Title: The Balkan Peninsula

Author: Frank Fox

Release date: May 13, 2012 [eBook #39688]

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bruce Albrecht, Margo Romberg and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

AGENTS

America The Macmillan Company 64 & 66 Fifth Avenue, New York

Australasia The Oxford University Press 205 Flinders Lane, Melbourne

Canada The Macmillan Company of Canada, Ltd. St. Martin's House, 70 Bond Street, Toronto

India Macmillan & Company, Ltd. Macmillan Building, Bombay 309 Bow Bazaar Street, Calcutta

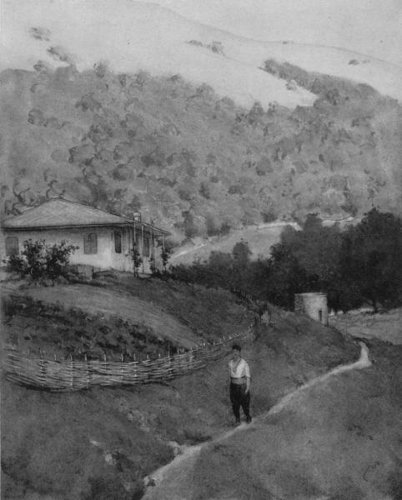

A BALKAN PEASANT

A BALKAN PEASANT

BY

FRANK FOX

AUTHOR OF

"AUSTRALIA," "BULGARIA," "SWITZERLAND," ETC.

PUBLISHED BY A. & C. BLACK, LTD.

4, 5, & 6 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W.

1915

This book was written in the spring of 1914, just before Germany plunged the world into the horrors of a war which she had long prepared, taking as a pretext a Balkan incident—the political murder of an Austrian prince by an Austrian subject of Serb nationality. Germany having prepared for war was anxious for an occasion which would range Austria by her side. If Germany had gone to war at the time of the Agadir incident, she knew that Italy would desert the Triple Alliance, and she feared for Austria's loyalty. A war pretext which made Austria's desertion impossible was just the thing for her plans.

It would be impossible to reshape this book so as to bring within its range the Great War, begun in the Balkans, and in all human probability[vi] to be decided finally by battles in the Balkans. I let it go out to the public as impressions of the Balkans dated from the end of 1913. It may have some value to the student of contemporary Balkan events.

My impressions of the Balkan Peninsula were chiefly gathered during the period 1912-13 of the war of the Balkan allies against Turkey, and of the subsequent war among themselves. I was war correspondent for the London Morning Post during the war against Turkey and penetrated through the Balkan Peninsula down to the Sea of Marmora and the lines of Chatalja. In war-time peoples show their best or their worst. As they appeared during a struggle in which, at first, the highest feelings of patriotism were evoked, and afterwards the lowest feelings of greed and cruelty, the Balkan peoples left me with a steady affection for the peasants and the common folk generally; a dislike and contempt, which made few exceptions, for the politicians and priests who governed their destinies. Perhaps when they settle down to a more peaceful existence—if ever they do—the[vii] inhabitants of the Balkan Peninsula will come to average more their qualities, the common people becoming less simple-minded, obedient, chaste, kind: their leaders learning wisdom rather than cunning, and getting some sense of the value of truth and also some sense of ruth to keep them from setting their countrymen at one another's throats. But at the present time the picture which I have to put before the reader, with its almost unbelievable contradictions of courage and gentleness on the one side and cowardly cruelty on the other, is a true one.

The true Balkan States are Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro, and Albania. Roumania is proud to consider herself a Western State rather than a semi-Eastern Balkan State, though both her position and her diplomacy link her closely with Balkan developments. Turkey, of course, cannot be considered in any sense as a Balkan State though she still holds the foot of the Balkan Peninsula. Greece has prouder aspirations than to be considered one of the struggling nationalities of the Balkans and dreams of a revival of[viii] the Hellenic Empire. But in considering the Balkan Peninsula it is not possible to exclude altogether the Turk, the Greek, the Roumanian. My aim will be to give a snapshot picture of the Balkan Peninsula, looking at it as a geographical entity for historical reference, and to devote more especial attention to the true Balkan States.

FRANK FOX.

