Title: Britain in the Middle Ages: A History for Beginners

Author: Florence L. Bowman

Release date: July 29, 2012 [eBook #40371]

Most recently updated: October 23, 2024

Language: English

Credits: Produced by Chris Curnow and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

BRITAIN IN THE MIDDLE AGES

A HISTORY FOR BEGINNERS

CAMBRIDGE UNIVERSITY PRESS

C. F. CLAY, Manager

LONDON: FETTER LANE, E. C. 4

| NEW YORK: | G. P. PUTNAM'S SONS | |

| BOMBAY | } | |

| CALCUTTA | } | MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd. |

| MADRAS | } | |

| TORONTO: | J. M. DENT AND SONS, Ltd. | |

| TOKYO: | MARUZEN-KABUSHIKI-KAISHA |

All Rights Reserved

THE ARMING OF A KNIGHT

BRITAIN IN THE MIDDLE AGES

A HISTORY FOR BEGINNERS

BY

FLORENCE L. BOWMAN, M.Ed.

FINAL HONOUR SCHOOL OF MODERN HISTORY, OXFORD

LECTURER IN EDUCATION, HOMERTON COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE

CAMBRIDGE

AT THE UNIVERSITY PRESS

1920

First Edition 1919

Second Edition 1920

PREFACE

Since, in the early stages of school work, it is more important to present, as vividly as possible, some of the fundamental historic ideas than to give any outline of events, it is hoped that this collection of stories, told from the chronicles, may provoke readers to discussion and further inquiry.

Questions have been included in the appendix, some suggesting handwork, both as a means of presentation in lessons and for illustrative purposes.

Considerable use has been made of literature as historic evidence. Stories like those of the Knights of the Round Table often leave us with a clearer impression of the spirit of the times than any historic record. Many books of the kind are now easily accessible and could be read side by side with the text. Collections of pictures, such as the Bayeux Tapestry, published by the Victoria and Albert Museum, and Foucquet's Chroniques de France, offer valuable opportunities for some research on the child's part.

F. L. BOWMAN.

Homerton College

December, 1918

CONTENTS

| CHAP. | PAGE | |

| I. | Before the Coming of the Romans | 1 |

| II. | The Romans | 3 |

| III. | The Saxons | 6 |

| IV. | The Saxon Village | 9 |

| V. | The Coming of Christianity | 15 |

| VI. | Alfred and the Danes | 20 |

| VII. | The Battle of Hastings | 27 |

| VIII. | Norman Kings | 31 |

| IX. | Norman Barons | 34 |

| X. | Norman Prelates | 39 |

| XI. | Norman Builders | 44 |

| XII. | Knighthood | 47 |

| XIII. | The Knights of the Round Table | 52 |

| XIV. | The Conquest of Ireland | 57 |

| XV. | The Coming of the Friars | 61 |

| XVI. | The Third Crusade | 64 |

| XVII. | The Loss of Normandy. The Signing of the Great Charter | 69 |

| XVIII. | The First Parliament | 71 |

| XIX. | The Conquest of Wales | 74 |

| XX. | The War with Scotland | 76 |

| XXI. | The War with France | 79 |

| XXII. | The War with France (continued) | 83 |

| XXIII. | The Black Death and the Peasants' Revolt | 85 |

| XXIV. | The War with France (continued) | 89 |

| XXV. | New Worlds | 95 |

| Suggestions for Study | 100 | |

| Bibliography | 102 | |

| Dates | 103 | |

| Time Chart | 104 |

ILLUSTRATIONS

| The arming of a Knight | FRONTISPIECE |

| From John Duke of Bedford's Book of Hours (15th century). In the British Museum | |

| TO FACE PAGE | |

| The Abbey of Citeaux | 18 |

| From Viollet-le-duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française | |

| A service in the chapel | 19 |

| From the Miracles de Notre Dame, collected by Miélot, Canon of S. Peter's at Lille, and finished on 10 April, 1456. In the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | |

| By arrangement with MM. Catala Frères, Paris | |

| Harold defeats and kills Tostig and the King of Norway at Stamford Bridge | 30 |

| From the Life of Edward the Confessor (about 1260). In the University Library, Cambridge | |

| A battle in the fifteenth century | 31 |

| By Jean Foucquet, from the Grandes chroniques de France (middle of the 15th century). In the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | |

| By arrangement with MM. Catala Frères, Paris | |

| Architect and builders | 44 |

| From a Bible written at Lille, about 1270. In the library of Mr S. C. Cockerell | |

| Building a church in the fifteenth century | 44 |

| By Jean Foucquet, from the Grandes chroniques de France (middle of the 15th century). In the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | |

| By arrangement with MM. Catala Frères, Paris | |

| The building of the temple of Jerusalem | 45 |

| From the Antiquités Judaïques, by Jean Foucquet (middle of the 15th century) | |

| By kind permission of MM. Plon-Nourrit et Cie, Paris | |

| A siege | 46 |

| From Viollet-le-duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française | |

| Gateway and drawbridge | 47 |

| From Viollet-le-duc, Dictionnaire raisonné de l'architecture française | |

| A court of justice, 1458. Duke of Alençon condemned for treason by Charles VII, King of France | 72 |

| By Jean Foucquet. From Le Boccace de Munich. In the Royal Library at Munich. | |

| The King is seated on his throne, and below him the princes, and on his right the Chancellor of France with bands of gold on his shoulder. Sentence is being read by one of the officers of the law. On the King's left the lords of the Church are seated and below are the chief officers of the realm. Outside the barrier is the royal guard | |

| The Parliament of Edward I | 73 |

| The Archbishops of Canterbury and York are seated just below Alexander King of Scotland, and Llewelyn Prince of Wales. The two behind are supposed to be the Pope's ambassadors. There are 19 mitred Abbots, 8 Bishops and 20 Peers present. The Chancellor and Judges are seated on the woolsacks. | |

| From Pinkerton, Iconographia Scotica. Probably drawn in the 16th century | |

| Preparing the feast | 88 |

| From the Luttrell Psalter (14th century). In the British Museum | |

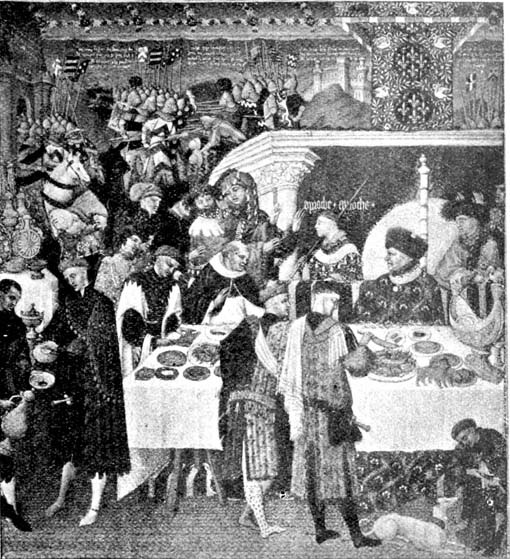

| The feast | 89 |

| From the Luttrell Psalter (14th century). In the British Museum | |

| A Christian of Constantinople borrowing money from a Jew and pledging his crucifix | 96 |

| From the Miracles de Notre Dame, collected by Jean Miélot, and finished on 10 April, 1456. In the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | |

| By arrangement with MM. Catala Frères, Paris | |

| Miélot in his study | 97 |

| From the Miracles de Notre Dame, collected by Jean Miélot, and finished on 10 April, 1456. In the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris | |

| By arrangement with MM. Catala Frères, Paris | |

| A printing press | 97 |

| A mark of Josse Badius Ascensius. From De Sacramentis of Thomas Waldensis, 1521. In the University Library, Cambridge | |

