Title: Ladies on Horseback

Author: Mrs. Power O'Donoghue

Release date: April 21, 2012 [eBook #39501]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Julia Miller and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

Transcriber's Note: The 15 pages of advertisements preceding the title page have been moved to the end of this book.

TO MY FRIEND

ALFRED E. T. WATSON, ESQ.,

AUTHOR OF "SKETCHES IN THE HUNTING FIELD," ETC.,

TO WHOM I OWE

MUCH OF MY SUCCESS AS A WRITER,

THESE PAGES

ARE GRATEFULLY INSCRIBED.

INTRODUCTION.

In preparing this work for the press, I may state that it is composed chiefly of a series of papers on horses and their riders, which appeared a short time since in the columns of The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. How they originally came to be written and published may not prove uninteresting.

One day, in the middle of February 1880, a goodly company, comprising many thousands of persons, assembled upon the lawn of a nobleman's residence in the vicinity of Dublin; ostensibly for the purpose of hunting, but in reality to gaze at and chronicle the doings of a very distinguished foreign lady, who had lately come to our shores. I was there, of course; and whilst we waited for the Imperial party, I amused myself by watching the moving panorama, and taking notes of costume and effect. Everybody who could procure anything upon which to ride, from a racehorse to a donkey, was there that day, and vehicles of all descriptions blocked up every available inch of the lordly avenues and well-kept carriage-drives.

There is for me so great an attraction in a number of "ladies on horseback" that I looked at them, and at them alone. One sees gentlemen riders every hour in the day, but ladies comparatively seldom; every hunting morning finds about a hundred and fifty mounted males ready for the start, and only on an average about six mounted females, of whom probably not more than the half will ride to hounds. This being the case, I always look most particularly at that which is the greater novelty, nor am I by any means singular in doing so.

On the day of which I write, however, ladies on horseback were by no means uncommon: I should say there were at least two hundred present upon the lawn. Some rode so well, and were so beautifully turned out, that the most hypercritical could find no fault; but of the majority—what can I say? Alas! nothing that would sound at all favourable. Such horses, such saddles, such rusty bridles, such riding-habits, such hats, whips, and gloves; and, above all, such coiffures! My very soul was sorry. I could not laugh, as some others were doing. I felt too melancholy for mirth. It seemed to me most grievous that my own sex (many of them so young and beautiful) should be thus held up to ridicule. I asked myself was it thus in other places; and I came to London in the spring, and walked in the Row, and gazed, and took notes, and was not satisfied. Perhaps I was too critical. There was very much to praise, certainly, but there was also much wherewith to find fault. The style of riding was bad; the style of dressing was incomparably worse. The well-got-up only threw into darker shadow the notable defects visible in the forms and trappings of their less fortunate sisterhood. I questioned myself as to how this could be best remedied. Remonstrance was impossible—advice equally so. Why could not somebody write a book for lady equestrians, or a series of papers which might appear in the pages of some fashionable magazine or journal, patronised and read by them? The idea seemed a good one, but I lacked time to carry it out, and so it rested in embryo for many months. Last June, whilst recovering from serious illness, my cherished project returned to my mind. Forbidden to write, and too weak to hold a pen, I strove feebly with a pencil to trace my thoughts upon odd scraps of paper, which I thrust away in my desk without any definite idea as to what should eventually become of them. In July, whilst staying at a country house near Shrewsbury, I one day came upon these shorthand jottings, and, having leisure-time upon my hands, set to work and put them into form. A line to the Editor of The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, with whom, I may state, I had had no previous acquaintance, brought an immediate reply, to send my work for consideration. I did so; called upon him by appointment when I came a few days later to London; made all arrangements in a three-minutes interview; and the first of my series of papers appeared shortly after. That they were successful, far beyond their deserts, is to me a proud boast. On their conclusion numerous firms negotiated with me for the copyright: with what result is known; and here to my publishers I tender my best thanks.

In arranging now these writings—put together and brought before the public at a time when I had apparently many years of active life before me—it is to me a melancholy reflection that the things of which they treat are gone from my eyes,—for alas! I can ride no more. Never again may my heart be gladdened with the music of the hounds, or my frame invigorated by the exercise which I so dearly loved. An accident, sudden and unexpected, has deprived me of my strength, and left me to speak in mournful whispers of what was for long my happiest theme. Yet why repine where so much is left? It is but another chapter in our life's history! We love and cling to one pursuit—and it passes from us; then another absorbs our attention,—it, too, vanishes; and so on—perhaps midway to the end—until the "looking back" becomes so filled with saddened memories, that the "looking forward" is alone left. And so we turn our wistful eyes where they might never have been directed, had the prospect behind us been less dark.

A few more words, and I close my preliminary observations and commence my subject. I cannot but be aware, from the nature of the correspondence which has flowed in upon me, that although far the greater number of my readers have agreed with me and entirely coincided in my views, not a few have been found to cavil. Let not such think that I am oblivious of their good intentions because I remain unconvinced by their arguments, and still prefer to maintain my own opinions, which I have not ventured to set forth without mature deliberation, and the most substantial reasons for holding them in fixity of tenure. I have spent some considerable time in turning over in my mind the advisability, or otherwise, of publishing, as a sort of appendix to this volume, a selection from the letters which were printed in The Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News with reference to my writings in that journal. After much deliberation I have decided upon suffering the entire number, with a few trifling exceptions, to appear. They only form a very small proportion of the voluminous correspondence with which the Editor and myself were favoured; but, such as they are, I give them—together with my replies,—not merely because they set forth the views and impressions of various persons upon topics of universal interest, but because I conceive that a large amount of useful information may be gleaned from them, and they may also serve to amuse my lady readers, who will doubtless be interested in the numerous queries which I was called upon to answer. Whether or not I have been able to fight my battles and maintain my cause, must be for others to determine.

I likewise subjoin a little paper on "Hunting in Ireland"—also already published—which brought me many letters: some of them from persons whose word should carry undoubted weight, fully coinciding in and substantiating my views with regard to the cutting up of grass-lands; whilst further on will be found my article entitled "Hunting in America," originally published in Life, and copied from that journal into so many papers throughout the kingdom, and abroad, that it is now universally known, and cannot be here presented in the form of a novelty,—but is given for the benefit of those who may not have chanced to meet with it, and for whom the subject of American sports and pastimes may happen to possess interest.

N. P. O'D.

CONTENTS.

| PART I. | |

| LEARNING. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| A Popular Error.—Excellence in Riding attainable without any Youthful Knowledge of the Art.—The Empress of Austria.—Her Proficiency.—Her Palace.—Her Occupations.—Her Disposition.—Her Thoughts and Opinions.—The Age at which to learn.—Courage indispensable.—Taste a Necessity | 1 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Learner's Costume.—The Best Teacher.—Your Bridle.—Your Saddle.—Your Stirrup.—Danger from "Safety-stirrup."—A Terrible Situation.—Learning to Ride without any support for the Foot | 11 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Mounting.—Holding the Reins.—Position in the Saddle.—Use of the Whip.—Trotting.—Cantering.—Riding from Balance.—Use of the Stirrup. Leaping.—Whyte Melville's opinion | 23 |

| PART II. | |

| PARK AND ROAD RIDING. | |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| How to Dress.—A Country-girl's ideas upon the subject.—How to put on your Riding-gear.—How to preserve it.—First Road-ride.—Backing.—Rearing, and how to prevent it | 44 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| Running away.—Three Dangerous Adventures.—How to act when placed in Circumstances of Peril.—How to Ride a Puller.— Through the City.—To a Meet of Hounds.—Boastful Ladies.—A Braggart's Resource | 62 |

