Title: Life histories of North American wood warblers, Part 1 (of 2)

Author: Arthur Cleveland Bent

Contributor: Winsor Marrett Tyler

Release date: June 28, 2012 [eBook #40100]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Tom Cosmas, Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

Note: In some quoted passages, the author uses three spaced asterisks to show a deleted section. These are displayed as * * *.

DOVER BOOKS ON BIRDS

Audubon’s Birds of America Coloring Book, John James Audubon. (23049-X) $2.25

Bird Study, Andrew J. Berger. (22699-9) $7.95

Bird Song and Bird Behavior, Donald J. Borror. (22779-0) Record and manual $4.95

Common Bird Songs, Donald J. Borror. (21829-5) Record and manual $4.95

Songs of Eastern Birds, Donald J. Borror. (22378-7) Record and album $4.95

Songs of Western Birds, Donald J. Borror. (22765-0) Record and album $4.95

Birds of the New York Area, John Bull. (23222-0) $7.50

What Bird Is This?, Henry H. Collins, Jr. (21490-7) $2.95

Hawks, Owls and Wildlife, John J. Craighead and Frank C. Craighead, Jr. (22123-7) $7.00

Cruickshank’s Photographs of Birds of America, Allan D. Cruickshank. (23497-5) $7.95

1001 Questions Answered about Birds, Allan Cruickshank and Helen Cruickshank. (23315-4) $4.50

Extinct and Vanishing Birds of the World, James C. Greenway, Jr. (21869-4) $7.95

Bird Migration, Donald R. Griffin. (20529-0) $4.50

A Guide to Bird Watching, Joseph J. Hickey. (21596-2) $4.95

Life Histories of

North American Wood Warblers

by

Arthur Cleveland Bent

in two parts

Part 1

Dover Publications, Inc.

New York

Published in the United Kingdom by Constable and Company, Limited, 10 Orange Street, London W. C. 2.

This Dover edition, first published in 1963, is an unabridged and unaltered republication of the work first published in 1953 by the United States Government Printing Office, as Smithsonian Institution United States National Museum Bulletin 203.

Standard Book Number: 486-21153-3

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc.

180 Varick Street

New York 14, N. Y.

ADVERTISEMENT

The scientific publications of the National Museum include two series, known, respectively, as Proceedings and Bulletins.

The Proceedings series, begun in 1878, is intended primarily as a medium for the publication of original papers, based on the collections of the National Museum, that set forth newly acquired facts in biology, anthropology, and geology, with descriptions of new forms and revisions of limited groups. Copies of each paper, in pamphlet form, are distributed as published to libraries and scientific organizations and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects. The dates at which these separate papers are published are recorded in the table of contents of each of the volumes.

The series of Bulletins, the first of which was issued in 1875, contains separate publications comprising monographs of large zoological groups and other general systematic treatises (occasionally in several volumes), faunal works, reports of expeditions, catalogs of type specimens, special collections, and other material of similar nature. The majority of the volumes are octavo in size, but a quarto size has been adopted in a few instances in which the larger page was regarded as indispensable. In the Bulletin series appear volumes under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, in octavo form, published by the National Museum since 1902, which contain papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum.

The present work forms No. 203 of the Bulletin series.

Remington Kellogg,

Director, United States National Museum.

CONTENTS

| Page | |

| Introduction | ix |

| Order PASSERIFORMES | 1 |

| Family Parulidae: Wood warblers | 1 |

| Mniotilta varia: Black-and-white warbler | 5 |

| Habits | 5 |

| Distribution | 14 |

| Protonotaria citrea: Prothonotary warbler | 17 |

| Habits | 17 |

| Distribution | 28 |

| Limnothlypis swainsonii: Swainson’s warbler | 30 |

| Habits | 30 |

| Distribution | 37 |

| Helmitheros vermivoros: Worm-eating warbler | 38 |

| Habits | 38 |

| Distribution | 45 |

| Vermivora chrysoptera: Golden-winged warbler | 47 |

| Habits | 47 |

| Distribution | 56 |

| Vermivora pinus: Blue-winged warbler | 58 |

| Habits | 58 |

| Distribution | 65 |

| Vermivora bachmanii: Bachman’s warbler | 67 |

| Habits | 67 |

| Distribution | 73 |

| Vermivora peregrina: Tennessee warbler | 75 |

| Habits | 75 |

| Distribution | 86 |

| Vermivora celata celata: Eastern orange-crowned warbler | 89 |

| Habits | 89 |

| Distribution | 94 |

| Vermivora celata orestera: Rocky Mountain orange-crowned warbler | 98 |

| Habits | 98 |

| Vermivora celata lutescens: Lutescent orange-crowned warbler | 99 |

| Habits | 99 |

| Vermivora celata sordida: Dusky orange-crowned warbler | 103 |

| Habits | 103 |

| Vermivora ruficapilla ruficapilla: Eastern Nashville warbler | 105 |

| Habits | 105 |

| Distribution | 113 |

| Vermivora ruficapilla ridgwayi: Western Nashville warbler | 116 |

| Habits | 116 |

| Vermivora virginiae: Virginia’s warbler | 119 |

| Habits | 119 |

| Distribution | 124 |

| Vermivora crissalis: Colima warbler [x] | 126 |

| Habits | 126 |

| Distribution | 129 |

| Vermivora luciae: Lucy’s warbler | 129 |

| Habits | 129 |

| Distribution | 134 |

| Parula americana pusilla: Northern parula warbler | 135 |

| Habits | 135 |

| Distribution | 145 |

| Parula americana americana: Southern parula warbler | 147 |

| Habits | 147 |

| Parula pitiayumi nigrilora: Sennett’s olive-backed warbler | 149 |

| Habits | 149 |

| Distribution | 152 |

| Parula graysoni: Socorro warbler | 152 |

| Habits | 152 |

| Distribution | 153 |

| Peucedramus taeniatus arizonae: Northern olive warbler | 153 |

| Habits | 153 |

| Distribution | 160 |

| Dendroica petechia aestiva: Eastern yellow warbler | 160 |

| Habits | 160 |

| Distribution | 178 |

| Dendroica petechia amnicola: Newfoundland yellow warbler | 182 |

| Habits | 182 |

| Dendroica petechia rubiginosa: Alaska yellow warbler | 184 |

| Habits | 184 |

| Dendroica petechia morcomi: Rocky Mountain yellow warbler | 185 |

| Habits | 185 |

| Dendroica petechia brewsteri: California yellow warbler | 186 |

| Habits | 186 |

| Dendroica petechia sonorana: Sonora yellow warbler | 189 |

| Habits | 189 |

| Dendroica petechia gundlachi: Cuban yellow warbler | 190 |

| Habits | 190 |

| Dendroica petechia castaneiceps: Mangrove yellow warbler | 191 |

| Habits | 191 |

| Dendroica magnolia: Magnolia warbler | 195 |

| Habits | 195 |

| Distribution | 209 |

| Dendroica tigrina: Cape May warbler | 212 |

| Habits | 212 |

| Distribution | 222 |

| Dendroica caerulescens caerulescens: Northern black-throated blue warbler | 224 |

| Habits | 224 |

| Distribution | 233 |

| Dendroica caerulescens cairnsi: Cairns’ warbler | 237 |

| Habits | 237 |

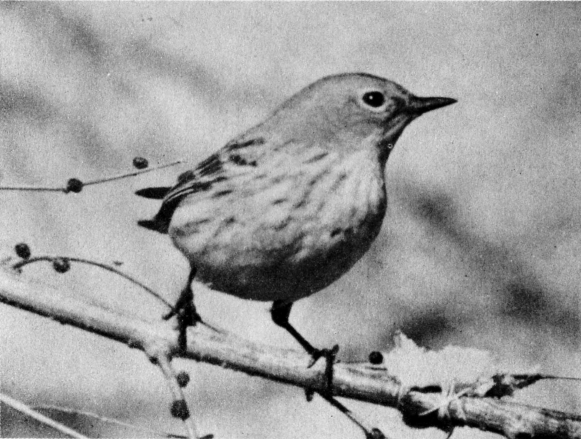

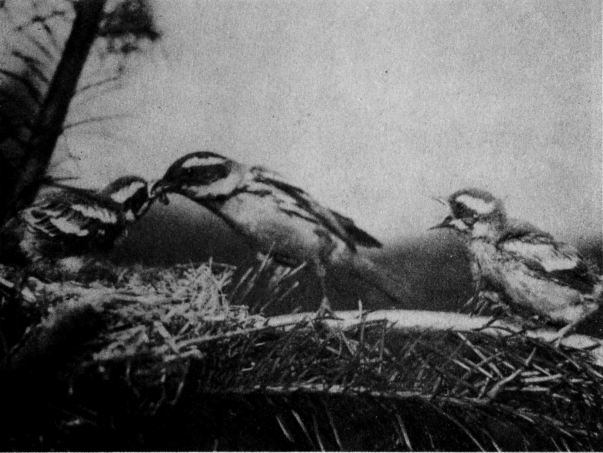

| Dendroica coronata coronata: Eastern myrtle warbler | 239 |

| Habits | 239 |

| Distribution | 254 |

| Dendroica coronata hooveri: Alaska myrtle warbler [xi] | 258 |

| Habits | 258 |

| Dendroica auduboni auduboni: Pacific Audubon’s warbler | 260 |

| Habits | 260 |

| Distribution | 271 |

| Dendroica auduboni nigrifrons: Black-fronted Audubon’s warbler | 273 |

| Habits | 273 |

| Dendroica nigrescens: Black-throated gray warbler | 275 |

| Habits | 275 |

| Distribution | 281 |

| Dendroica towndsendi: Townsend’s warbler | 282 |

| Habits | 282 |

| Distribution | 290 |

| Dendroica virens virens: Northern black-throated green warbler | 291 |

| Habits | 291 |

| Distribution | 304 |

| Dendroica virens waynei: Wayne’s black-throated green warbler | 308 |

| Habits | 308 |

| Dendroica chrysoparia: Golden-cheeked warbler | 316 |

| Habits | 316 |

| Distribution | 321 |

| Dendroica occidentalis: Hermit warbler | 321 |

| Habits | 321 |

| Distribution | 328 |

| Dendroica cerulea: Cerulean warbler | 329 |

| Habits | 329 |

| Distribution | 335 |

| Dendroica fusca: Blackburnian warbler | 337 |

| Habits | 337 |

| Distribution | 347 |

| Dendroica dominica dominica: Eastern yellow-throated warbler | 349 |

| Habits | 349 |

| Distribution | 358 |

| Dendroica dominica albilora: Sycamore yellow-throated warbler | 359 |

| Habits | 359 |

| Dendroica graciae graciae: Northern Grace’s warbler | 363 |

| Habits | 363 |

| Distribution | 367 |

This is the nineteenth in a series of bulletins of the United States National Museum on the life histories of North American birds. Previous numbers have been issued as follows:

107. Life Histories of North American Diving Birds, August 1, 1919.

113. Life Histories of North American Gulls and Terns, August 27, 1921.

121. Life Histories of North American Petrels and Pelicans and Their Allies, October 19, 1922.

126. Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl (part), May 25, 1923.

