Title: Collins' Illustrated Guide to London and Neighbourhood

Author: Anonymous

Release date: April 5, 2012 [eBook #39379]

Language: English

Credits: Transcribed from the 1873 William Collins, Sons and Company edition by David Price

Transcribed from the 1873 William Collins, Sons and Company edition by David Price, email ccx074@pglaf.org

BEING A

CONCISE

DESCRIPTION OF THE CHIEF PLACES OF INTEREST IN THE

METROPOLIS, AND THE BEST MODES OF

OBTAINING ACCESS

TO THEM: WITH INFORMATION RELATING

TO

RAILWAYS, OMNIBUSES, STEAMERS, &c.

With fifty-eight Illustrations by

Sargent and others,

AND

A CLUE-MAP BY BARTHOLOMEW.

LONDON:

WILLIAM COLLINS, SONS, AND COMPANY,

17 WARWICK SQUARE, PATERNOSTER

ROW.

1873.

In this work an attempt is made to furnish Strangers with a handy and useful Guide to the chief objects of interest in the Metropolis and its Environs: comprising also much that will be interesting to permanent Residents. After a few pages of General Description, the various Buildings and other places of attraction are treated in convenient groups or sections, according to their nature. Short Excursions from the Metropolis are then noticed. Tables, lists, and serviceable information concerning railways, tramways, omnibuses, cabs, telegraphs, postal rules, and other special matters, follow these sections. An Alphabetical Index at the end furnishes the means of easy reference.

The information is brought down to the latest date, either in the Text or in the Appendix at the end. And the Clue-map has, in like manner, been filled in with the recently opened lines of Railway, &c., as well as with indications of the Railways sanctioned, but not yet completed.

|

PAGE |

Hotel Charges |

|

General Description |

|

A First Glance at the City |

|

A First Glance at the West-End |

|

Palaces and Mansions, Royal and Noble |

|

Houses of Parliament; Westminster Hall; Government Offices |

|

St. Paul’s; Westminster Abbey; Churches; Chapels; Cemeteries |

|

British and South Kensington Museums; Scientific Establishments |

|

National Gallery; Royal Academy; Art Exhibitions |

|

Colleges; Schools; Hospitals; Charities |

|

The Tower; The Mint; The Custom House; The General Post-Office |

|

The Corporation; Mansion House; Guildhall; Monument; Royal Exchange |

|

The Temple; Inns of Court; Courts of Justice; Prisons |

|

Banks; Insurance Offices; Stock Exchange; City Companies |

|

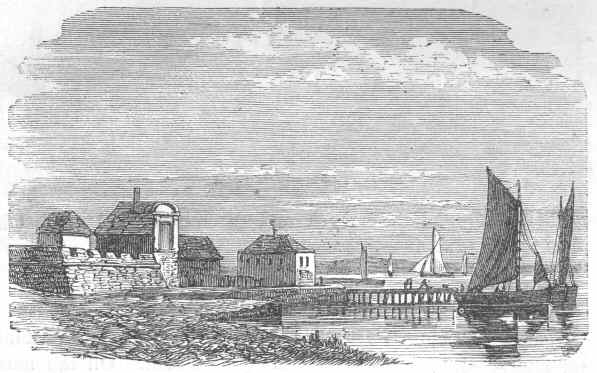

The River; Docks; Thames Tunnel; Bridges; Piers |

|

Food Supply; Markets; Bazaars; Shops |

|

Clubs; Hotels; Inns; Chop-Houses; Taverns; Coffee-Houses; Coffee-Shops |

|

Theatres, Concerts, and Other Places of Amusement |

|

Parks and Public Grounds; Zoological, Botanical, and Horticultural Gardens |

|

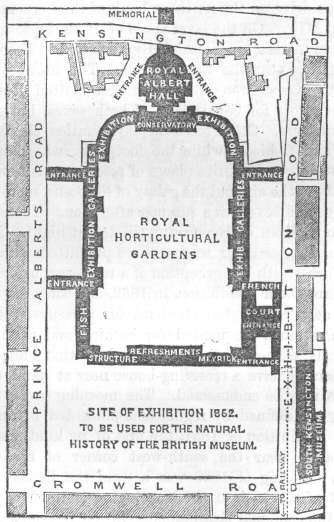

Albert Hall and International Exhibition |

|

Omnibuses; Cabs; Railways; Steamers |

|

Up the River |

|

Down the River |

|

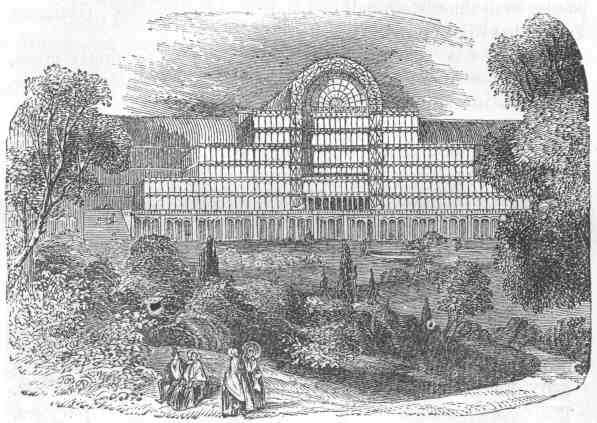

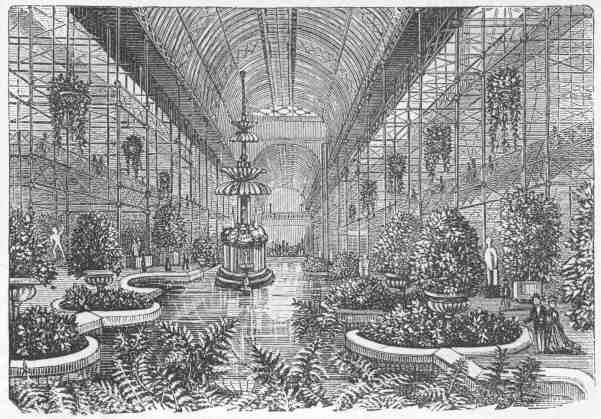

Crystal Palace, &c. |

|

APPENDIX. |

|

TABLES, LISTS, AND USEFUL HINTS— |

|

Suburban Towns and Villages, within Twelve Miles’ Railway-Distance |

|

Chief Omnibus Routes |

|

Tramways |

|

Clubs and Club-Houses |

|

The London Parcels’ Delivery Company |

|

Money-Order Offices, and Post-Office Savings-Banks |

|

London Letters, Postal and Telegraph System |

|

Reading and News-Rooms |

|

Chess-Rooms |

|

Theatres |

|

Concert Rooms |

|

Music Halls |

|

Modes of Admission to Various Interesting Places |

|

Principal, Public, and Turkish Baths |

|

Medicated Baths |

|

Cabs |

|

Hints to Strangers |

|

Commissionaires or Messengers |

|

The Great Interceptive Main Drainage System of London |

|

INDEX |

|

There is only one class of hotels in and near London of which the charges can be stated with any degree of precision. The old hotels, both at the West-End and in the City, keep no printed tariff; they are not accustomed even to be asked beforehand what are their charges. Most of the visitors are more or less recommended by guests who have already sojourned at these establishments, and who can give information as to what they have paid. Some of the hotels decline to receive guests except by previous written application, or by direct introduction, and would rather be without those who would regard the bill with economical scrutiny. The dining hotels, such as the London and the Freemasons’ Tavern, in London, the Artichoke and various whitebait taverns at Blackwall, the Trafalgar and Crown and Sceptre taverns at Greenwich, and the Castle and Star and Garter taverns at Richmond, are costly taverns for dining, rather than hotels at which visitors sojourn; and the charges vary with every different degree of luxury in the viands served, and the mode of serving. The hotels which can be more easily tested, in reference to their charges, are the joint-stock undertakings. These are of two kinds: one, the hotels connected with the great railway termini, such as the Victoria, the Euston, the Great Northern, the Great Western, the Grosvenor, the Charing Cross, the Midland and Cannon Street; while the other group are unconnected with railways, such as the Westminster Palace, the Langham, the Salisbury, the Inns of Court, Alexandra, &c.

Whether we consider London as the metropolis of a great and mighty empire, upon the dominions of whose sovereign the sun never sets, or as the home of more than three millions of people, and the richest city in the world to boot, it must ever be a place which strangers wish to visit. In these days of railways and steamers, the toil and cost of reaching it are, comparatively speaking, small; and, such being the case, the supply of visitors has very naturally been adjusted to the everyday increasing opportunities of gratifying so very sensible a desire. To such persons, on their arrival at this vast City of the Islands, we here, if they will accept us as their guides, beg to offer, ere going into more minute details, a

Without cumbering our narrative with the fables of dim legendary lore, with regard to the origin of London—or Llyn-Din, “the town on the lake,”—we may mention, that the Romans, after conquering its ancient British inhabitants, about a.d. 61, finally rebuilt and walled it in about a.d. 301; from which time it became, in such excellent hands, a place of not a little importance. Roman remains, such as fine tesselated pavements, bronzes, weapons, pottery, and coins, are not seldom turned up by the spade of our sturdy excavators while digging below the foundations of houses; and a few scanty fragments of the old Roman Wall, which was rather more than three miles round, are still to be seen. London, in the Anglo-Norman times, though confined originally by the said wall, grew up a dense mass of brick and wooden houses, ill arranged, unclean, p. 10close, and for the most part terribly insalubrious. Pestilence was the natural consequence. Up to the great plague of 1664–5, which destroyed 68,596, some say 100,000 persons—there were, dating from the pestilence of 1348, no fewer than some nine visitations of widely-spreading epidemics in Old London. When, in 1666, the great fire, which burnt 13,200 houses, spread its ruins over 436 acres, and laid waste 400 streets, came to force the Cockneys to mend their ways somewhat, and open out their over-cramped habitations, some good was effected. But, unfortunately, during the rebuilding of the City, Sir Christopher Wren’s plans for laying its streets out on a more regular plan, were poorly attended to: hence the still incongruous condition of older London when compared, in many instances, with the results of modern architecture, with reference to air, light, and sanitary arrangements. On account of the rubbish left by the fire and other casualties, the City stands from twelve to sixteen feet higher than it did in the early part of its history—the roadways of Roman London, for example, being found on, or even below, the level of the cellars of the present houses.

