Title: Narrative of the surveying voyages of His Majesty's ships Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836. Volume I. Proceedings of the First Expedition, 1826-1830

Author: Robert Fitzroy

Philip Parker King

Release date: February 23, 2012 [eBook #38961]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Marilynda Fraser-Cunliffe, Keith Edkins and

the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at

https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by the Posner Memorial Collection

(http://posner.library.cmu.edu/Posner/))

| Transcriber's note: |

A few typographical errors have been corrected. They

appear in the text like this, and the

explanation will appear when the mouse pointer is moved over the marked

passage. |

VOYAGES

OF THE

ADVENTURE AND BEAGLE.

———

VOLUME I.

NARRATIVE

OF THE

SURVEYING VOYAGES

OF HIS MAJESTY'S SHIPS

ADVENTURE AND BEAGLE,

BETWEEN

THE YEARS 1826 AND 1836,

DESCRIBING THEIR

EXAMINATION OF THE SOUTHERN SHORES

OF

SOUTH AMERICA,

AND

THE BEAGLE'S CIRCUMNAVIGATION OF THE GLOBE.

———

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

———

LONDON:

HENRY COLBURN, GREAT MARLBOROUGH STREET.

———

1839.

VOLUME I.

———

PROCEEDINGS

OF

THE FIRST EXPEDITION,

1826—1830,

UNDER THE COMMAND OF

CAPTAIN P. PARKER KING,

R.N., F.R.S.

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

THE EARL OF MINTO, G.C.B.,

FIRST LORD COMMISSIONER

OF THE

ADMIRALTY.

———

MY LORD:

I have the honour of dedicating to your lordship, as Head of the Naval Service, this narrative of the Surveying Voyages of the Adventure and Beagle, between the years 1826 and 1836.

Originated by the Board of Admiralty, over which Viscount Melville presided, these voyages have been carried on, since 1830, under his lordship's successors in office.

Captain King has authorized me to lay the results of the Expedition which he commanded, from 1826 to 1830, before your lordship, united to those of the Beagle's subsequent voyages.

I have the honour to be,

MY LORD,

Your lordship's obedient servant,

ROBERT FITZ-ROY.

In this Work, the result of nine years' voyaging, partly on coasts little known, an attempt has been made to combine giving general information with the paramount object—that of fulfilling a duty to the Admiralty, for the benefit of Seamen.

Details, purely technical, have been avoided in the narrative more than I could have wished; but some are added in the Appendix to each volume: and in a nautical memoir, drawn up for the Admiralty, those which are here omitted will be found.

There are a few words used frequently in the following pages, which may not at first sight be familiar to every reader, therefore I need hardly apologize for saying that, although the great Portuguese navigator's name was Magalhaens—it is generally pronounced as if written Magellan:—that the natives of Tierra del Fuego are commonly called Fuegians;—and that Chilóe is thus accented for reasons given in page 384 of the second volume.

In the absence of Captain King, who has entrusted to me the care of publishing his share of this work, I may have overlooked errors which he would have detected. Being hurried, and unwell, while attending to the printing of his volume, I was not able to do it justice.

It may be a subject of regret, that no paper on the Botany of Tierra del Fuego is appended to the first volume. Captain King took great pains in forming and preserving a botanical collection, aided by a person embarked solely for that purpose. He placed this collection in the British Museum, and was led to expect that a first-rate botanist would have examined and described it; but he has been disappointed.

In conclusion, I beg to remind the reader, that the work is unavoidably of a rambling and very mixed character; that some parts may be wholly uninteresting to most readers, though, perhaps, not devoid of interest to all; and that its publication arises solely from a sense of duty.

London, March 1839.

In 1825, the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty directed two ships to be prepared for a Survey of the Southern Coasts of South America; and in May, of the following year, the Adventure and the Beagle were lying in Plymouth Sound, ready to carry the orders of their Lordships into execution.

These vessels were well provided with every necessary, and every comfort, which the liberality and kindness of the Admiralty, Navy Board, and officers of the Dock-yards, could cause to be furnished.

On board the Adventure, a roomy ship, of 330 tons burthen, without guns,[1] lightly though strongly rigged, and very strongly built, were—

In the Beagle, a well-built little vessel, of 235 tons, rigged as a barque, and carrying six guns, were—

| Pringle Stokes | Commander and Surveyor. |

| E. Hawes | Lieutenant. |

| W. G. Skyring | Lieut. and Assist. Surveyor. |

| S. S. Flinn | Master. |

| E. Bowen | Surgeon. |

| J. Atrill | Purser. |

| J. Kirke | Mate. |

| B. Bynoe | Assistant Surgeon. |

| J. L. Stokes | Midshipman. |

| R. F. Lunie | Volunteer 1st Class. |

| W. Jones | Volunteer 2d Class. |

| J. Macdouall | Clerk. |

In the course of the voyage, several changes occurred among the officers, which it may be well to mention here.

In September, 1826, Lieutenant Hawes invalided: and was succeeded by Mr. R. H. Sholl, the senior mate in the Expedition.

In February, 1827, Mr. Ainsworth was unfortunately drowned; and, in his place, Mr. Williams acted, until superseded by Mr. S. S. Flinn, of the Beagle.

Lieutenant Cooke invalided in June, 1827; and was succeeded by Mr. J. C. Wickham.

In the same month Mr. Graves received information of his promotion to the rank of Lieutenant.

Between May and December, 1827, Mr. Bowen and Mr. Atrill invalided; besides Messrs. Lunie, Jones, and Macdouall: Mr. W. Mogg joined the Beagle, as acting Purser; and Mr. D. Braily, as volunteer of the second class.

Mr. Bynoe acted as Surgeon of the Beagle, after Mr. Bowen left, until December, 1828.

In August, 1828, Captain Stokes's lamented vacancy was temporarily filled by Lieutenant Skyring; whose place was taken by Mr. Brand.

Mr. Flinn was then removed to the Adventure; and Mr. A. Millar put into his place.

In December, 1828, the Commander-in-chief of the Station (Sir Robert Waller Otway) superseded the temporary arrangements of Captain King, and appointed a commander, lieutenant, master, and surgeon to the Beagle. Mr. Brand then invalided, and the lists of officers stood thus—

| T. Graves | Lieut. and Assist. Surveyor. |

| J. C. Wickham | Lieutenant. |

| S. S. Flinn | Master. |

| J. Tarn | Surgeon. |

| G. Rowlett | Purser. |

| G. Harrison | Mate. |

| W. W. Wilson | Mate. |

| E. Williams | Second Master. |

| J. Park | Assistant Surgeon. |

| A. Mellersh | Midshipman. |

| A. Millar | Master's Assistant. |

| J. Russell | Volunteer 2d Class. |

| G. Hodgskin | Clerk. |

| J. Anderson | Botanical Collector. |

In June, 1829, Lieutenant Mitchell joined the Adventure; and in February, 1830, Mr. A. Millar died very suddenly:—and very much regretted.

The following Instructions were given to the Senior Officer of the Expedition.

"By the Commissioners for executing the Office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland, &c.

"Whereas we think fit that an accurate Survey should be made of the Southern Coasts of the Peninsula of South America, from the southern entrance of the River Plata, round to Chilóe; and of Tierra del Fuego; and whereas we have been induced to repose confidence in you, from your conduct of the Surveys in New Holland; we have placed you in the command of His Majesty's Surveying Vessel the Adventure; and we have directed Captain Stokes, of His Majesty's Surveying Vessel the Beagle, to follow your orders.

"Both these vessels are provided with all the {xvi}means which are necessary for the complete execution of the object above-mentioned, and for the health and comfort of their Ships' Companies. You are also furnished with all the information, we at present possess, of the ports which you are to survey; and nine Government Chronometers have been embarked in the Adventure, and three in the Beagle, for the better determination of the Longitudes.

"You are therefore hereby required and directed, as soon as both vessels shall be in all respects ready, to put to sea with them; and on your way to your ulterior destination, you are to make, or call at, the following places, successively; namely; Madeira: Teneriffe: the northern point of St. Antonio, and the anchorage at St. Jago; both in the Cape Verd Islands: the Island of Trinidad, in the Southern Atlantic: and Rio de Janeiro: for the purpose of ascertaining the differences of the longitudes of those several places.

"At Rio de Janeiro, you will receive any supplies you may require; and make with the Commander-in-chief, on that Station, such arrangements as may tend to facilitate your receiving further supplies, in the course of your Expedition.

"After which, you are to proceed to the entrance of the River Plata, to ascertain the longitudes of the Cape Santa Maria, and Monte Video: you are then to proceed to survey the Coasts, Islands, and Straits; from Cape St. Antonio, at the south side {xvii}of the River Plata, to Chilóe; on the west coast of America; in such manner and order, as the state of the season, the information you may have received, or other circumstances, may induce you to adopt.

"You are to continue on this service until it shall be completed; taking every opportunity to communicate to our Secretary, and the Commander-in-Chief, your proceedings: and also, whenever you may be able to form any judgment of it, where the Commander-in-Chief, or our Secretary, may be able to communicate with you.

"In addition to any arrangements made with the Admiral, for recruiting your stores, and provisions; you are, of course, at liberty to take all other means, which may be within your reach, for that essential purpose.

"You are to avail yourself of every opportunity of collecting and preserving Specimens of such objects of Natural History as may be new, rare, or interesting; and you are to instruct Captain Stokes, and all the other Officers, to use their best diligence in increasing the Collections in each ship: the whole of which must be understood to belong to the Public.

"In the event of any irreparable accident happening to either of the two vessels, you are to cause the officers and crew of the disabled vessel to be {xviii}removed into the other, and with her, singly, to proceed in prosecution of the service, or return to England, according as circumstances shall appear to require; understanding that the officers and crews of both vessels are hereby authorized, and required, to continue to perform their duties, according to their respective ranks and stations, on board either vessel to which they may be so removed. Should, unfortunately, your own vessel be the one disabled, you are in that case to take the command of the Beagle: and, in the event of any fatal accident happening to yourself; Captain Stokes is hereby authorized to take the command of the Expedition; either on board the Adventure, or Beagle, as he may prefer; placing the officer of the Expedition who may then be next in seniority to him, in command of the second vessel: also, in the event of your inability, by sickness or otherwise, at any period of this service, to continue to carry the Instructions into execution, you are to transfer them to Captain Stokes, or to the surviving officer then next in command to you, who is hereby required to execute them, in the best manner he can, for the attainment of the object in view.

"When you shall have completed the service, or shall, from any cause, be induced to give it up; you will return to Spithead with all convenient expedition; and report your arrival, and proceedings, to our Secretary, for our information.

"Whilst on the South American Station, you are to consider yourself under the command of the Admiral of that Station; to whom we have expressed our desire that he should not interfere with these orders, except under peculiar necessity.

"Given under our hands the 16th of May 1826.

(Signed) "Melville.

"G. Cockburn.

"To Phillip P. King, Esq., Commander

of His Majesty's Surveying Vessel

Adventure, at Plymouth.

"By command of their Lordships.

(Signed) "J. W. Croker."

On the 22d of May, 1826, the Adventure and Beagle sailed from Plymouth; and, in their way to Rio de Janeiro, called successively at Madeira, Teneriffe, and St. Jago.

Unfavourable weather prevented a boat being sent ashore at the northern part of San Antonio; but observations were made in Terrafal Bay, on the south-west side of the island: and, after crossing the Equator, the Trade-wind hung so much to the southward, that Trinidad could not be approached without a sacrifice of time, which, it was considered, might be prejudicial to more important objects of the Expedition.

Both ships anchored at Rio de Janeiro on the {xx}10th of August, and remained there until the 2d of October, when they sailed to the River Plata.