130. Life Histories of North American Wild Fowl (part), June 27, 1925.

135. Life Histories of North American Marsh Birds, March 11, 1927.

142. Life Histories of North American Shore Birds (pt. 1), December 31, 1927.

146. Life Histories of North American Shore Birds (pt. 2), March 24, 1929.

162. Life Histories of North American Gallinaceous Birds, May 25, 1932.

167. Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey (pt. 1), May 3, 1937.

170. Life Histories of North American Birds of Prey (pt. 2), August 8, 1938.

174. Life Histories of North American Woodpeckers, May 23, 1939.

176. Life Histories of North American Cuckoos, Goatsuckers, Hummingbirds, and Their Allies, July 20, 1940.

179. Life Histories of North American Flycatchers, Larks, Swallows, and Their Allies, May 8, 1942.

191. Life Histories of North American Jays, Crows, and Titmice, January 27, 1947.

195. Life Histories of North American Nuthatches, Wrens, Thrashers, and Their Allies, July 7, 1948.

196. Life Histories of North American Thrushes, Kinglets, and Their Allies, June 28, 1949.

197. Life Histories of North American Wagtails, Shrikes, Vireos, and Their Allies, June 21, 1950.

The paragraphs on distribution for the Colima and Kirtland’s warblers were supplied by Dr. Josselyn Van Tyne with his contributions on these species.

All other data on distribution and migration were contributed by the Fish and Wildlife Service under the supervision of Frederick C. Lincoln.

The same general plan has been followed as explained in previous bulletins, and the same sources of information have been used. It does not seem necessary to explain the plan again here. The nomenclature of the Check-List of North American Birds (1931), with its supplements, of the American Ornithologists’ Union, has been followed. Forms not recognized in this list have not been included.

Many who have contributed material for previous Bulletins have continued to cooperate. Receipts of material from several hundred contributors has been acknowledged in previous Bulletins. In addition to these, our thanks are due to the following new contributors: G. A. Ammann, O. L. Austin, Jr., F. S. Barkalow, Jr., Ralph Beebe, H. E. Bennett, A. J. Berger, Virgilio Biaggi, Jr., C. H. Blake, Don Bleitz, B. J. Blincoe, L. C. Brecher, Jeanne Broley, Maurice Broun, J. H. Buckalew, I. W. Burr, N. K. Carpenter, May T. Cooke, H. L. Crockett, Grace Crowe, Ruby Curry, J. V. Dennis, E. von S. Dingle, M. S. Dunlap, J. J. Elliott, A. H. Fast, Edith K. Frey, J. E. Galley, J. H. Gerard, Lydia Getell, H. B. Goldstein, Alan Gordon, L. I. Grinnell, Horace Groskin, F. G. Gross, G. W. Gullion, E. M. Hall, R. H. Hansman, Katharine C. Harding, H. H. Harrison, J. W. Hopkins, N. L. Huff, Verna R. Johnston, Malcolm Jollie, R. S. Judd, M. B. Land, Louise de K. Lawrence, R. E. Lawrence, G. H. Lowery, J. M. Markle, C. R. Mason, D. L. McKinley, R. J. Middleton, Lyle Miller, A. H. Morgan, R. H. Myers, W. H. Nicholson, F. H. Orcutt, H. L. Orians, R. A. O’Reilly, A. A. Outram, G. H. Parks, K. C. Parkes, M. M. Peet, J. L. Peters, F. A. Pitelka, Mariana Roach, James Rooney, Jr., O. M. Root, G. B. Saunders, James Sawders, Mary C. Shaub, Dorothy E. Snyder, Doris Heustis Speirs, E. A. Stoner, P. B. Street, H. R. Sweet, E. W. Teale, A. B. Williams, G. G. Williams, R. B. Williams, Mrs. T. E. Winford, and A. M. Woodbury.

As the demand for these Bulletins is much greater than the supply, the names of those who have not contributed to the work during recent years will be dropped from the author’s mailing list.

Dr. Winsor M. Tyler has again read and indexed for this volume a large part of the current literature on North American birds and has contributed four complete life histories. Dr. Alfred O. Gross has written stories on the yellow-throats (Geothlypis trichas) and has contributed three other complete life histories. Edward von S. Dingle, Alexander Sprunt, Jr., and Dr. Josselyn Van Tyne have contributed two complete life histories each.

William George F. Harris has increased his valuable contribution to the work by producing the entire paragraphs on eggs, including descriptions of the eggs in their exact colors, assembling and averaging the measurements, and collecting and arranging the egg dates, as they appear under Distribution; the preparation of this last item alone required the handling of over 5,600 records.

Clarence F. Smith has furnished references to food habits of all the species of wood warblers. Aretas A. Saunders has contributed full and accurate descriptions of the songs and call notes of all the species with which he is familiar, based on his extensive musical records. Dr. Alexander F. Skutch has sent us full accounts of all the North American wood warblers that migrate through or spend the winter in Central America, with dates of arrival and departure. James Lee Peters has furnished descriptions of molts and plumages of several species and has copied several original descriptions of subspecies from publications that were not available to the author.

Eggs were measured for this volume by American Museum of Natural History (C. K. Nichols), California Academy of Sciences (R. T. Orr), Colorado Museum of Natural History (F. G. Brandenburg), C. E. Doe, W. E. Griffee, W. C. Hanna, E. N. Harrison, H. L. Heaton, A. D. Henderson, Museum of Comparative Zoology (W. G. F. Harris), and Museum of Vertebrate Zoology (M. Jollie).

The manuscript for this Bulletin was written in 1945; only important information could be added. If the reader fails to find in these pages anything that he knows about the birds, he can only blame himself for failing to send the information to—

The Author.

LIFE HISTORIES OF

NORTH AMERICAN WOOD WARBLERS

Order PASSERIFORMES: Family Parulidae

By Arthur Cleveland Bent

Taunton, Mass.

GENERAL REMARKS ON THE FAMILY PARULIDAE

Contributed by Winsor Marrett Tyler

The family of wood warblers, Parulidae, is the second largest family of North American birds, surpassed only in number of species by the family Fringillidae. The wood warblers occur only in the Western Hemisphere; they are distinct from the Old World warblers, Sylviidae, although the two families play a similar rôle in nature’s economy.

The wood warblers are largely nocturnal migrants, whose long journeys in the dark of night over sea and lake and along the coast expose them to many perils, one being the lighthouses they strike with frequently fatal results. Their notes are seldom heard from the night sky during their spring migration, but on many a calm, quiet night in August and September, as they fly overhead, their sharp, sibilant, staccato notes punctuate the rhythmic beat of the tree-crickets singing in the shrubbery and stand out clearly among the soft, whistled calls of the migrating thrushes.

The length of migration varies greatly; the pine warbler withdraws in winter only a short distance from the southern limit of its breeding range, whereas the most northerly breeding black-polls migrate from Alaska to the Tropics. In spring many species migrate at nearly the same time, apparently advancing northward in intermittent waves of great numbers during favorable nights. Flocks made up of sometimes a dozen species together flash about in their bright plumage during the week or two at the height of the migration and furnish days of great excitement to ornithologists. Their return in late summer and autumn is more leisurely and regular; in loose flocks they drift slowly by for several weeks, their southward passage evident even in daytime. The flocking begins early, soon after nesting is over, and to the north is apparent early in July, if closely watched for, even before the leaves begin to wither. The mixed fall flocks, with adults in winter plumage and young birds in duller colors, present many fascinating problems in identification as the birds move quietly along.

[Author’s Notes: When I asked Dr. Tyler to contribute these remarks we discussed Professor Cooke’s (1904) theory of trans-Gulf migration, which has been generally accepted until recently, when it was challenged by George C. Williams (1945). This paper started a discussion in which George H. Lowery, Jr. (1945), has taken a prominent part, and of which we have not yet heard the last. Routes of migration from South America to the United States are evidently well established through the West Indies and the Bahamas to the southeastern States; across the Caribbean to Jamaica, Cuba, and Florida; through Central America and directly across the Gulf from Yucután to the Gulf States; through eastern Mexico and Texas; and through western Mexico to the southwestern States. Professor Cooke was probably correct in assuming that the majority of wood warblers breeding in eastern North America migrate directly across the Caribbean or the Gulf. Some species may confine themselves to only one of the routes named, but we need more data to say just which species uses what route.]

The literature contains descriptions of several warblers not recognized as established species by the A. O. U. Check-List (1931). Some, described and illustrated by older writers such as Wilson and Audubon, cannot be identified; others are presumably hybrids; and one, Sylvia autumnalis Wilson, the autumn warbler, is clearly the black-poll in fall plumage. The first category includes Dendroica carbonata (Audubon), the carbonated warbler, of which the Check-List says “the published plates may have been based to some extent on memory”; D. montana (Wilson), the blue mountain warbler, which is “known only from the plates of Audubon and Wilson”; and Wilsonia (?) microcephala (Ridgway), the small-headed flycatcher, of which it says: “Known only from the works of Wilson and Audubon whose specimens came from New Jersey and Kentucky respectively. There is some question whether they represent the same species.”

