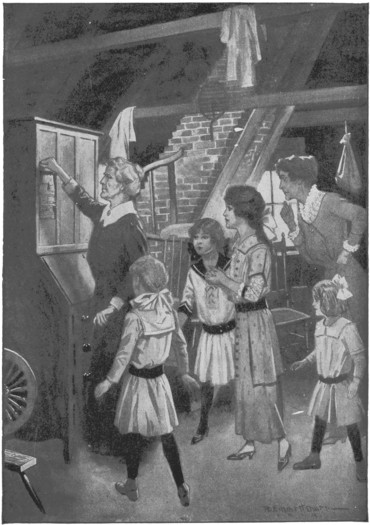

Finding the will. In a moment the panel dropped down, leaving in view a very narrow depository for papers. Frontispiece.

Title: The Corner House Girls

Author: Grace Brooks Hill

Illustrator: Robert Emmett Owen

Release date: February 1, 2012 [eBook #38743]

Most recently updated: December 17, 2023

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Roger Frank and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net

Finding the will. In a moment the panel dropped down, leaving in view a very narrow depository for papers. Frontispiece.

|

HOW THEY MOVED TO MILTON WHAT THEY FOUND AND WHAT THEY DID |

BY

GRACE BROOKS HILL

Author of “The Corner House Girls at School,” “The

Corner House Girls Under Canvas,” etc.

ILLUSTRATED BY

R. EMMETT OWEN

BARSE & HOPKINS

PUBLISHERS

NEW YORK, N. Y.—NEWARK, N. J.

BOOKS FOR GIRLS

The Corner House Girls Series

By Grace Brooks Hill

Illustrated.

|

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS AT SCHOOL THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS UNDER CANVAS THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS IN A PLAY THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS’ ODD FIND THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS ON A TOUR |

(Other volumes in preparation)

BARSE & HOPKINS

Publishers—New York

Copyright, 1915,

by

Barse & Hopkins

The Corner House Girls

Printed in U. S. A.

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

Finding the will. In a moment the panel dropped down, leaving in view a very narrow depository for papers

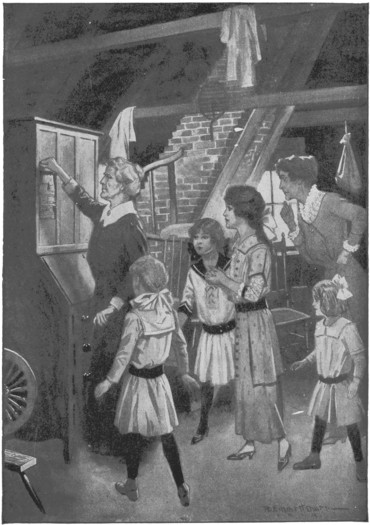

She forgot her kittens and everything else, and scrambled up the tree for dear life

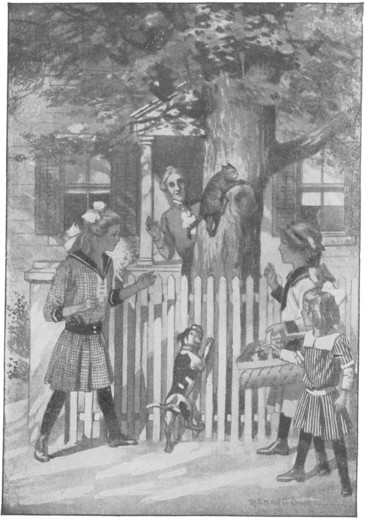

“Looker yere! Looker yere! Missie Ruth! There’s dem dried apples, buried in de groun’”

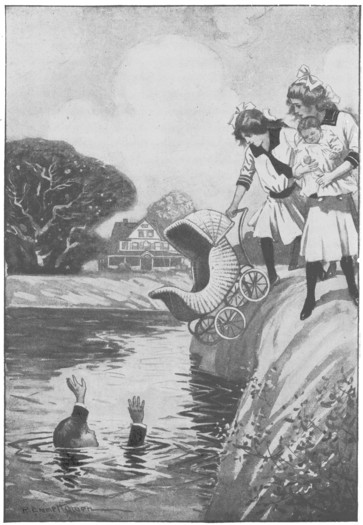

Up came Tommy again, his eyes open, gurgling a cry, and fighting to keep above the surface

THE CORNER HOUSE GIRLS

“Look out, Dot! You’ll fall off that chair as sure as you live, child!”

Tess was bustling and important. It was baking day in the Kenway household. She had the raisins to stone, and the smallest Kenway was climbing up to put the package of raisins back upon the cupboard shelf.

There was going to be a cake for the morrow. Ruth was a-flour to her elbows, and Aggie was stirring the eggs till the beater was just “a-whiz.”

Crash! Bang! Over went the chair; down came Dot; and the raisins scattered far and wide over the freshly scrubbed linoleum.

Fortunately the little busy-body was not hurt. “What did I tell you?” demanded the raisin-seeder, after Ruth had made sure there were no broken bones, and only a “skinned” place on Dot’s wrist. “What did I tell you? You are such a careless child!”

Dot’s face began to “cloud up,” but it did not rain, for Aggie said kindly:

“Don’t mind what she says, Dot. Leave those raisins to me. You run get your hat on. Tess has finished seeding that cupful. Now it’s time you two young ones went on that errand. Isn’t that so, Ruth?”

The elder sister agreed as she busily mixed the butter and flour. Butter was high. She put in what she thought they could afford, and then she shut her eyes tight, and popped in another lump!

On a bright and sunny day, like this one, the tiny flat at the top of the Essex Street tenement was a cheerful place. Ruth was a very capable housekeeper. She had been such for two years previous to their mother’s death, for Mrs. Kenway had been obliged to go out to work.

Now, at sixteen, Ruth felt herself to be very much grown up. It is often responsibility and not years that ages one.

If Ruth had “an old head on green shoulders,” there was reason for it. For almost all the income the Kenways had was their father’s pension.

The tide of misfortune which had threatened the family when the father was killed in the Philippines, had risen to its flood at Mrs. Kenway’s death two years before this day, and had now left the Kenway girls high and dry upon the strand of an ugly tenement, in an ugly street, of the very ugliest district of Bloomingsburg.

The girls were four—and there was Aunt Sarah Stower. There were no boys; there never had been any boys in the Kenway family. Ruth said she was glad; Aggie said she was sorry; and as usual Tess sided with the elder sister, while Dot agreed with the twelve-year-old Aggie that a boy to do the chores would be “sort of nice.”

“S’pose he was like that bad Tommy Rooney, who jumps out of the dark corners on the stairs to scare you, Dot Kenway?” demanded the ten-year-old Tess, seriously.

“Why, he couldn’t be like Tommy—not if he was our brother,” said the smallest girl, with conviction.

“Well, he might,” urged Tess, who professed a degree of experience and knowledge of the world far beyond that of her eight-year-old sister. “You see, you can’t always sometimes tell about boys.”

Tess possessed a strong sense of duty, too. She would not allow Dot, on this occasion, to leave the raisins scattered over the floor. Down the two smaller girls got upon their hands and knees and picked up the very last of the dried fruit before they went for their hats.

“Whistle, Dot—you must whistle,” commanded Tess. “You know, that’s the only way not to yield to temptation, when you’re picking up raisins.”

“I—I can’t whistle, Tess,” claimed Dot.

“Well! pucker up, anyway,” said Tess. “You can’t do that with raisins in your mouth,” and she proceeded to falteringly whistle several bars of “Yankee Doodle” herself, to prove to the older girls that the scattered raisins she found were going into their proper receptacle.

The Kenway girls had to follow many economies, and had learned early to be self-denying. Ruth was so busy and so anxious, she declared herself, she did not have time to be pretty like other girls of her age. She had stringy black hair that never would look soft and wavy, as its owner so much desired.

She possessed big, brown eyes—really wonderful eyes, if she had only known it. People sometimes said she was intellectual looking; that was because of her high, broad brow.

She owned little color, and she had contracted a nervous habit of pressing her lips tight together when she was thinking. But she possessed a laugh that fairly jumped out at you from her eyes and mouth, it was so unexpected.

Ruth Kenway might not attract much attention at first glance, but if you looked at her a second time, you were bound to see something in her countenance that held you, and interested you.

“Do smile oftener, Ruth,” begged jolly, roly-poly Agnes. “You always look just as though you were figuring how many pounds of round steak go into a dollar.”

“I guess I am thinking of that most of the time,” sighed the oldest Kenway girl.

Agnes was as plump as a partridge. When she tried to keep her face straight, the dimples just would peep out. She laughed easily, and cried stormily.

She said herself that she had “bushels of molasses colored hair,” and her blue eyes could stare a rude boy out of countenance—only she had to spoil the effect the next moment by giggling. Another thing, Agnes usually averaged two “soul chums” among her girl friends at school, per week!

Tess (nobody ever remembered she had been christened Theresa) had some of Ruth’s dignity and some of Aggie’s good looks. She was the quick girl at her books; she always got along nicely with grown-ups; they said she had “tact”; and she had the kindest heart of any girl in the world.

Dot, or Dorothy, was the baby, and was a miniature of Ruth, as far as seriousness of demeanor, and hair and eyes went. She was a little brunette fairy, with the most delicately molded limbs, a faint blush in her dark cheeks, and her steady gravity delighted older people. They said she was “such an old-fashioned little thing.”