| PART III. | |

| HUNTING. | |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Hunting-Gear.—Necessary Regard for Safe Shoeing.—Drive to the Meet.—Scene on arriving.—A Word with the Huntsman.—A Good Pilot.—The Covert-side.—Disappointment.—A Long Trot | 81 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| Hounds in Covert.—The First Fence.—Follow your Pilot.—A River-bath.—A Wise Precaution.—A Label advisable.—Wall and Water Jumping.—Advice to Fallen Riders.—Hogging.—More Tail | 98 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| Holding on to a Prostrate Horse.—Is it Wise or otherwise?—An Indiscreet Jump.—A Difficult Finish.—The Dangers of Marshy Grounds.—Encourage Humanity.—A Reclaimed Cabby! | 111 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Selfishness in the Field.—Fording a River.—Shirking a Fence. —Over-riding the Hounds.—Treatment of Tired Hunters.—Bigwig and the Major.—Naughty Bigwig.—Hapless Major | 120 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Feeding Horses.—Forage-biscuits.—Irish Peasantry.—A Cunning Idiot.—A Cabin Supper.—The Roguish Mule.—A Day at Courtown. —Paddy's Opinion of the Empress | 131 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Double-rise.—Pointing out the Right Foot.—The force of Habit.—Various kinds of Fault-finding.—Mr. Sturgess' Pictures.—An English Harvest-home.—A Jealous Shrew.—A Shy Blacksmith.—How Irishmen get Partners at a Dance | 144 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Subject of Feeding resumed.—Cooked Food recommended.—Effects of Raw Oats upon "Pleader."—Servants' Objections.—Snaffle-bridle, and Bit-and-Bridoon.—Kindness to the Poor.—An Unsympathetic Lady.—An Ungallant Captain.—What is a Gentleman?—Au Revoir! | 159 |

| PART IV. | |

| HUNTING IN IRELAND | 173 |

| PART V. | |

| HUNTING IN AMERICA | 183 |

| CORRESPONDENCE | 192 |

LADIES ON HORSEBACK.

PART I.

LEARNING.

CHAPTER I.

A POPULAR ERROR.—EXCELLENCE IN RIDING ATTAINABLE WITHOUT ANY YOUTHFUL KNOWLEDGE OF THE ART.—THE EMPRESS OF AUSTRIA.—HER PROFICIENCY.—HER PALACE.—HER OCCUPATIONS.—HER DISPOSITION.—HER THOUGHTS AND OPINIONS. —THE AGE AT WHICH TO LEARN.—COURAGE INDISPENSABLE.—TASTE A NECESSITY.

It is my belief that hints to ladies from a lady, upon a subject which now so universally occupies the female mind—hints, not offered in any cavilling nor carping spirit, but with an affectionate and sisterly regard for the interests of those addressed—cannot fail to be appreciated, and must become popular. Men write very well for men, but in writing for us ladies they cannot, however willing, enter into all the little delicacies and minutiæ of our tastes and feelings, and so half the effect is lost.

I do not purpose entering upon any discussion, nor, indeed, touching more than very lightly upon the treatment and management of the horse. A subject so exhaustive lies totally outside the limits of my pen, and has, moreover, been so ably treated by men of knowledge and experience, as to render one word further respecting the matter almost superfluous. I shall therefore content myself with surmising that the horses with which we may have to do throughout these remarks—be they school-horses, roadsters, or hunters—are at least sound, good-tempered, and properly trained. Their beauty and other attributes we shall take for granted, and not trouble ourselves about.

And now, in addressing my readers, I shall endeavour to do so as though I spoke to each separately, and so shall adopt the term "you," as being at once friendly and concise.

My subject shall be divided into three heads. First the acquirement of the equestrian art; second, road and park riding; third, hunting; with a few hints upon the costume, &c. required for each, and a slight sprinkling of anecdote here and there to enliven the whole.

I shall commence by saying that it is a mistake to imagine that riding, in order to be properly learnt, must be begun in youth: that nobody can excel as a horsewoman who has not accustomed herself to the saddle from a mere child. On the contrary some of the finest équestriennes the world has ever produced have known little or nothing of the art until the spring-time of their life was past. Her Imperial Majesty the Empress of Austria, and likewise her sister the ex-Queen of Naples, cared nothing about riding until comparatively late in life. I know little, except through hearsay, of the last-named lady's proficiency in the saddle, but having frequently witnessed that of the former, and having also been favoured with a personal introduction at the gracious request of the Empress, I can unhesitatingly say that anything more superb than her style of riding it would be impossible to conceive. The manner in which she mounts her horse, sits him, manages him, and bears him safely through a difficult run, is something which must be seen to be understood. Her courage is amazing. Indeed, I have been informed that she finds as little difficulty in standing upon a bare-backed steed and driving four others in long reins, as in sitting quietly in one of Kreutzman's saddles. In the circus attached to her palace at Vienna she almost daily performs these feats, and encourages by prizes and evidences of personal favour many of the Viennese ladies who seek to emulate her example. There has been considerable discussion respecting the question of the Empress's womanliness, and the reverse. Ladies have averred—oh, jealous ladies!—that she is not womanly; that her style of dressing is objectionable, and that she has "no business to ride without her husband!" These sayings are all open to but one interpretation; ladies are ever envious of each other, more especially of those who excel. The Empress is not only a perfect woman, but an angel of light and goodness. Nor do I say this from any toadyism, nor yet from the gratitude which I must feel for her kindly favour toward myself. I speak as I think and believe. Blessed with a beauty rarely given to mortal, she combines with it a sweetness of character and disposition, a womanly tenderness, and a thoughtful and untiring charity, which deserve to gain for her—as they have gained—the hearts as well as the loving respect and reverence of all with whom she has come in contact.

I was pleased to find, whilst conversing with her, that many of my views about riding were hers also, and that she considered it a pity—as I likewise do—that so many lady riders are utterly spoilt by pernicious and ignorant teaching. I myself am of opinion that childhood is not the best time to acquire the art of riding. The muscles are too young, and the back too weak. The spine is apt to grow crooked, unless a second saddle be adopted, which enables the learner to sit on alternate days upon the off-side of the horse; and to this there are many objections. The best time to learn to ride is about the age of sixteen. All the delicacy to which the female frame is subject during the period from the thirteenth to the fifteenth year has then passed away, and the form is vigorous and strong, and capable of enduring fatigue.

I know it to be a generally accepted idea that riding is like music and literature—the earlier it is learnt the better for the learner, and the more certain the proficiency desired to be attained. This is an entirely erroneous opinion, and one which should be at once discarded. I object, as a rule, to children riding. They cannot do so with any safety, unless put upon horses and ponies which are sheep-like in their demeanour; and from being accustomed to such, and to none other, they are nervous and frightened when mounted upon spirited animals which they feel they have not the strength nor the art to manage, and, being unused to the science of controlling, they suffer themselves to be controlled, and thus extinguish their chance of becoming accomplished horsewomen. I know ladies, certainly, who ride with a great show of boldness, and tear wildly across country after hounds, averring that they never knew what fear meant: why should they—having ridden from the time they were five years old? Very probably, but the bravery of the few is nothing by which to judge of a system which is, on the whole, pernicious. It is less objectionable for boys, because their shoulders are not apt to grow awry by sitting sideways, as little girls' do; nor are they liable to hang over upon one side; nor have they such delicate frames and weakly fingers to bring to the front. Moreover, if they tumble off, what matter? It does them all the good in the world. A little sticking-plaister and shaking together, and they are all right again. But I confess I don't like to see a girl come off. Less than a year ago a sweet little blue-eyed damsel who was prattling by my side as she rode her grey pony along with me, was thrown suddenly and without warning upon the road. The animal stumbled—her tiny hands lacked the strength to pull him together—she was too childish and inexperienced to know the art of retaining her seat. She fell! and the remembrance of uplifting her, and carrying her little hurt form before me upon my saddle to her parents' house, is not amongst the brightest of my memories.

We will assume, then, that you are a young lady in your sixteenth year, possessed of the desire to acquire the art of riding, and the necessary amount of courage to enable you to do so. This latter attribute is an absolute and positive necessity, for a coward will never make a horsewoman. If you are a coward, your horse will soon find it out, and will laugh at you; for horses can and do laugh when they what is usually termed "gammon" their riders. Nobody who does not possess unlimited confidence and a determination to know no fear, has any business aspiring to the art. Courage is indispensable, and must be there from the outset. All other difficulties may be got over, but a natural timidity is an insurmountable obstacle.

