Title: The Works of Robert G. Ingersoll, Complete Contents

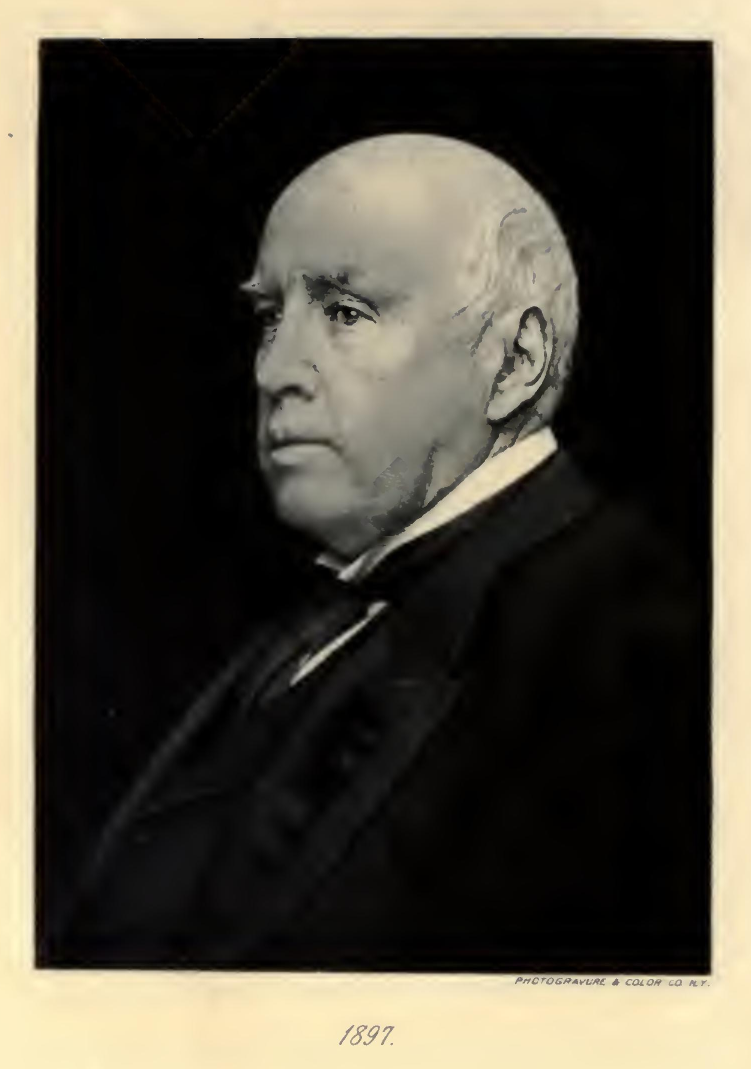

Author: Robert Green Ingersoll

Editor: David Widger

Release date: February 9, 2012 [eBook #38813]

Most recently updated: June 3, 2021

Language: English

Credits: David Widger

| VOLUME I. | VOLUME II. | VOLUME III. | VOLUME IV. | VOLUME V. |

VOLUME VI. |

| VOLUME VII. | VOLUME VIII. | VOLUME IX. | VOLUME X. | VOLUME XI. |

VOLUME XII. |

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME I.

THE LIBERTY OF MAN, WOMAN, AND CHILD.

I. WHAT WE MUST DO TO BE SAVED

(1872.)

An Honest God is the Noblest Work of Man—Resemblance of Gods to

their Creators—Manufacture and Characteristics of Deities—Their

Amours—Deficient in many Departments of Knowledge—Pleased with the

Butchery of Unbelievers—A Plentiful Supply—Visitations—One God's

Laws of War—The Book called the Bible—Heresy of Universalism—Faith

an unhappy mixture of Insanity and Ignorance—Fallen Gods, or

Devils—Directions concerning Human Slavery—The first Appearance of

the Devil—The Tree of Knowledge—Give me the Storm and Tempest of

Thought—Gods and Devils Natural Productions—Personal Appearance

of Deities—All Man's Ideas suggested by his Surroundings—Phenomena

Supposed to be Produced by Intelligent Powers—Insanity and Disease

attributed to Evil Spirits—Origin of the Priesthood—Temptation of

Christ—Innate Ideas—Divine Interference—Special Providence—The

Crane and the Fish—Cancer as a proof of Design—Matter and

Force—Miracle—Passing the Hat for just one Fact—Sir William Hamilton

on Cause and Effect—The Phenomena of Mind—Necessity and Free Will—The

Dark Ages—The Originality of Repetition—Of what Use have the Gods been

to Man?—Paley and Design—Make Good Health Contagious—Periodicity of

the Universe and the Commencement of Intellectual Freedom—Lesson of

the ineffectual attempt to rescue the Tomb of Christ from the

Mohammedans—The Cemetery of the Gods—Taking away Crutches—Imperial

Reason

(1869.)

The Universe is Governed by Law—The Self-made Man—Poverty generally

an Advantage—Humboldt's Birth-place—His desire for Travel—On what

Humboldt's Fame depends—His Companions and Friends—Investigations

in the New World—A Picture—Subjects of his Addresses—Victory of the

Church over Philosophy—Influence of the discovery that the World is

governed by Law—On the term Law—Copernicus—Astronomy—Aryabhatta—

Descartes—Condition of the World and Man when the morning of Science

Dawned—Reasons for Honoring Humboldt—The World his Monument

(1870.)

With his Name left out the History of Liberty cannot be Written—Paine's

Origin and Condition—His arrival in America with a Letter of

Introduction by Franklin—Condition of the Colonies—"Common Sense"—A

new Nation Born—Paine the Best of Political Writers—The "Crisis"—War

not to the Interest of a trading Nation—Paine's Standing at the Close

of the Revolution—Close of the Eighteenth Century in France-The

"Rights of Man"—Paine Prosecuted in England—"The World is my

Country"—Elected to the French Assembly—Votes against the Death of

the King—Imprisoned—A look behind the Altar—The "Age of Reason"—His

Argument against the Bible as a Revelation—Christianity of Paine's

Day—A Blasphemy Law in Force in Maryland—The Scotch "Kirk"—Hanging

of Thomas Aikenhead for Denying the Inspiration of the

Scriptures—"Cathedrals and Domes, and Chimes and Chants"—Science—"He

Died in the Land his Genius Defended,"

(1873.)

"His Soul was like a Star and Dwelt Apart"—Disobedience one of the

Conditions of Progress.—Magellan—The Monarch and the Hermit-Why

the Church hates a Thinker—The Argument from Grandeur and

Prosperity-Travelers and Guide-boards—A Degrading Saying—Theological

Education—Scotts, Henrys and McKnights—The Church the Great

Robber—Corrupting the Reason of Children—Monotony of Acquiescence: For

God's sake, say No—Protestant Intolerance: Luther and Calvin—Assertion

of Individual Independence a Step toward Infidelity—Salute to

Jupiter—The Atheistic Bug-Little Religious Liberty in America—God in

the Constitution, Man Out—Decision of the Supreme Court of Illinois

that an Unbeliever could not testify in any Court—Dissimulation—Nobody

in this Bed—The Dignity of a Unit

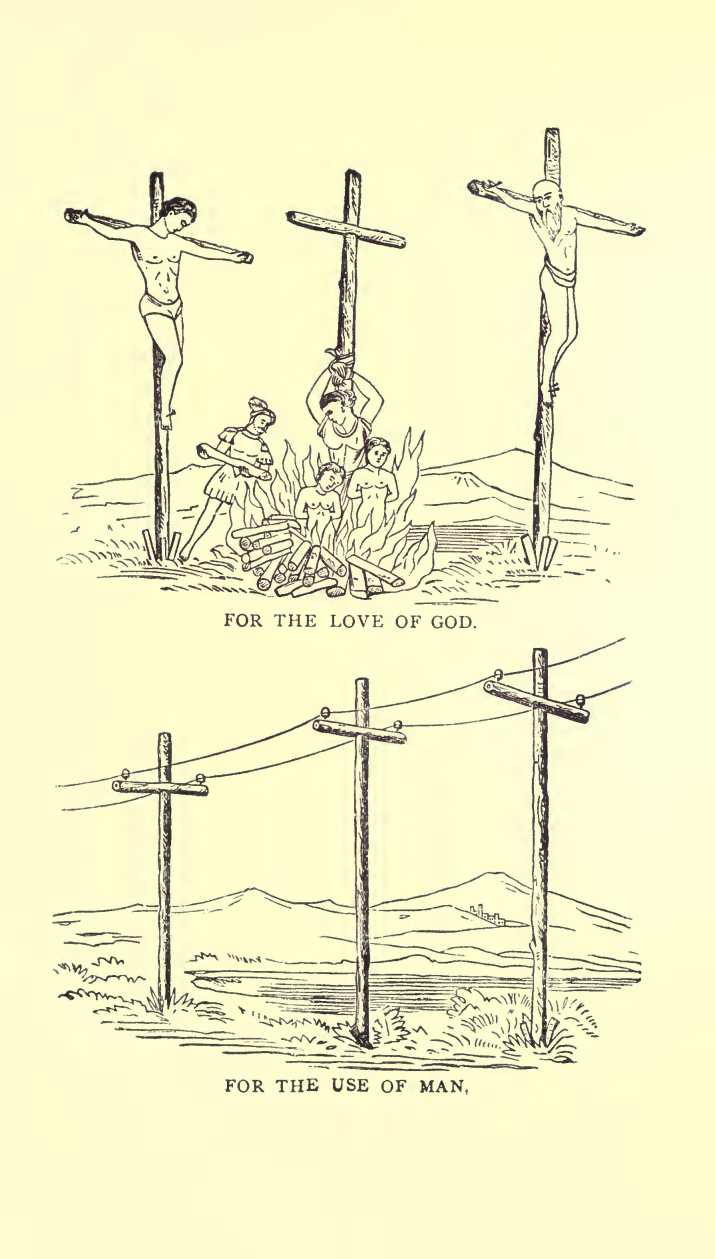

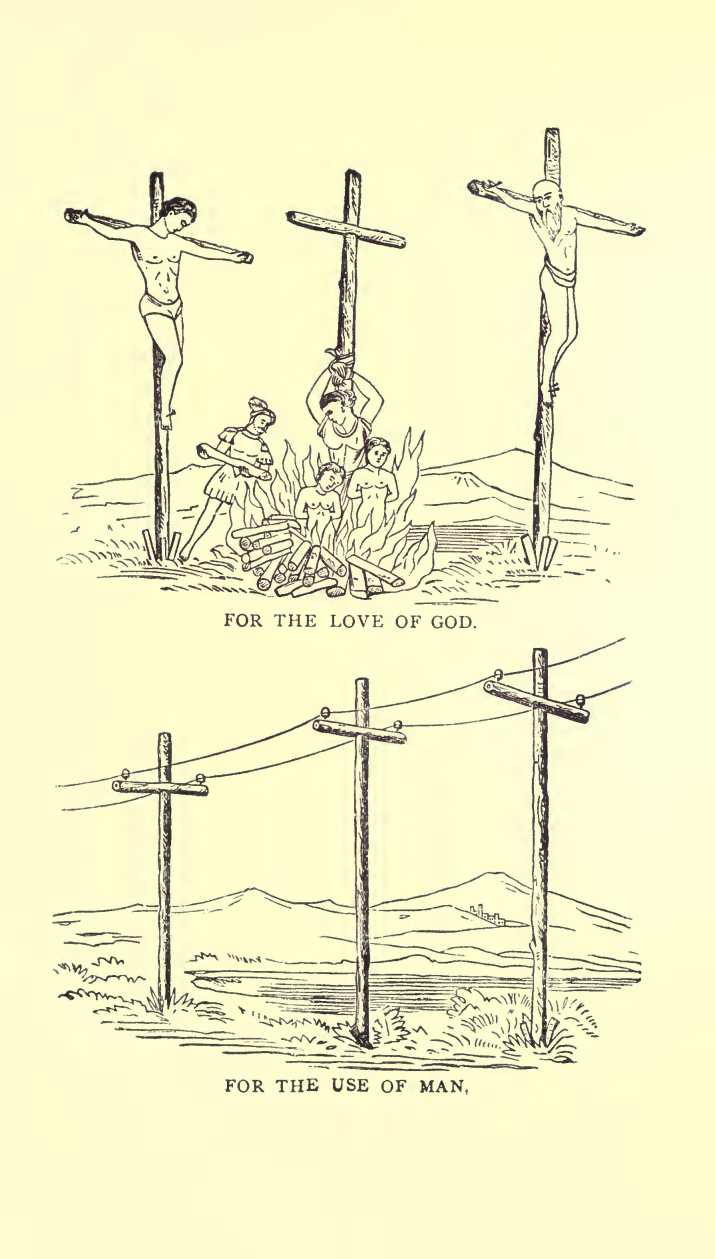

(1874.)

