Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, Vol IV. No. XX. January, 1852.

Author: Various

Release date: February 22, 2012 [eBook #38952]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David J. Cole and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

It is generally true in respect to great statesmen that they owe their celebrity almost entirely to their public and official career. They promote the welfare of mankind by directing legislation, founding institutions, negotiating treaties of peace or of commerce between rival states, and guiding, in various other ways, the course of public and national affairs, while their individual and personal influence attracts very little regard. With Benjamin Franklin, however, the reverse of this is true. He did indeed, while he lived, take a very active part, with other leading men of his time, in the performance of great public functions; but his claim to the extraordinary degree of respect and veneration which is so freely awarded to his name and memory by the American people, rests not chiefly upon this, but upon the extended influence which he has exerted, and which he still continues to exert upon the national mind, through the power of his private and personal character. The prevalence of habits of industry and economy, of foresight and thrift, of cautious calculation in the formation of plans, and energy and perseverance in the execution of them, and of the disposition to invest what is earned in substantial and enduring possessions, rather than to expend it in brief pleasures or for purposes of idle show—the prevalence of these traits, so far as they exist as elements of the national character in this country—is due in an incalculable degree to the doings and sayings and history of this great exemplar. Thus it is to his life and to his counsels that is to be attributed, in a very high degree, the formation of that great public sentiment prevailing so extensively among us, which makes it more honorable to be industrious than to be idle, and to be economical and prudent rather than extravagant and vain; which places substantial and unpretending prosperity above empty pretension, and real comfort and abundance before genteel and expensive display.

A very considerable portion of the effect which Franklin has produced upon the national character is due to the picturesque and almost romantic interest which attaches itself to the incidents of his personal history. In his autobiography he has given us a very full and a very graphic narrative of these incidents, and as the anniversary of his birth-day occurs during the present month, we can not occupy the attention of our readers at this time, in a more appropriate manner than by a brief review of the principal events of his life—so far as such a review can be comprised within the limits of a single article.

The ancestors of Franklin lived for many generations on a small estate in Northamptonshire, one of the central counties in England. The head of the family during all this time followed the business of a smith, the eldest son from generation to generation, being brought up to that employment.

The Franklin family were Protestants, and at one time when the Catholics were in power, during the reign of Mary, the common people were forbidden to possess or to read the English Bible. Nevertheless the Franklin family contrived to get possession of a copy of the Scriptures,[Pg 146] and in order to conceal it they kept it fastened on the under side of the seat of a little stool. The book was open, the back of the covers being against the seat, and the leaves being kept up by tapes which passed across the pages, and which were fastened to the seat of the stool at the ends. When Mr. Franklin wished to read his Bible to his family, he was accustomed to take up this stool and place it bottom upward upon his lap; and thus he had the book open before him. When he wished to turn over a leaf, he had to turn it under the tape, which, though a little inconvenient, was attended with no serious difficulty. During the reading one of the children was stationed at the door, to watch, and to give notice if an officer should be coming; and in case of an alarm the stool was immediately turned over and placed in its proper position upon the floor, the fringe which bordered the sides of it hanging down so as to conceal the book wholly from view. This was in the day of Franklin’s great-grandfather.

In process of time, after the Catholic controversy was decided, new religious dissensions sprang up between the Church of England and the Nonconformists. The family of Franklin were of the latter party, and at length Mr. Josiah Franklin—who was Benjamin Franklin’s father—concluded to join a party of his neighbors and friends, who had determined, in consequence of the restrictions which they were under in England, in respect to their religious faith and worship, to emigrate to America. Mr. Franklin came accordingly to Boston, and there, after a time, Benjamin Franklin was born. The place of his birth was in Milk-street, opposite to the Old South Church. The humble dwelling, however, in which the great philosopher was born, has long since disappeared. The magnificent granite warehouses of the Boston merchants now cover the spot, and on one of them is carved conspicuously the inscription, Birthplace of Franklin.

Mr. Josiah Franklin had been a dyer in England, but finding on his coming to Boston that there was but little to be done in that art in so new a country, he concluded to choose some other occupation; and he finally determined upon that of a tallow chandler. Benjamin was the youngest son. The others, as they gradually became old enough, were put to different trades, but as Benjamin showed a great fondness for his books, having learned to read of his own accord at a very early age, and as he was the youngest son, his father conceived the idea of educating him for the church. So they sent him to the grammar school, and he commenced his studies. He was very successful in the school, and rose from class to class quite rapidly; but still the plan of giving him a public education was at length, for some reason or other, abandoned, and Mr. Franklin took Benjamin into his store, to help him in his business. His duties here were to cut the wicks for the candles, to fill the moulds, to attend upon the customers, or to go of errands or deliver purchases about the town.

There was a certain mill-pond in a back part of the town, where Benjamin was accustomed to go sometimes, in his play-hours, with other boys, to fish. This mill-pond has long since been filled up, and its place is now occupied by the streets and warehouses of the city. In Franklin’s day, however, the place was somewhat solitary, and the shore of the pond being marshy, the boys soon trampled up the ground where they were accustomed to stand in fishing, so as to convert it into a perfect quagmire. At length young Franklin proposed to the boys that they should build a wharf, or pier, to stand upon—getting the materials for the purpose from a heap of stones that had been brought for a house which some workmen were building in the neighborhood. The boys at once acceded to the proposal. They all accordingly assembled at the spot one evening after the workmen had gone away for the night, and taking as many stones as they needed for the purpose, they proceeded to build their wharf.

The boys supposed very probably that the stones which they had taken would not be missed. The workmen, however, did miss them, and on making search the following morning they soon discovered what had become of them. The boys were thus detected, and were all punished.

Franklin’s father, though he was plain and unpretending in his manners, was a very sensible and well-informed man, and he possessed a sound judgment and an excellent understanding. He was often consulted by his neighbors and friends, both in respect to public and private affairs. He took great interest, when conversing with his family at table, in introducing useful topics of discourse, and endeavored in other ways to form in the minds of his children a taste for solid and substantial acquisitions. He was quite a musician, and was accustomed sometimes when the labors of the day were done, to play upon the violin and sing, for the entertainment of his family. This music Benjamin himself used to take great delight in listening to.

Young Benjamin did not like his father’s trade—that of a chandler—and it was for a long time undecided what calling in life he should pursue. He wished very much to go to sea, but his parents were very unwilling that he should do so. His father, accordingly, in order to make him contented and willing to remain at home, took great pains to find some employment for him that he would like, and he was accustomed to walk about the town with him to see the workmen employed about their various trades. It was at last decided that he should learn the trade of a printer. One reason why this trade was decided upon was that one of Benjamin’s older brothers was a printer, and had just returned from England with a press and a font of type, and was about setting up his business in Boston. So it was decided that Benjamin should be bound to him, as his apprentice; and this was accordingly done. Benjamin was then about twelve years old.

Benjamin had always from his childhood manifested a great thirst for reading, which thirst he had now a much better opportunity to gratify than ever before, as his connection with printers and booksellers gave him facilities for borrowing books. Sometimes he would sit up all night to read the book so borrowed.

Benjamin’s brother, the printer, did not keep house, but boarded his apprentices at a boarding house in the town. Benjamin pretty soon conceived the idea of boarding himself, on condition that his brother would pay to him the sum which he had been accustomed to pay for him to the landlady of the boarding house. By this plan he saved a large portion of the time which was allotted to dinner, for reading; for, as he remained alone in the printing office while the rest were gone, he could read, with the book in his lap, while partaking of the simple repast which he had provided.

Young Benjamin was mainly employed, of course, while in his brother’s office, in very humble duties; but he did not by any means confine himself to the menial services which were required of him, as the duty of the youngest apprentice. In fact he actually commenced his career as an author while in this subordinate position. It seems that several gentlemen of Boston, friends of his brother, used to write occasional articles for a newspaper which he printed; and they would sometimes meet at the office to discuss the subjects of their articles, and the effects that they produced. Benjamin determined to try his hand at this work. He accordingly wrote an article for the paper, and after copying it carefully in disguised writing, he put it late one night under the door. His brother found it there in the morning, and on reading it was much pleased with it. He read it to his friends when they came in—Benjamin being at work all the time near by, at his printing case, and enjoying very highly the remarks and comments which they made. He was particularly amused at the guesses that they offered in respect to the author, and his vanity was gratified at finding that the persons that they named were all gentlemen of high character for ingenuity and learning.