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | The Vexed Balkans | 1 |

| II. | The Turk in the Balkans | 19 |

| III. | The Fall of the Turkish Power | 37 |

| IV. | The Wars of 1912-13 | 53 |

| V. | A Chapter in Balkan Diplomacy | 78 |

| VI. | The Troubles of a War Correspondent in the Balkans | 94 |

| VII. | Jottings from my Balkan Travel Book | 124 |

| VIII. | The Picturesque Balkans | 149 |

| IX. | The Balkan Peoples in Art and Industry | 162 |

| X. | The Future of the Balkans | 175 |

| Index | 207 |

| FACING PAGE | |

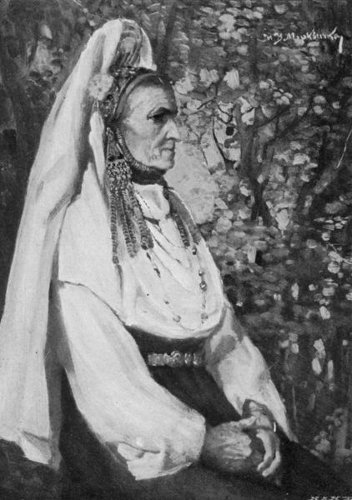

| A Balkan Peasant | Frontispiece |

| Trajan's Column in Rome | 7 |

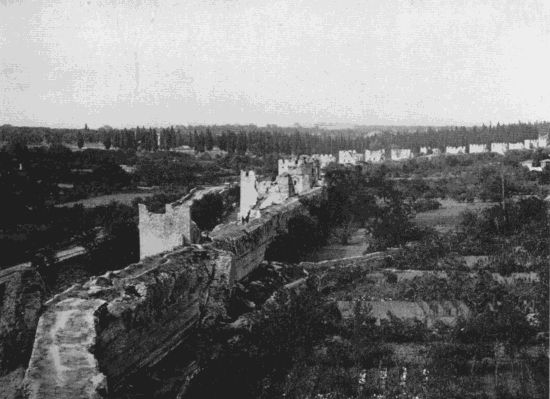

| The Walls of Constantinople from the Seven Towers | 10 |

| Sancta Sophia, Constantinople | 21 |

| King Peter of Serbia | 28 |

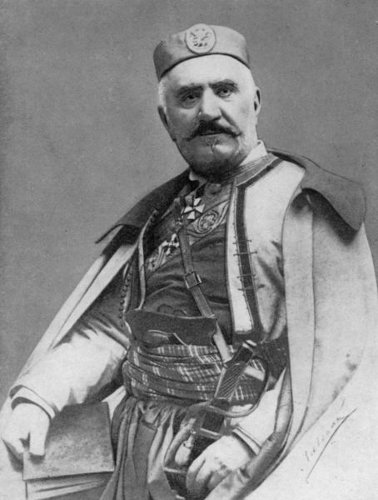

| King Nicolas of Montenegro | 33 |

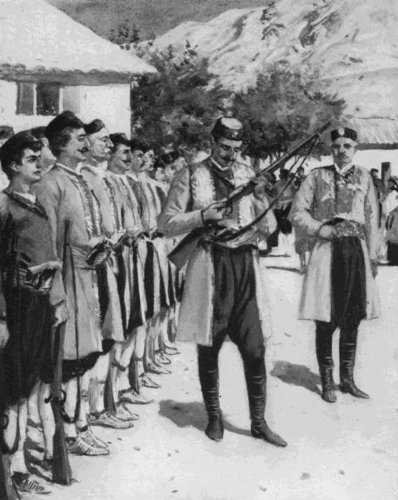

| Montenegrin Troops: Weekly Drill and Inspection of Weapons | 35 |

| The King of Roumania | 39 |

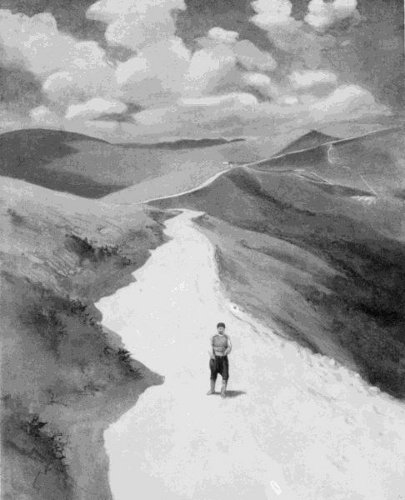

| The Shipka Pass | 42 |

| King Ferdinand of Bulgaria | 46 |

| King Ferdinand's Bodyguard | 48 |

| Bulgarian Infantry | 53 |

| Bulgarian Troops leaving Sofia | 60 |

| General Demetrieff, the Conqueror at Lule Burgas | 69 |

| Adrianople: A General View | 76 |

| Roumanian Soldiers in Bucharest | 85 |

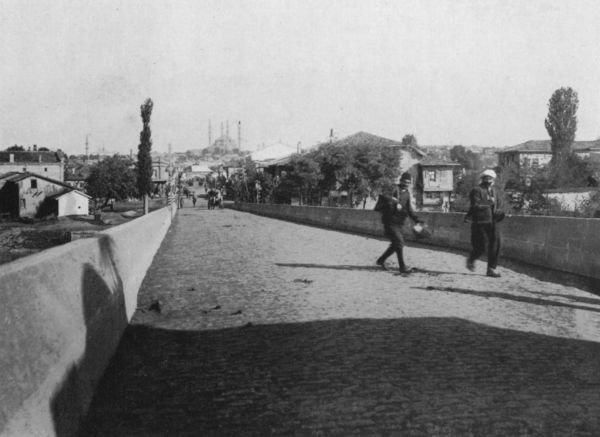

| Adrianople: View looking across the Great Bridge | 88 |

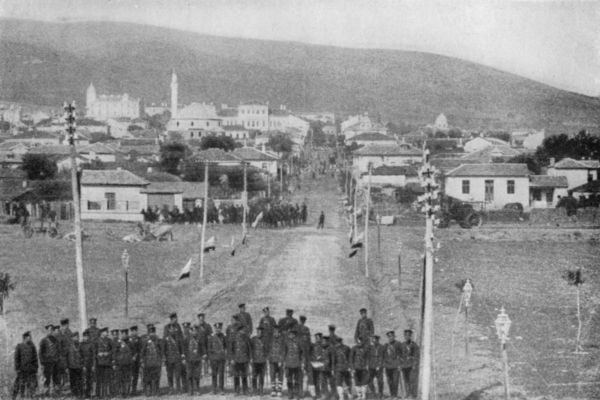

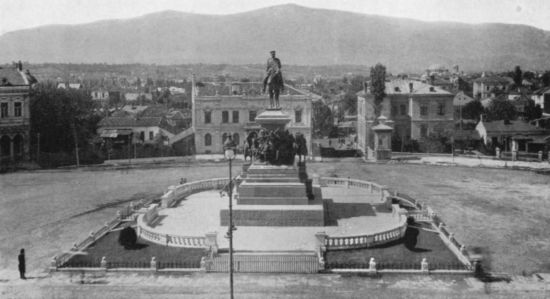

| General View of Stara Zagora, Bulgaria | 92 [xi] |

| Sofia: Commercial Road from Commercial Square | 101 |

| Bucharest: The Roumanian House of Representatives | 108 |

| General Savoff | 117 |

| Bulgarian Infantry | 124 |

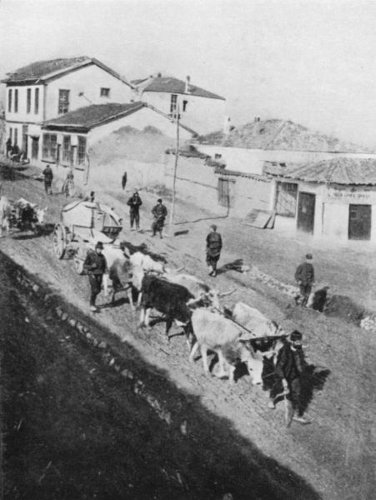

| Ox Transport in the Balkans | 133 |

| A Balkan Peasant Woman | 136 |

| A Bagpiper | 140 |

| Some Serbian Peasants | 149 |

| General View of Sofia | 156 |

| Bucharest | 161 |

| A Bulgarian Farm | 166 |

| Albanian Tribesmen | 176 |

| Greek Infantry | 181 |

| Podgorica, upon the Albanian Frontier | 188 |

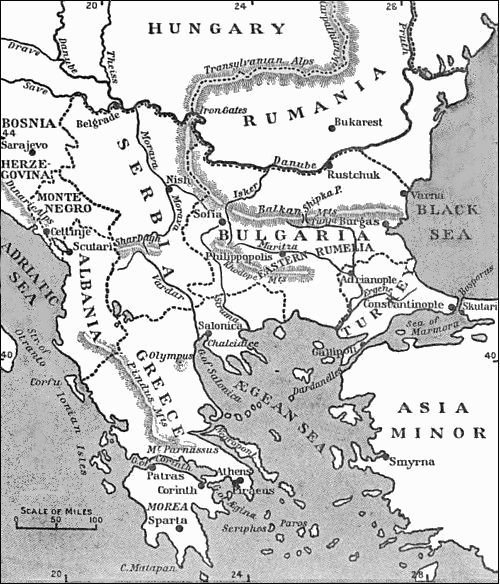

Sketch Map on page xii.

SKETCH MAP OF THE BALKAN PENINSULA

SKETCH MAP OF THE BALKAN PENINSULA

The Fates were unkind to the Balkan Peninsula. Because of its position, it was forced to stand in the path of the greatest racial movements of the world, and was thus the scene of savage racial struggles, and the depositary of residual shreds of nations surviving from great defeats or Pyrrhic victories and cherishing irreconcilable mutual hatreds. As if that were not enough of ill fortune imposed by geographical position, the great Roman Empire elected to come from its seat in the Italian Peninsula to die in the Balkan Peninsula, a long drawn-out death of many agonies, of many bloody disasters and desperate retrievals. For all the centuries of which history knows a blood-mist has hung over the Balkans; and for the[2] centuries before the dawn of written history one may surmise that there was the same constant struggle of warring races.

It seems fairly certain that when the Northern peoples moved down from their gloomy forests towards the Mediterranean littoral to mingle their blood with the early peoples of the Minoan civilisation and to found the Grecian and the Roman nations, the chief stream of these fierce hordes moved down by the valley of the Danube and debouched on the Balkan Peninsula. Doubtless they fought many a savage battle with the aborigines in Thessaly and Thrace. Of these battles we have no records, and no absolute certainty, indeed, that the Mediterranean shore was colonised by a race from the North, though all the facts that we are learning now from the researches of modern archaeologists point to that conclusion. But whatever the prehistoric state of the Balkan Peninsula, the first sure records from written history show it as a vexed area peopled by widely different and mutually warring races, and subject always to waves of war and invasion from the outside. The Slav historian Jireček concludes that the Balkan Peninsula was inhabited at the earliest times[3] known to history by many different tribes belonging to distinct races—the Thraco-Illyrians, the Thraco-Macedonians, and the Thraco-Dacians. At the beginning of the third century, the Slavs made their first appearance and, crossing the Danube, came to settle in the great plains between the river and the Balkan Mountains. Later, they proceeded southwards and formed colonies among the Thraco-Illyrians, the Roumanians, and the Greeks. This Slav emigration went on for several centuries. In the seventh century of the Christian era a Finno-ugric tribe reached the banks of the Danube. This tribe came from the Volga, and, crossing Russia, proceeded towards ancient Moesia, where it took possession of the north-east territory of the Balkans between the Danube and the Black Sea. These were the Bulgars or Volgars, near cousins to the Turks who were to come later. The Bulgars assumed the language of the Slavs, and some of their customs. The Serbs or Serbians, coming from the Don River district had been near neighbours of the Volgars or Bulgars (in the Slav languages "B" and "V" have a way of interchanging), and were without much doubt closely allied to them in race originally. Later, they diverged, tending more to the[4] Slav type, whilst the Bulgars approached nearer to the Turk type.

There may be traced, then, in the racial history of the Balkans these race types: a Mediterranean people inhabiting the sea-coast and possessing a fairly high civilisation, the records of which are being explored now in the Cretan excavations; an aboriginal people occupying the hinterland of the coast, not so highly cultivated as the coast dwellers (who had probably been civilised by Egyptian influences) but racially akin to them; a Northern people coming from the shores of the Baltic and the North Sea before the period of written history and combining ultimately with the people of the coast to found the Grecian civilisation, leaving in the hinterland, as they passed towards the sea, detachments which formed other mixed tribes, partly aboriginal, partly Nordic; various invading peoples of Semitic type from the Levant; the Romans, the Goths and the Huns, the Slavs and the Tartars, the Bulgars and the Serbs, the Normans, Saracens, and Turks. Because the Balkan Peninsula was on the natural path to a warm-water port from the north to the south of Europe; because it was on the track of invasion and counter-invasion between Asia[5] and Europe, all this mixture of races was forced upon it, and as a consequence of the mixture a constant clash of warfare. There was, too, a current of more peaceful communication for purposes of trade between the Levant and the Black Sea on the one side and the peoples of the Baltic Sea on the other side, which flowed in part along the Balkan Peninsula.

In Italy and her Invaders Mr. T. Hodgkin suggests:

During the interval from 540 to 480 b.c. there was a brisk commercial intercourse between the flourishing Greek colonies on the Black Sea, Odessos, Istros, Tyras, Olbia and Chersonesos—places now approximately represented by Varna, Kustendjix, Odessa, Cherson, and Sebastopol—between these cities and the tribes to the northward (inhabiting the country which has been since known as Lithuania), all of whom at the time of Herodotus passed under the vague generic name of Scythians. By this intercourse which would naturally pass up the valleys of the great rivers, especially the Dniester and the Dnieper, and would probably again descend by the Vistula and the Niemen, the settlements of the Goths were reached, and by its means the Ionian letter-forms were communicated to the Goths, to become in due time the magical and mysterious Runes.

