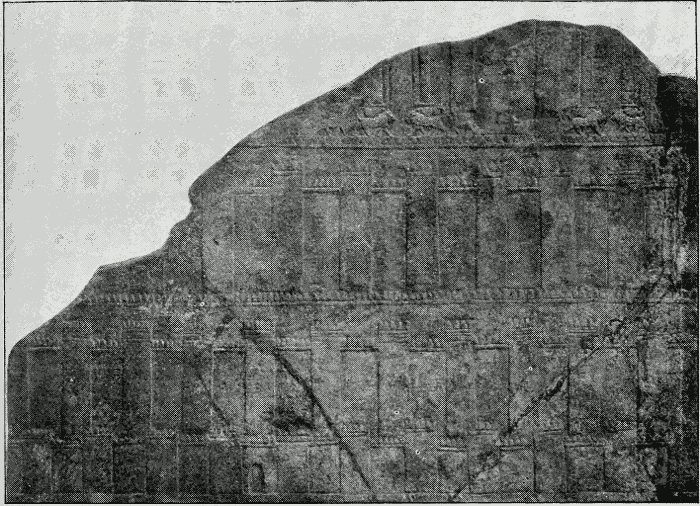

![Bas-relief and inscription of Hammurabi, generally regarded as the Biblical Amraphel (Gen. xiv. 1), apparently dedicated for the saving of his life. In this he bears the title (incomplete) of “King of Amoria” (the Amorites), lugal Mar[tu], Semitic Babylonian sar mât Amurrî (see page 315). Plate I.](images/frontispiece.png)

“There is a charm in finding ourselves, our common humanity, our puzzles, our cares, our joys, in the writings of men severed from us by race, religion, speech, and half the gulf of historical time, which no other literary pleasure can equal.”—Andrew Lang.

Foreword

The present work, being merely a record of things for the most part well known to students and others, cannot, on that account, contain much that is new. All that has been aimed at is, to bring together as many of the old discoveries as possible in a new dress.

It has been thought well to let the records tell their story as far as possible in their own way, by the introduction of translations, thus breaking the monotony of the narrative, and also infusing into it an element of local colour calculated to bring the reader into touch, as it were, with the thoughts and feelings of the nations with whom the records originated. Bearing, as it does, upon the life, history, and legends of the ancient nations of which it treats, controversial matter has been avoided, and the higher criticism left altogether aside.

Assyriology (as the study of the literature and antiquities of the Babylonians and Assyrians is called) being a study still in the course of development, improvements in the renderings of the inscriptions will doubtless from time to time be made, and before many months have passed, things now obscure may have new light thrown upon them, necessitating the revision of such portions as may be affected thereby. It is intended to utilize in future editions any new discoveries which may come to light, and every effort will be made to keep the book up to date.

For shortcomings, whether in the text or in the translations, the author craves the indulgence of the reader, merely pleading the difficult and exacting nature of the study, and the lengthy chronological period to which the book refers.

A little explanation is probably needful upon the question of pronunciation. The vowels in Assyro-Babylonian should [pg iv] be uttered as in Italian or German. Ḫ is a strong guttural like the Scotch ch in “loch”; m had sometimes the pronunciation of w, as in Tiamtu (= Tiawthu), so that the spelling of some of the words containing that letter may later have to be modified. The pronunciation of s and š is doubtful, but Assyriologists generally (and probably wrongly) give the sound of s to the former and sh to the latter. T was often pronounced as th, and probably always had that sound in the feminine endings -tu, -ti, -ta, or at, so that Tiamtu, for instance, may be pronounced Tiawthu, Tukulti-âpil-Êšarra (Tiglath-pileser), Tukulthi-âpil-Êšarra, etc., etc., and in such words as qâtâ, “the hands,” šumāti, “names,” and many others, this was probably always the case. In the names Âbil-Addu-nathanu and Nathanu-yâwa this transcription has been adopted, and may be regarded as correct. P was likewise often aspirated, assuming the sound of ph or f, and k assumed, at least in later times, a sound similar to ḫ (kh), whilst b seems sometimes to have been pronounced as v. G was, to all appearance, never soft, as in gem, but may sometimes have been aspirated. Each member of the group ph is pronounced separately. Ṭ is an emphatic t, stronger than in the word “time.” A terminal m represents the mimmation, which, in later times, though written, was not pronounced.

The second edition, issued in 1903, was revised and brought up to date, and a translation of the Laws of Ḫammurabi, with notes, and a summary of Delitzsch's Babel und Bibel, were appended. For the third edition the work has again been revised, with the help of the recently-issued works of King, Sayce, Scheil, Winckler, and others. At the time of going to press, the author was unable to consult Knudtzon's new edition of the Tel-el-Amarna tablets beyond his No. 228, but wherever it was available, improvements in the translations were made. In addition to revision, the Appendix has been supplemented by paragraphs upon the discoveries at Boghaz-Keui, a mutilated letter from a personage named Belshazzar, and translations of the papyri referring to the Jewish temple at Elephantine.

New material may still be expected from the excavations in progress at Babylon, Susa, Ḫattu, and various other sites in the nearer East.

Theophilus G. Pinches.

Chapter I. The Early Traditions Of The Creation.

To find out how the world was made, or rather, to give forth a theory accounting for its origin and continued existence, is one of the subjects that has attracted the attention of thinking minds among all nations having any pretension to civilization. It was, therefore, to be expected that the ancient Babylonians and Assyrians, far advanced in civilization as they were at an exceedingly early date, should have formed opinions thereupon, and placed them on record as soon as those opinions were matured, and the art of writing had been perfected sufficiently to enable a serviceable account to be composed.

This, naturally, did not take place all at once. We may take it for granted that the history of the Creation grew piece by piece, as different minds thought over and elaborated it. The first theories we should expect to find more or less improbable—wild stories of serpents and gods, emblematic of the conflicting powers of good and evil, which, with them, had their origin before the advent of mankind upon the earth.

But all men would not have the same opinion of the way in which the universe came into existence, [pg 010] and this would give rise, as really happened in Babylonia, to conflicting accounts or theories, the later ones less improbable than, and therefore superior to, the earlier. The earlier Creation-legend, being a sort of heroic poem, would remain popular with the common people, who always love stories of heroes and mighty conflicts, such as those in which the Babylonians and Assyrians to the latest times delighted, and of which the Semitic Babylonian Creation-story consists.

As the ages passed by, and the newer theories grew up, the older popular ones would be elaborated, and new ideas from the later theories of the Creation would be incorporated, whilst, at the same time, mystical meanings would be given to the events recorded in the earlier legends to make them fit in with the newer ones. This having been done, the scribes could appeal at the same time to both ignorant and learned, explaining how the crude legends of the past were but a type of the doctrines put forward by the philosophers of later and more enlightened days, bringing within the range of the intellect of the unlearned all those things in which the more thoughtful spirits also believed. By this means an enlightened monotheism and the grossest polytheism could, and did, exist side by side, as well as clever and reasonable cosmologies along with the strangest and wildest legends.

Thus it is that we have from the literature of two closely allied peoples, the Babylonians and the Hebrews, accounts of the Creation of the world so widely differing, and, at the same time, possessing, here and there, certain ideas in common—ideas darkly veiled in the old Babylonian story, but clearly expressed in the comparatively late Hebrew account.

It must not be thought, however, that the above theory as to the origin of the Hebrew Creation-story interferes in any way with the doctrine of its inspiration. We are not bound to accept the opinion so [pg 011] generally held by theologians, that the days of creation referred to in Genesis i. probably indicate that each act of creation—each day—was revealed in seven successive dreams, in order, to the inspired writer of the book. The opinion held by other theologians, that “inspiration” simply means that the writer was moved by the Spirit of God to choose from documents already existing such portions as would serve for our enlightenment and instruction, adding, at the same time, such additions of his own as he was led to think to be needful, may be held to be a satisfactory definition of the term in question.

Without, therefore, binding ourselves down to any hard and fast line as to date, we may regard, for the purposes of this inquiry, the Hebrew account of the Creation as one of the traditions handed down in the thought of many minds extending over many centuries, and as having been chosen and elaborated by the inspired writer of Genesis for the purpose of his narrative, the object of which was to set forth the origin of man and the Hebrew nation, to which he belonged, and whose history he was about to narrate in detail.