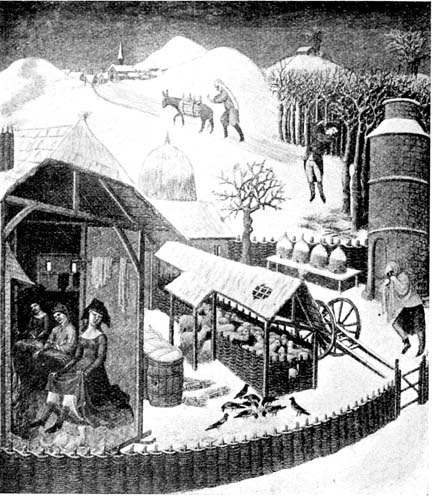

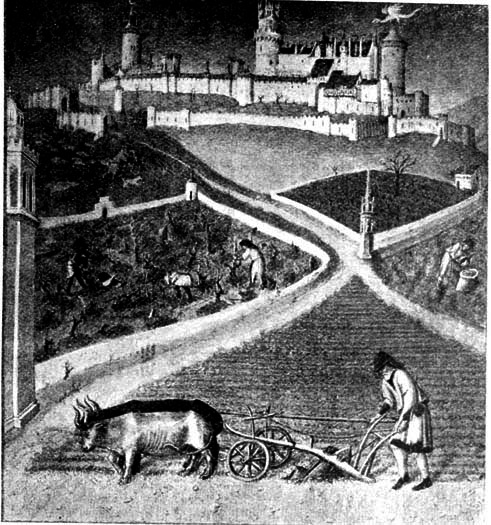

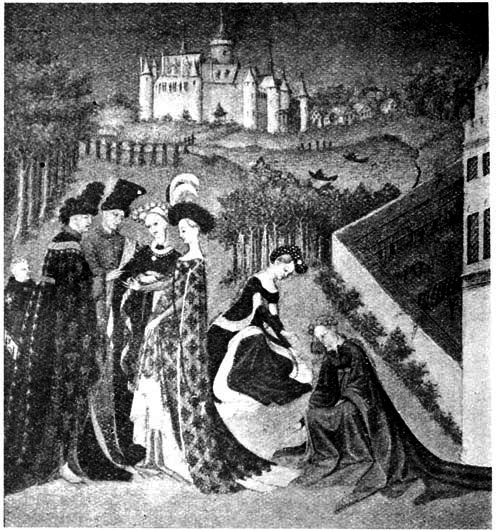

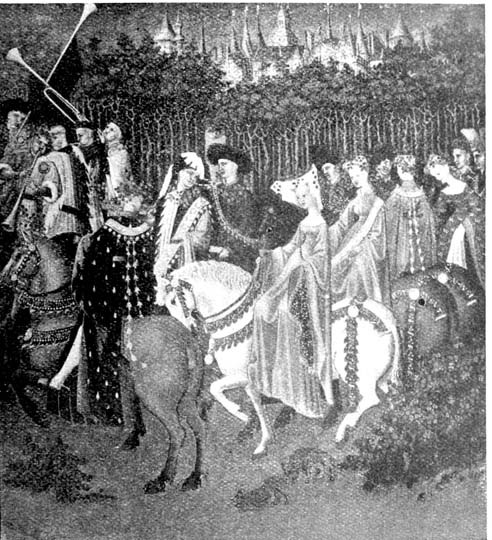

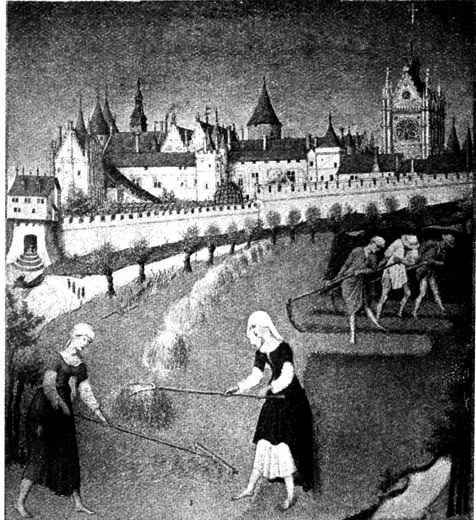

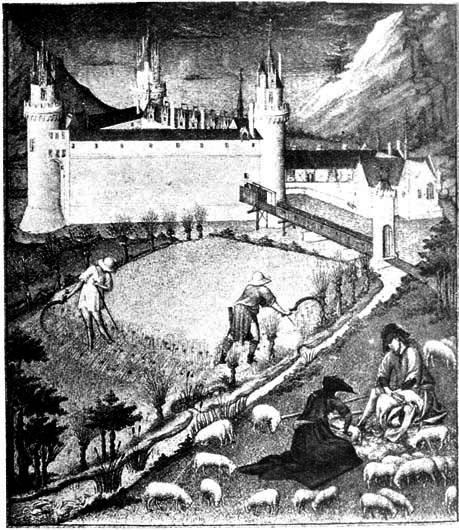

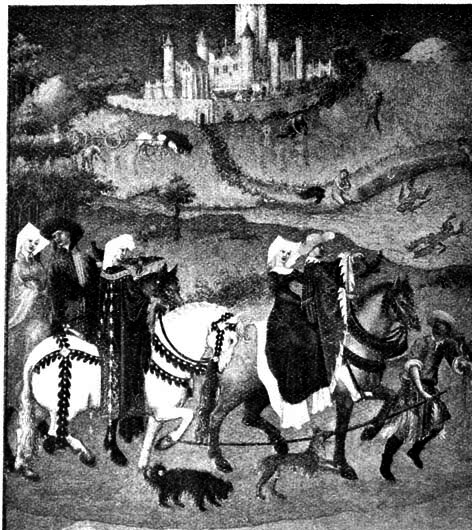

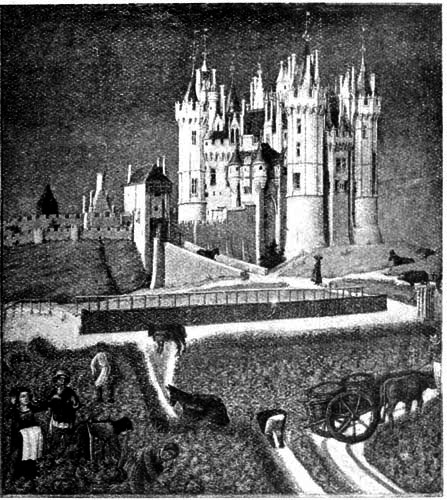

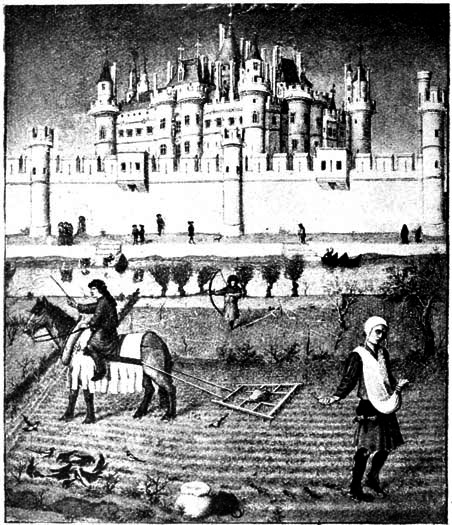

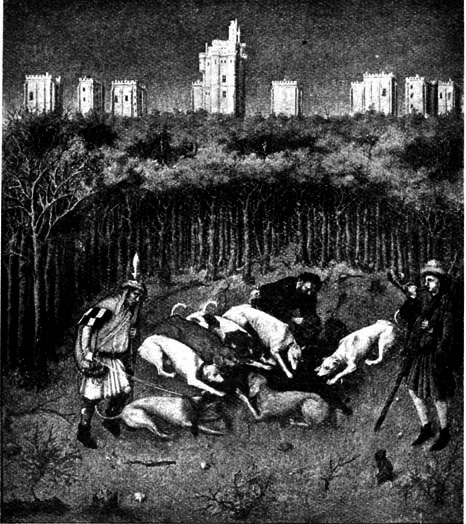

| The Twelve Months | AT END |

| From Les très riches heures de Jean de France, Duc le Berry, chiefly the work of Pol de Limbourg, painted between 1412 and 1416 and now in the Musée Condé, Chantilly | |

| By kind permission of MM. Plon-Nourrit et Cie, Paris |

CHAPTER I

BEFORE THE COMING OF THE ROMANS

The world is very old, and it has taken a long time to discover much of the ancient story of Britain. Scholars have found out many things because they are able now to read the signs on the rocks and under the soil. From the tools left behind, from the remains of dwellings and from treasures found in graves, we have learned about the ways of men in times before history was written down.

Once, it seems, Britain was a hot land. Great forests grew up everywhere. Strange wild creatures roamed about, and there were monsters in the waters.

Once, too, it was a very cold land, and the snow lay in the valleys and ice-glaciers came sliding down the mountains, making great river beds as they passed.

As it grew warmer, the ice melted and disappeared. The ice fields left pools of water behind them, the lakes that you find in the country still. The rivers, too, brimming over, flowed swiftly to the sea. Mighty rivers they must have been, broader and deeper than they are now.

When men came, they made their homes in the caves and in underground dwellings, and later they built mud huts. They hunted for their food, learned to weave clothes from the grasses, to make weapons from stone and to strike fire from the rocks. This is a very long story and we know little about it.

Of the Britons who dwelt here, we know something from those who had heard of them and wrote about them. Round about their villages, they made wattle-fences to keep away their enemies and the wild beasts that came out of the forests in winter nights.

They were shepherds and had many herds of sheep and cattle, and they grew a little corn. Sometimes, travellers from far-off lands came to visit them, to exchange their eastern coins for grain and skins.

The Britons loved beautiful things. They made cunning designs on their shields and helmets and with dainty tracings they ornamented their pots and jugs. They wove linen in fine patterns and knew how to make dyes. They were fond of music and told stories to one another of dragons and heroes and the great dreams of men.

When their chief died, they raised a mound over his grave; sometimes, too, great pillars of stone. They carried presents of corn and meat and fruit to put upon the grave, because they thought he might need them on his long journey. In some parts of the country, there are pillars of stone set up in circles. It is thought that perhaps the Britons used these as temples, praying and making their offerings under the sky, in sunshine and starshine.