It was Saturday. From the street below shrill voices rose in a nightmare of sound that broke in a nerve-racking wave upon the ears. Numerous wild Red Indians could make no more savage sounds, if they were burning a captive at the stake.

It was the children on the block, who had no other playground. Dot shuddered to venture forth into the turmoil of the street, and Tess had to acknowledge a faster beating of her own heart.

Dot had her “Alice-doll”—her choicest possession. They were going to the green grocer’s, at the corner, and to the drug store.

At the green grocer’s they were to purchase a cabbage, two quarts of potatoes, and two pennies’ worth of soup greens. At the drug store they would buy the usual nickel’s worth of peppermint drops for Aunt Sarah.

Every Saturday since Dot could remember—and since Tess could remember—and since Agnes could remember—even every Saturday since Ruth could remember, there had been five cents’ worth of peppermint drops bought for Aunt Sarah.

The larder might be very nearly bare; shoes might be out at toe and stockings out at heel; there might be a dearth of food on the table; but Aunt Sarah must not be disappointed in her weekly treat.

“It is the only pleasure the poor creature has,” their mother was wont to say. “Why deprive her of it? There is not much that seems to please Aunt Sarah, and this is a small thing, children.”

Even Dot was old enough to remember the dear little mother saying this. It was truly a sort of sacred bequest, although their mother had not made it a mandatory charge upon the girls.

“But mother never forgot the peppermints herself. Why should we forget them?” Ruth asked.

Aunt Sarah Stower was a care, too, left to the Kenway girls’ charge. Aunt Sarah was an oddity.

She seldom spoke, although her powers of speech were not in the least impaired. Moreover, she seldom moved from her chair during the day, where she sewed, or crocheted; yet she had the active use of her limbs.

Housework Aunt Sarah abhorred. She had never been obliged to do it as a girl and young woman; so she had never lifted her hand to aid in domestic tasks since coming to live with the Kenways—and Ruth could barely remember her coming.

Aunt Sarah was only “Aunt” to the Kenway girls by usage. She was merely their mother’s uncle’s half-sister! “And that’s a relationship,” as Aggie said, “that would puzzle a Philadelphia lawyer to figure out.”

As Tess and Dot came down the littered stoop of the tall brick house they lived in, a rosy, red-haired boy, with a snub nose and twinkling blue eyes, suddenly popped up before them. He was dressed in fringed leggings and jacket, and wore a band of feathers about his cap.

“Ugh! Me heap big Injun,” he exclaimed, brandishing a wooden tomahawk before the faces of the startled girls. “Scalp white squaw! Kill papoose!” and he clutched at the Alice-doll.

Dot screamed—as well she might. The thought of seeing her most beloved child in the hands of this horrid apparition——

“Now, you just stop bothering us, Tommy Rooney!” commanded Tess, standing quickly in front of her sister. “You go away, or I’ll tell your mother.”

“Aw—‘Tell-tale tit! Your tongue shall be split!’” scoffed the dancing Indian. “Give me the papoose. Make heap big Injun of it.”

Dot was actually crying. Tess raised her hand threateningly.

“I don’t want to hurt you, Tommy Rooney,” she said, decisively, “but I shall slap you, if you don’t let us alone.”

“Aw—would you? would you? Got to catch first,” shouted Tommy, making dreadful grimaces. His cheeks were painted in black and red stripes, and these decorations added to Dot’s fright. “You can’t scare me!” he boasted.

But he kept his distance and Tess hurried Dot along the street. There were some girls they knew, for they went to the public school with them, but Tess and Dot merely spoke to them and passed right on.

“We’ll go to the drug store first,” said the older girl. “Then we won’t be bothered with the vegetable bags while we’re getting Aunt Sarah’s peppermints.”

“Say, Tess!” said Dot, gulping down a dry sob.

“Yes?”

“Don’t you wish we could get something ’sides those old peppermint drops?”

“But Ruthie hasn’t any pennies to spare this week. She told us so.”

“Never does have pennies to spare,” declared Dot, with finality. “But I mean I wish Aunt Sarah wanted some other kind of candy besides peppermints.”

“Why, Dot Kenway! she always has peppermints. She always takes some in her pocket to church on Sunday, and eats them while the minister preaches. You know she does.”

“Yes, I know it,” admitted Dot. “And I know she always gives us each one before we go to Sunday School. That’s why I wish we could buy her some other kind of candy. I’m tired of pep’mints. I think they are a most unsat—sat’sfactory candy, Tess.”

“Well! I am amazed at you, Dot Kenway,” declared Tess, with her most grown-up air. “You know we couldn’t any more change, and buy wintergreen, or clove, or lemon-drops, than we could fly. Aunt Sarah’s got to have just what she wants.”

“Has she?” queried the smaller girl, doubtfully. “I wonder why?”

“Because she has,” retorted Tess, with unshaken belief.

The drops were purchased; the vegetables were purchased; the sisters were homeward bound. Walking toward their tenement, they overtook and passed a tall, gray haired gentleman in a drab morning coat and hat. He was not a doctor, and he was not dressed like a minister; therefore he was a curious-looking figure in this part of Bloomingsburg, especially at this hour.

Tess looked up slyly at him as she and Dot passed. He was a cleanly shaven man with thin, tightly shut lips, and many fine lines about the corners of his mouth and about his eyes. He had a high, hooked nose, too—so high, and such a barrier to the rest of his face, that his sharp gray eyes seemed to be looking at the world in general over a high board fence.

Dot was carrying the peppermint drops—and carrying them carefully, while Tess’ hands were occupied with the other purchases. So Master Tommy Rooney thought he saw his chance.

“Candy! candy!” he yelled, darting out at them from an areaway. “Heap big Injun want candy, or take white squaw’s papoose! Ugh!”

Dot screamed. Tess tried to defend her and the white bag of peppermints. But she was handicapped with her own bundles. Tommy was as quick—and as slippery—as an eel.

Suddenly the gentleman in the silk hat strode forward, thrust his gold-headed walking stick between Tommy’s lively legs, and tripped that master of mischief into the gutter.

Tommy scrambled up, gave one glance at the tall gentleman and fled, affrighted. The gentleman looked down at Tess and Dot.

“Oh, thank you, sir!” said the bigger girl. “We’re much obliged!”

“Yes! A knight to the rescue, eh? Do you live on this block, little lady?” he asked, and when he smiled his face was a whole lot pleasanter than it was in repose.

“Yes, sir. Right there at Number 80.”

“Number 80?” repeated the gentleman, with some interest. “Is there a family in your house named Kenway?”

“Oh, yes, sir! We’re the Kenways—two of them,” declared Tess, while Dot was a little inclined to put her finger in her mouth and watch him shyly.

“Ha!” exclaimed the stranger. “Two of Leonard Kenway’s daughters? Is your mother at home?”

“We—we haven’t any mother—not now, sir,” said Tess, more faintly.

“Not living? I had not heard. Then, who is the head of the household?”

“Oh, you want to see Ruth,” cried Tess. “She’s the biggest. It must be Ruth you want to see.”

“Perhaps you are right,” said the gentleman, eyeing the girls curiously. “If she is the chief of the clan, it is she I must see. I have come to inform her of her Uncle Peter Stower’s death.”

Tess and Dot were greatly excited. As they climbed up the long and semi-dark flights to the little flat at the top of the house, they clung tightly to each other’s hands and stared, round-eyed, at each other on the landings.

Behind them labored the tall, gray gentleman. They could hear him puffing heavily on the last flight.

Dot had breath left to burst open the kitchen door and run to tell Ruth of the visitor.

“Oh! oh! Ruthie!” gasped the little girl. “There’s a man dead out here and Uncle Peter’s come to tell you all about it!”

“Why, Dot Kenway!” cried Tess, as the elder sister turned in amazement at the first wild announcement of the visitor’s coming. “Can’t you get anything straight? It isn’t Uncle Peter who wants to see you, Ruth. Uncle Peter is dead.”

“Uncle Peter Stower!” exclaimed Aggie, in awe.

He was the Kenway girls’ single wealthy relative. He was considered eccentric. He was—or had been—a bachelor and lived in Milton, an upstate town some distance from Bloomingsburg, and had occupied, almost alone, the old Stower homestead on the corner of Main and Willow Streets—locally known as “the Old Corner House.”

“Do take the gentleman to the parlor door,” said Ruth, hastily, hearing the footstep of the visitor at the top of the stairs. “Dot, go unlock that door, dear.”

“Aunt Sarah’s sitting in there, Ruth,” whispered Aggie, hastily.

“Well, but Aunt Sarah won’t bite him,” said Ruth, hurriedly removing her apron and smoothing her hair.

“Just think of Uncle Peter being dead,” repeated Aggie, in a daze.

“And he was Aunt Sarah’s half brother, you know. Of course, neither her father nor mother was Uncle Peter’s father or mother—their parents were all married twice. And——”

“Oh, don’t!” gasped the plump sister. “We never can figure out the relationship—you know we can’t, Ruth. Really, Aunt Sarah isn’t blood-kin to us at all.”

“Uncle Peter never would admit it,” said Ruth, slowly. “He was old enough to object, mother said, when our grandfather married a second time.”

“Of course. I know,” acknowledged Aggie. “Aunt Sarah isn’t really a Stower at all!”

