Title: A Book About Doctors

Author: John Cordy Jeaffreson

Release date: July 8, 2012 [eBook #40161]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Irma Špehar and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

Spelling and punctuation are sometimes erratic. A few obvious misprints have been corrected, but in general the original spelling and typesetting conventions have been retained. Accents are inconsistent, and have not been standardised.

Author of "The Real Lord Byron," "The Real

Shelley," "A Book About Lawyers,"

etc., etc.

1904

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING CO.

NEW YORK AKRON, O. CHICAGO

Copyright, 1904,

by

THE SAALFIELD PUBLISHING COMPANY

The

WERNER COMPANY

Akron, O.

| PAGE. | |

| CHAPTER I. | |

| Something about Sticks, and rather less about Wigs | 5 |

| CHAPTER II. | |

| Early English Physicians | 18 |

| CHAPTER III. | |

| Sir Thomas Browne and Sir Kenelm Digby | 38 |

| CHAPTER IV. | |

| Sir Hans Sloane | 51 |

| CHAPTER V. | |

| The Apothecaries and Sir Samuel Garth | 63 |

| CHAPTER VI. | |

| Quacks | 82 |

| CHAPTER VII. | |

| John Radcliffe | 111 |

| CHAPTER VIII. | |

| The Doctor as a bon-vivant | 144 |

| CHAPTER IX. | |

| Fees | 163 |

| CHAPTER X. | |

| Pedagogues turned Doctors | 183 |

| CHAPTER XI. | |

| The Generosity and Parsimony of Physicians | 202 |

| CHAPTER XII. | |

| Bleeding | 225 |

| CHAPTER XIII. | |

| Richard Mead | 239 |

| CHAPTER XIV. | |

| Imagination as a Remedial Power | 255 |

| CHAPTER XV. | |

| Imagination and Nervous Excitement—Mesmer | 280 |

| CHAPTER XVI. | |

| Make way for the Ladies! | 287 |

| CHAPTER XVII. | |

| Messenger Monsey | 311 |

| CHAPTER XVIII. | |

| Akenside | 327 |

| CHAPTER XIX. | |

| Lettsom | 335 |

| CHAPTER XX. | |

| A few More Quacks | 345 |

| CHAPTER XXI. | |

| St. John Long | 356 |

| CHAPTER XXII. | |

| The Quarrels of Physicians | 374 |

| CHAPTER XXIII. | |

| The Loves of Physicians | 393 |

| CHAPTER XXIV. | |

| Literature and Art | 421 |

| CHAPTER XXV. | |

| Number Eleven—a Hospital Story | 442 |

| CHAPTER XXVI. | |

| Medical Buildings | 462 |

| CHAPTER XXVII. | |

| The Country Medical Man | 478 |

| PAGE | |

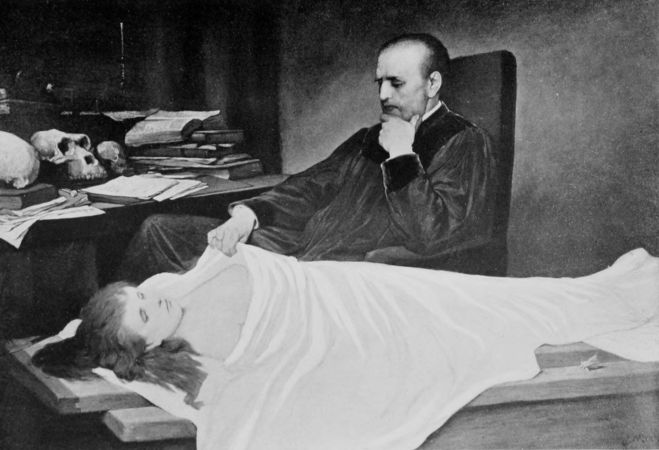

| Prof. Billroth's Surgical Clynic.[1] | Frontispiece |

| From the Original Painting by A. F. Seligmann. | |

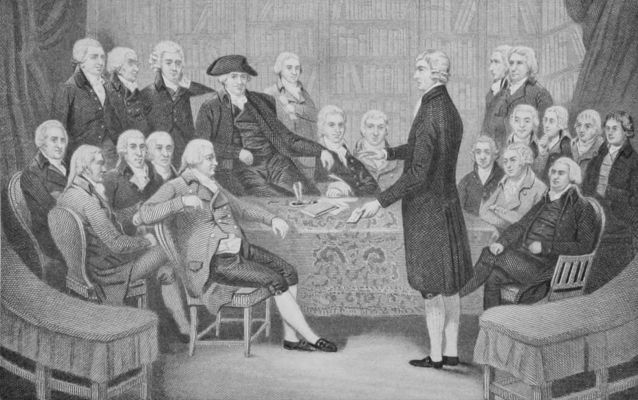

| The Founders of the Medical Society of London | 228 |

| From the Original Painting. | |

| An Accident[1] | 258 |

| From the Original Painting by Dagnan-Vouveret. | |

| The Anatomist | 374 |

| From the Original Painting by Max. |

The writer of this volume has endeavoured to collect, in a readable and attractive form, the best of those medical Ana that have been preserved by tradition or literature. In doing so, he has not only done his best to combine and classify old stories, but also cautiously to select his materials, so that his work, while affording amusement to the leisure hours of Doctors learned in their craft, might contain no line that should render it unfit for the drawing-room table. To effect this, it has been found necessary to reject many valuable and characteristic anecdotes—some of them entering too minutely into the mysteries and technicalities of medicine and surgery, and some being spiced with a humour ill calculated to please the delicacy of the nineteenth century.

Much of the contents of this volume has never before been published, but, after being drawn from a variety of manuscript sources, is now for the first time submitted to the world. It would be difficult to enumerate all the persons to whom the writer is indebted for access to documents, suggestions, critical notes, or memoranda. He cannot, however, let the present occasion go by without expressing his gratitude to the College of Physicians, for the prompt urbanity with which they allowed him to inspect the treasures of their library. To Dr. Munk, the learned librarian of the College—who for many years, in the[iv] scant leisure allowed him by the urgent demands of an extensive practice, has found a dignified pastime in antiquarian and biographic research—the writer's best thanks are due. With a liberality by no means always found in a student possessed of "special information," the Doctor surrendered his precious stores to the use of a comparative stranger, apparently without even thinking of the value of his gift. But even more than to the librarian of the College of Physicians the writer is indebted for assistance to his very kind friend Dr. Diamond, of Twickenham House—a gentleman who, to all the best qualities of a complete physician, unites the graces of a scholarly mind, an enthusiasm for art, and the fascinations of a generous nature.

Properly treated and fully expanded, this subject of "the stick" would cover all the races of man in all regions and all ages; indeed, it would hide every member of the human family. Attention could be called to the respect accorded in every chapter of the world's history, sacred and profane, to the rabdos—to the fasces of the Roman lictors, which every school-boy honours (often unconsciously) with an allusion when he says he will lick, or vows he won't be licked,—to the herald's staff of Hermes, the caduceus of Mercury, the wand of Æsculapius, and the rods of Moses and the contending sorcerers—to the mystic bundles of nine twigs, in honour of the nine muses, that Dr. Busby loved to wield, and which many a simple English parent believes Solomon, in all his glory, recommended as an element in domestic jurisdiction—to the sacred wands[6] of savage tribes, the staffs of our constables and sheriffs, and the highly polished gold sticks and black rods that hover about the anterooms of St. James's or Portsoken. The rule of thumb has been said to be the government of this world. And what is this thumb but a short stick, a sceptre, emblematic of a sovereign authority which none dares to dispute? "The stick," says the Egyptian proverb, "came down from heaven."

The only sticks, however, that we here care to speak about are physicians' canes, barbers' poles, and the twigs of rue which are still strewn before the prisoner in the dock of a criminal court. Why should they be thus strung together?

The physician's cane is a very ancient part of his insignia. It is now disused, but up to very recent times no doctor of medicine presumed to pay a professional visit, or even to be seen in public, without this mystic wand. Long as a footman's stick, smooth and varnished, with a heavy gold knob or cross-bar at the top, it was an instrument with which, down to the present century, every prudent aspirant to medical practice was provided. The celebrated "gold-headed cane" which Radcliffe, Mead, Askew, Pitcairn and Baillie successively bore is preserved in the College of Physicians, bearing the arms which those gentlemen assumed, or were entitled to. In one respect it deviated from the physician's cane proper. It has a cross-bar almost like a crook; whereas a physician's wand ought to have a knob at the top. This knob in olden times was hollow, and contained a vinaigrette, which the man of science always held to his nose when he approached a sick person, so that its fumes might[7] protect him from the noxious exhalations of his patient. We know timid people who, on the same plan, have their handkerchiefs washed in camphor-water, and bury their faces in them whenever they pass the corner of a dingy street, or cross an open drain, or come in contact with an ill-looking man. When Howard, the philanthropist, visited Exeter, he found that the medical officer of the county gaol had caused a clause to be inserted in his agreement with the magistrates, exonerating him from attendance and services during any outbreak of the gaol fever. Most likely this gentleman, by books or experience, had been enlightened as to the inefficacy of the vinaigrette.

But though the doctor, like a soldier skulking from the field of battle, might with impunity decline visiting the wretched captives, the judge was forced to do his part of the social duty to them—to sit in their presence during their trial in a close, fetid court; to brow-beat them when they presumed to make any declaration of their innocence beyond a brief "not guilty"; to read them an energetic homily on the consequences of giving way to corrupt passions and evil manners; and, finally, to order them their proper apportionments of whipping, or incarceration, or banishment, or death. Such was the abominable condition of our prisons, that the poor creatures dragged from them and placed in the dock often by the noxious effluvia of their bodies made seasoned criminal lawyers turn pale—partly, perhaps, through fear, but chiefly through physical discomfort. Then arose the custom of sprinkling aromatic herbs before the prisoners—so that if the health of his Lordship and[8] the gentlemen of the long robe suffered from the tainted atmosphere, at least their senses of smell might be shocked as little as possible. Then, also, came the chaplain's bouquet, with which that reverend officer was always provided when accompanying a criminal to Tyburn. Coke used to go circuit carrying in his hand an enormous fan furnished with a handle, in the shape of a goodly stick—the whole forming a weapon of offence or defence. It is not improbable that the shrewd lawyer caused the end of this cumbrous instrument to be furnished with a vinaigrette.

So much for the head of the physician's cane. The stick itself was doubtless a relic of the conjuring paraphernalia with which the healer, in ignorant and superstitious times, worked upon the imagination of the credulous. Just as the R[**symbol] which the doctor affixes to his prescription is the old astrological sign (ill-drawn) of Jupiter, so his cane descended to him from Hermes and Mercurius. It was a relic of old jugglery, and of yet older religion—one of those baubles which we know well where to find, but which our conservative tendencies disincline us to sweep away without some grave necessity.

The charming-stick, the magic Æsculapian wand of the Medicine-man, differed in shape and significance from the pole of the barber-surgeon. In the "British Apollo," 1703, No. 3, we read:—

ANSWER.[9]

The principal objection that can be made to this answer is that it leaves the question unanswered, after making only a very lame attempt to answer it. Lord Thurlow, in a speech delivered in the House of Peers on 17th of July, 1797, opposing the surgeons' incorporation bill, said that, "By a statute still in force, the barbers and surgeons were each to use a pole. The barbers were to have theirs blue and white, striped with no other appendage; but the surgeons', which was the same in other respects, was likewise to have a gallipot and a red rag, to denote the particular nature of their vocation."

But the reason why the surgeon's pole was adorned with both blue and red seems to have escaped the Chancellor. The chirurgical pole, properly tricked, ought to have a line of blue paint, another of red, and a third of white, winding round its length, in a regular serpentine progression—the blue representing the venous blood, the more brilliant colour the arterial, and the white thread being symbolic of the bandage used in tying up the arm after withdrawing the ligature. The stick itself is a sign that the operator[10] possesses a stout staff for his patients to hold, continually tightening and relaxing their grasp during the operation—accelerating the flow of the blood by the muscular action of the arm. The phlebotomist's staff is of great antiquity. It is to be found amongst his properties, in an illuminated missal of the time of Edward the First, and in an engraving of the "Comenii Orbis Pictus."

Possibly in ancient times the physician's cane and the surgeon's club were used more actively. For many centuries fustigation was believed in as a sovereign remedy for bodily ailment as well as moral failings, and a beating was prescribed for an ague as frequently as for picking and stealing. This process Antonius Musa employed to cure Octavius Augustus of Sciatica. Thomas Campanella believed that it had the same effect as colocynth administered internally. Galen recommended it as a means of fattening people. Gordonius prescribed it in certain cases of nervous irritability—"Si sit juvenis, et non vult obedire, flagelletur frequenter et fortiter." In some rural districts ignorant mothers still flog the feet of their children to cure them of chilblains. And there remains on record a case in which club-tincture produced excellent results on a young patient to whom Desault gave a liberal dose of it.

In 1792, when Sir Astley Cooper was in Paris, he attended the lectures of Desault and Chopart in the Hotel Dieu. On one occasion, during this part of his student course, Cooper saw a young fellow, of some sixteen years of age, brought before Desault complaining of paralysis in his right arm. Suspecting that the boy was only shamming, "Abraham,"[11] Desault observed, unconcernedly, "Otez votre chapeau."

Forgetting his paralytic story, the boy instantly obeyed, and uncovered his head.

"Donnez moi un baton!" screamed Desault; and he beat the boy unmercifully.

"D'ou venez vous?" inquired the operator when the castigation was brought to a close.

"Faubourg de St. Antoine," was the answer.

"Oui, je le crois," replied Desault, with a shrug—speaking a truth experience had taught him—"tous les coquins viennent de ce quartier la."

But enough for the present of the barber-surgeon and his pole. "Tollite barberum,"—as Bonnel Thornton suggested, when in 1745 (a year barbarous in more ways than one), the surgeons, on being disjoined from the barbers, were asking what ought to be their motto.

Next to his cane, the physician's wig was the most important of his accoutrements. It gave profound learning and wise thought to lads just out of their teens. As the horse-hair skull-cap gives idle Mr. Briefless all the acuteness and gravity of aspect which one looks for in an attorney-general, so the doctor's artificial locks were to him a crown of honour. One of the Dukes of Holstein, in the eighteenth century, just missed destruction through being warned not to put on his head a poisoned wig which a traitorous peruke-maker offered him. To test the value of the advice given him, the Duke had the wig put upon the head of its fabricator. Within twelve minutes the man expired! We have never heard of a physician[12] finding death in a wig; but a doctor who found the means of life in one is no rare bird in history.

The three-tailed wig was the one worn by Will Atkins, the gout doctor in Charles the Second's time (a good specialty then!). Will Atkins lived in the Old Bailey, and had a vast practice. His nostrums, some of which were composed of thirty different ingredients, were wonderful—but far less so than his wig, which was combed and frizzled over each cheek. When Will walked about the town, visiting his patients, he sometimes carried a cane, but never wore a hat. Such an article of costume would have disarranged the beautiful locks, or, at least, have obscured their glory.

One of the most magnificent wigs on record was that of Colonel Dalmahoy, which was celebrated in a song beginning:—

On Ludgate Hill, in close proximity to the Hall of the Apothecaries in Water Lane, the Colonel vended drugs and nostrums of all sorts—sweetmeats, washes for the complexion, scented oil for the hair, pomades, love-drops, and charms. Wadd, the humorous collector of anecdotes relating to his profession, records of him—

The last silk-coated physician was Henry Revell Reynolds, M. D., one of the physicians who attended George III. during his long and melancholy affliction. Though this gentleman came quite down to living times, he persisted to the end in wearing the costume—of a well-powdered wig, silk coat, breeches, stockings, buckled shoes, gold-headed cane, and lace ruffles—with which he commenced his career. He was the Brummel of the Faculty, and retained his fondness for delicate apparel to the last. Even in his grave-clothes the coxcombical tastes of the man exhibited themselves. His very cerements were of "a good make."

Whilst Brocklesby's wig is still bobbing about in the distance, we may as well tell a good story of him. He was an eccentric man, with many good points, one of which was his friendship for Dr. Johnson. The Duchess of Richmond requested Brocklesby to visit her maid, who was so ill that she could not leave her bed. The physician proceeded forthwith to Richmond House, in obedience to the command. On arriving there he was shown up-stairs by the invalid's husband, who held the post of valet to the Duke. The man was a very intelligent fellow, a character with whom all visitors to Richmond House conversed freely, and a vehement politician. In this last characteristic the Doctor resembled him. Slowly the physician and the valet ascended the staircase, discussing the fate of parties, and the merits of ministers. They became excited, and declaiming at the top of their voices entered the sick room. The valet—forgetful of his marital duties in the delights of an intellectual contest—poured in a broadside of sarcasms, ironical inquiries, and red-hot declamation; the doctor—with true English pluck—returning fire, volley for volley. The battle lasted for upwards of an hour, when the two combatants walked down-stairs, and the man of medicine took his departure. When the doctor arrived at his door, and was stepping from his carriage, it flashed across his mind that he had not applied his finger to his patient's pulse, or even asked her how she felt herself!

Previous to Charles II.'s reign physicians were in[15] the habit of visiting their patients on horse-back, sitting sideways on foot-cloths like women. Simeon Fox and Dr. Argent were the last Presidents of the College of Physicians to go their rounds in this undignified manner. With the "Restoration" came the carriage of the London physician. The Lex Talionis says, "For there must now be a little coach and two horses; and, being thus attended, half-a-piece, their usual fee, is but ill-taken, and popped into their left pocket, and possibly may cause the patient to send for his worship twice before he will come again to the hazard of another angel."

The fashion, once commenced, soon prevailed. In Queen Anne's reign, no physician with the slightest pretensions to practice could manage without his chariot and four, sometimes even six, horses. In our own day an equipage of some sort is considered so necessary an appendage to a medical practitioner, that a physician without a carriage (or a fly that can pass muster for one) is looked on with suspicion. He is marked down mauvais sujet in the same list with clergymen without duty, barristers without chambers, and gentlemen whose Irish tenantry obstinately refuse to keep them supplied with money. On the whole the carriage system is a good one. It protects stair carpets from being soiled with muddy boots (a great thing!), and bears cruelly on needy aspirants after professional employment (a yet greater thing! and one that manifestly ought to be the object of all professional etiquette!). If the early struggles of many fashionable physicians were fully and courageously written, we should have some heart-rending stories of the screwing and scraping and shifts by[16] which their first equipages were maintained. Who hasn't heard of the darling doctor who taught singing under the moustachioed and bearded guise of an Italian Count, at a young ladies' school at Clapham, in order that he might make his daily West-end calls between 3 p. m. and 6 p. m. in a well-built brougham drawn by a fiery steed from a livery stable? There was one noted case of a young physician who provided himself with the means of figuring in a brougham during the May-fair morning, by condescending to the garb and duties of a flyman during the hours of darkness. He used the same carriage at both periods of the four-and-twenty hours, lolling in it by daylight, and sitting on it by gaslight. The poor fellow forgetting himself on one occasion, so far as to jump in when he ought to have jumped on, or jump on when he ought to have jumped in, he published his delicate secret to an unkind world.

It is a rash thing for a young man to start his carriage, unless he is sure of being able to sustain it for a dozen years. To drop it is sure destruction. We remember an ambitious Phaeton of Hospitals who astonished the world—not only of his profession, but of all London—with an equipage fit for an ambassador—the vehicle and the steeds being obtained, like the arms blazoned on his panels, upon credit. Six years afterwards he was met by a friend crushing the mud on the Marylebone pavements, and with a characteristic assurance, that even adversity was unable to deprive him of, said that his health was so much deranged that his dear friend, Sir James Clarke, had prescribed continual walking exercise for him as the only means of recovering his powers of digestion.[17] His friends—good-natured people, as friends always are—observed that "it was a pity Sir James hadn't given him the advice a few years sooner—prevention being better than cure."

Though physicians began generally to take to carriages in Charles II.'s reign, it may not be supposed that no doctor of medicine before that time experienced the motion of a wheeled carriage. In "Stowe's Survey of London" one may read:—

"In the year 1563, Dr. Langton, a physician, rid in a car, with a gown of damask, lined with velvet, and a coat of velvet, and a cap of the same (such, it seems, doctors then wore), but having a blue hood pinned over his cap; which was (as it seems) a customary mark of guilt. And so came through Cheapside on a market-day."

The doctor's offence was one against public morals. He had loved not wisely—but too well. The same generous weakness has brought learned doctors, since Langton's day, into extremely ridiculous positions.

The cane, wig, silk coat, stockings, side-saddle, and carriage, of the old physician have been mentioned. We may not pass over his muff in silence. That he might have his hands warm and delicate of touch, and so be able to discriminate to a nicety the qualities of his patient's arterial pulsations, he made his rounds, in cold weather, holding before him a large fur muff, in which his fingers and fore-arm were concealed.

"Medicine is a science which hath been, as we have said, more professed than laboured, and yet more laboured than advanced; the labour having been, in my judgment, rather in circle than in progression. For I find much iteration, and small progression."—Lord Bacon's Advancement of Learning.

The British doctor, however, does not make his first appearance in sable dress and full-bottomed wig. Chaucer's physician, who was "groundit in Astronomy and Magyk Naturel," and whose "study was but lytyl in the Bible," had a far smarter and more attractive dress.

Taffeta and silk, of crimson and sky-blue colour, must have given an imposing appearance to this worthy gentleman, who, resembling many later doctors in his disuse of the Bible, resembled them also in his love of fees.

[19]Amongst our more celebrated and learned English physicians was John Phreas, born about the commencement of the fifteenth century, and educated at Oxford, where he obtained a fellowship on the foundation of Balliol College. His M. D. degree he obtained in Padua, and the large fortune he made by the practice of physic was also acquired in Italy. He was a poet and an accomplished scholar. Some of his epistles in MS. are still preserved in the Balliol Library and at the Bodleian. His translation of Diodorus Siculus, dedicated to Paul II., procured for him from that pontiff the fatal gift of an English bishopric. A disappointed candidate for the same preferment is said to have poisoned him before the day appointed for his consecration.

Of Thomas Linacre, successively physician to Henry VII., Henry VIII., Edward VI., and Princess Mary, the memory is still green amongst men. At his request, in conjunction with the representations of John Chambre, Fernandus de Victoria, Nicholas Halswell, John Fraunces, Robert Yaxley (physicians), and Cardinal Wolsey, Henry VIII. granted letters patent, establishing the College of Physicians, and conferring on its members the sole privilege of practicing, and admitting persons to practice, within the city, and a circuit of seven miles. The college also was empowered to license practitioners throughout the kingdom, save such as were graduates of Oxford and Cambridge—who were to be exempt from the jurisdiction of the new college, save within London and its precincts. Linacre was the first President of the College of Physicians. The meetings of the[20] learned corporation were held at Linacre's private house, No. 5, Knight-Rider Street, Doctors' Commons. This house (on which the Physician's arms, granted by Christopher Barker, Garter King-at-arms, Sept. 20, 1546, may still be seen,) was bequeathed to the college by Linacre, and long remained their property and abode. The original charter of the brotherhood states: "Before this period a great multitude of ignorant persons, of whom the greater part had no insight into physic, nor into any other kind of learning—some could not even read the letters and the book—so far forth, that common artificers, as smiths, weavers and women, boldly and accustomably took upon them great cures, to the high displeasure of God, great infamy of the Faculty, and the grievous hurt, damage, and destruction of many of the king's liege people."

Linacre died in the October of 1524. Caius, writing his epitaph, concludes, "Fraudes dolosque mire perosus, fidus amicis, omnibus juxta charus; aliquot annos antequam obierat Presbyter factus; plenus annes, ex hac vita migravit, multum desideratus." His motive for taking holy orders towards the latter part of his life is unknown. Possibly he imagined the sacerdotal garb would be a secure and comfortable clothing in the grave. Certainly he was not a profound theologian. A short while before his death he read the New Testament for the first time, when so great was his astonishment at finding the rules of Christians widely at variance with their practice, that he threw the sacred volume from him in a passion, and exclaimed, "Either this is not the gospel, or we are not Christians."

[21]Of the generation next succeeding Linacre's was John Kaye, or Key (or Caius, as it has been long pedantically spelt). Like Linacre (the elegant writer and intimate friend of Erasmus), Caius is associated with letters not less than medicine. Born of a respectable Norfolk family, Caius raised, on the foundation of Gonvil Hall, the college in the University of Cambridge that bears his name—to which Eastern Counties' men do mostly resort. Those who know Cambridge remember the quaint humour with which, in obedience to the founder's will, the gates of Caius are named. As a president of the College of Physicians, Caius was a zealous defender of the rights of his order. It has been suggested that Shakespeare's Dr. Caius, in "The Merry Wives of Windsor," was produced in resentment towards the president, for his excessive fervor against the surgeons.

Caius terminated his laborious and honourable career on July the 29th, 1573, in the sixty-third year of his age.[2] He was buried in his college chapel, in a tomb constructed some time before his decease, and marked with the brief epitaph—"Fui Caius." In the same year in which this physician of Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth died, was born Theodore Turquet de Mayerne, Baron Aulbone of France, and Sir Theodore Mayerne in England. Of Mayerne mention will be made in various places of these pages. There is some difficulty in ascertaining to how many[22] crowned heads this lucky courtier was appointed physician. After leaving France and permanently fixing himself in England, he kept up his connection with the French, so that the list of his monarch-patients may be said to comprise two French and three English sovereigns—Henry IV. and Louis XIII. of France, and James I., Charles I., and Charles II. of England. Mayerne died at Chelsea, in the eighty-second year of his age, on the 15th of March, 1655. Like John Hunter, he was buried in the church of St. Martin's-in-the-Fields. His library went to the College of Physicians, and his wealth to his only daughter, who was married to the Marquis of Montpouvillon. Though Mayerne was the most eminent physician of his time, his prescriptions show that his enlightenment was not superior to the prevailing ignorance of the period. He recommended a monthly excess of wine and food as a fine stimulant to the system. His treatise on Gout, written in French, and translated into English (1676) by Charles II.'s physician in ordinary, Dr. Thomas Sherley, recommends a clumsy and inordinate administration of violent drugs. Calomel he habitually administered in scruple doses. Sugar of lead he mixed largely in his conserves; pulverized human bones he was very fond of prescribing; and the principal ingredient in his gout-powder was "raspings of a human skull unburied." But his sweetest compound was his "Balsam of Bats," strongly recommended as an unguent for hypochondriacal persons, into which entered adders, bats, suckling whelps, earth-worms, hog's grease, the marrow of a stag, and the thigh-bone of an ox. After[23] such a specimen of the doctor's skill, possibly the reader will not care to study his receipts for canine madness, communicated to the Royal Society in 1687, or his "Excellent and well-approved Receipts and Experiments in Cookery, with the best way of Preserving." Nor will the reader be surprised to learn that the great physician had a firm belief in the efficacy of amulets and charms.

But the ignorance and superstition of which Mayerne was the representative were approaching the close of their career; and Sir Theodore's court celebrity and splendour were to become contemptible by the side of the scientific achievements of a contemporary. The grave closed over Mayerne in 1655; but in the December of 1652, the College of Physicians had erected in their hall a statue of Harvey, who died on the third of June, 1657, aged seventy-nine years.

Aubrey says of Harvey—"He was not tall, but of the lowest stature; round-faced, olivaster (waintscott) complexion; little eie—round, very black, full of spirit; his haire was black as a raven, but quite white twenty years before he dyed. I remember he was wont to drink coffee, which he and his brother Eliab did, before coffee-houses were in fashion in London. He was, as all the rest of his brothers, very cholerique; and in his younger days wore a dagger (as the fashion then was); but this doctor would be apt to draw out his dagger upon every slight occasion. He rode on horse-back with a foot-cloath to visit[24] his patients, his man following on foot, as the fashion then was, was very decent, now quite discontinued."

Harvey's discovery dates a new era in medical and surgical science. Its influence on scientific men, not only as a stepping-stone to further discoveries, but as a power rousing in all quarters a spirit of philosophic investigation, was immediately perceptible. A new class of students arose, before whom the foolish dreams of medical superstition and the darkness of empiricism slowly disappeared.

Of the physicians[3] of what may be termed the Elizabethan era, beyond all others the most sagacious and interesting, is William Bulleyn. He belongs to a bevy of distinguished Eastern Counties' physicians. Dr. Butts, Henry VIII.'s physician, mentioned in Strype's "Life of Cranmer," and made celebrated amongst doctors by Shakespeare's "Henry the Eighth," belonged to an honourable and gentle family sprinkled over Norfolk, Suffolk, and Cambridgeshire. The butcher king knighted him by the style of William Butts of Norfolk. Caius was born at Norwich; and the eccentric William Butler, of whom Mayerne, Aubrey, and Fuller tell fantastic stories, was born at Ipswich, about the year 1535.

William Bulleyn was born in the isle of Ely; but it is with the eastern division of the county of Suffolk that his name is especially associated. Sir William Bulleyn, the Sheriff of Norfolk and Suffolk in[25] the fifteenth year of Henry VII., and grandfather of the unfortunate Anne Boleyn, was one of the magnates of the doctor's family—members of which are still to be found in Ipswich and other parts of East Anglia, occupying positions of high respectability. In the reigns of Edward VI., Mary, and Elizabeth, no one ranked higher than William Bulleyn as botanist and physician. The record of his acuteness and learning is found in his numerous works, which are amongst the most interesting prose writings of the Elizabethan era. If Mr. Bohn, who has already done so much to render old and neglected authors popular, would present the public with a well-edited reprint of Bulleyn's works, he would make a valuable addition to the services he has already conferred on literature.

After receiving a preliminary education in the University of Cambridge, Bulleyn enlarged his mind by extended travel, spending much time in Germany and Scotland. During the reign of Queen Mary he practiced in Norwich; but he moved to Blaxhall, in Suffolk (of which parish it is believed his brother was for some years rector). Alluding to his wealthy friend, Sir Thomas Rushe, of Oxford, he says, with a pun, "I myself did know a Rushe, growing in the fenne side, by Orford, in Suffolke, that might have spent three hundred marks by year. Was not this a rush of estimation? A fewe sutche rushes be better than many great trees or bushes. But thou doste not know that countrey, where sometyme I did dwell, at a place called Blaxall, neere to that Rushe Bushe. I would all rushes within this realme were as riche in value." (The ancient family still maintain their connection[26] with the county.) Speaking of the rushes near Orford, in Suffolk, and about the isle of Ely, Bulleyn says, "The playne people make mattes and horse-collars of the greater rushes, and of the smaller they make lightes or candles for the winter. Rushes that growe upon dry groundes be good to strewe in halles, chambers, and galleries, to walk upon—defending apparell, as traynes of gownes and kirtles, from the dust."

He tells of the virtues of Suffolk sage (a herb that the nurses of that county still believe in as having miraculous effects, when administered in the form of "sage-tea"). Of Suffolk hops (now but little grown in the county) he mentions in terms of high praise—especially of those grown round Framlingham Castle, and "the late house of nunnes at Briziarde." "I know in many places of the country of Suffolke, where they brew theyr beere with hoppes that growe upon theyr owne groundes, as in a place called Briziarde, near an old famous castle called Framingham, and in many other places of the country." Of the peas of Orford the following mention is made:—"In a place called Orforde, in Suffolke, betwene the haven and the mayne sea, wheras never plow came, nor natural earth was, but stones onely, infinite thousand ships loden in that place, there did pease grow, whose roots were more than iii fadome long, and the coddes did grow uppon clusters like the keys of ashe trees, bigger than fitches, and less than the fyeld peason, very sweete to eat upon, and served many pore people dwelling there at hand, which els should have perished for honger, the scarcity of bread was so great.[27] In so much that the playne pore people did make very much of akornes; and a sickness of a strong fever did sore molest the commons that yere, the like whereof was never heard of there. Now, whether th' occasion of these peason, in providence of God, came through some shipwracke with much misery, or els by miracle, I am not able to determine thereof; but sowen by man's hand they were not, nor like other pease."[4]

In the same way one has in the Doctor's "Book of Simples" pleasant gossip about the more choice productions of the garden and of commerce, showing that horticulture must have been far more advanced at that time than is generally supposed, and that the luxuries imported from foreign countries were largely consumed throughout the country. Pears, apples, peaches, quinces, cherries, grapes, raisins, prunes, barberries, oranges, medlars, raspberries and strawberries, spinage, ginger, and lettuces are the good things thrown upon the board.

Of pears, the author says: "There is a kynd of peares growing in the city of Norwich, called the black freere's peare, very delicious and pleasaunt, and no lesse profitable unto a hoate stomacke, as I heard it reported by a ryght worshipful phisicion of the same city, called Doctour Manfield." Other pears, too, are mentioned, "sutch as have names as peare Robert, peare John, bishop's blessyngs, with other prety names. The red warden is of greate vertue,[28] conserved, roasted or baken to quench choller." The varieties of the apple especially mentioned are "the costardes, the greene cotes, the pippen, the queene aple."

Grapes are spoken of as cultivated and brought to a high state of perfection in Suffolk and other parts of the country. Hemp is humorously called "gallow grasse or neckweede." The heartesease, or paunsie, is mentioned by its quaint old name, "three faces in one hodde." Parsnips, radishes, and carrots are offered for sale. In the neighborhood of London, large quantities of these vegetables were grown for the London market; but Bulleyn thinks little of them, describing them as "more plentiful than profytable." Of figs—"Figges be good agaynst melancholy, and the falling evil, to be eaten. Figges, nuts, and herb grace do make a sufficient medicine against poison or the pestilence. Figges make a good gargarism to cleanse the throates."

The double daisy is mentioned as growing in gardens. Daisy tea was employed in gout and rheumatism—as herb tea of various sorts still is by the poor of our provinces. With daisy tea (or bellis-tea) "I, Bulleyn, did recover one Belliser, not onely from a spice of the palsie, but also from the quartan. And afterwards, the same Belliser, more unnatural than a viper, sought divers ways to have murthered me, taking part against me with my mortal enemies, accompanied with bloudy ruffins for that bloudy purpose." Parsley, also, was much used in medicine. And as it was the custom for the doctor to grow his own herbs in his garden, we may here see the origin of the old[29] nursery tradition of little babies being brought by the doctor from the parsley bed.[5]

Scarcely less interesting than "The Book of Simples" is Bulleyn's "Dialogue betweene Soarenes and Chirurgi." It opens with an honourable mention of many distinguished physicians and chirurgians. Dr. John Kaius is praised as a worthy follower of Linacre. Dr. Turner's "booke of herbes will always grow greene." Sir Thomas Eliot's "'castel of health' cannot decay." Thomas Faire "is not deade, but is transformed and chaunged into a new nature immortal." Androwe Borde, the father of "Merry Andrews," "wrote also wel of physicke to profit the common wealth withal." Thomas Pannel, the translator of the Schola Saternitana, "hath play'd ye good servant to the commonwealth in translating good bookes of physicke." Dr. William Kunyngham "hath wel travailed like a good souldiour agaynst the ignorant enemy." Numerous other less eminent practitioners are mentioned—such as Buns, Edwards, Hatcher, Frere, Langton, Lorkin, Wendy—educated at Cambridge; Gee and Simon Ludford, of Oxford; Huyck (the Queen's physician), Bartley, Carr; Masters, John Porter, of Norwich; Edmunds of York, Robert Baltrop, and Thomas Calfe, apothecary.

"Soft chirurgians," says Bulleyn, "make foul sores." He was a bold and courageous one. "Where the wound is," runs the Philippine proverb, "the plaster must be." Bulleyn was of the same opinion; but, in dressing a tender part, the surgeon is directed to have "a gladsome countenance," because "the[30] paciente should not be greatly troubled." For bad surgeons he has not less hostility than he has for

The state of medicine in Elizabeth's reign may be discovered by a survey of the best recipes of this physician, who, in sagacity and learning, was far superior to Sir Theodore Mayerne, his successor by a long interval.

"An Embrocation.—An embrocation is made after this manner:—℞. Of a decoction of mallowes, vyolets, barly, quince seed, lettice leaves, one pint; of barly meale, two ounces; of oyle of vyolets and roses, of each, an ounce and half; of butter, one ounce; and then seeth them all together till they be like a broathe, puttyng thereto, at the ende, four yolkes of eggs; and the maner of applying them is with peeces of cloth, dipped in the aforesaid decoction, being actually hoate."

"A Good Emplaster.—You shall mak a plaster with these medicines following, which the great learned men themselves have used unto their pacientes:—℞. Of hulled beanes, or beane flower that is without the brane, one pound; of mallow-leaves, two handfuls; seethe them in lye, til they be well sodden, and afterwarde let them be stamped and incorporate with four ounces of meale of lint or flaxe, two ounces of meale of lupina; and forme thereof a plaster with goat's grease, for this openeth the pores, avoideth the matter, and comforteth also the member; but if the place, after a daye or two of the application, fall more and more to blackness, it shall be necessary to go further, even to sacrifying and incision of the place."

[31]Pearl electuaries and pearl mixtures were very fashionable medicines with the wealthy down to the commencement of the eighteenth century. Here we have Bulleyn's recipe for

"Electuarium de Gemmis.—Take two drachms of white perles; two little peeces of saphyre; jacinth, corneline, emerauldes, granettes, of each an ounce; setwal, the sweate roote doronike, the rind of pomecitron, mace, basel seede, of each two drachms; of redde corall, amber, shaving of ivory, of each two drachms; rootes both of white and red behen, ginger, long peper, spicknard, folium indicum, saffron, cardamon, of each one drachm; of troch, diarodon, lignum aloes, of each half a small handful; cinnamon, galinga, zurubeth, which is a kind of setwal, of each one drachm and a half; thin pieces of gold and sylver, of each half a scruple; of musk, half a drachm. Make your electuary with honey emblici, which is the fourth kind of mirobalans with roses, strained in equall partes, as much as will suffice. This healeth cold diseases of ye braine, harte, stomack. It is a medicine proved against the tremblynge of the harte, faynting and souning, the weaknes of the stomacke, pensivenes, solitarines. Kings and noble men have used this for their comfort. It causeth them to be bold-spirited, the body to smell wel, and ingendreth to the face good coloure."

Truly a medicine for kings and noblemen! During the railway panic in '46 an unfortunate physician prescribed for a nervous lady:—

[32]This direction to a delicate gentlewoman, to swallow nightly two thousand four hundred and fifty railway shares, was regarded as evidence of the physician's insanity, and the management of his private affairs was forthwith taken out of his hands. But assuredly it was as rational a prescription as Bulleyn's "Electuarium de Gemmis."

"A Precious Water.—Take nutmegges, the roote called doronike, which the apothecaries have, setwall, gatangall, mastike, long peper, the bark of pomecitron, of mellon, sage, bazel, marjorum, dill, spiknard, wood of aloes, cubebe, cardamon, called graynes of paradise, lavender, peniroyall, mintes, sweet catamus, germander, enulacampana, rosemary, stichados, and quinance, of eche lyke quantity; saffron, an ounce and half; the bone of a harte's heart grated, cut, and stamped; and beate your spyces grossly in a morter. Put in ambergrice and musk, of each half a drachm. Distil this in a simple aqua vitæ, made with strong ale, or sackeleyes and aniseedes, not in a common styll, but in a serpentine; to tell the vertue of this water against colde, phlegme, dropsy, heavines of minde, comming of melancholy, I cannot well at thys present, the excellent virtues thereof are sutch, and also the tyme were to long."

The cure of cancers has been pretended and attempted by a numerous train of knaves and simpletons, as well as men of science. In the Elizabethan time this most terrible of maladies was thought to be influenced by certain precious waters—i. e. precious messes.

"Many good men and women," says Bulleyn, "wythin thys realme have dyvers and sundry medicines[33] for the canker, and do help their neighboures that bee in perill and daunger whyche be not onely poore and needy, having no money to spende in chirurgie. But some do well where no chirurgians be neere at hand; in such cases, as I have said, many good gentlemen and ladyes have done no small pleasure to poore people; as that excellent knyght, and worthy learned man, Syr Thomas Eliot, whose works be immortall. Syr William Parris, of Cambridgeshire, whose cures deserve prayse; Syr William Gascoigne, of Yorkshire, that helped many soare eyen; and the Lady Tailor, of Huntingdonshire, and the Lady Darrell of Kent, had many precious medicines to comfort the sight, and to heale woundes withal, and were well seene in herbes.

"The commonwealth hath great want of them, and of theyr medicines, whych if they had come into my handes, they should have bin written in my booke. Among al other there was a knight, a man of great worshyp, a Godly hurtlesse gentleman, which is departed thys lyfe, hys name is Syr Anthony Heveningham. This gentleman learned a water to kyll a canker of hys owne mother, whych he used all hys lyfe, to the greate helpe of many men, women, and chyldren."

This water "learned by Syr Anthony Heveningham" was, Bulleyn states on report, composed thus:—

"Precious Water to Cure a Canker:—Take dove's foote, a herbe so named, Arkangell ivy wyth the berries, young red bryer toppes, and leaves, whyte roses, theyr leaves and buds, red sage, selandyne, and woodbynde, of eche lyke quantity, cut or chopped and put[34] into pure cleane whyte wyne, and clarified hony. Then breake into it alum glasse and put in a little of the pouder of aloes hepatica. Destill these together softly in a limbecke of glasse or pure tin; if not, then in limbecke wherein aqua vitæ is made. Keep this water close. It will not onely kyll the canker, if it be duly washed therewyth; but also two droppes dayly put into the eye wyll sharp the syght, and breake the pearle and spottes, specially if it be dropped in with a little fenell water, and close the eys after."

There is reason to wish that all empirical applications, for the cure of cancer, were as harmless as this.

The following prescription for pomatum differs but little from the common domestic receipts for lip-salve in use at the present day:—

"Sickness.—How make you pomatum?

"Health.—Take the fat of a young kyd one pound, temper it with the water of musk roses by the space of foure dayes; then take five apples, and dresse them, and cut them in pieces, and lard them with cloves, then boyle them altogeather in the same water of roses, in one vessel of glasse; set within another vessel; let it boyle on the fyre so long until all be white; then wash them with ye same water of muske roses; this done, kepe it in a glass; and if you wil have it to smel better, then you must put in a little civet or musk, or of them both, and ambergrice. Gentilwomen doe use this to make theyr faces smoth and fayre, for it healeth cliftes in the lyppes, or in any other place of the hands and face."

The most laughable of all Bulleyn's receipts is one in which, for the cure of a child suffering under a[35] certain nervous malady, he prescribes "a smal yong mouse rosted." To some a "rosted mouse" may seem more palatable than the compound in which snails are the principal ingredient. "Snayles," says Bulleyn, "broken from the shelles and sodden in whyte wyne with oyle and sugar are very holsome, because they be hoat and moist for the straightnes of the lungs and cold cough. Snails stamped with camphory, and leven wil draw forth prycks in the flesh." So long did this belief in the virtue of snails retain its hold on Suffolk, that the writer of these pages remembers a venerable lady (whose memory is cherished for her unostentatious benevolence and rare worth) who for years daily took a cup of snail broth, for the benefit of a weak chest.

One minor feature of Bulleyn's works is the number of receipts given in them for curing the bites of mad dogs. The good man's horror of Suffolk witches is equal to his admiration of Suffolk dairies. Of the former he says, "I dyd know wythin these few yeres a false witch, called M. Line, in a towne of Suffolke called Derham, which with a payre of ebene beades, and certain charmes, had no small resort of foolysh women, when theyr chyldren were syck. To thys lame wytch they resorted, to have the fairie charmed and the spyrite conjured away; through the prayers of the ebene beades, whych she said came from the Holy Land, and were sanctifyed at Rome. Through whom many goodly cures were don, but my chaunce was to burn ye said beades. Oh that damnable witches be suffred to live unpunished and so many blessed men burned; witches be more hurtful in this realm than either quarten or pestilence. I know in[36] a towne called Kelshall in Suffolke, a witch, whose name was M. Didge, who with certain Ave Marias upon her ebene beades, and a waxe candle, used this charme for S. Anthonies fyre, having the sycke body before her, holding up her hande, saying—

"I could reherse an hundred of sutch knackes, of these holy gossips. The fyre take them all, for they be God's enemyes."

On leaving Blaxhall in Suffolk, Bulleyn migrated to the north. For many years he practised with success at Durham. At Shields he owned a considerable property. Sir Thomas, Baron of Hilton, Commander of Tinmouth Castle under Philip and Mary, was his patron and intimate friend. His first book, entitled "Government of Health," he dedicated to Sir Thomas Hilton; but the MS., unfortunately, was lost in a shipwreck before it was printed. Disheartened by this loss, and the death of his patron, Bulleyn bravely set to work in London, to "revive his dead book." Whilst engaged on the laborious work of recomposition, he was arraigned on a grave charge of murder. "One William Hilton," he says, telling his own story, "brother to the sayd Syr Thomas Hilton, accused me of no less cryme then of most cruel murder of his owne brother, who dyed of a fever (sent onely of God) among his owne frends, fynishing his lyfe in the Christian fayth. But this William Hilton caused me to be arraigned before that noble Prince, the Duke's Grace of Norfolke, for the same; to this end to have had me dyed shamefully; that with the covetous[37] Ahab he might have, through false witnes and perjury, obtayned by the counsel of Jezabell, a wineyard, by the pryce of blood. But it is wrytten, Testis mendax peribit, a fals witnes shal com to naught; his wicked practise was wisely espyed, his folly deryded, his bloudy purpose letted, and fynallye I was with justice delivered."

This occurred in 1560. His foiled enemy afterwards endeavoured to get him assassinated; but he again triumphed over the machinations of his adversary. Settling in London, he obtained a large practice, though he was never enrolled amongst the physicians of the college. His leisure time he devoted to the composition of his excellent works. To the last he seems to have kept up a close connection with the leading Eastern Counties families. His "Comfortable Regiment and Very Wholsome order against the moste perilous Pleurisie," was dedicated to the Right Worshipful Sir Robart Wingfelde of Lethryngham, Knight.

William Bulleyn died in London, on the 7th of January, 1576, and was buried in the church of St. Giles's, Cripplegate, in the same tomb wherein his brother Richard had been laid thirteen years before; and wherein John Fox, the martyrologist, was interred eleven years later.

Amongst the physicians of the seventeenth century were three Brownes—father, son, and grandson. The father wrote the "Religio Medici," and the "Pseudoxia Epidemica"—a treatise on vulgar errors. The son was the traveller, and author of "Travels in Hungaria, Servia, Bulgaria, Macedonia, Thessaly, Austria, Styria, Carinthia, Carniola, Friuli &c.," and the translator of the Life of Themistocles in the English version of "Plutarch's Lives" undertaken by Dryden. He was also a physician of Bartholomew's, and a favourite physician of Charles II., who on one occasion said of him, "Doctor Browne is as learned as any of the college, and as well bred as any of the court." The grandson was a Fellow of the Royal Society, and, like his father and grandfather, a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians; but he was by no means worthy of his distinguished progenitors. Alike unknown in literature, science, and art, he was a miserable sot, and was killed by a fall from his horse, between Southfleet and Gravesend, when in a state of intoxication. He was thus cut off in the July[39] of 1710, having survived his father not quite two years.

The author of the "Religio Medici" enjoys as good a chance of an immortality of fame as any of his contemporaries. The child of a London merchant, who left him a comfortable fortune, Thomas Browne was from the beginning of his life (Oct. 19, 1605) to its close (Oct. 19, 1682), well placed amongst the wealthier of those who occupied the middle way of life. From Winchester College, where his schoolboy days were spent, he proceeded to the University of Oxford, becoming a member of Broadgates Hall, i.e., Pembroke College—the college of Blackstone, Shenstone, and Samuel Johnson. After taking his B.A. and M.A. degrees, he turned his attention to medicine, and for some time practised as a physician in Oxfordshire. Subsequently to this he travelled over different parts of Europe, visiting France, Italy, and Holland, and taking a degree of Doctor in Physic at Leyden. Returning to England, he settled at Norwich, married a rich and beautiful Norfolk lady, named Mileham; and for the rest of his days resided in that ancient city, industriously occupied with an extensive practice, the pursuits of literature, and the education of his children. When Charles II. visited Norwich in 1671, Thomas Browne, M.D., was knighted by the royal hand. This honour, little as a man of letters would now esteem it, was highly prized by the philosopher. He thus alludes to it in his "Antiquities of Norwich"—"And it is not for some wonder, that Norwich having been for so long a time so considerable a place, so few kings have visited it; of which number among so many monarchs since the Conquest[40] we find but four; viz., King Henry III., Edward I., Queen Elizabeth, and our gracious sovereign now reigning, King Charles II., of which I had a particular reason to take notice."

Amongst the Norfolk people Sir Thomas was very popular, his suave and unobtrusive manners securing him many friends, and his philosophic moderation of temper saving him from ever making an enemy. The honour conferred on him was a subject of congratulation—even amongst his personal friends, when his back was turned. The Rev. John Whitefoot, M.A., Rector of Heigham, in Norfolk, in his "Minutes for the Life of Sir Thomas Browne," says, that had it been his province to preach his funeral sermon, he should have taken his text from an uncanonical book—"I mean that of Syracides, or Jesus, the son of Syrach, commonly called Ecclesiasticus, which, in the 38th chapter, and the first verse, hath these words, 'Honour a physician with the honour due unto him; for the uses which you may have of him, for the Lord hath created him; for of the Most High cometh healing, and he shall receive Honour of the King' (as ours did that of knighthood from the present King, when he was in this city). 'The skill of the physician shall lift up his head, and in the sight of great men shall he be in admiration'; so was this worthy person by the greatest man of this nation that ever came into this country, by whom also he was frequently and personally visited."

Widely and accurately read in ancient and modern literature, and possessed of numerous accomplishments, Sir Thomas Browne was in society diffident almost to shyness. "His modesty," says Whitefoot,[41] "was visible in a natural habitual blush, which was increased upon the least occasion, and oft discovered without any observable cause. Those who knew him only by the briskness of his writings were astonished at his gravity of aspect and countenance, and freedom from loquacity." As was his manner, so was his dress. "In his habit of cloathing he had an aversion to all finery, and affected plainness both in fashion and ornaments."

The monuments of Sir Thomas and his lady are in the church of St. Peter's, Mancroft, Norwich, where they were buried. Some years since Sir Thomas Browne's tomb was opened for the purpose of submitting it to repair, when there was discovered on his coffin a plate, of which Dr. Diamond, who happened at the time to be in Norwich, took two rubbings, one of which is at present in the writer's custody. It bears the following interesting inscription:—"Amplissimus vir Dr. Thomas Browne Miles Medicinæ Dr. Annos Natus et Denatus 19 Die Mensis Anno Dmi., 1682—hoc loculo indormiens corporis spagyrici pulvere plumbum in aurum convertit."

The "Religio Medici" not only created an unprecedented sensation by its erudition and polished style, but it shocked the nervous guardians of orthodoxy by its boldness of inquiry. It was assailed for its infidelity and scientific heresies. According to Coleridge's view of the "Religio Medici," Sir Thomas Browne, "a fine mixture of humourist, genius, and pedant," was a Spinosist without knowing it. "Had he," says the poet, "lived nowadays, he would probably have been a very ingenious and bold infidel in his real opinions, though the kindness of his nature[42] would have kept him aloof from vulgar, prating, obtrusive infidelity."

Amongst the adverse critics of the "Religio Medici" was the eccentric, gallant, brave, credulous, persevering, frivolous, Sir Kenelm Digby. A Mæcenas, a Sir Philip Sydney, a Dr. Dee, a Beau Fielding, and a Dr. Kitchener, all in one, this man is chief of those extravagant characters that astonish the world at rare intervals, and are found nowhere except in actual life. No novelist of the most advanced section of the idealistic school would dare to create such a personage as Sir Kenelm. The eldest son of the ill-fated Sir Everard Digby, he was scarcely three years old when his father atoned on the scaffold for his share in the gunpowder treason. Fortunately a portion of the family estate was entailed, so Sir Kenelm, although the offspring of attainted blood, succeeded to an ample revenue of about £3000 a-year. In 1618 (when only in his fifteenth year) he entered Gloucester Hall, now Worcester College, Oxford. In 1621 he commenced foreign travel. He attended Charles I. (then Prince of Wales) at the Court of Madrid; and returning to England in 1623, was knighted by James I. at Hinchinbroke, the house of Lord Montague, on the 23rd of October in that year. From that period he was before the world as courtier, cook, lover, warrior, alchemist, political intriguer, and man of letters. He became a gentleman of the bedchamber, and commissioner of the navy. In 1628 he obtained a naval command, and made his brilliant expedition against the Venetians and Algerians, whose galleys he routed off Scanderon. This achievement is celebrated by his client and friend, Ben Jonson:—

Returning from war, he became once more the student, presenting in 1632 the library he had purchased of his friend Allen, to the Bodleian Library, and devoting his powers to the mastery of controversial divinity. Having in 1636 entered the Church of Rome, he resided for some time abroad. Amongst his works at this period were his "Conference with a Lady about the Choice of Religion," published in 1638, and his "Letters between Lord George Digby and Sir Kenelm Digby, Knt., concerning Religion," not published till 1651. It is difficult to say to which he was most devoted—his King, his Church, literature, or his beautiful and frail wife, Venetia Stanley, whose charms fascinated the many admirers on whom she distributed her favours, and gained her Sir Kenelm for a husband when she was the discarded mistress of Richard, Earl of Dorset. She had borne the Earl children, so his Lordship on parting settled on her an annuity of £500 per annum. After her marriage, this annuity not being punctually paid, Sir Kenelm sued the Earl for it. Well might Mr. Lodge say, "By the frailties of that lady much of the noblest blood of England was dishonoured, for she[44] was the daughter of Sir Edward Stanley, Knight of the Bath, grandson of the great Edward, Earl of Derby, by Lucy, daughter and co-heir of Thomas Percy, Earl of Northumberland." Such was her unfair fame. "The fair fame left to Posterity of that Truly Noble Lady, the Lady Venetia Digby, late wife of Sir Kenelm Digby, Knight, a Gentleman Absolute in all Numbers," is embalmed in the clear verses of Jonson. Like Helen, she is preserved to us by the sacred poet.

In other and more passionate terms Sir Kenelm painted the same charms in his "Private Memoirs."

But if Sir Kenelm was a chivalric husband, he was not a less loyal subject. How he avenged in France the honour of his King, on the body of a French nobleman, may be learnt in a curious tract, "Sir Kenelme Digby's Honour Maintained. By a most courageous combat which he fought with Lord Mount le Ros, who by base and slanderous words reviled our King. Also the true relation how he went to the King of France, who kindly intreated him, and sent two hundred men to guard him so far as Flanders. And now he is returned from Banishment, and to his eternall honour lives in England."

Sir Kenelm's "Observations upon Religio Medici," are properly characterized by Coleridge as those of a pedant. They were written whilst he was kept a prisoner, by order of the Parliament, in Winchester House; and the author had the ludicrous folly to assert that he both read the "Religio Medici"[45] through for the first time, and wrote his bulky criticism upon it, in less than twenty-four hours. Of all the claims that have been advanced by authors for the reputation of being rapid workmen, this is perhaps the most audacious. For not only was the task one that at least would require a month, but the impudent assertion that it was accomplished in less than a day and night was contradicted by the title-page, in which "the observations" are described as "occasionally written." Beckford's vanity induced him to boast that "Vathek" was composed at one sitting of two days and three nights; but this statement—outrageous falsehood though it be—was sober truth compared with Sir Kenelm's brag.

But of all Sir Kenelm's vagaries, his Sympathetic Powder was the drollest. The composition, revealed after the Knight's death by his chemist and steward, George Hartman, was effected in the following manner:—English vitriol was dissolved in warm water; this solution was filtered, and then evaporated till a thin scum appeared on the surface. It was then left undisturbed and closely covered in a cool place for two or three days, when fair, green, and large crystals were evolved. "Spread these crystals," continues the chemist, "abroad in a large flat earthen dish, and expose them to the heat of the sun in the dog-days, turning them often, and the sun will calcine them white; when you see them all white without, beat them grossly, and expose them again to the sun, securing them from the rain; when they are well calcined, powder them finely, and expose this powder again to the sun, turning and stirring it often. Continue this until it be reduced to a white powder,[46] which put up in a glass, and tye it up close, and keep it in a dry place."

The virtues of this powder were unfolded by Sir Kenelm, in a French oration delivered to "a solemn assembly of Nobles and Learned Men at Montpellier, in France." It cured wounds in the following manner:—If any piece of a wounded person's apparel, having on it the stain of blood that had proceeded from the wound, was dipped in water holding in solution some of this sympathetic powder, the wound of the injured person would forthwith commence a healing process. It mattered not how far distant the sufferer was from the scene of operation. Sir Kenelm gravely related the case of his friend Mr. James Howel, the author of the "Dendrologia," translated into French by Mons. Baudoin. Coming accidentally on two of his friends whilst they were fighting a duel with swords, Howel endeavoured to separate them by grasping hold of their weapons. The result of this interference was to show the perils that

His hands were severely cut, insomuch that some four or five days afterwards, when he called on Sir Kenelm, with his wounds plastered and bandaged up, he said his surgeons feared the supervention of gangrene. At Sir Kenelm's request, he gave the knight a garter which was stained with his blood. Sir Kenelm took it, and without saying what he was about to do, dipped it in a solution of his powder of vitriol. Instantly the sufferer started.

"What ails you?" cried Sir Kenelm.

"I know not what ails me," was the answer; "but[47] I find that I feel no more pain. Methinks that a pleasing kind of freshnesse, as it were a cold napkin, did spread over my hand, which hath taken away the inflammation that tormented me before."

"Since that you feel," rejoined Sir Kenelm, "already so good an effect of my medicament, I advise you to cast away all your plaisters. Only keep the wound clean, and in moderate temper 'twixt heat and cold."

Mr. Howel went away, sounding the praises of his physician; and the Duke of Buckingham, hearing what had taken place, hastened to Sir Kenelm's house to talk about it. The Duke and Knight dined together; when, after dinner, the latter, to show his guest the wondrous power of his powder, took the garter out of the solution, and dried it before the fire. Scarcely was it dry, when Mr. Howel's servant ran in to say that his master's hand was worse than ever—burning hot, as if "it were betwixt coales of fire." The messenger was dismissed with the assurance that ere he reached home his master would be comfortable again. On the man retiring, Sir Kenelm put the garter back into the solution—the result of which was instant relief to Mr. Howel. In six days the wounds were entirely healed. This remarkable case occurred in London, during the reign of James the First. "King James," says Sir Kenelm, "required a punctuall information of what had passed touching this cure; and, after it was done and perfected, his Majesty would needs know of me how it was done—having drolled with me first (which he could do with a very good grace) about a magician and sorcerer." On the promise of inviolable secrecy, Sir Kenelm[48] communicated the secret to his Majesty; "whereupon his Majesty made sundry proofs, whence he received singular satisfaction."

The secret was also communicated by Sir Kenelm to Mayerne, through whom it was imparted to the Duke of Mayerne—"a long time his friend and protector." After the Duke's death, his surgeon communicated it to divers people of quality; so that, ere long, every country-barber was familiar with the discovery. The mention made of Mayerne in the lecture is interesting, as it settles a point on which Dr. Aikin had no information; viz.,—Whether Sir Theodore's Barony of Aubonne was hereditary or acquired? Sir Kenelm says, "A little while after the Doctor went to France, to see some fair territories that he had purchased near Geneva, which was the Barony of Aubonne."

For a time the Sympathetic Powder was very generally believed in; and it doubtless did as much good as harm, by inducing people to throw from their wounds the abominable messes of grease and irritants which were then honoured with the name of plaisters. "What is this?" asked Abernethy, when about to examine a patient with a pulsating tumour, that was pretty clearly an aneurism.

"Oh! that is a plaister," said the family doctor.

"Pooh!" said Abernethy, taking it off, and pitching it aside.

"That was all very well," said the physician, on describing the occurrence; "but that 'pooh' took several guineas out of my pocket."

Fashionable as the Sympathetic Powder was for several years, it fell into complete disrepute in this[49] country before the death of Sir Kenelm. Hartman, the Knight's attached servant, could, of his own experience, say nothing more for it than, when dissolved in water, it was a useful astringent lotion in cases of bleeding from the nose; but he mentions a certain "Mr. Smith, in the city of Augusta, in Germany, who told me that he had a great respect for Sir D. K.'s books, and that he made his sympatheticall powder every year, and did all his chiefest cures with it in green wounds, with much greater ease to the patient than if he had used ointments or plaisters."

In 1643 Sir Kenelm Digby was released from the confinement to which he had been subjected by the Parliament. The condition of his liberty was that he forthwith retired to the Continent—having previously pledged his word as a Christian and a gentleman, in no way to act or plot against the Parliament. In France he became a celebrity of the highest order. Returning to England with the Restoration, he resided in "the last fair house westward in the north portico of Covent Garden," and became the centre of literary and scientific society. He was appointed a member of the council of the Royal Society, on the incorporation of that learned body in the year 1663. His death occurred in his sixty-second year, on the 11th of June, 1665; and his funeral took place in Christ's Church, within Newgate, where, several years before, he had raised a splendid tomb to the memory of the lovely and abandoned Venetia. His epitaph, by the pen of R. Ferrar, is concise, and not too eulogistic for a monumental inscription:—

After his death, with the approval of his son, was published (1669), "The Closet of the Eminently Learned Sir Kenelme Digbie, Kt., Opened: Whereby is discovered Several ways for making of Metheglin, Sider, Cherry-Wine, &c.; together with excellent Directions for Cookery: as also for Preserving, Conserving, Candying, &c." The frontispiece of this work is a portrait of Sir Kenelm, with a shelf over his head, adorned with his five principal works, entitled, "Plants," "Sym. Powder," "His Cookery," "Rects. in Physick, &c.," "Sr. K. Digby of Bodyes."

In Sir Kenelm's receipts for cookery the gastronome would find something to amuse him, and more to arouse his horror. Minced pies are made (as they still are amongst the homely of some counties) of meat, raisins, and spices, mixed. Some of the sweet dishes very closely resemble what are still served on English tables. The potages are well enough. But the barley-puddings, pear-puddings, and oat-meal puddings give ill promise to the ear. It is recommended to batter up a couple of eggs and a lot of brown sugar in a cup of tea;—a not less impious profanation of the sacred leaves than that committed by the Highlanders, mentioned by Sir Walter Scott, who, ignorant of the proper mode of treating a pound of fragrant Bohea, served it up in—melted butter!

The lives of three physicians—Sydenham, Sir Hans Sloane, and Heberden—completely bridge over the uncertain period between old empiricism and modern science. The son of a wealthy Dorsetshire squire, Sydenham was born in 1624, and received the most important part of his education in the University of Oxford, where he was created Bachelor of Medicine 14th April, 1648. Settling in London about 1661, he was admitted a Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians 25th June, 1665. Subsequently he acquired an M.D. degree at Cambridge, but this step he did not take till 17th May, 1676. He also studied physic at Montpellier; but it may be questioned if his professional success was a consequence of his labours in any seat of learning, so much as a result of that knowledge of the world which he gained in the Civil war as a captain in the Parliamentary army. It was he who replied to Sir Richard Blackmore's inquiry after the best course of study for a medical student to pursue—"Read Don Quixote; it is a very good book—I read it still." Medical critics have felt[52] it incumbent on themselves to explain away this memorable answer—attributing it to the doctor's cynical temper rather than his scepticism with regard to medicine. When, however, the state of medical science in the seventeenth century is considered, one has not much difficulty in believing that the shrewd physician meant exactly what he said. There is no question but that as a practitioner he was a man of many doubts. The author of the capital sketch of Sydenham in the "Lives of British Physicians" says—"At the commencement of his professional life it is handed down to us by tradition, that it was his ordinary custom, when consulted by his patients for the first time, to hear attentively the story of their complaints, and then say, 'Well, I will consider of your case, and in a few days will order something for you.' But he soon discovered that this deliberate method of proceeding was not satisfactory, and that many of the persons so received forgot to come again; and he was consequently obliged to adopt the usual practice of prescribing immediately for the diseases of those who sought his advice." A doctor who feels the need for such deliberation must labour under considerable perplexity as to the proper treatment of his patient. But the low opinion he expressed to Blackmore of books as instructors in medicine, he gave publicly with greater decorum, but almost as forcibly, in a dedication addressed to Dr. Mapletoft, where he says, "The medical art could not be learned so well and so surely as by use and experience; and that he who would pay the nicest and most accurate attention to the symptoms of distempers would succeed best in finding out the true means of cure."

[53]Sydenham died in his house, in Pall Mall, on the 29th of December, 1689. In his last years he was a martyr to gout, a malady fast becoming one of the good things of the past. Dr. Forbes Winslow, in his "Physic and Physicians"—gives a picture, at the same time painful and laughable, of the doctor's sufferings. "Sydenham died of the gout; and in the latter part of his life is described as visited with that dreadful disorder, and sitting near an open window, on the ground floor of his house, in St. James's Square, respiring the cool breeze on a summer's evening, and reflecting, with a serene countenance and great complacency, on the alleviation to human misery that his skill in his art enabled him to give. Whilst this divine man was enjoying one of these delicious reveries, a thief took away from the table, near to which he was sitting, a silver tankard filled with his favourite beverage, small beer, in which a sprig of rosemary had been immersed, and ran off with it. Sydenham was too lame to ring his bell, and too feeble in his voice to give the alarm."

Heberden, the medical friend of Samuel Johnson, was born in London in 1710, and died on the 17th of May, 1801. Between Sydenham and Heberden came Sir Hans Sloane, a man ever to be mentioned honourably amongst those physicians who have contributed to the advancement of science, and the amelioration of society.

Pope says:—

Hans Sloane (the seventh and youngest child of Alexander Sloane, receiver-general of taxes for the county of Down, before and after the Civil war, and a commissioner of array, after the restoration of Charles II.) was born at Killileagh in 1660. An Irishman by birth, and a Scotchman by descent, he exhibited in no ordinary degree the energy and politeness of either of the sister countries. After a childhood of extreme delicacy he came to England, and devoted himself to medical study and scientific investigation. Having passed through a course of careful labour in London, he visited Paris and Montpellier, and, returning from the Continent, became the intimate friend of Sydenham. On the 21st of January, 1685, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society; and on the 12th of April, 1687, he became a Fellow of the College of Physicians. In the September of the latter year he sailed to the West Indies, in the character of physician to the Duke of Albemarle, who had been appointed Governor of Jamaica. His residence in that quarter of the globe was not of long duration. On the death of his Grace the doctor attended the Duchess back to England, arriving once more in London in the July of 1689. From that time he remained in the capital—his professional career, his social position, and his scientific reputation being alike brilliant. From 1694 to 1730, he was a physician of Christ's Hospital. On the 30th of November, 1693, he was elected Secretary of the Royal Society.[55] In 1701 he was made an M.D. of Oxford; and in 1705 he was elected into the fellowship of the College of Physicians of Edinburgh. In 1708 he was chosen a Fellow of the Royal Academy of Sciences of Paris. Four years later he was elected a member of the Royal Society of Berlin. In 1719 he became president of the College of Physicians; and in 1727 he was created President of the Royal Society (on the death of Sir Isaac Newton), and was appointed physician to King George II. In addition to these honours, he won the distinction of being the first[6] medical practitioner advanced to the dignity of a baronetcy.

In 1742, Sir Hans Sloane quitted his professional residence at Bloomsbury; and in the society of his library, museum, and a select number of scientific friends, spent the last years of his life at Chelsea, the manor of which parish he had purchased in 1722.

In the Gentleman's Magazine for 1748, there is a long but interesting account of a visit paid by the[56] Prince and Princess of Wales to the Baronet's museum. Sir Hans received his royal guests and entertained them with a banquet of curiosities, the tables being cleverly shifted, so that a succession of "courses," under glass cases, gave the charm of variety to the labours of observation.

In his old age Sir Hans became sadly penurious, grudging even the ordinary expenses of hospitality. His intimate friend, George Edwards, F.R.S., gives, in his "Gleanings of Natural History," some particulars of the old Baronet, which present a stronger picture of his parsimony than can be found in the pages of his avowed detractors.