Title: Cardigan

Author: Robert W. Chambers

Release date: February 22, 2012 [eBook #38958]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by David Starner, Melissa McDaniel and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This

file was produced from images generously made available

by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note:

Obvious typographical errors have been corrected. Inconsistent spelling and hyphenation in the original document have been preserved.

CARDIGAN

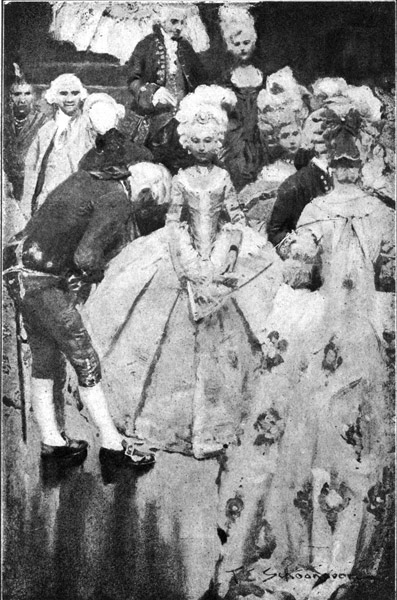

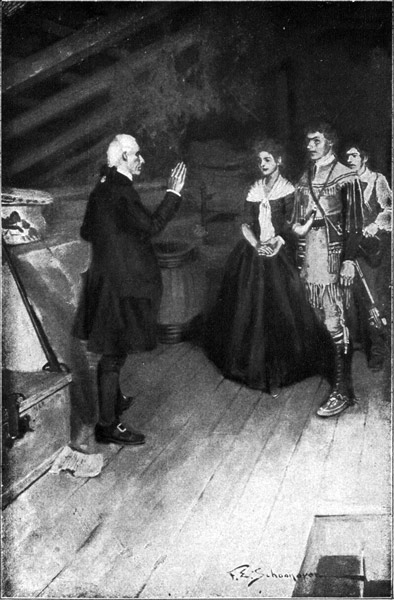

CARDIGAN AND SILVER HEELS

See p. 40

By ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

Author of "The Maid-at-Arms," "The Tree of Heaven,"

"Fighting Chance," etc.

Illustrated

A. L. BURT COMPANY, Publishers

NEW YORK

Published by arrangement with Harper & Brothers

Books by

ROBERT W. CHAMBERS

| Lorraine. Post 8vo | $1.25 |

| The Conspirators. Ill'd. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| A Young Man in a Hurry. Ill'd. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| Cardigan. Illustrated. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| The Maid-at-Arms. Illustrated. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| The King in Yellow. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| The Maids of Paradise. Ill'd. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| In Search of the Unknown. Ill'd. Post 8vo | 1.50 |

| Outdoorland. Ill'd in Colors. Sq. 8vo, net | 1.50 |

| Orchardland. Ill'd in Colors. Sq. 8vo, net | 1.50 |

| Riverland. Ill'd in Colors. Sq. 8vo, net | 1.50 |

| The Mystery of Choice. 16mo | 1.25 |

HARPER & BROTHERS, PUBLISHERS, N. Y.

Copyright, 1901, by Robert W. Chambers.

All rights reserved.

TO

MY FATHER

AND

MOTHER

This is the Land of the Pioneer,

Where a life-long feud was healed;

Where the League of the Men whose Coats were Red

With the Men of the Woods whose Skins were Red

Was riveted, forged, and sealed.

Now, by the souls of our Silent Dead,

God save our sons from the League of Red!

Plough up the Land of Battle

Here in our hazy hills;

Plough! to the lowing of cattle;

Plough! to the clatter of mills;

Follow the turning furrows'

Gold, where the deep loam breaks,

While the hand of the harrow burrows,

Clutching the clod that cakes;

North and south on the harrow's line,

Under the bronzed pines' boughs,

The silvery flint-tipped arrows shine

In the wake of a thousand ploughs!

Plough us the Land of the Pioneer,

Where the buckskinned rangers bled;

Where the Redcoats reeled from a reeking field,

And a thousand Red Men fled;

Plough us the land of the wolf and deer,

The land of the men who laughed at fear,

The land of our Martyred Dead!

Here where the ghost-flower, blowing,

Grows from the bones below,

Patters the hare, unknowing,

Passes the cawing crow:

Shadows of hawk and swallow,

Shadows of wind-stirred wood,

Dapple each hill and hollow,

Here where our dead men stood:

Wild bees hum through the forest vines

Where the bullets of England hummed,

And the partridge drums in the ringing pines

Where the drummers of England drummed.

This is the Land of the Pioneer,

Where a life-long feud was healed;

Where the League of the Men whose Coats were Red

With the Men of the Woods whose Skins were Red

Was riveted, forged, and sealed.

Now, by the blood of our Splendid Dead,

God save our sons from the League of Red!

R. W. C.

Broadalbin.

Those who read this romance for the sake of what history it may contain will find the histories from which I have helped myself more profitable.

Those antiquarians who hunt their hobbies through books had best drop the trail of this book at the preface, for they will draw but a blank covert in these pages. Better for the antiquarian that he seek the mansion of Sir William Johnson, which is still standing in Johnstown, New York, and see with his own eyes the hatchet-scars in the solid mahogany banisters where Thayendanegea hacked out polished chips. It would doubtless prove more profitable for the antiquarian to thumb those hatchet-marks than these pages.

But there be some simple folk who read romance for its own useless sake.

To such quiet minds, innocent and disinterested, I have some little confidences to impart: There are still trout in the Kennyetto; the wild ducks still splash on the Vlaie, where Sir William awoke the echoes with his flintlock; the spot where his hunting-box stood is still called Summer-House Point; and huge pike in golden-green chain-mail still haunt the dark depths of the Vlaie water, even on this fair April day in the year of our Lord 1900.

The Author.

On the 1st of May, 1774, the anchor-ice, which for so many months had silver-plated the river's bed with frosted crusts, was ripped off and dashed into a million gushing flakes by the amber outrush of the springtide flood.

On that day I had laid my plans for fishing the warm shallows where the small fry, swarming in early spring, attract the great lean fish which have lain benumbed all winter under their crystal roof of ice.

So certain was I of a holiday undisturbed by school-room tasks that I whistled up boldly as I sat on my cot bed, sorting hooks according to their sizes, and smoothing out my feather-flies to make sure the moths had not loosened wing or body. It was, therefore, with misgiving that I heard Peter and Esk go into the school-room, stamping their feet to make what noise they were able, and dragging their horn-books along the balustrade.

Now we had no tasks set us for three weeks, for our schoolmaster, Mr. Yost, journeying with the post to visit his mother in Pennsylvania, had been shot and scalped at Eastertide near Fort Pitt—probably by some drunken Delaware.

My guardian, Sir William Johnson, who, as all know, was Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Crown, had but recently returned from the upper castle with his secretary, Captain Walter Butler; and, preoccupied with the lamentable 2 murder of Mr. Yost, had found no time to concern himself with us or our affairs.

However, having despatched a messenger with strings and belts to remonstrate with the sachems of the Lenni-Lenape—they being, as I have said, suspected of the murder—we discovered that Sir William had also written to Albany for another schoolmaster to replace Mr. Yost; and it gave me, for one, no pleasure to learn it, though it did please Silver Heels, who wearied me with her devotion to her books.

So, hearing Esk and fat Peter on their way to the school-room, I took alarm, believing that our new schoolmaster had arrived; so seized my fish-rod and started to slip out of the house before any one might summon me. However, I was seen in the hallway by Captain Butler, Sir William's secretary, and ordered to find my books and report to him at the school-room.

I, of course, paid no heed to Mr. Butler, but walked defiantly down-stairs, although he called me twice in his cold, menacing voice. And I should have continued triumphantly out of the door and across the fields to the river had not I met Silver Heels dancing through the lower hallway, her slate and pencil under her arm, and loudly sucking a cone of maple sugar.

"Oh, Michael," she cried, "you don't know! Captain Butler has consented to instruct us until the new schoolmaster comes from Albany."

"Oh, has he?" I sneered. "What do I care for Mr. Butler? I'm going out! Let go my coat!"

"No, you're not! No, you're not!" retorted Silver Heels, in that teasing sing-song which she loved to make me mad withal. "Sir William says you are to take your ragged old book of gods and nymphs and be diligent lest he catch you tripping! So there, clumsy foot!"—for I had tried to trip her.

"Who told you that?" I answered, sulkily, snatching at her sugar.

"Aunt Molly; she set me to seek you. So now who's going fishing, my lord?"

The indescribable malice of her smile, her sing-song 3 mockery as she stood there swaying from her hips and licking her sugar-cone, roused all the sullen obstinacy in me.

"If I go," said I, "I won't study my books anyway. I'm too old to study with you and Peter, and I won't! You will see!"

