Title: The Catholic World, Vol. 01, April to September, 1865

Author: Various

Release date: April 4, 2012 [eBook #39367]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Don Kostuch

[Transcriber's notes]

This text is derived from

http://www.archive.org/details/catholicworld01pauluoft

Several scanned pages are obscured by being too closely glued at the

spine. I have interpolated the missing text where it seemed obvious

and left "??" where it was in doubt.

A few cases of inaccurate typesetting such as misplaced words or

lines have been corrected.

Although square brackets [] usually designate footnotes or

transcriber's notes, they do appear in the original text.

To future editors: The poetry has been formatted using

spaces and the "pre" tag. Modify these sections only with

care and reference to the original text.

This text includes Volume I;

Number 1—April 1865

Number 2—May 1865

Number 3—June 1865

Number 4—July 1865

Number 5—August 1865

Number 6—September 1865

[End Transcriber's notes]

NEW YORK:

LAWRENCE KEHOE, PUBLISHER,

7 BEEKMAN STREET.

1865.

Ancient Saints of God, The, 19.

Ars, A Pilgrimage to, 24.

Alexandria, The Christian Schools of, 33, 721.

Animal Kingdom, Unity of Type in the, 71.

Art, 136, 286, 420.

Art, Christian, 246.

Authors, Royal and Imperial, 323.

All-Hallow Eve, or the Test of Futurity, 500, 657, 785.

Arks, Noah's, 513.

Babou, Monsieur, 106.

Blind Deaf Mute, History of a, 826.

Church in the United States, Progress of the, 1.

Constance Sherwood, 78, 163, 349, 482, 600, 748.

Catholicism, The Two Sides of, 96, 669, 741.

Cardinal Wiseman in Rome, 117

Catacombs, Recent Discoveries in the, 129.

Chastellux, The Marquis de, 181.

Church of England, Workings of the Holy Spirit in the, 289.

Cochin China, French, 369.

Consalvi's Memoirs, 377.

Church History, A Lost Chapter Recovered, 414.

Canova, Antonio, 598.

Cathedral Library, The, 679.

Catholic Philosophy in the Thirteenth Century, 685.

De Guérin, Eugénie and Maurice, 214.

Divina Commedia, Dante's, 268.

Dinner by Mistake, A, 535.

Dramatic Mysteries of the Fifteenth and Sixteenth Centuries, 577.

Dublin May Morning, A, 825.

Extinct Species, 526.

Experience, Wisdom by, 851.

Falconry, Modern, 493.

Fifth Century, Civilization in the, 775.

Guérin, Eugénie and Maurice de, 214.

Glacier, A Night in a, 345.

Grand Chartreuse, A Visit to the, 830.

Hedwige, Queen of Poland, 145.

Heart and the Brain, 623.

Irish Poetry, Recent, 466.

Jem McGowan's Wish, 56.

Legends and Fables, The Truth of, 433.

London, Catholic Progress in, 703.

London, 836.

Laborers Gone to their Reward, 855.

Mont Cenis Tunnel, The, 60.

Mongols, Monks among the, 158.

Mourne, The Building of, 225.

Memoirs, Consalvi's, 377.

Maintenon, Madame de, 799.

Miscellany, 134, 280, 420, 567, 712, 858.

Nick of Time, The, 124.

Perilous Journey, A, 198.

Poucette, 260.

Prayer, What came of a, 697.

Russian Religious, A, 306.

Saints of God, The Ancient, 19.

Science, 134, 280, 712.

Streams, The Modern Genius of, 233.

Stolen Sketch, The, 314.

Swetchine, Madame, and her Salon, 456.

Shakespeare, William, 548.

St. Sophia, The Church and Mosque of, 641.

Species, The Origin and Mutability of, 845.

Three Wishes, The, 31.

Terrene Phosphorescence, 770.

Upfield, Many Years Ago at, 393.

Vanishing Race, A, 708.

Wiseman, Cardinal in Rome, 117.

Winds, The, 207.

Women, A City of, 514.

Wisdom by Experience, 851.

Young's Narcissa, 797.

POETRY

A Lie, 245.

Avignon, The Bells of, 783.

Domine Quo Vadis?76.

Dream of Gerontius, The, 517, 630.

Dorothea, Saint, 666.

Ex Humo, 33.

Gerontius, The Dream of, 517, 630.

Hans Euler, 237.

Limerick Bells, Legend of, 195.

Mary, Queen of Scots, Hymn by, 337.

Martin's Puzzle, 739.

Saint Dorothea, 666.

Speech, 829.

Twilight in the North, 344.

Unspiritual Civilization, 747.

{iv}

NEW PUBLICATIONS.

Archbishop Spalding's Pastoral, 144.

At Anchor, 287.

American Annual Cyclopaedia, US.

A Man without a Country, 720.

Banim's Boyne Water, 286.

Beatrice, Miss Kavanagh's, 574.

Cardinal Wiseman's Sermons, 139.

Cummings' Spiritual Progress, 140.

Christian Examiner, Reply to the, 144.

Correlation and Conservation of Forces, The, 288, 425.

Confessors of Connaught, 574.

Curé of Ars, Life of the, 575.

Ceremonial of the Church, 720.

Darras' History of the Church, 141, 575, 860.

England, Froude's History of, 715.

Faith, the Victory, Bishop McGill's, 428.

Grace Morton, 574.

Heylen's Progress of the Age, etc., 142.

Household Poems, Longfellow's, 719.

Irvington Stories, 143.

Irish Street Ballads, 720.

John Mary Decalogne, Life of, 576.

Lamotte Fouqué's Undine, etc142.

La Mère de Dieu, 432.

Life of Cicero, 573.

Moral Subjects, Card. Wiseman's Sermons on287.

Mystical Rose, The, 288.

Mater Admirabilis.429.

Month of Mary, 720.

Martyr's Monument, The, 860.

New Path, The, 288, 576.

Our Farm of Four Acres, 143.

Protestant Reformation, Abp. Spalding's History of the, 719.

Real and Ideal, 427.

Religious Perfection, Bayma's, 431.

Russo-Greek Church, The, 576.

Retreat, Meditations and Considerations for a, 720.

Songs for all Seasons, Tennyson's, 719.

Sybil, A Tragedy, 860.

Translation of the Iliad, Lord Derby's, 570.

Trübner's American and Oriental Literature, 576.

William Shakespeare, 860.

Whittier's Poems;860.

Young Catholic's Library, 432.

Year of Mary, 719.

[The following article will no doubt be interesting to our readers, not only for its intrinsic merit and its store of valuable information, but also as a record of the impressions made upon an intelligent foreign Catholic, during a visit to this country. As might have been expected, the author has not escaped some errors in his historical and statistical statements—most of which we have noted in their appropriate places. It will also be observed that while exaggerating the importance of the early French settlements in the development of Catholicism in the United States, he has not given the Irish immigrants as much credit as they deserve. But despite these faults, which are such as a Frenchman might readily commit, the article will amply repay reading.—ED. CATHOLIC WORLD.]

After the Spaniards had discovered the New World, and while they were fighting against the Pagan civilization of the southern portions of the continent, the French made the first [permanent] European settlement on the shores of America. They founded Port Royal, in Acaclia, in 1604, and from that time their missionaries began to go forth among the savages of the North. It was not until 1620 that the first colony of English Puritans landed in Massachusetts, and it then seemed not improbable that Catholicism was destined to be the dominant religion of the New World; but subsequent Anglo-Saxon immigration and political vicissitudes so changed matters, that by the end of the last century one might well have believed that Protestantism was finally and completely established throughout North America. God, however, prepares his ways according to his own good pleasure; and he knows how to bring about secret and unforeseen changes, which set at naught all the calculations of man. The weakness and internal disorders of the Catholic nations, in the eighteenth century, retarded only for a moment the progress of the Catholic Church; and Providence, combining the despised efforts of those who seemed weak with the faults of those who seemed strong, confounded the superficial judgments of philosophers, and prepared the way for a speedy religious transformation of America.

This transformation is going on in our own times with a vigor which seems to increase every year. The {2} causes which have led to it were, at the outset, so trivial that no writer of the last century would have dreamed of making account of them. Yet, already at that time, Canada, where Catholicism is now more firmly established than in any other part of America, possessed that faithful and energetic population which has increased so wonderfully during the last half century; and even in the United States might have been found many an obscure, but a patient and stout-hearted little congregation—a relic of the old English Church, which after three centuries of oppression was to arise and spread itself with a new life. But no one set store by the poor French colonists; England and Protestantism, together, it was thought, would soon absorb them; and as for the Papists of the United States, the wise heads did not even suspect their existence. The writer who should have spoken of their future would only have been laughed at.

The English Catholics, like the Puritans, early learned to look toward America as a refuge from persecution, and in 1634, under the direction of Lord Baltimore, they founded the colony of Maryland. Despite persecution from Protestants whom they had freely admitted into their community, they prospered, increased, and became the germ of the Church of the United States, now so large and flourishing.