The young author was so much encouraged by this attempt that he afterward sent in several other articles in the same way; they were all approved of and duly inserted in the paper. At length he made it known that he was the author of the articles. All were very much surprised, and Benjamin found that in consequence of this discovery he was regarded with much greater consideration by his brother’s friends, the gentlemen to whom his performances had been shown, but that his brother himself did not appear to be much pleased.

Benjamin was employed at various avocations connected with the newspaper, while in his brother’s service; sometimes in setting types, then in working off the sheets at the press, and finally in carrying the papers around the town to deliver them to the subscribers. Thus he was, at the same time, compositor, pressman, and carrier. This gave a very agreeable variety to his work, and the opportunities which he enjoyed for acquiring experience and information were far more favorable than they had ever been before.

In the efforts which young Franklin made to improve his mind, while in his brother’s office, he did not devote his time to mere reading, but applied himself vigorously to study. He was deficient, he thought, in a knowledge of figures, and so he procured an arithmetic, of his own accord, and went through it himself, with very little or no assistance. By proceeding very slowly and carefully in this work, leaving nothing behind that he did not fully understand, he so smoothed his own way as to go through the whole with very little embarrassment or difficulty. He also studied a book of English grammar. The book contained, moreover, brief treatises on Logic and Rhetoric, which were inserted at the end by way of appendix. These treatises Franklin studied too with great care. In a word, the time which he devoted to books was spent, not in seeking amusement, but in acquiring solid and substantial knowledge.[Pg 149]

Notwithstanding these advantages, however, Benjamin did not lead a very happy life as his brother’s apprentice. He found his brother a very passionate man and he was often used very roughly by him. Finally after the lapse of four or five years, during which various difficulties occurred which can not here be fully narrated, young Benjamin determined to run away, and seek his fortune in New York. In writing the history of his life, Franklin acknowledges that he was very censurable for taking such a step, and that in the disputes which had occurred between him and his brother, he himself was much in fault, having often needlessly irritated his brother by his saucy and provoking behavior. He, however, determined to go, and a young friend of his, named Collins, a boy of about his own age, helped him form and execute the plan of his escape.

The plan which they formed was for Benjamin to take passage secretly, in a New York sloop, which was then in Boston and about ready to sail. The boys made up a false story to tell the captain of the sloop in order to induce him to take Benjamin on board. Benjamin sold his books and such other little property as he possessed, to raise money, and at length, when the time arrived he went on board the sloop in a very private manner, and concealed himself there.

The captain of the sloop undoubtedly did wrong in taking such a boy away in this manner. He knew that Franklin was running away from home, though he was deceived by Collins’s story in respect to the cause of his flight.

The vessel soon sailed, with Franklin on board. The wind was fair and she had a very prosperous passage. In three days which was by no means a long time for such a voyage, she reached New York, and Benjamin landed safely.

He found himself, however, when landed, in a very forlorn and friendless condition. He knew no one, he was provided, of course, with no letters of introduction or recommendation, and he had very little money.

He applied at a printing office for employment. The printer, whose name was Bradford, said that he had workmen enough, but that he had a son in Philadelphia who was also a printer, and who had lately lost one of his principal hands. So our young hero determined to go to Philadelphia.

On his journey to Philadelphia he met with various romantic adventures. A part of the way he went by water, and very narrowly escaped shipwreck in a storm which suddenly arose, and which drove the vessel to the eastward, entirely out of her course, and came very near throwing her upon the shores of Long Island. He, however, at length reached Amboy in safety, and[Pg 150] thence he undertook to travel on foot through New Jersey to Burlington, a distance of about fifty miles, carrying his pack upon his back.

It rained violently all the day, and the unhappy adventurer became so exhausted with his exposures and suffering that he heartily repented of having ever left his home.

At length after two days of weary traveling, Franklin reached Burlington, on the Delaware, the point where he had expected to embark again on board a vessel in order to proceed down the river to Philadelphia. The regular packet, however, had just gone, and no other one was expected to sail for three days. It was then Saturday, and the next boat was not to go until Tuesday. Our traveler was very much disappointed to find that he must wait so long. In his perplexity he went back to the house of a woman where he had stopped to buy some gingerbread when he first came into town, and asked her what she thought he had better do. She offered to give him lodging in her house, until Tuesday, and inviting him in she immediately prepared some dinner for him, which, though it was very frugal and plain, was received with great thankfulness by the weary and wayworn traveler.

Our hero was not obliged to wait so long as he expected, after all; for that evening as he chanced to be walking along the shore of the river, a small vessel came by on its way to Philadelphia, and on his applying to the boatmen for a passage they agreed to take him on board. He accordingly embarked, and the vessel proceeded down the river. There was no wind, and the men spent the night in rowing. Franklin himself worked with the rest. Toward morning they began to be afraid that they had passed the city in the dark, and so they hauled their vessel up to the shore and landed. When daylight appeared they found that they were about five miles above the city. When they arrived at the city Franklin paid the boatmen a shilling for his passage. They were at first unwilling to receive it, on account of his having helped them to row, but he insisted that they should. He then counted up the money which he had left, and found that it amounted to just one dollar.

The first thing that he did was to go to a baker’s to buy something to eat. He asked for three-pence worth of bread. The baker gave him three good sized rolls for that money. His pockets were full of clothes and other such things, which he had put into them, and so he walked off up the street, holding one of his rolls under each arm and eating the third. It is a singular circumstance that while he was walking through the streets in this way, he passed by the house where the young woman resided who was destined in subsequent years to become his wife, and that she actually saw him as he passed, and took particular notice of him on account of the ridiculous appearance which he made.

Franklin went on in this manner up Market-street to Fourth-street, then down through Chestnut-street and apart of Walnut-street, until he came back to the river again at the place where the vessel lay. He came thus to the shore again in order to get a drink of water from the river, for he was thirsty.[Pg 151]

In fact the situation in which our young adventurer found himself at this time must have been extremely discouraging. He was in a strange town, hundreds of miles from home, without friends, without money, without even a place to lay his head, and scarcely knowing what to do or where to go. It is not strange, therefore, that, after taking his short walk around the streets of the town, he should find himself returning again toward the vessel that had brought him; since this vessel alone contained objects and faces in the least degree familiar to his eye.

It happened that among the passengers that had come down the river on board the vessel, there was a poor woman, who was traveling with her child, a boy of six or eight years of age. When Franklin came down to the wharf he found this woman sitting there with her child, both looking quite weary and forlorn; and, as he had already satisfied his hunger with eating only one of his rolls, he gave the other two to them. They received his charity very thankfully. It seems that they were waiting there for the vessel to sail again, as they were not intending to stop at Philadelphia, but were going farther down the river.

The way it happened that our young hero had provided himself with so much more bread than he needed, notwithstanding that his funds were so low, was this. When he went into the baker’s he asked first for biscuits, meaning such as he had been accustomed to buy in Boston. The baker told him that they did not make such biscuits in Philadelphia. He then asked for a three-penny loaf. The baker said they had no three-penny loaves. Franklin then asked him for three-penny worth of bread of any sort, and the baker gave him the three penny rolls. Franklin was surprised to find how much bread he got for his money, but he took the rolls, though he knew it was more than he would need, and so after eating one he had no very ready way of disposing of the other two. His giving them therefore to the poor woman and her boy was not quite as great a deed of benevolence as it might at first seem. It was, however, in this respect like other charitable acts, performed in this world, which will seldom bear any very rigid scrutiny.

It ought, however, to be added in justice to our hero, that instances frequently occurred during this period of his life in which he made real sacrifices for the comfort and welfare of others, and thus gave unquestionable evidence that he possessed a truly benevolent heart. In fact, his readiness to aid and assist others, whenever it was in his power to do so, constituted one of the most conspicuous traits in the philosopher’s character.