One fact which lends great probability to this theory is that undoubtedly, from very early times, the amber deposits of the Baltic, to which allusion has already been made, were known to the civilised world; and thus[6] the presence of the trader from the South among the settlements of the Guttones or Goths is naturally accounted for. Probably also there was for centuries before the Christian Era a trade in sables, ermines, and other furs, which were a necessity in the wintry North and a luxury of kings and nobles in the wealthier South. In exchange for amber and fur, the traders brought probably not only golden staters and silver drachmas, but also bronze from Armenia with pearls, spices, rich mantles suited to the barbaric taste of the Gothic chieftains. As has been said, this commerce was most likely carried on for many centuries. Sabres of Assyrian type have been found in Sweden, and we may hence infer that there was a commercial intercourse between the Euxine and the Baltic, perhaps 1300 years before Christ.

A few leading facts with dates should give a fairly clear impression of the story of the Balkan Peninsula. About 400 b.c. the Macedonian Empire was being founded. It represented the uprise of a hinterland Greek people over the decayed greatness of the coast-dwelling Greeks. At that time the northern part of the Balkan Peninsula was occupied by the Getae or Dacians. Phillip of Macedon made an alliance with the Getae. Alexander the Great of Macedonia thrashed them to subjection and carried a great wave of invasion into Asia from the Balkan Peninsula.

TRAJAN'S COLUMN IN ROME

TRAJAN'S COLUMN IN ROMEAbout the year 110 b.c. the Romans first came to the Balkan Peninsula, finding it inhabited as regards the south by the Greek peoples, as regards the north by the Getae or Dacians. The southern people were quickly subdued: the northern people were never really subdued by the Romans until the time of Trajan (the first century of the Christian era). He bridged the Danube with a great military bridge at the spot now known as Turnu-Severin, and Trajan's Column in Rome commemorated the victories which brought all the Balkan Peninsula under the Roman sway. Trajan found that the manners and customs of the Dacians were similar to those of the Germans. These sturdy Dacians were conquered but not exterminated by the Romans. Dacia across the Danube was made into a Roman colony, and the present kingdom of Roumania is supposed to represent the survival of that colony, which was a mixture of Roman and Dacian blood.

In the third century of the Christian era the Goths made their first appearance in the Balkan Peninsula. The Roman Empire had then entered into its period of decline. The invasions of the Visigoths, the Huns, the Vandals, the Ostrogoths,[8] and the Lombards were to come in turn to overwhelm the Roman civilisation. The Gothic invasion of the Balkan Peninsula was begun in the reign of the Roman Emperor Phillip. Crossing the Danube, the Goths ravaged Thrace and laid siege to Marcianople (now Schumla) without success. In a later invasion the Goths attacked Philippopolis and captured it after a great defeat of the Roman general, Decius the younger. Then the Roman Emperor (Decius the elder) himself took the field and was defeated and killed in a great battle near the mouth of the Danube (a.d. 251). That may be called the decisive date in the history of the fall of the Roman Empire. It was destined to retrieve that defeat, and to shine with momentary glory again for brief intervals, but the destruction of the Emperor and his army by the Goths in 251 was the sure presage of the doom of the Roman Power.

One direct result of the battle in which Decius was slain was to bring the headquarters of the Roman Empire to the Balkan Peninsula. It was found that a better stand could be made against the tide of Gothic invasion from a new capital closer to the Scythian frontier. Constantinople was planned and built, and became[9] the capital of the Roman Empire (a.d. 330), and thus brought to the Balkan stage the death throes of the mightiest world-power that history has known. From that date it is wise for the sake of clearness to speak of the Roman Empire as the Greek Empire, though it was some time after its settlement in Constantinople before it became rather Greek than Roman in character.

With the issue between the Goths and the Greek Empire, in which peaceful agreements often interrupted for a while fierce campaigns, I cannot deal here at any length. It soaked the Balkan Peninsula deep in blood. But it was only the first of the horrors that were to mark the death of the Empire. Late in the fourth century of the Christian Era there burst into the Balkans from the steppes of Astrakhan and the Caucasus—from very much the same district that was afterwards to supply the Bulgars and the Serbs—the Tartar hordes of the Huns. Of these Huns there is a vivid contemporary Gothic account.

We have ascertained that the nation of the Huns, who surpassed all others in atrocity, came thus into being. When Filimer, fifth king of the Goths after their departure from Sweden, was entering Scythia, with his people, as we have before described, he found[10] among them certain sorcerer-women, whom they called in their native tongue Haliorunnas (or Al-runas), whom he suspected and drove forth from the midst of his army into the wilderness. The unclean spirits that wander up and down in desert places, seeing these women, made concubines of them; and from this union sprang that most fierce people [of the Huns], who were at first little, foul, emaciated creatures, dwelling among the swamps, and possessing only the shadow of human speech by way of language.

Sébah & Joaillier

THE WALLS OF CONSTANTINOPLE FROM THE SEVEN TOWERS

With the Alani especially, who were as good warriors as themselves, but somewhat less brutal in appearance and manner of life, they had many a struggle, but at length they wearied out and subdued them. For, in truth, they derived an unfair advantage from the intense hideousness of their countenances. Nations whom they would never have vanquished in fair fight fled horrified from those frightful—faces I can hardly call them, but rather—shapeless black collops of flesh, with little points instead of eyes. No hair on their cheeks or chins gives grace to adolescence or dignity to age, but deep furrowed scars instead, down the sides of their faces, show the impress of the iron which with characteristic ferocity they apply to every male child that is born among them, drawing blood from its cheeks before it is allowed its first taste of milk. They are little in stature, but lithe and active in their motions, and especially skilful in riding, broad-shouldered, good at the use of the bow and arrows, with sinewy necks, and always holding their heads high in their pride. To sum up, these beings under the form of man hide the fierce nature of the beast!

Not a lovable people the Huns clearly:[11] and the modern peoples who have some slight ancestral kinship with them hate to be reminded of the fact. I remember the fierce indignation which a French war correspondent aroused in Bulgarian breasts by his description—which had eluded the censor—of the passage of a great Bulgarian train of ox wagons because he compared it to the passage of the Huns.

The Huns were, with the exception of the Persians who had vainly attacked the Greek States at an earlier period, the first successful Asiatic invaders of Europe. For a full century they ravaged the Empire, and the Balkan Peninsula felt the chief force of their barbarian rage. By the fifth century the waves of the Hun invasions had died away, leaving distinct traces of the Hunnish race in the Balkans. The Gepidae, the Lombards, and later the Hungarians and the Tartars then took up the task of ravaging the unhappy land which as the chief seat of power of the Greek Empire found itself the first objective of every invader because of that dignity and yet but poorly protected by that power. Constantinople was never taken by these barbarians, but at some periods little else than its walls stood secure against their ravages.

Meanwhile the first Saracens had appeared in the Peninsula, curiously enough not as invaders nor as enemies, but as mercenary soldiers in the army of the Greek Empire fighting against the Goths. To a Gothic chronicler we are again indebted for a vivid picture of these Saracens, "riding almost naked into battle, their long black hair streaming in the wind, wont to spring with a melancholy howl upon their chosen victim in battle and to suck his life-blood, biting at his throat." Perhaps the Gothic war correspondent of the day studied picturesqueness more than accuracy, like some of his modern successors. But, without a doubt, the first contact with Asiatics, whether Huns or Saracens, gave to the European peoples a horror and a terror which had never been inspired by their battles among themselves—battles by no means bloodless or merciful. As the Asiatic waves of invasion later developed in strength the unhappy Balkan Peninsula was doomed to feel their full force as they poured across the Bosphorus from Asia Minor, and across the Danube from the north-eastern Asiatic steppes.

It would be vain to attempt to chronicle even in the barest outline all the horrors inflicted upon[13] the Balkans from the date of the first invasion of the Huns in the fourth century to the first invasion of the Turks in the fourteenth century. To say that those ten centuries were filled with bloodshed suffices. But they also saw the development of the Balkan nationalities of to-day, and cannot therefore be passed over without some attention. Let us then glance at each Balkan nation during that period.

Roumania, inhabited by the people of the old Roman-Dacian colony, stood full in the way of the Northern invasions of Goths, of Huns, of Hungarians, of Tartars. It was almost submerged. But in the thirteenth century the country benefited by the coming of Teutonic and Norman knights. The two kingdoms or principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia (which, combined, make up modern Roumania) were founded in this century.