The Romans said that the Britons loved riding wild horses, which they had tamed, and they were so skilful that however fast they galloped, the rider could make the horse stand quite still at any moment. They sometimes rode in chariots and drove furiously. When they went into battle they armed their chariots with sharp knives and cut the enemy down on both sides. But they did not use their chariots often, for they would rather tend flocks in the fields than go to war.

CHAPTER II

THE ROMANS

The best soldiers in the world were the Romans, who came from the great city of Rome, far away in Italy. Everybody had heard of their mighty deeds, for they had conquered nearly every land except Britain, and to them Britain seemed to be in the farthest corner of the world, just on the edge, a land, no doubt, of dragons and strange wild people. Now the Romans had heard that there was meat and corn in plenty in the land, that there were tin mines, and tin was very useful for mixing with copper to make armour. So they invaded Britain.

The great Roman army moved very slowly through the land, for there were few roads. Sometimes the soldiers had to cut down trees to make their way through the forests, sometimes they had to cross the dismal fenlands, sometimes to make a bridge over a flooded river, or to wade knee-deep through the swamps. As they marched, they had to fight with the Britons.

The Scots had heard of their coming and were safely hiding in their fastnesses when the Romans reached the Borderland. Then the Romans built a great wall from sea to sea between the two countries, Scotland and Britain, a wall that must have taken several years to build even if they had thousands of men to build it. It was made of the finest stone, which they seem to have carried many miles across the country. It was nine feet wide and eighteen feet high and the turrets were placed so near together that the sentinels could call to one another and so send a message quickly. Below the wall, on the enemy's side, they dug a deep ditch, often having to make it through the hard limestone rock. Every mile, they built a spacious fort for the soldiers to rest in, well defended and quite close to the wall. Every four miles, there was a station, sometimes a small town, surrounded by a wide wall, too, where perhaps the chief officers lived. From station to station, from east to west, ran the great road, for the traffic of the army. Up to the gates of the stations, too, came the new Roman roads from the south, for the army sometimes had to call for help from other places and needed food and many things from the south. It must have been a stern duty to keep watch in the bleak winter months, and the soldiers seem to have had few comforts. The remains of this great wall still lie from Wallsend to the west coast.

At the cross-roads, by the great rivers, the Romans built their towns and camps all over Britain, just like those they had known in Italy. Every town was surrounded by a great wall, whence the soldiers could keep a look-out for the enemy, and nobody could enter the place except through the gates between sunrise and sunset. Outside the town, they sometimes built an amphitheatre, where games and wild beast fights were held on holidays.

The houses of the chief officers were built like those in sunny Italy. The most interesting room in the house was the bath-room, with a large tank, like a swimming bath, in the floor and a furnace to keep a good supply of hot water. The floor was paved with beautiful coloured tiles and scenes were painted on the walls. This room was very important, because the Roman often received his guests there and sometimes invited them to share in the ceremony of the bath. The garden was often lovely, there were orchards and smooth lawns and closely clipped hedges of box and yew, sometimes cut into fantastic shapes like birds and beasts. There were brightly coloured flowers, which had been brought from Italy—geraniums, roses and orchids. Then, there was the summer house, whose walls were made of tall trees growing close together, and inside were couches and rugs and sometimes even a little lake in the centre, where jellies and fruits were to be seen floating in beautiful dishes, to keep them cool and fresh, as though the summer in Britain were very hot.

There was much work to be done. The Roman officer had to visit the camps, driving in his chariot or carried in his litter by his slaves. He had to see that the road-making went on well, for the Romans made fine roads through Britain from north to south, to the east and to the west. He had to look after the building of the factories, where the wool was made into cloth and dyed in the famous purple dye, and if he lived in the south west, the tin mines in Cornwall had to be supervised. Sometimes, he had even to take the long and difficult journey to Rome. The Britons looked on at this new life with great fear and wonder, and soon they learned to make better houses, to raise better crops and to live in the towns.

When, three hundred years later, all the Romans were called to their own land to protect it against a strong enemy, the Britons were worse off than ever they had been before. Not only did the Scots come over the wall to burn and steal, but a new and a stronger enemy came over the seas from Denmark and Germany to seize the treasure that the Romans had left unguarded.

CHAPTER III

THE SAXONS

These sea robbers were the Angles and the Saxons, and Britain became Angleland or England. They were fine men, tall and strong, with long fair hair and blue eyes. The Britons gazed in wonder as boat after boat glided into the bays. Graceful, brightly coloured boats they were, with forty oars on each side and a magnificent sail, sometimes made of silk, embroidered with a dragon or a serpent, the gift of a great prince may be. Every sailor, as he stepped ashore, became a soldier, armed himself with his shield which he took from the vessel's side, and a sword, the best in the world, dearer to him than all other treasures, made by the chief, or by a famous blacksmith.

The Britons marked the chief long before he landed, for he stood at the prow or gave orders. His corselet was of beaten gold or bronze, his helmet too. If indeed he were a great champion, he carried on his helmet a pair of eagle's wings, or a cock's comb, as the reward of his bravery and skill in battle. All these men had been soldiers since they were twelve years old. They had learned "to run, to ride, to swim, to wrestle and to leap," so it is no wonder that the Britons fled before them in terror. Some fell into the hands of these stern warriors and became their servants, but those who lived in peace in the mountains of the west were called "Welsh," i.e. "foreigners," by all who heard of them afterwards. The Scots vanished into their fastnesses and the Saxons became lords of Britain.

The Saxons loved fighting and hunting, but when the hunt and the fight were over they came back to their spacious halls, where they hung up their swords and trophies and gathered round the banquet table or sat by the fire, making rhymes and listening to the tales and songs of the gleemen. While the mead cup was being passed round, they heard the songs about the gods and the great heroes of old, and sometimes they liked to think that Odin took a seat amongst them and told his tale. Odin, the one-eyed father of all the gods, crept in with a scarlet cloak wrapped round him, feasted with them, and, at dawn, the doors of the hall opened mysteriously, a great wind blew, and he was gone.

They had many stories about the gods and Valhalla, the home of the spirits, whither every good soldier hoped to journey at the end of his life. Thor was the great god of thunder; you could see his red beard, when the Northern light shone in the winter sky. Sometimes he drove by in his chariot with the sound of a storm, the lightning was the flash of his eye, and the thunder his mighty hammer striking the rocks as he passed.

The most beloved of the gods of the northmen was Baldur, the god of Spring. Once, he had a dream that a great cloud passed over him, and his mother, in sorrow, summoned all the things upon the earth to promise never to hurt her son. Everything promised, the mountains and the trees and the rocks and the rivers, everything except the little mistletoe, which grew at the palace gate and was so small that nobody thought it could do any harm. But Loki, the god of mischief, Baldur's brother, guided the hand of blind Hödur and so killed Baldur with an arrow made from the mistletoe.

Odin was very angry when he heard the news and mounted his war horse to ride to Valhalla, to fetch Baldur from the home of the spirits. But the old witch, who sat at the gates, would not let Baldur return to the earth until she heard that everything on the earth was weeping for him. Everything did weep, except Loki and the little mistletoe. So the witch allows Baldur to come back for three months every year, and then the earth puts on her freshest green, the flowers blossom, the corn ripens, and gods and men rejoice. Thus, the Saxons showed how much they loved the sunshine and the warmth and the south winds that come in the summer time.

When a hero died, the Saxons sent him on his journey to Valhalla, with food enough to last a week and with all his treasures, his sword and helmet, his hunting trophies and his most loved things. They liked best of all to send him on his boat across the unknown seas. They towed it to the harbour mouth, set fire to it, when the sun was going down, shouting as they watched it drift away, "Odin, receive thy Champion." They fancied Odin sat in the far North with all the gods waiting to welcome a brave man and to give him a seat of honour in his hall. For the Saxons thought a brave soldier the noblest of all men.

CHAPTER IV

THE SAXON VILLAGE

Though the Saxons loved fighting, they soon learned to love peace and to rule their kingdoms well. They divided the spoil amongst themselves and the chiefs rewarded their soldiers with lands. They built their villages as near the streams as they could, so that they might get water easily. They built them near the woods, if possible, so that they could get timber to build their houses and fuel for the winter; but not so near that an enemy could spring on them suddenly without a warning, or the packs of hungry wolves come prowling round in the long, dark nights. Any stranger who came in sight of the village must blow his horn three times loudly, else the Saxons killed him, for they feared anyone they did not know.

The soldiers who settled in the village were freemen, and they shared in the harvest of the soil. Only half the land was ploughed for seed and the other half was left fallow or idle for a year. In the ploughed land, they planted wheat or rye one year and barley next time, after a year's rest. Sometimes they divided the land and planted wheat in one half in October and barley in the other in March. When the ploughing was done, they were all very careful to throw up a little heap of earth to make a ridge between the strips in each field, so that each freeman might know his own strip in the wheat field and in the barley field too. He made bread from the wheat or rye and a drink from the barley, and if there were any to spare he would exchange it for some of the things he wanted very much, honey perhaps, for everybody needed that when there was no sugar.

