Title: The Evolution of Photography

Author: active 1854-1890 John Werge

Release date: February 13, 2012 [eBook #38866]

Language: English

Credits: E-text prepared by Albert László, Tom Cosmas, P. G. Máté, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team (http://www.pgdp.net) from page images generously made available by Internet Archive (http://www.archive.org)

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/evolutionofphoto00werguoft |

|

|

| THOMAS WEDGWOOD. From a Plaster Cast. |

JOSEPH NICÉPHORE NIÉPCE. From a Painting by L. Berger. |

|

|

| Rev. J. B. READE. From a Photograph by Maull & Fox. |

|

|

|

| HENRY FOX TALBOT. From a Calotype. |

SIR JOHN HERSCHEL. From a Daguerreotype. |

No previous history of photography, that I am aware of, has ever assumed the form of a reminiscence, nor have I met with a photographic work, of any description, that is so strictly built upon a chronological foundation as the one now placed in the hands of the reader. I therefore think, and trust, that it will prove to be an acceptable and readable addition to photographic literature.

It was never intended that this volume should be a text-book, so I have not entered into elaborate descriptions of the manipulations of this or that process, but have endeavoured to make it a comprehensive and agreeable summary of all that has been done in the past, and yet convey a perfect knowledge of all the processes as they have appeared and effected radical changes in the practice of photography.

The chronological record of discoveries, inventions, appliances, and publications connected with the art will, it is hoped, be received and considered as a useful and interesting table of reference; while the reminiscences, extending over forty years of unbroken contact with every phase of photography, and some of its pioneers, will form a vital link between the long past and immediate present, which may awaken pleasing recollections in some, and give encouragement to others to [iv] enter the field of experiment, and endeavour to continue the work of evolution.

At page 10 it is stated, on the authority of the late Robert Hunt, that some of Niépce’s early pictures may be seen at the British Museum. That was so, but unfortunately it is not so now. On making application, very recently, to examine these pictures, I ascertained that they were never placed in the care of the curator of the British Museum, but were the private property of the late Dr. Robert Brown, who left them to his colleague, John Joseph Bennett, and that at the latter’s death they passed into the possession of his widow. I wrote to the lady making enquiries about them, but have not been able to trace them further; there are, however, two very interesting examples of Niépce’s heliographs, and one photo-etched plate and print, lent by Mr. H. P. Robinson, on view at South Kensington, in the Western Gallery of the Science Collection.

For the portrait of Thomas Wedgwood, I am indebted to Mr. Godfrey Wedgwood; for that of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, to the Mayor of Chalons-sur-Saône; for the Rev. J. B. Reade’s, to Mr. Fox; for Sir John Herschel’s, to Mr. H. H. Cameron; for John Frederick Goddard’s, to Dr. Jabez Hogg; and for Frederick Scott Archer’s, to Mr. Alfred Cade; and to all those gentlemen I tender my most grateful acknowledgments. Also to the Autotype Company, for their care and attention in carrying out my wishes in the reproduction of all the illustrations by their beautiful Collotype Process.

JOHN WERGE.

London, June, 1890.

| INTRODUCTION | 1 |

| FIRST PERIOD. | |

| The Dark Ages | 3 |

| SECOND PERIOD. | |

| Publicity and Progress | 27 |

| THIRD PERIOD. | |

| Collodion Triumphant | 58 |

| FOURTH PERIOD. | |

| Gelatine Successful | 95 |

| CHRONOLOGICAL RECORD. | |

| Inventions, Discoveries, etc. | 126 |

| CONTRIBUTIONS TO PHOTOGRAPHIC LITERATURE. | 140 |

![]()

| Frontispiece | Portrait of Thomas Wedgwood. |

| „ | Portrait of Joseph Nicéphore Niépce. |

| „ | Portrait of Rev. J. B. Reade. |

| „ | Portrait of Henry Fox Talbot. |

| „ | Portrait of Sir John Herschel. |

| 27 | Portrait of L. J. M. Daguerre. |

| 27 | Portrait of John Frederick Goddard. |

| 27 | Copy of Instantaneous Daguerreotype. |

| 58 | Portrait of Frederick Scott Archer. |

| 58 | Hever Castle, Kent. |

| 95 | Portrait of Dr. R. L. Maddox. |

| 95 | Portrait of Richard Kennett. |

Archer, Frederick Scott, 58-69

Argentic Gelatino-Bromide Paper, 106

Abney’s Translation of Pizzighelli and Hubl’s Booklet, 109

A String of Old Beads, 309

Bacon, Roger, 3

Bennett, Charles, 102

Boston, 51

Bromine Accelerator, 29

Bingham, Robert J., 87

Burgess, J., 93

Cabinet Portraits, 84

Camera-Obscura, 3

Chronological Record, 126-139

Convention of 1889, 122

Claudet, A. F. J., 29, 86

Chlorine Accelerator, 29

Collodion Process (Archer’s), 68

Collodio-Chloride Printing Process, 81

Davy, Sir H., 9

Daguerre, L. J. M., 9, 43

Daguerreotype Process, 23, 24, 25

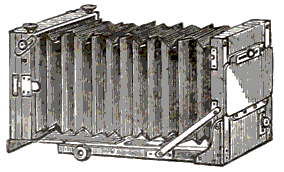

—— Apparatus Imported, 29

Diaphanotypes, 71

Dolland, J., 4

Donkin, W. F., 120

Draper, Dr., 107

Dublin Exhibition, 205-226

Eburneum Process, 82

Elliott & Fry, 96

Eosine, &c., 109

Errors in Pictorial Backgrounds, 231

First Photographic Portrait, 107

Fizeau, M., 6, 28

Flash-light Pictures, 118

Gelatino-Bromide Experiments, 91

Globe Lens, 78

Goddard, John Frederick, 28, 79

Harrison, W. H., 87

Heliographic Process, 11, 12, 13

Heliochromy, 88

Herschel, Dr., 6

Herschel, Sir John, 94

Hillotypes, 71

Hughes, Jabez, 55, 75

Hunt, Robert, 117

International Exhibitions, 42, 77, 82, 111

Johnson, J. R., 107

Kennett, R., 96

Lambert, Leon, 98

Laroche, Sylvester, 116

Lea, Carey, 101

“Lux Graphicus” on the Wing, 273-299

Lights and Lighting, 311

Maddox, Dr. R. L., 91

Magic Photographs, 83

Mawson, John, 85

Mayall, J. E., 54

Macbeth, Norman, 120

Montreal, 51

Morgan and Kidd, 106

[viii]