Liberty, a Word without which all other Words are Vain—The Church, the

Bible, and Persecution—Over the wild Waves of War rose and fell

the Banner of Jesus Christ—Highest Type of the Orthodox

Christian—Heretics' Tongues and why they should be Removed before

Burning—The Inquisition Established—Forms of Torture—Act of Henry

VIII for abolishing Diversity of Opinion—What a Good Christian was

Obliged to Believe—The Church has Carried the Black Flag—For what Men

and Women have been Burned—John Calvin's Advent into the

World—His Infamous Acts—Michael Servetus—Castalio—Spread of

Presbyterianism—Indictment of a Presbyterian Minister in Illinois for

Heresy—Specifications—The Real Bible

(1877.)

Dedication to Ebon C. Ingersoll—Preface—Mendacity of the Religious

Press—"Materialism"—Ways of Pleasing the Ghosts—The Idea of

Immortality not Born of any Book—Witchcraft and Demon-ology—Witch

Trial before Sir Matthew Hale—John Wesley a Firm Believer in

Ghosts—"Witch-spots"—Lycanthropy—Animals Tried and Convicted—The

Governor of Minnesota and the Grasshoppers—A Papal Bull against

Witchcraft—Victims of the Delusion—Sir William Blackstone's

Affirmation—Trials in Belgium—Incubi and Succubi—A Bishop

Personated by the Devil—The Doctrine that Diseases are caused by

Ghosts—Treatment—Timothy Dwight against Vaccination—Ghosts as

Historians—The Language of Eden—Leibnitz, Founder of the Science

of Language—Cosmas on Astronomy—Vagaries of Kepler and Tycho

Brahe—Discovery of Printing, Powder, and America—Thanks to the

Inventors—The Catholic Murderer and the Meat—Let the Ghosts Go

THE LIBERTY OF MAN, WOMAN, AND CHILD.

(1877.)

Liberty sustains the same Relation to Mind that Space does to

Matter—The History of Man a History of Slavery—The Infidel Our

Fathers in the good old Time—The iron Arguments that Christians

Used—Instruments of Torture—A Vision of the Inquisition—Models of

Man's Inventions—Weapons, Armor, Musical Instruments, Paintings,

Books, Skulls—The Gentleman in the Dug-out—Homage to Genius and

Intellect—Abraham Lincoln—What I mean by Liberty—The Man who cannot

afford to Speak his Thought is a Certificate of the Meanness of the

Community in which he Resides—Liberty of Woman—Marriage and the

Family—Ornaments the Souvenirs of Bondage-The Story of the Garden of

Eden—Adami and Heva—Equality of the Sexes-The word "Boss"—The Cross

Man-The Stingy Man—Wives who are Beggars—How to Spend Money—By

the Tomb of the Old Napoleon—The Woman you Love will never Grow

Old—Liberty of Children—When your Child tells a Lie—Disowning

Children—Beating your own Flesh and Blood—Make Home Pleasant—Sunday

when I was a Boy—The Laugh of a Child—The doctrine of Eternal

Punishment—Jonathan Edwards on the Happiness of Believing Husbands

whose Wives are in Hell—The Liberty of Eating and Sleeping—Water in

Fever—Soil and Climate necessary to the production of Genius—Against

Annexing Santo Domingo—Descent of Man—Conclusion

(1877.)

To Plow is to Pray; to Plant is to Prophesy, and the Harvest Answers and

Fulfills—The Old Way of Farming—Cooking an Unknown Art-Houses, Fuel,

and Crops—The Farmer's Boy—What a Farmer should Sell—Beautifying

the Home—Advantages of Illinois as a Farming State—Advantages of the

Farmer over the Mechanic—Farm Life too Lonely-On Early Rising—Sleep

the Best Doctor—Fashion—Patriotism and Boarding Houses—The Farmer and

the Railroads—Money and Confidence—Demonetization of Silver-Area of

Illinois—Mortgages and Interest—Kindness to Wives and Children—How

a Beefsteak should be Cooked—Decorations and Comfort—Let the Children

Sleep—Old Age

(1880.)

Preface—The Synoptic Gospels—Only Mark Knew of the Necessity of

Belief—Three Christs Described—The Jewish Gentleman and the Piece of

Bacon—Who Wrote the New Testament?—Why Christ and the Apostles wrote

Nothing—Infinite Respect for the Man Christ—Different Feeling for

the Theological Christ—Saved from What?—Chapter on the Gospel of

Matthew—What this Gospel says we must do to be Saved—Jesus and the

Children—John Calvin and Jonathan Edwards conceived of as Dimpled

Darlings—Christ and the Man who inquired what Good Thing he should

do that he might have Eternal Life—Nothing said about Belief—An

Interpolation—Chapter on the Gospel of Mark—The Believe or be Damned

Passage, and why it was written—The last Conversation of Christ with

his Disciples—The Signs that Follow them that Believe—Chapter on

the Gospel of Luke—Substantial Agreement with Matthew and Mark—How

Zaccheus achieved Salvation—The two Thieves on the Cross—Chapter

on the Gospel of John—The Doctrine of Regeneration, or the New

Birth—Shall we Love our Enemies while God Damns His?—Chapter on the

Catholics—Communication with Heaven through Decayed Saints—Nuns and

Nunneries—Penitentiaries of God should be Investigated—The

Athanasian Creed expounded—The Trinity and its Members—Chapter on the

Episcopalians—Origin of the Episcopal Church—Apostolic Succession

an Imported Article—Episcopal Creed like the Catholic, with a

few Additional Absurdities—Chapter on the Methodists—Wesley and

Whitfield—Their Quarrel about Predestination—Much Preaching for Little

Money—Adapted to New Countries—Chapter on the Presbyterians—John

Calvin, Murderer—Meeting between Calvin and Knox—The Infamy of

Calvinism—Division in the Church—The Young Presbyterian's Resignation

to the Fate of his Mother—A Frightful, Hideous, and Hellish

Creed—Chapter on the Evangelical Alliance—Jeremy Taylor's Opinion of

Baptists—Orthodoxy not Dead—Creed of the Alliance—Total Depravity,

Eternal Damnation—What do You Propose?—The Gospel of Good-fellowship,

Cheerfulness, Health, Good Living, Justice—No Forgiveness—God's

Forgiveness Does not Pay my Debt to Smith—Gospel of Liberty, of

Intelligence, of Humanity—One World at a Time—"Upon that Rock I

Stand"

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME II.

(1879.)

Preface—I. He who endeavors to control the Mind by Force is a

Tyrant, and he who submits is a Slave—All I Ask—When a Religion

is Founded—Freedom for the Orthodox Clergy—Every Minister an

Attorney—Submission to the Orthodox and the Dead—Bounden Duty of

the Ministry—The Minister Factory at Andover—II. Free Schools—No

Sectarian Sciences—Religion and the Schools—Scientific

Hypocrites—III. The Politicians and the Churches—IV. Man and Woman the

Highest Possible Titles—Belief Dependent on Surroundings—Worship of

Ancestors—Blindness Necessary to Keeping the Narrow Path—The Bible the

Chain that Binds—A Bible of the Middle Ages and the Awe it Inspired—V.

The Pentateuch—Moses Not the Author—Belief out of which Grew

Religious Ceremonies—Egypt the Source of the Information of Moses—VI.

Monday—Nothing, in the Light of Raw Material—The Story of Creation

Begun—The Same Story, substantially, Found in the Records of Babylon,

Egypt, and India—Inspiration Unnecessary to the Truth—Usefulness of

Miracles to Fit Lies to Facts—Division of Darkness and Light—VII.

Tuesday—The Firmament and Some Biblical Notions about it—Laws of

Evaporation Unknown to the Inspired Writer—VIII. Wednesday—The Waters

Gathered into Seas—Fruit and Nothing to Eat it—Five Epochs in the

Organic History of the Earth—Balance between the Total Amounts of

Animal and Vegetable Life—Vegetation Prior to the Appearance of the

Sun—IX. Thursday—Sun and Moon Manufactured—Magnitude of the Solar

Orb—Dimensions of Some of the Planets—Moses' Guess at the Size of Sun

and Moon—Joshua's Control of the Heavenly Bodies—A Hypothesis Urged

by Ministers—The Theory of "Refraction"—Rev. Henry Morey—Astronomical

Knowledge of Chinese Savants—The Motion of the Earth Reversed by

Jehovah for the Reassurance of Ahaz—"Errors" Renounced by Button—X.

"He made the Stars Also"—Distance of the Nearest Star—XI.

Friday—Whales and Other Living Creatures Produced—XII.

Saturday—Reproduction Inaugurated—XIII. "Let Us Make Man"—Human

Beings Created in the Physical Image and Likeness of God—Inquiry as

to the Process Adopted—Development of Living Forms According to

Evolution—How Were Adam and Eve Created?—The Rib Story—Age of

Man Upon the Earth—A Statue Apparently Made before the World—XIV.

Sunday—Sacredness of the Sabbath Destroyed by the Theory of Vast

"Periods"—Reflections on the Sabbath—XV. The Necessity for a Good

Memory—The Two Accounts of the Creation in Genesis I and II—Order

of Creation in the First Account—Order of Creation in the Second

Account—Fastidiousness of Adam in the Choice of a Helpmeet—Dr.

Adam Clark's Commentary—Dr. Scott's Guess—Dr. Matthew Henry's

Admission—The Blonde and Brunette Problem—The Result of Unbelief and

the Reward of Faith—"Give Him a Harp"—XVI. The Garden—Location of

Eden—The Four Rivers—The Tree of Knowledge—Andover Appealed

To—XVII. The Fall—The Serpent—Dr. Adam Clark Gives a Zoological

Explanation—Dr. Henry Dissents—Whence This Serpent?—XVIII.

Dampness—A Race of Giants—Wickedness of Mankind—An Ark Constructed—A

Universal Flood Indicated—Animals Probably Admitted to the Ark—How Did

They Get There?—Problem of Food and Service—A Shoreless Sea Covered

with Innumerable Dead—Drs. Clark and Henry on the Situation—The Ark

Takes Ground—New Difficulties—Noah's Sacrifice—The Rainbow as a

Memorandum—Babylonian, Egyptian, and Indian Legends of a Flood—XIX.