Beyond the ploughed lands, there was a piece of common ground, where all the freemen turned out their geese and cows and sheep and pigs, though the pigs liked the woods better, for there they could find acorns and hazel nuts.

There was a hayfield, too, and, when spring came, a fence was put all round it and it was carefully divided into strips, so that everyone had a share of the hay. The "hayward" was a busy man, for it was his duty to keep the woods, corn and meadows. In haytime, he looked after the mowers. In August, he was to be seen, rod in hand, in the cornfields, watching early and late, so that no beasts strayed and trampled down the corn.

When Lammastide came, all the freemen kept holiday for joy that harvest time had come.

Now, there was sure to be one man who had more treasure than the others, and oxen perhaps for the plough. It was very hard work trying to plough the fields with less than eight, so the other freemen were glad to borrow the oxen sometimes. But the chief, the rich man, made a bargain, that those who borrowed his oxen should pay him by doing three days' work a week for him in his fields, for they had no money. So, in time, he became lord over them.

Then he made a mill where all the corn should be ground into flour and every man who brought a sackful must pay so many handfuls of flour to the miller for his trouble. Not every village had a mill, so it sometimes happened that men travelled far to make a bargain with the miller, for they found it slow work to grind their own corn between the grindstones at home.

From an old writing [1] that we have still, we can find out many things about the peasants, for they tell how they spend their time. The ploughman says: "I work hard. I go out at daybreak driving the oxen to the field and I yoke them to the plough. Be it never so stark winter I dare not linger at home for awe of my lord, but having yoked my oxen and fastened share and coulter, every day I must plough a full acre or more. I have a boy driving the oxen with a goad-iron, who is hoarse with cold and shouting. And I do more also. I have to fill the bins of the oxen with hay, and water them and take out their litter. Mighty hard work it is, for I am not free." The shepherd says: "In the first morning I drive my sheep to their pasture and stand over them in heat and in cold, with my dogs, lest the wolves swallow them up; and I lead them back to their folds and milk them twice a day, and their folds I move, and I make cheese and butter and I am true to my lord."

The oxherd says: "When the ploughman unyokes the oxen, I lead them to pasture and all night I stand over them waking against thieves; and then again in the early morning I betake them, well-filled and watered, to the ploughman."

The King's hunter says: "I braid me nets and set them in fit places and set my hounds to follow up the wild game, till they come unsuspecting to the net and are caught therein, and I slay them in the net. With swift hounds I hunt down wild game. I take harts and boars and bucks and roes and sometimes wild hares. I give the King what I take because I am his hunter. He clothes me well and feeds me and sometimes gives me a horse or an arm-ring that I may pursue my craft merrily."

The fisherman says: "I go on board my boat and cast my net into the river and cast my angle and baits and what they catch I take. I cast the unclean fish away and take the clean for meat. The citizens buy my fish. I cannot catch as many as I could sell, eels and pike, minnows and trout and lampreys. Sometimes I fish in the sea, but seldom, for it is a far row for me to the sea. I catch there herring and salmon, porpoises and sturgeon and crabs, mussels, periwinkles, sea-cockles, plaice and fluke and lobsters and many of the like. It is a perilous thing to catch a whale. It is pleasanter for me to go to the river with my boat than to go with many boats whale-hunting."

The fowler says: "In many ways I trick the birds—sometimes with nets, with snares, with lime, with whistling, with a hawk, with traps. My hawks feed themselves and me in winter, and in Lent I let them fly off to the woods and I catch me young birds in harvest and tame them. But many feed the tamed ones the summer over, that they have them ready again."

The merchant says: "I go aboard my ships with my goods, and go over sea and sell my things and buy precious things which are not produced in this country and bring them hither to you, brocade and silk, precious gems and gold, various raiment and dye-stuffs, wine and oil, ivory, and brass and bronze, copper and tin, sulphur and glass and the like. And I wish to sell them dearer here than I buy them there, that I may get some profit wherewith I may feed myself and my wife and my sons."

While all the village people were busy at their work in the fields, they must have peace and order in the land. Every week, the lord and the freemen met together under the great oak tree to talk about business. If they heard of any evil deed done near their village, the lord rode out at the head of all the men who could ride or run, to find the evil doer, and they searched for miles, shouting "Hi! Hi!" and if they passed through any village, they summoned every freeman to follow in the chase. When the thief was found, he was brought back to his own village, and if he could not find any who would stand by him as "oath helpers," then none would listen to his tale. They said that only the great god could judge, so they prayed that Odin would send a sign. Sometimes, they bound the prisoner hand and foot and threw him into the village pond; if he floated they said, "He is not guilty." Sometimes, they burned the prisoner with hot irons or made him thrust his hand into boiling water; then the wounds were bound up; and if, after three days, they were healed and there was no scar, they said, "He is not guilty." But this did not happen often.

Sometimes, if the man had a bad character, they branded him on the forehead with the sign of a wolf's head and took him to the forest, where he had to live all the rest of his life, for no one would have an outlaw in a village. If a man were afraid of being made an outlaw, he must find a great lord and ask him to protect him. If the man promised to work for a lord or gave him a present of fish or corn or honey every year he could find a lord. If it should happen that he were caught by the Hue and Cry, on that day the word of his lord in his favour was worth more than the words of six freemen against him. So most people worked for a lord.

As time went on, the King began to call the lords and freemen together to ask them about a great war, or to make some new laws. They did not like going very much, for travelling was troublesome and dangerous. So the King usually asked only his cup-bearer and chamberlain and the great men of his court for advice.

[1] Ælfric's Dialogues.

CHAPTER V

THE COMING OF CHRISTIANITY

Some there were who had heard of Christ in the old days, but a band of monks landing on the coast of Kent brought the news again to this country. Pope Gregory had sent Augustine from Rome to tell the Saxons about Christ, for he was sorry that they loved Odin and Thor, and did not know any other god. Ethelbert, the King of Kent, had a Christian wife, and he was very anxious to know what these strangers had to say about the new God. But he was afraid that they might know how to work charms and to call out wicked spirits, so he let Augustine and his monks preach to the people out of doors, for he thought that they could not harm any one in the open air. When the Roman monks preached, many people became Christians, but the old Saxon poets sang sorrowful stories of Odin's anger, and how the gods had left the world for ever because the people were not faithful. Bede tells a story of how the old wise men of Northumbria met together to decide whether they would give up the old gods for Christ or not, and as they sat in solemn silence, thinking of this great thing, an old man rose and said, "The present life of man, O King, seems to me like the swift flight of a sparrow, who on a wintry night darts into the hall, as we sit at supper. He flies from the storms of wind and rain outside, and for a brief space abides in the warmth and light, and then vanishes again into the darkness whence he came. So is the life of man, for we know not whence we came nor whither we go. Therefore if this stranger can tell us anything more certain, we should hearken gladly to him." Thus, they became Christians. They built churches in their villages; first of wood, then of stone.

Many Christian teachers then came to England and built homes or monasteries, wherever they went, first of rough timber, then of stone. They made clearings in the forests and drained the fenlands, and the people followed and built houses for themselves near the monasteries, for they found that they could learn many things from the monks. The sick, the poor, the tired and the old were always welcome, and travellers too were glad to rest there, for there were no inns in those days.

The monks were ruled by an abbot, and the nuns, who lived in other houses, by an abbess. They took a vow of poverty and thought that they served God best by giving their time to prayer and praise.

They loved their monastery, and, as the centuries went by, they made it more and more beautiful. The people gave rich offerings and builders came from foreign lands, skilled in stonework and other arts. Carvings were made for the church, pictures were painted on the walls, and flowers and trees were brought from the Holy Land to plant in the gardens. In this way came the cedar trees and the juniper, and certain plants that now grow wild in parts of the country like the poisonous hellebore, the grape hyacinth and the little fritillary or snake's head. Great men brought gifts of frankincense and myrrh, to be burned in the church on holy days, or jewels for the altar, and silk from the east for hangings, but the greatest treasure of all was the "relic." People would travel many miles to see this, for those who saw it could be healed of their sickness or forgiven for their sins. There were many curious relics. There were little bits of wood, that men believed belonged to the real cross, on which Christ was crucified, and thorns, which were said to have come from His crown. S. Louis, King of France, built the beautiful Sainte Chapelle in Paris, where he might keep the crown of thorns, which the Crusaders brought from Palestine.

The monastery was usually built round a square garden or lawn. On one side was the church, on another the hall and large kitchens and pantries, for there were often visitors, some of high estate, and they must be royally feasted. In the Rule of S. Benedict it was written, "Let all guests who come to the monastery be entertained like Christ Himself; because He will say, 'I was a stranger and ye took me in'." The guest-house must stand apart "so that the guests, who are never wanting in a monastery, may not disquiet the brethren by their untimely arrivals." Anyone could claim a lodging for two nights, and in a few monasteries there was stabling provided for as many as three hundred horses.

There was a long dormitory where the monks slept. It was the custom for them to get up at midnight to make a procession into the church by the night stairs. There they said matins and lauds (the last three psalms), and then returned to the dormitory to sleep if it were winter until daybreak, if summer till sunrise. Only those who had worked hard in the fields all day were excused. They dressed by the light of the wicks set in oil in little bowls at either end of the dormitory.