Having thus given his bread to the woman, and obtained a draught of water from the river for himself, Franklin turned up the street again and went back into the town. He observed many well dressed people in the street, all going the same way. It was Sunday, and they were going to meeting. Franklin followed them, and took a seat in the meeting-house. It proved to be a meeting of the society of Friends, and as is usual in their meetings when no one is moved to speak, the congregation sat in silence. As there was thus no service to occupy Franklin’s attention,[Pg 152] and as he was weary with the rowing of the previous night and with the other hardships and fatigues which he had undergone, he fell asleep. He did not wake until the meeting was concluded, and not then until one of the congregation came and aroused him.

Early on Monday morning Franklin went to Mr. Bradford’s office to see if he could obtain employment. To his surprise he found Bradford the father there. He had come on from New York on horseback, and so had arrived before Franklin. Franklin found that young Bradford had obtained a workman in the place of the one he had lost, but old Mr. Bradford offered to go with him and introduce him to another printer named Keimer, who worked in the neighborhood.

Mr. Keimer concluded to take the young stranger into his employ, and he entered into a long conversation with Mr. Bradford about his plans and prospects in business, not imagining that he was talking to the father of his rival in trade. At length Mr. Bradford went away, and Franklin prepared to commence his operations.

He found his new master’s printing office, however, in a very crazy condition. There was but one press, and that was broken down and disabled. The font of type, too, the only one that the office contained, was almost worn out with previous usage. Mr. Keimer himself, moreover, knew very little about his trade. He was an author, it seems, as well as compositor, and was employed, when Franklin and Mr. Bradford came to see him, in setting up an elegy which he was composing and putting in type at the same time, using no copy.

Franklin, however took hold of his work with alacrity and energy, and soon made great improvements in the establishment. The press was repaired and put in operation. A new supply of types and cases was obtained. Mr. Keimer did not keep house, and so a place was to be looked for in some private family where the young stranger could board. The place finally decided upon was Mr. Read’s, the house where the young woman resided who has already been mentioned as having observed the absurd figure which Franklin had made in walking through the streets when he first landed. He presented a much better appearance now, for a chest of clothing which he and Collins had sent round secretly from Boston by water, had arrived, and this enabled him to appear now in quite a respectable guise.

It was in the fall of the year 1723, that Franklin came thus to Philadelphia. He remained there during the winter, but in the spring a very singular train of circumstances occurred, which resulted in leading him back to Boston. During the winter he worked industriously at his trade, and spent his leisure time in reading and study. He laid up the money that he earned, instead of squandering it, as young men in his situation often do, in transient indulgences. He formed many useful acquaintances among the industrious and steady young men in the town. He thus lived a very contented life, and forgot Boston, as he said, as much as he could. He still kept it a profound secret from his parents where he was—no one in Boston excepting Collins having been admitted to the secret.

It happened, however, that Captain Holmes, one of Franklin’s brothers-in-law who was a shipmaster, came about this time to Newcastle, a town about forty miles below Philadelphia, and there, hearing that Benjamin was at Philadelphia, he wrote to him a letter[Pg 153] urging him to return home. Benjamin replied by a long letter defending the step that he had taken, and explaining his plans and intentions in full. It happened that Captain Holmes was in company with Sir William Keith, the governor of the colony, when he received the letter; and he showed it to him. The governor was struck with the intelligence and manliness which the letter manifested, and as he was very desirous of having a really good printing office established in Philadelphia, he came to see Franklin when he returned to the city, and proposed to him to set up an office of his own. His father, the governor said, would probably furnish him with the necessary capital, if he would return to Boston and ask for it, and he himself would see that he had work enough, for he would procure the public printing for him. So it was determined that Franklin should take passage in the first vessel that sailed, and go to Boston and see his father. Of course all this was kept a profound secret from Mr. Keimer.

In due time Franklin took leave of Mr. Keimer and embarked; and after a very rough and dangerous passage he arrived safely in Boston. His friends were very much astonished at seeing him, for Captain Holmes had not yet returned. They were still more surprised at hearing the young fugitive give so good an account of himself, and of his plans and prospects for the future. The apprentices and journeymen in the printing office gathered around him and listened to his stories with great interest. They were particularly impressed by his taking out a handful of silver money from his pocket, in answer to a question which they asked him in respect to the kind of money which was used in Philadelphia. It seems that in Boston they were accustomed to use paper money almost altogether in those days.

Young Collins, the boy who had assisted Franklin in his escape the year before, was so much pleased with the accounts that the young adventurer brought back of his success in Philadelphia that he determined to go there himself. He accordingly closed up his affairs and set off on foot for New York, with the understanding that Franklin, who was to go on afterward by water, should join him there, and that they should then proceed together to Philadelphia.

After many long consultations Franklin’s father concluded that it was not best for Benjamin to attempt to commence business for himself in Philadelphia, and so Benjamin set out on his return. On his way back he had a narrow escape from a very imminent danger. A Quaker lady came to him one day, on board the vessel in which he was sailing to New York, and began to caution him against two young women who had come on board the vessel at Newport, and who were very forward and familiar in their manners.

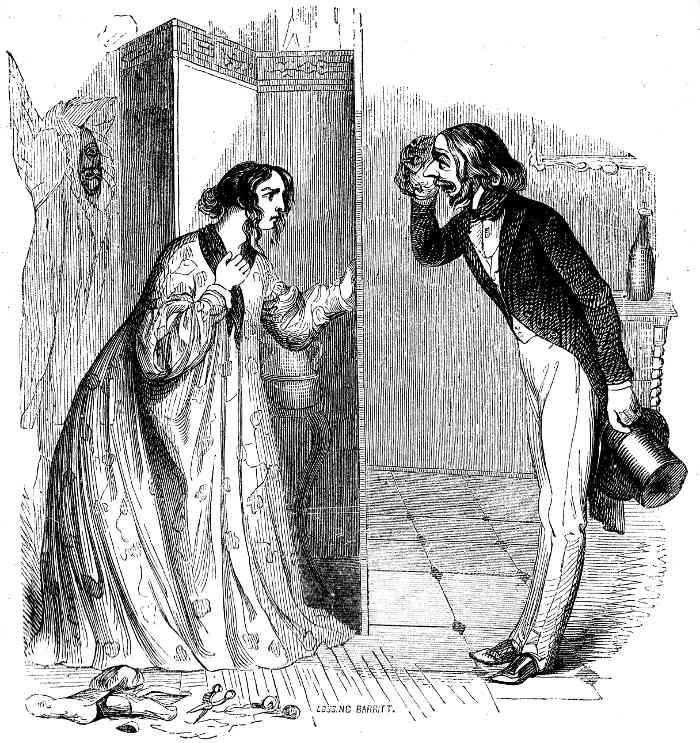

“Young man,” said she, “I am concerned for thee, as thou hast no friend with thee, and seems not to know much of the world, or of the snares youth is exposed to: depend upon it, these are very bad women. I can see it by all their actions, and if thou art not upon thy guard, they will draw thee into some danger; they are strangers to thee, and I advise thee, in a friendly concern for thy welfare, to have no acquaintance with them.” Franklin thanked the lady for her advice, and determined to follow it. When they arrived at New York the young women told him where they lived, and invited him to come and see them. But he avoided doing so, and it was well that he did, for a few days afterward he learned that they were both arrested as thieves. They had stolen something from the cabin of the ship during the voyage. If Franklin had been found in their company he might have been arrested as their accomplice.

It happened curiously enough that young Franklin attracted the notice and attention of a governor for the second time, as he passed through New York on this journey. It seems that the captain of the vessel in which he had made his voyage, happened to mention to the governor when he arrived in New York, that there was a young man among his passengers who had a[Pg 154] great many books with him, and who seemed to take quite an interest in reading; and the governor very kindly sent word back to invite the young man to call at his house, promising, if he would do so, to show him his library. Franklin very gladly accepted this invitation, and the governor took him into his library, and held considerable conversation with him, on the subject of books and authors. Franklin was of course very much pleased with this adventure.