The Hebrew story of the Creation, as detailed in Genesis i., may be regarded as one of the most remarkable documents ever produced. It must not be forgotten, however, that it is a document that is essentially Hebrew. For the author of this book the language of God and of the first man was Hebrew—a literary language, showing much phonetic decay. The retention of this matter (its omission not being essential at the period of the composition of the book) is probably due, in part, to the natural patriotism of the writer, overruling what ought to have been his inspired common-sense. How this is to be explained it is not the intention of the writer of this book to inquire, the account of the Creation and its parallels being the subject in hand at present.

The question of language apart, the account of the [pg 012] Creation in Genesis is in the highest degree a common-sense one. The creation of (1) the heaven, and (2) the earth; the darkness—not upon the face of the earth, but upon the face of the deep. Then the expansion dividing the waters above from the waters below on the earth. In the midst of this waste of waters dry land afterwards appears, followed by the growth of vegetation. But the sun and the moon had not yet been appointed, nor the stars, all of which come into being at this point. Last of all are introduced the living things of the earth—fish, and bird, and creeping thing, followed by the animals, and, finally, by man.

It is noteworthy and interesting that, in this account, the acts of creation are divided into seven periods, each of which is called a “day,” and begins, like the natural day in the time-reckoning of the Semitic nations, with the evening—“and it was evening, and it was morning, day one.” It describes what the heavenly bodies were for—they were not only to give light upon the earth—they were also for signs, for seasons, for days, and for years.

And then, concerning man, a very circumstantial account is given. He was to have dominion over everything upon the earth—the fish of the sea, the fowl of the air, the cattle, and every creeping thing. All was given to him, and he, like the creatures made before him, was told to “be fruitful, and multiply, and replenish the earth.” It is with this crowning work of creation that the first chapter of the Book of Genesis ends.

The second chapter refers to the seventh day—the day of rest, and is followed by further details of the creation, the central figure of which is the last thing created, namely, man. This chapter reads, in part, like a recapitulation of the first, but contains many additional details. “No plant of the field was yet in the earth, and no herb ... had sprung up: for the Lord [pg 013] God had not caused it to rain ..., and there was not a man to till the ground.” A mist, therefore, went up from the earth, and watered all the face of the ground. Then, to till the earth, man was formed from the dust of the ground, and the Lord God “breathed into his nostrils the breath of life, and man became a living soul.”

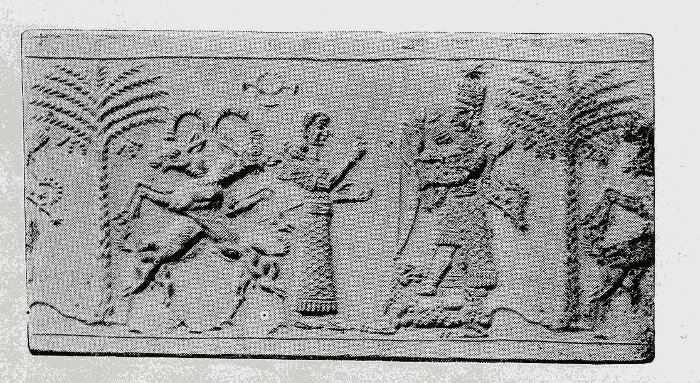

The newly-created man was, at this time, innocent, and was therefore to be placed by his Creator in a garden of delight, named Eden, and this garden he was to dress and keep. A hidden danger, however, lay in this pleasant retreat—the tree of knowledge of good and evil, of which he was forbidden to eat, but which was to form for him a constant temptation, for ever testing his obedience. All might have been well, to all appearance, but for the creation of woman, who, giving way to the blandishments of the tempter, in her turn tempted the man, and he fell. Death in the course of nature was the penalty, the earthly paradise was lost, and all chance of eating of the tree of life, and living for ever, disappeared on man's expulsion from his first abode of delight.

In the course of this narrative interesting details are given—the four rivers, the country through which they flowed, and their precious mineral products; the naming of the various animals by the man; the forming of woman from one of his ribs; the institution of marriage, etc.

Such is, in short, the story of the Creation as told in the Bible, and it is this that we have to compare with the now well-known parallel accounts current among the ancient Babylonians and Assyrians. And here may be noted at the outset that, though we shall find some parallels, we shall, in the course of our comparison, find a far greater number of differences, for not only were they produced in a different land, by a different people, but they were also produced under different conditions. Thus, Babylonian polytheism takes the place of the severe and uncompromising [pg 014] monotheism of the Hebrew account in Genesis; Eden was, to the Babylonians, their own native land, not a country situated at a remote distance; and, lastly, but not least, their language, thoughts, and feelings differed widely from those of the dwellers in the Holy Land.

The Babylonian story of the Creation is a narrative of great interest to all who occupy themselves with the study of ancient legends and folklore. It introduces us not only to exceedingly ancient beliefs concerning the origin of the world on which we live, but it tells us also of the religion, or, rather, the religious beliefs, of the Babylonians, and enables us to see something of the changes which those beliefs underwent before adopting the form in which we find them at the time this record was composed.

A great deal has been written about the Babylonian story of the Creation. As is well known, the first translation of these documents was by him who first discovered their nature, the late George Smith, who gave them to the world in his well-known book, The Chaldean Account of Genesis, in 1875. Since that time numerous other translations have appeared, not only in England, but also on the Continent. Among those who have taken part in the work of studying and translating these texts may be named Profs. Sayce, Oppert, Hommel, and Delitzsch, the last-named having both edited the first edition of Smith's book (the first issued on this subject on the Continent), and published one of the last and most complete editions of the whole legend yet placed before the public. To Prof. Sayce, as well as to Prof. Hommel, belongs the honour of many brilliant suggestions as to the tendency of the texts of the creation as a whole: Prof. Oppert was the first to point out that the last tablet of the series was not, as Smith thought, an “Address to primitive man,” but an address to the god Merodach as the restorer of order out of chaos; [pg 015] whilst Delitzsch has perhaps (being almost the last to write upon it) improved the translation more than many of his predecessors in the work.

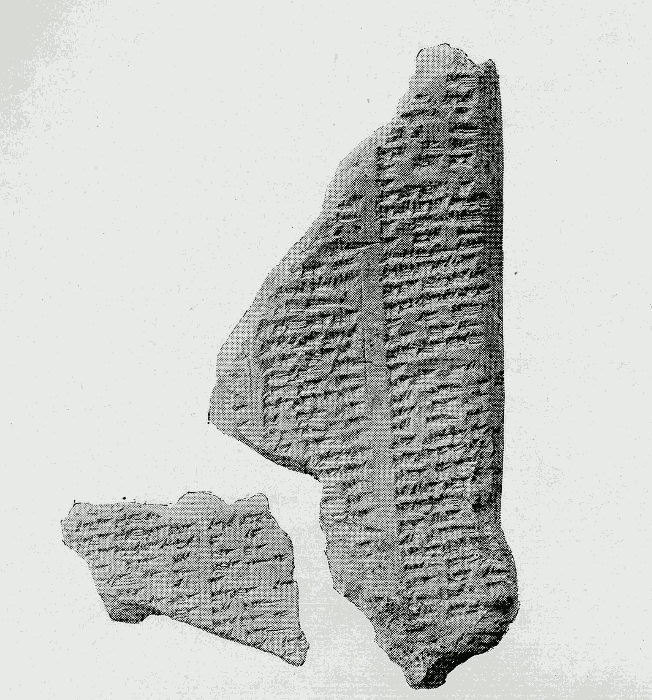

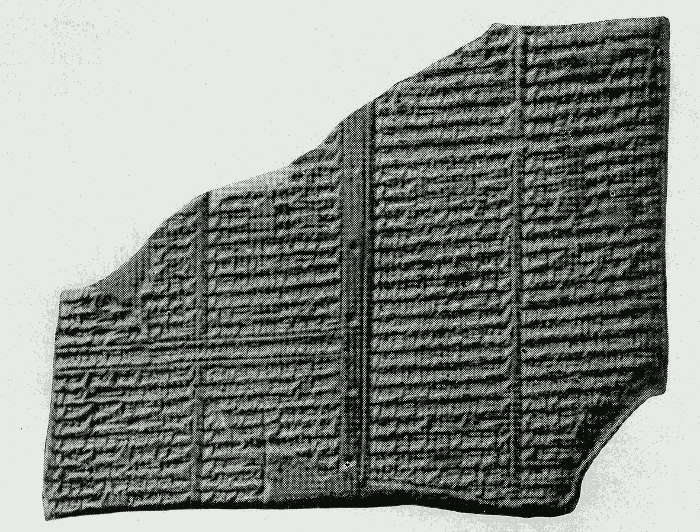

Before proceeding to deal with the legend itself, a few remarks upon the tablets and the text that they bear will probably not be considered out of place. There are, in all likelihood, but few who have not seen in the British Museum or elsewhere those yellow baked terra-cotta tablets of various sizes and shapes, upon which the Babylonians and Assyrians were accustomed to write their records. And well it is for the science of Assyriology that they used this exceedingly durable material. I have said that the tablets are yellow in colour, and this is generally the case, but the tint varies greatly, and may approach dark grey or black, and even appear as a very good sage-green. The smaller tablets are often cushion-shaped, but, with some few exceptions, they are rectangular, like those of larger size. The writing varies so considerably that the hand of the various scribes can sometimes be distinguished. In the best class of tablets every tenth line is often numbered—a proof that the Assyrians and Babylonians were very careful with the documents with which they had to deal. The Babylonian tablets closely resemble the Assyrian, but the style of the writing differs somewhat, and it is, in general, more difficult to read than the Assyrian. None of the tablets of the Creation-series are, unfortunately, perfect, and many of the fragments are mere scraps, but as more than one copy of each anciently existed, and has survived, the wanting parts of one text can often be supplied from another copy. That copies come from Babylon as well as from Nineveh is a very fortunate circumstance, as our records are rendered more complete thereby.

