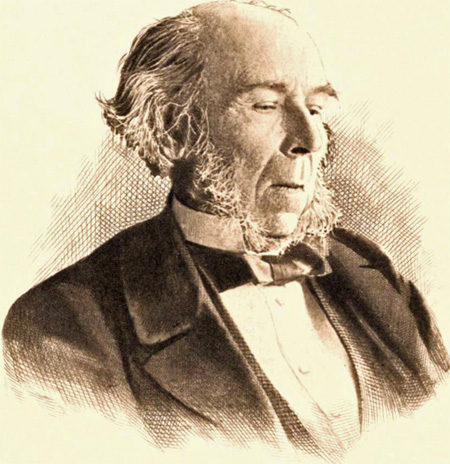

Title: Herbert Spencer

Author: J. Arthur Thomson

Release date: February 28, 2012 [eBook #39002]

Most recently updated: January 8, 2021

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Adam Buchbinder, Josephine Paolucci and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net.

(This book was produced from scanned images of public

domain material from the Google Print project.)

PUBLISHED IN LONDON BY

J. M. DENT & CO. AND IN NEW

YORK BY E. P. DUTTON & CO.

1906

PAGE

Introduction vii

CHAP.

I. Heredity 1

II. Nurture 7

III. Period of Practical Work 17

IV. Preparation for Life-Work 27

V. Thinking out the Synthetic Philosophy 37

VI. Characteristics: Physical and Intellectual 52

VII. Characteristics: Emotional and Ethical 74

VIII. Spencer as Biologist: The Data of

Biology 93

IX. Spencer as Biologist: Inductions of

Biology 110

X. Spencer as Champion of the Evolution-Idea 135

XI. As regards Heredity 154

XII. Factors of Organic Evolution 180

XIII. Evolution Universal 209

XIV. Psychological 232

XV. Sociological 242

XVI. The Population Question 259

XVII. Beyond Science 269

Conclusion 278

Index 283

This volume attempts to give a short account of Herbert Spencer's life, an appreciation of his characteristics, and a statement of some of the services he rendered to science. Prominence has been given to his Autobiography, to his Principles of Biology, and to his position as a cosmic evolutionist; but little has been said of his psychology and sociology, which require another volume, or of his ethics and politics, or of his agnosticism—the whetstone of so many critics. Our appreciation of Spencer's services is therefore partial, but it may not for that reason fail in its chief aim, that of illustrating the working of one of the most scientific minds that ever lived, "whose excess of science was almost unscientific."

The story of Spencer's life is neither eventful nor picturesque, but it commands the interest of all who admire faith, courage, and loyalty to an ideal. It is a story of plain living and high thinking, of one who, though vexed by an extremely nervous temperament, was as resolute as a Hebrew prophet in delivering his message. It is the story of a quiet servant of science, indifferent to conventional honours, careless about "getting on," disliking controversy, sensationalism, and noise, trusting to the power of truth alone, that it must prevail.

Another aspect of interest is that Spencer was an arch-heretic, one of the flowers of Nonconformity,[Pg viii] against theology and against metaphysics, against monarchy and against molly-coddling legislation, against classical education and against socialism, against war and against Weismann. So that we can hardly picture the man who has not some crow to pick with Spencer.

It is not to be wondered at, then, that we find extraordinary difference of opinion as to the value of the great Dissenter's deliverances. In 1894, Prof. Henry Sidgwick spoke of Herbert Spencer as "our most eminent living philosopher," and in the same sentence described him as "an impressive survival of the drift of thought in the first half of the nineteenth century." Some have likened him to a second Aristotle, while others assure us that the author of the Synthetic Philosophy was not a philosopher at all. Similarly there are scientists who tell us that Spencer may have been a great philosopher, but that he was too much of an a priori thinker to be of great account in science. Many critics, indeed, devote so much time and ability to demonstrating Spencer's incompetence, in this or that field of thought, that the reader is left with the impression that it must be a tower of strength which requires so many assaults. And there are others, neither philosophers nor scientists, who are content to dismiss Spencer with saying that the least in the Kingdom of Heaven is greater than he. Yet this much is conceded by most, that Herbert Spencer was an unusually keen intellectual combatant, who took the evolution-formula into his strong hands as a master-key, and tried (teaching others to try better) to open therewith all the locked doors of the universe—all the immediate, though none of the ultimate, riddles,[Pg ix] physical and biological, psychological and ethical, social and religious. And this also is conceded, that his life was signalised by absolute consecration to the pursuit of truth, by magnanimous disinterestedness as to rewards, by a resolute struggle against almost overwhelming difficulties, and by an entire fearlessness in delivering the message which he believed the Unknown had given him for the good of the world. In an age of specialism he held up the banner of the Unity of Science, and he actually completed, so far as he could complete, the great task of his life—greater than most men have even dreamed of—that of applying the evolution-formula to everything knowable. He influenced thought so largely, he inspired so many disciples, he left so many enduring works—enduring as seed-plots, if not also as achievements—that his death, writ large, was immortality.

Ancestry—Grandparents—Uncles—Parents

Remarkable parents often have commonplace children, and a genius may be born to a very ordinary couple, yet the importance of pedigree is so patent that our first question in regard to a great man almost invariably concerns his ancestry. In Herbert Spencer's case the question is rewarded.

Ancestry.—From the information afforded by the Autobiography in regard to ancestry remoter than grandparents, we learn that, on both sides of the house, Spencer came of a stock characterised by the spirit of nonconformity, by a correlated respect for something higher than legislative enactments, and by a regard for remote issues rather than immediate results. In these respects Herbert Spencer was true to his stock—an uncompromising nonconformist, with a conscience loyal to "principles having superhuman origins above rules having human origins," and with an eye ever directed to remote issues. Truly it required more than "ingrained nonconformity," loyalty to principles, and far-sighted prudence to[Pg 2] make a Herbert Spencer, and hundreds unknown to fame must have shared a similar heritage; but the resemblances between some of Spencer's characteristics and those of his stock are too close to be disregarded. Disown him as many nonconformists did, they could not disinherit him. Nonconformity was in his blood and bone of his bone.

Grandparents.—Spencer's maternal grandfather, John Holmes of Derby, was a business man and an active Wesleyan, with "a little more than the ordinary amount of faculty." The grandmother, née Jane Brettell, is described as "commonplace," but her portrait suggests a more charitable verdict. Spencer's paternal grandfather was a schoolmaster, a "mechanical teacher," somewhat oppressed by life, and "extremely tender-hearted." If, when a newspaper was being read aloud, there came an account of something cruel or very unjust, he would exclaim: "Stop, stop, I can't bear it!" Of this sensitive temperament his illustrious grandson had a large share. The most notable of the four grandparents was Catherine Spencer, née Taylor, "of good type both physically and morally." "Born in 1758 and marrying in 1786, when nearly 28, she had eight children, led a very active life, and lived till 1843: dying at the age of 84 in possession of all her faculties." A personal follower of John Wesley, intensely religious, indefatigably unselfish, combining unswerving integrity with uniform good temper and affection, "she had all the domestic virtues in large measures." Her grandson has said that "nothing was specially manifest in her, intellectually considered, unless, indeed, what would be called sound common[Pg 3] sense." Grandparents taken together count on an average for about a quarter of the individual inheritance, but we would note that in Herbert Spencer's case, Catherine Spencer should be regarded as a peculiarly dominant hereditary factor.