In the colonial archives of the Ministry of the Navy we have found a curious manuscript memoir upon Acadia, by Lamothe Cadillac, in which it is stated that in 1686 there were Catholic inhabitants in New York, and especially in Maryland, where they had seven or eight priests. Another paper preserved in the same archives mentions a Catholic priest residing in New York; and William Penn, who had established absolute toleration in the colony adjoining that of Maryland, speaks of an old Catholic priest who exercised the ministry in Pennsylvania.

The Catholics at this time are said to have composed a thirtieth part of the whole population of Maryland. This estimate seems to us too low. At all events, the increase of our unfortunate brethren in the faith was retarded by persecution and difficulties of all kinds which surrounded them. In the Puritan colonies of the North, they were absolutely proscribed. In the Southern colonies, of Virginia, Georgia, and Carolina, their condition was but little better; in New York they enjoyed a precarious toleration in the teeth of penal laws. In Maryland and Pennsylvania alone they were granted freedom of worship, and a legal status; though even in those colonies they were exposed to a thousand wrongs and vexations. Maryland persecuted them from time to time and banished their priests; and William Penn, in his tolerant conduct toward them, was bitterly opposed by his own people.

Nevertheless, despite difficulties and violence, the Anglo-American Catholics increased by little and little, wherever they got a foothold; the descendants of the old settlers multiplied; new ones came from England and Ireland; and a German immigration set in, especially in Pennsylvania, where several congregations of German Catholics were formed at a very early period. In the archives of this province we have found several valuable indications of the state of the Church in 1760. There were then two priests, one a Frenchman or an Englishman, named Robert Harding, the other a German of the name of Schneider. It seems probable that they were both Jesuits. [Footnote 1] In a letter to Governor Loudon, in 1757, Father Harding estimates the number of Catholics in Philadelphia and its immediate neighborhood at two thousand—English, Irish, and German; but in the absence of Father Schneider he could not be positive as to these figures. A letter from Gouverneur Morris in 1756 {3} speaks of the Catholics of Maryland and Pennsylvania as being very numerous and enjoying freedom of worship, and adds, that in Philadelphia there is a Jesuit who is a very able and talented man. The Abbé Robin, a chaplain in Rochambeau's army in 1781, informs us in his narrative that there were several Catholic churches at Fredericksburg, Va., and even a Catholic congregation at Charleston, S.C.

[Footnote 1: In De Courcy and Shea's "Catholic Church in the United States" pp. 211, 212, an account will be found of both these missionaries. The first mentioned was an Englishman. Both were— Jesuits. ED. C. W.]

The toleration accorded to the Jesuits in the United States was precarious, but it amounted in time to a pretty complete freedom; and as they were not disturbed when the order was suppressed in Europe, some of their brethren from abroad took refuge with them; so that in 1784, we find, according to Mr. C. Moreau, in his excellent work on the French emigrant priests in America, [Footnote 2] nineteen priests in Maryland, and five in Pennsylvania. To these we must add the priests of Detroit, Mich., Vincennes, Ind., and Kaskaskia and Cahokia, Ill., all four originally French-Canadian settlements which were ceded to England along with Canada, and after the American Revolution became parts of the United States. Counting, moreover, the missionaries scattered among the Indian tribes, we may safely say that the American Republic contained at the period of which we are speaking not fewer than thirty or forty ecclesiastics. The number of the faithful may be set down as 16,000 in Maryland, 7,000 or 8,000 in Pennsylvania, 3,000 at Detroit and Vincennes, and about 2,500 in southern Illinois; in all the other states together they hardly amounted to 1,500. In a total population therefore of 3,000,000 they numbered about 30,000, and of these 5,500 were of French origin. Such was the condition of the Church in the United States when it was regularly established in 1789 by the erection of an episcopal see at Baltimore, and the appointment, as bishop, of Mr. Carroll, an American priest, born of one of the oldest Catholic families of Maryland. The dispersion of the clergy of France, in 1790, soon afterward supplied America with numerous evangelical laborers, who gave a new impulse to the development which was just becoming apparent in the infant Church.

[Footnote 2: One vol. 12mo. Paris: Douniol.]

A few years before the French Revolution, Mr. Emery, superior of Saint Sulpice, guided by what we must term an extraordinary inspiration, came to the assistance of the American Church, and with the help of his brother Sulpitians and at the cost of the society, founded a theological seminary at Baltimore. His plans were already well matured when Bishop Carroll, soon after his appointment, entering heartily into the project, promised him a house and all the assistance he could give. Four Sulpitians accordingly set out from Paris in 1790, taking with them five Seminarians. They were supplied with 30,000 francs to defray the cost of their establishment, and to this modest sum the crisis which soon overtook the parent establishment allowed them to add but little; but this mite, bestowed by the Church of France in the last days of her wealth, was destined to become, like the widow's mite, the price of innumerable blessings.

Between 1791 and 1799 the storm of revolution drove twenty-three French priests to the United States. As the first apostles, when they set out from Rome, portioned out Germany and Gaul among themselves, so they divided this country, and most of them organized new communities of Christians, or by their zeal awakened communities that slept. Six of them, Flaget, Cheverus, Dubourg, Maréchal, Dubois, and David, became bishops.

The base of operations from which these peaceful but victorious invaders went forth was Baltimore, the episcopal see around which were gathered the old American clergy and the greater part of the Catholic population. It was here that the Sulpitians {4} had their seminary, and this establishment became a centre of attraction for a great many of these exiled priests who belonged to the Society of Saint Sulpice. Some (as MM. Ciquard, Matignon, and Cheverus) bent their steps from Baltimore toward the laborious missions among the intolerant and often fanatical Puritans of the North, where the Catholics—a mere handful—were found scattered far and wide; isolated in the midst of a Protestant population; deprived of priests and religious services, and in danger of totally forgetting the faith in which they had been baptized. Nothing discouraged these apostolic men. Aided by divine grace, they awakened the indifferent, converted heretics, gathered about them the few Catholics who immigrated from Europe, attracted all men by their affable and conciliating manners, their intelligence and education, and the disinterestedness of their lives. Soon on this apparently sterile soil Catholic parishes grew up and flourished in the midst of people who had never before seen a priest. Thus were founded the churches of Massachusetts, Maine, and Connecticut—so quickly that, in 1810 (that is to say, only eighteen years after the beginning of the missions), it was deemed advisable to erect for them another bishopric. Congregations had sprung up on every side as if by enchantment, and the venerable Abbé Cheverus was appointed their first bishop.

Others went westward. The Abbés Flaget, Badin, Barriere, Fournier, and Salmon carried the faith into Kentucky. There they found a few Catholic families who had emigrated from Maryland. With them they organized churches, which increased with prodigious rapidity, and were the origin of the present dioceses of Louisville, Covington, Nashville, and Alton.

The Abbés Richard, Levadour, Dilhiet, and several others, passed through the forest and the wilderness, and joined the old French colonies which still survived around the ruins of the French military posts in the Northwest and in the valley of the Mississippi. They found there a few missionaries, whom the Canadian Church still maintained in those distant countries; but their ranks were thin, and they were old and feeble. This precious reinforcement enabled them to give a fresh impetus to the French Catholic congregations over whom they kept watch in the forest. Detroit, Vincennes, Cahokia, Kaskaskia, and afterward St. Geneviève and St. Louis in Missouri, ceded to the United States in 1803, received the visits of these new apostles, and experienced the benefits of their intelligence and zeal. Nearly all the places where they fixed themselves have since given their names to large and flourishing bishoprics.

Several of the emigrant priests remained in Maryland and Virginia, and enabled the Sulpitians to complete the organization of their seminary, while at the same time they assisted Bishop Carroll in providing more perfectly and regularly for the wants of those central provinces which might be called the first home of American Catholicism. The number of the faithful everywhere increased remarkably. We can hardly estimate the extraordinary influence which these French missionaries exercised by their exemplary lives, their learning, their great qualities as men, and their virtues as saints; and the Anglo-Saxon inhabitants (who are thoroughly Protestant if you will, but for all that religious at bottom) were struck by their character all the more forcibly because it was so totally different from what their prejudices had led them to expect of the Catholic clergy.