In Maldonado,[3] their anchors were dropped on the 13th of the same month; and, till the 12th of November, each vessel was employed on the north side of the river, between Cape St. Mary and Monte Video.

| CHAPTER I. | |

| PAGE | |

| Departure from Monte Video—Port Santa Elena—Geological remarks—Cape Fairweather—Non-existence of Chalk—Natural History—Approach to Cape Virgins, and the Strait of Magalhaens (or Magellan) | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Enter the Strait of Magalhaens (or Magellan), and anchor off Cape Possession—First Narrow—Gregory Bay—Patagonian Indians—Second Narrow—Elizabeth Island—Freshwater Bay—Fuegian Indians—Arrival at Port Famine | 12 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Prepare the Beagle, and a decked boat (the Hope) for surveying the Strait—Beagle sails westward, and the Hope towards the south-east—Sarmiento's Voyage—and description of the colony formed by him at Port Famine—Steamer Duck—Large trees—Parroquets—Mount Tarn—Barometrical observations—Geological character—Report of the Hope's cruise | 26 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Deer seen—Hope sails again—Eagle Bay—Gabriel Channel—'Williwaws'—Port Waterfall—Natives—Admiralty Sound—Gabriel Channel—Magdalen Channel—Hope returns to Port Famine—San Antonio—Lomas Bay—Loss of boat—Master and two seamen drowned | 48 |

| {xxii} CHAPTER V. | |

| Lieutenant Sholl arrives—Beagle returns—Loss of the Saxe Coburg sealer—Captain Stokes goes to Fury Harbour to save her Crew—Beagle's proceedings—Bougainville's memorial—Cordova's memorial—Beagle's danger—Difficulties—Captain Stokes's boat-cruise—Passages—Natives—Dangerous service—Western entrance of the Strait of Magalhaens—Hope's cruise—Prepare to return to Monte Video | 65 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Trees—Leave Port Famine—Patagonians—Gregory Bay—Bysante—Maria—Falkner's account of the Natives—Indians seen on the borders of the Otway Water, in 1829—Maria visits the Adventure—Religious ceremony—Patagonian Encampment—Tomb of a Child—Women's employment—Children—Gratitude of a Native—Size of Patagonians—Former accounts of their gigantic height—Character—Articles for barter—Fuegians living with Patagonians—Ships sail—Arrive at Monte Video and Rio de Janeiro | 84 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Leave Rio de Janeiro—Santos—Sta. Catharina—Monte Video—Purchase the Adelaide schooner, for a Tender to the Adventure—Leave Monte Video—Beagle goes to Port Desire—Shoals off Cape Blanco—Bellaco Rock—Cape Virgins—Possession Bay—First Narrow—Race—Gregory Bay—View—Tomb—Traffic with Natives—Cordial meeting—Maria goes on board—Natives intoxicated—Laredo Bay—Port Famine | 106 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Find that the Cutter had been burned—Anxiety for the Beagle—Uxbridge Sealer—Beagle arrives—Her cruise—Bellaco Rock—San Julian—Santa {xxiii} Cruz—Gallegos—Adeona—Death of Lieutenant Sholl—Adelaide sails—Supposed Channel of San Antonio—Useless Bay—Natives—Port San Antonio—Humming-birds—Fuegians—Beagle sails—Sarmiento—Roldan—Pond—Whales—Structure—Scenery—Port Gallant | 118 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Detention in Port Gallant—Humming-birds in snow showers—Fuegians—Geological remarks—Canoes—Carving—Birds—Fish—Shag Narrows—Glaciers—Avalanches—Natives—Climate—Winter setting in—Adelaide loses a boat—Floods—Lightning—Scurvy—Adelaide's survey—Bougainville Harbour—Indians cross the Strait, and visit Port Famine—Sealing vessels sail—Scurvy increases—Adelaide sent for guanaco meat—Return of the Beagle—Captain Stokes very ill—Adelaide brings meat from the Patagonians—Death of Captain Stokes | 133 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Account of the Beagle's cruise—Borja Bay—Cape Quod—Stuart Bay—Cape Notch—Remarks on weather, and errors of Chart—Evangelists—Santa Lucia—Madre de Dios—Gulf of Trinidad—Port Henry—Puma's track—Humming-birds—Very bad weather—Campana Island—Dangers—Gale—Wet—Sick—Santa Barbara—Wager's beam—Wigwams—Guaineco Islands—Cape Tres Montes—St. Paul—Port Otway—Hoppner Sound—Cape Raper | 154 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| Leave Port Otway—San Quintin Sound—Gulf of Peñas—Kelly Harbour—St. Xavier Island—Death of Serjeant Lyndsey—Port Xavier—Ygnacio Bay—Channel's mouth—Bad weather—Perilous situation—Lose the yawl—Sick list—Return to Port Otway—Thence to Port Famine—Gregory Bay—Natives—Guanaco meat—Skunk—Condors—Brazilians—Juanico—Captain Foster—Changes of officers | 173 |

| {xxiv} CHAPTER XII. | |

| Adventure sails from Rio de Janeiro to the River Plata—Gorriti—Maldonado—Extraordinary Pampero—Beagle's losses—Ganges arrives—another Pampero—Go up the river for water—Gale, and consequent detention—Sail from Monte Video—part from Consorts—Port Desire—Tower Rock—Skeletons—Sea Bear Bay—Fire—Guanacoes—Port Desire Inlet—Indian graves—Vessels separate—Captain Foster—Chanticleer—Cape Horn—Kater Peak—Sail from St. Martin Cove—Tribute to Captain Foster—Valparaiso—Santiago—Pinto Heights—Chilóe—Aldunate | 189 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Beagle and Adelaide anchor in Possession Bay—Beagle passes the First Narrow—Fogs—Pecket Harbour—Adelaide arrives with Guanaco meat—Portuguese Seamen—Peculiar light—Party missing—Return—Proceed towards Port Famine—Fuegians—Lieut. Skyring—Adelaide sails to survey Magdalen and Barbara Channels—Views—Lyell Sound—Kempe Harbour—Cascade Bay—San Pedro Sound—Port Gallant—Diet—Rain—Awnings—Boat cruise—Warning—Jerome Channel—Blanket bags—Otway Water—Frequent rain—Difficulty in lighting fires | 212 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Place for a Settlement—Frost—Boats in danger—Narrow escape—Sudden change—Beagle Hills—Fuegian Painting—Tides—Medicine—Water warmer than the air—Jerome Channel—Mr. Stokes returns to the Beagle—Cape Quod—Snowy Sound—Whale Sound—Choiseul Bay—Return to the Beagle—Adelaide returns—Plan of operations—Difficulties removed—Preparations—Wear and tear of clothing—Ascend the Mountain de la Cruz—Sail from Port Gallant—Tides—Borja Bay—Cape Quod—Gulf of Xaultegua—Frost and snow—Meet Adelaide—Part—Enter Pacific—Arrive at Chilóe | 230 |

| {xxv} CHAPTER XV. | |

| Extracts from the Journals of Lieutenants Skyring and Graves—Magdalen Channel—Keats Sound—Mount Sarmiento—Barrow Head—Cockburn Channel—Prevalence of south-west winds—Melville Sound—Ascent of Mount Skyring—Memorial—Cockburn and Barbara Channels—Mass of Islets and Rocks—Hewett Bay—Cypress trees useful—Adelaide rejoins Beagle in Port Gallant—Captain King's narrative resumed—Plan of future proceedings—Adelaide arrives at Chilóe—Abstract of Lieutenant Skyring's account of her proceedings—Smyth Channel—Mount Burney—'Ancon sin Salida'—Natives—Kirke Narrow—Guia Narrow—Peculiar tides—Indians in plank Canoes—Passage to Chilóe | 251 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Chilóe—Its probable importance—Valdivia founds seven Cities; afterwards destroyed by the Indians—Migration of Spanish settlers—Province and Islands of Chilóe—Districts and population—Government—Defence—Winds—Town—Durability of wooden Buildings—Cultivation—Want of industry—Improvement—Dress—Habits of lower Classes—Morality—Schools—Language—Produce—Manufactures—Exports and imports—Varieties of wood—Alerse—Roads—Piraguas—Ploughs—Corn—Potatoes—Contributions—Birds—Shell-fish—Medical practitioners—Remedies—Climate | 269 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Chilóe the last Spanish possession in South America—Freyre's Expedition—Failure—Second Expedition under Freyre and Blanco—Quintanilla's capitulation—Chilóe taken—Aldunate placed in command—Chilóe a dependency of Chile—Beagle sails to sea coast of Tierra del Fuego—Adelaide repaired—Adelaide sails—Adventure goes to {xxvi} Valparaiso—Juan Fernandez—Fishery—Goats—Dogs—Geology—Botany—Shells—Spanish accounts—Anson's voyage—Talcahuano—Concepcion—Pinoleo—Araucanian Indians—Re-enter the Strait of Magalhaens—Fuegians | 298 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Adelaide's last cruise—Port Otway—San Quintin—Marine Islands—Unknown river or passage—San Tadeo—Isthmus of Ofqui—San Rafael—Sufferings and route of Wager's party—Channel's Mouth—Byron—Cheap—Elliot—Hamilton—Campbell—Indian Cacique—Passage of the Desecho—Osorio—Xavier Island—Jesuit Sound—Kirke's report—Night tides—Guaianeco Islands—Site of the Wager's wreck—Bulkely and Cummings—Speedwell Bay—Indigenous wild Potato—Mesier Channel—Fatal Bay—Death of Mr. Millar—Fallos Channel—Lieutenant Skyring's illness—English Narrow—Fish—Wigwams—Indians—Level Bay—Brazo Ancho—Eyre Sound—Seal—Icebergs—Walker Bay—Nature of the Country—Habits of the Natives—Scarcity of population | 323 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Sarmiento Channel—Ancon sin Salida—Cape Earnest—Canal of the Mountains—Termination of the Andes—Kirke Narrow—Easter Bay—Disappointment Bay—Obstruction Sound—Last Hope Inlet—Swans—Coots—Deer River—Lagoon—Singular Eddies—Passage of the Narrow—Arrival at Port Famine—Zoological remarks | 346 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| Beagle sails from San Carlos—Enters Strait—Harbour of Mercy—Cape Pillar—Apostles—Judges—Landfall Island—Cape Gloucester—Dislocation Harbour—Week Islands—Fuegians—Latitude Bay—Boat's crew in distress—Petrel—Passages—Otway Bay—Cape Tate—Fincham {xxvii} Islands—Deepwater Sound—Breaker Bay—Grafton Islands—Geological remarks—Barbara Channel—Mount Skyring—Compasses affected—Drawings—Provisions—Opportunities lost | 360 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| Skyring's chart—Noir Island—Penguins—Fuegians—Sarmiento—Townshend Harbour—Horace Peaks—Cape Desolation—Boat lost—Basket—Search in Desolation Bay—Natives—Heavy Gale—Surprise—Seizure—Consequences—Return to Beagle—Sail to Stewart Harbour—Set out again—Escape of Natives—Unavailing search—Discomforts—Tides—Nature of Coast—Doris Cove—Christmas Sound—Cook—York-Minster—March Harbour—Build a boat—Treacherous rocks—Skirmish with the Natives—Captives—Boat Memory—Petrel | 386 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| Mr. Murray returns—Go to New Year Sound—See Diego Ramirez Islands from Henderson Island—Weddell's Indian Cove—Sympiesometer—Return to Christmas Sound—Beagle sails—Passes the Ildefonso and Diego Ramirez Islands—Anchors in Nassau Bay—Orange Bay—Yapoos—Mr. Murray discovers the Beagle Channel—Numerous Natives—Guanacoes—Compasses affected—Cape Horn—Specimens—Chanticleer—Mistake about St. Francis Bay—Diego Ramirez Islands—Climate—San Joachim Cove—Barnevelt Isles—Evouts Isle—Lennox Harbour | 417 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| Set out in boats—Find Guanacoes—Murray Narrow—Birch Fungus—Tide—Channel—Glaciers—View—Mountains—Unbroken chain—Passages—Steam-vessels—Jemmy Button—Puma—Nest—Accident—Natives—Murray's Journal—Cape Graham—Cape Kinnaird—Spaniard {xxviii} Harbour—Valentyn Bay—Cape Good Success—Natives—Lennox Island—Strait le Maire—Good Success Bay—Accident—Tide race—San Vicente—San Diego—Tides—Soundings—North-East Coast—San Sebastian—Reflections—Port Desire—Monte Video—Santa Catharina—Rio de Janeiro | 438 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| A few Nautical remarks upon the passage round Cape Horn; and upon that through the Strait of Magalhaens, or Magellan | 463 |