Uncles.—Two of her children died in infancy, the only surviving daughter (b. 1788) was an invalid; then came Herbert Spencer's father, William George (b. 1790), and there were four other sons. Henry Spencer, a year and a half younger than Herbert Spencer's father, was "a favourable sample of the type," independent with "a strong dash of chivalry," an energetic, though in the end unsuccessful man of business, an ardent radical and with "a marked sense of humour." The next son, John, had strong individuality; he was a notably self-assertive, obstinate solicitor, successful only in out-living all his brothers. Thomas, the next brother, began active life as a school-teacher near Derby, was a student of St John's, Cambridge, achieved honours (ninth wrangler), and became a clergyman of the Church of England at Hinton. He was "a reformer," "anticipating great movements," a "radical," a "Free-Trader," a "teetotaler," "an intensified Englishman." The youngest son, William, "distinguished less by extent of intellectual acquisitions than by general soundness of sense, joined with a dash of originality," carried on his father's school, and was one of Herbert Spencer's teachers. He was a Whig and a nonconformist, but more moderate than his brothers in either direction.

These facts in regard to Herbert Spencer's uncles corroborate the general thesis that heredity counts[Pg 4] for much. The four uncles had individuality, rising sometimes to the verge of eccentricity; in their various paths of life they were independent, critical, self-assertive, and with a characteristic absence of reticence.

Parents.—George Spencer, Herbert's father (b. 1790) was "the flower of the flock." "To faculties which he had in common with the rest (except the humour of Henry and the linguistic faculty of Thomas), he added faculties they gave little sign of. One was inventive ability, and another was artistic perception, joined with skill of hand." He began very early to teach in his father's school, and was for most of his life a teacher. As such, he was noted for his reliance on non-coercive discipline, and at the same time for his firmness; he continually sought to stimulate individuality rather than to inform. His Inventional Geometry and Lucid Shorthand had some vogue for a time.

He was an unconventional person, as shown in little things—by his repugnance to taking off his hat, to donning signs of mourning, or to addressing people as "Esq." or "Revd.," and in big things by his pronounced "Whigism." With "a repugnance to all living authority" he combined so much sympathy and suavity that he was generally beloved. He found Quakerism "congruous with his nature in respect of its complete individualism and absence of ecclesiastical government." He had unusual keenness of the senses, delicacy of manipulation, and noteworthy artistic skill. A somewhat fastidious and finicking habit of trying to make things better was expressed in his annotations on dictionaries and the[Pg 5] like, but he had also a larger "passion for reforming the world." As his son notes, the one great drawback was lack of considerateness and good temper in his relations with his wife. For this, however, a nervous disorder was in part to blame. He lived to be over seventy.

Herbert Spencer's mother, née Harriet Holmes (1794-1867), introduced a new strain into the heritage. "So far from showing any ingrained nonconformity, she rather displayed an ingrained conformity." A Wesleyan by tradition rather than by conviction, she was constitutionally averse to change or adventure, non-assertive, self-sacrificing, patient, and gentle. "Briefly characterised, she was of ordinary intelligence and of high moral nature—a moral nature of which the deficiency was the reverse of that commonly to be observed: she was not sufficiently self-asserting: altruism was too little qualified by egoism."

Spencer did not think that he took after his mother except in some physical features. He had something of his father's nervous weakness, but he had not his large chest and well developed heart and lungs. Believing that "the mind is as deep as the viscera," he does not scruple to state that his "visceral constitution was maternal rather than paternal."

"Whatever specialities of character and faculty in me are due to inheritance, are inherited from my father. Between my mother's mind and my own I see scarcely any resemblances, emotional or intellectual. She was very patient; I am very impatient. She was tolerant of pain, bodily or mental; I am intolerant of it. She was little given to finding fault with others; I am greatly given to it. She was submissive; I am the reverse of submissive. So, too, in[Pg 6] respect of intellectual faculties, I can perceive no trait common to us, unless it be a certain greater calmness of judgment than was shown by my father; for my father's vivid representative faculty was apt to play him false. Not only, however, in the moral characters just named am I like my father, but such intellectual characters as are peculiar are derived from him" (Autobiography ii., p. 430).

Boyhood—School—At Hinton—At Home

Herbert Spencer was born at Derby on the 27th of April 1820. His father and mother had married early in the preceding year, at the age of about 29 and 25 respectively. Except a little sister, a year his junior, who lived for two years, he was practically the only child, for of the five infants who followed none lived more than a few days. As Spencer pathetically remarks: "It was one of my misfortunes to have no brothers, and a still greater misfortune to have no sisters." But is it not recompense enough of any marriage to produce a genius?

In reference to his father's breakdown soon after marriage, Spencer writes: "I doubt not that had he retained good health, my early education would have been much better than it was; for not only did his state of body and mind prevent him from paying as much attention to my intellectual culture as he doubtless wished, but irritability and depression checked that geniality of behaviour which fosters the affections and brings out in children the higher traits of nature. There are many whose lives would have been happier had their parents been more careful about themselves, and less anxious to provide for others."

Boyhood.—The father's ill-health had this compensation, that Herbert Spencer spent much of his childhood (æt. 4-7) in the country—at New Radford, near Nottingham. In his later years he had still vivid recollections of rambling among the gorse-bushes which towered above his head, of exploring the narrow tracks which led to unexpected places, and of picking the blue-bells "from among the prickly branches, which were here and there flecked with fragments of wool left by passing sheep." He was allowed freedom from ordinary "lessons," and enjoyed a long latent receptive period.

In 1827 the family returned to Derby, but for some time the boy's life was comparatively unrestrained. There was some gardening to do—an educational discipline far too little appreciated—and there was "almost nominal" school-drill; but there was plenty of time for exploring the neighbourhood, for fishing and bird-nesting, for watching the bees and the gnat-larvæ, for gathering mushrooms and blackberries. "Beyond the pleasurable exercise and the gratification of my love of adventure, there was gained during these excursions much miscellaneous knowledge of things, and the perceptions were beneficially disciplined." "Most children are instinctively naturalists, and were they encouraged would readily pass from careless observations to careful and deliberate ones. My father was wise in such matters, and I was not simply allowed but encouraged to enter on natural history."

He had the run of a farm at Ingleby during holidays; he enjoyed fishing in the Trent, in which he was within an ace of being drowned when about ten[Pg 9] years old; he was a keen collector of insects, watching their metamorphoses, and often drawing and describing his captures; and he was also encouraged to make models. In short, he had in a simple way not a few of the disciplines which modern pædagogics—helped greatly by Spencer himself—has recognised to be salutary.

In his boyhood Spencer was extremely prone to castle-building or day-dreaming—"a habit which continued throughout youth and into mature life; finally passing, I suppose, into the dwelling on schemes more or less practicable." For his tendency to absorption, without which there has seldom been greatness of achievement, he was often reproached by his father in the words: "As usual, Herbert, thinking only of one thing at a time."

He did not read tolerably until he was over seven years old, and Sandford and Merton was the first book that prompted him to read of his own accord. He rapidly advanced to The Castle of Otranto and similar romances, all the more delectable that they were forbidden fruits. While John Stuart Mill was working at the Greek classics, Herbert Spencer was reading novels in bed. But the appetite for reading was soon cloyed, and he became incapable of enjoying anything but novels and travels for more than an hour or two at a time.

School.—As to more definite intellectual culture, the first school period (before ten years) seems to have counted for little, and is interesting only because it revealed the boy's general aversion to rote-learning and dogmatic statements. Shielded from direct punishment, he lived in an atmosphere of reproof,[Pg 10] and this "naturally led to a state of chronic antagonism." But when he was ten (1830) he became one of his Uncle William's pupils, and this led to some progress. There was drawing, map-making, experimenting, Greek Testament without grammar, but comparatively little lesson-learning. "As a consequence, I was not in continual disgrace." The boy was quick in all matters appealing to reason, and "had a somewhat remarkable perception of locality and the relations of position generally, which in later life disappeared."

Apart from school he had the advantage of hearing discussions between his father and his friends on all sorts of topics, of preparing for the scientific demonstrations which his father occasionally gave, of sampling scientific periodicals which came to the Derby Philosophical Society of which his father was honorary secretary, and of reading such works as Rollin's Ancient History and Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. He was continually prompted to "intellectual self-help," and was continually stimulated by the question, "Can you tell me the cause of this?"