“But Aunt Sarah’s always said the property ought to come to her, when Uncle Peter died.”

“I hope he has left her something—I do hope so. It would help out a lot,” said Aggie, serious for the moment.

“Why—yes. It would be easier for us to get along, if she had her own support,” admitted Ruth.

“And we’d save five cents a week for peppermints!” giggled Aggie suddenly, seeing the little white bag of candy on the table.

“How you do talk, Ag,” said Ruth, admonishingly, and considering herself presentable, she went through the bedroom into the front room, or “parlor,” of the flat. Aggie had to stay to watch the cake, which was now turning a lovely golden brown in the oven.

The tall, gray gentleman with the sharp eyes and beak-like nose, had been ushered in by the two little girls and had thankfully taken a seat. He was wiping his perspiring forehead with a checked silk handkerchief, and had set the high hat down by his chair.

Those quick, gray eyes of his had taken in all the neat poverty of the room. A careful and tasteful young housekeeper was Ruth Kenway. Everything was in its place; the pictures on the wall were hung straight; there was no dust.

In one of the two rockers sat Aunt Sarah. It was the most comfortable rocker, and it was drawn to the window where the sun came in. Aunt Sarah had barely looked up when the visitor entered, and of course she had not spoken. Her knitting needles continued to flash in the sunlight.

She was a withered wisp of a woman, with bright brown eyes under rather heavy brows. There were three deep wrinkles between those eyes. Otherwise, Aunt Sarah did not show in her countenance many of the ravages of time.

Her hair was but slightly grayed; she wore it “crimped” on the sides, doing it up carefully in cunning little “pigtails” every night before she retired. She was scrupulous in the care of her hands; her plain gingham dress was neat in every particular.

Indeed, she was as prim and “old-maidish” as any spinster lady possibly could be. Nothing ever seemed to ruffle Aunt Sarah. She lived sort of a detached life in the Kenway family. Nothing went on that she was not aware of, and often—as even Ruth admitted—she “had a finger in the pie” which was not exactly needed!

“I am Mr. Howbridge,” said the visitor, rising and putting out his hand to the oldest Kenway girl, and taking in her bright appearance in a single shrewd glance.

On her part, Aunt Sarah nodded, and pressed her lips together firmly, flashing him another birdlike look, as one who would say: “That is what I expected. You could not hide your identity from me.”

“I am—or was,” said the gentleman, clearing his throat and sitting down again, but still addressing himself directly to Ruth, “Mr. Peter Stower’s attorney and confidant in business—if he could be said to be confidential with anybody. Mr. Stower was a very secretive man, young lady.”

Aunt Sarah pursed her lips and tossed her head, as though mentally saying: “You can’t tell me anything about that.”

Ruth said: “I have heard he was peculiar, sir. But I do not remember of ever seeing him.”

“You did see him, however,” said Mr. Howbridge. “That was when you were a very little girl. If I am not mistaken, it was when this lady,” and he bowed to the silent, knitting figure in the rocking-chair, “who is known as your Aunt Sarah, came to live with your mother and father.”

“Possibly,” said Ruth, hastily. “I do not know.”

“It was one of few events of his life, connected in any way with his relatives, of which Mr. Stower spoke to me,” Mr. Howbridge said. “This lady expressed a wish to live with your mother, and your Uncle Peter brought her. I believe he never contributed to her support?” he added, slowly.

Aunt Sarah might have been a graven image, as far as expressing herself upon this point went. Her needles merely flashed in the sunlight. Ruth felt troubled and somewhat diffident in speaking of the matter.

“I do not think either father or mother ever minded that,” she said.

“Ah?” returned Mr. Howbridge. “And your mother has been dead how long, my dear?” Ruth told him, and he nodded. “Your income was not increased by her death? There was no insurance?”

“Oh, no, sir.”

He looked at her for a moment with some embarrassment, and cleared his throat again before asking his next question.

“Do you realize, my dear, that you and your sisters are the only living, and direct, relatives of Mr. Peter Stower?”

Ruth stared at him. She felt that her throat was dry, and she could not bring her tongue into play. She merely shook her head slowly.

“Through your mother, my dear, you and your sisters will inherit your Great Uncle Peter’s property. It is considerable. With the old Corner House and the tenement property in Milton, bonds and cash in bank, it amounts to—approximately—a hundred thousand dollars.”

“But—but——Aunt Sarah!” gasped Ruth, in surprise.

“Ahem! your Aunt Sarah was really no relative of the deceased.”

Here Aunt Sarah spoke up for the first time, her knitting needles clicking. “I thank goodness I was not,” she said. “My father was a Maltby, but Mr. Stower, Peter’s father, always wished me to be called by his name. He always told my mother he should provide for me. I have, therefore, looked to the Stower family for my support. It was and is my right.”

She tossed her head and pursed her lips again.

“Yes,” said Mr. Howbridge. “I understand that the elder Mr. Stower died intestate—without making a will, my dear,” he added, speaking again to Ruth. “If he ever expressed his intention of remembering your Aunt Sarah with a legacy, Mr. Peter Stower did not consider it mandatory upon him.”

“But of course Uncle Peter has remembered Aunt Sarah in his will?” questioned the dazed Ruth.

“He most certainly did,” said Mr. Howbridge, more briskly. “His will was fully and completely drawn. I drew it myself, and I still have the notes in the old man’s handwriting, relating to the bequests. Unfortunately,” added the lawyer, with a return to a grave manner, “the actual will of Mr. Peter Stower cannot be found.”

Aunt Sarah’s needles clicked sharply, but she did not look up. Ruth stared, wide-eyed, at Mr. Howbridge.

“As was his custom with important papers, Mr. Stower would not trust even a safety deposit box with the custody of his will. He was secretive, as I have said,” began the lawyer again.

Then Aunt Sarah interrupted: “Just like a magpie,” she snapped. “I know ’em—the Stowers. Peter was always doing it when he was a young man—hidin’ things away—’fraid a body would see something, or know something. That’s why he wanted to get me out of the house. Oh, I knew his doin’s and his goin’s-on!”

“Miss Maltby has stated the case,” said Mr. Howbridge, bowing politely. “Somewhere in the old house, of course, Mr. Stower hid the will—and probably other papers of value. They will be found in time, we hope. Meanwhile——”

“Yes, sir?” queried Ruth, breathlessly, as the lawyer stopped.

“Mr. Stower has been dead a fortnight,” explained the lawyer, quietly. “Nobody knew as much about his affairs as myself. I have presented the notes of his last will and testament—made quite a year ago—to the Probate Court, and although they have no legal significance, the Court agrees with me that the natural heirs of the deceased should enter upon possession of the property and hold it until the complications arising from the circumstances can be made straight.”

“Oh, Aunt Sarah! I am so glad for you!” cried Ruth, clasping her hands and smiling one of her wonderful smiles at the little old lady.

Aunt Sarah tossed her head and pursed her lips, just as though she said, “I have always told you so.”

Mr. Howbridge cleared his throat again and spoke hastily: “You do not understand, Miss Kenway. You and your sisters are the heirs at law. At the best, Miss Maltby would receive only a small legacy under Mr. Stower’s will. The residue of the estate reverts to you through your mother, and I am nominally your guardian and the executor.”

Ruth stared at him, open mouthed. The two little girls had listened without clearly understanding all the particulars. Aggie had crept to the doorway (the cake now being on the table and off her mind), and she was the only one who uttered a sound. She said “Oh!”

“You children—you four girls—are the heirs in question. I want you to get ready to go to Milton as soon as possible. You will live in the old Corner House and I shall see, with the Probate Court, that all your rights are guarded,” Mr. Howbridge said.

It was Dorothy, the youngest, who seemed first to appreciate the significance of this great piece of news. She said, quite composedly:

“Then we can buy some candy ’sides those pep’mint drops for Aunt Sarah, on Saturdays.”

“Now,” said Tess, with her most serious air, “shall we take everything in our playhouse, Dot, or shall we take only the best things?”

“Oh-oo-ee!” sighed Dot. “It’s so hard to ’cide, Tess, just what is the best. ’Course, I’m going to take my Alice-doll and all her things.”

Tess pursed her lips. “That old cradle she used to sleep in when she was little, is dreadfully shabby. And one of the rockers is loose.”

“Oh, but Tess!” cried the younger girl. “It was hers. You know, when she gets really growed up, she’ll maybe want it for a keepsake. Maybe she’ll want dollies of her own to rock in it.”

Dot did not lack imagination. The Alice-doll was a very real personality to the smallest Kenway girl.

Dot lived in two worlds—the regular, work-a-day world in which she went to school and did her small tasks about the flat; and a much larger, more beautiful world, in which the Alice-doll and kindred toys had an actual existence.

“And all the clothes she’s outgrown—and shoes—and everything?” demanded Tess. Then, with a sigh: “Well, it will be an awful litter, and Ruth says the trunks are just squeezed full right now!”

The Kenways were packing up for removal to Milton. Mr. Howbridge had arranged everything with Ruth, as soon as he had explained the change of fortune that had come to the four sisters.

None of them really understood what the change meant—not even Ruth. They had always been used—ever since they could remember—to what Aggie called “tight squeezing.” Mr. Howbridge had placed fifty dollars in Ruth’s hand before he went away, and had taken a receipt for it. None of the Kenways had ever before even seen so much money at one time.