| Map of South America | Loose. |

| Strait of Magalhaens | Loose. |

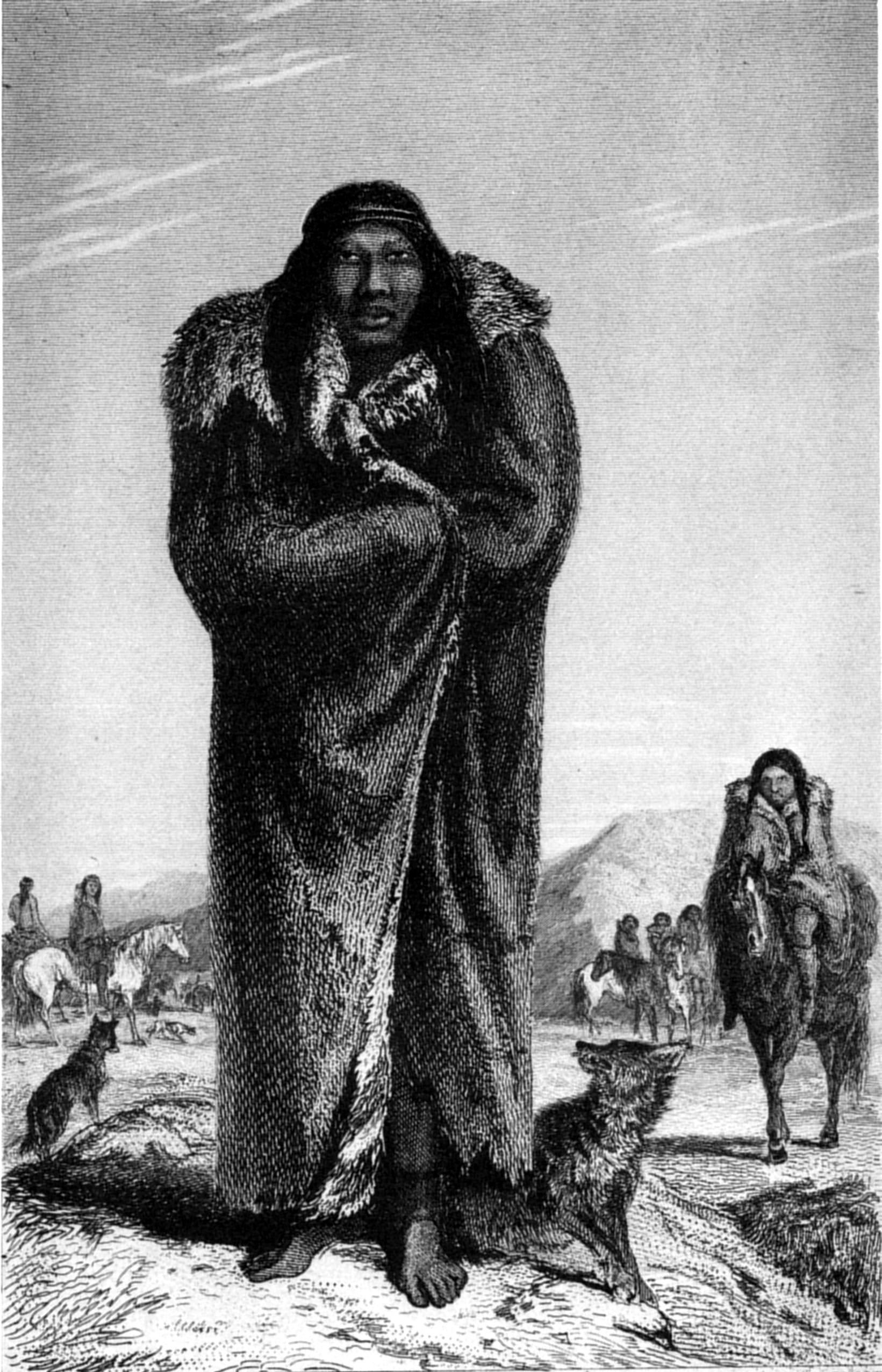

| Patagonian | Frontispiece. |

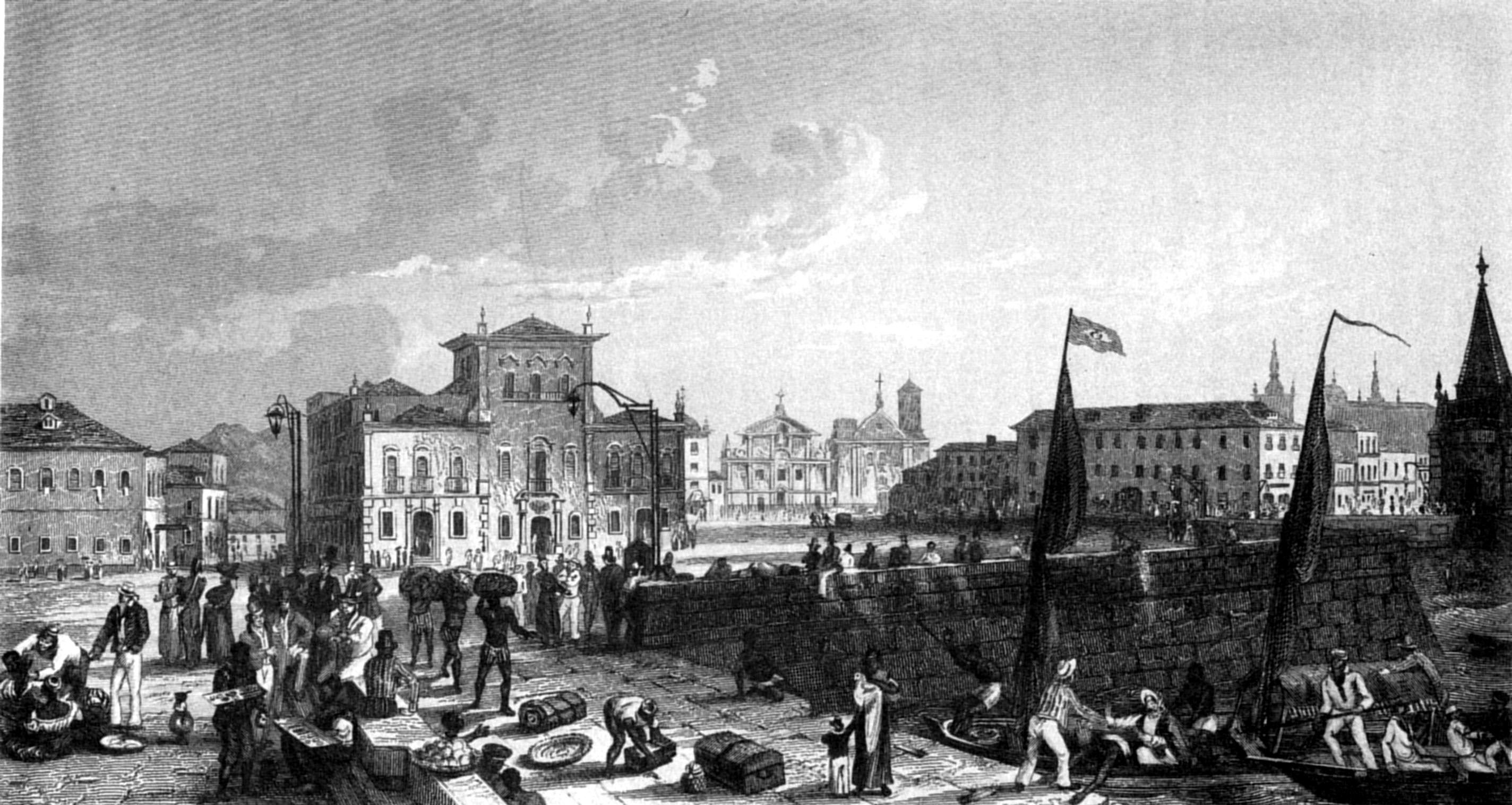

| Monte Video | to face page 1 |

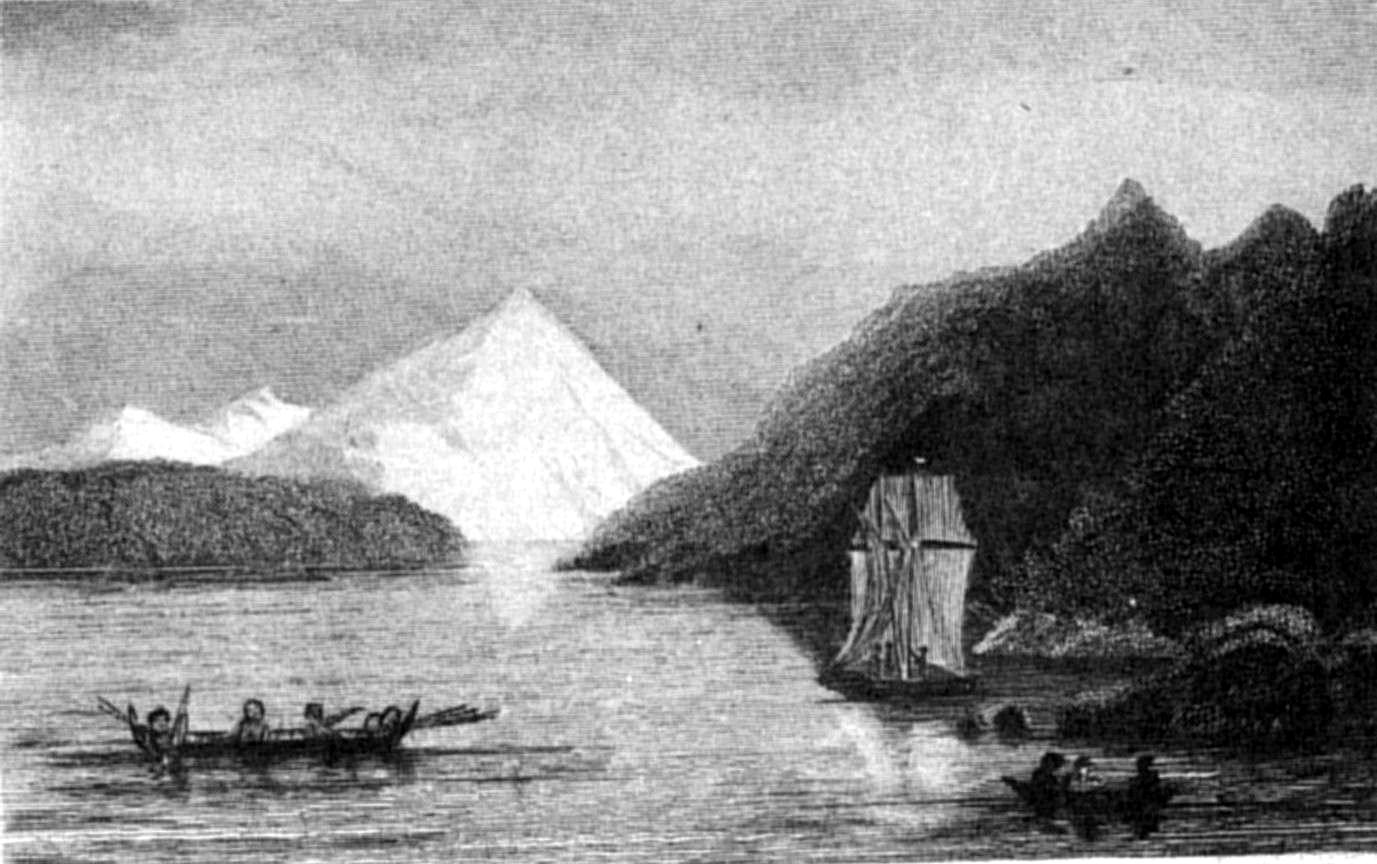

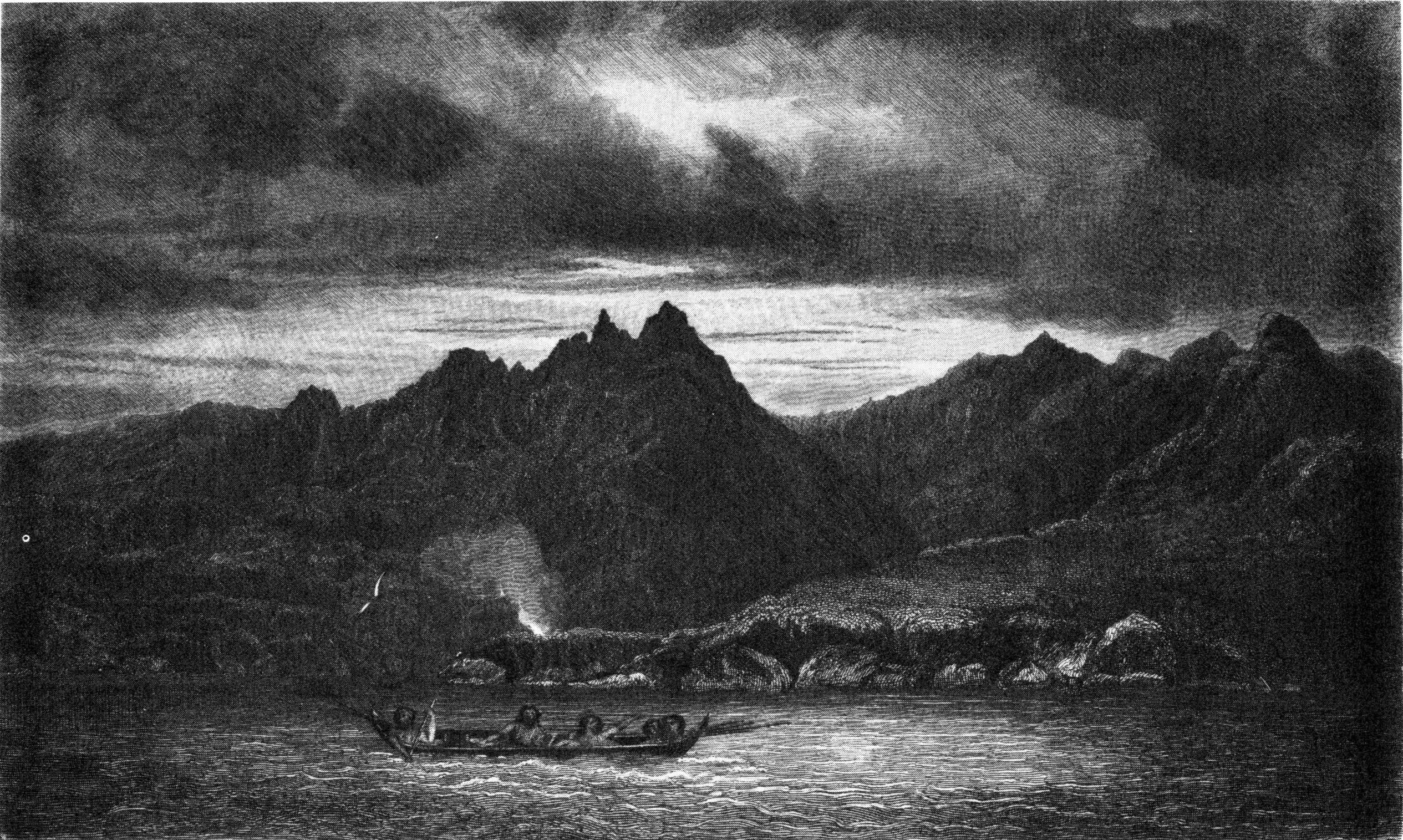

| Distant View of Mount Sarmiento (with two other views) | 26 |

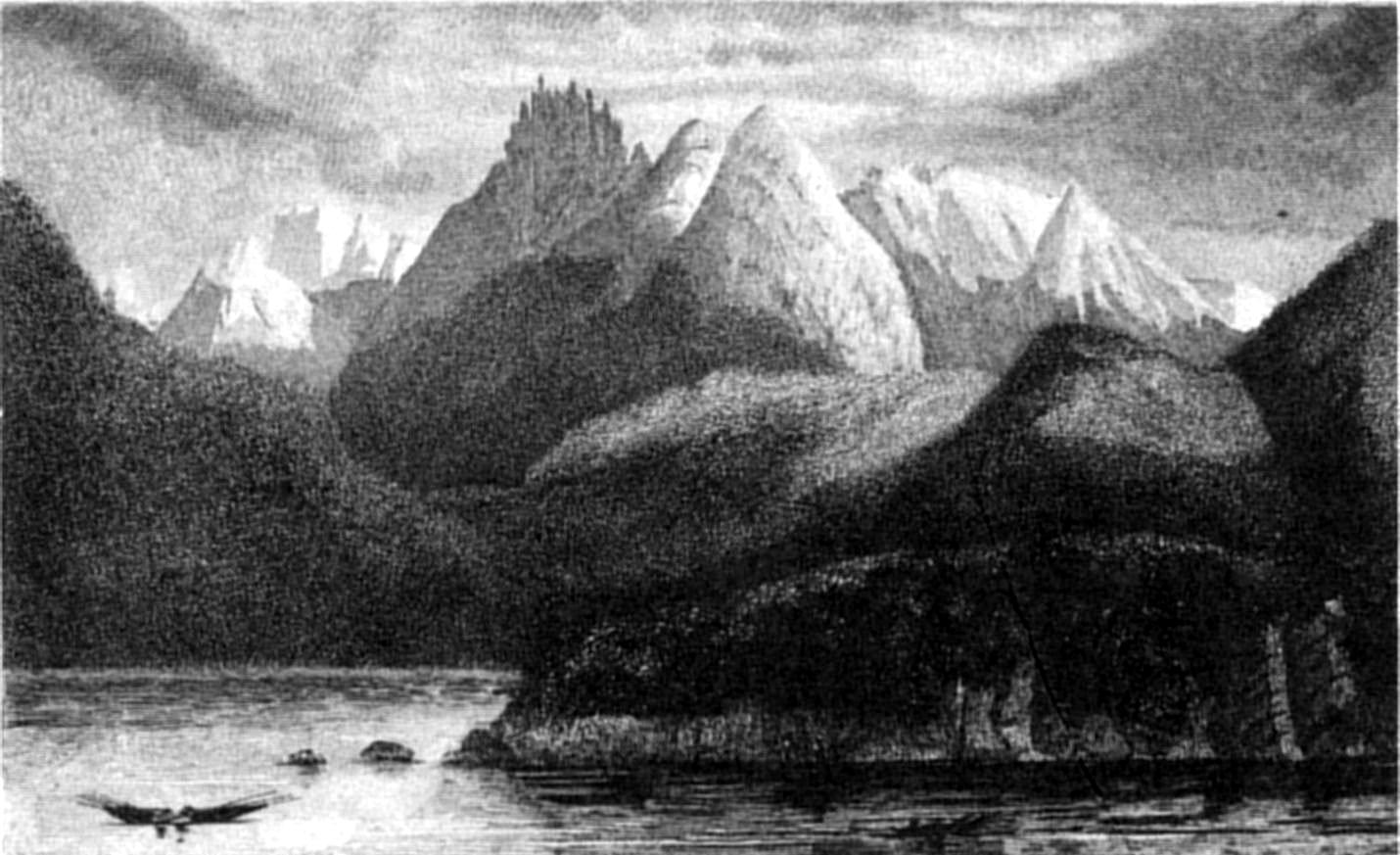

| Curious Peak—Admiralty Sound (with other views) | 52 |

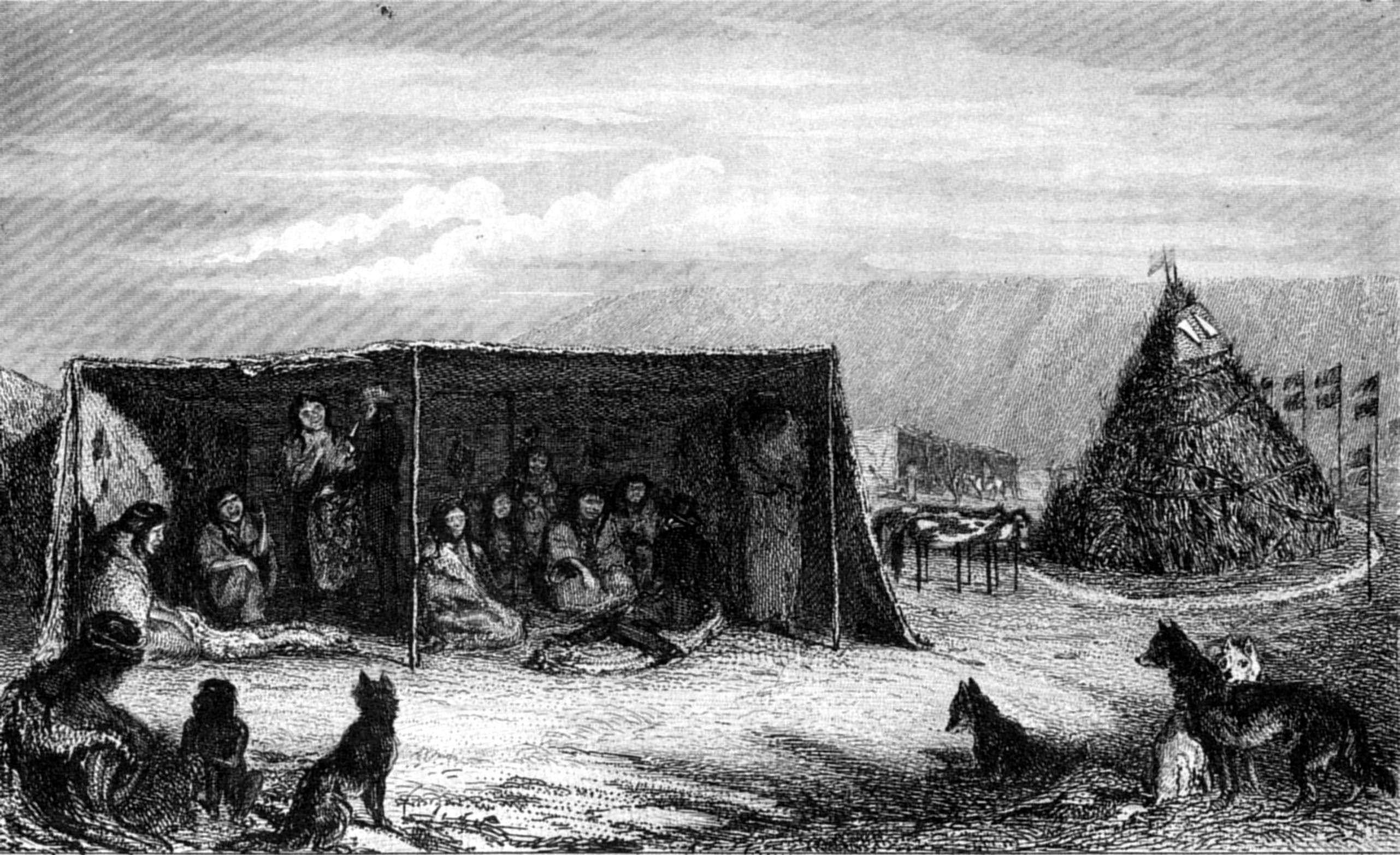

| Patagonian 'toldo' and tomb | 94 |

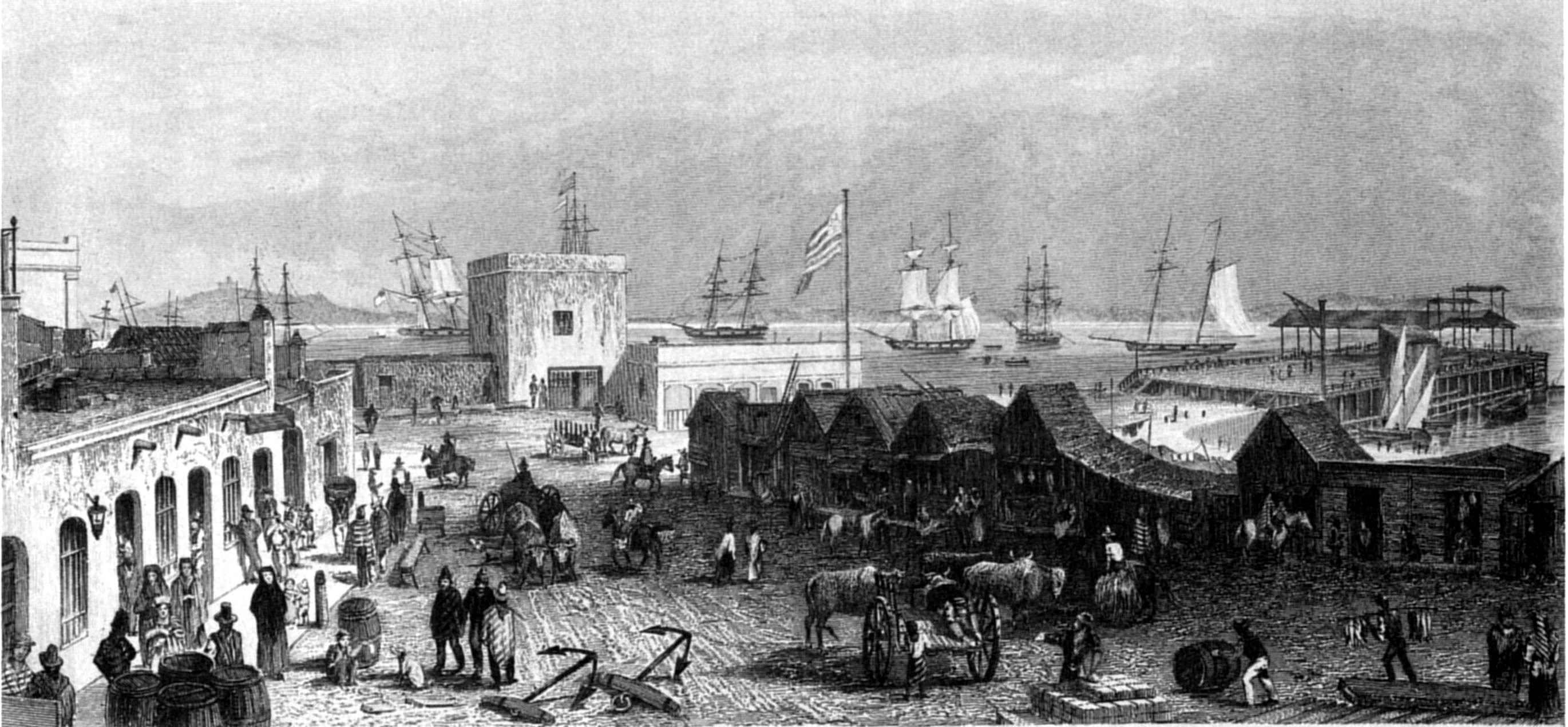

| Monte Video Mole | 105 |

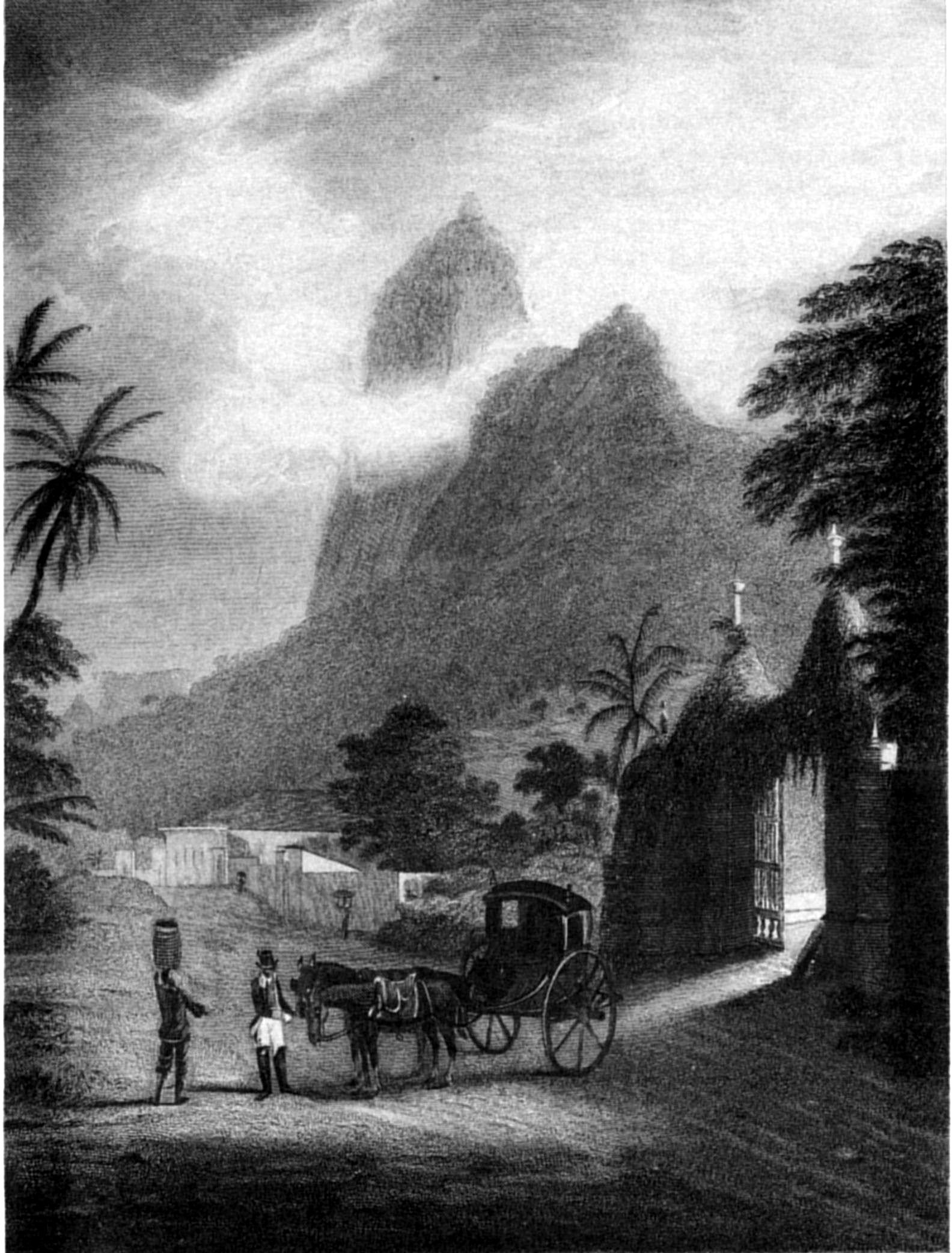

| Rio de Janeiro | 106 |

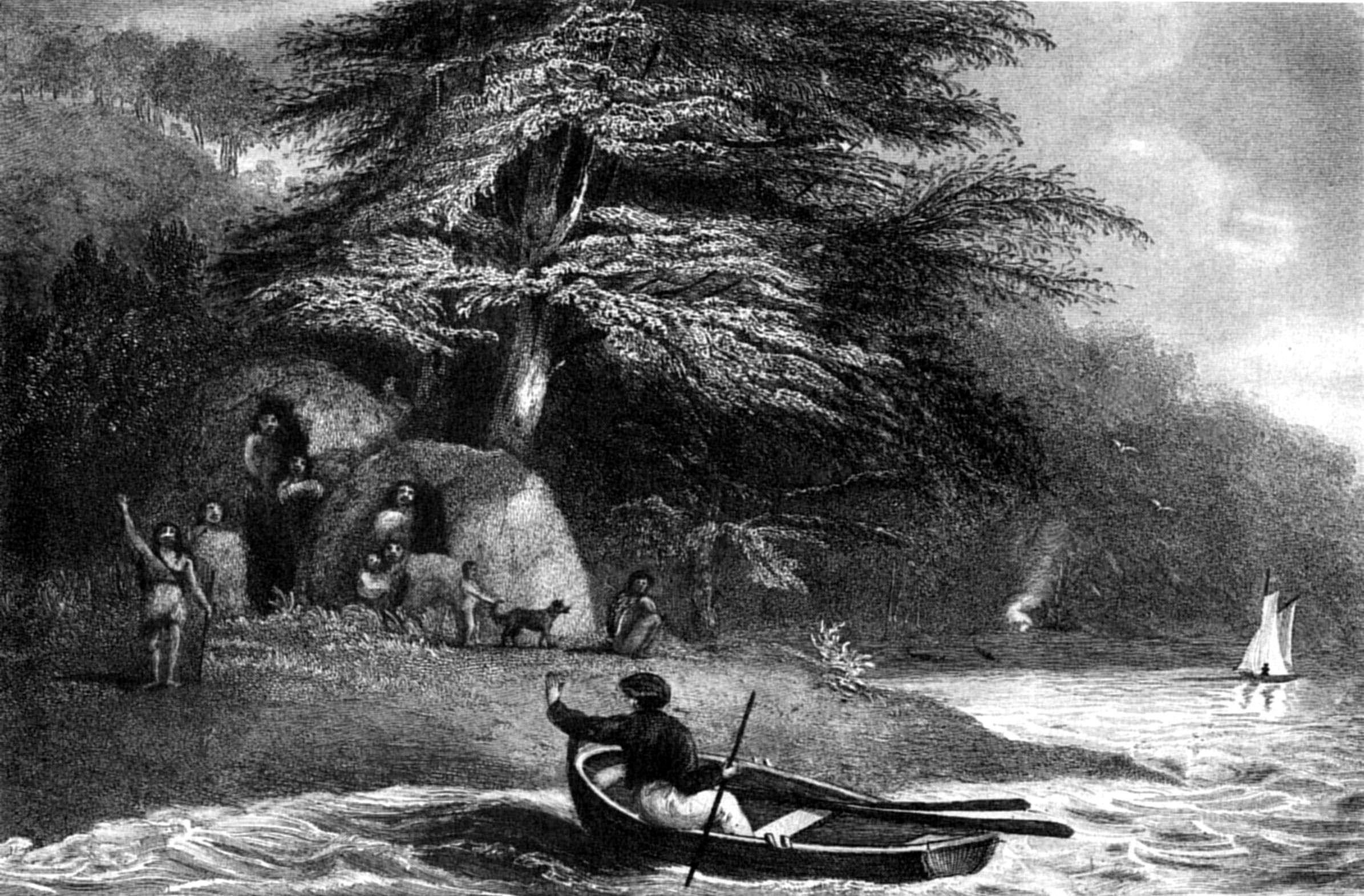

| Fuegian Wigwams at Hope Harbour, in the Magdalen Channel | 126 |

| Monte Video—Custom-House | 187 |

| Corcovado Mountain | 188 |

| Mount Sarmiento | 252 |

| San Carlos de Chilóe | 275 |

| Breast Ploughing in Chilóe | 287 |

| Point Arena—Chilóe (with other views) | 300 |

| South West opening of Cockburn Channel (with views of Headlands) | 407 |

| Wollaston Island, near Cape Horn | 433 |

| Chart of a part of South America, by Captain P. P. King | 463 |

Page 76, line 4 from bottom, for lying, read being.

118, Heading, line 4, for Beagle sailed, read Beagle sails.

123, line 17, insert narrow, before and shoal.

164, line 23, instead of the, read our.

174, line 6, for cuts, read cut.

193, line 5, for have, read had.

223, (Note) line 2 from bottom, for they, read he.

229, line 9, for was, read were.

265, line 8, after day, insert a colon instead of a comma.

273, line 21, after as well, insert as.

301, line 23, for Lieutenants Skyring and Graves again took with them, read Lieutenant Skyring again took with him.

411, line 2, dele the.

437, line 16, for contiue, read continue.

443, line 19, for wit, read with.

462, line 21, for Santa Catalina, read Santa Catharina.

473, line 17, after which is, insert a.

481, bottom line, for 53. 32. 30, read 53. 52. 30.

485, line 7, (of positions) for 53. 31, read 53. 51.

—— bottom line, for 11. 51, read 3. 26.