A cowardly rider labours under a two-fold disadvantage, for she not only suffers from her own cowardice, but actually imparts it to her horse. An animal's keen instinct tells him at once whether his master or his servant is upon his back. The moment your hands touch the reins the horse knows what your courage is, and usually acts accordingly.

No girl should be taught to ride who has not a taste, and a most decided one, for the art. Yet I preach this doctrine in vain; for, all over the world, young persons are forced by injudicious guardians to acquire various accomplishments for which they have no calling, and at which they can never excel. It is just as unwise to compel a girl to mount and manage a horse against her inclination, as it is to force young persons who have no taste for music to sit for hours daily at a piano, or thrust pencils and brushes into hands unwilling to use them. A love for horses, and an earnest desire to acquire the art of riding, are alike necessary to success. An unwilling learner will have a bad seat, a bad method, and clumsy hands upon the reins; whereas an enthusiast will seem to have an innate facility and power to conquer difficulties, and will possess that magic sense of touch, and facile delicacy of manipulation, which go so far toward making what are termed "good hands,"—a necessity without which nobody can claim to be a rider.

CHAPTER II.

LEARNER'S COSTUME.—THE BEST TEACHER.—YOUR BRIDLE.—YOUR SADDLE.— YOUR STIRRUP.—DANGER FROM "SAFETY-STIRRUP."—A TERRIBLE SITUATION. —LEARNING TO RIDE WITHOUT ANY SUPPORT FOR THE FOOT.

Having now discussed your age, your nerve, and your taste, we shall say a few words about your costume as a learner. Put on a pair of strong well-made boots; heels are not objectionable, but buttons are decidedly so, as they are apt to catch in the stirrup and cause trouble. Strong chamois riding-trousers, cloth from the hip down, with straps to fasten under the boots, and soft padding under the right knee and over the left, to prevent the friction of the pommels, which, to a beginner, generally causes much pain and uneasiness. A plain skirt of brown holland, and any sort of dark jacket, will suit your purpose quite well, for you are only going to learn; not to show off—yet. Your hat—any kind will do—must be securely fastened on, and your hair left flowing, for no matter how well you may fancy you have it fastened, the motion of the horse will shake it and make it feel unsteady, and the very first hairpin that drops out, up will go your hand to replace it, and your reins will be forgotten. As soon as you have put on a pair of strong loose gloves, and taken a little switch in your hand, you are ready to mount.

The nicest place in which you can learn is a well-tanned riding-school or large green paddock, and the nicest person to teach you is a lady or gentleman friend, who will have the knowledge and the patience to instruct you. Heaven help the learner who is handed over to the tender mercies of John, the coachman, or Jem, the groom! Servants are rarely able to ride a yard themselves, and their attempt at teaching is proportionately lame. Your horse having been led out, your attendant looks to his girthing, &c., as stable servants are not always too particular respecting these necessary matters.

The pleasantest bridle in which to ride is a plain ring-snaffle. Few horses will go in it; but, remember, I am surmising that yours has been properly trained. By riding in this bridle you have complete control over the movements of your horse—can, in fact, manage him with one hand, and you have the additional advantage of having fewer leathers to encumber and embarrass your fingers. A beginner is frequently puzzled to distinguish between the curb and the snaffle when riding with a double rein, and mistaking one for the other, or pulling equally at both, is apt to cause the horse much unnecessary irritation. It is lamentable to see the manner in which grown men and women, who ought to know so much better, tug and strain at their horses' mouths with an equal pull upon both reins, when riding, as is the custom, in a bit and bridoon. Perhaps of the two they draw the curb the tighter. It is not meant for cruelty—they do not appear to be aware that it is cruel: but there is no greater sign of utter ignorance. Horses are not naturally vicious, and very few of them who have had any sort of fair-play in training, really require a curb, or will go as well or pleasantly upon it as if ridden in a snaffle-bridle.

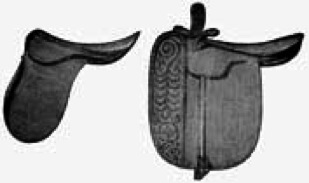

Your saddle is another most important point. Never commence, be your age ever so tender, by riding upon a pad. Accustom yourself from the beginning to the use of a properly constructed saddle, made as straight as a board, seat perfectly level, and scarcely any appearance of a pommel upon the off-side. A leaping-head, or what is commonly termed a third crutch, is, in my opinion, indispensable. To procure a saddle such as I describe you must have it made to order, for those of the present day are all made with something of a dip, which is most objectionable. I do not like the appearance of much stitching about a saddle. It has always appeared to me absurd to see the amount of elaborate embroidery which every old-fashioned saddle carries upon the near flap. Nothing could be more unnecessary than an outlay of labour upon a portion of the article which is always concealed beneath the rider's right leg. There might be some sense, although very little, in decorating the off-side and imparting to it something of an ornamental appearance; but in my opinion there cannot be too much simplicity about everything connected with riding appointments. A plainness, amounting even to severity, is to be preferred before any outward show. Ribbons, and coloured veils, and yellow gloves, and showy flowers are alike objectionable. A gaudy "get up" (to make use of an expressive common-place) is highly to be condemned, and at once stamps the wearer as a person of inferior taste. Therefore avoid it. Let your saddle be, like your personal attire, remarkable only for its perfect freedom from ornament or display. Have it made to suit yourself—neither too weighty, nor yet too small—and if you want to ride with grace and comfort, desire that it be constructed without one particle of the objectionable dip. There is a very old-established and world-noted firm in Piccadilly—Peat & Co.—where you can obtain an article such as I describe, properly made, and of durable materials, at quite a moderate cost. I can say, speaking from experience, that no trouble will be spared to afford you satisfaction, and that the workmanship will be not only lasting, but characterised by that neatness for which I am so strong an advocate. You should ride on your saddle, not in it, and you must learn to ride from balance or you will never excel, and this you can only do by the use of the level seat. A small pocket on the off-side, and a neat cross strap to support a waterproof, are of course necessary items.

Your stirrup is the next important matter. I strongly disapprove of the old-fashioned slipper, as also of the so-called "safety" stirrup, which is, in my opinion, the fruitful source of many accidents. Half the lamentable mischances with which our ears are from time to time shocked, are due to the pertinacity with which ladies will cling to this murderous safety stirrup. So long as they will persist in doing so, casualties must be looked for and must occur. The padding over the instep causes the foot to become firmly imbedded, and in the event of an accident the consequences are dire, for the mechanism of the stirrup is almost invariably stiff or out of order, or otherwise refuses to act. Mr. Oldacre was, I believe, the inventor of the padded stirrup, and for this we owe him or his memory little thanks, although the gratitude of all lady riders is undoubtedly due to him for his admirable invention and patenting of the third crutch, without which our seat in the saddle would be far less comfortable and less secure.

I dare say that I shall have a large section of aggrieved stirrup-makers coming down upon me with the phials of their wrath for giving publicity to this opinion, but in writing as I have done I merely state my own views, which I deem we are all at liberty to do; and looking upon my readers as friends, I warn them against an article of which I myself have had woful experience. I once purchased a safety stirrup at one of the best houses, and made by one of the best makers. The shopman showed it off to me in gallant style, expatiating upon its many excellencies, and adroitly managing the stiff machinery with his deft fingers, until I was fairly deceived, and gave him a handful of money for what subsequently proved a cause of trouble. I lost more than one good run with hounds through the breaking of this dearly-bought stirrup, having upon one occasion to ride quite a long distance away from the hunt to seek out a forge at which I might undergo repairs. Nor was this the worst, for one day, having incautiously plunged into a bog in my anxiety to be in at the death, my horse got stuck and began to sink, and of course I sought to release myself from him at once; but no, my foot was locked fast in that terrible stirrup, and I could not stir. My position was dreadful, for I had outridden my pilot, my struggling steed was momentarily sinking lower, and the shades of evening were fast closing in. I shudder to think what might have been my fate and that of my gallant horse had not the fox happily turned and led the hunt back along the skirts of the bog, thus enabling my cries for help to be heard by one or two brave spirits who came gallantly to my rescue. I have more than once since then been caught in a treacherous bog when following the chase, but never have I found any difficulty in jumping from my horse's back and helping him to struggle gamely on to the dry land, for I have never since ridden in a safety-stirrup, nor shall I ever be likely to do so again. It may be said, and probably with truth, that my servant had neglected to clean it properly from day to day, and that consequently the spring had got rusted and refused to act. Such may possibly have been the case, but might not the same thing occur to anyone, or at any time? Servants are the same all over the world, and yet you must either trust to them or spend half your time overlooking them in the stable and harness-room, which for a lady is neither agreeable nor correct.