In the cloisters were troughs for washing before meals, filled with water by taps; and above were little cupboards for towels.

Some monasteries had a library, for they were quite rich in books. Then there was a writing room, where the scribes were busy making beautiful copies of the precious books, some skilled in writing, others in painting and illuminating. When the writing was done, the artist brought his colours to make the capital letters and the little pictures in the text. There was music to be copied too, and the accounts of the Abbey must be kept neatly. Sometimes a chronicle was made of great events that happened. It is from such books as these that we have learned much about the story of the country.

THE ABBEY OF CITEAUX

A. Round this court, stables

and barns. H. Guest houses and abbot's quarters. N. The Church. I. The

kitchen. K. The dining hall. M. The dormitories. P. Cells of the

scribes. R. The hospital.

A SERVICE IN THE CHAPEL

The monks led peaceful lives in days when most men were busy about war.

The monks divided the hours between sunrise and sunset into twelve equal parts, so it happened that the hour in winter was twenty minutes shorter than in summer. Every three hours, there was a service in church, prime at the first, terce at the third, sext at the sixth and none at the ninth. After prime, on summer mornings, the monks were summoned by the Abbot to the chapter house and there each man received his task. The latest business was talked about and plans were made for the coming guests. Then each monk went to his business, some to the gate to give food to the poor and help to the sick, some to work in the orchard and garden, to spin or to weave, though in some monasteries this kind of work was done for the brethren. They had their first meal at midday in the hall in silence. While they ate, one of their number, who had already had his meal, would read to them from a book of sermons or the Lives of the Saints. After grace, the Miserere (Psalm 51) was sung through the cloister. In summer, they would rest in the afternoon, in the dormitory or perhaps in the cloister, on the sunny south side, where they could read or think or pray. In winter, they worked at this time, because their nights were long. Vespers was read at sunset, then came supper. Compline ended the day, but it sometimes happened that they lingered in the warming-house to chat with one another, but this was against rules.

Kings and princes found out what wise counsellors these men were and brought them to the courts to help them govern, though this was against the rules of the monastic orders.

Then, in those days, Abbots began to ride forth like princes, monasteries were full of treasure and monks forsook the humbler ways of life they had once followed.

CHAPTER VI

ALFRED AND THE DANES

After the Saxons had been in England many years, when their weapons had grown rusty and they had almost forgotten how to fight, bands of Danes came sailing over the North Sea to plunder the land. "God Almighty sent forth these fierce and cruel people like swarms of bees," says the chronicler. First, they carried away the beautiful things from the monasteries and churches, and then they came to live here. They drove the Saxons from their houses or built new villages by the side of the old ones. We know that they must have settled in Yorkshire and Lincolnshire, in Westmorland and Cumberland, because they gave Danish names to many places, such as Grimsby (Grim's town), Whitby, Appleby. In those days, the Danes grew very bold. "Ships came from the west ready for war with grinning heads and carven beaks," runs the legend, "the golden war banner" shining in the bows. They tried to conquer the west and south, as well as the north and east. In the land of the West Saxons, many battles were fought, and still the little band of hungry, worn-out soldiers stood at bay.

It was at this time that Alfred was made King and, like his father and brothers, was soon defeated and driven into Athelney, a little island in the west in the midst of a great swamp. There, he spent the winter drilling his soldiers and making plans to drive away the Danes in the spring time. A story is told of how he went into the Danish camp as a bard. He carried a harp, and while the mead cup was handed round, he sang the old sagas. When the feast was done and the chess board was brought out, the captains talked about the war, as they played their favourite game. So Alfred heard their plans.

The Danes were surprised when the spring came, for Alfred drove them out of his kingdom and made them promise never to come into the land of the West Saxons again.

But he did not try to drive them out of England, for he knew that it would be many years before his people would be strong enough, perhaps not until his own children were grown up. So he worked hard all his life to make his people good soldiers and thoughtful men, in order that, when the time came, they could drive the enemy across the seas and rule over the whole land in their stead.

"Formerly," said the King, "foreigners sought wisdom and learning in this land, now we should have to get them from abroad if we would have them." Alfred found his nobles careless and idle, they loved hunting and feasting and thought very little about ruling a kingdom or leading an army. They were too old to learn, but the king made up his mind that their children should grow up good soldiers and wise rulers. So he made a school at his court for these boys. There they learned the art of war and many other things too.

They read the history of their own country from Bede's Book, that had been kept at York. This book was written in Latin, so the King had to have it translated for them. He had heard of the fame of a great writer, Asser, who lived in South Wales. Messages were sent to him to ask him to come to Alfred's court to write the history of the reign. Asser did not wish to leave his beautiful home, but in the end, he promised to stay for six months every year; that is why we know so much about this great King.

Alfred turned into English some beautiful old Latin books that taught men how to rule well, and in the margins he himself wrote what he thought wise counsel. Two of these books had been written by Pope Gregory who sent Augustine to England, and at the beginning of one of them there are these words, "Alfred, King, turned each word of me into English and sent me to his writers, north and south, and bade them make more such copies that he might send them to the bishops."

Alfred loved reading and he wrote down all the wise sayings that he found. Asser tells the story of how the King came to do this.

"When we were one day sitting together in the royal chamber and were holding converse upon divers topics, as our wont was, it chanced that I repeated to him a quotation from a certain book. And when he had listened attentively to this with all his ears, and had carefully pondered it in the deep of his mind, suddenly he showed me a little book which he carried constantly in the fold of his cloak. In it were written the Daily Course and certain psalms and some prayers, which he had read in his youth, and he commanded that I should write that quotation in the same little book. And when he urged me to write that as quickly as possible, I said to him, 'Are you willing that I should write the quotation apart by itself on a small leaf? For we know not that at some time we shall not find some other such quotation or more than one, which will please you: and if it should so turn out unexpectedly we shall rejoice that we have kept this apart from the rest.'

"And when he heard this, he said 'Your counsel is good.' And I, hearing this and being glad, made ready a book of several leaves, in haste, and at the beginning of it I wrote that quotation according to his command. And on the same day, by his order, I wrote in the same book no less than three other quotations pleasing to him, as I had foretold."

"This book he used to call his handbook, because with the utmost care he kept it at his hand day and night and in it he found, as he said, no small comfort."

Alfred desired to hear of other lands, but there were hardly any maps in those days and no books of geography. Great travellers were welcomed at his court, for, when he was very young, he had paid a visit to Rome and had seen a little of foreign lands. Othere, the famous seaman, who had sailed in the Arctic regions, came to tell his stories of the frozen seas that men could walk upon and of the strange midnights when the sun shone as bright as by day. Othere spoke of whales and walruses and he brought their tusks of fine ivory to show the King. Wulfstan came, too, and he had travelled in Prussia and brought stories of a land rich in honey and fish.

Travellers came from the hot lands, from India and the far east. They brought presents of tiger skins and spices, of rich silks and jewels. They told stories of wonderful deserts, of the high snowy mountains and thick jungles, that they had passed on their long journey. The King delighted to read of elephants and lions and of "the beast we call lynx" that men said could see through trees and even stones.

"Or what shall I say," says the chronicler, "concerning the daily intercourse with the nations which dwell from the shores of Italy unto the uttermost bounds of Ireland? for I have seen and read letters and gifts sent to Alfred by Elias, patriarch of Jerusalem."

In this way the West Saxon folk heard of great, unknown countries and peoples, and the sons of the nobles learned not only "to run, to ride, to swim and to make runes or rhymes," but to be great rulers and adventurers as their forefathers had been.

Alfred was a very busy King, for not only had he to receive ambassadors and counsellors, but he had to ride through the land, seeing justice done, and restoring the ruined churches and monasteries. He taught the workers in gold and artificers of all kinds, "to build houses majestic and good, beyond all that had been built before. What shall I say of the cities and towns which he restored, and of the others which he built, where before there had never been any? Or of the work in gold and silver, incomparably made under his directions? Or of the halls and royal chambers wonderfully made of stone and wood by his command? Or of the royal residences built of stone, moved from their former positions and most beautifully set up in more fitting places by the King's command?"

The King gave many gifts to the craftsmen whom he had gathered from all lands, men skilled "in every earthly work," and he gave a portion "to the wayfaring men who came to him from every nation, lying near and far, and who sought from him wealth, and even to those who sought it not."

There were no clocks in those days and the King was much troubled, "for he had promised to give up to God half his services." "He could not equally distinguish the length of the hours by night, on account of the darkness: and oftentimes of the day, on account of storms and clouds." "After long reflection on these things he at length, by a useful and shrewd invention, commanded his chaplain to supply wax in sufficient quantities." "He caused the chaplain to make six candles of equal length, so that each candle might have twelve divisions marked upon it. These candles burned for twenty-four hours, a night and a day. But sometimes, from the violence of the wind, which blew through the doors and windows of the chambers or the canvas of the tents, they burned out before their time. The King then considered by what means he might shut out the wind; and so he ordered a lantern which was closed up, by the King's command, by a door made of horn. By this means, six candles lasted twenty-four hours, and when they went out others were lighted."