In the second category is Vermivora cincinnatiensis (Langdon), the Cincinnati warbler, described in 1880. “The unique type is regarded as a hybrid between Vermivora pinus (Linnaeus) and Oporornis formosa (Wilson).” Recently, in a letter dated August 3, 1948, Dr. George M. Sutton reports to Mr. Bent the discovery of a second Cincinnati warbler, taken in Michigan on May 28, 1948. He says: “Its bill and feet are large for Vermivora and its under tail coverts proportionately too long for that genus. It has only a faint suggestion of wing-barring and the merest shadow of a pattern on the outer rectrices. One of its most interesting and beautiful characters is the gray tipping of the feathers at the rear of the crown, as in O. formosus. The effect is very unusual, for the gray-tipped feathers are yellow. It is, in short, obviously a cross between Vermivora and Oporornis.”

The status of Vermivora leucobronchialis and V. lawrencii and the relationship between them puzzled ornithologists for upward of two generations. William Brewster (1876) described the former as a new species, and since that time, as Walter Faxon (1911) writes, “almost every conceivable hypothesis has been advanced by one writer or another to fix its true status in our bird-fauna.” In addition to being considered a valid species, it has been regarded as a hybrid (Brewster, 1881), as a dichromatic phase, that is, a leucochroic phase of V. pinus (Ridgway, 1887), as a mutant (Scott, 1905), and finally as a phase, “ancestral in character” (atavistic) of the goldenwing (C. W. Townsend, 1908).

Lawrence’s warbler is a very rare bird. The first specimen was described in 1874 (Herold Herrick, 1874), and since that time the bird was taken or seen infrequently, chiefly in regions where the breeding ranges of V. chrysoptera and V. pinus overlap. Consensus of opinion in the main regarded it as a hybrid between V. chrysoptera and V. pinus, as it combined characters of both the supposed parents. John Treadwell Nichols (1908) some years ago brought new light to the problem. He says:

In any discussion of the status of Lawrence’s and Brewster’s Warblers it is well to bear in mind the facts, including the much greater abundance of Brewster’s, are in accord with Mendel’s Law of Heredity, supposing both forms to be hybrids between Helminthophila pinus and H. chrysoptera. * * * All the first generation hybrids will be Brewster’s Warbler in plumage. In the next generation there will be pure Golden-winged Warblers, pure Blue-winged Warblers, pure Brewster’s Warblers, and pure Lawrence’s Warblers; also mixed birds of the first three forms, but none of the last form, which, being recessive, comes to light only when pure. The original hybrids then (which will be all Brewster’s in plumage) must be fertile with one another or with the parent species for any Lawrence’s to occur; and if they are perfectly fertile Lawrence’s must still remain a small minority. After the first generation the proportion of plumages of birds with mixed parentage should be: 9 Brewster’s, 3 chrysoptera, 3 pinus, 1 Lawrence’s.

This explanation removed the stumbling block, long believed to be insurmountable, that a black-throated bird, mating with a yellow-throated bird, could produce progeny having a white throat. Under Mendel’s Law the dominant color (white) of chrysoptera would appear by the suppression of the recessive black throat.

Fortunately, Walter Faxon (1913) not long afterward found a female blue-winged warbler mated with a goldenwing and was successful in following the resulting brood of young birds until they had acquired their first winter plumage when, fulfilling Mendel’s Law, they were all in “the garb of Helminthophila leucobronchialis,” thus establishing beyond a doubt the hybrid nature of the bird. At the end of his paper, Walter Faxon (1913) relates a bit of interesting ancient history regarding these three species of Vermivora. He says:

In my paper published in 1911, after stating the different hypotheses proposed in order to explain the relations existing among the Golden-winged, Blue-winged, Brewster’s, and Lawrence’s Warblers I added, half in jest, that the only hypothesis left for a new-comer in the field was this: that the Golden-winged and the Blue-winged Warblers themselves were merely two forms of one species. Curiously enough, not long after this I found that this very opinion had been expressed, and in a most unexpected quarter: in a letter dated Edinburgh, Sept. 15, 1835, Audubon wrote to Bachman that he suspected the golden-winged warbler and the blue-winged warbler were one species! That Audubon at that early date, ignorant (as he was assumed to be) of the existence of Brewster’s and Lawrence’s warblers, and but superficially acquainted with the golden-wing, should suspect that two birds so diverse as the blue-wing and the golden-wing were one species seemed incomprehensible, and in the light of what we now know about these birds, his surmise seemed to presuppose an almost superhuman faculty of prevision.

As a possible explanation of Audubon’s letter I have only this to offer: in the winter of 1876-77 Dr. Spencer Trotter discovered in the collection of the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia a specimen of Brewster’s warbler without a label, the third specimen known up to that time; on the bottom of the stand was written in the autograph of John Cassin, “J. C., 20 October, 1862,” and also a badly blurred legend “Not from Bell.” An appeal to J. G. Bell elicited the response that he remembered shooting a peculiar warbler in Rockland Co., N. Y., about the year 1832—a warbler something like a golden-wing, but lacking, although in high plumage, the black throat of that species; a great many years afterward, he sold this specimen in Philadelphia but knew nothing of its ultimate fate. Dr. Trotter justly inferred that the Philadelphia Academy specimen was in all probability the very bird shot by Bell.

Now as Audubon was intimately associated with Bell, is it not possible that he had examined this example of Brewster’s warbler? In that case, seeing that this bird’s characters were in part those of the blue-wing, in part those of the golden-wing, he may have inferred the interbreeding of these two birds, and so (rather unwarrantably, it is true) their identity. If this be not the explanation of the passage in Audubon’s letter to Bachman I have no other to suggest.

When Audubon came to publish his account of the Golden-winged Warbler in 1839 (Ornithological Biography, 1839, 5, p. 154) he said not a word about its connection with the Blue-winged Warbler.

Recently Karl W. Haller (1940) described “a new wood warbler from West Virginia” from two specimens, male and female, which he collected on May 30 and June 1, 1939, respectively, at points 18 miles apart, and proposed for it the new name Dendroica potomac, Sutton’s warbler. These birds resemble the yellow-throated warbler in plumage but lack streaks on the sides. They also suggest the parula warbler in having a faint yellowish wash on the back and, in the male, “an almost imperceptible hint of raw sienna” on the upper breast. The male sang a song much like the parula’s, but doubled by repetition.

Two more Sutton’s warblers have been carefully observed in the field: one at the point where the type was collected on May 21, 1942, by Maurice Brooks and Bayard H. Christy (1942); the second about 18 miles to the westward on June 21, 1944, by George H. Breiding and [5] Lawrence E. Hicks (1945). Another aberrant warbler has been described by Stanley G. Jewett (1944), who examined four specimens which show a curious intermingling of the plumage characters of the hermit and Townsend warblers.

[Author’s Note: Since the above was written, Kenneth C. Parkes (1951) has published a study of the genetics of the golden-winged—blue-winged warbler complex, to which the reader is referred.]

BLACK-AND-WHITE WARBLER

Contributed by Winsor Marrett Tyler

HABITS

The black-and-white warbler is one of the earliest spring warblers to reach its breeding-ground in the Transition Zone. Most of the other members of this family arrive in or pass through the region in mid-May or somewhat later, according to the season, when the oaks are in bloom and the opening flowers attract swarms of insects.

The black-and-white warbler, however, owing to its peculiar habit of feeding on the trunks and the large limbs of the trees, does not have to wait for the bounty supplied by the oaks but finds its special feeding-ground well stocked with food long before the oaks blossom or their leaves unfold. It comes with the yellow palm warbler late in April, when many of the trees are nearly bare, and not long after the pine warbler.

Mniotilta is a neat little bird, dressed in modest colors, at this season singing its simple but sprightly song as it scrambles over the bark—the black-and-white creeper, Alexander Wilson calls it.

Milton B. Trautman (1940), speaking of the spring migration at Buckeye Lake, Ohio, shows that the male birds are preponderant in the earliest flights. He says: “The first spring arrivals, chiefly males, were noted between April 16 and 30, and between May 1 and 5, 2 to 15 birds, mostly males, could be daily noted. The peak of migration usually lasted from May 6 to May 18, and then from 3 to 42 individuals, consisting of a few old males and the remainder females and young males, were daily observed. On May 18 or shortly thereafter a decided lessening in numbers occurred, and by May 23 all except an occasional straggler had left.”

Courtship.—Forbush (1929) gives this hint of courtship, which resembles the activities of most warblers at this season: “When the [6] females arrive there is much agitation, and often a long-continued intermittent pursuit, with much song and fluttering of black and white plumage, and much interference from rival males before the happy pair are united and begin nesting.”

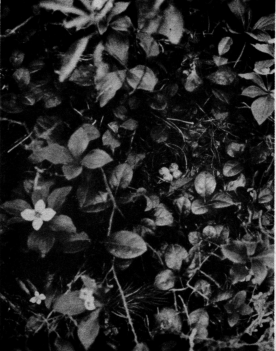

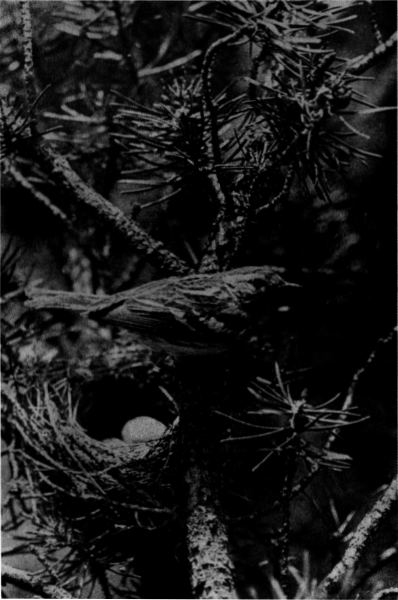

Nesting.—The black-and-white warbler usually builds its nest on the ground, tucking it away against a shrub or tree, or even under the shelter of an overhanging stone or bank. The nest is generally concealed among an accumulation of dead leaves which, arching over it, hides it from above. It is made, according to A. C. Bent (MS.), “of dry leaves, coarse grass, strips of inner bark, pine needles and rootlets, and is lined with finer grasses and rootlets and horsehair.” I have seen a nest made chiefly of pine needles on a base of dry leaves.