Bacchus and Babel—Interest Attaching to Noah—Where Did Our First

Parents and the Serpent Acquire a Common Language?—Babel and the

Confusion of Tongues—XX. Faith in Filth—Immodesty of Biblical

Diction—XXI. The Hebrews—God's Promises to Abraham—The Sojourning

of Israel in Egypt—Marvelous Increase—Moses and Aaron—XXII.

The Plagues—Competitive Miracle Working—Defeat of the Local

Magicians—XXIII. The Flight Out of Egypt—Three Million People in a

Desert—Destruction of Pharaoh ana His Host—Manna—A Superfluity of

Quails—Rev. Alexander Cruden's Commentary—Hornets as Allies of the

Israelites—Durability of the Clothing of the Jewish People—An Ointment

Monopoly—Consecration of Priests—The Crime of Becoming a Mother—The

Ten Commandments—Medical Ideas of Jehovah—Character of the God of

the Pentateuch—XXIV. Confess and Avoid—XXV. "Inspired" Slavery—XXVI.

"Inspired" Marriage-XXVII. "Inspired" War-XXVIII. "Inspired" Religious

Liberty—XXIX. Conclusion.

(1881.)

I—Religion makes Enemies—Hatred in the Name of Universal

Benevolence—No Respect for the Rights of Barbarians—Literal

Fulfillment of a New Testament Prophecy—II. Duties to God—Can we

Assist God?—An Infinite Personality an Infinite Impossibility-Ill.

Inspiration—What it Really Is—Indication of Clams—Multitudinous

Laughter of the Sea—Horace Greeley and the Mammoth Trees—A Landscape

Compared to a Table-cloth—The Supernatural is the Deformed—Inspiration

in the Man as well as in the Book—Our Inspired Bible—IV. God's

Experiment with the Jews—Miracles of One Religion never astonish the

Priests of Another—"I am a Liar Myself"—V. Civilized Countries—Crimes

once regarded as Divine Institutions—What the Believer in the

Inspiration of the Bible is Compelled to Say—Passages apparently

written by the Devil—VI. A Comparison of Books—Advancing a Cannibal

from Missionary to Mutton—Contrast between the Utterances of Jehovah

and those of Reputable Heathen—Epictetus, Cicero, Zeno,

Seneca—the Hindu, Antoninus, Marcus Aurelius—The Avesta—VII.

Monotheism—Egyptians before Moses taught there was but One God

and Married but One Wife—Persians and Hindoos had a Single Supreme

Deity—Rights of Roman Women—Marvels of Art achieved without the

Assistance of Heaven—Probable Action of the Jewish Jehovah incarnated

as Man—VIII. The New Testament—Doctrine of Eternal Pain brought to

Light—Discrepancies—Human Weaknesses cannot be Predicated of

Divine Wisdom—Why there are Four Gospels according to Irenæus—The

Atonement—Remission of Sins under the Mosaic Dispensation—Christians

say, "Charge it"—God's Forgiveness does not Repair an Injury—Suffering

of Innocence for the Guilty—Salvation made Possible by Jehovah's

Failure to Civilize the Jews—Necessity of Belief not taught in the

Synoptic Gospels—Non-resistance the Offspring of Weakness—IX. Christ's

Mission—All the Virtues had been Taught before his Advent—Perfect and

Beautiful Thoughts of his Pagan Predecessors—St. Paul Contrasted

with Heathen Writers—"The Quality of Mercy"—X. Eternal Pain—An

Illustration of Eternal Punishment—Captain Kreuger of the Barque

Tiger—XI. Civilizing Influence of the Bible—Its Effects on the

Jews—If Christ was God, Did he not, in his Crucifixion, Reap what

he had Sown?—Nothing can add to the Misery of a Nation whose King is

Jehovah

(1884.)

Orthodox Religion Dying Out—Religious Deaths and Births—The Religion

of Reciprocity—Every Language has a Cemetery—Orthodox Institutions

Survive through the Money invested in them—"Let us tell our Real

Names"—The Blows that have Shattered the Shield and Shivered the Lance

of Superstition—Mohammed's Successful Defence of the Sepulchre of

Christ—The Destruction of Art—The Discovery of America—Although

he made it himself, the Holy Ghost was Ignorant of the Form of this

Earth—Copernicus and Kepler—Special Providence—The Man and the Ship

he did not Take—A Thanksgiving Proclamation Contradicted—Charles

Darwin—Henry Ward Beecher—The Creeds—The Latest Creed—God as

a Governor—The Love of God—The Fall of Man—We are Bound

by Representatives without a Chance to Vote against Them—The

Atonement—The Doctrine of Depravity a Libel on the Human Race—The

Second Birth—A Unitarian Universalist—Inspiration of the

Scriptures—God a Victim of his own Tyranny—In the New Testament

Trouble Commences at Death—The Reign of Truth and Love—The Old

Spaniard who Died without an Enemy—The Wars it Brought—Consolation

should be Denied to Murderers—At the Rate at which Heathen are being

Converted, how long will it take to Establish Christ's Kingdom on

Earth?—The Resurrection—The Judgment Day—Pious Evasions—"We shall

not Die, but we shall all be Hanged"—"No Bible, no Civilization"

Miracles of the New Testament—Nothing Written by Christ or his

Contemporaries—Genealogy of Jesus—More Miracles—A Master of

Death—Improbable that he would be Crucified—The Loaves and Fishes—How

did it happen that the Miracles Convinced so Few?—The Resurrection—The

Ascension—Was the Body Spiritual—Parting from the Disciples—Casting

out Devils—Necessity of Belief—God should be consistent in the

Matter of forgiving Enemies—Eternal Punishment—Some Good Men who are

Damned—Another Objection—Love the only Bow on Life's dark Cloud—"Now

is the accepted Time"—Rather than this Doctrine of Eternal Punishment

Should be True—I would rather that every Planet should in its Orbit

wheel a barren Star—What I Believe—Immortality—It existed long before

Moses—Consolation—The Promises are so Far Away, and the Dead are so

Near—Death a Wall or a Door—A Fable—Orpheus and Eurydice.

(1885.)

I. Happiness the true End and Aim of Life—Spiritual People and

their Literature—Shakespeare's Clowns superior to Inspired

Writers—Beethoven's Sixth Symphony Preferred to the Five Books of

Moses—Venus of Milo more Pleasing than the Presbyterian Creed—II.

Religions Naturally Produced—Poets the Myth-makers—The Sleeping

Beauty—Orpheus and Eurydice—Red Riding Hood—The Golden Age—Elysian

Fields—The Flood Myth—Myths of the Seasons—III. The Sun-god—Jonah,

Buddha, Chrisnna, Horus, Zoroaster—December 25th as a Birthday of

Gods—Christ a Sun-God—The Cross a Symbol of the Life to Come—When

Nature rocked the Cradle of the Infant World—IV. Difference between

a Myth and a Miracle—Raising the Dead, Past and Present—Miracles

of Jehovah—Miracles of Christ—Everything Told except the Truth—The

Mistake of the World—V. Beginning of Investigation—The Stars as

Witnesses against Superstition—Martyrdom of Bruno—Geology—Steam and

Electricity—Nature forever the Same—Persistence of Force—Cathedral,

Mosque, and Joss House have the same Foundation—Science the

Providence of Man—VI. To Soften the Heart of God—Martyrs—The God was

Silent—Credulity a Vice—Develop the Imagination—"The Skylark" and

"The Daisy"—VII. How are we to Civilize the World?—Put Theology out

of Religion—Divorce of Church and State—Secular Education—Godless

Schools—VIII. The New Jerusalem—Knowledge of the Supernatural

possessed by Savages—Beliefs of Primitive Peoples—Science is

Modest—Theology Arrogant—Torque-mada and Bruno on the Day of

Judgment—IX. Poison of Superstition in the Mother's Milk—Ability

of Mistakes to take Care of Themselves—Longevity of Religious

Lies—Mother's religion pleaded by the Cannibal—The Religion of

Freedom—O Liberty, thou art the God of my Idolatry

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME III.

(1891.)

I. The Greatest Genius of our World—Not of Supernatural Origin or

of Royal Blood—Illiteracy of his Parents—Education—His Father—His

Mother a Great Woman—Stratford Unconscious of the Immortal

Child—Social Position of Shakespeare—Of his Personal

Peculiarities—Birth, Marriage, and Death—What we Know of Him—No Line

written by him to be Found—The Absurd Epitaph—II. Contemporaries

by whom he was Mentioned—III. No direct Mention of any of his

Contemporaries in the Plays—Events and Personages of his Time—IV.

Position of the Actor in Shakespeare's Time—Fortunately he was Not

Educated at Oxford—An Idealist—His Indifference to Stage-carpentry

and Plot—He belonged to All Lands—Knew the Brain and Heart of Man—An

Intellectual Spendthrift—V. The Baconian Theory—VI. Dramatists before

and during the Time of Shakespeare—Dramatic Incidents Illustrated in

Passages from "Macbeth" and "Julius Cæsar"—VII. His Use of the Work of

Others—The Pontic Sea—A Passage from "Lear"—VIII. Extravagance that

touches the Infinite—The Greatest Compliment—"Let me not live after

my flame lacks oil"—Where Pathos almost Touches the Grotesque—IX.

An Innovator and Iconoclast—Disregard of the "Unities"—Nature

Forgets—Violation of the Classic Model—X. Types—The Secret of

Shakespeare—Characters who Act from Reason and Motive—What they Say

not the Opinion of Shakespeare—XI. The Procession that issued from

Shakespeare's Brain—His Great Women—Lovable Clowns—His Men—Talent

and Genius—XII. The Greatest of all Philosophers—Master of the

Human Heart—Love—XIII. In the Realm of Comparison—XIV. Definitions:

Suicide, Drama, Death, Memory, the Body, Life, Echo, the

World, Rumor—The Confidant of Nature—XV. Humor and

Pathos—Illustrations—XVI. Not a Physician, Lawyer, or Botanist—He was

a Man of Imagination—He lived the Life of All—The Imagination had a

Stage in Shakespeare's Brain.

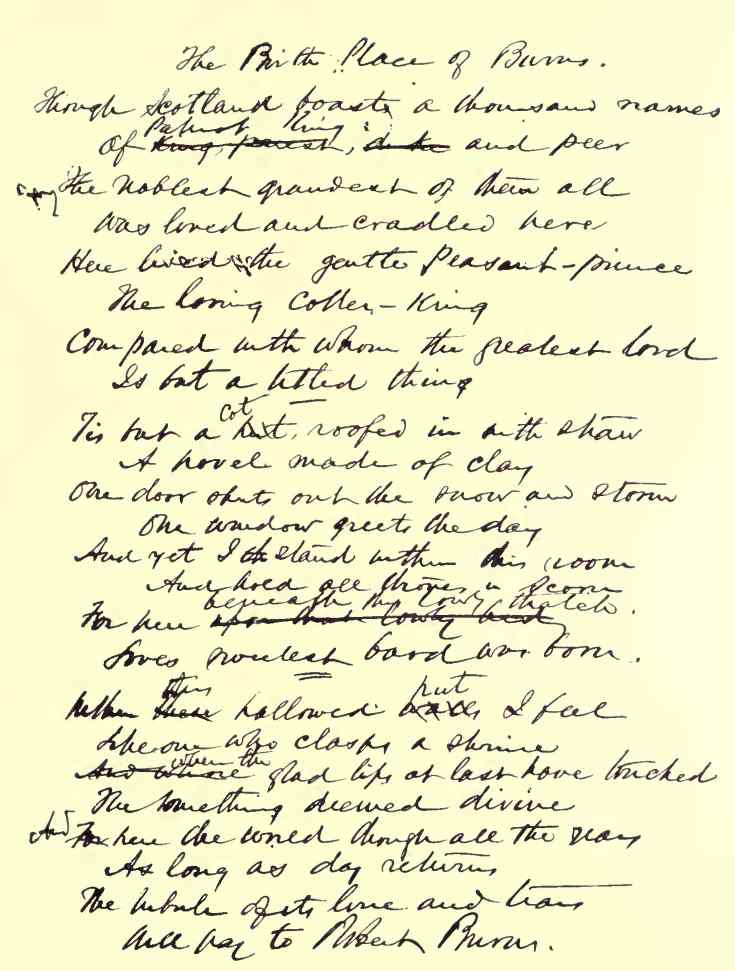

(1878.)

