Title: The City of Masks

Author: George Barr McCutcheon

Illustrator: May Wilson Preston

Release date: July 6, 2012 [eBook #40146]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Bruce Albrecht, Ernest Schaal, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Copyright, 1918

By DODD, MEAD AND COMPANY, Inc

PRINTED IN U. S. A.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER PAGE

I Lady Jane Thorne Comes to Dinner 1

II Out of the Four Corners of the Earth 12

III The City of Masks 24

IV The Scion of a New York House 37

V Mr. Thomas Trotter Hears Something to His Advantage 50

VI The Unfailing Memory 67

VII The Foundation of the Plot 79

VIII Lady Jane Goes About It Promptly 94

IX Mr. Trotter Falls into a New Position 110

X Putting Their Heads—and Hearts—Together 121

XI Winning by a Nose 134

XII In the Fog 155

XIII Not Clouds Alone Have Linings 172

XIV Diplomacy 188

XV One Night at Spangler's 202

XVI Scotland Yard Takes a Hand 219

XVII Friday for Luck 233

XVIII Friday for Bad Luck 250

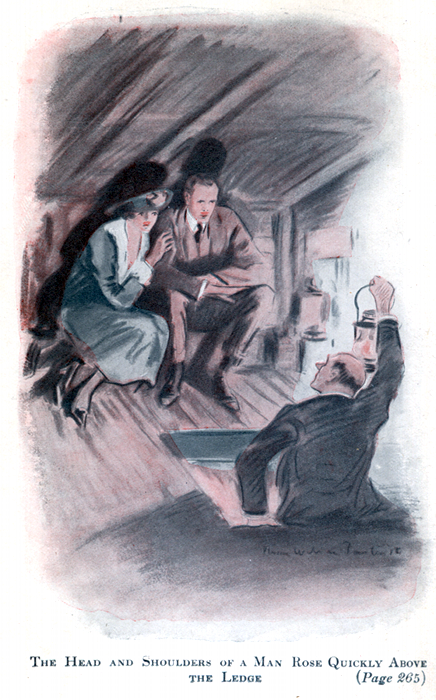

XIX From Darkness to Light 263

XX An Exchange of Courtesies 279

XXI The Bride-Elect 294

XXII The Beginning 307

THE Marchioness carefully draped the dust-cloth over the head of an andiron and, before putting the question to the parlour-maid, consulted, with the intensity of a near-sighted person, the ornate French clock in the centre of the mantelpiece. Then she brushed her fingers on the voluminous apron that almost completely enveloped her slight person.

"Well, who is it, Julia?"

"It's Lord Temple, ma'am, and he wants to know if you're too busy to come to the 'phone. If you are, I'm to ask you something."

The Marchioness hesitated. "How do you know it is Lord Eric? Did he mention his name?"

"He did, ma'am. He said 'this is Tom Trotter speaking, Julia, and is your mistress disengaged?' And so I knew it couldn't be any one else but his Lordship."

"And what are you to ask me?"

"He wants to know if he may bring a friend around tonight, ma'am. A gentleman from Constantinople, ma'am."

"A Turk? He knows I do not like Turks," said the Marchioness, more to herself than to Julia.

"He didn't say, ma'am. Just Constantinople."

[pg 2] The Marchioness removed her apron and handed it to Julia. You would have thought she expected to confront Lord Temple in person, or at least that she would be fully visible to him despite the distance and the intervening buildings that lay between. Tucking a few stray locks of her snow-white hair into place, she approached the telephone in the hall. She had never quite gotten over the impression that one could be seen through as well as heard over the telephone. She always smiled or frowned or gesticulated, as occasion demanded; she was never languid, never bored, never listless. A chat was a chat, at long range or short; it didn't matter.

"Are you there? Good evening, Mr. Trotter. So charmed to hear your voice." She had seated herself at the little old Italian table.

Mr. Trotter devoted a full two minutes to explanations.

"Do bring him with you," cried she. "Your word is sufficient. He must be delightful. Of course, I shuddered a little when you mentioned Constantinople. I always do. One can't help thinking of the Armenians. Eh? Oh, yes,—and the harems."

Mr. Trotter: "By the way, are you expecting Lady Jane tonight?"

The Marchioness: "She rarely fails us, Mr. Trotter."

Mr. Trotter: "Right-o! Well, good-bye,—and thank you. I'm sure you will like the baron. He is a trifle seedy, as I said before,—sailing vessel, you know, and all that sort of thing. By way of Cape Town,—pretty well up against it for the past year or two besides,—but [pg 3] a regular fellow, as they say over here."

The Marchioness: "Where did you say he is stopping?"

Mr. Trotter: "Can't for the life of me remember whether it's the 'Sailors' Loft' or the 'Sailors' Bunk.' He told me too. On the water-front somewhere. I knew him in Hong Kong. He says he has cut it all out, however."

The Marchioness: "Cut it all out, Mr. Trotter?"

Mr. Trotter, laughing: "Drink, and all that sort of thing, you know. Jolly good thing too. I give you my personal guarantee that he—"

The Marchioness: "Say no more about it, Mr. Trotter. I am sure we shall all be happy to receive any friend of yours. By the way, where are you now—where are you telephoning from?"

Mr. Trotter: "Drug store just around the corner."

The Marchioness: "A booth, I suppose?"

Mr. Trotter: "Oh, yes. Tight as a sardine box."

The Marchioness: "Good-bye."

Mr. Trotter: "Oh—hello? I beg your pardon—are you there? Ah, I—er—neglected to mention that the baron may not appear at his best tonight. You see, the poor chap is a shade large for my clothes. Naturally, being a sailor-man, he hasn't—er—a very extensive wardrobe. I am fixing him out in a—er—rather abandoned evening suit of my own. That is to say, I abandoned it a couple of seasons ago. Rather nobby thing for a waiter, but not—er—what you might call—"

The Marchioness, chuckling: "Quite good enough [pg 4] for a sailor, eh? Please assure him that no matter what he wears, or how he looks, he will not be conspicuous."

After this somewhat ambiguous remark, the Marchioness hung up the receiver and returned to the drawing-room; a prolonged search revealing the dust-cloth on the "nub" of the andiron, just where she had left it, she fell to work once more on the velvety surface of a rare old Spanish cabinet that stood in the corner of the room.

"Don't you want your apron, ma'am?" inquired Julia, sitting back on her heels and surveying with considerable pride the leg of an enormous throne seat she had been rubbing with all the strength of her stout arms.

Her mistress ignored the question. She dabbed into a tiny recess and wriggled her finger vigorously.

"I can't imagine where all the dust comes from, Julia," she said.

"Some of it comes from Italy, and some of it from Spain, and some from France," said Julia promptly. "You could rub for a hundred years, ma'am, and there'd still be dust that you couldn't find, not to save your soul. And why not? I'd bet my last penny there's dust on that cabinet this very minute that settled before Napoleon was born, whenever that was."

"I daresay," said the Marchioness absently.

More often than otherwise she failed to hear all that Julia said to her, or in her presence rather, for Julia, wise in association, had come to consider these lapses of inattention as openings for prolonged and rarely coherent soliloquies on topics of the moment. Julia, [pg 5] by virtue of long service and a most satisfying avoidance of matrimony, was a privileged servant between the hours of eight in the morning and eight in the evening. After eight, or more strictly speaking, the moment dinner was announced, Julia became a perfect servant. She would no more have thought of addressing the Marchioness as "ma'am" than she would have called the King of England "mister." She had crossed the Atlantic with her mistress eighteen years before; in mid-ocean she celebrated her thirty-fifth birthday, and, as she had been in the family for ten years prior to that event, even a child may solve the problem that here presents a momentary and totally unnecessary break in the continuity of this narrative. Julia was English. She spoke no other language. Beginning with the soup, or the hors d'œuvres on occasion, French was spoken in the house of the Marchioness. Physically unable to speak French and psychologically unwilling to betray her ignorance, Julia became a model servant. She lapsed into perfect silence.

The Marchioness seldom if ever dined alone. She always dined in state. Her guests,—English, Italian, Russian, Belgian, French, Spanish, Hungarian, Austrian, German,—conversed solely in French. It was a very agreeable way of symphonizing Babel.

The room in which she and the temporarily imperfect though treasured servant were employed in the dusk of this stormy day in March was at the top of an old-fashioned building in the busiest section of the city, a building that had, so far, escaped the fate of its immediate neighbours and remained, a squat and insignificant pygmy, elbowing with some arrogance the lofty [pg 6] structures that had shot up on either side of it with incredible swiftness.

It was a large room, at least thirty by fifty feet in dimensions, with a vaulted ceiling that encroached upon the space ordinarily devoted to what architects, builders and the Board of Health describe as an air chamber, next below the roof. There was no elevator in the building. One had to climb four flights of stairs to reach the apartment.

From its long, heavily curtained windows one looked down upon a crowded cross-town thoroughfare, or up to the summit of a stupendous hotel on the opposite side of the street. There was a small foyer at the rear of this lofty room, with an entrance from the narrow hall outside. Suspended in the wide doorway between the two rooms was a pair of blue velvet Italian portières of great antiquity and, to a connoisseur, unrivaled quality. Beyond the foyer and extending to the area wall was the rather commodious dining-room, with its long oaken English table, its high-back chairs, its massive sideboard and the chandelier that is said to have hung in the Doges' Palace when the Bridge of Sighs was a new and thriving avenue of communication.

At least, so stated the dealer's tag tucked carelessly among the crystal prisms, supplying the observer with the information that, in case one was in need of a chandelier, its price was five hundred guineas. The same curious-minded observer would have discovered, if he were not above getting down on his hands and knees and peering under the table, a price tag; and by exerting the strength necessary to pull the sideboard [pg 7] away from the wall, a similar object would have been exposed.

In other words, if one really wanted to purchase any article of furniture or decoration in the singularly impressive apartment of the Marchioness, all one had to do was to signify the desire, produce a check or its equivalent, and give an address to the competent-looking young woman who would put in an appearance with singular promptness in response to a couple of punches at an electric button just outside the door, any time between nine and five o'clock, Sundays included.

The drawing-room contained many priceless articles of furniture, wholly antique—(and so guaranteed), besides rugs, draperies, tapestries and stuffs of the rarest quality. Bronzes, porcelains, pottery, things of jade and alabaster, sconces, candlesticks and censers, with here and there on the walls lovely little "primitives" of untold value. The most exotic taste had ordered the distribution and arrangement of all these objects. There was no suggestion of crowding, nothing haphazard or bizarre in the exposition of treasure, nothing to indicate that a cheap intelligence revelled in rich possessions.

You would have sat down upon the first chair that offered repose and you would have said you had wandered inadvertently into a palace. Then, emboldened by an interest that scorned politeness, you would have got up to inspect the riches at close range,—and you would have found price-marks everywhere to overcome the impression that Aladdin had been rubbing his lamp all the way up the dingy, tortuous stairs.

You are not, however, in the shop of a dealer in [pg 8] antiques, price-marks to the contrary. You are in the home of a Marchioness, and she is not a dealer in old furniture, you may be quite sure of that. She does not owe a penny on a single article in the apartment nor does she, on the other hand, own a penny's worth of anything that meets the eye,—unless, of course, one excepts the dust-cloth and the can of polish that follows Julia about the room. Nor is it a loan exhibit, nor the setting for a bazaar.

The apartment being on the top floor of a five-story building, it is necessary to account for the remaining four. In the rear of the fourth floor there was a small kitchen and pantry from which a dumb-waiter ascended and descended with vehement enthusiasm. The remainder of the floor was divided into four rather small chambers, each opening into the outer hall, with two bath-rooms inserted. Each of these rooms contained a series of lockers, not unlike those in a club-house. Otherwise they were unfurnished except for a few commonplace cane bottom chairs in various stages of decrepitude.

The third floor represented a complete apartment of five rooms, daintily furnished. This was where the Marchioness really lived.

Commerce, after a fashion, occupied the two lower floors. It stopped short at the bottom of the second flight of stairs where it encountered an obstacle in the shape of a grill-work gate that bore the laconic word "Private," and while commerce may have peeped inquisitively through and beyond the barrier it was never permitted to trespass farther than an occasional sly, surreptitious and unavailing twist of the knob.

[pg 9] The entire second floor was devoted to work-rooms in which many sewing machines buzzed during the day and went to rest at six in the evening. Tables, chairs, manikins, wall-hooks and hangers thrust forward a bewildering assortment of fabrics in all stages of development, from an original uncut piece to a practically completed garment. In other words, here was the work-shop of the most exclusive, most expensive modiste in all the great city.

The ground floor, or rather the floor above the English basement, contained the salon and fitting rooms of an establishment known to every woman in the city as

DEBORAH'S.

To return to the Marchioness and Julia.

"Not that a little dust or even a great deal of dirt will make any different to the Princess," the former was saying, "but, just the same, I feel better, if I know we've done our best."

"Thank the Lord, she don't come very often," was Julia's frank remark. "It's the stairs, I fancy."

"And the car-fare," added her mistress. "Is it six o'clock, Julia?"

"Yes, ma'am, it is."

The Marchioness groaned a little as she straightened up and tossed the dust-cloth on the table. "It catches me right across here," she remarked, putting her hand to the small of her back and wrinkling her eyes.

"You shouldn't be doing my work," scolded Julia. "It's not for the likes of you to be—"

"I shall lie down for half an hour," said the Marchioness calmly. "Come at half-past six, Julia."

[pg 10] "Just Lady Jane, ma'am? No one else?"

"No one else," said the other, and preceded Julia down the two flights of stairs to the charming little apartment on the third floor. "She is a dear girl, and I enjoy having her all to myself once in a while."

"She is so, ma'am," agreed Julia, and added. "The oftener the better."

At half-past seven Julia ran down the stairs to open the gate at the bottom. She admitted a slender young woman, who said, "Thank you," and "Good evening, Julia," in the softest, loveliest voice imaginable, and hurried up, past the apartment of the Marchioness, to the fourth floor. Julia, in cap and apron, wore a pleased smile as she went in to put the finishing touches on the coiffure of her mistress.

"Pity there isn't more like her," she said, at the end of five minutes' reflection. Patting the silvery crown of the Marchioness, she observed in a less detached manner: "As I always says, the wonderful part is that it's all your own, ma'am."

"I am beginning to dread the stairs as much as any one," said the Marchioness, as she passed out into the hall and looked up the dimly lighted steps. "That is a bad sign, Julia."

A mass of coals crackled in the big fireplace on the top floor, and a tall man in the resplendent livery of a footman was engaged in poking them up when the Marchioness entered.

"Bitterly cold, isn't it, Moody?" inquired she, approaching with stately tread, her lorgnon lifted.

"It is, my lady,—extremely nawsty," replied Moody. "The trams are a bit off, or I should 'ave [pg 11] 'ad the coals going 'alf an hour sooner than—Ahem! They call it a blizzard, my lady."

"I know, thank you, Moody."

"Thank you, my lady," and he moved stiffly off in the direction of the foyer.

The Marchioness languidly selected a magazine from the litter of periodicals on the table. It was La Figaro, and of recent date. There were magazines from every capital in Europe on that long and time-worn table.

A warm, soft light filled the room, shed by antique lanthorns and wall-lamps that gave forth no cruel glare. Standing beside the table, the Marchioness was a remarkable picture. The slight, drooping figure of the woman with the dust-cloth and creaking knees had been transformed, like Cinderella, into a fairly regal creature attired in one of the most fetching costumes ever turned out by the rapacious Deborah, of the first floor front!

The foyer curtains parted, revealing the plump, venerable figure of a butler who would have done credit to the lordliest house in all England.

"Lady Jane Thorne," he announced, and a slim, radiant young person entered the room, and swiftly approached the smiling Marchioness.

"AM I late?" she inquired, a trace of anxiety in her smiling blue eyes. She was clasping the hand of the taut little Marchioness, who looked up into the lovely face with the frankest admiration.

"I have only this instant finished dressing," said her hostess. "Moody informs me we're in for a blizzard. Is it so bad as all that?"

"What a perfectly heavenly frock!" cried Lady Jane Thorne, standing off to take in the effect. "Turn around, do. Exquisite! Dear me, I wish I could—but there! Wishing is a form of envy. We shouldn't wish for anything, Marchioness. If we didn't, don't you see how perfectly delighted we should be with what we have? Oh, yes,—it is a horrid night. The trolley-cars are blocked, the omnibuses are stalled, and walking is almost impossible. How good the fire looks!"

"Cheerful, isn't it? Now you must let me have my turn at wishing, my dear. If I could have my wish, you would be disporting yourself in the best that Deborah can turn out, and you would be worth millions to her as an advertisement. You've got style, figure, class, verve—everything. You carry your clothes as if you were made for them and not the other way round."

"This gown is so old I sometimes think I was made [pg 13] for it," said the girl gaily. "I can't remember when it was made for me."

Moody had drawn two chairs up to the fire.

"Rubbish!" said the Marchioness, sitting down. "Toast your toes, my dear."

Lady Jane's gown was far from modish. In these days of swift-changing fashions for women, it had become passé long before its usefulness or its beauty had passed. Any woman would have told you that it was a "season before last model," which would be so distantly removed from the present that its owner may be forgiven the justifiable invention concerning her memory.

But Lady Jane's figure was not old, nor passé, nor even a thing to be forgotten easily. She was straight, and slim, and sound of body and limb. That is to say, she stood well on her feet and suggested strength rather than fragility. Her neck and shoulders were smooth and white and firm; her arms shapely and capable, her hands long and slender and aristocratic. Her dark brown hair was abundant and wavy;—it had never experienced the baleful caress of a curling-iron. Her firm, red lips were of the smiling kind,—and she must have known that her teeth were white and strong and beautiful, for she smiled more often than not with parted lips. There was character, intelligence and breeding in her face.

She wore a simple black velvet gown, close-fitting,—please remember that it was of an antiquity not even surpassed, as things go, by the oldest rug in the apartment,—with a short train. She was fully a head taller than the Marchioness, which isn't saying much when [pg 14] you are informed that the latter was at least half-a-head shorter than a woman of medium height.

On the little finger of her right hand she wore a heavy seal ring of gold. If you had known her well enough to hold her hand—to the light, I mean,—you would have been able to decipher the markings of a crest, notwithstanding the fact that age had all but obliterated the lines.

Dinner was formal only in the manner in which it was served. Behind the chair of the Marchioness, Moody posed loftily when not otherwise employed. A critical observer would have taken note of the threadbare condition of his coat, especially at the elbows, and the somewhat snug way in which it adhered to him, fore and aft. Indeed, there was an ever-present peril in its snugness. He was painfully deliberate and detached.

From time to time, a second footman, addressed as McFaddan, paused back of Lady Jane. His chin was not quite so high in the air as Moody's; the higher he raised it the less it looked like a chin. McFaddan, you would remark, carried a great deal of weight above the hips. The ancient butler, Cricklewick, decanted the wine, lifted his right eyebrow for the benefit of Moody, the left in directing McFaddan, and cringed slightly with each trip upward of the dumb-waiter.

The Marchioness and Lady Jane were in a gay mood despite the studied solemnity of the three servants. As dinner has no connection with this narrative except to introduce an effect of opulence, we will hurry through with it and allow Moody and McFaddan to draw back the chairs on a signal transmitted by Cricklewick, and return to the drawing-room with the two ladies.

[pg 15] "A quarter of nine," said the Marchioness, peering at the French clock through her lorgnon. "I am quite sure the Princess will not venture out on such a night as this."

"She's really quite an awful pill," said Lady Jane calmly. "I for one sha'n't be broken-hearted if she doesn't venture."

"For heaven's sake, don't let Cricklewick hear you say such a thing," said the Marchioness in a furtive undertone.

"I've heard Cricklewick say even worse," retorted the girl. She lowered her voice to a confidential whisper. "No longer ago than yesterday he told me that she made him tired, or something of the sort."

"Poor Cricklewick! I fear he is losing ambition," mused the Marchioness. "An ideal butler but a most dreary creature the instant he attempts to be a human being. It isn't possible. McFaddan is quite human. That's why he is so fat. I am not sure that I ever told you, but he was quite a slim, puny lad when Cricklewick took him out of the stables and made a very decent footman out of him. That was a great many years ago, of course. Camelford left him a thousand pounds in his will. I have always believed it was hush money. McFaddan was a very wide-awake chap in those days." The Marchioness lowered one eye-lid slowly.

"And, by all reports, the Marquis of Camelford was very well worth watching," said Lady Jane.

"Hear the wind!" cried the Marchioness, with a little shiver. "How it shrieks!"

"We were speaking of the Marquis," said Lady Jane.

"But one may always fall back on the weather," said [pg 16] the Marchioness drily. "Even at its worst it is a pleasanter thing to discuss than Camelford. You can't get anything out of me, my dear. I was his next door neighbour for twenty years, and I don't believe in talking about one's neighbour."

Lady Jane stared for a moment. "But—how quaint you are!—you were married to him almost as long as that, were you not?"

"My clearest,—I may even say my dearest,—recollection of him is as a neighbour, Lady Jane. He was most agreeable next door."

Cricklewick appeared in the door.

"Count Antonio Fogazario," he announced.

A small, wizened man in black satin knee-breeches entered the room and approached the Marchioness. With courtly grace he lifted her fingers to his lips and, in a voice that quavered slightly, declared in French that his joy on seeing her again was only surpassed by the hideous gloom he had experienced during the week that had elapsed since their last meeting.

"But now the gloom is dispelled and I am basking in sunshine so rare and soft and—"

"My dear Count," broke in the Marchioness, "you forget that we are enjoying the worst blizzard of the year."

"Enjoying,—vastly enjoying it!" he cried. "It is the most enchanting blizzard I have ever known. Ah, my dear Lady Jane! This is delightful!"

His sharp little face beamed with pleasure. The vast pleated shirt front extended itself to amazing proportions, as if blown up by an invisible though prodigious bellows, and his elbow described an angle of considerable [pg 17] elevation as he clasped the slim hand of the tall young woman. The crown of his sleek black toupee was on a line with her shoulder.

"God bless me," he added, in a somewhat astonished manner, "this is most gratifying. I could not have lifted it half that high yesterday without experiencing the most excruciating agony." He worked his arm up and down experimentally. "Quite all right, quite all right. I feared I was in for another siege. I cannot tell you how delighted I am. Ahem! Where was I? Oh, yes—This is a pleasure, Lady Jane, a positive delight. How charming you are look—"

"Save your compliments, Count, for the Princess," interrupted the girl, smiling. "She is coming, you know."

"I doubt it," he said, fumbling for his snuff-box. "I saw her this afternoon. Chilblains. Weather like this, you see. Quite a distance from her place to the street-cars. Frightful going. I doubt it very much. Now, what was it she said to me this afternoon? Something very important, I remember distinctly,—but it seems to have slipped my mind completely. I am fearfully annoyed with myself. I remember with great distinctness that it was something I was determined to remember, and here I am forgetting—Ah, let me see! It comes to me like a flash. I have it! She said she felt as though she had a cold coming on or something like that. Yes, I am sure that was it. I remember she blew her nose frequently, and she always makes a dreadful noise when she blows her nose. A really unforgettable noise, you know. Now, when I blow my nose, I don't behave like an elephant. I—"

[pg 18] "You blow it like a gentleman," interrupted the Marchioness, as he paused in some confusion.

"Indeed I do," he said gratefully. "In the most polished manner possible, my dear lady."

Lady Jane put her handkerchief to her lips. There was a period of silence. The Count appeared to be thinking with great intensity. He had a harassed expression about the corners of his nose. It was he who broke the silence. He broke it with a most tremendous sneeze.

"The beastly snuff," he said in apology.

Cricklewick's voice seemed to act as an echo to the remark.

"The Right-Honourable Mrs. Priestly-Duff," he announced, and an angular, middle-aged lady in a rose-coloured gown entered the room. She had a very long nose and prominent teeth; her neck was of amazing length and appeared to be attached to her shoulders by means of vertical, skin-covered ropes, running from torso to points just behind her ears, where they were lost in a matting of faded, straw-coloured hair. On second thought, it may be simpler to remark that her neck was amazingly scrawny. It will save confusion. Her voice was a trifle strident and her French execrable.

"Isn't it awful?" she said as she joined the trio at the fireplace. "I thought I'd never get here. Two hours coming, my dear, and I must be starting home at once if I want to get there before midnight."

"The Princess will be here," said the Marchioness.

"I'll wait fifteen minutes," said the new-comer [pg 19] crisply, pulling up her gloves. "I've had a trying day, Marchioness. Everything has gone wrong,—even the drains. They're frozen as tight as a drum and heaven knows when they'll get them thawed out! Who ever heard of such weather in March?"

"Ah, my dear Mrs. Priestly-Duff, you should not forget the beautiful sunshine we had yesterday," said the Count cheerily.

"Precious little good it does today," she retorted, looking down upon him from a lofty height, and as if she had not noticed his presence before. "When did you come in, Count?"

"It is quite likely the Princess will not venture out in such weather," interposed the Marchioness, sensing squalls.

"Well, I'll stop a bit anyway and get my feet warm. I hope she doesn't come. She is a good deal of a wet blanket, you must admit."

"Wet blankets," began the Count argumentatively, and then, catching a glance from the Marchioness, cleared his throat, blew his nose, and mumbled something about poor people who had no blankets at all, God help them on such a night as this.

Lady Jane had turned away from the group and was idly turning the leaves of the Illustrated London News. The smallest intelligence would have grasped the fact that Mrs. Priestly-Duff was not a genial soul.

"Who else is coming?" she demanded, fixing the little hostess with the stare that had just been removed from the back of Lady Jane's head.

Cricklewick answered from the doorway.

[pg 20] "Lord Temple. Baron—ahem!—Whiskers—eh? Baron Wissmer. Prince Waldemar de Bosky. Count Wilhelm Frederick Von Blitzen."

Four young men advanced upon the Marchioness, Lord Temple in the van. He was a tall, good-looking chap, with light brown hair that curled slightly above the ears, and eyes that danced.

"This, my dear Marchioness, is my friend, Baron Wissmer," he said, after bending low over her hand.

The Baron, whose broad hands were encased in immaculate white gloves that failed by a wide margin to button across his powerful wrists, smiled sheepishly as he enveloped her fingers in his huge palm.

"It is good of you to let me come, Marchioness," he said awkwardly, a deep flush spreading over his sea-tanned face. "If I manage to deport myself like the bull in the china shop, pray lay it to clumsiness and not to ignorance. It has been a very long time since I touched the hand of a Marchioness."

"Small people, like myself, may well afford to be kind and forgiving to giants," said she, smiling. "Dear me, how huge you are."

"I was once in the Emperor's Guard," said he, straightening his figure to its full six feet and a half. "The Blue Hussars. I may add with pride that I was not so horribly clumsy in regimentals. After all, it is the clothes that makes the man." He smiled as he looked himself over. "I shall not be at all offended or even embarrassed if you say 'goodness, how you have grown!'"

"The best tailor in London made that suit of clothes," said Lord Temple, surveying his friend with [pg 21] an appraising eye. Out of the corner of the same eye he explored the region beyond the group that now clustered about the hostess. Evidently he discovered what he was looking for. Leaving the Baron high and dry, he skirted the edge of the group and, with beaming face, came to Lady Jane.

"My family is of Vienna," the Baron was saying to the Marchioness, "but of late years I have called Constantinople my home."

"I understand," said she gently. She asked no other question, but, favouring him with a kindly smile, turned her attention to the men who lurked insignificantly in the shadow of his vast bulk.

The Prince was a pale, dreamy young man with flowing black hair that must have been a constant menace to his vision, judging by the frequent and graceful sweep of his long, slender hand in brushing the encroaching forelock from his eyes, over which it spread briefly in the nature of a veil. He had the fingers of a musician, the bearing of a violinist. His head drooped slightly toward his left shoulder, which was always raised a trifle above the level of the right. And there was in his soft brown eyes the faraway look of the detached. The insignia of his house hung suspended by a red ribbon in the centre of his white shirt front, while on the lapel of his coat reposed the emblem of the Order of the Golden Star. He was a Pole.

Count Von Blitzen, a fair-haired, pink-skinned German, urged himself forward with typical, not-to-be-denied arrogance, and crushed the fingers of the Marchioness in his fat hand. His broad face beamed with an all-enveloping smile.

[pg 22] "Only patriots and lovers venture forth on such nights as this," he said, in a guttural voice that rendered his French almost laughable.

"With an occasional thief or varlet," supplemented the Marchioness.

"Ach, Dieu," murmured the Count.

Fresh arrivals were announced by Cricklewick. For the next ten or fifteen minutes they came thick and fast, men and women of all ages, nationality and condition, and not one of them without a high-sounding title. They disposed themselves about the vast room, and a subdued vocal hubbub ensued. If here and there elderly guests, with gnarled and painfully scrubbed hands, preferred isolation and the pictorial contents of a magazine from the land of their nativity, it was not with snobbish intentions. They were absorbing the news from "home," in the regular weekly doses.

The regal, resplendent Countess du Bara, of the Opera, held court in one corner of the room. Another was glorified by a petite baroness from the Artists' Colony far down-town, while a rather dowdy lady with a coronet monopolized the attention of a small group in the centre of the room.

Lady Jane Thorne and Lord Temple sat together in a dim recess beyond the great chair of state, and conversed in low and far from impersonal tones.

Cricklewick appeared in the doorway and in his most impressive manner announced Her Royal Highness, the Princess Mariana Theresa Sebastano Michelini Celestine di Pavesi.

And with the entrance of royalty, kind reader, you [pg 23] may consider yourself introduced, after a fashion, to the real aristocracy of the City of New York, United States of America,—the titled riff-raff of the world's cosmopolis.

NEW YORK is not merely a melting pot for the poor and the humble of the lands of the earth. In its capacious depths, unknown and unsuspected, float atoms of an entirely different sort: human beings with the blood of the high-born and lofty in their veins, derelicts swept up by the varying winds of adversity, adventure, injustice, lawlessness, fear and independence.

Lords and ladies, dukes and duchesses, counts and countesses, swarm to the Metropolis in the course of the speeding year, heralded by every newspaper in the land, fêted and feasted and glorified by a capricious and easily impressed public; they pass with pomp and panoply and we let them go with reluctance and a vociferous invitation to come again. They come and they go, and we are informed each morning and evening of every move they have made during the day and night. We are told what they eat for breakfast, luncheon and dinner; what they wear and what they do not wear; where they are entertained and by whom; who they are and why; what they think of New York and—but why go on? We deny them privacy, and they think we are a wonderful, considerate and hospitable people. They go back to their homes in far-off lands,—and that is the end of them so far as we are concerned.

They merely pause on the lip of the melting pot, [pg 25] briefly peer into its simmering depths, and then,—pass on.

It is not with such as they that this narrative has to deal. It is not of the heralded, the glorified and the toasted that we tell, but of those who slip into the pot with the coarser ingredients, and who never, by any chance, become actually absorbed by the processes of integration but remain for ever as they were in the beginning: distinct foreign substances.

From all quarters of the globe the drift comes to our shores. New York swallows the good with the bad, and thrives, like the cannibal, on the man-food it gulps down with ravenous disregard for consequences or effect. It rarely disgorges.

It eats all flesh, foul or fair, and it drinks good red blood out of the same cup that offers a black and nauseous bile. It conceals its inward revulsion behind a bland, disdainful smile, and holds out its hands for more of the meat and poison that comes up from the sea in ships.

It is the City of Masks.

Its men and women hide behind a million masks; no man looks beneath the mask his neighbour wears, for he is interested only in that which he sees with the least possible effort: the surface. He sees his neighbour but he knows him not. He keeps his own mask in place and wanders among the millions, secure in the thought that all other men are as casual as he,—and as charitable.

From time to time the newspapers come forward with stories that amaze and interest those of us who remain, and always will remain, romantic and impressionable. [pg 26] They tell of the royal princess living in squalor on the lower east side; of the heir to a baronetcy dying in poverty in a hospital somewhere up-town; of the countess who defies the wolf by dancing in the roof-gardens; of the lost arch-duke who has been recognized in a gang of stevedores; of the earl who lands in jail as an ordinary hobo; of the baroness who supports a shiftless husband and their offspring by giving music-lessons; of the retiring scholar who scorns a life of idleness and a coronet besides; of shifty ne'er-do-wells with titles at homes and aliases elsewhere; of fugitive lords and forgotten ladies; of thieves and bauds and wastrels who stand revealed in their extremity as the sons and daughters of noble houses.

In this City of Masks there are hundreds of men and women in whose veins the blood of a sound aristocracy flows. By choice or necessity they have donned the mask of obscurity. They tread the paths of oblivion. They toil, beg or steal to keep pace with circumstance. But the blood will not be denied. In the breast of each of these drifters throbs the pride of birth, in the soul of each flickers the unquenchable flame of caste. The mask is for the man outside, not for the man inside.

Recently there died in one of the municipal hospitals an old flower-woman, familiar for three decades to the thousands who thread their way through the maze of streets in the lower end of Manhattan. To them she was known as Old Peg. To herself she was the Princess Feododric, born to the purple, daughter of one of the greatest families in Russia. She was never anything but the Princess to herself, despite the squalor in which she lived. Her epitaph was written in the bold, [pg 27] black head-lines of the newspapers; but her history was laid away with her mask in a graveyard far from palaces—and flower-stands. Her headstone revealed the uncompromising pride that survived her after death. By her direction it bore the name of Feododric, eldest daughter of His Highness, Prince Michael Androvodski; born in St. Petersburgh, September 12, 1841; died Jan. 7, 1912; wife of James Lumley, of County Cork, Ireland.

It is of the high-born who dwell in low places that this tale is told. It is of an aristocracy that serves and smiles and rarely sneers behind its mask.

When Cricklewick announced the Princess Mariana Theresa the hush of deference fell upon the assembled company. In the presence of royalty no one remained seated.

She advanced slowly, ponderously into the room, bowing right and left as she crossed to the great chair at the upper end. One by one the others presented themselves and kissed the coarse, unlovely hand she held out to them. It was not "make-believe." It was her due. The blood of a king and a queen coursed through her veins; she had been born a Princess Royal.

She was sixty, but her hair was as black as the coat of the raven. Time, tribulation, and a harsh destiny had put each its own stamp upon her dark, almost sinister, face. The black eyes were sharp and calculating, and they did not smile with her thin lips. She wore a great amount of jewellery and a gown of blue velvet, lavishly bespangled and generously embellished with laces of many periods, values and, you could say, nativity.

The Honourable Mrs. Priestly-Duff having been a [pg 28] militant suffragette before a sudden and enforced departure from England, was the only person there with the hardihood to proclaim, not altogether sotto voce, that the "get-up" was a fright.

Restraint vanished the instant the last kiss of tribute fell upon her knuckles. The Princess put her hand to her side, caught her breath sharply, and remarked to the Marchioness, who stood near by, that it was dreadful the way she was putting on weight. She was afraid of splitting something if she took a long, natural breath.

"I haven't weighed myself lately," she said, "but the last time I had this dress on it felt like a kimono. Look at it now! You could not stuff a piece of tissue paper between it and me to save your soul. I shall have to let it out a couple of—What were you about to say, Count Fogazario?"

The little Count, at the Marchioness's elbow, repeated something he had already said, and added:

"And if it continues there will not be a trolley-car running by midnight."

The Princess eyed him coldly. "That is just like a man," she said. "Not the faintest idea of what we were talking about, Marchioness."

The Count bowed. "You were speaking of tissue paper, Princess," said he, stiffly. "I understood perfectly."

Once a week the Marchioness held her amazing salon. Strictly speaking, it was a co-operative affair. The so-called guests were in reality contributors to and supporters of an enterprise that had been going on for the matter of five years in the heart of unsuspecting New York. According to his or her means, each of these [pg 29] exiles paid the tithe or tax necessary, and became in fact a member of the inner circle.

From nearly every walk in life they came to this common, converging point, and sat them down with their equals, for the moment laying aside the mask to take up a long-discarded and perhaps despised reality. They became lords and ladies all over again, and not for a single instant was there the slightest deviation from dignity or form.

Moral integrity was the only requirement, and that, for obvious reasons, was sometimes overlooked,—as for example in the case of the Countess who eloped with the young artist and lived in complacent shame and happiness with him in a three-room flat in East Nineteenth street. The artist himself was barred from the salon, not because of his ignoble action, but for the sufficient reason that he was of ignoble birth. Outside the charmed conclave he was looked upon as a most engaging chap. And there was also the case of the appallingly amiable baron who had fired four shots at a Russian Grand-Duke and got away with his life in spite of the vaunted secret service. It was of no moment whatsoever that one of his bullets accidentally put an end to the life of a guardsman. That was merely proof of his earnestness and in no way reflected on his standing as a nobleman. Nor was it adequate cause for rejection that certain of these men and women were being sought by Imperial Governments because they were political fugitives, with prices on their heads.

The Marchioness, more prosperous than any of her associates, assumed the greater part of the burden attending this singular reversion to form. It was she [pg 30] who held the lease on the building, from cellar to roof, and it was she who paid that important item of expense: the rent. The Marchioness was no other than the celebrated Deborah, whose gowns issuing from the lower floors at prodigious prices, gave her a standing in New York that not even the plutocrats and parvenus could dispute. In private life she may have been a Marchioness, but to all New York she was known as the queen of dressmakers.

If you desired to consult Deborah in person you inquired for Mrs. Sparflight, or if you happened to be a new customer and ignorant, you were set straight by an attendant (with a slight uplifting of the eyebrows) when you asked for Madame "Deborah."

The ownership of the rare pieces of antique furniture, rugs, tapestries and paintings was vested in two members of the circle, one occupying a position in the centre of the ring, the other on the outer rim: Count Antonio Fogazario and Moody, the footman. For be it known that while Moody reverted once a week to a remote order of existence he was for the balance of the time an exceedingly prosperous, astute and highly respected dealer in antiques, with a shop in Madison Avenue and a clientele that considered it the grossest impertinence to dispute the prices he demanded. He always looked forward to these "drawing-rooms," so to speak. It was rather a joy to disregard the aspirates. He dropped enough hs on a single evening to make up for a whole week of deliberate speech.

As for Count Antonio, he was the purveyor of Italian antiques and primitive paintings, "authenticity guaranteed," doing business under the name of "Juneo & [pg 31] Co., Ltd. London, Paris, Rome, New York." He was known in the trade and at his bank as Mr. Juneo.

Occasionally the exigencies of commerce necessitated the substitution of an article from stock for one temporarily loaned to the fifth-floor drawing-room.

During the seven days in the week, Mr. Moody and Mr. Juneo observed a strained but common equality. Mr. Moody contemptuously referred to Mr. Juneo as a second-hand dealer, while Mr. Juneo, with commercial bitterness, informed his patrons that Pickett, Inc., needed a lot of watching. But on these Wednesday nights a vast abyss stretched between them. They were no longer rivals in business. Mr. Juneo, without the slightest sign of arrogance, put Mr. Moody in his place, and Mr. Moody, with perfect equanimity, quite properly stayed there.

"A chair over here, Moody," the Count would say (to Pickett, Inc.,) and Moody, with all the top-lofty obsequiousness of the perfect footman, would place a chair in the designated spot, and say:

"H'anythink else, my lord? Thank you, sir."

On this particular Wednesday night two topics of paramount interest engaged the attention of the company. The newspapers of that day had printed the story of the apprehension and seizure of one Peter Jolinski, wanted in Warsaw on the charge of assassination.

As Count Andreas Verdray he was known to this exclusive circle of Europeans, and to them he was a persecuted, unjustly accused fugitive from the land of his nativity. Russian secret service men had run him to earth after five years of relentless pursuit. As a respectable, [pg 32] industrious window-washer he had managed for years to evade arrest for a crime he had not committed, and now he was in jail awaiting extradition and almost certain death at the hands of his intriguing enemies. A cultured scholar, a true gentleman, he was, despite his vocation, one of the most distinguished units in this little world of theirs. The authorities in Warsaw charged him with instigating the plot to assassinate a powerful and autocratic officer of the Crown. In more or less hushed voices, the assemblage discussed the unhappy event.

The other topic was the need of immediate relief for the family of the Baroness de Flamme, who was on her death-bed in Harlem and whose three small children, deprived of the support of a hard-working music-teacher and deserted by an unconscionably plebeian father, were in a pitiable state of destitution. Acting on the suggestion of Lord Temple, who as Thomas Trotter earned a weekly stipend of thirty dollars as chauffeur for a prominent Park Avenue gentleman, a collection was taken, each person giving according to his means. The largest contribution was from Count Fogazario, who headed the list with twenty-five dollars. The Marchioness was down for twenty. The smallest donation was from Prince Waldemar. Producing a solitary coin, he made change, and after saving out ten cents for carfare, donated forty cents.

Cricklewick, Moody and McFaddan were not invited to contribute. No one would have dreamed of asking them to join in such a movement. And yet, of all those present, the three men-servants were in a better position than any one else to give handsomely. They were, [pg 33] in fact, the richest men there. The next morning, however, would certainly bring checks from their offices to the custodian of the fund, the Hon. Mrs. Priestly-Duff. They knew their places on Wednesday night, however.

The Countess du Bara, from the Opera, sang later on in the evening; Prince Waldemar got out his violin and played; the gay young baroness from the Artists' Colony played accompaniments very badly on the baby grand piano; Cricklewick and the footmen served coffee and sandwiches, and every one smoked in the dining-room.

At eleven o'clock the Princess departed. She complained a good deal of her feet.

"It's the weather," she explained to the Marchioness, wincing a little as she made her way to the door.

"Too bad," said the Marchioness. "Are we to be honoured on next Wednesday night, your highness? You do not often grace our gatherings, you know. I—"

"It will depend entirely on circumstances," said the Princess, graciously.

Circumstances, it may be mentioned,—though they never were mentioned on Wednesday nights,—had a great deal to do with the Princess's actions. She conducted a pawn-shop in Baxter street. As the widow and sole legatee of Moses Jacobs, she was quite a figure in the street. Customers came from all corners of the town, and without previous appointment. Report had it that Mrs. Jacobs was rolling in money. People slunk in and out of the front door of her place of business, penniless on entering, affluent on leaving,—if you [pg 34] would call the possession of a dollar or two affluence,—and always with the resolve in their souls to some day get even with the leech who stood behind the counter and doled out nickels where dollars were expected.

It was an open secret that more than one of those who kissed the Princess's hand in the Marchioness's drawing-room carried pawnchecks issued by Mrs. Jacobs. Business was business. Sentiment entered the soul of the Princess only on such nights as she found it convenient and expedient to present herself at the Salon. It vanished the instant she put on her street clothes on the floor below and passed out into the night. Avarice stepped in as sentiment stepped out, and one should not expect too much of avarice.

For one, the dreamy, half-starved Prince Waldemar was rarely without pawnchecks from her delectable establishment. Indeed it had been impossible for him to entertain the company on this stormy evening except for her grudging consent to substitute his overcoat for the Stradivarius he had been obliged to leave the day before.

Without going too deeply into her history, it is only necessary to say that she was one of those wayward, wilful princesses royal who occasionally violate all tradition and marry good-looking young Americans or Englishmen, and disappear promptly and automatically from court circles.

She ran away when she was nineteen with a young attaché in the British legation. It was the worst thing that could have happened to the poor chap. For years they drifted through many lands, finally ending in New York, where, their resources having been exhausted, [pg 35] she was forced to pawn her jewellery. The pawn-broker was one Abraham Jacobs, of Baxter street.

The young English husband, disheartened and thoroughly disillusioned, shot himself one fine day. By a single coincidence, a few weeks afterward, old Abraham went to his fathers in the most agreeable fashion known to nature, leaving his business, including the princess's jewels, to his son Moses.

With rare foresight and acumen, Mrs. Brinsley (the Princess, in other words), after several months of contemplative mourning, redeemed her treasure by marrying Moses. And when Moses, after begetting Solomon, David and Hannah, passed on at the age of twoscore years and ten, she continued the business with even greater success than he. She did not alter the name that flourished in large gold letters on the two show windows and above the hospitable doorway. For twenty years it had read: The Royal Exchange: M. Jacobs, Proprietor. And now you know all that is necessary to know about Mariana, to this day a true princess of the blood.

Inasmuch as a large share of her business came through customers who preferred to visit her after the fall of night, there is no further need to explain her reply to the Marchioness.

When midnight came the Marchioness was alone in the deserted drawing-room. The company had dispersed to the four corners of the storm-swept city, going by devious means and routes.

They fared forth into the night sans ceremony, sans regalia. In the locker-rooms on the floor below each of these noble wights divested himself and herself of the [pg 36] raiment donned for the occasion. With the turning of a key in the locker door, barons became ordinary men, countesses became mere women, and all of them stole regretfully out of the passage at the foot of the first flight of stairs and shivered in the wind that blew through the City of Masks.

"I've got more money than I know what to do with, Miss Emsdale," said Tom Trotter, as they went together out into the bitter wind. "I'll blow you off to a taxi."

"I couldn't think of it," said the erstwhile Lady Jane, drawing her small stole close about her neck.

"But it's on my way home," said he. "I'll drop you at your front door. Please do."

"If I may stand half," she said resolutely.

"We'll see," said he. "Wait here in the doorway till I fetch a taxi from the hotel over there. Oh, I say, Herman, would you mind asking one of those drivers over there to pick us up here?"

"Sure," said Herman, one time Count Wilhelm Frederick Von Blitzen, who had followed them to the side-walk. "Fierce night, ain'd it? Py chiminy, ain'd it?"

"Where is your friend, Mr. Trotter," inquired Miss Emsdale, as the stalwart figure of one of the most noted head-waiters in New York struggled off against the wind.

"He beat it quite a while ago," said he, with an enlightening grin.

"Oh?" said she, and met his glance in the darkness. A sudden warmth swept over her.

AS Miss Emsdale and Thomas Trotter got down from the taxi, into a huge unbroken snowdrift in front of a house in one of the cross-town streets just off upper Fifth Avenue, a second taxi drew up behind them and barked a raucous command to pull up out of the way. But the first taxi was unable to do anything of the sort, being temporarily though explosively stalled in the drift along the curb. Whereupon the fare in the second taxi threw open the door and, with an audible imprecation, plunged into the drift, just in time to witness the interesting spectacle of a lady being borne across the snow-piled sidewalk in the arms of a stalwart man; and, as he gazed in amazement, the man and his burden ascended the half-dozen steps leading to the storm-vestibule of the very house to which he himself was bound.

His first shock of apprehension was dissipated almost instantly. The man's burden giggled quite audibly as he set her down inside the storm doors. That giggle was proof positive that she was neither dead nor injured. She was very much alive, there could be no doubt about it. But who was she?

The newcomer swore softly as he fumbled in his trousers' pocket for a coin for the driver who had run him up from the club. After an exasperating but seemingly necessary delay he hurried up the steps. He met the [pg 38] stalwart burden-bearer coming down. A servant had opened the door and the late burden was passing into the hall.

He peered sharply into the face of the man who was leaving, and recognized him.

"Hello," he said. "Some one ill, Trotter?"

"No, Mr. Smith-Parvis," replied Trotter in some confusion. "Disagreeable night, isn't it?"

"In some respects," said young Mr. Smith-Parvis, and dashed into the vestibule before the footman could close the door.

Miss Emsdale turned at the foot of the broad stairway as she heard the servant greet the young master. A swift flush mounted to her cheeks. Her heart beat a little faster, notwithstanding the fact that it had been beating with unusual rapidity ever since Thomas Trotter disregarded her protests and picked her up in his strong arms.

"Hello," he said, lowering his voice.

There was a light in the library beyond. His father was there, taking advantage, no doubt, of the midnight lull to read the evening newspapers. The social activities of the Smith-Parvises gave him but little opportunity to read the evening papers prior to the appearance of the morning papers.

"What is the bally rush?" went on the young man, slipping out of his fur-lined overcoat and leaving it pendant in the hands of the footman. Miss Emsdale, after responding to his hushed "hello" in an equally subdued tone, had started up the stairs.

"It is very late, Mr. Smith-Parvis. Good night."

"Never too late to mend," he said, and was supremely [pg 39] well-satisfied with what a superior intelligence might have recorded as a cryptic remark but what, to him, was an awfully clever "come-back." He had spent three years at Oxford. No beastly American college for him, by Jove!

Overcoming a cultivated antipathy to haste,—which he considered the lowest form of ignorance,—he bounded up the steps, three at a time, and overtook her midway to the top.

"I say, Miss Emsdale, I saw you come in, don't you know. I couldn't believe my eyes. What the deuce were you doing out with that common—er—chauffeur? D'you mean to say that you are running about with a chap of that sort, and letting him—"

"If you please, Mr. Smith-Parvis!" interrupted Miss Emsdale coldly. "Good night!"

"I don't mean to say you haven't the right to go about with any one you please," he persisted, planting himself in front of her at the top of the steps. "But a common chauffeur—Well, now, 'pon my word, Miss Emsdale, really you might just as well be seen with Peasley down there."

"Peasley is out of the question," said she, affecting a wry little smile, as of self-pity. "He is tooken, as you say in America. He walks out with Bessie, the parlour-maid."

"Walks out? Good Lord, you don't mean to say you'd—but, of course, you're spoofing me. One never knows how to take you English, no matter how long one may have lived in England. But I am serious. You cannot afford to be seen running around nights with fellows of that stripe. Rotten bounders, that's [pg 40] what I call 'em. Ever been out with him before?"