Sir William's favourite ferret, Vix, with muzzle on, came sneaking along the wall, and I grasped the lithe animal and thrust it at Silver Heels, whereupon she kicked my legs with her moccasins, which did not hurt, and ran up-stairs like a wild-cat.

There was nothing for me but to go to the school-room. I laid my rod in the corner, pocketed the ferret, dragged my books from under the library table, and went slowly up the stairs.

At sixteen I was as wilful a dunce as ever dangled feet in a school-room, knowing barely sufficient Latin to follow Cæsar through Gaul, loathing mathematics, scorning the poets, and even obstinately marring my pen-writing with a heavy backward stroke in defiance of Sir William and poor Mr. Yost.

As for mythology, my tow-head was over-crammed with kennel-lore and the multitude of small details bearing upon fishing and the chase, to accommodate the classics.

Destined, against my will, for Dartmouth College by my guardian, who very well understood that I desired to be a soldier, I had resolutely set myself against every school-room accomplishment, with the result that, at sixteen, I presented an ignorance which should have shamed a lad of ten, but did not mortify me in the least.

And now, to my dismay and rage, Sir William had set me once more in the school-room—and under Mr. Butler, too!

"Master Cardigan," said Mr. Butler when I entered the room, "Sir William desires you to prepare a recitation upon the story of Proserpine."

I muttered rebelliously, but jerked my mythology from the pile of books and began to thumb the leaves noisily. Presently tiring of dingy print, I moved up to the bench where sat the children, Peter and Esk, a-conning their horn-books.

Silver Heels pulled a face at me behind her French grammar book, and I pinched her arm smartly for her impudence. 4 Then, casting about for something to do, I remembered the ferret in my pocket, and dragged it out. Removing the silver bit I permitted the ferret to bite Peter's tight breeches, not meaning to hurt him; but Peter screeched and Mr. Butler birched him well, knowing all the while it was no fault of Peter's; yet such was the nature of the man that, when angry, the innocent must suffer when the guilty were beyond his wrath.

I had remuzzled the ferret, and Peter was smearing the tears from his cheeks, when Sir William came in, very angry, saying that Mistress Molly could hear us in the nursery, and that the infant had fallen a-roaring with his new teeth.

"I did it, sir," said I, "and Mr. Butler punished Peter—"

"Silence!" said Sir William, sharply. "Put that ferret out the window!"

"The ferret is your best one—Vix," I answered. "She will run to the warren and we shall have to dig her out—"

"Pocket her, then," said Sir William, hastily. "Who gave you leave to pouch my ferrets? Eh? What has a ferret to do in school? Eh? Idle again? Captain Butler, is he idle?"

"He is a dunce," said Mr. Butler, with a shrug.

"Dunce!" echoed Sir William, quickly. "Why should he be a dunce when I have taught him? Granted his Latin would shame a French priest, and his mathematics sicken a Mohawk, have I not read the poets with him?"

Mr. Butler, a gentleman and an officer of rank and fortune, whose degraded whims led him now to instruct youth as a pastime, sharpened a quill in silence.

"Gad," muttered Sir William, "have I not read mythology with him till I dreamed of nymphs and satyrs and capered in my dreams till Mistress Molly—but that's neither here nor there. Micky!"

"Sir," I replied, sulkily.

Then he began to question me concerning certain gods and demi-gods, and I gaped and floundered as though I were no better than the inky rabble ruled over by Mr. Butler.

Sir William lounged by the window in his spurred boots and scarlet hunting-coat, and smelling foul of the kennels, which, God knows, I do not find unpleasant; and at every 5 slap of the whip over his boots, he shot me through and through with a question which I had neither information nor inclination to answer before the grinning small fry.

Now to be hectored and questioned by Sir William like a sniffling lad with one eye on the birch and the other on Mr. Butler, did not please me. Moreover, the others were looking on—Esk with ink on his nose, Peter in tears, a-licking his lump of spruce, and that wild-cat thing, Silver Heels—

With every question of Sir William I felt I was losing caste among them. Besides, there was Mr. Butler with his silent, deathly laugh—a laugh that never reached his eyes—yellow, changeless eyes, round as a bird's.

Slap came the whip on the polished boot-tops, and Sir William was at it again with his gods and goddesses:

"Who carried off Proserpine? Eh?"

I looked sullenly at Esk, then at Peter, who put out his tongue at me. I had little knowledge of mythology beyond what concerned that long-legged goddess who loved hunting—as I did.

"Who carried off Proserpine?" repeated Sir William. "Come now, you should know that; come now—a likely lass, Proserpine, out in the bush pulling cowslips, bless her little fingers—when—ho!—up pops—eh?—who, lad, who in Heaven's name?"

"Plato!" I muttered at hazard.

"What!" bawled Sir William.

I felt for my underlip and got it between my teeth, and for a space not another word would I speak, although that hollow roar began to sound in Sir William's voice which always meant a scene. His whip, too, went slap-slap! on his boots, like the tail of a big dog rapping its ribs.

He was perhaps a violent man, Sir William, yet none outside of his own family ever suspected it or do now believe it, he having so perfect a control over himself when he chose. And I often think that his outbursts towards us were all pretence, and to test his own capacity for temper lest he had lost it in a long lifetime of self-control. At all events, none of us ever were the worse for his roaring, although it frightened us when very young; but we soon came to understand that it was as harmless as summer thunder. 6

"Come, sir! Come, Mr. Cardigan!" said Sir William, grimly. "Out with the gentleman's name—d'ye hear?"

It was the first time in my life that Sir William had spoken to me as Mr. Cardigan. It might have pleased me had I not seen Mr. Butler sneer.

I glared at Mr. Butler, whose face became shadowy and loose, without expression, without life, save for the fixed stare of those round eyes.

Slap! went Sir William's whip on his boots.

"Damme!" he shouted, in a passion, "who carried off that slut Proserpine?"

"The Six Nations, for aught I know!" I muttered, disrespectfully.

Sir William's face went redder than his coat; but, as it was ever his habit when affronted, he stood up very straight and still; and that tribute of involuntary silence which was always paid to him at such moments, we paid, sitting awed and quiet as mice.

"Turn the children free, Captain Butler," said Sir William, in a low voice.

Mr. Butler flung back the door. The children followed him, Esk bestowing a wink upon me, Peter grinning and toeing in like a Devon duck, and that wild-cat thing, Silver Heels—

"You need not wait, Captain Butler," said Sir William, politely.

Mr. Butler retired, leaving the door swinging. Out in the dark hallway I fancied I could still see his shallow eyes shining. I may have been mistaken. But all men know now that Walter Butler hath eyes that see as well by dark as by the light of the sun; and none know it so well as the people of New York Province and of Tryon County.

"Michael," said Sir William, "go to the slate."

I walked across the dusty school-room.

"Chalk!" shouted Sir William, irritated by my lagging steps.

I picked up a lump of chalk, balancing it in my palm as boys do a pebble in a sling.

Something in my eyes may have infuriated Sir William.

The next moment he had me by the arm, then by the collar, 7 whip whistling like the chimney wind—and whistling quite as idly, for the blow never fell.

I freed myself; he made no effort to hold me.

"Keep your lash for your hounds!" I stammered.

He did not seem to hear me, but I planted myself in a corner and cried out that he dare not lay his whip on me, which was a shameful thing to taunt him with, for he had promised me never to lay rod to me; and I knew, as all the world knows, that Sir William Johnson had never broken his word to man or savage.

But still I faced him, now hurling safe defiance, now muttering revenge, until the scornful rebuke in his eyes began to shame me into silence. Tingling already with self-contempt, I dropped my head a little, not so low but what I could see Sir William's bulk motionless before me.

Presently he said, as though to himself: "If the boy's a coward, no man can lay the sin to me."

"I am not a coward!" I burst out, all a-quiver again, "and I ask your pardon, sir, for daring you to lay whip on me,—knowing your promise!"

Sir William scowled at me.

"To prove it," I went on, desperately, still trembling at the word "coward," "I will give you leave to drive a fish-hook through my hand and cut it out with your knife; and I'll laugh at the pain—as did that Mohawk lad when you cut the pike-hook out of his hand!"

"What the devil have I to do with your fish-hook and your Mohawks!" shouted Sir William, with a hearty oath.

Mortified, I shrank back while he fumed and cracked his whip and swore I was doomed to folly and a most vicious future.

"You assume the airs of a man," he roared—"you with your sixteen unbirched years—you with your gross ignorance and grosser impudence! A vicious lad, a bad, undutiful, sullen lad, ever at odds with the others, never diligent save with the fishing-rod—a lazy, quarrelsome rustic, a swaggering, forest-running fellow, without the polish or the presence of a gentleman's son! Shame on you!"

I set my teeth and shut both eyes, opening one, however, when I heard him move. 8

"I'll polish you yet!" he said, with an oath; "I'll polish you, and I'll temper you like the edge on a Mohawk hatchet."

"One red belt," I added, impudently, meaning that I defied him.