At New York Franklin found his old friend Collins, who had arrived there some time before him. Collins had been, in former times, a very steady and industrious boy, but his character had greatly degenerated during Franklin’s absence. He had fallen into very intemperate habits, and Franklin found, on joining him at New York, that he had been intoxicated almost the whole time that he had been there. He had been gaming too, and had lost all his money, and was now in debt for his board, and wholly destitute. Franklin paid his bills, and they set off together for Philadelphia.

Of course Franklin had to pay all the expenses, both for himself and his companion, on the journey, and this, together with the charges which he had incurred for Collins in New York, soon exhausted his funds, and the two travelers would have been wholly out of money, had it not been that Franklin had received a demand to collect for a man in Rhode Island, who gave it to him when he came through. This demand was due from a man in Pennsylvania, and when the travelers reached the part of the country where this man resided, they called upon him and he paid them the money. This put Franklin in funds again, though as it was money which did not belong to him, he had no right to use it. He however considered himself compelled to use a part of it, by the necessity of the case; and Collins, knowing that his companion had the money, was continually asking to borrow small sums, and Franklin lent them to him from time to time, until at length such an inroad was made upon the trust funds which he held, that Franklin began to be extremely anxious and uneasy.

To make the matter worse Collins continued to addict himself to drinking habits, notwithstanding all that Franklin could do to prevent it. In fact Franklin soon found that his remonstrances and efforts only irritated Collins and made him angry, and so he desisted. When they reached Philadelphia the case grew worse and worse. Collins could get no employment, and he led a very dissipated life, all at Franklin’s expense. At length, however, an incident occurred which led to an open quarrel between them. The circumstances were these.

The two boys, with some other young men, went out one day upon the Delaware in a boat, on an excursion of pleasure. When they were away at some distance from the shore, Collins refused to row in his turn. He said that Franklin and the other boys should row him home. Franklin said that they would not. “Then,” said Collins. “You will have to stay all night upon the water. You can do just as you please.”

The other two boys were disposed to give up to Collins, unreasonable as he was. “Let us row,” said they, “what signifies it?” But Franklin, whose resentment was now aroused, opposed this, and persisted in refusing. Collins then declared that he would make him row or throw him overboard; and he came along, stepping on the thwarts, toward Franklin, as if to put his threat in execution. When he came near he struck at Franklin, but Franklin just at the instant thrust his head forward between Collins’s legs, and then rising suddenly with all his force he threw him over headlong into the water.

Franklin knew that Collins was a good swimmer, and so he felt no concern about his safety. He walked along to the stern of the boat, and asked Collins if he would promise to row if they would allow him to get on board again. Collins was very angry, and declared that he would not row. So the boys who had the oars pulled ahead a few strokes, to keep the boat out of Collins’s reach as he swam after her. This continued for some time—Collins swimming in the wake of the boat, and the boys pulling gently, so as just to keep the boat out of his reach—while Franklin himself stood in the stern, interrogating him from time to time, and vainly endeavoring to bring him to terms. At last finding him beginning to tire without showing any signs of yielding, for he was obstinate as well as unreasonable, the boys stopped and drew him on board, and then took him home dripping wet. Collins never forgave[Pg 155] Franklin for this. A short time after this incident, however, he obtained some engagement to go to the West Indies, and he went away promising to send back money to Franklin, to pay him what he owed him, out of the very first that he should receive. He was never heard of afterward.

In the mean time Franklin returned to his work in Mr. Keimer’s office. He reported the result of his visit to Boston, to Sir William, the governor, informing him that his father was not willing to furnish the capital necessary for setting up a printing office. Sir William replied that it would make no difference; he would furnish the capital himself, he said; and he proposed that Franklin should go to England in the next vessel, and purchase the press and type. This Franklin agreed to do.

In the mean time, before the vessel sailed, Franklin had become very much attached to Miss Read. He felt, he says, a great respect and affection for her, and he succeeded, as he thought, in inspiring her with the same feelings toward him. It was not, however, considered prudent to think of marriage immediately, especially as Franklin was contemplating so long a voyage.

Besides the company of Miss Read there were several young men in Philadelphia whose society Franklin enjoyed very highly at this time. His most intimate friend was a certain James Ralph. Ralph was a boy of fine literary taste and great love of reading. He had an idea that he possessed poetic talent, and used often to write verses, and he maintained that though his verses might be in some respects faulty, they were no more so than those which other poets wrote when first beginning. He intended, he said, to make writing poetry the business of his life. Franklin did not approve of such a plan as this; still he enjoyed young Ralph’s company, and he was accustomed sometimes on holidays to take long rambles with him in the woods on the banks of the Schuylkill. Here the two boys would sit together under the trees, for hours, reading, and conversing about what they had read.

At length the time arrived for the sailing of the ship in which Franklin was to go to England. The governor was to have given him letters of introduction and of credit, and Franklin called for them from time to time, but they were not ready. Finally he was directed to go on board the vessel, and was told that the governor would send the letters there, and that he would find them among the other letters, and could take them out at his leisure. Franklin supposed that all was right, and accordingly after taking leave of Miss Read, to whom he was now formally engaged, and who wished him heartily a good voyage and a speedy[Pg 156] return, he proceeded to Newcastle, where the ship was anchored, and went on board.

On the voyage Franklin met with a variety of incidents and adventures, which, however, can not be particularly described here. Among other things he made the acquaintance of a certain gentleman named Denham, a Friend, from Philadelphia, who afterward rendered him very essential service in London. He did not succeed in finding the governor’s letters immediately, as the captain told him, when he inquired for them, that the letters were all together in a bag, stowed away. He said, however, that he would bring out the bag when they entered the channel, and that Franklin would have ample time to look out the letters before they got up to London.

Accordingly when the vessel entered the channel the letters were all brought out, and Franklin looked them over. He did not find any that seemed very certainly intended for him, though there were several marked with his name, as if consigned to his care. He thought that these must be the governor’s letters, especially as one was addressed to a printer and another to a bookseller and stationer. He accordingly took them out, and on landing he proceeded to deliver them. He went first with the one which was addressed to the bookseller. The bookseller asked him who the letter was from. Franklin replied that it was from Sir William Keith. The bookseller replied that he did not know any such person, and on opening the letter and looking at the signature, he said angrily that it was from Riddlesden, “a man,” he added, “whom I have lately found to be a complete rascal, and I will have nothing to do with him or receive any letters from him.” So saying he thrust the letter back into Franklin’s hands.

Poor Franklin, mortified and confounded, went immediately to Mr. Denham to ask him what it would be best for him to do. Mr. Denham, when he had heard a statement of the case, said that in all probability no one of the letters which Franklin had taken was from the governor. Sir William, he added, was a very good-natured man, who wished to please every body, and was always ready to make magnificent offers and promises but not the slightest reliance could be placed upon any thing that he said.

So Franklin found himself alone and moneyless in London, and dependent wholly upon his own resources. He immediately began to seek employment in the printing offices. He succeeded in making an engagement with a Mr. Palmer, and he soon found a second-hand bookstore near the printing office, where he used to go to read and to borrow books—his love of reading continuing unchanged.

In a short time Franklin left Mr. Palmer’s and went to a larger printing office, one which was carried on by a printer named Watts. The place was near Lincoln’s Inn Fields, a well known part of London. Here he was associated with a large number of workmen, both compositors and pressmen. They were very much astonished at Franklin’s temperance principles, for he drank nothing but water, while they consumed immense quantities of strong beer. There was an ale-house near by, and a boy from it attended constantly at the printing office to supply the workmen with beer. These men had a considerable sum to pay every Saturday night out of their wages for the beer they had drank; and this kept them constantly poor. They maintained, however, that they needed the beer to give them strength to perform the heavy work required of them in the printing office. They drank strong beer, they said, in order that they might be strong to labor. Franklin’s companion at the press drank a pint before breakfast, a pint at breakfast, a pint between breakfast and dinner, a pint at dinner, a pint in the afternoon at six o’clock, and a pint when he had done his day’s work. Some others drank nearly as much.

Franklin endeavored to convince them that it was a mistake to suppose that the beer gave them[Pg 157] strength, by showing that he, though he drank nothing but water, could carry two heavy forms up-stairs to the press-room, at a time, taking one in each hand; while they could only carry one with both hands. They were very much surprised at the superior strength of the “water American,” as they called him, but still they would not give up drinking beer.