488, line 9, for Northern, read Southern.

489, line 4 from bottom, for 46. 03, read 46. 30; and for 40. 50, read 40. 05.

490, line 6, for 50°, read 49°.

491, line 6, for 36. 56, read 36. 16.

493, line 9, for 54. 30. 00, read 54. 05. 20; and for 73. 1. 30, read 73. 25. 30.

526, for Variation, read Dip.

529, line 8, for Harlau read Harlan.

531, line 6, for Keroda read Kerodon.

532, line 1, for Dumérel, read Duméril.

—— line 7, for Miloago, read Milvago.

—— line 19, for Sparoerius, read Sparverius.

533, line 16, dele Spix.

—— bottom line, for Silvia, read Sylvia, and in next page the same.

534, line 12, dele Fursa, Veillot.

—— line 10 from bottom, for Smaragdimis, read Smaragdinus.

536, line 9 from bottom, for Strutheo, read Struthio.

—— line 6 from bottom, for rinacea, read binacea.

537, line 14, for Totamus, read Totanus.

538, line 5, for subtas, read subtus.

—— lower lines, where Hœmatopus occurs, read Hæmatopus.

540, last line, for meneque, read mineque; and for pariè, read parcè.

541, line 12, for Catarrhoctes, read Catarrhactes.

—— line 2 from bottom, for ud, read ad.

543, line 13, for gracillimus, read gracillimis.

545, last line, for brachyptera, read brachypterus; for Patachonica, read Patachonicus.

SURVEYING VOYAGES

OF THE

ADVENTURE AND THE BEAGLE,

1826-1830.

Departure from Monte Video—Port Santa Elena—Geological remarks—Cape Fairweather—Non-existence of Chalk—Natural History—Approach to Cape Virgins, and the Strait of Magalhaens (or Magellan)

We sailed from Monte Video on the 19th of November 1826; and, in company with the Beagle, quitted the river Plata.

According to my Instructions, the Survey was to commence at Cape San Antonio, the southern limit of the entrance of the Plata; but, for the following urgent reasons, I decided to begin with the southern coasts of Patagonia, and Tierra del Fuego, including the Straits of Magalhaens.[4] In the first place, they presented a field of great interest and novelty; and secondly, the climate of the higher southern latitudes being so severe and tempestuous, it appeared important to encounter its rigours while the ships were in good condition—while the crews were healthy—and while the charms of a new and difficult enterprize had full force.