They were to abandon most of their poor possessions right here in the flat, for their great uncle’s old house was crowded with furniture which, although not modern, was much better than any of theirs. Aunt Sarah was going to take her special rocker. She insisted upon that.

“I won’t be beholden to Peter for even a chair to sit in!” she had said, grimly, and that was all the further comment she made upon the astounding statement of the lawyer, that the eccentric old bachelor had not seen fit to will all his property to her!

There was a bit of uncertainty and mystery about the will of Uncle Peter, and about their right to take over his possessions. Mr. Howbridge had explained that fully to Ruth.

There was no doubt in his mind but that the will he had drawn for Uncle Peter was still in existence, and that the old gentleman had made no subsequent disposal of his property to contradict the terms of the will the lawyer remembered.

There were no other known heirs but the four Kenway sisters. Therefore the Probate Court had agreed that the lawyer should enter into possession of the property on behalf of Ruth and her sisters.

As long as the will was not found, and admitted to probate, and its terms clearly established in law, there was doubt and uncertainty connected with the girls’ wonderful fortune. Some unexpected claimant might appear to demand a share of the property. It was, in fact, now allowed by the Court, that Mr. Howbridge and the heirs-at-law should occupy the deceased’s home and administer the estate, being answerable to the probate judge for all that was done.

To the minds of Tess and Dot, all this meant little. Indeed, even the two older girls did not much understand the complications. What Aunt Sarah understood she managed, as usual, to successfully hide within herself.

There was to be a wonderful change in their affairs—that was the main thing that impressed the minds of the four sisters. Dot had been the first to express it concretely, when she suggested they might treat themselves on Saturdays to something beside the usual five cents’ worth of peppermint drops.

“I expect,” said Tess, “that we won’t really know how to live, Dot, in so big a house. Just think! there’s three stories and an attic!”

“Just as if we were living in this very tenement all, all alone!” breathed Dot, with awe.

“Only much better—and bigger—and nicer,” said Tess, eagerly. “Ruth remembers going there once with mother. Uncle Peter was sick. She didn’t go up stairs, but stayed down with a big colored man—Uncle Rufus. She ’members all about it. The room she stayed in was as big as all these in our flat, put together.”

This was too wonderful for Dot to really understand. But if Ruth said it, it must be so. She finally sighed again, and said:

“I—I guess I’ll be ’fraid in such rooms. And we’ll get lost in the house, if it’s so big.”

“No. Of course, we won’t live all over the house. Maybe we’ll live days on the first floor, and sleep in bedrooms on the second floor, and never go up stairs on the other floors at all.”

“Oh, well!” said Dot, gaining sudden courage—and curiosity. “I guess I’d want to see what’s on them, just the same.”

There were people in the big tenement house quite as poor as the Kenways themselves. Among these poor families Ruth distributed the girls’ possessions that they did not wish to take to Milton. Tommy Rooney’s mother was thankful for a bed and some dishes, and the kitchen table. She gave Tommy a decisive thrashing, when she caught him jumping out of the dark at Dot on the very last day but one, before the Kenways left Essex Street for their new home.

Master Tommy was sore in spirit and in body when he met Tess and Dot on the sidewalk, later. There were tear-smears on his cheeks, but his eyes began to snap as usual, when he saw the girls.

“I don’t care,” he said. “I’m goin’ to run away from here, anyway, before long. Just as soon as I get enough food saved up, and can swap my alleys and chaneys with Billy Drake for his air-rifle.”

“Why, Tommy Rooney!” exclaimed Tess. “Where are you going to run to?”

“I—I——Well, that don’t matter! I’ll find some place. What sort of a place is this you girls are going to? Is it ’way out west? If it is, and there’s plenty of Injuns to fight with, and scalp, mebbe I’ll come there with you.”

Tess was against this instantly. “I don’t know about the Indians,” she said; “but I thought you wanted to be an Indian yourself? You have an Indian suit.”

“Aw, I know,” said Master Tommy. “That’s Mom’s fault. I told her I wanted to be a cowboy, but she saw them Injun outfits at a bargain and she got one instead. I never did want to be an Injun, for when you play with the other fellers, the cowboys always have to win the battles. Best we Injuns can do is to burn a cowboy at the stake, once in a while—like they do in the movin’ pitchers.”

“Well, I’m sure there are not any Indians at Milton,” said Tess. “You can’t come there, Tommy. And, anyway, your mother would only bring you back and whip you again.”

“She’d have to catch me first!” crowed the imp of mischief, who forgot very quickly the smarts of punishment. “Once I get armed and provisioned (I got more’n a loaf of bread and a whole tin of sardines hid away in a place I won’t tell you where!), I’ll start off and Mom won’t never find me—no, sir-ree, sir!”

“You see what a bad, bad boy he is, Dot,” sighed Tess. “I’m so glad we haven’t any brother.”

“Oh, but if we did have,” said Dot, with assurance, “he’d be a cowboy and not an Indian, from the very start!”

This answer was too much for Tess! She decided to say no more about boys, for it seemed as impossible to convince Dot on the subject as it was Aggie.

Aggie, meanwhile, was the busiest of the four sisters. There were so many girls she had to say good-by to, and weep with, and promise undying affection for, and agree to write letters to—at least three a week!—and invite to come to Milton to visit them at the old Corner House, when they once got settled there.

“If all these girls come at once, Aggie,” said Ruth, mildly admonitory, “I am afraid even Uncle Peter’s big house won’t hold them.”

“Then we’ll have an overflow meeting on the lawn,” retorted Aggie, grinning. Then she clouded up the very next minute and the tears flowed: “Oh, dear! I know I’ll never see any of them again, we’re going away so far.”

“Well! I wouldn’t boo-hoo over it,” Ruth said. “There will be girls in Milton, too. And by next September when you go to school again, you will have dozens of spoons.”

“But not girls like these,” said Aggie, sorrowfully. And, actually, she believed it!

This is not much yet about the old Corner House that had stood since the earliest remembrance of the oldest inhabitant of Milton, on the corner of Main and Willow Streets.

Milton was a county seat. Across the great, shaded parade ground from the Stower mansion, was the red brick courthouse itself. On this side of the parade there were nothing but residences, and none of them had been so big and fine in their prime as the Corner House.

In the first place there were three-quarters’ of an acre of ground about the big, colonial mansion. It fronted Main Street, but set so far back from that thoroughfare, that it seemed very retired. There was a large, shady lawn in front, and old-fashioned flower beds, and flowering shrubs. For some time past, the grounds had been neglected and some of the flowers just grew wild.

The house stood close to the side street, and its upper windows were very blank looking. Mr. Peter Stower had lived on the two lower floors only. “And that is all you will probably care to take charge of, Miss Kenway,” said Mr. Howbridge, with a smile, when he first introduced Ruth to the Corner House.

Ruth had only a dim memory of the place from that one visit to it when Uncle Peter chanced to be sick. She knew that he had lived here with his single negro servant, and that the place had—even to her infantile mind—seemed bare and lonely.

Now, however, Ruth knew that she and her sisters would soon liven the old house up. It was a delightful change from the city tenement. She could not imagine anybody being lonely, or homesick, in the big old house.

Six great pillars supported the porch roof, which jutted out above the second story windows. The big oak door, studded with strange little carvings, was as heavy as that of a jail, or fortress!

Some of the windows had wide sills, and others came right down to the floor and opened onto the porch like two-leaved doors.

There was a great main hall in the middle of the house. Out of this a wide stairway led upward, branching at the first landing, one flight going to the east and the other to the west chambers. There was a gallery all around this hall on the second floor.

The back of the Corner House was much less important in appearance than the main building. Two wings had been built on, and the floors were not on a level with the floors in the front of the house, so that one had to go up and down funny, little brief flights of stairs to get to the sleeping chambers. There were unexpected windows, with deep seats under them, in dark corners, and important looking doors which merely opened into narrow linen closets, while smaller doors gave entrance upon long and heavily furnished rooms, which one would not have really believed were in the house, to look at them from the outside.

“Oh-oo-ee!” cried Dot, when she first entered the big front door of the Corner House, clutching Tess tightly by the hand. “We could get lost in this house.”

Mr. Howbridge laughed. “If you stick close to this wise, big sister of yours, little one,” said the lawyer, looking at Ruth, “you will not get lost. And I guarantee no other harm will come to you.”

The lawyer had learned to have great respect for the youthful head of the Kenway household. Ruth was as excited as she could be about the old house, and their new fortune, and all. She had a little color in her cheeks, and her beautiful great brown eyes shone, and her lips were parted. She was actually pretty!

“What a great, great fortune it is for us,” she said. “I—I hope we’ll all know how to enjoy it to the best advantage. I hope no harm will come of it. I hope Aunt Sarah won’t be really offended, because Uncle Peter did not leave it to her.”

Aunt Sarah stalked up the main stairway without a word. She knew her way about the Corner House.

She took possession of one of the biggest and finest rooms in the front part, on the second floor. When she had lived here as a young woman, she had been obliged to sleep in one of the rear rooms which was really meant for the occupancy of servants.

Now she established herself in the room of her choice, had the expressman bring her rocking-chair up to it, and settled with her crocheting in the pleasantest window overlooking Main Street. There might be, as Aggie said rather tartly, “bushels of work” to do to straighten out the old house and make it homey; Aunt Sarah did not propose to lift her hand to such domestic tasks.