Of the obverse of the first tablet very little, unfortunately, remains, but what there is extant is of the highest interest. Luckily, we have the beginning of [pg 016] this remarkable legend, which runs, according to the latest and best commentaries, as follows—

Such is the tenor of the opening lines of the Babylonian story of the Creation, and the differences between the two accounts are striking enough. Before proceeding, however, to examine and compare them, a few words upon the Babylonian version may not be without value.

First we must note that the above introduction to the legend has been excellently explained and commented upon by the Syrian writer Damascius. The following is his explanation of the Babylonian teaching concerning the creation of the world—

“But the Babylonians, like the rest of the Barbarians, pass over in silence the one principle of the Universe, and they constitute two, Tauthé and Apason, [pg 017] making Apason the husband of Tauthé, and denominating her the mother of the gods. And from these proceeds an only-begotten son, Moumis, which, I conceive, is no other than the intelligible world proceeding from the two principles. From them, also, another progeny is derived, Daché and Dachos; and again a third, Kissaré and Assoros, from which last three others proceed, Anos, and Illinos, and Aos. And of Aos and Dauké is born a son called Belos, who, they say, is the fabricator of the world, the Creator.”

The likeness of the names given in this extract from Damascius will be noticed, and will probably also be recognized as a valuable verification of the certainty now attained by Assyriologists in the reading of the proper names. In Tiamtu, or, rather, Tiawthu, will be easily recognized the Tauthé of Damascius, whose son, as appears from a later fragment, was called Mummu (= Moumis). Apason he gives as the husband of Tauthé, but of this we know nothing from the Babylonian tablet, which, however, speaks of this Apason (apsû, “the abyss”), which corresponds with the “primæval ocean” of the Babylonian tablet.

In Daché and Dachos it is easy to see that there has been a confusion between Greek Λ and Δ, which so closely resemble each other. Daché and Dachos should, therefore, be corrected into Laché and Lachos, the Laḫmu and Laḫamu (better Laḫwu and Laḫawu) of the Babylonian text. They were the male and female personifications of the heavens. Anšar and Kišar are the Greek author's Assoros and Kisaré, the “Host of Heaven” and the “Host of Earth” respectively. The three proceeding from them, Anos, Illinos, and Aos, are the well-known Anu, the god of the heavens; Illil, for En-lila, the Sumerian god of the earth and the Underworld; and Aa or Ea, the god of the waters, who seems to have been [pg 018] identified by some with Yau or Jah. Aa or Ea was the husband of Damkina, or Dawkina, the Dauké of Damascius, from whom, as he says, Belos, i.e. Bel-Merodach, was born, and if he did not “fabricate the world,” at least he ordered it anew, after his great fight with the Dragon of Chaos, as we shall see when we come to the third tablet of the series.

After the lines printed above the text is rather defective, but it would seem that the god Nudimmud (Ae or Ea), “the wise and open of ear,” next came into existence. A comparison is then apparently made between these deities on the one hand, and Tiamtu, Apsû, and Mummu on the other—to the disadvantage of the latter. On Apsû complaining that he had no peace by day nor rest by night on account of the ways of the gods, their sons, it was at last determined to make war upon them.

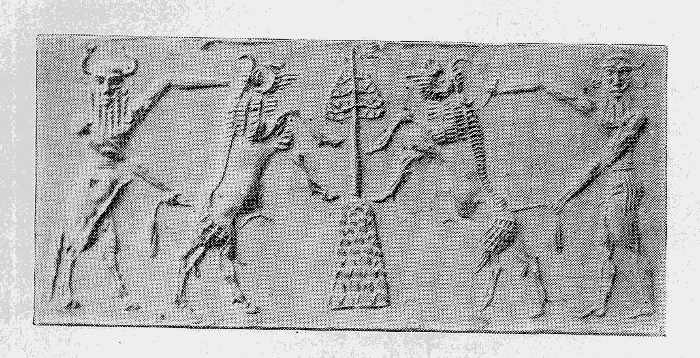

Such are the last verses of the first tablet of the so-called story of the Creation as known to the Babylonians, and though it would be better named if called the Story of Bêl and the Dragon, the references to the creation of the world that are made therein prevent the name from being absolutely incorrect, and it may, therefore, serve, along with the more correct one, to designate it still. As will be gathered from the above, the whole story centres in the wish of the goddess of the powers of evil to get creation—the production of all that is in the world—into her own hands. In this she is aided by certain gods, over whom she sets one, Kingu, her husband, as chief. In the preparations that she makes she exercises her creative powers to produce all kinds of dreadful monsters to help her against the gods whom she wishes to overthrow, and the full and vigorous description of her defenders, created by her own hands, adds much to the charm of the narrative, and shows well what the Babylonian scribes were capable of in this class of record.

The first tablet breaks off after the speech of Tiamtu to her husband Kingu. The second one begins by stating how Aa or Ea heard of the plot of Tiamtu and her followers against the gods of heaven. When his first wrath on account of this had somewhat abated, he went and related the whole, in practically the same words as the story is given on the two foregoing pages, to Anšar, his father, who in his turn became filled with rage, biting his lips, and uttering cries of deepest grief. In the mutilated lines which follow Apsû's subjugation seems to be referred to. After this is another considerable gap, and then comes the statement that Anšar applied to his son Anu, “the mighty and brave, whose power is great, whose attack irresistible,” saying that if he will only speak to her, the great Dragon's anger will be calmed and her rage disappear.

[pg 021]How the god excused himself to his father Anšar on account of his ignominious flight we do not know, the record being again defective at this point. With the same want of success the god Anšar then, as we learn from another part of the narrative, applied to the god Nudimmud, a deity who is explained in the inscriptions as being the same as the god Aa or Ea, but whom Professor Delitzsch is rather inclined to regard as one of the forms of Bêl.

In the end the god Merodach, the son of Aa, was asked to be the champion of the gods against the great emblem of the powers of evil, the Dragon of Chaos. To become, by this means, the saviour of the universe, was apparently just what the patron-god of the city of Babylon desired, for he seems immediately to have accepted the task of destroying the hated Dragon—

Anšar, without delay, calls his messenger Gaga, and directs him to summon all the gods to a festival, where with appetite they may sit down to a feast, to eat the divine bread and drink the divine wine, and there let Merodach “decide the fates,” as the one chosen to be their avenger. Then comes the message that Gaga was to deliver to Laḫmu and Laḫamu, in which the rebellion of Tiamtu is related in practically the same words as the writer used at the beginning of the narrative to describe Tiamtu's revolt. Merodach's proposal and request are then stated, and the message ends with the following words—

Laḫmu and Laḫamu having heard all the words of Anšar's message, which his messenger Gaga faithfully repeated to them, they, with the Igigi, or gods of the heavens, broke out in bitter lamentation, saying that they could not understand Tiamtu's acts.

Then all the great gods, who “decided the fates,” hastened to go to the feast, where they ate and drank, and, apparently with loud acclaim, “decided the fate” for Merodach their avenger.

Here follow the honours conferred on Merodach on account of the mighty deed that he had undertaken to do. They erected for him princely chambers, wherein he sat as the great judge “in the presence of his fathers,” and they praised him as the highest honoured among the great gods, incomparable as to his ordinances, changeless as to the word of his mouth, uncontravenable as to his utterances. None of them would go against the authority that was to be henceforth his domain.