There is something patriarchal and Homeric in the lives of these men, which read like the poetic legends in which nations have commemorated the history of their first establishment. We have seen the journal of one of these missionaries—the Abbé Bourg, {5} who labored further North, in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. His life was one long, perpetual Odyssey. In the spring he used to start from the Bay of Chaleur, traverse the northern coasts of New Brunswick, pass down the Bay of Fundy, make the entire circuit of the peninsula of Nova Scotia, and after a journey of five hundred leagues, performed in nine or ten months, visit the islands in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and so come back to his point of departure. From place to place, the news of his approach was sent forward by the settlers, so that whenever he stopped he found the faithful waiting for him, and whole families came fifteen or twenty leagues to meet him. Hardly had he arrived before he began the round of priestly labor, of confession and baptism, of burial and marriage. He was the arbiter of private quarrels, and often of public disputes. He found time withal to look after the education of the children—at least to make sure that they were well taught at home. Thus he would stay fifteen days perhaps in one place, a month in another, according to the number of the inhabitants. The first communion of the children crowned his visit. Then the man of God, with a last blessing on his weeping flock, disappeared for a whole year; and when the apparition so long desired, but so transitory, had passed, it left behind a halo of superhuman glory, which seemed to these pious people the glory rather of a prophet than of an ordinary man.

In such ways the marks of a messenger from God seemed more and more clearly and unmistakably stamped upon the Catholic missionary, and Protestants themselves began to yield to the subtle influence of so much real virtue and self-devotion. Conversions were frequent even among the descendants of the stern Puritans. Many of the most fervent Catholic families in the United States date from this period. A rich Presbyterian minister of Boston (Mr. John Thayer) was converted, and became a priest and an apostle. So God scattered the seed of grace behind the footsteps of his poor, persecuted children, who, despite their apparent misery, bore continually with them the wealth of the soul, the power of the Word, and the marvellous attraction of their sacrifices and virtues.

Providence, however, had not deployed so strong a force for no purpose beyond the capture of these converts. A very few missionaries might have sufficed for that; but it was now time to prepare the land for the great European immigration which was to cause the astonishing growth of the United States. Spreading themselves over the vast area of the Union, the emigrants found everywhere these veteran soldiers whom the French Revolution had sent forth into the New World as pioneers, tried both by the pains of persecution and the labors of apostleship. Before this great human tide the old emigrant priests were like the primitive rocks which arrest and fix geological deposits, The Catholic part of the tossing flood invariably settled around them and their disciples. All over the West the churches founded by the old French settlers increased, and new ones sprang up wherever a Catholic priest established himself. From that moment the grand progressive movement has never ceased. The blood of the martyrs of France, the spirit of her banished apostles, became fruitful of blessings, of which the American churches are daily sensible.

The first bishop in the United States had been appointed in 1789. Four years afterward another see was erected at New Orleans, La., which, ten years later, became a part of the United States; and in 1808, so rapid had been the Catholic development, that three new bishops were consecrated—one for Louisville, Ky., another for New York, and the third for Boston, Mass. Two of these sees were occupied by the French missionaries who had founded them—Bishop {6} Flaget at Louisville, and Bishop Cheverus at Boston. That of New York was entrusted to a venerable priest of English [Irish] origin—the Rev. Luke Concanen. In the whole United States there were then sixty-eight priests and about 100,000 Catholics. Lei us now glance at the rapid increase of the American Church up to our own day.

From the States of Maryland and Pennsylvania the Church was not long in spreading into Virginia, New York, Kentucky, and Ohio. The establishment of sees at Louisville and New York was followed by the erection of others at Philadelphia in 1809, and Richmond and Cincinnati in 1821. The two Carolinas, in which the Catholics had hitherto been an obscure and rigorously proscribed class, received a bishop at Charleston in 1820. New Orleans, a diocese of French creation, was divided in 1824 by the erection of the bishopric of Mobile. The old French colonies in the far West were the nucleus around which were formed other churches. The dioceses of St. Louis, Mo. (organized in 1826), Detroit, Mich. (1832), and Vincennes, Ind. (1834), all took their names from ancient French settlements, and were peopled almost exclusively by descendants of the French Canadians who were their first inhabitants.

Thus, in the course of twenty-six years, we see eight new sees erected, making the number of bishops in the United States thirteen. The number of the clergy amounted in 1830 to 232, and in 1834 probably exceeded 300. At the date of the next official returns (1840) there were 482 priests and three more bishoprics—those of Natchez, Miss., and Nashville, Tenn., both established in 1837, and that of Monterey in California, a country of Spanish settlement which had recently been annexed to the United States. [Footnote 3]

[Footnote 3: Monterey was not a part of the United States until 1848, nor a bishop's see until 1850. In place of it we should substitute Dubuque, made a see in 1837.—ED. C. W.]

But this increase was not comparable to that which followed between 1840 and 1850. In ten years the number of bishops was doubled by the erection of fifteen [seventeen] new sees. In 1840 there were sixteen; in 1850 thirty-one [thirty-three]. The growth during this period was most perceptible in the North and West. Among the new sees were Hartford, Conn., Albany and Buffalo, N. Y., Pittsburg, Penn., Cleveland, O., Chicago, Ill., Milwaukee, Wis., St. Paul, Minn., Oregon City and Nesqualy, Oregon, and Wheeling in Northern Virginia. The others were Little Rock, Ark., Savannah, Ga., Galveston, Texas, and Santa Fé, New Mexico. [Footnote 4] The clergy in 1850 numbered 1,800, having considerably more than doubled [nearly quadrupled] their number in ten years.

[Footnote 4: And San Francisco and Monterey—ED C. W.]

Thus we see that the Church was pressing hard and fast upon the old New England Puritans. They soon began to feel uneasy, and to oppose sometimes a violent resistance to her progress. In some of the States, especially Connecticut and New Hampshire, there were laws against the Catholics yet unrepealed; so that the dominant party had more ways of showing their hatred of the Church than by mere petty vexations. In Boston things went so far that a nunnery was pillaged and burned by a mob. It is from this time that we must date the origin of the Know-Nothing movement, directed ostensibly against foreigners, but undoubtedly animated in the main by hatred of Catholicism and alarm at its progress. The fretting and fuming of this political party was the last effort of Puritan antipathy. The Church prospered in spite of it; so the Puritans resigned themselves to witness her gradual aggressions with the best grace they could assume.

Ten new sees were established between 1850 and 1860, and eight of these were in the North or West—viz., Erie, Newark, Burlington, Portland, Fort Wayne, Sault St. Marie, Alton, and Brooklyn. Two were in the South—Covington and Natchitoches. There were thus in the United States, in 1860, forty-three bishoprics, with 2,235 priests. Let us now see how many Catholics were embraced in these dioceses, and what proportion they bore to the total population.

The number of the faithful it is not easy to determine accurately; for a false delicacy prevents the Americans from including the statistics of religious belief in their census-tables. Estimates are very variable. A work printed at Philadelphia in 1858 by a Protestant author sets down the number of Catholics as 3,177,140. Dr. Baird, a Protestant minister, published at Paris in 1857 an essay on religion in the United States—an essay, be it remarked, which showed the Catholics no favor—in which he estimated their number at 3,500,000. But neither of these estimates rests upon trustworthy data. They were certainly below the truth when they were made, and are therefore far from large enough now, for the yearly increase is very great.

Our own calculations are drawn partly from our personal observation, and partly from official documents published by various ecclesiastical authorities. The best criterion is undoubtedly the rate of increase of the clergy.

It must be evident that in America, more than in any other country, there is a logical relation between the number of the faithful and the number of the priests. As the clergy depend entirely upon the voluntary contributions of their people, there must be a fixed ratio between the growth of the flocks and the multiplication of pastors. If the clergy increase too fast, they endanger their means of support. Now, if priests cannot live in America without a certain number of parishioners to support them, we may take this number as a basis for calculating the minimum of the Catholic population; and we may safely say that the population will be in reality much greater than this minimum; because, as we can testify from experience, the churches never lack congregations, and in most places the number of the clergy is insufficient to supply even the most pressing religious wants of the people. One never sees a priest in the United States seeking for employment. On the contrary, the cry of spiritual destitution daily goes up from parishes and communities which have no pastors.