Our course was therefore southerly, and in latitude 45° south, a few leagues northward of Port Santa Elena, we first saw the coast of Patagonia. I intended to visit that port; and, on the 28th, anchored, and landed there.

Seamen should remember that a knowledge of the tide is of especial consequence in and near Port Santa Elena. During a calm we were carried by it towards reefs which line the shore, and were obliged to anchor until a breeze sprung up.

The coast along which we had passed, from Point Lobos to the north-east point of Port Santa Elena, appeared to be dry and bare of vegetation. There were no trees; the land seemed to be one long extent of undulating plain, beyond which were high, flat-topped hills of a rocky, precipitous character. The shore was fronted by rocky reefs extending two or three miles from high-water mark, which, as the tide fell, were left dry, and in many places were covered with seals.

As soon as we had secured the ships, Captain Stokes accompanied me on shore to select a place for our observations. We found the spot which the Spanish astronomers of Malaspina's Voyage (in 1798) used for their observatory, the most convenient for our purpose. It is near a very steep shingle (stony) beach at the back of a conspicuous red-coloured, rocky projection which terminates a small bay, on the western side, at the head of the port. The remains of a wreck, which proved to be that of an American whaler, the Decatur of New York, were found upon the extremity of the same point; she had been driven on shore from her anchors during a gale.

The sight of the wreck, and the steepness of the shingle beach just described, evidently caused by the frequent action of a heavy sea, did not produce a favourable opinion of the safety of the port: but as it was not the season for easterly gales, to which only the anchorage is exposed, and as appearances indicated a westerly wind, we did not anticipate danger.