Bulgaria.—In the seventh century Slavs had begun to settle in Bulgaria. The Bulgars or Volgars followed. They were akin to the Tartars and the Turks. Together Slavs and Bulgars formed the Bulgarian national type and founded a very robust nation which was almost constantly at war with the Greek Empire (with its capital[14] at Constantinople). At times Bulgaria seriously threatened Constantinople and the Greek Empire. A boastful inscription in the Church of the Forty Martyrs at Tirnovo, the ancient capital of Bulgaria, records:

In the year 1230, I, John Asên, Czar and Autocrat of the Bulgarians, obedient to God in Christ, son of the old Asên, have built this most worthy church from its foundations, and completely decked it with paintings in honour of the Forty holy Martyrs, by whose help, in the 12th year of my reign, when the Church had just been painted, I set out to Roumania to the war and smote the Greek army and took captive the Czar Theodore Komnenus with all his nobles. And all lands have I conquered from Adrianople to Durazzo, the Greek, the Albanian, and the Serbian land. Only the towns round Constantinople and that city itself did the Franks hold; but these too bowed themselves beneath the hand of my sovereignty, for they had no other Czar but me, and prolonged their days according to my will, as God had so ordained. For without him no word or work is accomplished. To him be honour for ever. Amen.

The wars were carried on under conditions of mutual ferocity which still rule in Bulgarian-Grecian conflicts. An incident of one campaign was that the Greek Emperor, Basil, the Bulgar-slayer, having captured a Bulgarian army, had the eyes torn out of all the men and sent them[15] home blinded, leaving, however, one eye to every centurion, so that the poor mutilated wretches might have guides. In the early part of the fourteenth century a Bulgarian Czar, Michael, almost captured Constantinople. He formed a league with the Roumanians and the Greeks against the Serbs, who were at the time promising to become the paramount power of the peninsula. But Czar Michael was defeated by the Serbs and Bulgaria became dependent upon Serbia, which was the position of affairs at the time of the first serious Turkish invasion of the Balkan Peninsula.

Serbia.—Invading tribes of Don Cossacks began to come in great numbers to the Balkan Peninsula in the sixth century. In the seventh century they were encouraged by the Greek Empire to settle in Serbia, on condition of paying tribute to Constantinople. They set up a kind of aristocratic republic of a Slav type. In the ninth century they began to fight with the neighbouring and kindred Bulgarians. Early in the tenth century (a.d. 917) the Bulgarians almost effaced Serbia from the map; but the Serbs recovered after half a century, only to come shortly afterwards under the sway of the Greeks. In the eleventh[16] century the Serbians held a very strong position and were able to harass the Greek Empire at Constantinople. They entered into friendly relations with the Pope of Rome, and for some time contemplated following the Roman rather than the Eastern Church. In the twelfth century King Stephen of Serbia was a valued ally of the Greek Empire against the Venetians. He established Serbia as a European "Power," and the Emperor Frederick Barbarossa visited his court at Belgrade. This king was the first of a succession of able and brave monarchs, and Serbia enjoyed a period of stable prosperity and power unusually lengthy for the Balkans. Except for the strife between the Eastern and Roman Catholic Churches for supremacy in Serbia, the nation was at peace within her own borders, and enjoyed not only a military but an economic predominance in the Balkans. Mining and handicrafts were developed, education encouraged, and the national organisation reached fully to the average standard of European civilisation at the time. By 1275 the Serbs were the chief power in the Balkans. They defeated the Greeks, marched right down to the Aegean and reached the famous monastery of Mount Athos, to which[17] the first King Stephen (Nemanya) had retired in 1195 when he abdicated.

In 1303 the Serbians forgot their quarrel with the Greeks and helped them against the Turks, undertaking an invasion of Asia Minor. In 1315 they again saved the Greek Empire from the Turks. When in 1336 Stephen Dushan, the greatest of Serbian kings, who has been compared to Napoleon because of his military genius and capacity for statesmanship, came to the throne, Bulgaria was under the suzerainty of Serbia, and the Serb monarch ruled over all that area comprised within the boundaries of Bulgaria, Serbia, Albania, Montenegro, and Greece by the recent treaty of Bucharest (1913). King Stephen Dushan was not only a great military leader, he was also a law-maker and a patron of learning. His death on December 13, 1356, at the Gates of Constantinople—he is said to have been poisoned—opened the way for the Turkish occupation of the Balkan Peninsula. That occupation was made possible in the first instance by the mutual jealousies of the Christian peoples of the Balkans. It was kept in existence for centuries by the same weaknesses arising from jealousy. In 1912 it was swept away in a month because in a spasm[18] of common sense the Balkan Christian peoples had united. In 1913 it was in part restored because internecine strife had broken out again among the Balkan natives recently allied. It will probably continue until the lesson of unity is learned again.

It seems to be difficult to speak without violent prejudice on the subject of the Turk in the Balkans. One school of prejudice insists that the Turk is the finest gentleman in the world, who has been always the victim and not the oppressor of the Christian peoples by whose side he lives, and whose territories he invaded with the best of motives and with the minimum of slaughter. The other school of prejudice credits the Turk with the most abominable cruelty, treachery, and lust, and will hear no good of him. In England the issue is largely a political one. A great Liberal campaign was once founded on a Turkish massacre of Bulgarians in the Balkans. That made it a party duty for Liberals to be pro-Bulgarian and anti-Turk, and almost a party duty for Conservatives to find all the[20] Christian and a few ex-Christian virtues in the Turk. Before attempting to judge the Turk of to-day, let us see how he stands in the light of history. It was in the fourth century that the first Saracens came to the Balkan Peninsula as allies of the Greek Empire against the Goths. They were thus called in by a Christian Power in the first instance. It was not until the fourteenth century that the Turks made a serious attempt to occupy the Balkan Peninsula. They were helped in their campaign considerably by the Christian Crusaders, who, incidentally to their warfare against the Infidel who held the Holy Sepulchre, had made war on the Greek Empire, capturing Constantinople, and thus weakening the power of Christian Europe at its threshold. Bulgaria, too, refused help to the Greeks when the Turkish invasion had to be beaten off. The Turks' coming to the Balkans was thus largely due to Christian divisions.

Sébah & Joaillier

SANCTA SOPHIA, CONSTANTINOPLE

Built by Justinian I, consecrated 538, converted into a Mohammedan mosque 1453. It is now thought that the design of its famous architect, Anthemius of Tralles, was never completed. The minarets and most of the erections in the foreground are Turkish

Without being able at the time to capture Constantinople, the invading Turks occupied soon a large tract of the Balkan Peninsula. By 1362 they had captured Philippopolis and Eski Zagora, two important centres of Bulgaria. It was not a violence to their conscience for some of the Bulgarian men after this to join the Turkish army as mercenaries. When the sorely-beset Greeks sent the Emperor John Paleologos to appeal for help to the Bulgarians, he was seized by them and kept as a prisoner.

A united Balkan Peninsula would have kept off the Turks, no doubt. But a set of small nations without any faculty of permanent cohesion, and hating and distrusting one another more thoroughly than they did the Turk, could do nothing. The Balkan nations of the time, though united they would have been really powerful, allowed themselves to be taken in detail and crushed under the heels of an invader who was alien in blood and in religion. In 1366 the Bulgarians became the vassals of the Turks, and the Serbians were defeated at Kossovo. The fall of the Greek Empire and the subjugation of Roumania followed in due course, and by the seventeenth century the Turks had penetrated to the very walls of Vienna. At one time it seemed as if all Europe would fall under the sway of Islam, for, as elsewhere than in the Balkans, there were Christian States which were treacherous to their faith. But that happily was averted. For the Balkan Peninsula, however,[22] there were now to be centuries of oppression and religious persecution. It will be convenient once again to set forth under three national headings the chief facts regarding the Turkish conquest of the Balkans.

Bulgaria.—By 1366 weakness in the field and civil dissensions had brought Bulgaria to the humiliation of becoming the vassal of the Turk. In 1393 the Turks, not content with mere suzerainty, occupied Bulgaria and converted it into a Turkish province. In 1398 the Hungarians and the Wallachians (Roumanians) made a gallant attempt to free Bulgaria from the Turkish yoke, but failed. Some of the Bulgarians joined in with their Turkish conquerors, abandoned the Christian religion for that of Islam, and were the ancestors of what are known to-day as the Pomaks. The rest of the people gave a reluctant obedience to the Turkish conqueror, preserving their Christian faith, their Slav tongue, and their sense of separate nationality. The Greeks, who had come to some kind of terms with the Turkish invaders, assisted to bring the Bulgarian people under subjection. The Greek church and the Greek tongue rather than the Turkish were sought to be imposed upon the Bulgarians. The[23] subject people accepted the situation with occasional revolts, but more tamely than some other Balkan nations. It was not a general meek acquiescence, though it was—possibly by chance, possibly because of the fact that a racial relationship existed between conqueror and conquered—not so fierce in protest as that of the Serbians. In writing that, I do not follow exactly the Bulgarian modern view, which represents as much more vivid the sufferings and the protests of the Bulgarian people, and ignores altogether the racial relationship which existed between Bulgarian and Turk, and enabled a section of the Bulgarian nation to fall into line with the conqueror and embrace his religion and his habits of life, a relationship which to this day shows its traces in the Bulgarian national life. But in Balkan history as written locally, there is usually a certain amount of political deflection from the facts. A modern Balkan historian, giving what may be called the official national account of the times of the Turkish domination, says (Bulgaria of To-day):

Had the rulers been of the same race and religion as the vanquished, the subjection might have been more tolerable. Ottoman domination was not, however, a[24] simple political domination. Ottoman tyranny was social as well as political. It was keenly and painfully felt in private as well as in public life; in social liberty, manners and morals; in the free development of national feeling; in short, in the whole scope of human life. According to our present notions, political domination does not infringe upon personal liberty, which is sacred for the conqueror. This is not the case with Turkish rule. The Bulgarians, like the other Christians of the Balkan Peninsula, were, both collectively and individually, slaves. The life, possessions, and honour of private individuals were in constant peril. The bulk of the people, after several generations, calmed down to passivity and inertia. From time to time the more vigorous element, the strongest individualities, protested. Some Bulgarian whose sister had been carried off to the harem of some pasha would take to the mountains and make war on the oppressors. The haidukes and voivodes, celebrated in the national songs, kept up in mountain fastnesses that spirit of liberty which later was to serve as a cement to unite the new Bulgarian nation.

But it is a noteworthy fact that the Osmanlis, being themselves but little civilised, did not attempt to assimilate the Bulgarians in the sense in which civilised nations try to effect the intellectual and ethnic assimilation of a subject race. Except in isolated cases, where Bulgarian girls or young men were carried off and forced to adopt Mohammedanism, the government never took any general measures to impose Mohammedanism or assimilate the Bulgarians to the Moslems. The Turks prided themselves on keeping apart from the Bulgarians, and this was fortunate for our nationality. Contented with their political supremacy and pleased to feel themselves[25] masters, the Turks did not trouble about the spiritual life of the rayas, except to try to trample out all desires for independence. All these circumstances contributed to allow the Bulgarian people, crushed and ground down by the Turkish yoke, to concentrate and preserve its own inner spiritual life. They formed religious communities attached to the churches. These had a certain amount of autonomy, and, beside seeing after the churches, could keep schools. The national literature, full of the most poetic melancholy, handed down from generation to generation and developed by tradition, still tells us of the life of the Bulgarians under the Ottoman yoke. In these popular songs, the memory of the ancient Bulgarian kingdom is mingled with the sufferings of the present hour. The songs of this period are remarkable for the oriental character of their times, and this is almost the sole trace of Moslem influence.

In spite of the vigilance of the Turks, the religious associations served as centres to keep alive the national feeling.

A conquered people which was allowed to keep up its religious institutions (with "a certain amount of autonomy"), and later to found national schools ("to keep alive the national feeling"), was not exactly ground to the dust. And truth compels the admission that Bulgaria under Turkish rule enjoyed a certain amount of material prosperity. When the Russian liberators of the nineteenth century came to[26] Bulgaria they found the peasants far more comfortable than were the Russian peasants of the day. The atrocities in Bulgaria which shocked Europe in 1875 were not the continuance of a settled policy of cruelty and rapine. They were the ferocious reprisals chiefly of Turkish Bashi-Bazouks (irregulars) following upon a Bulgarian rising. The Turks felt that they had been making an honest effort to promote the interests of the Bulgarian province. They had just satisfied a Bulgarian aspiration by allowing of the formation of an independent Bulgarian church, though this meant giving grave offence to the Greeks. Probably they felt that they had a real grievance against the Bulgars. After the Bulgarian atrocities of 1875 there ended the Turkish domination of the country.

Serbia.—In December 1356 the great Serbian king, Stephen Dushan, soldier, administrator, and economist, died before the walls of Constantinople, and the one hope of the Balkan Peninsula making a stand against the Turks was ended. Shortly after, the Turks had occupied Adrianople, their first capital in Europe, defeating heavily a combined Serbian and Greek army. Later the Serbian forces were again defeated by the great[27] Turkish sultan Amurath I., and the Serbian king was killed on the battle-field. King Lazar, who succeeded to the Serbian throne, made some headway against the invaders, but in 1389, at the Battle of Kossovo, the Serbian Empire came tumbling to ruins. The Turkish leader, Amurath, was killed in the fight, but his son Bajayet proved another Amurath and pressed home the victory. Serbia became a vassal state of Turkey.

But there was to be still a period of fierce resistance to the Turk. In 1413 the Turks, dissatisfied with the attitude of the Serbs, entered upon a new invasion of the territory of Serbia. In 1440 Sultan Amurath II. again overran the country and conquered it definitely, imposing not merely vassalage but armed occupation on its people. John Hunyad, "the White Knight of Wallachia," came to the rescue of the Serbs, and Amurath II. was driven back. An alliance between Serbs and Hungarians kept the Turk at bay for a time, and in 1444 Serbia could claim to be free once again. But the respite was a brief one. In 1453 Constantinople fell to the Turks, and the full tide of their strengthened and now undivided power was turned upon Serbia. A siege of Belgrade in 1457 was repulsed, but in 1459 Serbia was conquered and annexed[28] to European Turkey. Lack of unity among the Serbs themselves had contributed greatly to the national doom, but on the whole the Serbs had put up a gallant fight against the Turks. And even now a section of them, the Montenegrins, in their mountain fastnesses kept their liberty, and through all the centuries that were to follow never yielded to the Crescent.

The condition of the Serbs in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was very unhappy. They could come to no manner of contentment with Turkish rule, and sporadic revolts were frequent. At times the Hungarians from the other side of the Danube came to the aid of the revolters, but never in such strength as to shake seriously the Turkish power. Very many of the Serbs left their country in despair and sought refuge under the Austrian flag. To-day a big Serb element, under the flag of Austro-Hungaria, is one of the racial difficulties of the Dual Monarchy.

Underwood & Underwood

KING PETER OF SERBIA

The Serb exiles carried to their new homes their old sympathies, and largely because of their efforts Austria in 1788 went to the rescue of Serbia, and for a brief while the land again was free. But the Turkish power returned and[29] Serbia stumbled blindly, painfully through years of reprisals, which culminated in the great massacre of Serbs by Turks in 1804, which, like the Turkish massacre of Bulgarians in 1875, really declared the doom of the Turkish power in the country. Following this massacre George Petrovic, "Black George," or "Kara George," as the Serbians knew him, raised the standard of revolt among his countrymen. He was a fierce blood-stained man, this first liberator of the Serbs, a man on whose head was the blood of his father and his brother. His grim character was fitted for his grim task. The story of that task will come better within the scope of a following chapter, which will tell of the liberation of the Balkans from the Turks.

Roumania.—It was not until 1391 that the Turks crossed the Danube and attacked the kingdoms of Wallachia and Moldavia, and reduced Wallachia to the position of a tributary state. King Mirtsched made a gallant fight against the invaders, but the Turks proved too strong. That was the beginning of a Turkish dominance of Roumania, which was never so complete as that exercised over Bulgaria and Serbia, but left the two Roumanian kingdoms[30] of Wallachia and Moldavia as vassal states. Mutual jealousy between them prevented effective operations against the Turk, and helped to make their vassalage possible. In the fifteenth century both kingdoms had great rulers. Wallachia was ruled by Vlad the Impaler, an able but cruel man, who seems to have earned the infamy of inventing a form of torture still practised in the Balkans as a matter of religious proselytising, that of sitting the victim on a sharp stake, and leaving him to die slowly as the stake penetrated his body. Moldavia had as king Stephen the Great, who has no such ghastly reputation of cruelty. But able princes could effect little with communities weakened by the luxury of the nobles and the helpless poverty of the serfs. Still, the Roumanians had intervals of victory. In the sixteenth century Michael the Brave (whose memory is commemorated by a statue in Bucharest) drove the Turks back as far as Adrianople, liberating Roumania and Bulgaria. He annexed Moldavia and Transylvania to Wallachia, and was in a sense the founder of modern Roumania. But the union thus effected was not enduring and the Turkish ascendancy grew stronger. The Turkish suzerain forced upon the[31] Roumanian peoples governors of the Greek race, who carried on the work of oppression and spoliation with an industrious effectiveness quite beyond the capacity of the Turk, who at his worst is a fitful and indolent tyrant.

In the last quarter of the seventeenth century the Russian Power began to take a close interest in Roumania. In 1711 there was a definite Russian-Roumanian alliance. By this time the Roumanians were resolutely hostile to the Turkish domination. True, they had been spared most of the cruelties which were in Servia a customary and in Bulgaria an occasional concomitant of Turkish rule. But they were deeply injured by the corrupt, the luxurious, the exacting administration of the Greek rulers forced upon them by the Turkish government. Though they suffered little from massacre they suffered much from "squeeze." There was not only the greed of the Turk but the greed of the intermediate Greek to be satisfied. From 1711 until the final liberation of Roumania, Roumanian sympathies were generally with the Russians in the frequent wars waged by them against Turkey. In 1770 the Russians occupied Roumania and freed it for a time from the Turk, but in 1774 the[32] Roumanians went back to the Turkish suzerainty. During the Napoleonic wars Russia gave Roumania some reason to doubt the disinterestedness of her friendship by annexing the rich province of Bessarabia, a part of the natural territory of the Roumanian people. The year 1821 saw the outbreak of the Greek war of independence, in which Roumania took no part, having as little love for the Greek as for the Turk. She won one advantage for herself from the war, the right to have her native rulers under Turkish suzerainty. In 1828, as a result of a Russo-Turkish war, Roumania won almost complete freedom, conditional only on tribute being continued to be paid to the Sultan. She found a new master, however, in Russia, and was forced to keep up a Russian garrison within her borders, nominally as a protection against Turkey, really as a safeguard against the growth in her own people of a spirit of national independence. The Crimean War (1853) freed Roumania from this Russian garrison, and in 1856 the Treaty of Paris declared Roumania to be an independent principality under Turkish suzerainty.

Underwood & Underwood

KING NICOLAS OF MONTENEGRO

Montenegro.—The existence of Montenegro as a separate Balkan state dates back to the Battle of Kossovo. The Montenegrin is a Serbian Highlander, and whilst the Serbian Empire flourished, claimed for himself no separate national entity. When, however, the rest of Serbia was subjugated by the Turks, "the Black Mountain" held out, and there gathered within its little area of rocky hill fastnesses the free remnants of the Serbian race. The story of that little nation is quite the most wonderful in all the world. It transcends Sparta, and makes the fighting record of the Swiss seem tame. At the height of its power Montenegro had a population of perhaps 8000 males, and little source of riches from mines, from trade, or even from fertile agricultural land. Yet Montenegro kept the Turks from her own territory, and was able at times to give valuable help to the rest of Europe in withstanding the invasion of Islam.

The system of government instituted was that of a theocratic despotism: the head of the nation was its chief bishop, and he had the right to nominate a nephew (not a son—as a bishop of the Greek Communion he would be celibate) to succeed him. The Montenegrin dynasty was founded in 1696 by King Danilo I., and has endured to this day, though recently the functions[34] of the chief priest and king have been separated, and the present monarch is purely a civil ruler.

It is not possible here to give even the barest mention of the leading facts in the proud history of little Montenegro. In the seventeenth century she was the valued friend of Venice against the Turks; in the eighteenth century she was aided by Peter the Great of Russia; later she met without being subdued the warlike power of Napoleon. All the time, during every century, every year almost, there was constant warfare with the Turks. One campaign lasted without interruption from 1424 to 1436, and was marked by over sixty battles. The little population of the patch of rocks in the mountains was worn down by this incessant fighting, but was recruited by a steady flow of exiles from other parts of the Balkan Peninsula, anxious for freedom and for revenge on the Turk. Sometimes the tide of battle went sorely against the mountaineers, and almost all their country was put under the heel of the Moslem. But always one eyrie was kept for the free eagles, and from it they swooped down with renewed strength to send the invader once again across their borders. Repeatedly the Turk levied great armies for the conquest of Montenegro[35] (once the Turkish force reached to the number of 80,000). Repeatedly great European Powers which had proffered help or had been begged for help failed little Montenegro at a crisis. But never were the stout hearts of the Black Mountain quelled. In 1484, when Zablak had to be evacuated and the whole nation was confined to the little mountain fortress of Cettinje, Ivan the Black offered to his people the choice of ending the war and making peace with the Turks. They rejected the idea, and swore to stand by the freedom of Montenegro until the last. The oath was never broken. Right down to 1832 a free Montenegro faced Turkey. In that year the Turks, despairing of an occupation of the country, suggested that Montenegro should agree at least to pay tribute. That offer was rejected and yet another war entered upon. A war against Austria followed, in which the desperate Montenegrins used the type of their printing presses to make bullets for the soldiers.

MONTENEGRIN TROOPS

Weekly Drill and Inspection of Weapons

That there was lead type to be so used shows that the Montenegrins had not altogether neglected the arts of peace. In 1493 a printing press had been set up in Cettinje and the first Montenegrin book printed in the Cyrillic character.[36] During the next century this printing press was kept busy with the issue of the Gospels and psalters under the rule of the brave Bishop Babylas. The state of Montenegro at this time aroused the admiration of the Venetians, and there is extant a book in praise of Montenegro written in 1614 by a Venetian noble, Mariano Bolizza.

When the time came for the other Balkan States to throw off the Turkish yoke Montenegro was not reluctant to join in the movement for liberation, and she was later first in the field in the campaign of 1912.

This very brief record of the leading facts of Balkan history has now brought each of the peoples up to the stage at which the final and successful effort was made with the help of Russia to drive the Turks out of Balkan territory. The story of that effort will be told in the succeeding chapter.

In the nineteenth century the Turkish dominion was pushed back in all directions from the Balkan Peninsula. At the dawn of that century Montenegro was the only Balkan state entirely free from occupation, vassalage, or the duty of tribute to the Sublime Porte. At the close of that century Montenegro, Serbia, Roumania, Greece, and Bulgaria were all practically free and self-governing.

In 1804, as has been recorded, Kara George in Serbia raised the standard of revolt against Turkey. In 1806 the Serbs defeated the Turks in a pitched battle, and for a moment Serbia was free. But in 1812 when the Turkish power resolved upon a great invasion of Serbia, the heart of Kara George failed him and he left his country to its fate, taking refuge in Austria. Thus[38] deserted by their leader, the Serbs did not abandon the struggle altogether. Milosh Obrenovic stepped to the front as the national champion, and though he could make no stand against the Turkish troops in the open field he kept up an active revolt from a base in the mountains. The contest for national liberty went on with varying fortune. Troubles at this time were thickening around Turkey, and whenever she was engaged in war with Russia the oppressed nationalities within her borders took the opportunity to strike a blow for liberty. By 1839—it is not possible to make a record of all the dynastic changes and revolutions which filled the years 1812-1839—Serbia was practically free, with the payment of an annual tribute to Turkey as her only bond. During the Crimean War she kept her neutrality as between Russia and Turkey. The Treaty of Paris (1856) confirmed her territorial independence, subject to the payment of a tribute to Turkey. In 1867 the Turkish garrisons were withdrawn from Serbia; but the tribute was still left in existence until the date of the Treaty of Berlin.

Exclusive News Agency

THE KING OF ROUMANIA

Roumania in 1828 (then Wallachia and Moldavia) had won her territorial independence of Turkey subject only to payment of a tribute. The Treaty of Paris (1856) left her under a nominal suzerainty to Turkey. In 1859 the two kingdoms united to form Roumania, and in 1866 the late King Charles, as the result of a revolution, was elected prince of the united kingdom.

Bulgaria had remained a fairly contented Turkish province until the rising of 1875, and its cruel suppression by the Bashi-Bazouks. As a direct consequence of that massacre European diplomacy turned its serious attention to the Balkan Peninsula, and at a Conference demands were made upon Turkey for a comprehensive reform applying to Serbia, Montenegro, Bosnia, Herzegovina, and Bulgaria. The proposed reform was particularly drastic as applied to Bulgaria, which was still in effect Turkish territory, whilst all the other districts had achieved a practical freedom. It was proposed to create two Bulgarian provinces divided into Sandjaks and Kazas as administrative units, these to be subdivided into districts. Christian and Mohammedans were to be settled homogeneously in these districts. Each district was to have at its head a mayor and a district council,[40] elected by universal suffrage, and was to enjoy entire autonomy in local affairs. Several districts would form a Sandjak with a prefect (mutessarif) at its head who was to be Christian or Mohammedan, according to the majority of the population of the Sandjak. He would be proposed by the Governor-General, and nominated by the Porte for four years. Finally, every two Sandjaks were to be administered by a Christian Governor-General nominated by the Porte for five years, with consent of the Powers. He would govern the province with the help of a provincial assembly, composed of representatives chosen by the district councils for a term of four years. This assembly would nominate an administrative council. The provincial assembly would be summoned every year to decide the budget and the redivision of taxes. The armed force was to be concentrated in the towns and there would be local militia besides. The language of the predominant nationality was to be employed, as well as Turkish. Finally, a Commission of International Control was to supervise the execution of these reforms.

The Sublime Porte was still haggling about these reforms when Russia lost patience and[41] declared war upon Turkey on April 12, 1877. Moving through the friendly territory of Roumania, Russia attacked the Turkish forces in Bulgarian territory. In that war the Russians found that the Turks were a gallant foe, and the issue seemed to hang in the balance until Roumania and Bulgaria went actively to the help of the Russian forces. The Roumanian aid was exceedingly valuable. Prince Charles crossed the Danube at the head of 28,000 foot soldiers and 4000 cavalry. He was appointed Commander-in-Chief of the forces against Plevna, and his soldiers were chiefly responsible for the taking of the Grivica Redoubt which turned the tide of victory against the Turks. The Bulgarians did but little during the campaign: it was not possible that they should do much seeing that they could only put irregulars in the field. Nevertheless some high personal reputations for courage were made. During my stay with the Bulgarian army in 1912 I noted that there were of the military officers three classes, the men who had graduated in foreign military colleges—usually Petrograd,—very smart, very insistent on their military dignity, speaking usually three or four languages; officers who had been educated[42] at the Military College, Sofia; and the older Bulgarian type, dating sometimes from before the War of Liberation. Of these last the outstanding figure was General Nicolaieff, who as captain of a Bulgarian company rushed a Turkish battery beneath Shipka after the Russians had been held up so long that they were in despair. A fine stalwart figure General Nicolaieff showed when I met him at Yamboli, a hospital base town of which he was military commandant. Another soldier of the War of Liberation, a captain in rank, I travelled with for a day once between Kirk Kilisse and Chorlu. We chummed up and shared a meal of meat balls cooked with onions, rough country wine (these from his stores), and dates and biscuits (from my stores). He spoke neither English nor French, but a Bulgarian doctor who spoke French acted as interpreter, and the old officer, who after long entreaty at last had got leave to go down to the front in spite of his age, yarned about the hardships and tragedies of the fighting around Stara Zagora and the Shipka Pass. Some of the Bulgarians, he said, took the field with no other arms than staves and knives, and got their first rifles from the dead of the battle-fields.

THE SHIPKA PASS

THE SHIPKA PASS

[43] Serbia took a hand in this campaign, too, though she hesitated for some time, going to the aid of Russia through fear of Austria. Beginning late, at a time when the mountains were covered in the winter snows, the Serbians suffered severely from the weather, but won notable victories at Pirot, at Nish, and at Vranga. The Turks were in full retreat on Constantinople when the armistice and Treaty of San Stefano put an end to the war.

It seems to be one of the standing rules of Balkan wars and Balkan peace treaties that those who do the work shall not reap the reward, and that a policy of standing by and waiting is the wisest and most profitable. In this Russo-Turkish war the Roumanians had done invaluable work for the Russian cause. In return the Treaty of San Stefano robbed them shamefully. The Bulgarians had done little, except to stain the arms of the allies with a series of massacres of the Turks in reprisal for the previous atrocities inflicted upon them by the Bashi-Bazouks. The Bulgarians were awarded a tremendous prize of territory. If the grant had been confirmed it would have made Bulgaria the paramount power of the Balkan Peninsula. By the Treaty[44] of San Stefano, Bulgaria was made an autonomous principality subject to Turkey, with a Christian government and national militia. The Prince of Bulgaria was to be freely chosen by the people and accepted by the Sublime Porte, with the consent of the Powers. As regards internal government, it was agreed that an assembly of notables, presided over by an Imperial Commissioner and attended by a Turkish Commissioner, should meet at Philippopolis or Tirnova before the election of the Prince to draw up a constitutional statute similar to those of the other Danubian principalities after the Treaty of Adrianople in 1830. The boundaries of Bulgaria were to include all that is now Bulgaria, and the greater part of Thrace and Macedonia.

The European Congress of Berlin which revised the Treaty of San Stefano recognised that the motive of Russia was to create in Bulgaria a vast but weak state, which would obediently serve her interests and in time fall into her hands: and that the injury proposed to be done to Roumania was inspired by a desire to limit the progress of a courageous but an unfortunately independent-minded friend. The Congress was suspicious of the Bulgarian arrangement, and[45] clipped off much of the territory assigned to the new principality. The injury done to Roumania was allowed to stand. Then, as in 1912-1913, when Balkan boundaries were again under the discussion of an inter-European Conference, the vital interests of the great Powers surrounding the Balkan Peninsula were to keep its peoples divided and weak. Both Russia and Austria had more or less defined territorial ambitions in the Balkans: and it suited neither Power to see any one Balkan state rise to such a standard of greatness as would enable it to take the lead in a Balkan Union. Especially was it not the wish of Austria that any Balkan state should grow to be so strong as to kill definitely the hope she cherished of extending down the Adriatic and towards the Aegean.

By the Treaty of Berlin, which followed the Congress of Berlin, the greater part of the Balkan Peninsula was freed altogether from Turkish rule. Roumania and Serbia were relieved from all suggestion of tribute or vassalage. Bulgaria was left subject to a tribute (which was very quickly afterwards repudiated). Where the Turkish power was left in existence in European Turkey it was a threatened existence, for the[46] newly freed Christian peoples began at once to conspire to help to freedom their nationals left still under Turkish rule. The war of 1912 began to be prepared in 1878.

There was, however, a period of comparative peace. Roumania, though discontented, decided to bide her time. Her prince was crowned king with a crown made from the metal of Turkish cannon taken at Plevna. That was the only hint that she gave of keeping in mind the greatness of her services which had been so poorly rewarded.

Montenegro, whilst deprived of the great and the well-deserved expansion which the Treaty of San Stefano offered, had some benefit from the Treaty of Berlin. The area of the kingdom was doubled and it won access to the Adriatic. A little later the harbour of Dulcigno was ceded to Montenegro by Turkey under pressure from the Powers, and she was left with only one notable grievance, that of being shut off from Serbia by the Sanjak of Novi-Bazar, which Austria secured for Turkey, apparently with the idea of one day seizing it on her way down to Salonica.

Chusseau Flaviens

KING FERDINAND OF BULGARIA

Serbia increased her territory by one-fourth under the Treaty of Berlin, but was not allowed to extend towards the Adriatic, and, nurturing[47] as she did a dream of reviving the old Serbian Empire, was but poorly satisfied.

Bulgaria, if it had not been for the promises of the Treaty of San Stefano, might have been fairly content with the provisions of the Treaty of Berlin. She had been the first nation in the Balkans to yield to the Turks. She had allowed her sons to act as mercenary soldiers to aid the Turks against other Christians: and during the period of oppression she had suffered less than any from the rigours of the invader, had protested less than any by force of arms. Yet now she was given freedom as a gift won largely by the sacrifices of others. But, though having the most reason to be content, Bulgaria was the least contented of all the Balkan States. The restless ambition of the people guiding her destinies was manifested in an internal revolution which displaced the first prince (Alexander of Battenberg) and put on the throne the present king (Ferdinand of Coburg). Bulgaria, too, repudiated the friendly tutelage which Russia wished to exercise over her destinies.

The territorial settlement made by the Berlin Treaty was first broken by Bulgaria. That treaty had cut the ethnological Bulgaria into two,[48] leaving the southern half as a separate province under the name of Eastern Rumelia. In 1885 Eastern Rumelia was annexed to Bulgaria with the glad consent of its inhabitants, but in spite of the wishes of Russia. Serbia saw in this the threat of a Bulgarian hegemony in the Balkans, and demanded some territorial compensation for herself. This was refused. War followed. The Bulgarians were victorious at the Battle of Slivnitza, an achievement which was in great measure due to the organising ability of Prince Alexander. The victory secured Rumelia for Bulgaria. But no sense of gratitude to Prince Alexander survived, and the Russian intrigue which secured his abdication and flight was undoubtedly aided by a large section of the Bulgarian people. Stambouloff, a peasant leader of the Bulgarians and its greatest personality since the War of Liberation, was faithful to Alexander, but was not able to save him.

Underwood & Underwood

KING FERDINAND'S BODYGUARD

The Bulgarian throne after Alexander's abdication was offered to the King of Roumania. The acceptance of the offer would possibly have led to a real Balkan Federation. The united power of Roumania and Bulgaria, exercised wisely, could have gently pressed the other Balkan [49] peoples into a union. That, however, would have suited the aims neither of Russia nor of Austria, the two Empires which guided the destinies of the Balkans, chiefly in the light of their own selfish ends. The Roumanian king refused the throne of Bulgaria, and in 1887 Prince Ferdinand of Coburg became Prince of the State. It was not long before he fell out with Stambouloff, the able but personally unamenable patriot who chiefly had made modern Bulgaria. In the conflict between the two Prince Ferdinand proved the stronger. Stambouloff was dismissed from office, and in 1895 was assassinated in the streets of Sofia. No attempt was made to punish his murderers.

In 1908 Bulgaria shook off the last shred of dependence to Turkey. The bold action was the crown of a clever diplomatic intrigue by Prince Ferdinand. Since the murder of Stambouloff the Prince had been sedulously cultivating in public the friendship of Russia: but that had not prevented him carrying to a great pitch of mutual confidence a secret understanding with Austria. The Austrian Empire was anxious to annex formally the districts of Bosnia and Herzegovina, of which it had long been in[50] occupation. Objection to this would surely have come from Russia; but Russia was impotent for the time being after the disastrous war with Japan. Just as surely it would come from Serbia which would see thus definitely pass over to the one Power, which she had reason to fear, a section of Slav-inhabited country clearly connected to the Serbs by racial ties. Serbia, it might be expected, would have the support of France and England as well as Russia. For Bulgaria the offer to neutralise Serbia made to Austria all the difference between an action which was a little risky and an action which had no risk at all. Bulgaria supported Austria in the annexation, and, as was to have been expected, Serbia found protest impossible, since Russia, France, and England swallowed the affront to treaty obligations to which they were parties. It was Bulgaria's reward to have the support of the Triple Alliance in throwing off all fealty and tribute to the Sublime Porte. Prince Ferdinand became the Czar Ferdinand of Bulgaria.

Nor was that the end of Bulgarian ambition. The "big" Bulgaria of the San Stefano treaty floated before the eyes of her rulers constantly, and she began to prepare for a war against[51] Turkey, of which the prize should be Thrace and Macedonia. An obstacle in Macedonia was not only that the Turks were in occupation, but that the Greeks considered themselves entitled to the reversion of the estate. Rivalry between the three nations was responsible for the Macedonian horrors, which went on from year to year, and made one district of the Balkans a veritable hell on earth. These horrors have been set at the door of the "Unspeakable Turk." The Turk has quite enough to answer for in the many hideous crimes which he has undoubtedly committed. It is not quite just to hold him wholly responsible for the terrible state of Macedonia during the last few years. Greek and Bulgarian were alike interested in making it appear to the world that Turkish rule in Macedonia was impossible. To effect this they insisted that rapine and massacre should become normal. If the Turk did not wish for massacres he was stirred up to massacres. Christian pastors were not prevented by their Christian faith from murders of their own people, if it could be certain that the Turks would have the discredit of them. Side by side with the atrocities which were committed by Turks against Christians and Christians[52] against Turks, the two sets of warring Christians, the Bulgarian Exarchates and the Greek Patriarchates, attacked one another with a fiendish relentlessness, which equalled the most able efforts of the Turks in the way of rape, murder, and robbery.

In excuse for part of this, i.e. that part which stirred up the Turks to atrocities even when they wished to be peaceful, there could be pleaded the good object of striving for the end of all Turkish rule in Christian districts of the Balkans. The excuse will serve this far: that without a doubt a Christian community cannot be governed justly by the Turk, and the very strongest of steps are warranted to put an end to Turkish domination of a district largely inhabited by Christians. But no consideration, even that of exterminating Turkish rule, could justify all the Christian atrocities perpetrated in Macedonia: and there is certainly no shadow of an excuse for the atrocities with which Bulgarian sought to score against Greek and Greek against Bulgarian. The era of those atrocities has not yet closed. The Turk has been driven from Macedonia, but Greek and Bulgarian continue their feud. For the time the Greek is in the ascendant, whilst the Bulgarian broods over a revenge.

BULGARIAN INFANTRY

BULGARIAN INFANTRY

By 1912, Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia, and Montenegro had contrived, in spite of any past quarrels, in spite of the mutual jealousies even then being displayed in the recurring Macedonian massacres, of Christians by Christians as well as by Turks, to arrive at a sufficient degree of unity to allow them to make war jointly on Turkey. Bulgaria and Serbia concluded an offensive and defensive alliance, arranging for all contingencies and providing for the division of the spoils which it was hoped to win from the Turks. Between Bulgaria and Greece there was no such definite alliance, but a military convention only. The division of the spoil after the war was left to future determination, both Greek and Bulgarian probably having it clearly in his head that he would have all his own way after the war or[54] fight the issue out subsequently. A later Punch cartoon put this peculiarity of a Balkan alliance with pretty satire. Greece and Serbia were discussing what they should do with the spoils they were then winning from Bulgaria. "Of course we shall fight for them. Are we not allies?" said one of the partners.

I was through the war of 1912 as war correspondent for the London Morning Post, and followed the fortunes of the main Bulgarian army in the Thracian campaign. In this book I do not intend to attempt a history of the war but will give some impressions of it which, whilst not neglecting any of the chief facts in any part of the theatre of operations, will naturally be mainly based on observations with the Bulgarians.

First, with regard to the political side of the war, one could not but be struck by the exceedingly careful preparation that the Bulgarians had made for the struggle. It was no unexpected or sudden war. They had known for some time that war was inevitable, having made up their minds for a considerable time that the wrongs of their fellow-nationals in Macedonia and Thrace would have to be righted by force of arms. Attempts on the part of the Powers to enforce reforms[55] in the Christian Provinces of Turkey had, in the opinion of the Bulgars, been absolute failures, and they had done their best to make them failures, wishing for a destroyed Turkey not a reformed Turkey. In their opinion there was nothing to hope for except armed intervention on their part against Turkey. And, believing that, they had made most careful preparation extending over several years for the struggle. That preparation was in every sense admirable. For instance, it had extended, so far as I could gather, from informants in Bulgaria, to this degree: that they formed military camps in winter for the training of their troops. Thus they did not train solely in the most favourable time of the year for manœuvres, but in the unfavourable weather too, in case that time should prove the best for their war. The excellence of their artillery arm, and the proof of the scientific training of their officers, prove to what extent their training beforehand had gone.

When war became inevitable, the Balkan League having been formed, and the time being ripe for the war, Bulgaria in particular, and the Balkan States in general, were quite determined[56] that war should be. The Turks at this time were inclined to make reforms and concessions; they had an inclination to ease the pressure on their Christian subjects in the Christian provinces. Perhaps knowing—perhaps not knowing—that they were unready for war themselves, but feeling that the Balkan States were preparing for war, the Turks were undoubtedly willing to make great concessions. But whatever concessions the Turks might have offered, war would still have taken place. I do not think one need offer any harsh criticism about the Balkan nations for coming to that decision. If you have made your preparation for war—perhaps a very expensive preparation, perhaps a preparation which has involved very great commitments apart from expense—it is not reasonable to suppose that at the last moment you will consent to desist from making that war. The line which you may have been prepared to take before you made your preparations you may not be prepared to take after the preparations have been made. And, as the Turks found out afterwards, the terms which were offered to them before the outbreak of the war were not the same terms as would be listened to after that event.

[57] To a pro-Turk it all will seem a little unscrupulous. But it is after the true fashion of diplomacy or warlike enterprise. The simple position was that Turkey was obviously a decadent Power; that her territories were envied and that if there had not been a real grievance (there was a real grievance) one would have been manufactured to justify a war of spoliation. It not being necessary to manufacture a grievance, the existing one was carefully nursed and stimulated: and when the ripe time came for war the unreal pretext that war was the alternative to reform and could be avoided by reform was put forward. No reform would have stopped the war just as no "reform" would stop, say, San Marino attacking the British Empire if she wanted something which the British Empire has got and felt that she could get it by an attack.

I do not think that the Balkan League would have withdrawn from the war supposing the Turks before the outbreak of the war had offered autonomy of the Christian provinces. I was informed in very high quarters, and I believe profoundly, that if the Turks had offered so much at that time the war would still have taken place.

[58] There is another interesting lesson to be gleaned from the political side of this war. At the outset, the Powers, when endeavouring to prevent hostilities, made an announcement that, whatever the result of the war, no territorial benefit would be allowed to any of the participants; that is to say, the Balkan States were informed, on the authority of all Europe, that if they did go to war, and if they won victories they would be allowed no fruits from those victories. The Balkan States recognised, as I think all sensible people must recognise, that a victorious army makes its own laws. They treated this caveat which was issued by the Powers of Europe as a matter to be politely set aside; and ignored it.

Political experience seems to show that if a nation, under any circumstances, wishes its international rights to be respected, it must be ready to fight for them. There is proof from contemporary history in the respective fates of Switzerland and Korea. Both nations once stood in very much the same position internationally; that their independence was, in a sense, guaranteed. Korea's independence was guaranteed by both the United States and Great Britain. But the[59] independence of Korea has now vanished. Korea could not fight for herself, and nobody was going to fight for a nation which could not fight for herself. The independence of Switzerland is maintained because Switzerland would be a very thorny problem for any Power in search of territory to tackle. In case of an attack on Switzerland, that country would be able to help herself and her friends.

On the opposite side of the argument, we see the Balkan League entering upon a desperate war, warned that they would be allowed no territorial advantage from that war, but engaging upon it because they recognised that a victorious army makes its own laws.

It was of wonderful value to the Bulgarian generals entering upon this war that the whole Bulgarian nation was filled with the martial spirit—was, in a sense, wrapped up in the colours. Every male Bulgarian citizen was trained to the use of arms. Every Bulgarian citizen of fighting age was engaged either at the front or on the lines of communication. Before the war, every Bulgarian man, being a soldier, was under a soldier's honour; and the preliminaries of the war, the preparations for mobilisation in particular,[60] were carried out with a degree of secrecy that, I think, astonished every Court and every Military Department in Europe. The secret was so well kept that one of the diplomatists in Roumania left for a holiday three days before the declaration of war, feeling certain that there was to be no war. Bulgaria is not governed altogether autocratically, but is a very free democracy in some respects. It has a newspaper Press that, on ordinary matters, for delightful irresponsibility, might be matched in London. Yet not a single whisper of what the nation was designing and planning leaked abroad. Because the whole nation was a soldier, and the whole nation was under a soldier's honour, secrecy could be kept. No one abroad knew anything, either from the babbling of "Pro-Turks," or from the newspapers, that a great campaign was being designed.

Topical Press

BULGARIAN TROOPS LEAVING SOFIA

The Secret Service of Bulgaria before the war evidently had been excellent. They seemed to know all that was necessary to know about the country in which they were going to fight. This very complete knowledge of theirs was in part responsible for the arrangements which were made between the Balkan Allies for carrying on the[61] war. The Bulgarian people had made up their minds to do the lion's share of the work, and to have the lion's share of the spoils. They knew quite definitely the state of corruption to which the Turkish nation had come. When I reached Sofia, the Bulgarians told me they were going to be in Constantinople three weeks after the declaration of war. That was the view that they took of the possibilities of the campaign. And they kept their programme as far as Chatalja fairly closely.