[pg 023]His weapons were never to be defeated, his foes were to be smitten down, but as for those who trusted in him, the gods prayed him that he would grant them life, “pouring out,” on the other hand, the life of the god who had begun the evil against which Merodach was about to fight.

Then, so that he should see that they had indeed given him the power to which they referred, they laid in their midst a garment, and in accordance with their directions, Merodach spoke, and the garment vanished,—he spoke, and it reappeared—

Then all the gods called out, “Merodach is king!” and they gave him sceptre, throne, and insignia of royalty, and also an irresistible weapon, which should shatter his enemies.

Then the god armed himself for the fight, taking spear (or dart), bow, and quiver. To these he added [pg 024] lightning flashing before him, flaming fire filling his body; the net which his father Anu had given him wherewith to capture “kirbiš Tiamtu” or “Tiamtu who is in the midst,” he set north and south, east and west, in order that nothing of her might escape. In addition to all this, he created various winds—the evil wind, the storm, the hurricane, “wind four and seven,” the harmful, the uncontrollable (?), and these seven winds he sent forth, to confuse kirbiš Tiamtu, and they followed after him.

Next he took his great weapon called âbubu, and mounted his dreadful, irresistible chariot, to which four steeds were yoked—steeds unsparing, rushing forward, flying along, their teeth full of venom, foam-covered, experienced (?) in galloping, schooled for overthrowing. Merodach being now ready for the fray, he fared forth to meet the Dragon.

The sight of the enemy was so menacing, that even the great Merodach began to falter and lose courage, whereat the gods, his helpers, who accompanied him, were greatly disturbed in their minds, fearing approaching disaster. The king of the gods soon recovered himself, however, and uttered to the demon a longish challenge, on hearing which she became as one possessed, and cried aloud. Muttering then incantations and charms, she called the gods of battle to arms, and the great fight for the rule of the universe began.

Being now at the mercy of the conqueror, the divine victor soon made an end of the enemy of the gods, upon whose mutilated body, when dead, he stood triumphantly. Great fear now overwhelmed the gods who had gone over to her side, and fought against the heavenly powers, and they fled to save their lives. Powerless to escape, however, they were captured, and their weapons broken to pieces. Notwithstanding their cries, which filled the vast region, they had to bear the punishment which was their due, and were shut up in prison. The creatures whom Tiamtu had created to help her and strike terror into the hearts of the gods, were also brought into subjection, along with Kingu, her husband, from whom the tablets of fate were taken by the conqueror as things unmeet for Tiamtu's spouse to own. It is probable that we have here the true explanation of the origin of this remarkable legend, for the tablets of fate were evidently things which the king of heaven alone might possess, and Merodach, as soon as he had overcome his foe, pressed his own seal upon them, and placed them in his breast.

He had now conquered the enemy, the proud opposer of the gods of heaven, and having placed her defeated followers in safe custody, he was able to return to the dead and defeated Dragon of Chaos. He split open her skull with his unsparing weapon, hewed asunder the channels of her blood, and caused the north wind to carry it away to hidden places. His fathers saw this, and rejoiced with shouting, and brought him gifts and offerings.

[pg 026]And there, as he rested from the strife, Merodach looked upon her who had wrought such evil in the fair world as created by the gods, and as he looked, he thought out clever plans. Hewing asunder the corpse of the great Dragon that lay lifeless before him, he made with one half a covering for the heavens, keeping it in its place by means of a bolt, and setting there a watchman to keep guard. He also arranged this portion of the Dragon of Chaos in such a way, that “her waters could not come forth,” and this circumstance suggests a comparison with “the waters above the firmament” of the Biblical story in Genesis.

Passing then through the heavens, he beheld that wide domain, and opposite the abyss, he built an abode for the god Nudimmud, that is, for his father Aa as the creator.

With these words, which are practically a description of the creation or building, by Merodach, of the heavens, the fourth tablet of the Babylonian legend of the Creation comes to an end. It is difficult to find a parallel to this part of the story in the Hebrew account in Genesis.

The fifth tablet of the Babylonian story of the Creation is a mere fragment, but is of considerable interest and importance. It describes, in poetical language, in the style with which the reader has now become fairly familiar, the creation and ordering, by Merodach, of the heavenly bodies, as the ancient Babylonians conceived them to have taken place. The text of the first few stanzas is as follows—

[pg 027]The final lines of this portion seem to refer to the moon on the 7th and other days of the month, and [pg 028] would in that case indicate the quarters. “Sabbath” is doubtful on account of the mutilation of the first character, but in view of the forms given on pl. II. and p. 527 (šapattum, šapatti) the restoration as šapattu seems possible. It is described on p. 527 as the 15th of the month, but must have indicated also the 14th, according to the length of the month.

An exceedingly imperfect fragment of what is supposed to be part of the fifth tablet exists. It speaks of the bow with which Merodach overcame the Dragon of Chaos, which the god Anu, to all appearance, set in the heavens as one of the constellations. After this comes, apparently, a fragment that may be regarded as recording the creation of the earth, and the cities and renowned shrines upon it, the houses of the great gods, and the cities Nippuru (Niffer) and Asshur being mentioned. Everything, however, is very disconnected and doubtful.

The sixth tablet, judging from the fragment recognized by Mr. L. W. King, must have been one of special interest, as it to all appearance contained a description of the creation of man. Unfortunately, only the beginning of the text is preserved, and is as follows:—

Here come the remains of ten very imperfect lines, which probably related the consent of the other gods to the proposal, and must have been followed by a description of the way in which it was carried out. All this, however, is unfortunately not preserved. That the whole of Merodach's work received the approval of “the gods his fathers” is shown by the remains of lines with which the sixth tablet closes:—

What they proclaimed and announced was apparently his glorious names, as detailed in the seventh and last tablet of the series, which was regarded by George Smith as containing an address to primitive man, but which proves to be really an address to the god Merodach praising him on account of the great work that he had done in overcoming the Dragon, and in thereafter ordering the world anew. As this portion forms a good specimen of Babylonian poetry at its best, the full text of the tablet, with the exception of some short remains of lines, is here presented in as careful a translation as is at present possible.

The Seventh Tablet Of The Creation-Series, Also Known As The Tablet Of The Fifty-One Names.

1 Asari, bestower of planting, establisher of irrigation.

2 Creator of grain and herbs, he who causes verdure to grow.

[pg 030]3 Asari-alim, he who is honoured in the house of counsel, [who increases counsel?].

4 The gods bow down to him, fear [possesses them?].

5 Asari-alim-nunna, the mighty one, light of the father his begetter.

6 He who directs the oracles of Anu, Bel, [and Aa].

7 He is their nourisher, who has ordained....

8 He whose provision is fertility, sendeth forth....

9 Tutu, the creator of their renewal, [is he?].

10 Let him purify their desires, (as for) them, let them [be appeased].

11 Let him then make his incantation, let the gods [be at rest].

12 Angrily did he arise, may he lay low [their breast].

13 Exalted was he then in the assembly of the gods....

14 None among the gods shall [forsake him].

15 Tutu.1 “Zi-ukenna,” “life of the people”

16 “He who fixed for the gods the glorious heavens;”

17 Their paths they took, they set

18 May the deeds (that he performed) not be forgotten among men.

19 Tutu. “Zi-azaga,” thirdly, he called (him),—“he who effects purification,”

20 “God of the good wind,” “Lord of hearing and obedience,”

21 “Creator of fulness and plenty,” “Institutor of abundance,”

22 “He who changes what is small to great,”

23 In our dire need we scented his sweet breath.

24 Let them speak, let them glorify, let them render him obedience.

25 Tutu. “Aga-azaga,” fourthly, May he make the crowns glorious,

26 “The lord of the glorious incantation bringing the dead to life,”

27 “He who had mercy on the gods who had been overpowered,”

[pg 031]28 “He who made heavy the yoke that he had laid on the gods who were his enemies,

29 (And) for their despite (?), created mankind.”

30 “The merciful one,” “He with whom is lifegiving,”

31 May his word be established, and not forgotten,

32 In the mouth of the black-headed ones (mankind) whom his hands have made.

33 Tutu. “Mu-azaga,” fifthly, May their mouth make known his glorious incantation,

34 “He who with his glorious charm rooteth out all the evil ones,”

35 “Sa-zu,” “He who knoweth the heart of the gods,” “He who looketh at the inward parts,”

36 “He who alloweth not evil-doers to go forth against him,”

37 “He who assembleth the gods,” appeasing their hearts,

38 “He who subdueth the disobedient,”...

39 “He who ruleth in truth (and justice”), ...