While we were returning on board, the wind blew so strongly that we had much difficulty in reaching the ships, and the boats were no sooner hoisted up, and every thing {3}made snug, than it blew a hard gale from the S.W. The water however, from the wind being off the land, was perfectly smooth, and the ships rode securely through the night: but the following morning the gale increased, and veered to the southward, which threw a heavy sea into the port, placing us, to say the least, in a very uneasy situation. Happily it ceased at sunset. In consequence of the unfavourable state of the weather, no attempt was made to land in order to observe an eclipse of the sun; to make which observation was one reason for visiting this port.

The day after the gale, while I was employed in making some astronomical observations, a party roamed about in quest of game: but with little success, as they killed only a few wild ducks. The fire which they made for cooking communicated to the dry stubbly grass, and in a few minutes the whole country was in a blaze. The flames continued to spread during our stay, and, in a few days, more than fifteen miles along the coast, and seven or eight miles into the interior were overrun by the fire. The smoke very much impeded our observations, for at times it quite obscured the sun.

The geological structure of this part of the country, and a considerable portion of the coast to the north and south, consists of a fine-grained porphyritic clay slate. The summits of the hills near the coast are generally of a rounded form, and are paved, as it were, with small, rounded, siliceous pebbles, imbedded in the soil, and in no instance lying loose or in heaps; but those of the interior are flat-topped, and uniform in height, for many miles in extent. The valleys and lower elevations, notwithstanding the poverty and parched state of the soil, were partially covered with grass and shrubby plants, which afford sustenance to numerous herds of guanacoes. Many of these animals were observed feeding near the beach when we were working into the bay, but they took the alarm, so that upon landing we only saw them at a considerable distance. In none of our excursions could we find any water that had not a brackish taste. Several wells have been dug in the valleys, both near the sea and at a considerable distance from it, by the {4}crews of sealing vessels; but, except in the rainy season, they all contain saltish water. This observation is applicable to nearly the whole extent of the porphyritic country. Oyster-shells, three or four inches in diameter, were found, scattered over the hills, to the height of three or four hundred feet above the sea. Sir John Narborough, in 1652, found oyster-shells at Port San Julian; but, from a great many which have been lately collected there, we know that they are of a species different from that found at Port Santa Elena. Both are fossils.

No recent specimen of the genus Ostrea was found by us on any part of the Patagonian coast. Narborough, in noticing those at Port San Julian, says, "They are the biggest oyster-shells that I ever saw, some six, some seven inches broad, yet not one oyster to be found in the harbour: whence I conclude they were here when the world was formed."

The short period of our visit did not enable us to add much to natural history. Of quadrupeds we saw guanacoes, foxes, cavies, and the armadillo; but no traces of the puma (Felis concolor), or South American lion, although it is to be met with in the interior.

I mentioned that a herd of guanacoes was feeding near the shore when we arrived. Every exertion was made to obtain some of the animals; but, either from their shyness, or our ignorance of the mode of entrapping them, we tried in vain, until the arrival of a small sealing-vessel, which had hastened to our assistance, upon seeing the fires we had accidentally made, but which her crew thought were intended for signals of distress. They shot two, and sent some of the meat on board the Adventure. The next day, Mr. Tarn succeeded in shooting one, a female, which, when skinned and cleaned, weighed 168 lbs. Narborough mentions having killed one at Port San Julian, that weighed, "cleaned in his quarters, 268 lbs." The watchful and wary character of this animal is very remarkable. Whenever a herd is feeding, one is posted, like a sentinel, on a height; and, at the approach of danger, gives instant alarm by a loud neigh, when away they all go, at a hand-gallop, to the next eminence, where they quietly resume their feeding, {5}until again warned of the approach of danger by their vigilant 'look-out.'

Another peculiarity of the guanaco is, the habit of resorting to particular spots for natural purposes. This is mentioned in the 'Dictionnaire d'Histoire Naturelle,' in the 'Encyclopédie Méthodique,' as well as other works.

In one place we found the bones of thirty-one guanacoes collected within a space of thirty yards, perhaps the result of an encampment of Indians, as evident traces of them were observed; among which were a human jaw-bone, and a piece of agate ingeniously chipped into the shape of a spear-head.

The fox, which we did not take, appeared to be small, and similar to a new species afterwards found by us in the Strait of Magalhaens.

The cavia[5] (or, as it is called by Narborough, Byron, and Wood, the hare, an animal from which it differs both in appearance and habits, as well as flavour), makes a good dish; and so does the armadillo, which our people called the shell-pig.[6] This little animal is found abundantly about the low land, and lives in burrows underground; several were taken by the seamen, and, when cooked in their shells, were savoury and wholesome.

Teal were abundant upon the marshy grounds. A few partridges, doves, and snipes, a rail, and some hawks were shot. The few sea-birds that were observed consisted of two species of gulls, a grebe and a penguin (Aptenodytes Magellanica).

We found two species of snakes and several kinds of lizards. Fish were scarce, as were also insects; of the last, our {6}collections consisted only of a few species of Coleoptera, two or three Lepidoptera, and two Hymenoptera.

Among the sea-shells, the most abundant was the Patella deaurata, Lamk.; this, with three other species of Patella, one Chiton, three species of Mytilus, three of Murex, one of Crepidula, and a Venus, were all that we collected.

About the country, near the sea-shore, there is a small tree, whose stem and roots are highly esteemed for fuel by the crews of sealing-vessels which frequent this coast. They call it 'piccolo.' The leaf was described to me as having a prickle upon it, and the flower as of a yellow colour. A species of berberis also is found, which when ripe may afford a very palatable fruit.

Our short visit gave us no flattering opinion of the fertility of the country near this port. Of the interior we were ignorant; but, from the absence of Indians and the scarcity of fresh water, it is probably very bare of pasturage. Falkner, the Jesuit missionary, says these parts were used by the Tehuelhet tribes for burying-places: we saw, however, no graves, nor any traces of bodies, excepting the jaw-bone above-mentioned; but subsequently, at Sea Bear Bay, we found many places on the summits of the hills which had evidently been used for such a purpose, although then containing no remains of bodies. This corresponds with Falkner's account, that after a period of twelve months the sepulchres are formally visited by the tribe, when the bones of their relatives and friends are collected and carried to certain places, where the skeletons are arranged in order, and tricked out with all the finery and ornaments they can collect.

The ships sailed from Port Santa Elena on the 5th December, and proceeded to the southward, coasting the shore as far as Cape Two Bays.

Our object being to proceed with all expedition to the Strait of Magalhaens, the examination of this part of the coast was reserved for a future opportunity. On the 13th, we had reached within fifty miles of Cape Virgins, the headland at the entrance of the strait, but it was directly in the wind's eye {7}of us. The wind veering to S.S.W., we made about a west course. At day-light the land was in sight, terminating in a point to the S.W., so exactly like the description of Cape Virgins and the view of it in Alison's voyage, that without considering our place on the chart, or calculating the previous twenty-four hours' run, it was taken for the Cape itself, and, no one suspecting a mistake, thought of verifying the ship's position. The point, however, proved to be Cape Fairweather. It was not a little singular, that the same mistake should have been made on board the Beagle, where the error was not discovered for three days.[7]

From the appearance of the weather I was anxious to approach the land in order to anchor, as there seemed to be every likelihood of a gale; and we were not deceived, for at three o'clock, being within seven miles of the Cape, a strong wind sprung up from the S.W., and the anchor was dropped. Towards evening it blew so hard, that both ships dragged their anchors for a considerable distance.

On the charts of this part of the coast the shore is described to be formed of "chalk hills, like the coast of Kent." To geologists, therefore, especially, as they were not disposed to believe that such was the fact, this was a question of some interest. From our anchorage the appearance of the land favoured our belief of the existence of chalk. The outline was very level and steep; precipitous cliffs of whitish colour, stratified horizontally, with their upper part occasionally worn into hollows, strongly resembled the chalk cliffs of the English coasts.

The gale prevented our landing for three days, when (19th) a few minutes sufficed to discover that the cliffs were composed {8}of soft clay, varying in colour and consistence, and disposed in strata running horizontally for many miles without interruption, excepting where water-courses had worn them away. Some of the strata were very fine clay, unmixed with any other substance, whilst others were plentifully strewed with round siliceous gravel,[8] without any vestige of organic remains. The sea beach, from high-water mark to the base of the cliffs, is formed by shingle, with scattered masses of indurated clay of a green colour.[9] Between the high and low tide marks there is a smooth beach of the same green clay as the masses above-mentioned, which appears to have been hardened by the action of the surf to the consistence of stone. Generally this beach extends for about one hundred yards farther into the sea, and is succeeded by a soft green mud, over which the water gradually deepens. The outer edge of the clay forms a ledge, extending parallel with the coast, upon the whole length of which the sea breaks, and over it a boat can with difficulty pass at low water.

The very few shells we found were dead. Strewed about the beach were numbers of fish, some of which had been thrown on shore by the last tide, and were scarcely stiff. They principally belonged to the genus Ophidium; the largest that we saw measured four feet seven inches in length, and weighed twenty-four pounds. Many caught alongside the ship were, in truth, coarse and insipid; yet our people, who fed heartily upon them, called them ling, and thought them palatable. The hook, however, furnished us with a very wholesome and well-flavoured species of cod (Gadus). Attached to the first we found two parasitical animals; one was a Cymothoa, the other a species of Lernæa, which had so {9}securely attached itself under the skin, as not to be removed without cutting off a piece of the flesh with it. An undescribed species of Muræna was also taken.

Whilst we were on shore, the Beagle moved eight or nine miles nearer to the Cape, where Captain Stokes landed to fix positions of remarkable land. One peaked hill, from the circumstance of his seeing a large animal near it, he called Tiger Mount. Mr. Bowen shot a guanaco; and being at a distance in shore, unable to procure assistance, he skinned and quartered it with his pocket-knife, and carried it upon his shoulders to the boat.

Next morning the ships weighed, and proceeded towards Cape Virgins.

When a-breast of Cape Fairweather, the opening of the river Gallegos was very distinctly seen; but the examination of it was deferred to a future opportunity. Passing onward, the water shoaled to four fathoms, until we had passed extensive banks, which front the river.

Our approach to the entrance of the Strait, although attended with anxiety, caused sensations of interest and pleasure not easily to be described. Though dangers were experienced by some navigators who had passed it, the comparative facility with which others had effected the passage showed that, at times, the difficulties were easily surmounted, and we were willing to suppose that in the former case there might have been some little exaggeration.

The most complete, and, probably, the only good account of the navigation of the Strait of Magalhaens is contained in the narrative of Don Antonio de Cordova, who commanded the Spanish frigate Santa Maria de la Cabeza, on a voyage expressly for the purpose of exploring the strait. It was published under the title of 'Ultimo Viage al Estrecho de Magallanes.' That voyage was, however, concluded with only the examination of the eastern part, and a subsequent expedition was made, under the command of the same officer, the account of which was appended to the Cabeza's voyage; so that Cordova's expedition still retained the appellation of 'Ultimo {10}Viage, &c.' It is written in a plain and simple style, gives a most correct account of every thing seen, and should therefore be in the possession of every person who attempts the navigation of the strait.

Cordova's account of the climate is very uninviting. Speaking of the rigours of the summer months (January, February, and March), he says, "Seldom was the sky clear, and short were the intervals in which we experienced the sun's warmth: no day passed by without some rain having fallen, and the most usual state of the weather was that of constant rain."[10]

The accounts of Wallis and Carteret are still more gloomy. The former concludes that part of his narrative with the following dismal and disheartening description: "Thus we quitted a dreary and inhospitable region, where we were in almost continual danger of shipwreck for near four months, having entered the strait on the 17th of December, and quitted it on the 11th of April 1767: a region where, in the midst of summer, the weather was cold, gloomy, and tempestuous, where the prospects had more the appearance of a chaos than of nature; and where for the most part the valleys were without herbage and the hills without wood."

These records of Cordova and Wallis made me feel not a little apprehensive for the health of the crew, which could not be expected to escape uninjured through the rigours of such a climate. Nor were the narratives of Byron or Bougainville calculated to lessen my anxiety. In an account, however, of a voyage to the strait by M. A. Duclos Guyot, the following paragraph tended considerably to relieve my mind upon the subject:—"At length, on Saturday the 23d of March, we sailed out of that famous Strait, so much dreaded, after having experienced that there, as well as in other places, it was very fine, and very warm, and that for three-fourths of the time the sea was perfectly calm."

In every view of the case, our proximity to the principal scene of action occasioned sensations of a peculiar nature, in which, however, those that were most agreeable and hopeful {11}preponderated. The officers and crews of both ships were healthy, and elated with the prospect before them; our vessels were in every respect strong and sea-worthy; and we were possessed of every comfort and resource necessary for encountering much greater difficulties than we had any reason to anticipate.