Newton, Sir Isaac, 3

New York, 48, 71

Niagara, 50

Niépce, J. Nicéphore, 9, 11

Niépce de St. Victor, 88

Niagara, Pictures of, 140-158

Notes on Pictures in National Gallery, 245

Orthochromatic Plates, 115

Panoramic Lens and Camera, 76

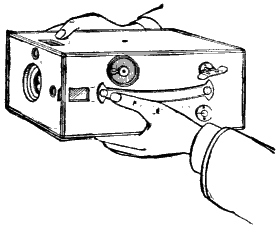

Pistolgraph, 76

Pensions to Daguerre and Niépce, 33

Philadelphia, 49

Ponton, Mungo, 22, 103

Poitevin, M., 85, 108

Porta, Baptista G., 3

Potash Bichromate, 22

Pouncy Process, 78

Pictures of the St. Lawrence, 158-169

Pinhole Camera, 117

Pizzighelli’s Platinum Printing, 118

Pictures of the Potomac, 183-196

Photography in the North, 226-231

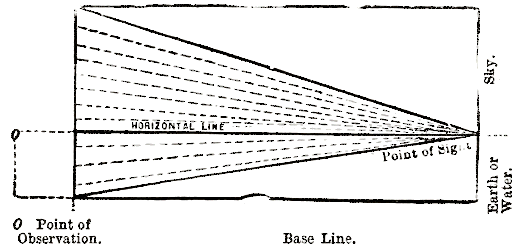

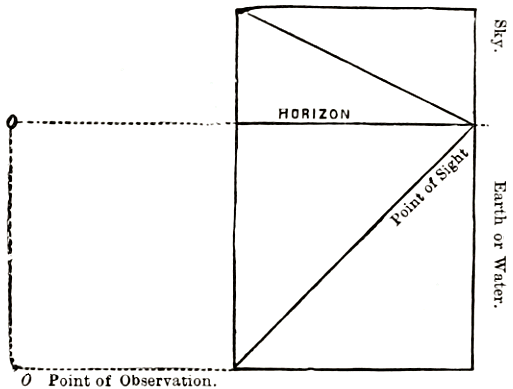

Perspective, 237-244

Photography and the Immured Pompeiians, 303

Rambles among Studios, 196-204

Reade, Rev. J. B., 15-22, 90

Rejlander, O. G., 98

Ritter, John Wm., 5

Rumford, Count, 5

Russell, Col., 117

Sable Island, 47

Salomon, Adam, 84

Sawyer, J. R., 121

Scheele, C. W., 4, 5

Senebier, 5

Simpson, George Wharton, 75, 103

Soda Sulphite, 109

Swan’s Carbon Process, 80

Stannotype, 107

Sutton, Thomas, 100

Spencer, J. A., 102

Stereoscopic Pictures, 119

Sharpness and Softness v. Hardness, 249

Simple Mode of Intensifying Negatives, 307

Talbot, Henry Fox, 14, 101

Talbot versus Laroche, 54

Taylor, Professor Alfred Swaine, 104

The Hudson River, 169-183

The Society’s Exhibition, 260

The Use of Clouds in Landscapes, 265

—— as Backgrounds in Portraiture, 269

Union of the North and South London Societies, 253

Vogel, Dr. H. W., 109

Washington, 49

Wedgwood Controversy, 80

Wedgwood, Thomas, 7, 8, 9

Whipple Gallery, 52

Wolcott Reflecting Camera, 28

Wollaston’s Diaphragmatic Shutter, 115

Wollaston, Dr., 6

Woodbury Process, 82

Wothlytype Printing Process, 81

Photography, though young in years, is sufficiently aged to be in danger of having much of its early history, its infantile gambols, and vigorous growth, obscured or lost sight of in the glitter and reflection of the brilliant success which surrounds its maturity. Scarcely has the period of an average life passed away since the labours of the successful experimentalists began; yet, how few of the present generation of workers can lay their fingers on the dates of the birth, christening, and phases of the delightful vocation they pursue. Many know little or nothing of the long and weary travail the minds of the discoverers suffered before their ingenuity gave birth to the beautiful art-science by which they live. What form the infant art assumed in the earlier stages of its life; or when, where, and how, it passed from one phase to another until it arrived at its present state of mature and profitable perfection. Born with the art, as I may say, and having graduated in it, I could, if I felt so disposed, give an interesting, if not amusing, description of its rise and progress, and the many difficulties and disappointments that some of the early practitioners experienced at a time when photographic A B C’s were not printed; its “principles and practice” anything but familiarly explained; and when the “dark room” was as dark as the grave, and as poisonous as a charnel-house, and only occasionally illumined by the glare of a “bull’s-eye.” But it is not my intention to enter the domain of romance, and give highly coloured or extravagant accounts of [2] the growth of so beautiful and fascinating an art-science. Photography is sufficiently facetious in itself, and too versatile in its powers of delineation of scenes and character, to require any verbose effort of mine to make it attractive. A record of bare facts is all I aim at. Whatever is doubtful I shall leave to the imagination of the reader, or the invention of the romance writer. To arrange in chronological order the various discoveries, inventions, and improvements that have made photography what it is; to do honour to those who have toiled and given, or sold, the fruits of their labour for the advancement of the art; to set at rest, as far as dates can succeed in doing so, any questionable point or order of precedence of merit in invention, application, or modification of a process, and to enable the photographic student to make himself acquainted with the epochs of the art, is the extent of my ambition in compiling these records.

With the hope of rendering this work readily referable and most comprehensive, I shall divide it into four periods. The first will deal broadly and briefly with such facts as can be ascertained that in any way bear on the accidental discovery, early researches, and ultimate success of the pioneers of photography.

The second will embrace a fuller description of their successes and results. The third will be devoted to a consideration of patents and impediments; and the fourth to the rise and development of photographic literature and art. A strict chronological arrangement of each period will be maintained, and it is hoped that the advantages to be derived from travelling some of the same ground over again in the various divisions of the subject will fully compensate the reader, and be accepted as sufficient excuse for any unavoidable repetition that may appear in the work. With these few remarks I shall at once enter upon the task of placing before the reader in chronological order the origin, rise, progress, and development of the science and art of photography.

More than three hundred years have elapsed since the influence and actinism of light on chloride of silver was observed by the alchemists of the sixteenth century. This discovery was unquestionably the first thing that suggested to the minds of succeeding chemists and men of science the possibility of obtaining pictures of solid bodies on a plane surface previously coated with a silver salt by means of the sun’s rays; but the alchemists were too much absorbed in their vain endeavours to convert the base metals into royal ones to seize the hint, and they lost the opportunity of turning the silver compounds with which they were acquainted into the mine of wealth it eventually became in the nineteenth century. Curiously enough, a mechanical invention of the same period was afterwards employed, with a very trifling modification, for the production of the earliest sun-pictures. This was the camera-obscura invented by Roger Bacon in 1297, and improved by a physician in Padua, Giovanni Baptista Porta, about 1500, and afterwards remodelled by Sir Isaac Newton.

Two more centuries passed away before another step was taken towards the revelation of the marvellous fact that Nature possessed within herself the power to delineate her own beauties, and, as has recently been proved, that the sun could [4] depict his own terrible majesty with a rapidity and fidelity the hand of man could never attain. The second step towards this grand achievement of science was the construction of the double achromatic combination of lenses by J. Dolland. With single combinations of lenses, such pictures as we see of ourselves to-day, and such portraits of the sun as the astronomers obtained during the late total eclipse, could never have been produced. J. Dolland, the eminent optician, was born in London 1706, and died 1762; and had he not made that important improvement in the construction of lenses, the eminent photographic opticians of the present day might have lived and died unknown to wealth and fame.

The observations of the celebrated Swedish chemist, Scheele, formed the next interesting link between the simple and general blackening of a lump of chloride of silver, and the gradations of blackening which ultimately produced the photographic picture on a piece of paper possessing a prepared surface of nitrate of silver and chloride of sodium in combination. Scheele discovered in 1777 that the blackening of the silver compound was due to the reducing power of light, and that the black deposit was reduced silver; and it is precisely the same effect of the action of light upon chloride of silver passing through the various densities of the negative that produces the beautiful photographic prints with which we are all familiar at the present time. Scheele was also the first to discover and make known the fact that chloride of silver was blackened or reduced to various depths by the varying action of the prismatic colours. He fixed a glass prism in a window, allowed the refracted sunbeams to fall on a piece of paper strewn with luna cornua—fused chloride of silver—and saw that the violet ray was more active than any of the other colours. Anyone, with a piece of sensitised paper and a prism, or piece of a broken lustre, can repeat and see for themselves Scheele’s interesting discovery; and anyone that can draw a head or [5] a flower may catch a sunbeam in a small magnifying glass, and make a drawing on sensitised paper with a pencil, as long as the sun is distant from the earth. It is the old story of Columbus and the egg—easy to do when you are shown or told how.

Charles William Scheele was born at Stralsund, Sweden, December 19th, 1742, and died at Koeping, on lake Moeler, May 21st, 1786. He was the real father of photography, for he produced the first photographic picture on record without camera and without lens, with the same chemical compound and the same beautiful and wonderful combination of natural colours which we now employ. Little did he dream what was to follow. But photography, like everything else in this world, is a process of evolution.

Senebier followed up Scheele’s experiments with the solar spectrum, and ascertained that chloride of silver was darkened by the violet ray in fifteen minutes, while the red rays were sluggish, and required twenty minutes to produce the same result.