"Which you will cover with a white belt before the fires in this hearth are dead," he answered, gulping down the disrespect.

He laid his heavy hand on the door, then, turning, he bade me write with the chalk on the slate the history of Proserpine in verse, and await his further pleasure.

Sir William had shut the school-room door upon me. I listened. Had he locked it I should have kicked the panelling out into the hallway.

Standing there alone in the school-room beside the great slate, I read in dull anger the names of those who, tasks ended, were now free of the hateful place; here Esk had left his name above his sum, all smears; here fat Peter had written seven times, "David did die and so must I."

With a bit of buckskin I dusted these scrawls from the slate, slowly, for I was not yet of a mind to begin my task.

I opened the window behind me. A sweet spring wind was blowing. Putting up my nose to scent it, I saw the sky bluer than a heron's egg, and a little white cloud a-sailing up there all alone.

That year the snow had gone out in April, and the same day the blue-birds flew into the sheep-fold. Now, on this second day of May, robins were already running over the ground below the school-room window, a-tilting for worms like jack-snipes along the creek.

Folding my arms to lean on the sill, I could see a corner of the northern block-house, with a soldier standing guard below in the sunshine, and I peppered him well with spit-balls, he being a friend of mine.

His mystified anger brought but temporary pleasure to me. Behind me lay that villanous slate, and my task to deal with the ravishment of that silly creature, Proserpine—and that, too, in verse! Had it been my long-legged Diana with her view-halloo and her hounds and shooting her arrows like a Huron squaw from the lakes! But no!—my business lay with a puny, cowslip-pulling maid who had strayed from the stockade and got her deserts, too, for aught I know. 9

Leaning there in the breezy casement I tried to forget the jade, attentively observing the birds and the young fruit-trees, Sir William's pride. Now that the snow had melted I could see where mice, working under the crust in midwinter, had fatally girdled two young apple-trees; and I was sorry, loving apples as I do.

For a while my mind was occupied in devising a remedy against girdling; then the distant sparkle of the river caught my eye, and straightway my thoughts slipped into their natural channel, smoothly as the river flowed there in the sunshine; and I laid my plans for the taking of that bull-trout who had so grossly deceived and flouted me the past year—ay, not only me, but also that master of the craft, Sir William himself.

Thinking of Sir William, my lagging thoughts drifted back again to my desk. It madded me to pine here, making rhymes, while outside the sweet wind whispered: "Come out, Michael—come out into the green delight!"

Now Sir William had bidden me, not only to write my verses, but also to bide here awaiting his good pleasure. That meant he would return by-and-by. I had no stomach for further quarrels. Besides, I was ashamed of my disrespect and temper, and indeed, selfish, idle beast that I was, I did truly love Sir William because I knew he was the greatest man of our times—and because he loved me.

Resolved at last to accomplish some verses as proof of a contrite and diligent spirit, I set to work; and this is what I made:

"Proserpine did roam the hills,

Intent on culling daffydills;

Alas, in gleeful girlish sport,

She wandered too far from the fort,

Forgetting that no belt of peace,

Bound the people of Pluto from war to cease;

Alas, old Pluto lay in wait,

To ambush all who stayed out late;

And with a dreadful war-whoop he

Ran after the doomed Proserpine—"

Absorbed in my task, and, moreover, considerably affected by the piteous plight of the maid, I stepped back from the slate and for a moment conceived a generous idea of introducing 10 somebody to rescue Proserpine and leave Pluto damaged—perhaps scalped. Reflection, however, dissuaded me from such a liberty, not that I found the anachronism at all discordant, for, living all my life in a family where Indians were oftener seen than white men, my hazy notions concerning classic myths were inextricably mixed with the reality of my own life, and were also gayly coloured by the legends I learned from my red neighbours. So, lazy dunce that I was, with but a fraction of my attention fixed on my tasks, mythology to me was but a Græco-Mohawk medley of jumbled fables, interesting only when they concerned war or the chase.

Still I did not feel at liberty to rescue Proserpine in my verses or plump a war-arrow into Pluto. Besides I knew it would enrage Sir William.

As I stood there, breathing hard, resolved to finish the wretched maiden quickly and let the metre go a-limping, behind me I heard the door stealthily open, and I knew that long-legged wild-cat thing, Silver Heels, had crept in, her moccasins making no noise.

I pretended not to notice her, knowing she had come to taunt me; and, for a space, she stood behind me, very still. Clearly, she was reading my verses, and I became angry. Not to show it, I made out to whistle and to draw a picture of a fish on the slate. Then she knew I had seen her and laughed hatefully.

"Oh," said I, "if there is somebody come a-prying, it must be Silver Heels!" And I turned around, pretending amazement at the justness of my hazard.

"You saw me," she answered, disdainfully.

"It is your hour for the stocks," I hinted.

"I won't go," she retorted.

To secure that grace of carriage and elegance of presence necessary for a young lady of quality, and to straighten her back, which truly was as straight as a pine, Sir William and Mistress Molly were accustomed to strap her to a pine plank and lock her in the stocks for an hour at noon, forbidding Peter, Esk, and me to tickle the soles of her feet.

It was noon now; I could hear the guard changing at the north block-house, tramp! tramp! tramp! across the stony way. 11

"If you don't go to the stocks now," I said, "you'll be sorry when you do go."

"If you tickle my feet, you great booby, I'll tell Sir William," she retorted, balancing defiantly from one heel to the other.

"Will you go, Silver Heels?" I insisted.

"My name isn't Silver Heels," she observed, still coolly tilting back and forth on heels and toes. "Call me by my right name and perhaps I'll go—and perhaps I won't. So there, Mr. Micky Dunce!"

"If I call you Felicity Warren, will you go?" I inquired cautiously.

"There! you have called me Felicity Warren!" she cried in triumph.

"I didn't," said I, in a temper; "I only said that there was such a person. But you are not that person! Anyway, you toe in like a Mohawk. Anyway, you're half wild-cat, half Mohawk."

"It's a lie!" she flashed; "I'm all white to the bones of my body!"

It was true. Indeed, she was kin to Sir William and niece to Sir Peter Warren, but, to torment her, we feigned to believe her one of Mistress Molly's brood, half Mohawk; and it madded her. Besides, had not the Mohawks dubbed her Silver Heels, a year ago, when, with naked flying feet, she had beaten us all in the foot-race before Sir William and half the people of the Six Nations?

The prize had been a Barlow jack-knife, which, before the race, I had looked upon as mine. Besides, I had rashly given my old knife to Esk, and that left me without a blade to notch whistles.

"You are a Mohawk," I said, resentfully; "also you are a cat-child beneath notice. When you are hungry you cry, 'Miau! Eso cautfore!'—like Peter."

"I don't!" she said, stamping her moccasin.

"Anyway," said I, disdaining to torment her further, "the guard is changed these ten minutes, and Sir William will come to find you here a-prying. Esogee cadagcariax," I added, incautiously.

"Who is Mohawk, now!" she cried, clapping her hands. 12 "Bah, Mister Micky, it is spoon-meat you require to make you run the faster after jack-knives!"

This outrageous taunt ruffled me, the more for her laughter. I attempted to hold my head in the air and look down at the presumptuous child, but it appeared she had grown very fast in the past months since the race, and I was disturbed to find her eyes already on a straight line with mine, though she was but fifteen and I sixteen.

"I'm as high as you," she said.

"I can jump and touch the ceiling," said I; and did so.

She strove in vain, then called me dunce, and vowed what brains I had were in my feet. For that, and because she pushed me, I seized the chalk and wrote high on the slate:

"Silver Heels is Mohock she toes in like ducks."

She caught up the buckskin to wipe out the taunt, jostling me till the ferret in my pocket jumped out and ran round and round the room.

I jostled her; then she gave me a blow and a quick shove, whereupon I stumbled, pulling her to the floor to rub her face with chalk. She twisted and turned, kicking and striking while I rubbed chalk into her skin, till of a sudden she coiled up and bit me clean through the hand.

I was on my feet with a bound; she also, all white in the face and her eyes aflame.

The blood began welling up, running into my palm and along the fingers to the floor. At that same instant I heard the door of the nursery open, and I knew that Sir William was coming through the hall to the school-room.

From instinct I thrust my wounded hand into my breeches-pocket.

"Don't tell!" whispered Silver Heels, in a fright; "don't tell—and here is the jack-knife."

She thrust it into my right hand, then sped across the floor to the open window, and over the sill, dropping light as a cat on the grass below.

My first impulse was to follow her and give her such a spank as Mistress Molly administered the day she trounced her for pushing Peter into the creek. However, it was already too late; Sir William came quickly along the hall, and I had scarce time to step to the slate when he marched in. 13

Sir William had changed his clothing for the buckskin hunting-shirt and breeches which he was accustomed to wear when angling. He carried, too, that light, seasoned rod, fashioned for him by Thayendanegea, and on his bosom he wore a bouquet of gayly coloured feather-flies, made by Mistress Molly during the winter.