As is usually the case with young workmen entering large establishments, where they are strangers, Franklin encountered many little difficulties at first, but he gradually overcame them all, and soon became a favorite both with his employer and his fellow workmen. He earned high wages, for he was so prompt, and so steady, that he was put to the best work. He took board at the house of an elderly woman, a widow, who lived not far distant, and who, after inquiring in respect to Franklin’s character, took him at a cheaper rate than usual, from the protection which she expected in having him in the house.

In a small room in the garret of the house where Franklin boarded, there was a lodger whose case was very singular. She was a Roman Catholic, and when young had gone abroad, to a nunnery, intending to become a nun; but finding that the climate did not agree with her she returned to England, where, though there was no nunnery, she determined on leading the life of a nun by herself. She had given away all her property, reserving only a very small sum which was barely sufficient to support life. The house had been let from time to time to various Catholic families, who all allowed the nun to remain in her garret rent free, considering it a blessing upon them to have her there. A priest visited her every day to receive her confessions; otherwise she lived in almost total seclusion. Franklin, however, was once permitted to pay her a visit. He found her cheerful and polite. She looked pale, but said that she was never sick. The room had scarcely any furniture except such as related to her religious observances.

Franklin mentions among other incidents which occurred while he was in London, that he taught two young men to swim, by only going twice with them into the water. One of these young men was a workman in the printing-office where Franklin was employed, named Wygate. Franklin was always noted for his great skill and dexterity as a swimmer, and one day, after he had taught the two young men to swim, as mentioned above, he was coming down the river Thames in a boat with a party of friends, and Wygate gave such an account of Franklin’s swimming as to excite a strong desire in the company to see what he could do. So Franklin undressed himself, and leaped into the water, and he swam all the way from Chelsea to Blackfriar’s bridge in London, accompanying the boat, and performing an infinite variety of dextrous evolutions in and under the water, much to the astonishment and delight of all the company. In consequence of this incident, Franklin had an application made to him some time afterward, by a certain nobleman, to teach his two sons to swim, with a[Pg 158] promise of a very liberal reward. The nobleman had accidentally heard of Franklin’s swimming from Chelsea to London, and of his teaching a person to swim in two lessons.

Franklin remained in London about eighteen months; at the end of that time one of his fellow workmen proposed to him that they two should make a grand tour together on the continent of Europe, stopping from time to time in the great towns to work at their trade, in order to earn money for their expenses. Franklin went to his friend, Mr. Denham, to consult him in respect to this proposal. Mr. Denham advised him not to accede to it, but proposed instead that Franklin should connect himself in business with him. He was going to return to America, he said, with a large stock of goods, there to go into business as a merchant. He made such advantageous offers to Franklin, in respect to this enterprise, that Franklin very readily accepted them, and in due time he settled up his affairs in London, and sailed for America, supposing that he had taken leave of the business of printing forever.

In the result, however, it was destined to be otherwise; for after a short time Mr. Denham fell sick and died, and then Franklin, after various perplexities and delays, concluded to accept of a proposal which his old master, Mr. Keimer, made to him, to come and take charge of his printing-office. Mr. Keimer had a number of rude and inexperienced hands in his employ, and he wished to engage Franklin to come, as foreman and superintendent of the office, and teach the men to do their work skillfully.

Franklin acceded to this proposal, but he did not find his situation in all respects agreeable, and finally his engagement with Mr. Keimer was suddenly brought to a close by an open quarrel. Mr. Keimer, it seems, had not been accustomed to treat his foreman in a very respectful or considerate manner, and one day when Franklin heard some unusual noise in the street, and put his head out a moment to see what was the matter, Mr. Keimer, who was standing below, called out to him, in a very rough and angry manner, to go back and attend to his business, adding some reproachful words which nettled Franklin exceedingly. He immediately afterward came up into the office, when a sharp contention and high words ensued. The end of the affair was that Franklin took his dismissal and went immediately away.

In a short time, however, Keimer sent for Franklin to come back, saying that a few hasty words ought not to separate old friends, and Franklin, after some hesitation, concluded to return. About this time Keimer had a proposition made to him to print some bank bills, for the state of New Jersey. A copper-plate press is required for this purpose, a press very different in its character from an ordinary press. Franklin contrived one of these presses for Mr. Keimer, the first which had been seen in the country. This press performed its function very successfully. Mr. Keimer and Franklin went together, with the press, to Burlington, where the work was to be done: for it was necessary that the bills should be printed under the immediate supervision of the government, in order to make it absolutely certain that no more were struck off than the proper number.

In printing these bills Franklin made the acquaintance of several prominent public men in New Jersey, some of whom were always present while the press was at work. Several of these gentlemen became very warm friends of Franklin, and continued to be so during all his subsequent life.

At last Franklin joined one of his comrades in the printing-office, named Meredith, in forming a plan to leave Mr. Keimer, and commence business themselves, independently. Meredith’s father was to furnish the necessary capital, and Franklin was to have the chief superintendence and care of the business. This plan being arranged, an order was sent out to England for a press and a font of type, and when the articles arrived the two young men left Mr. Keimer’s, and taking a small building near the market, which they thought would be suitable for their purpose, they opened their office, feeling much solicitude and many fears in respect to their success.

To lessen their expense for rent they took a glazier and his family into the house which they had hired, while they were themselves to board[Pg 159] in the glazier’s family. Thus the arrangement which they made was both convenient and economical.

This glazier, Godfrey, had long been one of Franklin’s friends, he was a prominent member, in fact, of the little circle of young mechanics, who, under the influence of Franklin’s example, spent their leisure time in scientific studies. Godfrey was quite a mathematician. He was self-taught, it is true, but still his attainments were by no means inconsiderable. He afterward distinguished himself as the inventor of an instrument called Hadley’s quadrant, now very generally relied upon for taking altitudes and other observations at sea. It was called by Hadley’s name, as is said, through some artifice of Hadley, in obtaining the credit of the invention, though Godfrey was really the author of it.

Though Godfrey was highly respected among his associates for his mathematical knowledge, he knew little else, and he was not a very agreeable companion. The mathematical field affords very few subjects for entertaining conversation, and besides Godfrey had a habit, which Franklin said he had often observed in great mathematicians, of expecting universal precision in every thing that was said, of forever taking exception to what was advanced by others, and of making distinctions, on very trifling grounds, to the disturbance of all conversation. He, however, became afterward an eminent man, and though he died at length at a distance from Philadelphia, his remains were eventually removed to the city and deposited at Laurel Hill, where a monument was erected to his memory.

The young printers had scarce got their types in the cases and the press in order, before one of Franklin’s friends, a certain George House, came in and introduced a countryman whom he had found in the street, inquiring for a printer. They did the work which he brought, and were paid five shillings for it.—Franklin says that this five shillings, the first that he earned as an independent man, afforded him a very high degree of pleasure. He was very grateful too to House, for having taken such an interest in bringing him a customer, and recollecting his own experience on this occasion, he always afterward felt a strong desire to help new beginners, whenever it was in his power.

A certain other gentleman evinced his regard for the young printers in a much more equivocal way. He was a person of some note in Philadelphia, an elderly man, with a wise look, and a very grave and oracular manner of speaking. This gentleman, who was a stranger to Franklin stopped one day at the door and asked Franklin if he was the young man who had lately opened a printing house. Being answered in the affirmative he told Franklin that he was very sorry for him, as he certainly could not succeed. Philadelphia, he said, was a sinking place. The people were already half of them bankrupts, or nearly so, to his certain knowledge. He then proceeded to present such a gloomy detail of the difficulties and dangers which Philadelphia was laboring under, and of the evils which were coming, that finally he brought Franklin into a very melancholy frame of mind.[Pg 160]

The young printers went steadily on, notwithstanding these predictions, and gradually began to find employment for their press. They obtained considerable business through the influence of the members of a sort of debating club which Franklin had established some time before. This club was called the Junto, and was accustomed to meet on Friday evenings for conversation and mutual improvement. The rules which Franklin drew up for the government of this club required that each member should, in his turn, propose subjects or queries on any point of Morals, Politics, or Natural Philosophy, to be discussed by the company; and once in three months to produce and read an essay of his own writing, on any subject that he pleased. The members of the club were all enjoined to conduct their discussion in a sincere spirit of inquiry after truth, and not from love of dispute or desire of victory. Every thing like a positive and dogmatical manner of speaking, and all direct contradiction of each other, was strictly forbidden. Violations of these rules were punished by fines and other similar penalties.