Calculations founded upon the statistics of "church accommodations" given in the United States census—that is, of the number of persons the churches are capable of holding—are not applicable to our case; because the Catholic churches, especially in the large cities, are thronged two or three times every Sunday by as many distinct congregations, while the Protestant churches have only one service for all. The capacity of the churches therefore gives us neither the actual number of worshippers nor the proportion between our own people and those of other denominations. We have taken, then, as the basis of our estimate, the ratio between the number of priests and the number of the faithful, correcting the result according to the circumstances of particular places. The first point is to establish this ratio, and we are led by the concurrent results of careful estimates made in some of the States, and special or general calculations which we have had opportunity of making in person, to fix it at the average of one priest for every 2,000 Catholics. But we have a very trustworthy method of verifying this estimate, and that is by comparison between the United States and the contiguous British Provinces, in which the statistics of religious belief are included in the general census. Setting aside Lower Canada, where the Catholic population is as compact as it is in France, we find that in Upper {8} Canada, a country which resembles the Western United States, the ratio in 1860 was one priest for every 1,850 Catholics, and in New Brunswick, a territory very like New England, one for every 2,400. Our average ratio of one for every 2,000 cannot, therefore, be far from the truth. We have made due account of all data by which this ratio could be either raised or lowered in particular times and places. We have ourselves made investigations in certain districts, and persons well qualified to speak on the subject have given us information about others. The result of our corrected calculation gives us 4,400,000 as the Catholic population of the United States in 1860, the date of the last general census. We shall give presently the distribution of this total among the several states; but we wish first to call attention to another fact of great importance which appears from our figures. In 1808 the Catholics were 100,000 in a total population of 6,500,000, or 1/65th of the whole; in 1830 they were 450,000 in 13,000,000, or 1/29th of the whole; in 1840, 960,000 in 17,070,000, or 1/18th; in 1850, 2,150,000 in 23,191,000, or 1/11th; and finally, in 1860 they were over 4,400,000 in 31,000,000, or 1/7th of the total population. It thus appears that for fifty years the Catholics have increased much faster than the rest of the inhabitants, and especially during the last two decades. Between 1840 and 1850 their ratio of increase was 125 per cent., while that of the whole population was only 36; and from 1850 to 1860 their ratio of increase was 109 per cent., while that of the whole people was 35.59. These figures, to be sure, are not mathematically certain, for they are deduced partly from estimates; but we are confident that, considering the imperfect materials at our disposal, we have come as near the exact truth as possible, both in the ratio of increase and in the total population. Official returns in the British Provinces confirm our calculations in a most remarkable manner; and we believe that, estimating the future growth on the most moderate scale, the Catholics will number in 1870 one-fifth of the whole population, and in 1900 not far from one-third.

Having traced the progress of the Church step by step in the United States, it will now be equally interesting and instructive to see how this progress has been made in different places. The Catholics are by no means uniformly dispersed over the country, and their increase has not been equally rapid in all the states. It will be worth our while to see in which quarters they are settled with the most compactness and in which they are widely dispersed; and thus we may predict without great risk which regions are destined to be the Catholic strongholds in the New World. We have already said that the proportion of the Catholics to the whole people in 1860 was as one to seven; but if we divide the country into two parts we shall find that in the Southern states there are only 1,200,000 Catholics in a population of 12,000,000—that is, they are 1/10th of the whole; while in the North they number 3,200,000 in 19,000,000, or more than 1/6th. Even these figures give but a very general idea of the distribution of the faithful. If we take the whole country, state by state, we shall find the proportions still more variable. In some places the Catholic element is already so strong that its ultimate preponderance can hardly be doubted, while its slow development in other quarters promises little for the future. The following tables will enable our readers to comprehend at once the distribution of the Catholics among the various states:

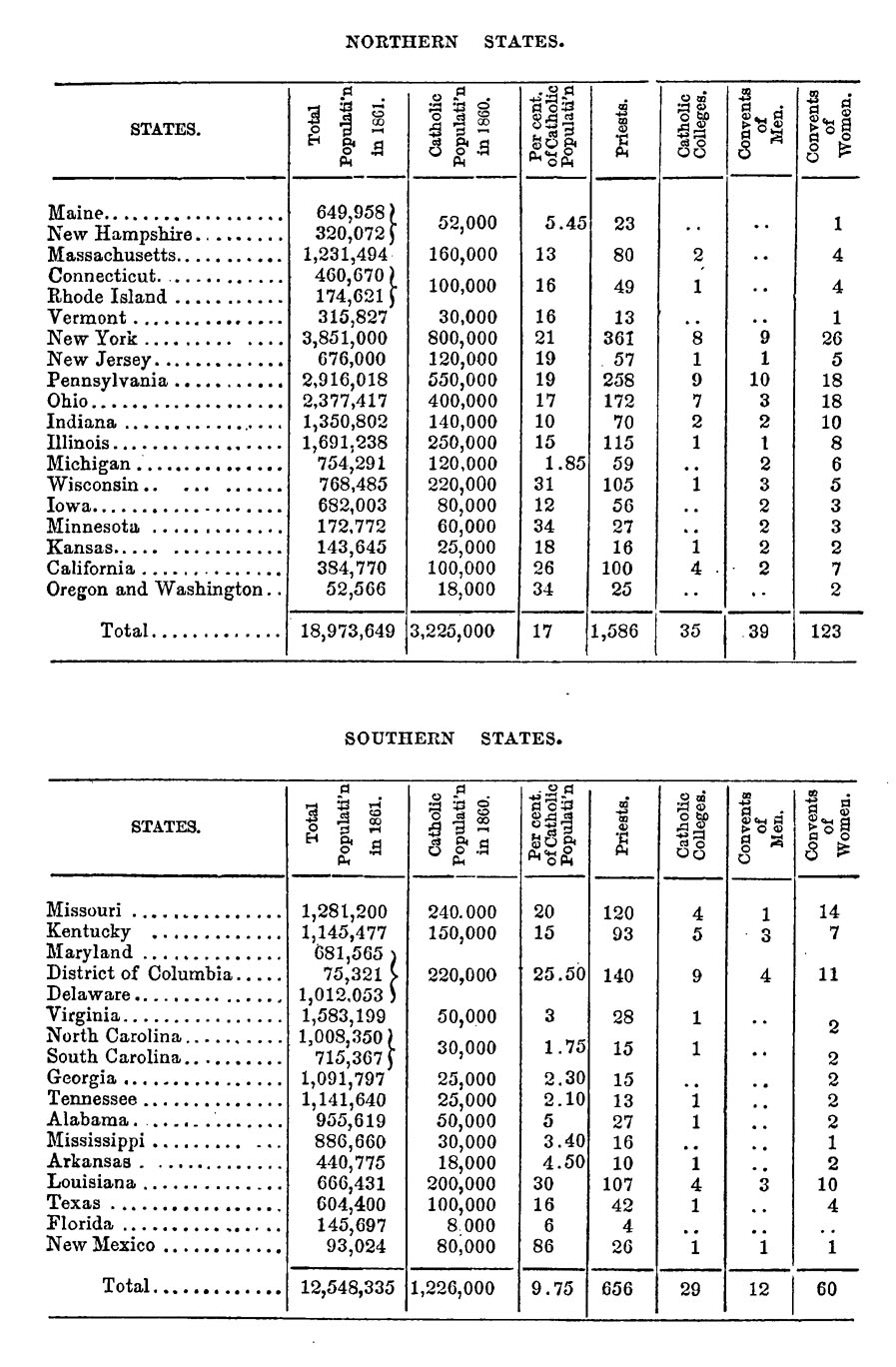

NORTHERN STATES.