40 “He who setteth aside injustice,” ...

41 Tutu. “Zi-si” (“He who bringeth about silence”), ...

42 “He who sendeth forth stillness.” ...

43 Tutu. “Suḫ-kur,” “Annihilator of the enemy,” ...

44 “Dissolver of their agreements,” ...

45 “Annihilator of everything evil.” ...

About 40 lines, mostly very imperfect, occur here, and some 20 others are totally lost. The text after this continues:—

107 “Then he seized the back part (?) of the head,which he pierced (?),

108 And as Kirbiš-Tiamtu he circumvented restlessly,

109 His name shall be Nibiru, he who seized Kirbišu (Tiamtu).

[pg 032]110 Let him direct the paths of the stars of heaven,

111 Like sheep let him pasture the gods, the whole of them.

112 May he confine Tiamtu, may he bring her life into pain and anguish,

113 In man's remote ages, in lateness of days,

114 Let him arise, and he shall not cease, may he continue into the remote future

115 As he made the (heavenly) place, and formed the firm (ground),

116 Father Bêl called him (by) his own name, “Lord of the World,”

117 The appellation (by) which the Igigi have themselves (always) called him.

118 Aa heard, and he rejoiced in his heart:

119 Thus (he spake): “He, whose renowned name his fathers have so glorified,

120 He shall be like me, and Aa shall be his name!

121 The total of my commands, all of them, let him possess, and

122 The whole of my pronouncements he, (even) he, shall make known.”

123 By the appellation “fifty” the great gods

124 His fifty names proclaimed, and they caused his career to be great (beyond all).

125 May they be accepted, and may the primæval one make (them) known,

126 May the wise and understanding altogether well consider (them),

127 May the father repeat and teach to the son,

128 May they open the ears of the shepherd and leader.

129 May they rejoice for the lord of the gods, Merodach,

130 May his land bear in plenty; as for him, may he have peace.

[pg 033]131 His word standeth firm; his command changeth not—

132 No god hath yet made to fail that which cometh forth from his mouth.

133 If he frown down in displeasure, he turneth not his neck,

134 In his anger, there is no god who can withstand his wrath.

135 Broad is his heart, vast is the kindness (?) of (his) ...

136 The sinner and evildoer before him are (ashamed?).”

The remains of some further lines exist, but they are very uncertain, the beginnings and ends being broken away. All that can be said is, that the poem concluded in the same strain as the last twelve lines preserved.

In the foregoing pages the reader has had placed before him all the principal details of the Babylonian story of the Creation, and we may now proceed to examine the whole in greater detail.

If we may take the explanation of Damascius as representing fairly the opinion of the Babylonians concerning the creation of the world, it seems clear that they regarded the matter of which it was formed as existing in the beginning under the two forms of Tiamtu (the sea) and Apsû (the deep), and from these, being wedded, proceeded “an only begotten son,” Mummu (Moumis), conceived by Damascius to be “no other that the intelligible world proceeding from the two principles,” i.e. from Tiamtu and Apsû. From these come forth, in successive generations, the other gods, ending with Marduk or Merodach, also named Bêl (Bêl-Merodach), the son of Aa (Ea) and his consort Damkina (the Aos and Dauké of Damascius).

Judging from the material that we have, the Babylonians seemed to have believed in a kind of evolution, for they evidently regarded the first creative [pg 034] powers (the watery waste and the abyss) as the rude and barbaric beginnings of things, the divine powers produced from these first principles (Laḫmu and Laḫamu, Anšar and Kišar, Anu, Ellila, and Aa, and finally Marduk), being successive stages in the upward path towards perfection, with which the first rude elements of creation were ultimately bound to come into conflict; for Tiamtu, the chief of the two rude and primitive principles of creation, was, notwithstanding this, ambitious, and desired still to be the creatress of the gods and other inferior beings that were yet to be produced. All the divinities descending from Tiamtu were, to judge from the inscriptions, creators, and as they advanced towards perfection, so also did the things that they created advance, until, by contrast, the works of Tiamtu became as those of the Evil Principle, and when she rebelled against the gods who personified all that was good, it became a battle between them of life and death, which only the latest-born of the gods, elected in consequence of the perfection of his power, to be king and ruler over “the gods his fathers,” was found worthy to wage. The glorious victory gained, and the Dragon of Evil subdued and relegated to those places where her exuberant producing power, which, to all appearance, she still possessed, would be of use, Merodach, in the fulness of his power as king of the gods, perfected and ordered the universe anew, and created his crowning work, Mankind. Many details are, to all appearance, wanting on account of the incompleteness of the series, but those which remain seem to indicate that the motive of the whole story was as outlined here.

In Genesis, however, we have an entirely different account, based, apparently, upon a widely different conception of the origin of the Universe, for one principle only appears throughout the whole narrative, be it Elohistic, Jehovistic, or priestly. “In the beginning [pg 035] God created the heavens and the earth,” and from the first verse to the last it is He, and He alone, who is Creator and Maker and Ruler of the Universe. The only passage containing any indication that more than one person took part in the creation of the world and all that therein is, is in verse 26, where God is referred to as saying, “Let us make man,” but that this is simply the plural of majesty, and nothing more, seems to be proved by the very next verse, where the wording is, “and God made man in his own image,” etc. There is, therefore, no trace of polytheistic influence in the whole narrative.

Let us glance awhile at the other differences.

To begin with, the whole Babylonian narrative is not only based upon an entirely different theory of the beginning of all things, but upon an entirely different conception of what took place ere man appeared upon the earth. “In the beginning God created the heavens and the earth,” implies the conception of a time when the heavens and the earth existed not. Not so, seemingly, with the Babylonian account. There the heavens and the earth are represented as existing, though in a chaotic form, from the first. Moreover, it is not the external will and influence of the Almighty that originates and produces the forms of the first creatures inhabiting the world, but the productive power residing in the watery waste and the deep:

It is question here of “seeding” (zaru) and “bearing” (âlādu), not of creating.

The legend is too defective to enable us to find out anything as to the Babylonian idea concerning the formation of the dry land. Testimony as to its non-existence [pg 036] at the earliest period is all that is vouchsafed to us. At that time none of the gods had come forth, seemingly because (if the restoration be correct) “the fates had not been determined.” There is no clue, however, as to who was then the determiner of the fates.

Then, gradually, and in the course of long-extended ages, the gods Laḫmu and Laḫamu, Anšar and Kišar, with the others, came into existence, as already related, after which the record, which is mutilated, goes on to speak of Tiamtu, Apsū, and Mummu.

These deities of the Abyss were evidently greatly disquieted on account of the existence and the work of the gods of heaven. They therefore took counsel together, and Apsū complained that he could not rest either night or day on account of them. Naturally the mutilated state of the text makes the true reason of the conflict somewhat uncertain. Fried. Delitzsch regarded it as due to the desire, on the part of Merodach, to have possession of the “Tablets of Fate,” which the powers of good and the powers of evil both wished to obtain. These documents, when they are first spoken of, are in the hands of Tiamtu (see p. 19), and she, on giving the power of changeless command to Kingu, her husband, handed them to him. In the great fight, when Merodach overcame his foes, he seized these precious records, and placed them in his breast—

To all appearance, Tiamtu and Kingu were in unlawful possession of these documents, and the king [pg 037] of the gods, Merodach, when he seized them, only took possession of what, in reality, was his own. What power the “Tablets of Fate” conferred on their possessor, we do not know, but in all probability the god in whose hands they were, became, by the very fact, creator and ruler of the universe for ever and ever.

This creative power the king of the gods at once proceeded to exercise. Passing through the heavens, he surveyed them, and built a palace called Ê-šarra, “The house of the host,” for the gods who, with himself, might be regarded as the chief in his heavenly kingdom. Next in order he arranged the heavenly bodies, forming the constellations, marking off the year; the moon, and probably the sun also, being, as stated in Genesis, “for signs, and for seasons, and for days and years,” though all this is detailed, in the Babylonian account, at much greater length. Indeed, had we the whole legend complete, we should probably find ourselves in possession of a detailed description of the Babylonian idea of the heavens which they studied so constantly, and of the world on which they lived, in relation to the celestial phenomena which they saw around them.