There is nothing so pleasant to ride in as a plain little racing-stirrup, from which the foot is in an instant freed. I have not for a long while back used anything else myself, nor has my foot ever remained caught, even in the most dangerous falls.

I conceive it to be an admirable plan to learn to ride without a stirrup at all. Of course I do not mean by this that a lady should ever go out park-riding or hunting sans the aid of such an appendage, but she should be taught the necessity of dispensing with it in case of emergency. The benefits arising from such training are manifold. First, it imparts a freedom and independence which cannot otherwise be acquired; secondly, it gives an admirable and sure seat over fences; thirdly, it is an excellent means of learning how to ride from balance; and fourthly, in spite of its apparent difficulties, it is in the end a mighty simplifier, inasmuch as, when the use of the stirrup is again permitted, all seems such marvellously plain sailing, that every obstacle appears to vanish from the learner's path. In short, a lady who can ride fairly well without a support for her foot, must, when such is added, be indeed an accomplished horsewoman. I knew a lady who never made use of a stirrup throughout the whole course of an unusually long life, and who rode most brilliantly to hounds. Few, however, could do this, nor is it by any means advisable, but to be able occasionally to dispense with the support is doubtless of decided benefit.

I have often found my training in this respect stand me in good stead, for it has more than once happened that in jumping a stiff fence, or struggling in a heavy fall, my stirrup-leather has given way, and I have had not alone to finish the run without it, but to ride many miles of a journey homeward.

Nothing could be more wearisome to an untutored horsewoman than a long ride without a stirrup. The weight of her suspended limb becomes after a moment or two most inconvenient and even painful, whilst the trot of the horse occasions her to bump continuously in the saddle,—for the power of rising without artificial aid would appear a sheer impossibility to an ordinary rider whose teaching had been entrusted to an ordinary teacher. I would have you then bear in mind that although I advocate practising without the assistance of a stirrup, I am totally against your setting out beyond the limits of your own lawn or paddock without this necessary support.

CHAPTER III.

MOUNTING.—HOLDING THE REINS.—POSITION IN THE SADDLE.—USE OF THE WHIP.—TROTTING.—CANTERING.—RIDING FROM BALANCE.—USE OF THE STIRRUP. —LEAPING.—WHYTE MELVILLE'S OPINION.

Having now seen that your bridle, saddle, and stirrup are in proper order, you prepare to mount, and this will probably take you some time and practice to accomplish gracefully, being quite an art in itself. Nothing is more atrocious than to see a lady require a chair to mount her animal, or hang midway against the side of the saddle when her cavalier gives her the helping hand. Lay your right hand firmly upon the pommel of your saddle, and the left upon the shoulder of your attendant, in whose hand you place your left foot. Have ready some signal sentence, as "Make ready, go!" or "one, two, three!" Immediately upon pronouncing the last syllable make your spring, and if your attendant does his duty properly you will find yourself seated deftly upon your saddle.

As I have already stated, this requires practice, and you must not be disappointed if a week or so of failure ensues between trial and success.

As soon as you are firmly seated, take your rein (which, as I have said, should be a single one) and adjust it thus. Place the near side under the little finger of your left hand, and the off one between your first and second fingers, bringing both in front toward the right hand, and holding them securely in their place with the pressure of your thumb. This is merely a hint as to the simplest method for a beginner to adopt, for there is really no fixed rule for holding reins, nor must you at all times hold them in one hand only, but frequently—and always when hunting—put both hands firmly to your bridle. Anything stiff or stereotyped is to be avoided. A good rider, such as we hope you will soon become, will change her reins about, and move her position upon the saddle, so as to be able to watch the surrounding scenery—always moving gracefully, and without any abrupt or spasmodic jerkings, which are just as objectionable as the poker-like rigidity which I wish you to avoid. How common it is to see ladies on horseback sitting as though they were afraid to budge a hair, with pinioned elbows and straightly-staring eyes. This is most objectionable; in fact, nothing can be more unsightly. A graceful, easy seat, is a good horsewoman's chief characteristic. She is not afraid of tumbling off, and so she does not look as though she were so; moreover, she has been properly taught in the commencement, and all such defects have been rectified by a careful supervision.

With regard to your whip, it must be held point downwards, and if you have occasion to touch your horse, give it to him down the shoulder, but always with temperance and kindly judgment. I once had a riding-master who desired me to hold my whip balanced in three fingers of my right hand, point upwards, the hand itself being absurdly bowed and the little finger stuck straight out like a wooden projection. My natural good sense induced me to rebel against anything so completely ridiculous, and I quietly asked my teacher why I was to carry my whip in that particular position. His answer was—"Oh, that you may have it ready to strike your horse on the neck." Shades of Diana! this is the way our daughters are taught in schools, and we marvel that they show so little for the heaps of money which we hopefully expend upon them.

Being then fairly seated upon your saddle, your skirt drawn down and arranged by your attendant, your reins in your hand and your whip arranged, you must proceed to walk your horse quietly around the enclosure, having first gently drawn your bridle through his mouth. You will feel very strange at first: much as though you were on the back of a dromedary and were completely at his mercy. Sit perfectly straight and erect, but without stiffness. Be careful not to hang over upon either side, and, above all things, avoid the pernicious habit of clutching nervously with the right hand at the off pommel to save yourself from some imaginary danger. So much does this unsightly habit grow upon beginners, that, unless checked, it will follow them through life. I know grown women who ride every day, and the very moment their horse breaks into a canter or a trot they lay a grim grip upon the pommel, and hold firmly on to it until the animal again lapses into a walk. And this they do unconsciously. The habit, given way to in childhood, has grown so much into second nature that to tell them of it would amaze them. I once ventured to offer a gentle remonstrance upon the subject to a lady with whom I was extremely intimate, and she was not only astonished, but so displeased with me for noticing it, that she was never quite the same to me afterwards; and so salutary was the lesson which I then received that I have since gone upon the principle of complete non-interference, and if I saw my fellow équestriennes riding gravely upon their horses' heads I would not suggest the rationality of transferring their weight to the saddle. And this theory is a good one, or at least a wise one; for humanity is so inordinately conceited that it will never take a hint kindly, unless asked for; and not always even then.

To sit erect upon your saddle is a point of great importance; if you acquire a habit of stooping it will grow upon you, and it is not only a great disfigurement, but not unfrequently a cause of serious accident, for if your horse suddenly throws up his head, he hits you upon the nose, and deprives you of more blood than you may be able to replace in a good while.

As soon as you can feel yourself quite at home upon your mount, and have become accustomed to its walking motion, your attendant will urge him into a gentle trot. And now prepare yourself for the beginning of sorrows. Your first sensation will be that of being shaken to pieces. You are, of course, yet quite ignorant of the art of rising in your saddle, and the trot of the horse fairly churns you. Your hat shakes, your hair flaps, your elbows bang to your sides, you are altogether miserable. Still, you hold on bravely, though you are ready to cry from the horrors of the situation.