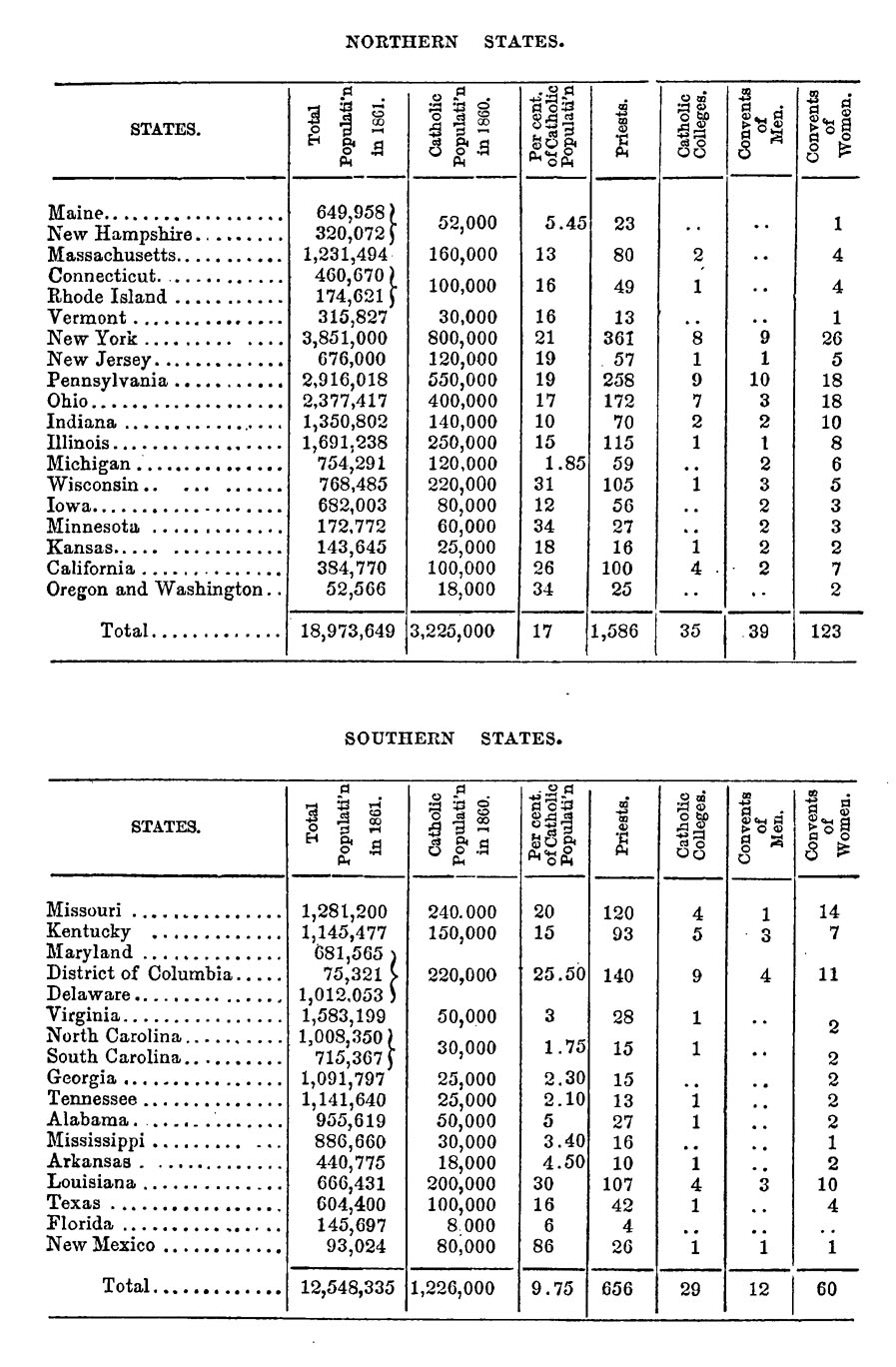

SOUTHERN STATES.

These tables show at a glance the disproportion between the Catholics of the North and those of the South. In only one Northern state (that of Maine) is the proportion of Catholics as small as 5.45 per cent, of the whole population; while there are no fewer than five Southern states in which it is less than three per cent. If we leave out New Mexico, Texas, Louisiana, Missouri, and Maryland, where the preponderance of the faithful is due to special causes, we find that in the other Southern states the average proportion is not above four per cent. In other words, in these regions the Church has little better than a nominal existence. This is partly because the stream of European immigration has always flowed in other directions, and partly because the negroes generally adhere to the Baptist or Methodist sects in preference to the Church.

But when we examine the tables more in detail, we see that in both sections the ratio of Catholics varies greatly in different states. It is easy to account for this difference in the South. Six states only have any considerable number of Catholic inhabitants. Louisiana and Missouri owe them to the old French colonies around which the Catholic settlers clustered. In New Mexico, more than three-fourths of the people are of Spanish-Mexican origin. Texas derives a great number of her inhabitants from Mexico, and has received a large Catholic emigration both from Europe and from the United States. Maryland, the germ of the American Church, owes her religious prosperity to the first English Catholic settlers; and the Church in Kentucky is an offshoot of that in Maryland. Such are the special causes of the great differences between the churches of the various Southern states. In the North there is less disparity. European immigration has produced a much more decided effect in this section than in the preceding. From this source come most of the faithful of New York, Oregon, California, Ohio, and New Jersey. In Ohio the Germans have done the principal part, and they have done much also in Pennsylvania and Wisconsin. The effect of conversions is more perceptible in Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, and New York than elsewhere. In many of the states, however, and especially in Pennsylvania, we find numerous descendants of English Catholic settlers, while the old French colonies of the West have had their influence upon the population of Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Illinois, and also of the northern part of New York, where the French Canadians are daily spreading their ramifications across the frontier. If we look now at the localities in which the proportion of Catholics is greatest, we shall notice several interesting points touching the laws which have determined the direction of the principal development of the Church, and which will probably promote it in the future. In the South there are what we may call three groups of states in which the Catholic element is notably stronger than in the others. One belongs exclusively to the Southern section, and consists of Louisiana, Texas, and New Mexico, having an aggregate Catholic population of 380,000 in 1,363,800, or 28 per cent. The other groups (Missouri, that is to say, and Maryland and Kentucky) form parts of much larger groups belonging to the Northern states. The first of these latter, and that to which Maryland and Kentucky are attached, consists of Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Ohio. Its aggregate population is 11,647,477, of whom the Catholics are 2,240,000, or nineteen per cent. This group contains the ancient establishments of Maryland and Pennsylvania—good old Catholic communities, in which the zeal and piety of the faithful possess that firm and decided character which comes of long practice and time-honored traditions. It contains, too, the magnificent seminary of Baltimore, founded and still directed by the Sulpitians. This is the largest and most complete {11} establishment of the kind in the United States, and derives from its connection with the Sulpitian house in Paris special advantages for superintending the education of young ecclesiastics, and training accomplished ministers for the sanctuary. Kentucky, likewise, has some important and noteworthy institutions, such as the seminary of St. Thomas and the college of St. Mary, both of which are in high repute at the West, and the magnificent Abbey of Our Lady of La Trappe at New Haven, with sixty-four religious, eighteen of whom are choir-monks. The Kentucky Catholics deserve a few words of special mention. The descendants, for the most part, of the first settlers of Maryland, who scattered, about a century ago, in order to people new countries, they partake in an eminent degree of the peculiar characteristics which have given to Kentuckians a reputation as the flower of the American people. They are more decidedly American than the Catholics of any other district, and they are remarkable for their homogeneousness, their education, and their attachment to the faith and traditions of the Church.

The most important and numerous Catholic population is found in the state of New York, where the faithful amount to no fewer than 800,000. They have here religious establishments of every kind. This condition of things is the result, in great measure, of the well-known ability of Archbishop Hughes, whose death has left a void which the American clergy will find it hard to fill. His reputation was not confined to the Empire City. He was as well known all over the Union as at his own see, and was everywhere regarded as one of the great men of the country. Although the progress of the faith in New York has been owing in a very great degree to immigration, it is in this city and in Boston that conversions have been most numerous; and in effecting these, Archbishop Hughes had a most important share. It is not surprising, then, that his death should have caused a profound sensation in the city, and that all religious denominations should have united in testifying respect for his memory.

It is difficult to apply a statistical table to the study of the question of conversions. These are mental operations of infinite variety, both in their origin and in their ways; for the methods of Providence are as many and as diverse as the shades of human thought upon which they act. It may be remarked, however, that the different Protestant sects furnish very unequal contingents to the little army of souls daily returning to the true faith; and it is a curious fact that the two sects which furnish the most are the Episcopalians, who, in their forms and traditions, approach nearest to the Catholic Church, and the Unitarians, who go to the very opposite extreme, and appear to push their philosophical and rationalistic principles almost beyond the pale of Christianity. These two sects generally comprise the most enlightened and intellectual people of North America. On the other hand, the denominations which embrace the more ignorant portions of the population (such as the Baptists, the Wesleyan Methodists, etc., etc.) furnish, in proportion to their numbers, but few converts. The principal Catholic review in the United States (Brownson's Review, published in New York) is edited by a well-known convert, whose name it bears, and who was formerly a Unitarian minister.

Further North—in New England—there is another Catholic group, of recent origin, formed of the Puritan states of Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island. The first see here was established by Bishop Cheverus only sixty years ago. These bishoprics, however, have already acquired importance; for in the diocese of Hartford the Catholics are now sixteen per cent, of the whole population, and the rapidity of their increase and the completeness of their church organization give us ground for bright hopes of their future progress. Immigration {12} here does much to promote conversions, and it will not be extravagant to anticipate that in the course of a few years the number of the faithful will be doubled. The Pilot, the most important Catholic journal in the country, is published in Boston.

The far West, only a few years ago, was a great wilderness, with only a few French posts scattered here and there in the Indian forest, like little islands in the midst of a great ocean. Now it is divided into several states, and counts millions of inhabitants. In this rapid transformation, Catholicism has not remained behind. Many dioceses have been established, and the quickness of their growth has already placed this group in the second rank so far as regards numerical importance, while all goes to show that Catholicism is destined here to preponderate greatly over all other denominations. The states of Missouri, Illinois, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota contained, in 1860, 4,575,000 souls, of whom 890,000, or 19 per cent., were Catholics. This is as large a proportion as we find in the central group. It is, moreover, rapidly rising, and only one thing is necessary to make these states before long the principal seats of Catholicism in the Union—that is, an adequate supply of priests. It is of the utmost importance that the demand for missionaries in these diocese be supplied at whatever cost.