"Always the tendency in himself, and the tendency strengthened in me, was to regard everything as naturally caused; and I doubt not that while the notion of causation was thus rendered much more definite in me than in most of my age, there was established a habit of seeking for causes, as well as a tacit belief in the universality of causation." "A tacit belief in the universality of causation" seems a big item to be put to the credit of a boy of thirteen, but we have the echo of it in Clerk Maxwell's continual[Pg 11] boyish question, "What is the go of this?" That the question of cause was acute in both cases implies that both had hereditarily fine brains, but it also suggests that the question is normal in those who are naturally educated. The sensitive, irritable, invalid father was no ideal parent, but he did not snub his son's inquisitiveness, nor coerce his independence, nor appeal to authority as such as a reason for accepting any belief.

Spencer has given in his Autobiography a picture of himself as a boy of thirteen. His constitution was distinguished "rather by good balance than by great vital activity"; there was "a large margin of latent power"; he was more fleet than any of his school-fellows. He was decidedly peaceful, but when enraged no considerations of pain or danger or anything else restrained him. He was affectionate and tender-hearted, but his most marked moral trait was disregard of authority. His memory was rather below par than above; he was "averse to lesson-learning and the acquisition of knowledge after the ordinary routine methods," but he picked up general information with facility; he could not bear prolonged reading or the receptive attitude. From about ten years of age to thirteen he habitually went on Sunday morning with his father to the Friends' Meeting House, and in the evening with his mother to the Methodist Chapel. "I do not know that any marked effect on me followed; further, perhaps, than that the alternation tended to enlarge my views by presenting me with differences of opinion and usage." While John Mill kept his son away from conventional religious influences, Spencer's father excluded none;[Pg 12] and the result seems to have been much the same in the two cases. In this and other connections, Prof. W. H. Hudson points out the contrast between the methods of the two fathers of the two remarkable sons—John Stuart Mill was constrained along carefully chosen paths, Herbert Spencer enjoyed more elbow-room and free-play, what German biologists call "Abänderungsspielraum."

At thirteen, Herbert Spencer had little Latin and less Greek; he was wholly uninstructed in "English"; he had no knowledge of mathematics, English history, ancient literature, or biography. "Concerning things around, however, and their properties, I knew a good deal more than is known by most boys." Through physics and chemistry in certain lines, through entomology and general natural history, through miscellaneous reading in physiology and geography, he had in many ways an intellectual grip of his environment; but on the lines of the "humanities" he was wofully uneducated.

On the other hand, his education had been stimulating and emancipating, and even as a boy of thirteen his intelligence was alert and independent. Much in the open air, he had kept an open mind. He had learned to use his brains and to enjoy nature. After that, everything is possible.

At Hinton.—When Herbert Spencer was thirteen (in the summer of 1833) his parents took him to his Uncle Thomas, at Hinton Charterhouse, near Bath. The journey was a revelation to the boy, and his early days at Hinton were full of delight, especially in regard to the new butterflies. But when he discovered that he had come to stay and to be schooled,[Pg 13] he had a feverish Heimweh, and soon followed his parents homewards. "That a boy of thirteen should, without any food but bread and water and two or three glasses of beer, and without sleep for two nights, walk 48 miles one day, 47 the next, and some 20 the third, is surprising enough." It was a rather absurd boyish escapade, mainly due to lack of parental frankness, but not without the compliment implied in all nostalgia, and it gives us an inkling of Spencer's obstinacy and doggedness.

A fortnight after the escapade, the runaway returned peacefully to Hinton—content with his dramatic assertion of himself. For about three years he remained under his uncle's tutorship, and this was a formative period. Hinton stands high in a hilly country, between Bath and Frome, with picturesque places all round. His uncle was "a man of energetic, strongly-marked character," "intellectually above the average," with a good deal of originality of thought. Like his kindly wife, he belonged to the evangelical school.

"The daily routine was not a trying one. In the morning Euclid and Latin, in the afternoon commonly gardening, or sometimes a walk; and in the evening, after a little more study, usually of algebra I think, came reading, with occasionally chess. I became at that time very fond of chess, and acquired some skill." The aversion to linguistic studies continued, but there was an enthusiasm for mathematics and physics. To a modern educationist the regime at Hinton cannot but seem narrow; there was no history, no letters, no concrete science, and no play. There was certainly no over-pressure, but there was some brain-stretching[Pg 14] and some salutary moral discipline. Stimulating, doubtless, was the table-talk and Mr Spencer's arguments with his nephew, whom he found "very deficient in the principle of Fear." We must not forget the visits to London (including the then private Zoological Gardens), or the first appearances in print—two letters in the newly started Bath Magazine on curiously shaped floating crystals of common salt, and on the New Poor Law! In June 1836, Herbert Spencer returned to Derby, benefited by the rural life and bracing climate of Hinton, "strong, in good health, and of good stature."

Looking backward after many years, Herbert Spencer felt that he was treated as a youth "with much more consideration and generosity than might have been expected. There was shown great patience in prosecuting what seemed by no means a hopeful undertaking." It is interesting, of course, to speculate what might have been the result if the boy's education had been less of a family affair; and it would be unfair to conclude that the success which attended the easy-going, personal, familiar instruction of this boy of uncommon brains would also attend a similar treatment of those of humbler parts. But would it not be well to make the experiment oftener, since the material abounds, and since the results of the conventional discipline of public schools and the like are not dazzlingly successful?

Spencer felt strongly, as he indulged in retrospect, that his well-meaning educators "had to deal with intractable material—an individuality too stiff to be easily moulded." That we may, in time, come to have not an occasional stiff haulm with a big ear, but a[Pg 15] whole crop of them, must be the prayer of all who believe in education and race-progress.

Another of Spencer's retrospective convictions is one that makes all human nature kin—that he was not so black as he was painted. His father and his uncle had been eminently "good" boys, and they gauged boy-nature by their own standard. Had he gone to a public school, Spencer thinks that his "extrinsically-wrong actions would have been many, but the intrinsically-wrong actions would have been few." This distinction will doubtless appeal to the wise.

At Home.—For a year and a half after leaving Hinton, Herbert Spencer remained at home, enjoying another period of freedom. He made in a day, without previous experience, a survey of his father's small property at Kirk Ireton—two fields and three cottages with their gardens; he made designs for a country house; he hit upon a remarkable property of the circle; and he fished. Meanwhile, however, his father who "held, and rightly held, that there are few functions higher than that of the educator," induced him to engage in school-work, and this experiment lasted for three months. It appears to have been directly a success, Spencer's lessons were at once "effective and pleasure-giving," and "complete harmony continued throughout the entire period"; it was not less important eventually, for we cannot doubt that part of the effectiveness of Herbert Spencer's book on Education is traceable to the fact that he had, for a term at least, personal experience of teaching.

Even at this early age (17 years) Spencer had ideals[Pg 16] of "intellectual culture, moral discipline, and physical training." But as he disliked mechanical routine, had a great intolerance of monotony, and had ideas of his own, it seems likely enough that if he had embraced the profession of teacher, he would sooner or later have "thrown it up in disgust." The experiment was not to be tried further, however, for in November 1837, his uncle William wrote from London that he had obtained for his nephew a post under Mr Charles Fox as a railway engineer. "The profession of a civil engineer had already been named as one appropriate for me; and this opening at once led to the adoption of it."