Henry Mousley (1916), writing of Hatley, Quebec, mentions moss as a component part of the nest, and says of three nests that they were all “heavily lined with long black and white horse hairs,” a peculiarity of coloration mentioned in one of Mr. Bent’s nests. Thomas D. Burleigh (1927b) speaks of a nest in Pennsylvania “built of dead leaves and rhododendron berry stems, lined with fine black rootlets and a few white hairs.” H. H. Brimley (1941) describes an exceptional nest. He says: “There was no particular departure from normal in its construction except for the fact that it was lined with a mixture of fine rootlets and very fine copper wire, such as is used in telephone cables. Fragments of such cable, discarded by repair men, were found nearby where a telephone line ran through the woods.”

Cordelia J. Stanwood (1910c) speaks of a nest “built in a depression full of leaves, behind a flat rock. * * * The cavity was shaped on a slant, the upper wall forming a partial roof. * * * It looked not unlike a small-sized nest of an Oven-bird. On the inside, the length was 21⁄2 inches, width 11⁄2 inches, depth 2 inches. On the outside, length 31⁄2 inches, width 21⁄2 inches, depth 21⁄2 inches. Thickness of wall at the top of nest, 1 inch; at the bottom, 1⁄2 inch.” Henry Mousley (1916) gives the average dimensions of three nests as “outside diameter 33⁄4, inside 13⁄4 inches; outside depth 21⁄4, inside 11⁄2 inches.”

F. A. E. Starr (MS.) writes to A. C. Bent from Toronto, Ontario, that all the nests he has found have been in broken-off stumps in low woods. “The cavity in the top of the stump,” he says, “is filled with old leaves, and the nest proper is made chiefly of strips of bark with grass and fiber.” Guy H. Briggs (1900) reports a nest “in a decayed hemlock stump, fifteen inches from the ground.” In such cases, of course, while the nest is well above the ground level, it rests on a firm foundation.

Audubon (1841) says: “In Louisiana, its nest is usually placed in some small hole in a tree,” but he quotes a letter to him from Dr. [7] T. M. Brewer on the subject, thus: “This bird, which you speak of as breeding in the hollows of trees, with us always builds its nest on the ground. I say always, because I never knew it to lay anywhere else. I have by me a nest brought to me by Mr. Appleton from Batternits, New York, which was found in the drain of the house in which he resided.”

Minot (1877) speaks of two nests found near Boston, Mass., well above the ground. He says: “The first was in a pine grove, in the cavity of a tree rent by lightning, and about five feet from the ground, and the other on the top of a low birch stump, which stood in a grove of white oaks.”

Gordon Boit Wellman (1905) states: “Toward the last of the incubation time one of the birds was constantly on the nest. I found the male sitting usually at about dusk, but I think the female sat on the eggs over night.”

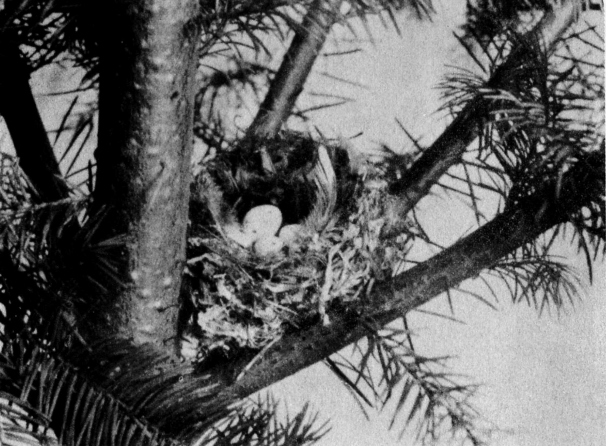

Eggs.—[Author’s Note: The black-and-white warbler usually lays 4 or 5 eggs to a set, normally 5, seldom fewer or more. These are ovate to short ovate and slightly glossy. The ground color is white or creamy white. Some are finely sprinkled over the entire surface with “cinnamon-brown,” “Mars brown,” and “dark purplish drab”; others are boldly spotted and blotched with “russet” and “Vandyke brown,” with underlying spots of “brownish drab,” “light brownish drab,” and “light vinaceous-drab.” Speckled eggs are commoner than the more boldly blotched type. The markings are usually concentrated at the large end, and on some of the heavily spotted eggs there is a solid wreath of different shades of russet and drab. The measurements of 50 eggs average 17.2 by 13.3 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measure 18.8 by 13.7, 17.9 by 14.7, 15.7 by 12.7, and 16.3 by 12.2 millimeters (Harris).]

Young.—Cordelia J. Stanwood (MS.) speaks of the nestlings a few days from the egg as “very dark gray, much like young juncos and Nashville warblers.” But when they leave the nest they are clearly recognizable as young black-and-white warblers, although they are slightly tinged with brownish. By mid-July, here in New England, they assume their first winter plumage, and, as both sexes of the young birds have whitish cheeks, they resemble very closely their female parent.

Unlike the young of some of the other warblers which remain near the ground for many days, the young black-and-white warblers shortly ascend to the branches of trees where they are fed by the old birds.

I find no definite record of the length of the incubation period, but in a nest I watched in 1914 it was close to 10 days. Burns (1921) gives the period of nestling life as 8 to 12 days.

Plumages.—[Author’s Note: Dr. Dwight (1900) calls the natal down mouse gray, and describes the juvenal plumage as follows: “Above, wood-brown streaked with dull olive-brown, the upper tail coverts dusky; median crown and superciliary stripe dingy white. Wings and tail dull black, edged chiefly with ashy gray, the tertiaries (except the proximal which is entirely black) broadly edged with white, buff tinged on the middle one. Two buffy white wing bands at tips of greater and median wing coverts. The outer two rectrices with terminal white blotches of variable extent on the inner webs. Below, dull white, washed on the throat and sides with wood-brown, obscurely streaked on throat, breast, sides and crissum with dull grayish black.”

A postjuvenal molt begins early in July, involving everything but the flight feathers; this produces in the young male a first winter plumage which is similar to the juvenal, but whiter and more definitely streaked. “Above, striped in black and white, the upper tail coverts black broadly edged with white; median crown and superciliary stripe pure white. The wing bands white. Below, pure white streaked with bluish black on sides of breast, flanks and crissum, the black veiled by overlapping white edgings; the chin, throat, breast and abdomen unmarked. Postocular stripe black; the white feathers of the sides of the head tipped with black.”

The first nuptial plumage is acquired by a partial prenuptial molt in late winter, which involves a large part of the body plumage, but not the wings or the tail. “The black streaks of the chin and throat are acquired, veiled with white, and the loral, subocular and auricular regions become jet-black. The brown primary coverts distinguish young birds and the chin is less often solidly black than in adults.”

The adult winter plumage is acquired by a complete postnuptial molt, beginning early in July. It differs from the first winter dress "in having the chin and throat heavily streaked with irregular chains of black spots veiled with white edgings, the wings and tail blacker and the edgings a brighter gray. * * * The female has corresponding plumages and moults, the first prenuptial moult often very limited or suppressed. In juvenal dress the wings and tail are usually browner with duller edgings and the streaking below obscure. In first winter plumage the streakings are dull and obscure everywhere, a brown wash conspicuous on the flanks and sides of the throat. The first nuptial plumage is gained chiefly by wear through which the brown tints are largely lost, the general color becoming whiter and the streaks more distinct. The adult winter plumage is rather less brown than the female first winter, the streaking less obscure and the wings and tail darker. The adult nuptial plumage, acquired partly [9] by moult, is indistinguishable with certainty from the first nuptial.”]

Food.—McAtee (1926) summarizes the food of the species thus:

In its excursions over the trunks and larger limbs of trees the Black and White Creeper is certainly not looking for vegetable food, and only a trace of such matter has been found in the stomachs examined. The food is chiefly insects but considerable numbers of spiders and daddy-long-legs also are eaten. Beetles, caterpillars, and ants are the larger classes of insect food, but moths, flies, bugs, and a few hymenoptera also are eaten. Among forest enemies that have been found in stomachs of this species are round-headed wood borers, leaf beetles, flea beetles, weevils, bark beetles, leaf hoppers, and jumping plant lice. The hackberry caterpillar, the hackberry psyllid, an oak leaf beetle Xanthonia 10-notata, and the willow flea beetle, are forms specifically identified. Observers have reported this warbler to feed also upon ordinary plant lice, and upon larvae of the gypsy moth.

Forbush (1929) adds the following observation: “The food of this bird consists mostly of the enemies of trees, such as plant-lice, scale-lice, caterpillars, both hairy and hairless, among them such destructive enemies of orchard, shade and forest trees as the canker-worm and the gipsy, brown-tail, tent and forest tent caterpillars. Wood-boring and bark-boring insects, click beetles, curculios and many other winged insects are taken. Sometimes when the quick-moving insects escape its sharp bill, it pursues them on the wing but most of its attention is devoted to those on the trees.”

H. H. Tuttle (1919), speaking of the male parent feeding the young birds, says: “The fare which he provided was composed entirely of small green caterpillars, cut up into half-lengths.”

