The Project Gutenberg eBook of A Hero of Liége: A Story of the Great War

Title: A Hero of Liége: A Story of the Great War

Author: Herbert Strang

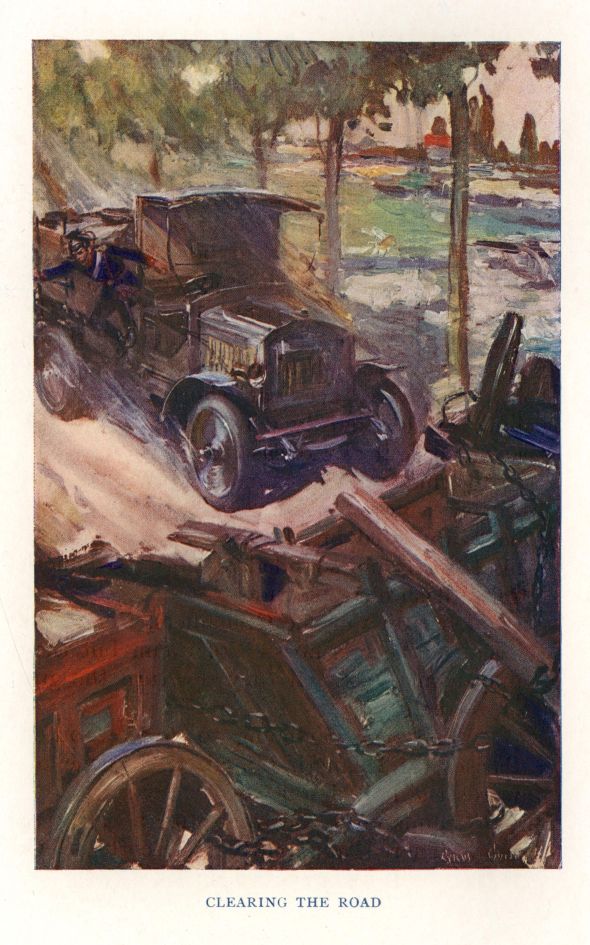

Illustrator: Cyrus Cuneo

Release date: March 14, 2012 [eBook #39150]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Al Haines

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I--THE OPENING OF THE GAME

At nine o'clock on Tuesday morning, August 4, Kenneth Amory walked into the private office of the head of the well-known firm of Amory & Finkelstein, gutta-percha manufacturers, of Cologne. Max Finkelstein, the head of the firm, swung round on his revolving chair, moved his hand backward over his brush-like crop of brownish hair, and looked up through his spectacles at Kenneth, his stout florid countenance wearing an expression of worry.

"I sent for you to tell you to pack up and get away by the first train," he said, in German. "Things are looking very black; the sooner you are home, the better."

"Our dear Max is jumpy," came in smooth tones from the third person in the room, the ends of his well-brushed moustache rising stiffly as he smiled. He was tall and slim--a contrast to his cousin Finkelstein, who had reached that period of life when good food, a successful business, and Germanic lack of exercise, tend to corpulence. "I tell him he need not worry," the speaker went on. "It will be as in '70."

"Provided that England----" Finkelstein was beginning, but Kurt Hellwig broke in with a laugh.

"Oh, England! England will protest a little, and preach a little, and take care not to get a scratch."

"Don't you be too sure of that," said Kenneth, rather warmly.

"No? You think otherwise?" Hellwig was smiling still. "Well, we shall see. Perhaps you have private information?"

His mocking smile and ironical tone brought a flush to Kenneth's cheeks.

"I don't want any private information to know what England will do," cried the boy.

"True, the public information is conclusive. England is helpless; she suffers from an internal complaint; she is breaking up."

"That will do, Kurt," said Finkelstein, anticipating an explosive word from Kenneth, who was quick-tempered, and apt to fall out with Hellwig. "Really, Ken, you will be safer at home, and if you don't go now you will lose your chance; all the trains will be required for the troops."

"I'd rather wait a little longer," replied Kenneth. "It's all so interesting. I've never seen a mobilisation before."

"It will do him good to see how we manage things in Germany," said Hellwig. "And since England will remain neutral, he will run no risk."

Finkelstein, easygoing and indolent where business was not concerned, yielded the point.

"Very well," he said. "Do as you please. But I recommend you to pack up in readiness for a sudden departure. For my part, I hope Kurt is right; I think of my business."

"We all think of our business," said Hellwig, with a slight stress upon the pronoun.

"Our business--yes," said Finkelstein. "We shall all suffer, I fear. But if it is as in '70----"

Kenneth did not wait to hear further discussion on the chances of the war. Remarking that he would see the others at lunch, he hurried away into the street. Awakened very early that morning by the rumbling of carts and the tramp of horses, he had got up and gone out, to watch the continual passage of regiments of infantry and cavalry, batteries of artillery, pontoon trains, commissariat and ammunition wagons, through the streets and the railway station. Everything was swift and systematic; the troops, though a little hazy as to their destination, were in high spirits; the war would soon be over, they assured their anxious friends.

It was all very new and exciting to Kenneth Amory, who had only vague memories of the English mobilisation for the South African war, when he was a child of four. His father had founded, with Max Finkelstein, an Anglo-German business which had attained great dimensions. Finkelstein controlled the German headquarters at Cologne; Amory looked after things in London. The latter died suddenly in the winter of 1912, leaving his son Kenneth, then nearly seventeen years of age, to the guardianship of Finkelstein, in whom he justly placed implicit confidence.

Since then Kenneth had spent much of his time in Germany, learning the business under Finkelstein's direction. He had a great liking for his father's partner, who was a keen man of business, scrupulously exact in his duties as guardian, and a "good fellow." Finkelstein had announced that Kenneth, as soon as he came of age, would be taken into partnership. The firm would still be Amory & Finkelstein.

When Kurt Hellwig spoke of "our business," his use of the first personal pronoun must be taken to have implied a commendable feeling: he had no actual share in the business. His connection with it was a proof of his cousin Max's kindness of heart. Hellwig had brilliant abilities; in particular, remarkable linguistic powers; but he had never been able to turn them to account in the various careers which he had successively attempted. Finkelstein had more than once lent him a helping hand; since Mr. Amory's death he had employed him as occasional representative in England. Needless to say, he did not entrust any matter of importance to his erratic cousin; and the salary he paid him was proportionate rather to relationship than to services.

Kenneth returned to Finkelstein's house for the midday lunch. Neither Finkelstein nor Hellwig was present.

"Father sent word that he was detained," said Frieda, Finkelstein's daughter, a little younger than Kenneth. "We are not to wait for him."

"He seemed very worried when I saw him this morning," said Kenneth. "Of course business will be at a standstill, especially if we come into the war."

"It will be hateful if you do," said the girl. "But you won't, Kurt says. We have done nothing to you."

"Kurt knows nothing about it. He thinks we are afraid to fight. He's wrong. Of course we are not concerned with your quarrel with Russia; but when it comes to your attacking France, quite unprovoked, and bullying Belgium to let you take the easy way, you can hardly expect us to look on quietly. But we won't talk about that, Frieda; you and I mustn't quarrel."

Frieda and Kenneth were very good friends. One bond of union between them was a common dislike of Kurt Hellwig, whose sarcastic tongue was a constant irritant. Kenneth related what had passed at the office that morning.

"Why has he come back?" said Frieda. "He has been away for weeks; I wish he would stay away altogether."

"Do you?"

"Of course I do. What do you mean?"

"I fancy Kurt thinks you admire him--because he wants you to, I suppose."

"Will you take me to Cousin Amalia's after lunch?" asked Frieda, with a disconcerting change of subject. "I promised to spend the rest of the day with her. And you'll fetch me this evening, won't you?"

After escorting Frieda to her cousin's, Kenneth strolled about, watching the war preparations, then turned homewards to pack his bag, as he had promised Finkelstein to do. On the way he bought a copy of the Cologne Gazette containing a mangled version of Sir Edward Grey's speech in the House of Commons on the previous day. When he had finished packing, he sat down with the paper at the open window of his room. Having risen early, he was rather tired, and the heat of the afternoon soon sent him to sleep.

He was wakened by voices near at hand. There was no one but himself in the room; after a moment's confusion of senses he realised that the sounds came up from the balcony beneath his window. It was reached from the drawing-room, and since it was shaded by a light awning, someone had evidently gone there for the sake of fresh air.