We may sum up the first two periods of Spencer's life. The period of childhood was marked by a more than usual freedom from the conventional responsibilities of juvenile tasks, by the large proportion of open-air life, and by much more intercourse with adults than with other children. The table talk between his father and uncles had an important moulding influence, all the more that there was "a comparatively small interest in gossip." "Their conversation ever tended towards the impersonal.... There was no considerable leaning towards literature.... It was rather the scientific interpretations and moral aspects of things which occupied their thoughts." The period of boyhood and of more definite education was marked by freedom and variety, by a relative absence of linguistic discipline, by a preponderance of scientific training, by much family influence, and by an unusual amount of independent thinking.

Engineering—Many Inventions—Glimpse of Evolution-Idea—A Resting Period—Beginning to Write—Experimenting with Life

Herbert Spencer's life after boyhood may be conveniently divided into four periods:—

1. For about ten years he was engaged in varied practical work—surveying, plan-making, engineering, secretarial business, and superintendence (1837-1846).

2. After an unattached couple of years, during which he continued his self-education, experimented, invented, and meditated, there began a period of miscellaneous literary work, of journalism, and essay-writing, during which he wrote his Principles of Psychology and felt his way to his System (1848-1860).

3. At the age of forty, he settled down to something like unity of occupation—developing and writing The Synthetic Philosophy (1860-1882).

4. Finally, during a prolonged period of pronounced invalidism, he withdrew almost completely from social life, husbanding his meagre supply of mental energy for the completion of his System, the revision of his works, and his Autobiography (1882-1903).

Engineering.—For about ten years (1837-46) Herbert Spencer had a varied experience of practical life. He began as assistant, at £80 a year, to Mr Charles Fox,[Pg 18] who had been one of Mr George Spencer's pupils,—a man of mechanical genius, who was at that time resident engineer of the London division of the "London and Birmingham" railway, and afterwards became well known as the designer and constructor of the Exhibition-Building of 1851. Spencer had surveying and measuring, drawing and calculating to do, and he threw off the slackness which marked his school-days. During the first six months in London he never went to any place of amusement and never read a novel, but gave his leisure to mathematical questions and to suggesting little inventions or improved methods.

A transference for the summer months to Wembly, near Harrow, gave him even more time for study, and we read of an appliance by which he proposed to facilitate some kinds of sewing. He seems to have pleased his employer well, for in September 1838 he was advanced to a post of draughtsman in connection with the "Gloucester and Birmingham" railway, at a salary of £120 yearly. Thus the next two years were spent at Worcester, where he had his first experience of working alongside of other young men, to whom he appeared rather an "oddity," though not one to be "quizzed." His "mental excursiveness" grew stronger and stronger, and had occasionally useful results, leading, for instance, to an article in The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal (May 1839) on a new plan of projecting the spiral courses in skew bridges, to a re-invention of Nicholson's Cyclograph, and to an improvement in the apparatus for giving and receiving the mail-bags carried by trains.

Many Inventions.—In 1840, Spencer became[Pg 19] engineering secretary to his chief, Captain Moorson, and went to live in the little village of Powick, about three miles out of Worcester. He enjoyed his work, and had the new experience of establishing relations with a number of children, with whom he soon became a favourite. Long afterwards, in his declining years he found much gratification in making friends with children, and referred to it quaintly as "a vicarious phase of the philoprogenitive instinct." It was at Powick that Spencer first began to have a conscience about his very defective spelling (his morals had always been sans reproche) and to take an interest in style. It was at Powick, too, in a physical and social environment that suited him, that Spencer invented his "Velocimeter," a little instrument for showing by inspection the velocity of an engine, and two or three other devices. He had inherited his father's constructive imagination, and his father's discipline had increased it. The father wrote on July 3rd, 1840, "I am glad you find your inventive powers are beginning to develop themselves. Indulge a grateful feeling for it. Recollect, also, the never-ceasing pains taken with you on that point in early life." And the son remarks gratefully that this conveys a lesson to educators; the inherited endowment is much, but the fostering of it is also much. "Culture of the humdrum sort, given by those who ordinarily pass for teachers, would have left the faculty undeveloped." On the whole, however, Spencer attached most importance to the hereditary endowment, for he goes on to say that Edison, "probably the most remarkable inventor who ever lived," was a self-trained man, and that Sir Benjamin[Pg 20] Baker, "the designer and constructor of the Forth Bridge, the grandest and most original bridge in the world, received no regular engineering education." It was at Powick, too, that place of many inventions, that Herbert Spencer (aetat. 20) made the intimate acquaintance of an "intelligent, unconventional, amiable, and in various ways attractive" young lady, who "tended to diminish his brusquerie." Luckily or unluckily, the young lady was engaged; and Spencer remarks, "It was pretty clear that had it not been for the pre-engagement our intimacy would have grown into something serious. This would have been a misfortune, for she had little or nothing and my prospects were none of the brightest." Here the ancestral prudence crops out.

Glimpses of Evolution-Idea.—The year 1840-41 was "a nomadic period," of bridge-building at Bromsgroove and Defford, of "castle-building," too, for he dreamt of making a fortune by successful inventions, of testing engines, and other routine duties,—a life involving considerable wear and tear which began to tell on Spencer's eyes. During this period he renewed his youth by collecting fossils, and "making a collection is," as he afterwards said, "the proper commencement of any natural history study; since, in the first place, it conduces to a concrete knowledge which gives definiteness to the general ideas subsequently reached, and, further, it creates an indirect stimulus by giving gratification to that love of acquisition which exists in all." It was then that the purchase of Lyell's Principles of Geology led him, curiously enough, to adopt the supposition that organic forms have arisen, not by special creation,[Pg 21] but by progressive modifications, physically caused and inherited. In spite of Lyell's chapter refuting Lamarck's views concerning the origin of species, it was with Lamarck that Spencer, at the age of twenty, sided. The idea of natural genesis was in harmony with the general idea of the order of Nature towards which Spencer had been growing. "My belief in it never afterwards wavered, much as I was, in after years, ridiculed for entertaining it."

"The incident illustrates the general truth that the acceptance of this or that particular belief, is in part a question of the type of mind. There are some minds to which the marvellous and the unaccountable strongly appeal, and which even resent any attempt to bring the genesis of them within comprehension. There are other minds which, partly by nature and partly by culture, have been led to dislike a quiescent acceptance of the unintelligible; and which push their explorations until causation has been carried to its confines. To this last order of minds mine, from the beginning, belonged."

Spencer's engagement with Capt. Moorson came to a natural termination, and an offer of a permanent post on the Birmingham and Gloucester railway was declined, one motive being a desire to prepare for the future by a course of mathematical study, another being to work at an idea his father had arrived at of an electro-magnetic engine. Thus his twenty-first birthday was spent at home in Derby, after an absence of three and a half years,—which had been on the whole "satisfactory, in so far as personal improvement and professional success were concerned."

A Resting Period.—But when he got home he found his study of a work on the Differential Calculus a weariness to the flesh. "To apply day after day merely with the general idea of acquiring information, or of increasing ability," was not in him, though he could work hard when the end in view was definite or large enough. Moreover an article in the Philosophical Magazine led to an immediate abandonment of the idea of an electro-magnetic engine. "Thus, within a month of my return to Derby, it became manifest that, in pursuit of a will-o'-the-wisp, I had left behind a place of vantage from which there might probably have been ascents to higher places."

As a consolation for what was at the time a disappointment, Herbert Spencer made a herbarium, which still retained in 1894 a specimen of Enchanter's Nightshade gathered in the grove skirting the river near Darley. In company with Edward Lott, with whom he formed a life-long friendship, he often spent the early summer morning, in rowing up the Derwent, which in those days was rural and not unpicturesque above Derby. As they rowed they sang popular songs, making the woods echo with their voices, and now and then arresting their "secular matins" for the purpose of gathering a plant. It is refreshing to read of Spencer having in his head a considerable stock of sentimental ballads.