Your attendant, by way of relieving you, changes the trot to a canter, and then you are suddenly transported to Elysium. The motion is heavenly. You have nothing to do but sit close to your saddle, and you are borne delightfully along. It is too ecstatic to last. Alas! it will never teach you to ride, and so you return to the trot and the shaking and the jogging, the horrors of which are worse than anything you have ever previously experienced. You try vainly to give yourself some ease, but fail utterly, and at length dismount—hot, tired, and disheartened.

But against this latter you must resolutely fight. Remember that nothing can be learned without trouble, and by-and-by you will be repaid. It is not everybody who has the gift of perseverance, and it is an invaluable attribute. It is a fact frequently commented upon, not alone by me but by many others also, that if you go for the hiring of a horse to any London livery-stable you will be sent a good-looking beast enough, but he will not be able to trot a yard. Canter, canter, is all that he can do. And why? He is kept for the express purpose of carrying young ladies in the Row, and these young ladies have never learnt to trot. They can dress themselves as vanity suggests in fashionably-cut habits, suffer themselves to be lifted to the saddle, and sit there, looking elegant and pretty, whilst their horse canters gaily down the long ride; but were the animal to break into a trot (which he is far too well tutored to attempt to do), they would soon present the same shaken, dilapidated, dishevelled, and utterly miserable appearance which you yourself do after your first experience of the difficulties which a learner has to encounter.

The art of rising in the saddle is said to have been invented by one Dan Seffert, a very famous steeplechase jockey, who had, I believe, been a riding-master in the days of his youth. If this be true—which there is no reason to doubt—we have certainly to thank him, for it is a vast improvement upon the jog-trot adopted by the cavalry, which, however well it may suit them and impart uniformity of motion to their "line-riding," is not by any means suited to a lady, either for appearances or for purposes of health.

You come up for your next day's lesson in a very solemn mood. You are, in fact, considerably sobered. You had thought it was all plain sailing: it looked so easy. You had seen hundreds of persons riding, trotting, and even setting off to hunt, and had never dreamed that there had been any trouble in learning. Now you know the difficulties and what is before you.

You recall your sufferings during your first days upon the ice, or on the rink. How utterly impossible it seemed that you could ever excel; how you tumbled about; how miserably helpless you felt, and how many heavy falls you got! Yet you conquered in the end, and so you will again.

You take courage and mount your steed. First you walk him a little, as yesterday; and then the jolting begins again. How are you ever to get into that rise and fall which you have seen with others, and so much covet? How are you to accomplish it? Only by doing as I tell you, and persevering in it. As your horse throws out his near foreleg press your foot upon your stirrup, in time to lift yourself slightly as his off foreleg is next thrown out. Watch the motion of his legs, press your foot, and at the same time slightly lift yourself from your saddle. For a long while, many days perhaps, it will seem to be all wrong; you have not got into it one bit; you are just as far from it apparently as when you commenced. You are hot and vexed, and you, perhaps, cry with mortification and disappointment, as I have seen many a young beginner do; bitterly worried and disheartened you are, and ready to give up, when, lo! quite suddenly, as though it had come to you by magic and not through your own steady perseverance, you find yourself rising and falling with the trot of the horse, and your labours are rewarded.

After this your lessons are a source of delight. You no longer come from them flushed and worried, but joyous and exultant and impatient for the next. You have begun to feel quite brave, and to throw out hints that you are longing for a good ride on the road. You now know how to make your horse trot and canter; the first by a light touch of your whip and a gentle movement of your bridle through his mouth; the second by a slight bearing of the rein upon the near side of his mouth, so as to make him go off upon the right leg, and a little warning touch of your heel. You fancy, in fact, that you are quite a horsewoman, and have already rolled up your hair into a neat knot, and hinted to papa that you should greatly like a habit. But, alas! you have plenty of trouble yet before you, plenty to learn, plenty of falls to get and to bear. At present you can ride fairly well on the straight; but you know nothing of keeping your balance in time of danger. Your horse is very quiet, but if he chanced to put back his ears you would be off.

You are taught to maintain your balance in the following way:—

Your attendant waits until your horse is cantering pretty briskly in a circle from left to right, when he suddenly cracks his whip close to the animal's heels, who immediately swerves and turns the other way. You have had no warning of the movement, and consequently you tumble off, and are put up again, feeling a little shaken and a good deal crestfallen. Most likely you will fall again and again, until you have thoroughly mastered the art of riding from balance.

This is a method I have seen adopted, especially in schools, with considerable success, but it is certainly attended with inconvenience to the learner, and with a goodly portion of the risk from falls which all who ride must of necessity run. To ride well from balance is not a thing which can be accomplished in a day, nor a month, nor perhaps a year. Many pass a life-time without practically comprehending the meaning of the term. They ride every day, hold on to the bridle, guide their horses, and trust to chance for the rest; but this is not true horsemanship. It could no more be called riding than could a piece of mechanical pianoforte-playing be termed music. When you have, after much difficulty and delay, mastered the obstacles which marred your progress, you will then have the happy consciousness of feeling that however your horse may shy or swerve, or otherwise depart from his good manners, you can sit him with the ease and closeness of a young centaur.

This art of riding from balance is not half sufficiently known. It is one most difficult to acquire, but the study is worth the labour. Nine-tenths of the lady equestrians, and perhaps even a greater number of gentlemen, ride from the horse's head; a detestable practice which cannot be too highly condemned. I must also warn you against placing too much stress upon the stirrup when your horse is trotting. You must bear in mind that the stirrup is intended for a support for the foot—not to be ridden from. By placing your right leg firmly around the up-pommel, and pressing the left knee against the leaping-head, you can accomplish the rise in your saddle with slight assistance from the stirrup; and this is the proper way to ride. The lazy, careless habit into which many women fall, of resting the entire weight of the body upon the stirrup, not only frequently causes the leathers to snap at most inconvenient times, but is the lamentable cause of half the sore backs and ugly galls from which poor horses suffer so severely.

Having at length perfected yourself in walking, trotting, cantering, and riding from balance, you have only to acquire the art of leaping—and then you will be finished, so far as teaching can make you so. Experience must do the rest.

It is a good thing, when learning, to mount as many different horses as you possibly can; always, of course, taking care that they are sufficiently trained not to endeavour to master you. Horses vary immensely in their action and gait of going: so much so, that if you do not accustom yourself to a variety you will take your ideas from one alone, and will, when put upon a strange animal, find yourself completely at sea.

Do not suffer anything to induce you to take your first leap over a bar or pole similar to those used in schools. The horse sees the daylight under it, knows well that it is a sham, goes at it unwillingly, does not half rise to it, drops his heels when in the air, and knocks it down with a crash,—only to do the same thing a second time, and a third, and a fourth also, if urged to do that which he despises.

Choose a nice little hurdle about two feet high, well interwoven with gorse; trot your horse gently up to it, and let him see what it is; then, turn him back and send him at it, sitting close glued to your saddle, with a firm but gentle grip of your reins, and your hands held low. To throw up the hands is a habit with all beginners, and should at once be checked. Fifty to one you will stick on all right, and, if you come off, why it's many a good man's case, and you must regard it as one of the chances of war.

The next day you may have the gorse raised another half-foot above the hurdle, and so on by degrees, until you can sit with ease over a jump of five feet. Always bear in mind to keep your hands quite down upon your horse's withers, and never interfere with his mouth. Sit well back, leave him his head, and he will not make a mistake. Of course, I am again surmising that he has been properly trained, and that you alone are the novice. To put a learner upon an untrained animal would be a piece of folly, not to say of wickedness, of which we hope nobody in this age of enlightenment would dream of being guilty. In jumping a fence or hurdle do not leave your reins quite slack; hold them lightly but firmly, as your horse should jump against his bridle, but do not pull him. A gentle support is alone necessary.