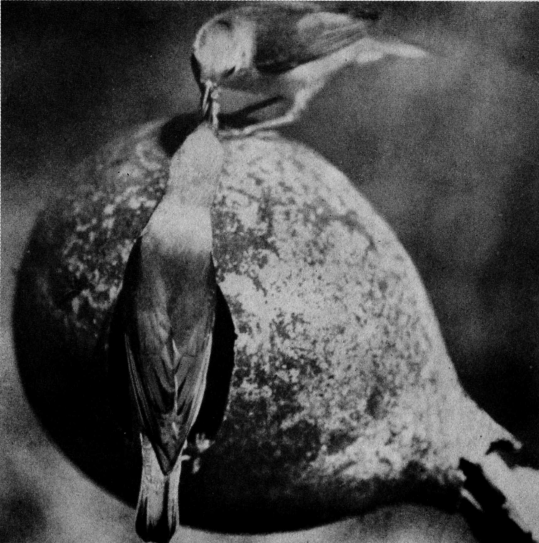

Behavior.—The black-and-white warbler seems set apart from others of the group, perhaps because of its marked propensity for clambering over the trunks of trees and their larger branches. Although, like other warblers, it seems at home among the smaller twigs, it spends a large part of its time on upright surfaces over which it moves easily and quickly, upward, downward, and spirally, with great agility and sureness of footing, constantly changing direction, and not using the tail for support. As it scrambles over the bark, it switches from side to side as if at each hop it placed one foot and then the other in advance, and even on slim branches it hops in the same way, the tail alternately appearing first on one side of the branch and then on the other; it reminds us of a little schoolgirl swishing her skirt from side to side as she walks down the street. The bird is alert and watchful, and if it starts an insect from the bark, or sees one flying near, it may pursue it and catch it in the air.

H. H. Tuttle (1919) describes an extreme example of behavior simulating a wounded bird. He says: “She struck the leaves with a slight thud and turned over on her side, while the toes of one [10]up-stretched leg clutched at the air and her tail spread slowly into a pointed fan. * * * Deceived for a moment then, I turned a step in her direction. She lay quite still except for a quivering wing. I reached out toward her with a small stick and touched her side; she screamed pitifully; I stretched out my hand to pick her up, but with a last effort she righted herself, and by kicking desperately with one leg, succeeded in pushing forward a few inches.”

We associate this warbler with dry, rocky hillsides where the ground is strewn with dead leaves, but the bird may breed also in the dry portions of shady, wooded swamps.

Voice.—The black-and-white is one of the high-voiced singers. Its song is made up of a series of squeaky couplets given with a back-and-forth rhythm, a seesawing effect, like the ovenbird’s song played on a fine, delicate instrument. It may be suggested by pronouncing the syllables we see rapidly four or five times in a whispered voice. In the distance the song has a sibilant quality; when heard near at hand a high, clear whistle may be detected in the notes. The final note in the song is the accented see.

Albert R. Brand (1938), in his mechanically recorded songs of warblers, placed the black-and-white’s song as the fourth highest in pitch in his last of 16 species, the black-poll, blue-winged, and the Blackburnian being higher. He gives the approximate mean (vibrations per second) of the black and white as 6,900 and of the blackpool as 8,900.

Aretas A. Saunders (MS.) says: “The pitch of the songs varies, according to my records, from B‴ to E‴′, a range of three and a half tones more than an octave. A single song, however, does not vary more than three and a half tones.”

A second song, not heard, I think, until the bird has been on its breeding ground for some time, is rather more pleasing, less monotonous, than the first. It is longer, somewhat faster, more lively, and is modulated in pitch. Francis H. Allen (MS.) speaks of it thus: “Later in the season a more elaborate song is very commonly heard. I have been accustomed to syllabify it as weesy, weesy, weesy, weesy, woosy, woosy, weesy, weesy. The notes indicated by woosy really differ from the others only by being pitched lower.”

Occasionally we hear aberrant songs which prove puzzling until we can see the singer. Allen remarks that he has heard several such songs, and I remember hearing one in which the lower note of each couplet was reduplicated, thereby strongly suggested one of the songs of the Blackburnian warbler. Sometimes Mniotilta sings during flight. I once heard a song from a bird flying within a few feet of me—at this range a sound of piercing sharpness.

Of the minor notes Andrew Allison (1907) says: “I know of no other warbler except the Chat that can produce so great a variety of sounds; and since nearly all of the notes resemble those of other warblers, this is a most confusing bird to deal with during the busy season of ‘waves’.”

The call note often has a buzzing quality, and often runs into a long chatter (also characteristic of the young bird), but it may be given so sharply enunciated that it suggests the chip of the black-poll. Allen (MS.) writes it chi, “like pebbles struck together,” and Cordelia J. Stanwood (1910) renders it sptz, saying “the sound resembled the noise made by a drop of syrup sputtering on a hot stove.”

Field marks.—The black-poll, in its spring plumage, and the black-and-white warbler resemble each other in coloration, but the latter bird may be readily distinguished by its white stripe down the center of the crown and the white line over the eye. The contrast in the behavior of the two birds separates them at a glance.

Enemies.—Like other birds which build on the ground, the black-and-white is subject, during the nesting season, to attacks by snakes and predatory mammals. A. D. DuBois (MS.) cites a case in which maggots destroyed a nestful of young birds.

Harold S. Peters (1936) reports that a fly, Ornithoica confluens Say, and a louse, Myrsidea incerta (Kellogg), have been found in the plumage of the black-and-white warbler.

Herbert Friedmann (1929) says: “This aberrant warbler is a rather uncommon victim of the Cowbird, only a couple dozen definite instances having come to my notice. * * * The largest number of Cowbirds’ eggs found in a single nest of this Warbler is five, together with three eggs of the owner.” George W. Byers (1950) reports a nest of this warbler, in Michigan, that held two eggs of the warbler and eight of the cowbird, on which the warbler was incubating. His photograph of the eggs suggests that they were probably laid by four different cowbirds.

Fall.—Several of the warblers show a tendency to stray from their breeding grounds soon after their young are able to care for themselves, perhaps even before the postnuptial molt is completed and long before the birds gather into the mixed autumn flocks. Among these early wandering birds the black-and-white warbler is a very conspicuous species, perhaps because it is one of our commoner birds or, more probably, because of its habit of feeding in plain sight on the trunks and low branches of dead or dying trees and shrubs instead of hiding, like other warblers, high up in the foliage. It may be that the warblers we see at some distance from their breeding grounds thus early in the season have already begun their migration toward the south: they often appear to be migrating.

Behind the house in Lexington, Mass., where I lived for years, there was a little hill, sparsely covered with locust trees, to the southward from my dooryard. This hill was a favorite resort for warblers in late summer. No warbler bred within a mile of the spot, except the summer yellowbird, to use the old name, yet soon after the first of July the black-and-white warblers began to assemble there. Not infrequently I have seen a single bird come to the hill, flying in from the north across Lexington Common, and join others there. The small company might remain for an hour or more, frequently singing (evidently adult males) as the birds fed in the locust trees.

Later in the season, as August advances, migration appears more evident. The birds now gather in larger numbers, sometimes as many as eight or ten; they pause in the locust trees for a shorter time before flying off; they are no longer in song; and the majority of the birds have white cheeks, most of them presumably young birds. Although they are almost silent as they climb about feeding, if you stand quietly in the midst of a company of four or five, now and then you may hear a faint note, and at once the note comes from all sides, each bird apparently reporting its whereabouts—a sound which calls to mind the south-bound migrants as they roam through the quiet autumn woods. Other warblers, unquestionably migrants, visit this hillside in August, notably the Tennessee, an early arrival who has already traveled a long way.

The fall migration of the black-and-white is long-drawn-out. The bird does not depend, like many of the warblers, on finding food among the foliage, so it may linger long after the trees are bare of leaves, sometimes, here in New England, well into October. I saw a bird in eastern Massachusetts on October 23, 1940, a very late date.

Winter.—Dr. Alexander F. Skutch (MS.) sent to A. C. Bent the following comprehensive account of the bird on its winter quarters: "None of our warblers is more catholic in its choice of a winter home than the black-and-white. Upon its departure from its nesting range, it spreads over a vast area from the Gulf States south to Ecuador and Venezuela, from the Pacific coast of Mexico and Central America eastward through the Antilles. And in the mountainous regions of its winter range it does not, like so many members of the family, restrict itself to a particular altitudinal zone, but on the contrary scatters from sea level high up into the mountains. As a result of this wide dispersion, latitudinal and altitudinal, it appears to be nowhere abundant in Central America during the winter months, yet it has been recorded from more widely scattered localities than most other winter visitants. On the southern coast of Jamaica, in December 1930, I found a greater concentration of individuals than I have ever seen in Central America during midwinter.

“Wintering throughout the length of Central America, from near sea level up to 9,000 feet and rarely higher, the black-and-white warbler is somewhat more abundant in that portion of its altitudinal range comprised between 2,000 or 3,000 and 7,000 or 8,000 feet above sea level. It is found in the heavy forest, in the more open types of woodland, among the shade trees of the coffee plantations, and even amid low second-growth with scattered trees. It creeps along the branches in exactly the same fashion in its winter as in its summer home. Solitary in its disposition, two of the kind are almost never seen together. The only time I have heard this warbler sing in Central America was also one of the very few occasions when I found two together. Early on the bright morning of September 1, 1933, when the warblers were arriving from the north, I heard the black-and-white’s weak little song repeated several times among the trees at the edge of an oak wood, at an altitude of 8,500 feet in the Guatemalan highlands. Looking into the tree tops, I saw two of these birds together. Apparently they were singing in rivalry, as red-faced warblers, Kaup’s redstarts, yellow warblers, and other members of the family solitary during the winter months will sing in the face of another of their kind, at seasons when they are usually silent. Often such songs lead to a pursuit or even a fight; but I have never seen black-and-white warblers actually engaged in a conflict in their winter home.

“Although intolerant of their own kind, the black-and-white warblers are not entirely hermits; for often a single one will attach itself to a mixed flock of small birds. In the Guatemalan highlands, during the winter months, such flocks are composed chiefly of Townsend’s warblers; and each flock, in addition to numbers of the truly gregarious birds, will contain single representatives of various species of more solitary disposition, among them often a lone black-and-white, so different in appearance and habits from any of its associates.