He approached the slate whereon my verses stared white and unfinished; and at first his brows knitted and he said, "Fudge, fudge, fudge!" Then of a sudden he sat down on the bench, clapping his hand to his brow.

"Oh Lord!" said he, and fell a-laughing, while I, hot, ashamed, and a little dizzy, my breeches-pocket being full of blood, gnawed my lips and glowered askance.

"The Lord's will be done," said he, taking breath. "Who am I to ordain, when He who fashioned yon tow-head designed it to hold neither Latin nor the classics?"

"It pleases you to laugh, sir," I muttered.

"Pleases me! Pleases me, quotha! Lad, it stabs me like a French dirk, nor can I guard the thrust in tierce! I have been wrong. A friar is not made with a twisted rope nor a man hanged with words. If you are not born a scholar, 'twas the mint-mark I could not read aright; and no blame to you, lad, no blame to you. Micky boy! Shall we leave Cæsar to go marching with his impedimenta and his Tenth Legion? Shall we consign the hypothenuse of all triangles to those who mend pens from the quills of wild-geese which better men have brought down with a single ball?"

I was regarding him wildly, uncertain of his meaning.

"Shall we," cried Sir William, heartily, "bid the nymphs and dryads farewell forever, lad, and save our learning for Roderick Random and a bowl of cider and the bitter nights of December?"

His meaning was dawning upon me slowly, for what with the pain of my hand and the dizziness, I was perhaps more stupid than usual.

"No," said Sir William, with a thump of his fist on his knee, "the college which my Lord Dartmouth has endowed is a haven for those who seek it, not a prison for men to be driven to."

He paused. 14

"I should have sought it," he said, dropping his head. "No wilderness, no wintry terrors, neither French scalping parties nor the savages of all the Canadas could have kept me from instruction had I, in my youth, been favoured by the opportunity I offer you."

I gazed at him in silence while the blood, overrunning my leather pocket, ran down to my knee-buckles.

"I was poor, without means, without counsel, save for the letters Sir Peter Warren wrote me. I traded for my daily bread; I read Ovid by lighted pine splinters; I worked—God knows I worked my flesh to the bone."

He sat, fingering the bunch of scarlet feather-flies in his breast.

"Our Lord gives us according to our needs—when we take it," he said, without irreverence. "I could have gone to England, to Oxford; I had saved enough. I did neither; I did not take the instruction I wished for, and God did not teach me Greek in my dreams," he added, bitterly.

The blood was now stealing down my stocking towards my shoe. I turned the leg so he could not observe it.

"Come, lad," he said, brightening up; "learning lies not always between thumbed leaves. I only wish that you bear yourself modestly and nobly through the world; that you keep faith with men, that your word once given shall never be withdrawn.

"This is the foundation. It includes courage. Further than that, I desire you, once a purpose formed and a course set, to steer fearlessly to the goal.

"I know you to be brave and honest; I know you to be a very Mohawk in the forest; I believe you to be merciful and tender underneath that boy's thoughtless and cruel hide.

"As for learning, I can do no more for you than I have done and have offered to do. If it pleases you, you may go to England, and learn the arts, bearing, and deportment you can never acquire here with us. No? Well, then, stay with us. I want you, Micky. We Irish are fond of each other—and I am an old man now—I am nigh sixty years, Michael—sixty years of battle. I would be glad of rest—with those I love." 15

My heart was very soft now. I looked at Sir William with an affection I had never before understood.

"There is one last thing I wish to add," he said, gravely, almost sadly. "Perhaps I may again refer to it—but I pray that it may not be necessary."

I sat up and rubbed my eyes to clear them from the sickly faintness which stole upward from my throbbing hand.

"It is this," he continued, in a low voice. "If it ever comes to you to choose between his Majesty our King and—and your native land—which God forbid!—go to your closet and kneel down, and stay there on your knees, hours, days!—until you have learned your own heart. Then—then—God go with you, Michael Cardigan."

He rose, and his face was years older. Slowly the colour came back into his cheeks; he fumbled with the brass-work on his fish-rod, then smiled.

"That is all," he said; "let Pluto chase Proserpine to hell, lad; and a devilish good place they say it is for those who like it! Where is that ferret? What! Running about unmuzzled! Hey! Vix! Vix! Come here, little reptile!"

"I'll catch her, sir," said I, stumbling forward.

But as I laid my hand on Vix the floor rose and struck me, and there I lay sprawling and senseless, with the blood running over the floor; and Sir William, believing me bitten by the ferret, pouched the poor beast and lifted me to a bench.

He must have seen my hand, however, for, when a cup of cold water set me spluttering and blinking, I found my hand tied up in Sir William's handkerchief and Sir William himself eying me strangely.

"How came that wound?" he said, bluntly.

I could not reply—or would not.

He asked me again whether the ferret bit me, and I was tempted to say yes. Treachery was abhorrent to me; I hated Silver Heels, but could not betray her, and it was easy to clap the blame on Vix.

"Sir?" I stammered.

"I asked what bit you," he said, icily.

I tried to say Vix, but the lie, too, stuck in my throat.

"I cannot tell you," I muttered. 16

"Then," said Sir William, with a strange smile of relief, "I shall not force you, Michael. May I honourably ask you how you come by this jack-knife?"

I shook my head. My face was on fire.

"Very well," he said. "Only remember that you are a man, now—a man of sixteen, and that I have to-day treated you as a man, and shall continue. And remember that a man's first duty is to protect the weaker sex, and his second duty is to endure from them all taunts, caprice, and torments without revenge. It is a hard lesson to learn, Micky, and only the true and gallant gentleman can ever learn it."

He smiled, then said:

"Pray find our little Silver Heels and return to her the jack-knife, which was her wampum-belt of faith in the honour of a gentleman."

And so he walked away, smoothing the fur of the red-eyed ferret against his breast.

When Sir William left me in the school-room, he left a lad of sixteen puffed up in a glow of pride. To be treated no longer as a fractious child—to be received at last as a man among men!

And what would Esk say? And Silver Heels, poor little mouse harnessed in the stocks below?

I had entered the school-room that morning a lazy, sullen, defiant lad, heavy-hearted, with chronic resentment against the discipline of those who had sent me into a hateful trap from the windows of which I could see the young, thirsty year quaffing spring sunshine. Now I was free to leave the accursed trap forever, a man of discretion, responsible before men, exacting from other men the same courtesies, attentions, and considerations which I might render them.

What a change had come to me, all in one brief May morning! As I stood there, resting my bandaged hand in the palm of the other, looking about me to realize the fortune which set my veins tingling, a great tide of benevolent condescension for the others swept over me, a ripple of pity and good-will for the hapless children whose benches lay in a row before me.

I no longer detested Silver Heels. I walked on tiptoe to her bench. There lay her slate and slate-pen; upon it I read a portion of the longer catechism. There, too, lay her quill and inky horn and a foolscap book sewed neatly and marked:

Felicity Warren

1774

HER BOOKE.

Poor child, doomed for years still to steep her little fingers in ink-powder while, with the powder I should require hereafter, 18 I expected to write fiercer tales on living hides with plummets cast in bullet-moulds!

Cramped with importance, I cast a contemptuous eye upon my poem which embellished the great slate, and scoured it partly out with the buckskin.

"My books," said I, to myself, "I will bestow upon Silver Heels and Esk;" and I carried out my philanthropic impulse, piling speller, reader, and arithmetic on Esk's bench; my Cæsar, my pair of globes, my compass, and my algebra I laid with Silver Heels's copy-book, first writing in the books, with some malice:

SILVER HEELS HER GIFT BOOKE FROM

MICHAEL CARDIGAN

BE DILIGENT AND OF GOOD THRIFT

KNOWLEDGE IS POWER.

For fat Peter, because I allowed Vix to bite his tight breeches, I left a pile of jacks beside his horn-book, namely, a slate-pen, three mended quills, a birchen box of ink-powder, a screw to trade with, two tops and an alley, pumice, a rule, and some wax.

Peter, though duck-limbed and half Mohawk, wrote very well in the Boston style, and could even copy in the Lettre Frisée—a poor art in some repute, but smelling to my nose of French flummery and deceit.

Having bestowed these gifts with a light heart, I walked slowly around the room, and I fear my walk was somewhat a strut.

I knew my small head was all swelled with vain imaginings; I saw myself in a flapped coat and lace, fingering the hilt of a sword at my hip, saluted by the sentries and the militia; I saw myself riding with Sir William as his deputy; I heard him say, "Mr. Cardigan, the enemy are upon us! We must fly!"—and I: "Sir William, fear nothing. The day is our own!" And I saw a lad of sixteen, with sword pointing upward and one hand twisted into Pontiac's scalp-lock, smile benignly upon Sir William, who had cast himself 19 upon my breast, protesting that I had saved the army, and that the King should hear of it.