Occasionally she was in the habit of interfering in the very things the girls did not need, or desire, help in, but in no other way did Aunt Sarah show her interest in the family life of the Kenways.

“And we’re all going to have our hands full, Ruth,” said Aggie, in some disturbance of mind, “to keep this big place in trim. It isn’t like a flat.”

“I know,” admitted Ruth. “There’s a lot to do.”

Even the older sister did not realize as yet what their change of fortune meant to them. It seemed to them as though the fifty dollars Mr. Howbridge had advanced should be made to last for a long, long time.

A hundred thousand dollars’ worth of property was only a series of figures as yet in the understanding of Ruth, and Agnes, and Tess, and Dot. Besides, there was the uncertainty about Uncle Peter’s will.

The fortune, after all, might disappear from their grasp as suddenly as it had been thrust into it.

It was the time of the June fruit fall when the Kenway girls came to the Old Corner House in Milton. A roistering wind shook the peach trees in the side yard and at the back that first night, and at once the trees pelted the grass and the flowers beneath their overladen branches with the little, hard green pellets that would never now be luscious fruit.

“Don’t you s’pose they’re sorry as we are, because they won’t ever be good for nothing?” queried Dot, standing on the back porch to view the scattered measure of green fruit upon the ground.

“Don’t worry about it, Dot. Those that are left on the trees will be all the bigger and sweeter, Ruth says,” advised Tess. “You see, those little green things would only have been in the way of the fruit up above, growing. The trees had too many children to take care of, anyway, and had to shake some off. Like the Old Woman Who Lived in a Shoe.”

“But I never did feel that she was a real mother,” said Dot, not altogether satisfied. “And it seems too bad that all those pretty, little, velvety things couldn’t turn into peaches.”

“Well, for my part,” said Tess, more briskly, “I don’t see how so many of them managed to cling on, that old wind blew so! Didn’t you hear it tearing at the shutters and squealing because it couldn’t get in, and hooting down the chimney?”

“I didn’t want to hear it,” confessed Dot. “It—it sounded worse than Tommy Rooney hollering at you on the dark stairs.”

The girls had slept very contentedly in the two great rooms which Ruth chose at the back of the house for their bedrooms, and which opened into each other and into one of the bathrooms. Aunt Sarah did not mind being alone at the front.

“I always intended havin’ this room when I got back into this house,” she said, in one of her infrequent confidences to Ruth. “I wanted it when I was a gal. It was a guest room. Peter said I shouldn’t have it. But I’m back in it now, in spite of him—ain’t I?”

Following Uncle Peter’s death, Mr. Howbridge had hired a woman to clean and fix up the rooms in the Corner House, which had been occupied in the old man’s lifetime. But there was plenty for Ruth and Agnes to do during the first few days.

Although they had no intention of using the parlors, there was quite enough for the Kenway girls to do in caring for the big kitchen (in which they ate, too), the dining-room, which they used as a general sitting-room, the halls and stairs, and the three bedrooms.

The doors of the other rooms on the two floors (and they seemed innumerable) Ruth kept closed with the blinds at the windows drawn.

“I don’t like so many shut doors,” Dot confided to Tess, as they were dusting the carved balustrade in the big hall, and the big, hair-cloth covered pieces of furniture which were set about the lower floor of it. “You don’t know what is behind them—ready to pop out!”

“Isn’t anything behind them,” said the practical Tess. “Don’t you be a little ‘’fraid-cat,’ Dot.”

Then a door rattled, and a latch clicked, and both girls drew suddenly together, while their hearts throbbed tumultuously.

“Of course, that was only the old wind,” whispered Tess, at last.

“Ye-es. But the wind wasn’t ever like that at home in Bloomingsburg,” stammered Dot. “I—I don’t believe I am going to like this big house, Tess. I—I wish we were home in Essex Street.”

She actually burst out crying and ran to Ruth, who chanced to open the dining-room door. Agnes was with her, and the twelve year old demanded of Tess:

“What’s the matter with that child? What have you been doing to her?”

“Why, Aggie! You know I wouldn’t do anything to her,” declared Tess, a little hurt by the implied accusation.

“Of course you haven’t, dear,” said Ruth, soothing the sobbing Dot. “Tell us about it.”

“Dot’s afraid—the house is so big—and the doors rattle,” said Tess.

“Ugh! it is kind of spooky,” muttered Aggie.

“O-o-o!” gasped Tess.

“Hush!” commanded Ruth, quickly.

“What’s ‘spooky’?” demanded Dot, hearing a new word, and feeling that its significance was important.

“Never you mind, Baby,” said Aggie, kissing her. “It isn’t anything that’s going to bite you.”

“I tell you,” said Ruth, with decision, “you take her out into the yard to play, Tess. Aggie and I will finish here. We mustn’t let her get a dislike for this lovely old house. We’re the Corner House girls, you know, and we mustn’t be afraid of our own home,” and she kissed Dot again.

“I—I guess I’ll like it by and by,” sobbed Dot, trying hard to recover her composure. “But—but it’s so b-b-big and scary.”

“Nothing at all to scare you here, dear,” said Ruth, briskly. “Now, run along.”

When the smaller girls had gone for their hats, Ruth said to Aggie: “You know, mother always said Dot had too much imagination. She just pictures things as so much worse, or so much better, than they really are. Now, if she should really ever be frightened here, maybe she’d never like the old house to live in at all.”

“Oh, my!” said Aggie. “I hope that won’t happen. For I think this is just the very finest house I ever saw. There is none as big in sight on this side of the parade ground. We must be awfully rich, Ruth.”

“Why—why I never thought of that,” said the elder sister, slowly. “I don’t know whether we are actually rich, or not. Mr. Howbridge said something about there being a lot of tenements and money, but, you see, as long as Uncle Peter’s will can’t be found, maybe we can’t use much of the money.”

“We’ll have to work hard to keep this place clean,” sighed Aggie.

“We haven’t anything else to do this summer, anyway,” said Ruth, quickly. “And maybe things will be different by fall.”

“Maybe we can find the will!” exclaimed Aggie, voicing a sudden thought.

“Oh!”

“Wouldn’t that be great?”

“I’ll ask Mr. Howbridge if we may look. I expect he has looked in all the likely places,” Ruth said, after a moment’s reflection.

“Then we’ll look in the unlikely ones,” chuckled Aggie. “You know, you read in story books about girls finding money in old stockings, and in cracked teapots, and behind pictures in the parlor, and inside the stuffing of old chairs, and——”

“Goodness me!” exclaimed Ruth. “You are as imaginative as Dot herself.”

Meanwhile Tess and Dot had run out into the yard. They had already made a tour of discovery about the neglected garden and the front lawn, where the grass was crying-out for the mower.

Ruth said she was going to have some late vegetables, and there was a pretty good chicken house and wired run. If they could get a few hens, the eggs would help out on the meat-bill. That was the way Ruth Kenway still looked at things!

The picket fence about the front of the old Corner House property was higher than the heads of the two younger girls. As they went slowly along by the front fence, looking out upon Main Street, they saw many people look curiously in at them. It doubtless seemed strange in the eyes of Milton people to see children running about the yard of the old Corner House, which for a generation had been practically shut up.

There were other children, too, who looked in between the pickets, too shy to speak, but likewise curious. One boy, rather bigger than Tess, stuck a long pole between two of the pickets, and when Dot was not looking, he turned the pole suddenly and confined her between it and the fence.

Dot squealed—although it did not hurt much, only startled her. Tess flew to the rescue.

“Don’t you do that!” she cried. “She’s my sister! I’ll just give it to you——”

But there came a much more vigorous rescuer from outside the fence. A long legged, hatless colored girl, maybe a year or two older than Tess, darted across Main Street from the other side.

“Let go o’ dat! Let go o’ dat, you Sam Pinkney! You’s jes’ de baddes’ boy in Milton! I done tell your mudder so on’y dis berry mawnin’——Yes-sah!”

She fell upon the mischievous Sam and boxed both of his ears soundly, dragging the pole out from between the pickets as well, all in a flash. She was as quick as could be.

“Don’ you be ’fraid, you lil’ w’ite gals!” said this champion, putting her brown, grinning face to an aperture between the pickets, her white teeth and the whites of her eyes shining.

“Dat no-’count Sam Pinkney is sho’ a nuisance in dis town—ya-as’m! My mudder say so. ’F I see him a-tantalizin’ you-uns again, he’n’ me’ll have de gre’tes’ bustification we ever did hab—now, I tell yo’, honeys.”

She then burst into a wide-mouthed laugh that made Tess and Dot smile, too. The brown girl added:

“You-uns gwine to lib in dat ol’ Co’ner House?”

“Yes,” said Tess. “Our Uncle Peter lived here.”

“Sho’! I know erbout him. My gran’pappy lived yere, too,” said the colored girl. “Ma name’s Alfredia Blossom. Ma mammy’s Petunia Blossom, an’ she done washin’ for de w’ite folks yere abouts.”

“We’re much obliged to you for chasing that bad boy away,” said Tess, politely. “Won’t you come in?”

“I gotter run back home, or mammy’ll wax me good,” grinned Alfredia. “But I’s jes’ as much obleeged to yo’. On’y I wouldn’t go inter dat old Co’ner House for no money—no, Ma’am!”

“Why not?” asked Tess, as the colored girl prepared to depart.

“It’s spooky—dat’s what,” declared Alfredia, and the next moment she ran around the corner and disappeared up Willow Street toward one of the poorer quarters of the town.

“There!” gasped Dot, grabbing Tess by the hand. “What does that mean? She says this old Corner House is ‘spooky,’ too. What does ‘spooky’ mean, Tess?”

By the third day after their arrival in Milton, the Kenway sisters were quite used to their new home; but not to their new condition.

“It’s just delightful,” announced Agnes. “I’m going to love this old house, Ruth. And to run right out of doors when one wants to—with an apron on and without ‘fixing up’—nobody to see one——”

The rear premises of the old Corner House were surrounded by a tight fence and a high, straggling hedge. The garden and backyard made a playground which delighted Tess and Dot. The latter seemed to have gotten over her first awe of the big house and had forgotten to ask further questions about the meaning of the mysterious word, “spooky.”

Tess and Dot established their dolls and their belongings in a little summer-house in the weed-grown garden, and played there contentedly for hours. Ruth and Aggie were working very hard. It was as much as Aunt Sarah would do if she made her own bed and brushed up her room.

“When I lived at home before,” she said, grimly, “there were plenty of servants in the house. That is, until Father Stower died and Peter became the master.”

Mr. Howbridge came on this day and brought a visitor which surprised Ruth.

“This is Mrs. McCall, Miss Kenway,” said the lawyer, who insisted upon treating Ruth as quite a grown-up young lady. “Mrs. McCall is a widowed lady for whom I have a great deal of respect,” continued the gentleman, smiling. “And I believe you girls will get along nicely with her.”

“I—I am glad to meet Mrs. McCall,” said Ruth, giving the widow one of her friendly smiles. Yet she was more than a little puzzled.

“Mrs. McCall,” said Mr. Howbridge, “will take many household cares off your shoulders, Miss Kenway. She is a perfectly good housekeeper, as I know,” and he laughed, “for she has kept house for me. If you girls undertook to take care of even a part of this huge house, you would have no time for anything else.”

“But——” began Ruth, in amazement, not to say panic.

“You will find Mrs. McCall just the person whom you need here,” said Mr. Howbridge, firmly.

She was a strong looking, brisk woman, with a pleasant face, and Ruth did like her at once. But she was troubled.

“I don’t see, Mr. Howbridge, how we can afford anybody to help us—just now,” Ruth said. “You see, we have so very little money. And we already have borrowed from you, sir, more than we can easily repay.”

“Ha! you do not understand,” said the lawyer, quickly. “I see. You think that the money I advanced before you left Bloomingsburg was a loan?”

“Oh, sir!” gasped Ruth. “We could not accept it as a gift. It would not be right——”

“I certainly do admire your independence, Ruth Kenway,” said the gentleman, smiling. “But do not fear. I am not lending you money without expecting to get full returns. It is an advance against your uncle’s personal estate.”

“But suppose his will is never found, sir?” cried Ruth.

“I know of no other heirs of the late Mr. Stower. The court recognizes you girls as the legatees in possession. There is not likely to be any question of your rights at all. But we hope the will may be found and thus a suit in Chancery be avoided.”

“But—but is it right for us to accept all this—and spend money, and all that—when there is still this uncertainty about the will?” demanded Ruth, desperately.

“I certainly would not advise you to do anything that was wrong either legally or morally,” said Mr. Howbridge, gravely. “Don’t you worry. I shall pay the bills. You can draw on me for cash within reason.”

“Oh, sir!”

“You all probably need new clothing, and some little luxuries to which you have not been always accustomed. I think I must arrange for each of you girls to have a small monthly allowance. It is good for young people to learn how to use money for themselves.”

“Oh, sir!” gasped Ruth, again.

“The possibility of some other person, or persons, putting in a claim to Mr. Peter Stower’s estate, must be put out of your mind, Miss Kenway,” pursued the kindly lawyer. “You have borne enough responsibility for a young girl, already. Forget it, as the boys say.

“Remember, you girls are very well off. You will be protected in your rights by the court. Let Mrs. McCall take hold and do the work, with such assistance as you girls may wish to give her.”

It was amazing, but very delightful. “Why, Ruth-ie!” cried Agnes, when they were alone, fairly dancing around her sister. “Do you suppose we are really going to be rich?”

To Ruth’s mind a very little more than enough for actual necessities was wealth for the Kenways! She felt as though it were too good to be true. To lay down the burden of responsibilities which she had carried for two years——well! it was a heavenly thought!

Milton was a beautiful old town, with well shaded streets, and green lawns. People seemed to have plenty of leisure to chat and be sociable; they did not rush by you without a look, or a word, as they had in Bloomingsburg.

“So, you’re the Corner House girls, are you? Do tell!” said one old lady on Willow Street, who stopped the Kenway sisters the first time they all trooped to Sunday School.

“Let’s see; you favor your father’s folks,” she added, pinching Agnes’ plump cheek. “I remember Leonard Kenway very well indeed. He broke a window for me once—years ago, when he was a boy.

“I didn’t know who did it. But Lenny Kenway never could keep anything to himself, and he came to me and owned up. Paid for it, too, by helping saw my winter’s wood,” and the old lady laughed gently.

“I’m Mrs. Adams. Come and see me, Corner House girls,” she concluded, looking after them rather wistfully. “It’s been many a day since I had young folks in my house.”

Already Agnes had become acquainted with a few of the storekeepers, for she had done the errands since their arrival in Milton. Now they were welcomed by the friendly Sabbath School teachers and soon felt at home. Agnes quickly fell in love with a bronze haired girl with brown eyes, who sat next to her in class. This was Eva Larry, and Aggie confided to Ruth that she was “just lovely.”

They all, even the little girls, strolled about the paths of the parade ground before returning home. This seemed to be the usual Sunday afternoon promenade of Milton folk. Several people stopped the Corner House girls (as they were already known) and spoke kindly to them.

Although Leonard Kenway and Julia Stower had moved away from Milton immediately upon their marriage, and that had been eighteen years before, many of the residents of Milton remembered the sisters’ parents, and the Corner House girls were welcomed for those parents’ sake.

“We certainly shall come and call on you,” said the minister’s wife, who was a lovely lady, Ruth thought. “It is a blessing to have young folk about that gloomy old house.”

“Oh! we don’t think it gloomy at all,” laughed Ruth.

When the lady had gone on, the Larry girl said to Agnes: “I think you’re awfully brave. I wouldn’t live in the Old Corner House for worlds.”

“Why not?” asked Agnes, puzzled. “I guess you don’t know how nice it is inside.”

“I wouldn’t care if it was carpeted with velvet and you ate off of solid gold dishes!” exclaimed Eva Larry, with emphasis.

“Oh, Eva! you won’t even come to see us?”

“Of course I shall. I like you. And I think you are awfully plucky to live there——”

“What for? What’s the matter with the house?” demanded Agnes, in wonder.

“Why, they say such things about it. You’ve heard them, of course?”

“Surely you’re not afraid of it because old Uncle Peter died there?”

“Oh, no! It began long before your Uncle Peter died,” said Eva, lowering her voice. “Do you mean to say that Mr. Howbridge—nor anybody—has not told you about it?”

“Goodness me! No!” cried Agnes. “You give me the shivers.”

“I should think you would shiver, you poor dear,” said Eva, clutching at Aggie’s arm. “You oughtn’t to be allowed to go there to live. My mother says so herself. She said she thought Mr. Howbridge ought to be ashamed of himself——”

“But what for?” cried the startled Agnes. “What’s the matter with the house?”

“Why, it’s haunted!” declared Eva, solemnly. “Didn’t you ever hear about the Corner House Ghost?”

“Oh, Eva!” murmured Agnes. “You are fooling me.”

“No, Ma’am! I’m not.”

“A—a ghost?”

“Yes. Everybody knows about it. It’s been there for years.”

“But—but we haven’t seen it.”

“You wouldn’t likely see it—yet. Unless it was the other night when the wind blew so hard. It comes only in a storm.”

“What! the ghost?”

“Yes. In a big storm it is always seen looking out of the windows.”

“Goodness!” whispered Agnes. “What windows?”

“In the garret. I believe that’s where it is always seen. And, of course, it is seen from outside. When there is a big wind blowing, people coming across the parade here, or walking on this side of Willow Street, have looked up there and seen the ghost fluttering and beckoning at the windows——”

“How horrid!” gasped Agnes. “Oh, Eva! are you sure?”

“I never saw it,” confessed the other. “But I know all about it. So does my mother. She says it’s true.”

“Mercy! And in the daytime?”

“Sometimes at night. Of course, I suppose it can be seen at night because it is phosphorescent. All ghosts are, aren’t they?”

“I—I never saw one,” quavered Agnes. “And I don’t want to.”

“Well, that’s all about it,” said Eva, with confidence. “And I wouldn’t live in the house with a ghost for anything!”

“But we’ve got to,” wailed Agnes. “We haven’t any other place to live.”

“It’s dreadful,” sympathized the other girl. “I’ll ask my mother. If you are dreadfully frightened about it, I’ll see if you can’t come and stay with us.”

This was very kind of Eva, Agnes thought. The story of the Corner House Ghost troubled the twelve-year-old very much. She dared not say anything before Tess and Dot about it, but she told the whole story to Ruth that night, after they were in bed and supposed the little girls to be asleep.

“Why, Aggie,” said Ruth, calmly, “I don’t think there are any ghosts. It’s just foolish talk of foolish people.”

“Eva says her mother knows it’s true. People have seen it.”

“Up in our garret?”

“Ugh! In the garret of this old house—yes,” groaned Agnes. “Don’t call it our house. I guess I don’t like it much, after all.”

“Why, Aggie! How ungrateful.”

“I don’t care. For all of me, Uncle Peter could have kept his old house, if he was going to leave a ghost in the garret.”

“Hush! the children will hear you,” whispered Ruth.

That whispered conversation between Ruth and Agnes after they were abed that first Sunday night of the Kenways’ occupancy of the Old Corner House, bore unexpected fruit. Dot’s ears were sharp, and she had not been asleep.

From the room she and Tess occupied, opening out of the chamber in which the bigger girls slept, Dot heard enough of the whispered talk to get a fixed idea in her head. And when Dot did get an idea, it was hard to “shake it loose,” as Agnes declared.

Mrs. McCall kept one eye on Tess and Dot as they played about the overgrown garden, for she could see this easily from the kitchen windows. Mrs. McCall had already made herself indispensable to the family; even Aunt Sarah recognized her worth.

Ruth and Agnes were dusting and making the beds on this Monday morning, while Tess and Dot were setting their playhouse to rights.

“I just heard her say so, so now, Tessie Kenway,” Dot was saying. “And I know if it’s up there, it’s never had a thing to eat since we came here to live.”

“I don’t see how that could be,” said Tess, wonderingly.

“It’s just so,” repeated the positive Dot.

“But why doesn’t it make a noise?”

“We-ell,” said the smaller girl, puzzled, too, “maybe we don’t hear it ’cause it’s too far up—there at the top of the house.”

“I know,” said Tess, thoughtfully. “They eat tin cans, and rubber boots, and any old thing. But I always thought that was because they couldn’t find any other food. Like those castaway sailors Ruth read to us about, who chewed their sealskin boots. Maybe such things stop the gnawing feeling you have in your stomach when you’re hungry.”

“I am going to pull some grass and take it up there,” announced the stubborn Dot. “I am sure it would be glad of some grass.”

“Maybe Ruth wouldn’t like us to,” objected Tess.

“But it isn’t Ruthie’s!” cried Dot. “It must have belonged to Uncle Peter.”

“Why! that’s so,” agreed Tess.

For once she was over-urged by Dot. Both girls pulled great sheafs of grass. They held it before them in the skirts of their pinafores, and started up the back stairs.

Mrs. McCall chanced to be in the pantry and did not see them. They would have reached the garret without Ruth or Agnes being the wiser had not Dot, laboring upward, dropped a wisp of grass in the second hall.

“What’s all this?” demanded Agnes, coming upon the scattered grass.

“What’s what?” asked Ruth, behind her.

“And on the stairs!” exclaimed Agnes again. “Why, it’s grass, Ruth.”

“Grass growing on the stairs?” demanded her older sister, wonderingly, and running to see.

“Of course not growing,” declared Agnes. “But who dropped it? Somebody has gone up——”

She started up the second flight, and Ruth after her. The trespassers were already on the garret flight. There was a tight door at the top of those stairs so no view could be obtained of the garret.

“Well, I declare!” exclaimed Agnes. “What are you doing up here?”

“And with grass,” said Ruth. “We’re all going to explore up there together some day soon. But you needn’t make your beds up there,” and she laughed.

“Not going to make beds,” announced Tess, rather grumpily.

“For pity’s sake, what are you going to do?” asked Agnes.

“We’re going to feed the goat,” said Dot, gravely.

“Going to feed what?” shrieked Agnes.

“The goat,” repeated Dot.

“She says there’s one up here,” Tess exclaimed, sullenly.

“A goat in the garret!” gasped Ruth. “How ridiculous. What put such an idea into your heads?”

“Aggie said so herself,” said Dot, her lip quivering. “I heard her tell you so last night after we were all abed.”

“A—goat—in—the—gar—ret!” murmured Agnes, in wonder.

Ruth saw the meaning of it instantly. She pulled Aggie by the sleeve.

“Be still,” she commanded, in a whisper. “I told you little pitchers had big ears. She heard all that foolishness that Larry girl told you.” Then to the younger girls she said:

“We’ll go right up and see if we can find any goat there. But I am sure Uncle Peter would not have kept a goat in his garret.”

“But you and Aggie said so,” declared Dot, much put out.

“You misunderstood what we said. And you shouldn’t listen to hear what other people say—that’s eavesdropping, and is not nice at all. Come.”

Ruth mounted the stairs ahead and threw open the garret door. A great, dimly lit, unfinished room was revealed, the entire size of the main part of the mansion. Forests of clothing hung from the rafters. There were huge trunks and chests, and all manner of odd pieces of furniture.

The small windows were curtained with spider’s lacework of the very finest pattern. Dust lay thick upon everything. Agnes sneezed.

“Goodness! what a place!” she said.

“I don’t believe there is a goat here, Dot,” said Tess, becoming her usual practical self. “He’d—he’d cough himself to death!”

“You can take that grass down stairs,” said Ruth, smiling. But she remained behind to whisper to Agnes:

“You’ll have to have a care what you say before that young one, Ag. It was ‘the ghost in the garret’ she heard you speak about.”

“Well,” admitted the plump sister, “I could see the whole of that dusty old place. It doesn’t seem to me as though any ghost would care to live there. I guess that Eva Larry didn’t know what she was talking about after all.”

It was not, however, altogether funny. Ruth realized that, if Agnes did not.

“I really wish that girl had not told you that silly story,” said the elder sister.

“Well, if there should be a ghost——”

“Oh, be still!” exclaimed Ruth. “You know there’s no such thing, Aggie.”

“I don’t care,” concluded Aggie. “The old house is dreadfully spooky. And that garret——”

“Is a very dusty place,” finished Ruth, briskly, all her housewifely instincts aroused. “Some day soon we’ll go up there and have a thorough house-cleaning.”

“Oh!”

“We’ll drive out both the ghost and the goat,” laughed Ruth. “Why, that will be a lovely place to play in on rainy days.”

“Boo! it’s spooky,” repeated her sister.

“It won’t be, after we clean it up.”

“And Eva says that’s when the haunt appears—on stormy days.”

“I declare! you’re a most exasperating child,” said Ruth, and that shut Agnes’ lips pretty tight for the time being. She did not like to be called a child.

It was a day or two later that Mrs. McCall sent for Ruth to come to the back door to see an old colored man who stood there, turning his battered hat around and around in his hands, the sun shining on his bald, brown skull.

“Good mawnin’, Missie,” said he, humbly. “Is yo’ one o’ dese yere relatifs of Mars’ Peter, what done come to lib yere in de ol’ Co’ner House?”

“Yes,” said Ruth, smiling. “I am Ruth Kenway.”

“Well, Missie, I’s Unc’ Rufus,” said the old man, simply.

“Uncle Rufus?”

“Yes, Missie.”

“Why! you used to work for our Uncle Peter?”

“Endurin’ twenty-four years, Missie,” said the old man.

“Come in, Uncle Rufus,” said Ruth, kindly. “I am glad to see you, I am sure. It is nice of you to call.”

“Yes, Missie; I ’lowed you’d be glad tuh see me. Das what I tol’ my darter, Pechunia——”

“Petunia?”

“Ya-as. Pechunia Blossom. Das her name, Missie. I been stayin’ wid her ever since dey turn me out o’ yere.”

“Oh! I suppose you mean since Uncle Peter died?”

“Ya-as, Missie,” said the old man, following her into the sitting room, and staring around with rolling eyes. Then he chuckled, and said: “Disher does seem lak’ home tuh me, Missie.”

“I should think so, Uncle Rufus,” said Ruth.

“I done stay here till das lawyer man done tol’ me I wouldn’t be wanted no mo’,” said the colored man. “But I sho’ does feel dat de ol’ Co’ner House cyan’t git erlong widout me no mo’ dan I kin git erlong widout it. I feels los’, Missie, down dere to Pechunia Blossom’s.”

“Aren’t you happy with your daughter, Uncle Rufus?” asked Ruth, sympathetically.

“Sho’ now! how you t’ink Unc’ Rufus gwine tuh be happy wid nottin’ to do, an’ sech a raft o’ pickaninnies erbout? Glo-ree! I sho’ feels like I was livin’ in a sawmill, wid er boiler fact’ry on one side an’ one o’ dese yere stone-crushers on de oder.”

“Why, that’s too bad, Uncle Rufus.”

“Yo’ see, Missie,” pursued the old black man, sitting gingerly on the edge of the chair Ruth had pointed out to him, “I done wo’k for Mars’ Peter so long. I done ev’ryt’ing fo’ him. I done de sweepin’, an’ mak’ he’s bed, an’ cook fo’ him, an’ wait on him han’ an’ foot—ya-as’m!

“Ain’t nobody suit Mars’ Peter like ol’ Unc’ Rufus. He got so he wouldn’t have no wimmen-folkses erbout. I ta’ de wash to Pechunia, an’ bring hit back; an’ I markets fo’ him, an’ all dat. Oh, I’s spry fo’ an ol’ feller, Missie. I kin wait on table quite propah—though ’twas a long time since Mars’ Peter done have any comp’ny an’ dis dinin’ room was fixed up for ’em.

“I tak’ care ob de silvah, Missie, an’ de linen, an’ all. Right smart of silvah Mars’ Peter hab, Missie. Yo’ sho’ needs Uncle Rufus yere, Missie. I don’t see how yo’ git erlong widout him so long.”

“Mercy me!” gasped Ruth, suddenly awakening to what the old man was getting at. “You mean to say you want to come back here to work?”

“Sho’ly! sho’ly!” agreed Uncle Rufus, nodding his head a great many times, and with a wistful smile on his wrinkled old face that went straight to Ruth’s heart.

“But, Uncle Rufus! we don’t need you, I’m afraid. We have Mrs. McCall—and there are only four of us girls and Aunt Sarah.”

“I ’member Mis’ Sarah very well, Missie,” said Uncle Rufus, nodding. “She’ll sho’ly speak a good word fo’ Uncle Rufus, Missie. Yo’ ax her.”

“But—Mr. Howbridge——”

“Das lawyer man,” said Uncle Rufus, “he neber jes’ understood how it was,” proposed the old colored man, gently. “He didn’t jes’ see dat dis ol’ Co’ner House was my home so long, dat no oder place seems jes’ right tuh me.”

“I understand,” said Ruth, softly, but much worried.

“Disher w’ite lady yo’ got tuh he’p, she’ll fin’ me mighty handy—ya-as’m. I kin bring in de wood fo’ her, an’ git up de coal f’om de cellar. I kin mak’ de paf’s neat. I kin mak’ yo’ a leetle bit gyarden, Missie—’taint too late fo’ some vegertables. Yo’d oughter have de lawn-grass cut.”

The old man’s catalog of activities suggested the need of a much younger worker, yet Ruth felt so sorry for him! She was timid about taking such a responsibility upon herself. What would Mr. Howbridge say?

Meanwhile the old man was fumbling in an inner pocket. He brought forth a battered wallet and from it drew a soiled, crumpled strip of paper.

“Mars’ Peter didn’t never intend to fo’get me—I know he didn’t,” said Uncle Rufus, earnestly. “Disher paper he gib me, Missie, jes’ de day befo’ he pass ter Glory. He was a kin’ marster, an’ he lean on Unc’ Rufus a powerful lot. Jes’ yo’ read dis.”

Ruth took the paper. Upon it, in a feeble scrawl, was written one line, and that unsigned:

“Take care of Uncle Rufus.”

“Who—whom did he tell you to give this to, Uncle Rufus?” asked the troubled girl, at last.

“He didn’t say, Missie. He warn’t speakin’ none by den,” said the old man. “But I done kep’ it, sho’ly, ’tendin’ tuh sho’ it to his relatifs what come yere to lib.”

“And you did right, Uncle Rufus, to bring it to us,” said Ruth, coming to a sudden decision. “I’ll see what can be done.”

Uncle Rufus was a tall, thin, brown negro, with a gently deprecating air and a smile that suddenly changed his naturally sad features into a most humorous cast without an instant’s notice.

Ruth left him still sitting gingerly on the edge of the chair in the dining-room, while she slowly went upstairs to Aunt Sarah. It was seldom that the oldest Kenway girl confided in, or advised with, Aunt Sarah, for the latter was mainly a most unsatisfactory confidante. Sometimes you could talk to Aunt Sarah for an hour and she would not say a word in return, or appear even to hear you!

Ruth felt deeply about the old colored man. The twist of soiled paper in her hand looked to Ruth like a direct command from the dead uncle who had bequeathed her and her sisters this house and all that went with it.

Since her last interview with Mr. Howbridge, the fact that they were so much better off than ever before, had become more real to Ruth. They could not only live rather sumptuously, but they could do some good to other people by the proper use of Uncle Peter’s money!

Here was a case in point. Ruth did not know but what the old negro would be more than a little useless about the Corner House; but it would not cost much to keep him, and let him think he was of some value to them.

So she opened her heart to Aunt Sarah. And Aunt Sarah listened. Indeed, there never was such a good audience as Aunt Sarah in this world before!

“Now, what do you think?” asked Ruth, breathlessly, when she had told the story and shown the paper. “Is this Uncle Peter’s handwriting?”

Aunt Sarah peered at the scrawl. “Looks like it,” she admitted. “Pretty trembly. I wouldn’t doubt, on’y it seems too kind a thought for Peter to have. He warn’t given to thinking of that old negro.”

“I suppose Mr. Howbridge would know?”

“That lawyer? Huh!” sniffed Aunt Sarah. “He might. But that wouldn’t bring you anything. If he put the old man out once, he would again. No heart nor soul in a lawyer. I always did hate the whole tribe!”

Aunt Sarah had taken a great dislike to Mr. Howbridge, because the legal gentleman had brought the news of the girls’ legacy, instead of telling her she was the heir of Uncle Peter. On the days when there chanced to be an east wind and Aunt Sarah felt a twinge of rheumatism, she was inclined to rail against Fate for making her a dependent upon the “gals’ charity,” as she called it. But she firmly clung to what she called “her rights.” If Uncle Peter had not left his property to her, he should have done so—that is the way she looked at it.

Such comment as Ruth could wring from Aunt Sarah seemed to bolster up her own resolve to try Uncle Rufus as a retainer, and tell Mr. Howbridge about it afterward.

“We’ll skimp a little in some way, to make his wages,” thought Ruth, her mind naturally dropping into the old groove of economizing. “I don’t think Mr. Howbridge would be very angry. And then—here is the paper,” and she put the crumpled scrap that the old colored man had given her, safely away.

“Take care of Uncle Rufus.”

She found Agnes and explained the situation to her. Aunt Sarah had admitted Uncle Rufus was a “handy negro,” and Agnes at once became enthusiastic over the possibility of having such a serving man.

“Just think of him in a black tail-coat and white vest and spats, waiting on table!” cried the twelve year old, whose mind was full of romantic notions gathered from her miscellaneous reading. “This old house just needs a liveried negro servant shuffling about it—you know it does, Ruth!”

“That’s what Uncle Rufus thinks, too,” said Ruth, smiling. What had appealed to the older girl was Uncle Rufus’ wistful and pleading smile as he stated his desire. She went back to the dining-room and said to the old man:

“I am afraid we cannot pay you much, Uncle Rufus, for I really do not know just how much money Mr. Howbridge will allow us to spend on living expenses. But if you wish to come——”

“Glo-ree!” exclaimed the old man, rolling his eyes devoutedly. “Das sho’ de good news for disher collud pusson. Nebber min’ payin’ me wages, Missie. I jes’ wanter lib an’ die in de Ol’ Co’ner House, w’ich same has been my home endurin’ twenty-four years—ya-as’m!”

Mrs. McCall approved of his coming, when Ruth told her. As Uncle Rufus said, he was “spry an’ pert,” and there were many little chores that he could attend to which relieved both the housekeeper and the Kenway girls themselves.

That very afternoon Uncle Rufus reappeared, and in his wake two of Petunia Blossom’s pickaninnies, tugging between them a bulging bag which contained all the old man’s worldly possessions.

One of these youngsters was the widely smiling Alfredia Blossom, and Tess and Dot were glad to see her again, while little Jackson Montgomery Simms Blossom wriggled, and grinned, and chuckled in a way that assured the Corner House girls of his perfect friendliness.

“Stan’ up—you!” commanded the important Alfredia, eyeing her younger brother with scorn. “What you got eatin’ on you, Jackson Montgom’ry? De wiggles? What yo’ s’pose mammy gwine ter say ter yo’ w’en she years you ain’t got yo’ comp’ny manners on, w’en you go ter w’ite folkses’ houses? Stan’ up—straight!”

Jackson was bashful and was evidently a trial to his sister, when she took him into “w’ite folks’ comp’ny.” Tess, however, rejoiced his heart with a big piece of Mrs. McCall’s ginger-cake, and the little girls left him munching, while they took Alfredia away to the summer house in the garden to show her their dolls and playthings.

Alfredia’s eyes grew big with wonder, for she had few toys of her own, and confessed to the possession of “jes’ a ol’ rag tar-baby wot mammy done mak’ out o’ a stockin’-heel.”

Tess and Dot looked at each other dubiously when they heard this. Their collection of babies suddenly looked to be fairly wicked! Here was a girl who had not even a single “boughten” dollie.

Dot gasped and seized the Alice-doll, hugging it close against her breast; her action was involuntary, but it did not signal the smallest Kenway girl’s selfishness. No, indeed! Of course, she could not have given away that possession, but there were others.

She looked down the row of her china playmates—some small, some big, some with pretty, fresh faces, and some rather battered and with the color in their face “smootchy.”

“Which could we give her, Dot?” whispered Tess, doubtfully. “There’s my Mary-Jane——”

The older sister proposed to give up one of her very best dolls; but Mary-Jane was not pink and pretty. Dot stepped up sturdily and plucked the very pinkest cheeked, and fluffiest haired doll out of her own row.

“Why, Dot! that’s Ethelinda!” cried Tess. Ethelinda had been found in Dot’s stocking only the previous Christmas, and its purchase had cost a deal of scrimping and planning on Ruth’s part. Dot did not know that; she had a firm and unshakable belief in Santa Claus.