Thus the King left behind him as he wished "a memory in good works," and, after him, his son and daughter drove the Danes eastward beyond Watling Street.

The northmen came back with the strong King Cnut, who conquered the whole country. Now Cnut was a great king before he took England, for he ruled Sweden and Denmark and was lord over Norway. When he was crowned King of England, he began to love this kingdom more than all his lands, and he made his home in London. He wanted to be a real English King, so he looked for the old laws of Alfred the Great and told the English people that he would rule as Alfred had done.

The King had a fine army of tall, strong soldiers, but he sent nearly all of them back to their own land and kept only three thousand house-companions for a body guard. The English people knew that he trusted them, for he could not have kept the land in order with so few soldiers, if the people had hated him. For seventeen years, there was a great peace in the land and ships could pass to and fro, carrying "skins, silks, costly gems and gold, besides garments, wine, oil, ivory, with brass and copper, and tin and silver and glass and such like."

When Cnut's two sons had reigned in the land, then the Saxons once more had a Saxon King.

CHAPTER VII

THE BATTLE OF HASTINGS

Edward the Confessor, the Saxon prince, had taken refuge in Normandy in the days when the Danish Kings ruled in England. There he learned to speak Norman French and to love Norman ways. When the Saxons chose him to be king, he brought some of his Norman friends to court with him. He was a man "full of grace and devoted to the service of God." He left the rule of his kingdom to three Saxon Earls, Siward the Stout, a man who struck terror to the hearts of the Scots, Leofric of the Marsh land, "wise in the things of God and men," and Godwin of Wessex.

There was much trouble because there were no heirs to the throne, and the Norman chroniclers say that the King promised his crown to William, Duke of Normandy. The Saxons did not know this, and if they had they would not have crowned him; so they chose Harold, son of Godwin and brother of the Queen, to rule after Edward the Confessor. They chose Harold for he was a man after their own heart, strong and fearless, like the heroes of old. Harold had two elder brothers, but they were cruel and lawless and the people feared them.

The Normans told a story of how Harold had been wrecked on the coast of Normandy, two years before this, and was taken before the Duke as a prisoner. The Duke would not let him go until he had sworn, with his hand upon the holy relics, that he would never claim the Saxon crown.

When Edward died, Harold forgot this oath and the people crowned him with much rejoicing. When the news reached the Duke of Normandy "he was in his park of Quévilly, near Rouen, with many knights and squires, going forth to the chase." He had in his hand the bow, ready strung and bent for the arrow. The messenger greeted him and took him aside to tell him. Then the Duke was very angry. "Oft he tied his mantle and oft he untied it again and he spoke to no man, neither dare any man speak to him." Then he bade his men cut down the trees in the great forests and build him ships to take his soldiers to England. When they were ready, there arose a great storm and for many weeks he waited by the sea shore for a fair wind and a good tide. Tostig, too, Harold's brother, became very jealous and asked for a half of the kingdom. And because Harold would not listen, Tostig went to Norway, to beg the great King Hadrada to call out his men and ships and sail for England. So the Northmen sailed up the river Humber and took York. Then, Harold and his soldiers marched to the North to fight against Tostig. When he had pitched his camp, he sent word to Tostig, "King Harold, thy brother, sends thee greeting, saying that thou shalt have the whole of Northumbria or even the third of his kingdom, if thou wilt make peace with him." "But," said Tostig, "what shall be given to the King of Norway for his trouble?"

"Seven feet of English ground," was the answer, "or as much more as is needful, seeing that he is taller than other men." Then said the Earl, "Go now and tell King Harold to get ready for battle, for never shall the Northmen say that Tostig left Hadrada, King of Norway, to join the enemy." And when Harold departed, the King of Norway asked who it was that had spoken so well. "That," said Tostig, "was my brother Harold." When Hadrada heard this he said, "That English king was a little man, but he stood strong in his stirrups." A great fight there was, and Hadrada fought fiercely, but he was killed by an arrow. When the sun set, the Northmen turned and fled, for Tostig, too, lay dead upon the field. That night there was a great feast in the Saxon camp.

As they held wassail, a messenger came riding into the camp, breathless with haste, for he had rested not day nor night in the long ride to the North. He shouted to those who stood by, "The Normans—the Normans are come—they have landed at Hastings—Thy land, O King, they will wrest from thee, if thou canst not defend it well." That night, the Saxons broke up their camp and hurried towards London. The wise men begged Harold to burn the land, that the enemy might starve, but Harold would not, for he said, "How can I do harm to my own people?" So they rode off to meet the Duke near Hastings.

Now Harold chose his battle-field very wisely, a rising ground, for most of his soldiers were on foot and many of the Normans were on horse-back and the King knew that it was hard riding up hill. So Harold stood under the Golden Dragon of Wessex watching the enemy below. In the front of the Normans rode their minstrel, throwing his sword into the air and catching it again, as he sang of the brave deeds of those knights of old, Roland and Oliver. Fierce was the onslaught, and soon the Normans turned to flee. Then were the Saxons so eager for the spoil that they came down from their high ground to chase the enemy. When the Duke saw this, he wheeled his men in battle array and the fight began again fiercer than ever. Then the Duke ordered a great shower of arrows to be shot up into the air, so that when they fell, they pierced many a good soldier. And Harold fell, shot through the eye by an arrow. Still, the Saxons fought on, for they held it shame to escape alive from the fields whereon their leader lay slain. That night, William pitched his tent where the King's banner had waved. Then came Gyda the mother of Harold to beg Harold's body from the Duke. But he gave orders that it should be buried by the seashore, "Harold guarded the cliffs when he was alive, let him guard them, now that he is dead," said William.

So the King's mother and his brothers hid in the rocky west, in Tintagel, for fear of the Duke's anger.

Then did William march slowly to London, burning and harrying the land, and all men feared him.

HAROLD DEFEATS AND KILLS TOSTIG AND THE KING OF NORWAY AT STAMFORD BRIDGE

A BATTLE IN THE 15TH CENTURY

There is a piece of "tapestry" still kept at Bayeux in France, showing how England was conquered. It was probably made later than the reign of William and perhaps was intended to go round the walls of the choir of Bayeux Cathedral, for it has been measured and found to be of the right length. Though it is old and torn and faded, we have been able to learn many things from it [2].

There were few histories written in those days, for the Normans were too busy fighting for their new lands and the English were too sorrowful to tell their story.

[2] There is a copy in Reading Museum. See Guide to Bayeux Tapestry, published by Textile Department, Victoria and Albert Museum.

CHAPTER VIII

THE NORMAN KINGS

The strong men of the north had not bowed to William the Conqueror on the field of Hastings, and when they heard that he was crowned, they armed themselves against him. The King marched towards the north slowly, burning and harrying the land as he passed, and his path was marked by flaming villages and hayricks.

When he came into Yorkshire, he laid waste the land, and for nine years not an acre was tilled beyond the Humber, and "dens of wild beasts and of robbers, to the great terror of the traveller, alone were to be seen."

The Saxons fled; some died of hunger by the wayside, some sold themselves as slaves, and a few hid themselves in the Fens, a great stretch of water and marsh land, in the east, dotted here and there with islands and sometimes crossed in winter on sledges. There Hereward the Wake built his camp in the swamps of Ely and there all true men gathered round him. He was bold and hardy and even William said of him, "if there had been in England three such men as he, they would have driven out the Normans."

The King gave orders that a causeway should be built across the Fens and he besieged the Saxons in Ely, and some said that Hereward was betrayed. But William pardoned him and sent him to Normandy to command his army. Many stories are told of his adventures. It was said that he was slain one day as he slept in an orchard, for there were many in the King's court who envied him.

The Conqueror was a wise king, and he desired to know what manner of kingdom he had conquered. "He held a great council and very deep speech with his wise men about this land, how it was peopled and by what men."

So he sent his clerks to every shire and commanded them to write down on a great roll all that they could find out about the country. They were to ask of the lord and of the freemen in the villages and of the monks in the monasteries these questions: How much land have you? Who gave you that land? What services do you owe the King for it? Have you paid them? How many people dwell upon your land? How many soldiers must you lend to the King if need be? How many cattle have you? Have you a mill? (if they had, they owed every third penny to the King). Have you a fish pond? (fish was a great luxury).

The lords and the monks were unwilling to answer, for they knew they must pay to the King all that was due. "So narrowly did the King make them seek out all this that there was not a single yard of land (shameful it is to tell, though he thought it no shame to do) nor one ox, nor one cow, nor one swine left out, that was not set down in his rolls, and all these rolls were afterwards brought to him." These records are called Domesday Book. The Kings, when they desired to get money or soldiers from the great lords and monks, turned to the Domesday Book.

When the book was brought to the King, he summoned the lords and freemen to come to do him "homage." These men came and they placed their hands between the King's hands and, kneeling before him, they promised to be the King's men and to follow him in time of need. "Hear, my lord," said the baron, "I become liege man of yours for life and limb … and I will keep faith and loyalty to you for life and death, God help me."

William I made great peace in the land, and, as he was dying, he called his three sons to him, and to Robert, the eldest, he gave Normandy and to William Rufus, England. Then Henry turned sorrowfully to his father, "And what, my father, do you give to me?" The King replied, "I bequeath £500 to you from my treasury." Then said Henry, "What shall I do with this money, having no corner of the earth I can call my own?" But his father replied, "My son, be content with your lot and trust heaven, Robert will have Normandy and William England. But you also in your turn will rule over the lands which are mine and you will be greater and richer than either of your brothers."

Rufus ruled over England thirteen years, and he was hated by the people. Robert gave Normandy to his brother for a sum of money; and thus Henry, when Rufus was dead, became Duke of Normandy and King of England. He married a Saxon lady and "there was great awe of him in the land, he made peace for man and beast."

CHAPTER IX

THE NORMAN BARONS

The Norman barons who came to England with William the Conqueror were much disappointed, for they had hoped to share the kingdom with him and to be great lords. But William had not given them as much land as they desired, and he had made Domesday Book so that they should render to him due service and payment in return for his gifts. The barons had not always paid that which they owed; and Henry I made a rule that all should come to his Court three times a year, to Winchester at the feast of Easter, to Westminster at Whitsuntide and to Gloucester at Mid-winter, when he wore his crown, and then they should do homage and pay their taxes.

To this court came the officers of the household, and the King appointed a Bishop to receive the money and priests to keep the accounts, since there were few among the nobles or citizens who could read, write and add figures. The money was counted out on a chequered table, and so the court came to be called the Exchequer.

The barons could not easily cheat the King; for, when their money had been counted out upon the table, some of it was melted on the furnace, lest it should contain base metal, and it was weighed in the balances, lest the coins should have been clipped. Then Domesday Book was searched and the priests read out what sum was due to the King from this lord.

When the Chancellor was satisfied, a tally was handed to the baron. This was a willow or hazel stick, shaped something like the blade of a knife, about an inch thick. Notches were cut in it to show the amount paid and the halfpennies were marked by small holes. The tally was then split down the middle through the notches, and the baron took one half so that he might show it to the Chancellor when he came to court to pay again, and the Chancellor kept the other half to prove that the baron was not cheating. Thus the King kept his barons in order and there was peace in the land.

Now Henry I had an only son, and to him he gave a ship, "a better one than which there did not seem to be in the fleet," but as he was sailing from Normandy to England, it struck upon a rock and all perished, save only a butcher, who was found in the morning clinging to a plank.

When the King heard the news, he was in great distress; for no woman had yet ruled in England and his daughter Matilda was married to a French Count, whom all the Normans hated for his fierce temper and overbearing ways. The King, nevertheless, made them swear to put her on the throne, but, when he died, the barons chose her cousin, Stephen, for "he was a mild man, soft and good, and did no justice."

Stephen quarrelled with the Chancellor and closed the Court of Exchequer where the barons had paid their dues, and he let the barons build castles and coin their own money. When he was in need of soldiers, he hired foreign ruffians, and because he could not pay them, he let them loose upon the land to plunder: thus he "undid all his cousins had done."

"The barons forswore themselves and broke their troth, for every nobleman made him a castle and held it against the King and filled the land full of castles. They put the wretched country folk to sore toil with their castle-building; and, when the castles were made, they filled them with devils and evil men. Then they took all those that they deemed had any goods, both by night and day, men and women alike, and put them in prison to get their gold and silver, and tortured them with tortures unspeakable. Many thousands they slew with hunger. I cannot nor may not tell all the horrors and all the tortures that they laid on wretched men in the land. And this lasted nineteen winters, while Stephen was King, and ever it was worse and worse.

"They laid taxes on the villages continually, and, when the wretched folk had no more to give them, they robbed and burned all the villages, so that thou mightest easily fare a whole day's journey and shouldst never find a man living in a village nor a land tilled. Then was corn dear, and flesh and cheese, and there was none in the land.

"If two or three men came riding to a village, all the village folk fled before them, deeming them to be robbers. Wheresoever men tilled, the earth bore no corn, for the land was fordone with such deeds, and they said openly that Christ and His Saints slept. Such, and more than we can say, we suffered nineteen winters for our sins." Then Stephen made a treaty with Matilda's son Henry and promised him the crown of England; for Henry was already a great prince, holding more lands than the monarch of France. Moreover, he was valiant in battle, strong in the Council chamber and never weary. The French King said of him, "Henry is now in England, now in Ireland, now in Normandy, he may be rather said to fly than go by horse or boat."

Henry II could ride all night and, if need were, sleep in the saddle. "His legs were bruised and livid with riding." "He was given beyond measure to the pleasures of hunting; and he would start off the first thing in the morning on a fleet horse and now traversing the woodland glades, now plunging into the forest itself, now crossing the ridges of the hills, would in this manner pass day after day in unwearied exertion; and when, in the evening, he reached home, he was rarely seen to sit down whether before or after supper. In spite of all the fatigue he had undergone, he would keep the whole court standing."

This tireless ruler, before he became King, had restored order in England, for he commanded the hired soldiers to be gone immediately, and they went as they had come like a flight of locusts. He destroyed more than a thousand castles, and those that were well built he kept for himself. "All folk loved him, for he did good justice."

He opened the Court of Exchequer, so that the Barons were forced to pay all they owed Stephen for the nineteen years of his reign. He visited all the courts of justice in the land, and no man durst do evil, for none knew where the King might be. He appointed judges to travel round the country and to sit at Westminster and hear complaints, for many had sought the King in vain, so swiftly did he travel from place to place. Thus the barons were made to fear the King and rule justly.

CHAPTER X

NORMAN PRELATES

There came one day, to the Abbey of Bec in Normandy, a great scholar named Lanfranc. The Abbot was building an oven, "working at it with his own hands. Lanfranc came up and said, 'God save you.' 'God bless you,' said the Abbot Herlwin. 'Are you a Lombard?' 'I am,' said Lanfranc. 'What do you want?' 'I want to become a monk.' Then the Abbot bade a monk named Roger, who was doing his work apart, to show Lanfranc the book of S. Benedict's Rule; which he read and answered that, with God's help, he would gladly observe it. Then the Abbot, hearing this and knowing who he was and from whence he came, granted him what he desired. And he, falling down at the mouth of the oven, kissed Herlwin's feet."

The fame of the Abbey of Bec spread far and wide. "Under Lanfranc," said the chronicler, "the Normans first fathomed the art of letters; for under the six dukes of Normandy, scarce anyone among the Normans had applied to studies, nor was there any teacher found, till God, the Provider of all things, brought Lanfranc to Normandy."

He was William the Conqueror's friend and counsellor and brought the Church into much honour when he became Archbishop of Canterbury.

Among the strangers, who came to Bec, was Anselm. He had long desired to be a monk and had travelled over the Alps from Italy to join the order. When he was young, he used "to listen gladly to his mother, and having heard from her that there is one God in Heaven above, ruling all things, he imagined that Heaven rested on the mountains, that the palace of God was there and that the way to it was up the mountains." Before he was fifteen, he had written to a certain Abbot asking him to make him a monk, but he would not, when he heard that Anselm had not spoken to his father about it.

Anselm was a scholar, too, and men counted it a great thing to have been taught by him. "He behaved so that all men loved him as their dear father." If any were sick, he nursed them; if any angry, he sought them out. It was said that even the King, Rufus, so harsh and terrible to all others, in his presence became gentle and gracious.

When he was Abbot of Bec, he gave so much to the poor that the monks were often in need of bread themselves. Many came to seek his advice, "whole days he would spend in giving counsel" and his nights in correcting the books that had been copied out.

When Lanfranc died, William Rufus brought the kingdom into much trouble and sorrow, by closing churches, taking their money and refusing to choose an Archbishop. It happened that the King fell ill and messengers were sent to Anselm begging him to see the King and show him the way to health. Anselm was stern and bade the King confess his sins, and those who stood round urged him to make Anselm Archbishop. When the King's choice was told him, Anselm trembled and turned pale. "Consider I am old and unfit for work, how can I bear the charge of all this church? I am a monk and I can honestly say I have shunned all worldly business. Do not entangle me in what I have never loved and am not fit for." The Archbishop of Canterbury was a great officer, for he anointed the King when he was crowned, he held many lands and must protect the Church against the King if need be, for the Church was rich and the King poor.

The bishops and barons would not listen and they dragged him back to the King, shouting, "A pastoral staff, a pastoral staff." When they had found one, the King pressed it into his hand, though he held his fist clenched, and the crowd shouted, "Long live the Bishop." The Archbishop soon after asked for a council, for the King was still robbing the Church and "the Christian religion had well-nigh perished in many men." Rufus was angry, "What good would come of this matter for you?"

"If not for me, at least, I hope, for God and for you."

"Enough, talk no more of it to me."

The Archbishop begged the King not to rob the Abbeys and the King answered, "What are the abbeys to you? Are they not mine? Go to! you do what you like with your farms and am I not to do what I like with my Abbeys?"

"They are not yours to waste and destroy and use for your wars."

The King said, "Your predecessor would not have dared to speak thus to my father. I will do nothing for you."

Then Anselm departed with speed and left him to his will.

"Yesterday," said the King, "I hated him much, to-day still more; to-morrow and ever after, he may be sure I shall hate him with more bitter hatred. As Father and Archbishop I will never hold him more; his blessing and prayers I utterly abhor and refuse."

Anselm asked leave to go to Rome, for the Archbishop must wear the white stole, woven from the wool of the sheep of S. Agnes in Rome and blessed by the Pope "the Father of all Christian people."

"From which Pope?" said the King, for there were two at this time.

"From Urban."

"Urban," said the King, "I have not acknowledged. By my customs, and by the customs of my father, no man may acknowledge a Pope in England without my leave. To challenge my power in this is as much as to deprive me of my crown."

Anselm, seeing that in no way could he bring the King to have respect for the Church, went to Rome to seek the Pope's help. He said to the bishops and barons, "Since you, the Shepherds of the Christian people, and you, who are called chiefs of the nation, refuse your counsel to me, your chief, except according to the will of one man, I will go to the chief shepherd and prince of all."

The Pope honoured Anselm by giving him the chief seat among the Cardinals, but he kept him waiting at the Court, for he feared to offend all other kings and tyrants.

It was the custom to read the laws of the Church once a year in S. Peter's Church in Rome, and there was gathered there a great crowd of pilgrims from many countries. The Bishop of Lucca, a man of great stature and loud voice, was chosen to read the laws. When he had got a little way, his eyes kindled and he called out, "One is sitting among us from the ends of the earth in modest silence, still and meek. But his silence is a loud cry. The deeper and gentler his humility and patience, the higher it rises before God, the more it should kindle us. This one man, this one man, I say, has come here in his cruel afflictions and wrongs to ask for your judgment. And this is his second year and what help has he found? If you do not all know whom I mean, it is Anselm, Archbishop of England," and he broke his staff and threw it on the ground.

"Brother, enough, enough," said the Pope, "good order shall be taken about this."

"There is good need, for otherwise the thing will not pass with Him who judges justly."

Anselm left Rome, for he knew the Pope could not help. With much patience and meekness, Anselm contended yet again with Henry I for the rights of the Church. Becket, too, Archbishop of Canterbury, the King's friend and servant, defended it once again in the days of Henry II—even with his life.

CHAPTER XI

NORMAN BUILDERS

The Normans were soldiers and rulers and great builders too. With the white stone, which they found in their own land, they built magnificent cathedrals, abbeys and churches, for they were cunning craftsmen and dreamers.

The Cathedral was vast and grand, with its stately pillars and roof so lofty that it was lost in dim shadows. The master mason, who planned it, took great joy in building and often travelled far to see the works of other men. There are pictures of him with his cap on his head, the sign that he was a master, and his compass in his hand.

All the years of his life, the ironmaster laboured to cast a beautiful peal of bells. One old man died of joy on the day that his bells were first rung, for they were almost perfect.

The Normans, who came to England, did not forget their art. They built Ely Cathedral in the midst of the Fens, and Durham, overlooking the river. "You might see churches rise in every village and monasteries in the towns and cities, built after a style unknown before," says William of Malmesbury.

At first, they built of the rough stone found in the quarries worked by the Romans in other days. Woods were cut down to give fuel for the lime-kilns, and machines were devised for lifting blocks of stone, roads and even waterways were made for this great traffic.

ARCHITECT AND BUILDERS

BUILDING A CHURCH IN THE 15TH CENTURY

IMAGINARY PICTURE OF THE BUILDING OF THE TEMPLE OF JERUSALEM, SHOWING GOTHIC ARCHITECTURE

So much work was there for the masons that there were not skilled craftsmen enough in the land to do all that was needed. As the years went by and the people gave to the Church of their riches, more new buildings were made and yet more decoration was used. Organs were built and stained glass of lovely hues was put in the windows, orange and blue and red, colours so rich they seemed almost to have caught and held the sunlight.

A monk, who was also an artist, wrote "Man's eye knoweth not whereon to gaze; if he look up at the vaults, they are as mantles embroidered with spring flowers; if he regard the walls, there is a manner of paradise; if he consider the light streaming through the windows, he marvelleth at the priceless beauty of the glass and at the variety of this most precious work."

So full of riches were these buildings that S. Bernard, and other preachers too, called to the monks to remember their vows of poverty and to return to humbler dwellings like those they had once built where they might worship God.

Round the Saxon earthworks, the Normans built strong walls that they might hold them against foreign foe or angry neighbour. By the rivers and on high rocks, they made great keeps or towers, first of timber, later of stone, where they could withdraw if pressed by foes. The stone walls were often 13 feet thick and round about there was a deep moat. The doorway was of stout oak barred with iron. Over this, they would drop the portcullis, a single grate of iron, worked from a chamber above by cords and chains round a windlass. Across the moat, they flung a drawbridge, which could be raised at pleasure. There were only a few rooms in the keep, storerooms below and chambers in the two stories above, for the Norman lord only sought shelter there in times of siege. In such a tower, he was safe enough if he had plenty of food and a well, secure from the enemy.

Sometimes the Normans built strong walls and another moat round about the keep, and towers where they kept watch by night and day, looking towards the four quarters of heaven lest an enemy should surprise them.

Much later, when the lord brought his family and soldiers to live in the castle, they made it still larger. Storerooms and stables were built round the courtyard and above these were the chambers of the lord and his followers. Here was a fine larder and a kitchen where the ox and wild boar were roasted whole and the mead was brewed and brown bread baked.

There was a great hall where everyone dined and where the servants slept at night. The floor was strewn with rushes, for there were no carpets until the days of Queen Eleanor, and then they were hung on the damp cold walls or put on the tables. Down the centre of the room ran a long table, sometimes fixed to the floor, sometimes on trestles, with wooden benches on either side, covered with osier matting. Under the table, the dogs gathered to gnaw the bones that were flung to them. For the meat was carried round on a spit and each man helped himself with a knife from his girdle.

A SIEGE

GATEWAY AND DRAWBRIDGE

So strong were these castles that, though the enemy used a ram, it was almost impossible to make a breach in the walls. If they brought scaling ladders, it was difficult to climb when the moat ran below and the archers shot from the ramparts. If they mined beneath the rock, the defenders could make a counter-mine. The besiegers could bring catapults to hurl heavy stones upon the walls, and siege towers to shoot their arrows high. These attacks were usually in vain, for the garrison of a castle only surrendered when there was famine.

These were days of great strife and turmoil, and strong was the King in whose reign it was said that "a man might travel through his realm with his bosom full of gold, unhurt."

CHAPTER XII

KNIGHTHOOD

In such troublous times when there was great fear abroad, when men feared the King, feared their neighbours and feared all foreigners, it seemed to them necessary that every lord should be trained to war. Yet they learned, too, to honour the courteous, gentle, generous knight, sworn to help the weak, and if need be to fight for the faith of Christ.

Every knight served his lord for many years before he was deemed worthy of knighthood. At seven years old he became a page, attending his lord and lady in hall and bower. From the chaplain and the ladies he heard of gentleness and courtesy and love. In the field, he was taught by the squires to cast a spear, bear a shield, and march with measured tread. With falconer and huntsman, he sought the mysteries of wood and river.

Then he became a squire, carving and serving in hall, offering the first cup of mead to his lord and the guests, carrying ewer and basin for them to wash after the meal. Upon him fell the duty of clearing the hall for dancing and minstrelsy and setting the tables for chess and draughts.

In the field, he learned to ride a war-horse and to practise warlike exercises. Armed with a lance he tilted at the quintain, a shield bound to a pole or spear fastened in the ground. After the Crusades, the figure of a Saracen, armed at all points and brandishing a wooden sabre, was set up instead of the shield. If the squire could not strike it in the centre of face or breast, it revolved rapidly and struck him in the back. Then there was the pel, a post or tree stump, six feet high. This he struck at certain points, marked as face and breast and legs, covering himself at the same time with a shield. He must learn also to scale walls, to swim, to bear heat, cold, hunger and fatigue.

If he were a "squire of the body" he bore the shield and armour of his lord in battle, cased and secured him in it and assisted him to mount his war-horse. To him fell the honour of defending the banner and securing the prisoners. If his lord were unhorsed, he must raise him and give him a new mount; if wounded, he must bear him to a place of safety. Froissart tells the story of a knight who fought as long as his breath served him and "at last at the end of the battle, his four squires took him and brought him out of the field and laid him under a hedgeside for to refresh him, and they unarmed him and bound up his wounds as well as they could."

The squire did not fight unless his lord was sore pressed, but he kept a careful watch, as did the son of the King of France, at Poitiers, standing by his father in the mêlée, though he was but fifteen, shouting "Guard thyself on thy right, father. Guard thyself on thy left, father," till he was taken prisoner.