Fragments of tablets have been spoken of that seem to belong to the fifth and sixth of the series, and one of them speaks of the building of certain ancient cities, including that now represented by the mounds known by the name of Niffer, which must, therefore, apart from any considerations of paleographic progression in the case of inscriptions found there, or evidence based on the depth of rubbish-accumulations, be one of the oldest known. It is probably on account of this that the Talmudic writers identified the site with the Calneh of Gen. x. 10, which, notwithstanding the absence of native confirmation, may very easily be correct, for the Jews of those days were undoubtedly in a better position to know than we are, after a lapse of two thousand years. The same text, strangely [pg 038] enough, also refers to the city of Aššur, though this city (which did not, apparently, belong to Nimrod's kingdom) can hardly have been a primæval city in the same sense as “Babel, and Erech, and Accad, and Calneh.”

The text of the Semitic Creation-story is here so mutilated as to be useless for comparative purposes, and in these circumstances the bilingual story of the Creation, published by me in 1891, practically covering, as it does, the same ground, may be held, in a measure, to supply its place. Instead, therefore, of devoting to this version a separate section, I insert a translation of it here, together with a description of the tablet upon which it is written.

This second version of the Creation-story is inscribed on a large fragment (about four and a half inches high) of a tablet found by Mr. Rassam at Sippar (Abu Habbah) in 1882. The text is very neatly written in the Babylonian character, and is given twice over, that is, in the original (dialectic) Akkadian, with a Semitic (Babylonian) translation. As it was the custom of the Babylonian and Assyrian scribes, for the sake of giving a nice appearance to what they wrote, to spread out the characters in such a way that the page (as it were) was “justified,” and the ends of the lines ranged, like a page of print, it often happens that, when a line is not a full one, there is a wide space, in the middle, without writing. In the Akkadian text of the bilingual Creation-story, however, a gap is left in every line, sufficiently large to accommodate, in slightly smaller characters, the whole Semitic Babylonian translation. The tablet therefore seems to be written in three columns, the first being the first half of the Akkadian version, the second (a broad one) the Semitic translation, and the third the last half of the Akkadian original text, separated from the first part to allow of the Semitic version being inserted between.

[pg 039]The reason of the writing of the version already translated and in part commented upon is not difficult to find—it was to give an account of the origin of the world and the gods whom they worshipped. The reason of the writing of the bilingual story of the Creation, however, is not so easy to decide, the account there given being the introduction to one of those bilingual incantations for purification, in which, however, by the mutilation of the tablet, the connecting-link is unfortunately lost. But whatever the reason of its being prefixed to this incantation, the value and importance of the version presented by this new document is incontestable, not only for the legend itself, but also for the linguistic material which a bilingual text nearly always offers.

The following is a translation of this document—

Here the obverse breaks off, and the end of the bilingual story of the Creation-story is lost. How many more lines were devoted to it we do not know, nor do we know how the incantation proper, which followed it, and to which it formed the introduction, began. Where the text (about half-way down on the reverse) again becomes legible, it reads as follows—

The last line but one is apparently the title, and is followed by the first line of the next tablet. From [pg 042] this we see that this text belonged to a series of at least two tablets, and that the tablet following the above had an introduction of an astronomical or astrological nature.

It will be noticed that this text not only contains an account of the creation of gods and men, and flora and fauna, but also of the great and renowned sites and shrines of the country where it originated. It is in this respect that it bears a likeness to the fragmentary portions of the intermediate tablets of the Semitic Babylonian story of the Creation, or Bêl and the Dragon, and this slight agreement may be held to justify, in some measure, its introduction here. The bilingual version, however, differs very much in style from that in Semitic only, and seems to lack the poetical form which characterizes the latter. This, indeed, was to be expected, for poetical form in a translation which follows the original closely is an impossibility, though the poetry of words and ideas which it contains naturally remains. It is not unlikely that the original Sumerian text is in poetical form, as is suggested by the cesura, and the recurring words.

In the bilingual account of the Creation one seems to get a glimpse of the pride that the ancient Babylonians felt in the ancient and renowned cities of their country. The writer's conception of the wasteness and voidness of the earth in the beginning seems to have been that the ancient cities Babel, Niffer, Erech and Eridu had not yet come into existence. For him, those sites were as much creations as the vegetation and animal life of the earth. Being, for him, sacred sites, they must have had a sacred, a divine foundation, and he therefore attributes their origin to the greatest of the gods, Merodach, who built them, brick, and beam, and house, himself. Their renowned temples, too, had their origin at the hands of the Divine Architect of the Universe.

A few words are necessary in elucidation of what [pg 043] follows the line, “When within the sea there was a stream.” “In that day,” it says, “Êridu was made, Ê-sagila was constructed—Ê-sagila which the god Lugal-du-azaga founded within the Abyss. Babylon he built, Ê-sagila was completed.” The connection of Ê-sagila, “the temple of the lofty head,” which was within the Abyss, with Êridu, shows, with little or no doubt, that the Êridu there referred to was not the earthly city of that name, but a city conceived as lying also “within the Abyss.” This Êridu, as we shall see farther on, was the “blessed city,” or Paradise, wherein was the tree of life, and which was watered by the twin stream of the Tigris and the Euphrates.

But there was another Ê-sagila than that founded by the god Lugal-du-azaga within the Abyss, namely the Ê-sagila at Babylon, and it is this fane that is spoken of in the phrase following that mentioning the temple so called within the Abyss. To the Babylonian, therefore, the capital of the country was, in that respect, a counterpart of the divine city that he regarded as the abode of bliss, where dwelt Nammu, the river-god, and the sun-god Dumuzi-Abzu, or “Tammuz of the Abyss.” Like Sippar too, Babylon was situated in what was called the plain, the edina, of which Babylonia mainly consisted, and which is apparently the original of the Garden of Eden.

The present text differs from that of the longer (Semitic) story of the Creation, in that it makes Merodach to be the creator of the gods, as well as of mankind, and all living things. This, of course, implies that it was composed at a comparatively late date, when the god Merodach had become fully recognized as the chief divinity, and the fact that Aa was his father had been lost sight of, and practically forgotten. The goddess Aruru is apparently introduced into the narrative out of consideration for the [pg 044] city Sippar-Aruru, of which she was patron. In another text she is called “Lady of the gods of Sippar and Aruru.” There is also a goddess (perhaps identical with her) called Gala-aruru, “Great Aruru,” or “the great one (of) Aruru,” who is explained as “Ištar the star,” on the tablet K. 2109.

After the account of the creation of the beasts of the field, the Tigris and the Euphrates, vegetation, lands, marshes, thickets, plantations and forests, which are named, to all appearance, without any attempt at any kind of order, “The lord Merodach” is represented as creating those things which, at first, he had not made, namely, the great and ancient shrines in whose antiquity and glorious memories the Babylonian—and the Assyrian too—took such delight. The list, however, is a short one, and it is to be supposed that, in the lines that are broken away, further cities of the kingdom of Babylon were mentioned. That this was the case is implied by the reverse, which deals mainly—perhaps exclusively—with the great shrine of Borsippa called Ê-zida, and identified by many with the Tower of Babel. How it was brought in, however, we have no means of finding out, and must wait patiently for the completion of the text that will, in all probability, ultimately be discovered.

The reverse has only the end of the text, which, as far as it is preserved, is in the form of an “incantation of Êridu,” and mentions “the glorious fountain of the Abyss,” which to was to “purify” or “make glorious” the pathway of the personified fane referred to. As it was the god Merodach, “the merciful one,” “he who raises the dead to life,” “the lord of the glorious incantation,” who was regarded by the Babylonians as revealing to mankind the “incantation of Êridu,” which he, in his turn, obtained from his father Aa, we may see in this final part of the legend not only a glorification of the chief deity of the Babylonians, but also a further testimony of the fact that the composition [pg 045] must belong to the comparatively late period in the history of Babylonian religion, when the worship of Merodach had taken the place of that of his father Aa.

Of course, it must not be supposed that the longer account of the Creation was told so shortly as the bilingual narrative that we have introduced here to supply the missing parts of the longer version. Everything was probably recounted at much greater length, and in confirmation of this there is the testimony of the small fragment of the longer account, translated on p. 28. This simply contains the announcement that Merodach had made cunning plans, and decided to create man from his own blood, and [to form?] his bones, but there must have been, in the long gap which then ensues, a detailed account of the actual creation of the human race, probably with some reference to the formation of animals. One cannot base much upon this mutilated fragment, but, as the first translator has pointed out, the object in creating man was seemingly to ensure the performance of the service (or worship) of the gods, and the building of their shrines, prayer and sacrifice, with the fear of God, being duties from which there was no escape.