It was during this fallow year that at the age of one-and-twenty he went with his father on a walking tour in the Isle of Wight, and first saw the sea. "The emotion produced in me was, I think, a mixture of joy and awe,—the awe resulting from the manifestation of size and power, and the joy, I suppose, from the[Pg 23] sense of freedom given by limitless expanse." His father and he were good companions.

We read of various activities during this period,—of investigations, with inadequate mathematics, concerning the strength of girders, of experiments in electrotyping and the like, of botanical excursions, of some enthusiastic exercise in part-singing, drawing and modelling. In the early summer of 1842 Spencer paid a visit to his old haunts at Hinton. "The journey left its mark because, in the course of it, I found that practice in modelling had increased my perception of beauty in form. A good-looking girl, who was one of our fellow-passengers for a short interval, had remarkably fine eyes: and I had much quiet satisfaction in observing their forms." Our hero had not much sense of humour.

Beginning to write.—Of greater importance is the fact that Spencer began in 1842 to write letters to The Nonconformist on social problems, in which prominence was given to such conceptions as the universality of law and causation, progressive adaptation in organisms and in Man, and the tendency to equilibrium through self-adjustment. "Every day in every life there is a budding out of incidents severally capable of leading to large results; but the immense majority of them end as buds, only now and then does one grow into a branch, and very rarely does such a branch outgrow and overshadow all others." The visit to Hinton led to political conversations with Thomas Spencer, to a letter of introduction to the editor of The Nonconformist, to the letters on "The Proper Sphere of Government," to the Social Statics and eventually to the Synthetic Philosophy!

Spencer's next activity was an inquiry into his father's system of short-hand, which he found to be better than Pitman's. He passed to speculations on the methods to be followed in forming a universal language, and to shrewd criticisms of the decimal system of enumeration. In the autumn of 1842 he interested himself enthusiastically in "The Complete Suffrage Movement." For a youth of twenty-two he took a big plunge into politics. "It produced in me a high tide of mental energy"; the signature on a draft democratic bill "has a sweep and vigour exceeding that of any other signature I ever made, either before or since."

In the spring of 1843 Herbert Spencer went to London and tried very unsuccessfully to get editors to accept his wares. He made a pamphlet of his Nonconformist letters, but perhaps a hundred copies were sold! "The printer's bill was £10 2s. 6d., and the publisher's payment to me on the first year's sales was fourteen shillings and threepence!"

Experimenting with Life.—Spencer's half year in London came to little. As he says, he was too much "in the mood of Mr Micawber,—waiting for something to turn up, and waiting in vain." So he raised the siege and retreated to Derby. There he read Mill's System of Logic, Carlyle's Sartor Resartus and some of Emerson's essays. He tried his hand at improving watches, printing-presses, type-making, and what not; he speculated on the rôle of carbon in the earth's history, and on phrenology; and in 1844 he migrated to Birmingham to be sub-editor of a short-lived paper called The Pilot.

It was then that he made a superficial acquaintance[Pg 25] with Kant's Critique of Pure Reason, only to give it "summary dismissal." He was deterred from pursuing the acquaintance by the "utter incredibility" of the proposition that time and space are "nothing but" subjective forms, and by "want of confidence in the reasonings of any one who could accept a proposition so incredible."

After about a month of sub-editing, he reverted to his former profession of railway engineer, having been commissioned to help with mapping out a projected branch line between Stourbridge and Wolverhampton. The country was dreary enough, but Spencer had abundant open-air work, and it was during this short period that he made a lasting friendship with Mr W. F. Loch which was important in his life.

Then followed an interval, partly in London and partly in the fields of Warwickshire, occupied in various ways connected with railway development, which was then becoming a mania. He seems to have done his work effectively, but it led to no important personal results, and the failure of his chief employer's schemes in 1846 ended Spencer's connection with railway projects and engineering. In afterwards discussing the question whether he should have made a good engineer or not, Spencer notes with his characteristic self-impartiality that he had adequate inventiveness but insufficient patience, enough of intelligence but too little tact. He had an "aversion to mere mechanical humdrum work," "inadequate regard for precedent," no interest in financial details, and a "lack of tact in dealing with men, especially superiors." The frank analysis is interesting, especially[Pg 26] in indicating how Spencer was weak where Darwin was strong, in "la patience suivie," in dogged persistence at detailed work. It may seem strange to say this when we think of his indomitable perseverance with his life-work, but this was quite consistent with a "constitutional idleness," with a shirking from everything tedious except his own thinking. As Thomas Hardy says of one of his characters, "he was a thinker by instinct, but he was only a worker by effort." He never learned or tried to learn what it was to put his nose to the grindstone: he would not learn "lessons," he recoiled from languages, he baulked at the differential calculus, he trifled with Kant and Comte, he was always "an impatient reader." He elected to think for himself, and had the defect of this rare quality.

More Inventions—Sub-editing—Avowal of Evolutionism—Friendships—Books and Essays—Crystallisation of his Thought—Settling to Life-work

Thrown out of regular employment once more, Spencer was left free for a time to follow his own bent. He lived a "miscellaneous and rather futile kind of life," reading a little and thinking much over a proposed book on Social Statics, holidaying a good deal and trying in vain to make money by inventions.

More Inventions.—In 1845 he had a scheme of quasi-aerial locomotion: not a flying machine but "something uniting terrestrial traction with aerial suspension"; but even on paper it broke down. In 1846 he patented an effective "binding pin" for fastening loose sheets, which might have been a financial success if it had been properly pushed. About the same time he was speculating on a method of multiplying decorative patterns,—a sort of "mental kaleidoscope," and on a systematic nomenclature for colours, analogous to that on which the points of the compass are named. More ambitious was a new planing engine and an improvement in type-making, but neither got much beyond the paper stage. In fact Spencer discovered, as so many have done, that[Pg 28] it is one thing to invent and another thing to make inventions boil the pot. For a year and a half, he lamented, time and energy and money had been simply thrown away. The proceeds of the binding pin just about served to pay for his share in the cost of the planing machine patent.

Seven years spent in experimenting towards a livelihood had not brought Spencer much success. In point of fact he was "stranded," and there was talk of emigration to New Zealand, or of "reverting to the ancestral profession" of teaching, but the year of suspense ended with his appointment (1848) as sub-editor in The Economist office, at a salary of one hundred guineas a year. "Thus an end was at last put to the seemingly futile part of my life which filled the space between twenty-one and twenty-eight—futile in respect of material progress, but in other respects perhaps not futile."

He had enjoyed a varied intercourse with men and things during these seven lean years of railway-making, sub-editing, experimenting, inventing; he had had experience of field work and office work, of doing what he was told and of exercising authority; he had had time for drawing, modelling, music, and some natural history; he had come to know something of life's ups and downs. "In short, there had been gained a more than usually heterogeneous, though superficial, acquaintance with the world, animate and inanimate. And along with the gaining of it had gone a running commentary of speculative thought about the various matters presented." Vivendo discimus.

Sub-editing.—Spencer's duties as sub-editor of The Economist were not onerous; he had abundant leisure[Pg 29] for reading and reflection, for music and that pleasant conversation which is one of the ends of life. He had great Sunday evening talks with his broad-minded philanthropic uncle Thomas who had come to live in London, and he began to know interesting people, notably, perhaps, Mr G. H. Lewes. His reading was mainly in connection with the journal he had charge of, and Coleridge's Idea of Life, with its doctrine of individuation, was the only serious work which seems to have left any impression during that early period. He tried Ruskin but recoiled disappointed from his "multitudinous absurdities." He also tried vegetarianism but found that it lowered his bodily and mental vigour.

