Title: Harper's New Monthly Magazine, No. VI, November 1850, Vol. I

Author: Various

Release date: July 6, 2012 [eBook #40147]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Judith Wirawan, David Kline, and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

t was a glorious October morning, mild and brilliant, when I left Boston to visit Concord and Lexington. A gentle land-breeze during the night had borne the clouds back to their ocean birth-place, and not a trace of the storm was left except in the saturated earth. Health returned with the clear sky, and I felt a rejuvenescence in every vein and muscle when, at dawn, I strolled over the natural glory of Boston, its broad and beautifully-arbored Common. I breakfasted at six, and at half-past seven left the station of the Fitchburg rail-way for Concord, seventeen miles northwest of Boston. The country through which the road passed is rough and broken, but thickly settled. I arrived at the Concord station, about half a mile from the centre of the village, before nine o'clock, and procuring a conveyance, and an intelligent young man for a guide, proceeded at once to visit the localities of interest in the vicinity. We rode to the residence of Major James Barrett, a surviving grandson of Colonel Barrett, about two miles north of the village, and near the residence of his venerated ancestor. Major Barrett was eighty-seven years of age when I visited him; and his wife, with whom he had lived nearly sixty years, was eighty. Like most of the few survivors of the Revolution, they were remarkable for their mental and bodily vigor. Both, I believe, still live. The old lady—a small, well-formed woman—was as sprightly as a girl of twenty, and moved about the house with the nimbleness of foot of a matron in the prime of life. I was charmed with her vivacity, and the sunny radiance which it seemed to shed throughout her household; and the half hour that I passed with that venerable couple is a green spot in the memory.

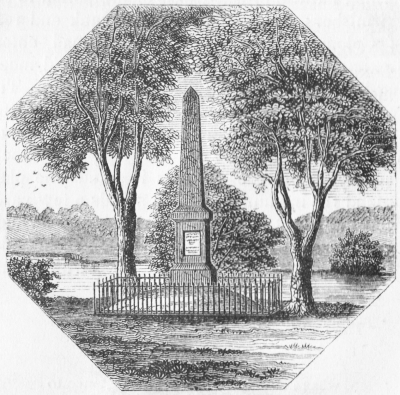

MONUMENT AT CONCORD.

MONUMENT AT CONCORD.

Major Barrett was a lad of fourteen when the British incursion into Concord took place. He was too young to bear a musket, but, with every lad and woman in the vicinity, he labored in concealing the stores and in making cartridges for those who went out to fight. With oxen and a cart, himself, and others about his age, removed the stores deposited at the house of his grandfather, into the woods, and concealed them, a cart-load in a place, under pine boughs. In such haste were they obliged to act on the approach of the British from Lexington, that, when the cart was loaded, lads would march on each side of the oxen and goad them into a trot. Thus all the stores were effectually concealed, except some carriage-wheels. Perceiving the enemy near, these were cut up and burned; so that Parsons found nothing of value to destroy or carry away.

From Major Barrett's we rode to the monument erected at the site of the old North Bridge, where the skirmish took place. The road crosses the Concord River a little above the site of the North Bridge. The monument stands a few rods westward of the road leading to the village, and not far from the house of the Reverend[Pg 722] Dr. Ripley, who gave the ground for the purpose. The monument is constructed of granite from Carlisle, and has an inscription upon a marble tablet inserted in the eastern face of the pedestal.[2] The view is from the green shaded lane which leads from the highway to the monument, looking westward. The two trees standing, one upon each side, without the iron railing, were saplings at the time of the battle; between them was the entrance to the bridge. The monument is reared upon a mound of earth a few yards from the left bank of the river. A little to the left, two rough, uninscribed stones from the field mark the graves of the two British soldiers who were killed and buried upon the spot.

We returned to the village at about noon, and started immediately for Lexington, six miles eastward.

Concord is a pleasant little village, including within its borders about one hundred dwellings. It lies upon the Concord River, one of the chief tributaries of the Merrimac, near the junction of the Assabeth and Sudbury Rivers. Its Indian name was Musketaquid. On account of the peaceable manner in which it was obtained, by purchase, of the aborigines, in 1635, it was named Concord. At the north end of the broad street, or common, is the house of Col. Daniel Shattuck, a part of which, built in 1774, was used as one of the depositories of stores when the British invasion took place. It has been so much altered, that a view of it would have but little interest as representing a relic of the past.

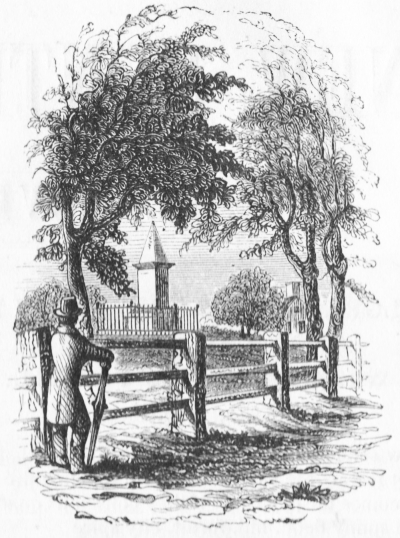

MONUMENT AT LEXINGTON.[4]

MONUMENT AT LEXINGTON.[4]

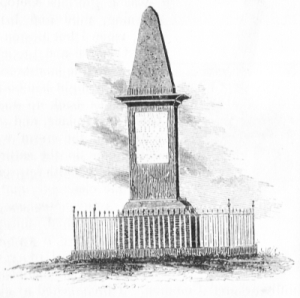

The road between Concord and Lexington passes through a hilly but fertile country. It is easy for the traveler to conceive how terribly a retreating army might be galled by the fire of a concealed enemy. Hills and hillocks, some wooded, some bare, rise up every where, and formed natural breast-works of protection to the skirmishers that hung upon the flank and rear of Colonel Smith's troops. The road enters Lexington at the green whereon the old meeting-house stood when the battle occurred. The town is upon a fine rolling plain, and is becoming almost a suburban residence for citizens of Boston. Workmen were inclosing the Green, and laying out the grounds in handsome plats around the monument, which stands a few yards from the street. It is upon a spacious mound; its material is granite, and it has a marble tablet on the south front of the pedestal, with a long inscription.[3] The design of the monument is not at all graceful, and, being surrounded by[Pg 723] tall trees, it has a very "dumpy" appearance. The people are dissatisfied with it, and doubtless, ere long, a more noble structure will mark the spot where the curtain of the revolutionary drama was first lifted.

NEAR VIEW OF THE MONUMENT.

NEAR VIEW OF THE MONUMENT.

After making the drawings here given, I visited and made the sketch of "Clark's House." There I found a remarkably intelligent old lady, Mrs. Margaret Chandler, aged eighty-three years. She has been an occupant of the house, I believe, ever since the Revolution, and has a perfect recollection of the events of the period. Her version of the escape of Hancock and Adams is a little different from the published accounts. She says that on the evening of the 18th of April, 1775, some British officers, who had been informed where these patriots were, came to Lexington, and inquired of a woman whom they met, for "Mr. Clark's house." She pointed to the parsonage; but in a moment, suspecting their design, she called to them and inquired if it was Clark's tavern that they were in search of. Uninformed whether it was a tavern or a parsonage where their intended victims were staying, and supposing the former to be the most likely place, the officers replied, "Yes, Clark's tavern." "Oh," she said, "Clark's tavern is in that direction," pointing toward East Lexington. As soon as they departed, the woman hastened to inform the patriots of their danger, and they immediately arose and fled to Woburn. Dorothy Quincy, the intended wife of Hancock, who was at Mr. Clark's, accompanied them in their flight.