“This warbler arrives and departs early. It has been recorded during the first week of August in Guatemala, and by the latter part of the month in Costa Rica and Panamá. In Costa Rica, it appears not to linger beyond the middle or more rarely the end of March; while for northern Central America my latest date is April 22.

“Early dates of fall arrival in Central America are: Guatemala—passim (Griscom), August 3; Sierra de Tecpán, August 23, 1933; Santa María de Jesús, August 6, 1934; Huehuetenango, August 14, 1934. Honduras—Tela, August 19, 1930. Costa Rica—San José (Cherrie), August 20; Carrillo (Carriker), September 1; San Isidro de Coronado, September 8, 1935; Basin of El General, September 19, 1936; Vara Blanca, September 5, 1937; Murcia, September 11, 1941. Panamá—Canal Zone (Arbib and Loetscher), August 24, 1933, and [14] August 29, 1934. Ecuador—Pastaza Valley, below Baños, October 17, 1939.

“Late dates of spring departure from Central America are: Costa Rica—Basin of El General, February 23, 1936, March 10, 1939, March 26, 1940, March 3, 1942, March 18, 1943; Vara Blanca, March 13, 1938; Guayabo (Carriker), March 30; Juan Viñas (Carriker), March 21. Honduras—Tela, April 22, 1930. Guatemala—Motagua Valley, near Los Amates, April 17, 1932; Sierra de Tecpán, February 20, 1933.”

The bird has a wide winter range, as shown above. Dr. Thomas Barbour (1943) speaks of it thus in Cuba: “Common in woods and thickets. A few arrive in August, and by September they are very abundant, especially in the overgrown jungles about the Ciénaga.”

Edward S. Dingle (MS.) has sent to A. C. Bent a remarkable winter record of a black-and-white warbler seen on Middleburg plantation, Huger, S. C., on January 13, 1944.

DISTRIBUTION

Range.—Canada to northern South America.

Breeding range.—The black-and-white warbler breeds north to southwestern Mackenzie, rarely (Simpson and Providence; has been collected at Norman); northern Alberta (Chipewyan and McMurray); central Saskatchewan (Flotten Lake, probably Grand Rapids, and Cumberland House); southern Manitoba (Duck Mountain, Lake St. Martin, Winnipeg, and Indian Bay); central Ontario (Kenora, Pagwachuan River mouth, and Lake Abitibi; has occurred at Piscapecassy Creek on James Bay, and at Moose Factory); southern Quebec (Lake Tamiskaming, Blue Sea Lake, Quebec, Mingan, and Mascanin; has occurred at Sandwich Bay, Labrador); and central Newfoundland (Deer Lake, Nicholsville, Lewisport, and Fogo Island). East to Newfoundland (Fogo Island and White Bear River); Nova Scotia (Halifax and Yarmouth); the Atlantic coast to northern New Jersey (Elizabeth and Morristown); eastern Pennsylvania (Berwyn); Maryland (Baltimore and Cambridge); eastern Virginia (Ashland and Lawrenceville); North Carolina (Raleigh and Charlotte); South Carolina (Columbia and Aiken); and central Georgia (Augusta and Milledgeville). South to central Georgia (Milledgeville); south central Alabama (Autaugaville); north-central Mississippi (Starkville and Legion Lake); northern Louisiana (Monroe; rarely to southern Louisiana, Bayou Sora); and northeastern and south-central Texas (Marshall, Dallas, Classen, Kerrville, and Junction). West to central Texas (Junction and Palo Dura Canyon); central Kansas (Clearwater); central-northern Nebraska (Valentine); possibly eastern Montana (Glasgow); central Alberta (Camrose, Glenevis, and Lesser [15] Slave Lake); to southwestern Mackenzie (Simpson). There is a single record of its occurrence in June at Gautay, Baja California, 25 miles south of the international border.

Winter range.—In winter the black-and-white warbler is found north to southern Texas (Cameron County, occasionally Cove, and Texarkana); central Mississippi, occasionally (Clinton); accidental in winter at Nashville, Tenn.; southern Alabama (Fairfield); southern Georgia (Lumber City, occasionally Milledgeville, and Athens); and rarely to central-eastern South Carolina (Edisto Island and Charleston). East to the coast of South Carolina, occasionally (Charleston); Georgia (Blackbeard Island); Florida (St. Augustine, New Smyrna, and Miami); the Bahamas (Abaco, Watling, and Great Abaco Islands); Dominican Republic (Samaná); Puerto Rico; Virgin Islands and the Lesser Antilles to Dominica; and eastern Venezuela (Paria Peninsula). South to northern Venezuela (Paria Peninsula, Rancho Grande, and Mérida); west-central Colombia (Bogotá); and central Ecuador (Pastazo Valley). West to central and western Ecuador (Pastazo Valley and Quito); western Colombia (Pueblo Rico); western Panamá (Dvala); El Salvador (Mount Cacaguatique); western Guatemala (Mazatenango); Guerrero (Acapulco and Coyuca); Colima (Manzanillo); northwestern Pueblo (Metlatayuca); western Nuevo León (Monterey); and southern Texas (Cameron County). It also occurs casually in the Cape region of Baja California and in southern California (Dehesa and Carpenteria). There are also several records in migration from California and from western Sinaloa.

Migration.—Late dates of spring departure from the winter home are: Venezuela—Yacua, Paria Peninsula, March 20. Colombia—Santa Marta region, March 12. Panamá—Gatún, March 26. Costa Rica—El General, April 9. Honduras—Tola, April 22. Guatemala—Quiriguá, April 17. Veracruz—El Conejo, May 15. Puerto Rico—Algonobo, April 27. Haiti—Île à Vache, May 6. Cuba—Habana, May 25. Bahamas—Abaco, May 6. Florida—Orlando, May 21. Georgia—Cumberland, May 26. Louisiana—Avery Island, April 27.

Early dates of spring arrival are: South Carolina—Clemson College, March 20. North Carolina—Weaverville, March 3. Virginia—Lawrenceville, March 23. District of Columbia—Washington, March 30. New York—Corning, April 18. Massachusetts—Stockbridge, April 16. Vermont—St. Johnsbury, April 19. Maine—Lewiston, April 27. Quebec—Montreal, April 26. Nova Scotia—Wolfville, April 29. Mississippi—Deer Island, March 4. Louisiana—Schriever, March 8. Arkansas—March 12. Tennessee—Nashville, March [16] 20. Illinois—Chicago, April 17. Michigan—Ann Arbor, April 6. Ohio—Toledo, April 7. Ontario—Guelph, April 22. Missouri—Marionville, April 3. Iowa—Grinnell, April 16. Wisconsin—Milwaukee, April 20. Minnesota—Lanesboro, April 23. Kansas—Independence, April 1. Omaha—April 21. North Dakota—April 28. Manitoba—Winnipeg, April 28. Alberta—Edmonton, May 6; McMurray, May 15. Mackenzie—Simpson, May 22.

Late dates of fall departure are: Alberta—Athabaska Landing, September 11. Manitoba—Aweme, September 22. North Dakota—Argusville, October 2. Minnesota—Minneapolis, October 10. Iowa—Davenport, October 1. Missouri—Columbia, October 24. Wisconsin—Madison, October 7. Illinois—Port Byron, October 15. Ontario—Hamilton, October 3. Michigan—Detroit, October 15. Ohio—Youngstown, October 15. Kentucky—Danville, October 14. Tennessee—Athens, October 17. Arkansas—Winslow, October 17. Louisiana—New Orleans, October 25. Mississippi—Gulfport, November 19. Quebec—Quebec, September 18. New Brunswick—St. John, September 19. Nova Scotia—Yarmouth, September 23. Maine—Portland, October 17. New Hampshire—Ossipee, October 18. Massachusetts—Cambridge, October 15. New York—New York, October 6. Pennsylvania—Atglen, October 29. District of Columbia—Washington, October 18. Virginia—Charlottesville, October 18. North Carolina—Raleigh, October 29. South Carolina—Charleston, November 15. Georgia—Savannah, October 29.

Early dates of fall arrival are: South Carolina—Charleston, July 19. Florida—Pensacola, July 12. Cuba—Artemisa, Pinar del Río, August 1. Dominican Republic—Ciudad Trujillo, September 27. Puerto Rico—Mayagüez, October 9. Louisiana—New Orleans, July 21. Mississippi—Bay St. Louis, July 4. Michoacán—Tancitaro, August 7. Guatemala—Huehuetenango, August 14. Honduras—Cantarranas, August 7. Costa Rica—San José, August 20. Panamá—Tapia, Canal Zone, August 24. Colombia—Bonda, Santa Marta region, August 21. Ecuador—Pastaza Valley, October 17. Venezuela—Estado Carabobo Las Trincheras, October 9.

Banding.—A single banding recovery is of considerable interest: A black-and-white banded at Manchester, N. H., on August 31, 1944, was found on March 17, 1945, at Friendship P. O., Westmoreland, Jamaica.

Casual records.—This warbler is casual in migration or winters in Bermuda, having been recorded in six different years from October to May.

At Tingwall, Shetland Islands, north of Scotland one was picked up on November 28, 1936. This is almost as far north as the northernmost [17] record of occurrence in North America and later than it is normally found in the United States.

A specimen was collected near Pullman, Wash., on August 15, 1948, the first record for the State.

Egg dates.—Massachusetts: 31 records, May 18 to June 14; 17 records, May 25 to June 3, indicating the height of the season.

New Jersey: 7 records, May 18 to June 8.

Tennessee: 3 records, May 1 to 17.

North Carolina: 6 records, April 20 to 28.

West Virginia: 7 records, May 6 to 29 (Harris).