He worked hard at his first book, sitting late over it with an assiduity to which he looked back with astonishment in after years. The subject of the book was "A system of Social and Political Morality" and he had great searchings for a suitable title, his own preference for "Demostatics" yielding finally in favour of "Social Statics." This phrase had been used by Comte as the heading of one of the divisions of his Sociology, but Spencer was quite unaware of this, and at that time "knew nothing more of Auguste Comte, than that he was a French philosopher." There were also great difficulties in securing publication, although to get the work printed and circulated without loss was as much as he hoped for. "At that time I was, and have since remained, one of those classed by Dr Johnson as fools—one whose motive in writing books was not, and never has been, that of making money."

What Spencer calls "an idle year" (1850-1)[Pg 30] followed the publication of Social Statics, but it was then that he attended a course of lectures by Prof. Owen on Comparative Osteology, and doubtless got a firmer hold of those principles of organic architecture which make even dry bones live. It was then, too, that he had walks with George Henry Lewes, which were profitable on both sides. Lewes received an impulse which awakened interest in scientific inquiries, and Spencer became interested in philosophy at large. He read Lewes's Biographical History of Philosophy, and there was one memorable ramble during which a volume by Milne-Edwards in Lewes's bag was the means of vivifying for Spencer the idea of "the physiological division of labour." "Though the conception was not new to me, as is shown towards the end of Social Statics, yet the mode of formulating it was; and the phrase thereafter played a part in the course of my thought." About the same time, in preparing a review of Carpenter's Physiology, he came across von Baer's formula expressing the course of development through which every living creature passes—"the change from homogeneity to heterogeneity"; and from this very important consequences ensued.

Through Lewes he got to know Carlyle, but the acquaintance was never deepened. While he admired Carlyle's vigour and originality, he was repelled by his passionate incoherence of thought, his prejudices, his dogmatism, his "insensate dislike of science." "Carlyle's nature was one which lacked co-ordination, alike intellectually and morally. Under both aspects, he was, in a great measure, chaotic." To Carlyle, on the other hand, Spencer appeared "an unmeasurable ass."

Avowal of Evolutionism.—In 1852 Spencer definitely began his work as a pioneer of Evolution Doctrine by publishing the famous Leader article on "The Development Hypothesis," in which he avowed his belief that the whole world of life is the result of an age-long process of natural transmutation. In the same year he wrote for The Westminster Review another important essay, "A Theory of Population deduced from the General Law of Animal Fertility," in which he sought to show that the degree of fertility is inversely proportionate to the grade of development, or conversely that the attainment of higher degrees of evolution must be accompanied by lower rates of multiplication. Towards the close of the article he came within an ace of recognising that the struggle for existence was a factor in organic evolution. It is profoundly instructive to find that at a time when pressure of population was practically interesting men's minds, not Spencer only, but Darwin and Wallace, were being independently led from this social problem to a biological theory of organic evolution. There could be no better illustration, as Prof. Geddes has pointed out, of the Comtian thesis that science is a "social phenomenon."

Friendships.—About this time a strong friendship arose between Spencer and Miss Evans (George Eliot). To him she was "the most admirable woman, mentally," he ever met, and he speaks enthusiastically of her large intelligence working easily, her remarkable philosophical powers, her habitual calm, her deep and broad sympathies. It is interesting to learn that he strongly advised her to write novels, and that she tried in vain to induce him to[Pg 32] read Comte. As they were often together and the best of friends, the gossips had it that he was in love with her and that they were about to be married. "But neither of these reports was true."

Another friendship, formed about the same time, was an important factor in Spencer's life; he got to know Huxley and thus came into close touch with a scientific worker of the first rank, useful alike in suggestion and in criticism. He found another friend in Tyndall, whom he greatly admired for his combination of the poetic with the scientific mood, for "his passion for Nature quite Wordsworthian in its intensity," and for his interest in "the relations between science at large and the great questions which lie beyond science."

In 1853, by the death of his uncle Thomas, who had persistently overworked himself, Spencer received a bequest of £500. On the strength of this and the extended literary connections which the good offices of Mr Lewes and Mr (afterwards Prof.) David Masson had secured for him, he resigned his sub-editorship of The Economist in order to obtain leisure for larger works. He always believed in burning his ships before a struggle.

Looking back on the "Economist" period, Spencer felt that his later career had been "mainly determined by the conceptions which were then initiated and the friendships which were formed."

Books and Essays.—Spencer's life of greater freedom began with a holiday in Switzerland (1853), which "fully equalled his anticipations in respect of its grandeur, but did not do so in respect of its beauty." The tour was greatly enjoyed, for Spencer was a lover of mountains, but some excesses in walking[Pg 33] seem to have overtaxed his heart, and immediately after his return "there commenced cardiac disturbances which never afterwards entirely ceased; and which doubtless prepared the way for the more serious derangements of health subsequently established."

For a time he settled down to essay-writing; e.g., on "Method in Education," in which he sought to justify his own experience of his father's non-coercive liberating methods by affiliating these with the Method of Nature; on "Manners and Fashions," in which he protested against unthinking subservience to social conventions, some of which are mere survivals of more primitive times without present-day justification; on "The Genesis of Science," in which he showed how the sciences have grown out of common knowledge; and on "Railway Morals and Railway Policy," in which he made some salutary disclosures with characteristic fearlessness.

Spencer's second book, "The Principles of Psychology," began to be written in 1854 in a summer-house at Tréport, and it was in the same year that the author made his first acquaintance with Paris. Preoccupied with his task, he wandered from Jersey to Brighton, from London to Derby, often writing about five hours a day, and thinking with but little intermission. The result was that he finished the book in about a year and almost finished his own career. The nervous breakdown that followed cost him a year and a half for recuperation, and his pursuit of truth was ever afterwards involved with a pursuit of health.

In search of health Spencer reverted to the best of his ability to a simple life, but he found it difficult[Pg 34] not to think. Thought rode behind him when he tried horseback exercise, and novels brought only sleeplessness. He tried yachting and he tried fishing, shower-baths and sea-bathing, playing with children and sleeping in a haunted room, but the cure was slow; music was almost the only thing he could enjoy with impunity. It was when fishing one morning in Loch Doon that he vented his first oath, at the age of thirty-six, because his line was tangled, and became, he tells us, more fully aware of the irritability produced by his nervous disorder!

As entire idleness seemed futile, and as two and a half years had elapsed since he had made any money, Spencer returned to London (1857)—to a home with children—and began in a leisurely way to write more essays. He composed the article on "Progress: its Law and Cause" at the pathetically slow rate of about half a page per day, and the effort proved beneficial. A significant essay entitled, "Transcendental Physiology," dates from the same year, and during an angling holiday in Scotland he wrote another on the "Origin and Function of Music." Starting from the fact that feeling tends to discharge itself in muscular contractions, including those of the vocal organs, he sought to show that music is a development of the natural language of the emotions.

Crystallisation of his Thought.—Spencer settled down in London in a home "with a lively circle," and pursued his calling as a thinker with quiet resolution. He had Sunday afternoon walks and talks with Huxley, and he occasionally dined out to meet interesting people such as Buckle and Grote; but the tenor of his life was uninterrupted by much incident.[Pg 35] In this year he published a volume of essays new and old, Essays: Scientific, Political, and Speculative; and this was probably in part responsible for a great unification in Spencer's thought. It was in the beginning of 1858 that he made the first sketch of his System, and on the 9th of January he wrote to his father as follows: "Within the last ten days my ideas on various matters have suddenly crystallised into a complete whole. Many things which were before lying separate have fallen into their places as harmonious parts of a system that admits of logical development from the simplest general principles."

In this annus mirabilis (1858) when Darwin and Wallace read their papers at the Linnæan Society expounding the idea of Natural Selection, Spencer was also thinking keenly along evolutionary lines. He ventured on a defence of the Nebular Hypothesis and a criticism of Owen's Vertebral Theory of the Skull; and he was working at the question of the form and symmetry of animals, which he interpreted as "determined by the relations of the parts to incident forces." Vigorous as he was in his intelligence, he was still unable to work for more than about three hours a day, and his pecuniary prospects were dismal. In view of his determination to go on working out his System, it was a fortunate chance that led him in an emergency to discover that he could greatly increase his productivity by dictating instead of writing.