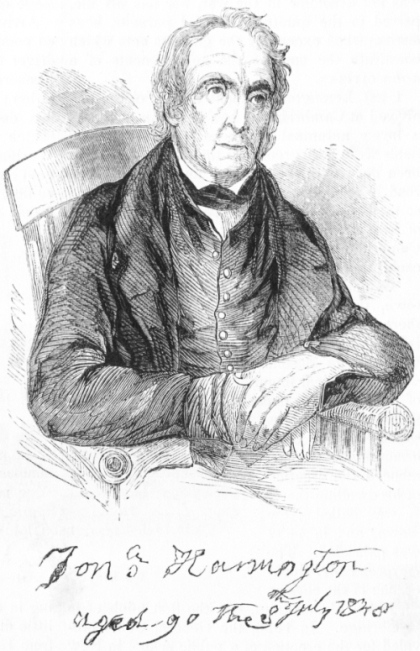

I next called upon the venerable Abijah Harrington, who was living in the village. He was a lad of fourteen at the time of the engagement. Two of his brothers were among the minute men, but escaped unhurt. Jonathan and Caleb Harrington, near relatives, were killed. The former was shot in front of his own house, while his wife stood at the window in an agony of alarm. She saw her husband fall, and then start up, the blood gushing from his breast. He stretched out his arms toward her, and then fell again. Upon his hands and knees he crawled toward his dwelling, and expired just as his wife reached him. Caleb Harrington was shot while running from the meeting-house. My informant saw almost the whole of the battle, having been sent by his mother to go near enough, and be safe, to obtain and convey to her information respecting her other sons, who were with the minute men. His relation of the incidents of the morning was substantially such as history has recorded. He dwelt upon the subject with apparent delight, for his memory of the scenes of his early years, around which cluster so much of patriotism and glory, was clear and full. I would gladly have listened until twilight to the voice of such experience, but time was precious, and I hastened to East Lexington, to visit his cousin, Jonathan Harrington, an old man of ninety, who played the fife when the minute men were marshaled on the Green upon that memorable April morning. He was splitting fire-wood in his yard with a vigorous hand when I rode up; and as he sat in his rocking-chair, while I sketched his placid features, he appeared no older than a man of seventy. His brother, aged eighty-eight, came in before my sketch was finished, and I could not but gaze with wonder upon these strong old men, children of one mother, who were almost grown to manhood when the first battle of our Revolution occurred! Frugality and temperance, co-operating with industry, a cheerful temper, and a good constitution, have lengthened their days, and made their protracted years hopeful and happy.[5] The aged fifer apologized for the[Pg 724] rough appearance of his signature, which he kindly wrote for me, and charged the tremulous motion of his hand to his labor with the ax. How tenaciously we cling even to the appearance of vigor, when the whole frame is tottering to its fall! Mr. Harrington opened the ball of the Revolution with the shrill war-notes of the fife, and then retired from the arena. He was not a soldier in the war, nor has his life, passed in the quietude of rural pursuits, been distinguished except by the glorious acts which constitute the sum of the achievements of a GOOD CITIZEN.

I left Lexington at about three o'clock, and arrived at Cambridge at half past four. It was a lovely autumnal afternoon. The trees and fields were still green, for the frost had not yet been busy with their foliage and blades. The road is Macadamized the whole distance; and so thickly is it lined with houses, that the village of East Lexington and Old Cambridge seem to embrace each other in close union.

Cambridge is an old town, the first settlement there having been planted in 1631, contemporaneous with that of Boston. It was the original intention of the settlers to make it the metropolis of Massachusetts, and Governor Winthrop commenced the erection of his dwelling there. It was called New Town, and in 1632 was palisaded. The Reverend Mr. Hooker, one of the earliest settlers of Connecticut, was the first minister in Cambridge. In 1636, the General Court provided for the erection of a public school in New Town, and appropriated two thousand dollars for that purpose. In 1638, the Reverend John Harvard, of Charlestown, endowed the school with about four thousand dollars. This endowment enabled them to exalt the academy into a college, and it was called Harvard University in honor of its principal benefactor.

Cambridge has the distinction of being the place where the first printing-press in America was established. Its proprietor was named Day, and the capital that purchased the materials was furnished by the Rev. Mr. Glover. The first thing printed was the "Freeman's Oath," in 1636; the next was an almanac; and the next the Psalms, in metre.[6] Old Cambridge (West Cambridge, or Metonomy, of the Revolution), the seat of the University, is three miles from West Boston Bridge, which connects Cambridge with Boston. Cambridgeport is about half way between Old Cambridge and the bridge, and East Cambridge occupies Lechmere's Point, a promontory fortified during the siege of Boston in 1775.

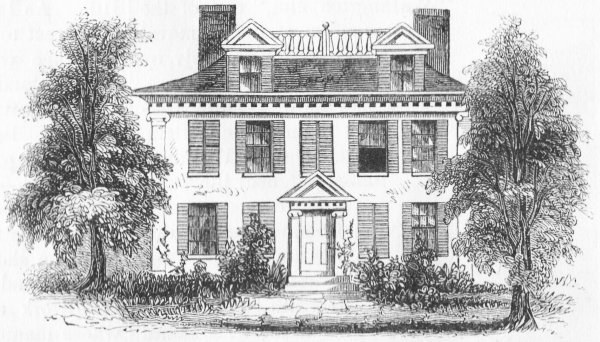

WASHINGTON'S HEAD-QUARTERS AT CAMBRIDGE.

WASHINGTON'S HEAD-QUARTERS AT CAMBRIDGE.

Arrived at Old Cambridge, I parted company with the vehicle and driver that conveyed me from Concord to Lexington, and hither; and, as the day was fast declining, I hastened to sketch the head-quarters of Washington, an elegant and spacious edifice, standing in the midst of shrubbery and stately elms, a little distance from the street, once the highway from Harvard University to Waltham. At this mansion, and at Winter Hill, Washington passed most of his time, after taking command of the Continental army, until the evacuation of Boston in the following spring. Its present owner is Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Professor of Oriental languages in Harvard University, and widely known in the world of literature as one of the most gifted men of the age. It is a spot worthy of the residence of an American bard so endowed, for the associations which hallow it are linked with the noblest themes that ever awakened the inspiration of a child of song.

then to the thoughtful dweller must come the spirit of the place and hour to weave a gorgeous[Pg 725] tapestry, rich with pictures, illustrative of the heroic age of our young republic. My tarry was brief and busy, for the sun was rapidly descending—it even touched the forest tops before I finished the drawing—but the cordial reception and polite attentions which I received from the proprietor, and his warm approval of, and expressed interest for the success of my labors, occupy a space in memory like that of a long, bright summer day.

This mansion stands upon the upper of two terraces, which are ascended each by five stone steps. At each front corner of the house is a lofty elm—mere saplings when Washington beheld them, but now stately and patriarchal in appearance. Other elms, with flowers and shrubbery, beautify the grounds around it; while within, iconoclastic innovation has not been allowed to enter with its mallet and trowel, to mar the work of the ancient builder, and to cover with the vulgar stucco of modern art the carved cornices and paneled wainscots that first enriched it. I might give a long list of eminent persons whose former presence in those spacious rooms adds interest to retrospection, but they are elsewhere identified with scenes more personal and important. I can not refrain, however, from noticing the visit of one, who, though a dark child of Africa and a bond-woman, received the most polite attention from the commander-in-chief. This was Phillis, a slave of Mr. Wheatley, of Boston. She was brought from Africa when between seven and eight years old. She seemed to acquire knowledge intuitively; became a poet of considerable merit, and corresponded with such eminent persons as the Countess of Huntingdon, Earl of Dartmouth, Reverend George Whitefield, and others. Washington invited her to visit him at Cambridge, which she did a few days before the British evacuated Boston; her master among others, having left the city by permission, and retired, with his family, to Chelsea. She passed half an hour with the commander-in-chief, from whom and his officers she received marked attention.[7]

THE RIEDESEL HOUSE, CAMBRIDGE.[8]

THE RIEDESEL HOUSE, CAMBRIDGE.[8]

A few rods above the residence of Professor Longfellow is the house in which the Brunswick general, the Baron Riedesel, and his family were quartered, during the stay of the captive army of Burgoyne in the vicinity of Boston. I was not aware when I visited Cambridge, that the old mansion was still in existence; but, through the kindness of Mr. Longfellow, I am able to present the features of its southern front, with a description. In style it is very much like that of Washington's head-quarters, and the general appearance of the grounds around is similar. It is shaded by noble linden-trees, and adorned with shrubbery, presenting to the eye all the attractions noticed by the Baroness of Riedesel in her charming letters.[Pg 726][9] Upon a window-pane on the north side of the house may be seen the undoubted autograph of that accomplished woman, inscribed with a diamond point. It is an interesting memento, and is preserved with great care. The annexed is a facsimile of it.

During the first moments of the soft evening twilight I sketched the "Washington elm," one of the ancient anakim of the primeval forest, older, probably, by a half century or more, than the welcome of Samoset to the white settlers. It stands upon Washington-street, near the westerly corner of the Common, and is distinguished by the circumstance that, beneath its broad shadow, General Washington first drew his sword as commander-in-chief of the Continental army, on the 3d of July, 1775. Thin lines of clouds, glowing in the light of the setting sun like bars of gold, streaked the western sky, and so prolonged the twilight by reflection, that I had ample time to finish my drawing before the night shadows dimmed the paper.