Poetry and Poets—Milton, Dante, Petrarch—Old-time Poetry in

Scotland—Influence of Scenery on Literature—Lives that are

Poems—Birth of Burns—Early Life and Education—Scotland Emerging from

the Gloom of Calvinism—A Metaphysical Peasantry—Power of the Scotch

Preacher—Famous Scotch Names—John Barleycorn vs. Calvinism—Why Robert

Burns is Loved—His Reading—Made Goddesses of Women—Poet of Love: His

"Vision," "Bonnie Doon," "To Mary in Heaven"—Poet of Home:

"Cotter's Saturday Night," "John Anderson, My Jo"—Friendship: "Auld

Lang-Syne"—Scotch Drink: "Willie brew'd a peck o' maut"—Burns the

Artist: The "Brook," "Tam O'Shanter"—A Real Democrat: "A man's a man

for a' that"—His Theology: The Dogma of Eternal Pain, "Morality,"

"Hypocrisy," "Holy Willie's Prayer"—On the Bible—A Statement of his

Religion—Contrasted with Tennyson—From Cradle to Coffin—His Last

words—Lines on the Birth-place of Burns.

(1894.)

I. Simultaneous Birth of Lincoln and Darwin—Heroes of Every

Generation—Slavery—Principle Sacrificed to Success—Lincoln's

Childhood—His first Speech—A Candidate for the Senate against

Douglass—II. A Crisis in the Affairs of the Republic—The South Not

Alone Responsible for Slavery—Lincoln's Prophetic Words—Nominated for

President and Elected in Spite of his Fitness—III. Secession and

Civil War—The Thought uppermost in his Mind—IV. A Crisis in the

North—Proposition to Purchase the Slaves—V. The Proclamation of

Emancipation—His Letter to Horace Greeley—Waited on by Clergymen—VI.

Surrounded by Enemies—Hostile Attitude of Gladstone, Salisbury,

Louis Napoleon, and the Vatican—VII. Slavery the Perpetual

Stumbling-block—Confiscation—VIII. His Letter to a Republican

Meeting in Illinois—Its Effect—IX. The Power of His Personality—The

Embodiment of Mercy—Use of the Pardoning Power—X. The Vallandigham

Affair—The Horace Greeley Incident—Triumphs of Humor—XI. Promotion of

General Hooker—A Prophecy and its Fulfillment—XII.—States Rights vs.

Territorial Integrity—XIII. His Military Genius—The Foremost Man in

all the World: and then the Horror Came—XIV. Strange Mingling of Mirth

and Tears—Deformation of Great Historic Characters—Washington now

only a Steel Engraving—Lincoln not a Type—Virtues Necessary in a

New Country—Laws of Cultivated Society—In the Country is the Idea

of Home—Lincoln always a Pupil—A Great Lawyer—Many-sided—Wit and

Humor—As an Orator—His Speech at Gettysburg contrasted with the

Oration of Edward Everett—Apologetic in his Kindness—No Official

Robes—The gentlest Memory of our World.

(1894.)

I. Changes wrought by Time—Throne and Altar Twin Vultures—The King and

the Priest—What is Greatness?—Effect of Voltaire's Name on Clergyman

and Priest—Born and Baptized—State of France in 1694—The Church

at the Head—Efficacy of Prayers and Dead Saints—Bells and Holy

Water—Prevalence of Belief in Witches, Devils, and Fiends—Seeds of

the Revolution Scattered by Noble and Priest—Condition in England—The

Inquisition in full Control in Spain—Portugal and Germany burning

Women—Italy Prostrate beneath the Priests, the Puritans in America

persecuting Quakers, and stealing Children—II. The Days of Youth—His

Education—Chooses Literature as a Profession and becomes a Diplomat—In

Love and Disinherited—Unsuccessful Poem Competition—Jansenists

and Molinists—The Bull Unigenitus—Exiled to Tulle—Sent to the

Bastile—Exiled to England—Acquaintances made there—III. The Morn

of Manhood—His Attention turned to the History of the Church—The

"Triumphant Beast" Attacked—Europe Filled with the Product of his

Brain—What he Mocked—The Weapon of Ridicule—His Theology—His

"Retractions"—What Goethe said of Voltaire—IV. The Scheme of

Nature—His belief in the Optimism of Pope Destroyed by the Lisbon

Earthquake—V. His Humanity—Case of Jean Calas—The Sirven Family—The

Espenasse Case—Case of Chevalier de la Barre and D'Etallonde—Voltaire

Abandons France—A Friend of Education—An Abolitionist—Not

a Saint—VI. The Return—His Reception—His Death—Burial at

Romilli-on-the-Seine—VII. The Death-bed Argument—Serene Demise of

the Infamous—God has no Time to defend the Good and protect the

Pure—Eloquence of the Clergy on the Death-bed Subject—The

Second Return—Throned upon the Bastile—The Grave Desecrated by

Priests—Voltaire.

A Testimonial to Walt Whitman—Let us put Wreaths on the Brows of the

Living—Literary Ideals of the American People in 1855—"Leaves of

Grass"—Its reception by the Provincial Prudes—The Religion of the

Body—Appeal to Manhood and Womanhood—Books written for the

Market—The Index Expurgatorius—Whitman a believer in

Democracy—Individuality—Humanity—An Old-time Sea-fight—What is

Poetry?—Rhyme a Hindrance to Expression—Rhythm the Comrade of

the Poetic—Whitman's Attitude toward Religion—Philosophy—The Two

Poems—"A Word Out of the Sea"—"When Lilacs Last in the Door"—"A Chant

for Death"—

The History of Intellectual Progress is written in the Lives of

Infidels—The King and the Priest—The Origin of God and Heaven, of

the Devil and Hell—The Idea of Hell born of Ignorance, Brutality,

Cowardice, and Revenge—The Limitations of our Ancestors—The Devil

and God—Egotism of Barbarians—The Doctrine of Hell not an Exclusive

Possession of Christianity—The Appeal to the Cemetery—Religion and

Wealth, Christ and Poverty—The "Great" not on the Side of Christ and

his Disciples—Epitaphs as Battle-cries—Some Great Men in favor of

almost every Sect—Mistakes and Superstitions of Eminent Men—Sacred

Books—The Claim that all Moral Laws came from God through

the Jews—Fear—Martyrdom—God's Ways toward Men—The Emperor

Constantine—The Death Test—Theological Comity between Protestants and

Catholics—Julian—A childish Fable still Believed—Bruno—His Crime,

his Imprisonment and

(1890.)

"Old Age"—"Leaves of Grass"

(1881.)

Martyrdom—The First to die for Truth without Expectation of Reward—The

Church in the Time of Voltaire—Voltaire—Diderot—David Hume—Benedict

Spinoza—Our Infidels—Thomas Paine—Conclusion.

(1884.)

I. The Natural and the Supernatural—Living for the Benefit of

your Fellow-Man and Living for Ghosts—The Beginning of Doubt—Two

Philosophies of Life—Two Theories of Government—II. Is our God

superior to the Gods of the Heathen?—What our God has done—III. Two

Theories about the Cause and Cure of Disease—The First Physician—The

Bones of St. Anne Exhibited in New York—Archbishop Corrigan and

Cardinal Gibbons Countenance a Theological Fraud—A Japanese Story—The

Monk and the Miraculous Cures performed by the Bones of a Donkey

represented as those of a Saint—IV.—Two Ways of accounting for Sacred

Books and Religions—V-Two Theories about Morals—Nothing Miraculous

about Morality—The Test of all Actions—VI. Search for the

Impossible—Alchemy—"Perpetual Motion"—Astrology—Fountain of Perpetual

Youth—VII. "Great Men" and the Superstitions in which they have

Believed—VIII. Follies and Imbecilities of Great Men—We do not know

what they Thought, only what they Said—Names of Great Unbelievers—Most

Men Controlled by their Surroundings—IX. Living for God in Switzerland,

Scotland, New England—In the Dark Ages—Let us Live for Man—X. The

Narrow Road of Superstition—The Wide and Ample Way—Let us Squeeze the

Orange Dry—This Was, This Is, This Shall Be.

(1894.)

The Truth about the Bible Ought to be Told—I. The Origin of the

Bible—Establishment of the Mosaic Code—Moses not the Author of the

Pentateuch—Some Old Testament Books of Unknown Origin—II. Is the Old

Testament Inspired?—What an Inspired Book Ought to Be—What the Bible

Is—Admission of Orthodox Christians that it is not Inspired as to

Science—The Enemy of Art—III. The Ten Commandments—Omissions and

Redundancies—The Story of Achan—The Story of Elisha—The Story of

Daniel—The Story of Joseph—IV. What is it all Worth?—Not True, and

Contradictory—Its Myths Older than the Pentateuch—Other Accounts

of the Creation, the Fall, etc.—Books of the Old Testament Named

and Characterized—V. Was Jehovah a God of Love?—VI. Jehovah's

Administration—VII. The New Testament—Many Other Gospels besides

our Four—Disagreements—Belief in Devils—Raising of the Dead—Other

Miracles—Would a real Miracle-worker have been Crucified?—VIII.

The Philosophy of Christ—Love of

Enemies—Improvidence—Self-Mutilation—The Earth as a

Footstool—Justice—A Bringer of War—Division of Families—IX. Is Christ

our Example?—X. Why should we place Christ at the Top and Summit of the

Human Race?—How did he surpass Other Teachers?—What he left Unsaid,

and Why—Inspiration—Rejected Books of the New Testament—The Bible and

the Crimes it has Caused.

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME IV.

(1896.)

I. Influence of Birth in determining Religious Belief—Scotch, Irish,

English, and Americans Inherit their Faith—Religions of Nations

not Suddenly Changed—People who Knew—What they were Certain

About—Revivals—Character of Sermons Preached—Effect of Conversion—A

Vermont Farmer for whom Perdition had no Terrors—The Man and his

Dog—Backsliding and Re-birth—Ministers who were Sincere—A Free Will

Baptist on the Rich Man and Lazarus—II. The Orthodox God—The

Two Dispensations—The Infinite Horror—III. Religious Books—The

Commentators—Paley's Watch Argument—Milton, Young, and Pollok—IV.

Studying Astronomy—Geology—Denial and Evasion by the Clergy—V. The

Poems of Robert Burns—Byron, Shelley, Keats, and Shakespeare—VI.