There has existed much difference of opinion as to the correct mode of spelling the name of the celebrated navigator who discovered this Strait. The French and English usually write it Magellan, and the Spaniards Magallanes; but by the Portuguese (and he was a native of Portugal) it is universally written Magalhaens. Admiral Burney and Mr. Dalrymple spell it Magalhanes, which mode I have elsewhere adopted, but I have since convinced myself of the propriety of following the Portuguese orthography for a name which, to this day, is very common both in Portugal and Brazil.

Enter the Straits of Magalhaens (or Magellan), and anchor off Cape Possession—First Narrow—Gregory Bay—Patagonian Indians—Second Narrow—Elizabeth Island—Freshwater Bay—Fuegian Indians—Arrival at Port Famine.

A contrary tide and light winds detained us at anchor near Cape Virgins until four o'clock in the afternoon, when, with the turn of the tide, a light air carried us past Dungeness Point, aptly named by Wallis from its resemblance to that in the English Channel. A great number of seals were huddled together upon the bank, above the wash of the tide, whilst others were sporting about in the surf. Cape Possession was in sight, and with the wind and tide in our favour we proceeded until ten o'clock, when the anchor was dropped. At daylight we found ourselves six miles to the eastward of the cape. The anchor was then weighed, and was again dropped at three miles from the cape until the afternoon, when we made another attempt; but lost ground, and anchored a third time. Before night a fourth attempt was made, but the tide prevented our making any advance, and we again anchored.

Mount Aymond[11] and "his four sons," or (according to the old quaint nomenclature) the Asses' Ears, had been in sight all day, as well as a small hummock of land on the S.W. horizon, which afterwards proved to be the peaked hillock upon Cape Orange, at the south side of the entrance to the First Narrow.

At this anchorage the tide fell thirty feet, but the strength of the current, compared with the rate at which we afterwards found it to run, was inconsiderable. Here we first experienced {13}the peculiar tides of which former navigators have written. During the first half of the flood[12] or westward tide, the depth decreased, and then, after a short interval, increased until three hours after the stream of tide had begun to run to the eastward.

The following morning (21st) we gained a little ground. Our glasses were directed to the shore in search of inhabitants, for it was hereabouts that Byron, and Wallis, and some of the Spanish navigators held communication with the Patagonian Indians; but we saw none. Masses of large sea-weed,[13] drifting with the tide, floated past the ship. A description of this remarkable plant, although it has often been given before, may not be irrelevant here. It is rooted upon rocks or stones at the bottom of the sea, and rises to the surface, even from great depths. We have found it firmly fixed to the ground more than twenty fathoms under water, yet trailing along the surface for forty or fifty feet. When firmly rooted it shows the set of the tide or current. It has also the advantage of indicating rocky ground: for wherever there are rocks under water, their situation is, as it were, buoyed by a mass of sea-weed[14] on the surface of the sea, of larger extent than that of the danger below. In many instances perhaps it causes unnecessary alarm, since it often grows in deep water; but it should not be entered without its vicinity having been sounded, especially if seen in masses, with the extremities of the stems trailing along the surface. If there be no tide, or if the wind and tide are the same way, the plant lies smoothly upon the water, but if the wind be against the tide, the leaves curl up and are visible at a distance, giving a rough, rippling appearance to the surface of the water.

During the last two days the dredge had furnished us with a few specimens of Infundibulum of Sowerby (Patella trochi-formis, Lin.), and some dead shells (Murex Magellanicus) were brought up by the sounding-lead.

We made another attempt next morning, but again lost {14}ground, and the anchor was dropped for the eighth time. The threatening appearances of the clouds, and a considerable fall of the barometer indicating bad weather, Captain Stokes agreed with me in thinking it advisable to await the spring-tides to pass the First Narrow: the ships were therefore made snug for the expected gale, which soon came on, and we remained several days wind-bound, with top-masts struck, in a rapid tide-way, whose stream sometimes ran seven knots. On the 28th, with some appearance of improving weather, we made an attempt to pass through the Narrow. The wind blowing strong, directly against us, and strengthening as we advanced, caused a hollow sea, that repeatedly broke over us. The tide set us through the Narrow very rapidly, but the gale was so violent that we could not show more sail than was absolutely necessary to keep the ship under command. Wearing every ten minutes, as we approached either shore, lost us a great deal of ground, and as the anchorage we left was at a considerable distance from the entrance of the Narrows, the tide was not sufficient to carry us through. At slack water the wind fell, and as the weather became fine, I was induced to search for anchorage near the south shore. The sight of kelp, however, fringing the coast, warned me off, and we were obliged to return to an anchorage in Possession Bay. The Beagle had already anchored in a very favourable berth; but the tide was too strong to permit us to reach the place she occupied, and our anchor was dropped a mile astern of her, in nineteen fathoms. The tide was then running five, and soon afterwards six miles an hour. Had the western tide set with equal strength, we should have succeeded in passing the Narrow. Our failure, however, answered the good purpose of making us more acquainted with the extent of a bank that lines the northern side of Possession Bay, and with the time of the turn of tide in the Narrow; which on this day (new moon) took place within a few minutes of noon.

As we passed Cape Orange, some Indians were observed lighting a fire under the lee of the hill to attract our notice; but we were too busily engaged to pay much attention to {15}their movements. Guanacoes also were seen feeding near the beach, which was the first intimation we had of the existence of that animal southward of the Strait of Magalhaens.

When day broke (29th) it was discovered that the ship had drifted considerably during the night. The anchor was weighed, and with a favourable tide we reached an anchorage a mile in advance of the Beagle. We had shoaled rather suddenly to eight fathoms, upon which the anchor was immediately dropped, and on veering cable the depth was eleven fathoms. We had anchored on the edge of a bank, which soon afterwards, by the tide falling, was left dry within one hundred yards of the ship. Finding ourselves so near a shoal, preparations were made to prevent the ship from touching it. An anchor was dropped under foot, and others were got ready to lay out, for the depth alongside had decreased from eleven to seven fathoms, and was still falling. Fortunately we had brought up to leeward of the bank, and suffered no inconvenience; the flood made, and as soon as possible the ship was shifted to another position, about half a mile to the S.E., in a situation very favourable for our next attempt to pass the Narrow. This night the tide fell thirty-six feet, and the stream ran six knots.

The ensuing morning we made another attempt to get through the Narrow, and, from having anchored so close to its entrance, by which the full benefit of the strength, as well as the whole duration of the tide was obtained, we succeeded in clearing it in two hours, although the distance was more than twenty miles, and the wind directly against us, the sea, as before, breaking repeatedly over the ship.

After emerging from the Narrow we had to pass through a heavy 'race' before we 'reached' out of the influence of the stream that runs between the First and Second Narrow, but the tide lasted long enough to carry us to a quiet anchorage. In the evening we weighed again, and reached Gregory Bay, where the Beagle joined us the next morning.

Since entering the Strait, we had not had any communication {16}with the Beagle on account of the weather, and the strength of the tide; this opportunity was therefore taken to supply her with water, of which she had only enough left for two days.

The greater part of this day was spent on shore, examining the country and making observations. Large smokes[15] were noticed to the westward. The shore was strewed with traces of men and horses, and other animals. Foxes and ostriches were seen; and bones of guanacoes were lying about the ground.

The country in the vicinity of this anchorage seemed open, low, and covered with good pasturage. It extends five or six miles, with a gradual ascent, to the base of a range of flat-topped land, whose summit is about fifteen hundred feet above the level of the sea. Not a tree was seen; a few bushes[16] alone interrupted the uniformity of the view. The grass appeared to have been cropped by horses or guanacoes, and was much interspersed with cranberry plants, bearing a ripe and juicy, though very insipid fruit.

Next day the wind was too strong and adverse to permit us to proceed. In the early part of the morning an American sealing vessel, returning from the Madre de Dios Archipelago on her way to the Falkland Islands, anchored near us. Mr. Cutler, her master, came on board the Adventure, passed the day and night with us, and gave me much useful information respecting the nature of the navigation, and anchorages in the Strait. He told me there was an Englishman in his vessel who was a pilot for the strait, and willing to join the ship. I gladly accepted the offer of his services.

In the evening an Indian was observed on horseback riding to and fro upon the beach, but the weather prevented my sending a boat until the next morning, when Lieutenant Cooke went on shore to communicate with him and other Indians who appeared, soon after dawn, upon the beach. On landing, he was received by them without the least distrust. They were eight or ten in number, consisting of an old man and his wife, three young men, and the rest children, all mounted on {17}good horses. The woman, who appeared to be about fifty years of age, was seated astride upon a pile of skins, hung round with joints of fresh guanaco meat and dried horse-flesh. They were all wrapped in mantles, made chiefly of the skins of guanacoes, sewed together with the sinews of the same animal. These mantles were large enough to cover the whole body. Some were made of skins of the 'zorillo,' or skunk, an animal like a pole-cat, but ten times more offensive; and others, of skins of the puma.

The tallest of the Indians, excepting the old man, who did not dismount, was rather less than six feet in height. All were robust in appearance, and with respect to the head, length of body, and breadth of shoulders, of gigantic size; therefore, when on horseback, or seated in a boat, they appeared to be tall, as well as large men. In proportion to the parts above-mentioned, their extremities were very small and short, so that when standing they seemed but of a moderate size, and their want of proportion was concealed by the mantle, which enveloped the body entirely, the head and feet being the only parts exposed.

When Mr. Cooke landed, he presented some medals[17] to the oldest man, and the woman; and suspended them round their necks. A friendly feeling being established, the natives dismounted, and even permitted our men to ride their horses, without evincing the least displeasure, at the free advantage taken of their good-nature. Mr. Cooke rode to the heights, whence he had a distinct view of the Second Narrow, and Elizabeth Island, whither, he explained to the Indians who accompanied him, we were going.

Mr. Cooke returned to the ship with three natives, whom he had induced to go with us to Elizabeth Island; the others were to meet them, and provide us with guanaco meat, to which arrangement the elders of the family had, after {18}much persuasion, assented. At first they objected to their companions embarking with us, unless we left hostages for their safety; but as this was refused, they did not press the point, and the three young men embarked. They went on board singing; in high glee.

While the ship was getting under way, I went ashore to a larger number of Indians who were waiting on the beach. When my boat landed they were mounted, and collected in one place. I was surprised to hear the woman accost me in Spanish, of which, however, she knew but a few words. Having presented medals to each of the party, they dismounted (excepting the elders), and in a few minutes became quite familiar. By this time Captain Stokes had landed, with several of his officers, who increased our party to nearly double the number of theirs: notwithstanding which they evinced neither fear nor uneasiness. The woman, whose name was Maria, wished to be very communicative; she told me that the man was her husband, and that she had five children. One of the young men, whom we afterwards found to be a son of Maria, who was a principal person of the tribe, was mounted upon a very fine horse, well groomed, and equipped with a bridle and saddle that would have done credit to a respectable horseman of Buenos Ayres or Monte Video. The young man wore heavy brass spurs, like those of the Guachos of Buenos Ayres. The juvenile and feminine appearance of this youth made us think he was Maria's daughter, nor was it until a subsequent visit that our mistake was discovered. The absence of whiskers and beard gives all the younger men a very effeminate look, and many cannot be distinguished, in appearance, from the women, but by the mode in which they wrap their mantles around them, and by their hair, which is turned up and confined by a fillet of worsted yarn. The women cross their mantle over the breast like a shawl, and fasten it together with two iron pins or skewers, round which are twisted strings of beads and other ornaments. They also wear their hair divided, and gathered into long tresses or tails, which hang one before each ear; and those who have short hair, wear false tails made of horse-hair. Under {19}their mantle the women wear a sort of petticoat, and the men a triangular piece of hide instead of breeches. Both sexes sit astride, but the women upon a heap of skins and mantles, when riding. The saddles and stirrups used by the men are similar to those of Buenos Ayres. The bits, also, are generally of steel; but those who cannot procure steel bits have a sort of snaffle, of wood, which must, of course, be frequently renewed. Both sexes wear boots, made of the skins of horses' hind legs, of which the parts about the hock joints serve for the heels. For spurs, they use pieces of wood, pointed with iron, projecting backwards two or three inches on each side of the heel, connected behind by a broad strap of hide, and fastened under the foot and over the instep by another strap.

The only weapons which we observed with these people were the 'bolas,' or balls, precisely similar to those used by the Pampas Indians; but they are fitter for hunting than for offence or defence. Some are furnished with three balls, but in general there are only two. These balls are made of small bags or purses of hide, moistened, filled with iron pyrites, or some other heavy substance, and then dried. They are about the size of a hen's egg, and attached to the extremities of a thong, three or four yards in length. To use them, one ball is held in the hand, and the other swung several times around the head until both are thrown at the object, which they rarely miss. They wind round it violently, and if it be an animal, throw it down. The bolas, with three balls, similarly connected together, are thrown in the same manner.