PROTONOTARIA CITREA (Boddaert)

PROTHONOTARY WARBLER

HABITS

I do not like the above name for the golden swamp warbler. The scientific name Protonotaria, and evidently the common name, were apparently both derived from the Latin protonotarius, meaning first notary or scribe. I sympathize with Bagg and Eliot (1937), who exclaimed:

What a name to saddle on the Golden Swamp-bird! Wrongly compounded in the first place, wrongly spelled, wrongly pronounced! We understand that Protonotarius is the title of papal officials whose robes are bright yellow, but why say “First Notary” in mixed Greek and Latin, instead of Primonotarius? Proto is Greek for first, as in prototype. Why and when did it come to be misspelled Protho? Both Wilson and Audubon wrote Protonotary Warbler, a name seemingly first given to the bird by Louisiana Creoles. Both etymology and sense call for stress on the third syllable, yet one most often hears the stress laid on the second. Here, certainly, is a bothersome name fit only to be eschewed!

The scientific name cannot be changed under the rules of nomenclature, but a change in the common name would seem desirable. However, the name does not make the bird or detract from its charm and beauty. It will still continue to thrill with delight the wanderer in its swampy haunts.

The center of abundance of the prothonotary warbler as a breeding bird in this country is in the valleys of the Mississippi River and its tributaries, notably the Ohio, the Wabash, and the Illinois Rivers. Its summer range extends eastward into Indiana and Ohio, northward into southern Ontario, Wisconsin, Michigan, and Minnesota, and westward into Iowa, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, and eastern Texas—wherever it can find suitable breeding grounds.

It also breeds in the Atlantic Coast States from Virginia to Florida.

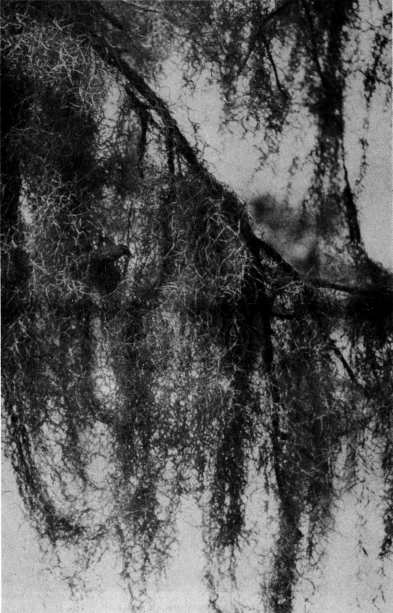

It is essentially a bird of the damp and swampy river bottoms and low-lying woods, which are flooded at times and in which woodland pools have been left by the receding water. Perhaps this warbler abounds more than anywhere else in the valley of the lower Wabash, where William Brewster (1878) found it to be—

one of the most abundant and characteristic species. Along the shores of the rivers and creeks generally, wherever the black willow (Salix niger) grew, a few pairs were sure to be found. Among the button-bushes (Cephalanthus occidentalis) that fringed the margin of the peculiar long narrow ponds scattered at frequent intervals over the heavily timbered bottoms of the Wabash and White Rivers, they also occurred more or less numerously. Potoka Creek, a winding, sluggish stream, thickly fringed with willows, was also a favorite resort; but the grand rendezvous of the species seemed to be about the shores of certain secluded ponds lying in what is known as the Little Cypress Swamp. Here they congregated in astonishing numbers, and early in May were breeding almost in colonies. In the region above indicated two things were found to be essential to their presence, namely, an abundance of willows and the immediate proximity of water. * * * So marked was this preference, that the song of the male heard from the woods indicated to us as surely the proximity of some river, pond, or flooded swamp, as did the croaking of frogs or the peep of the Hylas.

Dr. Chapman (1907) writes of this bird in its haunts:

The charm of its haunts and the beauty of its plumage combine to render the Prothonotary Warbler among the most attractive members of the family. I clearly recall my own first meeting with it in the Suwanee River region of Florida. Quietly paddling my canoe along one of the many enchanting, and, I was then quite willing to believe, enchanted streams which flowed through the forests into the main river, this glowing bit of bird-life gleamed like a torch in the night. No neck-straining examination with opera-glass pointed to the tree-tops, was required to determine his identity, as, flitting from bush to bush along the river’s bank, his golden plumes were displayed as though for my special benefit.

Dr. Lawrence H. Walkinshaw (1938) says that the golden swamp warbler “nests rather abundantly along southwestern-Michigan rivers. * * * Winding streams, bordered densely with oak, maple, ash, and elm, shallow ponds with groups of protruding willows and flooded, heavily shaded bottom-lands are favorite nesting habitats for the Prothonotary Warbler (Protonotaria citrea). Such habitats occur along the banks of the Kalamazoo River and its tributary the Battle Creek River in Calhoun County, Michigan.”

Territory.—The males arrive on the breeding grounds a few days or a week before the females come and immediately try to establish their territories, select the nesting sites, and even build nests. Dr. Walkinshaw (1941) writes:

The Prothonotary Warbler is a very strongly territorial species. When a male takes possession of a certain area he continually drives off all opponents [19] if he is able. At certain areas in Michigan I have watched these birds battle intermittently for two or three days, usually for the same bird house, one male finally taking possession. In addition I have observed them to drive off House Wrens (Troglodytes aedon), Black-capped Chickadees (Penthestes atricapillus) and Yellow Warblers (Dendroica aestiva). * * * The male Prothonotary Warbler selects the territory, selecting the nesting site before he becomes mated for the first nest, but thereafter both birds inspect the new nest sites.

On observations made near Knoxville, Tenn., Henry Meyer and Ruth Reed Nevius (1943) found that—

three males established territories. Male I arrived April 14. By the next day he was singing on an area 550 feet long and for the most part not more than 200 feet wide. It included three kinds of habitats: (a) a grassy terrace on which several nesting boxes were located, (b) river banks densely covered with small trees and bushes, and (c) a small open orchard which constituted the connecting link between the terrace and the river bank. Male II arrived on April 18 and occupied a narrow territory along a brook confined by wooded slopes and which contained two lotus ponds. The area was about 400 feet long and 100 feet wide. A nesting box was on a stake above one of the ponds. Male III appeared May 5 in the terraced area being claimed by Male I. During the day, the 2 males sang energetically and flew often only a few inches apart. Male I maintained his territory and Male III disappeared.

There were a number of nesting boxes on the area that the males investigated, carrying nesting material into some of them while they were waiting for the females to arrive. The mate of the first male came on April 20, and—

on this day this pair communicated by their full call-note. Twice the male was seen pursuing the female rapidly in a small semi-circle and pausing, called a soft, full note which was later heard only when the two sexes were together.

The mate of Male II came April 22, four days after the latter’s arrival.

Combat with other species found within the territories of these birds was observed. Combat with the Bluebird was most frequent but one or more indications of opposition was noticed with the Flicker, Downy Woodpecker, Acadian Flycatcher, Tufted Titmouse, Robin, and Cardinal.

The males sing persistently and energetically from the time that they arrive on their territories, hoping to attract their mates, but they are not always successful, especially in regions where the species is rare or not very common, and their nest-building brings no occupant. Edward von S. Dingle writes to me that, at Summerton, S. C., a male prothonotary warbler built a nest in a low stub, but no female was ever seen. He sang frequently and remained in the vicinity for several weeks. And Frederic H. Kennard, in far-away Massachusetts, mentions in his notes that he saw one and watched it for several days, June 16-20, 1890. “He sang loudly and clearly and sweetly, and seemed to like a particular place by the side of the river, for when I returned later in the day, he was still there, on the other side of the river.” On June 19, he watched him for half an hour. He was [20] always in the same locality. On a later search, no nest or no mate could be found.

Courtship.—Brewster (1878a) gives the following full account of this performance:

Mating began almost immediately after the arrival of the females, and the “old, old story” was told in many a willow thicket by the little golden-breasted lovers. The scene enacted upon such occasions was not strikingly different from that usual among the smaller birds; retiring and somewhat indifferent coyness on the part of the female; violent protestations and demonstrations from the male, who swelled his plumage, spread his wings and tail, and fairly danced around the object of his affections. Sometimes at this juncture another male appeared, and then a fierce conflict was sure to ensue. The combatants would struggle together most furiously until the weaker was forced to give way and take to flight. On several occasions I have seen two males, after fighting among the branches for a long time, clinch and come fluttering together to the water beneath, where for several minutes the contest continued upon the surface until both were fairly drenched. The males rarely meet in the mating season without fighting, even though no female may be near. Sometimes one of them turns tail at the outset; and the other at once giving chase, the pursuer and pursued, separated by a few inches only, go darting through the woods, winding, doubling, now careering away up among the tree-tops, now down over the water, sweeping close to the surface until the eye becomes weary with following their mad flight. During all this time the female usually busies herself with feeding, apparently entirely unconcerned as to the issue. Upon the return of the conqueror her indifference, real or assumed, vanishes, he receives a warm welcome, and matters are soon arranged between them.