The principal causes of this remarkable increase are, first, the crowds of immigrants attracted by the great extent of fertile land thrown open to settlers; and, secondly, the fact that the Catholic immigrants on their arrival clustered, so to speak, around the old French settlements, where the missionaries still maintained the discipline and worship of the Church. At first, therefore, it was easy to direct this great influx of people, since they naturally tended toward the pre-existing centres of faith. The consequence was that the Church lost by apostacies fewer members than one might have supposed, and fewer than were lost in other places. But now the daily augmenting crowds of immigrants are dispersing themselves through less solitary regions. They are coming under more direct and various influences; and hence the necessity for increasing the number of churches and parish priests becomes daily more and more urgent. At the same time, the means at the disposal of the bishops become daily less and less adequate for supplying this want, especially since the people of the country, new and unsettled as they are, and absorbed in material cares, furnish but few candidates for the priesthood. Here we see a glorious field for the far-reaching benevolence of the Society for the Propagation of the Faith. Nowhere, we believe, will the sending forth of pious and devoted priests produce fruits comparable to those of which the past gives promise to the future in this part of the United States. We spoke just now of the old French colonies, and our readers will perhaps be surprised that we should have made so much account of those poor little villages, which numbered hardly more than from 500 to 1,500 souls each when the Yankees began to come into the country. Nevertheless, we have not exaggerated their importance. It is not only that they served as centres and rallying-points; but so rapid is the multiplication of families in America that this French population which, if brought together in one mass in 1800, would have counted at most 14,000 souls, now numbers, including both the original settlements and the swarms of emigrants who have gone from them to the West, not fewer than 80,000. Their descendants are always easily recognized. Detroit, and its neighborhood in Michigan, Vincennes (Ind.), Cahokia and Kaskaskia (Ill.), St. Louis, St. Geneviève, Carondelet, etc. (Mo.), Green Bay and Prairie du Chien (Wis.), St. Paul (Minn.)—all these old settlements have preserved the deep imprint of our race. Even in the new colonies which were afterward drawn from them, the French population have uniformly kept up the practice of their religion, {13} the use of their mother tongue, and a lively recollection of their origin. Of this fact we have obtained proof in several instances from careful personal observation. Small and poor, therefore, as these settlements were, they had a powerful moral influence upon the great immigration of the nineteenth century. The Catholic immigrants felt drawn toward them by the attraction of a community of thought and customs; and God, whose Providence rules our lives, directed the movement by his own inscrutable methods.

While the Catholic element was increasing at the rate of 80, 125, and 109 per cent, every ten years, other religious denominations showed an increase of only twenty or twenty-five per cent. Some remained stationary, and a few even lost ground. Whence comes this continued and increasing disparity in the development of different portions of the same people? The principal reason assigned for it is the immense emigration from Ireland to America. As the number of Catholics in the United States when the emigration began was very small, every swarm of fresh settlers added much more to their ratio of increase than to that of other denominations. Ten added to ten gives an increase of 100 per cent.; but the same number added to 100 gives only ten per cent. At first sight, this seems a sufficient explanation; but we shall find, when we come to examine it, that it does not really account for our increase. If the growth of the American Catholic Church were the result wholly of immigration, we should find that as the number of Catholic inhabitants increased, the apparent effect of this immigration would be diminished. In other words, the ratio of increase would gradually fall to an equality with that of other denominations. But, so far from this being the case, the difference between our ratio of increase and that of the Protestant sects is as great as ever--is even growing greater. The ratio which was ten per cent. a year between 1830 and 1840, rose to 12.50 per cent, a year between 1840 and 1850, and was 10.09 per cent, between 1850 and 1860. There are other causes, therefore, beside European emigration to which we must look for an explanation of Catholic progress in America. If we study with a little attention the extent to which immigration has influenced the development of the whole population of the country, and the exact proportion of the Catholic part of this immigration, we shall find confirmation of the conclusions to which we have been led by the simple testimony of figures. Immigration has never furnished more than six or seven per cent. of the decennial increase of the population of the United States, the growth of which has been at the rate of thirty-five per cent, during the same period. Immigration, therefore, contributed to it only one-fifth. Again, of these immigrants, including both Irish and Germans, not more than one-third have been Catholics. Moreover, we must take account of the considerable number of members that the Church has lost in the course of their dispersion all over the country.

Clearly, then, the influence of immigration is not enough to account for the rapid progress of the faith. A careful analysis of the Catholic population at different tunes, and in different places, enables us to specify two other causes.

1. The Catholics are principally distributed at the North among the free states, where the population increases much faster than it does at the South; and the Catholic families, it has been observed, multiply much faster than the others, in consequence, no doubt, of their more active and regular habits of life, sustained morality, respect for the marriage tie, and regard for domestic obligations. This difference in fecundity is quite perceptible wherever the Catholic element {14} is strong—as in Canada, and the states of New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Wisconsin, etc., and, among the Southern states, in Louisiana, Maryland, and Missouri.

2. Another cause of increase is the conversion of Protestants—a cause which operates slowly, quietly, and, at first, imperceptibly, but with that constant and uniform power—reminding us of the great operations of nature—which is almost always the sign of a Providential agency. Eloquent theorists and brilliant writers on statistics, preferring salient facts and striking phenomena—what they call the great principles of science—too often overlook or despise those obscure movements which act quietly upon the human conscience. Yet how much more powerful is this mysterious action—like the continual dropping of water—than the showy effects which captivate so many thinkers, whose organs of perception seem dazzled by the glow of their imagination! Such was the nature of the invisible operation which was inaugurated by the preaching of the martyrs of the faith whom the French Revolution cast forth like seed all over the world. The rules of political economy had nothing to do with it. It acted in the secret chambers of men's hearts and the retirement of their meditative moments, and it has gone on without interruption to the present moment, increasing year by year. The Church seizes upon the convictions of grown men; reaches the young by her admirable systems of education; impresses all by her living, persuasive propagandism, made beautiful by the zeal and devotion and holiness of her missionaries. Simple and dignified, without the affectation of dignity— austere, without fanaticism—their presence alone roots up old prejudices, while their preaching and example fill the soul with new lights and with anxieties which nothing but their instructions can set at rest. Thus, wherever they go, the thoughts and comparisons which they suggest multiply conversions all around them. You have only to question a few Catholic families in the older states about their early religious history, and you will see how important an element in the prosperity of the Church is this force of attraction—so important, that the following statement may almost be taken as a general law: Wherever a Catholic priest establishes himself, though there be not a Catholic family in the place, it is almost certain that by the end of a time which varies from five to ten years, he will be surrounded by a Catholic community large enough to form a parish and support a clergyman. This rule seems to us to have no exception except in some of the southern states. We have no hesitation in stating it broadly of even those parts of New England in which the anti-Catholic feeling is now strongest.

We shall presently have occasion to show that the only thing which prevents the American Church from increasing, perhaps doubling, the rapidity of its progress, is the scarcity of ecclesiastics and missionaries, from which all the dioceses are suffering.

We have explained the important part which converts have played in this progress. The inquiry naturally arises: Whence come so many conversions? What are the causes which generally lead to them? These are delicate and difficult questions. We have no wish to speak ill of the Protestant clergy. Most of them are certainly honorable men, estimable husbands and good fathers; but we cannot help observing that they lack the sacerdotal character so conspicuous in the Catholic priest. Their ministry and their teaching cannot fully satisfy the soul; and whenever a calm and unprejudiced comparison is drawn between them and the Catholic clergy, it is strange if the former do not suffer by the contrast, and behold their flocks, little by little, passing over to the side of the Church. This comparison is one motive which often leads Protestants, not precisely into {15} the bosom of the faith, but to the study of Catholic doctrine; and this is a step by no means easy to persuade them to take; for, of every ten Protestants who honestly study the faith, seven or eight end by becoming Catholics. The Americans are a people of a strong religious bent. Nothing which concerns the great question of religion is indifferent to them. They study and reflect upon such matters much more than we skeptical and critical Frenchmen. The conversions resulting from such frequent consideration of religious matters ought, therefore, to be far more numerous in America, and even in England, than in other countries.

There are doubtless many other causes which contribute to the same result. Among them are mixed marriages, which generally turn out to the advantage of the Church, especially in the case of educated people in the upper ranks in society. Not only are the children of these marriages brought up Catholics, but almost always, as experience has shown us, the Protestant parent becomes a Catholic too.

The excellent houses of education directed by religious orders are another active cause of conversions. If elementary education is almost universal in the United States, it is nevertheless true that the higher institutions of learning are exceedingly defective. The colleges and boarding-schools founded under the direction of the Catholic clergy, though inferior to those of France in the thoroughness of the education they impart and the amount of study required of their pupils, are yet vastly superior to all other American establishments in their method, their discipline, and the attainments of their professors. The consequence is that they are resorted to by numbers of Protestant youth of both sexes. No compulsion is used to make them Catholics; no undue influence is exerted; the press, free as it is, rarely finds excuse for complaint on this score; but facts and doctrines speak for themselves. The good examples and affectionate solicitude which surround these young people, and the friendships they contract, leave a deep impression on their minds, and plant the seed of serious thought, which sooner or later bears fruit. Various circumstances may lead to the final development of this seed. Now perhaps a first great sorrow wakens it into life; now it is quickened by new ideas born of study and experience; in one case the determining influence may be a marriage; in another, intercourse with Catholic society; and not a few may be moved by the falsity of the notions of Catholicism which they find current among Protestants, and which their own experience enables them to detect. This motive operates oftener than people suppose, and generally with those who at school or college seemed most bitterly hostile to the faith. In tine, those who have been educated at Catholic institutions are less prejudiced and better prepared for the action of divine grace, which Providence may send through any one of a thousand channels.