That absurd and vulgar theory about "lifting a horse at his fences," so freely affected by the ignorant youth of the present day, cannot be too strongly deprecated. That same "lifting" has broken more horses' shoulders and more asses' necks than anything else on record. A good hunter with a bad rider upon his back will actually shake his head free on coming up to a fence. He knows that he cannot do what is expected of him if his mouth is to be chucked and worried, any more than you or I could under similar circumstances, and so he asserts his liberty. How often, in a steeplechase, one horse early deprived of his rider will voluntarily go the whole course and jump every obstacle in perfect safety, even with the reins dangling about his legs, yet never make a mistake; whilst a score or so of compeers will be tumbling at every fence. And why? The answer is plain and simple. The free horse has his head, and his instinct tells him where to put his feet; whereas the animals with riders upon their backs are dragged and pulled and sawn at, until irritation deprives them of sense and sight, and, rushing wildly at their fences (probably getting another tug at the moment of rising), they fall, and so extinguish their chance of a win.

I do not, of course, in saying this, mean for a moment to question the judgment and horsemanship of very many excellent jockeys, whose ability is beyond comment and their riding without reproach. I speak of the rule, not of the few exceptions.

Half the horses who fall in the hunting-field are thrown down by their riders; this is a fact too obvious to be contradicted. Men over-riding their horses, treating them with needless cruelty, riding them when already beaten: these are the fruitful causes of falls in the field, together with that most objectionable practice of striving to "lift" an animal who knows his duties far better than the man upon his back. It is a pity, and my heart has often bled to see how the noblest of God's created things is ill-treated and abused by the human brute who styles himself the master. It is, indeed, a disgrace to our humanity that this priceless creature, given to a man with a mind highly wrought, sensitive, yearning for kindness, and capable of appreciating each word and look of the being whose willing slave it is, should be treated with cruelty, and in too many cases regarded but as a sort of machine to do the master's bidding. Who has not seen, and mourned to see, the tired, patient horse, spurred and dragged at by a remorseless rider, struggling gamely forward in the hunting-field, with bleeding mouth and heaving, bloody flanks, to enable a cruel task-master to see the end of a second run, and even of a third, after having carried him gallantly through a long and intricate first? It is a piece of inhumanity which all humane riders see and deplore every day throughout the hunting season. We cannot stop it, but we can speak against it and write it down, and discountenance it in every possible way, as we are all bound to do. Why will not men be brought to see that in abusing their horses they are compassing their own loss? that in taxing the powers of a beaten animal they are riding for a fall, and are consequently endangering the life which God has given them?

There is much to be learnt in the art of fencing besides hurdle-leaping. A good timber-jumper will often take a ditch or drain in a very indifferent manner. I have seen a horse jump a five-barred gate in magnificent style, yet fall short into a comparatively narrow ditch; and vice versâ; therefore, various kinds of jumps must be kept up, persevered in, and kept constantly in practice. Two things must always be preserved in view; never sit loosely in your saddle, and always ride well from balance, never from your horse's head. In taking an up jump leave him abundance of head-room, and sit well back, lest in his effort he knock you in the face. If the jump is a down one—what is known as an "ugly drop"—follow the same rules; but, when your horse is landing, give him good support from the bridle, as, should the ground be at all soft or marshy, he might be apt to peck, and so give you an ugly fall.

It is a disputed point whether or not horses like jumping. I am inclined to coincide in poor Whyte-Melville's opinion that they do not. He was a good authority upon most subjects connected with equine matters, and so he ought to know; but of one thing I am positively certain: they abhor schooling. However a horse may tolerate or even enjoy a good fast scurry with hounds, there can be no doubt that he greatly dislikes being brought to his fences in cold blood. He has not, when schooling, the impetus which sends him along, nor the example or excitement to be met with in the hunting-field. The horse is naturally a timid animal, and this is why he so frequently stops short at his fences when schooling. He mistrusts his own powers. When running with hounds he is borne along by speed and by excitement, and so goes skying over obstacles which appal him when trotted quietly to them on a schooling day. It is just the difference which an actor feels between a chilling rehearsal and the night performance, when the theatre is crowded and the clapping of hands and the shouting of approving voices lend life and spirit to the part he plays.

You will probably get more falls whilst schooling than ever you will get in the hunting-field, but a few weeks' steady practice over good artificial fences or a nice natural country, will give you a firm seat and an amount of confidence which will stand to you as friends.

PART II.

PARK AND ROAD RIDING.

CHAPTER IV.

HOW TO DRESS.—A COUNTRY-GIRL'S IDEAS UPON THE SUBJECT.—HOW TO PUT ON YOUR RIDING-GEAR.—HOW TO PRESERVE IT.—FIRST ROAD-RIDE.—BACKING. —REARING, AND HOW TO PREVENT IT.

Having now mastered the art of riding, you will of course be desirous of appearing in the parks and on the public roadways, and exhibiting the prowess which it has cost you so much to gain.

For your outfit you will require, in addition to the articles already in your possession, a nice well-made habit of dark cloth. If you are a very young girl, grey will be the most suitable; if not, dark blue. If you live in London, pay a visit to Mayfair, and get Mr. Wolmershausen to make it for you; if in Dublin, Mr. Scott, of Sackville Street, will do equally well; indeed, for any sort of riding-gear, ladies' or gentlemen's, he is not to be excelled. If you are not within easy distance of a city, go to the best tailor you can, and give him directions, which he must not be above taking. Skirt to reach six inches below the foot, well shaped for the knee, and neatly shotted at end of hem just below the right foot; elastic band upon inner side, to catch the left toe, and to retain the skirt in its place. It should be made tight and spare, without one inch of superfluous cloth; jacket close-fitting, but sufficiently easy to avoid even the suspicion of being squeezed; sleeves perfectly tight, except at the setting on, where a slight puffiness over the shoulder should give the appearance of increased width of chest. No braiding nor ornamentation of any sort to appear. A small neat linen collar, upright shape, with cuffs to correspond, should be worn with the habit, no frilling nor fancy work being admissible—the collar to be fastened with a plain gold or silver stud.

The nicest hat to ride in is an ordinary silk one, much lower than they are usually made, and generally requiring to be manufactured purposely to fit and suit the head. Of course, if you are a young girl, the melon shape will not be unsuitable, but the other is more in keeping, more becoming, and vastly more economical in the end, although few can be induced to believe this. It is the custom in many households to purchase articles for their cheapness, without any regard to quality or durability, and this you should endeavour to avoid. Speaking from experience, the best things are always the cheapest. I pay from a guinea to a guinea and a half for a good silk hat, and find that it wears out four felt ones of the quality usually sold at ten and sixpence. There is no London house at which you can procure better articles or better value than at Lincoln, Bennett, & Co., Sackville Street, Piccadilly. For nearly half a century they have been the possessors of an admirable contrivance, which should be seen to be appreciated, by which not alone is the size of the head ascertained, but its precise shape is definitely marked and suited, thus avoiding all possibility of that distressing pressure upon the temples, which is a fruitful source of headache and discomfort to so many riders. Hats made at this firm require no elastics—if it be considered desirable to dispense with such—as the fit is guaranteed. Never wear a veil on horseback, except it be a black one, and nothing with a border looks well. A plain band of spotted net, just reaching below the nostrils, and gathered away into a neat knot behind, is the most distingué. Do not wear anything sufficiently long to cover the mouth, or it will cause you inconvenience on wet and frosty days. For dusty roads a black gauze veil will be found useful, but avoid, as you would poison, every temptation to wear even the faintest scrap of colour on horseback. All such atrocities as blue and green veils have happily long since vanished, but, even still, a red bow, a gaudy flower stuck in the button-hole, and, oh, horror of horrors! a pocket handkerchief appearing at an opening in the bosom, looking like a miniature fomentation—these still occasionally shock the eyes of sensitive persons, and cause us to marvel at the wearer's bad taste.

I was once asked to take a young lady with me for a ride in the park, to witness a field-day, or polo match, or something or another of especial interest which happened to be going forward. I would generally prefer being asked to face a battery of Zulus rather than act as chaperone to young lady équestriennes, who are usually ignorant of riding, and insufferably badly turned out. However, upon this occasion I could not refuse. The lady's parents were kind, amiable country folks, who had invested a portion of their wealth in sending their daughter up to town to get lessons from a fashionable riding-master, and to ride out with whomsoever might be induced to take her.