"Often, Mr. Smith-Parvis," she replied calmly. "I am sure you would like him if you knew him better. He is really a very—"

"Nonsense! He is a good chauffeur, I've no doubt,—Lawrie Carpenter says he's a treasure, but I've no desire to know him any better. And I don't like to think of you knowing him quite as well as you do, Miss Emsdale. See what I mean?"

"Perfectly. You mean that you will go to your mother with the report that I am not a fit person to be with the children. Isn't that what you mean?"

"Not at all. I'm not thinking of the kids. I'm thinking of myself. I'm pretty keen about you, and—"

"Aren't you forgetting yourself, Mr. Smith-Parvis?" she demanded curtly.

"Oh, I know there'd be a devil of a row if the mater ever dreamed that I—Oh, I say! Don't rush off in a huff. Wait a—"

But she had brushed past him and was swiftly ascending the second flight of stairs.

He stared after her in astonishment. He couldn't understand such stupidity, not even in a governess. There wasn't another girl in New York City, so far as he knew, who wouldn't have been pleased out of her boots to receive the significant mark of interest he was bestowing upon this lowly governess,—and here was she turning her back upon,—Why, what was the matter with her? He passed his hand over his brow and blinked a couple of times. And she only a paid governess! It was incredible.

[pg 41] He went slowly downstairs and, still in a sort of daze, found himself a few minutes later pouring out a large drink of whiskey in the dining-room. It was his habit to take a bottle of soda with his whiskey, but on this occasion he overcame it and gulped the liquor "neat." It appeared to be rather uplifting, so he had another. Then he went up to his own room and sulked for an hour before even preparing for bed. The more he thought of it, the graver her unseemly affront became.

"And to have her insult me like that," he said to himself over and over again, "when not three minutes before she had let that bally bounder carry her up—By gad, I'll give her something to think about in the morning. She sha'n't do that sort of thing to me. She'll find herself out of a job and with a damned poor reference in her pocket if she gets gay with me. She'll come down from her high horse, all right, all right. Positions like this one don't grow in the park. She's got to understand that. She can't go running around with chauffeurs and all—My God, to think that he had her in his arms! The one girl in all the world who has ever really made me sit up and take notice! Gad, I—I can't stand it—I can't bear to think of her cuddling up to that—The damned bounder!"

He sprang to his feet and bolted out into the hall. He was a spoiled young man with an aversion: an aversion to being denied anything that he wanted.

In the brief history of the Smith-Parvis family he occupied many full and far from prosaic pages. Smith-Parvis, Senior, was not a prodigal sort of person, and yet he had squandered a great many thousands of dollars in his time on Smith-Parvis, Junior. It costs [pg 42] money to bring up young men like Smith-Parvis, Junior; and by the same token it costs money to hold them down. The family history, if truthfully written, would contain passages in which the unbridled ambitions of Smith-Parvis, Junior, overwhelmed everything else. There would be the chapters excoriating the two chorus-girls who, in not widely separated instances, consented to release the young man from matrimonial pledges in return for so much cash; and there would be numerous paragraphs pertaining to auction-bridge, and others devoted entirely to tailors; to say nothing of uncompromising café and restaurant keepers who preferred the Smith-Parvis money to the Smith-Parvis trade.

The young man, having come to the conclusion that he wanted Miss Emsdale, ruthlessly decided to settle the matter at once. He would not wait till morning. He would go up to her room and tell her that if she knew what was good for her she'd listen to what he had to say. She was too nice a girl to throw herself away on a rotter like Trotter.

Then, as he came to the foot of the steps, he remembered the expression in her eyes as she swept past him an hour earlier. It suddenly occurred to him to pause and reflect. The look she gave him, now that he thought of it, was not that of a timid, frightened menial. Far from it! There was something imperious about it; he recalled the subtle, fleeting and hitherto unfamiliar chill it gave him.

Somewhat to his own amazement, he returned to his room and closed the door with surprising care. He usually slammed it.

"Dammit all," he said, half aloud, scowling at his [pg 43] reflection in the mirror across the room, "I—I wonder if she thinks she can put on airs with me." Later on he regained his self-assurance sufficiently to utter an ultimatum to the invisible offender: "You'll be eating out of my hand before you're two days older, my fine lady, or I'll know the reason why."

Smith-Parvis, Junior, wore the mask of a gentleman. As a matter-of-fact, the entire Smith-Parvis family went about masked by a similar air of gentility.

The hyphen had a good deal to do with it.

The head of the family, up to the time he came of age, was William Philander Smith, commonly called Bill by the young fellows in Yonkers. A maternal uncle, name of Parvis, being without wife or child at the age of seventy-eight, indicated a desire to perpetuate his name by hitching it to the sturdiest patronymic in the English language, and forthwith made a will, leaving all that he possessed to his only nephew, on condition that the said nephew and all his descendants should bear, henceforth and for ever, the name of Smith-Parvis.

That is how it all came about. William Philander, shortly after the fusion of names, fell heir to a great deal of money and in due time forsook Yonkers for Manhattan, where he took unto himself a wife in the person of Miss Angela Potts, only child of the late Simeon Potts, Esq., and Mrs. Potts, neither of whom, it would seem, had the slightest desire to perpetuate the family name. Indeed, as Angela was getting along pretty well toward thirty, they rather made a point of abolishing it before it was too late.

The first-born of William Philander and Angela was christened Stuyvesant Van Sturdevant Smith-Parvis, [pg 44] after one of the Pottses who came over at a time when the very best families in Holland, according to the infant's grandparents, were engaged in establishing an aristocracy at the foot of Manhattan Island.

After Stuyvesant,—ten years after, in fact,—came Regina Angela, who languished a while in the laps of the Pottses and the Smith-Parvis nurses, and died expectedly. When Stuyvie was fourteen the twins, Lucille and Eudora, came, and at that the Smith-Parvises packed up and went to England to live. Stuyvie managed in some way to make his way through Eton and part of the way through Oxford. He was sent down in his third year. It wasn't so easy to have his own way there. Moreover, he did not like Oxford because the rest of the boys persisted in calling him an American. He didn't mind being called a New Yorker, but they were rather obstinate about it.

Miss Emsdale was the new governess. The redoubtable Mrs. Sparflight had recommended her to Mrs. Smith-Parvis. Since her advent into the home in Fifth Avenue, some three or four months prior to the opening of this narrative, a marked change had come over Stuyvesant Van Sturdevant. It was principally noticeable in a recently formed habit of getting down to breakfast early. The twins and the governess had breakfast at half-past eight. Up to this time he had detested the twins. Of late, however, he appeared to have discovered that they were his sisters and rather interesting little beggars at that.

They were very much surprised by his altered behaviour. To the new governess they confided the somewhat startling suspicion that Stuyvie must be having [pg 45] softening of the brain, just as "grandpa" had when "papa" discovered that he was giving diamond rings to the servants and smiling at strangers in the street. It must be that, said they, for never before had Stuyvie kissed them or brought them expensive candies or smiled at them as he was doing in these wonderful days.

Stranger still, he never had been polite or agreeable to governesses—before. He always had called them frumps, or cats, or freaks, or something like that. Surely something must be the matter with him, or he wouldn't be so nice to Miss Emsdale. Up to now he positively had refused to look at her predecessors, much less to sit at the same table with them. He said they took away his appetite.

The twins adored Miss Emsdale.

"We love you because you are so awfuly good," they were wont to say. "And so beautiful," they invariably added, as if it were not quite the proper thing to say.

It was obvious to Miss Emsdale that Stuyvesant endorsed the supplemental tribute of the twins. He made it very plain to the new governess that he thought more of her beauty than he did of her goodness. He ogled her in a manner which, for want of a better expression, may be described as possessive. Instead of being complimented by his surreptitious admiration, she was distinctly annoyed. She disliked him intensely.

He was twenty-five. There were bags under his eyes. More than this need not be said in describing him, unless one is interested in the tiny black moustache that looked as though it might have been pasted, with great precision, in the centre of his long upper lip,—directly beneath [pg 46] the spreading nostrils of a broad and far from aristocratic nose. His lips were thick and coarse, his chin a trifle undershot. Physically, he was a well set-up fellow, tall and powerful.

For reasons best known to himself, and approved by his parents, he affected a distinctly English manner of speech. In that particular, he frequently out-Englished the English themselves.