Volney, Gibbon, and Thomas Paine—Voltaire's Services to Liberty—Pagans

Compared with Patriarchs—VII. Other Gods and Other Religions—Dogmas,

Myths, and Symbols of Christianity Older than our Era—VIII. The Men

of Science, Humboldt, Darwin, Spencer, Huxley, Haeckel—IX. Matter and

Force Indestructible and Uncreatable—The Theory of Design—X. God an

Impossible Being—The Panorama of the Past—XI. Free from Sanctified

Mistakes and Holy Lies.

(1897.)

I. The Martyrdom of Man—How is Truth to be Found—Every Man should be

Mentally Honest—He should be Intellectually Hospitable—Geologists,

Chemists, Mechanics, and Professional Men are Seeking for the Truth—II.

Those who say that Slavery is Better than Liberty—Promises are not

Evidence—Horace Greeley and the Cold Stove—III. "The Science of

Theology" the only Dishonest Science—Moses and Brigham Young—Minds

Poisoned and Paralyzed in Youth—Sunday Schools and Theological

Seminaries—Orthodox Slanderers of Scientists—Religion has nothing

to do with Charity—Hospitals Built in Self-Defence—What Good has the

Church Accomplished?—Of what use are the Orthodox Ministers, and

What are they doing for the Good of Mankind—The Harm they are

Doing—Delusions they Teach—Truths they Should Tell about the

Bible—Conclusions—Our Christs and our Miracles.

(1896.)

I. "There is no Darkness but Ignorance"—False Notions Concerning

All Departments of Life—Changed Ideas about Science, Government and

Morals—II. How can we Reform the World?—Intellectual Light the First

Necessity—Avoid Waste of Wealth in War—III. Another Waste—Vast Amount

of Money Spent on the Church—IV. Plow can we Lessen Crime?—Frightful

Laws for the Punishment of Minor Crimes—A Penitentiary should be a

School—Professional Criminals should not be Allowed to Populate the

Earth—V. Homes for All-Make a Nation of Householders—Marriage

and Divorce-VI. The Labor Question—Employers cannot Govern

Prices—Railroads should Pay Pensions—What has been Accomplished

for the Improvement of the Condition of Labor—VII. Educate the

Children—Useless Knowledge—Liberty cannot be Sacrificed for the Sake

of Anything—False worship of Wealth—VIII. We must Work and Wait.

(1897.)

I. Our fathers Ages Ago—From Savagery to Civilization—For the

Blessings we enjoy, Whom should we Thank?—What Good has the Church

Done?-Did Christ add to the Sum of Useful Knowledge—The Saints—What

have the Councils and Synods Done?—What they Gave us, and What they

did Not—Shall we Thank them for the Hell Here and for the Hell of

the Future?—II. What Does God Do?—The Infinite Juggler and his

Puppets—What the Puppets have Done—Shall we Thank these

Gods?—Shall we Thank Nature?—III. Men who deserve our Thanks—The

Infidels, Philanthropists and Scientists—The Discoverers and

Inventors—Magellan—Copernicus—Bruno—Galileo—Kepler, Herschel,

Newton, and LaPlace—Lyell—What the Worldly have Done—Origin and

Vicissitudes of the Bible—The Septuagint—Investigating the Phenomena

of Nature—IV. We thank the Good Men and Good Women of the Past—The

Poets, Dramatists, and Artists—The Statesmen—Paine, Jefferson,

Ericsson, Lincoln. Grant—Voltaire, Humboldt, Darwin.

(1886.)

Prayer of King Lear—When Honesty wears a Rag and Rascality a Robe-The

Nonsense of "Free Moral Agency "—Doing Right is not Self-denial-Wealth

often a Gilded Hell—The Log House—Insanity of Getting

More—Great Wealth the Mother of Crime—Separation of Rich and

Poor—Emulation—Invention of Machines to Save Labor—Production and

Destitution—The Remedy a Division of the Land—Evils of Tenement

Houses—Ownership and Use—The Great Weapon is the Ballot—Sewing

Women—Strikes and Boycotts of No Avail—Anarchy, Communism, and

Socialism—The Children of the Rich a Punishment for Wealth—Workingmen

Not a Danger—The Criminals a Necessary Product—Society's Right

to Punish—The Efficacy of Kindness—Labor is Honorable—Mental

Independence.

(1895.)

I. The Old Testament—Story of the Creation—Age of the Earth and

of Man—Astronomical Calculations of the Egyptians—The Flood—The

Firmament a Fiction—Israelites who went into Egypt—Battles of the

Jews—Area of Palestine—Gold Collected by David for the Temple—II. The

New Testament—Discrepancies about the Birth of Christ—Herod and

the Wise Men—The Murder of the Babes of Bethlehem—When was Christ

born—Cyrenius and the Census of the World—Genealogy of Christ

according to Matthew and Luke—The Slaying of Zacharias—Appearance of

the Saints at the Crucifixion—The Death of Judas Iscariot—Did

Christ wish to be Convicted?—III. Jehovah—IV. The Trinity—The

Incarnation—Was Christ God?—The Trinity Expounded—"Let us pray"—V.

The Theological Christ—Sayings of a Contradictory Character—Christ a

Devout Jew—An ascetic—His Philosophy—The Ascension—The Best that Can

be Said about Christ—The Part that is beautiful and Glorious—The Other

Side—VI. The Scheme of Redemption—VII. Belief—Eternal Pain—No Hope

in Hell, Pity in Heaven, or Mercy in the Heart of God—VIII. Conclusion.

(1898.)

I. What is Superstition?—Popular Beliefs about the Significance

of Signs, Lucky and Unlucky Numbers, Days, Accidents, Jewels,

etc.—Eclipses, Earthquakes, and Cyclones as Omens—Signs and Wonders

of the Heavens—Efficacy of Bones and Rags of Saints—Diseases and

Devils—II. Witchcraft—Necromancers—What is a Miracle?—The Uniformity

of Nature—III. Belief in the Existence of Good Spirits or Angels—God

and the Devil—When Everything was done by the Supernatural—IV. All

these Beliefs now Rejected by Men of Intelligence—The Devil's Success

Made the Coming of Christ a Necessity—"Thou shalt not Suffer a Witch

to Live"—Some Biblical Angels—Vanished Visions—V. Where are Heaven

and Hell?—Prayers Never Answered—The Doctrine of Design—Why Worship

our Ignorance?—Would God Lead us into Temptation?—President McKinley's

Thanks giving for the Santiago Victory—VI. What Harm Does Superstition

Do?—The Heart Hardens and the Brain Softens—What Superstition has Done

and Taught—Fate of Spain—Of Portugal, Austria, Germany—VII. Inspired

Books—Mysteries added to by the Explanations of Theologians—The

Inspired Bible the Greatest Curse of Christendom—VIII. Modifications

of Jehovah—Changing the Bible—IX. Centuries of Darkness—The Church

Triumphant—When Men began to Think—X. Possibly these Superstitions are

True, but We have no Evidence—We Believe in the Natural—Science is the

Real Redeemer.

(1899.)

I. If the Devil should Die, would God Make Another?—How was the Idea

of a Devil Produced—Other Devils than Ours—Natural Origin of these

Monsters—II. The Atlas of Christianity is The Devil—The Devil of the

Old Testament—The Serpent in Eden—"Personifications" of Evil—Satan

and Job—Satan and David—III. Take the Devil from the Drama

of Christianity and the Plot is Gone—Jesus Tempted by the Evil

One—Demoniac Possession—Mary Magdalene—Satan and Judas—Incubi

and Succubi—The Apostles believed in Miracles and Magic—The Pool of

Bethesda—IV. The Evidence of the Church—The Devil was forced to

Father the Failures of God—Belief of the Fathers of the Church

in Devils—Exorcism at the Baptism of an Infant in the Sixteenth

Century—Belief in Devils made the Universe a Madhouse presided over by

an Insane God—V. Personifications of the Devil—The Orthodox Ostrich

Thrusts his Head into the Sand—If Devils are Personifications so are

all the Other Characters of the Bible—VI. Some Queries about the

Devil, his Place of Residence, his Manner of Living, and his Object in

Life—Interrogatories to the Clergy—VII. The Man of Straw the Master

of the Orthodox Ministers—His recent Accomplishments—VIII. Keep the

Devils out of Children—IX. Conclusion.—Declaration of the Free.

(1860-64.)

The Prosperity of the World depends upon its Workers—Veneration for the

Ancient—Credulity and Faith of the Middle Ages—Penalty for Reading

the Scripture in the Mother Tongue—Unjust, Bloody, and Cruel Laws—The

Reformers too were Persecutors—Bigotry of Luther and Knox—Persecution

of Castalio—Montaigne against Torture in France—"Witchcraft" (chapter

on)—Confessed Wizards—A Case before Sir Matthew Hale—Belief

in Lycanthropy—Animals Tried and Executed—Animals received

as Witnesses—The Corsned or Morsel of Execution—Kepler an

Astrologer—Luther's Encounter with the Devil—Mathematician

Stoefflers, Astronomical Prediction of a Flood—Histories Filled with

Falsehood—Legend about the Daughter of Pharaoh invading Scotland and

giving the Country her name—A Story about Mohammed—A History of the

Britains written by Archdeacons—Ingenuous Remark of Eusebius—Progress

in the Mechanic Arts—England at the beginning of the Eighteenth

Century—Barbarous Punishments—Queen Elizabeth's Order Concerning

Clergymen and Servant Girls—Inventions of Watt, Arkwright, and

Others—Solomon's Deprivations—Language (chapter on)—Belief that the

Hebrew was< the original Tongue—Speculations about the Language

of Paradise—Geography (chapter on)—The Works of Cosmas—Printing

Invented—Church's Opposition to Books—The Inquisition—The

Reformation—"Slavery" (chapter on)—Voltaire's Remark on Slavery as

a Contract—White Slaves in Greece, Rome, England, Scotland, and

France—Free minds make Free Bodies—Causes of the Abolition of White

Slavery in Europe—The French Revolution—The African Slave Trade,

its Beginning and End—Liberty Triumphed (chapter head)—Abolition of

Chattel Slavery—Conclusion.

(1899.)

I. Belief in God and Sacrifice—Did an Infinite God Create the Children

of Men and is he the Governor of the Universe?—II. If this God Exists,

how do we Know he is Good?—Should both the Inferior and the Superior

thank God for their Condition?—III. The Power that Works for

Righteousness—What is this Power?—The Accumulated Experience of the

World is a Power Working for Good?—Love the Commencement of the Higher

Virtues—IV. What has our Religion Done?—Would Christians have been

Worse had they Adopted another Faith?—V. How Can Mankind be Reformed

Without Religion?—VI. The Four Corner-stones of my Theory—VII. Matter

and Force Eternal—Links in the Chain of Evolution—VIII. Reform—The

Gutter as a Nursery—Can we Prevent the Unfit from Filling the World

with their Children?—Science must make Woman the Owner and Mistress

of Herself—Morality Born of Intelligence—IX. Real Religion and Real

Worship.

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME V.

INGERSOLL'S INTERVIEWS ON TALMAGE.

A VINDICATION OF THOMAS PAINE.

INGERSOLL'S SIX INTERVIEWS ON TALMAGE.

(1882.)

Preface—First Interview: Great Men as Witnesses

to the Truth of the Gospel—No man should quote

the Words of Another unless he is willing to

Accept all the Opinions of that Man—Reasons of

more Weight than Reputations—Would a general

Acceptance of Unbelief fill the Penitentiaries?—

My Creed—Most Criminals Orthodox—Relig-ion and

Morality not Necessarily Associates—On the

Creation of the Universe out of Omnipotence—Mr.