As more time could not be spared we went on board, reminding the natives, on leaving them, of their promise to bring us some guanaco meat. Aided by the tide, the ships worked to windward through the Second Narrow, and reached an anchorage out of the strength of tide, but in an exposed situation. The wind having been very strong and against the tide, the ship had much motion, which made our Patagonian passengers very sick, and heartily sorry for trusting themselves afloat. One of them, with tears in his eyes, begged to be landed, but was soon convinced of the difficulty of compliance, {20}and satisfied with our promise of sending him ashore on the morrow.

After we anchored, the wind increased to a gale, in which the ship pitched so violently as to injure our windlass. Its construction was bad originally, and the violent jerks received in Possession Bay had done it much damage. While veering cable, the support at one end gave way, and the axle of the barrel was forced out of the socket, by which some of the pawls were injured. Fortunately, dangerous consequences were prevented, and a temporary repair was soon applied.

The Beagle, by her better sailing, had reached a more advanced situation, close to the N.E. end of Elizabeth Island, but had anchored disadvantageously in deep water, and in the strength of the tide. Next morning we made an attempt to pass round Elizabeth Island, but found the breeze so strong that we were forced to return, and were fortunate enough to find good anchorage northward of the island, out of the tide.

The Patagonians, during the day, showed much uneasiness at being kept on board so much longer than they expected; but as they seemed to understand the cause of their detention, and as their sickness ceased when we reached smooth water, they gradually recovered their good-humour, and became very communicative. As well as we could understand their pronunciation, their names were 'Coigh,' 'Coichi,' and 'Aighen.' The country behind Cape Negro they called 'Chilpéyo;' the land of Tierra del Fuego, 'Oschērri;' Elizabeth Island, 'Tŭrrĕtterr;' the island of Santa Magdalena, 'Shrēe-ket-tup;' and Cape Negro, 'Oērkrĕckur.' The Indians of Tierra del Fuego, with whom they are not on friendly terms, are designated by them 'Săpāllĭŏs.' This name was applied to them in a contemptuous tone.

Aighen's features were remarkably different from those of his companions. Instead of a flat nose, his was aquiline and prominent, and his countenance was full of expression. He proved to be good-tempered, and easily pleased; and whenever a shade of melancholy began to appear, our assurance of {21}landing him on the morrow restored his good-humour, which was shown by singing and laughing.

The dimensions of Coichi's head were as follows:—

| From the top of the fore part of the head | to the eyes | 4 inches. |

| Dodo | to the tip of the nose | 6 |

| Dodo | to the mouth | 7 |

| Dodo | to the chin | 9 |

| Width of the head across the temples | 7½ | |

| Breadth of the shoulders | 18½ |

The head was long and flat, at the top; the forehead broad and high, but covered with hair to within an inch and a half of the eyebrow, which had scarcely any hair. The eyes were small, the nose was short, the mouth wide, and the lips thick. Neck short, and shoulders very broad. The arms were short, and wanting in muscle, as were also the thighs and legs. The body was long and large, and the breast broad and expanded. His height was nearly six feet.

The next day we rounded Elizabeth Island, and reached Cape Negro, where we landed the Indians, after making them several useful presents, and sending some trifles by Aighen to Maria, who, with her tribe, had lighted large fires about the country behind Peckett's Harbour, to invite us to land. Our passengers frequently pointed to them, telling us that they were made by Maria, who had brought plenty of guanaco meat for us.

Our anxiety to reach Port Famine prevented delay, and, as soon as the boat returned, we proceeded along the coast towards Freshwater Bay, which we reached early enough in the afternoon to admit of a short visit to the shore.

From Cape Negro the country assumed a very different character. Instead of a low coast and open treeless shore, we saw steep hills, covered with lofty trees, and thick underwood. The distant mountains of Tierra del Fuego, covered with snow, were visible to the southward, some at a distance of sixty or seventy miles.

We had now passed all the difficulties of the entrance, and had reached a quiet and secure anchorage.

The following day was calm, and so warm, that we thought if Wallis and Cordova were correct in describing the weather they met with, Duclos Guyot was equally entitled to credit; and we began to hope we had anticipated worse weather than we should experience. But this was an unusually fine day, and many weeks elapsed, afterwards, without its equal. The temperature of the air, in the shade on the beach, was 67½°, on the sand 87½°; and that of the water 55°. Other observations were made, as well as a plan of the bay, of which there is a description in the Sailing Directions.

Here we first noticed the character of the vegetation in the Strait, as so different from that of Cape Gregory and other parts of the Patagonian coast, which is mainly attributable to the change of soil; the northern part being a very poor clay, whilst here a schistose sub-soil is covered by a mixture of alluvium, deposited by mountain streams; and decomposed vegetable matter, which, from the thickness of the forests, is in great quantity.

Two specimens of beech (Fagus betuloides and antarctica), the former an evergreen,—and the winter's bark (Wintera aromatica), are the only trees of large size that we found here; but the underwood is very thick, and composed of a great variety of plants, of which Arbutus rigida, two or three species of Berberis, and a wild currant (Ribes antarctica, Bankes and Solander MSS.), at this time in flower, and forming long clustering bunches of young fruit, were the most remarkable. The berberis produces a berry of acidulous taste, that promised to be useful to us. A species of wild celery, also, which grows abundantly near the sea-shore, was valuable as an antiscorbutic. The trees in the immediate vicinity of the shore are small, but the beach was strewed with trunks of large trees, which seemed to have been drifted there by gales and high tides. A river falls into the bay, by a very narrow channel, near its south end; but it is small, and so blocked up by trees as not to be navigable even for the smallest boat: indeed, it is merely a mountain torrent, varying in size according to the state of the weather.

Tracks of foxes were numerous about the beach, and the footsteps of a large quadruped, probably a puma, were observed. Some teal and wild ducks were shot; and several geese were seen, but, being very wary, they escaped.

Upon Point St. Mary we noticed, for the first time, three or four huts or wigwams made by the Fuegian Indians, which had been deserted. They were not old, and merely required a slight covering of branches or skins to make them habitable. These wigwams are thus constructed: long slender branches, pointed at the end, are stuck into the ground in a circular or oval figure; their extremities are bent over, so as to form a rounded roof, and secured with ligatures of rush; leaving two apertures, one towards the sea, and the other towards the woods. The fire is made in the middle, and half fills the hut with smoke. There were no Indians in the bay when we arrived, but, on the following evening, Lieutenant Sholl, in walking towards the south end of the bay, suddenly found himself close to a party which had just arrived in two canoes from the southward. Approaching them, he found there were nine individuals—three men, and the remainder women and children. One of the women was very old, and so infirm as to require to be lifted out of the canoe and carried to the fire. They seemed to have no weapons of any consequence; but, from our subsequent knowledge of their habits, and disposition, the probability is they had spears, bows, and arrows concealed close at hand. The only implement found amongst them was a sort of hatchet or knife, made of a crooked piece of wood, with part of an iron hoop tied to the end. The men were very slightly clothed, having only the back protected by a seal's skin; but the females wore large guanaco mantles, like those of the Patagonian Indians, whom our pilot told us they occasionally met for the purpose of barter. Some of the party were devouring seal's flesh, and drinking the oil extracted from its blubber, which they carried in bladders. The meat they were eating was probably part of a sea lion (Phoca jubata); for Mr. Sholl found amongst them a portion of the neck of one of those animals, which is {24}remarkable for the long hair, "like a lion's mane," growing upon it. They appeared to be a most miserable, squalid race, very inferior, in every respect, to the Patagonians. They did not evince the least uneasiness at Mr. Sholl's presence, or at our ships being close to them; neither did they interfere with him, but remained squatting round their fire while he staid near. This seeming indifference, and total want of curiosity, gave us no favourable opinion of their character as intellectual beings; indeed, they appeared to be very little removed from brutes; but our subsequent knowledge of them has convinced us that they are not usually deficient in intellect. This party was perhaps stupified by the unusual size of our ships, for the vessels which frequent this Strait are seldom one hundred tons in burthen.

We proceeded next morning at an early hour. The Indians were already paddling across the bay in a northerly direction. Upon coming abreast of them, a thick smoke was perceived to rise suddenly from their canoes; they had probably fed the fire, which they always carry in the middle of their canoe, with green boughs and leaves, for the purpose of attracting our attention, and inviting us to communicate with them.

It was remarked that the country begins to be covered with trees at Cape Negro; but they are stunted, compared with those at Freshwater Bay. Near this place, also, the country assumes a more verdant aspect, becoming also higher, and more varied in appearance. In the neighbourhood of Rocky Point some conspicuous portions of land were noticed, which, from the regularity of their shape, and the quantity as well as size of the trees growing at the edges, bore the appearance of having been once cleared ground; and our pilot Robinson (possessing a most inventive imagination) informed us that they were fields, formerly cleared and cultivated by the Spaniards, and that ruins of buildings had been lately discovered near them. For some time his story obtained credit, but it proved to be altogether void of foundation. These apparently cleared tracts were afterwards found to be occasioned by unusual poverty of soil, and by being overrun with thick {25}spongy moss, the vivid green colour of which produces, from a distance, an appearance of most luxuriant pasture land. Sir John Narborough noticed, and thus describes them: "The wood shows in many places as if there were plantations: for there were several clear places in the woods, and grass growing like fenced fields in England, the woods being so even by the sides of it."[18]

The wind, after leaving Freshwater Bay, increased, with strong squalls from the S.W., at times blowing so hard as to lay the ship almost on her broadside. It was, however, so much in our favour, that we reached the entrance of Port Famine early, and after some little detention from baffling winds, which always render the approach to that bay somewhat difficult, the ships anchored in the harbour.

Prepare the Beagle, and our decked boat (the Hope) for surveying the Strait—Beagle sails westward, and the Hope towards the south-east—Sarmiento's voyage—and description of the colony formed by him at Port Famine—Steamer-duck—Large trees—Parroquets—Mount Tarn—Barometrical observations—Geological character—Report of the Hope's cruize.

In almost every account published of the Strait of Magalhaens, so much notice has been taken of Port Famine, that I had long considered it a suitable place for our purposes; and upon examination I found it offered so many advantages, that I did not hesitate to make it our head-quarters. As soon, therefore, as the ship was moored, tents were pitched, our decked-boat was hoisted out and hauled on shore, to be coppered and equipped for the survey;—and Captain Stokes received orders to prepare the Beagle for examining the western part of the Strait; previous to which she required to be partially refitted, and supplied with fuel and water.

For several days after our arrival, we had much rain and strong south-westerly wind, with thick clouds, which concealed the high land to the southward; allowing us only now and then a partial glimpse. One evening (11th) the air was unusually clear, and many of the mountains in that direction were distinctly defined. We had assembled to take leave of our friends in the Beagle, and were watching the gradual appearance of snow-capped mountains which had previously been concealed, when, bursting upon our view, as if by magic, a lofty mountain appeared towering among them; whose snowy mantle, strongly contrasted with the dark and threatening aspect of the sky, much enhanced the grandeur of the scene.

This mountain was the "Snowy Volcano" (Volcan Nevado) of Sarmiento, with whose striking appearance that celebrated navigator seems to have been particularly impressed, so minute and excellent is his description. It is also mentioned in the account of Cordova's voyage.[19] The peculiar shape of its summit as seen from the north would suggest the probability of its being a volcano, but we never observed any indication of its activity. Its volcanic form is perhaps accidental, for, seen from the westward, its summit no longer resembles a crater. From the geological character of the surrounding rocks its formation would seem to be of slate. It is in a range of mountains rising generally two or three thousand feet above the sea; but at the N.E. end of the range are some, at least four thousand feet high. The height of the "Snowy Volcano," or as we have called it, Mount Sarmiento,[20] was found, by trigonometrical measurement, to be six thousand eight hundred feet[21] above the level {28}of the sea. It is the highest land that I have seen in Tierra del Fuego; and to us, indeed, it was an object of considerable interest, because its appearance and disappearance were seldom failing weather guides. In our Meteorological Diary, a column was ruled for the insertion of its appearances.[22]

This clear state of the atmosphere was followed by a heavy fall of rain, with northerly and easterly winds, which did not, however, last long.

In the vicinity of our tents erected on the low land, on the S.W. side of the bay, were several ponds of water, perfectly fit for immediate use; but, perhaps, too much impregnated with vegetable matter to keep good for any length of time. Captain Stokes, therefore, filled his tanks from the river; but as that water did not keep well, it was probably taken into the boat too near the sea. This, however, was unavoidable, except by risking the boats among a great number of sunken trees in the bed of the river.

The Beagle sailed on the 15th, to survey the western entrance of the Strait, with orders to return to Port Famine by the end of March.

Our decked boat, the Hope, being ready, the command of her was given to Mr. Wickham, who was in every way qualified for the trust. We were, however, much mortified by finding that she leaked so considerably as to oblige us to unload, and again haul her on shore. When ready for sea, she sailed under the direction of my assistant-surveyor, Mr. Graves, to examine the St. Sebastian channel and the deep opening to the S.E. of Cape Valentyn. Her crew consisted of seven men, besides Mr. Wickham, and Mr. Rowlett, the purser.