The awning concealed the speakers from Kenneth's view, but in a few moments he recognised Hellwig's voice. The other speaker was a man and a stranger. Kenneth at first paid no attention to them; Hellwig had many acquaintances, and was fond of entertaining them. But presently he caught a sentence that made him suddenly alert.

"The bridge has been mined."

It was the stranger speaking, in German. Kenneth rose silently from his chair, and leant out of the window, so that he should not miss a word.

"The train can be fired at any moment, thanks to our forethought in tunnelling between the mill-house and the bridge."

"That is well," said Hellwig, in the tone of a superior commending the report brought him by a subordinate. "Get back as quickly as you can, and tell them to be ready to act instantly on receipt of a marconigram."

"The stations are closed to private messages," remarked the visitor.

"Yes: but mine will get through. What news have you?"

"When I left yesterday the Belgians were becoming alive to their danger. They are mobilising feverishly. The forts at Liége are fully manned. But many people refuse to believe that we shall go to extremes and invade their territory. They say that its inviolability is guaranteed by treaty."

Hellwig laughed.

"Keep in touch with London," he said. "In a few hours I shall be cut off from London except through Amsterdam, and I shall have to move my headquarters there. You remember the address?"

"As before?"

"Yes. Send there any information that comes through from London, and keep me informed of your whereabouts."

"There was talk, as I came through, of possible English intervention. I learn that crowds clamoured for war in front of Buckingham Palace last night."

"A mistake: they were shouting against war. The British government will not dare to strike: even if they do, they will be too late. We are ready: they are not. Before they have made up their minds we shall be across the Belgian frontier and into France."

The conversation continued for a few minutes longer, then the visitor rose to go. Acting on impulse, Kenneth ran out of his room, and was nearing the foot of the staircase as the two men came from the drawing-room. He had the Cologne Gazette in his hand.

"Have you read Sir Edward Grey's speech?" he asked Hellwig.

"Not yet. Is it worth the trouble?" replied Hellwig in his smooth mocking tones.

"I thought you hadn't, or you wouldn't be so cock-sure," Kenneth returned. "I rather think the British government have already made up their minds."

"So you have been eavesdropping?" said Hellwig quickly.

"You are a spy!" cried Kenneth--"you and your friend."

"Is that any concern of yours?"

"Only to this extent; that I'll have nothing more to do with you," said Kenneth hotly, conscious at the moment that it was a foolish thing to say, and feeling the more irritated.

"That will kill me," sighed Hellwig.

"And Max shall know it," Kenneth went on. "He doesn't know that you've been up to this sort of thing, I'm sure."

"Certainly; Max shall know that I am doing something for my country. You are, no doubt, doing wonders for yours."

"I wouldn't do such dirty work as yours," cried Kenneth, more and more angry under Hellwig's calmness.

At this moment the outer door opened, and Frieda came in from the street.

"What is the matter?" she asked, looking from Kenneth's flushed face to Hellwig's smiling one, upon which, however, there flickered now a shade of embarrassment.

"The fellow is a spy!" Kenneth burst out.

"I was explaining, my dear cousin, that I am doing at least something for my country," Hellwig said.

"We should have preferred that it were anything else," said Frieda coldly. "Come, Ken, I've something to say to you."

She hurried along the corridor, not heeding Hellwig's bow as she passed. Kenneth followed her. Hellwig shrugged, and left the house with his friend.

"How did it come out?" asked Frieda, when Kenneth was alone with her in the drawing-room.

"They were talking under my window. He accused me of eavesdropping. I couldn't help hearing them at first; and when I found out what they were at, of course I listened. You have come back alone?"

"Yes. I met Father. He says that your government has sent us an ultimatum, and war is certain. You must go home at once. Father sent me to tell you."

"All right. He sneered about my doing wonders for my country. I'll do something better than spying. I'll volunteer for the Flying Corps."

"Oh, don't do that! It's so dangerous."

"No more dangerous than being in the firing line."

"But why do anything at all--of that sort, I mean? War is horrible--horrible!"

"It is, for everyone. I'm sure none of our people wanted it. But if we're in for it, every fellow who can do anything will be required, and you wouldn't wish me to skulk at home while others fight?"

"I'd rather you should fight than spy. You must make haste. Martial law is proclaimed. Father called at the station, and found that there will be a train at half-past nine to-night: it will probably be the last. And the stationmaster said that anyone who wanted to secure a seat must be early, for there's sure to be a great rush. Have you done your packing?"

"Yes; there's only one bag I need take. The less baggage the better. I'll run down to the station and get my ticket now, to make sure of it."

"Don't be long. Father will be back to dinner, and he wants to say goodbye to you, and to give you some messages for business friends in London."

Kenneth hurried to the station. There were signs of new excitement in the streets. Newsvendors were shouting that Belgium was invaded. People thronged the beer-shops, eagerly discussing the situation. Already there were cries of "Down with the English!" Tourists of all nationalities were flocking to the station and to the landing-stage for the Rhine steamers. Soldiers were everywhere.

At the station ticket office there was a long queue of people waiting. Kenneth saw little chance of obtaining a ticket for some time; but being well acquainted with the stationmaster, he sought his assistance and was provided with a written pass.

"I can't guarantee that you will get beyond Aix-la-Chapelle," said the official. "You must take your chance."

Kenneth set off to return. Attracted by a crowd at the door of one of the hotels, he went up to discover the cause of the assemblage. A mountain of luggage was piled on the pavement, and the distracted owners, turned out of the hotel, were vainly seeking porters to convey it to the station. The riff-raff of the streets were jeering at them. Kenneth turned away, feeling that the scene was ominous.

He had walked only a short distance from the spot when a hand touched his shoulder from behind.

"You are under arrest, sir," said a police sergeant, who was accompanied by two constables.

"Nonsense," said Kenneth, good-humouredly. "You have mistaken your man."

"Your name is Kenneth Amory?" said the sergeant.

"Something like that," said Kenneth, amused at the man's pronunciation.

"There is no mistake, then. You are arrested."

"Indeed! On what charge?"

"As a suspect."

"Suspected of what?"

"Of spying."

This took Kenneth's breath away. Mechanically he walked a few steps beside the officer, the two constables following. Then realising the nature of the charge against him, he stopped short.

"It is false!" he cried. "I am no spy. Where is your warrant? What right have you to arrest me?"

"No warrant is needed," replied the sergeant, courteously enough. "You will no doubt clear yourself if you are innocent."

"Of course I am innocent. My friends will prove that. Oh! I won't give you any trouble: the sooner I get to the police-station, the better."

"That is reasonable," said the sergeant.

They marched on. Kenneth looked eagerly at all the passers-by in the hope of finding a friend who would vouch for him; but he recognised no familiar face. On reaching the station he was searched, but deprived of nothing except his pocket-book and the letters it contained.

"They are only private letters," he explained. "The whole matter is ridiculous. You will let me write a note to a friend, who will speak for me?"

"Certainly," said the officer, "provided I see what you say."

Kenneth quickly scribbled a note to Max Finkelstein, and handed it to the officer, who remarked that it had nothing suspicious about it, and placed it in an envelope which Kenneth addressed.

"I shall be released as soon as Herr Finkelstein comes?" asked Kenneth.

"That is doubtful," replied the officer. "It will probably be necessary to bring you before the magistrate to-morrow."

"But I am going to England to-night."

"To England! That is suspicious. Herr Finkelstein may have influence. We shall see."

A short conversation, carried on in low tones, ensued between the sergeant and his superior officer. They were consulting as to where the prisoner should be placed: the cells, it appeared, were full. Ultimately Kenneth was taken to a room on the ground floor. The window was barred and shuttered on the outside, and light entered only by two small round apertures in the shutters.

"A black hole, this," he said to the sergeant.

"It will not be for long, if you are innocent," replied the man.

Then he shut and locked the door; Kenneth was left to himself.

CHAPTER II--THE FIRST TRICK

With the door shut, the room was almost wholly dark. It contained no furniture but a plain deal table and a wooden chair. Kenneth sat down and ruminated. His position was annoying, but also mildly exciting. It would be something to tell his people when he got home, that he had been arrested as a spy.

It was now five o'clock. Dinner was at seven: his train left at half-past nine, and the stationmaster had advised him to be at the station at least an hour in advance. He had addressed his note to Finkelstein at the office, and expected that his friend would arrive within half an hour or so and procure his release. In the absence of any evidence against him a prolonged detention would surely be impossible.

Perhaps half an hour had passed when he heard footsteps on the passage; the key turned in the lock, and he started up, expecting to see Finkelstein. But there entered a constable, bringing a mug of beer and a piece of rye bread.

"My friend Herr Finkelstein has not come?" Kenneth asked.

"Nobody has come for you," replied the man.

"My note was taken to him?"

"If you wrote a note, I daresay it was."

"Aren't you sure?"

"I have only just come on duty, sir."

The constable set the food on the table and went out, locking the door.

Anticipating dinner, Kenneth was not tempted to eat the coarse fare provided. He was still not seriously alarmed, though his annoyance grew with the passing minutes. Finkelstein never left his office until half-past six; there was plenty of time for him to have received the note--unless there had been delay in delivering it. This possibility was somewhat perturbing.

Kenneth began to wonder what had led to his arrest. He was quite unknown to the police; nothing in his appearance was aggressively English. So far as he knew he had no enemy in Cologne, so that it seemed unlikely that anyone had put the police on his track out of sheer malice.

His thoughts reverted to the incident of the afternoon. The discovery that Hellwig was in the German secret service, surprising as it was, made clear certain things that had puzzled him. During his frequent visits to London, Hellwig was accustomed to stay at the Amorys' house, and had many callers who came to see him privately, on the firm's business, as Kenneth had supposed. It seemed only too probable now that they were agents in the work of espionage.

A sudden suspicion flashed into Kenneth's mind. Was it possible that his arrest was due to Hellwig? From what he had overheard it was clear that Hellwig was a man of considerable authority in the secret service. A word from him would no doubt suffice. But what could his motive be? Kenneth was under no illusion as to the man's character. He had always thoroughly disliked and distrusted him, and felt instinctively that the dislike was mutual. Could it be that Hellwig, knowing himself discovered, and fearing that Kenneth, on his return to London, would inform the authorities, had taken this step to save himself? It seemed an unnecessary precaution, for if war broke out between Britain and Germany, Hellwig would make no more journeys to London for some time to come.

The more Kenneth thought over the matter, the more convinced he became that Hellwig, whatever his motive might be, had caused his arrest. The conviction destroyed his confidence in an early release. The man would stick at nothing. He would have foreseen an application to Finkelstein, and taken steps to forestall it. What if the note should never reach Finkelstein?

Kenneth was now thoroughly alarmed. The Germans had a short way with spies, or those they regarded as spies, even during peace; it was likely to be shorter and sharper than ever on the outbreak of war. The prospect of being taken out and shot sent cold thrills through him.

Contemplating this dark eventuality he heard heavy footsteps overhead. He looked up, and for the first time saw a glint of light from the ceiling in one corner of the room. The footsteps passed: all was silent again.

Kenneth sat thinking. If his suspicions were well founded, he felt that his doom was sealed. It would be easy for a man like Hellwig to fabricate evidence against him. In default of Finkelstein's assistance, which Hellwig would take care to prevent, his only means of safety lay in flight. But what chance was there of escaping from this locked and shuttered room? An examination of the window showed the hopelessness of it.

The faint streak of light above again attracted his notice. Noiselessly drawing the table beneath it, he mounted to examine its source. A portion of the plaster had fallen away from the ceiling, and the light filtered through a narrow crack in the flooring above. This discovery, under pressure of circumstances, gave him a gleam of hope. Taking out his pocket knife, he began to scrape quietly at the plaster, gradually enlarging the hole. What there might be above he could not tell; judging by the passing in and out of the footsteps the room was unoccupied.

While he was engaged on this work he heard steps in the passage without. Springing down, he swept on to the floor, and under the table, the plaster he had scraped from the ceiling, then stood waiting eagerly. Perhaps it was Finkelstein at last.

The door opened. A man was thrust into the room, and the door again locked. The newcomer swore.

"You're an Englishman?" cried Kenneth.

"Do I find a companion in adversity?" said the man. "We can condole."

"Who are you?"

"What is your father? How many horses does he keep? Bless me, how this reminds me of my innocent childhood! 'More light,' as Goethe said. But I can see well enough to know that you are a youngster. Sad, sad!"

Peering at the stranger, Kenneth saw a man of about thirty-five, with hair en brosse, Germanic moustache, and a German military uniform.

"I should pass in a crowd, one would think," the man went on, smiling under Kenneth's scrutiny. "But Fate is unkind."

"You are a spy?" said Kenneth.

"And you, my friend?"

"No. They say so, but I'm not."

"They say so, and they will have their way. Ah, well! They say also, that it is a sweet and comely thing to die for one's country. I always thought I should die in my boots."

"Can they prove it against you?"

"A scrap of paper! They can't read it, but what matters that? A note in cipher is evidence enough. But I shall not die unavenged: they are crying in the streets that war is declared, and I fancy that Emperor William has bitten a little more than he can chew. What brings you to this deplorable extremity?"

"I don't know: a private enemy, I think."

"Well, the rain falls on the just and the unjust. I'm sorry for you. Haven't you any friend, though, who can get this door unlocked?"

Kenneth explained briefly what had happened. Then, feeling a strange liking for his companion, he added:

"When you came in, I was wondering about the chances of escape."

"A waste of brain tissue, unless you have some talisman. But tell me, you have some definite idea?"

"You see that hole in the ceiling? I was enlarging it."

"Ha! A man of action! Nil desperandum, eh? Let me have a look at it."

He mounted on the table, and thrust his hand into the opening.

"I say, youngster," he said, a note of eagerness in his voice, "there is a chance, on my life there is. The boards above are not over firm. We may be skipping out of the frying-pan into the fire, but one can only die once. Continue with your work; I'll mount guard and warn you of anyone approaching."

Kenneth scraped away with his penknife, until the hole was large enough to admit his head and shoulders. The light, coming through a single crack, did not increase, so that the enlargement of the hole might easily escape notice if a constable entered. The stranger put the chair on the table.

"Mount on that," he said; "put your back against the boards, and shove--gently."

Kenneth did as he was instructed. The pressure of his back started the nails, and a plank rose, with an alarming creak.

"That won't be heard through the rumble of traffic outside," said the man. "Wait a little. You don't know anything of the room above?"

"Nothing. I heard somebody go in and out a while ago; I think it is empty."

"Well now: let us keep cool. We can get into the room: that is certain. Can we get out of it? We shall have to descend the stairs. Our chance of life depends on one half-minute. 'Can a man die better than facing fearful odds?' Look here: we'll toss. Heads: we'll go up; tails--why, hang it, we'll still go up! Fortuna fortibus! Wait till we hear the rumble of the next artillery wagon; then! ..."

They had not long to wait. Heavy traffic passed at short intervals.

"Now!" said the stranger.

Kenneth gave a heave. In a moment two planks were removed. Resting his arms on the edges of those on either side of the gap, he hoisted himself up. His companion quickly followed. They stood in the room.

The next half minute was filled to breathlessness. It was a bedroom. A street lamp outside threw a little light into it. Hanging from a peg on the door was a policeman's tunic and helmet.

"Fortune's our friend," murmured the stranger.

In ten seconds he had helped Kenneth to don the uniform. They crept out of the room, and peeped over the stair rail. The way was clear. All sounds within were smothered by the noise in the street. They stole downstairs, past the closed door of the guardroom, through the outer door, and into the open. "War with England!" shouted a newsman at the corner.

"We win the first trick!" chuckled the stranger, as they hurried along.

CHAPTER III--THE SECOND TRICK

"The first trick--yes: but what are trumps?" said Kenneth, in reply to his companion's remark.

"Toujours l'audace!" the stranger answered. "But my life isn't worth a moment's purchase. I owe you a few minutes; 'for this relief much thanks.' Leave me now, and make for your friends. They will look after you. I have none."

"Not a bit of it," replied Kenneth instantly. "We stick together. I know a quiet place where we can consult. Step out briskly, as if we have important business on hand."

"There's nothing hypothetical about that," murmured the other. "On, then!"

They hurried along the street, which was crowded with persons of all ages, some talking excitedly, others cheering and singing patriotic songs. Now and then there was a cry of "Down with England!" The two fugitives walked quickly, dodging among the crowd to avoid the wearers of military or police uniforms, their own uniforms clearing a way for them. As they passed a beershop, the outside tables of which were thronged, the drinkers cheered them and broke lustily into the song of Deutschland über Alles.

As soon as possible they turned into a side street, less populous; and Kenneth, who knew the city well, directed his course towards the river, to a little secluded nook, where he hoped it would be possible to hold a quiet consultation. In the hurry of escape and the anxious transit of the streets he had been unable to devote a moment's thought to their future action. It was clear that their safety hung by a thread; their only chance was to lay their plans calmly, taking due account of the present circumstances and future contingencies.

They reached their destination. There was nobody about.

"We may have a few minutes to ourselves," said Kenneth. He took out his watch. "It is nearly ten o'clock. My train has gone, so that's out of the question."

"You were leaving?"

"Yes; my friends thought I had better go; that was before war with England was certain. I suppose it is true?"

"The time limit has not expired, certainly; but there can't be any doubt about it. Germany can't afford to yield about Belgium, and we can't afford to let her have a walk over. We may be quite sure that no Englishman of fighting age will get away now without trouble. But your friends will protect you; again I say, don't consider me."

"That's all right. In any case I don't want to get Max Finkelstein into a row."

"Of Amory & Finkelstein?"

"Yes; I'm Kenneth Amory. Do you speak German, by the way?"

"Like a native. I was at school at Heidelberg."

"That's a help. But for the life of me I can't think of a way of getting out. When they discover our escape they'll watch the stations, the piers, and the roads. Our uniforms won't be a bit of use."

"Oh! for the wings of a dove!--or an eagle would be more to the purpose."

"By Jove! that gives me an idea. I've done some flying; I was going to try for a place in our Flying Corps. If we could only bag an aeroplane!"

"A sheer impossibility, I should say."

Kenneth stood silent in the attitude of one deep in thought. Every now and again his right eyelid twitched--a little involuntary mannerism which came into play at such times. His companion watched him curiously. At last a look of resolution chased the doubt from his face.

"It's the only way," he said; "we must have a try. There are plenty in Cologne. They've been using a new aviation ground lately; the regular aerodrome was too small for them. They don't fly at night. All the machines will be in their hangars. Of course they'll be under guard; but we might get hold of one by a trick. Give me another minute or two to think it out: I know the place well."

After a few minutes' silence there ensued an earnest conversation between the two. The upshot of it was that they hurried by unfrequented roads to the new aviation ground. It was a large enclosure defended by a wooden fence about eight feet high, with barbed wire along the top. A sentry stood at the gate near the sheds. The whole place was in darkness, but a little beyond it, on the far side of the road, shone the lights of a beershop.

Leaving his companion in a dark corner, Kenneth hastened alone to the beershop. At the tables outside sat several men, mechanics in appearance. Kenneth slackened his pace to a policeman's walk, and passed by, throwing a keen glance at the men, who gave him a perfunctory salute. On reaching the remotest table he whispered a word or two to the man drinking alone there. The man left his bock, and rising, joined Kenneth, who had drawn back into the darkness.

"You can be discreet?" he said.

"What is it, Herr Policeman?" the man replied, doubtfully.

"It is a question of a spy. One of the mechanics is suspected. Do you know a short dark man who has recently come in?"

The question was a bait cast at a venture; Kenneth was elated at the man's reply.

"Yes, to be sure; there is a new fellow, mechanic to Herr Lieutenant Breul. None of us liked the look of him. If he is a spy! ... Not that he is particularly short."

"Well, not so very short."

"Nor more than common dark."

"Not a gipsy, perhaps; but still, rather dark and certainly not tall."

"That's the fellow to a hair. He's a boor: why, he called me a stupid pig only this morning. That's suspicious in itself; for I'm not a stupid pig; I can prove it by my school certificates."

"Of course; you wouldn't be employed here if you were a stupid pig. Well now, Herr Lieutenant Breul ought to be warned."

"That's true. The Herr Lieutenant is not here now; he has gone for the night with the other officers. But it would be better to arrest the man at once. A spy! We'll do for him, me and my mates."

"Not so fast. We must make sure of the man. I ought to hold him under observation. But it is important to keep the matter quiet. The question is, can you manage to let me have a sight of the man without attracting attention?"

The man scratched his head.

"You don't want to enter by the gate, Herr Policeman?"

"No. It would never do to let it get about that a spy was found here."

"Well, it's not an easy matter, but I'll go to the sheds and see what can be done."

The man went away, Kenneth hastened to the spot where he had left his companion.

"Things look possible," he said. "But your uniform is a difficulty. A German officer mustn't enter the enclosure like a thief, and without the password you can't go in by the gate."

"I must simply bluff it out. I'm a friend of Lieutenant Breul. I've played many parts in my time--not without success."

"Come along then. There's no time to lose."

They hurried back to the dark corner in which Kenneth had interviewed the mechanic. In a few minutes he returned.

"This is a friend of the Herr Lieutenant's," said Kenneth. "I met him just beyond the gate, and he agrees with me that this disgraceful matter must be kept secret. Have you had any success?"

"The fellow is overhauling the Herr Lieutenant's engine in preparation for a start to-morrow. He is the only man at work."

"That's very suspicious," said Kenneth. "Don't you think, Herr Captain, that we had better climb the fence and keep a watch on the man? Who knows what mischief he may be doing?"

"I'll go back to the gate and meet you inside," replied his companion.

"I think you had better come with me, Herr Captain," said Kenneth, "Your presence would guarantee me if any soldier within chanced to suppose that I was intruding."

"Very well," returned the other, with seeming reluctance. "But you also must guarantee me against damage to my clothes."

"That is easily done. This man will throw his coat over the wire."

"Certainly, Herr Policeman," said the mechanic, whom the presence of an officer had quite reassured.

They moved off to a spot beyond the sheds. The mechanic laid his coat upon the wire, and assisted the fugitives to mount. Then he hurried back to the gate, entered the enclosure, and met them near the furthest shed. The whirring of a propeller was audible.

"That's the shed," he said, pointing to the half-open door through which a bright light was streaming. "He's at work there, running the engine."

"Very well," said Kenneth. "You had better get your coat and make yourself scarce. You won't want to appear in this."

"Not I," said the man.

"The Herr Lieutenant will reward you," said Kenneth's companion. He knew German officers too well to tip the man in the English way.

The mechanic slipped away into the darkness. The Englishmen went to the shed. They opened the door and entered boldly. A man was bending over the engine, spanner in hand, adjusting a nut on the carburetter. He had not noticed the opening of the door or the entrance of the strangers. Suddenly he felt a hand on his shoulder, and looking up, was amazed to hear an officer say, through the noise of the propeller:

"Villain, you are under arrest."

Dumbfounded, he stared stupidly at the officer, and feebly protesting, stood back from the machine. Meanwhile Kenneth had taken a tin of petrol from a cupboard in the corner of the shed, and was filling up the tank. When this was done, he ran his eye rapidly over the monoplane, tested the stays, and finding all in good order, said in English:

"We'll lock this fellow in the cupboard. Then you throw the door open, come back quickly, and get into the seat beside me. The engine is running well, and it will only take a few seconds to get off."

At the first words of English the mechanic shouted with alarm; but his cry was drowned by the whirring of the propeller, and before he could repeat it he was locked into the cupboard. Then the Englishman carried out Kenneth's instructions. As soon as he was in his place, Kenneth threw the engine into gear, and the machine glided forward out of the shed into the dimly lit open space beyond. In a few yards it began to rise. There were shouts of surprise from the few men about the grounds and the mechanics in the beershop outside, scarcely heard by the airmen.

The monoplane soared up and up, unnoticed by the noisy multitudes in the crowded streets below. It was soon out of sight. Suddenly a beam of blinding light flashed upon it from some point high above the ground.

"The searchlight on the cathedral steeple," shouted Kenneth to his companion. "But there's no danger; they'll recognise it as a Taube."

The searchlight followed its course for a few minutes; then was shut off.

"The second trick is to us!" cried the passenger.

But Kenneth did not hear him. His whole attention was given to the machine.

CHAPTER IV--IN NEUTRAL TERRITORY

The sky was clear; there was very little wind; and Kenneth realised that the conditions could hardly have been more propitious. For some minutes he was too closely occupied with the mechanism to consider direction. The monoplane was strange to him. His experience of flying had been almost wholly gained in the machines of his friend Remi Pariset, son of the manager of the Antwerp branch of Amory & Finkelstein. Pariset was a lieutenant in the Belgian flying corps, and Kenneth had frequently accompanied him in flights, at first as passenger only, afterwards being allowed to try his hand in the pilot's seat. It had long been his aim to gain the pilot's certificate in England, and, as he had told Frieda Finkelstein, he hoped on the outbreak of war to get a commission in the Royal Flying Corps.

Though he had never before managed a monoplane of the type of that which he had appropriated, he had often watched the German airmen, and after a little uncertainty in his manipulation of the controls, he "felt" the machine, and recognised that it would give him no trouble. Then he had leisure to determine his course.

His first idea had been to make all speed to the Belgian coast, and take ship for England. But recollection of the conversation overheard between Hellwig and his visitor suggested that he might possibly do some preliminary service to the Belgians. A bridge was to be blown up. There could be no doubt that this operation was part of the German plan of campaign, and if it could be frustrated, this would represent so much gain to the defending force. The river spanned by the bridge had not been named, but there was a clue in the fact that the bridge was near a mill. His intention now, therefore, was to alight somewhere in Belgium and communicate his discovery to the military authorities.

In the hurry of departure he was quite oblivious of the direction of his flight. Now that he had time to consider it, he saw by the compass that he was flying towards the north-east. Bringing the monoplane round, he set his course for the south-west, hoping to pick up in half an hour or so the lights of Aix-la-Chapelle. He failed to locate the railway line from Cologne to Aix, and the few scattered points of light in the black expanse below gave him no landmarks.

After a while it occurred to him to switch on the electric light that illuminated the dial of a small clock. It was a quarter to eleven. He must have been flying for nearly half an hour, but neither to right or left nor straight ahead was there any sign of the expected lights of Aix. The country over which he was passing seemed to be hilly; it was possible that the lights of the city were hidden by the shoulder of a hill.

Presently his companion shouted that he heard the sound of big guns away to the left. Kenneth listened, but could hear nothing through the droning whirr of the propeller.

Every now and then he glanced at the clock, the only indication of the distance he had covered. When midnight was past, he felt sure that unless he had completely miscalculated his direction he must by this time have crossed the German frontier. He was thinking of landing and trying to discover where he was, when he caught sight in the starlight of a broad river flowing immediately beneath him from south-west to north-east. This, he had no doubt, was the Meuse, but he knew nothing of the course of the river, and could not determine whether he was in Belgium or Holland. At any rate he was out of Germany.

Dropping a few hundred feet, and seeing below him a broad expanse of fields, apparently flat, he thought it safe to risk a descent. No lights were visible. A rapid swoop brought the machine into a meadow of long grass ripe for hay, and he came lightly to the ground.

"I make you my compliments," said his companion, as they climbed out of their seats. "It is my first aerial voyage, and I am pretty sure that no one has ever tempted the empyrean under such exciting circumstances. But why did you come down? I hoped we should find ourselves at Ostend."

"I'll tell you my reason. I don't know where I am, but we had better camp here till morning, and then explore. Keep a look-out while I glance over the engine; we must be ready to get off again at a moment's notice."

He switched on the light and made a careful examination of the engine; then, rubbing his dirty hands on the grass, he threw himself down beside his companion.

"We've had uncommon luck," he said.

"You under-estimate the personal equation," returned the other. "I consider myself supremely lucky in having met you. Your daring is as great as your ingenuity, Amory. By the way, I have the advantage of you. I have as many names as the chameleon has colours, but the names given me in baptism were Lewis Granger. Now we're quits on that score."

"Thanks. You are a spy, I suppose?"

"Well, that rather opprobrious term would cover me, I presume. A sensitive person might prefer to call himself a secret agent. What's in a name?"

"It's pretty dangerous work, anyhow, and I'm jolly glad you're out of the Germans' clutches. You asked why I came down. It's because I'm a sort of secret agent too."

"You don't say so!"

"Oh, it's quite involuntary. I happened to overhear a conversation a few hours before I was nabbed. I'll tell you about it."

"Wait. I have no credentials. Do you think it wise to confide in a stranger?"

"That's all right," said Kenneth, who had taken an instant liking to the man. "We're in the same boat. What I overheard was a scheme for blowing up a bridge somewhere in Belgium, and I thought that before going on to England I might put the Belgians up to it."

"That's worth a few hours' delay. What you say confirms my own knowledge of the extraordinary minuteness of the German plans. 'Somewhere in Belgium,' you say. You don't know where?"

"No. The name of the river was not mentioned either by Hellwig or----"

"Hellwig! Does his Christian name happen to be Kurt?"

"Yes. Do you know him?"

"I have crossed swords with him--not literally, you understand, though nothing would please me better than a bout with him with the buttons off. I have one or two scores to settle with him. His Christian name would be more truly descriptive with the loss of a T. But how in the world did you come across him? He's not the kind of man I should expect to meet in your company."

"He's the cousin of my poor father's partner, Max Finkelstein. Max gives him a salary; he doesn't earn a penny of it, but Max is a kind-hearted beggar. He wouldn't do it if he knew that Hellwig was a--secret agent."

"Don't mind my feelings, my dear fellow," said Granger, with a laugh. "We're a very mixed lot, I assure you. Do you mind repeating what you overheard, as nearly as you can remember it?"

When the story was told, Granger acknowledged that ignorance of the position of the bridge was an obstacle to forewarning the Belgian authorities.

"Still, they ought to know every inch of the probable theatre of war," he said, "and may spot the place at once."

"We'll see in the morning," said Kenneth. "Meanwhile we had better take watch and watch about during the rest of the night. I don't suppose any one will come by while it's dark, but it's as well to be on the safe side. I'll take first watch."

"Very well. It will be light in less than five hours. I'll snooze for a couple of hours; wake me then."

The night was warm, and Kenneth, in his policeman's coat, suffered no discomfort. His watch passed undisturbed, and he was very sleepy when he roused Granger.

About five o'clock he was wakened from a sound sleep by a nudge from his companion.

"Sorry to disturb you," said Granger, "but there's a group of peasants approaching with scythes. Evidently they are going to mow the meadow."

Kenneth started up.

"Belgians?" he asked.

"Or Dutch," replied Granger. "We shall soon know."

The peasants, more than a dozen in number, came straight towards the aeroplane. Recognising the German uniforms, as the two men rose from the ground, they halted, consulted for a moment or two, then advanced, holding their scythes threateningly.

"I fancy they're Dutch," said Granger. "My good friends," he called in Dutch, "will you tell us where we are?"

On hearing their own tongue the men consulted again. Then one of them left the party, and hurried back by the way he had come. The rest advanced slowly, keeping close together, not replying to the question, and wearing an air of suspicion and hostility.

"They have sent a man back to his village to warn the authorities," said Granger. "We must find out where we are."

The peasants halted at a little distance, and stood in an attitude of watchfulness.

"We are not Germans, in spite of our dress," Granger continued. "As a matter of fact, we are Englishmen who have lost our way."

The stolid Dutchmen looked round upon one another with a knowing air as much as to say "We have heard that story before." Granger tried again.

"Come, come, it is the truth, I assure you. All we want is to know where we are; then we will pursue our journey."

There was again a consultation among the group. Then one of them said, pugnaciously:

"You are near Weert, as you know very well."

"Weert is some few miles north-east of Maestricht," Granger remarked to Kenneth. "We don't want to know any more. I think we had better be off. They don't believe we are not Germans, and as neutrals they will hold us up if we wait until the village authorities arrive. I hope they won't show fight, for we are absolutely unarmed, and those scythes are rather formidable implements."

"We're in an awkward hole, certainly," said Kenneth. "By the look of them they'll set on to us as soon as they see us making ready to go."

"The police took my revolver when they searched me," said Granger; "otherwise we might intimidate them."

"I wonder--" began Kenneth, thrusting his hand into the inner pocket of his coat. "By Jove! What luck! Here's the policeman's revolver. Keep them back with that while I start the engine. I shall only be a minute or two."

Granger took the revolver unobtrusively. Kenneth went to the front of the aeroplane and swung the propeller round, the peasants watching him at first without understanding. When the engine began to fire, however, they realised the meaning of the movements, and came on brandishing their scythes. Granger, standing close by the seat, lifted the revolver.

"Now, my good men," he said amiably, "we are going to leave you, as you appear not to relish our company. If any of you come within a dozen yards of us I shall fire."

The men came to a halt, scowling at the little weapon pointed at them by a steady arm. Kenneth got into his seat.

"I'm ready," he said.

Granger slowly backed and handed him the revolver, with which Kenneth covered the peasants as his companion clambered up beside him. Even before Granger was seated the aeroplane began to move. The peasants scattered out of its path, cursing the German pigs. It rose into the air; Kenneth swung it round to the south-west, and in half a minute it was sailing away out of danger. Glancing round, Granger smiled as he caught sight of a half squadron of Dutch cavalry galloping into the meadow behind them.

CHAPTER V--A CLOSE CALL

Remembering that they had crossed the Meuse the night before, Kenneth steered to the left until he sighted the river, then deflected southward, and followed its course, keeping on the side of the left bank.

There was no means of telling at what point he would cross the northern frontier of Belgium. Ascending to a great height, in order to escape shots from either Belgian or Dutch frontier guards, he soon discovered a town of some size extended on both banks of the river. This could only be Maestricht. Within twenty minutes of passing this he came in sight of a much more considerable town through which the river flowed spanned by several bridges.

"Better land now," shouted Granger, "or they'll be taking shots at us from the forts. This is Liége."

Almost before he had finished speaking the monoplane began to rock like a ship at sea, and Kenneth had to exert his utmost skill to preserve its equilibrium. A shell had burst a few hundred yards below them. Some seconds later they heard the dull thunder of the gun's discharge. Clearly it was no longer safe to continue the southward course. Kenneth swerved to the right, and making a steep vol plane, swooped into the cornfield of a farmhouse close by the high road.

The people of the farm, at the sight of the German uniforms, fled precipitately for shelter. Already "the terror of the German name" had become a by-word in the countryside.

"We are in hot water, I'm afraid," said Granger. "Strip off your coat; you're all right underneath."

Kenneth had hardly taken off his coat and helmet when there was a sound of galloping horses. A dozen Belgian mounted infantrymen dashed up the road, leapt the low wall of the farm steading, and shouted to them to surrender. Granger whipped out his pocket handkerchief and waved it in the air. The Belgians dismounted, and part of them advanced, the lieutenant at their head with revolver pointed, the men covering the fugitives with their rifles.

"You are our prisoners," said the officer in bad German.

"Charmed, my dear sir," replied Granger in excellent French. "Contrary to appearances, we are not Germans, but Englishmen."

"Ah bah!" snorted the lieutenant. "You wear German uniforms."

"L'habit ne fait pas le moine," said Granger with a smile. "The fact is as I state it: we are Englishmen who have escaped from Cologne."

"The aeroplane is German," the officer persisted.

"We commandeered it, there being no English machine available. Unluckily we have no papers on us to prove our nationality; they were taken from us by the Germans who arrested us as spies."

"Bah!" said the lieutenant again. That two Englishmen arrested as spies should have been able to escape on a German monoplane laid too great a strain upon his imagination. "You are my prisoners. Hand over your arms."

Granger at once gave up the revolver, and Kenneth allowed himself to be searched. The officer rummaged the aeroplane for plans and other incriminating documents, then ordered two of his men to mount guard over it, and marched the prisoners through the farmyard to the road, under the gratified glances of the farm people at their windows. Kenneth carried his policeman's uniform.

After walking about a mile, they came to a regiment encamped in a field beside the road. The lieutenant led his prisoners to the commanding officer, and explained the circumstances of their capture.

"You say you are English?" he said, scanning the two men.

"I assure you that is the truth," replied Granger. "We were both arrested as spies in Cologne, but by an ingenious stratagem of my friend here we obtained possession of a German aeroplane, and are delighted to find ourselves in Belgian territory, among a friendly people."

"You speak very good French."

"Which is not to our discredit, I hope," said Granger with a smile.

The Colonel was plainly even more incredulous than his subordinate. A man who spoke such good French must be a German spy! He took up the receiver of a field telephone. Ascertaining that an aide de camp was at the other end of the wire he said:

"Two men, one in police, the other in military uniform, German, have landed from a Taube monoplane west of Liers. They say they are English, but they are clearly German spies. I await orders."

The prisoners, who had heard all, watched his face grimly set as he held the receiver to his ear.

"It's extraordinary, the persistence of a fixed idea," said Granger in a low tone to Kenneth. "If he heard us speaking English I suppose he would take it as a clinching proof that we are Germans! The uniforms, our salvation in Cologne, are here our damnation."

"They'll send us to the General, won't they? He won't be such an ass."

"We shall see."

A few minutes passed. Then the look of blank expectancy on the Colonel's face gave way to a look of satisfaction. He laid down the receiver.

"Shoot them!" he said laconically, turning to the lieutenant.

Granger smiled at Kenneth, whose cheeks had gone red with indignation rather than pale from fear.

"What rot!" said the boy.

"I said I should die in my boots," remarked Granger. "My fate has been hanging over me these ten years. But there's a chance for you. Why not tell them about the bridge?"

"They'd only think I was funking, and wouldn't believe me. I won't do it."

They were led away towards a clump of trees on the outskirts of the camp. The lieutenant was selecting his firing party. A crowd of troopers, some in uniform, others in their shirt sleeves, came flocking around. One or two officers moved more leisurely towards the scene. Suddenly one of these started, and hurried forward with an exclamation of surprise.

"Mon Dieu, it's you, Ken!" he cried, seizing Kenneth's hand.

"Hullo, Remi," said Kenneth, his face lighting up. "Just tell your colonel I'm not a German, will you?"

"Of course I will. And your friend?"

"As English as I am. This is my pal, Remi Pariset," he said to Granger.

"I am delighted to meet you," said Granger, bowing, "even though our acquaintance should prove of the shortest."

Pariset, asking his fellow lieutenant to delay, ran to the Colonel, and returned immediately with him.

"I beg a thousand pardons, gentlemen," said the Colonel. "I am desolated at the injustice I have unwittingly done you. Pray accept my apologies."

"Not at all, Colonel," said Granger. "Appearances were against us. You were quite justified in your suspicions; it was our misfortune that we couldn't change our dress on the way.... I've had many a close shave," he added in an undertone to Kenneth, "but was never quite so near my quietus."

"I was feeling rather rummy," Kenneth confessed: "a queer feeling, not exactly fear; a sort of emptiness."

When the troopers learnt the truth, they broke into cries of "Vivent les Anglais! Vive l'Angleterre!" and the prisoners found themselves the idols of the camp. They were invited to join the officers at lunch, and ate with good appetites, having had no food but rye bread and beer since the previous midday. The officers drank their health with hilarity when Granger had related the trick by means of which they had escaped from Cologne, and Kenneth was toasted with embarrassing fervour.

"The bridge! That will be a clincher," whispered Granger in his ear.

Kenneth's French was not so good as his German, but he managed, even though haltingly, to convey to his interested auditors the gist of the scheme he had overheard. The officers were much concerned. None of them was able to identify the place from the bare description which was all that Kenneth could give them. The bridge was clearly not in the line of the Germans' probable advance; its destruction could only be meant to assist them. But the clues, slight though they were, must be followed up, and the Colonel declared that he would communicate with headquarters about the matter.

After lunch he took Kenneth aside.

"I gather that you have not known your companion long?" he said.

"That is true," replied Kenneth. "I met him for the first time yesterday."

"You will pardon me, I am sure. Lieutenant Pariset's voucher for you is sufficient; but in such times as these I should not be doing my duty if I allowed Mr. Granger to be at large without enquiry. Will you explain that to him, and ask him to give me a reference to a British authority?"

"Certainly. I am sure you will find things all right."

"The dear man!" laughed Granger when Kenneth told him this. "He needn't have been so careful of my feelings as to ask you to break it to me. I've no doubt I can satisfy him."

He mentioned the name of an official high in the British Foreign Office.

"A telegram to that address will bring me a character," he said. "Meanwhile I am out of work, and a sort of prisoner on parole. I am sorry, because I fear it means that we shall be separated for a time. You, I suppose, will want to be up and doing."

"Yes. I've talked things over with Pariset, and he wants me to go with him in his aeroplane in search of that bridge. But we'll meet again before long. I'm jolly glad we came across each other."

They shook hands cordially and parted.

Meanwhile Lieutenant Pariset had been in consultation with the commander of the Belgian Flying Corps. It had been decided that Pariset, accompanied by Kenneth, should make a reconnaissance in his aeroplane along the railway lines with a view to discover the bridge that was threatened. The German monoplane, though faster than his own, was discarded: it would certainly have been fired upon as it crossed the Belgian lines. There was no clue as to the direction in which the bridge lay, whether north, east, south or west of Liége. But it seemed certain that the Germans would not wish to blow up any bridges on the east. They would rather preserve them, in order to facilitate their advance. It was more probable that the bridge in question was on a section of the railway by which reinforcements, either French or Belgian, might be despatched to Liége. It was therefore decided to scout to the west and south.

Early in the afternoon Pariset and Kenneth started, working towards Brussels by way of Tirlemont and Louvain. Kenneth had been provided with field-glasses, through which he closely scanned every bridge and culvert, while Pariset piloted the machine. Flying low, they were able to examine the line thoroughly. All that Kenneth had to guide him was the knowledge that the bridge was near a mill. There was a tunnel between them. It was therefore pretty clear that the bridge and the mill could not be far apart.

They flew over the main line as far as Brussels without discovering any bridge that fulfilled the conditions. Then they retraced their course and scouted along the branch lines running south from Louvain, Tirlemont and Landen respectively. Within a few hours they had examined the whole triangular district that had Brussels, Liége, and Namur at its angles. At Namur they descended for a short rest, then set off again, to try their luck on the lines running from the French frontier.

Both felt somewhat discouraged. To trace the many hundreds of miles of railway that crossed the country between the Meuse and the Somme promised to be work for a week. Indeed, it was getting dark by the time they had run through the coal-mining and manufacturing district between Mons and Valenciennes. Alighting at the latter place, they heard that great numbers of German troops had already crossed the Belgian frontier, and the forts of Liége were being attacked. There was much excitement in the town, and Pariset had some difficulty in getting petrol to replenish his tanks.

Next morning they set off early along the line running eastward through Maubeuge to Charleroi. It seemed unlikely that they would find the spot they sought in the midst of a manufacturing district, but if they were to succeed, nothing must be left untried.

Towards ten o'clock they were crossing a stream to the south-east of Charleroi when Kenneth suddenly gave a shout. He had noticed on the stream a water-mill, between which and a larger river, apparently the Sambre, the railway crossed the stream on a brick bridge of four arches. The mill was at least two hundred yards from the bridge, a distance that seemed too great to have been tunnelled; but it was the first spot he had seen that in any way conformed to the particulars he had overheard, and it appeared worth while to examine the place more closely.

The importance of the bridge was obvious. Its destruction would seriously delay the transport of any French troops that might be sent northwards to support Namur or Liége, and correspondingly assist the Germans in an attempt to take either of those towns by a coup de main.

At Kenneth's shout Pariset turned his head, understood that some discovery had been made, and nodded. He did not at once prepare to alight. If Germans were in possession of the mill they would notice the sudden cessation of the noise of the propeller, which they must have heard, and might take warning from the descent of the aeroplane in their neighbourhood. Luckily he had been flying low, so that the course of the machine could not be followed for any considerable distance. Having run out of sight beyond a wood, he selected an open field for his descent, and alighted a few hundred yards from a farmhouse.

"Have you found it?" asked Pariset eagerly.

"I saw a mill and a railway bridge," replied Kenneth; "but we were going too fast for me to be sure it's the right place."

"Well, we shall have to find that out. We'll get the farmer to help us run the machine into his yard, and then reconnoitre."

The farmer and a group of his men were already hurrying towards them. In a few words Pariset enlisted their help. The aeroplane was run into the yard, and placed behind a row of ricks that concealed it from the outside.

"We should like some bread and cheese and beer," Pariset said to the farmer. "May we come in?"

"Surely, monsieur," was the reply. "Come in and welcome. Ah! these are terrible times. I don't know how long I shall have a roof over my head. But they say the English are coming to help us. Is that true?"

"Quite true. My friend here is an Englishman."

"Thank God! Oh! les braves Anglais! All will be well now. Come in, messieurs; you shall have the best I can give you."

CHAPTER VI--THE OLD MILL

Sitting in the farm-kitchen, and eating the farmer's homely fare, Pariset talked a little about the war, and led the way discreetly to the questions he was eager to ask.

"The mill, monsieur? 'Tis twenty years since it was used. I used to send my corn to it, but nowadays I send it to Charleroi, where a steam-mill grinds it more cheaply. The old miller is a good friend of mine, but he retired twenty years ago; he's a warm man, to be sure. That's his house yonder:" he pointed to a cottage half a mile away across the fields. "We often have a gossip over a mug of beer."

"It's just as well he made his money before steam-mills became so common," said Pariset. "I suppose it wasn't worth any one's while to keep the water-mill going?"

"No; there's no money in milling of the old sort now. But it goes to my heart to see the old mill idle. Such a loss, too. But the miller can stand it; he's a warm man, as I told you. And after all, he has made a little out of it lately. But it's a come-down, that's what I say."

"It is idle, you said."

"Yes, to be sure, and always will be. But the miller has let it for two years past. He makes a little out of it, and so do I, not so much as I should like, for the gentleman is only there now and then. He's a Swiss gentleman that keeps a hotel in Namur. A great fisherman, he is; he'll fish for hours in the millpond, and I wonder he has the patience for it, for there's not much to be caught there since the grinding stopped. Still, I don't complain; he buys my eggs and butter when he comes there, two or three times a year perhaps. He's there now, with a few friends of his."

"I should like to have a chat with your friend the miller," said Pariset.

"He'd like it too, monsieur. He doesn't have much company, and he'd like to hear about things from an officer; you can't believe what you read in the papers. I'll take you across the fields."

In a few minutes they were seated in a cosy little parlour, opposite a sturdy countryman, hale and hearty in spite of his seventy odd years. He asked shrewd questions about the war, foresaw great trouble for his country, but, like the farmer, was cheered by the news that "les braves Anglais" were coming once more to her rescue. When Pariset led up to the subject of his mill he became animated.

"Ah! the old mill is a rare old place," he said with a chuckle. "The things I could tell you! There was more than milling in the old days. Times are changed. We're all for law now. But in my grandfather's time--why, monsieur, he's dead and gone this forty years, so it will do him no harm if I tell you he was a smuggler. Many and many a barrel of good brandy used to get across the border without paying duty. Why, underneath the old mill there are cellars and passages where he used to store contraband worth thousands of francs. I used to steal down there when I was a boy, and ma foi! it made my skin creep, though there was nothing to be afraid of. But 'tis fifty years since my old grandfather closed them down, and they've never been opened up since."

"Your present tenant is a hotel-keeper, I hear. He would be interested to know about the smuggling."

"That he was, to be sure. He laughed when I told him about it. 'We can't get rich that way nowadays,' said he. He seems to have plenty of money, though; pays me a good rent. 'Tis strange what whims gentlemen have. A month's fishing in the pond wouldn't feed him for a week. He calls it sport; well, in my young days I liked something more lively. But the fishing is just an excuse; he comes there now and then for a change and quiet, though he's not a solitary, like some fishermen. He has a party of friends sometimes; all Swiss like himself."

"French Swiss?" asked Pariset.

"No, German Swiss. For my part, I've no great liking for German Swiss. They're only one remove from Germans. But his money is good, and it's something to make a little money out of the old mill after all these years."

The old man spoke quite frankly, and evidently had no suspicions about his tenant. Pariset thought it safe to disillusion him.

"Would you be surprised to learn that your fisherman is actually a German?" he said.

"But that is impossible," said the miller. "He would have gone back to Germany, because of the war."

"Unless he is a spy! We have reason to believe that he is, and that he is using your mill for the benefit of the enemy. That is what has brought us here."

"Sacre nom de nom!" the old man ejaculated, and the farmer thumped the table and swore. "Is that the truth, monsieur?"

"We suspect him of intending to blow up the railway bridge at a given signal."

"Ah! the villain! And he will use the underground passages. That is why he pays me a high rent, parbleu! But he has come to the end of his tether. You are here to arrest him?"

"No. We have no men with us. We came to learn whether our suspicions were justified. We are not sure of our man yet."

"Bah!" shouted the old man, red with fury. "It is certain. He has fooled me. I will raise the countryside. We will fall on these Germans. Before night they shall lie in the dungeons of Charleroi."

"Do you think that is the way to go to work?" Pariset asked tactfully. "They would hardly allow themselves to be caught napping; at the first alarm they would no doubt blow up the bridge, and I take it that to prevent that is even more important than to seize the men themselves--though our aim should be to do both."

"It is true, monsieur. I am an old man. This is the day of young men. Oh that I were forty years younger and able to serve my country! But you will not let them go? You will bring some of our brave soldiers here and capture the villains?"

"There may not be time for that. We must meet craft with craft. If we could only reconnoitre the mill we might be able to hit upon a plan. My uniform would give me away, if I approached the place as I am; you could no doubt lend me some clothes to disguise myself?"

"Surely, monsieur; but----"

He broke off, eyeing Pariset's face, with its small military moustache, doubtfully.

At this moment they heard the rumble of a heavy vehicle on the road.

"It is the beer, compère," said the farmer, glancing out of the window.

"Ah! the beer!" repeated the miller. "I might have known they were Germans! Every week they have a barrel delivered from Charleroi, and it is not the local brew, but the Lion brew from Munich."

He had moved to the window, followed by his visitors. A heavy dray laden with beer was lumbering down the road. As it came opposite to the house the drayman hailed the miller, pulling up his horses.

"The Germans are shelling Liége," he said. "Maybe 'tis the last time I shall come this way. Your good tenants had better clear out."

"Good tenants!" cried the old man explosively.

"Quiet!" said Pariset, touching him on the sleeve. "Don't tell him they are Germans."

"Ah! You are right, monsieur. But my blood boils. You are going to the mill?" he asked the drayman.

"Yes. 'Tis only a small barrel to-day--not the big one they usually have. There aren't so many of them, seemingly. I was just loading up the usual nine gallons when the order came from the office to take a four-and-a-half instead."

Pariset glanced quickly at Kenneth.

"They're going to clear out soon," he said in a low tone. "It looks as though we're only just in time."

They drew aside from the others while the miller gossiped with the drayman.

"I say, you talked of disguising yourself," said Kenneth. "Why shouldn't you take the drayman's place and deliver the beer? You could then take stock of the place and the people."

"A capital notion! I must take the drayman into my confidence. Wait a minute," he called out of the window, as the man was about to drive on. In a few words he explained the plan to the miller.

"Parbleu, monsieur, but look at his size!" said the old man.

"Yes, that's a difficulty, I admit," said Pariset ruefully. "He would make three of me. The Germans aren't fools, and if they saw me with his smock flapping about me they would smell a rat."

"And your face and hands, monsieur--no, decidedly you could not pass for a drayman."

Pariset bit his nails in perplexity. Kenneth stared musingly at the dray.

"I've an idea!" he said. "Pretend that the drayman has been called up. The brewer is short-handed, and has to send clerks out of the office to deliver the beer: two clerks equal one drayman. Besides, if I go with you, I may catch sight of that fellow I saw with Hellwig, and make sure he's our man."

"The very thing! Your clothes are all right; I must borrow a suit from the miller. But wait: won't Hellwig's man recognise you?"

"I'll guard against that--smear my face with rust off the cask-hoops, and borrow a slouch hat which I'll keep well down over my eyes. It's worth trying."

Delighted with the plan, the miller furnished them with the necessary garments. In a few minutes Pariset, got up passably as a clerk, went out to the drayman, who was becoming impatient. The man swore when he learnt that his customers were suspected to be spies, and readily agreed to remain in the miller's house and await the issue of the stratagem. Meanwhile Kenneth had rubbed his cheeks and hands with rust, and in the low flopping hat lent him by the miller would hardly have been recognised by his friends, much less, he hoped, by a man who had seen him for only a few minutes.

"I had better drive," said Kenneth; "then I can keep in the background while you are delivering the cask, if you can tackle it alone."

"That will be easy enough. I see there's a ladder or inclined plane or whatever they call it on the dray. I've only to roll the cask down and trundle it to the door. I don't suppose they'll let me carry it inside."

Kenneth took the reins, and drove off, Pariset, who also had smeared face and hands, dangling his legs over the tail of the dray. They jogged down the road, passed under the railway bridge, and came in due course to the mill.

The premises were surrounded by an old and dilapidated wall, but they noticed that along its top ran a row of formidable spikes, apparently of recent date. The front door of the mill-house faced the road. It was stoutly built of oak studded with nails, and was flanked on both sides by barred windows. The smuggling miller who built the place had evidently made himself secure against surprise.

When the dray drew up before the door, Pariset sprang down and jerked the iron bell-pull. From the driver's seat Kenneth saw a face appear for an instant at one of the windows. After a short interval the bolts were withdrawn, the door opened, and a man stood on the threshold. Kenneth tingled; he had recognised him instantly as the man who had been in conversation with Hellwig. He turned his head so as not to show his full face, pulled his hat lower over his eyes, and hoped that the recognition had not been mutual. And he listened anxiously, wondering how Pariset would acquit himself in his novel part, and wishing for the moment that Granger was in his place.

Pariset, however, was cool and collected. He took the bull by the horns.

"I am sorry I am late, monsieur," he said, "but the fact is that all our carters are called up for transport purposes. Being anxious not to disappoint a valued customer, my master has sent us out of the office. We shan't be able to come again, for we're called up ourselves--all through those pigs of Germans, who are said to be across the frontier. We shan't be able to deliver any more beer, I'm afraid. It's a wonder we've any horses left."

The German merely grunted in answer to this.

"We're in for a very bad time," Pariset went on, as he hoisted the end of the cask on to the doorstep. "Hadn't you better go back to Switzerland, monsieur? Pardon the suggestion, but we don't know what may happen. If these German pigs come south----"

"Just roll it into the lobby," interrupted the German. "Here's the money. By the way, have you seen an aeroplane in the neighbourhood?"

"Yes, we saw one an hour or so ago. It was flying north-east. I shouldn't be surprised if it was German. The pigs are capable of anything. But they'll get a reception that will surprise them. Our little army--but there! You know what your own army would do, and your turn may come in Switzerland sooner than you think. Thank you: I am sorry we shan't be able to serve you again, by the look of things."

He laid the cask in the lobby, pocketed the money, and returned to the dray.

Meanwhile Kenneth had seized the opportunity to take a careful look around. It was clear that it would not be easy to take the place by a rush without giving the inmates sufficient time to fire the mine beneath the bridge. The fact that the German had come to the door himself, instead of the deaf old countryman whom he was said to employ as a man-of-all-work, showed that he was on the alert. Nothing would be easier than to overpower the man himself; but if any noise were made in so doing his companions would instantly come to his assistance, and at the first sign that the plot had been discovered the bridge would be blown up. It seemed that the ruse would prove fruitless after all.

In turning the horses for the journey back, Kenneth contrived to bring the dray close against the wall, so that from his high seat he was able to look over. Through the open window of a room giving on the yard he saw a party of four men playing cards at a table. Close to the right hand of each stood a tall beer glass.

"That explains why they are such good customers of the brewery," he thought.

Pariset, sitting at the back of the dray with his face to the door, began to hum a tune, and Kenneth caught the words "En avant!" He whipped up the horses, big Flemish beasts that were evidently unaccustomed to go above a walking pace, and the heavy vehicle lumbered away.

"Why did you want me to hurry?" asked Kenneth, when they were some distance along the road.

"Because that fellow was standing at the door watching us," Pariset replied. "I wonder if he is suspicious?"

"I shouldn't think so. You played your part quite naturally. But we are right, Remi: that's the fellow I saw with Hellwig."

"Ah!" was all that Pariset said then.

CHAPTER VII--A HORNET'S NEST

"I am not at all happy about this," said Pariset, after a brief silence.

"We haven't learnt very much, certainly," said Kenneth.

"I don't mean that. We have learnt enough if that is your man. But I see no means of preventing the destruction of the bridge."

"We might fly to Charleroi and send a squadron of lancers back. There are only five men to deal with, apparently."

"That's not the difficulty. The point is that at the first sign of molestation they would fire the mine. You may depend upon it that they are picked men, with resolution enough to do their job, even at the cost of their lives. It would not be much use to capture them after the mischief was already done."

"The mine is to be fired on receipt of a marconigram."

"You didn't tell me that. It may happen at any minute, then. They must have wireless rigged up in the mill-house. We might have cut a wire, but with wireless we are helpless."

"Unless we could get into the mill," Kenneth suggested.