Talmage's Theory about the Pro-duction of Light

prior to the Creation of the Sun—The Deluge and

the Ark—Mr. Talmage's tendency to Belittle the

Bible Miracles—His Chemical, Geological, and

Agricultural Views—His Disregard of Good Manners-

-Second Interview: An Insulting Text—God's Design

in Creating Guiteau to be the Assassin of

Garfield—Mr. Talmage brings the Charge of

Blasphemy—Some Real Blasphemers—The Tabernacle

Pastor tells the exact Opposite of the Truth about

Col. Ingersoll's Attitude toward the Circulation

of Immoral Books—"Assassinating" God—Mr.

Talmage finds Nearly All the Invention of Modern

Times Mentioned in the Bible—The Reverend

Gentleman corrects the Translators of the Bible in

the Matter of the Rib Story—Denies that Polygamy

is permitted by the Old Testament—His De-fence of

Queen Victoria and Violation of the Grave of

George Eliot—Exhibits a Christian Spirit—Third

Interview: Mr. Talmage's Partiality in the

Bestowal of his Love—Denies the Right of Laymen

to Examine the Scriptures—Thinks the Infidels

Victims of Bibliophobia —He explains the Stopping

of the Sun and Moon at the Command of Joshua—

Instances a Dark Day in the Early Part of the

Century—Charges that Holy Things are Made Light

of—Reaffirms his Confidence in the Whale and

Jonah Story—The Commandment which Forbids the

making of Graven Images—Affirmation that the

Bible is the Friend of Woman—The Present

Condition of Woman—Fourth Interview: Colonel

Ingersoll Compared by Mr. Talmage tojehoiakim, who

Consigned Writings of Jeremiah to the Flames—An

Intimation that Infidels wish to have all copies

of the Bible Destroyed by Fire—Laughter

Deprecated—Col. Ingersoll Accused of Denouncing

his Father—Mr. Talmage holds that a Man may be

Perfectly Happy in Heaven with His Mother in Hell-

-Challenges the Infidel to Read a Chapter from St.

John—On the "Chief Solace of the World"—Dis-

covers an Attempt is being made to Put Out the

Light-houses of the Farther Shore—Affirms our

Debt to Christianity for Schools, Hospitals,

etc.—Denies that Infidels have ever Done any

Good—

Fifth Interview: Inquiries if Men gather Grapes of

Thorns, or Figs of Thistles, and is Answered in

the Negative—Resents the Charge that the Bible is

a Cruel Book—Demands to Know where the Cruelty of

the Bible Crops out in the Lives of Christians—

Col. Ingersoll Accused of saying that the Bible

is a Collection of Polluted Writings—Mr. Talmage

Asserts the Orchestral Harmony of the Scriptures

from Genesis to Revelation, and Repudiates the

Theory of Contradictions—His View of Mankind

Indicated in Quotations from his Confession of

Faith—He Insists that the Bible is Scientific—

Traces the New Testament to its Source with St.

John—Pledges his Word that no Man ever Died for a

Lie Cheerfully and Triumphantly—As to Prophecies

and Predictions—Alleged "Prophetic" Fate of the

Jewish People—Sixth Interview: Dr. Talmage takes

the Ground that the Unrivalled Circulation of the

Bible Proves that it is Inspired—Forgets' that a

Scientific Fact does not depend on the Vote of

Numbers—Names some Christian Millions—His

Arguments Characterized as the Poor-est, Weakest,

and Best Possible in Support of the Doctrine of

Inspira-tion—Will God, in Judging a Man, take

into Consideration the Cir-cumstances of that

Man's Life?—Satisfactory Reasons for Not Believ-

ing that the Bible is inspired.

THE TALMAGIAN CATECHISM.

The Pith and Marrow of what Mr. Talmage has been

Pleased to Say, set forth in the form of a Shorter

Catechism.

A VINDICATION OF THOMAS PAINE.

(1877.)

Letter to the New York Observer—An Offer to Pay

One Thousand Dollars in Gold for Proof that Thomas

Paine or Voltaire Died in Terror because of any

Religious Opinions Either had Expressed—

Proposition to Create a Tribunal to Hear the

Evidence—The Ob-server, after having Called upon

Col. Ingersoll to Deposit the Money, and

Characterized his Talk as "Infidel 'Buncombe,'"

Denies its Own Words, but attempts to Prove them—

Its Memory Refreshed by Col. Ingersoll and the

Slander Refuted—Proof that Paine did Not Recant -

-Testimony of Thomas Nixon, Daniel Pelton, Mr.

Jarvis, B. F. Has-kin, Dr. Manley, Amasa

Woodsworth, Gilbert Vale, Philip Graves, M. D.,

Willet Hicks, A. C. Hankinson, John Hogeboom, W.

J. Hilton, Tames Cheetham, Revs. Milledollar and

Cunningham, Mrs. Hedden, Andrew A. Dean, William

Carver,—The Statements of Mary Roscoe and Mary

Hindsdale Examined—William Cobbett's Account of a

Call upon Mary Hinsdale—Did Thomas Paine live the

Life of a Drunken Beast, and did he Die a Drunken,

Cowardly, and Beastly Death?—Grant Thorbum's

Charges Examined—Statement of the Rev. J. D.

Wickham, D.D., shown to be Utterly False—False

Witness of the Rev. Charles Hawley, D.D.—W. H.

Ladd, James Cheetham, and Mary Hinsdale—Paine's

Note to Cheetham—Mr-Staple, Mr. Purdy, Col. John

Fellows, James Wilburn, Walter Morton, Clio

Rickman, Judge Herttell, H. Margary, Elihu Palmer,

Mr.

XV

Lovett, all these Testified that Paine was a

Temperate Man—Washington's Letter to Paine—

Thomas Jefferson's—Adams and Washing-ton on

"Common Sense"—-James Monroe's Tribute—

Quotations from Paine—Paine's Estate and His

Will—The Observer's Second Attack (p. 492):

Statements of Elkana Watson, William Carver, Rev.

E. F. Hatfield, D.D., James Cheetham, Dr. J. W.

Francis, Dr. Manley, Bishop Fenwick—Ingersoll's

Second Reply (p. 516): Testimony Garbled by the

Editor of the Observer—Mary Roscoeand Mary Hins-

dale the Same Person—Her Reputation for Veracity-

-Letter from Rev. A. W. Cornell—Grant Thorburn

Exposed by James Parton—The Observer's Admission

that Paine did not Recant—Affidavit of

William B. Barnes.

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME VI.

THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION; INGERSOLL'S OPENING PAPER

THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION, BY JEREMIAH S. BLACK.

THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION, BY ROBERT G. INGERSOLL.

THE FIELD-INGERSOLL DISCUSSION.

A REPLY TO THE REV. HENRY M. FIELD, D.D.

A LAST WORD TO ROBERT G. INGERSOLL

COL. INGERSOLL TO MR. GLADSTONE.

THE CHURCH ITS OWN WITNESS, By Cardinal Manning.

ROME OR REASON: A REPLY TO CARDINAL MANNING.

IS CORPORAL PUNISHMENT DEGRADING?

THE CHRISTIAN RELIGION; INGERSOLL'S OPENING PAPER

(1881.)

I. Col. Ingersoll's Opening Paper—Statement of the Fundamental Truths

of Christianity—Reasons for Thinking that Portions of the Old Testament

are the Product of a Barbarous People—Passages upholding

Slavery, Polygamy, War, and Religious Persecution not Evidences of

Inspiration—If the Words are not Inspired, What Is?—Commands of

Jehovah compared with the Precepts of Pagans and Stoics—Epictetus,

Cicero, Zeno, Seneca, Brahma—II. The New Testament—Why were

Four Gospels Necessary?—Salvation by Belief—The Doctrine of

the Atonement—The Jewish System Culminating in the Sacrifice of

Christ—Except for the Crucifixion of her Son, the Virgin Mary would be

among the Lost—What Christ must have Known would Follow the Acceptance

of His Teachings—The Wars of Sects, the Inquisition, the Fields of

Death—Why did he not Forbid it All?—The Little that he Revealed—The

Dogma of Eternal Punishment—Upon Love's Breast the Church has Placed

the Eternal Asp—III. The "Inspired" Writers—Why did not God furnish

Every Nation with a Bible?

II. Judge Black's Reply—His Duty that of a Policeman—The Church not

in Danger—Classes who Break out into Articulate Blasphemy—The

Sciolist—Personal Remarks about Col. Ingersoll—Chief-Justice Gibson of

Pennsylvania Quoted—We have no Jurisdiction or Capacity to Rejudge the

Justice of God—The Moral Code of the Bible—Civil Government of the

Jews—No Standard of Justice without Belief in a God—Punishments for

Blasphemy and Idolatry Defended—Wars of Conquest—Allusion to Col.

Ingersoll's War Record—Slavery among the Jews—Polygamy Discouraged by

the Mosaic Constitution—Jesus of Nazareth and the Establishment of

his Religion—Acceptance of Christianity and Adjudication upon its

Divinity—The Evangelists and their Depositions—The Fundamental Truths

of Christianity—Persecution and Triumph of the Church—Ingersoll's

Propositions Compressed and the Compressions Answered—Salvation as a

Reward of Belief—Punishment of Unbelief—The Second Birth, Atonement,

Redemption, Non-resistance, Excessive Punishment of Sinners, Christ and

Persecution, Christianity and Freedom of Thought, Sufficiency of the

Gospel, Miracles, Moral Effect of Christianity.

III. Col. Ingersoll's Rejoinder—How this Discussion Came About—Natural

Law—The Design Argument—The Right to Rejudge the Justice even of a

God—Violation of the Commandments by Jehovah—Religious Intolerance

of the Old Testament—Judge Black's Justification of Wars of

Extermination—His Defence of Slavery—Polygamy not "Discouraged" by the

Old Testament—Position of Woman under the Jewish System and under that

of the Ancients—a "Policeman's" View of God—Slavery under Jehovah

and in Egypt—The Admission that Jehovah gave no Commandment against

Polygamy—The Learned and Wise Crawl back in Cribs—Alleged Harmony of

Old and New Testaments—On the Assertion that the Spread of Christianity

Proves the Supernatural Origin of the Gospel—The Argument applicable to

All Religions—Communications from Angels ana Gods—Authenticity of

the Statements of the Evangelists—Three Important Manuscripts—Rise

of Mormonism—Ascension of Christ—The Great Public Events alleged

as Fundamental Truths of Christianity—Judge Black's System

of "Compression"—"A Metaphysical Question"—Right and

Wrong—Justice—Christianity and Freedom of Thought—Heaven and

Hell—Production of God and the Devil—Inspiration of the Bible

dependent on the Credulity of the Reader—Doubt of Miracles—The

World before Christ's Advent—Respect for the Man Christ—The Dark

Ages—Institutions of Mercy—Civil Law.

THE FIELD-INGERSOLL DISCUSSION.

(1887.)

An Open Letter to Robert G. Ingersoll—Superstitions—Basis of

Religion—Napoleon's Question about the Stars—The Idea of God—Crushing

out Hope—Atonement, Regeneration, and Future Retribution—Socrates and

Jesus—The Language of Col. Ingersoll characterized as too Sweeping—The

Sabbath—But a Step from Sneering at Religion to Sneering at Morality.