Spencer made various efforts (1859-60) to secure some Government appointment which would afford him a steady income and yet leave him free for his life-work, but as nothing came of these, he went on quietly with his essay-writing, with many[Pg 36] pleasant holidays interspersed, and produced his "Illogical Geology," "The Social Organism," "Prison Ethics," "The Physiology of Laughter," and so on.

Settling to his life-work.—Baffled in other plans, he at length organised a scheme of publishing his projected series of volumes by subscription. His influential friends headed the list and four hundred names were soon secured in Britain; the disinterested energy of an American admirer, Prof. E. S. Youmans, raised the total to six hundred. And thus Spencer, at the age of forty, handicapped by lack of means and health, calmly sat down to a task which was calculated to occupy him for twenty years.... "To think that an amount of mental exertion great enough to tax the energies of one in full health and vigour, and at his ease in respect of means, should be undertaken by one who, having only precarious resources, had become so far a nervous invalid that he could not with any certainty count upon his powers from one twenty-four hours to another! However, as the result proved, the apparently unreasonable hope was entertained, if not wisely, still fortunately. For though the whole of the project has not been executed, yet the larger part of it has." In one form of faith Spencer was in no wise lacking.

Thinking by Stratagem—The System Grows—Difficulties—Italy—Habits of Work—Sociology—Ill-health—Citizenship—Visit to America—Closing Years

Having theoretically secured the requisite number of subscribers to the projected series of volumes, Spencer tried to settle down to "something like unity of occupation." In the Spring of 1860 he began the First Principles—only to break down before he had finished the first chapter; and the same depressing experience was continually repeated. Fortunately for Spencer's peace of mind, his uncle William left him some money; one may well say fortunately, since the number of defaulters in the subscription list was so large that in the absence of other resources even the first volume could not have been published.

Thinking by Stratagem.—Spencer's devices for keeping off the cerebral congestion which work induced were many and various—some almost laughable, if the whole business had not been so tragic. He would ramble into the country, find a sheltered nook or sunny bank, do a little work, and move on like a "Scholar Gipsy"; he would take his amanuensis on the Regent's Park water, row vigorously for five minutes, dictate for fifteen, and so on da capo; he[Pg 38] frequented an open racquet-court at Pentonville, and sandwiched games and First Principles; even in the Highlands he would dictate while he rowed. It was altogether like thinking by stratagem, and the tension of working against time became so irksome, that he issued a notice to the subscribers that successive numbers would come out when they were ready. Nevertheless, he completed the First Principles in June 1862.

The System Grows.—Having safely set forth his doctrine, Spencer turned with zest to relaxation, acting as cicerone to his friends at the International Exhibition, climbing in Wales, fishing in Scotland, revisiting Paris, and so forth. The years passed in alternate work and play, and the next great event was the publication of the first volume of the Principles of Biology in 1864. In spite of inadequate preparation Spencer produced by the strength of his intelligence a biological classic. At the time, of course, little notice was taken of it; thus in "The Athenæum" of 5th November 1864, a paragraph concerning the book commenced thus: "This is but one of two volumes, and the two but a part of a larger work: we cannot therefore but announce it." "In 1864," Spencer says, "not one educated person in ten or more knew the meaning of the word Biology; and among those who knew it, whether critics or general readers, few cared to know anything about the subject" (Autobiography, ii. p. 105).

It was in the same year (1864) that Spencer formulated his views on the classification of the sciences and his reasons for dissenting from the philosophy of Comte.

Of considerable interest was the formation of a[Pg 39] decemvirate of Spencer's friends, which was first called "The Blastodermic" and afterwards the "X" club. It consisted of Huxley, Tyndall, Hooker, Lubbock, Frankland, Busk, Hirst, Spottiswoode, and Spencer, with one vacancy which was never filled up. The members dined together occasionally and talked at large. "Among its members were three who became Presidents of the Royal Society, and five who became Presidents of the British Association. Of the others one was for a time President of the College of Surgeons; another President of the Chemical Society; and a third of the Mathematical Society...." "Of the nine I was the only one who was fellow of no society, and had presided over nothing." The club lasted for at least twenty-three years (1887), and had considerable influence both on its members and externally.

In 1865 Spencer took considerable interest in a new weekly journal, called "The Reader," in which many prominent workers were implicated, but the enterprise ended in disappointment, unless, indeed, it was a step towards the establishment of Nature. In this and the following year he busied himself with an investigation regarding circulation in plants,—the only concrete piece of biological work he ever indulged in. But the great event of 1866 was the completion of The Principles of Biology.

Difficulties.—In the beginning of 1866 Spencer found that many of the subscribers to his serial publications had withdrawn, and that not a few were much in arrears, and he sorrowfully decided that he must abandon his undertaking. It was at this juncture that he discovered what stuff his friends were made of. Mr John Stuart Mill wrote proposing[Pg 40] to help to indemnify Spencer for losses incurred, and offering to guarantee the publisher against any loss on the next treatise. He called this "a simple proposal of co-operation for an important public purpose, for which you give your labour and have given your health." As Spencer felt himself obliged to decline this generous proposal, the next move among his friends was to arrange to take a large number of copies (250) for distribution. To this, with mingled feelings of satisfaction and dissatisfaction, Spencer agreed. Meanwhile, however, his American admirers, organised by Professor Youmans, invested in Spencer's name a sum of 7000 dollars as a fund to ensure the continued publication of his works. This, in combination with an improvement in Spencer's financial position, consequent on his father's death (1866), made publication once more secure without the aid of the subsidising scheme proposed by his English friends.

In September 1866 Herbert Spencer settled himself in London, en pension at 37 Queen's Gardens, Lancaster Gate, which remained his home for over a score of years. Henceforth he was less of a nomad, and he secured himself against all interruptions by taking a secret study a few doors off.

There are two records for the beginning of 1867 which are interesting in their contrast. The first is that Spencer declined without hesitation certain overtures by his friends that he should stand for the professorship of Moral Philosophy at University College, London, and for a similar post in Edinburgh; the second is that he invented a most elaborate invalid-bed, which, like most of his inventions, fell flat.

The invalid-bed had been suggested by his mother's prolonged feebleness, but it was not long to be used. Spencer was left in 1867 with no nearer relatives than cousins. In reference to his mother, we quote with all reverence one of the few strong personal touches in the Autobiography.

"Thus ended a life of monotonous routine, very little relieved by positive pleasures. I look back upon it regretfully: thinking how small were the sacrifices which I made for her in comparison with the great sacrifices which, as a mother, she made for me in my early days. In human life, as we at present know it, one of the saddest traits is the dull sense of filial obligations which exists at the time when it is possible to discharge them with something like fulness, in contrast with the keen sense of them which arises when such discharge is no longer possible."

In the spring of 1867 Spencer finished publishing the second volume of the Biology, and immediately set to work to recast First Principles. And as if that was not enough, he began in the same year, with the help of his secretary, Mr David Duncan, his collection of sociological data, which was intended to afford the foundation for a treatise on the Principles of Sociology. In spite of occasional holidays at Yarrow, at Glenelg, and in other delightful places, the usual nemesis of industry was not avoided. Spencer's nerve-centres, which could never endure prolonged attention, showed the usual symptoms of over-fatigue; and though he tried morphia and skating, hydropathy and rackets, he had to give up work early in 1868. He betook himself to Italy for rest, attracted partly by the fact that Vesuvius was in eruption! About this time he was elected a member of the Athenæum Club, the[Pg 42] sedative amenities of which proved a useful prophylactic in after years.