Well, the young lady's horse was the first arrival: a hired hack—usual style; bones protruding—knees well over—rusty bridle—greasy reins—dirty girths—and dilapidated saddle, indifferently polished up for the occasion.

The young lady herself came next, stepping daintily out of a cab, as though she were quite mistress of the situation. Ye gods! What a get up! I was positively electrified. Her habit—certainly well made—was of bright blue cloth, with worked frills at the throat and wrists. She wore a brilliant knot of scarlet ribbon at her neck, and a huge bouquet in her button-hole. Her hat was a silk one, set right on the back of her head, with a velvet rosettte and steel buckle in front, and a long veil of grey gauze streaming out behind. When we add orange gloves, and a riding-whip with a gaudy tassel appended to it, you have the details of a costume at once singular and unique.

I did not at first know whether to get a sudden attack of the measles or the toothache, and send her out with my groom to escort her, but discarding the thought as ill-natured, I compromised matters by bringing her to my own room, and effecting alterations in her toilet which soon gave her a more civilised appearance. I set the hat straight upon her head, and bound it securely in its place, removed from it the gauze and buckle, and tied on one of my own plain black veils of simple spotted net. I could not do away with the frillings, for they were stitched on as though they were never meant to come off; but the red bow I replaced with a silver arrow, threw away the flowers, removed the whip-tassel, and substituted a pair of my own gloves for the cherished orange kid. Then we set out.

I wanted to go a quiet way to the park, so as to avoid the streets of the town, but she would not have it. Nothing would do that girl but to go bang through the most crowded parts of the city, the hired hack sliding over the asphalte, and the rider (all unconscious of her danger) bowing delightedly to her acquaintances as she passed along. Poor girl! that first day out of the riding-school was a gala day for her.

The nicest gloves for riding are pale cream leather, worked thickly on the backs with black. A few pairs of these will keep you going, for they clean beautifully. A plain riding-whip without a tassel, and a second habit of dark holland if you live in the country, will complete your necessary outfit.

I shall now give you a few hints as to the best method of putting on your riding gear, and of preserving the same after rain or hard weather. Your habit-maker will, of course, put large hooks around the waist of your bodice, and eyes of corresponding size attached to the skirt, so that both may be kept in their place, but if you have been obliged to entrust your cloth to a country practitioner, who has neglected these minor necessaries, be sure you look to them yourself, or you will some day find that the opening of your skirt is right at your back, and that the place shaped out for your knee has twisted round until it hangs in unsightly crookedness in front of the buttons of your bodice.

Let it be a rule with you to avoid using any pins. Put two or three neat stitches in the back of your collar, so as to affix it to your jacket, having first measured to see that the ends shall meet exactly evenly in front, where you will fasten them neatly with a stud. The ordinary system of placing one pin at the back of the collar and one at either end is much to be deprecated. Frequently one of these pins becomes undone, and then the discomfort is incalculable, especially if, as often occurs, you are out for a long day, and nobody happens to be able to accommodate you with another.

Pinning cuffs is also a reprehensible habit, for the reason just stated. Two or three little stitches where they will not show, upon the inner side of the sleeve, will hold the cuff securely in its place and prevent it turning round or slipping up or down, any of which will be calculated to cause discomfort to the rider.

It is not a bad method, either, to stitch a small button at the back of the neck of the jacket, upon the inner side, upon which the collar can be secured, fastening the cuffs in the same manner to buttons attached to the inner portion of each sleeve. In short, anything in the shape of a device which will check the unseemly habit of using a multiplicity of pins, may be regarded as a welcome innovation, and at once adopted.

It is a good plan, when you undress from your ride, to ascertain whether your collar and cuffs are sufficiently clean to serve you another day, and if they are not, replace them at once by fresh ones; for it may happen that when you go to attire yourself for your next ride, you may he too hurried to look after what should always be a positive necessity, namely, perfectly spotless linen.

There is a material, invented in America and as yet but little known amongst us here, which is invaluable to all who ride. It is called Celluloid, and from it collars, cuffs, and shirt-fronts are manufactured which resemble the finest and whitest linen, yet which never spot, never crush, never become limp, and never require washing, save as one would wash a china saucer, in a basin of clear water, using a fine soft towel for the drying process. I do not know the nature of the composition, but I can certainly bear testimony to its worth, and being inexpensive as well as convenient, it cannot fail, when known, to become highly popular.

The adjusting of your hat is another important item. Stitch a piece of black elastic (the single-cord round kind is the best) from one side—the inner one of course—to the other, of just sufficient length to catch well beneath your hair. This elastic you can stretch over the leaf of your hat at the back, and then, when the hat is on and nicely adjusted to your taste in front, you have only to put back your hand and bring the band of elastic deftly under your hair. The hat will then be immovable, and the elastic will not show. In fastening your veil, a short steel pin with a round black head is the best. The steel slips easily through the leaf of the hat, and the head, being glossy and large, is easily found without groping or delay, whenever you may desire to divest yourself of it.

I shall now tell you how to proceed with the various items of your toilet on coming home, after being overtaken by stress of weather. No matter how wealthy you may be, or how many servants you may be entitled to keep, always look after these things yourself.

Hang the skirt of your habit upon a clothes-horse, with a stick placed across inside to extend it fully. Leave it until thoroughly dry, and then brush carefully. The bodice must be hung in a cool dry place, but never placed near the fire, or the cloth will shrink, and probably discolour.

Dip your veil into clear cold water, give it one or two gentle squeezes, shake it out, and hang it on a line, spreading it neatly with your fingers, so that it may take no fold in the drying.

Your hat comes next. Dip a fine small Turkey sponge, kept for the purpose and freed from sand, into a basin of lukewarm water, and draw it carefully around the hat. Repeat the process, going over every portion of it, until crown, leaf, and all are thoroughly cleansed; then hang in a cool, airy place to dry. In the morning take a soft brush, which use gently over the entire surface, and you will have a perfectly new hat. No matter how shabby may have been your headpiece, it will be quite restored, and will look all the better for its washing. This is one of the chief advantages of silk hats. Do not omit to brush after the washing and drying process, or your hat will have that unsightly appearance of having been ironed, which is so frequently seen in the hunting-field, because gentlemen who are valeted on returning from their sport care nothing about the management of their gear, but leave it all to the valet, who gives the hat the necessary washing, but is too lazy or too careless to brush it next day, and his master takes it from his hand and puts it on without ever noticing its unsightliness. Sometimes it is the master himself whose clumsy handiwork is to blame; but be it master or servant, the result is too often the same.

Should your gloves be thoroughly, or even slightly wetted, stretch them upon a pair of wooden hands kept for the purpose, and if they are the kind which I have recommended to you—I mean the best quality of double-stitched cream leather—they will be little the worse.

Having now, I think, exhausted the subject of your clothing, and given you all the friendly hints in my power, I am ready to accompany you upon your first road ride.

Go out with every confidence, accompanied of course by a companion or attendant, and make up your mind never to be caught napping, but to be ever on the alert. You must not lose sight of the fact that a bird flitting suddenly across, a donkey's head laid without warning against a gate, a goat's horns appearing over a wall, or even a piece of paper blown along upon the ground, may cause your horse to shy, and if you are not sitting close at the time, woe betide you! Always remember the rule of the road, keep to your left-hand side, and if you have to pass a vehicle going your way, do so on the right of it. Never neglect this axiom, no matter how lonely and deserted the highway may appear, for recollect that if you fail to comply with it, and that any accident chances to occur, you will get all the blame, and receive no compensation.

Never trot your horse upon a hard road when you have a bit of grass at the side on which you can canter him. Even if there are only a few blades it will be sufficient to take the jar off his feet.

If you meet with a hill or high bridge, trot him up and walk him quietly down the other side. If going down a steep decline, sit well back and leave him his head, at the same time keeping a watchful hand upon the rein for fear he should chance to make a false step, that you may be able to pull him up; but do not hold him tightly in, as many timid riders are apt to do, thus hobbling his movements and preventing him seeing where he is to put his feet. If he has to clamber a steep hill with you, leave him unlimited head-room, for it is a great ease to a horse to be able to stretch his neck, instead of being held tightly in by nervous hands, which is frequently the occasion of his stumbling.