A Reply to the Rev. Henry M. Field, D. D.—Honest Differences of

Opinion—Charles Darwin—Dr. Field's Distinction between Superstition

and Religion—The Presbyterian God an Infinite Torquemada—Napoleon's

Sensitiveness to the Divine Influence—The Preference of Agassiz—The

Mysterious as an Explanation—The Certainty that God is not what he

is Thought to Be—Self-preservation the Fibre of Society—Did

the Assassination of Lincoln Illustrate the Justice of God's

Judgments?—Immortality—Hope and the Presbyterian Creed—To a Mother

at the Grave of Her Son—Theological Teaching of Forgiveness—On

Eternal Retribution—Jesus and Mohammed—Attacking the Religion of

Others—Ananias and Sapphira—The Pilgrims and Freedom to Worship—The

Orthodox Sabbath—Natural Restraints on Conduct—Religion and

Morality—The Efficacy of Prayer—Respect for Belief of Father and

Mother—The "Power behind Nature"—Survival of the Fittest—The Saddest

Fact—"Sober Second Thought."

A Last Word to Robert G. Ingersoll, by Dr. Field—God not a

Presbyterian—Why Col. Ingersoll's Attacks on Religion are Resented—God

is more Merciful than Man—Theories about the Future Life—Retribution

a Necessary Part of the Divine Law—The Case of Robinson

Crusoe—Irresistible Proof of Design—Col. Ingersoll's View of

Immortality—An Almighty Friend.

Letter to Dr. Field—The Presbyterian God—What the Presbyterians

Claim—The "Incurably Bad"—Responsibility for not seeing Things

Clearly—Good Deeds should Follow even Atheists—No Credit in

Belief—Design Argument that Devours Itself—Belief as a Foundation

of Social Order—No Consolation in Orthodox Religion—The "Almighty

Friend" and the Slave Mother—a Hindu Prayer—Calvinism—Christ not the

Supreme Benefactor of the Race.

COLONEL INGERSOLL ON CHRISTIANITY.

(1888.)

Some Remarks on his Reply to Dr. Field by the Hon. Wm. E.

Gladstone—External Triumph and Prosperity of the Church—A Truth Half

Stated—Col. Ingersoll's Tumultuous Method and lack of Reverential

Calm—Jephthah's Sacrifice—Hebrews xii Expounded—The Case of

Abraham—Darwinism and the Scriptures—Why God demands Sacrifices of

Man—Problems admitted to be Insoluble—Relation of human Genius

to Human Greatness—Shakespeare and Others—Christ and the Family

Relation—Inaccuracy of Reference in the Reply—Ananias and

Sapphira—The Idea of Immortality—Immunity of Error in Belief from

Moral Responsibility—On Dishonesty in the Formation of Opinion—A

Plausibility of the Shallowest kind—The System of Thuggism—Persecution

for Opinion's Sake—Riding an Unbroken Horse.

Col. Ingersoll to Mr. Gladstone—On the "Impaired" State of the human

Constitution—Unbelief not Due to Degeneracy—Objections to the

Scheme of Redemption—Does Man Deserve only Punishment?—"Reverential

Calm"—The Deity of the Ancient Jews—Jephthah and Abraham—Relation

between Darwinism and the Inspiration of the Scriptures—Sacrifices to

the Infinite—What is Common Sense?—An Argument that will Defend every

Superstition—The Greatness of Shakespeare—The Absolute Indissolubility

of Marriage—Is the Religion of Christ for this Age?—As to Ananias and

Sapphira—Immortality and People of Low Intellectual Development—Can

we Control our Thought?—Dishonest Opinions Cannot be Formed—Some

Compensations for Riding an "Unbroken Horse."

(1888.)

"The Church Its Own Witness," by Cardinal Manning—Evidence

that Christianity is of Divine Origin—The Universality of the

Church—Natural Causes not Sufficient to Account for the Catholic

Church—-The World in which Christianity Arose—Birth of Christ—From

St Peter to Leo XIII.—The First Effect of Christianity—Domestic

Life's Second Visible Effect—Redemption of Woman from traditional

Degradation—Change Wrought by Christianity upon the Social, Political

and International Relations of the World—Proof that Christianity is of

Divine Origin and Presence—St. John and the Christian Fathers—Sanctity

of the Church not Affected by Human Sins.

A Reply to Cardinal Manning—I. Success not a Demonstration of either

Divine Origin or Supernatural Aid—Cardinal Manning's Argument

More Forcible in the Mouth of a Mohammedan—Why Churches Rise and

Flourish—Mormonism—Alleged Universality of the Catholic Church—Its

"inexhaustible Fruitfulness" in Good Things—The Inquisition and

Persecution—Not Invincible—Its Sword used by Spain—Its Unity not

Unbroken—The State of the World when Christianity was Established—The

Vicar of Christ—A Selection from Draper's "History of the Intellectual

Development of Europe"—Some infamous Popes—Part II. How the Pope

Speaks—Religions Older than Catholicism and having the Same Rites

and Sacraments—Is Intellectual Stagnation a Demonstration of Divine

Origin?—Integration and Disintegration—The Condition of the World 300

Years Ago—The Creed of Catholicism—The "One true God" with a Knowledge

of whom Catholicism has "filled the World"—Did the Catholic Church

overthrow Idolatry?—Marriage—Celibacy—Human Passions—The Cardinal's

Explanation of Jehovah's abandonment of the Children of Men for

four thousand Years—Catholicism tested by Paganism—Canon Law

and Convictions had Under It—Rival Popes—Importance of a Greek

"Inflection"—The Cardinal Witnesses.

(1889.)

Preface by the Editor of the North American Review—Introduction, by the

Rev. S. W. Dike, LL. D.—A Catholic View by Cardinal Gibbons—Divorce

as Regarded by the Episcopal Church, by Bishop, Henry C. Potter—Four

Questions Answered, by Robert G. Ingersoll.

Reply to Cardinal Gibbons—Indissolubility of Marriage a Reaction

from Polygamy—Biblical Marriage—Polygamy Simultaneous and

Successive—Marriage and Divorce in the Light of Experience—Reply

to Bishop Potter—Reply to Mr. Gladstone—Justice Bradley—Senator

Dolph—The argument Continued in Colloquial Form—Dialogue between

Cardinal Gibbons and a Maltreated Wife—She Asks the Advice of Mr.

Gladstone—The Priest who Violated his Vow—Absurdity of the Divorce

laws of Some States.

REPLY TO DR. LYMAN ABBOTT.

(1890)

Dr. Abbott's Equivocations—Crimes Punishable by Death under Mosaic

and English Law—Severity of Moses Accounted for by Dr. Abbott—The

Necessity for the Acceptance of Christianity—Christians should be

Glad to Know that the Bible is only the Work of Man and that the New

Testament Life of Christ is Untrue—All the Good Commandments, Known

to the World thousands of Years before Moses—Human Happiness of

More Consequence than the Truth about God—The Appeal to Great

Names—Gladstone not the Greatest Statesman—What the Agnostic Says—The

Magnificent Mistakes of Genesis—The Story of Joseph—Abraham as a

"self-Exile for Conscience's Sake."

REPLY TO ARCHDEACON FARRAR.

(1890.)

Revelation as an Appeal to Man's "Spirit"—What is Spirit and what is

"Spiritual Intuition"?—The Archdeacon in Conflict with St. Paul—II.

The Obligation to Believe without Evidence—III. Ignorant Credulity—IV.

A Definition of Orthodoxy—V. Fear not necessarily Cowardice—Prejudice

is Honest—The Ola has the Advantage in an Argument—St.

Augustine—Jerome—the Appeal to Charlemagne—Roger Bacon—Lord Bacon

a Defender of the Copernican System—The Difficulty of finding out

what Great Men Believed—Names Irrelevantly Cited—Bancroft on the

Hessians—Original Manuscripts of the Bible—VI. An Infinite Personality

a Contradiction in Terms—VII. A Beginningless Being—VIII. The

Cruelties of Nature not to be Harmonized with the Goodness of a

Deity—Sayings from the Indian—Origen, St. Augustine, Dante, Aquinas.

IS CORPORAL PUNISHMENT DEGRADING?

(1890.)

A Reply to the Dean of St. Paul—Growing Confidence in the Power of

Kindness—Crimes against Soldiers and Sailors—Misfortunes Punished

as Crimes—The Dean's Voice Raised in Favor of the Brutalities of the

Past—Beating of Children—Of Wives—Dictum of Solomon.

DETAILED CONTENTS OF VOLUME VII.

THE LIMITATIONS OF TOLERATION.

A REPLY TO THE CINCINNATI GAZETTE AND CATHOLIC TELEGRAPH.

AN INTERVIEW ON CHIEF JUSTICE COMEGYS.

A REPLY TO REV. DRS. THOMAS AND LORIMER.

A REPLY TO REV. JOHN HALL AND WARNER VAN NORDEN.

A REPLY TO THE REV. DR. PLUMB.

A REPLY TO THE NEW YORK CLERGY ON SUPERSTITION.

(1877.)

Answer to San Francisco Clergymen—Definition of Liberty, Physical

and Mental—The Right to Compel Belief—Woman the Equal of Man—The

Ghosts—Immortality—Slavery—Witchcraft—Aristocracy of the

Air—Unfairness of Clerical Critics—Force and Matter—Doctrine of

Negation—Confident Deaths of Murderers—Childhood Scenes returned to

by the Dying—Death-bed of Voltaire—Thomas Paine—The First

Sectarians Were Heretics—Reply to Rev. Mr. Guard—Slaughter of

the Canaanites—Reply to Rev. Samuel Robinson—Protestant

Persecutions—Toleration—Infidelity and Progress—The

Occident—Calvinism—Religious Editors—Reply to the Rev. Mr.

Ijams—Does the Bible teach Man to Enslave his Brothers?—Reply to

California Christian Advocate—Self-Government of French People at

and Since the Revolution—On the Site of the Bastile—French

Peasant's Cheers for Jesus Christ—Was the World created in Six

Days—Geology—What is the Astronomy of the Bible?—The Earth the Centre

of the Universe—Joshua's Miracle—Change of Motion into Heat—Geography

and Astronomy of Cosmas—Does the Bible teach the Existence of

that Impossible Crime called Witchcraft?—Saul and the Woman of

Endor—Familiar Spirits—Demonology of the New Testament—Temptation of

Jesus—Possession by Devils—Gadarene Swine Story—Test of Belief—Bible

Idea of the Rights of Children—Punishment of the Rebellious

Son—Jephthah's Vow and Sacrifice—Persecution of Job—The Gallantry

of God—Bible Idea of the Rights of Women—Paul's Instructions to

Wives—Permission given to Steal Wives—Does the Bible Sanction

Polygamy and Concubinage?—Does the Bible Uphold and Justify Political

Tyranny?—Powers that be Ordained of God—Religious Liberty of

God—Sun-Worship punishable with Death—Unbelievers to be damned—Does

the Bible describe a God of Mercy?—Massacre Commanded—Eternal

Punishment Taught in the New Testament—The Plan of Salvation—Fall

and Atonement Moral Bankruptcy—Other Religions—Parsee

Sect—Brahmins—Confucians—Heretics and Orthodox.

(1879.)

Rev. Robert Collyer—Inspiration of the Scriptures—Rev. Dr.

Thomas—Formation of the Old Testament—Rev. Dr. Kohler—Rev. Mr.

Herford—Prof. Swing—Rev. Dr. Ryder.

TO THE INDIANAPOLIS CLERGY.

(1882.)