John Wm. Ritter, born at Samitz, in Silesia, corroborated the experiments of Scheele, and discovered that chloride of silver was blackened beyond the spectrum on the violet side. He died in 1810; but he had observed what is now called the fluorescent rays of the spectrum—invisible rays which unquestionably exert themselves in the interests and practice of photography.

Many other experiments were made by other chemists and philosophers on the influence of light on various substances, but none of them had any direct bearing on the subject under consideration until Count Rumford, in 1798, communicated to the Royal Society his experiments with chloride of gold. Count Rumford wetted a piece of taffeta ribbon with a solution of chloride of gold, held it horizontally over the clear flame of a wax candle, and saw that the heat decomposed the gold solution, and stained the ribbon a beautiful purple. Though [6] no revived gold was visible, the ribbon appeared to be coated with a rich purple enamel, which showed a metallic lustre of great brilliancy when viewed in the sunlight; but its photographic value lay in the circumstance of the hint it afterwards afforded M. Fizeau in applying a solution of chloride of gold, and, by means of heat, depositing a fine film of metallic gold on the surface of the Daguerreotype image, thereby increasing the brilliancy and permanency of that form of photographic picture. A modification of M. Fizeau’s chloride of gold “fixing process” is still used to tone, and imparts a rich purple colour to photographic prints on plain and albumenized papers.

In 1800, Dr. Herschel’s “Memoirs on the Heating Power of the Solar Spectrum” were published, and out of his observations on the various effects of differently coloured darkening glasses arose the idea that the chemical properties of the prismatic colours, and coloured glass, might be as different as those which related to heat and light. His suspicions were ultimately verified, and hence the use of yellow or ruby glass in the windows of the “dark room,” as either of those coloured glasses admit the luminous ray and restrain the violet or active photographic ray, and allow all the operations that would otherwise have to be performed in the dark, to be seen and done in comfort, and without injury to the sensitive film.

The researches of Dr. Wollaston, in 1802, had very little reference to photography beyond his examination of the chemical action of the rays of the spectrum, and his observation that the yellow stain of gum guaiacum was converted to a green colour in the violet rays, and that the red rays rapidly destroyed the green tint the violet rays had generated.

1802 is, however, a memorable year in the dark ages of photography, and the disappointment of those enthusiastic and indefatigable pursuers of the sunbeam must have been grievous indeed, when, after years of labour, they found the means of catching shadows as they fell, and discovered that they could not keep them.

[7] Thomas Wedgwood, son of the celebrated potter, was not only the first that obtained photographic impressions of objects, but the first to make the attempt to obtain sun-pictures in the true sense of the word. Scheele had obtained the first photographic picture of the solar spectrum, but it was by accident, and while pursuing other chemical experiments; whereas Wedgwood went to work avowedly to make the sunbeam his slave, to enlist the sun into the service of art, and to compel the sun to illustrate art, and to depict nature more faithfully than art had ever imitated anything illumined by the sun before. How far he succeeded everyone should know, and no student of photography should ever tire of reading the first published account of his fascinating pastime or delightful vocation, if it were but to remind him of the treasures that surround him, and the value of hyposulphite of soda. What would Thomas Wedgwood not have given for a handful of that now common commodity? There is a mournfulness in the sentence relative to the evanescence of those sun-pictures in the Memoir by Wedgwood and Davy that is peculiarly impressive and desponding contrasted with our present notions of instability. We know that sun-pictures will, at the least, last for years, while they knew that at the most they would endure but for a few hours. The following extracts from the Memoir published in June, 1802, will, it is hoped, be found sufficiently interesting and in place here to justify their insertion.

“White paper, or white leather moistened with solution of nitrate of silver, undergoes no change when kept in a dark place, but on being exposed to the daylight it speedily changes colour, and after passing through different shades of grey and brown becomes at length nearly black.... In the direct beams of the sun, two or three minutes are sufficient to produce the full effect, in the shade several hours are required, and light transmitted through different coloured glasses acts upon it with different degrees of intensity. Thus it is found [8] that red rays, or the common sunbeams passed through red glass, have very little action upon it; yellow and green are more efficacious, but blue and violet light produce the most decided and powerful effects.... When the shadow of any figure is thrown upon the prepared surface, the part concealed by it remains white, and the other parts speedily become dark. For copying paintings on glass, the solution should be applied on leather, and in this case it is more readily acted on than when paper is used. After the colour has been once fixed on the leather or paper, it cannot be removed by the application of water, or water and soap, and it is in a high degree permanent. The copy of a painting or the profile, immediately after being taken, must be kept in an obscure place; it may indeed be examined in the shade, but in this case the exposure should be only for a few minutes; by the light of candles or lamps as commonly employed it is not sensibly affected.

“No attempts that have been made to prevent the uncoloured parts of the copy or profile from being acted upon by the light have as yet been successful. They have been covered by a thin coating of fine varnish, but this has not destroyed their susceptibility of becoming coloured, and even after repeated washings, sufficient of the active part of the saline matter will adhere to the white parts of leather or paper to cause them to become dark when exposed to the rays of the sun....

“The images formed by means of a camera-obscura have been found to be too faint to produce, in any moderate time, an effect upon the nitrate of silver. To copy these images was the first object of Mr. Wedgwood, in his researches on the subject, and for this purpose he first used the nitrate of silver, which was mentioned to him by a friend, as a substance very sensible to the influence of light; but all his numerous experiments as to their primary end proved unsuccessful.”

From the foregoing extracts from the first lecture on [9] photography that ever was delivered or published, it will be seen that those two eminent philosophers and experimentalists despaired of obtaining pictures in the camera-obscura, and of rendering the pictures obtained by superposition, or cast shadows, in any degree permanent, and that they were utterly ignorant and destitute of any fixing agents. No wonder, then, that all further attempts to pursue these experiments should, for a time, be abandoned in England. Although Thomas Wedgwood’s discoveries were not published until 1802, he obtained his first results in 1791, and does not appear to have made any appreciable advance during the remainder of his life. He was born in 1771, and died in 1805. Sir Humphry Davy was born at Penzance 1778, and died at Geneva in 1828, so that neither of them lived to see the realization of their hopes.

From the time that Wedgwood and Davy relinquished their investigation, the subject appears to have lain dormant until 1814, when Joseph Nicéphore Niépce, of Chalons-sur-Saône, commenced a series of experiments with various resins, with the object of securing or retaining in a permanent state the pictures produced in the camera-obscura, and in 1824, L. J. M. Daguerre turned his attention to the same subject. These two investigators appear to have carried on their experiments in different ways, and in total ignorance of the existence and pursuits of the other, until the year 1826, when they accidentally became acquainted with each other and the nature of their investigations. Their introduction and reciprocal admiration did not, however, induce them to exchange their ideas, or reveal the extent of their success in the researches on which they were occupied, and which both were pursuing so secretly and guardedly. They each preserved a marked reticence on the subject for a considerable time, and it was not until a deed of partnership was executed between them that they confided their hopes and fears, their failures with this substance, and their prospects of [10] success with that; and even after the execution of the deed of partnership they seem to have jealously withheld as much of their knowledge as they decently could under the circumstances.

Towards the close of 1827 M. Niépce visited England, and we receive the first intimation of his success in the production of light-drawn pictures from a note addressed to Mr. Bauer, of Kew. It is rather curious and flattering to find that the earliest intimation of the Frenchman’s success is given in England. The note which M. Niépce wrote to Mr. Bauer is in French, but the following is a translation of the interesting announcement:—“Kew, 19th November, 1827. Sir,—When I left France to reside here, I was engaged in researches on the way to retain the image of objects by the action of light. I have obtained some results which make me eager to proceed.... Nicéphore Niépce.” This is the first recorded announcement of his partial success.

In the following December he communicated with the Royal Society of London, and showed several pictures on metal plates. Most of these pictures were specimens of his successful experiments with various resins, and the subjects were rendered visible to the extent which the light had assisted in hardening portions of the resin-covered plates. Some were etchings, and had been subjected to the action of acid after the design had been impressed by the action of light. Several of these specimens, I believe, are still extant, and may be seen on application to the proper official at the British Museum. M. Niépce named these results of his researches Heliography, and Mr. Robert Hunt gives their number, and a description of each subject, in his work entitled, “Researches on Light.” M. Niépce met with some disappointment in England on account of the Royal Society refusing to receive his communication as a secret, and he returned to France rather hurriedly. In a letter dated “Chalons-sur-Saône, 1st March, 1828,” he says, “We arrived here 26th February”; and, in a letter written by Daguerre, February 3rd, 1828, we find that savant consoling his brother experimentalist for his lack of encouragement in England.