Then, unbidden, the apparition of Mr. Butler rose into my vain dreaming, and, though I am no prophet, nor can I claim the gift of seeing behind the veil, yet I swear that Walter Butler appeared to me all aflame and bloody with scalps bunched at his girdle—and the scalps were not of the red men!

Now my imagination smoking into fire, I saw myself dogging Mr. Butler with firelock a-trail and knife loosened, on! on! through fathomless depths of forest and by the still deeps of shadowy lakes, fording the roaring tumble of rivers, swimming silent pools as otters swim, but tracking him, ever tracking Captain Butler by the scent of his reeking scalps.

There was a dew on my eyebrows as I waked into sense. Yet again I fell straightway to imagining the glories of my young future. Truly I painted life in cloying colours; and always, when I accomplished gallant deeds, there stood Silver Heels to observe me, and to marvel, and to stamp her little moccasins in vexation that I, the pride and envy of all men, applauded, courted, nay, worshipped—I, the playmate she had in her silly ignorance flouted, now stood so far beyond her that she dared not twitch the skirt of my coat nor whisper, "Sir Michael, pray condescend to notice one who passes her entire life in admiring your careless exploits."

Perhaps I would smile at her—yes, I certainly should speak to her—not with familiarity. But I would be magnanimous; she should receive gifts, spoils from wars, and I would select a suitable husband for her from the officers of my household who adored me! No, I would not be hasty concerning a husband. That would be foolish, for Silver Heels must remain heart-whole and fancy-free to concentrate her envious admiration upon me.

In a sort of ecstasy I paraded the school-room, the splendour of my visions dulling eyes and ears, and it was not until he had called me thrice that I observed Mr. Butler standing within the doorway.

The unwelcome sight cleared my brains like a dash of spring-water in the face.

"It is one o'clock," said Mr. Butler, "and time for your 20 carving lesson. Did you not hear the bugles from the forts?"

"I heard nothing, sir," said I, giving him a surly look, which he returned with that blank stare of the eyes, noticeable in hawks and kites and foul night birds surprised by light.

"Sir William dines early," he said, as I followed him through the dim hallway, past the nursery, and down stairs. "If he has to wait your pleasure for his slice of roast, you will await his pleasure for the remainder of the day in the school-room."

"It is not true!" I said, stopping short in the lower hallway. "I am free of that ratty pit forever! And of the old ferret, too," I added, insolently.

"By your favour," said Mr. Butler, "may I ask whether your erudition is impairing your bodily health, that you leave school so early in life, Master Cardigan?"

"If you were a real schoolmaster," said I, hotly, "I would answer you with a kennel lash, but you are an officer and a gentleman." And in a low voice I bade him go to the devil at his convenience.

"One year more and I could call you out for this," he said, staring at me.

"You can do it now!" I retorted, angrily, raising myself a little on my toes.

Suddenly all the hatred and contempt I had so long choked back burst out in language I now blush for. I called him a coward, a Huron, a gentleman with the instincts of a pedagogue. I heaped abuse upon him; I dared him to meet me; nay, I challenged him to face me with rifle or sword, when and where he chose. And all the time he stood staring at me with that deathly laugh which never reached his eyes.

"Measure me!" I said, venomously; "I am as tall as you, lacking an inch. I am a man! This day Sir William freed me from that spider-web you tenant, and now in Heaven's name let us settle that score which every hour has added to since I first beheld you!"

"And my honour?" he asked, coldly.

"What?" I stammered. "I ask you to maintain it with rifle or rapier! Blood scours tarnished names!" 21

"Not your blood," he said, with a stealthy glance at the dining-room door; "not the blood of a boy. That would rust my honour. Wait, Master Cardigan, wait a bit. A year runs like a spotted fawn in cherry-time!"

"You will not meet me?" I blurted out, mortified.

"In a year, perhaps," he said, absently, scarcely looking at me as he spoke.

Then from within the dining-hall came Sir William's roar: "Body o' me! Am I to be kept here at twiddle-thumbs for lack of a carver!"

I stepped back in an instant, bowing to Mr. Butler.

"I will be patient for a year, sir," I said. And so opened the door while he passed me, and into the dining-hall.

"I am sorry, sir," said I, but Sir William cut me short with:

"Damnation, sir! I am asking a blessing!"

So I buried my nose in my hollowed hand and stood up, very still.

Having given thanks in a temper, Sir William's frown relaxed and he sat down and tucked his finger-cloth under his neck with an injured glance at me.

"Zounds!" he said, mildly; "hell hath no fury like a fisherman kept waiting. Captain Butler, bear me out."

"I am no angler," said Mr. Butler, in his deadened voice.

"That is true," observed Sir William, as though condoling with Mr. Butler for a misfortune not his fault. "Perhaps some day the fever may scorch you—like our young kinsman Micky—eh, lad?"

I said, "Perhaps, sir," with eyes on the smoking joint before me. It was Sir William's pleasure that I learn to carve; and, in truth, I found it easy, save for the carving of a goose or of those wild-ducks we shot on the great Vlaie.

We were but four to dine that day: Sir William, Mr. Butler, Silver Heels, and myself. Mistress Molly remained in the nursery, where were also Peter and Esk, inasmuch as they slobbered and fouled the cloth, and so fed in the play-room.

Colonel Guy Johnson remained at Detroit, Captain John Johnson was on a mission to Albany, Thayendanegea in Quebec, and Colonel Claus, with his lady, had gone to Castle 22 Cumberland. There were no visiting officers or Indians at Johnson Hall that week, and our small company seemed lost in the great dining-hall.

Having carved the juicy joint, the gilly served Sir William, then Mr. Butler, then Silver Heels, whom I had scarcely noticed, so full was I of my quarrel with Mr. Butler. Now, as Saunders laid her plate, I gave her a look which meant, "I did not tell Sir William," whereupon she smiled at her plate and clipped a spoonful from a dish of potatoes.

"Good appetite and good health, sir," said I, raising my wine-glass to Sir William.

"Good health, my lad!" said Sir William, heartily.

Glasses were raised again and compliments said, though my face was sufficient to sour the Madeira in Mr. Butler's glass.

"Your good health, Michael," said Silver Heels, sweetly.

I pledged her with a patronizing amiability which made her hazel-gray eyes open wide.

Now, coxcomb that I was, I sat there, dizzied by my new dignity, yet carefully watching Sir William to imitate him, thinking that, as I was now a man, I must observe the carriage, deportment, and tastes of men.

When Sir William declined a dish of jelly, I also waved it away, though God knew I loved jellies.

When Sir William drank the last of the winter's ale, I shoved aside my small-beer and sent for a mug.

"It will make a humming-top of your head," said Sir William. "Stick to small-beer, Micky."

Mortified, I tossed off my portion, and was very careful not to look at Silver Heels, being hot in the face.

Mr. Butler and Sir William spoke gravely of the discontent now rampant in the town of Boston, and of Captain John Johnson's mission to Albany. I listened greedily, sniffing for news of war, but understood little of their discourse save what pertained to the Indians.

Some mention, indeed, was made of rangers, but, having always associated militia and rangers with war on the Indians, I thought little of what they discussed. I even forgot my new dignity, and secretly pinched a bread crumb into the shape of a little pig which I showed to Silver Heels. She 23 thereupon pinched out a dog with hound's ears for me to admire.

I was roused by Sir William's voice in solemn tones to Mr. Butler: "Now, God forbid I should live to see that, Captain Butler!" and I pricked up my ears once more, but made nothing of what followed, save that there were certain disloyal men in Massachusetts and New York who might rise against our King and that our Governor Tryon meant to take some measures concerning tea.

"Well, well," burst out Sir William at length; "in evil days let us thank God that the fish still swim! Eh, Micky? I wish the ice were out."

"The anchor-ice is afloat, and the Kennyetto is free, sir," I said, quickly.

"How do you know?" asked Sir William, laughing.

I had, the day previous, run across to the Kennyetto to see, and I told him so.

He was pleased to praise my zeal and to say I ran like a Mohawk, which praise sounded sweet until I saw Silver Heels's sly smile, and I remembered the foot-race and the jack-knife.

But I was above foot-races now. Others might run to amuse me; I would look on—perhaps distribute prizes.

"Some day, Sir William, will you not make me one of your deputies?" I asked, eagerly.

"Hear the lad!" cried Sir William, pushing back his chair. "On my soul, Captain Butler, it is time for old weather-worn Indian commissioners like me to resign and make way for younger blood! And his Majesty might be worse served than by Micky here; eh, Captain Butler?"

"Perhaps," said Mr. Butler, in his dead voice.

Sir William rose and we all stood up. The Baronet, brushing Silver Heels on his way to the door, passed his arm around her and tilted her chin up.

"Now do you go to Mistress Mary and beg her to place you in the stocks for an hour; and stay there in patience for your body's grace. Will you promise me, Felicity?"