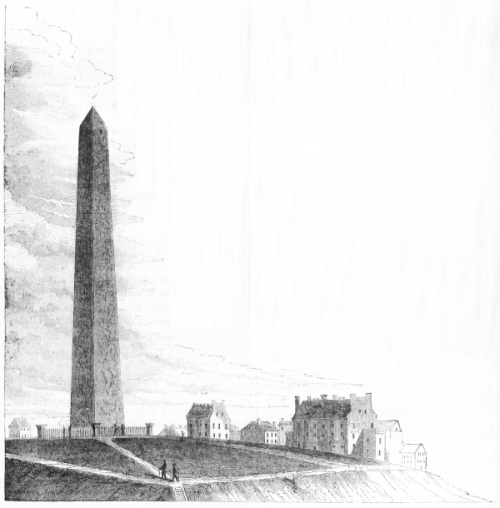

Early on the following morning I procured a chaise to visit Charlestown and Dorchester Heights. I rode first to the former place, and climbed to the summit of the great obelisk that stands upon the site of the redoubt upon Breed's Hill. As I ascended the steps which lead from the street to the smooth gravel-walks upon the eminence whereon the "Bunker Hill Monument" stands, I experienced a feeling of disappointment and regret, not easily to be expressed. Before me was the great memento, huge and grand—all that patriotic reverence could wish—but the ditch scooped out by Prescott's toilers on that starry night in June, and the mounds that were upheaved to protect them from the shots of the astonished Britons, were effaced, and no more vestiges remain of the handiwork of those in whose honor and to whose memory this obelisk was raised, than of Roman conquests in the shadow of Trajan's column—of the naval battles of Nelson around his monument in Trafalgar-square, or of French victories in the Place Vendôme. The fosse and the breast-works were all quite prominent when the foundation-stone of the monument was laid, and a little care, directed by good taste, might have preserved them in their interesting state of half ruin until the passage of the present century, or, at least, until the sublime centenary of the battle should be celebrated. Could the visitor look upon the works of the patriots themselves, associations a hundred-fold more interesting would crowd the mind, for wonderfully suggestive of thought[Pg 727] are the slightest relics of the past when linked with noble deeds. A soft green sward, as even as the rind of a fair apple, and cut by eight straight gravel-walks, diverging from the monument, is substituted by art for the venerated irregularities made by the old mattock and spade. The spot is beautiful to the eye untrained by appreciating affection for hallowed things; nevertheless, there is palpable desecration that may hardly be forgiven.

BUNKER HILL MONUMENT.[10]

BUNKER HILL MONUMENT.[10]

The view from the top of the monument, for extent, variety, and beauty, is certainly one of the finest in the world. A "York shilling" is charged for the privilege of ascending the monument. The view from its summit is "a shilling show" worth a thousand miles of travel to see. Boston, its harbor, and the beautiful country around, mottled with villages, are spread out like a vast painting, and on every side the eye may rest upon localities of great historical interest, Cambridge, Roxbury, Chelsea, Quincy, Medford, Marblehead, Dorchester, and other places, where

and the numerous sites of small fortifications which the student of history can readily call to mind. In the far distance, on the northwest, rise the higher peaks of the White Mountains of New Hampshire; and on the northeast, the peninsula of Nahant, and the more remote Cape Anne may be seen. Wonders which present science and enterprise are developing and forming are there exhibited in profusion. At one glance from this lofty observatory may be seen seven railroads,[11] and many other avenues connecting the city with the country; and ships from almost every region of the globe dot the waters of the harbor. Could a tenant of the old grave-yard on Copp's Hill, who lived a hundred years ago, when the village upon Tri-mountain was fitting out its little armed flotillas against the French in Acadia, or sending forth its few vessels of trade along the neighboring coasts, or occasionally to cross the Atlantic, come forth and stand beside us a moment, what a new and wonderful world would be presented to his vision! A hundred years ago!

They were men wise in their generation, but ignorant in practical knowledge when compared with the present. In their wildest dreams, incited by tales of wonder that spiced the literature of their times, they never fancied any thing half so wonderful as our mighty dray-horse,

WASHINGTON.[13]

WASHINGTON.[13]

I lingered in the chamber of the Bunker Hill monument as long as time would allow, and descending, rode back to the city, crossed to South Boston, and rambled for an hour among the remains of the fortifications upon the heights of the peninsula of Dorchester. The present prominent remains of fortifications are those of intrenchments cast up during the war of 1812, and have no other connection with our subject than the circumstance that they occupy the site of the works constructed there by order of Washington. These were greatly reduced in altitude when the engineers began the erection of the forts now in ruins, which are properly preserved with a great deal of care. They occupy the summits of two hills, which command Boston Neck on the left, the city of Boston in front, and the harbor on the right. Southeast from the heights, pleasantly situated among gentle hills, is the village of Dorchester, so called in memory of a place in England of the same name, whence many of its earliest settlers came. The stirring events which rendered Dorchester Heights famous are universally known.

I returned to Boston at about one o'clock, and passed the remainder of the day in visiting places of interest within the city—the old South meeting-house, Faneuil Hall, the Province House, and the Hancock House. I am indebted to John Hancock, Esq., nephew of the patriot, and present proprietor and occupant of the "Hancock House," on Beacon-street, for polite attentions while visiting his interesting mansion, and for information concerning matters that have passed under the eye of his experience of threescore years. He has many mementoes of his eminent kinsman, and among them a beautifully-executed miniature of him, painted in London, in 1761, while he was there at the coronation of George III.

Near Mr. Hancock's residence is the State House, a noble structure upon Beacon Hill, the corner-stone of which was laid in 1795, by Governor Samuel Adams, assisted by Paul Revere, master of the Masonic grand lodge. There I sketched the annexed picture of the colossal statue of Washington, by Chantrey, which stands in the open centre of the first story; also the group of trophies from Bennington, that hang over the door of the Senate chamber. Under these trophies, in a gilt frame, is a copy of the reply of the Massachusetts Assembly to General Stark's letter, that accompanied the presentation of the trophies. It was written fifty years ago.

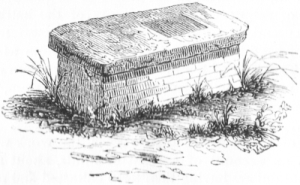

MATHER'S VAULT.

MATHER'S VAULT.

After enjoying the view from the top of the State House a while, I walked to Copp's Hill, a little east of Charlestown Bridge, at the north end of the town, where I tarried until sunset in the ancient burying-ground. The earliest name of this eminence was Snow Hill. It was subsequently named after its owner, William Copp.[14] It came into the possession of the Ancient and Honorable Artillery Company by mortgage; and when, in 1775, they were forbidden by Gage to parade on the Common, they went to this, their own ground, and drilled in defiance of his threats. The fort, or battery, that was built there by the British, just before the battle of Bunker Hill, stood near its southeast brow, adjoining the burying-ground. The remains of many eminent men repose in that little cemetery. Close by the entrance is the vault of the Mather family. It is covered by a plain, oblong structure of brick, three feet high and about six feet long, upon which is laid a heavy brown stone slab, with a tablet of slate, bearing the names of the principal tenants below.[15]

I passed the forenoon of the next day in the rooms of the Massachusetts Historical Society, where every facility was afforded me by Mr. Felt, the librarian, for examining the assemblage of things curious collected there.[16] The printed books and manuscripts, relating principally to American history, are numerous, rare, and valuable.

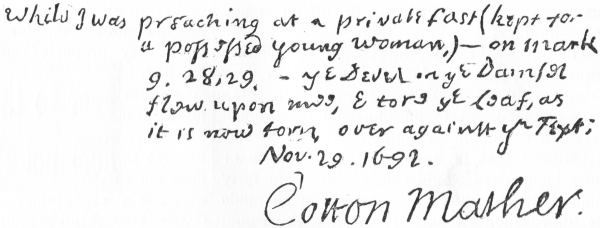

There is also a rich depository of the autographs of the Pilgrim fathers and their immediate descendants. There are no less than twenty-five large folio volumes of valuable manuscript letters and other documents; besides which are six thick quarto manuscript volumes—a commentary on the Holy Scriptures—in the handwriting of Cotton Mather. From an autograph letter of that singular man the annexed fac-simile of his writing and signature is given. Among the portraits in the cabinet of the society are those of Governor Winslow, supposed to have been painted by Vandyke, Increase Mather, and Peter Faneuil, the founder of Faneuil Hall.

MATHER'S WRITING.

MATHER'S WRITING.

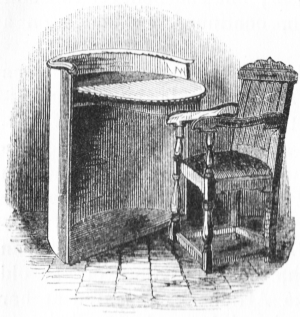

SPEAKER'S DESK AND WINTHROP'S CHAIR.