Rev. David Walk—Character of Jesus—Two or Three Christs Described

in the Gospels—Christ's Change of Opinions—Gospels Later than the

Epistles—Divine Parentage of Christ a Late Belief—The Man Christ

probably a Historical Character—Jesus Belittled by his Worshipers—He

never Claimed to be Divine—Christ's Omissions—Difference between

Christian and other Modern Civilizations—Civilization not Promoted

by Religion—Inventors—French and American Civilization: How

Produced—Intemperance and Slavery in Christian Nations—Advance due to

Inventions and Discoveries—Missionaries—Christian Nations Preserved by

Bayonet and Ball—Dr. T. B. Taylor—Origin of Life on this Planet—Sir

William Thomson—Origin of Things Undiscoverable—Existence after

Death—Spiritualists—If the Dead Return—Our Calendar—Christ and

Christmas-The Existence of Pain—Plato's Theory of Evil—Will God do

Better in Another World than he does in this?—Consolation—Life Not a

Probationary Stage—Rev. D.O'Donaghue—The Case of Archibald Armstrong

and Jonathan Newgate—Inequalities of Life—Can Criminals live a

Contented Life?—Justice of the Orthodox God Illustrated.

(1883.)

Are the Books of Atheistic or Infidel Writers Extensively

Read?—Increase in the Number of Infidels—Spread of Scientific

Literature—Rev. Dr. Eddy—Rev. Dr. Hawkins—Rev. Dr. Haynes—Rev.

Mr. Pullman—Rev. Mr. Foote—Rev. Mr. Wells—Rev. Dr. Van Dyke—Rev.

Carpenter—Rev. Mr. Reed—Rev. Dr. McClelland—Ministers Opposed to

Discussion—Whipping Children—Worldliness as a Foe of the Church—The

Drama—Human Love—Fires, Cyclones, and Other Afflictions as Promoters

of Spirituality—Class Distinctions—Rich and Poor—Aristocracies—The

Right to Choose One's Associates—Churches Social Affairs—Progress

of the Roman Catholic Church—Substitutes for the Churches—Henry

Ward Beecher—How far Education is Favored by the Sects—Rivals of the

Pulpit—Christianity Now and One Hundred Years Ago—French Revolution

produced by the Priests—Why the Revolution was a Failure—Infidelity

of One Hundred Years Ago—Ministers not more Intellectual than a Century

Ago—Great Preachers of the Past—New Readings of Old Texts—Clerical

Answerers of Infidelity—Rev. Dr. Baker—Father Fransiola—Faith and

Reason—Democracy of Kindness—Moral Instruction—Morality Born of Human

Needs—The Conditions of Happiness—The Chief End of Man.

THE LIMITATIONS OF TOLERATION.

(1888.)

Discussion between Col. Robert G. Ingersoll, Hon. Frederic R. Coudert,

and ex-Gov. Stewart L. Woodford before the Nineteenth Century Club of

New York—Propositions—Toleration not a Disclaimer but a Waiver of the

Right to Persecute—Remarks of Courtlandt Palmer—No Responsibility for

Thought—Intellectual Hospitality—Right of Free Speech—Origin of the

term "Toleration"—Slander and False Witness—Nobody can Control his own

Mind: Anecdote—Remarks of Mr. Coudert—Voltaire, Rousseau, Hugo, and

Ingersoll—General Woodford's Speech—Reply by Colonel Ingersoll—A

Catholic Compelled to Pay a Compliment to Voltaire—Responsibility for

Thoughts—The Mexican Unbeliever and his Reception in the Other Country.

(1891.)

Christianity's Message of Grief—Christmas a Pagan Festival—Reply

to Dr. Buckley—Charges by the Editor of the Christian Advocate—The

Tidings of Christianity—In what the Message of Grief Consists—Fear

and Flame—An Everlasting Siberia—Dr. Buckley's Proposal to Boycott the

Telegram—Reply to Rev. J. M. King and Rev. Thomas Dixon, Jr. Cana Day

be Blasphemed?—Hurting Christian feelings—For Revenue only What is

Blasphemy?—Balaam's Ass wiser than the Prophet—The Universalists—Can

God do Nothing for this World?—The Universe a Blunder if Christianity

is true—The Duty of a Newspaper—Facts Not Sectarian—The Rev.

Mr. Peters—What Infidelity Has Done—Public School System not

Christian—Orthodox Universities—Bruno on Oxford—As to Public

Morals—No Rewards or Punishments in the Universe—The Atonement

Immoral—As to Sciences and Art—Bruno, Humboldt, Darwin—Scientific

Writers Opposed by the Church—As to the Liberation of Slaves—As to

the Reclamation of Inebriates—Rum and Religion—The Humanity

of Infidelity—What Infidelity says to the Dying—The Battle

Continued—Morality not Assailed by an Attack on Christianity—The

Inquisition and Religious Persecution—Human Nature Derided by

Christianity—Dr. DaCosta—"Human Brotherhood" as exemplified by

the History of the Church—The Church and Science, Art and

Learning——Astronomy's Revenge—Galileo and Kepler—Mrs. Browning:

Science Thrust into the Brain of Europe—Our Numerals—Christianity and

Literature—Institution's of Learning—Stephen Girard—James Lick—Our

Chronology—Historians—Natural Philosophy—Philology—Metaphysical

Research—Intelligence, Hindoo, Egyptian—Inventions—John

Ericsson—Emancipators—Rev. Mr. Ballou—The Right of Goa to

Punish—Rev. Dr. Hillier—Rev. Mr. Haldeman—George A. Locey—The "Great

Physician"—Rev. Mr. Talmage—Rev. J. Benson Hamilton—How Voltaire

Died—The Death-bed of Thomas Paine—Rev. Mr. Holloway—Original

Sin—Rev. Dr. Tyler—The Good Samaritan a Heathen—Hospitals and

Asylums—Christian Treatment of the Insane—Rev. Dr. Buckley—The

North American Review Discussion—Judge Black, Dr. Field,

Mr. Gladstone—Circulation of Obscene Literature—Eulogy of

Whiskey—Eulogy of Tobacco—Human Stupidity that Defies the Gods—Rev.

Charles Deems—Jesus a Believer in a Personal Devil—The Man Christ.

(1892.)

Reply to the Western Watchman—Henry D'Arcy—Peter's

Prevarication-Some Excellent Pagans-Heartlessness of a

Catholic—Wishes do not Affect the Judgment—Devout Robbers—Penitent

Murderers—Reverential Drunkards—Luther's Distich—Judge

Normile—Self-destruction.

(1894.)

Col. Ingersoll's First Letter in The New York World—Under what

Circumstances a Man has the Right to take his Own Life—Medicine and the

Decrees of God—Case of the Betrayed Girl—Suicides not Cowards—Suicide

under Roman Law—Many Suicides Insane—Insanity Caused by Religion—The

Law against Suicide Cruel and Idiotic—Natural and Sufficient Cause for

Self-destruction—Christ's Death a Suicide—Col. Ingersoll's Reply to his

Critics—Is Suffering the Work of God?—It is not Man's Duty to

Endure Hopeless Suffering—When Suicide is Justifiable—The

Inquisition—Alleged Cowardice of Suicides—Propositions

Demonstrated—Suicide the Foundation of the Christian

Religion—Redemption and Atonement—The Clergy on Infidelity

and Suicide—Morality and Unbelief—Better injure yourself than

Another—Misquotation by Opponents—Cheerful View the Best—The

Wonder is that Men endure—Suicide a Sin (Interview in The New

York Journal)—Causes of Suicide—Col. Ingersoll Does Not Advise

Suicide—Suicides with Tracts or Bibles in their Pockets—Suicide a Sin

(Interview in The New York Herald)—Comments on Rev. Alerle St. Croix

Wright's Sermon—Suicide and Sanity (Interview in The York World)—As to

the Cowardice of Suicide—Germany and the Prevalence of Suicide—Killing

of Idiots and Defective Infants—Virtue, Morality, and Religion.

(1891.)

Reply to General Rush Hawkins' Article, "Brutality and Avarice

Triumphant"—Croakers and Prophets of Evil—Medical Treatment

for Believers in Universal Evil—Alleged Fraud in Army

Contracts—Congressional Extravagance—Railroad "Wreckers"—How

Stockholders in Some Roads Lost Their Money—The Star-Route

Trials—Timber and Public Lands—Watering Stock—The Formation

of Trusts—Unsafe Hotels: European Game and Singing Birds—Seal

Fisheries—Cruelty to Animals—Our Indians—Sensible and Manly

Patriotism—Days of Brutality—Defence of Slavery by the Websters,

Bentons, and Clays—Thirty Years' Accomplishment—Ennobling Influence of

War for the Right—The Lady ana the Brakeman—American Esteem of Honesty

in Business—Republics do not Tend to Official Corruption—This the Best

Country in the World.

A REPLY TO THE CINCINNATI GAZETTE AND CATHOLIC TELEGRAPH.

(1878.)

Defence of the Lecture on Moses—How Biblical Miracles are sought to

be Proved—Some Non Sequiturs—A Grammatical Criticism—Christianity

Destructive of Manners—Cuvier and Agassiz on Mosaic Cosmogony—Clerical

Advance agents—Christian Threats and Warnings—Catholicism the Upas

Tree—Hebrew Scholarship as a Qualification for Deciding Probababilities

—Contradictions and Mistranslations of the Bible—Number of Errors in

the Scriptures—The Sunday Question.

AN INTERVIEW ON CHIEF JUSTICE COMEGYS.

(1881.)

Charged with Blasphemy in the State of Delaware—Can a Conditionless

Deity be Injured?—Injustice the only Blasphemy—The Lecture

in Delaware—Laws of that State—All Sects in turn Charged with

Blasphemy—Heresy Consists in making God Better than he is Thought

to Be—A Fatal Biblical Passage—Judge Comegys—Wilmington

Preachers—States with Laws against Blasphemy—No Danger of Infidel

Mobs—No Attack on the State of Delaware Contemplated—Comegys a

Resurrection—Grand Jury's Refusal to Indict—Advice about the Cutting

out of Heretics' Tongues—Objections to the Whipping-post—Mr. Bergh's

Bill—One Remedy for Wife-beating.

A REPLY TO REV. DRS. THOMAS AND LORIMER.

(1882.)

Solemnity—Charged with Being Insincere—Irreverence—Old Testament

Better than the New—"Why Hurt our Feelings?"—Involuntary Action of

the Brain—Source of our Conceptions of Space—Good and Bad—Right and

Wrong—The Minister, the Horse and the Lord's Prayer—Men Responsible

for their Actions—The "Gradual" Theory Not Applicable to

the Omniscient—Prayer Powerless to Alter Results—Religious

Persecution—Orthodox Ministers Made Ashamed of their

Creed—Purgatory—Infidelity and Baptism Contrasted—Modern Conception

of the Universe—The Golden Bridge of Life—"The Only Salutation"—The

Test for Admission to Heaven—"Scurrility."

A REPLY TO REV. JOHN HALL AND WARNER VAN NORDEN.

(1892.)

Dr. Hall has no Time to Discuss the subject of Starving

Workers—Cloakmakers' Strike—Warner Van Norden of the Church Extension

Society—The Uncharitableness of Organized Charity—Defence of the

Cloakmakers—Life of the Underpaid—On the Assertion that Assistance

encourages Idleness and Crime—The Man without Pity an Intellectual

Beast—Tendency of Prosperity to Breed Selfishness—Thousands Idle