[11] In December, 1829, the two French investigators joined issue by executing a deed of co-partnery, in which they agreed to prosecute their researches in future in mutual confidence and for their joint advantage; but their interchange of thought and experience does not appear to have been of much value or advantage to the other; for an examination of the correspondence between MM. Niépce and Daguerre tends to show that the one somewhat annoyed the other by sticking to his resins, and the other one by recommending the use of iodine. M. Niépce somewhat ungraciously expresses regret at having wasted so much time in experimenting with iodine at M. Daguerre’s suggestion, but ultimate results fully justified Daguerre’s recommendation, and proved that he was then on the right track, while M. Niépce’s experiments with resins, asphaltum, and other substances terminated in nothing but tedious manipulations, lengthy exposures, and unsatisfactory results. To M. Niépce, most unquestionably, is due the honour of having produced the first permanent sun-pictures, for we have seen that those obtained by Wedgwood and Davy were as fleeting as a shadow, while those exhibited by M. Niépce in 1827 are still in their original condition, and, imperfect as they are, they are likely to retain their permanency for ever. Their fault lay in neither possessing beauty nor commercial applicability.

As M. Niépce died at Chalons-sur-Saône in 1833, and does not appear to have improved his process much, if any, after entering into partnership with M. Daguerre, and as I may not have occasion to allude to him or his researches again, I think this will be the most fitting place to give a brief description of his process, and his share in the labours of bringing up the wonderful baby of science, afterwards named Photography, to a safe and ineffaceable period of its existence.

The Heliographic process of M. Niépce consists of a solution of asphaltum, bitumen of Judea, being spread on metal or glass plates, submitted to the action of light either by superposition [12] or in the camera, and the unaffected parts dissolved away afterwards by means of a suitable solvent. But, in case any student of photography should like to produce one of the first form of permanent sun-pictures, I shall give here the details of M. Niépce’s own modus operandi for preparing the solution of bitumen and coating the plate:—

“I about half fill a wine-glass with this pulverised bitumen; I pour upon it, drop by drop, the essential oil of lavender until the bitumen is completely saturated. I afterwards add as much more of the essential oil as causes the whole to stand about three lines above the mixture, which is then covered and submitted to a gentle heat until the essential oil is fully impregnated with the colouring matter of the bitumen. If this varnish is not of the required consistency, it is to be allowed to evaporate slowly, without heat, in a shallow dish, care being taken to protect it from moisture, by which it is injured and at last decomposed. In winter, or in rainy weather, the precaution is doubly necessary. A tablet of plated silver, or well cleaned and warm glass, is to be highly polished, on which a thin coating of the varnish is to be applied cold, with a light roll of very soft skin; this will impart to it a fine vermilion colour, and cover it with a very thin and equal coating. The plate is then placed upon heated iron, which is wrapped round with several folds of paper, from which, by this method, all moisture had been previously expelled. When the varnish has ceased to simmer, the plate is withdrawn from the heat, and left to cool and dry in a gentle temperature, and protected from a damp atmosphere. In this part of the operation a light disc of metal, with a handle in the centre, should be held before the mouth, in order to condense the moisture of the breath.”

In the foregoing description it will be observed how much importance M. Niépce attached to the necessity of protecting the solution and prepared plate from moisture, and that no precautions are given concerning the effect of white light. It [13] must be remembered, however, that the material employed was very insensitive, requiring many hours of exposure either in the camera or under a print or drawing placed in contact with the prepared surface, and consequently such precaution might not have been deemed necessary. Probably M. Niépce worked in a subdued light, but there can be no doubt about the necessity of conducting both the foregoing operations in yellow light. Had M. Niépce performed his operations in a non-actinic light, the plates would certainly have been more sensitive, and the unacted-on parts would have been more soluble; thus rendering both the time of exposure and development more rapid.

After the plate was prepared and dried, it was exposed in the camera, or by superposition, under a print, or other suitable subject, that would lie flat. For the latter, an exposure of two or three hours in bright sunshine was necessary, and the former required six or eight hours in a strong light. Even those prolonged exposures did not produce a visible image, and the resultant picture was not revealed to view until after a tedious process of dissolving, for it could scarcely be called development. M. Niépce himself says, “The next operation then is to disengage the shrouded imagery, and this is accomplished by a solvent.” The solvent consisted of one measure of the essential oil of lavender and ten of oil of white petroleum or benzole. On removing the tablet from the camera or other object, it was plunged into a bath of the above solvent, and left there until the parts not hardened by light were dissolved. When the picture was fully revealed, it was placed at an angle to drain, and finished by washing it in water.

Except for the purpose of after-etching, M. Niépce’s process was of little commercial value then, but it has since been of some service in the practice of photo-lithography. That, I think, is the fullest extent of the commercial or artistic advantages derived from the utmost success of M. Niépce’s discoveries; but what he considered his failures, the fact that he employed [14] copper plates coated with silver for his heliographic tablets, and endeavoured to darken the clean or clear parts of the silvered plates with the fumes of iodine for the sake of contrast only, may be safely accepted as the foundation of Daguerre’s ultimate success in discovering the extremely beautiful and workable process known as the Daguerreotype.

M. Niépce appears to have done very little more towards perfecting the heliographic process after joining Daguerre; but the latter effected some improvements, and substituted for the bitumen of Judea the residuum obtained by evaporating the essential oil of lavender, without, however, attaining any important advance in that direction. After the death of M. Nicéphore Niépce, a new agreement was entered into by his son, M. Isidore Niépce, and M. Daguerre, and we must leave those two experimentalists pursuing their discoveries in France while we return to England to pick up the chronological links that unite the history of this wonderful discovery with the time that it was abandoned by Wedgwood and Davy, and the period of its startling and brilliant realization.

In 1834, Mr. Henry Fox Talbot, of Lacock Abbey, Wilts, “began to put in practice,” as he informs us in his memoir read before the Royal Society, a method which he “had devised some time previously, for employing to purposes of utility the very curious property which has been long known to chemists to be possessed by the nitrate of silver—namely, to discolouration when exposed to the violet rays of light.” The statement just quoted places us at once on the debateable ground of our subject, and compels us to pause and consider to what extent photography is indebted to Mr. Talbot for its further development at this period and five years subsequently. In the first place, it is not to be supposed for a moment that a man of Mr. Talbot’s position and education could possibly be ignorant of what had been done by Mr. Thomas Wedgwood and Sir Humphry Davy. Their experiments were published in the Journal of the Royal [15] Institution of Great Britain in June, 1802, and Mr. Talbot or some of his friends could not have failed to have seen or heard of those published details; and, in the second place, a comparison between the last records of Wedgwood and Davy’s experiments, and the first published details of Mr. Talbot’s process, shows not only that the two processes are identically the same, but that Mr. Talbot published his process before he had made a single step in advance of Wedgwood and Davy’s discoveries; and that his fixing solution was not a fixer at all, but simply a retardant that delayed the gradual disappearance of the picture only a short time longer. Mr. Talbot has generally been credited with the honour of producing the first permanent sun-pictures on paper; but there are grave reasons for doubting the justice of that honour being entirely, if at all, due to him, and the following facts and extracts will probably tend to set that question at rest, and transfer the laurel to another brow.

To the late Rev. J. B. Reade is incontestably due the honour of having first applied tannin as an accelerator, and hyposulphite of soda as a fixing agent, to the production and retention of light-produced pictures; and having first obtained an ineffaceable photograph upon paper. Mr. Talbot’s gallate of silver process was not patented or published till 1841; whereas the Rev. J. B. Reade produced paper negatives by means of gallic acid and nitrate of silver in 1837. It will be remembered that Mr. Wedgwood had discovered and stated that the chloride of silver was more sensitive when applied to white leather, and Mr. Reade, by inductive reasoning, came to the conclusion that tanned paper and silver would be more sensitive to light than ordinary paper coated with nitrate of silver could possibly be. As the reverend philosopher’s ideas on that subject are probably the first that ever impregnated the mind of man, and as his experiments and observations are the very earliest in the pursuit of a gallic acid accelerator and developer, I will give them in his own words.—“No one can dispute my claim to be the first to [16] suggest the use of gallic acid as a sensitiser for prepared paper, and hyposulphite of soda as a fixer. These are the keystones of the arch at which Davy and Young had laboured—or, as I may say in the language of another science, we may vary the tones as we please, but here is the fundamental base. My use of gallate of silver was the result of an inference from Wedgwood’s experiments with leather, ‘which is more readily acted upon than paper’ (Journal of the Royal Institution, vol. i., p. 171). Mrs. Reade was so good as to give me a pair of light-coloured leather gloves, that I might repeat Wedgwood’s experiment, and, as my friend Mr. Ackerman reminds me, her little objection to let me have a second pair led me to say, ‘Then I will tan paper.’ Accordingly I used an infusion of galls in the first instance in the early part of the year 1837, when I was engaged in taking photographs of microscopic objects. By a new arrangement of lenses in the solar microscope, I produced a convergence of the rays of light, while the rays of heat, owing to their different refractions, were parallel or divergent. This fortunate dispersion of the calorific rays enabled me to use objects mounted in balsam, as well as cemented achromatic object glasses; and, indeed, such was the coolness of the illumination, that even infusoria in single drops of water were perfectly happy and playful (vide abstracts of the ‘Philosophical Transactions,’ December 22nd, 1836). The continued expense of an artist—though, at first, I employed my friend, Lens Aldons—to copy the pictures on the screen was out of the question. I therefore fell back, but without any sanguine expectations as to the result, upon the photographic process adopted by Wedgwood, with which I happened to be well acquainted. It was a weary while, however, before any satisfactory impression was made, either on chloride or nitrate paper. I succeeded better with the leather; but my fortunate inability to replenish the little stock of this latter article induced me to apply the tannin solution to paper, and thus I was at once [17] placed, by a very decided step, in advance of earlier experimenters, and I had the pleasure of succeeding where Talbot acknowledges that he failed.

“Naturally enough, the solution which I used at first was too strong, but, if you have ever been in what I may call the agony of a find, you can conceive my sensations on witnessing the unwilling paper become in a few seconds almost as black as my hat. There was just a passing glimpse of outline, ‘and in a moment all was dark.’ It was evident, however, that I was in possession of all, and more than all, I wanted, and that the dilution of so powerful an accelerator would probably give successful results. The large amount of dilution greatly surprised me; and, indeed, before I obtained a satisfactory picture, the quantity of gallic acid in the infusion must have been quite homœopathic; but this is in exact accordance with modern practice and known laws. In reference to this point, Sir John Herschel, writing from Slough, in April, 1840, says to Mr. Redman, then of Peckham (where I had resided), ‘I am surprised at the weak solution employed, and how, with such, you have been able to get a depth of shadow sufficient for so very sharp a re-transfer is to me marvellous.’ I may speak of Mr. Redmond as a photographic pupil of mine, and at my request, he communicated the process to Sir John, which, ‘on account of the extreme clearness and sharpness of the results,’ to use Sir John’s words, much interested him.

“Dr. Diamond also, whose labours are universally appreciated, first saw my early attempts at Peckham in 1837, and heard of my use of gallate of silver, and was thus led to adopt what Admiral Smyth then called ‘a quick mode of taking bad pictures’; but, as I told the Admiral in reply, he was born a baby. Whether our philosophical baby is ‘out of its teens’ may be a question; at all events, it is a very fine child, and handles the pencil of nature with consummate skill.

“But of all the persons who heard of my new accelerator, it is [18] most important to state that my old and valued friend, the late Andrew Ross, told Mr. Talbot how first of all, by means of the solar microscope, I threw the image of the object on prepared paper, and then, while the paper was yet wet, washed it over with the infusion of galls, when a sufficiently dense negative was quickly obtained. In the celebrated trial, “Talbot versus Laroche,” Mr. Talbot, in his cross-examination, and in an almost breathless court, acknowledged that he had received this information from Ross, and from that moment it became the unavoidable impression that he was scarcely justified in taking out a patent for applying my accelerator to any known photogenic paper.

“The three known papers were those impregnated with the nitrate, chloride, and the iodide of silver—the two former used by Wedgwood and Young, and the latter by Davy. It is true that Talbot says of the iodide of silver that it is quite insensitive to light, and so it is as he makes it; but when he reduces it to the condition described by Davy—viz., affected by the presence of a little free nitrate of silver—then he must acknowledge, with Davy, that ‘it is far more sensitive to the action of light than either the nitrate or the muriate, and is evidently a distinct compound.’ In this state, also, the infusion of galls or gallic acid is, as we all know, most decided and instantaneous, and so I found it to be in my early experiments. Of course I tried the effects of my accelerator on many salts of silver, but especially upon the iodide, in consequence of my knowledge of Davy’s papers on iodine in the ‘Philosophical Transactions.’ These I had previously studied, in conjunction with my chemical friend, Mr. Hodgson, then of Apothecaries’ Hall. I did not, however, use iodised paper, which is well described by Talbot in the Philosophical Magazine for March, 1838, as a substitute for other sensitive papers, but only as one among many experiments alluded to in my letter to Mr. Brayley.

“My pictures were exhibited at the Royal Society, and also at Lord Northampton’s, at his lordship’s request, in April, 1839, [19] when Mr. Talbot also exhibited his. In my letter to Mr. Brayley, I did not describe iodised pictures, and, therefore, it was held that exhibition in the absence of description left the process legally unknown. Mr. Talbot consequently felt justified in taking out a patent for uniting my known accelerator with Davy’s known sensitive silver compound, adopting my method (already communicated to him) with reference to Wedgwood’s papers, and adding specific improvements in manipulation. Whatever varied opinion may consequently be formed as to the defence of the patent in court, there can be but one as to the skill of the patentee.

“It is obvious that, in the process so conducted by me with the solar microscope, I was virtually within my camera, standing between the object and the prepared paper. Hence the exciting and developing processes were conducted under one operation (subsequently patented by Talbot), and the fact of a latent image being brought out was not forced upon my attention. I did, however, perceive this phenomenon upon one occasion, after I had been suddenly called away, when taking an impression of the Trientalis Europæa—and surprised enough I was, and stood in astonishment to look at it. But with all this, I was only, as the judge said, “very hot.” I did not realize the master fact that the latent image which had been developed was the basis of photographic manipulation. The merit of this discovery is Talbot’s, and his only, and I honour him greatly for his skill and earlier discernment. I was, indeed, myself fully aware that the image darkened under the influence of my sensitiser, while I placed my hand before the lens of the instrument to stop out the light; and my solar mezzotint, as I then termed it, was, in fact, brought out and perfected under my own eye by the agency of gallic acid in the infusion, rather than by the influence of direct solar action. But the notion of developing a latent image in these microscopic photographs never crossed my mind, even after I had witnessed such development [20] in the Trientalis Europæa. My original notion was that the infusion of galls, added to the wet chloride or nitrate paper while the picture was thrown upon it, produced only a new and highly sensitive compound; whereas, by its peculiar and continuous action after the first impact of light on the now sensitive paper, I was also, as Talbot has shown, employing its property of development as well as excitement. My ignorance of its properties was no bar to its action. However, I threw the ball, and Talbot caught it, and no man can be more willing than myself to acknowledge our obligations to this distinguished photographer. He compelled the world to listen to him, and he had something worth hearing to communicate; and it is a sufficient return to me that he publicly acknowledged his obligation to me, with reference to what Sir David Brewster calls ‘an essential part of his patent’ (vide North British Review, No. 14 article—‘Photography’).

“Talbot did not patent my valuable fixer. Here I had the advantage of having published my use of hyposulphite of soda, which Mr. Hodgson made for me in 1837, when London did not contain an ounce of it for sale. The early operators had no fixer; that was their fix; and, so far as any record exists, they got no further in this direction than ‘imagining some experiments on the subject!’ I tried ammonia, but it acted too energetically on the picture itself to be available for the purpose. It led me, however, to the ammonia nitrate process of printing positives, a description of which process (though patented by Talbot in 1843) I sent to a photographic brother in 1839, and a quotation from my letter of that date has already appeared in one of my communications to Notes and Queries. On examining Brande’s Chemistry, under the hope of still finding the desired solvent which should have a greater affinity for the simple silver compound on the uncoloured part of the picture than for the portion blackened by light, I happened to see it stated, on Sir John Herschel’s authority, that hyposulphite [21] of soda dissolves chloride of silver. I need not now say that I used this fixer with success. The world, however, would not have been long without it, for, when Sir John himself became a photographer in the following year, he first of all used hyposulphite of ammonia, and then permanently fell back upon the properties of his other compound. Two of my solar microscope negatives, taken in 1837, and exhibited with several others by Mr. Brayley in 1839 as illustrations of my letter and of his lecture at the London Institution, are now in the possession of the London Photographic Society. They are, no doubt, the earliest examples of the agency of two chemical compounds which will be co-existent with photography itself, viz., gallate of silver and hyposulphite of soda, and my use of them, as above described, will sanction my claim to be the first to take paper pictures rapidly, and to fix them permanently.

“Such is a short account of my contribution to this interesting branch of science, and, in the pleasure of the discovery, I have a sufficient reward.”

These lengthy extracts from the Rev. Mr. Reade’s published letter render further comment all but superfluous, but I cannot resist taking advantage of the opportunity here afforded of pointing out to all lovers of photography and natural justice that the progress of the discovery has advanced to a far greater extent by Mr. Reade’s reasoning and experiments than it was by Mr. Talbot’s ingenuity. The latter, as Mr. Reade observes, only “caught the ball” and threw it into the Patent Office, with some improvements in the manipulations. Mr. Reade generously ascribes all honour and glory to Mr. Talbot for his shrewdness in seizing what he had overlooked, viz., the development of the latent image; but there is a quiet current of rebuke running all through Mr. Reade’s letter about the justice of patenting a known sensitiser and a known accelerator, which he alone had combined and applied to the successful production of a negative on paper. Mr. Talbot’s patent process was nothing more, yet he [22] endeavoured to secure a monopoly of what was in substance the discovery and invention of another. Mr. Talbot was either very precipitate, or ill-advised, to rush to the Patent Office with his modification, and even at this distant date it is much to be regretted that he did so, for his rash act has, unhappily for photography, proved a pernicious precedent. Mr. Reade gave his discoveries to the world freely, and the “pleasure of the discovery” was “a sufficient reward.” All honour to such discoverers. They, and they only, are the true lovers of science and art, who take up the torch where another laid it down, or lost it, and carry it forward another stage towards perfection, without sullying its brightness or dimming the flame with sordid motives.

The Rev. J. B. Reade lived to see the process he discovered and watched over in its embryo state, developed with wondrous rapidity into one of the most extensively applied arts of this marvellous age, and died, regretted and esteemed by all who knew him, December 12th, 1870. Photographers, your occupations are his monument, but let his name be a tablet on your hearts, and his unselfishness your emulation!

The year 1838 gave birth to another photographic discovery, little thought of and of small promise at the time, but out of which have flowed all the various modifications of solar and mechanical carbon printing. This was the discovery of Mr. Mungo Ponton, who first observed and announced the effects of the sun’s rays upon bichromate of potash. But that gentleman was unwise in his generation, and did not patent his discovery, so a whole host of patent locusts fell upon the field of research in after years, and quickly seized the manna he had left, to spread on their own bread. Mr. Mungo Ponton spread a solution of bichromate of potash upon paper, submitted it under a suitable object to the sun’s rays, and told all the world, without charge, that the light hardened the bichromate to the extent of its action, and that the unacted-upon portions could be dissolved away, leaving the [23] object white upon a yellow or orange ground. Other experimenters played variations on Mr. Ponton’s bichromate scale, and amongst the performers were M. E. Becquerel, of France, and our own distinguished countryman, Mr. Robert Hunt.

During the years that elapsed between the death of M. Niépce and the period to which I have brought these records, little was heard or known of the researches of M. Daguerre, but he was not idle, nor had he abandoned his iodine ideas. He steadily pursued his subject, and worked with a continuity that gained him the unenviable reputation of a lunatic. His persistency created doubts of his sanity, but he toiled on solus, confident that he was not in pursuit of an impossibility, and sanguine of success. That success came, hastened by lucky chance, and early in January, 1839, M. Daguerre announced the interesting and important fact that the problem was solved. Pictures in the camera-obscura could be, not only seen, but caught and retained. M. Daguerre had laboured, sought, and found, and the bare announcement of his wonderful discovery electrified the world of science.

The electric telegraph could not then flash the fascinating intelligence from Paris to London, but the news travelled fast, nevertheless, and the unexpected report of M. Daguerre’s triumph hurried Mr. Talbot forward with a similar statement of success. Mr. Talbot declared his triumph on the 31st of January, 1839, and published in the following month the details of a process which was little, if any, in advance of that already known.

Daguerre delayed the publication of his process until a pension of six thousand francs per annum had been secured to himself, and four thousand francs per annum to M. Isidore Niépce for life, with a reversion of one-half to their widows. In the midst of political and social struggles France was proud of the glory of such a marvellous discovery, and liberally rewarded her fortunate sons of science with honourable distinction and [24] substantial emolument. She was proud and generous to a chivalrous extent, for she pensioned her sons that she might have the “glory of endowing the world of science and of art with one of the most surprising discoveries” that had been made on her soil; and, because she considered that “the invention did not admit of being secured by patent;” but avarice and cupidity frustrated her noble and generous intentions in this country, and England alone was harassed with injunctions and prosecutions, while all the rest of the world participated in the pleasure and profits of the noble gift of France.

In July, 1839, M. Daguerre divulged his secret at the request and expense of the French Government, and the process which bore his name was found to be totally different, both in manipulation and effect, from any sun-pictures that had been obtained in England. The Daguerreotype was a latent image produced by light on an iodised silver plate, and developed, or made visible, by the fumes of mercury; but the resultant picture was one of the most shimmering and vapoury imaginable, wanting in solidity, colour, and firmness. In fact, photography as introduced by M. Daguerre was in every sense a wonderfully shadowy and all but invisible thing, and not many removes from the dark ages of its creation. The process was extremely delicate and difficult, slow and tedious to manipulate, and too insensitive to be applied to portraiture with any prospect of success, from fifteen to twenty minutes’ exposure in bright sunshine being necessary to obtain a picture. The mode of proceeding was as follows:—A copper plate with a coating of silver was carefully cleaned and polished on the silvered side, that was placed, silver side downwards, over a vessel containing iodine in crystals, until the silvered surface assumed a golden-yellow colour. The plate was then transferred to the camera-obscura, and submitted to the action of light. After the plate had received the requisite amount of exposure, it was placed over a box containing mercury, the fumes of which, on the application [25] of a gentle heat, developed the latent image. The picture was then washed in salt and water, or a solution of hyposulphite of soda, to remove the iodide of silver, washed in clean water afterwards, and dried, and the Daguerreotype was finished according to Daguerre’s first published process.

The development of the latent image by mercury subliming was the most marvellous and unlooked-for part of the process, and it was for that all-important thing that Daguerre was entirely indebted to chance. Having put one of his apparently useless iodized and exposed silver plates into a cupboard containing a pot of mercury, Daguerre was greatly surprised, on visiting the cupboard some time afterwards, to find the blank looking plate converted into a visible picture. Other plates were iodized and exposed and placed in the cupboard, and the same mysterious process of development was repeated, and it was not until this thing and the other thing had been removed and replaced over and over again, that Daguerre became aware that quicksilver, an article that had been used for making mirrors and reflecting images for years, was the developer of the invisible image. It was indeed a most marvellous and unexpected result. Daguerre had devoted years of labour and made numberless experiments to obtain a transcript of nature drawn by her own hand, but all his studied efforts and weary hours of labour had only resulted in repeated failures and disappointments, and it appeared that Nature herself had grown weary of his bungling, and resolved to show him the way.