SPEAKER'S DESK AND WINTHROP'S CHAIR.

CHURCH'S SWORD.

CHURCH'S SWORD.

PHILIP'S SAMP-PAN.

PHILIP'S SAMP-PAN.

I had the pleasure of meeting, at the rooms of the society, that indefatigable antiquary, Dr. Webb, widely known as the American correspondent of the "Danish Society of Northern Antiquarians" at Copenhagen. He was sitting in the chair that once belonged to Governor Winthrop, writing upon the desk of the speaker of the Colonial Assembly of Massachusetts, around which the warm debates were carried on concerning American liberty, from the time when James Otis denounced the Writs of Assistance, until Governor Gage adjourned the Assembly to Salem, in 1774. Hallowed by such associations, the desk is an interesting relic. Dr. Webb's familiarity with the collections of the society, and his kind attentions, greatly facilitated my search among the six thousand articles for things curious connected with my subject and made my brief visit far more profitable to myself than it would otherwise have been. Among the relics preserved are the chair that belonged to Governor Carver; the sword of Miles Standish; the huge key of Port Royal gate; a samp-pan, that belonged to Metacomet, or King Philip; and the sword reputed to have been used by Captain Church when he cut off that unfortunate sachem's head. The dish is about twelve inches in diameter, wrought out of an elm knot with great skill. The sword is very rude, and was doubtless made by a blacksmith of the colony. The handle is a roughly-wrought piece of ash, and the guard is made of a wrought-iron plate.

It is a difficult puzzle to reconcile the existence of certain superstitions that continue to have wide influence with the enlightenment of the nineteenth century. When we have read glowing paragraphs about the wonderful progress accomplished by the present generation; when we have regarded the giant machinery in operation for the culture of the people—moved, in great part, by the collective power of individual charity; when we have examined the stupendous results of human genius and ingenuity which are now laid bare to the lowliest in the realm; we turn back, it must be confessed, with a mournful despondency, to mark the debasing influence of the old superstitions which have survived to the present time.

The superstitions of the ancients formed part of their religion. They consulted oracles as now men pray. The stars were the arbiters of their fortunes. Natural phenomena, as lightning and hurricanes, were, to them, awful expressions of the anger of their particular deities. They had their dies atri and dies albi; the former were marked down in their calendars with a black character to denote ill-luck, and the latter were painted in white characters to signify bright and propitious days. They followed the finger posts of their teachers. Faith[Pg 730] gave dignity to the tenets of the star-gazer and fire-worshiper.

The priests of old taught their disciples to regard six particular days in the year as days fraught with unusual danger to mankind. Men were enjoined not to let blood on these black days, nor to imbibe any liquid. It was devoutly believed that he who ate goose on one of those black days would surely die within forty more; and that any little stranger who made his appearance on one of the dies atri would surely die a sinful and violent death. Men were further enjoined to let blood from the right arm on the seventh or fourteenth of March; from the left arm on the eleventh of April; and from either arm on the third or sixth of May, that they might avoid pestilential diseases. These barbaric observances, when brought before people in illustration of the mental darkness of the ancients, are considered at once to be proof positive of their abject condition. We thereupon congratulated ourselves upon living in the nineteenth century; when such foolish superstitions are laughed at; and perhaps our vanity is not a little flattered by the contrast which presents itself, between our own highly cultivated condition, and the wretched state of our ancestors.

Yet Mrs. Flimmins will not undertake a sea-voyage on a Friday; nor would she on any account allow her daughter Mary to be married on that day of the week. She has great pity for the poor Red Indians who will not do certain things while the moon presents a certain appearance, and who attach all kinds of powers to poor dumb brutes; yet if her cat purrs more than usual, she accepts the warning, and abandons the trip she had promised herself on the morrow.

Miss Nippers subscribes largely to the fund for eradicating superstitions from the minds of the wretched inhabitants of Kamschatka; and while she is calculating the advantages to be derived from a mission to the South Sea Islands, to do away with the fearful superstitious reverence in which these poor dear islanders hold their native flea: a coal pops from her fire, and she at once augurs from its shape an abundance of money, that will enable her to set her pious undertaking in operation; but on no account will she commence collecting subscriptions for the anti-drinking-slave-grown-sugar-in-tea society, because she has always remarked that Monday is her unlucky day. On a Monday her poodle died, and on a Monday she caught that severe cold at Brighton, from the effects of which she is afraid she will never recover.

Mrs. Carmine is a very strong-minded woman. Her unlucky day is Wednesday. On a Wednesday she first caught that flush which she has never been able to chase from her cheeks, and on one of these fatal days her Maria took the scarlet fever. Therefore, she will not go to a pic-nic on a Wednesday, because she feels convinced that the day will turn out wet, or that the wheel will come off the carriage. Yet the other morning, when a gipsy was caught telling her eldest daughter her fortune, Mrs. Carmine very properly reproached the first-born for her weakness, in giving any heed to the silly mumblings of the old woman. Mrs. Carmine is considered to be a woman of uncommon acuteness. She attaches no importance whatever to the star under which a child is born—does not think there is a pin to choose between Jupiter and Neptune; and she has a positive contempt for ghosts; but she believes in nothing that is begun, continued, or ended on a Wednesday.

Miss Crumple, on the contrary, has seen many ghosts, in fact, is by this time quite intimate with one or two of the mysterious brotherhood; but at the same time she is at a loss to understand how any woman in her senses, can believe Thursday to be a more fortunate day than Wednesday, or why Monday is to be black-balled from the Mrs. Jones's calendar. She can state on her oath, that the ghost of her old schoolfellow, Eliza Artichoke, appeared at her bedside on a certain night, and she distinctly saw the mole on its left cheek, which poor Eliza, during her brief career, had vainly endeavored to eradicate, with all sorts of poisonous things. The ghost, moreover, lisped—so did Eliza! This was all clear enough to Miss Crumple, and she considered it a personal insult for any body to suggest that her vivid apparitions existed only in her over-wrought imagination. She had an affection for her ghostly visitors, and would not hear a word to their disparagement.

The unearthly warnings which Mrs. Piptoss had received had well-nigh spoiled all her furniture. When a relative dies, the fact is not announced to her in the commonplace form of a letter; no, an invisible sledge-hammer falls upon her Broadwood, an invisible power upsets her loo-table, all the doors of her house unanimously blow open, or a coffin flies out of the fire into her lap.

Mrs. Grumple, who is a very economical housewife, looks forward to the day when the moon re-appears, on which occasion she turns her money, taking care not to look at the pale lady through glass. This observance, she devoutly believes, will bring her good fortune. When Miss Caroline has a knot in her lace, she looks for a present; and when Miss Amelia snuffs the candle out, it is her faith that the act defers her marriage a twelvemonth. Any young lady who dreams the same dream two consecutive Fridays, will tell you that her visions will "come true."

Yet these are exactly the ladies, who most deplore the "gross state of superstition" in which many "benighted savages" live, and willingly subscribe their money for its eradication. The superstition so generally connected with Friday, may easily be traced to its source. It undoubtedly and confessedly has its origin in scriptural history: it is the day on which the Saviour suffered. The superstition is the more[Pg 731] revolting from this circumstance; and it is painful to find that it exists among persons of education. There is no branch of the public service, for instance, in which so much sound mathematical knowledge is to be found, as in the Navy. Yet who are more superstitious than sailors, from the admiral down to the cabin boy? Friday fatality is still strong among them. Some years ago, in order to lessen this folly, it was determined that a ship should be laid down on a Friday, and launched on a Friday; that she should be called "Friday," and that she should commence her first voyage on a Friday. After much difficulty a captain was found who owned to the name of Friday; and after a great deal more difficulty men were obtained, so little superstitious, as to form a crew. Unhappily, this experiment had the effect of confirming the superstition it was meant to abolish. The "Friday" was lost—was never, in fact, heard of from the day she set sail.

Day-fatality, as Miss Nippers interprets it, is simply the expression of an undisciplined and extremely weak mind; for, if any person will stoop to reason with her on her aversion to Mondays, he may ask her whether the death of the poodle, or the catching of her cold, are the two greatest calamities of her life; and, if so, whether it is her opinion that Monday is set apart, in the scheme of Nature, so far as it concerns her, in a black character. Whether for her insignificant self there is a special day accursed! Mrs. Carmine is such a strong-minded woman, that we approach her with no small degree of trepidation. Wednesday is her dies ater, because, in the first place, on a Wednesday she imprudently exposed herself, and is suffering from the consequences; and, in the second place, on a Wednesday her Maria took the scarlet fever. So she has marked Wednesday down in her calendar with a black character; yet her contempt for stars and ghosts is prodigious. Now there is a consideration to be extended to the friends of ghosts, which Day-fatalists can not claim. Whether or not deceased friends take a more airy and flimsy form, and adopt the invariable costume of a sheet to visit the objects of their earthly affections, is a question which the shrewdest thinkers and the profoundest logicians have debated very keenly, but without ever arriving at any satisfactory conclusion.