As for Miss Emsdale, she was a long time going to sleep. The encounter with the scion of the house had left her in a disturbed frame of mind. She laid awake for hours wondering what the morrow would produce for her. Dismissal, no doubt, and with it a stinging rebuke for what Mrs. Smith-Parvis would consider herself justified in characterizing as unpardonable misconduct in one employed to teach innocent and impressionable young girls. Mingled with these dire thoughts were occasional thrills of delight. They were, however, of short duration and had to do with a pair of strong arms and a gentle, laughing voice.

In addition to these shifting fears and thrills, there were even more disquieting sensations growing out of the unwelcome attentions of Smith-Parvis, Junior. They were, so to speak, getting on her nerves. And now he had not only expressed himself in words, but had actually threatened her. There could be no mistake about that.

Her heart was heavy. She did not want to lose her position. The monthly checks she received from Mrs. Smith-Parvis meant a great deal to her. At least half of her pay went to England, and sometimes more than half. A friendly solicitor in London obtained the [pg 47] money on these drafts and forwarded it, without fee, to the sick young brother who would never walk again, the adored young brother who had fallen prey to the most cruel of all enemies: infantile paralysis.

Jane Thorne was the only daughter of the Earl of Wexham, who shot himself in London when the girl was but twelve years old. He left a penniless widow and two children. Wexham Manor, with all its fields and forests, had been sacrificed beforehand by the reckless, ill-advised nobleman. The police found a half-crown in his pocket when they took charge of the body. It was the last of a once imposing fortune. The widow and children subsisted on the charity of a niggardly relative. With the death of the former, after ten unhappy years as a dependent, Jane resolutely refused to accept help from the obnoxious relative. She set out to earn a living for herself and the crippled boy. We find her, after two years of struggle and privation, installed as Miss Emsdale in the Smith-Parvis mansion, earning one hundred dollars a month.

It is safe to say that if the Smith-Parvises had known that she was the daughter of an Earl, and that her brother was an Earl, there would have been great rejoicing among them; for it isn't everybody who can boast an Earl's daughter as governess.

One night in each week she was free to do as she pleased. It was, in plain words, her night out. She invariably spent it with the Marchioness and the coterie of unmasked spirits from lands across the seas.

What was she to say to Mrs. Smith-Parvis if called upon to account for her unconventional return of the night before? How could she explain? Her lips were [pg 48] closed by the seal of honour so far as the meetings above "Deborah's" were concerned. A law unwritten but steadfastly observed by every member of that remarkable, heterogeneous court, made it impossible for her to divulge her whereabouts or actions on this and other agreeable "nights out." No man or woman in that company would have violated, even under the gravest pressure, the compact under which so many well-preserved secrets were rendered secure from exposure.

Stuyvesant, in his rancour, would draw an ugly picture of her midnight adventure. He would, no doubt, feel inspired to add a few conclusions of his own. Her word, opposed to his, would have no effect on the verdict of the indulgent mother. She would stand accused and convicted of conduct unbecoming a governess! For, after all, Thomas Trotter was a chauffeur, and she couldn't make anything nobler out of him without saying that he wasn't Thomas Trotter at all.

She arose the next morning with a splitting headache, and the fear of Stuyvesant in her soul.

He was waiting for her in the hall below. The twins were accorded an unusually affectionate greeting by their big brother. He went so far as to implant a random kiss on the features of each of the "brats," as he called them in secret. Then he roughly shoved them ahead into the breakfast-room.

Fastening his gaze upon the pale, unsmiling face of Miss Emsdale, he whispered:

"Don't worry, my dear. Mum's the word."

He winked significantly. Revolted, she drew herself up and hurried after the children, unpleasantly conscious [pg 49] of the leer of admiration that rested upon her from behind.

He was very gay at breakfast.

"Mum's the word," he repeated in an undertone, as he drew back her chair at the conclusion of the meal. His lips were close to her ear, his hot breath on her cheek, as he bent forward to utter this reassuring remark.

TWO days later Thomas Trotter turned up at the old book shop of J. Bramble, in Lexington Avenue.

"Well," he said, as he took his pipe out of his pocket and began to stuff tobacco into it, "I've got the sack."

"Got the sack?" exclaimed Mr. Bramble, blinking through his horn-rimmed spectacles. "You can't be serious."

"It's the gospel truth," affirmed Mr. Trotter, depositing his long, graceful body in a rocking chair facing the sheet-iron stove at the back of the shop. "Got my walking papers last night, Bramby."

"What's wrong? I thought you were a fixture on the job. What have you been up to?"

"I'm blessed if I know," said the young man, shaking his head slowly. "Kicked out without notice, that's all I know about it. Two weeks' pay handed me; and a simple statement that he was putting some one on in my place today."

"Not even a reference?"

"He offered me a good one," said Trotter ironically. "Said he would give me the best send-off a chauffeur ever had. I told him I couldn't accept a reference and a discharge from the same employer."

"Rather foolish, don't you think?"

[pg 51] "That's just what he said. I said I'd rather have an explanation than a reference, under the circumstances."

"Um! What did he say to that?"

"Said I'd better take what he was willing to give."

Mr. Bramble drew up a chair and sat down. He was a small, sharp-featured man of sixty, bookish from head to foot.

"Well, well," he mused sympathetically. "Too bad, too bad, my boy. Still, you ought to thank goodness it comes at a time when the streets are in the shape they're in now. Almost impossible to get about with an automobile in all this snow, isn't it? Rather a good time to be discharged, I should say."

"Oh, I say, that is optimism. 'Pon my soul, I believe you'd find something cheerful about going to hell," broke in Trotter, grinning.

"Best way I know of to escape blizzards and snow-drifts," said Mr. Bramble, brightly.

The front door opened. A cold wind blew the length of the book-littered room.

"This Bramble's?" piped a thin voice.

"Yes. Come in and shut the door."

An even smaller and older man than himself obeyed the command. He wore the cap of a district messenger boy.

"Mr. J. Bramble here?" he quaked, advancing.

"Yes. What is it? A telegram?" demanded the owner of the shop, in some excitement.

"I should say not. Wires down everywheres. Gee, that fire looks good. I gotta letter for you, Mr. Bramble." He drew off his red mittens and produced [pg 52] from the pocket of his thin overcoat, an envelope and receipt book. "Sign here," he said, pointing.

Mr. Bramble signed and then studied the handwriting on the envelope, his lips pursed, one eye speculatively cocked.

"I've never seen the writing before. Must be a new one," he reflected aloud, and sighed. "Poor things!"

"That establishes the writer as a woman," said Trotter, removing his pipe. "Otherwise you would have said 'poor devils.' Now what do you mean by trifling with the women, you old rogue?" The loss of his position did not appear to have affected the nonchalant disposition of the good-looking Mr. Trotter.

"God bless my soul," said Mr. Bramble, staring hard at the envelope, "I don't believe it is from one of them, after all. By 'one of them,' my lad, I mean the poor gentlewomen who find themselves obliged to sell their books in order to obtain food and clothing. They always write before they call, you see. Saves 'em not only trouble but humiliation. The other kind simply burst in with a parcel of rubbish and ask how much I'll give for the lot. But this,—Well, well, I wonder who it can be from? Doesn't seem like the sort of writing—"

"Why don't you open it and see?" suggested his visitor.

"A good idea," said Mr. Bramble; "a very clever thought. There is a way to find out, isn't there?" His gaze fell upon the aged messenger, who warmed his bony hands at the stove. He paused, the tip of his forefinger inserted under the flap. "Sit down and [pg 53] warm yourself, my friend," he said. "Get your long legs out of the way, Tom, and make room for him. That's right! Must be pretty rough going outside for an old codger like you."

The messenger "boy" sat down. "Yes, sir, it sure is. Takes 'em forever in this 'ere town to clean the snow off'n the streets. 'Twasn't that way in my day."

"What do you mean by your 'day'?"

"Haven't you ever heard about me?" demanded the old man, eyeing Mr. Bramble with interest.

"Can't say that I have."

"Well, can you beat that? There's a big, long street named after me way down town. My name is Canal, Jotham W. Canal." He winked and showed his toothless gums in an amiable grin. "I used to be purty close to old Boss Tweed; kind of a lieutenant, you might say. Things were so hot in the old town in those days that we used to charge a nickel apiece for snowballs. Five cents apiece, right off the griddle. That's how hot it was in my day."

"My word!" exclaimed Mr. Bramble.

"He's spoofing you," said young Mr. Trotter.

"My God," groaned the messenger, "if I'd only knowed you was English I'd have saved my breath. Well, I guess I'll be on my way. Is there an answer, Mr. Bramble?"