The realization of his hopes was more accidental than inferential. The compounds with which he worked, neither produced a visible nor a latent image capable of being developed with any of the chemicals with which he was experimenting. At last accident rendered him more service than reasoning, and occult properties produced the effect his mental and inductive faculties failed to accomplish; and here we observe the great [26] difference between the two successful discoverers, Reade and Daguerre. At this stage of the discovery I ignore Talbot’s claim in toto. Reade arrived at his results by reasoning, experiment, observation, and judiciously weakening and controlling the re-agent he commenced his researches with. He had the infinite pleasure and disappointment of seeing his first picture flash into existence, and disappear again almost instantly, but in that instant he saw the cause of his success and failure, and his inductive reasoning reduced his failure to success; whereas Daguerre found his result, was puzzled, and utterly at a loss to account for it, and it was only by a process of blind-man’s bluff in his chemical cupboard that he laid his hands on the precious pot of mercury that produced the visible image.

That was a discovery, it is true; but a bungling one, at best. Daguerre only worked intelligently with one-half of the elements of success; the other was thrust in his way, and the most essential part of his achievement was a triumphant accident. Daguerre did half the work—or, rather, one-third—light did the second part, and chance performed the rest, so that Daguerre’s share of the honour was only one-third. Reade did two-thirds of the process, the first and third, intelligently; therefore to him alone is due the honour of discovering practical photography. His was a successful application of known properties, equal to an invention; Daguerre’s was an accidental result arising from unknown causes and effects, and consequently a discovery of the lowest order. To England, then, and not to France, is the world indebted for the discovery of photography, and in the order of its earliest, greatest, and most successful discoverers and advancers, I place the Rev. J. B. Reade first and highest.

|

|

|

L. J. M. DAGUERRE. Used Iodine, 1839. |

JOHN FREDERICK GODDARD. Applied Bromine, 1840. |

|

|

|

NEW YORK. Copy of Instantaneous Daguerreotype, 1854. |

|

1839 has generally been accepted as the year of the birth of Practical Photography, but that may now be considered an error. It was, however, the Year of Publicity, and the progress that followed with such marvellous rapidity may be freely received as an adversely eloquent comment on the principles of secrecy and restriction, in any art or science, like photography, which requires the varied suggestions of numerous minds and many years of experiment in different directions before it can be brought to a state of workable certainty and artistic and commercial applicability. Had Reade concealed his success and the nature of his accelerator, Talbot might have been bungling on with modifications of the experiments of Wedgwood and Davy to this day; and had Daguerre not sold the secret of his iodine vapour as a sensitiser, and his accidentally discovered property of mercury as a developer, he might never have got beyond the vapoury images he produced. As it was, Daguerre did little or nothing to improve his process and make it yield the extremely vigorous and beautiful results it did in after years. As in Mr. Reade’s case with the Calotype process, Daguerre threw the ball and others caught it. Daguerre’s advertised improvements of his process were lamentable failures and roundabout ways to obtain sensitive amalgams—exceedingly [28] ingenious, but excessively bungling and impractical. To make the plates more sensitive to light, and, as Daguerre said, obtain pictures of objects in motion and animated scenes, he suggested that the silver plate should first be cleaned and polished in the usual way, then to deposit successively layers of mercury, and gold, and platinum. But the process was so tedious, unworkable, and unsatisfactory, no one ever attempted to employ it either commercially or scientifically. In publishing his first process, with its working details, Daguerre appears to have surrendered all that he knew, and to have been incapable of carrying his discovery to a higher degree of advancement. Without Mr. Goddard’s bromine accelerator and M. Fizeau’s chloride of gold fixer and invigorator, the Daguerreotype would never have been either a commercial success or a permanent production.

1840 was almost as important a period in the annals of photography as the year of its enunciation, and to the two valuable improvements and one interesting importation, the Daguerreotype process was indebted for its success all over the world; and photography, even as it is practised now, is probably indebted for its present state of advancement to Mr. John Frederick Goddard, who applied bromine, as an accelerator, to the Daguerreotype process this year. In the early part of the Daguerreotype period it was so insensitive there was very little prospect of being able to take portraits with it through a lens. To meet this difficulty Mr. Wolcott, an American optician, constructed a reflecting camera and brought it to London. It was an ingenious contrivance, but did not fully answer the expectations of the inventor. It certainly did not require such a long exposure with this camera as when the rays from the image or sitter passed through a lens; but, as the sensitised plate was placed between the sitter and the reflector, the picture was necessarily small, and neither very sharp nor satisfactory. This was a mechanical contrivance to shorten the time of exposure, which [29] partially succeeded, but it was chemistry, and not mechanics, that effected the desirable result. Both Mr. Goddard and M. Antoine F. J. Claudet, of London, employed chlorine as a means of increasing the sensitiveness of the iodised silver plate, but it was not sufficiently accelerative to meet the requirements of the Daguerreotype process. Subsequently Mr. Goddard discovered that the vapour of bromine, added to that of iodine, imparted an extraordinary degree of sensitiveness to the prepared plate, and reduced the time of sitting from minutes to seconds. The addition of the fumes of bromine to those of iodine formed a compound of bromo-iodide of silver on the surface of the Daguerreotype plate, and not only increased the sensitiveness, but added to the strength and beauty of the resulting picture, and M. Fizeau’s method of precipitating a film of gold over the whole surface of the plate still further increased the brilliancy of the picture and ensured its permanency. I have many Daguerreotypes in my possession now that were made over forty years ago, and they are as brilliant and perfect as they were on the day they were taken. I fear no one can say the same for any of Fox Talbot’s early prints, or even more recent examples of silver printing.

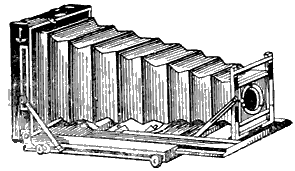

Another important event of this year was the importation of the first photographic lens, camera, &c., into England. These articles were brought from Paris by Sir Hussey Vivian, present M.P. for Glamorganshire (1889). It was the first lot of such articles that the Custom House officers had seen, and they were at a loss to know how to classify it. Finally they passed it under the general head of Optical Instruments. Sir Hussey told me this, himself, several years before he was made a baronet. What changes fifty years have wrought even in the duties of Custom House officers, for the imports and exports of photographic apparatus and materials must now amount to many thousands per annum!

Having described the conditions and state of progress photography [30] had attained at the time of my first contact with it, I think I may now enter into greater details, and relate my own personal experiences from this period right up to the end of its jubilee celebration.

I was just fourteen years old when photography was made practicable by the publication of the two processes, one by Daguerre, and the other by Fox Talbot, and when I heard or read of the wonderful discovery I was fired with a desire to obtain a sight of these “sun-pictures,” but the fire was kept smouldering for some time before my desire was gratified. Nothing travelled very fast in those days. Railroads had not long been started, and were not very extensively developed. Telegraphy, by electricity, was almost unknown, and I was a fixture, having just been apprenticed to an engraving firm hundreds of miles from London. But at last I caught sight of one of those marvellous drawings made by the sun in the window of the Post Office of my native town. It was a small Daguerreotype which had been sent there along with a notice that a licence to practise the “art” could be obtained of the patentee. I forget now what amount the patentee demanded for a licence, but I know that at the time referred to it was so far beyond my means and hopes that I never entertained the idea of becoming a licencee. I believe some one in the neighbourhood bought a licence, but either could not or did not make use of it commercially.