In the last tablet of the series—that recording the praises of Merodach and his fifty new names,—there are a few points that are worthy of examination. In the first place, the arrangement of the first part is noteworthy. The principal name that was given to him seems not to have been Merodach, as one would expect from the popularity of the name in later days, but Tutu, which occurs in the margin, at the head of six of the sections, and was probably prefixed to at least three more. This name Tutu is evidently an Akkadian reduplicate word, from the root tu, “to beget,” and corresponds with the explanation of the word given by the list of Babylonian gods, K. 2107; muâllid îlāni, mûddiš îlāni, “begetter of the gods, renewer [pg 046] of the gods”—a name probably given to him on account of his identification with his father, Aa, for, according to the legend, Merodach was rather the youngest than the oldest of the gods, who are even called, as will be remembered, “his fathers.” In the lost portion at the beginning of the final tablet he was also called, according to the tablet here quoted, Gugu = muttakkil îlāni, “nourisher of the gods”; Mumu = mušpiš îlāni, “increaser (?) of the gods”; Dugan = banî kala îlāni, “maker of all the gods”; Dudu = muttarrû îlāni, “saviour (?) of the gods”; Šar-azaga = ša šipat-su êllit, “he whose incantation is glorious”; and Mu-azaga = ša tû-šu êllit, “he whose charm is glorious” (cf. p. 31, l. 33). After this we have Ša-zu or Ša-sud = mûdê libbi īlāni or libbi rûḳu, “he who knoweth the heart of the gods,” or “the remote of heart” (p. 31, l. 35); Zi-uḳenna = napšat napḫar îlāni, “the life of the whole of the gods” (p. 30, l. 15); Zi-si = nasiḫ šabuti, “he who bringeth about silence” (p. 31, l. 41); Suḫ-kur = muballû aabi, “annihilator of the enemy” (p. 31, l. 43); and other names meaning muballû napḫar aabi, nasiḫ raggi, “annihilator of the whole of the enemy, rooter out of evil,” nasiḫ napḫar raggi, “rooter out of the whole of the evil,” êšû raggi, “troubler of the evil (ones),” and êšû napḫar raggi, “troubler of the whole of the evil (ones).” All these last names were probably enumerated on the lost part of the tablet between where the obverse breaks off and the reverse resumes the narrative, and the whole of the fifty names conferred upon him, which were enumerated in their old Akkadian forms and translated into Semitic Babylonian in this final tablet of the Creation, were evidently repeated in the form of a list of gods, on the tablet in tabular form from which the above renderings are taken.

Hailed then as the vanquisher of Kirbiš-Tiamtu, the great Dragon of Chaos, he is called by the name of Nibiru, “the ferry,” a name of the planet Jupiter as [pg 047] the traverser of the heavens (one of the points of contact between Babylonian and Greek mythology), the stars of which he was regarded as directing, and keeping (lit. pasturing) like sheep. (Gods and stars may here be regarded as convertible terms.) His future is then spoken of, and “father Bêl” gives him his own name, “lord of the world.” Rejoicing in the honours showered on his son, and not to be outdone in generosity, Aa decrees that henceforth Merodach shall be like him, and that he shall be called Aa, possessing all his commands, and all his pronouncements—i.e. all the wisdom which he, as god of deep wisdom, possessed. Thus was Merodach endowed with all the names, and all the attributes, of the gods of the Babylonians—“the fifty renowned names of the great gods.”

This was, to all intents and purposes, symbolic of a great struggle, in early days, between polytheism and monotheism—for the masses the former, for the more learned and thoughtful the latter. Of this we shall have further proof farther on, when discussing the name of Merodach. For the present be it simply noted, that this is not the only text identifying Merodach with the other gods.

The reference to the creation of mankind in line 29 of the obverse (p. 31) is noteworthy, notwithstanding that the translation of one of the words—and that a very important one—is very doubtful. Apparently man was created to the despite of the rebellious gods, but there is also just the possibility that there exists here an idiomatic phrase meaning “in their room.” If the latter be the true rendering, this part of the legend would be in striking accord with Bishop Avitus of Vienne, with the old English poet Caedmon, and with Milton in his Paradise Lost. In connection with this, too, the statement in the reverse, lines 113 and 114, where “man's remote ages” is referred to, naturally leads one to ask, Have we here [pg 048] traces of a belief that, in ages to come (“in lateness of days”), Merodach was to return and live among men into the remote future? The return of a divinity or a hero of much-cherished memory is such a usual thing among popular beliefs, that this may well have been the case likewise among the Babylonians.

The comparison of the two accounts of the Creation—that of the Hebrews and that of the Babylonians, that have been presented to the reader—will probably have brought prominently before him the fact, that the Babylonian account, notwithstanding all that has been said to the contrary, differs so much from the Biblical account, that they are, to all intents and purposes, two distinct narratives. That there are certain ideas in common, cannot be denied, but most of them are ideas that are inseparable from two accounts of the same event, notwithstanding that they have been composed from two totally different standpoints. In writing an account of the Creation, statements as to what are the things created must of necessity be inserted. There is, therefore, no proof of a connection between two accounts of the Creation in the fact that they both speak of the formation of dry land, or because they both state that plants, animals, and man were created. Connection may be inferred from such statements that the waters were the first abode of life, or that an expansion was created dividing the waters above from those below. With reference to such points of contact as these just mentioned, however, the question naturally arises, Are these points of similarity sufficient to justify the belief that two so widely divergent accounts as those of the Bible and of the Babylonian tablets have one and the same origin? In the mind of the present writer there seems to be but one answer, and that is, that the two accounts are practically distinct, and are the production of people having entirely different ideas upon the subject, though they may have influenced each other [pg 049] in regard to certain points, such as the two mentioned above. For the rest, the fact that there is—

No direct statement of the creation of the heavens and the earth;

No systematic division of the things created into groups and classes, such as is found in Genesis;

No reference to the Days of Creation;

No appearance of the Deity as the first and only cause of the existence of things—

must be held as a sufficient series of prime reasons why the Babylonian and the Hebrew versions of the Creation-story must have had different origins.

As additional arguments may also be quoted the polytheism of the Babylonian account; the fact that it appears to be merely the setting to the legend of Bêl and the Dragon, and that, as such, it is simply the glorification of Merodach, the patron divinity of the Babylonians, over the other gods of the Assyro-Babylonian Pantheon.

Sidelights:—Merodach.

To judge from the inscriptions of the Babylonians and Assyrians, one would say that there were not upon the earth more pious nations than they. They went constantly in fear of their gods, and rendered to them the glory for everything that they succeeded in bringing to a successful conclusion. Prayer, supplication, and self-debasement before their gods seem to have been their delight.

sings Ludlul the sage, and one of a list of sayings is to the following effect—

Many a penitential psalm and hymn of praise exists to testify to the piety of the ancient nations of Assyria and Babylonia. Moreover, this piety was, to all appearance, practical, calling forth not only self-denying offerings and sacrifices, but also, as we shall see farther on, lofty ideas and expressions of the highest religious feeling.

And the Babylonians were evidently proud of their religion. Whatever its defects, the more enlightened—the scribes and those who could read—seem to have felt that there was something in it that gave it the very highest place. And they were right—there was in this gross polytheism of theirs a thing of high merit, and that was, the character of the chief of their gods, Merodach.

We see something of the reverence of the Babylonians and Assyrians for their gods in almost all of their historical inscriptions, and there is hardly a single communication of the nature of a letter that does not call down blessings from them upon the person to whom it is addressed. In many a hymn and pious expression they show in what honour they held them, and their desire not to offend them, even involuntarily, is visible in numerous inscriptions that have been found.

Here the text breaks off, but sufficient of it remains to show of what the devotion of the Babylonians and Assyrians to their gods consisted, and what their beliefs really were. For some reason or other, the writer recognizes that the divinity whom he worships is displeased with him, and apparently comes to the conclusion that the consort of the god is displeased also. He therefore prays and humbles himself before them, asking that his misdeeds may be forgotten, and that he may be separated from his sins, by which he feels himself to be bound and fettered. He imagines to himself that the seven winds, or a little bird, or a fish, or a beast of the field, or the waters of a stream, may carry his sin away, and that the flowing waters of the river may cleanse him from his sin, making him pure in the eyes of his god as a chain of gold, and precious to him as the most precious thing that he can think of, namely, a diamond ring (upon such material and worldly similes did the thoughts of the Babylonians run). He wishes his life (or his soul—the word in the original is napišti, which Zimmern translates Seele) to be saved, to pass away from his evil state, and to dwell with his god, from whom he begs for a sign in the form of a propitious dream, a dream that shall come true, showing that he is in reality once more in the favour of his god, who, he hopes, will deliver him into the gracious hands of the merciful Merodach, that he and all his city may praise his great divinity.