The members of this club having become much interested in Franklin’s character from what they had seen of him at the meetings, were strongly disposed to aid him in obtaining business now that he had opened an office of his own. They were mostly mechanics, being engaged in different trades, in the city. One of them was the means of procuring quite a large job for the young printers—the printing of a book in folio. While they were upon this job, Franklin employed himself in setting the type, his task being one sheet each day, while Meredith worked the press. It required great exertion to carry the work on at the rate of one sheet per day, especially as there were frequent interruptions, on account of small jobs which were brought in from time to time. Franklin was, however, very resolutely determined to print a sheet a day, though it required him sometimes to work very late, and always to begin very early. So determined was he to continue doing a sheet a day of the work, that one night when he had imposed his forms and thought his day’s work was done, and by some accident one of the forms was broken, and two pages thrown into pi, he immediately went to work, distributed the letter, and set up the two pages anew before he went to bed.

This indefatigable industry was soon observed by the neighbors, and it began to attract considerable attention; so that at length, when certain people were talking of the three printing-offices that there were now in Philadelphia, and predicting that they could not all be sustained, some one said that whatever might happen to the other two, Franklin’s office must succeed, “For the industry of that Franklin,” said he, “is superior to any thing I ever saw of the kind. I see him still at work every night when I go home, and he is at work again in the morning before his neighbors are out of bed.” As the character of Franklin’s office in this respect became generally known, the custom that came to it rapidly increased. There were still, however, some difficulties to be encountered.

Franklin was very unfortunate in respect to his partner, so far as the work of the office was concerned, for Meredith was a poor printer, and his habits were not good. In fact the sole reason why Franklin had consented to associate himself with Meredith was that Meredith’s father was willing to furnish the necessary capital for commencing business. His father was persuaded to do this in hopes that Franklin’s influence over his son might be the means of inducing him to leave off his habits of drinking. Instead of this, however, he grew gradually worse. He neglected his work, and was in fact often wholly incapacitated from attending to it, by the effects of his drinking. Franklin’s friends regretted his connection with such a man, but there seemed to be now no present help for it.[Pg 161]

It happened, however, that things took such a turn, a short time after this, as to enable Franklin to close his partnership with Meredith in a very satisfactory manner. In the first place Meredith himself began to be tired of an occupation which he was every day more and more convinced that he was unfitted for. His father too found it inconvenient to meet the obligations which he had incurred for the press and types, as they matured; for he had bought them partly on credit. Two gentlemen, moreover, friends of Franklin, came forward of their own accord, and offered to advance him what money he would require to take the whole business into his own hands. The result of all this was that the partnership was terminated, by mutual consent, and Meredith went away. Franklin assumed the debts, and borrowed money of his two friends to meet the payments as they came due; and thenceforward he managed the business in his own name.

After this change, the business of the office went on more prosperously than ever. There was much interest felt at that time on the question of paper money, one party in the state being in favor of it and the other against it. Franklin wrote and printed a pamphlet on the subject. The title of it was The Nature and Necessity of a Paper Currency. This pamphlet was very well received, and had an important influence in deciding the question in favor of such a currency. In consequence of this Franklin was employed to print the bills, which was very profitable work. He also obtained the printing of the laws, and of the proceedings of the government, which was of great advantage to him.

About this time Franklin enlarged his business by opening a stationery store in connection with his printing office. He employed one or two additional workmen too. In order, however, to show that he was not above his business, he used to bring home the paper which he purchased at the stores, through the streets on a wheelbarrow.

The engagement which Franklin had formed with Miss Read before he went to London had been broken off. This was his fault and not hers; as the rupture was occasioned by his indifference and neglect. When her friends found that Franklin had forsaken her, they persuaded her to marry another man. This man, however, proved to be a dissolute and worthless fellow, having already a wife in England, when he married Miss Read. She accordingly refused to live with him, and he went away to the West Indies, leaving Miss Read at home, disconsolate and wretched.

Franklin pitied her very much, and attributed her misfortunes in a great measure to his unfaithfulness to the promises which he had made her. He renewed his acquaintance with her, and finally married her. The wedding took place on the 1st of September, 1730; Franklin was at this time about twenty-five years of age. It was reported that the man who had married her was dead. At all events her marriage with him was wholly invalid.

At the time when Franklin commenced his business in Philadelphia there was no bookstore in any place south of Boston. The towns on the sea coast which have since grown to be large and flourishing cities, were then very small, and comparatively insignificant; and they afforded to the inhabitants very few facilities of any kind. Those who wished to buy books had no means of doing it except to send to England for them.

In order to remedy in some measure the difficulty which was experienced on this account, Franklin proposed to the members of the debating society which has already been named, that they should form a library, by bringing all their books together and depositing them in the room where the society was accustomed to hold its meetings. This was accordingly[Pg 162] done. The members brought their books, and a foundation was thus laid for what afterward became a great public library. The books were arranged on shelves which were prepared for them in the club-room, and suitable rules and regulations were made in respect to the use of them by the members.

With the exception that he appropriated one or two hours each day to the reading of books from the library, Franklin devoted his time wholly to his business. He took care, he said, not only to be, in reality, industrious and frugal, but to appear so. He dressed plainly; he never went to any places of diversion; he never went out a-hunting or shooting, and he spent no time in taverns, or in games or frolics of any kind. The people about him observed his diligence, and the consequence was that he soon acquired the confidence and esteem of all who knew him. Business came in, and his affairs went on more and more smoothly every day.

It was very fortunate for him that his wife was as much disposed to industry and frugality as himself. She assisted her husband in his work by folding and stitching pamphlets, tending shop, purchasing paper, rags, and other similar services. They kept no servants, and lived in the plainest and most simple manner. Thus all the money which was earned in the printing office, or made by the profits of the stationery store, was applied to paying back the money which Franklin had borrowed of his friends, to enable him to settle with Meredith. He was ambitious to pay this debt as soon as possible, so that the establishment might be wholly his own. His wife shared in this desire, and thus, while they deprived themselves of no necessary comfort, they expended nothing for luxury or show. Their dress, their domestic arrangements, and their whole style of living, were perfectly plain.

Franklin’s breakfast, for example, for a long time, consisted only of a bowl of bread and milk, which was eaten from a two-penny earthen porringer and with a pewter spoon. At length, however, one morning when called to his breakfast he found a new china bowl upon the table, with a silver spoon in it. They had been bought for him by his wife without his knowledge, who justified herself for the expenditure by saying that she thought that her husband was as much entitled to a china bowl and silver spoon as any of her neighbors.

About this time Franklin adopted a very systematic and formal plan for the improvement of his moral character. He made out a list of the principal moral virtues, thirteen in all, and then made a book of a proper number of pages, and wrote the name of one virtue on each page. He then, on each page, ruled a table which was formed of thirteen lines and seven columns. The lines were for the names of the thirteen virtues, and the columns for the days of the week. Each page therefore represented one week, and Franklin was accustomed every night to examine himself, and mark down in the proper column, and opposite to the names of the several virtues, all violations of duty in respect to each one respectively, which he could recollect that he had been guilty of during that day. He paid most particular attention each week to one particular virtue, namely, the one which was[Pg 163] written on the top of the page for that week, without however neglecting the others—following in this respect, as he said, the example of the gardener who weeds one bed in his garden at a time.

He had several mottos prefixed to this little book, and also two short prayers, imploring divine assistance to enable him to keep his resolution. One of these prayers was from Thomson:

The other was composed by himself, and was as follows.

“O Powerful Goodness! Bountiful Father! Merciful Guide! Increase in me that wisdom which discovers my truest interest. Strengthen my resolution to perform what that wisdom dictates. Accept my kind offices to thy other children as the only return in my power for thy continual favors to me.”

Franklin persevered in his efforts to improve himself in moral excellence, by means of this record, for a long time. He thought he made great progress, and that his plan was of lasting benefit to him. He found, however, that he could not, as at first he fondly hoped, make himself perfect. He consoled himself at last, he said, by the idea that it was not best, after all, for any one to be absolutely perfect. He used to say that this willingness on his part to be satisfied with retaining some of his faults, when he had become wearied and discouraged with the toil and labor of removing them, reminded him of the case of one of his neighbors, who went to buy an ax of a smith. The ax, as is usual with this tool, was ground bright near the edge, while the remainder of the surface of the iron was left black, just as it had come from the forge. The man wished to have his ax bright all over, and the smith said that he would grind it bright if the man would turn the grindstone.

So the man went to the wheel by which it seems the grindstone was turned, through the intervention of a band, and began his labor. The smith held the ax upon the stone, broad side down, leaning hard and heavily. The man came now and then to see how the work went on. The brightening he found went on slowly. At last, wearied with the labor, he said that he would take the ax as it then was, without grinding it any more. “Oh, no,” said the smith, “turn on, turn on; we shall have it bright by-and-by. All that we have done yet has only made it speckled.” “Yes,” said the man, “but I think I like a speckled ax best.” So he took it away.

In the same manner Franklin said that he himself seemed to be contented with a character somewhat speckled, when he found how discouraging was the labor and toil required to make it perfectly bright.

During all this time Franklin went on more and more prosperously in business, and was continually enlarging and extending his plans. He printed a newspaper which soon acquired an extensive circulation. He commenced the publication of an almanac, which was continued afterward[Pg 164] for twenty-five years, and became very celebrated under the name of Poor Richard’s Almanac. At length the spirit of enterprise which he possessed went so far as to lead him to send one of his journeymen to establish a branch printing-office in Charleston, South Carolina. This branch, however, did not succeed very well at first, though, after a time, the journeyman who had been sent out died, and then his wife, who was an energetic and capable woman, took charge of the business, and sent Franklin accounts of the state of it promptly and regularly. Franklin accordingly left the business in her hands, and it went on very prosperously for several years: until at last the woman’s son grew up, and she purchased the office for him, with what she had earned and saved.

Notwithstanding the increasing cares of business, and the many engagements which occupied his time and attention, Franklin did not, during all this time, in any degree remit his efforts to advance in the acquisition of knowledge. He studied French, and soon made himself master of that language so far as to read it with ease. Then he undertook the Italian. A friend of his, who was also studying Italian, was fond of playing chess, and often wished Franklin to play with him. Franklin consented on condition that the penalty for being beaten should be to have some extra task to perform in the Italian grammar—such as the committing to memory of some useful portion of the grammar, or the writing of exercises. They were accordingly accustomed to play in this way, and the one who was beaten, had a lesson assigned him to learn, or a task to perform, and he was bound upon his honor to fulfill this duty before the next meeting.

After having acquired some proficiency in the Italian language Franklin took up the Latin. He had studied Latin a little when a boy at school, at the time when his father contemplated educating him for the church. He had almost entirely forgotten what he had learned of the language at school, but he found, on looking into a Latin Testament, that it would be very easy for him to learn the language now, on account of the knowledge which he had acquired of French and Italian. His experience in this respect led him to think that the common mode of learning languages was not a judicious one. “We are told,” says he, “that it is proper to begin first with the Latin, and having acquired that, it will be more easy to attain those modern languages which are derived from it; and yet we do not begin with the Greek in order more easily to acquire the Latin.” He then compares the series of languages to a staircase. It is true that if we contrive some way to clamber to the upper stair, by the railings or by some other method, without using the steps, we can then easily reach any particular stair by coming down, but still the simplest and the wisest course would seem to be to walk up directly from the lower to the higher in regular gradation.

“I would therefore,” he adds, “offer it to the consideration of those who superintend the education of our youth, whether, since many of those who begin with the Latin quit the same after spending some years, without having made any great proficiency, and what they have learned becomes almost useless, so that their time has been lost, it would not have been better to have begun with the French, proceeding to the Italian and Latin; for though after spending the same time they should quit the study of languages, and never arrive at the Latin, they would, however, have acquired another tongue or two that, being in modern use, might be serviceable to them in common life.”

It was now ten years since Franklin had been at Boston, and as he was getting well established in business, and easy in his circumstances, he concluded to go there and visit his relations. His brother, Mr. James Franklin, the printer to whom he had been apprenticed when a boy, was not in[Pg 165] Boston at this time. He had removed to Newport. On his return from Boston, Franklin went to Newport to see him. He was received by his brother in a very cordial and affectionate manner, all former differences between the two brothers being forgotten by mutual consent. He found his brother in feeble health, and fast declining—and apprehending that his death was near at hand. He had one son, then ten years of age, and he requested that in case of his death Benjamin would take this child and bring him up to the printing business. Benjamin promised to do so. A short time after this his brother died, and Franklin took the boy, sent him to school for a few years, and then took him into his office, and brought him up to the business of printing. His mother carried on the business at Newport until the boy had grown up, and then Franklin established him there, with an assortment of new types and other facilities. Thus he made his brother ample amends for the injury which he had done him by running away from his service when he was a boy.

On his return from Boston, Franklin found all his affairs in Philadelphia in a very prosperous condition. His business was constantly increasing, his income was growing large, and he was beginning to be very widely known and highly esteemed, throughout the community. He began to be occasionally called upon to take some part in general questions relating to the welfare of the community at large. He was appointed postmaster for Philadelphia. Soon after this he was made clerk of the General Assembly, the colonial legislature of Pennsylvania. He began, too, to pay some attention to municipal affairs, with a view to the better regulation of the public business of the city. He proposed a reform in the system adopted for the city watch. The plan which had been pursued was for a public officer to designate every night a certain number of householders, taken from the several wards in succession, who were to perform the duty of watchmen. This plan was, however, found to be very inefficient, as the more respectable people, instead of serving themselves, would pay a fine to the constable to enable him to hire substitutes; and these substitutes were generally worthless men who spent the night in drinking, instead of faithfully attending to their duties.

Franklin proposed that the whole plan should be changed; he recommended that a tax should be levied upon the people, and a regular body of competent watchmen employed and held to a strict responsibility in the performance of their duty. This plan was adopted, and proved to be a very great improvement on the old system.

It was also much more just; for people were taxed to pay the watchmen in proportion to their property, and thus they who had most to be protected paid most.

Franklin took a great interest, too, about this time, in promoting a plan for building a large public edifice in the heart of the city, to accommodate the immense audiences that were accustomed to assemble to hear the discourses of the celebrated Mr. Whitefield. The house was built by public contribution. When finished, it was vested in trustees, expressly for the use of any preacher of any religious persuasion, who might desire to address the people of Philadelphia. In fact, Franklin was becoming more and more a public man, and soon after this time, he withdrew almost altogether from his private pursuits, and entered fully upon his public career. The history of his adventures in that wider sphere must be postponed to some future Number.[Pg 166]

[1] Entered, according to Act of Congress, in the year 1852, by Harper and Brothers, in the Clerk’s Office of the District Court of the Southern District of New York.