Silver Heels began to pout and tease, hooking her fingers in Sir William's belt, but the Baronet packed her off with his message to Mistress Molly, and went out to the portico 24 where one of his damned Scotch gillies attended with gaff, spear, and net-sack.

"Oho," thought I, "so it's salmon in the Sacondaga!" And I fell to teasing that he might take me, too.

"No, Micky," he said, soberly; "it's less for sport than for quiet reflection that I go. Don't sulk, lad. To-morrow, perhaps."

"Is it a promise, sir?" I cried.

"Perhaps," he laughed, "if the cards turn up right."

That meant he had some Indian affair on hand, and I fell back, satisfied that his rod was a ruse, and that he was really bound for one of the council fires at the upper castle.

So he went away, the sentry at the south block-house presenting his firelock, and I back into the hall, whistling, enchanted with my new liberty, yet somewhat concerned as to the disposal of so vast an amount of time, now all my own.

I had now been enfranchised nearly three hours, and had already used these first moments of liberty in picking a mortal quarrel with Mr. Butler. I had begun rashly; I admitted that; yet I could not regret the defiance. Soon or late I felt that Mr. Butler and I would meet; I had believed it for years. Now that at last our tryst was in sight, it neither surprised nor disturbed me, nor, now that he was out of my sight, did I feel impatient to settle it, so accustomed had I become to waiting for the inevitable hour.

I strolled through the hallway, hands in pockets, whistling "Amaryllis," a tune that smacked on my lips; and so came to the south casement. Pressing my nose to the pane, I looked into the young orchard where the robins ran in the new grass; and I found it delicious to linger in-doors, knowing I was free to go out when I chose, and none to cry, "Come back!"

In the first flush of surprise and pleasure, I have noticed that the liberated seldom venture instantly into that freedom so dearly desired. Open the cage of a thrush that has sung all winter of freedom, and lo! the little thing, creeping out under the sky, runs back to the cage, fearing the sweet freedom of its heart's desire.

So I; and mounted the stairway, seeking my own little chamber. Here I found Esk and Peter at play, letting down 25 a string from the open window, baited with corn, and the pullets jumping for it with great outcry and flapping of wings.

So I played with them for a while, then put them out, and bolted the door despite their cries and kicks.

Sitting there on my cot I surveyed my domain serenely, proud as though it had been a mansion and all mine.

There were my books, not much thumbed save Roderick Random and the prints of Le Brun's Battles of Alexander. Still I cherished the others because gifts of Sir William or relics of my honoured father—the two volumes called An Introduction to Sir Isaac Newton's Philosophy; two volumes of Chambers's Dictionary; all the volumes of The Gentleman's Magazine from 1748; Titan's Loves of the Gods—an immodest print which I hated; my beloved "Amaryllis," called A New Musical Design, and well bound; and last a manuscript much faded and eaten by mice, yet readable, and it was a most lovely song composed long since by a Mr. Pepys, the name of which was "Gaze not on Swans!"

My chamber was small, yet pleasing. Upon the walls I had placed, by favour of Sir William, pictures of the best running-horses at Newmarket, also four prints of a camp by Watteau, well executed, though French. Also, there hung above the door a fox's mask, my whip, my hunting-horn, my spurs, and two fish-rods made for me by Joseph Brant, who is called Thayendanegea, chief of the Mohawk and of the Six Nations, and brother to Aunt Molly, who is no kin of mine, though her children are Sir William's, and he is my kinsman.

In this room also I kept my black lead-pencil made by Faber, a ream of paper from England, and a lump of red sealing-wax.

I had written, in my life, but two letters: one three years since I wrote to Sir Peter Warren to thank him for a sum of money sent for my use; the other to a little girl named Marie Livingston, whom I knew in Albany when Sir William took me for the probating of papers which I do not yet understand.

She wrote me a letter, which was delivered by chance, the express having been scalped below Fonda's Bush, and signed 26 "your cozzen Marie," Mr. Livingston being kin to Sir William. I had not yet written again to her, though I had meant to do so these twelve months past. She had yellow hair which was pleasing, and she did not resemble Silver Heels in complexion or manner, having never flouted me. Her father gave me two peaches, some Salem sweets called Black Jacks, and a Delaware basket to take home with me, heaped with macaroons, crisp almonds, rock-candy, caraways, and suckets. These I prudently finished before coming again to Johnson Hall, and I remember I forgot to save a sucket for Silver Heels; and her anger when I gave her the Delaware basket all sticky inside; and how Peter licked it and blubbered while still a-licking.

Thus, as I sat there on my cot, scenes of my life came jostling me like long-absent comrades, softening my mood until I fell to thinking of those honoured parents I had never seen save in the gray dreams which mazed my sleep. For the day that brought life to me had robbed my honoured mother of her life; and my father, Captain Cardigan, lying with Wolfe before Quebec, sent a runner to Sir William enjoining him to care for me should the chance of battle leave me orphaned.

So my father, with Wolfe's own song on his lips:

"Why, soldiers, why

Should we be melancholy boys?

Why, soldiers, why?

Whose business 'tis to die—"

fell into Colonel Burton's arms at the head of Webb's regiment, and his dying eyes saw the grenadiers wipe out the disgrace of Montmorency with dripping bayonets. So he died, with a smile, bidding Webb's regiment God-speed, and sending word to the dying Wolfe that he would meet him a minute hence at Peter's gate in heaven.

Thus came I naturally by my hatred for the French, nor was there in all France sufficient wampum to wipe away the feud or cover the dear phantom that stood in my path as I passed through life my way.

Now, as I sat a-thinking by the window, below me the robins in all the trees had begun their wild-wood vespers—hymns 27 of the true thrush, though not rounded with a thrush's elegance.

The tree-shadows, too, had grown in length, and the afternoon sun wore a deeper blazonry through the hill haze in the west.

Fain to taste of the freedom which was now mine, I went out and down the stairs, passing my lady Silver Heels strapped to a back-board and in a temper with her sampler.

"Oh, Micky," she said, "my bones ache, and Mistress Molly is with the baby, and the key is there on that brass nail."

"It would be wrong if I released you," said I, piously, meaning to do it, nevertheless.

"Oh, Micky," she said, with a kind of pitiful sweetness which at times she used to obtain advantages from me.

So I took the key and unlocked the stocks, giving her feet a pinch to let her know I was not truly as soft-hearted as she might deem me, nor too easily won by woman's beseeching.

And now, mark! No sooner was she free than she gave me a slap for the pinch and away she flew like a tree-lynx with the pack in cry.

"This," thought I, "is a woman's gratitude," and I locked the stocks again, wishing Silver Heels's feet were in them.

"Best have it out at once with Mistress Molly," thought I, and went to the nursery. But before I could knock on the door, Mistress Molly heard me with her ears of a Mohawk, and came to the door with one finger on her lips.

Truly the sister of Thayendanegea was a stately and comely lady, and a beauty, too, being little darker than some French ladies I have seen, and of gracious and noble presence.

Bearing and mien were proud, yet winning; and, clothed always as befitted the lady of Sir William Johnson, none who came into her presence could think less of her because of her Mohawk blood or the relation she bore to Sir William—an honest one as she understood it.

She ruled the Hall with dignity and with an authority that none dreamed of opposing. At table she was silent, 28 yet gracious; in the nursery she reigned a beloved and devoted mother; and if ever a man's wife remained his sweetheart to the end, Molly Brant was Sir William's true-love while his life endured.

"Why did you release Felicity from the stocks, Michael?" said she, in a whisper.

So her quick Indian ear had heard the click of that lock!

"I had come to tell you of it, Aunt Mary," said I.

She looked at me keenly, then smiled.

"A sin confessed is half redressed. I had meant to release Felicity some time since, but the baby had fretted herself to sleep in my arms and I feared to put her down. But, Michael, remember in future to ask permission when you desire to play with Felicity."

"Play with Felicity!" I said, scornfully. "I am past the playing age, Aunt Molly, and I only released her because I thought her back ached."

Mistress Molly looked at me again, long and keenly.

"Little savage," she said, gently, "mock at my people no more. I should chide you for misusing Peter, but—I will say nothing. You make my heart heavy sometimes."

"I do honour and love you, Aunt Molly!" I said; "it was not that I mocked at Peter, but his breeches were so tight that I wondered if Vix could bite him. I shall now go to the garden and allow Peter to kick my shins. Anyway, I gave him all my quills and a plummet and a screw."

She laughed silently, bidding me renounce my intention regarding Peter, and so dismissed me, with her finger on her lips conjuring silence.

So I pursued my interrupted way to the garden where the robins carolled in every young fruit-tree, and the blue shadows wove patterns on the grass.

Peter and Esk were on the ground playing at marbles, with Silver Heels to judge between them.

Esk, perceiving me, cried out: "Knuckle down at taws, Micky! Come on! Alleys up and fen dubs!"