From being a city hemmed within a wall, London expanded in all directions, and thus gradually formed a connection with various clusters of dwellings in the neighbourhood. It has, in fact, absorbed towns and villages to a considerable distance around: the chief of these once detached seats of population being the city of Westminster. By means of bridges, it has also absorbed Southwark and Bermondsey, Lambeth and Vauxhall, on the south side of the Thames, besides many hamlets and villages beyond the river.

By these extensions London proper, by which we mean the City, has gradually assumed, if we may so speak, the conditions of an existence like that of a kernel in a thickly surrounding and ever-growing mass. By the census of 1861, the population of the City was only 112,247; while including that with the entire metropolis, the number was 2,803,034—or twenty-five times as great as the former! It may here be remarked, that the population of the City is becoming smaller every year, on account of the substitution of public buildings, railway stations and viaducts, and large warehouses, p. 11in place of ordinary dwelling-houses. Fewer and fewer people live in the City. In 1851, the number was 127,869; it lessened by more than 15,000 between that year and 1861; while the population of the whole metropolis increased by as many as 440,000 in the same space of time.

If we follow the Registrar-General, London, as defined by him, extends north and south between Norwood and Hampstead, and east and west between Hammersmith and Woolwich. Its area is stated as 122 square miles. From the census returns of 1861, we find that its population then was 2,803,921 souls. It was, in 1871, 3,251,804. The real city population was 74,732.

The growth of London to its present enormous size may readily be accounted for, when we reflect that for ages it has been the capital of England, and the seat of her court and legislature; that since the union with Scotland and Ireland, it has become a centre for those two countries; and that, being the resort of the nobility, landed gentry, and other families of opulence, it has drawn a vast increase of population to minister to the tastes and wants of those classes; while its fine natural position, lying as it does on the banks of a great navigable river, some sixty miles from the sea, and its generally salubrious site and soil—the greater part of London is built on gravel, or on a species of clay resting on sand—alike plead in its favour.

At one time London, like ancient Babylon, might fairly have been called a brick-built city. It is so, of course, still, in some sense. But we are greatly improving: within the last few years a large number of stucco-fronted houses, of ornamental character, have been erected; and quite recently, many wholly of stone, apart altogether from the more important public buildings, which of course are of stone. Of distinct houses, there are now the prodigious number of 500,000, having, on an average, about 7.8 dwellers to a house. For our own part we are somewhat sceptical as to this average. But we quote it as given by a professedly good authority.

The Post-Office officials ascertained that there was built in one year alone, as long ago as 1864, no fewer than 9,000 new houses. p. 12Though, by comparison with the houses of Edinburgh and some other parts of the kingdom, many of these are small structures, with but two rooms, often communicating, on a floor, a visitor to London will find no difficulty in seeing acres of substantial residences around him as he strolls along through the wide, quiet squares of Bloomsbury, the stuccoed and more aristocratic quarters of Belgravia and South Kensington, or by the old family mansions of the nobility and gentry in, say, Cavendish, Grosvenor, or Portman Squares, and the large and more modern houses of many of our wealthy citizens in Tyburnia and Westburnia, farther westward of the Marble Arch. But of this more anon.

We have often heard foreigners laughingly remark of sundry London houses—apropos of the deep, open, sunk areas, bordered by iron railings, of many of them—that they illustrate, in some sense, our English reserve, and love of carrying out our island proverb—viz., that “every Englishman’s house is his castle,”—in its entirety, by each man barricading himself off from his neighbours advances by a fortified fosse!

Without particular reference to municipal distinctions, London may (to convey a general idea to strangers) be divided into four principal portions—the City, which is the centre of corporate influence, and where the greatest part of the business is conducted; the East End, in which are the docks, and various commercial arrangements for shipping; the West End, in which are the palaces of the Queen and Royal family, the Houses of Parliament, Westminster Abbey, and the residences of most of the nobility and gentry; and the Southwark and Lambeth division, lying on the south side of the Thames, containing many manufacturing establishments, but few public buildings of interest. Besides these, the northern suburbs, which include the once detached villages of Hampstead, Highgate, Stoke Newington, Islington, Kingsland, Hackney, Hornsey, Holloway, &c., and consist chiefly of private dwellings for the mercantile and middle classes, may be considered a peculiar and distinct division. It is, however, nowhere possible to say (except when separated by the river) exactly where any one division begins or ends; throughout the vast compass of the city and p. 13suburbs, there is a blending of one division with that contiguous to it. The outskirts, on all sides, comprise long rows or groups of villas, some detached or semi-detached, with small lawns or gardens.

The poet Cowper, in his Task, more than a hundred years ago, appreciatively spoke of

“The villas with which London stands begirt,

Like a swarth Indian with his belt of beads.”

We wonder what he would think now of the many houses of this kind which extend, in some directions, so far out of town, that there seems to be no getting beyond them into the country.

From the Surrey division there extends southward and westward a great number of those ranges of neat private dwellings, as, for instance, towards Camberwell, Kennington, Clapham, Brixton, Dulwich, Norwood, Sydenham, &c.; and in these directions lie some of the most pleasant spots in the environs of the metropolis.

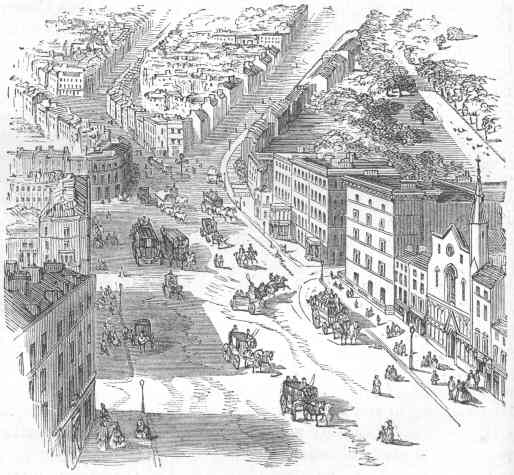

The flowing of the Thames from west to east through the metropolis has given a general direction to the lines of street; the principal thoroughfares being, in some measure, parallel to the river, with the inferior, or at least shorter, streets branching from them. Intersecting the town lengthwise, or from east to west, are three great leading thoroughfares at a short distance from each other, but gradually diverging at their western extremity. One of these routes begins in the eastern environs, near Blackwall, and extends along Whitechapel, Leadenhall Street, Cornhill, the Poultry, Cheapside, Newgate Street, Holborn, and Oxford Street. The other may be considered as starting at London Bridge, and passing up King William Street into Cheapside, at the western end of which it makes a bend round St. Paul’s Churchyard; thence proceeds down Ludgate Hill, along Fleet Street and the Strand to Charing Cross, where it sends a branch off to the left to Whitehall, and another diagonally to the right, up Cockspur Street; this leads forward into Pall Mall, and sends an offshoot up Waterloo Place into Piccadilly, which proceeds westward to Hyde Park Corner. These two are the main lines in the metropolis, and are among the first traversed by strangers. It will be observed that they unite in Cheapside, which therefore becomes an excessively crowded p. 14thoroughfare, particularly at the busy hours of the day. More than 1000 vehicles per hour pass through this street in the business period of an average day, besides foot-passengers! To ease the traffic in Cheapside, a spacious new thoroughfare, New Cannon Street, has been opened, from near London Bridge westward to St. Paul’s Churchyard. The third main line of route is not so much thronged, nor so interesting to strangers. It may be considered as beginning at the Bank, and passing through the City Road and the New Road to Paddington and Westbourne. The New Road here mentioned has been re-named in three sections—Pentonville Road, from Islington to King’s Cross; Euston Road, from King’s Cross to Regent’s Park; and Marylebone Road, from Regent’s Park to Paddington. The main cross branches in the metropolis are—Farringdon Street, leading from Blackfriars Bridge to Holborn, and thence by Victoria Street to the King’s Cross Station; the Haymarket, leading from Cockspur Street; and Regent Street, already mentioned. There are several important streets leading northward from the Holborn and Oxford Street line—such as Portland Place, Tottenham Court Road, King Street, and Gray’s Inn Lane. The principal one in the east is St. Martin’s-le-Grand and Aldersgate Street, which, by Goswell Street, lead to Islington; others are—Bishopsgate Street, leading to Shoreditch and Hackney; and Moorgate Street, leading northwards. A route stretching somewhat north-east—Whitechapel and Mile End Roads—connects the metropolis with Essex. It is a matter of general complaint that there are so few great channels of communication through London both lengthwise and crosswise; for the inferior streets, independently of their complex bearings, are much too narrow for regular traffic. But this grievance, let us hope, is in a fair way of abatement, thanks to sundry fine new streets, and to the Thames Embankment, which, proceeding along the northern shore of the river, now furnishes a splendid thoroughfare right away from Westminster Bridge to Blackfriars Bridge, by means of which the public are now enabled to arrive at the Mansion House by a wide street—called Queen Victoria Street, and, by the Metropolitan District Railway, to save time on this route from the west.

p. 15We shall have occasion again to allude to the Thames Embankment some pages on, and therefore, for the present, we will take

London is too vast a place to be traversed in the limited time which strangers usually have at their disposal. Nevertheless, we may rapidly survey the main lines of route from east to west, with some of the branching offshoots. All the more important buildings, and places of public interest, will be found specially described under the headings to which they properly belong.

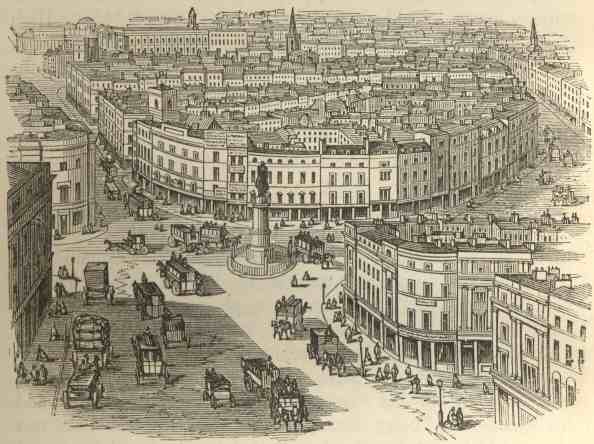

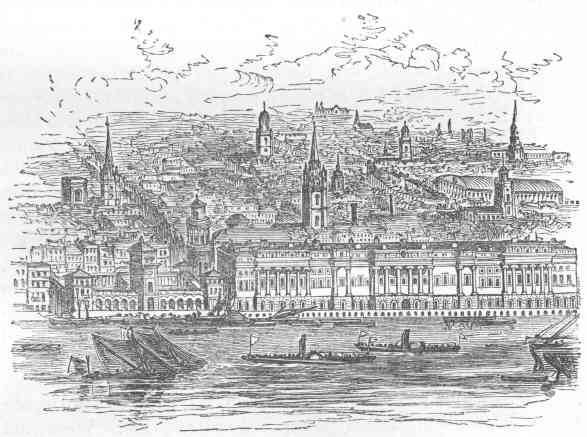

The most striking view in the interior of the city is at the open central space whence Threadneedle Street, Cornhill, Lombard Street, King William Street, Walbrook, Cheapside, and Princes Street, radiate in seven different directions. (See illustration.) While the corner of the Bank of England abuts on this space on the north, it is flanked on the south by the Mansion House, and on the east by the Royal Exchange. It would be a curious speculation to inquire how much money has been spent in constructions and reconstructions in and around this spot during half a century. The sum must be stupendous. Before new London Bridge was opened, the present King William Street did not exist; to construct it, houses by the score, perhaps by the hundred, had to be pulled down. Many years earlier, when the Bank of England was rebuilt, and a few years later, when the Royal Exchange was rebuilt, vast destructions of property took place, to make room for structures larger than those which had previously existed for the same purposes. For some distance up all the radii of which we have spoken, the arteries which lead from this heart of the commercial world, a similar process has been going on to a greater or less extent. Banking-houses, insurance-offices, and commercial buildings, have been built or rebuilt at an immense cost, the outlay depending rather on the rapidly increasing value of the ground than on the actual charge for building. If this particular portion of the city, this busy centre of wealth, should ever be invaded by such railway schemes as 1864, 1865, and 1866 produced, it is difficult to imagine what amounts would have to be p. 16paid for the purchase and removal of property. Time was when a hundred thousand pounds per mile was a frightful sum for railways; but railway directors (in London at least) do not now look aghast at a million sterling per mile—as witness the South-Eastern and the Chatham and Dover Companies, concerning which we shall have to say more in a future page.

The seven radii of which we have spoken may be thus briefly

described, as a preliminary guide to visitors: 1. Leaving

this wonderfully-busy centre by the north, with the Poultry on

one hand and the Bank of England on the other, we pass in front

of many fine new commercial buildings in Princes and Moorgate p. 17Streets;

indeed, there is not an old house here, for both are entirely

modern streets, penetrating through what used to be a close mass

of small streets and alleys. Other fine banking and

commercial buildings may be seen stretching along either side in

Lothbury and Gresham Streets. Farther towards the north, a

visitor would reach the Finsbury Square region, beyond which the

establishments are of less important character. 2. If,

instead of leaving this centre by the north, he turns north-east,

he will pass through Threadneedle Street between the Bank and the

Royal Exchange;

next will be found the Stock Exchange, on the left hand;

then the Sun Fire Office, and the Bank of London (formerly the

Hall of Commerce); on the opposite side the City Bank, Merchant

Taylor’s School, and the building that was once the South

Sea House; beyond these is the great centre for foreign merchants

in Broad Street, Winchester Street, Austin Friars, and the

vicinity. 3. If, p. 18again, the route be selected due

east, there will come into view the famous Cornhill, with its

Royal Exchange, its well-stored shops, and its alleys on either

side crowded with merchants, brokers, bankers, coffee-houses, and

chop-houses; beyond this, Bishopsgate Street branches out on the

left, and Gracechurch Street on the right, both full of memorials

of commercial London; and farther east still, Leadenhall Street,

with new buildings on the site of the late East India House,

leads to the Jews’ Quarter around Aldgate and

Houndsditch—a strange region, which few visitors to London

think of exploring. “Petticoat Lane,” perhaps

one of the most extraordinary marts for old clothes, &c., is

on the left of Aldgate High Street. It is well worth a

visit by connoisseurs of queer life and character, who are able

to take care of themselves, and remember to leave their valuables

at home. 4. The fourth route from the great city centre

leads through Lombard Street and Fenchurch Street—the one

the head-quarters of the great banking firms of London; the other

exhibiting many commercial buildings of late erection: while

Mincing Lane and Mark Lane are the head-quarters for many

branches of the foreign, colonial, and corn trades. 5. The

fifth route takes the visitor through King William Street to the

Monument, Fish Street Hill, Billingsgate, the Corn Exchange, the

Custom House, the Thames Subway, the Tower, the Docks, the Thames

Tunnel, London Bridge, and a host of interesting places, the

proper examination of which would require something more than

merely a brief visit to London. Opposite this quarter, on

the Surrey side of the river, are numerous shipping wharfs,

warehouses, porter breweries, and granaries. The fire that

occurred at Cotton’s wharf and depôt and other wharfs

near Tooley Street, in June, 1861, illustrated the vast scale on

which merchandise is collected in the warehouses and wharfs

hereabout. [18] Of the dense mass of streets

lying away from p.

19the river, and eastward of the city proper, comprising

Spitalfields, Bethnal Green, Whitechapel, Stepney, &c.,

little need be said here; the population is immense, but,

excepting the Bethnal Green Museum and Victoria Park, there are

few objects interesting; nevertheless the observers of social

life in its humbler phases would find much to learn here.

6. The southern route from the great city centre takes the

visitor, by the side of the Mansion House, through the new

thoroughfare, Queen Victoria Street—referred to at a

previous page—to the river-side.

next will be found the Stock Exchange, on the left hand;

then the Sun Fire Office, and the Bank of London (formerly the

Hall of Commerce); on the opposite side the City Bank, Merchant

Taylor’s School, and the building that was once the South

Sea House; beyond these is the great centre for foreign merchants

in Broad Street, Winchester Street, Austin Friars, and the

vicinity. 3. If, p. 18again, the route be selected due

east, there will come into view the famous Cornhill, with its

Royal Exchange, its well-stored shops, and its alleys on either

side crowded with merchants, brokers, bankers, coffee-houses, and

chop-houses; beyond this, Bishopsgate Street branches out on the

left, and Gracechurch Street on the right, both full of memorials

of commercial London; and farther east still, Leadenhall Street,

with new buildings on the site of the late East India House,

leads to the Jews’ Quarter around Aldgate and

Houndsditch—a strange region, which few visitors to London

think of exploring. “Petticoat Lane,” perhaps

one of the most extraordinary marts for old clothes, &c., is

on the left of Aldgate High Street. It is well worth a

visit by connoisseurs of queer life and character, who are able

to take care of themselves, and remember to leave their valuables

at home. 4. The fourth route from the great city centre

leads through Lombard Street and Fenchurch Street—the one

the head-quarters of the great banking firms of London; the other

exhibiting many commercial buildings of late erection: while

Mincing Lane and Mark Lane are the head-quarters for many

branches of the foreign, colonial, and corn trades. 5. The

fifth route takes the visitor through King William Street to the

Monument, Fish Street Hill, Billingsgate, the Corn Exchange, the

Custom House, the Thames Subway, the Tower, the Docks, the Thames

Tunnel, London Bridge, and a host of interesting places, the

proper examination of which would require something more than

merely a brief visit to London. Opposite this quarter, on

the Surrey side of the river, are numerous shipping wharfs,

warehouses, porter breweries, and granaries. The fire that

occurred at Cotton’s wharf and depôt and other wharfs

near Tooley Street, in June, 1861, illustrated the vast scale on

which merchandise is collected in the warehouses and wharfs

hereabout. [18] Of the dense mass of streets

lying away from p.

19the river, and eastward of the city proper, comprising

Spitalfields, Bethnal Green, Whitechapel, Stepney, &c.,

little need be said here; the population is immense, but,

excepting the Bethnal Green Museum and Victoria Park, there are

few objects interesting; nevertheless the observers of social

life in its humbler phases would find much to learn here.

6. The southern route from the great city centre takes the

visitor, by the side of the Mansion House, through the new

thoroughfare, Queen Victoria Street—referred to at a

previous page—to the river-side.

It will therefore be useful for a stranger to bear in mind, that the best centre of observation in the city is the open spot between the Bank, the Mansion House, and the Royal Exchange; where more omnibuses assemble than at any other spot in the world; and whence he can ramble in any one of seven different directions, sure of meeting with something illustrative of city life. The 7th route, not yet noticed, we will now follow, as it proceeds towards the West End.

The great central thoroughfare of Cheapside, which is closely lined with the shops of silversmiths and other wealthy tradesmen, is one of the oldest and most famous streets in the city—intimately associated with the municipal glories of London for centuries past. Many of the houses in Cheapside and Cornhill have lately been rebuilt on a scale of much grandeur. Some small plots of ground in this vicinity have been sold at the rate of nearly one million sterling per acre! On each side of Cheapside, narrow streets diverge into the dense mass behind—Ironmonger Lane, King Street, Milk Street, and Wood Street, on the north; and among others, Queen Street, Bread Street, where Milton was born, and where stood the famous Mermaid Tavern, where Shakespeare and Raleigh, Ben Jonson and his young friends, Beaumont and Fletcher, those twin-dramatists, loved to meet, to enjoy “the feast of reason and the flow of soul,” to say nothing of a few flagons of good Canary wine, Bow Lane, and Old ’Change, on the south. The greater part of these back streets, with the lanes adjoining, are occupied by the offices or warehouses of wholesale dealers in cloth, silk, hosiery, lace, &c., and are resorted to by London and country shopkeepers for p. 20supplies. Across the north end of King Street stands the Guildhall; and a little west, the City of London School and Goldsmiths’ Hall. At the western end of Cheapside is a statue of the late Sir Robert Peel, by Behnes. Northward of this point, in St. Martin’s-le-Grand, are the buildings of the Post and Telegraph Offices; beyond this the curious old Charter House; and then a line of business streets leading towards Islington. Westward are two streets, parallel with each other, and both too narrow for the trade to be accommodated in them—Newgate Street, celebrated for its Blue Coat Boys and, till the recent removal of the market to Smithfield, for its carcass butchers; and Paternoster Row, still more celebrated for its publishers and booksellers. In Panyer Alley, leading out of Newgate Street, is an old stone bearing the inscription:

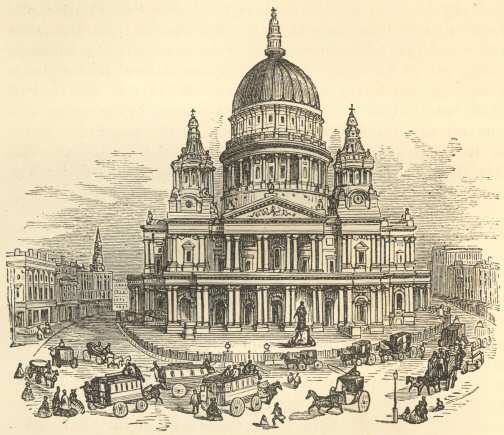

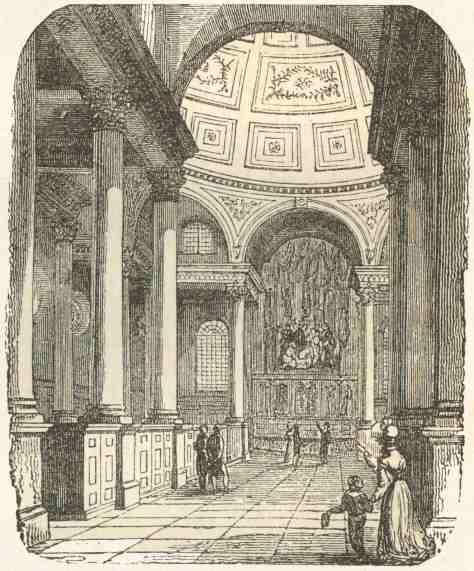

At the west end of Newgate Street a turning to the right gives access to the once celebrated Smithfield and St. John’s Gate. South-west of Cheapside stands St. Paul’s Cathedral, that first and greatest of all the landmarks of London. In the immediate vicinity of St. Paul’s, the names of many streets and lanes (Paternoster Row, Amen Corner, Ave Maria Lane, Creed Lane, Godliman Street, &c.) give token of their former connection with the religious structure and its clerical attendants. The enclosed churchyard is surrounded by a street closely hemmed in with houses, now chiefly dedicated to trade: those on the south side being mostly wholesale, those on the north retail. An open arched passage on the south side of the churchyard leads to Doctors’ Commons, once the headquarters of the ecclesiastical lawyers.

Starting from St. Paul’s Churchyard westward, we proceed down Ludgate Street and Ludgate Hill, places named from the old Lud-gate, which once formed one of the entrances to the city ‘within the walls.’ The Old Bailey, on the right, contains the Central Criminal Court and Newgate Prison, noted places in connection with the trial and punishment of criminals. On the left of Ludgate Hill is a maze of narrow streets; among which the chief buildings are the new Ludgate Hill Railway Station, Apothecaries’ Hall, and the printing office of the all-powerful Times newspaper, in Printing-House Square. The printer of the Times, Mr. Goodlake, if applied to by letter, enclosing card of any respectable person, will grant an order to go over it, at 11 o’clock only, when the second edition of “the Thunderer” is going to press. At the bottom of Ludgate Hill we come to the valley in which the once celebrated Fleet River, now only a covered sewer, ran north and p. 22south from St. Pancras to Blackfriars, where it entered the Thames. A new street, called Victoria Street, formed by pulling down many poor and dilapidated houses, marks part of this valley; while Farringdon Street, where a market, mostly for green stuff, is held, occupies another part. Newgate Street and Ludgate Hill are on the east of the Fleet Valley; Holborn and Fleet Street on the west. The Holborn Valley Viaduct crosses at this spot. And of this wonderful triumph of engineering skill we have now to speak.

It was an eventful day in the annals of the Corporation of the City of London, when Queen Victoria, on November 6, 1869, declared Blackfriars Bridge—about which more hereafter—and Holborn Valley Viaduct formally open. The Holborn Valley improvements, it should be remembered, were nothing short of the actual demolition and reconstruction of a whole district, formerly either squalid, over-blocked, and dilapidated in some parts, or over-steep and dangerous to traffic in others. But a short time ago that same Holborn Valley was one of the most heart-breaking p. 23impediments to horse-traffic in London. Imagine Holborn Hill sloping at a gradient of 1 in 18, while the opposite rising ground of Skinner Street—now happily done away—rose at about 1 in 20. Figure to yourself the fact, that everything on wheels, and every foot passenger entering the City by the Holborn route, had to descend 26 feet to the Valley of the Fleet, and then ascend a like number to Newgate, and you will at once see the grand utility of levelling up so objectionable a hollow. To attempt to give a stranger to London even a faint idea of what has been accomplished by Mr. Haywood’s engineering skill, by a necessarily brief description here, is an invidious task. Nevertheless, we must essay it; premising, by-the-by, that if our readers while in London do not go to see the Viaduct for themselves, our trouble will be three parte thrown away. The whole structure is cellular, to begin with. To strip the subject of crabbed technicalities, imagine for a moment a long succession of—let us call them—railway-like arches supporting the carriage-way: these large vaults being available for other purposes. Outside this carriage-way, and under the edge of the foot-paths on either side, is a subway, some 7 feet wide and 11 feet or so high. Against the walls of this sub-way are fixed, readily connectable, gas mains and water mains and telegraph tubes. This was the first time all these important pipes had been so cleverly arranged in one easily accessible place. They are ventilated and partially lighted through the pavement, and by gas. Under each sub-way goes a sewer, with a path beside it for the sewer men when at work. Outside the sub-way are ordinary house vaults of two or three storeys high, according to the height of the Viaduct. These are divided by transverse walls; and, when houses are built against it, the Holborn Valley Viaduct will be shut out from sight, except in the case of the simple iron girder bridge over Shoe Lane, and the London, Chatham, and Dover bridge, with its sub-ways for gas and water pipes, and the fine bridge over Farringdon Street. You will, we trust, now see how marvellously every yard of space has been utilized by the engineer, from the roadway down to the very foundations. A few words must now be said about the splendid bridge over Farringdon Street. This has public staircases running p. 24up inside handsome stone buildings—the upper parts of which have been let for business purposes. It is a handsome skew bridge of iron, toned to a deep bronze green by enamel paint, and richly ornamented; its plinths above ground, its moulded bases, and its shafts, are respectively of grey, black, and exquisitely polished red granite. Its capitals are of grey granite, also polished, and set off by bronze foliage. Bronze lions, and four statues of Fine Art, Science, Commerce, and Agriculture, stand on the parapet-line on handsome plinths. These, and the projecting balconies and dormer window of the stone buildings just named, with their four statues of bygone civic worthies,—Fitz Aylwin, Sir William Walworth, Sir Thomas Gresham, and Sir Hugh Myddleton,—enhance the effect of the whole.

Poor Chatterton, “the marvellous boy, the sleepless soul that perished in his pride,” after poisoning himself, in 1770, ere he was eighteen years of age, in Brooke Street, on the north side of Holborn, was laid in a pauper’s grave, in what was then the burying-ground of Shoe Lane Workhouse, and is now converted to very different purposes.

Let us now come to Fleet Street. This thoroughfare—the main artery from St. Paul’s to the west—for many years has been emphatically one of literary associations, full as it is of newspaper and printing-offices. The late Angus B. Reach used humorously to call it, “The march of intellect.” Wynkyn de Worde, the early printer, lived here, and two of his books were “fynysshed and emprynted in Flete Streete, in ye syne of ye Sonne.” The Devil tavern, which stood near Temple Bar, on the south side, was a favourite hostelrie of Ben Jonson. At the Mitre, near Mitre Court, Dr. Johnson, Goldsmith, and Boswell, held frequent rendezvous. The Cock was one of the oldest and least altered taverns in Fleet Street. The present poet-laureate, in one of his early poems, “A Monologue of Will Waterproof,” has immortalized it, in the lines beginning—

“Thou plump head waiter at the Cock,

To which I most resort,

How goes the time? Is ’t nine o’clock?

Then fetch a pint of port!”

Dr. Johnson lived many years either in Fleet Street, in Gough Square, in the Temple, in Johnson’s Court, in Bolt Court, &c., &c.; and in Bolt Court he died. William Cobbett, and Ferguson the astronomer, were also among the dwellers in that court. John Murray (the elder) began the publishing business in Falcon Court. Some of the early meetings of the Royal Society and of the Society of Arts took place in Crane Court. Dryden and Richardson both lived in Salisbury Court. Shire Lane (now Lower Serle’s Place), close to Temple Bar on the north, can count the names of Steele and Ashmole among its former inhabitants. Izaak Walton lived a little way up Chancery Lane. At the confectioner’s shop, nearly opposite that lane, Pope and Warburton first met. Sir Symonds p. 26D’Ewes, ‘Praise-God Barebones,’ Michael Drayton, and Cowley the poet, all lived in this street. Many of the courts, about a dozen in number, branching out of Fleet Street on the north and south, are so narrow that a stranger would miss them unless on the alert. Child’s Banking House, the oldest in London, is at the western extremity of Fleet Street, on the south side, and also occupies the room over the arch of Temple Bar. St. Bride’s Church exhibits one of Wren’s best steeples. St. Dunstan’s Church, before it was modernized, had two wooden giants in front, that struck the hours with clubs on two bells—a duty which they still fulfil in the gardens belonging to the mansion of the Marquis of Hertford in the Regent’s Park. North of Fleet Street are several of the Inns of Court, where lawyers congregate; and southward is the most famous of all such Inns, the large group of buildings constituting the Temple. In the cluster of buildings lying east from the Temple once existed the sanctuary of Whitefriars, or Alsatia, as it was sometimes called, a description of which is given by Scott in the Fortunes of Nigel. The streets here are still narrow and of an inferior order, but all appearance of Alsatians and their pranks is gone. The boundary of the city, at the western termination of Fleet Street, is marked by Temple Bar, consisting of a wide central archway, and a smaller archway at each side for foot-passengers. There are doors in the main avenue which can be shut at pleasure; but, practically, they are never closed, except on the occasion of some state ceremonial, when the lord mayor affects an act of grace in opening them to royalty. The structure was designed by Sir Christopher Wren, and erected in 1672. The heads of decapitated criminals, after being boiled in pitch to preserve them, were exposed on iron spikes on the top of the Bar. Horace Walpole, in his Letters to Montague, mentions the fact of a man in Fleet Street letting out “spy-glasses,” at a penny a peep, to passers-by, when the heads of some of the hapless Jacobites were so exposed. The last heads exhibited there were those of two Jacobite gentlemen who took part in the rebellion of 1745, and were executed in that year. Their heads remained a ghastly spectacle to the citizens till 1772, when they were blown down one night in a gale of wind.

p. 27Having thus noticed some of the interesting objects east of Temple Bar, we will now take

The Strand—so called because it lies along the bank of the river, now hidden by houses—is a long, somewhat irregularly built street, in continuation westward from Temple Bar; the thoroughfare being incommoded by two churches—St. Clement Dane’s and St. Mary’s—in the middle of the road. On the site of the latter church once stood the old Strand Maypole. The new Palace of Justice, about whose site there have been so many Parliamentary discussions, will stand on what is at present a huge unsightly space of boarded-in waste ground, formerly occupied by a few good houses, between Temple Bar and Clement’s Inn, and many wretched back-slums. Not having the gift of prophecy as to its future, and warned by so many long delays in its case, we hazard no conjecture as to the time when it will gladden our eyes. In the seventeenth century the Strand was a species of country road, connecting the city with Westminster; and on its southern side stood a number of noblemen’s residences, with gardens towards the river. The pleasant days are long since past when mansions and personages, political events and holiday festivities, marked the spots now denoted by Essex, Norfolk, Howard, Arundel, Surrey, Cecil, Salisbury, Buckingham, Villiers, Craven, and Northumberland Streets—a very galaxy of aristocratic names. The most conspicuous building on the left-hand side is Somerset House, a vast range of government offices. Adjoining this on the east (occupying the site once intended for an east wing to that structure), and entering by a passage from the Strand, is a range of rather plain, but massive brick buildings, erected about thirty years ago for the accommodation of King’s College; and adjoining it on the west, abutting on the street leading to Waterloo Bridge, is a still newer range of buildings appropriated to government offices—forming a west wing to the whole mass. The Strand contains no other public structure of architectural importance, except the spacious new Charing Cross Railway Station and Hotel on the south side. The eastern half of p. 28the Strand, however, is thickly surrounded by theatres—Drury Lane, Covent Garden, the Olympic, the Charing Cross, the Adelphi, the Vaudeville, the Lyceum, the Gaiety (built on the site of Exeter ’Change and the late Strand Music Hall, as is the Queen’s on that of St. Martin’s Hall in Long Acre), the Globe, and the Strand Theatres, are all situated hereabouts. Exeter Hall is close by, and—pardon the contrast of ideas—so is Evans’s Hotel and Supper Rooms, long famous for old English glees, madrigals, chops and steaks, and as a place for friendly re-unions, without the objectionable features of many musical halls.

Northumberland House, the large mansion with the lion on the summit, overlooking Charing Cross, is the ancestral town residence of the Percies, Dukes of Northumberland. Over the way is St. Martin’s Church, where lie the bones of many famous London watermen—the churchyard used to be called “The Waterman’s Churchyard”—and those of that too celebrated scoundrel and housebreaker, Jack Sheppard, hanged in 1724. There also lies the once famous sculptor, Roubilac, several monuments from whose chisel you can see in Westminster Abbey. Here, too, are interred the witty, but somewhat licentious dramatist, Farquhar, author of The Beau’s Stratagem; the illustrious Robert Boyle, a philosopher not altogether unworthy to be named in the same category with Lord Bacon and Sir Isaac Newton; and John Hunter, the distinguished anatomist.

The open space is called Charing Cross, from the old village of Charing, where stood a cross erected by Edward the First, in memory of his Queen Eleanor. Wherever her bier rested, there her sorrowful husband erected a cross, or, as Hood whimsically said, in his usual punning vein, apropos of the cross at Tottenham,

“A Royal game of Fox and Goose

To play for such a loss;

Wherever she put down her orts,

There he—set up a cross!”

At the time of the Reformation you could have walked with fields all the way on the north side of you from the city to Charing Cross. The history of the fine statue of Charles the First, by Le Sœur, is p. 29curious. It was made in Charles the First’s reign, but, on the civil war breaking out ere it could be erected, was sold by the Parliament to a brazier, who was ordered to demolish it. He, however, buried it, and it remained underground till after the Restoration, when it was erected in 1674. It marks a central point for the West End.

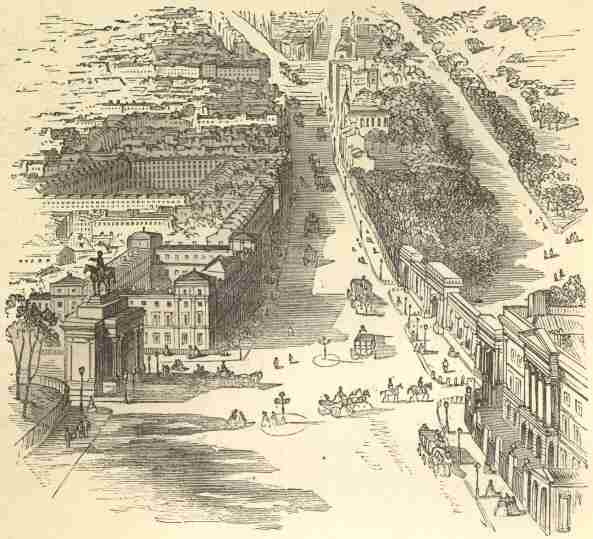

Southward are Whitehall and the Palace of Westminster; to the west, Spring Gardens, leading into St. James’s Park; north-west lie Pall Mall and Regent Street. By-the-way, it just occurs to us that the old game Paille Maille, from which Pall Mall took its name, was a sort of antique forerunner of croquet! The former game, much beloved by Charles the Second, was played by striking a wooden ball with a mallet through hoops of iron, one of which stood at each end of an alley. Eastward is the Strand. On the north, Trafalgar Square, with Nelson’s statue and Landseer’s four noble lions couchant—which alone are worth a visit—at its base. There are also statues to George IV., Sir Charles James Napier, p. 30and Sir Henry Havelock. A statue of George the Third—with, we think, in an equestrian sense, one of the best “seats” for a horseman in London—is close by. The National Gallery bounds the northern side. Of the two wells which supply the fountains in this square, one is no less than 400 feet deep.

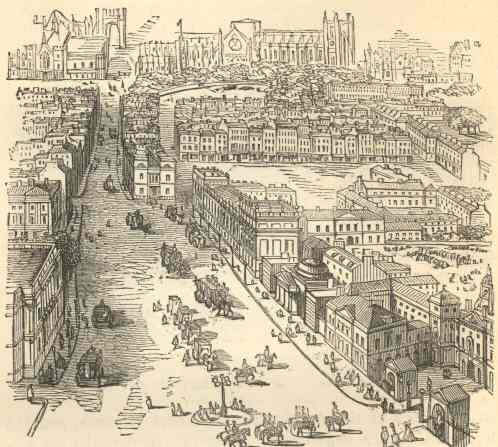

Turning southward from this important western centre, the visitor will come upon the range of national and government buildings—the Admiralty, the Horse Guards, the Treasury, the Home Office, &c., &c.—in Whitehall, particulars of which will be given a few pages further on under Government Offices. Then there are the fine Banqueting House at Whitehall, and some rather majestic mansions in and near Whitehall Gardens—especially one just erected by the Duke of Buccleuch. Beyond these, in the same general direction, are the magnificent Houses of Parliament, Marochetti’s equestrian statue of Richard Cœur de Lion, Westminster Abbey, Westminster Hall, Mr. Page’s beautiful new Westminster Bridge, and a number of other objects well worthy of attention.

Returning to Charing Cross, the stranger may pursue his tour through Cockspur Street to Pall Mall, and thence proceed up Regent Street. As he enters this new line of route, he will perceive that the buildings assume a more important aspect. They are for the most part stucco-fronted, and being frequently re-painted, they have a light and cheerful appearance. In the Haymarket are Her Majesty’s Theatre and the Haymarket Theatre; and near at hand are many club-houses and Exhibition-rooms. Pall Mall displays a range of stone-fronted club-houses of great magnificence. At the foot of Regent Street is the short broad thoroughfare of Waterloo Place, lined with noble houses, and leading southwards to St. James’s Park. Here stands the column dedicated to the late Duke of York; not far from which is the Guards’ Memorial, having reference to troops who fell in the Crimea. From this point, for about a mile in a northerly direction, is the line of Waterloo Place, Regent Street, and Portland Place, forming the handsomest street in London. At a point a short way up we cross Piccadilly, and enter a curve in the thoroughfare, called the Quadrant; at the corners of which, and also in Upper Regent Street, are some of the p. 31most splendid shops in London, several being decorated in a style of great magnificence. Regent Street, during the busy season in May and June, and during the day from one till six o’clock, exhibits an extraordinary concourse of fashionable vehicles and foot-passengers; while groups of carriages are drawn up at the doors of the more elegant shops. Towards its upper extremity Regent Street crosses Oxford Street. The mass of streets west from it consist almost entirely of private residences, with the special exception of Bond Street. In this quarter are St. James’s, Hanover, Berkeley, Grosvenor, Cavendish, Bryanstone, Manchester, and Portman Squares—the last four being north of Oxford Street; and in connection with these squares are long, quiet streets, lined with houses suited for an affluent order of inhabitants. In and north from Oxford Street, there are few public buildings deserving particular attention; but a visitor may like to know that hereabouts are the Soho, Baker Street, and London Crystal Palace Bazaars. The once well-known Pantheon is now a wine merchant’s stores.

The residences of the nobility and gentry are chiefly, as has been said, in the western part of the metropolis. In this quarter there have been large additions of handsome streets, squares, and terraces within the last thirty years. First may be mentioned the district around Belgrave Square, usually called Belgravia, which includes the highest class houses. North-east from this, near Hyde Park, is the older, but still fashionable quarter, comprehending Park Lane and May Fair. Still farther north is the modern district, sometimes called Tyburnia, being built on the ground adjacent to what once was “Tyburn,” the place of public executions. This district, including Hyde Park Square and Westbourne Terrace, is a favourite place of residence for city merchants and other wealthy persons. Lying north and north-east from Tyburnia are an extensive series of suburban rows of buildings and detached villas, which are ordinarily spoken of under the collective name St. John’s Wood: Regent’s Park forming a kind of rural centre to the group. Standing higher and more airy than Belgravia, and being easily accessible from Oxford Street, this is one of the most agreeable of the suburban districts.

If, instead of the Strand and Piccadilly route, or the Holborn and Oxford Street route, a visitor takes the northernmost main route, he will find less to interest him. The New Road, in its several parts of City Road, Pentonville Road, Euston Road, and Marylebone Road, forms a broad line of communication from the city to Paddington, four miles in length. Though very important as one of the arteries of the metropolis, it is singularly deficient in public buildings. In going from the Bank to Paddington, we pass by or near Finsbury Square and Circus, the buildings and grounds of the Artillery Company at Moorfields, the once famous old Burial-ground at Bunhill Fields, St. Luke’s Lunatic Asylum, the Chapel in the City Road associated with the memory of John Wesley, the old works of the New River Company at Pentonville, the Railway stations at King’s Cross (Great Northern), and St. Pancras (Midland),—the vast span of this station’s roof is noteworthy,—and Euston Square (L. and N. Western), several stations p. 33of the Metropolitan Underground Railway, St. Pancras and Marylebone churches, and the entrance to the beautiful Regent’s Park. But beyond these little is presented to reward the pedestrian.

It is well for a visitor to bear in mind, however, that all the routes we have here sketched have undergone, or are undergoing, rapid changes, owing chiefly to the wonderful extension of railways. Cannon Street, Finsbury, Blackfriars, Snow Hill, Ludgate Hill, Smithfield, Charing Cross, Pimlico, &c., have been stripped of hundreds, nay, thousands of houses.

These two preliminary glances at the City and the West End having (as we will suppose) given the visitor some general idea of the Metropolis, we now proceed to describe the chief buildings p. 34and places of interest, conveniently grouped according to their character—beginning with Palatial Residences.

St. James’s Palace.—This is an inelegant brick structure, having its front towards Pall Mall. Henry VIII. built it in 1530, on the site of what was once an hospital for lepers. The interior consists of several spacious levée and drawing rooms, besides other state and domestic apartments. This palace is only used occasionally by the Queen for levées and drawing-rooms; for which purposes, notwithstanding its awkwardness, the building is better adapted than Buckingham Palace. The fine bands of the Foot Guards play daily at eleven, in the Colour Court, or in an open quadrangle on the east side. The Chapel Royal and the German Chapel are open on Sundays—the one with an English service, and the other with service in German.

Buckingham Palace.—This edifice stands at the west end of the Mall in St. James’s Park, in a situation much too low in reference to the adjacent grounds on the north. The site was occupied formerly by a brick mansion, which was pulled down by order of George IV. The present palace (except the front towards the park) was planned and erected by Mr. Nash. When completed, after various capricious alterations, about 1831–2, it is said to have cost about £700,000. The edifice is of stone, with a main centre, and a wing of similar architecture projecting on each side, forming originally an open court in front; but the palace being too small for the family and retinue of the present sovereign, a new frontage has been built, forming an eastern side to the open court. There is, however, little harmony of style between the old and new portions. The interior contains many magnificent apartments, both for state and domestic purposes. Among them are the Grand Staircase, the Ball-room, the Library, the Sculpture Gallery, the Green Drawing-room, the Throne Room, and the Grand Saloon. The Queen has a collection of very fine pictures in the various rooms, among which is a Rembrandt, for which George IV. gave 5000 guineas. In the garden is an elegant summer-house, adorned with frescoes by Eastlake, Maclise, Landseer, Stanfield, and other distinguished painters. This costly palace, however, with all its p. 35grandeur, was so badly planned, that in a number of the passages lamps are required to be kept lighted even during the day. Strangers are not admitted to Buckingham Palace except by special permission of the Lord Chamberlain, which is not easily obtained. In the front was once the Marble Arch, which formed an entry to the Palace, and which cost £70,000; but it was removed to the north-east corner of Hyde Park in 1851.

Marlborough House.—This building, the residence of the Prince and Princess of Wales, is immediately east of St. James’s Palace, being separated from it only by a carriage-road. It was built by Sir Christopher Wren, in 1709, as a residence for the great Duke p. 36of Marlborough. The house was bought from the Marlborough family by the Crown in 1817, as a residence for the Princess Charlotte. It was afterwards occupied in succession by Leopold (the late king of the Belgians) and the Dowager Queen Adelaide. More recently it was given up to the Government School of Design; and the Vernon and Turner pictures were for some time kept there. The building underwent various alterations preparatory to its occupation by the Prince of Wales.

Kensington Palace.—This is a royal palace, though no longer inhabited by royalty, occupying a pleasant situation west of Hyde Park. It was built by Lord Chancellor Finch late in the 17th century; and soon afterwards sold to William III. Additions were made to it from time to time. Certain portions of the exterior are regarded as fine specimens of brickwork; and the whole, though somewhat heavy in appearance, is not without points of interest. During the last century Kensington Palace was constantly occupied by members of the royal family. Many of them were born there, and many died there also. The present Queen was born in the palace in 1819. The Prince and Princess of Teck reside there at present. This, like the other royal palaces, is maintained at the expense of the nation; though not now used as a royal residence, pensioned or favoured families occupy it.

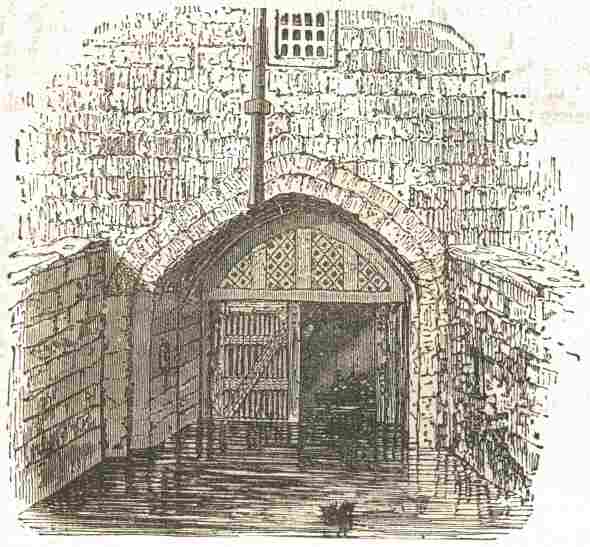

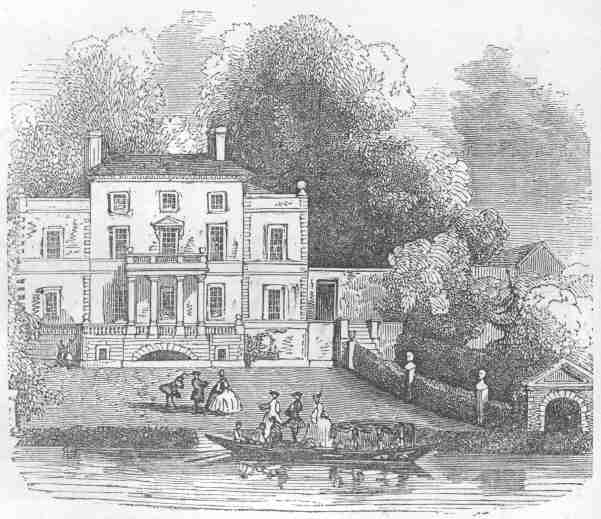

Lambeth Palace.—This curious and interesting building, situated in a part of the metropolis seldom visited by strangers, is the official residence of the archbishops of Canterbury. It is on the south bank of the Thames, between Westminster and Vauxhall Bridges. The structure has grown up by degrees during the six centuries that Lambeth has been the archiepiscopal residence; and on that account exhibits great diversities of style. Leaving unnoticed the private and domestic apartments, the following are the portions of the irregular cluster possessing most interest. The Chapel, some say, was erected in the year 1196; it is in early English, with lancet windows and a crypt; but the roof, stained windows, and carved screens, are much more recent. The archbishops are always consecrated in this chapel. The Lollard’s Tower, at the western end of the chapel, was named from some Lollards or Wickliffites supposed p. 37to have been imprisoned there. It is about 400 years old. The uppermost room, with strong iron rings in the walls, appears to p. 38have been the actual place of confinement; there are many names and inscriptions cut in the thick oak wainscoting. The Hall, about 200 years old, is 93 feet long by 78 feet wide; it is noticeable for the oak roof, the bay windows, and the arms of several of the archbishops. The Library, 250 years old, contains about 15,000 volumes and numerous manuscripts, many of them rare and curious. The Gatehouse is a red brick structure, with stone dressings. The Church, near it, is one of the most ancient in the neighbourhood of London; it has been recently restored in good taste. Simon of Sudbury, Archbishop of Canterbury, was murdered here, in 1381, by Wat Tyler’s mob, who stormed the palace, burned its contents, and destroyed all the registers and public papers. Lambeth Palace is not, as a rule, shewn to strangers.

Mansions of the Nobility.—London is not well

supplied with noble mansions of an attractive character; they

possess every comfort interiorly, but only a few of them have

architectural pretensions. Northumberland House,

lately alluded to, at the Charing Cross extremity of the south

side of the Strand, looks more like a nobleman’s mansion

than most others in London. It was built, in about 1600, by

the Earl of Northampton, and came into the hands of the Percies

in 1642. Stafford House is perhaps the most finely

situated mansion in the metropolis, occupying the corner of St.

James’s and the Green Parks, and presenting four complete

fronts, each having its own architectural character. The

interior, too, is said to be the first of its kind in

London. The mansion was built by the Duke of York, with

money lent by the Marquis of Stafford, afterwards Duke of

Sutherland; but the Stafford family became owners of it, and have

spent at least a quarter of a million sterling on the house and

its decorations. Apsley House, at the corner of

Piccadilly and Hyde Park, is the residence of the Dukes of

Wellington, and is closely associated with the memory of

the Duke. The shell of the house, of brick, is old;

but stone frontages, enlargements, and decorations, were

afterwards made. The principal room facing Hyde Park, with

seven windows, is that in which the Great Duke held the

celebrated Waterloo Banquet, on the 18th of June in every year,

from 1816 to 1852. p. 39The windows were blocked up with

bullet-proof iron blinds from 1831 to the day of his death in

1852; a rabble had shattered them during the Reform excitement,

and he never afterwards would trust King Mob.

Devonshire House, in Piccadilly, faces the Green Park,

and has a screen in front. It has no particular

architectural character; but the wealthy Dukes of Devonshire have

collected within it valuable pictures, books, gems, and treasures

of various kinds. Grosvenor House, the residence of

the Marquis of Westminster, is situated in Upper Grosvenor

Street, and is celebrated for the magnificent collection of

pictures known as the Grosvenor Gallery; p. 40a set of four

of these pictures, by Rubens, cost £10,000.

Bridgewater House, facing the Green Park, is a costly

modern structure, built by Sir Charles Barry for the Earl of

Ellesmere, and finished in 1851. It is in the Italian

Palazzo style. Its chief attraction is the magnificent

Bridgewater Gallery of pictures, a most rare and choice

assemblage. This gallery contains no fewer than 320

pictures, valued at £150,000 many years ago—though

they would now, doubtless, sell for a much higher sum. [40] Holland House, Kensington,

is certainly the most picturesque mansion in the metropolis; it

has an old English look about it, both in the house and its

grounds. The mansion was built in 1607, and was celebrated

as being the residence, at one time of Addison, at another of the

late Lord Holland. The stone gateway on the east of the

house was designed by Inigo Jones. Chesterfield

House, in South Audley Street, was built for that Earl of

Chesterfield whose “Advice to his Son” has run

through so many editions; the library and the garden are

especially noted. Buccleuch House, in Whitehall

Gardens, is recently finished. Lansdowne House, in

Berkeley Square, the town residence of the Marquis of Lansdowne,

contains some fine sculptures and pictures, ancient and

modern. Scarcely less magnificent, either as buildings or

in respect of their contents, than the mansions of the nobility,

are some of those belonging to wealthy commoners—such as

Mr. Holford’s, a splendid structure in Park Lane; Mr.

Hope’s, in Piccadilly, now the Junior Athenæum

Club; and Baron Rothschild’s, near Apsley House, lately

rebuilt.

Devonshire House, in Piccadilly, faces the Green Park,

and has a screen in front. It has no particular

architectural character; but the wealthy Dukes of Devonshire have

collected within it valuable pictures, books, gems, and treasures

of various kinds. Grosvenor House, the residence of

the Marquis of Westminster, is situated in Upper Grosvenor

Street, and is celebrated for the magnificent collection of

pictures known as the Grosvenor Gallery; p. 40a set of four

of these pictures, by Rubens, cost £10,000.

Bridgewater House, facing the Green Park, is a costly

modern structure, built by Sir Charles Barry for the Earl of

Ellesmere, and finished in 1851. It is in the Italian

Palazzo style. Its chief attraction is the magnificent

Bridgewater Gallery of pictures, a most rare and choice

assemblage. This gallery contains no fewer than 320

pictures, valued at £150,000 many years ago—though

they would now, doubtless, sell for a much higher sum. [40] Holland House, Kensington,

is certainly the most picturesque mansion in the metropolis; it

has an old English look about it, both in the house and its

grounds. The mansion was built in 1607, and was celebrated

as being the residence, at one time of Addison, at another of the

late Lord Holland. The stone gateway on the east of the

house was designed by Inigo Jones. Chesterfield

House, in South Audley Street, was built for that Earl of

Chesterfield whose “Advice to his Son” has run

through so many editions; the library and the garden are

especially noted. Buccleuch House, in Whitehall

Gardens, is recently finished. Lansdowne House, in

Berkeley Square, the town residence of the Marquis of Lansdowne,

contains some fine sculptures and pictures, ancient and

modern. Scarcely less magnificent, either as buildings or

in respect of their contents, than the mansions of the nobility,

are some of those belonging to wealthy commoners—such as

Mr. Holford’s, a splendid structure in Park Lane; Mr.

Hope’s, in Piccadilly, now the Junior Athenæum

Club; and Baron Rothschild’s, near Apsley House, lately

rebuilt.

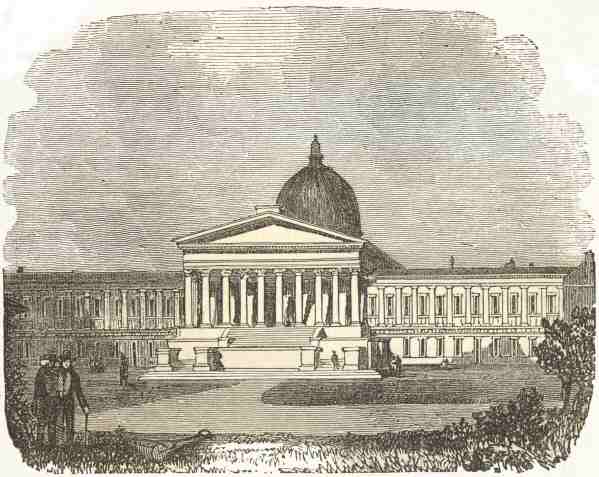

Houses of Parliament.—This is the name usually

given to the New Palace of Westminster, which is not only

Sir Charles Barry’s greatest work, but is in all respects

one of the most remarkable structures of the age. The

building, which occupies a site close to p. 41the river,

and close also to the beautiful new Westminster Bridge, was

constructed in consequence of the burning of the old Houses of

Parliament in 1834. It is perhaps the finest modern Gothic

structure in the world—at least for civil purposes; but is

unfortunately composed of a stone liable to decay; and, to be

critical, its ornaments and details generally are on too minute a

scale for the magnitude of the building. The entire

structure covers nearly eight acres.

Certain old plain law courts on the north are intended to be

removed. The chief public entrance is by Westminster Hall,

which forms a vestibule to the Houses of Parliament and their

numerous committee-rooms. The rooms and staircases are

almost inconceivably numerous; and there are said to be two miles

of passages and corridors! The river front, raised upon a

fine terrace of Aberdeen granite, is 900 feet in length, and

profusely adorned with statues, heraldic shields, and tracery,

carved in stone. The other façades are nearly as

elaborate, but are not so well seen. It is a gorgeous

structure, which, so long ago as 1859, had cost over two

millions. A further cost of £107,000, for frescoes,

statuary, p.

42&c., &c., had been incurred by the end of March,

1860; and the constant outgoings for maintenance of the fabric,

and additions thereto, must every year represent a heavy

sum. Nevertheless, the two main chambers in which

Parliament meets are ill adapted for sight and hearing. On

Saturdays, both Houses can be seen free, by order from the Lord

Chamberlain, easily obtained at a neighbouring office; and

certain corridors and chambers are open on other days of the

week. Admission to the sittings of the two Houses can only

be obtained by members’ orders; as the benches appropriated

in this way are few in number, such admissions are highly prized,

especially when any important debate is expected. On the

occasion when the Queen visits the House of Lords, to open or

prorogue Parliament, visitors are only admitted by special

arrangements.

Certain old plain law courts on the north are intended to be

removed. The chief public entrance is by Westminster Hall,

which forms a vestibule to the Houses of Parliament and their

numerous committee-rooms. The rooms and staircases are

almost inconceivably numerous; and there are said to be two miles

of passages and corridors! The river front, raised upon a

fine terrace of Aberdeen granite, is 900 feet in length, and

profusely adorned with statues, heraldic shields, and tracery,

carved in stone. The other façades are nearly as

elaborate, but are not so well seen. It is a gorgeous

structure, which, so long ago as 1859, had cost over two

millions. A further cost of £107,000, for frescoes,

statuary, p.

42&c., &c., had been incurred by the end of March,

1860; and the constant outgoings for maintenance of the fabric,

and additions thereto, must every year represent a heavy

sum. Nevertheless, the two main chambers in which

Parliament meets are ill adapted for sight and hearing. On

Saturdays, both Houses can be seen free, by order from the Lord

Chamberlain, easily obtained at a neighbouring office; and

certain corridors and chambers are open on other days of the

week. Admission to the sittings of the two Houses can only

be obtained by members’ orders; as the benches appropriated

in this way are few in number, such admissions are highly prized,

especially when any important debate is expected. On the

occasion when the Queen visits the House of Lords, to open or

prorogue Parliament, visitors are only admitted by special

arrangements.

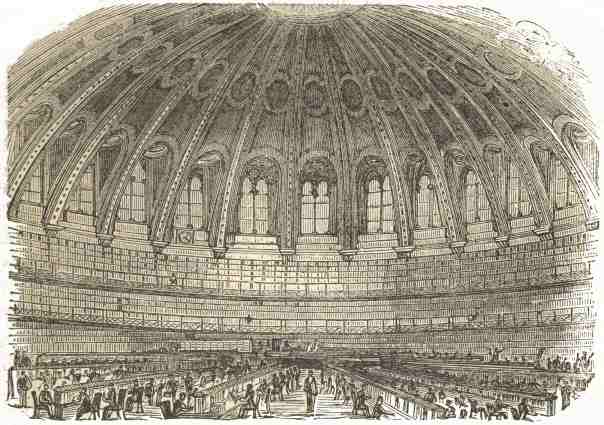

Among the multitude of interesting objects in this stupendous structure, the following may be briefly mentioned. The House of Peers is 97 feet long, 45 wide, and 45 high. It is so profusely painted and gilt, and the windows are so darkened by deep-tinted stained glass, that the eye can with difficulty make out the details. At the southern end is the gorgeously gilt and canopied throne; near the centre is the woolsack, on which the Lord Chancellor sits; at the end and sides are galleries for peeresses, reporters, and strangers; and on the floor of the house are the cushioned benches for the peers. At either end are three frescoes—three behind the throne, and three over the strangers’ gallery. The three behind the throne are—“Edward III. conferring the Order of the Garter on the Black Prince,” by C. W. Cope; “The Baptism of Ethelbert,” by Dyce; and “Henry Prince of Wales committed to Prison for assaulting Judge Gascoigne,” by C. W. Cope. The three at the other end are—“The Spirit of Justice,” by D. Maclise; “The Spirit of Chivalry,” by the same; and “The Spirit of Religion,” by J. C. Horsley. In niches between the windows and at the ends are eighteen statues of Barons who signed Magna Charta. The House of Commons, 62 feet long, 45 broad, and 45 high, is much less elaborate than the House of Peers. The Speaker’s Chair is at the north end; and there are galleries along the sides and ends. In a gallery behind p. 43the Speaker the reporters for the newspapers sit. Over them is the Ladies’ Gallery, where the view is ungallantly obstructed by a grating. The present ceiling is many feet below the original one: the room having been to this extent spoiled because the former proportions were bad for hearing.

Strangers might infer, from the name, that these two chambers, the Houses of Peers and of Commons, constitute nearly the whole building; but, in truth, they occupy only a small part of the area. On the side nearest to Westminster Abbey are St. Stephen’s Porch, St. Stephen’s Corridor, the Chancellor’s Corridor, the Victoria Tower, the Royal Staircase, and numerous courts and corridors. At the south end, nearest Millbank, are the Guard Room, the Queen’s Robing Room, the Royal Gallery, the Royal Court, and the Prince’s Chamber. The river front is mostly occupied by Libraries and Committee Rooms. The northern or Bridge Street end displays the Clock Tower and the Speaker’s Residence. In the interior of the structure are vast numbers of lobbies, corridors, halls, and courts. The Saturday tickets, already mentioned, admit visitors to the Prince’s Chamber, the House of Peers, the Peers’ Lobby, the Peers’ Corridor, the Octagonal Hall, the Commons’ Corridor, the Commons’ Lobby, the House of Commons, St. Stephen’s Hall, and St. Stephen’s Porch. All these places are crowded with rich adornments. The Victoria Tower, at the south-west angle of the entire structure, is one of the finest in the world: it is 75 feet square and 340 feet high; the Queen’s state entrance is in a noble arch at the base. The Clock Tower, at the north end, is 40 feet square and 320 feet high, profusely gilt near the top. After two attempts made to supply this tower with a bell of 14 tons weight, and after both failed, one of the so-called ‘Big Bens,’ the weight of which is about 8 tons, (the official name being ‘St. Stephen,’) now tells the hour in deep tones. There are, likewise, eight smaller bells to chime the quarters. The Clock is by far the largest and finest in this country. There are four dials on the four faces of the tower, each 22½ feet in diameter; the hour-figures are 2 feet high and 6 feet apart; the minute-marks are 14 inches apart; the hands weigh more than 2 cwt. the pair; the minute-hand is 16 feet long, and the hour-hand p. 449 feet; the pendulum is 15 feet long, and weighs 680 lbs.; the weights hang down a shaft 160 feet deep. Besides this fine Clock Tower, there is a Central Tower, over the Octagonal Hall, rising to a height of 300 feet; and there are smaller towers for ventilation and other purposes.

Considering that there are nearly 500 carved stone statues in and about this sumptuous building, besides stained-glass windows, and oil and fresco paintings in great number, it is obvious that a volume would be required to describe them all. In the Queen’s Robing Room are painted frescoes from the story of King Arthur; and in the Peers’ Robing Room, subjects from Biblical history. The Royal Gallery is in the course of being filled with frescoes and stained windows illustrative of English history. Here, among others, specially note the late D. Maclise’s stupendous fresco, 45 feet long by 12 feet high, representing “The Meeting of Wellington and Blucher after the Battle of Waterloo;” and the companion fresco, “The Death of Nelson.”

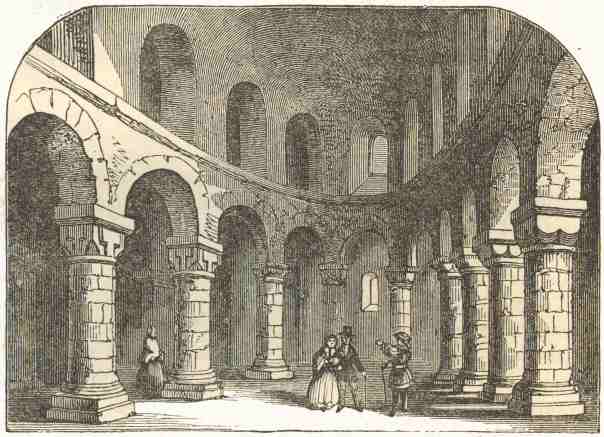

Westminster Hall.—Although now made, in a most ingenious manner, to form part of the sumptuous edifice just described, Westminster Hall is really a distinct building. It was the old hall of the original palace of Westminster, built in the time of William Rufus, but partly re-constructed in 1398. The carved timber roof is regarded as one of the finest in England. The hall is 290 feet long, 68 wide, and 110 high. There are very few buildings in the world so large as this unsupported by pillars. The southern end, both within and without, has been admirably brought into harmony with the general architecture of the Palace of Parliament. Doors on the east side lead to the House of Commons; doors on the west lead to the Courts of Chancery, Queen’s Bench, Common Pleas, Exchequer, Probate, and Divorce, &c. No building in England is richer in associations with events relating to kings, queens, and princes, than Westminster Hall. St. Stephen’s Crypt, lately restored with great splendour, is entered from the south end of the Hall.

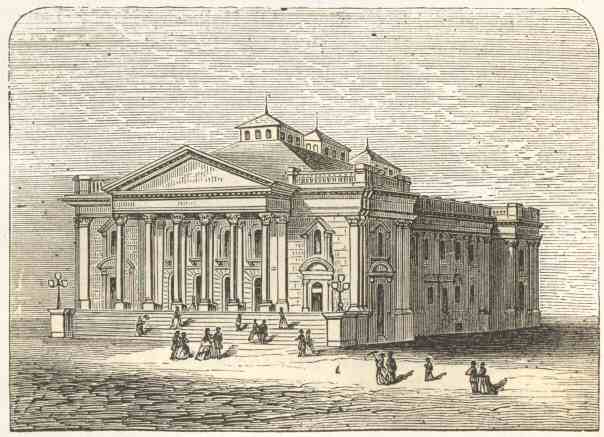

Somerset House, in the Strand, was built in 1549 by the Protector Somerset; and, on his attainder and execution, fell to the Crown. p. 45Old Somerset House was pulled down in 1775, and the present building erected in 1780, after the designs of Sir Wm. Chambers. The rear of the building faces the Thames, its river frontage being 600 feet long, and an excellent specimen of Palladian architecture. In Somerset House are several Government offices—among the rest, a branch of the Admiralty, the Inland Revenue, and the Registrar-General’s department. More than 900 clerks are employed in the various offices. The rooms in which Newspaper Stamps are produced by ingenious processes, and those in which the Registrar-General keeps his voluminous returns of births, marriages, and deaths, are full of interest; but they are not accessible for mere curiosity. The learned Societies are removed to Burlington House, Piccadilly.

Government Offices.—A few words will suffice for

the other p.

46West-End Government offices. The Admiralty,

in Whitehall, is the head-quarters of the Naval Department.

The front of the building was constructed about 1726; and the

screen, by the brothers Adam, about half-a-century later.

Most of the heads of the Admiralty have official residences

connected with the building. The Horse Guards, a

little farther down Whitehall, is the head-quarters of the

commander-in-chief. It was built about 1753, and has an

arched entrance leading into St. James’s Park.

The two cavalry sentries, belonging either to the Life

Guards or to the Oxford Blues, always attract the notice of

country visitors, to whom such showy horsemen are a rarity.

The Treasury, the Office of the p. 47Chancellor

of the Exchequer, the Home Office, the

Privy-council Office, and the Board of Trade,

together occupy the handsome range of buildings at the corner of

Whitehall and Downing Street. The interior of this building

is in great part old; after many alterations and additions, the

present front, in the Italian Palazzo style, was built by Sir

Charles Barry in 1847. The Foreign Office, the

India Office, and the Colonial Office, occupy the

handsome new buildings southward of Downing Street. The

War Office in Pall Mall is a makeshift arrangement: it

occupies the old quarters of the Ordnance Office, and some

private houses converted to public use. After many

discussions as to architectural designs, &c., the so-called

“Battle of the Styles” ended in a compromise: the

Gothic architect (Mr. G. G. Scott, R.A.) was employed; but an

Italian design was adopted for the new Foreign and India

Offices.

The two cavalry sentries, belonging either to the Life

Guards or to the Oxford Blues, always attract the notice of

country visitors, to whom such showy horsemen are a rarity.

The Treasury, the Office of the p. 47Chancellor

of the Exchequer, the Home Office, the

Privy-council Office, and the Board of Trade,

together occupy the handsome range of buildings at the corner of

Whitehall and Downing Street. The interior of this building

is in great part old; after many alterations and additions, the

present front, in the Italian Palazzo style, was built by Sir

Charles Barry in 1847. The Foreign Office, the

India Office, and the Colonial Office, occupy the

handsome new buildings southward of Downing Street. The

War Office in Pall Mall is a makeshift arrangement: it

occupies the old quarters of the Ordnance Office, and some

private houses converted to public use. After many

discussions as to architectural designs, &c., the so-called

“Battle of the Styles” ended in a compromise: the

Gothic architect (Mr. G. G. Scott, R.A.) was employed; but an

Italian design was adopted for the new Foreign and India

Offices.