Some time after that, a Miss Wigley, from London, came to the town to practise Daguerreotyping, but she did not remain long, and could not, I think, have made a profitable visit. If so, it could scarcely be wondered at, for the sun-pictures of that period were such thin, shimmering reflections, and distortions of the human face divine, that very few people were impressed either by the process or the newest wonder of the world. At that early period of photography, the plates were so insensitive, the sittings so long, and the conditions so terrible, it was not [31] easy to induce anyone either to undergo the ordeal of sitting, or to pay the sum of twenty-one shillings for a very small and unsatisfactory portrait. In the infancy of the Daguerreotype process, the sitters were all placed out-of-doors, in direct sunshine, which naturally made them screw up or shut their eyes, and every feature glistened, and was painfully revealed. Many amusing stories have been told about the trials, mishaps, and disappointments attending those long and painful sittings, but the best that ever came to my knowledge was the following. In the earliest of the forties, a young lady went a considerable distance, in Yorkshire, to sit to an itinerant Daguerreotypist for her portrait, and, being limited for time, could only give one sitting. She was placed before the camera, the slide drawn, lens uncapped, and requested to sit there until the Daguerreotypist returned. He went away, probably to put his “mercury box” in order, or to have a smoke, for it was irksome—both to sitter and operator—to sit or stand doing nothing during those necessarily long exposures. When the operator returned, after an absence of fifteen or twenty minutes, the lady was sitting where he left her, and appeared glad to be relieved from her constrained position. She departed, and he proceeded with the development of the picture. The plate was examined from time to time, in the usual way, but there was no appearance of the lady. The ground, the wall, and the chair whereon she sat, were all visible, but the image of the lady was not; and the operator was completely puzzled, if not alarmed. He left the lady sitting, and found her sitting when he returned, so he was quite unable to account for her mysterious non-appearance in the picture. The mystery was, however, explained in a few days, when the lady called for her portrait, for she admitted that she got up and walked about as soon as he left her, and only sat down again when she heard him returning. The necessity of remaining before the camera was not recognised by that sitter. I afterwards reversed that result myself by focussing [32] the chair, drawing the slide, uncapping the lens, sitting down, and rising leisurely to cap the lens again, and obtained a good portrait without showing a ghost of the chair or anything else. The foregoing is evidence of the insensitiveness of the plates at that early period of the practice of photography; but that state of inertion did not continue long, for as soon as the accelerating properties of bromine became generally known, the time of sitting was greatly reduced, and good Daguerreotype views were obtained by simply uncapping the lens as quickly as possible. I have taken excellent views in that manner myself in England, and, when in America, I obtained instantaneous views of Niagara Falls and other places quite as rapidly and as perfect as any instantaneous views made on gelatine dry plates, one of which I have copied and enlarged to 12 by 10 inches, and may possibly reproduce the small copy in these pages.

In 1845 I came into direct contact with photography for the first time. It was in that year that an Irishman named McGhee came into the neighbourhood to practise the Daguerreotype process. He was not a licencee, but no one appeared to interfere with him, nor serve him with an injunction, for he carried on his little portrait business for a considerable time without molestation. The patentee was either very indifferent to his vested interests, or did not consider these intruders worth going to law with, for there were many raids across the borders by camera men in those early days. Several circumstances combined to facilitate the inroads of Scotch operators into the northern counties of England. Firstly, the patent laws of England did not extend to Scotland at that time, so there was a far greater number of Daguerreotypists in Edinburgh and other Scotch towns in the early days of photography than in any part of England, and many of them made frequent incursions into the forbidden land without troubling themselves about obtaining a licence, but somehow they never remained long at a time; they were either afraid of consequences, or did not meet [33] with patronage sufficient to induce them to continue their sojourns beyond a few of the summer weeks. For many years most of the early Daguerreotypists were birds of passage, frequently on the wing. Among the earliest settlers in London, were Mr. Beard (patentee), Mr. Claudet, and Mr. J. E. Mayall—the latter is still alive, 1889—and in Edinburgh, Messrs. Ross and Thompson, Mr. Howie, Mr. Poppawitz, and Mr. Tunny—the latter was a Calotypist—with most of whom it was my good fortune to become personally acquainted in after years.

Secondly, a great deal of ill-feeling and annoyance were caused by the incomprehensible and somewhat underhanded way in which the English patent was obtained, and these feelings induced many to poach on photographic preserves, and even to defy injunctions; and, while lawsuits were pending, it was not uncommon for non-licencees to practise the new art with the impunity and feelings common to smugglers. Mr. Beard, the English patentee, brought many actions at law against infringers of his patent rights, the most memorable of which was that where Mr. Egerton, 1, Temple Street, Whitefriars, the first dealer in photographic materials, and agent for Voightlander’s lenses in London, was the defendant. During that trial it came out in evidence that the patentee had earned as much as forty thousand pounds in one year by taking portraits and fees from licencees. Though the judgment of the Court was adverse to Mr. Egerton, it did not improve the patentee’s moral right to his claim, for the trial only made it all the more public that the French Government had allowed M. Daguerre six thousand francs (£240), and M. Isidore Niépce four thousand francs (£160) per annum, on condition that their discoveries should be published, and made free to all the world. This trial did not in any way improve Mr. Beard’s financial position, for eventually he became a bankrupt, and his establishments in King William Street, London Bridge, and the Polytechnic Institute, in Regent Street, were extinguished. [34] Mr. Beard, who was the first to practise Daguerreotyping commercially in this country, was originally a coal merchant. I think Mr. Claudet practised the process in London without becoming a licencee, either through previous knowledge, or some private arrangement made with Daguerre before the patent was granted to Mr. Beard. It was while photography was clouded with this atmosphere of dissatisfaction and litigation, that I made my first practical acquaintance with it in the following manner:—

Being anxious to obtain possession of one of those marvellous sun-pictures, and hoping to get an idea of the manner in which they were produced, I paid a visit, one sunny morning, to Mr. McGhee, the Daguerreotypist, dressed in my best, with clean shirt, and stiff stand-up collar, as worn in those days. I was a very young man then, and rather particular about the set of my shirt collar, so you may readily judge of my horror when, after making the financial arrangements to the satisfaction of Mr. McGhee, he requested me to put on a blue cotton quasi clean “dickey,” with a limp collar, that had evidently done similar duty many times before. You may be sure I protested, and inquired the reason why I should cover up my white shirt front with such an objectionable article. I was told if I did not put it on my shirt front would be solarized, and come out blue or dirty, whereas if I put on the blue “dickey” my shirt front would appear white and clean. What “solarized” meant, I did not know, nor was it further explained, but, as I very naturally wished to appear with a clean shirt front, I submitted to the indignity, and put on the limp and questionably clean “dickey.” While the Daguerreotypist was engaged with some mysterious manipulations in a cupboard or closet, I brushed my hair, and contemplated my singular appearance in the mirror somewhat ruefully. O, ye sitters and operators of to-day! congratulate yourselves on the changes and advantages that have been wrought in the [35] practice of photography since then. When Mr. McGhee appeared again with something like two wooden books in his hand, he requested me to follow him into the garden; which was only a back yard. At the foot of the garden, and against a brick wall with a piece of grey cloth nailed over it, I was requested to sit down on an old chair; then he placed before me an instrument which looked like a very ugly theodolite on a tripod stand—that was my first sight of a camera—and, after putting his head under a black cloth, told me to look at a mark on the other side of the garden, without winking or moving till he said “done.” How long I sat I don’t know, but it seemed an awfully long time, and I have no doubt it was, for I know that I used to ask people to sit five and ten minutes, afterwards. The sittings over, I was requested to re-enter the house, and then I thought I would see something of the process; but no. Again Mr. McGhee went into the mysterious chamber, and shut the door quickly. In a little time he returned and told me that the sittings were satisfactory—he had taken two—and that he would finish and deliver them next day. Then I left without obtaining the ghost of an idea of the modus operandi of producing portraits by the sun, beyond the fact that a camera had been placed before me. Next day the portraits were delivered according to promise, but I confess I was somewhat disappointed at getting so little for my money. It was a very small picture that could not be seen in every light, and not particularly like myself, but a scowling-looking individual, with a limp collar, and rather dirty-looking face. Whatever would mashers have said or done, if they had gone to be photographed in those days of photographic darkness? I was, however, somewhat consoled by the thought that I, at last, possessed one of those wonderful sun-pictures, though I was ignorant of the means of production.