The strongest argument against the positive existence of ghosts, is, that they appear only to people of a certain temperament, and under certain exciting circumstances. The obtuse, matter-of-fact man, never sees a ghost; and we may take it as a natural law, that none of these airy visitants ever appeared to an attorney. But the attorney, Mr. Fee Simple, we are assured, holds Saturday to be an unlucky day. It was on a Saturday that his extortionate bill in poor Mr. G.'s case, was cut down by the taxing master; and it was on a Saturday that a certain heavy bill was duly honored, upon which he had hoped to reap a large sum in the shape of costs. Therefore Mr. Fee Simple believes that the destinies have put a black mark against Saturday, so far as he is concerned.

The Jew who thought that the thunder-storm was the consequence of his having eaten a slice of bacon, did not present a more ludicrous picture, than Mr. Fee Simple presents with his condemned Saturday.

We have an esteem for ghost-inspectors, which it is utterly impossible to extend to Day-fatalists. Mrs. Piptoss, too, may be pitied; but Mog, turning her money when the moon makes her re-appearance, is an object of ridicule. We shall neither be astonished, nor express condolence, if the present, which Miss Caroline anticipates from the knot in her lace, be not forthcoming; and as for Miss Amelia, who has extinguished the candle, and to the best of her belief lost her husband for a twelvemonth, we can only wish for her, that when she is married, her lord and master will shake her faith in the prophetic power of snuffers. But of all the superstitions that have survived to the present time, and are to be found in force among people of education and a thoughtful habit, Day-fatalism is the most general, as it is the most unfounded and preposterous. It is a superstition, however, in which many great and powerful thinkers have shared, and by which they have been guided; it owes much of its present influence to this fact; but reason, Christianity, and all we have comprehended of the great scheme of which we form part, alike tend to demonstrate its absurdity, and utter want of all foundation.

MADAME ROLAND.

MADAME ROLAND.

The Girondists were led from their dungeons in the Conciergerie to their execution on the 31st of October, 1793. Upon that very day Madame Roland was conveyed from the prison of St. Pélagié to the same gloomy cells vacated by the death of her friends. She was cast into a bare and miserable dungeon, in that subterranean receptacle of woe, where there was not even a bed. Another prisoner, moved with compassion, drew his own pallet into her cell, that she might not be compelled to throw herself for repose upon the cold, wet stones. The chill air of winter had now come, and yet no covering was allowed her. Through the long night she shivered with the cold.

The prison of the Conciergerie consists of a series of dark and damp subterranean vaults, situated beneath the floor of the Palace of Justice. Imagination can conceive of nothing more dismal than these sombre caverns, with long and winding galleries opening into cells as dark as the tomb. You descend by a flight of massive stone steps into this sepulchral abode, and, passing through double doors, whose iron strength time has deformed but not weakened, you enter upon the vast labyrinthine prison, where the imagination wanders affrighted through intricate mazes of halls, and arches, and vaults, and dungeons, rendered only more appalling by the dim light which struggles through those grated orifices which pierced the massive walls. The Seine flows by upon one side, separated only by the high way of the quays. The bed of the Seine is above the floor of the prison. The surrounding earth was consequently saturated with water, and the oozing moisture diffused over the walls and the floors the humidity of the sepulchre. The plash of the river; the rumbling of carts upon the pavements overhead; the heavy tramp of countless footfalls, as the multitude poured into and out of the halls of justice, mingled with the moaning of the prisoners in those solitary cells. There were one or two narrow courts scattered in this vast structure, where the prisoners could look up the precipitous walls, as of a well, towering high above them, and see a few square yards of sky. The gigantic quadrangular tower, reared above these firm foundations, was formerly the imperial palace from which issued all power and law. Here the French kings reveled in voluptuousness, with their prisoners groaning beneath their feet. This strong-hold of feudalism had now become the tomb of the monarchy. In one of the most loathsome of these cells, Maria Antoinette, the daughter of the Cæsars, had languished in misery as profound as mortals can suffer, till, in the endurance of every conceivable insult, she was dragged to the guillotine.

It was into a cell adjoining that which the hapless queen had occupied that Madame Roland was cast. Here the proud daughter of the emperors of Austria and the humble child of the artisan, each, after a career of unexampled vicissitudes, found their paths to meet but a few steps from the scaffold. The victim of the monarchy and the victim of the Revolution were conducted to the same dungeons and perished on the same block. They met as antagonists in the stormy arena of the French Revolution. They were nearly of equal age. The one possessed the prestige of wealth, and rank, and ancestral power; the other, the energy of vigorous and cultivated mind. Both were endowed with unusual attractions of person, spirits invigorated by enthusiasm, and the loftiest heroism. From the antagonism of life they met in death.

The day after Madame Roland was placed in the Conciergerie, she was visited by one of the notorious officers of the revolutionary party, and very closely questioned concerning the friendship she had entertained for the Girondists. She frankly avowed the elevated affection and esteem with which she cherished their memory, but she declared that she and they were the cordial friends of republican liberty; that they wished to preserve, not to destroy, the Constitution. The examination was vexatious and intolerant in the extreme. It lasted for three hours, and consisted in an incessant torrent of criminations, to which she was hardly permitted to offer one word in reply. This examination taught her the nature of the accusations which would be brought against her. She sat down in her cell that very night, and, with a rapid pen, sketched that defense which has been pronounced one of the most eloquent and touching monuments of the Revolution.

Having concluded it, she retired to rest, and[Pg 733] slept with the serenity of a child. She was called upon several times by committees sent from the revolutionary tribunal for examination. They were resolved to take her life, but were anxious to do it, if possible, under the forms of law. She passed through all their examinations with the most perfect composure, and the most dignified self-possession. Her enemies could not withhold their expressions of admiration as they saw her in her sepulchral cell of stone and of iron, cheerful, fascinating, and perfectly at ease. She knew that she was to be led from that cell to a violent death, and yet no faltering of soul could be detected. Her spirit had apparently achieved a perfect victory over all earthly ills.

The upper part of the door of her cell was an iron grating. The surrounding cells were filled with the most illustrious ladies and gentlemen of France. As the hour of death drew near, her courage and animation seemed to increase. Her features glowed with enthusiasm; her thoughts and expressions were refulgent with sublimity, and her whole aspect assumed the impress of one appointed to fill some great and lofty destiny. She remained but a few days in the Conciergerie before she was led to the scaffold. During those few days, by her example and her encouraging words, she spread among the numerous prisoners there an enthusiasm and a spirit of heroism which elevated, above the fear of the scaffold, even the most timid and depressed. This glow of feeling and exhilaration gave a new impress of sweetness and fascination to her beauty. The length of her captivity, the calmness with which she contemplated the certain approach of death, gave to her voice that depth of tone and slight tremulousness of utterance which sent her eloquent words home with thrilling power to every heart. Those who were walking in the corridor, or who were the occupants of adjoining cells, often called for her to speak to them words of encouragement and consolation.

Standing upon a stool at the door of her own cell, she grasped with her hands the iron grating which separated her from her audience. This was her tribune. The melodious accents of her voice floated along the labyrinthine avenues of those dismal dungeons, penetrating cell after cell, and arousing energy in hearts which had been abandoned to despair. It was, indeed, a strange scene which was thus witnessed in these sepulchral caverns. The silence, as of the grave, reigned there, while the clear and musical tones of Madame Roland, as of an angel of consolation, vibrated through the rusty bars, and along the dark, damp cloisters. One who was at that time an inmate of the prison, and survived those dreadful scenes, has described, in glowing terms, the almost miraculous effects of her soul-moving eloquence. She was already past the prime of life, but she was still fascinating. Combined with the most wonderful power of expression, she possessed a voice so exquisitely musical, that, long after her lips were silenced in death, its tones vibrated in lingering strains in the souls of those by whom they had ever been heard. The prisoners listened with the most profound attention to her glowing words, and regarded her almost as a celestial spirit, who had come to animate them to heroic deeds. She often spoke of the Girondists who had already perished upon the guillotine. With perfect fearlessness she avowed her friendship for them, and ever spoke of them as our friends. She, however, was careful never to utter a word which would bring tears into the eye. She wished to avoid herself all the weakness of tender emotions, and to lure the thoughts of her companions away from every contemplation which could enervate their energies.

Occasionally, in the solitude of her cell, as the image of her husband and of her child rose before her, and her imagination dwelt upon her desolated home and her blighted hopes—her husband denounced and pursued by lawless violence, and her child soon to be an orphan—woman's tenderness would triumph over the heroine's stoicism. Burying, for a moment, her face in her hands, she would burst into a flood of tears. Immediately struggling to regain composure, she would brush her tears away, and dress her countenance in its accustomed smiles. She remained in the Conciergerie but one week, and during that time so endeared herself to all as to become the prominent object of attention and love. Her case is one of the most extraordinary the history of the world has presented, in which the very highest degree of heroism is combined with the most resistless charms of feminine loveliness. An unfeminine woman can never be loved by men. She may be respected for her talents, she may be honored for her philanthropy, but she can not win the warmer emotions of the heart. But Madame Roland, with an energy of will, an inflexibility of purpose, a firmness of stoical endurance which no mortal man has ever exceeded, combined that gentleness, and tenderness, and affection—that instinctive sense of the proprieties of her sex—which gathered around her a love as pure and as enthusiastic as woman ever excited. And while her friends, many of whom were the most illustrious men in France, had enthroned her as an idol in their hearts, the breath of slander never ventured to intimate that she was guilty even of an impropriety.

The day before her trial, her advocate, Chauveau de la Garde, visited her to consult respecting her defense. She, well aware that no one could speak a word in her favor but at the peril of his own life, and also fully conscious that her doom was already sealed, drew a ring from her finger, and said to him,

"To-morrow, I shall be no more. I know the fate which awaits me. Your kind assistance can not avail aught for me, and would but endanger you. I pray you, therefore, not to come to the tribunal, but to accept of this last testimony of my regard."

The next day she was led to her trial. She attired herself in a white robe, as a symbol of her innocence, and her long dark hair fell in thick curls on her neck and shoulders. She emerged from her dungeon the vision of unusual loveliness. The prisoners who were walking in the corridors gathered around her, and with smiles and words of encouragement she infused energy into their hearts. Calm and invincible she met her judges. She was accused of the crimes of being the wife of M. Roland and the friend of his friends. Proudly she acknowledged herself guilty of both those charges. Whenever she attempted to utter a word in her defense, she was brow-beaten by the judges, and silenced by the clamors of the mob which filled the tribunal. The mob now ruled with undisputed sway in both legislative and executive halls. The serenity of her eye was untroubled, and the composure of her disciplined spirit unmoved, save by the exaltation of enthusiasm, as she noted the progress of the trial, which was bearing her rapidly and resistlessly to the scaffold. It was, however, difficult to bring any accusation against her by which, under the form of law, she could be condemned. France, even in its darkest hour, was rather ashamed to behead a woman, upon whom the eyes of all Europe were fixed, simply for being the wife of her husband and the friend of his friends. At last the president demanded of her that she should reveal her husband's asylum. She proudly replied,

"I do not know of any law by which I can be obliged to violate the strongest feelings of nature."

This was sufficient, and she was immediately condemned. Her sentence was thus expressed:

"The public accuser has drawn up the present indictment against Jane Mary Phlippon, the wife of Roland, late Minister of the Interior, for having wickedly and designedly aided and assisted in the conspiracy which existed against the unity and indivisibility of the Republic, against the liberty and safety of the French people, by assembling at her house, in secret council, the principal chiefs of that conspiracy, and by keeping up a correspondence tending to facilitate their treasonable designs. The tribunal having heard the public accuser deliver his reasons concerning the application of the law, condemns Jane Mary Phlippon, wife of Roland, to the punishment of death."

She listened calmly to her sentence, and then rising, bowed with dignity to her judges, and, smiling, said,

"I thank you, gentlemen, for thinking me worthy of sharing the fate of the great men whom you have assassinated. I shall endeavor to imitate their firmness on the scaffold."

With the buoyant step of a child, and with a rapidity which almost betokened joy, she passed beneath the narrow portal, and descended to her cell, from which she was to be led, with the morning light, to a bloody death. The prisoners had assembled to greet her on her return, and anxiously gathered around her. She looked upon them with a smile of perfect tranquillity, and, drawing her hand across her neck, made a sign expressive of her doom. But a few hours elapsed between her sentence and her execution. She retired to her cell, wrote a few words of parting to her friends, played upon a harp, which had found its way into the prison, her requiem, in tones so wild and mournful, that, floating in the dark hours of the night, through these sepulchral caverns, they fell like unearthly music upon the despairing souls there incarcerated.

The morning of the 10th of November, 1793, dawned gloomily upon Paris. It was one of the darkest days of that reign of terror which, for so long a period enveloped France in its sombre shades. The ponderous gates of the court-yard of the Conciergerie opened that morning to a long procession of carts loaded with victims for the guillotine. Madame Roland had contemplated her fate too long, and had disciplined her spirit too severely, to fail of fortitude in this last hour of trial. She came from her cell scrupulously attired for the bridal of death. A serene smile was upon her cheek, and the glow of joyous animation lighted up her features as she waved an adieu to the weeping prisoners who gathered around her. The last cart was assigned to Madame Roland. She entered it with a step as light and elastic as if it were a carriage for a pleasant morning's drive. By her side stood an infirm old man, M. La Marche. He was pale and trembling, and his fainting heart, in view of the approaching terror, almost ceased to beat. She sustained him by her arm, and addressed to him words of consolation and encouragement in cheerful accents and with a benignant smile. The poor old man felt that God had sent an angel to strengthen him in the dark hour of death. As the cart heavily rumbled along the pavement, drawing nearer and nearer to the guillotine, two or three times, by her cheerful words, she even caused a smile faintly to play upon his pallid lips.

The guillotine was now the principal instrument of amusement for the populace of Paris. It was so elevated that all could have a good view of the spectacle it presented. To witness the conduct of nobles and of ladies, of boys and of girls, while passing through the horrors of a sanguinary death, was far more exciting than the unreal and bombastic tragedies of the theatre, or the conflicts of the cock-pit and the bear garden. A countless throng flooded the streets; men, women, and children, shouting, laughing, execrating. The celebrity of Madame Roland, her extraordinary grace and beauty, and her aspect, not only of heroic fearlessness, but of joyous exhilaration, made her the prominent object of the public gaze. A white robe gracefully enveloped her perfect form, and her black and glossy hair, which for some reason the executioners had neglected to cut, fell in rich profusion to her waist. A keen November blast[Pg 735] swept the streets, under the influence of which, and the excitement of the scene, her animated countenance glowed with all the ruddy bloom of youth. She stood firmly in the cart, looking with a serene eye upon the crowds which lined the streets, and listening with unruffled serenity to the clamor which filled the air. A large crowd surrounded the cart in which Madame Roland stood, shouting, "To the guillotine! to the guillotine!" She looked kindly upon them, and, bending over the railing of the cart, said to them, in tones as placid as if she were addressing her own child, "My friends, I am going to the guillotine. In a few moments I shall be there. They who send me thither will ere long follow me. I go innocent. They will come stained with blood. You who now applaud our execution will then applaud theirs with equal zeal."

Madame Roland had continued writing her memoirs until the hour in which she left her cell for the scaffold. When the cart had almost arrived at the foot of the guillotine, her spirit was so deeply moved by the tragic scene—such emotions came rushing in upon her soul from departing time and opening eternity, that she could not repress the desire to pen down her glowing thoughts. She entreated an officer to furnish her for a moment with pen and paper. The request was refused. It is much to be regretted that we are thus deprived of that unwritten chapter of her life. It can not be doubted that the words she would then have written would have long vibrated upon the ear of a listening world. Soul-utterances will force their way over mountains, and valleys, and oceans. Despotism can not arrest them. Time can not enfeeble them.

The long procession arrived at the guillotine, and the bloody work commenced. The victims were dragged from the carts, and the ax rose and fell with unceasing rapidity. Head after head fell into the basket, and the pile of bleeding trunks rapidly increased in size. The executioners approached the cart where Madame Roland stood by the side of her fainting companion. With an animated countenance and a cheerful smile, she was all engrossed in endeavoring to infuse fortitude into his soul. The executioner grasped her by the arm. "Stay," said she, slightly resisting his grasp; "I have one favor to ask, and that is not for myself. I beseech you grant it me." Then turning to the old man, she said, "Do you precede me to the scaffold. To see my blood flow would make you suffer the bitterness of death twice over. I must spare you the pain of witnessing my execution." The stern officer gave a surly refusal, replying, "My orders are to take you first." With that winning smile and that fascinating grace which were almost resistless, she rejoined, "You can not, surely, refuse a woman her last request." The hard-hearted executor of the law was brought within the influence of her enchantment. He paused, looked at her for a moment in slight bewilderment, and yielded. The poor old man, more dead than alive, was conducted upon the scaffold and placed beneath the fatal ax. Madame Roland, without the slightest change of color, or the apparent tremor of a nerve, saw the ponderous instrument, with its glittering edge, glide upon its deadly mission, and the decapitated trunk of her friend was thrown aside to give place for her. With a placid countenance and a buoyant step, she ascended the platform. The guillotine was erected upon the vacant spot between the gardens of the Tuileries and the Elysian Fields, then known as the Place de la Revolution. This spot is now called the Place de la Concorde. It is unsurpassed by any other place in Europe. Two marble fountains now embellish the spot. The blood-stained guillotine, from which crimson rivulets were ever flowing, then occupied the space upon which one of these fountains has been erected; and a clay statue to Liberty reared its hypocritical front where the Egyptian obelisk now rises. Madame Roland stood for a moment upon the elevated platform, looked calmly around upon the vast concourse, and then bowing before the colossal statue, exclaimed, "O Liberty! Liberty! how many crimes are committed in thy name." She surrendered herself to the executioner, and was bound to the plank. The plank fell to its horizontal position, bringing her head under the fatal ax. The glittering steel glided through the groove, and the head of Madame Roland was severed from her body.

Thus died Madame Roland, in the thirty-ninth year of her age. Her death oppressed all who had known her with the deepest grief. Her intimate friend Buzot, who was then a fugitive, on hearing the tidings, was thrown into a state of perfect delirium, from which he did not recover for many days. Her faithful female servant was so overwhelmed with grief, that she presented herself before the tribunal, and implored them to let her die upon the same scaffold where her beloved mistress had perished. The tribunal, amazed at such transports of attachment, declared that she was mad, and ordered her to be removed from their presence. A man-servant made the same application, and was sent to the guillotine.

The grief of M. Roland, when apprized of the event, was unbounded. For a time he entirely lost his senses. Life to him was no longer endurable. He knew not of any consolations of religion. Philosophy could only nerve him to stoicism. Privately he left, by night, the kind friends who had hospitably concealed him for six months, and wandered to such a distance from his asylum as to secure his protectors from any danger on his account. Through the long hours of the winter's night he continued his dreary walk, till the first gray of the morning appeared in the east. Drawing a long stilletto from the inside of his walking-stick, he placed the head of it against the trunk of a tree, and threw himself upon the sharp weapon. The point pierced his heart, and he fell lifeless upon[Pg 736] the frozen ground. Some peasants passing by discovered his body. A piece of paper was pinned to the breast of his coat, upon which there were written these words: "Whoever thou art that findest these remains, respect them as those of a virtuous man. After hearing of my wife's death, I would not stay another day in a world so stained with crime."

Science, whose aim and end is to prove the harmony and "eternal fitness of things," also proves that we live in a world of paradoxes; and that existence itself is a whirl of contradictions. Light and darkness, truth and falsehood, virtue and vice, the negative and positive poles of galvanic or magnetic mysteries, are evidences of all-pervading antitheses, which, acting like the good and evil genii of Persian Mythology, neutralize each other's powers when they come into collision. It is the office of science to solve these mysteries. The appropriate symbol of the lecture-room is a Sphinx; for a scientific lecturer is but a better sort of unraveler of riddles.

Who would suppose, for instance, that water—which every body knows, extinguishes fire—may, under certain circumstances, add fuel to flame, so that the "coming man," who is to "set the Thames on fire," may not be far off. If we take some mystical gray-looking globules of potassium (which is the metallic basis of common pearl-ash) and lay them upon water, the water will instantly appear to ignite. The globules will swim about in flames, reminding us of the "death-fires" described by the Ancient Mariner, burning "like witches' oil" on the surface of the stagnant sea. Sometimes even, without any chemical ingredient being added, fire will appear to spring spontaneously from water; which is not a simple element, as Thales imagined, when he speculated upon the origin of the Creation, but two invisible gases—oxygen and hydrogen, chemically combined. During the electrical changes of the atmosphere in a thunder-storm, these gases frequently combine with explosive violence, and it is this combination which takes place when "the big rain comes dancing to the earth." These fire-and-water phenomena are thus accounted for; certain substances have peculiar affinities or attractions for one another; the potassium has so inordinate a desire for oxygen, that the moment it touches, it decomposes the water, abstracts all the oxygen, and sets free the hydrogen or inflammable gas. The potassium, when combined with the oxygen, forms that corrosive substance known as caustic potash, and the heat, disengaged during this process, ignites the hydrogen. Here the mystery ends; and the contradictions are solved; Oxygen and hydrogen when combined, become water; when separated the hydrogen gas burns with a pale, lambent flame. Many of Nature's most delicate deceptions are accounted for by a knowledge of these laws.

Your analytical chemist sadly annihilates, with his scientific machinations, all poetry. He bottles up at pleasure the Nine Muses, and proves them—as the fisherman in the Arabian Nights did the Afrite—to be all smoke. Even the Will-o'-the-Wisp can not flit across its own morass without being pursued, overtaken, and burnt out by this scientific detective policeman. He claps an extinguisher upon Jack-o'-Lantern thus: He says that a certain combination of phosphorus and hydrogen, which rises from watery marshes, produces a gas called phosphureted hydrogen, which ignites spontaneously the moment it bubbles up to the surface of the water and meets with atmospheric air. Here again the Ithuriel wand of science dispels all delusion, pointing out to us, that in such places animal and vegetable substances are undergoing constant decomposition; and as phosphorus exists under a variety of forms in these bodies, as phosphate of lime, phosphate of soda, phosphate of magnesia, &c., and as furthermore the decomposition of water itself is the initiatory process in these changes, so we find that phosphorus and hydrogen are supplied from these sources; and we may therefore easily conceive the consequent formation of phosphureted hydrogen. This gas rises in a thin stream from its watery bed, and the moment it comes in contact with the oxygen of the atmosphere, it bursts into a flame so buoyant, that it flickers with every breath of air, and realizes the description of Goethe's Mephistopheles, that the course of Jack-o'-Lantern is generally "zig-zag."

Who would suppose that absolute darkness may be derived from two rays of light! Yet such is the fact. If two rays proceed from two luminous points very close to each other, and are so directed as to cross at a given point on a sheet of white paper in a dark room, their united light will be twice as bright as either ray singly would produce. But if the difference in the distance of the two points be diminished only one-half, the one light will extinguish the other, and produce absolute darkness. The same curious result may be produced by viewing the flame of a candle through two very fine slits near to each other in a card. So, likewise, strange as it may appear, if two musical strings be so made to vibrate, in a certain succession of degrees, as for the one to gain half a vibration on the other, the two resulting sounds will antagonize each other and produce an interval of perfect silence. How are these mysteries to be explained? The Delphic Oracle of science must again be consulted, and among the high priests who officiate at the shrine, no one possesses more recondite knowledge, or can recall it more instructively than Sir David Brewster. "The explanation which philosophers have given," he observes, "of these remarkable phenomena, is very satisfactory, and may easily be understood. When a wave is made on the surface of a still pool of water by plunging a stone into it, the wave advances along the surface, while the water itself is never carried forward,[Pg 737] but merely rises into a height and falls into a hollow, each portion of the surface experiencing an elevation and a depression in its turn. If we suppose two waves equal and similar, to be produced by two separate stones, and if they reach the same spot at the same time, that is, if the two elevations should exactly coincide, they would unite their effects, and produce a wave twice the size of either; but if the one wave should be put so far before the other, that the hollow of the one coincided with the elevation of the other, and the elevation of the one with the hollow of the other, the two waves would obliterate or destroy one another; the elevation, as it were, of the one filling up half the hollow of the other, and the hollow of the one taking away half the elevation of the other, so us to reduce the surface to a level. These effects may be exhibited by throwing two equal stones into a pool of water; and also may be observed in the Port of Batsha, where the two waves arriving by channels of different lengths actually obliterate each other. Now, as light is supposed to be produced by waves or undulations of an ethereal medium filling all nature, and occupying the pores of the transparent bodies; and as sound is produced by undulations or waves in the air: so the successive production of light and darkness by two bright lights, and the production of sound and silence by two loud sounds, may be explained in the very same manner as we have explained the increase and obliteration of waves formed on the surface of water."

The apparent contradictions in chemistry are, indeed, best exhibited in the lecture-room, where they may be rendered visible and tangible, and brought home to the general comprehension. The Professor of Analytical Chemistry, J.H. Pepper, who demonstrates these things in the Royal Polytechnic Institution, is an expert manipulator in such mysteries; and, taking a leaf out of his own magic-book, we shall conjure him up before us, standing behind his own laboratory, surrounded with all the implements of his art. At our recent visit to this exhibition we witnessed him perform, with much address, the following experiments: He placed before us a pair of tall glass vessels, each filled, apparently, with water; he then took two hen's eggs, one of these he dropped into one of the glass vessels, and, as might have been expected, it immediately sank to the bottom. He then took the other egg, and dropped it into the other vessel of water, but, instead of sinking as the other had done, it descended only half way, and there remained suspended in the midst of the transparent fluid. This, indeed, looked like magic—one of Houdin's sleight-of-hand performances—for what could interrupt its progress? The water surrounding it appeared as pure below as around and above the egg, yet there it still hung like Mahomet's coffin, between heaven and earth, contrary to all the well-established laws of gravity. The problem, however, was easily solved. Our modern Cagliostro had dissolved in one half of the water in this vessel as much common salt as it would take up, whereby the density of the fluid was so much augmented that it opposed a resistance to the descent of the egg after it had passed through the unadulterated water, which he had carefully poured upon the briny solution, the transparency of which, remaining unimpaired, did not for a moment suggest the suspicion of any such impregnation. The good housewife, upon the same principle, uses an egg to test the strength of her brine for pickling.

Every one has heard of the power which bleaching gas (chlorine) possesses in taking away color, so that a red rose held over its fumes will become white. The lecturer, referring to this fact, exhibited two pieces of paper; upon one was inscribed, in large letters, the word "Proteus;" upon the other no writing was visible; although he assured us the same word was there inscribed. He now dipped both pieces of paper in a solution of bleaching-powder, when the word "Proteus" disappeared from the paper upon which it was before visible; while the same word instantly came out, sharp and distinct, upon the paper which was previously a blank. Here there appeared another contradiction: the chlorine in the one case obliterating, and in the other reviving the written word; and how was this mystery explained? Easily enough! Our ingenious philosopher, it seems, had used indigo in penning the one word which had disappeared; and had inscribed the other with a solution of a chemical substance, iodide of potassium and starch; and the action which took place was simply this: the chlorine of the bleaching solution set free the iodine from the potassium, which immediately combined with the starch, and gave color to the letters which were before invisible. Again—a sheet of white paper was exhibited, which displayed a broad and brilliant stripe of scarlet—(produced by a compound called the bin-iodide of mercury)—when exposed to a slight heat the color changed immediately to a bright yellow, and, when this yellow stripe was crushed by smartly rubbing the paper, the scarlet color was restored, with all its former brilliancy. This change of color was effected entirely by the alteration which the heat, in the one case, and the friction, in the other, produced in the particles which reflected these different colors; and, upon the same principle, we may understand the change of the color in the lobster-shell, which turns from black to red in boiling; because the action of the heat produces a new arrangement in the particles which compose the shell.

With the assistance of water and fire, which have befriended the magicians of every age, contradictions of a more marvelous character may be exhibited, and even the secret art revealed of handling red-hot metals, and passing through the fiery ordeal. If we take a platinum ladle, and hold it over a furnace until it becomes of a bright red heat, and then project cold water into its bowl, we shall find that the water will remain[Pg 738] quiescent and give no sign of ebullition—not so much as a single "fizz;" but, the moment the ladle begins to cool, it will boil up and quickly evaporate. So also, if a mass of metal, heated to whiteness, be plunged in a vessel of cold water, the surrounding fluid will remain tranquil so long as the glowing white heat continues; but, the moment the temperature falls, the water will boil briskly. Again—if water be poured upon an iron sieve, the wires of which are made red hot, it will not run through; but, on the sieve cooling, it will run through rapidly. These contradictory effects are easily accounted for. The repelling power of intense heat keeps the water from immediate contact with the heated metal, and the particles of the water, collectively, retain their globular form; but, when the vessel cools, the repulsive power diminishes, and the water coming into closer contact with the heated surface its particles can no longer retain their globular form, and eventually expand into a state of vapor. This globular condition of the particles of water will account for many very important phenomena; perhaps it is best exhibited in the dew-drop, and so long as these globules retain their form, water will retain its fluid properties. An agglomeration of these globules will carry with them, under certain circumstances, so much force that it is hardly a contradiction to call water itself a solid. The water-hammer, as it is termed, illustrates this apparent contradiction. If we introduce a certain quantity of water into a long glass tube, when it is shaken, we shall hear the ordinary splashing noise as in a bottle; but, if we exhaust the air, and again shake the tube, we shall hear a loud ringing sound, as if the bottom of the tube were struck by some hard substance—like metal or wood—which may fearfully remind us of the blows which a ship's side will receive from the waves during a storm at sea, which will often carry away her bulwarks.

It is now time to turn to something stronger than water for more instances of chemical contradictions. The chemical action of certain poisons (the most powerful of all agents), upon the human frame, has plunged the faculty into a maze of paradoxes; indeed, there is actually a system of medicine, advancing in reputation, which is founded on the principle of contraries. The famous Dr. Hahnemann, who was born at Massieu in Saxony, was the founder of it, and, strange to say, medical men, who are notorious for entertaining contrary opinions, have not yet agreed among themselves whether he was a very great quack or a very great philosopher. Be this as it may, the founder of this system, which is called Homœopathy, when translating an article upon bark in Dr. Cullen's Materia Medica, took some of this medicine, which had for many years been justly celebrated for the cure of ague. He had not long taken it, when he found himself attacked with aguish symptoms, and a light now dawned upon his mind, and led him to the inference that medicines which give rise to the symptoms of a disease, are those which will specifically cure it, and however curious it may appear, several illustrations in confirmation of this principle were speedily found. If a limb be frost-bitten, we are directed to rub it with snow; if the constitution of a man be impaired by the abuse of spirituous liquors, and he be reduced to that miserable state of enervation when the limbs tremble and totter, and the mind itself sinks into a state of low muttering delirium, the physician to cure him must go again to the bottle and administer stimulants and opiates.

It was an old Hippocratic aphorism that two diseases can not co-exist in the same body, wherefore, gout has actually been cured by the afflicted person going into a fenny country and catching the ague. The fatality of consumption is also said to be retarded by a common catarrh; and upon this very principle depends the truth of the old saying, that rickety doors hang long on rusty hinges. In other words, the strength of the constitution being impaired by one disease has less power to support the morbid action of another.

We thus live in a world of apparent contradictions; they abound in every department of science, and beset us even in the sanctuary of domestic life. The progress of discovery has reconciled and explained the nature of some of them; but many baffle our ingenuity, and still remain involved in mystery. This much, however, is certain, that the most opposed and conflicting elements so combine together as to produce results, which are strictly in unison with the order and harmony of the universe.

A descent into the Crater of the Volcano of Kilauea in the Sandwich Islands, may be accomplished with tolerable ease by the north-eastern cliff of the crater, where the side has fallen in and slidden downward, leaving a number of huge, outjutting rocks, like giants' stepping-stones, or the courses of the pyramid of Ghizeh.

By hanging to these, and the mere aid of a pole, you may descend the first precipice to where the avalanche brought up and was stayed—a wild region, broken into abrupt hills and deep glens, thickly set with shrubs and old ohias, and producing in great abundance the Hawaiian whortleberry (formerly sacred to the goddess of the volcano), and a beautiful lustrous blackberry that grows on a branching vine close to the ground. Thousands of birds find there a safe and warm retreat; and they will continue, I suppose, the innocent warblers, to pair and sing there, till the fires from beneath, having once more eaten through its foundations, the entire tract, with all its miniature mountains and woody glens, shall slide off suddenly into[Pg 739] the abyss below to feed the hunger of all-devouring fire.

No one who passes over it, and looks back upon the tall, jagged cliffs at the rear and side, can doubt that it was severed and shattered by one such ruin into its present forms. And the bottomless pits and yawning caverns, in some places ejecting hot steam, with which it is traversed, prove that the raging element which once sapped its foundations is still busy beneath.

The path that winds over and down through this tract, crossing some of these unsightly seams by a natural bridge of only a foot's breadth, is safe enough by daylight, if one will keep in it. But be careful that you do not diverge far on either side, or let the shades of night overtake you there, lest a single mis-step in the grass and ferns, concealing some horrible hole, or an accidental stumble, shall plunge you beyond the reach of sunlight into a covered pen-stock of mineral fire, or into the heart of some deep, sunken cavern.