Should your horse show temper and attempt to back with you, leave him the rein, touch him lightly with your heel, and speak encouragingly to him; should he persist, your attendant must look to the matter; but a horse who possesses this dangerous vice should never be ridden by a lady. I have surmised that yours has been properly trained, and doubtless you might ride for the greater portion of a lifetime without having to encounter a decided jibber, but it is as well to be prepared for all emergencies. Should a horse at any time rear with you, throw the rein loose, sit close, and bring your whip sharply across his flank. If this is not effectual, you may give him the butt-end of it between the ears, which will be pretty sure to bring him down. This is a point, however, upon which I write with considerable reserve, for many really excellent riders find fault with the theory set forth and adopted by me. One old sportsman in particular shows practically how seriously he objects to it by suffering himself to be tumbled back upon almost daily by a vicious animal, in preference to adopting coercive measures for his own safety.

My reasons for striking a rearing horse are set forth with tolerable clearness in one of the letters which form an appendix to this volume; but, although I do it myself, I do not undertake the responsibility of advising others to do likewise, especially if a nervous timidity form a portion of their nature. I am strongly of opinion, however, that decisive measures are at times an absolute necessity, and that the most effectual remedy for an evil is invariably the best to adopt. I have heard it said by two very eminent horsemen that to break a bottle of water between the ears of a rearing animal is an excellent and effectual cure. Perhaps it may be—and, on such authority, we must suppose that it is—but I should not care to be the one to try it, although I consider no preventive measure too strong to adopt when dealing with so dangerous a vice. A horse may be guilty of jibbing, bolting, kicking, or almost any other fault, through nervousness or timidity, but rearing is a vicious trick, and must be treated with prompt determination. It would be useless to speak encouragingly to a rearer; he is vexing you from vice, not from nervousness, and so he needs no reassurance—do not waste words upon him, but bring him to his senses with promptitude, or whilst you are dallying he may tumble back upon you, and put remonstrance out of your power for some time to come, if not for ever. In striking him, if you do so, do not indulge in the belief that you are safe because he drops quickly upon his fore-legs, but on the contrary, be fully prepared for the kick or buck which will be pretty sure to follow, and which (unless watched for) will be likely to unseat even a most skilful rider. Both rearing and plunging may, however, be effectually prevented by using the circular bit and martingale, procurable at Messrs. Davis, saddlers, 14, Strand, London. This admirable contrivance should be fitted above the mouthpiece of an ordinary snaffle or Pelham bridle. It is infinitely before any other which I have seen used for the same purpose, has quite a separate headstall, and should be put on and arranged before the addition of the customary bridle. Being secured to the breastplate by a standing martingale, it requires no reins.

CHAPTER V.

RUNNING AWAY.—THREE DANGEROUS ADVENTURES.—HOW TO ACT WHEN PLACED IN CIRCUMSTANCES OF PERIL.—HOW TO RIDE A PULLER.—THROUGH THE CITY.—TO A MEET OF HOUNDS.—BOASTFUL LADIES.—A BRAGGART'S RESOURCE.

In the event of a horse running away, you must of course be guided by circumstances and surroundings, but my advice always is, if you have a fair road before you, let him go. Do not attempt to hold him in, for the support which you afford him with the bridle only helps the mischief. Leave his head quite loose, and when you feel him beginning to tire—which he will soon do without the support of the rein—flog him until he is ready to stand still. I warrant that a horse treated thus, especially if you can breast him up hill, will rarely run away a second time. He never forgets his punishment, nor seeks to put himself in for a repetition of it.

I have been run away with three times in my life, but never a second time by the same horse. It may amuse you to hear how I escaped upon each occasion.

The first time, I was riding a beautiful little thoroughbred mare, which a dear lady friend—now, alas! dead—had asked me to try for her. The mare had been a flat-racer, and, having broken down in one of her trials, had been purchased at a cheap rate, being still possessed of beauty and a considerable turn of speed.

Well, we got on splendidly together for an hour or so on the fifteen acres, Phœnix Park, but, when returning homewards, some boys who were playing close by struck her with a ball on the leg. In a second she was off like the wind, tearing down the long road which leads from the Phœnix to the gates. She had the bit between her teeth, and held it like a vice. My only fear was lest she should lose her footing and fall, for the roadway was covered from edge to edge with new shingle. On she went in her mad career, amidst the shrieks of thousands, for the day was Easter Monday, and the park was crowded. Soldiers, civilians, lines of policemen strove to form a barrier for her arrest. In vain! She knocked down some, fled past others, and continued her headlong course.

All this time I was sitting as if glued to my saddle. At the mare's first starting I had endeavoured to pull her up, but finding that this was hopeless, I left the rein loose upon her neck. Having then no support for her head, she soon tired, and the instant I felt her speed relaxing I took up my whip and punished her within an inch of her life. I made her go when she wanted to stop, and only suffered her to pull up just within the gates, where she stood covered with foam and trembling in every limb.

Her owner subsequently told me that during the three years which she afterwards kept her she never rode so biddable a mare.

I must not forget to mention the comic side of the adventure as well as the more serious. It struck me as being particularly ludicrous upon that memorable occasion that an old gentleman, crimson with wrath, actually attacked my servant in the most irate manner because he had not clattered after me during the progress of the mare's wild career. "How dare you, sir," cried this irascible old gentleman, "how dare you attempt to neglect your young lady in this cowardly manner?" Nor was his anger at all appeased when informed that I as a matron was my own care-taker, and that my attendant had strict injunctions not to follow me in the event of my horse being startled or running away.

My next adventure was much more serious, and occurred also within the gates of the Phœnix Park.

Some troops were going through a variety of manœuvres preparing for a field-day, and a knot of them had been posted behind and around a large tree with fixed bayonets in their hands. Suddenly they got the order to move, and at the same instant the sun shone out and glinted brilliantly upon the glittering steel. I was riding a horse which had lately been given me; a fine, raking chestnut, with a temper of his own to manage. He turned like a shot, and sped away at untold speed. I had no open space before me; therefore I durst not let him go. It was an enclosed portion of the park, thickly studded with knots of trees, and I knew that if he bore me through one of these my earthly career would most probably be ended. I strove with all the strength and all the art which I possessed to pull him up. It was of no use. I might as well have been pulling at an oak-tree; it only made him go the faster.

Happily my presence of mind remained. I saw at once that my only chance was to breast him against the rails of the cricket-ground, and for these I made straight, prepared for the shock and for the turn over which I knew must inevitably follow. He dashed up to the rails, and when within a couple of inches of them he swerved with an awful suddenness, which, only that I was accustomed to ride from balance, must have at once unseated me, and darted away at greater speed than ever. Right before me was a tree, one heavy bough of which hung very low—and straight for this he made, nor could I turn his course. I knew my fate, and bent on a level with my saddle, but not low enough, for the branch caught me in the forehead and sent me reeling senseless to the ground.

I soon got over the shock, although my arm (which was badly torn by a projecting branch) gave me some trouble after; but the bough was cut down the next day by order of the Lord Lieutenant, and the park-rangers still point out the spot as the place where "the lady was nearly killed."

My third runaway was a hunting adventure, and occurred only a few months since.

I had a letter one morning from an old friend, informing me that a drag-hunt was to take place about thirty miles from Dublin to finish the season with the county harriers, and that he, my friend, wished very much that I would come down in my habit by the mid-day train and ride a big bay horse of his, respecting which he was desirous of obtaining my opinion. I never take long to make up my mind, so, after a glance at my tablets, which showed me that I was free for the day, I donned my habit, and caught the specified train.

At the station at the end of my journey I found the big bay saddled and awaiting me, and having mounted him I set off for the kennels, from a field near which the drag was to be run. I took the huntsman for a pilot, knowing that the servant, who was my attendant, was rather a duffer at the chase.