"Fen dubs your granny!" I replied, scornfully, clean forgetting my new dignity. "Dubs all, and bull's-eyes up is what I play, unless you want to put in agates?" I added, covetously. 29

Esk shook his head in alarm, muttering that his agates were for shooters; but fat Peter, sprawling belly down at the ring, offered to put up an agate against four bull's-eyes, two agates, and twelve miggs, and play dubs and span in a round fat.

The proposition was impudent, unfair, and thoroughly Indian. I was about to spurn it when Silver Heels chirped up, "Micky doesn't dare."

"Put up your agate, Peter," said I, coolly, ignoring Silver Heels; and I fished the required marbles from my pocket and placed them in the ring.

"My shot," announced Peter, hurriedly, crowding down on the line, another outrage which, considering the presence of Silver Heels, I passed unnoticed.

Peter shot and clipped a migg out of the ring. He shot again and grazed an agate, shouting "Dubs!" to the derision of us all.

Then I squatted down and sent two bull's-eyes flying, but, forestalled by Peter's hysterical "Fen dubs!" was obliged to replace one. However, I shot again and it was dubs all, and I pocketed both of my agates and Peter's also.

This brought on a wrangle, which Silver Heels settled in my favour. Then I sat down and, with deadly accuracy, "spun," from which comfortable position, and without spanning, I skinned the ring, leaving Peter grief-stricken, with one migg in his grimy fist.

"You may have them," said I, condescendingly, dropping my spoils into Silver Heels's lap.

She coloured with surprise and pleasure, scarcely finding tongue to say, "Thank you, Micky."

Peter, being half Indian, demanded more play. But I was satiated and, already remembering my dignity, regretted the lapse into children's pastimes. I quieted Peter by giving him the remainder of my marbles, explaining that I had renounced such games for manlier sport, which statement, coupled with my lavish generosity, impressed Peter and Esk, if it had not effect upon Silver Heels.

I sat down on the stone bench near the bee-hives and drew from my pocket the jack-knife given me by Silver Heels as a bribe to silence. 30

"Come over here, Silver Heels," I said, with patronizing kindness.

"What for?" she demanded.

"Oh, don't come then," I retorted, whereat she rose from the grass with her skirt full of marbles and came over to the stone bench.

After a moment she seated herself, eying the knife askance. I had opened the blade. Lord, how I hated to give it back!

"Take it," said I, closing the blade, but not offering it to her.

"Truly?" she stammered, not reaching out her hand, for fear I should draw it away again to plague her.

I dropped the knife into her lap among the marbles, thrilling at the spectacle of my own generosity.

She seized it, repeating:

"King, King, double King!

Can't take back a given thing!"

"You needn't say 'King, King, double King,'" said I, offended; "for I was not going to take it back, silly!"

"Truly, Michael?" she asked, looking up at me. Then she added, sweetly, "I am sorry I bit you."

"Ho!" said I, "do you think you hurt me?"

She said nothing, playing with the marbles in her lap.

I sat and watched the bees fly to and fro like bullets; in the quiet even the hills, cloaked in purple mantles, smoked with the steam of hidden snow-drifts still lingering in ravines where arbutus scents the forest twilight.

The robins had already begun their rippling curfew call; crickets creaked from the planked walk. Behind me the voices of Peter and Esk rose in childish dispute or excited warning to "Knuckle down hard!" Already the delicate spring twilight stained the east with primrose and tints of green. A calm star rose in the south.

Presently Silver Heels pinched me, and I felt around to pinch back.

"Hush," she whispered, jogging my elbow a little, "there is a strange Indian between us and the block-house. He has a gun, but no blanket!"

For a moment a cold, tight feeling stopped my breath, not 31 because a strange Indian stood between me and the block-house, but because of that instinct which stirs the fur on wild things when taken unawares, even by friends.

My roughened skin had not smoothed again before I was on my feet and advancing.

Instantly, too, I perceived that the Indian was a stranger to our country. Although an Iroquois, and possibly of the Cayuga tribe, yet he differed from our own Cayugas. He was stark naked save for the breech-clout. But his moccasins were foreign, so also was the pouch which swung like a Highlander's sporran from his braided clout-string, for it was made of the scarlet feathers of a bird which never flew in our country, and no osprey ever furnished the fine snow-white fringe which hung from it, falling half-way between knee and ankle.

Observing him at closer range, I saw he was in a plight: his flesh dusty and striped with dry blood where thorns had brushed him; his eyes burning with privation, and sunk deep behind the cheek-bones.

As I halted, he dropped the rifle into the hollow of his left arm and raised his right hand, palm towards me.

I raised my right hand, but remained motionless, bidding him lay his rifle at his feet.

He replied in the Cayuga language, yet with a foreign intonation, that the dew was heavy and would dampen the priming of his rifle; that he had no blanket on which to lay his arms, and further, that the sentinels at the block-houses were watching him with loaded muskets.

This was true. However, I permitted him to advance no closer until I hailed a soldier, who came clumping out of the stables, and who instantly cocked and primed his musket.

Then I asked the strange Cayuga what he wanted.

"Peace," he said, again raising his hand, palm out; and again I raised my hand, saying, "Peace!"

From the scarlet pouch he drew a little stick, six inches long, and painted red.

"Look out," said I to the soldier, "that is a war-stick! If he shifts his rifle, aim at his heart."

But the runner had now brought to light from his pouch other sticks, some blood-red, some black ringed with white. 32 These he gravely sorted, dropping the red ones back into his pouch, and naïvely displaying the black and white rods in a bunch.

"War-ragh-i-ya-gey!" he said, gently, adding, "I bear belts!"

It was the title given by our Mohawks to Sir William, and signified, "One who unites two peoples together."

"You wish to see Chief Warragh," I repeated, "and you come with your pouch full of little red sticks?"

He darted a keen glance at me, then, with a dignified gesture, laid his rifle down in the dew.

A little ashamed, I turned and dismissed the soldier, then advanced and gave the silent runner my hand, telling him that although his moccasins and pouch were strange, nevertheless the kin of the Cayugas were welcome to Johnson Hall. I pointed at his rifle, bidding him resume it. He raised it in silence.

"He is a belt-bearer," I thought to myself; "but his message is not of peace."

I said, pleasantly:

"By the belts you bear, follow me!"

The dull fire that fever kindles flickered behind his shadowy eyes. I spoke to him kindly and conducted him to the north block-house.

"Bearer of belts," said I, passing the sentry, and so through the guard-room, with the soldiers all rising at attention, and into Sir William's Indian guest-room.

My Cayuga must have seen that he was fast in a trap, yet neither by word nor glance did he appear to observe it.

The sun had set. A chill from the west sent the shivers creeping up my legs as I called a soldier and bade him kindle a fire for us. Then on my own responsibility I went into the store-room and rummaged about until I discovered a thick red blanket. I knew I was taking what was not mine; I knew also I was transgressing Sir William's orders. Yet some instinct told me to act on my own discretion, and that Sir William would have done the same had he been here.

A noise at the guard door brought me running out of the store-room to find my Cayuga making to force his way out, and the soldiers shoving him into the guest-room again. 33

"Fall back!" I cried, my wits working like shuttles; and quickly added in the Cayuga tongue: "Cayugas are free people; free to stay, free to go. Open the door for my brother who fears his brother's fireside!"

There was a silence; the soldiers stood back respectfully; a sergeant opened the outer door. But the Indian, turning his hot eyes on me, swung on his heel and re-entered the guest-room, drawing the flint from his rifle as he walked.

I followed and laid the thick red blanket on his dusty shoulders.

"Sergeant," I called, "send McCloud for meat and drink, and notify Sir William as soon as he arrives that his brothers of the Cayuga would speak to him with belts!"

I was not sure of the etiquette required of me after this, not knowing whether to leave the Cayuga alone or bear him company. Tribes differ, so do nations in their observance of these forms. One thing more puzzled me: here was a belt-bearer with messages from some distant and strange branch of the Cayuga tribe, yet the etiquette of their allies, our Mohawks, decreed that belts should be delivered by sachems or chiefs, well escorted, and through the smoke of council fires never theoretically extinguished between allies and kindred people.

One thing I of course knew: that a guest, once admitted, should never be questioned until he had eaten and slept.

But whether or not I was committing a breach of etiquette by squatting there by the fire with my Cayuga, I did not know.

However, considering the circumstances, I called out for a soldier to bring two pipes and tobacco; and when they were fetched to me, I filled one and passed it to the Cayuga, then filled the other, picked a splinter from the fire, lighted mine, and passed the blazing splinter to my guest.

If his ideas on etiquette were disturbed, he did not show it. He puffed at his pipe and drew his blanket close about his naked body, staring into the fire with the grave, absent air of a cat on a wintry night.