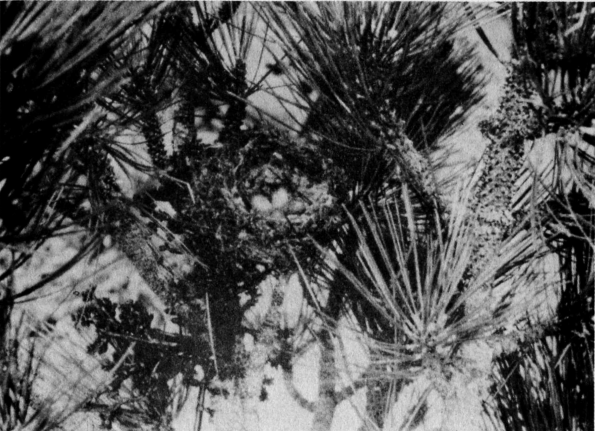

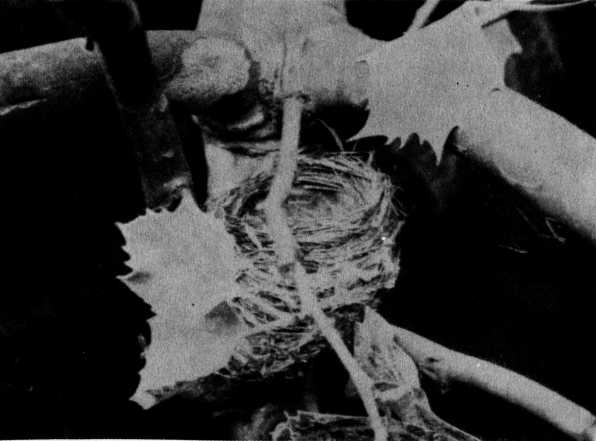

Nesting.—The prothonotary warbler and Lucy’s warbler are the only two American warblers that habitually build their nests in cavities, usually well concealed. The normal, and probably the original, primitive, nestling sites are in natural cavities in trees and most nests are still to be found in such situations today. The prothonotary is not at all particular as to the species of trees, nests having been found in many kinds of trees, although perhaps a slight preference is shown for dead willow stumps. Nor is it particular as to the size or condition of the cavity, or its location, though quite often choosing one over water or near it. The height above the ground or water varies from 3 feet or less to as much as 32 feet but there are more nests below 5 feet than there are above 10, the height of the majority being between 5 and 10 feet. The size and shape of the cavity are of little concern; if the cavity is too deep, the industrious little birds fill it with nesting material up to within a few inches of the top; sometimes a very shallow cavity is used, so that the bird can be plainly seen from a distance as it sits on the nest. The old deserted holes of woodpeckers or chickadees are favorite nesting sites; the entrances to these have often been enlarged by other agencies, or are badly weathered. In very rotten [21] stumps, the warblers have been known to excavate partially or to enlarge a cavity.

The nests built by the males in early spring, referred to above, are probably rarely used as brood nests and might be classed as dummy nests. The family nest is built almost entirely by the female, with encouragement and a little help from her mate, who accompanies her to and from the nest and in the search for material; much of the soft, green moss used extensively in the nest is often obtainable from fallen logs and stumps in the vicinity.

Brewster (1878a) mentions a nest taken from a deep cavity that “when removed presents the appearance of a compact mass of moss five or six inches in height by three or four in diameter. When the cavity is shallow, it is often only scantily lined with moss and a few fine roots. The deeper nests are of course the more elaborate ones. One of the finest specimens before me is composed of moss, dry leaves, and cypress twigs. The cavity for the eggs is a neatly rounded, cup-shaped hollow, two inches in diameter by one and a half in depth, smoothly lined with fine roots and a few wing-feathers of some small bird.”

In Dr. Walkinshaw’s (1938) Michigan nests, “moss constituted the bulk of the nesting material in nearly all cases, completely filling the nest space whether it was large or small. On top of this the nest proper was shaped and a rough lining of coarse grape-bark, dead leaves, black rootlets procured from the river-banks, and poison-ivy tendrils was added. Above this a lining of much finer rootlets, leaf-stems, and very fine grasses was used.”

In addition to the materials listed above Meyer and Nevius (1943) mention hackberry leaves, hairs, pine needles, horsehair, and cedar bark in their Tennessee nests. They say that from 6 to 10 days were required for nest construction, and that from 3 to 5 days more elapsed before the first eggs were laid. Their four nests were all in bird-boxes; one was in an orchard over plowed ground, one over a lotus pond in a wooded ravine, and two were over lily pools near buildings.

Dr. Walkinshaw (1938) publishes a map showing the location of 21 nesting boxes along the winding banks of the Battle Creek River, in Calhoun County, Mich., and writes: “Of the 28 nests found during 1937, 19 were in bird-houses over running water, 6 were in stubs over water (2 of which were over running water), and the other 3 were in natural holes back from the river bank. Of 44 nests found from 1930 through 1937, excluding the 21 in bird-houses, six were over running water in old woodpecker holes, one in a bridge-support in a slight depression, and nine in natural holes over standing water. Seven [22] were in old woodpecker holes from two to a hundred and sixty feet back from the river-bank.”

Many and varied are the odd nesting sites occupied by prothonotary warblers. Dr. Thomas S. Roberts (1936) writes:

The vagaries of this bird in choosing artificial nesting-places are shown by the positions of the following nests. On the La Crosse railroad bridge: in a cigar-box nailed on the engine-house on top of the draw; on one of the piers; in a metal ventilator-cap four inches in diameter, that had fallen and lodged just at the point where the draw banged against the pier, and close under the tracks; in a shallow cavity in a piece of slab-wood nailed to a trestle-support close under the road-bed of the railroad; these all far out in the middle of the Mississippi River. Still others are: in a Bluebird box on a low post by a switching-house and busy railroad platform; in a cleft in a pile in the river; in a tin cup in a barn, to reach which the birds entered through a broken pane of glass; in a pasteboard box on a shelf in a little summer-house; in an upright glass fruit jar in a house-boat; and other similar situations. In most cases the birds had to carry the nesting-material long distances, especially to the places on the bridge.

John W. Moyer (1933) relates an interesting story that was told to him by people living in a farm house along the Kankakee River. A pair of these warblers built their nests and raised their broods for three consecutive seasons in the pocket of an old hunting-coat, hung in a garage; each year the man cleaned out the nest and used the coat in the fall, and the next spring the birds used it again. M. G. Vaiden tells me of a similar case.

Nests have been found in buildings, on beams and other supports. Louis W. Campbell (1930) reports two on shelves in sheds, one in a small paper sack partly filled with staples and another in a coffee can similarly filled. Nests in cans in various situations have been found a number of times, and others have been reported in a tin pail hung under a porch, in a mail box, in a box on a moving ferry boat, in a Chinese lantern on a pavilion, and in an old hornets’ nest.

Dr. Walkinshaw writes to me: “At Reelfoot Lake, Tenn., during July, 1940, I found 8 nests of the prothonotary warbler, all built a few feet above the water in small natural holes in cypress knees. Evidently these are regular late-summer nesting sites.” The knees were farther under water earlier in the season. Most of his 76 Michigan nests were over water, or less than 100 feet from it; but 10 were 300 or more feet away from it and 2 were over 400 feet away. M. G. Vaiden tells me of a pair that nested in the tool box of a log-loading machine that was in daily operation, hauling logs.

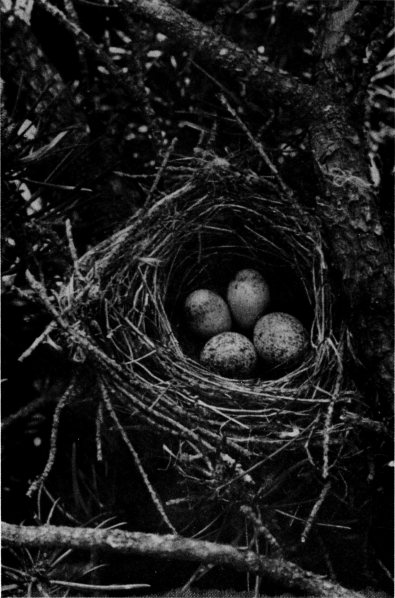

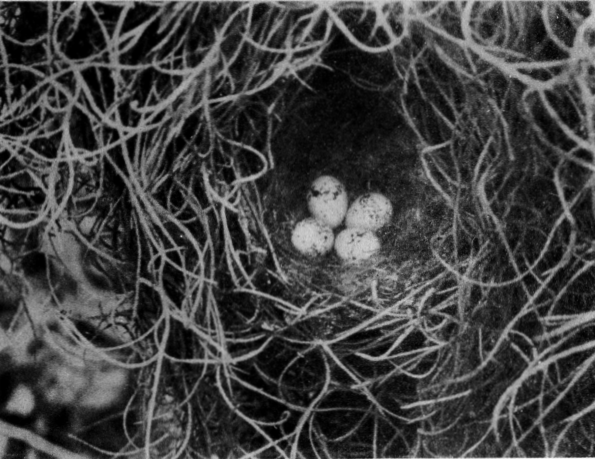

Eggs.—From 3 to 8 eggs have been found in nests of the prothonotary warbler, from 4 to 6 seem to be the commonest numbers, 7 is a fairly common number, and at least 3 sets of 8 have been reported; in the J. P. Norris series of 70 sets are 34 sets of 6, 15 sets of 7, and 2 sets of 8.

The eggs vary in shape from ovate to short ovate, and they are more or less glossy. The eggs are undoubtedly the most striking of the warblers’ eggs, with their rich creamy, or rose-tinted cream, ground color, boldly and liberally spotted and blotched with “burnt umber,” “bay,” “chestnut brown,” and “auburn,” intermingled with spots and undertones of “light Payne’s gray,” “Rood’s lavender,” “violet-gray,” and “purplish gray.” There is quite a variation in the amount of markings, which are generally more or less evenly scattered over the entire egg; some are sparingly spotted and blotched, while others are so profusely marked as almost to obscure the ground color (Harris).

J. P. Norris (1890b), in his description of his 70 sets, describes 2 eggs in each of 2 sets as “unmarked, save for four or five indistinct specks of cinnamon.” These were in sets of 6 eggs each. Pure white, unmarked eggs were once taken by R. M. Barnes (1889). Dr. Walkinshaw (1938) gives the measurements of 78 eggs as averaging 18.47 by 14.55 millimeters; the eggs showing the four extremes measured 20 by 15, 19 by 16, and 17 by 13 millimeters.

Incubation.—The eggs are laid, usually one each day, very early in the morning; Dr. Walkinshaw (1941) says between 5:00 and 7:00 a. m. in Michigan; Meyer and Nevius (1943), in Tennessee, saw the female enter the nest to lay as early as 5:00 a. m. on May 2, and as early as 4:44 on May 23, remaining in the nest from 28 to 36 minutes on different occasions. The period of incubation is recorded as 12, 131⁄2, and 14 days by different observers; about 13 seems to be the average, according to Dr. Walkinshaw (MS.), probably depending on conditions and the method of reckoning. Incubation seems to be performed entirely by the female, but the male feeds her to some extent while she is on the nest. Incubation starts the day before the last egg is laid.

Young.—Meyer and Nevius (1943) write: