Title: The Cultural History of Marlborough, Virginia

Author: C. Malcolm Watkins

Release date: July 16, 2012 [eBook #40255]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Pat McCoy, Chris Curnow, Joseph Cooper and the

Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

TRANSCRIBER NOTES:

The List of Illustrations on page vi has been added to this project as an aid to the reader. It does not appear in the original book.

Additional Transcriber Notes can be found at the end of this project

[Pg i]

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION

UNITED STATES NATIONAL MUSEUM

BULLETIN 253

WASHINGTON, D.C.

1968

[Pg ii]

[Pg iii]

An Archeological and Historical Investigation

of the

Port Town for Stafford County and the

Plantation of John Mercer, Including Data

Supplied by Frank M. Setzler and Oscar H. Darter

C. MALCOLM WATKINS

Curator of Cultural History

Museum of History and Technology

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION PRESS

SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION · WASHINGTON, D.C. · 1968

[Pg iv]

Publications of the United States National Museum

The scholarly and scientific publications of the United States National Museum include two series, Proceedings of the United States National Museum and United States National Museum Bulletin.

In these series, the Museum publishes original articles and monographs dealing with the collections and work of its constituent museums—The Museum of Natural History and the Museum of History and Technology—setting forth newly acquired facts in the fields of anthropology, biology, history, geology, and technology. Copies of each publication are distributed to libraries, to cultural and scientific organizations, and to specialists and others interested in the different subjects.

The Proceedings, begun in 1878, are intended for the publication, in separate form, of shorter papers from the Museum of Natural History. These are gathered in volumes, octavo in size, with the publication date of each paper recorded in the table of contents of the volume.

In the Bulletin series, the first of which was issued in 1875, appear longer, separate publications consisting of monographs (occasionally in several parts) and volumes in which are collected works on related subjects. Bulletins are either octavo or quarto in size, depending on the needs of the presentation. Since 1902 papers relating to the botanical collections of the Museum of Natural History have been published in the Bulletin series under the heading Contributions from the United States National Herbarium, and since 1959, in Bulletins titled "Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology," have been gathered shorter papers relating to the collections and research of that Museum.

This work forms volume 253 of the Bulletin series.

Frank A. Taylor

Director, United States National Museum

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Washington, D.C. 20402—Price $3.75

[Pg v]

| Page | ||

| Preface | vii | |

| History | 3 | |

| I. | Official port towns in Virginia and origins of Marlborough | 5 |

| II. | John Mercer’s occupation of Marlborough, 1726-1730 | 15 |

| III. | Mercer’s consolidation of Marlborough, 1730-1740 | 21 |

| IV. | Marlborough at its ascendancy, 1741-1750 | 27 |

| V. | Mercer and Marlborough, from zenith to decline, 1751-1768 | 49 |

| VI. | Dissolution of Marlborough | 61 |

| Archeology and Architecture | 65 | |

| VII. | The site, its problem, and preliminary tests | 67 |

| VIII. | Archeological techniques | 70 |

| IX. | Wall system | 71 |

| X. | Mansion foundation (Structure B) | 85 |

| XI. | Kitchen foundation (Structure E) | 101 |

| XII. | Supposed smokehouse foundation (Structure F) | 107 |

| XIII. | Pits and other structures | 111 |

| XIV. | Stafford courthouse south of Potomac Creek | 115 |

| Artifacts | 123 | |

| XV. | Ceramics | 125 |

| XVI. | Glass | 145 |

| XVII. | Objects of personal use | 155 |

| XVIII. | Metalwork | 159 |

| XIX. | Conclusion | 173 |

| General Conclusions | 175 | |

| XX. | Summary of findings | 177 |

| Appendixes | 181 | |

| A. | Inventory of George Andrews, Ordinary Keeper | 183 |

| B. | Inventory of Peter Beach | 184 |

| C. | Charges to account of Mosley Battaley | 185 |

| D. | “Domestick Expenses,” 1725 | 186 |

| E. | John Mercer’s reading, 1726-1732 | 191 |

| F. | Credit side of John Mercer’s account with Nathaniel Chapman | 193 |

| G. | Overwharton Parish account | 194 |

| H. | Colonists identified by John Mercer according to occupation | 195 |

| I. | Materials listed in accounts with Hunter and Dick, Fredericksburg | 196 |

| J. | George Mercer’s expenses while attending college | 197 |

| K. | John Mercer’s library | 198 |

| L. | Botanical record and prevailing temperatures, 1767 | 209 |

| M. | Inventory of Marlborough, 1771 | 211 |

| Index | 213 | |

[Pg vi]

| Figure | |

| John Mercer's Bookplate | 1 |

| Survey plates of Marlborough | 2 |

| Portrait of John Mercer | 3 |

| The Neighborhood of John Mercer | 4 |

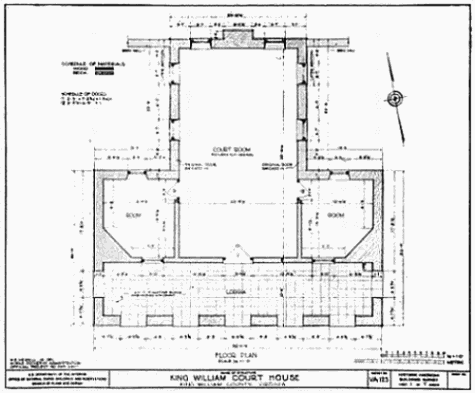

| King William Courthouse | 5 |

| Mother-of-pearl counters | 6 |

| John Mercer's Tobacco-cask symbols | 7 |

| Wine-bottle seal | 8 |

| French horn | 9 |

| Hornbook | 10 |

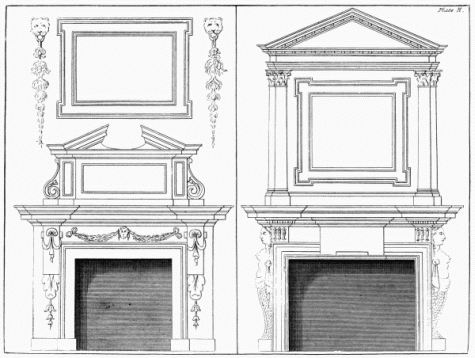

| Fireplace mantels | 11 |

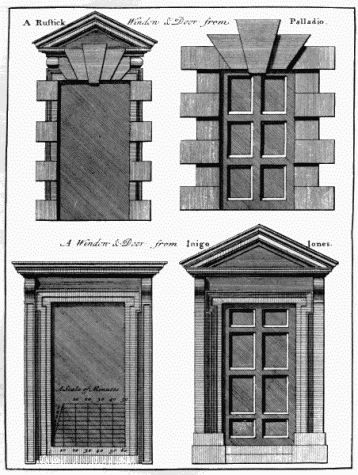

| Doorways | 12 |

| Table-desk | 13 |

| Archeological survey plan | 14 |

| Portrait of Ann Roy Mercer | 15 |

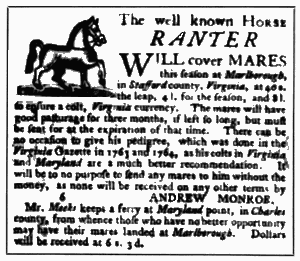

| Advertisement of the services of Mercer's stallion Ranter | 16 |

| Page from Maria Sibylla Merian's Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium efte Veranderung Surinaamsche Insecten | 17 |

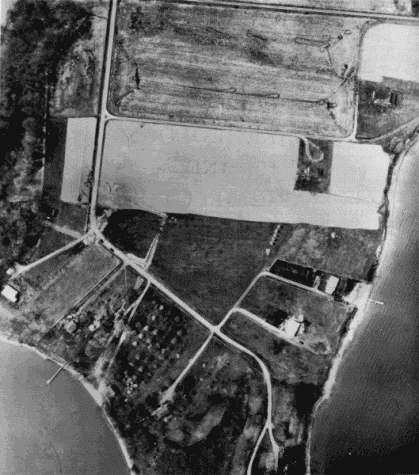

| Aerial Photograph of Marlborough | 18 |

| Highway 621 | 19 |

| Excavation plan of Marlborough | 20 |

| Excavation plan of wall system | 21 |

| Looking north | 22 |

| Outcropping of stone wall | 23 |

| Junction of stone Wall A | 24 |

| Looking north in line with Walls A and A-II | 25 |

| Wall A-II | 26 |

| Junction of Wall A-I | 27 |

| Wall E | 28 |

| Detail of Gateway in Wall E | 29 |

| Wall B-II | 30 |

| Wall D | 31 |

| Excavation plan of Structure B | 32 |

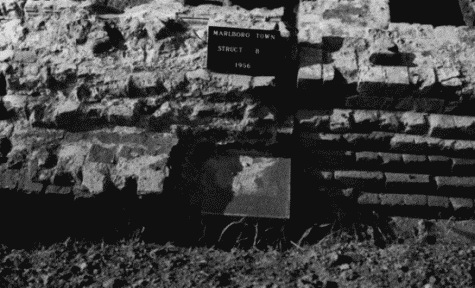

| Site of Structure B | 33 |

| Southwest corner of Structure B | 34 |

| Southwest corner of Structure B | 35 |

| South wall of Structure B | 36 |

| Cellar of Structure B | 37 |

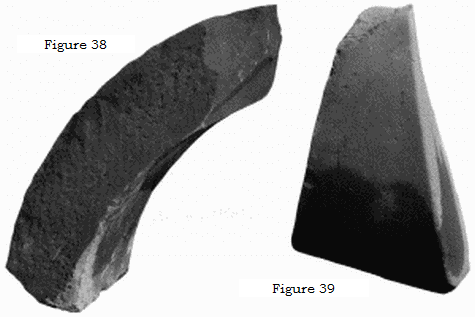

| Section of red-sandstone arch | 38 |

| Helically contoured red-sandstone | 39 |

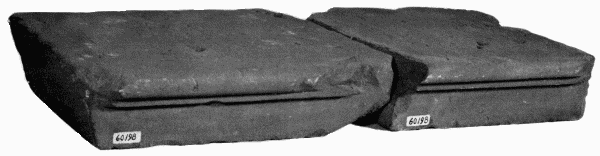

| Cast-concrete block | 40 |

| Dressed red-sandstone block | 41 |

| Fossil-embedded black sedimentary stone | 42 |

| Foundation of porch at north end of Structure B | 43 |

| Plan of mansion house | 44 |

| The Villa of “the magnificent Lord Leonardo Emo” | 45 |

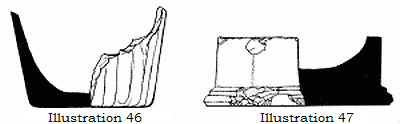

| Excavation plan of Structure E | 46 |

| Foundation of Structure E | 47 |

| Paved floor of Room X, Structure E | 48 |

| North wall of Structure E | 49 |

| Wrought-iron slab | 50 |

| Excavation plan of structures north of Wall D | 51 |

| Structure F | 52 |

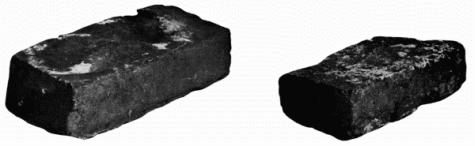

| Virginia brick from Structure B | 53 |

| Structure D | 54 |

| Refuse found at exterior corner of Wall A-II and Wall D | 55 |

| Excavation plan of Structure H | 56 |

| Structure H | 57 |

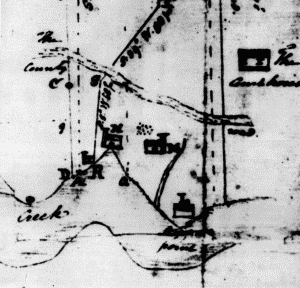

| 1743 drawing showing location of Stafford courthouse | 58 |

| Enlarged detail from figure 58 | 59 |

| Excavation plan of Stafford courthouse foundation | 60 |

| Hanover courthouse | 61 |

| Plan of King William courthouse | 62 |

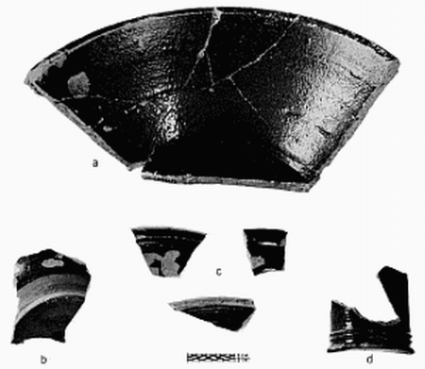

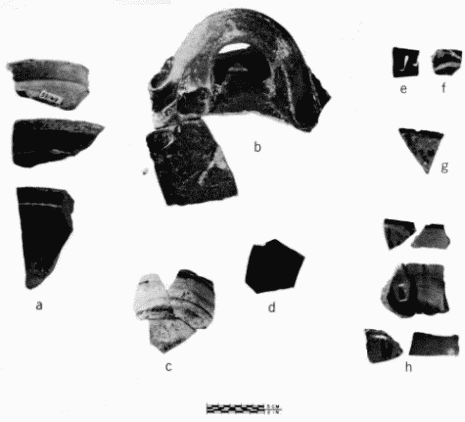

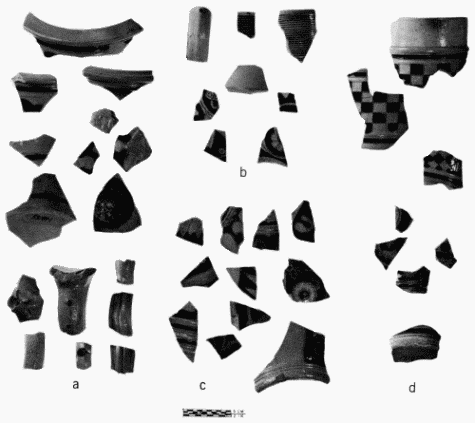

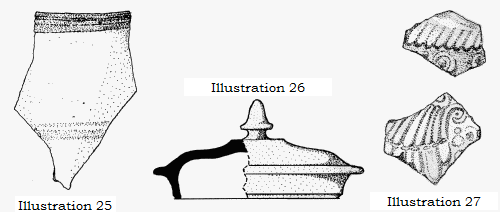

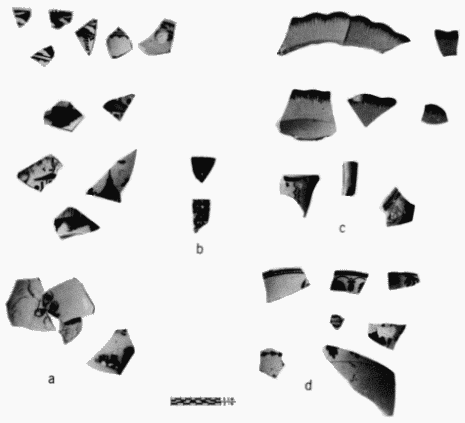

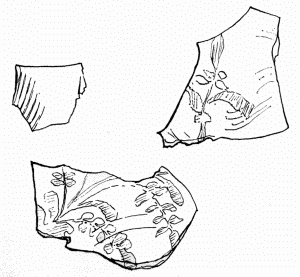

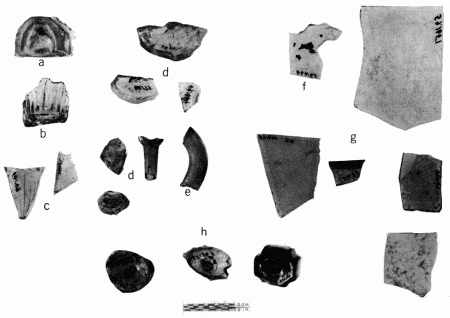

| Tidewater-type pottery | 63 |

| Miscellaneous common earthenware types | 64 |

| Buckley-type high-fired ware | 65 |

| Westerwald stoneware | 66 |

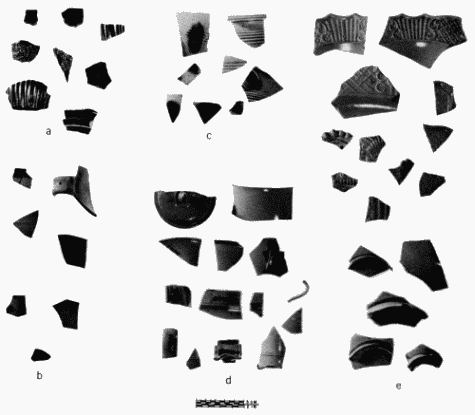

| Fine English stoneware | 67 |

| English Delftware | 68 |

| Delft plate | 69 |

| Delft plate | 70 |

| Whieldon-type tortoiseshell ware | 71 |

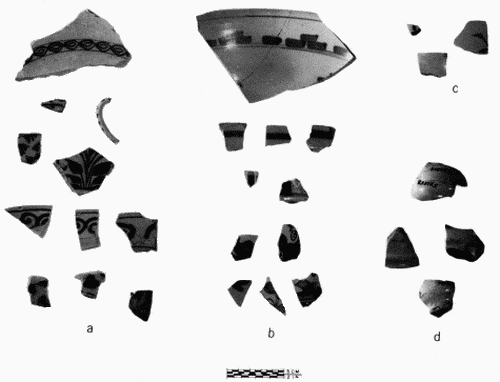

| Queensware | 72 |

| Fragment of Queensware | 73 |

| English white earthenwares | 74 |

| Polychrome Chinese porcelain | 75 |

| Blue-and-white Chinese porcelain | 76 |

| Blue-and-white Chinese porcelain | 77 |

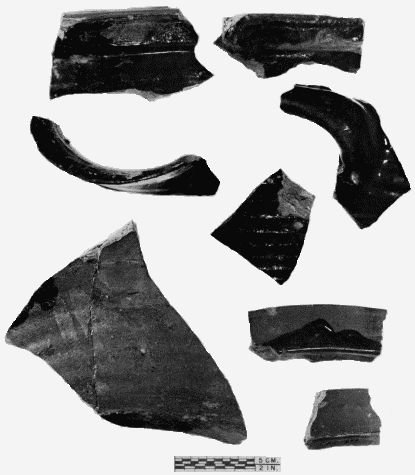

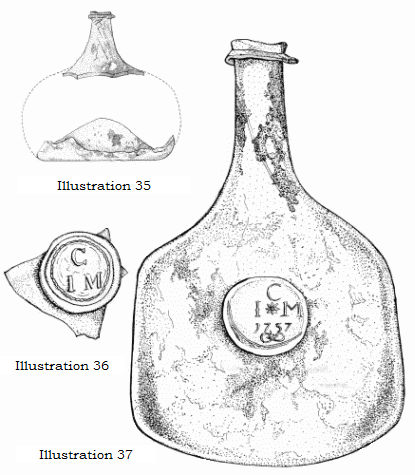

| Wine bottle | 78 |

| Bottle seals | 79 |

| Octagonal spirits bottle | 80 |

| Snuff bottle | 81 |

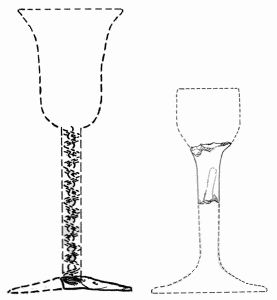

| Glassware | 82 |

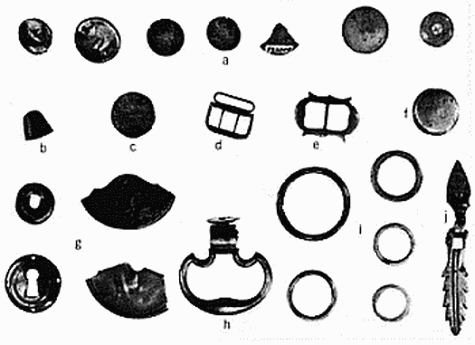

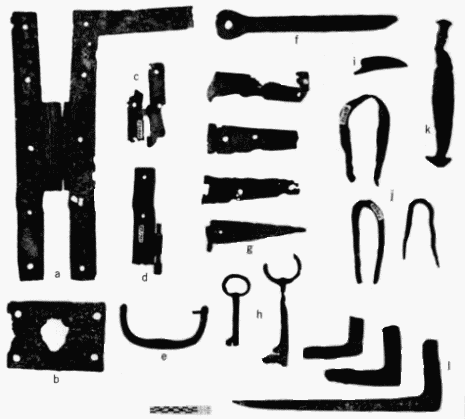

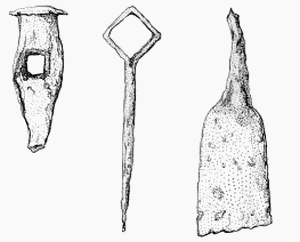

| Small metalwork | 83 |

| Personal miscellany | 84 |

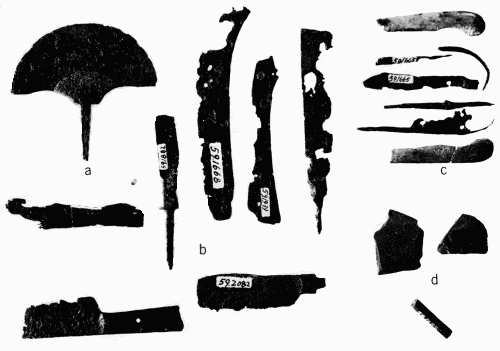

| Cutlery | 85 |

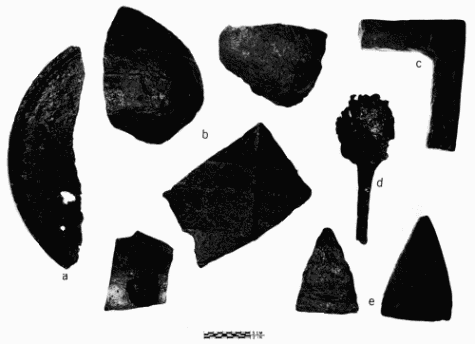

| Metalwork | 86 |

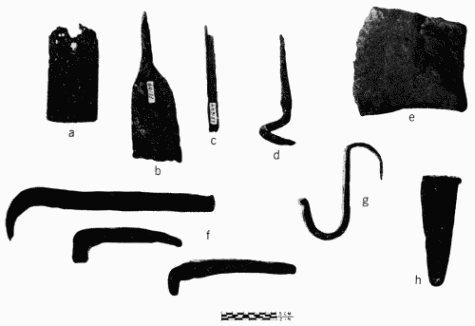

| Ironware | 87 |

| Iron door and chest hardware | 88 |

| Tools | 89 |

| Scythe | 90 |

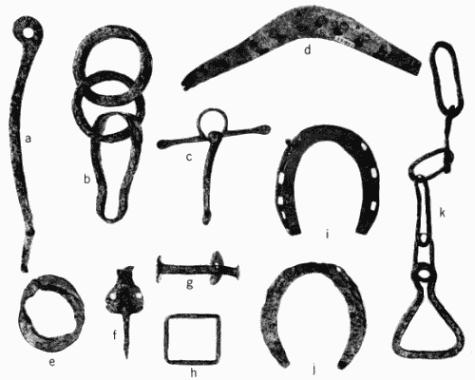

| Farm gear | 91 |

| Illustration | |

| Front and back cast-concrete block | 1 and 2 |

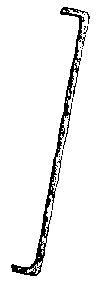

| Iron tie bar | 3 |

| Cross section of plaster cornice molding from Structure B | 4 |

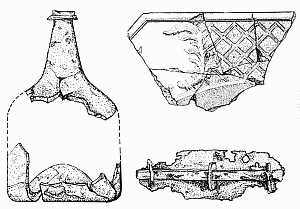

| Reconstructed wine bottle | 5 |

| Fragment of molded white salt-glazed platter | 6 |

| Iron bolt | 7 |

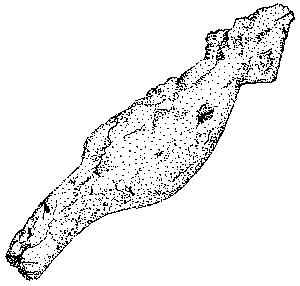

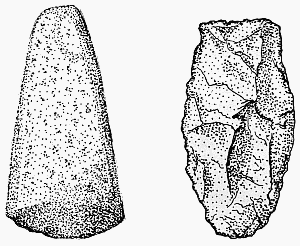

| Stone scraping tool | 8 |

| Indian celt | 9 |

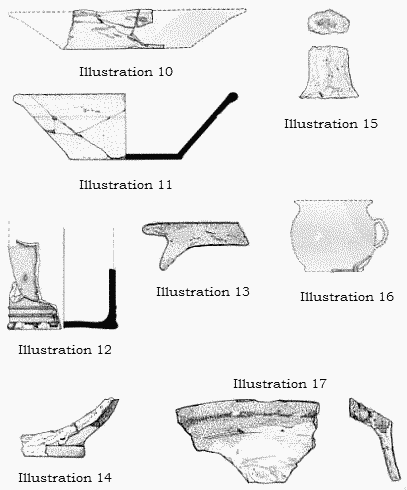

| Milk pan | 10 |

| Milk pan | 11 |

| Ale mug | 12 |

| Cover of jar | 13 |

| Base of bowl | 14 |

| Handle of pot lid or oven door | 15 |

| Buff-earthenware cup | 16 |

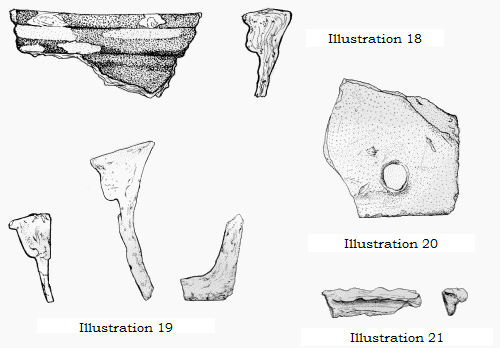

| High-fired earthenware pan rim | 17 |

| High-fired earthenware jar rim | 18 |

| Rim and base profiles of high-fired earthenware jars | 19 |

| Base sherd from unglazed red-earthenware water cooler | 20 |

| Rim of an earthenware flowerpot | 21 |

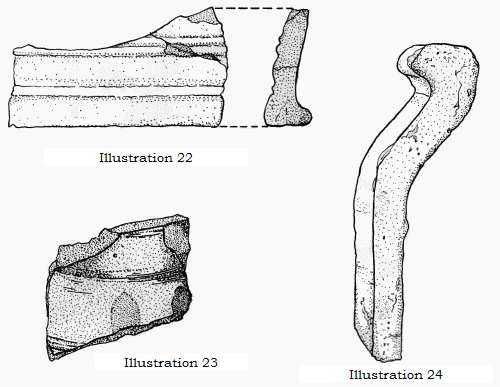

| Base of gray-brown, salt-glazed-stoneware ale mug | 22 |

| Stoneware jug fragment | 23 |

| Gray-salt-glazed-stoneware jar profile | 24 |

| Drab-stoneware mug fragment | 25 |

| Wheel-turned cover of white, salt-glazed teapot | 26 |

| Body sherds of molded, white salt-glaze-ware pitcher | 27 |

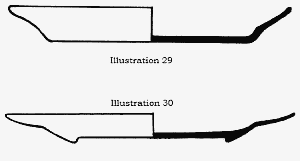

| English delftware washbowl sherd | 28 |

| English delftware plate | 29 |

| English delftware plate | 30 |

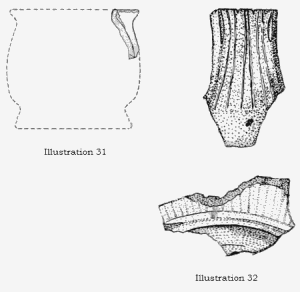

| Delftware ointment pot | 31 |

| Sherds of black basaltes ware | 32 |

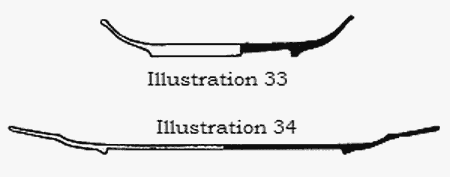

| Blue-and-white Chinese porcelain saucer | 33 |

| Blue-and-white Chinese porcelain plate | 34 |

| Beverage bottle | 35 |

| Beverage-bottle seal | 36 |

| Complete beverage bottle | 37 |

| Cylindrical beverage bottle | 38 |

| Cylindrical beverage bottle | 39 |

| Octagonal, pint-size beverage bottle | 40 |

| Square gin bottle | 41 |

| Square snuff bottle | 42 |

| Wineglass, reconstructed | 43 |

| Cordial glass | 44 |

| Sherds of engraved-glass wine and cordial glasses | 45 |

| Clear-glass tumbler | 46 |

| Octagonal cut-glass trencher salt | 47 |

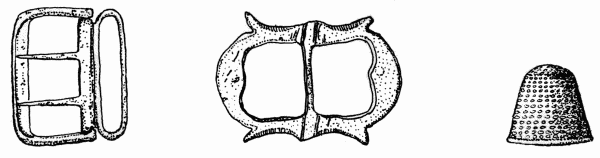

| Brass buckle | 48 |

| Brass knee buckle | 49 |

| Brass thimble | 50 |

| Chalk bullet mold | 51 |

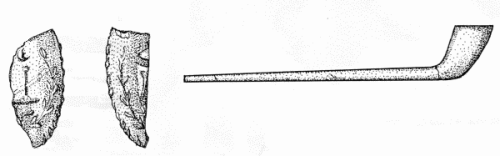

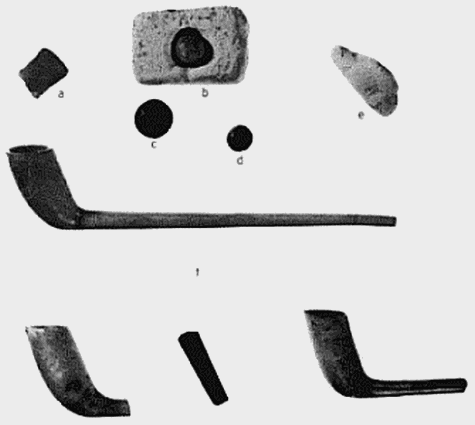

| Fragments of tobacco-pipe bowl | 52 |

| White-kaolin tobacco pipe | 53 |

| Slate pencil | 54 |

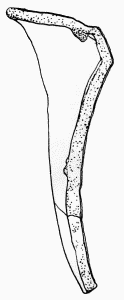

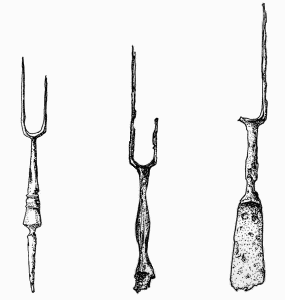

| Fragment of long-tined fork | 55 |

| Fragment of long-tined fork | 56 |

| Fork with two-part handle | 57 |

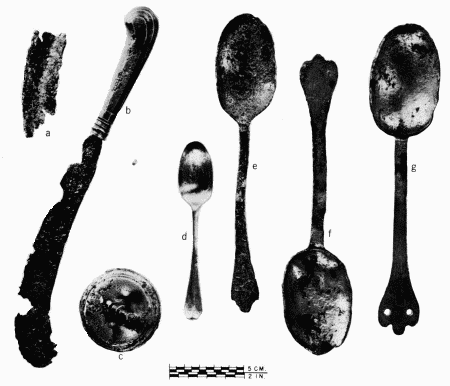

| Trifid-handle pewter spoon | 58 |

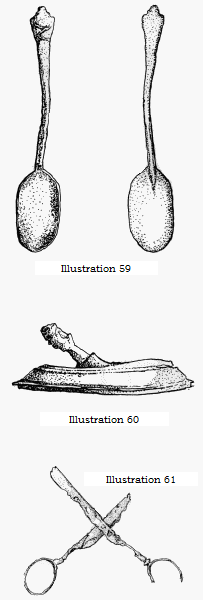

| Wavy-end pewter spoon | 59 |

| Pewter teapot lid | 60 |

| Steel scissors | 61 |

| Iron candle snuffers | 62 |

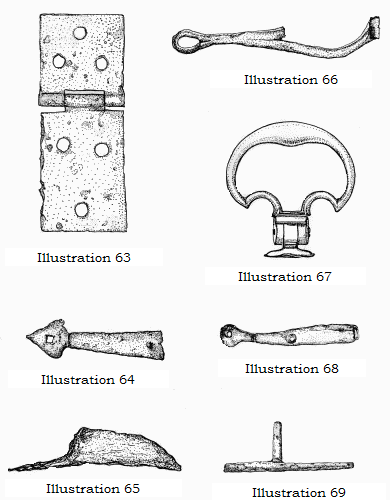

| Iron butt hinge | 63 |

| End of strap hinge | 64 |

| Catch for door latch | 65 |

| Wrought-iron hasp | 66 |

| Brass drop handle | 67 |

| Wrought-iron catch or striker | 68 |

| Iron slide bolt | 69 |

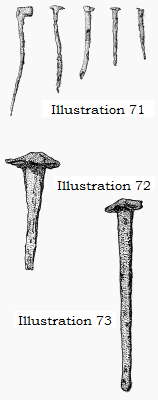

| Series of wrought-iron nails | 70 |

| Series of wrought-iron flooring nails and brads | 71 |

| Fragment of clouting nail | 72 |

| Hand-forged spike | 73 |

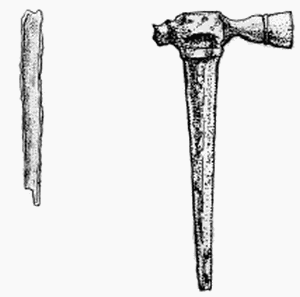

| Blacksmith's hammer | 74 |

| Iron wrench | 75 |

| Iron scraping tool | 76 |

| Bit or gouge chisel | 77 |

| Jeweler's hammer | 78 |

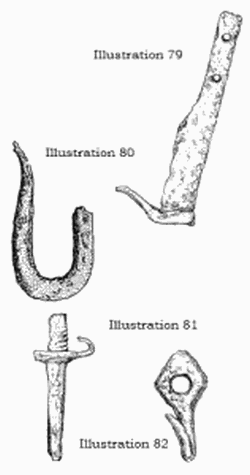

| Wrought-iron colter from plow | 79 |

| Hook used with wagon | 80 |

| Bolt with wingnut | 81 |

| Lashing hook from cart | 82 |

| Hilling hoe | 83 |

| Iron reinforcement strip from back of shovel handle | 84 |

| Half of sheep shears | 85 |

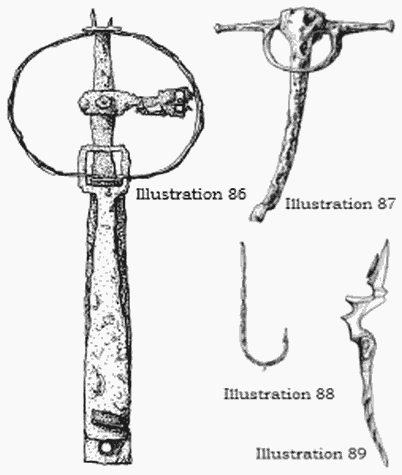

| Animal trap | 86 |

| Iron bridle bit | 87 |

| Fishhook | 88 |

| Brass strap handle | 89 |

A number of people participated in the preparation of this study. The inspiration for the archeological and historical investigations came from Professor Oscar H. Darter, who until 1960 was chairman of the Department of Historical and Social Sciences at Mary Washington College, the women’s branch of the University of Virginia. The actual excavations were made under the direction of Frank M. Setzler, formerly the head curator of anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution. None of the investigation would have been possible had not the owners of the property permitted the excavations to be made, sometimes at considerable inconvenience to themselves. I am indebted to W. Biscoe, Ralph Whitticar, Jr., and Thomas Ashby, all of whom owned the excavated areas at Marlborough; and T. Ben Williams, whose cornfield includes the site of the 18th-century Stafford County courthouse, south of Potomac Creek.

For many years Dr. Darter has been a resident of Fredericksburg and, in the summers, of Marlborough Point on the Potomac River. During these years, he has devoted himself to the history of the Stafford County area which lies between these two locations in northeastern Virginia. Marlborough Point has interested Dr. Darter especially since it is the site of one of the Virginia colonial port towns designated by Act of Assembly in 1691. During the town’s brief existence, it was the location of the Stafford County courthouse and the place where the colonial planter and lawyer John Mercer established his home in 1726. Tangible evidence of colonial activities at Marlborough Point—in the form of brickbats and potsherds still can be seen after each plowing, while John Mercer’s “Land Book,” examined anew by Dr. Darter, has revealed the original survey plats of the port town.

In this same period and as early as 1938, Dr. T. Dale Stewart (then curator of physical anthropology at the Smithsonian Institution) had commenced excavations at the Indian village site of Patawomecke, a few hundred yards west of the Marlborough Town site. The aboriginal backgrounds of the area including Marlborough Point already had been investigated. As the result of his historical research connected with this project, Dr. Stewart has contributed fundamentally to the present undertaking by foreseeing the excavations of Marlborough Town as a logical step beyond his own investigation.

Motivated by this combination of interests, circumstances, and historical clues, Dr. Darter invited the Smithsonian Institution to participate in an archeological investigation of Marlborough. Preliminary tests made in August 1954 were sufficiently rewarding to justify such a project. Consequently, an application for funds was prepared jointly and was submitted by Dr. Darter through the University of Virginia to the American Philosophical Society. In January 1956 grant number 159, Johnson Fund (1955), for $1500 was assigned to the program. In addition, the Smithsonian Institution contributed the professional services necessary for field research and directed the purchase of microfilms and photostats, the drawing of maps and illustrations, and the preparation and publication of this report. Dr. Darter hospitably provided the use of his Marlborough Point cottage during the period of excavation, and Mary Washington College administered the grant. Frank Setzler directed the excavations during a six-week period in April and May 1956, while interpretation of cultural material and the searches of historical data related to it were carried out by C. Malcolm Watkins.

At the commencement of archeological work it was expected that traces of the 17th- and early 18th-century town would be found, including, perhaps, the foundations of the courthouse. This expectation was not realized, although what was found from the[Pg viii] Mercer period proved to be of greater importance. After completion, a report was made in the 1956 Year Book of the American Philosophical Society (pp. 304-308).

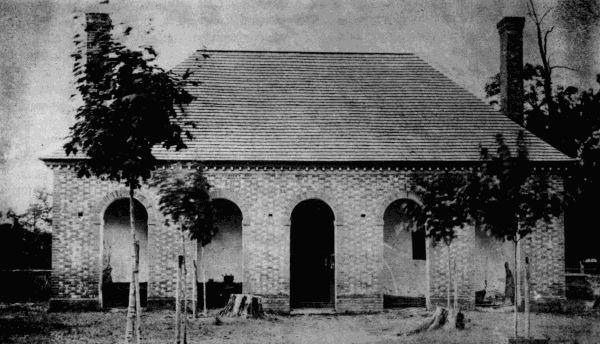

After the 1956 excavations, the question remained whether the principal foundation (Structure B) might not have been that of the courthouse. Therefore, in August 1957 a week-long effort was made to find comparative evidence by digging the site of the succeeding 18th-century Stafford County courthouse at the head of Potomac Creek. This disclosed a foundation sufficiently different from Structure B to rule out any analogy between the two.

It should be made clear that—because of the limited size of the grant—the archeological phase of the investigation was necessarily a limited survey. Only the more obvious features could be examined within the means at the project’s disposal. No final conclusions relative to Structure B, for example, are warranted until the section of foundation beneath the highway which crosses it can be excavated. Further excavations need to be made south and southeast of Structure B and elsewhere in search of outbuildings and evidence of 17th-century occupancy.

Despite such limitations, this study is a detailed examination of a segment of colonial Virginia’s plantation culture. It has been prepared with the hope that it will provide Dr. Darter with essential material for his area studies and, also, with the wider objective of increasing the knowledge of the material culture of colonial America. Appropriate to the function of a museum such as the Smithsonian, this study is concerned principally with what is concrete—objects and artifacts and the meanings that are to be derived from them. It has relied upon the mutually dependent techniques of archeologist and cultural historian and will serve, it is hoped, as a guide to further investigations of this sort by historical museums and organizations.

Among the many individuals contributing to this study, I am especially indebted to Dr. Darter; to the members of the American Philosophical Society who made the excavations possible; to Dr. Stewart, who reviewed the archeological sections at each step as they were written; to Mrs. Sigrid Hull who drew the line-and-stipple illustrations which embellish the report; Edward G. Schumacher of the Bureau of American Ethnology, who made the archeological maps and drawings; Jack Scott of the Smithsonian photographic laboratory, who photographed the artifacts; and George Harrison Sanford King of Fredericksburg, from whom the necessary documentation for the 18th-century courthouse site was obtained.

I am grateful also to Dr. Anthony N. B. Garvan, professor of American civilization at the University of Pennsylvania and former head curator of the Smithsonian Institution’s department of civil history, for invaluable encouragement and advice; and to Worth Bailey formerly with the Historic American Buildings Survey, for many ideas, suggestions, and important identifications of craftsmen listed in Mercer’s ledgers.

I am equally indebted to Ivor Noël Hume, director of archeology at Colonial Williamsburg and an honorary research associate of the Smithsonian Institution, for his assistance in the identification of artifacts; to Mrs. Mabel Niemeyer, librarian of the Bucks County Historical Society, for her cooperation in making the Mercer ledgers available for this report; to Donald E. Roy, librarian of the Darlington Library, University of Pittsburgh, for providing the invaluable clue that directed me to the ledgers; to the staffs of the Virginia State Library and the Alexandria Library for repeated courtesies and cooperation; and to Miss Rodris Roth, associate curator of cultural history at the Smithsonian, for detecting Thomas Oliver’s inventory of Marlborough in a least suspected source.

I greatly appreciate receiving generous permissions from the University of Pittsburgh Press to quote extensively from the George Mercer Papers Relating to the Ohio Company of Virginia, and from Russell & Russell to copy Thomas Oliver’s inventory of Marlborough.

To all of these people and to the countless others who contributed in one way or another to the completion of this study, I offer my grateful thanks.

C. Malcolm Watkins

Washington, D.C.

1967

ESTABLISHING THE PORT TOWNS

The dependence of 17th-century Virginia upon the single crop—tobacco—was a chronic problem. A bad crop year or a depressed English market could plunge the whole colony into debt, creating a chain reaction of overextended credits and failures to meet obligations. Tobacco exhausted the soil, and soil exhaustion led to an ever-widening search for new land. This in turn brought about population dispersal and extreme decentralization.

After the Restoration in 1660 the Virginia colonial government was faced not only with these economic hazards but also with the resulting administrative difficulties. It was awkward to govern a scattered population and almost impossible to collect customs duties on imports landed at the planters’ own wharves along hundreds of miles of inland waterways. The royal governors and responsible persons in the Assembly reacted therefore with a succession of plans to establish towns that would be the sole ports of entry for the areas they served, thus making theoretically simple the task of securing customs revenues. The towns also would be centers of business and manufacture, diversifying the colony’s economic supports and lessening its dependence on tobacco. To men of English origin this establishment of port communities must have seemed natural and logical.

The first such proposal became law in 1662,

establishing a port town for each of the major river

valleys and for the Eastern Shore. But the law’s

sponsors were doomed to disappointment, for the

towns were not built.[1] After a considerable lapse,

a new act was passed in 1680, this one better implemented

and further reaching. It provided for a port

town in each county, where ships were to deliver

their goods and pick up tobacco and other exports

from town warehouses for their return voyages.[2]

One of its most influential supporters was William

Fitzhugh of Stafford County, a wealthy planter and

distinguished leader in the colony.[3] “We have now

resolved a cessation of making Tobo next year,”

he wrote to his London agent, Captain Partis, in

1680. “We are also going to make Towns, if you

can meet with any tradesmen that will come and live[Pg 6]

[Pg 7]

at the Town, they may have privileges and immunitys.”[4]

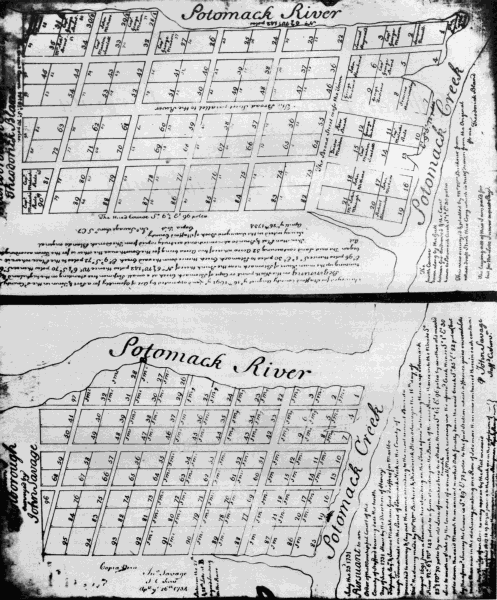

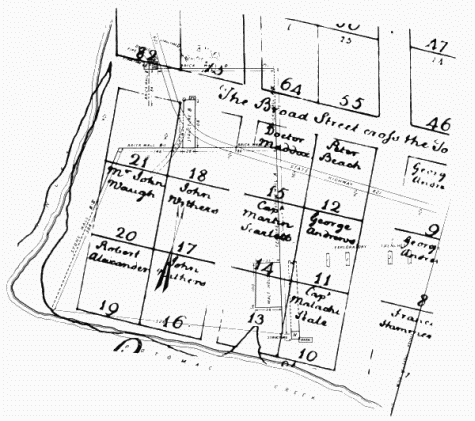

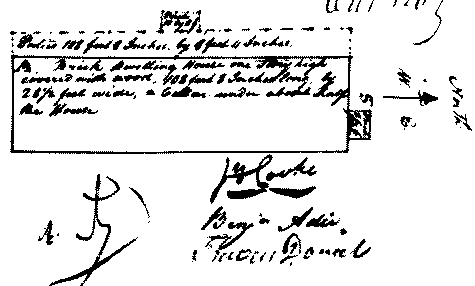

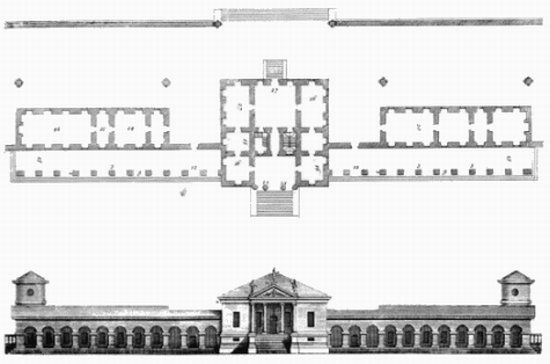

Figure 2.—Survey plats of Marlborough as copied in

John Mercer’s Land Book showing at bottom, John

Savage’s, 1731; and top, William Buckner’s and

Theodorick Bland’s, 1691. (The courthouse probably

stood in the vicinity of lot 21.)

Figure 2.—Survey plats of Marlborough as copied in

John Mercer’s Land Book showing at bottom, John

Savage’s, 1731; and top, William Buckner’s and

Theodorick Bland’s, 1691. (The courthouse probably

stood in the vicinity of lot 21.)

Some of these towns actually were laid out, each on a 50-acre tract of half-acre lots, but only 9 tracts were built upon. The Act soon lagged and collapsed. It was unpopular with the colonists, who were obliged to transport their tobacco to distant warehouses and to pay storage fees; it was ignored by shipmasters, who were in the habit of dealing directly with planters at their wharves and who were not interested in making it any easier for His Majesty’s customs collectors.[5]

Nevertheless, efforts to come up with a third act began in 1688.[6] William Fitzhugh, especially, was articulate in his alarm over Virginia’s one-crop economy, the effects of which the towns were supposed to mitigate. At this time he referred to tobacco as “our most despicable commodity.” A year later, he remarked, “it is more uncertain for a Planter to get money by consigned Tobo then to get a prize in a lottery, there being twenty chances for one chance.”[7]

In April 1691 the Act for Ports was passed, the House, significantly, recording only one dissenting vote.[8] Unlike its predecessor, which encouraged trades and crafts, this Act was justified purely on the basis of overcoming the “great opportunity ... given to such as attempt to import or export goods and merchandises, without entering or paying the duties and customs due thereupon, much practised by greedy and covetous persons.” It provided that all exports and imports should be taken up or set down at the specified ports and nowhere else, under penalty of forfeiting ship, gear, and cargo, and that the law should become effective October 1, 1692. The towns again were to be surveyed and laid out in 50-acre tracts. Feoffees, to be appointed, would grant half-acre lots on a pro rata first-cost basis. Grantees “shall within the space of four months next ensueing such grant begin and without delay proceed to build and finish on each half acre one good house, to containe twenty foot square at the least, wherein if he fails to performe them such grant to be void in law, and the lands therein granted lyable to the choyce and purchase of any other person.” Justices of the county courts were to fill vacancies among the feoffees and to appoint customs collectors.[9]

THE PORT TOWN FOR STAFFORD COUNTY

The difficulties confronting the central and local governing bodies in putting the Acts into effect are illustrated by the attempts to establish a port town for Stafford County. Under the act of 1680 a town was to be built at “Peace Point,” where the Catholic refugee Giles Brent had settled nearly forty years before, but there is no evidence that even so much as a survey was made there. The 1691 Act for Ports located the town at Potomac Neck, where Accokeek Creek and Potomac Creek converge on the Potomac River. Situated about three miles below the previously designated site, it was again on Brent property, lying within a tract leased for life to Captain Malachi Peale, former high sheriff of Stafford. On October 9, 1691, the Stafford Court “ordered that Mr. William Buckner deputy Surveyor of this County shall on Thursday next ... repair to the Malachy Peale neck being the place allotted by act of assembly for this Town and Port of this County and shall then and there Survey and Lay Out the said Towne or Port ... to the Interest that all the gentlemen of and all other of the Inhabitants may take up such Lot and Lots as be and they desire....” On the same day John Withers and Matthew Thompson, both justices of the peace, were appointed “Feoffees in Trust.” Young Giles Brent, “son and heir of Giles Brent Gent. late of this county deced” and not yet 21, selected Francis Hammersley as his guardian.[Pg 8] Hammersley in this capacity became the administrator of Brent’s affairs, and accordingly it was agreed that 13,000 pounds of tobacco should be paid to him in exchange for the 50 acres of town land owned by Brent.[10]

Actually, 52 acres were surveyed, “two of the said acres being the Land belonging to and laid out for the Court House according to a former Act of Assembly and the other fifty acres pursuant to the late Act for Ports.” The “former Act of Assembly” which had been passed in 1667 had stipulated the allotment of two-acre tracts for churches and court houses, which in case the lots “be deserted ye land shall revert to ye 1st proprietor....”[11] For the extra two acres Hammersley was given 800 pounds of tobacco in addition. Of the total of 13,800 pounds, 3450 were set aside to compensate Malachi Peale for the loss of his leasehold.

The order for the survey to be made was a formality, since the plat had actually been drawn ahead of time by Buckner on August 16, nearly two months before; clearly the Staffordians were eager to begin their town. Buckner’s plat was copied by his superior, Theodorick Bland, and entered in the now-missing Stafford Survey Book. John Savage, a later surveyor, in 1731 provided John Mercer with a duplicate of Bland’s copy, which has survived in John Mercer’s Land Book (fig. 2).[12]

On February 11, 1692, the feoffees granted 27 lots to 15 applicants. John Mercer’s later review of the town’s history in this period states that “many” of the lots were “built on and improved.”[13] Two ordinaries were licensed, one in 1691 and one in 1693, but no business activity other than the Potomac Creek ferry seems to have been conducted.[14] Any future the town might have had was erased by the same adverse reactions that had killed the previous port acts. The merchants and shippers used their negative influence and on March 22, 1693, a “bill for suspension of ye act for Ports &c. till their Majts pleasure shall be known therein or till ye next assembly” passed the house. In due course the act was reviewed and returned unsigned for further consideration. William Fitzhugh, on October 17, 1693, dutifully read the recommendation of the Committee of Grievances and Properties “That the appointment of Ports & injoyneing the Landing and Shipping of all goods imported or to be exported at & from the same will (considering the present circumstances of the Country) be very injurious & burthensome to the Inhabitants thereof and traders thereunto.”[15] Doubtless dictated by the Board of Trade in London, the recommendation was a defeat for those who, like Fitzhugh, sought by the establishment of towns to break tobacco’s strangle-hold on Virginia.

THE ACT FOR PORTS OF 1705 AND THE NAMING OF MARLBOROUGH

Nevertheless, the town idea was hard to kill. In 1705 Stafford’s port town, along with those in the other counties, was given a new lease on life when still another Act for Ports, introduced by Robert Beverley, was passed. This Act repeated in substance the provisions of its immediate forerunner, but provided in addition extravagant inducements to settlement. Those who inhabited the towns were exempted from three-quarters of the customs duties paid by others; they were freed of poll taxes for 15 years; they were relieved from military mustering outside the towns and from marching outside, excepting the “exigency” of war (and then only for a distance of no more than 50 miles). Goods and “dead provision” were not to be sold outside within a 5-mile radius, and ordinaries (other than those within the towns) were not permitted closer than 10 miles to the towns’ boundaries, except at courthouses and ferry landings. Each town was to be a free “burgh,” and, when it had grown to 30 families “besides ordinary keepers,” “eight principal inhabitants” were to be chosen by vote of the “freeholders and inhabitants of the town of twenty-one years of age and upwards, not being servants or apprentices,” to be called “benchers of the guild-hall.” These eight “benchers” would govern the town for life or until removal, selecting a “director” from among themselves. When 60 families had settled, “brethren assistants of the guild hall” were to be elected similarly to serve as a common council. Each town was to have two market days a week and an annual five-day fair. The towns listed under the Act were virtually the same as before, but this[Pg 9] time each was given an official name, the hitherto anonymous town for Stafford being called Marlborough in honor of the hero of the recent victory at Blenheim.[16]

The elaborate vision of the Act’s sponsors never was realized in the newly christened town, but there was in due course a slight resumption of activity in it. George Mason and William Fitzhugh, Jr. (the son of William Fitzhugh of Stafford County) were appointed feoffees in 1707, and a new survey was made by Thomas Gregg. The following year seven more lots were granted, and for an interval of two years Marlborough functioned technically as an official port.[17]

Inevitably, perhaps, history repeated itself. In 1710 the Act for Ports, like its predecessors, was rescinded. The reasons given in London were brief and straightforward; the Act, it was explained, was “designed to Encourage by great Priviledges the settling in Townships.” These settlements would encourage manufactures, which, in turn, would promote “further Improvement of the said manufactures, And take them off from the Planting of Tobacco, which would be of Very Ill consequence,” thus lessening the colony’s dependence on the Kingdom, affecting the import of tobacco, and prejudicing shipping.[18] Clearly, the Crown did not want the towns to succeed, nor would it tolerate anything which might stimulate colonial self-dependence. The Virginia colonists’ dream of corporate communities was not to be realized.

Most of the towns either died entirely or struggled on as crossroads villages. A meager few have survived to the present, notably Norfolk, Hampton, Yorktown, and Tappahannock. Marlborough lasted as a town until about 1720, but in about 1718 the courthouse and several dwellings were destroyed by fire and “A new Court House being built at another Place, all or most of the Houses that had been built in the said Town, were either burnt or suffered to go to ruin.”[19]

The towns were artificial entities, created by acts of assembly, not by economic or social necessity. In the few places where they filled a need, notably in the populous areas of the lower James and York Rivers, they flourished without regard to official status. In other places, by contrast, no law or edict sufficed to make them live when conditions did not warrant them. In sparsely settled Stafford especially there was little to nurture a town. It was easier, and perhaps more exciting, to grow tobacco and gamble on a successful crop, to go in debt when things were bad or lend to the less fortunate when things were better. In the latter case land became an acceptable medium for the payment of debts. Land was wealth and power, its enlargement the means of greater production of tobacco—tobacco again the great gamble by which one would always hope to rise and not to fall. When one could own an empire, why should one worry about a town?

ESTABLISHING COURTHOUSES

The administrative problems that contributed to the establishment of the port towns also called for the erection of courthouses. As early as 1624 lower courts had been authorized for Charles City and Elizabeth City in recognition of the colony’s expansion, and ten years later the colony had been divided into eight counties, with a monthly court established in each. By the Restoration the county courts possessed broadly expanded powers and were the administrative as well as the judicial sources of local government. In practice they were largely self-appointive and were responsible for filling most local offices. Since the courts were the vehicles of royal authority, it followed that the physical symbols of this authority should be emphasized by building proper houses of government. At Jamestown orders were given in 1663 to build a statehouse in lieu of the alehouses and ordinaries where laws had been made previously.[20]

In the same year, four courthouses annually were ordered for the counties, the burgesses having been empowered to “make and Signe agreements wth any that will undertake them to build, who are to give good Caution for the effecting thereof with good sufficient bricks, Lime, and Timber, and that the same be well wrought and after they are finished to be approved by an able surveyor, before order be given them for their pay.”[21] Such buildings were to [Pg 10]take the place of private dwellings and ordinaries in the same way as did the statehouse at Jamestown. It was no accident that legislation for houses of government coincided with that for establishing port towns. Each reflected the need for administering the far-flung reaches of the colony and for maintaining order and respect for the crown in remote places.

THE COURTHOUSE IN THE PORT TOWN FOR STAFFORD COUNTY

Stafford County, which had been set off from Westmoreland in 1664, was provided with a courthouse within a year of its establishment. Ralph Happel in Stafford and King George Courthouses and the Fate of Marlborough, Port of Entry, has given us a detailed chronicle of the Stafford courthouses, showing that the first structure was situated south of Potomac Creek until 1690, when it presumably burned.[22] The court, in any event, began to meet in a private house on November 12, 1690, while on November 14 one Sampson Darrell was appointed chief undertaker and Ambrose Bayley builder of a new courthouse. A contract was signed between them and the justices of the court to finish the building by June 10, 1692, at a cost of 40,000 pounds of tobacco and cash, half to be paid in 1691 and the remainder upon completion.[23]

With William Fitzhugh the presiding magistrate of the Stafford County court as well as cosponsor of the Act for Ports, it was foreordained that the new courthouse should be tied in with plans for the port town. The Act for Ports, however, was still in the making, and it was not possible to begin the courthouse until after its passage in the spring. On June 10, 1691, it was “Ordered by this Court that Capt. George Mason and Mr. Blande the Surveyor shall immediately goe and run over the ground where the Town is to Stand and that they shall then advise and direct Mr Samson Darrell the Cheife undertaker of the Court house for this County where he shall Erect and build the same.”[24]

The court’s order was followed by a hectic sequence that reflects, in general, the irresponsibilities, the lack of respect for law and order, and the frontier weaknesses which made it necessary to strengthen authority. It begins with Sampson Darrell himself, whose moral shortcomings seem to have been legion (hog-stealing, cheating a widow, and refusing to give indentured servants their freedom after they had earned it, to name a few). Darrell undoubtedly had the fastidious Fitzhugh’s confidence, for certainly without that he would not have been appointed undertaker at all. In his position in the court, Fitzhugh would have been instrumental in selecting both architect and architecture for the courthouse, and Darrell seems to have met his requirements. Fitzhugh, in fact, had sufficient confidence in Darrell to entrust him with personal business in London in 1688.[25]

Although several months elapsed before a site was chosen, enough of the new building was erected by October to shelter the court for its monthly assembly. In the course of this session, there occurred a “most mischievous and dangerous Riot,”[26] which rather violently inaugurated the new building. During this disturbance, the pastor of Potomac Parish, Parson John Waugh,[27] upbraided the court while it was “seated” and took occasion to call Fitzhugh a Papist. The court, taking cognizance of “disorders, misrules and Riots” and “the Fatal consequences of such unhappy malignant and Tumultuous proceeding,” thereupon restricted the sale of liquor on court days (thus revealing what was at least accessory to the disturbance).[28] Fitzhugh’s letter to the court concerning this episode mentions the “Court House” and the “Court house yard,” adding to Happel’s ample[Pg 11] documentation that the new building was by now in use.

During the November session, James Mussen was ordered into custody for having “dangerously wounded Mr. Sampson Darrell.”[29] This suggests that the sequence of disturbances may have been associated with the unfinished state of the courthouse, which, like the town, symbolized the purposes of Fitzhugh and the property-owning aristocracy. Certain it is that Darrell, publicly identified with Fitzhugh, was violently assaulted and that “a complaint was made to this Court that Sampson Darrell the chief undertaker of the building and Erecting of a Court house for this county had not performed the same according to articles of agreement.” He and Bayley accordingly were put under bond to finish the building by June 10, 1692. By February Bayley was complaining that he had not been paid for his work, “notwithstanding your petr as is well known to the whole County hath done all the carpenters work thereof and is ready to perform what is yet wanting.” On May 12, less than a month from the deadline for completion, Darrell was ordered to pay Bayley the money owing, and Bayley was instructed to go on with the work. Nearly six months later, on November 10, Darrell again was directed to pay Bayley the full balance of his wages, but only “after the said Ambrose Bayley shall have finished and Compleatly ended the Court house.”[30]

No description of the courthouse has been found. The Act of 1663 seems to have required a brick building, although its wording is ambiguous. Even if it did stipulate brick, the law was 28 years old in 1691, and its requirements probably were ignored. Although Bayley, the builder, was a carpenter, this would not preclude the possibility that he supervised bricklayers and other artisans. Brick courthouses were not unknown; one was standing in Warwick when the Act for Ports was passed in 1691. Yet, the York courthouse, built in 1692, was a simple building, probably of wood.[31] In any case, the Stafford courthouse was a structure large enough to have required more than a year and a half to build, but not so elaborate as to have cost more than 40,000 pounds of tobacco.

LOCATION OF THE STAFFORD COURTHOUSE

The location of the building is indicated by a notation on Buckner’s plat of the port town: “The fourth course (runs) down along by the Gutt between Geo: Andrew’s & the Court house to Potomack Creek.” A glance at the plat (fig. 2) will disclose that the longitudinal boundaries of all the lots south of a line between George Andrews’ “Gutt” run parallel to this fourth course. Plainly, the courthouse was situated near the head of the gutt, where the westerly boundary course changed, near the end of “The Broad Street Across the Town.” It may be significant that the foundation (Structure B) on which John Mercer’s mansion was later built is located in this vicinity.

In or about the year 1718 the courthouse “burnt Down,”[32] while it was reported as “being become ruinous” in 1720, with its “Situation very inconvenient for the greater part of the Inhabitants.” It was then agreed to build a new courthouse “at the head of Ocqua Creek.”[33] Aquia Creek was probably meant, but this must have been an error and the “head of Potomac Creek” intended instead. Happel shows that it was built on the south side of Potomac Creek. Thus, the burning of the Marlborough courthouse in 1718 merely speeded up the forces that led to the end of the town’s career.

MARLBOROUGH PROPERTY OWNERS

Not only was Marlborough foredoomed by external decrees and adverse official decisions, but much of its failure was rooted in the local elements by which it was constituted. The great majority of lot holders were the “gentlemen” who were so carefully distinguished from “all other of the Inhabitants” in the order to survey the town in 1691. Most were leading personages in Stafford, and we may assume that their purchases of lots were made in the interests of investment gains, not in establishing homes or businesses. Only three or four yeomen and ordinary keepers seem to have settled in the town.

Sampson Darrell, for example, held two lots, but he[Pg 12] lived at Aquia Creek.[34] Francis Hammersley was a planter who married Giles Brent’s widow and lived at “The Retirement,” one of the Brent estates.[35] George Brent, nephew of the original Giles Brent, was law partner of William Fitzhugh, and had been appointed Receiver General of the Northern Neck in 1690. His brother Robert also was a lot holder. Both lived at Woodstock, and presumably they did not maintain residences at the port town.[36] Other leading citizens were Robert Alexander, Samuel Hayward, and Martin Scarlett, but again there is little likelihood that they were ever residents of the town. John Waugh, the uproarious pastor of Potomac Parish, also was a lot holder, but he lived on the south side of Potomac Creek in a house which belonged to Mrs. Anne Meese of London. His failure to pay for that house after 11 years’ occupancy of it, which led to a suit in which Fitzhugh was the prosecutor, does not suggest that he ever arrived at building a house in the port town.[37]

Captain George Mason was a distinguished individual who lived at “Accokeek,” about a mile and a half from Marlborough. He certainly built in the town, for in 1691 he petitioned for a license to “keep an ordinary at the Town or Port for this county.” The petition was granted on condition that he “find a good and Sufficient maintenance and reception both for man and horse.” Captain Mason was grandfather of George Mason of Gunston Hall, author of the Virginia Bill of Rights, and was, at one time or another, sheriff, lieutenant colonel and commander in chief of the Stafford Rangers, and a burgess. He participated in putting down the uprising of Nanticoke Indians in 1692, bringing in captives for trial at the unfinished courthouse in March of that year.[38] Despite his interest in the town, however, it is unlikely that he ever lived there.

Another lot owner was Captain Malachi Peale, whose lease of the town land from the Brents had been purchased when the site was selected. He also was an important figure, having been sheriff. He may well have lived on one of his three lots, since he was a resident of the Neck to begin with. John Withers, one of the first feoffees and a justice of the peace, was a lot holder also. George Andrews and Peter Beach, somewhat less distinguished, were perhaps the only full-time residents from among the first grantees. After 1708 Thomas Ballard and possibly William Barber were also householders.

Thus, few of the ingredients of an active community were to be found at Marlborough, the skilled craftsmen or ship’s chandlers or merchants who might have provided the vitality of commerce and trade not having at any time been present.

HOUSING

It is likely that most of the houses in the town conformed to the minimum requirements of 20 by 20 feet. They were probably all of wood, a story and a half high with a chimney built against one end. Forman describes a 20-foot-square house foundation at Jamestown, known as the “House on Isaac Watson’s Land.” This had a brick floor and a fireplace large enough to take an 8-foot log as well as a setting for a brew copper. The ground floor consisted of one room, and there was probably a loft overhead providing extra sleeping and storage space.[39] The original portion of the Digges house at Yorktown, built following the Port Act of 1705 and still standing, is a brick house, also 20 feet square and a story and a half high. Yet, brick houses certainly were not the rule. In remote Stafford County, shortly before the port town was built, the houses of even well-placed individuals were sometimes extremely primitive. William Fitzhugh wrote in 1687 to his lawyer and merchant friend Nicholas Hayward in London, “Your brother Joseph’s building that Shell, of a house without Chimney or partition, & not one tittle of workmanship about it more than a Tobacco house work, carry’d him into those Arrears with your self & his other Employees, as you found by his Accots. at his death.”[40] Ancient English puncheon-type construction, with studs and posts set three feet into the ground, was still in use at Marlborough in 1691, as we know from the contract for building a prison[Pg 13] quoted by Happel.[41] No doubt the houses there varied in quality, but we may be sure that most were crude, inexpertly built, of frame or puncheon-type construction, and subject to deterioration by rot and insects.

FURNISHINGS OF TWO MARLBOROUGH HOUSES

Like George Mason, George Andrews ran an ordinary at the port town, having been licensed in 1693, and he also kept the ferry across Potomac Creek.[42] He died in 1698, leaving the property to his grandson John Cave. From the inventory of his estate recorded in the Stafford County records (Appendix A) we obtain a picture not only of the furnishings of a house in the port town, but also of what constituted an ordinary.[43] We are left with no doubt that as a hostelry Andrews’ house left much to be desired. There were no bedsteads, although six small feather beds with bolsters and one old and small flock bed are listed. (Flock consisted of tufted and fragmentary pieces of wool and cotton, while “Bed” referred not to a bedframe or bedstead but to the tick or mattress.) There were two pairs of curtains and valances. In the 17th century a valance was “A border of drapery hanging around the canopy of a bed.”[44] Curtains customarily were suspended from within the valance from bone or brass curtain rings on a rod or wire, and were drawn around the bed for privacy or warmth. Where high post bedsteads were used, the curtains and valances were supported on the rectangular frame of the canopy or tester. Since George Andrews did not list any bedsteads, it is possible that his curtains and valances were hung from bracketed frames above low wooden frames that held the bedding. Six of his beds were covered with “rugs,” one of which was “Turkey work.” There is no indication of sheets or other refinements for sleeping.

Andrews’ furniture was old, but apparently of good quality. Four “old” cane chairs, which may have dated back as far as 1660, were probably English, of carved walnut. The “old” table may have had a turned or a joined frame, or possibly may have been a homemade trestle table. An elegant touch was the “carpet,” which undoubtedly covered it. Chests of drawers were rare in the 17th century, so it is surprising to find one described here as “old.” A “cupboard” was probably a press or court cupboard for the display of plates and dishes and perhaps the pair of “Tankards” listed in the inventory. The latter may have been pewter or German stoneware with pewter mounts. The “couch” was a combination bed and settee. As in every house there were chests, but of what sort or quality we can only surmise. A “great trunk” provided storage.

Andrews’ hospitality as host is symbolized by his lignum vitae punchbowl. Punch itself was something of an innovation and had first made its appearance in England aboard ships arriving from India early in the 1600’s. It remained a sailor’s drink throughout most of the century, but had begun to gain in general popularity before 1700 in the colonies. What is more remarkable here, however, is the container. Edward M. Pinto states that such lignum vitae “wassail” bowls were sometimes large enough to hold five gallons of punch and were kept in one place on the table, where all present took part in the mixing. They were lathe-turned and usually stood on pedestals.[45] George Andrews’ nutmeg graters, silver spoons, and silver dram cup for tasting the spirits that were poured into the punch were all elegant accessories.

Another resident whose estate was inventoried was Peter Beach.[46] One of his executors was Daniel Beach, who was paid 300 pounds of tobacco annually from 1700 to 1703 for “sweeping” and “cleaning” the courthouse (Appendix B). Beach’s furnishings were scarcely more elaborate than Andrews’. Unlike Andrews, he owned four bedsteads, which with their curtains and fittings (here called “furniture”) varied in worth from 100 to 1500 pounds of tobacco. Here again was a cupboard, while there were nine chairs with “flag” seats and “boarded” backs (rush-seated chairs, probably of the “slat-back” or “ladder-back” variety). Eight more chairs and five stools were not described. A “parcel of old tables” was listed, but only one table appears to have been in use. There were pewter and earthenware, but a relatively few cooking utensils. An “old” pewter tankard was probably the most elegant drinking vessel, while one[Pg 14] candlestick was a grudging concession to the need for artificial light. The only books were two Bibles; the list mentions a single indentured servant.

THE GREGG SURVEY

In 1707, after the revival of the Port Act, the new county surveyor, Thomas Gregg, made another survey of the town. This was done apparently without regard to Buckner’s original survey. Since Gregg adopted an entirely new system of numbering, and since his survey was lost at an early date, it is impossible to locate by their description the sites of the lots granted in 1708 and after.

Forty years later John Mercer wrote:

It is certain that Thomas Gregg (being the Surveyor of Stafford County) did Sep 2d 1707 make a new Survey of the Town.... it is as certain that Gregg had no regard either to the bounds or numbers of the former Survey since he begins his Numbers the reverse way making his number 1 in the corner at Buckner’s 19 & as his Survey is not to be found its impossible to tell how he continued his Numbers. No scheme I have tried will answer, & the Records differ as much, the streets according to Buckner’s Survey running thro the House I lived in built by Ballard tho his whole lot was ditched in according to the Bounds made by Gregg.[47]

Whatever the intent may have been in laying out formal street and lot plans, Marlborough was essentially a rustic village. If Gregg’s plat ran streets through the positions of houses on the Buckner survey, and vice versa, it is clear that not much attention was paid to theoretical property lines or streets. Ballard apparently dug a boundary ditch around his lot, according to Virginia practice in the 17th century, but the fact that this must have encroached on property assigned to somebody else on the basis of the Buckner survey seems not to have been noted at the time. Rude houses placed informally and connected by lanes and footpaths, the courthouse attempting to dominate them like a village schoolmaster in a class of country bumpkins, a few outbuildings, a boat landing or two, some cultivated land, and a road leading away from the courthouse to the north with another running in the opposite direction to the creek—this is the way Marlborough must have looked even in its best days in 1708.

THE DEATH OF MARLBOROUGH AS A TOWN

Could this poor village have survived had the courthouse not burned? It was an unhappy contrast to the vision of a town governed by “benchers of the guild hall,” bustling with mercantile activity, swarming on busy market days with ordinaries filled with people. This fantasy may have pulsated briefly through the minds of a few. But, after the abrogation of the Port Act in 1710, there was little left to justify the town’s existence other than the courthouse. So long as court kept, there was need for ordinaries and ferries and for independent jacks-of-all-trades like Andrews. But with neither courthouse nor port activity nor manufacture, the town became a paradox in an economy and society of planters.

Remote and inaccessible, uninhabited by individuals whose skills could have given it vigor, Marlborough no longer had any reason for being. It lingered on for a short time, but when John Mercer came to transform the abandoned village into a flourishing plantation, “Most of the other Buildings were suffered to go to Ruin, so that in the year 1726, when your Petitioner [i.e., Mercer] went to live there, but one House twenty-feet square was standing.”[48]

FOOTNOTES:

[1] William Waller Hening, The Statutes at Large Being a Collection of All the Laws of Virginia (New York, 1823), vol. 2, pp. 172-176.

[2] Ibid., vol. 2, pp. 471-478.

[3] William Fitzhugh was founder of the renowned Virginia family that bear his name. As chief justice of the Stafford County court, burgess, merchant, and wealthy planter, he epitomized the landed aristocrat in 17th-century Virginia. See “Letters of William Fitzhugh,” Virginia Magazine of History & Biography (Richmond, 1894), vol. 1, p. 17 (hereinafter designated VHM), and William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World (1676-1701), edit. Richard Beale Davis (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, for the Virginia Historical Society, 1963).

[4] VHM, op. cit., p. 30.

[5] Robert Beverley, The History and Present State of Virginia, edit. Louis B. Wright (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1947), p. 88; Philip Alexander Bruce, Economic History of Virginia, 2nd ed. (New York: P. Smith, 1935), vol. 2, pp. 553-554.

[6] Journals of the House of Burgesses of Virginia (hereinafter designated JHB) 1659/60-1693, edit. H. R. McIlwaine (Richmond, Virginia: Virginia State Library, 1914), pp. 303, 305, 308, 315.

[7] “Letters of William Fitzhugh,” VHM (Richmond, 1895), vol. 2, pp. 374-375.

[8] JHB 1659/60-1693, op. cit. (footnote 6), p. 351.

[9] Hening, op. cit. (footnote 1), vol. 3, pp. 53-69.

[10] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694 (MS bound with order book for 1664-1688, but paginated separately), pp. 175, 177, 180, 189.

[11] “Mills,” VHM (Richmond, 1903), vol. 10, pp. 147-148.

[12] John Mercer’s Land Book (MS., Virginia State Library).

[13] JHB, 1742-1747; 1748-1749 (Richmond, 1909), pp. 285-286.

[14] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, pp. 184, 357.

[15] Hening, op. cit. (footnote 1), vol. 3, pp. 108-109.

[16] Ibid., pp. 404-419.

[17] “Petition of John Mercer” (1748), (Ludwell papers, Virginia Historical Society), VHM (Richmond, 1898), vol. 5, pp. 137-138.

[18] Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 1652-1781, edit. William P. Palmer, M.D. (Richmond, 1875), vol. 1, pp. 137-138.

[19] JHB, 1742-1747; 1748-1749 (Richmond, 1909), pp. 285-286.

[20] Hening, op. cit. (footnote 1), vol. 2, pp. 204-205.

[21] JHB, (1659/60-1693), op. cit. (footnote 6), p. 28.

[22] Ralph Happel, “Stafford and King George Courthouses and the Fate of Marlborough, Port of Entry,” VHM (Richmond, 1958), vol. 66, pp. 183-194.

[23] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, p. 187.

[24] Ibid., p. 122.

[25] William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World (1676-1701), op. cit. (footnote 3), p. 241.

[26] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, p. 194.

[27] Ibid., p. 182.

[28] In Virginia recurrent English fears of Catholic domination were reflected at this time in hysterical rumors that the Roman Catholics of Maryland were plotting to stir up the Indians against Virginia. In Stafford County these suspicions were inflamed by the harangues of Parson John Waugh, minister of Stafford Parish church and Chotank church. Waugh, who seems to have been a rabble rouser, appealed to the same small landholders and malcontents as those who, a generation earlier, had followed Nathaniel Bacon’s leadership. So seriously did the authorities at Jamestown regard the disturbance at Stafford courthouse that they sent three councillors to investigate. See “Notes,” William & Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine (Richmond, 1907), 1st ser., vol. 15, pp. 189-190 (hereinafter designated WMQ) [1]; and Richard Beale Davis’ introduction to William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World, op. cit. (footnote 3), pp. 35-39, and p. 251.

[29] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, p. 167.

[30] Ibid., pp. 194, 267, 313.

[31] Hening, op. cit. (footnote 1), vol. 3, p. 60; Edward M. Riley, “The Colonial Courthouses of York County, Virginia,” William & Mary College Quarterly Historical Magazine (Williamsburg, 1942), 2nd ser., vol. 22, pp. 399-404 (hereinafter designated WMQ [2]).

[32] Petition of John Mercer, loc. cit. (footnote 17).

[33] Executive Journals of the Council of Colonial Virginia (Richmond, 1930), vol. 2, p. 527.

[34] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, p. 251.

[35] John Mercer’s Land Book, loc. cit. (footnote 12); William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World, op. cit. (footnote 3), p. 209.

[36] Ibid., pp. 76, 93, 162, 367.

[37] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, p. 203; William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World, op. cit. (footnote 3), pp. 209, 211.

[38] Ibid., pp. 184, 230; John Mercer’s Land Book, op. cit. (footnote 12); William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World, op. cit. (footnote 3), p. 38.

[39] Henry Chandlee Forman, Jamestown and St. Mary’s (Baltimore, 1938), pp. 135-137.

[40] William Fitzhugh and His Chesapeake World, op. cit. (footnote 3), p. 203.

[41] Happel, op. cit. (footnote 22), p. 186; Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, pp. 210-211.

[42] Stafford County Order Book, 1689-1694, p. 195.

[43] Stafford County Will Book, Liber Z, pp. 168-169.

[44] A New English Dictionary on Historical Principles (Oxford, 1928), vol. 10, pt. 2, p. 18.

[45] Edward H. Pinto, Treen, or Small Woodware Throughout the Ages (London, 1949), p. 20.

[46] Stafford County Will Book, Liber Z, pp. 158-159.

[47] John Mercer’s Land Book, loc. cit. (footnote 12).

[48] Petition of John Mercer, loc. cit. (footnote 17).

MERCER’S ARRIVAL IN STAFFORD COUNTY

By 1723 Marlborough lay abandoned. George Mason (III), son of the late sheriff and ordinary keeper in the port town, held the now-empty title of feoffee, together with Rice Hooe. In that year Mason and Hooe petitioned the General Court “that Leave may be given to bring in a Bill to enable them to sell the said Land [of the town] the same not being built upon or Inhabited.” The petition was put aside for “consideration,” but within a week—on May 21, 1723—it was “ordered That Rice Hooe & George Mason be at liberty to withdraw their petition ... and that the Committee to whom it was referred be discharged from proceeding thereon.”[49]

This curious sequence remains unexplained. Had the committee informally advised the feoffees that their cause would be rejected, suggesting, therefore, that they withdraw their petition? Or had something unexpected occurred to provide an alternative solution to the problem of Marlborough?

Possibly it was the latter, and the unexpected occurrence may have been the arrival in Stafford County of young John Mercer. There is no direct evidence that Mercer was in the vicinity as early as 1723; but we know that he appeared before 1725, that he had by then become well acquainted with George Mason, and that he settled in Marlborough in 1726.

Mercer’s remarkable career began with his arrival in Virginia at the age of 16. Born in Dublin in 1704, the son of a Church Street merchant of English descent—also named John Mercer—and of Grace Fenton Mercer, John was educated at Trinity College, and then sailed for the New World in 1720.[50] How Mercer arrived in Virginia or what means he brought with him are lost to the record. From his own words written toward the end of his life we know that he was not overburdened with wealth:

“Except my education I never got a shilling of my fathers or any other relations estate, every penny I ever got has been by my own industry & with as much fatigue as most people have undergone.”[51]

From his second ledger (the first, covering the years 1720-1724, having been lost) we learn that he was engaged in miscellaneous trading, sailing up and down the rivers in his sloop and exchanging goods along the way. Where his home was in these early years we do not know, but it would appear that he had been active in the Stafford County region for some time, judging from the fact that by 1725 he had accumulated £322 4s. 5½d. worth of tobacco in a[Pg 16] warehouse at the falls of the Rappahannock.[52] He certainly had encountered George Mason before then, and probably Mason’s uncles, John, David, and James Waugh, the sons of Parson John Waugh, all of whom owned idle Marlborough properties.

Mercer’s friendship with the Masons was sufficiently well established by 1725 that on June 10 of that year he married George’s sister Catherine. This marriage, most advantageous to an aspiring young man, was celebrated at Mrs. Ann Fitzhugh’s in King George County with the Reverend Alexander Scott of Overwharton Parish in Stafford County officiating.[53] Thus, allied to an established family that was “old” by standards of the time and sponsored socially by a representative of the Fitzhughs, Mercer was admitted at the age of 21 to Virginia’s growing aristocracy.

In this animated and energetic youth, the Masons and Waughs probably saw the means of bringing Marlborough back to life. Mercer, for his part, no doubt recognized the advantages that Marlborough offered, with its sheltered harbor and landing, its fertile, flat fields, and airy situation. That it could be acquired piecemeal at a minimum of investment through the provisions of the Act for Ports was an added inducement.

JOHN MERCER AS A TRADER

During 1725 Mercer pressed ahead with his trading enterprises. From his ledger we learn that he sold Richard Ambler of Yorktown 710 pounds of “raw Deerskins” for £35 10s. and bought £200 worth of “sundry goods” from him. Between October 1725 and February 1726 he sold a variety of furnishings and equipment to Richard Johnson, ranging from a “horsewhip” and a “silk Rugg” to “½ doz. Shoemaker’s knives” and an “Ivory Comb.” In return he received two hogsheads of tobacco, “a Gallon of syder Laceground,” and raw and dressed deerskins. He maintained a similar long account with Mosley Battaley (Battaille) (Appendix C). From William Rogers of Yorktown[54] he bought £12 3s. 6d. worth of earthenware, presumably for resale. The tobacco which he had accumulated at the falls of the Rappahannock he sold for cash to the Gloucester firm of Whiting & Montague, paying Peter Kemp two pounds “for the extraordinary trouble of yr coming up so far for it.”

His sloop was the principal means by which Mercer conducted his business. Occasionally he rented it for hire, once sharing the proceeds of a load of oystershells with George Mason and one Edgeley, who had sailed the sloop to obtain the shells. Only one item shows that Mercer extended his mercantile activities to slaves: on February 18, 1726, he sold a mulatto[Pg 17] woman named Sarah to Philemon Cavanaugh “to be paid in heavy tobacco each hhd to weigh 300 Neat.”

That Mercer was turning in the direction of a legal career is revealed in his first account of “Domestick Expenses” for the fall of 1725 (Appendix D). We find that he was attending court sessions far and wide: “Cash for Exps at Stafford & Spotsylvania,” “Cash for Exps Urbanna,” the same for “Court Ferrage at Keys.” He already was reading in the law, and lent “March’s Actions of Slander,” “Washington’s Abridgmt of ye Statutes,” and “an Exposition of the Law Terms” to Mosley Battaley.

SETTING UP HOUSEKEEPING

Mercer’s domestic-expense account is full of evidence that he was preparing to set up housekeeping. He bought “1 China punch bowl,” 10s.; “6 glasses,” 3s.; “1 box Iron & heaters,” 2s. 6d.; “1 pr fine blankets,” 1s. 13d.; “Earthen ware,” 10s.; “5 Candlesticks,” 17s. 6d.; “1 Bed Cord,” 2s.; “3 maple knives & forks,” 2s.; “1 yew haft knife & fork & 1 pr Stilds [steelyards?],” 1s. 10½d.; “1 pr Salisbury Scissors,” 2s. 6d.; and “1 speckled knife & fork,” 5d.

In addition, he accepted as payment for various cloth and materials sold to Mrs. Elizabeth Russell the following furniture and furnishings:

| Ster. | £ | s. | d. | |

| By a writing desk | Do | 5 | ||

| By a glass & Cover | Do | 7 | 6 | |

| By 18l Pewter at ¼ | Do | 1 | 4 | |

| By 6 tea Cups & Sawcers 2/ | Do | 12 | ||

| By 2 Chocolate Cups 1/ | Do | 2 | ||

| By 2 Custard Cups 9d | Do | 1 | 6 | |

| By 1 Tea Table painted with fruit | Do | 14 | ||

| By 6 leather Chairs @ 7/ | 2 | 2 | ||

| By a small walnut eating table | 8 | |||

| By ½ doz. Candlemoulds | 10 | |||

| By a Tea table | 18 | |||

| By a brass Chafing dish | 5 | |||

| By 6 copper tart pans | 6 |

At the time of this purchase, the only house standing at Marlborough was that built by Thomas Ballard in 1708. It was inherited by his godson David Waugh,[55] who now apparently offered to let his niece Catherine and her new husband occupy it. Mercer later referred to it as “the House I lived in built by Ballard.”[56] From his own records we know that he moved to Marlborough in 1726. He did so probably in the summer, since on June 11 he settled with Charles McClelland for “cleaning out ye house.” Unoccupied for years and small in size, it was a humble place in which to set up housekeeping, and indeed must have needed “cleaning out.” It also must have needed extensive repairs, since Mercer purchased 1500 tenpenny nails “used about it.”

Throughout 1726 Mercer acquired household furnishings, made repairs and improvements, and obtained the necessities of a plantation. On February 1 he acquired “3 Ironbacks” (cast-iron firebacks for fireplaces) for £8 4s. 2d., as well as “2 pr hand Irons” for 15s. 5d., from Edmund Bagge. From George Rust he bought “3 Cows & Calves” for £7 10s., a featherbed for £3 10s., and an “Iron pot” for 5s.

His reckoning with John Dogge opens with a poignant note, “By a Child’s Coffin”: Mercer’s first-born child had died. On the same account was “an Oven,” bought for 17 shillings. Dogge also was credited with “bringing over 10 sheep from Sumners” (a plantation at Passapatanzy, south of Potomac Creek). Rawleigh Chinn was paid for “plowing up & fencing in my yard” and for “fetching 3 horses over the Creek.” Also credited to Chinn was an item revealing Mercer’s sporting enthusiasm: “went on ye main race ... 15/.”

From Alexander Buncle, Mercer acquired one dozen table knives, three chamber-door locks, two pairs of candle snuffers, and two broad axes. His account with Alexander McFarlane in 1726, the credit side of which is quoted here in part, is a further illustration of the variety of hardware and consumable goods that he required:

| £ | s. | d. | |

| 2 pr men’s Shooes | 9 | ||

| 1 Razor & penknife | 2 | 6 | |

| 2¼ gall Rum | 6 | 9 | |

| 9 gals. molasses | 13 | ||

| 121 brown Sugar | 6 | ||

| 6¼ double refined Do 20d | 10 | 5 | |

| 1 felt hat | 2 | 4 | |

| 1 qt Limejuice | 1 | ||

| 2 doz. Claret | 1 | 10 | |

| 2 lanthorns | 6 | ||

| 1 funnell | 7½ | ||

| [Pg 18]1 quart & 1 pint tin pot | 1 | 10½ | |

| * * * | |||

| By 2 doz & 8 bottles Claret | 2 | 8 | |

| By a woman’s horsewhip | 3 | ||

| By 1oz Gunpowder | |||

| By 10l Shot | |||

| By 1 woms bound felt [hat] |

Mercer’s comments, added three years later to this record, signify the complexities of credit accounting in the plantation economy: “In July 1729 I settled Accounts wth Mr McFarlane & paid him off & at the same time having Ed Barry’s note on him for 1412l Tobo (his goods being extravagantly dear) I paid him 1450l Tobo to Mr Thos Smith to ballns accts.”

Another of Mercer’s accounts was with Edward Simm. From Simm, Mercer acquired the following in 1726:

| £ | s. | d. | |

| 1 horsewhip | 4 | ||

| 1 fine hat | 12 | ||

| 9 yds bedtick ¾ | 1 | 10 | |

| 1 pr Spurs | 8 | ||

| 1 Curry Comb & brush | 2 | 9 | |

| 2 pr mens Shooes 5/ | 10 | ||

| 1 pr Chelloes | 1 | 10 | |

| 2 pr woms gloves 2/ | 4 | ||

| 2 pr Do thread hose | 9 | ||

| 2 pr mens worsted do | 8 | ||

| 2 pr chkr yarn | 3 | 4 | |

| 1 Sifter | 2 | ||

| 1 frying pan | 4 | 6 | |

| 7 quire of paper 1¼ | 9 | 8 | |

| 6 silk Laces 4d | 2 |

ACQUIRING LAND AND BUILDING A NEW HOUSE

Mercer’s first actual ownership of property came as a result of his marriage. In 1725 he purchased from his wife Catherine 885 acres of land near Potomac Church for £221 5s. and another tract of 1610 acres on Potomac Run for £322.[57] His occupancy of the Ballard house, meanwhile, was arranged on a most informal basis, three years having been allowed to pass before he paid his first and only rent—a total of 12 shillings—to his uncle-in-law David Waugh.

In January 1730 the following appears under “Domestick Expenses”: “To bringing the frame of my house from Jervers to Marlbro ... 40/.” Associated with this are items for 2000 tenpenny nails, 2000 eightpenny nails, and 1000 sixpenny nails, together with “To Chandler Fowke for plank,” “To Jno Chambers &c. bring board from Landing,” and “To John Chambers & Robt Collins for bringing Bricks & Oyster Shells.”

In the same month the account of Anthony Linton and Henry Suddath includes the following:

| By building a house at Marlborough when finished by agreement | £10.0.0 |

| By covering my house & building a Chimney | 3.0.0 |

Clearly, the Mercers had outgrown the temporary shelter which the little Ballard house had given them. Now a new house was under construction, with the steps plainly indicated. To obtain timber of sufficient size to frame the house it was necessary to go where the trees grew. The nearest thickly forested area was north of Potomac Creek and Potomac Run. The appropriate timbers apparently grew on property owned by Mercer but occupied by the widow of James Jervis (or “Jervers”). Not only did the trees grow there, but we may be sure that there they were also felled, hewn, and cut, and the finished members fitted together on the ground to form the frame of the new house. It was a time-honored English building practice to prepare the timbers where they were felled, shaping them, drilling holes for “trunnels” (wooden pegs or “tree nails”), inscribing coded numbers with lumber markers, and then knocking the prefabricated members apart and transporting them to the building site.[58]

Oystershells and bricks for the chimney were brought from Cedar Point and Boyd’s Hole, south of Marlborough, by Chambers and Collins. Shells were probably burned at the house site to make lime for mortar. Chambers was paid 12 pence a day for 32½ days’ work spread over a period from October 1730 to February 1731. Hugh French had been paid for 1000 bricks on August 24, 1730, while James Jones, on October 3, 1730, was recompensed three shillings for “9 days of work your Man plaistering my House & making 2 brick backs.”

Figure 4.—The neighborhood of John Mercer. Detail from J. Dalrymple’s revision (1755)

of the map of Virginia by Joseph Fry and Peter Jefferson. Marlborough is incorrectly

designated “New Marleboro.” (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

Figure 4.—The neighborhood of John Mercer. Detail from J. Dalrymple’s revision (1755)

of the map of Virginia by Joseph Fry and Peter Jefferson. Marlborough is incorrectly

designated “New Marleboro.” (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

[Pg 20]The new house was thus brought to completion early in 1731. That it was a plain and simple house is apparent from the small amount of labor and the relatively few quantities of material. It appears to have had two fireplaces only and one chimney. Although the house was wooden, there is no evidence that it had any paint whatsoever, inside or out.

FURNISHING THE HOUSE

Other than a child’s chair and a bedstead costing 10 shillings, purchased from Enoch Innes in 1729, little furniture was acquired before 1730. Listed in “Domestick Expenses” for 1729-1730 are minor accessories for the new house, such as HL hinges, closet locks, a “scimmer,” a pair of brass candlesticks, milk pans, pestle and mortar, “½ doz plates,” a “Cullender,” a candlebox, earthenware, and a pepperbox, together with several handtools.

MERCER’S VARIED ACTIVITIES AND INTERESTS

The agricultural aspects of a plantation were increasingly in evidence. In 1729 Rawleigh Chinn was paid for “helping to kill the Hogs,” “pasturage of my cattle,” and “making a gate.” Edward Floyd was credited with £4 6s. 7½d. for “Wintering Cattle, taking care of my horse & Sheep to Aug. 1729.” John Chinn seems to have been Mercer’s jockey, for as early as 1729 he was entering the races which abounded in Virginia, and “went on ye race wth Colt 1729.”

In this early period we find considerable evidence of a typical young Virginian’s fondness for gaming and sport. One finds scattered through Mercer’s account with Robert Spotswood such items as “To won at the Race ... 8.9” and “To won at Liew at Colo Mason’s ... 7.3.” (Loo was an elegant 18th-century game played with Chinese-carved mother-of-pearl counters.) Mercer participated in several sporting events at Stafford courthouse, for court sessions continued, as in the previous century, to be social as well as legal and political occasions. This is illustrated in a credit to Joseph Waugh: “By won at a horse race at Stafford Court and Attorney’s fee ... £1.”; on the debit side of Enoch Innes’s account: “To won at Quoits & running with you ... 1/3”; and in Thomas Hudson’s account, where four shillings were marked up “To won pitching at Stafford Court.”

Mercer’s diversions were few enough, nevertheless, and it is apparent that he devoted more time to reading than to gaming. In 1726 he borrowed from John Graham (or Graeme) a library of 56 volumes belonging to the “Honble Colo Spotswood”[59] (Appendix E). Ranging from the Greek classics to English history, and including Milton, Congreve, Dryden, Cole’s Dictionary, “Williams’ Mathematical Works,” and “Present State of Russia,” they were the basis for a solid education. That they included no lawbooks at a time when Mercer was preparing for the law is an indication of his broad taste for literature and learning.

Marlborough, we can see, was occupied by a young man of talent, energy, and creativity. He alone, of the many men who had envisioned a center of enterprise on Potomac Neck, was possessed of the drive and the simple directness to make it succeed. For George Mason and the Waughs, Mercer was the ideal solution for their Marlborough difficulties.

FOOTNOTES:

[49] JHB, 1712-1726 (Richmond, 1912), pp. 336, 373.

[50] “Journals of the Council of Virginia in Executive Session 1737-1763,” VHM (Richmond, 1907), vol. 14, pp. 232-235.

[51] George Mercer Papers Relating to the Ohio Company of Virginia, comp. and edit. by Lois Mulkearn (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 1954), p. 204.

[52] John Mercer’s Ledger B is the principal source of information for this chapter. It was begun in 1725 and ended in 1732. The original copy is in the library of the Bucks County Historical Society, Doylestown, Pennsylvania, a photostatic copy being in the Virginia State Library. Further footnoted references to the ledger are omitted, since the source in each case is recognizable.

[53] James Mercer Garnet, "James Mercer," WMQ [1] (Richmond, 1909), vol. 17, pp. 85-98. Mrs. Ann Fitzhugh was the widow of William Fitzhugh III, who died in 1713/14. She was the daughter of Richard Lee and lived at “Eagle’s Nest” in King George County (see “The Fitzhugh Family,” VHM [Richmond, 1900], vol. 7, pp. 317-318).

[54] William Rogers, who died in 1739, made earthenware and stoneware at Yorktown after 1711. See C. Malcolm Watkins and Ivor Noël Hume, “The ‘Poor Potter’ of Yorktown” (paper 54 in Contributions from the Museum of History and Technology, U.S. National Museum Bulletin 249, by various authors; Washington: Smithsonian Institution), 1967.