Now, stealing a glance at his scalp-lock, I saw by the fire-light the stumps of two quills, with a few feather-fronds still clinging to them, fastened in the knot on his crown. 34 The next covert glance told me that they were the ragged stubs of the white-headed eagle's feathers, and that my guest was a chief. This set me in a quandary. What was a strange Cayuga chief doing here without escort, without blanket, yet bearing belts? Etiquette absolutely forbade a single question. Was I, in my inexperience, treating him properly? Would my ignorance of what was due him bring trouble and difficulty to Sir William when he returned?

Suddenly resolved to clear Sir William of any suspicion of awkwardness, and at the risk of my being considered garrulous, I rose and said:

"My brother is a man and a chief; he will understand that in the absence of my honoured kinsman, Sir William Johnson, and in the absence of officers in authority, the hospitality of Johnson Hall falls upon me.

"Ignorant of my brother's customs, I bid him welcome, because he is naked, tired, and hungry. I kindle his fire; I bring him pipe and food; and now I bid him sleep in peace behind doors that open at his will."

Then the Cayuga rose to his full noble height, bending his burning eyes on mine. There was a silence; and so, angry or grateful, I knew not which, he resumed his seat by the fire, and I went out through the guard-room into the still, starry night.

But I did not tarry to sniff at the stars nor search the dewy herbage for those pale blossoms which open only on such a night, hiding elf-pearls in their fairy petals. Straightway I sought Mistress Molly in the nursery, and told her what I had done. She listened gravely and without comment or word of blame or praise, which was like all Indians. But she questioned me, and I described the strange belt-bearer from his scalp-lock to the sole of his moccasin.

"Cayuga," she said, softly; "what make was his rifle?"

"Not English, not French," I said. "The barrel near the breech bore figures like those on Sir William's duelling pistols."

"Spanish," she said, dreamily. "In his language did he pronounce agh like ahh?"

"Yes, Aunt Molly."

She remained silent a moment, thoughtful eyes on mine. 35 Then she smiled and dismissed me, but I begged her to tell me from whence my Cayuga came.

"I will tell you this," she said. "He comes from very, very far away, and he follows some customs of the Tuscaroras, which they in turn borrow from a tribe which lives so far away that I should go to sleep in counting the miles for you."

With that she shut the nursery door, and I, no wiser than before, and understanding that Mistress Molly did not mean I should be wiser, sat down on the stairs to think and to wait for Sir William.

A moment later a man on horseback rode out of our stables at a gallop and clattered away down the hill. I listened for a moment, then thought of other things.

At late candle-light, Sir William still tarrying, I went to the north block-house, where Mr. Duncan, the lieutenant commanding the guard, received me with unusual courtesy, the reason of which I did not at the time suspect.

"An express from Sir William has at this moment come in," said he. "Sir William is aware that a belt-bearer from Virginia awaits him."

"How could Sir William, who is at Castle Cumberland, know that?" I began, then was silent, as it flashed into my mind that Mistress Molly had sent an express to Sir William as soon as I had told her about the strange Cayuga. That was the galloping horseman I had heard.

Pondering and perplexed, I looked up to find Mr. Duncan smiling at me.

"I understand," said he, "that Sir William is pleased to approve your conduct touching the strange Cayuga."

"How do you know?" I asked, quickly, my heart warming with pleasure.

"I know this," said Mr. Duncan, laughing, "that Sir William has left something for you with me, a present, in fact, which I am to deliver to you on the morrow."

"What is it, Mr. Duncan?" I teased; but the laughing officer shook his head, retiring into the guard-room and pretending to be afraid of me.

The soldiers, lounging around the settles, pipes between their teeth, looked on with respectful grins. Clearly, even they appeared to know what Sir William had sent to me from Castle Cumberland.

As I stood in the guard-room, eager, yet partly vexed, away below in the village the bell in the new stone church began to ring.

"What is that?" I asked, in surprise. 37

The soldiers had all risen, taking their muskets from the racks, straightening belts and bandoleers. In the stir and banging of gun-stocks on the stone floor, my question perhaps was not heard by Mr. Duncan, for he stood silent, untwisting his sword knots and eying the line which the sergeant, who carried the halberd, was forming in the room.

A drummer and a trumpeter took station, six paces to the right and front; the sergeant, at a carry, advanced and saluted with, "Parade is formed, sir."

"'Tention!" sang out Mr. Duncan. "Support arms! Carry arms! Trail arms! File by the left flank! March!" And with drawn claymore on his shoulder he passed out into the starlight.

I followed; and now, standing by the block-house gate, far away in the village I heard the rub-a-dub of a drum and a loud trumpet blowing.

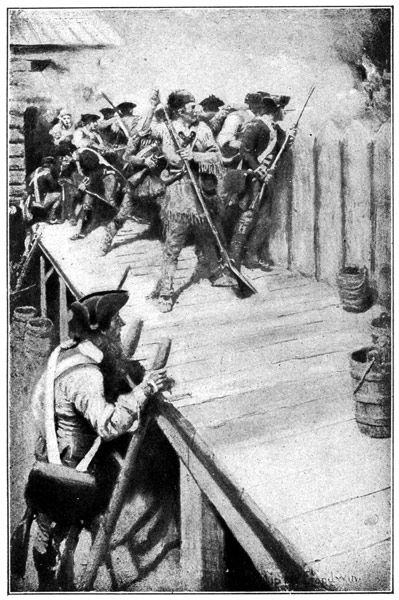

Nearer and nearer came the drum; the trumpet ceased. And now I could hear the tramp, tramp, tramp of infantry on the hill's black crest.

"Present arms!" cried Mr. Duncan, sharply.

A dark mass which I had not supposed to be moving, suddenly loomed up close in front of us, taking the shape of a long column, which passed with the flicker of starlight on musket and belt, tramp, tramp, tramp to the ringing drum-beats.

Then our drum rattled and trumpet sang prettily, while Mr. Duncan rendered the officer's salute as a dark stand of colours passed, borne furled and high above the slanting muskets.

Baggage wains began to creak by, great shapeless hulks rolling in on the black ocean of the night, with soldiers half asleep on top, and teamsters afoot, heads hanging drowsily and looped raw-hides trailing.

The last yoke of oxen passed, dragging a brass cannon.

"'Tention!" said Mr. Duncan. "Support arms! Trail arms! 'Bout face! By the right flank, wheel! March!"

Back into the block-house filed the guard, the drummer bearing his drum flat on his hip, the trumpeter swinging his instrument to his shoulder-knots.

Mr. Duncan sent his claymore ringing into the scabbard, 38 wrapped his plaid around his throat, and strolled off towards the new barracks, east of the Hall.

"What troops were those, sir?" I asked, respectfully.

"Three companies of Royal Americans from Albany," said he. Then, noticing my puzzled face, he added, "There is to be a big council fire held here, Master Cardigan. Did you not know it?"

"No," said I, slowly, reluctant to admit that I had not shared Sir William's confidence.

"Look yonder," said Mr. Duncan.

Far out in the pale starlight, south and west of the Hall, I saw fires kindled, one by one, until the twinkle of their lights ran for a mile across the uplands. On a hill in the north a signal fire sent long streamers of flame straight up into the sky; other beacons flashed out in the darkness, some so distant that I could not be certain they were more than sparks of my imagination.

"It is the Six Nations gathering," said Mr. Duncan. "We expect important guests."

"What for?" I asked.

"I don't know," said Mr. Duncan, gravely. "Good-night, Mr. Cardigan."

"Good-night, sir," I said, thoughtfully; then cried after him, "and my present, Mr. Duncan?"

"To-morrow," he answered, and passed on his way a-laughing.

I walked quickly back to the Hall, where I encountered Esk and Peter, well bibbed, cleaning the last crumb from their bowls of porridge.

"Did you see the soldiers?" cried Esk, tapping upon his bowl and marching up and down the hallway.

"Look out of the back windows," added Peter. "The Onondaga fires are burning on the hills."

"Oneidas," corrected Esk.

"Onondagas," persisted Peter, smearing his face with his spoon to lick it.

"Where is Silver Heels?" I asked.

Mistress Molly came into the hall from the pantry, keys jingling at her girdle, and took Peter by his sticky fingers, bidding Esk follow. 39

"Bed-time," she said, with her pretty smile. "Michael, Felicity is being dressed by Betty. If Sir William does not return, you will dine with Felicity alone; and I expect you to conduct exactly like Sir William, and refrain from kicking under the table."

"Yes, Aunt Molly," said I, delighted.

Esk and Peter, being instantly hustled bedward, left lamenting and asserting that they too were old enough to imitate Sir William.

Silver Heels, with her hair done by Betty, and a blue sash over her fresh-flowered cambric, passed them on the stairs coming down, pausing to wish Mistress Molly good-night, and to slyly pinch fat Peter.

"Felicity," said Mistress Molly, "will you conduct as befits your station?"

"Oh la, Aunt Molly!" she answered, with that innocent, affected lisp which I knew was ever the forerunner of mischief.

She made her reverence, waiting on the landing until she heard the nursery door close, then flung both legs astride the balustrade and slid down like a flash.