And lastly, Catholicism acts upon the Americans through the medium of the habits and customs to which it gradually attaches them, the result of which is that in the growth of the population the Church makes a constant, an insensible, and what we might call a spontaneous increase. It is a well-known fact that the Catholic families of North America, as a general rule, are distinguished by a character of stability, good order, and moderation which is often wanting in the Yankee race. Now this turns to the advantage of the Church; for it is evident that a people which fixes itself permanently where it has once settled, which concentrates itself, so to speak, has a better chance of acquiring a predominance in the long run than one of migratory habits, always in pursuit of some better state which always eludes it. This truth is nowhere more apparent than in a county of Upper Canada where we spent nearly three years. The county of Glengarry was settled {16} in 1815 by Scotchmen, some of whom were Catholics. The colony increased partly by the natural multiplication of the settlers, partly by immigration, until about 1840, when immigration almost totally ceased, all the lands being occupied. The population was then left to grow by natural increase alone. The Protestants at that time were considerably in the majority; but by 1850 the proportions began to change, and out of 17,576 inhabitants 8,870 were Catholics. In 1860 the majority was completely reversed, and in a population of 21,187 there were 10,919 Catholics; in other words, the latter, by the regular operation of natural causes, had gained every year from one to two per cent, upon the whole. It would not be easy to give a detailed explanation of this fact; we are only conscious that some mysterious and irresistible agency is gradually augmenting the proportion of the Catholic element in American society and weakening the Protestant.

American society might be compared to a troubled expanse of water holding various substances in solution. The solid bottom upon which the waters rest is formed by the deposit of these substances, and day after day, during the moments of rest which follow every agitation of the waves, more and more of the Catholic element is precipitated which the waters bring with them at each successive influx, but fail to carry off again. It is by this human alluvium that our religion grows and extends itself; and if this growth is wonderful, it may be that the effect of the infusion of so much sound doctrine into American society will prove equally astonishing and precious.

Great stress has often been laid upon the good qualities of the American people, but comparatively few have spoken of their faults; not because they had none, but because their faults were lost sight of in the brilliancy of their material prosperity. But recent events have led to more reflection upon this point; so it will not astonish our readers if we point oat one or two, such as the decay of thoughtful, systematic, methodical intelligence among them, in comparison with Europeans; their narrowness of mind; their inaptitude for general ideas; and their sensibly diminishing delicacy of mind. These defects show an unsuspected but serious and rapid degeneracy of the Anglo-American race, and the decline has already perhaps gone further than one would readily believe. If Catholicism, which tends eminently to develop a spirit of method and order, broadness of view and delicacy of sentiment, should combat successfully these failings, it would render a signal service to the United States in return for the liberty which they have granted it.

But Catholics, we should add, are indebted to the United States for something more than simple liberty. They have there learned to appreciate their real power. They have learned by experience how little they have to fear from pure universal liberty, how much strength and influence they can acquire in such a state of society. There is this good and this evil in liberty—that it always proves to the advantage of the strong; so that when there is question of the relations between man and man, it must be a well-regulated liberty, or it will result in the oppression of the weak. But the case is different when it comes to a question of discordant doctrines: man has everything to gain by the triumph of sound, strong principles and the destruction of false and specious theories. In such a contest, let but each side appear in its true colors, and we have nothing to fear for the cause of truth. The United States will at least have had the merit of affording an opportunity for a powerful demonstration of the truth; and great as are the advantages which the Catholic Church can confer upon the country, she herself will reap still greater advantages by conferring them; for it will turn to her benefit in her action upon the world at large.

In fact, the experience of the Church {17} in America has doubtless gone for something in the familiarity which religious minds are gradually acquiring with the principles of political liberty; and thus the growth of American Catholicism is allied to the world-wide reaction which is now taking place after the religious eclipse of the last century. This transformation of the United States, in truth, is only one marked incident in the intellectual revolution which is drawing the whole world toward the Catholic Church—England as well as America, Germany as well as England, even Bulgaria in the far East. The foreign press brings us daily the signs of this progress; and nothing can be easier than to point them out in France under our own eyes. But unfortunately we have been too much in the habit, for the last century, of leading a life of continual mortification, too conscious that we were laughed at by the leaders of public opinion. We crawled along in fear and trembling, creeping close to the walls, dreading at every step to give offence, or to cause scandal, or to lose some of our brethren. Accustomed to see our ranks thinned and whole files carried off in the flower of their youth, we stood in too great fear of the deceitful power of doctrines which seemed to promise everything to man and ask nothing from him in return. And therefore many of us still find it hard to understand the new state of things in which we are making progress without external help. This progress, however, inaugurated by the energy of a few, the perseverance of all, and the overruling hand of divine Providence, is unquestionably going on, and may easily be proved. We have only to visit our churches, attend some of the special retreats for men, or look at the Easter communions, to see what long steps faith and religious practice have taken within the last forty years. The change is most perceptible among the educated classes and in the learned professions. We have heard old professors express their astonishment in comparing the schools of the present time with those of their youth. It was then almost impossible to find a young man at the École Polytechnique, at St. Cyr, or at the École Centrale, with enough faith and enough courage openly to profess his religion; now it may be said that a fifth or perhaps a fourth part of the students openly and unhesitatingly perform their Easter duty. We ourselves remember that no longer ago than 1830 it required a degree of courage of which few were found capable to manifest any religious sentiment in the public lyceums. Voltairianism—or to speak better, an intolerant fanaticism—delighted to cover these faithful few with public ridicule; while now, if we may believe the best authorized accounts, it is only a small minority who openly profess infidelity. We can affirm that in the School of Law the change is quite as great, and it has begun to operate even in that time-honored stronghold of materialism, the School of Medicine.

But what must strike us most forcibly in the examination of these questions is the fact, already pointed out by the Abbé Meignan, that the progress of religion has kept even pace with the extension of free institutions. Wherever the liberal régime has been established, the reaction in favor of religion has become stronger, no doubt because liberty places man face to face with the consequences of his own acts and the necessities of his feeble nature. Man is never so powerfully impelled to draw near to God as when he becomes conscious of his own weakness; never so deeply impressed with the emptiness of false doctrines as when he has experienced their nothingness in the practical affairs of life. The violence of external disorder soon leads him to, reflect upon the necessity of solid, methodical, moral education, such as regulates one's life, and such as the Church alone can impart. And therefore the great change of sentiment of which we have spoken is perceptible chiefly among the educated and liberal classes, while with the ignorant and {18} vulgar infidelity holds its own and is even gaining. The educated classes, more thoughtful, knowing the world and having experience of men, see further and calculate more calmly the tendency of events; with the common people reason and plain sense are often overpowered by the violence of their temperament and the impetuosity of their passions. Ignorance and inordinate desires do the rest, and they imagine that man will know how to conduct without knowing how to govern himself.

Whatever demagogues may say, history proves that the head always rules the body. The period of discouragement and apprehension is past. We shall yet, no doubt, have to go through trials, and violent crises, and perhaps cruel persecutions; but we may hope everything from the future. And why not? If we study the history of the Jewish people, we shall see how God chastises his people in order to rouse them from their moral torpor, and raise them up from apparent ruin by unforeseen means. Weakness, in his hand, at once becomes strength; he asks of us nothing but faith and courage. We have traced his Providence in the methods by which he has stimulated the growth of the American Church—methods all the more effectual because, unlike our own vain enterprises, they worked for a long time in silence and obscurity. These Western bishoprics remained almost unknown up to the day when, the light bursting forth all at once, the world beheld a Church already organized, already strong, where it had not suspected even her existence.

There is a magnificent and instructive scene in Athalie, where the veil of the temple is rent, and discloses to the eyes of the terrified queen, Joas, whom she had believed dead, standing in his glory surrounded by an army. Even so, it seems to us, was the American Church suddenly revealed in all her vigor to the astonished world, when her bishops came two years ago to take their place in the council at Rome. And the same progress is making all over the globe. Noiseless and unobtrusive, it attracts no attention from the world; it is overlooked by Utopian theorists; it goes on quietly in the domain of conscience; but the day will come when its light will break forth and astonish mankind by its brightness. Such are the ways of God!

NOTE.—The greater part of the materials for the preceding article were written or collected during the course of a journey which we made in the United States in 1860. Since then the progress of Catholicism has necessarily been somewhat checked by the events of the lamentable civil war which is desolating the country; but the check has been far less serious than might have reasonably been apprehended. Religion has been kept apart from political dissensions and public disorders; it has only had to suffer the common evils which war, mortality, and general impoverishment have inflicted upon the whole people. If all these things are to have any bad effect upon the progress of the Church, it will be in future years, not now. In fact, all the documents which we have been able to collect show that the numbers of both the faithful and the clergy, instead of falling off, have gone on increasing. In thirty-eight dioceses there are now 275 more priests than there were in 1860; from the five other sees, namely, those of New Orleans, Galveston, Mobile, Natchitoches, and Charleston, we have no returns. This increase is confined almost entirely to the regions in which the Church was already strongest; elsewhere matters have remained about stationary.

Of this number of 275 priests added to the Church in the course of three years, 251 belong to the following fourteen dioceses, namely: Baltimore, Pittsburg, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Brooklyn, Albany, Alton, Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul, Detroit, Fort Wayne, Vincennes, and Hartford. The last-named belongs to the {19} Northeastern or New England group, all the others to the Central and Western. Thus fourteen dioceses alone show nine-tenths of the total increase, and the others divide the remaining tenth among them in very minute fractions. From some states, it is true, the returns are very meagre, and from others they are altogether wanting; but the disproportion is so strong as to leave no doubt that the future conquests of the Church in the United States will be gained, as we have already said, principally in the Middle and Western States.

E. R.

We often practically divide the saints into three classes. The ancient saints, those of the primitive age of Christianity, we consider as the patrons of the universal Church, watching over its well-being and progress, but, excepting Rome, having only a general connection with the interests of particular countries, still less of individuals.

The great saints of the middle age, belonging to different races and countries, have naturally become their patrons, being more especially reverenced and invoked in the places of their births, their lives, and still more their deaths; whence, St. Willibrord, St. Boniface, and St. Walburga are more honored in Germany, where they died, than in England, where they were born.

The third class includes the more modern saints, who spoke our yet living languages, printed their books, followed the same sort of life, wore the same dress as we do, lived in houses yet standing, founded institutions still flourishing, rode in carriages, and in another generation would have traveled by railway. Such are St. Charles, St. Ignatius, St. Philip, St. Teresa, St. Vincent, B. Benedict Joseph, and many others. Toward these we feel a personal devotion independent of country; nearness of time compensating for distance of place. There is indeed one class of saints who belong to every age and every country; devotion toward whom, far from diminishing, increases the further we recede from their time and even their land. For we are convinced that a Chinese convert has a more sensitive and glowing devotion toward our Blessed Lady, than a Jewish neophyte had in the first century. When I hear this growth of piety denounced or reproached by Protestants, I own I exult in it.

For the only question, and there is none in a Catholic mind, is whether such a feeling is good in itself; if so, growth in it, age by age, is an immense blessing and proof of the divine presence. It is as if one told me that there is more humility now in the Church than there was in the first century, more zeal than in the third, more faith than in the eighth, more charity than in the twelfth. And so, if there is more devotion now than there was 1,800 years ago toward the Immaculate Mother of God, toward {20} her saintly spouse, toward St. John, St. Peter, and the other Apostles, I rejoice; knowing that devotion toward our divine Lord, his infancy, his passion, his sacred heart, his adorable eucharist, has not suffered loss or diminution, but has much increased. It need not be, and it is not, as John the Baptist said, "He must increase, and I diminish." Both here increase together; the Lord, and those who best loved him.

But this is more than a subject of joy: it is one of admiration and consolation. For it is the natural course of things that sympathies and affections should grow less by time. We care and feel much less about the conquests of William I., or the prowess of the Black Prince, than we do about the victories of Nelson or Wellington; even Alfred is a mythical person, and Boadicea fabulous; and so it is with all nations. A steadily increasing affection and intensifying devotion (as in this case we call it) for those remote from us, in proportion as we recede from them, is as marvellous—nay, as miraculous—as would be the flowing of a stream from its source up a steep hill, deepening and widening as it rose. And such I consider this growth, through succeeding ages, of devout feeling toward those who were the root, and seem to become the crown, or flower, of the Church. It is as if a beam from the sun, or a ray from a lamp, grew brighter and warmer in proportion as it darted further from its source.

I cannot but see in this supernatural disposition evidence of a power ruling from a higher sphere than that of ordinary providence, the laws of which, uniform elsewhere, are modified or even reversed when the dispensations of the gospel require it; or rather, these have their own proper and ordinary providence, the laws of which are uniform within its system. And this is one illustration, that what by every ordinary and natural course should go on diminishing, goes on increasing. But I read in this fact an evidence also of the stability and perpetuity of our faith; for a line that is ever growing thinner and thinner tends, through its extenuation, to inanition and total evanescence; whereas one that widens and extends as it advances and becomes more solid, thereby gives earnest and proof of increasing duration.

When we are attacked about practices, devotions, or corollaries of faith—"developments," in other words—do we not sometimes labor needlessly to prove that we go no further than the Fathers did, and that what we do may be justified from ancient authorities? Should we not confine ourselves to showing, even with the help of antiquity, that what is attacked is good, is sound, and is holy; and then thank God that we have so much more of it than others formerly possessed? If it was right to say "Ora pro nobis" once in the day, is it not better to say it seven times a day; and if so, why not seventy times seven? The rule of forgiveness may well be the rule of seeking intercession for it. But whither am I leading you, gentle reader? I promised you a story, and I am giving you a lecture, and I fear a dry one. I must retrace my steps. I wished, therefore, merely to say that, while the saints of the Church are very naturally divided by us into three classes—holy patrons of the Church, of particular portions of it, and of its individual members—there is one raised above all others, which passes through all, composed of protectors, patrons, and nomenclators, of saints themselves. For how many Marys, how many Josephs, Peters, Johns, and Pauls, are there not in the calendar of the saints, called by those names without law of country or age!

But beyond this general recognition of the claims of our greatest saints, one cannot but sometimes feel that the classification which I have described is carried by us too far; that a certain human dross enters into the composition of our devotion; we perhaps nationalize, or even individualize, {21} the sympathies of those whose love is universal, like God's own, in which alone they love. We seem to fancy that St. Edward and St. Frideswida are still English; and some persons appear to have as strong an objection to one of their children bearing any but a Saxon saint's name as they have to Italian architecture. We may be quite sure that the power and interest in the whole Church have not been curtailed by the admission of others like themselves, first Christians on earth, then saints in heaven, into their blessed society; but that the friends of God belong to us all, and can and will help us, if we invoke them, with loving impartiality. The little history which I am going to relate serves to illustrate this view of saintly intercession; it was told me by the learned and distinguished prelate whom I shall call Monsig. B. He has, I have heard, since published the narrative; but I will give it as I heard it from his lips.

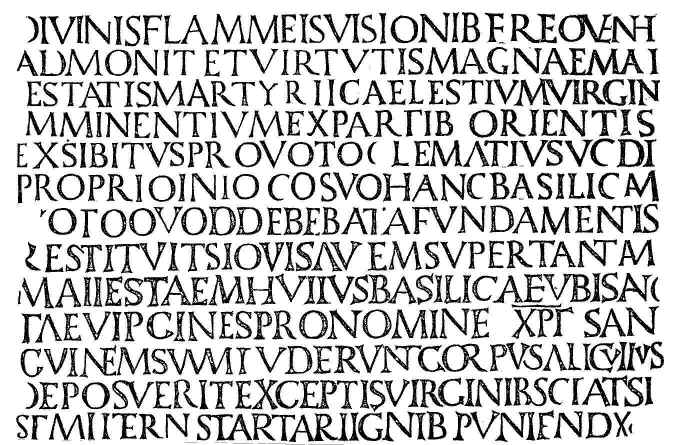

On the 30th of last month—I am writing early in August—we all commemorated the holy martyrs, Sts. Abdon and Sennen. This in itself is worthy of notice. Why should we in England, why should they in America, be singing the praises of two Persians who lived more than fifteen hundred years ago? Plainly because we are Catholics, and as such in communion with the saints of Persia and the martyrs of Decius. Yet it may be assumed that the particular devotion to these two Eastern martyrs is owing to their having suffered in Rome, and so found a place in the calendar of the catacombs, the basis of later martyrologies. Probably after having been concealed in the house of Quirinus the deacon, their bodies were buried in the cemetery or catacomb of Pontianus, outside the present Porta Portese, on the northern bank of the Tiber. In that catacomb, remarkable for containing the primitive baptistery of the Church, there yet remains a monument of these saints, marking their place of sepulture. [Footnote 5] Painted on the wall is a "floriated" and jewelled cross; not a conventional one such as mediaeval art introduced, but a plain cross, on the surface of which the painter imitated natural jewels, and from the foot of which grow flowers of natural forms and hues; on each side stands a figure in Persian dress and Phrygian cap, with the names respectively running down in letters one below the other:

SANCTVS ABDON: SANCTVS SENNEN.