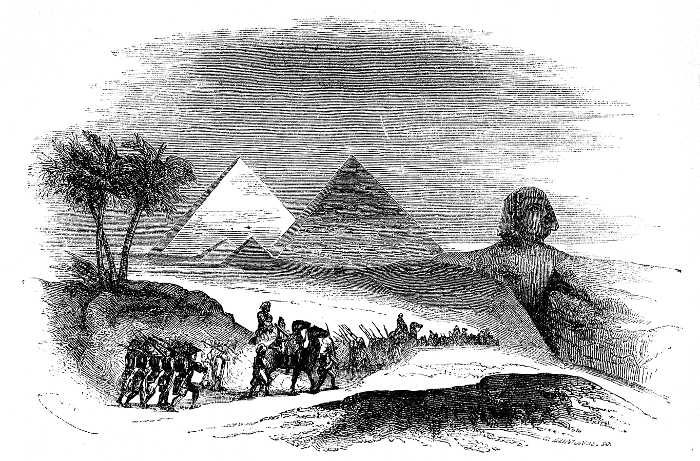

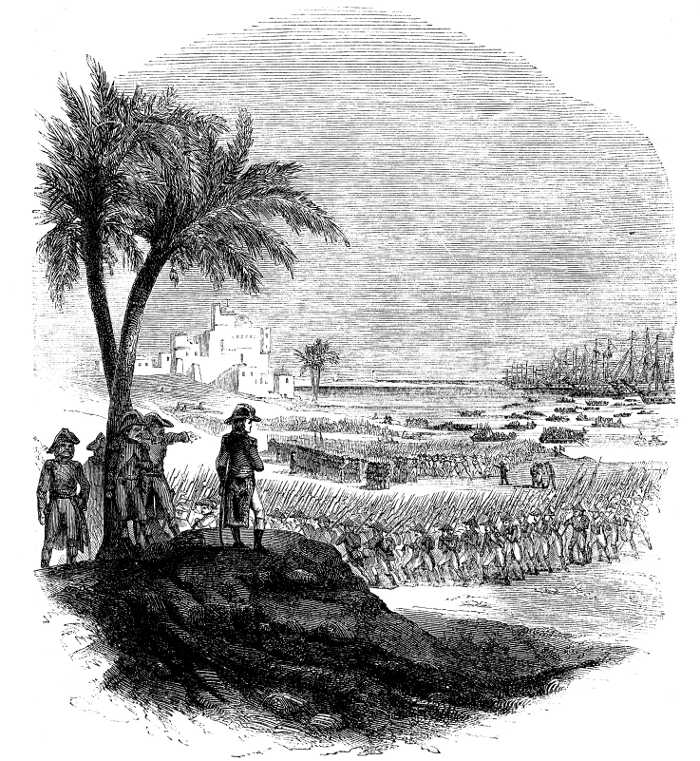

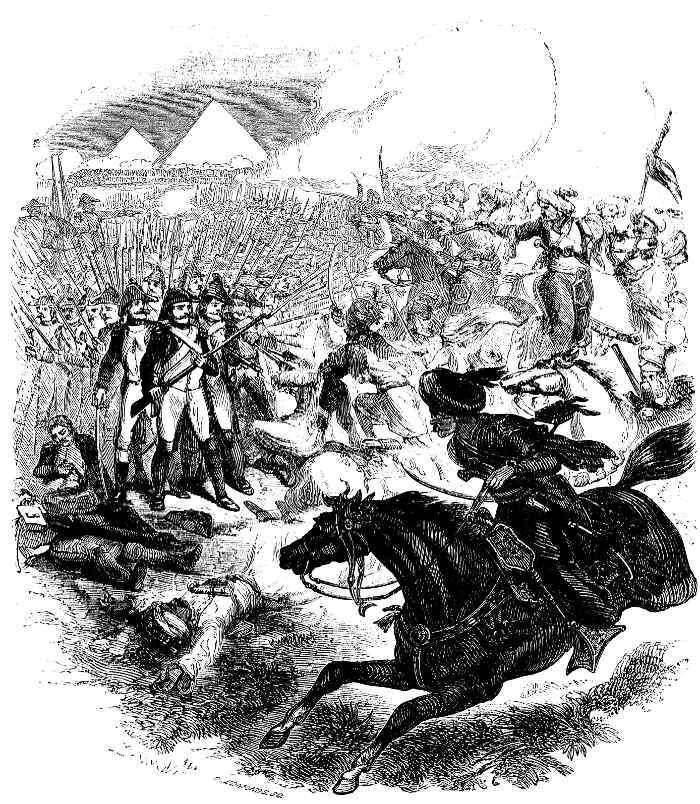

Napoleon’s Expedition to Egypt was one of the most magnificent enterprises which human ambition ever conceived. When Napoleon was a schoolboy at Brienne, his vivid imagination became enamored of the heroes of antiquity, and ever dwelt in the society of the illustrious men of Greece and Rome. Indulging in solitary walks and pensive musings, at that early age he formed vague and shadowy, but magnificent conceptions of founding an Empire in the East, which should outvie in grandeur all that had yet been told in ancient or in modern story. His eye wandered along the shores of the Persian Gulf, and the Caspian Sea, as traced upon the map, and followed the path of the majestic floods of the Euphrates, the Indus, and the Ganges, rolling through tribes and nations, whose myriad population, dwelling in barbaric pomp and pagan darkness, invited a conqueror. “The Persians,” exclaimed this strange boy, “have blocked up the route of Tamerlane, but I will open another.” He, in those early dreams, imagined himself a conqueror, with Alexander’s strength, but without Alexander’s vice or weakness, spreading the energies of civilization, and of a just and equitable government, over the wild and boundless regions which were lost to European eyes in the obscurity of distance.

When struggling against the armies of Austria, upon the plains of Italy, visions of Egypt and of the East blended with the smoke and the din of the conflict. In the retreat of the Austrians before his impetuous charges, in the shout of victory which incessantly filled his ear, swelling ever above the shrieks of the wounded and the groans of the dying, Napoleon saw but increasing indications that destiny was pointing out his path toward an Oriental throne.

When the Austrians were driven out of Italy, and the campaign was ended, and Napoleon, at Montebello, was receiving the homage of Europe, his ever-impetuous mind turned with new interest to the object of his early ambition. He often passed hours, during the mild Italian evenings, walking with a few confidential friends in the magnificent park of his palace, conversing with intense enthusiasm upon the illustrious empires, which have successively overshadowed those countries, and faded away. “Europe,” said he, “presents no field for glorious exploits; no great empires or revolutions are to be found but in the East, where there are six hundred millions of men.”

Upon his return to Paris, he was deaf to all the acclamations with which he was surrounded. His boundless ambition was such that his past achievements seemed as nothing. The most brilliant visions of Eastern glory were dazzling his mind. “They do not long preserve at Paris,” said he, “the remembrance of any thing. If I remain long unemployed, I am undone. The renown of one, in this great Babylon, speedily supplants that of another. If I am seen three times at the opera, I shall no longer be an object of curiosity. I am determined not to remain in Paris. There is nothing here to be accomplished. Every thing here passes away. My glory is declining. This little corner of Europe is too small to supply it. We must go to the East. All the great men of the world have there acquired their celebrity.”

When requested to take command of the army of England, and to explore the coast, to judge of the feasibility of an attack upon the English in their own island, he said to Bourrienne, “I am [Pg 167]perfectly willing to make a tour to the coast. Should the expedition to Britain prove too hazardous, as I much fear that it will, the army of England will become the army of the East, and we will go to Egypt.”

He carefully studied the obstacles to be encountered in the invasion of England, and the means at his command to surmount them. In his view, the enterprise was too hazardous to be undertaken, and he urged upon the Directory the Expedition to Egypt. “Once established in Egypt,” said he, “the Mediterranean becomes a French Lake; we shall found a colony there, unenervated by the curse of slavery, and which will supply the place of St. Domingo; we shall open a market for French manufactures through the vast regions of Africa, Arabia, and Syria. All the caravans of the East will meet at Cairo, and the commerce of India, must forsake the Cape of Good Hope, and flow through the Red Sea. Marching with an army of sixty thousand men, we can cross the Indus, rouse the oppressed and discontented native population, against the English usurpers, and drive the English out of India. We will establish governments which will respect the rights and promote the interests of the people. The multitude will hail us as their deliverers from oppression. The Christians of Syria, the Druses, and the Armenians, will join our standards. We may change the face of the world.” Such was the magnificent project which inflamed this ambitious mind.

England, without a shadow of right, had invaded India. Her well-armed dragoons had ridden, with bloody hoofs, over the timid and naked natives. Cannon, howitzers, and bayonets had been the all-availing arguments with which England had silenced all opposition. English soldiers, with unsheathed swords ever dripping with blood, held in subjection provinces containing uncounted millions of inhabitants. A circuitous route of fifteen thousand miles, around the stormy Cape of Good Hope, conducted the merchant fleets of London and Liverpool to Calcutta and Bombay; and through the same long channel there flooded back upon the maritime isle the wealth of the Indies.