Italy.—Of Spencer's Tour in Italy the Autobiography gives us some interesting reminiscences. He arrived in Naples in a state of extreme exhaustion, wearied with the voyage, wearied with a menu in which tunny was the pièce de résistance, and finding comfort only in the shelter of his Inverness cape. And yet, the day after his arrival, the author of Social Statics might have been seen giving swift chase to an audacious thief who had taken advantage of the philosopher's preoccupation to abstract his opera-glass. "Most likely had the young fellow had a knife about him I should have suffered, perhaps fatally, for my imprudence." A few days later, the same characteristic rashness impelled him to ascend the burning mountain without a guide and at great risk. "How to account for the judicial blindness I displayed, I do not know; unless by regarding it as an extreme instance of the tendency which I perceive in myself to be enslaved by a plan once formed—a tendency to become for a time possessed by one thought to the exclusion of others."

Nothing that Spencer saw in Italy impressed him so much as "the dead town" of Pompeii. The man who "took but little interest in what are called histories" was stirred by this concrete historical fossil. "It aroused sentiments such as no written record had ever done." He enjoyed Rome, but rather for its harmonious colouring than for its historical associations, of which he had no vivid perception. He was more irritated than pleased by the old masters. He got most pleasure from the[Pg 43] scenery, but Italy is "a land of beautiful distances and ugly foregrounds." Companionless and impatient, his chief thought was how to get home most comfortably, and so he returned no better than he went.

Habits of Work.—About this time the tide had turned as regarded the sale of his works, and he wrote gratefully "the remainder of my life-voyage was through smooth waters." As the Autobiography shows, it was a quiet and uneventful voyage. Periods of work alternated with holidays, many parts of the country were visited, and angling became more and more his best recreation. "Nothing else served so well to rest my brain and fit it for resumption of work." Another resource was billiards, which he greatly enjoyed. He never could remember whist or similar games.

On fine mornings he used to spend two or three hours on the Serpentine, alternating rowing and dictating. After his morning's work and after lunch he used to walk through Kensington Gardens, Hyde Park, and the Green Park, without more than a quarter of a mile upon pavement, to the Athenæum Club, where he skimmed through periodicals and books, and played his game. Thereafter he sauntered back to dinner at seven, "which was followed by such miscellaneous ways of passing the time without excitement as were available. Thus passed my ordinary days." By this time he had given up novel-reading, only treating himself to one about once a year, and then in a dozen or more instalments. He did not care to multiply social relations, he "avoided acquaintanceships and cultivated only friendships." "There is in me very little of the besoin de parler; and hence I do not care to[Pg 44] talk with those in whom I feel no interest." And thus, though far from being a recluse, he lived his life of thought quietly.

In 1871 Spencer was nominated for the office of Lord Rector at the University of St Andrews, but he declined the honour for the sake of his work. He also declined the honorary degree of Doctor of Laws from the same University, and subsequently, similar honours, chiefly on the ground "that the advance of thought will be most furthered, when the only honours to be acquired by authors are those spontaneously yielded to them by a public which is left to estimate their merits as well as it can."

The first (synthetic) volume of the new edition of the Psychology begun in 1867 was finished in 1870, the second (analytic) volume begun in 1870 was completed in the end of 1872. Having become much interested in the well-known "International Scientific Series," Spencer contributed to it in 1873 the volume known as The Study of Sociology, which has done much in Britain and America to secure the position of Sociology as a workable science. It was unusually successful for a book of its kind, and brought Spencer about £1500.

Sociology.—From 1867 onwards Spencer had been collecting Sociological Data to serve as a basis for generalised interpretation. With the help of Mr David Duncan, Mr James Collier, and Dr Scheppig, this big piece of work made steady progress, and its publication began to be discussed in 1871. It was hoped that the plan of "exhibiting sociological phenomena in such wise that comparisons of them in their co-existences and sequences, as occurring among[Pg 45] various peoples in different stages, were made easy, would immensely facilitate the discovery of sociological truths." The first part of this Descriptive Sociology was published in 1873, but the demand for it was very slight; not quite 200 copies were asked for in eight months. "I had," Spencer says, "greatly over-estimated the amount of desire which existed in the public mind for social facts of an instructive kind. They greatly preferred those of an uninstructive kind." In this and similar connections, the reader of the Autobiography cannot but be impressed by two facts,—on the one hand, the chivalrous eagerness on the part of American friends to be allowed to lessen Spencer's pecuniary burden, and, on the other hand, the almost ultra-sensitive resoluteness which Spencer exhibited in declining these offers.

In 1874, with the materials and memoranda of a quarter of a century around him, the thinker, who was blamed for not being inductive, set himself to write the Principles of Sociology, "feeling much as might a general of division who had become commander-in-chief; or rather, as one who had to undertake this highest function in addition to the lower functions of all his subordinates of the first, second, and third grades. Only by deliberate method persistently followed was it possible to avoid confusion."

The period of work on the Sociology was broken by some delightful holidays in the Highlands and elsewhere, by the British Association meeting at Belfast (1874) when Tyndall gave his famous Presidential Address, and by the usual ill-health. The first volume was completed in 1877. Apart from the[Pg 46] nemesis of nerves, Spencer's life at this time seems to have been a happy one; he was fairly free from pecuniary cares; he was no longer tied to a serial issue of his publications; he could afford pleasant holidays, and he had a small circle of loyal friends. The philosopher began a series of annual picnics, which he seems to have engineered with great skill; in various ways he acted up to what he says was his habitual maxim, "Be a boy as long as you can." In 1877 he had the excitement of a shipwreck near Loch Carron, and the encouragement of having his Descriptive Sociology translated into Russian.

Ill-Health.—In spite of all his care, the year 1878 opened with a serious illness, and this prompted him to begin dictating The Data of Ethics lest an aggravation of his ill-health should hinder him from raising this coping-stone of his system. Just before Christmas of this year, he went with Prof. Youmans to the Riviera, and for a couple of months was more than usually successful in combining work and play. He finished The Data of Ethics in June 1879, and Ceremonial Institutions later in the year. As a reward of industry, and as a safeguard against too much of it, a holiday up the Nile in pleasant company was then arranged, and Spencer entered upon it in great spirits. But an ill-considered meal at Alexandria brought on dyspepsia and morbid fancies, and he was forced to return at the first cataract. He had seen many of the sights and was inevitably impressed, but he seems to have been glad to get out of the "melancholy country"—"the land of decay and death—dead men, dead races, dead creeds," as it appeared to his jaundiced eyes.

On his return journey he spent three days in Venice, but though he derived much pleasure from the general effects, he was repelled by the obtrusiveness and superficiality of the decorations. He regarded St Mark's as "a fine sample of barbaric architecture"; "it has the trait distinctive of semi-civilised art—excess of decoration"; "it is archæologically, but not æsthetically precious."

The entry in his journal for Feb. 12th, 1880 reads: "Home at 7-10; heartily glad—more pleasure than in anything that occurred during my tour."

Although he did not greatly enjoy his tour in Egypt, and brought back his packet of work unopened, the break seems to have been "decidedly beneficial." "It has apparently worked some kind of constitutional change; for, marvellous to relate, I am now able to drink beer with impunity and, I think, with benefit—a thing I have not been able to do for these fifteen years or more." He thought that it had also perhaps furthered his work to have had contact with people in a lower stage of civilisation.

In 1881 Spencer published the eighth part of his Descriptive Sociology and put a full stop to the undertaking which left him with a deficit of between three and four thousand pounds, and which had half-killed two secretaries.

Spencer's next task was the completion of Political Institutions, another instalment of the Sociology, which he had begun in 1879, and he was at this time also occupied in considering and answering the more formidable of the criticisms which his system had aroused, and in revising new editions of the First Principles and The Study of Sociology. It is interesting[Pg 48] to note that the last work was carefully revised sentence by sentence five times.