Fragment though it be, in its beginning, development, and climax, it is, to all intents and purposes, perfect, and a worthy specimen of compositions of this class.

It is noteworthy that the suppliant almost re-echoes [pg 053] the words of the Psalmist in those passages where he speaks of his guarding the court of the temple of his god and dwelling in his temple (Ê-sagila, the renowned temple at Babylon), wherein, along with other deities, the god Merodach was worshipped—the merciful one, into whose gracious hands he wished to be delivered. The prayer that his sin might be carried away by a bird, or a fish, etc., brings up before the mind's eye the picture of the scapegoat, fleeing, laden with the sins of the pious Israelite, into the desert to Azazel.

To all appearance, the worshipper, in the above extract, desires to be delivered by the god whom he worships into the hands of the god Merodach. This is a point that is worthy of notice, for it seems to show that the Babylonians, at least in later times, regarded the other deities in the light of mediators with the chief of the Babylonian Pantheon. As manifestations of him, they all formed part of his being, and through them the suppliant found a channel to reconciliation and forgiveness of his sins.

In this there seems to be somewhat of a parallel to the Egyptian belief in the soul, at death, being united with Osiris. The annihilation of self, however, did not, in all probability, recommend itself to the Babylonian mind any more than it must have done to the mind of the Assyrian. To all appearance, the preservation of one's individuality, in the abodes of bliss after death, was with them an essential to the reality of that life beyond the grave. If we adopt here Zimmern's translation of napišti by “soul,” the necessity of interpreting the above passage in the way here indicated seems to be rendered all the greater.

The Creation legend shows us how the god Merodach was regarded by the Babylonians as having attained his high position among the “gods his fathers,” and the reverence that they had for this deity is not only testified to by that legend, but also by the many documents of a religious nature that exist. [pg 054] This being the case, it is only natural to suppose, that he would be worshipped both under the name of Merodach, his usual appellation, and also under any or all of the other names that were attributed to him by the Babylonians as having been conferred upon him by the gods at the time of his elevation to the position of their chief.

Not only, therefore, was he called Marduk (Amaruduk, “the brightness of day”), the Hebrew Merodach, but he bore also the names of Asaru or Asari, identified by the Rev. C. J. Ball and Prof. Hommel with the Egyptian Osiris—a name that would tend to confirm what is stated above concerning the possible connection between the Egyptian and Babylonian beliefs in the immortality of the soul. This name Asaru was compounded with various other (explanatory) epithets, making the fuller names Asari-lu-duga (probably “Asari, he who is good”), Asari-lu-duga-namsuba (“Asari, he who is good, the charm”), Asari-lu-duga-namtî (“Asari, he who is good, the life”), Asari-alima (“Asari, the prince”), Asari-alima-nuna (“Asari, the prince, the mighty one”), etc., all showing the estimation in which he was held, and testifying to the sacredness of the first component, which, as already remarked, has been identified with the name of Osiris, the chief divinity of the Egyptians. Among his other names are (besides those quoted from the last tablet of the story of the Creation and the explanatory list that bears upon it) some of apparently foreign origin, among them being Amaru (? short for Amar-uduk) and Sal-ila, the latter having a decidedly western Semitic look.2 As “the warrior,” he seems to have borne the name of Gušur (? “the strong”); another of his Akkadian appellations was Gudibir, and as “lord” of all the world he was called Bêl, the equivalent of the Baal of the Phœnicians [pg 055] and the Beel of the Aramæans. In astronomy his name was given to several stars, and he was identified with the planet Jupiter, thus making him the counterpart of the Greek and Latin Zeus or Jove.

As has been said above, Merodach was the god that was regarded by the Babylonians and Assyrians as he who went about doing good on behalf of mankind. If he saw a man in affliction—suffering, for instance, from any malady—he would go and ask his father Aa, he who knew all things, and who had promised to impart all his knowledge to his royal son, what the man must do to be cured of the disease or relieved of the demon which troubled him. The following will give some idea of what the inscriptions detailing these charms and incantations, which the god was supposed to obtain from his father, were like—

(Here come abbreviations of the set phrases stating that the god Merodach perceived the man who was suffering, and went to ask his father Aa, dwelling in the Abyss, how the man was to be healed of the sickness that afflicted him. In the texts that give the wanting parts, Aa is represented as asking his son Merodach what it was that he did not know, and in what he could still instruct him. What he (Aa) knows, that Merodach shall also know. He then tells Merodach to go and work the charm.)

The numerous incantations of this class, in which the god Merodach is represented as playing the part of benefactor to the sick and afflicted among mankind, and interesting himself in their welfare, are exceedingly numerous, and cover a great variety of maladies and misfortunes. No wonder, therefore, that the Babylonians looked upon the god, their own god, with eyes of affection, and worship, and reverence. Indeed, it is doubtful whether the Hebrews themselves, the most God-fearing nation of their time, looked upon the God of their fathers with as much affection, or reverence, as did the Babylonians regard the god Merodach. They show it not only in the inscriptions of the class quoted above, but also in numerous other texts. All the kings of Babylonia, and not a few of those of Assyria, with one consent pay him homage, and testify to their devotion. The names of princes and common people, too, often bear witness to the veneration that they felt for this, the chief of their gods. “Merodach is lord of the gods,” “Merodach is master of the word,” “With Merodach is life,” “The dear one of the gods is Merodach,” “Merodach is our king,” “(My, his, our) trust is Merodach,” “Be gracious to me, O Merodach,” “Direct me, O Merodach,” “Merodach protects,” “Merodach has given a brother” (Marduk-nadin-aḫi, the name of one of Nebuchadrezzar's sons), “A judge is Merodach,” etc., etc., are some of the names compounded with that of this popular divinity. Merodach was not so much in use, as the component part of a name, as the god of wisdom, Nebo, but it is not by any means improbable that this is due to the reverence in which he was held, which must, at times, have led the more devout to avoid the pronunciation of his name any more than was necessary, though, if that was the case, it never reached the point of an utter prohibition against its utterance, such as caused the pronunciation of the Hebrew Yahwah to become [pg 058] entirely lost even to the most learned for many hundred years. Those, therefore, who wished to avoid the profanation, by too frequent utterance, of this holy name, could easily do so by substituting the name of some other deity, for, as we have seen above, the names of all the gods could be applied to him, and the doctrine of their identification with him only grew in strength—we know not under what influence—as time went on, until Marduk or Merodach became synonymous with the word îlu, “God,” and is even used as such in a list where the various gods are enumerated as his manifestations. The portion of the tablet in question containing these advanced ideas is as follows—

81-11-3, 111.

As this tablet is not complete, there is every probability that the god Merodach was identified, on the lost portion, with at least as many deities as appear on the part that time has preserved to us.

This identification of deities with each other would [pg 059] seem to have been a far from uncommon thing in the ancient East during those heathen times. A large number of deities of the Babylonian Pantheon are identified, in the Assyrian proper names, with a very interesting divinity whose name appears as Aa, and which may possibly turn out to be only one of the many forms that are met with of the god Ya'u or Jah, who was not only worshipped by the Hebrews, but also by the Assyrians, Babylonians, Hittites, and other nations of the East in ancient times. Prof. Hommel, the well-known Assyriologist and Professor of Semitic languages at Munich, suggests that this god Yâ is another form of the name of Ea, which is possible, but any assimilation of the two divinities is probably best explained upon the supposition that the people of the East in ancient times identified them with each other in consequence of the likeness between the two names.

In any case, the identification of a large number of the gods—perhaps all of them—with a deity whose name is represented by the group Aa, is quite certain. Thus we have Aššur-Aa, Ninip-Aa, Bel-Aa, Nergal-Aa, Šamaš-Aa, Nusku-Aa, Sin-Aa, etc., and it is probable that the list might be greatly extended. Not only, however, have we a large number of deities identified with Aa, but a certain number of them are also identified with the deity known as Ya, Ya'u, or Au, the Jah of the Hebrews. Among these may be cited Bêl-Yau, “Bel is Jah,” Nabû-Yâ', “Nebo is Jah,” Aḫi-Yau, “Aḫi is Jah,” a name that would seem to confirm the opinion which Fuerst held, that aḫi was, in this connection, a word for “god,” or a god. In Ya-Dagunu, “Jah is Dagon,” we have the elements reversed, showing a wish to identify Jah with Dagon, rather than Dagon with Jah, whilst another interesting name, Au-Aa, shows an identification of Jah with Aa, two names which have every appearance of being etymologically connected.